Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Protecting the Mental Health of Esports Players: A Qualitative Case Study on Their Stress, Coping Strategies, and Social Support Systems

1 Department of eSports, Division of Culture & Arts, Osan University, Gyeonggi-do, 18119, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Sport & Leisure Studies, Division of Arts & Health Care, Myongji College, Seoul, 03656, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Hyunkyun Ahn. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1301-1334. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068251

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Recently, the global esports industry has experienced remarkable growth, leading to an expansion in the scale and influence of professional player communities. However, despite this outward growth, systems to protect players’ mental health remain inadequate. Comprehensive analysis of structural risk factors, including performance pressure, public evaluation, and career instability, remains insufficient. This study, aimed to explore stressors encountered by esports athletes, coping strategies, and the role of social support systems in safeguarding mental health. Using the transactional model of stress and coping, the job demands–resources model, and social support theory, the study adopts an integrated perspective to examine challenges faced by athletes in the competitive esports environment. Methods: A qualitative case study was conducted involving in-depth interviews and non-participant observations with 11 esports athletes who competed at national or international levels, as well as two team managers. Thematic analysis identified recurring patterns in the data, and credibility was ensured through triangulation and cross-review among researchers. Results: Esports athletes experience multiple interacting stressors, including performance demands, emotional strain during matches, and continuous evaluation on social media. In response, they employed coping strategies—problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance-based, which provided temporary relief but often led to burnout and self-regulation failure owing to absence of support systems. Social support networks had ambivalent effects: while offering comfort, they also intensified pressure through negative feedback and high expectations from fans and online communities. Conclusion: The findings show that mental health issues among esports athletes are not only related to individual factors but are closely linked to performance-driven structures, competitive environments, and social relationships. This study integrates the transactional model of stress and coping, the Job Demands–Resources model, and social support theoryto provide comprehensive analysis. It also offers practical recommendations, including psychological counseling, emotional labor programs, and improved communication with families and fan communities.Keywords

Esports is redefining the concept of modern sports by merging digital innovation with a culture of competition. In 2024, the global esports market was projected to reach $187.7 billion [1], illustrating how esports has evolved from a niche pastime into a mainstream cultural and economic force. Beyond industry growth, esports is driving significant shifts in media and sociocultural landscapes, challenging the traditional paradigms of sports. As its popularity grows, it is being recognized as a large market sport with a global fanbase and a strong presence on major media platforms [2]. South Korea, notably, was among the first countries to institutionalize esports through an official league system, enabling esports athletes to engage in regular high-level competition. This structure has allowed players to develop technical proficiency and strategic thinking through systematic training and real-game environments, ultimately contributing to their continued success on the international stage [2]. Corresponding advances have not matched this rapid industrial and cultural expansion in mental health research and support systems. Conversely, while the esports industry continues to expand quickly, the academic and institutional conversation about safeguarding players’ mental health remains insufficient. This mismatch has intensified the underlying tension of a “structural disconnect” between the industry framework and health-related research [3].

Esports athletes operate in highly competitive environments, facing performance demands and training intensities comparable to those of traditional sports athletes. However, the unique nature of esports—namely, its digital platform-based, non-standardized match structures, repetitive strategic execution, and reliance on rapid real-time responses—requires sustained high levels of concentration over extended periods. This environment not only leads to physical fatigue but also contributes to cognitive overload and emotional exhaustion, creating conditions that make esports athletes particularly vulnerable to mental burnout. Most notably, the constant evaluation of performance in real-time and the ongoing competitive pressure significantly heighten their psychological stress, making it a central factor in the deterioration of their mental health [4]. Recent studies report that over 80% of professional esports athletes experience major mental health challenges—including depression, anxiety, and burnout—due to continuous high-intensity training and dense competition schedules [5,6].

Esports athletes often undergo intensive training sessions lasting 10 to 12 h daily, primarily focused on enhancing strategic thinking and fine motor control. However, these can result in more than just physical fatigue, as such conditions can lead to cognitive overload and neurological depletion [4,5]. Over time, this may result in mental burnout, particularly under the pressures of real-time performance evaluation and ongoing competition, which reinforce the persistent psychological burden of maintaining one’s ranking. The careers of these athletes also tend to be significantly shorter and more unstable than those in traditional sports, making esports athletes especially vulnerable to anxiety and obsessive thinking in environments where performance decline can lead to contract termination or premature retirement [7]. These structural conditions serve as major contributing factors to long-term mental health deterioration and failures in self-regulation [8].

The team-based structure of esports also generates unique psychological pressures for these players. According to some studies, intense competition between starting players and substitutes within teams heightens internal tensions, complicating interpersonal relationships among team members [3,4]. This competitive structure tends to operate on a survival basis rather than fostering cooperation, potentially hindering the development of trust and emotional stability among players. Consequently, there is a risk of simultaneously weakening team affiliation and intensifying individual psychological instability.

Meanwhile, the esports competitive environment is characterized by unpredictable technical variables, such as network latency, sudden shifts in game meta, and patch changes [5]. These external factors have a direct impact on the athletes’ performance, particularly when the outcome of a match is influenced by technical errors or environmental changes. Such situations can lead athletes to experience a loss of control over gameplay, resulting in added psychological strain. This, in turn, can amplify stress responses and negatively affect the overall psychological stability throughout the competition.

Stress during competition directly influences the physiological response of a player. Studies have reported that esports athletes experience physiological reactions, such as a sudden increase in heart rate, elevated cortisol levels, and heightened sympathetic nervous system activation during matches [9]. These physiological responses resemble those experienced by traditional sports athletes under stress; however, the key difference is in the esports context, where recovery time is often insufficient, leading to continuous and repetitive stress exposure [4]. Moreover, the accumulation of stress responses can impair decision-making abilities, slow reaction times, and disrupt emotional regulation, ultimately resulting in poor performance [10].

The mental stress experienced by esports athletes is influenced not only by internal competitive factors but also by external ones. Because of the inherent connection between esports and real-time streaming and online communities, esports athletes are often required to interact directly with fans during gameplay [10]. While this environment offers opportunities for positive feedback, it also exposes the players to immediate criticism and malicious comments following poor performance. According to the research, such negative feedback and continuous social evaluation can diminish the player’s self-efficacy and also contribute to long-term emotional instability and depressive symptoms [7].

In contrast, traditional sports athletes generally have designated recovery periods after competitions, during which they receive psychological support from their team and coaching staff. However, esports athletes often face real-time evaluations within streaming environments, requiring immediate reactions to external feedback [4]. This structural characteristic imposes significant psychological burdens on these athletes and, over time, exacerbates mental health challenges. Moreover, unlike traditional sports, esports does not possess sufficient institutional resources to alleviate or manage these psychological pressures. Consequently, the mental health issues these athletes face need to be understood not only as individual concerns but also as problems embedded within the structural and environmental esports context.

As esports athletes face significant psychological pressures to maintain their performance levels and their careers, this affects not only their short-term performance but also their long-term job stability. Studies on traditional sports have indicated that, in addition to physical fatigue, psychological exhaustion, identity crises, and anxiety related to social evaluation are critical factors influencing athletes’ sustained performance and career stability [10]. In esports, however, performance outcomes are the primary determinant of career continuity, making performance pressure even more pronounced compared with that in other sports [7].

This psychological pressure also significantly impacts their career planning. As an emerging industry, esports athletes face uncertainties regarding their career paths after retirement, with many unsure about their future prospects [8]. In contrast, traditional sports typically offer more opportunities for athletes to transition into coaching roles or related industries. However, esports athletes face challenges in securing stable career paths post-retirement. As a result, players who fail to achieve consistent performance can experience economic instability, identity confusion, and long-term difficulties in career planning. Research indicates that such uncertainties elevate stress levels, acting as major contributors to psychological burnout and increasing the risk of early retirement [7].

Career sustainability among esports athletes is not only a personal challenge but also an industry challenge related to the instability of the esports industry’s structure. Unlike traditional sports, which often feature well-established league systems and consistent athlete management frameworks that support career transitions, esports is devoid of a structured career management system. Moreover, the rapidly evolving gaming environment and frequent meta changes impose continuous adaptive pressure on athletes. If the popularity of a specific game declines, players of that game are at an increased risk of experiencing professional instability. Therefore, job security for esports athletes needs to be examined from an industry structure perspective to explore strategies that can support their career sustainability.

As noted, these esports athletes are required to maintain high performance in extremely competitive environments without institutional support systems that could help alleviate their psychological and emotional burdens. Conventional sports have relatively well-established systems involving sports psychologists, mental coaches, and emotional education programs that systematically address the psychological stress athletes experience during training and competition [8]. In contrast, esports does not provide formal access routes to such resources, leading athletes to rely heavily on individual efforts or informal social networks. This reliance exacerbates disparities in support across players [11].

The absence of such structured systems also weakens esports athletes’ self-regulation abilities and leads to repeated use of emotion-focused or avoidance-based coping strategies, which, over time, can contribute to psychological burnout and performance decline. Social support resources—such as teams, coaches, family, and fans—potentially serve as crucial protective factors; however, they often function ineffectively owing to performance-centered organizational cultures, the lack of psychological education, and the negative stigma associated with mental health issues [7]. This structural deficiency may cause players to perceive help-seeking behaviors as a form of “psychological exposure,” creating barriers that intensify self-censorship and psychological isolation.

As the industry grows, with the number of esports athletes increasing exponentially, the lack of structured support for their mental health has become a societal issue that requires attention. To understand this better, our study analyzes the psychological burden and stress factors esports athletes are experiencing, focusing on how coping strategies and social support systems influence mental health in an integrated manner. The mental health issues of esports athletes have been examined from a limited perspective in previous studies, focusing primarily on game addiction or individual psychological vulnerabilities [6]. However, they do not adequately account for contextual and environmental factors, including intra-team dynamics, real-time public evaluations, and the structural pressures inherent in digital environments [5]. To address these limitations, in this study, we aimed to conduct an integrated analysis of the complex stressors and mental health challenges experienced by esports athletes, considering structural, psychological, and social perspectives. Through this approach, our aim is to empirically demonstrate the need to establish psychological support systems applicable across the esports industry. As a complex field, we require a better understanding of the stress, coping mechanisms, and mental health issues these esports athletes face daily in this high-pressure and dynamic environment. For this analysis, an integrative approach that applies three theoretical frameworks was used: the transactional model of stress and coping, the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, and social support theory. Each model offers a distinct yet complementary role in examining the mental health challenges experienced by esports athletes. The transactional model explains how athletes cognitively appraise stressors and select coping strategies in response to psychological demands. The JD-R model provides a structural perspective by analyzing how performance pressure and resource imbalances in the esports environment contribute to mental health vulnerability. Social support theory is used to explore how internal and external support systems—including teams, coaches, and fans—impact athletes’ experiences of stress and coping processes. By integrating these frameworks, a multidimensional analytical lens that addresses the limitations of single-theory approaches was proposed in this study, thus providing a theoretical foundation for developing practical mental health support strategies within digital and future-oriented sports industries. Using this integrated approach, the following research questions were addressed in this study:

Research Question 1: What are the primary stress factors experienced by esports athletes, and how do these factors affect their mental health?

Research Question 2: What coping strategies do esports athletes employ to manage stress, and how do these strategies impact their mental well-being?

Research Question 3: How do social support systems (such as teams, coaches, fans, and organizations) function to maintain the mental health and performance of esports athletes within their competitive environment?

2.1 Transactional Model of Stress and Coping

The transactional model of stress and coping explains how stress arises from an individual’s process of evaluating environmental demands and responding to them [12]. The core concepts of this model are cognitive appraisal and coping strategies, emphasizing the continuous interaction between the individual and the environment.

Stress is not merely an external stimulus but varies according to how the individual appraises the situation. In this process, primary appraisal determines whether a specific situation is perceived as a loss, threat, or challenge, whereas secondary appraisal assesses whether the individual’s resources and abilities can cope effectively with the stressor [13].

The primary coping strategies for stress among esports athletes are problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping [12]. Problem-focused coping strategies target the root cause of the stress, including improving match analysis, teamwork, and technical training. Conversely, emotion-focused coping strategies regulate emotional responses during stressful situations, manifested as emotional expressions or avoidance behaviors.

Studies indicate that when athletes use problem-focused coping to enhance performance, this generally results in reduced stress. Conversely, emotion-focused coping may provide short-term emotional relief but can increase the risk of psychological burnout over the long term [14,15].

These coping strategies can be further categorized from a temporal perspective into reactive coping and preventive coping. Reactive coping occurs after a stressor has emerged, while anticipatory coping involves preparing for potential stress before it arises [16]. In esports, where uncertainty is high and rapid decision-making is essential, anticipatory coping is particularly crucial. This proactive approach often manifests as pre-match strategy analysis and psychological training, allowing the players to recognize and regulate stress factors in advance. Such anticipatory coping not only aids in maintaining performance but also plays a vital role in safeguarding mental health, the key focus of our study [17].

For this reason, we chose the transactional model of stress and coping to analyze the stress factors encountered by esports athletes, how they respond to these stressors, and the impact of specific coping strategies on mental health protection. Despite its strengths, the model has limitations in addressing organizational and environmental sources of stress. To address these gaps, the transactional model was integrated in this study with the JD-R model, which captures stressors at the occupational level, and social support theory, which emphasizes the role of interpersonal and systemic support structures. By examining how individual-level appraisals and coping strategies interact with job demands, resource availability, and social support, we aim to develop a comprehensive framework that compensates for the limitations of relying on any single model.

2.2 Job Demands-Resources Model

The JD-R model explains how the balance between job demands and job resources within a work environment affects both mental health and job performance [18]. This model is particularly useful in analyzing the interaction between burnout and engagement in high-demand work settings, highlighting how the interplay between demands and resources influences stress levels and performance outcomes [19]. In other words, when job demands are high and there are inadequate resources, the risk of burnout increases. Conversely, when resources are sufficient, job engagement and motivation are likely to improve [20].

Applying the JD-R model to the work environment of esports athletes reveals that high-intensity training and performance pressure act as job demands, whereas coaching support and psychological resources function as protective factors. The model can assess how the balance between these job demands and resources affects the mental health and performance of esports athletes.

Specifically, for esports athletes, job demands include maintaining performance and coping with performance pressure, leading to continuous physical and psychological strain. The resources refer to positive factors that individuals can use during their job performance [21]. These resources can mitigate the negative effects of job demands and help maintain performance. Among the essential resources for esports athletes are mental coaching and psychological counseling, both crucial for stress regulation and mental health protection.

Clear coaching roles and feedback can also serve as resources for maintaining performance and reducing stress. Providing clear role definitions and strategic feedback can help athletes reduce decision-making confusion during matches and alleviate performance anxiety [6]. According to the JD-R model, resources do not merely function as stress alleviators but also facilitate job engagement [19]. For instance, providing athletes with appropriate training support and feedback can increase their motivation and improve their performance [20]. The model suggests that with adequate resources, athletes can maintain their mental health and maximize their performance even under high job demands. Conversely, when resources are insufficient, the risk of burnout and performance decline increases [21]. The JD-R model emphasizes the buffering effect of resources, suggesting that providing sufficient resources mitigates the negative impact of job demands [21].

Applying the JD-R model to analyze job demands and resources among esports athletes underscores the need for strategic interventions aimed at their mental health protection. In particular, when these players are provided with sufficient psychological and physical resources, it can alleviate job stress and help maintain consistent performance. Thus, the JD-R model assesses the negative factors and incorporates resource buffering and motivational effects, expanding our conceptual framework [21]. Therefore, we comprehensively examine the work environment of esports athletes using the JD-R model, focusing on how the balance between their job demands and resources influences their mental health and performance. The JD-R model shows the structural characteristics of job roles and the impact of JD-R balance on psychological outcomes; nevertheless, it does not sufficiently address the individual mechanisms of stress appraisal and the coping strategies of selection. To supplement the structural focus of the JD-R model. The transactional model of stress and coping [13] and social support theory [22] were incorporated in this study. Through this theoretical integration, we aim to clarify how esports athletes cognitively perceive and use available resources during stressful situations, including the influence of social contexts. This comprehensive approach enriches our empirical understanding of how mental health and sustained performance are maintained in high-pressure esports environments.

Social support theory emphasizes the role of social networks in providing psychological stability and adaptability when individuals experience stress [22]. This theory categorizes social support into three main types: emotional support, informational support, and instrumental support. These forms of support contribute to regulating stress responses and enhancing mental well-being and performance [23].

One of the core hypotheses of the theory is the stress-buffering hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that social support mitigates the negative effects of stressors, thereby protecting mental health and resilience [22]. In the context of esports, players face high-performance expectations, real-time feedback systems, and technical issues, which increase stress levels. In this environment, social support can serve as a crucial mechanism for alleviating stress responses.

Specifically, emotional support plays a role in managing anxiety and pressure during competitions, enhancing psychological stability [24]. Support from the coaching staff and teammates can also bolster self-efficacy and improve coping skills, which are essential for maintaining performance under pressure [24]. Conversely, informational support (such as strategic advice) can activate problem-focused coping, enabling athletes to effectively utilize strategies that maintain performance.

In the esports milieu, social support is primarily provided through digital platforms, unlike traditional sports, presenting unique opportunities and challenges. Streaming platforms and online communities can offer positive emotional support to the players. However, these can also exacerbate psychological burdens when there is negative feedback and criticism rooted in anonymity [6].

According to the research, support and encouragement from fans can serve as motivational factors for athletes, whereas excessive expectations and critical perspectives can adversely affect their mental health [25]. Furthermore, collaboration and support between the team members and their coaching staff can play crucial roles in maintaining performance and managing stress. However, internal conflicts or unclear role expectations within the team can, conversely, increase stress levels [26].

Recent studies suggest that social identity theory serves as a key factor in mediating or moderating the psychological effects of social support [27]. When shared identity and cohesion within a team are high, athletes tend to positively interpret and internalize the social support they receive, which, in turn, leads to better psychological stability and resilience [25]. Conversely, when trust among teammates is low or when an individualistic and competition-oriented culture prevails, the protective effects of social support are weaker.

In the esports context, team identity varies significantly depending on the cultural background and the organizational practices. For instance, in Korean esports, systematic coaching and group training support team-based social identity, whereas in Western esports, personal branding and autonomy are emphasized [5]. These structural differences act as important contextual factors that influence not only how esports athletes perceive and utilize social support but also the magnitude of its effect.

In our study, we analyze the mental health and performance of esports athletes using social support theory, integrating the stress-buffering hypothesis, self-efficacy theory, and social identity theory to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the environment. Through this, we empirically examine how social support in the esports industry impacts these players’ psychological adaptation and performance outcomes, ultimately proposing effective intervention strategies. Furthermore, our findings can provide foundational data for expanding the role of social support not only in traditional sports but also in other digital competitive contexts.

Regarding theoretical background, we reviewed existing studies that primarily addressed stress and coping models, the JD-R model, and social support theory within traditional sports or general occupational settings. However, the present study distinguishes itself from previous research in the following ways. First, this study explores stress factors and coping mechanisms within the unique digital competitive environment of esports, thereby extending the theoretical application to a digital-based sports context. Second, when applying the JD-R model, this study specifically incorporates the distinctive job demands inherent in esports (extreme uncertainty and real-time feedback systems), providing an in-depth analysis of new job characteristics in the digital era that previous studies have not sufficiently explored. Finally, in applying social support theory, this study carefully examines how the unique communication structure of the digital environment (such as online communities and streaming platforms) impacts athletes’ mental health and performance. Through these approaches, this study aims to address the limitations of previous research and expand the theoretical interpretation, specifically within the context of esports. Moreover, in previous research on mental health in esports, the single-theory approaches have been mostly adopted or involved examination of limited aspects of psychological well-being [5,6], without a comprehensive, integrative framework. In this study, that gap was addressed by combining individual-level appraisal and coping mechanisms from the transactional model, the structural job characteristics and demand–resource balance from the JD-R model, and the psychological buffering functions of social support theory. Through this integrated lens, we reveal the dynamic interactions between structural demands and personal–social contexts that have not been addressed in previous research. Such an approach provides a more systematic and in-depth understanding of the mental health issues faced by esports athletes. It is expected to make a significant theoretical contribution to the field.

Our study explores the psychological dynamics related to stress, coping strategies, and social support among esports athletes. As noted, we employ three theoretical frameworks for this: the transactional model of stress and coping, the JD-R model, and social support theory. These frameworks provide a comprehensive, integrated perspective for analyzing how individual, organizational, and interpersonal factors within esports affect the athletes’ mental health and performance.

We use a qualitative case study approach to investigate complex and multidimensional phenomena within a specific context [28,29]. The case study is a qualitative research method that analyzes a participant’s life experiences in depth and derives theoretical insights from them [29]. Following the interpretivist paradigm, we emphasize that social reality is subjectively constructed through the interactions between the participants and the researchers [30]. This approach is appropriate for understanding how stress factors, coping strategies, and social support interact within the high-pressure and dynamic environment of esports.

We adhered to a systematic process in our research design, defining the research problem, selecting participants through purposive sampling, collecting data through semi-structured interviews, identifying recurring patterns through thematic analysis, and integrating the derived results within the theoretical framework. We employed reflective research and triangulation of our data sources to ensure the rigor and credibility of the study [30,31].

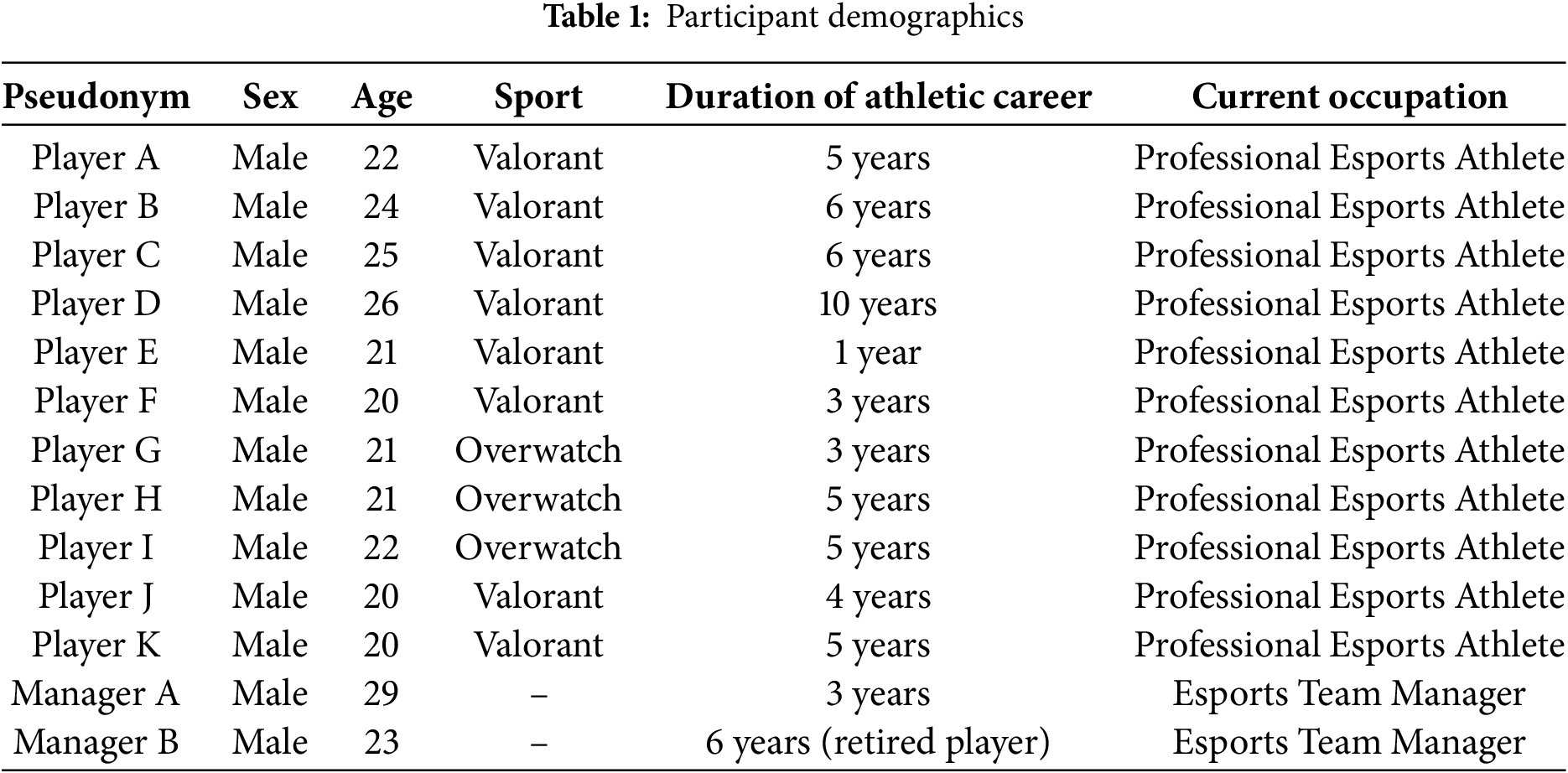

We interviewed 11 esports athletes with at least one year of experience at the national or international level, as well as two esports team managers. Participant recruitment was conducted through direct contact with esports organizations and professional networks, including recommendations from experts. In selecting participants, we intentionally included individuals aligned with the theoretical focus of this study. Specifically, we recruited athletes frequently exposed to high-stress situations (aligned with the transactional model). Additionally, we included those facing high job demands and with access to diverse resources (in line with the JD-R model). Players who actively engaged in team interactions (reflecting the social support theory) were also selected. These selections were made based on expert recommendations and pre-interview assessments to ensure that each participant showed characteristics relevant to the three theoretical perspectives. Participants were recruited within South Korea, and no financial compensation was provided. However, participants were offered materials related to mental training and psychological skills to support their future performance management and self-regulation improvement. This approach enabled the inclusion of individuals with relevant expertise and experience in the competitive esports environment. Additionally, participants were selected to represent various roles within the team (team leader and support player) and across different game genres, reflecting the diverse roles and responsibilities within the esports ecosystem. The purposive sampling method was employed to ensure diversity in demographic backgrounds, game genres, and team structures [32,33]. The purposive sampling approach was designed to capture the core constructs proposed by each framework, including various stressors, the balance between job demands and resources, and the different forms of social support. Consequently, this approach enhanced the theoretical alignment and explanatory depth of the study’s analysis. The ages of the participants ranged from 20 to 26 years, and their athletic careers spanned from 1 to 10 years.

The small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings; however, the qualitative approach facilitates rich, contextually grounded insights. Rather than aiming for statistical generalization, we sought to gain an in-depth understanding of the complex psychological dynamics these athletes were experiencing. The participants’ general characteristics are presented in Table 1.

We collected data between January and April 2025 through two primary methods: in-depth semi-structured interviews and non-participant observations of esports competitions. Interviews and observations were primarily conducted in settings that reflected the authenticity of the esports environment, including official training facilities, stadiums, team offices, or other mutually agreed-upon locations with participants. Data were collected in real-time contexts, including during team training sessions, post-match environments, and actual competition settings, thus capturing the situational specificity of the esports domain. All data were collected and recorded with the prior informed consent of the participants. Each of the 11 participants took part in three to five interviews, with the number of sessions adjusted individually according to data saturation. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 min and was conducted either face-to-face or remotely. The semi-structured interview format offered consistency and flexibility, allowing researchers to effectively explore new themes and the unique experiences of the participants [34].

In addition to the interviews, we conducted non-participant observations two to three times during each participant’s esports competition process. This supplemented our interview data by providing a contextual understanding of the participants’ behaviors, interactions, and stress responses in real-time competitive situations. Our focus was on team dynamics, communication between players, non-verbal cues, and reactions to performance pressure. These observations offered insights into aspects that may not have been explicitly mentioned during the interviews. Non-participant observation, as a method, is particularly valuable in capturing natural behaviors and contextual details, especially in dynamic environments, such as esports, where stress and coping mechanisms manifest spontaneously [35].

We designed the interview questions to focus on participants’ psychological responses to stress, coping mechanisms, and experiences with social support. The interview guide was created using core concepts of the transactional model of stress and coping, the JD-R model, and social support theory. Specifically, questions are grounded in the transactional model on how athletes appraise stressors and select coping strategies. Using the JD-R model, we examined participants’ views on job demands and the resources available. Informed by social support theory, we also investigated the types, frequency, and perceived effectiveness of social support received from within and outside the team. To ensure theoretical clarity, each question was systematically associated with the key constructs of these models. Major topics included performance pressure, team dynamics, interactions with fans, and the impact of organizational structure on mental health. The participants shared their experiences managing stress in high-stakes competitive situations, their perceptions of support from team members and their coaching staff, and the influence of external pressures, such as fan expectations, on their coping strategies.

To address sensitive topics, interviews were conducted empathetically to ensure participant comfort, with informed consent obtained beforehand. Psychological support resources were made available; however, none of the participants requested assistance. Non-participant observations were carefully conducted to minimize interference with participants’ activities, ensuring the authenticity of observed behaviors [35].

The researchers recorded and transcribed all the interviews and then verified data accuracy by involving participants in the process. Instead of employing traditional member checking, we adopted member reflection, encouraging participants to actively engage in interpreting the research findings. This collaborative and iterative approach enhanced the credibility of the results [36].

We used thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns within the data. The coding process consisted of three stages. In the initial coding phase, we assigned codes across the entire dataset—comprising interview transcripts and observational notes—based on key concepts derived from the three theoretical models: the transactional model of stress and coping, the JD-R model, and social support theory. During the focused coding phase, similar codes and cases were grouped into broader categories, followed by refining these categories to align with the central constructs of each theoretical framework. Finally, in the theoretical coding phase, interview and observational data were synthesized to derive core themes that captured the interactions among stress factors, coping strategies, JD-R, and social support systems. This multi-stage approach allowed us to integrate the interpersonal dynamics emphasized in the transactional model, structural aspects highlighted in the JD-R model, and the role of social support networks in shaping athletes’ mental health experiences.

To comprehensively understand the participants’ subjective experiences and behavioral contexts, we concurrently analyzed the data from the interviews and the non-participant observations. To maintain consistency and rigor, two researchers independently coded the interview transcripts, followed by iterative codebook comparisons to ensure the reliability of the thematic coding refinement, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion [31,37].

We also used triangulation to enhance the validity of the analysis by cross-referencing data from the interviews and the non-participant observations [30,32]. This multifaceted approach systematically strengthened the credibility and depth of the analysis. We further verified the identified themes through reflective discussions among the research team, grounded in the literature [30,38].

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sogang University (Approval Number: SGUIRB-A-2501-02). All participants provided written informed consent and were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. To ensure anonymity, we used pseudonyms, with all personally identifiable information removed from the data. Throughout the research process, the research team maintained an ethical stance centered on participant well-being, emphasizing reliability and mutual respect in data collection and analysis.

To ensure reliability and validity, we employed systematic procedures. Throughout the research process, we conducted peer debriefings at major stages to verify the accuracy of the coding frameworks and thematic interpretations. As noted, we used triangulation to integrate the interview and non-participant observation data with the theoretical framework analyses to interpret participants’ experiences from multiple perspectives. Additionally, we held iterative reviews to refine our analytical procedures and maintain consistency in the coding. These methodological strategies supported the study in meeting the rigorous standards of qualitative inquiry, contributing to the reliability of our results and the validity of the interpretations.

4.1 Performance Pressure and the Multilayered Aspects of Psychological Stress

Our interviews and observations confirmed that esports athletes faced continuous performance pressure in the results-oriented team structure. This included competition for starting positions, anxiety about making mistakes during the match, and ongoing external evaluations through live streaming and social media. Their psychological pressure arose not from a single cause but from complex, multilayered sources, intensifying their emotional responses and stress perceptions. In particular, structural factors linking short-term performance declines to changes in status or economic instability were environmental aspects that created anxiety. Herein, we discuss in detail how these multilayered stress factors influenced the structural conditions of the performance-centered environment and impacted the mental health of the players.

4.1.1 Performance-Centric Ideology and Intra-Team Competition Structure

Based on our observations, we found that the esports environment operated as a performance-centered structure, demanding consistent achievement from the players. While this structure has the positive function of enhancing extrinsic motivation and competitiveness, it simultaneously acts as a significant factor negatively affecting individual mental health. Specifically, the competitive atmosphere within the teams appeared to operate more on survival than on cooperation, creating challenges in building trust and emotional stability among the players. Stress in this context was not merely an external factor but accumulated as a persistent and chronic psychological overload within the structural framework, weakening the players’ resilience and self-regulation capabilities.

Player A reported experiencing extreme anxiety when his performance temporarily declined, as it could immediately result in demotion or loss of a starting position.

“If my performance dropped even once, I would immediately be moved to a substitute or trainee position.

That made me constantly anxious.”

This statement reflects the persistent evaluation and instability inherent in the performance-centered structure of esports. In particular, the perception that performance directly determines survival internalizes stress factors.

Player C felt that intra-team competition operated as a survival mechanism rather than fostering cooperation, deepening emotional isolation.

“Even though we are all competing for the starting position, honestly, sometimes it feels like we’re not even

part of the same team. They’re competitors, after all.”

This perception highlights the esports team culture where competition takes precedence over collaboration. Unlike traditional sports that emphasize teamwork, esports athletes see other teammates as potential threats, leading to a lack of social support and intensified emotional distress.

Player H expressed feeling pressured when mistakes during training were met with silent reactions from coaches or managers.

“If I make a mistake even once, the coach or manager’s expression immediately changes. Even without

saying a word, it feels like pressure.”

This reaction reflects the internalized stress response induced by non-verbal evaluation systems. There is no explicit reprimand; however, implied expectations and expressions of disappointment weaken players’ self-efficacy and inadvertently strengthen performance compulsion.

Player F shared an episode where unexpected team reshuffling just before a match disrupted psychological stability.

“When the team lineup was suddenly changed just two days before the match, I was really stressed out.

After that, I couldn’t sleep properly.”

This case illustrates how unpredictability and loss of control heighten mental stress, suggesting that external changes can significantly undermine psychological stability and lead to physiological stress responses, such as sleep disturbance.

Manager B pointed out the emotionally restrictive environment that emerges when performance is unsatisfactory, where players feel reluctant to express their feelings.

“Even when feeling unwell or struggling, it’s hard to speak up. Some players who did express their difficulties

ended up being replaced.”

This indicates that in the esports environment, performance evaluations create a culture of self-censorship and emotional suppression, leading to psychological withdrawal and isolation.

The performance-centric mindset, while outwardly promoting rational competition, results in subjective experiences characterized by suspended identity, breakdown of sustainable cooperative relationships, and unstable self-worth. Even within the team community, players experience structural loneliness, compelled to endure challenges individually, which exacerbates mental vulnerability. This performance-oriented team structure and heightened competition among team members reflect the core patterns of “excessive job demands” and “insufficient resources” as conceptualized in the JD-R model. Particularly, constant evaluation and chronic uncertainty appear to weaken players’ self-efficacy and psychological resilience. This increases the risk of burnout and deterioration in mental health [9,20]. This study empirically shows how an imbalance between job demands and resources in the esports context contributes to players’ struggles with self-regulation and their heightened psychological vulnerability.

4.1.2 Psychological Responses and Emotional Burden during Matches

The interviews revealed that the esports players often experienced intense psychological pressure when encountering sudden mistakes, tension, or unpredictable variables during matches. In particular, mistakes made during a game were not merely technical errors but also factors that exacerbated subsequent psychological reactions and emotional burdens. This highlights not only individual emotional regulation abilities but also the team dynamics and real-time external evaluations that create complex stress responses.

Player B recalled feeling both embarrassment and withdrawal after making an unexpected mistake during a critical match.

“I made a mistake just once, and after that, I couldn’t concentrate. My mind went blank, and I just thought

it was over.”

Such emotional responses can be interpreted as the perception of one’s mistake as a threat within the dual mechanism of primary and secondary evaluation. This response indicates a lack of internal resources to overcome the perceived threat.

Player D pointed out that technical issues during matches (network delays) could affect the entire team atmosphere.

“During the game... there was a conflict. I couldn’t respond properly, and I ended up swearing. The teammates’ slightly annoyed tone made me feel even more withdrawn.”

This reaction reflects not only individual stress but also the intertwining of team communication and emotional interactions, indicating that failures in emotional regulation could lead to performance decline within a structural context.

Player H described how a minor mistake during a match emotionally escalated and subsequently impacted the entire game.

“When I made a subtle control mistake at first, everyone on the team just stayed silent. They didn’t say anything, but I felt a lot of pressure. It really hit me that I messed up, and I kept feeling more and more withdrawn after that.”

This statement demonstrates that cognitive interpretations and emotional reactions to stress-inducing situations unfold in real-time during matches. The subtle social cues perceived by players can function as mechanisms that amplify psychological burdens.

Manager A mentioned the rapid shift in the atmosphere within the team after mistakes or misjudgments during a match.

“If someone makes a mistake, the whole team’s mood just drops. Even without saying anything, everyone

just looks at each other. That atmosphere becomes an even greater burden for the player.”

This illustrates how changes in the emotional atmosphere during matches transfer psychological pressure to individual players, highlighting how emotional reactions can escalate at the team level.

In summary, we found that psychological responses and emotional burdens during matches were not merely individual issues (feeling tense or losing concentration) but complex issues that encompassed performance pressure, intra-team dynamics, and overlapping external evaluations. Considering this context, managing stress during esports matches should not solely focus on technical training but should also include psychological preparation, emotional regulation, and a team-based emotional support system. Mistakes made during matches, heightened tension, and emotional contagion within teams can be seen as overlapping outcomes of limitations in primary and secondary appraisal and coping strategy breakdowns, according to the transactional model of stress and coping. Repeated failures in emotion regulation and diminished concentration in situations with insufficient psychological or social resources can be interpreted through the integrated lens of the transactional and JD-R models [12]. This study highlights how the emotional burden faced by esports athletes during competition results from the interaction between structural demands and the availability—or lack—of coping resources.

4.1.3 Social Networking Service (SNS) Reactions and External Evaluation Stress

We found that the esports players were evaluated not only on their performance in the competition but also constantly through streaming, SNS, and fan communities. Compared with traditional sports, this feedback environment is much faster and more direct, acting as a critical factor affecting players’ emotional stability. In particular, the players noted that real-time comments after a match, YouTube clips, and community reactions could immediately impact them, with some showing tendencies to either avoid them or excessively worry about them.

Player I mentioned that immediate online feedback, such as SNS and YouTube comments, during personal broadcasting caused significant emotional stress.

“After broadcasting, comments start coming in right away, and there are a lot of negative ones. Seeing the

‘dislike’ count suddenly spike on YouTube really gets to me mentally.”

This highlights how negative feedback from real-time evaluation environments can trigger an immediate stress response among the players. Such evaluations particularly act as factors that undermine players’ self-esteem and induce immediate psychological anxiety.

Manager B described the attitudes and internal reactions of players regarding SNS responses.

“I’ve seen some negative posts come up, but the players don’t seem to worry about them that much.”

The implication is that players have different coping strategies, with some choosing avoidance to minimize emotional harm. However, such strategies can lead to long-term fatigue, indicating that mere avoidance may not be sufficient for maintaining mental well-being in the face of sustained SNS feedback.

Manager A pointed out that some players managed stress through personal broadcasting or by actively managing fan relationships.

“Some players are really good at managing fans, while others don’t seem to grasp the importance of it. Many

try to talk about their feelings on personal broadcasts or use them to relieve stress.”

This indicates that some players use streaming and SNS activities as tools for “emotional regulation” and “identity maintenance,” showing that internal resilience and recovery strategies against external evaluation vary.

Player I pointed to the psychological reaction of trying to avoid SNS comments as a coping mechanism.

“I try to avoid looking at those comments while dealing with stress.”

While this strategy serves as a psychological defense against negative feedback, it also reveals a limitation in cases where critical comments are structurally repetitive, suggesting that self-regulation avoidance alone may not be adequate.

We observed that the external evaluations from SNS induced a “dual emotional burden” on players. While positive reactions might enhance their motivation, negative feedback could also result in identity damage, reduced self-efficacy, and chronic stress. In esports, in particular, where real-time streaming environments expose players to immediate evaluations compared with those in traditional sports, the repetitive feedback cycle without recovery time poses a structural threat to mental health. Consequently, from the perspective of the transactional model of stress and coping and the JD-R model, external evaluation factors (demands) that disrupt the balance with internal resources may lead to mental burnout. This phenomenon illustrates how excessive external job demands—such as real-time SNS reactions and public evaluations—combined with insufficient social support, can lead to a substantial psychological burden, as described in the JD-R model. Moreover, athletes use various strategies to manage negative feedback from the perspective of the transactional model of stress and coping, including avoidance and emotional suppression. However, when structural and repetitive stressors persist without adequate internal or external resources, these coping mechanisms may fail, leading to chronic burnout and reduced self-efficacy. This situation further underscores the absence of the buffering effect described in social support theory [22]. Overall, in this study, the structural threat mechanisms were outlined through which SNS-based evaluations and social feedback affect the mental health of esports athletes.

4.2 Stress Coping and Psychological Recovery Strategies

As noted, in highly competitive esports environments, players employ various methods to manage stress, including problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and avoidance strategies. Depending on the situation, these strategies are often mixed, and sometimes supplementary methods for concentration recovery (music, meditation, and caffeine) are utilized. However, some coping strategies provide only temporary relief, leading to repeated exhaustion and a cycle of self-regulation failure. We examined how players perceived and regulated their stress, assessing the pathways through which their stress perceptions and coping strategies connected to their psychological recovery.

4.2.1 Comparison of Coping Strategies: Problem-Focused, Emotion-Focused, and Avoidant

The esports athletes indicated that they frequently encountered repetitive and unpredictable stress situations during competitions, prompting them to adopt various coping strategies. We categorized these into the three mentioned above: problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping, following the transactional model of stress by Lazarus and Folkman [12]. We also qualitatively analyzed how the participants implemented each strategy. Despite facing the same stress conditions, players demonstrated differing coping methods, revealing the complexity of stress management and recovery strategies.

Problem-Focused Coping:

This strategy involves identifying the cause of stress and structurally addressing it.

Player C actively coped with performance pressure by switching training methods, analyzing strategies, and setting routines.

“I kept organizing feedback separately. I also repeatedly watched replays to analyze where I fell short.”

This response demonstrates a typical problem-focused coping approach, emphasizing self-analysis and systematic improvement. This not only contributes to performance enhancement but also to a sense of control.

Emotion-Focused Coping:

Instead of removing the stressor directly, this approach focuses on regulating emotional responses to ensure temporary stability. It includes expressing emotions, psychological shifts, and personal recovery activities.

Player G dealt with heightened emotions after a game by isolating himself and listening to music.

“After the game, I just put on my headphones and listened to music. I don’t talk to anyone. Sometimes I just

don’t feel like talking because my feelings are too mixed up.”

This statement reflects an emotion-focused coping pattern, aiming to recharge emotional energy while minimizing social interaction.

Avoidance Coping:

This strategy aims to bypass stressful situations without confronting them directly. We found that some players interviewed deliberately avoided SNS, interviews, or feedback situations, or blocked external stimuli on competition days.

Player J stated that to protect their mental state from harmful comments, he deliberately minimized SNS use.

“I hardly ever check SNS. If I do, I feel like my mentality will crumble. I just turn it off after the game.”

Avoidance of SNS reflects an attempt to maintain emotional stability by controlling informational exposure.

Player D tried to intentionally forget mistakes to avoid a stress-related recall.

“After making a mistake, I just try to forget it. If I keep thinking about it, I can’t focus on the next game.”

Such cognitive avoidance is aimed at blocking the recurrence of negative emotions, providing short-term emotional relief, although it may lead to avoidance learning in the long run.

We found that problem-focused coping was more prevalent among the experienced players or those proficient in game strategies, suggesting a positive relationship with self-efficacy. In contrast, emotion-focused coping and avoidance strategies were temporary measures, often employed when stress levels became excessive. Notably, the athletes frequently used avoidance coping when dealing with uncontrollable factors, such as SNS criticism and performance anxiety. This pattern aligns with the concept of ‘excessive demands and insufficient resources’ in the JD-R model, wherein coping responses are shaped by the availability of psychological resources, social support, and cognitive interpretations of stress. The players’ psychological resources, social support availability, and cognitive stress appraisals influenced their adoption of different coping strategies, demonstrating a dynamic adaptation process. This typology and selection process of coping strategies directly shows the concepts of cognitive appraisal and strategic flexibility emphasized in the transactional model of stress and coping. The fact that athletes adopt different coping mechanisms even in similar environments suggests that individual cognitive resources influence the strategic combination of coping, the availability of social support, and levels of self-efficacy [12]. Moreover, the repeated use of avoidance strategies may represent a short-term adaptive response in situations of limited resources, as described in the JD-R model. However, such strategies can lead to burnout and a failure of self-regulation over time, highlighting the importance of sustained psychological and structural support.

4.2.2 Supplementary Strategies for Maintaining Concentration and Recovery

We found that the esports athletes utilized various informal and self-directed supplementary strategies to maintain performance. Specifically, they often consumed excessive amounts of caffeine and adopted routine-based regulation behaviors and non-medical stress relief to sustain continuous concentration and psychological recovery. This reflects a survival strategy in the absence of formal mental health support systems that serves as a means of self-regulation and a method of emotional recovery.

Player E mentioned using a specific supplement to maintain focus and recover from fatigue after training.

“Before a match, I always drink a caffeinated beverage as part of my routine. Without it, I can’t concentrate.”

This can be interpreted as a self-regulation method, with the athlete deliberately inducing a physiological arousal state to optimize performance. Simultaneously, it corresponds with a preparation coping strategy while also indicating potential psychological dependency.

Player B emphasized that maintaining a consistent routine and supplementary habits contributed to emotional stability.

“Before matches, I deliberately turn on a meditation app and close my eyes. The game works better when

my mind is calm rather than just my body.”

This is an emotional regulation strategy utilizing psychophysiological stimulation. Such emotion-focused coping strategies are internalized through repetitive routines, potentially leading to enhanced self-efficacy. However, Player B also admitted to frequently using alcohol as a stress relief method during periods of intense conflict within the team and pressure to perform.

“I kind of like drinking. Meeting up with people I like, having a drink together—it’s like the only escape. At

least for that moment, I don’t think about the game.”

This behavior might serve as a temporary escape strategy to alleviate stress. However, in the long term, it could lead to negative psychological dependence and health issues, demonstrating the dual nature of informal coping strategies.

Player G described personal emotional recovery through listening to music as an everyday strategy.

“After matches, I just put on my earphones and listen to music to organize my feelings. It’s much more

comfortable than talking to anyone.”

This approach reflects a self-centered internal recovery method positioned between avoidance coping and emotion-focused coping. While it may offer temporary psychological stabilization, it might not address accumulated fatigue and stress.

However, Manager A noted that some athletes used routines as a psychological stabilization resource, emphasizing that maintaining routines can serve as a psychological anchor in uncertain environments.

“I think routines are really important. When routines break down, their mentality breaks down too. Having

routines seems to help them keep their balance, even in unstable environments.”

This statement reflects a managerial perspective on routines functioning as a means of emotional regulation for these athletes. It also highlights the need to explore the gap between the perceived importance of routines and the athletes’ actual experiences.

Ultimately, we found that the various supplementary strategies employed by the players shared the common goals of “regaining control” and “emotional stabilization.” These self-defensive strategies emerged from the uncertainty and real-time feedback inherent in the esports environment. The behaviors, appearing as emotion-focused or avoidance coping rather than problem-focused coping, served as self-directed survival strategies in the absence of formal support systems. From the JD-R model perspective, these strategies act as informal resources that mitigate job demands, temporarily delaying psychological exhaustion. However, strategies with potential risks, such as alcohol consumption, may lead to long-term mental and physical harm, underscoring the need for more systematic and formal mental health support programs. The frequent use of informal and self-directed supplementary strategies—such as caffeine consumption, personalized routines, or listening to music—clearly illustrates the utility and limitations of informal resources as defined by the JD-R model. When organizational support is lacking, players actively seek their resources to secure short-term emotional stability. However, this reliance may gradually increase the risk of psychological dependency and lead to accumulated fatigue over time. This pattern also aligns with the resource-compensation and self-regulation reinforcement mechanisms described in the transactional model of stress and coping.

4.2.3 Cycle of Repetitive Burnout and Self-Regulation Failure

The esports athletes indicated that they often experienced repetitive psychological burnout and self-regulation failure while striving to maintain performance under constant pressure. This phenomenon goes beyond the mere accumulation of fatigue; stress factors become internalized, leading to the incapacitation of individual recovery mechanisms, forming a “cyclic burnout structure” with long-term effects on mental health. In particular, repetitive occurrences, such as competition outcomes, slumps, and individual mistakes, contribute to lowered self-esteem, weakened self-efficacy, diminished emotional responses, and ultimately, a failure in emotional regulation, forming a noticeable vicious circle.

Player G recalled experiencing emotional exhaustion after repeated failures:

“After failing so many times, I just stopped feeling angry and felt like giving up.”

This statement reflects emotional desensitization owing to repetitive failure, indicating signs of diminished self-efficacy and helplessness. In the JD-R model, this exemplifies the typical manifestation of burnout when job demands exceed available resources.

Player E described the struggle between slumps and performance anxiety:

“On days when my shots don’t hit, I feel irritated all day, and it even affects my practice. I know it, but I

just can’t help it.”

This statement illustrates a lack of effective self-regulation, as emotional coping strategies become repetitive without achieving stability. According to the transactional stress model, failure occurs when the secondary appraisal inadequately processes negative emotions.

Player C pointed out the structural reality of being unable to rest even after burnout:

“Even when I want to take a break, I can’t because of the team’s atmosphere. So, it just keeps piling up.”

This points to how team expectations and dynamics in the esports structural environment suppress personal recovery cycles, which is in line with the “resource depletion” burnout pathway in the JD-R model.

Player I expressed a sense of collapse when self-regulation failure persisted:

“Now I get what it means when people say they are falling apart. No matter how I try to change my mindset,

it just doesn’t work.”

This statement suggests that when self-regulation failure and stress tolerance deterioration accumulate, it becomes challenging to achieve integrated self-recovery. This situation reflects a decline in self-efficacy and greater repetitive burnout.

Manager B addressed the impact of repetitive failures and internal evaluation systems on players’ emotional regulation:

“When players fail repeatedly, they feel that higher-ups don’t view them favorably anymore. This makes

them more anxious, lose control over their emotions, and eventually push themselves to the breaking point.”

This insight suggests that self-regulation failure extends beyond individual psychological issues arising from internalizing performance pressure and interacting with the organizational structure.

Ultimately, we found that the psychological burnout and self-regulation failure experienced by these athletes were not merely problems of stress intensity but a structural cycle rooted in the absence of psychological and environmental resources needed for recovery. Both the JD-R model and the transactional stress model recognize this, indicating that practical psychological recovery interventions should focus on creating a “recovery-friendly environment” and enhancing autonomous regulation capabilities. The recurring cycle of burnout and failure in self-regulation represents a common psychological downward spiral that occurs when the imbalance between job demands and resources becomes severe, as described in the JD-R model. According to the transactional model of stress and coping, the repeated use of maladaptive coping strategies leads to a decrease in resilience and self-efficacy, indicating that such issues cannot be easily resolved without making structural changes to the environment. This study highlights the importance of integrating these two theoretical frameworks in understanding the mechanisms of psychological exhaustion among esports athletes.

4.3 The Mechanisms of Social Support and Its Psychological Impacts

In our conversations, we found that in the esports context, social support served as a crucial resource for emotional stability and performance consistency. However, rather than being reliable, its effects had an ambivalent pattern. Teammates, coaches, family, friends, and fandom at times provided emotional support. Yet, they also acted in ways that intensified performance pressure or amplified stress factors. Particularly, ambiguous role expectations within the team, performance-oriented feedback from coaches, avoidant attitudes from family and friends, and extreme reactions from fan communities reveal the duality and incompleteness of social support. We examined these contrasting experiences to comprehensively analyze the practical mechanisms and psychological impacts of social support networks that shape the mental environment for esports athletes.

4.3.1 Team and Coaching Staff: The Boundary between Support and Pressure

We found that the esports coaching staff played a crucial role in enhancing player skills and managing performance. However, this role did not necessarily translate into psychological support. Some players perceived feedback from coaches not as emotional support but rather as control and pressure, highlighting the structural limitations when the support system fails as a psychological resource.

Player B explained that the coach’s behavior before and after matches caused psychological discomfort:

“Before the game, they barely say anything, but after it’s over, the first thing they say is, ‘Why did you do

that?’ rather than showing support.”

Such experiences illustrate why the athletes may perceive coaching feedback not as technical guidance but as performance evaluation. When emotional support is absent or limited, players can internalize instructions or criticism as an emotional burden.

Player C described the atmosphere within the team and the sense of distance from the coach:

“Honestly, I don’t talk to the coach about my worries. I’m afraid I might lose my chance to play.”

This statement implies that players suppress their emotions and avoid sharing their mental state, suggesting that the power dynamics within the team do not guarantee psychological safety. In this context, the role of “judge” overshadowed the coach’s role of “supporter” by inhibiting players from expressing themselves.

Player I candidly described the atmosphere during training regarding expectations:

“Even when I’m not feeling well, the atmosphere is like, ‘You should be able to handle that.’ The coach also

says, ‘You can do it.’”

This implication is that “team expectations” may transform into pressure that disregards the physical and mental limits of individual players. From the JD-R model perspective, when job demands exceed available resources, this can lead to emotional exhaustion.

Manager B criticized the culture where the coaching staff approached players only with a focus on performance:

“The reality is that coaches are under pressure themselves to produce results, so they focus on performance

rather than being supportive.”

This comment highlights that the coaches are also trapped within a structure of performance pressure, which limits their capacity to act as emotional support providers. This structural issue indicates that coaches, much like players, occupy a dual position where they cannot adequately function as psychological resources.

Ultimately, although teams and coaching staffs should act as “official supporters” for players, based on the players’ comments, their interactions often focus more on control and evaluation. From the perspective of social support theory, when emotional support is insufficient, internal team interactions may inadvertently transform into stressors. Additionally, the JD-R model highlights how a lack of resources (resource inadequacy) within this context can increase the risk of burnout. The psychological burden and imbalance seen in coach–player interactions align with the theoretical propositions of social support theory and the JD-R model. Specifically, the absence of formal support resources may reduce athletes’ psychological assets, increasing the risk of burnout and emotional exhaustion [20,22]. This study shows how coaching staff can either mitigate or exacerbate athletes’ mental health conditions in the esports context, depending on whether they act as technical instructors and providers of psychological resources.

4.3.2 Family and Friends: Silenced Emotions, Covert Recovery Resources

We found that family and friends could serve as potential emotional resources and recovery channels for some esports athletes. However, other participants indicated that rather than offering explicit support, many were silent or avoided or limited their interaction. Particularly, the athletes who debuted on the professional stage at a young age often experienced a sense of distance from their families, disconnection from friends, and isolation from general society. This exacerbated their psychological isolation. Nevertheless, some players, albeit in a highly limited way, still recalled or relied on family or past connections as sources of emotional support, suggesting that, although not overtly visible, these connections may serve as covert resources for psychological recovery.

Player G described a situation where the family context suppressed emotional expression:

“I don’t really talk to my mom. I just don’t want to make her worry. At home, I just act like nothing’s wrong.”

The implication is that the family can act as a psychological burden rather than a relief, leading athletes to suppress their emotions. While intended to protect their family from worry, this ultimately results in the athletes choosing emotional isolation, potentially accumulating long-term psychological fatigue.

Player I reflected on the lack of friendships:

“I don’t really have long-time friends. Ever since elementary school, I’ve been moving around with training

camps and changing teams.”

We learned that frequent relocations and training camps hindered the esports athletes’ abilities to establish stable social networks, limiting their capacity to share emotions or alleviate stress. As a result, the lack of informal relationships became a factor that weakened emotional resilience.

Player K shared experiences hinting at familial tension from a young age:

“My parents didn’t really like me playing games before. We used to argue a lot. Now, they just kind of watch.”

In this person’s case, choosing esports as a career itself became a source of conflict within the family, leading to emotional distance. Nevertheless, Player K interpreted the passive parental acceptance as a form of emotional tolerance.

Player J recalled past relationships with teammates as stronger than familial bonds:

“There was a senior I trained with since middle school, and even without words, he always took care of me.

I don’t know how I would have managed without him.”

This depiction of mentor-mentee relationships transcends conventional friendships or familial ties, forming a “field-centered emotional shield” in a structurally isolated environment. It functions as a replacement for conventional social support networks.

Manager A noted that athletes often showed signs of emotional recovery after visiting home or spending time with family:

“They definitely look brighter after visiting home. Spending time with parents seems to help them

emotionally.”

This observation implies that family, despite being sporadic and unofficial as a support network, still plays a role in psychological recovery when briefly reconnected.

The above comments reveal the presence of unofficial and personal emotional networks outside of formal support systems. However, such support remains mostly informal and coincidental, falling short of being consistent or structured recovery resources. From a social support theory perspective, family and friends could serve as critical emotional buffers; however, in the esports context, they appear not to function as practical support systems owing to structural limitations. This represents the “informality and insufficiency of resources” from the JD-R model’s perspective, contributing to emotional regulation failure and an increased risk of burnout. The roles and limitations of informal networks, including family and friends, are closely aligned with the buffering function highlighted in social support theory and the discussion of “informal resources” within the JD-R model. Our findings show that while relationships with family and friends may sometimes serve as psychological recovery resources, their benefits are often limited by structural factors, including unstable family dynamics or social isolation. When these limitations are present, informal ties may not only fail to alleviate stress but also exacerbate emotional exhaustion and psychological vulnerability.

4.3.3 Ambivalence of Fandom and Online Communities