Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Role of the Progesterone Receptor Family in Alzheimer’s Disease

1 Department of Neurology, Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, 221004, China

2Division of Human Anatomy, College of Allied Health Science, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA

* Corresponding Author: Fang Hua. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1169-1184. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.064879

Received 26 February 2025; Accepted 18 April 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurological disorder characterized primarily by a progressive decline in cognitive and behavioral functions. The pathogenesis of AD has not been fully elucidated till now. The progesterone receptor (PR) family has recently attracted increasing attention and has become the focus of potential links to factors such as the pathogenesis and pathological changes of AD due to its role in the central nervous system. This article summarizes the progress of research progress on the PR family in AD, including its role in pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and potential therapeutic strategies.Keywords

AD is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that is the most common cause of dementia. It is mainly characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive and behavioral functions [1]. According to estimates by the Alzheimer’s Association, the number of people over 65 years old in the United States currently suffering from AD is as high as 6.9 million; furthermore, this number may double by 2060 [2]. As AD continues to rise in prevalence, it not only imposes heavy financial burdens on the families of patients but also seriously impacts the social economy. At the time of this writing, the pathogenesis of AD is still unclear; therefore, an in-depth exploration of the pathogenesis of AD and the development of innovative treatments for AD is necessary.

The progesterone receptor (PR) family is a member of the steroid hormone nuclear receptor superfamily, through which progesterone exerts its effects on female reproduction, such as the menstrual cycle and pregnancy [3]. Previously, PRs have attracted much attention, mainly in the female reproductive system [4–6]. However, recent research suggests that the roles of PR family members in the central nervous system may be more complex and widespread than previously understood [7–9]. The progesterone receptor family consists of the classical progesterone receptor (PR), progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1), and progesterone receptor membrane component 2 (PGRMC2) [10]. They are involved not only in biological processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and metabolic regulation [11–13] but also in important tasks such as neuroprotection, synaptic plasticity, and cognitive function [10,14,15].

This article systematically reviews the latest research on the progesterone receptor family in the field of AD and hopefully provides a novel target for research on and treatment strategies for AD.

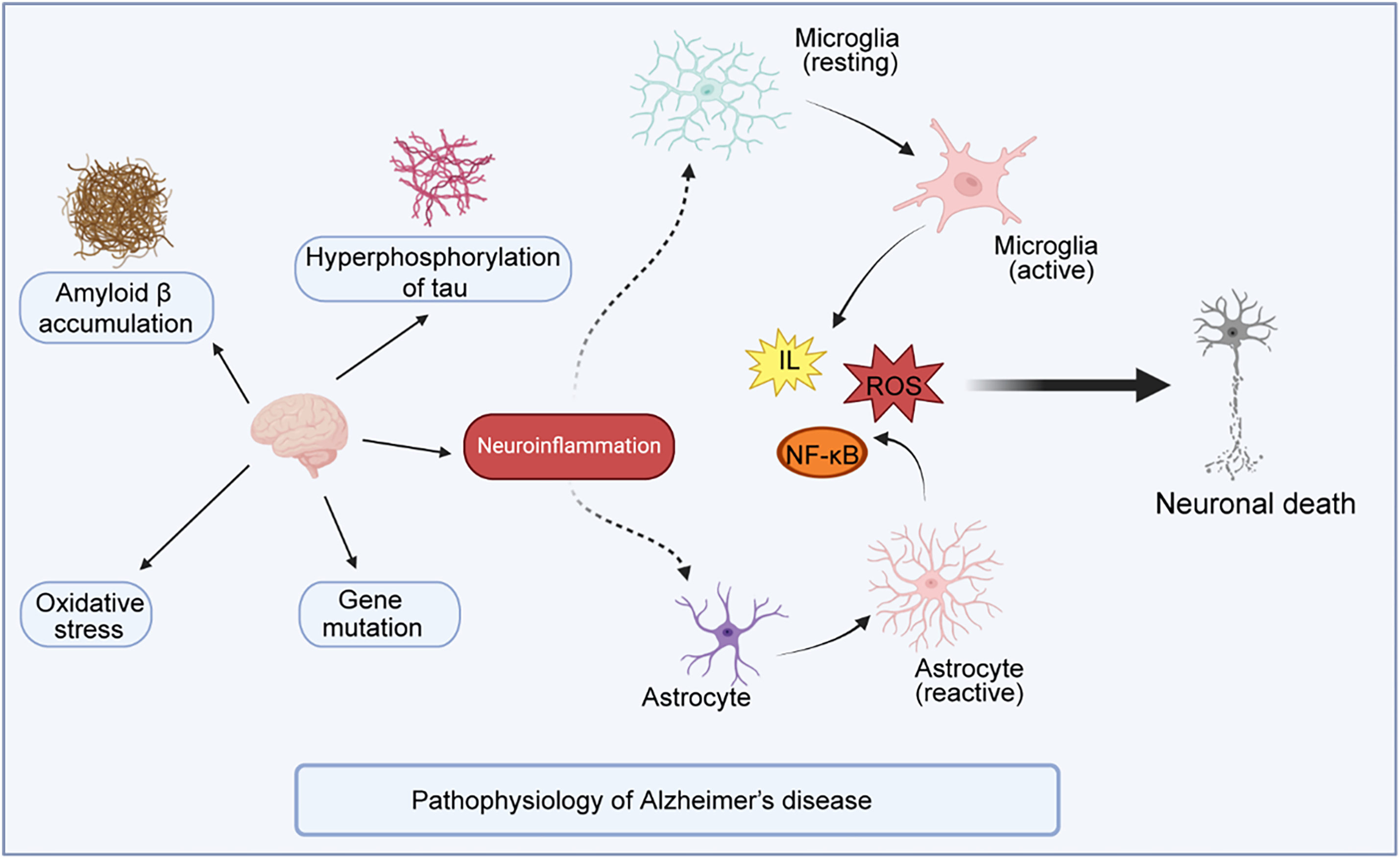

While the pathogenesis of AD remains incompletely understood, current research has demonstrated that a variety of complex factors may be involved (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Illustrates the current hypotheses of AD pathogenesis

The figure illustrates the current hypotheses of AD pathogenesis, which primarily involve amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition, tau hyperphosphorylation, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and gene mutation. Among these, amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau protein are considered the main factors. Increasing evidence suggests that neuroinflammation plays a crucial role in the progression of AD. The interaction between Aβ and tau leads to the excessive activation of microglia and astrocytes, the primary cells responsible for the brain’s inflammatory response. Overactivation of microglia and astrocytes results in the release of harmful substances such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., Interleukins (ILs) through signaling pathways like Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB), exacerbating neuronal damage and ultimately leading to neuronal death.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis is widely accepted as a primary mechanism in AD pathogenesis. According to this hypothesis, the extensive accumulation of neurotoxic Aβ plaques in the brain is the fundamental driving force in the development of AD [16].

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a single-transmembrane protein that is highly expressed in the brain and is primarily synthesized by neurons, blood vessels, blood cells, and astrocytes. Scholarly evidence has indicated that APP plays a critical role in brain development, memory formation, and synaptic plasticity [17,18]. Under normal physiological conditions, APP is predominantly cleaved by α-secretase, thereby producing soluble APPα (sAPPα)—a fragment with neurotrophic properties that supports neuronal survival and enhances synaptic function. In the pathological context of AD, APP is preferentially cleaved by β-secretase and γ-secretase, generating Aβ peptide fragments, primarily Aβ40 and Aβ42. These Aβ peptides exhibit low structural stability, particularly Aβ42, which has a higher propensity to aggregate into insoluble fibrillar structures, leading to amyloid plaque formation [19]. This amyloidogenic pathway is central to AD pathology development.

Under physiological conditions, Aβ is a soluble monomeric peptide generated by APP cleavage, with its production and clearance maintained in dynamic equilibrium. In AD pathology, however, this balance is disrupted; either increased Aβ production or reduced clearance leads to its progressive accumulation in brain tissue. Under specific conditions, monomeric Aβ readily self-aggregates into Aβ oligomers. As these oligomers continue to accumulate, they form larger fibrils, eventually resulting in amyloid plaque formation. These abnormal deposits initiate a cascade of pathological cellular events, causing synaptic loss, neurodegeneration, extensive neuronal death, and ultimately driving the onset and progression of AD [20].

2.2 Abnormal Phosphorylation of Tau Protein

The formation of intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), composed of abnormal and hyperphosphorylated tau protein aggregates, is also considered a key pathogenic hypothesis in AD.

Tau protein, a microtubule-associated protein (MAP), is widely distributed within the cytoplasm and axons of neurons. Researchers have gradually elucidated its structure since its discovery in 1975. Tau protein comprises four functional domains: the N-terminal projection domain, the proline-rich region (PRR), the microtubule-binding region (MTBR), and the C-terminal domain [21]. Tau protein is typically classified as a naturally disordered protein, with its primary physiological function being the stabilization of microtubules. Under normal conditions, tau protein’s intrinsically unfolded state reduces the likelihood of misfolding, aggregation, or accumulation, both intracellularly and extracellularly. However, when tau protein experiences pathological alterations, it undergoes abnormal folding and aggregation, resulting in neurodegenerative disorders collectively known as tauopathies. While tau protein phosphorylation is essential for normal physiological functioning, elevated phosphorylation levels can result in the self-aggregation and hyperphosphorylation of tau—a key hallmark of various tauopathies. The hyperphosphorylation of tau protein alters its conformation and charge, exposing the microtubule-binding domain and facilitating self-aggregation and oligomerization. These aggregated tau proteins ultimately form insoluble NFTs. The structure of these tau aggregates disrupts axonal transport and progressively induces microtubule instability [22]. Tau protein levels are significantly elevated in patients with AD, with hyperphosphorylated tau increasing fourfold. These misfolded tau proteins not only lose their ability to stabilize microtubules but also enhance their aggregation propensity, exhibiting neurotoxic effects. Ultimately, the functional imbalance between tau proteins and microtubules results in decreased synaptic plasticity and axonal transport deficits, contributing to cognitive dysfunction. Furthermore, hyperphosphorylated tau can activate microtubule-disrupting proteins such as katanin, further exacerbating the disruption of microtubule assembly [23].

Several studies have indicated that Aβ may facilitate the pathological progression of tau protein by activating specific kinases, thereby enhancing tau aggregation. Tau protein plays a critical role in Aβ-induced cognitive dysfunction, suggesting that the interaction between Aβ and tau may serve as a significant pathological driver in AD development [24].

2.3 Immune Inflammatory Response

Persistent immune-inflammatory response in AD has increasingly been recognized by experts as the third core pathological change associated with the disease. Numerous studies have demonstrated that neuroinflammation is not merely a concomitant phenomenon of AD pathology but also a central driver of disease progression [25]. Neuroinflammation arises from pathological damage to the peripheral or central nervous systems, triggering an inflammatory response in the central nervous system. This response leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), chemokines, and complement cytokines, as well as small molecules such as prostaglandins, nitric oxide (NO), and ROS.

Acute neuroinflammation acts as the brain’s protective response to stimuli such as neural injury and infection. Prolonged inflammation can transition from acute to chronic, thereby perpetuating irritation within the nervous system. Chronic inflammation continuously releases various inflammatory cytokines, resulting in a pro-inflammatory response that surpasses the anti-inflammatory response, exacerbating inflammation and ultimately damaging neurons, leading to diverse pathological changes in the body [26]. Brain homeostasis becomes disrupted in patients with AD, whose brain microenvironment and glial cell characteristics are altered. Microglia predominantly exhibits an activated anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype that releases anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, while enhancing their phagocytic functions. However, persistent inflammation can shift microglia to an activated pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, thereby exacerbating inflammatory responses. This transition results in increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18, alongside impaired phagocytic function, enlarged microglial cell bodies, shortened processes, and rounded morphology. Research has indicated that in the early stages of AD, microglial activation may aim to repair damage, whereas microglia can become detrimental in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD), producing pro-inflammatory molecules that contribute to neuronal damage [27]. Astrocytes are similar to microglia in that they maintain homeostasis and supply metabolites and growth factors to neurons. In AD, reactive astrocytes are found in proximity to Aβ plaques. Like microglia, astrocytes detect Aβ aggregates in a Toll-like receptor (TLR)/Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)-dependent manner, thereby activating downstream target genes and producing cytokines [28]. The responses of astrocytes are mediated by four signaling pathways: Janus kinase (JAK)/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3), calcium/calcineurin (CN)/nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), NF-κB, and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways [29]. The excessive production of neurotoxic factors disrupts the homeostasis of APP processing in astrocytes, resulting in increased Aβ accumulation and toxicity. During the pathological progression of AD, persistent neuroinflammation damages the blood-brain barrier, allowing peripheral immune cells, such as monocytes and macrophages, to infiltrate the central nervous system, exacerbating neuronal damage through interactions with microglia and astrocytes [30].

Neuroinflammation is a principal mechanism underlying AD. It is closely associated with the pathologies of Aβ and tau proteins, and it exacerbates neuronal damage and dysfunction through the release of inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, and the disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). The dual roles of microglia and astrocytes in neuroinflammation position them as both protectors of the nervous system and contributors to the progression of AD pathology [31,32].

Oxidative stress has garnered considerable attention in recent years as a significant factor in the pathogenesis of AD. Oxidative stress refers to the imbalance between free radicals and the antioxidant systems in the body, which leads to the excessive production of ROS and other free radicals, thereby potentially damaging proteins, lipids, and DNA in cells. ROS include superoxide anions (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH), all of which are generated during normal cellular metabolism. At low concentrations, ROS can function as signaling molecules that participate in cell growth, apoptosis, and immune response. However, when ROS production exceeds the clearance capacity of intracellular antioxidant systems, oxidative stress is triggered, resulting in damage to cellular components. Neurons are particularly sensitive to ROS due to their high metabolic activity, substantial oxygen consumption, and abundant mitochondria, which are the primary source of ROS production [33,34]. Studies have shown that numerous mutations occur in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the brains of patients with AD, potentially compromising the function of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and leading to electron leakage and excessive ROS production. Furthermore, the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential exacerbates the oxidative stress response in AD [35]. Aβ oligomers and fibrotic plaques can adhere to the lipid bilayer of membranes, inducing lipid peroxidation, compromising membrane integrity, causing calcium influx imbalances, and further promoting oxidative stress. Neuroinflammation is also a significant source of oxidative stress in AD patients, as activated microglia and astrocytes release large amounts of inflammatory factors and ROS in response to Aβ. These ROS accumulate at the site of inflammation, intensifying local oxidative stress. ROS not only directly damages neurons but also further contributes to the pathological progression of AD by inducing cell apoptosis and necrosis [36].

According to whether there is a family history, AD is divided into sporadic AD (SAD) and familial hereditary AD (FAD). APP and presenilins (PSEN1 and PSEN2) are key causative genes in AD [37]. Furthermore, SAD accounts for more than 90% of AD cases. The main genes affecting the incidence of SAD include apolipoprotein E (ApoE), clusterin gene, complement receptor 1, and phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein (PICALM) [38]. As AD research has deepened, many new AD gene loci have been discovered, including cholesterol metabolism genes (CH25H, ABCAL, CH24H), and angiotensin-converting enzyme genes [37].

Other factors affect the onset of AD, such as neurotransmitter imbalance, oxidative stress, and aging [39–41]. The pathogenesis of AD involves complex interactions among multiple aspects and factors, and researchers are still conducting in-depth explorations to fully understand the causes of this disease.

3 Potential Role of PR in Sex-Differentiated AD Risk

In AD, the prevalence is significantly higher in females than in males, suggesting that sex differences may contribute substantially to the pathogenesis of AD [42]. Following menopause, estrogen and progesterone levels in women decline markedly, and this hormonal shift may be associated with an elevated risk of developing AD. Estrogen exerts multiple neuroprotective effects, including the promotion of neuronal survival, attenuation of neuroinflammation, and enhancement of cognitive function [43]. PR is also expressed in the brain and may play a role in modulating neuronal survival and function [44].

Progesterone exerts neuroprotective effects by modulating neurotransmitter systems and influencing the synaptic structure and function of neurons. This function is particularly important in postmenopausal women [45]. Estrogen and progesterone act synergistically in the brain to regulate neuronal survival and function. Estrogen exerts neuroprotective effects primarily through binding to estrogen receptor β (ERβ), whereas progesterone enhances these effects via activation of the PR. Studies have demonstrated that prolonged estrogen deficiency promotes neurodegeneration, accelerates cognitive decline, and markedly increases the risk of AD in postmenopausal women. Therefore, maintaining optimal hormone levels may be important for the prevention of AD [46].

Studies have demonstrated significant sex differences in the relationship between apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele dosage and tau protein deposition in the brain. Female APOE ε4 carriers exhibited decreased levels of Aβ42 and increased concentrations of total tau and phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid, whereas male carriers were younger and demonstrated lower Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores. These findings suggest that sex plays a critical regulatory role in modulating the impact of the APOE ε4 allele on tau pathology in the brain, and that females may exhibit greater sensitivity to the effects of the APOE ε4 allele [47]. Another study published in Neurology investigated three estrogen receptor (ER) variants—GPER1, ERβ (ESR2), and ERα (ESR1)—in relation to AD features, as an indirect approach to assess the association between estrogen signaling and AD in women. ER DNA methylation and RNA expression, and to a lesser extent ER polymorphisms, were found to be associated with cognitive and pathological features of AD in women, with weaker associations observed in men [48].

Non-classical isoforms of progesterone receptors, including PGRMC1/2, offer novel insights into sex-specific differences in neurobiology. PGRMC1 maintains synaptic integrity by activating the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 5 (ERK5)–brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling axis in astrocytes [49]. In in vitro experiments, treatment with the PGRMC1-specific antagonist AG205 significantly attenuated the progesterone-induced enhancement of glucose uptake in Aβ-injured neurons, whereas the classical PR antagonist RU486 exhibited no such effect. These findings suggest that progesterone primarily facilitates neuronal glucose uptake via PGRMC1-mediated mechanisms [50]. However, there are no reports on the role of PGRMC2 in Alzheimer’s disease.

In summary, the progesterone receptor system modulates sex differences in AD through classical synergy, epigenetic mechanisms, and non-classical pathways. Dysregulation of the ERβ–PR axis exacerbates women’s sensitivity to postmenopausal hormonal fluctuations, The APOE ε4 allele establishes a positive feedback loop with PR attenuation via metabolic-inflammatory pathways, and functional defects in the non-classical receptor PGRMC1, further diminish women’s neuroprotective capacity. Therefore, investigating the potential role of the progesterone receptor in sex-related AD risk is crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of AD pathogenesis and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

4 Progesterone Receptor Family

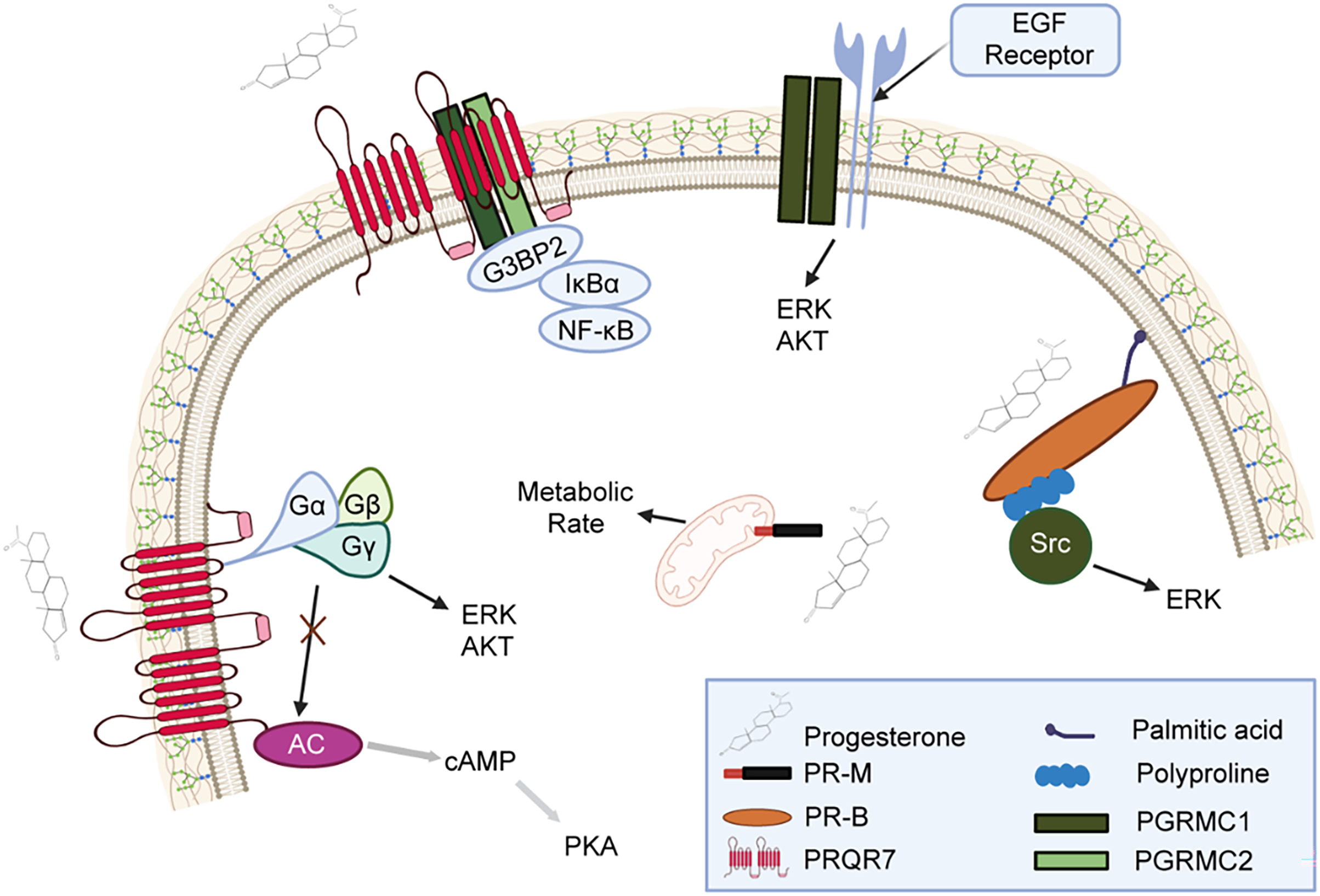

The exploration of the progesterone receptor family originated from extensive research on the role of progesterone receptors in the reproductive system. The progesterone membrane receptor family includes multiple members, the most well-known of which is the classic PR. PR was originally found to bind to progesterone and regulate cyclic changes in the female reproductive system [51]. However, with the advancement of technology and the deepening of research, scholars have gradually realized that the progesterone membrane receptor family also includes emerging members, such as PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 [10]. These receptors are widely distributed in the human reproductive system, nervous system, and other tissues and are essential for regulating hormone signals, maintaining physiological balance, and various other life processes [5,11,49] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Mechanisms of progesterone and its related receptors in signaling pathways

This figure illustrates how progesterone binds to receptors such as Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component (PR-M), Progesterone Receptor Isoform B (PR-B), and Progestin and AdipoQ Receptor 7 (PAQR7), activating multiple signaling pathways. The N-terminal region of PR-B contains a polyproline domain that binds to the Src homology 3 (SH3) domain of Src kinase. Additionally, this domain is essential for the ligand-activated PR-B to stimulate Src and subsequently activate ERK signaling. PR-M appears to be a truncated form of PR, with its primary feature being its localization to the outer mitochondrial membrane. PR-M mediates progesterone’s ability to increase cellular metabolism in vitro. PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 interact with GAP SH3 Domain-Binding Protein 2 (G3BP2), which binds to Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B alpha (IκBα), and IκBα binds to NF-κB/p65, thus restricting NF-κB/p65 to the cytoplasm and regulating its transcriptional activity. PGRMC1 also binds to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and regulates Protein Kinase B (Akt) and ERK signaling pathways. G protein-coupled receptors regulate the production of Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) through the modulation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), thereby inhibiting the protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway.

The progesterone receptor is a nuclear hormone receptor with two main subtypes: PR-A and PR-B. They are isomers produced by different splicing methods of the same gene but differ in the N-terminal region. PR-B contains an additional amino acid sequence, making it longer than PR-A [52]. PR mainly exists in the endometrium, ovaries, and other reproductive system tissues. Its classic function is to regulate the endometrium during the pregnancy cycle to promote the implantation of the fertilized egg [53]. The PR regulates developmental processes as well as proliferation and differentiation during pregnancy and it also plays an important role in the progression of endocrine-dependent breast cancer [11]. Moreover, PR activity is regulated by estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen affects PR activity by increasing its expression and changing its conformation. Progesterone is a natural agonist of PR that can activate the PR and regulate the expression of its target genes [54]. Overall, the PR is a crucial receptor in female reproductive physiology that plays an irreplaceable role in the normal progression of the menstrual cycle, maintenance of pregnancy, and breast development [53].

PGRMC1 is a 195-residue membrane-bound protein that contains a short luminal peptide, an N-terminal transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal cytochrome b5-related heme-binding domain. Furthermore, it is a multifunctional heme-binding protein [55]. Mammalian PGRMC1 was first purified and cloned from pig liver membranes during research on membrane-bound receptors in 1996 [56]. PGRMC1 is a non-classical progesterone receptor that is distributed in multiple tissues, including brain tissues, the liver, and the kidney [57]. Studies have shown that overexpression of PGRMC1 may mediate breast cancer proliferation and development by altering lipid metabolism and activating key oncogenic signaling pathways in vitro and in xenograft mouse models [58]. In addition, PGRMC1 has been found to enhance cardiac function and reduce cardiac lipid accumulation by increasing fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial respiration [59]. Moreover, the conditional knockout of PGRMC1 has been suggested to lead to reduced fertility and the occurrence of endometrial tumors in mice. PGRMC1 has also been found to play an important role in female fertility and uterine homeostasis [60]. Overall, PGRMC1 primarily participates in various biological processes, such as heme metabolism, the development of reproductive system tumors, and systemic metabolism [61–63].

PGRMC2 is a member of the progesterone receptor family. Several studies have indicated that PGRMC2 plays an important role in intracellular heme transport. The use of small molecule PGRMC2 agonists can significantly improve the diabetic characteristics of diabetic mice [64]. A study on PGRMC2 knockout mice found that the knockout of PGRMC2 causes premature reproductive senescence in female mice [65]. In addition, knocking out PGRMC2 in female zebrafish has been found to lead to reduced fertility and reduced progesterone synthesis [66]. Overall, PGRMC2 plays an important role in fat metabolism, tumors, and hormone regulation, among others [64,66,67].

The three main members discussed above, and other known or unknown family members form the PR family. The family’s members interact in various ways and play indispensable roles in maintaining normal physiological status by binding to hormones and regulating signaling pathways on the cell membrane [68–70]. The currenting understanding of the progesterone receptor family has deepened, causing researchers to realize that it may play an important role in the nervous system and is closely related to the occurrence and development of many neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease [71].

5 Progesterone Signaling Pathways

The progesterone signaling mechanism is divided into classical and non-classical pathways. The classical pathway is mainly mediated by progesterone receptors.

Progesterone is a lipophilic hormone that can easily cross the cell membrane and enter cells. The PR can recognize and bind to progesterone hormones. Progesterone molecules enter cells through diffusion and bind to the PR inside the cell to form a PR–progesterone complex. When stimulated by progesterone, the PR undergoes conformational changes, exposing DNA binding sites and being released from the heat shock protein (such as HSP90) complex. PR can also bind to specific progesterone response elements (PRE) via its DNA binding domain (DBD) to initiate the transcription of target genes. The PR, a transcription factor, further recruit’s cofactor complexes (such as the transcription cofactor Src) to activate target genes for transcription through interaction with RNA polymerase II. The termination process of progesterone signal transduction is mainly achieved through receptor degradation. The degradation of PR is usually completed through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway [5,72].

5.2 Non-Classical Progesterone Signaling Pathway

The non-classical progesterone signaling pathway refers to the pathway by which progesterone directly regulates gene expression through membrane receptors or other signaling molecules in the cytoplasm rather than the traditional nuclear receptor PR. Its main signaling pathways include the membrane-bound progesterone receptor (mPR) pathway, the signaling regulation pathway of the EGF receptor and PGRMC2, and the PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 pathways [73] (Fig. 2).

5.2.1 Membrane-Bound Progesterone Receptor (mPR) Pathway

The mPR family is a crucial component of the non-classical pathway. mPR is a member of the G protein–coupled receptor family and contains multiple subtypes, including mPRα, mPRβ, and mPRγ. Progesterone binds to mPR through the extracellular region, activates mPR receptors, and activates G proteins. G proteins can inhibit the activity of AC, thereby reducing the generation of cAMP and affecting the activity of PKA. This process does not rely on nuclear PR; instead, it directly regulates the intracellular second messenger system through mPR. The mPR pathway serves various rapid regulatory functions in the reproductive system [73], with studies showing that mPR can promote the maintenance of luteal cell function by activating Protein Kinase C (PKC) and calcium ion pathways [74]. Moreover, the mPR signaling pathway plays a neuroprotective role within the nervous system. Several researchers have indicated that after mPR activation, the pathway can promote the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins and inhibit neuronal apoptosis by reducing cAMP levels or increasing calcium ion concentrations [7].

5.2.2 Signal Regulation Pathway of EGF Receptor Binding to PGRMC1

PGRMC1 can form a complex with EGFR in which PGRMC1 physically binds to the intracellular domain or extracellular domain of EGFR through its transmembrane domain. PGRMC1 may act as a cofactor to stabilize EGFR activity, enhance the conformational stability of EGFR, prevent EGFR degradation, thereby prolonging the duration of signal transduction. Under the influence of PGRMC1, the kinase domain of EGFR undergoes conformational changes, which can promote its autophosphorylation process. After the phosphorylation site of EGFR is activated, the phosphorylated tyrosine residues attract downstream signaling molecules, particularly those with Src homology 2 (SH2) domains or phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domains, further initiating downstream signaling pathways [75]. After PGRMC1 binds to EGFR, it primarily triggers two key signaling pathways: the ERK/MAPK pathway and the PI3K/Akt pathway. In the ERK/MAPK pathway, after EGFR phosphorylation, its intracellular domain can bind to the Grb2 protein containing the SH2 domain. Grb2 forms a complex with the son of sevenless (SOS), which, as a guanylate exchange factor, can convert Ras-GDP into active Ras-GTP. After activation, Ras-GTP transmits the signal to Raf kinase. Raf then activates downstream MEK, which further phosphorylates and activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Activated ERK translocates to the cell nucleus and can regulate the expression of cell cycle-related genes and promote cell proliferation [76]. In the PI3K/Akt pathway, the phosphorylation sites of EGFR can also recruit PI3K. PI3K is activated after binding to EGFR and catalyzes the conversion of Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). The generated PIP3 then acts as a second messenger to attract Akt to the cell membrane. Akt activation at the membrane is completed by phosphorylation through the synergistic action of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 1 (PDK1) and Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 2 (mTORC2), then, it is fully activated [77]. PGRMC1 has been found to promote breast cancer growth by altering the phosphoproteinome and enhancing the EGFR/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [78]. Activating the PGRMC1/EGFR/Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor (GLP-1R)/PI3K/Akt pathway in the brain can exert neuroprotective effects on the nervous system [79].

5.2.3 PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 Pathway

PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 are mainly localized in the cytoplasm, where they interact with one another. G3BP2 is a multifunctional protein widely involved in essential biological processes such as cellular stress response, RNA metabolism, cell proliferation and signal transduction [80]. Both PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 interact with G3BP2 and form a complex in the cytoplasm. PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 regulate a common pathway, of which one of the common elements is G3BP2 [70]. G3BP2 interacts with NFκB inhibitor α (IκBα) to bind NFκB/p65, thereby retaining NFκB/p65 in the cytoplasm and restricting its transcriptional activity. However, IκBα is not the only factor contributing to the cytoplasmic localization of NFκB/p65 [81]. PGRMC1, PGRMC2, and G3BP2 also regulate the cytoplasmic localization and transcriptional activity of NFκB/p65. PGRMC1 and PGRMC2 has been determined to regulate granulosa cell mitosis and apoptosis by modulating the cellular localization and activity of NFκB/p65 [80].

6 The Linkage between the Progesterone Receptor Family and Alzheimer’s Disease

Research on the role of the PR family in AD has included multiple aspects at the molecular, cellular, and biological levels. Although the progesterone receptor family plays a more important role in the reproductive system, an increasing number of studies have shown that progesterone receptors are widely expressed in the central nervous system and play an indispensable role there, particularly in cognition and neurological processes. Moreover, in terms of neuroprotection, it may have direct or indirect effects on the pathogenesis of AD.

Evidence has increasingly shown that the PR also plays an important role in the central nervous system [82,83], especially in neural processes related to memory and cognition [84,85]. PRs are widely distributed in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and other areas closely linked to cognitive functions [86]. Studies have shown that the PR is involved in regulating neuronal function and synaptic plasticity [50,87,88]—processes that are closely related to learning and memory. During the pathological progression of AD, the abnormal expression or dysfunction of PRs may lead to abnormal neuronal and synaptic functions, thereby affecting cognitive function.

PGRMC1 is a member of the PR family. As research on PGRMC1 continues to deepen, studies have increasingly found that PGRMC1 plays an indispensable role in the nervous system. Studies have shown that this may be related to neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity [89,90], by regulating PGRMC1 and its downstream signaling pathways, it affects the apoptosis of rat hippocampal nerve cells, thereby influencing the cognitive function of rats [89]. In terms of PR receptor agonists, the PR agonist Nestorone has shown promising results in neurodegenerative disease models. For example, in Wobbler mutant mice, 10-day treatment with Nestorone significantly improved motor neuron vacuolization, restored the expression of choline acetyltransferase and glutamine synthetase, and reduced the proliferation of GFAP-positive astrocytes and Iba1-positive microglia [91]. Additionally, Nestorone downregulated the mRNA levels of CD11b, TNFα, iNOS, and NFκB, while upregulating the inhibitory factor IκBα, thereby suppressing neuroinflammation and providing neuroprotection [92]. Reports have shown that progesterone has been shown to attenuate Aβ25-35-induced neuronal toxicity by activating the Ras signaling pathway via PGRMC1 [93] in in vitro experiments. The preliminary research findings of our research group indicate that the inhibition of PGRMC1 exacerbates neonatal hypoxic-ischemic cerebral damage in male mice [14]. Moreover, PGRMC1 has been found to penetrate the survival of human brain microvascular endothelial cells in AD [94]. Studies have shown that PGRMC1 may have a neuroprotective effect and help reduce stress damage to neurons [95]. PGRMC1 is also involved in the regulation of synaptic plasticity [93]. Furthermore, damage to neurons and synapses is one of the pathological features of AD [96]. An increasing amount of evidence has found that the abnormal expression or dysfunction of PGRMC1 may be related to the pathogenesis of AD.

Currently, little is known about the role of PGRMC2 in the nervous system. Previous studies by our research group have shown that PGRMC2 is expressed in neuronal cells, microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells in the nervous systems of mice. The application of PGRMC2 agonists can exert a certain neuroprotective effect on mice with middle cerebral artery occlusion and promote the stability of the inflammatory balance in the brain [10]. These functions may impact neuronal health in AD contexts. Future studies should further explore the neurobiological role of PGRMC2 to help comprehensively understand the potential role of PGRMC2 in Alzheimer’s disease.

In summary, the progesterone receptor family plays a multi-level role in Alzheimer’s disease involves complex regulatory networks from the molecular level to the overall level. The abnormal expression or dysfunction of the progesterone receptor family may directly or indirectly affect neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, inflammatory response, and other biological processes related to AD pathogenesis. Therefore, a comprehensive study of the role of the progesterone receptor family in AD will help us gain a more comprehensive understanding of the role of this family in the context of neurological health and disease. More in-depth experimental and clinical studies are needed in the future to reveal the specific role of the progesterone receptor family in AD.

Members of the progesterone receptor family, especially the classic PR, PGRMC1, PGRMC2, have gradually emerged with multifunctional roles in the nervous system, such as cell survival, apoptosis, and synaptic plasticity [97], which are closely related to the occurrence and development of neurological diseases such as AD. Previous research on PGRMC1 has identified its effects on neuronal protection and synaptic plasticity [93,95,97], strongly suggesting that PR may be a potential target for AD treatment. Although the function of PGRMC2 in the nervous system has not yet been fully elucidated, previous studies by our research group have found that PGRMC2 has a neuroprotective effect and promotes the stability of inflammatory balance in the brain [10], which is a preliminary indicator pointing the way for future research.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fang Hua; draft manuscript preparation: Taiyang Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Niu Y, Zhang Y, Zha Q, Shi J, Weng Q. Bioinformatics to analyze the differentially expressed genes in different degrees of Alzheimer’s disease and their roles in progress of the disease. J Appl Genet. 2025;66(1):73–85. doi:10.1007/s13353-024-00827-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Apr;19(4):1598–695. doi:10.1002/alz.13016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Artimovic P, Badovska Z, Toporcerova S, Spakova I, Smolko L, Sabolova G, et al. Oxidative stress and the Nrf2/PPARgamma axis in the endometrium: insights into female fertility. Cells. 2024;13(13):1081. doi:10.3390/cells13131081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cope DI, Monsivais D. Progesterone receptor signaling in the uterus is essential for pregnancy success. Cells. 2022;11(9):1474. doi:10.3390/cells11091474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Peluso JJ. Progesterone signaling and mammalian ovarian follicle growth mediated by progesterone receptor membrane component family members. Cells. 2022;11(10):1632. doi:10.3390/cells11101632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Mirihagalle S, Hughes JR, Miller DJ. Progesterone-induced sperm release from the oviduct sperm reservoir. Cells. 2022;11(10):1622. doi:10.3390/cells11101622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Thomas P, Pang Y. Anti-apoptotic actions of allopregnanolone and ganaxolone mediated through membrane progesterone receptors (PAQRs) in neuronal cells. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:417. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.00417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cahill MA. Quo vadis PGRMC? Grand-scale biology in human health and disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2022;27(11):318. doi:10.31083/j.fbl2711318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Petersen SL, Intlekofer KA, Moura-Conlon PJ, Brewer DN, Del Pino Sans J, Lopez JA. Novel progesterone receptors: neural localization and possible functions. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:164. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhou C, Zhu T, Ni W, Zhou H, Song J, Wang M, et al. Gain-of-function of progesterone receptor membrane component 2 ameliorates ischemic brain injury. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023;29(6):1585–601. doi:10.1111/cns.14122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Grimm SL, Hartig SM, Edwards DP. Progesterone receptor signaling mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(19):3831–49. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2016.06.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Westhoff CL, Guo H, Wang Z, Hibshoosh H, Polaneczky M, Pike MC, et al. The progesterone-receptor modulator, ulipristal acetate, drastically lowers breast cell proliferation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;192(2):321–9. doi:10.1007/s10549-021-06503-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Szydlowska I, Grabowska M, Nawrocka-Rutkowska J, Piasecka M, Starczewski A. Markers of cellular proliferation, apoptosis, estrogen/progesterone receptor expression and fibrosis in selective progesterone receptor modulator (Ulipristal Acetate)-treated uterine fibroids. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4):562. doi:10.3390/jcm10040562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sun X, Hu Y, Zhou H, Wang S, Zhou C, Lin L, et al. Inhibition of progesterone receptor membrane component-1 exacerbates neonatal hypoxic-ischemic cerebral damage in male mice. Exp Neurol. 2022;347(5):113893. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Acharya KD, Nettles SA, Sellers KJ, Im DD, Harling M, Pattanayak C, et al. The progestin receptor interactome in the female mouse hypothalamus: interactions with synaptic proteins are isoform specific and ligand dependent. eNeuro. 2017;4(5):ENEURO.0272-17.2017. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0272-17.2017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Antonioni A, Raho EM, Di Lorenzo F. Is blood pTau a reliable indicator of the CSF status? A narrative review. Neurol Sci. 2024;45(6):2471–87. doi:10.1007/s10072-023-07258-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. O'Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:185–204. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Thinakaran G, Koo EH. Amyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing, and function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(44):29615–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800019200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Anishma Payyappilliparambil N, Jayalakshmi J, Sachithra Thazhathuveedu S, Archana D, Subin Mary Z, Bijo M. Flavonoid and chalcone scaffolds as inhibitors of BACE1: recent updates. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2024;27(9):1243–56. doi:10.2174/1386207326666230731092409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ma C, Hong F, Yang S. Amyloidosis in Alzheimer’s disease: pathogeny, etiology, and related therapeutic directions. Molecules. 2022;27(4):1210. doi:10.3390/molecules27041210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Sotiropoulos I, Galas MC, Silva JM, Skoulakis E, Wegmann S, Maina MB, et al. Atypical, non-standard functions of the microtubule associated Tau protein. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):91. doi:10.1186/s40478-017-0489-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Reive BS, Lau V, Sanchez-Lafuente CL, Henri-Bhargava A, Kalynchuk LE, Tremblay ME, et al. The inflammation-induced dysregulation of reelin homeostasis hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2024;100(4):1099–119. doi:10.3233/JAD-240088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hoover BR, Reed MN, Su J, Penrod RD, Kotilinek LA, Grant MK, et al. Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2010;68(6):1067–81. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang H, Wei W, Zhao M, Ma L, Jiang X, Pei H, et al. Interaction between abeta and tau in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(9):2181–92. doi:10.7150/ijbs.57078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhao K, Liu J, Sun T, Zeng L, Cai Z, Li Z, et al. The miR-25802/KLF4/NF-κB signaling axis regulates microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;118:31–48. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2024.02.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Calsolaro V, Edison P. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: current evidence and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(6):719–32. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Fanlo-Ucar H, Picón-Pagès P, Herrera-Fernández V, Ill-Raga G, Muñoz FJ. The dual role of amyloid beta-peptide in oxidative stress and inflammation: unveiling their connections in alzheimer’s disease etiopathology. Antioxidants. 2024;13(10):1208. doi:10.3390/antiox13101208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fakhoury M. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for Therapy. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(5):508–18. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666170720095240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lee EJ, Park JS, Lee YY, Kim DY, Kang JL, Kim HS. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms of an MMP-8 inhibitor in lipoteichoic acid-stimulated rat primary astrocytes: involvement of NF-kappaB, Nrf2, and PPAR-gamma signaling pathways. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):326. doi:10.1186/s12974-018-1363-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Singh D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as the modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):206. doi:10.1186/s12974-022-02565-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen Y, Yu Y. Tau and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: interplay mechanisms and clinical translation. J Neuroinflammation. 2023;20(1):165. doi:10.1186/s12974-023-02853-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kwon HS, Koh SH. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener. 2020;9(1):42. doi:10.1186/s40035-020-00221-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. van der Pol A, van Gilst WH, Voors AA, van der Meer P. Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: past, present and future. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(4):425–35. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu D, Chan SL, de Souza-Pinto NC, Slevin JR, Wersto RP, Zhan M, et al. Mitochondrial UCP4 mediates an adaptive shift in energy metabolism and increases the resistance of neurons to metabolic and oxidative stress. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8(3):389–414. doi:10.1385/NMM:8:3:389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ionescu-Tucker A, Cotman CW. Emerging roles of oxidative stress in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;107(5):86–95. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.07.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bai R, Guo J, Ye XY, Xie Y, Xie T. Oxidative stress: the core pathogenesis and mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;77(8):101619. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2022.101619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chen YG. Research progress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Chin Med J. 2018;131(13):1618–24. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.235112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Carrasquillo MM, Belbin O, Hunter TA, Ma L, Bisceglio GD, Zou F, et al. Replication of CLU, CR1, and PICALM associations with alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(8):961–4. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Monteiro AR, Barbosa DJ, Remião F, Silva R. Alzheimer’s disease: insights and new prospects in disease pathophysiology, biomarkers and disease-modifying drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;211:115522. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ferreira-Vieira TH, Guimaraes IM, Silva FR, Ribeiro FM. Alzheimer’s disease: targeting the cholinergic system. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(1):101–15. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666150716165726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu RM. Cellular senescence, and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):1989. doi:10.3390/ijms23041989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lopez-Lee C, Torres ERS, Carling G, Gan L. Mechanisms of sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2024;112(8):1208–21. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2024.01.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, Vattulainen P, Gissler M, Ylikorkala O, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:l665. doi:10.1136/bmj.l665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Rossetti MF, Cambiasso MJ, Holschbach MA, Cabrera R. Oestrogens and Progestagens: synthesis and action in the brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2016;28(7):4105. doi:10.1111/jne.12402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Barth C, Crestol A, de Lange AG, Galea LAM. Sex steroids and the female brain across the lifespan: insights into risk of depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11(12):926–41. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00224-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chen Z, Zhao D, Cheng M, Yang F, Liu Y, Chang J, et al. Female-sensitive multifunctional phytoestrogen nanotherapeutics for tailored management of postmenopausal Alzheimer’s disease. Nano Today. 2024;54:102119. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2023.102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yan S, Zheng C, Paranjpe MD, Li Y, Li W, Wang X, et al. Sex modifies APOE epsilon4 dose effect on brain tau deposition in cognitively impaired individuals. Brain. 2021;144(10):3201–11. doi:10.1093/brain/awab160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Oveisgharan S, Yang J, Yu L, Burba D, Bang W, Tasaki S, et al. Estrogen receptor genes, cognitive decline, and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2023;100(14):e1474–87. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000206833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Su C, Cunningham RL, Rybalchenko N, Singh M. Progesterone increases the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from glia via progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1)-dependent ERK5 signaling. Endocrinology. 2012;153(9):4389–400. doi:10.1210/en.2011-2177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wu H, Wu ZG, Shi WJ, Gao H, Wu HH, Bian F, et al. Effects of progesterone on glucose uptake in neurons of Alzheimer’s disease animals and cell models. Life Sci. 2019;238:116979. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Brodowska A, Grabowska M, Bittel K, Ciecwiez S, Brodowski J, Szczuko M, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor immunoexpression in fallopian tubes among postmenopausal women based on time since the last menstrual period. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9195. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Islam MS, Afrin S, Jones SI, Segars J. Selective progesterone receptor modulators-mechanisms and therapeutic utility. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(5):bnaa012. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnaa012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP. 90 YEARS OF PROGESTERONE: new insights into progesterone receptor signaling in the endometrium required for embryo implantation. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020;65(1):T1–14. doi:10.1530/JME-19-0212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Mauvais-Jarvis F, Lange CA, Levin ER. Membrane-initiated estrogen, androgen, and progesterone receptor signaling in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(4):720–42. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnab041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Cahill MA, Jazayeri JA, Kovacevic Z, Richardson DR. PGRMC1 regulation by phosphorylation: potential new insights in controlling biological activity. Oncotarget. 2016;7(32):50822–7. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.10691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. McGuire MR, Espenshade PJ. PGRMC1: an enigmatic heme-binding protein. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;241(5):108326. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Jo SL, Baek IJ, Ko JW, Kwun HJ, Shin HJ, Hong EJ. Hepatic progesterone receptor membrane component 1 attenuates ethanol-induced liver injury by reducing acetaldehyde production and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2023;324(6):G442–51. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00206.2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Asperger H, Stamm N, Gierke B, Pawlak M, Hofmann U, Zanger UM, et al. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 regulates lipid homeostasis and drives oncogenic signaling resulting in breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):75. doi:10.1186/s13058-020-01312-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lee SR, Heo JH, Jo SL, Kim G, Kim SJ, Yoo HJ, et al. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 reduces cardiac steatosis and lipotoxicity via activation of fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial respiration. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8781. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88251-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. McCallum ML, Pru CA, Niikura Y, Yee SP, Lydon JP, Peluso JJ, et al. Conditional ablation of progesterone receptor membrane component 1 results in subfertility in the female and development of endometrial cysts. Endocrinology. 2016;157(9):3309–19. doi:10.1210/en.2016-1081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Ahmed IS, Chamberlain C, Craven RJ. S2RPgrmc1: the cytochrome-related sigma-2 receptor that regulates lipid and drug metabolism and hormone signaling. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(3):361–70. doi:10.1517/17425255.2012.658367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lin ST, May EW, Chang JF, Hu RY, Wang LH, Chan HL. PGRMC1 contributes to doxorubicin-induced chemoresistance in MES-SA uterine sarcoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(12):2395–409. doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1831-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Lee SR, Mukae M, Jeong KJ, Park SH, Shin HJ, Kim SW, et al. PGRMC1 ablation protects from energy-starved heart failure by promoting fatty acid/pyruvate oxidation. Cells. 2023;12(5):752. doi:10.3390/cells12050752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Galmozzi A, Kok BP, Kim AS, Montenegro-Burke JR, Lee JY, Spreafico R, et al. PGRMC2 is an intracellular haem chaperone critical for adipocyte function. Nature. 2019;576(7785):138–42. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1774-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Clark NC, Pru CA, Yee SP, Lydon JP, Peluso JJ, Pru JK. Conditional ablation of progesterone receptor membrane component 2 causes female premature reproductive senescence. Endocrinology. 2017;158(3):640–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

66. Wu XJ, Williams MJ, Patel PR, Kew KA, Zhu Y. Subfertility and reduced progestin synthesis in Pgrmc2 knockout zebrafish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2019;282(104):113218. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.113218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Peluso JJ, Pru JK. Progesterone receptor membrane component (PGRMC)1 and PGRMC2 and their roles in ovarian and endometrial cancer. Cancers. 2021;13(23):5953. doi:10.3390/cancers13235953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Kowalczyk W, Waliszczak G, Jach R, Dulinska-Litewka J. Steroid receptors in breast cancer: understanding of molecular function as a basis for effective therapy development. Cancers. 2021;13(19):4779. doi:10.3390/cancers13194779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Liu J, Wang Z, Zhou J, Wang J, He X, Wang J. Role of steroid receptor-associated and regulated protein in tumor progression and progesterone receptor signaling in endometrial cancer. Chin Med J. 2023;136(21):2576–86. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000002537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Peluso JJ, Griffin D, Liu X, Horne M. Progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (PGRMC1) and PGRMC-2 interact to suppress entry into the cell cycle in spontaneously immortalized rat granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 2014;91(5):104. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.114.122986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Luo W, Pryzbyl KJ, Bigio EH, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, Redei EE. Reduced hippocampal and anterior cingulate expression of antioxidant enzymes and membrane progesterone receptors in Alzheimer’s disease with depression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;89(1):309–21. doi:10.3233/JAD-220574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Medina-Laver Y, Rodriguez-Varela C, Salsano S, Labarta E, Dominguez F. What do we know about classical and non-classical progesterone receptors in the human female reproductive tract? A review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(20):11278. doi:10.3390/ijms222011278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Garg D, Ng SSM, Baig KM, Driggers P, Segars J. Progesterone-mediated non-classical signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(9):656–68. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2017.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Ashley RL, Clay CM, Farmerie TA, Niswender GD, Nett TM. Cloning and characterization of an ovine intracellular seven transmembrane receptor for progesterone that mediates calcium mobilization. Endocrinology. 2006;147(9):4151–9. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Ahmed IS, Rohe HJ, Twist KE, Craven RJ. Pgrmc1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1) associates with epidermal growth factor receptor and regulates erlotinib sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(32):24775–82. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.134585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Wee P, Wang Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers. 2017;9(5):52. doi:10.3390/cancers9050052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Hassanein SS, Abdel-Mawgood AL, Ibrahim SA. EGFR-dependent extracellular matrix protein interactions might light a candle in cell behavior of non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:766659. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.766659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Pedroza DA, Rajamanickam V, Subramani R, Bencomo A, Galvez A, Lakshmanaswamy R. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 promotes the growth of breast cancers by altering the phosphoproteome and augmenting EGFR/PI3K/AKT signalling. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(8):1326–35. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-0992-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Cao T, Tang M, Jiang P, Zhang B, Wu X, Chen Q, et al. A Potential mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of progesterone and allopregnanolone on ketamine-induced cognitive deficits. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:612083. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.612083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Peluso JJ, Pru CA, Liu X, Kelp NC, Pru JK. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 and 2 regulate granulosa cell mitosis and survival through a NFKappaB-dependent mechanismdagger. Biol Reprod. 2019;100(6):1571–80. doi:10.1093/biolre/ioz043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Prigent M, Barlat I, Langen H, Dargemont C. IkappaBalpha and IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complexes are retained in the cytoplasm through interaction with a novel partner, RasGAP SH3-binding protein 2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(46):36441–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004751200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Gonzalez SL, Coronel MF, Raggio MC, Labombarda F. Progesterone receptor-mediated actions and the treatment of central nervous system disorders: an up-date of the known and the challenge of the unknown. Steroids. 2020;153(4):108525. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2019.108525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Ghoumari AM, Abi Ghanem C, Asbelaoui N, Schumacher M, Hussain R. Roles of progesterone, testosterone and their nuclear receptors in central nervous system myelination and remyelination. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3163. doi:10.3390/ijms21093163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Joshi S, Williams CL, Kapur J. Limbic progesterone receptors regulate spatial memory. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2164. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-29100-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Frye CA, Lembo VF, Walf AA. Progesterone’s effects on cognitive performance of male mice are independent of progestin receptors but relate to increases in GABAA activity in the hippocampus and cortex. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:552805. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.552805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Singh M, Su C, Ng S. Non-genomic mechanisms of progesterone action in the brain. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:159. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Schumacher M, Mattern C, Ghoumari A, Oudinet JP, Liere P, Labombarda F, et al. Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;113(Suppl. 1):6–39. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Foy MR, Baudry M, Akopian GK, Thompson RF. Regulation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity by estrogen and progesterone. Vitam Horm. 2010;82(Pt 1):219–39. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(10)82012-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Cao T, Wang L, Jiao S, Chen H, Lin C, Zhang B, et al. The Involvement of PGRMC1 signaling in cognitive impairment induced by long-term clozapine treatment in rats. Neuropsychobiology. 2023;82(6):1–13. doi:10.1159/000533148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Bali N, Arimoto JM, Iwata N, Lin SW, Zhao L, Brinton RD, et al. Differential responses of progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (Pgrmc1) and the classical progesterone receptor (Pgr) to 17β-estradiol and progesterone in hippocampal subregions that support synaptic remodeling and neurogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153(2):759–69. doi:10.1210/en.2011-1699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Meyer M, Gonzalez Deniselle MC, Garay L, Sitruk-Ware R, Guennoun R, Schumacher M, et al. The progesterone receptor agonist Nestorone holds back proinflammatory mediators and neuropathology in the wobbler mouse model of motoneuron degeneration. Neuroscience. 2015;308:51–63. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Cihankaya H, Theiss C, Matschke V. Little helpers or mean rogue-role of microglia in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):993. doi:10.3390/ijms22030993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Izzo NJ, Xu J, Zeng C, Kirk MJ, Mozzoni K, Silky C, et al. Alzheimer’s therapeutics targeting amyloid beta 1-42 oligomers II: sigma-2/PGRMC1 receptors mediate Abeta 42 oligomer binding and synaptotoxicity. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111899. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Xu X, Ruan X, Ju R, Wang Z, Yang Y, Cheng J, et al. Progesterone receptor membrane component-1 may promote survival of human brain microvascular endothelial cells in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2022;37(4):15333175221109749. doi:10.1177/15333175221109749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Guennoun R, Labombarda F, Gonzalez Deniselle MC, Liere P, De Nicola AF, Schumacher M. Progesterone and allopregnanolone in the central nervous system: response to injury and implication for neuroprotection. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;146:48–61. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. DeTure MA, Dickson DW. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14(1):32. doi:10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Theis V, Theiss C. Progesterone effects in the nervous system. Anat Rec. 2019;302(8):1276–86. doi:10.1002/ar.24121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools