Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Caregiving Stress in Parents of Children with Leukemia

1 Department of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

2 Department of Education, Yunnan Minzu University, Kunming, 650500, China

* Corresponding Author: Yue Yuan. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion and Psychosocial Support in Vulnerable Populations: Challenges, Strategies and Interventions)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 12 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071212

Received 02 August 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

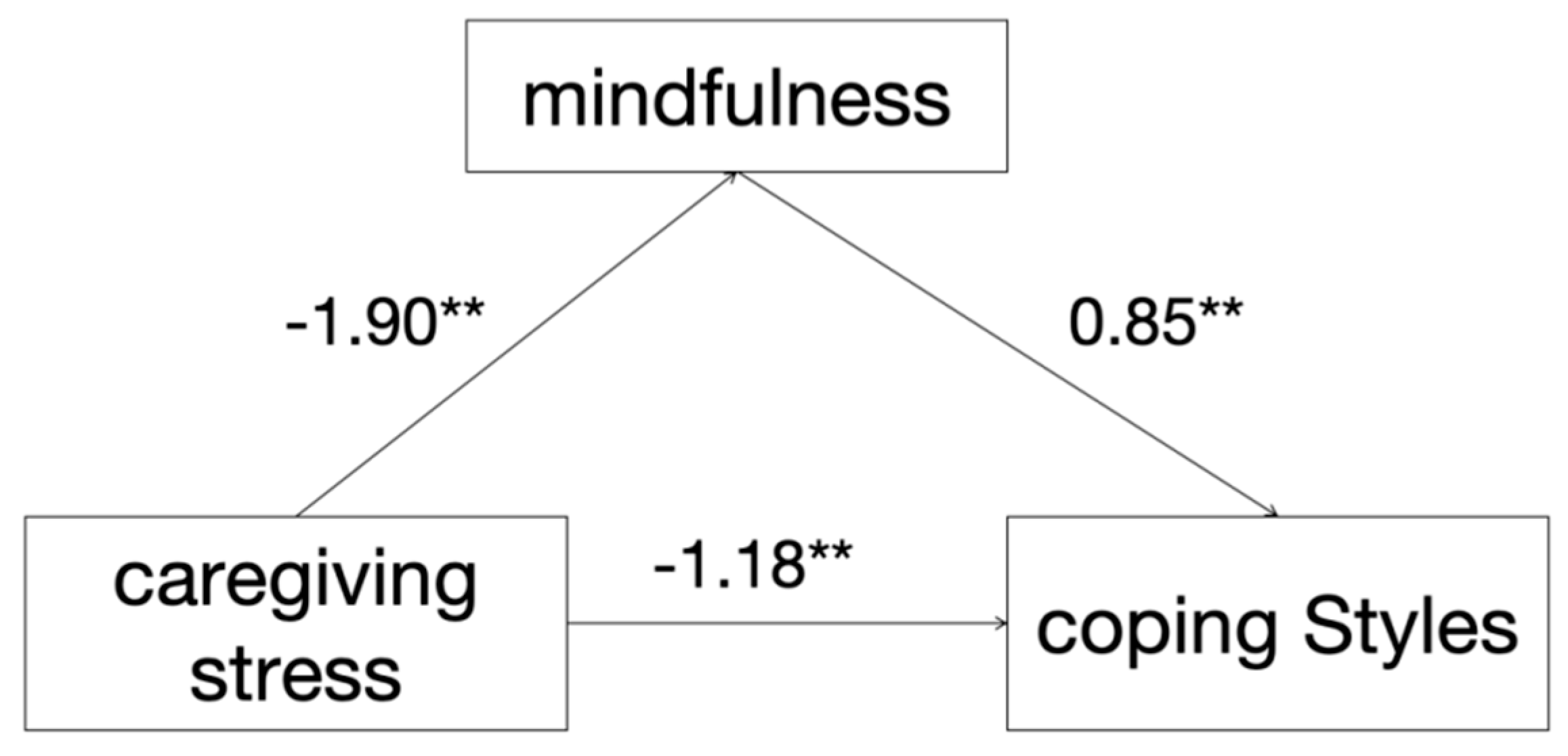

Background: Childhood leukemia, a malignant proliferative disorder of the hematopoietic system and the most common childhood cancer, poses a significant threat to the lives and health of affected children. For parents, a leukemia diagnosis in their child is a profoundly traumatic event. As primary caregivers, they endure immense psychological distress and caregiving stress throughout the prolonged and demanding treatment process, which can adversely affect their own well-being and caregiving capacity. However, the psychological mechanisms, such as the role of mindfulness, linking caregiver stress to parental coping strategies remain underexplored, and evidence-based interventions to support these parents are needed. Methods: In Study 1, we administered a cross-sectional survey to 242 parents of children with leukemia who were hospitalized at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University between January and August 2024. Participants completed measures assessing caregiver burden, mindful attention awareness, and parental coping style. In Study 2, we further evaluated the effects of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention. Results: The results of Study 1 revealed: (1) The caregiving stress significantly and negatively predicted coping style (β = −1.18, 95% CI [−2.18, −0.18], p < 0.01). (2) Caregiving stress also significantly and negatively predicted mindfulness (β = −1.90, 95% CI [−2.43, −1.38], p < 0.01). (3) Conversely, mindfulness significantly and positively predicted coping style (β = 0.85, 95% CI [0.62, 1.07], p < 0.01). These findings suggest that mindfulness mediates the relationship between caregiver burden and coping style. In Study 2, the experimental group showed a significant decrease in caregiver stress post-intervention (t = 2.24, p < 0.05), a significant increase in mindfulness (t = −4.61, p < 0.001), and a significant improvement in coping style (t = −2.36, p < 0.01). No significant changes were observed in the control group. Conclusion: MBSR can effectively enhance mindfulness and promote adaptive coping strategies, while reducing caregiver burden among parents of children with leukemia.Keywords

Leukemia, a malignant hematologic disorder characterized by the clonal proliferation of hematopoietic cells and their infiltration into peripheral blood and various tissues, represents the most prevalent childhood malignancy, accounting for 30%–40% of all pediatric cancers [1]. Notably, it exhibits the highest mortality rate among pediatric and adolescent cancers [1]. In China, the overall age-standardized incidence of childhood leukemia was 87.1 per million, making it the most common childhood cancer and accounting for about 30%–40% of all pediatric malignancies [2]. The treatment of pediatric acute leukemia typically requires an extended therapeutic course of 2–3 years, accompanied by substantial medical expenses [3]. Treatment challenges such as poor compliance, complications, and disease recurrence may lead to therapeutic failure or even mortality [4]. A leukemia diagnosis constitutes a profoundly traumatic event for parents, who, as primary caregivers, endure tremendous caregiving stress during the prolonged and repetitive chemotherapy process. However, despite the clear need for psychosocial support, there is a notable scarcity of research exploring effective interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), specifically for this vulnerable caregiver population.

Multiple stressors significantly impact parental well-being, including: the physical suffering of children undergoing chemotherapy and invasive procedures; the substantial financial burden of treatment; and the psychological distress caused by prognostic uncertainty. These cumulative stressors frequently manifest as psychological disturbances (e.g., anxiety and depression) and physical symptoms (e.g., insomnia and fatigue) among caregivers [5,6]. Research indicates that caregivers of children with acute leukemia experience consistently elevated levels of psychological distress, financial strain, and social isolation [7].

1.1 Caregiving Stress of Parents of Children with Leukemia

Stress refers to a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being [8,9]. In this study, the caregiving stress of parents of children with leukemia is defined as the pressure experienced by these parents—who serve as primary caregivers—in multiple domains including physical health, social life, psychology, work, and economy during the long-term process of caring for their children. Caregivers of children with leukemia need to take on long-term responsibilities such as daily care and emotional support, while also enduring the psychological anguish of the potential loss of their loved ones. This results in varying degrees of physical, psychological, and economic burdens, which in turn give rise to caregiving stress of different intensities [10,11].

The diagnosis of leukemia itself constitutes a significant traumatic event for parents. Moreover, the prolonged treatment process, the uncertainty surrounding the disease, and the lack of experience in caring for such an illness exert intense psychological stress on the parents of children with leukemia, imposing a heavy psychological burden and even post-traumatic stress disorder [11]. Numerous studies have indicated that parents of children with leukemia are prone to psychological issues such as depression and anxiety, as well as family conflicts [12]. A study involving 238 parents of children with leukemia revealed that these parents generally experience psychological distress and negative emotions. Compared to parents of children with other illnesses, they are more susceptible to negative psychological states like depression, self-blame, and post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly in the early stages of their child’s illness [13].

In addition, parents of children with leukemia generally face substantial economic pressure. The long-term course of the disease in children with leukemia, repeated chemotherapy, complex and diverse treatment modalities, bone marrow transplantation, various complications during treatment, outpatient follow-ups, and job resignation due to caregiving needs all impose a heavy economic burden on families [3,14].

1.2 Coping Styles of Parents of Children with Leukemia

Coping styles refer to the cognitive and behavioral strategies adopted by individuals when facing setbacks, stress, and related emotional distress, which can be categorized into positive coping and negative coping [15]. Positive coping is characterized by a problem-solving orientation, where individuals proactively seek internal and external resources and construct strategies to address issues. In contrast, negative coping involves a tendency to adopt avoidance, denial, fantasy, or other such approaches to deal with problems.

Dhakouani et al. found that mothers of children with leukemia are profoundly affected by their children’s cancer during caregiving, experiencing clinically significant anxiety and depression [16]. Research indicates that the negative coping styles of parents of children with leukemia are positively correlated with the uncertainty of the disease. Uncertainties regarding treatment efficacy, the possibility of recurrence, and prognosis may lead parents to adopt negative coping strategies. However, targeted psychological counseling and health education can reduce the level of disease uncertainty, encouraging parents to employ more positive coping styles [17].

Negative emotions such as anxiety among caregivers of children with leukemia can impact parents’ ability to cope with the disease, their capacity to care for their children, and family well-being. These, in turn, may affect the child’s cooperation with treatment, the effectiveness of care, and the occurrence of treatment-related complications [18]. Consequently, research on the stress responses, psychological reactions, coping styles, and intervention methods of parents of children with malignant tumors has attracted increasing attention [15].

This study aims to explore the impact of mindfulness on the caregiving stress and coping styles of parents of children with leukemia, thereby examining the effectiveness of mindfulness in improving their coping styles.

Mindfulness refers to the conscious, non-judgmental focus on the present moment, as well as the non-judgmental and accepting attitude toward one’s internal and external experiences [19,20]. It encompasses three interacting components—attention control, self-awareness and emotional regulation—which collectively enhance an individual’s self-regulatory capacity [19]. A large body of empirical research has demonstrated that mindfulness can help individuals alleviate stress [21,22].

MBSR is the most commonly used mindfulness intervention. It can alleviate symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression by improving emotional regulation abilities [23]. MBSR enhances individuals’ cognitive control over negative ruminative thoughts, thereby increasing emotional flexibility and strengthening the ability to disengage from negative emotional and cognitive stimuli [24]. MBSR has been widely applied to adolescents [19], lung cancer patients [25], individuals with multiple sclerosis [26], as well as non-clinical populations such as participants with various medical complaints [27], employees [28], and community residents [29].

Beyond stress reduction, MBSR has been shown to improve self-compassion and empathy, and exert regulatory effects on emotional exhaustion and work stress in various populations [30], including reducing parental burnout [31]. Furthermore, meta-analytic evidence indicates that MBSR significantly enhances psychological functioning by alleviating symptoms of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress [32].

Furthermore, it is crucial to consider the unique socio-cultural context in which caregiving occurs. Within Chinese family culture, parental identity is often deeply intertwined with concepts of collective responsibility and self-sacrifice (jia-ting ben-wei). Parents, particularly mothers, are socialized to prioritize family needs above their own, leading to a potent but potentially burdensome caregiving role identity. Simultaneously, cultural norms emphasizing emotional restraint (e.g., “endure and forbear,” ren-nai) may discourage the open expression of distress, complicating emotional regulation. The Lazarus and Folkman model posits that coping effectiveness depends on the individual’s appraisal of resources. We propose that mindfulness may serve as a critical internal resource within this cultural context. It does not require parents to relinquish their deep commitment but may help them relate to this role and their emotions in a more flexible and self-compassionate manner, thereby transforming a potentially rigid and exhausting identity into a more sustainable one.

In summary, while MBSR has demonstrated efficacy in improving psychological functioning across various populations, its application for parents of children with leukemia remains underexplored. Specifically, there is a lack of studies that simultaneously examine the interrelationships between caregiving stress, mindfulness, and coping styles in this group, and robust empirical evidence from randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the effectiveness of MBSR in alleviating their unique burdens is still limited. This study aims to address these gaps by investigating the mediating role of mindfulness in the relationship between caregiving stress and coping styles (Study 1), and by evaluating the efficacy of an MBSR program in reducing stress and improving coping strategies through a RCT supplemented with qualitative interviews (Study 2).

2 Study 1: The Relationship between Caregiving Stress, Mindfulness and Coping Styles among Parents of Children with Leukemia

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Northwest Normal University (Approval No.: [2023028]). Prior to the survey, researchers explained the purpose and content of the study to the participants, promised that the data collected would be used solely for scientific research and kept strictly confidential, and obtained written informed consent from the participants after they agreed to participate.

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit parents of children with leukemia who met the inclusion criteria and were hospitalized at the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Center of a Grade III Level A hospital in Qingdao (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University) from January 2024 to August 2024 for the questionnaire survey. For any questions encountered by the parents during the completion of the questionnaire, researchers provided answers using standardized instructions.

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit as many eligible parents as possible during the study period from January to August 2024. All eligible parents present on the ward during the data collection period were invited to participate by a member of the research team. A total of 250 questionnaires were distributed. Eight parents declined to participate, citing lack of time or interest, resulting in 242 distributed questionnaires. After excluding 21 questionnaires (excluding those with excessive missing values or identical responses for all items), 221 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis, yielding an effective response rate of 91.32%. The final analysis was conducted on these 221 valid questionnaires.

Inclusion Criteria:

- (1)Children with leukemia: Confirmed diagnosis of leukemia at any stage of treatment; stable condition (non-critical) as determined by the attending oncologist.

- (2)Parents of the children: Voluntarily participate in this study; have normal comprehension ability (as confirmed through direct communication during the recruitment process) and no known diagnosis of mental-related illnesses (based on self-report and verified through conversation with the research team); serve as long-term primary caregivers of the children with leukemia; agree to participate in the study and sign the informed consent form.

Exclusion Criteria:

- (1)Children with leukemia: Complicated with other congenital diseases or mental illnesses (e.g., autism); children with recurrent leukemia.

- (2)Parents of the children: Have a history of or currently suffer from mental illnesses; have cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, malignant tumors, or other such conditions (e.g., hypertension, heart disease).

- (3)Have participated in mindfulness-based, meditation, or similar programs within the past year.

All respondents completed a demographic section and a set of self-report measures assessing various outcomes, including:

- (1)Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire collected data on:

Child characteristics: age, gender, time since diagnosis, treatment duration, and only-child status. Parent characteristics: age, gender, educational level, employment status, economic status, family structure, number of children, and medical payment methods.

- (2)Caregiver Stress Index (CSI)

The CSI [33], Chinese version adapted by Chan et al. [34], demonstrated good reliability and validity in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.93). This 13-item dichotomous scale (“Yes” = 1, “No” = 0) assesses caregiver burden, with total scores ≥7 indicating significant stress. Higher scores reflect greater caregiving pressure.

- (3)Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The MAAS [35], Chinese version revised by Chen et al. [36], is a 15-item unidimensional scale that assesses a core characteristic of mindfulness: attentional awareness to present-moment experiences. Respondents rate how frequently they have each experience (e.g., ‘I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present’) on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = “Almost always” to 5 = “Almost never”). The total score is calculated as the mean of all items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindful attention awareness. It is important to note that the MAAS primarily measures this one facet of mindfulness rather than its multidimensional aspects. In this study, the scale showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.890).

- (4)Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP)

The CHIP [37], Chinese version translated by Zhong et al. [38], evaluates coping strategies among parents of chronically ill children. The 45-item instrument uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always”), with higher scores indicating better coping capacity. This measure has demonstrated good cross-cultural applicability in Chinese populations.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and the PROCESS macro version 4.0 for mediation analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic and study variables. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between caregiving stress, mindfulness, and coping styles. Prior to the main analyses, several preliminary checks were conducted. The assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity for regression analyses were checked visually through histograms, P-P plots, and scatterplots of residuals, and were deemed satisfactory. To assess the potential for common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was performed. Furthermore, the absence of multicollinearity was confirmed by the variance inflation factor (VIF) values all below 10.

To test the mediating role of mindfulness, Model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used with 5000 bootstrap samples. This method is robust to non-normality and provides bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals for the indirect effect. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05 for all analyses. Beyond statistical significance, effect size indices were also examined and reported. For the mediation analysis, the completely standardized indirect effect is reported as an effect size measure.

The results of Harman’s single-factor test indicated no severe common method bias in the data. Specifically, the unrotated factor analysis yielded 16 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor accounting for 29.34% of the variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40% [39].

2.2.2 Demographic Information of Children with Leukemia and Their Parents

A total of 221 parents of children with leukemia were included in this survey. The average age of the parents was 36.87 ± 5.65 years, with the youngest being 23 years old and the oldest 56 years old. The average age of the children with leukemia was 71.05 ± 47.58 months, ranging from 11 months to 193 months. Detailed demographic information of the children and their parents is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic information of children with Leukemia and their parents.

| Item | Group | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of parents | ≤30 years | 15 | 6.79 |

| 31–40 years | 159 | 71.95 | |

| ≥41 years | 47 | 21.27 | |

| Parents’ education | Primary school or below | 8 | 3.62 |

| Secondary/High school education | 105 | 47.51 | |

| College/University degree | 103 | 46.61 | |

| Postgraduate degree or higher | 5 | 2.26 | |

| Relationship to the child patient | Father | 46 | 20.81 |

| Mother | 175 | 79.19 | |

| Employment status changes due to child’s illness | Yes | 124 | 56.11 |

| No | 97 | 43.89 | |

| Family income (RMB) | <3000 | 36 | 16.29 |

| 3000–4999 | 61 | 27.60 | |

| 5000–10,000 | 71 | 32.13 | |

| >10,000 | 53 | 23.98 | |

| Gender of leukemia kid | Male | 122 | 55.20 |

| Female | 99 | 44.80 | |

| Age of leukemia kid | ≤1 year | 4 | 1.81 |

| 2–3 years | 62 | 28.05 | |

| 3–6 years | 57 | 25.79 | |

| 7–12 years | 73 | 33.03 | |

| ≥13 years | 25 | 11.31 | |

| Medical Insurance Type of Pediatric Patient: | Urban/Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance | 138 | 62.44 |

| Non-local Medical Insurance (New Rural Cooperative) | 25 | 11.31 | |

| Medical Scheme | 52 | 23.53 | |

| Commercial Health Insurance | 4 | 1.81 | |

| Self-pay | 2 | 0.90 | |

| Other | 0 | 0.00 | |

| No siblings | Yes | 83 | 37.56 |

| No | 138 | 62.44 | |

| Duration of Treatment: | <3 months | 77 | 34.84 |

| 3–12 months | 69 | 31.22 | |

| 1–3 years | 54 | 24.43 | |

| ≥4 years | 21 | 9.50 |

Table 2: Correlation analysis between demographic information and caregiving stress.

| Item | 1. Age | 2. Education | 3. Employment Status Changes due to Child’s Illness | 4. Family Income | 5. No Siblings | 6. Caregiving Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | −0.15* | 1 | ||||

| 3 | −0.05 | 0.19** | 1 | |||

| 4 | −0.13 | 0.53** | 0.32** | 1 | ||

| 5 | 0.17* | −0.18** | −0.12 | −0.06 | 1 | |

| 6 | −0.18** | 0.15* | 0.34** | 0.14* | −0.17** | 1 |

Table 2 presents a correlation matrix examining the relationships between key demographic variables and the level of caregiving stress experienced by parents of children with leukemia. The analysis reveals several statistically significant correlations. Most notably, changes in employment status due to the child’s illness demonstrate the strongest positive correlation with caregiving stress (r = 0.34, p < 0.01), suggesting that parents who had to alter their work situation reported significantly higher levels of stress. Furthermore, higher educational attainment and higher family income were also positively correlated with stress (r = 0.15, p < 0.05 and r = 0.14, p < 0.05, respectively). This potentially indicates that parents with higher socioeconomic status may experience unique stressors, such as greater occupational disruptions or higher expectations.

Conversely, the data shows that older parent age and the child having siblings (i.e., not being an only child) were associated with lower levels of reported caregiving stress (r = −0.18, p < 0.01 and r = −0.17, p < 0.01, respectively). This suggests that greater life experience and the presence of other children in the family may serve as protective factors, potentially by providing emotional support and caregiving responsibilities.

In summary, Table 2 identifies specific demographic factors that are significantly associated with the caregiving burden in this population. These findings help to delineate which subgroups of parents may be most vulnerable to high stress and are therefore in greatest need of targeted psychosocial support interventions.

2.2.3 Relationships between Caregiving Stress, Mindfulness, and Coping Styles among Parents of Children with Leukemia

Pearson product-moment correlation analysis revealed significant correlations among caregiving stress (Table 3), mindfulness and coping styles of the parents: caregiving stress was significantly negatively correlated with mindfulness (r = −0.35, p < 0.01); caregiving stress was significantly negatively correlated with coping styles (r = −0.26, p < 0.01); mindfulness were significantly positively correlated with coping styles (r = 0.52, p < 0.01).

Table 3: Correlation analysis of caregiving stress, mindfulness, and coping styles.

| Variable | Caregiving Stress | Mindfulness | Coping Styles |

|---|---|---|---|

| caregiving stress | 1 | ||

| mindfulness | −0.35** | 1 | |

| coping styles | −0.26** | 0.52** | 1 |

2.2.4 Caregiving Stress and Coping Styles among Parents of Children with Leukemia: The Mediating Role of Mindfulness

A mediating model involving caregiving stress, mindfulness, and coping styles of parents of children with leukemia was established using Model 4 in the PROCESS macro of SPSS 26.0 with 5000 bootstrap samples. The results showed: caregiving stress of the parents significantly negatively predicted their coping styles (β = −1.18, p < 0.01), 95%CI [−2.18, −0.18]; caregiving stress significantly negatively predicted mindfulness (β = −1.90, p < 0.01), 95% CI [−2.43, −1.38]; mindfulness significantly positively predicted their coping styles (β = 0.85, p < 0.01), 95% CI [0.62, 1.07]. In addition, the direct effect of caregiving stress on coping styles was significant (β = −1.18, p < 0.01), 95% CI [−2.18, −0.18]. The mediating model is presented in Fig. 1. The indirect effect of ‘caregiving stress → mindfulness → coping styles’ was significant, B = 0.02, BootSE = 0.01, 95% BootCI [0.00, 0.04]. The completely standardized indirect effect was 0.09, 95% BootCI [0.01, 0.16]. Additionally, the mediation effect explains approximately 10% of the total variance (R-squared mediation effect size = 0.10, 95% BootCI [0.04, 0.16]). The ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect was 0.20, indicating that mindfulness mediated about 20% of the total effect of caregiving stress on coping styles.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the mediation model (**p < 0.01).

The caregiving stress of parents of children with leukemia is significantly negatively correlated with their mindfulness and coping styles, while their mindfulness is significantly positively correlated with their coping styles. Moreover, mindfulness partially mediated the relationship between caregiving stress and coping styles among these parents. This indicates that while higher caregiving stress directly predicts poorer coping, a significant portion of this effect is explained through its negative impact on mindfulness. Furthermore, despite efforts to control for common method variance, the cross-sectional nature of Study 1 prevents any definitive causal inferences regarding the relationships between caregiving stress, mindfulness, and coping styles. The proposed mediation model is based on theoretical assumptions, and longitudinal or experimental designs are needed to establish causality.

3 Study 2: Intervention of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on Caregiving Stress and Coping Styles in Parents of Leukemia Patients

Building upon the correlational and mediational findings of Study 1, which established the relationship between caregiving stress, mindfulness, and coping styles, Study 2 aimed to evaluate the efficacy of an MBSR intervention in alleviating stress and improving coping strategies among this population through an RCT.

Study 2 adopted an RCT design to evaluate the effectiveness of the mindfulness intervention. An a priori power analysis was performed using G*Power Win-3.1.9.2 software [40]. With an effect size of 0.50 and a statistical power of 0.80, the calculation indicated that the minimum sample size required for each group was 26.

Based on the data from Study 1, 60 parents of children with leukemia were recruited for Study 2, who met the following criteria: caregiving stress score > 7, their children had stable conditions, and the parents themselves had no diagnosis of mental illness or cognitive impairment. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (MBSR) or the waitlist control group using a computer-generated random number sequence. The allocation sequence was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE) prepared by an independent research assistant not involved in recruitment or intervention delivery. Due to the nature of the behavioral intervention, participants could not be blinded to their group assignment. However, research assistants responsible for data collection and statistical analysis were blinded to group allocation to minimize assessment bias. The experimental group received an 8-week mindfulness intervention, while the control group received no intervention. Given the vulnerable nature of the population, ethical considerations were paramount. Participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time without penalty. The MBSR instructor was trained to monitor participants for signs of distress during sessions. A licensed clinical psychologist was on call to provide support if needed, although no such instances occurred during this study. The group environment also provided inherent peer support.

No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of caregiving stress, mindfulness, or coping styles before the intervention. An independent samples t-test on the basic characteristics of the two groups also revealed no significant differences; detailed comparisons of general information are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Comparison of demographic information between the experiment and control group before intervention.

| Item | t | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age of parent | 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Education | 0.99 | 0.33 |

| Employment status changes due to child’s illness | 0.78 | 0.38 |

| Family income | 0.75 | 0.39 |

| Age of child | 0.06 | 0.82 |

| No siblings | 0.29 | 0.59 |

| Duration of treatment | 0.07 | 0.79 |

The same as Study 1.

This program consists of 8 intervention sessions, with each session lasting 90 min, conducted once a week, supplemented by 25-min daily home practice [20]. The standard MBSR protocol was adapted to enhance its cultural appropriateness for Chinese parents. This included using Mandarin Chinese for all instructions and materials, incorporating examples relevant to the caregiving context of childhood leukemia, and utilizing the widely accessible WeChat platform for support and communication, which is deeply integrated into daily life in China. These adaptations were made in consultation with clinical experts in psycho-oncology to ensure the core principles of MBSR were maintained while improving participant engagement and relevance. The MBSR program was delivered by a certified instructor who had completed professional MBSR teacher training and had over three years of experience in delivering mindfulness interventions. To support their individual practice, each parent (all of whom were confirmed users of the WeChat app) was provided with an electronic version of the mindfulness levels training manual, and a dedicated WeChat group was established for the experimental group to facilitate the distribution of relevant materials, promote communication on course learning, address questions, and guide practice. This approach was part of our cultural adaptation strategy to leverage a widely accessible platform deeply integrated into daily life in China. Intervention fidelity was monitored through regular supervision sessions and by reviewing session outlines to ensure adherence to the standardized MBSR protocol. Attendance logs were also maintained for each session. The final intervention is presented in Table 5.

Prior to the intervention, participants were informed of the program’s purpose, methods, content, and schedule. They signed an informed consent form and agreed not to disclose any details of the intervention. The intervention was implemented in accordance with the process outlined in Table 5. During the MBSR intervention, parents in both groups received routine health education, while the experimental group additionally participated in weekly mindfulness training. To ensure the effectiveness and interactivity of the sessions, the experimental group attended 90-min mindfulness training sessions once a week in the demonstration classroom of the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department, which included 60 min of instruction and 30 min of practice and discussion, totaling 8 weeks. Furthermore, parents in the experimental group were required to engage in 25-min daily individual practice, revisiting the content covered in the previous session. To support their individual practice, each parent was provided with an electronic version of the mindfulness levels training manual, and a WeChat group was established for the experimental group to facilitate the distribution of relevant materials, promote communication on course learning, address questions, and guide practice.

Data were collected at the beginning of the study and after 8 weeks of intervention. Participants were required to record their daily practice, including practice location, content, duration, frequency, and reflections, in a unified MBSR record book provided to them. Follow-up checks (either via phone calls or WeChat video calls) were conducted once daily to monitor implementation progress and address any doubts.

Table 5: Implementation plan of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR).

| Week | Section | Purpose | Main Intervention | Homework |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Mindfulness | Establishing the group and trust, learning mindfulness eating. | (1) Group members introduce themselves to get acquainted, and a WeChat group named “Encountering Happiness” is created. (2) Introduce the theoretical knowledge of MBSR, as well as the 8-week course plan and arrangements. (3) Guide parents of children with leukemia in mindfulness eating training. | Mindful raisin-eating exercise |

| 2 | Emotions and Stress | Focusing on inner feelings, learning to control emotions through mindful breathing. | (1) Group members express their emotions and stress through self-narration or writing. (2) Guide parents in mindful breathing exercises. | 3-min mindful breathing accompanied by music. |

| 3 | Mindful Meditation | Conscious awareness, focusing on the present moment. | (1) Explain the content and methods of mindful meditation to parents. (2) Guide parents in practicing mindful meditation. | Meditation practice accompanied by music. |

| 4 | Body Scan | Allowing awareness to fly through every part of the body to achieve a state of deep relaxation and awareness. | (1) Introduce the content and practice skills of mindful walking and body scan. (2) Guide parents in practicing mindful walking and body scan. | Practicing mindful walking and body scan following audio instructions. |

| 5 | Mindful Yoga | Integrating mindfulness into physical activities to relieve stress. | (1) Explain the specific content, skills, and methods of mindful yoga. (2) Guide parents in practicing mindful yoga. | Practicing mindful yoga following videos. |

| 6 | Integration into Life | Discussing current interpersonal relationships and communication. | (1) Teach the skills and methods of mindful listening and mindful sitting. (2) Group members discuss issues related to self and family social interactions. (3) Guide parents in practicing mindful listening. | Practicing mindful listening with natural sound audio. |

| 7 | Positive Living | Strengthening and consolidating MBSR techniques for practical application. | (1) Strengthen the previously learned MBSR techniques. (2) Select mindfulness techniques suitable for parents and guide them in practice. | Parents freely choose suitable mindfulness techniques for practice. |

| 8 | The Rest of Life | Embarking on a mindful life journey, integrating mindfulness into future life. | (1) Encourage parents to internalize the practice and develop their own characteristic patterns. Enable participants to start a lifelong mindfulness journey after the 8-week course. (2) Encourage participants to apply MBSR techniques in future life. | Practicing mindfulness techniques daily and integrating mindfulness into life. |

3.3.1 Comparison of Caregiving Stress among Parents of Children with Leukemia before and after Intervention

Data analysis in this study was performed using SPSS 26.0. There was no significant difference in stress levels between the experimental group and the control group before the intervention (t = −0.40, p > 0.05). A paired samples t-test was conducted on the caregiving stress scores of the two groups after the intervention. The results showed that the caregiving stress of parents in the experimental group was significantly lower after the intervention than before (t = 2.24, p < 0.05), while there was no significant difference in the caregiving stress of the control group before and after the experiment (t = 1.10, p > 0.05). These findings indicate that MBSR significantly reduced the caregiving stress of parents of children with leukemia. Details are shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Comparison of caregiving stress between the two groups before and after intervention.

| Group | Before Intervention | After Intervention | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 9.27 ± 2.23 | 8.80 ± 2.17 | 2.24* | <0.05 |

| Control group | 9.07 ± 1.64 | 8.83 ± 1.56 | 1.10 | 0.28 |

3.3.2 Comparison of Mindfulness among Parents of Children with Leukemia before and after Intervention

Before the intervention, there was no significant difference in mindfulness between the experimental group and the control group (t = −1.94, p > 0.05). After eight weeks of MBSR intervention, mindfulness levels of parents in the experimental group were significantly higher than those before the intervention (t = −4.61, p < 0.01). In contrast, there was no significant difference in mindfulness in the control group between the two assessments (t = −0.92, p > 0.05). These results indicate that MBSR significantly improved mindfulness levels of parents of children with leukemia, as detailed in Table 7.

Table 7: Comparison of mindfulness between the two groups before and after intervention (Mean ± SD).

| Group | Before Intervention | After Intervention | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 53.23 ± 11.07 | 55.73 ± 9.74 | −4.61** | <0.01 |

| Control group | 47.63 ± 11.29 | 47.90 ± 10.77 | −0.92 | 0.37 |

3.3.3 Comparison of Coping Styles among Parents of Children with Leukemia before and after Intervention

Before the intervention, there were no significant differences in the total scores of coping styles or scores of each dimension between the two groups (t = −0.99, p > 0.05). After eight weeks of intervention, the total scores of coping styles among parents in the experimental group were significantly higher than those before the intervention (t = −2.36, p < 0.01), while no significant difference was observed in the control group (t = 0.68, p > 0.05). These results indicate that MBSR significantly enhanced the positive coping styles of parents of children with leukemia, as detailed in Table 8.

Table 8: Comparison of coping styles between the two groups before and after intervention (Mean ± SD).

| Group | Before Intervention | After Intervention | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 167.90 ± 21.85 | 172.27 ± 23.40 | −2.36** | <0.01 |

| Control group | 161.40 ± 28.79 | 162.10 ± 28.93 | 0.68 | 0.17 |

3.4 Post-Intervention Interviews

Ten parents from the experimental group were purposively selected to ensure diversity in gender, age, and child’s treatment phase to provide a rich array of perspectives on the intervention experience.

Based on the research objectives and combined with the results of the previous quantitative study, the following interview outline was formulated:

- (1)After completing the MBSR course, what help and changes do you feel it has brought to you?

- (2)Among the 8-week courses, which part did you like the most?

- (3)How do you feel about your child’s illness now? Do you think this course has influenced your feelings or contributed to your current changes?

- (4)What impact has the 8-week course had on your attitude toward life and lifestyle in the future?

- (5)Will you continue practicing MBSR after the course ends?

Interviews were conducted in the conversation room of the ward to ensure a quiet environment without disturbances. Interviewers first introduced the basic information of the study to the interviewees, promised the principles of confidentiality and anonymity to gain their trust, and finally obtained their signed informed consent.

Interviewers conducted the interviews according to the outline, encouraging interviewees to express their feelings and thoughts about the 8-week MBSR course comprehensively and thoroughly. The outline was adjusted based on the actual progress of the interviews. For ambiguous or incomplete statements, interviewers promptly repeated the information or asked follow-up questions to explore comprehensive information as much as possible. During the interviews, interviewers maintained neutral language, avoided any suggestive or inductive behaviors and remarks, and the duration of each interview was 30–45 min. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was reached, which was achieved after 10 interviews, as no new substantive themes emerged from the data.

The interview transcripts were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis following the approach by Braun and Clarke [41]. This involved six-phase framework of familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report.

Firstly, familiarization with the data. Two researchers repeatedly listened to the audio recordings and read the verbatim transcripts multiple times to gain an in-depth understanding of the content while noting down initial ideas. Secondly, generating initial codes. Two researchers independently conducted line-by-line coding of the transcripts to identify meaningful units relevant to the research questions. Thirdly, searching for themes: The researchers then collated these codes into potential broader themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. Fourthly, reviewing themes. This phase involved a two-level review. To begin with, the coded data extracts were reviewed to assess if they formed a coherent pattern. Then, the entire data set was revisited to ensure the themes accurately reflected the meanings evident in the data as a whole. The themes were refined, split, combined, or discarded as necessary. Fifthly, defining and naming themes. Ongoing analysis was conducted to refine the specifics of each theme and the overall story the analysis tells. Clear definitions and concise names were generated for each theme. Lastly, producing the report. The final step involved selecting vivid, compelling extract examples to illustrate the themes within the manuscript. To ensure the trustworthiness of the analysis, coding discrepancies between the two researchers were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached (Table 9).

Table 9: Summary of themes from qualitative interviews on MBSR experience.

| Theme | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Alleviating Caregiving Stress | 1.1 Stress Regulation | Using MBSR techniques (e.g., three-minute breathing space) to actively manage feelings of stress. |

| 1.2 Improved Sleep | Using mindfulness meditation to improve sleep quality, thereby indirectly reducing stress and fatigue. | |

| 2. Reducing Anxiety | 2.1 Emotional Control | Maintaining a calmer state of mind during anxiety-provoking situations, such as medical procedures. |

| 2.2 Positive Impact on Child | The parent’s increased calmness leads to improved child cooperation, creating a positive feedback loop. | |

| 3. Enhancing Self-Compassion | 3.1 Reduced Self-Blame | Letting go of excessive guilt and self-reproach regarding the child’s illness. |

| 3.2 Recognition of Self-Efficacy | Gaining a more objective and confident view of one’s own caregiving abilities. | |

| 4. Better Awareness of the Present Moment | 4.1 Improved Focus | Enhanced ability to concentrate on current caregiving tasks, reducing distractibility. |

| 4.2 Solution-Oriented Application | Applying mindfulness directly to specific caregiving challenges to improve care quality. | |

| 5. Improving Parent-Child and Family Relationships | 5.1 Increased Patience and Understanding | Becoming more patient with the child and better understanding their behavior. |

| 5.2 Reduced Family Conflict | Improved emotional regulation leading to a calmer demeanor and more harmonious family interactions. |

Theme 1: Alleviating Caregiving Stress

Stress was a key word mentioned by most interviewee parents of children with leukemia. They stated that after receiving MBSR training, they could better regulate their own stress and improve their stress resistance. This theme comprised two codes: Stress Regulation (Code 1.1, n = 2), referring to the active use of MBSR techniques to manage stress, and Improved Sleep (Code 1.2, n = 1), concerning the use of mindfulness to improve sleep quality and indirectly reduce fatigue.

N6: “Leukemia is a highly malignant disease, and my biggest worry is whether my child can recover. With long-term chemotherapy, accidents may occur at every step. I have to take care of my child wholeheartedly, fearing any oversight, which brings me great stress. However, after MBSR training, when I feel extremely stressed, I use the three-minute breathing space, and my mood gradually relaxes. (Code1.1)”

N3: “I was already a light sleeper. In the hospital, nurses’ regular rounds and my child’s crying at night further disrupted my sleep. When I couldn’t fall asleep at night, I listened to audio to practice mindful meditation. Gradually, my sleep improved, and I felt more energetic the next day, which allowed me to take better care of my child. (Code1.2)”

Theme 2: Reducing Anxiety

Most interviewees reported that after MBSR training, they could better control their negative emotions and maintain a calm state of mind. This theme included Emotional Control (Code 2.1, n = 1), the ability to maintain calm during procedures, and Positive Impact on Child (Code 2.2, n = 1), where the parent’s calmness improved the child’s cooperation.

N4: “It’s really painful for my child to have this disease. He often needs to undergo lumbar puncture, and I dare not tell him in advance. The procedure is usually done in the afternoon, but I start feeling anxious from the morning. Every time, my child cries uncontrollably in the examination room, while I feel restless outside. After learning mindful walking (Code2.1), I started practicing it—walking slowly in the corridor and experiencing the moment, which helps me relax and regain strength. When my child finishes the procedure, I give him a thumbs-up and firmly yet gently carry him back to the ward in the head-low horizontal position as instructed by the doctors. Moreover, I notice that as I change, my child cries less and cooperates more. (Code2.2)”

Theme 3: Enhancing Self-Compassion

During the interviews, some parents stated that through practice, they improved their acceptance level, learned to care for themselves in life, and treated others with tolerance and kindness. Mindfulness training helped them gain a comprehensive understanding of themselves and reduce self-criticism. Mindfulness training helped them gain a comprehensive understanding of themselves and reduce self-criticism. The two codes were Reduced Self-Blame (Code 3.1, n = 2), letting go of guilt about the child’s illness, and Recognition of Self-Efficacy (Code 3.2, n = 1), gaining confidence in one’s caregiving abilities.

N8 (Code3.1): “I often reflect on whether I failed to protect myself from radiation during pregnancy or ate something inappropriate, which caused my child to get this disease. After mindfulness training, I no longer blame myself excessively, which used to make me extremely painful.”

N10 (Code3.1&3.2): “Every time my child gets an infection after chemotherapy, I scold myself for not taking good care of him (Code3.1). I even recall every operation the doctors and nurses performed on my child, wondering if it increased the risk of infection. Through mindfulness practice, I realized that medical staff are making great efforts to take care of my child—for example, they strictly disinfect their hands every time they contact him. Then I noticed that I have also done a good job in hygiene and disinfection, and I feel more confident in taking care of my child. (Code3.1)”

Theme 4: Better Awareness of the Present Moment

Some caregivers of children with leukemia mentioned that after learning mindfulness, they could concentrate better and become more aware of their own bodies. This was reflected in Improved Focus (Code 4.1, n = 2), the enhanced ability to concentrate on tasks, and Solution-Oriented Application (Code 4.2, n = 1), applying mindfulness directly to solve caregiving problems.

N9 (Code4.2): “I feel that mindfulness has taught me a way to solve problems. I applied the raisin exercise to the care of my child after methotrexate chemotherapy. I can calm down and think about how to cooperate with medical staff in the rescue plan on time, how to meticulously guide my family to cook soft and easy-to-digest meals, how to instruct my child to chew slowly, and how to ensure thorough mouth rinsing every time. I focused on every detail, and this time, my child’s oral mucosa was not damaged at all.”

N5 (Code4.1): “I used to constantly wonder why God chose my child to get this disease, which made me unable to concentrate. Sometimes, the IV drip would finish, and I wouldn’t notice until the neighbor’s child or their parent reminded me. After learning MBSR, I learned to be aware of the present moment, and my concentration has improved. The past cannot be changed, so I should seize the present and cherish every day with my child.”

Theme 5: Improving Parent-Child and Family Relationships

Many interviewees also mentioned that MBSR training helped them build more harmonious relationships with their families and children. This consisted of Increased Patience and Understanding (Code 5.1, n = 1), becoming more patient and understanding with the child, and Reduced Family Conflict (Code 5.2, n = 1), wherein improved emotional regulation led to a calmer home environment.

N1 (Code5.1): “Body scan and mindful yoga not only relax my body but also make me more patient when interacting with my child. When my child acts unreasonably, I no longer yell like before. Instead, I have improved the quality of companionship, better understood the intentions behind my child’s behaviors, and our parent-child relationship has become more harmonious.”

N7 (Code5.2): “My husband said that my temper has improved a lot recently. I no longer haggle over trivial matters, and when problems arise, I handle them calmly instead of flying into a rage. Our family has become more harmonious.”

While the reported experiences were overwhelmingly positive, a few participants mentioned initial challenges with consistent daily practice due to the demanding caregiving schedule. However, they noted that the group support via WeChat helped them overcome this barrier.

3.5 Integration of Qualitative Findings with Quantitative Results

The qualitative interviews provided rich, contextualized insights that elucidate and expand upon the quantitative outcomes. The following themes illustrate how participants experienced the changes measured in the questionnaires.

3.5.1 Elucidating the Reduction in Caregiving Stress: From Overwhelm to Regulated Response

The quantitative results indicated a significant decrease in caregiving stress scores within the experimental group following the intervention (Table 6). This statistical improvement was further elucidated by the qualitative theme of Alleviating Caregiving Stress, which uncovered the specific mechanisms behind this change. Participants described a transition from a state of persistent and overwhelming worry to one in which they could actively regulate stress in real time. For instance, N6 linked the documented reduction in stress directly to the application of a learned MBSR technique: “After MBSR training, when I feel extremely stressed, I use the three-minute breathing space, and my mood gradually relaxes.” This account demonstrates that the quantitative decline in stress scores corresponded to a tangible, acquired skill in self-regulation, reflecting a shift beyond mere numerical change toward functional coping.

3.5.2 Explaining the Enhancement in Mindfulness: A Shift in Awareness and Focus

A significant post-intervention increase in mindfulness scores was observed in the experimental group (Table 7). The qualitative data under the theme Better Awareness of the Present Momentvividly illustrated what this enhancement entailed in everyday contexts. Rather than remaining an abstract construct, heightened mindfulness manifested as concrete improvements in focus and present-centeredness—qualities that directly counter the distractibility captured by the MAAS scale. As N5 shared, “I used to constantly wonder why God chose my child... unable to concentrate. After learning MBSR, I learned to be aware of the present moment, and my concentration has improved.” This narrative confirms that the quantitative gains in mindfulness translated into an increased capacity to attend to essential caregiving responsibilities.

3.5.3 Unpacking the Improvement in Coping Styles: From Passive Suffering to Active Problem-Solving

Coping style scores improved significantly in the experimental group after the intervention (Table 8). Qualitatively, this shift was embodied in the theme Solution-Oriented Application, which reflected a move away from helplessness toward proactive and engaged coping. Parents reported applying mindfulness principles directly to navigate caregiving challenges. N9 offered a compelling example: “I applied the raisin exercise to the care of my child after methotrexate chemotherapy. I can calm down and think about how to cooperate with medical staff... how to meticulously guide my family to cook... I focused on every detail.” This account reveals that the intervention promoted a constructive, problem-solving approach to coping, aligning with the positive behavioral changes that the CHIP instrument is designed to assess.

3.5.4 Revealing the Underlying Mechanism: Improved Emotional Regulation and Self-Compassion

Aligned with the mediation model from Study 1, which identified mindfulness as a mechanism influencing coping, the qualitative themes of Reducing Anxiety and Enhancing Self-Compassion provided deeper insight into this pathway. Interviews illuminated how and why mindfulness facilitated this mediation: the non-judgmental aspect of the practice was pivotal for emotional regulation. N4, for example, used mindful walking to manage anxiety during her child’s medical procedures. Additionally, mindfulness appeared to mitigate self-blame—a common source of psychological distress. As N8 expressed, “After mindfulness training, I no longer blame myself excessively, which used to make me extremely painful.” This illustrates how cultivating mindfulness reduced negative self-referential thinking, thereby freeing cognitive and emotional resources for more adaptive coping, as quantitatively suggested.

The findings of this study indicate that MBSR exerts multiple positive effects on parents of children with leukemia. Specifically, MBSR can enhance these parents’ mindfulness levels and effectively reduce the caregiving stress they experience. Additionally, it improves their coping capacities, with notable advancements in doctor-patient relationships and social interactions. Furthermore, MBSR enables parents to better stay mindful of the present moment, strengthens their emotional regulation skills, and supports the maintenance of a harmonious family environment.

This study makes a novel contribution by demonstrating, through an integrated mixed-methods design, the potential mechanisms and benefits of MBSR for a vulnerable and understudied population: parents of children with leukemia in China. While prior research has established the efficacy of MBSR in other groups, our findings specifically illuminate its role in alleviating the unique caregiving stress and improving coping strategies in this context. Besides, we employed a mixed-methods approach that triangulates quantitative RCT results with rich qualitative insights, providing a deeper understanding of how and why the intervention may work; and uniquely combined a mediation model (from Study 1) with an experimental test of an intervention (in Study 2), moving beyond correlation to examine causality and mechanism. The results of this study indicate that mindfulness plays a mediating role between caregiving stress and coping styles of parents of children with leukemia, and mindfulness intervention can help these parents alleviate caregiving stress and improve their positive coping styles.

A key strength of this study lies in its mixed-methods approach, which allowed for a more nuanced understanding than either methodology could achieve alone. The quantitative results provided objective, generalizable evidence for the efficacy of the MBSR intervention in reducing stress, enhancing mindfulness, and improving coping styles. The qualitative findings, in turn, illuminated the lived experience and underlying mechanisms of these changes. They explained how stress was reduced (through acquired self-regulation skills), what increased mindfulness felt like (improved focus and present-moment awareness), and why coping styles shifted (through reduced self-blame and a solution-oriented mindset). This triangulation of data not only reinforces the validity of our quantitative findings but also provides a rich, contextualized account of the intervention’s impact, highlighting its practical relevance for the daily lives of these caregivers. The qualitative data thus fulfilled a crucial complementary function, giving voice and meaning to the numbers.

4.1 Impact of MBSR on Caregiving Stress of Parents of Children with Leukemia

The threat to their children’s lives posed by leukemia and the pain of treatment easily lead to negative emotions such as anxiety and immense caregiving stress in parents, who are the primary caregivers. This, in turn, affects the recovery and growth of the children [16]. Our findings suggest that MBSR may effectively reduce the caregiving stress of parents of children with leukemia, which is consistent with research results on infertile patients [42], cancer patients [43], and pregnancy stress [44]. Consistent with previous studies, the effectiveness of MBSR in reducing caregiving stress in our sample aligns with its efficacy in other high-stress populations [43,44]. This supports the theoretical premise that MBSR’s core mechanism—cultivating non-judgmental present-moment awareness—is effective across various contexts by disrupting maladaptive cognitive patterns like rumination and catastrophic thinking, which are common in caregivers facing chronic stress.

The possible reasons for this are as follows: The slow and deep breathing exercises in mindfulness training can help parents of children with leukemia rebalance the abnormally activated sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves during stress, thereby reducing emotional experiences and cognitive evaluations in the stress state [45]. Additionally, studies have shown that mindfulness can enhance brain attention, reduce the density of the amygdala, and increase brain plasticity, thereby effectively regulating emotions [46] and improving sleep structure and quality [47]. Post-intervention interviews in Study 2 revealed that mindfulness can guide parents to face the disease positively, proactively embrace and experience the current environment and negative emotions instead of blindly resisting and avoiding them, as resistance and avoidance often exacerbate negative emotions. Through MBSR, parents can detach themselves from their inherent thoughts and focus on the present moment. For example, by deepening their understanding of leukemia, they realize that many of their past guilt and fears about the future are just personal thoughts rather than facts, thus becoming more tolerant and accepting of themselves, and alleviating caregiving stress and anxiety.

The significant reduction in caregiving stress following the MBSR intervention can be understood through its impact on the participants’ caregiving role identity. In the Chinese context, where “good parents” are expected to be omni-competent and selfless, the inability to alleviate a child’s suffering can lead to profound self-criticism and role-related strain. The non-judgmental stance cultivated by mindfulness may have allowed parents to observe these self-critical thoughts and cultural expectations without being completely governed by them. By learning to approach their caregiving struggles with acceptance rather than harsh judgment, they may have softened the rigid link between their child’s illness outcome and their own self-worth, thereby alleviating the unique intensity of caregiving stress rooted in Chinese familialism.

4.2 Impact of MBSR on Mindfulness of Parents of Children with Leukemia

Parents of children with leukemia experience more negative emotions, which can be passed on to their children through parenting. mindfulness are positively correlated with positive emotions and negatively correlated with negative emotions [35]. Individuals with high mindfulness have fewer negative emotions and higher levels of positive feelings, subjective well-being, and psychological resilience [19]. The results of Study 2 showed that the total mindfulness score of the experimental group was significantly higher after the intervention than before, while there was no significant difference in the total mindfulness score of the control group before and after the intervention, indicating that MBSR can improve mindfulness levels of parents of children with leukemia. The MAAS measures an individual’s mindfulness level in areas such as cognition, emotion, and physiology. Mindfulness practices (such as meditation, mindful yoga, and body scan) can improve parents’ internal focus and perception of what is happening in the present moment, thereby enhancing their cognitive and self-behavioral regulation abilities, and ultimately achieving the goal of alleviating emotions and improving mindfulness. Therefore, if these findings are replicated in larger, more definitive trials, a potential implication could be the future integration of MBSR principles into supportive care programs and health education for this parent population.

4.3 Impact of MBSR Training on Coping Styles of Parents of Children with Leukemia

In the long-term treatment process of children with leukemia, parents, as the main caregivers, play a crucial role. The coping styles they adopt directly determine the environment and quality of care in which the children undergo complex chemotherapy. Through MBSR intervention, mindfulness acted as a partial mediator between caregiving stress and coping styles, as the direct effect remained significant. This is consistent with the research results of Yang, who applied MBSR to the intervention of parents of children with cerebral palsy [48]. Studies have found that mindfulness can positively predict “confrontation” in positive coping styles, negatively predict “avoidance and submission” in coping styles, and significantly predict health-promoting behaviors, indicating that improving mindfulness can prompt parents of children with leukemia to adopt more positive coping styles when facing the disease and help promote the physical and mental health of caregivers [49].

MBSR enables parents of children with leukemia to learn to accept everything in the present without judgment. In addition, studies examining the effects of mindfulness training on cognitive behaviors using Stroop and prospective memory tasks have shown that mindfulness training can significantly improve cognitive function [50]. In this study, mindfulness acts on the cognitive processing process of parents of children with leukemia, enabling them to consciously increase positive rumination, which is beneficial for individuals’ positive psychological adjustment. As previous research has emphasized, mindfulness training focuses on cognitive or attentional training [20], improving practitioners’ control functions to a certain extent, such as the ability to maintain attention and inhibit interference [51]. By practicing mindfulness techniques, parents of children with leukemia adjust their cognitive and thinking patterns, more actively tap into their own potential, and in the group intervention mode, more actively communicate with parents of other children about care experiences, thereby improving their coping abilities.

4.4 Impact of MBSR on Emotional Regulation of Parents of Children with Leukemia

The interview results of this study showed that MBSR training can improve the emotional regulation ability of parents of children with leukemia, enhance self-compassion, help them better perceive the present moment, maintain a stable mindset, alleviate anxiety, and maintain good parent-child relationships and a harmonious family atmosphere. Mindfulness, through a non-judgmental attitude, allows individuals to accept negative emotions such as guilt, self-denial, loss of confidence, and all psychological reactions related to anxiety [52], reducing rumination and self-criticism [53].

Moreover, self-compassion is also related to positive and optimistic psychological qualities [54,55]. A meta-analysis based on mindfulness and self-compassion showed that mindfulness intervention has a positive impact on self-compassion levels [56]. The huge blow of their children’s leukemia often leaves parents in a state of anxiety, with difficulty concentrating. They bear enormous parental stress in long-term care, and family conflicts become prominent. MBSR training enables parents to be more aware of the present moment, have a peaceful state of mind, better raise their children, create a good family environment, and provide a harmonious, safe, and happy environment for their children after discharge, which is more conducive to the children’s disease recovery and happy growth. While the reports were predominantly positive, it is important to acknowledge potential barriers to implementation, such as the time demands of daily practice amidst intense caregiving schedules. Future interventions should consider these practical challenges and explore ways to enhance adherence.

The qualitative findings on reduced anxiety and improved emotional regulation resonate deeply with cross-cultural psychology. The Chinese cultural script of emotional control, while promoting surface-level harmony, can lead to internal emotional dissonance. MBSR’s core component of present-moment awareness and acceptance offers a culturally congruent “internal space” for parents to acknowledge and process their fear, anger, and sadness privately, without the perceived social cost of public expression. This is not merely relaxation but a fundamental retraining of their relationship with inner experience. Instead of suppressing emotions (which is effortful and often futile), they learned to “be with” them mindfully. This process aligns with traditional Chinese concepts of mental cultivation (xiu-yang) but is operationalized through a contemporary, evidence-based protocol, making it both familiar and novel to participants.

Findings suggest that the MBSR program may be a beneficial intervention for enhancing mindfulness, reducing caregiving stress, and improving coping strategies among parents of children with leukemia. However, these results are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution; further research with larger and more diverse samples is needed to confirm their efficacy.

4.5 Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the use of a convenience sample recruited from a single tertiary hospital in China limits the generalizability of our findings. Participants from this specific healthcare setting may not be fully representative of the broader population of parents of children with leukemia, particularly those from rural areas, lower socioeconomic backgrounds, or those treated in community hospitals. Furthermore, our sample encompassed children at various stages of treatment; the effectiveness of MBSR might differ for parents of children newly diagnosed versus those in maintenance therapy or survivorship. Future multi-center studies with stratified sampling across diverse socioeconomic regions and specific disease stages are needed to confirm the efficacy and applicability of our findings.

Second, the reliance on self-report measures for primary outcomes, while practical, is susceptible to social desirability and recall bias. The use of a waitlist control design, although ethical and appropriate for a preliminary RCT, does not control for non-specific effects such as the attention from instructors or the peer support inherent in the group setting. Therefore, the observed benefits, while promising, could be partially attributed to these factors. Future trials would benefit from employing active control groups (e.g., receiving standard psychoeducation or supportive group therapy) to more rigorously isolate the specific effects of the mindfulness components.

Third, the potential for self-selection and dropout bias must be considered. Parents who volunteered for the study and completed the 8-week intervention might have been more motivated or possessed certain personality traits (e.g., higher baseline openness to mindfulness) than those who declined or dropped out. This may limit the representativeness of our sample and the generalizability of the intervention’s effectiveness to all caregivers in this population. Future implementation research should explore strategies to enhance recruitment and adherence among more diverse and potentially more burdened caregivers.

Finally, the absence of a long-term follow-up assessment means we cannot determine the durability of the positive effects observed immediately post-intervention. It remains unclear whether the gains in mindfulness, reductions in stress, and improved coping strategies were maintained over time. Future studies should include follow-up assessments at 3, 6, and 12 months to evaluate the long-term efficacy of MBSR and investigate the potential need for booster sessions to sustain benefits.

This study demonstrates that MBSR is a beneficial intervention for reducing caregiving stress and improving coping styles among parents of children with leukemia. Through a mixed-methods approach, we found that mindfulness mediates the relationship between caregiving stress and coping styles (Study 1), and that an 8-week MBSR program significantly enhanced mindfulness, reduced stress, and promoted more adaptive coping strategies (Study 2). Qualitative interviews further revealed that participants experienced improved emotional regulation, self-compassion, present-moment awareness, and family relationships. In summary, MBSR shows great potential as a supportive psychological intervention for parents of children with leukemia, helping them manage stress more effectively and adopt healthier coping mechanisms. Integrating mindfulness-based approaches into routine supportive care for these caregivers may contribute to better family well-being and improved patient outcomes.

In summary, our mixed-methods findings suggest that MBSR works for Chinese parents of children with leukemia not by changing their fundamental caregiving values, but by transforming their psychological relationship with those values and the associated stressors. It mitigates the burdensome aspects of a strong caregiving role identity by infusing it with self-compassion, and it provides a sanctioned, internal pathway for emotional regulation that circumvents the cultural taboo against overt emotional expression. This cross-cultural interpretation enriches the stress-coping model by illustrating how mindfulness operates as a metacognitive resource that interacts with culturally shaped appraisals and coping potentials.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; methodology, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; software, Yue Yuan; validation, Jinpan Wang; formal analysis, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; investigation, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; resources Jinpan Wang; data curation, Yue Yuan; writing—original draft preparation, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; writing—review and editing, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; visualization, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; supervision, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; project administration, Yue Yuan, Jinpan Wang; funding acquisition, Jinpan Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Northwest Normal University (Approval No.: [2023028]). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Miranda-Filho A , PiEros M , Ferlay J , Soerjomataram I , Monnereau A , Bray F . Epidemiological patterns of leukaemia in 184 countries: a population-based study. Lancet Haematol. 2018; 5( 1): e14. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30232-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zheng R , Peng X , Zeng H , Zhang S , Chen T , Wang H , et al. Incidence, mortality and survival of childhood cancer in China during 2000–2010 period: a population-based study. Cancer Lett. 2015; 363( 2): 176– 80. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Frey S , Blankart CR , Stargardt T . Economic burden and quality-of-life effects of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016; 34( 5): 479– 98. doi:10.1007/s40273-015-0367-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hunger SP , Raetz EA . How I treat relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the pediatric population. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2020; 136( 16): 1803– 12. doi:10.1182/blood.2019004043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kaltenbaugh D , Klem ML , Hu L , Turi E , Haines A , Lingler JH . Using web-based interventions to support caregivers of patients with cancer: a systematic review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015; 42( 2): 156– 64. doi:10.1188/15.ONF.156-164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. McCullough A , Ruehrdanz A , Jenkins MA , Gilmer MJ , Olson J , Pawar A , et al. Measuring the effects of an animal-assisted intervention for pediatric oncology patients and their parents: a multisite randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2018; 35( 3): 159– 77. doi:10.1177/1043454217748586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nakayama N , Mori N , Ishimaru S , Ohyama W , Yuza Y , Kaneko T , et al. Factors associated with posttraumatic growth among parents of children with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2017; 26( 9): 1369– 75. doi:10.1002/pon.4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lazarus RS , Folkman S . Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

9. Lu S , Wei F , Li G . The evolution of the concept of stress and the framework of the stress system. Cell Stress. 2021; 5( 6): 76. doi:10.15698/cst2021.06.250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Polizzi C , Perricone G , Fontana V , D’Angelo P , Jankovic M , Nichelli F , et al. The relation between maternal locus of control and coping styles of pediatric leukemia patients during treatment. Pediatr Rep. 2020; 12( 1): 7– 13. doi:10.4081/pr.2020.7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. He S , You L , Zheng J , Bi Y . Uncertainty and personal growth through positive coping strategies among Chinese parents of children with acute leukemia. Cancer Nurs. 2016; 39( 3): 205– 12. doi:10.1097/ncc.0000000000000279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang X , Pan X , Pan Y , Wang Y . Effects of preventive care on psychological state and complications in leukemia patients receiving chemotherapy. Am J Transl Res. 2023; 15( 1): 184– 92. [Google Scholar]

13. Nam GE , Warner EL , Morreall DK , Kirchhoff AC , Kinney AY , Fluchel M . Understanding psychological distress among pediatric cancer caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016; 24( 7): 3147– 55. doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3136-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yucel E , Zhang S , Panjabi S . Health-related and economic burden among family caregivers of patients with acute myeloid leukemia or hematological malignancies. Adv Ther. 2021; 38( 10): 5002– 24. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01872-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Han J , Liu JE , Xiao Q . Coping strategies of children treated for leukemia in China. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017; 30: 43– 7. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2017.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dhakouani S , Karoui M , Jammeli S , Kammoun R , Ellouz F . Coping strategies among mothers of children with leukemia in Tunisia. Eur Psychiatry. 2022; 65( 1): S659. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu Y , Chen J , Tang J , Ni S , Xue H , Pan C . Cost of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia care in Shanghai, China. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009; 53( 4): 557– 62. doi:10.1002/pbc.22127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jensen SK , Sezibera V , Murray SM , Brennan RT , Betancourt TS . Intergenerational impacts of trauma and hardship through parenting. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021; 62( 8): 989– 99. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yuan Y . Mindfulness training on the resilience of adolescents under the COVID-19 epidemic: a latent growth curve analysis. Personal Individ Differ. 2021; 172: 110560. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kabat-Zinn J . Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010; 10( 2): 144– 56. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shi J , Wang RJ , Wang FY . Mind–body health technique liu zi jue: its creation, transition, and formalization. SAGE Open. 2020; 10( 2): 215824402092702. doi:10.1177/2158244020927024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Skottnik L , Linden D . Mental imagery and brain regulation-new links between psychotherapy and neuroscience. Front Psychiatry. 2019; 10: 779. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]