Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Static Analysis Techniques for Secure Software: A Systematic Review

1 Department of Computer Science, Murang’a University of Technology, Murang’a, 75-10200, Kenya

2 Department of Information Technology, Murang’a University of Technology, Murang’a, 75-10200, Kenya

* Corresponding Author: Brian Mweu. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 417-437. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.071765

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 10 October 2025

Abstract

Static analysis methods are crucial in developing secure software, as they allow for the early identification of vulnerabilities before the software is executed. This systematic review follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines to assess static analysis techniques for software security enhancement. We systematically searched IEEE Xplore, Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Digital Library, SpringerLink, and ScienceDirect for journal articles published between 2017 and 2025. The review examines hybrid analyses and machine learning integration to enhance vulnerability detection accuracy. Static analysis tools enable early fault detection but face persistent challenges. These include high false-positive rates, scalability issues, and usability concerns. Our findings provide guidance for future research and methodological advancements to create better tools for secure software development.Keywords

Code analysis tools have gained importance in detecting software system vulnerabilities before deployment. These tools utilize algorithms and heuristics to scrutinize source code without executing it [1]. They facilitate the early identification of security issues such as buffer overflows, Structured Query Language (SQL) injection, and input validation flaws. Incorporating them into Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipelines allows for the prompt resolution of security issues, thereby lowering the costs associated with fixing vulnerabilities in production [2].

Recent advancements in automated integration reflect this trend. For instance, Sorald employs metaprogramming templates to propose solutions for static analysis warnings, achieving a 65% success rate in addressing violations across 161 GitHub repositories [3]. This automated method eases developers’ workload while maintaining code quality standards.

Despite their effectiveness, static analysis tools face significant challenges in real-world deployment. Recent studies have incorporated machine learning (ML) to enhance detection accuracy, although translating laboratory precision to practical effectiveness remains difficult. Hybrid approaches that merge static and dynamic analyses are also becoming popular for comprehensive security evaluations.

However, there is a lack of detailed reviews systematically comparing these techniques across various software environments, hindering researchers and practitioners from making informed choices about technique selection for specific environments. A systematic review is needed to consolidate existing knowledge, identify research gaps, and guide future advancements.

This article outlines the strengths and weaknesses of static analysis techniques, highlights research gaps, and suggests improved vulnerability detection methods. Our extensive survey includes the integration of code analysis with dynamic and ML approaches, aiding developers in choosing suitable techniques to enhance code quality and security.

2 Unique Contributions of This Review

In this review, we uniquely link the constraints of static analysis with innovative solutions. We explore well-known limitations such as high false positive rates, inflexible rules, and insensitivity to context, and connect them with real innovations that tackle these challenges. Recent reviews indicate that even the latest analyzers can overlook subtle vulnerabilities [4].

We are the first to systematically compare computational cost with detection accuracy across different static analysis paradigms. Our study offers practical advice for selecting tools in resource-limited environments, showing that rule-based tools like SonarJava offer speed but lower accuracy, whereas ML-based tools like VulDetector achieve higher detection rates at a higher computational cost.

Unlike other reviews that portray machine learning integration as inherently advantageous, we provide the first critical assessment of the limitations of ML-based vulnerability detection. We thoroughly discuss issues such as bias propagation, interpretability challenges, and cross-domain generalization problems. This critical framework goes beyond the limitations of current literature that did not address practical implementation constraints.

We establish the first formal classification of static analysis problems into tool-level (false positives), architectural (semantic comprehension), and systemic (scalability) constraints. This model enables solution development at a specific level rather than generic enhancement. Human-centered adoption analysis:

We identify specific developer and organizational factors influencing tool adoption, a topic rarely covered in static analysis surveys. Building on developer-focused work [5], we demonstrate why usability, actionable feedback, and managerial support are more important than detection capability alone.

We provide empirical evidence of the effectiveness of hybrid approaches with tools like AndroShield [6] and learning-based approaches like NS-Slicer [7]. By translating each technical issue into real-world solution examples, our survey is more practically oriented compared to previous theoretical reviews.

Our tabular research gap categorization offers clear direction for future research and sets our survey apart from previous ones lacking comprehensive gap analysis. We integrate human and organizational issues with technical assessment, offering a complete picture of static analysis adoption missing in existing reviews.

Research Questions

1. What technical limitations prevent static analysis tools from detecting complex vulnerabilities?

2. How effective are hybrid static-dynamic and machine learning approaches in improving vulnerability detection?

3. Which organizational factors influence static analysis tool adoption in development workflows?

3 Taxonomy of Static Analysis Techniques

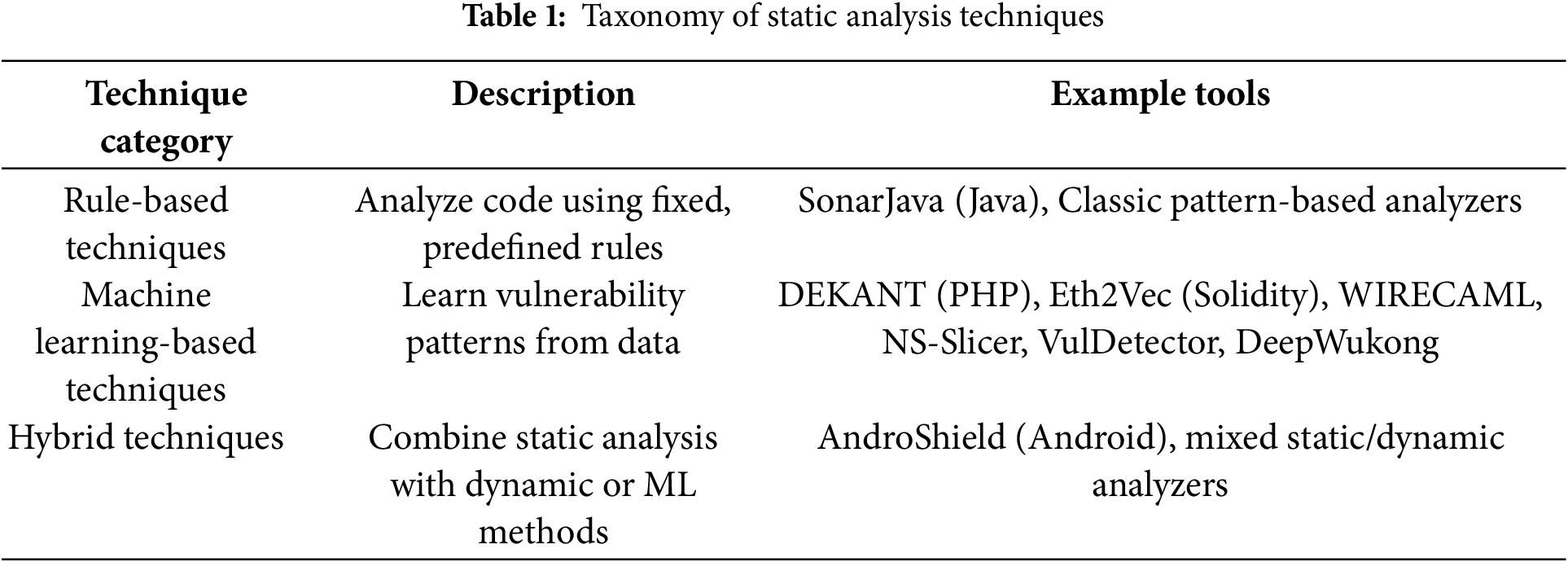

Static analysis techniques can be systematically categorized into three primary approaches, each with distinct characteristics and applications as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 classifies static analysis techniques into three main categories based on their underlying methodologies and implementation approaches.

3.1 Rule-Based methods

These techniques evaluate code by comparing it to pre-established, human-designed rules or patterns. While they quickly identify common security issues, they might not detect new ones. Examples of such tools include SonarJava, a rule-based Java analyzer with numerous rules, and other conventional static analyzers that rely on pattern matching.

3.2 Machine Learning-Based Methods

These techniques develop models using code and vulnerability data to automatically detect patterns linked to security flaws. They are capable of adapting to new types of vulnerabilities without requiring the programmer to define explicit rules. Some examples are DEKANT (PHP, sequence-model-based), Eth2Vec (Ethereum smart contracts, neural network-based), WIRECAML (web languages, ML-based data-flow analysis), NS-Slicer (multilingual, learning-based program slicing), VulDetector (C/C++, graph-based ML), and DeepWukong (multilingual, deep learning-based).

These approaches integrate static analysis with additional techniques, often involving dynamic analysis or machine learning-enhanced static analysis. By utilizing multiple analysis strategies, they strive to minimize incorrect alerts and detect a greater number of instances. For instance, AndroShield employs both static and dynamic analysis for Android applications.

This study followed a systematic review protocol in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure methodological rigor, transparency, and reproducibility in reviewing static analysis techniques for secure software development. The protocol was designed to gather, evaluate, and synthesize existing literature on static analysis methods. This includes their effectiveness in vulnerability detection, integration with machine learning techniques, and organizational factors influencing adoption.

4.1 Search Strategy and Data Sources

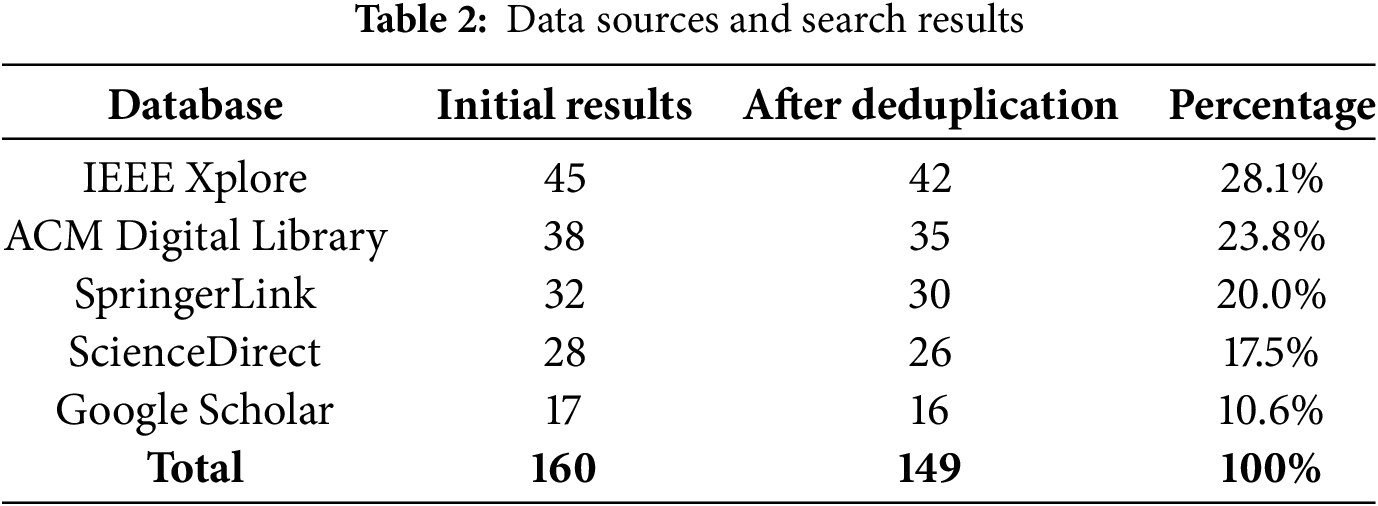

A comprehensive search strategy was developed using a three-tier approach to ensure exhaustive coverage of relevant literature. The search was conducted between March 2025 and May 2025 across five major electronic databases. The following search strings were systematically applied across all databases with results summarized in Table 2.

Primary Search String:

(“static analysis” OR “static code analysis” OR “source code analysis”) AND (“software security” OR “vulnerability detection” OR “secure software development” OR “security vulnerability”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “hybrid analysis” OR “dynamic analysis”)

Secondary Search String:

(“static analysis” AND (“false positives” OR “false positive reduction”)) OR (“vulnerability detection” AND (“developer workflows” OR “developer adoption”)) OR (“secure software development” AND (“organizational culture” OR “organizational factors”))

Tertiary Targeted Searches:

(“static analysis” AND “machine learning” AND “vulnerability detection” AND (2023 OR 2024 OR 2025)) (“hybrid static dynamic analysis” AND “software security”) (“AI-driven vulnerability detection” AND “static analysis”) (“deep learning” AND “code vulnerability” AND “detection”)

Search strings were adapted to accommodate each database’s specific syntax requirements while maintaining semantic consistency. Search parameters were limited to peer-reviewed articles, English language publications, and the timeframe 2017–2025. These search strings were adapted for each database’s specific syntax requirements. Search limits included: peer-reviewed articles, English language, publication years 2017–2025.

4.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

The criteria for inclusion in this study encompassed peer-reviewed conference papers and journal articles published between 2017 and 2025, specifically concentrating on static analysis techniques for software security or vulnerability detection. Selected studies needed to present empirical results (quantitative or qualitative) or offer significant methodological contributions. All papers considered were required to be in English and address at least one of the key research questions related to the limitations of static analysis, hybrid approaches, or organizational factors affecting the application and effectiveness of these security analysis techniques.

Exclusion Criteria

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were rigorously applied to filter out studies that did not adhere to the stringent academic standards set for this research. To ensure the integrity and reliability of the evidence base, non-peer-reviewed materials such as gray literature, technical reports, and workshop abstracts were omitted. Studies lacking detailed methodologies were also excluded, along with duplicate or largely similar research from the same groups, to avoid bias and the overemphasis of certain findings.

The time frame was strictly adhered to by excluding studies published before 2017 or in languages other than English. Furthermore, research focusing solely on dynamic analysis without any static analysis elements was considered outside the scope of this study, as were general software testing studies not specifically aimed at detecting security vulnerabilities. This approach ensured that all included research directly contributed to enhancing static analysis from a software security standpoint.

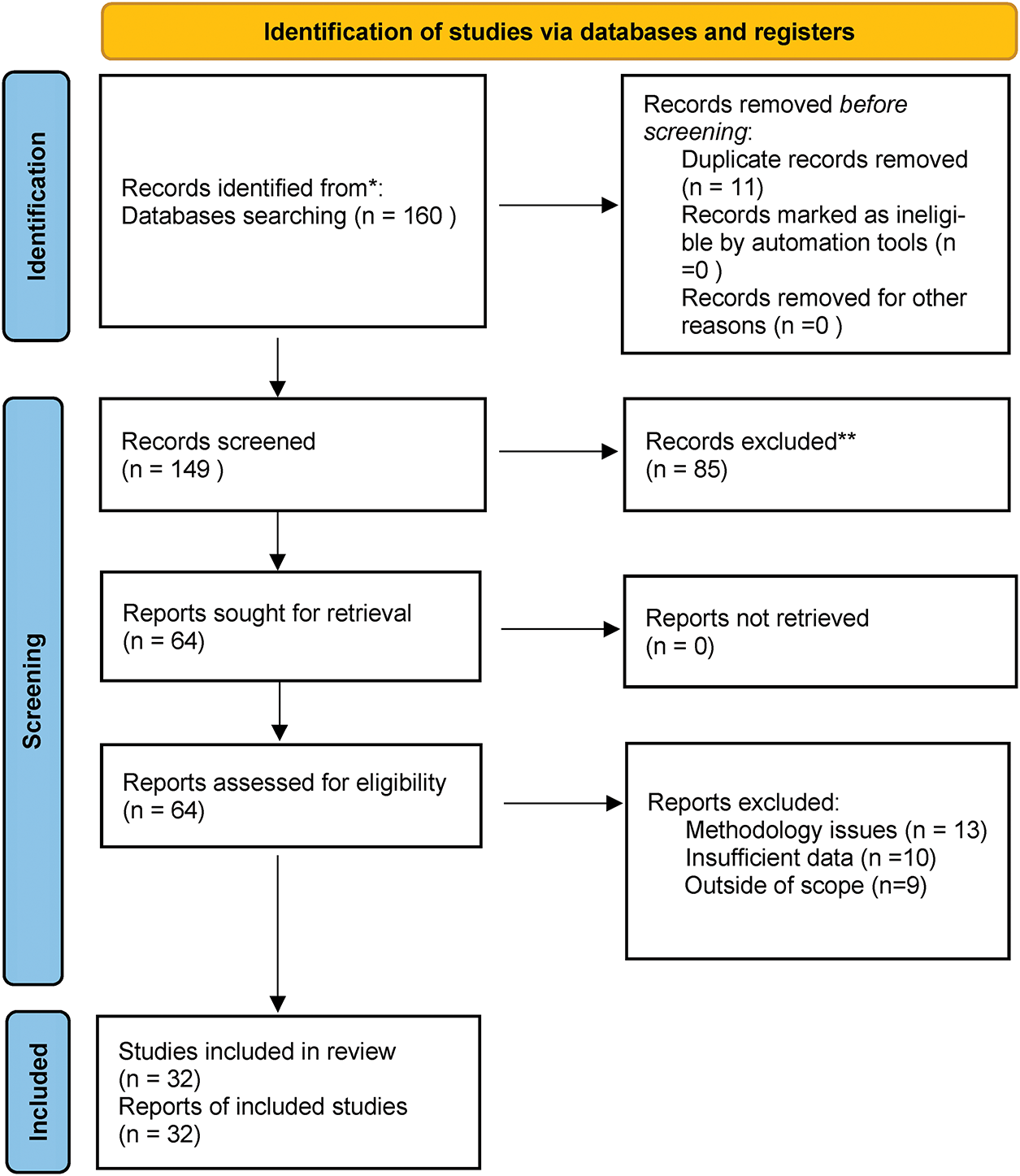

The study selection followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines as illustrated in Fig. 1. The process involved multiple screening phases to ensure only relevant and high-quality studies were included in the final analysis.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Stage 1: First Search and Deduplication

The initial search phase across all the databases selected yielded a total of 160 papers that potentially meet the research requirements. During this phase, reference management software was utilized to identify and remove duplicate entries, and 11 duplicate papers were removed from the initial pool. Following deduplication, a total of 149 single papers remained and were sent to the subsequent screening stages of the systematic review.

Stage 2: Title Screening

BM and JN, the two independent reviewers, carried out the title screening stage by screening all 149 of the initial unique papers solely on the basis of their titles. During the screening process, clearly irrelevant papers outside the research’s intended area were discarded, and 47 papers incompatible with the purposes of the study were discarded. This screening process demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.84, indicating strong agreement between the two reviewers. Following title screening, 102 articles entered the abstract evaluation phase.

Stage 3: Abstract Screening

Both reviewers independently did a detailed assessment of the remaining 102 articles’ abstracts based on the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine their suitability for answering the research questions. Out of the extensive process of evaluation, 38 papers were excluded due to non-applicability to the specific questions of research under consideration in the systematic review. Any conflict or disputes occurring between the reviewers were solved systematically through discussion, and six such conflicts were required to be solved. While conducting the screening, 64 papers were selected for comprehensive full-text examination.

Stage 4: Full-Text Assessment

The stage of full-text screening involved a careful evaluation of the whole papers in relation to the broad set of inclusion criteria for the research. At this critical stage, 30 papers were excluded due to various methodological and scope reasons: 13 papers were excluded due to poor or ambiguous methodology, 10 papers lacked sufficient empirical data to support their findings, and 9 papers were identified as outside the defined scope of the study. This rigorous testing process ultimately provided a final sample of 32 papers that met all inclusion criteria and were hence included in the systematic review.

Quality Control Measures

To ensure that the reliability and validity of the screening process were protected, several quality control measures were followed during the selection process. There were recurrent calibration meetings with the principal reviewers to ensure uniform evaluation standards and decision-making strategies. Where conflicts could not be resolved through discussion between the two primary reviewers, third reviewer opinion was sought, and this occurred with two unresolved conflicts at the screening phase. In addition to this, a complete decision audit trail was maintained for the entire selection process so that transparency and reproducibility of the systematic review process could be ensured.

4.4 Data Extraction and Analysis

A detailed and standardized data extraction form was developed methodically and stringently pilot-tested on five selected papers in order to determine its effectiveness and reliability before full implementation on the whole sample. In the process, three varied categories of information were extracted in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of each study. Attributes used in the study involved pertinent information like publication year, geography, type of research, population size, evaluation metrics, geographic location, and the actual domains of software upon which the work was performed.

Technical content focused on the critical analytic aspects, recording the static analysis techniques applied, integration with machine learning or dynamic analysis techniques if applicable, the actual types of vulnerabilities discovered, and quantitative performance metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score measurements. Organizational topics addressed the human and situational variables like developer adoption problems, organizational implementation factors, and large-scale tool usability testing. To maintain consistency and accuracy of extraction, the lead reviewer (BM) did all the steps of data extraction, while the second reviewer (JN) did verification on 20% of the documents to ascertain reliability and minimize extraction errors.

The research employed a qualitative synthesis method with thematic analysis techniques to systematically identify and classify recurring patterns and themes that occurred within the collected literature. Through conducting such an exhaustive analytical process, three main and interconnected themes were established that collectively outline the character of static analysis research in software security today.

The first theme was on technical limitations and issues surrounding the latest state-of-the-art static analysis tools, considering their computational needs and detection features. The second theme was on varying integration techniques that combine static analysis with dynamic analysis methods and machine learning approaches to enhance overall detection effectiveness. The third theme investigated the key human and organizational variables that have a significant influence on the adoption and successful implementation of static analysis tools in real-world software development environments.

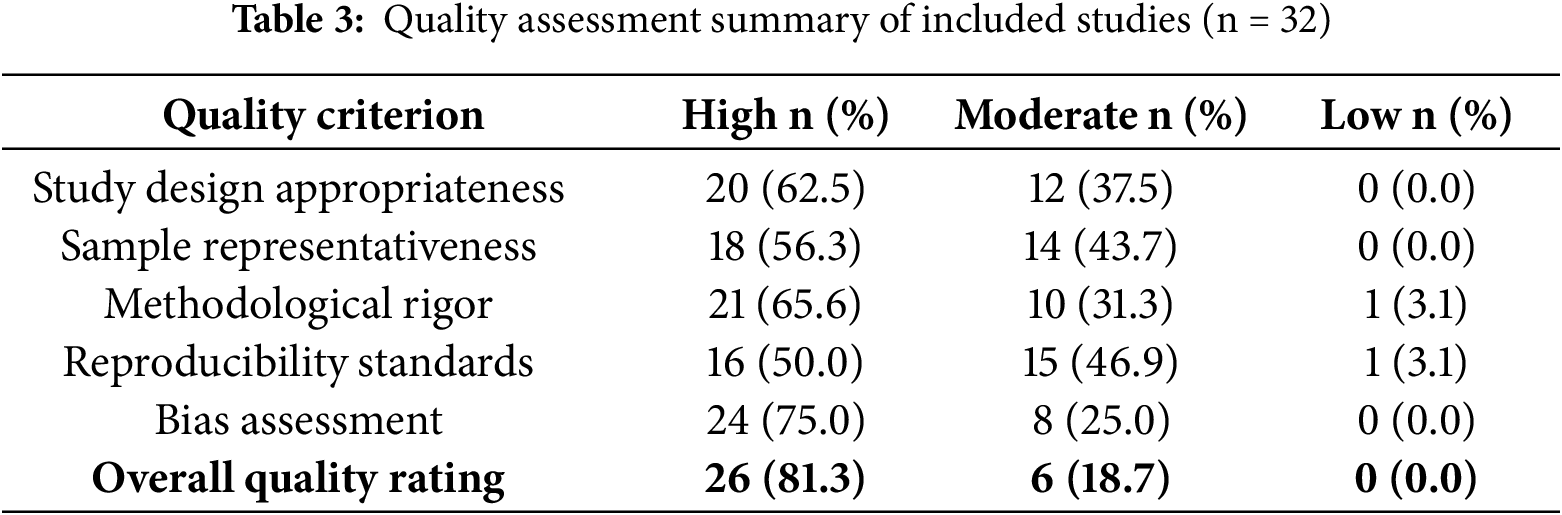

The research underwent a rigorous methodological quality evaluation, utilizing adapted criteria from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist to ensure standardized evaluation criteria. The model assessed five fundamental aspects of research quality. The applicability of the study design ensured alignment between the research questions and the methodology, while sample representativeness evaluated the adequacy of the dataset, instruments, and participant samples.

The rigor of evaluation concentrated on the validity and reliability of the measurement and measurement strategy. Reproducibility criteria determined whether there was enough methodological detail to allow for replication. Bias filtering identified potential sources of systematic error that could undermine validity. Studies were categorized as high, moderate, or low quality, with all studies achieving at least moderate quality for inclusion in the systematic review. The quality assessment results are presented in Table 3.

Quality ratings based on adapted CASP criteria: study design appropriateness, sample representativeness, methodological rigor, reproducibility standards, and bias assessment. All studies met at least moderate quality standards for inclusion in the systematic review.

This systematic review was conducted as secondary research that analyzed published research literature without primary data collection. All studies utilized were publicly available in academic databases and referenced according to scholarly standards and ethical guidelines. As this was a secondary study using only published literature, institutional review board or ethics committee approval was not required. This systematic review was not registered in a public registry. No formal protocol was prepared for this review.

5.1 Static Analysis Limitations

Since their inception, static analysis techniques have undergone significant evolution, becoming essential tools for detecting security vulnerabilities in software, especially in web applications. Static analysis tools are employed to identify the metadata and binary code of software without running it. This allows for the early identification of potential threats. However, their effectiveness can differ based on the type of software they are intended to examine.

Comprehensive evaluations reveal systematic limitations across current tools. Alqaradaghi and Kozsik’s assessment of static analysis tools demonstrates that even latest analyzers may miss hidden vulnerabilities, with performance varying significantly across different vulnerability types [4]. A significant problem with code inspection tools is their propensity to generate a large number of false positives. Yuan et al. demonstrate that traditional pattern-matching approaches in SQL injection detection generate substantial false alerts due to their inability to understand program semantics and execution environments [8]. This issue forces developers to manually review each alert to verify its accuracy [8]. This not only increases their workload but also results in critical vulnerabilities being overlooked due to alert fatigue.

Code analyzers face challenges with complex vulnerabilities involving intricate programming logic. The challenge extends beyond rule obsolescence to fundamental architectural limitations. Ferreira et al. show that dependency graph analysis can address some scalability issues, but complexity remains a barrier for comprehensive vulnerability detection in large JavaScript applications [9]. Research shows deep learning techniques with explainable Artificial Intelligence (AI) can improve detection by adapting to new attack patterns and providing explanations for vulnerability detection [9].

Code inspection methods struggle with extensive codebases, as increasing complexity reduces analyzer precision, causing performance issues and false negatives [10]. They also fail to consider the broader context like development environment, team practices, and application type, which is crucial for identifying context-specific vulnerabilities. Researchers have explored hybrid approaches combining static and dynamic analysis techniques, such as methods for detecting vulnerabilities in Android applications [6].

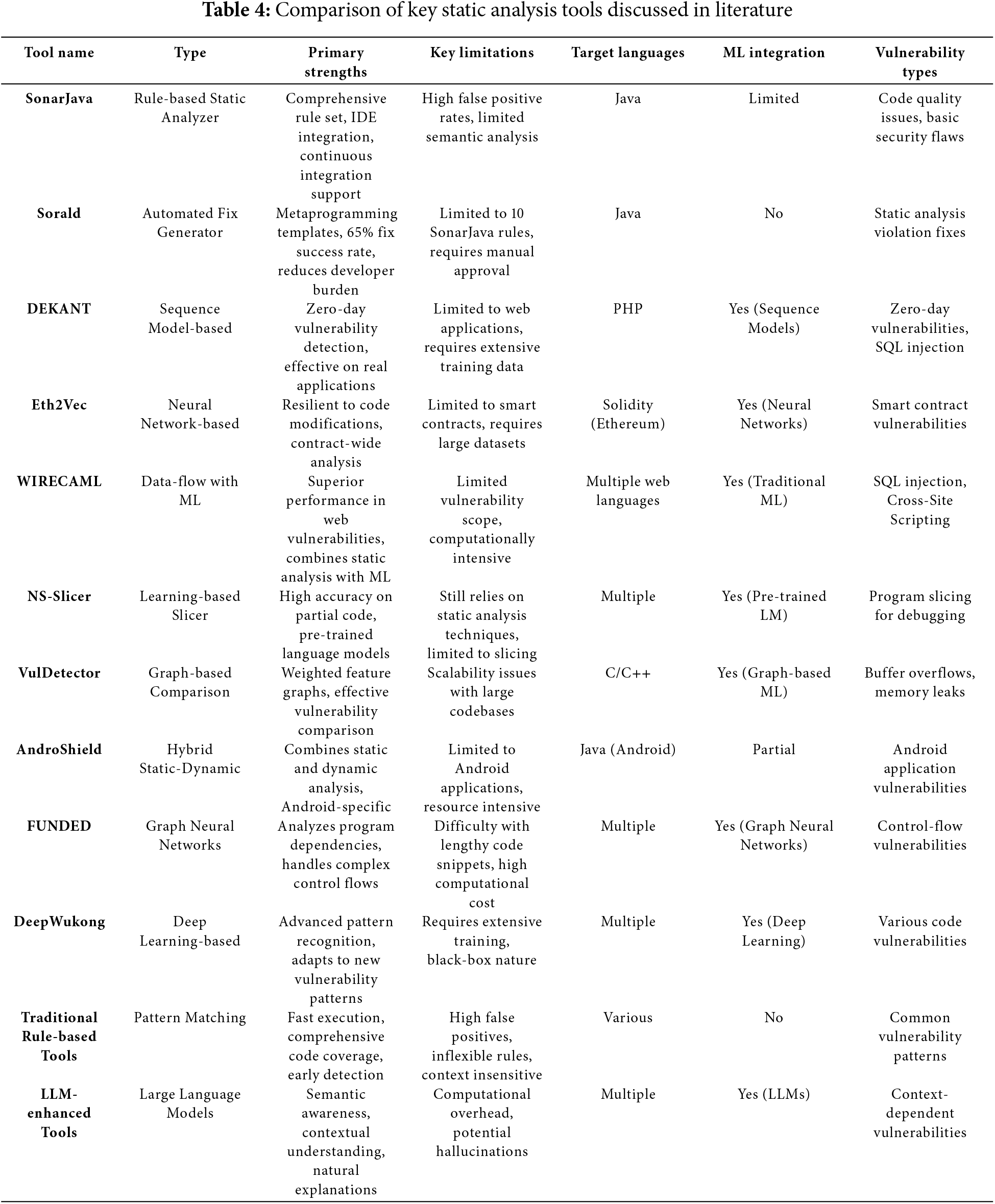

Machine learning integration in static tools has improved efficiency, with AI-driven tools using deep learning models to identify security weaknesses in real time [11]. These techniques combine program analysis with AI to identify high-severity weaknesses automatically. Manual code reviews help offset limitations and provide thorough vulnerability identification [9]. These systems require continuous improvement and integration with other methods to address software vulnerabilities effectively. A comprehensive comparison of the key static analysis tools discussed in the literature is presented in Table 4, highlighting their respective strengths, limitations, and technical characteristics.

Table 4 illustrates a transition from traditional inspection tools to modern ones incorporating machine learning and hybrid methods: This shift reflects attempts to overcome rule-based systems’ limitations, while introducing challenges related to computational demands and tool complexity.

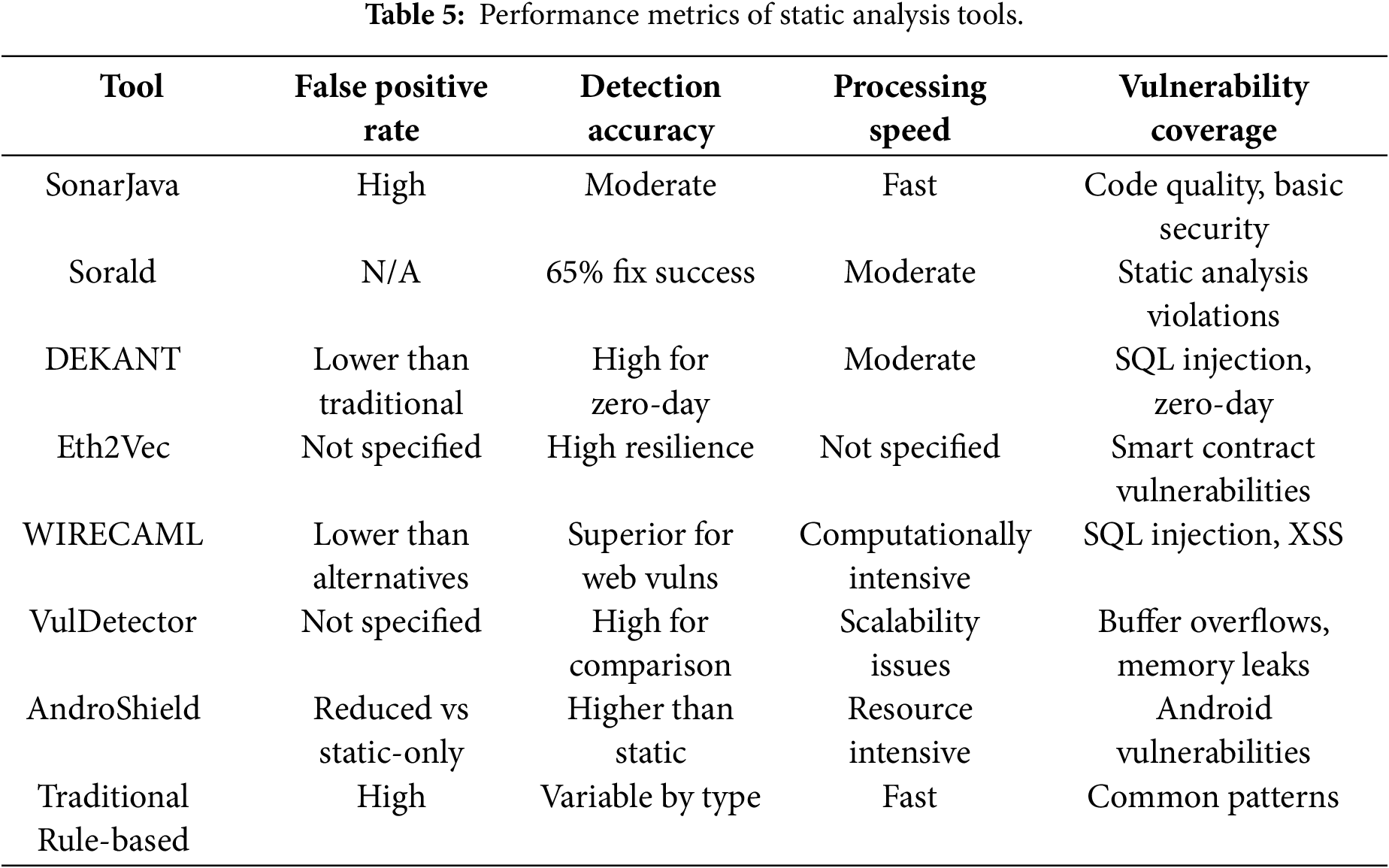

The performance characteristics of these tools, including their detection accuracy and computational requirements, are further detailed in Table 5.

Performance data extracted from empirical studies. N/A indicates metric not reported in source studies.

5.2 Hybrid Static-Dynamic Analysis with Machine Learning

The integration of static and dynamic methods for vulnerability detection in secure software development has various advantages and disadvantages. Static analysis provides comprehensive code coverage and early detection capabilities, but its effectiveness varies by vulnerability type. Yuan et al.’s program transformation approach for SQL injection detection shows that targeted static methods can achieve better precision when designed for specific vulnerability classes [12]. However, as static tools can be helpful in the detection at an early stage, they tend to miss vulnerabilities due to their lack of semantic knowledge and context-sensitivity [13].

Dynamic analysis in executing code in a containment can identify real-time vulnerabilities more precisely and reduce false positives of static analysis. But it requires extensive test case generation and execution, which can be memory-intensive [14]. Advanced integration approaches address traditional limitations through architectural innovations. Multiversion dependency graphs optimize JavaScript analysis by balancing information richness with scalability [9].

Meanwhile, Large Language Model (LLM) integration introduces semantic awareness that traditional rule-based systems lack, with GPT-based approaches showing promise in source code inspection for web applications [15]. Blending the two techniques seeks to leverage their complementary strengths while offsetting their respective weaknesses.

Static analysis alone often struggles to navigate all possible execution paths and frequently results in false positives, as demonstrated in various performance studies assessing their effectiveness in detecting vulnerabilities [4]. To address these shortcomings, utilizing dynamic analysis allows for the examination of an app’s behavior during runtime, leading to more precise and realistic detection of vulnerabilities. Similarly, Ref. [7] proposes employing program slicing to reduce source code complexity before test generation for efficient combined static and dynamic analysis in software verification. Emphasis is given by the NS-Slicer, a new learning-based static program slicing technique, to the use of program slicing to reduce source code before test generation. The method is highly significant for early bug detection and enables both manual and automatic debugging through the prediction of static program slices for complete and partial code.

When integrating the two methods for detecting software vulnerabilities, certain trade-offs must be considered. Code analyzers meticulously scrutinize the code without running it, allowing for the early detection of issues like buffer overflows and memory leaks. On the other hand, dynamic analysis evaluates the software’s behavior during execution, uncovering vulnerabilities that might not be visible through static code analysis [16].

Static analysis is often criticized for its high rate of false positives, which frequently stems from a lack of understanding of execution capabilities. Conversely, dynamic analysis addresses this issue by assessing the actual execution, thereby verifying the authenticity of detected issues and minimizing false positives [17]. By integrating both static and dynamic analysis, a more thorough security testing framework is established.

Static analysis can examine the entire codebase for potential vulnerabilities at any stage of development, while dynamic analysis evaluates the application’s interactions in various environments, thereby broadening the scope of security testing. These hybrid techniques offer improved accuracy, reduced false positives, and improved ability to cope with complex, dynamic software environments, ultimately resulting in the generation of more secure and trustworthy software applications [18].

Contemporary work proposes promising software verification methods integrating dynamic and static analysis. Research [19] shows, that deep learning-based hybrid approaches can significantly enhance intrusion detection capabilities in industrial wireless sensor networks. This demonstrates the promise of dual-mode strategies that leverage advanced machine learning techniques, such as Frechet and Dirichlet models, to improve security detection across various networked systems [19].

Static analysis identifies potential runtime errors, including false alarms. Dynamic analysis through test generation validates these alerts, but test generation may timeout on large programs before checking all alerts. To deal with this, program slicing has been proposed by researchers to reduce source code complexity before generating tests [20]. Observation-based slicing offers a dynamic means of determining beneficial chunks of code by observing the behavior of the program rather than relying on static analysis only. The approach has the capability to overcome certain limitations of static slicing based on syntactic code analysis.

Static slicing, although useful in debugging and code understanding, has issues in handling partial or incomplete code fragments and lacks capturing runtime data. The NS-Slicer, a static slicing algorithm based on learning, aims to bridge these gaps by employing a pre-trained language model to analyze variable-statement relationships within source code. It makes good predictions of static slices for partial and full code with high accuracy but still relies on static analysis techniques [21]. This indicates the complementary nature of different analysis techniques and suggests that combining multiple slicing approaches can further enhance the effectiveness of hybrid static-dynamic analysis.

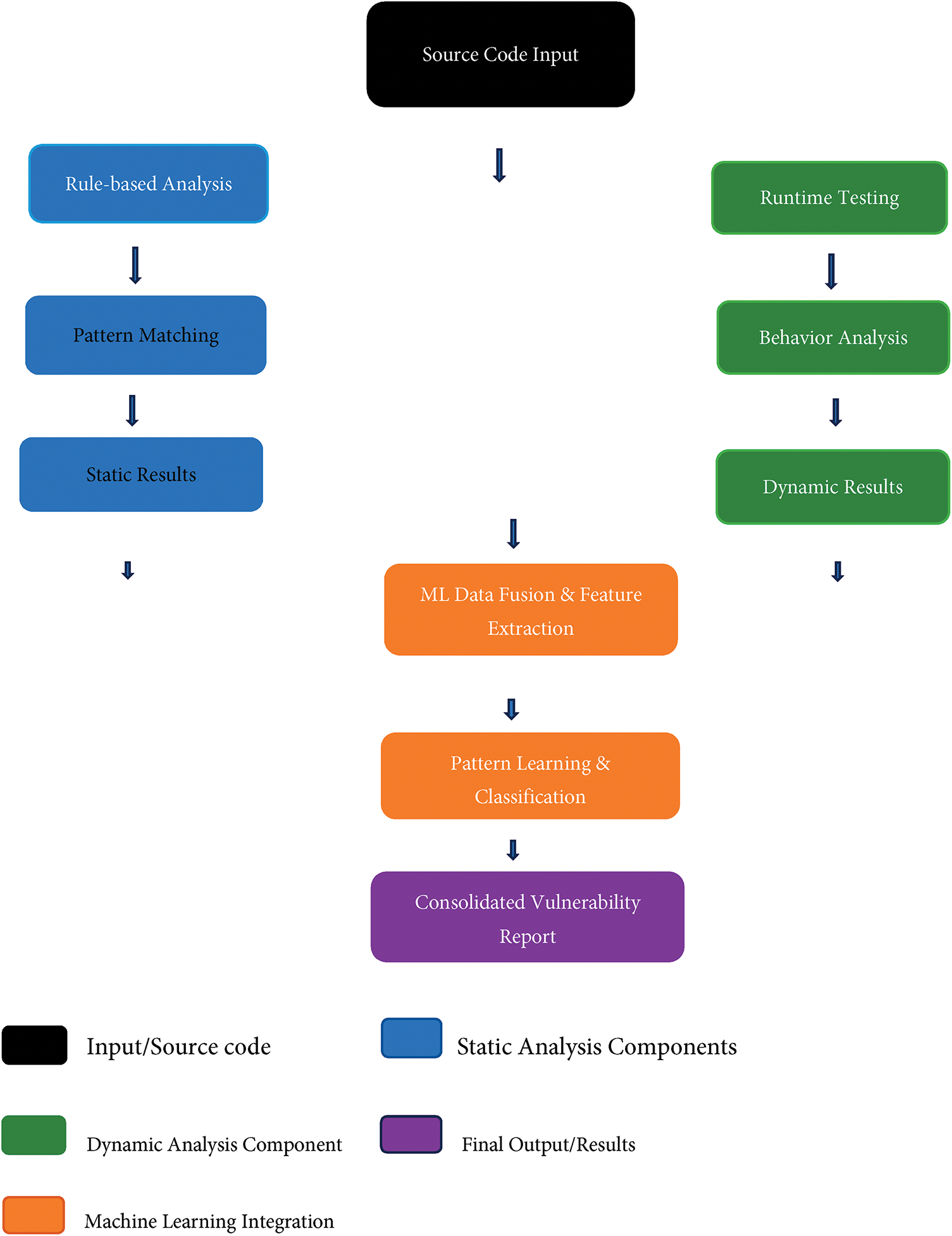

The comprehensive framework for integrating static analysis, dynamic analysis, and machine learning components is illustrated in Fig. 2, which demonstrates the interconnected nature of these approaches in achieving effective vulnerability detection. The framework shows how source code inputs are fed through multiple layers of analysis, with static analysis components identifying likely vulnerabilities, dynamic analysis components validating the findings at runtime, and machine learning integration enhancing detection accuracy through pattern recognition and automated decision-making.

Figure 2: Hybrid static-dynamic analysis framework with machine learning integration

Challenges and Trade-Offs

Nevertheless, both static and dynamic analysis come with their own resource requirements. Automated scanners can be computationally intensive because they thoroughly scrutinize the code. Conversely, dynamic analysis necessitates suitable runtime environments, which might take additional time to establish and conduct tests. Striking a balance between these factors to improve performance without compromising security is a considerable challenge [22].

Despite the integration, handling false negatives can be challenging, as some vulnerabilities, particularly those that are intricate and stem from advanced programming logic, might not be detected. False negatives continue to be a concern because each type of analysis has its own limitations, which can lead to certain vulnerabilities being overlooked [9].

The intricacy of integration requires careful coordination to ensure that the outcomes from both analyses are consistent and do not inundate the development team with excessive data. This complexity often demands specialized expertise or tools to fully leverage its potential without missing crucial insights [4].

5.3 Traditional Machine Learning Integration

Machine learning techniques for static code analysis have demonstrated significant potential in improving the detection of vulnerabilities. These methods seek to address the shortcomings of conventional rule-based inspection tools by autonomously identifying patterns linked to vulnerabilities within extensive codebases.

Several research studies have indicated machine learning’s effectiveness in identifying vulnerabilities. For example, several recent AI-inclined vulnerability detection frameworks have demonstrated significant improvement in identifying zero-day attacks and sophisticated security threats with the use of advanced neural network models [11]. Similarly, machine learning-driven methods for detecting Internet of Things (IoT) vulnerabilities have demonstrated better accuracy in identifying control-flow related vulnerabilities compared to traditional static analyzers, particularly when applied to multilingual software systems [23]. The Eth2Vec tool used neural networks for language processing to detect vulnerabilities in Ethereum smart contracts, showing resilience against code modifications [24].

However, the effectiveness of these methods can be affected by various factors. A comparative analysis indicated that incorporating control dependency can greatly enhance detection efficiency, and the choice of neural network architecture also influences outcomes [25]. Furthermore, the integration of data-flow analysis with machine learning, as seen in the WIRECAML tool, outperformed other tools in identifying SQL injection and Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities [26].

Limitations and Biases of ML-Based Approaches

The use of machine learning for identifying vulnerabilities faces several significant challenges that impede its practical application. One major issue is the quality of training data, as models need vast amounts of labeled vulnerability data to reach standard accuracy levels [7]. The absence of comprehensive and varied datasets results in models that can identify certain vulnerabilities but struggle to adapt to new attack patterns. Another critical challenge is the lack of model interpretability. Deep learning models function as black boxes offering limited insight into their decision-making processes [9]. This lack of transparency makes it difficult for developers to understand why specific code snippets are flagged, reducing trust and hindering integration into production environments.

Bias propagation is another major concern. Models trained on historical vulnerability data may perpetuate existing biases, overlooking vulnerabilities in less common code patterns or languages [25]. DEKANT’s subpar performance across different programming environments exemplifies the issue of cross-domain generalization. Additionally, practical deployment is constrained by computational costs. Methods like FUNDED face scalability challenges with large codebases due to their high computational demands, leading to trade-offs between detection accuracy and usability in resource-limited settings.

To address evolving attack patterns, ML-based methods require regular retraining, which involves maintenance overhead [11]. Without frequent updates, systems may experience a decline in performance, missing out on newly discovered types of vulnerabilities. The complexity of integration also poses challenges for adoption, as ML-based systems provide probabilities that require further interpretation compared to deterministic rule-based analyzers [27].

Deep learning approaches can be effectively integrated with static analysis to enhance vulnerability detection in source code, addressing some limitations of traditional methods while leveraging the strengths of both techniques. Static analysis tools often rely on predefined rules and lack semantic analysis capabilities, leading to spurious warnings and false negatives [9]. Deep learning methods, on the other hand, can learn vulnerability features during the training process without requiring predefined detection rules [9]. By combining these approaches, we can potentially overcome the limitations of static analysis while benefiting from the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning.

Among the promising integration approaches is to utilize deep learning models to complement static analysis with specialization in areas where traditional methods are lacking. For instance, expert systems and artificial intelligence can be applied to examine complex code structures and extract semantic information that static analysis cannot [27]. Latest advancements in AI-based vulnerability discovery in IoT and embedded systems demonstrate this aspect by utilizing advanced machine learning technique to identify and categorize vulnerabilities in device firmware as well as network traffic that are normally challenging for traditional static analysis tools to handle comprehensively [28].

5.5 Developer Adoption and Organizational Factors in Static Analysis Implementation

The adoption of static analysis tools in software development is influenced by organizational factors and developer workflows. For successful integration of such tools, strong leadership is essential in creating an environment conducive to innovation by providing necessary resources and support [29]. The organizational culture should foster innovation and change through willingness to embrace new tools. Organizations that are flexible generally succeed more in implementing new technologies [30].

Having personnel who are trained and skilled can greatly impact the understanding and utilization of static tools. Enough training ensures that developers are capable of using these tools to their fullest extent [30]. The simplicity with which developers can use these static tools facilitates their seamless integration into existing workflows. Conversely, tools that necessitate substantial alterations in developers’ work processes often encounter resistance. In essence, making static analysis reports easier to interpret can enhance their adoption rates [3].

Results from static analysis tools must be practical and useful. Developers often face the challenge of determining if the reported issues are pertinent or merely false positives. Nevertheless, tools that offer straightforward and actionable insights without inundating developers with unnecessary information are more likely to be embraced and utilized effectively [3]. Understanding why developers choose to use these static tools is essential. Often, developers may prioritize certain features, such as the tool’s capability to identify significant security flaws or issues related to the codebase’s style [5].

5.6 Detection Accuracy vs. Computational Cost Trade-Offs

When selecting a static analysis method, one must consider the balance between detection accuracy and computational expense. Traditional rule-based systems, such as SonarJava, execute quickly and cover a wide range of code with minimal computational demands, making them ideal for continuous integration [3]. However, their speed can lead to more false positives and limited semantic analysis capabilities, necessitating additional manual verification.

Machine learning-based methods offer greater accuracy in identifying vulnerabilities but require significantly more computing power. Techniques like VulDetector, which utilize graph-based machine learning, excel in detecting buffer overflows and memory leaks but struggle with scalability in large codebases due to their computational intensity [10]. Similarly, deep learning methods like DeepWukong provide advanced pattern detection but require extensive training time and substantial processing power [4].

Hybrid static-dynamic approaches strike a balance between computational cost and precision. AndroShield, a hybrid static and dynamic analysis tool for Android apps, offers more detailed analysis than static methods while maintaining moderate resource requirements [6]. However, this approach increases the complexity of the test environment and the time needed to run analyses.

The computational burden is particularly significant when employing sophisticated techniques. Tools based on graph neural networks, such as FUNDED, face challenges in processing long code subsequences due to high computational costs, limiting their real-time analysis capabilities in development environments. Program slicing techniques, like those used in NS-Slicer, offer an intermediate solution by simplifying source code before analysis, enhancing computational efficiency without sacrificing detection effectiveness [21].

Integrating Large Language Models presents the greatest computational challenge. Although LLM-augmented tools improve semantic sensitivity and contextual understanding, they come with enormous computational demands and may introduce latency issues unsuitable for resource-limited environments [31]. Companies must carefully consider whether the increased accuracy justifies the higher infrastructure and processing costs.

The scalability factor adds complexity to these trade-offs. Comparative research shows that detection accuracy tends to decrease as codebase complexity increases, regardless of the computational resources used [25]. This suggests that sheer computational power cannot fully compensate for inherent algorithmic limitations, underscoring the importance of selecting techniques based on specific project needs and constraints.

The systematic review evaluated static methods of analysis for software development security based on their effectiveness, integration capability, and organizational determinants for adoption. The findings outline ongoing challenges and opportunities of improving vulnerability detection in modern software systems.

6.1 Challenges and Limitations of Existing Static Analysis Tools (RQ1)

Our systematic analysis reveals three critical limitation categories that require different solution approaches. Tool-level limitations include false positive rates that create alert fatigue, as evidenced by Sorald’s need to automate fix suggestions to reduce developer burden [3].

Architectural limitations involve inadequate semantic understanding, where traditional pattern-matching fails to capture program context [13]. Systemic limitations encompass scalability challenges that worsen with codebase complexity, though innovative approaches like dependency graph optimization show promise for specific domains [9].

These findings suggest that future improvements require coordinated advances across multiple dimensions rather than incremental enhancements to existing approaches.

6.2 Static Analysis Coupling with Dynamic and Machine Learning Methods (RQ2)

The combination of static and dynamic analysis with machine learning techniques holds significant promise for enhancing the precision of vulnerability detection and minimizing false positives. Hybrid approaches that integrate static and dynamic methods capitalize on their respective strengths while avoiding their individual limitations. Static analysis offers rapid processing and comprehensive code coverage, whereas dynamic analysis provides enhanced validation during runtime.

Incorporating machine learning into detection systems has yielded encouraging outcomes in identifying vulnerabilities. The DEKANT approach, which relies on sequence models, effectively detected zero-day vulnerabilities in WordPress plugins and PHP code. When it comes to control-flow related vulnerabilities, graph embedding techniques utilizing graph convolutional networks outperformed traditional static analyzers. Eth2Vec demonstrated resilience to code modifications while pinpointing vulnerabilities in Ethereum smart contracts through neural network-based language processing.

Conventional machine learning techniques offer a way to overcome the limitations of rule-based static analysis by automatically identifying vulnerability patterns in extensive codebases. However, their effectiveness is influenced by factors like the architecture of neural networks and the inclusion of control dependencies. The WIRECAML tool, which integrates data-flow analysis with machine learning, outperformed other tools in identifying SQL injection and Cross-Site Scripting vulnerabilities.

Deep learning methods excel because they can identify vulnerability patterns during training without relying on predefined detection rules. The FUNDED approach utilizes graph neural networks to analyze program control, data, and call dependencies, which are often missed by static analysis tools. Nonetheless, deep learning methods encounter challenges when processing lengthy code segments and differentiating between vulnerability-related information and irrelevant data.

Machine learning methods for detecting vulnerabilities face several challenges. One major issue is the need for large amounts of labeled vulnerability data to achieve accuracy. The interpretability of deep learning models remains challenging due to their “black box” nature. Models also struggle with cross-domain generalization and face computational constraints, particularly in resource-limited environments.

6.3 Impact of Organizational Factors and Developer Practices (RQ3)

The adoption and effectiveness of static analysis tools are directly impacted by developer practices and organizational factors. Key elements for successful deployment include organizational backing and leadership dedication. Companies that foster a culture of innovation and are open to incorporating new tools into existing workflows report higher success rates in implementation.

Educating staff and enhancing their skills are crucial for understanding and utilizing these tools effectively. Proper training allows developers to fully leverage the capabilities of static analysis. The ease of use of a tool is closely linked to its adoption rate tools that require significant changes to workflows are often resisted. User-friendly interfaces and seamless integration into current development processes promote acceptance.

The practicality of static analysis results significantly affects adoption. Developers face challenges in distinguishing between genuine issues and false positives. Tools that provide clear, actionable insights without overwhelming developers with unnecessary data tend to be more widely adopted. Sorald exemplifies this by using metaprogramming templates to address static analysis warnings, achieving 65% effectiveness in resolving violations.

Developer preferences show a tendency towards products that can identify critical security vulnerabilities alongside code structure issues. Managing integration complexity is essential to incorporate analysis results without overwhelming development teams with excessive information. This complexity often necessitates expert skills or tools to maximize the potential of static analysis without losing valuable insights.

The trade-off between detection accuracy and computational cost greatly influences tool selection. Traditional rule-based tools like SonarJava operate quickly with minimal computational expense, making them ideal for continuous integration, but they generate more false alarms. Machine learning approaches offer greater precision but come with higher computational costs. Hybrid solutions like AndroShield have moderate resource costs but increased environmental complexity.

Understanding these organizational dynamics is crucial for the successful implementation of static analysis. Tools must seamlessly integrate into developer workflows and organizational settings to effectively achieve security objectives.

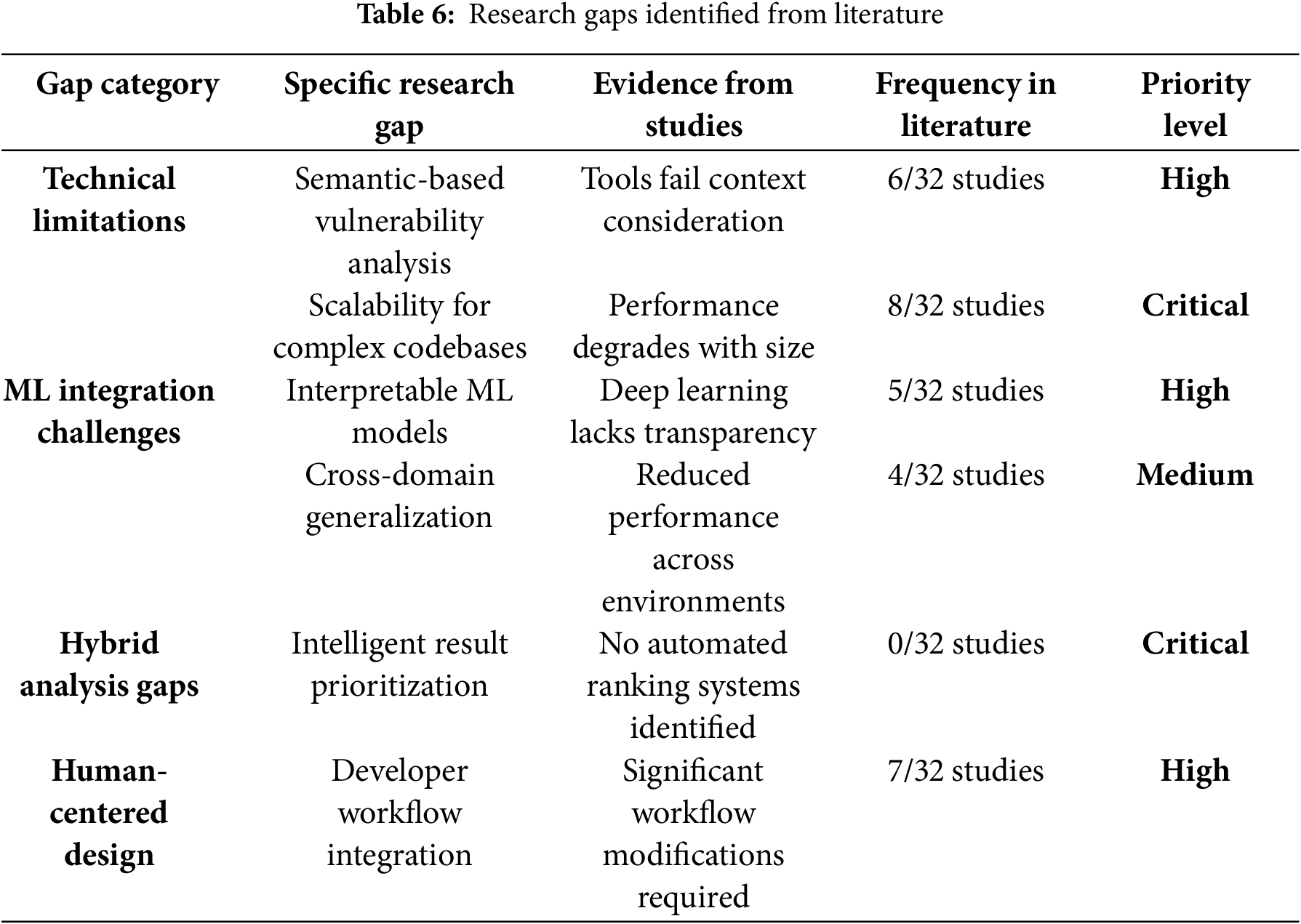

Based on our systematic analysis, several critical research gaps emerge that require attention to advance static analysis techniques for secure software development. These gaps are summarized in Table 6.

Frequency indicates how many of the 32 selected studies addressed each gap: Priority levels assigned based on impact on practical adoption and security effectiveness.

The systematic analysis reveals several critical research gaps that limit static analysis effectiveness and adoption. These gaps span technical, methodological, and organizational dimensions, requiring targeted research efforts to advance the field.

6.4.1 Technical Limitations: The Fundamental Issue

The most common issue identified is the scalability of large codebases (8/32 studies), which stems from a fundamental architectural problem. This issue persists because existing static analysis techniques were originally designed for relatively small, monolithic applications and face challenges with:

• Modern microservices architectures

• Large enterprise codebases

• Cross-language dependency analysis

Semantic-based vulnerability analysis gap identified in 6 out of 32 studies highlights a fundamental problem: while tools can detect syntactic patterns, they lack an understanding of code semantics and the context of business logic. This limitation contributes to the persistently high rates of false positives, despite advancements in technology.

6.4.2 ML Integration: The Promise vs. Reality Gap

The issue of interpretability, highlighted in 5 out of 32 studies, poses a significant challenge for businesses considering adoption. Although machine learning methods are achieving higher detection rates, they function as “black box” systems, raising liability concerns in environments where safety is critical. Companies require an understanding of the reasons behind the detection of a vulnerability, not just the fact that it has been identified.

Additionally, cross-domain generalization, noted in 4 out of 32 studies, indicates that machine learning models trained on a specific language or type of vulnerability struggle to adapt in multi-environment contexts. This suggests that current training methods are overly specialized.

6.4.3 Human-Centered Design: The Adoption Bottleneck

Issues with integrating developer workflows (7/32 studies) suggest that technical proficiency alone is inadequate. Tools that necessitate significant changes to existing workflows often face resistance to adoption, even if they are highly effective in detection.

7 Conclusion and Future Directions

Our systematic review identifies a fundamental transition in static analysis research from addressing individual tool limitations to developing integrated architectural solutions. Evidence from recent innovations like automated fix generation [3] and semantic-aware analysis [32] suggests that future breakthroughs will emerge from combining multiple complementary approaches rather than optimizing single-method tools. The integration of machine learning and hybrid approaches appears promising, with tools like DEKANT and Eth2Vec demonstrating improved detection capabilities. However, the high computational costs and organizational limitations continue to be significant barriers to widespread adoption.

Future studies need to focus on four major areas:

Technical Advances

To identify vulnerability patterns in intricate codebases, advanced machine learning models should replace traditional rule-based methods. These adaptive learning systems need to offer scalability and enhance semantic sensitivity to the code context, thereby minimizing false positives.

Methodological Innovation

Intelligent prioritization systems should automatically assess static analysis reports by actual risk levels, thereby minimizing developer alert fatigue and ensuring that critical vulnerabilities receive immediate attention. Such smart systems enable developers to concentrate on genuine security concerns rather than irrelevant warnings.

Human-Centered Design

Principles of user-centric design should tackle usability challenges by enhancing interface design, report visualization, and workflow integration, while also considering the cognitive needs of developers and the organizational context. Tools need to seamlessly integrate into current development workflows without necessitating significant changes to these processes.

Emerging Technologies

Developers can now easily access and implement human-like vulnerability explanations and contextual patch suggestions powered by large language models. Additionally, quantum computing holds the potential to solve current scalability challenges associated with managing extensive and intricate codebases. The future of static analysis must integrate technical innovation with organizational implementation strategies to foster the development of secure software.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge Murang’a University of Technology for availing resources such as access to databases and expertise. We also acknowledge the use of AI-assisted tools (e.g., Paperpal AI) for language polishing and structural adjustments. All intellectual contributions, analysis, and conclusions are those of the authors.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Systematic review design and protocol: Brian Mweu, John Ndia; Literature search and study selection: Brian Mweu; Data extraction and quality assessment: Brian Mweu; Data analysis and synthesis: Brian Mweu; Manuscript writing and revision: Brian Mweu, John Ndia. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lomio F, Iannone E, De Lucia A, Palomba F, Lenarduzzi V. Just-in-time software vulnerability detection: are we there yet? J Syst Softw. 2022;188(3):111283. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2022.111283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Aneesh A, Filieri A, Gias AU, Wang R, Zhu L, Casale G. Quality-aware DevOps research: where do we stand? IEEE Access. 2021;9:44476–89. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3064867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Etemadi K, Monperrus M, Mascha MF, Jiang Y, Söderberg E, Baudry B, et al. Sorald: automatic patch suggestions for SonarQube static analysis violations. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2023;20(4):2794–810. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3167316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Alqaradaghi M, Kozsik T. Comprehensive evaluation of static analysis tools for their performance in finding vulnerabilities in java code. IEEE Access. 2024;12(4):55824–42. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3389955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Do LNQ, Ali K, Wright JR. Why do software developers use static analysis tools? a user-centered study of developer needs and motivations. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2022;48(3):835–47. doi:10.1109/tse.2020.3004525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alzubi JA, Qiqieh I, Singh A, Alzubi OA. A blended deep learning intrusion detection framework for consumable edge-centric IoMT industry. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):2049–57. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3350231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yadavally A, Nguyen TN, Wang S, Li Y. A learning-based approach to static program slicing. Proc ACM Program Lang. 2024;8(OOPSLA1):83–109. doi:10.1145/3649814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yuan Y, Yu L, Lu Y, Zhu K, Huang H, Zhao J. A static detection method for SQL injection vulnerability based on program transformation. Appl Sci. 2023;13(21):11763. doi:10.3390/app132111763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ferreira M, Jia L, Santos JF, Monteiro M, Brito T, Coimbra ME, et al. Efficient static vulnerability analysis for JavaScript with multiversion dependency graphs. Proc ACM Program Lang. 2024;8(PLDI):417–41. doi:10.1145/3656394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cui L, Hao Z, Fei H, Jiao Y, Yun X. AndroShield: detecting vulnerabilities using weighted feature graph comparison. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Security. 2020;16:2004–17. doi:10.1109/tifs.2020.3047756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cheng X, Xu G, Sui Y, Wang H, Hua J. DeepWukong. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2021;30(3):1–33. doi:10.1145/3436877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Batur Şahin C, Abualigah L. A novel deep learning-based feature selection model for improving the static analysis of vulnerability detection. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33(20):14049–67. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06047-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Szabó Z, Bilicki V. A new approach to web application security: utilizing GPT language models for source code inspection. Future Internet. 2023;15(10):326. doi:10.3390/fi15100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen L, Wang H, Zhang Y. A hybrid static tool to increase the usability and scalability of dynamic detection of malware. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER); 2023 Mar 21–24; Macau, China: IEEE; 2023. p. 156–67. [Google Scholar]

15. Tadhani JR, Vekariya V, Sorathiya V, Alshathri S, El-Shafai W. Securing web applications against XSS and SQLi attacks using a novel deep learning approach. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1803. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48845-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chakraborty S, Ray B, Ding Y, Krishna R. Deep learning based vulnerability detection: are we there yet? IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2022;48(9):3280–96. doi:10.1109/tse.2021.3087402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wen C, Jiang Y, Xiao G, Wang H, Zhang W, Li Z, et al. Automatically inspecting thousands of static bug warnings with large language model: how far are we? ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data. 2024;18(7):1–34. doi:10.1145/3653718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Amin A, Hindy H, Eldessouki A, Abdeen N, Hegazy I, Magdy MT. AndroShield: automated android applications vulnerability detection, a hybrid static and dynamic analysis approach. Information. 2019;10(10):326. doi:10.3390/info10100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alzubi OA, Qiqieh I, Al-Zoubi AM, Alzubi JA. An IoT intrusion detection approach based on salp swarm and artificial neural network. Int J Netw Manag. 2024;35(1):e2296. doi:10.1002/nem.2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nina H, Villavicencio M, Pow-Sang JA. Systematic mapping of the literature on secure software development. IEEE Access. 2021;9:36852–67. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3062388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang X, Chen Y, Liu Z. Automatic static vulnerability detection for machine learning libraries: are we there yet? In: Proceedings of the 31st IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE); 2023 Oct 9–12; Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar]

22. Alzubi OA. A deep learning-based frechet and dirichlet model for intrusion detection in IWSN. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2021;42(2):873–83. doi:10.3233/jifs-189756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Alweshah M, Hammouri A, Alzubi O, Alkhalaileh S. Intrusion detection for the internet of things (IoT) based on the emperor penguin colony optimization algorithm. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2022;14(5):6349–66. doi:10.1007/s12652-022-04407-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ashizawa N, Cruz JP, Yanai N, Okamura S. Eth2Vec: learning contract-wide code representations for vulnerability detection on ethereum smart contracts. In: Proceedings of the 3rd ACM International Symposium on Blockchain and Secure Critical Infrastructure; 2021 Jun 7; Virtual. p. 47–59. doi:10.1145/3457337.3457841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kronjee J, Vranken H, Hommersom A. Discovering software vulnerabilities using data-flow analysis and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security; 2018 Aug 27–30; Hamburg, Germany. p. 1–10. doi:10.1145/3230833.3230856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li J, Zhang M, Wu X. A systematic literature review on automated software vulnerability detection using machine learning. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(1):1–38. doi:10.1145/3699711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Andrade R, Torres J, Ortiz-Garcés I. Enhancing security in software design patterns and antipatterns: a framework for LLM-based detection. Electronics. 2025;14(3):586. doi:10.3390/electronics14030586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kumar S, Patel R, Singh A. Vul-Mixer: efficient and effective machine learning-assisted software vulnerability detection. Electronics. 2024;13(13):2538. doi:10.3390/electronics13132538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Alzubi OA, Qiqieh I, Alazab M, Alrabea A, Alzubi JA, Awajan A. Optimized machine learning-based intrusion detection system for fog and edge computing environment. Electronics. 2022;11(19):3007. doi:10.3390/electronics11193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Menon S, Suresh M. Factors influencing organizational agility in higher education. Benchmarking. 2020;28(1):307–32. doi:10.1108/bij-04-2020-0151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Thompson M, Davis K, Johnson R. Machine-learning-based vulnerability detection and classification in internet of things device security. Electronics. 2023;12(18):3927. doi:10.3390/electronics12183927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Garcia M, Rodriguez P, Silva A. A comprehensive analysis on software vulnerability detection datasets: trends, challenges, and road ahead. Int J Inf Secur. 2024;23(4):1089–125. doi:10.1007/s10207-024-00888-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools