Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

TRIM32 Promotes Glycolysis in Keloid Fibroblasts and Progression of Keloid Scars via Regulation of the PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway

1 Department of Burn, Yixing People’s Hospital, Yixing, 214200, China

2 Department of Dermatology and Venereal Disease, Hangzhou Xixi Hospital, Hangzhou Sixth People’s Hospital, Hangzhou Xixi Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, 310023, China

* Corresponding Author: Hua Jin. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1529-1543. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066479

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: The present study investigated whether Tripartite Motif-Containing Protein 32 (TRIM32) contributes to the aberrant activation of keloid fibroblasts (KFs) via glycolysis. Methods: The expression levels of TRIM32, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), hexokinase 2 (HK2), and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) in normal human skin fibroblasts (NFs) and KFs were analyzed using RT-qPCR analyses and western blotting. Cellular proliferation, invasion, and migration were evaluated using Transwell, wound healing, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), and cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assays. The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) was measured using the XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer. Glucose uptake and ATP production were measured using specific assay kits. The expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was determined by immunofluorescence assays. The expression levels of collagen I, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), fibronectin (FN), and components of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling pathway were quantified by western blotting. Results: The expression of TRIM32 and glycolysis-related proteins was significantly elevated in KFs compared to that in NFs. TRIM32 overexpression enhanced the proliferation, invasion, and migration of KFs, as well as extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, glucose uptake, and ATP production, while TRIM32 silencing produced the opposite effects. The glycolysis inhibitor, 2-deoxy-glucose (2-DG), significantly suppressed the biological functions of KFs; however, TRIM32 overexpression effectively counteracted the inhibitory effects of 2-DG. TRIM32 activated the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in KFs. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 decreased cellular glycolysis, with TRIM32 overexpression mitigated these inhibitory effects. Conclusion: This study demonstrated that TRIM32 enhances the viability of KFs by regulating glycolytic activity, potentially mediated via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby suggesting novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of keloids.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileKeloids represent a proliferative scarring condition characterized by the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) and the abnormal proliferation of fibroblasts [1]. The expansion of a keloid beyond its original boundary and subsequent invasion into adjacent normal skin tissues resembles tumor-like behavior, leading to its classification as a benign dermal tumor [2,3]. Keloid formation typically results from trauma, infection, or burns, and is frequently accompanied by pain, itching, discomfort, and occasional bleeding. These lesions persist without spontaneous regression and exhibit high recurrence rates, often causing significant psychological distress in patients [4]. The conventional treatments include surgical excision, laser therapy, radiotherapy, or a combination of surgery and steroid injection [5]; however, no method consistently ensures a cure or effectively reduces the recurrence rates. Keloids remain among the most challenging dermatological conditions. Targeting the proliferation, invasion, and migration of fibroblasts, as well as ECM formation and deposition, may offer an effective strategy for inhibiting the progression of keloid scars.

Glycolysis was first identified and characterized in cancer cells. To facilitate rapid proliferation and malignant transformation, tumor cells shift from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis, generating energy by producing lactic acid through elevated glucose consumption [6,7]. Recent studies have established metabolic reprogramming as a critical factor in fibrotic conditions, including keloids [8]. Research indicates that keloid tissues exhibit enhanced glucose metabolism compared to that in normal skin, characterized by increased glucose uptake by fibroblasts, elevated lactate production, and increased activity of glycolytic enzymes [9]. Consequently, glycolysis represents a potential target for inhibiting the activation of keloid fibroblasts (KFs).

The proteins in the tripartite motif (TRIM) family consist of over 70 protein members that play key roles in cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, autophagy, and muscle homeostasis [10]. TRIM-Containing Protein 32 (TRIM32) is a member of the TRIM family that participates in various physiological processes, including inflammatory cell damage, oxidative stress, muscle regeneration, and tumorigenesis [11]. Research indicates that the inhibition of TRIM32 reduces high glucose-induced apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammatory injury in podocytes by modulating the protein kinase B (AKT)/glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β)/nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway [12]. Furthermore, TRIM32 has been shown to enhance the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells by activating the β-connexin signaling pathway [13]. Recent studies have identified the roles of TRIM32 in glycolysis-mediated cell growth. TRIM32 silencing has been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit the proliferation of gastric cancer cells in vitro [14]. TRIM32 promotes glycolysis and tumor progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by accelerating the degradation of fructose-bisphosphatase 2 (FBP2) via direct interactions [15]. Studies have additionally revealed that TRIM32 expression is upregulated in keloid tissues compared to that in normal skin samples [16]. The previse role of TRIM32 in the activation of KFs through glycolysis warrants further investigation.

It has been demonstrated that the proliferation of KFs is enhanced via the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathway [17], and that the long-chain non-coding RNA, uc003jox.1, promotes the invasion and proliferation of KFs by activating PI3K/AKT signaling [18]. It has been additionally observed that TRIM32 facilitates glycolysis and activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [14], while AKT signaling promotes glycolytic activity [19]. The present study aimed to investigate whether TRIM32 promotes glycolysis via the AKT signaling pathway.

Human KFs and normal skin fibroblasts (NFs) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (USA). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Hyclone, Cat. No. SH30022, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 10270-106, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (100 IU/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. P0389, St. Louis, MO, USA). All the cells were maintained at 37°C in a sterile incubator in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All the cell lines were regularly screened for Mycoplasma contamination to ensure experimental reliability, and the results confirmed the absence of Mycoplasma contamination in all cell lines.

Negative control (Ov-NC) and TRIM32 overexpression (Ov-TRIM32) plasmids (Hanbio, Shanghai, China) were constructed to induce TRIM32 overexpression in KFs. TRIM32 expression was downregulated in KFs using an siRNA targeting TRIM32 (siRNA-TRIM32: 5′-AUAACUCCCUCAAGGUAUAUATT-3′) and a negative control siRNA (siRNA-NC: 5′-UGAAGUUGAGAAGUCCAAUAGTT-3′) (Hanbio, China). The plasmids or siRNAs were transfected into KFs using Lipofectamine 2000 regent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The transfected cells were harvested after 48 h of incubation for subsequent experiments.

2.3 Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the transfected and control KFs using TRIzol reagent (T9108, Takara, Dalian, China), and cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (RR067A, Takara). We subsequently conducted qPCR using an ABI Prism 7300 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The relative mRNA expression levels were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Table S1).

Total proteins were extracted from the transfected and control KFs using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, P0013C, Shanghai, China). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 23225, Waltham, MA, USA). The total protein (40 μg) was subsequently separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membranes (Merck Millipore, Cat. No. IPVH00010, Hessen, Germany). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. The membranes were subsequently incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit (1:2000, ab6721, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or goat anti-mouse (1:2000, ab205719, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) antibodies) for 1 h at room temperature. The protein bands were visualized using an ECL reagent (Epizyme, Cat No. 23451, Shanghai, China). The density of the target protein bands was analyzed using ImageJ software (v.3.0) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The primary antibodies used in this study included: TRIM32 (1:1000, Cat. No. ab96612, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1; 1:800, Cat. No. ab150299, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), hexokinase 2 (HK2; 1:1000, Cat. No. 2867, CST, Danvers, MA, USA), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1; 1:1000, Cat. No. 3062, CST, Danvers, USA), PI3K (1:1000, Cat. No. 4292, CST, Danvers, USA), phosphorylated PI3K (p-PI3K; 1:1000, Cat. No. 4228, CST, Danvers, USA), β-actin (1:1000, Cat. No. 4967, CST, Danvers, USA), collagen I (1:1000, Cat. No. 72026, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), p-AKT (1:2000, Cat. No. 66444-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), AKT (1:2000, Cat. No. 10176-2-AP, Proteintech), fibronectin (FN; 1:2000, Cat. No. 15613-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and alpha-smooth muscle actin (1:1000, Cat. No. 14395-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China). The AKT inhibitor LY294002 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat. No. #124005, USA) [20].

2.5 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assays

KFs from the different treatment groups were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3000 cells/well and cultured in an incubator. The wells were supplemented with 100 μL fresh DMEM and 10 μL CCK-8 reagent (C0038, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After 30 min of incubation at 37°C, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6 Determination of Cell Proliferation with 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) Assays

EdU assays were performed using the EdU Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (C0071S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, KFs from the different treatment groups were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well. EdU reagent (50 μL) was added to the cells, followed by nuclear staining with DAPI reagent (C1005, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The cells were subsequently visualized and photographed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Cat. No. CKX53, Tokyo, Japan).

Control or transfected KFs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. When the cells in the culture reached 80%–90% confluence, the monolayer was scratched with the tip of a 200 μL pipette. After 24 h of incubation, images were captured using a microscope (CK40, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and the wound areas in each treatment group were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Transfected or control KFs were suspended in 100 μL serum-free DMEM at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and seeded into the upper chambers of Matrigel-coated 24-well plates. The lower chamber was filled with 500 μL of complete medium, and the cells were incubated for 24 h. The invaded cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet reagent (C0121, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for an additional 15 min. Cell invasion was quantified by counting the stained cells in randomly selected fields under a microscope (CK40, Olympus Corporation).

2.9 Measurement of Glucose Absorption and ATP Production

Glucose uptake was measured using a Glucose Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, #K606-100, Exton, PA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The transfected and control KFs were separately seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well. After 8 h of attachment, the cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 24 h. After collecting the supernatant, the glucose levels were measured using a Glucose Assay Kit (Abcam, Cat. No. ab65333, Cambridge, UK). Glucose uptake was indirectly determined by measuring the residual glucose in the cell culture medium. The ATP levels in the transfected and control KFs were quantified using an ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat. No. S0026), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cells were lysed in ATP assay buffer, mixed with ATP working solution, and incubated at room temperature for ten seconds. The relative light units (RLUs) were measured using a luminometer (Winooski, VT, USA). The protein concentrations in the samples were determined using a BCA kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and the ATP levels were calculated based on a standard curve. All the measurements were performed in triplicate for each sample and standard.

2.10 Immunofluorescence Experiments

KFs from the different treatment groups were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well and incubated overnight. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized by incubating with 0.1% TritonX-100 reagent for 5 min. The cells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (ST023, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and incubated overnight at 4°C with an α-SMA primary antibody (1:150,14395-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody (1:200, Cat. No. RGAR002, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclear staining was performed using DAPI reagent (Beyotime, Cat. No. C1005, Shanghai, China), and images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (CK40, Olympus Corporation).

2.11 Detection of Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR)

The ECAR was measured using an XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Following the manufacturer’s instructions, KFs treated with the glycolysis inhibitor, 2-DG (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. D8375), were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 ×104 cells/well, and the ECAR was measured using the Seahorse XP glycolytic Stress Test Kit (Agilent Technologies, Cat. No. #103017100). Data analysis was performed using Seahorse software, and the ECAR was expressed in mpH/min.

All the experiments were independently conducted in at least triplicate. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (v8.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), and the results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical significance of the inter-group differences was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t-tests, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

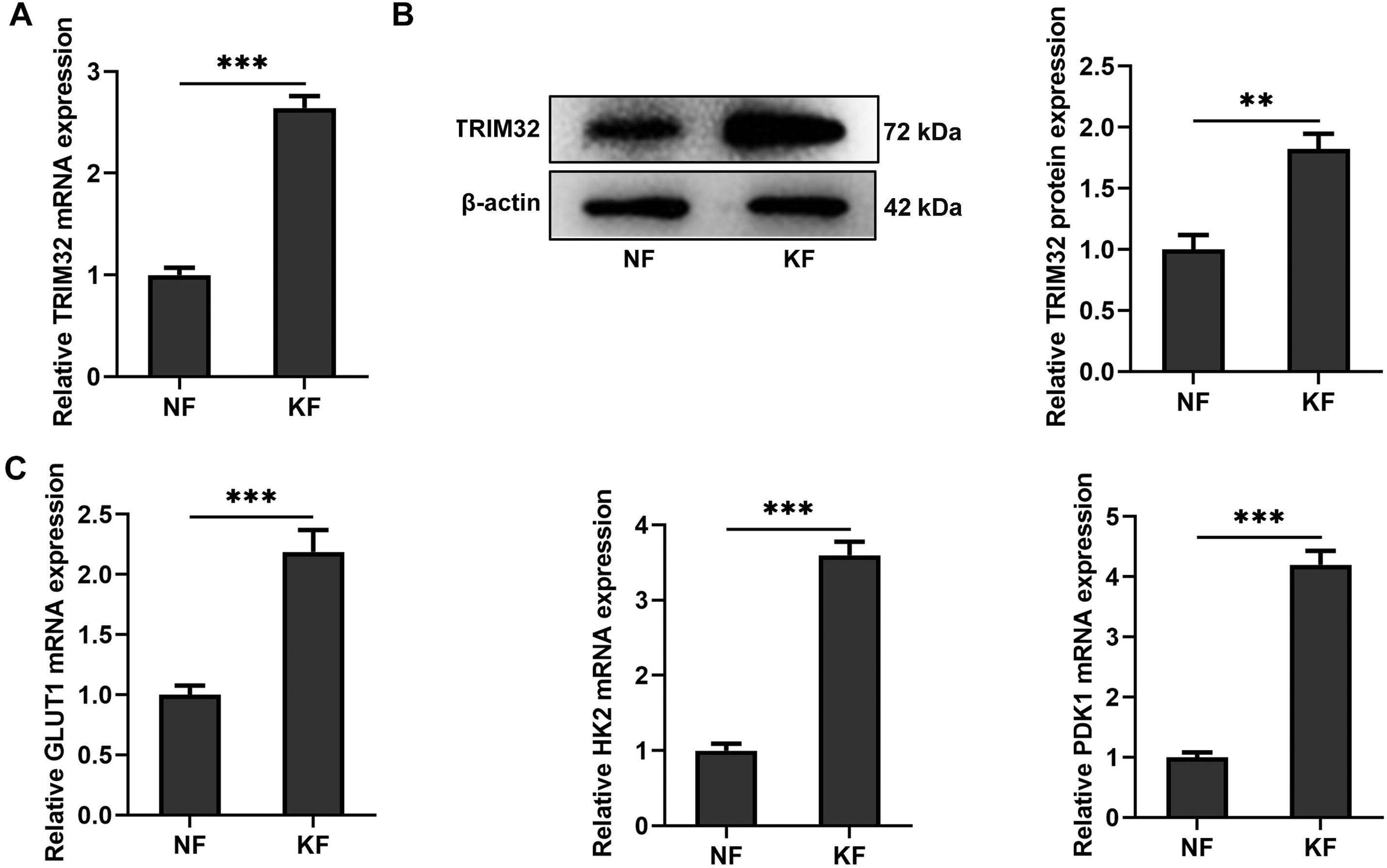

3.1 KFs Exhibited Elevated TRIM32 Expression and Enhanced Glycolytic Activity

The expression levels of TRIM32 and glycolysis-related proteins in KFs were initially investigated in this study. Western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses revealed that TRIM32 expression was significantly elevated in KFs compared to that in NFs (Fig. 1A,B). The expression levels of GLUT1, HK2, and PDK1 were also upregulated in the KF group relative to those in the NF group (Fig. 1C,D). These preliminary findings demonstrated that TRIM32 expression and glycolytic activity were elevated in KFs.

Figure 1: Keloid fibroblasts (KFs) exhibit elevated TRIM32 expression and glycolytic activity. (A, B). Expression levels of TRIM32 in human KFs and normal fibroblasts (NFs), as determined by western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses. (C, D) Expression levels of glycolysis-related proteins (GLUT1, HK2, and PDK1), as determined by western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

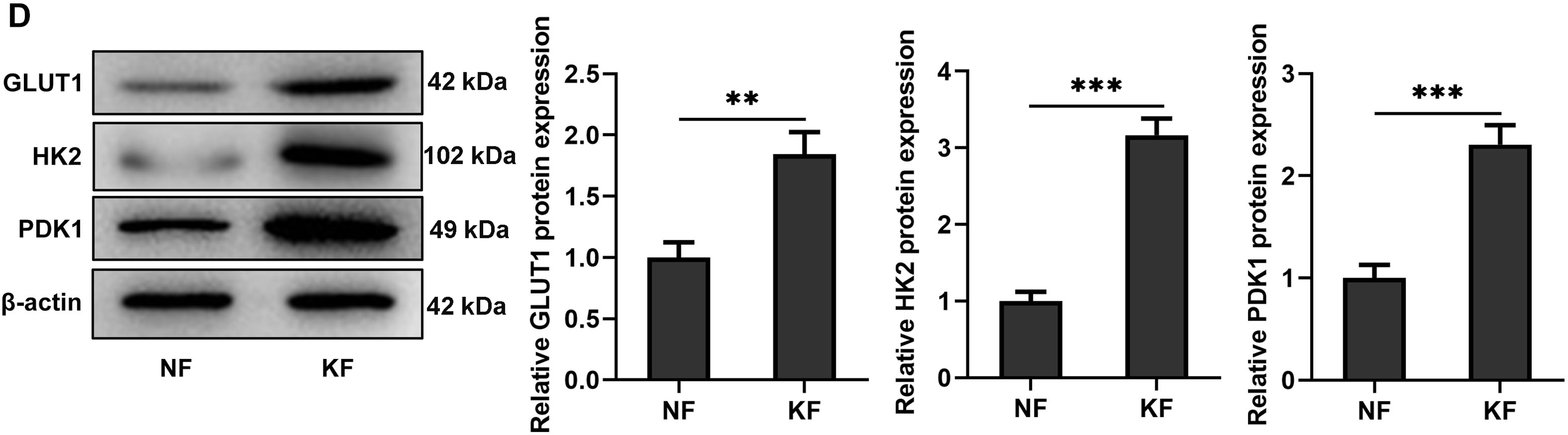

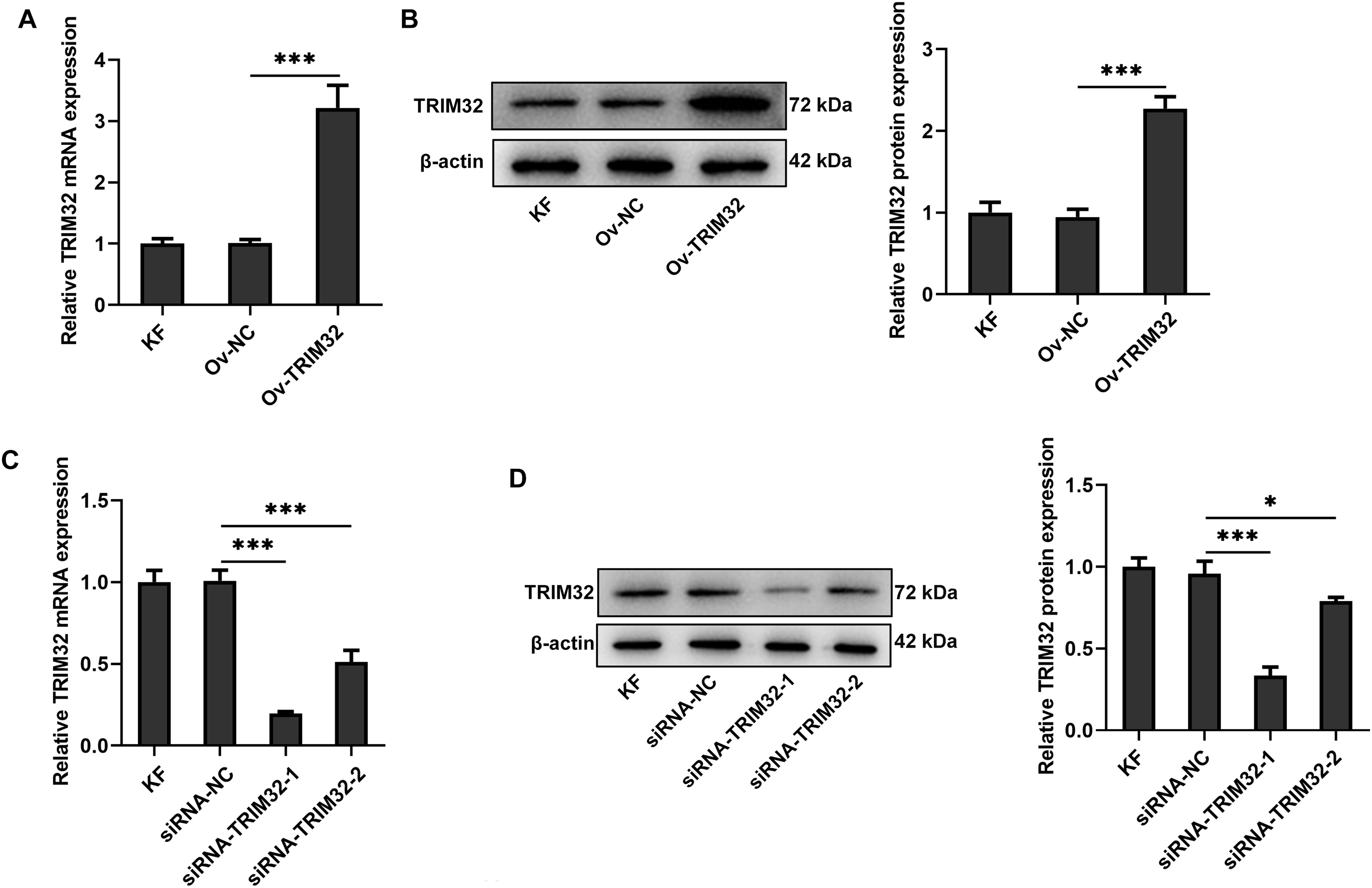

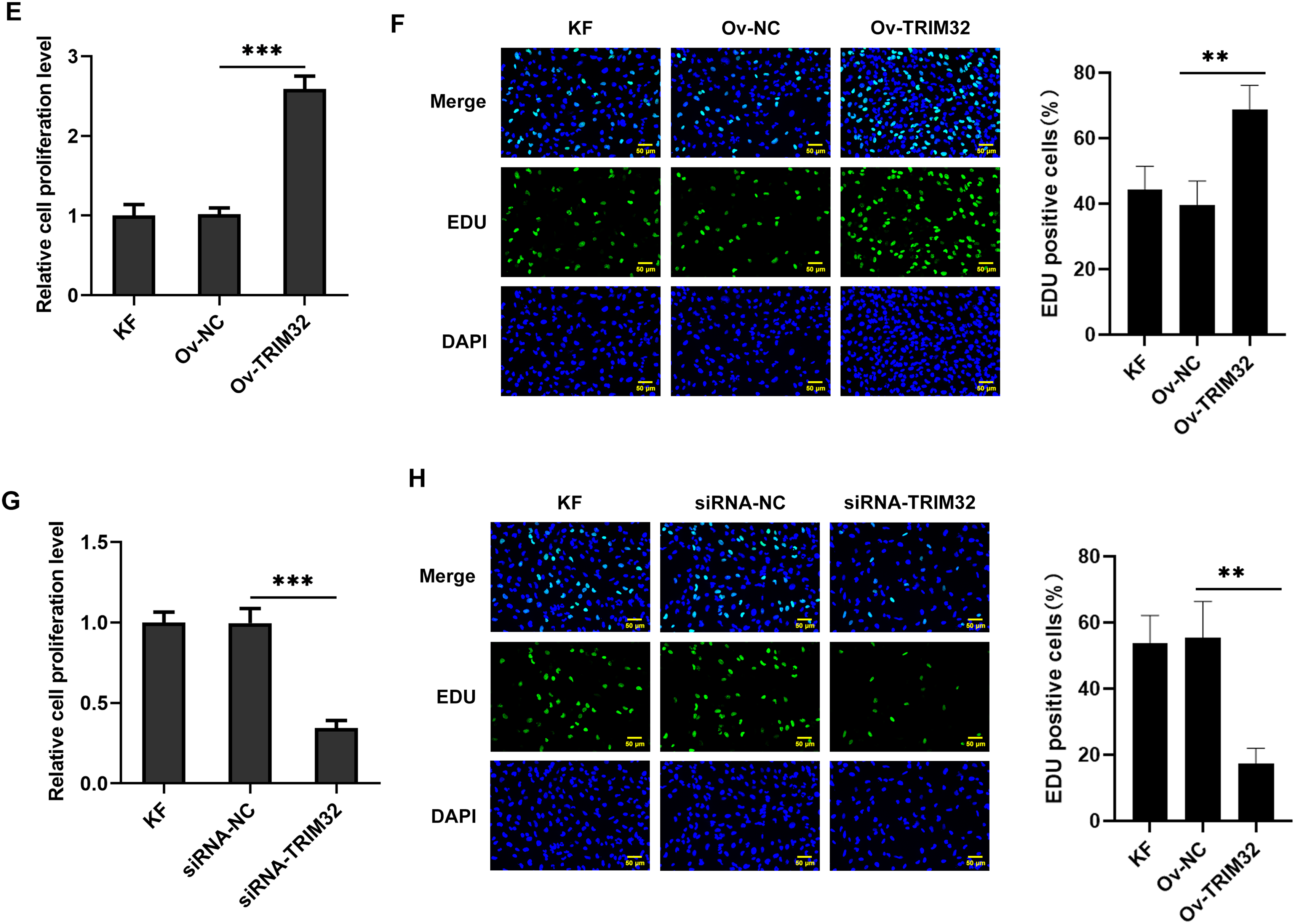

3.2 TRIM32 Expression Affects the Proliferation, Invasion, and Migration of KFs

To investigate the role of TRIM32 in KFs, the gene was either knocked down or overexpressed in KFs and NFs. The transfection efficiency was assessed by western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses. The findings revealed that siRNA-TRIM32-1 exhibited the highest knockdown efficiency and was therefore selected for subsequent experiments (Fig. 2A–D). The proliferative, invasive, and migratory potential of the KFs were subsequently assessed. CCK-8 and EdU assays revealed that the upregulation of TRIM32 significantly enhanced cell proliferation (Fig. 2E,F), while TRIM32 silencing suppressed the proliferation of KFs (Fig. 2G,H). Transwell and wound healing assays demonstrated that TRIM32 overexpression increased the invasive and migratory potential of KFs, whereas TRIM32 silencing significantly diminished these effects compared to those in the control group (Fig. 3A–D). These findings indicate that TRIM32 likely plays a crucial role in the proliferation, invasion, and migration of KFs.

Figure 2: Effects of TRIM32 expression on the proliferation, invasion, and migration of human keloid fibroblasts (KFs). Evaluation of (A, B) TRIM32 overexpression and (C, D) TRIM32 knockdown in human KFs. Evaluation of cell proliferation through EdU and CCK-8 assays following (E, F) TRIM32 overexpression and (G, H) TRIM32 knockdown; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Figure 3: Effects of TRIM32 expression on the invasion and migration of human keloid fibroblasts (KFs). Evaluation of cell migration and invasion using Transwell and wound healing assays following (A, B) TRIM32 overexpression and (C, D) TRIM32 knockdown; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

3.3 TRIM32 Expression Altered ECM Deposition in KFs

The effects of TRIM32 expression on ECM deposition in KFs were evaluated through western blotting and immunofluorescence assays. As illustrated in Fig. 4A,B, the expression levels of collagen I, α-SMA, and FN were elevated in KFs overexpressing TRIM32 compared to those in the control group, while TRIM32 silencing produced the opposite effects. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that the expression levels of α-SMA were similarly elevated following TRIM32 overexpression, whereas TRIM32 knockdown produced the opposite effect (Fig. 4C,D). These findings suggest that alterations in TRIM32 expression influenced ECM deposition in KFs.

Figure 4: TRIM32 expression alters extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition in human keloid fibroblasts (KFs). (A, B) The expression levels of collagen I, α-SMA, and FN were determined by western blotting following TRIM32 overexpression or knockdown. (C, D) The expression of α-SMA following TRIM32 overexpression or interference was determined by immunofluorescence assays; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

3.4 TRIM32 Regulates Glycolytic Activity in KFs

We subsequently investigated whether the alterations in TRIM32 expression influenced glycolytic activity in KFs. Compared to that in the KF group, the ECAR was elevated in the Ov-TRIM322 group, but significantly reduced in the siRNA-TRIM32 group, as illustrated in Fig. 5A,B. Furthermore, the Ov-TRIM32 group exhibited a marked increase in glucose uptake and ATP production (Supplementary Fig. S1A,B), while the siRNA-TRIM32 group exhibited a significant reduction in glucose uptake and ATP production (Supplementary Fig. S1C,D). Western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses revealed that the expression levels of GLUT1, HK2, and PDK1 were significantly upregulated in the Ov-TRIM32 group compared to those in the KF group (Fig. 5C,D), but markedly downregulated following TRIM32 silencing (Fig. 5E,F). These findings collectively indicate that TRIM32 serves as a positive regulator of glycolytic activity in KFs.

Figure 5: TRIM32 regulates glycolytic activity in human keloid fibroblasts (KFs). (A, B) Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in KFs following TRIM32 overexpression and knockdown. Expression levels of glycolysis-related proteins, GLUT1, HK2, and PDK1, in KFs, as determined by RT-qPCR analysis and western blotting following (C, D) TRIM32 overexpression and (E, F) TRIM32 knockdown. The data are presented as the mean ± SD; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

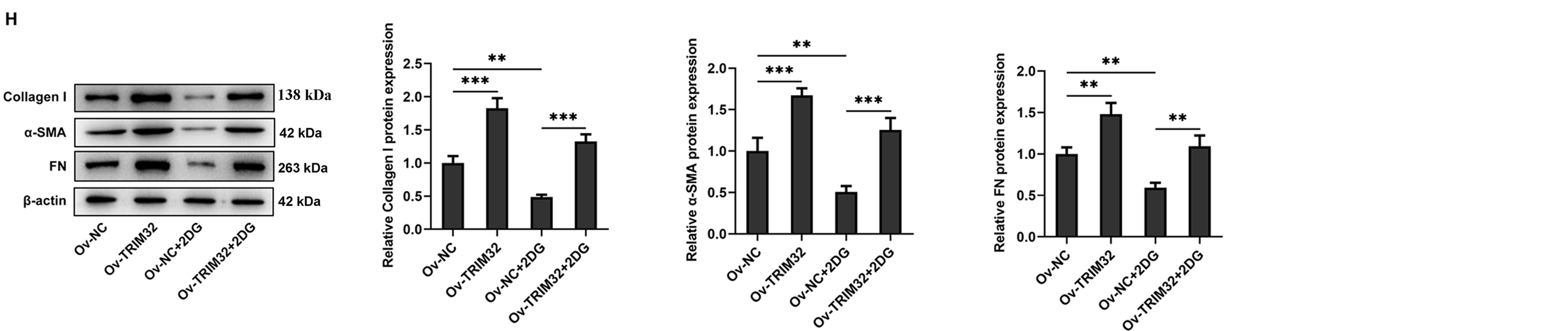

3.5 TRIM32 Enhances KF Proliferation, Invasion, Migration, and ECM Production by Promoting Glycolysis

The role of glycolysis in promoting KF proliferation, invasion, migration, and ECM production was further verified by administering the glycolysis inhibitor, 2-DG (0.5 mM). The findings revealed that, compared to that observed in the Ov-NC group, the ECAR was significantly reduced in the Ov-NC+2-DG group (Fig. 6A), which was accompanied by the downregulation of glycolysis-related proteins at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6B,C), a marked reduction in cell proliferation, invasion, and migration (Fig. 6D–G), and a notable reduction in ECM deposition (Fig. 6H,I). Notably, TRIM32 overexpression significantly reversed the effects induced by 2-DG. These findings collectively indicated that TRIM32 potentially regulates the activity of KFs via the modulation of glycolytic activity.

Figure 6: TRIM32 enhances human keloid fibroblasts (KFs) proliferation, invasion, migration, and extracellular matrix (ECM) production by promoting glycolysis. (A) Detection of Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in KFs. ***p < 0.001 (Ov-TRIM32 vs. Ov-NC); #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 (Ov-NC+2-DG vs. OV-NC), and $p < 0.05, $$p < 0.01, $$$p < 0.001 (Ov-TRIM32+2-DG vs. Ov-NC+2-DG). (B, C) Expression of glycolysis-related proteins, as determined through RT-qPCR analyses and western blotting. (D, E) Evaluation of cell proliferation through CCK-8 and EdU assays. (F, G) Evaluation of cell invasion and migration through wound healing and Transwell assays. (H) Expression levels of collagen I, α-SMA, and FN, as determined through western blotting. (I) Detection of α-SMA expression through immunofluorescence assays. The data are presented as the mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

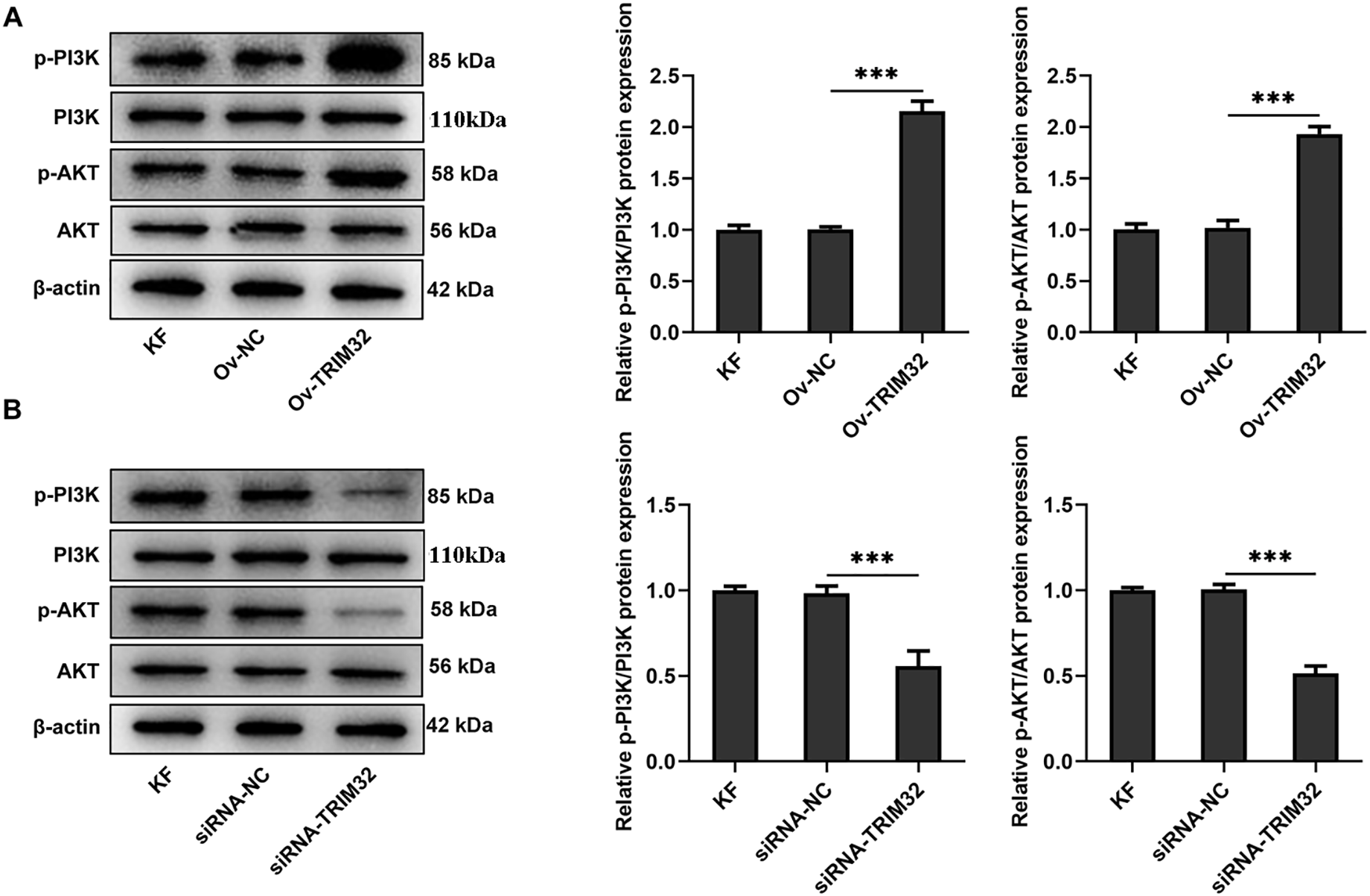

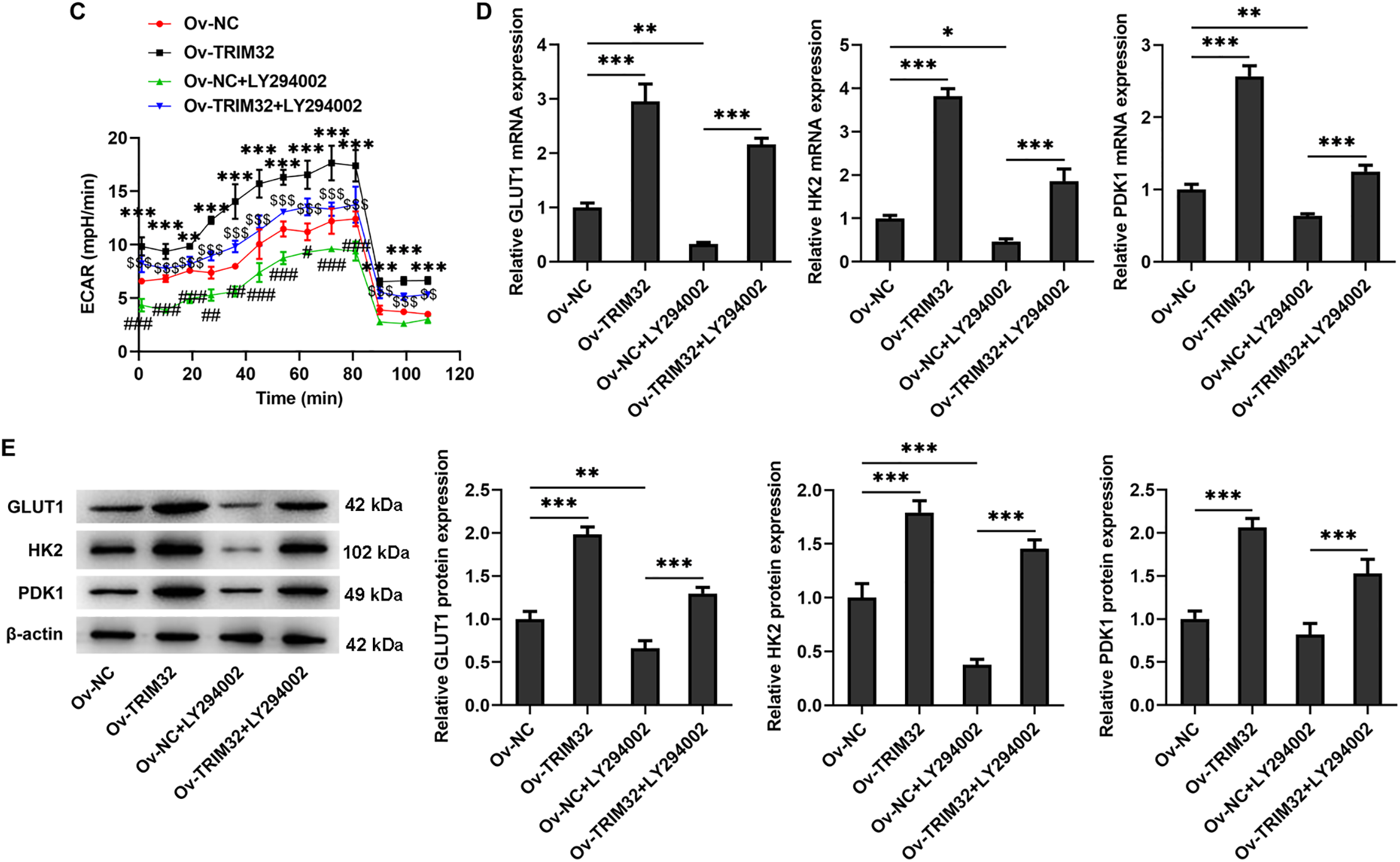

3.6 TRIM32 Enhances Glycolytic Activity in KFs by Activating PI3K/AKT Signaling

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway was subsequently investigated to elucidate the mechanism by which TRIM32 regulates glycolytic activity in KFs. The results demonstrated that TRIM32 overexpression significantly upregulated the levels of phosphorylated PI3K and AKT (Fig. 7A), while TRIM32 silencing produced the opposite effects (Fig. 7B). Treatment with the AKT inhibitor, LY294002 (10 μM), significantly decreased glycolytic activity in the KFs. However, TRIM32 overexpression significantly mitigated the inhibitory effect of LY294002 (Fig. 7C,D). Additionally, LY294002 (10 μM) significantly downregulated the expression levels of glycolysis-related proteins, and this reduction was significantly attenuated by TRIM32 overexpression (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7: TRIM32 enhances glycolytic activity in human keloid fibroblasts (KFs) by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. (A, B). Alterations in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway following TRIM32 overexpression or knockdown, as determined by western blotting; ***p < 0.001. (C) Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) measurement in KFs; **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 (Ov-TRIM32 vs. Ov-NC); #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 (Ov-NC+LY294002 vs. OV-NC), and $$p < 0.01, $$$p < 0.001 (Ov-TRIM32+LY294002 vs. Ov-NC+LY294002). (D, E) Expression levels of glycolysis-related proteins, as determined by RT-qPCR analyses and western blotting; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Keloids are tumor-like, benign cutaneous fibroproliferative lesions that remain resistant to current therapeutic approaches. Research indicates that fibroblasts play a crucial role in the development of keloids. The healing of skin injuries is regulated by multiple cytokines and growth factors [21], with fibroblasts playing a significant regulatory role in keloid formation [22–24]. Following injury, dermal fibroblasts become activated and differentiate into myofibroblasts, leading to increased α-SMA expression. These cells subsequently proliferate and migrate to the site of the wound, where they synthesize a complex ECM primarily consisting of collagen I and III, and secrete substantial quantities of collagen, thereby contributing to the initial formation of keloids [25,26]. Under normal conditions, fibroblasts either become inactive or undergo apoptosis following the restoration of tissue integrity [27]. However, following stimulation by pro-survival signals from the fibrotic microenvironment, KFs remain active, continuously secrete ECM, and evade apoptosis, thereby contributing to the accumulation of scar tissue [28]. Therefore, the effective inhibition of KF proliferation, invasion, migration, and ECM deposition may represent a viable strategy for suppressing scar proliferation. The present study demonstrated that TRIM32 expression is elevated in KFs, and that the overexpression of TRIM32 promotes KF proliferation, invasion, migration, and ECM deposition, while TRIM32 silencing produced the opposing effects. These findings collectively suggest that this modulatory effect is likely mediated via PI3K/AKT signaling-driven glycolytic activity in KFs.

TRIM32 functions as a key cellular regulator that contributes to the progression of various diseases and mediates numerous physiological and pathological processes, including cell growth, muscle regeneration, immune responses, and carcinogenesis [29]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the overexpression of TRIM32 accelerates the progression of rheumatoid arthritis by increasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in fibroblast-like synoviocytes [30]. The inhibition of TRIM32 has been shown to increase the therapeutic susceptibility of gliomas to temozolomide, thereby suppressing tumor proliferation [31]. Additionally, TRIM32 promotes the invasion and proliferation of gastric cancer cells by activating β-catenin signaling [13]. The present study revealed that TRIM32 expression was upregulated in the KFs, consistent with the findings of recent research suggesting TRIM32 as a potential biomarker for acne scarring, with elevated levels observed in keloid tissues. Although the precise role of TRIM32 in keloid formation remains unclear, further experiments demonstrated that the overexpression of TRIM32 enhanced the proliferation, invasion, and migration of KFs. Additionally, the upregulation of collagen I, αSMA, and FN expression indicated that TRIM32 overexpression increased the deposition of ECM. However, the precise mechanism by which TRIM32 regulates the activity of KFs requires further investigation.

Glycolysis serves as a crucial energy source for keloids, supporting the high energy demands of rapid fibroblast proliferation. Previous research has demonstrated that glycolysis is enhanced in KFs, characterized by an increase in the activities of glycolysis-related enzymes, including GLUT1, HK2, PDK1, and pyruvate kinase M2 [9]. Consequently, targeting glycolysis may represent an effective approach for inhibiting the progression of KFs. Lu et al. demonstrated that inhibition of the activity of GLUT1, a key glycolytic enzyme, reduces the proliferation of fibroblasts [32]. Wang et al. demonstrated that the inhibition of phosphoglycerate kinase 1 decreases glycolytic activity, thereby reducing KF proliferation, migration, invasion, and expression of type I collagen [16]. The present study similarly confirmed that the expression of glycolysis-related enzymes, including GLUT1, HK2, and PDK1, was upregulated in KFs, compared to that in NFs, while treatment with the glycolysis inhibitor, 2-DG, suppressed KF proliferation, invasion, migration, and ECM deposition. These findings confirmed that glycolysis plays a significant role in the progression of KFs and the development of keloids.

Previous research has demonstrated that TRIM32 plays a significant role in the growth and proliferation of gastric cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma cells via the regulation of glycolysis [13,15,33]. The present study revealed that the modulation of TRIM32 expression altered the glycolytic pathway in KFs, with TRIM32 overexpression effectively counteracting the inhibitory effects of 2-DG on KF proliferation, invasion, migration, and ECM deposition. These findings suggest that TRIM32 may promote the progression of KFs via the regulation of glycolysis. The present study additionally established that the upregulation of TRIM32 expression in KFs activated the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, and further elucidated its role in mediating glycolytic activity. Wang et al. demonstrated that TRIM32 enhances the proliferation and apoptotic resistance of gastric cancer cells by activating AKT signaling and targeting glycolytic metabolism [17]. However, this study has certain limitations, as follows: (1) the mechanisms by which TRIM32 regulates the PI3K/AKT pathway, whether directly or indirectly, were not investigated, and (2) although our study demonstrated the effects of TRIM32 on the expression of glycolysis-related proteins, further studies are necessary for validating the alterations in enzyme activity using specific assays.

Altogether, the study revealed that TRIM32 enhances glycolysis through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby promoting KF proliferation, invasion, migration, and ECM deposition. These findings suggest promising novel targets and signaling mechanisms for the treatment of keloid scars.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yi Zhang and Hua Jin; data collection: Hua Jin; analysis and interpretation of results: Yi Zhang; manuscript preparation: Yi Zhang and Hua Jin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data reported in this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Figure S1: Detection of glucose uptake and ATP production in KFs following TRIM32 overexpression and knockdown. (A, C) Glucose uptake and (B, D) ATP production were determined in transfected and control KFs; ***p < 0.001. Table S1: Sequences of the primers used in the study. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.066479/s1.

References

1. Andrews JP, Marttala J, Macarak E, Rosenbloom J, Uitto J. Keloids: the paradigm of skin fibrosis—pathomechanisms and treatment. Matrix Biol. 2016;51:37–46. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2016.01.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Shi K, Qiu X, Zheng W, Yan D, Peng W. miR-203 regulates keloid fibroblast proliferation, invasion, and extracellular matrix expression by targeting EGR1 and FGF2. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1282–8. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lyons AB, Peacock A, Braunberger TL, Viola KV, Ozog DM. Disease severity and quality of life outcome measurements in patients with keloids: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45(12):1477–83. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hawash AA, Ingrasci G, Nouri K, Yosipovitch G. Pruritus in keloid scars: mechanisms and treatments. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101(10):adv00582. doi:10.2340/00015555-3923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Qi W, Xiao X, Tong J, Guo N. Progress in the clinical treatment of keloids. Front Med. 2023;10:1284109. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1284109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gao S, Shi X, Yue C, Chen Y, Zuo L, Wang S. Comprehensive analysis of competing endogenous RNA networks involved in the regulation of glycolysis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncologie. 2024;26(4):587–602. doi:10.1515/oncologie-2024-0074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Du L, Dou K, Liang N, Sun J, Bai R. miR-194-5p suppresses the Warburg effect in ovarian cancer cells through the IGF1R/PI3K/AKT axis. Biocell. 2023;47(3):547–54. doi:10.32604/biocell.2023.025048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang Q, Wang P, Qin Z, Yang X, Pan B, Nie F, et al. Altered glucose metabolism and cell function in keloid fibroblasts under hypoxia. Redox Biol. 2021;38:101815. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2020.101815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Li Q, Qin Z, Nie F, Bi H, Zhao R, Pan B, et al. Metabolic reprogramming in keloid fibroblasts: aerobic glycolysis and a novel therapeutic strategy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496(2):641–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Watanabe M, Hatakeyama S. TRIM proteins and diseases. J Biochem. 2017;161(2):135–44. doi:10.1093/jb/mvw087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bawa S, Piccirillo R, Geisbrecht ER. TRIM32: a multifunctional protein involved in muscle homeostasis, glucose metabolism, and tumorigenesis. Biomolecules. 2021;11(3):408. doi:10.3390/biom11030408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Chen Z, Tian L, Wang L, Ma X, Lei F, Chen X, et al. TRIM32 inhibition attenuates apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammatory injury in podocytes induced by high glucose by modulating the Akt/GSK-3β/Nrf2 pathway. Inflammation. 2022;45(3):992–1006. doi:10.1007/s10753-021-01597-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wang C, Xu J, Fu H, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yang D, et al. TRIM32 promotes cell proliferation and invasion by activating β-catenin signalling in gastric cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(10):5020–8. doi:10.1111/jcmm.13784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ito M, Migita K, Matsumoto S, Wakatsuki K, Tanaka T, Kunishige T, et al. Overexpression of E3 ubiquitin ligase tripartite motif 32 correlates with a poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(5):3131–8. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Yang X, Ma H, Zhang M, Wang R, Li X. TRIM32 promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma progression by enhancing FBP2 ubiquitination and degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;678:165–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.08.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang X, Wang X, Liu Z, Liu L, Zhang J, Jiang D, et al. Identification of inflammation-related biomarkers in keloids. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1351513. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1351513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang Q, Yang X, Ma J, Xie X, Sun Y, Chang X, et al. PI3K/AKT pathway promotes keloid fibroblasts proliferation by enhancing glycolysis under hypoxia. Wound Repair Regen. 2023;31(2):139–55. doi:10.1111/wrr.13067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Bu W, Fang F, Zhang M, Zhou W. Long non-coding RNA uc003jox.1 promotes keloid fibroblast proliferation and invasion through activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J Craniofac Surg. 2023;34(2):556–60. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000009122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hu X, Xu Q, Wan H, Hu Y, Xing S, Yang H, et al. PI3K-Akt-mTOR/PFKFB3 pathway mediated lung fibroblast aerobic glycolysis and collagen synthesis in lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Lab Invest. 2020;100(6):801–11. doi:10.1038/s41374-020-0404-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang X, Jin M, Yao X, Liu J, Yang Y, Huang J, et al. Upregulation of LncRNA WT1-AS inhibits tumor growth and promotes autophagy in gastric cancer via suppression of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2024;17:e18761429318398. doi:10.2174/0118761429318398240918063450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453(7193):314–21. doi:10.1038/nature07039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Deng CC, Hu YF, Zhu DH, Cheng Q, Gu JJ, Feng QL, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and increased mesenchymal fibroblasts in human fibrotic skin diseases. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3709. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24110-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chao H, Zheng L, Hsu P, He J, Wu R, Xu S, et al. IL-13RA2 downregulation in fibroblasts promotes keloid fibrosis via JAK/STAT6 activation. JCI Insight. 2023;8(6):e157091. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.157091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang Y, Chen Y, Wu J, Shi X. BMP1 promotes keloid by inducing fibroblast inflammation and fibrogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2024;125(7):e30609. doi:10.1002/jcb.30609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Henderson NC, Rieder F, Wynn TA. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature. 2020;587(7835):555–66. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2938-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu X, Chen W, Zeng Q, Ma B, Li Z, Meng T, et al. Single-cell RNA-sequencing reveals lineage-specific regulatory changes of fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells in keloids. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142(1):124–35.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2021.06.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Hinz B, Lagares D. Evasion of apoptosis by myofibroblasts: a hallmark of fibrotic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(1):11–31. doi:10.1038/s41584-019-0324-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Feng Y, Wu JJ, Sun ZL, Liu SY, Zou ML, Yuan ZD, et al. Targeted apoptosis of myofibroblasts by elesclomol inhibits hypertrophic scar formation. EBioMedicine. 2020;54:102715. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Jeong SY, Choi JH, Kim J, Woo JS, Lee EH. Tripartite motif-containing protein 32 (TRIM32what does it do for skeletal muscle? Cells. 2023;12(16):2104. doi:10.3390/cells12162104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Liang T, Song M, Xu K, Guo C, Xu H, Zhang H, et al. TRIM32 promotes inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Scand J Immunol. 2020;91(6):e12876. doi:10.1111/sji.12876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cai Y, Gu WT, Cheng K, Jia PF, Li F, Wang M, et al. Knockdown of TRIM32 inhibits tumor growth and increases the therapeutic sensitivity to temozolomide in glioma in a p53-dependent and-independent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;550:134–41. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.02.098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Lu YY, Wu CH, Hong CH, Chang KL, Lee CH. GLUT-1 enhances glycolysis, oxidative stress, and fibroblast proliferation in keloid. Life. 2021;11(6):505. doi:10.3390/life11060505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wang L, Song YY, Wang Y, Liu XX, Yin YL, Gao S, et al. RHBDF1 deficiency suppresses melanoma glycolysis and enhances efficacy of immunotherapy by facilitating glucose-6-phosphate isomerase degradation via TRIM32. Pharmacol Res. 2023;198:106995. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools