Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Targeting c-Src/PKCα/MAPK/NF-κB: Salvianolic Acid A as a Protective Agent against Silica Nanoparticle-Induced Lung Inflammation

1 Institute of Translational Medicine and New Drug Development, College of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, 40402, Taiwan

2 School of Dentistry, College of Oral Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, 11031, Taiwan

3 School of Medicine, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, 24205, Taiwan

4 Graduate Institute of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Science, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, 24205, Taiwan

5 Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Taoyuan, Taoyuan, 33378, Taiwan

6 School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, 33302, Tawan

7 Department of Nursing, Division of Basic Medical Sciences, and Chronic Diseases and Health Promotion Research Center, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Chiayi, 61363, Taiwan

8 Department of Respiratory Care, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Chiayi, 61363, Taiwan

9 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, 61363, Taiwan

10 School of Chinese Medicine, College of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, 40402, Taiwan

11 Department of Medical Research, China Medical University Hospital, China Medical University, Taichung, 40402, Taiwan

12 Division of Medical Genetics, China Medical University Children’s Hospital, Taichung, 40447, Taiwan

13 Research Center for Chinese Herbal Medicine, Graduate Institute of Health Industry Technology, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan, 33303, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Chuen-Mao Yang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Inflammation and Immune Regulation: From Genotoxicity to Apoptosis)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1265-1290. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066223

Received 01 April 2025; Accepted 17 June 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Silica nanoparticles (SiNPs), commonly utilized in industrial and biomedical fields, are known to provoke pulmonary inflammation by elevating cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) levels in human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (HPAEpiCs). Salvianolic acid A (SAA), a water-soluble polyphenol extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen), possesses well-documented antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Nevertheless, its potential to counteract SiNP-induced inflammatory responses in the lung has not been thoroughly explored. Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the protective role and mechanistic actions of SAA against SiNP-triggered inflammation in both cellular and animal models. Methods: HPAEpiCs were pre-incubated with SAA prior to SiNP exposure to investigate changes in COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) secretion. A murine model of SiNP-induced lung inflammation was used for in vivo validation. Key inflammatory signaling proteins, including c-Src, PKCα, p42/p44 MAPK, and NF-κB p65, were analyzed for phosphorylation status. NF-κB promoter activity was also assessed. Pharmacological inhibitors and siRNA-mediated silencing were employed to verify the signaling cascade responsible for COX-2 regulation. Results: SAA treatment markedly suppressed SiNP-induced upregulation of COX-2 and PGE2 in both HPAEpiCs and mouse lung tissues. SAA also reduced the activation (phosphorylation) of c-Src, PKCα, p42/p44 MAPK, and NF-κB p65, alongside diminishing NF-κB transcriptional activity. Functional studies using inhibitors and gene silencing further supported the involvement of these pathways in mediating the observed anti-inflammatory effect. Conclusion: By concurrently targeting several upstream pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, SAA demonstrates robust potential in alleviating SiNP-induced lung inflammation. These results highlight SAA as a promising candidate for therapeutic intervention in environmentally triggered respiratory conditions.Keywords

Silica nanoparticles (SiNPs) have garnered significant attention due to their unique properties, making them highly valuable in various fields such as medicine, industry, and commercial applications. These applications include their use as drug delivery carriers, imaging agents, and components in biosensors, owing to their biocompatibility, high surface area, and ease of surface modification [1]. However, the widespread utilization of SiNPs inevitably leads to human exposure through multiple routes, including intravenous injection, inhalation, oral intake, and transdermal absorption [1]. With the increasing prevalence of SiNPs in industrial and medical practices, there is an urgent need to assess their potential risks to human health and establish regulatory guidelines.

Despite their beneficial applications, numerous studies have raised concerns about the adverse health effects associated with SiNPs exposure, particularly on the respiratory system [2]. The lungs, being one of the primary routes of nanoparticle exposure, are highly susceptible to SiNP-induced toxicity. SiNPs exposure is known to induce lung inflammation, injury, fibrosis, and granulomatous inflammation, as demonstrated in vivo through intratracheal and intranasal instillation in model organisms [3–5]. Additionally, occupational and environmental studies have reported respiratory complications in workers exposed to silica-containing dusts, including silicosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and lung cancer, which share similar pathological features, such as fibrosis and persistent inflammation, with nanoparticle-induced lung damage [6,7]. These findings highlight the need for a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying SiNP-induced respiratory toxicity to develop effective therapeutic strategies.

The inflammatory response induced by SiNPs is closely associated with the upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) across various cell types, as our previous research has demonstrated [8,9]. COX-2 is an inducible enzyme that converts arachidonic acid (AA) into prostanoids, including prostaglandins (PGs), thromboxanes (TXs), and related molecules, which serve as key mediators in the processes of inflammation and pain [10]. Dysregulation of COX-2 signaling has been implicated in various pathological conditions, including COPD, asthma, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [10–12]. Although conventional anti-inflammatory drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and COX-2 selective inhibitors, have been widely used to alleviate inflammation by targeting COX-2, they often carry significant side effects, including gastrointestinal damage, cardiovascular risk, and impaired renal function, which limit their long-term use [10,13,14]. Moreover, these drugs primarily act by blocking COX-2 enzymatic activity, without addressing the upstream signaling pathways and oxidative stress that contribute to chronic inflammation and tissue damage, potentially limiting their effectiveness in complex inflammatory conditions.

Salvianolic acid A (SAA) represents one of the principal water-soluble phenolic compounds isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza, a traditional Chinese medicinal plant extensively employed for its pharmacological benefits [15]. Unlike conventional NSAIDs, SAA exerts its anti-inflammatory effects through a multi-target approach, providing a broader therapeutic spectrum [16]. It not only inhibits COX-2 expression but also modulates multiple upstream signaling pathways. Specifically, Liu et al. demonstrated that SAA suppresses c-Src signaling to protect cerebrovascular endothelial cells from ischemic injury [17]. Moreover, studies on related inflammatory models have shown that COX-2 expression can be regulated via PKCα, p42/p44 MAPK, and NF-κB cascades [18,19], suggesting that these pathways may also be involved in the anti-inflammatory mechanism of SAA. Additionally, SAA activates the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway, reducing oxidative stress and preventing cellular damage, a feature particularly beneficial for managing chronic inflammatory and fibrotic diseases [20–22]. Clinical studies have also suggested that SAA can reduce inflammation without the significant gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal side effects commonly associated with NSAIDs, making it a promising candidate for long-term therapeutic use [16,23,24].

Moreover, SAA’s ability to inhibit multiple pro-inflammatory mediators, including interleukins (e.g., IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), positions it as a more comprehensive therapeutic agent for respiratory diseases [16,23,24]. Recent studies have demonstrated that SAA effectively attenuates lung injury in animal models of acute lung inflammation and fibrosis by modulating these pathways, supporting its potential clinical application in nanoparticle-induced lung disorders [25,26]. This multi-target therapeutic profile, combined with a favorable safety profile, underscores the potential of SAA to address the limitations of conventional anti-inflammatory therapies, providing a more integrated approach to managing complex inflammatory diseases.

Here, we aimed to investigate the effects of SAA on SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression in both in vivo and in vitro settings. Specifically, we sought to elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which SAA targets the signaling components in human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (HPAEpiCs). By understanding these mechanisms, we hope to provide insights into the potential therapeutic applications of SAA in treating SiNPs-induced pulmonary inflammation and injury. Our research focuses on the suppression of key signaling pathways, including c-Src, PKCα, p42/p44 MAPK, and NF-κB, which are known to be involved in the regulation of COX-2 expression and inflammatory responses in lung tissue. Additionally, this work contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of bioactive compounds in mitigating nanoparticle-induced health risks, paving the way for safer industrial and medical practices involving nanotechnology.

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) (#11330032), fetal bovine serum (FBS) (#A5256701), TRIzol™ Reagent (#15596018), and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase Kit (#28025013) were purchased from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA. The BioTrace™ NT Nitrocellulose Transfer Membrane (#66485) was obtained from Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY, USA. GenMute™ siRNA Transfection Reagent (#SL100568-HepG2) was purchased from SignaGen Laboratories, Frederick, MD, USA. Src Kinase Inhibitor II (Srci II) (#sc-222325) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA. Ro318220 (#HY-13866A), Gö6976 (#HY-10183), U0126 (#HY-12031A), and helenalin (#HY-119970) were purchased from MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA. Anti-β-actin antibody (#4967), anti-COX2 antibody (#12282), anti-GAPDH antibody (#2118), anti-phospho-c-Src (Tyr416) antibody (#2101), anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (#9101), anti-phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) antibody (#3033), anti-Src antibody (#2109), anti-PKCα antibody (#59754), anti-p44/42 MAPK antibody (#9102), and anti-NF-κB p65 antibody (#8242) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA. The anti-phospho-PKCα (Ser657) antibody (#ab180848) was purchased from Abcam, Cambridge, UK. Peroxidase-AffiniPure™ Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (#111-035-003) and Peroxidase-AffiniPure™ Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (#115-035-003) were sourced from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA. Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Reagent A (#23228) and Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Reagent B (#23224) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA. Silica nanoparticles (SiNPs, nanopowder; particle size 10–20 nm) (#637238) and Salvianolic Acid A (SAA) (#SML4045) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA.

2.2 Animals Experimental Design

All procedures involving animals were carried out in full compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines [27] and received prior approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung University (Approval No. CGU 16-046). The study also adhered to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Male ICR (Institute of Cancer Research) mice, 6 to 8 weeks old and weighing around 25 g, were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center in Taipei, Taiwan. Only male mice were used to minimize the influence of hormonal variations on experimental outcomes. The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility with a controlled temperature of 25 ± 2°C and a 12 h light/dark cycle, with free access to autoclaved food and water. Cages were cleaned and sterilized regularly to maintain a clean and controlled environment, reducing the risk of infection and stress. Fifteen mice (n = 5 per group) were randomly divided into three experimental groups: a sham group (50 μL of sterile saline), a SiNPs group (10 mg/kg SiNPs), and an SAA + SiNPs group (50 mg/kg SAA administered by intraperitoneal injection 1 h before the SiNPs challenge, followed by 10 mg/kg SiNPs). SiNPs were administered via intratracheal instillation to ensure direct delivery to the lungs, as previously described [3]. Each mouse received a total dose of 10 mg/kg of SiNPs, which corresponds to 0.25 mg for a 25 g mouse. The SiNPs suspension was prepared in sterile saline and ultrasonicated for 15 min before administration to ensure uniform dispersion and prevent nanoparticle aggregation. Mice were anesthetized and positioned on a near-vertical board, with their tongues gently withdrawn using lined forceps to expose the trachea. The SiNPs suspension was then carefully instilled into the trachea, allowing the particles to be aspirated into the lungs over a 24 h period. The sham group received an equivalent volume (50 μL) of sterile saline using the same method. The SiNPs used in this study were high-purity, uncoated particles with a diameter of approximately 50 nm (purity > 99%). At the end of the experimental period, mice were sacrificed using a high dose of pentothal (100 mg/kg, i.p.) to ensure humane euthanasia. Lung tissues were collected for further analysis, with the right superior and post caval lobes used for protein extraction and the right middle and inferior lobes used for mRNA expression analysis of COX-2. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was obtained via a tracheal cannula by instilling 1 mL of ice-cold PBS. To ensure objectivity, data collection and analysis for both in vivo and in vitro experiments were conducted in a blinded fashion, with investigators unaware of group assignments.

2.3 Immunohistochemical Staining

At 24 h after SiNPs administration, left lung tissues were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, and processed for paraffin embedding. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and treated with 5 mg/mL BSA in PBS to block non-specific binding. COX-2 expression was detected by incubation with anti-COX-2 primary antibody (1:300, 16 h at 4°C), followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, 1 h at room temperature). The signal was visualized using 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (0.5 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, D5637, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer for 5 min in the dark.

HPAEpiCs (ScienCell Research Laboratories, 3200, San Diego, CA, USA) were confirmed to be mycoplasma-free and cultured as previously described [28]. Cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and Antibiotic-Antimycotic Solution (Invitrogen, 15240062, Carlsbad, CA, USA), containing 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL gentamicin, and 250 ng/mL amphotericin B. Cells were seeded at appropriate densities in 12-well plates (1 mL/well), 6-well plates (2 mL/well), or 10 cm dishes (10 mL/dish). Upon reaching confluence, they were serum-starved overnight in serum-free DMEM/F-12 to induce quiescence. All experiments were conducted using cells at passages 5–7. According to the manufacturer, HPAEpiCs are human lung-derived alveolar epithelial cells characterized by cytokeratin-18/19 positivity, and are known to retain epithelial properties under standard culture conditions.

Growth-arrested HPAEpiCs were treated with various concentrations of SiNPs at 37°C for the indicated time periods. For experiments involving pharmacological inhibitors, the compounds were added 1 h prior to SiNPs exposure, while SAA was applied 2 h in advance. Cell harvesting and protein extraction were performed according to standard protocols [29]. After treatment, cells were rinsed thoroughly, collected, and denatured by heating at 95°C for 15 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 45000× g for 15 min at 4°C to obtain whole-cell extracts. Protein samples were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (66485, Pall Corporation). Membranes were blocked and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted at 1:1000, as listed in Section 2.1. After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000, 111035003, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or goat anti-mouse IgG (1:2000, 115035003, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), depending on the source of the primary antibody. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34577, Waltham, MA, USA) and captured using the Azure Biosystems 260 imaging system (Dublin, CA, USA). Band intensities were quantified using UN SCAN IT gel analysis software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT, USA).

Total RNA was extracted from SiNP-treated HPAEpiCs using TRIzol reagent. RNA quality was assessed spectrophotometrically. As described previously [30], 5 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA and analyzed by real-time PCR using the StepOnePlus™ system (Applied Biosystems™/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). COX-2 and GAPDH expression levels were quantified using gene-specific primers and the 2(Ct COX-2–Ct GAPDH) method (Ct = threshold cycle). The primer sequences were:

COX-2:

Sense: 5′-CAAACTGAAATTTGACCCAGAACTAC-3′

Anti-sense: 5′-ACTGTTGATAGTTGTATTTCTGGTCATGA-3′

GAPDH:

Sense: 5′-GCCAGCCGAGCCACAT-3′

Anti-sense: 5′-CTTTACCAGAGTTAAAAGCAGCCC-3′

2.7 Measurement of PGE2 Release

HPAEpiCs rendered quiescent by serum starvation were pretreated with specific pharmacological inhibitors and subsequently exposed to SiNPs or vehicle control at 37°C for the indicated durations. Following treatment, supernatants were collected, and PGE2 levels were measured using a PGE2 ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, ADI901001, Farmingdale, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.8 Transient Transfection with siRNAs

HPAEpiCs were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured until they reached approximately 80% confluence. SMARTpool siRNAs targeting scramble control, c-Src (SASI_Hs01_00112905, NM_198291.3), PKCα (SASI_Hs01_00018817, NM_002737), p42 (SASI_Hs01_00058601, NM_004364), and p65 (SASI_Hs01_00171091, NM_021975) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPAEpiCs were transfected with 100 nM siRNA using GenMute™ reagent (SL100568-HepG2, SignaGen Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After sequential incubation in complete and serum-free DMEM/F-12 medium to ensure quiescence, cells were treated with SiNPs for the indicated durations.

To assess cell viability, confluent HPAEpiCs were growth-arrested in serum-free DMEM/F-12 overnight, then treated with SAA. Viability was evaluated using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, CK04, Kumamoto, Japan), and absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, VT, USA).

2.10 Analysis of Luciferase Reporter Gene Activity

NF-κB transcriptional activity was assessed using the NF-κB Reporter Assay Kit (BPS Bioscience, 60614, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Firefly and Renilla luciferase signals were quantified with the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, E1910, Madison, WI, USA), and luminescence was recorded using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, VT, USA). Firefly signals were normalized to Renilla signals.

2.11 Statistical Analysis of Data

All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from a minimum of three independent experiments. Statistical evaluation was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Group differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

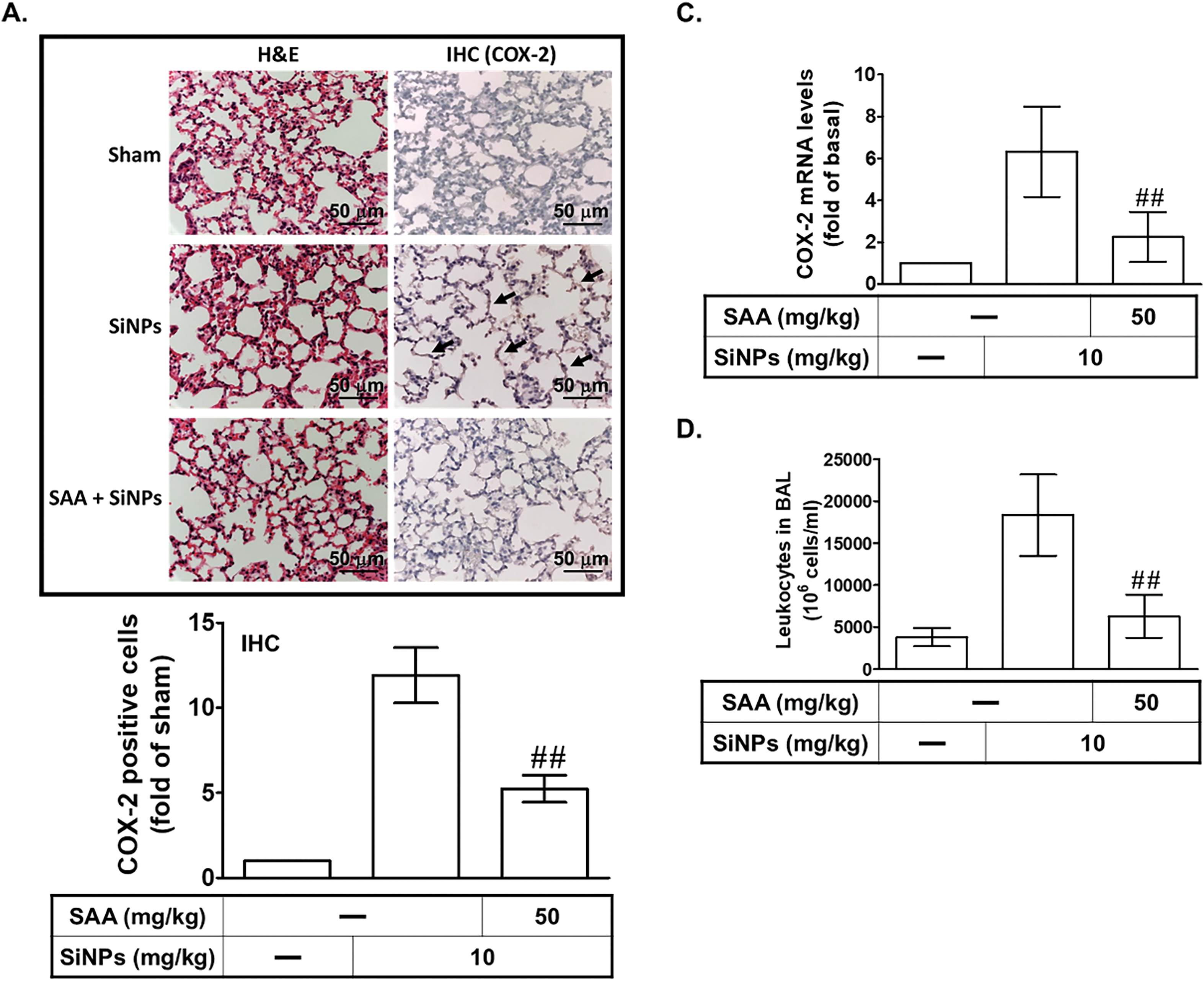

3.1 SAA Mitigates SiNP-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation and COX-2 Upregulation in Mice

Our previous study established that SiNPs induce alveolar inflammation [8]. In this study, we further explored the impact of SiNPs on COX-2 expression and the mitigating effects of SAA, focusing on both molecular and cellular responses. As shown in Fig. 1A, immunohistochemical staining revealed a significant increase in COX-2 protein expression in lung sections from SiNPs-treated mice. This upregulation of COX-2 was markedly reduced in mice pre-administered with SAA, compared to untreated mice, demonstrating the compound’s ability to modulate inflammatory protein expression at the tissue level. To validate these observations, we employed Western blot and real-time PCR analyses, which confirmed elevated levels of COX-2 protein and mRNA in lung tissues from SiNPs-exposed mice (Fig. 1B,C). These molecular analyses further reinforced the robust inflammatory response elicited by SiNPs and the therapeutic efficacy of SAA in reversing these effects. Remarkably, SAA treatment led to a significant downregulation of both COX-2 protein and mRNA expression in these mice, highlighting SAA’s potential to counteract SiNPs-induced inflammatory responses at the molecular level. Furthermore, leukocyte recruitment to pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells is a hallmark of lung inflammation, contributing to the pathological processes of various lung diseases [14]. Our data indicated that SiNPs-stimulated mice exhibited a substantial increase in leukocytes within the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), as shown in Fig. 1D. This observation underscores the systemic impact of SiNP exposure on immune cell infiltration, exacerbating pulmonary inflammation. Notably, SAA pretreatment significantly reduced the number of leukocytes, suggesting its efficacy in mitigating SiNPs-induced pulmonary inflammation by modulating immune cell activity in addition to suppressing COX-2 expression. These combined data strongly suggest that the accumulation of SiNPs triggers pulmonary inflammatory responses, characterized by increased COX-2 expression and leukocyte infiltration, which can be effectively attenuated by SAA. Given these findings, we extended our investigation to elucidate the signaling pathways involved in SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression and how SAA modulates these pathways. Specifically, we aimed to understand the molecular targets of SAA within the inflammatory signaling cascades, providing deeper insights into its role as a potential therapeutic agent. Understanding these mechanisms could provide deeper insights into the therapeutic potential of SAA in treating SiNPs-related pulmonary inflammation and guide future research into nanoparticle-induced respiratory diseases.

Figure 1: SAA alleviates SiNP-induced pulmonary inflammation and COX-2 expression in vivo. (A) Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of SAA (50 mg/kg) or vehicle 1 h prior to intratracheal instillation of SiNPs (10 mg/kg). After 24 h, lung tissues were collected for histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses. H&E staining was used to assess inflammation and structural damage, while IHC staining for COX-2 visualized inflammatory protein expression. Representative images are shown for the sham group (50 μL sterile saline), SiNPs group (10 mg/kg SiNPs), and SAA + SiNPs group (50 mg/kg SAA plus 10 mg/kg SiNPs). Arrows indicate COX-2 expression in alveolar cells. (B,C) Lung homogenates were analyzed for COX-2 protein and mRNA levels using Western blot and real-time PCR, respectively. (D) Total leukocyte counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were determined for each group. Data are presented as mean ± SD from five independent experiments. ##p < 0.01 compared to the SiNPs group

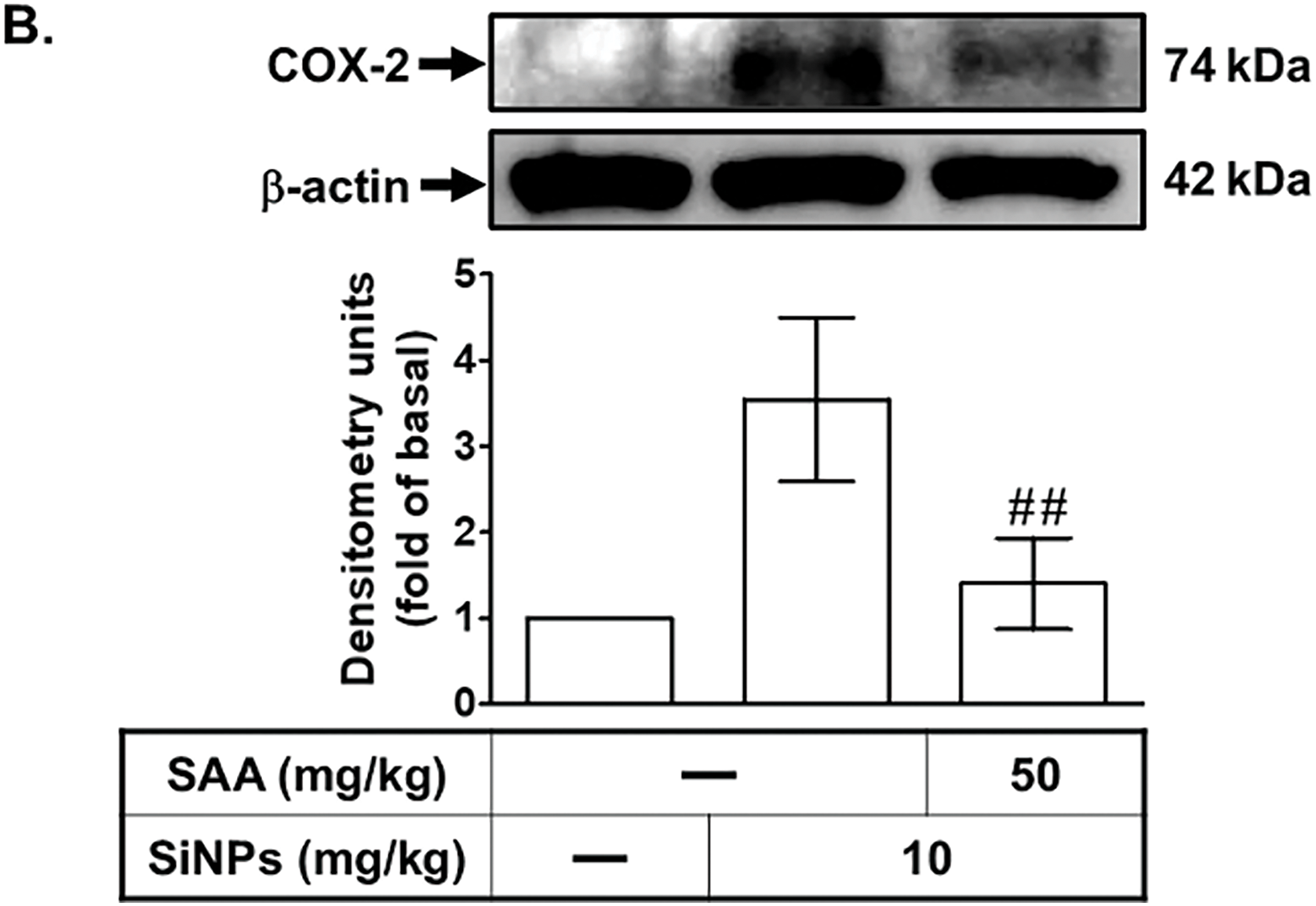

3.2 SAA Inhibits SiNPs-Induced COX-2 Expression and PGE2 Production in HPAEpiCs

To assess the effect of SAA on cell viability, HPAEpiCs were treated with SAA at various concentrations. As shown in Fig. 2A, cells treated with 0, 1, 10, 50, or 100 μM SAA for 24 h demonstrated that 1 and 10 μM SAA did not significantly affect cell viability, while higher concentrations (50 and 100 μM) caused marked cytotoxicity, significantly reducing cell viability. These findings indicate that 1 and 10 μM SAA are non-cytotoxic, while higher concentrations are detrimental to cell survival, underscoring the importance of selecting appropriate SAA concentrations for subsequent experiments. To examine the time-dependent effects of SAA on cell viability, HPAEpiCs were treated with 10 μM SAA for 0, 8, 12, 24, or 48 h. As shown in Fig. 2B, no significant reduction in cell viability was observed at any of the tested time points, confirming that 10 μM SAA is well-tolerated over extended exposure periods. To further investigate the effect of SAA on SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression, HPAEpiCs were pretreated with 1, 5, or 10 μM SAA for 2 h before SiNPs stimulation. As shown in Fig. 2C, SAA significantly reduced COX-2 protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating that SAA effectively modulates inflammatory pathways triggered by nanoparticle exposure. To assess the effect of SAA on COX-2 mRNA expression, HPAEpiCs were pretreated with 10 μM SAA for 2 h before SiNPs stimulation. As shown in Fig. 2D, SAA significantly reduced COX-2 mRNA levels, reinforcing its capability to suppress inflammation at the transcriptional level. Finally, to evaluate the effect of SAA on the secretion of downstream inflammatory mediators, PGE2 levels were measured. As shown in Fig. 2E, SAA significantly reduced PGE2 secretion, confirming its ability to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. Together, these findings highlight the potential of SAA as a therapeutic agent in mitigating SiNPs-induced inflammation in pulmonary cells. By effectively downregulating COX-2 expression, reducing PGE2 secretion, and maintaining cell viability at optimized concentrations, SAA could play a critical role in treating lung inflammation caused by nanoparticle exposure.

Figure 2: SAA inhibits SiNP-induced COX-2 expression and PGE2 production in HPAEpiCs. (A) Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of SAA (0, 1, 10, 50, 100 μM) for 24 h to assess cytotoxicity. (B) Cells were treated with 10 μM SAA for varying durations (0, 8, 12, 24, 48 h) to evaluate time-dependent effects on cell viability. (C) HPAEpiCs were pretreated with SAA (1, 5, or 10 μM) for 2 h prior to SiNP stimulation, and COX-2 protein expression was analyzed by Western blot. (D) COX-2 mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR after pretreatment with 10 μM SAA for 2 h followed by SiNP exposure. (E) PGE2 levels in the culture supernatant were assessed under the same conditions as (D). Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. ##p < 0.01 compared with the control group (A); ##p < 0.01 compared with cells exposed to SiNPs alone (C–E)

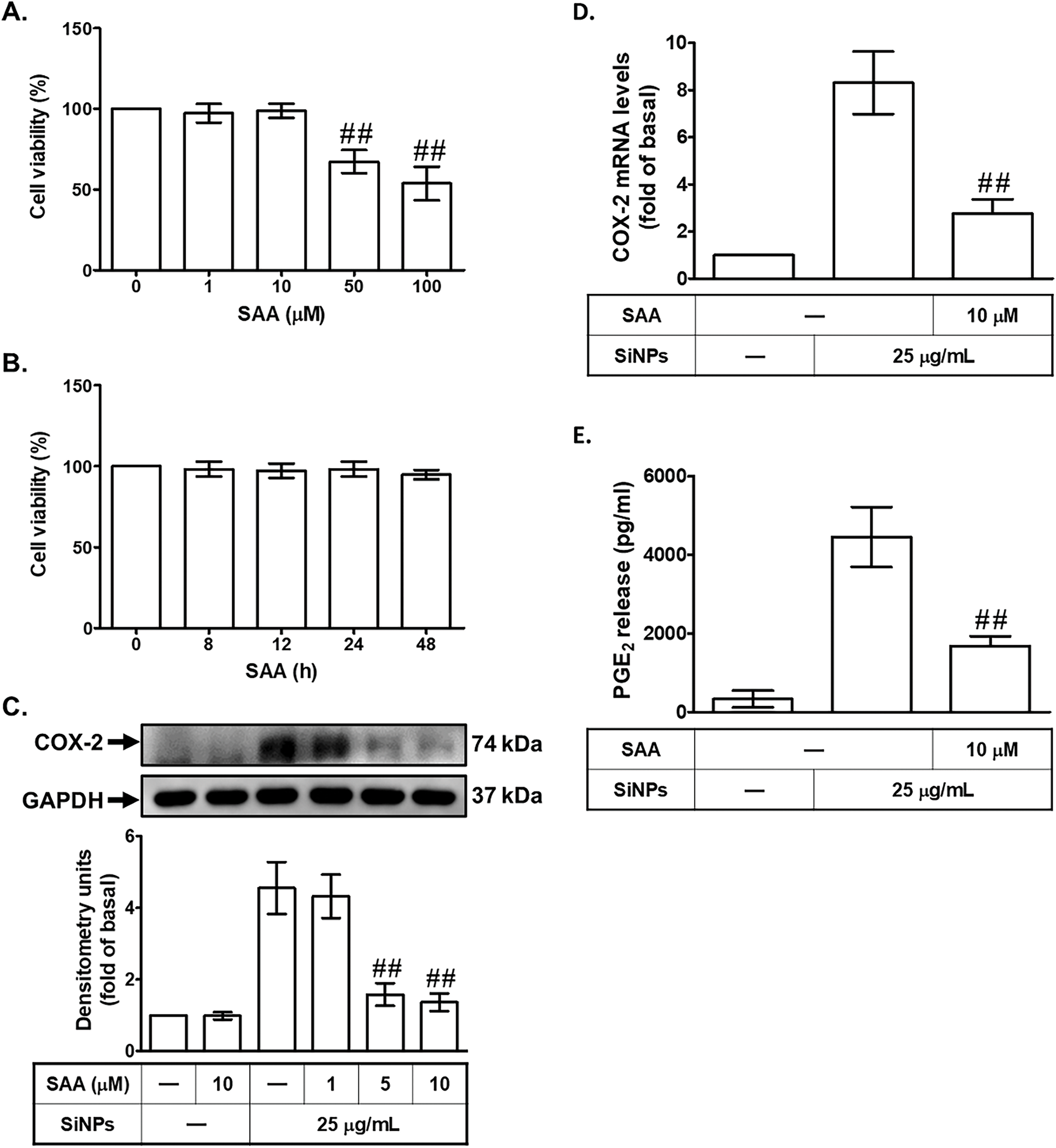

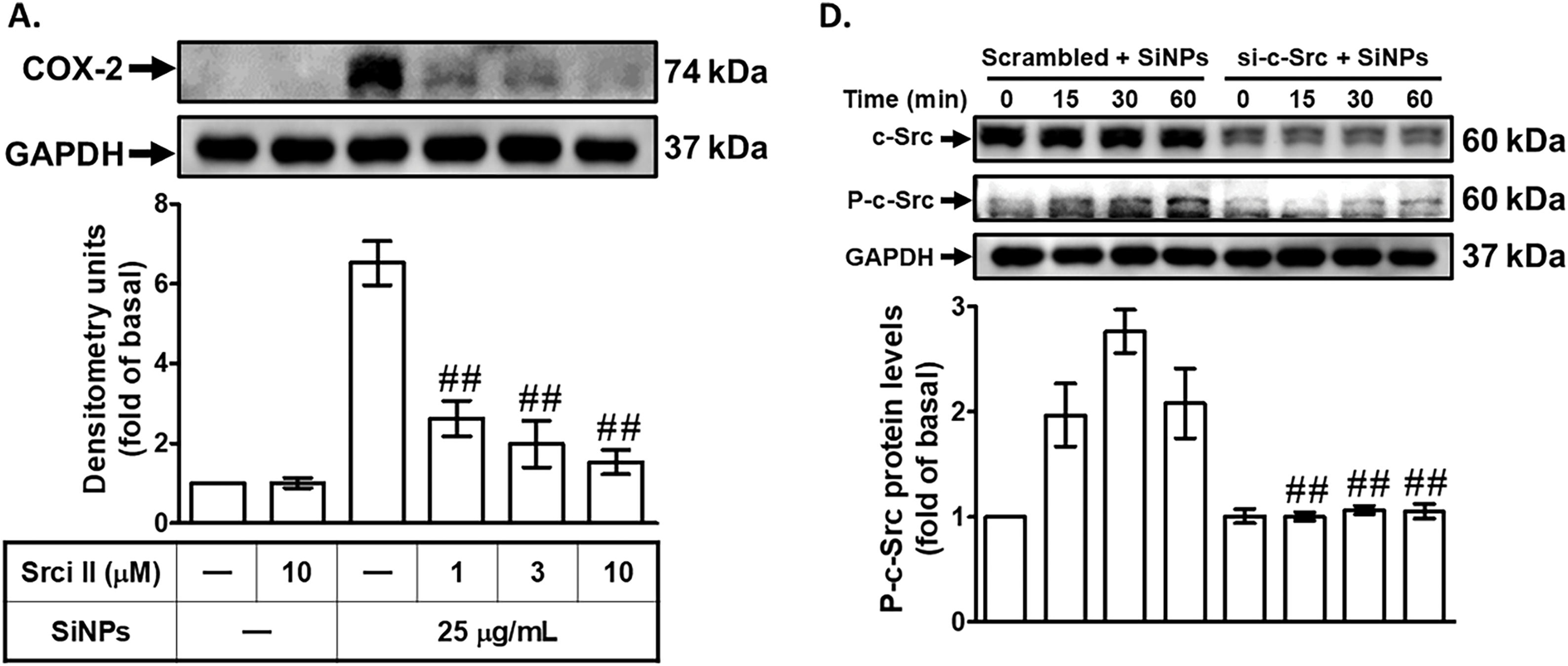

3.3 SAA Attenuates SiNPs-Induced COX-2 Expression by Suppressing c-Src Activation

Previous research has indicated that COX-2 expression can be mediated through Src kinase activity, a critical component of several inflammatory signaling pathways [31]. To explore the role of c-Src in SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression, we pretreated HPAEpiCs with Src inhibitor II (Srci II) before SiNPs exposure. Preincubation with Srci II significantly reduced SiNPs-induced COX-2 protein and mRNA expression (Fig. 3A,B), demonstrating the importance of c-Src in mediating the inflammatory response triggered by nanoparticles. This suggests that c-Src activation is crucial for the upregulation of COX-2 in response to SiNPs, highlighting its role as a key regulatory node in this process. To further investigate the role of c-Src, we transfected HPAEpiCs with c-Src siRNA, an approach that enables specific suppression of the c-Src gene. As shown in Fig. 3C, cells transfected with c-Src siRNA exhibited a decrease in COX-2 protein levels compared to cells transfected with scrambled siRNA, reinforcing the importance of c-Src in regulating COX-2 expression. This finding emphasizes that c-Src signaling is an upstream regulator of COX-2 expression in SiNP-exposed cells. Additionally, we examined the necessity of c-Src phosphorylation for COX-2 expression by exposing HPAEpiCs to SiNPs for various time periods. The results indicated that transfection with c-Src siRNA significantly reduced c-Src phosphorylation induced by SiNPs (Fig. 3D). Consistent with these findings, pretreatment with SAA also substantially decreased c-Src phosphorylation in HPAEpiCs exposed to SiNPs (Fig. 3E). This demonstrates that SAA can inhibit the activation of c-Src, which is a key mediator of COX-2 expression in response to SiNPs. Furthermore, we observed that Srci II reduced SiNPs-induced PGE2 generation in HPAEpiCs (Fig. 3F), indicating that c-Src activity is also necessary for PGE2 production. This reinforces the close relationship between c-Src activation and downstream inflammatory mediators. These results collectively suggest that SAA exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing the phosphorylation of c-Src, thereby downregulating SiNPs-stimulated COX-2 expression and subsequent PGE2 production. By targeting c-Src activation, SAA effectively interferes with a critical pathway that drives inflammation in response to nanoparticle exposure. The implications of these findings are significant, as they highlight the potential of SAA to interfere with critical signaling pathways involved in inflammation, offering a promising therapeutic approach for conditions associated with nanoparticle-induced pulmonary inflammation. These insights open new avenues for further research to explore the broader applicability of SAA in managing inflammatory diseases caused by environmental and occupational nanoparticle exposure.

Figure 3: SAA reduces SiNP-induced COX-2 expression by inhibiting c-Src activation. (A,B) HPAEpiCs were pretreated with Srci II at various concentrations or at 10 μM for 1 h, followed by exposure to 25 μg/mL SiNPs. COX-2 protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels were analyzed by Western blot and real-time PCR, respectively. (C) Knockdown of c-Src by siRNA reduced both total c-Src and COX-2 protein expression in response to SiNPs. (D) Transfection with c-Src siRNA suppressed both total and phosphorylated c-Src protein levels following SiNP treatment at 0, 15, 30, and 60 min. (E) Pretreatment with SAA (10 μM) attenuated the phosphorylation of c-Src over the same time course. (F) Srci II pretreatment reduced PGE2 secretion in the supernatant after SiNP exposure. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. ##p < 0.01 compared with cells exposed to SiNPs alone (A,B,E,F); ##p < 0.01 compared to cells treated with SiNPs + scrambled siRNA (C,D)

3.4 SAA Attenuates SiNPs-Induced COX-2 Expression by Inhibiting PKC Phosphorylation

The role of PKC activation in SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression was investigated by pretreating HPAEpiCs with either a non-selective PKC inhibitor (Ro318220) or a PKCα inhibitor (Gö6976) before exposure to SiNPs. PKC, a family of serine/threonine kinases, plays a pivotal role in regulating cellular signaling pathways involved in inflammation and other pathological processes [32]. As shown in Fig. 4A,B, both Ro318220 and Gö6976 significantly reduced SiNPs-induced COX-2 protein and mRNA expression, providing compelling evidence that PKCα activation is critical for the upregulation of COX-2 in response to SiNPs. This finding underscores the importance of PKCα as a central mediator in the inflammatory cascade triggered by nanoparticle exposure. Additionally, transfection of HPAEpiCs with PKCα siRNA effectively knocked down PKCα protein expression and attenuated SiNPs-induced COX-2 protein levels (Fig. 4C). This result further highlights the specific involvement of PKCα in mediating COX-2 expression following SiNPs exposure and validates its role as a potential therapeutic target. Further analysis revealed that SiNPs-induced PKCα phosphorylation occurred in a time-dependent manner, which was significantly suppressed by PKCα siRNA transfection, as shown in Fig. 4D. However, PKCα siRNA did not significantly reduce SiNPs-induced c-Src phosphorylation, indicating that PKCα acts downstream of c-Src in this signaling pathway. As shown in Fig. 4E, transfection with c-Src siRNA significantly reduced SiNPs-induced PKCα phosphorylation, demonstrating that c-Src activation is required for PKCα phosphorylation in this context. This finding supports the notion that c-Src is an upstream regulator of PKCα in the signaling cascade leading to COX-2 expression. Moreover, Fig. 4F demonstrates that SAA pretreatment significantly inhibited PKCα phosphorylation in SiNPs-stimulated HPAEpiCs, suggesting that SAA interferes with this critical signaling event, potentially by targeting upstream c-Src activation. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4G, pretreatment with Ro318220 or Gö6976 significantly reduced PGE2 generation in SiNPs-stimulated HPAEpiCs, further confirming the essential role of PKCα activation in the inflammatory response. These findings collectively suggest that SAA exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting both c-Src and PKCα activation, thereby downregulating SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression and subsequent PGE2 production. This highlights the interconnected nature of c-Src and PKCα signaling in the inflammatory response to nanoparticle exposure and underscores the therapeutic potential of SAA in targeting this signaling axis. Future studies should further explore the broader applicability of SAA in other models of inflammation and investigate its efficacy and safety in clinical settings to establish its potential as a viable treatment option for nanoparticle-induced pulmonary inflammation.

Figure 4: SAA reduces SiNP-induced COX-2 expression by suppressing PKCα phosphorylation. (A,B) Cells were pretreated with Ro318220 or Gö6976 at the indicated concentrations for 1 h, then stimulated with 25 μg/mL SiNPs. COX-2 protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels were measured using Western blot and real-time PCR, respectively. (C) Knockdown of PKCα by siRNA led to a reduction in both PKCα and COX-2 protein expression in response to SiNPs. (D) Silencing PKCα suppressed its own protein expression and phosphorylation, but did not affect c-Src phosphorylation. (E) In contrast, c-Src siRNA reduced PKCα phosphorylation, indicating that c-Src acts upstream of PKCα activation. (F) Pretreatment with SAA (10 μM, 2 h) attenuated the phosphorylation of PKCα induced by SiNPs. (G) Pretreatment with Ro318220 (1 μM) or Gö6976 (3 μM) significantly decreased PGE2 secretion in the culture supernatant following SiNP exposure. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. ##p < 0.01 compared with cells exposed to SiNPs alone (A,B,F,G); ##p < 0.01 compared to cells treated with SiNPs + scrambled siRNA (C–E)

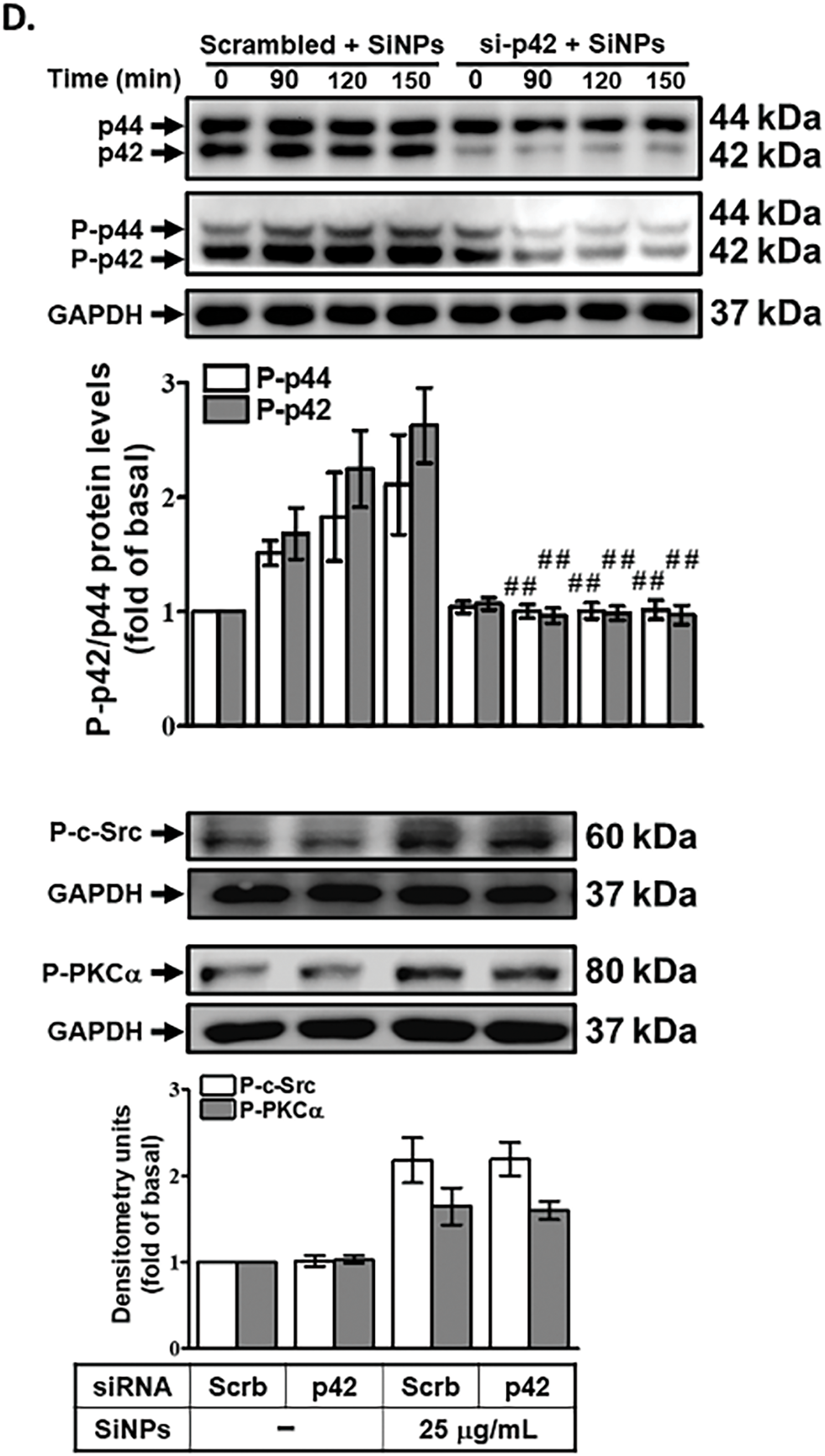

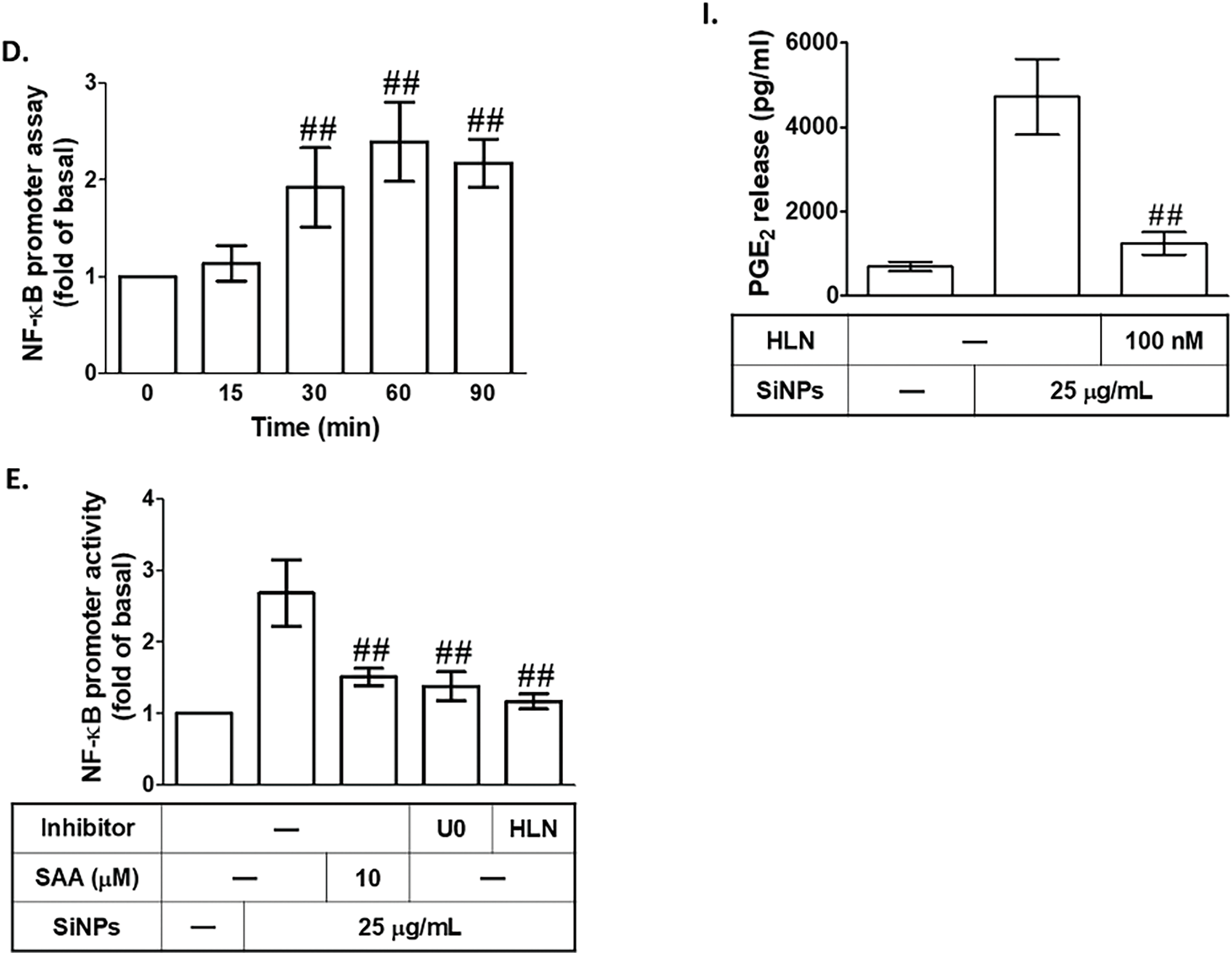

3.5 SAA Inhibits SiNPs-Induced COX-2 Expression by Suppressing p42/p44 MAPK Phosphorylation

To investigate the role of p42/p44 MAPK in SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression, we treated HPAEpiCs with a potent and selective MEK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, prior to SiNPs exposure. MEK1/2 is a well-established upstream kinase that directly activates p42/p44 MAPK through phosphorylation, making it an ideal target to probe the involvement of p42/p44 MAPK in inflammatory signaling [33]. Preincubation with U0126 significantly reduced SiNPs-induced COX-2 protein and mRNA expression in HPAEpiCs (Fig. 5A,B), demonstrating that p42/p44 MAPK activation is critical for the upregulation of COX-2 in response to SiNPs. This finding highlights the pivotal role of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway in mediating the inflammatory effects of nanoparticles. To further validate the involvement of p42/p44 MAPK in this process, we employed siRNA transfection targeting p42. This approach allows for specific gene silencing and provides direct evidence of the functional role of p42. As shown in Fig. 5C, transfection with p42 siRNA effectively decreased COX-2 protein levels in SiNPs-treated HPAEpiCs, confirming that p42/p44 MAPK is a key signaling component in the induction of COX-2 expression by SiNPs. This reduction underscores the direct contribution of p42/p44 MAPK to the inflammatory cascade initiated by SiNP exposure. Fig. 5D demonstrates that SiNPs-induced phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK in HPAEpiCs was significantly suppressed by p42 siRNA, confirming that p42/p44 MAPK is directly involved in this signaling pathway. However, transfection with p42 siRNA did not reduce SiNPs-induced phosphorylation of c-Src or PKCα, indicating that p42/p44 MAPK acts downstream of these kinases and does not provide feedback regulation to upstream signals. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 5E, transfection with PKCα siRNA significantly reduced p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation in SiNPs-stimulated HPAEpiCs, indicating that PKCα acts as an upstream regulator of p42/p44 MAPK in this signaling pathway. This finding highlights the critical role of PKCα in mediating the activation of downstream MAPK pathways, which are essential for the upregulation of COX-2 in response to SiNPs exposure. Moreover, pretreatment with SAA effectively inhibited the SiNPs-induced phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK, demonstrating SAA’s ability to interfere with this critical signaling event (Fig. 5F). This inhibition aligns with SAA’s previously documented anti-inflammatory properties and further supports its role in modulating key components of inflammatory pathways. Finally, as shown in Fig. 5G, pretreatment with the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 significantly reduced PGE2 production in SiNPs-stimulated HPAEpiCs, confirming the essential role of p42/p44 MAPK activation in the inflammatory response. This finding underscores the importance of this signaling axis in regulating downstream inflammatory mediators and highlights the potential of MAPK inhibitors to counteract nanoparticle-induced inflammation. Together, these findings suggest that SAA inhibits COX-2 expression by suppressing the activation of p42/p44 MAPK, which is dependent on PKCα activity in HPAEpiCs. By targeting this signaling axis, SAA effectively reduces both COX-2 expression and PGE2 production, thereby mitigating the inflammatory response induced by SiNPs. The implications of these results are significant, as they highlight the therapeutic potential of SAA in treating inflammation caused by nanoparticle exposure. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which SAA modulates PKCα and p42/p44 MAPK signaling pathways provides valuable insights into its role in inflammation and offers a basis for developing targeted interventions to combat pulmonary diseases associated with environmental and occupational hazards. Future studies should further explore the long-term efficacy and safety of SAA in preclinical and clinical models, evaluating its potential to prevent or treat chronic inflammatory conditions arising from nanoparticle exposure.

Figure 5: SAA suppresses SiNP-induced COX-2 expression by inhibiting p42/p44 MAPK activation. (A,B) HPAEpiCs were pretreated with U0126 (various doses or 10 μM) before SiNPs exposure. COX-2 protein (A) and mRNA (B) expression were assessed by Western blot and real-time PCR, respectively. (C) Knockdown of p42 by siRNA reduced SiNP-induced COX-2 expression and p42/p44 MAPK protein levels. (D) p42 siRNA did not alter PKCα or c-Src phosphorylation but suppressed phospho-p42/p44 MAPK expression in SiNP-treated cells. (E) Silencing PKCα attenuated p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation in response to SiNPs. (F) Pretreatment with SAA (10 μM, 2 h) inhibited SiNP-induced phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK. (G) U0126 pretreatment reduced PGE2 secretion following SiNP exposure. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. ##p < 0.01 compared with cells exposed to SiNPs alone (A,B,F,G); ##p < 0.01 compared to cells treated with SiNPs + scrambled siRNA (C–E)

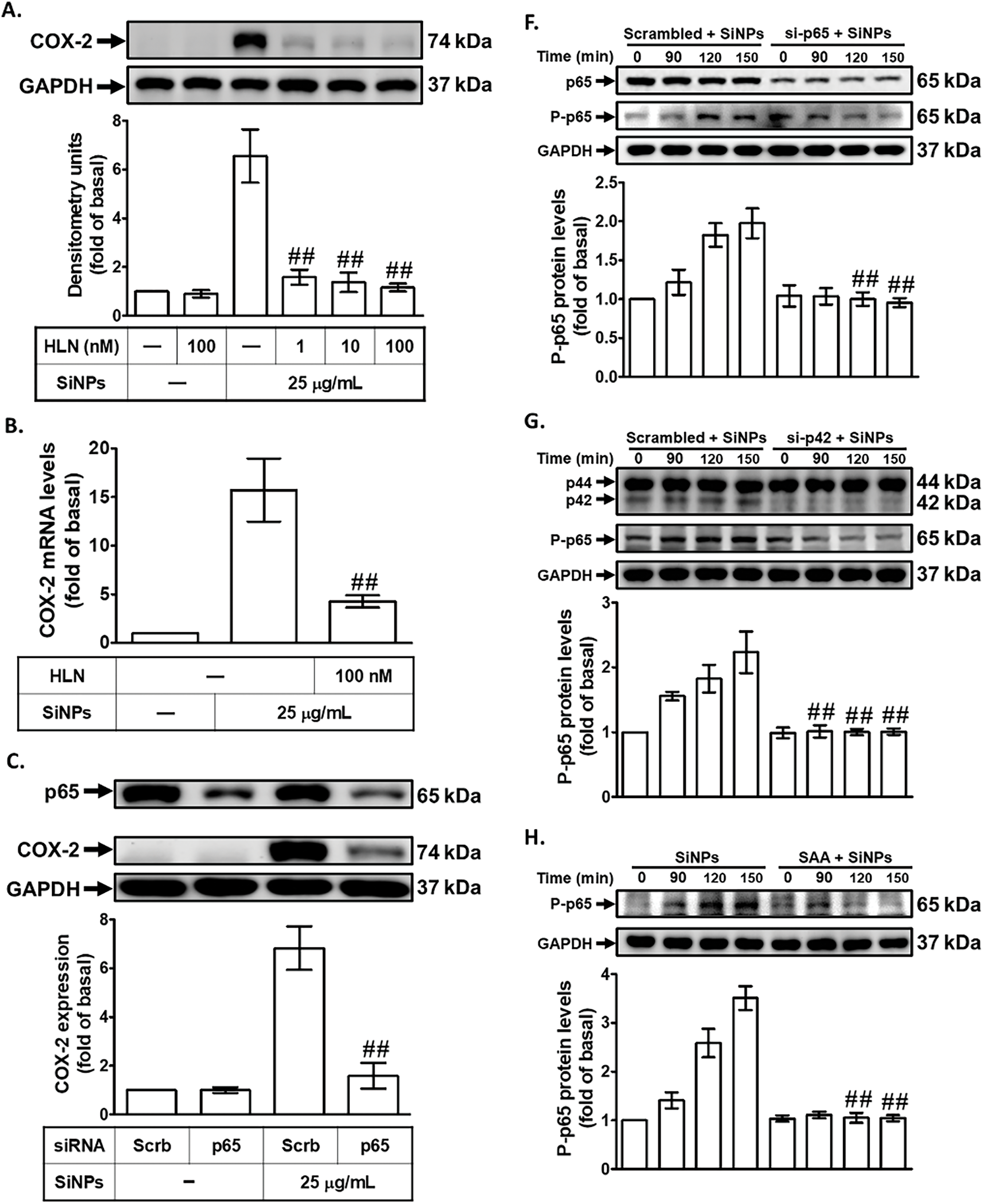

3.6 SAA Attenuates COX-2 Expression by Downregulating NF-κB Activation and Translocation in SiNPs-Treated HPAEpiCs

To investigate the effect of SAA on COX-2 protein and mRNA expression in SiNPs-treated HPAEpiCs, we focused on the transcriptional regulation of COX-2, particularly the role of NF-κB. NF-κB is a key transcription factor that binds to the COX-2 promoter and plays a crucial role in inflammatory responses, orchestrating the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory mediators [18]. Dysregulated NF-κB activation has been implicated in the progression of various inflammatory and pathological conditions, making it a critical target for therapeutic intervention [34]. To determine whether NF-κB activation is required for SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression in HPAEpiCs, we pretreated the cells with helenalin, a selective NF-κB inhibitor known to inhibit NF-κB DNA-binding activity [35]. This pretreatment significantly reduced SiNPs-induced COX-2 protein (Fig. 6A) and mRNA expression (Fig. 6B), providing strong evidence for the involvement of NF-κB in this inflammatory response. Further validating the role of NF-κB, we used p65 (an NF-κB subunit) siRNA to downregulate p65 protein expression. As shown in Fig. 6C, transfection with p65 siRNA also reduced SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression, confirming the pivotal role of p65 in regulating COX-2 levels. To further investigate the time-dependent activation of NF-κB in response to SiNPs, we measured NF-κB promoter activity in HPAEpiCs at various time points following SiNPs exposure. As shown in Fig. 6D, SiNPs treatment significantly increased NF-κB promoter activity in a time-dependent manner, reaching its peak at 60 min. This indicates that NF-κB is rapidly activated in response to SiNPs stimulation, aligning with its established role as a key transcriptional regulator of inflammatory responses. To assess the potential of SAA to inhibit this activation, HPAEpiCs were pretreated with SAA, U0126, or helenalin before SiNPs stimulation. As shown in Fig. 6E, each of these treatments significantly reduced SiNPs-induced NF-κB promoter activity, confirming that SAA can effectively inhibit NF-κB activation. This finding further supports the role of SAA in downregulating COX-2 expression by suppressing NF-κB activation and translocation, a critical step in the inflammatory cascade. Western blot analysis revealed that SiNPs stimulation led to increased phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 between 90 and 150 min after treatment, indicating a robust and sustained activation of this pathway (Fig. 6F,G). This phosphorylation was significantly reduced by transfection with either NF-κB p65 siRNA or p42 siRNA, highlighting the critical role of these upstream signaling molecules in NF-κB activation. Additionally, SAA preincubation effectively suppressed NF-κB p65 phosphorylation (Fig. 6H), suggesting that SAA inhibits COX-2 expression by targeting the PKCα/p42/p44 MAPK/NF-κB signaling axis. This finding supports the role of SAA as a potent modulator of inflammatory signaling, capable of disrupting key molecular events that drive inflammation. Moreover, helenalin pretreatment significantly reduced SiNPs-induced PGE2 production (Fig. 6I), emphasizing the broader anti-inflammatory effects of NF-κB inhibition. Taken together, these results suggest that SAA’s ability to downregulate NF-κB phosphorylation is crucial for its inhibitory effect on COX-2 expression. By targeting multiple components of this signaling pathway, SAA effectively mitigates the inflammatory response induced by SiNPs, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic agent for nanoparticle-induced inflammation.

Figure 6: SAA attenuates COX-2 expression by downregulating NF-κB activation in SiNPs-treated HPAEpiCs. (A,B). HPAEpiCs were pretreated with varying doses of helenalin (HLN) prior to SiNPs exposure. COX-2 protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels were analyzed using Western blot and real-time PCR, respectively. (C) Knockdown of p65 by siRNA reduced SiNP-induced COX-2 and p65 protein expression. (D) SiNPs rapidly increased NF-κB promoter activity over time. (E) Pretreatment with SAA, U0126, or HLN attenuated SiNP-induced NF-κB activation. (F,G) Transfection with p65 or p42 siRNA suppressed SiNP-induced phosphorylation of p65. (H) SAA pretreatment reduced p65 phosphorylation after SiNP challenge. (I) HLN treatment reduced PGE2 production in SiNP-stimulated cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. ##p < 0.01 compared with cells exposed to SiNPs alone (A,B,E,H,I); ##p < 0.01 compared to cells treated with SiNPs + scrambled siRNA (C,F,G); ##p < 0.01 compared with the control group (D)

Several studies have noted the harm of nanoparticles to living organisms [36]. Babaei et al. reported that workers with chronic exposure to nanoparticles have some skin conditions accompanied by higher expression of inflammatory cytokines [7]. Nanoparticles can enter the body through different channels and cause damage to various organs, with the lungs being one of the primary targets. There is an increasing amount of research on how nanoparticles can cause or worsen lung inflammation [6]. Different concentrations of SiNPs have been reported to induce a pulmonary inflammatory response by increasing pulmonary cells and the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators in mice [37]. Wang et al. showed that intratracheal instillation of SiNPs causes severe lung injury accompanied by significant lung tissue edema and infiltration of inflammatory cells in mice [3]. Our study found that exposure to SiNPs resulted in tissue edema and increased levels of COX-2 protein and gene expression in mice. Although the time and dose of stimulation varied, our results were consistent with previous studies.

As previously discussed, accumulating evidence supports the significant anti-inflammatory activity of SAA, as confirmed by multiple independent investigations. Salvianolic acids are capable of reducing intracellular oxidative stress, which shields cells from free radical damage, and also modulate intracellular kinase-associated signaling pathways, contributing to their anti-inflammatory effect [15]. The first question in this study sought to ascertain whether SAA could provide prevention or protection from SiNPs-caused inflammation. It has been reported that SAA inhibited the development of inflammation by reducing the levels of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated macrophages [38]. In a study conducted by Feng et al., it was observed that SAA has anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic effects by decreasing the expression of inflammatory factors such as MMP-1, MMP-13, COX-2, and iNOS in IL-1β-stimulated cells [16]. Similarly, results of Wu et al. suggested that SAA also downregulated the expression of inflammatory mediators, specifically NO, TNF-α, IL-6, COX-2, PGE2, and MMPs, in mouse chondrocytes that were triggered by IL-1β [39]. Thus, we have investigated the influence of SAA on the production of COX-2 under SiNPs treatment. This study confirmed that SAA markedly attenuated SiNP-induced upregulation of COX-2 under both in vitro and in vivo conditions.

Recent studies have shown that blocking the Src kinase can prevent lung inflammation by interfering with inflammatory signaling pathways. Src family kinase inhibitors have been found to impair neutrophil function and reduce inflammation [31]. In addition, inhibiting the Src kinase may hinder Src family kinase phosphorylation and affect other signaling pathways, ultimately improving lung injury and inflammation [40,41]. Consistent with previous findings, our study suggests that c-Src plays a key role in mediating SiNP-induced COX-2 expression, as evidenced by the reduced expression following pretreatment with a selective inhibitor (Srci II) and c-Src-targeted siRNA transfection. Interestingly, our research indicates that SAA can suppress the activation of c-Src triggered by SiNPs, potentially serving as a link between SAA and the decrease in COX-2 expression observed in response to SiNPs. Sperl et al. [42] proposed that the modulatory action of SAA is associated with its interference in SH2 domain-mediated interactions among Src family kinases such as Src and Lck. Additionally, the potential therapeutic properties of SAA have been observed in several diseases, including preventing cerebrovascular endothelial injury by acute ischemic stroke [17], and LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI) and NETosis [25], through its ability to suppress c-Src phosphorylation. Thus, the protective role of SAA in response to SiNP exposure may be attributed, at least in part, to its ability to inhibit c-Src-mediated signaling.

Regarding the mechanism of SAA inhibiting SiNPs-induced inflammation, our results revealed that PKCα phosphorylation could be triggered by SiNPs in a time-dependent manner, which was decreased under SAA or c-Src siRNA treatment. This indicates that PKCα is involved in the signaling pathway of SAA against SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression as a downstream component of c-Src. The role of PKCα in the induction of COX-2 protein was further confirmed by Ro318220, Gö6976, or transfection with PKCα siRNA, all of which attenuated COX-2 expression. The relationship between c-Src and PKCα is intricate and involves multiple mechanisms. However, our findings support the research conducted by Mizrachy-Schwartz et al., which suggests that c-Src is upstream and leads to the phosphorylation of PKCα to regulate AMPK [43]. Tan et al. reported that PKCα is co-immunoprecipitated with c-Src and PKCα expression and activity can be decreased by inhibiting c-Src [44]. Activation of PKC regulates various cellular functions, with its most notable effects in airway epithelial cells being the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [32]. Although information about the interaction between SAA and PKCα is limited in the previous research, our results provide some tentative initial evidence that SAA may possess anti-inflammatory effects that are associated with the c-Src-dependent activation of PKCα.

To further explore the anti-inflammatory effects of SAA, we examined its impact on the MAPK signaling pathway. The MAPK family consists of three key subgroups: p42/p44 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), and p38 MAPKs, all of which are involved in regulating essential physiological and pathological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation [45]. In our previous study, we demonstrated that activation of p38 MAPKs and JNK1/2 plays a crucial role in mediating COX-2 expression induced by SiNPs in HPAEpiCs [8]. The present work further substantiates the involvement of MAPKs in the SiNP-induced upregulation of COX-2 in these cells. Treatment with the MEK1/2-specific inhibitor U0126 resulted in a notable reduction of both COX-2 mRNA and protein levels following SiNP stimulation. Similarly, silencing of p42 MAPK via siRNA significantly decreased COX-2 expression and MAPK phosphorylation in response to SiNPs, reinforcing the importance of MAPK activation in this inflammatory process. Previous studies have also reported the role of MAPKs in the anti-inflammatory action of SAA [46,47]. In line with these findings, we observed that SAA treatment suppressed SiNP-induced phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK in HPAEpiCs, indicating that ERK1/2 is involved in mediating SAA’s protective effects. Moreover, transfection with PKCα-targeted siRNA markedly inhibited the phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK induced by SiNPs, suggesting that PKCα acts upstream of MAPK in this signaling cascade. Based on these results, it is likely that SAA suppresses COX-2 expression and exerts its anti-inflammatory function by interfering with c-Src-dependent PKCα signaling, which governs the activation of p42/p44 MAPK in SiNP-exposed HPAEpiCs.

NF-κB serves as a key transcription factor involved in regulating pro-inflammatory gene expression and is commonly activated at sites of inflammation across a wide range of pathological conditions [19]. Its activation leads to the transcriptional upregulation of multiple cytokines and chemokines associated with inflammatory responses. Within the 5′-flanking region of the human COX-2 gene, NF-κB binding motifs have been identified among several potential regulatory elements [48,49]. In our study, we observed that the elevated expression of COX-2 and the enhanced production of PGE2 induced by SiNPs were markedly suppressed by either helenalin, a selective NF-κB inhibitor, or by siRNA targeting the p65 subunit of NF-κB. These findings highlight the involvement of NF-κB in SiNP-induced COX-2 expression in HPAEpiCs. Furthermore, we demonstrated that SAA treatment significantly attenuated SiNP-induced p65 phosphorylation, similar to the effect observed with p65 siRNA, suggesting that SAA interferes with NF-κB activation. SiNPs also led to a rapid increase in NF-κB promoter activity, which was significantly diminished by pretreatment with SAA, U0126, or helenalin, further supporting the role of NF-κB in mediating the inflammatory response. Although previous research has linked MAPK activation to NF-κB regulation, our results specifically indicate that p42/p44 MAPK is critically involved in activating NF-κB in response to SiNPs. We showed that silencing p42 MAPK or inhibiting MEK1/2 substantially reduced p65 phosphorylation and activation, thereby reinforcing the connection between MAPK signaling and NF-κB activation in this context. Taken together, these data suggest that SAA mitigates SiNP-induced inflammatory responses in HPAEpiCs by modulating NF-κB activation through a signaling cascade involving c-Src, PKCα, and p42/p44 MAPK. These findings provide strong support for the potential use of SAA as a therapeutic agent targeting NF-κB signaling in nanoparticle-induced pulmonary inflammation.

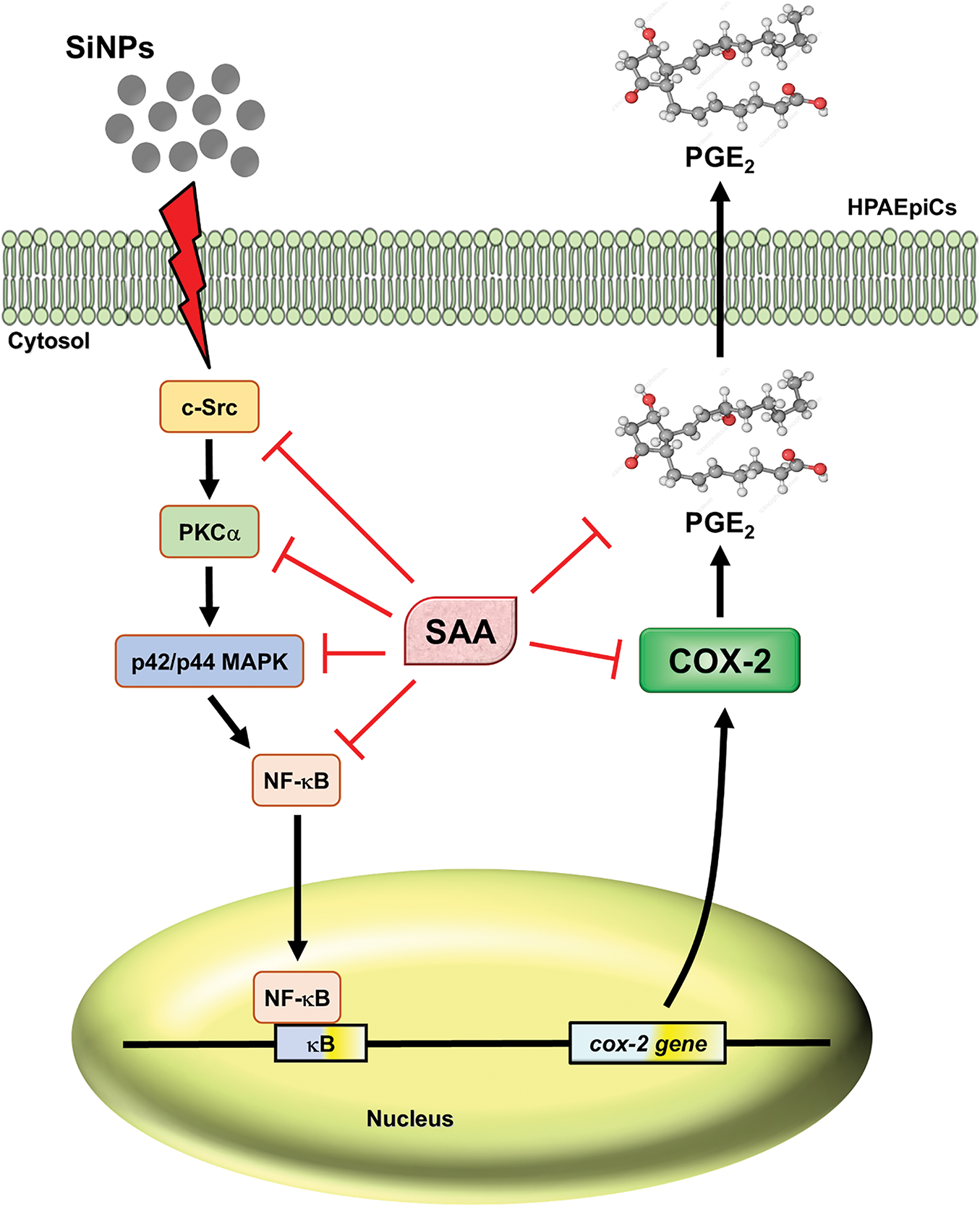

In summary, we found that SAA provided prevention or protection from SiNPs-caused inflammation, which not only reduced the inflammatory response in the lungs of mice but also attenuated COX-2 expression and PGE2 production in SiNPs-induced HPAEpiCs. According to our results, the mechanism by which SAA attenuates SiNPs-induced COX-2 expression may be mediated through the c-Src/PKCα/p42/p44 MAPK/NF-κB pathway (Fig. 7). The experimental findings of this study shed new light on SAA and its potential intervention for the management of nanoparticle-induced inflammatory lung disease. This study opens avenues for further research to explore the broader implications of SAA in treating various inflammatory conditions and its potential integration into therapeutic protocols for diseases caused by environmental and occupational exposure to nanoparticles. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the current study used only a single dose and time point for in vivo SiNPs exposure, which may not fully reflect the complexity of real-world, chronic or low-dose environmental exposures. Second, the use of male mice only limits the generalizability of the findings across sexes, as hormonal influences may modulate inflammatory responses. Third, although key signaling pathways were dissected, the contribution of other pathways and potential crosstalk mechanisms remains to be explored. Finally, while our results support the therapeutic potential of SAA, further pharmacokinetic and toxicological evaluations are necessary before clinical translation.

Figure 7: Proposed mechanism of SAA-mediated inhibition of SiNPs-induced inflammatory signaling in HPAEpiCs. This figure presents a proposed signaling mechanism by which SAA reduces SiNP-induced COX-2 expression and PGE2 secretion in HPAEpiCs. Upon stimulation with SiNPs, c-Src undergoes rapid phosphorylation, initiating the activation of PKCα and subsequent phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK. These signaling events culminate in the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, a key regulator of COX-2 gene transcription and PGE2 production. Pretreatment with SAA disrupts this cascade at multiple levels. Specifically, SAA inhibits c-Src phosphorylation, thereby attenuating the downstream activation of PKCα and p42/p44 MAPK. This suppression further prevents NF-κB p65 activation, leading to reduced expression of COX-2 and diminished secretion of PGE2. The diagram highlights the multi-level regulatory effect of SAA, providing mechanistic insight into its potent anti-inflammatory action against SiNP-induced pulmonary inflammation

Acknowledgement: The authors are deeply appreciative of Rou-Ling Cho for her invaluable technical assistance.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan [Grant number: NSTC111-2320-B-030-013], as well as the Chang Gung University of Science Foundation, Taiwan [Grant number: ZRRPF6N0011].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yan-Jyun Lin, Chuen-Mao Yang, I-Ta Lee, Wen-Bin Wu; data collection: Yan-Jyun Lin, Hui-Ching Tseng, Wei-Ning Lin; analysis and interpretation of results: Yan-Jyun Lin, Chien-Chung Yang, Chiang-Wen Lee, Wen-Bin Wu, Hui-Ching Tseng, Li-Der Hsiao, Wei-Ning Lin; draft manuscript preparation: Yan-Jyun Lin, I-Ta Lee, Chuen-Mao Yang; project administration and funding acquisition: Wen-Bin Wu, Chiang-Wen Lee, Chuen-Mao Yang, Fuu-Jen Tsai; software and visualization: Yan-Jyun Lin, Li-Der Hsiao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Approval: All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Chang Gung University (Approval Document No. CGU 16-046), in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ding R, Li Y, Yu Y, Sun Z, Duan J. Prospects and hazards of silica nanoparticles: biological impacts and implicated mechanisms. Biotechnol Adv. 2023;69:108277. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Huang Y, Li P, Zhao R, Zhao L, Liu J, Peng S, et al. Silica nanoparticles: biomedical applications and toxicity. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151:113053. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wang M, Li J, Dong S, Cai X, Simaiti A, Yang X, et al. Silica nanoparticles induce lung inflammation in mice via ROS/PARP/TRPM2 signaling-mediated lysosome impairment and autophagy dysfunction. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17(1):23. doi:10.1186/s12989-020-00353-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang L, Tian J, Li N, Wang Y, Jin Y, Bian H, et al. Exosomal miRNA reprogramming in pyroptotic macrophage drives silica-induced fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and pulmonary fibrosis. J Hazard Mater. 2025;483:136629. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lv S, Li Y, Li X, Zhu L, Zhu Y, Guo C et al. Silica nanoparticles triggered epithelial ferroptosis via miR-21-5p/GCLM signaling to contribute to fibrogenesis in the lungs. Chem Biol Interact. 2024;399:111121. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2024.111121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou X, Jin W, Ma J. Lung inflammation perturbation by engineered nanoparticles. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1199230. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1199230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Babaei V, Ashtarinezhad A, Torshabi M, Teimourian S, Shahmirzaie M, Abolghasemi J, et al. High inflammatory cytokines gene expression can be detected in workers with prolonged exposure to silver and silica nanoparticles in industries. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5667. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-56027-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lin YJ, Yang CC, Lee IT, Wu WB, Lin CC, Hsiao LD, et al. Reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of EGFR/Akt/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and JNK1/2/FoxO1 and AP-1 pathways in human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells leads to up-regulation of COX-2/PGE2 induced by silica nanoparticles. Biomedicines. 2023;11(10):2628. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11102628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wu WB, Lee IT, Lin YJ, Wang SY, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. Silica nanoparticles shed light on intriguing cellular pathways in human tracheal smooth muscle cells: revealing COX-2/PGE2 production through the EGFR/Pyk2 signaling axis. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):107. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12010107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Tejwani V, Villabona-Rueda AF, Khare P, Zhang C, Le A, Putcha N, et al. Airway and systemic prostaglandin E2 association with COPD symptoms and macrophage phenotype. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2023;10(2):159–69. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.2022.0375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Park GY, Christman JW. Involvement of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandins in the molecular pathogenesis of inflammatory lung diseases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(5):L797–805. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00513.2005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang SD, Chen PT, Hsieh MH, Wang JY, Chiang CJ, Lin LJ. Xin-Yi-Qing-Fei-Tang and its critical components reduce asthma symptoms by suppressing GM-CSF and COX-2 expression in RBL-2H3 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;330(2):118105. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2024.118105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Sautebin L, Dugo L, Serraino I, De Sarro A, et al. Protective effects of Celecoxib on lung injury and red blood cells modification induced by carrageenan in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63(4):785–95. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00908-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ikdahl E, Kerola A, Sollerud E, Semb AG. Cardiovascular implications of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a comprehensive review, with emphasis on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Cardiol. 2024;19:e27. doi:10.15420/ecr.2024.24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Li CX, Xu Q, Jiang ST, Liu D, Tang C, Yang WL. Anticancer effects of salvianolic acid A through multiple signaling pathways (review). Mol Med Rep. 2025;32(1):176. doi:10.3892/mmr.2025.13541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Feng S, Cong H, Ji L. Salvianolic acid a exhibits anti-inflammatory and antiarthritic effects via inhibiting NF-κB and p38/MAPK pathways. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:1771–8. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S235857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu CD, Liu NN, Zhang S, Ma GD, Yang HG, Kong LL, et al. Salvianolic acid A prevented cerebrovascular endothelial injury caused by acute ischemic stroke through inhibiting the Src signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42(3):370–81. doi:10.1038/s41401-020-00568-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Yang CC, Hsiao LD, Su MH, Yang CM. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2 expression via PKCα-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinases and NF-κB cascade in human cardiac fibroblasts. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:569802. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.569802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kim J, Lim CM, Kim N, Kim HG, Hong JT, Yang Y et al. Mutated IL-32θ (A94V) inhibits COX2, GM-CSF and CYP1A1 through AhR/ARNT and MAPKs/NF-κB/AP-1 in keratinocytes exposed to PM10. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1994. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-83159-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li S, Wang R, Song F, Chen P, Gu Y, Chen C et al. Salvianolic acid A suppresses CCl4-induced liver fibrosis through regulating the Nrf2/HO-1, NF-κB/IκBα, p38 MAPK, and JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathways. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2023;46(2):304–13. doi:10.1080/01480545.2022.2028822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Martins-Gomes C, Nunes FM, Silva AM. Thymus spp. aqueous extracts and their constituent salvianolic acid a induce Nrf2-dependent cellular antioxidant protection against oxidative stress in caco-2 cells. Antioxidants. 2024;13(11):1287. doi:10.3390/antiox13111287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhou F, Yao L, Lu X, Li Y, Han X, Wang P. Therapeutic targeting of GSK3β-regulated Nrf2 and NFκB signaling pathways by salvianolic acid a ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis. Front Med. 2022;9:804899. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.804899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang HF, Wang YL, Gao C, Gu YT, Huang J, Wang JH, et al. Salvianolic acid A attenuates kidney injury and inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(12):1855–64. doi:10.1038/s41401-018-0026-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ling Y, Jin L, Ma Q, Huang Y, Yang Q, Chen M, et al. Salvianolic acid A alleviated inflammatory response mediated by microglia through inhibiting the activation of TLR2/4 in acute cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Phytomedicine. 2021;87:153569. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu Q, Zhu CL, Li HR, Xie J, Guo Y, Li P, et al. Salvianolic acid a protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting neutrophil NETosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:7411824. doi:10.1155/2022/7411824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wang P, Sun Y, Zhang R, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Guo S, et al. Salvianolic acid a attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by activating AMPK/SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2025;39(5):e70282. doi:10.1002/jbt.70282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40(9):1769–77. doi:10.1177/0271678x20943823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yang CM, Lin CC, Yang CC, Cho RL, Hsiao LD. Mevastatin-induced AP-1-dependent HO-1 expression suppresses vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression and monocyte adhesion on human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells challenged with TNF-α. Biomolecules. 2020;10(3):381. doi:10.3390/biom10030381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lee IT, Yang CC, Lin YJ, Wu WB, Lin WN, Lee CW, et al. Mevastatin-induced HO-1 expression in cardiac fibroblasts: a strategy to combat cardiovascular inflammation and fibrosis. Environ Toxicol. 2025;40(2):264–80. doi:10.1002/tox.24429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yang CC, Hsiao LD, Wang CY, Lin WN, Shih YF, Chen YW, et al. HO-1 upregulation by kaempferol via ROS-dependent Nrf2-ARE cascade attenuates lipopolysaccharide-mediated intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells. Antioxidants. 2022;11(4):782. doi:10.3390/antiox11040782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Yang CC, Lee IT, Lin YJ, Wu WB, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. Thrombin-induced COX-2 expression and PGE2 synthesis in human tracheal smooth muscle cells: role of PKCδ/Pyk2-dependent AP-1 pathway modulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(20):15130. doi:10.3390/ijms242015130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Xiao Q, Wang D, Li D, Huang J, Ma F, Zhang H, et al. Protein kinase C: a potential therapeutic target for endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2023;37(9):108565. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2023.108565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ronkina N, Gaestel M. MAPK-activated protein kinases: servant or partner? Annu Rev Biochem. 2022;91(1):505–40. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-081720-114505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kaszycki J, Kim M. Epigenetic regulation of transcription factors involved in NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-kB signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1529756. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1529756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Lyss G, Knorre A, Schmidt TJ, Pahl HL, Merfort I. The anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene lactone helenalin inhibits the transcription factor NF-kappaB by directly targeting p65. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(50):33508–16. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.50.33508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Portugal J, Bedia C, Amato F, Juárez-Facio AT, Stamatiou R, Lazou A, et al. Toxicity of airborne nanoparticles: facts and challenges. Environ Int. 2024;190:108889. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2024.108889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Park EJ, Kang MS, Jin SW, Lee TG, Lee GH, Kim DW, et al. Multiple pathways of alveolar macrophage death contribute to pulmonary inflammation induced by silica nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2021;15(8):1087–101. doi:10.1080/17435390.2021.1969461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Huang J, Qin Y, Liu B, Li GY, Ouyang L, Wang JH. In silico analysis and experimental validation of molecular mechanisms of salvianolic acid A-inhibited LPS-stimulated inflammation, in RAW264.7 macrophages. Cell Prolif. 2013;46(5):595–605. doi:10.1111/cpr.12056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wu Y, Wang Z, Lin Z, Fu X, Zhan J, Yu K. Salvianolic acid a has anti-osteoarthritis effect in vitro and in vivo. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:682. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. El-Hashim AZ, Khajah MA, Renno WM, Babyson RS, Uddin M, Benter IF, et al. Src-dependent EGFR transactivation regulates lung inflammation via downstream signaling involving ERK1/2, PI3Kδ/Akt and NFκB induction in a murine asthma model. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9919. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09349-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Severgnini M, Takahashi S, Tu P, Perides G, Homer RJ, Jhung JW, et al. Inhibition of the Src and Jak kinases protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):858–67. doi:10.1164/rccm.200407-981OC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Sperl B, Seifert MHJ, Berg T. Natural product inhibitors of protein-protein interactions mediated by Src-family SH2 domains. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(12):3305–9. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Mizrachy-Schwartz S, Cohen N, Klein S, Kravchenko-Balasha N, Levitzki A. Up-regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase in cancer cell lines is mediated through c-Src activation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(17):15268–77. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.211813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Tan M, Li P, Sun M, Yin G, Yu D. Upregulation and activation of PKC alpha by ErbB2 through Src promotes breast cancer cell invasion that can be blocked by combined treatment with PKC alpha and Src inhibitors. Oncogene. 2006;25(23):3286–95. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Moens U, Kostenko S, Sveinbjørnsson B. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPKs) in inflammation. Genes. 2013;4(2):101–33. doi:10.3390/genes4020101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chuang CY, Ho YC, Lin CW, Yang WE, Yu YL, Tsai MC, et al. Salvianolic acid A suppresses MMP-2 expression and restrains cancer cell invasion through ERK signaling in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;252(3):112601. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.112601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Diao HY, Zhu W, Liu J, Yin S, Wang JH, Li CL. Salvianolic acid a improves rat kidney injury by regulating MAPKs and TGF-β1/smads signaling pathways. Molecules. 2023;28(8):3630. doi:10.3390/molecules28083630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Tanabe T, Tohnai N. Cyclooxygenase isozymes and their gene structures and expression. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:95–114. doi:10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00024-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kang YJ, Mbonye UR, DeLong CJ, Wada M, Smith WL. Regulation of intracellular cyclooxygenase levels by gene transcription and protein degradation. Prog Lipid Res. 2007;46(2):108–25. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2007.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools