Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Role of Mindfulness in Foreign Language Anxiety: A Systematic Review of Correlational and Intervention Studies

1 Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Macau, Macau, 999078, China

2 Faculty of Education, University of Macau, Macau, 999078, China

* Corresponding Author: Yijie Li. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(9), 1279-1300. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068399

Received 28 May 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) represents a substantial affective barrier that undermines cognitive performance, motivation, and retention in language learners. Emerging evidence highlights mindfulness-based interventions as promising strategies for enhancing emotional regulation and reducing anxiety across educational contexts. This review synthesizes current research on mindfulness as a psychological intervention, aims to evaluate its efficacy in alleviating FLA, and discusses its broader implications for health-focused educational policy and practice. Methods: Following PRISMA guidelines, we systematically reviewed studies examining the relationships between mindfulness and FLA. Our search of four major databases (November 2023) initially identified 346 articles using terms like “mindfulness AND language anxiety.” After screening, 14 studies met our criteria: (1) empirical research in English on mindfulness-FLA relationships; (2) no publication date restrictions. Two independent reviewers selected studies, excluding two due to methodological limitations. We conducted a narrative synthesis given the study heterogeneity (9 correlational and 5 intervention studies). Results: 9 non-intervention studies demonstrated that mindfulness is negatively associated with FLA, with 3 studies highlighting the mediating roles of self-efficacy and resilience. 5 intervention studies reported inconsistent results regarding the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing FLA. Conclusions: The findings suggest that while mindfulness holds promise as a tool to address FLA, its mechanisms and effectiveness require further investigation. This study underscores the need for rigorous research, including Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), to inform evidence-based integration of mindfulness into foreign language curricula. For educational policymakers and practitioners, these insights highlight the importance of adopting mindfulness interventions cautiously, ensuring they are tailored to students’ needs and supported by evidence.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileFollowing the PRISMA guidelines [1] for systematic reviews, this study investigates Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA), a well-established affective phenomenon that interferes with second or foreign language acquisition. Defined as a specific type of performance anxiety, FLA involves intense feelings of apprehension, self-doubt, and tension during language learning tasks [2]. These emotional states not only impede learners’ performance but are also associated with broader psychological distress, including avoidance behaviors and low self-esteem [3–5]. From a psychological health perspective, FLA shares fundamental characteristics with general anxiety disorders, including intrusive thoughts, physiological arousal, and difficulties in emotion regulation [6]. As such, FLA can be understood not only as a barrier to academic success but also as a psychological burden with implications for learners’ mental health. According to previous studies [7–9], 30% to 80% of students report experiencing FLA. This disproportionate prevalence is particularly salient among Chinese learners, where FLA frequently manifests as classroom silence, diminished motivation, and impaired linguistic performance [10].

Mindfulness has emerged as a promising approach for managing a wide range of anxiety-related conditions, including those experienced in educational settings. Defined as purposeful, present-moment awareness coupled with non-judgmental acceptance of internal experiences [11], mindfulness encourages individuals to observe their thoughts and emotions without reacting to them. Bishop et al. [12] conceptualize mindfulness through two main components: self-regulation of attention and an attitude of curiosity and openness toward experience. These processes support emotional regulation by reducing maladaptive stress responses and enhancing cognitive flexibility, both of which are clinically significant for treating anxiety disorders [13]. Research across clinical and educational domains has shown that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) can reduce symptoms of generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and performance-related stress [14–18].

Mindfulness exerts its therapeutic effects through reduced emotional reactivity, improved attentional control, and physiological regulation of stress responses [17], which directly align closely with the emotional, cognitive, and bodily aspects of FLA. In academic contexts, mindfulness has also been shown to improve student mental health by reducing stress and fostering emotional resilience [19]. Importantly, mindfulness may support language learners by helping them disengage from perfectionism and fear of negative evaluation, two key contributors to FLA [14]. While mindfulness is gaining traction in school-based mental health programs, its potential role in addressing FLA remains underexplored.

1.1 FLA and Its Determinants: A Health Psychology Perspective

FLA is increasingly recognized as not merely a performance-related challenge but also a mental health concern that intersects with educational, cognitive, and emotional domains. Defined as the experience of apprehension and worry specifically related to second language learning, FLA can disrupt learners’ cognitive processing, reduce classroom participation, and impair academic performance [2,6]. From a health psychology standpoint, FLA shares critical affective and physiological characteristics with generalized and social anxiety disorders, including elevated heart rate, intrusive thoughts, avoidance behaviors, and cognitive distortions such as catastrophizing or fear of negative evaluation [3–5]. These parallels highlight the need to address FLA not only as a pedagogical challenge but as an affective disorder requiring psychologically informed interventions.

The antecedents of FLA can be broadly categorized into external (contextual) and internal (personal) factors. Externally, the classroom environment has consistently emerged as a crucial determinant of anxiety levels in language learners. Research has shown that emotionally supportive classroom environments, those characterized by mutual respect, teacher encouragement, and low threat perception, can significantly reduce anxiety and foster positive learner engagement [20–22]. The physical organization of learning spaces, such as flexible seating arrangements that facilitate peer interaction, also contributes to learners’ comfort and perceived psychological safety [23]. Moreover, interpersonal dynamics, including peer relationships and the quality of student-teacher communication, influence learners’ sense of belonging and thus their vulnerability to anxiety [24].

From a psychological health perspective, interventions that enhance the social-emotional climate of the classroom may have downstream effects on anxiety regulation. MBIs, in particular, have been shown to foster prosocial behavior, increase empathy, and reduce interpersonal conflict in educational settings [25,26]. A systematic review by Monsillion et al. [27] further demonstrated that MBIs improve teachers’ self-compassion and perceived efficacy, both of which have been linked to improved classroom environments and more supportive learning conditions, therefore helping to reduce students’ language learning related anxieties. These findings position mindfulness not only as a personal coping tool but also as a systemic factor capable of influencing the psychosocial context in which FLA arises.

On the internal side, FLA is associated with individual learner differences that are psychologically and biologically mediated. Learners’ perceived language competence, their relative standing in class, and dispositional factors such as emotional intelligence, self-regulation, and self-motivation significantly shape anxiety levels [28,29]. Research also points to the importance of psychological resilience, as reflected in traits like grit and willingness to communicate, which may buffer the emotional impact of language learning stressors [30,31]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have highlighted foreign language self-efficacy as a key construct in this domain, showing a reciprocal relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and FLA [32]. Learners with higher self-efficacy are more likely to interpret challenges as surmountable and less likely to experience debilitating anxiety.

From a health psychology perspective, this relationship is particularly meaningful because self-efficacy influences not only academic outcomes but also emotional resilience and mental health [33,34]. Mindfulness practices have been found to enhance self-efficacy by increasing metacognitive awareness and emotional stability, both of which allow learners to remain focused and less reactive under stress [35,36]. These findings provide strong theoretical justification for investigating mindfulness as an intervention for FLA, particularly in learning environments where psychological distress is common and performance pressures are high. Yet, despite increasing empirical interest in mindfulness across educational contexts, the specific intersection of mindfulness and FLA has received limited attention in the form of comprehensive or integrative analysis.

1.2 Addressing FLA through Mindfulness: Mental Health-Oriented Strategies in Education

Educational and psychological research has developed a range of interventions aimed at mitigating FLA [36,37]. Classroom-based approaches typically focus on modifying environmental and instructional variables to foster a sense of emotional safety. For instance, interventions that emphasize peer collaboration, teacher support, learner autonomy, and positive reinforcement have been associated with reduced anxiety and improved learner confidence [38]. These techniques are often categorized into individual (e.g., self-monitoring, preparation strategies) and interactional (e.g., cooperative learning, teacher-student dialogue) modalities, and aim to cultivate affective conditions conducive to language learning.

In addition to these pedagogical interventions, psychological strategies grounded in positive psychology have gained attention for their potential to reshape learners’ emotional responses. One such approach involves having students recall and reflect on past academic successes, thereby reinforcing self-efficacy and reducing anticipatory anxiety [37]. These affective interventions are aligned with a strengths-based model of mental health, encouraging learners to engage with their experiences from a more empowered and emotionally balanced standpoint.

Existing strategies for addressing FLA typically emphasize specific aspects of the anxiety experience, whether environmental or cognitive in nature. While these approaches may indirectly influence psychophysiological states—for instance, through positive recall of past achievements—MBIs offer a more comprehensive framework by simultaneously engaging multiple response domains. Through mechanisms such as enhanced attentional control, non-judgmental awareness, and physiological downregulation, mindfulness has demonstrated efficacy in reducing generalized, social, and performance-related anxiety in diverse populations [13,15]. In educational settings, MBIs have been shown to lower academic stress, enhance emotional resilience, and support executive functioning—all of which are relevant to the cognitive demands of second language learning [19].

Emerging evidence suggests that mindfulness may be particularly suited to addressing two core drivers of FLA: perfectionistic thinking and fear of negative evaluation [14,39]. By training learners to observe thoughts non-reactively, mindfulness may help reduce rumination and evaluative self-judgment—two processes that heighten vulnerability to language learning anxiety [14]. Furthermore, the physiological benefits of mindfulness—such as reductions in cortisol levels and sympathetic nervous system activation—can support a calmer, more regulated bodily state during performance tasks [11,15]. These findings support the integration of mindfulness not only as a coping strategy but as a holistic, health-promoting intervention that aligns with contemporary models of educational well-being.

Despite these promising developments, few studies have explored the specific role of mindfulness in language learning contexts, and even fewer have focused on its application to FLA. This gap underscores the need for targeted research that evaluates both the effectiveness of MBIs in reducing FLA and the contextual factors that influence their implementation. Such work is essential for advancing our understanding of how evidence-based mental health strategies can be embedded within pedagogical practices to enhance learning outcomes and emotional well-being simultaneously.

Although mindfulness-based approaches have been increasingly adopted to support student mental health and classroom well-being, their specific impact on FLA has yet to be comprehensively reviewed. While existing research offers evidence of mindfulness reducing general anxiety and improving learning-related emotional outcomes, there is limited synthesis regarding its role in the language learning domain. The specific ways mindfulness may reduce FLA, along with practical classroom application difficulties, require further investigation.

This review aims to bridge that gap by systematically synthesizing the empirical literature examining the relationship between mindfulness and FLA. The review encompasses both correlational studies examining the relationships between mindfulness traits and FLA, as well as intervention studies assessing the impact of mindfulness-based programs on FLA among language learners.

To structure this review, two overarching research questions are proposed:

1. What is the nature of the relationship between mindfulness and FLA among language learners?

To address this question, three competing hypotheses are examined:

Hypothesis 1a: Mindfulness is positively associated with FLA.

Hypothesis 1b: Mindfulness is negatively associated with FLA.

Hypothesis 1c: Mindfulness is indirectly associated with FLA through potential mediating variables.

2. What are the effects of MBIs on reducing FLA, and how are these effects moderated by cultural, methodological, and implementational factors?

2.1 Literature Search Strategy

Following PRISMA guidelines (Supplementary Material S1) [1], data were systematically extracted using a standardized form that included study design (correlational/intervention), sample characteristics, mindfulness/FLA measurement tools, and key findings. Concurrently, this systematic review was conducted across multiple academic databases, such as the American Search Complete, ERIC, Web of Science, and Scopus. To minimize the publication bias and ensure a comprehensive search, both peer-reviewed studies and dissertations were included, with the research process concluding in November 2023. In the search strategy, relevant keywords were employed: “Mindfulness OR meditation” AND “language anxiety”; “mindful” AND “foreign OR second language”; “language anxiety” AND “meditation”; “mindful” AND “language learning”; and “foreign OR second language” AND “meditation.” Next, no date restrictions were applied during the search.

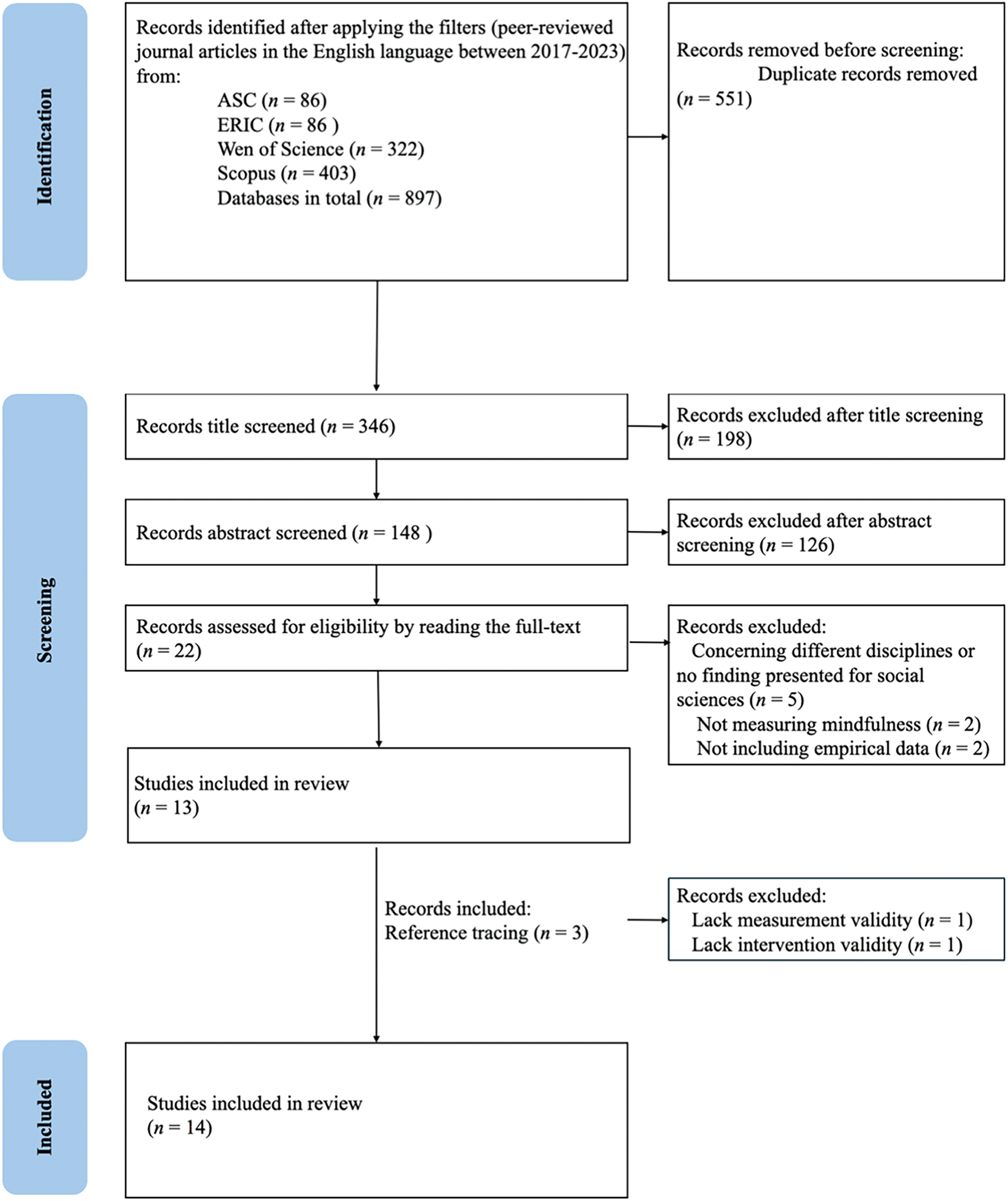

The outcomes following the search of the American Search Complete database produced 86 titles and abstracts; Eric produced 86 titles and abstracts; Web of Science produced 322 titles and abstracts; and Scopus generated 403 titles and abstracts. After eliminating any duplicates, 346 papers that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria have undergone further evaluation.

2.2 Screening Process and Eligibility Criteria

We applied specific inclusion criteria after conducting literature searches and screening abstracts, as shown in Fig. 1. First, articles had to be written and published in English. Second, the studies needed to examine the relationship between mindfulness and FLA. Third, studies needed to be empirical research, excluding review studies. The exclusion criteria refer to studies that are not written or published in English, as well as those that discuss mindfulness in contexts unrelated to FLA. Furthermore, we excluded studies that did not include mindfulness or FLA measurements.

Figure 1: Flow chart with the process of study selection

Following the application of those criteria, thirteen abstracts were identified, along with one published article [40] derived from the author’s PhD dissertation [41]. After conducting a reference tracing on these 14 papers, we found one more master’s thesis [42] and one more doctoral thesis [43]. Upon re-evaluation during the revision process, we have excluded these two theses for the following methodological reasons. Öz [42] lacked rigorous quality controls in its research design, particularly in measurement validity, which did not meet our updated quality thresholds for inclusion. Del Mar Thomas [43] employed an exceptionally minimal intervention protocol (two 5-min audio-guided sessions) that differed substantially from the more robust interventions (typically 4–12 week programs) examined in other included studies, creating problematic heterogeneity in intervention intensity. Therefore, we ultimately locked in 14 papers. One author carried out the literature search, screening, review, and data collection of articles, and another one repeated it, with disagreements solved thanks to discussions. Due to the limited number of articles and variations in research design, a systematic review was conducted instead of a meta-analysis.

Two authors independently evaluated the methodological quality of included studies based on study design, sample size, confounding control, and outcome measurement. Initial inter-rater agreement was 91% (Cohen’s κ = 0.87, 95% CI 0.82–0.92), and discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

For the subsequent data extraction (e.g., study characteristics, outcomes, and effect estimates), the two reviewers first independently coded a subset of studies (20%) to ensure consistency. Remaining extractions were performed by one reviewer and verified by the second. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

The results were systematically tabulated to summarize study characteristics (e.g., design, sample size) and reported outcomes. Given the substantial heterogeneity in study methodologies and outcome measures, a narrative synthesis approach was adopted without statistical meta-analysis. To examine temporal trends in the literature, we additionally created a bar chart visualizing the annual distribution of included studies.

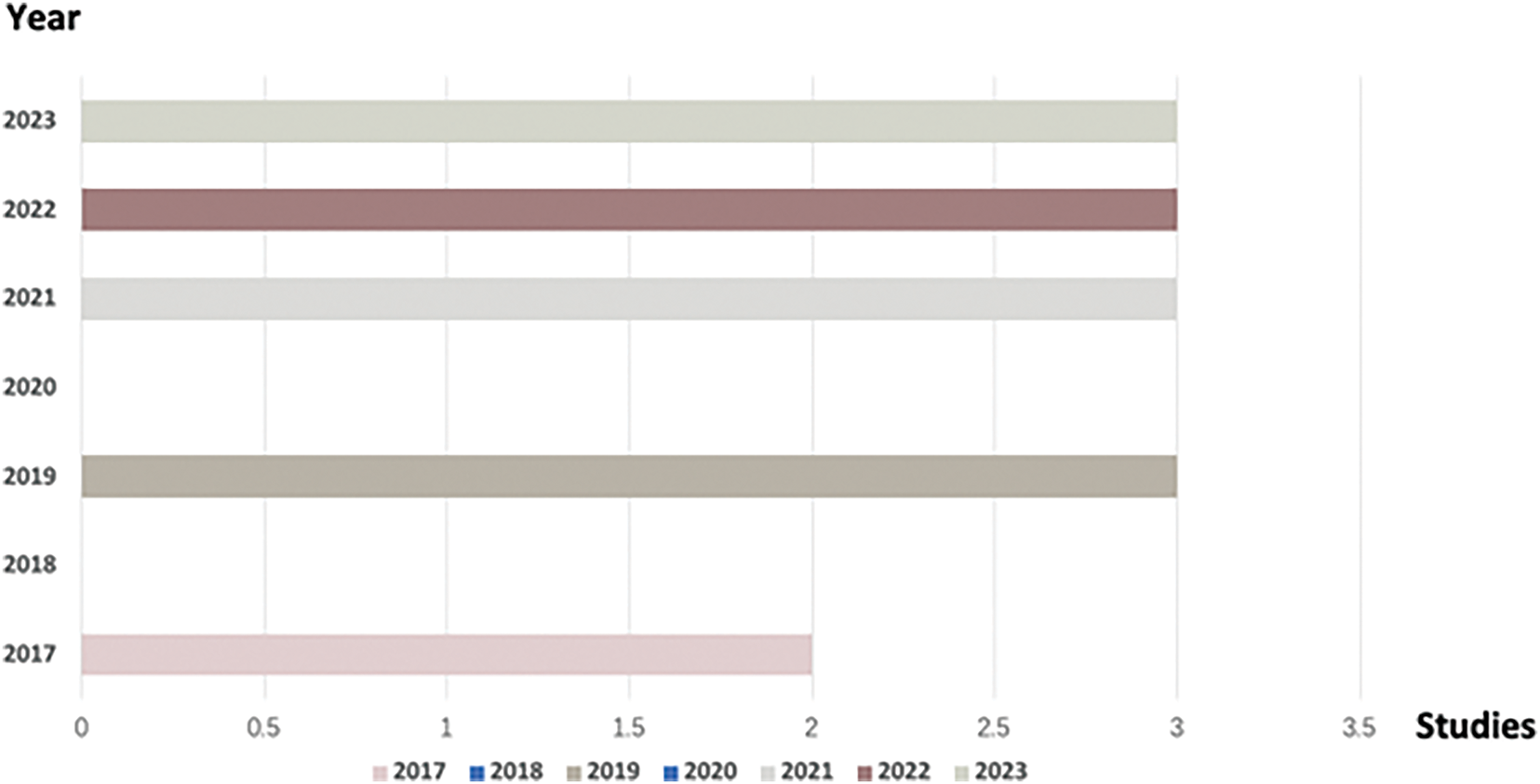

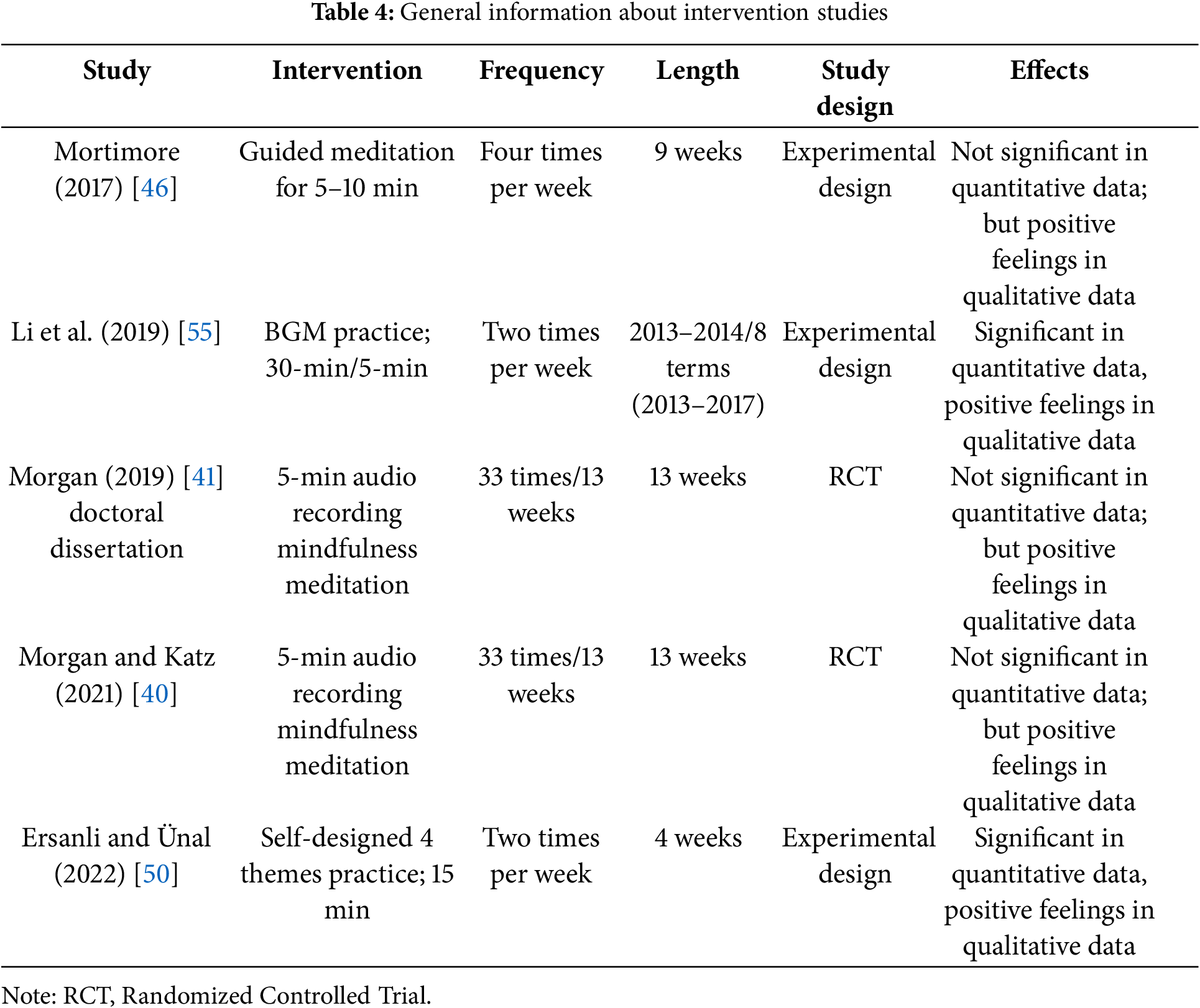

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the 14 included studies. There is no time constraint in the literature search procedure for acquiring a comprehensive collection of mindfulness-related FLA research across different publication years. All studies examining the correlation between mindfulness and FLA (n = 14) have been conducted during the last seven years (2017–2023). Fig. 2 comprehensively showcases the yearly trends in the number of studies conducted within a particular field or research area. This visual representation provides valuable insights into the evolution of research activity over time, highlighting periods of increased interest and potential areas of emerging significance.

Figure 2: Yearly trends in study counts

Regarding the research design, 9 out of the 14 studies analyzed in this review utilized correlation tests to examine the relationship between mindfulness and other relevant variables. In addition, 5 studies used mindfulness interventions in the classrooms, demonstrating online guided mindfulness meditation recordings or teacher-led mindfulness exercises as intervention methods. Only 2 studies [40,41] used randomized controlled trials, while the majority of intervention studies employed a quasi-experimental design.

The distribution of the research background includes the United States (n = 3), mainland China (n = 3), Thailand (n = 2), Turkey (n = 1), Iran (n = 2), Iraq (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), and Indonesia (n = 1). Among these 14 studies, the majority of the research background was in Asia (including 9 non-intervention studies and 1 intervention study), with English as the foreign language of the participants. The remaining four studies took place in the United States and Spain. The participants, regardless of their nationality, spoke Spanish, Chinese, and English, with some considering one or more of these languages as foreign to them.

All 14 empirical studies involved a total of 4867 participants. The main focus on college students is evident, with 12 out of 14 studies targeting this population. For the study on adult students, except for Shen [44], who did not provide specific age specifications for participants, the average age of university participants was between 18.3 and 20.979 years old. Choomchaiyo and Varma’s study [45] included a diverse participant pool, spanning ages 18 to 55 and encompassing students, employees, employers, and self-employed individuals. Meanwhile, Mortimore’s [46] research focused solely on elementary school students. The gender distribution is as follows: 59.1% of the population are females, while 30.5% are males. With the exception of Alsharhani et al. [47] and Geng [48], who did not provide information on the gender distribution in their investigations, the remaining 12 studies exhibited a consistent pattern of having a higher number of female participants compared to male participants.

3.2 Non-Intervention Studies Design and Outcomes

3.2.1 Research Design and Measurements

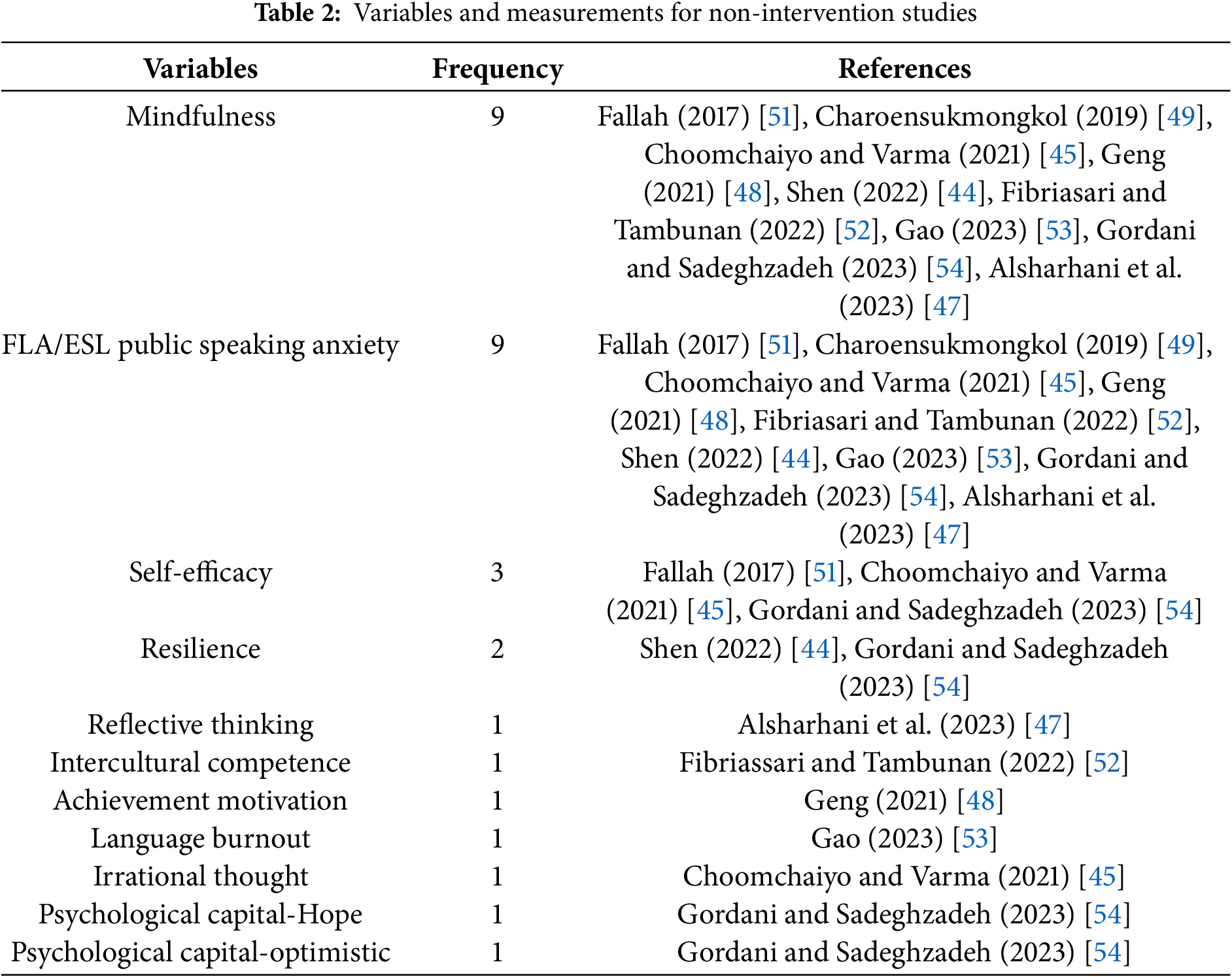

All the non-intervention studies employ a quantitative research design and test the correlations of variables. Clearly, in Table 2, in addition to mindfulness and FLA, the variables considered in these 9 non-intervention studies encompass a wide range of constructs, including self-efficacy, resilience, language proficiency, burnout, irrational thought, reflective thinking, intercultural competence, achievement motivation, and psychological capital (hope, optimism). Notably, both mindfulness and FLA prove to be recurring themes across these nine studies, followed by self-efficacy investigated by three [45,51,54] and resilience considered by two [44,54].

Furthermore, a total of 26 distinct questionnaires, together with students’ course performance scores, were employed as measurement tools to assess these diverse constructs. It is noteworthy that, regarding the measurement of mindfulness, among the nine non-intervention studies reviewed, four [49,51–53] employed the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) for the assessment of trait mindfulness. Meanwhile, four studies [44,45,48,54] utilized the Five-Facts Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) for the measurement of trait mindfulness. Besides the mainly used MAAS and FFMQ, Alsharhani et al. [47] in their study recruited the Langer Mindfulness Scale as the measurement tool. This scale is designed to follow the Western understanding of mindfulness, different from MAAS and FFMQ’s Eastern tradition used in the clinical context [56].

3.2.2 The Relationship between Mindfulness and FLA

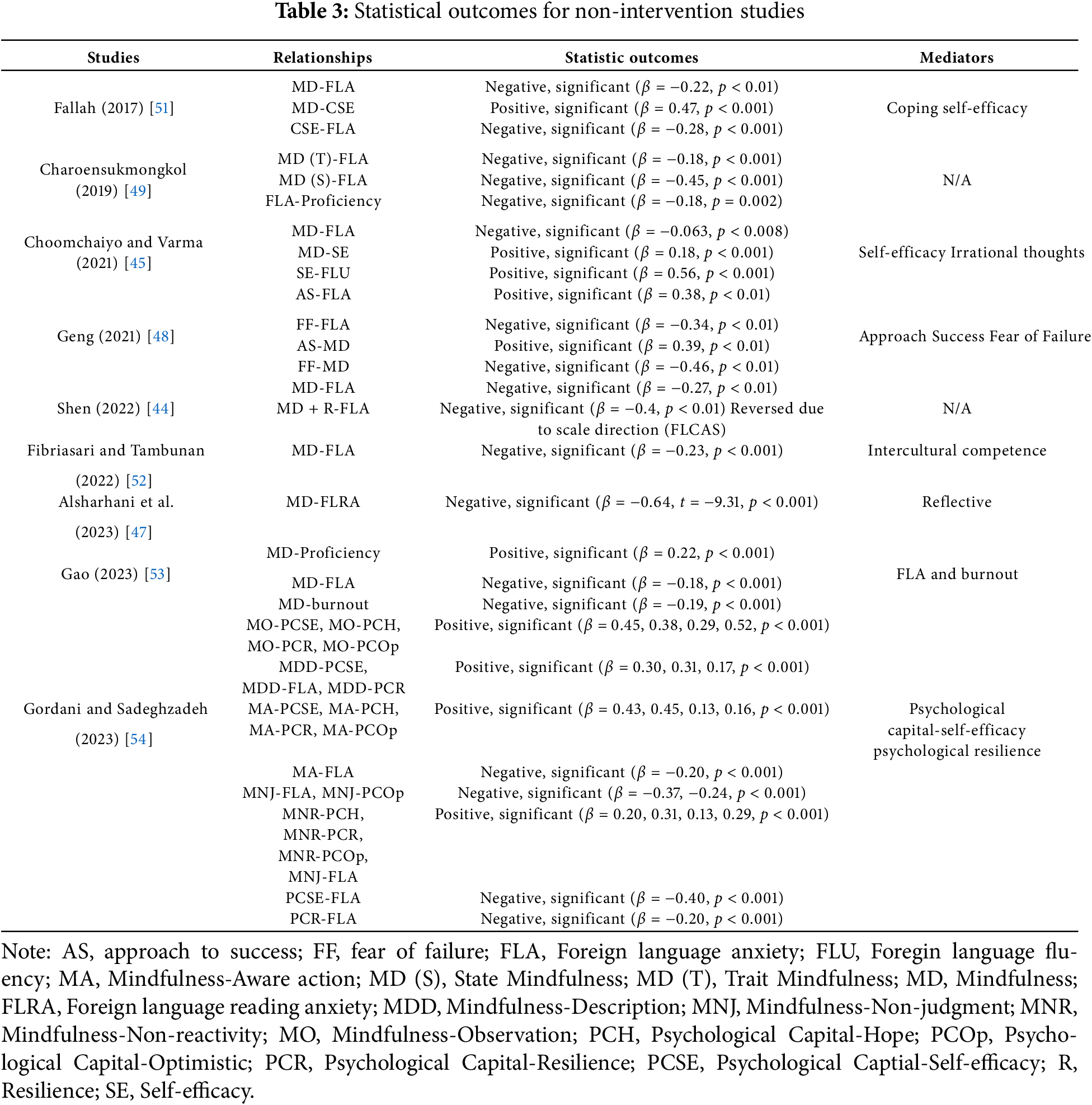

Based on Table 3, it is evident that all 9 non-intervention studies have consistently established a significant negative correlation between mindfulness and FLA. As such, it is implied that individuals who have a higher trait of mindfulness experience less anxiety when learning a foreign language. Moreover, among these studies, 3 have successfully demonstrated that self-efficacy and resilience mediate the relationship between mindfulness and FLA [45,51,54]. This result highlights the potential of mindfulness interventions for reducing anxiety in language learners.

Among the nine non-interventional studies, 7 mainly focus on assessing mindfulness as a unified trait, while 2 studies [48,54] explore the intricate relationship between the 5 facets of mindfulness and FLA. Specifically, Gordani and Sadeghzadeh [54] revealed a positive correlation between the Describing and Non-Reactivity facets of mindfulness and FLA (0.31, 0.29, p < 0.001), while pointing to a negative correlation between the Acting with awareness and Non-judgment facets of mindfulness and FLA (−0.20, −0.37, p < 0.001). While Geng [48] reported that Observing, Describing, and Acting with awareness have a significant negative relation to FLA, and no significant correlation between other facets.

Results for Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b: Direct Association between Mindfulness and FLA. Charoensukmongkol’s [49] study of Thai university students, employing Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, revealed that trait mindfulness significantly predicted reduced English-speaking anxiety (β = −0.18, p < 0.001), while state mindfulness showed an even stronger inverse association (β = −0.45, p < 0.001). Similarly, Fallah’s [51] structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis of Iranian EFL learners reported a significant negative correlation between mindfulness and FLA (r = −0.22, p < 0.01). This pattern was replicated by Fibriasari and Tambunan [52] in Indonesian French learners (r = −0.23, p < 0.001), suggesting cross-cultural robustness.

Results for Hypothesis 1c: Indirect Associations through Mediating Variables. Beyond direct effects, mindfulness appears to mitigate FLA through multiple psychological mechanisms. Fallah [51] identified coping self-efficacy as a partial mediator, with mindfulness positively correlated with self-efficacy (r = 0.47, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy inversely linked to FLA (r = −0.28, p < 0.001). Choomchaiyo and Varma [45] further incorporated irrational beliefs and self-efficacy into a mediation model, demonstrating that mindfulness indirectly reduces FLA by modulating cognitive appraisal processes. Gordani and Sadeghzadeh [54] delineated facet-specific effects, showing that acting with awareness and non-judgment—two mindfulness facets—were particularly predictive of lower FLA (e.g., β = −0.40, p < 0.001), with psychological capital (e.g., resilience, self-efficacy) serving as key mediators.

3.3 Intervention Studies Design and Outcomes

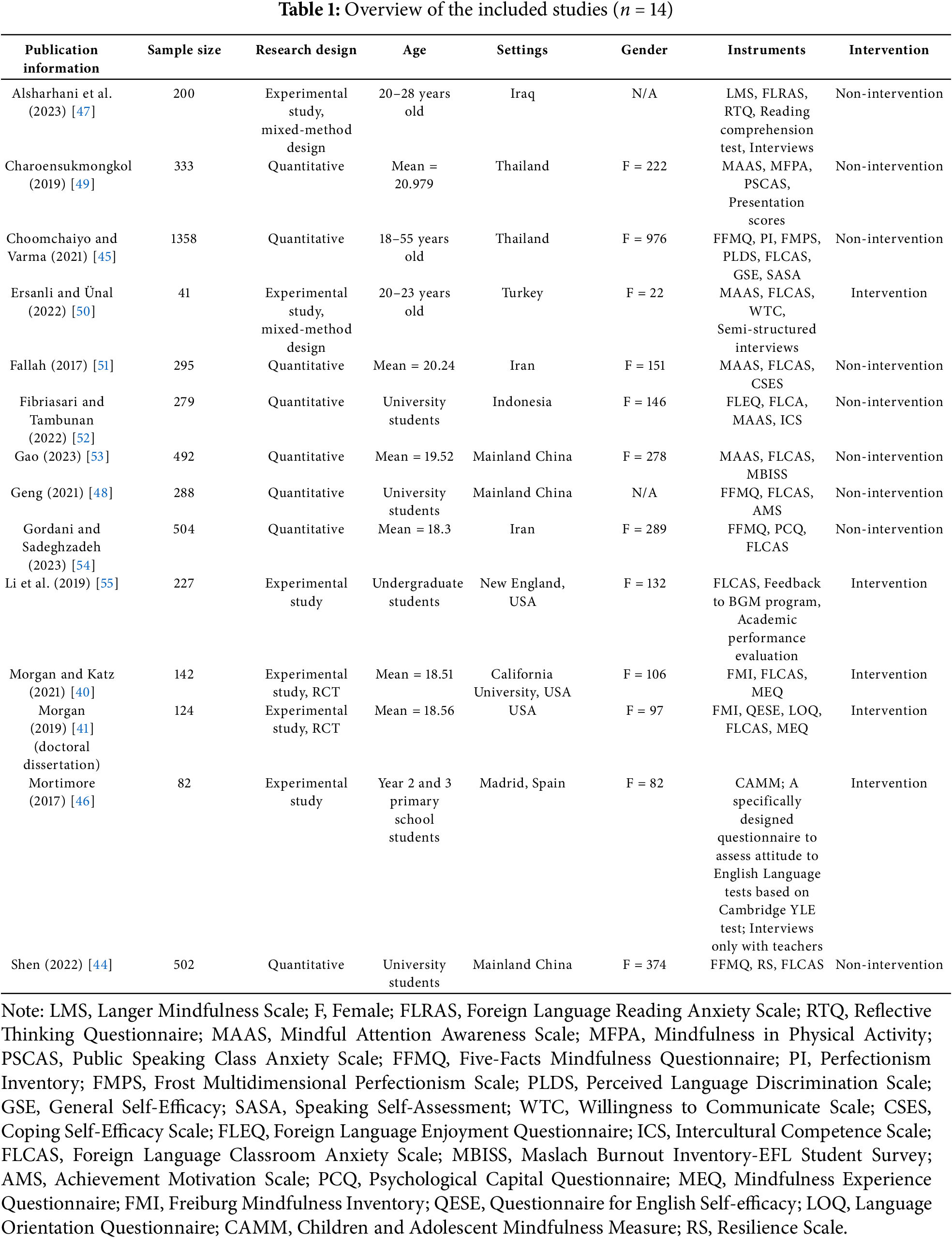

All five intervention studies [40,41,46,50,55] included a control group and utilized a mixed methodology, employing self-report questionnaires to assess targeted participants before and after the intervention for comparative purposes. Additionally, these studies gathered participant perceptions through semi-structured interviews or open-ended questionnaires.

3.3.2 Intervention Length and Frequency

The majority of mindfulness interventions typically last for about 5–10 min per session, while Ersanli and Ünal [50] extended the duration to up to 15 min per session. Four intervention studies [40,41,46,50] have reported intervention durations ranging from 4 to 13 weeks. Li et al. [55] implemented two interventions, a pilot trial and a full study, spanning a duration of six years.

3 studies [40,41,55] conducted pre-existing mindfulness meditation recordings as intervention methods, but only 2 studies [46,50] employed face-to-face teacher-lead mindfulness exercises in the classroom. The 2 teacher-led intervention studies [46,50] created their own mindfulness curricula that were specially designed for their study purposes. Mortimore [46] created meditation scripts tailored for minors, whereas Ersanli and Ünal [50] devised a weekly mindfulness program with distinct topics.

All five intervention trials included preliminary information on familiarizing students with mindfulness-related concepts before the intervention began. The mindfulness methods cited in these 5 intervention studies include body scanning, breathing exercises, cognitive and emotional processing, perception, and daily practice, which correspond to all mindfulness intervention methods used in other fields in the past [57].

3.3.4 Intervention Measurements

These 5 studies used multiple measurement tools; Table 4 summarizes the outcome measurement tools used in each study. In addition to the widely used MAAS questionnaire in non-intervention studies, Morgan and Katz [40] also used the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory to measure trait mindfulness. This is a multidimensional scale that includes different dimensions of mindfulness, such as awareness of the present, non-critical acceptance, and openness to experience, developed by Walach et al. [58] in 2006. Mortimore [46] specifically designed the Children and Adolescent Mindfulness Scale for 9-year-old adolescents because of their unique population structure.

Regarding qualitative data, 2 intervention studies [40,41] used the Mindfulness Experience Questionnaire. Morgan [41] developed this self-report questionnaire, which comprises nine open-ended questions, to provide participants with a comprehensive understanding of their feelings and experiences with mindfulness interventions. Li et al. [55] developed a self-made questionnaire based on a bilingual guided meditation program. The original design of this program aimed to promote a relaxed and positive mindset, which in turn reduced student anxiety in Chinese as a foreign language class [59]. Mortimore [46] used field observations to collect qualitative data. Ersanli and Ünal [50] used semi-structured interviews to get feedback from participants. These qualitative methods, such as open-ended questionnaires and interviews, provide participants with the opportunity to express their feelings and attitudes toward mindfulness in the classroom.

Based on previous non-intervention research findings [60], we expect higher levels of mindfulness to be associated with lower levels of FLA. However, the intervention studies’ results partially contradict this expectation. Of the 5 intervention studies examined [40,41,46,50,55], 2 demonstrated mindfulness intervention’s effectiveness in reducing foreign language classroom anxiety [50,55], while the remaining 3 studies reported non-significant or inconsistent statistical findings. The qualitative data results of all 5 studies indicate that students have a positive perception of mindfulness intervention in foreign language classrooms.

4.1 The Relationship between Trait Mindfulness and FLA

A consistent body of non-intervention research supports a significant negative relationship between trait mindfulness and FLA. All 9 studies included in this review [44,45,47–49,51–54] reported inverse associations between trait mindfulness and various forms of language-related anxiety, including speaking anxiety, classroom anxiety, and reading anxiety. These findings were observed across diverse linguistic, cultural, and instructional contexts, encompassing participants from Iran, Thailand, China, Iraq, Indonesia, and multi-lingual Western educational settings, indicating a high degree of generalizability.

The theoretical explanation for this relationship can be found in the self-regulatory and attentional control functions of mindfulness [12,13]. Mindfulness, characterized by present-focused awareness and a non-reactive orientation, has been shown to modulate the intensity and frequency of anxiety-provoking thoughts and physiological arousal [35,60]. Within the context of language learning, learners high in mindfulness may interpret ambiguous or evaluative classroom situations with greater cognitive flexibility and reduced affective interference. Gao [53] and Fan and Cui [19] further emphasize that mindfulness can lower anxiety indirectly by reducing academic burnout and promoting emotional stability, both of which are relevant to sustained performance in language classrooms.

Importantly, this consistent inverse relationship offers a foundational rationale for the use of mindfulness in educational intervention. Since mindfulness appears to reduce the cognitive and emotional manifestations of FLA, its incorporation into pedagogical practice may help alleviate anxiety without altering curriculum content. Furthermore, mindfulness training may support broader educational objectives by facilitating emotion regulation and attentional stability, skills that are crucial in cognitively demanding environments such as second-language acquisition. Although the overall trend suggests a negative association between mindfulness and FLA, this pattern is not uniformly reflected across all components of mindfulness. Several studies indicate that certain facets may relate to FLA in distinct or even opposing ways, which necessitates a more fine-grained analysis of mindfulness subdimensions.

4.1.1 Variation across Mindfulness Facets in Their Associations with FLA

While mindfulness is generally negatively correlated with FLA, several studies point to important distinctions at the facet level. Specifically, the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) [61] has allowed researchers to disaggregate mindfulness into facets and analyze their unique contributions to anxiety regulation. Not all of these dimensions appear to be uniformly beneficial.

Among the reviewed studies, Geng [48], Gordani and Sadeghzadeh [54] provided detailed analyses of these components. Their findings suggest that Acting with awareness and Non-judgment are significantly and negatively correlated with FLA, whereas Observing and, in some cases, Describing show either non-significant or even positive correlations. For instance, Gordani and Sadeghzadeh [54] reported a positive correlation between the Describing and Non-reactivity facets and FLA, and a negative correlation between Acting with awareness and Non-judgment and FLA. Similarly, Geng [48] found that Observing, Describing, and Acting with awareness were negatively associated with FLA, but Non-judgment and Non-reactivity did not show a significant relationship. These findings point to potential inconsistencies in how mindfulness components influence language anxiety.

A possible explanation lies in the temporal and functional sequence of mindfulness skill development. According to Desrosiers et al. [62] and Sherwood et al. [63], heightened awareness of internal states (such as through the observing and Describing facets) without corresponding development in regulatory capacities (such as non-reactivity) may increase anxiety sensitivity, as individuals become more aware of distressing symptoms without the means to modulate them. This imbalance in mindfulness training might paradoxically exacerbate learners’ attentiveness to linguistic errors or fear of negative evaluation—two core antecedents of FLA, particularly in early stages of practice [2,39].

These facet-level findings have significant implications for intervention design. Programs that promote mindfulness should not assume that all mindfulness practices will uniformly reduce anxiety. When implementing MBIs, practitioners should consider the temporal dynamics between different mindfulness facets, as they may not develop simultaneously. Therefore, MBIs targeting FLA should prioritize skills that have been empirically linked to anxiety reduction, specifically, practices that enhance awareness in action. Caution is warranted when integrating practices that focus solely on emotional noticing (e.g., Describing and Non-reactivity), particularly in populations without prior training in emotion regulation. Such practices may be more effective when implemented after foundational regulatory skills have been established.

4.1.2 Indirect Relationships between Mindfulness and FLA

7 of the reviewed non-intervention studies suggest that mindfulness is indirectly associated with FLA [45,47,48,51–54]. This relationship is often mediated by factors such as self-efficacy and resilience, which play critical roles in how mindfulness influences FLA [45,51,54].

Self-efficacy is defined as one’s belief in their ability to perform specific tasks, achieve goals, or handle challenging situations [64]. The mediating role of self-efficacy found in this review strongly corroborates previous findings that mindfulness enhances self-efficacy through non-judgmental awareness, enabling learners to appraise language abilities without self-critical bias [35]. Therefore, mindfulness training may reduce cognitive distortions (e.g., catastrophizing language errors) and foster objective task evaluation [65–67], which aligns with Bandura and Wessels’s [68] theory of self-efficacy as a buffer against perceived threat.

Resilience is the capacity to confront adversity while maintaining emotional stability [30,31]. Li et al. [69] found that mindfulness and academic self-efficacy jointly predict a large amount of the total variance in resilience, reinforcing Flach’s [70] theory that these constructs constitute psychological strengths. Resilience then alleviates FLA by promoting adaptive coping strategies (e.g., problem-focused practice rather than avoidance) during language learning anxiety [44]. Collectively, these findings highlight the processes through which mindfulness may mitigate FLA, not through direct effects, but by cultivating self-efficacy and resilience, which in turn foster a more adaptive psychological environment for language learning.

4.2 The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on FLA

5 intervention studies investigated the impact of structured mindfulness-based practices on FLA, with mixed empirical outcomes. These studies varied substantially in terms of intervention format, duration, and frequency. 2 studies employed short, audio-guided mindfulness meditations over extended periods, 33 sessions across 13 weeks [40,41], but reported no statistically significant reductions in FLA, despite participants’ positive subjective responses. Similarly, Mortimore [46], using brief daily meditation in a primary school setting over nine weeks, did not observe quantitative improvements in FLA but noted favorable qualitative feedback from teachers and students.

In contrast, Ersanli and Ünal [50] implemented a face-to-face, theme-based mindfulness program (15 min per session, twice weekly for four weeks) and found significant reductions in FLA in both quantitative and qualitative measures. Li et al. [55] also reported statistically significant reductions in anxiety following a structured practice, delivered twice weekly, although specific dosage details were inconsistently reported across sessions.

Overall, interventions involving mindfulness practice yielded inconsistent quantitative results. Only 2 studies [50,55] demonstrated statistically significant anxiety reduction, while the remaining three reported null quantitative effects but observed positive participant perceptions. This divergence suggests that implementation factors, such as delivery mode (face-to-face vs. audio-guided), degree of engagement, and instructional context, may moderate the efficacy of mindfulness training on FLA. These findings highlight the need for more controlled, theory-driven interventions that not only measure quantitative anxiety outcomes but also attend to delivery quality and learner engagement.

4.2.1 Cultural Context Differences

Cultural factors profoundly moderate mindfulness integration in FLA, as evidenced by Odgers et al. [71], who observed differential effects of mindfulness interventions on general anxiety reduction between Iranian and Western adolescents, with Iranian participants showing more pronounced benefits. Similarly, our review identified a pattern where studies conducted in Eastern cultural contexts [44,50] generally reported stronger positive effects compared to those in Western settings [40,41,46].

The differential efficacy of mindfulness interventions for FLA across Eastern and Western cultural contexts can be attributed to three key cultural differences. First, cognitive framing differences play a crucial role since Eastern and Western conceptualizations of mindfulness may have important differences [72]. Eastern learners, particularly in Buddhist-influenced regions, are more likely to perceive mindfulness as “attention training” rather than clinical intervention [49], creating immediate cognitive congruence that enhances treatment adherence, whereas Western participants often require cultural translation of mindfulness concepts [72]. Second, collectivist vs. individualist orientations modulate the intervention pathway. In collectivist classrooms, mindfulness primarily reduces FLA by diminishing face-threat sensitivity [73]. When students become less preoccupied with social evaluation (e.g., fear of losing face due to speaking errors), classroom participation rates increase [39,74]. This accounts for why mindfulness interventions show significantly greater improvement in reducing speech-avoidance behaviors in the Asian study [50] than the study in the USA [40]. Finally, Eastern cultures tend to value keeping emotions calm and controlled. This matches well with mindfulness practices that teach emotional balance, making anxiety reduction more effective [75]. Western cultures often encourage people to express emotions openly, while mindfulness could slightly reduce its impact as a new concept. Mortimore’s [46] study reported a similar phenomenon, noting that mindfulness interventions showed limited effectiveness. The author suggests that this insignificant effect could arise from participants’ discomfort with unfamiliar techniques or negative associations with directives to “calm down,” which might paradoxically increase stress rather than reduce it. Culture influences not only how mindfulness is taught but also how it works, requiring culturally adapted interventions rather than direct translations.

4.2.2 Methodological and Implementation Variations

The divergence between quantitative and qualitative results highlights the challenges of measuring the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions. For instance, while students may report feeling more relaxed and less anxious after mindfulness sessions, these changes might not be accurately captured by standardized anxiety scales. Standardized scales rely on generalized indicators, failing to capture context-specific anxiety (e.g., FLA), which explains why quantitative scores often contradict qualitative reports [40,46]. This potential confounding factor underscores the limitations of relying solely on quantitative measures to evaluate the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions. This discrepancy underscores the importance of incorporating qualitative data, such as student interviews or reflective journals, to complement quantitative measures and provide a more holistic understanding of the intervention’s impact [76].

The effectiveness of mindfulness interventions in reducing FLA depends considerably on how they are designed and implemented. Studies [40,50] show significant variation in approach, with differences in session length, program structure, and integration into language curricula influencing outcomes. For instance, Morgan and Katz [40] used short, five-minute mindfulness exercises guided by audio recordings over 13 weeks, whereas Ersanli and Ünal [50] implemented a more structured four-week program featuring 15-min sessions tailored specifically to language learners, including breath awareness, body scanning, and emotional regulation techniques.

Strohmaier’s [77] meta-regression study suggests that there was no evidence that larger doses are more helpful than smaller doses for predicting psychological outcomes. Additionally, greater contact, intensity, and actual use of MBIs predicting increased mindfulness correspond with previous research and theory. The intervention studies reviewed by this study suggest the same tendency: Ersanli and Ünal’s [50] face-to-face intervention lasts shorter than Morgan and Katz’s [40] audio-recording mindfulness meditation, but Ersanli and Ünal’s [50] intervention proved more effective in reducing FLA. Longer mindfulness practices may become less effective over time because the extended time commitment and frustration from struggling to stay focused often lead to self-criticism, making shorter sessions more manageable and preferred [78,79]. Current findings suggest optimal mindfulness practice prioritizes quality engagement over duration, calling for future studies to identify culturally adapted delivery formats that maximize both effectiveness and adherence.

4.2.3 Implications for Integrating Mindfulness in Classrooms

Integrating mindfulness into educational settings is still in its early stages, and educators and policymakers must approach it with careful consideration. Firstly, cultural differences must be carefully considered to ensure mindfulness practices align with students’ values and learning norms [71]. For example, in collectivist cultures where emotional restraint is valued, mindfulness exercises emphasizing non-judgmental observation may resonate more naturally than expressive techniques preferred in individualist settings. Culturally adapted programs can enhance engagement and effectiveness [49,72].

Secondly, mindfulness integration should be methodologically sound. Programs need proper duration (e.g., 4 weeks) and session length (e.g., 15 min) to cultivate skills, and they should be embedded within language curricula rather than isolated add-ons [50]. Pairing face-to-face mindfulness with metacognitive strategies (e.g., reflective journaling) could further help students transfer mindfulness skills to anxiety-provoking language tasks.

Thirdly, teachers delivering mindfulness interventions should receive proper training or collaborate with qualified mindfulness instructors [80]. Without adequate preparation, educators may struggle to adapt mindfulness techniques to classroom dynamics or address students’ emotional responses, undermining the intervention’s potential benefits. Training ensures fidelity to the program’s design while allowing for pedagogical flexibility.

4.3 Limitations and Future Directions

This systematic review has several limitations. First, the limited number of randomized controlled trials in existing intervention studies restricts causal conclusions. Future research should employ rigorous RCT designs with active control groups (e.g., relaxation training) to better distinguish mindfulness-specific effects from general intervention benefits. In addition, the predominance of short-term assessments leaves the longitudinal effects of mindfulness on FLA unexamined; sustained benefits and their impact on language learning trajectories remain unknown. Future work should implement follow-up assessments at 6–12-month intervals to examine skill retention and potential sleeper effects on FLA.

The sample characteristics also constrain generalizability. Most participants reviewed under this topic were university students, leaving other age groups and proficiency levels underrepresented. Future researchers may prioritize K-12 populations and beginner-level learners, as these groups may experience FLA more acutely and benefit differently from mindfulness training. Finally, while no adverse effects were reported in the reviewed studies, preliminary evidence suggests mindfulness may cause transient discomfort (e.g., increased tension) [81]. Future interventions should incorporate standardized adverse effect monitoring protocols and assess individual differences in emotional vulnerability that may moderate treatment responses.

This review examined the relationship between mindfulness and FLA by synthesizing evidence from both correlational and intervention studies. Across nine non-intervention studies, a clear and consistent pattern emerged: higher levels of mindfulness are associated with lower levels of FLA. This suggests that mindfulness, through mechanisms such as improved emotional regulation, attentional control, and self-awareness, can help learners manage the anxiety often experienced in language learning. The mediating roles of self-efficacy and resilience further highlight that mindfulness not only reduces anxiety directly but also strengthens learners’ confidence and ability to cope with challenges. In contrast, the findings from the five intervention studies were less consistent. While some MBIs successfully reduced FLA, others reported limited or no measurable effects. These variations appear to stem from differences in program design, delivery methods, and cultural context. Shorter, face-to-face interventions tailored to the classroom environment showed greater promise compared to longer, audio-guided programs. This underscores the need for careful adaptation of mindfulness practices to the specific needs, cultural values, and learning conditions of language students.

The evidence reviewed here offers important implications for educators and policymakers. Mindfulness should not be seen as a one-size-fits-all solution but as a complementary tool that, when thoughtfully implemented, can foster emotional resilience and reduce language-related anxiety. However, the limited number of randomized controlled trials and the absence of long-term follow-up data call for more rigorous research. Future studies should examine the sustained effects of MBIs, explore how different facets of mindfulness contribute to FLA reduction, and test culturally adapted interventions across diverse learner populations. In conclusion, mindfulness holds considerable potential to enhance language learning by addressing the psychological barriers posed by FLA. Yet, its integration into language education must be guided by empirical evidence, cultural sensitivity, and a clear understanding of its mechanisms to ensure both effectiveness and sustainability.

Acknowledgement: We are deeply grateful to Katherine Hoi Ying Chen, Associate Professor at the University of Macau, for her invaluable support and guidance throughout this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Hui Yang and Yijie Li; data collection: Hui Yang; analysis and interpretation of results: Hui Yang and Yijie Li; draft manuscript preparation: Hui Yang and Yijie Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068399/s1.

References

1. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA, 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Horwitz EK, Horwitz MB, Cope J. Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod Lang J. 1986;70(2):125–32. doi:10.2307/327317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. He D. Framework for foreign language learning anxiety. In: Yu Xeditor. Foreign language learning anxiety in China: theories and applications in English language teaching. Abingdon, UK: Taylor Francis Group; 2018. p. 1–12. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-7662-6_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hu X, Zhang X, McGeown S. Foreign language anxiety and achievement: a study of primary school students learning English in China. Lang Teach Res. 2021;3(4):1–22. doi:10.1177/13621688211032332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kamarulzaman MH, Ibrahim N, Yunus MM, Ishak NM. Language anxiety among gifted learners in Malaysia. Engl Lang Teach. 2013;6(3):20–9. [Google Scholar]

6. MacIntyre PD, Gardner RC. The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Lang Learn. 1994;44(2):283–305. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Horwitz E. Language anxiety and achievement. Annu Rev Appl Linguist. 2001;21:112–26. [Google Scholar]

8. Liu H. Understanding EFL undergraduate anxiety in relation to motivation, autonomy, and language proficiency. Electron J Foreign Lang Teach. 2012;9:123–39. [Google Scholar]

9. Tóth Z. Foreign language anxiety and the advanced language learner: a study of Hungarian students of English as a foreign language. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars; 2010. 240 p. [Google Scholar]

10. Liu M, Jackson J. An exploration of Chinese EFL learners’ unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. Mod Lang J. 2008;92(1):71–86. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00687.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constr Hum Sci. 2003;8(2):73–83. [Google Scholar]

12. Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2004;11(3):230–41. [Google Scholar]

13. Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2):169–83. doi:10.1037/a0018555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Frank JL, Reibel D, Broderick P, Cantrell T, Metz S. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on educator stress and well-being: results from a pilot study. Mindfulness. 2015;6(2):208–16. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0246-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(6):763–71. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Meiklejohn J, Phillips C, Freedman ML, Griffin ML, Biegel G, Roach A, et al. Integrating mindfulness training into K-12 education: fostering the resilience of teachers and students. Mindfulness. 2012;3(4):291–307. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0094-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Roeser RW. The emergence of mindfulness-based interventions in educational settings. In: Karabenick S, Urdan Teditors. Motivational interventions. Leeds, UK: Emerald; 2014. p. 379–419. doi: 10.1108/S0749-742320140000018010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Verhaeghen P. Mindfulness and academic performance meta-analyses on interventions and correlations. Mindfulness. 2023;14(6):1305–16. doi:10.1007/s12671-023-02138-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fan L, Cui F. Mindfulness, self-efficacy, and self-regulation as predictors of psychological well-being in EFL learners. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1332002. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1332002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li C, Dewaele JM. How classroom environment and general grit predict foreign language classroom anxiety of Chinese EFL students. J Psychol Lang Learn. 2021;3(2):86–98. doi:10.52598/jpll/3/2/6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li C, Huang J, Li B. The predictive effects of classroom environment and trait emotional intelligence on foreign language enjoyment and anxiety. System. 2021;96(1):102393. doi:10.1016/j.system.2020.102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Young DJ. Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: what does language anxiety research suggest? Mod Lang J. 1991;75(4):426–39. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1991.tb05378.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Choi HH, Van Merriënboer JJ, Paas F. Effects of the physical environment on cognitive load and learning: towards a new model of cognitive load. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):225–44. doi:10.1007/s10648-014-9262-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jiang Y, Dewaele JM. How unique is the foreign language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? System. 2019;82(1):13–25. doi:10.1016/j.system.2019.02.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Meyer L, Eklund K. The impact of a mindfulness intervention on elementary classroom climate and student and teacher mindfulness: a pilot study. Mindfulness. 2020;11(4):991–1005. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01317-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pinazo D, Garcia-Prieto LT, Garcia-Castellar R. Implementation of a program based on mindfulness for the reduction of aggressiveness in the classroom. Rev Psicodidact. 2020;25(1):30–5. doi:10.1016/j.psicoe.2019.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Monsillion J, Zebdi R, Romo-Desprez L. School mindfulness-based interventions for youth, and considerations for anxiety, depression, and a positive school climate—a systematic literature review. Children. 2023;10(5):861. doi:10.3390/children10050861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Tóth Z. Predictors of foreign-language anxiety: examining the relationship between anxiety and other individual learner variables. In: UPRT 2007: empirical studies in English applied linguistics. Pretoria, South Africa: Lingua Franca Csoport; 2007. p. 123–48. [Google Scholar]

29. Yan JX, Horwitz EK. Learners’ perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: a qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Lang Learn. 2008;58(1):151–83. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00437.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi:10.1002/da.10113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(4):730–49. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhou S, Chiu MM, Dong Z, Zhou W. Foreign language anxiety and foreign language self-efficacy: a meta-analysis. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(35):31536–50. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-04110-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lin M, Wolke D, Schneider S, Margraf J. Bullying history and mental health in university students: the mediator roles of social support, personal resilience, and self-efficacy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Qin LL, Peng J, Shu ML, Liao XY, Gong HJ, Luo BA, et al. The fully mediating role of psychological resilience between self-efficacy and mental health: evidence from the study of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2023;11(3):420. doi:10.3390/healthcare11030420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Luberto CM, Cotton S, McLeish AC, Mingione CJ, O’Bryan EM. Mindfulness skills and emotion regulation: the mediating role of coping self-efficacy. Mindfulness. 2014;5(4):373–80. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0190-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Soysa CK, Wilcomb CJ. Mindfulness, self-compassion, self-efficacy, and gender as predictors of depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being. Mindfulness. 2015;6(2):217–26. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0247-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jin Y, Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD. Reducing anxiety in the foreign language classroom: a positive psychology approach. System. 2021;101(1):102604. doi:10.1016/j.system.2021.102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Toyama M, Yamazaki Y. Classroom interventions and foreign language anxiety: a systematic review with narrative approach. Front Psychol. 2021;12:614184. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.614184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yılmaz T, De Jong E. The role of native speaker peers on language learners’ fear of negative evaluation and language anxiety. Bogazici Univ J Educ. 2024;41(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

40. Morgan WJ, Katz J. Mindfulness meditation and foreign language classroom anxiety: findings from a randomized control trial. Foreign Lang Ann. 2021;54(2):389–409. doi:10.1111/flan.12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Morgan WJ. Investigating the effects of mindfulness meditation on L2 learners’ self-efficacy in an instructed foreign language context [dissertation]. Tuscaloosa, AL, USA: University of Alabama; 2019. [Google Scholar]

42. Öz S. The effects of mindfulness training on students’ L2 speaking anxiety, willingness to communicate, level of mindfulness and L2 speaking performance [master’s thesis]. Istanbul, Türkiye: Bahçeşehir Üniversitesi; 2017. [Google Scholar]

43. Thomas MDM. The role of mindfulness-meditation in reducing writing anxiety in Spanish as a second language college students [dissertation]. San Germán, Puerto Rico: Inter-American University of Puerto Rico; 2022. [Google Scholar]

44. Shen Y. Mitigating students’ anxiety: the role of resilience and mindfulness among Chinese EFL learners. Front Psychol. 2022;13:940443. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.940443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Choomchaiyo N, Varma P. The influences of mindfulness on foreign language fluency mediated by irrational thoughts, foreign language anxiety and self-efficacy on Thai English learners. Scholar Hum Sci. 2021;13(2):166. [Google Scholar]

46. Mortimore L. Mindfulness and foreign language anxiety in the bilingual primary classroom. Educ Y Futuro. 2017;37:15–43. [Google Scholar]

47. Alsharhani HK, Ghonsooly B, Meidani EN. Probing the relationship among reading anxiety, mindfulness, reflective thinking, and reading comprehension ability of Iraqi intermediate and advanced EFL learners. Train Lang Cult. 2023;7(3):9–22. [Google Scholar]

48. Geng Y. The relationships among mindfulness, achievement motivation and foreign language classroom anxiety of non-English majors. Int J Soc Sci Educ Res. 2021;4(7):133–43. [Google Scholar]

49. Charoensukmongkol P. The role of mindfulness in reducing English language anxiety among Thai college students. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 2019;22(4):414–27. doi:10.1080/13670050.2016.1264359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ersanli CY, Ünal T. Impact of mindfulness training on EFL learners’ willingness to speak, speaking anxiety levels and mindfulness awareness levels. Educ Q Rev. 2022;5(4):429–48. doi:10.31014/aior.1993.05.04.634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Fallah N. Mindfulness, coping self-efficacy and foreign language anxiety: a mediation analysis. Educ Psychol. 2017;37(6):745–56. doi:10.1080/01443410.2016.1149549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Fibriasari H, Tambunan YLB. Impact of strategy based instructions and mindfulness on foreign language anxiety and enjoyment of Indonesian French learning student: moderating role of intercultural competence. Eurasian J Appl Linguist. 2022;8(3):270–86. [Google Scholar]

53. Gao X. Mindfulness and foreign language learners’ self-perceived proficiency: the mediating roles of anxiety and burnout. J Multiling Multicult Dev. 2024;2023(10):1–18. doi:10.1080/01434632.2022.2150196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Gordani Y, Sadeghzadeh M. Mindfulness and the mediating role of psychological capital in predicting the foreign language anxiety. J Psycholinguist Res. 2023;52(5):1785–97. doi:10.1007/s10936-023-09938-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Li C, Cai QA, Elias S, Wilson-Jones L. Mindfulness and well-being: a mixed methods study of bilingual guided meditation in higher education. J Res Initiat. 2019;5(1):3. [Google Scholar]

56. Pirson M, Langer EJ, Bodner T, Zilcha-Mano S. The development and validation of the Langer mindfulness scale-enabling a socio-cognitive perspective of mindfulness in organizational contexts. Fordham Univ Sch Bus Res Pap. 2012;25(3):1–54. doi:10.1007/s10804-018-9282-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zenner C, Herrnleben-Kurz S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2014;5:603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

58. Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness—the freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Pers Individ Differ. 2006;40(8):1543–55. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Li C, Cai Q, Elias S. Mindful in two tongues: enhancing second-language learning using bilingual guided meditation. In: American Psychological Association (APA) annual convention; 2018 Aug 9–12; San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

60. Hill CLM, Updegraff JA. Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion. 2012;12(1):81–90. doi:10.1037/a0026355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assess. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Desrosiers A, Klemanski DH, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Mapping mindfulness facets onto dimensions of anxiety and depression. Behav Ther. 2013;44(3):373–84. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Sherwood A, Carydias E, Whelan C, Emerson LM. The explanatory role of facets of dispositional mindfulness and negative beliefs about worry in anxiety symptoms. Pers Individ Differ. 2020;160:109933. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.109933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 1986. 640 p. [Google Scholar]

65. Mitsea E, Drigas A, Skianis C. Digitally assisted mindfulness in training self-regulation skills for sustainable mental health: a systematic review. Behav Sci. 2023;13(12):1008. doi:10.3390/bs13121008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Noetel M, Ciarrochi J, Van Zanden B, Lonsdale C. Mindfulness and acceptance approaches to sporting performance enhancement: a systematic review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2019;12(1):139–75. doi:10.1080/1750984x.2017.1387803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Sharma PK, Kumra R. Relationship between mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress: mediating role of self-efficacy. Pers Individ Differ. 2022;186(9):111363. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Bandura A, Wessels S. Self-efficacy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997. p. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

69. Li H, Srisawat P, Voracharoensri S. The influence of mindfulness, resilience, and self-efficacy on foreign language anxiety among Chinese college students. J Educ Learn. 2025;19(4):2024–32. doi:10.11591/edulearn.v19i4.23075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Flach FF. Resilience: discovering new strength at times of stress. New York, NY, USA: Ballantine Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

71. Odgers K, Dargue N, Creswell C, Jones MP, Hudson JL. The limited effect of mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23(3):407–26. doi:10.1007/s10567-020-00319-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Christopher MS, Charoensuk S, Gilbert BD, Neary TJ, Pearce KL. Mindfulness in Thailand and the united states: a case of apples versus oranges? J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(6):590–612. doi:10.1002/jclp.20580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Markus HR, Kitayama S. Cultural variation in the self-concept. In: The self: interdisciplinary approaches. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1991. p. 18–48. [Google Scholar]

74. Aida Y. Horwitz, and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: the case of students of Japanese. Mod Lang J. 1994;78(2):155–68. doi:10.2307/329005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Lim N. Cultural differences in emotion: differences in emotional arousal level between the East and the West. Integr Med Res. 2016;5(2):105–9. doi:10.1016/j.imr.2016.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Frank P, Marken M. Developments in qualitative mindfulness practice research: a pilot scoping review. Mindfulness. 2022;13(1):17–36. doi:10.1007/s12671-021-01748-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Strohmaier S. The relationship between doses of mindfulness-based programs and depression, anxiety, stress, and mindfulness: a dose-response meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Mindfulness. 2020;11(6):1315–35. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01319-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Banerjee M, Cavanagh K, Strauss C. A qualitative study with healthcare staff exploring the facilitators and barriers to engaging in a self-help mindfulness-based intervention. Mindfulness. 2017;8(6):1653–64. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0740-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Boggs JM, Beck A, Felder JN, Dimidjian S, Metcalf CA, Segal ZV. Web-based intervention in mindfulness meditation for reducing residual depressive symptoms and relapse prophylaxis: a qualitative study. J Med Int Res. 2014;16(3):e87. doi:10.2196/jmir.3129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Sansom SA, Crane RS. Mindfulness-based interventions: teaching assessment criteria (MBI: TAC). In: Medvedev ON, Krägeloh CU, Siegert RJ, Singh NN, editors. Handbook of assessment in mindfulness research. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-77644-2_129-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Britton WB, Lindahl JR, Cooper DJ, Canby NK, Palitsky R. Defining and measuring meditation-related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs. Clin Psychol Sci. 2021;9(6):1185–204. doi:10.1177/2167702621996340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools