Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experiences of COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit Physicians and Hospital Administrators: Qualitative Findings from Focus Groups

1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

2 School of Nursing, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725, USA

3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

* Corresponding Author: Traci N. Adams. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Safeguarding the Mental Health of Disaster Survivors and Frontline Healthcare Workers During Pandemics)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1369-1382. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066495

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: While quantitative research has determined that emotional distress and psychiatric illness among frontline healthcare workers increased with the COVID-19 pandemic, detailed qualitative data describing their personal experiences are needed in order to make appropriate plans to address provider mental health in future pandemics. This study aims to further explore the psychological effects of the pandemic on COVID-19 ICU clinicians and administrators through focus groups. Methods: Two separate 2-h focus groups of physicians were conducted, one with frontline faculty clinicians and another with administrators. Qualitative data analysis was conducted. Results: In September and November 2023, volunteer samples were recruited from the pulmonary and critical care medicine division of The University of Texas Southwestern physicians who served during the pandemic primarily as clinicians (N = 6) or in major administrative roles (N = 5). Perceptions of both administrators’ and clinicians’ pandemic experiences were coded into the same 7 qualitative themes: planning, sense of community and isolation, disparities and inequalities, communication and listening, leadership, effects of the pandemic, and emotional/psychiatric/coping responses. Effects of the pandemic were the most coded theme in both groups; second was disparities and inequalities for clinicians and pandemic planning for administrators. Thematic content is summarized separately for clinicians and administrators, illustrated with representative quotes. Conclusion: This study adds detailed qualitative findings to enrich existing quantitative knowledge on frontline COVID-19 workers’ emotional responses. Both clinicians and administrators identified helpful and non-helpful institutional responses. These findings are consistent with prior studies of disaster worker experiences and may help to inform efforts to address provider mental health in future pandemics.Keywords

A review of published research suggests that emotional distress (including burnout) and psychiatric illness increased with the COVID-19 pandemic [1–3]. This literature consists largely of online survey studies, describing social isolation (53%), fear of infecting others (67%), occupational distress (76%), burnout (45%), job dissatisfaction (21%), insomnia (60%–86%), problem drinking (7%), anxiety or depression (6%–60%), and passive death wish or suicidal ideation (13%) [4–6], as well as self-reported poor/fair mental health (MH) (28%) and intact overall well-being (49%) [7–9]. While quantitative data abound, qualitative descriptions of the pandemic experiences of frontline physicians are needed to provide contextual details. Qualitative data on frontline ICU physicians is lacking, and it is important to understand in greater detail a complex topic such as physician MH, which allows researchers to look beyond the responses available in quantitative research to learn and confirm the meaning and rationale behind the quantitative results. This deeper understanding can better inform attempts to alleviate physician MH burden during future pandemics.

To explore the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline healthcare workers, focus groups were conducted with physicians who provided COVID-19 care. Although revisiting pandemic experiences is understandably mentally and emotionally difficult, findings from these focus groups were expected to encourage and inform future pandemic planning efforts at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) and around the world.

Volunteer samples of all clinical and administrative COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) faculty physicians were recruited through email and word of mouth at the Dallas County public hospital (Parkland Health and Hospital System, PHHS) and the academic hospital (William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, CUH) affiliated with UTSW. The pulmonary critical care medicine (PCCM) division was selected for sampling a unified physician discipline with a clinical understanding of COVID-19 ICU work.

Two separate 2-h focus groups were conducted with frontline clinicians and administrators, respectively, in September and November 2023 to identify topics and themes of importance to their primary pandemic positions. Administrators and clinicians participated in separate groups because they each had different roles during the pandemic, with clinicians performing the bulk of the front-line patient care and administrators taking a larger role in allocating staff and resources to each hospital’s COVID-19 units and existing pulmonary/critical care services. The methodology benefited from the lead facilitator’s (Carol S. North) extensive experience with focus group research and qualitative data analysis [10–12]. The approach was drawn from medical qualitative research traditions, rather than forcing the material to fit into any pre-existing framework or theory, which limits our ability to allow the emergence of unique findings and is consistent with previously published focus group studies [10–12].

Focus group participants completed demographic and COVID-19 ICU worker surveys (Appendix A). The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. Potentially identifying information (i.e., names, specific titles) was removed. Two authors identified and preliminarily defined themes separately for both groups and then assigned thematic codes to passages, ultimately reaching a consensus by refining definitions [10–12]. Excellent thematic interrater reliability was achieved (mean kappa values = 0.87 [0.80–0.92] for clinicians and 0.92 [0.85–1.00] for administrators). The UTSW Institutional Review Board considered this to be a quality improvement study and, therefore, was deemed non-regulated human subjects research.

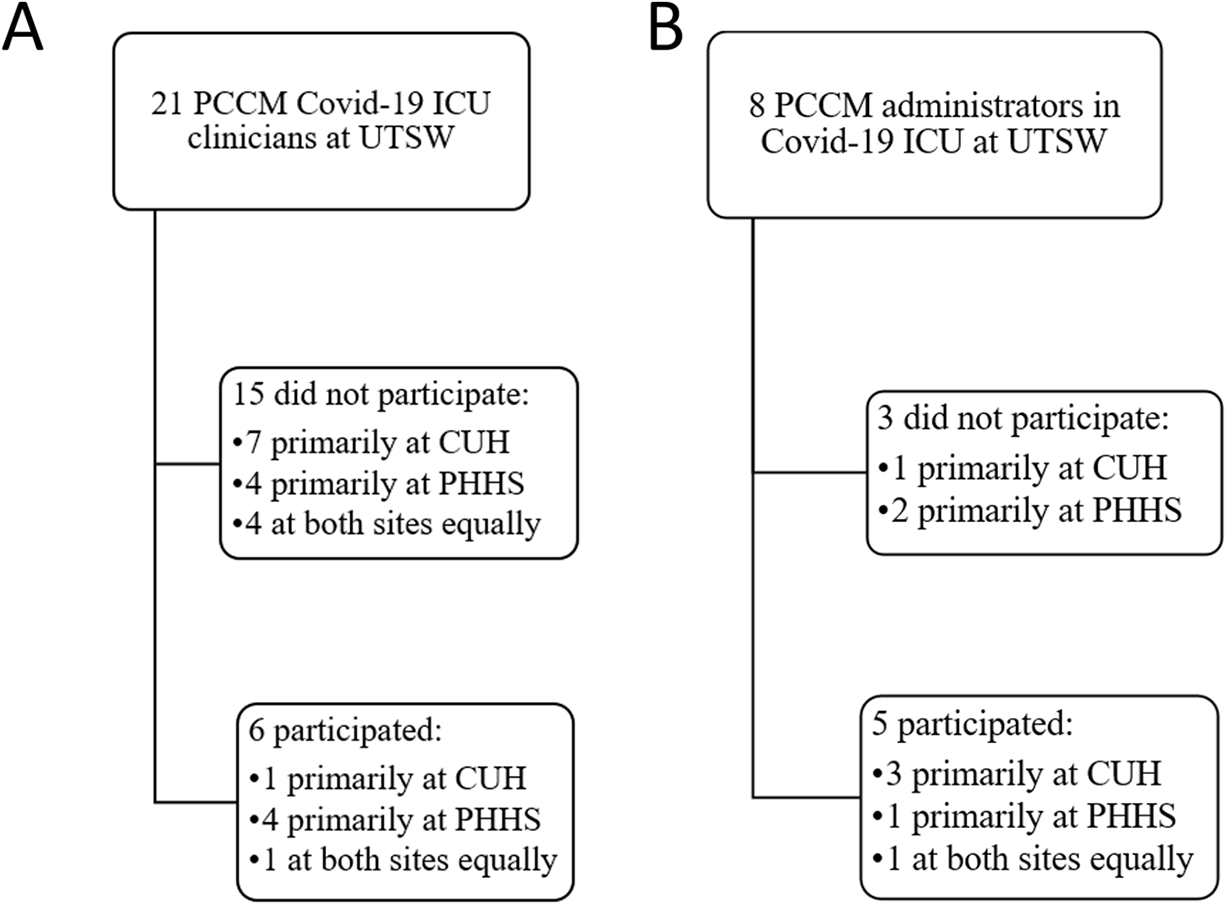

The focus groups included physicians serving primarily as clinicians (N = 6) or in major administrative roles (N = 5) during the pandemic (Fig. 1). Table 1 lists participants’ characteristics.

Figure 1: Flow chart. (A) Clinician focus group participation; (B) Administrator focus group participation. Note: PCCM, pulmonary critical care medicine; UTSW, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; CUH, William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital; PHHS, Parkland Health & Hospital System

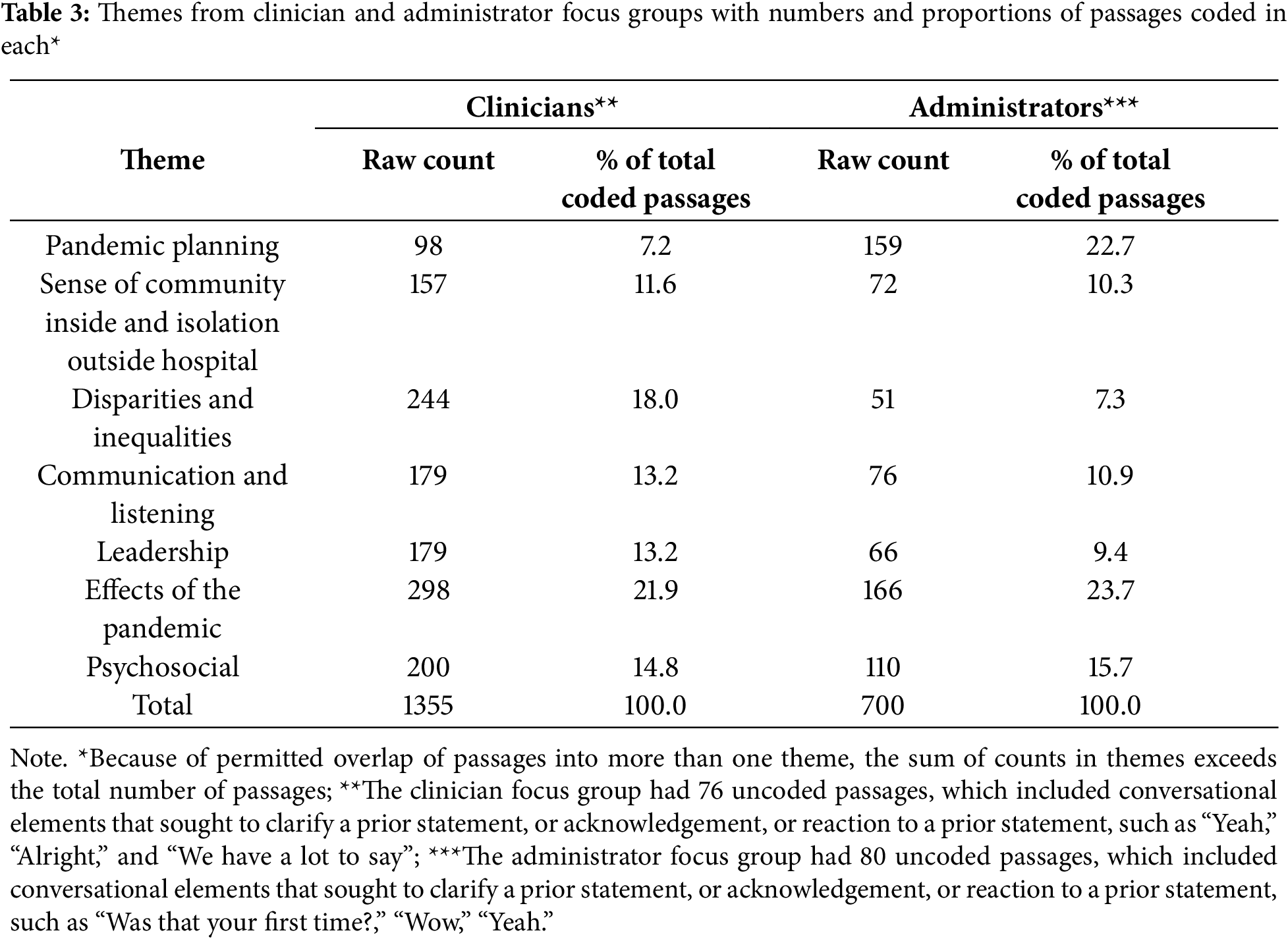

Perceptions of administrators’ and clinicians’ experiences were coded into the same 7 themes identified for both: planning, sense of community and isolation, disparities and inequalities, communication and listening, leadership, effects of the pandemic, and emotional/psychiatric/coping responses (Table 2). The total number of passages generated by clinicians was 833, with 757 coded into themes, and by administrators was 423, with 353 coded into themes (Table 3). Effects of the pandemic were the most coded theme in both groups; second was disparities and inequalities for clinicians and pandemic planning for administrators. The content of themes is summarized separately for clinicians and administrators below and illustrated with representative quotes.

This theme revolves around pandemic planning. Clinicians expressed concerns that pandemic planning was inadequate to address staffing shortages. One clinician commented, “There wasn’t a plan...It’s much more work than you would have been doing, and it seems endless... We needed 12 more people...5 times the staffing.” Clinicians were concerned about the personal risk of ICU COVID-19 work, especially for pregnant and lactating female clinicians who intubated patients before vaccination and adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) was available.

3.1.2 Sense of Isolation and Community

This theme covers feelings of isolation (e.g., “You feel like you’re alone”), which diminished over time, contrasted with increasing camaraderie with their colleagues, e.g., “You were one of the first to open up about struggling, which I think then led us to probably all feel a little bit more vocal,” “It was the solidarity with you guys that kept me going....” and “...we needed each other...” Clinicians expressed gratitude for a “ton of support” from other disciplines and professionals, including surgery, anesthesia, residents, and advanced practice providers: “We couldn’t have functioned without them.”

3.1.3 Disparities and Inequalities

This theme pertains to perceived workplace inequalities and disparities between the needed hospital resources and support provided by hospitals during the pandemic. One clinician recounted: “What I remember the most about the pandemic is the inequity of the 2 sides [CUH and PHHS], the inequity of how the faculty were treated, between men and women, and even for the vaccine rollout.” Some clinicians felt their assignment to the Covid-19 ICU while other faculty were spared “tell[s] you that your life is not valuable.” They deemed it inappropriate for unvaccinated pregnant and lactating women to work in the COVID-19 ICU without adequate PPE, and inconsistent with policies excluding older clinicians. Clinicians were appalled that some divisions outside of PCCM did not participate in the care of patients with COVID-19. They objected to the inequity of early vaccination allocation for them. They recounted further inequalities of faculty financial reimbursements for frontline pandemic work: “Residents got moonlighting pay. Nursing got overtime and hazard pay as they very much deserved…but no one thought we deserved that.”

3.1.4 Communication and Listening

This theme focuses on communication among colleagues, between clinicians and leadership, and between providers and patients and their families. Clinicians described how valuable it was to be able to communicate their own emotional struggles at work: “Hearing from a colleague [who is] also struggling, that’s a very important part of validating how you feel.” They communicated their concerns about PPE, vaccine availability, workload, support from other departments, and infection transmission to leadership via emails, phone calls, and Zoom meetings. Clinicians expressed disappointment that vaccination opportunities were not communicated to everyone in a timely manner. Communication failures also included a lack of dissemination of information about employee MH resources during the pandemic.

Good communication examples were taking on responsibilities by psychiatry residents and palliative care providers to systematically call patients’ families to update them on the status of their loved ones in the ICU. One said, “I’m grateful for that because I didn’t have time to call the families.”

This theme addresses both supportive and unsupportive leadership attributes. Supportive attributes by leadership from both their own and other departments were described: “The chief of surgery was doing [hospital] ward [care] for Covid-19 patients…acting as a hospitalist” and “We were fortunate enough to have leaders not only literally in [the Covid-19 ICU] but also...advocating for us.”

Unsupportive leadership attributes included unrealistic expectations of patient volumes (“‘One of us can care for 60 intubated patients…’—that’s what he said!”); dismissing clinicians’ concerns over infection transmission, PPE shortage, and their MH; and not accepting help from other services.

This theme identifies both positive and negative ramifications of the pandemic. Positive effects of the pandemic included the formation of unexpected friendships: “I have a [new] relationship with [another Covid-19 ICU worker] because of Covid-19.” Clinicians also agreed that the pandemic led to mentality changes about establishing limits, including willingness to “set boundaries” and “advocate for ourselves” at work. Substantial negative effects of the pandemic mentioned were inordinate morbidity and mortality and difficult work conditions. One clinician lamented about the inability to provide timely intervention on a deteriorating patient during the intense surge of clinical volume and acuity: “...I think about that man. I remember his name….” Clinicians recalled making sacrifices to meet work demands, for example: “One day was 14 h [that] I didn’t leave to pee or eat.”

The emotional toll of the pandemic led some clinicians to change their work structure considerably, such as by refusing ICU shifts. Clinicians recalled friction between themselves and their own and their patients’ families regarding COVID-19 vaccination and treatment decisions. One particularly antagonistic situation with a patient’s wife was recounted: “She would insult us and scream at us and then finally [she said], ‘My husband’s going to die and you’re doing nothing…’ ”.

This theme concerns emotions experienced during and after the pandemic. Clinicians mentioned fear and nervousness, anger, guilt, distress, and gratitude. Fear and nervousness arose from concerns about infection transmission and having to pump breast milk at work. One clinician recounted, “Before my first shift, I was so anxious I was to the point [of] making myself sick because I was wound up [with thoughts] that I was going to...die.” Another described unpleasant memories and anxiety during hospital calls. Public opinions about vaccination elicited clinicians’ anger. Clinicians felt guilty over being protected from working early in the pandemic. Discussing and reliving their COVID-19 experience generated distress. They expressed gratitude for the validation of their feelings by colleagues and family.

Clinicians reported coping with their emotions through support from colleagues and by seeking treatment. One clinician acknowledged being prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for intense anxiety and was still taking it. After completing intensive therapy, another said, “I can do my job now, but, I’m not the same person that I was.” Clinicians expressed frustration with workplace MH crisis support services, which were neither timely nor easily accessible. One clinician lamented: “You send an e-mail when you’re in crisis.... Look, I need some sort of help here, and they go, okay, here’s a list of people...then you start calling these people…none of them pick up.” Another recounted, “I don’t think I would’ve gotten the help that I needed had I not completely broken.”

This theme pertains to disaster preparedness. Administrators described “very forward-thinking” and “participatory” parts of pre-pandemic planning. The hospitals had anticipated the needs for extra equipment, “...buying and renting a whole bunch of extra stuff even beyond that initial [time] when we were starting to look at the projection [of] where this is going.” They acknowledged fortuitous occurrences: “We were very lucky…the workload could have been much, much worse.” However, they felt caught off guard by the pandemic, especially regarding clinician MH needs: “We should have been more proactive in screening and reaching out to people, and not just making them aware that the resources were available.” They identified pressing needs to start preparing now for the next pandemic.

3.2.2 Sense of Isolation (Outside Hospital) and Community (In Hospital)

This theme reflects feelings of isolation from the public outside the hospital and a sense of community and camaraderie with colleagues inside the hospital. One administrator expressed exasperation over pandemic-related behaviors that contributed to patient morbidity and mortality: “With the Delta variant, [just about] the only people who were dying were those who had not been immunized. That really hurt.” Collegiality proliferated among colleagues—even from other divisions and hospitalists—who participated in inpatient COVID-19 care: “It was a very nice moment in COVID-19 [when] a group of intensivists...all of a sudden became brothers in arms” and “There were days where I enjoyed coming to work, just because of...the camaraderie. I just loved working with other specialties together, [with] perspectives [of] residents and support staff from different specialties.”

3.2.3 Disparities and Inequalities

This theme addresses differences applied to gender and age groups, employment positions, and hospitals. One administrator considered census inequities to present the most salient institutional disparity, characterized as 2–5 times higher in one hospital than another. A high COVID-19 ICU census befell a hospital without proportionately higher numbers of PCCM workers, placing all the burden on just a few clinicians. Other administrators pinpointed discrepancies in staffing, use of other department faculty, and numbers of PCCM faculty leaders at different hospitals. For future pandemic planning, an organizational strategy was suggested for UTSW institutional leadership to assume a much bigger role in workforce planning for both hospitals.

3.2.4 Communication and Listening

This theme’s content emphasizes the importance of communication and listening at community levels, with patients’ families, and between and within hospital divisions. In the community and with patients’ families, encouragement of vaccination was consistently communicated.

Within the PCCM division, formal faculty gatherings facilitated communication. “We had a call every week. I called it ‘Lessons Learned’ because [it] was for the people who had not been on service the last week to know what was going on.” Communicating census information in weekly mass emails to PCCM faculty was considered indispensable.

This theme identifies both positive and negative leadership attributes and challenges to them. Positive leadership included learning from past experiences, working with other people, cooperation, honesty, positivity, willingness to make changes, understanding global systems, following the current hospital census, and learning from past experiences with Ebola. One administrator praised the leadership: “I thought they did a great job of bringing people together, getting everybody involved.” Negative leadership included failure to collaborate with others, allowing one person to speak for everyone, and not anticipating problems. Administrators acknowledged the failure to gather frontline worker observations: “Had I to do it again I think I would [institute] much more systematic mandatory feedback.”

Leadership challenges included managing inherent competition between clinical work and leadership responsibilities, with some administrators working in the COVID-19 ICU while simultaneously balancing administrative duties and others forsaking COVID-19 ICU work to maximize their leadership capacities. Administrators encountered substantial impediments to instilling motivation for clinicians to do pandemic work: “How do you get people to do what they don’t want to do but you need them to do?” Another described difficulties in achieving a balanced leadership approach: “You want to be positive…but you also have to be brutally honest about when stuff is not working and something needs to be done, and get it done.”

This theme is composed of both positive and negative consequences of the pandemic. Practices pertaining to census management, staffing, PPE, and vaccination were noted to affect workplace procedures and patient care.

Many positive effects were noted. These included empathy for others in disaster (“I read the news about the war in Ukraine differently after COVID-19”), incorporation of certified nurse anesthetists into the PHHS ICU workforce (“They were fantastic”), stronger relationships (“camaraderie and getting to know people”), leadership opportunities (“People who had not had a chance to lead were put in leadership positions”), and development of workplace disaster training.

Negative effects were also mentioned. Among them were relentless patient mortality (“They just started coming and dying, and coming and dying”), extensive undesirable changes to ICU rotation structures and schedules (conversion of a post-anesthesia care unit and an operating room area together into a COVID-19 ICU unit, “The Tank”), and long-lasting damage to the workforce (increased workloads, expanded clinical responsibilities and canceled vacations for several years), and hospital supply shortages (“We had gone through all [our] ventilators” and “We got close [to running out]…we had like five nitric oxide generators”).

Administrators’ comments emphasized long-lasting negative workforce consequences of the pandemic: “It just went on and on…If you did not turn it off, you were on or in that office for 3 years.” They observed, “We have so many faculty even today [who] are still suffering,” “wounded people” with “psychological fallout” including nightmares and PTSD. One administrator harbored long-lasting negative sentiments against working in a future pandemic: “I’m not going to do it again.”

3.2.7 Emotional/Psychiatric/Coping Responses

This theme characterizes frontline workers emotional responses to the pandemic and coping strategies. Emotions mentioned were bereavement, shock and fear, and feeling betrayed, dehumanized, scarred, disappointed, and “really mad.” Administrators had “no control over when it ends” and a sense of “no light at the end of the tunnel,” with some feeling too upset to even enter the ICU. Many feelings were vividly expressed; for example, the emotional experience of COVID-19 was depicted as “an intense brain-occupying lesion.” Various administrator comments portrayed various COVID-19 experiences as happy, proud, fun, and lucky.

Administrators described the psychiatric illness in the clinicians: “I mourn [redacted faculty name’s psychiatric illness] every day; [redacted name] can’t even walk in the door of the hospital anymore.” One comment captured the severity of the pandemic’s psychological effects on physicians who will have “a lot of PTSD in the [next] generations.” Other comments emphasized the importance of future planning for the next pandemic to include the proactively establishment of a system to identify and address frontline workers’ psychiatric needs.

Various strategies for emotional coping with the pandemic were noted. Rest, recreation, and social support, especially nurturing by their families, proved helpful, for example: “My wife gave me a good meal, she took care of me.” In contrast, family responsibilities (“If you’ve got children you’ve got to take care of, I wouldn’t know how I would be able to do it”), exhaustion, and inability to take time off to care for their own MH were identified as coping hindrances. One suggestion for ensuring that clinicians make time to cope was to mandate time off for that purpose.

This article reveals the qualitative experiences of COVID-19 ICU clinicians and administrators in 2 focus groups. This study’s findings add rich qualitative detail to deepen existing knowledge from quantitative research on the psychological effects of the pandemic on frontline COVID-19 workers.

Not surprisingly, clinicians and administrators discussed the same themes; however, emphasis on injustice and unfairness was more prominent for clinicians, and pandemic planning was more prominent for administrators. Suggestions for future pandemic preparedness, including planning for the psychiatric effects of a pandemic, were discussed. By conducting and analyzing administrator and clinician groups separately, this article allowed for each group’s emphases to emerge spontaneously and demonstrated that while there are many similarities between administrators and clinicians, their experiences during the pandemic were distinct. Whether these differences were due to the administrator vs. clinician role or the demographic differences between administrators and clinicians is unclear. The separate analysis of each group also allowed administrators to discuss lessons learned and different approaches they might take during a future pandemic. This information may inform efforts to address the mental health of clinicians and administrators during a future pandemic.

Both focus groups identified both helpful and not-helpful institutional responses, complementing the findings of other disaster worker studies. A study of employees of New York City companies highly affected by the 11 September 2001, terrorist attacks revealed that a post-disaster workplace balance between productivity and flexibility was important to their well-being [13]. The current study’s workers described similar needs for flexibility during the pandemic. The severe distress they described is also consistent with the existing body of disaster MH research on frontline healthcare workers (reviewed in this article’s Introduction), demonstrating substantial MH effects of the COVID-19 pandemic [7–9,14].

Both clinicians and administrators in the current study acknowledged inequalities and disparities. Gender inequality in healthcare has been well described, including the small proportion of women comprising hospital and academic medical center leadership [15–17]. The current study’s clinicians stated that this pre-existing inequality was reflected in the inclusion of vulnerable pregnant and lactating women in the COVID-19 workforce, while older individuals (who were predominantly male) were excluded from frontline work until vaccines were available.

Strengths of this study include the richness of the qualitative data elicited spontaneously through non-directive focus group methods and systematic content analysis and comparison and contrast of groups of clinicians with administrators. Limitations include the small sample size of only 11 participants in two focus groups and the recruitment of participants from only one division within one institution. In addition, the volunteer sample, reflecting considerable nonparticipation, may have generated sampling bias (i.e., if those most upset by their COVID-19 experience avoided participation), potentially minimizing the negative and overemphasizing the positive findings. Recall bias may also be present, as the focus groups were conducted in 2023, and fatigue and emotional exhaustion following the pandemic may have limited participant reflections, though notably, both discussions were robust and animated. Despite the small volunteer sample, these focus group findings may be generalizable, as indicated by consistent findings from quantitative COVID-19 ICU literature and qualitative disaster MH literature more broadly.

This study’s participants were already talking about preparing for the next pandemic, and findings from these focus groups will help guide these efforts. Planning for future pandemics at UTSW is currently underway, and will include mobilizing Psychiatry to meet frontline workers’ MH needs, obtaining systematic feedback from frontline clinicians, mandating time off, and guarding against disparities in frontline work. Institutions may consider planning for equitable assignment of clinicians to frontline work, hazard pay, and mental health support in future crises. National guidelines may be of benefit to standardize this pre-pandemic planning across institutions, and future qualitative studies that include a diverse sample of frontline physicians across institutions may help to inform these guidelines. The PCCM division is providing education to make UTSW employees aware of available MH resources. Insights from COVID-19 ICU experiences of this study’s clinicians and administrators may encourage other institutions to evaluate their COVID-19 experience as well as inform their pandemic planning efforts.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge the contributions of our focus group participants.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Traci N. Adams, Haley Belt, E. Whitney Pollio, Leah Cohen, Roma M. Mehta, Hetal J. Patel, Rosechelle M. Ruggiero, and Carol S. North contributed to the conceptualization, writing, and/or editing of the manuscript and approve of the final version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Transcripts are unavailable for this study due to the sensitive nature of the information and the potential to be able to identify subjects.

Ethics Approval: The UTSW Institutional Review Board considered this to be a quality improvement study and, therefore, was deemed non-regulated human subjects research. Based on the non-regulated nature of the research, participation in the group was considered to be consent for participation in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Survey Administered to All Focus Group Participants:

Please circle one answer for each of the following questions:

Date ____________

Gender: Male Female

Age: ________

Race: White Black Other (fill in) _______________________

Hispanic Ethnicity: Yes No

Marital status at the start of the pandemic (March 2020): Married Not married

(If not married): cohabitating with significant other at the start of the pandemic (March 2020): Yes No

Number of children living with you at the start of the pandemic (March 2020): _____________

Number of children living with you at the end of the pandemic (December 2021) ___________

Faculty rank: Assistant professor Associate professor Full professor

Year graduated from pulmonary and critical care fellowship: __________

Year started on faculty at UTSW: _____________

Primary practice site during the pandemic: CUH Parkland

% administrative time (significant administrative role, not including the 15% academic time): _______

Administrative role title(s): _____________________________

Did you know if psychiatric assistance was available at UTSW (i.e., EAP, psych department)? Yes No

Do you know any frontline workers at UTSW who could not access psychiatry care in a timely manner? Yes No

Time spent in Covid-19 front line work: <1 week 1 week-1 month >1 month

Were you in TCU (“The Tank”) at Parkland (defined as the converted PACU/OR which was open between March 2020 and July 2020): Yes No

Were weeks added to your inpatient schedule as a result of the pandemic? Yes No

If so, estimated # of weeks: ______________ or don’t know _____

Estimated number of prone chest tubes placed: _________ or don’t know but at least 1 ____

Estimated number of prone central lines or quintons placed: ____ or don’t know but at least 1 _____

Did you lodge outside of your home during the pandemic to avoid infecting household contacts (i.e., staying in hotel or hospital call rooms): Yes No

Were you infected with COVID-19? Yes No

If so, estimated date(s) ____________________________

References

1. Tong J, Zhang J, Zhu N, Pei Y, Liu W, Yu W, et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among frontline healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1096857. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1096857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Neisewander B, Jorgensen S, Dixon LB. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(12):1477–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.721206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Covid Mental Health Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700–12. [Google Scholar]

4. Stafseth SK, Skogstad L, Raeder J, Hovland IS, Hovde H, Ekeberg O, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care personnel in Norwegian ICUs during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, a prospective, observational cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):7010. doi:10.3390/ijerph192315424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ezzat A, Li Y, Holt J, Komorowski M. The global mental health burden of COVID-19 on critical care staff. Br J Nurs. 2021;30(11):634–42. doi:10.12968/bjon.2021.30.11.634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Reignier J, Argaud L, Bruneel F, Courbon P, et al. Symptoms of mental health disorders in critical care physicians facing the second COVID-19 wave: a cross-sectional study. Chest. 2021;160(3):944–55. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Greenberg N, Weston D, Hall C, Caulfield T, Williamson V, Fong K. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occup Med. 2021;71(2):62–7. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqaa220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Magnavita N, Soave PM, Antonelli M. A one-year prospective study of work-related mental health in the intensivists of a COVID-19 hub hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9888. doi:10.3390/ijerph18189888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Magnavita N, Soave PM, Antonelli M. Treating anti-vax patients, a new occupational stressor-data from the 4th wave of the prospective study of intensivists and COVID-19 (PSIC). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):5889. doi:10.3390/ijerph19105889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Roaten K, Browne S, Pollio DE, Khan F, North CS. Comparison of violence risk screening experiences of emergency department clinicians. Hosp Pract. 2022;50(4):289–97. doi:10.1080/21548331.2022.2108272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Hong BA, Gordon MR, Kim YS, Lind L, et al. The business of healing: focus group discussions of readjustment to the post-9/11 work environment among employees of affected agencies. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(7):713–8. doi:10.1097/jom.0b013e3181e48b01. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. North CS, Pollio DE, Pfefferbaum B, Megivern D, Vythilingam M, Westerhaus ET, et al. Concerns of Capitol Hill staff workers after bioterrorism: focus group discussions of authorities’ response. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(8):523–7. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000172598.82779.12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Neria Y, DiGrande L, Adams BG. Posttraumatic stress disorder following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks: a review of the literature among highly exposed populations. Am Psychol. 2011;66(6):429–46. doi:10.1037/a0024791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. DeSalvo KB, Hyre AD, Ompad DC, Menke A, Tynes LL, Muntner P. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in a New Orleans workforce following Hurricane Katrina. J Urban Health. 2007;84(2):142–52. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9147-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Berlin G, Robinson N, Sharma M. Women in the healthcare industry: an update. McKinsey & Company. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/women-in-healthcare-and-life-sciences-the-ongoing-stress-of-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

16. Haines AC, McKeown E. Exploring perceived barriers for advancement to leadership positions in healthcare: a thematic synthesis of women’s experiences. J Healthc Organ Manag. 2023;37(3):360–78. doi:10.1108/jhom-02-2022-0053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mucheru D, McAuliffe E, Kesale A, Gilmore B. A rapid realist review on leadership and career advancement interventions for women in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):856. doi:10.1186/s12913-024-11348-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools