Open Access

Open Access

MINI REVIEW

Emerging Roles of Fc Receptor-Like 1 in Immunotherapy of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

1 Department of Pharmacology and Immunology, Medical University of South Carolina, 173 Ashley Avenue, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

2 Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Administration Medical Center, 109 Bee St, Charleston, SC 29401, USA

3 Department of Neurosurgery, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucas Street, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

* Corresponding Author: Azizul Haque. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Genetic Biomarkers of Cancer: Insights into Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1859-1871. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068773

Received 05 June 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Fc Receptor-Like 1 (FCRL1), a member of the FCRL family, contains two immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) in its cytoplasmic domain and plays a critical role in B-cell biology. Its expression begins in pre-B-cells, dynamically shifts during B-cell development, and contributes to the regulation of human B-cell activation. Notably, FCRL1 is overexpressed in subsets of naive and memory B-cells, as well as in malignant B-cells, including those in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), an aggressive and often treatment-resistant hematological malignancy. Among FCRL family members, FCRL1 stands out as a promising immunotherapeutic target due to its selective expression in malignant B-cells and its functional role in proliferation. Given the limited efficacy of current therapies for relapsed/refractory DLBCL, targeting FCRL1 could address an unmet clinical need by offering a novel, mechanism-based approach to modulate B-cell signaling and enhance anti-tumor immunity. This mini-review highlights the therapeutic potential of FCRL1-directed strategies, supporting their further exploration in preclinical models and future clinical trials for DLBCL and other B-cell malignancies.Keywords

Antigen (Ag) recognition of tumor cells is essential for host defense, as well as potentiating the destruction and clearance of malignant cells. However, lymphoid malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia often have insufficient anti-tumor immune responses [1–3]. The transformation of these cells compromises host defense, and many of these malignant cells evolve mechanisms to escape immune recognition [4,5]. Specifically, B-cell tumors vary greatly in how they behave in the body as well as in their clinical presentation [6]. While leukemic cells typically involve the bone marrow and peripheral blood, B-cell lymphomas usually produce masses in the lymph nodes or other tissues. Plasma cell tumors differ because they typically originate within the bones and can generate systemic symptoms due to the production of antibodies or immunoglobulins [7,8]. In any case, all of these neoplasms have the capacity to spread to various other tissues within the body. While current treatments such as chemotherapy and/or radiation are typically effective, they are largely non-specific and can cause damage to the healthy tissues that surround the targeted cancer cells.

Antibody-based immunotherapy is gaining momentum in treating cancer, but its effectiveness varies among cancer types and patients. Targeted immunotherapies have significantly advanced the treatment of B-cell malignancies, particularly through the use of monoclonal antibody treatments and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies [9,10]. CAR-T cells have shown remarkable success in killing malignant cells and specifically treating B-cell malignancies because they are able to target specific antigens [11], although antigen escape and toxicities remain a problem. CAR-T cells are a great example of the importance of identifying reliable tumor-associated antigens that can be used for treatment.

Because of the importance of finding biomarkers for prognosis, as well as possible therapeutic targets, for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and other B-cell malignancies, Fc receptor-like 1 (FCRL1) is being explored as a potential target. The interaction between antibodies and Fc receptors (FcRs) on immune cells is a critical factor in determining the activity of antibodies in the body. FCRL proteins have been seen almost exclusively in B-cells, including malignant B-cells. FCRL1 is distinct within its family due to the fact that it contains two immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motifs (ITAMs) and is highly expressed in several non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas. However, little is known about the functioning of these proteins in humans, so more exploration is needed. The FCRL isoform also appears to inhibit recognition of CD4+ T cells, and consequently would hinder T cell immunosurveillance of B-cell lymphoma, which may lead to unchecked growth of lymphoma. Studies suggest targeted antibody immunotherapy could be a first-line treatment strategy for B-cell lymphoma due to the success of rituximab, a chimeric antibody that binds to and eliminates cells expressing the pan-B cell marker CD20 [12,13]. Since FCRL isoforms also regulate signals to B-cells after ligation, antibody targeting FCRL isoform(s) may have a completely different mechanism of action from antibodies that bind to and eliminate malignant cells expressing tumor antigens. Antibodies targeting specific FCRL molecules could boost immune recognition of B-cell lymphomas and inhibit tumor growth, so they are worthy of being explored.

The primary objective of this mini-review is to focus on the role of Fc Receptor-Like (FCRL) proteins, particularly FCRL1, in modulating immune recognition and evasion in B-cell lymphomas, with the goal of developing targeted antibody-based immunotherapies. Given that B-cell malignancies often evade immune surveillance through mechanisms that impair antigen recognition [14,15], this review hypothesizes that FCRL1, a predominantly B-cell-expressed molecule, plays a critical role in suppressing T-cell immunosurveillance and immune-mediated tumor clearance. By characterizing the function of FCRL1 in human B-cell lymphomas, the research aims to determine whether targeting this specific FCRL isoform can enhance immune recognition and inhibit tumor growth, offering a more precise therapeutic approach compared to conventional chemotherapy and radiation.

The rationale for this study stems from the limited understanding of FCRL1’s role in human B-cell malignancies, despite evidence suggesting its involvement in B-cell signaling and immune regulation [16,17]. Given the success of antibody therapies, like rituximab, in treating B-cell lymphomas [12,18], the study posits that an antibody targeting FCRL1 may function differently by modulating immune activation rather than simply inducing cell depletion. Since FCRL1 may obstruct CD4+ T-cell recognition, its blockade could restore immunosurveillance and improve tumor clearance. Thus, this review seeks to cover the mechanistic role of FCRL1 in immune evasion and evaluate its potential as a novel immunotherapeutic target for B-cell lymphomas, which could lead to more effective and selective treatment strategies. While the importance and role of FCRL1 in B cells and DLBCL are reported, this mini-review highlights the critical role of FCRL1 in B-cell biology and its therapeutic potential for aggressive B-cell malignancies, particularly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). FCRL1, which contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), regulates B-cell activation and is overexpressed in malignant B-cells, suggesting its involvement in tumor survival and proliferation. Given its selective expression in lymphoma cells and the limited efficacy of current DLBCL therapies, FCRL1 emerges as a promising immunotherapeutic target. By modulating B-cell signaling and enhancing anti-tumor immunity, FCRL1-directed strategies could address an unmet clinical need in relapsed/refractory disease. This report underscores the rationale for further preclinical and clinical exploration of FCRL1 targeting, offering a novel mechanism-based approach to improve outcomes in DLBCL and other B-cell malignancies.

Studies suggest that there are two different groups of lymphomas: (a) Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), and (b) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) [7,19]. During class switching and somatic hypermutation, there is a high risk of transforming mutations, so lymphomas commonly stem from germinal center and post-germinal center B-cells. Because of this variance in B-cell development and maturation, when B-cell malignancies arise, there could be a potential influence on immune recognition and tumor clearance. However, the functional interactions of these cells with other components of the immune system remain unclear.

B-cell lymphomas are a type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) that originates in B-cells. It is the most common type of lymphoma, and about 85% of all NHLs in the United States are related to B-cells [7,20–22]. NHL typically originates in lymphoid tissues but can spread to other organs. NHLs are known to be a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative malignancies with varying patterns of behavior and responses to treatment. Common symptoms associated with general lymphomas include painless enlargement of one or more lymph node areas, which are associated with fever, night sweats, and weight loss. While most B-cell lymphomas are NHLs, there are many different subtypes of B-cell NHLs [21,23], such as Burkitt lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), follicular lymphoma (FL), and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Prognosis and treatment depend on the subtype and stage of the cancer at diagnosis. The most common and aggressive type of non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma in Western countries is DLBCL [24–26], and it accounts for about 25% to 30% of all NHLs [27].

DLBCL develops from abnormal B-cells, and when examined under a microscope, the cells appear more spread out (hence the name diffuse) compared to other B-cell malignancies, which remain clumped together [28,29]. It can either develop as a transformation from a less aggressive form of lymphoma or as a first occurrence. Although the disease can occur in childhood, the occurrence of DLBCL likely increases with age, and the majority of patients are over the age of 60 at diagnosis [30]. The most common symptom of DLBCL is swollen lymph nodes in the affected area; these lumps can most often be detected from the surface, but sometimes, they are deep in the body and cannot be felt. Although it is most commonly seen in lymph nodes, about 40% of people develop DLBCL outside of their lymph nodes, known as extranodal disease [31]. Symptoms vary between patients with DLBCL depending on where it is in the body and what tissues are affected. In some cases, patients may even experience flu-like symptoms or weight loss.

There are three main molecular subtypes of DLBCL: activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL, germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL, and unclassifiable/type 3 DLBCL [32,33]. ABC DLBCL arises from post-germinal center B-cells (such as plasmablasts) and is typically more aggressive and less responsive to treatment. In contrast, GCB DLBCL typically originates from germinal center B-cells and is more responsive to current treatments. Unclassifiable/type 3 DLBCL has differing molecular characteristics from ABC and GCB types. Type 3 DLBCL typically responds better to treatment than ABC DLBCL, but not as well as GCB DLBCL. Although largely still unknown, studies suggest that FCRL1 expression may vary between the subtypes [16,17,34]. FCRL1 is seen to be more highly expressed in GCB DLBCL compared to ABC DLBCL. This difference in expression patterns may contribute to more subtype-specific immunotherapies and improve treatment outcomes for patients.

3 B-Cell Lymphomas and Current Therapies

The current first-line treatment for DLBCL is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, known as Rituximab, used in combination with harsh chemotherapy drugs; these drug combinations, along with Rituximab are known as R-CHOP (R = Rituximab, C = Cyclophosphamide, H = Doxorubicin Hydrochloride/Hydroxy-daunomycin, O = Vincristine Sulfate/Oncovin, P = Prednisone) [24,35,36]. The R-CHOP combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy drugs may also be used in combination with radiation therapy if the DLBCL is caught in an early stage [36,37]. R-CHOP has been shown to have high remission rates, but there are also major downfalls to using this treatment. One major downfall is that CD20 is present on both malignant and healthy B-cells, so targeting this antigen causes the depletion of healthy cells as well as cancerous cells. This can weaken the patient’s immune system and leave them more susceptible to other infections. Other side effects of using the R-CHOP treatment range from short-term problems such as nausea and hair loss to long-term problems such as heart problems and relapse.

Epcoritamab and Glofitamab may also be used as immunotherapy for treating relapsed or refractory DLBCL [38]; they are bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) that attach T-cells (on the CD3 antigen) and lymphoma cells (on the CD20 antigen) to each other, so the T-cells can remain within close proximity to the lymphoma cells to fight [39]. Many patients benefit from CD20-targeted therapies because of its high expression on tumor cells, but those who relapse after treatment may consider a new CD19-targeted therapy (e.g., Loncastuximab tesirine) because the CD19 antigen has been found to be expressed in most B-cell malignancies [40]. The use of CAR-T cell therapies that target the CD19 antigen, such as axicabtagene ciloleucel, tisagenlecleucel, or lisocabtagene maraleucel, has also been shown to benefit a patient who has relapsed. Similar to R-CHOP, these treatments come with their own downfalls. Some of the biggest downfalls of using BiTEs or CAR-T therapies are the possibilities of antigen escape, off-tumor toxicity, and incomplete tumor clearance.

In addition to R-CHOP, CD19, and CD20 targeted therapies, many other combinations of chemotherapy drugs, radiation therapies, stem cell therapies, and immunotherapies are used to treat DLBCL, depending on the patient’s circumstances. Each of these therapies comes with its own set of limitations, which highlights the need for additional biomarkers that can be more selectively expressed on malignant cells.

4 Fc Receptors and Fc Receptor-Like (FCRL) Proteins

An Fc Receptor (FcR) is a protein that contributes to the immune system and is found on the cell surface of many different types of immune cells [41]. FcRs are thought to be key components of currently used antibody-mediated therapies for lymphoma and other cancers. These receptors recognize and bind to the Fc region of an antibody, opposite to the antigen-binding sites, to stimulate an immune response. Fc Receptor-Like (FCRL) proteins are a subgroup of immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) lymphocyte receptors that are clustered on the long arm of chromosome 1. While some members are found in both B and T cells, FCRL expression is mostly seen in B-cells, including malignant B-cells [42–46].

Members of the human FCRL family consist of six type-1 transmembrane glycoproteins (FCRL1–6) that are attached to the surface of the cell [47,48], as well as two intracellular proteins (FCRLA, FCRLB) that are able to be secreted. Each of the FCRL1–6 proteins expresses immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) domains on the surface of the cells (extracellular regions/N-terminus), immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibiting motif (ITIM) and/or activating motif (ITAM)—like sequences in their cytoplasmic tails (C-terminus) [48], suggesting that they transmit activatory and/or inhibitory signals to B-cells after ligation [43,49]. These FCRL proteins have shown the potential to regulate human B-cell responses. FCRL2–6 have each been found to have at least one ITIM-like motif, and FCRL2, FCRL3, and FCRL5 have both ITIM and ITAM-like sequences, suggesting the capability of dual modulation [48,50]. FCRL1 and FCRL5 differ from the rest of the family members because they contain two of the same sequences in their cytoplasmic tails. FCRL5 contains two ITIM-like motifs and is the largest FCRL family member with nine extracellular Ig-like domains, whereas FCRL1 contains two ITAM-like motifs, suggesting that it is a co-activation receptor [51,52]. Studies also found FCRL1 and FCRL5 to be expressed more than the other members of the human FCRL family in B-cells [53,54], indicating that these proteins may be potential targets for antibody-based treatments of B-cell malignancies such as leukemias and lymphomas. Further research has been conducted on the FCRL family members, indicating that ITIM-like motifs (present in FCRL2–6) have adversely affected B-cell antigen activation [55], drawing even more attention to FCRL1. In addition to its two ITAM-like motifs, FCRL1 contains three extracellular Ig-like domains and no ITIM-like motifs [51,52]. FCRL1 is also the only protein in the family with a negatively charged glutamic acid residue in its transmembrane domain, whereas FCRL2–6 are hydrophobic and have no charge. The restricted distribution of FCRL1 among B-lineage cells, its tightly regulated expression patterns during germinal center B-cell development, and its role in promoting cellular and humoral immune responses suggest its involvement in B-cell transformation [17]. These distinct differences between FCRL1 and the rest of the FCRL family give reason for FCRL1 to be a key player in B-cell lymphoma, and the main focus of the FCRL family as a target.

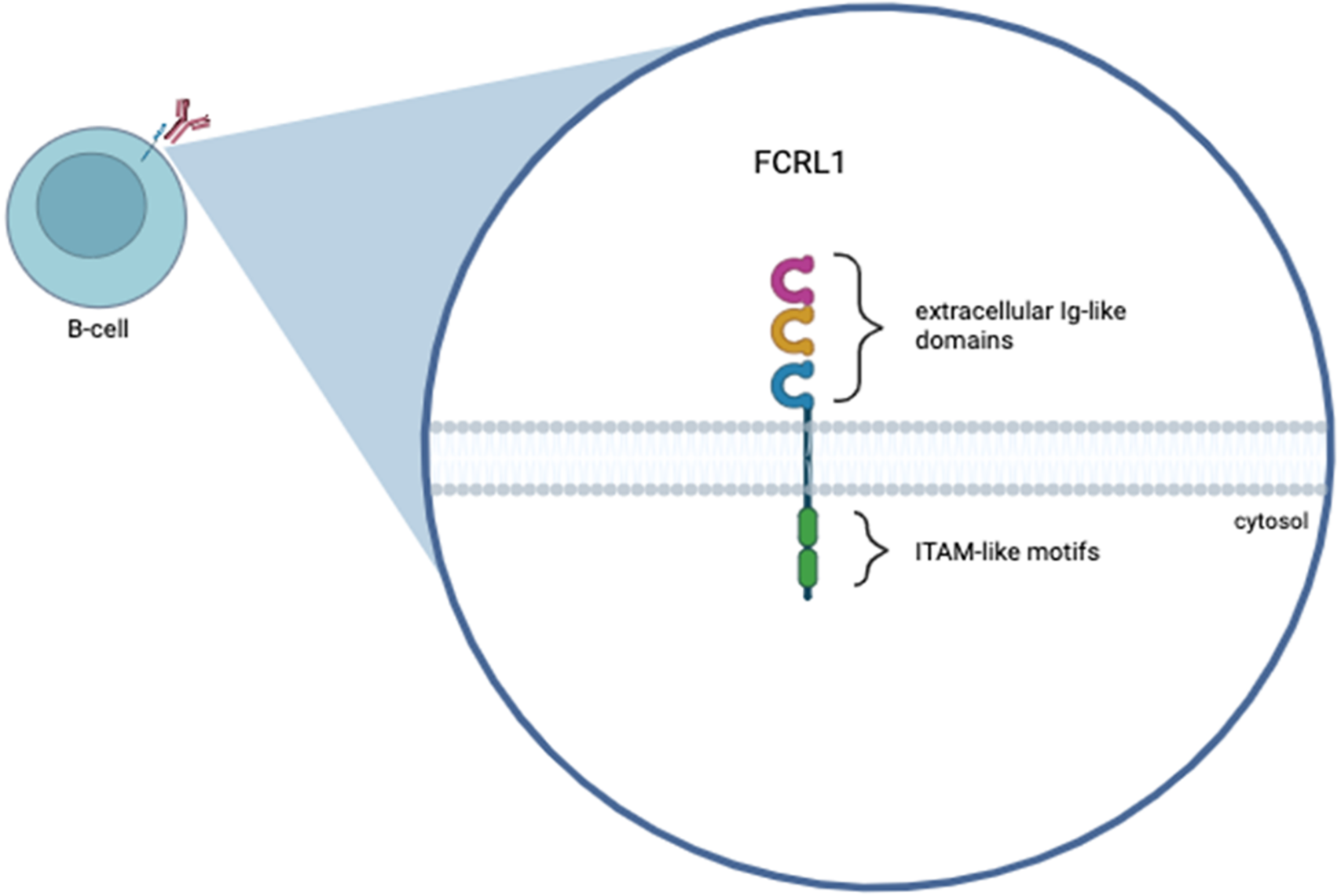

FCRL1 is a protein-coding gene. The protein it encodes features three extracellular C2-type immunoglobulin domains, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail containing two ITAMs (Fig. 1). The idea of FCRL1 as a potential target for antibody-based treatments of B-cell malignancies has already begun to be explored. Du et al. found 83% of patients (34/41) with a type of B-cell lymphoma, such as CLL, FL, MCL, or hairy cell leukemia (HCL), to express FCRL1 proteins on their malignant cells [47]. By using FCRL1-specific mAbs, this group also confirmed the frequent expression of FCRL1 on CLL, FL, and some other B-cell malignancies. Although Du et al. do not explicitly talk about DLBCL within patients, cell lines REC1, OCI-Ly7, and SU-DHL-6, which are associated with DLBCL, were also included in the study. The REC1 cell line showed the highest expression of FCRL1 out of all cell lines used in the study [47], proving the benefit of including DLBCL when looking at FCRL1 as a potential target for antibody-based treatments. Several other studies also indicated differential expression levels of FCRL1 transcripts by primary FL, CLL, MCL, and DLBCL [56,57], CLL, and in some cases BL, showing the highest expression. However, DLBCL is the most aggressive type of B-cell NHL, and the role and mechanisms of FCRL1 in DLBCL remain unclear. Thus, this mini-review focuses on the role of FCRL1 in B-cell NHLs, particularly DLBCL.

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the human FCRL1 protein. FCRL1 is a cell-surface membrane protein that belongs to the FCRL family. The figure shows three Ig-like extracellular domains, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain with two immunoreceptor-tyrosine activation motifs. This figure was created using Biorender software (version 201)

5.1 FCRL1 Expression and Signaling

FCRL1 expression has also been shown to differ between the ABC (activated B-cell-like) and GCB (germinal center B-cell-like) subtypes of DLBCL [16,17], reflecting the biological heterogeneity of these subgroups. Studies indicate that FCRL1 is more highly expressed in the GCB subtype compared to the ABC subtype [17], consistent with its association with germinal center B-cells, where FCRL1 is commonly upregulated during B-cell maturation. This differential expression may contribute to the distinct clinical behaviors and therapeutic responses observed between ABC and GCB DLBCL, as FCRL1 has been implicated in modulating BCR signaling and immune regulation. The stronger expression in GCB DLBCL suggests a potential role in germinal center-derived lymphomagenesis or tumor microenvironment interactions, whereas its lower expression in ABC DLBCL may reflect the more aggressive, post-germinal center nature of this subtype. Further research is needed to correlate expression levels with disease progression and therapeutic response.

While FCRL1 is known to modulate B-cell activation and proliferation through its immunoreceptor ITAMs, the specific downstream signaling pathways it engages in DLBCL remain poorly defined. Unlike canonical ITAM-containing receptors like the BCR, where the signaling cascade through SYK, BTK, and PLCγ2 is well characterized, the extent to which FCRL1 engages similar or distinct effectors remains unclear. Furthermore, it is unknown whether FCRL1 signaling functions independently or cooperatively with chronic active BCR signaling, which is a key driver in the ABC subtype of DLBCL.

Less information is available on whether FCRL1 amplifies BCR signals, modulates threshold sensitivity to antigen, or provides survival cues under tonic signaling conditions. However, it remains possible that FCRL1 acts as a co-receptor, influencing BCR microcluster formation, immunological synapse stability, or downstream kinase activation. Additionally, the interplay between FCRL1 and other regulators of B-cell fate (e.g., PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, or MAPK pathways) has not been systematically mapped in the DLBCL context. Addressing this gap requires further investigation on dissecting FCRL1-associated signalosomes using loss-of-function studies in FCRL1-high DLBCL models. A deeper mechanistic understanding of how FCRL1 drives or supports lymphomagenesis could provide a rationale for targeting this molecule directly or in combination with established pathway inhibitors.

5.2 FCRL1 and Lymphoma Immunotherapy

Because of FCRL1’s expression on malignant B-cells and emerging role in modulating B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, it has become a promising candidate for antibody-based interventions. Unlike current therapies that target CD19 or CD20, FCRL1 may offer a distinct therapeutic mechanism by modulating intracellular activation pathways that would be critical for the survival and proliferation of B-cell lymphomas. Recent studies have begun to explore how FCRL1 influences tumor behavior and responses to treatments, which may lay the groundwork for future therapy options.

Zhao et al. investigated the functional role of FCRL1 by generating FCRL1-deficient CH27 (CH27-FCRL1-KO) cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 approach with a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [58]; these cells targeted the third exon of the FCRL1 gene. They were able to compare the strength of B-cell receptor signaling by measuring the amount of BCRs that accumulated at synapses. Quantitative analysis revealed that, upon BCR cross-linking alone, CH27-FCRL1-KO cells showed markedly reduced accumulation of BCRs in the immunological synapse when compared to the CH27 wild-type cells. Because CH27 cells are a mouse B-cell lymphoma cell line, the results can be considered a topic needing more exploration for human B-cell lymphoma cell lines. The findings from this study indicate FCRL1 plays an important role in promoting tumor growth. Furthermore, Zhao et al. examined the distribution of FCRL1 molecules during BCR engagement to understand why deficiency in FCRL1 proteins leads to impaired BCR-mediated activation of B-cells due to the lack of FCRL1 ligation [58]. The analysis of the unusual distribution of both BCR and FCRL1 proteins within the immunological synapse of B-cells suggested that FCRL1 ligation could strongly induce the aggregation of FCRL1 molecules, but not BCRs. Overall, this study provided evidence that the expression of FCRL1 plays a positive regulatory function in B-cell activation and antibody responses, suggesting that more in-depth studies are required to explore its potential antibody-based therapeutic use in patients with malignant B-cell lymphomas.

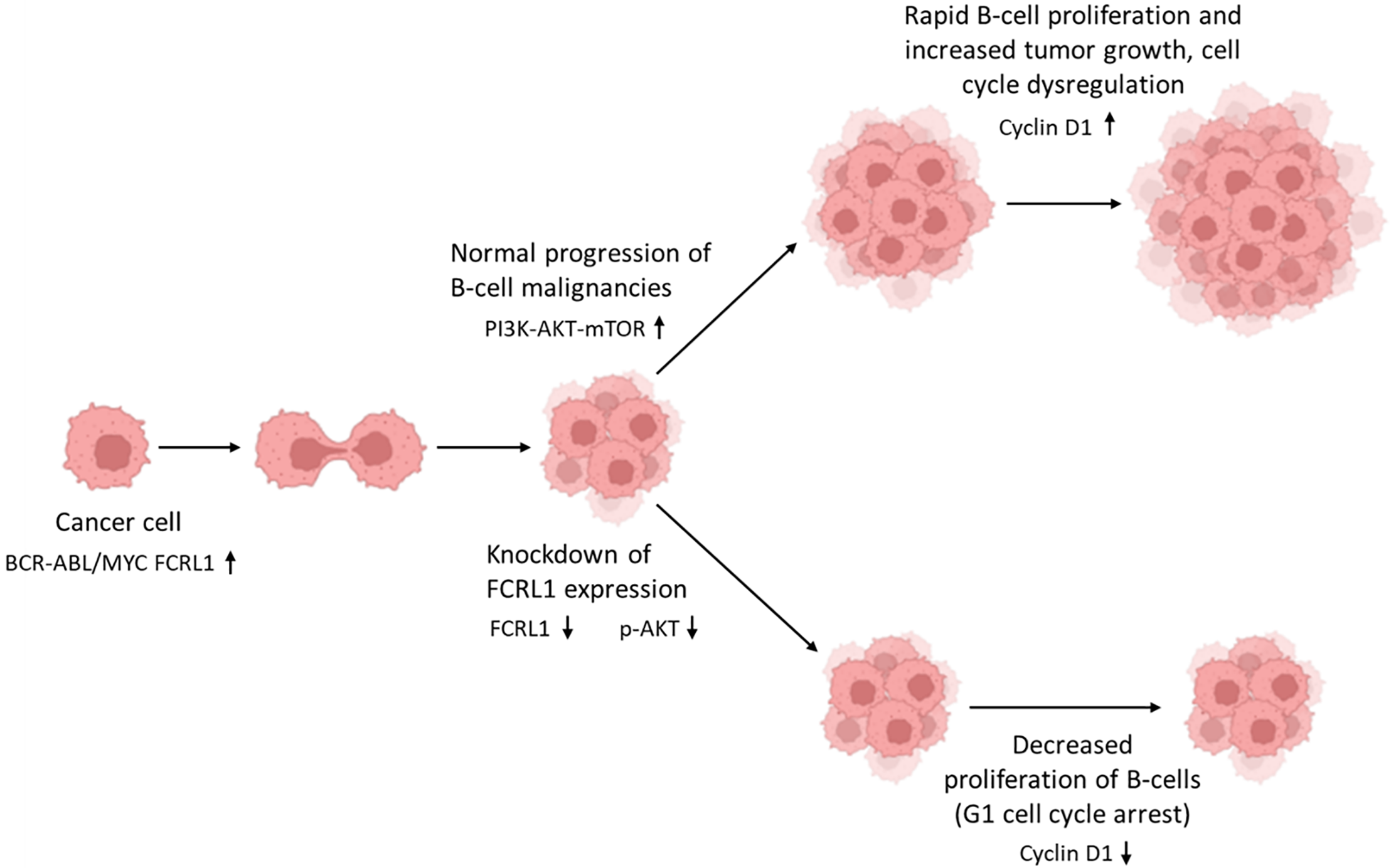

Yousefi et al. expanded the study of FCRL1 to include DLBCL cells and compared the levels to healthy controls [52]. Results from this study indicated a notable overexpression of FCRL1 on the neoplastic B-cells of DLBCL patients compared to the non-malignant B-cells of healthy controls in both protein (p < 0.0001) and mRNA (p < 0.001) [52]. When analyzing the ablation of FCRL1 expression, there was reduced B-cell proliferation within DLBCL, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Since upregulation of FCRL1 proteins has the potential to amplify B-cell activation, and abnormal expression of this protein has been reported in DLBCL cell lines as well as BL, CLL, MCL, HCL, and FL patients [52,53], FCRL1 could be involved in the pathogenesis of B-cell malignancies, specifically DLBCL. DLBCL was especially emphasized in the study by Yousefi et al. because FCRL1 was able to be detected in 80.7% of DLBCL patients [52], highlighting the importance of FCRL1 as a marker for DLBCL and its importance in immunotherapy. Quantitative studies reveal that FCRL1 is expressed at significantly higher levels in malignant B-cells compared to healthy B-cells [17,34,47,52]. In normal B-cell populations, FCRL1 shows restricted and transient expression, primarily during early B-cell development, with minimal to undetectable levels in mature naïve or memory B-cells. In contrast, malignant B-cells such as those in CLL, DLBCL, MCL, exhibit pronounced FCRL1 upregulation, often confirmed by qPCR, flow cytometry, and RNA sequencing. For instance, CLL cells demonstrate 5- to 10-fold higher FCRL1 mRNA levels than normal B-cells, with protein expression similarly elevated. This differential expression suggests FCRL1 as a potential biomarker for B-cell malignancies and implies its functional role in promoting survival, proliferation, or immune evasion in transformed B-cells.

Figure 2: FCRL1 knockdown impairs B-cell lymphoma growth by disrupting pro-survival signaling. In B-cell malignancies driven by BCR-ABL and MYC oncogenic signaling, FCRL1 overexpression sustains cancer cell proliferation via activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, leading to elevated Cyclin D1 expression and unchecked tumor growth. Following FCRL1 knockdown, malignant B-cells exhibit reduced PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling (low pAKT), resulting in downregulation of Cyclin D1 and subsequent G1 cell cycle arrest. This suppression of proliferative drivers correlates with significantly reduced tumor growth, highlighting FCRL1 as a potential therapeutic target in B-cell malignancies. This figure was created using Biorender software (version 201)

6 Current Standards, Synergy with Newer Immunotherapies, Advantages and Future Directions

FCRL1 represents a novel target that could address key limitations of existing therapies like R-CHOP and CD19/CD20-directed agents [16,52]. While R-CHOP combines chemotherapy with anti-CD20 (rituximab), resistance often arises from CD20 loss or TP53 mutations [59,60]. FCRL1, however, is expressed on malignant B cells (e.g., CLL, NHL) while largely absent on plasma cells, potentially sparing humoral immunity [16,17]. This makes it a promising alternative for CD20-low or CD19-negative relapses, where current standards fail. Additionally, FCRL1’s restricted expression on malignant cells may reduce off-target toxicity compared to broader B-cell depletion strategies.

FCRL1 could complement next-generation immunotherapies by overcoming antigen escape mechanisms. BiTEs (e.g., CD20 × CD3 or CD19 × CD3) and CAR-T therapies are highly effective but limited by CD19/CD20 downregulation in relapsed disease [61–63]. An FCRL1-targeted approach, whether through bispecifics (FCRL1 × CD3), CAR-T cells, or antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), could provide a salvage option for such cases. Preclinical data suggest FCRL1 CAR-T efficacy, positioning it as a sequential therapy post-CD19 CAR-T failure or even as part of dual-targeted strategies to prevent relapse [64–66]. Although still early, these approaches offer hope for more precise and effective treatments for B-cell lymphomas.

Researchers are also considering combining FCRL1 therapies with other treatments, such as checkpoint inhibitors or drugs that block cancer survival signals. Unlike CD19/CD20, FCRL1’s expression profile may offer a more tumor-selective window, enabling mechanisms like ADCs or immune redirection, with fewer side effects. Challenges remain, including defining optimal combinations (e.g., with R-CHOP or checkpoint inhibitors) and monitoring for FCRL1 loss as a resistance mechanism. Clinical trials will be crucial to validate whether FCRL1 targeting can fill unmet needs in refractory B-cell malignancies, particularly where current standards and newer immunotherapies fall short.

FCRL1 has emerged as a highly promising therapeutic target in B-cell malignancies, particularly due to its selective overexpression in aggressive cancers like DLBCL and its potential role in driving tumor progression. Its unique expression pattern, abundant in malignant B-cells but largely absent in normal plasma cells, positions it as an ideal candidate for precision immunotherapy, minimizing off-target toxicity and preserving humoral immunity. This specificity is especially valuable in addressing CD19/CD20-negative relapses, a major clinical challenge where current therapies like R-CHOP or CD19-directed CAR-T cells often fail. The development of FCRL1-targeted modalities, including bispecific antibodies, next-generation CAR-T cells, and ADCs, could circumvent antigen escape mechanisms that limit the durability of existing treatments.

Beyond its therapeutic potential, FCRL1 may also serve as a diagnostic or prognostic biomarker, enabling earlier detection and risk stratification, a critical advancement for elderly patients who constitute the majority of DLBCL cases and face poorer outcomes. However, gaps remain in understanding FCRL1’s biological functions in normal B-cell development and its precise oncogenic mechanisms. Future research must prioritize translational studies with diverse patient cohorts, including underrepresented demographics, varied disease stages, and genetic backgrounds, to ensure broad applicability. In addition, investigating FCRL1’s interplay with tumor microenvironmental factors and resistance pathways (e.g., FCRL1 loss or downregulation) will be essential for optimizing therapeutic strategies.

Clinically, the greatest promise of FCRL1 lies in addressing unmet needs in refractory or relapsed disease, where salvage options are limited. Early-phase trials should explore combination approaches, such as pairing FCRL1-directed therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors or targeted agents, to maximize efficacy and overcome resistance. While challenges like on-target/off-tumor effects or adaptive immune evasion require careful monitoring, preclinical data robustly support FCRL1’s candidacy for rapid clinical translation. Ultimately, successful targeting of FCRL1 could redefine treatment paradigms for high-risk B-cell malignancies, offering a much-needed lifeline to patients with otherwise dismal prognoses.

Acknowledgement: We thank Denise Matzelle, Shelby Mozingo, and Olivia Bauwens for technical assistance.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by funding from the Veterans Administration (I01 BX006101-01). This work was also supported in part by funding from the Veterans Administration (IO1 BX001262). Dr. Narendra L. Banik is the recipient of RCS Award (IK6 BX005964) from the Department of Veterans Administration.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Writing the manuscript, creating the figures, and editing the manuscript: Kayce Blumenstock; editing the manuscript: Vandana Zaman, Camille Green and Narendra L. Banik; study conception, design of manuscript, and editing of the manuscript and figures: Azizul Haque. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jiménez-Morales S, Aranda-Uribe IS, Pérez-Amado CJ, Ramírez-Bello J, Hidalgo-Miranda A. Mechanisms of immunosuppressive tumor evasion: focus on acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front Immunol. 2021;12:737340. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.737340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Chung H, Cho H. Recent advances in cellular immunotherapy for lymphoid malignancies. Blood Res. 2023;58(4):166–72. doi:10.5045/br.2023.2023177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Gummlich L. Shared immunosuppressive mechanism between pregnancy and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024;24(9):595. doi:10.1038/s41568-024-00731-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Seliger B. Strategies of tumor immune evasion. BioDrugs. 2005;19(6):347–54. doi:10.2165/00063030-200519060-00002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Galassi C, Chan TA, Vitale I, Galluzzi L. The hallmarks of cancer immune evasion. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(11):1825–63. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2024.09.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, de Oliveira Araujo IB, Berti E, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1720–48. doi:10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Sharonov GV, Serebrovskaya EO, Yuzhakova DV, Britanova OV, Chudakov DM. B cells, plasma cells and antibody repertoires in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(5):294–307. doi:10.1038/s41577-019-0257-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Pioli PD. Plasma cells, the next generation: beyond antibody secretion. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2768. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ying PT, Weng WW, Tang YM. Advances in structural designs of chimeric antigen receptor T cells—review. J Exp Hematol. 2022;30(6):1902–6. (In Chinese). doi:10.19746/j.cnki.issn.1009-2137.2022.06.043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mi JQ, Xu J, Zhou J, Zhao W, Chen Z, Melenhorst JJ, et al. CAR T-cell immunotherapy: a powerful weapon for fighting hematological B-cell malignancies. Front Med. 2021;15(6):783–804. doi:10.1007/s11684-021-0904-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. El-Khazragy N, Ghozy S, Emad P, Mourad M, Razza D, Farouk YK, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells immunotherapy: challenges and opportunities in hematological malignancies. Immunotherapy. 2020;12(18):1341–57. doi:10.2217/imt-2020-0181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Barraclough A, Hawkes EA. Antibody and immunotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2023;60(5):338–45. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2023.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Colombat P, Brousse N, Salles G, Morschhauser F, Brice P, Soubeyran P, et al. Rituximab induction immunotherapy for first-line low-tumor-burden follicular lymphoma: survival analyses with 7-year follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(9):2380–5. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Qiu Z, Khalife J, Ethiraj P, Jaafar C, Lin AP, Holder KN, et al. IRF8-mutant B cell lymphoma evades immunity through a CD74-dependent deregulation of antigen processing and presentation in MHCII complexes. Sci Adv. 2024;10(28):eadk2091. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adk2091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Varano G, Lonardi S, Sindaco P, Pietrini I, Morello G, Balzarini P, et al. B-cell receptor silencing reveals the origin and dependencies of high-grade B-cell lymphomas with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements. Blood Cancer Discov. 2025;6(4):364–93. doi:10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-25-0099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chen Z, Miao C, Zhang Y, Huang J, Sun Y, Chen J, et al. FcRL1, a new B-cell-activating co-receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(13):6306. doi:10.3390/ijms26136306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mamidi MK, Huang J, Honjo K, Li R, Tabengwa EM, Neeli I, et al. FCRL1 immunoregulation in B cell development and malignancy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1251127. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1251127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Singh V, Gupta D, Almasan A. Development of novel anti-Cd20 monoclonal antibodies and modulation in Cd20 levels on cell surface: looking to improve immunotherapy response. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2015;7(11):347–58. doi:10.4172/1948-5956.1000373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Jiang M, Bennani NN, Feldman AL. Lymphoma classification update: t-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphomas, and histiocytic/dendritic cell neoplasms. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(3):239–49. doi:10.1080/17474086.2017.1281122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Larouche JF, Berger F, Chassagne-Clément C, Ffrench M, Callet-Bauchu E, Sebban C, et al. Lymphoma recurrence 5 years or later following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical characteristics and outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2094–100. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shingleton J, Wang J, Baloh C, Dave T, Davis N, Happ L, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas: malignancies arising from mature B cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2021;11(3):a034843. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a034843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. de Carvalho PS, Leal FE, Soares MA. Clinical and molecular properties of human immunodeficiency virus-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:675353. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.675353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Aslani A, Morsali S, Mousavi SE, Choupani S, Yekta Z, Nejadghaderi SA. Adult Hodgkin lymphoma incidence trends in the United States from 2000 to 2020. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):20500. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69975-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Armengol M, Santos JC, Fernández-Serrano M, Profitós-Pelejà N, Ribeiro ML, Roué G. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors in B-cell lymphoma. Cancers. 2021;13(2):214. doi:10.3390/cancers13020214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Guo Z, Wang C, Shi X, Wang Z, Tao J, Ma J, et al. Advances in proteomics in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Review). Oncol Rep. 2024;51(6):87. doi:10.3892/or.2024.8746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li Y, Liu X, Chang Y, Fan B, Shangguan C, Chen H, et al. Identification and validation of a DNA damage repair-related signature for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022(1):2645090. doi:10.1155/2022/2645090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mamgain G, Singh PK, Patra P, Naithani M, Nath UK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and new insights into its pathobiology and implication in treatment. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(8):4151–8. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2432_21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Abramson JS, Shipp MA. Advances in the biology and therapy of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: moving toward a molecularly targeted approach. Blood. 2005;106(4):1164–74. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-02-0687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Augé H, Notarantonio AB, Morizot R, Quinquenel A, Fornecker LM, Hergalant S, et al. Microenvironment remodeling and subsequent clinical implications in diffuse large B-cell histologic variant of Richter syndrome. Front Immunol. 2020;11:594841. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.594841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yamasaki S. Appropriate treatment intensity for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the older population: a review of the literature. Hematol Rep. 2024;16(2):317–30. doi:10.3390/hematolrep16020032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen X, Wang J, Liu Y, Lin S, Shen J, Yin Y, et al. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: novel insights and clinical perception. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1404298. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1404298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Weber T, Schmitz R. Molecular subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma: biology and implications for clinical practice. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24(1):13–21. doi:10.1007/s11912-021-01155-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Berhan A, Almaw A, Damtie S, Solomon Y. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCLepidemiology, pathophysiology, risk stratification, advancement in diagnostic approaches and prospects: narrative review. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):184. doi:10.1007/s12672-025-01958-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Al-Amodi HS, Bedair HM, Gohar S, Mohamed DA, Abd El Gayed EM, Nazih M, et al. FCRL1 and BAFF mRNA expression as novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: expression signatures predict R-CHOP therapy response and survival. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1269. doi:10.3390/ijms26031269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Caratelli S, Sconocchia T, Arriga R, Coppola A, Lanzilli G, Lauro D, et al. FCγ chimeric receptor-engineered T cells: methodology, advantages, limitations, and clinical relevance. Front Immunol. 2017;8:457. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Lanier CM, Razavian NB, Smith S, D.’Agostino RBJr, Hughes RT. The impact of initial tumor bulk in DLBCL treated with DA-EPOCH-R vs. R-CHOP: a secondary analysis of alliance/CALGB 50303. Leuk Lymphoma. 2024;65(14):2199–206. doi:10.1080/10428194.2024.2393753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Hong JH, Lee HH, Jung SE, Park G, O. JH, Jeon YW, et al. Emerging role of consolidative radiotherapy after complete remission following R-CHOP immunochemotherapy in stage III-IV diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a single institutional and case-matched control study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:578865. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.578865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Davis JA, Granger K, Sakowski A, Goodwin S, Herbst A, Smith D, et al. Dual target dilemma: navigating epcoritamab vs. glofitamab in relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023;16(12):915–8. doi:10.1080/17474086.2023.2285978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Abou Dalle I, Dulery R, Moukalled N, Ricard L, Stocker N, El-Cheikh J, et al. Bi- and Tri-specific antibodies in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: current data and perspectives. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14(1):23. doi:10.1038/s41408-024-00989-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Cheson BD, Nowakowski G, Salles G. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: new targets and novel therapies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(4):68. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00456-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ben Mkaddem S, Benhamou M, Monteiro RC. Understanding Fc receptor involvement in inflammatory diseases: from mechanisms to new therapeutic tools. Front Immunol. 2019;10:811. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Hatzivassiliou G, Miller I, Takizawa J, Palanisamy N, Rao PH, Iida S, et al. IRTA1 and IRTA2, novel immunoglobulin superfamily receptors expressed in B cells and involved in chromosome 1q21 abnormalities in B cell malignancy. Immunity. 2001;14(3):277–89. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00109-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Guselnikov SV, Ershova SA, Mechetina LV, Najakshin AM, Volkova OY, Alabyev BY, et al. A family of highly diverse human and mouse genes structurally links leukocyte FcR, gp42 and PECAM-1. Immunogenetics. 2002;54(2):87–95. doi:10.1007/s00251-002-0436-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Nakayama Y, Weissman SM, Bothwell AL. BXMAS1 identifies a cluster of homologous genes differentially expressed in B cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285(3):830–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.5231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Miller I, Hatzivassiliou G, Cattoretti G, Mendelsohn C, Dalla-Favera R. IRTAs: a new family of immunoglobulinlike receptors differentially expressed in B cells. Blood. 2002;99(8):2662–9. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.8.2662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Davis RS, Wang YH, Kubagawa H, Cooper MD. Identification of a family of Fc receptor homologs with preferential B cell expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(17):9772–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.171308498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Du X, Nagata S, Ise T, Stetler-Stevenson M, Pastan I. FCRL1 on chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hairy cell leukemia, and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma as a target of immunotoxins. Blood. 2008;111(1):338–43. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-07-102350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Li FJ, Won WJ, Becker EJ, Easlick JL, Tabengwa EM, Li R, et al. Emerging roles for the FCRL family members in lymphocyte biology and disease. Fc Recept Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;382:29–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07911-0_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Davis RS, Stephan RP, Chen CC, Dennis GJr, Cooper MD. Differential B cell expression of mouse Fc receptor homologs. Int Immunol. 2004;16(9):1343–53. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxh137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Davis RS. FCRL regulation in innate-like B cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1362(1):110–6. doi:10.1111/nyas.12771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Leu CM, Davis RS, Gartland LA, Fine WD, Cooper MD. FcRH1: an activation coreceptor on human B cells. Blood. 2005;105(3):1121–6. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-06-2344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Yousefi Z, Sharifzadeh S, Zare F, Eskandari N. Fc receptor-like 1 (FCRL1) is a novel biomarker for prognosis and a possible therapeutic target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mol Biol Rep. 2023;50(2):1133–45. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-08104-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kazemi T, Asgarian-Omran H, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Shabani M, Memarian A, Sharifian RA, et al. Fc receptor-like 1-5 molecules are similarly expressed in progressive and indolent clinical subtypes of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(9):2113–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.23751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Haga CL, Ehrhardt GRA, Boohaker RJ, Davis RS, Cooper MD. Fc receptor-like 5 inhibits B cell activation via SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(23):9770–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703354104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Rostamzadeh D, Kazemi T, Amirghofran Z, Shabani M. Update on fc receptor-like (FCRL) family: new immunoregulatory players in health and diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22(6):487–502. doi:10.1080/14728222.2018.1472768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403(6769):503–11. doi:10.1038/35000501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Rosenwald A, Wright G, Wiestner A, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, et al. The proliferation gene expression signature is a quantitative integrator of oncogenic events that predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(2):185–97. doi:10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00028-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Zhao X, Xie H, Zhao M, Ahsan A, Li X, Wang F, et al. Fc receptor-like 1 intrinsically recruits c-Abl to enhance B cell activation and function. Sci Adv. 2019;5(7):eaaw0315. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw0315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Falchi L, Vardhana SA, Salles GA. Bispecific antibodies for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma: promises, unknowns, and opportunities. Blood. 2023;141(5):467–80. doi:10.1182/blood.2021011994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Lu T, Zhang J, Xu-Monette ZY, Young KH. The progress of novel strategies on immune-based therapy in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2023;12(1):72. doi:10.1186/s40164-023-00432-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Sun L, Romancik JT. The development and application of bispecific antibodies in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Pers Med. 2025;15(2):51. doi:10.3390/jpm15020051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Bennett R, Dickinson M. SOHO state of the art updates and next questions | current evidence and future directions for bispecific antibodies in large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024;24(12):809–20. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2024.05.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Brouwer-Visser J, Fiaschi N, Deering RP, Cygan KJ, Scott D, Jeong S, et al. Molecular assessment of intratumoral immune cell subsets and potential mechanisms of resistance to odronextamab, a CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(3):e008338. doi:10.1136/jitc-2023-008338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Guo Z, Tu S, Yu S, Wu L, Pan W, Chang N, et al. Preclinical and clinical advances in dual-target chimeric antigen receptor therapy for hematological malignancies. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(4):1357–68. doi:10.1111/cas.14799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Lamble AJ, Moskop A, Pulsipher MA, Maude SL, Summers C, Annesley C, et al. INSPIRED symposium part 2: prevention and management of relapse following chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Transplant Cell Ther. 2023;29(11):674–84. doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2023.08.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Negishi S, Girsch JH, Siegler EL, Bezerra ED, Miyao K, Sakemura RL. Treatment strategies for relapse after CAR T-cell therapy in B cell lymphoma. Front Pediatr. 2024;11:1305657. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1305657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools