Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Parental Marital Conflict and Adolescent Short Video Dependence: A Chain Mediation Model

School of Sports Science, Jishou University, Jishou, 416000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yang Liu. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adolescent and Youth Mental Health: Toxic and Friendly Environments)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 11 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.073529

Received 19 September 2025; Accepted 17 November 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: This study aims to investigate the underlying mechanisms between parental marital conflict and adolescent short video dependence by constructing a chain mediation model, focusing on the mediating roles of experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress). Methods: Conducted in January 2025, the research recruited 4125 adolescents from multiple Chinese provinces through convenience sampling; after data cleaning, 3957 valid participants (1959 males, 1998 females) were included. Using a cross-sectional design, measures included parental marital conflict, experiential avoidance, anxiety, depression, stress, and short video dependence. Results: Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations among all variables. Mediation analysis using the SPSS PROCESS macro showed that parental marital conflict directly predicted short video dependence (β = 0.269, p < 0.001), and also significantly predicted experiential avoidance (β = 0.519, p < 0.001), anxiety (β = 0.072, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.067, p < 0.001), and stress (β = 0.048, p < 0.05). Experiential avoidance further predicted anxiety (β = 0.521, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.489, p < 0.001), stress (β = 0.408, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (β = 0.244, p < 0.001). While both anxiety (β = 0.050, p < 0.05) and depression (β = 0.116, p < 0.001) positively predicted short video dependence, stress did not (β = 0.019, p = 0.257). Overall, experiential avoidance, anxiety, depression, and stress significantly mediated the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence. Conclusion: These findings confirm that parental marital conflict not only directly influences adolescent short video dependence but also operates through a chain mediation pathway involving experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance, highlighting central psychological mechanisms and providing theoretical support for integrated mental health and behavioral interventions.Keywords

With the arrival of the 5G epoch, optimal circumstances have been established for the swift expansion of short form videos. Data reveals that by the conclusion of 2024, TikTok had amassed 2.05 billion registered, and boasted a worldwide monthly active user count of 1.69 billion [1]. By contrast, Twitter boasted 372.9 million users, YouTube recorded 2.527 billion users, and Instagram had 1.628 billion users [2]. Short videos, with their concise and highly entertaining format, significantly activate the reward neural circuits of users [3]. Nevertheless, exposure to this form of media also entails possible hazards. A multitude of research findings have shown that short video platforms have emerged as the most commonly utilized applications among adolescents, with their utilization rate reaching as high as 65.3% [4]. For adolescents, the problem of addiction to short video applications is becoming increasingly prominent, posing significant challenges to their physical and mental health [5]. In the United States, adolescents have a high frequency of using video applications such as YouTube and TikTok, with approximately 16% of adolescents reporting that they “almost always” access or use YouTube, and among those using TikTok, about 17% indicated that they “almost always” use the application [6]. Moreover, according to a recent nationwide survey carried out in China in 2024, it was discovered that 61.8% of middle school students and 65.1% of high school students engaged in the use of short videos [7]. Research has shown that adolescents are the main force in short video social media, exhibiting a strong sense of belonging and dependence on these platforms, with their behavior often exceeding the normal usage time and scope of social media [5]. Short video dependence refers to a behavioral addiction phenomenon in which individuals suffer from impaired physiological, psychological, and social functioning due to excessive use of short video content or platforms [8]. Adolescents who are overly dependent on short videos tend to exhibit significant deficiencies in attention concentration, time management, and learning motivation. Moreover, their social skills may deteriorate in real-life settings, potentially leading to social anxiety [9]. In summary, this dependent behavior can lead to numerous negative impacts, including psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, or stress [10]. Given the widespread use of short videos among adolescents and the profound impact of this dependency behavior on their development, this study aims to explore the factors influencing short video dependence among adolescents, with the expectation of better protecting their mental health and promoting their comprehensive development.

Within the overlapping domain of adolescent mental well being and online activities, factors related to the family environment are gradually becoming a crucial vantage point for understanding the processes behind internet dependent behaviors. Statistics indicate that the global proportion of adults aged 35–39 who are divorced or separated has doubled from 2% in the 1970s to 4% in the 2000s [11]. Additionally, a cross-sectional study conducted in 2019 involving 51,124 Chinese students revealed that 10.72% of the surveyed students had parents who were divorced [12]. As one of the core dimensions of family functioning [13], parental marital relationships shape the emotional atmosphere of the family. Therefore, this study identifies parental marital conflict as the core independent variable and delves into its negative impacts on adolescents. Parental marital conflict refers to the various contradictions, disagreements, and discordant interaction patterns that emerge between parents within the marital relationship [14]. According to Family Systems Theory [15], marital conflict, as a central negative interaction indicator within the family system, not only reflects the breakdown of the emotional bond between spouses but also permeates parenting behaviors through a spillover effect [16,17]. Moreover, studies grounded in Neurobiological Theory [18] have illustrated that persistent family strife can trigger the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in teenagers. This activation results in irregular cortisol level variations, subsequently heightening their vulnerability to challenges in managing emotions and controlling behaviors [19]. When individuals’ basic psychological needs are unmet, they often resort to more negative coping strategies [20]. Adolescents who fail to meet their psychological needs within the family may turn to the internet for compensation [21], engaging in dependency behaviors such as excessive immersion in short videos and the internet to escape family conflicts [22]. Although the negative impacts of parental marital conflict on adolescents have been well-documented, few studies have explored the influence of parental marital conflict on adolescent short video dependence within this context. Based on this, this study proposes Hypothesis 1: Parental marital conflict is significantly positively correlated with adolescent short video dependence.

Frequent verbal arguments, physical altercations, or cold wars between parents can disrupt the emotional atmosphere of the family [23]. Adolescents often employ negative coping strategies, such as seeking immediate relief by avoiding negative emotions, a phenomenon theoretically termed experiential avoidance (Experiential Avoidance, EA) [24]. Experiential avoidance refers to the tendency of individuals to evade negative internal experiences (such as emotions, thoughts, and physiological sensations) through cognitive, emotional, or behavioral strategies [25]. While this avoidance strategy may temporarily help individuals ignore their negative experiences to achieve short-term adaptation, it can also lead to increased emotional disturbances, such as anxiety, depression, and stress [26]. A study on adolescent mental health found that approximately 40% to 50% of adolescents reported using avoidance strategies when facing emotional disturbances, especially when encountering social adaptation difficulties or family conflicts [27]. Instead of directly addressing problems or emotions, adolescents often choose to avoid them. According to Behaviorist theory [28], when individuals engage in avoidance behaviors, their negative internal experiences may be temporarily alleviated but are likely to re-emerge in the future [29]. Moreover, numerous studies have shown that experiential avoidance behaviors can increase adolescents’ susceptibility to short video dependence [30]. Short video platforms provide an escape from reality, with engaging and mindless content that diverts adolescents’ attention from real-life problems [3]. This short-term relief, however, comes at the cost of long-term dependence. For example, adolescents may find it difficult to control their viewing time, remain preoccupied with short videos even while engaged in other activities, and experience withdrawal-like symptoms when attempting to reduce usage [5]. This study focuses on experiential avoidance as the core mediating mechanism and explores its key role between parental marital conflict and adolescents’ short-video dependence. In summary, parental marital conflict fosters an environment conducive to experiential avoidance in adolescents, which in turn significantly increases the risk of short video dependence [30,31]. Based on these findings, this study proposes Hypothesis 2: Experiential avoidance mediates the relationship between parental marital conflict and adolescent short video dependence.

According to the Emotion Regulation Theory [32], when individuals are confronted with emotional distress that cannot be effectively managed, they tend to adopt specific strategies to regulate this uncomfortable state. Parental marital conflict is a potent stressor in the lives of adolescents [33], not only inducing experiential avoidance behaviors but also causing negative emotional disturbances [34]. Emotional dysregulation denotes the incapacity of an individual to efficiently regulate their emotions. It is mainly typified by adverse emotional states like anxiety, depressive feelings, and stress, all of which hinder the healthy handling of stressful situations and difficulties [35]. A representative meta-analysis comprising 1.53 million individuals from 113 countries showed that the prevalence of emotional disturbance increased from 25% in 2009 to 31% in 2021 [36]. Moreover, the severity of common emotional disturbances, including anxiety, depression, and stress, is deepening and has become a growing concern among young people worldwide [37]. In the United States, approximately 70% of adolescents experience stress or anxiety daily, and nearly 90% regard stress as a major issue facing their generation [38]. Furthermore, as per the Global Burden of Disease report issued by the World Health Organization, it is predicted that depression will surpass other conditions to become the top global disease burden by 2030 [39]. Severe distress, high incidence and mortality rates, and psychosocial dysfunction are often associated with emotional disturbances [40]. The family is a crucial environment for adolescent development, and parental conflicts can disrupt the harmony and stability of the home [14]. When parents involve their adolescent children in conflicts, the children may perceive these conflicts as having a greater negative impact than the parents realize, and frequent involvement may lead to depression, anxiety, behavioral problems, or difficulties at school [41]. According to Stress Theory [42], stressors activate an individual’s stress response. When adolescents are exposed to the chronic stressor of parental marital conflict, their psychological stress levels can significantly increase [43]. This stress can make adolescents feel helpless and, in turn, affect their emotional regulation abilities [44]. Under such circumstances, adolescents are highly likely to seek ways to alleviate their emotions, and short video platforms provide a convenient means of escaping reality [45]. The diverse content and immersive experience of short videos can temporarily divert adolescents’ attention and offer relief from emotional disturbances [46]. However, while this escape behavior may provide short-term stress relief, it can lead to excessive dependence on short videos and increase the risk of short video addiction in the long term [47]. Studies have shown that adolescents with higher levels of emotional disturbance are more prone to short video addiction as a means of escaping various challenges in life [48]. In summary, parental marital conflict indirectly affects the risk of adolescent short video dependence by increasing their psychological stress, forming the second mediating pathway from parental marital conflict to adolescent short video dependence. Based on these findings, this study proposes Hypothesis 3: Emotional disturbances (anxiety, depression, and stress) mediate the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence.

Unlike most existing studies focusing on a single mediating variable or simple pathway, this study is the first to systematically construct the chain mediation model “parental marital conflict → experiential avoidance → emotional disturbance → short-video dependence”, aiming to reveal how parental marital conflict affects adolescents’ short-video dependence via the dual psychological mechanisms of experiential avoidance and emotional distress. Based on the preceding discussion, the impact of experiential avoidance on adolescent emotional disturbance can be explained through dual pathways of behavioral inhibition and cognitive distortion [49]. On one hand, experiential avoidance leads to adolescents missing out on opportunities to practice problem-solving, resulting in a behavioral inhibition effect [50]. When adolescents cope with parental marital conflict by avoiding conflict situations or suppressing their inner feelings, their core abilities, such as emotional management, are unlikely to be effectively developed [51]. The lack of these abilities generalizes to other life domains, such as academics and social interactions, making adolescents more likely to exhibit withdrawal behaviors when facing new stressors, thereby exacerbating the accumulation of emotional disturbance [52]. On the other hand, experiential avoidance enhances sensitivity to emotional disturbance through a cognitive distortion mechanism. Long-term suppression of negative emotions leads adolescents to doubt their own coping abilities, forming negative cognitions [53]. This cognitive bias not only reduces psychological resilience but also increases the subjective evaluation intensity of stress events, leading to a significant rise in stress levels [54]. Additionally, positive emotions are negatively correlated with anxiety and depression, while negative emotions are positively correlated with anxiety [55] and depression [56]. When individuals face chronic family conflicts, such as parental marital conflict, experiential avoidance may provide temporary relief from negative emotions but hinders effective problem-solving in reality, thereby continuously causing emotional disturbance [57]. The increased level of emotional disturbance further weakens individuals’ self-control abilities, making them more likely to rely on external stimuli, such as short videos, to seek escape and thereby increasing the risk of dependence [58]. Based on the above theoretical and analytical framework, this study proposes Hypothesis 4: Experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress) play a chain-mediating role between parental marital conflict and adolescent short video dependence.

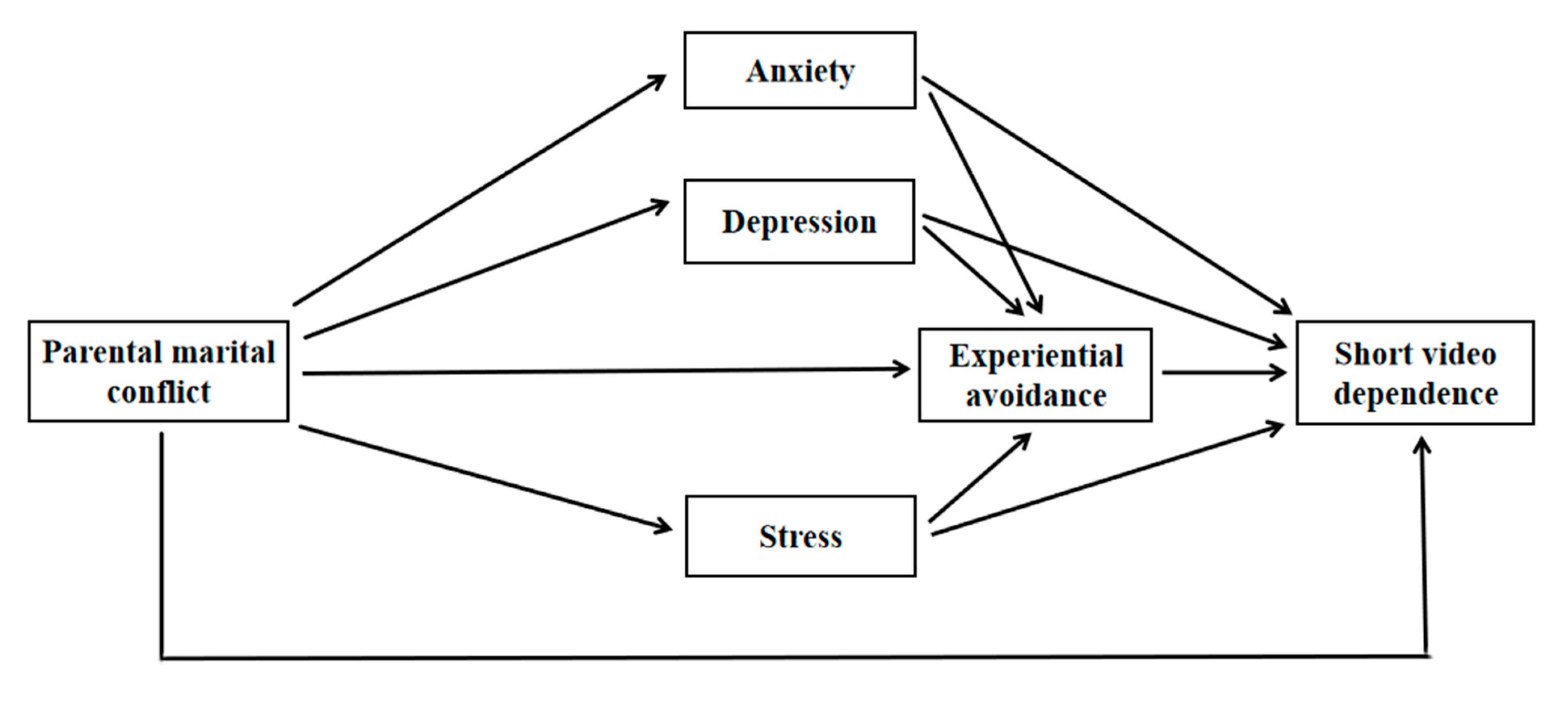

Unlike previous studies that predominantly focus on single mediators or simple pathways, this research systematically constructs a chain mediation model of “parental marital conflict → emotional distress (anxiety, depression, and stress) → experiential avoidance → short-form video dependence” (see Fig. 1). The present study aims to examine whether anxiety, depression, and stress operate through differential pathways in the relationship between parental marital conflict and short-form video dependence, and to investigate the role of experiential avoidance as a crucial bridge between emotional distress and behavioral dependence.

Figure 1: Hypothetical mediation model.

In January 2025, this study employed a convenience sampling method to recruit an initial sample of 4125 adolescents from five provinces in China: Hunan, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Anhui. The sampling strategy considered geographical representation (in the central-eastern, northwestern, and southwestern regions), economic development gradients (from high to low), and demographic diversity to enhance the approximate representativeness of the sample relative to the broader Chinese adolescent population. This study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Jishou University (Approval No.: JSDX-2024-0086), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data were collected using standardized paper-based questionnaires administered collectively at the class level. Prior to data collection, a passive informed consent procedure was implemented: informed consent forms were distributed to students through their schools for guardians to review. The forms clearly outlined the study’s purpose, content, privacy protection measures (including anonymization), and the principle of voluntary participation, noting that participants could withdraw at any time without negative consequences. If no objection was returned within 15 calendar days, consent was assumed by default [59].

The questionnaire was standardized and included detailed instructions to minimize errors. A pilot test indicated an average completion time of 10 min, aligning with adolescents’ cognitive characteristics. After data collection, a dual quality control mechanism was applied to screen the returned questionnaires: first, manual verification of response times was used to exclude outliers that fell significantly outside the normal range; second, pattern recognition techniques were employed to identify and exclude invalid responses with systematic biases, such as consecutive identical answers. This rigorous data-cleaning process ensured the validity and reliability of the final analytical sample, providing a high-quality foundation for subsequent statistical analysis. After excluding invalid responses, the final sample comprised 3957 valid questionnaires, yielding an effective response rate of 93.97%. The sample included 1959 boys (49.5%) and 1998 girls (50.5%), with a mean age of 14.71 ± 1.44 years. Among the participants, 149 were elementary school students (3.8%), 1786 were junior high school students (45.1%), and 2022 were senior high school students (51.1%).

2.2.1 Parental Marital Conflict

In this study, the Parental Marital Conflict scale was assessed using the Children’s Perception of Inter-parental Conflict Scale, which was developed by Grych et al. [60] and revised by Chi et al. [61] to be applicable to the Chinese population. The scale consists of five items and employs a 4-point Likert scoring method (1 = “never”, 4 = “often”), with higher scores indicating greater perceived marital conflict between parents. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this survey was 0.781. The validity of this scale has been established in prior studies [62].

In this study, the degree of Experiential Avoidance was assessed using the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (Version 2), which was developed by Fledderus et al. [63] and adapted for the Chinese population by Cao et al. [64]. The questionnaire consists of seven items and employs a 7-point Likert scoring method (1 = “never”, 7 = “always”), with higher scores indicating a greater degree of Experiential Avoidance and lower levels of psychological flexibility. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this survey was 0.917. This tool has been validated and utilized in diverse populations in previous studies [65,66,67].

In this study, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2) [68] was employed to assess the anxiety levels of adolescents. Comprising two items, the scale utilizes a 4-point Likert scoring system (1 = never; 4 = always), with total scores ranging from 2 to 8. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety. The Cronbach’s α for the GAD-2 in this study was 0.814. This tool has been validated and utilized in diverse populations in previous studies [69].

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) [70], developed by Levis et al., was used to evaluate the depression levels of adolescents. This scale also consists of two items and employs a 4-point Likert scoring system (1 = never; 4 = always), with total scores ranging from 2 to 8. Higher scores signify more severe depression. The Cronbach’s α for depression in this study was 0.715.

The stress levels among the participants were evaluated through a single item assessment tool created by Elo et al. [71]. This particular measurement approach has been extensively utilized in research focusing on Chinese adolescents. It has shown adequate sensitivity and ecological validity in large scale psychological investigations [72]. Respondents were queried about whether they had encountered feelings of tension, restlessness, or ongoing concerns that disrupted their sleep during the previous period. Their answers were rated on a five points Likert scale, where “1” signified “never” and “5” indicated “always”. Higher scores corresponded to greater perceived stress levels. This tool has been validated and utilized in diverse populations in previous studies [73].

In this study, the Short Video Dependence Scale developed by Wang et al. [74] was employed to assess the degree of short video dependence among adolescents. This scale has been validated for use in adolescent research [9]. The questionnaire comprises three dimensions with a total of 13 items, namely behavioral and cognitive changes, physical impairment, and social attachment. Responses are scored using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”, 5 = “strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating a more severe level of problematic short video dependence. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this survey was 0.868. This tool has been validated and utilized in diverse populations in previous studies [75,76].

In this study, gender, age, and educational stage were included as covariates in the statistical model to control for the potential confounding effects of these demographic variables on the relationships among the primary study variables, thus improving the reliability of the results and making them more straightforward to understand.

Firstly, descriptive and correlational analyses of the variables were conducted using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Subsequently, the SPSS macro program PROCESS Model 81 was applied to construct the model through 5000 resampling iterations. In this model, parental marital conflict was designated as the independent variable, short video dependence as the outcome variable, and experiential avoidance, depression, and anxiety as mediating variables. Finally, the bias-corrected Bootstrap method (with 5000 random resamples) was employed to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mediating effects and to test the conditional indirect effects of experiential avoidance on depression and anxiety. The significance level for statistical analysis was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

In order to evaluate the influence of common variance bias, Harman’s single factor test was utilized in this research. The results of the analysis showed that, prior to principal component factor rotation, two factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 were identified. The first factor explained 35.61% of the variance, which is less than the 40% benchmark. Consequently, it can be concluded that this study does not suffer from substantial common method bias.

3.2 Descriptive Analysis of the Main Variables

The results presented in Table 1 indicate significant differences between genders in parental marital conflict (t = −3.87, p < 0.001), experiential avoidance (t = −4.57, p < 0.001), anxiety (t = −4.99, p < 0.001), depression (t = −4.85, p < 0.001), stress (t = −5.26, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (t = −5.35, p < 0.001). Specifically, females scored higher than males on all these variables. Additionally, significant differences were observed across different academic stages for parental marital conflict (F = 15.34, p < 0.001), experiential avoidance (F = 31.07, p < 0.001), anxiety (F = 12.12, p < 0.001), depression (F = 22.80, p < 0.001), stress (F = 19.83, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (F = 32.61, p < 0.001). Specifically, parental marital conflict, experiential avoidance, anxiety, stress, and short video dependence were significantly higher in the high school stage compared to the primary and junior high school stages. In contrast, depression was significantly higher in the primary school stage compared to the junior high and high school stages.

Table 1: Descriptive analysis of the main variables.

| Variables | Gender | Educational Stage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | t | Primary School | Junior High School | High School | F | ||

| Parental marital conflict | Mean | 10.24 | 10.67 | −3.87*** | 10.30 | 10.13 | 10.75 | 15.34*** |

| SD | 3.50 | 7.03 | 3.56 | 3.53 | 3.40 | |||

| Experiential avoidance | Mean | 20.83 | 22.34 | −4.57*** | 21.40 | 20.20 | 22.83 | 31.07*** |

| SD | 10.40 | 10.26 | 10.00 | 10.48 | 10.11 | |||

| Anxiety | Mean | 3.69 | 3.95 | −4.99*** | 3.93 | 3.67 | 3.94 | 12.12*** |

| SD | 1.68 | 1.67 | 1.80 | 1.70 | 1.64 | |||

| Depression | Mean | 3.88 | 4.12 | −4.85*** | 4.23 | 3.82 | 4.14 | 22.80*** |

| SD | 1.56 | 1.50 | 1.67 | 1.53 | 1.52 | |||

| Stress | Mean | 2.37 | 2.55 | −5.26*** | 2.43 | 2.35 | 2.56 | 19.83*** |

| SD | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.07 | |||

| Short video dependence | Mean | 35.96 | 37.80 | −5.35*** | 37.40 | 35.37 | 38.19 | 32.61*** |

| SD | 10.99 | 10.67 | 11.02 | 11.02 | 10.54 | |||

3.3 Correlation Analysis among the Main Variables

As indicated in Table 2, parental marital conflict was significantly positively correlated with experiential avoidance (r = 0.528, p < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.349, p < 0.001), depression (r = 0.329, p < 0.001), stress (r = 0.269, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (r = 0.282, p < 0.001). Experiential avoidance was also significantly positively correlated with anxiety (r = 0.560, p < 0.001), depression (r = 0.530, p < 0.001), stress (r = 0.440, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (r = 0.398, p < 0.001). Additionally, anxiety was significantly positively correlated with depression (r = 0.701, p < 0.001), stress (r = 0.493, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (r = 0.314, p < 0.001). Depression was significantly positively correlated with stress (r = 0.459, p < 0.001) and short video dependence (r = 0.327, p < 0.001). Finally, stress was significantly positively correlated with short video dependence (r = 0.236, p < 0.001).

Table 2: Correlation analysis among the main variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Parental marital conflict | - | |||||

| 2 Experiential avoidance | 0.528*** | - | ||||

| 3 Anxiety | 0.349*** | 0.560*** | - | |||

| 4 Depression | 0.329*** | 0.530*** | 0.701*** | - | ||

| 5 Stress | 0.269*** | 0.440*** | 0.493*** | 0.459*** | - | |

| 6 Short video dependence | 0.282*** | 0.398*** | 0.314*** | 0.327*** | 0.236*** | - |

3.4 Test of the Mediating Model among the Main Variables

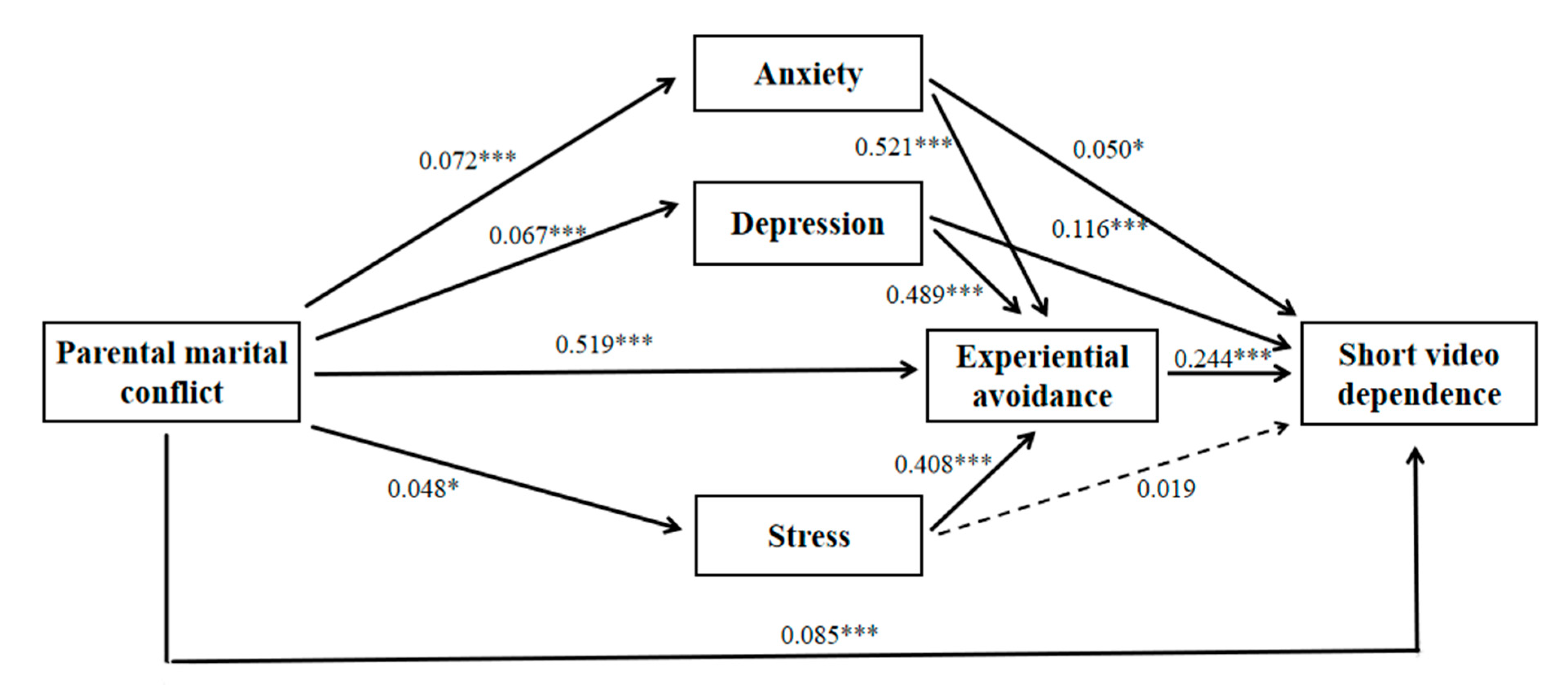

After controlling for demographic variables, the results presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2 indicate a significant positive correlation between parental marital conflict and short video dependence (β = 0.269, p < 0.001), which remains significant even after the introduction of mediating variables. Additionally, parental marital conflict is significantly positively correlated with experiential avoidance (β = 0.519, p < 0.001), anxiety (β = 0.072, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.067, p < 0.001), and stress (β = 0.048, p < 0.05). Furthermore, experiential avoidance is significantly positively correlated with anxiety (β = 0.521, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.489, p < 0.001), stress (β = 0.408, p < 0.001), and short video dependence (β = 0.244, p < 0.001). Anxiety (β = 0.050, p < 0.05) and depression (β = 0.116, p < 0.001) are also significantly positively correlated with short video dependence, while stress and short video dependence (β = 0.019, p = 0.257) are not significantly correlated. Finally, experiential avoidance, anxiety (β = 0.521, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.489, p < 0.001), and stress (β = 0.408, p < 0.001) mediate the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence significantly. The proportion of each path is shown in Table 4.

Table 3: Test of the mediating model among the main variables.

| Outcome Variables | Predictor Variables | β | SE | t | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short video dependence | Parental marital conflict | 0.269 | 0.015 | 17.705*** | 0.312 | 106.820*** |

| Experiential avoidance | Parental marital conflict | 0.519 | 0.013 | 38.468*** | 0.538 | 402.712*** |

| Anxiety | Parental marital conflict | 0.072 | 0.015 | 4.655*** | 0.565 | 370.058*** |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.521 | 0.016 | 33.456*** | |||

| Depression | Parental marital conflict | 0.067 | 0.016 | 4.202*** | 0.534 | 316.032*** |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.489 | 0.016 | 30.653*** | |||

| Stress | Parental marital conflict | 0.048 | 0.017 | 2.880* | 0.447 | 196.788*** |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.408 | 0.017 | 24.161*** | |||

| Short video dependence | Parental marital conflict | 0.085 | 0.017 | 5.022*** | 0.440 | 118.307*** |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.244 | 0.020 | 12.097*** | |||

| Anxiety | 0.050 | 0.022 | 2.337* | |||

| Depression | 0.116 | 0.021 | 5.586*** | |||

| Stress | 0.019 | 0.017 | 1.134 |

Figure 2: Chain mediation model diagram. Note: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Table 4: Analysis of the mediating model paths among the main variables.

| Intermediate Path | Effect Size | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | Proportion of Mediating Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.269 | 0.015 | 0.239, 0.299 | |

| Direct effect | 0.085 | 0.017 | 0.052, 0.118 | |

| Total indirect effect | 0.184 | 0.012 | 0.161, 0.206 | 68.40% |

| Parental marital conflict → Experiential avoidance → Short video dependence | 0.125 | 0.012 | 0.102, 0.147 | 46.47% |

| Parental marital conflict → Anxiety→ Short video dependence | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.001, 0.008 | 1.49% |

| Parental marital conflict → Depression → Short video dependence | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.004, 0.013 | 2.97% |

| Parental marital conflict → Stress → Short video dependence | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001, 0.003 | 0.37% |

| Parental marital conflict → Experiential avoidance → Anxiety → Short video dependence | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.001, 0.026 | 5.20% |

| Parental marital conflict → Experiential avoidance→ Depression → Short video dependence | 0.029 | 0.006 | 0.018, 0.042 | 10.78% |

| Parental marital conflict → Experiential avoidance → Stress → Short video dependence | 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.004, 0.012 | 1.49% |

This study is a cross-sectional investigation examining the relationships among parental marital conflict, experiential avoidance, emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress), and short video dependence, with the aim of evaluating the mediating roles of experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance. The findings reveal that parental marital conflict influences adolescents’ short video dependence both directly and indirectly through experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress). Moreover, experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress) partially mediate the impact of parental marital conflict on short video dependence. Specifically, parental marital conflict is associated with higher levels of experiential avoidance, which in turn is related to elevated levels of emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress). Higher levels of anxiety and depression within emotional disturbance are more predictive of adolescents’ short video dependence.

This study demonstrates a positive correlation between parental marital conflict and adolescent short video dependence, a finding that is consistent with previous research results [77]. According to the Emotional Safety Theory [78], parental marital conflict undermines the family’s emotional safety base, leaving adolescents in a state of chronic vigilance. This sense of insecurity spills over into parent-child interactions, specifically manifested as adolescents reducing their emotional needs toward parents and parents decreasing emotional responsiveness due to their own emotional exhaustion, which forms a vicious cycle of emotional alienation and ultimately leads to a significant decline in the quality of parent-child interactions [79]. From a biological perspective, adolescents who are chronically exposed to parental marital conflict experience persistent activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [80]. The overactivity of the HPA axis promotes the excessive secretion of cortisol (a stress hormone), which in turn increases the sensitivity of the amygdala and impairs the regulatory function of the prefrontal cortex [81]. As a core region for emotional processing, the heightened sensitivity of the amygdala makes adolescents more vigilant to negative stimuli, thereby exacerbating feelings of anxiety and unease. Meanwhile, the weakened inhibitory control of the prefrontal cortex over impulsive behaviors undermines adolescents’ self-control in resisting the temptation of short videos [5]. Moreover, the instant feedback features of short videos (such as likes and comments) can rapidly activate the brain’s dopamine reward system [45]. When adolescents fail to obtain emotional satisfaction in real-life parent-child relationships, the surge in dopamine triggered by short videos serves as an alternative compensatory mechanism [82]. Long-term reliance on this compensation can lead to changes in synaptic plasticity, forming a dependency neural circuit of “short video use-dopamine release-enhanced pleasure”, which further consolidates the dependent behavior [83]. Therefore, the evidence presented above validates Hypothesis 1 of this study: Parental marital conflict can positively predict adolescent short video dependence.

The present research revealed that there is a positive association between parental marital conflict and experiential avoidance, and this discovery aligns with prior investigations [84]. Based on attachment theory [85], a firm and reassuring parent child bond serves as an essential cornerstone for a child’s emotional growth. However, parental marital conflict is often accompanied by a decline in the quality of parent-child interactions, leaving children more susceptible to emotional neglect [86]. To cope with the chronic unmet emotional needs, children gradually internalize an avoidant coping pattern, adopting experiential avoidance as a habitual strategy to evade the pain of being neglected [87]. Furthermore, the results of this study are in accordance with previous investigations, which have shown that parental marital discord can seep into the family’s external social sphere, undermining the social support systems available to children [88]. When adolescents lack sufficient social support, they tend to experience feelings of isolation and powerlessness. These emotions, in turn, further strengthen their inclination towards experiential avoidance. They often resort to avoiding social interactions and retreating into their own worlds to alleviate internal stress [89]. Furthermore, the findings of this research indicated that there is a positive relationship linking experiential avoidance and short video addiction among teenagers. Existing literature has elucidated the complex psychological mechanisms underlying this relationship. Experiential avoidance not only drives adolescents to use short video viewing as an escape mechanism through physiological and emotional regulation pathways but also exacerbates their dependence on short videos through emotional dysregulation and cognitive biases [47]. Individuals with high levels of experiential avoidance are prone to negative appraisals of their own capabilities and life situations, such as perceiving themselves as powerless to change their circumstances and viewing the real world as a source of distress [90]. Under these circumstances, adolescents may be more inclined to use short videos as a means to alleviate discomfort. Targeted interventions addressing experiential avoidance in adolescents, particularly through cognitive-behavioral correction, emotional regulation skills training, and the reconstruction of family support systems, can help reduce the risk of short video dependence [91,92,93]. Therefore, the evidence presented above supports Hypothesis 2 of this study: Experiential avoidance mediates the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence.

This study found that parental marital conflict is positively correlated with levels of emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress), a finding consistent with previous research [94]. As a negative factor in the family environment, parental marital conflict can have adverse effects on adolescents in multiple aspects [95]. From a psychological perspective, adolescents are undergoing a crucial stage of physical and mental maturation. During this time, their self regulatory capacities and skills for handling stress are comparatively less developed [96]. When constantly exposed to the adverse family environment created by parental marital conflict, they may experience a continuous accumulation of negative emotions, thereby maintaining high levels of anxiety, depression, and stress [97,98]. The study also found that adolescents’ levels of emotional disturbance are positively correlated with short video dependence [99,100], and there is a complex psychological mechanism underlying the relationship between emotional disturbance and short video dependence among adolescents [101,102]. Parental conflict can trigger negative expectations in adolescents, which is a core risk factor for problematic internet use. In high-conflict family environments, adolescents, due to a lack of emotional support, may turn to the internet as a means of psychological compensation, thereby exacerbating internet use problems [103]. Moreover, according to Social Learning Theory [104], if parents frequently use their mobile phones in daily life or resort to scrolling through their phones to avoid conflicts, adolescents are likely to observe and imitate such behaviors [105]. Additionally, the various big-data-driven content on short video platforms that caters to adolescents’ preferences can also serve as a model, further reinforcing their dependence on and addictive behaviors related to short videos [5]. Therefore, interventions targeting adolescents’ emotional disturbances, particularly through fostering healthy emotion-regulation strategies and enhancing self-efficacy, can help reduce the risk of short video dependence [106]. In this study, the association between stress levels and short video dependence was not significant, possibly due to the heterogeneity of stress types and the moderating effects of sample characteristics (e.g., adolescents may be more inclined to cope with specific stressors through immediate emotional venting or self-compensation) [101,107]. Moreover, protective factors such as psychological resilience may buffer the negative impact of stress, and the absence of such variables in this study may limit the model’s explanatory power [108]. Future research could employ longitudinal designs and multiple mediator models to further clarify the dynamic mechanisms involved. Thus, the evidence presented above supports Hypothesis 3 of this study: Emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress) mediates the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence.

The present study found that experiential avoidance is positively correlated with adolescents’ emotional disturbance levels (anxiety, depression, and stress), consistent with previous research findings [109]. Adolescents are in a developmental stage where their cognitive abilities are not yet fully mature. When confronted with family conflicts and other issues, they struggle to employ mature cognitive strategies to manage negative emotions and are more likely to resort to avoidance strategies [110]. According to Emotion Processing Theory [111], negative emotions require adaptive processing to be alleviated and regulated; however, experiential avoidance hinders this normal emotional processing [112]. From a neurobiological perspective [113], chronic experiential avoidance can alter brain neuroplasticity, weakening the prefrontal cortex’s regulatory control over the limbic system [114]. The prefrontal cortex, a key brain region responsible for emotion regulation, decision-making, and problem-solving, becomes less effective when its function is impaired. This impairment makes it difficult for adolescents to cope effectively with stressors and adopt adaptive behaviors, ultimately leading to a sustained increase in stress levels [115]. Additionally, a longitudinal tracking survey of 6504 adolescents over a decade revealed that those with higher levels of experiential avoidance experienced a significant increase in stress levels in subsequent assessments and were more likely to develop psychological problems such as anxiety and depression [116]. Moreover, research has shown that adequate social support and care from school teachers and peers can mitigate adolescents’ negative emotions and reduce the adverse effects of emotional disturbance on their physical and mental health [117]. Schools and society can also effectively reduce adolescents’ stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms and improve their psychological well-being and overall life satisfaction by incorporating cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, and positive psychology approaches into online mental health interventions [118]. These interventions can also alleviate psychological suffering. Therefore, the evidence presented above supports Hypothesis 4 of this study: Experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress) mediate the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence in a chain-mediating manner.

This study employed a cross-sectional design, utilizing a stratified sampling method to conduct a large-scale survey of 3954 adolescents and collect multidimensional data. A highly representative adolescent sample database was established. The sample size is in line with the norms of large-sample research in social sciences, which significantly enhances the external validity and generalizability of the research findings, providing a robust data foundation for the reliability and applicability of the study’s conclusions. In terms of methodology, this study innovatively applied structural equation modeling and the Bootstrap method to construct a chain mediation model: “Parental marital conflict → Experiential avoidance → Emotional disturbance (Anxiety, Depression, and Stress) → Short video dependence”. It should be specifically noted that within the dimension of emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and stress demonstrate significantly different impacts on short-form video dependence: depression exhibits the most substantial predictive effect, anxiety shows a weaker association, while the pathway involving stress does not reach statistical significance. This finding not only challenges the theoretical convention of treating negative emotions as a unitary construct by identifying depression as the core emotional factor linking family conflict with short-form video dependence, but also calls for more targeted intervention strategies. Accordingly, we propose the following recommendations: schools should prioritize depression screening and implement targeted training programs; clinical practice should develop interventions specifically designed to alleviate depression, addressing the compensatory belief of “seeking pleasure through short-form videos”; families should focus on recognizing depressive symptoms in adolescents and replace short-form video use with rewarding experiences through family activities; at the policy level, public health campaigns should emphasize the connection between depression and media dependence while prioritizing the allocation of corresponding intervention resources. These measures collectively establish a precision intervention framework centered on depression prevention and management, thereby providing a scientific basis for disrupting the specific pathway from parental marital conflict to short-form video dependence. Regarding future research directions, this study proposes three areas for expansion. First, longitudinal tracking studies and experimental intervention designs could be adopted to further clarify the causal relationships between variables and to verify the actual effectiveness of intervention measures. Second, it is suggested that the scope of research variables be broadened to include factors such as self-control ability and social support. A more comprehensive theoretical model could be constructed, and cross-cultural comparative studies could be conducted to explore the moderating effects of cultural backgrounds on variable relationships. Third, the integration of biosensing technology and big data analysis is advocated to collect multimodal data. This would allow for an in-depth exploration of the mechanisms underlying short video dependence in adolescents from physiological, psychological, and behavioral perspectives, providing a multidimensional basis for the development of scientifically sound and effective intervention strategies.

The current study acknowledges several limitations in terms of research design, variable exploration, and data collection. From the perspective of the passive informed consent procedure adopted in this study, while it ensured the feasibility of large-scale investigation, it may theoretically not have fully achieved the depth of guardian engagement attainable through active consent procedures. Future research should, where conditions permit, employ active consent procedures to further enhance the rigor of ethical practice. From the perspective of research design, although cross-sectional studies can reveal the correlation between parental marital conflict and adolescent short video dependence, the lack of time-series data precludes the determination of causality. Future research should employ longitudinal tracking studies to clarify this relationship. In terms of variable system construction, the current study has focused solely on experiential avoidance and emotional disturbance (including anxiety, depression, and stress) as chained mediating variables. However, the multidimensionality of adolescent psychological development suggests that protective factors such as self-esteem and social support may also mediate or moderate the relationship between parental marital conflict and short video dependence. Future research should develop more comprehensive multi-variable mediating-moderating models to deepen the understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Regarding the relationships among variables, the interactive mechanisms through which parental marital conflict influences experiential avoidance, emotional disturbance, and short video dependence in adolescents remain to be further explored. Future research should emphasize intervention studies to provide more targeted strategies for addressing adolescent mental health issues. In terms of data collection, the current study relied primarily on adolescent self-report questionnaires, which are susceptible to social desirability bias and may introduce systematic errors. Prospective research endeavors ought to contemplate combining diverse data streams, such as parental accounts, teacher appraisals, behavioral observations, and physiological assessments. This approach can mitigate the impact of subjective elements and boost the scientific validity and trustworthiness of the research outcomes.

The present study systematically elucidates the chained mechanism of action between parental marital conflict, experiential avoidance, emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress), and short video dependence. By employing structural equation modeling, we validated the dynamic transmission pathway of “parental marital conflict → experiential avoidance → emotional disturbance (anxiety, depression, and stress) → short video dependence”. This study presents an innovative viewpoint for building theories within the realm of adolescent psychological health. It also paves the way for developing new approaches to interventions designed to enhance adolescents’ mental wellness.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Lei Yang is mainly responsible for constructing the research framework, organizing the literature, collecting and analyzing data, and writing the initial draft of the paper. Yang Liu leads the research design and theoretical modeling, revises and approves the content of the entire paper, and is responsible for subsequent academic communication and manuscript coordination. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Yang Liu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All the procedures of this study comply with the ethical standards stipulated in the “Ethical Review Measures for Human Life Sciences and Medical Research” issued by the National Health Commission of China, and have been approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Jishou University (Approval Number: JSDX-2024-0086). Before data collection, we obtained the informed consent of all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Singh S . How Many People Use TikTok 2025 (Users Statistics) [Datasets]. Boston, MA, USA: Demandsage; 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.demandsage.com/tiktok-user-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

2. TikTok User Statistics—Who Is Using TikTok in 2024? [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://tridenstechnology.com/zh/tiktok-%e7%94%a8%e6%88%b7%e7%bb%9f%e8%ae%a1/. [Google Scholar]

3. Zheng C . Research on the flow experience and social influences of users of short online videos. A case study of DouYin. Sci Rep. 2023; 13: 3312. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-30525-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ye J , Wang W , Huang D , Ma S , Chen S , Dong W , et al. Short video addiction scale for middle school students: development and initial validation. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 9903. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-92138-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lu L , Liu M , Ge B , Bai Z , Liu Z . Adolescent addiction to short video applications in the mobile Internet era. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 893599. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.893599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dept B from the Glued-to-Their-Screens . More than 15% of teens say they’re on YouTube or TikTok “almost constantly”—slashdot [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://news.slashdot.org/story/23/12/12/0257220/more-than-15-of-teens-say-theyre-on-youtube-or-tiktok-almost-constantly. [Google Scholar]

7. Liu M , Zhuang A , Norvilitis JM , Xiao T . Usage patterns of short videos and social media among adolescents and psychological health: a latent profile analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2024; 151: 108007. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.108007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang P , Yang YC , Che RJ , Xu Y , Li YJ , Zhang L , et al. Impact of short-video social media dependence on mental health among middle school students. Clin Med. 2025; 45: 55– 7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Mao Z , Jiang YZ . Latent classes of adolescents’ short-video media use tendencies and their relationships with personality traits. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2022; 31: 8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

10. Ye JH , Wu YT , Wu YF , Chen MY , Ye JN . Effects of short video addiction on the motivation and well-being of Chinese vocational college students. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 847672. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.847672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Herre B , Samborska V , Ortiz-Ospina E , Roser M . Marriages and Divorces [Internet]. Oxford, UK: Our World Data; 2020 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/marriages-and-divorces. [Google Scholar]

12. Wang W , Yin R , Cao W , Wang Y , Zhang T , Yan Y , et al. Assessing parental marital quality and divorce related to youth sexual experiences and adverse reproductive health outcomes among 50,000 Chinese college students. Reprod Health. 2022; 19( 1): 219. doi:10.1186/s12978-022-01531-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chiang SC , Bai S . Reciprocal influences among marital relationship, parent–adolescent relationship, and youth depressive symptoms. J Marriage Fam. 2022; 84( 4): 962– 81. doi:10.1111/jomf.12836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. van Dijk R , van der Valk IE , Deković M , Branje S . A meta-analysis on interparental conflict, parenting, and child adjustment in divorced families: examining mediation using meta-analytic structural equation models. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020; 79: 101861. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Baptist J , Hamon RR . Family systems theory. In: Adamsons K , Few-Demo AL , Proulx C , Roy K , editors. Sourcebook of family theories and methodologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 209– 26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-92002-9_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. El-Sheikh M , Whitson SA . Longitudinal relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Vagal regulation as a protective factor. J Fam Psychol. 2006; 20: 30– 9. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bolze SDA , Schmidt B , Böing E , Crepaldi MA . Conflitos conjugais e parentais em famílias com crianças: características e estratégias de resolução. Paid Ribeirão Preto. 2017; 27( Suppl 1): 457– 65. doi:10.1590/1982-432727s1201711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sandi C . Understanding the neurobiological basis of behavior: a good way to go. Front Neurosci. 2008; 2( 2): 129– 30. doi:10.3389/neuro.01.046.2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang J , Lam SP , Kong AP , Ma RC , Li SX , Chan JW , et al. Family conflict and lower morning Cortisol in adolescents and adults: modulation of puberty. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 22531. doi:10.1038/srep22531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Renninger D , Bachner J , García-Massó X , Molina-García J , Reimers AK , Marzi I , et al. Motivation and basic psychological needs satisfaction in active travel to different destinations: a cluster analysis with adolescents living in Germany. Behav Sci. 2023; 13( 3): 272. doi:10.3390/bs13030272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kardefelt-Winther D . A conceptual and methodological critique of Internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory Internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2014; 31: 351– 4. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chaplin TM , Sinha R , Simmons JA , Healy SM , Mayes LC , Hommer RE , et al. Parent–adolescent conflict interactions and adolescent alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2012; 37( 5): 605– 12. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Brock RL , Kochanska G . Interparental conflict, children’s security with parents, and long-term risk of internalizing problems: a longitudinal study from ages 2 to 10. Dev Psychopathol. 2016; 28( 1): 45– 54. doi:10.1017/S0954579415000279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Crowley MJ , van Noordt SJR , Castagna PJ , Vaca FE , Wu J , Lejuez CW , et al. Avoidance in adolescence: the balloon risk avoidance task (BRAT). J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2022; 44( 2): 297– 311. doi:10.1007/s10862-021-09928-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hayes SC , Strosahl K , Wilson KG , Bissett RT , Pistorello J , Toarmino D , et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: a preliminary test of a working model. Psychol Rec. 2004; 54( 4): 553– 78. doi:10.1007/BF03395492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Malicki S , Ostaszewski P . Experiential avoidance as a functional dimension of a transdiagnostic approach to psychopathology. Postępy Psychiatr I Neurol. 2014; 23( 2): 61– 71. doi:10.1016/j.pin.2014.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Huang DQ . Characteristics of College Students’ Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies and Its Pedagogical Implications. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020; 41( 7): 1151– 4. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200327-00450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Staddon J . Theoretical behaviorism. In: Contemporary behaviorisms in debate. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77395-3_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kashdan TB , Barrios V , Forsyth JP , Steger MF . Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behav Res Ther. 2006; 44( 9): 1301– 20. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. García-Oliva C , Piqueras JA . Experiential avoidance and technological addictions in adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2016; 5( 2): 293– 303. doi:10.1556/2006.5.2016.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kato T . The mediating role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between rumination and depression. Curr Psychol. 2024; 43( 11): 10339– 45. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-05199-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Emotion Regulation Theory: an Exploration [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.grouporttherapy.com/blog/emotion-regulation-theory. [Google Scholar]

33. Goeke-Morey MC , Papp LM , Cummings EM . Changes in marital conflict and youths’ responses across childhood and adolescence: a test of sensitization. Dev Psychopathol. 2013; 25( 1): 241– 51. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lucas-Thompson RG , Goldberg WA . Family relationships and children’s stress responses. In: Benson JB , editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011. p. 243– 99. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-386491-8.00007-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Saint Arnault D , Sakamoto S , Moriwaki A . A cross-cultural study of the experiential structure of emotions of distress: preliminary findings in a sample of female Japanese and American college students. Psychologia. 2005; 48( 4): 254– 67. doi:10.2117/psysoc.2005.254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Daly M , Macchia L . Global trends in emotional distress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023; 120( 14): e2216207120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2216207120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Griggs S . Hope and mental health in young adult college students: an integrative review. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017; 55( 2): 28– 35. doi:10.3928/02793695-20170210-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Carebot ABA . Stress and Anxiety in Teens: Facts, Statistics, Symptoms and Treatment 2023. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://carebotaba.com/teen-stress-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

39. Lépine J-P , Briley M . The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011; 7( Sup1): 3– 7. doi:10.2147/ndt.s19617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cassano P , Fava M . Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res. 2002; 53( 4): 849– 57. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00304-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Parents May Underestimate Impact of Involving Adolescent Children in Conflicts [Internet]. University Park, PA, USA: Penn State University; 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/parents-may-underestimate-impact-involving-adolescent-children-conflicts. [Google Scholar]

42. Biggs A , Brough P . Stress and coping theory. In: Handbook of concepts in health, health behavior and environmental health. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 1– 23. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-0821-5_39-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lucas-Thompson RG , Lunkenheimer ES , Dumitrache A . Associations between marital conflict and adolescent conflict appraisals, stress physiology, and mental health. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017; 46( 3): 379– 93. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1046179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Burkholder AR , Koss KJ , Hostinar CE , Johnson AE , Gunnar MR . Early life stress: effects on the regulation of anxiety expression in children and adolescents. Soc Dev. 2016; 25( 4): 777– 93. doi:10.1111/sode.12170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gao Y , Hu Y , Wang J , Liu C , Im H , Jin W , et al. Neuroanatomical and functional substrates of the short video addiction and its association with brain transcriptomic and cellular architecture. Neuroimage. 2025; 307: 121029. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2025.121029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Journault AA , Cernik R , Charbonneau S , Sauvageau C , Giguère CÉ , Jamieson JP , et al. Learning to embrace one’s stress: the selective effects of short videos on youth’s stress mindsets. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2024; 37( 1): 29– 44. doi:10.1080/10615806.2023.2234309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Liao M . Analysis of the causes, psychological mechanisms, and coping strategies of short video addiction in China. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1391204. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Jiang L , Yoo Y . Adolescents’ short-form video addiction and sleep quality: the mediating role of social anxiety. BMC Psychol. 2024; 12( 1): 369. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-01865-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Papachristou H , Theodorou M , Neophytou K , Panayiotou G . Community sample evidence on the relations among behavioural inhibition system, anxiety sensitivity, experiential avoidance, and social anxiety in adolescents. J Context Behav Sci. 2018; 8: 36– 43. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Barker TV , Buzzell GA , Fox NA . Approach, avoidance, and the detection of conflict in the development of behavioral inhibition. New Ideas Psychol. 2019; 53: 2– 12. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Orsillo SM , Roemer L . The mindful way through anxiety: break free from chronic worry and reclaim your life. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Researchgate; 2011. [Google Scholar]

52. Gu C , Ma X , Li Q , Li C . Can the effect of problem solvers’ characteristics on adolescents’ cooperative problem solving ability be improved by group sizes? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19( 24): 16575. doi:10.3390/ijerph192416575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Danitz SB , Orsillo SM , Beard C , Björgvinsson T . The relationship between personal growth and psychological functioning in individuals treated in a partial hospital setting. J Clin Psychol. 2018; 74( 10): 1759– 74. doi:10.1002/jclp.22627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Thoern HA , Grueschow M , Ehlert U , Ruff CC , Kleim B . Attentional bias towards positive emotion predicts stress resilience. PloS One. 2016; 11( 3): e0148368. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Usán Supervía P , Salavera Bordás C , Quílez Robres A . The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between resilience and satisfaction with life in adolescent students. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022; 15: 1121– 9. doi:10.2147/prbm.s361206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Song Y , Xiao Z , Zhang L , Shi W . Trait depression and subjective well-being: the chain mediating role of community feeling and self-compassion. Behav Sci. 2023; 13( 6): 448. doi:10.3390/bs13060448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Long DJ . Avoidance: The Band-Aid Solution to Long-Term Problems [Internet]. Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA: The Psychology Group Fort Lauderdale; 2019 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://thepsychologygroup.com/avoidance/. [Google Scholar]

58. Wolff M , Enge S , Kräplin A , Krönke KM , Bühringer G , Smolka MN , et al. Chronic stress, executive functioning, and real-life self-control: an experience sampling study. J Pers. 2021; 89( 3): 402– 21. doi:10.1111/jopy.12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Eaton DK , Lowry R , Brener ND , Grunbaum JA , Kann L . Passive versus active parental permission in school-based survey research: does the type of permission affect prevalence estimates of risk behaviors? Eval Rev. 2004; 28( 6): 564– 77. doi:10.1177/0193841x04265651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Grych JH , Seid M , Fincham FD . Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: the children’s perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Dev. 1992; 63( 3): 558– 72. doi:10.2307/1131346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Chi LP , Xin ZQ . The revision of children’s perception of marital conflict scale. Chin Ment Health J. 2003; 17( 8): 554– 6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

62. Yang L , Liu Y , Yan C , Chen Y , Zhou Z , Shen Q , et al. The relationship between early warm and secure memories and healthy eating among college students: anxiety as mediator and physical activity as moderator. Psychiatry. 2025: 1– 20. doi:10.1080/00332747.2025.2530353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Fledderus M , Oude Voshaar MAH , ten Klooster PM , Bohlmeijer ET . Further evaluation of the psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II. Psychol Assess. 2012; 24( 4): 925– 36. doi:10.1037/a0028200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Cao J , Ji Y , Zhu ZH . Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the acceptance and action questionnaire-second edition (AAQ-II) in college students. Chin Ment Health J. 2013; 27: 873– 7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

65. Yi Z , Wang W , Wang N , Liu Y . The relationship between empirical avoidance, anxiety, difficulty describing feelings and Internet addiction among college students: a moderated mediation model. J Genet Psychol. 2025; 186( 4): 288– 304. doi:10.1080/00221325.2025.2453705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wang J , Wang N , Liu Y , Zhou Z . Experiential avoidance, depression, and difficulty identifying emotions in social network site addiction among Chinese university students: a moderated mediation model. Behav Inf Technol. 2025: 1– 14. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2025.2455406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Wang J , Tang L , Liu Y , Wu X , Zhou Z , Zhu S . Physical activity moderates the mediating role of depression between experiential avoidance and Internet addiction. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 20704. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-07487-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Byrd-Bredbenner C , Eck K , Quick V . GAD-7, GAD-2, and GAD-mini: psychometric properties and norms of university students in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021; 69: 61– 6. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Peng J , Liu M , Wang Z , Xiang L , Liu Y . Anxiety and sleep hygiene among college students, a moderated mediating model. BMC Public Health. 2025; 25( 1): 3233. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-24441-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Levis B , Sun Y , He C , Wu Y , Krishnan A , Bhandari PM , et al. Accuracy of the PHQ-2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening to detect major depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020; 323( 22): 2290. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Elo AL , Leppänen A , Jahkola A . Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003; 29( 6): 444– 51. doi:10.5271/sjweh.752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Puolakanaho A , Muotka JS , Lappalainen R , Lappalainen P , Hirvonen R , Kiuru N . Adolescents’ stress and depressive symptoms and their associations with psychological flexibility before educational transition. J Adolesc. 2023; 95( 5): 990– 1004. doi:10.1002/jad.12169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Yin J , Cheng X , Yi Z , Deng L , Liu Y . To explore the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality of college students based on the mediating effect of stress and subjective well-being. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13( 1): 932. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-03303-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Mao Z , Jiang YZ , Jin TL , Wang CQ . Preliminary development of the problematic short-form video use scale for college students. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2022; 31( 5): 462– 8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

75. Shen Q , Wang H , Liu M , Li H , Zhang T , Zhang F , et al. The impact of childhood emotional maltreatment on adolescent insomnia: a chained mediation model. BMC Psychol. 2025; 13( 1): 506. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02803-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Gan Y , He Z , Liu M , Ran J , Liu P , Liu Y , et al. A chain mediation model of physical exercise and BrainRot behavior among adolescents. Sci Rep. 2025; 15: 17830. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-02132-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Wang J , Wang M , Lei L . Longitudinal links among paternal and maternal harsh parenting, adolescent emotional dysregulation and short-form video addiction. Child Abuse Negl. 2023; 141: 106236. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Davies PT , Martin MJ . The reformulation of emotional security theory: the role of children’s social defense in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2013; 25( 4pt2): 1435– 54. doi:10.1017/s0954579413000709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Feinberg ME , Kan ML , Hetherington EM . The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. J Marriage Fam. 2007; 69: 687– 702. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00400.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Kelly RJ , Thompson MJ , El-Sheikh M . Exposure to parental interpartner conflict in adolescence predicts sleep problems in emerging adulthood. Sleep Health. 2024; 10( 5): 576– 82. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2024.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Dunlavey CJ . Introduction to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: healthy and dysregulated stress responses, developmental stress and neurodegeneration. J Undergrad Neurosci Educ. 2018; 16( 2): R59– 60. [Google Scholar]

82. Guo J , Chai R . Adolescent short video addiction in China: unveiling key growth stages and driving factors behind behavioral patterns. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1509636. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1509636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Lüscher C , Malenka RC . Drug-evoked synaptic plasticity in addiction: from molecular changes to circuit remodeling. Neuron. 2011; 69( 4): 650– 63. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Biglan A , Gau JM , Jones LB , Hinds E , Rusby JC , Cody C , et al. The role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between family conflict and depression among early adolescents. J Context Behav Sci. 2015; 4( 1): 30– 6. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Rogier G , Muzi S , Morganti W , Pace CS . Self-criticism and attachment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pers Individ Differ. 2023; 214: 112359. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2023.112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Tian W , Wang F , Wang M . Parental marital quality and children’s depression in China: the different mediating roles of parental psychological aggression and corporal punishment. J Fam Violence. 2023; 38( 2): 275– 85. doi:10.1007/s10896-022-00364-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Wang Y , Tian J , Yang Q . Experiential avoidance process model: a review of the mechanism for the generation and maintenance of avoidance behavior. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024; 34( 2): 179– 90. doi:10.5152/pcp.2024.23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Li X , Wang Y , Zhang Z . The impact of parental marital conflict on child development and its mechanisms. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021; 29( 3): 512– 7. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2021.00875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Dou F , Xu K , Li Q , Qi F , Wang M . Perceived social support and experiential avoidance in adolescents: a moderated mediation model of individual relative deprivation and subjective social class. J Psychol. 2024; 158( 4): 292– 308. doi:10.1080/00223980.2023.2296122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Lin RM , Xiong XX , Shen YL , Lin N , Chen YP . The heterogeneity of negative problem orientation in Chinese adolescents: a latent profile analysis. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 1012455. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1012455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Holmqvist Larsson K , Andersson G , Stern H , Zetterqvist M . Emotion regulation group skills training for adolescents and parents: a pilot study of an add-on treatment in a clinical setting. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020; 25( 1): 141– 55. doi:10.1177/1359104519869782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Morgan RD . Cognitive behavioral therapies used in correctional treatment. In: Jeglic E , Calkins C , editors. Handbook of evidence-based mental health practice with sex offenders. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 321– 44. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-51741-9_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Zhang J , Zhang Y , Xu F . Does cognitive-behavioral therapy reduce internet addiction? Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019; 98: e17283. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000017283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Liu D , Vazsonyi AT . Longitudinal links between parental emotional distress and adolescent delinquency: the role of marital conflict and parent–child conflict. J Youth Adolesc. 2024; 53( 1): 200– 16. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01921-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Zhou N , Buehler C . Adolescents’ responses to marital conflict: the role of cooperative marital conflict. J Fam Psychol. 2017; 31( 7): 910– 21. doi:10.1037/fam0000341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. WHO . Mental Health of Adolescents 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. [Google Scholar]

97. Sun Y , Li Y . Children’s well-being during parents’ marital disruption process: a pooled time-series analysis. J Marriage Fam. 2002; 64( 2): 472– 88. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00472.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Lawrence TI . Parental support, marital conflict, and stress as predictors of depressive symptoms among African American adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022; 27( 3): 630– 43. doi:10.1177/13591045211070163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Chao M , Lei J , He R , Jiang Y , Yang H . TikTok use and psychosocial factors among adolescents: comparisons of non-users, moderate users, and addictive users. Psychiatry Res. 2023; 325: 115247. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Augner C , Vlasak T , Aichhorn W , Barth A . The association between problematic smartphone use and symptoms of anxiety and depression—a meta-analysis. J Public Health. 2023; 45( 1): 193– 201. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Liu Y , Ni X , Niu G . Perceived stress and short-form video application addiction: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2021; 12: 747656. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Cheng X , Su X , Yang B , Zarifis A , Mou J . Understanding users’ negative emotions and continuous usage intention in short video platforms. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2023; 58: 101244. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2023.101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Wang LX , Dou K , Li JB , Zhang MC , Guan JY . The association between interparental conflict and problematic Internet use among Chinese adolescents: testing a moderated mediation model. Comput Hum Behav. 2021; 122: 106832. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Rumjaun A , Narod F . Social learning theory—albert bandura. In: Akpan B , Kennedy TJ , editors. Science education in theory and practice. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-43620-9_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Laursen B , Veenstra R . Toward understanding the functions of peer influence: a summary and synthesis of recent empirical research. J Res Adolesc. 2021; 31( 4): 889– 907. doi:10.1111/jora.12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Yang J , Ti Y , Ye Y . Offline and online social support and short-form video addiction among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of emotion suppression and relatedness needs. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2022; 25( 5): 316– 22. doi:10.1089/cyber.2021.0323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Nagaraj S , Goodday S , Hartvigsen T , Boch A , Garg K , Gowda S , et al. Dissecting the heterogeneity of “in the wild” stress from multimodal sensor data. npj Digit Med. 2023; 6: 237. doi:10.1038/s41746-023-00975-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Helmreich I , Kunzler A , Chmitorz A , König J , Binder H , Wessa M , et al. Psychological interventions for resilience enhancement in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; 2017( 2): 1– 45. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Yoo SY , Park SM , Choi CH , Chung SJ , Bhang SY , Kim JW , et al. Harm avoidance, daily stress, and problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13: 962189. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.962189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Compas BE , Jaser SS , Bettis AH , Watson KH , Gruhn MA , Dunbar JP , et al. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017; 143( 9): 939– 91. doi:10.1037/bul0000110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]