Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

C-Myc Reduces Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reperfusion-Induced Neuronal Pyroptosis through the SRSF1/NLRP1 Axis

1 Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Haikou Hospital, Xiangya Medical College of Central South University, Haikou, 570208, China

2 Department of Neurosurgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, 233099, China

* Corresponding Author: Ning Gao. Email:

#Siliang Liu and Hong Tang are co-first authors, contributed equally to this study

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1245-1264. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.064396

Received 14 February 2025; Accepted 15 May 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

Objectives: NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing (NLRP) 1-mediated pyroptosis plays a key role in the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (CIRI). C-Myc is reported to play a major role in CIRI. However, the mechanism remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate whether c-Myc affects CIRI by regulating Serine/Arginine-rich Splicing Factor 1 (SRSF1)/NLRP1-mediated pyroptosis. Methods: Oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) induced neuroblastoma cells for the establishment of an in vitro CIRI model. The levels of c-Myc and SRSF1, cell viability, the expression of pyroptosis-related factors, and the interaction between SRSF1 and NLRP1 were evaluated. Results: The expression of c-Myc and SRSF1 was decreased in OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells. c-Myc overexpression increased c-Myc and SRSF1 expression and cell viability in OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells while inhibiting NLRP1, Caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), IL-18, and lactate dehydrogenase levels and pyroptosis. C-Myc was positively correlated with SRSF1. SRSF1 low expression reversed the effects of c-Myc on the above indicators in OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells. Mechanically, SRSF1 interacted with NLRP1. SRSF1 was negatively correlated with NLRP1. The NLRP1 activator muramyl dipeptide (MDP) reversed the SRSF1 effect on OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells. Conclusion: Our results indicated that c-Myc reduced OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cell pyroptosis by inhibiting NLRP1 activation by positive feedback SRSF1 signal. Our findings suggested that the c-Myc/SRSF1 axis might be a new strategy for treating CIRI in the clinic.Keywords

Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (CIRI) is a complex cascade of pathological and physiological processes [1]. CIRI is harmful because it may lead to brain damage, cognitive dysfunction, neurodegenerative diseases, and other serious consequences [2]. Recently, clinical symptomatic treatment of CIRI is mainly based on drugs, including thrombolysis agents, antioxidants, calcium channel antagonists, and vasodilator drugs [3,4]. However, the high fatality rate of CIRI is a health problem in the medical community, and its complex and unclear pathogenesis hinders the development of clinical treatment [5]. In addition, during the CIRI process, brain cells experience various harmful stimuli, such as hypoxia and ischemia, which will lead to a series of abnormal biochemical changes in the cells, which may eventually lead to pyroptosis [6]. At the same time, cell pyroptosis can lead to the reduction of the number of brain cells, the intensification of the inflammatory response, vascular damage, etc., aggravating the degree of CIRI [7]. Therefore, pyroptosis may play an important role in the CIRI process.

NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing (NLRP1) 1 is a member of the inflammasome [8]. NLRP1 activation can promote the self-shearing of the Caspase1 precursor through the protein complex formed by the binding of Caspase1 and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), thus inducing pyroptosis [9]. C-C chemokine receptor type 5 activation promotes neuronal pyroptosis after intracerebral hemorrhage through NLRP1 [10]. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation inhibition attenuates neuronal pyroptosis after traumatic brain injury via NLRP1 [11]. These studies indicate that NLRP1 activation is closely related to pyroptosis. In addition, studies have shown that curcumin can alleviate neuronal pyroptosis in CIRI by inhibiting NLRP1 [12]. Therefore, NLRP1 activation inhibition may alleviate pyroptosis in CIRI.

Serine/Arginine-rich Splicing Factor 1 (SRSF1) is a critical RNA splicing factor [13]. In neurological diseases, nuclear output inhibition of SRSF1-dependent C9ORF72 duplicate transcripts can reduce neurotoxicity and alleviate neuronal damage [14]. In the quantitative proteome of neurons after cerebral ischemia, SRSF1 was found to present a differentially high expression [15]. SRSF1 can play a regulatory role in the signal transduction pathway, affecting the physiological processes of tumor cells, such as autophagy and growth [16,17]. However, the association of SRSF1 with NLRP1 and pyroptosis in CIRI remains unclear.

Both c-Myc and SRSF1 are important transcriptional regulators and are closely related to cancer development and progression [18]. For example, through a β-TrCP/c-Myc/SRSF1 positive feedback loop, circPVT1 promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis [19]. LncRNA SNHG7 accelerates prostate cancer through SRSF1/c-Myc [20]. C-Myc expression was up-regulated in CIRI [21]. Studies have shown that interferon gamma accelerates CIRI through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/c-Myc signaling pathway [22]. In addition, c-Myc-induced long non-coding RNA maternally expressed gene 3 triggers the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to activate mitochondrial autophagy by upregulation of rhotekin, thus aggravating renal ischemia-reperfusion injury [23]. However, the underlying molecular mechanism by which c-Myc induces pyroptosis in CIRI remains unclear.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the c-Myc mechanism of pyroptosis in CIRI. We hypothesized that c-Myc might regulate NLRP1 expression by modulating SRSF1 signaling, thereby participating in pyroptosis in CIRI. Our findings may provide an important supplementary reference for the development of new therapeutic strategies in CIRI.

2.1 Cell Culture and Treatment

Human neuroblastoma cell lines (SH-SY5Y, AW-CCH335; and SK-N-SH, AW-CCH037; Abiowell, Changsha, China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (iCell-01000, Icell, Shanghai, China) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (AWC0219a, Abiowell) and 1% antibiotics (AWH0529a, Abiowell) in a 5% CO2 cell incubator at 37°C. In CIRI studies, SH-SY5Y [24–27] and SK-N-SH cells [28–30] have been widely used as in vitro models. SH-SY5Y and SK-N-SH cells were induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) to construct a CIRI model in vitro. Briefly, to initiate oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD), SH-SY5Y and SK-N-SH cells were cultured for 4 h [31] or 6 h [29] in a glucose-free DMEM in a three-gas incubator at 37°C, 0.5% O2, 94.5% N2, and 5% CO2, respectively. To simulate reperfusion, the glucose-free DMEM was removed, and the cells were grown in complete DMEM at 37°C for 24 h in 95% air and 5% CO2. The cells in the control group were cultured under normal conditions and treated in the same way, except that they were not exposed to OGD. After OGD/R, cells were transfected with si-SRSF1 and treated with 100 μM of the NLRP1 activator muramyl dipeptide (MDP) for 24 h [32].

Plasmids overexpression (oe)-C-Myc (HG-HO354870), oe-SRSF1 (HG-HO078166), small interfering (si)-SRSF1 (HG-Si078166), and the negative control (oe-NC and si-NC) were purchased from Changsha Abiowell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The sequence of siRNA is as follows. si-SRSF1: 5′-ACTGCCTACATCCGGGTTAAA-3′. si-NC: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′. After the preparation of the plasmid, the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (11668500, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) (5 μL) was used to transfect the overexpressed/knockdown plasmid (3 μg) into the corresponding group. The transfection efficiency was evaluated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and western blotting (WB) 48 h after transfection.

2.3 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

The cells were seeded in 24-well plates (3 × 104 per well). 300 μL of CCK8 (C0037, Beyotime, Changsha, China) medium mix was added to the cells. After 4 h of incubation, the optical density values of cells at 450 nm were measured using a microplate reader (MB-530, HEALES, Shenzhen, China).

The cells treated as mentioned above were digested with trypsin without EDTA, followed by centrifugation at 2000 rpm (H1650R, Cence, Changsha, China) for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of binding buffer and then mixed with FAM-YVAD-FMK FITC and propidium iodide (PI) from the FAM-YVAD-FMK FITC cell apoptosis detection kit (ab219935, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, without light, cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry (A00-1-1102, Beckman, Brea, CA, USA).

According to the instruction manuals of the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay kit (A020-2-2, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), the LDH level was determined. The optical density at 440 nm was measured using a microplate reader (MB-530, Huisong, Shenzhen, China).

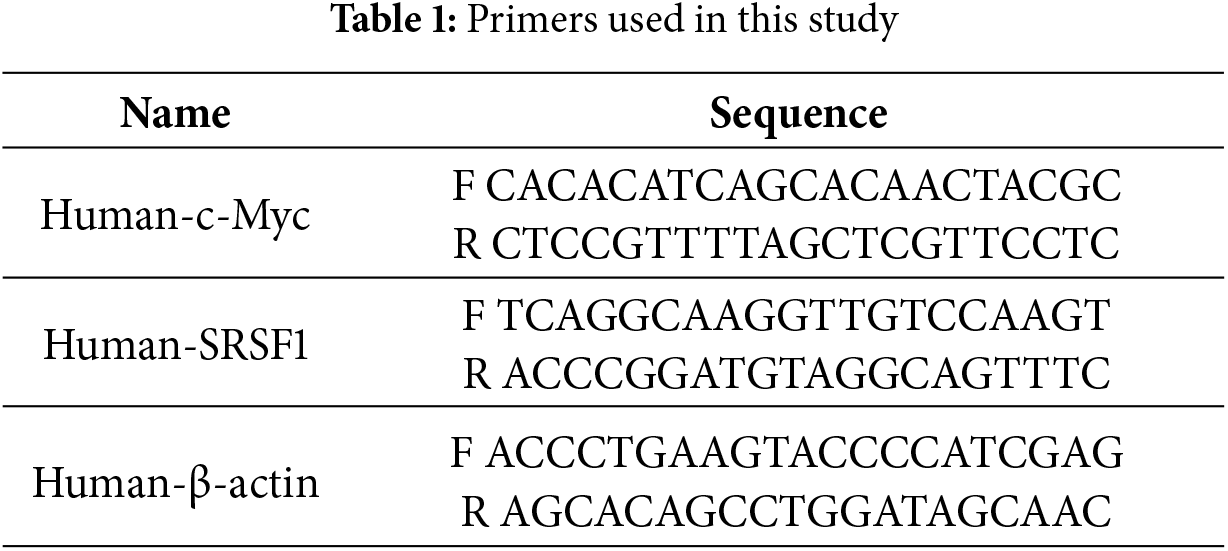

The cells were added to Trizol reagent (15596026, Thermo fisher, MA, USA) for mRNA extraction. cDNA was synthesized with the use of an mRNA reverse transcription kit (CW2569, CWBIO, Beijing, China). The cDNA template was amplified by qRT-PCR using the UltraSYBR Mixture (CW2601, CWBIO). The mRNA expression was assessed by the 2−ΔΔCt method. β-actin was utilized as an internal control. The primers are listed in Table 1.

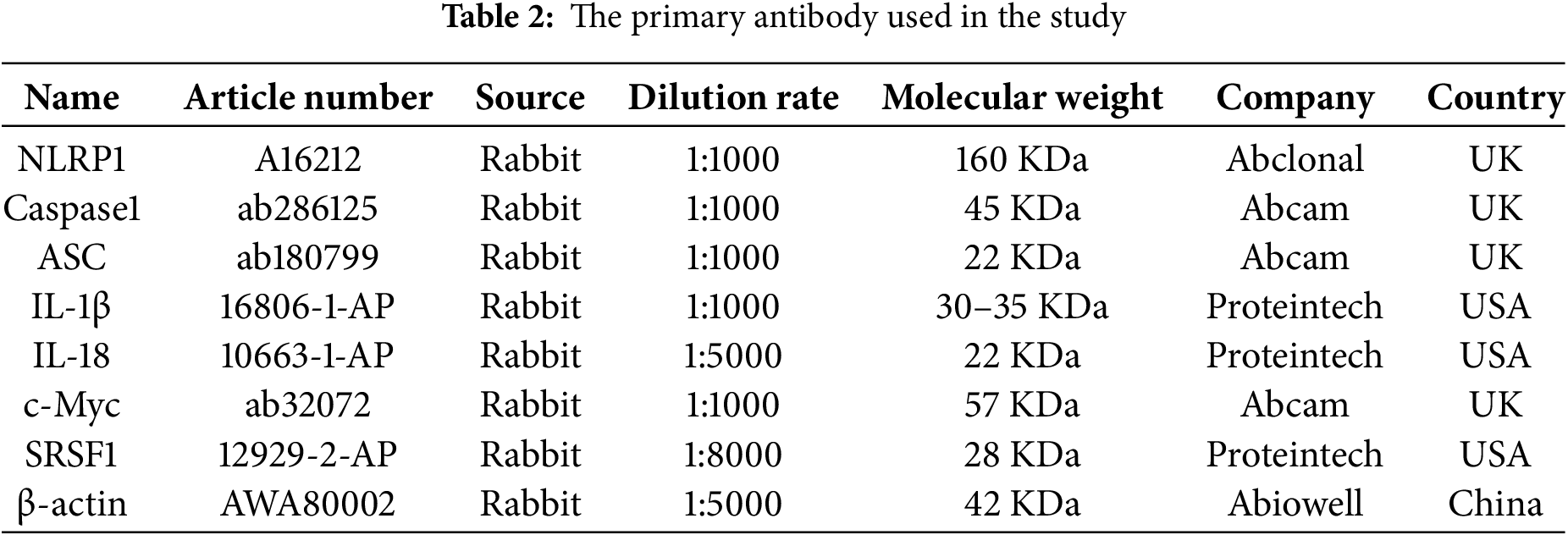

After extracting proteins with RIPA (P0013B, Beyotime), the total protein concentration in cells was determined by the BCA method. The proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (FFN08, Beyotime). Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk powder for 90 min and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the protein bands were incubated with secondary antibody HRP goat anti-mouse IgG (SA00001-1, 1:5000, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA) or HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG (SA00001-1, 1:5000, Proteintech) at room temperature for 90 min. β-actin was used as an internal control. Information on the antibodies used is listed in Table 2. ECL chemiluminescence solution (32209, Thermo Fisher) was used to incubate the membrane for 1 min, and the gel imaging system (ChemiScope6100, CLINX, Shanghai, China.) was used for imaging. The exposed image strips were analyzed with Quantity One professional grayscale analysis software (v4.6.8, BIO-RAD).

2.8 Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

The cells were collected 48 h after transfection and lysed in RIPA Lysis Buffer supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitors (P1050, Beyotime) to prepare cell lysates. The extracted cell proteins were randomly divided into Input, IgG, and IP groups. In the IgG and IP group centrifuge tube, cell proteins were respectively incubated overnight at 4°C with normal rabbit IgG antibody (B900610, Proteintech) or SRSF1 antibody (12929-2-AP, Rabbit, 1:8000, Proteintech). 20 μL of protein A/G magnetic beads (PR40025, Proteintech) were added to each tube to capture the antibody-protein complexes overnight at 4°C. SRSF1 (12929-2-AP, Rabbit, 1:8000, Proteintech) and NLRP1 (A16212, Rabbit, 1:1000, Proteintech) were analyzed by WB.

After the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, 0.3% Triton X-100 was used to permeable for 30 min. 5% BSA (SW3015, Solarbio, Beijing, China) was sealed at 37°C for 90 min. Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies Caspase1 (AWA44822, 1:100, Abiowell) at 4°C. Sections were incubated with secondary antibody, including CoraLite488-conjugated Affinipure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:200, SA00013-2, Proteintech, USA) at 37°C for 60 min. The sections were preserved in buffered glycerin and observed under a fluorescence microscope (BA210T, Motic, Singapore).

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons of the results were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was employed to analyze the data between the two groups. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for multi-group comparisons. When p < 0.05, it was considered to be statistically significant.

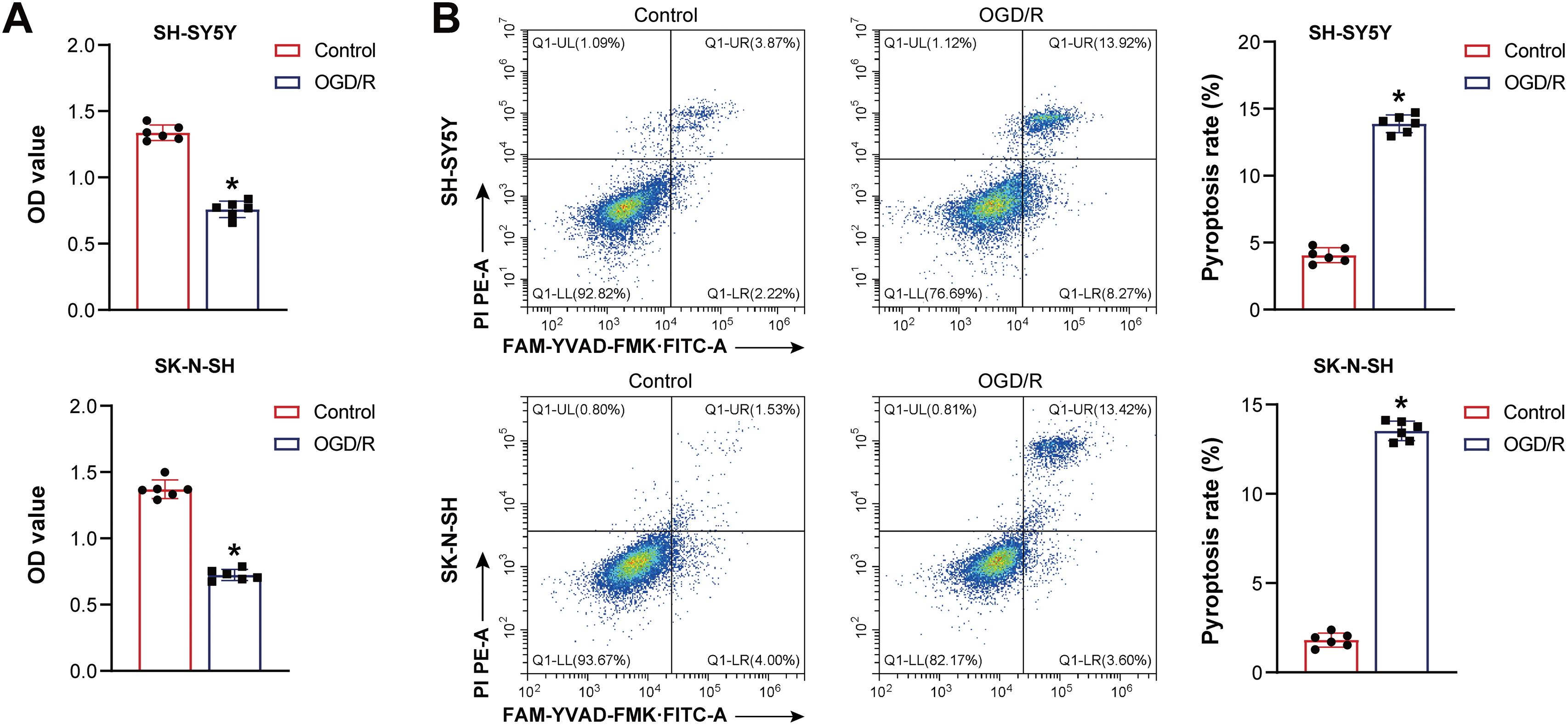

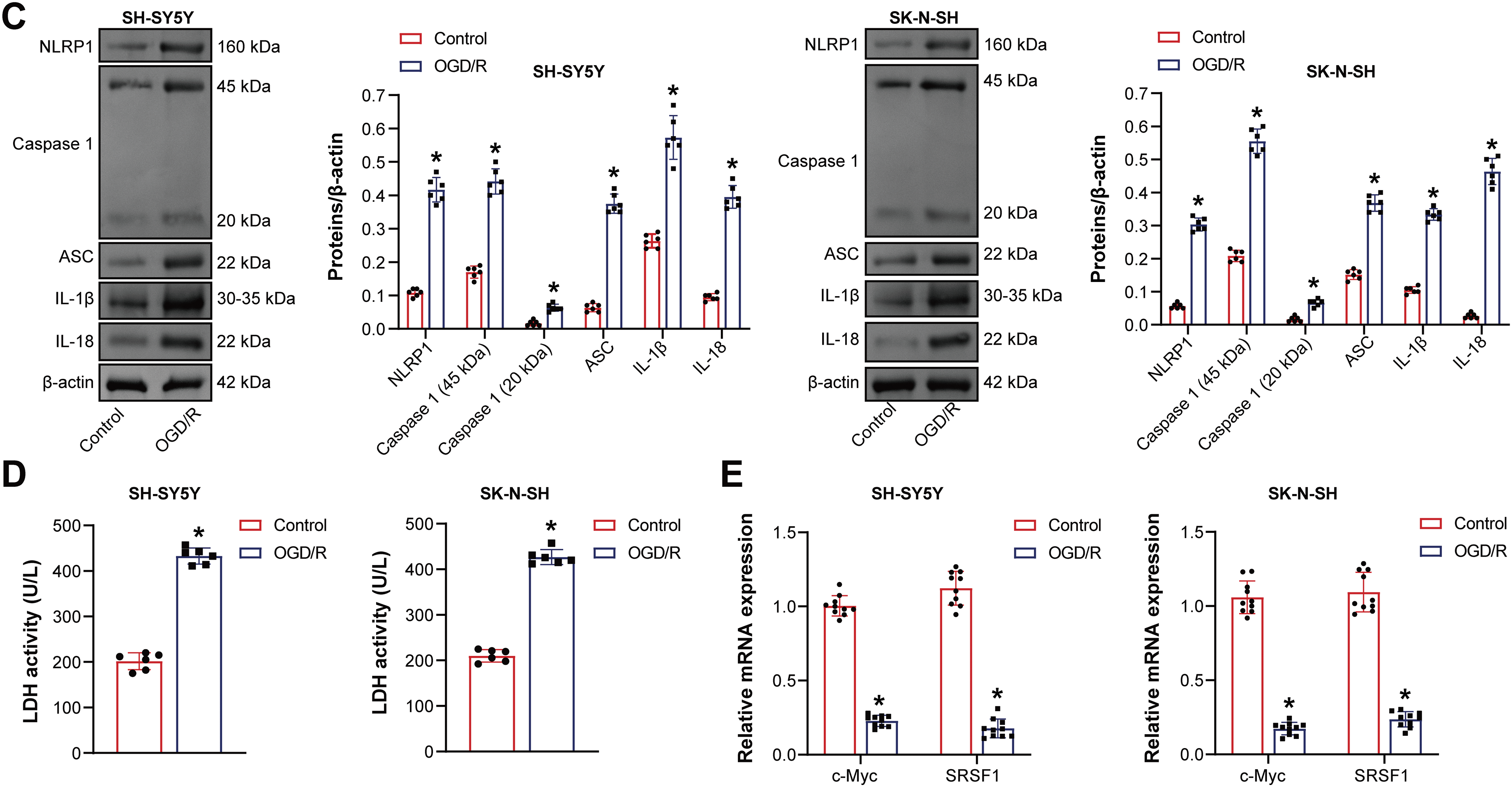

3.1 OGD/R-Induced Neuroblastoma Pyroptosis

Firstly, pyroptosis in neuroblastoma cells induced by OGD/R was investigated. OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cell viability decreased (Fig. 1A). The OGD/R model promoted neuroblastoma pyroptosis (Fig. 1B). NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), and IL-18 expression were elevated in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 1C). LDH level was elevated in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 1D). C-Myc and SRSF1 expression were decreased in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 1E). Our findings suggested that neuroblastoma cells induced by OGD/R exhibited pyroptosis.

Figure 1: The oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) model promoted the pyroptosis of neuroblastoma cells. (A) Cell viability was measured by CCK-8. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of pyroptosis. (C) NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing (NLRP) 1, Caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), and IL-18 protein expression. (D) A biochemical kit was used to detect lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. (E) C-Myc and Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) mRNA expression. n = 6. *p < 0.05 vs. Control group

3.2 C-Myc Overexpression Reduced the Pyroptosis of Neuroblastoma Cells Induced by OGD/R

Previous studies have shown that c-Myc is involved in pyroptosis [33]. Here, c-Myc effects on neuroblastoma pyroptosis induced by OGD/R were further explored. Oe-c-Myc increased c-Myc expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 2A). Oe-c-Myc increased cell viability in neuroblastoma subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 2B). Oe-c-Myc inhibited neuroblastoma pyroptosis subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 2C). Oe-c-Myc inhibited NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, and IL-18 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 2D). Oe-c-Myc reduced LDH levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 2E). In addition, immunofluorescence results show that oe-c-Myc inhibited Caspase1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 2F). Our findings suggested that c-Myc inhibited neuroblastoma pyroptosis subjected to OGD/R.

Figure 2: C-Myc reduced oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R)-induced pyroptosis of neuroblastoma cells. (A) qRT-PCR and WB were used to detect c-Myc expression. (B) Cell viability was measured by CCK-8. (C) Pyroptosis was detected by flow cytometry. (D) NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing (NLRP) 1, Caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), and IL-18 expression were detected by WB. (E) A biochemical kit was used to detect lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. (F) Caspase-1 level was assessed by immunofluorescence. Overexpression, oe. n = 6. ap < 0.05 vs. Control group. bp < 0.05 vs. oe-NC group

3.3 C-Myc Inhibited OGD/R-Induced Neuroblastoma Pyroptosis by SRSF1/NLRP1 Axis

Co-IP experiment results showed that there is an interaction between the c-Myc protein and the SRSF1 protein [19]. Here, c-Myc was positively correlated with SRSF1 (Fig. 3A). Oe-c-Myc promoted c-Myc and SRSF1 levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R, which were reversed by si-SRSF1 (Fig. 3B,C). Oe-c-Myc increased cell viability in neuroblastoma subjected to OGD/R, which was reversed by si-SRSF1 (Fig. 3D). Oe-c-Myc inhibited pyroptosis in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Si-SRSF1 reversed the inhibitory effect of oe-c-Myc on the pyroptosis of neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Si-SRSF1 promoted pyroptosis in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 3E). Oe-c-Myc inhibited NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, and IL-18 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Si-SRSF1 reversed this effect and promoted NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, and IL-18 levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 3F). Oe-c-Myc reduced LDH levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Si-SRSF1 reversed this effect and increased LDH levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 3G). Moreover, immunofluorescence results showed that oe-c-Myc reduced Caspase1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Si-SRSF1 prevented this phenomenon (Fig. 3H). Our findings suggested that c-Myc inhibited neuroblastoma pyroptosis subjected to OGD/R via the SRSF1/NLRP1 axis.

Figure 3: C-Myc reduced oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R)-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis by regulating the SRSF1/NLRP1 axis. (A) The correlation between c-Myc and Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1). C-MYC and SRSF1 levels were detected by qRT-PCR (B) and WB (C). (D) Cell viability was measured by CCK-8. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of pyroptosis. (F) NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing (NLRP) 1, Caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), and IL-18 protein levels. (G) Biochemical kit analysis of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. (H) Caspase-1 level was assessed by immunofluorescence. Overexpression, oe. Small interfering, si. n = 6. ap < 0.05 vs. Control group. bp < 0.05 vs. oe-NC group. cp < 0.05 vs. oe-c-Myc+si-NC group

3.4 SRSF1 Overexpression Inhibited OGD/R-Induced Neuroblastoma Pyroptosis

SRSF1 effects on OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis were further investigated. Oe-SRSF1 increased SRSF1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 4A). Oe-SRSF1 increases neuroblastoma cell viability subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 4B). Oe-SRSF1 inhibited neuroblastoma pyroptosis subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 4C). Oe-SRSF1 inhibited NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, and IL-18 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 4D). Oe-SRSF1 reduced LDH levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 4E). Immunofluorescence results showed that oe-SRSF1 reduced Caspase1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R (Fig. 4F). Co-IP results showed that SRSF1 interacted with NLRP1 (Fig. 4G). SRSF1 was negatively correlated with NLRP1 (Fig. 4H). Our findings suggested that SRSF1 reduced neuroblastoma pyroptosis subjected to OGD/R.

Figure 4: SRSF1 reduces oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R)-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis. (A) Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) protein expression. (B) Cell viability was assessed by CCK-8. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of pyroptosis. (D) NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing (NLRP) 1, Caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), and IL-18 protein expression. (E) Biochemical kit analysis of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. (F) Caspase-1 level was assessed by immunofluorescence. (G) Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was used to verify the interaction between SRSF1 and NLRP1. (H) The correlation between SRSF1 and NLRP1. Overexpression, oe. n = 6. *p < 0.05 vs. Control group. &p < 0.05 vs. oe-NC group

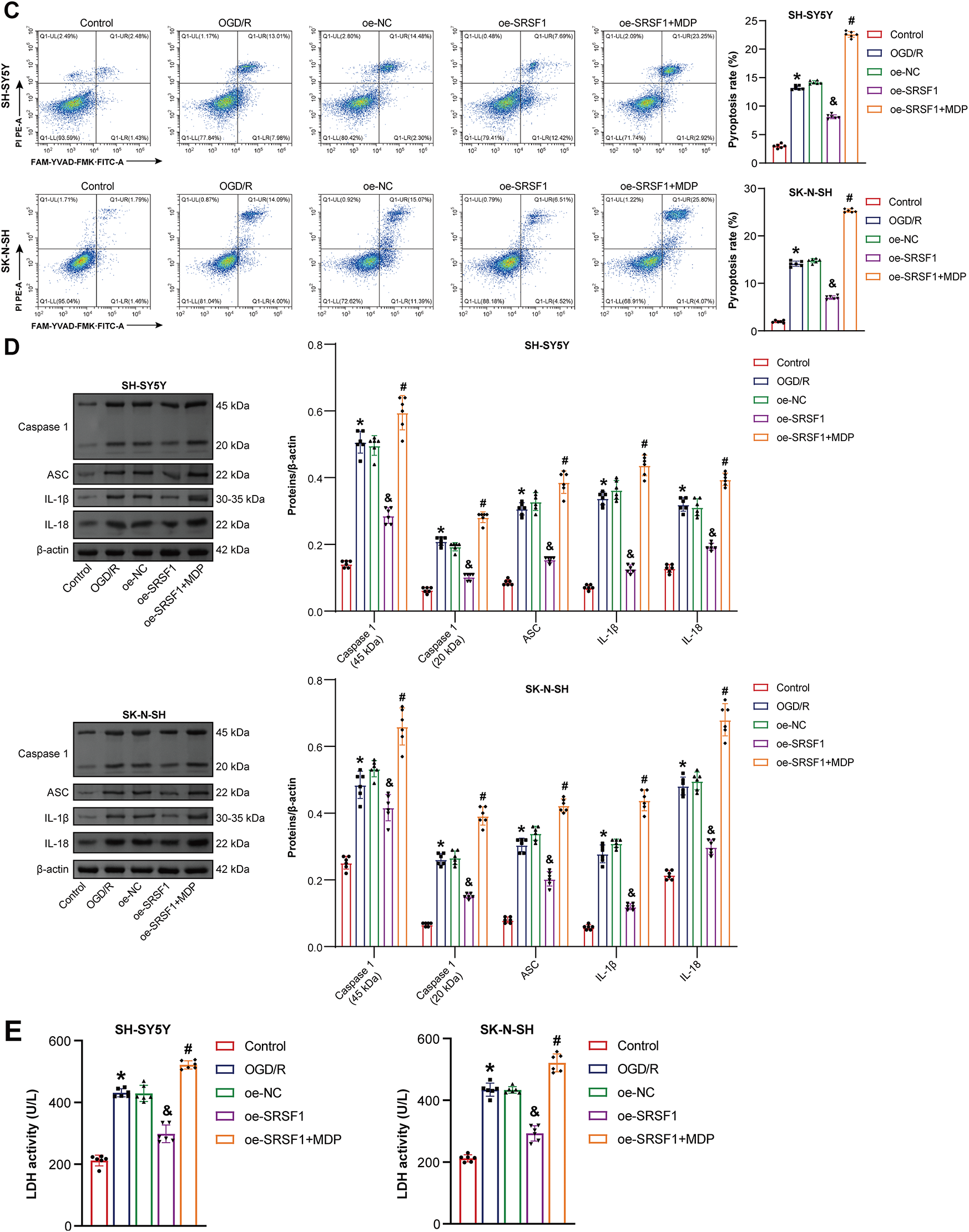

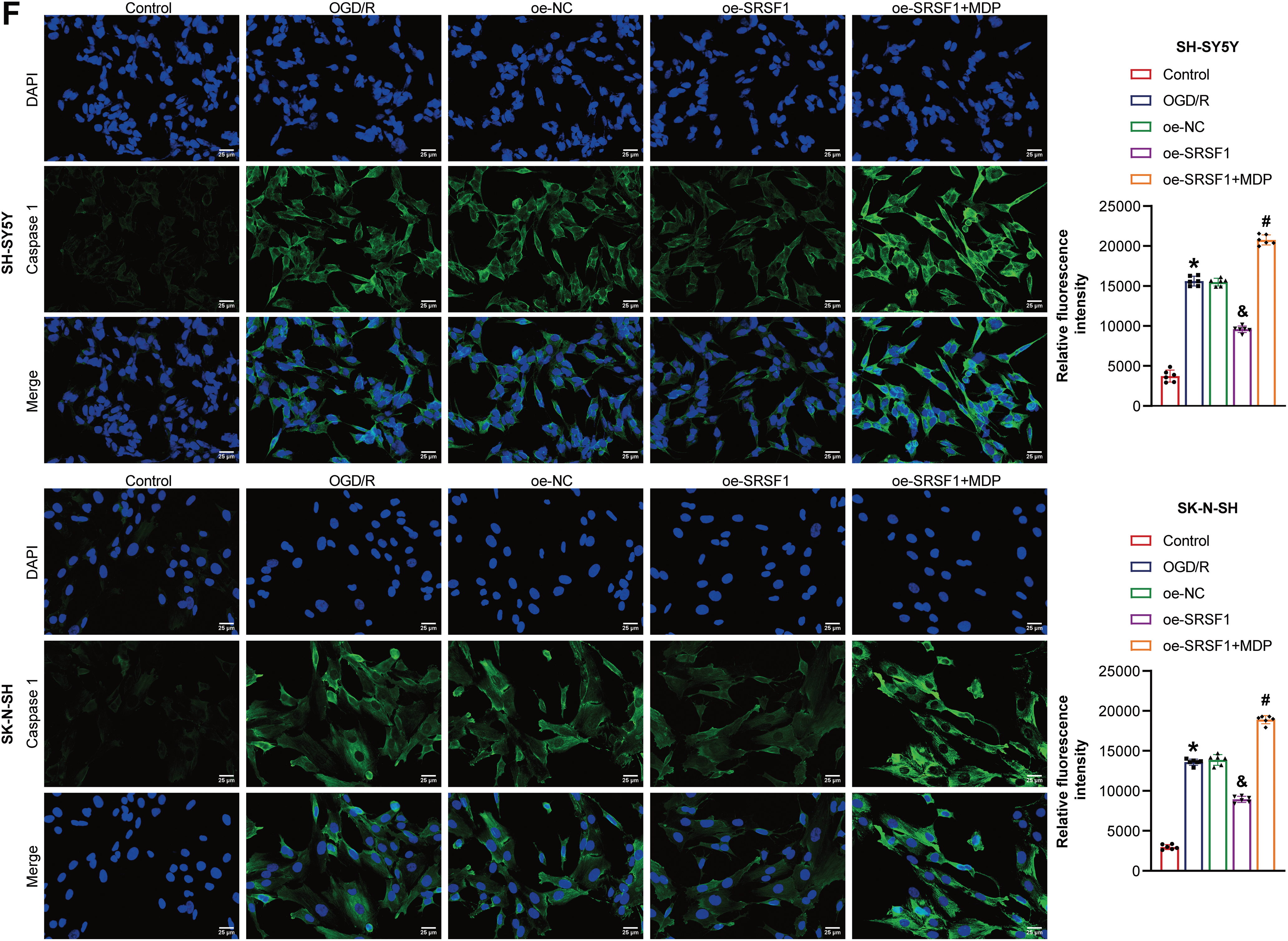

3.5 SRSF1 Reduced OGD/R-Induced Neuroblastoma Pyroptosis by Inhibiting NLRP1 Activation

The mechanism of SRSF1 on OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis was further explored. Oe-SRSF1 promoted SRSF1 expression in OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells and inhibited NLRP1 expression. Compared with the oe-SRSF1 group, there was no significant difference in SRSF1 expression in the oe-SRSF1+MDP group, while promoting NLRP1 expression (Fig. 5A). Oe-SRSF1 increased OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cell viability. These effects were interrupted by MDP (Fig. 5B). Oe-SRSF1 inhibited OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis. MDP reversed this effect (Fig. 5C). Oe-SRSF1 inhibited Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, and IL-18 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R, and this effect was reversed by MDP (Fig. 5D). Oe-SRSF1 reduced LDH levels in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. MDP reversed the inhibition of oe-SRSF1 on LDH level in OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells (Fig. 5E). Immunofluorescence results showed that oe-SRSF1 decreased Caspase1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R, which was interrupted by MDP (Fig. 5F). Our findings suggested that SRSF1 reduced OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis by inhibiting NLRP1 activation.

Figure 5: SRSF1 reduced oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R)-induced neuroblastoma pyroptosis by inhibiting NLRP1 activation. (A) Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) and NLRP1 expression were detected by WB. (B) Cell viability was assessed by CCK-8. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of pyroptosis. (D) Caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), and IL-18 protein expression. (E) A biochemical kit was used to detect lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. (F) Caspase-1 level was assessed by immunofluorescence. Overexpression, oe. n = 6. *p < 0.05 vs. Control group. &p < 0.05 vs. oe-NC group. #p < 0.05 vs. oe-SRSF1 group

Here, we found that c-Myc and SRSF1 expression were inhibited in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. C-Myc overexpression increased c-Myc expression and cell viability in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R, while decreasing NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, IL-18, and LDH levels and pyroptosis. C-Myc overexpression promoted SRSF1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Si-SRSF1 reversed c-Myc overexpression effects on the above indicators in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. SRSF1 interacted with NLRP1. MDP reversed OE-SRSF1 effects on neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Our results showed that c-Myc positively feedbacked SRSF1 signal to inhibit NLRP1 activation, thereby reducing neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R pyroptosis.

Neuroinflammation caused by neuronal pyroptosis is a key mediator in the CIRI-induced pathogenic cascade [34]. Inhibiting neuronal pyroptosis could alleviate CIRI [35]. Emerging evidence suggests that targeted inhibition of Caspase1-mediated neuronal pyroptosis holds therapeutic potential for CIRI [36]. Mechanistically, the interaction between NLRP1 inflammasome and ASC leads to the release of Caspase1-dependent inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β [37]. Previous studies have demonstrated that intermittent theta-burst stimulation inhibits Caspase1, IL-1β, IL-18, ASC, and NLRP1 levels, thereby alleviating CIRI [38]. C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) up-regulates NLRP1, ASC, Caspase1, IL-1β, and IL-18 levels, promoting neuronal cell pyroptosis and neural function deficit after CIRI [10]. In addition, miR-155-5p inhibition increases OGD/R-induced cell viability and decreases LDH activity and pyroptosis, thereby improving CIRI [39]. DEAD-box helicase 3 X-linked gene (DDX3X) deficiency increases OGD/R-induced N2a cell viability, reduces NLRP1, Caspase1, and LDH levels, and inhibits pyroptosis [40]. Previous studies have suggested that regulating pyroptosis might become a promising strategy for the treatment of CIRI. Our results showed that c-Myc overexpression increased c-Myc expression and cell viability in OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cells while inhibiting NLRP1, Caspase1, ASC, IL-1β, IL-18, and LDH levels and pyroptosis. Our findings indicated that c-Myc might be a potential therapeutic option for CIRI.

The current evidence confirms that SRSF1 plays a key role in ischemia-reperfusion injury diseases, including renal ischemia-reperfusion injury [41] and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [42]. Moreover, SRSF1 represses p53-mediated autophagy and apoptosis to mitigate ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial damage [43], suggesting that SRSF1 might be involved in the disease progression of CIRI. The current data revealed that c-Myc promoted SRSF1 expression in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. C-Myc was positively correlated with SRSF1. Si-SRSF1 reversed c-Myc overexpression effects on the above indicators in neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. There was an interaction between SRSF1 and NLRP1. SRSF1 was negatively correlated with NLRP1. MDP reversed OE-SRSF1 effects on neuroblastoma cells subjected to OGD/R. Our results showed that c-Myc positively feedbacked SRSF1 signal to inhibit NLRP1 activation and reduced CIRI model pyroptosis.

There are some limitations. In this study, inhibition of NLRP1 activation by c-Myc positive feedback SRSF1 signaling was demonstrated to reduce OGD/R-induced pyroptosis of neuroblastoma cells at the cellular level. In future projects, c-Myc positive feedback SRSF1 signal effects on NLRP1 activation, inhibition on CIRI, and other molecular mechanisms will be further explored in vivo. It needs to be further confirmed that c-Myc and SRSF1 might be diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for CIRI. Microglial activation and pyroptosis [44], astrocyte pyroptosis [7], and endothelial pyroptosis [45] play important roles in CIRI. It is important to further explore the mechanism of c-Myc on activation and pyroptosis of microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells after CIRI. The current evidence confirms that c-Myc, as a transcription factor, promotes the expression of SRSF1, consequently facilitating the biosynthesis of circPVT1 [19]. Our current study aligns with this finding. In our investigation, c-Myc promoted the expression of SRSF1, which in turn suppressed the level of NLRP3. Within the context of this study, c-Myc serves as the upstream regulatory factor, while SRSF1 acts as the downstream effector. There is an interaction between c-Myc and SRSF1, through which SRSF1 could affect the expression of c-Myc. For example, SNHG7 regulates c-Myc by targeting SRSF1 [20]. Nonetheless, the data from our study collectively indicate that in this specific research system, c-Myc primarily plays the role of an upstream regulator of SRSF1. We acknowledge that the intracellular regulatory network is highly intricate, and feedback regulation might occur under various conditions. This phenomenon will undoubtedly be a crucial area for future research endeavors.

Our findings suggested that c-Myc reduced OGD/R-induced neuroblastoma cell pyroptosis by inhibiting NLRP1 activation through positive feedback SRSF1 signal. The c-Myc/SRSF1 axis might be a promising therapeutic strategy for clinical CIRI.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by a fund from the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 821MS156).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Ning Gao and Siliang Liu; data collection: Siliang Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Siliang Liu, Hong Tang, Ying Xia, Zhengtao Yu, and Ning Gao; figure preparation: Ning Gao; draft manuscript preparation and manuscript revision: Siliang Liu and Hong Tang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| CIRI | Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury |

| NLRP 1 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 1 |

| ASC | Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD |

| SRSF1 | Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 1 |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| OGD/R | Oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion |

| OGD | Oxygen-glucose deprivation |

| MDP | Muramyl dipeptide |

| Oe | Overexpression |

| Si | Small interfering |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| WB | Western blotting |

| CCK-8 | Cell counting kit-8 |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| Co-IP | Coimmunoprecipitation |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1beta |

| CCR5 | C-C chemokine receptor 5 |

| DDX3X | DEAD-box helicase 3 X-linked gene |

References

1. Mahemuti Y, Kadeer K, Su R, Abula A, Aili Y, Maimaiti A, et al. TSPO exacerbates acute cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by inducing autophagy dysfunction. Exp Neurol. 2023;369(2):114542. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2023.114542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ibrahim AA, Abdel Mageed SS, Safar MM, El-Yamany MF, Oraby MA. MitoQ alleviates hippocampal damage after cerebral ischemia: the potential role of SIRT6 in regulating mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation. Life Sci. 2023;328:121895. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cakir T, Yucetas SC, Yazici GN, Sunar M, Arslan YK, Suleyman H. Effects of benidipine hydrochloride on ischemia reperfusion injury of rat brain. Turk Neurosurg. 2021;31(3):310–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Chen X, Yao Z, Peng X, Wu L, Wu H, Ou Y, et al. Eupafolin alleviates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats via blocking the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22(6):5135–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Xie Q, Ma R, Li H, Wang J, Guo X, Chen H. Advancement in research on the role of the transient receptor potential vanilloid channel in cerebral ischemic injury (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(2):881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Zhang Q, Jia M, Wang Y, Wang Q, Wu J. Cell death mechanisms in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Neurochem Res. 2022;47(12):3525–42. doi:10.1007/s11064-022-03697-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li J, Xu P, Hong Y, Xie Y, Peng M, Sun R, et al. Lipocalin-2-mediated astrocyte pyroptosis promotes neuroinflammatory injury via NLRP3 inflammasome activation in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Neuro Inflamm. 2023;20(1):148. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2606918/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Song AQ, Gao B, Fan JJ, Zhu YJ, Zhou J, Wang YL, et al. NLRP1 inflammasome contributes to chronic stress-induced depressive-like behaviors in mice. J Neuro Inflamm. 2020;17(1):178. doi:10.1186/s12974-020-01848-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Jung E, Kim YE, Jeon HS, Yoo M, Kim M, Kim YM, et al. Chronic hypoxia of endothelial cells boosts HIF-1α-NLRP1 circuit in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;204(7767):385–93. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yan J, Xu W, Lenahan C, Huang L, Wen J, Li G, et al. CCR5 activation promotes NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis via CCR5/PKA/CREB pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2021;52(12):4021–32. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.120.033285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Cao Y, Shi M, Liu L, Zuo Y, Jia H, Min X, et al. Inhibition of neutrophil extracellular trap formation attenuates NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis via STING/IRE1α pathway after traumatic brain injury in mice. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1125759. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1125759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Huang L, Li X, Liu Y, Liang X, Ye H, Yang C, et al. Curcumin alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2021;18(2):189–96. doi:10.2174/1567202618666210607150140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wan L, Lin KT, Rahman MA, Ishigami Y, Wang Z, Jensen MA, et al. Splicing factor SRSF1 promotes pancreatitis and KRASG12D-mediated pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(7):1678–95. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-22-1013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Castelli LM, Cutillo L, Souza CDS, Sanchez-Martinez A, Granata I, Lin YH, et al. SRSF1-dependent inhibition of C9ORF72-repeat RNA nuclear export: genome-wide mechanisms for neuroprotection in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16(1):53. doi:10.1101/2021.04.12.438950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hsu SY, Chen CH, Mukda S, Leu S. Neuronal Pnn deficiency increases oxidative stress and exacerbates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Antioxidants. 2022;11(3):466. doi:10.3390/antiox11030466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Liu S, Wang Y, Wang T, Shi K, Fan S, Li C, et al. CircPCNXL2 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by interacting with STRAP to regulate ERK signaling in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):35. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-01950-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lv Y, Zhang W, Zhao J, Sun B, Qi Y, Ji H, et al. SRSF1 inhibits autophagy through regulating Bcl-x splicing and interacting with PIK3C3 in lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):108. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00495-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Du JX, Luo YH, Zhang SJ, Wang B, Chen C, Zhu GQ, et al. Splicing factor SRSF1 promotes breast cancer progression via oncogenic splice switching of PTPMT1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):171. doi:10.1186/s13046-021-01978-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mo Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Deng X, Yan Q, Fan C, et al. Circular RNA circPVT1 promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis via the β-TrCP/c-Myc/SRSF1 positive feedback loop. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01659-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Liu J, Yuan JF, Wang YZ. METTL3-stabilized lncRNA SNHG7 accelerates glycolysis in prostate cancer via SRSF1/c-Myc axis. Exp Cell Res. 2022;416(1):113149. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2022.113149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Amin N, Du X, Chen S, Ren Q, Hussien AB, Botchway BOA, et al. Therapeutic impact of thymoquninone to alleviate ischemic brain injury via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2021;25(7):597–612. doi:10.1080/14728222.2021.1952986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang H, Zhang T, Wang D, Jiang Y, Guo T, Zhang Y, et al. IFN-γ regulates the transformation of microglia into dendritic-like cells via the ERK/c-myc signaling pathway during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Neurochem Int. 2020;141(145):104860. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu D, Liu Y, Zheng X, Liu N. c-MYC-induced long noncoding RNA MEG3 aggravates kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury through activating mitophagy by upregulation of RTKN to trigger the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(2):191. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-03466-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Prakash R, Vyawahare A, Sakla R, Kumari N, Kumar A, Ansari MM, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-targeting nanomicelles for preventing ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammatory injury. ACS Nano. 2023;17(9):8680–93. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c01760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yuan ZL, Mo YZ, Li DL, Xie L, Chen MH. Inhibition of ERK downregulates autophagy via mitigating mitochondrial fragmentation to protect SH-SY5Y cells from OGD/R injury. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):204. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01211-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen X, Yang T, Zhou Y, Mei Z, Zhang W. Astragaloside IV combined with ligustrazine ameliorates abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via Drp1 SUMO/deSUMOylation in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30(4):e14725. doi:10.1111/cns.14725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang L, Liu C, Wang L, Tang B. Astragaloside IV mitigates cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury via inhibition of P62/Keap1/Nrf2 pathway-mediated ferroptosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;944:175516. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.175516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li X, Xia K, Zhong C, Chen X, Yang F, Chen L, et al. Neuroprotective effects of GPR68 against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via the NF-κB/Hif-1α pathway. Brain Res Bull. 2024;216:111050. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2024.111050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao L, Chen Y, Li H, Ding X, Li J. Deciphering the neuroprotective mechanisms of RACK1 in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: pioneering insights into mitochondrial autophagy and the PINK1/Parkin axis. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30(8):e14836. doi:10.1111/cns.14836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Dai Y, Sheng Y, Deng Y, Wang H, Zhao Z, Yu X, et al. Circ_0000647 promotes cell injury by modulating miR-126-5p/TRAF3 axis in oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion-induced SK-N-SH cell model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;104(2):108464. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shi Y, Yi Z, Zhao P, Xu Y, Pan P. MicroRNA-532-5p protects against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by directly targeting CXCL1. Aging. 2021;13(8):11528–41. doi:10.18632/aging.202846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Li M, Sun T, Wu X, An P, Wu X, Dang H. Autophagy in the HTR-8/SVneo cell oxidative stress model is associated with the NLRP1 inflammasome. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021(1):2353504. doi:10.1155/2021/2353504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Li N, Wang W, Jiang WY, Xiong R, Geng Q. Cytosolic DNA-STING-NLRP3 axis is involved in murine acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(7):e228. doi:10.1002/ctm2.228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu X, Zhang M, Liu H, Zhu R, He H, Zhou Y, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes attenuate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced neuroinflammation and pyroptosis by modulating microglia M1/M2 phenotypes. Exp Neurol. 2021;341(28):113700. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li Z, Pang Y, Hou L, Xing X, Yu F, Gao M, et al. Exosomal OIP5-AS1 attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by negatively regulating TXNIP protein stability and inhibiting neuronal pyroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;127(70):111310. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Jin F, Jin L, Wei B, Li X, Li R, Liu W, et al. miR-96-5p alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice by inhibiting pyroptosis via downregulating caspase 1. Exp Neurol. 2024;374(6):114676. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.114676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Nakajo T, Katayoshi T, Kitajima N, Tsuji-Naito K. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 attenuates IL-1β secretion by suppressing NLRP1 inflammasome activation by upregulating the NRF2-HO-1 pathway in epidermal keratinocytes. Redox Biol. 2021;48:102203. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2021.102203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Luo L, Liu M, Fan Y, Zhang J, Liu L, Li Y, et al. Intermittent theta-burst stimulation improves motor function by inhibiting neuronal pyroptosis and regulating microglial polarization via TLR4/NFκB/NLRP3 signaling pathway in cerebral ischemic mice. J Neuro Inflamm. 2022;19(1):141. doi:10.1186/s12974-022-02501-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Shi Y, Li Z, Li K, Xu K. miR-155-5p accelerates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion inflammation injury and cell pyroptosis via DUSP14/ TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway. Acta Biochim Pol. 2022;69(4):787–93. doi:10.18388/abp.2020_6095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Liu Y, Gui Y, Tang H, Yu J, Yuan Z, Liu L, et al. DDX3X deficiency attenuates pyroptosis induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation in N2a cells. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2023;20(2):197–206. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2411334/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Sun Z, Wu J, Bi Q, Wang W. Exosomal lncRNA TUG1 derived from human urine-derived stem cells attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by interacting with SRSF1 to regulate ASCL4-mediated ferroptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):297. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1255884/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Yan H, Li H, Yin DH, Zhang ZZ, Zhang QY, Ren ZY, et al. The PIWI-interacting RNA CRAPIR alleviates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury by reducing p53-mediated apoptosis via binding to SRSF1. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2025;13:1–14. doi:10.1038/s41401-025-01534-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Su Q, Lv XW, Xu YL, Cai RP, Dai RX, Yang XH, et al. Exosomal LINC00174 derived from vascular endothelial cells attenuates myocardial I/R injury via p53-mediated autophagy and apoptosis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;23:1304–22. doi:10.1016/j.omtn.2021.02.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Fang H, Fan LL, Ding YL, Wu D, Zheng JY, Cai YF, et al. Pre-electroacupuncture ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting microglial RhoA/pyrin/GSDMD signaling pathway. Neurochem Res. 2024;49(11):3105–17. doi:10.1007/s11064-024-04228-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang X, Yang Q, Zhang R, Zhang Y, Zeng W, Yu Q, et al. Sodium Danshensu ameliorates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting CLIC4/NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated endothelial cell pyroptosis. Biofactors. 2024;50(1):74–88. doi:10.1002/biof.1991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools