Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

3,9-Di-O-Methylnissolin Inhibits Gastric Cancer Progression by the RIPK2-Mediated Suppression of the NF-κB Pathway

1 The First Clinical Medical College, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China

2 Department of Geriatrics Gerontology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China

3 Department of Gastroenterology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China

4 Gansu Province Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yuping Wang. Email: ; Yongning Zhou. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1967-1983. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.069869

Received 02 July 2025; Accepted 08 September 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Gastric cancer (GC) is a prevalent cause of death. 3,9-Di-O-methylnissolin (DOM) is a flavonoid isolated from Astragalus membranaceus. It has anticancer and anti-inflammatory effects, but its effect and mechanism of action on GC are not very clear. Methods: The appropriate concentration was selected after observing the effects of varying concentrations of DOM on the viability of GC cells, which was examined through the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. The receptor-interacting protein kinase 2 (RIPK2) overexpression plasmid was transfected into GC cells, which were then treated with DOM. Cell cycle and proliferation, RIPK2 levels, and inflammatory factor levels were evaluated by flow cytometry, cell colony formation assay, Hoechst 33,258 fluorescence, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay, Transwell assay, immunofluorescence, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), respectively. The nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway was detected using immunofluorescence and Western blot. Results: The appropriate concentrations of DOM were found to be 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL. At these concentrations, in GC cells, DOM could significantly reduce EdU-positive cells; decrease the colony formation, migration, and invasion rates; block the cell cycle; increase the Hoechst 33,258 fluorescence intensity and apoptosis rate; and significantly reduce p-IκBα and p-NF-κB p65 expressions. Moreover, DOM notably reduced the high level of RIPK2. After the overexpression of RIPK2, these effects were significantly reversed in GC cells, and interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 contents were clearly elevated. Conclusion: DOM can suppress the level of RIPK2 and inhibit the activation of the NF-κB signaling, thereby reducing inflammation; inhibiting the malignant progression of GC cells; and promoting cycle arrest.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

One of the main causes of death in humans is cancer [1]. Gastric cancer (GC) is a frequent gastrointestinal cancer that has a considerable incidence worldwide [2]. In 2022, approximately 970,000 new cases of GC and 660,000 deaths due to GC occurred [3]. GC is still an important condition that threatens human health and causes a global cancer burden [4,5]. GC survival rate is poor, and distant metastasis is a cause of cancer recurrence [6]. The basis of cancer cell metastasis is cancer cell growth. Therefore, inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing cell death are the keys to the treatment of cancer. Apoptosis is a typical way of cell death induced by various stimuli [7], which has a non-negligible effect on the development of tumors. In GC cells, the regulation mechanism of apoptosis is often disordered.

At present, no specific drugs have been identified for the treatment of GC. Although radical gastrectomy is a curative treatment for early GC, the occurrence of GC is largely hidden, and the early clinical manifestations are not obvious. The majority of patients are not identified until the advanced stage, and at that point, surgical resection is no longer effective [8,9]. In recent years, GC treatment methods have included radiotherapy and chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. However, the effect of chemotherapy in most patients is not ideal, and GC often metastasizes and relapses after treatment [10]. GC is prone to developing resistance to immunotherapy. Although emerging targeted therapy has good therapeutic effects, it still faces many clinical challenges because of its high price and small scope of application [11]. Thus, investigating promising anticancer strategies with greater effectiveness and fewer side effects is essential.

In recent years, the significant effects of natural products extracted from the plant world have been widely studied for the treatment of tumors. Natural extracts have low toxicity and few side effects, and their active ingredients can simultaneously target multiple therapeutic pathways [12]. Therefore, exploring and discovering natural plant extracts with anti-GC effects is highly important.

As newly identified antitumor drugs, flavonoids have attracted much attention because of their few adverse reactions [13]. Flavonoids can reduce GC cell proliferation and migration, inhibit invasion in the human body, and promote their apoptosis [14–16]. 3,9-Di-O-methylnissolin (DOM) is a flavonoid compound isolated from Astragalus membranaceus [17]. Studies have confirmed that DOM has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [18]. In addition, DOM is the main active compound of Danggui Buxue Decoction, and in vivo experiments have confirmed that Danggui Buxue Decoction can inhibit metastatic colon cancer by inhibiting apoptosis [19]. Therefore, we speculate that DOM has the potential to treat cancer.

With advancements in molecular biology, the focus of research seeking new cancer treatments has shifted to finding effective signaling pathways for intervention [20]. The initiation and development of GC involve multiple genes and are related to the activation of many pathways. Therefore, revealing the key pathways involved in GC needs to start with regulation at the gene and molecular levels.

Receptor-interacting protein kinase 2 (RIPK2) is a member of the RIPK family. Every member of the RIPK family possesses a similar serine-threonine kinase domain that has a catalytic site essential for both structure and function [21], and RIPK2 has additional tyrosine kinase activity. RIPK2 is distributed in a variety of tissues [22]. It is an important molecule that mediates the signal transduction of NOD1 and NOD2 [23], which is related to the inflammatory response. It also participates in the development of tumors as an effective activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) [21]. RIPK2 is correlated with the initiation and development of tumors [24,25]. Inhibition of RIPK2 can inhibit the metastasis of prostate and colorectal cancer, and its overexpression is correlated with cancer progression [26,27]. RIPK2 gene polymorphisms are linked to the risk of bladder cancer, and RIPK2 may promote chronic inflammation of the bladder, causing the development of bladder cancer [28]. Therefore, RIPK2 may play an important role as a key regulatory factor in malignant tumors and inflammation. Moreover, previous research has shown that DOM can relieve GC-related cachexia by targeting RIPK2. The key potential mechanism is that RIPK2 overexpression affects adipogenesis through the ASK1 and PPARα pathways [29]. In addition, studies have shown that RIPK2 can regulate the proliferation of GC cells via activating the NF-κB pathway [30]. Unfortunately, it is not clear whether DOM can regulate GC progression and inflammation by activating the NF-κB signaling through RIPK2.

In summary, we hypothesized that DOM could regulate GC progression by stimulating the NF-κB signaling pathway through RIPK2. Therefore, this study used DOM to explore its mechanism of action in altering the development of GC cells. It detected the RIPK2 level and interfered with its expression. It investigated the specific mechanisms by which DOM inhibited GC cell malignant biological behavior by regulating RIPK2 to elucidate the mechanism by which DOM suppressed GC.

The human gastric mucosal cell line GES-1 and human GC cells (AGS and HGC-27) were purchased from Huatuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (HTX1964, HTX1739, HTX1740, Shenzhen, China). After routine resuscitation from cryogenic storage, the cells were inoculated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (C2703, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (C0226, Beyotime) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P1400, Solarbio, Beijing, China) and cultured in an incubator (MiDi-40, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). When the cell confluence reached 70%–80%, the cells were passaged. All cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination by the mycoplasma kits (CA1080, Solarbio), and the cells without mycoplasma were used in subsequent experiments.

2.2 The Appropriate Dose of DOM Was Selected by a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

GES-1, AGS, and HGC-27 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells/well (100 μL per well) and treated with 0, 100, 200, 400, 800, or 1000 μg/mL DOM (B21803, Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), respectively. GES-1 cells were cultured for 24 or 48 h. AGS and HGC-27 cells were cultured for 24 h. Then, 10 μL of CCK-8 working solution (CA1210, Solarbio) was added to each well and gently mixed with the medium. The cells were returned to the cell incubator and incubated for 2 h. A microplate reader (Synergy H1, Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to detect the OD450 value of each well, and the appropriate dosage and time of DOM were selected according to the OD value.

2.3 5-Ethynyl-2′-Deoxyuridine (EdU) Staining

The growth of cells was evaluated with an EdU kit (C10310-1, RiboBio, Guangzhou, China). AGS and HGC-27 cells were divided into a control group and 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL DOM treatment groups. The GC cells in the DOM treatment groups were treated with the corresponding doses of DOM for 24 h. Then, the GC cells were incubated with 10 μM EdU staining mixture in the dark for 1 h, washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), fixed, and permeabilized with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 0.3% Triton X-100. After the cells were subjected to EdU and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, they were coverslipped with an antifluorescence quenching sealing agent. A fluorescence microscope (MF52-N, Guangzhou Ming-Mei Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) was used to take photos. Three fields of vision were randomly selected to calculate the percentage of EdU-positive cells in each group.

2.4 Hoechst 33258 Fluorescence Staining

After AGS and HGC-27 cells were cultured for 24 h, the cells were fixed with an appropriate amount of 4% PFA for 20 min and then stained with Hoechst 33258 staining solution (C0021, Solarbio) at room temperature for 20 min. In normal cells, the nucleus was light blue, and its shape was clearly visible; in apoptotic cells, uneven nuclear staining was bright blue with strong fluorescence. The apoptosis rate was calculated as the percentage of apoptotic cells divided by the total number of cells.

Ninety microliters of diluted Matrigel (DMEM:Matrigel = 8:1) was added to the top Transwell chamber and allowed to gel for 3 h in the incubator. GC cells were digested with trypsin and centrifuged. The cell density was adjusted to 1 × 105 cells/mL. Two hundred microliters of cell suspension without FBS was added to the upper chamber of the Transwell, and 500 μL of complete medium (containing 10% FBS) was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h of culture, the cells on the surface of the lower chamber membrane were fixed with methanol at room temperature for 15 min and then incubated with 1% crystal violet (G1063, Solarbio) staining solution at room temperature for 20 min. Finally, the chamber was observed under an optical microscope (CX23, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and images of the cells were collected. ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.8.0, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to analyze the number of cells that invaded through the Matrigel.

GC cells were divided into the control group, RIPK2 overexpression (oe-RIPK2) group, and negative control (oe-NC) group. The oe-RIPK2 (Gene ID: NM_003821.6) and negative control oe-NC plasmids were purchased from Ruibo Biological Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). The control group was transfected with liposomes without any treatment. The oe-NC group was transfected with oe-NC, and the oe-RIPK2 group was transfected with oe-RIPK2. The transfection procedure was performed with LipofectamineTM 3000 (L3000001, Invitrogen, Austin, TX, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well 24 h before transfection. During transfection, the corresponding reagents were added and mixed evenly. The cell culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium. After the cells were cultured in an incubator for 6 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium, and then the subsequent experiment was carried out.

2.7 Cell Colony Formation Assay

A total of 200 AGS or HGC-27 cells were inoculated into dishes containing complete medium. To evenly distribute the cells, the culture dish was slowly rotated for 1 min after the cells were inoculated. After the cells had adhered, they were treated with 200, 400, or 800 μg/mL DOM. The cell growth status and density were observed during the culture process. When the cells had formed colonies visible to the naked eye, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min (G1063, Solarbio). The cells were observed under a microscope, and colonies formed number was calculated using ImageJ software.

AGS and HGC-27 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 5 × 105 cells/well. When the cell density was close to 100%, the plate was scratched with a 20 μL pipette tip. The cells were incubated with DOM-containing medium for 24 h. The scratch area was photographed with a microscope at 0 and 24 h.

2.9 Detection of Apoptosis by Flow Cytometry (FCM)

An Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (CA1020, Solarbio) detected apoptosis. AGS and HGC-27 cells were digested with trypsin (T1350, Solarbio) without EDTA. The cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well. After 48 h of culture, the different levels of DOM were added, and the culture was continued for 24 h. After centrifugation, the cells were collected in a flow cytometry tube. Then, 100 μL of 1× binding buffer was added to resuspend the cells, and 2.5 μL of Annexin V and 5 μL of PI were added at the same time. After mixing, the reaction was carried out for 15 min, and the apoptosis rate was determined using FCM (BD FACSCaliburTM, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.10 Detection of the Cell Cycle by FCM

AGS and HGC-27 cells were treated with DOM for 24 h, washed with PBS, centrifuged, and collected in a flow cytometry tube. The cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and incubated at 4°C overnight. The ethanol was discarded, and PBS was added to resuspend the cells. Then, 100 μL of PI reagent was added to each tube, and the reaction was carried out for 30 min in the dark. The cell cycle distribution after each drug treatment was detected by FCM.

AGS and HGC-27 cells (3 × 104 cells/well) were cultured in 12-well plates and transfected. After 6 h, the GC cells were treated with DOM for 24 h, fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min, and infiltrated with 0.5% Triton X-100 (IR9073, Solarbio) for 15 min. The cells were blocked with blocking solution (P0260, Beyotime) for 1 h and then incubated with primary anti-NF-κB p65 (ab32536, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-RIPK2 (ab8428, 1:100, Abcam) antibodies overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG (GB22303, GB21303, Servicebio, Wuhan, China), was added and incubated for 1 h in the dark. The nuclei were stained with DAPI staining solution (C0065, Solarbio) for 10 min, and the sealing agent (S2110, Solarbio) was added. The samples were coverslipped and photographed using the fluorescence microscope.

2.12 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The culture medium of GC cells was transferred to sterile centrifuge tubes, and the supernatants were collected after centrifugation. Interleukin (IL)-6 (SEKH-0013, Solarbio), IL-1β (SEKH-0002, Solarbio), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, SEKH-0047, Solarbio) levels were determined by ELISA. The supernatant and antibody mixture were incubated in an ELISA plate for 1 h. One hundred microliters of substrate was included and incubated in the dark for 10 min, and then 100 μL of termination reaction mixture was added. The OD value was detected by a microplate reader (Synergy H1, Agilent) to evaluate the contents of inflammatory factors.

After intervention, the GC cells were collected, and the proteins were extracted using a protein extraction kit (R0010, Solarbio). After centrifugation, the protein concentration was detected with a BCA kit (PC0020, Solarbio). After separation by gel electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (G6047, Servicebio) and blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h. Primary antibodies against rabbit anti-Ki-67 (ab92742, 1:5000, Abcam), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (ab92552, 1:10000, Abcam), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 (ab181286, 1:1000, Abcam), IκBα (9242, 1:1000, Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA), MMP-9 (ab137867, 1:1000, Abcam), cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteinase (caspase) 3 (ab184787, 1:2000, Abcam), cleaved-caspase 3 (ab2302, 1:500, Abcam), cyclin D1 (ab134175, 1:10000, Abcam), cyclin E1 (ab33911, 1:1000, Abcam), Bax (ab32503, 1:10000, Abcam), Bcl2 (ab182858, 1:2000, Abcam), RIPK2 (ab8428, 1:1000, Abcam), p-IκBα (2859, 1:1000, Cell Signaling), NF-κB p65 (ab32536, 1:5000, Abcam), p-NF-κB p65 (ab239882, 1:1000, Abcam), and β-actin (ab8226, 1:1000, Abcam) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. The samples were exposed to a diluted HRP-labeled secondary antibody (ab205718, 1:10000, Abcam) at room temperature for 2 h. The ECL chemiluminescence solution (PE0010, Solarbio) was added, and a gel imaging system (Tanon 5200 Multi, Tianneng Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used for imaging. The protein gray values were analyzed by ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the data were normally distributed according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and are presented as the means ± standard deviations. One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons among multiple groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 DOM Inhibited GC Cell Proliferation and Caused G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest

RIPK2 is relatively highly expressed in AGS and HGC-27 cells [30]; thus, these cells were selected for experiments, and GES-1 cells were used as controls. Different concentrations of DOM had no substantial effect on the cell viability of GES-1 cells at 24 or 48 h (Fig. 1A), indicating that DOM was not toxic to normal gastric cells. Moreover, after 24 h of DOM exposure, the cell viability of AGS and HGC-27 cells decreased with increasing dose, but when the DOM concentration was 1000 μg/mL, the viability was less than 50% (Fig. 1B). The IC50 of AGS cells was 858 μg/mL, and that of HGC-27 cells was 835.6 μg/mL. Therefore, we selected 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL DOM for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1: DOM inhibited GC cell proliferation and caused G0/G1 cell cycle arrest. (A) GES-1 cells were intervened to various levels of DOM for 24 or 48 h, and CCK-8 assayed the GES-1 cell viability. There were no meaningful discrepancies in cell viability. (B) The cell viability of AGS and HGC-27 cells was tested through the CCK-8 assay. The cell viability declined significantly when DOM intervention, and the IC50 of AGS cells was 858 μg/mL, and that of HGC-27 cells was 835.6 μg/mL. (C,D) EdU staining detected the proliferation of GC cells after DOM treatment. EdU positive rates were significantly reduced (×40, 50 μm). (E,F): The cell clone formation assay detected the proliferation of GC cells when DOM intervention. The colony formation ability of cells was significantly reduced. (G,H) The cell cycle was detected using FCM. The G0–G1 stage part in GC cells was notably increased, and the S stage part was evidently decreased. (I–K) The expressions of proteins related to cell proliferation and cycle were detected using WB. Ki67, PCNA, Cyclin D1, and Cyclin E1 levels were significantly decreased after DOM treatment. n = 6, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

On this basis, after treatment with DOM for 24 h, the percentage of EdU-positive cells and colony formation ability were significantly reduced (Fig. 1C–F), indicating that DOM could reduce the proliferation ability of GC cells. Since the cell cycle regulates cell fate and plays a key role in cancer progression [31], the FCM results revealed that after DOM treatment, the proportion of AGS and HGC-27 cells in the G0–G1 phase raised markedly, whereas that in the S phase lessened significantly (Fig. 1G–H). Thus, DOM could significantly increase the number of GC cells in the G0–G1 phase and reduce the number of S-and M-phase cells.

Cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 can regulate the cell cycle, and reducing their expression can hinder tumor growth [32,33]; Ki67 and PCNA can be used as markers of cell proliferation activity [34]. Ki67, PCNA, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1 expressions were markedly declined after DOM treatment (Fig. 1I–K), indicating that DOM inhibited GC cell proliferation and encouraged cell cycle arrest. Overall, the above experiments showed that DOM could restrain GC cell proliferation and promote G0/G1 cycle arrest, suggesting that DOM had an anti-GC effect.

3.2 DOM Induced GC Apoptosis and Restrained Cellular Migration and Invasion

We also found that untreated GC cells grew well and adhered firmly, and that the cells were closely connected. The nuclei were evenly stained blue with Hoechst 33258, resulting in uniform blue fluorescence. After DOM treatment, the GC cells became round and detached, and the cell spacing became significantly greater. The cells were stained bright blue with Hoechst 33258. With increasing drug concentration, the blue fluorescence became stronger; that is, the phenomenon of apoptosis became more obvious. After quantification, the apoptosis rates of the GC cells rose significantly in response to DOM treatment (Fig. 2A,B). FCM experiments also revealed the same results. The apoptosis rate increased significantly with increasing DOM concentration (Fig. 2C,D), indicating that DOM promoted GC apoptosis.

Figure 2: DOM induced GC cell apoptosis and restrained cell migration and invasion. (A,B) The apoptosis of AGS and HGC-27 cells was found using Hoechst 33258 fluorescence stain. GC cells were uniform in size, clear in morphology, uniform in dispersion, and blue in nucleus. After DOM treatment, the cellular nuclei were bright blue, unevenly stained, smaller in size, and stronger in fluorescence. After quantification, the apoptosis rate was significantly increased (×40, 50 μm). (C,D) The apoptosis was tested using FCM, and the apoptosis rate increased significantly with the increase in DOM concentration. (E,F) The cell migration was tested through a wound healing assay. The migration rate lowered significantly with DOM concentration rises (×10, 200 μm). (G,H) The cell invasion was tested by the Transwell assay. The invasion number declined significantly with DOM concentration rises (×20, 100 μm). (I–M) The expressions of apoptosis-, migration-, and invasion-related proteins were noticed using WB. It can be seen that after DOM treatment, MMP-2, MMP-9, and Bcl2 protein expressions were significantly decreased, and Bax and cleaved-caspase 3 protein expressions were significantly increased. n = 6, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Subsequently, the migration rate and invasive cell number were significantly reduced after DOM treatment (Fig. 2E–H), indicating that DOM could reduce the migration and invasion of GC cells. MMP-2 and MMP-9 are associated with cell migration and invasion [35]; Bax, Bcl2, and caspase are apoptosis indicators [36]. After DOM treatment, MMP-2, MMP-9, and Bcl2 levels were significantly lessened, and Bax and cleaved-caspase 3 expressions were markedly raised (Fig. 2I–M). In conclusion, DOM promoted GC apoptosis and inhibited migration and invasion. These findings, combined with those of previous experiments, indicate that DOM inhibited the malignant progression of GC.

3.3 DOM Suppressed the Level of RIPK2 in GC Cells

We also showed that RIPK2 was localized in the cytoplasm by immunofluorescence and WB. Compared to GES-1 cells, the fluorescence intensity and protein expression of RIPK2 in GC cells were substantially greater. The fluorescence intensity and protein expression of RIPK2 significantly decreased after DOM treatment (Fig. 3A–D), indicating that DOM significantly suppressed the expression of RIPK2 in GC cells.

Figure 3: DOM inhibited the level of RIPK2 in GC cells. (A,B) The level of RIPK2 was detected by immunofluorescence. It was found that the fluorescence intensity of RIPK2 decreased markedly after DOM intervention (×40, 50 μm). (C,D) The protein level of RIPK2 was analyzed with WB, and it was markedly increased in GC cells and significantly decreased after DOM treatment. n = 6, ***p < 0.001 vs. GES-1 group; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 vs. AGS group; &&&p < 0.001 vs. HGC-27 group

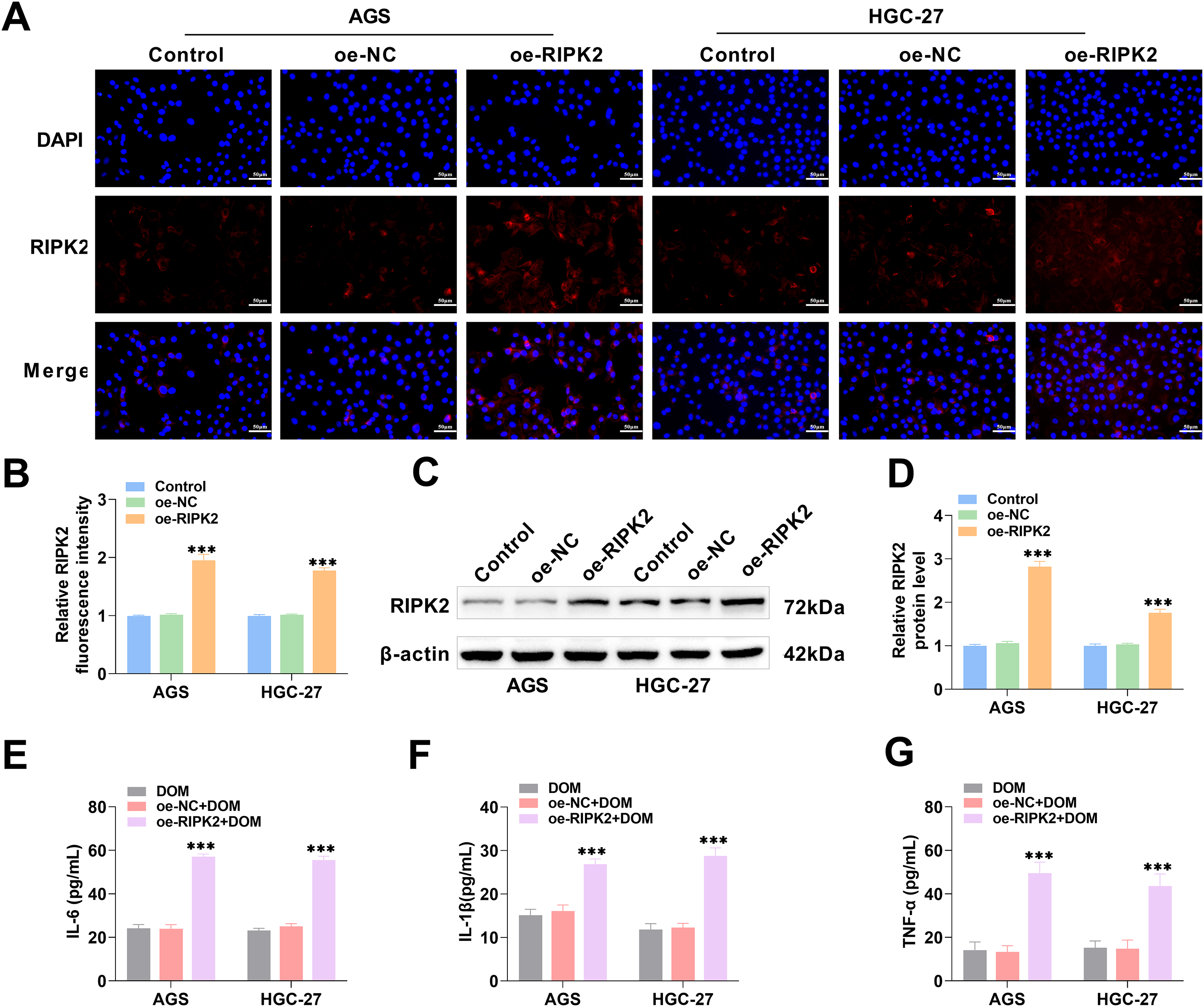

3.4 DOM Suppressed RIPK2 to Reduce the Inflammatory Response of GC Cells

The occurrence of gastric cancer is associated with the inflammatory response [37]. RIPK2 was overexpressed, and the transfection efficiencies were examined using immunofluorescence and WB. The fluorescence intensity and protein level of RIPK2 were markedly raised (Fig. 4A–D), indicating that RIPK2 was effectively highly expressed. The cells were then divided into the 800 μg/mL DOM treatment (DOM) group, the RIPK2 overexpression (DOM + oe-RIPK2) group, and the negative control (DOM + oe-NC) group. The contents of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were notably elevated after RIPK2 overexpression (Fig. 4E–G), indicating that RIPK2 overexpression aggravated the inflammatory response of GC cells, whereas RIPK2 inhibition reduced the inflammatory response. These findings indicate that DOM might reduce the inflammation of GC cells by inhibiting RIPK2.

Figure 4: DOM inhibited RIPK2 to improve the inflammatory response of GC cells. (A–D) RIPK2 was overexpressed in GC cells, and the transfection efficiency was examined using immunofluorescence and WB. It was highly expressed (×40, 50 μm). (E–G) The contents of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in GC cells were detected with ELISA, which showed a significant increase after RIPK2 overexpression. n = 6, ***p < 0.001

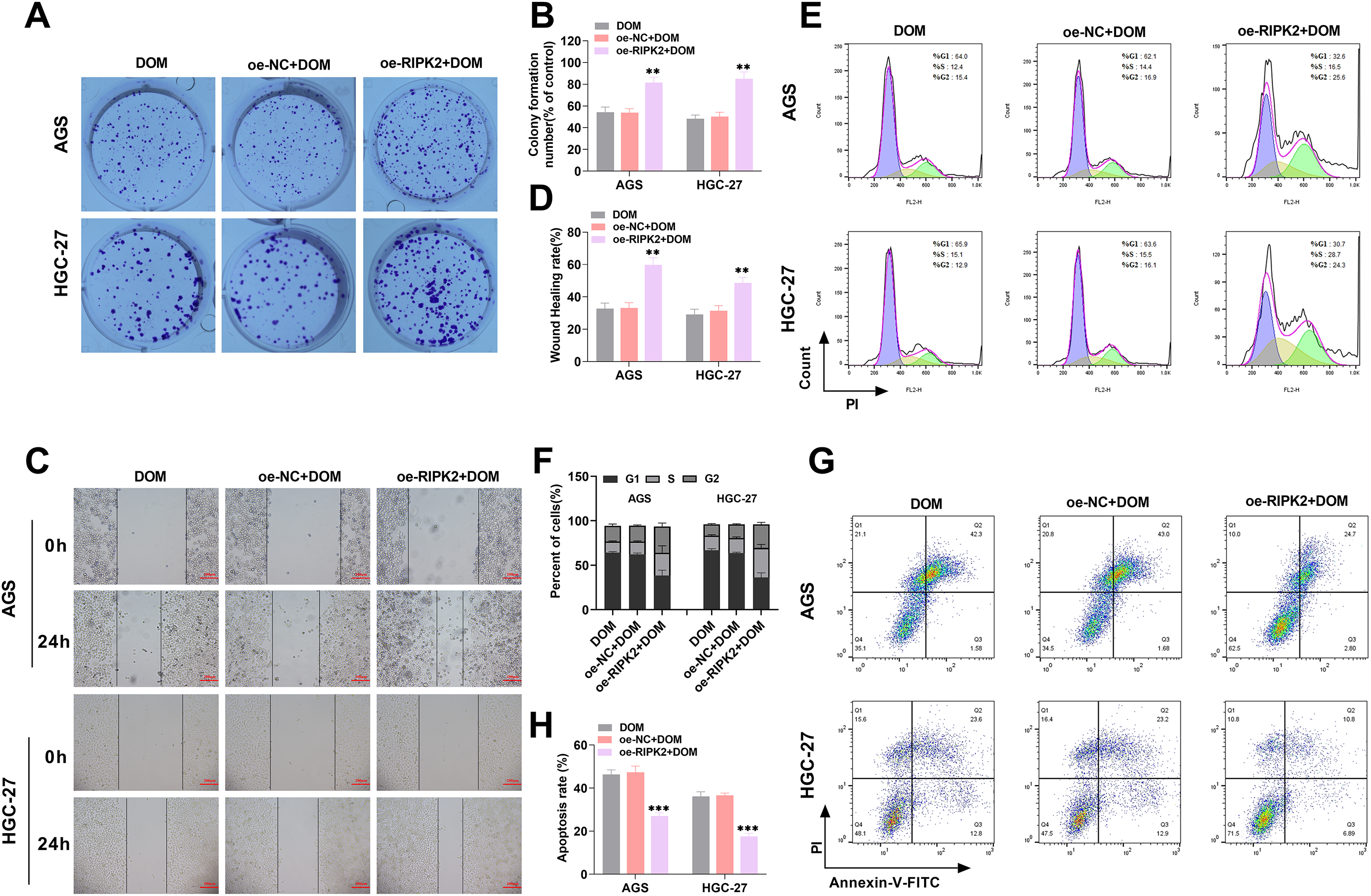

3.5 DOM Suppressed RIPK2 to Inhibit GC Progression

To further investigate the roles of RIPK2 in DOM’s effects on GC, after the overexpression of RIPK2, colony formation experiments revealed that colony formation ability was significantly increased (Fig. 5A,B), indicating that the proliferation of GC cells was increased; the migration rates of AGS and HGC-27 cells were also significantly increased (Fig. 5C,D). In addition, the proportion of cells in the G0–G1 phase was significantly decreased, the proportion of those in the S phase was markedly increased (Fig. 5E,F), and apoptotic cells were markedly decreased (Fig. 5G,H). These results indicated that overexpression of RIPK2 reduced the proportion of GC cells in the G0–G1 phase, increased the proportion in the S phase, promoted cellular growth, and inhibited apoptosis. In contrast, the inhibition of RIPK2 expression inhibited GC progression. In summary, DOM inhibited GC progression by inhibiting RIPK2 expression.

Figure 5: DOM-mediated RIPK2 to inhibit GC progression. (A,B) The proliferation of AGS and HGC-27 cells was analyzed with the cell clone formation test. The cell proliferation ability was significantly increased after RIPK2 overexpression. (C,D) The cell migration was tested using the wound healing assay, and it was markedly increased after RIPK2 overexpression (×10, 200 μm). (E,F) The cell cycle was detected using FCM, and it was found that the G0-G1 stage part was evidently diminished, and the S stage was notably raised after RIPK2 overexpression. (G,H) The apoptosis of GC cells was noticed using FCM, and the apoptosis rate was significantly decreased after RIPK2 overexpression. n = 6, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

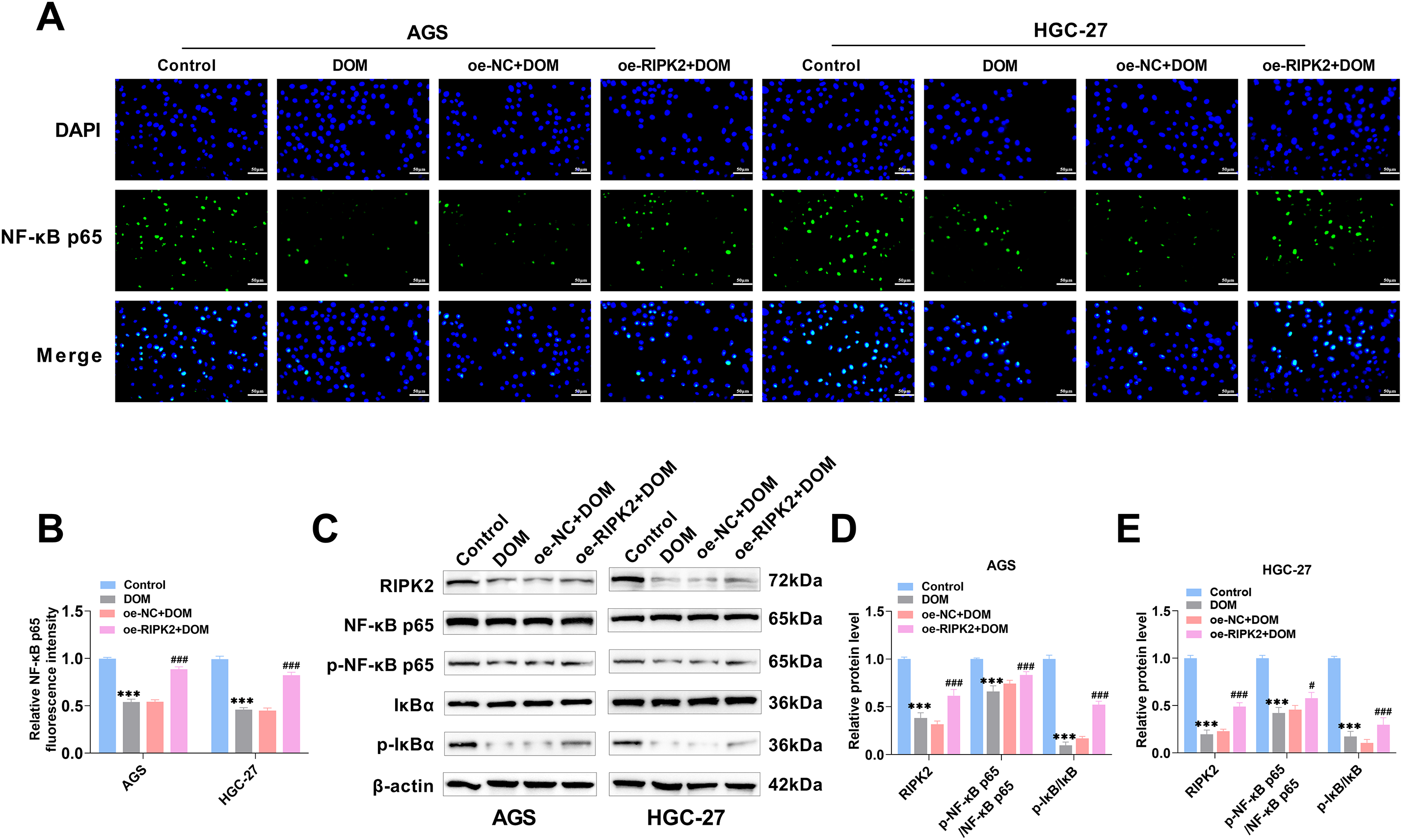

3.6 DOM-Mediated RIPK2 to Inhibit the Activation of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway

To explore the related pathways by which DOM affects GC cells, the cells were separated into a normal (Control) group, a DOM treatment (DOM) group, a RIPK2 overexpression (DOM + oe-RIPK2) group, and a negative control (DOM + oe-NC) group. The fluorescence intensity of NF-κB p65 located in the nucleus of GC cells decreased significantly after DOM treatment, and the fluorescence intensity increased significantly after RIPK2 overexpression (Fig. 6A,B), indicating that RIPK2 overexpression promoted the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway; that is, the suppression of RIPK2 expression inhibited the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Moreover, the WB experimental results confirmed this conclusion. After DOM treatment, RIPK2, p-IκBα, and p-NF-κB p65 expressions of AGS and HGC-27 cells were significantly decreased, and they were significantly increased after RIPK2 overexpression (Fig. 6C–E). In conclusion, DOM might inhibit RIPK2, which inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Figure 6: DOM-mediated RIPK2 to inhibit the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A,B) NF-κB p65 nuclear localization was found with immunofluorescence. It was localized in the nucleus. The fluorescence intensity of NF-κB p65 was markedly decreased when DOM treatment and significantly raised when RIPK2 overexpression (×40, 50 μm). (C–E) The expressions of the NF-κB signaling pathway proteins were tested by WB. RIPK2, p-IκBα, and p-NF-κB p65 proteins were significantly lessened after DOM treatment, and significantly increased after RIPK2 overexpression. n = 6, ***p < 0.001 vs. Control group; #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 vs. DOM + oe-NC group

GC is a heterogeneous malignant tumor. Although significant progress has been made in medical technology, GC is still regarded as a key public health problem, the treatment of which is mainly limited by its late diagnosis, high degree of tumor recurrence, side effects of chemotherapy, and the emergence of drug resistance [38]. Therefore, it is imperative to find alternative treatments to conventional chemotherapy or to combine natural products with classic chemotherapy drugs to improve the overall outcomes of GC patients who have characteristics associated with poor prognoses. Recently, interest in the study of natural extracts has increased, and many bioactive compounds have shown very valuable biological, pharmacological, and medical properties, including potential anticancer activity.

In previous experiments [29] involving a RIPK2-overexpressing transgenic mouse model, our group has shown that DOM inhibits RIPK2-mediated lipid homeostasis dysfunction and lipid biosynthesis reduction through the RIPK2/ASK1/PPARα signaling, thereby preventing GC, indicating that DOM has an anti-GC effect. Unfortunately, previous studies have only been conducted in vivo. Therefore, to address this research gap, this study further explored whether the possible mechanism by which DOM antagonizes GC through RIPK2 is related to inflammation and the NF-κB pathway via in vitro cell experiments. The data of this study showed that DOM could inhibit the level of RIPK2 and inhibit the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, inhibiting the inflammatory response and malignant biological behavior of GC cells, which indicated that one of the mechanisms by which DOM antagonizes GC was by inhibiting the inflammatory response through suppression of the RIPK2/NF-κB signaling.

An imbalance between the proliferation and death of GC cells is the direct cause of GC formation [39]. PCNA and Ki67 are cell proliferation markers. PCNA is an essential substance for DNA replication and DNA repair. Ki67 is expressed only in the nucleus during cell proliferation, and the levels of both are closely associated with cell proliferation ability [40]. An imbalance between Bax and Bcl2 in the Bcl2 protein family can lead to apoptosis. This occurs because the transfer of Bax to mitochondria changes the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane and releases cytochrome C, which in turn activates the caspase cascade and leads to apoptosis [36]. Caspase 3 is the main effector protein of apoptosis; cleaved-caspase 3 is its activated form, and its level can reflect the degree of apoptosis [41]. Moreover, cancer has unlimited cell proliferation ability, so interruption of the cancer cell cycle is a vital means to prevent cancer development [42]. The cell cycle is regulated by various proteins belonging to the cyclin family and is carried out in strict accordance with the order of G0/G1→S→G2→M. Cyclins abnormal expression leads to cell cycle disruption [43]. The main function of cyclin D1 and cyclin E1 is to promote the conversion of the G1/S phase [44]. They are considered to be the main cyclins connected to positive regulation of the cell cycle, and they promote the proliferation of tumor cells [32,33]. Metastasis is the primary reason for chemotherapy failure and tumor death, and GC is an aggressive and metastatic cancer [45]. High expressions of the MMP-2 and MMP-9 proteins of tumor tissues are connected to tumor cell migration by degrading the components of the ECM, leading to the formation of new tumor lesions and promoting cell migration and invasion [35,46]. This study revealed that DOM could significantly reduce the EdU-positive rate and colony formation ability and increase the G0/G1 stage ratio of cells. Ki67, PCNA, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1 protein expressions were also notably reduced. Meanwhile, after DOM treatment, GC cells were stained bright blue, and apoptotic bodies appeared. The apoptosis rate increased significantly, the migration and invasion rates decreased significantly, the MMP-2, MMP-9, and Bcl2 proteins lessened significantly, and the Bax and cleaved-caspase 3 proteins increased significantly. In conclusion, the results found that DOM inhibited the malignant progression of GC cells.

RIPK2 is important for tumor formation and progression. RIPK2 is upregulated in a variety of tumor tissues [47], and RIPK2 can regulate tumor proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and the tumor microenvironment through a variety of signaling pathways [48–50]. The inflammatory response is vital for the immune microenvironment. The development of tumors is related to inflammation in the microenvironment and an imbalance in the activity of various immune cells [51]. Gastric ‘inflammation-cancer’ transformation is a pathological process that involves the gradual development of superficial gastritis→atrophic gastritis→intestinal metaplasia→atypical hyperplasia→GC [39]. Therefore, inflammation is also closely related to GC progression. RIPK2 is considered an important linker molecule of innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and inflammation. It has been reported that it can interact with a variety of proteins and participate in multichannel signal transduction, thus exerting corresponding physiological functions, such as mediating the production of inflammatory cytokines [22,52].

RIPK2 was highly expressed in GC cells, and DOM markedly suppressed the level of RIPK2. After RIPK2 overexpression, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 contents were increased, and colony formation ability, migration ability, and invasion ability were also evidently enhanced. The proportion of cells in the G0/G1 stage and the percentage of apoptotic cells were significantly decreased, suggesting that RIPK2 overexpression might promote malignant progression by aggravating the inflammatory response of GC cells and altering the tumor immune microenvironment. In turn, the inhibition of RIPK2 might inhibit GC progression by inhibiting adverse inflammatory environments. In summary, DOM might reduce the inflammatory response of cancer cells via suppressing the expression of RIPK2, hence inhibiting the proliferation and metastasis of GC cells and thus exerting a tumor suppressor effect.

RIPK2 can bind to proteins belonging to the Toll and NOD-like receptor families and regulate the NF-κB pathway. RIPK2 activation can further activate IκB kinase, promote the transfer of NF-κB dimers (such as p65/p50) to the nucleus, and activate the inflammatory and immune responses of the body [53]. Given that NF-κB is important for the transcription of genes related to inflammation, it is considered to be a regulatory factor connecting inflammation and cancer. The regulatory mechanism involves NF-κB activation, which can lead to inflammatory cell recruitment and expression in the tumor environment, resulting in excessive or chronic tissue damage and inflammation, and regulating cancer cell biological behavior, such as targeting Bcl2 and cyclins, affecting cell growth and death [54]. RIPK2 can resist paclitaxel-and ceramide-induced apoptosis by activating the NF-κB pathway [48], which can also promote ovarian cancer cell proliferation [50]. After DOM treatment, NF-κB p65 was localized in GC cell nuclei, and p-IκBα and p-NF-κB p65 expressions were notably reduced, effects that were reversed after RIPK2 overexpression. Combined with the above experimental results, one of the mechanisms by which DOM inhibited GC progression was by inhibiting the expression of RIPK2, which inhibited the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

In summary, DOM reduced the NF-κB signaling pathway by inhibiting RIPK2 expression, thereby reducing the inflammatory response and inhibiting the growth, migration, and invasion of GC cells; promoting apoptosis and cycle arrest; and playing a role in the treatment of GC. In summary, this research studied the impact of DOM on GC cells and explored the related molecular mechanisms. DOM is a potential therapeutic agent and is anticipated to become a candidate medication for GC therapy, thereby providing new ideas for the development of new anticancer drugs. However, unfortunately, this study is limited to tumor cell experiments. In the future, we will further validate the antitumor mechanisms of DOM via animal experiments. Moreover, due to the lack of a separate RIPK2 overexpression control group in this study, it is impossible to distinguish whether the anti-tumor effect of DOM is specifically dependent on the RIPK2 pathway. Therefore, we will solve this problem in subsequent studies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Hospital Fund of The First Hospital of Lanzhou University (grant number ldyyyyn2023-46), the Science and Technology Project of Gansu Province Key Research and Development Program (grant number 21YF5FA120), the Gansu Province Health Industry Research Project (grant number GSWSKY2020-12), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82160498).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Yun Zhou, Shixiong Liu; data collection: Ya Zheng; analysis and interpretation of results: Yongning Zhou, Yuping Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Yun Zhou, Shixiong Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviation

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

| Caspase | cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase |

| CCK-8 | cell counting kit-8 |

| DOM | 3,9-di-O-methylnissolin |

| EdU | 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| GC | gastric cancer |

| IL | interleukin |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-B |

| PCNA | proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| PFA | paraformaldehyde |

| RIPK2 | receptor-interacting protein kinase 2 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

1. Ashrafizadeh M. Cell death mechanisms in human cancers: molecular pathways therapy resistance and therapeutic perspective. J Cancer Biomol Ther. 2024;1(1):17–40. doi:10.62382/jcbt.v1i1.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. López MJ, Carbajal J, Alfaro AL, Saravia LG, Zanabria D, Araujo JM, et al. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;181(3):103841. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Thrift AP, Wenker TN, El-Serag HB. Global burden of gastric cancer: epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(5):338–49. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00747-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Röcken C. Predictive biomarkers in gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(1):467–81. doi:10.1007/s00432-022-04408-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Das S, Shukla N, Singh SS, Kushwaha S, Shrivastava R. Mechanism of interaction between autophagy and apoptosis in cancer. Apoptosis. 2021;26(9–10):512–33. doi:10.1007/s10495-021-01687-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Guan WL, He Y, Xu RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):57. doi:10.1186/s13045-023-01451-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xia JY, Aadam AA. Advances in screening and detection of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2022;125(7):1104–9. doi:10.1002/jso.26844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wang Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Lu S, Chen H. Progress of gastric cancer surgery in the era of precision medicine. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(4):1041–9. doi:10.7150/ijbs.56735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Patel TH, Cecchini M. Targeted therapies in advanced gastric cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(9):70. doi:10.1007/s11864-020-00774-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wan Y, Wang J, Xu JF, Tang F, Chen L, Tan YZ, et al. Panax ginseng and its ginsenosides: potential candidates for the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced side effects. J Ginseng Res. 2021;45(6):617–30. doi:10.1016/j.jgr.2021.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ponte LGS, Pavan ICB, Mancini MCS, da Silva LGS, Morelli AP, Severino MB, et al. The hallmarks of flavonoids in cancer. Molecules. 2021;26(7):2029. doi:10.3390/molecules26072029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Z, Lv J, Li X, Lin Q. The flavonoid Astragalin shows anti-tumor activity and inhibits PI3K/AKT signaling in gastric cancer. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2021;98(5):779–86. doi:10.1111/cbdd.13933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Han SH, Lee JH, Woo JS, Jung GH, Jung SH, Han EJ, et al. Myricetin induces apoptosis and autophagy in human gastric cancer cells through inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Heliyon. 2022;8(5):e09309. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Li Y, Dong M, Qin H, An G, Cen L, Deng L, et al. Mulberrin suppresses gastric cancer progression and enhances chemosensitivity to oxaliplatin through HSP90AA1/PI3K/AKT axis. Phytomedicine. 2025;139(8):156441. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Li W, Sun YN, Yan XT, Yang SY, Kim S, Lee YM, et al. Flavonoids from Astragalus membranaceus and their inhibitory effects on LPS-stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine production in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2014;37(2):186–92. doi:10.1007/s12272-013-0174-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Aobulikasimu N, Zheng D, Guan P, Xu L, Liu B, Li M, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of isoflavonoids from radix astragali in hepatoprotective potential against LPS/D-gal-induced acute liver injury. Planta Med. 2023;89(4):385–96. doi:10.1055/a-1953-0369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Feng SH, Zhao B, Zhan X, Motanyane R, Wang SM, Li A. Danggui buxue decoction in the treatment of metastatic colon cancer: network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:705–20. doi:10.2147/dddt.S293046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hussen BM, Azimi T, Hidayat HJ, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. NF-KappaB interacting LncRNA: review of its roles in neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;139(3):111604. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Eng VV, Wemyss MA, Pearson JS. The diverse roles of RIP kinases in host-pathogen interactions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2021;109:125–43. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lin HB, Naito K, Oh Y, Farber G, Kanaan G, Valaperti A, et al. Innate immune Nod1/RIP2 signaling is essential for cardiac hypertrophy but requires mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein for signal transductions and energy balance. Circulation. 2020;142(23):2240–58. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.119.041213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hofmann SR, Girschick L, Stein R, Schulze F. Immune modulating effects of receptor interacting protein 2 (RIP2) in autoinflammation and immunity. Clin Immunol. 2021;223(20):108648. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. You J, Wang Y, Chen H, Jin F. RIPK2: a promising target for cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1192970. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1192970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Duggan BM, Cavallari JF, Foley KP, Barra NG, Schertzer JD. RIPK2 dictates insulin responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in obese male mice. Endocrinol. 2020;161(8):bqaa086. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqaa086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yan Y, Zhou B, Qian C, Vasquez A, Kamra M, Chatterjee A, et al. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 2 (RIPK2) stabilizes c-Myc and is a therapeutic target in prostate cancer metastasis. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):669. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28340-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lu C, Liu H, Liu T, Sun S, Zheng Y, Ling T, et al. RIPK2 promotes colorectal cancer metastasis by protecting YAP degradation from ITCH-mediated ubiquitination. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):248. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07599-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Guirado M, Gil H, Saenz-Lopez P, Reinboth J, Garrido F, Cozar JM, et al. Association between C13ORF31, NOD2, RIPK2 and TLR10 polymorphisms and urothelial bladder cancer. Hum Immunol. 2012;73(6):668–72. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2012.03.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou Y, Liu S-X, Zheng Y, Song S-R, Cao Y-B, Qao Y-Q, et al. Methynissolin confers protection against gastric carcinoma via targeting RIPK2. J Funct Foods. 2024;119(3):106327. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2024.106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang Q, Tian S, Liu Z, Dong W. Knockdown of RIPK2 inhibits proliferation and migration and induces apoptosis via the NF-κB signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Front Genet. 2021;12:627464. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.627464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Jamasbi E, Hamelian M, Hossain MA, Varmira K. The cell cycle, cancer development and therapy. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(11):10875–83. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07788-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu X, Wang S, Li J, Zhang J, Liu D. Regulatory effect of traditional Chinese medicines on signaling pathways of process from chronic atrophic gastritis to gastric cancer. Chin Herb Med. 2022;14(1):5–19. doi:10.1016/j.chmed.2021.10.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Montalto FI, De Amicis F. Cyclin D1 in cancer: a molecular connection for cell cycle control adhesion and invasion in tumor and stroma. Cells. 2020;9(12):2648. doi:10.3390/cells9122648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Subramaniam N, Kannan P, Sundaram J, Mari A, Velli SK, Salam S, et al. Potential chemopreventive role of boldine against hepatocellular carcinoma via modulation of cell cycle proteins in rat model. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2021;21(18):2546–52. doi:10.2174/1871520621666210203102854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Winkler J, Abisoye-Ogunniyan A, Metcalf KJ, Werb Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5120. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18794-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zheng J, Zeng L, Tang M, Lin H, Pi C, Xu R, et al. Novel ferrocene derivatives induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3097. doi:10.3390/ijms22063097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Gullo I, Grillo F, Mastracci L, Vanoli A, Carneiro F, Saragoni L, et al. Precancerous lesions of the stomach, gastric cancer and hereditary gastric cancer syndromes. Pathologica. 2020;112(3):166–85. doi:10.32074/1591-951x-166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zhang T, Chen W, Jiang X, Liu L, Wei K, Du H, et al. Anticancer effects and underlying mechanism of Colchicine on human gastric cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(1):bsr20181802. doi:10.1042/bsr20181802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhong YL, Wang PQ, Hao DL, Sui F, Zhang FB, Li B. Traditional Chinese medicine for transformation of gastric precancerous lesions to gastric cancer: a critical review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;15(1):36–54. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v15.i1.36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Pyra A, Adamiak-Godlewska A, Lewkowicz D, Bałon B, Cybulski M, Semczuk-Sikora A, et al. Inter-component immunohistochemical assessment of proliferative markers in uterine carcinosarcoma. Oncol Lett. 2022;24(4):363. doi:10.3892/ol.2022.13483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Rashidbaghan A, Mostafaie A, Yazdani Y, Mansouri K. Urtica dioica agglutinin (a plant lectin) has a caspase-dependent apoptosis induction effect on the acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line. Cell Mol Biol. 2020;66(6):121–6. doi:10.14715/cmb/2020.66.6.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Moussa RS, Park KC, Kovacevic Z, Richardson DR. Ironing out the role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21 in cancer: novel iron chelating agents to target p21 expression and activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133(Pt 10):276–94. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.03.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Bonelli P, Tuccillo FM, Borrelli A, Schiattarella A, Buonaguro FM. CDK/CCN and CDKI alterations for cancer prognosis and therapeutic predictivity. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014(5192):361020. doi:10.1155/2014/361020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Li Z, Liu J, Zhang X, Fang L, Zhang C, Zhang Z, et al. Prognostic significance of cyclin D1 expression in renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26(3):1401–9. doi:10.1007/s12253-019-00776-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li GZ, Doherty GM, Wang J. Surgical management of gastric cancer: a review. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(5):446–54. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.0182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gam DH, Park JH, Kim JH, Beak DH, Kim JW. Effects of allium sativum stem extract on growth and migration in melanoma cells through inhibition of VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 genes expression. Molecules. 2021;27(1):21. doi:10.3390/molecules27010021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang H, Ma Y, Zhang Q, Liu R, Luo H, Wang X. A pancancer analysis of the carcinogenic role of receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase-2 (RIPK2) in human tumours. BMC Med Genomics. 2022;15(1):97. doi:10.1186/s12920-022-01239-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Jaafar R, Mnich K, Dolan S, Hillis J, Almanza A, Logue SE, et al. RIP2 enhances cell survival by activation of NF-ĸB in triple negative breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497(1):115–21. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Shen Y, Lin H, Chen K, Ge W, Xia D, Wu Y, et al. High expression of RIPK2 is associated with Taxol resistance in serous ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2022;15(1):48. doi:10.1186/s13048-022-00986-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhang W, Wang Y. Activation of RIPK2-mediated NOD1 signaling promotes proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells via NF-κB pathway. Histochem Cell Biol. 2022;157(2):173–82. doi:10.1007/s00418-021-02055-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Li L, Yu R, Cai T, Chen Z, Lan M, Zou T, et al. Effects of immune cells and cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88(2):106939. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Jost PJ, Vucic D. Regulation of cell death and immunity by XIAP. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2020;12(8):a036426. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a036426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. He S, Wang X. RIP kinases as modulators of inflammation and immunity. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(9):912–22. doi:10.1038/s41590-018-0188-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Peng C, Ouyang Y, Lu N, Li N. The NF-κB signaling pathway the microbiota and gastrointestinal tumorigenesis: recent advances. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1387. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools