Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Preventive Effects of Tai Chi on Depression and Perceived Stress in Healthy Older South Korean Adults: A Quasi-Experimental Study

1 Division of Global Sport Industry, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Gyeonggi-do, 17035, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Health and Human Performance, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204, USA

* Corresponding Author: Yoonjung Park. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: From Tradition to High-Intensity: Examining the Psychological and Emotional Impacts of Exercise Types)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(8), 1133-1148. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069800

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Population aging is occurring at a rapid speed all over the world, bringing considerable public health challenges, including for the mental health of older adults. Considering that older populations are prone to depression and stress, the need for effective preventive interventions is critical. Thus, we conducted a study aimed at exploring the preventive impact of a community-based Tai Chi program over 8 weeks on depression and perceived stress in healthy older adults in South Korea. Methods: A quasi-experimental design was utilized, with 63 older adults participating (31 individuals in the Tai Chi group and 32 in the control group). The Tai Chi intervention was a supervised session 3 times per week. Data were obtained anonymously at baseline and post-intervention (week 8), with validated measures, including the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Korean version of the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument. Data analysis included frequency distributions, descriptive statistics, and repeated measures analysis of variance to examine group × time interaction effects. Results: Baseline characteristics were comparable between groups. A repeated measures analysis of variance revealed significant group × time interaction effects for depression (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.868, F1, 57 = 8.63, p = 0.005, partial η2 = 0.13) and perceived stress (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.831, F1, 57 = 11.62, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.17). In particular, participants in the Tai Chi group had significantly greater reductions in depression and perceived stress than participants in the control group. Conclusions: These results suggest that Tai Chi may contribute to more favorable changes in depression and perceived stress among healthy older adults compared to no intervention, suggesting its usefulness as a culturally appropriate intervention for sustainable enhancement of mental health and successful aging in rapidly aging societies, including South Korea.Keywords

The world population is aging rapidly. In 2021, the population aged 65 years and older was approximately 761 million. By 2050, this figure is projected to reach around 1.6 billion. Nearly one billion people will be older than 65 years, representing almost one in eight individuals globally. This demographic transition presents major challenges for public health, specifically, mental health [1]. In fact, approximately 14% of elderly individuals are affected by psychological disorders like depression, stress, and anxiety. These conditions significantly affect their quality of life and functional independence [2]. Depression among seniors is associated with a reduction in emotional well-being, reduces social engagement, exacerbates chronic health conditions, and increases mortality risk [3]. Additionally, perceived stress, reflecting individuals’ subjective sense of feeling overwhelmed by life’s demands, further contributes to mental and physical health deterioration, intensifying cognitive decline, weakening immune responses, and raising the risk of cardiovascular diseases [4]. Collectively, these conditions underscore the importance of viable preventive approaches to promote elderly individuals’ quality of life, emotional well-being, social participation, and physical health [5].

Maintaining the quality of life of elderly people encompasses various dimensions, including physical health, emotional well-being, and active social participation. International studies stress that older people report several benefits when they consistently maintain strong social networks, actively participate in social and physical activities, and regularly engage in meaningful daily activities. These benefits include higher life satisfaction, lower mental health problems, and better functional autonomy [6–8]. Thus, intervention programs that promote these types of participation are essential for healthy and energetic aging worldwide.

South Korea exemplifies this demographic transition, having become a society with a significantly large elderly population (over 20% aged 65 and above) within only 17 years, considerably faster than other advanced nations [9]. This rapid demographic transition has accelerated as a result of rapid economic growth and advances in healthcare, in turn resulting in extremely low levels of fertility. This growing elderly population bears considerable social and psychological burdens. Older South Koreans increasingly live alone or solely with other seniors, raising risks of isolation, loneliness, and related psychological conditions [10,11]. Economic insecurity is still a part of life for many individuals, with more than one-third of elderly South Koreans still involved in the workforce primarily for financial need as opposed to choice [5]; These changing family structures and diminished social support networks highlight the urgent need for community-based, culturally appropriate preventive programs targeting the aging population in South Korea [5,9].

Preventive mental health strategies focus on the promotion and maintenance of psychological well-being, working to prevent the initiation and progression of mental disorders [12]. Such approaches target processes that are associated with positive health outcomes rather than focusing on conditions that are already clinical in nature, with the intention of trying to promote resilience and decrease risks of mental decline [13]. Successful preventive strategies among older adults commonly include lifestyle alterations, exercise, and psychosocial interventions that reduce stress and depressive symptoms [14]. Enhancing physical and social environments is also recommended for supporting elderly people’s participation in meaningful activities to enhance their mental health and overall well-being [15].

Physical exercise has emerged as a key non-pharmacological strategy for healthy aging, preventing frailty and falls, improving balance and functional autonomy, and enhancing older adults’ quality of life [16]. Among various physical exercises, Tai Chi is a traditional Chinese mind-body practice characterized by slow movements combined with conscious breathing practice and meditative components, which has the potential to serve as a preventative approach [17]. Tai Chi originated in China, but it has naturally integrated into Korean society. Its strong cultural acceptability in Korea can be attributed to its philosophical roots in Taoism. Along with Confucianism and Buddhism, Taoism is one of the major philosophical traditions that have greatly influenced Korean mindsets and cultural customs [18]. Taoism emphasizes a simple lifestyle in harmony with nature. This ideology is closely linked to the core principles of Tai Chi, which seek optimal health and balance through natural breathing, mindful movement, and body-mind integration [19]. In Korea, Tai Chi training programs are widely provided in public places such as parks, community centers, and apartment complexes. Most of these programs allow participation for free or at a minimum cost. The soft, low-intensity breathing and coordinated movements of Tai Chi make it easy for anyone to access and practice, regardless of age, gender, or health status. The ease of performance and low barriers to entry are important factors in the widespread and practical use of Tai Chi as a preventive health care practice in Korea [20].

Multiple meta-analytic reviews and individual studies have generally supported the psychological value of Tai Chi in seniors, implicating its potential as a preventive strategy for maintaining mental health [21–27]. For example, Leung et al. [21] conducted a systematic review of RCTs studying the efficacy of Tai Chi among older adults and found that Tai Chi significantly decreased depressive symptoms and anxiety while simultaneously improving cognitive function, sleep quality, and overall psychological well-being. Their various analyses stressed the role of Tai Chi as a low-intensity exercise with great health benefits in the older population when practiced as a structured and mindful routine in improving emotional health and cognitive function. Chen and Xu [24] obtained similar findings in their comprehensive meta-analysis. Specifically, they found that the elderly individuals who participated in the systematic Tai Chi training showed significantly improved psychological resilience, as well as a higher quality of life and decreased depression and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, Yin et al. [25] reported that Tai Chi significantly reduced anxiety and depression compared to general exercise without mindful elements. This effect was explained by the fact that mindfulness factors unique to Tai Chi, such as focused breathing and intentional movements, regulate stress-related hormonal responses.

However, previous research has mostly focused on clinical or patient populations, with limited exploration of preventive effects in healthy elderly populations. Additionally, there is a scarcity of preventive research on Tai Chi within specific cultures, especially within rapidly aging societies such as South Korea. The absence of empirical data examining Tai Chi’s preventive effects among healthy older adults represents a significant gap in the existing literature. Certainly, this underlines the need for investigations of Tai Chi’s preventive efficacy in these distinct demographic contexts.

We specifically target depression and perceived stress as key outcomes because these conditions significantly influence older adults’ quality of life and functional independence. Depression profoundly impacts emotional well-being and social participation, while perceived stress represents the everyday psychological strain that can lead to broader mental and physical health problems if unaddressed. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the preventive efficacy of Tai Chi on depressive symptoms and perceived stress among healthy older adults in South Korea, using a quasi-experimental design. Specifically, we focus on the following two main questions: (1) Does participation in Tai Chi reduce depressive symptoms in elderly participants? (2) Does Tai Chi effectively lower the perceived stress level within this population? By clarifying these effects, we will provide important insights into how Tai Chi can play a role in maintaining sustainable mental health and promoting vigorous and healthy aging as a culturally appropriate preventive program.

2.1 Participants and Recruitment

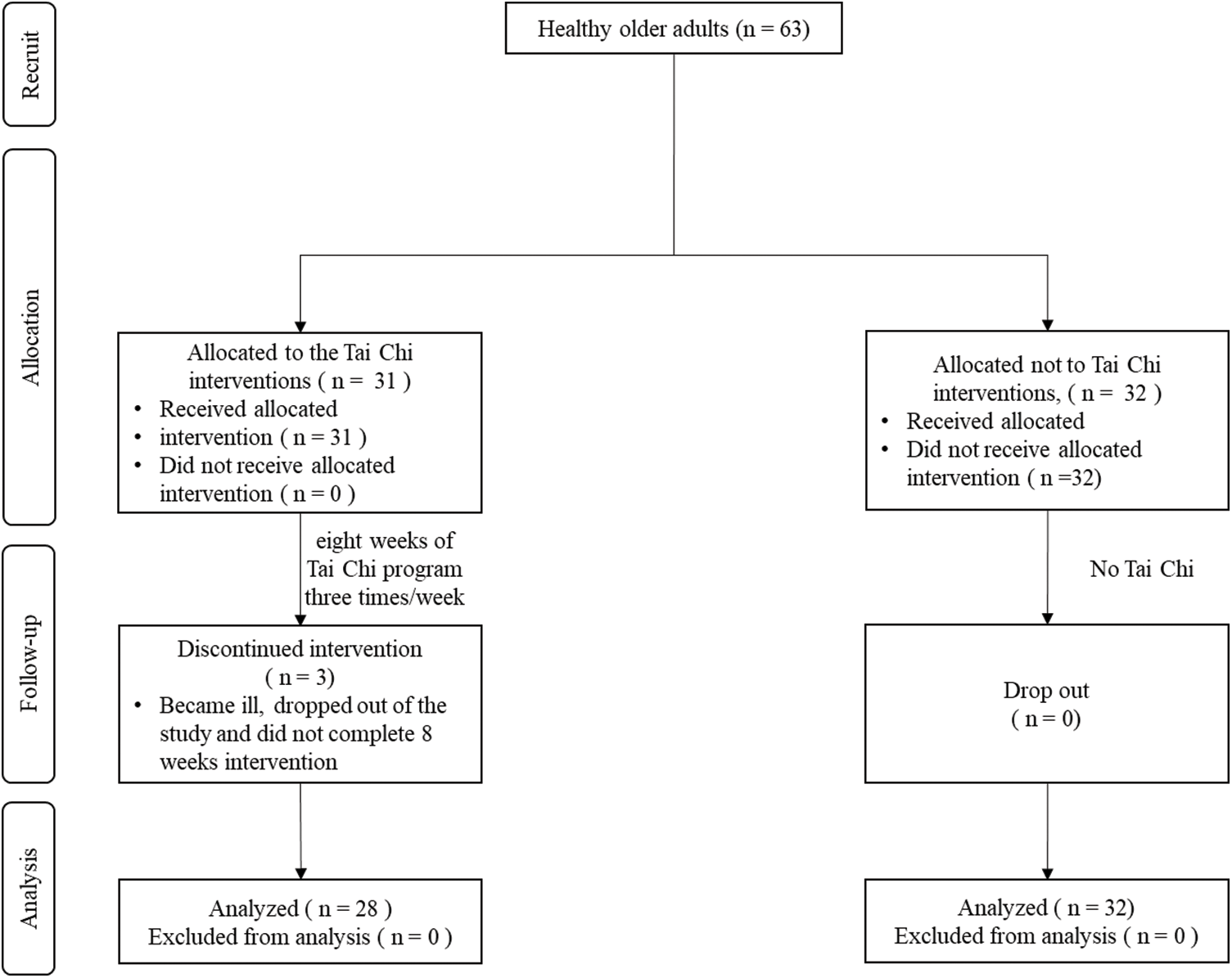

This study, conducted in Seoul, South Korea, over an 8-week period between 21 October 2024, and 15 December 2024, used a non-randomized quasi-experimental design with an inactive control group. Participants for the Tai Chi intervention were recruited via flyers distributed in public spaces and prominently placed banners within community settings (i.e., community centers, local recreation facilities, and residential complexes). A certified Tai Chi instructor was recruited and agreed to conduct structured classes in a designated outdoor community area. The role of the instructor was to lead the Tai Chi training sessions at a level suitable for older adults and to oversee the compliance and safety of each participant throughout the study. For the control group, participants were recruited through a range of online announcements (e.g., community websites, social media postings) and traditional offline methods (e.g., posters and flyers distributed in community venues). Furthermore, a snowball sampling method was employed, whereby initial participants referred the study to people they knew, which helped further expand recruitment. Participants in the control group were instructed to avoid participation in any form of structured Tai Chi or related mind-body practice throughout the duration of the study. To illustrate participant flow clearly, a CONSORT-style participant flowchart detailing recruitment, exclusions, and dropouts was created in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Research flow diagram

The sampling method combines online and offline advertising and snowball sampling. This method was chosen to maximize access to the community and to secure sufficiently diverse and representative participants from the local elderly population. Convenience sampling and snowball sampling methods have the potential for self-selection bias (e.g., high motivation or health concerns) due to voluntary participation. However, this bias was minimized by clearly conveying that the purpose of the intervention was preventive rather than therapeutic.

Initially, 67 participants were recruited (35 Tai Chi and 32 control); after applying inclusion/exclusion criteria, the final analysis included 63 participants (31 Tai Chi and 32 control). Before enrollment, participants were screened according to the eligibility criteria. To be eligible to participate, participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) 60 years of age or older at the time of recruitment; 2) ability to perform low-intensity physical exercise safely, determined through a short health interview conducted by researchers, assessing participants’ self-reported medical history, mobility limitations, chronic musculoskeletal conditions, and cardiovascular risk factors. Participants identified with potential health risks were instructed to withdraw from participation; 3) not having a history of diagnosed psychiatric disorders (e.g., clinical depression, severe anxiety disorders) or serious cognitive impairments (e.g., dementia, Alzheimer’s disease); and 4) a commitment and willingness to participate consistently across the full duration of the 8-week intervention. Participants were excluded if they had severe medical conditions prohibiting low-intensity exercise participation (e.g., recent stroke, unstable cardiac conditions, severe arthritis significantly limiting mobility).

The appropriate sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 software, specifically for a repeated-measure ANOVA (within-between interaction), targeting a significance level of 0.05, 95% statistical power, and an effect size of 0.5 based on prior study protocols examining Tai Chi interventions in similar older adult populations [26]. Results indicated at least 54 participants were needed; accounting for an expected dropout rate of 12% [27], the target sample size was set at 60 participants to ensure sufficient statistical power. No additional adjustments were made for multiple analyses or covariates.

Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-SF), validated by Cho et al. [28] and Jang et al. [29]. The questionnaire consists of 15 questions, while participants are instructed to answer each question with “yes” or “no”, with total scores ranging from 0 to 15. The higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms, with scores of 0–5 indicating normal mood, 6–9 indicating mild depression, and 10–15 suggesting severe depression [29]. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was reported as 0.89 in the previous literature [30] and 0.84 in the current study. To assess perceived stress, the Korean-translated Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument (BEPSI-K) is a validated instrument used to assess stress. The BEPSI-K is the Korean version of the stress assessment scale developed by Frank and Zyzanski [31], translated and validated by Yim et al. [32]. It is composed of five items and utilizes a 5-point Likert response scale (1–5). Total scores range from 5 to 25, with higher scores reflecting greater perceived stress. Scores from 5–9 indicate low stress, 10–15 moderate stress, and 16–25 high stress levels requiring targeted intervention or support. Cronbach’s α (internal consistency) was 0.80 in a previous study [29] and was 0.80 in this study. Additional cultural validation specifically for this study’s sample was not conducted due to prior extensive validation in comparable Korean populations [29,30]. Both instruments were self-administered in a paper-based format.

Before the baseline assessment, the researchers contacted participants by phone or text message (e.g., SMS or KakaoTalk) to confirm their participation in the study and 222 explain how to access and fill out the baseline questionnaire. The willingness to participate was clarified through the informed consent process. Participants received detailed written and oral explanations of the purpose, procedure, potential risks and benefits, and confidentiality of the study. Thereafter, they agreed to participate in the study through a written (paper-based) consent form. Trained research assistants oversaw the questionnaire preparation and responded to participants’ questions to ensure accurate data collection. Research assistants participated in training sessions conducted by the principal investigator. These included detailed training on how to manage questionnaires, strategies to verify participants’ understanding, procedures for handling incomplete or unclear responses, and ethical considerations (confidentiality, voluntary participation, etc.).

Participants in the Tai Chi group attended supervised classes three times weekly over eight weeks (60 min per session). To increase the rate of participation in the intervention, attendance records were managed in detail for each class session. Participants who were absent from the class were individually contacted or sent messages to encourage continued participation. If they faced difficulties in participation, they received support to resolve them. At the end of the 8-week intervention, the participants were recontacted individually by telephone or direct message to remind them to complete the posttest questionnaires. At posttest, the same procedure (paper-based questionnaires) used to collect data at baseline was repeated to maintain consistency. Participants who completed the study were provided with monetary compensation of 50,000 Korean won (about 35.90 U.S. dollars) upon completing the study as compensation. In order to ensure privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality, participants were assigned unique identification codes at baseline, engaging in self-identification to allow matching of pre- and post-intervention data without participants revealing their identities. Pseudonyms were used to keep track of individual participants’ collected data, and data were handled confidentially. For confidentiality purposes, the data collected through paper questionnaires were originally safely stored in locked cabinets in the first author’s laboratory. Since then, the data have been digitized and stored in Dropbox, a password-protected cloud storage service, and access is limited to only approved research team members. The study was approved by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Institutional Review Board (IRB; No. HIRB-20241017-004), ensuring adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki and international ethical standards.

The intervention used in this study was a structured Tai Chi program consisting of three one-hour sessions per week over eight weeks, for a total of 24 sessions. Each session was held from 6:30 to 7:30 A.m. at a designated outdoor park in the apartment complex. The session schedule was planned in consideration of appropriate weather conditions (i.e., avoiding cold weather or rainy weather and choosing a mild season) and accessibility to outdoor places. These steps were taken to maximize the attendance and participation of participants.

The intervention program was specially modified and structured for this study. A systematic manual was developed to ensure the standardization and reproducibility of the intervention. This manual specifically describes the content, order, time allocation, and educational guidelines of each session. An accredited instructor with more than 10 years of experience in Tai Chi was selected as the Tai Chi instructor. The instructor received additional training from the research team before the start of the intervention regarding the session progress, interaction with participants, and safety management policies. The instructor thoroughly supervised each session to check the performance status of individual participants, provide immediate feedback, modify actions if necessary, and ensure participants’ safety during the arbitration period. Any side effects or safety-related issues encountered during the study period were systematically recorded and monitored. The instructor systematically measured intervention fidelity by recording participant attendance in each session and checking the exact operation performance. In addition, the research assistant regularly conducted fidelity checks to ensure that each session was conducted consistently according to the research protocol. Participants were asked to report any problems or inconveniences immediately, and protocols were prepared and operated to respond quickly to any issues. No negative events or adverse reactions (e.g., falls, injuries, or serious discomfort) were reported during the intervention period.

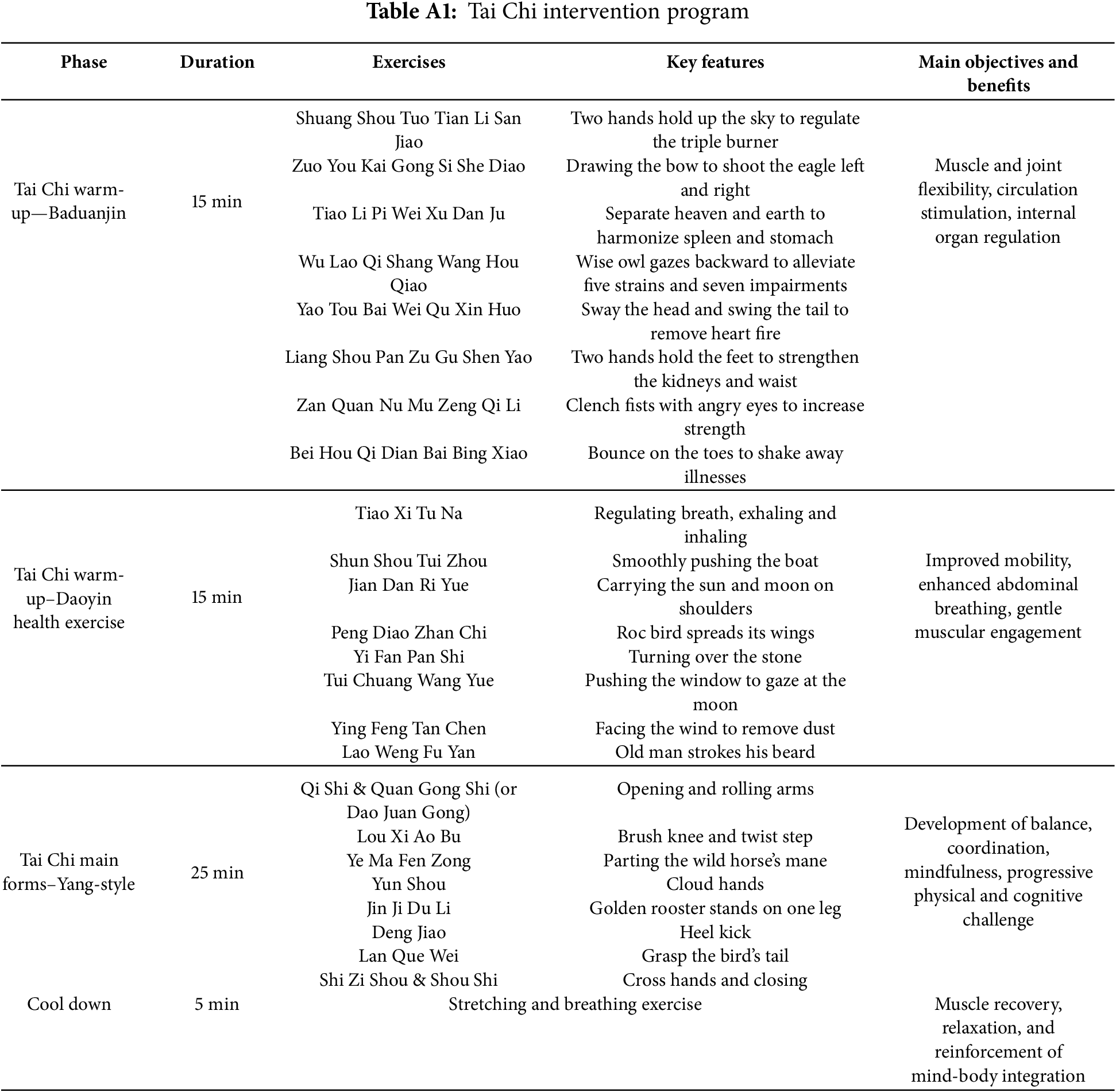

Throughout the intervention, the entire training sequence, from the warm-up to the Tai Chi routines, was consistently performed at every session. Each 60-min session included the three sequential phases (see Table A1): the warm-up, main Tai Chi practice, and cool-down.

The 30-min Tai Chi warm-up exercise consisted of two routines to activate the entire body and promote relaxation. These were Baduanjin and Daoyin Health Exercises. First, Baduanjin (15 min) involved eight movements, such as “Two Hands Hold Up the Sky” and “Drawing the Bow to Shoot the Eagle,” each performed repeatedly. These movements were designed to enhance muscular and joint flexibility, stimulate circulation, and regulate internal organ functions [33]. Next, Daoyin Health Exercises (15 min) focused on abdominal breathing combined with gentle movements, such as “Regulating Breath” and “Smoothly Pushing the Boat” [33,34]. Participants repeated each of these eight movements three times, shifting weight from side to side to engage different muscle groups and enhance overall mobility.

Following the warm-up exercise, participants practiced the main Tai Chi practice session (25 min), primarily engaging in the foundational Yang-style 8-form Tai Chi sequence. The main objectives of this sequence were to improve balance, enhance coordination, reduce stress, and foster mindfulness and body awareness. This sequence included movements such as “Opening and rolling arms”, “Brushing knee and twisting step”, and “Cloud hands.” Toward the end of the training period, selected movements from the more advanced 24-form routine were demonstrated to progressively challenge participants and enhance skill development [35]. Finally, each session concluded with a cool-down exercise (5 min). This session involves gentle stretching movements, relaxation, and breathing exercises to facilitate recovery and reinforce the mind-body benefits achieved during the Tai Chi session. The Tai Chi protocol combining 8-form and selected 24-form movements was chosen based on prior evidence demonstrating psychological and physical benefits, ensuring progressive intensity and complexity suitable for older adults [35].

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For the demographic variables, frequency and descriptive statistics were calculated. Crosstab analyses were conducted to evaluate categorical demographic variables (e.g., sex, marital status) for equivalence between groups at baseline. Independent samples t-tests examined group differences at baseline on continuous demographic variables such as age, perceived physical and psychological health, and outcome variables including depression and perceived stress. The effects of the intervention on the primary psychological outcomes were analyzed using mixed repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA, group × time). Normality and homogeneity of variance were verified via Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, and effect sizes (partial eta squared) were reported alongside ANOVA results to enhance interpretability.

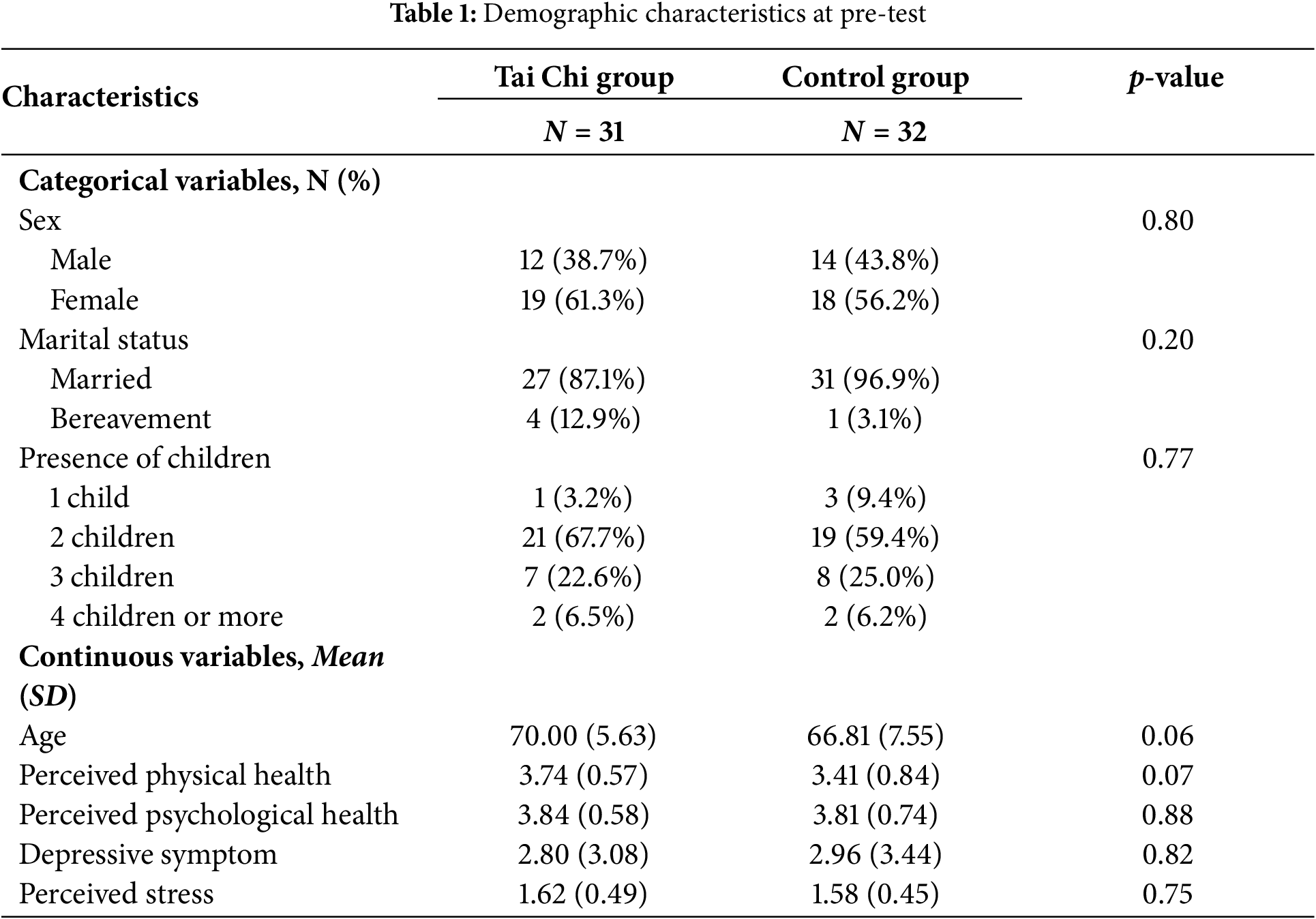

A total of 63 older adults participated, with 31 assigned to the Tai Chi intervention group and 32 to the control group. Crosstab analyses confirmed balanced distribution (p > 0.05) across demographic variables (sex, marital status, and presence of children), with no missing data.

Independent sample t-tests indicated no significant baseline differences between groups for age (t61 = 1.90, p = 0.06), perceived physical health (t61 = 1.85, p = 0.07), perceived psychological health (t61 = 0.16, p = 0.88), depression (t61 = −0.33; p = 0.82), and perceived stress (t61 = −1.37, p = 0.75). Given mild positive skewness observed in depressive symptom scores, we also conducted a Mann-Whitney U test as a supplementary analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test similarly indicated no significant differences in depressive symptoms between groups at baseline (Mann-Whitney U = 462.000, z = −0.263, p = 0.792). All psychometric measures demonstrated acceptable properties, and assumptions of homogeneity of variance were confirmed (Levene’s test, all p > 0.05). Collectively, these analyses confirmed baseline comparability between the groups, supporting the validity of subsequent intervention comparisons. All the information can be seen in Table 1.

3.2 Preventive Effects of Tai Chi on Depression and Perceived Stress

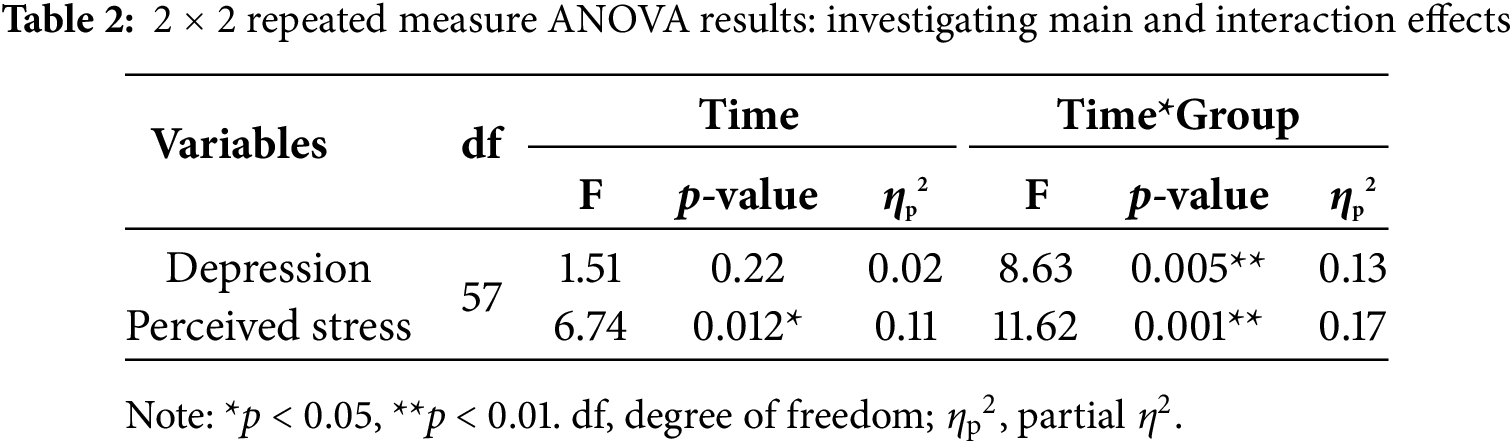

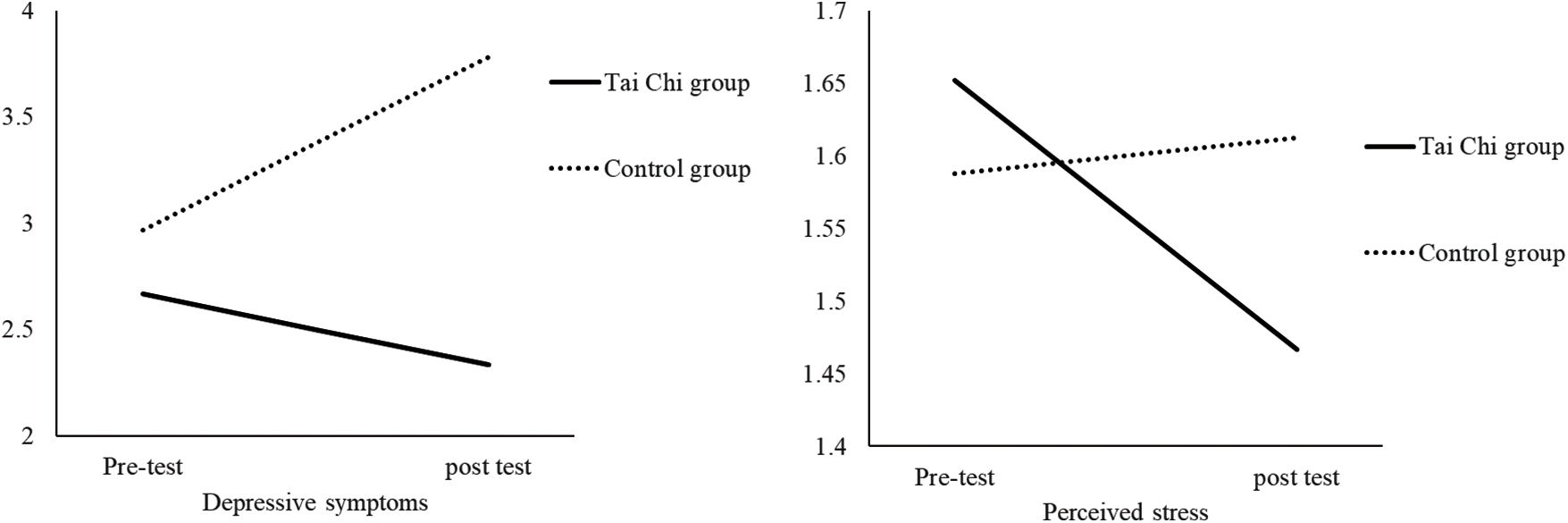

A 2 (group: Tai Chi vs. control) × 2 (time: pre-test vs. post-test) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of the intervention on depression and perceived stress scores (Table 2 and Fig. 2). For depression, the multivariate test revealed a statistically significant interaction between time and group, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.868, F1, 57 = 8.63, p = 0.005, partial η2 = 0.13. This indicates that changes in depression scores over time significantly differed between the Tai Chi and control groups. While the follow-up paired t-tests indicated that the Tai Chi group did not show statistically significant decreases in depression scores within their group (p > 0.05), their depression levels were slightly decreased (Meanpre = 2.80 [SD = 3.08] and Meanpost = 2.50 [SD = 3.19]), indicating a small to moderate improvement. The control group demonstrated a slight deterioration (Meanpre = 2.96 [SD = 3.44] and Meanpost = 3.78 [SD = 3.04]). For perceived stress, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of time, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.882, F1, 57 = 6.74, p = 0.012, partial η2 = 0.11, indicating a general reduction in stress across the sample from pre- to post-test. Importantly, there was also a significant interaction effect between time and group, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.831, F1, 57 = 11.62, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.17. Similar to depression, although within-group analyses did not reveal significant reductions in perceived stress for the Tai Chi group, their stress scores changed significantly differently compared to the control group. Specifically, the Tai Chi group demonstrated a slight decrease (Meanpre = 1.62 [SD = 0.49] and Meanpost = 1.48 [SD = 0.45]) while the control group either showed increased stress levels over the intervention period (Meanpre = 1.58 [SD = 0.46] and Meanpost = 1.61 [SD = 0.40]).

Figure 2: Changes in depressive symptoms (left) and perceived stress (right) during the intervention phase

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether Tai Chi is effective in preventing depression and perceived stress in healthy elderly people in South Korea. The findings indicate that Tai Chi may contribute to preventing depressive symptoms and perceived stress in healthy older adults, with a significant differential effect compared to the control group. Although some intra-group changes were not statistically significant, the effect size showed a clinically significant improvement, and a small to moderate decrease was observed in the mean scores of GDS-SF and BEPSI-K. These results are of practical importance, especially for elderly adults, as even minor changes can greatly contribute to the quality of life among this population. Specifically, the repeated measures ANOVA revealed a statistically significant interaction effect between group and time for depression and perceived stress scores. This interaction indicates that the pattern of change in depressive symptoms and perceived stress over time differed significantly between the groups. Tai Chi group showed a trend toward decreased depression and perceived stress levels, while the control group did not exhibit such improvements.

The observed discrepancies between statistical significance and clinical significance highlight important implications when interpreting preventive study results. In healthy groups with relatively mild symptoms, small but consistent changes are of great significance in primary prevention strategies. Such changes can reflect the early mitigation of risk factors that may develop into more serious conditions in the future [36]. Thus, while these minute improvements may not meet the traditional statistical significance standards, they are very important in terms of maintaining and improving the quality of life and preventing the onset or exacerbation of mental health problems [37]. Therefore, the results of this study emphasize that, when evaluating the effect of preventive mental health interventions for healthy elderly people, not only statistical significance but also clinical significance should be considered.

One reason for the lack of statistically significant changes in depression and stress scores within the Tai Chi intervention group may be that the baseline depression and stress levels of the intervention group participants were already relatively low, a phenomenon commonly known as the “ceiling effect”. The baseline GDS-SF score for the Tai Chi group was 2.80, which is well below the threshold score (≥5) commonly used to indicate mild depressive symptoms [38]. Similarly, their average baseline score of 1.64 on BEPSI-K is within the no stress range (<5), reflecting an initially low level of perceived stress [32]. Given these low initial scores, participants likely had limited room for measurable improvement, thereby potentially reducing statistical power to detect significant within-group changes. This ceiling effect not only affects statistical power but also has broader implications for the criteria for selecting participants. The selection criteria in this study were intentionally targeted at healthy older adults to evaluate primary prevention effects. This approach resulted in the inclusion of individuals with a relatively low probability of showing significant improvement in the mental health scale originally developed for the clinical group [39,40]. Thus, while standardized tools such as GDS-SF and BEPSI-K are valid and reliable, they may have some limitations in the sensitive detection of progressive mental health improvements in healthy populations [32,41]. Other factors may also have lowered the likelihood of detecting statistical significance within the intervention group, such as the limited sample size, diversity of individual responsiveness, and duration and intensity of the intervention. Overall, although the intervention group did not show a statistically significant internal improvement, the observed differences in depressive symptoms and perceived stress between the intervention group and the control group nonetheless indicate the possibility that Tai Chi may provide preventive mental health benefits to elderly adults.

The preventive effect of Tai Chi found in this study may be attributed to various interacting mediators across physiological, psychological, and neurological domains [17]. On a physiological level, frequent Tai Chi practice may promote emotional wellness through a reduction in activity of the sympathetic nervous system [42], decreased levels of stress hormones including cortisol [43], as well as reduced inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 [44,45], all of which are highly related to depression and perceived stress. Psychologically, Tai Chi also combines elements of mindfulness, deep breathing, and meditation to increase participants’ self-efficacy, emotional awareness, and stress-coping skills [46–49], which in turn have the potential to decrease perceived stress and depression. The underlying mechanisms involving changes in the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain known for emotional control, cognitive function, and psychosocial resilience, can also be addressed neurologically through Tai Chi practice. Increased activity in the prefrontal cortex may help regulate mood and stress [17]. Recent meta-analyses further support these mechanisms by linking Tai Chi practice to improved psychological outcomes in older adults [21,23,25].

In addition, the quasi-experimental and non-randomized study design of this study could have caused selection bias and affected the observed results. In particular, participants who voluntarily participated in the Tai Chi arbitration group may have shown differences in their motivation level, health interest, or other unmeasured characteristics compared to the control group. Therefore, although the results of this study are positive, causality and generalizability should be interpreted carefully. Future studies should apply a fully randomized controlled design to confirm these preliminary results and identify stronger causal relationships.

This study makes a theoretical contribution to the literature on preventive mental health interventions. Previous studies have mainly focused on reducing symptoms in groups with distinct clinical symptoms. Meanwhile, research on strategies to prevent mental health issues in relatively healthy elderly people has been insufficient. Focusing on this theoretical gap, this study empirically proved that preventive interventions such as Tai Chi can be effective in maintaining mental health and preventing worsening symptoms in groups with good initial mental health conditions. This preventive approach is consistent with public health objectives targeting preventive strategies to support elderly adults’ mental health and well-being, consistent with policies such as the World Health Organization’s (WHO) “Healthy Aging” plan.

This study enhances the theoretical framework of health promotion by showing the ways in which mind–body interventions such as Tai Chi can be effectively integrated into preventive health strategies at the community level. Furthermore, these findings represent a meaningful contribution to the healthcare and mental health promotion literature base by suggesting the appropriateness of culturally relevant, accessible, and sustainable preventive interventions. In addition, this study supports and expands existing theoretical frameworks, including biopsychosocial models and primary prevention frameworks of mental health. In doing so, the study emphasizes the importance of a holistic approach that integrates well-being at the physical, psychological, and social levels. As mental health challenges related to aging become an increasing global concern, identifying effective interventions that can be widely implemented in community settings is crucial. Therefore, this study suggests that tai chi is a sustainable, cost-effective, and culturally appropriate preventive intervention method. In doing so, the study fills an important gap in the existing theoretical and empirical understanding of mental health promotion, especially in healthy older adults.

The results of the present study have several potential implications for practice and preventive mental health among healthy older adults. First, our findings indicate that Tai Chi is a feasible preventive strategy that can be integrated into community settings such as community centers, senior living facilities, or other public places that older adult residents use regularly. Community health managers and policy makers should prioritize that such programs are affordable, well-publicized, and easily accessible. Furthermore, they also need to convey the preventive aspect of such programs through their publications and promotion to enroll healthy older adults, indicating that Tai Chi is for clinical and preventive health purposes. However, for the successful implementation of the intervention program, it is necessary to fully consider and address potential obstacles to implementation, such as initial costs, training of professional leaders, and cultural adaptation efforts.

Second, health policy managers can develop a public health campaign that emphasizes the preventive mental health effects of tai chi for healthy elderly people based on the results of this study. Strategies that clearly convey not only therapeutic effects but also preventive effects will be able to attract the attention of participants in the community and promote widespread participation.

The results of this study also provide a useful basis for healthcare application developers to explore the possibility of effectively integrating Tai Chi guidelines and guidance into mobile and web-based health promotion apps for older people. However, it is necessary to fully recognize and address practical limitations. These include difficulties that elderly people may experience in accessing and utilizing digital technology, lack of digital utilization capabilities, and initial resistance to digital mediation. Therefore, developers need to consider developing a user-friendly digital platform that provides virtual tai chi classes, educational videos, personalized feedback, and motivation tools that reflect the needs and preferences of elderly individuals. Such digital health solutions can increase the reach, scalability, and sustainability of preventive mental health interventions, thereby serving as an effective complement to traditional face-to-face community programs.

4.4 Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides some valuable insights, several limitations should be recognized, each suggesting avenues for future inquiry. First, this study utilized a quasi-experimental design without randomization. However, being practical and applicable in real-world community settings, this design has introduced possible selection bias given that participants may have self-selected into the Tai Chi or control group. It could mean that volunteers from the Tai Chi group were more highly motivated from the outset or were more health-conscious, both of which could have affected their compliance with the intervention and their responses to the dependent measures. In addition, the non-randomized design of this study has a limitation. Specifically, the participants do not sufficiently control confounding variables, such as additional physical activities that may have been performed outside the study. Future studies should use a fully randomized controlled design to clarify the causal relationship more clearly and reduce this bias.

Second, the relatively short 8-week duration of the intervention may have limited meaningful changes, especially among healthy older adults who tend to display ceiling effects on mental health assessments. An extended intervention period, with additional follow-up assessments (e.g., 6-month or 12-month assessments), would allow for increased investigation into longer-term preventive effects and the understanding of ongoing mental health benefits of Tai Chi use.

Third, since participants in this study were mainly recruited from a local community in Korea, the generalizability of the findings to elderly people in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts may be limited. The current study also did not conduct moderation analyses to explore individual heterogeneity systematically. Future research—including multicenter studies with more diverse populations—should examine potential moderating factors such as age, sex, baseline mental health status, or adherence rates to strengthen the study’s external validity and better understand which individuals benefit most from Tai Chi intervention. In addition, since the evaluation was based on a self-report psychological measurement tool, there is a possibility of social desirability bias and/or recall bias. Future studies can increase the validity of the evaluation by combining objective physiological indicators (e.g., cortisol level, heart rate variability) and observation data to more precisely explore and document the preventive mental health effects of Tai Chi.

Another limitation is that there was no measurement tool to evaluate program participation or subjective compliance. Future studies should consider the utilization of active control groups (e.g., different exercise types), explore subgroup analyses (e.g., based on sex or socioeconomic status), examine physiological mechanisms using biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory markers and stress hormones), and broader outcomes including quality of life, psychological well-being, and resilience.

In conclusion, results suggest that Tai Chi holds promise as an effective strategy for promoting mental health problems in healthy elderly people. This study highlights the importance of prioritizing primary prevention over treatment and underscores the need for early, proactive strategies to support sustainable mental health. Additionally, this study showed that Tai Chi program can be successfully implemented within the specific cultural context of Korea, where the practice is widely accepted and integrated into daily life. Future studies should investigate the long-term effects of Tai Chi and explore additional factors (e.g., program intensity, participant characteristics, and delivery methods) that may enhance its effectiveness as a preventive mental health strategy.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Keunsoo Lee, a certified Tai Chi instructor, for leading the intervention sessions, and to Juhee Hwang for her valuable assistance with the data collection process.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) & funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF-2021M3A9E4080780) and Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (2024).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Ye Hoon Lee and Yoonjung Park; Data collection: Ye Hoon Lee; Analysis and interpretation of results: Ye Hoon Lee and Yoonjung Park; Draft manuscript preparation: Ye Hoon Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first Author, Ye Hoon Lee, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Institutional Review Board (IRB) under reference HIRB-20241017-004.

Informed Consent: All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

References

1. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World social report 2023: leaving no one behind in an ageing world [Internet]; 2023. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2023/01/2023wsr-chapter1-.pdf. [Google Scholar]

2. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global health data exchange (GHDx) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 20]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/. [Google Scholar]

3. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates. [Google Scholar]

4. Cohen S, Gianaros PJ, Manuck SB. A stage model of stress and disease. Pers Psychol Sci. 2016;11(4):456–63. doi:10.1177/1745691616646305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. World Health Organization. Mental health of older adults [Internet]; 2021. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults. [Google Scholar]

6. Netz Y, Goldsmith R, Shimony T, Arnon M, Zeev A. Loneliness is associated with an increased risk of sedentary life in older Israelis. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(1):40–7. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.715140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Cattan M, White M, Bond J, Learmouth A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc. 2005;25(1):41–67. doi:10.1017/s0144686x04002594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bowling A. Ageing well: quality of life in old age. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

9. Seo Y, Lau C. South Korea becomes ‘super-aged society, new data shows. CNN [Internet]; 2024 Dec 24. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.cnn.com/2024/12/24/asia/south-korea-super-aged-society-intl-hnk/index.html. [Google Scholar]

10. Ewe K. How South Korea is tackling its demographic crisis. TIME [Internet]; 2024 Jan 24. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://time.com/6696414/south-korea-elderly-workforce/. [Google Scholar]

11. Baek JY, Lee E, Jung HW, Jang IY. Geriatrics fact sheet in Korea 2021. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2021;25(2):65–71. doi:10.4235/agmr.21.0063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Arango C, Díaz-Caneja CM, McGorry PD, Rapoport J, Sommer IE, Vorstman JA, et al. Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(7):591–604. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30057-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. World Health Organization. Prevention of mental disorders: effective interventions and policy options. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924159215X. [Google Scholar]

14. Singh V, Kumar A, Gupta S. Mental health prevention and promotion—A narrative review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:898009. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.898009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. World Health Organization. Ageing and health [Internet]; 2023. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. [Google Scholar]

16. Miranda P, Yanez-Yanez R, Quinta-Pena P. Strength training to prevent falls on the elderly: a systematic review. Salud Barranquilla. 2024;40(1):216–38. doi:10.14482/sun.40.01.650.452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chan AS, Cheung MC, Sze SL, Leung WW, Shi D. Shaolin dan tian breathing fosters relaxed and attentive mind: a randomized controlled neuro-electrophysiological study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011(1):180704. doi:10.1093/ecam/nep153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kim HS. Review of Tai Chi papers issued in Korean academic journals from 2000 to 2021. J Korean Soc Philos Sport Dance Martial Arts. 2023;31(4):98–114. doi:10.31694/PM.2023.12.31.4.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kim SH. A study on taoist studies in Korea. J Stud Taoism Cult. 2008;28:9–35. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

20. Yang FC, Desai AB, Esfahani P, Sokolovskaya TV, Bartlett DJ. Effectiveness of Tai Chi for health promotion of older adults: a scoping review of meta-analyses. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;16(6):700–16. doi:10.1177/15598276211001291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Leung L, Tam H, Ho J. Effectiveness of tai chi on older adults: a systematic review of systematic reviews with re-meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;103(2):104796. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2022.104796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Park M, Song R, Ju K, Shin J, Seo J, Fan X, et al. Effects of tai chi and qigong on cognitive and physical functions in older adults: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):352. doi:10.1186/s12877-023-04070-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang D, Wang P, Lan K, Zhang Y, Pan Y. Effectiveness of tai chi exercise on overall quality of life and its physical and psychological components among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2020;53(10):e10196. doi:10.1590/1414-431X202010196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chen XJ C, Xu DT. Effects of tai chi chuan on the physical and mental health of the elderly: a systematic review. Phys Act Health. 2021;5(1):21–7. doi:10.5334/paah.70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yin J, Yue C, Song Z, Sun X, Wen X. The comparative effects of tai chi versus non-mindful exercise on measures of anxiety, depression and general mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;337:202–14. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.06.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Recchia F, Yu A, Ng T, Fong D, Chan D, Cheng C, et al. Study protocol for a comparative randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi and conventional exercise training on alleviating depression in older insomniacs. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2024;22(1):194–201. doi:10.1016/j.jesf.2023.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ferraro F, Zhou Y, Roldan A, Edris R. Multimodal respiratory muscle training and Tai Chi intervention with healthy older adults: a double-blind randomized placebo control trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2025;42:527–34. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.12.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Cho M, Bae J, Seo K, Ham B, Kim J, Lee D, et al. Validation of geriatric depression scale, Korean Version (GDS) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. J Korean Neuropsych Asso. 1999;38:48–63. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

29. Jang Y, Small B, Haley W. Cross-cultural comparability of the Geriatric Depression Scale: comparison between older Koreans and older Americans. Aging Men Health. 2001;5(1):31–7. doi:10.1080/13607860020020618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Shim K, Kim W. The effects of Korean mindfulness-based stress reduction program on pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and depression in elders: focus on elderly women. Korean J Heal Psych. 2018;23(3):611–29. doi:10.17315/kjhp.2018.23.3.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Frank SH, Zyzanski SJ. Stress in the clinical setting: the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument. J Fam Pract. 1988;26:533–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

32. Yim JH, Bae JM, Choi SS, Kim SW, Hwang HS, Huh BY. The validity of modified Korean-translated BEPSI (Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument) as instrument of stress measurement in outpatient clinic. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 1996;17:42–53. [Google Scholar]

33. Park JK. Wushu Tai Chi. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Seolim Cultural Publisher; 1997. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

34. Ko YK. Traditional Yang-style Tai Chi. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Book Lab; 2017. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

35. Cho YB. Yang-style Tai Chi (Taichi 85 style). Seoul, Republic of Korea: Tohyang Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

36. Kazdin AE. The meanings and measurement of clinical significance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(3):332–9. doi:10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Cuijpers P, Turner EH, Koole SL, van Dijke A, Smit F. What is the threshold for a clinically relevant effect? The case of major depressive disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(5):374–8. doi:10.1002/da.22249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDSrecent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment and intervention. New York, NY, USA: The Haworth Press; 1986. p. 165–73. doi:10.1300/j018v05n01_09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Garin O. Ceiling effect. Encycl Qual Life Well-Being Res. 2024;31:631–3. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. McHorney CA, Tarlov AR. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res. 1995;4(4):293–307. doi:10.1007/bf01593882. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Friedman B, Heisel MJ, Delavan RL. Psychometric properties of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in functionally impaired, cognitively intact, community-dwelling elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1570–6. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53461.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kreibig SD. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: a review. Biol Psychol. 2010;84(3):394–421. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Nedeljkovic M, Ausfeld-Hafter B, Streitberger K, Seiler R, Wirtz PH. Taiji practice attenuates psychobiological stress reactivity—a randomized controlled trial in healthy subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(8):1171–80. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Irwin MR, Olmstead R. Mitigating cellular inflammation in older adults: a randomized controlled trial of tai chi chih. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):764–72. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182330fd3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Sprod LK, Janelsins MC, Palesh OG, Carroll JK, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, et al. Health-related quality of life and biomarkers in breast cancer survivors participating in tai chi chuan. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(2):146–54. doi:10.1007/s11764-011-0205-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Jin P. Efficacy of tai chi, brisk walking, meditation, and reading in reducing mental and emotional stress. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36(4):361–70. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(92)90072-a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wayne PM, Kaptchuk TJ. Challenges inherent to tai chi research: part I—tai chi as a complex multicomponent intervention. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(1):95–102. doi:10.1089/acm.2007.7170a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, et al. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):564–70. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kingston J, Chadwick P, Meron D, Skinner TC. A pilot randomized control trial investigating the effect of mindfulness practice on pain tolerance, psychological wellbeing, and physiological activity. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):297–300. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools