Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Human-Derived Low-Molecular-Weight Protamine (hLMWP) Conjugates Enhance Skin Cell Penetration and Physiological Activity

1 Department of Biocosmetics, Dongshin University, 185, Gunjae-ro, Naju, 58245, Jeonnam, Republic of Korea

2 Medicinal Nano-Material Research Institute, BIO-FD&C Co., Ltd., 106, Sandan-gil, Hwasun, 58141, Jeonnam, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Kyung Mok Park. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Understanding Cellular Mechanisms in Wound Healing During Therapeutic Interventions)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1435-1448. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065199

Received 06 March 2025; Accepted 04 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

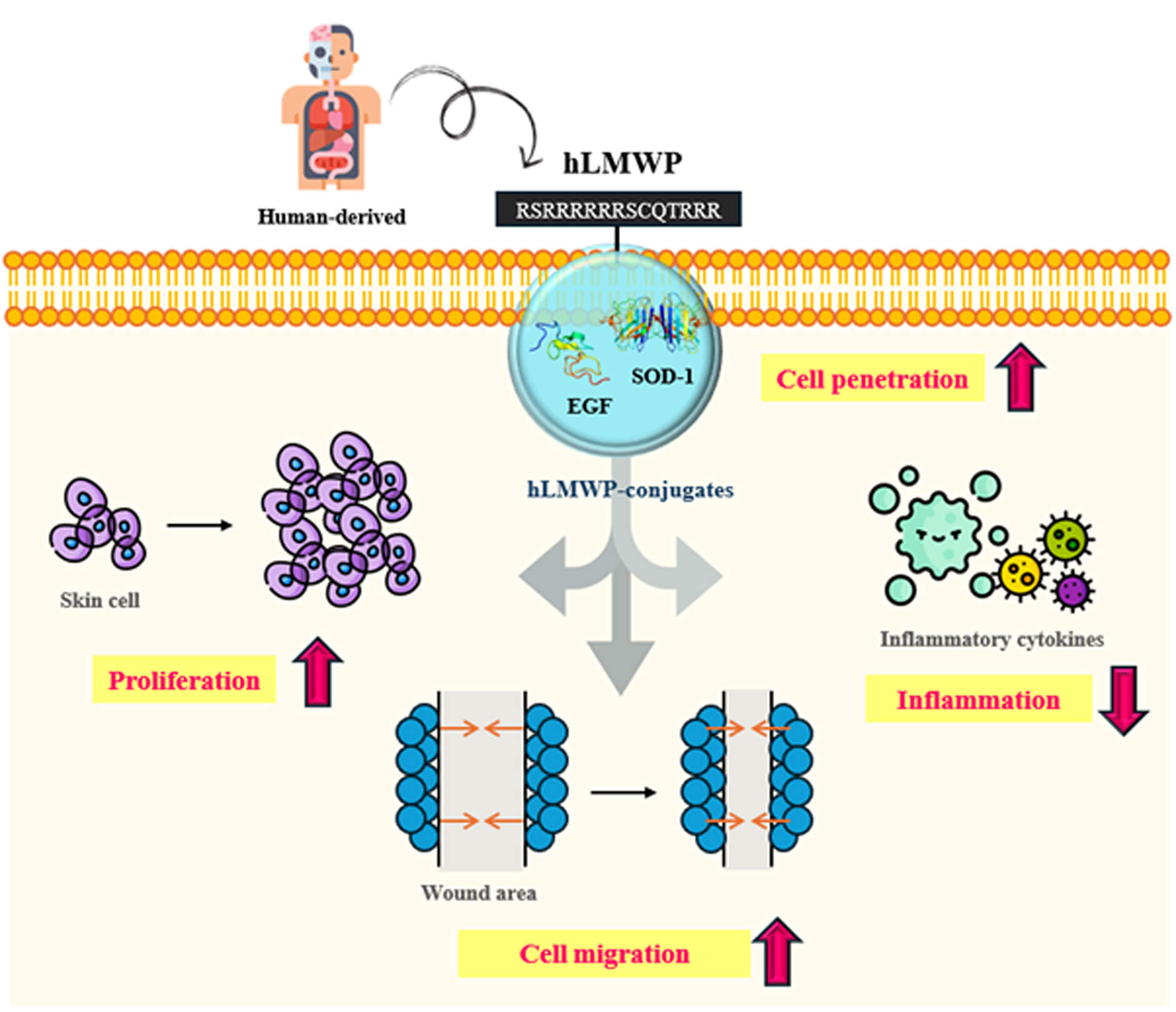

Background: The efficient transdermal delivery of biologically active molecules remains a major challenge because of the structural barrier of the stratum corneum, which limits the penetration of large or hydrophilic molecules. Low-molecular-weight protamine (LMWP) has a structure similar to that of the HIV TAT protein-derived peptide and is a representative cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) used to increase cell permeability. However, protamine has been reported to have many toxicities and side effects. Objectives: We developed human-derived low-molecular-weight protamine (hLMWP), which is based on fish-derived LMWP but designed using human protein sequences to improve safety and functionality. As it is derived from human proteins, it may reduce side effects and immune rejection during long-term or repeated administration. Additionally, we confirmed in our preliminary study that hLMWP enhances permeability compared to LMWP. In this study, we evaluated physiological activities and skin cell penetration of hLMWP conjugates to assess the potential applications of hLMWP. Methods: cDNA sequences for hLMWP-EGF (His) and hLMWP-SOD-1 (His) were synthesized by connecting hLMWP (RSRRRRRRSCQTRRR) to the N-terminus of Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD-1), respectively, with a 6 His-tag added to the C-terminus. The constructs were cloned into a pET-41b(+) expression vector and expressed in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL cells. Expressed proteins were purified using a nickel column and eluted with imidazole buffer. Protein purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and concentrations were quantified using a BCA assay. To evaluate the functional properties of these hLMWP-protein conjugates, a series of in vitro assays were conducted using keratinocyte and macrophage cell lines. These included assessments of permeability, proliferation, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory activity. Results: The results demonstrated that hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 exhibited superior biological activities, including increased cell proliferation, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory effects, compared to EGF and SOD-1. Moreover, hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 significantly enhanced the skin permeability of both EGF and SOD-1, as shown by Franz diffusion cell assay and immunofluorescence analysis. Conclusion: Our findings demonstrate that hLMWP significantly enhances skin permeability and biological activity of functional proteins such as EGF and SOD-1 while maintaining safety. This suggests its potential for application in transdermal drug delivery, regenerative medicine, and cosmeceutical formulations.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The skin is the largest organ in the human body and serves as a barrier as well as a primary target for delivering drugs and active ingredients [1]. The outermost layer of the skin epidermis is the stratum corneum, which acts as the first barrier from the external environment and is very important for drug absorption [2–4]. However, owing the structural characteristics of the skin, the delivery of drugs and bioactive substances through the skin and transdermal routes remains difficult.

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and Protein Transduction Domains (PTDs), which are able to transport various molecules through the cell membrane, have received considerable attention [5,6]. Among these, low-molecular-weight protamine (LMWP) is primarily derived from natural protamine, which is extracted mainly from the sperm of fish, such as salmon [7]. Although protamine is commonly used in clinical practice, it remains a drug with toxicity and adverse effects. According to various studies, protamine toxicity can cause mild hypotension, vascular collapse, and cardiac arrest [8–10]. It has also been reported to cause a wide range of adverse effects, including cardiovascular effects, hypersensitivity reactions, and hemostatic function [11–13].

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) is a protein composed of 53 amino acids with three disulfide bonds. It promotes skin regeneration, wound healing, cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, and modulates the inflammatory response by specifically binding to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) present on the cell surface. EGF has also been studied as a potential therapeutic agent for skin aging, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory skin disorders [14–16]. Recently, the use of EGF in the field of dermatology has increased due to advancements in drug delivery systems and nanotechnology [17–20].

Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD-1) is an antioxidant enzyme that protects skin cells from oxidative damage and inflammation by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) [21]. SOD is classified into three types according to its location. For example, SOD-1 is distributed in the cytoplasm [22]. SOD-1 has been studied for its protective effects against oxidative stress-related skin damage, inflammation and cancer, and is considered a potential therapeutic agent for conditions such as UV-induced aging and chronic dermatitis [23–25]. It is also considered to show high potential for use in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industries [26]. However, EGF and SOD-1 have large molecular weights and hydrophilic properties, that limit their skin permeability and result in low bioavailability [27,28].

To overcome these limitations, we developed a human-derived low-molecular-weight protamine (hLMWP) that is similar to LMWP but originates from human proteins. LMWP consists of a representative 14-residue sequence (VSRRRRRRGGRRRR) derived from fish protamine and is rich in arginine residues that impart strong cell penetrability. In contrast, hLMWP was designed using human-derived sequences (RSRRRRRRSCQTRRR) while retaining similar physicochemical characteristics, such as high positive charge, to ensure membrane permeability. It maintains the unique cationic and low-molecular-weight characteristics of LMWP, allowing the active substance to interact effectively with the cell membrane and achieve efficient cell penetration.

Moreover, non-human-derived therapeutic agents have been associated with issues of toxicity and immunogenicity. One strategy to address these issues is humanization, which involves modifying human-derived sequences to reduce immune responses and improve biocompatibility [29,30]. hLMWP is derived from human proteins, it may exhibit low toxicity and reduce immune responses. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the physiological activity and skin cell permeability of the hLMWP conjugates hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1.

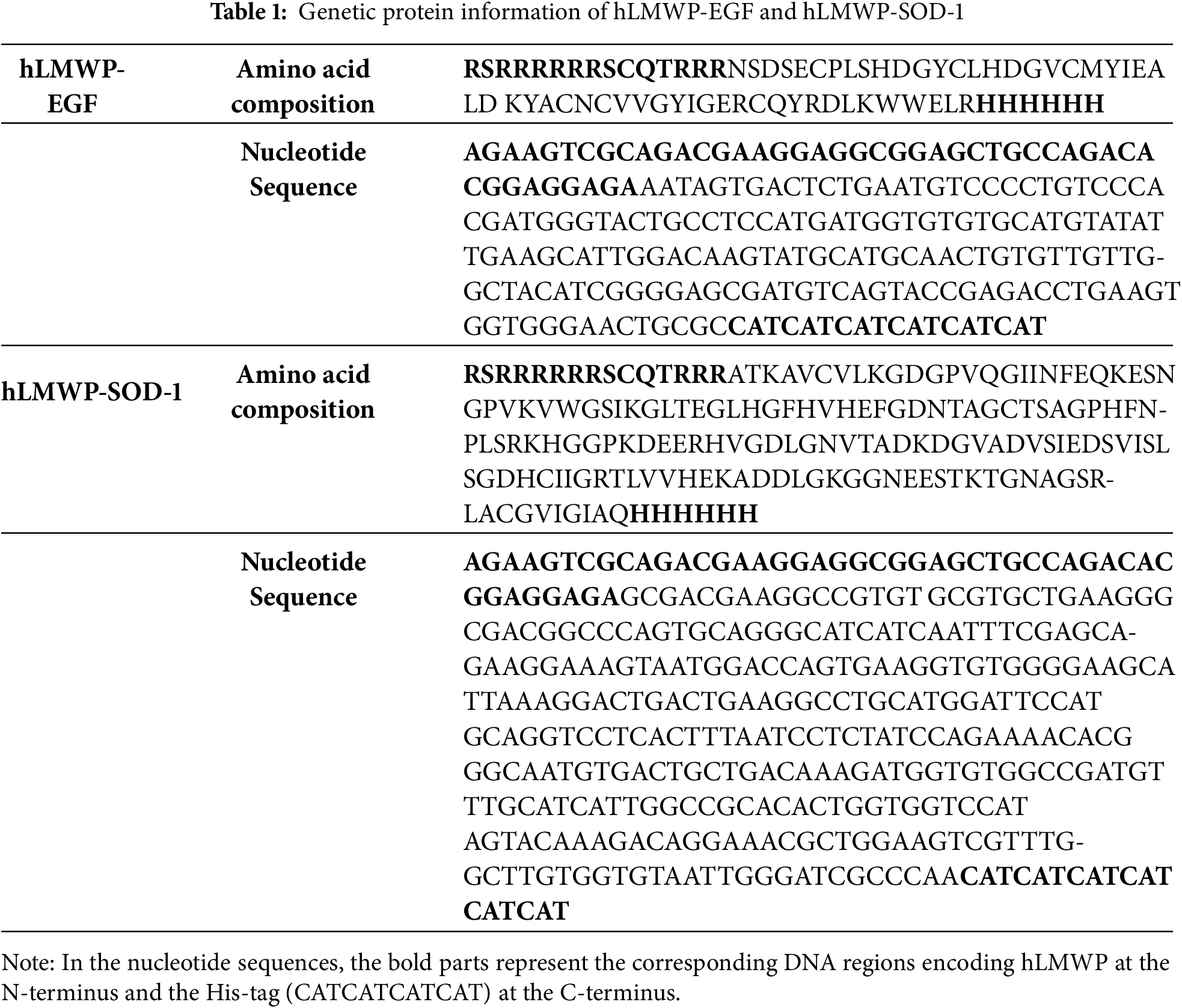

2.1 Gene Synthesis and Recombinant Plasmid Cloning

LMWP-EGF and SOD-1 synthesized by BIO-FD&C Co. Ltd. (Hwasun, Jeonnam, Republic of Korea). The gene sequences for hLMWP-EGF (His) and hLMWP-SOD-1 (His) were engineered by linking the hLMWP peptide (RSRRRRRRSCQTRRR) to the N-terminal end of EGF and SOD-1, respectively, and adding a 6× His-tag to the C-terminal region for purification (Table 1). Based on the synthesized cDNA sequences of hLMWP-EGF (His) and hLMWP-SOD-1 (His), primers containing the Nde I and Xho I restriction enzyme recognition sites were designed for the sense and antisense ends, respectively. Using a purified TA cloning plasmid as a template, PCR was carried out. The resulting PCR products were purified via agarose gel electrophoresis and then enzymatically digested with Nde I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA, R0111S) and Xho I (New England Biolabs, R0146S).

To clone hLMWP-EGF (His) and hLMWP-SOD-1 (His) into the pET-41b(+) protein expression vector, the pET-41b(+) expression vector was double-digested with Nde I and Xho I enzymes to facilitate directional cloning. The digestion products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis, and only the vectors confirmed to be properly digested with restriction enzymes were isolated and purified using gel extraction. Recombinant plasmids were constructed by ligating the purified hLMWP-EGF (His) and hLMWP-SOD-1 (His) gene inserts into the pET-41b(+) vector at a 3:1 insert-to-vector molar ratio.

2.2 Expression and Purification of Recombinant hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1

The constructed plasmids were introduced into BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL competent cells to initiate protein expression. Transformed cells were plated on LB agar containing 100 μg/mL kanamycin (LPS Solution, KAN025, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) and incubated at 37°C. The colonies were observed and identified after 18 h of incubation. The colonies produced after culture were inoculated into 10 mL of LB medium containing the same concentration of kanamycin, and when the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.8, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; GoldBio, I2481C50, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Protein expression was induced by incubating the cultures either at 37°C for 3 h or overnight at 25°C. Colonies exhibiting confirmed protein expression in BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL and Rosetta (DE3) strains were cultured under appropriate conditions, and glycerol stocks were prepared for long-term storage. The cell cultures were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in detergent-free lysis buffer, and subjected to ultrasonication. It was resuspended in 2% sarcosine buffer, and the cell walls were disrupted by ultrasonic disruption. The supernatant was reacted on a Ni column and hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 were eluted with imidazole buffer. The purity of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and quantified using GelAnalyzer software 23.1.1 (Istvan Lazar, http://www.gelanalyzer.com/, accessed on 3 July 2025). hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 concentrations were quantified using a BCA kit (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). To reduce the risk of endotoxin contamination, purified proteins were treated using the ToxinCleanic Endotoxin Removal Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, L00351) prior to use in cell-based experiments.

To reduce the risk of endotoxin contamination, recombinant proteins were purified using the ToxinCleanic Endotoxin Removal Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, L00351), and tested using the ToxinSensor™ Gel Clot Endotoxin Assay Kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) to ensure endotoxin levels were below acceptable in vitro thresholds, prior to use in cell-based experiments. HaCaT and RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, 11995123) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 26140079) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were sub-cultured every 2–3 days. All cell lines used in this study were maintained under sterile conditions according to standard aseptic techniques.

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5,-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, M2128) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). HaCaT and RAW264.7 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates, and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Each cell was treated with the sample for 48 h and 24 h, respectively. MTT solution (5 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline) was added to the cells and incubated for 3 h. The medium was removed, and DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Multiskan Sky, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 51119500).

Cell proliferation was determined using the cell proliferation reagent WST-1 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany, 5015944001) and a BrdU colorimetric kit (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany, 11647229001) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. HaCaT cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates and treated with hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 for 48 h and 24 h, respectively. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

When the cells reached approximately 80% confluence, a wound was created by scratching the monolayer with a 200 μL tip, and the wells were washed with PBS. HaCaT cells were treated with hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 for 24 h. Images were acquired with EVOS™ M5000 imaging system (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and quantification was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; https://imagej.net/, accessed on 3 July 2025).

2.7 Measurement of Hyaluronic Acid Content

The hyaluronic acid content was measured using the Quantikine® ELISA Hyaluronan immunoassay kit (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN, USA, DHYAL0). HaCaT cells were treated with hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 for 24 h. Hyaluronic acid levels were determined using the centrifuged cell supernatant, following the instructions provided by the assay manufacturer.

NO radical scavenging activity was measured using Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, G4410). RAW264.7 cells were treated with hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 for 24 h. The culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C using a Combi-514R centrifuge (Hanil Science Industrial Co., Ltd., Incheon, Repubblic of Korea). Next, 50 μL of the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of 1X Griess reagent and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The absorbance was then recorded at 540 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

2.9 Measurement of Inflammatory Cytokine Levels

The inhibitory effect of pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) production in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells was treated with hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 for 24 h. The inhibitory effect on the production of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) was confirmed by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s (R&D Systems, MTA00B, M6000B and MLB00C) instructions. The supernatant obtained after collecting the culture medium following treatment with hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 was used for analysis.

2.10 Immunofluorescence (IF) Assay

HaCaT cells treated with hLMWP-EGF or hLMWP-SOD-1 for 48 h were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized using 0.25% Triton X-100. Next, the cells were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4°C with 6× His-tag antibodies (1:400; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Chamber slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor Plus 555 secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, A32732) for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were mounted ProLong® Gold Antifade Mountant-DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36935) and analyzed using the EVOS™ M5000 imaging system (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantification of the data was performed by measuring the fluorescence intensity using ImageJ software and the average values were calculated.

2.11 Franz Diffusion Cell Assay

Permeability analysis using of the transdermal absorption system was conducted using a DHC-6TD Franz diffusion cell (Logan Instruments Corp., Somerset, NJ, USA) in a static diffusion cell format. The PermeaPlain Barrier Membrane (PB-M) was placed on top of the receptor chamber, and the lower part of the Franz diffusion cell was filled with 5 mL of the receptor fluid (distilled water). The hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 at a concentration of 1 mg/mL were placed in the donor chamber, and the system was maintained at 32°C and 600 rpm for 24 h to mix the receptor fluid. Distilled water, which was used to dissolve the samples, used as a control in this assay. The samples were collected from the receptor chamber of the static diffusion apparatus. A sample was collected from the receiving chamber of the static diffusion device and quantitative analysis was performed by measuring the concentration of the transmitted protein using the Human EGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN, USA, DEG00) and the Human Superoxide Dismutase 1 ELISA kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab119520).

Statistical analysis of the experimental data points was performed by ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range test using SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, Chicago, IL, USA) and Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

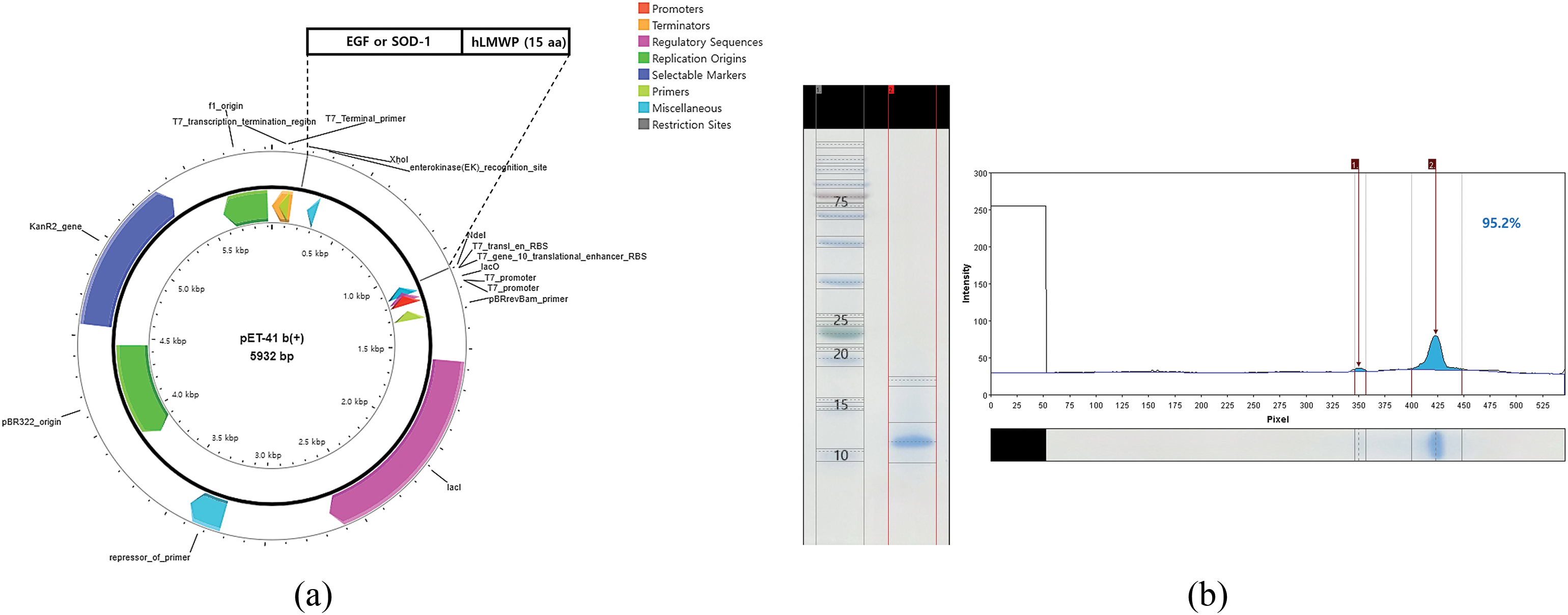

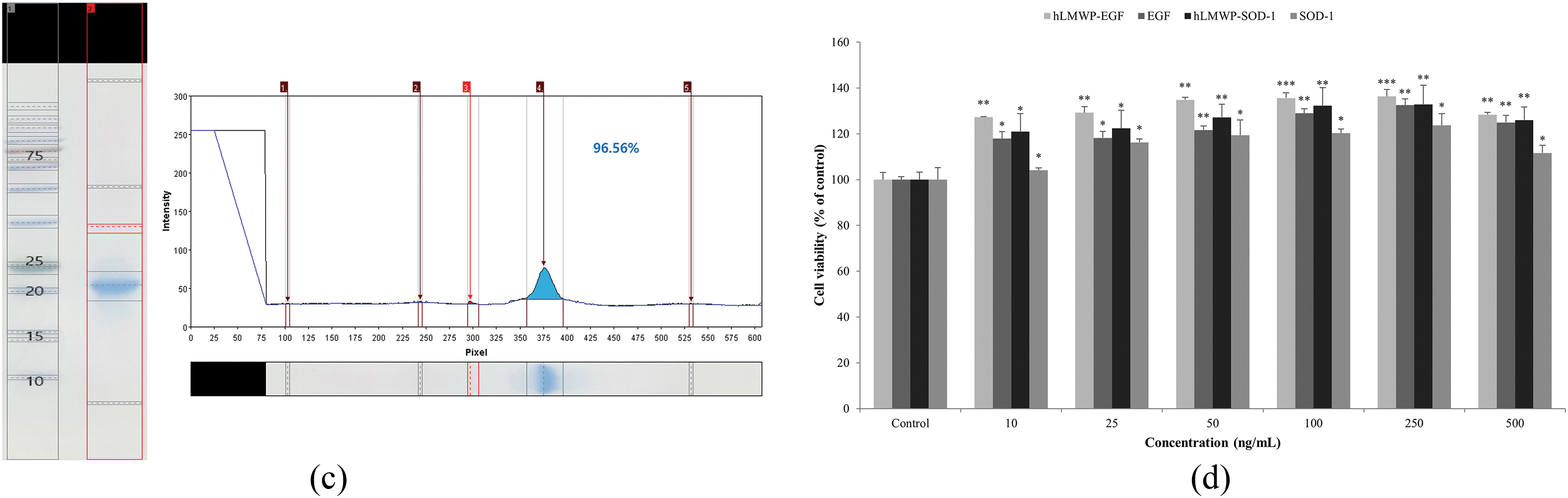

3.1 Construction of Expression Vector and Expression and Purification of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1

The cDNA was inserted into the pET-41b(+) vector using Nde I and Xho I restriction sites and transformed into BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL cells for expression (Fig. 1a). hLMWP-EGF showed a single band at 9.24 kDa, and hLMWP-SOD-1 showed a single band at 18.96 kDa, consistent with their expected molecular weights. hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 exhibited high purity levels of 95.2% and 96.56%, respectively (Fig. 1b,c). hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 were not cytotoxic at concentrations of up to 500 ng/mL in HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that hLMWP did not exhibit cytotoxicity in vitro and may have potential as a carrier for safe skin-penetrating peptides within cells.

Figure 1: Evaluation of the expression, purification, and cellular effects of hLMWP-conjugated EGF and SOD-1 proteins. (a) Plasmid map of pET-41b(+)-hLMWP EGF and pET-41b(+)-hLMWP-SOD-1. Purity of (b) hLMWP-EGF and (c) hLMWP-SOD-1 by SDS-PAGE analysis. Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on (d) cell viability in HaCaT keratinocytes. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard (SD) of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control

3.2 Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on Cell Proliferation

The WST-1 assay results showed that hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 induced superior cell proliferation compared to the control group at all concentrations (Fig. 2a). Moreover, hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 showed enhanced cell proliferation compared to EGF and SOD-1. The BrdU assay results also indicated a significant increase in cell proliferation at concentrations of 250 ng/mL or higher compared to the control group (Fig. 2b). Consistent with the WST-1 assay results, the conjugation of hLMWP to EGF and SOD-1 resulted in superior cell proliferation.

Figure 2: Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on (a) WST-1 and (b) BrdU in HaCaT keratinocytes. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard (SD) of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control

3.3 Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on Cell Migration

We performed wound healing assays to evaluate the effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on the migration of HaCaT keratinocytes. When hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 were used to treat the wounded cells for 24 h, the wound distance was significantly reduced (Fig. 3a,c). Specifically, hLMWP-EGF decreased the wound distance by 30.4% and 27.6% compared with EGF at concentrations of 250 and 500 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 3b). hLMWP-SOD-1 reduced the wound distance by 21.4% and 8.7% compared to SOD-1 alone at concentrations of 250 and 500 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3: Effects of (a,b) hLMWP-EGF and (c,d) hLMWP-SOD-1 on wound healing and (e) hyaluronic acid production in HaCaT keratinocytes. Cells were treated with 100–500 ng/mL of hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 for 24 h. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard (SD) of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control. Scale bars: 50 μm (a,c)

Hyaluronic acid, a major component of the extracellular matrix, plays an important role in tissue regeneration by promoting cell migration and proliferation [31]. hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1 and SOD-1 increased hyaluronic acid content in HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 3e). In particular, hLMWP-EGF and hLWP-SOD-1 significantly affected hyaluronic acid production compared to EGF and SOD-1. hLMWP-EGF increased hyaluronic acid content by 14.0% compared with EGF, and hLMWP-SOD-1 increased hyaluronic acid content by 12.5% compared with SOD-1 at a concentration of 500 ng/mL. These results implied that hLMWP binding can increase cell migration.

3.4 Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on Inflammation Inhibition

To confirm the anti-inflammatory effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1, we investigated their effects on the viability of RAW264.7 cells. hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 did not exhibit cytotoxicity at concentration up to 500 ng/mL (Fig. 4a). hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 inhibited LPS-induced NO production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4b). In particular, at 500 ng/mL, hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 inhibited NO production by 22.0% and 22.8%, respectively, compared with EGF and SOD-1. Additionally, hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, and SOD-1 reduced the levels of inflammatory cytokines such as LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. hLMWP-EGF reduced the LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β levels by up to 24.9%, 28.8%, and 64.1%, respectively (Fig. 4c). hLMWP-SOD-1 reduced LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β levels by up to 52.5%, 24.5%, and 58.7%, respectively (Fig. 4d). These results suggest that hLMWP binding of enhances the anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 4: Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on (a) cell viability in RAW264.7 cells. Inhibitory effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on (b) NO production and (c,d) inflammatory cytokines. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard (SD) of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control and ###p < 0.001 compared to the LPS

3.5 Effects of hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 on Cell Penetration Enhancement

To compare cell permeability according to hLMWP binding, HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with 500 ng/mL hLMWP-EGF, EGF, hLMWP-SOD-1, or SOD-1, and permeability was analyzed using immunofluorescence staining. The 6× His-tag is used for protein purification and detection and interacts with the Alexa 555-conjugated antibody to produce a fluorescent signal. Therefore, the red staining indicated that permeation occurred through the cell membrane. Both hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 exhibited strong fluorescence signals (Fig. 5a,c). As quantified using ImageJ, hLMWP-EGF increased cell permeability by 32.4-fold compared to EGF, and hLMWP-SOD-1 increased cell permeability by 6.2-fold compared to SOD-1 (Fig. 5b,d).

Figure 5: Effect of (a,b) hLMWP-EGF and (c,d) hLMWP-SOD-1 on cell penetration rate in HaCaT keratinocytes. Scale bars: 50 μm (a,c). Effect of (e) hLMWP-EGF and (f) hLMWP-SOD-1 on transdermal absorption using Franz cell. Uptake differences between systems may result from barrier complexity, protein stability, and assay-specific permeability mechanisms. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard (SD) of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 compared to the EGF or SOD-1

Additionally, the effect of hLMWP binding on permeability was quantitatively assessed using Franz cell diffusion assay. For permeation analysis using the transdermal absorption system, the sample that penetrated the receiving compartment was quantitatively recovered and analyzed using EGF and SOD-1 ELISA kits. hLMWP-EGF exhibited a 2.49-fold increase in permeability compared wiht EGF, and hLMWP-SOD-1 achieved a 2.04-fold increase compared with SOD-1 (Fig. 5e,f). These results indicate that hLMWP effectively enhanced permeability.

The delivery of bioactive molecules through the skin barrier is a critical challenge in dermatological and pharmaceutical research. Over the years, various strategies have been explored to overcome the problem of penetration through the barrier [32–34]. Chemical enhancers, such as ethanol and surfactants, increase the fluidity of the lipid layers in the stratum corneum but are often associated with irritation, cytotoxicity, and skin barrier damage. Physical methods, including microneedling, iontophoresis, and ultrasound, have shown considerable promise, but require specialized equipment and may not be suitable for all applications. Lipid-based carriers, such as liposomes and nanostructured lipid carriers, may be more biocompatible, but have limitations in terms of stability and encapsulation efficiency.

Several well-known CPPs such as TAT and penetratin have demonstrated strong cell-penetrating capabilities, but have also raised concerns regarding cytotoxicity and immunogenicity under certain conditions [35,36]. LMWP, a CPPs, is derived from natural protamine extracted from fish sperm and is known to enhance skin penetration by improving permeability without significantly disturbing the natural barrier of the skin compared to chemical or physical methods. However, protamine has been reported to be toxic and to have various adverse effects. In contrast, hLMWP was designed using human protein sequences to improve both biocompatibility and permeability.

We manufactured human protein-derived hLMWP while maintaining the characteristics of LMWP, and evaluated their effects on cytotoxicity, cell permeability, and physiological activity of these conjugates. hLMWP conjugated to EGF and SOD-1 was found to significantly enhance skin permeability and biological activity. hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 were purified in high yields and expressed as single bands at 9.24 kDa and 18.96 kDa, respectively. These sizes were consistent with the calculated molecular weights, indicating the successful expression and purification of the recombinant protein. hLMWP conjugates demonstrated additional benefits, including the ability to promote cell migration, elevate hyaluronic acid production, and reduce inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6).

Immunofluorescence analysis showed that hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 significantly enhanced the permeability of keratinocytes. Also, hLMWP-EGF and hLMWP-SOD-1 increased the permeability of keratinocytes and enhanced the permeability of BP-M cellulose membranes, which have structural properties similar to those of the skin epidermis, in a permeability assay using Franz diffusion cells. However, the degree of permeability enhancement differed between the immunofluorescence assay and the Franz diffusion assay. The differences in permeability seen between immunofluorescence and Franz diffusion data may be due to differences in barrier complexity, protein stability, and transport mechanisms. Immunofluorescence is derived from absorption through a single cell membrane, whereas Franz diffusion uses a dense PB-M membrane. It can also be affected by long-term incubation and physical resistance during analysis.

This increase in permeability is important because it is directly related to increased biological activities, including cell proliferation, wound healing, and anti-inflammation. In the WST-1 assay, although the absorbance at 250 ng/mL appeared slightly higher than at 500 ng/mL, there was no statistically significant difference between the two concentrations. In addition, WST-1 and BrdU assays are based on different measurement principles—metabolic activity and DNA synthesis, respectively. Therefore, a discrepancy between the results may be observed. Although this study focused on transdermal delivery, the ability of hLMWP to enhance permeability through biological barriers is noteworthy. This property suggests potential applicability in other therapeutic areas where effective macromolecule delivery is needed, such as metabolic or cardiovascular diseases.

In this study, we did not directly elucidate the cellular uptake mechanism of hLMWP. However, previous studies have shown that many CPPs are internalized through various pathways, including clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin-mediated uptake, macropinocytosis, and receptor-independent translocation [37,38]. Given the structural similarity and cationic nature of hLMWP to protamine-based CPPs, similar uptake mechanisms are likely involved. However, further studies using pathway-specific inhibitors and mechanistic analyses are needed to clarify the exact internalization route of hLMWP.

In conclusion, hLMWP enhanced the permeability and physiological activity of growth factors and functional proteins without cytotoxicity in vitro. These results suggest that hLMWP has the potential to improve the transdermal delivery and efficacy of functional proteins or large molecules with low permeability in the biomedical and cosmetic fields. However, further in vivo studies are required to evaluate its long-term safety, immunogenicity, and pharmacokinetic properties. In particular, hLMWP-conjugated proteins may hold promise for the delivery of macromolecules in chronic dermatoses or other skin-related conditions. In addition, the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying its cellular uptake should be further elucidated to support future clinical applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) and Startups (MSS), Republic of Korea, under the “Regional Specialized Industry Development Plus Program (R&D, S3363773)” supervised by the Korea Technology and Information Promotion Agency (TIPA) for SMEs.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Seo Yeon Shin and Kyung Mok Park; methodology, Nu Ri Song, Kyung Mok Park, Sa Rang Choi, Ki Min Kim and Jae Hee Byun; formal analysis, Seo Yeon Shin, Seong Sim Kim, Seong Ju Park and So Jeong Chu; investigation, Nu Ri Song, Kyung Mok Park, Sa Rang Choi, Ki Min Kim and Jae Hee Byun; writing—original draft preparation, Seo Yeon Shin; writing—review and editing, Kyung Mok Park; visualization, Seo Yeon Shin, Seong Sim Kim, Seong Ju Park and So Jeong Chu; supervision, Su Jung Kim, Dai Hyun Jung and Kyung Mok Park; project administration, Su Jung Kim, Dai Hyun Jung and Kyung Mok Park. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Kyung Mok Park, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akhtar N, Pathak K. Recent advances in transdermal drug delivery systems: a review. Biomater Res. 2021;25(1):1–16. doi:10.1186/s40824-021-00226-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ramadon D, McCrudden MTC, Courtenay AJ, Donnelly RF. Enhancement strategies for transdermal drug delivery systems: current trends and applications. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12(4):758–91. doi:10.1007/s13346-021-00909-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bhowmik B, Aravind RAS, Gowda DV. Recent trends and advances in fungal drug delivery. J Chem Pharm Res. 2016;8(4):169–78. [Google Scholar]

4. Dubey A, Prabhu P, Kamath JV. Nano structured lipid carriers: a novel topical drug delivery system. Int J PharmTech Res. 2012;4(1):705–14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0846.2006.00179.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hasannejad-Asl B, Pooresmaeil F, Takamoli S, Dabiri M, Bolhassani A. Cell penetrating peptide: a potent delivery system in vaccine development. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1072685. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1072685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Shoari A, Tooyserkani R, Tahmasebi M, Löwik DWPM. Delivery of various cargos into cancer cells and tissues via cell-penetrating peptides: a review of the last decade. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(9):1391. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13091391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. He H, Ye J, Liu E, Liang Q, Liu Q, Yang VC. Low molecular weight protamine (LMWPa nontoxic protamine substitute and an effective cell-penetrating peptide. J Control Release. 2014;193(9):63–73. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Katz NM, Kim YD, Siegelman R, Ved SA, Ahmed SW, Wallace RB. Hemodynamics of protamine administration. Comparison of right atrial, left atrial, and aortic injections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94(6):881–6. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(19)36160-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Crivellari M, Landoni G, D’Andria Ursoleo J, Ferrante L, Oriani A. Protamine and heparin interactions: a narrative review. Ann Card Anaesth. 2024;27(3):203–9. doi:10.4103/aca.aca_117_23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Takeichi T, Morimoto Y, Yamada A, Tanaka T. A case of the effective inhalation of nitric oxide therapy for caused severe pulmonary hypertension with protamine neutralization of systemic heparinization during totally endo-scopic minimally invasive cardiac surgery. J Extra-Corpor Technol. 2024;56(3):120–4. doi:10.1051/ject/2024018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Levy JH, Ghadimi K, Kizhakkedathu JN, Iba T. What’s fishy about protamine? Clinical use, adverse reactions, and potential alternatives. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21(7):1714–23. doi:10.1016/j.jtha.2023.04.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cobb CA III, Fung DL. Shock due to protamine hypersensitivity. Surg Neurol. 1982;17(4):245–6. doi:10.1016/0090-3019(82)90112-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Adkins JR, Hardy JD. Sodium heparin neutralization and the anticoagulant effects of protamine sulfate. Arch Surg. 1967;94(2):175–7. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330080013004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Cohen S. The epidermal growth factor (EGF). Cancer. 1983;51(10):1787–91. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19830515)51:10<1787::aid-cncr2820511004>3.0.co;2-a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Hardwicke J, Schmaljohann D, Boyce D, Thomas D. Epidermal growth factor therapy and wound healing—past, present and future perspectives. Surgeon. 2008;6(3):172–7. doi:10.1016/s1479-666x(08)80114-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Shin SH, Koh YG, Lee WG, Seok J, Park KY. The use of epidermal growth factor in dermatological practice. Int Wound J. 2023;20(6):2414–23. doi:10.1111/iwj.14075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Shakhakarmi K, Seo JE, Lamichhane S, Thapa C, Lee S. EGF, a veteran of wound healing: highlights on its mode of action, clinical applications with focus on wound treatment, and recent drug delivery strategies. Arch Pharm Res. 2023;46(4):299–322. doi:10.1007/s12272-023-01444-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Koppe Raghu P, Bansal KK, Thakor P, Bhavana V, Madan J, Rosenholm JM, et al. Evolution of nanotechnology in delivering drugs to eyes, skin and wounds via topical route. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13(8):167. doi:10.3390/ph13080167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Khan A, Mostafa HM, Almohammed KH, Singla N, Bhatti Z, Siddique MI. Advances in nanotechnology in drug delivery systems for burn wound healing: a review. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2025;18(1):373–86. doi:10.13005/bpj/3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim J, Jang JH, Lee JH, Choi JK, Park WR, Bae IH, et al. Enhanced topical delivery of small hydrophilic or lipophilic active agents and epidermal growth factor by fractional radiofrequency microporation. Pharm Res. 2012;29(7):2017–29. doi:10.1007/s11095-012-0729-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Sheng Y, Abreu IA, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ, Miller AF, Teixeira M, et al. Superoxide dismutases and superoxide reductases. Chem Rev. 2014;114(7):3854–918. doi:10.1021/cr4005296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Schaar CE, Dues DJ, Spielbauer KK, Machiela E, Cooper JF, Senchuk M, et al. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(2):e1004972. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wei M, He X, Liu N, Deng H. Role of reactive oxygen species in ultraviolet-induced photodamage of the skin. Cell Div. 2024;19(1):1. doi:10.1186/s13008-024-00107-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zheng M, Liu Y, Zhang G, Yang Z, Xu W, Chen Q. The applications and mechanisms of superoxide dismutase in medicine, food, and cosmetics. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1675. doi:10.3390/antiox12091675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Fujiwara T, Dohi T, Maan ZN, Rustad KC, Kwon SH, Padmanabhan J, et al. Age-associated intracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency potentiates dermal fibroblast dysfunction during wound healing. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(4):485–92. doi:10.1111/exd.13404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Islam MN, Rauf A, Fahad FI, Emran TB, Mitra S, Olatunde A, et al. Superoxide dismutase: an updated review on its health benefits and industrial applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(26):7282–300. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1913400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Chen J, Li H, Chen J. Human epidermal growth factor coupled to different structural classes of cell penetrating peptides: a comparative study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;105(Pt 1):336–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Carillon J, Rouanet JM, Cristol JP, Brion R. Superoxide dismutase administration, a potential therapy against oxidative stress related diseases: several routes of supplementation and proposal of an original mechanism of action. Pharm Res. 2013;30(11):2718–28. doi:10.1007/s11095-013-1113-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zinsli LV, Stierlin N, Loessner MJ, Schmelcher M. Deimmunization of protein therapeutics—recent advances in experimental and computational epitope prediction and deletion. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;19(4791):315–29. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2020.12.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gordon C, Raghu A, Greenside P, Elliott H. Generative humaniztion for therapeutic antibodies. arXiv:2412.04737. 2024. [Google Scholar]

31. Litwiniuk M, Krejner A, Speyrer MS, Gauto AR, Grzela T. Hyaluronic acid in inflammation and tissue regeneration. Wounds. 2016;28(3):78–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

32. Phatale V, Vaiphei KK, Jha S, Patil D, Agrawal M, Alexander A. Overcoming skin barriers through advanced transdermal drug delivery approaches. J Control Release. 2022;351(1):361–76. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.09.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Khare N, Shende P. Microneedle system: a modulated approach for penetration enhancement. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2021;47(8):1183–92. doi:10.1080/03639045.2021.1992421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Desai P, Patlolla RR, Singh M. Interaction of nanoparticles and cell-penetrating peptides with skin for transdermal drug delivery. Mol Membr Biol. 2010;27(7):247–59. doi:10.3109/09687688.2010.522203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. El-Andaloussi S, Järver P, Johansson HJ, Langel U. Cargo-dependent cytotoxicity and delivery efficacy of cell-penetrating peptides: a comparative study. Biochem J. 2007;407(2):285–92. doi:10.1042/BJ20070507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Brooks N, Esparon S, Pouniotis D, Pietersz GA. Comparative immunogenicity of a cytotoxic T cell epitope delivered by penetratin and TAT cell penetrating peptides. Molecules. 2015;20(8):14033–50. doi:10.3390/molecules200814033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Madani F, Lindberg S, Langel U, Futaki S, Gräslund A. Mechanisms of cellular uptake of cell-penetrating peptides. J Biophys. 2011;2011(6):414729. doi:10.1155/2011/414729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bechara C, Sagan S. Cell-penetrating peptides: 20 years later, where do we stand? FEBS Lett. 2013;587(12):1693–702. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools