Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Mitochondrial Stress, Melatonin, and Neurodegenerative Diseases: New Nanopharmacological Approaches

1 Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Químicas, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Tecnológicas, Universidad Católica de Cuyo, San Juan, 5400, Argentina

2 Instituto de Medicina y Biología Experimental de Cuyo (IMBECU), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (CONICET), Mendoza, 5500, Argentina

3 Departamento de Patología, Área de Farmacología, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina

4 Department of Structural and Functional Biology, Institute of Biosciences, UNESP-São Paulo State University, P.O. Box 18618-689, Botucatu, São Paulo, 510, Brazil

5 Department of Cell Systems and Anatomy, Long School of Medicine, UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

6 Applied Biomedical Sciences, School of Osteopathic Medicine, University of the Incarnate Word, San Antonio, TX 78209, USA

7 Department of Biomolecular Sciences, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, Urbino, 61029, Italy

8 Department of Biological, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, University of Palermo, Viale delle Scienze, Bldg. 16, Palermo, 90128, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Walter Manucha. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2245-2282. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071830

Received 13 August 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are characterized by progressive neuronal loss, which is closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. These pathologies involve a complex interplay of genetics, protein misfolding, and cellular stress, culminating in impaired energy metabolism, an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), and defective mitochondrial quality control. The accumulation of damaged mitochondria and dysregulation of pathways such as the Integrated Stress Response (ISR) are central to the pathogenesis of these conditions. This review explores the critical relationship between mitochondrial stress and neurodegeneration, highlighting the molecular mechanisms and biomarkers involved. It delves into the multifaceted role of melatonin as a potent neuroprotective agent. Melatonin, a lipophilic indoleamine, is produced both in the pineal gland and locally within mitochondria, where it exerts powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects. Its unique ability to neutralize multiple free radicals and its cascade-based antioxidant action make it superior to conventional antioxidants. Its mechanisms of action are discussed, including signaling pathway modulation and enhancement of the brain’s clearance system (the glymphatic system). Despite its potential, melatonin’s low bioavailability and rapid metabolism limit its therapeutic efficacy. In this context, nanopharmacology emerges as a promising strategy. Nanoparticles such as liposomes, polymers, and solid lipids can encapsulate melatonin and protect it from degradation, facilitating its transport across the blood-brain barrier. Preclinical evidence has shown that melatonin-loaded nanoparticles significantly improve cognitive function, reduce oxidative stress, and restore mitochondrial homeostasis in models of AD, PD, and ALS. In conclusion, the synergistic combination of melatonin and nanopharmacology offers a multimodal and highly targeted approach for mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction in NDs. While challenges remain in optimizing the formulation and safety of these nanocarriers, this combination represents a crucial frontier for developing more effective and specific treatments in the future.Keywords

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) represent a group of pathologies characterized by neuronal loss and progressive degeneration of specific areas of the nervous system. These pathologies mainly include Parkinson’s disease (PD), Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s disease (HD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and the underlying mechanisms involve genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic factors, microbiome imbalance, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, lifestyle, and excitotoxicity [1]. Mechanistically, there are several molecular aspects associated with NDs which are of particular importance to neuronal damage.

In PD, while caspase-3 triggers early synaptic damage, Ras-related protein (Rab1) offers neuroprotection by regulating membrane trafficking and blocking dopamine D3 receptors, thus reducing neuroinflammation. ALS, also known as motor neuron disease, is caused by degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in muscle weakness and eventual paralysis. In most ALS subtypes, Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) pathology is central, with nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic aggregation in motor neurons occurring in about 97% of cases. While TDP-43 mutations are rare, their mislocalization is a hallmark feature. Other protein aggregates may appear in specific ALS forms, including dipeptide repeat proteins in C9ORF72-related ALS and misfolded Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) or neurofilamentous inclusions in SOD1-linked ALS [2]. HD is a complex late-onset ND caused by a Cytosine, Adenine, and Guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeat in the gene encoding the huntingtin protein with an expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) tract; loss of huntingtin disrupts intracellular transport by impairing the dynein/dynactin complex and spindle orientation during mitosis. It also affects gene expression by failing to regulate Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) transcription through REST/NRSF inhibition. Additionally, huntingtin loss alters synaptic connectivity, leading to abnormal excitatory synapse formation and gliosis [3]. AD is primarily driven by the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau (pTau) protein. Altered amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing leads to toxic Aβ production, and intraneuronal Aβ may initiate and sustain neurodegeneration independently of APP. Abnormal protein interactions—such as filamin A (FLNA) binding to α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors—promote Aβ signaling and inflammation, which can be disrupted by drugs like simufilam [4].

Despite advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of NDs, several limitations remain in the field. Current therapeutic approaches often fail to address the multifactorial nature of these disorders, which involve not only protein aggregation but also mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and impaired cellular quality control. Moreover, many promising compounds display poor bioavailability, limited ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, or lack disease-specific targeting, leading to inconsistent clinical outcomes. These challenges underscore the need for novel strategies that integrate mechanistic insights with innovative delivery systems. The purpose of this review is to critically examine the interplay between mitochondrial stress and neurodegeneration, highlight the unique role of melatonin as a neuroprotective molecule, and evaluate how nanopharmacological approaches may overcome the pharmacokinetic and delivery barriers that limit melatonin’s clinical potential. In doing so, we aim to identify specific gaps that must be addressed to translate these experimental findings into effective therapeutic strategies for patients with ND.

2 Mitochondrial Stress and Neurodegenerative Diseases

2.1 Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration

Aging results from the gradual and random buildup of damage to essential biomolecules, impairing cellular function over time. While this process is uncontrollable, it is influenced by both genetic makeup and environmental factors. Various genetic mutations and treatments have been shown to extend lifespan across species, mainly by enhancing cellular stress responses. This suggests that an organism’s longevity is closely tied to its ability to manage internal and external stress [5]. Although the exact role of each stress response pathway in aging is not yet fully understood, these mechanisms are key to how aging progresses.

NDs exhibit region- and disease-specific alterations in brain energy metabolism, including reduced glucose uptake, impaired tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and insufficient metabolic support from astrocytes and oligodendrocytes to neurons [6]. These changes occur alongside mitochondrial dysfunctions and might include genetic defects, calcium imbalance, and proteinopathies—commonly observed in AD, PD, ALS, and HD [7]. Mitochondria are essential for cellular energy, signaling, and survival, especially in neurons. Mitochondrial dynamics such as fusion, fission, biogenesis, and mitophagy maintain their function and integrity, and dysfunctions in these processes are linked to aging and NDs, especially PD, AD, HD, ALS, and Friedreich’s ataxia. Mitochondrial biogenesis is regulated by Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), and Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), while mitophagy, the clearance of damaged mitochondria, was governed by the PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin pathway [8]. Notably, aging impairs these mechanisms, resulting in dysfunctional mitochondrial accumulation, oxidative stress, and cell death, which are all involved in the development and severity of NDs.

Growing evidence suggests that stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis is a promising therapeutic strategy for both primary and secondary mitochondrial disorders. In mouse models with OXPHOS deficiencies, compounds that activate mitochondrial biogenesis—particularly via the AMPK/PGC-1α pathway has been shown to correct OXPHOS defects, including in cases of cytochrome oxidase deficiency, as previously reviewed [9]. In the context of NDs, enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of PGC-1α, Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NRF2), or AMPK has demonstrated neuroprotective effects in models of PD and HD [10]. Mitophagy is a crucial quality control mechanism that selectively removes damaged or excess mitochondria, helping maintain cellular energy balance and mitochondrial health, especially in aging cells like neurons. This process is essential for preserving energy homeostasis at the organismal level. A key player in mitophagy is Dynamin-related protein 1 homolog in C. elegans (DCT-1), regulated by Dauer formation 16/Forkhead Box protein O (DAF-16/FOXO) transcription factor, and functionally related to mammalian Nip3-like protein X (NIX)/BCL2/Adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3-like (BNIP3L) and BCL2/Adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3). While knocking down dct-1 or pdr-1 (a Parkin orthologue) has little effect on normal animals, it significantly shortens lifespan in long-lived daf-2 and eat-2 mutants, linking mitophagy to longevity pathways. Deficiency in mitophagy leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased stress sensitivity, which activates mitochondrial retrograde signaling through Skinhead-1 (SKN-1), which, in turn, promotes both mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy by upregulating dct-1 [11]. Disruption of this coordination with aging leads to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and loss of cellular function.

More recently, Iqbal et al. investigated how neural stem cells (NSCs) respond to mitochondrial dysfunction [12]. Using an Opa1-inducible knockout model, which mimics mitochondrial impairment seen in aging, the authors demonstrate that disrupted mitochondrial dynamics lead to reduced NSC activation and progenitor proliferation, resulting in impaired neurogenesis and cognitive decline. Remarkably, these effects can be partially reversed by reducing oxidative stress under hypoxic conditions. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that the Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) pathway, part of the integrated stress response (ISR), plays a central role in helping NSCs adapt to metabolic stress. Loss of ATF4 worsened NSC survival, while its overexpression improved cell proliferation and resistance to stress. Further analysis using an SLC7A11 mutant, a target gene of ATF4 involved in glutathione synthesis, confirmed that ATF4 helps preserve NSC viability through oxidative stress defense. This ATF4-driven activation of the ISR pathway is crucial for protecting NSCs under mitochondrial stress, and modifying this pathway may be beneficial for preserving neural function in aging and neurodegenerative conditions.

Mitochondrial transplantation involves replacing damaged mitochondria with healthy, functional ones. This is done by isolating mitochondria from healthy tissue and delivering them to affected areas via local or circulatory injection to restore cellular energy function. In the case of NDs, some experimental studies are being performed. Chang and co-workers showed that peptide-mediated delivery (PMD) of healthy mitochondria into PD rat models significantly improved mitochondrial function and neuronal survival [13]. Using allogeneic or xenogeneic mitochondria, PMD resisted oxidative stress, reduced dopaminergic neuron loss, restored complex I activity, and improved motor function. The transplanted mitochondria were effectively transported from the medial forebrain bundle to the substantia nigra, supporting their role in protecting and regenerating dopaminergic neurons.

2.2 Neurodegenerative Diseases Associated with Mitochondrial Stress

There is a consensus that mitochondrial stress is associated with the onset of many NDs, and this is likely due to impaired mitochondrial dynamics (fusion/fission imbalance), reduced OXPHOS efficiency, elevated ROS production, defective mitophagy, etc. An important study by Haakonsen and colleagues identified a large E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, termed. Stress-induced filamentous inclusions (SIFI)—composed of Ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component N-recognin 4 (UBR4), Potassium channel modulatory factor 1 (KCMF1), and calmodulin—as a crucial regulator of the ISR triggered by mitochondrial import stress [14]. SIFI targets and degrades cleaved DELE1 (cDELE1) and active Heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) kinase, two central activators of ISR, thereby terminating the stress signal once mitochondrial function is restored. This degradation is guided by specific degron motifs that are shared with mitochondrial targeting sequences, allowing SIFI to also clear mislocalized mitochondrial precursors. When SIFI is disrupted, such as through mutations in UBR4 found in cases of early-onset neurodegeneration, ISR signaling becomes chronically active, leading to cellular stress and neuronal damage. These findings highlight that controlled shutdown of stress responses is essential for neuronal survival and suggest new therapeutic avenues for NDs linked to chronic ISR activation.

Another important process associated with mitochondrial stress is the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mtUPR). The mtUPR is activated when unfolded or misfolded proteins accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix, triggering chaperones, proteases, and the antioxidant system to restore mitochondrial proteostasis and cellular function. In NDs like AD, PD, Huntington’s, ALS, and Friedreich’s Ataxia, mtUPR modulation has shown therapeutic potential by reducing mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration, highlighting it as a promising target for treatment [15]. In the central nervous system (CNS), misfolded proteins can result in oxidative damage, which contributes to mitochondrial impairment and plays a key role in the progression of NDs. Patients with such conditions often experience early mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to disrupted energy metabolism and neuronal vulnerability [16].

In PD, gene mutations such as α-synuclein, Parkinson protein 7 (PARK7), Parkin, PINK1, and Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) disrupt mitochondrial dynamics and function [17]. For instance, α-synuclein aggregates impair mitophagy, while PINK1 deletion increases mitochondrial oxidative stress [18]. PD is further associated with decreased complex I activity, increased oxidative damage, and impaired antioxidant defences [16]. In addition, complex I inhibitors, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and rotenone, also induce mitochondrial dysfunction mimicking the pathological aspects of PD at low doses, leading to neurodegeneration. Interestingly, the MitoPark mouse model, which lacks Transcription factor a, mitochondrial (TFAM) in dopaminergic neurons, replicates key PD features, including dopamine neuron loss, motor deficits, and inclusion body formation [19]. AD is marked by the accumulation of Aβ and pTau, both of which are linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. Increased oxidative stress and decreased activity of complex IV have also been implicated in the progression of this pathology [16]. As a burden of malfunction, mitochondrial oxidative stress enhances γ-secretase activity via lipid peroxidation, thus increasing Aβ production, whereas elevated ROS and calcium levels also promote Tau aggregation [8]. Deficiency in mitochondrial Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) of mice has been linked to pTau aggregates, but antioxidant administration is useful in reversing this condition. Targeting mitophagy has shown promise in reducing Aβ accumulation, highlighting the therapeutic potential of restoring mitochondrial quality.

In HD, the mutant protein Huntingtin forms aggregates that disrupt mitochondrial fission-fusion balance and impair axonal transport [20]. It also destabilizes mitochondrial membranes and increases vulnerability to calcium and apoptotic signals. ROS levels are also higher in HD patients and in mouse models, which leads to mitochondrial damage, reduced motility, and increased fragmentation. Notably, reduced activity of complex II and an increase in cortical lactate levels is frequently observed in HD [16]. Additionally, mutant Huntingtin interferes with Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-mediated mitophagy, preventing the clearance of damaged mitochondria and worsening neurodegeneration [21]. In ALS, a key pathological feature is impaired mitophagy, and familial ALS is likely associated with mutations in Cu/Zn SOD1, whereas oxidative stress is thought to be involved in sporadic ALS. ALS models, like Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1) G93A mutation (SOD1G39A) mice, show reduced phagosome numbers and downregulation of mitophagy-related proteins PINK1 and Parkin [22]. In double-knockout models lacking these proteins, neuromuscular degeneration and axonal swelling are worsened, mirroring ALS symptoms.

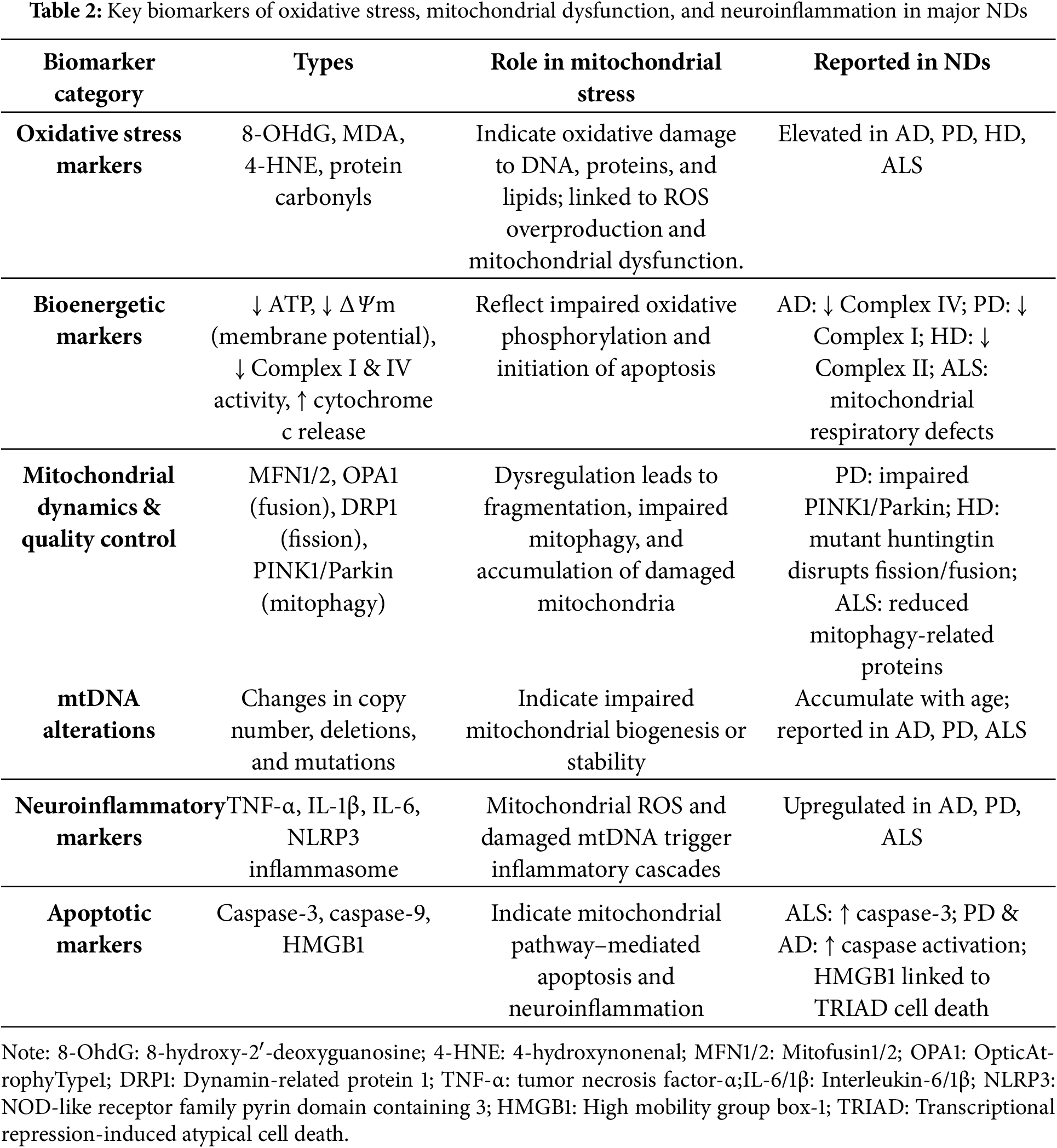

Table 1 compares the similarities and differences of mitochondrial stress mechanisms in AD, PD, HD, and ALS.

2.3 Biomarkers of Mitochondrial Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Oxidative stress is a common feature of major NDs and represents a key target for therapeutic intervention [23]. It is closely linked with microRNA (miRNA) networks, as oxidative stress alters miRNA expression, while miRNAs regulate genes involved in the oxidative response. Together, they influence critical processes like mitochondrial dysfunction, proteostasis disruption, and neuroinflammation, all of which contribute to neuronal death. A thorough review of the literature highlights the central role of oxidative stress in ND development. It contributes to neuronal damage through multiple pathways, such as oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids; mitochondrial dysfunction; Aβ accumulation; activation of glial cells; increased inflammation and cytokine production; and impaired protein degradation via the proteasome [24]. The main oxidative stress markers in NDs are 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and protein carbonyls [6].

Mitochondrial function and bioenergetics can be assessed through several key markers that reflect disruptions in ATP production and electron transport chain (etc) activity [25]. One of the indicators of mitochondrial dysfunction in ND is the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), which signals impaired mitochondrial integrity. Reduced ATP levels also point to compromised oxidative phosphorylation, highlighting the cell’s diminished energy-producing capacity. Additionally, the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria is a hallmark of outer membrane permeabilization and is closely associated with the initiation of apoptosis. Furthermore, decreased activity of mitochondrial Complex I, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD) + hydrogen (H) dehydrogenase (NADH dehydrogenase) and Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) is frequently observed in disorders such as PD, underscoring the relevance of these enzymes in maintaining proper mitochondrial respiratory function.

Mitochondrial dynamics and quality control are involved in NDs, being regulated by several markers associated with changes in mitochondrial morphology, turnover, and maintenance. The dynamin-like GTPases Mitofusin 1 and 2 (MFN1 and MFN2), along with Optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), are essential proteins that mediate mitochondrial fusion, and alterations in their expression or function indicate impaired mitochondrial dynamics. On the other hand, Dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) is crucial for mitochondrial fission, and its overactivation is commonly associated with excessive mitochondrial fragmentation and cellular stress. Additionally, as previously described, the proteins PINK1 and Parkin play central roles in mitophagy, the selective degradation of damaged mitochondria [26]. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) serves as an important indicator of mitochondrial genetic stability. Changes in mtDNA copy number—either increases or decreases—can reflect alterations in mitochondrial biogenesis or degradation, depending on the disease and its stage. Moreover, the accumulation of mtDNA deletions and mutations is commonly observed with aging and disease progression, particularly in neurodegenerative conditions such as PD and AD.

The neuroinflammatory and apoptotic markers related to mitochondrial function reflect the complex interplay between mitochondrial stress, inflammation, and cell death in NDs. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) are often upregulated in response to mitochondrial damage, contributing to sustained neuroinflammation [27]. The activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9, which follows the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, is a key indicator of apoptosis. Beyond triggering cell death, High-Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) released during transcriptional repression-induced atypical cell death (TRIAD) also promotes inflammatory signaling in the brain, suggesting a possible connection between neurodegenerative processes and neuroinflammatory responses [28]. Also, the nod-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome (NLRP3 inflammasome) is activated by mitochondrial ROS and damaged mtDNA, further promoting inflammatory responses in the nervous system.

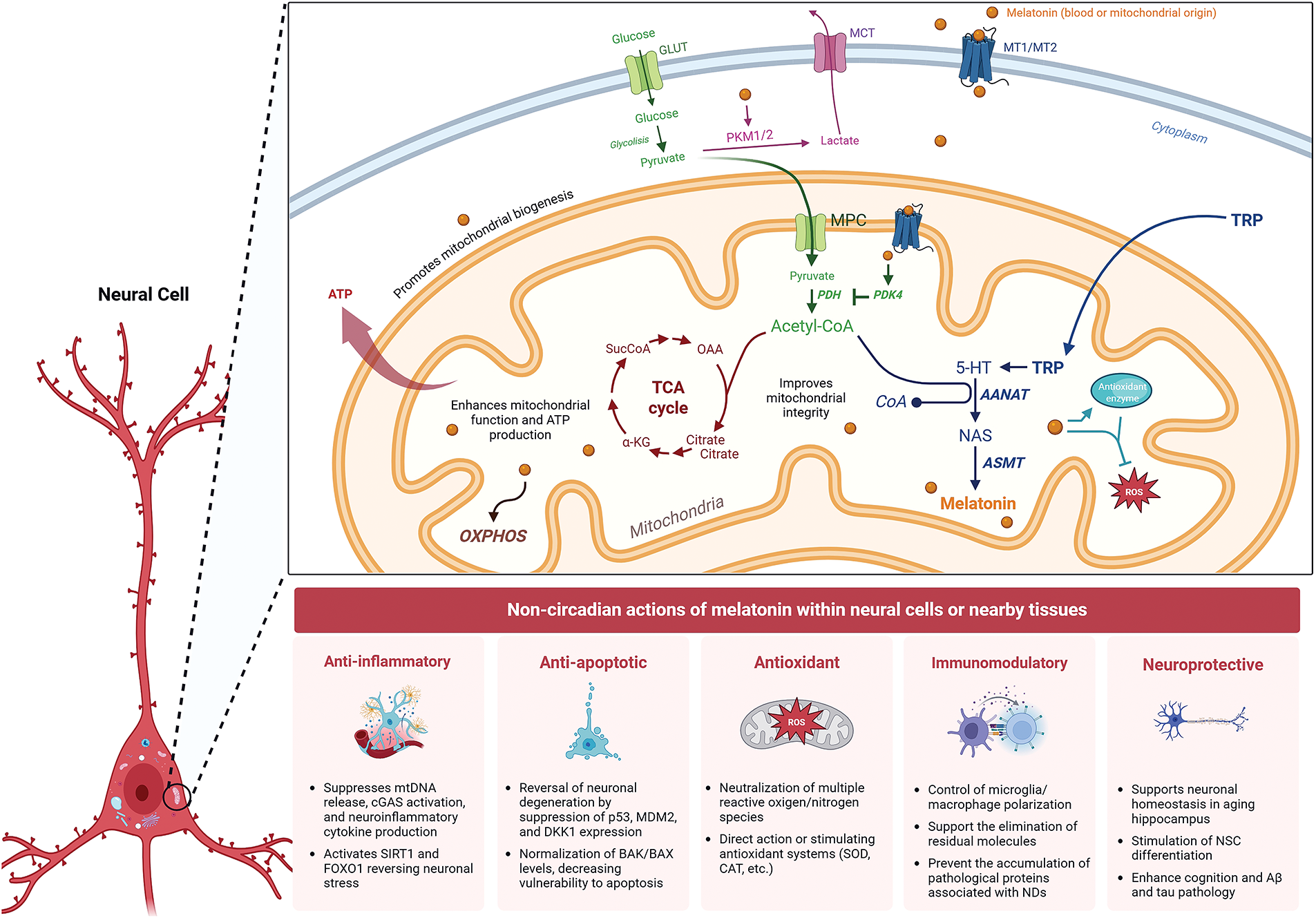

Table 2 summarizes the main biomarkers associated with oxidative processes and mitochondrial stress across NDs.

The biomarkers discussed in Section 2.3—ranging from oxidative stress markers to mitochondrial dysfunction indicators—are critical in understanding the pathological progression of NDs. These biomarkers not only reflect the underlying cellular damage but also highlight the key areas where therapeutic interventions can be targeted to slow or reverse disease progression. Among potential therapeutic agents, melatonin stands out due to its multifaceted ability to address these very stressors. By acting as a potent antioxidant, modulating mitochondrial function, and enhancing cellular clearance systems, melatonin holds promise in mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage. In the following section, we explore the mechanisms through which melatonin exerts its neuroprotective effects, offering a potential strategy for intervening in the mitochondrial stress pathways implicated in NDs.

3 Melatonin as a Neuroprotective Agent

3.1 Overview of Melatonin: Synthesis and Mechanism of Action

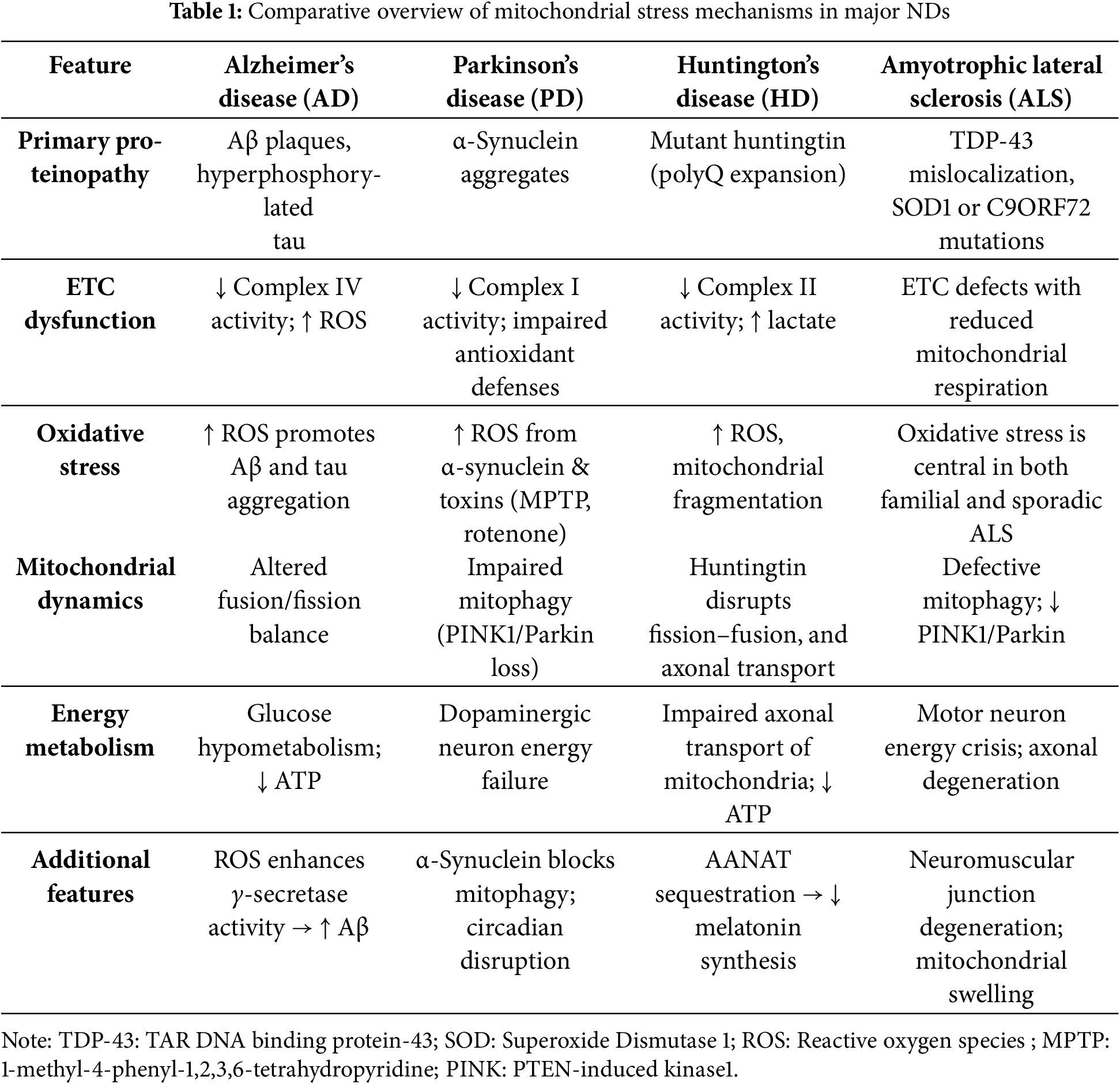

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is a lipophilic indoleamine produced by the pineal gland at night, and in a non-circadian manner by perhaps all cells. Pineal-derived melatonin primarily regulates the master circadian oscillator, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, likely after its release into the cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral clocks via the blood melatonin cycle; both of these actions require an interaction of melatonin with specific membrane receptors [29]. However, the majority of melatonin is likely produced in the mitochondria of various tissues throughout the body, where it plays key roles in metabolic regulation and redox balance (Fig. 1). Unlike pineal melatonin, this extrapineal production acts locally within cells or nearby tissues, rather than being released into the bloodstream [30,31]. Particularly in mitochondria, melatonin is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial permeability, activation of sirtuins, mitochondrial signaling pathways, and modulation of noncoding RNAs [32]. These non-circadian actions of melatonin are closely linked to inflammation control, including microglia/macrophage polarization, modulation of immune signals, and mitochondrial protection, ultimately enhancing antioxidant defenses. In addition to functioning as a chronobiotic agent, melatonin has many other cellular properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and anti-apoptotic functions, as well as a neuroprotective action [29,33–35].

Figure 1: Mechanisms of melatonin action on mitochondrial function and cellular health in neurons. Current evidence suggests that melatonin is synthesized in the mitochondrial matrix and also enters the cell exogenously to regulate mitochondrial metabolism, redox state, oxidative phosphorylation, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and antioxidant enzymes. In a neural cell, melatonin, of pineal or mitochondrial origin, can cross the cell membrane via MT1/MT2 receptors, which are also present in the mitochondrial membrane. Energy metabolism is supported by glucose uptake via Glucose Transporter (GLUT) and its conversion to pyruvate through cytoplasmic glycolysis. Pyruvate enters the mitochondrion via the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC), where it is converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), feeding the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for ATP generation. Melatonin can influence mitochondrial metabolism by regulating acetyl-CoA concentration through modulation of pyruvate kinase M1/2 (PKM1/2) activity, directing pyruvate conversion to lactate, and by inhibiting PDH via activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4). Simultaneously, melatonin is synthesized from tryptophan (TRP) imported into the mitochondria, where it is converted to serotonin (5-HT) and subsequently to melatonin by the enzymes arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT) and acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (ASMT). Mitochondrial melatonin exerts direct intracellular effects and may also be secreted to act in a paracrine or autocrine manner. MCT: monocarboxylate transporter; NAS: N-acetylserotonin, OXPHOS: Oxidative Phosphorylation. Created with biorender.com

The production of melatonin is dependent on the precursor, serotonin, and relies on the transcription, translation, and activation of key enzymes, including arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase (AANAT), acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (ASMT), and tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH); AANAT is considered the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of melatonin [36]. Due to the widespread distribution of its membrane receptors, termed Melatonin receptors 1, 2 and 3 (MT1, MT2, and MT3), melatonin functions as a pleiotropic molecule whose actions extend beyond its established antioxidant properties. Its diverse effects are mediated through distinct primary mechanisms: interaction with membrane receptors, binding to nuclear receptors, crossing the cell membrane to associate with intracellular proteins, and direct free radical scavenging independent of receptors [37,38]. Regarding melatonin-receptor activation in the brain, MT1 receptors are widely distributed throughout the nervous system, including regions such as the hippocampus, suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), caudate, putamen, and retina, among others [39]. In contrast, MT2 receptors are primarily found in the hippocampus, SCN, and retina. Both MT1 and MT2 are expressed in neurons and glial cells across the cerebral and cerebellar cortex, thalamus, and pineal gland [40].

Compared with classical antioxidants such as vitamin C and vitamin E, melatonin displays several mechanistic advantages. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is a water-soluble antioxidant that primarily functions by donating electrons to neutralize reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) and by regenerating other antioxidants, such as vitamin E, from their oxidized forms. However, its activity is largely confined to the aqueous compartments of the cell, and excessive doses may paradoxically exert pro-oxidant effects by reducing transition metals and driving Fenton chemistry. Vitamin E (α-tocopherol), in contrast, is lipid-soluble and localizes predominantly within cellular and mitochondrial membranes, where it prevents lipid peroxidation by stabilizing polyunsaturated fatty acids against radical attack. Nonetheless, vitamin E requires regeneration by vitamin C or other reducing agents to restore its antioxidant capacity once oxidized to the tocopheroxyl radical, limiting its effectiveness in sustained oxidative environments [41].

3.2 Melatonin’s Antioxidant Properties: A General Overview

Melatonin stands out from classic antioxidants due to its unique cascade reaction, where it and its metabolites can sequentially neutralize multiple reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species (RNS) (Fig. 1). Unlike traditional antioxidants that typically neutralize only one free radical, a single melatonin molecule can scavenge up to ten. Comparative studies have shown that melatonin often outperforms antioxidants like vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione, and NADH. This superior protective effect is largely attributed to melatonin’s ability to generate active metabolites that continue scavenging free radicals after the initial interaction [42,43]. Their metabolites possessing antioxidant features include cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin, 2- and 4-hydroxymelatonin, N-nitrosomelatonin, N-(1-formyl-5-methoxy-3-oxo-2, 3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ylidenemethyl) acetamide, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxyknuramine (AFMK), N-acetyl-5-methoxyknuramine (AMK), among others [44]. Based on its direct antioxidant action or via stimulating antioxidant systems (SOD, catalase, glutathione, etc.), melatonin is capable of scavenging a wide variety of oxidant species, including hydroxyl radicals (.OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion (O2−), singlet oxygen, nitric oxide (NO), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), hypochlorite radicals, and lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO−).

Melatonin levels are much more concentrated in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), compared to its concentration in the blood, and may provide enhanced protection against oxidative stress [45]. This differential distribution suggests that melatonin is synthesized in the CNS—including in the choroid plexus [46]– contributes significantly to its high CSF levels, reinforcing its role as a potent neuroprotective agent. Importantly, AANAT enzyme exhibits a circadian expression pattern in the rat choroid plexus and appears colocalized with mitochondria of epithelial cells, specifically, in the choroid plexus, melatonin is believed to be regulated by hormones and by endogenous clock machinery.

Mitochondria play a central role in cellular energy metabolism, producing about 95% of ATP through OXPHOS in aerobic cells. However, this process also generates ROS, which must be efficiently neutralized to prevent mitochondrial damage and impaired ATP production. According to the mitochondrial theory of aging, accumulated oxidative damage to these organelles contributes significantly to the aging of cells, tissues, and organisms. Although conventional antioxidants have been proposed as potential therapies to prevent age-related diseases and mitochondrial dysfunction, their effectiveness in slowing disease progression or aging remains rather limited. In this context, from an ancient and well-developed relationship, melatonin—whether synthesized within mitochondria or transported into them—acts as a multifunctional molecule that has been consistently shown to protect cells from damage under a variety of conditions, including neurodegeneration [47–50].

4 Melatonin in Neurodegenerative Disease Pathogenesis

NDs involve progressive neuronal loss and functional decline, often linked to the accumulation of misfolded proteins due to disrupted protein dynamics and genetic factors. Melatonin has shown promise in enhancing cognition and inhibiting oxidative stress, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent [51]. The evidence supporting melatonin’s role in combating neurodegeneration and promoting brain health is extensive and well-established over time (Fig. 1). On the basis of neuroprotection’s mechanisms, melatonin is able to suppress neuroinflammatory markers, including Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and proinflammatory cytokines, while activating SIRT1, a key pathway linked to longevity and neuroprotection. Additionally, the melatonin treatment, from 6 to 12 months of age, promotes proteasome activity and modulates the neuroprotective growth arrest-specific 6/Tyro3, Axl, and MerTK receptor family (Gas6/TAM) signaling pathway in AD (3xTg-AD) transgenic mice, which enhanced cognition and lowered Aβ and tau pathology [52]. Still looking at SIRT1, long-term melatonin treatment (10 mg/kg for 6 months) reversed neuronal stress and degeneration by restoring SIRT1, Forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1), and melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2) expression while suppressing p53, Murine double minute 2 (MDM2), and Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) [53]. These findings suggest that melatonin supports neuronal homeostasis in the aging hippocampus, potentially offering protection against neurodegenerative processes like those seen in AD (Fig. 1). A previous experimental study by Mendivil-Perez et al. (2017) investigated the potential of melatonin to promote NSC differentiation through mitochondrial modulation, aiming to enhance NSC-based therapies for NDs like PD and AD [54]. NSCs were treated with melatonin (25 μM), and assessments included proliferation and differentiation markers, mitochondrial function (mass, DNA content, respiratory complex levels, membrane potential, ATP synthesis), oxidative stress biomarkers, and in vivo engraftment. Notably, melatonin stimulated NSC differentiation into neurons and oligodendrocytes by enhancing mitochondrial function while preventing oxidative stress (Fig. 1). Moreover, melatonin pretreatment improved NSC engraftment in a neurodegenerative mouse model, which was likely due to mitochondrial activation.

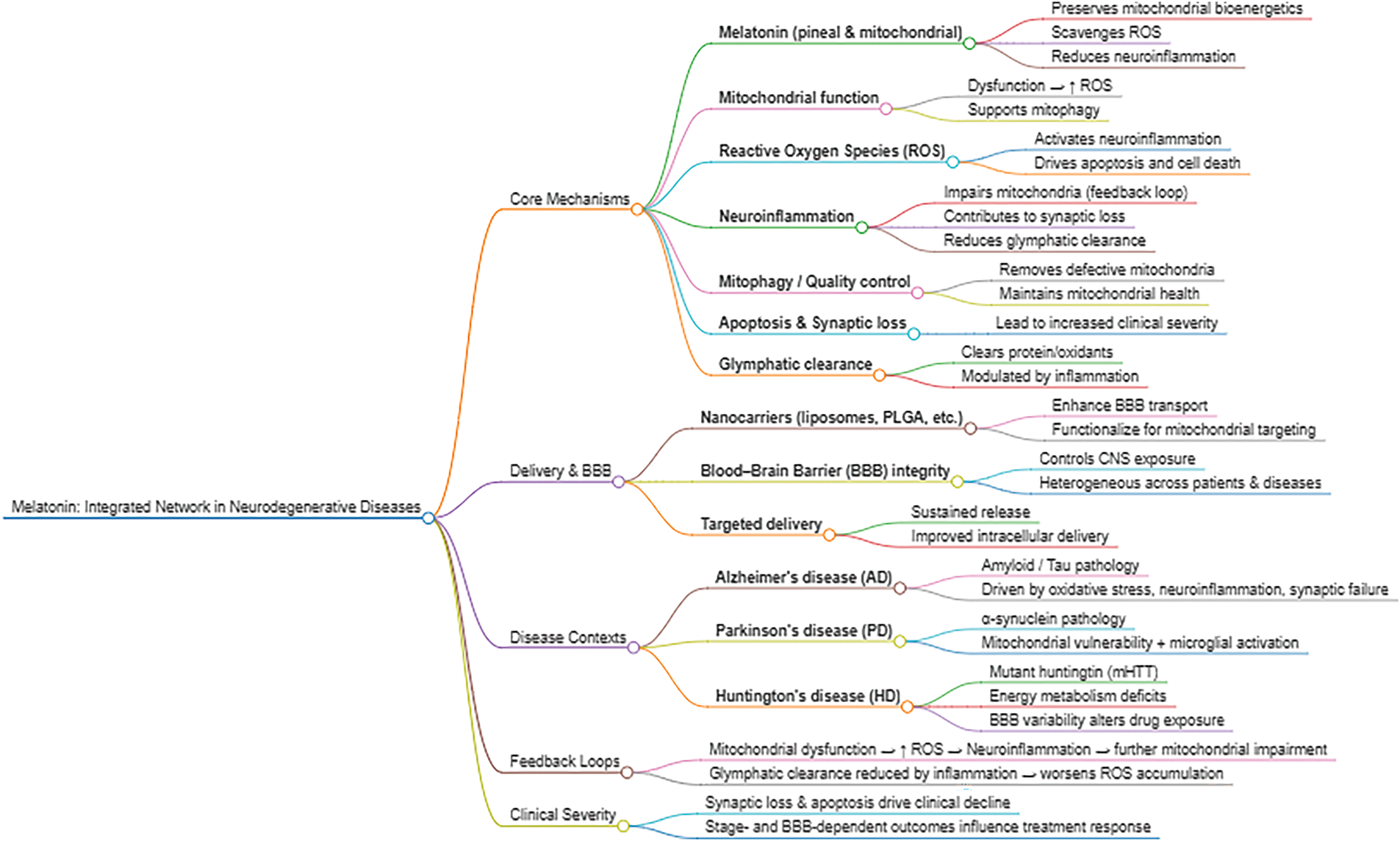

Our group recently compiled the common molecular features shared across most NDs whereby melatonin can modulate. As a versatile antioxidant synthesized within neuronal mitochondria, melatonin effectively reduces electron leakage from the etc, boosts ATP production, and neutralizes ROS/RNS; through the SIRT3/FOXO signaling pathway, melatonin also enhances the activity of key antioxidant enzymes such as SOD2 and glutathione peroxidase (Fig. 1). From a metabolic standpoint, neuronal glucose utilization is influenced by melatonin. In NDs, neurons often shift to a Warburg-type metabolic profile, which prevents pyruvate from entering mitochondria, lowering acetyl-CoA production. Since acetyl-CoA feeds mitochondria for both energy generation, i.e., via the citric acid cycle and OXPHOS, and for melatonin synthesis, this metabolic shift leads to reduced melatonin levels accompanied by aerobic glycolysis [6].

Recent findings involving brain tissue have revealed the existence of a specialized clearance pathway known as the glymphatic system, which relies on the movement of CSF through perivascular channels and its interaction with lymphatic vessels located in the dura mater. This coordinated mechanism facilitates the removal of harmful substances, including neurotoxic aggregates like Aβ. Emerging evidence suggests that melatonin—secreted in high concentrations by the pineal gland directly into the CSF—may enhance glymphatic function. By promoting CSF flow and supporting the clearance of waste molecules, melatonin could play a critical role in maintaining brain homeostasis and preventing the buildup of pathological proteins associated with NDs [29]. NDs involve multiple interacting factors, including mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired glymphatic clearance. The glymphatic system is highly active during slow-wave sleep, facilitating the removal of neurotoxic proteins such as Aβ and phosphorylated tau. In NDs, however, sleep disturbances are common and disrupt glymphatic flow, thereby accelerating protein accumulation and neuronal injury. This interplay creates a vicious cycle, where impaired clearance further worsens sleep quality and circadian dysregulation. By restoring circadian rhythmicity and improving sleep consolidation through its chronobiotic actions, melatonin may indirectly enhance glymphatic function, supporting brain homeostasis. Thus, melatonin’s dual role—as a regulator of sleep-wake cycles and as a mitochondrial/antioxidant agent—positions it uniquely to counteract two converging pathological drivers of neurodegeneration: metabolic stress and impaired waste clearance [55].

A recent review on brain aging and neurodegeneration discussed the effectiveness of melatonin-based treatments for well-known NDs in both experimental and clinical studies [56]. Of note, melatonin and its metabolites—AFMK and AMK—help protect the brain from oxidative damage by preserving mitochondrial function, particularly as the brain ages. Clinical trials have consistently demonstrated that melatonin can slow brain aging while providing neuroprotection in progressive NDs, which often occur alongside insomnia. Importantly, early melatonin supplementation appears to enhance its neuroprotective benefits. Despite these promising results, further high-quality studies are essential, particularly those focusing on elderly individuals already showing signs of brain aging or neurodegeneration.

5 Evidence Supporting Melatonin’s Neuroprotective Effects: Focus on Mitochondrial Effects

Melatonin has been widely recognized as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-Aβ aggregation agent (Fig. 1). As a mitochondrial-active agent, melatonin administered to AD animals, enhanced the activity of mitochondria, accompanied by attenuation of Aβ accumulation in the hippocampus and frontal cortex and synaptic dysfunction [57]. Besides ameliorating memory and anxiety, melatonin also prevented the reduction of mitochondrial area of the neuron while improving its ultrastructure in neurons of Cornu Ammonis 1 (CA1) region of the hippocampus. The same group further documented that oral administration of melatonin to rats displaying sporadic AD resulted in an increased number of excitatory synapses and hippocampal synaptic density [58]. Dragicevic and colleagues showed that mitochondrial function is restored by melatonin in the AD mice model [59]. Among their beneficial effects, Aβ levels were significantly decreased in isolated brain mitochondria together with a complete restoration of respiratory rates, ATP levels, and mitochondrial membrane potential in the hippocampus, striatum, and cortex; these events were dependent on melatonin receptor activation.

Based on an in vitro AD model using SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells treated with okadaic acid, Özşimşek et al. studied the effects of melatonin involved with Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) ion channel-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction [60]. Seven experimental groups were established to assess the roles of melatonin and the TRPA1 antagonist, termed AP18. By challenging SH-SY5Y cells with melatonin, a significant reduction in cytosolic Ca2+ levels, apoptosis, mitochondrial depolarization, and oxidative stress was observed compared to untreated AD cells. These protective effects were diminished when TRPA1 channels were blocked by AP18, suggesting that melatonin’s neuroprotective actions in AD may be mediated via TRPA1 modulation. A previous study explored the effects of melatonin on mitochondrial structure and function in 20E2 cells (HEK293 cells expressing mutant APP), a cellular model of AD. Wang et al. evaluated cell viability, mitochondrial biogenesis markers (PGC-1α, Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1 and 2-NRF1 and NRF2-, TFAM), mitochondrial membrane potential, Na+/K+-ATPase, and cytochrome c oxidase activity, ATP levels, mitochondrial DNA/nuclearDNA ratio, and mitochondrial ultrastructure with and without melatonin treatment [61]. Melatonin significantly enhanced mitochondrial function e biogenesis, cell viability, and ATP production, while improving mitochondrial integrity and reducing amyloidogenic APP processing (Fig. 1). These findings suggest that melatonin supports mitochondrial health in AD cells via the PGC-1α–NRF–TFAM pathway, offering potential therapeutic value. More recently, a proteomic study with Nanoscale Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry was conducted to identify protein expression changes in an AD-like model using SH-SY5Y cells exposed to Aβ42 with or without pretreatment with melatonin. Curiously, Aβ42 exposure increased intracellular Aβ42/40 and ptau (Thr181)/total tau ratios, disrupted mitochondrial function, and elevated oxidative stress. Melatonin pretreatment reversed these effects by reducing pathogenic protein accumulation, preserving mitochondrial integrity, and regulating apoptosis- and AD-related protein expression [62].

Reinforcing the observations related to melatonin use, O’Neal-Moffitt and colleagues investigated the administration of melatonin in drinking water from 4 to 16 months of age in AβPP(swe)/PSEN1dE9 (2xAD) transgenic mouse model, to both MT-intact and MT-deficient AD and control mice [63]. Behavioral testing at 15 months showed that melatonin improved spatial memory in a receptor-dependent manner but enhanced non-spatial cognition independently of MTNRs. In addition to reducing amyloid plaque burden and plasma Aβ1-42 levels regardless of receptor status, its effect on antioxidant gene expression required MTNRs. Additionally, melatonin fully prevented the AD-related increase in cytochrome c oxidase activity only in mice with intact MTNRs, showing a receptor-dependent mitochondrial response. Another study still demonstrated the role of melatonin in improving cognitive function and reducing pathology in an Aβ1-42-induced mouse model of AD by analyzing cognitive performance, brain levels of Aβ1-42, beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), and p-tau, mitochondrial integrity, apoptosis-related proteins (caspase-3, B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2-Bcl-2), and tau-regulating enzymes (Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta-GSK-3β, Protein Phosphatase 2A-PP2A). Melatonin treatment improved cognition, reduced mitochondrial damage, and lowered levels of Aβ1-42, BACE1, p-tau, caspase-3, and GSK-3β, while increasing Bcl-2 and PP2A expression. These results suggest that melatonin improves cognitive function by protecting mitochondria altering molecular signaling [64].

Growing evidence pointed to the exposure to paraquat (PQ)—a nonselective, highly toxic herbicide—to be causative of PD. Administration of melatonin to PQ-induced C57BL/6J mice prevented motor deficits and dopaminergic neuron loss [65]. At the mitochondrial level, melatonin protected primary midbrain neurons and SK-N-SH cells from oxidative stress, impaired mitochondrial function, and disrupted axonal mitochondrial transport. Also, melatonin reversed the PQ-induced reduction of kinesin family member 5A (KIF5A), a key motor protein for mitochondrial transport. Overexpression of KIF5A mitigated PQ-induced neurotoxicity, while KIF5A knockdown blocked melatonin’s protective effects. Additionally, inhibition of melatonin’s MT2 receptor (MTNR1B) abolished its neuroprotective actions, suggesting that melatonin acts against neurodegeneration via KIF5A-dependent mitochondrial transport and MT2 receptor signaling. Although melatonin exerts both receptor-dependent and receptor-independent effects, studies using MT2 antagonism in PD models suggest that part of its neuroprotective action is mediated by MT2 receptors, which are enriched in brain regions affected by PD, such as the hippocampus and substantia nigra. However, this contribution is difficult to quantify, since receptor distribution is not always directly correlated with experimental outcomes. More recently, melatonin has also been documented to protect mitochondria of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in the PQ-induced rat model of PD [66]. Among the beneficial effects, melatonin reduced PQ-induced oxidative stress, preserved mitochondrial integrity, and protected dopaminergic neurons from damage. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway using LY294002 blocked Nrf2 activation and abolished the neuroprotective effects of melatonin, thereby indicating that melatonin exerts its effects by activating the Nrf2 pathway through PI3K/AKT signaling, highlighting the critical role of the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 axis in melatonin-mediated neuroprotection in PD.

Aranda-Martínez and colleagues investigated whether melatonin restores circadian rhythms and clock gene function in a zebrafish embryo model of PD induced by MPTP [67]. MPTP-treated embryos disrupted the day-night melatonin rhythm, altered clock gene expression, advanced the activity phase, and caused a shift in mitochondrial dynamics toward fission, leading to increased apoptosis. Notably, in Parkinsonian embryos, treatment with melatonin (1 μM) reversed these effects by restoring circadian rhythms, normalizing clock gene expression, correcting mitochondrial dynamics, and reducing apoptosis. These findings suggest that chronodisruption may be an early pathological event in PD and that melatonin could help reestablish circadian homeostasis. A previous study from the same group showed the melatonin’s potential to both prevent and rescue early neurodegenerative damage in PD models. In zebrafish embryos exposed to MPTP, mitochondrial complex I was inhibited while synuclein was accumulated. MPTP suppressed expression of the Parkin/PINK1/Parkinson disease protein 7 (PARK7, also known as DJ-1) pathway, impairing the mitochondrial quality control network (Parkin/PINK1/DJ-1/Mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase 1-MUL1) and preventing removal of damaged mitochondria. Remarkably, melatonin administered either during or after MPTP exposure prevented or reversed these effects, restoring expression of mitochondrial-related genes, reactivating the quality control network, and recovering motor function [68]. By observing the role of melatonin on Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase and Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS and nNOS) in MPTP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction using knockout mice, it was found that melatonin effectively preserved mitochondrial respiration, reduced NOS activity, and improved motor performance, despite similar mitochondrial impairment occurring in both iNOS- and nNOS-deficient mice. These results suggest that melatonin’s neuroprotective effects operate independently of iNOS-derived nitric oxide and support its potential to counteract pathways of neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in PD [69].

Mutant huntingtin toxicity is linked to a reduction in mitochondrial MT1 levels in both HD models and patient tissues. While wild-type mice exhibit abundant MT1 receptors in brain mitochondria, these levels are markedly diminished in HD mice. Importantly, melatonin treatment prevents huntingtin-induced caspase activation and maintains MT1 receptor expression, suggesting that melatonin’s neuroprotective effects rely on functional MT1 signaling. These findings highlight a pathological mechanism in which huntingtin-driven loss of mitochondrial MT1 receptors increases neuronal vulnerability and may contribute to the progression of neurodegeneration in HD [70].

Melatonin deficiency has been associated with disruption in mitochondrial stability, leading to the release of mtDNA and activation of a cytosolic DNA-driven inflammatory pathway in neurons. Using AANAT knockout mice, which lack melatonin synthesis, elevated mitochondrial oxidative stress, reduced membrane potential, and increased mtDNA release were observed [71]. Notably, the released mtDNA triggered the cGAS/STING/IRF3 (Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/Stimulator of Interferon Genes/Interferon Regulatory Factor 3) signaling cascade, promoting neuroinflammation. Similar patterns were found in HD models, where exogenous melatonin suppressed mtDNA release, cGAS activation, and inflammatory cytokine production. These findings highlight the role of melatonin in maintaining mitochondrial and immune homeostasis in aging and NDs, with AANAT knockout mice serving as a potential model of accelerated brain aging. To reinforce the value of melatonin production in brain areas, a recent study using an R6/2 mouse model of HD found that AANAT protein expression was diminished specifically in synaptosomal mitochondria of the forebrain, correlating with reduced melatonin levels in those regions, while non-synaptosomal mitochondria remained unaffected. In addition, in full-length mutant huntingtin knock-in cells, AANAT was found sequestered within huntingtin protein aggregates, potentially reducing its functional availability. These results support the conclusion that melatonin biosynthesis is compromised in HD due to both protein aggregation and mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly at synaptic sites [72]. Using AANAT knockout (AANAT-KO) neurons lacking melatonin synthesis, Jauhari and colleagues documented that mature neurons—but not undifferentiated neural progenitors—exhibited disrupted metabolic reprogramming and elevated pro-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 homologous antagonist killer (BAK) and BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX) [73]. Of special significance, these alterations were absent in neurons expressing AANAT. Importantly, supplementation with exogenous melatonin during neuronal differentiation restored proper metabolic function and normalized BAK/BAX levels (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that melatonin is essential for the metabolic shift to OXPHOS during neuronal development and that its deficiency impairs this process, increasing vulnerability to apoptosis.

Motor neuron degeneration in ALS, particularly in the SOD1(G93A) transgenic mouse model, is driven by mechanisms including oxidative stress, inflammation, and caspase-mediated cell death. In 2013, Zhang and co-workers reported that melatonin treatment significantly delayed symptom onset, slowed neurological decline, and extended survival in ALS mice [74]. It also preserved motor neurons and prevented spinal cord atrophy. Mechanistically, melatonin inhibited activation of the Receptor-Interacting Protein 2-Rip2/caspase-1 signaling pathway, suppressed cytochrome c release, and reduced caspase-3 expression and activity. Notably, disease progression in ALS mice was associated with a reduction in both endogenous melatonin levels and melatonin receptor MT1 expression in the spinal cord. These results emphasize melatonin’s neuroprotective potential in ALS, suggesting that targeting the Rip2/caspase-1/cytochrome c axis or restoring MT1 signaling could offer novel therapeutic strategies.

5.1.1 Preclinical Studies on Melatonin: Mechanism of Action

Antioxidant Mechanism

Melatonin’s antioxidant properties are central to its neuroprotective effects, acting by neutralizing free radicals and reducing oxidative stress in various ND models.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): In AD models, melatonin administration has been shown to reduce oxidative stress markers such as lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyls. Dragicevic et al. demonstrated that melatonin effectively attenuates Aβ-induced oxidative damage and restores mitochondrial membrane potential.

Parkinson’s Disease (PD): Similar effects are seen in PD models, where melatonin reduces oxidative damage to dopaminergic neurons and enhances mitochondrial function. Studies show that melatonin’s antioxidant action helps improve the activity of mitochondrial complexes and reduces oxidative damage in substantia nigra neurons.

Huntington’s Disease (HD): Preclinical studies show mixed results in HD models. While some research highlights melatonin’s ability to reduce ROS and prevent neuronal apoptosis, others find that melatonin’s antioxidant effects have limited impact on cognitive function, possibly due to the complex interaction of mutant huntingtin with mitochondrial dynamics.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): In ALS models, melatonin’s antioxidant effects reduce oxidative stress in motor neurons, providing neuroprotection and preserving mitochondrial integrity. This reduction in oxidative damage may slow the progression of ALS, but further studies are needed to determine its full impact on disease progression.

Mitochondrial Function and Bioenergetics

Melatonin’s ability to enhance mitochondrial bioenergetics, improving ATP production and restoring mitochondrial integrity, has been a focal point of preclinical research.

Alzheimer’s Disease: In AD, melatonin has been shown to improve mitochondrial function by enhancing ATP production and restoring mitochondrial membrane potential. Dragicevic et al. found that melatonin reduces Aβ accumulation in brain mitochondria and improves synaptic function. These findings suggest that melatonin not only alleviates oxidative damage but also improves mitochondrial bioenergetics, which is crucial for maintaining neuronal health.

Parkinson’s Disease: Melatonin has been reported to improve mitochondrial complex I activity in PD models, where mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of the disease. Preclinical data suggest that melatonin restores mitochondrial bioenergetics and reduces dopaminergic neuron loss, potentially slowing disease progression. Studies by Hardeland et al. indicated that melatonin improves mitochondrial respiration and reduces the effects of neurotoxic agents like MPTP.

Huntington’s Disease: In HD, research demonstrates that melatonin increases mitochondrial biogenesis and improves energy metabolism. However, the impact of melatonin on mitochondrial function in HD models is less consistent. Some studies report significant improvement in mitochondrial integrity, while others suggest that the effect is limited by the pathological role of the mutant huntingtin protein, which disrupts mitochondrial dynamics.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Studies on ALS models have shown that melatonin enhances mitochondrial function, particularly by stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane potential and improving ATP production. Melatonin’s effects on mitochondrial function help preserve motor neurons and reduce the severity of disease symptoms. However, the impact on long-term survival is still uncertain and requires further investigation.

Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Quality Control

Melatonin has been shown to regulate mitophagy, the selective autophagic removal of damaged mitochondria, an important mechanism for maintaining mitochondrial quality.

Alzheimer’s Disease: Preclinical studies suggest that melatonin enhances mitophagy, particularly by activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated pathways, which are critical for the degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria. This enhancement of mitophagy helps maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and may contribute to the observed neuroprotective effects in AD models.

Parkinson’s Disease: Melatonin has a well-documented role in promoting mitophagy in PD models. Research indicates that melatonin restores PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy, which is often impaired in PD, leading to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and neuronal degeneration. Studies by Galano et al. support the idea that melatonin’s ability to regulate mitophagy may help alleviate oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in PD.

Huntington’s Disease: In HD, the mutant huntingtin protein disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and impairs mitophagy, making this an important area of investigation for melatonin’s effects. Some studies suggest that melatonin can restore mitophagy by upregulating PINK1 and Parkin expression, while others report limited improvement, possibly due to the complex interactions between mutant huntingtin and mitochondrial pathways.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): ALS models show that melatonin can restore mitophagy, particularly by enhancing the PINK1/Parkin pathway. This leads to a reduction in mitochondrial dysfunction and an improvement in motor neuron survival. Melatonin’s role in mitophagy is particularly important in ALS, where mitochondrial dysfunction is a central pathological feature.

Circadian Regulation and Sleep

Melatonin’s role as a chronobiotic agent is critical in NDs, where sleep disturbances exacerbate disease pathology by impairing the glymphatic clearance system, which removes neurotoxic proteins from the brain.

Alzheimer’s Disease: Preclinical evidence shows that melatonin restores normal sleep patterns and enhances glymphatic clearance, which is disrupted in AD. By improving sleep quality, melatonin indirectly supports the removal of Aβ, a hallmark of AD pathology.

Parkinson’s Disease: Similar to AD, sleep disturbances are common in PD, and melatonin has been shown to improve sleep-wake cycles. Research indicates that melatonin enhances glymphatic function by improving sleep quality, thereby facilitating the clearance of neurotoxic proteins.

Huntington’s Disease: In HD, sleep disturbances are also prevalent, and melatonin treatment has been shown to restore circadian rhythms and improve sleep. While the effects on glymphatic clearance are not fully understood, the improvement in sleep quality may help mitigate some of the disease’s neurodegenerative effects.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): While research in ALS is more limited, some studies suggest that melatonin can improve sleep quality, which may help reduce neuroinflammation and promote overall neuronal health. However, its direct effect on glymphatic clearance remains uncertain.

Comparative Evaluation of Research Results

1. Antioxidant Mechanism: Melatonin consistently shows strong antioxidant effects across all models, particularly in AD and PD. In HD, its antioxidant benefits are less pronounced, likely due to the complexity of mutant huntingtin’s effects on mitochondria. In ALS, antioxidant effects are observed but require further validation in long-term studies.

2. Mitochondrial Function: Preclinical studies demonstrate that melatonin enhances mitochondrial function and bioenergetics, particularly in AD and PD. In HD, results are mixed, with some studies reporting mitochondrial benefits and others showing limited effects due to huntingtin-related dysfunction. In ALS, melatonin’s impact on mitochondrial function is significant, although its long-term therapeutic potential remains uncertain.

3. Mitophagy: Melatonin’s role in regulating mitophagy is well-documented in PD and ALS, where it restores PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy. In HD, melatonin’s impact is less consistent, possibly due to mutant huntingtin’s interference with mitochondrial dynamics.

4. Circadian Regulation: Sleep disturbances are a common feature in NDs, and melatonin’s ability to restore circadian rhythms and improve sleep quality has been widely supported across AD, PD, and HD models. Its effect on ALS models is less clear but suggests potential benefits in reducing neuroinflammation and promoting neuronal health.

The utilization of melatonin as a promising therapeutic approach to combat NDs in humans, particularly in aging populations, has gained increasing scientific support due to its diverse nature of actions [75]. Melatonin exerts a multifaceted neuroprotective effect through its potent antioxidant properties, which help neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress while maintaining neuronal functionality and integrity. Additionally, its anti-inflammatory actions suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines while promoting protective immune pathways, helping to mitigate chronic neuroinflammation often observed in AD and PD. Melatonin also plays a critical role in restoring circadian rhythm integrity, improving sleep quality and cognitive performance, which are frequently impaired in NDs.

While melatonin treatment has shown limited effectiveness in alleviating cognitive decline and psychiatric or behavioral symptoms in individuals with AD, especially at advanced stages, some benefit has been observed in improving sleep disturbances in patients with mild to moderate AD. Also, melatonin use by AD patients exhibits a reduced incidence of sundowning, a characteristic of this condition [76]. In contrast, individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have responded more positively, showing improvements in sleep, cognition, mood, and behavioral symptoms. Despite mixed clinical outcomes, melatonin remains a compound of interest due to its unique ability to regulate circadian rhythms and combat oxidative stress—functions that are crucial in ND prevention. Melatonin levels naturally decline with age, a factor believed to increase susceptibility to conditions like AD [77]. Restoring melatonin may improve sleep quality and help stabilize biological rhythms, potentially slowing disease progression. Unlike conventional antioxidants such as vitamins C and E—which can generate harmful pro-oxidant by-products—melatonin neutralizes free radicals without producing toxic intermediates, making it a more efficient and safer antioxidant [75]. These properties underscore the need for further research into melatonin’s therapeutic role in NDs.

Extensive research on melatonin has highlighted its potential to alleviate various clinical symptoms associated with AD. Early case reports demonstrated notable improvements in cognitive performance, behavioral disturbances, sleep quality, and sundowning symptoms with melatonin supplementation of 2 mg during the first to third week of treatment [78]. For example, treatment in AD-affected twins and individuals with sundown syndrome showed positive responses, including enhanced sleep and mood regulation with carefully timed melatonin dosing. Melatonin has also been shown to reduce rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and reinforce circadian rhythms, contributing to improved sleep-wake patterns and reduced daytime drowsiness. Moreover, combining melatonin with bright light therapy has been reported to enhance these effects, especially in managing sundowning symptoms [79]. Although melatonin appears beneficial for stabilizing biological rhythms and slowing cognitive deterioration in many cases, inconsistencies across studies emphasize the need for more robust clinical trials to determine its effectiveness and identify which patient populations are most likely to benefit.

Exploring complementary therapies alongside melatonin supplementation may enhance its effectiveness in managing PD. Research indicates variability in endogenous melatonin levels among PD patients, even during supplementation, suggesting individual differences in absorption or metabolism. Clinical studies have assessed how exogenously administered melatonin influences PD symptoms. Notably, clinical controlled trials reported significant improvements in sleep disturbances among PD patients receiving melatonin treatment [80], highlighting its potential role in addressing one of the most common non-motor symptoms of the disease. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial was conducted in 26 PD patients to assess the effects of melatonin on oxidative stress and mitochondrial function [81]. Participants received 25 mg of melatonin or a placebo twice daily for three months. Melatonin significantly reduced plasma levels of lipoperoxides, nitric oxide metabolites, and carbonyl groups, while increasing catalase activity. Additionally, melatonin enhanced mitochondrial complex I activity and the respiratory control ratio compared to placebo, without affecting membrane fluidity. These findings suggest that melatonin may improve mitochondrial efficiency and reduce oxidative damage in PD patients, supporting its therapeutic potential.

In brain tissue samples from HD patients, the expression of AANAT—the rate-limiting enzyme in melatonin synthesis—was significantly reduced in both the pineal gland and striatum compared to healthy controls. Despite this reduction in AANAT protein, mRNA levels were paradoxically elevated, suggesting an ineffective compensatory feedback mechanism. These findings indicate that melatonin production is impaired in HD patients, likely contributing to disease pathology [72].

Only a few clinical studies have explored melatonin’s potential in treating ALS. In one early ALS study, three patients received nightly doses of 30–60 mg of slow-release melatonin over 13 months. Results showed that one individual experienced a noticeable slowing of disease progression, while the others showed a reduced rate of decline during follow-up [82]. A more recent trial involving 31 ALS patients administered 30 mg of melatonin at bedtime for two years alongside standard treatments. While this high dose effectively reduced oxidative stress markers, it did not produce measurable improvements in clinical symptoms or slow neurodegeneration [83]. These findings suggest that although melatonin may help manage oxidative stress in ALS, its impact on disease progression remains uncertain and warrants further investigation, especially relative to melatonin dose and duration of treatment.

While preclinical evidence in models of HD and ALS is compelling, clinical data remain scarce and often inconsistent. Most available studies are limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneous patient populations, and variability in dosing regimens, duration of treatment, and outcome measures. These factors make it difficult to establish clear conclusions regarding efficacy. Furthermore, differences in trial design and the absence of standardized biomarkers for monitoring mitochondrial function and oxidative stress in patients represent additional obstacles. The inconsistent effects of melatonin observed in HD models may reflect fundamental differences in disease stage and BBB integrity. In early stages, when synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction predominate but neuronal loss is still limited, melatonin’s antioxidant and mitochondrial-protective actions appear more effective. By contrast, in advanced stages, widespread neuronal degeneration may diminish the capacity of melatonin to restore function. Moreover, BBB integrity is variably affected across HD models and disease progression. In some cases, a relatively intact BBB may limit central drug penetration, while in others, barrier disruption alters both the degree and regional distribution of melatonin exposure. Together, these factors help explain why similar dosing regimens can yield divergent outcomes, underscoring the need for stage-specific and BBB-conscious therapeutic strategies in future research. Addressing these limitations through well-designed, adequately powered clinical trials will be crucial to translating the promising preclinical findings of melatonin into effective therapeutic strategies for HD and ALS.

6 Nanopharmacological Approaches in Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment

Nanopharmacology is an evolving field that has shown significant promise in the treatment of NDs. It utilizes nanoparticles (NPs) as carriers for drug delivery, offering numerous advantages over traditional therapeutic approaches [84]. In the context of NDs, where issues such as poor drug bioavailability, BBB penetration, and side effects from systemic drug administration are prevalent, nanopharmaceuticals present a new frontier for effective treatment [85].

6.1 Introduction to Nanopharmacology

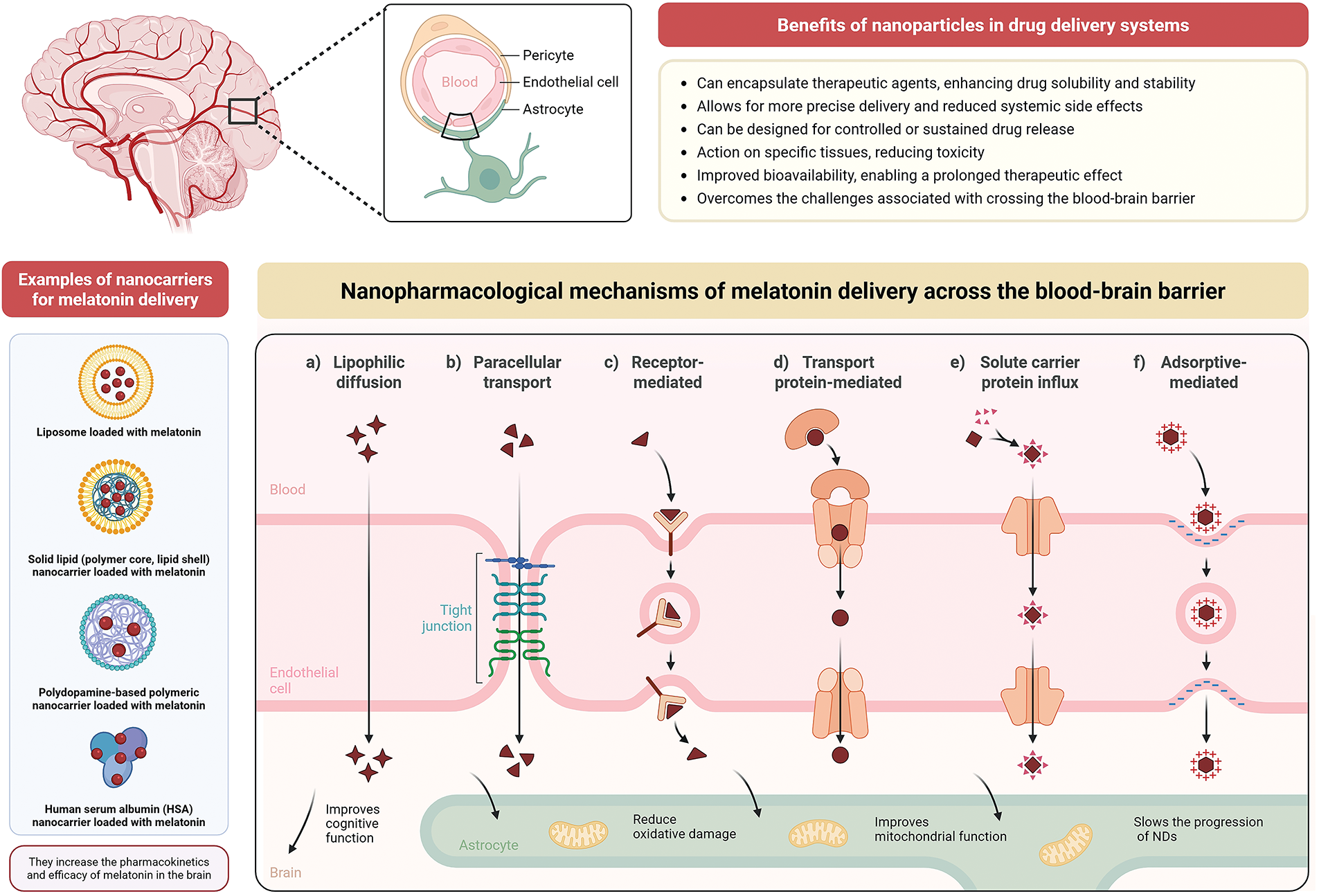

Nanopharmacology refers to the application of nanotechnology in drug formulation and delivery. Nanoparticles, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm in size, are engineered to carry therapeutic agents, such as drugs or biologics, to specific tissues or organs with improved efficacy and reduced toxicity [86]. In the context of NDs, these nanoparticles can be designed to target the brain and CNS, addressing the challenges associated with crossing the BBB (Fig. 2) [87].

Figure 2: Mechanisms and types of nanoparticles for melatonin delivery across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and their implications for mitochondrial targeting processes in the brain. The BBB is composed of endothelial cells, astrocytes, and pericytes, which regulate the entry of substances from the bloodstream into the central nervous system (CNS). Nanoparticles have been explored as efficient systems for delivering melatonin to the brain, enhancing its bioavailability, stability, pharmacokinetics, and therapeutic efficacy. Examples of nanocarriers used to encapsulate melatonin include liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (with a polymeric core and lipid shell), polydopamine-based nanocarriers, and human serum albumin (HSA) nanocarriers. These carriers can diffuse melatonin (symbols in dark red) into nervous tissue through various nanopharmacological mechanisms, including: a) Lipophilic diffusion: allowing passive transport of small lipophilic molecules; b) Paracellular transport: through tight junctions between endothelial cells; c) Receptor-mediated endocytosis: where nanoparticles bind to specific receptors on the endothelial membrane; d) Transport protein-mediated uptake: facilitating the entry of molecules through specific transporters; e) Solute carrier protein influx: using pathways similar to those of endogenous nutrients and metabolites; and f) Adsorptive-mediated endocytosis: based on non-specific electrostatic interactions between nanoparticles and the cell surface. These mechanisms enable melatonin-loaded nanoparticles to cross the BBB and exert neuroprotective effects in the CNS, such as improving cognitive function and restoring mitochondrial function by reducing oxidative stress, consequently, slowing the progression of NDs. Additional general benefits of using nanoparticles in drug delivery systems include enhanced solubility and stability, controlled release, targeted action, reduced systemic side effects, and the ability to overcome physiological barriers like the BBB. Created with biorender.com

6.2 Benefits of Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery Systems

Nanoparticles offer several advantages in drug delivery, particularly for treating NDs. They can encapsulate therapeutic agents, enhancing drug solubility and stability, which leads to improved bioavailability [88]. By adjusting their surface properties—such as modifying surface charge or adding targeting ligands—nanoparticles can be directed to specific regions of the brain or neural tissue, allowing for more precise delivery and reduced systemic side effects. A major challenge in central nervous system therapies is the BBB, which limits the entry of most drugs [89]. Nanoparticles are uniquely capable of crossing this barrier through mechanisms like receptor-mediated endocytosis, diffusion through tight junctions, or by engaging with transport proteins found on endothelial cells. This ability significantly increases the potential for effective treatment of conditions such as AD and PD disease [90]. Furthermore, nanoparticles can be designed for controlled or sustained drug release, enabling a prolonged therapeutic effect and reducing the need for frequent dosing. This approach also lowers the likelihood of adverse effects associated with fluctuating drug levels by maintaining a more consistent release over time (Fig. 2) [91].

6.3 Types of Nanoparticles Used in Neuropharmacology

Several types of nanoparticles have been investigated for their potential in drug delivery systems targeting NDs (Fig. 2). Liposomes, which are lipid-based nanoparticles, can encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs. Their biocompatibility and ability to be surface-modified make them suitable for improving drug release profiles and targeting specific sites, with notable applications in delivering antioxidants, anti-inflammatory agents, and neuroprotective compounds such as melatonin [92]. Polymeric nanoparticles, typically made from biodegradable polymers like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG), offer considerable flexibility in drug loading, sustained release, and compatibility with biological systems, making them effective for brain-targeted therapies [93]. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, including those made from gold, silver, and iron oxide, provide unique advantages such as magnetic responsiveness and low toxicity, allowing for more precise delivery of therapeutic agents [94]. Solid lipid nanoparticles represent another innovative approach, offering enhanced drug stability due to their solid-state form at body temperature. They are especially effective in transporting lipophilic molecules like melatonin across the BBB [95].

6.4 Nanocarriers for Melatonin Delivery

Melatonin is a neuroprotective agent with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and mitochondrial protective properties, making it a candidate for the treatment of NDs. However, its poor bioavailability and rapid metabolism limit its therapeutic potential. Nanocarriers have emerged as an effective means to enhance melatonin’s bioavailability, stability, and delivery to the brain (Fig. 2) [96]. Several studies have explored the use of nanoparticles to deliver melatonin in ND models. The use of liposomal, polymeric, and solid lipid nanoparticle-based systems has been shown to enhance the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of melatonin in the brain [97].

In vivo studies have shown that melatonin-loaded nanoparticles are capable of significantly reducing neurodegenerative symptoms in animal models. For example, studies using polymeric nanoparticles loaded with melatonin have demonstrated improvements in cognitive function, reduced oxidative stress, and mitigated mitochondrial dysfunction in rodent models [98,99]. Similarly, in vitro studies have shown that melatonin-loaded nanocarriers protect neural cells from oxidative damage, apoptosis, and inflammation, highlighting their potential for clinical translation [100]. These formulations not only enhance the therapeutic effects of melatonin but also improve its half-life, ensuring prolonged and controlled delivery to the affected neural tissues. Moreover, the encapsulation of melatonin in nanoparticles minimizes its potential for side effects, such as the gastrointestinal disturbances seen with oral administration [101,102].

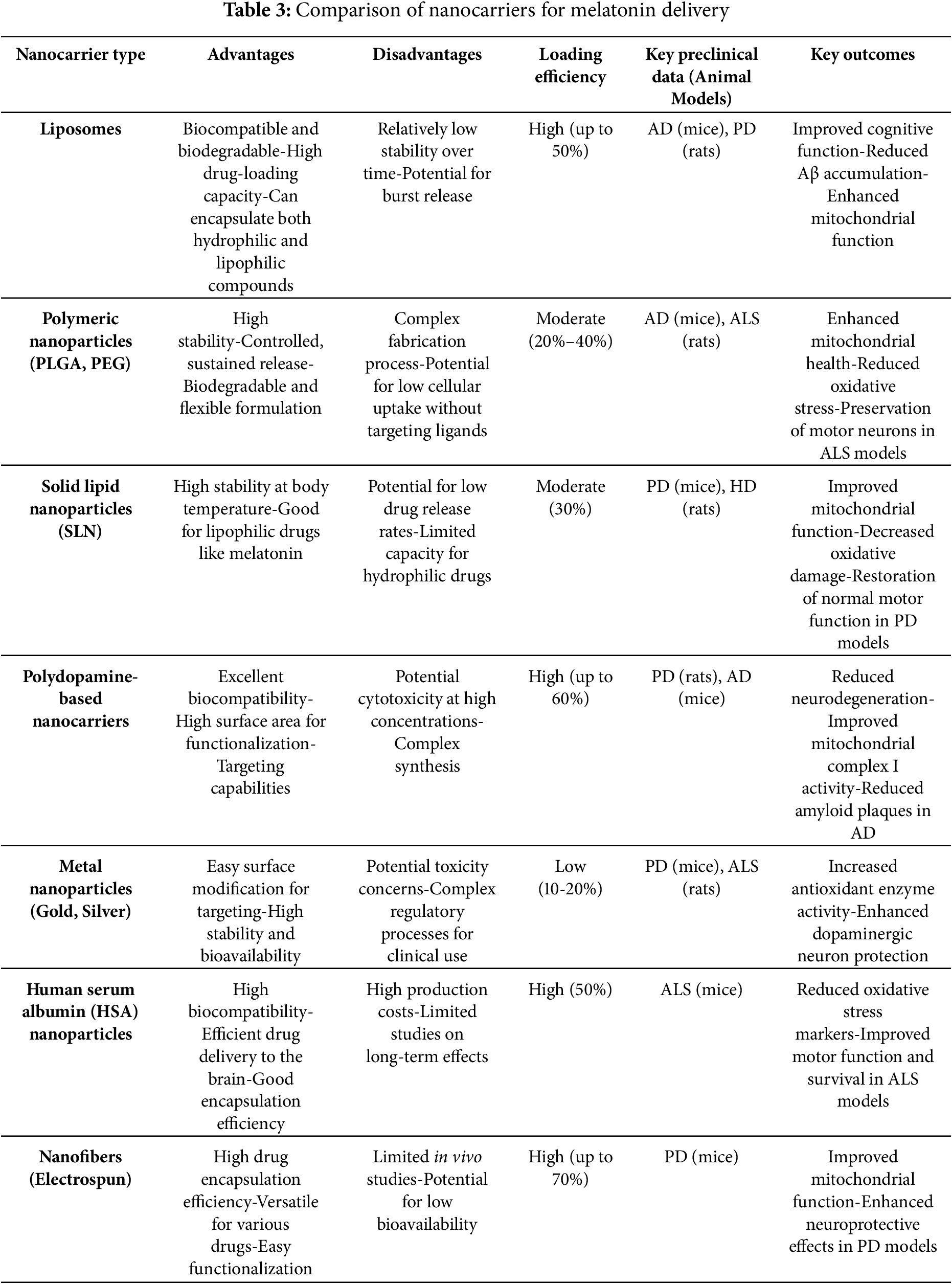

Table 3 summarizes and compare the advantages and disadvantages of different nanocarriers in melatonin delivery.

6.5 Real-World Bottlenecks for Nanocarrier Translation

Despite encouraging preclinical findings, the clinical translation of melatonin-loaded nanocarriers faces several obstacles. One of the most pressing challenges lies in manufacturing and scale-up. Many promising systems are designed at laboratory scale, where reproducibility is relatively easy to control, but the same methods often fail under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions. Issues such as batch variability, high production costs, and the complexity of purification steps can slow progress [103]. Early collaboration with process engineers and the adoption of scalable, standardized platforms—such as liposomes or PLGA-based formulations—may help bridge the gap between bench and bedside.

Concerns regarding safety, immunogenicity, and long-term clearance also remain. Nanocarriers frequently accumulate in the liver, spleen, or other organs, raising questions about chronic toxicity and immune activation. To move forward, long-term toxicological studies in both rodents and non-rodents, together with careful design of biodegradable materials that follow predictable clearance pathways, are required to build confidence in their clinical use [104].

Another barrier is the regulatory landscape, which continues to evolve unevenly across different jurisdictions. The absence of harmonized definitions and standardized assays for nanoparticle characterization complicates approval processes. Early dialogue with regulatory agencies, together with the use of well-established analytical parameters such as particle size, surface charge, drug loading, and release kinetics, can provide clearer pathways toward approval [105].

Heterogeneity of the BBB presents a further complication. Its permeability varies not only across individuals but also with age, disease stage, and comorbidities, which means that findings in animal models do not always translate reliably to human patients. Incorporating companion diagnostics, such as imaging or cerebrospinal fluid markers, and exploring alternative delivery routes like intranasal administration may help overcome these inconsistencies and guide patient stratification in clinical studies [106].

Finally, challenges in clinical trial design make it difficult to demonstrate neuroprotection or disease modification. NDs often progress slowly, and conventional endpoints may be too insensitive to detect therapeutic benefit. The limited availability of standardized biomarkers for mitochondrial dysfunction adds to this difficulty. Innovative trial designs that integrate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessments, alongside emerging mitochondrial and oxidative stress biomarkers, could provide earlier indications of efficacy and accelerate the evaluation of melatonin nanotherapies [107].

7 Melatonin Nanopharmacology: A Targeted Strategy for Mitigating Mitochondrial Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases

7.1 Role of Nanoparticles in Enhancing Melatonin’s Therapeutic Efficacy