Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Stretch Enhances Secretion of Extracellular Vehicles from Airway Smooth Muscle Cells via Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling in Relation to Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury

Changzhou Key Laboratory of Respiratory Medical Engineering, Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Health Sciences, School of Medical and Health Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

* Corresponding Authors: MINGZHI LUO. Email: ; LINHONG DENG. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

BIOCELL 2025, 49(5), 833-855. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.063869

Received 26 January 2025; Accepted 18 April 2025; Issue published 27 May 2025

Abstract

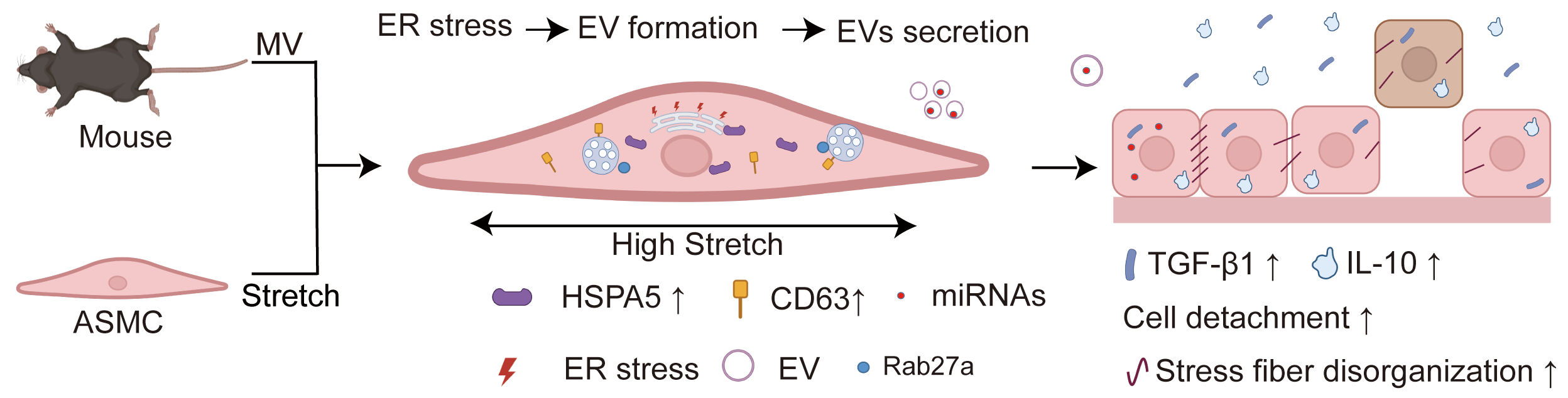

Background: Mechanical ventilation (MV) provides life support for patients with severe respiratory distress but can simultaneously cause ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). However, due to a poor understanding of its mechanism, there is still a lack of effective remedies for the often-deadly VILI. Recent studies indicate that the stretch associated with MV can enhance the secretion of extracellular vesicles (EVs) and induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs), both of which can contribute to VILI. But whether MV-associated stretch enhances the secretion of EVs via ER stress in ASMCs as an underlying mechanism of VILI remains unknown. Methods: In this study, we exposed cultured human ASMCs to stretch (13% strain) and mouse models to MV at tidal volume (18 mL/kg). Subsequently, the amount of secreted EVs in the culture medium of ASMCs and the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of mouse models was quantitatively evaluated by ultracentrifugation, transmission electron microscopy, Western blot, flow cytometry, and nanoparticle tracking analysis. The cultured ASMCs and the lung tissues of mouse models were assessed for expression of biomarkers of EVs (cluster of differentiation antigen 63, CD63), ER stress (heat shock protein family A member 5, HSPA5), and EVs regulating molecule Rab27a by immunofluorescence microscopy, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), respectively. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in EVs from ASMCs were measured with miRNA whole genome sequencing (miRNA-Seq). Results: We found that stretch enhanced EV secretion from cultured ASMCs. In addition, the cultured ASMCs and the mouse models were either or not pretreated with ER stress inhibitor (tauroursodeoxycholic acid, TUDCA)/EV secretion inhibitor (GW4869) prior to stretch or MV. We found that MV-associated stretch enhanced the expression of CD63, HSPA5, and Rab27a in cultured ASMCs and BALF/lung tissues of mouse models, which could all be attenuated with TUDCA/GW4869 pretreatment. miRNA-Seq data show that differentially expressed miRNAs in EVs mainly modulate gene transcription. Furthermore, the EVs from cultured ASMCs under stretch tended to enhance detachment and expression of inflammatory cytokines, i.e., transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), interleukin-10 (IL-10) in cultured airway epithelial cells. The expression of TGF-β1 and IL-10 in BALF of the mouse models also increased in response to MV, which was attenuated together with partial improvement of lung injury by pretreatment with TUDCA, GW4869/Rab27a siRNAs. Conclusion: Taken together, our data indicate that MV-associated stretch can enhance the secretion of EVs from ASMCs via ER stress signaling to mediate airway inflammation and VILI, which provides new insight for further exploring EVs for the diagnosis and treatment of VILI.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileMechanical ventilation (MV) provides life-saving intervention for critically ill patients with repiratory diseases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but at the same time, it can induce deadly pathological responses in the pulmonary airways including inflammation, epithelial shedding and barrier disruption, which are collectively known as ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). Both in vivo and in vitro evidence have suggested that VILI may be largely attributable to the stretch (>10% strain) of the pulmonary system during MV, and lowering the tidal volume of ventilation does seem to protect some ARDS patients from VILI [1–4]. However, at present, this strategy is very difficult, and even impossible to apply with optimal ventilator settings for individual patients at the bedside, because of the limited knowledge of the respiratory system’s mechanotransduction in response to stretch. Alternatively, it may be a more applicable strategy to pharmacologically interfere with the upstream injurious responsive pathways activated by the MV-associated stretch for the benefit of ameliorating VILI in clinical treatment [5,6]. Therefore, it is imperative to explore the cellular mechanisms underlying injurious lung response to MV for a potential target of effective and safe prevention of VILI.

Recently, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been considered to be of great therapeutic potential, as they provide novel intercellular communication mechanisms in mediating diverse pathological processes, including airway inflammation [7–9]. It has been widely demonstrated that the secretion of EVs from cells can be enhanced by various external chemical stimuli via enhancing the Rab family of small GTPases, including Rab27a [10–14]. Much less is known, however, about the mechanical regulation of the secretion of EVs and their role in mediating pathophysiological processes, especially in the lung.

Several previous studies suggest that the secretion of EVs in the lung can be enhanced during MV, which plays the role of novel mediators of VILI, in addition to the canonical pro-inflammatory cytokines [15–17]. As important mechanosensitive cells, airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) are known to be capable of responding to stretch to enhance secretory phenotypes in airway inflammatory diseases such as asthma [18–20]. It is unknown, however, whether ASMCs would respond to MV-associated stretch to enhance secretion of EVs for mediating VILI.

In our previous study based on cell mechanics assay and data-driven bioinformatics analysis, we found that ASMCs mainly respond to stretch with enhanced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [21]. This is in line with reports that ER stress enhances secretion of EVs in various types of cells, either in vitro or in vivo [22–26]. Therefore, we hypothesized that MV-associated stretch may enhance secretion of EVs from ASMCs via ER stress signaling and thus induce lung injury.

To test this hypothesis, we quantitatively evaluated the secretion of EVs from cultured human ASMCs exposed to stretch, and mice subjected to MV, together with an assessment of ER stress and Rab27a expression in the ASMCs and lung tissues, the differentially expressed miRNAs in EVs as well as the effect of ASMC-secreted EVs on the cultured airway epithelial cells. The findings may provide evidence that links MV-associated stretch to secretion of EVs via ER stress of ASMCs, as a novel underlying pathological mechanism of VILI.

2.1 Cell Culture Experiment with Stretch

Primary human ASMCs (BeNa Culture Collection, #BNCC339826, Beijing, China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #11885092, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #16000-044), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #15140122,) in an incubator containing 5% CO2 humidified at 37°C. ASMCs remained free of Mycoplasma contamination throughout the experiments. Exponentially proliferating ASMCs at passages 3–8 were first plated on type I collagen (Advanced BioMatrix, #5153, Poway, CA, USA)-coated Bioflex 6-well plates (2 × 104 cells/cm2) for 24 h and then changed to the non-serum medium. Subsequently, the cultured ASMCs were exposed to the cyclic stretch of 13% strain amplitude at 0.5 Hz oscillation frequency for 72 h by using Flexcell 5000 (FlexCell International, Hillsborough, NC, USA), simulating the stretch of small airways during high tidal volume MV. Cells that underwent the same procedure but without exposure to the cyclic stretch were used as Static controls.

2.2 Animal Experiment with Mechanical Ventilation

The animal experiment of the VILI mouse model was approved by the Biomedical Studies Ethics Committee of Changzhou University (IACUC No. 20200327048) following the relevant institutional guidelines and regulations of animal care and use. C57BL/6 mice (male, age 6–8 weeks, weight 18–22 g) were purchased from Cavens Lab Animal Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China, and housed in the specific pathogen-free conditions at room temperature (RT, ~25°C) and 50%–60% of relative humidity with 12/12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. The VILI mouse model has been established as previously described [27]. Anesthetized C57BL/6 mice were ventilated using an injurious high tidal volume strategy (tidal volume = 18 mL/kg) for 3 h. Mice that underwent the same procedure but kept breathing spontaneously without MV were used as Controls. For ER stress/EV secretion inhibition experiments, mice were delivered by aspiration before ventilation protocols with either 1 mg/kg tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA, an ER stress inhibitor, Solarbio, #IT0790, Beijing, China), 2.5 mg/kg GW4869 (an EV secretion inhibitor, MedChem Express, #6823-69-4, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), or saline (Vehicle, 50 μL), respectively [21,28].

2.3 Preparation of EVs from Cell Culture Media and BALF

When exposure to either stretch or high tidal volume MV was complete, during cell or animal experiments, the conditioned media from cultured ASMCs or BALF from the mouse were collected as the raw sample. Then the raw sample was centrifuged at 500× g for 20 min at 4°C, followed by 2000× g for 10 min at 4°C, respectively, to remove cell debris.

Then, the supernatant of the centrifuged raw sample was first filtered via a 0.4 µm sterile syringe to collect EVs smaller than 400 nm, and the filtered supernatant was kept on ice before being further purified by ultracentrifugation. The ultracentrifuge units (Amicon, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) were pre-equilibrated by centrifuging with sterile phosphate buffer solution (PBS) for 10 min at 4°C. Afterwards, the filtered supernatant was placed in the ultracentrifuge device and centrifuged at 110,000× g for 70 min. The precipitated sample of EVs was washed with PBS and centrifuged again at 100,000× g for 70 min. The EVs were then suspended in buffer (40 mM HEPES at pH 7.5 and 100 mM KCl) and stored at −80°C before use for characterization and experiments.

2.4 Characterization of the Prepared EVs

The prepared EVs were characterized for morphology and size by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with negative staining. Briefly, the EVs stored at −80°C were thawed on ice, followed by fixation with paraformaldehyde (PFA, 4% in PBS, 100 μL) for 5 min. Then, 10 µL of sample was added onto the Formvar/carbon-coated copper grids. Subsequently, 30 µL 2% phosphotungstic acid was added to the samples to negatively stain the EVs at RT for 5 min. The grids were washed three times with PBS and dried under an incandescent lamp. Finally, the negatively stained EVs were examined for morphology and size under TEM (Hitachi, HT7800, Japan) at 100 kV.

The prepared EVs and cultured ASMCs were assessed for protein expression of biomarkers of EVs (cluster of differentiation antigen 63, CD63) and ER stress (heat shock protein family A member 5, HSPA5) by Western blot (WB). Briefly, EVs or cells were lysed using a lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #FNN0021). Lysates were diluted with 4× Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad, #1610747, Hercules, CA, USA) and loaded with equal amounts of protein into SDS-PAGE gels. The protein was transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Roche Applied Science, #3010040001, Mannheim, Germany) with a pore size of 0.45 μm and blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h. The membrane was then probed with the following antibodies: anti-CD63 (1:1000, Abcam, #ab216130, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-HSPA5 (1:500, BOSTER, #BA2042, Wuhan, China), anti-Rab27a (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #PA5-79904) and anti-Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:5000, GeneTex, #GTX100118, Irvine, CA, USA) rabbit polyclonal antibodies at RT for 1 h. After washing with 1× Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% of Tween-20 (TBST) three times, membranes were incubated with goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000, DyLight 800, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #SA5-10036) or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000, DyLight 680, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #35518) (RT, 1 h). Signals were measured with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). For quantification, the intensity of the immunoblots was calculated by subtracting the background, and the relative expression of the target gene was normalized to the intensity of the reference and presented as a ratio to that of the Control.

The prepared EVs were further analyzed for the concentration and size distribution by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using ZetaView PMX 110 nanoparticle tracking analyzer (Particle Metrix, Meerbusch, Germany), bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay using TECAN M1000 microplate reader (Infinite Männedorf, Switzerland) and flow cytometry (FCM) using Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, East Rutherford, NJ, USA), respectively. For FCM analysis, the EVs were incubated with blocking solution (10% normal goat serum, Abcam, #ab7481) for 10 min, then stained with CD63 exosome capture beads (Abcam, #ab239686) in the dark for 12 h at 4°C and washed with Dio staining for 10 min at 37°C, and then run through the flow cytometer.

2.5 Assessment of EVs and ER Stress in ASMCs by Immunofluorescence

ASMCs were fixed and then incubated with mouse anti-CD63 (1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #967-MSM2-P0) or rabbit anti-HSPA5 (1:100, BOSTER, #BA2042) antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse (1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A-21121) or Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A-11035) at RT for 1 h in the dark. The nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/mL, Beyotime Biotechnology, #C1005) for 10 min. Cells were then observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM710, Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) with ×100 objective. Acquisition parameters were kept constant throughout the experiments.

The numbers of CD63 and HSPA5 puncta in the fluorescent images of the ASMCs were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.53t, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The data from three independent experiments in which the average number of CD63 and HSPA5 puncta per cell was analyzed. The colocalization of CD63 and HSPA5 in the ASMCs was also analyzed using the colocalization analysis procedure of ImageJ. Pearson coefficient and 2D intensity histograms were recorded to quantify the degree of CD63 and HSPA5 colocalization.

2.6 Assessment of Rab27a mRNA Expression with/without siRNA Transfection in ASMCs by qPCR

The Rab27a mRNA expression in ASMCs was knocked down by transfection of Rab27a siRNA (Table S1, General Biosystems, Chuzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ASMCs at 50%–80% confluence were serum-deprived for 24 h and then transfected with either the scramble or Rab27a siRNA by Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #L3000015) for 72 h in Opti-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #31985062) before the experiment.

The mRNA expression of Rab27a in ASMCs after Rab27a siRNA transfection or stretch treatment was also quantified with primers for Rab27a and GAPDH (Table S1, General Biosystems) by qPCR. Briefly, total RNA from ASMCs was purified using TRI Reagent RNA Isolation Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA #T9424), and the RNA was quantified with a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, 1st-strand cDNA was generated based on RNA with the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #K1622). PCR was performed with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, #A25742, Foster City, CA, USA) using the StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Fold changes in mRNA expression of Rab27a were calculated by using 2−△△CT method, where

Cell activity of ASMCs treated with Rab27a siRNA or scramble was tested with the cell counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Beyotime Biotechnology, #C0040) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Beyotime Biotechnology, #ST316) assays as previously described [4].

2.7 Assessment of the miRNAs in EVs from ASMCs by Whole-Genome-Wide miRNAs Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

To screen the regulating miRNAs in EVs from ASMCs, a miRNA-Seq method was used as previously reported [21]. Briefly, the total RNAs in EVs either from static or stretch groups of ASMCs were purified using the RNAisoTM Plus Kit (TaKaRa, #9108/9109, Tokyo, Japan) and then were used to construct a miRNA library using the Illumina TruSeqTM Small RNA Library Prep kit (Illumina, RS-122-2001, San Diego, CA, USA) by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). For miRNA-Seq, miRNA was ligated with 3′ and 5′ adaptors, reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA, labeled with indexed primers by PCR amplification (12 cycles), and purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, #28104, Germantown, MD, USA). 140–150 bp fractions were separated by polyacrylamide electrophoresis with 6% Novex TBE PAGE gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then the purity and concentration were measured with the High Sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent Technologies, #G2938-90321, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a Bioanalyzer 2100. Then, the miRNA-Seq was performed on the Illumina HiSeqTM 2000 sequencer machine.

The miRNA-Seq results were used to screen the differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miNRAs, counts ≥ 1, fold change > 2, p < 0.05) in EVs from ASMCs cultured in either static or stretch conditions using the DESeq2 software package based on the online platform of Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com), which is available via customer account [29,30].

The target mRNAs of the DE-miRNAs were further predicted by miRanda, TargetScan, and RNAhybrid on the Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com). Then the associated gene functions and signaling pathways of target mRNAs in response to stretch were enriched with Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, performed by the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID 6.8, http://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov, free online access for any user), respectively, and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 was considered significant.

2.8 Assessment of ER Stress in Lung Tissue by Immunohistochemistry

ER stress in lung tissue was evaluated by the protein expression of ER stress biomarker HSPA5 by immunohistochemistry (IHC). In brief, the lung tissue slice was deparaffinized and hydrated. The slice was incubated in boiled citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0) for 15 min for antigen retrieval. Then it was incubated with endogenous peroxidase blocking buffer (Elabscience, #E-IR-R115, Wuhan, China) for 25 min in the dark, and was washed 3 times with PBS. Afterwards it was immersed in 10% horse serum (Sigma, #H0146) in PBS as a blocking solution for 1 h at RT, washed 3 times in PBS for 5 min, and then incubated with HSPA5 antibody (1:100, #BA2042, BOSTER) in PBS containing 5% horse serum for 1 h at RT. Subsequently, it was washed 3 times in PBS for 5 min, then incubated in a diluted (1:10,000) HRP-AffiniPure Goat Rabbit IgG (H + L) (BOSTER, #BM3894, 1:500) for 1 h at RT. Finally, it was incubated for 3 min in DAB solution [DAB (3, 3-diaminobenzidine) horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate kit (with nickel), Beyotime Biotechnology, #P0203] for visualization of HSPA5. The lung tissue slice stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) was used for histological examination with the HE Stain Kit (Solarbio, #G1120). All stained lung tissue slices were sealed with cover-slips using a mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA), and subsequently examined by optical microscopy (Olympus CKX53, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with ×40 objective, and ImageJ was used to quantify the alveolar wall thickness and the expression of HSPA5 by optical density of IHC staining.

2.9 Treatment of Airway Epithelial Cells with EVs from Cultured ASMCs

Human bronchial airway epithelial (BEAS-2B) cell line (#iCell-h023, ATCC CRL3588) was purchased from iCell Bioscience Inc. and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. BEAS-2B remained free of mycoplasma contamination. Before the experiment, subconfluent, exponential proliferating, and cubic-like healthy BEAS-2B cells were plated on a cell culture dish at 1 × 104 cells/cm2 and incubated for 24 h. Then the BEAS-2B cells were treated for 72 h with either the EVs derived from the medium or the medium per se of the cultured ASMCs.

2.10 Assessment of Stress Fibers, Cell Attachment, and Inflammatory Cytokines

The stress fibers and nuclei of BEAS-2B cells were labeled with fluorescent fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated phalloidin and DAPI, respectively, as described earlier, for examination of the cell structure. Stained cells were observed with laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM710, Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) using ×63 objective. Acquisition parameters were kept constant throughout the experiments. These fluorescence images, captured as described above, were further evaluated for quantitative distribution of the stress fibers. Briefly, a single cell was separated and stored in a 200 × 200-pixel image and was then converted to a binary image. Then the fractal dimension of stress fibers in a single cell was analyzed with the fractal box count by using ImageJ (version 1.53t). More than 30 cells in each experimental group were analyzed, and the averaged D value was used for the following quantitative comparison.

Cell attachment of BEAS-2B was measured by using a cell attachment assay as previously described [4]. Briefly, cells were inoculated into plates precoated with poly-l-lysine (Beyotime Biotechnology, #C0313, 10 μg/mL in PBS, 60 min, 37°C) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Non-adherent cells were then removed by washing with PBS. The remaining cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and stained with 0.4% methylene blue for 5 min. Methylene blue inside cells was eluted with HCl (0.1 M), and the optical density was determined at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite F50, TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland).

The concentration of inflammatory cytokines, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) in the media of cultured BEAS-2B cells (Abcam, #ab100647 and #ab185986), or in the BALF of mouse models (Abcam, #ab119557 and #ab255729) was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a special kit.

Data were analyzed with a distribution test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov method) using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All data followed Normal distribution and were therefore presented as means ± standard derivation (SD), and group size (n) represents the number of independent experiments. GraphPad Prism 8.0 was used for statistical analysis. Comparisons of means between the 2 groups were performed by an unpaired Student t-test. Comparisons of means among more than 2 groups were performed by One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Post Hoc test (Turkey HSD method) or Two-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey HSD method. The effect sizes of experimental treatments were calculated as Cohen’s d or ω2 for t-test or ANOVA, as d = 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, or ω2 = 0.01, 0.06, 0.14 represent a small, medium, and large effect, respectively. The significance of the mean comparisons is represented by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with the control group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared with stretch or MV group).

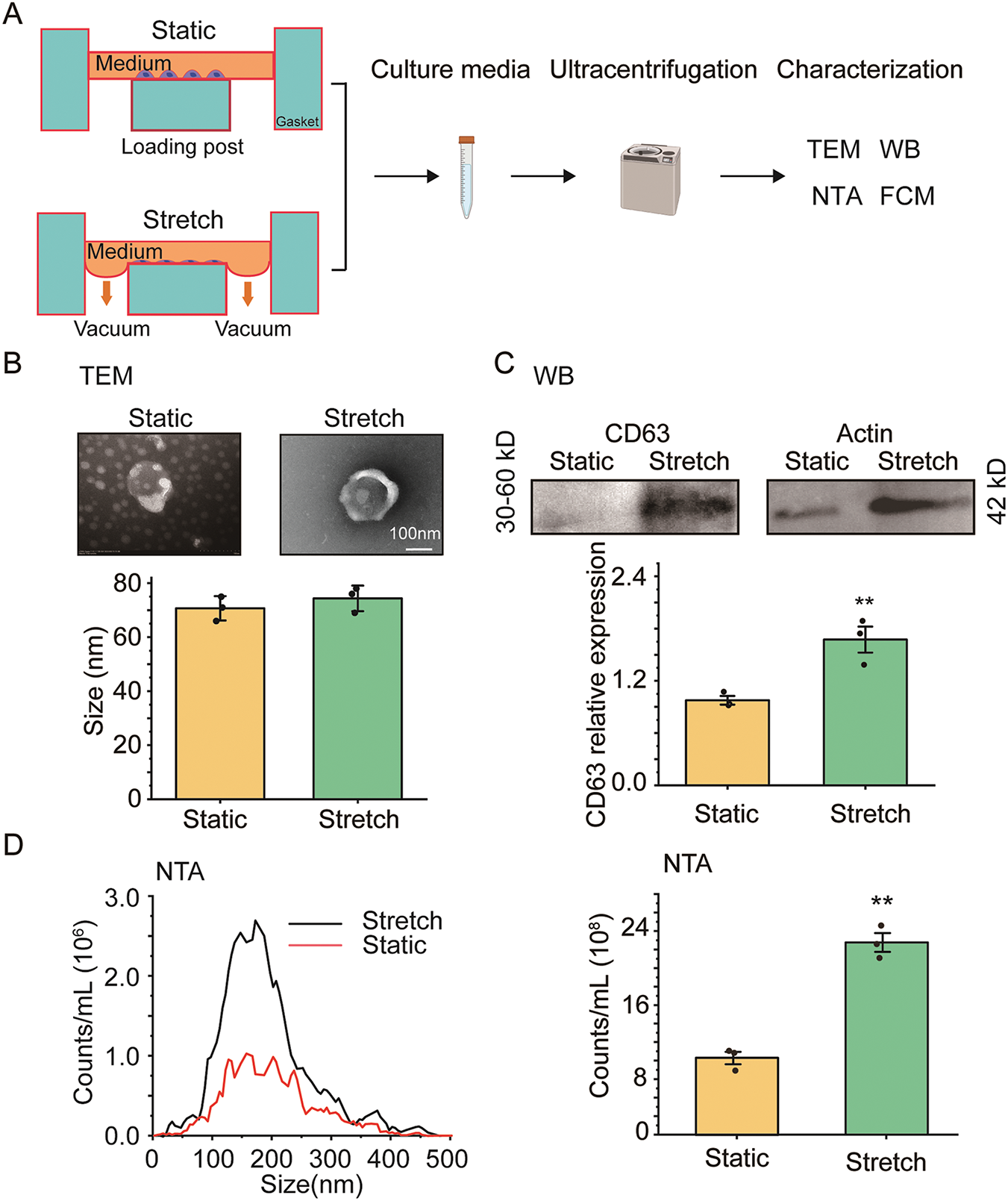

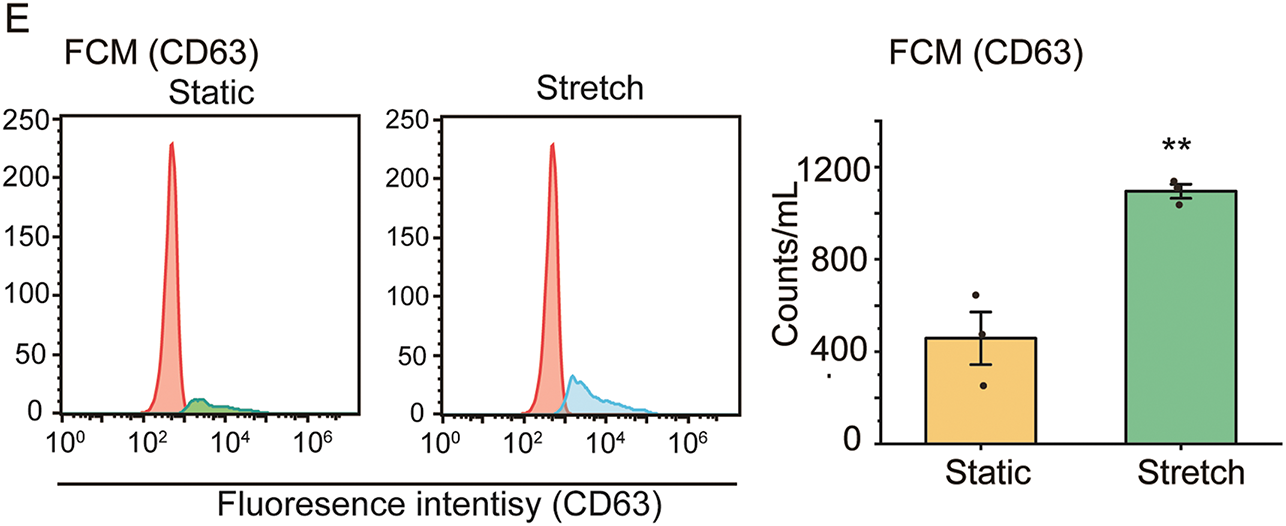

3.1 MV-Associated Stretch Enhanced Secretion of EVs from ASMCs

ASMCs cultured on flexible membrane substrate were either or not exposed to stretch (13% strain, 0.5 Hz) simulating the strain on bronchial airways during high tidal volume MV, and afterwards the supernatant was collected from the culture media and evaluated for EVs using various techniques as shown in Fig. 1A. TEM revealed that EVs had typical membrane-bound and round morphological features (Fig. 1B upper panel). The size of secreted EVs did not change when the cells were exposed to stretch (Stretch) as compared to their static counterparts (Static) (74 ± 32 nm vs. 70 ± 24 nm, p > 0.05, d = 0.17, Fig. 1B lower panel). However, the protein expression of EV biomarker (CD63) assessed by WB increased ~1.6 fold in the EVs secreted by ASMCs exposed to stretch as compared to the static ones (Fig. 1C). In addition, the quantitative analysis of the number and size distribution of EVs, and the CD63-positive counts in EVs by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and flow cytometry (FCM), respectively, confirmed that stretch enhanced the number of EVs secreted from ASMCs (Fig. 1D,E).

Figure 1: The effect of stretch on the secretion of extracellular vehicles (EVs) from cultured human airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs). (A) Schematic flow chart of static and stretch (13% strain) treatment of ASMCs for 72 h, and subsequent preparation and characterization of EVs collected from the culture media. The characterization includes transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Western blot (WB), nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and flow cytometry (FCM); (B–E) Morphology and quantified size (TEM), CD63 protein expression (WB), size distribution, and quantified count of EVs from Static and Stretch (NTA and FCM). Static: cells cultured in static conditions for 72 h, Stretch: cells cultured under stretch (13% strain, 0.5 Hz) conditions for 72 h, CD63: biomarker protein expressed by EVs. Scale bar = 100 nm, data presented as means ± SD, experiments were repeated three times (n = 3), **p < 0.01

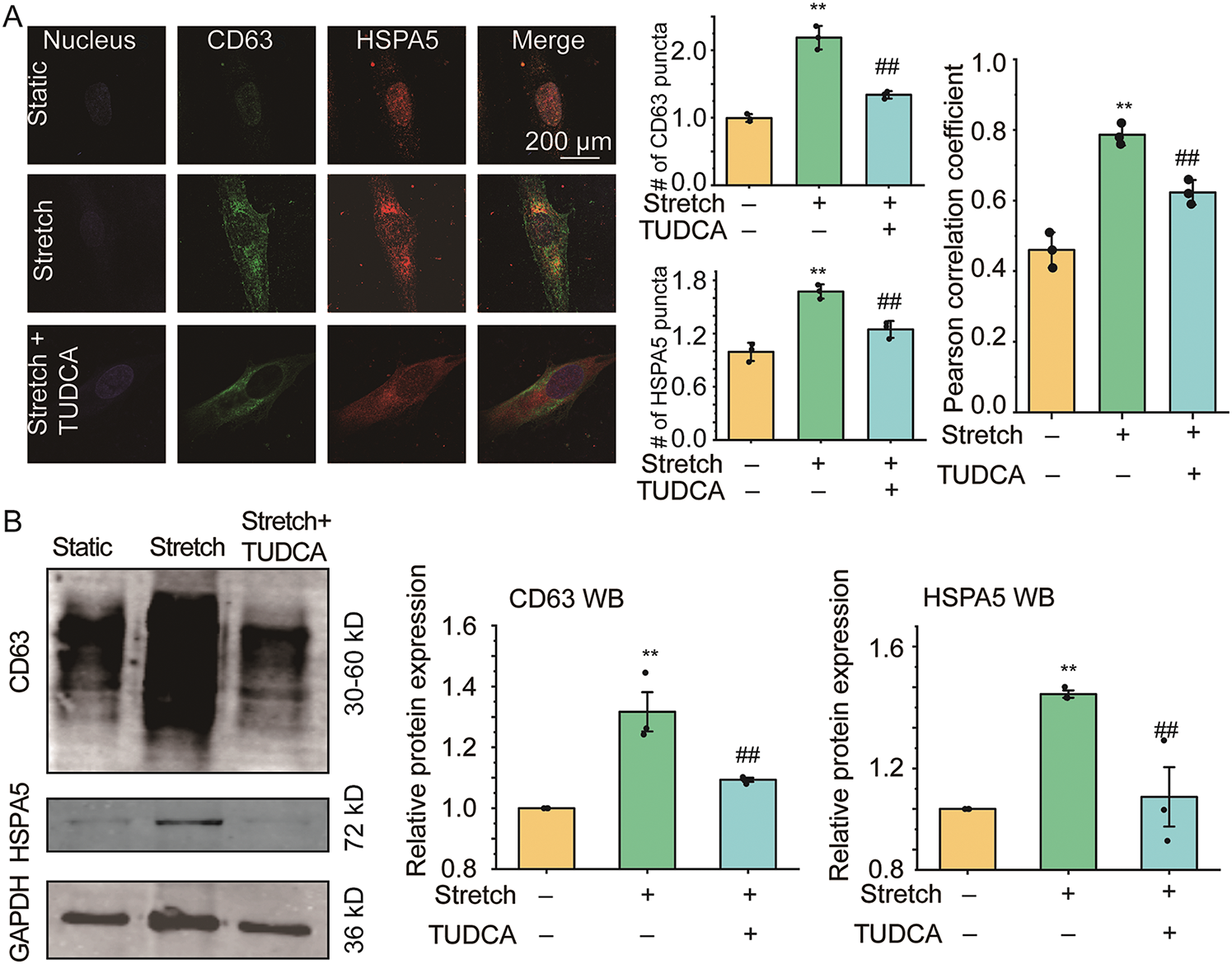

3.2 The Stretch-Enhanced Secretion of EVs Was Dependent on ER Stress

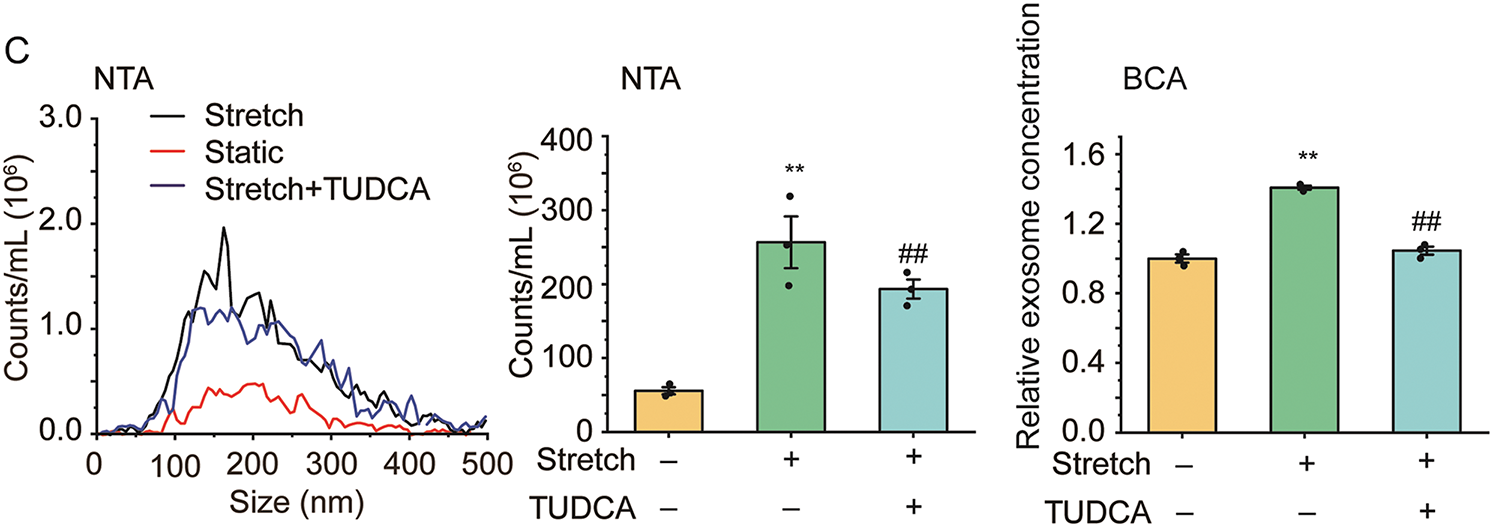

To elucidate the role of ER stress in the enhancement of EVs in cultured ASMCs during stretch, the cells were pretreated with ER stress inhibitor TUDCA and then exposed to stretch. Subsequently, the cells were immunostained for the biomarkers of EVs and ER stress (i.e., CD63 and HSPA5), and then analyzed by fluorescence optical microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2A, left panel, positive signals of CD63 and HSPA5 appeared to be distributed in a punctate manner in the cultured ASMCs in all cases. However, the cells exposed to stretch displayed enhanced CD63 and HSPA5 positive structures, especially around the nuclei, as compared to the static cells, which appeared to be attenuated by the pretreatment with TUDCA. Quantified image analysis (Fig. 2A middle panel) confirmed that the number of punctate CD63 and HSPA5 positive signals increased by 2.18, and 1.67 fold, respectively in the stretched cells compared to the static cells (both p = 0.001), and the effect size measured by ω2 was 0.89 and 0.86, respectively, indicating a strong effect. These increases were significantly attenuated by the pretreatment with TUDCA. Furthermore, the stretch appeared to enhance the colocalization of the fluorescent CD63 and HSPA5 puncta inside the ASMCs, which was confirmed quantitatively by the variation of the Pearson correlation coefficient between CD63 and HSPA5 signals (Fig. 2A right panel). WB, NTA, and BCA results also showed similar patterns of enhancement and attenuation of the protein expression of CD63 and HSPA5 inside the ASMCs, as well as the number and concentration of EVs secreted from the ASMCs (Fig. 2B,C).

Figure 2: The effect of stretch on EVs and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in ASMCs. (A) Left to right: representative immunofluorescence images of CD63/HSPA5 in ASMCs acquired with confocal microscopy (×100 objective), the quantified CD63/HSPA5 puncta number inside ASMCs (ImageJ), and Pearson coefficient of the pixel-intensity correlation of CD63/HSPA5 in ASMCs (ImageJ, scale bar = 200 μm); (B) Protein expression of CD63/HSPA5 in ASMCs (WB); (C) Size distribution and quantified counts, as well as protein concentration of EVs in ASMCs (NTA and BCA). ER: endoplasmic reticulum; HSPA5: biomarker protein of ER stress; TUDCA: tauroursodeoxycholic acid, ER stress inhibitor; NTA, nanoparticle tracking analysis; BCA: bicinchoninic acid assay; data present as means ± SD, experiments were repeated three times (n = 3), **p < 0.01 compared with Static, ##p < 0.01 compared with Stretch

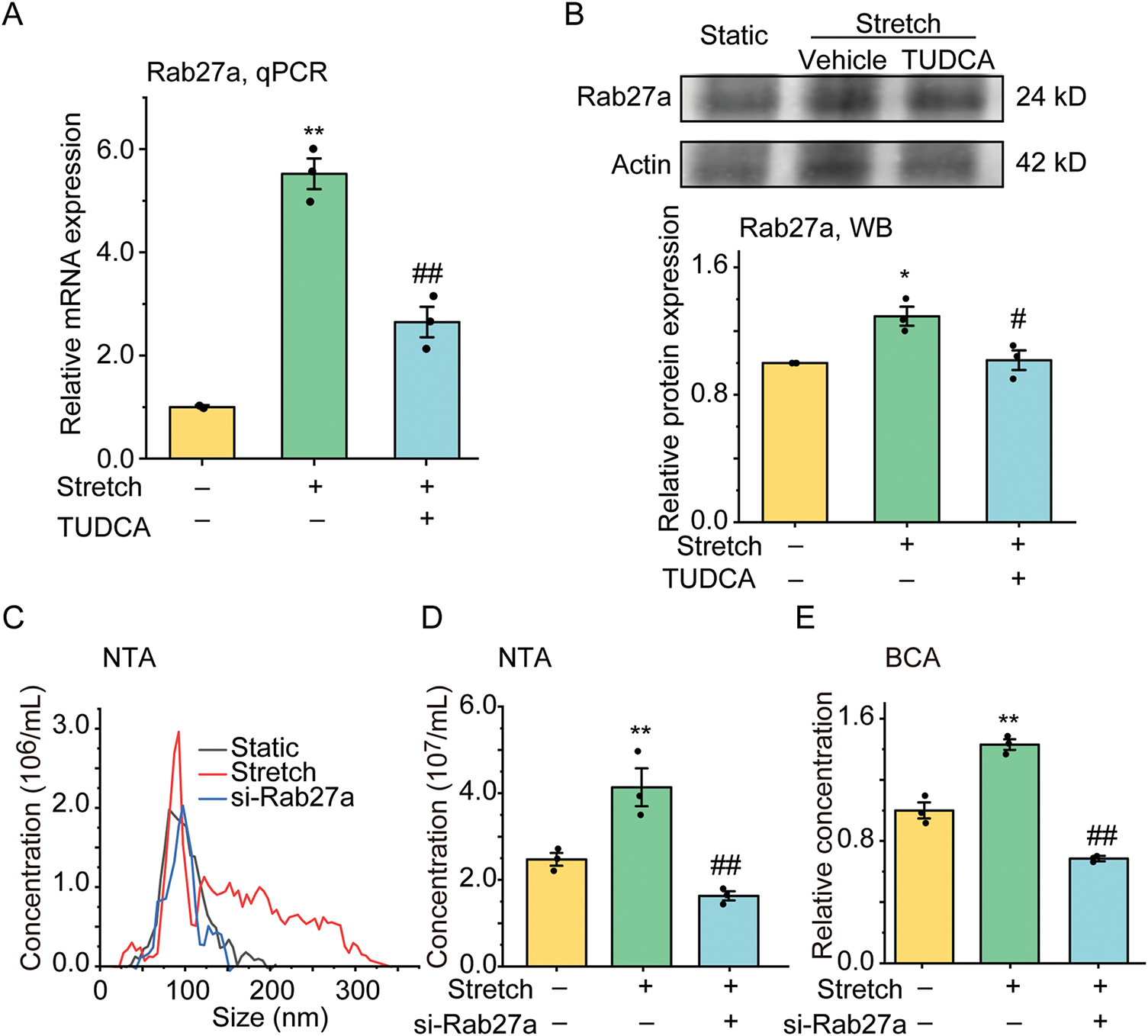

3.3 Rab 27a Mediated ER Stress-Associated EVsecretion Enhanced by Stretch

To explore whether Rab27a meditated ER stress-associated EV secretion enhanced by stretch, we detected Rab27a mRNA and protein expression by qPCR (Fig. 3A) and WB (Fig. 3B). The results show that stretch increased mRNA and protein expression of Rab27a by 5.52 fold (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.86) and 1.29 fold (p = 0.011, ω2 = 0.54), respectively, both of which were partially attenuated by TUDCA (down to 2.64 fold for mRNA, p = 0.003, ω2 = 0.71, and 1.02 fold for protein, p = 0.019, ω2 = 0.54, vs. Stretch group).

Figure 3: The effect of stretch on the mRNA and protein expression of Rab27a in ASMCs pretreated with TUDCA and the secretion of EVs from ASMCs pretreated with Rab27a siRNA. (A,B) The mRNA, and protein expression of Rab27a in ASMCs measured by qPCR, and WB, respectively; (C–E) Size distribution, and quantified counts, as well as protein concentration of EVs in ASMCs evaluated by NTA and BCA. TUDCA: tauroursodeoxycholic acid, ER stress inhibitor, NTA: nanoparticle tracking analysis, BCA: bicinchoninic acid assay, data present as means ± SD, experiments were repeated three times (n = 3), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with Static, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared with Stretch

Then we tested whether increased Rab27a mediated the stretch-enhanced secretion of EVs from ASMCs by pretreating the cells with Rab27a/Scramble siRNA. The transfection efficiency of Rab27a siRNA in ASMCs was measured by qPCR and the results show that Rab27a mRNA expression was significantly decreased to about 35% by Rab27a siRNA pretreatment (Fig. S1A), which did not impact the cell activity as measured by CCK-8 (Fig. S1B) and MTT (Fig. S1C), compared to the cells transfected with Scramble siRNA. Importantly, the pretreatment with Rab27a siRNA completely abolished the stretch-enhanced secretion of EVs ASMCs as measured by NTA (Fig. 3C,D), and BCA (Fig. 3E).

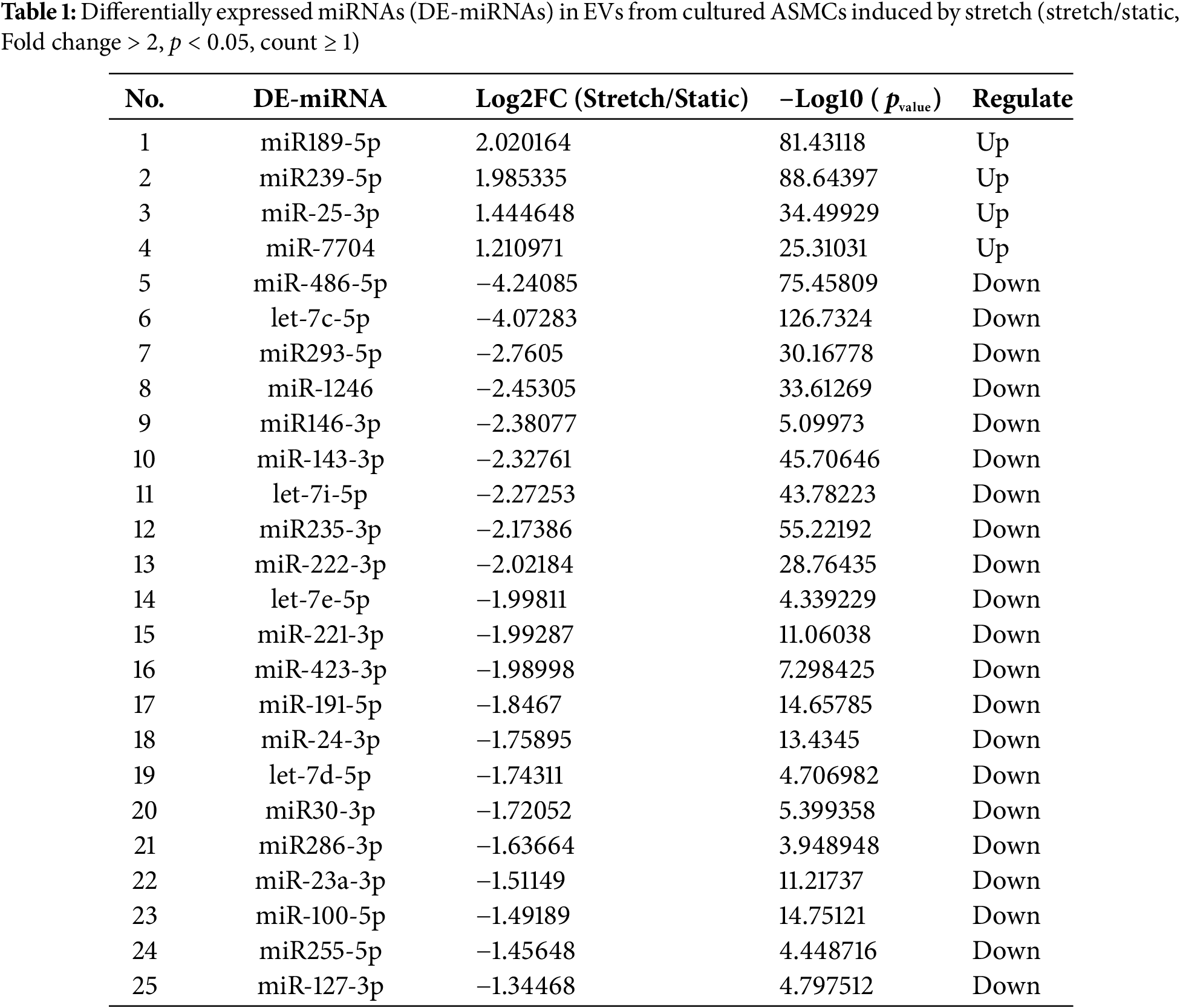

3.4 Differentially Expressed miRNAs in EVs from ASMCs Enriched in Modulating Gene Transcription

The miRNAs in EVs from ASMCs exposed to static or stretch conditions were tested by miRNA-Seq. We found a total of 25 DE-miRNAs, among which 4 were upregulated, and 21 were downregulated (Table 1). The target mRNA prediction of these DE-miRNAs is shown in Table S2. The results show that 4 miRNAs were targeted by 687 mRNAs and 21 miRNAs were targeted by 1885 mRNAs. Since 229 of these mRNAs overlapped in targeting both up-and down-regulated miRNAs, 2343 mRNAs were predicted to target the total 25 DE-miRNAs.

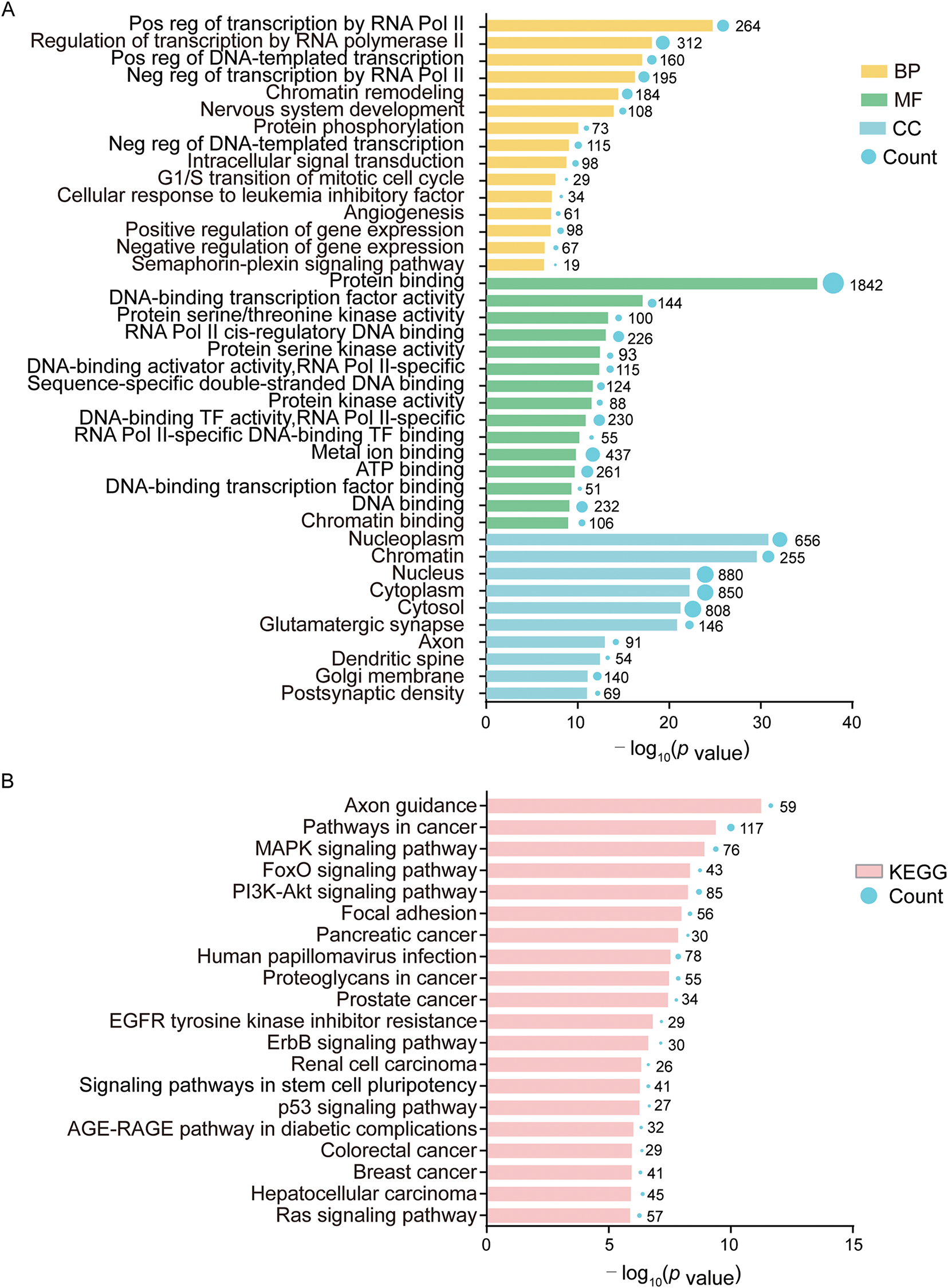

The GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis of 2343 target mRNAs were analyzed by using DAVID. As shown in Fig. 4A and Table S3, GO analysis indicated that gene transcription-related biological processes (BP) were enriched, including positive regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II, regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II, positive regulation of DNA-templated transcription, negative regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II, chromatin remodeling, negative regulation of DNA-templated transcription, positive regulation of gene expression, negative regulation of gene expression, etc. Molecular function (MF) was enriched in gene expression including DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II cis-regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding, DNA-binding transcription activator activity, RNA polymerase II-specific, sequence-specific double-stranded DNA binding, DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II-specific, RNA polymerase II-specific DNA-binding transcription factor binding, DNA-binding transcription factor binding, DNA binding, chromatin binding, etc. Cellular component (CC) was also enriched in gene transcription including nucleoplasm, chromatin, and nucleus. These data suggest that EVs from stretched ASMCs contained miRNAs which can regulate gene transcription in target cells. As shown in Fig. 4B and Table S4, KEGG pathway analysis indicated that MAPK, ErbB, FoxO, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways, as well as Focal adhesion, were all enriched to various extents in ASMCs when cultured with stretch.

Figure 4: Bioinformatical analysis of 25 DE-miRNAs and 2343 target mRNAs. (A) Gene Ontology (GO) analysis in biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC); (B) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. Term is the gene function or signaling pathway annotation of GO or KEGG, and the count is the number of genes enriched in this term. Experiments were repeated three times (n = 3)

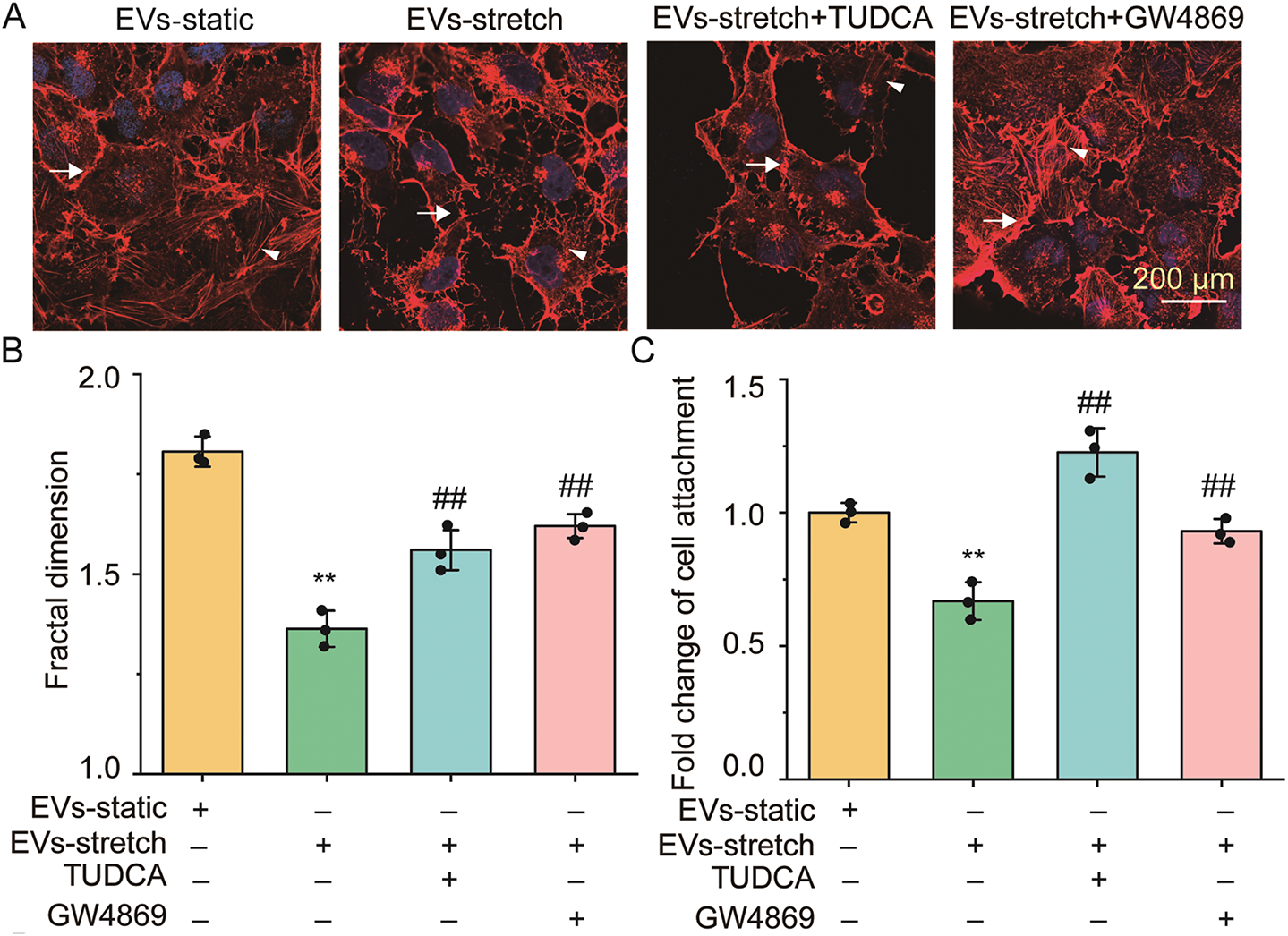

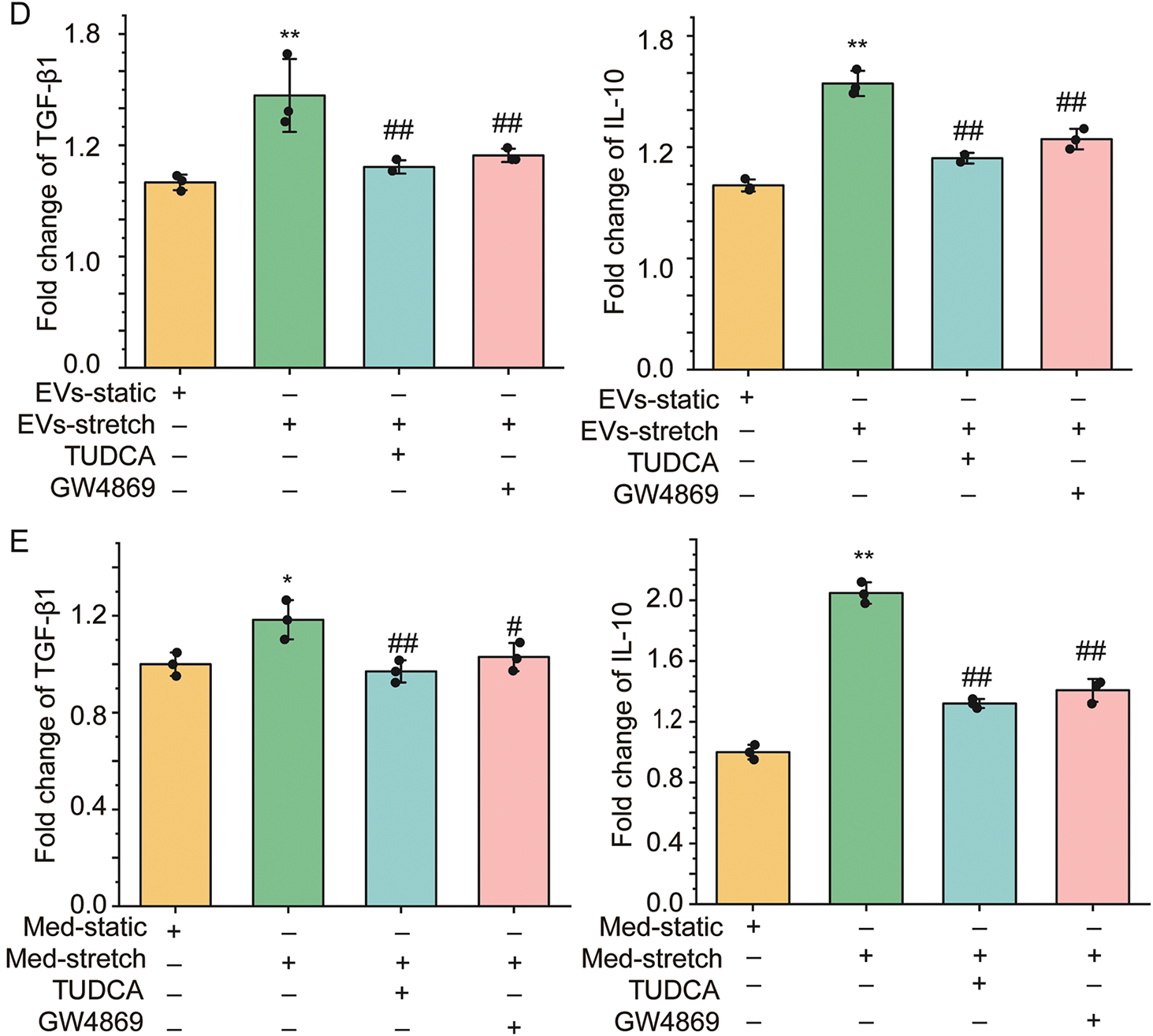

3.5 EVs from Stretched-ASMCs Promoted Airway Epithelial Inflammation

To explore whether the stretch-enhanced secretion of EVs via ER stress from ASMCs is involved in airway epithelial injury, we treated BEAS-2B cells with EVs derived from the media, or the media (Med) per se of cultured ASMCs under either static or stretched conditions (i.e., EVs-static and EVs-stretch, or Med-static and Med-stretch). Subsequently, we evaluated the structure of stress fibers and secretion of inflammatory cytokines of the cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, BEAS-2B cells treated with EVs-static displayed canonical cubic structures with abundant stress fibers both between and inside the cells (indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively). In contrast, the stress fibers in the cells treated with EVs-stretch appeared disorganized, and much lost at the cell-cell junctions, which was partially reversed when BEAS-2B cells were treated with EVs from stretched cells pretreated with inhibitors TUDCA/GW4869 (EVs-stretch + TUDCA/GW4869). Fig. 5B,C shows that the quantified fractal dimension and the fold change of cell attachment decreased from 1.80 ± 0.03 to 1.36 ± 0.04 (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.96), and from 1 to ~0.67 (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.88), respectively, when the cells were treated with EVs-stretch as compared to EVs-static, which was reversible to various extents by TUDCA/GW4869. Fig. 5D shows that EVs-stretch promoted TGF-β1 and IL-10 secretion of BEAS-2B cells (1.46 ± 0.12 fold, p = 0.006, ω2 = 0.57, and 1.58 ± 0.06 fold, p = 0.002, ω2 = 0.98, respectively) as compared with EVs-static. And these effects were attenuated with TUDCA/GW4869. Similar effects on TGF-β1 and IL-10 secretion were observed with BEAS-2B cells treated with Med-static, Med-stretch, TUDCA/GW4869 (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that ASMCs under stretch can secrete excessive EVs as a response to ER stress, which in turn can induce airway epithelial damage and inflammation.

Figure 5: The effect of EVs from ASMCs treated with stretch on functions of airway epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells. (A) Representative images of stress fibers of BEAS-2B cells treated with EVs from ASMCs of different conditions. Arrows and arrowheads indicate stress fibers between and inside the cells, respectively. EVs-static, EVs-stretch, EVs-stretch + TUDCA, EVs-stretch + GW4869 indicates EVs derived from culture medium of ASMCs in static, stretch, stretch with pretreatment of TUDCA, stretch with pretreatment of GW4869, respectively. GW4869: EV secretion inhibitor, scale bar = 200 μm; (B) Quantified fractal dimension of BEAS-2B cells treated with EVs of different conditions (ImageJ); (C) Quantified cell attachment of BEAS-2B cells treated with EVs of different conditions (cell adhesion assay); (D,E) Variation of TGF-β1 and IL-10 secretion from BEAS-2B cells treated with EVs, or the media (Med-) per se from cultured ASMCs of different conditions (ELISA). Data present as means ± SD, experiments were repeated three times (n = 3), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared with EVs/Med-static; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 compared with EVs/Med-stretch

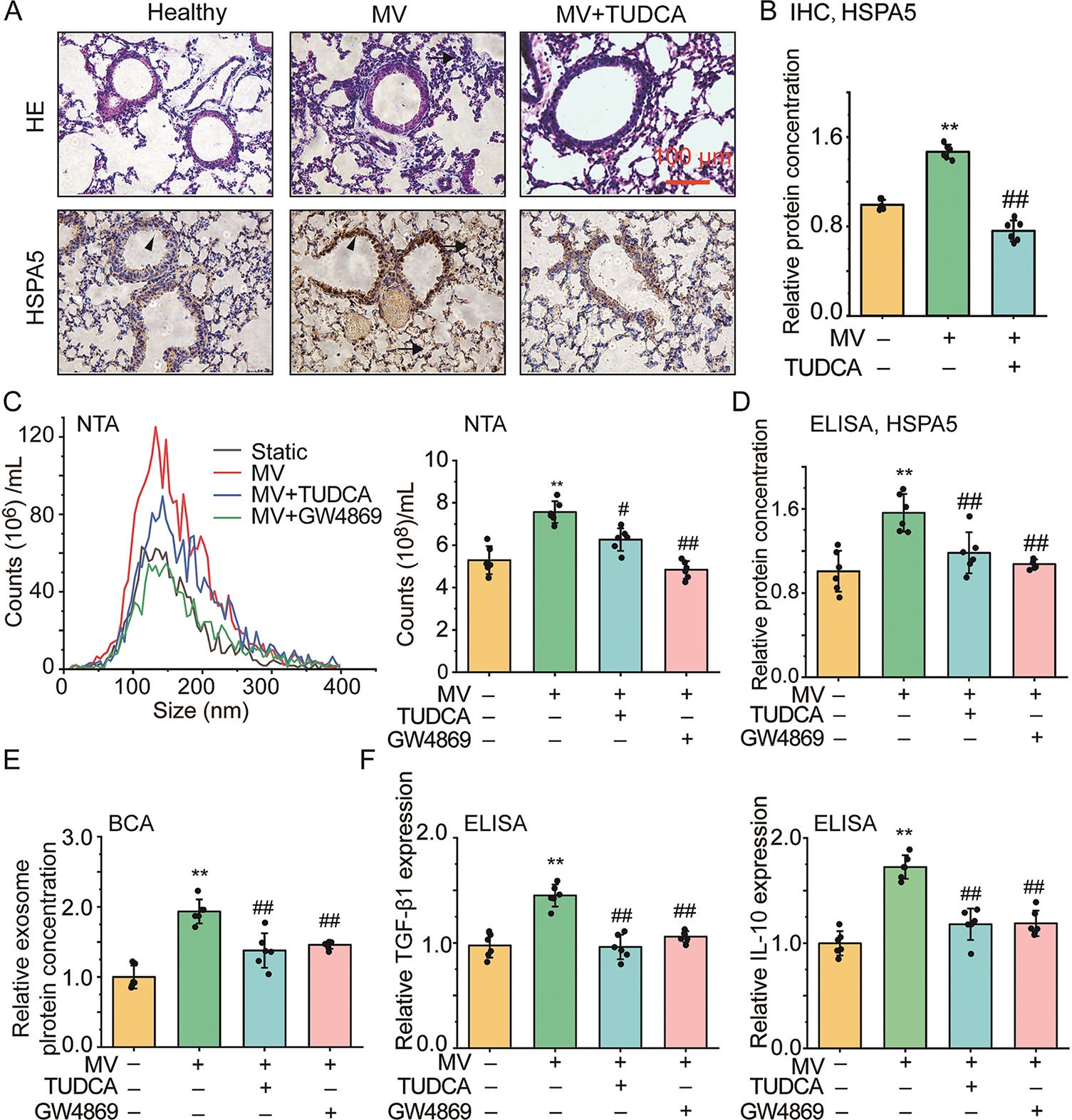

3.6 High Tidal Volume MV Enhanced EVs via ER Stress in a Mouse Model

We first evaluated the effect of tidal volume (6, 12, 18, 24 mL/kg) and time (1.5, 3 h) of MV on the extent of lung injury in mice by analyzing the morphological changes of lung tissue via HE staining (Fig. S2A) and the inflammatory TGF-β1 concentration (Fig. S2B)/cell number in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (Fig. S2C) via ELISA/cell counting, respectively. The data show that as the tidal volume and time was increased from 6 to 18 mL/kg, and 1.5 to 3 h, respectively, the mice exhibited an increasing extent of lung injury, which was manifested as airway inflammation and epithelial shedding in the lung tissue together with TGF-β1 concentration and cell number in the BALF. However, when the tidal volume was further increased from 18 to 24 mL/kg, there seemed no further enhancement of lung injury, particularly in the TGF-β1 concentration. The effect of time on the lung injury, particularly the cell number in the BALF, also appeared to peak at 3 h. It thus suggests that the MV-induced lung injury in the mouse model might have peaked at 18 mL/kg, 3 h. Therefore, we used 18 mL/kg, 3 h as the high tidal volume MV throughout the following animal experiments.

To demonstrate in vivo the stretch-induced EVs via ER stress signaling and airway inflammatory response as a mechanistic link between MV and VILI, we evaluated the airway inflammation, secretion of EVs, and ER stress in either the lung tissue slides or BALF from C57BL/6 mice under 18 mL/kg, 3 h high tidal volume MV with/without 30 min pretreatment of TUDCA/GW4869. In Fig. 6A, the representative images of lung tissue slice with HE staining (the upper panel), and IHC staining (the lower panel) demonstrate clear alveolar collapse (arrow indicated), and enhanced HSPA5 expression (arrowhead indicated) in the mice under MV as compared to the spontaneously breathing controls (Healthy vs. MV), which was attenuated with TUDCA (MV + TUDCA vs. MV). The quantified HSPA5 protein expression in lung tissue shows that MV enhanced HSPA5 protein expression by ~1.5 fold in the lung tissue (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.93), which was attenuated with TUDCA (Fig. 6B). In addition, as shown in Fig. S3 the average alveolar wall thickness increased from 2.82 ± 0.22 μm to 5.79 ± 0.31 (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.91) when the mice changed from being spontaneous breathing to MV, which was attenuated if the mice were pretreated with TUDCA or GW 4869 (MV vs. MV + TUDCA, 5.79 ± 0.31 vs. 3.55 ± 0.22 μm, p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.78, MV vs. MV + GW4869, 5.79 ± 0.31 vs. 4.10 ± 0.22 μm, p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.85).

Figure 6: The effect of mechanical ventilation on secretion of EVs, ER stress, airway inflammation and injury in mouse models of VILI. (A) Representative images of lung tissue slides with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) or immunohistochemistry (IHC, HSPA5) staining (scale bar = 100 μm, arrows indicate alveolar collapse, arrowhead indicate HSPA5 expression). Healthy, MV, MV + TUDCA/GW4869 indicates mice breathed spontaneously, under 18 mL/kg mechanical ventilation (MV), MV with pretreatment of TUDCA/GW4869, respectively; (B) Protein expression of HSPA5 in lung tissue with IHC staining from C57BL/6 mice treated with different conditions, respectively; (C–E) Size distribution and quantified count, HSPA5, as well as protein concentration of EVs isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of mice treated with different conditions; (F) Relative TGF-β1 and IL-10 secretion in BALF from mice treated with different conditions. Data present as means ± SD, experiments were repeated six times (n = 6), ** p < 0.01 compared with Healthy, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 compared with MV

Fig. 6C shows that as assessed by NTA the size distribution (left panel) of EVs derived from BALF was similar in all cases with an average of ~150 nm, regardless of MV and inhibitor treatment, but the total number (right panel) significantly increased with MV compared to spontaneous breathing (static vs. MV, 5.29 ± 0.65 ×108 vs. 7.56 ± 0.51 ×108, p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.76), whereas the increase with MV was attenuated to variable degrees by TUDCA/GW4869. The ELISA-quantified HSPA5 protein expression in BALF shows that MV enhanced HSPA5 protein expression by ~1.5 fold in BALF (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.57), which was attenuated with TUDCA/GW4869 (Fig. 6D). The BCA-quantified protein content concentration of EVs in BALF was similarly up/down-regulated with MV and inhibitor treatment (Fig. 6E). Moreover, the results from ELISA shown in Fig. 6F indicate that MV also enhanced the secretion of TGF-β1 by ~1.4 fold (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.76) and IL-10 by ~1.7 fold (p = 0.001, ω2 = 0.88), which was largely attenuated with TUDCA and GW4869. These data provide in vivo evidence that MV can enhance the secretion of EVs in an ER stress-dependent manner, which can be linked to airway inflammatory response and airway injury and thus can be targeted pharmacologically for preventing or treating VILI.

In this study, we identified that MV-associated stretch enhanced secretion of EVs via ER stress-Rab27a signaling, which could promote airway inflammation in both cultured ASMCs and mouse models. These findings provide key evidence to link the stretch on ASMCs during MV to airway inflammation and injury through the pathway of stretch-responsive secretion of EVs and corresponding ER stress. This novel mechanism is important for better understanding the underlying pathological processes of VILI.

It is well known that the MV and related stretch can induce release of inflammatory cytokines from airway cells, such as IL-6, 8, and 10, both in vivo and in vitro [31]. Such high-level cytokines during VILI can amplify lung injury in ARDS patients [32]. However, much less is known about how airway cells respond to MV-associated stretch and initiate downstream inflammatory responses. In this study, by using ASMCs cultured in vitro under stretch conditions and mouse models under MV, we revealed that MV-associated stretch clearly enhanced HSPA5 protein expression in ASMCs, airway tissue, and BALF. Such increases in HSPA5 protein expression observed in various assays strongly indicate the occurrence of ER stress in the highly stretched ASMCs since HSPA5 is a canonical stress sensor [33,34]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that stretch on the airway walls during MV will induce responsive ER stress in the airway cells, particularly the ASMCs, and consequently lead to diverse airway injury responses including airway inflammation.

On the other hand, molecules such as HSPA5 that prime the inflammatory response of the airways to stretch are the most attractive biomarkers for early diagnosis of VILI, which is key to the timely modulation of MV parameters for individual patients to improve the clinical outcomes. HSPA5 is the master molecule for the unfolded protein response (UPR) in ER stress, which can respond to stretch by translocation to the nucleus, the mitochondria, and the cell surface [35]. In this study, HSPA5 in the ASMCs appeared to be enriched around nuclei in response to stretch. We also found that HSPA5 secretion was enhanced by MV and associated stretch, suggesting HSPA5 may be a potential diagnostic marker of stretch-related lung injury [36–38]. Apart from this upstream ER stress sensor, the downstream ER stress response molecules such as activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), and inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) can all play essential roles in initiating the inflammatory response, which remain to be further explored [39].

As regards therapeutic application, previous reports have shown that inhibition of MV-induced ER stress could mitigate VILI in mouse models [40,41]. Consistent with these reports, we confirmed in this study that ER stress is involved in the mediation of airway epithelial cell detachment and inflammatory cytokine secretion in response to stretch in the ASMCs cultured in vitro and alveolar collapse in the mouse model under high tidal volume MV in vivo. These studies together suggest that ER stress can initiate abundant downstream cellular activities such as cell detachment, inflammation, and even cell death to promote VILI. Thus, it implies that modulation of ER stress in airway cells including ASMCs may be a promising strategy for preventing or mitigating the risk of VILI in patients under MV, especially those with ARDS [42].

Furthermore, ER stress has been reported to enhance secretion of epithelial-derived EVs in BALF of patients with lung injury due to hypoxia, and the EVs activated macrophage-mediated airway inflammatory responses via Rho kinase 1 (ROCK1) pathway [43]. Recent studies have also reported that multiple types of cells, including pleural macrophages and muscle progenitor cells, can respond to stretch with enhanced secretion of EVs via mediators such as Cav-1 and YAP [31,44–46]. In this study, we demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo that MV-associated stretch could enhance secretion of EVs from ASMCs in an ER stress-dependent manner. In addition, the MV-associated stretch also enhanced Rab27a expression in an ER stress-dependent manner, and the inhibition of Rab27a completely abolished the stretch-enhanced EV secretion. These results suggest that stretch may enhance the secretion of EVs from ASMCs via the ER stress-Rab27a mediatory axis.

In fact, EVs contain a variety of inflammatory factors that can lead to airway inflammation and injury, including cytokines, caspases, and microRNAs [47,48]. In this study, we demonstrated that the EVs secreted from ASMCs cultured in stretch conditions contained 25 differentially expressed miRNAs that may modulate gene transcription of targeted cells. We also found that the secreted EVs seemed to disrupt the stress fibers inside and between the airway epithelial cells, together with upregulation of inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10, which could all be attenuated by inhibition of the ER stress or the secretion of EVs. These data suggest a direct link between the stretch on airways during MV and the pathological processes of VILI through ER stress-Rab27a signaling and the corresponding secretion of EVs from ASMCs.

It’s noteworthy that these findings have limitations in several aspects. For example, the current study only evaluated the interplay between ER stress response and EV secretion in either cultured ASMCs or mouse models subjected to relatively short periods of stretch or MV, which may be more relevant to acute VILI. The long-term effect of MV on lung injury needs to be systematically investigated with both in vitro and in vivo models, to determine whether there are unique mechanisms for chronic VILI other than the ER stress-Rab27a signaling and EV secretion axis. It also remains to be fully explored how the stretch-induced EVs from ASMCs initiate airway inflammation, including neutrophil and macrophage recruitment, and then result in injurious processes in the airway epithelium such as the activation of inflammasomes, the disruption of focal adhesions between cells and cell-matrix, and the extrusion of epithelial cells [20]. Furthermore, we did not consider other cell types such as airway epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and immune cells for their response to MV-associated stretch and involvement in the modulation of EV stress and EV secretion in relation to airway and lung injury. Further investigations of these aspects in the future are critical for ascertaining the direct causality between the stretch-enhanced EV secretion via ER stress and the lung injury. And ultimately, the therapeutic potential of targeting EV secretion and/or ER stress signaling pathways need to be validated with clinical studies of MV-treated ARDS patients, using authorized drugs such as TUDCA.

Taken together, we conclude that stretch imposed on ASMCs can cause the cells to secrete EVs as a consequence of endoplasmic reticulum stress. This provides a new mechanistic link between stretch on ASMCs and VILI in patients under high tidal volume mechanical ventilation. Therefore, it may be possible to target the EV secretion and/or endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in ASMCs for early diagnosis and optimal interference of VILI.

Acknowledgement: We thank Mingxing Ouyang (Changzhou University) for the technical support in the informatical analysis and Xiang Wang (Changzhou University) for the design of the experiments.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), Grants No. 12072048 to M.L., 12272063, and 11532003 to L.D., and partially supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Leading Plan of High-Tech Industry in Hunan Province, China, Grant No. 2020SK2018 to L.D.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mingzhi Luo, Linhong Deng; data collection: Changyu Sun, Jia Guo, Xiangrong Zhang, Jing Zhang, Xuanyu Shi; analysis and interpretation of results: Lei Liu, Yan Pan, Jingjing Li; draft manuscript preparation: Mingzhi Luo, Linhong Deng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Approval: All animal studies were approved by the Biomedical Studies Ethics Committee of Changzhou University (IACUC No. 20200327048).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.063869/s1.

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| ASMCs | Airway smooth muscle cells |

| ATF6 | Activating transcription factor 6 |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| BP | Biological processes |

| CC | Cellular component |

| CCK-8 | Cell couning Kit-8 |

| CD63 | Cluster of differentiation antigen 63 |

| DAB | 3,3N-Diaminobenzidine Tertrahydrochloride |

| DAVID | Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery |

| DE | Differentially expressed |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FCM | Flow cytometry |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| HSPA5 | Heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 5 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IRE1 | Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| MF | Molecular function |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| miRNA-Seq | MicroRNA whole genome sequencing |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide |

| MV | Mechanical ventilation |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| PERK | Protein kinase R (PKR)-like ER kinase |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| PBS | Phosphate buffer solution |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene difluoride |

| ROCK1 | Rho kinase 1 |

| RT | Room temperature |

| SD | Standard derivation |

| TBST | Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% of Tween-20 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-β1 |

| TUDCA | Tauroursodeoxycholic acid |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| VILI | Ventilator-induced lung injury |

| WB | Western blot |

References

1. Luo M, Wang C, Guo J, Wen K, Yang C, Ni K, et al. High stretch modulates cAMP/ATP level in association with purine metabolism via miRNA-mRNA interactions in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Cells. 2024;13(2):100. doi:10.3390/cells13020110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Amato MBP, Barbas CSV, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(6):347–54. doi:10.1056/NEJM199802053380602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Luo M, Gu R, Wang C, Guo J, Zhang X, Ni K, et al. High stretch associated with mechanical ventilation promotes piezo1-mediated migration of airway smooth muscle cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1748. doi:10.3390/ijms25031748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Uhlig S, Uhlig U. Pharmacological interventions in ventilator-induced lung injury. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(11):592–600. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wen K, Ni K, Guo J, Bu B, Liu L, Pan Y, et al. MircroRNA let-7a-5p in airway smooth muscle cells is most responsive to high stretch in association with cell mechanics modulation. Front Physiol. 2022;13:830406. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.830406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–28. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Buzas EI, György B, Nagy G, Falus A, Gay S. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(6):356–64. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2014.19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Piszczatowska K, Czerwaty K, Cyran AM, Fiedler M, Ludwig N, Brzost J, et al. The emerging role of small extracellular vesicles in inflammatory airway diseases. Diagnostics. 2021;11(2):222. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11020222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lu Y, Zhao L, Mao J, Liu W, Ma W, Zhao B. Rab27a-mediated extracellular vesicle secretion contributes to osteogenesis in periodontal ligament-bone niche communication. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):8479. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-35172-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. King HW, Michael MZ, Gleadle JM. Hypoxic enhancement of exosome release by breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(1):421. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L, Palleschi S, De Milito A, et al. Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):34211–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.041152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Le M, Fernandez-Palomo C, McNeill FE, Seymour CB, Rainbow AJ, Mothersill CE. Exosomes are released by bystander cells exposed to radiation-induced biophoton signals: reconciling the mechanisms mediating the bystander effect. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173685. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bala S, Babuta M, Catalano D, Saiju A, Szabo G. Alcohol promotes exosome biogenesis and release via modulating Rabs and miR-192 expression in human hepatocytes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:787356. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.787356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wilson MR, Takata M. Inflammatory mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury: a time to stop and think? Anaesthesia. 2013;68(2):175–8. doi:10.1111/anae.12085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang Y, Xie W, Feng Y, Xu Z, He Y, Xiong Y, et al. Epithelial-derived exosomes promote M2 macrophage polarization via Notch2/Socs1 during mechanical ventilation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;50(1):96. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2022.5152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Koh MW, Baldi RF, Soni S, Handslip R, Tan YY, O’Dea KP, et al. Secreted extracellular cyclophilin a is a novel mediator of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(4):421–30. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009-3545OC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Asano S, Ito S, Morosawa M, Furuya K, Naruse K, Sokabe M, et al. Cyclic stretch enhances reorientation and differentiation of 3-D culture model of human airway smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2018;16:32–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2018.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Schwingshackl A. The role of stretch-activated ion channels in acute respiratory distress syndrome: finally a new target? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;311(3):L639–52. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00458.2015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Bagley DC, Russell T, Ortiz-Zapater E, Stinson S, Fox K, Redd PF, et al. Bronchoconstriction damages airway epithelia by crowding-induced excess cell extrusion. Science. 2024;384(6691):66–73. doi:10.1126/science.adk2758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yang C, Guo J, Ni K, Wen K, Qin Y, Gu R, et al. Mechanical ventilation-related high stretch mainly induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and thus mediates inflammation response in cultured human primary airway smooth muscle cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3811. doi:10.3390/ijms24043811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kanemoto S, Nitani R, Murakami T, Kaneko M, Asada R, Matsuhisa K, et al. Multivesicular body formation enhancement and exosome release during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;480(2):166–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Collett GP, Redman CW, Sargent IL, Vatish M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress stimulates the release of extracellular vesicles carrying danger-associated molecular pattern (Damp) molecules. Oncotarget. 2018;9(6):6707–17. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Kakazu E, Mauer AS, Yin M, Malhi H. Hepatocytes release ceramide-enriched pro-inflammatory extracellular vesicles in an Ire1α-dependent manner. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(2):233–45. doi:10.1194/jlr.M063412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jia L, Zhang W, Li T-T, Liu Y, Piao C, Ma Y, et al. ER stress dependent microparticles derived from smooth muscle cells promote endothelial dysfunction during thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Clin Sci. 2017;131(12):1287–99. doi:10.1042/CS20170252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. He C, Hua W, Liu J, Fan L, Wang H, Sun G. Exosomes derived from endoplasmic reticulum-stressed liver cancer cells enhance the expression of cytokines in macrophages via the Stat3 signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(1):589–600. doi:10.3892/ol.2020.11609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wilson MR, Petrie JE, Shaw MW, Hu C, Oakley CM, Woods SJ, et al. High-fat feeding protects mice from ventilator-induced lung injury, via neutrophil-independent mechanisms. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):e831–9. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319(5867):1244–7. doi:10.1126/science.1153124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Huang P, Li F, Mo Z, Geng C, Wen F, Zhang C, et al. A comprehensive RNA study to identify circrna and mirna biomarkers for docetaxel resistance in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:669270. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.669270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ren Y, Yu G, Shi C, Liu L, Guo Q, Han C, et al. Majorbio cloud: a one-stop, comprehensive bioinformatic platform for multiomics analyses. iMeta. 2022;1(2):e12. doi:10.1002/imt2.12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Baldi RF, Koh MW, Thomas C, Sabbat T, Wang B, Tsatsari S, et al. Ventilator-induced lung injury promotes inflammation within the pleural cavity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2024;71(1):43–52. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2023-0332OC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ranieri VM, Suter PM, Tortorella C, De Tullio R, Dayer JM, Brienza A, et al. Effect of mechanical ventilation on inflammatory mediators in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(1):54–61. doi:10.1001/jama.282.1.54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. You K, Wang L, Chou C, Liu K, Nakata T, Jaiswal A, et al. Qrich1 dictates the outcome of er stress through transcriptional control of proteostasis. Science. 2021;371(6524):eabb6896. doi:10.1126/science.abb6896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Costa-Mattioli M, Walter P. The integrated stress response: from mechanism to disease. Science. 2020;368(6489):eaat5314. doi:10.1126/science.aat5314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chang H, Chen C, Huang K. Mechanical stretch-induced NLRP3 inflammasome expression on human annulus fibrosus cells modulated by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):7951. doi:10.3390/ijms23147951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yousof T, Sharma H, Austin RC, Fox-Robichaud AE. Stressing the endoplasmic reticulum response as a diagnostic tool for sepsis. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10(15):812. doi:10.21037/atm-22-3120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Li F, Lin Q, Shen L, Zhang Z, Wang P, Zhang S, et al. The diagnostic value of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related specific proteins GRP78 and CHOP in patients with sepsis: a diagnostic cohort study. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10(8):470. doi:10.21037/atm-22-1445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Dolinay T, Aonbangkhen C, Zacharias W, Cantu E, Pogoriler J, Stablow A, et al. Protein kinase R-like endoplasmatic reticulum kinase is a mediator of stretch in ventilator-induced lung injury. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):157. doi:10.1186/s12931-018-0856-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Grootjans J, Kaser A, Kaufman RJ, Blumberg RS. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(8):469–84. doi:10.1038/nri.2016.62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ye L, Zeng Q, Dai H, Zhang W, Wang X, Ma R, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is involved in ventilator-induced lung injury in mice via the Ire1α-Traf2-NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;78(2015):106069. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zeng Q, Ye L, Ling M, Ma R, Li J, Chen H, et al. Tlr4/Traf6/Nox2 signaling pathway is involved in ventilation-induced lung injury via endoplasmic reticulum stress in murine model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96:107774. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lin JH, Walter P, Yen TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3(1):399–425. doi:10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Moon HG, Cao Y, Yang J, Lee JH, Choi HS, Jin Y. Lung epithelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles activate macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses via ROCK1 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(12):e2016. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Shaver M, Gomez K, Kaiser K, Hutcheson JD. Mechanical stretch leads to increased caveolin-1 content and mineralization potential in extracellular vesicles from vascular smooth muscle cells. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12860-024-00504-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Guo S, Debbi L, Zohar B, Samuel R, Arzi RS, Fried AI, et al. Stimulating extracellular vesicles production from engineered tissues by mechanical forces. Nano Lett. 2021;21(6):2497–504. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c04834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Mullen M, Williams K, LaRocca T, Duke V, Hambright WS, Ravuri SK, et al. Mechanical strain drives exosome production, function, and miRNA cargo in C2C12 muscle progenitor cells. J Orthop Res. 2023;41(6):1186–97. doi:10.1002/jor.25467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Yuan Z, Bedi B, Sadikot RT. Bronchoalveolar lavage exosomes in lipopolysaccharide-induced septic lung injury. Jove-J Vis Exp. 2018;135(135):57737. doi:10.3791/57737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Piao L, Park HJ, Seo EH, Kim TW, Shin JK, Kim SH. The effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress on the expression of exosomes in ventilator-induced lung injury. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(2):1050–8. doi:10.21037/apm-19-551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools