Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Relationship between Dark Personality Traits and TikTok Addiction among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Social Ostracism

1 School of Public Administration, North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

2 School of Foreign Studies, North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongliang Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Causes, Consequences and Interventions for Emerging Social Media Addiction)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1335-1351. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.067246

Received 28 April 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Recent years have witnessed the rapid rise of TikTok, a short-video social platform, which has sparked concerns about its potential for misuse and addiction. TikTok addiction has been associated with various psychological and social issues. This study aims to explore the mediating role of social ostracism in the relationship between the Dark Triad (Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, and Narcissism) and TikTok addiction. Methods: Data were collected from 425 Chinese college students through convenience sampling, using three validated scales: the Dirty Dozen, the Social Ostracism Scale, and the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with AMOS 24 revealed significant patterns. Results: Narcissism had direct positive effects on both social ostracism (β = 0.115, p < 0.01) and TikTok addiction (β = 0.223, p < 0.05), while Psychopathy only had a direct positive effect on social ostracism (β = 0.147, p < 0.05). Contrary to expectations, Machiavellianism did not show significant direct effects on either social ostracism (β = −0.031, p > 0.05) or TikTok addiction (β = 0.135, p > 0.05). Mediation analysis confirmed that social ostracism acted as a positive mediator, amplifying the effects of Psychopathy (β = 0.049, p < 0.05) and Narcissism (β = 0.052, p < 0.01) on TikTok addiction. In other words, higher levels of Psychopathy and Narcissism were linked to greater experiences of social ostracism, which in turn were linked to higher levels of TikTok addiction. Conclusion: These findings suggest an important role for social ostracism in linking Narcissism and Psychopathy to TikTok addiction. Addressing social ostracism and these dark personality traits through targeted interventions may be important in reducing TikTok addiction risks among individuals with such traits.Keywords

Social media addiction is a growing public health concern, particularly among young adults whose digital engagement is often intensive. College students, navigating identity formation and social connection, appear especially vulnerable to developing problematic usage patterns [1–3]. Among the plethora of platforms, TikTok has rapidly emerged as a dominant global force since its 2017 launch. By 2024, it boasts an estimated 2.05 billion registered users and over 1 billion monthly active users, fundamentally reshaping digital communication [4]. TikTok’s highly personalized and algorithmically driven “For You Page” could deliver endless streams of short-form video content, which creates distinct psychological dynamics. This format fosters intense “flow” states and effortless, prolonged scrolling, potentially heightening the risk of compulsive use compared to other platforms [5–7].

“TikTok addiction” is characterized by compulsive use, loss of control, and adverse impacts on mental well-being. Its concerns have escalated alongside the platform’s growth [1–3]. Understanding the drivers of this platform-specific addiction requires examining individual susceptibility factors. Personality traits are established as critical predictors of social media addiction vulnerability. Existing research has extensively linked dimensions of the Big Five Personality (e.g., high Neuroticism, low Conscientiousness) to problematic use of social media [8,9]. However, the role of socially aversive or “dark” personality traits, specifically the Dark Triad of Machiavellianism (strategic manipulation, cynicism), Narcissism (grandiosity, entitlement, need for admiration), and Psychopathy (impulsivity, callousness, low empathy), remains relatively underexplored within TikTok’s unique ecology [10,11]. While studies on general social media use suggest all three Dark Triad traits correlate with addiction [12], their specific interactions with TikTok’s features are poorly understood.

TikTok’s environment may uniquely amplify risks associated with the Dark Triad. The algorithm’s propensity to create highly personalized, often extreme or niche content “rabbit holes” can cater to and reinforce manipulative tendencies (Machiavellianism), grandiosity and attention-seeking (Narcissism), or sensation-seeking and callousness (Psychopathy). Furthermore, the platform facilitates anonymous or pseudonymous expression, allowing individuals high in Dark Triad traits to engage in hostile communication, manipulation, dominance displays, and superficial interactions with significantly reduced risk of real-world repercussions [13,14]. This lowered barrier to antisocial online behavior could fuel compensatory use and addiction.

Besides, there is a significant theoretical gap involving the potential mediating role of social ostracism in the extant literature. It refers to the experience of interpersonal exclusion or rejection. Individuals high in Dark Triad traits often provoke social ostracism in face-to-face settings due to their manipulative, self-centered, and unempathetic behaviors [15,16]. Compensatory Internet Use Model [17] suggests that such rejected individuals may turn to online environments, like social media, to fulfill thwarted belongingness and self-esteem needs [18,19]. TikTok, with its promise of connection, validation (e.g., through likes, followers), and curated social spaces, might become a particularly attractive refuge. However, whether social ostracism mediates the relationship between the distinct Dark Triad traits and TikTok addiction remains untested. Existing research frequently treats the Dark Triad as a unitary construct or examines traits in isolation, neglecting their potentially unique direct and indirect (via ostracism) pathways to addiction within specific platform contexts like TikTok [11,15].

To address these gaps, this study investigates both the direct effects of Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy on TikTok addiction and their indirect effects mediated through experiences of social ostracism. This study is based on the hypothesis that each Dark Triad trait has a distinct relationship with TikTok addiction. These traits may either directly influence addiction or act indirectly through increased ostracism. The aim of this study is to explore how these dark personality traits interact with specific features of TikTok to drive addiction. This study examines these relationships among Chinese university students. It aims to contribute to the literature in several ways: (1) shedding light on platform-specific addiction mechanisms, (2) broadening our understanding of the Dark Triad beyond general social media use, and (3) providing insights for more targeted interventions.

2.1 Compensatory Internet Use Model as the Lens

Kardefelt-Winther’s [17] Compensatory Internet Use Model provides a framework for understanding problematic internet use. It views it as a coping mechanism aimed at addressing unmet psychosocial needs rather than a pathological obsession. Dark personality traits like Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy often lead to social exclusion. This is because individuals with these traits tend to manipulate others and remain emotionally detached. As a result, they may experience a loss of belonging and struggle with low self-worth. [20]. This exclusion creates significant psychosocial voids that drive individuals toward compensatory behaviors, steering them to platforms like TikTok, which offers an efficient reward system. TikTok’s algorithm delivers continuous affirmation via personalized content, replacing the social validation typically gained offline with virtual recognition. Additionally, the platform’s anonymity provides a low-risk outlet for expressing hostile tendencies that may not be voiced in face-to-face interactions [13]. At the same time, the platform’s short-form, immersive experience helps users quickly alter their mood, offering an immediate escape from the distress caused by social rejection. Over time, this reliance on compensatory behaviors can evolve into TikTok addiction, marked by a loss of control and negative life impact [1–3]. Thus, social ostracism acts as a mediator between dark personality traits and addiction. The social deficits caused by these traits are transformed into compulsive platform engagement through ongoing compensatory use.

2.2 TikTok and TikTok Addiction

TikTok, a short-video social platform developed by ByteDance, was launched in May 2017 with the mission “to inspire creativity and bring joy”. It allows users to create and explore short videos directly on their smartphones, enabling the sharing of creative ideas and meaningful moments. The platform offers a range of features: users can create videos by clicking the “+” icon on the homepage, add sounds and effects, and use editing tools like the library. Eligible creators can activate the video gift feature to earn diamonds and generate revenue. On the Discover page, users can browse trending videos or search for specific content. TikTok is available on both mobile and PC, with the PC web version divided into four sections: Recommended, Following, Explore, and Live. Through TikTok Live, creators can interact with their audience in real time, host multi-person broadcasts, and set up live events to notify viewers about upcoming streams. The platform’s subtitle and translation tools auto-generate titles, subtitles, and text sticker translations, helping to overcome language barriers. The For You section recommends videos based on user interests and engagement, with an option to provide feedback by selecting “Not Interested” to refresh the feed. Additional features include series videos, special effects, real-time subscriptions, and subscriber-only content. As of 2024, TikTok has 2.05 billion registered users worldwide, with over 1 billion monthly active users. It is also available in more than 150 countries and regions [4].

The rapid growth of TikTok has sparked increasing concerns over its potential for misuse [21]. Improper use of TikTok is commonly considered a type of social media addiction. It is characterized by symptoms such as difficulty controlling screen time, psychological withdrawal when access is limited, strong urges to continue using the platform, and an inability to stop despite its negative impact on daily life [2,22]. Research has shown that social media addiction can lead to a range of mental health issues, including depression, social anxiety, psychological distress, and sleep disorders [1,23,24]. TikTok addiction is a subset of the broader category of social media addiction, sharing common addiction mechanisms, effects, and coping strategies. However, it also has unique characteristics linked to the platform’s specific features. TikTok, with its focus on short, fragmented, and entertaining videos, creates a format that quickly captivates users. This leads to addictive behaviors that differ from those found on platforms focused on images, text, or long-form videos [25]. Studies have suggested that certain groups, such as women, younger individuals, low-income populations, and those with lower education levels, are at a higher risk of developing an addiction to TikTok [6,7]. Although these findings provide valuable insight into the risk factors associated with TikTok addiction, the underlying mechanisms driving this addiction remain an area for further research.

2.3 Dark Triad and TikTok Addiction

Personality traits are the stable and enduring patterns of behavior, thought processes, and emotional responses that define an individual. These traits play a key role in shaping how a person perceives the world, interacts with others, and copes with various life situations. Research has shown that personality traits can be strong indicators of social media addiction tendencies. For example, Blackwell et al. [8] found that higher Extraversion and higher Neuroticism positively predicted frequent social media use. Similarly, in Zhang et al.’s [26] study on short-video-based social media addiction, higher Agreeableness was identified as a protective factor, while higher Extraversion and higher Neuroticism remained as risk factors. Montag and Markett [9], examining TikTok addiction, confirmed that higher Neuroticism was a strong risk predictor. They also found that higher Conscientiousness helped mitigate the risk of TikTok addiction. These findings highlight the strong connection between personality traits and social media addiction, particularly TikTok addiction, shedding light on how certain traits predict and influence social media usage patterns. However, they primarily center on the Big Five personality traits and largely overlook the influence of dark personality traits, such as those found in the Dark Triad.

The Big Five represent broad dimensions of personality that focus on normal psychological patterns and behaviors. In contrast, the Dark Triad is centered on antisocial traits [27]. The Dark Triad includes Machiavellianism, which involves manipulation, deceit, and self-interest in relationships; Narcissism, marked by an inflated sense of self-importance, a need for admiration, and a disregard for others; and Psychopathy, characterized by impulsivity, a lack of empathy, and an indifference to societal norms. These three traits are linked to antisocial behavior and have negative impacts on interpersonal relationships and social interactions. Recent studies have examined how these dark traits relate to social media addiction [12]. For example, Tang et al. [10] showed that all three Dark Triad traits are positively linked to social media addiction. Wang et al. [11] highlighted the distinct links between these traits and addiction symptoms, with Machiavellianism associated with conflict, Psychopathy with aggression, and Narcissism with withdrawal. They also found that Narcissism had the strongest impact on the overall relationship network. Moreover, in the study by Liao et al. [28], Machiavellianism and Narcissism had a direct effect on social media addiction, while Psychopathy did not directly influence social media addiction. While these studies have advanced our understanding of how dark personality traits contribute to social media addiction, more research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms at play, particularly in relation to platform-specific addictions like TikTok.

2.4 Social Ostracism as a Potential Mediator

We proposed that social ostracism may serve as a potential mediator in the relationship between the Dark Triad and social media addiction, as it is closely linked to both. Social ostracism refers to the experience of exclusion or isolation from others or society, which makes it difficult for individuals to integrate into social environments or circles [29]. For instance, in a school setting, when certain students deliberately exclude a peer from activities or isolate them, this exemplifies social ostracism. Research has shown that individuals with Dark Triad are more prone to experiencing social ostracism [30–32]. For example, Huang et al. [15] found that the Dark Triad positively predicts social ostracism, which may, in turn, lead to school bullying. Similarly, in organizational psychology, Xu et al. [16] revealed that the Dark Triad not only directly predicts workplace ostracism but also indirectly influences it through self-serving cognition. On the other hand, previous studies have suggested a strong link between social ostracism and social media addiction [33,34]. Arslan and Coşkun [18] found that social ostracism directly predicts social media addiction, with mindfulness acting as a protective factor. Lim [19] also demonstrated that social ostracism exacerbates addiction to platforms like Facebook. Yue et al. [35] further confirmed this relationship in more recent research.

While these studies have deepened our understanding of the connections between the Dark Triad, social ostracism, and social media addiction, there are still several gaps in the current literature. First, although these studies suggest that social ostracism might mediate this relationship, empirical research is lacking to confirm this. Second, there is limited exploration of how the Dark Triad influences the addiction mechanisms specific to short-video platforms like TikTok. Third, existing studies typically treat the Dark Triad as a unified construct, overlooking the distinct characteristics of Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, and Narcissism. This hinders the identification of the specific mechanisms through which each trait contributes to TikTok addiction. Finally, most research has not analyzed all three Dark Triad traits and TikTok addiction within the same model, treating them as independent variables. However, as these traits often coexist within individuals, it is crucial to examine them together to better understand their combined effects and potential interactions. To address these gaps, our aim is to test whether social ostracism mediates the relationship between the three Dark Triad traits and TikTok addiction.

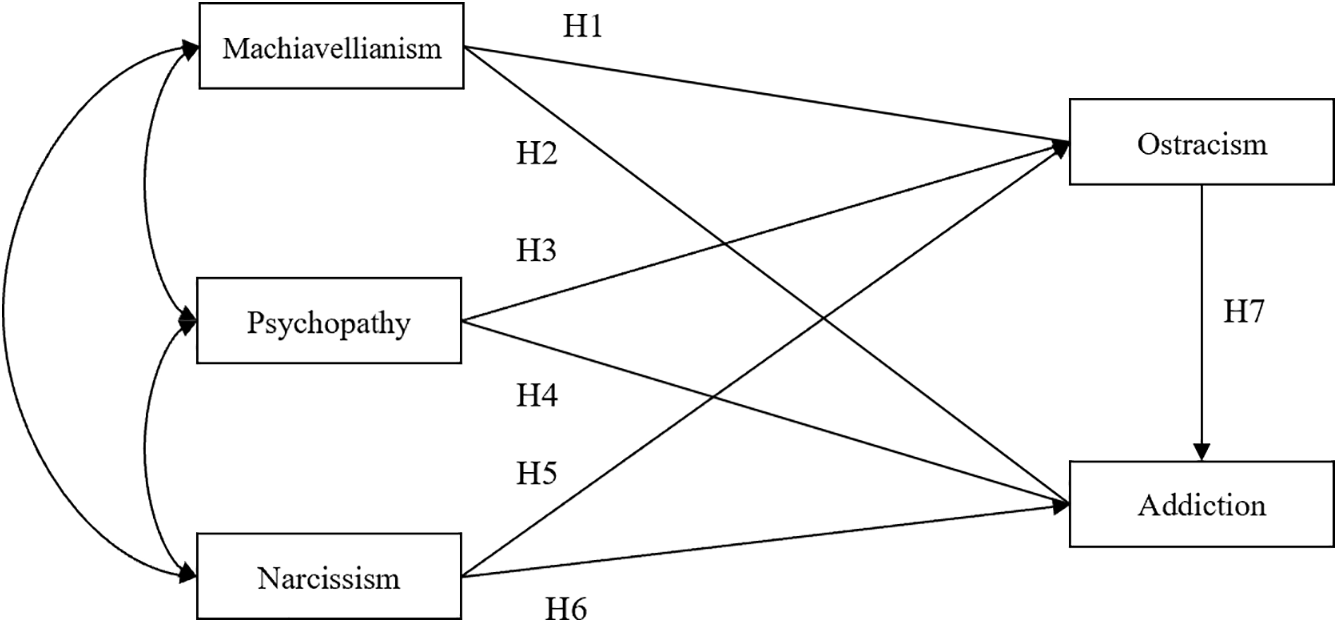

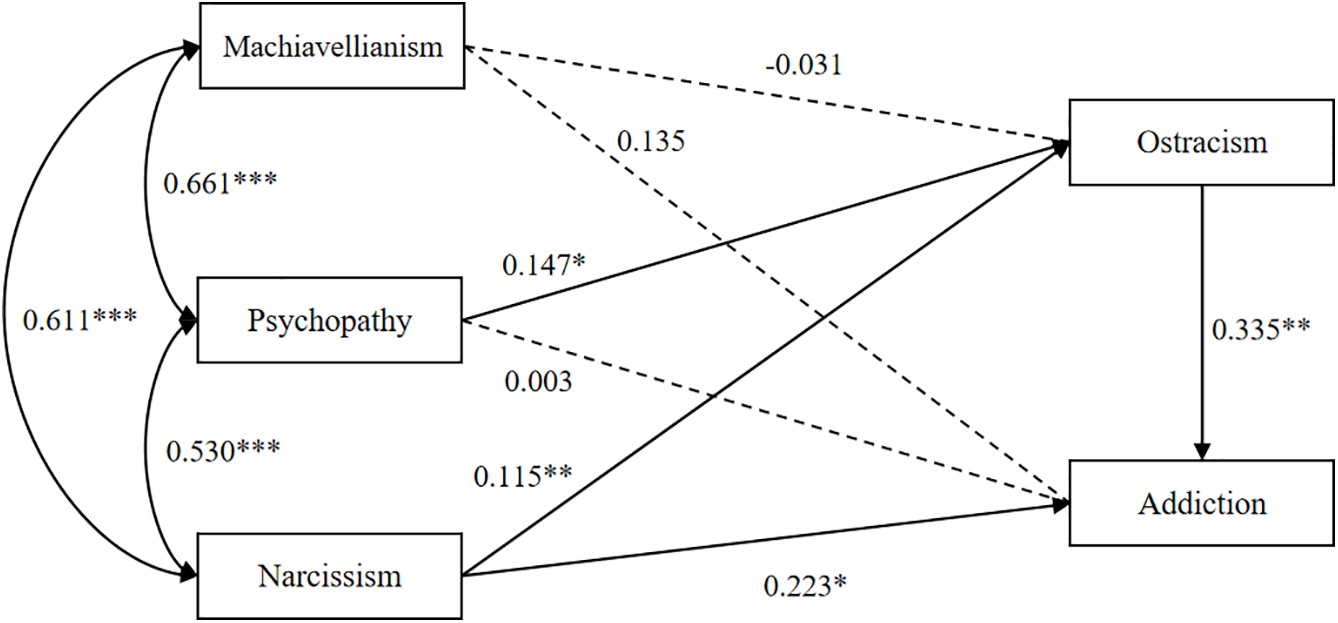

Drawing on the Compensatory Internet Use Model [17] and recent empirical advances [32–34], we propose a conceptual model (illustrated in Fig. 1) to examine both direct and mediating effects. Specifically, we hypothesize that each component of the Dark Triad (Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, and Narcissism) exhibits positive associations with TikTok addiction. Furthermore, these traits are expected to link with higher levels of social ostracism, which in turn increase vulnerability to TikTok addiction. Crucially, social ostracism is hypothesized to act as a mediator linking each Dark Triad trait to TikTok addiction. The following hypotheses formalize these proposed relationships:

Figure 1: The proposed model on the Dark Triad, social ostracism, and TikTok addiction. Note: H, hypothesis

Direct Effects:

Hypothesis 1: Machiavellianism positively explains TikTok addiction.

Hypothesis 2: Machiavellianism positively explains social ostracism.

Hypothesis 3: Psychopathy positively explains TikTok addiction.

Hypothesis 4: Psychopathy positively explains social ostracism.

Hypothesis 5: Narcissism positively explains TikTok addiction.

Hypothesis 6: Narcissism positively explains social ostracism.

Hypothesis 7: Social ostracism positively explains TikTok addiction.

Mediation Effects:

Hypothesis 8: Social ostracism mediates the relationship between Machiavellianism and TikTok addiction.

Hypothesis 9: Social ostracism mediates the relationship between Psychopathy and TikTok addiction.

Hypothesis 10: Social ostracism mediates the relationship between Narcissism and TikTok addiction.

We used convenience sampling to recruit undergraduate participants from a university in Henan, China. To increase the diversity of the sample, we purposively distributed questionnaires across five academic disciplines: Chinese Education, English, Visual Communication, Hydraulic and Hydroelectric Engineering, and Environmental Design. Participants were required to be full-time students aged 18 or older, active TikTok users for over three months, and voluntarily willing to complete the survey.

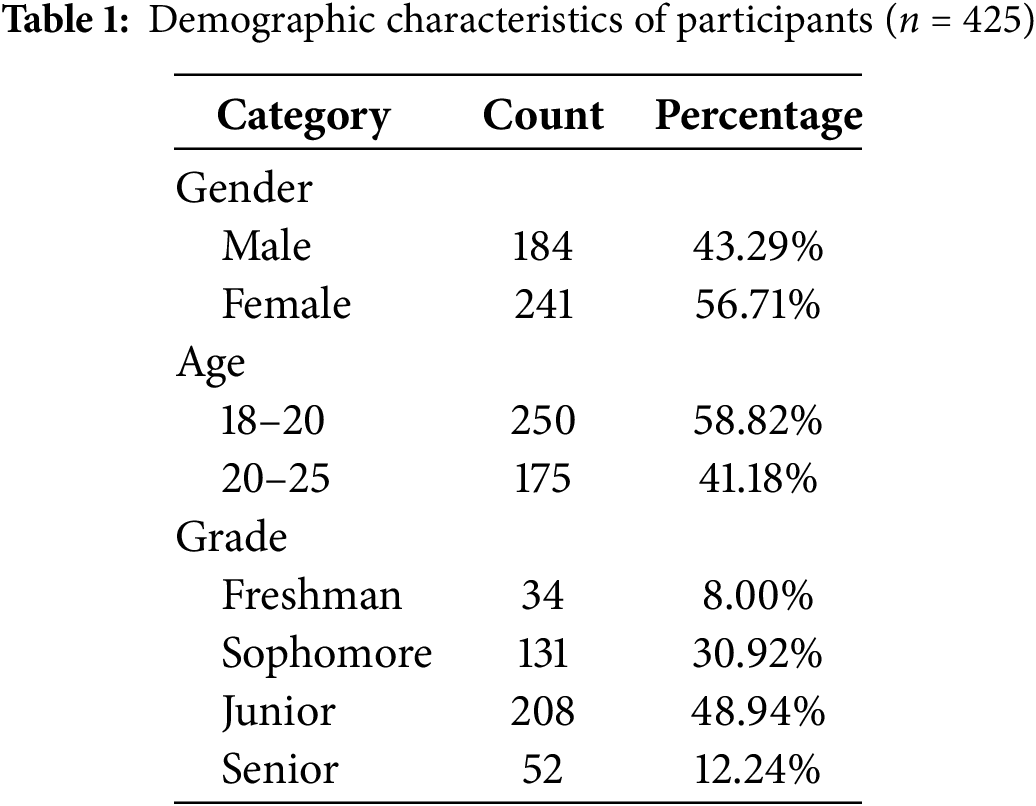

The survey was administered through Wenjuanxing, a secure online platform. Before participation, all participants were detailed the research objectives, data anonymity and encryption, the voluntary nature of participation with explicit withdrawal rights. They were also informed that no financial compensation would be provided. Formal electronic informed consent was obtained from all 558 initial participants. After excluding 133 invalid responses due to uniform answering, the final sample consisted of 425 participants (Mean age = 20.271, standard deviation [SD] = 1.770). The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

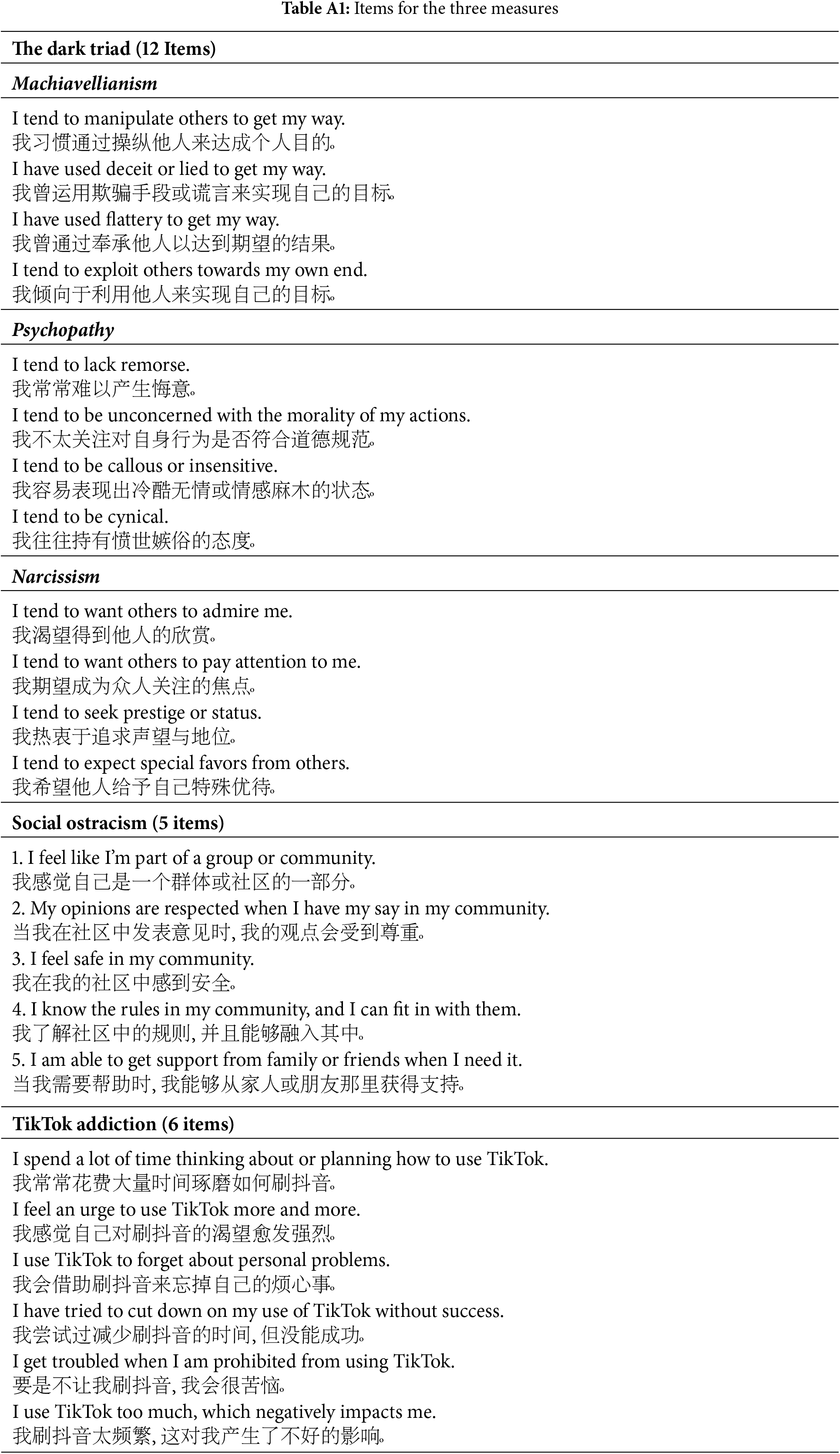

All self-report scales underwent rigorous translation: three bilingual researchers performed initial translations, followed by professional back-translation verification for conceptual accuracy. Participants completed the validated Chinese versions (full items in Table A1). Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power (No. NCWUSFS20250303).

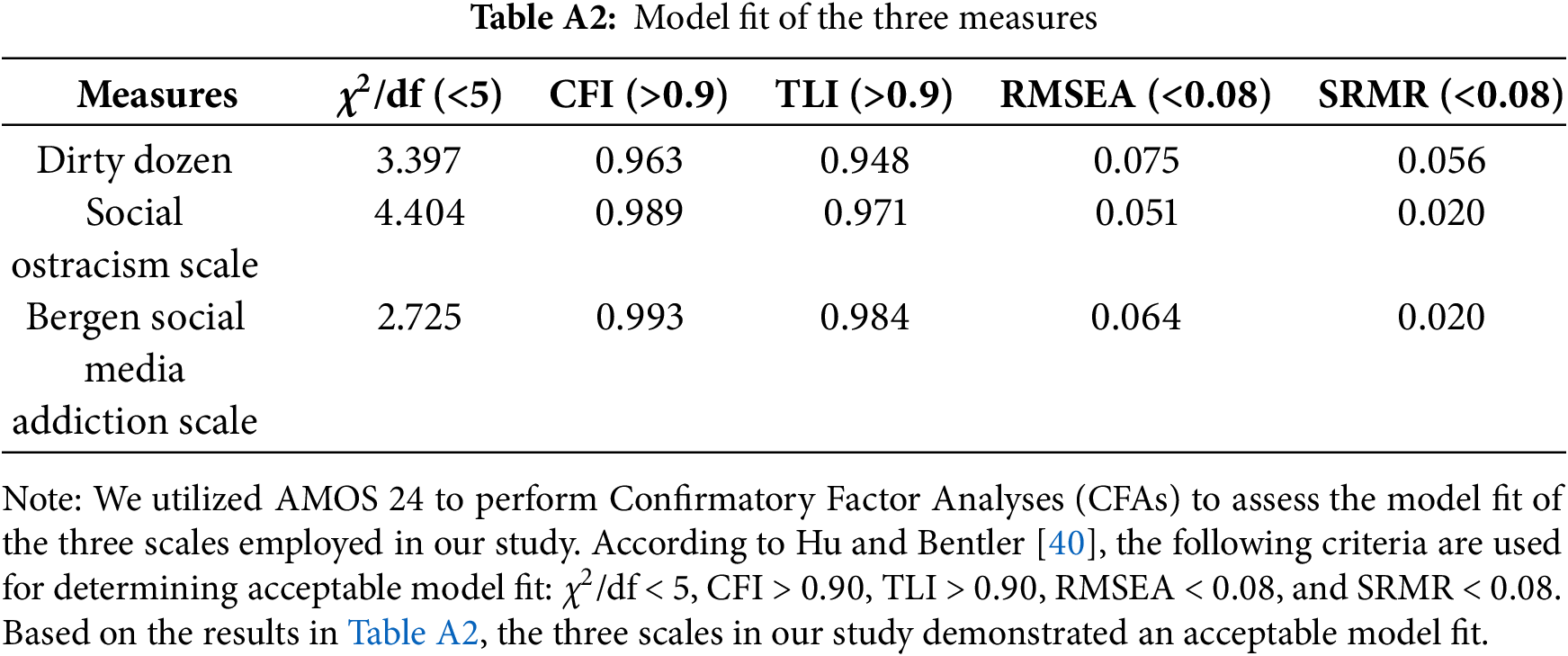

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted to examine the factor structure of the measures utilized in this study, with detailed results provided in Table A2.

We utilized the 12-item Dirty Dozen scale, which is a brief assessment tool for the Dark Triad, as devised by Jonason and Webster [36]. This scale was employed to evaluate the participants’ levels of Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy, with each trait assessed through four specific items. The participants were asked to rate each item on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores on this scale correspond to a higher degree of dark personality traits. The reliability of this scale in our study was found to be high. The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.903, which exceeded the threshold of 0.7 [37].

We adopted the 5-item Social Ostracism Scale developed by O’Donnell et al. [38] to assess participants’ perceived social ostracism. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). All items were reversely scored. Higher scores on this scale indicate a higher level of perceived social ostracism. The reliability of this scale in our study was found to be high, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.899 (>0.7) [37].

3.2.3 Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

We adapted the 6-item Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale developed by Leung et al. [39] to measure participants’ TikTok addiction. The items were modified to suit the TikTok context. Participants rated each item on a 6-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale indicated a greater degree of TikTok addiction. The reliability of the scale in our study was found to be excellent, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.911 (>0.7) [37].

Data analyses were performed using AMOS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Initially, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS 24.0 evaluated the three measures’ fit using standard indices including comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with detailed threshold criteria and results presented in Table A2 [40]. Afterward, descriptive statistics computed in SPSS 26.0 focused on assessing normality assumptions through skewness and kurtosis evaluation, as these are essential prerequisites for covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) [41]. Subsequent Pearson correlation analysis examined bivariate relationships between variables, with correlation coefficients interpreted using Cohen’s conventional criteria: r = 0.10 (small effect), 0.30 (medium effect), and 0.50 (large effect) [42]. Finally, path analysis via CB-SEM tested the hypothesized structural relationships. Direct effect was judged to be significant based on p < 0.05. Mediation effects were examined using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples [43], where indirect effects were deemed statistically significant if the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) excluded zero.

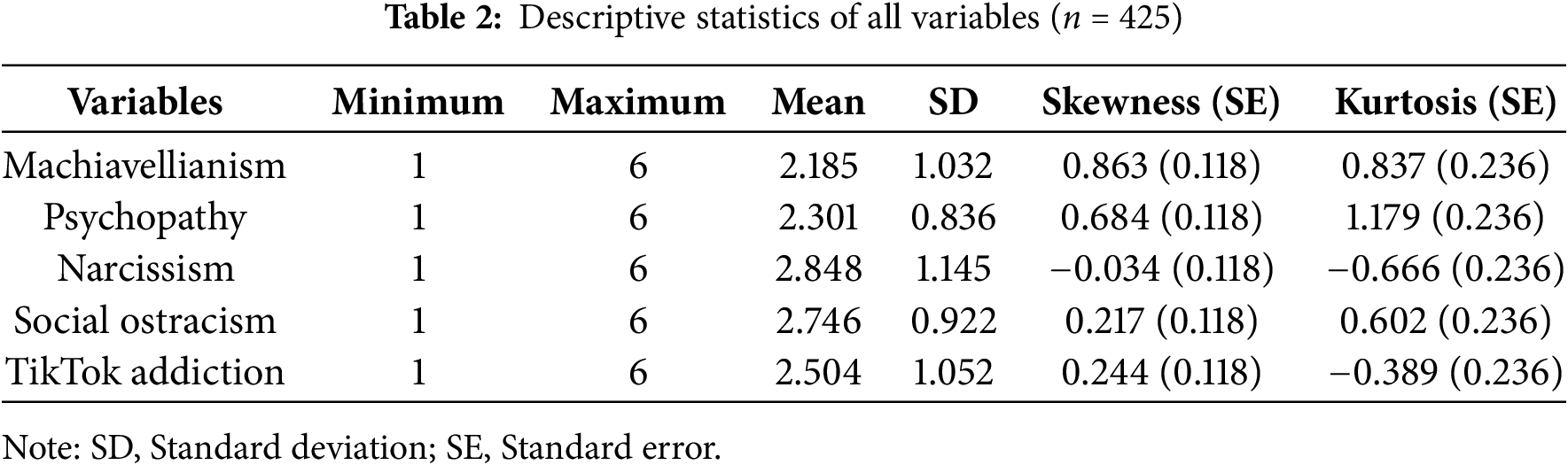

To begin with, we conducted a descriptive statistical analysis on the dataset. As illustrated in Table 2, the mean of the five variables was generally low, spanning from 2.185 to 2.746. This suggests that participants tended to have relatively low to moderate levels of the measured constructs. Furthermore, in line with the criteria established by Kline [41], skewness and kurtosis values within the range of −2 to +2 are usually taken as evidence of a normal distribution. In our case, the skewness and kurtosis values varied between −0.666 and 1.179, which confirms that the data distribution was normal. This finding sets a solid foundation for our subsequent CB-SEM analysis.

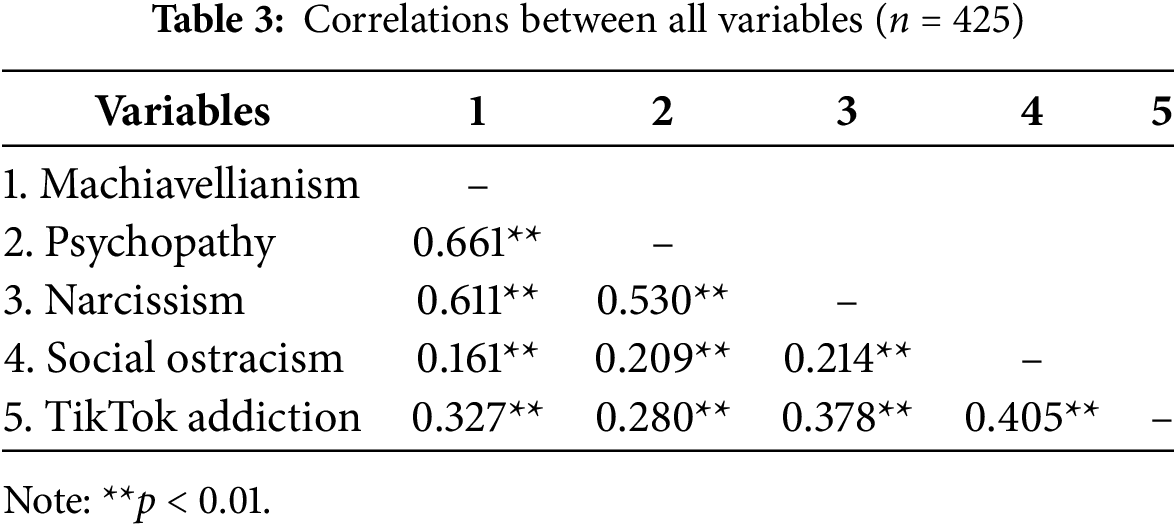

Next, we conducted a Pearson correlation analysis to examine variable relationships. As shown in Table 3, correlations between the three dark personality traits and both social ostracism and TikTok addiction ranged from 0.164 to 0.378. According to Cohen’s conventional criteria, these coefficients represent small to medium effect sizes (0.10 ≤ r < 0.30 = small; 0.30 ≤ r < 0.50 = medium) [42]. These findings establish preliminary support for further analysis, as Kline [41] confirms correlation is a necessary precondition for CB-SEM.

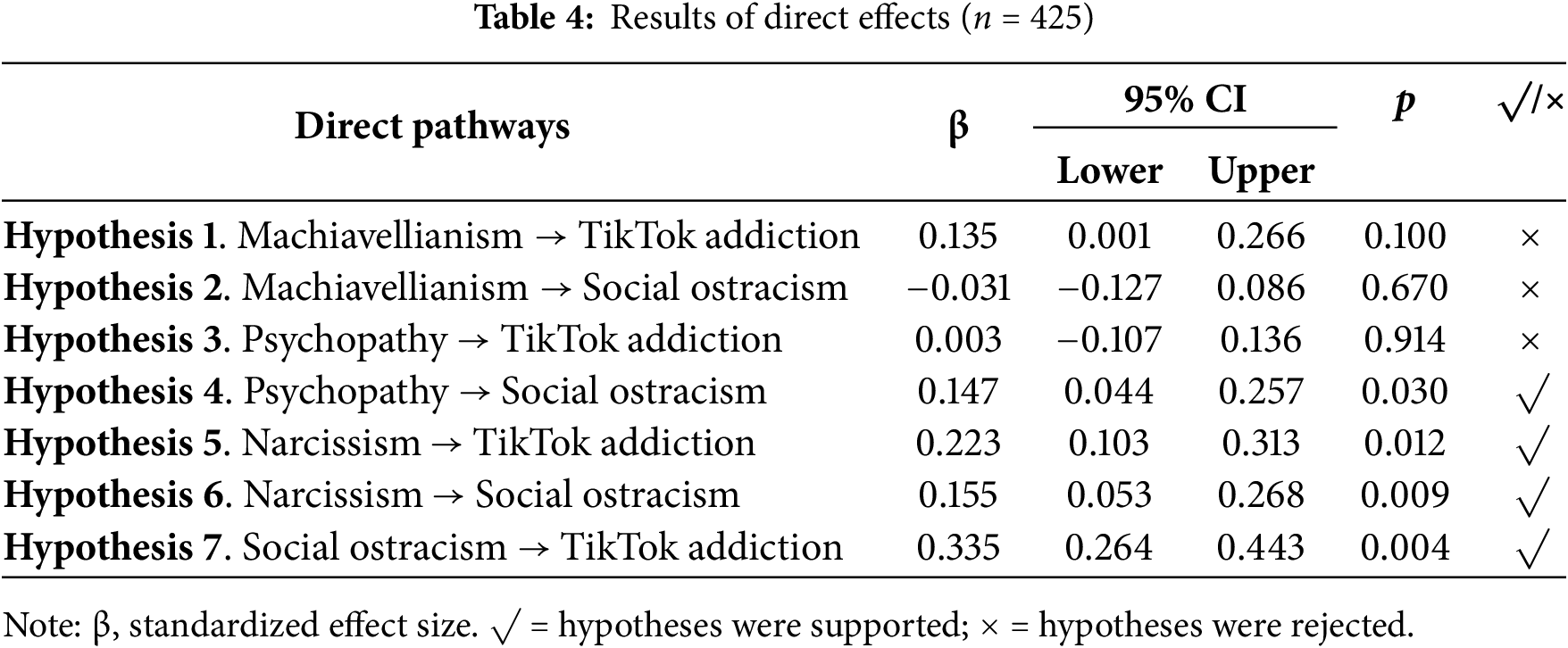

We conducted an SEM analysis to examine the relationships between our variables. The mediation model resulting from this analysis is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The mediation model on the Dark Triad, social ostracism, and TikTok addiction (n = 425). Note: All coefficients were standardized; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Solid lines represent significant pathways, while dotted lines indicate non-significant ones

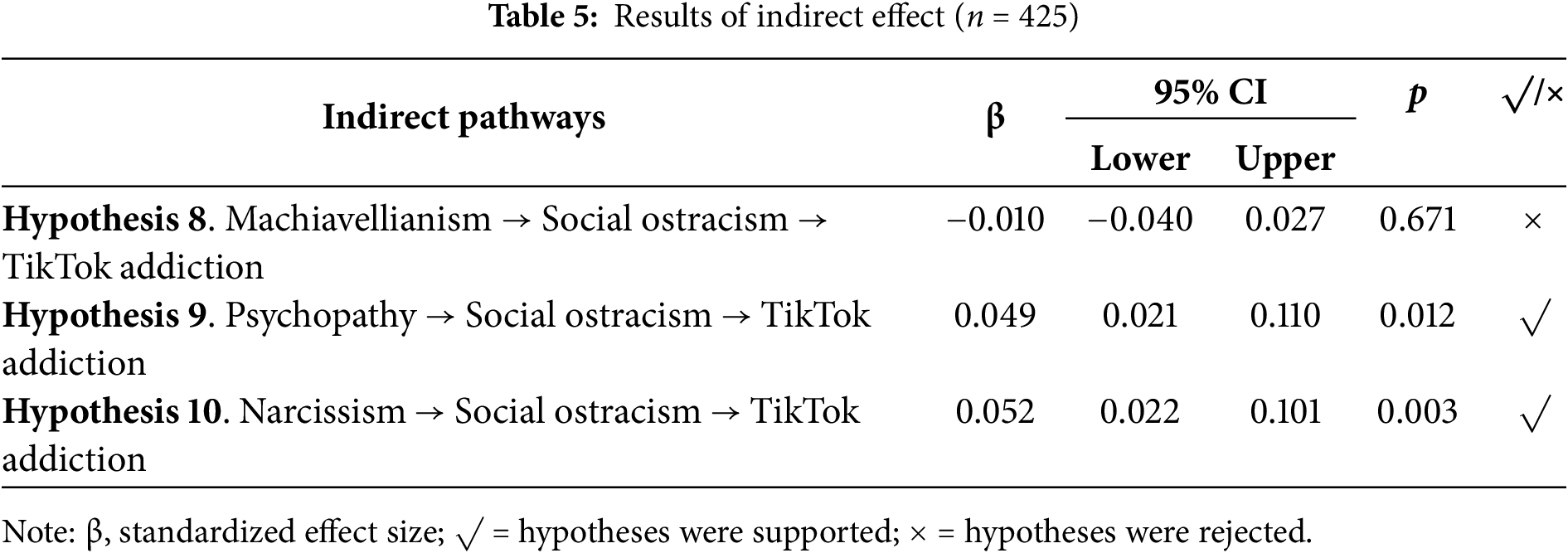

Regarding direct effects (Table 4), Machiavellianism showed no significant association with TikTok addiction (β = 0.135, p > 0.05) or social ostracism (β = −0.031, p > 0.05), leading to rejection of Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. Psychopathy was not significantly linked to TikTok addiction (β = 0.003, p > 0.05) but demonstrated a positive direct relationship with social ostracism (β = 0.147, p < 0.05), resulting in rejection of Hypothesis 3 but support for Hypothesis 4. Narcissism was positively associated with both TikTok addiction (β = 0.223, p < 0.05) and social ostracism (β = 0.155, p < 0.05). Similarly, social ostracism exhibited a positive direct association with TikTok addiction (β = 0.335, p < 0.05). Consequently, Hypothesis 5, Hypothesis 6, and Hypothesis 7 were all supported.

Regarding indirect effects, Table 5 indicates that social ostracism did not mediate the relationship between Machiavellianism and TikTok addiction (β = −0.010, 95%CI [−0.040, 0.027]), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis 8. However, both Hypothesis 9 and Hypothesis 10 were supported, as social ostracism mediated the positive effect of Psychopathy on TikTok addiction (β = 0.049, 95%CI [0.021, 0.110]), as well as the positive effect of Narcissism on TikTok addiction (β = 0.052, 95%CI [0.022, 0.101]).

Given the growing concerns regarding problematic TikTok use, we investigated how dark personality traits influence TikTok addiction through the mediation of social ostracism. Initially, we validated the potential of CB-SEM. Subsequently, a mediation analysis was performed to test our hypotheses, uncovering several interesting findings.

In detail, contrary to hypotheses derived from general social media addiction research [10,11], Machiavellianism failed to directly predict TikTok addiction (Hypothesis 1 rejected) and showed no association with social ostracism (Hypothesis 2 rejected). This contradicts the findings of Tang et al. [10], which identified Machiavellianism as a robust predictor of addiction across platforms like Facebook and Twitter. The inconsistency may stem from TikTok’s algorithmic structure and interaction norms. Unlike text-based platforms where Machiavellian individuals strategically manipulate narratives or curate follower networks (e.g., spreading misinformation on Twitter), TikTok’s emphasis on short, visually driven content limits opportunities for calculated, long-term social engineering. The platform’s “For You” page algorithm autonomously distributes content based on engagement metrics rather than user-driven networking, reducing the utility of Machiavellian tactics (e.g., building alliances, exploiting hierarchical relationships). Consequently, individuals high in Machiavellianism may perceive TikTok as less rewarding for their manipulative goals, leading to disengagement or non-addictive use.

Furthermore, while social ostracism was found to directly and positively predict TikTok addiction, aligning with previous studies [18,35] and supporting Hypothesis 7, the absence of mediation through social ostracism (Hypothesis 8 rejected) challenges findings in organizational psychology. Xu et al. [16] found that Machiavellianism has consistently been shown to predict ostracism in workplace environments. This divergence suggests TikTok’s environment may alter the psychological impact of Machiavellian tendencies rather than buffer real-world consequences. Specifically, the platform’s structure could mitigate the affective outcomes of offline ostracism through features enabling compensatory use. For instance, the platform’s anonymity and ephemeral interactions (e.g., fleeting comments, transient trends) provide a low-risk environment where manipulative behaviors face reduced immediate social accountability. This may prevent the negative affective states typically following offline ostracism, while still requiring future research to examine online behavioral consequences. Thus, while Machiavellianism correlates with ostracism in tangible social contexts [15], its psychological sequelae may be attenuated through TikTok’s detached, algorithm-driven environment. This setting facilitates compensatory use, which may reduce the pathway to ostracism.

Psychopathy did not directly predict TikTok addiction (Hypothesis 3 rejected), conflicting with the network analysis of Wang et al. [11]. They highlighted Psychopathy as a key node in general social media addiction. However, it positively predicted social ostracism (Hypothesis 4 supported), which mediated its relationship with addiction (Hypothesis 9 supported). This indirect pathway aligns with the Arslan and Coşkun [18] model, where ostracism drives compensatory social media use. However, it diverges by identifying Psychopathy as the antecedent, a pathway that has received less attention in the context of short-video platforms. The lack of a direct Psychopathy-TikTok addiction link may reflect platform-specific constraints. TikTok’s community guidelines and content moderation (e.g., filtering hate speech, banning troll accounts) may suppress overtly antisocial behaviors linked to Psychopathy, such as cyberbullying or harassment, although we did not directly assess behavioral manifestations or platform enforcement mechanisms. As a result, psychopathic individuals may speculatively channel their impulsivity into passive, binge-watching behaviors rather than active rule-breaking. This is particularly true in the absence of data on specific usage patterns (e.g., active vs. passive engagement), which makes their platform use less overtly “addictive” by traditional metrics. The mediation through social ostracism, noting that ostracism was assessed in terms of real-world experiences, suggests that psychopathic users’ interpersonal difficulties offline (e.g., callousness, poor empathy) provoke exclusion. This exclusion, in turn, drives them to seek solace in TikTok’s immersive content. This mirrors the findings of Lim [19] on Facebook addiction but introduces a novel personality-driven mechanism. Unlike Lim’s focus on surveillance use as the mediator, this study positions Psychopathy as a predisposing factor for ostracism, which then exacerbates addiction. This pathway has been—underexplored in short-video platform research.

Narcissism directly predicted TikTok addiction (Hypothesis 5 supported) and social ostracism (Hypothesis 6 supported), with ostracism further mediating its effect on addiction (Hypothesis 10 supported). These results align with the emphasis of Wang et al. [11] on Narcissism’s centrality in social media addiction networks, but extend them by incorporating a platform-specific mediator. The direct effect underscores TikTok’s unique capacity to gratify narcissistic needs. Features like viral challenges, duets, and real-time follower metrics provide immediate validation, enabling users to curate a grandiose self-image. For example, narcissistic individuals may compulsively post content to maintain perceived social status, driven by the “like”-based reward system on the platform. This mechanism is less salient in text-heavy platforms like Twitter. The mediation via social ostracism introduces a paradox: while narcissistic users actively seek admiration, their self-centered behaviors (e.g., dominating conversations, showing off) may alienate peers in offline contexts, as observed in the study of Huang et al. [15] on school bullying. It should be noted that while TikTok may serve as a compensatory space for offline rejection, narcissistic behaviors could also provoke online ostracism through negative feedback or exclusion from digital communities. This suggests that platform affordances don’t universally prevent social consequences. This exclusion could intensify their reliance on TikTok as an alternative arena for social validation, creating a feedback loop where offline rejection fuels online compensatory behavior. Additionally, the current operationalization primarily reflects grandiose narcissism; future investigations should examine how vulnerable narcissism might differentially relate to ostracism and compensatory patterns. This dual pathway (direct and indirect) distinguishes Narcissism from other Dark Triad traits, revealing how narcissistic individuals may rely on social media to offset real-world interpersonal failures.

It is important to note that the significant bivariate correlations observed between specific Dark Triad traits (Machiavellianism, Psychopathy) and both TikTok addiction and social ostracism were diminished to non-significance in SEM. This discrepancy can likely be attributed to the differing analytical methods used. Bivariate correlations capture the zero-order association between two variables, while SEM paths represent unique direct effects, estimated by simultaneously accounting for the shared variance among all variables in the model. The decrease in path coefficients suggests that the initial bivariate relationships were partially confounded by the covariance among the Dark Triad traits themselves in the model. The non-significant direct paths in the SEM indicate that, after statistically controlling for the overlapping variance between Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, and Narcissism, none of these traits have an independent direct effect on TikTok addiction or social ostracism in this model. This pattern emphasizes the importance of considering multivariate context. It highlights that the apparent associations observed in isolation may reflect broader shared underlying mechanisms or suppression effects among the predictors, which emerge when examining their joint influence. This indicates that the collective constellation of the Dark Triad plays a more critical role in predicting the outcomes within this framework than any single trait’s unique contribution.

In summary, the findings suggest that social media addiction mechanisms may not generalize uniformly across platforms [10,11]. Three TikTok-specific affordances could potentially explain these divergences. First, TikTok’s “For You” page appears to reduce user agency in content discovery, privileging engagement metrics over social networking. This design may reduce opportunities for Machiavellianism’s strategic utility while potentially constraining psychopathic antisocial expression and amplifying narcissistic visibility. Second, short video formats might discourage sustained interaction, potentially limiting Machiavellian users’ capacity to cultivate manipulative relationships or psychopathic users’ engagement in prolonged harassment. Third, TikTok’s emphasis on aesthetics and performance could facilitate narcissistic self-presentation, whereas text-centric platforms (e.g., Reddit) may favor other traits like intellectual expression. Notably, while Montag and Markett [9] linked neuroticism to TikTok addiction via depression-driven scrolling, this study’s correlational data suggests Dark Triad traits might operate through distinct pathways tied to self-presentation (narcissism) and impulsive coping (psychopathy). Collectively, these platform-contingent patterns highlight the need to move beyond “one-size-fits-all” models of social media addiction.

6 Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study provides new insights by offering a systematic investigation of Dark Triad mechanisms on short-video platforms. Our exploratory results suggest that TikTok’s design may influence these traits in distinct ways: Narcissism seems linked to both direct and ostracism-mediated pathways to addiction, Psychopathy shows indirect effects via ostracism, while Machiavellianism did not exhibit significant relationships. These platform-specific patterns challenge the assumption that the Dark Triad has uniform effects across different social media platforms [10,11].

From a theoretical perspective, our findings tentatively suggest that TikTok may be more favorable for narcissistic self-presentation compared to other strategies like manipulative behavior (Machiavellianism) or antisocial behavior (Psychopathy), though this interpretation requires further validation. Cross-platform comparisons could provide valuable insights by exploring how similar behaviors are manifested on TikTok vs. image-based platforms such as Instagram. Experimental studies examining how specific platform features influence the expression of traits could further strengthen causal inferences. It is important to note that the dual-pathway model of narcissism proposed in this study should be interpreted with caution, as it was not formally tested against competing mediation models. Longitudinal research could help confirm these preliminary findings.

From a practical standpoint, the implications of this research should be approached cautiously. Platform developers might consider interventions such as adjustable algorithm transparency to disrupt cycles of compulsive validation-seeking. Educational programs could help adolescents recognize maladaptive coping mechanisms that link social exclusion to compensatory platform use. However, clinical applications remain speculative until future research can determine whether improving social skills can effectively reduce experiences of ostracism among at-risk users in both offline and online settings.

7 Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Several important limitations warrant consideration. The cross-sectional design precludes causal claims regarding the observed relationships, particularly the mediation pathways involving social ostracism. The exclusive reliance on self-report measures raises concerns about shared-method variance potentially inflating observed associations, especially for socially sensitive traits where participants may self-censor. Our sample of 18–25-year-old Chinese university students further limits generalizability to other demographic groups and cultural contexts. Methodologically, measuring Psychopathy and Narcissism as unidimensional constructs may obscure differential relationships across subtypes (e.g., grandiose vs. vulnerable Narcissism). Besides, the use of the Dirty Dozen scale, which has been criticized for its brevity by Jones and Paulhus [44] (only 4 items per trait), potentially oversimplifying Dark Triad constructs and compromising discriminant validity. Moreover, the Bergen scale’s origins in general social media addiction research may inadequately capture TikTok-specific behavioral patterns [39].

These limitations naturally inform priorities for future research. Longitudinal designs should examine temporal sequences, particularly whether offline ostracism precedes compensatory TikTok use. Multi-method approaches combining behavioral tracking with qualitative interviews could mitigate self-report biases while exploring how trait expressions manifest in-platform. Expanding sampling diversity across cultures and age groups would strengthen generalizability. Critically, future work should investigate online ostracism dynamics, exploring whether dark traits provoke exclusion through digital mechanisms like unfollowing or negative feedback. It should also examine how such online rejection influences subsequent platform engagement. Besides, disaggregating Psychopathy and Narcissism into validated subdimensions would clarify component-specific pathways. Moreover, developing platform-specific addiction scales remains essential for short-video contexts.

This study provides a comprehensive examination of how Dark Triad traits relate to TikTok addiction, shedding light on platform-specific relationships between personality and behavior. The findings suggest Narcissism is significantly associated with addictive patterns through observed direct connections and compensatory pathways potentially linking offline ostracism to platform engagement. Notably, Narcissism not only correlates with TikTok addiction but may also relate to increased platform validation-seeking following social exclusion, pointing to a cyclical pattern worthy of further investigation. Psychopathy, meanwhile, demonstrates indirect associations with addiction via social ostracism, hinting that its antisocial tendencies could manifest as compensatory use within TikTok’s environment. In contrast, Machiavellianism showed no significant relationships with addiction, implying that TikTok’s algorithmic curation and ephemeral interactions might limit opportunities for strategic social behaviors typically associated with this trait. Collectively, these patterns highlight how platform architectures may differentially moderate dark personality expressions, advancing context-sensitive understanding of social media addiction and underscoring the need for tailored intervention approaches.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the support from North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, China. The university had no role in the design or implementation of this study. The authors declare that AI tools were used only for polishing the language.

Funding Statement: The study reported in this paper represents a contribution to “Research Project on the Construction of Smart Teaching Capabilities in New Era Mingde College English (Grant No. 2022YB0099)” at Henan Provincial Department of Education.

Author Contributions: We declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published previously, and is not currently under consideration for publication elsewhere. The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Shijie Li: Writing—Original Draft, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Formal Analysis; Yongliang Wang: Conceptualization, Review & Editing, and Supervision. We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors, and there are no other individuals who meet the criteria for authorship but are not listed. Furthermore, we confirm that the order of authors as presented in the manuscript has been agreed upon by all of us. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Yongliang Wang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The Ethics Committee of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power approved the study, and the ethical approval number is NCWUSFS20250303.

Informed Consent: The informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

References

1. Jain L, Velez L, Karlapati S, Forand M, Kannali R, Yousaf RA, et al. Exploring problematic TikTok use and mental health issues: a systematic review of empirical studies. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2025;16:21501319251327303. doi:10.1177/21501319251327303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Smith T, Short A. Needs affordance as a key factor in likelihood of problematic social media use: validation, latent Profile analysis and comparison of TikTok and Facebook problematic use measures. Addict Behav. 2022;129:107259. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Caponnetto P, Lanzafame I, Prezzavento GC, Fakhrou A, Lenzo V, Sardella A, et al. Does TikTok addiction exist? A qualitative study. Health Psychol Res. 2025;13:127796. doi:10.52965/001c.127796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Rosales I2.05 billion people are on TikTok right now (2024 stats & facts). [cited 2025 Jun 20] Available from: https://joingenius.com/statistics/how-many-people-are-on-tiktok/#:~:text=As%20of%202024%2C%20TikTok%20has%20amassed%202.05%20billion,rise%20as%20a%20dominant%20force%20in%20social%20media. [Google Scholar]

5. Ye J-H, Zheng J, Nong W, Yang X. Potential effect of short video usage intensity on short video addiction, perceived mood enhancement (‘TikTok brain’and attention control among Chinese adolescents. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27:271–86. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.059929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lewin KM, Ellithorpe ME, Meshi D. Social comparison and problematic social media use: relationships between five different social media platforms and three different social comparison constructs. Pers Individ Differ. 2022;199:111865. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2022.111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Huang Q, Hu M, Chen H. Exploring stress and problematic use of short-form video applications among middle-aged Chinese adults: the mediating roles of duration of use and flow experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:132. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Blackwell D, Leaman C, Tramposch R, Osborne C, Liss M. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Pers Individ Differ. 2017;116:69–72. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Montag C, Markett S. Depressive inclinations mediate the association between personality (neuroticism/conscientiousness) and TikTok use disorder tendencies. BMC Psychol. 2024;12:81. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-01541-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Tang WY, Reer F, Quandt T. The interplay of the Dark Triad and social media use motives to social media disorder. Pers Individ Differ. 2022;187:111402. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang M, Su Y, Yang S, Xu K, Zhang S, Xue H, et al. A network analysis of the relationship between Dark Triad traits and social media addiction in adults. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2025. doi:10.1007/s11469-024-01425-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Turan ME, Adam F, Kaya A, Yıldırım M. The mediating role of the dark personality triad in the relationship between ostracism and social media addiction in adolescents. Educ Inf Technol. 2024;29:3885–901. doi:10.1007/s10639-023-12002-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. March E. 20-Psychopathy: cybercrime and cyber abuse. In: Marques PB, Paulino M, Alho L, editors. Psychopathy and criminal behavior. Cambridge,MA, USA: Academic Press; 2022. p. 423–44. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-811419-3.00015-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Elhami Athar M. Exploring the multidimensional nature of the psychopathy construct in social media context: insights from Instagram. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2025;17:100603. doi:10.1016/j.chbr.2025.100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Huang Y, Gan X, Jin X, Rao S, Guo B, He Z, et al. The relationship between the Dark Triad and bullying among Chinese adolescents: the role of social exclusion and sense of control. Front Psychol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1173860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Xu X, Kwan HK, Wei F, Wang Y. Who is likely to be ostracized? The easy target is the Dark Triad. Asia Pac J Manag. 2024. doi:10.1007/s10490-024-09972-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31:351–4. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Arslan G, Coşkun M. Social exclusion, self-forgiveness, mindfulness, and internet addiction in college students: a moderated mediation approach. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20:2165–79. doi:10.1007/s11469-021-00506-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lim M. Social exclusion, surveillance use, and Facebook addiction: the moderating role of narcissistic grandiosity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3813. doi:10.3390/ijerph16203813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Williams KD. Ostracism. Rev Psychol. 2007;58:425–52. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Scherr S, Wang KX. Explaining the success of social media with gratification niches: motivations behind daytime, nighttime, and active use of TikTok in China. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;124. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tian XX, Bi XH, Chen H. How short-form video features influence addiction behavior? Empirical research from the opponent process theory perspective. Inf Technol People. 2023;36:387–408. doi:10.1108/itp-04-2020-0186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Çiçek I, Sanli ME, Arslan G, Yildrim M. Problematic social media use, satisfaction with life, and levels of depressive symptoms in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediation role of social support. Psihologija. 2024;57:177–97. doi:10.2298/psi220613009c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Çiftci N, Sarman A, Çoban M. The relationship between social media addiction, insomnia, and depression in adolescents. Psychol Health Med. 2025;1–16. doi:10.1080/13548506.2025.2465659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yao N, Chen J, Huang S, Montag C, Elhai JD. Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic TikTok use severity: the mediating role of boredom proneness and distress intolerance. Comput Hum Behav. 2023;145:107751. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.107751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang L, Zhuo X-F, Xing K, Liu Y, Lu F, Zhang J-Y, et al. The relationship between personality and short video addiction among college students is mediated by depression and anxiety. Front Psychol. 2024. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1465109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wu H, Chen Z. Exploring the dark triad’s impact on second language burnout: a structural equation modeling approach. Int J TESOL Stud. 2025;250401. doi:10.58304/ijts.250401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liao CP, Wu CC, Chiu ECH. Digital vulnerability: exploring the mediating role of FoMO in the relationship between Dark Triad personality and social media addiction. J Consum Aff. 2025;59:e70002. doi:10.1111/joca.70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Williams KD, Nida SA. Ostracism and social exclusion: implications for separation, social isolation, and loss. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;47:101353. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Pu J, Gan X. When love constrains: the impact of parental psychological control on dark personality development in adolescents. Pers Indiv Differ. 2025;238. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2025.113093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang C, Guo J, Zhou X, Shen Y, You J. The Dark Triad traits and suicidal ideation in Chinese adolescents: mediation by social alienation. J Res Pers. 2023;102:104332. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Pu J, Gan X. The potential roles of social ostracism and loneliness in the development of Dark Triad traits in adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Pers. 2025. doi:10.1111/jopy.13018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Dorrestein M, Nutley SB, Thorell LB. Screen time, addictive use of social media, motives for social media use and social media content: interrelations and associations with psychosocial problems. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2025. doi:10.1007/s11469-025-01491-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li K-P, Niu G-f, Jin S-Y, Shi X-H. Social exclusion and video game addiction among college students: the mediating roles of depression and maladaptive cognition. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:31639–49. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-06749-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yue H, Yue X, Zhang X, Liu B, Bao H. Exploring the relationship between social exclusion and social media addiction: the mediating roles of anger and impulsivity. Acta Psychol. 2023;238:103980. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Jonason PK, Webster G. The dirty dozen: a concise measure of the Dark Triad. Psychol Assess. 2010;22:420–32. doi:10.1037/a0019265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Viladrich C, Angulo-Brunet A, Doval E. A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Anales de Psicologia. 2017;33:755–82. doi:10.6018/analesps.33.3.268401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. O’Donnell P, Hannigan A, Ibrahim N, O’Donovan D, Elmusharaf K. Developing a tool for the measurement of social exclusion in healthcare settings. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21:35. doi:10.1186/s12939-022-01636-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Leung H, Pakpour AH, Strong C, Lin Y-C, Tsai M-C, Griffiths MD, et al. Measurement invariance across young adults from Hong Kong and Taiwan among three internet-related addiction scales: bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMASSmartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABASand Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part A). Addict Behav. 2020;101:105969. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria vs. new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th ed. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

42. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

43. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression based approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

44. Jones DN, Paulhus DL. Introducing the short Dark Triad (SD3a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment. 2014;21:28–41. doi:10.1177/1073191113514105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools