Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Positive Youth Development and Pro-Environmental Behaviours: Examining the Role of Gender among Spanish University Students

Department of Social, Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Huelva, Huelva, 21007, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Diego Gómez-Baya. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adolescent and Youth Mental Health: Toxic and Friendly Environments)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1265-1278. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068013

Received 19 May 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: The climate crisis demands urgent action from all sectors of society, including young people in higher education. While previous research has explored individual and contextual predictors of pro-environmental behaviour (PEB), the contribution of Positive Youth Development (PYD) remains underexplored. This study investigates the relationship between PYD dimensions (Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring) and two environmental outcomes: environmental habits and climate change awareness, considering gender differences. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with a sample of 1779 students from 10 universities in Andalusia (Spain). Data were collected through an online survey assessing PYD indicators, PEB, and sociodemographic variables. Descriptive statistics, t-tests, correlation analyses, and multiple mediation models were performed. Results: Descriptive analyses indicated moderate levels of PYD dimensions and PEB across the sample. Among the 5 Cs, Caring had a positive association with environmental habits (r = 0.22, p < 0.001) and climate change awareness (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). Character also had a positive effect on both environmental habits (r = 0.23, p < 0.001) and climate change awareness (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). Competence and Confidence were not significantly associated, and Connection demonstrated limited predictive value, potentially influenced by contextual or social factors. Gender differences were also identified, with women showing higher scores in Character (d = 0.29, p < 0.001), Caring (d = 0.63, p < 0.001), environmental habits (d = 0.20, p < 0.001) and climate change awareness (d = 0.40, p < 0.001), while men scored higher in Competence (d = 0.57, p < 0.001) and Confidence (d = 0.22, p < 0.001). Mediation analyses indicated that the association between gender and environmental habits was totally explained by Character (β = −0.02; 95% CI: −0.04; −0.01) and Caring (β = −0.04; 95% CI: −0.05, −0.02). Furthermore, the relationship between gender and climate change awareness was partially mediated by Character (β = −0.03; 95% CI: −0.05; −0.02) and Caring (β = −0.05; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.03). Conclusions: Females showed more environmental habits and climate change awareness than males, because of their greater scores in both Caring and Character dimensions of PYD. These findings highlight the importance of the PYD for promoting PEB and engaged citizens among young adults. Gender-sensitive and interdisciplinary interventions, such as environmental volunteering and community-based programmes, are recommended for university contexts to enhance sustainable development behaviours and values.Keywords

Increasing evidence highlights how climate change affects not only the physical environment but also the psychosocial well-being and mental health of populations. Global climate change, through acute, sub-acute, and persistent events, has been linked to a rise in mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, especially among vulnerable populations [1,2]. Moreover, growing evidence suggests that exposure to natural environments can improve mental health by reducing stress, promoting psychological well-being, and enhancing social cohesion, thereby supporting public policies that prioritise sustainable and equitable urban planning [3]. Simultaneously, a lack of preparation among health professionals and students to address climate-related health impacts points to a gap in the integration of sustainability and climate crisis content in education systems [4]. This educational shortcoming not only weakens institutional capacity to respond effectively but also limits the potential to raise awareness and encourage interdisciplinary action [5,6]. Socioeconomic and cultural conditions also appear to shape perceptions and levels of engagement with climate change mitigation efforts [7]. In higher education, this is particularly relevant because universities play a critical role in shaping the next generation of leaders capable of addressing environmental crises.

University students today face immense opportunities and complex challenges. One of the most urgent issues is climate change, which has wide-ranging effects on ecosystems, economies, and societies [8]. Addressing this global issue requires collective action grounded in social justice, environmental stewardship, and sustainable development [9]. Frameworks such as Positive Youth Development (PYD) provide useful insights into strengthening young people’s resilience and capacity for environmental engagement. This model focuses on the transition to adulthood and emphasises how positive outcomes emerge from the interaction between individual strengths and external developmental assets [10,11]. PYD is organized through the “5 Cs”: Competence (perceived self-efficacy), Confidence (positive self-esteem), Connection (constructive relationships), Character (a sense of ethics and integrity), and Caring (empathy and compassion) [12,13]. Together, these dimensions promote a trajectory toward meaningful contributions to oneself, family, and society, often referred to as a sixth “C”: Contribution [14].

Given the urgency of environmental challenges, research has begun to explore the association between PYD and environmental outcomes such as pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs). PEBs are defined as “actions aimed at conserving the planet’s socio-physical resources” and are influenced by demographic and contextual factors such as gender, age, and social environment [15,16]. Several studies have suggested that women and individuals in rural settings tend to exhibit higher PEB levels [17–19]. Environmental education is considered essential in fostering sustainable behaviours, particularly within university contexts, to obtain the associated benefits [20,21]. For example, the ECO-MIND protocol, conducted among young adults in Bangladesh, Uganda, and the Netherlands, investigated how everyday contact with urban green spaces influences both mental health and PEB, with nature connectedness acting as a central mediating factor [22]. A recent meta-analysis also revealed significant links between ambient temperature and increased mental health risks, including suicide, psychiatric hospitalisations, and diminished community well-being, reinforcing the need for public health interventions [23].

Despite the growing interest in PYD, empirical research on its relationship with environmental values and behaviours remains limited. For instance, a study in Ghana with youth and emerging adults found that Character was positively associated with environmental responsibility, whereas Competence was negatively elated with rejecting pollution as necessary for industrial growth. Confidence and Caring were also linked to stronger environmental attitudes, although Confidence showed a negative association with conservation intentions [24]. Among adolescents in Norway, Character, Competence and Caring were positively related to PEB, whereas Confidence showed a negative association [25]. Notably, empathy, a component of Caring, has been identified as a key predictor of everyday sustainable actions such as energy conservation [26]. Experiences in nature have also promoted PYD outcomes and support the development of environmental values [27]. Thus, more research about PYD and environmental behaviours is still needed with samples of emerging adults. As well, no study to date, as far as we know, has been conducted with Spanish samples. Furthermore, different components can be separately examined, integrating results about pro-environmental habits and climate change awareness, and their associations with the 5 Cs of PYD. Finally, there is a lack of evidence that addresses gender differences when examining these variables.

More research is still needed to guide the program design in universities to implement interdisciplinary approaches that not only foster environmental knowledge and sustainable habits but also cultivate a strong sense of environmental citizenship among students [20,21]. This study examines the relationship between PYD and pro-environmental behaviours among undergraduate students in Andalusia (Spain), by gender. Specifically, it seeks to determine the predictive role of each of the 5 Cs on PEB. Based on previous evidence, we hypothesize that the PYD dimensions of Caring, Character, and Connection will show stronger associations with pro-environmental behaviours. Moreover, some gender differences are expected, with women reporting more PEB and greater scores in the PYD correlates.

The final sample consisted of 1779 undergraduate students (age range = 18–29; Mean = 20.32, standard deviation [SD] = 1.84), of whom 65.9% were women. Participants were recruited from ten universities across the Andalusia region (Spain), including the University of Almería, University of Cádiz, University of Córdoba, University of Granada, University of Huelva, University of Jaén, University of Málaga, University of Sevilla, Pablo de Olavide University (Seville), and Loyola University (Seville and Córdoba). A convenience sampling strategy was employed to ensure geographical representation, with degree programmes and academic years selected randomly. Participants were distributed across the following academic disciplines: Social Sciences and Law (49.4%), Sciences and Engineering (22.2%), Arts and Humanities (15.1%), and Health Sciences (13.3%). Regarding academic year, 55.1% were first-year students, 39.1% second-year, and 5.7% third to sixth year. Most students lived in family homes (47.1%), whereas only 2.9% shared accommodation with other students. Employment status data showed that 64.9% were not actively seeking work, whereas 21% held temporary jobs. In terms of habitat, 37.5% lived in cities with more than 300,000 inhabitants, 32.4% lived in cities between 50,001 and 300,000, and the remainder lived in smaller towns or rural areas.

This cross-sectional study forms part of the first phase of a longitudinal, mixed-method research project (quantitative and qualitative), conducted from March to June 2023. Data collection for this phase followed a quantitative design through an anonymous self-reported online survey administered via Qualtrics. All participating universities approved their involvement in the study. Before participation, students were provided with an information sheet and written informed consent. The inclusion criterion was enrollment in one of these Andalusian universities. The exclusion criterion was applied for those aged 29 or older. Professors at each university facilitated the dissemination of the survey link, and students completed the questionnaire during class time. The survey included instruments measuring Positive Youth Development, lifestyle, and sociodemographic variables, and took approximately 30 min to complete. Participation was voluntary, students were informed about data use, and no compensation was provided. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Huelva on 10 January 2019 (reference: UHU-1259711) [28].

2.3.1 Positive Youth Development

The short version of the PYD instrument developed by Geldhof et al. [29], adapted into Spanish for adolescent and youth populations by Gómez-Baya et al. [30], was used. This version includes 34 items across five subscales corresponding to the 5 Cs: Competence (6 items), Confidence (6 items), Character (8 items), Connection (8 items), and Caring (6 items). Sample items include: ‘I do very well in my university coursework’, ‘I feel very supported at my university’, ‘I feel happy with myself most of the time’, and ‘I never do things I know I shouldn’t do’. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The overall PYD score was calculated as the mean of the five dimensions. The instrument showed good internal consistency reliability for the total scale (α = 0.88), as well as for most dimensions (Competence: α = 0.73; Confidence: α = 0.77; Connection: α = 0.77; Caring: α = 0.82). Character had lower reliability (α = 0.59).

2.3.2 Pro-Environmental Behaviours

Pro-environmental behaviours were measured using a 10-item scale designed to assess the frequency of environmentally responsible actions. The scale comprised two subscales: four items adapted from the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas scale [31] and six items developed specifically for this study. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The first subscale was rated from ‘Always’ or ‘Almost Always’ to ‘Never’ or ‘Rarely’. Sample items include: ‘When feasible, I try to walk or cycle to places’ and ‘During the cold months, I try to keep the heating high enough to wear short sleeves or light clothing’. The second subscale, focused on climate awareness, was rated from ‘Definitely Yes’ to ‘Definitely No’. Example items include: ‘If I had to buy electrical appliances, I would prioritise the price being low over energy efficiency’ and ‘If I were driving on a motorway, I would try to drive at a lower speed than the maximum allowed (120 km/h) to save fuel’. The final score was obtained by averaging the responses of both subscales. The overall scale showed adequate reliability (α = 0.67).

Sample size estimation was performed using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7, Universität Kiel, Germany). Based on a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and accounting for potential attrition, a minimum sample size of 1320 participants was deemed sufficient. Data were analysed using SPSS 27.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). First, descriptive statistics were calculated for overall PYD, the 5 Cs, environmental habits, and climate awareness. Next, Student’s t-tests were used to assess differences in overall PYD and the 5 Cs based on environmental habits and climate awareness, as well as to examine gender differences. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) (d < 0.20 = negligible; 0.20–0.49 = small; 0.50–0.79 = medium; ≥0.80 = large). Subsequently, Pearson´s correlation analysis was used to explore the associations between the 5 Cs, overall PYD, environmental habits, and climate awareness. Finally, a multiple mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS with 10,000 bootstrap samples. An age-adjusted model was applied to examine whether the relationship between gender and the outcome variables (environmental habits and climate awareness) was mediated by the five PYD dimensions.

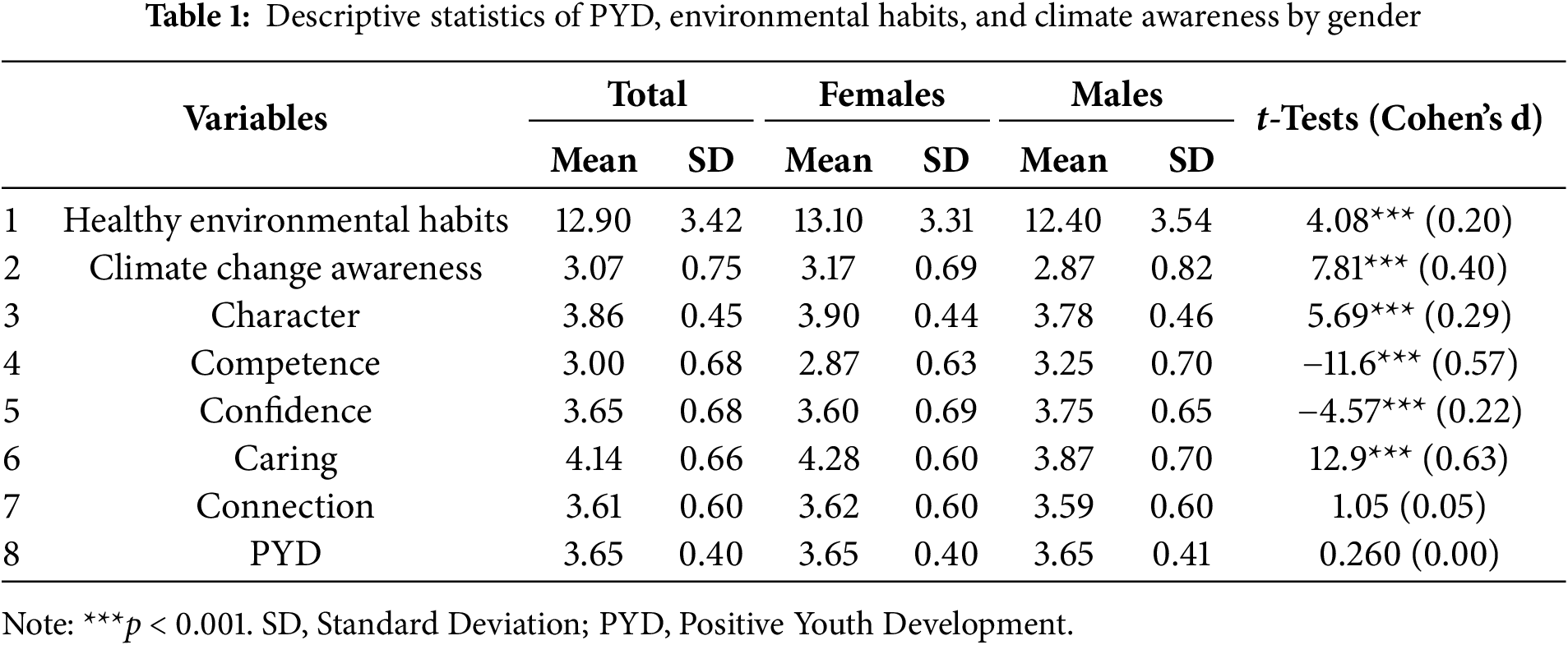

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for pro-environmental behaviours, the five PYD dimensions (5 Cs), and the overall PYD score by gender. Results indicate moderate levels of overall PYD. Regarding environmental variables, participants reported moderate levels of environmental habits (Mean = 12.90, SD = 3.42) and climate awareness (Mean = 3.07, SD = 0.75). Female students scored significantly higher than male students on both measures. Among the 5 Cs, Caring (Mean = 4.14, SD = 0.66) and Character (M = 3.86, SD = 0.45) showed the highest mean scores, while Competence had the lowest (Mean = 3.00, SD = 0.68). In terms of gender differences, females scored significantly higher in Caring and Character, whereas males scored higher in Competence and Confidence. No significant differences were found for Connection or the overall PYD.

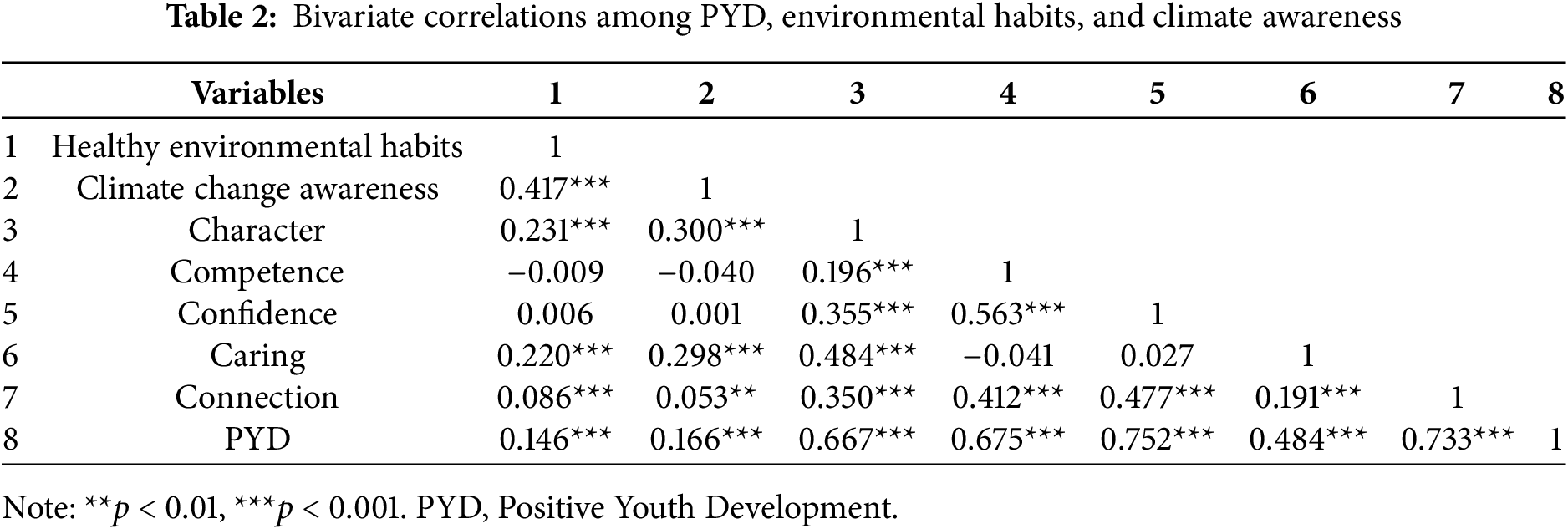

3.2 Bivariate Correlations among PYD and Environmental Variables

Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between environmental habits, climate awareness, the 5 Cs, and overall PYD. Environmental habits were positively correlated with climate awareness, Character (r = 0.231), Caring, and Connection. Climate awareness also showed significant positive correlations with Character (r = 0.300), Caring, and Connection. No significant associations were found between either environmental variable and Competence or Confidence. Both environmental variables were positively associated with the overall PYD.

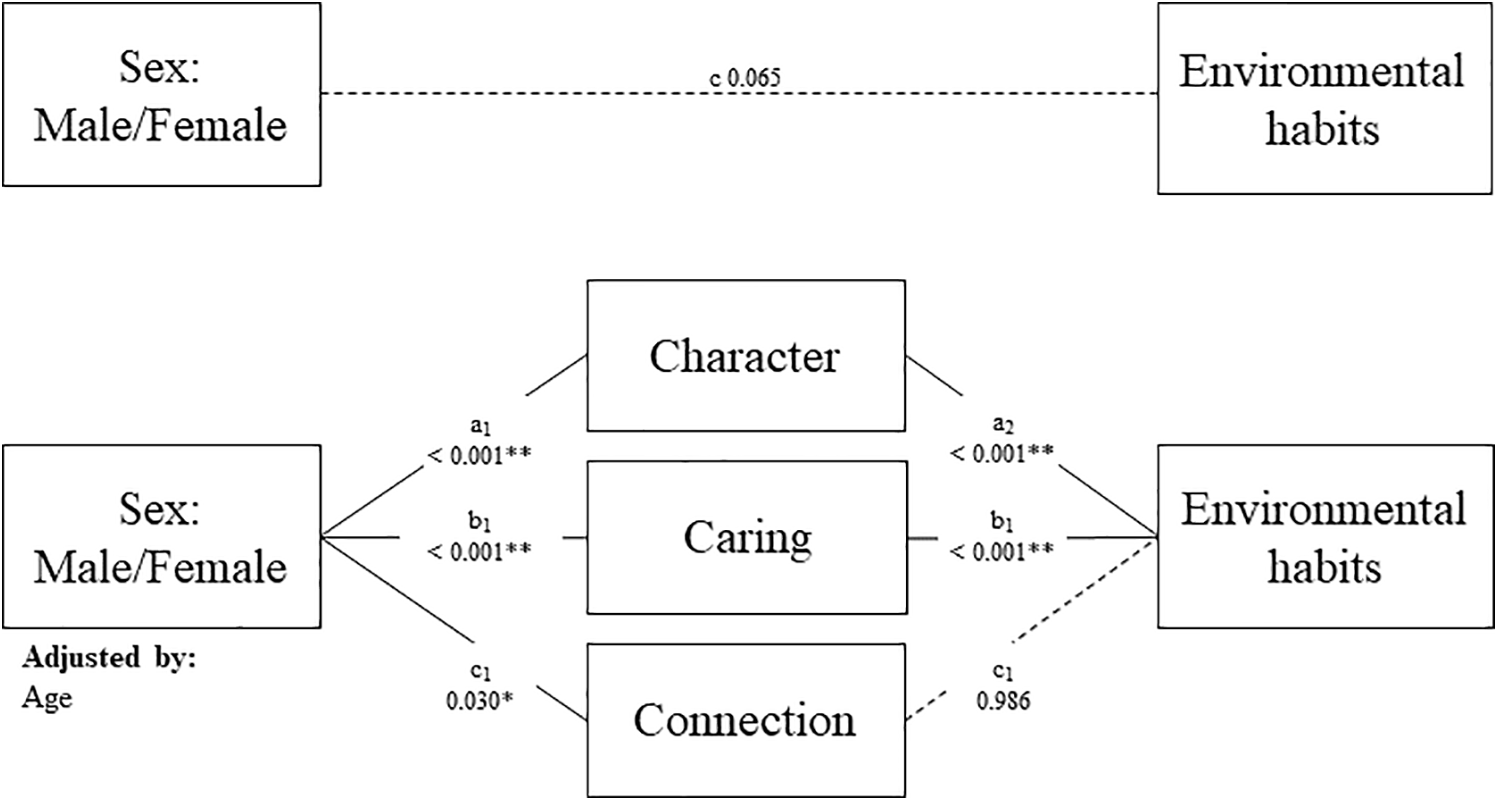

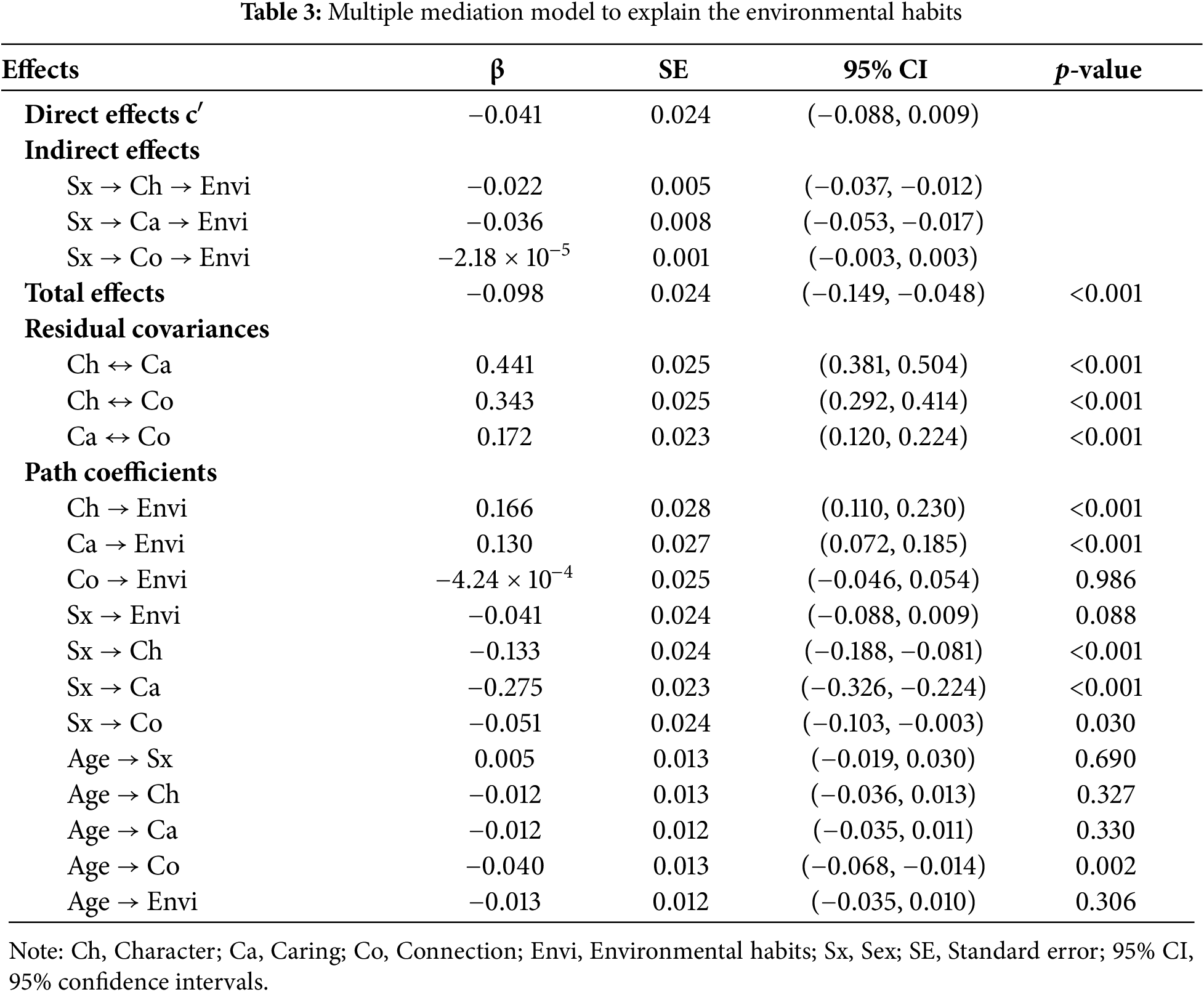

3.3 Multiple Mediation Analysis: Environmental Habits

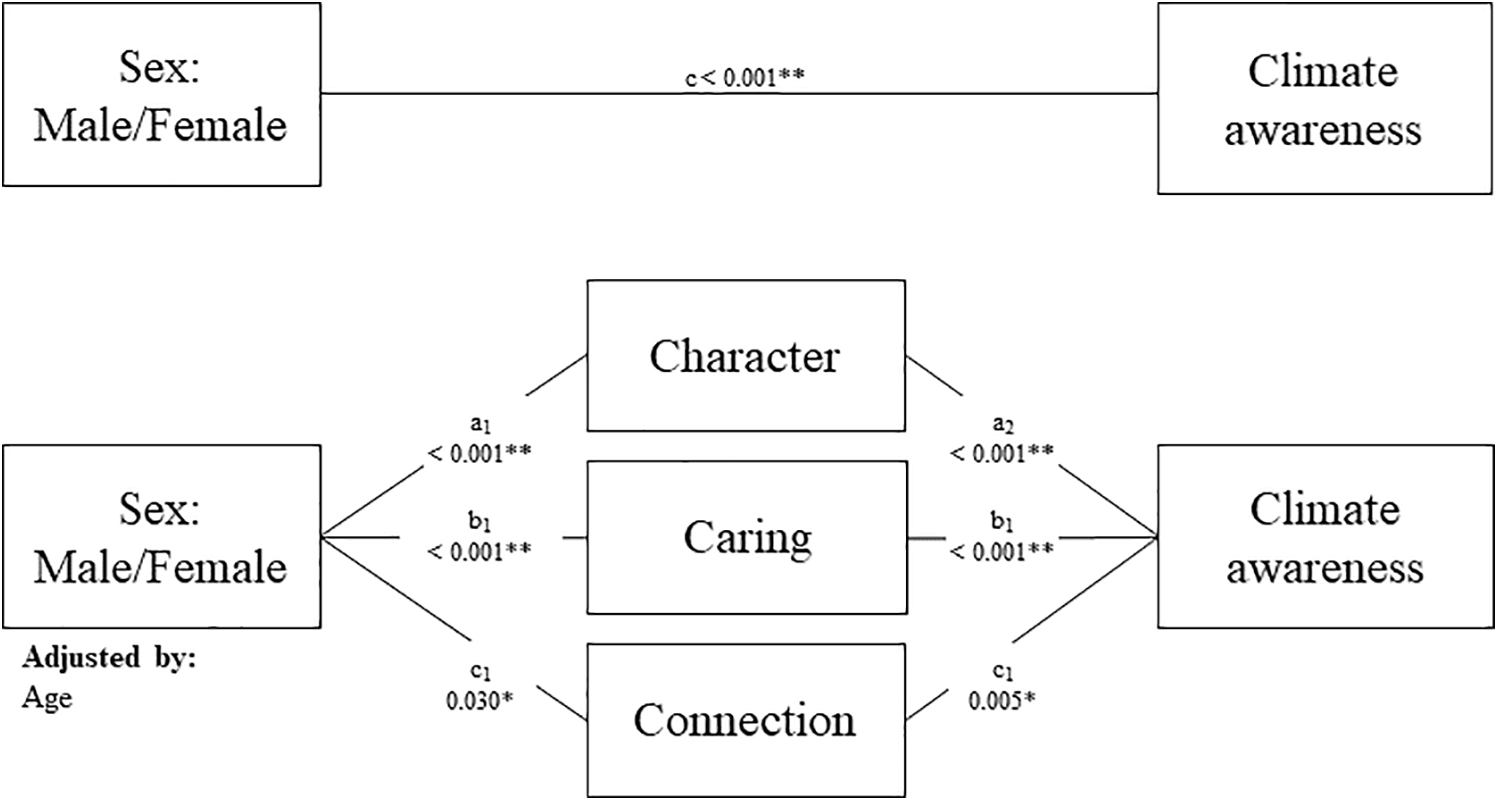

The mediation model (Fig. 1 and Table 3) revealed no significant direct effect of gender on environmental habits. However, significant indirect effects were found via Character and Caring, indicating that these two PYD dimensions mediated the relationship between gender and environmental habits. Connection did not show a significant mediating effect. The model explained a small portion of the variance (R2 = 0.072), although the total effect of gender on environmental habits was statistically significant.

Figure 1: Mediation model for environmental habits and the 5 Cs. Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. β, unstandardized regression coefficients. SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval. If zero was not included in the 95% CI of the estimate, the indirect effect (Ind) is statistically significant.

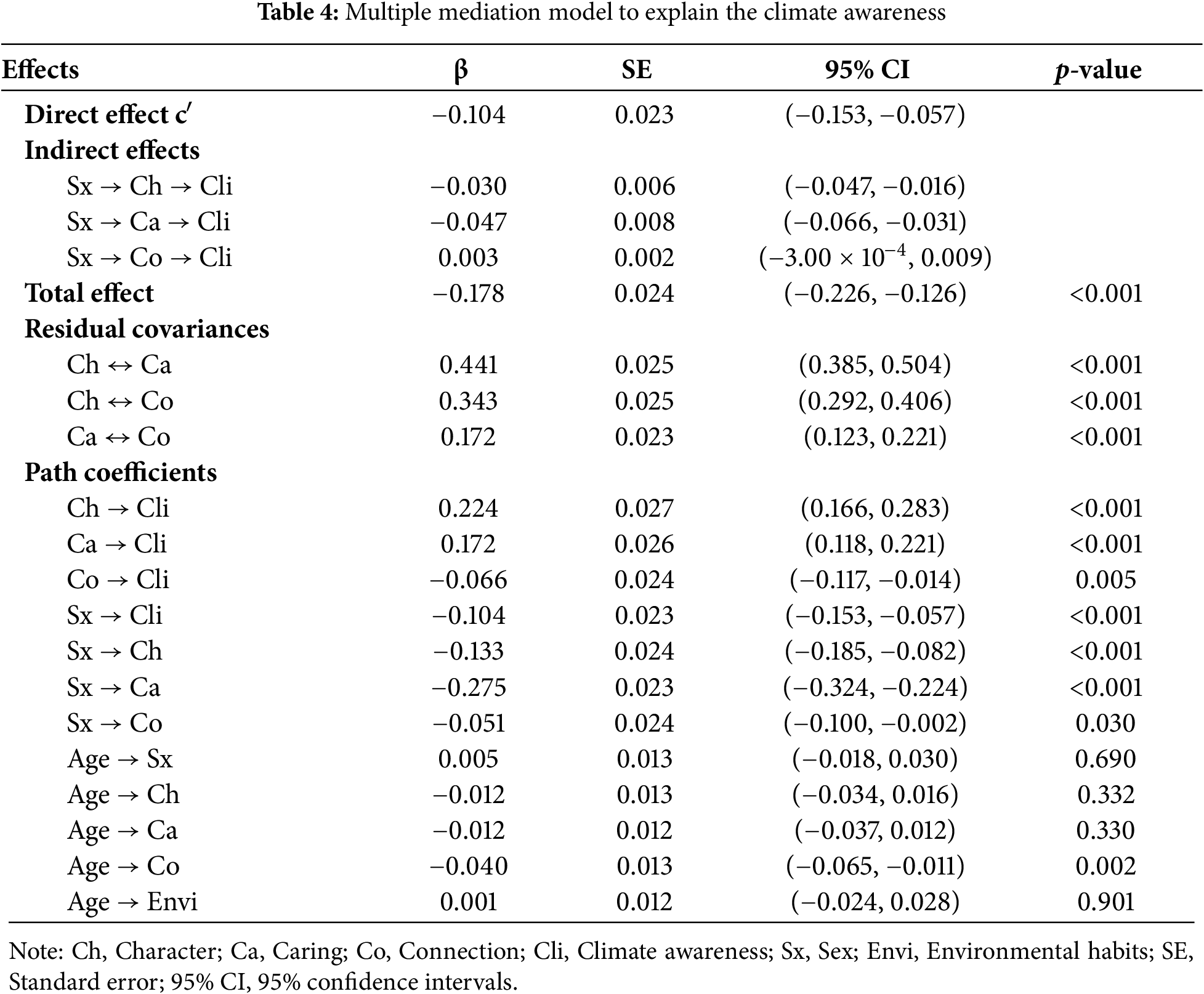

3.4 Multiple Mediation Analysis: Climate Awareness

Fig. 2 and Table 4 illustrate the mediation analysis for climate awareness. In this model, both direct and indirect effects of gender were significant. Gender directly predicted climate awareness, and indirect effects were observed through Character and Caring. Connection did not emerge as a significant mediator, although it showed a positive but non-significant trend. The total effect was significant, and the explained variance in this model was higher (R2 = 0.132), suggesting a stronger influence of gender on climate awareness than on environmental habits.

Figure 2: Mediation model for climate awareness and the 5 Cs. Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. β, unstandardized regression coefficients; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval. If zero was not included in the 95% CI of the estimate, the indirect effect (Ind) is statistically significant.

This study examined the relationship between PYD and pro-environmental behaviours in a sample of Andalusian university students. We examined the predictive effect of the 5 Cs on environmental outcomes, considering gender differences.

The findings highlight the role of Character and Caring as key predictors of pro-environmental behaviours. Character, associated with integrity and moral responsibility, emerged as the strongest predictor for both environmental habits and climate awareness, followed by Caring [15]. These results are consistent with previous literature emphasising the influence of ethical values and empathy on sustainable behaviour [26,29]. Environmental education may play a reinforcing role by fostering the development of the 5 Cs, especially Character and Caring, as essential competencies within sustainability programmes [32]. The relatively limited contribution of Connection suggests that pro-environmental behaviours are influenced not only by perceived social relationships but also by a wide combination of personal and contextual factors, which should be considered [32,33]. Although Competence and Confidence relate to self-efficacy and skill development, they may not be sufficient to drive sustainable behaviours in the absence of relevant environmental experiences or perceived urgency regarding climate change [34,35].

Gender differences reveal distinct associations with PYD dimensions and pro-environmental behaviours. Female students scored higher in Character, Caring, and both environmental variables, reinforcing findings that link female gender to heightened empathy and environmental awareness [17,18,36]. Conversely, male students scored higher in Competence and Confidence, dimensions that showed weaker associations with environmental outcomes, consistent with results from European samples [36,37]. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating gender-sensitive approaches into educational interventions to enhance the effectiveness of sustainability strategies [38].

The results partially support the initial hypothesis, reinforcing the need to promote ethical and social values as fundamental pillars in addressing environmental challenges within the PYD framework [14,39]. Beyond their predictive value, Character and Caring reflect broader civic competencies essential for developing responsible and engaged citizens committed to sustainability [40]. While previous studies have highlighted associations between Competence, Caring, and pro-environmental behaviours, the present findings suggest that Character may also play a significant role [24,25]. The lack of a significant effect for Connection may reflect the absence of strong social networks or opportunities for environmental participation in this context, although previous research suggests that its relevance may increase in community-based or collective action settings [32]. Although Connection did not significantly predict environmental outcomes in the present study, its positive correlations with climate awareness suggest that future research should explore whether its influence is moderated by variables such as social interaction or involvement in sustainability-related group activities [7,41].

Importantly, since the present study did not include variables that directly measure the mechanisms underlying the PYD–PEB relationship (e.g., motivation, identity, or perceived behavioural control), it cannot offer a detailed explanation of the processes driving this association. Future studies should incorporate potential mediators and moderators to explore these underlying pathways more comprehensively.

These findings have important implications for the design of higher education educational strategies. Programmes that embed the development of the 5 Cs, particularly Character and Caring, may be effective in fostering pro-environmental behaviours [32]. Prior studies show that combining experiential learning with ethical reflection can yield multiple positive outcomes, including enhanced critical thinking, civic engagement, and a sense of environmental responsibility [42,43]. Examples include environmental volunteering, interdisciplinary debates, and local community projects, which provide meaningful opportunities for students to engage with sustainability challenges while developing social competencies [44,45]. Additionally, the gender differences identified suggest the need to tailor interventions to specific needs and strengths. Strategies that enhance Competence and Confidence in female students may increase their environmental self-efficacy, whereas promoting Caring and Character among male students could strengthen their ethical engagement and empathy towards environmental issues [37,46].

Environmental education may also benefit from interdisciplinary frameworks that integrate PYD with environmental literacy. Such approaches can promote personal growth and social competencies, including ethical values and civic participation [32,47,48]. This dual focus not only fosters the development of the 5 Cs but also helps build stronger links between youth and their communities [43]. In Spain, the Spanish Network of Health Promoting Universities has launched several campaigns to promote sustainable behaviours, such as food waste reduction [49]. Likewise, the World Health Organisation has produced guidance for policymakers to implement behavioural science strategies that enhance the likelihood of effective climate action [50].

Although environmental knowledge (EK) was not assessed in this study, prior research suggests that it may act as a precursor to pro-environmental behaviour [51]. Future studies could benefit from examining EK alongside PYD dimensions to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the cognitive and ethical drivers of environmental action [52,53].

4.2 Limitations and Future Research Lines

This study has several limitations. First, as it employed a cross-sectional design, it was not possible to establish causality or directionality in the observed relationships. Longitudinal research is needed to determine the temporal sequencing between PYD dimensions and pro-environmental outcomes.

Second, data were collected through self-report measures, which may be subject to biases such as social desirability and limited introspective accuracy. Moreover, certain contextual or motivational factors (such as community participation, perceived behavioural control, or direct exposure to climate change) that could have influenced the results were not assessed in this study. These variables may play a key role in explaining the mechanisms underlying the relationship between PYD and environmental outcomes and should be addressed in future research.

Third, another limitation comes from the sample composition, since women are overrepresented, and future research may collect data from gender-balanced samples. Moreover, because a convenience sample was used, the results cannot be generalized to the sample of Andalusian undergraduates. Future research may follow sampling procedures to have a representative sample.

Despite these limitations, the study includes a large and diverse sample from multiple universities and academic disciplines, which enhances the generalisability of the findings. Additionally, the use of validated instruments (such as the PYD short form and the Pro-environmental Behaviours Scale) supports the reliability and robustness of the results. This study shows that the dimensions of PYD, particularly Character and Caring, significantly influence both pro-environmental behaviour and climate awareness among Andalusian university students. The observed gender differences point to distinct developmental pathways in adopting sustainable behaviours, while the limited role of Connection underscores the complex and multifactorial nature of these processes. These findings support the need for interdisciplinary approaches that integrate youth development and environmental education frameworks. They also provide an empirical foundation for designing more effective educational strategies aimed at sustainability. Nevertheless, the study also highlights the need for further research to address the methodological and contextual limitations, such as the cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data. With appropriate integration of the PYD framework into educational programmes, universities can become powerful agents of change, equipping young people to lead in the creation of more sustainable and resilient communities.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research and the APC were funded by the Excellence Project of the Consejeria de Universidad, Investigacion e Innovacion of Junta de Andalucia (Spain), granted to DG-B, entitled Positive Youth Development in Andalusian University Students: Longitudinal Analysis of Gender Differences in Well-Being Trajectories, Health-Related Lifestyles and Social and Environmental Contribution (PROYEXCEL_00303).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Esther López-Bermúdez; methodology, Esther López-Bermúdez, Diego Gómez-Baya; formal analysis, Esther López-Bermúdez, Diego Gómez-Baya; writing—original draft preparation, Esther López-Bermúdez, María Soledad Palacios-Gálvez, Francisco José García-Moro, Diego Gómez-Baya; writing—review and editing, Esther López-Bermúdez, María Soledad Palacios-Gálvez, Francisco José García-Moro, Diego Gómez-Baya; supervision, María Soledad Palacios-Gálvez, Francisco José García-Moro; funding acquisition, Diego Gómez-Baya. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Diego Gómez-Baya, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the bioethics committee of the University of Huelva on 10 January 2019 (UHU-1259711), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Ca | Caring |

| Ch | Character |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| Cli | Climate awareness |

| Co | Connection |

| EK | Environmental knowledge |

| Envi | Environmental habits |

| M | Mean |

| PEB | Pro-environmental behaviours |

| PYD | Positive Youth Development |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| Sx | Sex |

References

1. Gawrych M. Climate change and mental health: a review of current literature. Psychiatr Pol. 2022;56(4):903–15. doi:10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/131991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Palinkas LA, Wong M. Global climate change and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;32:12–6. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bratman GN, Anderson CB, Berman MG, Cochran B, De Vries S, Flanders J, et al. Nature and mental health: an ecosystem service perspective. Sci Adv. 2019;5(7):eaax0903. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax0903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Jiménez-García M, Pérez-Peña M-C, López-Sánchez J-A. Influence of education and the media on the awareness of climate change. Cult Educ. 2023;35(4):1001–36. doi:10.1080/11356405.2023.2229178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Aronsson J, Nichols A, Warwick P, Elf M. Nursing students’ and educators’ perspectives on sustainability and climate change: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2024;80(8):3072–85. doi:10.1111/jan.15950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ccami-Bernal F, Barriga-Chambi F, Quispe-Vicuña C, Fernandez-Guzman D, Arredondo-Nontol R, Arredondo-Nontol M, et al. Health science students’ preparedness for climate change: a scoping review on knowledge, attitudes, and practices. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):648. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05629-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Romanello M, Napoli CD, Green C, Kennard H, Lampard P, Scamman D, et al. The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet. 2023;402(10419):2346–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01859-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Special report on “global warming of 1.5°C—summary for policy makers”. 2018 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/. [Google Scholar]

9. Menton M, Larrea C, Latorre S, Martinez-Alier J, Peck M, Temper L, et al. Environmental justice and the SDGs: from synergies to gaps and contradictions. Sustain Sci. 2020;15(6):1621–36. doi:10.1007/s11625-020-00789-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dimitrova R, Wiium N. Handbook of positive youth development: advancing the next generation of research, policy and practice in global contexts. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-70262-5_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gomez-Baya D, Santos T, Gaspar de Matos M. Developmental assets and positive youth development: an examination of gender differences in Spain. Appl Dev Sci. 2022;26(3):516–31. doi:10.1080/10888691.2021.1906676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Lewin-Bizan S, Bowers EP, Boyd MJ, Mueller MK, et al. Positive youth development: processes, programs, and problematics. J Youth Dev. 2011;6(3):40–64. doi:10.5195/JYD.2011.174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Murry VM. Positive youth development in 2020: theory, research, programs, and the promotion of social justice. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31(4):1114–34. doi:10.1111/jora.12609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Almerigi JB, Smith EP, Bowers EP, Geldhof GJ, et al. Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. J Early Adolesc. 2005;25(1):17–71. doi:10.1177/0272431604272461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Corral-Verdugo V, Frías M, García C. Introduction to the psychological dimensions of sustainability. In: Corral-Verdugo V, García C, Frías M, editors. Psychological approaches to sustainability: current trends in theory, research and applications. New York, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

16. Gifford R. Environmental psychology matters. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65(1):541–79. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Casaló LV, Escario JJ, Rodriguez-Sanchez C. Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Res Conserv Recycl. 2019;149:56–64. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.05.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen X, Peterson MN, Hull V, Lu C, Lee GD, Hong D, et al. Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour in urban China. Environ Conserv. 2011;38(1):45–52. doi:10.1017/S037689291000086X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chileshe B, Moonga MS. Disparities in pro-environmental behaviour between rural and urban areas in Zambia. Multidiscip J Lang Soc Sci Educ. 2019;2(1):196–215. [Google Scholar]

20. Jurdi-Hage R, Hage H, Chow H. Cognitive and behavioural environmental concern among university students in a Canadian city: implications for institutional interventions. Aust J Env Educ. 2019;35(1):28–61. doi:10.1017/aee.2018.48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pizmony-Levy O, Michel JO. Pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in higher education: investigating the role of formal and informal factors. New York, NY, USA: Academic Commons—Columbia University; 2018. doi:10.7916/D85M7J8N. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bubalo M, van den Broek K, Helbich M, Labib SM. ECO-MIND: enhancing pro-environmental behaviours and mental health through nature contact for urban youth—a research protocol for a multi-country study using geographic ecological momentary assessment and mental models. BMJ Open. 2024;14(10):e083578. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-083578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Thompson R, Lawrance EL, Roberts LF. Ambient temperature and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7(7):e580–9. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00104-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Kabir RS, Wiium N. Positive youth development and environmental concerns among youth and emerging adults in Ghana. In: Dimitrova R, Wiium N, editors. Handbook of positive youth development: advancing the next generation of research, policy and practice in global contexts. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 81–94. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-70262-5_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bøhlerengen M, Wiium N. Environmental attitudes, behaviors, and responsibility perceptions among norwegian youth: associations with positive youth development indicators. Front Psychol. 2022;13:844324. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.844324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Metzger A, Alvis LM, Oosterhoff B. The intersection of emotional and sociocognitive competencies with civic engagement in middle childhood and adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(8):1663–83. doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0842-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Bowers EP, Larson LR, Parry BJ. Nature as an ecological asset for positive youth development: empirical evidence from rural communities. Front Psychol. 2021;12:688574. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.688574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Gomez-Baya D, Mendoza R, Morales E, Paíno S, Salinas JA, Martín C, et al. Protocolo de Investigación del proyecto “Desarrollo Positivo Juvenil en Estudiantes Universitarios Españoles”. Análisis Modif Conducta. 2022;48(178):15–26. (In Spanish). doi:10.33776/amc.v48i178.7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Geldhof GJ, Bowers EP, Boyd MJ, Mueller MK, Napolitano CM, Schmid KL, et al. Creation of short and very short measures of the Five Cs of positive youth development. J Res Adolesc. 2014;24(1):163–76. doi:10.1111/jora.12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gomez-Baya D, Reis M, Gaspar de Matos M. Positive youth development, thriving and social engagement: an analysis of gender differences in Spanish youth. Scand J Psychol. 2019;60(6):559–68. doi:10.1111/sjop.12577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. CIS (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas). Ecología y medio ambiente. estudio n° 2.590. Madrid, Spain: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas; 2005 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/web/Bloques_Tematicos/Publicaciones_Divulgacion_Y_Noticias/Documentos_Tecnicos/personas_sociedad_y_ma/cap9.pdf. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

32. Ardoin NM, Bowers AW, Kannan A, O’Connor K. Positive youth development outcomes and environmental education: a review of research. Int J Ado Youth. 2022;27(1):475–92. doi:10.1080/02673843.2022.2147442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gomez-Baya D, Tomé G, Branquinho C, Gaspar De Matos M. Environmental action and PYD. Environmental action as asset and contribution of positive youth development. EREBEA. 2020;10:53–68. doi:10.33776/erebea.v10i0.4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Reser JP, Bradley GL, Ellul MC. Encountering climate change: ‘Seeing’ is more than ‘believing’. WIREs Clim Change. 2014;5(4):521–37. doi:10.1002/wcc.286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pereira T, Freire T. Positive youth development in the context of climate change: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:786119. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.786119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wiium N, Wreder LF, Chen B-B, Dimitrova R. Gender and positive youth development: advancing sustainable development goals in Ghana. Z Für Psychol. 2019;22782(2):134–8. doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Martin-Barrado AD, Gomez-Baya D. A scoping review of the evidence of the 5Cs model of positive youth development in europe. Youth. 2024;4(1):56–79. doi:10.3390/youth4010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. de Jesus MC, Dutra-Thomé L, Pereira AS. Developmental assets and positive youth development in Brazilian university students. Front Psychol. 2022;13:977507. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.977507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Hickman G, Riemer M. A theory of engagement for fostering collective action in youth leading environmental change. Ecopsychology. 2016;8(3):167–73. doi:10.1089/eco.2016.0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mediavilla ME, Medina S, González I. Diagnóstico de sensibilidad medioambiental en estudiantes universitarios. Educ Educ. 2020;23(2):179–97. (In Spanish). doi:10.5294/edu.2020.23.2.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Rodríguez FL, Mejía DL, Sánchez JO. Conocimientos y percepciones sobre el cambio climático en estudiantes universitarios. Divers Perspect Psicol. 2022;18(1):130–45. (In Spanish). doi:10.15332/22563067.6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ernst J, Schwartz J. Environmental service and outdoor adventure as a context for positive youth development: an evaluation of the crow river trail guards program. J Youth Dev. 2013;8(2):57–75. doi:10.5195/jyd.2013.96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Klein S, Watted S, Zion M. Contribution of an intergenerational sustainability leadership project to the development of students’ environmental literacy. Environ Educ Res. 2021;27(12):1723–58. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.1968348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Delia J, Krasny ME. Cultivating positive youth development, critical consciousness, and authentic care in urban environmental education. Front Psychol. 2018;8:2340. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Schusler TM, Krasny ME. Environmental action as context for youth development. J Environ Educ. 2010;41(4):208–23. doi:10.1080/00958960903479803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Briggs L, Krasny M, Stedman RC. Exploring youth development through an environmental education program for rural indigenous women. J Environ Educ. 2019;50(1):37–51. doi:10.1080/00958964.2018.1502137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. UNESCO. Intergovernmental conference on environmental education: Tbilisi, 14–26 October 1977. Final report [Internet]. 1978 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: http://www.gdrc.org/uem//ee/EE-Tbilisi_1977.pdf. [Google Scholar]

48. Wiium N, Dimitrova R. Positive youth development across cultures: introduction to the special issue. Child Youth Care Forum. 2019;48(2):147–53. doi:10.1007/s10566-019-09488-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. REUPS—Spanish Network of Healthy Universities. ¿Qué es la REUPS? [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://unisaludables.com/. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

50. Williams O, Gould A. Responding to the climate crisis: applying behavioural science [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://phwwhocc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/PHW-BSU-Responding-to-the-Climate-Change-Eng-final-2-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

51. Burgos-Espinoza II, García-Alcaraz JL, Gil-López AJ, Díaz-Reza JR. Effect of environmental knowledge on pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors: a comparative analysis between engineering students and professionals in Ciudad Juárez (Mexico). J Environ Stud Sci. 2024;26(5):409. doi:10.1007/s13412-024-00991-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Frick J, Kaiser F, Wilson M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal Ind Differ. 2004;37(8):1597–613. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Kollmuss A, Agyeman J. Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environ Educ Res. 2002;8(3):239–60. doi:10.1080/13504620220145401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools