Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

High Expression of KRT6A in Cervical Cancer and Its Promoting Effects on Cell Proliferation and Invasion

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225001, China

2 Department of Clinical Medicine, Yangzhou University Medical College, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225009, China

3 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Non-Coding RNA Basic and Clinical Transformation, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225009, China

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yixing Hospital of Chinese Traditional Medicine Affiliated to Yangzhou University Medical College, Yangzhou University, Yixing, 214200, China

5 Department of Pathology, Yixing People’s Hospital, Yixing, 214200, China

* Corresponding Authors: Linqian Shi. Email: ; Qian Gao. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2399-2413. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071255

Received 03 August 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Keratin 6A (KRT6A) has been implicated in the progression of multiple malignancies; however, its expression pattern and biological role in cervical cancer (CC) have not been elucidated. This study aims to investigate KRT6A expression in CC tissues and evaluate its effects on cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion, thereby assessing its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target. Methods: Differentially expressed genes were screened from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset (GSE9750) using the thresholds |log2FC| > 2 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. Immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate KRT6A protein expression in tumor tissues. Stable KRT6A knockdown was established in CC cell lines to assess proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion in vitro. A nude-mouse xenograft model was used to evaluate tumor growth in vivo. Results: KRT6A expression was significantly increased in CC tissues relative to adjacent non-tumor tissues (p = 0.019). Patients with KRT6A-positive tumors had a significantly lower 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate than those with KRT6A-negative tumors (45.16% vs. 78.57%; p = 0.009). KRT6A was identified as an independent prognostic indicator for CC (p = 0.044). In vitro, KRT6A silencing significantly reduced colony formation, proliferation, migration, and invasion in SiHa and HeLa cells in comparison to controls (p < 0.05). In vivo, tumors in the KRT6A knockdown group were significantly smaller, with reduced expression of both KRT6A and Ki-67 in tumor tissues (p < 0.05). Conclusion: KRT6A is overexpressed in CC and associates with adverse clinicopathological features and poor PFS. Knockdown of KRT6A suppresses cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, indicating that KRT6A may represent a promising prognostic biomarker and potential target for treating CC.Keywords

Cervical cancer (CC) is a common female cancer and represents a major global health concern [1,2]. It accounts for about 6.5% of all cancers worldwide [3], with an estimated rate of 11.01 per 100,000 in China [4]. Long-term infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) has been recognized as primary to CC etiology [5]. Although national programs offering free HPV vaccination for adolescents and CC screening for women between the ages of 35 and 64 years in rural regions have been implemented in China, the incidence of CC continues to rise [6,7]. Advancements in screening technologies and therapeutic approaches have significantly improved the prognosis of patients diagnosed at early stages. For instance, a five-year disease-free survival rate exceeding 90% has been reported among patients with early-stage CC who underwent radical hysterectomy [8]. However, for patients diagnosed at advanced stages, reliable early warning biomarkers and effective targeted therapies remain lacking [9,10]. Therefore, further investigation into CC-related molecular pathways and the identification of novel biomarkers are required [11,12].

Keratins are expressed in epithelial cells, functioning primarily to maintain cellular structural integrity and continuity, and are commonly recognized as indicators of epithelial differentiation [13–15]. Recent studies have revealed that keratins may also act as regulatory elements involved in apical-basal polarity, protein synthesis, motility, membrane trafficking, and signal transduction [16–18]. Emerging evidence suggests that Keratin 6A (KRT6A), a keratin family member [19–21], is involved in the pathogenesis of several types of malignancies by acting as a functional regulator [22]. Nevertheless, its expression profile and biological function in CC remain inadequately characterized.

In this study, KRT6A was investigated to elucidate its potential role in CC progression, to provide theoretical support for its application in early diagnosis, prognostic evaluation, and targeted therapy development.

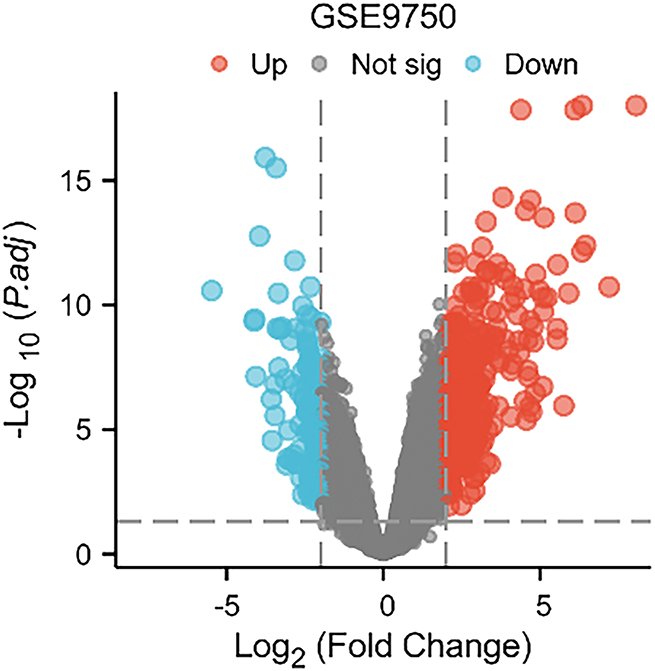

The transcriptomic data of CC tissues were retrieved from the GSE9750 dataset in the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accessed on 20 October 2025). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in CC tissues were identified. The criteria for DEGs expression screening were set as an absolute fold change (|log2FC|) > 2 and an adjusted p-value (false discovery rate, FDR) < 0.05.

2.2 Clinical Sample Collection

The tissue array containing a total of 45 pairs of CC samples and adjacent non-tumor tissues with follow-up data was obtained from Shanghai Yingbeilan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (No. YP-FDU961, Shanghai, China).

2.3 Immunohistochemical (IHC) Analysis

Sections of paraffin-embedded CC tissues were first deparaffinized in 100% xylene and rehydrated in an ethanol gradient. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by immersion in 3% H2O2 for 10 min. Slides were then rinsed and subjected to antigen retrieval by boiling in citrate buffer using a microwave at medium power for 3 min, followed by cooling to room temperature (RT). After discarding the buffer, the sections were incubated with blocking serum (5% bovine serum albumin (BSA); Beyotime, Shanghai, China; Cat. No. ST023). The blocking solution was blotted off, and the slides were incubated with anti-KRT6A antibodies (1:100, A19827, Abclonal, Wuhan, China) at 4°C for 24 h. After washing, the slides were incubated with streptavidin-bound horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibody (1:200, N3453, Shanghai Shangbao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at RT for 2 h. Chromogenic development was carried out using DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine, 1:50; T15132, Shanghai Shangbao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), followed by hematoxylin (C0105S, Beyotime Biotech, Beijing, China) counterstaining. Stained slides were examined under a light microscope (CK40; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) to evaluate immunoreactivity.

2.4 Cell Recovery and Subculture

Frozen human immortalized cervical squamous epithelial cells (Ect1/E6E7) and CC cell lines (CaSki, HeLa, SiHa, and C33A) were retrieved and thawed. All cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination using PCR-based assays, and no contamination was detected during the study. After complete thawing, cells were centrifuged (100× g for 3 min). After discarding the cryopreservation medium, 1 × 105 cells/mL were grown in culture dishes containing 7 mL of complete DMEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat. No. 11965092) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6 h, followed by washing with PBS and continued growth in fresh medium. When 90% confluent, cells were passaged by washing with PBS, digestion with trypsin (1 mL, 1 min), neutralization with 3 mL complete medium, and centrifugation at 100× g for 3 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 3 mL of fresh medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat. No. 11965092), transferred to a new dish, and supplemented with 5 mL of complete medium for further incubation.

A lentiviral vector encoding a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting KRT6A was constructed by BGI Genomics. The sequence for KRT6A-specific shRNA (shRNA-KRT6A-1) was 5′-CCA GCAGGAAGAGCUAUA-3′, and the control shRNA sequence (Control-shRNA) was 5′-CCTA AGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCGCTC-3′. After the optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI) was determined via a preliminary lentiviral transduction assay, lentiviral particles for both shRNA-KRT6A-1 and shRNA-Control were thawed at RT. SiHa and HeLa cells with approximately 50% confluency were counted, and virus solutions were prepared using complete culture medium (DMEM high glucose; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat. No. 11965092) to achieve an MOI of 30. The cells were washed twice with sterile PBS and treated with the virus-containing medium for 72 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. During infection, green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was monitored every 12 h using a fluorescence microscope (CKX53; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). When GFP-positive cells exceeded 80% of the population, the medium was removed, and fresh medium was added for 72 h. Cells were then subcultured in the same puromycin-containing medium (2 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat. No. P8833) for two weeks. After selection, morphologically healthy cells were harvested. The efficiency of KRT6A knockdown was confirmed by Quantitative Real-time Polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blotting. Successfully transfected cells were cryopreserved and labeled as shRNA-KRT6A-SiHa, shRNA-Control-SiHa, shRNA-KRT6A-HeLa, and shRNA-Control-HeLa, respectively.

Total RNA was isolated from CC cells or tumor tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NDULTRAGL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a first-strand synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat. No. K1622) and amplified using qRT-PCR with SYBR Green, with GAPDH as the endogenous reference.

The primer sequences were: KRT6A F: 5′-AGGACCTGGTGGAGGACTTC-3′; KRT6A R: 5′-C TGGGACAGCTCTGCATCAT-3′; GAPDH F: 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′; GAPDH R: 5′-GAA GATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′.

PCR reaction mixture (25 μL) included: 2× GoTaq Green Master Mix (12.5 μL), forward primer (10 μM; 0.5 μL), reverse primer (10 μM; 0.5 μL), nuclease-free water (11 μL), and cDNA template (0.5 μL). The thermal cycling conditions were: 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 50 s, 57°C for 50 s, and 72°C for 80 s. The calculation of the relative expression levels was carried out while employing the method of the 2−ΔΔCt.

Protein extraction from CC tissues and cultured cell lines was performed using lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche), followed by incubation on ice for 20 min. 80 μg of total protein was extracted and separated via SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked using 5% BSA (Cat. No. ST023, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and treated with anti-KRT6A antibodies (1:800, A19827, Abclonal, Wuhan, China) and GAPDH (1:1000, AC002, Abclonal, Wuhan, China) overnight at 4°C, followed by washing and treatment with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000, N3453, Shanghai Shangbao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at RT for 2 h. Signal detection was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (ChemiDoc™ XRS+, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). All the western blotting shown in the present study was based on independent experiments and not on technical repeats.

2.8 Cell Proliferation Assay (CCK-8)

shRNA-KRT6A-SiHa, shRNA-Control-SiHa, shRNA-KRT6A-HeLa, and shRNA-Control-HeLa cells were inoculated in 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) followed by their incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. At 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (Cat. No. KTC011001, Amyjet, Wuhan, China) was introduced to individual wells for 30 min. Absorbances at 450 nm were read using a microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Each time point included six replicate wells.

2.9 Colony Formation Assay (CFA)

Cells (1 × 104/well) from each group were plated in 6-well plates and cultured overnight. When colonies > 50 cells were visible under a microscope (CKX53; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), the medium was discarded, and 500 μL of 6% paraformaldehyde was added to each well for fixation at RT overnight. The wells were then rinsed with running water for 10 min and stained with 1% crystal violet (CV; 200 μL/well) for 30 min in the dark. Colonies were counted after washing and drying.

2.10 Wound Healing Assay (WHA)

shRNA-KRT6A-SiHa, shRNA-Control-SiHa, shRNA-KRT6A-HeLa, and shRNA-Control-HeLa cells (2 × 105/well) were inoculated in 12-well plates and grown overnight. When confluence reached over 90%, ten linear scratches were made in each well using a sterile pipette tip. The width of the wound was recorded under a microscope. After 24 h of incubation, the wound area was imaged again, and the migration distance was measured using ImageJ software (version 1.53; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.11 Transwell Assay for Migration and Invasion

Matrigel (1 mg/mL; Cat. No. YT2388, ITTABIO, Beijing, China) was prepared and added to the upper chambers of Transwell inserts (500 μL per well), allowing it to solidify. The inserts were placed into 12-well plates, and 1 mL of complete medium was added to the lower chambers. Cells from each group (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded into the upper chambers and incubated for 48 h. After incubation, cells on the upper membrane surface were removed. The cells on the underside were fixed with 500 μL of 6% paraformaldehyde overnight at RT. After fixation, membranes were washed for 10 min under running water and air-dried. Cells were stained with 1% CV (200 μL/well) for 30 min in the dark, then washed and dried. Cell invasion and migration were quantified by counting stained cells under a microscope (CKX53; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and images were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.53; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

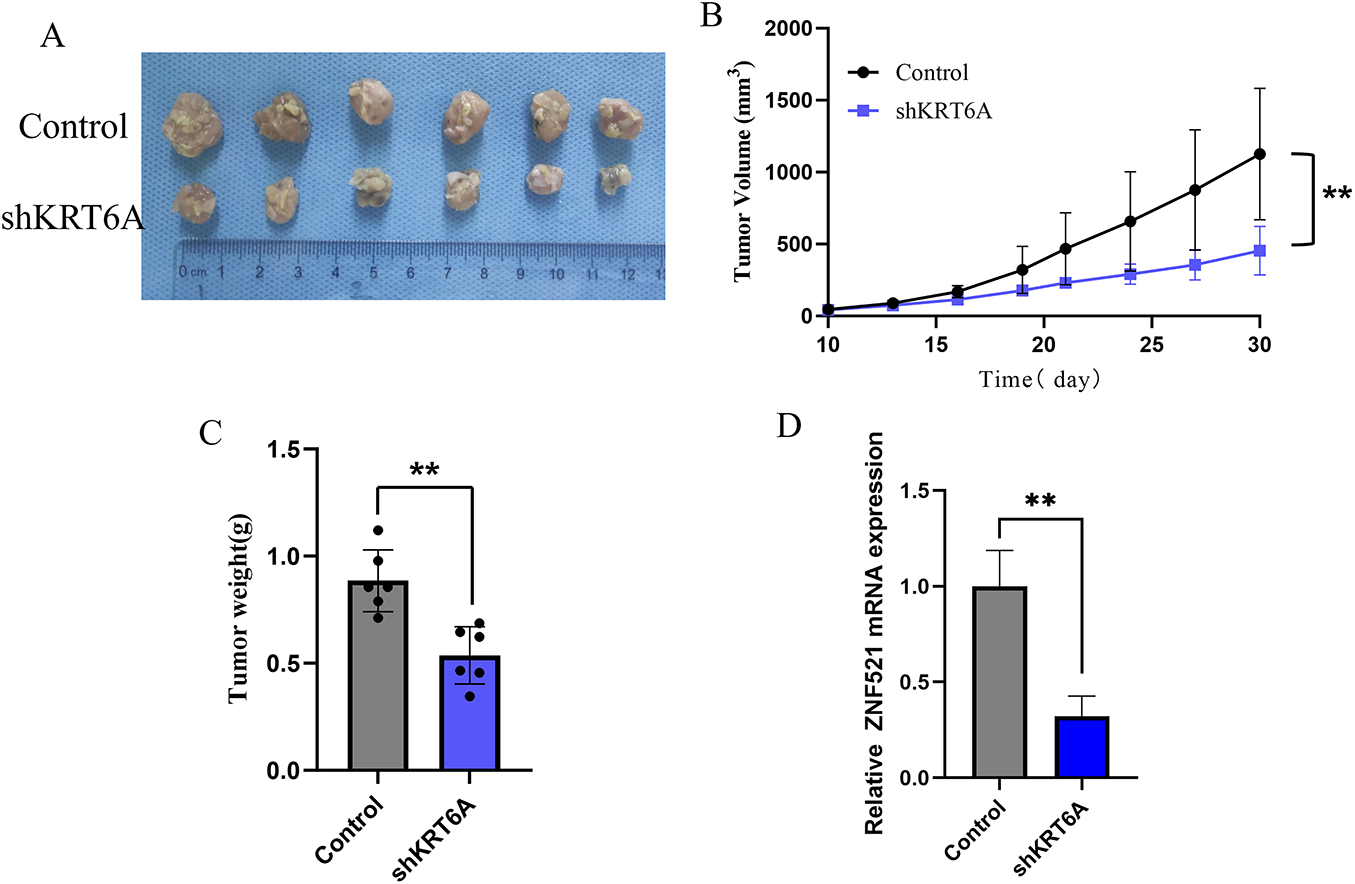

2.12 Xenograft Mouse Model and IHC

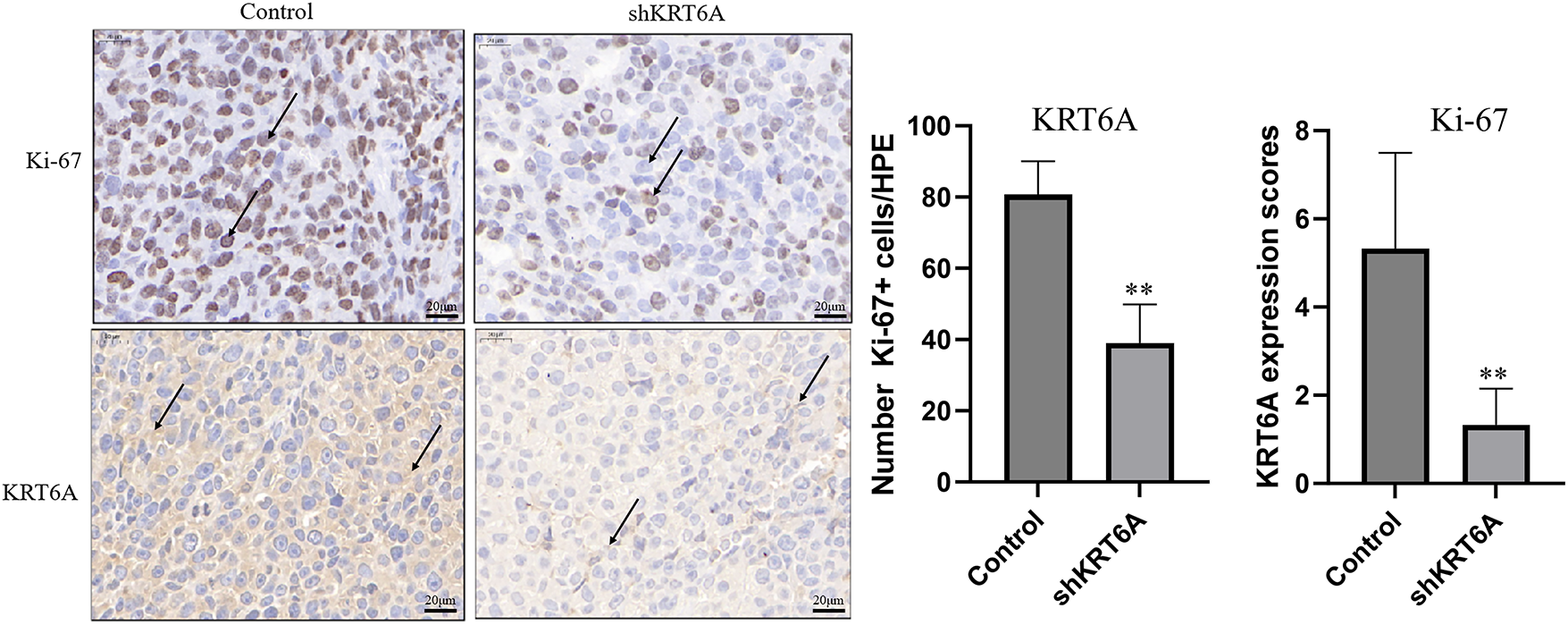

Twelve nude mice (BALB/c-nu/nu, 4–6 weeks old, 18–22 g) were purchased from Shanghai Experimental Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle, controlled temperature (22 ± 2°C), and humidity (50 ± 10%). According to the random number table method, mice were randomly divided into two groups with 6 mice in each group. Cells were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL, and 0.1 mL of the cell suspension was injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flank of each mouse using a sterile syringe at a 45° angle following isoflurane anesthesia (2%–4% in oxygen) and disinfection of the injection site with 75% ethanol. Tumor volume was measured starting on day 10 after injection, using a caliper to measure the length (L) and width (W) of the tumors, and the tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Volume = 0.5 × L × W2. On day 30, tumors were excised and photographed following the euthanasia of all the mice. The levels of KRT6A mRNA in the tumors were determined by qRT-PCR. IHC staining was also carried out to detect the protein levels of KRT6A (1:100, A19827, Abclonal, Wuhan, China) and Ki-67 (1:100, A21861, Abclonal, Wuhan, China).

Experiments were performed under a project license (No. 2024-KY-086) granted by the ethics board of Yixing Hospital of Chinese Traditional Medicine Affiliated to Yangzhou University Medical College, in compliance with Chinese guidelines for the care and use of animals.

All statistical evaluations were conducted using SPSS 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of continuous variables. Normally distributed data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (x ± S) and analyzed via t-tests. Non-normally distributed data are given as median (P25, P75) and were compared using Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages [n (%)] and compared using the chi-square (χ2) test. Kaplan–Meier (K-M) curves were utilized to examine survival distributions. Univariate analysis (UVA) and multivariate analysis (MVA) using Cox regression models were used to determine independent prognostic indicators. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 Analysis of KRT6A Levels in CC from the GEO Dataset

The mRNA transcriptome data of CC tissues from the GSE9750 dataset in the GEO database were analyzed. Genes showing |logFC| > 2 and FDR < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Among these, KRT6A was found to be highly expressed in CC tissues (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Transcriptomic profile from the GSE9750 dataset in the GEO database

3.2 Levels of KRT6A in CC Tissues

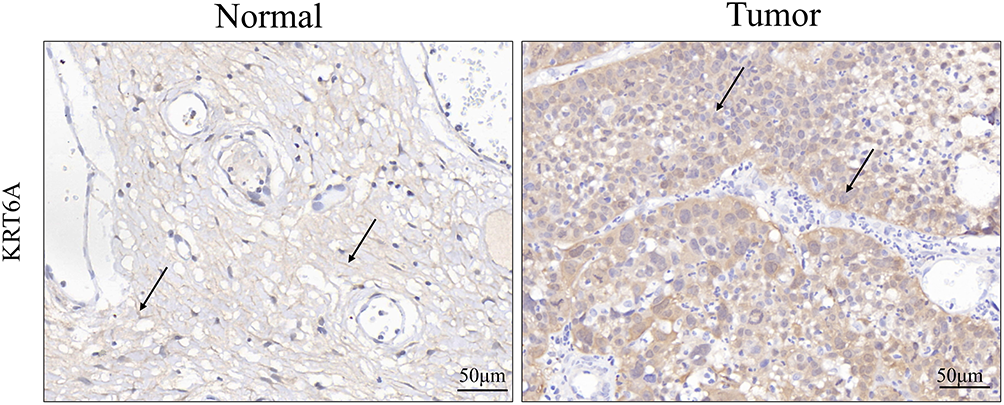

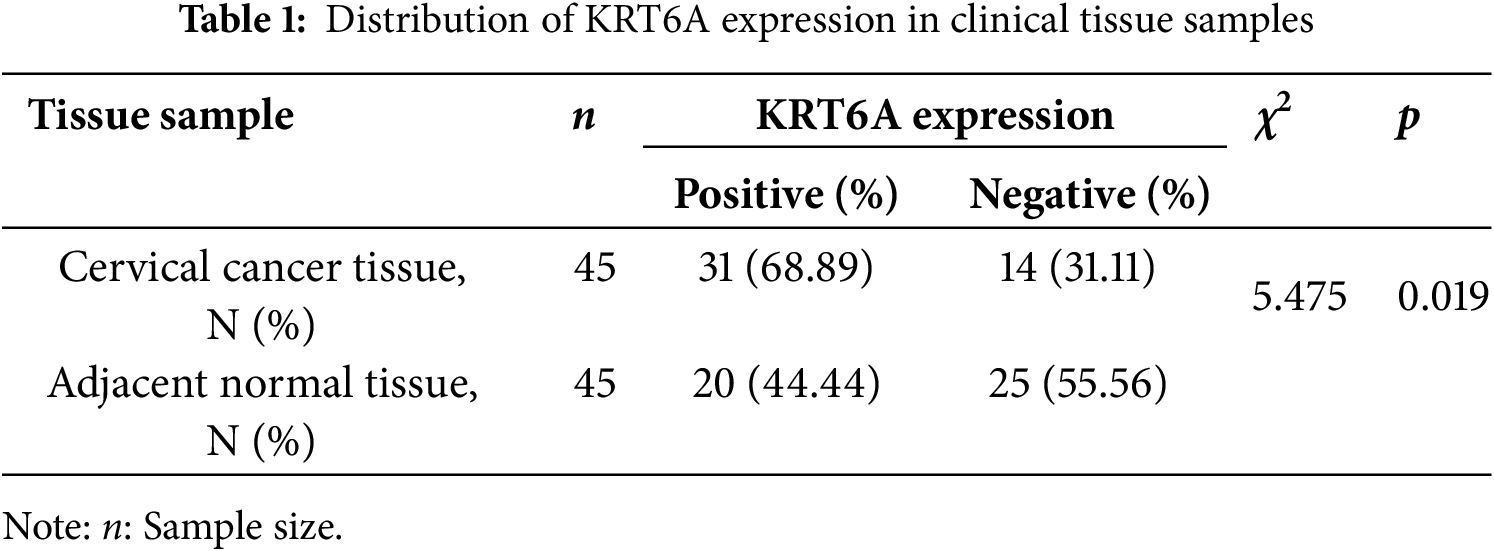

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining revealed significantly increased levels of KRT6A in CC tissues relative to adjacent non-tumor tissues. The protein was primarily localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2). Quantitative analysis indicated significantly higher KRT6A positivity in cancer tissues in comparison to adjacent non-tumor tissues (68.89% vs. 44.44%, p = 0.019) (Table 1).

Figure 2: Immunohistochemical staining of KRT6A in CC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues (n = 45). The black arrow indicates representative positive staining

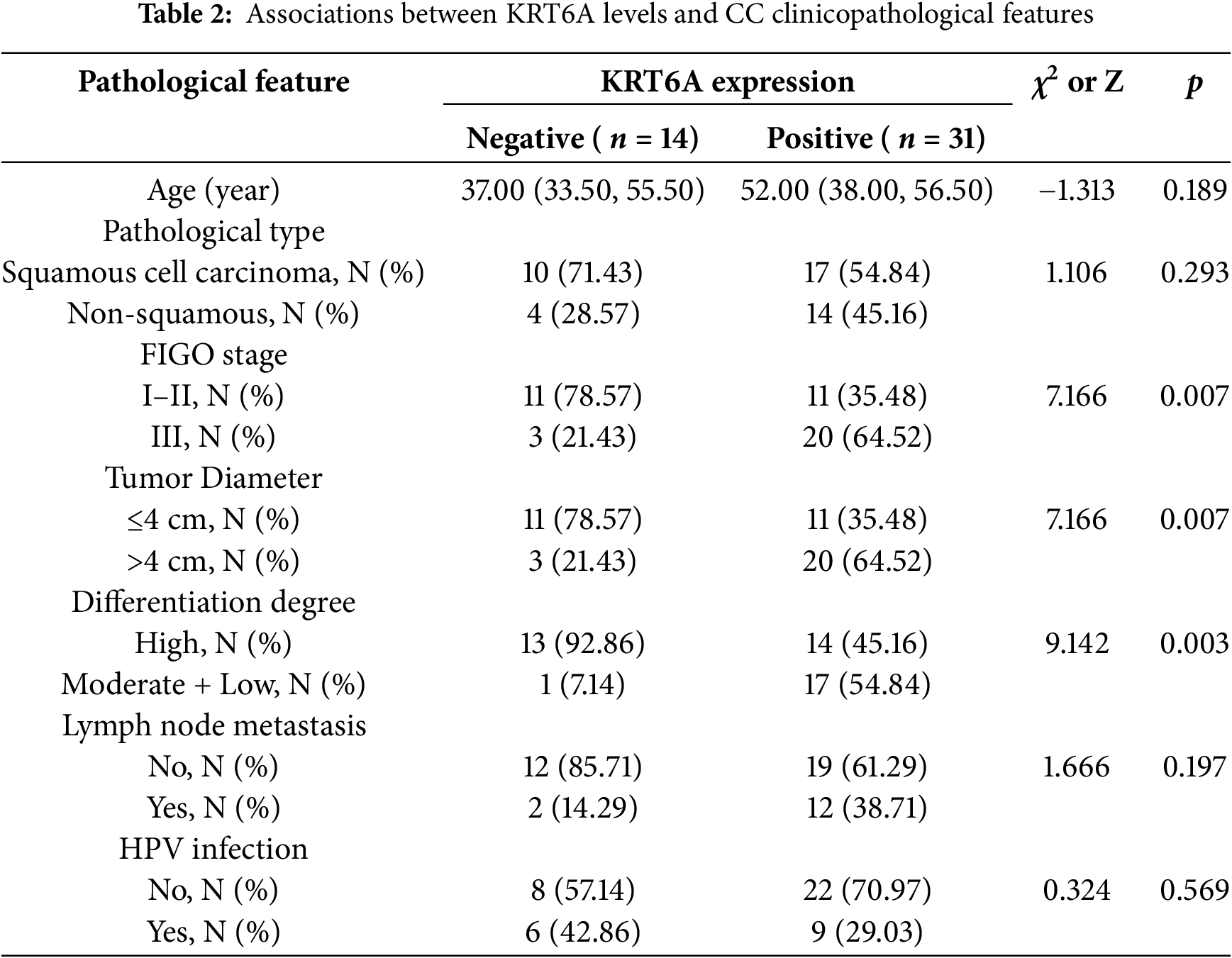

3.3 Correlation between KRT6A Expression and Clinicopathological Features of CC

Based on IHC results, CC cases were grouped into KRT6A-positive (n = 31) and KRT6A-negative (n = 14) groups. The association between KRT6A levels and clinical parameters was assessed. The results indicated significant associations between positive KRT6A expression and FIGO stage (p = 0.007), tumor size (p = 0.007), and histological differentiation (p = 0.003) (Table 2).

3.4 Impact of KRT6A Expression on Progression-Free Survival (PFS)

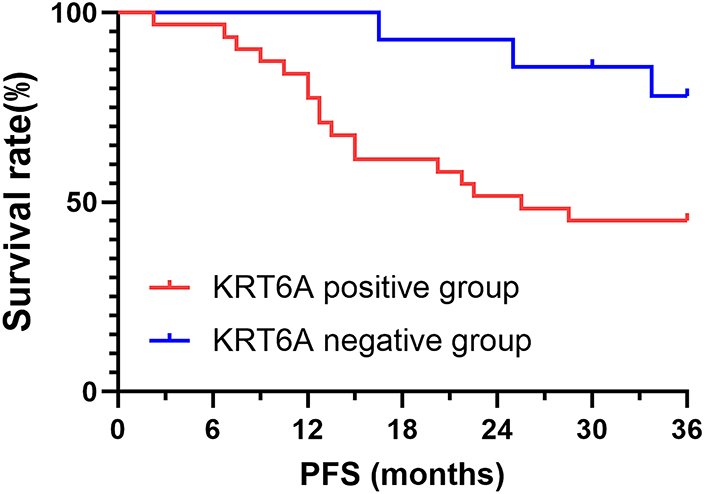

All 45 patients were followed for a period of three years. The mean PFS in the KRT6A-positive group was 25.50 months, with a survival rate of 45.16%, while the median survival time of the KRT6A-negative group was not reached, and the survival rate was 78.57%; the differences between the groups were statistically significant (p = 0.009) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: K-M curves of PFS stratified by KRT6A expression status

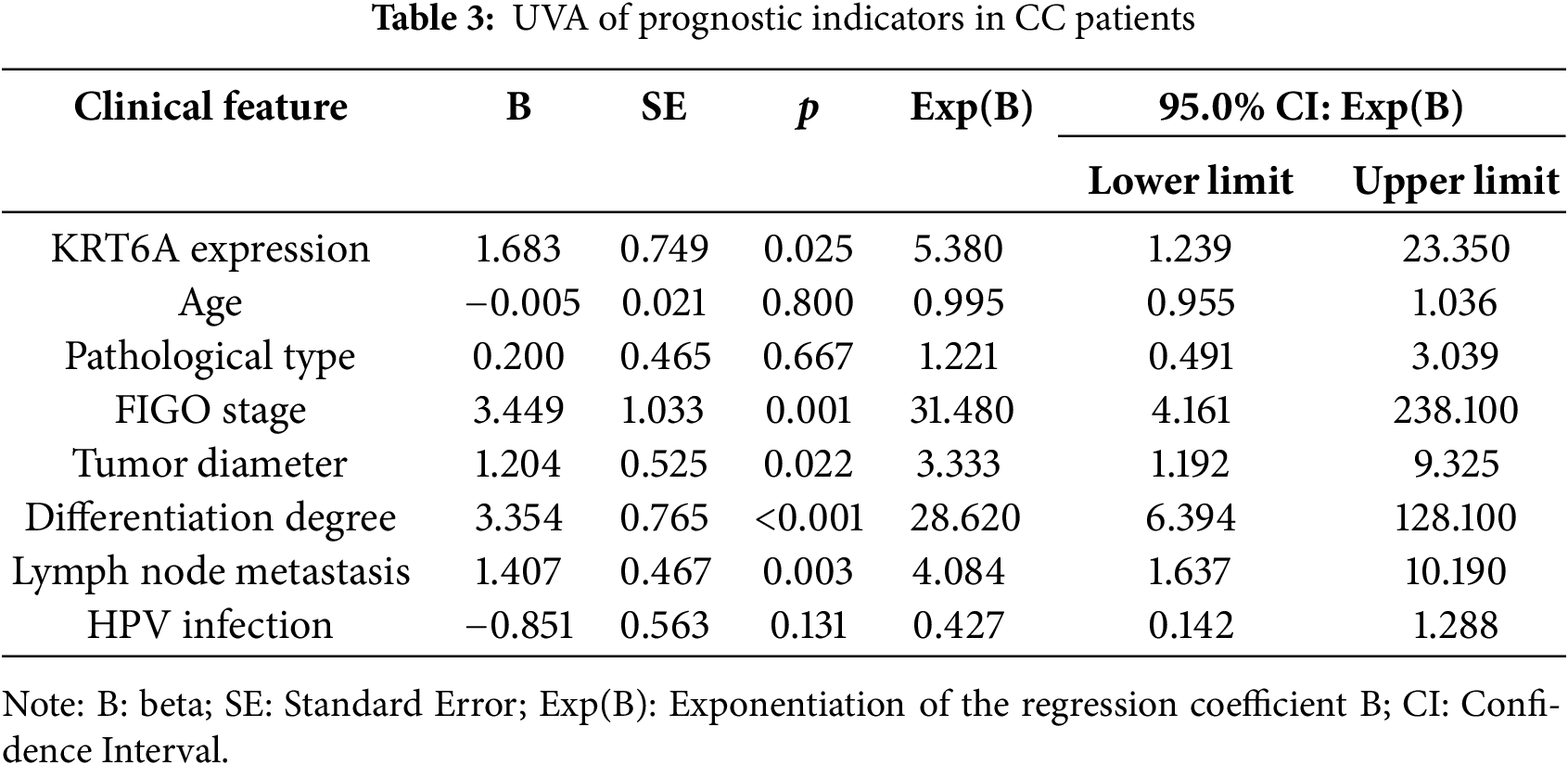

3.5 UVA and MVA of Prognostic Factors in CC

UVA indicated that KRT6A levels (p = 0.025), FIGO stage (p = 0.001), tumor size (p = 0.022), differentiation status (p < 0.001), and lymph node metastasis (LNM) (p = 0.003) were significantly linked with patient prognosis (Table 3). Subsequent multivariate Cox analysis identified KRT6A expression (p = 0.044), tumor size (p = 0.008), differentiation status (p = 0.012), and LNM (p = 0.033) as independent prognostic risk factors in CC patients (Table 4).

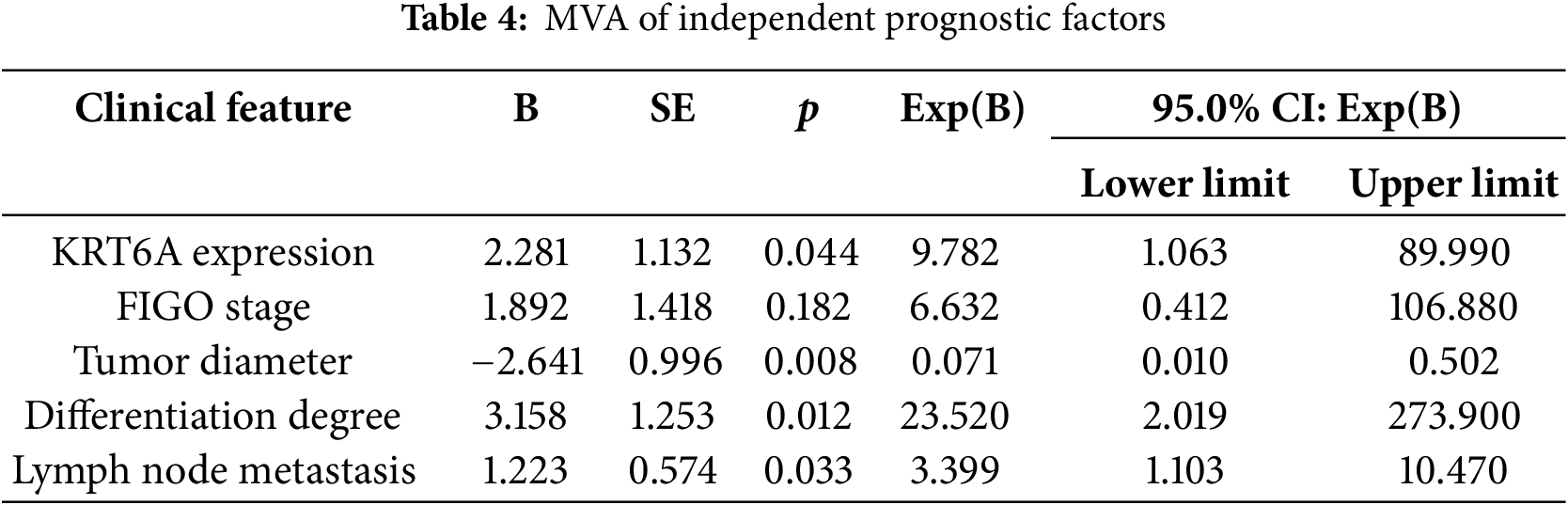

3.6 Expression of KRT6A in CC Cell Lines

The KRT6A expression levels in CC cell lines were assessed by qRT-PCR and WB. Compared to the immortalized cervical epithelial cell line Ect1/E6E7, KRT6A expression was found to be elevated in CasKi, SiHa, HeLa, and C33A cells, with notably higher expression observed in SiHa and HeLa cells (Fig. 4A,B). Consequently, HeLa and SiHa cells were selected for subsequent functional studies.

Figure 4: The expression level of KRT6A in CC cells. (A) qPCR measurement of KRT6A mRNA levels in CC cell lines; (B) Western Blotting analysis showing the effect of shRNA-mediated KRT6A knockdown on KRT6A protein levels. (C) qPCR quantification of KRT6A mRNA in SiHa and HeLa cells after knockdown; (D) WB showing KRT6A protein expression following knockdown. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To further explore the biological role of KRT6A and its potential regulatory mechanisms in CC cells, KRT6A-targeting shRNA sequences were synthesized and transfected into HeLa and SiHa cells. The results of the WB analysis indicated that the levels of KRT6A mRNA and protein were significantly downregulated in both cell lines after transfection with KRT6A-specific shRNA compared with controls (Fig. 4C,D).

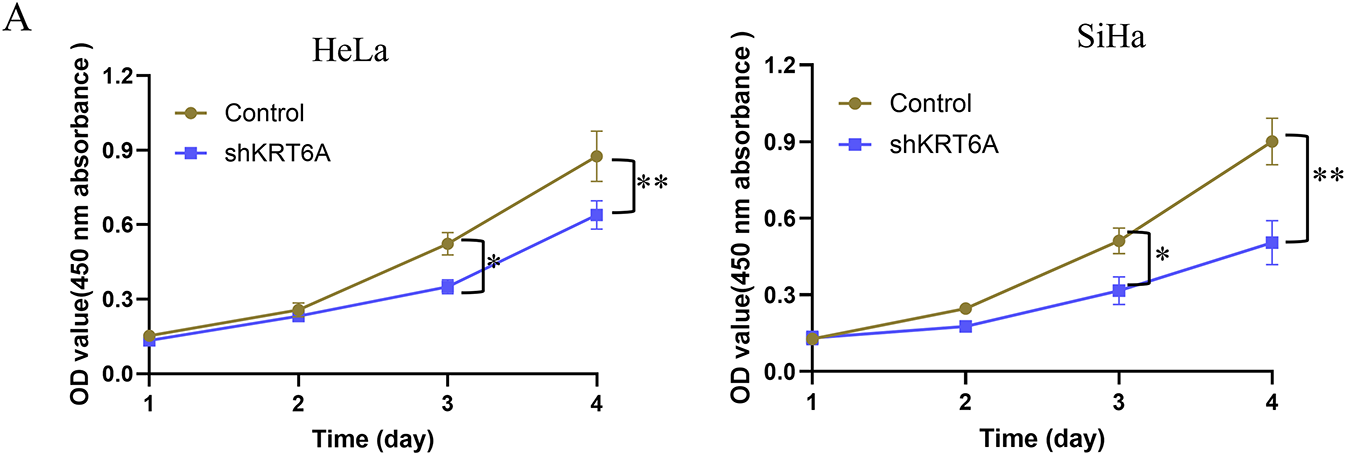

3.7 Effects of KRT6A Knockdown on Proliferation of HeLa and SiHa Cells

CCK-8 assays revealed that the proliferative capacities of SiHa and HeLa cells were significantly inhibited starting from day 3 (72 h) following KRT6A knockdown compared to the control group (Fig. 5A). Additionally, CFAs demonstrated a marked reduction in colony-forming ability in KRT6A-silenced cells compared to controls (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5: Effects of KRT6A knockdown on the proliferative ability of CC cells. (A) CCK-8 assays showing inhibition of proliferation in HeLa and SiHa cells following KRT6A knockdown. (B) CFA demonstrates decreased clonogenic capacity of SiHa and HeLa cells upon KRT6A knockdown. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

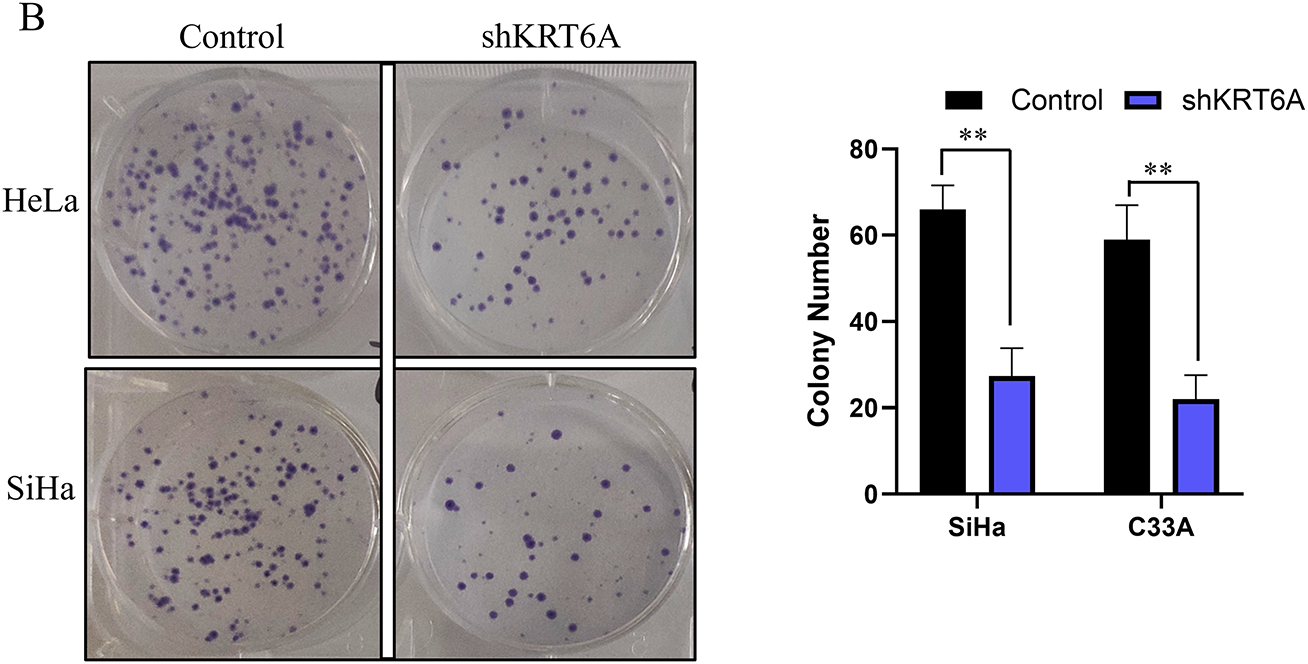

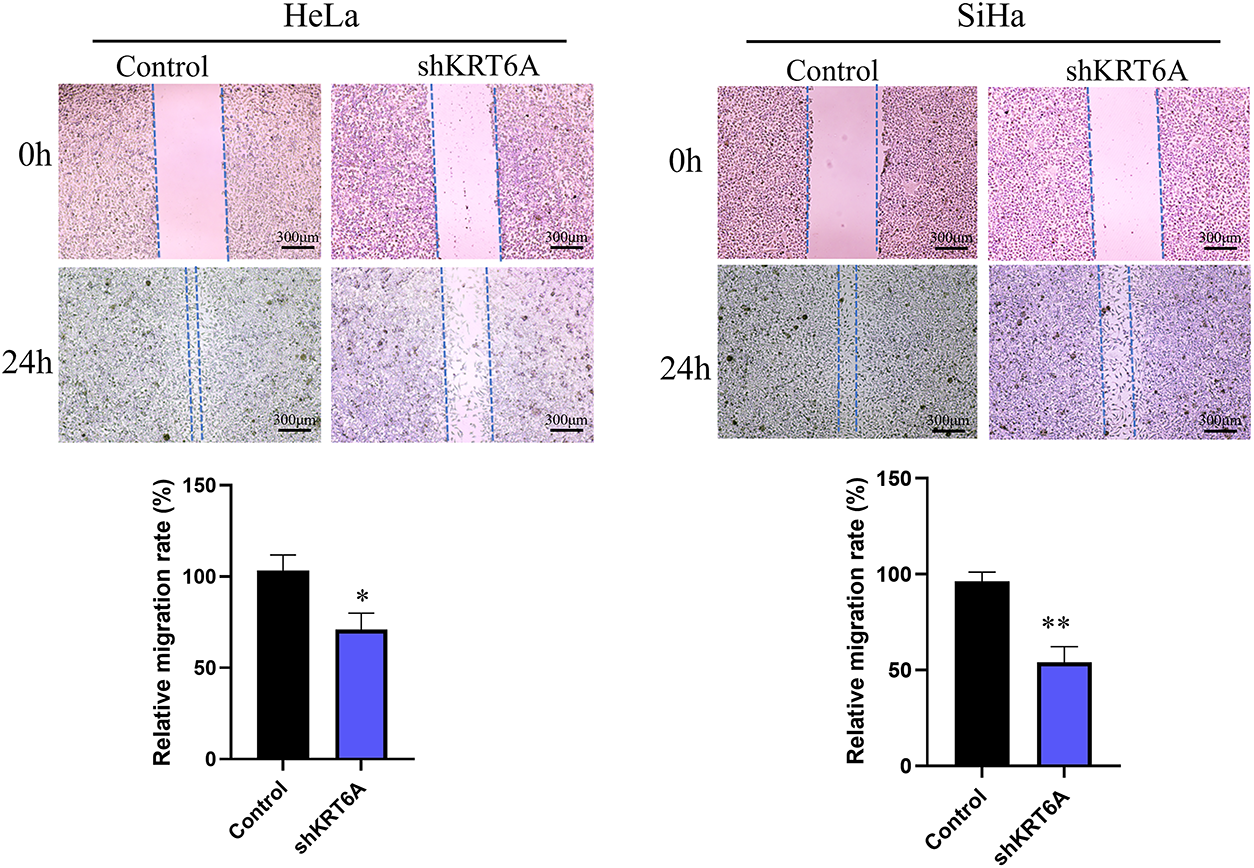

3.8 KRT6A Knockdown Inhibits Migration and Invasion of HeLa and SiHa Cells

WHA indicated that cell migration was significantly suppressed in both SiHa and HeLa cells after KRT6A silencing compared to controls (Fig. 6). Furthermore, Transwell assays confirmed that both migratory and invasive abilities were significantly decreased in KRT6A-knockdown cells relative to the control group (Fig. 7).

Figure 6: Wound healing assay showing reduced migration of SiHa and HeLa cells following KRT6A knockdown. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Figure 7: Transwell migration and invasion assays demonstrating inhibitory effects of KRT6A knockdown on HeLa and SiHa cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **p < 0.01

3.9 In Vivo Xenograft Model Validates Inhibitory Effect of KRT6A Knockdown on CC Cell Proliferation

Relative to the Control group, the tumor tissues in the KRT6A knockdown (shKRT6A) group exhibited a significantly reduced size and volume (Fig. 8A). Growth curve analysis demonstrated a significantly slower tumor growth rate in the shKRT6A group (Fig. 8B). Further weighing of the tumor tissues revealed that the weight of tumors in the shKRT6A group was significantly decreased in comparison to the Control group (Fig. 8C). Measurement of KRT6A levels in tumor tissues showed significantly lower KRT6A mRNA levels in the shKRT6A group relative to controls (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8: In vivo nude mouse experiment assessing the effects of KRT6A knockdown on CC cell proliferation. (A) Morphology of tumor tissues excised 30 days after subcutaneous injection in nude mice. (B) Tumor growth curves measured starting from day 10 post-injection. (C) Analysis of tumor weights at the endpoint. n = 6. (D) qPCR detection of KRT6A mRNA expression levels in tumor tissues. n = 6. **p < 0.01

Additionally, IHC analysis of the tumor tissues indicated that the Ki-67 expression level was significantly less in the shKRT6A group in comparison to the Control group, suggesting that KRT6A knockdown significantly inhibited the proliferative capacity of CC cells. Concurrently, KRT6A protein levels were also substantially decreased in the shKRT6A group (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Knockdown of KRT6A inhibits the expression of Ki-67 in xenograft tumor tissues. IHC staining was used to measure the expression of Ki-67 and KRT6A in xenograft tumor tissues. Black arrows indicate representative positively stained cells. The intensities of Ki-67 and KRT6A were both decreased in xenograft tumors from sh KRT6A-transfected cells. **p < 0.01

In recent years, aberrant KRT6A expression has been identified in various malignancies. Han et al. [23] reported that KRT6A protein levels were significantly increased in melanoma tissues relative to benign nevi. Similarly, Wang et al. [24] observed a marked upregulation of KRT6A in lung adenocarcinoma, particularly among patients harboring EGFR mutations. Furthermore, growing evidence has suggested that KRT6A expression is associated with several pathological features of tumors and may influence patient prognosis. For instance, Hoggarth et al. [25] demonstrated that KRT6A was linked to more aggressive subtypes of urothelial carcinoma. Harada-Kagitani et al. [26] found that elevated KRT6A in colorectal cancer was correlated with higher tumor budding grades and poorer clinical outcomes. MVA confirmed the KRT6A level as independently predictive of overall survival and PFS. Comparable findings have also been noted in breast cancer [27]. These studies collectively point to the potential role of KRT6A in prognosis evaluation and targeted therapy across different cancer types, including CC.

In this study, overexpression of KRT6A in CC was identified through the GEO database screening and further verified by immunohistochemical analysis. Elevated KRT6A expression was significantly associated with LNM, poor differentiation, advanced FIGO stage, and shortened PFS in CC patients. Multivariable analysis supported KRT6A as an independent prognostic factor. These findings highlight a close association between KRT6A and tumor aggressiveness, reinforcing its potential as a prognostic indicator and therapeutic target in CC.

The biological functions of KRT6A in tumor cells have also been gradually elucidated. Chen et al. [28] demonstrated that silencing KRT6A significantly reduced cell viability and proliferation in bladder cancer cells. Che et al. [29] reported that overexpression of KRT6A induced proliferation and invasion in lung cancer cells, while Xu et al. [30] showed that KRT6A knockdown led to diminished proliferative and invasive capacities. These findings suggest that KRT6A may act as an oncogenic factor. In the present study, CC cell lines with stable KRT6A knockdown were constructed via lentiviral transduction. A series of in vitro assays, including CCK-8, CFA, WHA, and invasion and migration experiments, revealed that KRT6A silencing significantly inhibited these malignant phenotypes in CC cells. These results indicate that KRT6A contributes to the malignant behavior of CC by enhancing proliferation, clonogenicity, and invasiveness. Moreover, in vivo xenograft experiments in nude mice further confirmed the tumor-promoting effect of KRT6A. Tumor volumes derived from KRT6A-silenced CC cells were significantly reduced. Ki-67, a widely used proliferation marker, was also found to be downregulated in xenograft tumors, indirectly reflecting suppressed proliferative activity. These in vivo findings were consistent with the in vitro data and provided additional support for the oncogenic role of KRT6A in CC progression.

In this study, we identified KRT6A as a potential prognostic biomarker for cervical cancer aggressiveness. However, the mechanisms through which KRT6A contributes to tumor progression are not fully understood but may involve several key processes. First, a study has shown that in lung adenocarcinoma, the down-regulation of KRT6A significantly increases the expression level of E-cadherin and decreases the level of N-cadherin [31]. This indicates that the overexpression of KRT6A may enhance the invasiveness of CC by promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Secondly, a previous study has shown that KRT6A expression is closely linked with the ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK pathways in keratinocytes [32]. It raises the possibility that KRT6A might influence MAPK signaling to regulate CC aggressiveness, although further studies are needed to confirm this in cervical cancer models.

This study has several limitations. First, the tissue microarray was derived from a single cohort at one center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader cervical cancer populations. Second, the relatively small sample size (n = 45) reduces the statistical power and increases the risk of bias. Larger, multicenter studies with expanded cohorts and more comprehensive clinical information will be needed to validate the prognostic significance of KRT6A in cervical cancer.

In conclusion, KRT6A exhibits considerable potential as a prognostic indicator and target in CC treatment. Its expression is closely linked to key pathological features and adverse clinical outcomes. Silencing of KRT6A impaired CC cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Future investigations should evaluate the regulatory processes associated with KRT6A function, which may provide a theoretical foundation for developing targeted therapies against CC.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Yixing Taodu Light Science and Technology Research Plan, Grant Number: 2024SF14.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Linqian Shi, Qian Gao; data collection: Yan Cao; analysis and interpretation of results: Juanying Yang, Zhuxiu Wang, Zeliang Zhuang, Linqian Shi; draft manuscript preparation: Min Ma and Zhuxiu Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data would be available to other researchers upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Animal experiments were performed under a project license (No. 2024-KY-086) granted by the ethics board of Yixing Hospital of Chinese Traditional Medicine Affiliated to Yangzhou University Medical College, in compliance with Chinese guidelines for the care and use of animals. The human tissue microarray used in this study was commercially obtained from Shanghai Yingbeilan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All tissue samples were anonymized, and the supplier confirmed that informed consent had been obtained from all donors and that ethical approval had been granted for the collection and research use of these specimens.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sahasrabuddhe VV. Cervical cancer: precursors and prevention. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2024;38(4):771–81. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2024.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Momenimovahed Z, Mazidimoradi A, Amiri S, Nooraie Z, Allahgholi L, Salehiniya H. Temporal trends of cervical cancer between 1990 and 2019, in Asian countries by geographical region and socio-demographic index, and comparison with global data. Oncologie. 2023;25(2):119–48. doi:10.1515/oncologie-2022-1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jha AK, Mithun S, Sherkhane UB, Jaiswar V, Osong B, Purandare N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction models used in cervical cancer. Artif Intell Med. 2023;139(3):102549. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wu S, Jiao J, Yue X, Wang Y. Cervical cancer incidence, mortality, and burden in China: a time-trend analysis and comparison with England and India based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1358433. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1358433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yuan M, Zhao X, Wang H, Hu S, Zhao F. Trend in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates in China, 2006–2030: a Bayesian age-period-cohort modeling study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32(6):825–33. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Nisha P, Srushti P, Bhavarth D, Kaif M, Palak P. Comprehensive review on analytical and bioanalytical methods for quantification of anti-angiogenic agents used in treatment of CervicalCancer. Curr Pharm Anal. 2023;19(10):735–44. doi:10.2174/0115734129270020231102081109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nitecki R, Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Krause KJ, Tergas AI, Wright JD, et al. Survival after minimally invasive vs open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1019–27. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zeng Q, Feng K, Yu Y, Lv Y. Hsa_Circ_0000021 sponges miR-3940-3p/KPNA2 expression to promote cervical cancer progression. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2024;17:e170223213775. doi:10.2174/1874467216666230217151946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zheng W, Mu H, Chen J, Wang C, Hou L. Circ_0002762 regulates oncoprotein YBX1 in cervical cancer via mir-375 to regulate the malignancy of cancer cells. Protein Pept Lett. 2023;30(2):162–72. doi:10.2174/0929866530666230104155209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Shao J, Zhang C, Tang Y, He A, Zhu W. Knockdown of circular RNA (CircRNA)001896 inhibits cervical cancer proliferation and stemness in vivo and in vitro. Biocell. 2024;48(4):571–80. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.049092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zheng Y, Wang Y, Zou C, Hu B, Zhao M, Wu X. Tumor-associated macrophages facilitate the proliferation and migration of cervical cancer cells. Oncologie. 2022;24(1):147–61. doi:10.32604/oncologie.2022.019236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ogunnigbagbe O, Bunick CG, Kaur K. Keratin 1 as a cell-surface receptor in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877(1):188664. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang W, Fan Y. Structure of keratin. In: Fibrous proteins. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2021. p. 41–53. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-1574-4_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu L, Sun L, Zheng J, Cui L. Berberine modulates Keratin 17 to inhibit cervical cancer cell viability and metastasis. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2021;41(6):521–31. doi:10.1080/10799893.2020.1830110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang L, Shang Y, Zhang J, Yuan J, Shen J. Recent advances in keratin for biomedical applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;321(5):103012. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2023.103012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ghantous Y, Mozalbat S, Nashef A, Abdol-Elraziq M, Sudri S, Araidy S, et al. EMT dynamics in lymph node metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers. 2024;16(6):1185. doi:10.3390/cancers16061185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Pranke IM, Chevalier B, Premchandar A, Baatallah N, Tomaszewski KF, Bitam S, et al. Keratin 8 is a scaffolding and regulatory protein of ERAD complexes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(9):503. doi:10.1007/s00018-022-04528-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lehmann SM, Leube RE, Schwarz N. Keratin 6a mutations lead to impaired mitochondrial quality control. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):636–47. doi:10.1111/bjd.18014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen M, Wang Y, Wang M, Xu S, Tan Z, Cai Y, et al. Keratin 6A promotes skin inflammation through JAK1-STAT3 activation in keratinocytes. J Biomed Sci. 2025;32(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12929-025-01143-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li Y, Wu Q. KRT6A inhibits IL-1β-mediated pyroptosis of keratinocytes via blocking IL-17 signaling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2024;34(4):1–11. doi:10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2023050039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Xiao J, Kuang X, Dai L, Zhang L, He B. Anti-tumour effects of Keratin 6A in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Respir J. 2020;14(7):667–74. doi:10.1111/crj.13182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Han W, Xu WH, Wang JX, Hou JM, Zhang HL, Zhao XY, et al. Identification, validation, and functional annotations of genome-wide profile variation between melanocytic nevus and malignant melanoma. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020(1):1840415. doi:10.1155/2020/1840415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang Q, Sun N, Li J, Huang F, Zhang Z. Liquid-liquid phase separation in the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma: an integrated analysis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2025;25(4):323–34. doi:10.2174/0115680096345676241001081051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hoggarth ZE, Osowski DB, Slusser-Nore A, Shrestha S, Pathak P, Solseng T, et al. Enrichment of genes associated with squamous differentiation in cancer initiating cells isolated from urothelial cells transformed by the environmental toxicant arsenite. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;374(3):41–52. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2019.04.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Harada-Kagitani S, Kouchi Y, Shinomiya Y, Kodama M, Ohira G, Matsubara H, et al. Keratin 6A is expressed at the invasive front and enhances the progression of colorectal cancer. Lab Invest. 2024;104(7):102075. doi:10.1016/j.labinv.2024.102075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Pu S, Zhou Y, Xie P, Gao X, Liu Y, Ren Y, et al. Identification of necroptosis-related subtypes and prognosis model in triple negative breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:964118. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.964118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Chen Y, Ji S, Ying J, Sun Y, Liu J, Yin G. KRT6A expedites bladder cancer progression, regulated by miR-31-5p. Cell Cycle. 2022;21(14):1479–90. doi:10.1080/15384101.2022.2054095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Che D, Wang M, Sun J, Li B, Xu T, Lu Y, et al. KRT6A promotes lung cancer cell growth and invasion through MYC-regulated pentose phosphate pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:694071. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.694071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Xu Q, Yu Z, Mei Q, Shi K, Shen J, Gao G, et al. Keratin 6A (KRT6A) promotes radioresistance, invasion, and metastasis in lung cancer via p53 signaling pathway. Aging. 2024;16(8):7060–72. doi:10.18632/aging.205742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Yang B, Zhang W, Zhang M, Wang X, Peng S, Zhang R. KRT6A promotes EMT and cancer stem cell transformation in lung adenocarcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2020;19(5):1533033820921248. doi:10.1177/1533033820921248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yoshida A, Yamamoto K, Ishida T, Omura T, Itoh T, Nishigori C, et al. Sunitinib decreases the expression of KRT6A and SERPINB1 in 3D human epidermal models. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(3):337–46. doi:10.1111/exd.14230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools