Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Apoptosis in Human Gastric Cancer Cells is Triggered by Petasites japonicus Extract via ROS-Dependent MAPK Pathway Activation

Department of Longevity and Biofunctional Medicine, Pusan National University School of Korean Medicine, Yangsan, 50612, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Byung Joo Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Natural Product-Based Anticancer Drug Discovery)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2365-2375. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072715

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Petasites japonicus (PJ) is a traditional medicinal herb widely used in East Asia for treating diverse ailments. However, its anticancer properties and underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated. This study investigated the anticancer potential and molecular mechanisms of the methanol extract of Petasites japonicus (PJE) in human adenocarcinoma gastric stomach (AGS) cells. Methods: AGS cells were treated with various concentrations of PJE, and cell viability was measured using MTT and CCK-8 assays. Apoptotic cell death was evaluated by the cell cycle, caspase-3 and -9 activity assays, and western blotting. To elucidate the underlying signaling mechanisms, we also examined the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Results: PJE significantly decreased AGS cell viability and increased the sub-G1 population, indicating apoptosis. PJE upregulated Bcl–2–associated X protein (Bax) expression while downregulating B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and surviving. Increased cleavage of caspase-3, caspase-9, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1 confirmed the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Moreover, PJE induced phosphorylation of MAPKs and induced a dose-dependent increase in ROS generation. Conclusions: PJE triggers apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through ROS-dependent mitochondrial and MAPK signaling, leading to potent anticancer effects. These findings highlight PJ as a promising natural source for developing new therapeutic agents for gastric cancer.Keywords

The global incidence of gastric cancer continues to increase, making it the fifth most frequently diagnosed malignancy worldwide [1,2]. The most common type of gastric cancer is adenocarcinoma. Early gastric cancer is associated with a good prognosis after surgery; however, advanced gastric cancer does not have a good prognosis following surgery alone [3,4]. Administering the best-performing chemotherapy does not necessarily result in satisfactory clinical outcomes [5,6]. Hence, gaining a deeper understanding of methods to overcome difficulties in gastric cancer treatment will expand the scope of novel therapeutic strategies.

Historically, humans have used various methods to avoid pain caused by diseases. Amongst these methods, plants have been employed for treatments as they also play a major role in daily life, eventually developing medicinal plants in modern times [7]. Despite their therapeutic efficacy, chemotherapy drugs are frequently associated with adverse side effects, including nausea, vomiting, mucosal inflammation, neuropathy, and alopecia in normal cells [8]. In addition, more than 90% of cancer patient deaths undergoing chemotherapy are associated with multidrug resistance (MDR) [9,10].

Among the various chemotherapy treatments, natural products have attracted considerable attention as sources of anticancer agents for more than half a century, with amazing chemical diversity [8]. As a result, natural products were used clinically, and many improvements were made by discovering new natural-friendly cancer treatment opportunities [11]. Petasites japonicus (PJ) is a perennial herbaceous plant found in China, Japan, and Korea, especially in sunlit hillside forests and wetlands around valleys [12–14]. It has a unique fragrance, bitter taste, and is used as a medicinal herb in oriental medicine. It is known to be an effective expectorant and diuretic. It is also known to be an effective treatment for diseases, such as migraine, gastric ulcer, asthma, etc. [12–14].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of the methanol extract of Petasites japonicus (PJE) on human gastric cells and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved, including apoptosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways.

PJE were prepared by referring to methods described in a previous study [15]. PJ contains chlorogenic acid 0.94 ± 0.05 mg/g, 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid 1.62 ± 0.05 mg/g, and 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid 1.53 ± 0.03 mg/g [15–17]. PJE was stored in the Department of Longevity and Biofunctional Medicine at the School of Korean Medicine of Pusan National University (Voucher No. 2021-010).

AGS human gastric adenocarcinoma cells (No. 21739) were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Catalog number 11875093; contains amino acids, vitamins, inorganic salts, and glucose) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Catalog number A5256701, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Catalog number 15240062, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. All cultures were verified free of mycoplasma contamination.

2.3 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assay

Cell viabilities were assessed using an MTT assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, No. CT01). AGS cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well, and after treatment with 10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL of PJE for 24 h, MTT solution (20 μL, 5 mg/mL) was added to each well, and it was incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide. Cell viability was assessed by measuring absorbance at 570 nm with a SpectraMax iD3 Multi-Mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA), and results were expressed relative to the control group. For the control group, cells were incubated in the absence of PJE (0 μg/mL) to serve as the untreated control.

AGS cell viability was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Abbkine Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China, Catalog number KTA1020). Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and exposed to different concentrations of PJE (10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL) for 24 h. After treatment, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax iD3 Multi-Mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

AGS cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. After treatment with various concentrations of PJE (10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL) for 24 h, cells were collected, and cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μL of PBS and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol, followed by incubation at 4°C for 2 h. After fixation, cells were washed once with PBS and then incubated in 500 μL of staining solution containing 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No. P4170) and 100 μg/mL RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. R4875) for analysis. The suspension was incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark to ensure proper DNA staining. A fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACScan; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used with excitation at 488 nm and emission collected at 617 nm using a SpectraMax iD3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were processed using CellQuest software (Version 5.1; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

AGS cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 89900), and protein concentrations were measured using the protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 23225). Proteins were separated by 10%–12% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Cat. No. 4561096) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Cat. No. IPVH00010) for 90 min at 4°C. Primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution at 4°C overnight) against survivin (#2808), ERK (#9102), p-ERK (#9106), JNK (#9252), p-JNK (#9251), p38 (#9212), and p-p38 (#9216) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), and BCl-2 (#sc-783), Bax (#sc-493), caspase-3 (#sc-7148), caspase-9 (#sc-7885), PARP-1 (#sc-7150), and β-actin (#sc-47778) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Secondary antibodies (HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG; 1:5000 dilution; Santa Cruz #SC-2004, #SC-2005) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Protein band intensities were quantified using a GS-710 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and analyzed with ImageJ software (v1.52a, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Protein molecular weight markers (CHEMBIO, Howell, NY, USA) were used to estimate the molecular sizes of the detected proteins.

To evaluate caspase-3 (BioMol, Plymouth, PA, USA, G-HUFI00393.96) and -9 activity (BioMol, G-HUFI00393.96), the Cellular Activity Assay Kit Plus was utilized. Cell lysates were transferred to a 96-well microplate (Corning, NY, USA) at 50 μL per well and incubated with 400 μM Ac-DEVD-p-nitroaniline (pNA) to measure caspase-3 activity and with Ac-LEHD-pNA to measure caspase-9 activity (BioMol, Plymouth, PA, USA). It was gently mixed and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the dark to prevent light-sensitive substrate degradation. Caspase activity was calculated by measuring the release of pNA from the respective substrates, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm every 10 min at 37°C per μg protein per minute using a SpectraMax iD3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

AGS cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with PJE. The cell pellets were in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium (Catalog number 11875093; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Catalog number A5256701, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog number 15240062). Then, ROS generations were assessed using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA; Catalog number D399, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry (FACS; Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 488 and 525 nm, respectively. Data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Version 5.1; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The ROS levels of PJE-treated cells were normalized to the untreated control.

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple group comparisons. Statistical calculations were carried out using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) software. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 PJE Induces Cell Death in AGS Cells

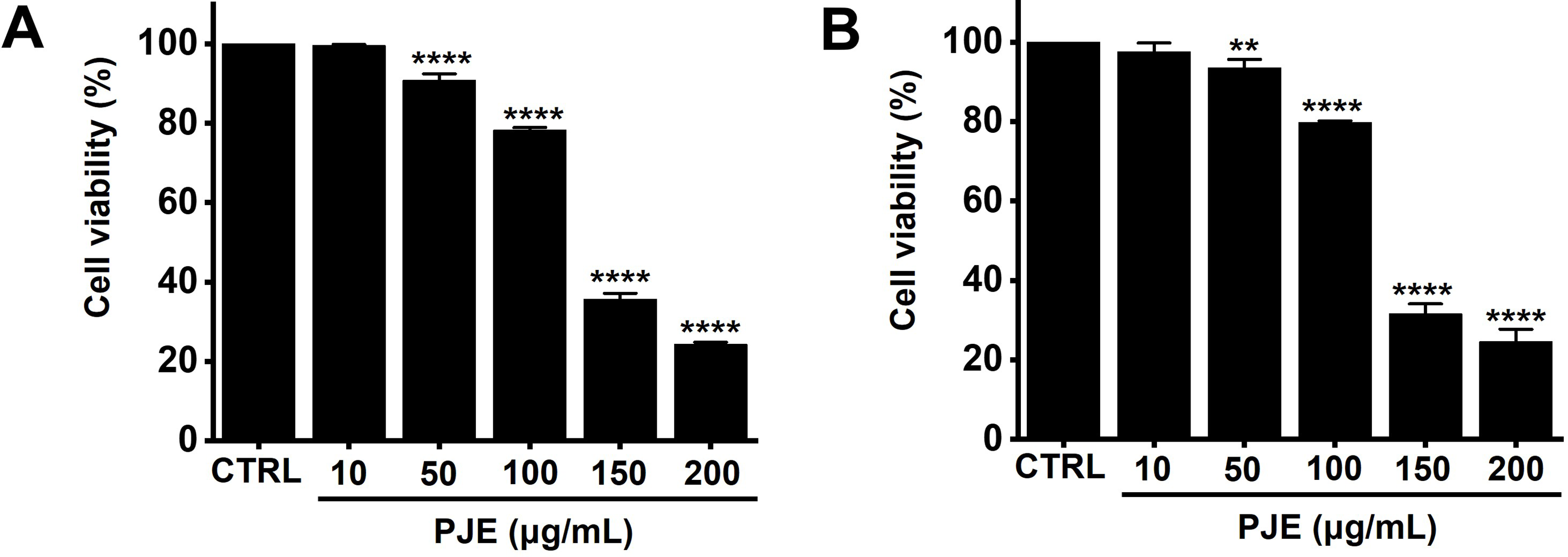

AGS cells treated with PJE at concentrations of 10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in viability, with reductions of 99.6 ± 0.3%, 90.9 ± 1.6%, 78.2 ± 0.7%, 35.6 ± 1.6%, and 24.3 ± 0.5% after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 1A). Similarly, viability checked via the CCK-8 assay showed decreases of 97.6 ± 2.2%, 93.5 ± 2.2%, 79.8 ± 0.4%, 31.6 ± 2.5%, and 24.5 ± 3.2% at the corresponding concentrations (Fig. 1B). To determine whether this cytotoxicity was attributable to apoptosis, cell cycle analysis was performed.

Figure 1: Effects of PJE on AGS cell proliferation. AGS cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PJE (10–200 μg/mL) for 24 h, and cell viability was subsequently assessed via (A) MTT assay and (B) CCK-8 assay. Statistical significance is indicated as **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001. CTRL, Control. PJE, methanol extract of PJ

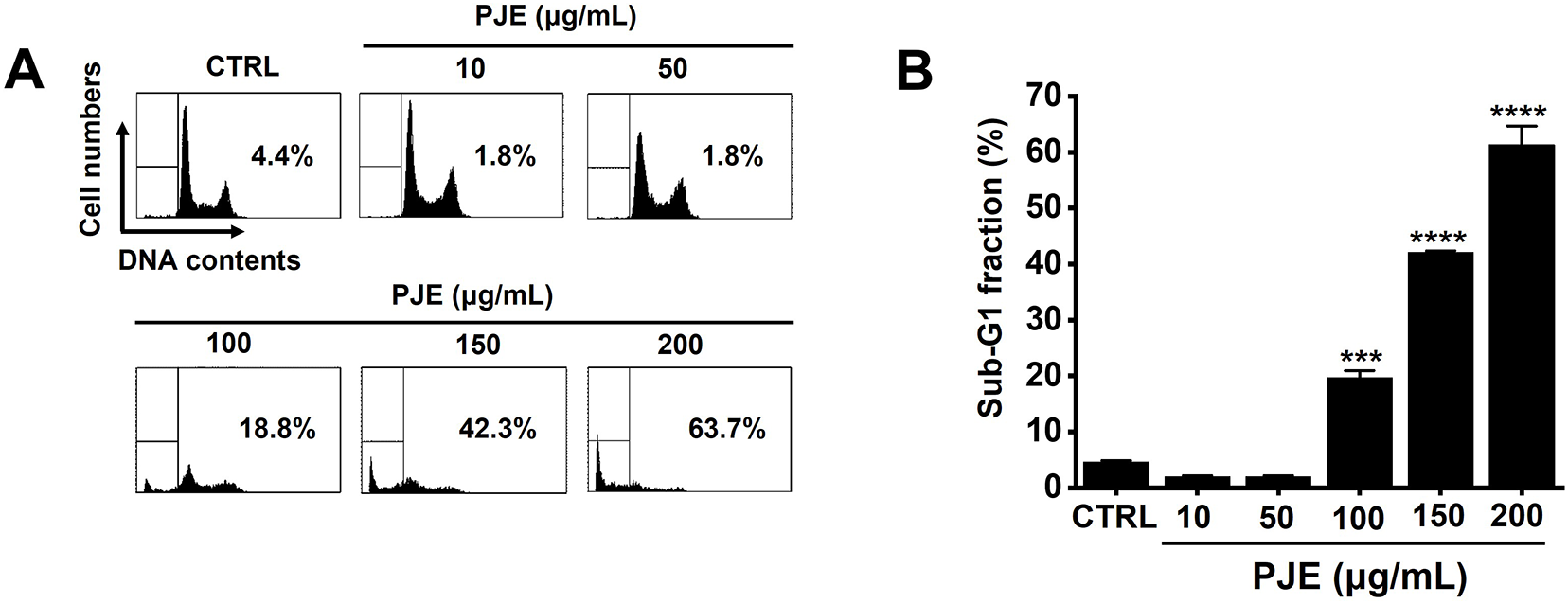

A concentration-dependent increase in sub-G1 phase cells was observed, reaching 2.0 ± 0.2%, 1.9 ± 0.2%, 19.7 ± 1.3%, 42.1 ± 0.3%, and 61.4 ± 3.3% at 10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL of PJE, respectively (Fig. 2). These results suggest that apoptosis is a major mechanism underlying PJE-induced cell death.

Figure 2: PJE-induced increase in sub-G1 cell population. (A) DNA content analysis was performed using flow cytometry (FACS). (B) Quantitative summary of sub-G1 phase cell percentages. Statistical significance is shown as ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. CTRL, Control. PJE, methanol extract of PJ

3.2 Apoptosis Induced by PJE is Mediated through the Mitochondrial Pathway

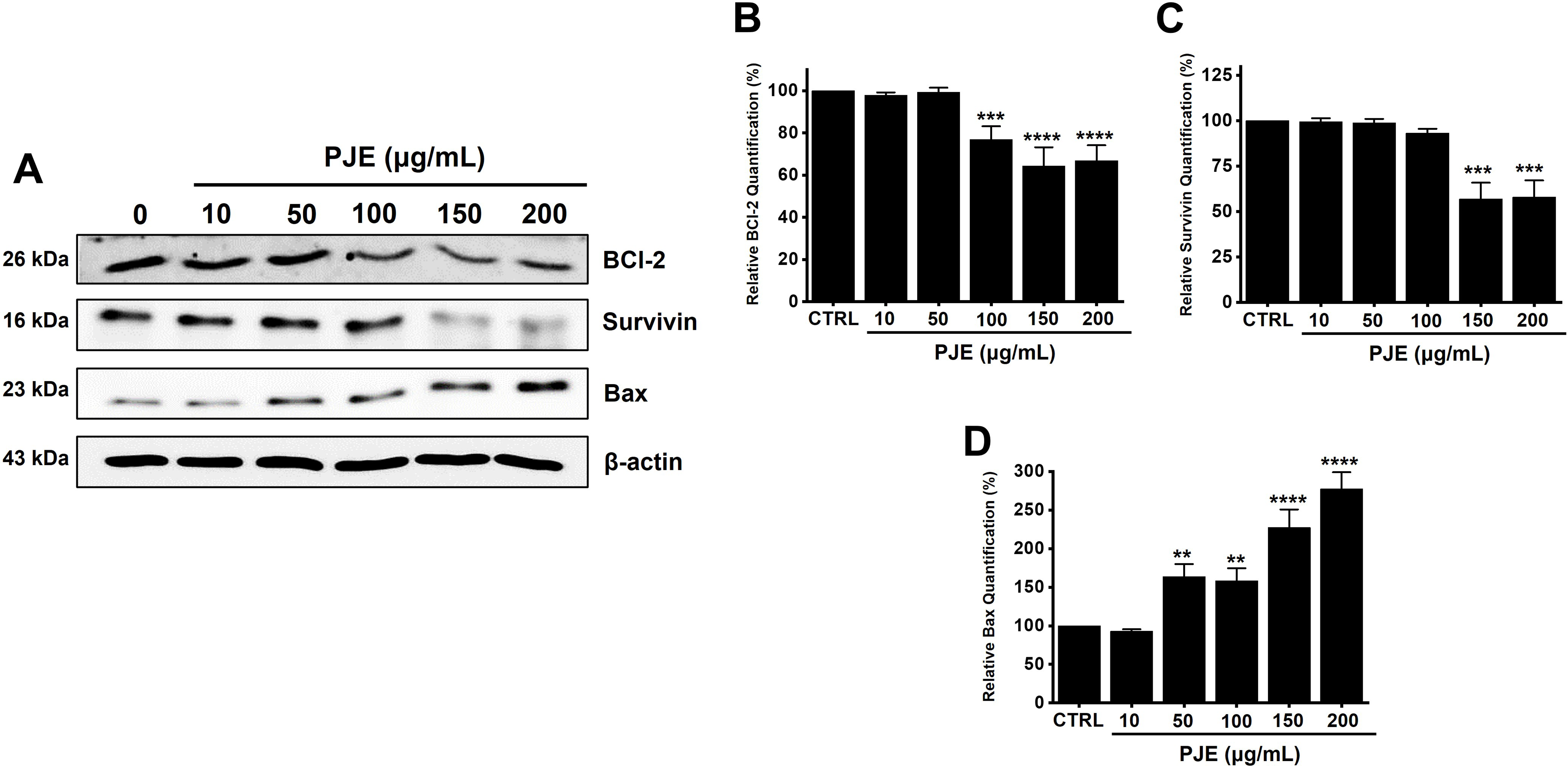

Treatment with PJE resulted in a decrease in survivin and BCl-2 protein levels, but Bax expression was elevated (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis showed that BCl-2 levels were reduced to 97.7 ± 1.5% at 10 μg/mL, 99.3 ± 2.2% at 50 μg/mL, 76.7 ± 6.4% at 100 μg/mL, 64.2 ± 8.9% at 150 μg/mL, and 66.8 ± 7.4% at 200 μg/mL of PJE (Fig. 3B). Similarly, survivin levels decreased to 99.5 ± 2.0% at 10 μg/mL, 98.8 ± 2.2% at 50 μg/mL, 93.1 ± 2.5% at 100 μg/mL, 56.9 ± 9.0% at 150 μg/mL, and 58.0 ± 9.2% at 200 μg/mL (Fig. 3C). In contrast, Bax expression was upregulated by 92.8 ± 2.7% at 10 μg/mL, 163.5 ± 16.4% at 50 μg/mL, 158.2 ± 16.4% at 100 μg/mL, 227.4 ± 23.3% at 150 μg/mL, and 277.3 ± 21.7% at 200 μg/mL of PJE (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3: Regulation of B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCl-2), survivin, and BCl-2-associated X protein (Bax) by PJE treatment. (A) Expression levels of BCl-2, survivin, and Bax were modulated following PJE exposure. Relative protein levels of (B) BCl-2, (C) survivin, and (D) Bax were normalized to β-actin. Statistical significance is indicated as **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. CTRL, control. PJE, methanol extract of PJ. BCl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2. Bax, BCl-2-associated X protein

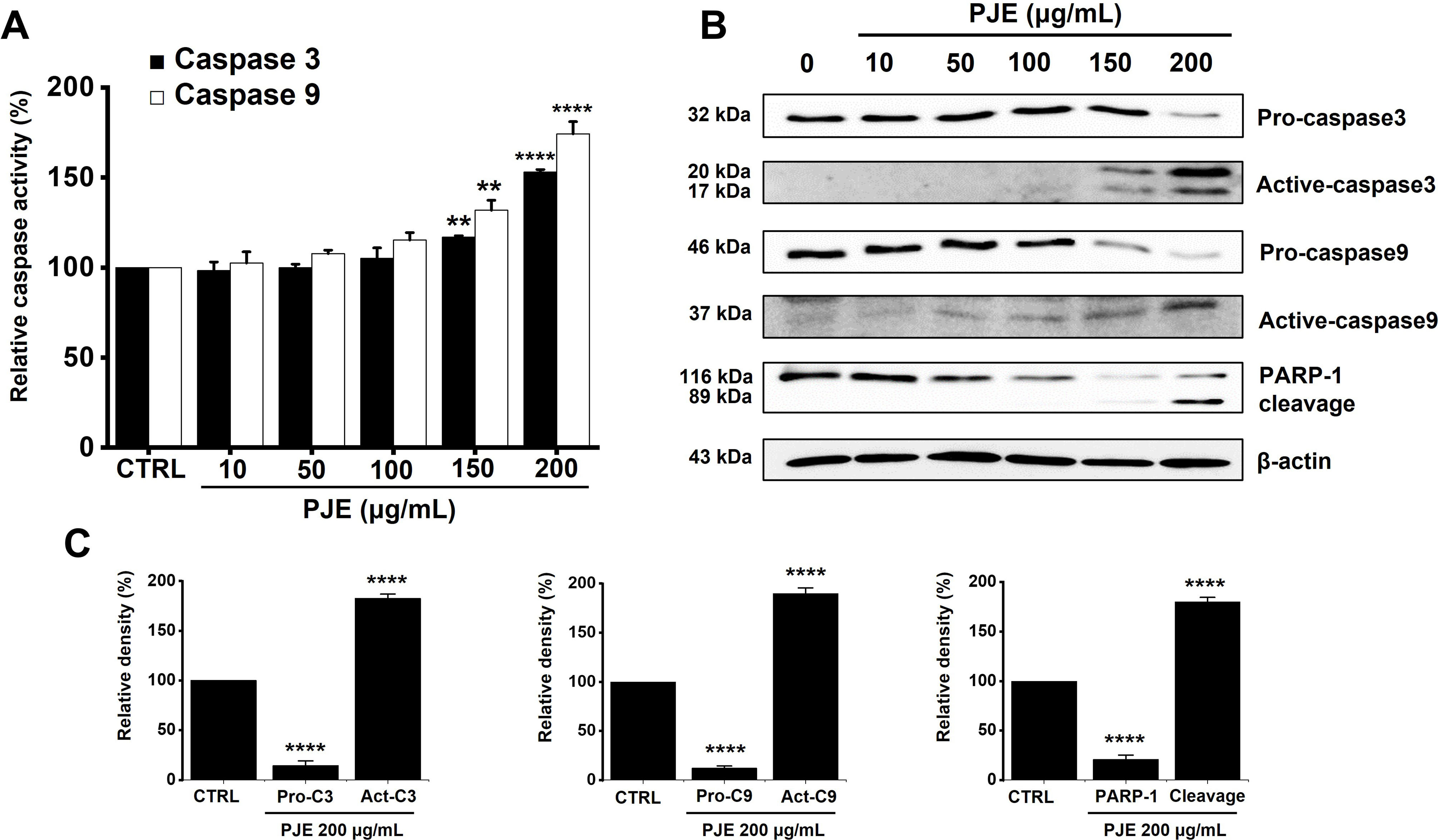

Furthermore, PJE treatment led to a concentration-dependent elevation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 activities. Caspase-3 activity increased by 98.3 ± 4.8% at 10 μg/mL, 99.9 ± 2.1% at 50 μg/mL, 105.1 ± 5.9% at 100 μg/mL, 116.8 ± 0.8% at 150 μg/mL, and 153.1 ± 1.3% at 200 μg/mL (Fig. 4A). Similarly, caspase-9 activity levels rose by 102.5 ± 6.3% at 10 μg/mL, 107.7 ± 2.0% at 50 μg/mL, 115.2 ± 4.2% at 100 μg/mL, 131.8 ± 5.6% at 150 μg/mL, and 174.2 ± 6.8% at 200 μg/mL (Fig. 4A). Western blot analysis revealed that PJE reduced the expression of procaspase-3, procaspase-9, and PARP-1, accompanied by an increase in their cleaved, active forms, indicating a concentration-dependent induction of apoptosis in AGS cells (Fig. 4B,C). Full-length PARP-1 (116 kDa) decreased, while the cleaved form (89 kDa) increased, constituting approximately 60%–70% of total PARP-1 at 200 μg/mL, indicating caspase-mediated PARP-1 cleavage. Similarly, full-length pro-caspase-3 (~32 kDa) gradually decreased, while cleaved caspase-3 appeared as two bands corresponding to the large (~20 kDa) and small (~17 kDa) subunits. The ratio of cleaved caspase-3 to total caspase-3 was nearly unchanged up to 100 μg/mL, increased to 10%–20% at 150 μg/mL, and reached 80%–90% at 200 μg/mL. These findings demonstrate that PJE induces strong, concentration-dependent activation of caspase-3 and PARP-1 cleavage, consistent with the progression of apoptosis. These findings indicate that PJE induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway.

Figure 4: Increasing effect of PJE on caspase activations. (A) PJE increased caspase-3 and -9 activities. (B) PJE decreased the expression of pro-caspase and increased the active-caspase and PARP-1 cleavage. (C) Western blot results were quantified, showing relative levels of procaspase-3, procaspase-9, PARP-1, and their cleaved forms. β-actin: internal control. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. CTRL, control. PJE, methanol extracts of PJ. Pro-C3, Pro-caspase3. Pro-C9, Pro-caspase9

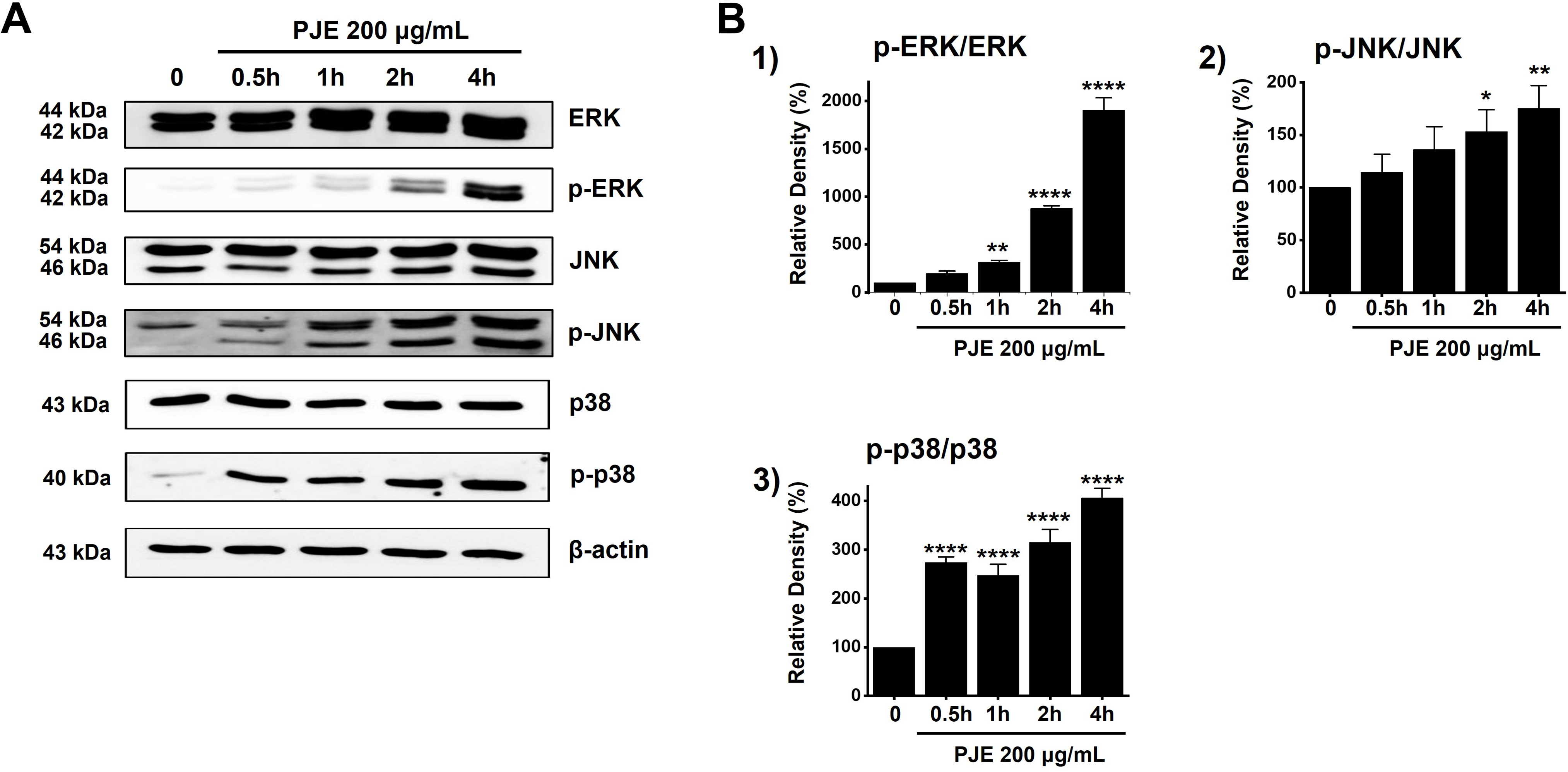

3.3 PJE Induces Apoptosis through the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway

To assess the role of the MAPK signaling pathway in PJE-induced cell death, we examined the phosphorylation status of MAPK proteins. We selected 200 μg/mL PJE based on previous experiments showing that this concentration effectively induced cell death without causing excessive nonspecific cytotoxicity, thus allowing reliable evaluation of intracellular signaling events. Results showed that phosphorylation levels increased progressively following treatment with PJE for 0.5 to 4 h (Fig. 5A). The relative density (%) was calculated by setting the ratio of phosphorylated to total protein at 0 h to 100%, and expressing the changes at other time points relative to this value. The relative p-ERK density levels were increased by 197.3 ± 24.5% at 0.5 h, 316.4 ± 18.4% at 1 h, 876.5 ± 29.2% at 2 h, and 1904.8 ± 129.1% at 4 h by PJE, respectively (Fig. 5B1). Also, PJE increased the relative p-JNK density levels by 114.6 ± 16.9% at 0.5 h, 136.2 ± 21.7% at 1 h, 153.2 ± 20.6% at 2 h, and 175.2 ± 21.7% at 4 h (Fig. 5B2). Relative p-p38 density levels were also increased by 274.0 ± 11.3% at 0.5 h, 247.2 ± 22.9% at 1 h, 315.1 ± 26.5% at 2 h, and 406.1 ± 19.5% at 4 h with PJE (Fig. 5B3). The data suggest that activation of the MAPK pathway plays a role in the cytotoxic effects of PJE.

Figure 5: Increasing effect of PJE on MAPK pathways. (A) The phosphorylation levels were increased by western blot analysis. (B) Phosphorylated levels are indicated as band densities relative to that of β-actin. Phosphorylation levels were quantified as the ratio of phosphorylated protein to total protein based on band densities. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. CTRL, control. ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase. PJE, methanol extracts of PJ

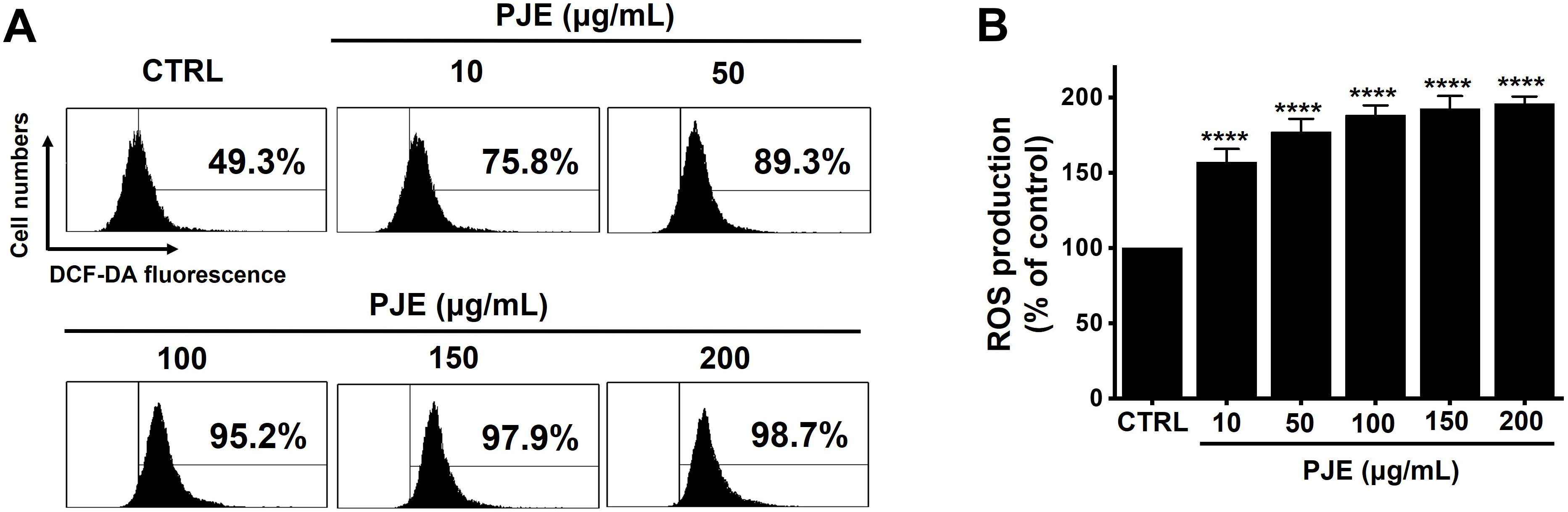

3.4 Apoptosis Induced by PJE is Mediated through the Generation of ROS

PJE induced a concentration-dependent elevation of ROS levels (Fig. 6A). Specifically, ROS levels rose to 157.1 ± 8.7% at 10 μg/mL, 176.9 ± 8.8% at 50 μg/mL, 188.1 ± 6.6% at 100 μg/mL, 192.4 ± 8.5% at 150 μg/mL, and 195.8 ± 4.8% at 200 μg/mL of PJE (Fig. 6B). The data suggest that ROS production plays a significant role in PJE-induced cell death.

Figure 6: Increasing effect of PJE on ROS. (A) The ROS production was examined. (B) DCF-DA positive cells were increased with PJE. ****p < 0.0001. CTRL, control. PJE, methanol extracts of PJ. ROS, reactive oxygen species

Currently, methods of chemotherapy include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy, which are controlling cancer growth, prolonging patient survival, and improving quality of life [18]. But it has many limitations and disadvantages. For example, complications such as postoperative bleeding and infection can occur, and recurrence and metastasis are very common [18]. Recently, cancer treatment has evolved into a variety of comprehensive treatments. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is recognized as a significant element in the therapeutic process [19]. As a key branch of complementary and alternative medicine, TCM has a longstanding history of use in many Asian countries, particularly China [19]. Emerging evidence highlights the role of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in preventing and managing cancer. TCM interventions can reduce treatment-related adverse effects, mitigate patient complications, and improve overall quality of life and survival outcomes [20].

PJ, a perennial species of the Asteraceae family, commonly forms clustered growths in areas with moderate humidity throughout Korea, Japan, and China, and it exhibits anti-oxidative, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and anti-carcinogenic activities [21–24]. Moreover, anti-cancer effects have also been reported in cervical carcinoma HeLa cells, breast cancer cells, and Hep3B hepatocellular cells [12,13,25,26]. However, its effect on AGS cells has not been explored. In this study, we suggested a possible apoptotic mechanism for PJ. Results revealed that PJE exhibited high anti-tumor activity on AGS cells by inducing apoptosis. The present study revealed that PJE exerts cytotoxic effects on AGS gastric cancer cells by promoting apoptosis (Figs. 1 and 2). This apoptotic response appears to be involved in the modulation of the BCl-2/Bax expression ratio and downregulation of survivin (Fig. 3). In addition, treatment with PJE enhanced the active caspase-3 and -9 levels (Fig. 4). Further study indicated that PJE-induced apoptosis involves activation of the MAPK signaling cascade and elevated ROS generation (Figs. 5 and 6). Collectively, these findings suggest that PJE triggers apoptosis via ROS-dependent MAPK pathways, leading to mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic cell death.

Intrinsic apoptosis is induced through mitochondria. Alternatively, extrinsic apoptosis is majorly self-induced (or cytosolic cell death) as opposed to death by genomic instability or expression of oncogenes [27]. Currently, the known mechanisms of apoptosis include intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis. Recently, another mechanism known as necroptosis was discovered, which is associated with almost all human diseases, such as cancer, degenerative diseases, brain diseases, and immune diseases [28]. Therefore, these apoptotic mechanisms are being studied in the context of these diseases [27,28]. Interchange between intracellular signaling mechanisms, discovery of new mechanisms, and establishment of animal models based on them can help expand the current knowledge on cell death. Ultimately, human diseases and lifespan can be controlled through the discovery of new compounds and bio-new drugs that can modulate cell death in the future. In this study, PJ-induced cell death corresponded to intrinsic apoptosis, which causes cell death by mitochondria, and it is considered that in-depth research related to this mechanism is needed for the future.

Among the pathways that regulate apoptosis, MAPK regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis, and is a representative signaling pathway that transmits extracellular stimuli from cell membranes to intracellular nuclei [29]. MAPK can be largely classified as ERK (cell signaling enzyme), JNK (c-JUN N-terminal activator), and p38 MAPK, and activation of p38 MAPK, which is classified as a stress activator, is known to induce inflammatory reactions and cell death [29,30]. ERK is also considered a good target for the treatment of several malignant tumors, as it is the stage of activating transcription factors, and its location itself is the last stage in various activities related to cell division and cancer development [29,30]. In this study, it was found that the MAPK mechanism was involved in cell death by PJ (Fig. 5). Normal cells become cancer cells for some cause, cancer cells metastasize through some process, and die. Understanding accurate signal transmission of whether to induce apoptosis will lead to the development of cancer treatments without side effects that selectively suppress only cancer cells. From this point of view, in order to understand the action of new anticancer drugs, it is necessary to accurately understand various signaling pathways, including MAPK, occurring within cancer cells.

The role of ROS has been widely examined across multiple human diseases, with particular attention to cancer [31]. While moderate levels of ROS are essential for regulating key cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, and migration, excessive ROS accumulation can lead to cancer cell death [32]. Because of their ability to modulate ROS levels, antioxidants are considered useful agents for both cancer prevention and therapy [31]. Elevated levels of intracellular ROS have the potential to harm various cellular structures—including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, membranes, and organelles—thereby triggering apoptotic pathways [32]. Mitochondria are central to the initiation of apoptosis, and excessive mitochondrial ROS can lead to cytochrome c release, promoting intrinsic apoptotic signaling [33,34]. In this study, PJ elevated ROS levels in AGS cells, contributing to apoptotic cell death (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that PJ possesses anticancer potential through ROS-mediated apoptosis, and further investigation into the interplay between ROS and MAPK signaling is warranted.

However, this study has several limitations. First, the present findings are based solely on in vitro experiments using a single gastric cancer cell line (AGS). Therefore, the observed cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of PJE may not fully represent its activity in other gastric cancer cell types or in vivo conditions. Second, although the involvement of ROS and MAPK pathways in PJE-induced apoptosis was demonstrated, the use of specific inhibitors or gene-silencing approaches would provide stronger evidence for the causal relationship between these pathways and apoptosis. Third, PJE is a crude extract containing multiple phytochemicals, and the specific active compounds responsible for the observed effects were not identified. Further studies using fractionation, compound isolation, and animal models are required to confirm the anticancer efficacy and elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms of PJ in vivo.

Our findings provide strong evidence that PJE suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation via activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, underscoring its potential as a novel anticancer therapy.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Woo-Gyun Choi and Byung Joo Kim; Methodology, Woo-Gyun Choi; Software, Woo-Gyun Choi; Validation, Woo-Gyun Choi; Formal analysis, Woo-Gyun Choi; Investigation, Woo-Gyun Choi and Byung Joo Kim; Resources, Woo-Gyun Choi; Data curation, Woo-Gyun Choi and Byung Joo Kim; Writing—original draft preparation, Woo-Gyun Choi; Writing—review and editing, Woo-Gyun Choi and Byung Joo Kim; Visualization, Woo-Gyun Choi; Supervision, Byung Joo Kim; Project administration, Byung Joo Kim; Funding acquisition, Byung Joo Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| PJ | Petasites japonicus |

| PJE | Methanol extract of Petasites japonicus |

| AGS | Adenocarcinoma Gastric Stomach |

| BCl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bax | BCl-2–associated X protein |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| JNK | C-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| DCF-DA | 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting kit-8 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

References

1. Thrift AP, Wenker TN, El-Serag HB. Global burden of gastric cancer: epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(5):338–49. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00747-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Mamun TI, Younus S, Rahman MH. Gastric cancer-Epidemiology, modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, challenges and opportunities: an updated review. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2024;41:100845. doi:10.1016/j.ctarc.2024.100845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Katai H, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Morita S, Yamada T, Bando E, et al. Survival outcomes after laparoscopy- assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage IA or IB gastric cancer (JCOG0912a multi-centre, non- inferiority, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(2):142–51. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30332-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):11–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ishigami H, Fujiwara Y, Fukushima R, Nashimoto A, Yabusaki H, Imano M, et al. Phase III trial comparing intraperitoneal and intravenous paclitaxel plus S–1 versus cisplatin plus S–1 in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis: PHOENIX–GC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1922–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.77.8613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yamashita K, Hosoda K, Niihara M, Hiki N. History and emerging trends in chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2021;5(4):446–56. doi:10.1002/ags3.12439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Petrovska BB. Historical review of medicinal plants’ usage. Pharmacogn Rev. 2012;6(11):1–5. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.95849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Huang M, Lu JJ, Ding J. Natural products in cancer therapy: past, present and future. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2021;11(1):5–13. doi:10.1007/s13659-020-00293-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu S, Khan AR, Yang X, Dong B, Ji J, Zhai G. The reversal of chemotherapy-induced multidrug resistance by nanomedicine for cancer therapy. J Control Release. 2021;335:1–20. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Naeem A, Hu P, Yang M, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu W, et al. Natural products as anticancer agents: current status and future perspectives. Molecules. 2022;27(23):8367. doi:10.3390/molecules27238367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod. 2020;83(3):770–803. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hwang YJ, Wi HR, Kim HR, Park KW, Hwang KA. Induction of apoptosis in cervical carcinoma HeLa cells by Petasites japonicus ethanol extracts. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2015;24:665–72. doi:10.1007/s10068-015-0087-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kim HJ, Park SY, Lee HM, Seo DI, Kim YM. Antiproliferative effect of the methanol extract from the roots of Petasites japonicus on Hep3B hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9(5):1791–6. doi:10.3892/etm.2015.2296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hiemori-Kondo M. Antioxidant compounds of Petasites japonicus and their preventive effects in chronic diseases: a review. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2020;67(1):10–8. doi:10.3164/jcbn.20-58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Choi NR, Choi WG, Kwon MJ, Park J, Kim YT, Lee MJ, et al. Methanol extract of Petasites japonicus promotes apoptosis via the MAPK and ROS-dependent signaling pathways. Pharmacogn Mag. 2024;20:389–401. doi:10.1177/09731296231216167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Choi JY, Desta KT, Saralamma VVG, Lee SJ, Lee SJ, Kim SM, et al. LC-MS/MS characterization, anti-inflammatory effects and antioxidant activities of polyphenols from different tissues of Korean Petasites japonicus (Meowi). Biomed Chromatogr. 2017;31(12):1–9. doi:10.1002/bmc.4033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Hiemori-Kondo M, Nii M. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of antioxidant activity of Petasites japonicus Maxim. flower buds extracts. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2020;84(3):621–32. doi:10.1080/09168451.2019.1691913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Qi F, Zhao L, Zhou A, Zhang B, Li A, Wang Z, et al. The advantages of using traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunctive therapy in the whole course of cancer treatment instead of only terminal stage of cancer. Biosci Trends. 2015;9(1):16–34. doi:10.5582/bst.2015.01019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Xiang Y, Guo Z, Zhu P, Chen J, Huang Y. Traditional Chinese medicine as a cancer treatment: modern perspectives of ancient but advanced science. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):1958–75. doi:10.1002/cam4.2108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Liang W, Yew DT, Hon KL, Wong CK, Kwok TC, Leung PC. Indispensable value of clinical trials in the modernization of traditional Chinese medicine: 12 years’ experience at CUHK and future perspectives. Am J Chin Med. 2014;42(3):587–604. doi:10.1142/S0192415X14500384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hwang KA, Hwang YJ, Park DS, Kim J, Om AS. In vitro investigation of antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activities of Korean wild edible vegetable extracts and their correlation with apoptotic gene expression in HepG2 cells. Food Chem. 2011;125(2):483–7. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang FJ, Wang Q, Wang Y, Guo ML. Anti-allergic effects of total bakkenolides from Petasites tricholobus in ovalbumin-sensitized rats. Phytother Res. 2011;25(1):116–21. doi:10.1002/ptr.3237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lee JS, Yang EJ, Yun CY, Kim DH, Kim IS. Suppressive effect of Petasites japonicus extract on ovalbumin- induced airway inflammation in an asthmatic mouse model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133(2):551–7. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sok DE, Oh SH, Kim YB, Kang HG, Kim MR. Neuroprotection by extract of Petasites japonicus leaves, a traditional vegetable, against oxidative stress in brain of mice challenged with kainic acid. Eur J Nutr. 2006;45(2):61–9. doi:10.1007/s00394-005-0565-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kang HG, Jeong SH, Cho JH. Antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic effect of methanol extracts of Petasites japonicus Maxim leaves. J Vet Sci. 2020;11(1):51–8. doi:10.4142/jvs.2010.11.1.51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Tzoneva R, Uzunova V, Stoyanova T, Borisova B, Momchilova A, Pankov R, et al. Anti-cancer effect of Petasites hybridus L. (Butterbur) root extract on breast cancer cell lines. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2021;35(1):853–61. doi:10.1080/13102818.2021.1932594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi:10.1080/01926230701320337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Seo J, Nam YW, Kim S, Oh DB, Song J. Necroptosis molecular mechanisms: recent findings regarding novel necroptosis regulators. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53(6):1007–17. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00634-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Guo YJ, Pan WW, Liu SB, Shen ZF, Xu Y, Hu LL. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(3):1997–2007. doi:10.3892/etm.2020.8454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yue J, Lopez JM. Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2346. doi:10.3390/ijms21072346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Nakamura H, Takada K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(10):3945–52. doi:10.1111/cas.15068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(12):931–47. doi:10.1038/nrd4002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signaling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(12):2977–92. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5(5):415–8. doi:10.1023/a:1009616228304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools