Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring the Associations between Sedentary Time, Social Support, Social Rejection and Psychological Distress: A Network Analysis in Students

1 School of Future Education, Beijing Normal University, Zhuhai, 519087, China

2 College of Physical Education and Sport, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China

3 The Affiliated High School of South China Normal University, Guangzhou, 510635, China

4 School of Physical Education and Sport, Ningxia University, Yinchuan, 750021, China

* Corresponding Authors: Guofeng Qu. Email: ; Lijia Hou. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work as the first author

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Social and Behavioral Determinants of Mental Health: From Theory to Practice)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2026, 28(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.073592

Received 21 September 2025; Accepted 12 December 2025; Issue published 28 January 2026

Abstract

Background: Amid the global rise in adolescent sedentary behavior and psychological distress, extant research has largely focused on variable-level associations, neglecting symptom-level interactions. This study applies network analysis, aims to delineate the interconnections among sedentary time, social support, social exclusion, and psychological distress in Chinese students, and to identify core and bridge symptoms to inform targeted interventions. Methods: This study employed a cross-sectional design to investigate the complex relationships among sedentary behavior, social support, social exclusion, and psychological distress among Chinese students. The research involved 459 high school and university students, using network analysis and mediation models to examine these relationships. Results: Network analysis revealed that the network had a density of 58.33% and an average edge weight of 0.11. In terms of centrality, stress had the highest expected influence (EI = 1.135), acting as the core amplifier in the network. Sedentary behavior demonstrated the highest bridging expected influence, functioning as a critical bridge for cross-community transmission. Conversely, friend support showed the lowest bridging EI with a negative value, indicating its effectiveness in blocking cross-community diffusion and alleviating symptoms. Conclusion: With stress acting as the most influential “core engine” within the symptom network and sedentary behavior serving as the key “bridge” for cross-community transmission, interventions should first target stress to weaken the overall symptom cascade, followed by reducing sedentary behavior or enhancing friend support to disrupt cross-community pathways, thereby achieving a core-bridge dual blockade.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSedentary behavior, specifically, refers to any activity performed in a seated, reclined, or lying down position during waking hours and with an energy expenditure of less than 1.5 metabolic equivalent units (METs) [1]. Common sedentary behaviors include prolonged periods of sitting still as well as a variety of screen time activities such as watching television, using a computer or tablet, and playing video games. In recent years, a large number of studies have confirmed that sedentary behaviors are associated with a variety of health risks, including cardiovascular disease [2], obesity [3], declining executive functioning [4], and lower levels of mental health [5,6]. However, global monitoring data show that about half of children and adolescents spend more than 2 h of screen time per day [7]. Specifically in the United States, the average daily sitting time of adolescents increased from 7 h to 8.2 h between 2007 and 2016 [8]. In China, although related studies may reveal some changing trends [9], the prevalence of sedentary behavior among school-age adolescents remains a problem.

Among adolescent students, their psychological vulnerability and sensitivity make them susceptible to various factors, such as poor academic performance and poor health behaviors [10]. A Norwegian study showed that the rate of psychological distress among adolescents nearly doubled from 15% to 30% between 2006 and 2019 [11]. In China, the prevalence of mental disorders among school-aged children and adolescents has also reached an all-time high of 17.5% [12]. These psychological disturbances are not only strongly associated with health risk behaviors [13], but also with higher academic stress during the student years [14]. Specifically, when adolescents lack the resources needed to cope with various pressures and demands, stressors are perceived as a threat, which is highly likely to be detrimental to their mental health and well-being [15]. Once adolescents are incapable of coping with a situation, negative stress and consequent bad feelings can develop [16]. Although physical activity is often seen as a protective factor in health behaviors to cope with stress and maintain students’ psychological well-being, it may further exacerbate psychological distress due to the increase in sedentary time, which can crowd out “physical activity” time. Lee and Kim (2018) noted that after Controlling for confounding variables, sedentary behavior remains a risk factor for anxiety, depression, and stress [17].

In addition, an increase in sedentary time means a corresponding decrease in the time invested in social relationship building, which can lead to a gradual weakening of adolescents’ connections with others. In this situation, adolescents are more likely to experience social exclusion and feelings of isolation from their group. Werneck et al. (2019) showed that both low and high intensity sedentary behaviors (especially watching TV) were associated with a higher likelihood of social isolation [18]. Baumbach et al. (2023) conducted a longitudinal study that showed that higher levels of physical activity was negatively associated with perceived social exclusion [19]. Similarly, in a meta-analysis it was shown that sedentary behavior was associated with bullying victimization among adolescent children [20]. The experience of bullying further heightens adolescents’ sensitivity to signals of social exclusion [21], and this perceived social exclusion can have an impact on adolescents’ mental health and emotional well-being in school, which can lead to psychological distress [22,23].

Social support, i.e., the social and psychological assistance an individual receives or perceives from family, friends, and the community, is widely recognized as a protective factor for mental health and can be effective in preventing psychological distress [24,25]. The study by Fitzpatrick et al. (2024) particularly emphasizes the role of family and friend support in mitigating the important role of adolescent psychological distress [26]. At the same time, it has also been noted that sedentary individuals tend to engage in fewer planned activities, and in turn receive less social support [27]. A meta-analysis by Harandi et al. (2017) further confirms the positive impact of social support on mental health [28]. Social exclusion and social support are two distinct yet related constructs that collectively constitute an individual’s social network. The former represents a deprivation of social relationships, while the latter signifies the acquisition of positive resources. In this context, optimizing the structure of one’s social network is crucial for both reducing sedentary behavior and alleviating mental health problems.

In summary, there is a significant association between sedentarism, social exclusion, social support and psychological distress, which is also reflected in its dimensions, such as family support, friend support versus other support in social support, and anxiety, depression and stress in psychological distress. However, previous studies have mostly focused on examining the overall associations among these variables, failing to reveal in depth the complex patterns of interactions among the dimensions. Network analysis provides a novel perspective: it allows the dimensions to be viewed as nodes in a network, and the connections (edges) between the nodes are constructed using multiple regression coefficients, which can visualize the interdependencies between the variables.

Therefore, this study proposes to adopt a network analysis approach to clearly map the network of associations among these variables in a sample of Chinese adolescent students, and to identify core and bridge symptoms within the symptom network, providing a theoretical basis for future interventions. We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: In the network model of sedentary behavior, social support, social exclusion, and psychological distress, correlations exist both within and across domains.

Hypothesis 2: There are key symptoms in the network model that influence other symptoms.

Hypothesis 3: The network model is tightly connected by a small number of core symptoms.

In June 2025, we conducted a survey using convenience sampling at a high school and a large university in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, China. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, as well as other relevant laws, regulations, and ethical codes. This study has also been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, Beijing Normal University (Approval No.: BNU202506090156). All investigators completed formal training prior to data collection to ensure study integrity.

Following the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies [29], we developed a questionnaire to collect data on basic demographics, sedentary time, psychological distress, social exclusion, and social support. After confirming students’ consent to participate, we provided them with a link to the questionnaire. A priori power analysis was conducted using the “powerly” package (version 1.10.0) in R to determine the required sample size. The analysis was performed with a candidate sample size range of 200 to 1000, a target sensitivity of 0.60, and a target statistical power of 0.80. The analysis recommended a sample size of 384 [30]. To ensure the robustness of our findings and to account for potential data attrition, we planned to recruit a total of 400 participants; a total of 472 participants completed the survey. After processing the collected data, 13 invalid questionnaires (due to patterned responses or excessively short completion times) were excluded, resulting in 459 valid responses and a validity rate of 97.3%. Among the valid participants, 381 (82.94%) were male, and 78 (17.06%) were female. The mean age of the participants was 18 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.86). The sample included 229 middle school students and 230 undergraduate students.

Sedentary time was assessed primarily based on self-reported data from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [31]. For example, how much time per day have you spent sitting in the last seven days? Studies have shown that self-reported sitting time has acceptable reliability for both men and women, whether using the long or short form. In addition, a significant correlation was shown between self-reported total sitting time and accelerometer counts (below 100 per minute) [32].

In this study, the Ostracism Experience Scale for Adolescents (OES-A) was developed by Cordier et al. (2013) [33] was used to assess the level of perceived social exclusion of students. The scale consists of 11 self-assessment entries on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always), and it contains two dimensions of rejection and neglect. The total score ranges from 5 to 55, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived social exclusion. Its Chinese version, Zhang et al. (2018) was developed and showed good reliability and validity [34]. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of this scale in this study is 0.697.

Perceived social support was assessed using the 12-item Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) [35]. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 12 to 84. Higher scores reflect greater perceived support. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.959).

Anxiety, depression, and stress were measured by using the DASS-21 scale [36] using the Chinese validated version [37]. The scale consists of three subscales: stress (e.g., “I find it hard to calm myself down”), depression (e.g., “I feel sad and down”), and anxiety (e.g., “I feel dry mouth”), with each subscale having 7 entries each. All entries were rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always), with higher scores indicating higher levels of corresponding psychological distress. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale was 0.920 for the stress subscale, 0.922 for the depression subscale, and 0.889 for the anxiety subscale.

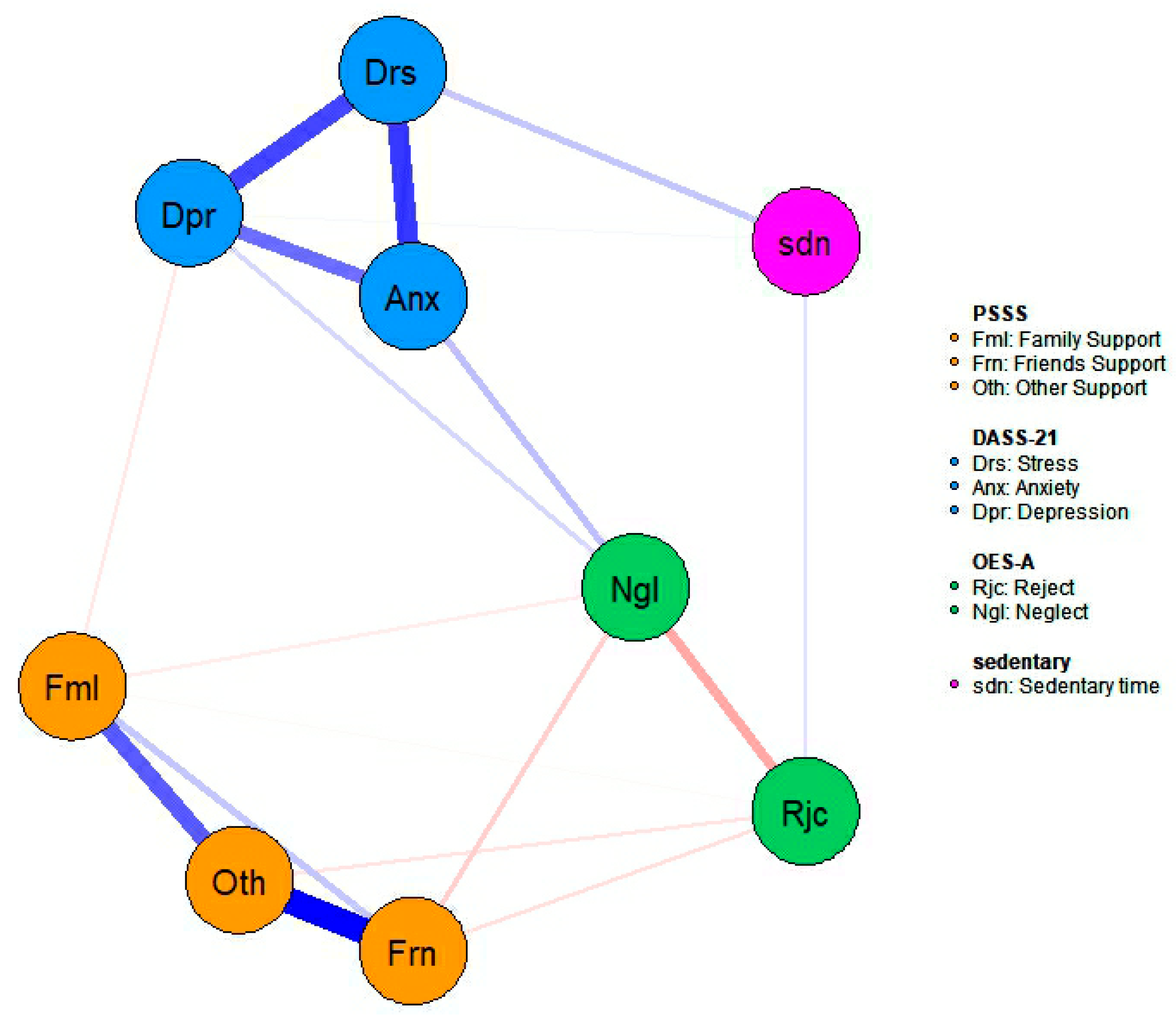

In this study, SPSS 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for descriptive statistics. All network analyses were conducted using R 4.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The “qgraph” (version 1.9.8) in the R package was utilized to estimate and construct the network. The network structure was created through the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM), and polynomial coefficients. EBIC was used to select the best model, LASSO was used to control sparsity, and GGM was used to display the structure diagram [38,39]. In the network model, the “nodes” represent the core variables of the study: psychological distress, social support, social rejection, and sedentary time. To clearly distinguish these variables in the figure, we used a color code, where blue nodes represent psychological distress, green represents social rejection, orange represents social support, and pink represents sedentary time. The “edges” are the connection lines between nodes. The thickness of the edges reflects the correlation, with red edges indicating negative correlation and blue edges indicating positive correlation.

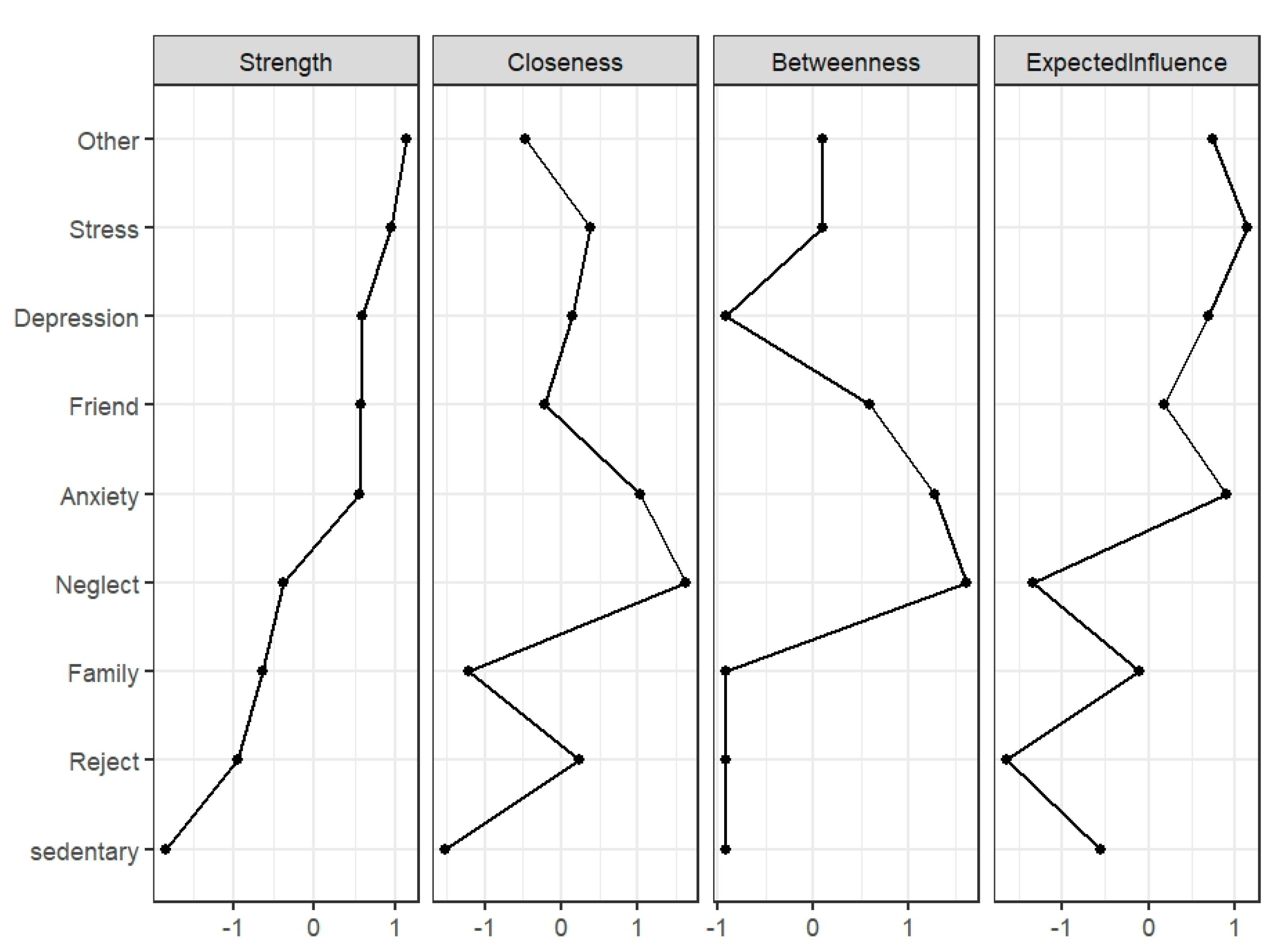

The “bootnet” (version 1.6.0) in the R package was used to measure the centrality index, and Betweenness, Closeness, Strength, and Expected Influence (EI) were used to estimate the central symptoms affecting the network structure and the adolescents’ psychological distress, social support, and exclusion. However, considering the instability of betweenness and closeness centralities, we ultimately chose to use strength and EI centralities for interpreting the results. Bridge Expected Impact was employed to measure bridge symptoms [40], to examine the relationship between sedentary time, social support and exclusion, and psychological discomfort in teenagers. A pie chart with a circle around each network node shows predictable values. The R package “mgm” (version 1.2.15) calculates predictable values by indicating how much other nodes explain a network node [41].

In this study, the analysis of centrality, stability, and edge accuracy was utilized to validate the stability and correctness of the network structure. When examining the stability of nodes in the network structure, the case discard bootstrap test was adopted, with 5000 bootstrap samples being carried out. The stability was quantified by the stability coefficient, where a coefficient greater than 0.50 was considered optimal, and the minimum value was 0.25. The non-parametric bootstrap test (with 5000 bootstrap samples) was employed to estimate the 95% edge confidence interval, which was used to measure the correctness of edges. The less the overlap of confidence intervals, the higher the accuracy. In addition, the non-parametric bootstrap test was also used to conduct 5000 bootstrap samples for the variability of nodes and edges.

In order to in order to test for gender and school section differences, we used the R package “NetworkComparisonTest (NCT)” (version 2.2.2) [42] for further analysis. Specifically, this includes the network structure invariance test, the global strength invariance test, and the edge strength invariance test.

Table 1 shows the mean, SD, skewness, and kurtosis of each variable for 459 participants grouped by gender. Judging from the skewness and kurtosis indicators, the data of each variable basically conform to a normal distribution [43].

Table 1: Descriptive statistical results of each variable.

| Variable | Female (N = 381), Mean ± SD | Male (N = 78), Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.816 ± 1.796 | 18.923 ± 1.932 | 0.517 | −0.861 | / |

| Sedentary time | 7.782 ± 3.680 | 8.180 ± 3.649 | 0.409 | 0.081 | / |

| OES-A | 30.682 ± 5.209 | 31.539 ± 5.761 | −0.012 | 1.221 | 0.697 |

| PASS | 58.874 ± 16.458 | 57.359 ± 15.495 | −0.338 | −0.180 | 0.959 |

| DASS-21 | 13.937 ± 13.249 | 16.295 ± 13.367 | 0.925 | 0.459 | 0.967 |

| Stress | 5.347 ± 4.867 | 6.180 ± 5.011 | 0.752 | −0.008 | 0.920 |

| Anxiety | 4.221 ± 4.253 | 4.859 ± 4.130 | 1.104 | 1.023 | 0.889 |

| Depression | 4.370 ± 4.637 | 5.256 ± 4.863 | 1.109 | 0.932 | 0.922 |

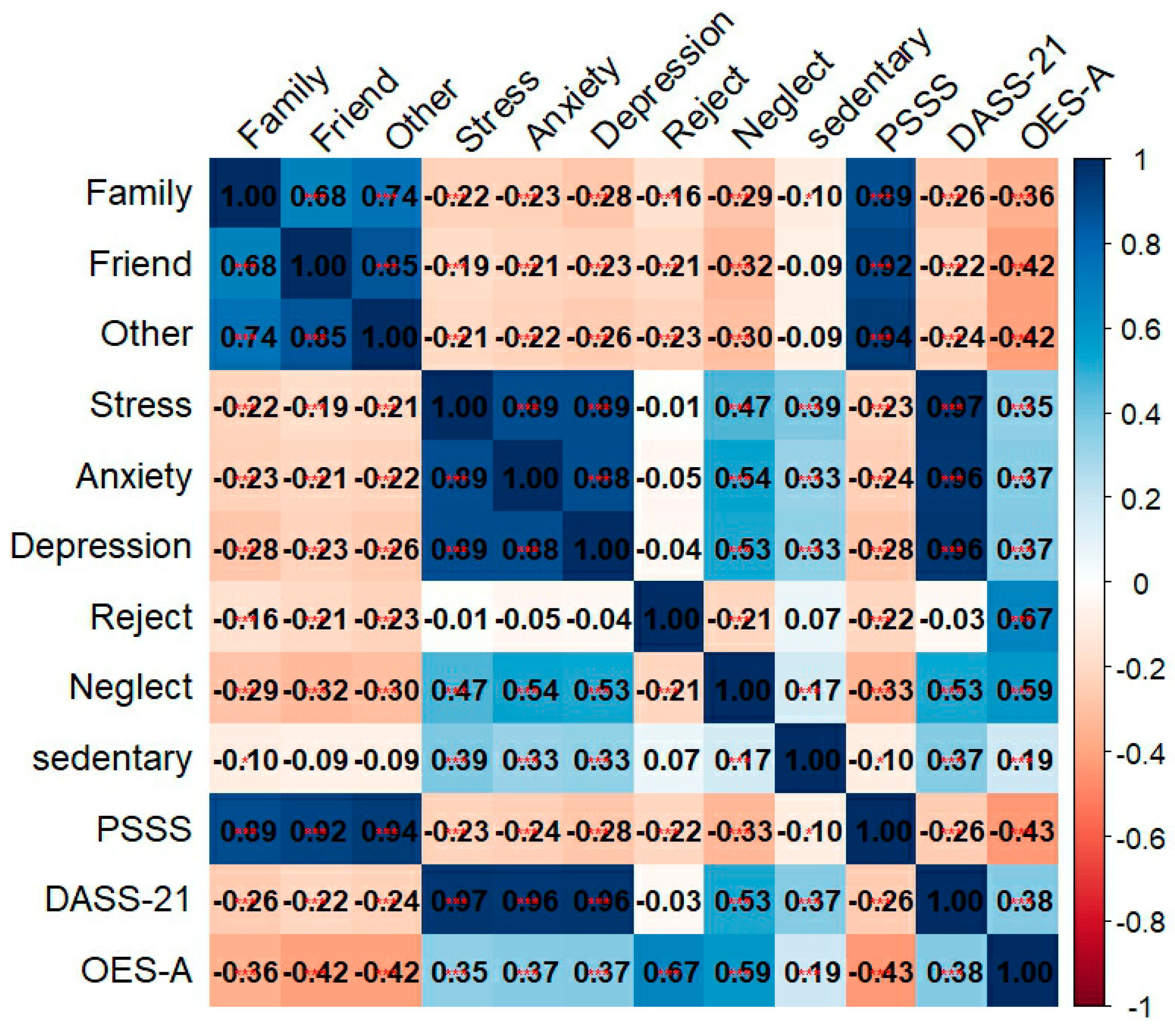

The correlation coefficients between different variables are shown in Fig. 1 to examine the association between them. The results of the analysis showed that sedentary time was moderately positively correlated with psychological distress (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), weakly positively correlated with social exclusion (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), and even more weakly correlated with social support (r = 0.10, p < 0.001). In addition, perceived social support was significantly negatively correlated with social exclusion (r = −0.43, p < 0.001) and psychological distress (r = −0.26, p < 0.001). Finally, there was also a moderate positive correlation between social exclusion and psychological distress (r = 0.38, p < 0.001).

Figure 1: Correlation coefficient between different nodes. Note: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Abbreviations: OES-A, Social exclusion; PASS, Social support; DASS-21, Psychological distress.

As shown in Fig. 2, we constructed a “Sedentary-Social Support-Social Exclusion-Psychological Distress” network with 9 nodes and up to 36 possible connections. The density of the network is 58.33%, with 21 non-zero connections and an average weight of 0.11. The analysis shows that in terms of social support, “other support” has the strongest correlation with “support from friends”, and in terms of psychological distress, “depression” has the strongest correlation with “support from friends”. In terms of psychological distress, the strongest association was between “depression” and “anxiety”. In addition, the core cross-community associations were: sedentary and “stress” and “rejection”, neglect and anxiety, and family support and depression.

Figure 2: The network structure of sedentary behavior, social support, social exclusion, and psychological distress.

3.4 Central and Bridging Symptoms

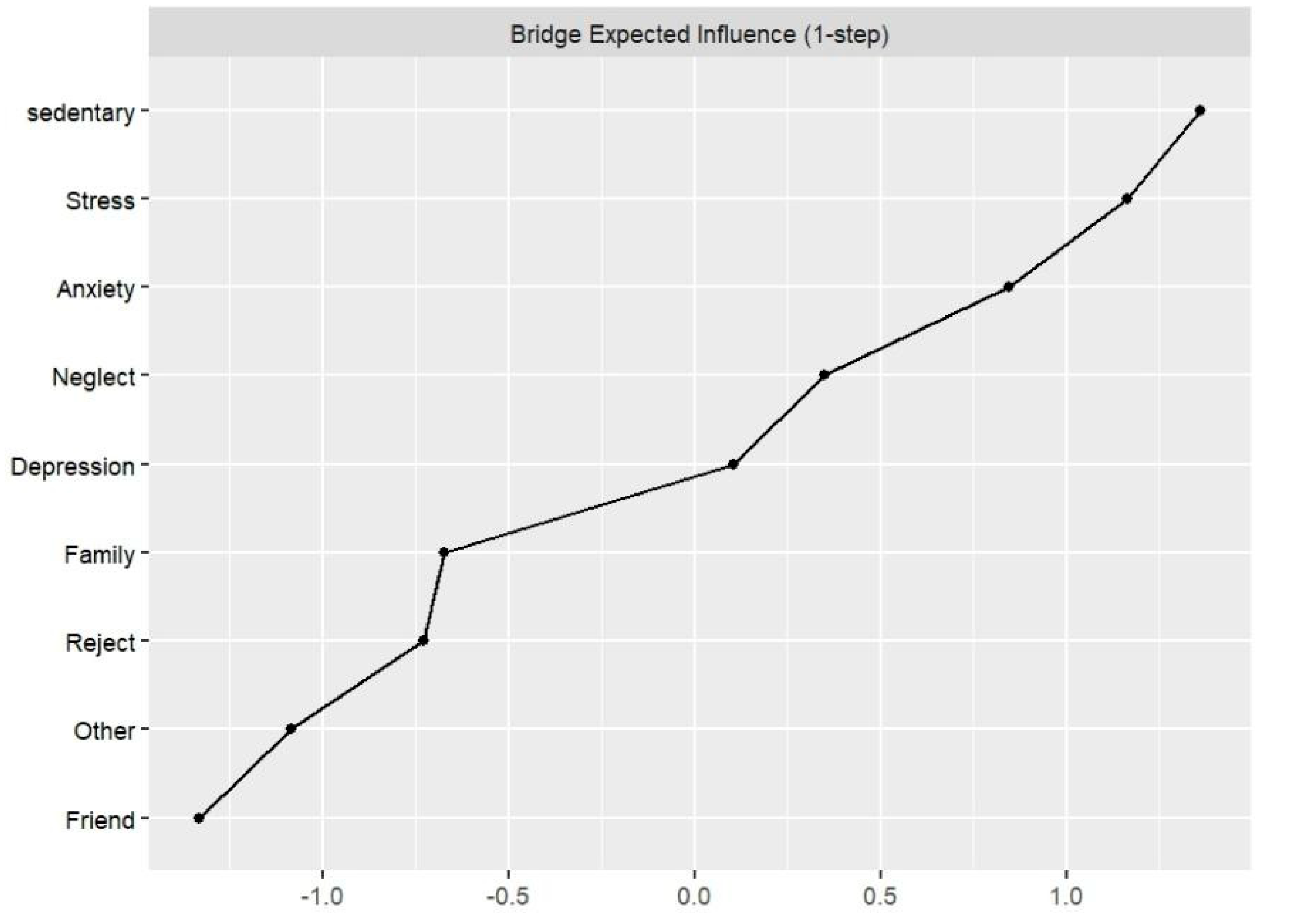

Table S1 and Fig. 3 show the Centrality of each network node. The core symptoms for strength, closeness, betweenness, and expected impact centralities were “Other support”, “neglect”, “neglect”, and “stress”, with standardized centrality indices of 1.135, 1.636, 1.615, and 1.135, respectively. Fig. 4 shows the expected impact of bridging between network communities where sedentary, stress and anxiety were identified as the most significant factors linking sedentary-social support-social exclusion-psychological distress, which may lead to the co-existence of prolonged sedentary, perceived less social support, more social exclusion and psychological distress.

Figure 3: Comparison chart of strength, closeness, betweenness and expected influence of different nodes.

Figure 4: The expected impacts of bridges at each node.

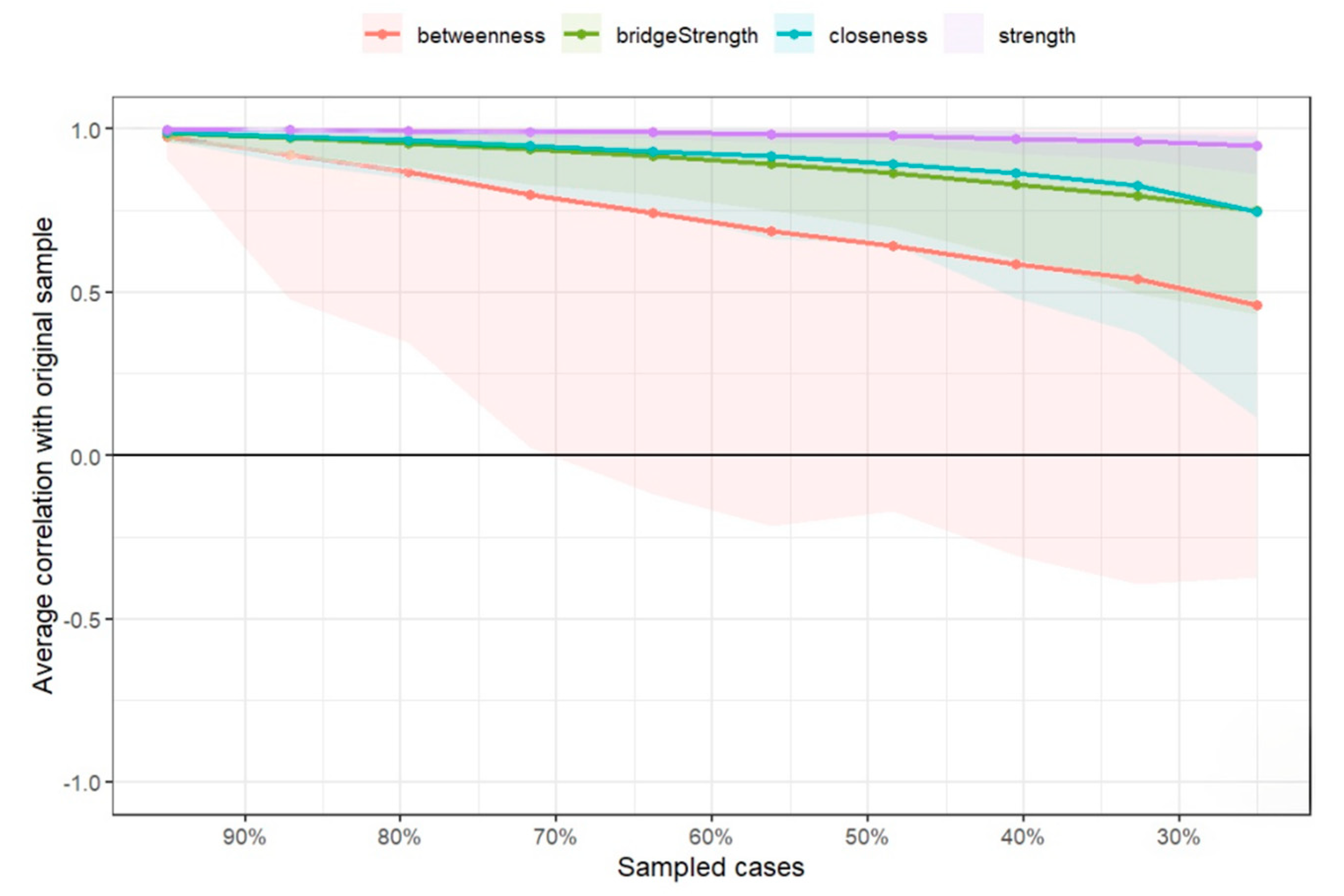

3.5 Network Stability and Accuracy

Regarding the stability of the network shown in Fig. 5, the Edge and Strength centrality standardized coefficients (CS-C) were calculated with the help of the case-dropping bootstrap program to be 0.75. This value indicates that the network has good stability, meaning that the main findings remain unchanged even if up to 75% of the samples are deleted (r = 0.7). In terms of the accuracy of the current network, the results of the edge bootstrap 95% confidence intervals show that the confidence intervals are narrower, which is a good indication that the edges presented in Fig. S1 have a high level of confidence. In addition, the bootstrap difference test results show that most of the comparisons between expected impact and node strength are statistically significant, as can be seen in Figs. S2 and S3.

Figure 5: The correlation between node centrality indicators and the original sample under different sampling ratios.

Network Comparison Test (NCT) results revealed no significant gender differences in global network strength (Female: 2.41 vs. Male: 2.27; Strength Difference (S) = 0.14, p = 0.63), network structure (Network Invariance Measure (M) = 0.17, p = 0.76), or any individual edge weights following Holm-Bonferroni correction (all p > 0.05). Additionally, the high school and college groups did not present statistically significant differences in the comparison of network global strength (2.25 vs. 2.32, S = 0.07, p = 0.78) and network structure (M = 0.19, p = 0.28). Combined with the prior gender analysis, these findings indicate that network characteristics are invariant across both gender and school segments. The corresponding network structures are visualized in Figs. S4 and S5.

The main purpose of the present study was to examine the psychological network of sedentary time, psychological distress, and social factors in an incidental sample of adolescents on the one hand. On the other hand, it was to examine the role of social indicators in the relationship between sedentary time and psychological distress. This is the first study to simultaneously examine the structure of psychological distress networks and their associations with sedentariness and social indicators in a Chinese student population. This study employs network and mediation modeling to provide a novel understanding of psychological distress, examining its connections to sedentariness and perceived social states. These advanced analytical approaches offer new frameworks for conceptualizing and addressing psychological distress.

The network structure provided in this study reveals associations between sedentariness and social indicators and psychological distress at the symptom level in a Chinese student population, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. In the constructed network, we observed that the strongest edges existed within variables. In contrast, edges between different variables were weaker than edges within variables, which is consistent with previous findings [44,45]. In our study, we observed the strongest cross-variate edges between “sedentary” and “stress”, “neglect” and “anxiety”, and “family support” and “depression”. Although much weaker than the within-variable margins, the findings confirm that some dimensions of psychological distress may be strongly associated with sedentary and social indicators.

In the network analysis of the present study, sedentary, as the only behavioral indicator, we observed a positive correlation with stress, but did not find a relationship with the anxiety and depression dimensions, which means that sedentary behaviors predicted an increase in psychological distress more in terms of stress. Sedentary behavior may lead to increased stress [46], which in turn is a significant predictor of depression and anxiety in the student population [47]. Therefore, the correlation between sedentary and psychological distress may be more of a contribution to the stress association. In addition, neglect is likewise a risk factor for anxiety symptoms in the Chinese student population, and in social exchange theory, relationships are essentially an exchange of values. When individuals feel that they are not valued in a relationship, they will doubt their own value, resulting in anxiety and feelings of loss [48]. As for social support, family support is associated with being a preventive factor for depression, and parental and family support is most closely related to the protective role of adolescents against depression, more important than any other source [49]. Research suggests that parental support influences the development of children’s mental health, which in turn may contribute to the prevention of depression [50]. In the estimated psychological network, the most central nodes by strength were other support, stress, and depression. In terms of expected influence, the most impactful nodes were stress, anxiety, and other support. The central role of stress was emphasized in both estimates, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2.

In addition, the view that social support is a protective factor for mental health in traditional psychiatry remains supported after controlling for the effects of all domains in our study [24]. However, more specifically, when compared to family support, other support and friend support did not show a significant association with any dimension of psychological distress (anxiety, depression, and stress) relative to family support. This also emphasizes the fundamental role of the family. It also points to the importance of preventing psychological distress among Chinese students through family support interventions. The specificity within this variable is also reflected in the social exclusion domain, where “feeling neglected” is a better predictor of psychological distress among Chinese students than “feeling rejected”. This may reveal that individuals are more sensitive to the need for a sense of belonging and constant attention in the Chinese cultural context [51]. Compared to explicit rejection, the feeling of being “ignored” and not taken seriously may be more likely to erode an individual’s sense of self-worth and trigger deeper feelings of anxiety, depression, and stress. In the context of Chinese society’s emphasis on collective and relational networks, an individual’s feeling of being marginalized and invisible may have a greater psychological impact than being rejected outright, as it touches on a deeper intrinsic need to be “needed” and “valuable”.

The Expected Impact for Bridging (BEI) measures a node’s capacity to connect and activate different communities [52,53]. Disconnecting bridging nodes inhibits the spread of influence and reduces co-occurrence [40]. Sedentary behavior had the highest BEI. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that sedentary behavior may lead to changes in psychological distress and social indicators [54], thereby supporting Hypothesis 3. This implies that an increase in sedentary time acts as an efficient “risk radiator”, simultaneously and rapidly disseminating risk across multiple dimensions, including psychological distress (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress) and social functioning (e.g., exacerbated social exclusion, diminished social support). Furthermore, through BEI analysis, friend support exhibited the lowest negative BEI, which is consistent with previous research identifying nodes with high negative BEI as protective factors [53]. Therefore, friend support scarcely functions as a “risk bridge”; instead, it acts more like an “isolation gate”. It not only rarely connects other symptoms but also weakens the pathways through which social exclusion and sedentary behavior spread to psychological distress, thereby becoming the most secure “guardian node” in the network. This suggests that friend support may be more useful as a protective factor to promote mental health and maintain good social adjustment, a finding with important clinical reference value. Therefore, creating more opportunities for children to interact with peers while reducing their sedentary time may be an effective strategy for intervention practices to promote their mental health development.

This study is not without limitations. First, the use of only self-reported information also limits the conclusions drawn from this study. Second, this study was cross-sectional and therefore, causal inferences could not be made. Third, the sample’s representativeness is limited due to a gender imbalance (overrepresentation of females), even though it included both high school and university students. Fourth, Low internal consistency reliability for some measures, such as the OES, may have compromised the stability and accuracy of the results.

Psychological distress is a prevalent problem in the student population and has a serious impact on their mental health, hence the need to identify its risk and preventive factors. Different concepts are included in sedentary, social indicators, and psychological distress. New statistical models, such as network analysis, help us to better understand and analyze these concepts. Therefore, it is crucial to reveal the factors associated with psychological distress and analyze the relationship between them in preventive and protective services. The results of this study provide evidence for the relationship between sedentariness, social indicators, and psychological distress.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Yuyang Nie and Kunkun Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Management, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing; Xiaofei Liu: Manuscript Revision, Review, Language Polishing, Editing; Tianci Wang: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data Management, Writing—Original Draft; Cong Liu: Conceptualization, Project Management, Data Collation, Survey; Kangli Du and Yuxian Cao: Methodology, Data Processing; Lijia Hou: Supervision, Investigation, Writing—Review and Editing of the Original Draft; Guofeng Qu: Project Management, Investigation, Resource Provision, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Ethics Approval: This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, Beijing Normal University (Approval No.: BNU202506090156), and has obtained written informed consent from all subjects to ensure that they participate in this study on a voluntary basis.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.073592/s1.

References

1. Tremblay MS , Aubert S , Barnes JD , Saunders TJ , Carson V , Latimer-Cheung AE , et al. Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)—terminology consensus project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017; 14( 1): 75. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Paudel S , Ahmadi M , Phongsavan P , Hamer M , Stamatakis E . Do associations of physical activity and sedentary behaviour with cardiovascular disease and mortality differ across socioeconomic groups? A prospective analysis of device-measured and self-reported UK biobank data. Br J Sports Med. 2023; 57( 14): 921– 9. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-105435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. DeMattia L , Lemont L , Meurer L . Do interventions to limit sedentary behaviours change behaviour and reduce childhood obesity? A critical review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2007; 8( 1): 69– 81. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2006.00259.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li S , Guo J , Zheng K , Shi M , Huang T . Is sedentary behavior associated with executive function in children and adolescents? A systematic review. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 832845. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.832845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Reyes-Molina D , Alonso-Cabrera J , Nazar G , Parra-Rizo MA , Zapata-Lamana R , Sanhueza-Campos C , et al. Association between the physical activity behavioral profile and sedentary time with subjective well-being and mental health in Chilean University students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19( 4): 2107. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Pfefferbaum B , Van Horn RL . Physical activity and sedentary behavior in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022; 24( 10): 493– 501. doi:10.1007/s11920-022-01366-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Thomas G , Bennie JA , De Cocker K , Castro O , Biddle SJH . A descriptive epidemiology of screen-based devices by children and adolescents: a scoping review of 130 surveillance studies since 2000. Child Indic Res. 2020; 13( 3): 935– 50. doi:10.1007/s12187-019-09663-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang L , Cao C , Kantor ED , Nguyen LH , Zheng X , Park Y , et al. Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001–2016. JAMA. 2019; 321( 16): 1587– 97. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cai Y , Zhu X , Wu X . Overweight, obesity, and screen-time viewing among Chinese school-aged children: national prevalence estimates from the 2016 physical activity and fitness in China—the youth study. J Sport Health Sci. 2017; 6( 4): 404– 9. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2017.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sharp J , Theiler S . A review of psychological distress among university students: pervasiveness, implications and potential points of intervention. Int J Adv Couns. 2018; 40( 3): 193– 212. doi:10.1007/s10447-018-9321-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Krokstad S , Weiss DA , Krokstad MA , Rangul V , Kvaløy K , Ingul JM , et al. Divergent decennial trends in mental health according to age reveal poorer mental health for young people: repeated cross-sectional population-based surveys from the HUNT study, Norway. BMJ Open. 2022; 12( 5): e057654. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li F , Cui Y , Li Y , Guo L , Ke X , Liu J , et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in school children and adolescents in China: diagnostic data from detailed clinical assessments of 17,524 individuals. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022; 63( 1): 34– 46. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ye YL , Wang PG , Qu GC , Yuan S , Phongsavan P , He QQ . Associations between multiple health risk behaviors and mental health among Chinese college students. Psychol Health Med. 2016; 21( 3): 377– 85. doi:10.1080/13548506.2015.1070955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kristensen SM , Larsen TMB , Urke HB , Danielsen AG . Academic stress, academic self-efficacy, and psychological distress: a moderated mediation of within-person effects. J Youth Adolesc. 2023; 52( 7): 1512– 29. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01770-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Murberg TA , Bru E . The role of coping styles as predictors of depressive symptoms among adolescents: a prospective study. Scand J Psychol. 2005; 46( 4): 385– 93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2005.00469.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Schraml K , Perski A , Grossi G , Simonsson-Sarnecki M . Stress symptoms among adolescents: the role of subjective psychosocial conditions, lifestyle, and self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2011; 34( 5): 987– 96. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lee E , Kim Y . Effect of university students’ sedentary behavior on stress, anxiety, and depression. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019; 55( 2): 164– 9. doi:10.1111/ppc.12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Werneck AO , Collings PJ , Barboza LL , Stubbs B , Silva DR . Associations of sedentary behaviors and physical activity with social isolation in 100,839 school students: the Brazilian scholar health survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019; 59: 7– 13. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Baumbach L , König HH , Hajek A . Associations between changes in physical activity and perceived social exclusion and loneliness within middle-aged adults–longitudinal evidence from the German ageing survey. BMC Public Health. 2023; 23( 1): 274. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15217-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. García-Hermoso A , Hormazabal-Aguayo I , Oriol-Granado X , Fernández-Vergara O , Del Pozo Cruz B . Bullying victimization, physical inactivity and sedentary behavior among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020; 17( 1): 114. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-01016-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kiefer M , Sim EJ , Heil S , Brown R , Herrnberger B , Spitzer M , et al. Neural signatures of bullying experience and social rejection in teenagers. PLoS One. 2021; 16( 8): e0255681. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Arslan G . School-based social exclusion, affective wellbeing, and mental health problems in adolescents: a study of mediator and moderator role of academic self-regulation. Child Indic Res. 2018; 11( 3): 963– 80. doi:10.1007/s12187-017-9486-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yu X , Du H , Li D , Sun P , Pi S . The influence of social exclusion on high school students’ depression: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023; 16: 4725– 35. doi:10.2147/prbm.s431622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. McLean L , Gaul D , Penco R . Perceived social support and stress: a study of 1st year students in Ireland. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2023; 21( 4): 2101– 21. doi:10.1007/s11469-021-00710-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alsubaie MM , Stain HJ , Webster LAD , Wadman R . The role of sources of social support on depression and quality of life for university students. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2019; 24( 4): 484– 96. doi:10.1080/02673843.2019.1568887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Fitzpatrick MM , Anderson AM , Browning C , Ford JL . Relationship between family and friend support and psychological distress in adolescents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2024; 38( 6): 804– 11. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2024.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Swed S , Alibrahim H , Bohsas H , Nashwan AJ , Elsayed M , Almoshantaf MB , et al. Mental distress links with physical activities, sedentary lifestyle, social support, and sleep problems: a Syrian population cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2023; 13: 1013623. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1013623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Harandi TF , Taghinasab MM , Nayeri TD . The correlation of social support with mental health: a meta-analysis. Electron Physician. 2017; 9( 9): 5212– 22. doi:10.19082/5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Vandenbroucke JP , von Elm E , Altman DG , Gøtzsche PC , Mulrow CD , Pocock SJ , et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014; 12( 12): 1500– 24. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Constantin MA , Schuurman NK , Vermunt JK . A general Monte Carlo method for sample size analysis in the context of network models. Psychol Meth. 2023: 1– 22. doi:10.1037/met0000555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Craig CL , Marshall AL , Sjöström M , Bauman AE , Booth ML , Ainsworth BE , et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Phys Exerc. 2003; 35( 8): 1381– 95. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000078924.61453.fb. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Rosenberg DE , Bull FC , Marshall AL , Sallis JF , Bauman AE . Assessment of sedentary behavior with the international physical activity questionnaire. J Phys Act Health. 2008; 5( s1): S30– 44. doi:10.1123/jpah.5.s1.s30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Cordier R , Milbourn B , Martin R , Buchanan A , Chung D , Speyer R . A systematic review evaluating the psychometric properties of measures of social inclusion. PLoS ONE. 2017; 12( 6): e0179109. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang DH , Huang LQ , Dong Y . Reliability and validity of the ostracism experience scale for adolescents in Chinese adolescence. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2018; 26( 6): 1123– 6. (In Chinese). doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zimet GD , Dahlem NW , Zimet SG , Farley GK . The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52( 1): 30– 41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lovibond PF , Lovibond SH . The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995; 33( 3): 335– 43. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Gong X , Xie XY , Xu R , Luo YJ . Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2010; 18( 4): 443– 6. (In Chinese). doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Epskamp S , Borsboom D , Fried EI . Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018; 50( 1): 195– 212. doi:10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Epskamp S , Cramer AOJ , Waldorp LJ , Schmittmann VD , Borsboom D . qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat Soft. 2012; 48( 4): 1– 18. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jones PJ , Ma R , McNally RJ . Bridge centrality: a network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivar Behav Res. 2021; 56( 2): 353– 67. doi:10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Haslbeck JMB , Waldorp LJ . How well do network models predict observations? On the importance of predictability in network models. Behav Res Meth. 2018; 50( 2): 853– 61. doi:10.3758/s13428-017-0910-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. van Borkulo CD , van Bork R , Boschloo L , Kossakowski JJ , Tio P , Schoevers RA , et al. Comparing network structures on three aspects: a permutation test. Psychol Methods. 2023; 28( 6): 1273– 85. doi:10.1037/met0000476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kline RB . Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications; 2023. [Google Scholar]

44. Yang M , Wei W , Ren L , Pu Z , Zhang Y , Li Y , et al. How loneliness linked to anxiety and depression: a network analysis based on Chinese university students. BMC Public Health. 2023; 23( 1): 2499. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-17435-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Owczarek M , Nolan E , Shevlin M , Butter S , Karatzias T , McBride O , et al. How is loneliness related to anxiety and depression: a population-based network analysis in the early lockdown period. Int J Psychol. 2022; 57( 5): 585– 96. doi:10.1002/ijop.12851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ashdown-Franks G , Koyanagi A , Vancampfort D , Smith L , Firth J , Schuch F , et al. Sedentary behavior and perceived stress among adults aged ≥50 years in six low- and middle-income countries. Maturitas. 2018; 116: 100– 7. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Saravanan C , Wilks R . Medical students’ experience of and reaction to stress: the role of depression and anxiety. Sci World J. 2014; 2014( 1): 737382. doi:10.1155/2014/737382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bowker JC , Adams RE , Fredstrom BK , Gilman R . Experiences of being ignored by peers during late adolescence: linkages to psychological maladjustment. Merrill Palmer Q. 2014; 60( 3): 328. doi:10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.60.3.0328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Gariépy G , Honkaniemi H , Quesnel-Vallée A . Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016; 209( 4): 284– 93. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Boudreault-Bouchard AM , Dion J , Hains J , Vandermeerschen J , Laberge L , Perron M . Impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological distress: results of a four-year longitudinal study. J Adolesc. 2013; 36( 4): 695– 704. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhou S , Liu G , Huang Y , Huang T , Lin S , Lan J , et al. The contribution of cultural identity to subjective well-being in collectivist countries: a study in the context of contemporary Chinese culture. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1170669. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1170669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Chen C , Li F , Liu C , Li K , Yang Q , Ren L . The relations between mental well-being and burnout in medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: a network analysis. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 919692. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.919692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Liu C , Ren L , Rotaru K , Liu X , Li K , Yang W , et al. Bridging the links between big five personality traits and problematic smartphone use: a network analysis. J Behav Addict. 2023; 12( 1): 128– 36. doi:10.1556/2006.2022.00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Barbosa BCR , de Menezes-Júnior LAA , de Paula W , dos Santos Chagas CM , Machado EL , de Freitas ED , et al. Sedentary behavior is associated with the mental health of university students during the Covid-19 pandemic, and not practicing physical activity accentuates its adverse effects: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24( 1): 1860. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19345-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools