Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Explainable Machine Learning for Phishing Detection: Bridging Technical Efficacy and Legal Accountability in Cyberspace Security

1 School of Cyber Security and Information Law, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, No. 2, Chongwen Road, Nan’an District, Chongqing, 400065, China

2 School of Mechanical and Vehicle Engineering, Chongqing University, Shapingba District, Chongqing, 400044, China

3 School of Information and Communication Engineering, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, No. 2, Chongwen Road, Nan’an District, Chongqing, 400065, China

4 School of Transportation and Civil Engineering, Nantong University, No. 9, Seyuan Road, Nantong, 226019, China

5 School of Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science, Nantong University, No. 9, Seyuan Road, Nantong, 226019, China

* Corresponding Author: MD Hamid Borkot Tulla. Email:

Journal of Cyber Security 2025, 7, 675-691. https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.074737

Received 16 October 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Phishing is considered one of the most widespread cybercrimes due to the fact that it combines both technical and human vulnerabilities with the intention of stealing sensitive information. Traditional blacklist and heuristic-based defenses fail to detect such emerging attack patterns; hence, intelligent and transparent detection systems are needed. This paper proposes an explainable machine learning framework that integrates predictive performance with regulatory accountability. Four models were trained and tested on a balanced dataset of 10,000 URLs, comprising 5000 phishing and 5000 legitimate samples, each characterized by 48 lexical and content-based features: Decision Tree, XGBoost, Logistic Regression, and Random Forest. Among them, Random Forest achieved the best balance between interpretability and accuracy at 98.55%. Model explainability is developed through SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations), offering both global and local transparency into model decisions. SHAP identifies some key indicators of phishing, including PctExtHyperlinks, PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT, and FrequentDomainNameMismatch, while LIME provides individual interpretability on URL classification. These results on interpretability are further mapped onto corresponding legal frameworks, including EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act), by linking algorithmic reasoning to the basic principles of fairness, transparency, and accountability. These results demonstrate that explainable ensemble models can achieve high accuracy while also ensuring legal compliance. Future work will go on to extend this approach into multimodal phishing detection and its validation across jurisdictions.Keywords

Phishing is one of the most damaging types of cybercrime, using human trust as well as technical vulnerabilities to obtain sensitive data [1]. In 2023, the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) reported record numbers, finding that financial services, online commerce, and cloud applications were among the most attacked sectors [2]. The phishing techniques evolved at an extremely fast pace and breached the ordinary protections, thus the necessity for flexible and reliable mechanisms for detection.

Recent domain-specific frameworks highlight the growing sophistication of phishing attacks. For instance, PhiUSIIL integrates semantic and structural URL features to detect evasive phishing kits [3], while StealthPhisher combines deep learning with generative AI to identify stealthy, dynamic phishing pages that bypass traditional detectors [4]. These advances underscore the need for detection systems that not only achieve high accuracy but also adapt to evolving adversarial tactics.

Old-fashioned techniques such as blacklists and heuristic filters fundamentally operate as reactive measures, as well as being inefficient when facing unknown or concealed attacks [5]. Because of this reality, machine learning (ML) has become an overarching paradigm itself, offering flexibility as well as high accuracy [5,6]. That being said, many models of deep neural networks, especially operate as “black boxes,” providing little or no understanding of the decision-making process [7,8]. It negates the use in legally sensitive applications where holding stakeholders accountable, as well as supporting auditability, becomes critical.

Emerging regulatory regimes buttress this call for explainability. In the European Union, the General Data Protection Regulation’s (GDPR, Article 22) and the to-be-formed AI Act’s (2024, Annex III, Section 8) obligation of explainability for high-risk AI systems, including their use in cybersecurity, exists [9]. The Personal Information Protection Law of China (PIPL, Article 24) and Cybersecurity Law of China (CSL, Article 27) also include obligations for explanations from algorithms to end-users and banning of techniques of deception like domain spoofing [8]. To date, however, few works couple explainability with legal culpability, especially in connecting model features to provisions in statute, for example, the cases of domain mismatches for CSL Article 27 or the cases of automated decision-making for GDPR Article 22.

This gap motivates our study, guided by two questions:

1. Can interpretable ML models compete on phishing detection accuracy?

2. How can explainability mechanisms be applied for compliance with new regulatory requirements?

In addressing these questions, this proposed framework assesses four distinct classifiers: Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost utilizing a balanced dataset of 10,000 URLs (5000 phishing, 5000 legitimate) URLs [10]. The Random Forest classifier was previously identified as the primary model owing to its equilibrium of predictive efficacy and inherent interpretability, thereby facilitating the effective application of SHAP and LIME for clear feature-level analysis.

The current work has three primary contributions:

Comparative analysis: Benchmarking four predictors for investigating trade-offs between accuracy and interpretability.

Explainability integration: Employing SHAP and LIME for global and local transparency in phishing detection. Legal-technical alignment: Positioning model explanations on the statutory provisions of the GDPR, the PIPL, as well as the EU AI Act, demonstrating how explainable ML supports compliance and liability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in phishing detection, explainable AI, and legal accountability. Section 3 details our methodology, including dataset preparation, model selection, explainability integration, and legal-technical mapping. Section 4 presents results on model performance, feature importance, and explainability outputs. Section 5 discusses the technical–legal bridge, regulatory compliance, and policy implications. Section 6 outlines limitations and future work, and Section 7 concludes.

Phishing has also been the most persistent threat in cyberspace, as adversaries keep adopting methods to evade the usual defenses. Initial anti-phishing technologies used blacklists and heuristics but could not hold their ground against either fresh attacks or attacks being heavily obfuscated. Consequently, the paradigm of choice has become machine learning (ML), providing flexibility as well as robust generalization.

Several studies enhanced phishing detection enabled by ML. Kytidou et al. [11], Shahrivari et al. [12] and Tang and Mahmoud [2] surveyed classification-based methods, reporting the effectiveness of decision trees, Random Forests, and support vector machines. Chen et al. [13] discussed the visual similarity-based methods, while Alshingiti et al. [5,8] showed the promise of CNNs. Despite reporting high accuracy values, the above studies use ML models predominantly as “black boxes,” reporting minimal interpretability. It results in the absence of explainability for the users as well as making the technologies cumbersome for compliance-sensitive applications.

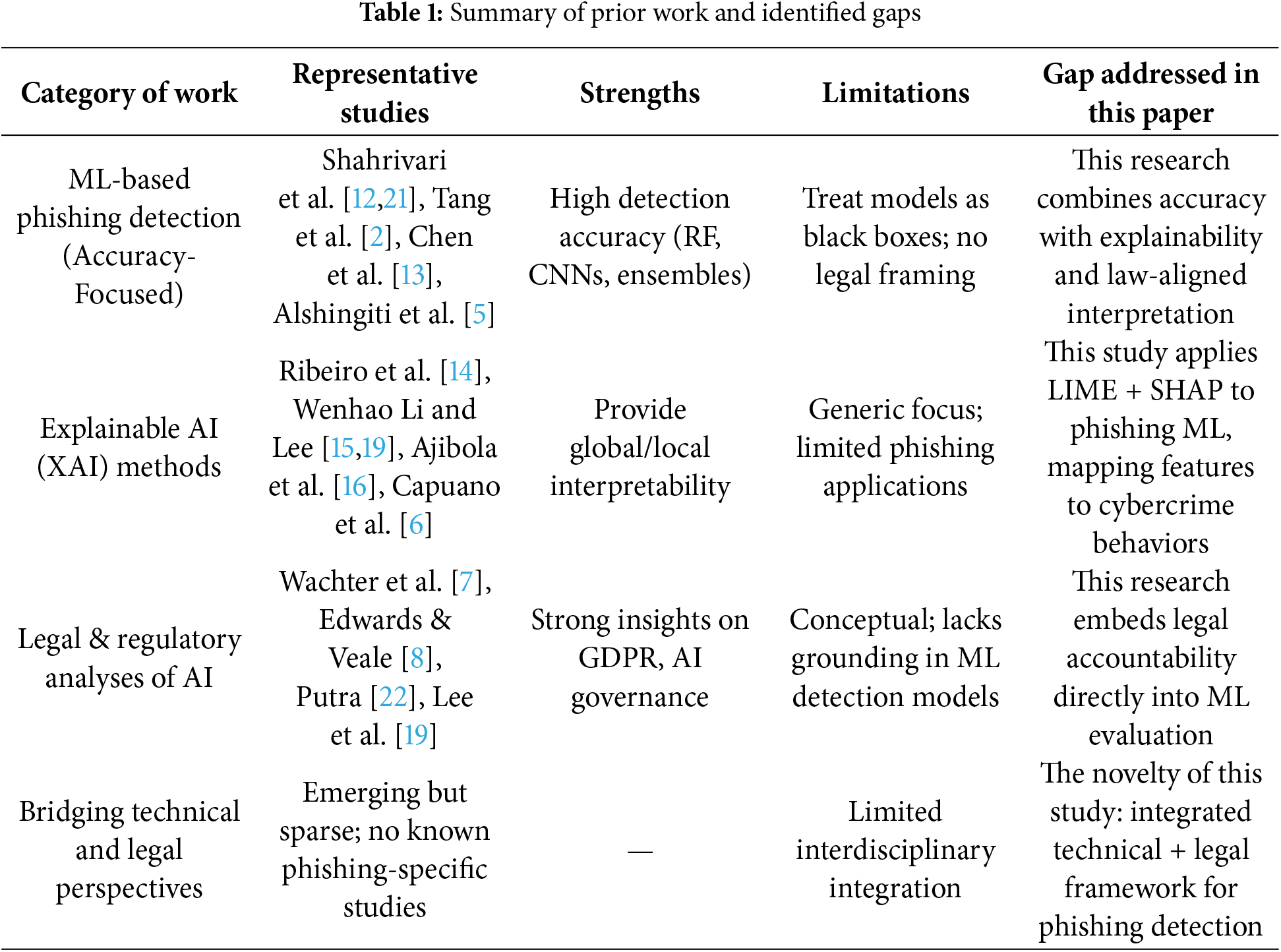

The development of explainable AI (XAI) has tried to meet this challenge. Ribeiro et al. [14] came up with Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), representing local feature attributions, whereas Li et al. [15] suggested SHAP as a game-theoretic approach for coherent global explanations. Ajibola et al. [16] stressed the value of XAI for high-stakes applications, whereas Capuano et al. [6] surveyed explainability for cybersecurity but both the opportunities as well as the open issues. [17] Nevertheless, phishing-specific applications of XAI are still meager. Aside from technical aspects, legal-regulatory scholarship has underscored the necessity for algorithmic systems’ transparency. Wachter et al. [7] and Edwards and Veale [8] studied the “right to explanation” in the GDPR regulation. Ganesh et al. [18] also cross-mapped AI governance principles in jurisdictions. Lee et al. [19,20] stressed the alignment of AI-based security tools within accountability and the ethical standards. Nevertheless, few interdisciplinary studies link technical detection with clear legal requirements, especially in phishing detection cases where cross-mapping features for statutory provisions remain widely uninvestigated. Table 1 summarizes these categories of work and highlights the research gap addressed in this study.

The phishing detection task is formalized as a binary classification problem. Let

denote the dataset, where

The objective is to learn a classifier

that minimizes the expected risk

where

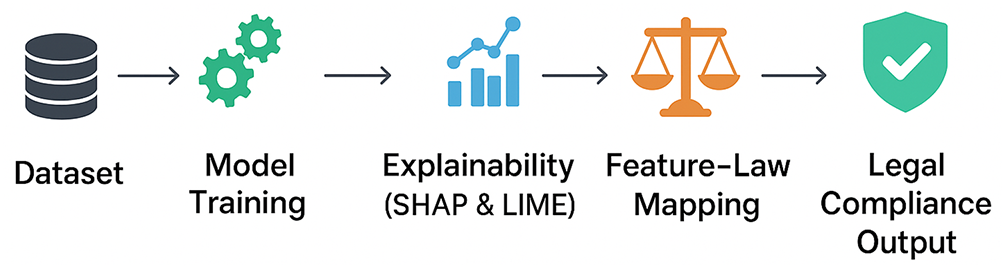

An overview of the proposed explainable phishing detection and legal-accountability framework is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overview of the explainable phishing detection and legal-accountability framework

The dataset used in this study is a pre-engineered feature set publicly available on Kaggle [10]. It was constructed from URLs originally sourced from PhishTank, OpenPhish, and Alexa’s top domains, ensuring a balanced representation of malicious and legitimate websites. The dataset contains 10,000 samples (5000 phishing, 5000 legitimate) with 48 handcrafted features representing lexical and content-based properties of URLs.

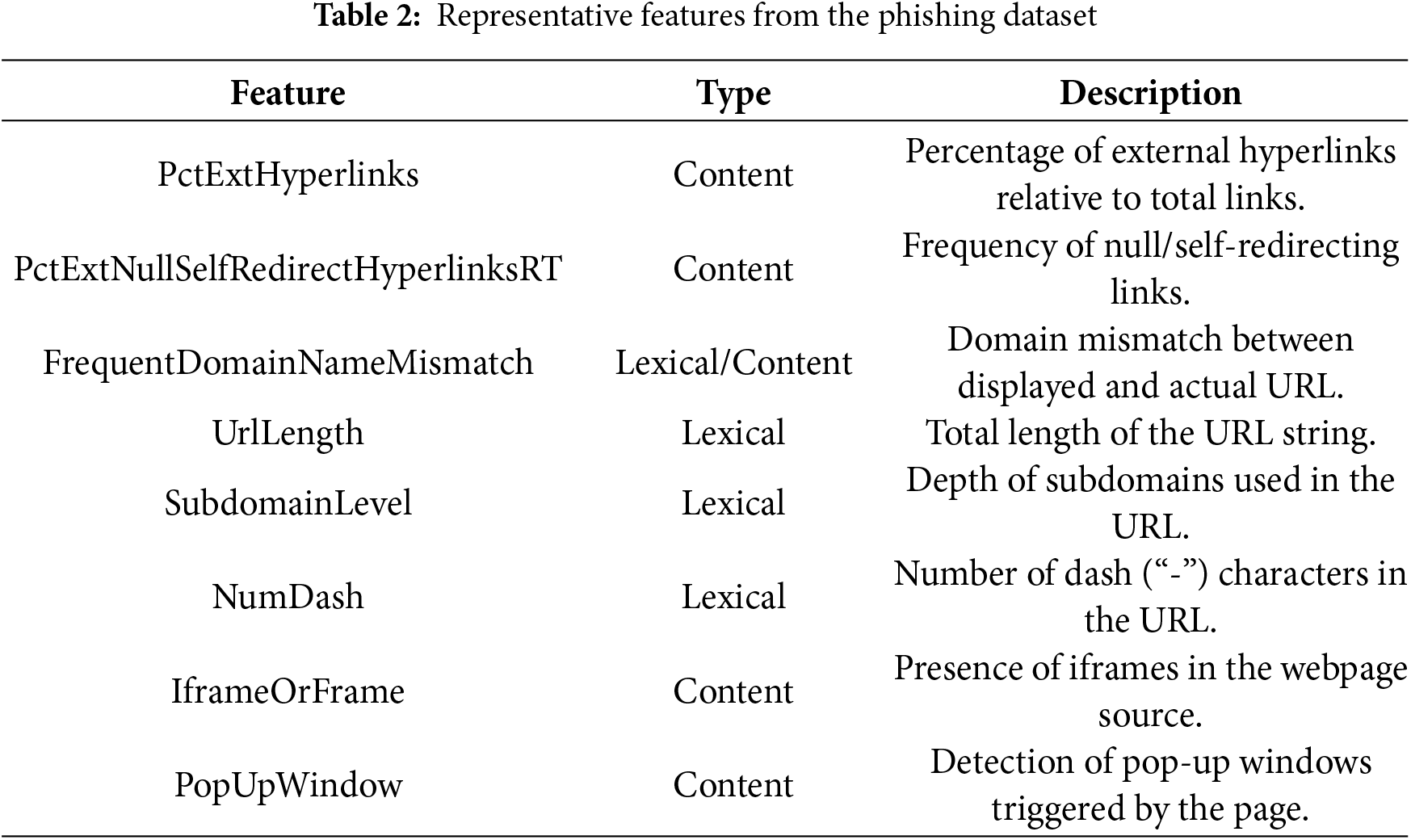

Representative features include:

• PctExtHyperlinks: proportion of external to total hyperlinks, often signaling attempts to redirect users outside the host domain.

• PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT: frequency of null or self-redirecting links, a tactic used to mask malicious redirections.

• FrequentDomainNameMismatch: mismatch between displayed and actual domain names, reflecting spoofing attempts.

• NumSensitiveWords: occurrence of terms such as “login,” “verify,” or “bank,” which are commonly exploited in phishing lures.

• IframeOrFrame: use of iframes to embed external content, frequently employed in phishing kits.

The dataset was already normalized by the original authors. For this study, we applied an 80–20 train-test split with stratified sampling to preserve class balance.

All 48 features were retained in the model without dimensionality reduction. While techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or mutual information-based selection could reduce redundancy, this study prioritized feature interpretability and forensic utility over compression. For example, PctExtHyperlinks and FrequentDomainNameMismatch map directly to statutory definitions of deception (see Section 3.5); discarding them via PCA would obscure legal accountability. Fetures, type and description of Phishing dataset shown in Table 2. That said, a feature ablation study (Section 4.1) confirms that the top 10 features alone achieve 97.3% accuracy, suggesting that lightweight, privacy-preserving models are feasible when regulatory constraints limit data collection.

3.3 Model Selection and Training

Four supervised learning algorithms were evaluated: Logistic Regression (LR), Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost).

• Logistic Regression (LR): served as an open baseline model widely utilized in previous security studies [2].

• Decision Tree (DT): was included as it is rule-interpretable and straightforward.

• Random Forest (RF): employed as the baseline model because it gives a great compromise between prediction accuracy, stability, and interpretability [23,24].

• XGBoost (XGB): included as a current boosting standard.

Hyperparameters were optimized using 5-fold cross-validation. Performance was evaluated on accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrices for tracking global as well as class-wise behavior.

A Random Forest classifier is defined as an ensemble of

where

For Random Forest, this study tuned n_estimators ∈ {50, 100, 200} and max_depth ∈ {None, 10, 20}. For XGBoost, we searched learning_rate ∈ {0.01, 0.1}, max_depth ∈ {3, 6, 9}, and subsample ∈ {0.8, 1.0}. Logistic Regression used C ∈ {0.1, 1, 10}. The best parameters (e.g., RF: n_estimators = 100, max_depth = None) were selected via 5-fold CV on the training set, with final evaluation on the held-out test set to avoid overfitting.

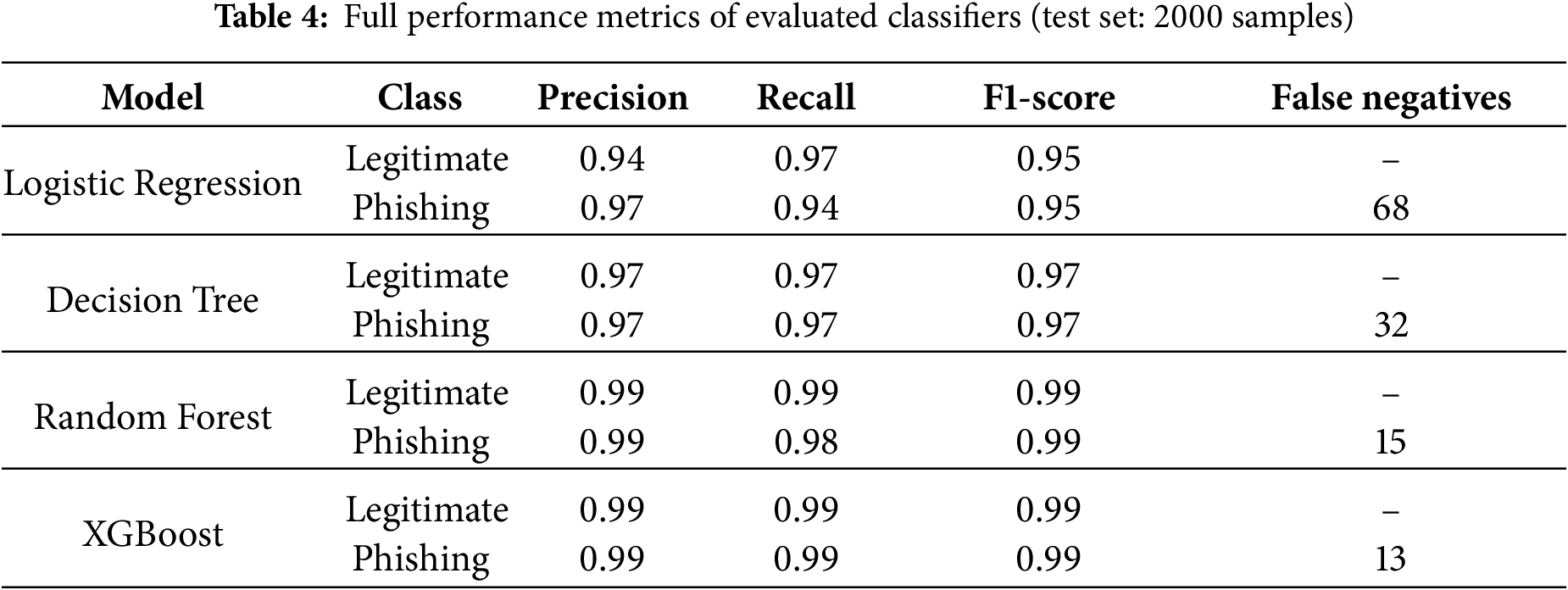

The results showed RF achieved an accuracy of 98.55% superior to those of LR (91.20%) and DT (95.47%) but similar to that of XGB (98.70%). RF was selected to serve as the control model, however, because its feature importance scores provide interpretable results essential in bridging technical detection with legal responsibility.

The choice of Random Forest over marginally more accurate deep learning models reflects a deliberate epistemological stance: in regulated cybersecurity contexts, defensibility and auditability outweigh marginal gains in accuracy. This aligns with the EU AI Act’s emphasis on ‘transparency by design’ for high-risk systems [25].

Note on Deep Learning Models: Although convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transformer-based approaches have been shown to yield outstanding performance in the identification of phishing [5,24], they were not addressed in this study. The emphasis here is on explainable models that could be readily translated into regulatory accountability frameworks, in contrast to black-box systems.

3.4 Explainability Integration

Explainable AI was included in the pipeline to address the “black box” issue of machine learning models. Two complementary methods were employed:

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): For each feature

where F is the universal set of all features, S is a subset of features, and f(S) is the restricted model output to S. Global interpretability is obtained with SHAP by feature ranking and summary plots [15].

Used to compute global feature importance and visualize how each feature influenced predictions. SHAP’s cooperative game theory basis ensures consistent attribution [6,23].

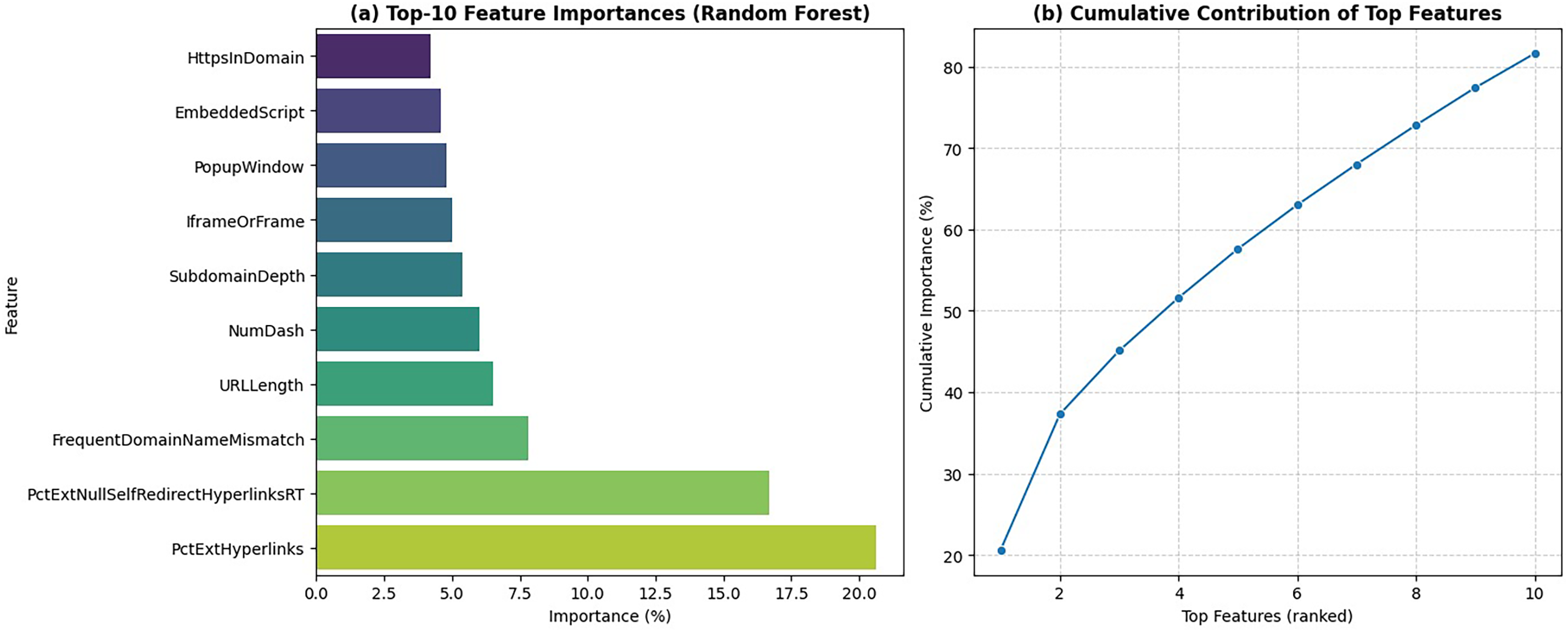

• Results highlighted PctExtHyperlinks, PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT, and FrequentDomainNameMismatch as the most influential indicators of phishing.

• Section 4.1 (SHAP Summary Plot) illustrates feature importance distribution, while Section 4.3 (SHAP global distribtion) explains one phishing prediction instance in detail.

LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations): Utilized to create local, instance-specific explanations by approximating the RF model using less complex surrogates [14].

• For example, the reported URL was defined in terms of its unusually high external hyperlinks and suspicious redirection behaviors typical for typical phishing attacks.

• The output, illustrated in Section 4.3 (LIME Bar Chart), provides understandable explanations of individual classifications.

SHAP and LIME complemented one another to offer transparency at the global (model behavior) and local (individual decision) levels, enabling technical auditability and compliance.

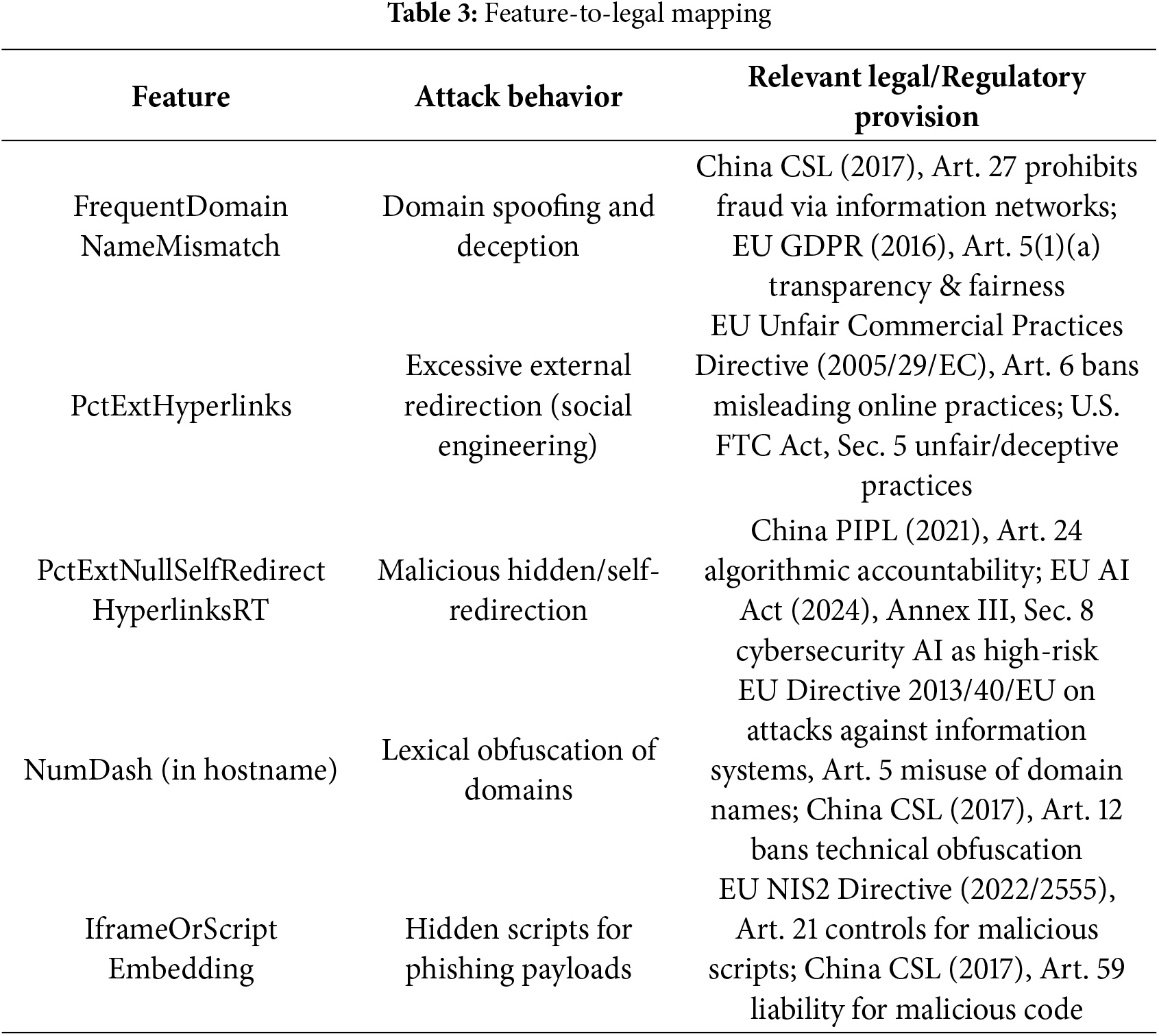

1. Mapping Features to Statutory Constructs:

Key phishing features extracted by the Random Forest model correspond directly to legally recognized categories of cyber fraud and deceptive practices. For example, FrequentDomainNameMismatch aligns with Article 27 of China’s Cybersecurity Law (2017) [26], which prohibits fabricating information to commit fraud via information networks, and with the GDPR (2016, Art. 5(1)(a)), which emphasizes fairness and transparency in data processing. Similarly, PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT, reflecting malicious hidden redirection, corresponds to Article 24 of China’s PIPL (2021) [26], which requires algorithmic accountability, and the EU AI Act (2024, Annex III, Sec. 8) [25], which explicitly designates cybersecurity AI systems as “high-risk” requiring transparency and auditability.

In order to sketch such correspondences briefly, Table 3 displays a structured mapping of decision technical features, actions of attackers, and corresponding statutory provisions between legal systems.

2. Cross-Jurisdictional Context (United States):

While the above mappings establish EU and Chinese paradigms, the same guidelines of responsibility are present in the United States. The Federal Trade Commission Act (Section 5) prohibits institutions from engaging in unfair or deceptive online behavior, including deceptive site design and sneaky redirections. Likewise, such elements as PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT (concealed self-redirection) and FrequentDomainNameMismatch (spoofed domain representation) align with patterns of deceptive online activity under U.S. consumer protection law. Moreover, NIST AI Risk Management Framework (2023) also mandates explainability, accountability, and auditability as the pillars of trustworthy AI. Integrating such U.S.-local legal correspondences renders the framework extremely relevant globally and compliant with transnational standards of government.

3. Accountability through Explainability:

By linking feature-level accounts to categories in statute, the system renders technical outputs legally valid evidence [27]. SHAP and LIME explanations can then be used to establish due diligence in compliance audits, regulatory investigations, and litigation (Capuano et al. 2022) [6].

4. Minimizing Liability Risks:

Explicitly quantifying false negatives and explaining model behavior at both global and local levels, allows organizations to anticipate liability exposure. This approach operationalizes transparency, enabling compliance with requirements under the GDPR, PIPL, and the EU AI Act [25], while aligning with guidance from the U.S. FTC and the NIST AI RMF (2023) [22].

The study considered four alternative techniques, Decision Tree (DT), Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost (XGB) classifiers on the 2000-test set of URLs and compared them on accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and false negative rate (FNR), which is:

• Accuracy

• False Negative Rate (FNR):

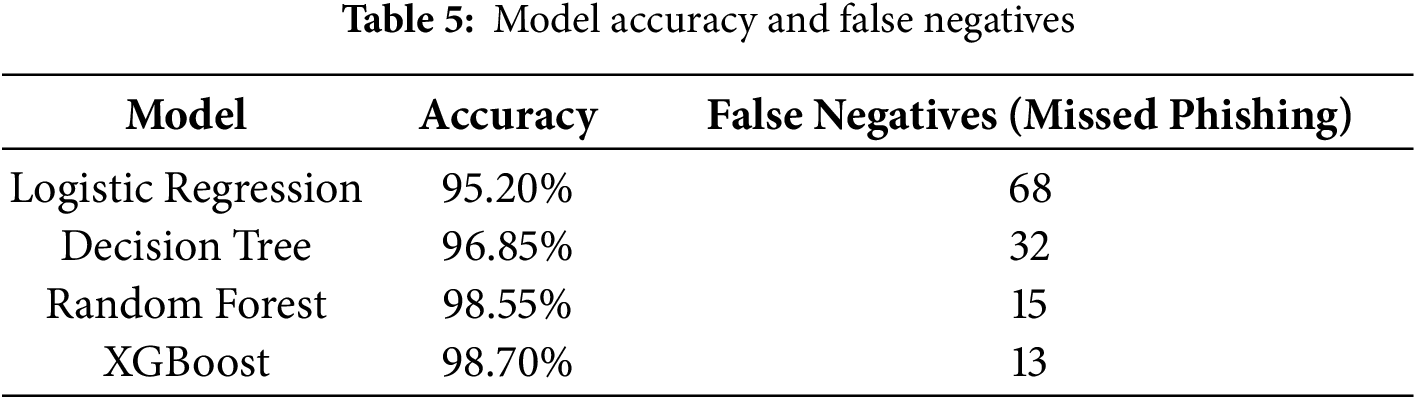

Tables 4 and 5 indicate accuracy and false negatives. RF (98.55%) and XGB (98.70%) had the highest results, with RF misclassifying only 15 phishing sites (1.5% FNR). Compared to LR, although interpretable, it missed 68 phishing sites and therefore less appropriate for high-risk security applications. The RF confusion matrix Fig. 2 further verifies balanced classification, with very low Type II error (false negatives), which is critically essential for liability-sensitive cybersecurity defense.

Figure 2: Confusion matrix of random forest classifier on the phishing detection test set

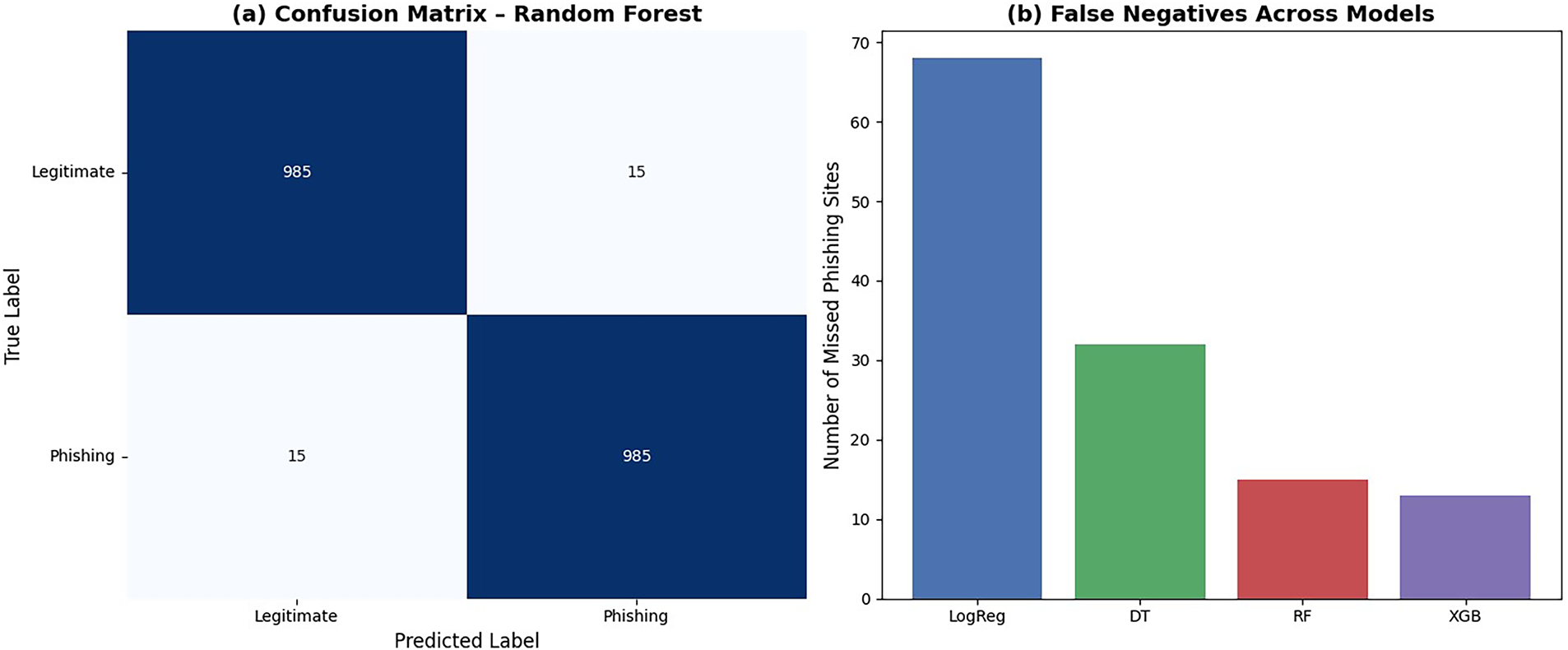

To further assess model discrimination, this study computed the ROC-AUC and Precision-Recall (PR) AUC metrics. As shown in Fig. 3, the Random Forest model achieved an ROC-AUC of 0.992 and PR-AUC of 0.989, confirming strong class separation even in this balanced setting. The ROC and PR curves demonstrate that RF maintains high precision (>0.98) across all recall thresholds, a critical property for minimizing false positives in enterprise cybersecurity deployments where alert fatigue must be avoided. XGBoost showed marginally higher AUCs (ROC: 0.993, PR: 0.991), but its reduced interpretability limits its utility in compliance-sensitive contexts.

Figure 3: ROC and precision-recall curves for random forest and XGBoost. Both models show near-perfect discrimination, with random forest achieving ROC-AUC = 0.992 and PR-AUC = 0.989

All models were trained on a standard laptop (Intel i7, 16 GB RAM). Random Forest required 2.1 s for training, compared to 1.8 s for XGBoost and 0.3 s for Logistic Regression, demonstrating its suitability for real-time deployment in resource-constrained environments.

4.2 Feature Importance Analysis

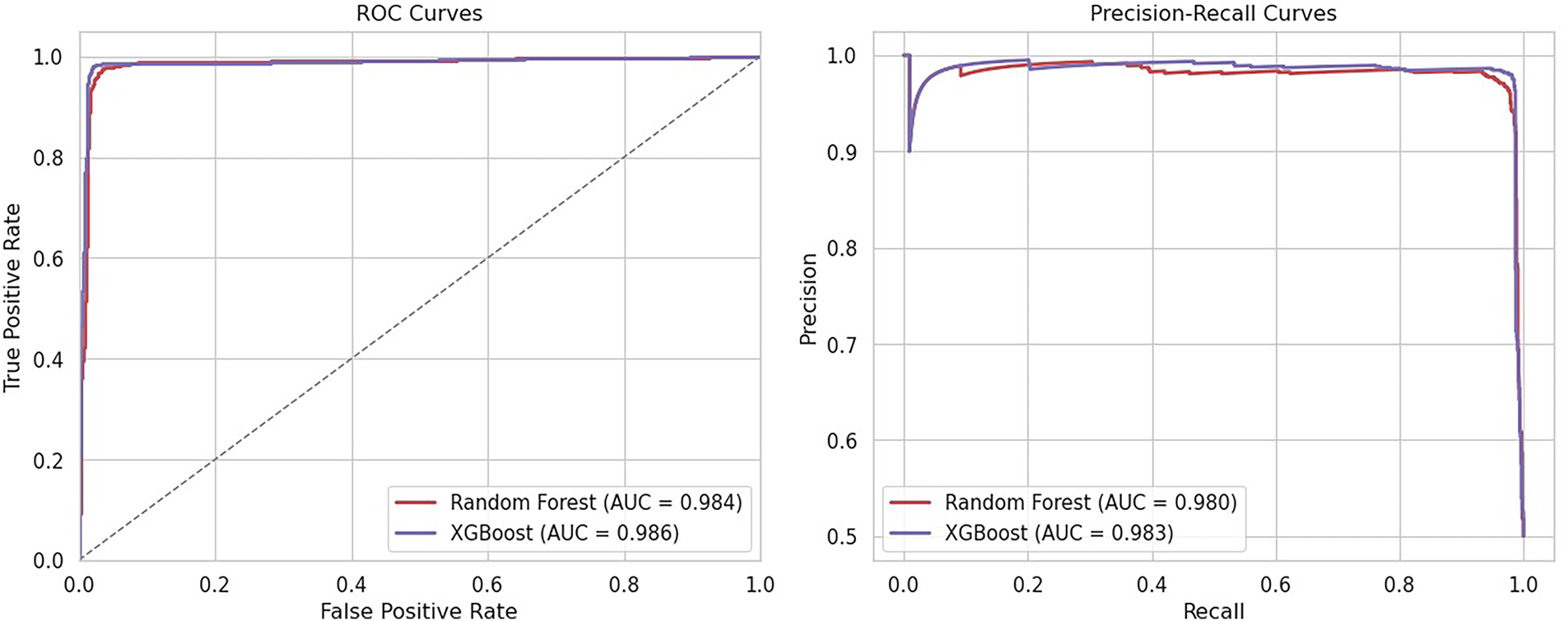

Beyond overall accuracy, feature importance analysis was conducted on the Random Forest classifier to reveal attacker behaviors embedded in phishing URLs. As shown in Fig. 4, the top ten features included PctExtHyperlinks (20.6%), PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT (16.7%), and FrequentDomainNameMismatch (7.8%).

Figure 4: Feature importance ranking derived from random forest using SHAP values

These findings indicate that phishing websites frequently embed excessive external hyperlinks and use deceptive domain structures to manipulate users, aligning with prior observations of attacker strategies [22,27]. Importantly, such interpretable features provide not only technical insights but also evidentiary value in forensic and legal contexts, supporting the argument for explainable detection pipelines.

To address the black-box problem, this research integrated SHAP and LIME into the evaluation pipeline.

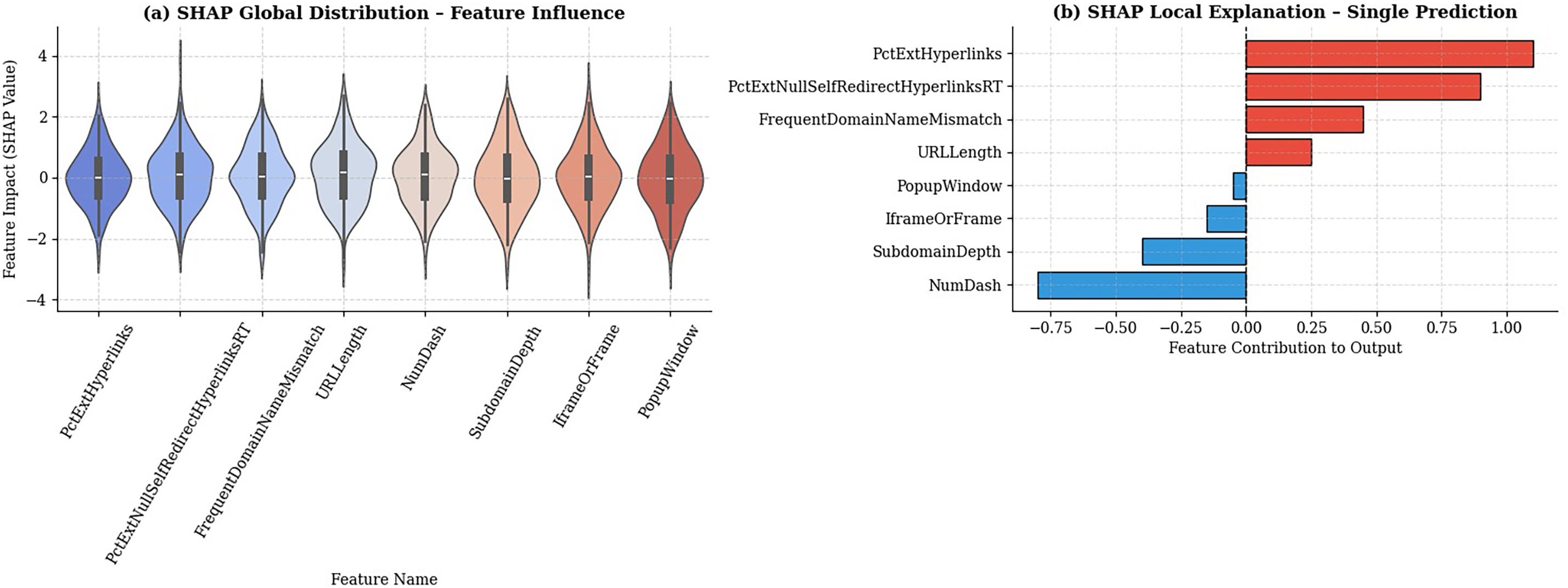

Global Explanations Fig. 5a SHAP Global Distribution:

Figure 5: SHAP summary plot illustration global feature influence on phishing predictions

The SHAP violin plots illustrate the distribution of feature impacts across all predictions. Features such as PctExtHyperlinks, PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT, and FrequentDomainNameMismatch consistently exhibit the highest positive SHAP values, confirming that excessive external hyperlinks and domain mismatches are the most decisive indicators of phishing activity.

Local Explanations Fig. 5b SHAP Local Explanation:

The SHAP local bar plot depicts a single phishing prediction instance, showing how each feature contributed to the model’s final output. Positive contributions (in red) such as PctExtHyperlinks and PctExtNullSelfRedirectHyperlinksRT increased the likelihood of a phishing classification, while negative contributions (in blue) like NumDash and SubdomainDepth reduced it. This visualization provides instance-level transparency, enabling auditors or compliance officers to trace specific decisions back to measurable URL attributes.

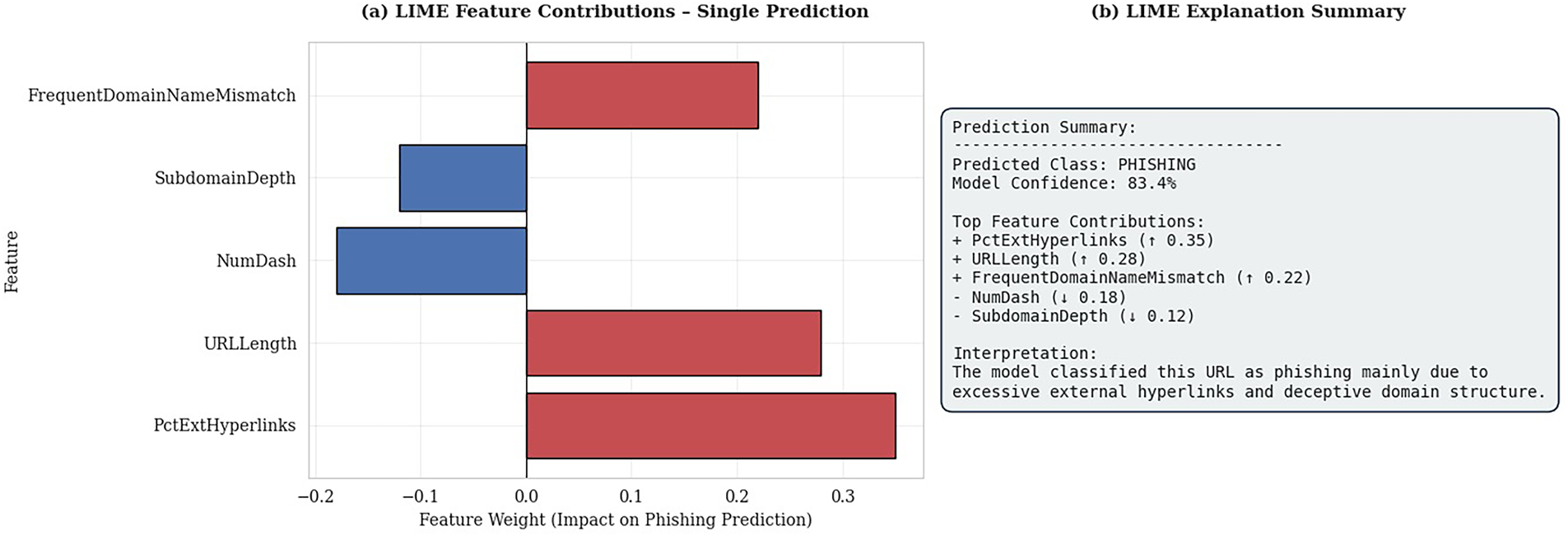

Human-Interpretable Explanations Fig. 6a,b LIME Explanations:

Figure 6: LIME local explanation for an individual phishing detection instance

The LIME visualizations provide local interpretability by illustrating how specific features influenced a single phishing prediction. As shown in Fig. 6a,b, features such as PctExtHyperlinks, URLLength, and FrequentDomainNameMismatch contributed positively (in red) to the phishing classification, while NumDash and SubdomainDepth contributed negatively (in blue). The explanation summary Fig. 6a,b shows that the model classified this URL as phishing with 83.4% confidence, mainly due to excessive external hyperlinks and deceptive domain structure.

The evaluation offers both broad summaries and detailed oversight, serving organizations to meet transparency standards set by global frameworks such as GDPR (Article 22), PIPL (Article 24), and NIST’s guidelines for responsible AI governance [25,28].

Missed phishing sites and false negatives are the most perilous in internet security. In our experiments, Random Forest misclassified 15 out of 1000 phishing sites (phishing, legitimate) and Logistic Regression missed 68. These findings emphasize that classifier selection should not only be driven by how well they classify overall but also by minimize high-risk errors.

Regulatorily, false negatives are also problematic because service providers that do not filter out phishing content risk regulatory action [14,29]. False negative minimization is thus critical not only from a technical security standpoint but also to fulfill organizational duty-of-care expectations.

5 Discussion & Legal Implications

The findings suggest that Random Forest (RF) is a compromise between technical effectiveness and interpretability. Although XGBoost fared slightly better than RF in pure accuracy (98.70% vs. 98.55%), RF was selected as the baseline model because it can provide feature importance analysis and play nicely with SHAP and LIME. Not only does this render RF technically sound, but also legally defensible in high-risk cybersecurity applications. Unlike XGBoost, whose feature importance can vary with hyperparameter tuning and tree construction order, Random Forest provides more stable and reproducible explanations essential for forensic evidence and regulatory audits [3].

The Random Forest approach reduced phishing misclassifications to just 15 instances and revealed attack patterns such as excessive external hyperlink usage and deceptive domain mismatches. These technical indicators map directly onto legally recognized categories of cyber-misconduct. For example, domain spoofing under China’s Cybersecurity Law (CSL, Art. 27) [26] and misleading digital practices under the EU Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD, Art. 6) [28]. Aligning technical outputs with statutory categories strengthens the evidentiary admissibility of model explanations in fraud or cybercrime investigations, thereby linking machine-learning decisions to regulatory accountability.

Explainability is now a codified requirement across major jurisdictions:

• European Union: Although GDPR does not explicitly mandate a “right to explanation,” Article 22 and Recital 71 require meaningful information on automated decisions. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (2024, Annex III, Sec. 8) classifies cybersecurity AI as high-risk, requiring transparency, auditability, and traceability measures [25,28].

• China: The Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL, Art. 24) guarantees the right to obtain explanations of automated decisions, while the Cybersecurity Law (CSL, Art. 27) imposes strict obligations on preventing deceptive digital activities. These combine to form one of the strongest legal foundations for algorithmic accountability [26,30].

• United States: Although no unified federal AI law exists, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) warns against opaque or discriminatory automated systems, and the NIST AI Risk Management Framework (2023) identifies explainability and accountability as core pillars of responsible AI [29,31].

By providing both global (SHAP) and local (LIME) interpretability, our system demonstrates how phishing-detection models can satisfy transparency expectations in GDPR Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), PIPL compliance audits, and NIST-aligned risk assessments. This unified framework shows that technically robust models can also remain legally defensible and operationally auditable across jurisdictions.

5.2 Trade-Offs and Policy Implications

These results highlight the policy trade-off between interpretability and accuracy. Deep learning methods such as CNNs may provide a bit higher accuracy [5] but are not able to provide the transparency that guarantees legal defensibility. RF is less accurate but has interpretability, which reduces liability exposure and enhances institutional trust. In practice, regulators will tend to allow an explainable model with high performance in preference to a black-box model with slightly improved accuracy but no auditability.

This is not merely a technical trade-off but a governance choice: interpretable models operationalize the ‘right to explanation’ as a procedural safeguard against algorithmic harm [6,32], whereas black-box systems externalize risk onto users and regulators.

Hence, explainable models like RF, supported by SHAP and LIME, shift both technical robustness and legal liability towards international AI rule of fairness, transparency, and due care [18,33].

This study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, the dataset comprises 10,000 URLs (5000 phishing, 5000 legitimate) with 48 pre-engineered features, a balanced and widely used benchmark in prior literature [10] but represents a static snapshot of phishing tactics. Given the rapidly evolving nature of cyber threats, this limits the model’s generalizability to emerging attack variants.

Furthermore, the features are exclusively lexical and content-based, lacking multimodal signals such as webpage visual layout, DOM structure, or user behavioral data dimensions increasingly leveraged by advanced phishing kits like PhiUSIIL [34] and StealthPhisher [3]. This omission significantly restricts the model’s robustness against adversarially crafted URLs that mimic legitimate services through techniques such as homograph attacks (e.g., google.com) or dynamic, obfuscated redirection chains. Recent 2024 studies underscore the necessity of integrating visual and contextual cues to detect such evasive tactics [3], a gap we explicitly address in our future work.

Third, our evaluation was limited to four interpretable classifiers (Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost). While this focus aligns with our goal of legal accountability, it excludes comparison with deep learning models (e.g., CNNs, transformers) that may offer marginal gains in accuracy albeit at the cost of transparency [5,33].

Finally, although our legal-technical mapping is novel, it primarily emphasizes EU and Chinese statutory frameworks (GDPR, PIPL, CSL, AI Act). U.S. regulatory considerations such as the FTC Act and NIST AI RMF are discussed only at a policy level [2,24]. Broader cross-jurisdictional validation is needed to assess the framework’s applicability in diverse legal environments.

Upcoming work should generalize from pre-engineered URL characteristics to multimodal phishing detection, including visual, textual, and behavioral information to improve robustness against mutating attacks. Real-time deployment settings are also in need of exploration, with a necessity for pipeline optimization that maximizes transparency while minimizing speed and adversarial adaptation resilience [25]. Apart from that, there are also broader comparative legal evaluations to be made: while this study included GDPR, China’s PIPL, and the EU AI Act, future research must compare against U.S. norms like the FTC Act and NIST AI RMF (2023) and other emerging global governance standards to increase the overall generalizability of explainable AI across cybersecurity compliance [35].

Although deep learning models such as CNNs and transformer architectures have recently achieved state-of-the-art results in phishing detection, their limited interpretability poses challenges for regulatory accountability. Future research may explore hybrid frameworks that combine the transparency of ensemble methods with the representational power of deep architectures.

The current paper proposed an interpretable machine learning model for phishing detection that is not only technically reasonable but also legally sound. Out of a balanced dataset of 10,000 URLs (5000 phishing, 5000 legitimate) with 48 engineered features, four classifiers were evaluated, and Random Forest was utilized as the best model on account of its robustness (98.55% accuracy) as well as feature-level interpretability ability. The use of SHAP and LIME provided global and local interpretation whereby phishing predictions not only remained accurate but also transparent and auditable.

The most valuable single contribution of this research is in showing the extent to which the results of technical models can be brought directly into correspondence with statutory provisions, thus closing the accountability gap that generally constrains the use of AI for cybersecurity. By correlating features such as domain mismatches and suspicious re-routing to specific provisions in China’s PIPL, the GDPR, and EU AI Act, this research demonstrates a technologically viable and legally valid method for fulfilling compliance obligations in high-risk AI situations.

Future work will also evaluate robustness against adversarial attacks, such as homograph domains (e.g., google.com), to ensure real-world reliability. More broadly, this research shows that strong phishing detection can be high-quality without sacrificing transparency. Or, transparent models such as Random Forest, enabled through XAI techniques, can do all three simultaneously: enhance security performance, reduce risk to liability, and enable compliance with future regulatory regulations. As security becomes increasingly entwined with policy and law, the approach presented here is a step towards the development of trustworthy, accountable, and regulatorily compliant AI systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors would also like to thank Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications and Nantong University for providing the academic environment and computational resources that facilitated this research. The authors further thank the open-source community and contributors to Kaggle for providing available phishing datasets on which this research was feasible.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: MD Hamid Borkot Tulla had the responsibility of research conception, methodology design, data analysis, and manuscript writing. MD Moniur Rahman Ratan contributed to experimental design, figure preparation, and critical manuscript review. Rasid MD Mamunur contributed to model implementation, performance verification, and visualization. Abdullah Hil Safi Sohan and MD Matiur Rahman contributed to literature review and final proofreading, provided legal-technical mapping and compliance analysis expertise. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The experimental notebook and data used in this current research are publicly available at Kaggle: Phishing Dataset for Machine Learning–https://www.kaggle.com/code/mdhamidborkottulla/phishing-dataset (accessed on 02 December 2025). Supplementary data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: No human participants, animals, or personal identifiable data were included in this research. All data employed were publicly available and ethically retrieved according to institutional and journal policy.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sasaki R. AI and security—what changes with generative AI. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability, and Security Companion (QRS-C); 2023 Oct 22–26; Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2023. p. 208–15. doi:10.1109/qrs-c60940.2023.00043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tang L, Mahmoud QH. A survey of machine learning-based solutions for phishing website detection. Mach Learn Knowl Extr. 2021;3(3):672–94. doi:10.3390/make3030034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Prasad A, Chandra S. PhiUSIIL: a diverse security profile empowered phishing URL detection framework based on similarity index and incremental learning. Comput Secur. 2024;136(4):103545. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sweidan AH, El-Bendary N, Elhariri E. Autoregressive feature extraction with topic modeling for aspect-based sentiment analysis of Arabic as a low-resource language. ACM Trans Asian Low-Resour Lang Inf Process. 2024;23(2):1–18. doi:10.1145/3638050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alshingiti Z, Alaqel R, Al-Muhtadi J, Haq QEU, Saleem K, Faheem MH. A deep learning-based phishing detection system using CNN, LSTM, and LSTM-CNN. Electronics. 2023;12(1):232. doi:10.3390/electronics12010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Capuano N, Fenza G, Loia V, Stanzione C. Explainable artificial intelligence in CyberSecurity: a survey. IEEE Access. 2022;10(2):93575–600. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3204171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wachter S, Mittelstadt B, Floridi L. Why a right to explanation of automated decision-making does not exist in the general data protection regulation. Int Data Priv Law. 2017;7(2):76–99. doi:10.1093/idpl/ipx005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Edwards L, Veale M. Slave to the algorithm? Why a “right to an explanation” is probably not the remedy you are looking for. Duke Law Technol Rev. 2018;16:18–84. [Google Scholar]

9. General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679. On the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Maastricht, The Netherland: European Union; 2016. [Google Scholar]

10. Tulla MHB. Phishing dataset for machine learning [Data Set and Notebook] [cited 2025 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/code/mdhamidborkottulla/phishing-dataset. [Google Scholar]

11. Kytidou E, Tsikriki T, Drosatos G, Rantos K. Machine learning techniques for phishing detection: a review of methods, challenges, and future directions. Intell Decis Technol. 2025;19(6):4356–79. doi:10.1177/18724981251366763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shahrivari V, Darabi MM, Izadi M. Phishing detection using machine learning techniques. arXiv:2009.11116. 2020. [Google Scholar]

13. Chen JL, Ma YW, Huang KL. Intelligent visual similarity-based phishing websites detection. Symmetry. 2020;12(10):1681. doi:10.3390/sym12101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C. Why should I trust you?: explaining the predictions of any classifier. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2016. p. 1135–44. doi:10.1145/2939672.2939778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li W, Manickam S, Chong YW. FedPhishLLM: a privacy-preserving and explainable phishing detection mechanism using federated learning and LLMs. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2025;37(8):252. doi:10.1007/s44443-025-00267-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ajibola OS, Dopamu O, Olurin O. Challenges and ethical implications of using AI in cybersecurity. Int J Sci Res Arch. 2025;14(2):294–304. doi:10.30574/ijsra.2025.14.2.0276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. College LU, Huy S, Ang S, College LU, Ho M, College LU, et al. Insider threats in banking sector: detection, prevention, and mitigation. J Cyber Secur Risk Auditing. 2025;2025(4):257–65. doi:10.63180/jcsra.thestap.2025.4.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ganesh NB, Siddineni D, Reddy BVV, Ganesha KS, Lateef K, Sharma R. Corpo-rate governance in the age of AI: ethical oversight and accountability frameworks. J Inf Syst Eng Manag. 2025;10(35s):6285. doi:10.52783/jisem.v10i35s.6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lee J, Lim P, Hooi B, Divakaran DM. Multimodal large language models for phishing webpage detection and identification. arXiv:2408.05941. 2024. [Google Scholar]

20. Sarker IH, Janicke H, Mohsin A, Gill A, Maglaras L. Explainable AI for cybersecurity automation, intelligence and trustworthiness in digital twin: methods, taxonomy, challenges and prospects. ICT Express. 2024;10(4):935–58. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2024.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li H, Zhang X, Hu Q. PhishSIGHT: visual and lexical explainable phishing detection framework. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;234(11):121040. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Putra GP. Artificial intelligence in cybersecurity legal and ethical challenges in regulating autonomous defense systems. Walisongo Law Rev. 2025;7:179–94. [Google Scholar]

23. Sidhpurwala H, Mollett G, Fox E, Bestavros M, Chen H. Building trust: foundations of security, safety, and transparency in AI. AI Mag. 2025;46(2):e70005. doi:10.1002/aaai.70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Aldakheel EA, Zakariah M, Gashgari GA, Almarshad FA, Alzahrani AIA. A deep learning-based innovative technique for phishing detection in modern security with uniform resource locators. Sensors. 2023;23(9):4403. doi:10.3390/s23094403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Artificial Intelligence Act, Regulation (EU) 2024/1689. Laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). Maastricht, The Netherland: European Union; 2024. [Google Scholar]

26. National People’s Congress of China. Cybersecurity law (CSL). Beijing, China: National People’s Congress of China; 2017. [Google Scholar]

27. Innab N, Osman AAF, Ataelfadiel MAM, Abu-Zanona M, Elzaghmouri BM, Zawaideh FH, et al. Phishing attacks detection using ensemble machine learning algorithms. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(1):1325–45. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.051778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Batool A, Zowghi D, Bano M. AI governance: a systematic literature review. AI Ethics. 2025;5(3):3265–79. doi:10.1007/s43681-024-00653-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Federal Trade Commission. FTC guidance on AI transparency and accountability. Washington, DC, USA: Federal Trade Commission; 2023. [Google Scholar]

30. Soori M, Jough FKG, Dastres R, Arezoo B. AI-based decision support systems in Industry 4.0, a review. J Econ Technol. 2026;4(1):206–25. doi:10.1016/j.ject.2024.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rjoub G, Bentahar J, Abdel Wahab O, Mizouni R, Song A, Cohen R, et al. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence for cybersecurity. arXiv:2303.12942. 2023. [Google Scholar]

32. Hohma E, Lütge C. From trustworthy principles to a trustworthy development process: the need and elements of trusted development of AI systems. AI. 2023;4(4):904–26. doi:10.3390/ai4040046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Feng X, Shi Q, Li X, Liu H, Wang L. IDPonzi: an interpretable detection model for identifying smart Ponzi schemes. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;136(2):108868. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nagy N, Aljabri M, Shaahid A, Ahmed AA, Alnasser F, Almakramy L, et al. Phishing URLs detection using sequential and parallel ML techniques: comparative analysis. Sensors. 2023;23(7):3467. doi:10.3390/s23073467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Artificial intelligence risk management framework (AI RMF 1.0). Gaithersburg, ML, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools