Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Role of Pesticides in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes: A Review of Possible Mechanisms

1 Department of Medical and Life Sciences, University Center of La Cienega, University of Guadalajara (CUCI-UdeG), Ocotlan, CP 47810, Mexico

2 Department of Biological Sciences, University Center of the Coast, University of Guadalajara (CUCosta-UdeG), Puerto Vallarta, CP 48280, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: JOEL SALAZAR-FLORES. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(5), 767-787. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.062225

Received 13 December 2024; Accepted 10 March 2025; Issue published 27 May 2025

Abstract

Pesticides are chemical substances used to eliminate various pests. Currently, more than two million tons of pesticides are used annually in developing and developed countries. One of the chronic diseases associated with pesticide poisoning is diabetes. This review aimed to elucidate the mechanisms of action involved in the development of diabetes after pesticide poisoning. Relevant information was collected between January and May 2024, using databases such as PubMed, Google Academic, and Elsevier. Pesticides reduce the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in the intestine, thereby decreasing the release of insulin. Moreover, pesticides are metabolized to acetic acid by intestinal microbiota. This contributes to gluconeogenesis in the liver. In addition, the accumulation of pesticides in adipose tissue affects pancreatic beta-cells (β-cells) through increases in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and the release of leptin, resulting in insulin resistance and impairments of appetite control and energy balance. These alterations caused by pesticides can contribute to the development of diabetes by affecting many organic systems.Keywords

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder caused by a lack of insulin or a failure of the cells to respond to insulin, which increases blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia) [1]. Complications of hyperglycemia include symptoms such as polyuria, fatigue, excessive thirst, and decreased performance; while in the long term, it causes deterioration of various tissues and organs (eyes, liver, blood vessels), increasing the occurrence of pathologies such as cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, blindness and neuropathy [2,3].

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are the main types of diabetes [4]. In 2021, approximately 8.4 million people worldwide were reported to have T1DM [5]; which usually develops in young adults as a result of a reaction in which the immune system mistakenly destroys beta-cells (β-cells) causing insulin deficiency [6,7]. T2DM accounts for nearly 90% of the approximately 537 million cases of diabetes and is characterized by insulin resistance and insufficient insulin secretion [8–10]. Although T2DM was known as a disorder that occurred in adulthood, rates of this disease in children and adolescents have increased in recent years [11,12]. Worldwide, Brazil (33 per 1000), Canada (5.7 per 1000), Mexico (4 per 1000) and the United States (1.8 per 1000) have the highest prevalence of T2DM in adolescents [13].

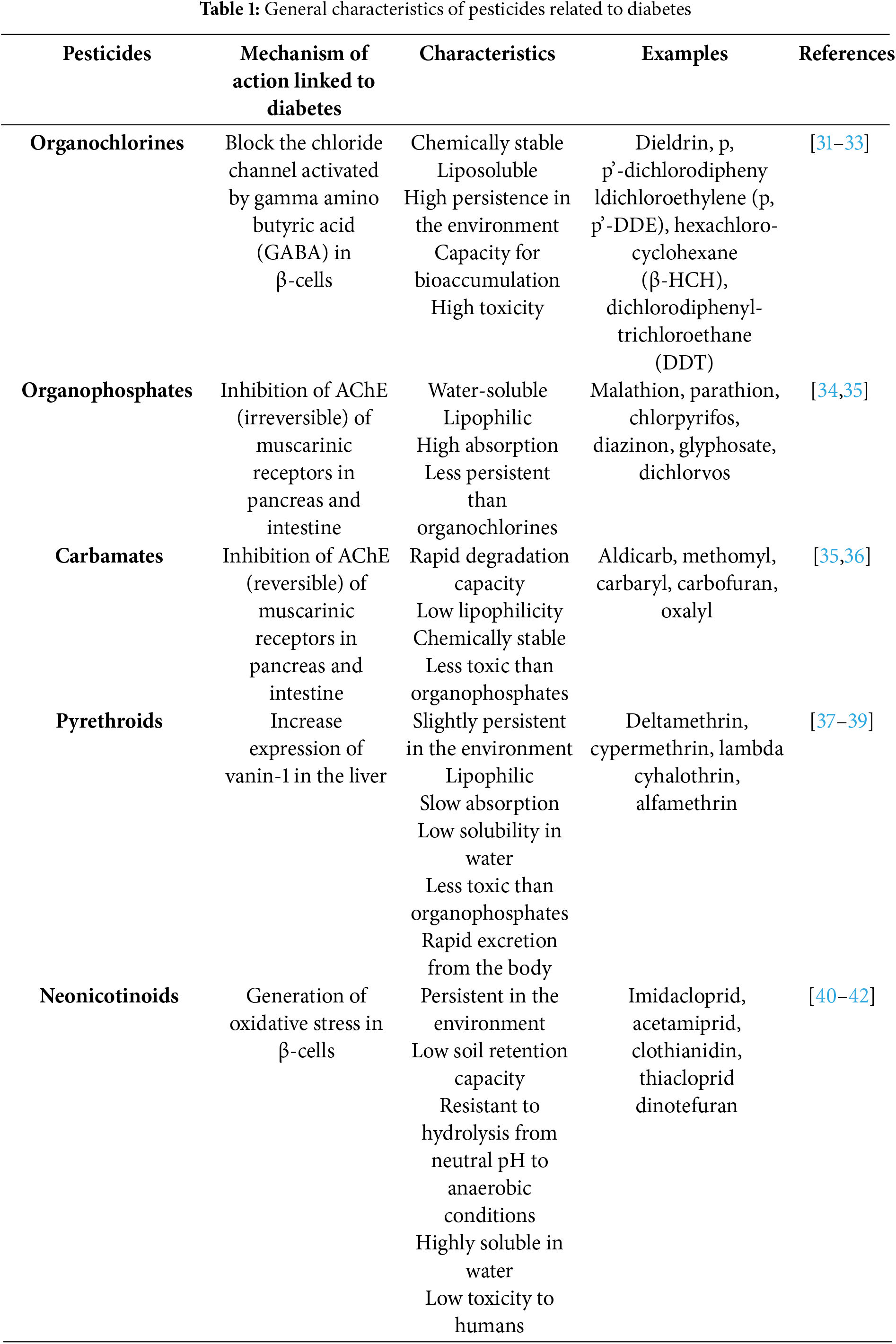

In addition to known risk factors (genetics, sedentary way of life, smoking, and alcoholism), exposure to pesticides can contribute to the development of diabetes [14,15]. Pesticides are chemical substances used to prevent, control, or eliminate different pests that reduce agricultural production [16]. They can be classified according to their chemical composition, mainly into organochlorines (OCs), organophosphates (OPs), carbamates, pyrethroids, and neonicotinoids [17].

OCs are persistent in the environment for a long time and due to their lipophilic capacity, they accumulate in adipose tissue [18]. The main toxicological effect of OPs is the irreversible inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which causes deterioration of the respiratory tract and neuromuscular transmission; they accumulate in the environment for long periods due to their frequent application and moderate persistence [19,20]. Carbamates are thermally unstable, water-soluble, and have high polarity; they are AChE inhibitors; however, their toxic action is reversible unlike OPs [21]. Pyrethroids are synthetic organic insecticides which, due to their limited cutaneous absorption and ability to rapidly transform substances, although some authors report that these pesticides are less toxic than OCs, OPs, and carbamates, some of its metabolites are detected in fatty tissues due to their high lipophilicity, therefore its toxic effect should not be dismissed [22,23]. Neonicotinoids act on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and can persist for a long time in soil and water, with a half-life of up to three years and have a high toxicological potential in organisms [24–26]. In addition, different studies have confirmed the participation of these substances in the development of diabetes [27–30]. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of these pesticides.

Although there is evidence that pesticides are involved in the development of diabetes [43], it is necessary to clarify the set of molecular interactions that may be involved in the development of the disease and how the alteration of one organ can affect the functionality of another. This study aimed to elucidate the mechanisms of action associated with exposure to these substances in the different organs involved in the development of diabetes. In our review, we found that OCs, OPs, carbamates, pyrethroids, and neonicotinoids affect the functioning of different organs involved in the development of diabetes, such as the intestine, liver, adipose tissue, and pancreas.

Relevant information was collected between January and May 2024, using databases such as PubMed, Google Academic, Scopus, Web of Science, and Elsevier; using the keywords “pesticides”, “diabetes mellitus”, “intestine”, “liver”, “adipose tissue”, “pancreas” “organochlorines”, “organophosphates”, “carbamates”, “pyrethroids”, “neonicotinoids”. The main selection criteria were articles describing the link in diabetes triggered by the mechanisms of action of pesticides, articles mostly updated (last 5 years); including articles on animal models. We discarded articles on animal models that described the link between diabetes and pesticides but not at the intestinal, liver, adipose tissue, and pancreas levels.

2.1 Mechanisms of Action at the Intestinal Level

The intestine is one of the target organs for the action and/or effect of different pesticides. Microorganisms that live in the intestine in a symbiotic relationship constitute a set of organisms known as gut microbiota (GM) [44,45]. GM is responsible for regulating intestinal integrity, and improving the function and metabolism of the liver and peripheral tissue; these characteristics together can prevent diseases such as obesity, T2DM, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [46]. However, pesticides can affect GM function, trigger changes in the microbiome, and cause gut inflammation through excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [47,48]. The scientific literature has demonstrated the effects of OCs and OPs on GM (reduction of the Bacteroides genus) and of OPs and carbamates on muscarinic receptors in the intestine (inhibition of AChE), as described below.

The hydrolytic and bio-transformative reactions that some OCs undergo in the intestine generate toxic metabolites which increase the risk of glucose intolerance [45,49]. For example, p,p′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p′-DDE), the major metabolite of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), may accumulate in the fat and be transported up the food chain. A study in mice fed 2 mg/kg body weight of p,p′-DDE for 8 weeks significantly increased body fat mass and fasting blood glucose [50].

In addition, it has been reported that exposure of rodents to p,p′-DDE led to the reduction of the genus Bacteroides (belonging to the phylum Bacteroidetes) in GM, a change which is associated with obesity and diabetes [51,52]. A study in mice revealed that the commensal bacteria Bacteroides acidifaciens (BA) can directly interact with intestinal epithelial cells and inhibit dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) activation, thereby increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (Fig. 1A) [53].

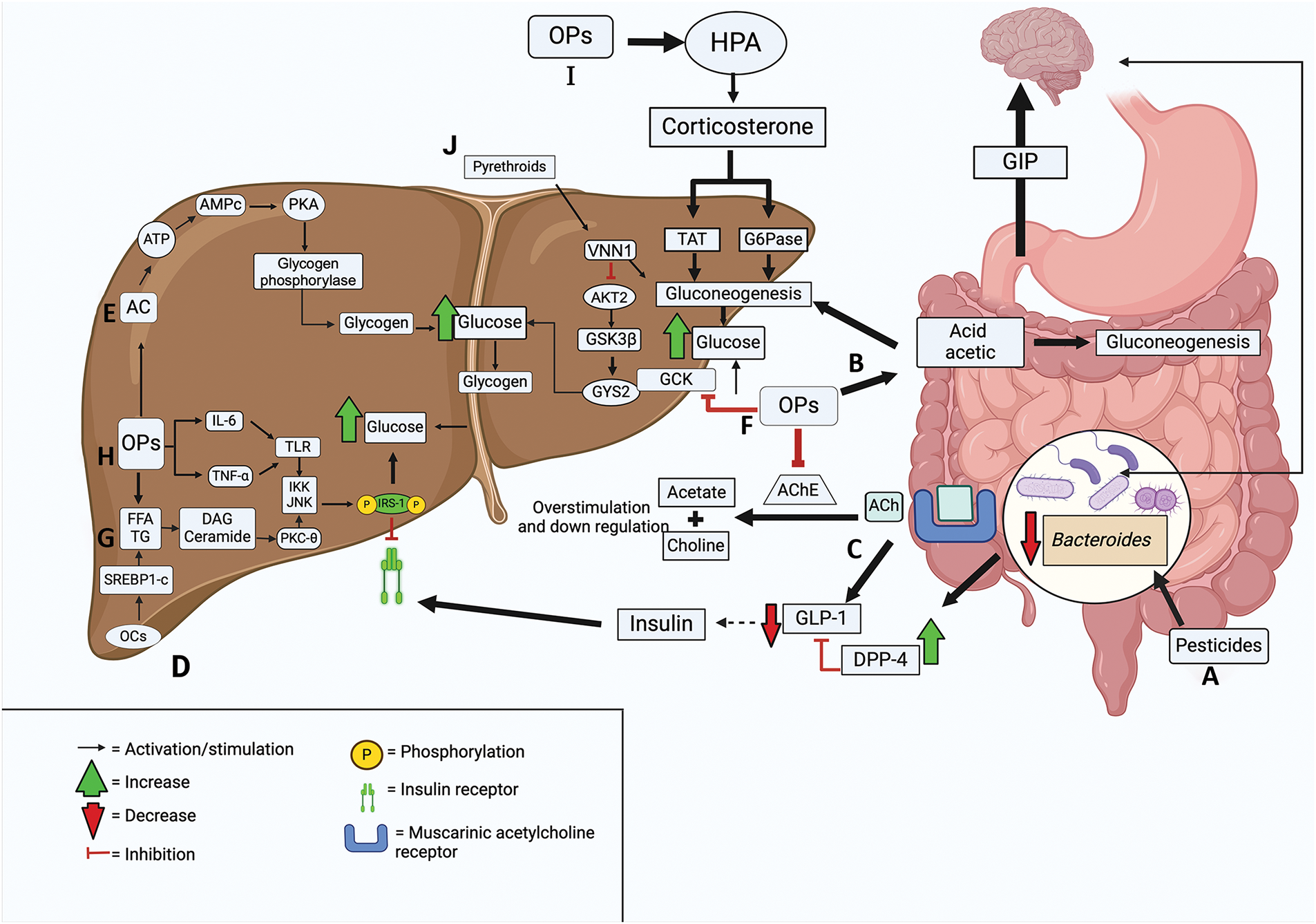

Figure 1: Mechanisms of pesticide toxicity in the intestine and liver. A. Pesticides can eliminate the Bacteroides genus from gut microbiota (GM) by blocking dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DDP-4) inhibition, resulting in reduced, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion. B. Organophosphates (OPs) are metabolized by intestinal microbiota to acetic acid, resulting in increased gluconeogenesis in the liver and intestine. C. OPs and carbamates overstimulate muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors, thereby decreasing GLP-1 secretion and causing, in turn, a decrease in the incretin effect. D. Organochlorines (OCs) induce lipogenesis via activation of sterol response element binding protein 1c (SREBP1-c). E. OPs produce a long-lasting upregulation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), increasing glucose production. F. OPs inhibit glucokinase (GCK), an enzyme that lowers glucose levels. G. Pesticides increase triglyceride and free fatty acids (FFA) synthesis, causing accumulation of diacylglycerol (DAG) and ceramide. H. OPs stimulate inteleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), phosphorylate insuline receptor substrates 1 (IRS-1), and increase glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. I. OPs stimulate gluconeogenesis by activating hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA). J. Pyrethroids activate Vanin-1 (VNN1), blocking the conversion of glucose to glycogen. Abbreviations: AChE, Acetylcholinesterase; AKT2, Protein Kinase B2; AMPc, Cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; G6Pase, Glucose-6-phosphatase; GIP, Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; GSK3β, Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; GYS2, Glycogen synthase; IKK, Inhibitory-κB kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; PKA, Protein Kinase A; PKC-θ, Protein kinase C theta; TAT, Tyrosine aminotransferase; TG, Triglycerides; TLR, Toll-like receptor. Created in BioRender

GLP-1 stimulates insulin release, inhibits gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in the liver, delays gastric emptying and inhibits gastric motility, induces satiety and reduces food intake, and promotes glucose utilization in skeletal muscle and liver, decreasing blood glucose levels [54–57]. Therefore, the elimination of the Bacteroides genus in GM by OCs may reduce GLP-1 expression and contribute to hyperglycemia [58,59]. The loss of microorganisms in GM and drift from the ancestral microbial environment is known as dysbiosis (Fig. 1A) [60].

In GM, Bacteroides spp. is a key regulator of obesity due to its capacity to promote branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism in brown adipose tissue; the increased BCAA catabolism inhibits obesity [61].

Chronic exposure to the organophosphate chlorpyrifos in mice on a normal-fat diet resulted in increased Proteobacteria phyla and decreased Bacteroidetes phyla; this increased the percentage of body weight. The altered microbiota could decrease insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance (Fig. 1A) [62].

Another possible mechanism explaining the influence of OPs on glucose homeostasis is their biotransformation by GM to acetic acid (Fig. 1B). The anaerobic metabolism of the GM can metabolize insoluble plant fibers, such as cellulose, generating disaccharides or glucose; it can be degraded in glycolysis and produce two pyruvate molecules. Pyruvate can be used to synthesize acetyl-CoA, the latter can enter the Krebs cycle or be used as a precursor in the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids such as acetate (an ionic form of acetic acid) by a fermentative route [63]. Acetate can be absorbed into the apical and basolateral membrane of colonocytes by passive diffusion or through specialized transporters, and reach peripheral and hepatic circulation via the portal pathway. Approximately 70% of the exogenous acetate is absorbed by the liver and can be used as a co-substrate for the synthesis of glucogenic amino acids (glutamine and glutamate); they serve as a substrate for glucose synthesis through gluconeogenesis [64]. Gluconeogenesis is a pathway that requires high ATP concentration, which can be obtained through the oxidation of fatty acids and the synthesis of acetyl-CoA to feed the Krebs cycle and synthesize malate and oxalacetate; the latter act as precursors of phosphoenolpyruvate which can feed gluconeogenesis [65,66]. The acetate produced by the degradation of OPs could function as a substrate in the synthesis of acetyl-CoA in liver cells and thus in the synthesis of metabolic intermediates from the Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis. This was demonstrated in a study that administered a dose of 28 μg/kg of body weight/day of monocrotophos to mice for 180 days [67].

AChE inhibitor pesticides may also impair glucose homeostasis by disrupting the incretin effect [68]. The incretin effect is defined as an increased insulin release triggered by oral glucose intake, relative to intravenous administration of the same amount of glucose, and it is regulated by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 [69].

Incretin secretion from the intestine is important for the proper functioning of insulin. When carbohydrates are ingested, K cells in the duodenum secrete GIP to the brain through the vagus nerve; therefore, acetylcholine (ACh) is released and stimulates muscarinic receptors on L cells located in the colon and distal ileum, which increases GLP-1 secretion. In this way, GLP-1 may increase insulin release and reduce blood glucose [70].

In OPs and carbamates intoxication, an overstimulation of muscarinic receptors occurs as a consequence of excessive accumulation of ACh [71]. This overstimulation causes a down-regulation of muscarinic receptors resulting in a decrease in GLP-1 secretion, and in turn, a decrease in the incretin effect (Fig. 1C) [72].

A comparative study between patients with acute poisoning due to OPs and carbamates, and patients occasionally exposed to these same pesticides, demonstrated significantly lower GLP-1 levels in patients with acute poisoning. This result supports the theory that these pesticides may decrease the incretin effect, contributing to the development of T2DM [27].

2.2 Mechanisms of Action in the Liver

The liver plays a key role in glucose homeostasis; it can store glucose (during food intake) as glycogen, and when required, produce it through gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, this maintains normal blood glucose levels [73]. The proper functioning of the liver can be altered by different pesticides. The toxic effects of OCs (lipotoxicity), OPs (up-regulation of adenylyl cyclase, decreased glucokinase, accumulation of fatty acid intermediates, activation of interleukins and glucocorticoid-activated gluconeogenesis) and pyrethroids (activation of vanin-1) are described below.

The metabolites of OCs, i.e., β-hexachlorocyclohexane (β-HCH) and p,p′-DDE can increase fatty acid synthesis through activation of sterol response element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) and lead to lipotoxicity (Fig. 1D) [74].

Lipotoxicity refers to the harmful effects caused by excessive levels of free fatty acids (FFAs), with deleterious effects on glucose homeostasis [75]. For example, the accumulation of FFAs causes the generation of ROS. In hepatocytes, ROS causes overactivation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), leading to insulin resistance, in part through inhibitory phosphorylation of serine located on insulin receptor substrates 1 (IRS-1) and 2 (IRS-2) [76,77].

Exposure to 10 mg/kg/day of β-HCH for 8 weeks elevated hepatic levels of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), mainly via stearate accumulation, and decreased levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). SFA accumulation provides excessive substrates for the synthesis of triglycerides (TG), leading to lipotoxicity and steatosis and may worsen glucose and insulin homeostasis, especially among individuals predisposed to insulin resistance [78–80].

In hepatocytes, both diazinon and chlorpyrifos produce a long-lasting upregulation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) [81]. AC catalyzes the conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). In turn, cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) that phosphorylates the beta subunit of glycogen phosphorylase, thus stimulating glucose production from glycogen (Fig. 1E) [82,83].

In mice treated with 20 mg/kg of body weight of dichlorvos, glucokinase (GCK) enzyme activity was decreased [84]. In the liver, GCK reduces elevated blood glucose levels. The glucose excreted is stored mostly as glycogen, helping to prevent hyperglycemia and ensure adequate hepatic glycogen stores to stabilize blood glucose levels between meals. Consequently, the reduction of GCK activity by dichlorvos decreases glycogen storage and glucose uptake, which contributes to the development of diabetes (Fig. 1F) [85–87].

OPs increase the rates of synthesis TG and FFA, consequently, the fatty acid intermediates diacylglycerol (DAG) and ceramide accumulate; this causes autophosphorylation of protein kinase C theta (PKC-θ), which activates inhibitory-kB kinase (IKK) and JNK. IKK and JNK are two kinases that stimulate the phosphorylation of serine in IRS-1 (Fig. 1G). This phosphorylation blocks the union between IRS and the insulin receptor, promoting the degradation of IRS-1 [88].

Moreover, OPs stimulate proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), which activate the Toll-like receptor (TLR) inducing inflammatory signaling pathways in metabolic cells through the kinases PKC, IKK, and JNK. These kinases can inhibit insulin signaling through serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (Fig. 1H) [89].

In animal studies, exposure to 15 mg of Diazinon for 28 days was shown to increase TNF-α levels [90]. Another study indicated that exposure to a lower dose (3 mg/kg) for 14 days of the same pesticide upregulated TNF-α and IL-6 genes [91]. In humans, one study indicated that levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) were significantly increased in a group of adults exposed to OPs [92].

Another mechanism through which OPs induce gluconeogenesis is the regulation of glucocorticoids. The glucocorticoids are hormones secreted by the adrenal cortex and regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Glucocorticoids stimulate gluconeogenesis in the liver through the activation of genes such as pyruvate carboxylase (PC), Cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK1), 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 1 (PFKFB1), fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP1), glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and the glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) transporter, and they up-regulate the expressions of enzymes involved in ceramide synthesis, i.e., ceramide synthase 1 (Cers1), ceramide synthase 6 (Cers6) and serine palmitoyaltransferase (Sptlc2), leading to impairment of insulin signaling [93].

OPs increase blood levels of corticosterone by activating HPA. In rodents, subcutaneous administration of 50 mg kg−1 (single dose) of chlorpyrifos showed activation of HPA, as well as increases in activities of hepatic G6Pase and hepatic tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT), which were correlated with increases in corticosterone levels (Fig. 1I) [94]. In addition, other studies have indicated elevated levels of corticosterone, TAT, and G6Pase after oral administration of 1.8 mg/kg body weight of monocrotophos; as a result, gluconeogenesis is stimulated and blood glucose levels are increased [95,96].

Pyrethroids can increase hepatic expression of vanin-1 (VNN1), which blocks the activation of protein kinase B2 (AKT2), an important regulator of gluconeogenesis (Fig. 1J) [39]. AKT2 activation leads to dephosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK3β), which promotes glycogen synthase 2 (GYS2) activation, favoring the conversion of glucose to glycogen [97]. In a study in mice fed 6 μg/kg body weight/day of cypermethrin for 12 days and a high-calorie diet, exposure to it upregulated VNN1 expression, impairing the AKT2 pathway, reducing the conversion of glucose to glycogen and stimulating gluconeogenesis. In patients with T2DM, excessive gluconeogenesis in the liver contributes to hyperglycemia [98].

2.3 Mechanisms of Action in Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue participates in the maintenance of energy homeostasis by storing triglycerides and secreting adipokines which are important for regulating glucose and lipid metabolism [99]. Adipose tissue is made up of adipocytes which have the potential to increase in size, thereby increasing fat storage. In obesity, when adipocytes grow to a certain size, a signal is activated to indicate the need to produce new adipocytes (adipogenesis), increasing the size of adipose tissue [100].

In adipose tissue, the toxic effects of OPs (activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and generation of oxidative stress) and Neonicotinoids (inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPKα) phosphorylation) contribute to adipogenesis and glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) failure, which impairs insulin release and glucose uptake. These effects are described below.

OPs may accumulate in adipose tissue due to their hydrophobic nature, and by activating PPARγ, they enhance adipogenesis (Fig. 2A) [70]. The activation of PPARγ enhances adipocyte proliferation, thereby improving their functionality [101,102].

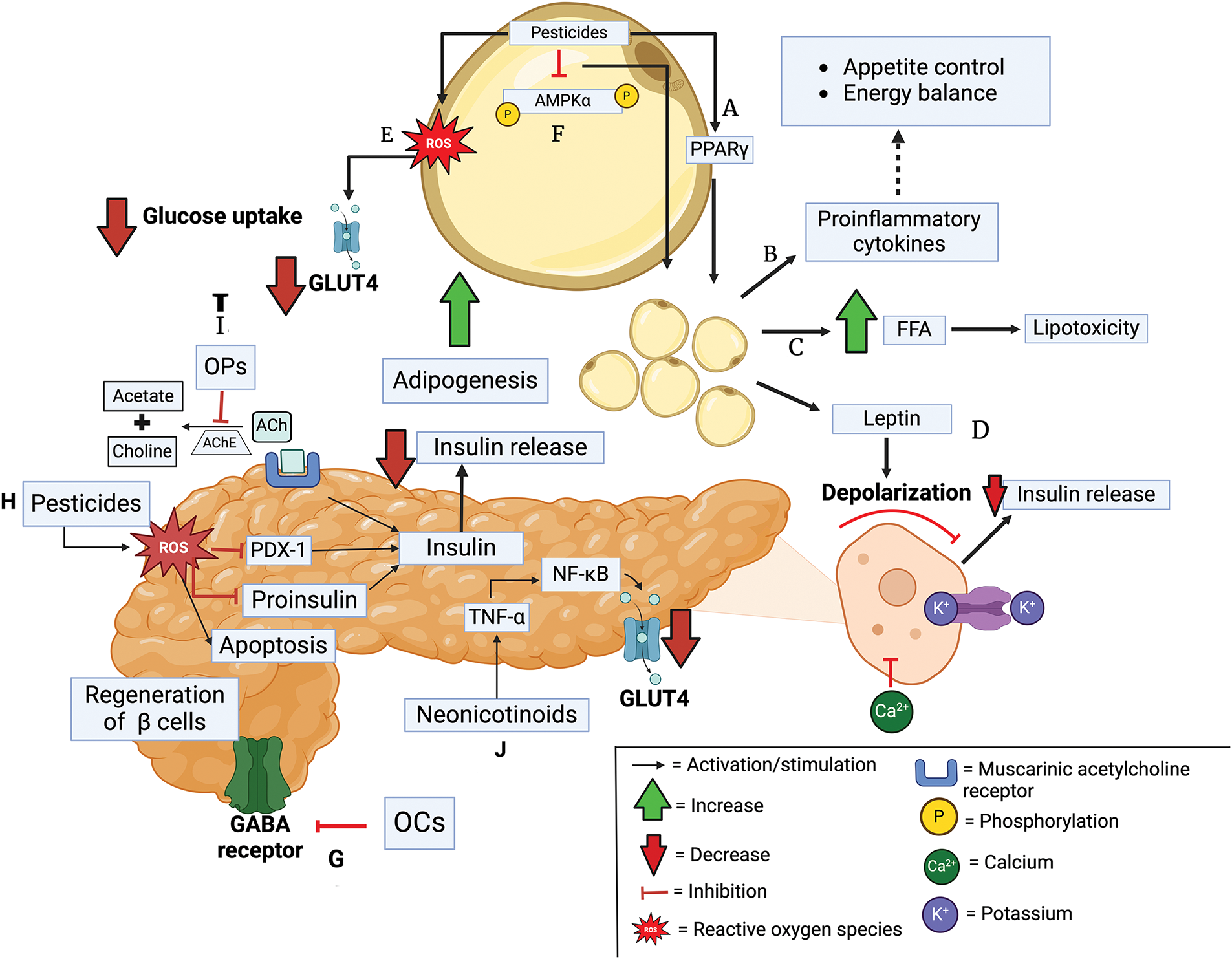

Figure 2: Mechanisms of pesticide toxicity in adipose tissue and pancreas. A. Pesticides activate PPARγ, increasing adipogenesis. B. This stimulates proinflammatory cytokines. C. Increasing blood free fatty acids (FFA). D. It produces the release of leptin. E. Pesticides generate oxidative stress by altering the expression of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4). F. Pesticides contribute to adipogenesis by inhibiting phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα). G. Organochlorines (OCs) inhibit gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors. H. Pesticides generate reactive species oxygen (ROS), causing damage in β-cells. I. Organophosphates (OPs) impair insulin secretion via inhibition of pancreatic acetylcholinesterase (AChE). J. Neonicotinoids activate tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which reduces GLUT4 gene expression. Abbreviations: ACh, Acetylcholine; NF-κB, factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; PDX-1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Created in BioRender.

A study showed that in mouse preadipocytes treated with fenthion (40 μM), PPARγ transcription was significantly activated, which stimulated lipid accumulation [103]. In addition, preadipocytes treated with different doses of diazinon (1 μM, 10 μM, and 100 μM) increased the expression of PPARγ and multiple adipogenic genes, thus promoting adipogenesis [104]. Similarly, endrin enhanced the expressions of specific transcription factors, including PPARγ, and caused increases in triglyceride secretion [105].

These morpho-functional changes in adipose tissue also increase the levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 leading to damage in the pathways involved in appetite control and energy balance (Fig. 2B) [106,107]. In addition, FFA will no longer be stored in adipose tissue, resulting in elevated FFA concentration in blood (Fig. 2C), where they can reach the liver and via fatty acid intermediaries or by stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines cause IRS-1 degradation, decreasing glucose uptake and increasing blood glucose levels. Furthermore, these proinflammatory cytokines increase the β-cell response, leading to compensation of the islets through an increase in β-cell mass, causing their dysfunction and subsequent apoptosis [108].

When there is excess adipose tissue mass, the release of leptin activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in pancreatic β-cells. This prevents membrane depolarization, which blocks the opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels, preventing the entry of Ca2+ ions into the β-cells and preventing the release of insulin (Fig. 2D) [109,110].

The constant accumulation of OPs within adipose tissue generates oxidative stress (Fig. 2E) [70]. Oxidative stress impairs the binding of nuclear factor to the GLUT4 promoter, thereby reducing its expression [111]. A study showed that paraquat induced oxidative stress in adipocyte mitochondria and decreased GLUT4 translocation, decreasing glucose uptake into cells leading to insulin resistance [112].

Imidacloprid may enhance adipogenesis by inhibiting the phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα) in adipocytes (Fig. 2F) [113]. Furthermore, studies in rodents suggest that oral administration of 6 mg/kg of body weight/day of imidacloprid can elicit its effects on the liver and adipocytes through decreased expression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ) and/or sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), two regulators of AMPK, which impairs lipid and glucose metabolism. Imidacloprid may partially influence glucose homeostasis through induction of cellular oxidative stress [114]. Oxidative stress through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase serine kinase (p38 MAPK), which phosphorylates and neutralizes IRS-1, is associated with reduced insulin signaling and glucose transport [115].

2.4 Mechanisms of Action in the Pancreas

The pancreas is critically involved in the control of glucose homeostasis since this organ is home to β-cells, which are responsible for synthesizing and secreting insulin when glucose levels are high [116]. Therefore, the toxic effects of OCs (inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors), OPs (oxidative stress and AChE inhibition), and neonicotinoids (oxidative stress and TNF-α activation) cause pancreatic cell dysfunction contributing to the development of T2DM.

OCs inhibit gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, leading to continuous neuro-depolarization, as β-cells also express GABA receptors (Fig. 2G). In addition to stimulating insulin release, GABA activation regenerates β-cells and inhibits apoptosis. Therefore, exposure to OCs may damage β-cell functionality [33,117].

OPs cause cytotoxicity in the pancreas through oxidative stress and β-cell apoptosis (Fig. 2H) [118,119]. In pancreatic β-cells, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity and mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) are the main sources of free radicals [120]. Oxidative stress impairs proinsulin vesicle fusion in the plasma membrane, decreases insulin exocytosis and release, reduces insulin production, and induces β-cell apoptosis [121–123]. In addition, excess free radicals inhibit pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1 (PDX-1) which is involved in insulin gene expression [124]. PDX1 is maintained at elevated levels in β-cells, where it is required for efficient insulin gene transcription; therefore, PDX1 inhibition contributes to the development of diabetes [125].

OPs generate muscarinic overstimulation that impairs insulin secretion by altering pancreatic AChE activity (Fig. 2I) [126]. Under normal conditions, stimulation of muscarinic receptors in β-cell increases Ca2+ concentration, which enhances the efficiency of exocytosis, thus activating insulin secretion. Thus, altered receptor stimulation then impairs insulin release [127].

A study revealed that oral consumption of 45 mg/kg of imidacloprid induced ROS in β cells, causing their apoptosis and consequently reduced insulin production and elevated blood glucose levels [42]. Another mechanism by which imidacloprid disrupts glucose homeostasis is through the inhibition of GLUT4 in pancreatic acinar cells by the exacerbation of TNF-α (Fig. 2J). TNFα increases nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (Nf-kB) expression, which reduces GLUT4 gene expression resulting in hyperglycemia [128,129].

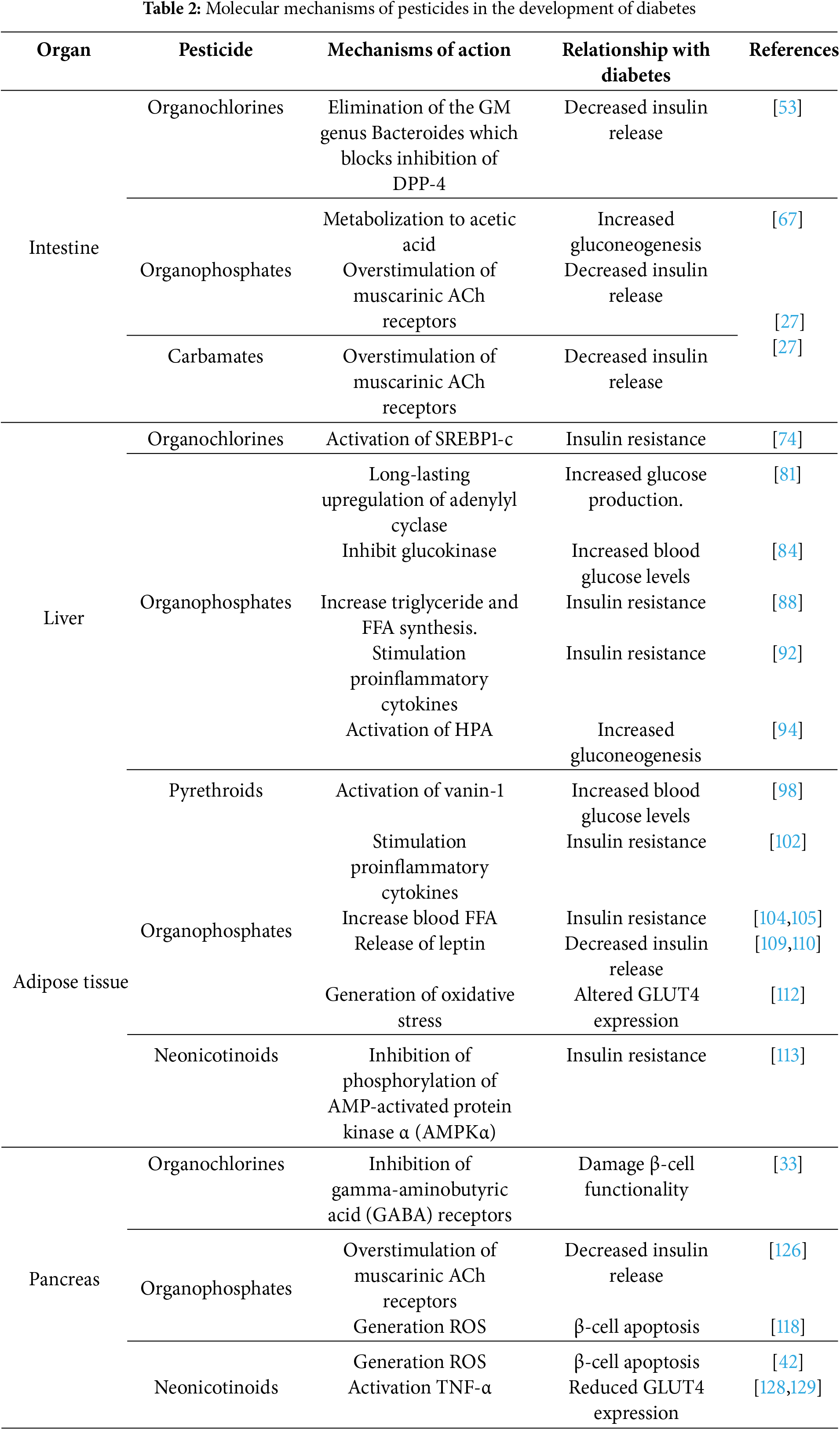

Table 2 summarizes the mechanisms of action of the different pesticides addressed in this review and their link with diabetes.

2.5 Comparative Analysis of the Revision

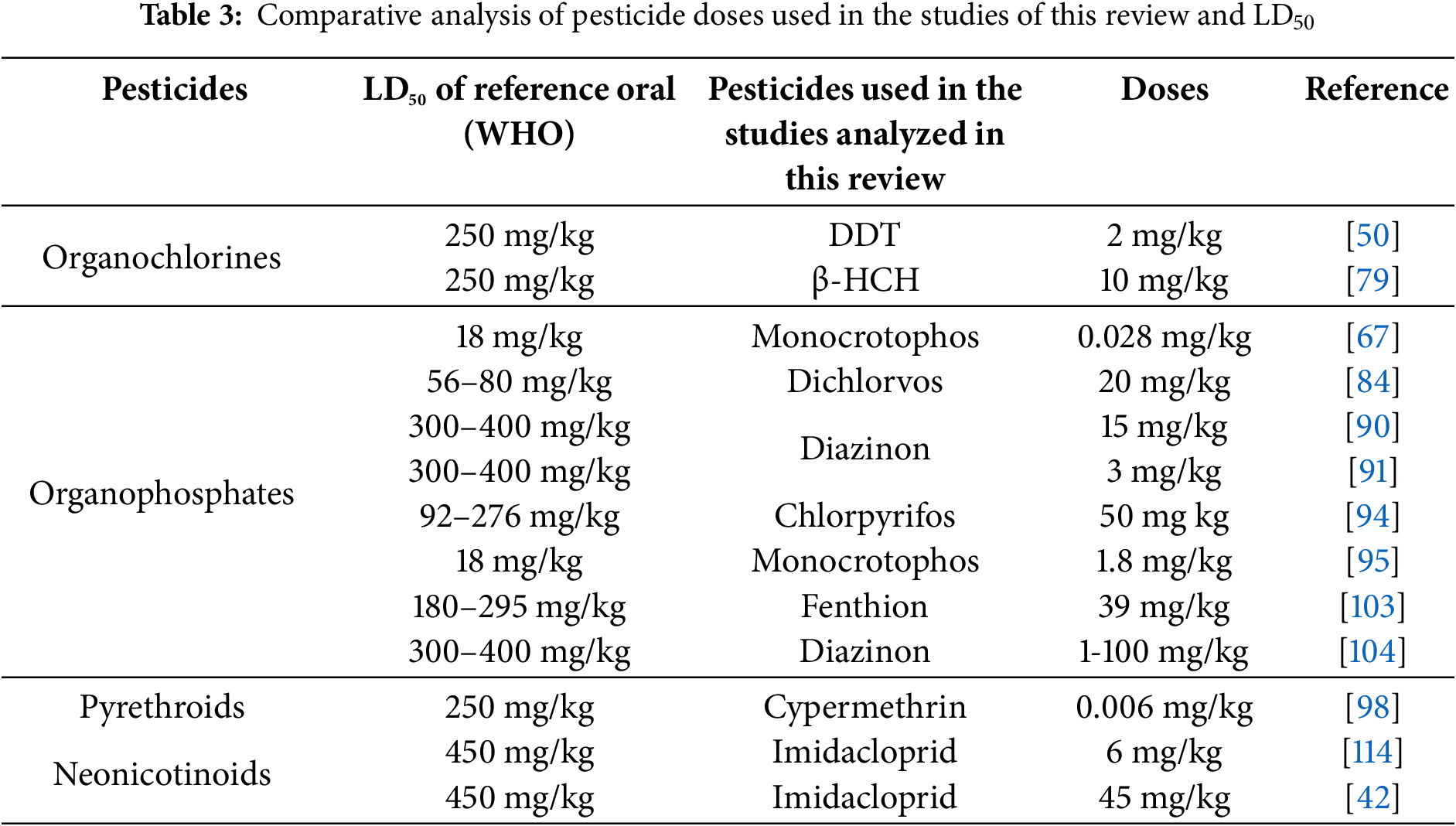

To obtain more detailed and accurate information on the effects of pesticides used in the studies in this review, a comparison was made between the doses used in these studies with the WHO-reported lethal dose 50 (LD50). This comparison showed that, despite the use of doses lower than LD50, harmful effects were obtained in the different organs involved in the regulation of synthesis and release and insulin. This could be due to many factors (diet, age, strain, etc.). However one important aspect would be that the doses of the reference studies could be considered an exposure over time, because the test animals may have been exposed for a different period (days).

Table 3 shows the comparison of doses used per pesticide group with LD50 for rats according to WHO [130].

There is increasing evidence of the involvement of different pesticides in the development of diabetes. This review has grouped the molecular mechanisms by which pesticides alter the functioning of the intestine, liver, pancreas, and adipose tissue; and has shown how, by causing dysfunction in one organ, they affect the other organs through the alteration of glucose homeostasis, which can trigger diabetes due to their multi-organ effects.

Pesticides can exert their negative effects on the intestine and subsequently damage the liver. Both OCs and OPs cause GM dysbiosis by eliminating bacteria that participate in glucose homeostasis. For example, they reduce the phyla of Bacteroidetes bacteria, which can decrease the expression of GLP-1, an increase involved in insulin release. Similarly, OPs and carbamates after muscarine overstimulation and subsequent downregulation reduce GLP-1 secretion by impairing insulin binding to the insulin receptor in the liver. In the gut, OPs can also be metabolized by the microbiota to acetic acid, which is directed to the liver and converted to glucose via gluconeogenesis. These mechanisms may contribute to hyperglycemia.

OPs and neonicotinoids can increase adipose tissue mass and damage β cells through the release of leptin, which activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in pancreatic β-cells, preventing membrane depolarization, which blocks Ca2+ entry and decreases insulin release. Furthermore, increased adipocyte size prevents FFA from being stored in adipocytes, thereby increasing FFA levels in the bloodstream, where they can be transported to the liver and cause IRS-1 degradation through the accumulation of fatty acid intermediates or by stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines; this results in decreased glucose uptake and increased blood glucose levels. In addition, both pesticides generate oxidative stress, which alters the expression of GLUT4, increased blood glucose levels.

The results of this review suggest that further studies are needed to assess the interaction between the molecular mechanisms exposed because we suggest that exposure to pesticides can first alter the functioning of an organ and then trigger subsequent adverse effects on organs related to the development of diabetes. In addition, new studies will need to take into account the effects of simultaneous exposure to several types of pesticides that may cause further damage to the organs responsible for glucose homeostasis. This damage could be because pesticides are almost always marketed as a mixture of substances, which can trigger substance-dependent toxicological effects, in addition to or by interaction between two or more substances. This approach deserves greater attention from the scientific community, as molecular mechanisms of synergism between OPs have been proposed, or by prior exposure to OCs. In addition, the potential interaction between endocrine-disrupting pesticides and the cumulative toxicity of OPs and OCs leads to estrogenic effects and neurological diseases. Such synergistic and/or antagonistic mechanisms may not be free of some harmful effects on organs such as the liver, and pancreas, among others, and have a direct relationship with the appearance of public health diseases.

These findings will serve to raise awareness about the relationship between exposure to pesticides and the development of diabetes, especially for at-risk populations or more vulnerable groups, and thus contribute to preventing the high prevalence of diabetes and the high costs of treating this disease.

Although this review provided a better understanding of the mechanisms of action of pesticides and their relationship with diabetes, more studies in humans are required. In addition, these studies should include the effect of a single pesticide and its relationship with diabetes, controlling for confounding variables. On the other hand, one of the main limitations of this review is that the data analysis comes from studies carried out mainly in animal models since most of the studies consulted in this review.

Acknowledgement: We thank CONACyT for the master's scholarship to C.A.F.-G. (Scholarship number: 842940).

Funding Statement: We believe we can only thank CONACYT for the master's scholarship awarded to one of the authors, which was mentioned in the acknowledgments.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Carlos Alfonso Flores Gutierréz, Joel Salazar-Flores; methodology, Erandis Dheni Torres-Sánchez; software, Emmanuel Reyes-Uribe; validation, Joel Salazar-Flores, Erandis Dheni Torres-Sánchez, Juan Heriberto Torres-Jasso; formal analysis, Carlos Alfonso Flores Gutierréz; investigation, Carlos Alfonso Flores Gutierréz; resources, Juan Heriberto Torres-Jasso; data curation, Erandis Dheni Torres-Sánchez; writing—original draft preparation, Carlos Alfonso Flores Gutierréz; writing—review and editing, Joel Salazar-Flores; visualization, Emmanuel Reyes-Uribe; supervision, Erandis Dheni Torres-Sánchez; project administration, Juan Heriberto Torres-Jasso; funding acquisition, Joel Salazar-Flores. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JSF, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Guo X, Wang H, Song Q, Li N, Liang Q, Su W, et al. Association between exposure to organophosphorus pesticides and the risk of diabetes among US adults: cross-sectional findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chemosphere. 2022;301:134471. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Cole JB, Florez JC. Genetics of diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(7):377–90. doi:10.1038/s41581-020-0278-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Harreiter J, Roden M. Diabetes mellitus: definition, classification, diagnosis, screening and prevention (Update 2023). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2023;135(Suppl 1):7–17. doi:10.1007/s00508-022-02122-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Demir S, Nawroth PP, Herzig S, Ekim Üstünel B. Emerging targets in type 2 diabetes and diabetic complications. Adv Sci. 2021;8(18):e2100275. doi:10.1002/advs.202100275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Gregory GA, Robinson TIG, Linklater SE, Wang F, Colagiuri S, de Beaufort C, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, and mortality of type 1 diabetes in 2021 with projection to 2040: a modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(10):741–60. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00218-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yachmaneni Jr AJr, Jajoo S, Mahakalkar C, Kshirsagar S, Dhole S. A comprehensive review of the vascular consequences of diabetes in the lower extremities: current approaches to management and evaluation of clinical outcomes. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e47525. doi:10.7759/cureus.47525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Liu S, Zhao Y, Yu YU, Ye D, Wang Q, Wang Z, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells modulate unfolded protein response and preserve β-cell mass in type 1 diabetes. BIOCELL. 2024;48(7):1115–26. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.050493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmad E, Lim S, Lamptey R, Webb DR, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2022;400(10365):1803–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01655-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, Larrea-Sebal A, Siddiqi H, Uribe KB, et al. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):6275. doi:10.3390/ijms21176275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Liu T, Kong X, Wei J. Unraveling the molecular crossroads: T2DM and Parkinson’s disease interactions. BIOCELL. 2024;48(12):1735–49. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.056272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Perng W, Conway R, Mayer-Davis E, Dabelea D. Youth-onset type 2 diabetes: the epidemiology of an awakening epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(3):490–9. doi:10.2337/dci22-0046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Strati M, Moustaki M, Psaltopoulou T, Vryonidou A, Paschou SA. Early onset type 2 diabetes mellitus: an update. Endocrine. 2024;85(3):965–78. doi:10.1007/s12020-024-03772-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. La Grasta Sabolic L, Marusic S, Cigrovski Berkovic M. Challenges and pitfalls of youth-onset type 2 diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2024;15(5):876–85. doi:10.4239/wjd.v15.i5.876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Alam S, Hasan MK, Neaz S, Hussain N, Hossain MF, Rahman T. Diabetes mellitus: insights from epidemiology, biochemistry, risk factors, diagnosis, complications and comprehensive management. Diabetology. 2021;2(2):36–50. doi:10.3390/diabetology2020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Park S, Kim S-K, Kim J-Y, Lee K, Choi JR, Chang S-J, et al. Exposure to pesticides and the prevalence of diabetes in a rural population in Korea. Neurotoxicology. 2019;70:12–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2018.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. He B, Ni Y, Jin Y, Fu Z. Pesticides-induced energy metabolic disorders. Sci Total Environ. 2020;729(1–4):139033. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ahmad MF, Ahmad FA, Alsayegh AA, Zeyaullah M, AlShahrani AM, Muzammil K, et al. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e29128. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Ajiboye TO, Kuvarega AT, Onwudiwe DC. Recent strategies for environmental remediation of organochlorine pesticides. Appl Sci. 2020;10(18):6286. doi:10.3390/app10186286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kaushal J, Khatri M, Arya SK. A treatise on Organophosphate pesticide pollution: current strategies and advancements in their environmental degradation and elimination. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;207(1):111483. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yao R, Yao S, Ai T, Huang J, Liu Y, Sun J. Organophosphate pesticides and pyrethroids in farmland of the Pearl River Delta, China: regional residue, distributions and risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1017. doi:10.3390/ijerph20021017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Mustapha MU, Halimoon N, Johar WLW, Shukor MY. An overview on biodegradation of carbamate pesticides by soil bacteria. Pertanika J Sci Technol. 2019;27(2):547–63. [Google Scholar]

22. Tang W, Wang D, Wang J, Wu Z, Li L, Huang M, et al. Pyrethroid pesticide residues in the global environment: an overview. Chemosphere. 2018;191(1–9):990–1007. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ravula AR, Yenugu S. Pyrethroid based pesticides-chemical and biological aspects. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2021;51(2):117–40. doi:10.1080/10408444.2021.1879007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rico A, Arenas-Sánchez A, Pasqualini J, García-Astillero A, Cherta L, Nozal L, et al. Effects of imidacloprid and a neonicotinoid mixture on aquatic invertebrate communities under Mediterranean conditions. Aquat Toxicol. 2018;204(8):130–43. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.09.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Q, Li Z, Chang CH, Lou JL, Zhao MR, Lu C. Potential human exposures to neonicotinoid insecticides: a review. Environ Pollut. 2018;236:71–81. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Reynoso EC, Torres E, Bettazzi F, Palchetti I. Trends and perspectives in immunosensors for determination of currently-used pesticides: the case of glyphosate, organophosphates, and neonicotinoids. Biosensors. 2019;9(1):20. doi:10.3390/bios9010020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rathish D, Senavirathna I, Jayasumana C, Agampodi S, Siribaddana S. A low GLP-1 response among patients treated for acute organophosphate and carbamate poisoning: a comparative cross-sectional study from an agrarian region of Sri Lanka. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26(3):2864–72. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3818-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wen J, Liu Q, Geng S, Shi X, Wang J, Yao X, et al. Impact of imidacloprid exposure on gestational hyperglycemia: a multi-omics analysis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;280:116561. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Tyagi S, Siddarth M, Mishra BK, Banerjee BD, Urfi AJ, Madhu SV. High levels of organochlorine pesticides in drinking water as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: a study in north India. Environ Pollut. 2021;271:116287. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhao M, Wei D, Wang L, Xu Q, Wang J, Shi J, et al. The interaction of inflammation and exposure to pyrethroids is associated with impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes. Expo Health. 2024;16(4):959–71. doi:10.1007/s12403-023-00602-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Baratzhanova G, Fournier A, Delannoy M, Baubekova A, Altynova N, Djansugurova L, et al. The mode of action of different organochlorine pesticides families in mammalians. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2024;110:104514. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2024.104514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Qi S-Y, Xu X-L, Ma W-Z, Deng S-L, Lian Z-X, Yu K. Effects of organochlorine pesticide residues in maternal body on infants. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:890307. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.890307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Heusinkveld HJ, Westerink RHS. Organochlorine insecticides lindane and dieldrin and their binary mixture disturb calcium homeostasis in dopaminergic PC12 cells. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(3):1842–8. doi:10.1021/es203303r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Salazar-Flores J, Lomelí-Martínez SM, Ceja-Gálvez HR, Torres-Jasso JH, Torres-Reyes LA, Torres-Sánchez ED. Impacts of pesticides on oral cavity health and ecosystems: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11257. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Mdeni NL, Adeniji AO, Okoh AI, Okoh OO. Analytical evaluation of carbamate and organophosphate pesticides in human and environmental matrices: a review. Molecules. 2022;27(3):618. doi:10.3390/molecules27030618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Nasrabadi M, Nazarian M, Darroudi M, Marouzi S, Harifi-Mood MS, Samarghandian S, et al. Carbamate compounds induced toxic effects by affecting Nrf2 signaling pathways. Toxicol Rep. 2024;12(9):148–57. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2023.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Marques LP, Joviano-Santos JV, Souza DS, Santos-Miranda A, Roman-Campos D. Cardiotoxicity of pyrethroids: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic options for acute and long-term toxicity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2022;50(6):1737–51. doi:10.1042/BST20220593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ahamad A, Kumar J. Pyrethroid pesticides: an overview on classification, toxicological assessment and monitoring. J Hazard Mater Adv. 2023;10(1):100284. doi:10.1016/j.hazadv.2023.100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yu H, Cui Y, Guo F, Zhu Y, Zhang X, Shang D, et al. Vanin1 (VNN1) in chronic diseases: future directions for targeted therapy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;962(4):176220. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.176220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Veedu SK, Ayyasamy G, Tamilselvan H, Ramesh M. Single and joint toxicity assessment of acetamiprid and thiamethoxam neonicotinoids pesticides on biochemical indices and antioxidant enzyme activities of a freshwater fish Catla catla. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2022;257(1):109336. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2022.109336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Xu X, Wang X, Yang Y, Ares I, Martínez M, Lopez-Torres B, et al. Neonicotinoids: mechanisms of systemic toxicity based on oxidative stress-mitochondrial damage. Arch Toxicol. 2022;96(6):1493–520. doi:10.1007/s00204-022-03267-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. El Gazzar WB, Bayoumi H, Youssef HS, Ibrahim TA, Abdelfatah RM, Gamil NM, et al. Role of IRE1α/XBP1/CHOP/NLRP3 signalling pathway in neonicotinoid imidacloprid-induced pancreatic dysfunction in rats and antagonism of lycopene: in vivo and molecular docking simulation approaches. Toxics. 2024;12(7):445. doi:10.3390/toxics12070445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wei Y, Wang L, Liu J. The diabetogenic effects of pesticides: evidence based on epidemiological and toxicological studies. Environ Pollut. 2023;331(Pt 2):121927. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Berg G, Rybakova D, Fischer D, Cernava T, Vergès M-CC, Charles T, et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome. 2020;8(1):103. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Utembe W, Kamng’ona AW. Gut microbiota-mediated pesticide toxicity in humans: methodological issues and challenges in the risk assessment of pesticides. Chemosphere. 2021;271(Suppl. 4):129817. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Canfora EE, Meex RCR, Venema K, Blaak EE. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):261–73. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0156-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Syromyatnikov MY, Isuwa MM, Savinkova OV, Derevshchikova MI, Popov VN. The effect of pesticides on the microbiome of animals. Agriculture. 2020;10(3):79. doi:10.3390/agriculture10030079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Shi X, Xu T, Gao M, Bi Y, Wang J, Yin Y, et al. Combined exposure of emamectin benzoate and microplastics induces tight junction disorder, immune disorder and inflammation in carp midgut via lysosome/ROS/ferroptosis pathway. Water Res. 2024;257(15):121660. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2024.121660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2016;2(1):16003. doi:10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhan J, Liang Y, Liu D, Ma X, Li P, Zhai W, et al. Pectin reduces environmental pollutant-induced obesity in mice through regulating gut microbiota: a case study of p,p’-DDE. Environ Int. 2019;130:104861. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liu Q, Shao W, Zhang C, Xu C, Wang Q, Liu H, et al. Organochloride pesticides modulated gut microbiota and influenced bile acid metabolism in mice. Environ Pollut. 2017;226:268–76. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Fontané L, Benaiges D, Goday A, Llauradó G, Pedro-Botet J. Influencia de la microbiota y de los probióticos en la obesidad. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2018;30(6):271–9. doi:10.1016/j.arteri.2018.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yang J-Y, Lee Y-S, Kim Y, Lee S-H, Ryu S, Fukuda S, et al. Gut commensal Bacteroides acidifaciens prevents obesity and improves insulin sensitivity in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(1):104–16. doi:10.1038/mi.2016.42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. González N, Acitores A, Sancho V, Valverde I, Villanueva-Peñacarrillo ML. Effect of GLP-1 on glucose transport and its cell signalling in human myocytes. Regul Pept. 2005;126(3):203–11. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2004.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Liu J, Yang K, Yang J, Xiao W, Le Y, Yu F, et al. Liver-derived fibroblast growth factor 21 mediates effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 in attenuating hepatic glucose output. eBioMedicine. 2019;41(Suppl. 3):73–84. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Mathiesen DS, Bagger JI, Bergmann NC, Lund A, Christensen MB, Vilsbøll T, et al. The effects of dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonism on glucagon secretion—a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17):4092. doi:10.3390/ijms20174092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Xiong X, Lu W, Qin X, Luo Q, Zhou W. Downregulation of the GLP-1/CREB/adiponectin pathway is partially responsible for diabetes-induced dysregulated vascular tone and VSMC dysfunction. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127(24):110218. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Grunddal KV, Jensen EP, Ørskov C, Andersen DB, Windeløv JA, Poulsen SS, et al. Expression profile of the GLP-1 receptor in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas in adult female mice. Endocrinology. 2022;163(1). doi:10.1210/endocr/bqab216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Otsuka M, Huang J, Tanaka T, Sakata I. Identification of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in mice stomach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024;704:149708. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Álvarez J, Fernández Real JM, Guarner F, Gueimonde M, Rodríguez JM, Saenz de Pipaon M, et al. Gut microbes and health. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44(7):519–35. doi:10.1016/j.gastrohep.2021.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Yoshida N, Yamashita T, Osone T, Hosooka T, Shinohara M, Kitahama S, et al. Bacteroides spp. promotes branched-chain amino acid catabolism in brown fat and inhibits obesity. iScience. 2021;24(11):103342. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Liang Y, Zhan J, Liu D, Luo M, Han J, Liu X, et al. Organophosphorus pesticide chlorpyrifos intake promotes obesity and insulin resistance through impacting gut and gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):19. doi:10.1186/s40168-019-0635-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Huertas-Molina OF, Colombian Agricultural Research Corporation-AGROSAVIA, Londoño-Vásquez D, Olivera-Angel M, University of Antioquia, University of Antioquia. Hipercetonemia: bioquímica de la producción de ácidos grasos volátiles y su metabolismo hepático. Rev Udca Actual Divulg Cient. 2020;23(1). doi:10.31910/rudca.v23.n1.2020.1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud D-J, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(9):2325–40. doi:10.1194/jlr.R036012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Melkonian EA, Asuka E, Schury MP. Physiology, Gluconeogenesis. [Updated 2023 Nov 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FLStatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 9]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541119/. [Google Scholar]

66. Anderson R, Pladna KM, Schramm NJ, Wheeler FB, Kridel S, Pardee TS. Pyruvate dehydrogenase inhibition leads to decreased glycolysis, increased reliance on gluconeogenesis and alternative sources of acetyl-CoA in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers. 2023;15(2):484. doi:10.3390/cancers15020484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Velmurugan G, Ramprasath T, Swaminathan K, Mithieux G, Rajendhran J, Dhivakar M, et al. Gut microbial degradation of organophosphate insecticides-induces glucose intolerance via gluconeogenesis. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):8. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1134-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Sarath A, David J, Krishnaveni K, Kumar RS. Pesticide from farm to clinic: possible association between pesticides and diabetes mellitus. Int J Multidiscip Curr Res. 2021;9:600–5. doi:10.14741/ijmcr/v.9.6.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Nauck MA, Müller TD. Incretin hormones and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2023;66(10):1780–95. doi:10.1007/s00125-023-05956-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Chung YL, Hou YC, Wang IK, Lu KC, Yen TH. Organophosphate pesticides and new-onset diabetes mellitus: from molecular mechanisms to a possible therapeutic perspective. World J Diabetes. 2021;12(11):1818–31. doi:10.4239/wjd.v12.i11.1818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Moreira S, Silva R, Carrageta DF, Alves MG, Seco-Rovira V, Oliveira PF, et al. Carbamate pesticides: shedding light on their impact on the male reproductive system. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8206. doi:10.3390/ijms23158206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Rathish D, Agampodi SB, Jayasumana MACS, Siribaddana SH. From organophosphate poisoning to diabetes mellitus: the incretin effect. Med Hypotheses. 2016;91(Suppl 2):53–5. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2016.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Hatting M, Tavares CDJ, Sharabi K, Rines AK, Puigserver P. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411(1):21–35. doi:10.1111/nyas.13435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Ji G, Xu C, Sun H, Liu Q, Hu H, Gu A, et al. Organochloride pesticides induced hepatic ABCG5/G8 expression and lipogenesis in Chinese patients with gallstone disease. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):33689–702. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.9399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Lytrivi M, Castell A-L, Poitout V, Cnop M. Recent insights into mechanisms of β-cell lipo- and glucolipotoxicity in type 2 diabetes. J Mol Biol. 2020;432(5):1514–34. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2019.09.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Yazıcı D, Sezer H. Insulin resistance, obesity and lipotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:277–304. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Sakurai Y, Kubota N, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T. Role of insulin resistance in MAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):4156. doi:10.3390/ijms22084156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Saturated fat and cardiometabolic risk factors, coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes: a fresh look at the evidence. Lipids. 2010;45(10):893–905. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3393-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Liu Q, Wang Q, Xu C, Shao W, Zhang C, Liu H, et al. Organochloride pesticides impaired mitochondrial function in hepatocytes and aggravated disorders of fatty acid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):46339. doi:10.1038/srep46339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Roumans KHM, Lindeboom L, Veeraiah P, Remie CME, Phielix E, Havekes B, et al. Hepatic saturated fatty acid fraction is associated with de novo lipogenesis and hepatic insulin resistance. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1891. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15684-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Slotkin TA. Does early-life exposure to organophosphate insecticides lead to prediabetes and obesity? Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31(3):297–301. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. De Mingo OA. Role of rho family GTPases and glycogen phosphorylase in lymphocyte proliferation [doctoral dissertation]; 2009. [Google Scholar]

83. Khannpnavar B, Mehta V, Qi C, Korkhov V. Structure and function of adenylyl cyclases, key enzymes in cellular signaling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2020;63:34–41. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2020.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Romero-Navarro G, Lopez-Aceves T, Rojas-Ochoa A, Fernandez Mejia C. Effect of dichlorvos on hepatic and pancreatic glucokinase activity and gene expression, and on insulin mRNA levels. Life Sci. 2006;78(9):1015–20. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.06.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Agius L. Hormonal and metabolite regulation of hepatic glucokinase. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36(1):389–415. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-051145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Matschinsky FM, Wilson DF. The central role of glucokinase in glucose homeostasis: a perspective 50 years after demonstrating the presence of the enzyme in islets of Langerhans. Front Physiol. 2019;10:148. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Ashcroft FM, Lloyd M, Haythorne EA. Glucokinase activity in diabetes: too much of a good thing? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2023;34(2):119–30. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2022.12.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Lasram MM, Dhouib IB, Annabi A, El Fazaa S, Gharbi N. A review on the molecular mechanisms involved in insulin resistance induced by organophosphorus pesticides. Toxicology. 2014;322(5):1–13. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2014.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Camacho-Pérez MR, Covantes-Rosales CE, Toledo-Ibarra GA, Mercado-Salgado U, Ponce-Regalado MD, Díaz-Resendiz KJG, et al. Organophosphorus pesticides as modulating substances of inflammation through the cholinergic pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4523. doi:10.3390/ijms23094523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Birdane YO, Avci G, Birdane FM, Turkmen R, Atik O, Atik H. The protective effects of erdosteine on subacute diazinon-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(15):21537–46. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17398-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Onukak CE, Femi-Akinlosotu OM, Obasa AA, Folarin OR, Ajibade TO, Igado OO, et al. Epigallocatechin -3-gallate mitigates diazinon neurotoxicity via suppression of pro-inflammatory genes and upregulation of antioxidant pathways. Res Sq. 2024;26(3):22. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-5341630/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Aziz A, Elawady NS, Rizk MY, Hakim SA, Shahy SA, Shafy EM. Inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress biomarkers and clinical manifestations of organophosphorus pesticides-exposed researchers. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(4):2235–45. [Google Scholar]

93. Kuo T, McQueen A, Chen T-C, Wang J-C. Regulation of glucose homeostasis by glucocorticoids. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;872:99–126. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2895-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Acker CI, Nogueira CW. Chlorpyrifos acute exposure induces hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in rats. Chemosphere. 2012;89(5):602–8. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.05.059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Joshi AKR, Rajini PS. Hyperglycemic and stressogenic effects of monocrotophos in rats: evidence for the involvement of acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2012;64(1–2):115–20. doi:10.1016/j.etp.2010.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Nagaraju R, Joshi AKR, Rajini PS. Organophosphorus insecticide, monocrotophos, possesses the propensity to induce insulin resistance in rats on chronic exposure: monocrotophos induces insulin resistance in rats. J Diabetes. 2015;7(1):47–59. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Petersen MC, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(4):2133–223. doi:10.1152/physrev.00063.2017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Wei Y, Liu W, Liu J. Environmentally relevant exposure to cypermethrin aggravates diet-induced diabetic symptoms in mice: the interaction between environmental chemicals and diet. Environ Int. 2023;178(108090):108090. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2023.108090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Carvajal C. Adipose tissue, obesity and insulin resistance. Leg Med Costa Rica. 2015;32(2):138–44. [Google Scholar]

100. Torrades S. Type 2 diabetes: how to stop lipotoxicity. Offarm: Pharm Soc. 2005;24(4):118–22. [Google Scholar]

101. Ros Pérez M, Medina-Gómez G. Obesity, adipogenesis and insulin resistance. Endocrinol Nutr. 2011;58(7):360–9. doi:10.1016/j.endonu.2011.05.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Miranda CS, Silva-Veiga FM, Fernandes-da-Silva A, Guimarães Pereira VR, Martins BC, Daleprane JB, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors-alpha and gamma synergism modulate the gut-adipose tissue axis and mitigate obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2023;562(4):111839. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2022.111839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Andrews FV, Kim SM, Edwards L, Schlezinger JJ. Identifying adipogenic chemicals: disparate effects in 3T3-L1, OP9 and primary mesenchymal multipotent cell models. Toxicol in Vitro. 2020;67(6):104904. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2020.104904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Smith A, Yu X, Yin L. Diazinon exposure activated transcriptional factors CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins α (C/EBPα) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and induced adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2018;150(4):48–58. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Seok JW, Park JY, Park HK, Lee H. Endrin potentiates early-stage adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells by activating the mammalian target of rapamycin. Life Sci. 2022;288(3–5):120151. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(5):E745–51. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Shinsyu A, Bamba S, Kurihara M, Matsumoto H, Sonoda A, Inatomi O, et al. Inflammatory cytokines, appetite-regulating hormones, and energy metabolism in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(2):1469–79. doi:10.3892/ol.2020.11662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Ying W, Fu W, Lee YS, Olefsky JM. The role of macrophages in obesity-associated islet inflammation and β-cell abnormalities. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(2):81–90. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0286-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Sánchez JC. Physiological profile of leptin. Colombia Médica. 2005;36(1):50–9. [Google Scholar]

110. Basain Valdés JM, Valdés Alonso MDC, Pérez Martínez M, Díaz J, Linares Valdés MDLÁ. The role of leptin as an afferent signal in the regulation of energy homeostasis . Cuban J Pediatr. 2016;88(174–80. [Google Scholar]

111. Pessler D, Rudich A, Bashan N. Oxidative stress impairs nuclear proteins binding to the insulin responsive element in the GLUT4 promoter. Diabetologia. 2001;44(12):2156–64. doi:10.1007/s001250100024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Fazakerley DJ, Minard AY, Krycer JR, Thomas KC, Stöckli J, Harney DJ, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes insulin resistance without disrupting oxidative phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(19):7315–28. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA117.001254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Park Y, Kim Y, Kim J, Yoon KS, Clark J, Lee J, et al. Imidacloprid, a neonicotinoid insecticide, potentiates adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(1):255–9. doi:10.1021/jf3039814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Sun Q, Xiao X, Kim Y, Kim D, Yoon KS, Clark JM, et al. Imidacloprid promotes high fat diet-induced adiposity and insulin resistance in male C57BL/6J mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(49):9293–306. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Bengal E, Aviram S, Hayek T. P38 MAPK in glucose metabolism of skeletal muscle: beneficial or harmful? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6480. doi:10.3390/ijms21186480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Perego C, Da Dalt L, Pirillo A, Galli A, Catapano AL, Norata GD. Cholesterol metabolism, pancreatic β-cell function and diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865(9):2149–56. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Fiorina P. GABAergic system in b-cells: from autoimmunity target to regeneration tool. Diabetes. 2013;62(11):3674–6. doi:10.2337/db13-1243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Newsholme P, Morgan D, Rebelato E, Oliveira-Emilio HC, Procopio J, Curi R, et al. Insights into the critical role of NADPH oxidase(s) in the normal and dysregulated pancreatic beta cell. Diabetologia. 2009;52(12):2489–98. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1536-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Sun W, Lei Y, Jiang Z, Wang K, Liu H, Xu T. BPA and low-Se exacerbate apoptosis and mitophagy in chicken pancreatic cells by regulating the PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. J Adv Res. 2024;67(6):61–69. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2024.01.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Hurrle S, Hsu WH. The etiology of oxidative stress in insulin resistance. Biomed J. 2017;40(5):257–62. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2017.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Robertson RP, Harmon JS. Pancreatic islet β-cell and oxidative stress: the importance of glutathione peroxidase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(19):3743–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Drews G, Krippeit-Drews P, Düfer M. Oxidative stress and beta-cell dysfunction. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460(4):703–18. doi:10.1007/s00424-010-0862-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Gerber PA, Rutter GA. The role of oxidative stress and hypoxia in pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;26(10):501–18. doi:10.1089/ars.2016.6755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Singh V, Ubaid S. Role of silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1) in regulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Inflammation. 2020;43(5):1589–98. doi:10.1007/s10753-020-01242-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Tang Z-C, Chu Y, Tan Y-Y, Li J, Gao S. Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox-1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and diabetes mellitus. Chin Med J. 2020;133(3):344–50. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Zhao L, Liu Q, Jia Y, Lin H, Yu Y, Chen X, et al. The associations between organophosphate pesticides (OPs) and respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease: a review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Toxics. 2023;11(9):741. doi:10.3390/toxics11090741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Gilon P, Henquin JC. Mechanisms and physiological significance of the cholinergic control of pancreatic β-cell function. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(5):565–604. doi:10.1210/edrv.22.5.0440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Khalil SR, Awad A, Mohammed HH, Nassan MA. Imidacloprid insecticide exposure induces stress and disrupts glucose homeostasis in male rats. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;55(2):165–74. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2017.08.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Ha L-X, Wu Y-Y, Yin T, Yuan Y-Y, Du Y-D. Effect of TNF-alpha on endometrial glucose transporter-4 expression in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome through nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway activation. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021;72(6):965–73. doi:10.26402/jpp.2021.6.13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. World Health Organization. Principles for evaluating health risks in children associated with exposure to chemicals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006 [cited 2025 Mar 9]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43604/924157237X_eng.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools