Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Computational Tools Identify Novel Mechanisms for Feline Color-Pointed Phenotypes Based on Tyrosinase Mutations

1 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA

2 Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA

* Corresponding Author: Ingrid R. Niesman. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2433-2455. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071078

Received 31 July 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Objective: Tyrosinase is the rate-limiting enzyme in the generation of melanin. The feline tyrosinase mutation, G302R, confers temperature-sensitive loss of function, resulting in the familiar Siamese cat phenotype. Crystal or cryoEM structures are elusive for any mammalian tyrosinase to date. Protein misfolding is suggested as a basis for phenotypes resulting from mutant tyrosinases, but this hypothesis needs structural confirmation. Our objective for this study is to confirm misfolding of mutant tyrosinase as a basis for temperature-sensitive phenotypes compared to catalytic dysfunction that may be responsible for other tyrosinase mutant breed phenotypes. Methods: We have employed AlphaFold3 to compare structural alignments of four well-characterized feline tyrosinase mutations to wild type (WT) feline tyrosinase; Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W, Mocha delI274-L312+2aa, and Albino del401-529 lacking the transmembrane and C-terminus domains. Results: The manifestations of the bulkier side chains of the Siamese positively charged arginine (R) and the Burmese hydrophobic tryptophan (W) are evident locally. But interestingly, the major differences between the structures lie in the usually ignored signal peptide (SP) regions of each mutant. As the maturation of the nascent tyrosinase peptide is highly dependent on accurate and early cleavage of the SP, we hypothesize these structural anomalies may form the basis for misfolded or truncated final enzyme forms, leading to the observed phenotypes seen in these cats. Conclusions: We have identified enzyme dysfunction and protein misfolding as separate mechanisms for feline coat phenotypes resulting from tyrosinase mutations.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileTyrosinase is the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of melanocyte-localized melanin and in the generation of dopamine in the brain, two disparate yet related synthetic pathways. Melanocytes, residing in the skin, contain the cellular organelle melanosomes where tyrosine (Y) is converted to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine [1] and DOPAquinone to Indole-5,6-quinone using catalytic tyrosinase, resulting in eumelanin pigmentation. On the other hand, within specific neurons, DOPAquinone spontaneously converts to Aminochrome, followed by an NADPH-requiring reaction to Leucoaminochrome. Neuronal localized tyrosinase then generates 5,6-Indolequinone, which polymerizes into the black pigment neuromelanin, unlike the monomeric eumelanin [2–4].

Full-length wild type (WT) tyrosinase sequences, whether human, mouse, or feline, are highly conserved (88% identical for human and 83% identical for mouse). As is consistent across plant, animal, and fungal species, the mammalian Type I membrane Cu-binding glycoprotein consists of a binuclear copper (Cu2+) enzyme active site, defined as CuA and CuB, an N-terminus signal peptide (SP), an intraluminal domain, a short transmembrane domain (TM), and a flexible α-helix cytosolic C-terminal tail. CuA binds to H180, H202, and H211, while CuB binds to H363, H367, and H390 in either human, mouse, or feline tyrosinase [5]. These ions and their localization are critical for the catalytic activity of tyrosinase [6]. The cysteine-rich domain, AA20-118, consists of critical disulfide bonds at C24, C35, C36, C46, C55, C89, C91 and C100 in all three species. As previously described [7], the six consensus glycosylation sites N86, N111, N161, N230, N337, and N371 [8] are critical for proper folding.

Full-length human tyrosinase X-ray crystallography (XRC) data have proven difficult to obtain. In 2016, Lai et al. used a baculovirus expression system to obtain high yields of a truncated (AA19-456) deglycosylated human protein, which provided preliminary X-ray diffraction resolution down to 3.5 Å [9]. Yet, as of late 2024, no reliable full-length structure of a glycosylated mammalian tyrosinase has been reported [10], only structures for the eukaryotic Agaricus bisporus and two bacterial species [6]. Proper folding of tyrosinase relies on a minimum of two N-linked glycosylation sites to allow interaction with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localized chaperone, calnexin, during translation within the lumen of the ER [7,11]. Thus, in vitro expression approaches for resolving high-resolution structures of the mammalian tyrosinase protein have fallen short.

There is even less information on the structure of feline tyrosinase. Although rarely used as a model system, cats are closely aligned with humans in the development of temperature-sensitive forms of albinism [12–14] and neurodegeneration (ND) [15–19]. Emerging evidence suggests a close link between tyrosinase activity and the development of neurodegeneration, particularly in the development of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (reviewed by [2,20]). Considering this hypothetical link, understanding the structural basis for feline coat colorization therefore takes on greater significance if specific subpopulations of domestic cats could be used as real-world, real-time model systems to follow and track symptomology for neurodegeneration.

In a widely reported publication, Lyons et al. first described the point mutations in feline tyrosinase resulting in the distinctive Siamese partial albinism color-pointing phenotype (G302R) and the breed-distinguishing coloring of the Burmese cat (G227W) [21]. Recently, an additional pedigree within the Burmese breed was found to have a major deletion and duplication region within exon 2, resulting in an unusual “mocha” coloration [22]. Full albinism is the result of total loss-of-function for tyrosinase. In domestic felines, a frame shift mutation in exon 2 (c.975delC) results in a truncated protein [23], causing a recessive phenotype. While another group found full deletion of the transmembrane and C-terminus domains in a male albino feline (c.1204C > T) with loss of 25% of the full-length protein [24].

Biochemical conversion of substrates, such as L-DOPA or tyrosine, is the gold standard for measuring tyrosinase enzymatic function. The enzyme needs to fold properly to expose the catalytic site to the required substrate(s) for oxidation reactions to occur. For tyrosinase specifically, without an experimentally verifiable structure, biological and biochemical approaches have been employed to elucidate the mechanism for tyrosinase mutational phenotypes [25–29]. Whereas ER retention and accelerated degradation of misfolded or aggregated tyrosinase is the dominant hypothesis, abnormal post-translational modifications [25,30] or failure to bind the substrates tyrosine (Y) or the more commonly oxidized l-DOPA [31] are possible mechanisms for the described murine mutants. We have used an AI-based approach to compare computationally derived feline tyrosinase mutants to WT feline tyrosinase, looking for changes or differences in (1) catalytic site architecture; (2) substrate H-bonding; (3) cytosolic C-terminus oligomerization sites; and (4) N-terminus SP differences, expecting to find major differences in catalytic site microstructure. Interestingly, changes from WT between Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W, and especially Mocha delI275-L312+2aa within the catalytic site are present. However, major changes in folded protein localization are detected for the critical SP domain.

Our previous work has indicated that mutant Siamese G302R feline tyrosinase aggregates in the ER and is rapidly degraded [29] at non-permissive temperatures, providing a tentative ER stress basis for the partial albinism phenotype. Understanding the actual synthesis and maturation of tyrosinase provides additional insights into the mechanism. Tyrosinase is translated by ribosomes in the ER, post-translationally modified in the ER, and finally packaged for transport to the Golgi. Integral to this process for tyrosinase is signal peptide targeting to the ER membrane by the signal recognition particle (SRP), which allows the growing nascent peptide access to the final ER exit site once it is completed. Without proper binding of the SRP, the critical timing of SP cleavage cannot occur, affecting both protein folding and final post-translational maturation of the enzyme [32]. Examples of SP mutations are known to increase ER stress [33], prevent cellular signaling [34], and cause human disease [35].

The rationale for this study is embedded in the idea that cats, particularly color-pointed phenotypes, are a potential unexplored model of ER stress–induced neuronal injury. Previously, we have postulated direct connections between maladaptive ER stress, a physiological response to protein synthesis and degradative imbalances within the ER milieu leading to cell dysfunction or death via Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) pathways, and the origins of neurodegeneration in domestic cats [36]. For confirmation of our hypothesis, a determination of a misfolded structural mechanism of the potential Siamese G302R mutant verses loss of catalytic function of the mutant tyrosinase is necessary.

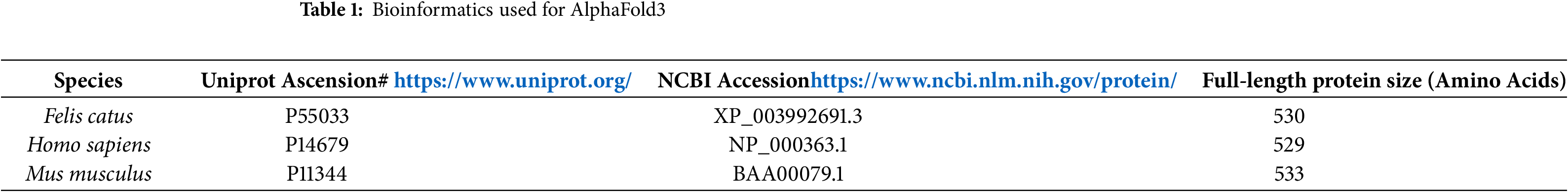

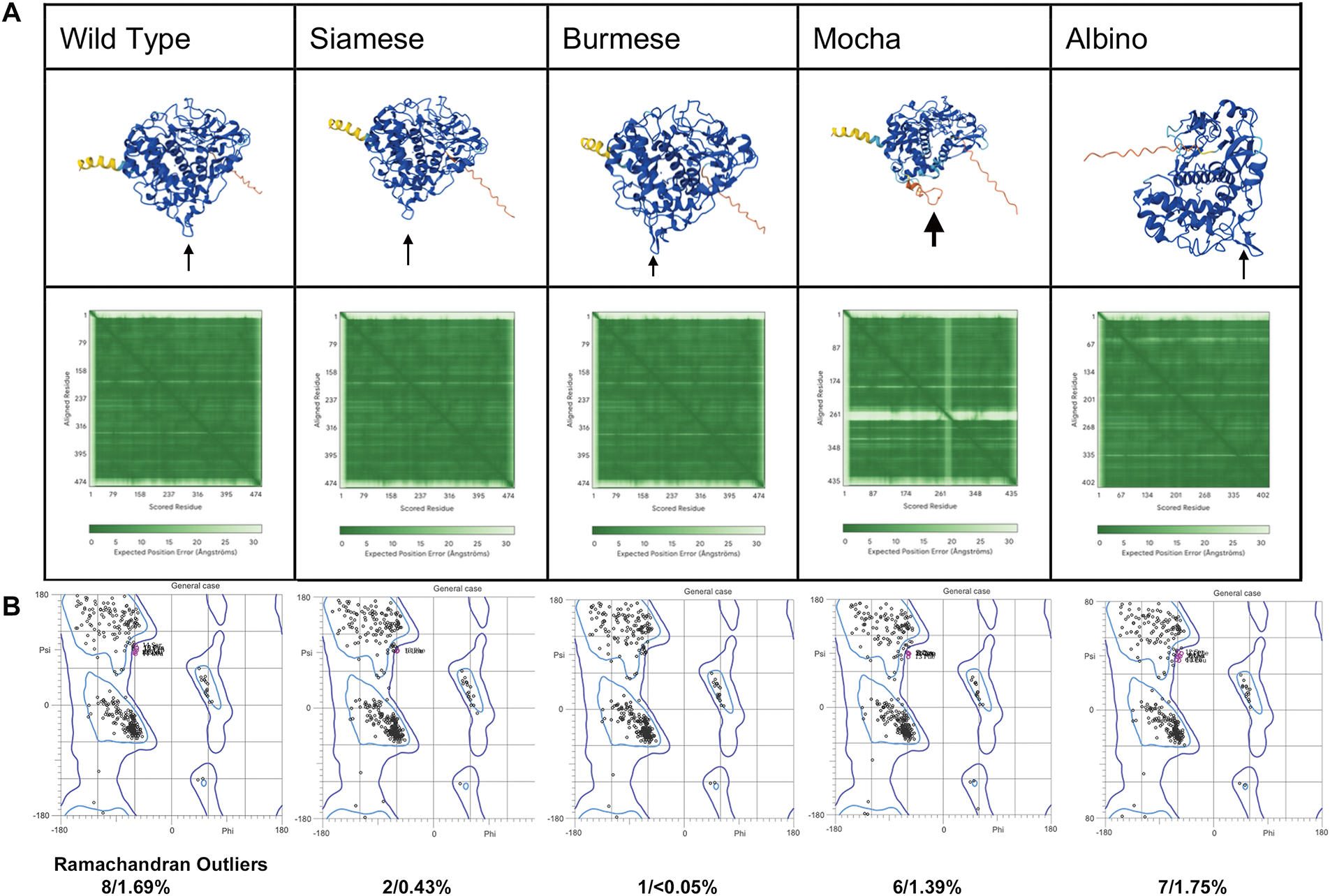

The full-length or (-) transmembrane domain tyrosinase protein sequences obtained from feline, human, and mouse species were uploaded to AlphaFold3 [37]. Table 1 are the bioinformatic details on amino acid sequences used for all AlphaFold3 structures. Highest ranked predictions (0) were visualized using PyMol (Schrodinger, LLC; version 3.1.4.1). Specifically for initial feline mutant tyrosinase analysis, the TM domain (AA473-501) was removed. Predictive models were analyzed using Molprobity to generate Ramachandran plots and identify outliers. All alignments, measurements, and visualization were performed with PyMol after saving and converting AlphaFold3.cif raw files into .PDB files.

Docking simulations were performed using the Pymol plugin Autodock Vina, through DockingPie 1.2.1. Alphafold3 structures were opened into the program, along with a file containing L-tyrosine (Y). Feline tyrosinase was selected as the receptor, while Y was selected as the ligand. The grid coordinates were selected, centering on the two Cu2+ cations, including as much of the active site as possible. The grid dimensions were expanded until consistent docking affinity numbers were achieved, and reasonable docking site models were presented. Each feline tyrosinase was measured in three rounds and averaged. Docking affinities are measured in kcal/mol.

3.1 Key Differences Exist between Feline, Human, and Mouse Predicted AlphaFold 3 Structures

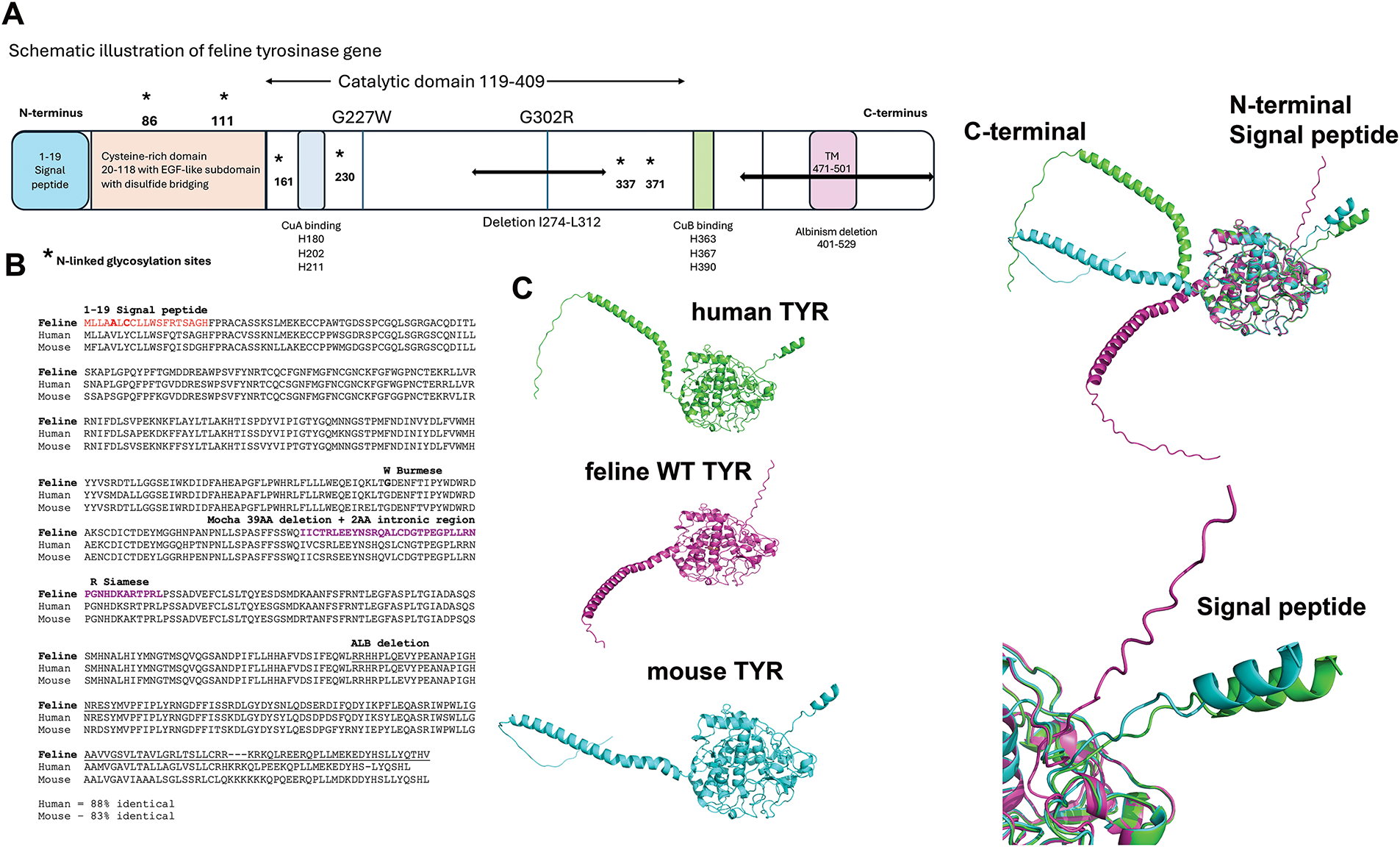

Fig. 1A shows the feline full-length tyrosinase-coded protein, consisting of a signal peptide (AA1-19), a cysteine-rich domain with critical disulfide bonding and an EGF-like subdomain, two Cu2+ ions in the active site pocket, a short transmembrane domain, and a lengthy C-terminal cytosolic domain. As glycosylation has been shown to be crucial for chaperone-assisted folding for tyrosinase, the asparagine (N) residues have been highlighted. As a ubiquitously identified enzyme among species as diverse as bacteria through mammals, the physiological importance for survival is high. Homology among mammalian species compared to feline sequences is 88% for human and 83% for mouse, with most differences being small point mutations (Fig. 1B). Visualization of AlphaFold3 predicted structure reveals a lack of an α-helix within the SP for the WT feline protein, seen in human and mouse SP. Three nucleotide differences, human-mouse 5 V to feline 5 A, human-mouse 7Y to feline 7C, and human-mouse 14Q to feline 14R form the basis for this structural change. More critically, the alignment of the human and mouse SP is very close, with similar positioning. One additional change is human-feline15T to mouse 15I. The outlier is the feline SP, which deviates from human and mouse at the inflection point of feline R14 by 5.1 Å. The difference in localization between the human and mouse SP is potentially caused by a polarity change from A17 (human) and D17 (mouse). The mouse D17 shows differences in hydrogen bonds that shift the SP over slightly from the human location. A higher magnification inset of this region is shown in the bottom right panel of Fig. 1C. Predictive confidence scores for human, mouse, and feline (WT) generated by AlphaFold3 are listed in Table 2.

Figure 1: Alignments of wild type (WT) human, feline, and mouse tyrosinase. (A) Schematic of the feline tyrosinase gene with mutations and deletions analyzed is marked. (B) Gene alignments for human, feline, and mouse sequences. (C) AlphaFold3 generated structures for human, feline, and mouse folded tyrosinases. Signal peptide (SP) and C-terminal ends are clearly defined between the species

The pTM, an indication of the potential quality of the structure, is highest for WT feline over human or mouse, possibly based on the less disordered fraction returned from the model.

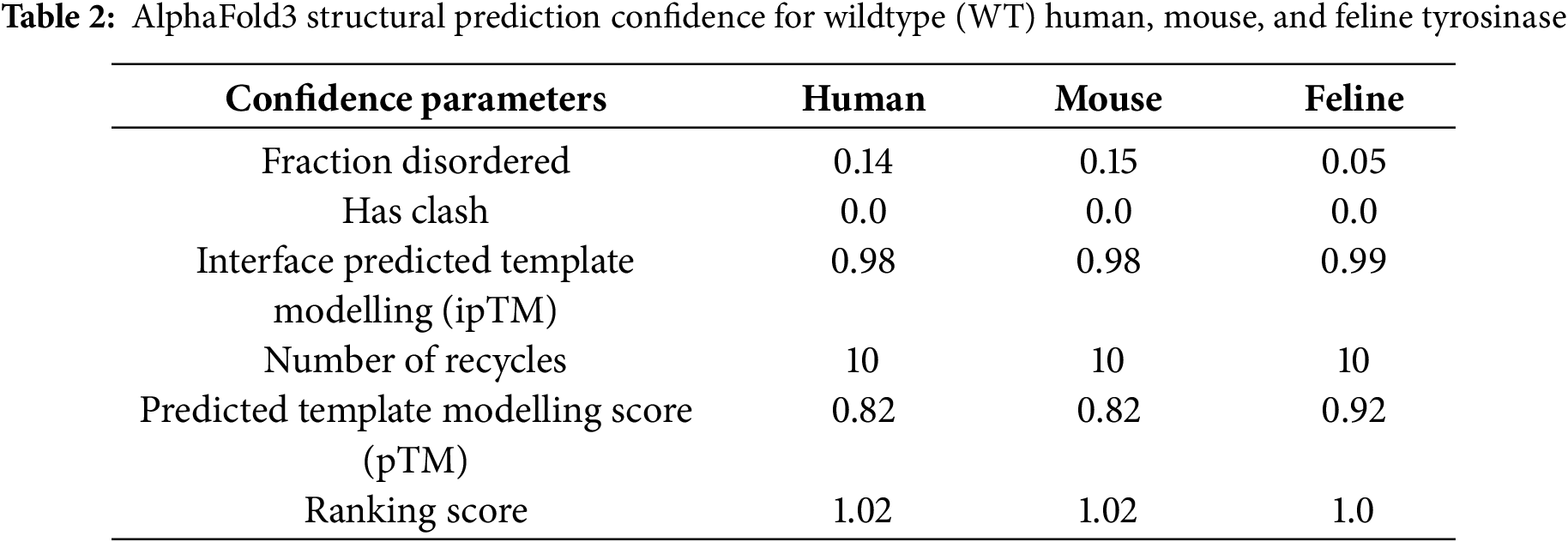

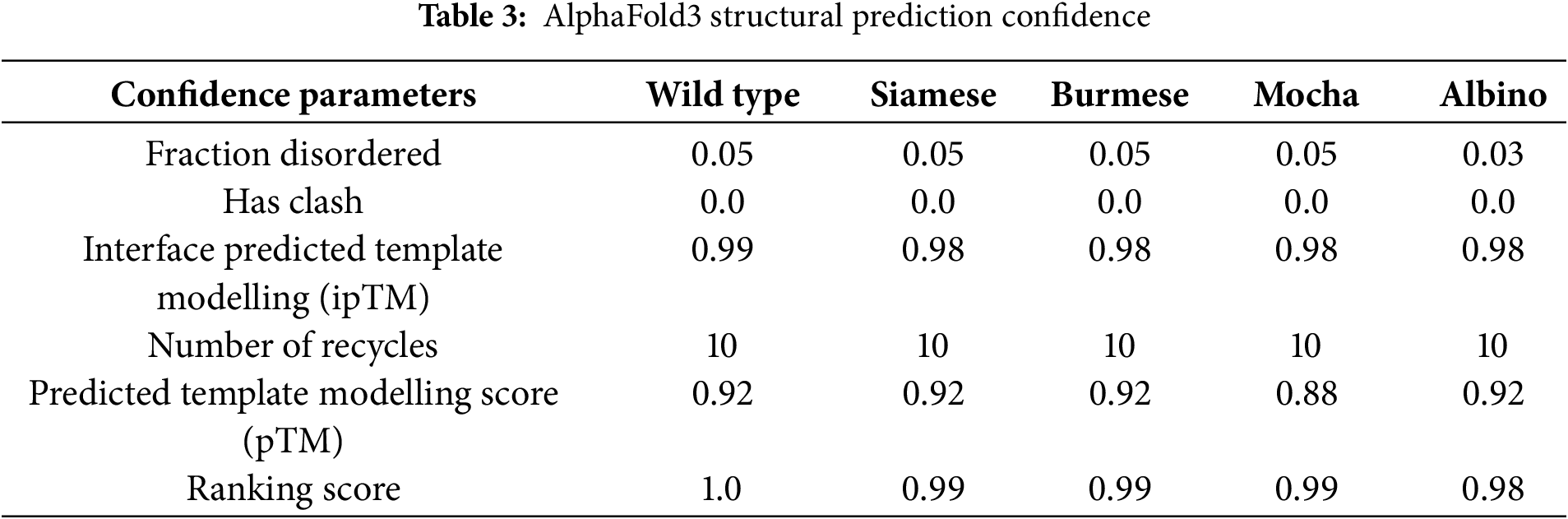

3.2 Confidence in the AlphaFold3 Predictive Structure for Feline Tyrosinase without X-Ray Crystallography or cryoEM Models

The AI AlphaFold3 server and other publications that have attempted to model the protein structure of mammalian tyrosinases [9,10,38–41] have used tyrosinase-related proteins with solved crystal structures, namely TYRP1 [40,42,43], or bacterial tyrosinases [44], as the basis for their models. Although the homology between tyrosinase and TYRP1 is close (40%–50% sequence identity), TYRP1 is a Zn2+ containing membrane protein. Our assumption throughout our analysis is that our AlphaFold3 model is strictly predictive and not definitive. In our initial analyses, we included the SP and excluded the transmembrane (TM) domain for the mutant comparisons, as the TM domain is not involved in the overall final folding for an active enzyme. Images represented in Fig. 2A are the predicted AlphaFold3 structures for all feline tyrosinases analyzed. AlphaFold3 returned high levels of confidence for ordered regions of the protein, moderate levels of confidence for disordered regions, and comparatively low levels of structural confidence for the SP itself, based on Predictive Alignment Errors (PAE) plots (Fig. 2A, bottom panels). The pTM values (Table 3) returned during modeling show a high level of consensus between the predicted and hypothetical structure, with slightly decreased confidence for the mutants compared to WT feline tyrosinase. The lowest level of confidence is the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa mutant, which has a large catalytic site deletion and two mismatched amino acids. Most notably, the consistent loop defined by G254–I274 (small arrows) is modeled at high confidence except for the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa mutant (large arrow). This region, immediately preceding the deleted segments, begins with G254 but ends with N274. The loss of isoleucine appears critical in maintaining structural confidence in this flexible loop. Compared to human and mouse tyrosinase-derived pTMs of 0.82, feline tyrosinase folding appears better suited for computational modeling.

Figure 2: Confidence Levels for predictive AlphaFold 3 models. (A) AlphaFold3 models of feline tyrosinases and the predicted alignment errors (PAE) designations (below). Small arrows indicate the G254-I274 loop; the large arrow shows the effect of losing I274 on the ordered structure for the Mocha mutant. (B) General case Ramachandran plots for each fTYR(s) and the percentage of amino acid outliers from Molprobity analysis

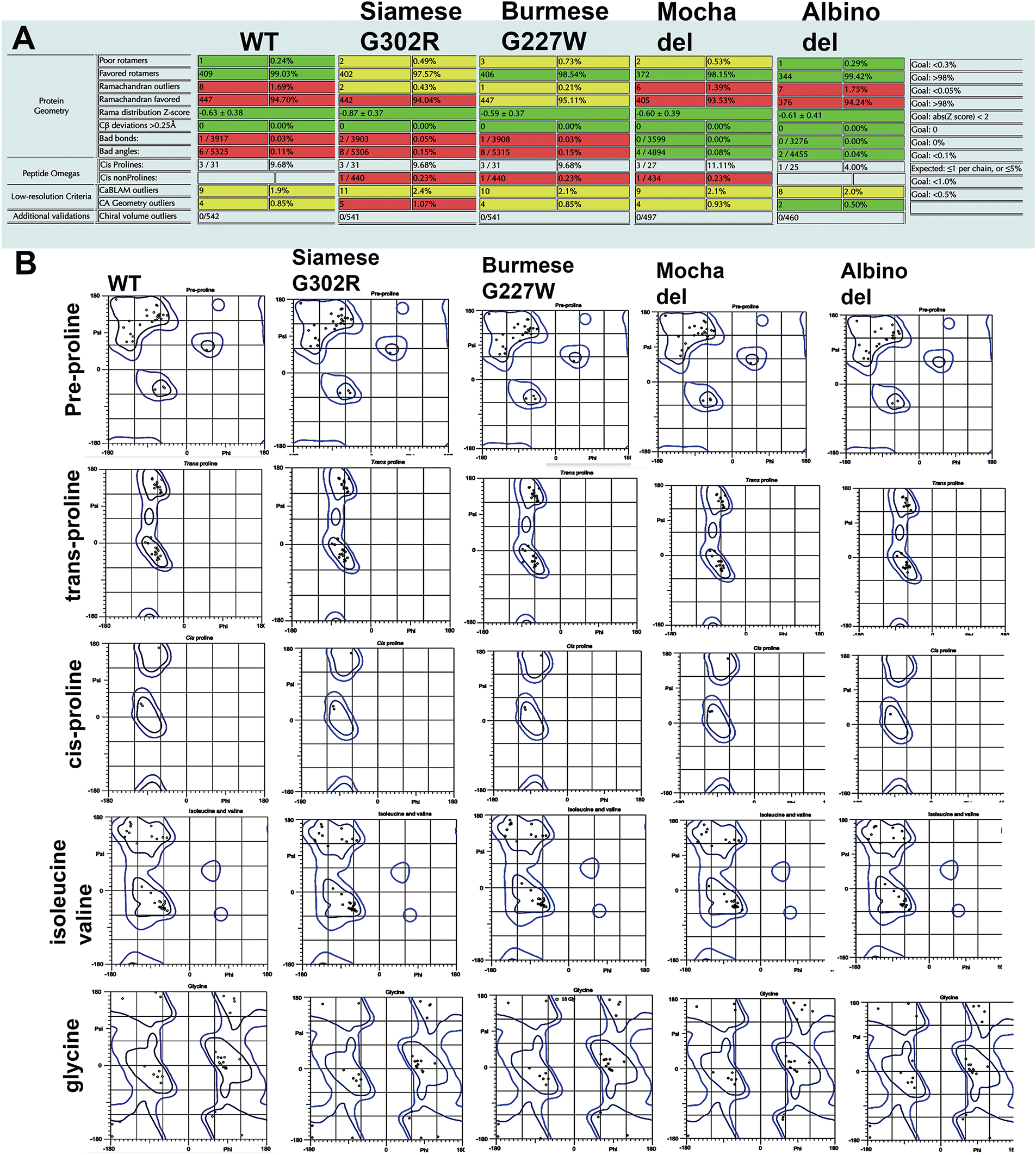

Ramachandran plots were generated for all cases (general, isoleucine and valine, pre-proline, glycine, trans-/cis proline), for each feline tyrosinase model. Fig. 2B represents the comparison between general cases. Full case analysis can be found in Fig. A1. The plots do not reveal any major changes β-sheets or α-helix stability between protein folding in this static view of structure. However, as we will propose, a better view of differences in folding is a dynamic one during ER translation for feline tyrosinase.

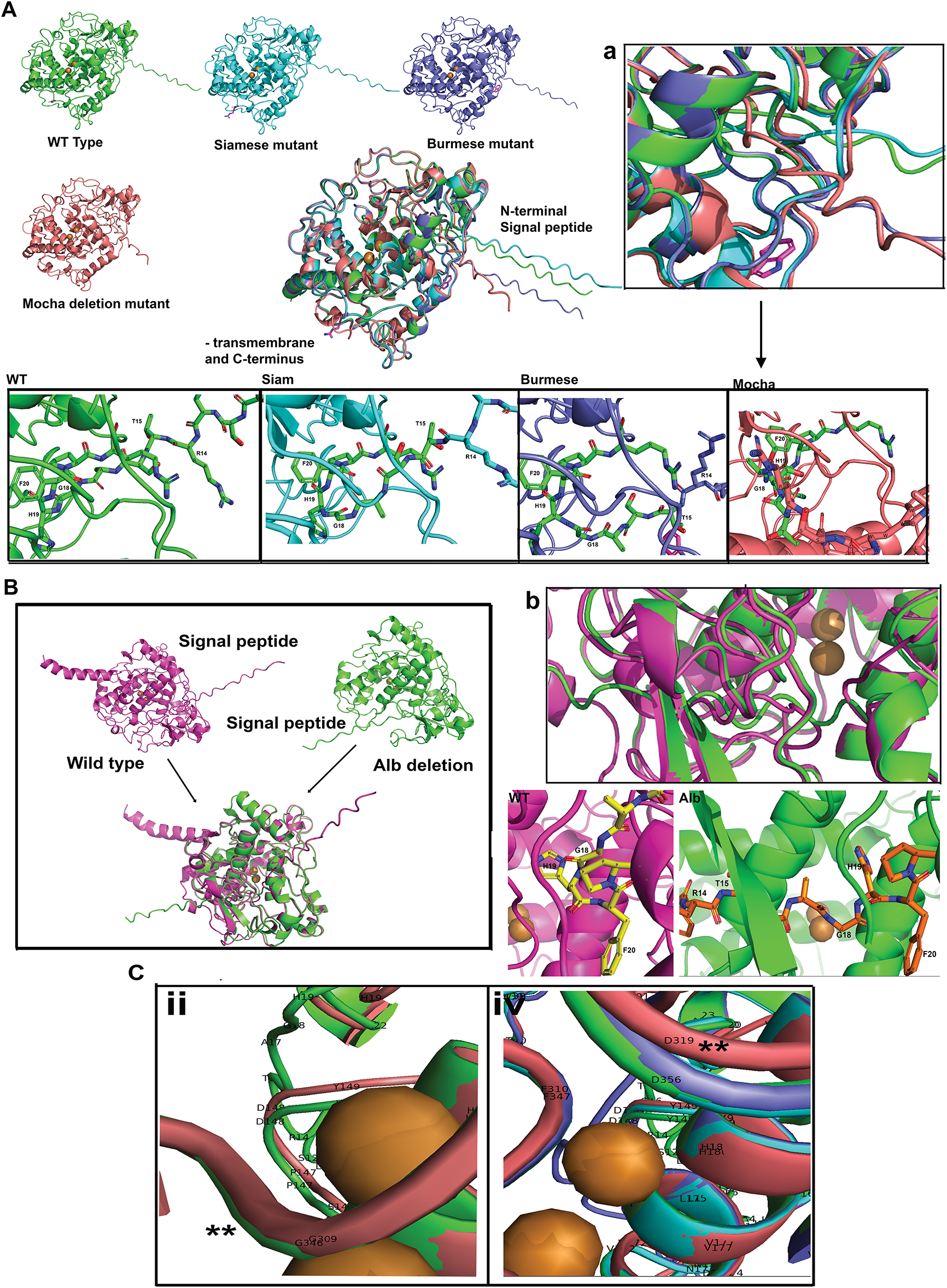

3.3 Feline Mutant Tyrosinase SP is Spatially Displaced before Amino Acids G18 and H19, Leading to Possible Differential Cleavage during Early Phases of ER Translation

Fig. 3A depicts the predicted AlphaFold3 folded structures for Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W, and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa compared to WT without the TM and cytoplasmic C-terminal tail domains (AA471-529) using aligned PyMol files. Since our initial interest was direct changes in the feline catalytic site (AA119-409), we didn’t expect to see any dramatic changes within the C-terminal end, given the mutations were localized near at least one of the known Cu2+ binding sites. When aligned, significantly different localization for each feline mutant SP was evident. Measured distances from WT L3 to mutant L3 residues confirmed these spatial changes: Burmese G227W 9 Å, Siamese G302R 12.2 Å, and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa 34.6 Å. Whereas the confidence pIDDT for the disordered SP AA1-17 segment is low, beginning at the folded region of G18 and H19, pIDDT approaches higher levels of confidence, 70 > 90. By F20, the predictive confidence is within the highest levels, pIDDT > 90. The higher magnification view (Fig. 3Aa) shows the different orientations and alignments of the differential spatial separation. From Fig. 3Aa evidence, the smaller deviation of the Burmese SP may be an effect of the bulkier ringed tryptophan (G227W) sterically hindering the Burmese SP path, or could be caused through additional stabilizing H-bonding of the W227 to the α-helix AA L208-K224 (data not shown). A higher magnification view is found in Fig. A2C. The Siamese SP begins deviation near R14 and T15, close to the beginning of the folded region. By F20 and P21, all mutants coalesce together. The major deviations for Siamese G302R and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa occur well before the H19 residue, with Siam looping away and the Mocha coming in from the opposite spatial domain. Due to the extensive deletion of 39 amino acids and the addition of 2 non-homologous replacements (N, L), major differences in residue nomenclature are noted for the Mocha mutant (Fig. 3C ii, iv; Note: ii and iv are symbolic designations, not sequential, for easier identification within each image). Our Mocha delI274-L312+2aa model lacks the G227W mutation, as lineage suggests the cat sequenced with a homozygous deletion, did not have the W, and appeared to be the lightest coloration and therefore the most likely to show alterations in folding and enzyme activity [22].

Figure 3: The SPs of feline mutant tyrosinases are highly deviated from WT feline tyrosinase. (A) WT, Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W, Mocha delI274-L312+2aa tyrosinase AlphaFold3 predicted structures, aligned using PyMol, showing the extent of SP differences. (Below) Insets are magnified views of R14-F20 regions for each mutant. (a) Representative higher magnification inset of the aligned SP regions. (B) Full-length with TM WT tyrosinase and Albino del401-529 tyrosinase. The SPs are localized to polar opposite sides of the predicted models; right insets are R14-F20 regions. (b) Representative higher magnification inset of each aligned SP region. (C) Amino acid localization changes in Mocha deletion from WT tyrosinase, (ii) Mocha G309 (red) and WT G346 (green); (iv) Mocha D319 and WT, Siam G302R, Burmese G227W mutants D356. Note: ii and iv are symbolic designations, not sequential, for easier identification within each image. The symbols ** mark the region of homology of structure within the deleted segment

The full albinism mutant (Albino del401-529) recently described [24] lacks the entire TM and the majority of the C-terminus. In order to assess the role of these domains on the loss-of-function phenotype, we used the full-length WT to compare with the Albino del401-529, as depicted in Fig. 3B. PyMol alignments do not show significant catalytic disruptions near the required Cu2+ ions, but do show the Albino del401-529 SP is located at a significant degree of spatial location compared to WT. As in the other described mutants, the SPs coalesce at the folded H19-P21 region. Fig. 3Bb is a higher magnification view of the H19 region where the Albino (green) and WT (pink) SP begin to align. Within the aligned PyMol sequences, the Albino del401-529 SP is closely aligned where the WT C-terminus amino acids H405 through E409 would reside, just past the Albino deletion at L401. Overall, the Albino del401-529 folding appears less compacted than WT, potentially indicating changes in stability.

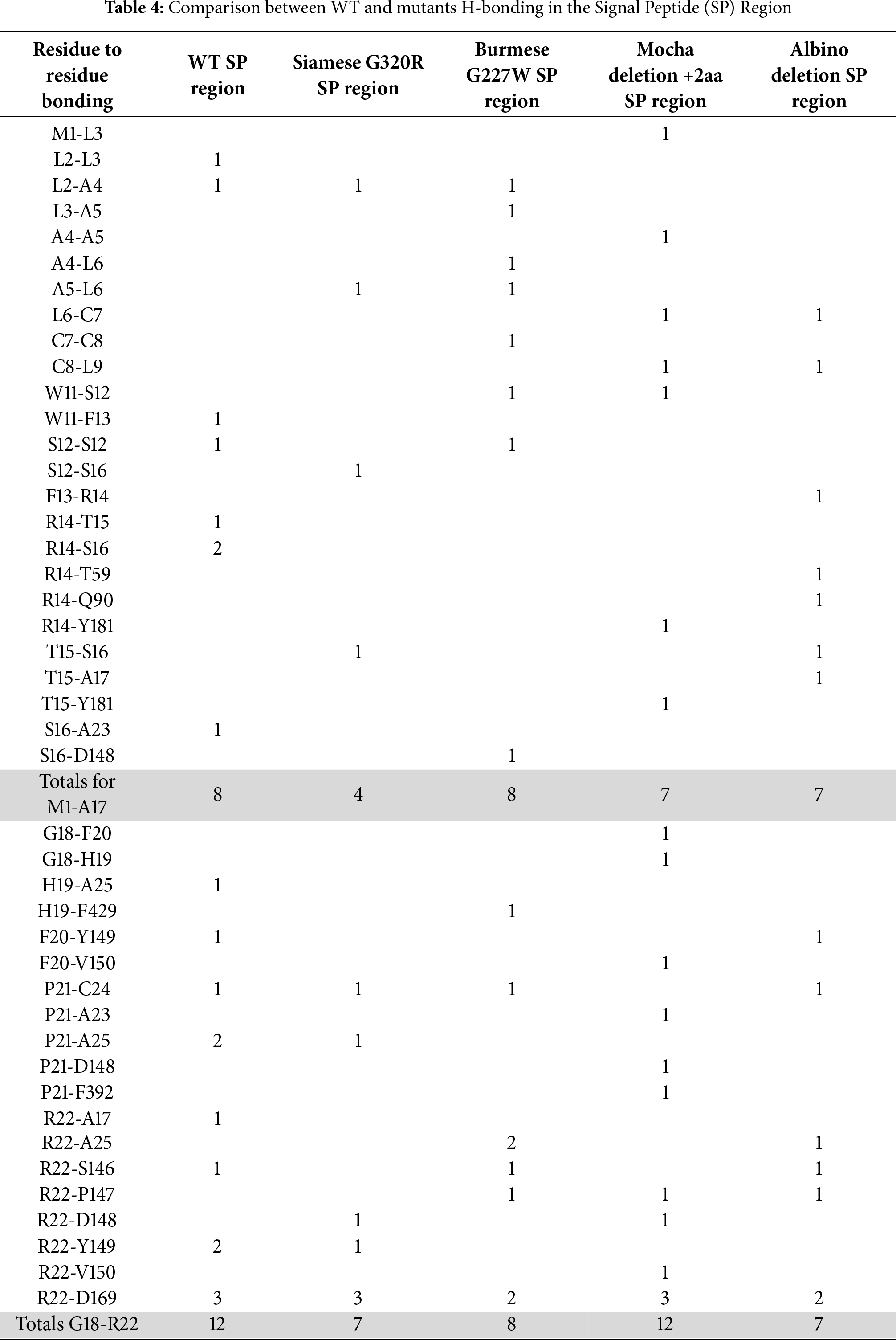

3.4 H-Bonding Changes in Feline Mutant Tyrosinase SP Amino Acids (AA1-P22) Indicate Stability and Flexibility Differences and Notable Novelty for the Mocha Mutant

Table 4 lists all the visible H-bonds in the SP region found by PyMol. The SP bonding was divided into the disordered domain (AA 1–17) and the predicted folded domain for each feline tyrosinase (AA 18–22). The two distinct domains are tabulated separately and divided by a gray line. The Burmese G227W and Albino del401-529 have between 4–6 novel interactions, and the Siamese G320R has only one novel interaction when compared to WT. However, Mocha delI274-L312+2aa has 11 unique bonds that extend from either the disordered domain or the folded domain to amino acids in regions inconsistent with the WT structure, R14–Y181, F20–V150, P21-F392, and R22–V150. Only the F392 would necessarily be displaced by the Mocha deletion; the other H-bonds represent a significant change from WT. Burmese G227W has one unique H-bond, H19-F429, that is likely synonymous with the P21–F392 given the deletion loss nomenclature, indicating this is probably breed specific. Except for the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa with only a slight net loss of 1 H-bond over WT and a total of 19 H-bonds, the trend is for the mutants to lose H-bonds in the SP regions. WT totals 20 H-bonds, Burmese G227W has 16 H-bonds, Albino del401-529 has 14 H-bonds. While Siamese G302R shows a net loss of 7 H-bonds, leading to a total of just 11.

From the tabulated data presented in Table 4, the most critical H-bonding for feline tyrosinase SP structure surrounds residues R22 and D169. WT, Siamese G302R and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa have three bonds between R22 and D169, Burmese G227W and Albino del401-529 have two. Other critical residues nearby are F20 and P21, which are consistently bonded to either A23, C24, and A25 within an α-helix, between all the tyrosinases. C24 is recognized for the crucial disulfide bonding within the Cys-rich domain, which provides structural stability. Mocha delI274-L312+2aa lacks a P21-C24 bond that all others predict and instead bonds P21-A25. Greater variability exists in the disordered domain, with the Siamese G302R displaying the least consistent number of bonds predicted. This fits with our hypothesis that the Siamese phenotype is the result of ER retention and enhanced degradation. The more flexible the SP, the less likely the signal recognition particle (SRP) is to assist in proper ER membrane insertion for proper translation.

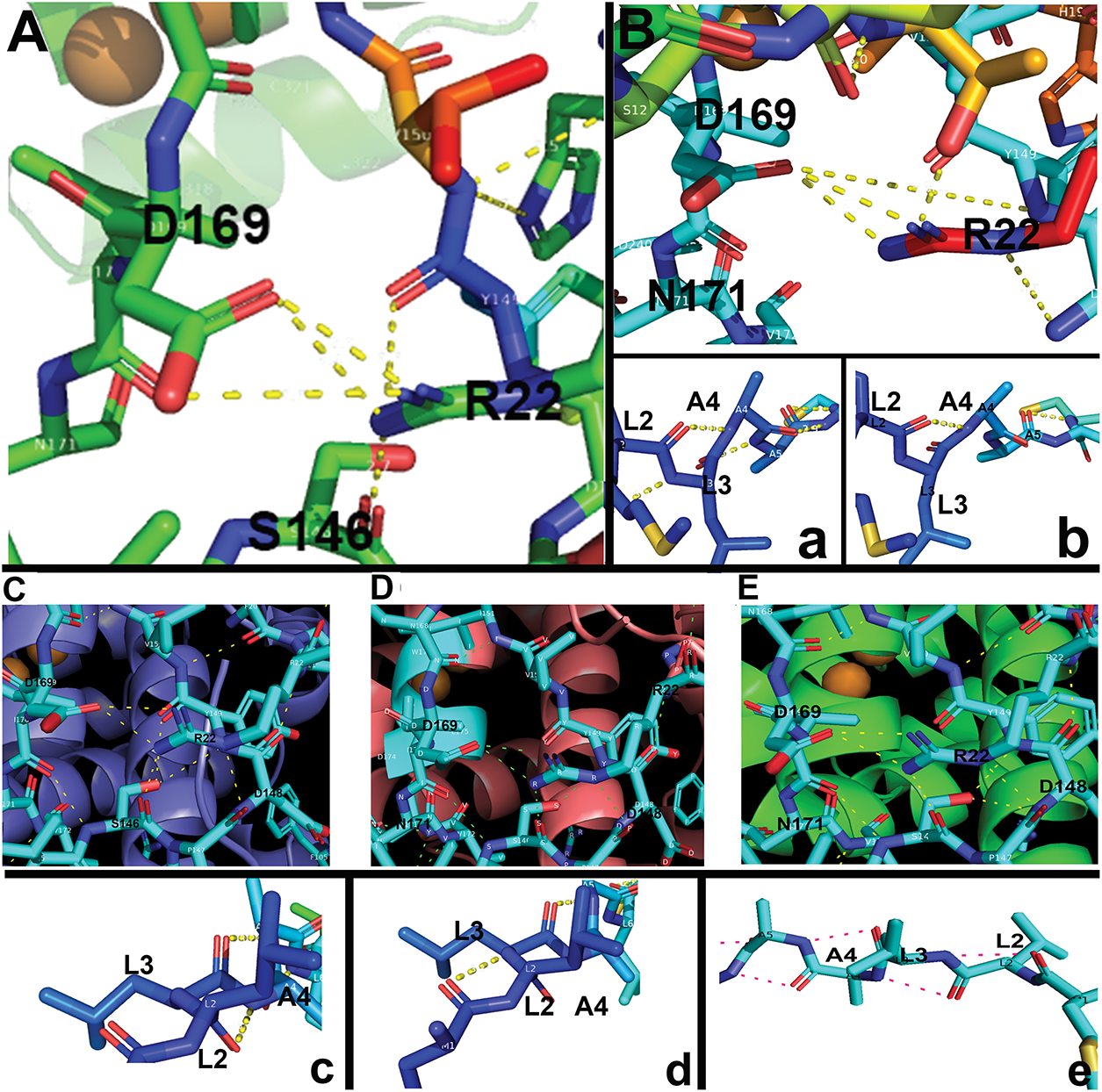

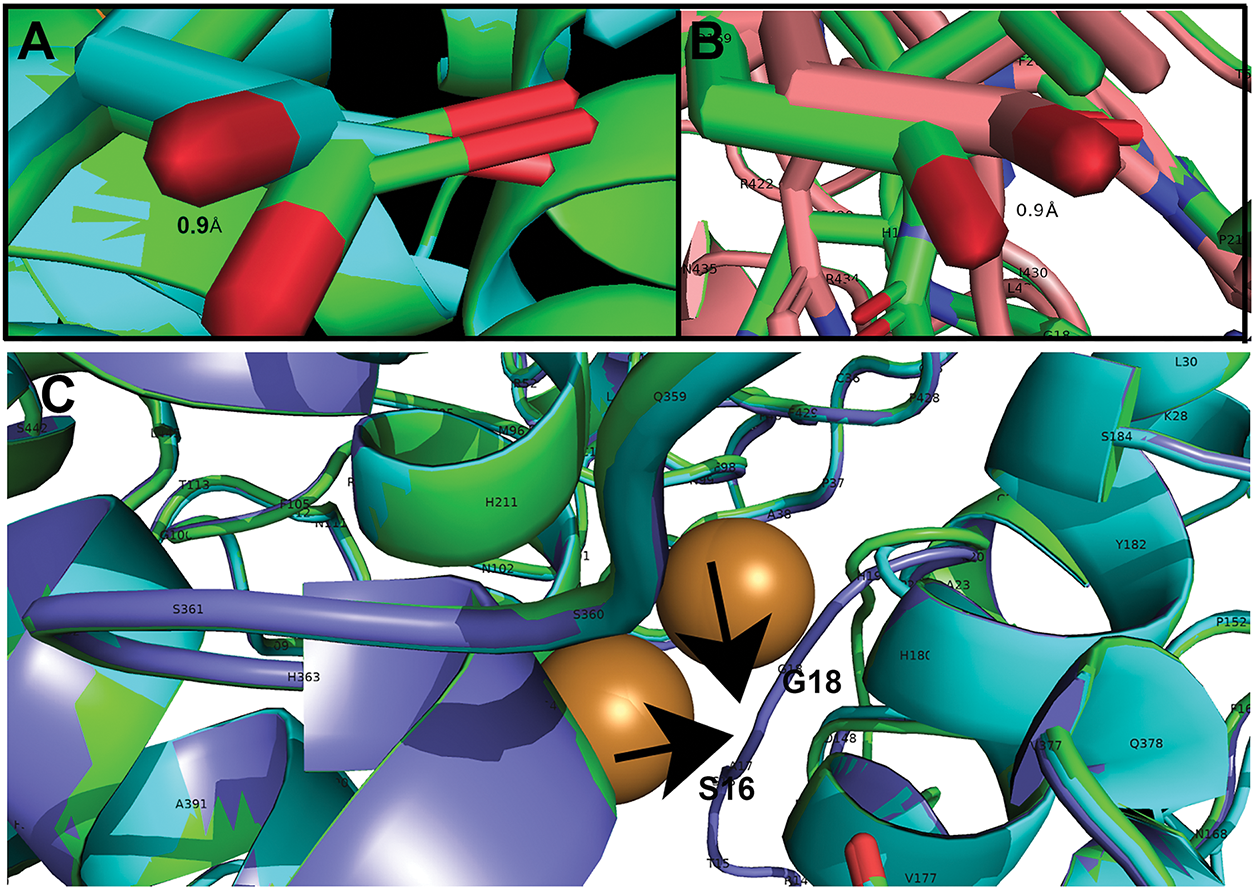

Fig. 4 graphically demonstrates the bonding patterns found by PyMol analysis. Fig. 4A–E centers on the critical R22-D169 bonding in the folded region for all groups. A small 0.9 Å rotational shift around D169 for Siamese G302R and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa (Fig. A2A,B) results in minor bonding differences. Overall, the stabilizing folded region for each SP’s proximity to the Cu2+ binding active site remains similar. Therefore, the displacement of the SP disordered domains occurs around F13 to S16. The outlier, Albino del401-529, still has the critical R22-D169 bonds, even though its SP-predicted localization varies widely from WT. The three prominent α-helices surrounding CuA and CuB are retained, so the folded SP domain appears intact, albeit from the polar opposite direction. Fig. 4A–E represents PyMol analysis of each N-terminal amino acid within the disordered SP in similar orientations. Burmese G227W and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa both have more bonds than WT in the most distal N-terminal regions, as noted in Table 4. Between M1-S12, Burmese G227W has six H-bonds, Mocha delI274-L312+2aa has five. While WT exhibits only 2. Since the Burmese breed is generally considered only a minor color-pointed phenotype, the stability gained from the increased H-bonding in the disordered domain may provide additional platforms for SRP and Sec61 proper insertion into the ER membrane, despite the displacement locally during translation. The Burmese and Mocha cats still generate melanin through a tyrosinase-based mechanism to varying degrees, unlike the Albino del401-529 cats, who are amelanotic.

Figure 4: Critical H-bonding patterns between WT and mutant tyrosinases. (A) WT R22 and D169 H-bonds (a) WT L2-A5 H-bonds. (B) Siamese G302R R22 and D169 H-bonds (b) Siamese G302R L2-A5 H-bonds. (C) Burmese G227W R22 and D169 H-bonds (c) Burmese G227W L2-A5 H-bonds. (D) Mocha delI274-L312+2aa R22 and D169 H-bonds (d) Mocha delI274-L312+2aa M1-A5 H-bonds. (E) Albino del401-529 R22 and D169 H-bonds (e) Albino del401-529 M1-A4 H-bonds

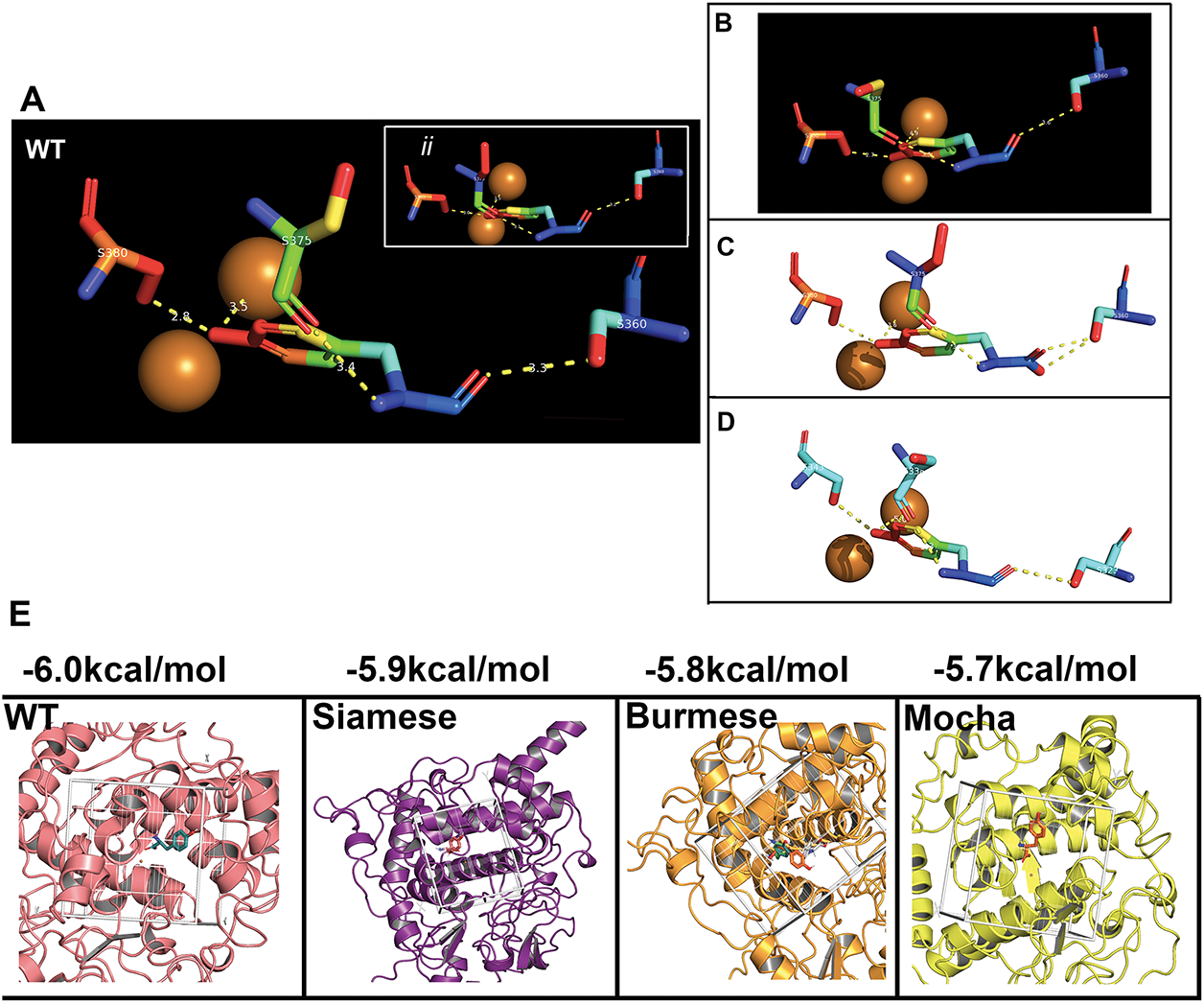

3.5 Using L-Tyrosine (Y) as a Docking Substrate in AlphaFold3 Uncovers Potential H-Bonding Changes in Substrate Binding within the Enzyme Active Site (AA 119-409)

WT and Siamese G302R tyrosinase both produce black melanin, indicating the enzyme is still functional and capable of oxidizing substrates, albeit temperature dependent for the Siamese phenotype. In the extreme example, the Albino del401-529 modeled results all-white cats with pink noses and pads and blue eyes, indicating a tyrosinase-null phenotype. Burmese G227W and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa tyrosinase produce medium to light sable coats, with only limited degrees of temperature dependence. Coat coloration is complex in domestic cats, with dominance, co-dominance, and recessive genes in play [45]. The goal of this study is to understand the potential for misfolding of the tyrosinase enzyme as the basis for aberrant melanin generation, and not to delve into complex breeding. Our results and conclusions do not reflect the effects of multiple gene mutations, hetero- or homozygous alleles, or mixed lineages in real-world felines.

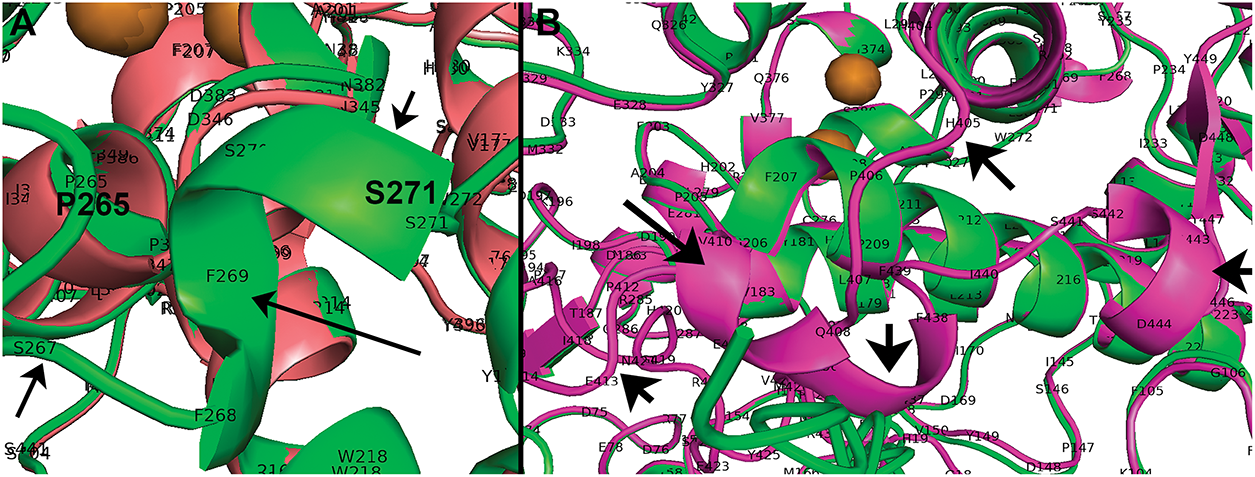

In Fig. 5, we have analyzed H-bonding details of the catalytic active site at the protein level and found only minimal changes when Y is docked in AlphaFold3. Mocha delI274-L312+2aa phenotype appears to be the most affected, in line with the resultant lighter coat variant. Insights from Fig. 2A demonstrating less structural confidence in the loop preceding the large deletion suggest binding of substrates in the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa active site may be weaker through interactions with the histidine residues of CuB. Using PyMol measurements, we have uncovered differences in spatial relationships with some mutant feline tyrosinases and the critical Cu2+ cations. WT, Siamese G320R, Burmese G227W, and Albino del401-529 have a calculated inter-Cu2+ ion (CuA to CuB) spacing of 4.1 Å. Within Mocha delI274-L312+2aa, this spacing is decreased to 3.9 Å (data not shown). Within the active site pocket, all other phenotypes had D356 looping near the H180 region Cu2+, while Mocha delI274-L312+2aa D319 is in a similar region (Fig. 3C,iv). WT and Siamese G302R had measured the spatial distance between the H180 region CuA and D356 of 19.3 Å. For Burmese G227W and Albino del401-529, the distance increased to 19.4 Å. The distance between the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa D319 and H180 region Cu2+ was increased to 19.6 Å. Mocha delI274-L312+2aa was further missing a short α-helix segment near the catalytic site represented by WT P265-S271 (Fig. A3A).

Figure 5: L-Tyrosine docking in the feline tyrosinase active site. (A) WT bonding to critical residues of S360, S375, and S380 with H-bonding to CuB, inset (ii) shows the same pattern for the Albino deletion as expected. Note; ii is a symbolic designation, not sequential for easier identification within the image. (B,C) Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W. (D) Mocha del +2aa bonding with synonymous Serine residues bonded, but folding of the model reflects different amino acid numbering; S323, S338, and S343. (E). Results of the Docking Affinity measurements for Wild type, Siamese G302R, Burmese G2227W and Mocha del+2aa. Boxed areas represent the ligand binding site for each tyrosinase, and the measured average of three simulations is above

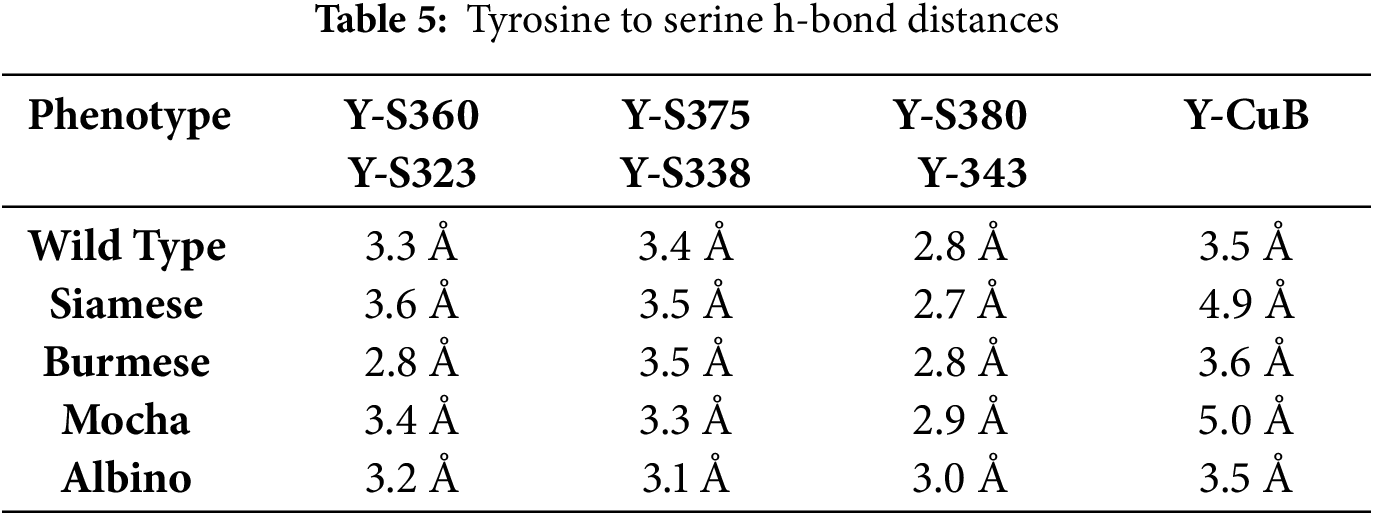

From the analysis, there are three critical residues that H-bond with Y; all serine(s), S360, S375, and S380. For the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa, the corresponding serine(s) are S323, S338, and S343. Table 5 lists all the calculated distances for the feline tyrosinase Y interactions within the putative active site. Fig. 5A (WT) and inset ii (Albino del) [Note; ii is a symbolic designation, not sequential for easier identification within each image] have nearly identical H-bonding and spacing to the Y substrate, which would be expected as the deletion only affects the cytoplasmic domain, leaving the catalytic site intact (Fig. A3B showing the missing regions). Both the Siamese G302R (Fig. 5B) and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa (Fig. 5D) deviate from WT, particularly in terms of Y-CuB spacing, generating potentially weaker H-bonding, which could partially explain the temperature-sensitive nature of the enzyme in these phenotypes. The Burmese (Fig. 5C) Y-CuB H-bond is only slightly increased over WT. The critical H-bond from our analysis appears to be Y-S360 (Y-S323), the closest amino acid to the predicted H363 CuB-interacting amino acid. Lai et al. previously reported the same critical bonding to docked Y with human tyrosinase and a similar close relationship to CuB [9]. For the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa, weakening this specific bond even more with increasing temperature could reduce the oxidative capacity of tyrosinase and therefore decrease the generation of the downstream substrates.

Further analysis to delve deeper into the actual docking affinities of Y between the groups demonstrate the gradual loss of affinity (Fig. 5E). Both the Burmese G227W and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa display the greatest declines with Mocha delI274-L312+2aa deviating from WT −6.0 to −5.7 kcal/mol, indicating the increased distances measured from WT values are potentially destabilizing the catalytic site, leading to reduction in melanin generation overall.

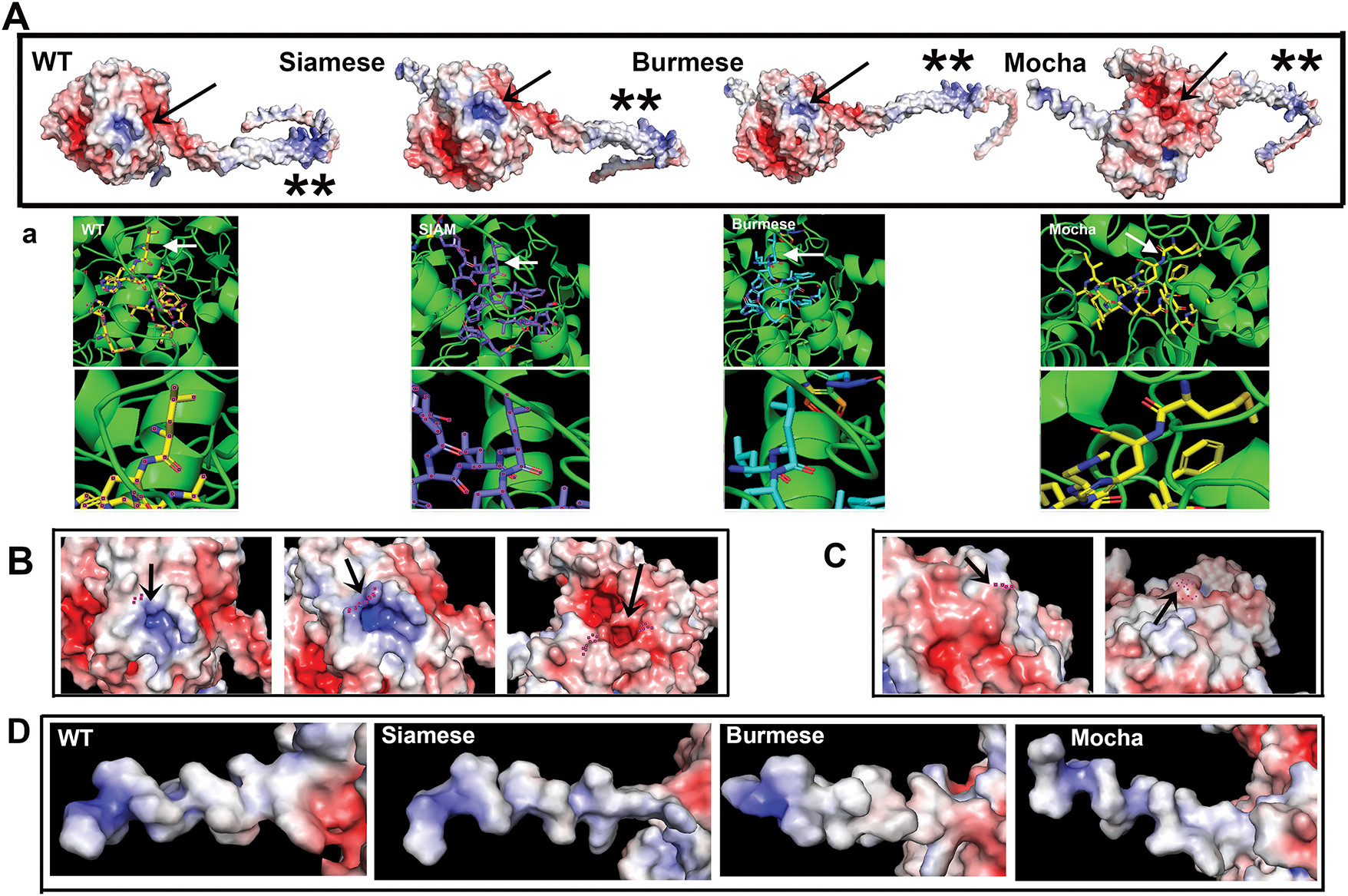

3.6 Electrostatic Analysis Reveals Changes in the Catalytic Site of Mocha Deli274-L312+2aa Compared to WT, Siamese G302R and Burmese G227W

To further look for potential changes induced by the point mutants or deletions of the protein, PyMol models were subjected to APBS electrostatic analysis. Areas of greatest interest were SP distal N-terminus amino acids, the catalytic site, and the proposed critical C-terminal oligomerizing amino acid C500 [46]. Fig. 6A panels display the full-length tyrosinases with the arrows delineating the active site pocket and asterisks indicating the cytoplasmic C-terminal tails. WT, Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W pockets are positively charged with neutral areas surrounding the region. Mocha delI274-L312+2aa pocket, on the other hand, is negatively charged and surrounded by negative charges. Images seen in Fig. 6B are higher magnification views with Siamese G302R (middle panel), G > R location marked with an arrow. To determine any residual effects from the Burmese G > W mutation, which is outside of the immediate active site pocket, WT and Burmese were compared in Fig. 6C. There is only a moderate reduction in negative charge within this region, supporting the hypothesis that the effects of the Burmese G227W mutation are modest, resulting in reasonable generation of melanin.

Figure 6: Electrostatic analysis reveals a differential shift in active site charge for the Mocha deletion. (A) Representations of full-length feline tyrosinases centered on the active site (arrows) C-terminal tails to the right. The symbols ** show the similarity in charge for the C500 oligomerization region between all the tyrosinases, indicating all the presented mutants should be able to oligomerize. (a) Below each feline tyrosinase is the PyMol aligned active site amino acids, demonstrating that the electrostatic alignments are equivalent. (B) Arrows center on the active site. WT and Siamese (left and middle) have Siamese R302 and WT G302 marked, (right) Mocha with a Cu2+ H marking the active site for comparison, since AA 302 is deleted. (C) WT (left) and Burmese (right) with G > W marked (dots and arrows). (D) SP electrostatic charge distribution from initiating M (left) towards the folded region (right)

Two other aspects of tyrosinase electrostatic interactions may affect tyrosinase maturation and oligomerization [46,47]. C500 is implicated in homodimer formation for mouse tyrosinase, a requirement for full enzyme activity within a melanosome [46]. This residue is conserved between human, mouse, and feline proteins. Feline tyrosinase mutants all display a similar positive charge in the C500 region, concluding that each could still effectively oligomerize if proper folding within the ER is completed. Our analysis does not take physiological parameters, such as ER pH, oxidative ER, and aqueous ionic environments, into account. Albino del401-529, however, would be unable to oligomerize as it lacks the C500 amino acid entirely. Additionally, Albino del401-529 lacks the TM domain, making it unable to insert into the melanosome membrane if it were able to exit the ER.

The SP must interact with the Signal Recognition Particle (SRP) and Sec61 for the nascent peptide insertion into the ER membrane in the proper orientation [48–50]. This binding interaction relies heavily on positive electrostatic charges in the more distal amino acids of the SP. Fig. 6D highlights the charge distribution for WT, Siamese G302R, Burmese G227W, and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa on the SP. Interestingly, the Siamese G302R and Mocha delI274-L312+2aa appear the most similar, with alternating regions of neutrality and positive charges. As both mutants have the more obvious phenotypes, initial delays in association with SRP may initiate some level of translational dysfunction. WT and Burmese G227W are positively charged from AA 1 or 2, suggesting SRP can associate at the earliest phases of translation, resulting in increased generation of properly folded final proteins.

The major structural difference between all the analyzed feline mutant tyrosinases is the spatial displacement of the critical SP, suggesting that anchoring the SP in the appropriate orientation within the ER membrane plays a major role in the required tyrosinase SP cleavage. This early cleavage step is required for downstream glycosylation by oligosaccharide transferase (OST) and interaction with the folding chaperone binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP/GRP78) and the chaperone calnexin, allowing proper tyrosinase folding within the ER [32]. Even small spatial deviations can lead to misdirected translocation by Sec61 or anchoring orientation defects.

Sec61 is a multimer channel forming protein that nascent peptide chains need for transport to the ER membrane. Like SRP, the SP uses the positive charge and hydrophobic regions for the transient interaction with Sec61, but the positive charge needs to be positioned towards the cytoplasmic direction of the ER outer leaflet for this interaction to occur [51]. As H-bonding differences are apparent in the SP between WT and mutant feline tyrosinases, the changes in flexibility or rigidity introduced by these changes may further move the SP out of a favorable position, generating truncated or misfolded proteins leading to aggregation and enhanced ER degradation.

Previous studies have shown that the first bound chaperone BiP/GRP78 is able to associate with human mutant and albino tyrosinases, yet is also responsible for ER retention of the misfolded proteins, leading to accelerated degradation [52–54]. As BiP/GRP78 associates prior to SP cleavage, the ER retention, aggregation, and enhanced degradation reported for Siamese G302R in [29] are supported by the structural data presented. The role of signal peptides in protein misfolding is a recent and novel discovery. When the SP is deleted from human serum amyloid A (SSA1.1), an oligomeric hexamer rather than a tetramer occurs as the protein misfolds and stabilizes into pathogenic amyloid fibrils [55].

Our structural model for feline tyrosinase mutations does not extend to the wide variations seen in domestic or other fancy breed cats’ colorations. A sex-linked orange coloration, resulting from a 5kb deletion causing melanocytes to express ArhGap36, was recently published [56,57], demonstrating the complexity of feline coat colorations and patterns. Another study finds a 95 kb deletion near the c-KIT gene, resulting in a unique dark/white coloration termed salmiak [58]. Tabby variant genes were published in 2021 [59]. The Burmese breed has the widest variation in coloration. We modeled the originally described sable and the lighter variant mocha, which are known tyrosinase-based colorations. Similar to a described amber variant in Norwegian Forest cats [60] that is described as D84N transmembrane substitution within the Melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) gene, a reddish Burmese coat is determined by a 3 bp deletion and a F146 deletion from MC1R [61].

Because the Burmese breed exhibits a broad variation in coat colors, resulting from modification by downstream genes such as TYRP1/2 and MC1R [45], we suspected the two variants we modeled would have more limited changes from the WT structure. This appears to be the case in a sable-coated Burmese. The tyrosinase enzyme can hydroxylate Y to downstream substrates sufficiently to produce dark even colored cats. However, the Burmese Mocha structure is the most dramatically changed. Missing a large portion of the α-helix near the CuB region results in weakening of H-bonding around the active site and effectively pulls the distance between CuA and CuB apart by an additional 1.5 Å. The catalytic site appears compromised, resulting in a significantly lighter coat than the very dark typical Burmese, indicative of a reduction in overall melanin generation. With the exaggerated Mocha SP displacement and alternating SP electrostatic charges, a decrease in Y affinity docking, combined with greater Cu2+ ion distance and a highly negatively charged active site pocket, the conclusion that the Mocha delI274-L312+2aa phenotype is a combination of majority catalytic loss and more modest ER retention is evident.

Unlike our previous work on Siamese G302R mutant tyrosinase, there are no published studies using transfected fluorescently tagged mutants to track aggregation and degradation for Burmese G227W, Mocha delI274-L312+2aa, or the modeled Albino del401-529. As interest in mechanisms of human albinism (OCA) is high, a recent study using a similar cell biology methodology with eight Chinese patient TYR variants confirms biochemically that ER retention and enhanced degradation occur. However, traditional degradation processes through quality control were found only for mutations in the catalytic site. While non-traditional lysosomal-based degradation occurs for the mutations outside of the catalytic site [62]. As our variant mutations reside within the catalytic site, we should expect our mutants to follow this pattern. Yet, this is not apparently the case for all feline tyrosinase mutants. Another study using molecular dynamic simulations for two human point mutations, P406L and R402Q, suggests the possibility of catalytic inhibition due to flexibility within the catalytic subdomain [63]. Without all possible modes of analysis, structural, biochemical, and molecular dynamic simulations, our conclusions about catalytic dysfunction are assumptions, but fit with our current understanding from our data and human-based experiments.

The Albino del401-529 phenotype can be explained by the loss of the anchoring TM domain. If the protein is unable to insert into the melanosome membrane, the untethered intraluminal enzyme is unable to catalyze any substrate. This is less likely since a folded protein would need to exit the ER and pass through the Golgi prior to transport to a melanosome. Alternatively, the highly mislocated SP could prevent translation entirely by blocking SRP and or Sec16 from inserting the nascent chain into the ER membrane. Or lastly, the truncated peptide misfolds and is degraded. Western blot or RT-PCR data would be required to fully establish which mechanism or a mix of both is responsible for the null phenotype. Either way, our Albino model serves as a null-control for our analysis, with highly predictable mechanisms for total loss-of-function.

AlphaFold3 is limited in its predictive nature for single-point mutations and doesn’t take temperature variations into account during computational modeling. But given the lack of any published tyrosinase mammalian structure and the need to understand what role tyrosinase dysregulation could play in feline behavior, pigmentation diseases, and feline cognitive dysfunction syndrome (fCDS), AI-driven AlphaFold3 has provided key insights into feline tyrosinase dysfunction. One of our goals for this study was the determination of the temperature-sensitive mechanism for the Siamese mutant, assuming at least a partial part of the mechanism would be based on predictive secondary structure. Our structural data, however, supports a cell biology ER retention, aggregation, and degradation model rather than solely a protein structural mechanism for the Siamese temperature-sensitive loss-of-function. The Siamese color-pointing phenotype may partially be the result of weakened Cu2+ ion interactions within the active site pocket, but aggregation and degradation of the misfolded protein remain primary mechanisms for the observed color-pointing phenotype. At lower than typical Siamese temperatures, the kinetic energy from molecular motion is decreased, favoring slower folding with higher fidelity and fewer misfolded proteins generated. H-bonds and disulfide bridges form more easily, again favoring proper folding and allowing synthesis of more functional enzymes [64]. The result is increased generation of melanin. At normal body temperatures, the process speeds up with a resultant increase in misfolded and aggregated ER proteins that colocalize with calnexin, as we have previously published.

There has been a long-standing supposition that behavior and coat coloration have a tentative link in many animals [65–67] due to the neural crest embryonic origin of the CNS and melanocytes. Siamese cats, in particular, have known obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) behaviors [68,69]. OCD is typically associated with dysfunctional levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine and the dopaminergic system [70–72]. A key enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine is tyrosinase. Furthermore, tyrosinase dysregulation is associated with increased incidents of melanoma and neurodegeneration (ND) (reviewed by [2,73]). With the physiology of felines and humans closely aligned, cats have been underrepresented in scientific literature, grant funding, and disease modeling. As an example, fCDS bears very similar symptomology and neurodegenerative markers as human Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and PD [15,18,19,74–76]. A prime hypothesis in the early stages of development of these pathologies revolves around the notion that misfolded proteins, e.g., α-synuclein in PD, are the initial triggering events [77–79]. Aggregated misfolded tyrosinase is potentially a degenerative trigger in neurons within the substantia nigra [80].

Our reliance on strictly computational structures limits our final conclusions in terms of actual physiological results. Although we were able to previously express WT and Siamese G302R proteins in vivo in human cell lines [29], we were unable to express in vitro purified proteins. Having kinetic studies and molecular dynamic simulations in parallel would strengthen our conclusions that multiple mechanisms play distinct roles in color-pointing phenotypes.

In summary, using predictive computational modeling, we have described three mechanisms for four different physiological feline tyrosinase mutant phenotypes. (a) Burmese dark sable-colored cats have a functional tyrosinase enzyme. Tyrosinase misfolding is likely minimal. Coloration variants are determined by downstream pigment genes [45]; (b) Mocha Burmese delI274-L312+2aa phenotype is a result of likely but not conclusive enzyme dysfunction; tyrosinase misfolding and aggregation mechanisms may contribute to the reduced melanin generation in a temperature-sensitive manner; (c) Siamese color-pointing is a direct result of misfolded and aggregated tyrosinase leading to upregulation of Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) pathways and enhanced degradation (reviewed by [81]). The upregulation of these pathways is suspected in the etiology of many human ND [82,83]; (d) Albino del410-529 phenotype is activity-null, with either a truncated misfolded protein, lack of translation entirely, or loss of anchoring TM within a melanosome. Given the wide variation in Albino phenotypes, more detailed structural and biochemical comparisons are needed to understand the underlying tyrosinase dysfunction for this population of domestic cats.

Through our previous work and presented structural data, we propose that temperature-sensitive color-pointed breeds, such as Siamese, represent a unique and novel population of cats that can serve as model systems, especially for ND, based on the suggestion that misfolded tyrosinase can be an early triggering event. Color-pointed Siamese phenotypic cats, whether a fancy breed lineage or random mutation within a domestic cat litter, can be tracked through their lifecycle and early signalments of fCDS recognized. Any therapeutic interventions can be realized in nearly real-time to determine the efficacy, benefiting individual cats, their owners, and ultimately human patients.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to thank Dr. Tom Huxford for helpful conversations about the feasibility of this study, the early guidance for structural biochemistry, and support for Helen Fenske in his lab. Grace Chao, a current Ph.D. candidate, provided useful insights into applications possible in PyMol software and manuscript editing. Natalie Gude provided useful edits and comments to improve the overall analyses presented.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Ingrid R. Niesman; Data collection: Helen Fenske, Ingrid R. Niesman; Analysis and interpretation of results: Ingrid R. Niesman, Helen Fenske; Draft manuscript preparation: Ingrid R. Niesman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: AlphaFold 3 predictive models and subsequent.pse files are available at this link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/121O1qN67do5FVk_m7MrQsc_tj13eDFMT?usp=share_link (accessed on 30 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.071078/s1.

Appendix

Figure A1: Full molprobity analysis results from all feline tyrosinase mutants. (A) Summary statistics categories; Protein Geometry, Peptide Omegas, Low-resolution Criteria and Additional Validation. Far right column are the target goals for each category. (B) Additional MolProbity Ramachandran plots not included in Fig. 2

Figure A2: Essential differences in structure from WT feline tyrosinase. (A) Siamese (aqua) D169 deviation from WT (green) leading to loss of 1 H-bond to R22. (B) Mocha (pink) D169 deviation leading to loss of 1 H-bond to R22. (C) Burmese (purple) signal peptide (SP) loop deviation from WT (green) between S16 and H19. Loop is pulled closer to CuA and CuB. Arrows point to the deviated loop of the Burmese G227W region

Figure A3: PyMol views of deleted segments for Mocha and Albino compared to WT feline tyrosinase. (A) WT (green) segment P265-S271 α-helix missing Mocha (pink). (B) Missing C-terminus of Albino (green) from H405-A416 WT (pink). Arrows point to areas of missing segments based on PyMol alignments

References

1. Dolinska MB, Sergeev YV. Molecular Modeling of the multiple-substrate activity of the human recombinant intra-melanosomal domain of tyrosinase and its OCA1B-related mutant variant P406L. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(6):3373. doi:10.3390/ijms25063373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jin W, Stehbens SJ, Barnard RT, Blaskovich MAT, Ziora ZM. Dysregulation of tyrosinase activity: a potential link between skin disorders and neurodegeneration. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2024;76(1):13–22. doi:10.1093/jpp/rgad107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Chang TS. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(6):2440–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Zolghadri S, Bahrami A, Hassan Khan MT, Munoz-Munoz J, Garcia-Molina F, Garcia-Canovas F, et al. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2019;34(1):279–309. doi:10.1080/14756366.2018.1545767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lai X, Wichers HJ, Soler-Lopez M, Dijkstra BW. Structure and Function of human tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related proteins. Chemistry. 2018;24(1):47–55. doi:10.1002/chem.201704410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Noh H, Lee SJ, Jo HJ, Choi HW, Hong S, Kong KH. Histidine residues at the copper-binding site in human tyrosinase are essential for its catalytic activities. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2020;35(1):726–32. doi:10.1080/14756366.2020.1740691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Branza-Nichita N, Negroiu G, Petrescu AJ, Garman EF, Platt FM, Wormald MR, et al. Mutations at critical N-glycosylation sites reduce tyrosinase activity by altering folding and quality control. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(11):8169–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.11.8169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ujvari A, Aron R, Eisenhaure T, Cheng E, Parag HA, Smicun Y, et al. Translation rate of human tyrosinase determines its N-linked glycosylation level. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(8):5924–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.m009203200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lai X, Soler-Lopez M, Wichers HJ, Dijkstra BW. Large-scale recombinant expression and purification of human tyrosinase suitable for structural studies. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161697. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Toay S, Sheri N, MacDonald I, Sergeev YV. Human recombinant tyrosinase destabilization caused by the double mutation R217Q/R402Q. Protein Sci. 2025;34(2):e70029. doi:10.1002/pro.70029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Branza-Nichita N, Petrescu AJ, Dwek RA, Wormald MR, Platt FM, Petrescu SM. Tyrosinase folding and copper loading in vivo: a crucial role for calnexin and alpha-glucosidase II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261(3):720–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Giebel LB, Tripathi RK, King RA, Spritz RA. A tyrosinase gene missense mutation in temperature-sensitive type I oculocutaneous albinism. A human homologue to the Siamese cat and the Himalayan mouse. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(3):1119–22. doi:10.1172/jci115075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tripathi RK, Giebel LB, Strunk KM, Spritz RA. A polymorphism of the human tyrosinase gene is associated with temperature-sensitive enzymatic activity. Gene Expr. 1991;1(2):103–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. King RA, Townsend D, Oetting W, Summers CG, Olds DP, White JG, et al. Temperature-sensitive tyrosinase associated with peripheral pigmentation in oculocutaneous albinism. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(3):1046–53. doi:10.1172/jci115064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sordo L, Gunn-Moore DA. Cognitive dysfunction in cats: update on neuropathological and behavioural changes plus clinical management. Vet Rec. 2021;188(1):e3. doi:10.1002/vetr.3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Cerna P, Gardiner H, Sordo L, Tornqvist-Johnsen C, Gunn-Moore DA. Potential causes of increased vocalisation in elderly cats with cognitive dysfunction syndrome as assessed by their owners. Animals. 2020;10(6):1092. doi:10.3390/ani10061092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Gunn-Moore DA. Cognitive dysfunction in cats: clinical assessment and management. Top Companion Anim Med. 2011;26(1):17–24. doi:10.1053/j.tcam.2011.01.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gunn-Moore D, Moffat K, Christie LA, Head E. Cognitive dysfunction and the neurobiology of ageing in cats. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48(10):546–53. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2007.00386.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Chambers JK, Tokuda T, Uchida K, Ishii R, Tatebe H, Takahashi E, et al. The domestic cat as a natural animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3(1):78. doi:10.1186/s40478-015-0258-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ascsillan AA, Kemeny LV. The skin-brain axis: from UV and pigmentation to behaviour modulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(11):6199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Lyons LA, Imes DL, Rah HC, Grahn RA. Tyrosinase mutations associated with Siamese and Burmese patterns in the domestic cat (Felis catus). Anim Genet. 2005;36(2):119–26. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01253.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Yu Y, Grahn RA, Lyons LA. Mocha tyrosinase variant: a new flavour of cat coat coloration. Anim Genet. 2019;50(2):182–6. doi:10.1111/age.12765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Imes DL, Geary LA, Grahn RA, Lyons LA. Albinism in the domestic cat (Felis catus) is associated with a tyrosinase (TYR) mutation. Anim Genet. 2006;37(2):175–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01409.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Abitbol M, Bosse P, Grimard B, Martignat L, Tiret L. Allelic heterogeneity of albinism in the domestic cat. Anim Genet. 2017;48(1):127–8. doi:10.1111/age.12503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Berson JF, Frank DW, Calvo PA, Bieler BM, Marks MS. A common temperature-sensitive allelic form of human tyrosinase is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum at the nonpermissive temperature. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(16):12281–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.16.12281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Svedine S, Wang T, Halaban R, Hebert DN. Carbohydrates act as sorting determinants in ER-associated degradation of tyrosinase. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 14):2937–49. doi:10.1242/jcs.01154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Halaban R, Svedine S, Cheng E, Smicun Y, Aron R, Hebert DN. Endoplasmic reticulum retention is a common defect associated with tyrosinase-negative albinism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(11):5889–94. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.11.5889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Halaban R, Cheng E, Zhang Y, Moellmann G, Hanlon D, Michalak M, et al. Aberrant retention of tyrosinase in the endoplasmic reticulum mediates accelerated degradation of the enzyme and contributes to the dedifferentiated phenotype of amelanotic melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(12):6210–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.12.6210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Niesman IR. Siamese cat tyrosinase has enhanced proteasome degradation and increased cellular aggregation. Int J Psych Behav Anal. 2022;8:184. doi:10.1101/2020.06.03.132613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Halaban R, Moellmann G, Tamura A, Kwon BS, Kuklinska E, Pomerantz SH, et al. Tyrosinases of murine melanocytes with mutations at the albino locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(19):7241–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.19.7241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Halaban R, Cheng E, Svedine S, Aron R, Hebert DN. Proper folding and endoplasmic reticulum to golgi transport of tyrosinase are induced by its substrates, DOPA and tyrosine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):11933–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.m008703200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang N, Hebert DN. Tyrosinase maturation through the mammalian secretory pathway: bringing color to life. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19(1):3–18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00288.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Bossio S, Perrotta ID, Lofaro D, La Russa D, Rago V, Bonofiglio R, et al. The Missense variant in the signal peptide of alpha-GLA gene, c.13 A/G, promotes endoplasmic reticular stress and the related pathway’s activation. Genes. 2024;15(7):947. doi:10.3390/genes15070947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Crockett JC, Mellis DJ, Shennan KI, Duthie A, Greenhorn J, Wilkinson DI, et al. Signal peptide mutations in RANK prevent downstream activation of NF-kappaB. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(8):1926–38. doi:10.1002/jbmr.399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gao M, Chen L, Yang J, Dong S, Cao Q, Cui Z, et al. Multimodal mechanisms of pathogenic variants in the signal peptide of FIX leading to hemophilia B. Blood Adv. 2024;8(15):3893–905. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2023012432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Niesman IR. Stress and the domestic cat: have humans accidentally created an animal mimic of neurodegeneration? Front Neurol. 2024;15:1429184. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1429184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R, Green T, Pritzel A, et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. 2024;630(8016):493–500. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Gupta G, Sinha S, Mitra N, Surolia A. Probing into the role of conserved N-glycosylation sites in the tyrosinase glycoprotein family. Glycoconj J. 2009;26(6):691–5. doi:10.1007/s10719-008-9213-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Faure C, Min Ng Y, Belle C, Soler-Lopez M, Khettabi L, Saidi M, et al. Interactions of phenylalanine derivatives with human tyrosinase: lessons from experimental and theoretical studies. ChemBioChem. 2024;25(12):e202400235. doi:10.1002/cbic.202400235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Decker H, Tuczek F. The recent crystal structure of human tyrosinase related protein 1 (HsTYRP1) solves an old problem and poses a new one. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56(46):14352–4. doi:10.1002/anie.201708214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Young KLII, Kassouf C, Dolinska MB, Anderson DE, Sergeev YV. Human tyrosinase: temperature-dependent kinetics of oxidase activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):895. doi:10.3390/ijms21030895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Jackson IJ, Chambers DM, Budd PS, Johnson R. The tyrosinase-related protein-1 gene has a structure and promoter sequence very different from tyrosinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(14):3799–804. doi:10.1093/nar/19.14.3799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Patel M, Sergeev Y. Functional in silico analysis of human tyrosinase and OCA1 associated mutations. J Anal Pharm Res. 2020;9(3):81–9. doi:10.15406/japlr.2020.09.00356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Favre E, Daina A, Carrupt PA, Nurisso A. Modeling the met form of human tyrosinase: a refined and hydrated pocket for antagonist design. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2014;84(2):206–15. doi:10.1111/cbdd.12306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Schmidt-Kuntzel A, Eizirik E, O’Brien SJ, Menotti-Raymond M. Tyrosinase and tyrosinase related protein 1 alleles specify domestic cat coat color phenotypes of the albino and brown loci. J Hered. 2005;96(4):289–301. doi:10.1093/jhered/esi066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Francis E, Wang N, Parag H, Halaban R, Hebert DN. Tyrosinase maturation and oligomerization in the endoplasmic reticulum require a melanocyte-specific factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(28):25607–17. doi:10.1074/jbc.m303411200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Peterson JH, Woolhead CA, Bernstein HD. Basic amino acids in a distinct subset of signal peptides promote interaction with the signal recognition particle. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(46):46155–62. doi:10.1074/jbc.m309082200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Janda CY, Li J, Oubridge C, Hernandez H, Robinson CV, Nagai K. Recognition of a signal peptide by the signal recognition particle. Nature. 2010;465(7297):507–10. doi:10.1038/nature08870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Hainzl T, Sauer-Eriksson AE. Signal-sequence induced conformational changes in the signal recognition particle. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7163. doi:10.1038/ncomms8163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hainzl T, Huang S, Merilainen G, Brannstrom K, Sauer-Eriksson AE. Structural basis of signal-sequence recognition by the signal recognition particle. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(3):389–91. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Rehan S, Tranter D, Sharp PP, Craven GB, Lowe E, Anderl JL, et al. Signal peptide mimicry primes Sec61 for client-selective inhibition. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(9):1054–62. doi:10.1101/2022.07.03.498529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Popescu CI, Paduraru C, Dwek RA, Petrescu SM. Soluble tyrosinase is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation substrate retained in the ER by calreticulin and BiP/GRP78 and not calnexin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):13833–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.m413087200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Toyofuku K, Wada I, Valencia JC, Kushimoto T, Ferrans VJ, Hearing VJ. Oculocutaneous albinism types 1 and 3 are ER retention diseases: mutation of tyrosinase or Tyrp1 can affect the processing of both mutant and wild-type proteins. FASEB J. 2001;15(12):2149–61. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0216com. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Pobre KFR, Poet GJ, Hendershot LM. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone BiP is a master regulator of ER functions: getting by with a little help from ERdj friends. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(6):2098–108. doi:10.1074/jbc.rev118.002804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wu JL, Chen YR. Signal peptide stabilizes folding and inhibits misfolding of serum amyloid A. Protein Sci. 2022;31(12):e4485. doi:10.1002/pro.4485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Kaelin CB, McGowan KA, Trotman JC, Koroma DC, David VA, Menotti-Raymond M, et al. Molecular and genetic characterization of sex-linked orange coat color in the domestic cat. Curr Biol. 2025;35(12):2826–36e5. doi:10.1101/2024.11.21.624608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Toh H, Au Yeung WK, Unoki M, Matsumoto Y, Miki Y, Matsumura Y, et al. A deletion at the X-linked ARHGAP36 gene locus is associated with the orange coloration of tortoiseshell and calico cats. Curr Biol. 2025;35(12):2816–25. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2025.03.075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Anderson H, Salonen M, Toivola S, Blades M, Lyons LA, Forman OP, et al. A new Finnish flavor of feline coat coloration, salmiak, is associated with a 95-kb deletion downstream of the KIT gene. Anim Genet. 2024;55(4):676–80. doi:10.1111/age.13438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lyons LA, Buckley RM, Harvey RJ. the 99 Lives Cat Genome Consortium. Mining the 99 lives cat genome sequencing consortium database implicates genes and variants for the ticked locus in domestic cats (Felis catus). Anim Genet. 2021;52(3):321–32. doi:10.1111/age.13059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Peterschmitt M, Grain F, Arnaud B, Deleage G, Lambert V. Mutation in the melanocortin 1 receptor is associated with amber colour in the Norwegian Forest Cat. Anim Genet. 2009;40(4):547–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01864.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Gustafson NA, Gandolfi B, Lyons LA. Not another type of potato: mC1R and the russet coloration of Burmese cats. Anim Genet. 2017;48(1):116–20. doi:10.1111/age.12505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Wang X, Liu K, Meng Y, Chen J, Zhong Z. The degradation of TYR variants derived from Chinese OCA families is mediated by the ERAD and ERLAD pathway. Gene. 2025;932:148907. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2024.148907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Woods T, Sergeev YV. Evaluating the cysteine-rich and catalytic subdomains of human tyrosinase and OCA1-related mutants using 1 mus molecular dynamics simulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(17):13032. doi:10.3390/ijms241713032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Rosa M, Roberts CJ, Rodrigues MA. Connecting high-temperature and low-temperature protein stability and aggregation. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176748. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0176748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Buggia LB. Questions about coat color and aggression in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;239(10):1289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

66. Stelow EA, Bain MJ, Kass PH. The relationship between coat color and aggressive behaviors in the domestic cat. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2016;19(1):1–15. doi:10.1080/10888705.2015.1081820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Reissmann M, Ludwig A. Pleiotropic effects of coat colour-associated mutations in humans, mice and other mammals. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013;24(6–7):576–86. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.03.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Knight RW. Predisposition of Siamese cats to eat woollen articles. Vet Rec. 1967;81(24):641–2. doi:10.1136/vr.81.24.641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Bamberger M, Houpt KA. Signalment factors, comorbidity, and trends in behavior diagnoses in cats: 736 cases (1991–2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;229(10):1602–6. doi:10.2460/javma.229.10.1602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Dong MX, Chen GH, Hu L. Dopaminergic system alteration in anxiety and compulsive disorders: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:608520. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.608520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Escobar AP, Martinez-Pinto J, Silva-Olivares F, Sotomayor-Zarate R, Moya PR. Altered grooming syntax and amphetamine-induced dopamine release in EAAT3 overexpressing mice. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:661478. doi:10.3389/fncel.2021.661478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Vellucci L, Ciccarelli M, Buonaguro EF, Fornaro M, D’Urso G, De Simone G, et al. The neurobiological underpinnings of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in psychosis, translational issues for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Biomolecules. 2023;13(8):1220. doi:10.3390/biom13081220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Krainc T, Monje MHG, Kinsinger M, Bustos BI, Lubbe SJ. Melanin and neuromelanin: linking skin pigmentation and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2023;38(2):185–95. doi:10.1002/mds.29260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Sordo L, Martini AC, Houston EF, Head E, Gunn-Moore D. Neuropathology of aging in cats and its similarities to human Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging. 2021;2:684607. doi:10.3389/fragi.2021.684607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Poncelet L, Ando K, Vergara C, Mansour S, Suain V, Yilmaz Z, et al. A 4R tauopathy develops without amyloid deposits in aged cat brains. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;81:200–12. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.05.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Vidal-Palencia L, Font C, Rebollada-Merino A, Santpere G, Andres-Benito P, Ferrer I, et al. Primary feline tauopathy: clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and genetic studies. Animals. 2023;13(18):2985. doi:10.3390/ani13182985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Colla E. Linking the endoplasmic reticulum to Parkinson’s disease and alpha-synucleinopathy. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:560. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Yadav K, Yadav A, Vashistha P, Pandey VP, Dwivedi UN. Protein misfolding diseases and therapeutic approaches. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2019;20(12):1226–45. doi:10.2174/1389203720666190610092840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Miraglia F, Betti L, Palego L, Giannaccini G. Parkinson’s disease and alpha-synucleinopathies: from arising pathways to therapeutic challenge. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2015;15(2):109–16. doi:10.2174/1871524915666150421114338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Carballo-Carbajal I, Laguna A, Romero-Gimenez J, Cuadros T, Bove J, Martinez-Vicente M, et al. Brain tyrosinase overexpression implicates age-dependent neuromelanin production in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):973. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08858-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Almanza A, Carlesso A, Chintha C, Creedican S, Doultsinos D, Leuzzi B, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling—from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J. 2019;286(2):241–78. doi:10.1111/febs.14608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Moreno JA, Halliday M, Molloy C, Radford H, Verity N, Axten JM, et al. Oral treatment targeting the unfolded protein response prevents neurodegeneration and clinical disease in prion-infected mice. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(206):206ra138. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3006767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Muneer A, Shamsher Khan RM. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Chonnam Med J. 2019;55(1):8–19. doi:10.4068/cmj.2019.55.1.8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools