Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Time-Course of Changes in Astrocyte Endfeet Damage in the Hippocampus Following Experimental Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Kangwon National University Hospital, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, 24289, Gangwon, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Oral Anatomy & Developmental Biology, College of Dentistry, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Research Institute of Oral Sciences, College of Dentistry, Gangnung-Wonju National University, Gangneung, 25457, Gangwon, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Anatomy, College of Korean Medicine, Dongguk University, Gyeongju, 38066, Gyeongbuk, Republic of Korea

5 Department of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Dankook University, Cheonan, 31116, Chungnam, Republic of Korea

6 Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health Science, Youngsan University, Yangsan, 50510, Gyeongnam, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Choong-Hyun Lee. Email: ; Ji Hyeon Ahn. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(6), 1071-1083. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065506

Received 14 March 2025; Accepted 07 May 2025; Issue published 24 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Astrocyte endfeet (AEF) serves as a key element of the blood-brain barrier and is important for the survival and maintenance of neuronal function. However, the immunohistochemical and ultrastructural changes of AEF in the CA1 and CA3 areas of the hippocampus over time following cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury have not been well elucidated. Objectives: We investigated chronological changes in AEF in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 area from 3 h to 10 days following transient forebrain ischemia (TFI), and examined their association with neuronal death and tissue repair following IR injury. Changes in the CA3 area were also examined at 10 days post-TFI for comparative purposes. Methods: Neuronal death was confirmed using histochemistry, immunohistochemistry, and histofluorescence. Changes in AEF were examined by double immunofluorescence with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for ultrastructural changes. Results: Significant TFI-induced neuronal death occurred in the CA1 area on day 5 following IR injury and persisted until 10 days after TFI, while no neuronal death (or loss) was found in the CA3 area after TFI. Looking at TFI-induced changes in AEF, at 3 and 6 h after TFI, GFAP-immunoreactive (+) AEF in the CA1 area appeared swollen and harbored enlarged, dark mitochondria, and the swelling was reduced by 1-day post-TFI. On 2 and 5 days following TFI, GFAP+ AEF were markedly enlarged and fragmented, containing shrunken mitochondria, vacuolations, and sparse organelles. Ten days post-TFI, the ends of GFAP+ astrocytic processes extended to microvessels, appeared edematous, and were filled with cellular debris. In the CA3 area, AEF was slightly dilated at 10 days after TFI. These findings indicate that damage to or disruption of AEF in the CA1 area occurs in the early phase after 5-min TFI but is rarely observed in the CA3 area. Conclusion: Taken together, damage to or disruption of AEF following ischemic insults may be strongly linked to neuronal death/loss.Keywords

The Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) has a unique anatomical feature characterized by an incomplete Willis Circle resulting from the absence of the posterior communicating arteries [1]. Consequently, the gerbil is frequently employed as a model for transient forebrain ischemia (TFI) by occlusion of the bilateral common carotid arteries (BCCA) [2]. A transient occlusion and reperfusion in the forebrain induces IR injury, resulting in delayed neuronal death of pyramidal neurons in the cornu ammonis (CA) 1 area of the hippocampus, which is highly vulnerable to ischemic conditions, approximately 4 to 5 days following ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury [3,4].

The mechanisms underlying delayed neuronal death involve complex processes such as glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, arachidonate-mediated oxidative stress, and caspase activation, which ultimately lead to neuronal apoptosis [5–8]. Recently, blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction, which involves various interacting cells such as neurons, astrocytes, endothelial cells, pericytes, and smooth muscle cells of the vasculature, has been identified as a mechanism of IR injury that eventually leads to neuronal death [9,10].

Astrocytes play crucial roles in maintaining neuronal homeostasis, providing metabolic support, regulating the blood flow and BBB permeability, and repairing damaged tissue [11–13]. Astrocyte endfeet (AEF) are the terminal structures of astrocytes that contact the capillary basement membrane and pericytes within the neurovascular unit, mediating communication between neurons, glial cells, and vasculature [14]. After cerebral IR injury, astrocytes and AEF undergo rapid and pronounced changes [15], and the dysfunction of AEF can disrupt astrocyte-neuron communication, exacerbating neuronal damage and contributing to the pathological process of IR injury [16,17].

Previous studies have investigated the ultrastructural changes in astrocytes/AEF following brain injuries, such as cerebral hypoperfusion [18] and traumatic brain injury [19]. Wu et al. [18] reported that slight vacuolar degeneration was detected in the AEF layer encircling the capillaries, which might be associated with astrocytic degeneration, in the rat thalamus at 3 weeks after non-infarct-induced cerebral hypoperfusion. In addition, Castejón [19] showed that swollen AEF with dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum, AEF detached from the capillary basement membrane, and fragmented AEF were observed in the cerebral cortex, depending on the severity of traumatic brain injury. However, the chronological ultrastructural changes of AEF after cerebral IR injury, which might be associated with delayed neuronal death following IR injury, remain incompletely understood. Therefore, in this study, we examined the chronological changes in the ultrastructure of AEF after IR injury through TFI to elucidate its relationship with delayed neuronal death and tissue repair in the CA1 area of the gerbil hippocampus. Changes in the CA3 area were also examined at 10 days post-TFI for comparative perspective. Understanding the interplay between AEF dysfunction and neuronal death following cerebral IR injury is critical for identifying potential targets and developing effective therapeutic strategies.

2.1 Experimental Animals and Ethics Statement

Male gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus; six months old, weighing between 65 and 75 g) were sourced from the Experimental Animal Center of Kangwon National University in Chuncheon, South Korea and kept under standard conditions in a pathogen-free environment (light/dark cycle, 12:12; temperature, 24 ± 2°C; humidity, 57 ± 5%) having unrestricted access to water and food. Animal care followed the guidelines outlined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [20]. The research protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Kangwon National University (approval number: KW-200113-1, dated 13 January 2020).

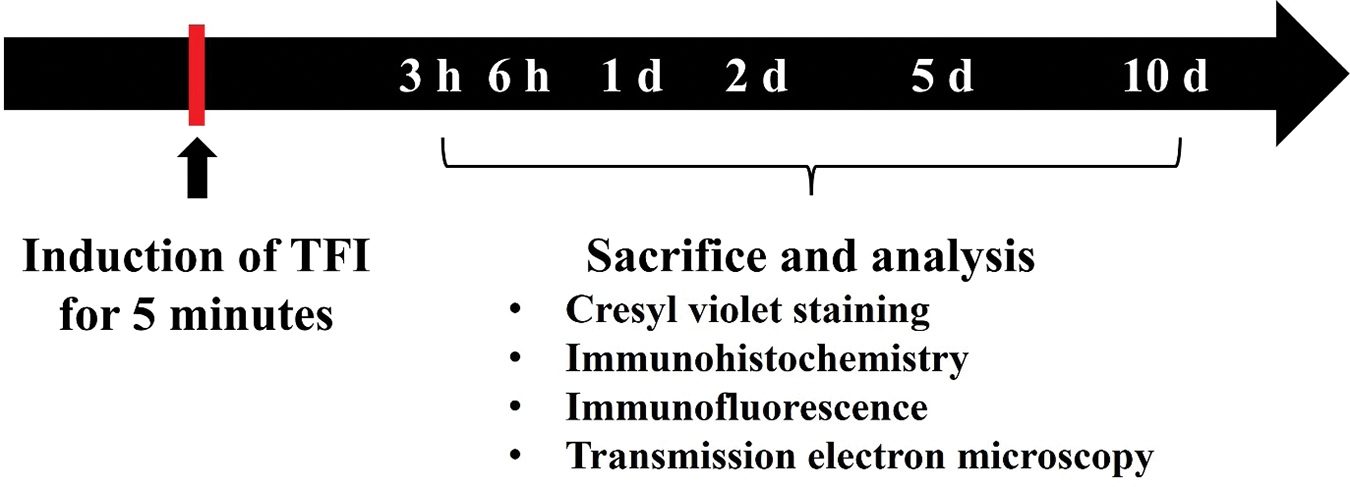

A total of 70 animals were randomly assigned to the following groups: (1) sham group (n = 10), which underwent a sham TFI procedure for 5 min, and (2) TIF group (n = 60), which underwent a TFI procedure for 5 min. In the sham group, gerbils (n = 7 for immunohistochemistry, n = 3 for ultrastructural analysis) were sacrificed 10 days after sham TFI operation to minimize animal usage. For the TFI groups, animals (n = 7 per time point for immunohistochemistry, n = 3 per time point for ultrastructural analysis) were sacrificed at designated times (3, 6 h, 1, 2, 5, and 10 days after TFI operation) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Timeline of the experiment. The gerbils were subjected to 5 min of TFI and sacrificed at designated times (3, 6 h, 1, 2, 5, and 10 d after TFI) for immunohistochemical staining (n = 7 per time point) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) examination (n = 3 per time point)

The procedure for TFI induction was performed as previously described [21]. Gerbils were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane (4 L/min; Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA). Under anesthesia, the gerbils were placed in the supine position, and a midline incision was made on the neck. The BCCA was separated from the carotid sheath and then ligated with non-traumatic 0.69 N clips (Yasargil FE 723K; Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany) for 5 min. To verify complete BCCA occlusion, central retinal arteries were examined using an ophthalmoscope (Heine Optotechnik, Herrsching, Germany). During the procedure, the body temperature was monitored and maintained at 37 ± 0.3°C using a rectal temperature probe (Fine Science Tools, TR-100, Foster City, CA, USA). For the sham TFI group, the same surgical steps were performed without occluding the BCCA. Post-surgery, the gerbils were housed in incubators set to 24 ± 1°C with a relative humidity of 55 ± 5%.

2.3 Preparation of Histological Tissue Sections

Hippocampal tissue sections from gerbil brains were prepared following the method outlined in our previous research [22]. Briefly, animals were deeply anesthetized through an intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium (JW Pharm. Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea). After anesthesia, transcardial perfusion was performed using 100 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were then removed and further fixed in the same solution for 5 h, and subsequently immersed in 30% sucrose to prevent freezing-induced damage. Finally, coronal brain sections (30 μm thickness) were obtained using a sliding microtome (Leica Biosystems, SM2010R, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.3.1 Histochemistryfor Cresyl Violet (CV)

To explore the distribution and morphology of hippocampal cells in both the sham and TFI groups, CV histochemistry was performed. As described in a previously published study [23], brain sections were treated with 1.0% CV acetate (Sigma-Aldrich Co., C5042, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 20 min, rinsed with water, dehydrated with absolute ethanol, and cleared using xylene. Finally, the sections were mounted with Canada balsam for microscopic examination.

Immunohistochemical staining for neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) was conducted to evaluate neuronal survival in the CA1 and CA3 areas of the hippocampus after TFI. Following a previously established avidin-biotin complex technique [22], brain slices were first incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide solution to reduce endogenous peroxidase and then treated with 5% normal horse serum (Vector Laboratories, S-2000, Newark, CA, USA) to block non-specific immunoreactions. The sections were then exposed to mouse anti-NeuN antibody (diluted 1:1150; Chemicon International, MAB377, Temecula, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, they were incubated with a biotin-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:230; Vector Laboratories, BA-2000) for 2 h at room temperature. The signal enhancement was achieved using an avidin-biotin complex (diluted 1:230; Vector Laboratories, PK-6100). Visualization of the immunoreaction was completed by applying 0.03% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich Co., D5637). Finally, the stained slices were dehydrated through graded ethanol and coverslipped using Canada balsam.

The quantification of NeuN-immunostained cells was conducted as described in our previous studies [22]. From each gerbil, five brain slices were chosen at intervals of 150 μm. NeuN-immunostained cells in the CA1 and CA3 areas were visualized under ×200 magnification using a BX53 upright microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and corresponding distal images were captured. The mean number of NeuN-immunostained neurons was calculated from a 250 × 250 μm area positioned at the center of the stratum pyramidale, using the cellSens Standard imaging software (version 1.18, Olympus).

2.3.3 Fluoro-Jade B (F-J B) Histofluorescence

To detect neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 areas, F-J B histofluorescence staining was applied. As described previously [22], brain slices were immersed in 1% sodium hydroxide and 0.06% potassium permanganate (Sigma-Aldrich Co., 7722-64-7), washed with water, and then incubated with 0.0004% F-J B solution (Histochem Inc., 1FJC, Jefferson, AR, USA). After staining, sections were cleared with xylene and mounted using dibutyl phthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX, Sigma-Aldrich Co., 06522).

To quantify F-J B positive neurons, fluorescent images were obtained using a BX53 fluorescence microscope (Olympus) under blue light excitation (450–490 nm), and analysis was conducted following the same method used for NeuN-immunostained neurons counting.

2.3.4 Double Immunofluorescence for Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP)/Glucose Transporter 1 (GLUT1)

To identify AEF and endothelial cells-key constituents of the BBB-in the CA1 and CA3 areas of the hippocampus, dual-labeling immunofluorescence was performed according to protocols from earlier studies [23,24]. Tissue sections were incubated with two primary antibodies: mouse anti-GFAP (diluted 1:1100; Merck-Millipore, MAB360, Burlington, MA, USA) and rabbit anti-GLUT1 (diluted 1:1000; Chemicon, CBL242). After thorough washing, sections were treated with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:550; Invitrogen, 10544773, Waltham, MA, USA) and Alexa Fluor® 546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (diluted 1:550; Invitrogen, 10348502). The sections were subsequently cleared in xylene and mounted using DPX medium (Sigma-Aldrich Co.).

Immunolabeled structures were examined using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and fluorescent images of GFAP-and GLUT1-immunostained structures were captured in both CA1 and CA3 areas.

2.4 Ultrastructural Examination of AEF Using TEM

To examine ultrastructural changes in AEF in the CA1 and CA3 areas, hippocampal tissues were prepared for general TEM and observed as previously described [23]. According to the general TEM procedure, the animals were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (JW Pharm. Co., Ltd.), and the animals underwent perfusion fixation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Tissues from the CA1 and CA3 areas were cut into approximately 1 mm3 pieces and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, followed by thorough rinsing and sequential dehydration in graded ethanol and acetone. The tissues were then embedded in Epon 812 epoxy resin using the PELCO Eponate 12™ Kit (18010, Clovis, CA, USA). Ultrathin sections (50 nm) were cut with a UC-7 ultramicrotome (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), mounted on copper grids, and contrasted with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate staining. The ultrastructure of AEF was then examined using a Philips EM400 transmission electron microscope (Koninklijke Philips N.V., Amsterdam, Netherlands) operating at 100 kV.

The statistical evaluations were performed using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Group differences were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Bonferroni’s post hoc test was applied for multiple comparisons when appropriate. Values are presented in graphs as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3.1 Neuronal Damage/Death Following TFI

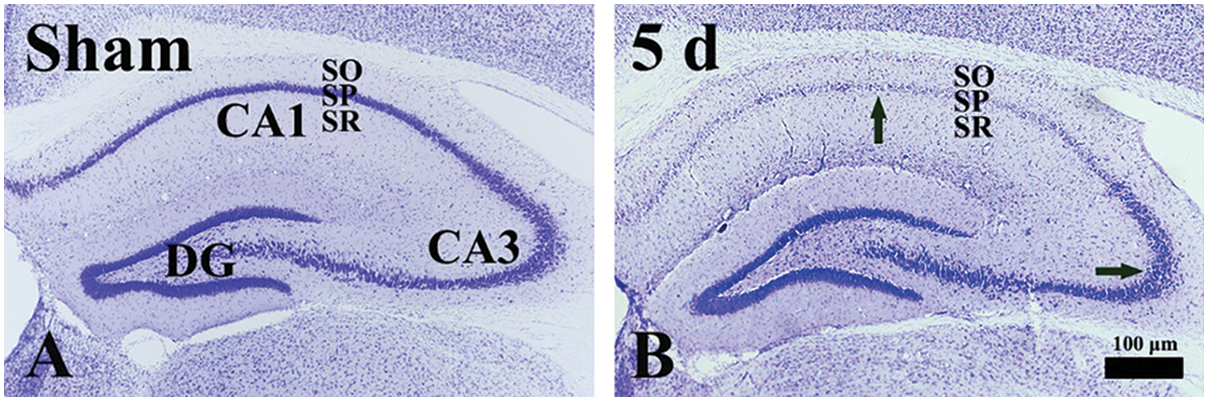

CV is a dye used in neuroscience to visualize the Nissl substance, which is the rough endoplasmic reticulum found in neurons. In the sham group, hippocampal cells exhibited distinct staining with CV in the hippocampus, particularly pyramidal cells, the principal neurons that make up the stratum pyramidale (Fig. 2A). In the TFI group, CV-stained pyramidal cells were noticeably damaged in the CA1 area at 5 days after 5-min TFI (Fig. 2B). However, CV-stained pyramidal cells in the CA3 area showed no differences compared to those of the sham group at 5 days post-TFI (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: CV histochemistry in the gerbil hippocampus of the sham (A) and TFI (B) groups at 5 days post-TFI. In the sham group, CV-stained pyramidal cells of the stratum pyramidale (SP). At 5 days after TFI, CV-stained cells in the SP of the CA1 area are severely damaged (a black arrow in the CA1 area). In contrast, CV-stained cells in the SP of the CA3 area are well preserved (a black arrow in the CA3 area). DG, dentate gyrus; SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum

3.1.2 NeuN-Immunostained Cells

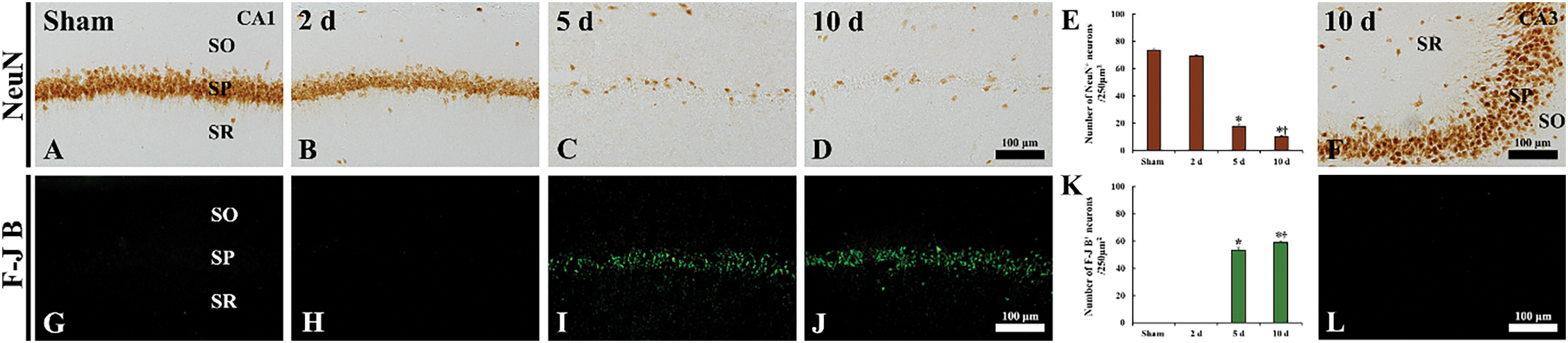

NeuN is a protein that is expressed in mature neurons and is used as a marker for neuronal differentiation and maturation. In the sham group, numerous NeuN-immunostained cells were located in the CA1 stratum pyramidale of the hippocampus; these cells, as principal neurons, were pyramidal in shape (Fig. 3A). In the TFI group, at 2 days post-TFI, the pattern of NeuN immunoreactivity and the number of NeuN-immunostained cells (mean: 69.3 ± 0.6/250 μm2) in the CA1 area were comparable to those in the sham group (Fig. 3B,E). However, at 5 and 10 days after TFI, only a few NeuN-immunostained neurons (mean: 17.5 ± 1.5/250 μm2 and 10.4 ± 0.4/250 μm2, respectively) were observed in the stratum pyramidale of the CA1 area (Fig. 3C–E). In contrast, in the CA3 area of the TFI group, NeuN-immunostained neurons were well preserved in the stratum pyramidale at 10 days after TFI, similar to the sham group (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3: Immunohistochemical staining for NeuN (A–D, F) and histofluorescence staining with F-J B (G–J, L) in the CA1 area of the sham (A, G) and TFI (B–D, H–J) groups at 2, 5, and 10 days post-TFI, and in the CA3 area of the TFI group (F, L) at 10 days post-TFI. In the sham group, abundant NeuN-immunostained cells and no F-J B-positive cells are observed in the stratum pyramidale (SP) of the CA1 area. In the TFI group, the findings at 2 days after TFI are similar to those of the sham group; however, at 5 and 10 days after TFI, a few NeuN-immunostained cells and numerous F-J B-positive cells are observed in the SP of the CA1 area. In contrast, numerous NeuN-immunostained cells and no F-J B positive cells are found in the SP of the CA3 area. SO, stratum oriens; SR, stratum radiatum. (E, K) Quantification of NeuN-immunostained cells (E) and F-J B-positive cells (K) in the SP of the CA1 area. *p < 0.05 vs. sham group; †p < 0.05 vs. previous time point. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM (n = 7 per group)

F-J B, an anionic fluorescein derivative, is utilized to label degenerating or dying neurons. In the sham group, no F-J B-positive cells were observed in the stratum pyramidale of hippocampal CA1 (Fig. 3G,K). Similarly, in the TFI group, no F-J B-positive cells were detected in the CA1 area at 2 days post-TFI (Fig. 3H,K). However, at 5 and 10 days after TFI, numerous F-J B-positive cells were detected in the stratum pyramidale of hippocampal CA1, with mean numbers of 53.2 ± 1.9 and 59.2 ± 0.9 cells/250 μm2, respectively (Fig. 3I–K). In contrast, in the CA3 area, F-J B-positive cells were not observed in the stratum pyramidale even at 10 days post-TFI (Fig. 3L).

3.2 Immunohistochemical AEF Changes Following TFI

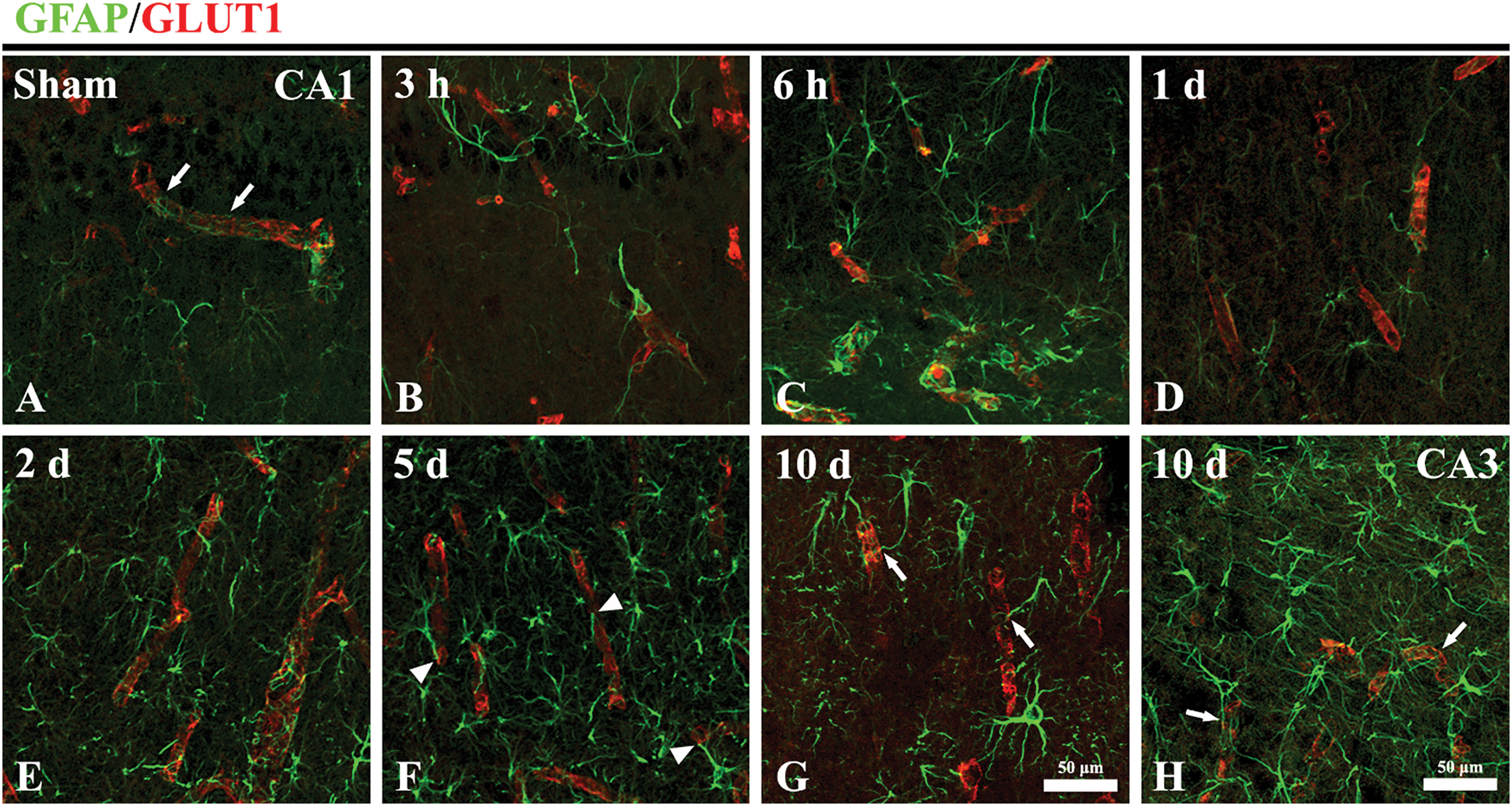

Changes in AEF following TFI were examined by double immunofluorescence staining for GFAP (an astrocyte marker) and GLUT1 (a marker for endothelial cells and/microvessels). In the sham group, GFAP immunoreactivity was observed in astrocyte somata, their processes, and AEF (Fig. 4A). GFAP-immunostained AEF appeared thin and closely ensheathed the GLUT1-immunostained microvessels in the CA1 area (Fig. 4A). In the TFI group, at 3 and 6 h after TFI, AEF appeared swollen and blunted, failing to properly enwrap GLUT1-immunostained microvessels in the CA1 area (Fig. 4B,C), indicating early structural damage of AEF following IR injury. At 1 day after TFI, the swelling of GFAP-immunostained AEF in the CA1 area was reduced (Fig. 4D), suggesting a transient structural recovery. However, at 2 and 5 days after TFI, GFAP-immunostained AEF became more blunted and fragmented and failed to adequately encase the GLUT1-immunostained microvessels in the CA1 area (Fig. 4E,F), indicating further progression of AEF damage. By 10 days after TFI, the ends of GFAP-immunostained processes appeared hypertrophied and extended toward the microvessels, re-establishing partial contact in the CA1 area (Fig. 4G). In contrast, in the CA3 area, AEF were only mildly swollen and still adequately enveloped GLUT1-immunostained microvessels at 10 days after TFI (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4: Double immunohistofluorescence staining for GFAP (green; a marker of AEF) and GLUT1 (Red; a marker of endothelial cells and/microvessels) in the CA1 area of the sham (A) and TFI (B–G) groups at 3 and 6 h, and 1, 2, 5, and 10 days post-TFI, and in the CA3 area of the TFI group (H) at 10 days post-TFI. In the sham group, GFAP-immunostained AEF (arrows) exhibit a thin morphology and closely envelop GLUT1-immunostained microvessels in the CA1 area. In the TFI group, AEF in the CA1 area becomes swollen at 3 and 6 h after TFI. At 1 day after TFI, the swelling of GFAP-immunostained AEF is partially reduced in the CA1 area. However, at 2 and 5 days after TFI, GFAP-immunostained AEF in the CA1 area appear fragmented and fail to completely enwrap the GLUT1-immunostained microvessels (arrowheads). By 10 days post-TFI, the ends of GFAP-immunostained processes (arrows) extend toward and partially wrap the GLUT1-immunostained microvessels in the CA1 area. In contrast, in the CA3 area, AEF are slightly swollen but still properly enclose the GLUT1-immunostained microvessels (arrows) at 10 days after TFI

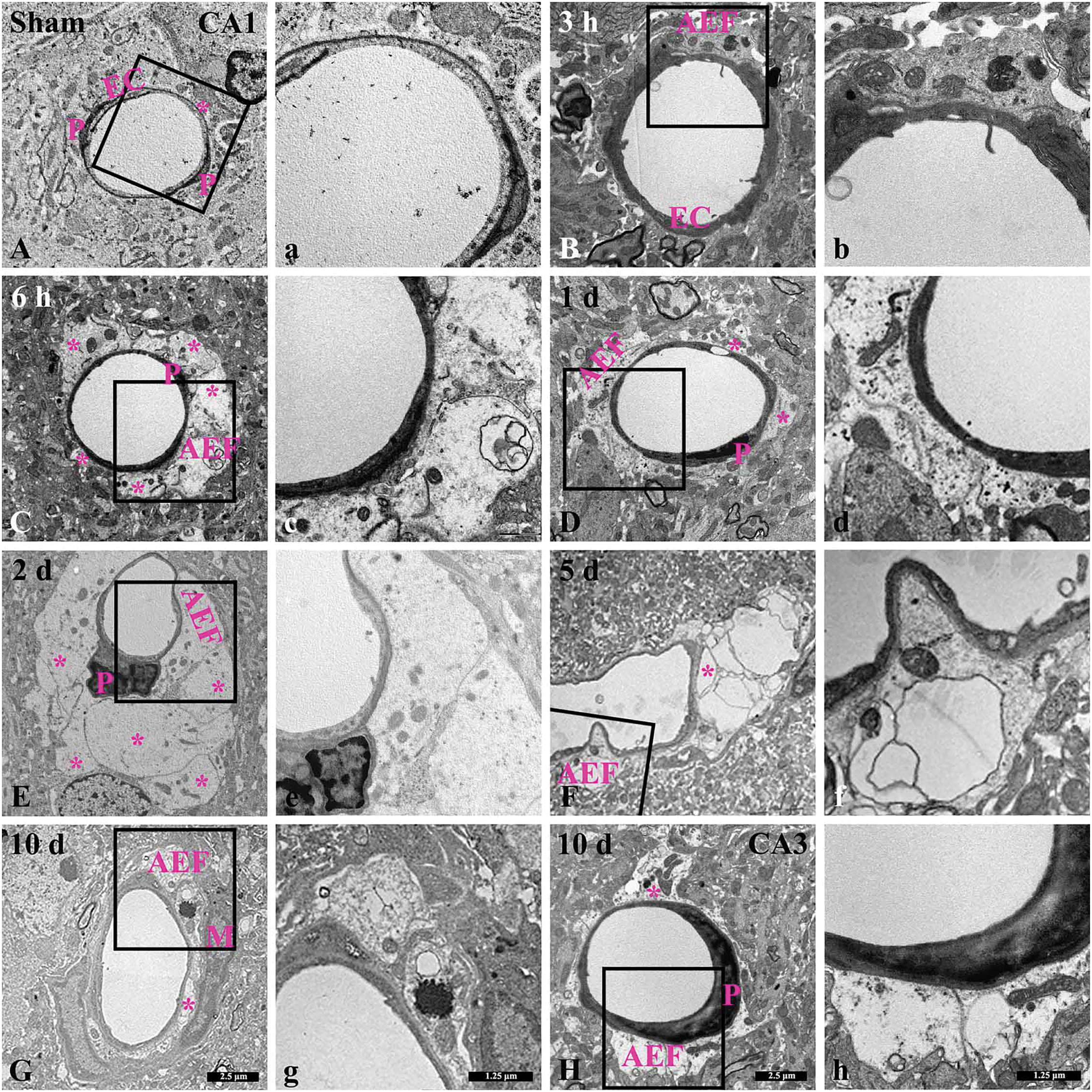

3.3 Ultrastructural AEF Changes Following TFI

Ultrastructural changes of AEF after TFI in the hippocampus were examined using a transmission electron microscope. In the sham group, AEF in the CA1 area wrapped the basement membrane in a very thin layer, which surrounded endothelial cells and pericytes (Fig. 5A,a). In the CA1 area after TFI, the fine structures of AEF were apparently and dramatically changed over time. At 3 h after TFI, the AEF region was markedly swollen and contained enlarged dark mitochondria, along with intraluminal protrusions of endothelial cells (Fig. 5B,b). At 6 h after TFI, AEF became further pale and enlarged, containing darker mitochondria (Fig. 5C,c). At 1 day after TFI, the swelling of AEF was reduced, and the darkness of mitochondria was diminished (Fig. 5D,d). At 2 days after TFI, AEF were severely swollen, compressed microvessels, exhibited vacuolation, and contained shrunken mitochondria (Fig. 5E,e). At 5 days after TFI, AEF were vacuolated and destroyed with scant organelles, along with irregular luminal surfaces of endothelial cells (Fig. 5F,f). At 10 days after TFI, edematous AEF filled with cellular debris (interstitial material) were observed, and the AEF relatively evenly wrapped endothelial cells (Fig. 5G,g). On the other hand, in the CA3 area, changes in AEF after TFI were insignificant, showing that AEF became slightly swollen at 10 days after TFI (Fig. 5H,h).

Figure 5: Low-(A–H) and high-(a–h) magnification images of ultrastructural changes of AEF in the CA1 area of the sham (A, a) and TFI (B–G, b–g)groups at 3 and 6 h, and 1, 2, 5, 10 days post-TFI, and in the CA3 area of the TFI group (H, h) at 10 days post-TFI. In the sham group, intact AEF (asterisks) contain typical mitochondria surrounding microvessels in the CA1 area. In the TFI group, AEF in the CA1 area appear swollen and contain enlarged and dark mitochondria at 3 and 6 h after TFI. At 1 day after TFI, AEF swelling temporarily decreases in the CA1 area. However, at 2 days post-TFI, AEF are severely enlarged and contain shrunken mitochondria in the CA1 area. At 5 days post-TFI, AEF are severely damaged, with vacuolations and scant organelles in the CA1 area. At 10 days post-TFI, AEF are edematous and filled with cellular debris (interstitial material) in the CA1 area. However, AEF (asterisk) in the CA3 area appears structurally typical at 10 days after TFI. EC, endothelial cell; M, microglia; P, pericyte

In this study, we examined the temporal structural alterations of AEF in the gerbil hippocampus from 3 h to 10 days following IR injury induced by a 5-min TFI, and explored their potential association with TFI-induced neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 area.

In the present study, IR-induced neuronal death following TFI was identified in the stratum pyramidale, a region populated by pyramidal cells (principal neurons), in the hippocampal CA1 area at 5 days post-TFI using CV staining, NeuN immunolabeling, and F-J B histofluorescence, and this degeneration persisted up to 10 days post-TFI. However, no neuronal death is found in the CA3 area after TFI. Similar to our results, previous studies using a gerbil model of TFI showed that the number of CA1 pyramidal neurons was significantly reduced compared with the sham group at 3–5 days after 5-min TFI [3,4,21], whereas CA3 pyramidal neurons were not damaged by 5-min TFI [21]. In a rat model of transient global cerebral ischemia using the 4-vessel occlusion method, loss of CA1 pyramidal cells occurred several days after the transient ischemia [25,26]. On the other hand, it has been reported that the suppression of intracellular Ca2+ overload in CA3 astrocytes [27], the high expression of glial glutamate transporter-1 [28], and removal of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors [29] in the CA3 area contribute to the intrinsic resistance of CA3. Taken together, IR injury in the hippocampus induces delayed neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 area, although the time of neuronal death slightly depends on the animal species or the methods of IR injury induction.

The BBB plays an important role in cerebral homeostasis [9,10]. Its disruption following IR injury leads to brain edema through several stages: reactive hyperemia due to increased BBB permeability, hypoperfusion caused by microvascular obstruction from swelling of AEF and endothelial cells, and increased paracellular permeability [9]. Indeed, IR injury following TFI induces dynamic structural responses in AEF around microvessels [16]. In this study, we examined structural changes in AEF in the hippocampus using double immunostaining for GFAP/GLUT1 and TEM and found that, in the sham group, GFAP-immunostained astrocyte end processes tightly enclosed GLUT1-immunostained microvessels, and the ultrastructure of AEF properly surrounded microvessels. In the TFI group, however, AEF in the CA1 area became swollen, with mitochondria that appeared enlarged and darkened at 3 and 6 h post-TFI, while AEF edema temporarily decreased at 1 day post-TFI. These results are in agreement with a previous study using a gerbil model, which reported AEF swelling as early as 3 h post-ischemia in the hippocampal CA1 area [23]. de Souza et al. [30] reported that pale and edematous AEF lacked glycogen granules in the CA1 area at 3 and 12 h after transient global cerebral ischemia in a rat model using the 4-vessel occlusion method. In addition, Ito et al. [31] reported that the thickness of AEF and the number and size of mitochondria increased during the acute post-ischemic period (5 h after ischemia), followed by a decrease in the subacute period (12 and 48 h after ischemia) in the cerebral cortex of a gerbil model of repeated brief cerebral ischemia. Taken together, AEF undergo rapid edema and mitochondrial damage as immediate and major ultrastructural responses to cerebral IR injury. In our current study, at 2 days post-TFI, AEF contained shrunken mitochondria and were severely edematous, compressing microvessels in the CA1 area. Furthermore, on day 5 post-TFI, the ends of GFAP-immunostained astrocytes appeared blunted and detached from GLUT1-immunostained microvessels under light microscopy, and the AEF were severely damaged, exhibiting vacuolations and containing few organelles under TEM. However, in the CA3 area, where neuronal death was absent, AEF were slightly swollen but properly surrounded by GLUT1-immunostained microvessels at 10 days after TFI. Similar to our results, a previous study reported that highly edematous AEF surrounding capillaries with diminished lumens appeared in the CA1 area at 1 day post-reperfusion, preceding neuronal death following transient global ischemia [30]. Moreover, previous study indicated that punctate and discontinuous aquaporin 4-immunoreactive AEF along CD31-immunoreactive microvessels were found in the cerebral cortex of mice at 1 day after ischemia [32], and that ruptured AEF, degradation of the microvascular basement membrane, and excessive water accumulation around microvessels occurred in the basal ganglia at 16 and 48 h after ischemia in a rodent model of focal ischemia [33]. Considering all the findings, we suggest that AEF dysfunction-such as vascular compression due to excessive AEF swelling, degeneration of AEF organelles, and loss of endfeet coverage-apparently occurs prior to neuronal death following IR injury.

It is well known that severe edema of AEF compresses microvessels, resulting in impaired cerebral blood flow regulation. It has been reported that increased capillary constriction leads to impaired neurovascular coupling, which is related to increased levels of 20-HETE, a potent vasoconstrictor produced by enzymes (cytochrome P450A enzymes, CYP4A) released by AEF [34], and a large K+ efflux from AEF via large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels [35]. Meanwhile, functional assessment related to structural changes in AEF can be conducted by evaluating BBB permeability through the leakage of intravascular substances into the brain parenchyma. Heithoff et al. [36] reported that, in a mouse model of tamoxifen-inducible astrocyte ablation, BBB damage and the leakage of large plasma proteins like fibrinogen and the small molecule cadaverine into brain parenchyma were observed as soon as astrocyte loss was detected, suggesting that astrocytes play a crucial role in maintaining BBB integrity in adult mouse brain. In our previous studies using 5-min TFI gerbil model, BBB breakdown in the hippocampal CA1 area was indicated by IgG and albumin extravasation [22–24]: IgG was detected intravascularly at 3 h after TFI, appeared in cellular components at 6 h post-TFI, and was prominently detected in the parenchyma on day 1 after TFI, along with increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-1β [22–24], and albumin was observed in cellular components from 1 day post-TFI and in the parenchyma by 2 days post-TFI [22]. Moreover, Kim et al. [37] demonstrated that reperfusion-induced disruption of endothelial cell junctions was significantly correlated with AEF damage in a mouse focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion model. CU06-1004 (a synthetic small molecule that acts as an endothelial dysfunction blocker), administered 20 min after reperfusion, reduced AEF swelling by stabilizing endothelial cell junctions and downregulating aquaporin 4, leading to decreased Evans blue extravasation and infarct volume [37]. Based on those results, it is suggested that impaired blood flow regulation due to vascular compression and increased permeability due to BBB disruption are closely related to delayed neuronal cell death after TFI.

In this experiment, at 10 days post-TFI, the ends of GFAP-immunostained astrocyte processes in the CA1 area were swollen and extended around microvessels, and TEM revealed that the ends of the processes were filled with cellular debris. Mills et al. [38] reported astrocyte plasticity, in which adjacent astrocytes project their processes to envelop vascular vacancies after astrocyte cell death caused by IR injury in a mouse model of transient photothrombotic stroke. Moreover, Zhou et al. [39] reported that, in type 2 diabetic stroke mice, L-4F (an apolipoprotein A member I mimetic peptide) treatment exhibited neuroprotective effects by promoting neurovascular remodeling, such as the reduction of BBB leakage, an increase in tight junction proteins, and an increase in AEF density at 21 days after ischemia, indicating that the increase in AEF coverage is related to neural tissue recovery in the chronic phase after ischemia [39]. Taken together, AEF can undergo remodeling to functionally interact with neighboring structures such as microvessels, neurons, and glial cells, contributing to the restoration of tissue integrity during the chronic phase after ischemia.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, since our analysis relied on TEM and double immunofluorescence to investigate ultrastructural changes, the study was qualitative in nature and had a limited sample size, making it difficult to perform quantitative analysis. Second, although we observed a clear temporal association between AEF damage and ischemic neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 area, we did not include any therapeutic intervention to directly confirm a causal relationship. While the absence of AEF damage and neuronal death in the ischemia-resistant CA3 area supports our hypothesis, further studies involving pharmacological or genetic modulation of AEF swelling are needed to clarify this causal link.

The findings of this study showed that edematous AEF with mitochondrial damage occurred immediately in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 area after 5-min TFI. In addition, AEF disruption, including excessive swelling, compression of microvessels, organelle degeneration, and loss of AEF coverage, occurred prior to neuronal death, followed by AEF remodeling that interacted with surrounding cells after neuronal death. Based on these results, we propose that the rapid swelling of AEF in the hippocampal CA1 area following TFI increases vascular compression, and the subsequent disruption of AEF is closely linked to delayed neuronal death (characterized by the death of CA1 pyramidal cells at 5 days after TFI). Moreover, in the chronic phase after IR injury, surviving astrocyte processes display a complex response for tissue remodeling.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to appreciate Hyun Sook Kim and Seung Uk Lee for their technical help in this study.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by 2024 Research Grant from Kangwon National University (M.C.S) and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1A2C1094224) (J.H.A).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design, Myoung Cheol Shin, Moo-Ho Won, Choong-Hyun Lee, and Ji Hyeon Ahn; data collection, Tae-Kyeong Lee, Dae Won Kim, and Joon Ha Park; analysis and interpretation of results, Tae-Kyeong Lee, Dae Won Kim, and Joon Ha Park; draft manuscript preparation, Myoung Cheol Shin, Moo-Ho Won, Choong-Hyun Lee, and Ji Hyeon Ahn; funding acquisition, Myoung Cheol Shin and Ji Hyeon Ahn. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, a Committee of Kangwon National University) (protocol code KW-200113-1 on 13 January 2020). Every effort was made to minimize animal suffering, and the number of animals was kept to a minimum.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| AEF | Astrocyte endfeet |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| CA | Cornu ammonis |

| CV | Cresyl violet |

| F-J B | Fluoro-Jade B |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| IR | Ischemia-reperfusion |

| NeuN | Neuronal nuclear antigen |

| TFI | Transient forebrain ischemia |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

References

1. Grain B, Westerkam W, Harrison A, Nadler J. Selective neuronal death after transient forebrain ischemia in the Mongolian gerbil: a silver impregnation study. Neuroscience. 1988;27(2):387–402. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(88)90276-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Okada T, Kataoka Y, Takeshita A, Mino M, Morioka H, Kusakabe KT, et al. Effects of transient forebrain ischemia on the hippocampus of the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatusan immunohistochemical study. Zool Sci. 2013;30(6):484–9. doi:10.2108/zsj.30.484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Res. 1982;239(1):57–69. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(82)90833-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Nitatori T, Sato N, Waguri S, Karasawa Y, Araki H, Shibanai K, et al. Delayed neuronal death in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the gerbil hippocampus following transient ischemia is apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1995;15(2):1001–11. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.15-02-01001.1995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. White BC, Sullivan JM, DeGracia DJ, O’Neil BJ, Neumar RW, Grossman LI, et al. Brain ischemia and reperfusion: molecular mechanisms of neuronal injury. J Neurol Sci. 2000;179(1–2):1–33. doi:10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00386-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Mao R, Zong N, Hu Y, Chen Y, Xu Y. Neuronal death mechanisms and therapeutic strategy in ischemic stroke. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38(10):1229–47. doi:10.1007/s12264-022-00859-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Shen Z, Xiang M, Chen C, Ding F, Wang Y, Shang C, et al. Glutamate excitotoxicity: potential therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151(1):113125. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhu G, Wang X, Chen L, Lenahan C, Fu Z, Fang Y, et al. Crosstalk between the oxidative stress and glia cells after stroke: from mechanism to therapies. Front Immunol. 2022;13:852416. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.852416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lin L, Wang X, Yu Z. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in the brain: mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;5(4):213 doi: 10.4172/2167-0501.1000213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Solár P, Zamani A, Lakatosová K, Joukal M. The blood-brain barrier and the neurovascular unit in subarachnoid hemorrhage: molecular events and potential treatments. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022;19(1):29. doi:10.1186/s12987-022-00312-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Deitmer JW, Theparambil SM, Ruminot I, Noor SI, Becker HM. Energy dynamics in the brain: contributions of astrocytes to metabolism and pH homeostasis. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1301. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.01301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hart CG, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Recent insights on astrocyte mechanisms in CNS homeostasis, pathology, and repair. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(10):2427–62. doi:10.1002/jnr.24922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Schiera G, Di Liegro CM, Schirò G, Sorbello G, Di Liegro I. Involvement of astrocytes in the formation, maintenance, and function of the blood-brain barrier. Cells. 2024;13(2):150. doi:10.3390/cells13020150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Muoio V, Persson P, Sendeski M. The neurovascular unit-concept review. Acta Physiol. 2014;210(4):790–8. [Google Scholar]

15. Panickar KS, Norenberg MD. Astrocytes in cerebral ischemic injury: morphological and general considerations. Glia. 2005;50(4):287–98. doi:10.1002/glia.20181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Díaz-Castro B, Robel S, Mishra A. Astrocyte endfeet in brain function and pathology: open questions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2023;46(1):101–21. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-091922-031205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Cohen-Salmon M, Slaoui L, Mazaré N, Gilbert A, Oudart M, Alvear-Perez R, et al. Astrocytes in the regulation of cerebrovascular functions. Glia. 2021;69(4):817–41. doi:10.1002/glia.23924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wu JS, Chen XC, Chen H, Shi YQ. A study on blood-brain barrier ultrastructural changes induced by cerebral hypoperfusion of different stages. Neurol Res. 2006;28(1):50–8. doi:10.1179/016164106x91870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Castejón OJ. Electron microscopy of astrocyte changes and subtypes in traumatic human edematous cerebral cortex: a review. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2013;37(6):417–24. doi:10.3109/01913123.2013.831157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Council NR. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2011. 246 p. [Google Scholar]

21. Lee TK, Kim H, Song M, Lee JC, Park JH, Ahn JH, et al. Time-course pattern of neuronal loss and gliosis in gerbil hippocampi following mild, severe, or lethal transient global cerebral ischemia. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14(8):1394–403. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.06.235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lee C-H, Ahn JH, Lee T-K, Sim H, Lee J-C, Park JH, et al. Comparison of neuronal death, blood-brain barrier leakage and inflammatory cytokine expression in the hippocampal CA1 region following mild and severe transient forebrain ischemia in gerbils. Neurochem Res. 2021;46(11):2852–66. doi:10.1007/s11064-021-03362-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ahn JH, Chen BH, Park JH, Shin BN, Lee TK, Cho JH, et al. Early IV-injected human dermis-derived mesenchymal stem cells after transient global cerebral ischemia do not pass through damaged blood-brain barrier. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(7):1646–57. doi:10.1002/term.2692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lee TK, Kang IJ, Sim H, Lee JC, Ahn JH, Kim DW, et al. Therapeutic effects of decursin and angelica gigas nakai root extract in gerbil brain after transient ischemia via protecting BBB leakage and astrocyte endfeet damage. Molecules. 2021;26(8):2161. doi:10.3390/molecules26082161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kirino T, Tamura A, Sano K. Delayed neuronal death in the rat hippocampus following transient forebrain ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;64(2):139–47. doi:10.1007/bf00695577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Frassetto S, Schetinger MRC, Schierholt R, Webber A, Bonan CD, Wyse AT, et al. Brain ischemia alters platelet ATP diphosphohydrolase and 5′-nucleotidase activities in naive and preconditioned rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33(11):1369–77. doi:10.1590/s0100-879x2000001100017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sun C, Fukushi Y, Wang Y, Yamamoto S. Astrocytes protect neurons in the hippocampal CA3 against ischemia by suppressing the intracellular Ca2+ overload. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:280. doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang M, Li WB, Liu YX, Liang CJ, Liu LZ, Cui X, et al. High expression of GLT-1 in hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus subfields contributes to their inherent resistance to ischemia in rats. Neurochem Int. 2011;59(7):1019–28. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2011.08.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Dennis SH, Jaafari N, Cimarosti H, Hanley JG, Henley JM, Mellor JR. Oxygen/glucose deprivation induces a reduction in synaptic AMPA receptors on hippocampal CA3 neurons mediated by mGluR1 and adenosine A3 receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31(33):11941–52. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1183-11.2011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. de Souza Pagnussat A, Faccioni-Heuser MC, Netto CA, Achaval M. An ultrastructural study of cell death in the CA1 pyramidal field of the hippocapmus in rats submitted to transient global ischemia followed by reperfusion. J Anat. 2007;211(5):589–99. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00802.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ito U, Hakamata Y, Kawakami E, Oyanagi K. Degeneration of astrocytic processes and their mitochondria in cerebral cortical regions peripheral to the cortical infarction: heterogeneity of their disintegration is closely associated with disseminated selective neuronal necrosis and maturation of injury. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2173–81. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.108.534990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hawkes CA, Michalski D, Anders R, Nissel S, Grosche J, Bechmann I, et al. Stroke-induced opposite and age-dependent changes of vessel-associated markers in co-morbid transgenic mice with Alzheimer-like alterations. Exp Neurol. 2013;250(Suppl. 1):270–81. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.09.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kwon I, Kim EH, del Zoppo GJ, Heo JH. Ultrastructural and temporal changes of the microvascular basement membrane and astrocyte interface following focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(3):668–76. doi:10.1002/jnr.21877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Gonzalez-Fernandez E, Staursky D, Lucas K, Nguyen BV, Li M, Liu Y, et al. 20-HETE enzymes and receptors in the neurovascular unit: implications in cerebrovascular disease. Front Neurol. 2020;11:983. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.00983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Koide M, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Wellman GC. Inversion of neurovascular coupling by subarachnoid blood depends on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(21):E1387–95. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121359109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Heithoff BP, George KK, Phares AN, Zuidhoek IA, Munoz-Ballester C, Robel S. Astrocytes are necessary for blood-brain barrier maintenance in the adult mouse brain. Glia. 2021;69(2):436–72. doi:10.1101/2020.03.16.993691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kim DY, Zhang H, Park S, Kim Y, Bae CR, Kim YM, et al. CU06-1004 (endothelial dysfunction blocker) ameliorates astrocyte end-feet swelling by stabilizing endothelial cell junctions in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Med. 2020;98(6):875–86. doi:10.1007/s00109-020-01920-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mills III WA, Woo AM, Jiang S, Martin J, Surendran D, Bergstresser M, et al. Astrocyte plasticity in mice ensures continued endfoot coverage of cerebral blood vessels following injury and declines with age. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1794. doi:10.1101/2021.05.08.443259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou M, Li R, Venkat P, Qian Y, Chopp M, Zacharek A, et al. Post-stroke administration of L-4F promotes neurovascular and white matter remodeling in type-2 diabetic stroke mice. Front Neurol. 2022;13:863934. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.863934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools