Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Connection Paradox: How Social Support Facilitates Short Video Addiction and Solitary Well-Being among Older Adults in China

1 School of Journalism and Communication, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, 210097, China

2 School of Modern Circulation, Guangxi International Business Vocational College, Nanning, 530007, China

* Corresponding Author: Hao Gao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Causes, Consequences and Interventions for Emerging Social Media Addiction)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 7 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.072986

Received 08 September 2025; Accepted 12 December 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: In the Chinese context, the impact of short video applications on the psychological well-being of older adults is contested. While often examined through a pathological lens of addiction, this perspective may overlook paradoxical, context-dependent positive outcomes. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to challenge the traditional Compensatory Internet Use Theory by proposing and testing a chained mediation model that explores a paradoxical pathway from social support to life satisfaction via problematic social media use. Methods: Data were collected between July and August 2025 via the Credamo online survey platform, yielding 384 valid responses from Chinese older adults aged 60 and above. Key constructs were assessed using the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), Simplified UCLA Loneliness Scale, and Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). A chained mediation model was tested using stepwise regression and non-parametric bootstrapping (5000 resamples), controlling for age, gender, household income, and health status. Results: The analysis revealed a paradoxical pathway, which was clarified by a key statistical suppression effect. Social support significantly and positively predicted problematic usage (β = 0.157, p = 0.002). After controlling for the suppressor effect of social support, problematic usage in turn negatively predicted social connectedness (β = −0.177, p < 0.001). Finally, reduced social connectedness—reflecting a state of solitude—positively predicted life satisfaction (β = −0.227, p < 0.001). Conclusion: The findings suggest that for older adults with sufficient offline social support, these resources may serve a “social empowerment” function. This empowerment allows behaviors measured as “problematic usage” to be theoretically reframed as a form of “deep immersive entertainment”. This immersion appears to occur alongside a state of “high-quality solitude”, which ultimately is associated with higher life satisfaction. This study provides a novel, non-pathological theoretical perspective on the consequences of high engagement with emerging social media, offering empirical grounds for non-abstinence-based intervention strategies.Keywords

Against the backdrop of an intensifying global trend of population aging, China’s demographic shift is particularly pronounced, elevating the quality of life and mental health of older adults to a critical social issue. Concurrently, the rise of emerging social media, epitomized by short-form videos (SFVs), has profoundly reshaped daily life with their engaging and accessible nature, rapidly penetrating the elderly demographic [1]. SFVs have become a vital platform for this group to access information, find entertainment, and even engage in social interaction. As of June 2025, China’s internet user base reached 1.123 billion, with an internet penetration rate of 79.7%. Among them, the number of netizens aged 60 and above reached 161 million, and the rural netizen population grew to 322 million, both demonstrating sustained growth [2]. Data also indicate that SFVs are the primary application for new internet users (accounting for 37.3%), with new users predominantly comprising adolescents aged 10–19 (49.0%) and the “silver generation” (20.8%) [3]. Multiple surveys have revealed that the SFV usage rate among Chinese adults aged 60 and over has surpassed 60%, with average daily usage time on an upward trend [4]. Regarding usage intensity, some reports note that a portion of older adults spend over three hours per day on these platforms [5], with over 100,000 elderly users reportedly online almost all day [6]. This deep penetration has established SFVs as a key variable profoundly influencing the quality of life of older adults.

However, the impact of SFVs on the mental health of older adults is far from a simple dichotomy of “benefits” versus “drawbacks”; it presents an increasingly complex and paradoxical picture. On one hand, SFVs can serve as a bridge connecting the elderly to the outside world, mitigating loneliness by strengthening interpersonal relationships and improving intergenerational interactions, thereby enhancing psychological well-being [7,8]. On the other hand, the algorithmic recommendation systems, fragmented nature, and highly stimulating content characteristic of these platforms have given rise to problems of excessive use and even addiction [9]. Existing research has identified a tendency toward SFV addiction as a new risk factor for depression among rural elderly populations, revealing a significant positive correlation with depressive symptoms [10,11]. Nevertheless, simply classifying this phenomenon as a pathological behavior in need of intervention may overlook the complex motivations and contextual factors behind it. The central argument of this study is to challenge the a priori and undifferentiated assumption that behaviors measured as “addiction” or “problematic use” are inherently negative, and it hypothesizes that under certain conditions, such behaviors may represent non-pathological experiences with potentially positive functions.

Currently, academic discourse on the motivations and effects of SFV use among older adults is dominated by two classic, opposing theoretical perspectives. One mainstream viewpoint, grounded in Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) [12,13], posits that older adults are active media consumers who selectively use SFVs to satisfy their diverse needs, thereby generating positive effects on their mental health [14]. In contrast, the Compensatory Internet Use Theory (CIUT) proposes that when individuals are unable to obtain sufficient emotional and social support in real life, they turn to the online world for compensation [15,16], a pattern that can escalate into addiction and ultimately damage their mental health [6,10,11].

This theoretical divergence is further reflected in conflicting and even paradoxical findings in empirical research on several core relationships. Although the studies mentioned above have generally revealed a negative correlation between SFV addiction and life satisfaction [11,17], a recent review has pointed out that findings in this area are far from consistent and are, in fact, fraught with contradictions [18]. For example, a study by Varela et al. found that after controlling for demographic variables and coping styles, the association between social media addiction and life satisfaction was no longer significant [19]. This raises a critical question: as a readily available and low-cost form of entertainment, could the immersive experience provided by SFVs itself become a direct driver of life satisfaction for certain elderly populations? This study argues that the key lies in distinguishing the nature of such behavior: when it stems from deficiencies in real life, it may constitute a risk behavior; however, when the needs of real life are adequately fulfilled, the same behavioral pattern may transform into a positive experience that can be termed “deep immersive entertainment”.

Furthermore, contradictions surrounding the sense of social connectedness and its relationship with well-being are equally prominent. Nearly all studies have a priori treated a “weakened sense of social connectedness” or a “sense of loneliness” as a negative psychological state. This presupposition overlooks a fundamental societal transformation in China from a traditional “acquaintance society” to a modern “stranger society,” inherently weakening traditional social connectedness [20]. To theoretically ground this relationship, the analysis draws on Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) [21]. SST posits that as time horizons shrink, older adults prioritize emotionally meaningful goals over knowledge-acquisition or extensive social networking [21]. Consequently, a lower level of broad social connectedness—often misinterpreted as involuntary loneliness—may actually reflect a strategic, ‘active social withdrawal’ to conserve emotional energy. Based on this perspective, this study raises a more subversive question: for older adults who are active participants in a “mediated society,” could the immersive experience achieved through short videos represent a self-chosen and undisturbed state of high-quality solitude? This study defines high-quality solitude as a self-initiated state of aloneness that is perceived as positive, pleasurable, and restorative. It is essentially distinct from loneliness, which is an involuntary and distressing emotional experience. In this state, older adults can temporarily detach themselves from the pressures of social roles and interpersonal obligations, freely immersing in personal interests, and thereby attaining psychological calmness and fulfillment.

In summary, the current research gap is rooted in a fragmented and outdated research paradigm. Existing models universally presume that “social support” is necessarily a protective factor against addiction [6] and that a “sense of social connectedness” is the sole pathway to “life satisfaction.” Such a prescriptive framework precludes other possibilities. This study aims to challenge and reconstruct this predetermined pathway. Different from the Compensatory Internet Use Theory, which frames usage as a remedy for deficits, a ‘Social Empowerment’ perspective grounded in Self-Determination Theory [22] is proposed. It argues that for older adults with sufficient social support, offline support acts as a ‘secure base’ that satisfies the need for relatedness. This sense of security empowers them to use short videos in a more intrinsic and unburdened way, as tools to satisfy personal interests and entertainment needs, thereby leading to prolonged, deep immersive entertainment. Under this empowerment mechanism, deep immersion is no longer driven by the desire to escape from reality but by the pursuit of high-quality solitude—a self-chosen, pleasurable state of aloneness that, in turn, may become a new source of life satisfaction [23,24]. Therefore, this study proposes and tests a subversive chain mediation model to explore the potentially paradoxical relationships among social support, problematic short-video use, sense of social connectedness, and life satisfaction.

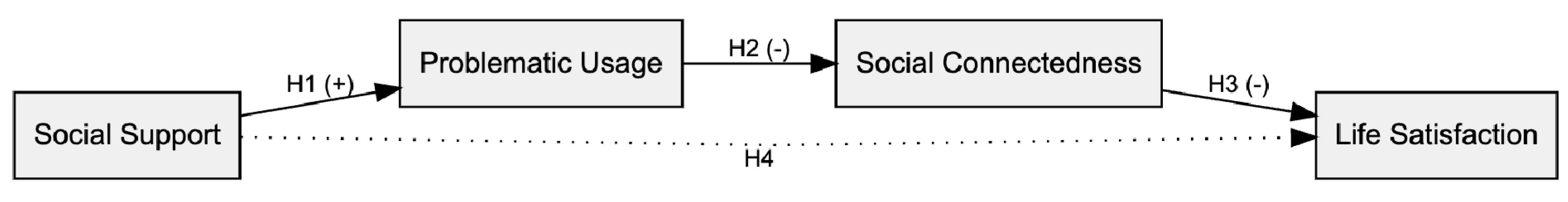

Based on the foregoing analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Social support positively and significantly influences the problematic usage of SFVs among older adults.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Problematic usage of SFVs negatively and significantly influences the sense of social connectedness among older adults (i.e., fosters “solitude”).

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The sense of social connectedness negatively and significantly influences life satisfaction among older adults (i.e., a state of solitude enhances life satisfaction).

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Problematic usage and the sense of social connectedness play a chain mediating role between social support and life satisfaction among older adults.

The hypothesized model is visually presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The hypothesized chained mediation model of social support and life satisfaction.

2.1 Participants and Procedure

This study targeted Chinese older adults aged 60 years and above. Data were collected between July 25 and 01 August 2025, through Credamo, a well-established online survey platform in China. The platform distributed the survey link to pre-screened panel members who met the age criterion (≥60 years). To ensure the authenticity and independence of the responses during the collection process, the platform employed IP address and device fingerprint technologies to strictly restrict duplicate submissions. A total of 400 responses were initially received.

To ensure data quality and authenticity, several control measures were implemented. First, the platform employed IP address and device fingerprint technologies to prevent duplicate submissions from the same user. Second, an attention-check question was embedded in the questionnaire to identify inattentive participants. Third, questionnaires completed in an unusually short time (below the 10th percentile of completion time) or displaying clear straight-line response patterns were deemed invalid. After applying these quality control procedures, 16 invalid responses were excluded, resulting in 384 valid samples.

The final sample covered a diverse range of demographic categories. To assess its representativeness, key demographic characteristics were compared with data from the 56th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development [25]. The gender distribution of the sample (male: 49.2%; female: 50.8%) closely matched national statistics (male: 50.4%; female: 49.6%). In terms of educational attainment and household income, the sample similarly reflected the socio-economic diversity of China’s elderly population, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent analyses.

According to Cohen’s [26] guidelines for statistical power, the present sample size was sufficient to support the proposed chain mediation model. A post-hoc power analysis conducted using G*Power 3.1 further confirmed this adequacy. For a multiple regression model including up to seven predictors (four core variables and three control variables), at a significance level of α = 0.05, a sample size of 384 achieved a statistical power of 0.99 to detect a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15). This result indicates that the statistical power of the analysis was robust, ensuring the stability and reliability of the findings.

This study tested a chained mediation model with the following core pathway: Social Support (X) → Problematic Usage (M1) → Social Connectedness (M2) → Life Satisfaction (Y). All core constructs were measured using established scales, adapted where necessary, and assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Internal consistency reliability was evaluated for each scale. The core constructs and their corresponding measurement scales, along with the reliability coefficients, are summarized in Table 1.

2.2.1 Independent Variable (X): Social Support

Social support refers to the emotional experiences and tangible assistance received from one’s social network, regarded as an essential external resource influencing older adults’ digital behaviors [27]. Measurement was based on the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), widely applied in China [28,29,30]. Five items (Q37–Q41) assessed dimensions including support from friends, neighborhood relations, family support, disclosure, and group participation. The mean score represented the construct. Cronbach’s α was 0.86, indicating good reliability.

2.2.2 Mediator 1 (M1): Problematic Usage of Short Videos

Problematic usage was conceptualized as excessive and difficult-to-control immersion in short video platforms [31,32]. Measurement was adapted from the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), which includes six items (Q18–Q23) capturing the six core dimensions of addictive behavior [33,34]. Prior studies have confirmed its longitudinal invariance, making it a robust tool for assessing problematic use [35]. Higher mean scores indicated stronger addictive tendencies. Cronbach’s α was 0.89, demonstrating excellent reliability.

2.2.3 Mediator 2 (M2): Social Connectedness

Social connectedness reflects the subjective sense of closeness with others. In this study, it was treated as the inverse of loneliness [36,37,38]. The simplified UCLA Loneliness Scale was used [39,40]. Eight items (Q29–Q36) were included; items 31 and 34 were positively worded, while the other six were reverse-coded before averaging. Higher scores represented stronger connectedness (i.e., lower loneliness). Cronbach’s α was 0.91, indicating excellent reliability.

2.2.4 Dependent Variable (Y): Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction, as the cognitive dimension of subjective well-being, refers to a global evaluation of one’s quality of life [41]. It was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [42]. Five items (Q24–Q28) were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction. Cronbach’s α was 0.93 [43], reflecting excellent reliability.

Table 1: Summary of core measures.

| Variable (English) | Role in Model | No. of Items | Reference Scale | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support | Independent Variable (X) | 5 | Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) | 0.86 |

| Problematic Usage | Mediator (M1) | 6 | Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) | 0.89 |

| Social Connectedness | Mediator (M2) | 8 | Simplified UCLA Loneliness Scale | 0.91 |

| Life Satisfaction | Dependent Variable (Y) | 5 | Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) | 0.93 |

To minimize confounding influences, age, gender, household income, and health status were included as control variables in all regression analyses. Existing research has confirmed that these demographic and health-related factors significantly affect older adults’ social media use, social support, and life satisfaction [44,45,46]. Therefore, including these controls enhances the accuracy of the estimated results.

First, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to examine the distribution of core variables and their preliminary associations. Subsequently, chained mediation effects were examined using a stepwise regression approach in Python (version 3.13.5) with the statsmodels package (version 0.14.4). Three models were specified. Model 1 tested Path a1 (Social Support → Problematic Usage), with social support as the independent variable and problematic usage as the dependent variable. Model 2 tested Path d21 (Problematic Usage → Social Connectedness), with social support and problematic usage as predictors and social connectedness as the outcome. Model 3 tested Path b2 (Social Connectedness → Life Satisfaction), with social support, problematic usage, and social connectedness simultaneously entered as predictors, and life satisfaction as the dependent variable. The significance of regression coefficients across these models provided preliminary evidence for chained mediation.

To further ensure robustness, indirect effects were tested using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure with 5000 resamples. Bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for all indirect and chained mediation pathways. An indirect effect was considered significant if its confidence interval did not include zero. This combined approach allowed both path-level interpretation and rigorous inference of indirect effects.

This study complied with established ethical standards. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University (Approval No. NNU202506056). Before participation, all respondents were required to read a detailed informed consent form, which outlined the purpose of the study, principles of anonymity, and voluntary participation. Only participants who explicitly selected “agree” could proceed to the questionnaire; those who chose “disagree” were automatically exited from the survey.

This section reports the statistical findings from testing the proposed model. First, descriptive statistics and correlation analyses are presented to provide an overview of the data. Then, the stepwise regression and bootstrap results for the chained mediation model are detailed.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

To examine the distribution of core variables and their preliminary associations, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed (see Table 2).

Table 2: Means, standard deviations, and correlations among core variables.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Support | 3.52 | 0.68 | – | |||

| 2. Problematic Usage | 3.10 | 0.89 | 0.17** | – | ||

| 3. Social Connectedness | 3.58 | 0.45 | −0.48** | 0.11* | – | |

| 4. Life Satisfaction | 2.89 | 0.77 | 0.28** | 0.32** | −0.24** | – |

The descriptive results indicate that the sample scored slightly above the midpoint on all measures. The correlation results revealed significant associations among all four variables. Notably, the correlation analysis uncovered some preliminary findings that contradict traditional theoretical expectations and certain hypotheses, highlighting the need for further analysis. First, social support was positively correlated with problematic use (r = 0.17, p < 0.01), which contradicts the predictions of compensatory use theory. Second, and most crucially, a weak but significant positive correlation was found between problematic use and the sense of social connectedness (r = 0.11, p < 0.05). This result is in the opposite direction to our hypothesis H2. However, as noted below, this bivariate inconsistency highlights the potential presence of a suppression effect, necessitating multivariate regression for clarification.

This bivariate correlation, which is inconsistent with the direction of subsequent path analysis results, statistically suggests the possibility of a suppression effect in the model. Such an effect typically occurs when a third variable (likely social support in this case) is correlated with both other variables, “obscuring” their true relationship. This preliminary finding challenges the simple possibility of social connectedness being a moderating variable and emphasizes the necessity of using mediation models to uncover these complex dynamics. This will be further tested and clarified in the subsequent mediation analysis.

3.2 Chained Mediation Analysis

To test whether problematic usage and social connectedness jointly mediated the relationship between social support and life satisfaction, stepwise regression analyses were conducted while controlling for age, gender, household income, and health status. Prior to interpreting the path coefficients, Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) were examined to rule out multicollinearity. All VIF values were below 2.5, well within the acceptable threshold, indicating that the regression results are robust and not artifacts of collinearity.

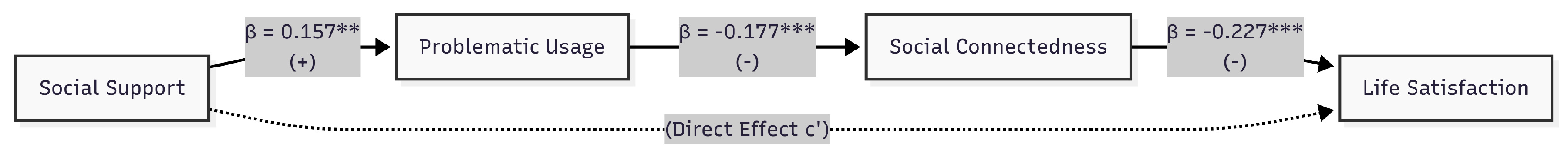

3.2.1 Step 1: Path a1 (Social Support → Problematic Usage)

Regression results showed that social support significantly and positively predicted problematic usage (β = 0.157, p = 0.002). It supports H1, indicating that higher levels of social support were associated with stronger short video addiction tendencies. The direction of this effect contradicts compensatory internet use theory, which posits that offline support should serve as a protective factor [6].

3.2.2 Step 2: Path d21 (Problematic Usage → Social Connectedness)

With both social support and problematic usage entered as predictors, problematic usage significantly and negatively predicted social connectedness (β = –0.177, p < 0.001). It supports H2, consistent with the “social displacement” hypothesis that time spent online reduces offline interaction opportunities [17,47,48]. It is important to note that the path coefficient (negative) here is in contrast to the zero-order correlation coefficient (positive) between the two variables, which clearly confirms the suppression effect predicted earlier. Specifically, after controlling for the social support variable in the regression model, the “true” negative impact of problematic use on the sense of social connectedness became evident. This suggests that social support, as a classic suppressor variable, exerts a strong negative predictive effect on the sense of social connectedness (statistically removing the variance associated with high offline support), thus masking the slight displacement effect of problematic use on offline social interactions. This finding provides strong statistical support for the validity of our chain mediation model and reveals deeper dynamic relationships between the variables than simple correlational analysis, thereby strengthening the case for the applicability of the model.

3.2.3 Step 3: Path b2 (Social Connectedness → Life Satisfaction)

When all predictors were included, social connectedness significantly and negatively predicted life satisfaction (β = –0.227, p < 0.001). It supports H3, showing that stronger connectedness (i.e., lower loneliness) was associated with lower life satisfaction, challenging the conventional assumption that connection is inherently linked to well-being.

Since all three core paths were statistically significant, problematic usage and social connectedness jointly mediated the effect of social support on life satisfaction, supporting H4. To further validate these effects, non-parametric bootstrap analyses with 5000 resamples were conducted. The chained indirect effect (Social Support → Problematic Usage → Social Connectedness → Life Satisfaction) was significant, with a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval [0.014, 0.062], excluding zero. It confirms that the mediation effect was statistically robust.

Taken together, these results reveal a paradoxical psychological transmission pathway: higher social support, rather than serving as a buffer, enabled greater problematic video use (deep immersion), which reduced social connectedness (indicating high-quality solitude), and ultimately ultimately predicted higher life satisfaction. It challenges conventional compensatory models and underscores the need for new theoretical perspectives on digital media and well-being among older adults. The final path diagram with standardized coefficients is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Path diagram and coefficients for the chained mediation model. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The data analysis in this study reveals a chain mediation pathway that subverts conventional wisdom: higher social support, rather than acting as a protective factor as commonly assumed, positively predicted a greater tendency for video addiction (β = 0.157). Furthermore, a weaker sense of social connectedness (i.e., a stronger sense of solitude) did not lead to negative outcomes but instead significantly predicted higher life satisfaction (β = −0.227). These statistically significant findings not only directly address the research questions posed in the introduction but also compel a deeper theoretical examination of the nature of “problematic use,” the role of social support, and the complex relationship between “solitude” and “well-being” in the digital lives of older adults.

First, the core of this study’s pathway identified in the mediating role of “problematic use.” Although the addiction scale used for measurement is well-established and typically carries negative pathological connotations, the model presented in this study reveals a more nuanced picture. This behavior is predicted by positive social support and has a robust direct positive predictive effect on life satisfaction. Contrary to the findings of Varela et al. (2023), who suggested that the link between social media use and well-being might disappear after controlling for confounding variables, the results of the current study remained significant even after strictly controlling for age, gender, income, and health status. This robustness suggests that for the elderly participants in this study, what is measured as “problematic use” is not merely a statistical artifact or a pathological issue requiring intervention, but rather should be understood as a form of “deep immersive entertainment.”

This interpretation is corroborated from a platform technology perspective. The addictive nature of SFVs stems mainly from their design: personalized algorithmic recommendations, fragmented content delivery, and platform mechanics intended to disrupt the user’s perception of time systematically guide users into a state of immersion [9,49,50]. Therefore, user “immersion” is a result of interaction with platform technology, not purely a matter of individual loss of control. Furthermore, this interpretation offers a new lens through which to reconcile the contradictory findings in existing empirical research. Although most studies have found a strong correlation between addiction and negative emotions like depression [10,11], the findings of the current study, consistent with those of Sala et al. [19], demonstrate that the negative impact of addictive behavior on life satisfaction is not absolute. The key distinction lies in the differing motivations driving immersive behavior: When immersion serves as an escape from “life monotony” or “psychological emptiness” [4,51], it is akin to a risk behavior. However, when these potential risk factors are buffered by sufficient social support (as observed in this sample), the same immersive behavior transforms into a source of pure entertainment and gratification.

Second, the findings redefine the role of social support: from “social compensation” to “social empowerment.” To address the causality concerns inherent in cross-sectional data, we ground this finding in Self-Determination Theory (SDT). We argue that established offline social support acts as a “secure base” that fulfills the need for relatedness, thereby empowering older adults to explore the digital world with greater autonomy and confidence. In direct opposition to the predictions of the classic Compensatory Internet Use Theory [16], this study found that social support has a significant positive predictive effect on video addiction. This discovery not only subverts theoretical expectations but also enters into a direct dialogue with empirical studies that found social support to be a significant negative predictor of SFV addiction [6,11].

This mechanism also explains the “suppression effect” revealed in the statistical analysis (Table 2 vs. Regression Step 2). It was found that social support positively predicts problematic use but negatively predicts the need for social connectedness. This implies that social support initially “masks” the isolating effect of video use. Under the “Social Empowerment” mechanism, social support no longer serves to “compensate” for deficits but serves as a foundational resource that provides older adults with psychological security and autonomy. When older adults possess a stable emotional support network in their real lives [29], their inherent sense of security is strengthened, thereby reducing the motivation to use the internet as a tool to escape social anxiety or dissatisfaction with reality. The core distinction from the CIUT theory lies in the fact that the study participants are not “offline deficient” individuals, but rather “offline affluent” ones. For this group, psychological security functions as a “license” [22], empowering them to explore and enjoy short videos more freely and purely to fulfill personal interests and entertainment needs [14]. Therefore, for this well-supported group, social support does not serve as a “protective” factor to curb excessive use but rather encourages deep immersive entertainment without the anxiety of losing social ties.

The third point addresses the paradox of loneliness through an exploration of the concept of “high-quality solitude.” The most counterintuitive finding of this study is that a weaker sense of social connectedness significantly predicted higher life satisfaction. It is acknowledged that “High-Quality Solitude” was not measured by a specific scale in this study; however, this construct provides the most logical inference for the observed data pattern. If the reduced connectedness represented distressful loneliness, it would negatively predict life satisfaction. The fact that it consistently predicts higher satisfaction (β = −0.227) rules out the “distress” hypothesis and supports the interpretation of this state as positive and restorative.

The proposed “High-Quality Solitude” hypothesis provides an integrative explanatory framework. First, it is clearly defined as a self-chosen state of aloneness that is perceived as psychologically restorative. This “restorative function” refers to the ability of individuals to temporarily disengage from the mental exhaustion caused by constant role-playing, thereby regaining a sense of inner order. This is fundamentally different from the involuntary and painful experience of “loneliness” or “social isolation,” which refers to an objective lack of social ties [52]. Second, this concept is particularly relevant in the cultural context of East Asian societies. Against the backdrop of the transformation from traditional collectivist cultures to modern societies, older adults often bear immense pressure to maintain family and community relationships [53]. After fulfilling their primary social and familial responsibilities, the opportunity to break free from the frequent, and sometimes even ritualistic, pressures of offline social interactions can be seen as a form of liberation. Therefore, actively choosing undisturbed solitude through digital media is not a social failure but a positive expression of autonomy and personal identity in later life.

In this context, short videos serve as the perfect companion for “High-Quality Solitude.” Their media mechanisms operate on several levels: First, the personalized immersive experience creates an “information cocoon” aligned with personal interests, providing continuous mental nourishment without the need for complex social negotiation. Second, short videos offer low-cost social connectedness (e.g., liking/commenting). It maintains a “weak connection” with the outside world, fulfilling a minimal sense of belonging while avoiding the high emotional energy investment required in real interpersonal interactions. Ultimately, this self-chosen “digital solitude” constitutes a new, positive paradigm of happiness for contemporary older adults [23,24].

Overall, the three core concepts proposed in this study—deep immersion, social empowerment, and high-quality solitude—not only resolve the paradoxes observed in the data but, more importantly, systematically respond to and optimize the somewhat one-dimensional research paradigm criticized in the introduction. The fundamental theoretical contribution of this study lies in demonstrating, with empirical evidence, that when older adults are treated as complete and active participants in a “mediated society,” rather than as passive and isolated subjects, their seemingly “problematic” behaviors and enjoyment of solitude are no longer “problems” requiring correction. Instead, they emerge as rational strategies of well-being aligned with both their life stage and contemporary social conditions.

Specifically, this study makes two theoretical contributions. First, by proposing and testing the “social empowerment” model, it delineates the applicability boundaries of classical compensatory internet use theory to older adults with strong offline support. It provides a new perspective on the role of social support in digital media use. Second, the hypothesis of “high-quality solitude” deepens scholarly understanding of the relationship between loneliness and well-being, revealing that in specific life stages, solitude may serve as a positive psychological resource. It opens new directions for future research in both gerontology and media psychology.

As a study focused on the consequences and interventions for emerging social media addiction, our findings provide disruptive insights for interventions. Traditional intervention models are primarily based on an abstinence-oriented logic, aiming to reduce usage. However, this study demonstrates that for older adults with sufficient social support, forced interventions that restrict what we conceptualize as “deep immersive entertainment” may inadvertently deprive them of a vital source of well-being. Therefore, this study proposes a new intervention framework grounded in empowerment and optimization, rather than treatment and abstinence:

Individual and Family Level: From Control to Empowerment. The focus of intervention should shift away from restricting screen time toward enhancing digital literacy. Families and communities can organize activities to teach older adults how to identify misinformation, protect personal privacy, and use platform tools to filter unwanted content. Such strategies optimize their experience of “high-quality solitude,” maximizing its benefits while mitigating risks.

Social Service Level: From Offline to Online Expansion. The design of eldercare services and community programs should recognize the value of online leisure. Beyond organizing traditional offline activities, initiatives should also include online interest groups (e.g., short video production, virtual book clubs) that channel solitary immersion into community sharing, enriching “high-quality solitude” without imposing additional social pressure.

Platform Design Level: From Connection to Optimized Immersion. Internet platforms should transcend the obsession with “connecting everything” and instead provide features that enhance older adults’ personalized immersion. Examples include simplified “senior-friendly” modes, higher-quality content streams, easier bookmarking and review functions, and reduced unnecessary social notifications. The ultimate goal should be to create a comfortable and private “mental garden” rather than a social square burdened with interactional pressures.

5.3 Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has several limitations that also point to promising avenues for future research. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw firm causal inferences. While the analyzed model is grounded in theoretical frameworks such as Self-Determination Theory, the data cannot completely rule out bidirectional relationships or reverse causality—for instance, the possibility that older adults who are heavily engaged in short videos might elicit specific forms of social attention. Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to validate the temporal order and uncover dynamic changes among these variables. Second, regarding the construct of “high-quality solitude,” it is acknowledged that this concept was inferred from the statistical relationship between low connectedness and high satisfaction, rather than measured by a dedicated scale. Therefore, quantitative measures alone may not fully capture the nuance of this experience. Qualitative interviews are urgently needed to capture older adults’ own narratives of “loneliness” versus “solitude,” thereby rigorously testing and enriching this hypothesis. Third, future studies should explore potential boundary conditions, such as personality traits (e.g., introversion/extraversion) or pre-retirement occupational types, which may moderate the chained mediation model proposed in this study. Finally, as the sample is focused on China, a society with a collectivistic cultural background where offline social obligations can be particularly demanding, whether the “social empowerment” and “high-quality solitude” models apply to older adults in Western, individualistic cultures is a crucial question that awaits future cross-cultural investigation.

By constructing and testing a chained mediation model, this study systematically explored the mechanisms through which social support is linked to life satisfaction among older adults. After clarifying a key statistical suppression effect, the findings revealed that social support positively predicted problematic usage, which in turn negatively predicted social connectedness (thereby reflecting a state of solitude), ultimately demonstrating a positive indirect effect on life satisfaction. These results challenge traditional compensatory internet use theory and introduce the novel explanatory concepts of social empowerment and high-quality solitude. Together, they provide fresh theoretical perspectives and practical insights into the sources of subjective well-being among older adults in the digital era.

Importantly, these findings also hold policy relevance. As China and many other societies face rapid population aging alongside digital transformation, the results suggest that media policies and digital governance strategies should move beyond abstinence-oriented approaches. Instead, they should emphasize empowering older adults through digital literacy, inclusive platform design, and recognition of digital leisure as a legitimate form of well-being. Such a perspective not only better aligns with the lived realities of older adults but also contributes to building more age-friendly digital ecosystems in aging societies.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Guangxi Philosophy and Social Science Research Project, grant number 24XWC002.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: investigation, Yue Cui; writing—original draft preparation, Yue Cui; data curation, Ziqing Yang; funding acquisition, Ziqing Yang; writing—review and editing, Hao Gao; supervision, Hao Gao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Hao Gao, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study complied with established ethical standards. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University (Approval No. NNU202506056). Before participation, all respondents were required to read a detailed informed consent form, which outlined the purpose of the study, principles of anonymity, and voluntary participation. Only participants who explicitly selected “agree” could proceed to the questionnaire; those who chose “disagree” were automatically exited from the survey.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| β | Beta coefficient (used in regression analysis) |

| SFV | short-form video |

| UGT | Uses and Gratifications Theory |

| SSRS | Social Support Rating Scale |

| BSMAS | Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale |

| UCLA | University of California, Los Angeles |

| SWLS | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| CIs | confidence intervals |

| M | mean |

| SD | standard deviation |

| p | p-value (statistical significance level) |

References

1. Zhang J , Ibrahim O . Social media short video addiction for the elderly: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2024; 14( 12): 4718– 31. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v14-i12/24105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. CNNIC . The 54th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development [Internet]. Beijing, China: China Internet Network Information Center; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0911/MAIN1726017626560DHICKVFSM6.pdf. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

3. CNNIC . The 53rd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development [Internet]. Beijing, China: China Internet Network Information Center; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0325/MAIN1711355296414FIQ9XKZV63.pdf. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Li Y , Liu Q , Wang Y . The research on the usage behavior of TikTok short video platform in the elderly group. J Educ Humanit Soc Sci. 2022; 5: 189– 97. doi:10.54097/ehss.v5i.2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wen X , Zhou Y , Li Y , Li X , Qu P . Perceived overload on short video platforms and its influence on mental health among the elderly: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024; 17: 2347– 62. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S459426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jia Y , Liu T , Yang Y . The relationship between real-life social support and internet addiction among older people in China. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 981307. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.981307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li C , Wang Y . Short-form video applications usage and functionally dependent adults’ depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional study based on a national survey. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2024; 17: 3099– 111. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S491498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang R , Su Y , Lin Z , Hu X . The impact of short video usage on the mental health of elderly people. BMC Psychol. 2024; 12( 1): 612. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-02125-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liao M . Analysis of the causes, psychological mechanisms, and coping strategies of short video addiction in China. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1391204. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dong P , Zhang X , Yin W , Shi Y , Xu M , Li H , et al. Relationship between short video addiction tendency and depression among rural older adults: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2025; 27: e75938. doi:10.2196/75938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Özbek MG , Karaş H . Associations of depressive symptoms and perceived social support with addictive use of social media among elderly people in Turkey. Psychogeriatrics. 2022; 22( 1): 29– 37. doi:10.1111/psyg.12770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Katz E , Blumler JG , Gurevitch M . Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In: Blumler JG , Katz E , editors. The uses of mass communications: current perspectives on gratifications research. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 1974. p. 19– 32. [Google Scholar]

13. Ruggiero TE . Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Commun Soc. 2000; 3( 1): 3– 37. doi:10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hutto CJ , Bell C , Farmer S , Fausset C , Harley L , Nguyen J , et al. Social media gerontology: understanding social media usage among older adults. Web Intell. 2015; 13( 1): 69– 87. doi:10.3233/WEB-150310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Brand M , Wegmann E , Stark R , Müller A , Wölfling K , Robbins TW , et al. The interaction of person–affect–cognition–execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019; 104: 1– 10. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kardefelt-Winther D . A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Human Behav. 2014; 31: 351– 4. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Koçak O , Arslan H , Erdoğan A . Social media use across generations: from addiction to engagement. Eur Integr Stud. 2021; 15( 1): 63– 77. doi:10.5755/j01.eis.1.15.29080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cotten SR , Schuster AM , Seifert A . Social media use and well-being among older adults. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022; 45: 101293. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Varela JJ , Pérez JC , Rodríguez-Rivas ME , Chuecas MJ , Romo J . Well-being, social media addiction and coping strategies: the moderating role of coping mechanisms in adolescents. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 10497769. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1211431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhao Z , Wan R , Ma J . Social change and birth cohorts decreased resilience among college students in China: a cross-temporal meta-analysis, 2007–2020. Pers Individ Dif. 2022; 196: 111716. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2022.111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Carstensen LL . Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol Aging. 1992; 7( 3): 331– 8. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Deci EL , Ryan RM . The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000; 11( 4): 227– 68. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Long CR , Averill JR . Solitude: an exploration of benefits of being alone. J Theory Soc Behav. 2003; 33( 1): 21– 44. doi:10.1111/1468-5914.00204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Coplan RJ , Ooi LL , Baldwin D . Does it matter when we want to be alone? Exploring developmental timing effects in the implications of unsociability. New Ideas Psychol. 2019; 53: 47– 57. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. China Internet Network Information Center . The 55th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development [Internet]. Beijing, China: Internet Network Information Center; 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202505/P020250514564119130448.pdf. [Google Scholar]

26. Cohen J . A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992; 112( 1): 155– 9. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ao SH , Zhu Y , Wang J , Zhao X . eHealth use and psychological health improvement among older adults: the sequential mediating roles of social support and self-esteem. Digit Health. 2025; 11: 1– 14. doi:10.1177/20552076251346659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gui J , Liang K , Yang Y , Du L . Protective and risk factors of social support for healthcare workers in high-pressure occupational settings. Front Psychol. 2025; 16: 1547777. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1547777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ke X , Liu C , Li N . Social support and quality of life: a cross-sectional study on survivors eight months after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10: 573. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xiao SY . Social support rating scale. In: Wang XD , Wang XL , Ma H , editors. Mental health rating scale manual. Updated edtion. Beijing, China: Chinese Mental Health Journal Press; 1999. p. 127– 31. [Google Scholar]

31. Chang CW , Chen JS , Huang SW , Potenza MN , Su JA , Chang KC , et al. Problematic smartphone use and two types of problematic use of the internet and self-stigma among people with substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2023; 147: 107807. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Varona MN , Muela A , Machimbarrena JM . Problematic use or addiction? A scoping review on conceptual and operational definitions of negative social networking sites use in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2022; 134: 107400. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Andreassen CS , Pallesen S , Griffiths MD . The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2016; 64: 287– 93. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Monacis L , de Palo V , Griffiths MD , Sinatra M . Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J Behav Addict. 2017; 6( 2): 178– 86. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Gomez R , Zarate D , Brown T , Hein K , Stavropoulos V . The Bergen-Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS): longitudinal measurement invariance across a two-year interval. Clin Psychol. 2024; 28( 2): 185– 94. doi:10.1080/13284207.2024.2341816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Russell DW . UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996; 66( 1): 20– 40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hays RD , DiMatteo MR . A short-form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1987; 51( 1): 69– 81. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wickramaratne PJ , Yangchen T , Lepow L , Patra BG , Glicksburg B , Talati A , et al. Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 10): e0275004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Russell D , Peplau LA , Ferguson ML . Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1978; 42( 3): 290– 4. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Russell D , Peplau LA , Cutrona CE . The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980; 39( 3): 472– 80. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Fernández-Portero C , Alarcón D , Padura AB . Dwelling conditions and life satisfaction of older people through residential satisfaction. J Environ Psychol. 2017; 49: 1– 7. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Diener E , Emmons RA , Larsen RJ , Griffin S . The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985; 49( 1): 71– 5. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Nunnally JC , Bernstein IH . Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

44. Lei X , Matovic D , Leung W-Y , Viju A , Wuthrich VM . The relationship between social media use and psychosocial outcomes in older adults: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2024; 36( 9): 714– 46. doi:10.1017/S1041610223004519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liu PL , Yeo TED . Social grooming on social media and older adults’ life satisfaction: testing a moderated mediation model. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2024; 42( 4): 913– 29. doi:10.1177/08944393231220487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wei N , Sun D , Li J . The impact of active social media use on the mental health of older adults. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13: 434. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02642-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kraut R , Patterson M , Lundmark V , Kiesler S , Mukophadhyay T , Scherlis W . Internet paradox: a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol. 1998; 53( 9): 1017– 31. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.9.1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Kraut R , Kiesler S , Boneva B , Cummings J , Helgeson V , Crawford A . Internet paradox revisited. J Soc Issues. 2002; 58( 1): 49– 74. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Montag C , Yang H , Elhai JD . On the psychology of TikTok use: a first glimpse from empirical findings. Front Public Health. 2021; 9: 641673. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.641673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zulli D , Zulli DJ . Extending the internet meme: conceptualizing technological mimesis and imitation publics on the TikTok platform. New Media Soc. 2020; 24( 8): 1872– 90. doi:10.1177/1461444820983603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wang D , Liu X , Chen K , Gu C , Zhao H , Zhang Y , et al. Risks and protection: a qualitative study on the factors for internet addiction among elderly residents in Southwest China communities. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24( 1): 531. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-17980-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Verduyn P , Ybarra O , Résibois M , Jonides J , Kross E . Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2017; 11( 1): 274– 302. doi:10.1111/sipr.12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Valkenburg P , Beyens I , Pouwels JL , van Driel II , Keijsers L . Social media use and adolescents’ self-esteem: heading for a person-specific media effects paradigm. J Commun. 2021; 71( 1): 56– 78. doi:10.1093/joc/jqaa039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools