Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Effect and Mechanism of Thalidomide in Ameliorating Crohn’s Disease-Related Intestinal Fibrosis

1 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Nanjing Jinling Hospital, Jinling School of Clinical Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, 210000, China

2 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Nanjing Jinling Hospital, Nanjing, 210000, China

3 Pathology Department, Nanjing Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210000, China

4 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Nanjing Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210000, China

5 Institute of Laboratory Medicine, Nanjing Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210000, China

* Corresponding Author: Fangyu Wang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1505-1528. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066504

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: A common side effect of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is intestinal fibrosis, which frequently leads to intestinal blockage and stricture formation. Although Thalidomide (THD) has shown anti-fibrotic benefits in hepatic and renal models, little is known about how it affects intestinal fibrosis and the underlying processes. The present research examines the molecular targets of THD and its potential as a treatment for intestinal fibrosis brought on by colitis. Methods: Clinical samples from Crohn’s disease (CD) patients with intestinal strictures treated with infliximab (IFX) and THD combined with IFX were collected. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) was used to develop a mouse model of intestinal fibrosis in C57BL/6 mice. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (Anti-TNFα), THD, or a combination of the two were administered to the mice. Body weight, colon length, histology, and disease activity index were used to evaluate the disease’s severity. In vitro, THD was tested on colonic fibroblast lines (CCD-18Co and MPF) to assess its effects on cell proliferation, motility, and transdifferentiation. To examine changes in gene expression and signaling pathway modifications, namely in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) pathway, RNA sequencing, qRT-PCR, and Western blotting were carried out. Results: In DSS-induced colitis, THD therapy lowered fibrosis, as seen by downregulated fibrotic markers (α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen I, and collagen III) and decreased collagen deposition. Mechanistically, THD prevented fibroblasts from transdifferentiating and decreased their vitality. Furthermore, THD inhitited the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in vivo and in vitro. Conclusion: THD inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade and suppresses colonic fibroblast transdifferentiation, which protects against DSS-induced colitis-associated fibrosis, especially when combined with anti-TNFα therapy.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileTransmural inflammation, which can affect any region from the mouth to the anus, is a characteristic of Crohn’s disease (CD), a chronic recurrent inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal system [1]. This pathological process leads to loss of intestinal compliance, impaired wound healing, and excessive collagen accumulation, ultimately resulting in intestinal fibrosis and stricture formation [2]. At the time of diagnosis, most CD patients exhibit an inflammatory phenotype. However, as the disease progresses, approximately 50% of patients develop complications such as strictures, fistulas, or abscesses, which frequently necessitate surgical intervention. Surgical intervention does not prevent recurrence or arrest the underlying pathological processes responsible for complications [3,4].

The thickness of the muscularis propria and mucosa, mostly due to mesenchymal cell growth, is one of the histological characteristics of CD-related strictures [5–7]. Fibroblasts, the principal cellular components of connective tissue, play a key role in maintaining tissue integrity [8]. During chronic tissue injury, fibroblasts can differentiate into myofibroblasts, which produce excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, contributing to fibrosis. Myofibroblasts also regulate growth factors through paracrine and autocrine mechanisms, making them pivotal players in tissue repair and remodeling. In the intestinal mucosa of CD patients, distinct cellular phenotypes exhibit interconversion [9]. In the damaged mucosal environment, activated myofibroblasts multiply and migrate, expressing α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and encouraging extracellular matrix deposition. This confers contractile properties to the intestinal tissue, exacerbating fibrotic remodeling and stricture formation [10].

Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) is considered a key driver of fibrosis, exerting potent pro-fibrotic effects, and is pivotal in CD and other fibrotic disorders [11]. TGF-β1 is a crucial modulator of fibroblast activation, promoting fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation and improving proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis [12–14]. Furthermore, TGF-β1 induces fibroblasts to increase the output of pro-fibrotic markers, such as α-SMA and fibronectin [15].

The mechanisms underlying intestinal fibrosis and ECM accumulation share similarities with fibrogenesis in other organs [16]. The expression levels of Acta2 and Col1α1 and Col3α1 increase significantly as liver and renal fibrosis progresses [17,18]. Research findings indicated that fibroblasts influenced by IBD showed a markedly increased rate of collagen production [19]. In particular, the proportions of type I and type III collagen fibrils have increased. Interestingly, type III collagen fibrils are significantly more prevalent in the submucosal layer of CD patients’ constricted intestinal mucosa. In the damaged intestinal mucosal tissue, activated myofibroblasts exhibit proliferation and migration, facilitating the formation of collagen-rich ECM and expressing α-SMA, which confers contractile capability to the intestinal tissue. However, research in this area remains limited due to a lack of standardized scoring systems for quantifying fibrosis severity and insufficient data from clinical studies. Currently, no approved anti-fibrotic therapies specifically targeting intestinal fibrosis [20]. Therapeutic approaches for CD have changed significantly over the last 20 years, most notably with the introduction of Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (Anti-TNFα), allowing many patients to have long-term disease control. However, despite these therapeutic advancements, the incidence of fibrostenosing complications has not declined, emphasizing the unmet need for effective antifibrotic strategies [21]. Anti-inflammatory drugs have shown limited efficacy in preventing or reversing fibrosis in CD, suggesting the significance of non-inflammatory mechanisms in its pathogenesis. No specific anti-fibrotic therapies have been approved for CD-associated fibrosis [22]. Challenges have hindered the development of targeted anti-fibrotic agents for clinical trials in translating experimental findings into viable therapies, and there is a lack of consensus on defining fibrosis endpoints in clinical studies.

Thalidomide (THD), a synthetic derivative of glutamic acid, was originally developed as an anti-nausea agent but was subsequently withdrawn due to its severe teratogenicity. However, THD was then brought back into use to treat several inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), discoid lupus erythematosus, stomatitis, Behcet’s syndrome, leprosy, and erythema nodosum [23]. THD treats idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and has shown notable anti-fibrotic benefits and immunomodulatory capabilities [24]. Furthermore, THD has shown promising therapeutic potential in treating liver cirrhosis, renal fibrosis, multiple sclerosis, and radiation-induced fibrosis in both clinical and experimental models [25–27]. Given these findings, THD may possess direct anti-fibrotic effects on intestinal fibrosis, warranting further investigation into its underlying mechanisms. As an immunosuppressant (IMM), THD has been shown to enhance treatment outcomes, mitigate loss of response to infliximab (IFX), and reduce long-term complications. These effects may be attributed to its ability to minimize immunogenicity and modulate drug concentrations [28]. Patients who have developed antidrug antibodies and lost their response to anti-TNF medications have benefited greatly from adding IMM to anti-TNF therapy [29,30]. Therefore, combination therapy is not only essential for the maintenance treatment of CD but may be critical in managing CD-associated fibrosis.

The current study investigated the possible function and mode of action of THD in the management and treatment of intestinal fibrosis. With an emphasis on the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B/Mammalian Target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) pathway as a putative regulatory mechanism, we evaluated THD’s inhibitory effects on fibroblast activation, proliferation, and migration.

2.1 Human Intestinal Tissue Collection

Human intestinal samples were taken from surgical patients at Nanjing University’s Jinling Hospital’s IBD Center. For histological examination, surgically removed specimens were sectioned at 4 μm, paraffin-embedded, and preserved in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. The Jinling Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study (Approval No. 2021NZKY-001-01), which was carried out strictly in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before being included in the study, all individuals provided written informed permission.

2.2 Animal Experiments and Drug Treatment

The Laboratory Animal Center of Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University, provided the female C57BL/6 mice (5 weeks old, 18–20 g) (License No. SCXK[SU] 2021-0013). The Laboratory Animal Research Center provided the animals with conventional housing conditions, which included a 12-h light/dark cycle and 23 ± 3°C. After one week of acclimatization, chronic colitis was induced by administering 1.5% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; MP Biomedicals, 0216011080, Irvine, CA, USA) in 7 days, followed by 14 days of normal water. This cycle was repeated three times to induce intestinal fibrosis [31].

(i) A control group; (ii) a DSS group; (iii) a DSS group with Anti-TNFα (Abcam, ab205587, Cambridge, MA, USA); (iv) a DSS group with THD (Changzhou Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., H32026130, Changzhou, China); and (v) a DSS group with THD in combination with Anti-TNFα were the five groups (n = 12 per group) to which sixty mice were randomly assigned. In week 7, THD was dissolved in 0.5 mL olive oil and given intragastrically once daily for two consecutive weeks. The mice were administered 50 mg/kg body weight per day (150 mg/m2/day) of the drug. Anti-TNFα was administered intraperitoneal injection at 5 mg/kg in weeks 7 and 9. At the study endpoint, mice were sacrificed, colonic tissues were harvested, and samples were either processed for histology or preserved at −80°C for molecular assays. Every procedure met institutional and ethical requirements and was authorized by Jinling Hospital’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (Approval No. 2021DZGKJDWLS-00143).

2.3 Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Expression levels of fibrosis-associated genes, including Col1α1, Col3α1, α-SMA, BGN, FBN1, FBLN1, and FBLN5, were quantified by qRT-PCR. TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15596018, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to complete total RNA isolation, and PrimeScript™ reverse transcription kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, RR047A) were used to synthesize cDNA. Amplification was done with SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takaro Bio, RR420A, Dalian, China). Every reaction was performed in triplicate, and gene expression was standardized to 18S rRNA (Table S1). Gene expression levels were normalized relative to the reference gene GAPDH and quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

2.4 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

As directed by the manufacturer, the ELISA was used to measure the amounts of cytokines in the isolated colonic tissues. The analyzed cytokines comprised mouse TNF-α (Abcam, ab10890), TGF-β (Abcam, ab277719), IL-6 (Abcam, ab100713), IL-17 (Abcam, ab213869), IL-10 (Abcam, 108870).

2.5 Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

Protease and phosphatase inhibitors were added to RIPA buffer (Beyotime, P0013B, Shanghai, China) to produce intestinal tissue homogenates and cell lysates. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Vazyme, E801, Nanjing, China). After blocking the membranes with 5% non-fat milk, they were incubated at 4°C for the whole night. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:1000 against α-SMA (Abcam, ab314895), Col1α1(Abcam, ab270946), Col3α1(Abcam, ab7535), vimentin (Abcam, ab94527), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Abcam, ab94527), mTOR (Abcam, ab94527) and p-mTOR (Abcam, ab94527). The goat anti-mouse (Abcam, ab205719) or anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, ab97051) secondary antibodies (1:2000) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were incubated for 1 h at 25°C. An imaging device was used to view and digitize protein bands (Cel Doc™ Ez System, BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.6 Histopathological Analysis

Colonic tissue sections were evaluated double-blindly using a standardized histological scoring system (Table S2). The total microscopic score was computed based on the sum of individual histological parameters. Colonic tissues were sectioned for histological analysis after being paraffin-embedded and preserved in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Beyotime, C0105S, Shanghai, China) was utilized to evaluate tissue morphology. For each animal, a minimum of six sections were analyzed, with ten randomly selected microscopic fields per section identified using automated field selection. Fluorescence microscopy (Nikon 80i, Tokyo, Japan) was used for image acquisition. The Sirius Red Staining Kit (Solarbio, G1472, Wuxi, China) and Masson’s Trichrome Staining Kit (Solarbio, G1343) were used to measure collagen deposition. In Masson’s staining, collagen fibers were visualized as blue. Sirius Red staining, viewed under polarized light (BX43, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), differentiated collagen types, with type I appearing orange-red and type III green.

2.7 Cell Culture and Treatments

Human colonic fibroblasts (CCD-18Co; GNHu43) and murine primary fibroblasts (MPF) were procured from The Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). CCD-18Co cells were kept at 37°C in humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) (Manassas, 30-2003, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; ScienCell, 0025, Shanghai, China). Before treatment, cells were serum-starved for 24 h. MPF cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Manassas, 30-2002) enriched with 10% FBS under identical incubation conditions. The CCD-18Co cell and MPF cell was routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoSEQTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4460626) on a monthly basis, and all experimental procedures were performed with mycoplasma-negative cells (Ct value > 35). For fibroblast activation, cells were treated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) (MesGen Biotechnology, MTG9020, Shanghai, China). A control group, a TGF-β1 group, a TGF-β1 with Anti-TNFα group, a TGF-β1 with THD group, and a TGF-β1 with THD in conjunction with Anti-TNFα group were the five experimental groups into which cells were subsequently separated.

Fibroblast motility was assessed utilizing Transwell inserts (Corning, 353097, Corning, NY, USA). Serum-starved fibroblasts (1.5 × 105) were seeded into the upper chambers containing serum-free medium with TGF-β1, THD, Anti-TNFα, or their combination. EMEM or DMEM containing 20% FBS as a chemoattractant was used to fill the lower chambers. Cells that had moved to the membrane’s underside after 24 h were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and photographed to be quantified.

2.9 CCK-8 Cell Viability Assay

The CCK-8 test (Beyotime, C0038) was used to assess the viability of the cells. In 96-well plates, CCD-18Co or MPF cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. They were kept for 24 h at 37°C in a humid environment with 5% CO2. Fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β (5 ng/mL) and incubated for 24 h. Then the cells were incubated with different concentrations (0, 100, 400, 800, 1600 μg/mL) of THD for 24 h. After adding 10 μL of CCK-8 solution to each well, the samples were again incubated at 37°C. A microplate reader was used to measure the sample’ absorbance at 450 nm after 2-h incubation period (SpectraMax®i3x, Gene Company Limited, Shanghai, China).

Cell viability (10%) = (OD sample-OD blank)/(OD control-OD blank) × 100%.

2.10 Immunohistochemical Analyses

Colonic sections were stained for α-SMA (Yanhui Biotechnology Co. Ltd., AF1032, Shanghai, China), Col1α1(Abcam, ab270946), and Col3α1(Abcam, ab216430) to evaluate fibrotic protein expression. Tissues were paraffin-embedded, cut into 5 μm slices, and fixed for 24 h in 4% neutral-buffered formalin. The H2O2 was used to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity following deparaffinization and rehydration. After reducing non-specific binding with 1% BSA, sections were incubated with primary antibodies (1:200) for an entire night at 4°C. After washing, the HSP70-Homolog RadB (HRB) secondary antibodies (Abcam, ab221913) (1:200) were applied for 1 h at room temperature and then dropped with freshly prepared 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen solution. During microscopic analysis, once the positive signal turned brownish-yellow, the color development was stopped by washing the sections with distilled water. Following this, the nuclei were stained with hematoxylin (Abcam, ab220365) for 3 min, after which the samples underwent dehydration and mounting processes. Images were captured with a Nikon 80i light microscope (DS-Fi3, Nikon Corporation, Japan).

2.11 Transcriptome Sequencing and Pathway Enrichment Analysis (RNA-Seq)

Total RNA from CCD-18Co and MPF cells was extracted and purified utilizing TRIzol® reagent. Differentially expressed genes in fibroblasts stimulated by TGF-β1 were identified through RNA sequencing analysis. The limma package in R 4.1.3 was used to perform differential genes. The ggplot2 and heatmap software were used to generate the volcano plots and heatmaps, respectively. Using the clusterProfiler software, enrichment analyses were performed for the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO). Genes exhibiting significant enrichment, as characterized by a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1. The top 20 KEGG pathways and GO enrichment analysis results were then selected for additional analysis. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) evaluates whether a gene set shows significant co-expression under experimental conditions by assessing the enrichment of the gene set within a ranked list of differentially expressed genes. Cytoscape version 3.9.1 was used to depict the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, which was built using information taken from the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/).

GraphPad Prism 9 was used for statistical studies (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Each experiment was independently replicated three times. Two-group comparisons were evaluated utilizing Student’s t-test, while one-way ANOVA was adopted for analyses involving more than two groups. Results are summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with statistical significance denoted as p < 0.05.

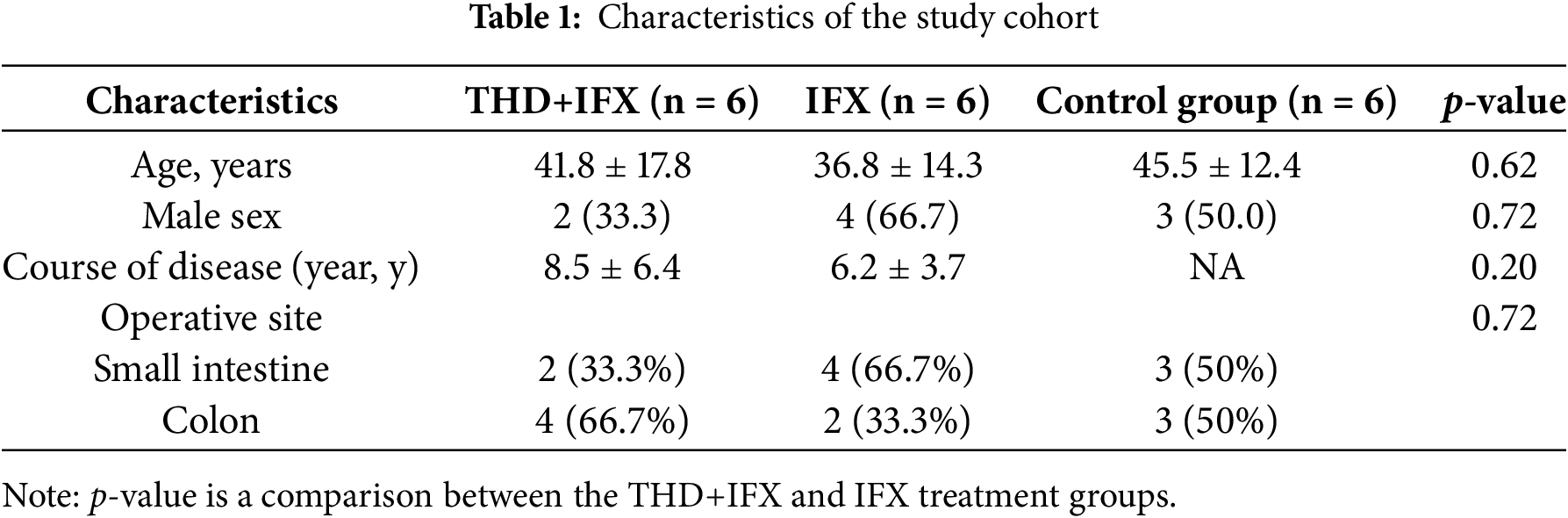

3.1 Study Cohort Baseline Characteristics (Intention-to-Treat Population)

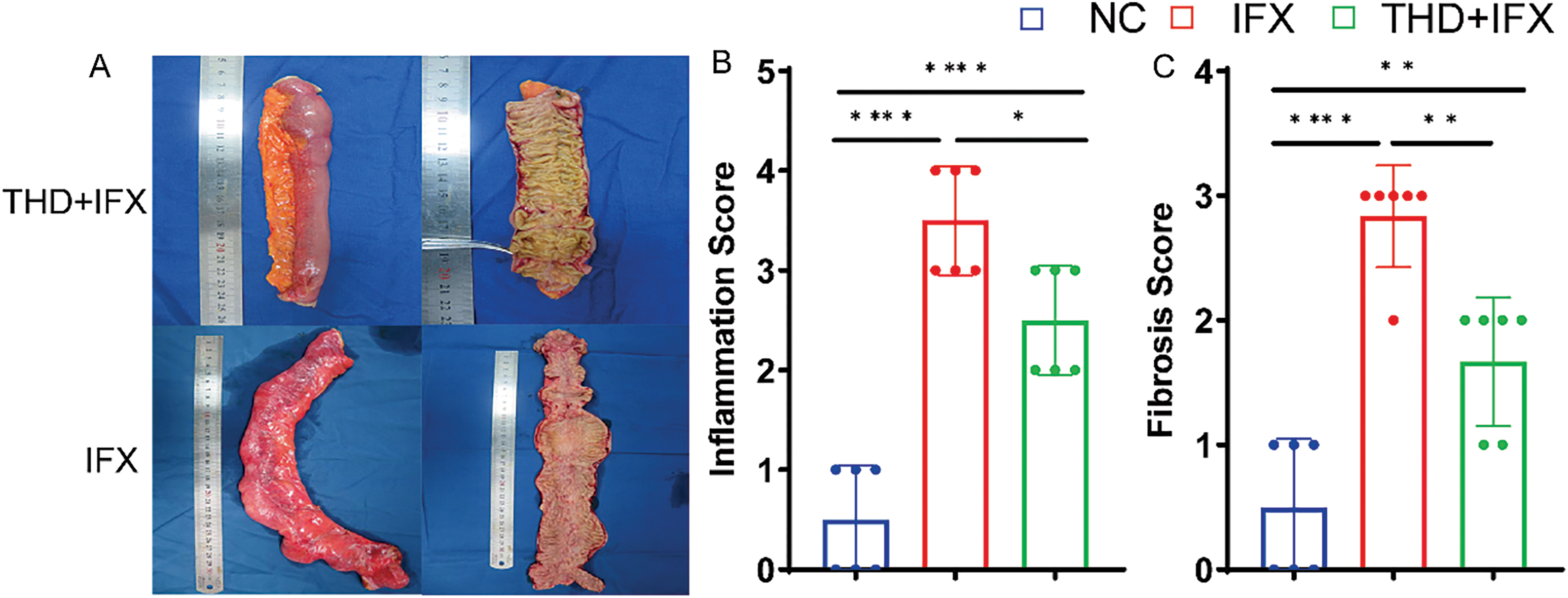

Surgical specimens were obtained from twelve CD patients with intestinal strictures (Fig. 1A). Among these patients, six had received prior IFX therapy, while the remaining six were treated with a combination of THD and IFX before surgery. The six control samples consisted of normal tissues adjacent to the narrowed regions, obtained during the first surgical intervention from treatment-naïve CD patients. Table 1 summarizes the baseline clinical characteristics of the entire study cohort, along with a comparison between the IFX monotherapy group and the THD+IFX combination therapy group. Age, -sex surgery site, and disease duration did not significantly differ between the IFX monotherapy and THD+IFX combination therapy groups.

Figure 1: THD combined with IFX improves intestinal fibrosis in CD patients. (A) Representative surgical specimens of intestinal stenosis from CD patients treated with THD combined with IFX vs. IFX alone (n = 6 per group). (B) Comparison of inflammatory scores in intestinal specimens between the THD combined with IFX group and the IFX group (p = 0.017). (C) Comparison of fibrosis scores in intestinal specimens between the THD combined with IFX group and the IFX group (p = 0.003). (D) Histological staining of surgical specimens using H&E, Masson’s trichrome, and Sirius Red (40×). (E,F) Immunohistochemical detected the expression of Col1α1, Col3α1, and α-SMA in surgical specimens from CD patients (40×). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001

The colonic inflammation and histopathological scores were higher in the IFX monotherapy group relative to the THD+IFX combination therapy group (Fig. 1B,C). HE staining of surgical specimens from stenotic segments revealed characteristic epithelial defects, inflammatory cell infiltration, severe crypt injury, and extensive depletion of goblet cells (Fig. 1D). We used Sirius red staining and Masson’s trichrome to evaluate the degree of fibrosis. The findings showed that the THD+IFX group significantly decreased collagen deposition in the colonic mucosa and submucosa when compared to the IFX monotherapy group. In addition, the THD+IFX group’s colonic tissue showed significantly lower levels of Col1α, Col3α, and α-SMA expression than the IFX group, according to immunohistochemistry tests (Fig. 1E,F). These findings indicate that IFX when combined with THD exerts a protective effect against collagen deposition and CD-related fibrosis.

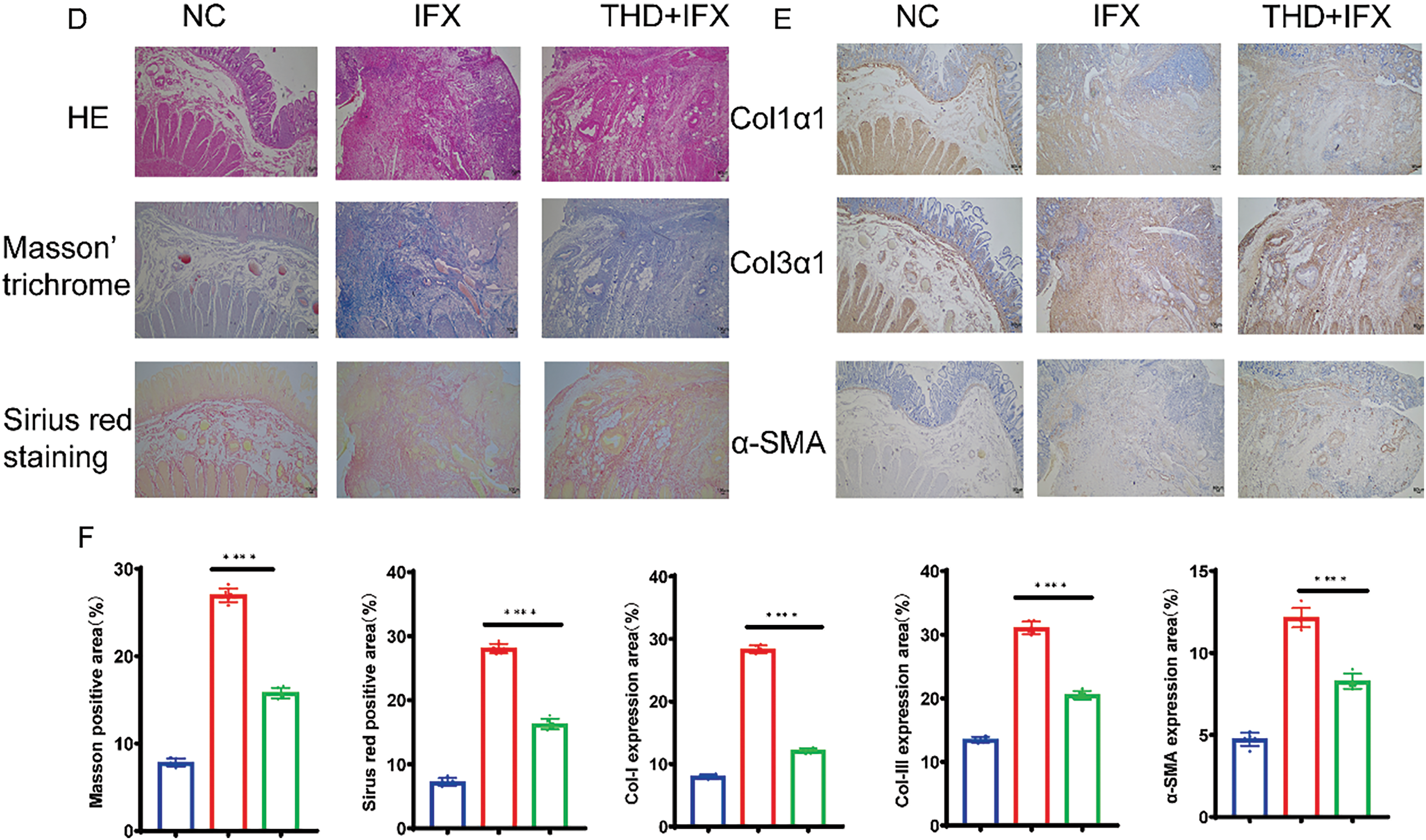

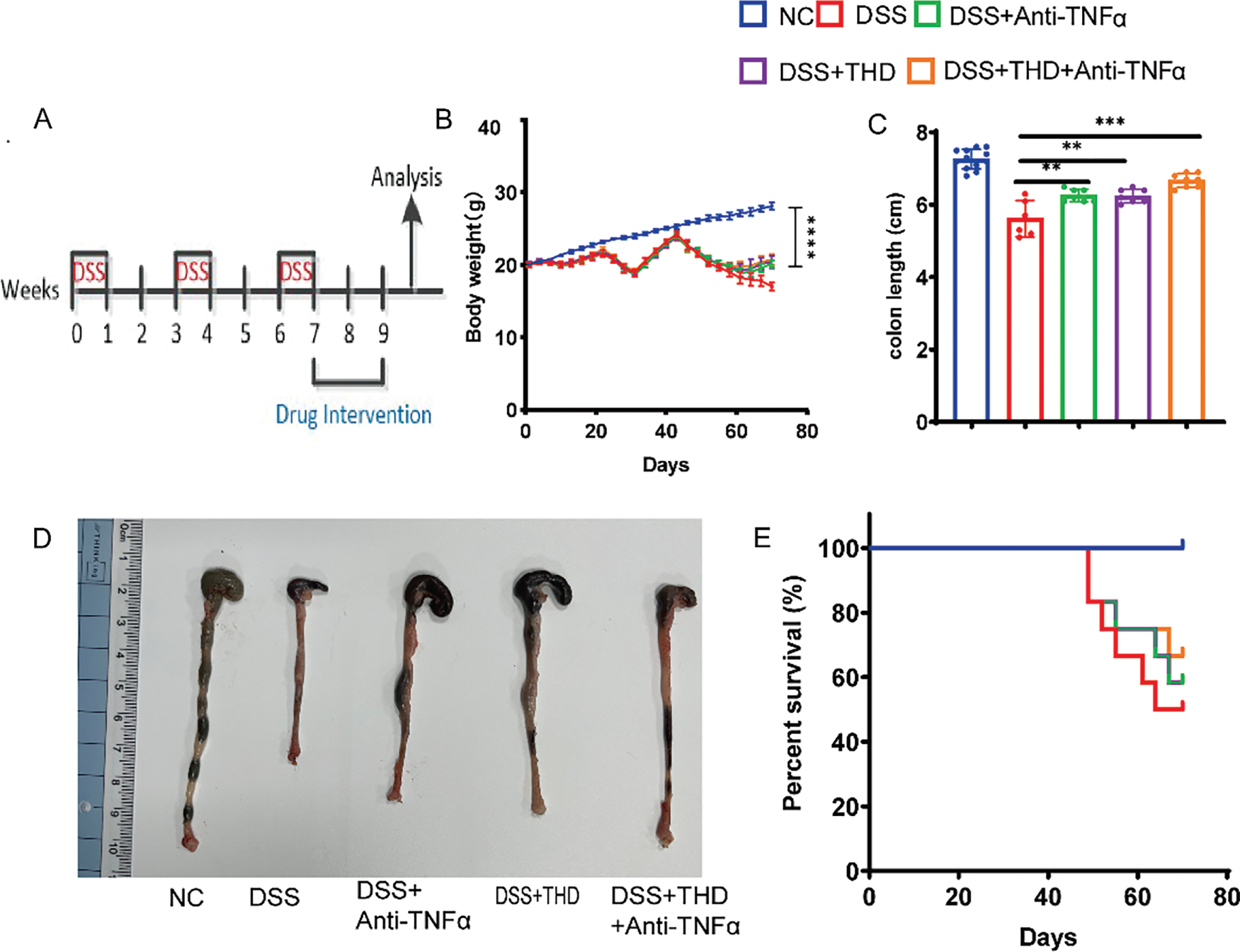

3.2 THD Alleviated Intestinal Fibrosis in DSS-Induced Chronic Colitis

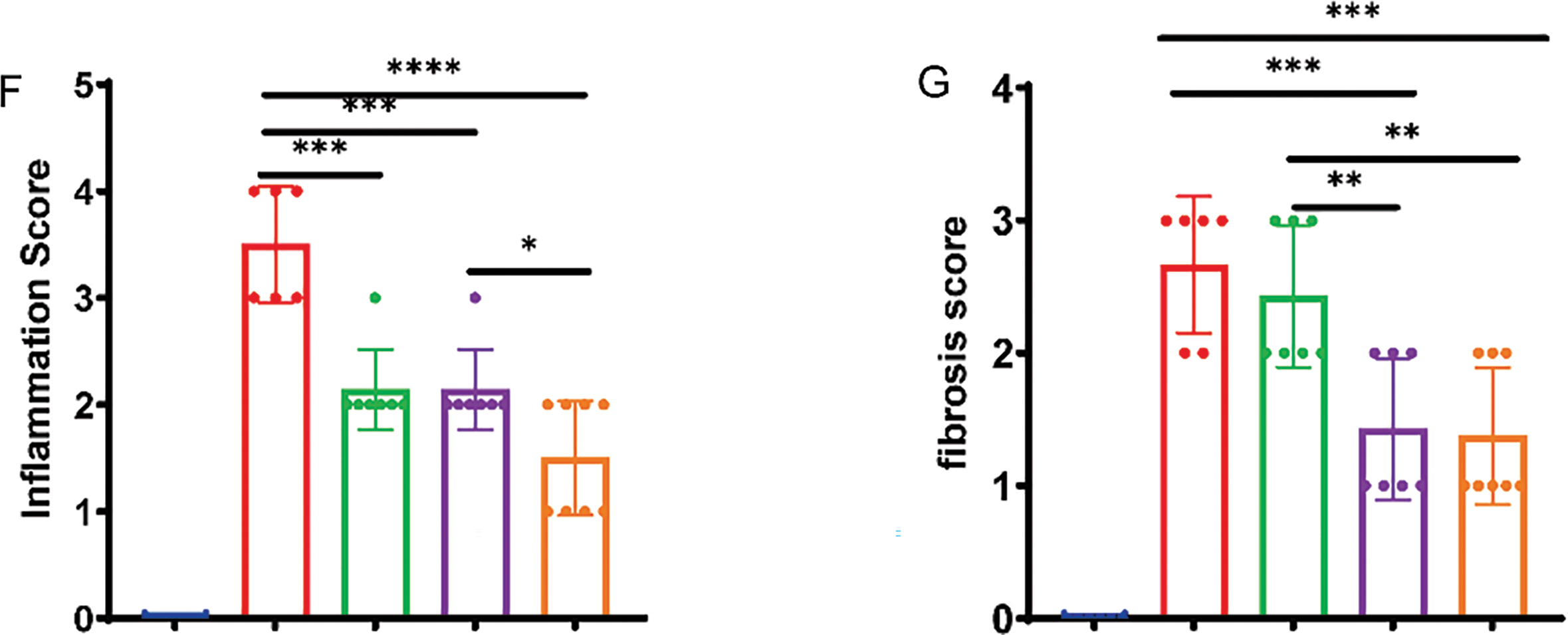

Using repeated cycles of DSS administration, we established a mouse model of colonic fibrosis to further explore the therapeutic potential of THD in a chronic intestinal fibrosis (Fig. 2A). THD, Anti-TNFα, and their combination were administered after the establishment of intestinal fibrosis to assess their therapeutic effects. DSS-treated mice exhibited significant weight loss and marked colon shortening compared to the NC group. However, treatment with THD, anti-TNFα, or their combination effectively increased the body weight of mice and preserved colon length in DSS-induced mice (Fig. 2B–D). Survival rates were recorded as 50%, 58.3%, 58.3%, and 66.7% in the DSS, Anti-TNFα group, THD group, and THD combined with Anti-TNFα group, respectively (Fig. 2E). THD alone and THD in combination with Anti-TNFα reduced the inflammatory scores and fibrosis scores in DSS-induced mice (Fig. 2F,G).

Figure 2: Therapeutic administration of THD reduces intestinal colitis in the DSS-induced mouse model. (A) Experimental protocol for DSS-induced colitis in mice (n = 12 per group). (B) Impact of THD on mouse body weight. (C) Colon length measurements among groups. (D) Colon samples that are representative of each category. (E) Survival rates of mice across different treatment groups. (F) Inflammatory scores of the colon tissues in different mouse groups. (G) Fibrosis scores of the colon tissues in different mice. *p < 0.05 vs. DSS group; **p < 0.01 vs. DSS group; ***p < 0.001 vs. DSS group; ****p < 0.0001 vs. DSS group

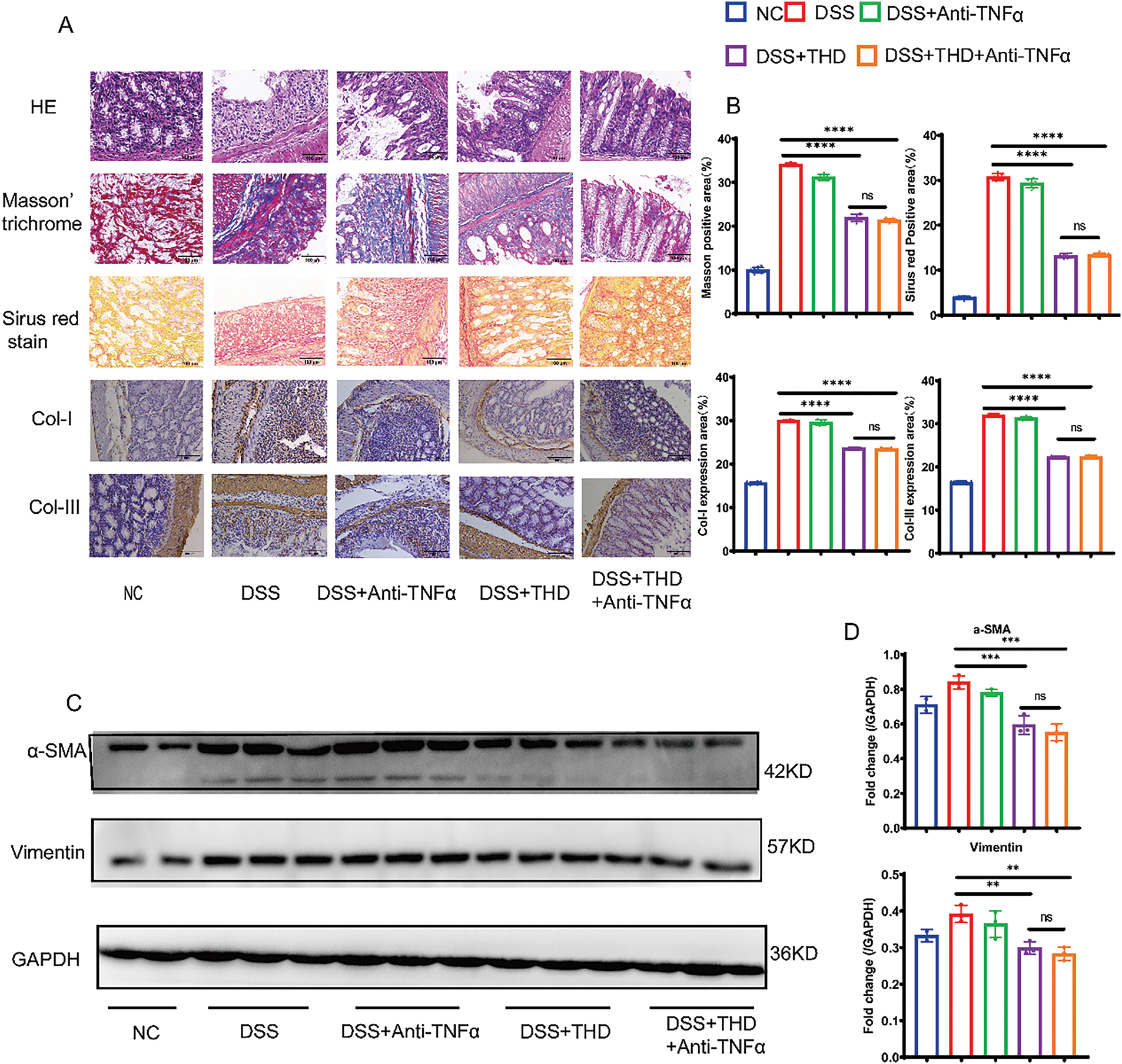

3.3 Impact of THD on Pathological Changes in the Intestinal Mucosa of Mice

Treatment with THD histopathological evaluation revealed that DSS-induced colonic tissue exhibited epithelial defects, inflammatory cell infiltration, severe crypt injury, and goblet cell depletion. Sirius Red and Masson’s Trichrome staining were used to measure the amount of fibrotic collagen deposition in the mucosal and submucosal layer of DSS-induced mice. Collagen fibers were visible as blue in Masson’s Trichrome and red in Sirius Red staining. The DSS group showed significant Col-I/Col-III in the intestinal mucosa and submucosa in comparison to the NC group (Fig. 3A,B). As Col-I/Col-III are key biomarkers of intestinal fibrosis, their reduction following THD or THD in combination with anti-TNFα treatment suggests an anti-fibrotic effect. Histopathological analyses further confirmed that THD alone and combined with Anti-TNFα exerted protective effects against fibrosis-associated collagen deposition. To further assess fibroblast activity, α-SMA and vimentin, two well-established fibroblast markers, were analyzed. The DSS group exhibited significantly elevated α-SMA and vimentin expression. In contrast, the levels of proliferative proteins were markedly decreased in the THD treated group (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3: In the DSS-induced mouse model, intestinal fibrosis is decreased by therapeutic THD treatment. (A,B) H&E, Masson staining, and Sirus red stain of the colon tissues (400×), Immunohistochemical expression of collagen I and collagen III (200×) in different mouse groups. (C,D) Western blotting and quantification of α-SMA and vimentin protein expression (n = 3 independent experiments). **p < 0.01 vs. DSS group; ***p < 0.001 vs. DSS group; ****p < 0.0001 vs. DSS group; ns DSS + THD vs. DSS + THD + Anti-TNFα p ≥ 0.05

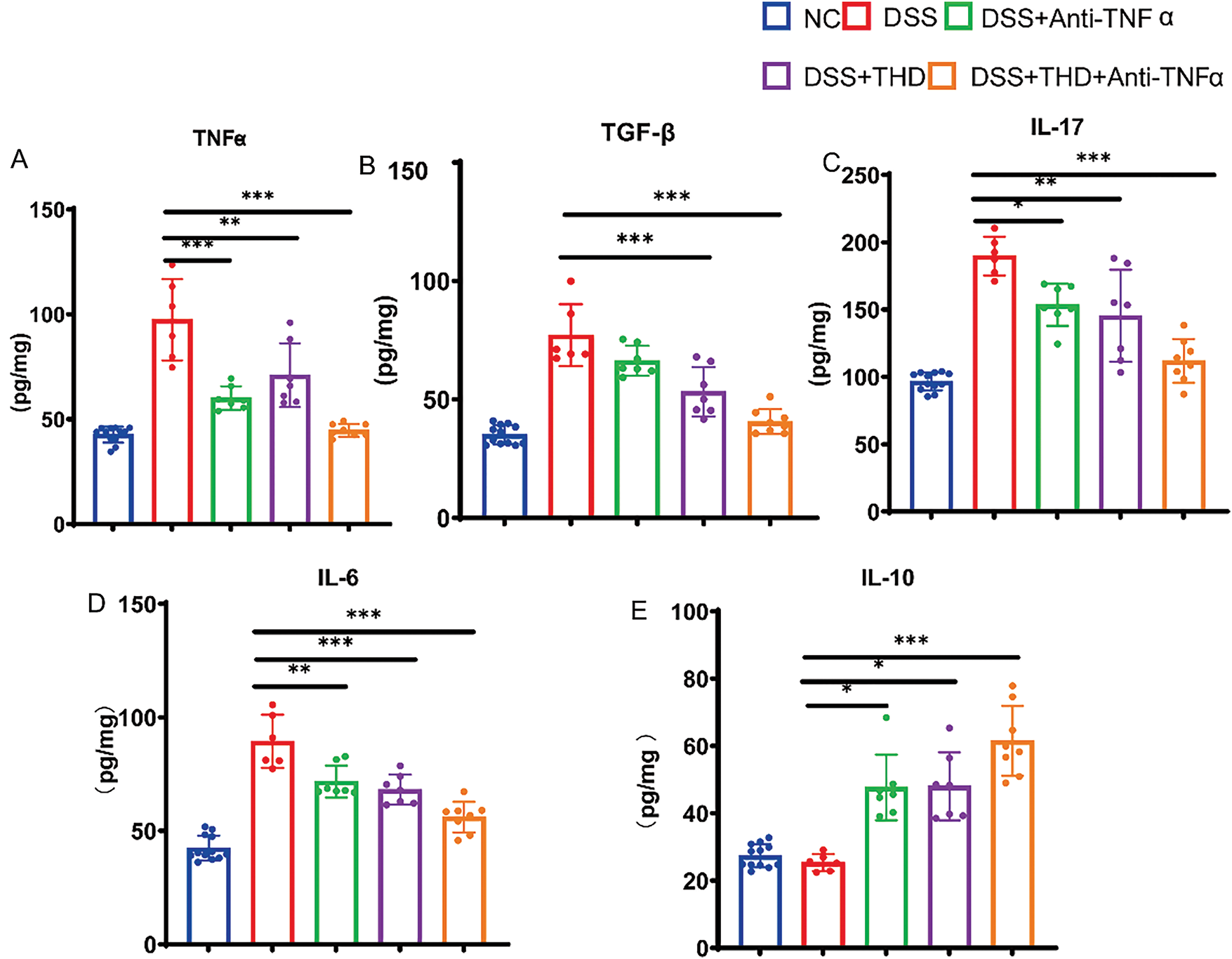

3.4 The Impact of THD on Inflammatory Mediators in the Intestinal Mucosa of DSS-Induced Mice

To examine the influence of THD on the production of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in DSS-induced mice, colonic tissue samples were analyzed. DSS may reduce IL-10 secretion while increasing TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-17 production. However, THD and THD in combination with anti-TNFα may increase the release of IL-10 while suppressing the synthesis of TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-17 (Fig. 4A–E).

Figure 4: THD affects the production of Inflammatory cytokines in DSS-induced mice. (A–E) In the colonic tissue of mice, THD increases the synthesis of IL-10 while suppressing the production of TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-17, and IL-6. *p < 0.05 vs. DSS group; **p < 0.01 vs. DSS group; ***p < 0.001 vs. DSS group

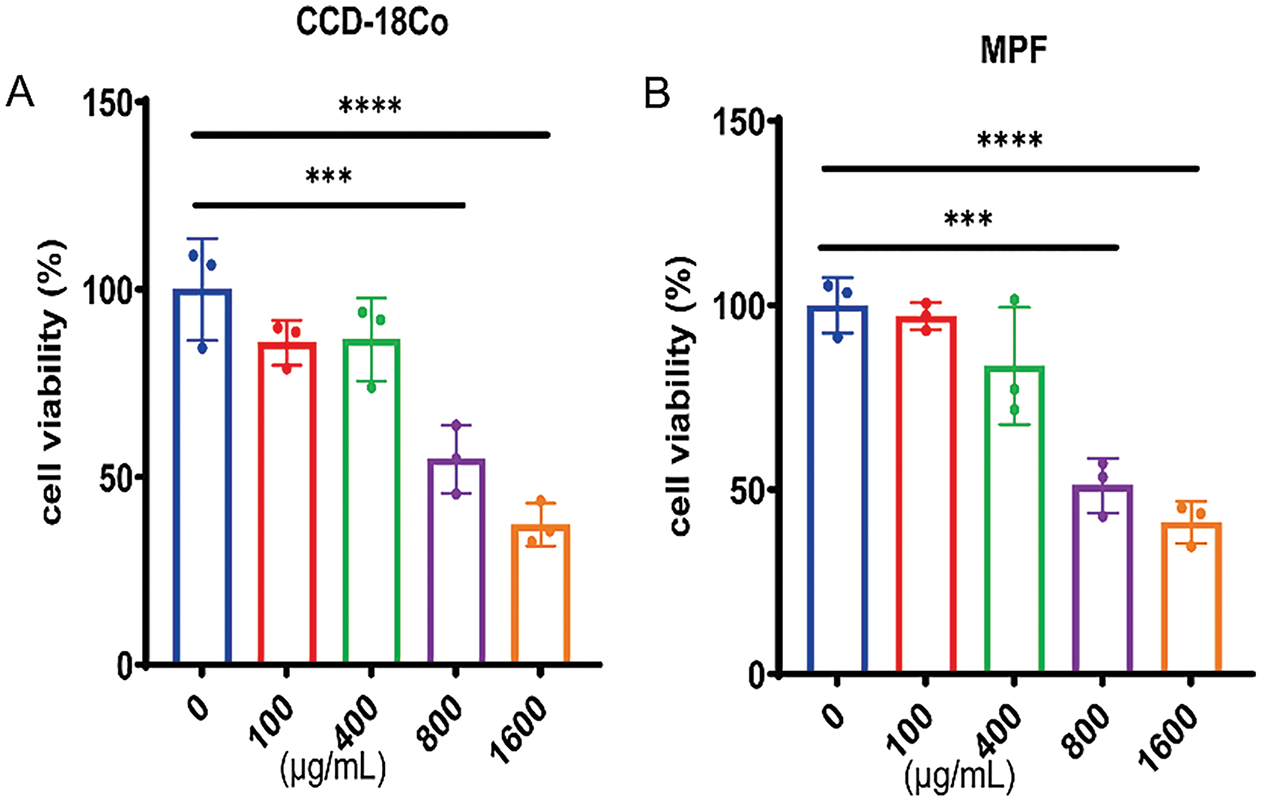

3.5 THD Inhibits TGF-β1-Induced Cell Proliferation, Fibroblast Differentiation, and Collagen Synthesis in CCD-18Co and MPF Cells

To assess the effect of THD on fibroblast proliferation, CCD-18Co and MPF cells were pretreated with THD at concentrations of 0, 100, 400, 800, and 1600 μg/mL. The CCK-8 assay revealed that treatment with 800 μg/mL of THD effectively suppressed cell proliferation, reducing cell numbers to basal levels in both colonic fibroblasts (Fig. 5A,B). We then focused on the effect of THD on fibroblast motility. Both THD alone and THD in combination with Anti-TNFα reduced myofibroblast motility. However, in CCD-18Co, there was no discernible difference in the suppression of cell motility between these two groups (Fig. 6A). Collagen accumulation is a hallmark of myofibroblast activation. It is a key contributor to intestinal fibrosis. We assessed Col-I/Col-III mRNA and protein expression to investigate the impact of THD on collagen synthesis. The concentration of THD in CCD-18Co or MPF cells was 100 μg/mL, whereas the concentration of Anti-TNFα was 50 μg/mL. Fibroblasts were initially exposed to 2 h of TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) stimulation, followed by treatment with THD or Anti-TNFα for 46 h. Subsequently, cellular proteins were harvested for further analysis. As expected, both THD alone and THD in combination with Anti-TNFα notably diminished Col-I/Col-III at both the transcriptional and protein levels in CCD-18Co (Fig. 6B,C).

Figure 5: The impact of THD on the cell viability in colonic fibroblast. (A,B) THD inhibits TGF-β1-induced cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (0, 100, 400, 800, 1600 μg/mL) over 24 h (n = 3 independent experiments). ***p < 0.001 vs. 0 μg/mL group. ****p < 0.0001 vs. 0 μg/mL group

Figure 6: THD attenuates TGF-β1-induced proliferation and collagen production in CCD-18Co. (A) The Transwell test (n = 3 separate trials) was used to assess cell migration. Quantification of the number of migrating cells and representative microscope pictures are shown. Scale bars: 200 μm. (B) Collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA relative mRNA expression levels in CCD-18Co. (C) Western blot analysis and quantification of Collagen I, Collagen III, and α-SMA protein expression levels. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation derived from three replicate experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. TGF-β1 group; **p < 0.01 vs. TGF-β1 group. ***p < 0.001 vs. TGF-β1 group; ****p < 0.0001 vs. TGF-β1 group; ns TGF-β1 + THD vs. TGF-β1 + THD + Anti-TNFα p ≥ 0.05

In particular, TGF-β1-induced fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition was significantly prevented by co-treatment with THD, either alone or in conjunction with anti-TNFα, as demonstrated by decreased α-SMA expression in CCD-18Co (Fig. 6C). As shown in Fig. 7A–C, the experimental results of MPF cells are highly consistent with those of CCD-18Co cells.

Figure 7: In MPF cells, THD inhibits TGF-β1-induced collagen synthesis and proliferation. (A) The Transwell test (n = 3 separate trials). Quantification of the number of migrating cells and representative microscope pictures are shown. Scale bars: 200 μm. (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA in MPF cells. (C) Western blot analysis and quantification of Collagen I, Collagen III, and α-SMA protein expression levels. The results are the mean ± standard deviation derived from three replicate experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. TGF-β1 group; **p < 0.01 vs. TGF-β1 group; ***p < 0.001 vs. TGF-β1 group; ****p < 0.0001 vs. TGF-β1 group; ns TGF-β1 + THD vs. TGF-β1 + THD + Anti-TNFα p ≥ 0.05

3.6 THD Down-Regulated BGN, FBN1, FBLN1, FBLN5, and PI3K-AKT Pathway-Related Genes

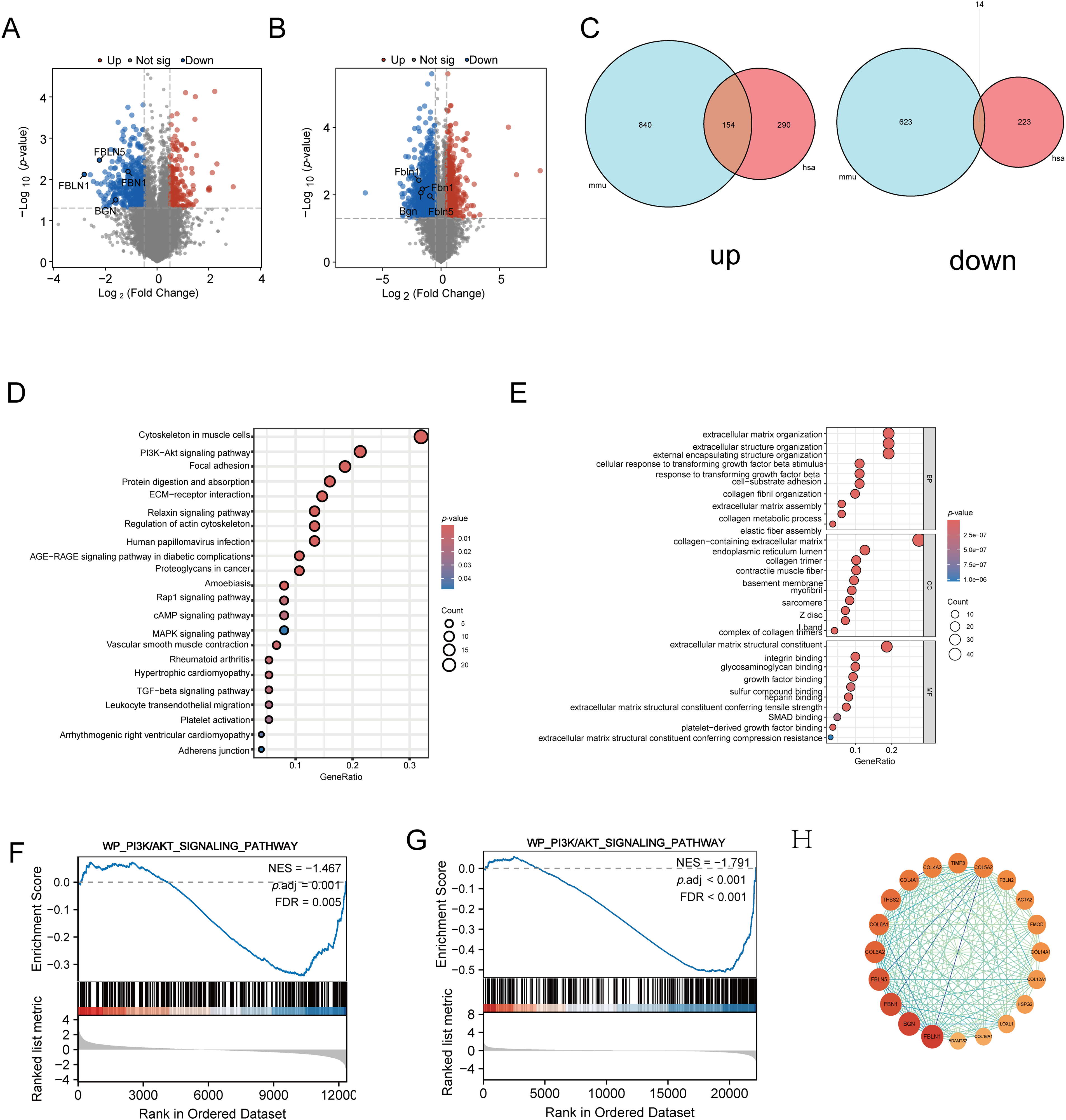

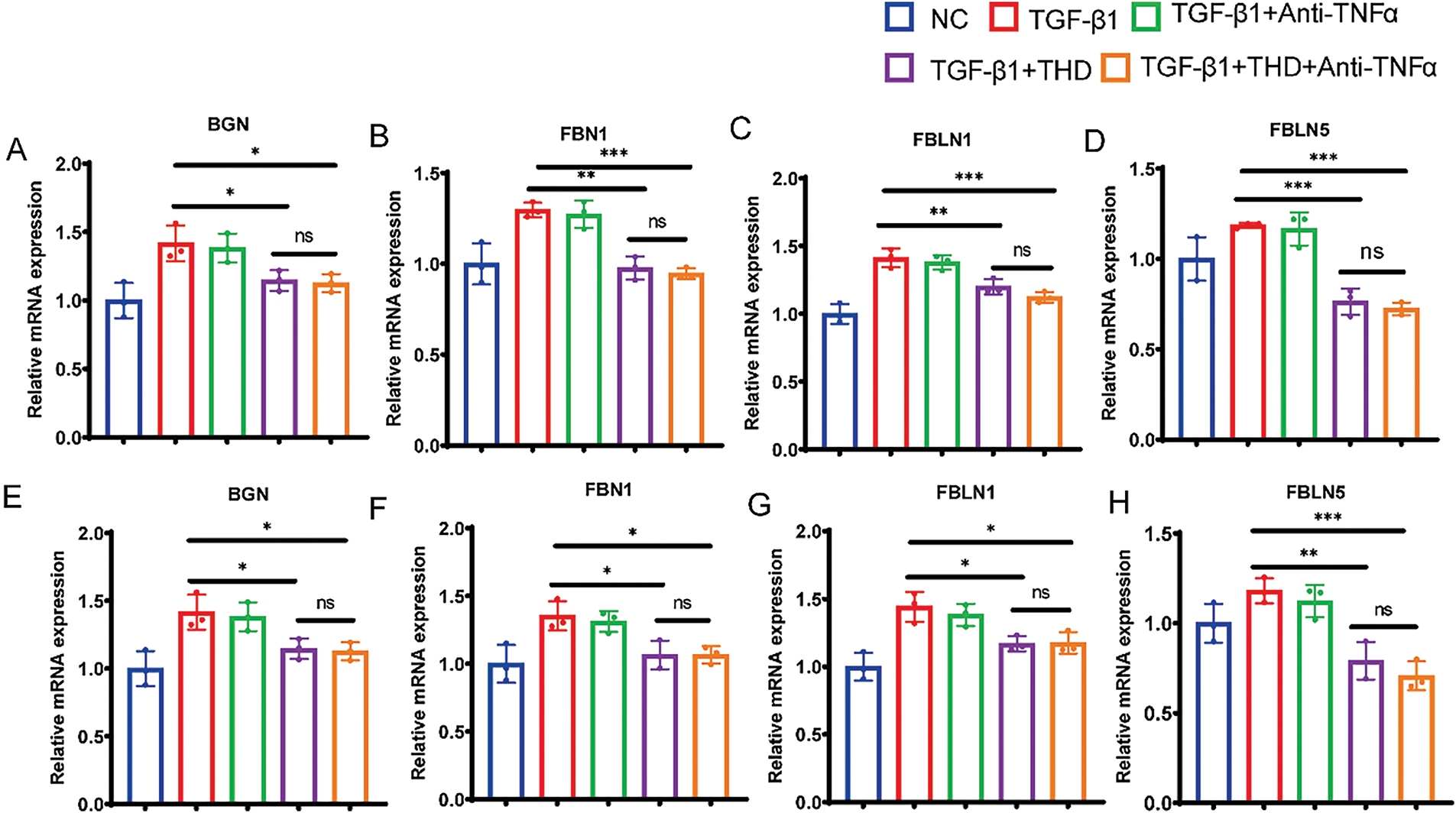

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the anti-fibrotic effects of THD, transcriptome sequencing analysis was performed on CCD-18Co and MPF cells with and without THD treatment (each group n = 3). Volcano plot analysis revealed significant differences in gene expression profiles between the THD-treated and control groups in fibroblasts (Fig. 8A,B). A total of 681 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened out in CCD-18Co cells, while 1631 DEGs were detected in MPF cells. Among these, 168 genes were commonly differentially expressed between the two cell types. 14 DEGs were downregulated in both cell types in the THD-treated group as compared to the NC group (Fig. 8C). KEGG enrichment analysis identified the top 20 signaling pathways influenced by THD in the context of intestinal fibrosis in the intersection of genes. Important pathways included those linked to focal adhesion, the PI3K/AKT pathway, and the cytoskeleton in muscle cells (Figs. 8D and S1A,C). The THD group’s interested gene alterations, according to GO enrichment analysis, are primarily enriched in extracellular matrix structure, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, and extracellular matrix organization (Figs. 8E and S1B,D). The KEGG database’s Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed that the two cells’ differential genes were enriched in the PI3K/AKT pathway (Fig. 8F,G). BGN, FBLN1, FBLN5, and FBN1 gene expression showed significant intergroup differences in both cell types (Figs. 8H and S1E,F). The transcriptome sequencing results were confirmed through RT-qPCR in both cells (Fig. 9A–H).

Figure 8: Transcriptomic analysis reveals differentially expressed genes and enriched pathways modulated by THD in colonic fibroblasts. (A,B) A volcano graphic showing the genes that are expressed differently in CCD-18Co cells and MPF cells. (C) Venn diagram illustrating shared differentially expressed genes between CCD-18Co and MPF cells. (D) KEGG enrichment histogram of the intersection of genes. (E) GO enrichment BarPlot of the intersection of genes. (F,G) GSEA of PI3K/AKT Pathway in fibroblasts. (H) Protein-Protein interaction analysis of intersected genes. mmu: Mus musculus; has: Homo sapiens

Figure 9: RT-q RCR quantification of the interested genes. (A–D) RT-qPCR quantification of the BGN, FBN1, FBLN1, FBLN5 in CCD-18Co cells (n = 3 independent experiments). (E–H) RT-qPCR quantification of BGN, FBN1, FBLN1, FBLN5 in MPF cells (n = 3 independent experiments). *p < 0.05 vs. TGF-β1 group; **p < 0.01 vs. TGF-β1 group. ***p < 0.001 vs. TGF-β1 group. ns TGFβ1 + THD vs. TGFβ1 + THD + Anti-TNFα p ≥ 0.05

3.7 THD Attenuated Intestinal Fibrosis by Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT Pathway

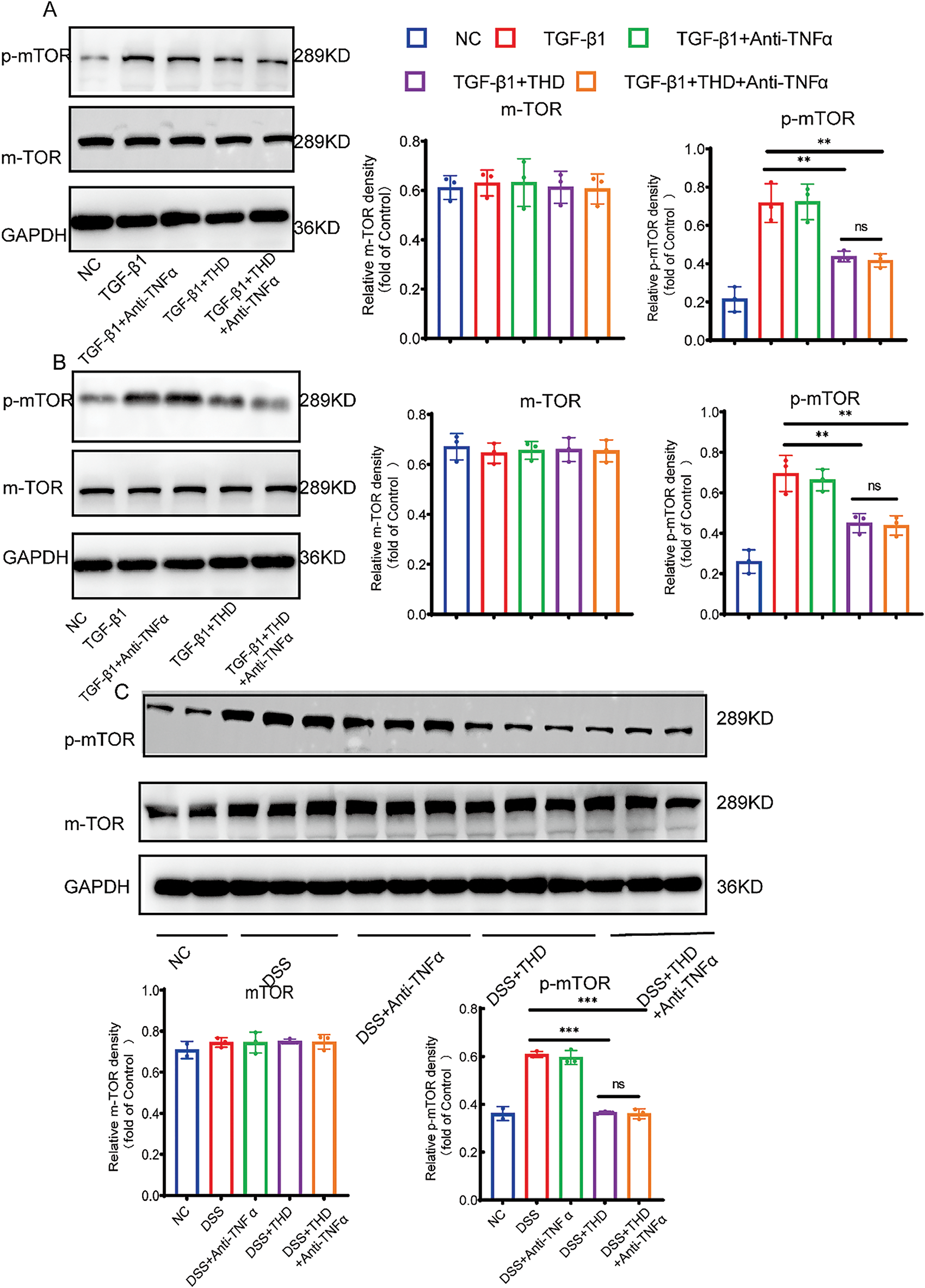

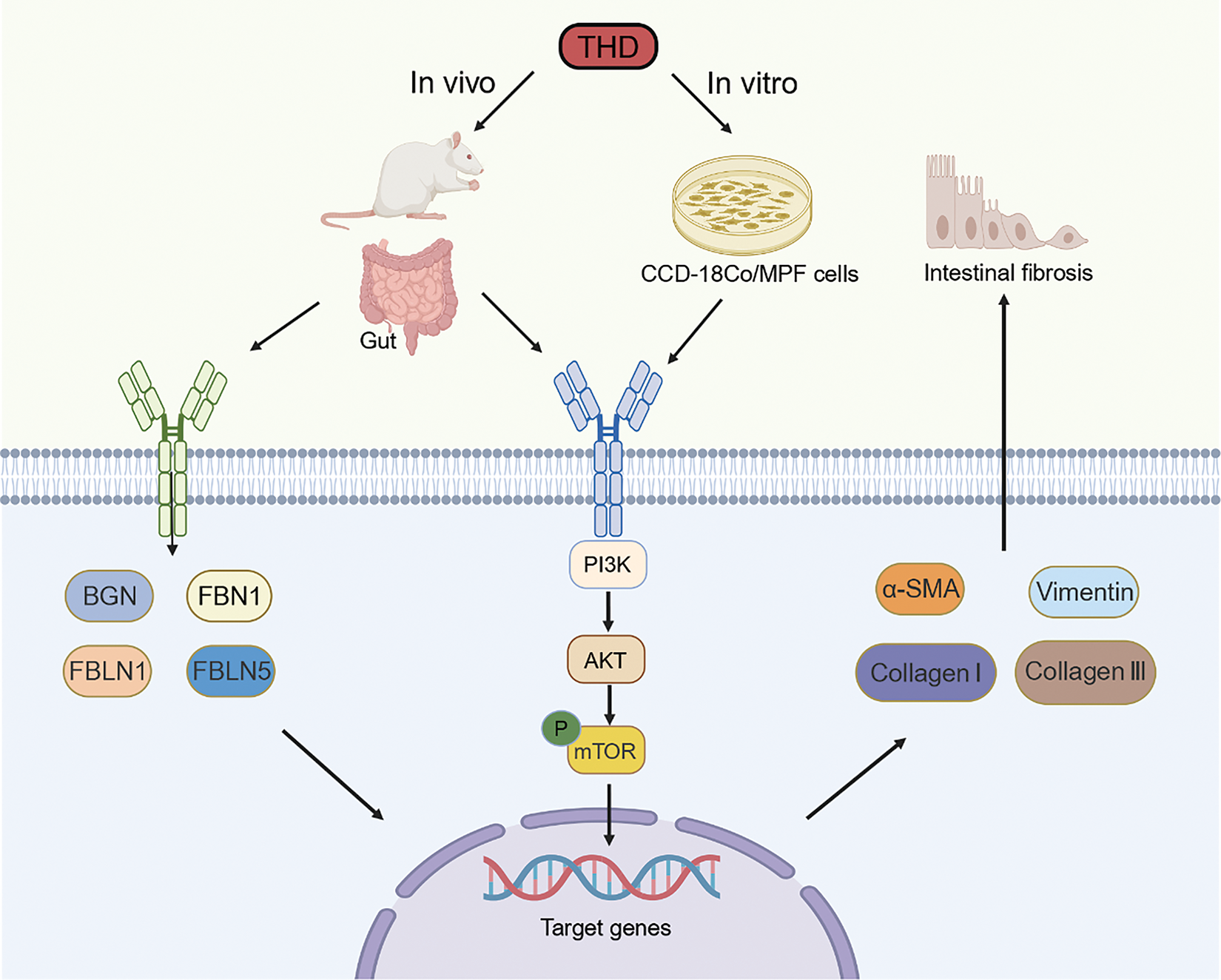

We examined fibrosis-associated signaling pathways in intestinal tissues and fibroblasts to investigate the mechanisms behind THD’s anti-fibrotic actions. To further assess the impact of THD on PI3K/AKT pathway activation, we examined TGF-β1-induced CCD-18Co and MPF cells. As shown in Fig. 10, TGF-β1 significantly activated the non-canonical PI3K/AKT pathway, modulating downstream pro-fibrotic signaling and protein expression. Specifically, TGF-β1 treatment markedly increased p-mTOR expression, whereas pretreatment with THD alone or in combination with Anti-TNFα notably reduced mTOR phosphorylation levels (Fig. 10A,B). Furthermore, in DSS-treated mice, we also observed that THD inhibited mTOR phosphorylation (Fig. 10C). In summary, our findings suggest that the therapeutic benefits of THD in chronic colitis-associated fibrosis are mediated, at least in part, through downregulation of mTOR phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT pathway and inhibition of key fibrosis-associated genes (Fig. 11).

Figure 10: THD suppresses the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. (A,B) Western blot analysis of mTOR and phosphorylated mTOR levels in CCD-18Co and MPF cells (n = 3 independent experiments). (C) Western blot analysis of mTOR and phosphorylated mTOR in colonic tissues from different mouse groups. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns p ≥ 0.05

Figure 11: Schematic diagram of the mechanism underlying THD-mediated alleviation of CD-associated intestinal fibrosis. Schematic representation illustrating the proposed mechanism of THD action: THD may suppress CD-associated intestinal fibrosis by downregulating gene and protein expression in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (Figure was created with Biorender.com)

Intestinal fibrotic stenosis associated with CD represents a common and clinically challenging complication. The incidence and surgical treatment rates for intestinal strictures in CD remain high, burdening healthcare systems and patients alike [32]. In this investigation, we showed that THD therapy greatly reduced the overproduction of ECM components, especially collagen type I and III, and cell proliferation. The anti-fibrotic effects of THD and its combination with anti-TNFα appeared to be mediated via suppression of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, a pathway well-known for its role in organ fibrosis. These findings suggest that THD-based treatments hold significant potential as promising therapeutic strategies for intestinal fibrosis associated with CD.

The pathological hallmark of intestinal fibrosis involves the excessive synthesis and deposition of collagen, leading to intestinal wall thickening and fibrotic stricture formation [33]. The anatomical distribution of fibrosis in CD correlates with the location and severity of inflammation, as fibrotic changes are rarely observed in areas without active or prior inflammation [34]. Our study observed marked deposition of type I and III collagen in the submucosal layers of stenotic intestinal tissues from CD patients. Additionally, the fibrosis marker α-SMA expression was significantly increased in these tissues, while adjacent normal regions exhibited minimal collagen deposition and low α-SMA expression. Importantly, surgical specimens from patients treated with THD in combination with IFX displayed lower fibrosis scores, reduced collagen I and III deposition, and decreased α-SMA expression compared to specimens from patients treated with IFX alone. These findings suggest a synergistic anti-fibrotic effect when THD is used in conjunction with anti-TNFα therapy. Our results support the hypothesis that THD, particularly when combined with anti-TNFα agents, may effectively attenuate intestinal fibrosis in CD.

To probe into the in vivo effects of THD, we employed a DSS-induced colitis model, which mimics chronic intestinal inflammation and fibrosis through Th1-mediated immune responses [35]. THD is associated with side effects such as peripheral neuropathy, dermatitis, sedation, and respiratory depression [36]. In therapeutic settings, individuals with CD are advised to take between 50 to 200 mg/kg daily. Based on previous research in fibrotic diseases of other organs and to minimize adverse effects, we selected a low dose of 50 mg/kg for use in our mouse model to enhance clinical relevance and safety. IFX, a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody composed of 75% human and 25% murine sequences, lacks cross-reactivity with TNFα from non-primate species. Thus, we used an Anti-TNFα antibody specifically designed to inhibit murine TNFα for our animal experiments. The dosage was determined based on clinical IFX doses, which typically range from 5 to 10 mg/kg. Mesenchymal cells can differentiate into fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, or smooth muscle cells, with phenotypic plasticity influenced by inflammatory cytokine signaling. Upon activation and differentiation into myofibroblasts, these cells express α-SMA and vimentin and exhibit markedly increased ECM production. Importantly, α-SMA and vimentin are widely recognized as markers of myofibroblast activation and are not expressed in quiescent fibroblasts [11]. In our study, the expression levels of α-SMA and vimentin were notably elevated in the intestinal mucosa of DSS-induced fibrotic mice, indicating the activation and transdifferentiation of fibroblasts. THD may inhibit the conversion of fibroblasts into activated myofibroblasts—a critical step in the progression of fibrosis. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of THD-based regimens in managing CD-associated intestinal fibrosis. However, further research is necessary to ascertain the ideal initiation timing, length of maintenance therapy, and suitable dose techniques for THD in clinical environments.

Myofibroblasts migrate into injured tissues and play a central role in regulating ECM synthesis and turnover, ultimately contributing to fibrotic remodeling [37]. Our results indicated that TGF-β1 prompted the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and markedly increased the mRNA and protein levels of collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA. The pro-fibrotic effects were significantly diminished by THD, both independently and in conjunction with anti-TNFα. These findings are consistent with previous studies on pulmonary and renal fibroblasts [27,38]. Our results suggest that THD exerts anti-fibrotic effects at the cellular level. The ability of THD to reversibly suppress cell proliferation further supports its potential as a therapeutic agent for fibrosis.

Evidence indicates that TGF-β1 also activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [39]. Fibrotic diseases induced by agents such as bleomycin, including pulmonary fibrosis and liver cirrhosis, have been shown to promote ECM accumulation primarily via activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis [40]. Recent studies have shown that biglycan (BGN) is closely associated with fibrotic processes in multiple tissues and organs, such as the myocardium and liver [41,42]. Moreover, fibrillin-1 (FBN1) has been recognized as a critical component implicated in various fibrotic diseases, including scleroderma [43]. Fibulin-1 (FBLN1) has been found to display increased expression levels in lung fibrosis tissues induced by bleomycin [44]. Fibulin-5 (FBLN5), an extracellular matrix protein essential for elastic fiber assembly and angiogenesis, plays a pivotal role in sustaining the fibrotic phenotype; its deficiency may substantially impair this process [45]. These genes are well-documented as being associated with fibrosis and are regulated through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [46,47]. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that THD exerts its anti-fibrotic effect by suppressing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade. The mTOR pathway, particularly the rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 complex, is critical in modulating cell proliferation, protein synthesis, and transcription [48]. Zhao et al. documented that amphiregulin (Areg) promoted the proliferation, migration, and collagen I production of human intestinal fibroblasts via activation of the mTOR pathways [49]. Similarly, Mitra et al. found that the dual mTOR inhibitor OSI-027—targeting both mTORC1 and mTORC2 effectively suppressed TGF-β1-induced expression of α-SMA, collagen Iα1, and collagen IIIα1 [50]. In our experimental models, both in vitro and in vivo, THD alone or in combination with Anti-TNFα distinctly reduced the phosphorylation of mTOR, indicating inhibition of this signaling pathway.

Currently, the combination of IFX and azathioprine represents the standard first-line therapy for CD [51]. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this combination benefits established intestinal fibrosis. In contrast, THD has demonstrated both anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects and is already in clinical use for fibrotic conditions affecting various organs. Its safety and efficacy profiles have been established in other disease contexts, and it remains a relatively cost-effective option suitable for a wide range of patients. The combination of THD and IFX offers the dual benefits of controlling inflammation and inhibiting fibrogenesis, particularly in CD patients presenting with an obstructive phenotype.

Reversing CD-associated intestinal strictures at an early stage may significantly reduce the need for surgical intervention [52]. While our current research focuses on the terminal outcomes of CD-associated intestinal fibrosis, future therapeutic efforts should prioritize early intervention to halt or reverse fibrotic progression. During the early stages of fibrosis, pro-fibrotic stimuli can induce epithelial and endothelial cells to lose their polarity and transition into a mesenchymal phenotype through Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and Endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) [53,54], respectively. Our future studies will investigate whether THD can interfere with EMT and EndoMT processes, thereby inhibiting early development or even reversing the progression of intestinal fibrosis.

The present study utilized CCD-18Co and MPF fibroblast cell lines as in vitro models. However, the degree to which these cell lines reflect the characteristics of primary fibroblasts derived from stenotic intestinal tissues remains uncertain. Furthermore, regional heterogeneity in fibroblasts from different stricture sites may influence experimental outcomes. Thus, the applicability of these fibroblast lines as models for intestinal fibrosis warrants further validation. While our investigation identified key proteins affected by THD treatment, our analysis of the associated signaling pathways remains preliminary. In particular, the role of the immune response in the anti-fibrotic effects of THD has not yet been elucidated. Additionally, we have not explored the impact of THD on MMPs and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), both of which are critical regulators of ECM turnover and intestinal homeostasis.

Our study demonstrated that THD treatment significantly suppressed fibroblast proliferation, inhibited fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation, and reduced collagen synthesis in vitro and vivo. Mechanistically, these effects appear to involve the downregulation of genes associated with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis. Collectively, our findings provide novel and compelling evidence supporting the potential of THD, particularly in combination with anti-TNFα, as a promising strategy for the management of CD-associated intestinal fibrosis.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript drafting, Xiaoyue Feng and Yu Liu; data acquisition and manuscript drafting, Bei Yuan, Ying Kang, Juan Wei, and Kang Jiang; conception, design, and data interpretation, as well as revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, Weijun Xu, Xinyi Xia, and Fangyu Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data would be available to other researchers upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Jinling Hospital (Approval No. 2021NZKY-001-01) and implemented in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was gathered from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Jinling Hospital and complied with institutional and ethical guidelines (Approval No. 2021DZGKJDWLS-00143).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.0665041/s1.

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| THD | Thalidomide |

| DSS | Dextran sulfate sodium |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| ECM | Excessive extracellular matrix |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of rapamycin |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| Acta2 | Actin alpha 2, smooth muscle |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-beta 1 |

| Anti-TNFα | Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IMM | Immunosuppressant |

| IFX | Infliximab |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatedehydrogenase |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| HRB | HSP70-Homolog RadB |

| DAB | 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine |

| mmu | Mus musculus |

| has | Homo sapiens |

| Areg | Amphiregulin |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| EndoMT | Endothelial-mesenchymal transition |

References

1. Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel JF, Ungaro RC. Approach to the management of recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease patients: a user’s guide for adult and pediatric gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(1):47–65. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Bai X, Zhang H, Ruan G, Lv H, Li Y, Li J, et al. Long-term disease behavior and surgical intervention analysis in hospitalized patients with Crohn’s disease in China: a retrospective cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(Suppl 2):S35–35S41. doi:10.1093/ibd/izab295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lu C, Baraty B, Lee Robertson H, Filyk A, Shen H, Fung T, et al. Systematic review: medical therapy for fibrostenosing Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(12):1233–46. doi:10.1111/apt.15750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Michelassi F, Mege D, Rubin M, Hurst RD. Long-term results of the side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty in Crohn disease: 25-year follow-up and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):130–7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu J, Di B, Xu LL. Recent advances in the treatment of IBD: targets, mechanisms and related therapies. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2023;71–72(2016):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2023.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Rizzo G, Rubbino F, Elangovan S, Sammarco G, Lovisa S, Restelli S, et al. Dysfunctional extracellular matrix remodeling supports perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease by a mechanoregulated activation of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;15(3):741–64. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2022.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Sánchez-Duffhues G, García de Vinuesa A, van de Pol V, Geerts ME, de Vries MR, Janson SG, et al. Inflammation induces endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and promotes vascular calcification through downregulation of BMPR2. J Pathol. 2019;247(3):333–46. doi:10.1002/path.5193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Younesi FS, Miller AE, Barker TH, Rossi F, Hinz B. Fibroblast and myofibroblast activation in normal tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(8):617–38. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00716-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xu J, Wang X, Chen J, Chen S, Li Z, Liu H, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote colon epithelial integrity and regeneration by elevating circulating IGF-1 in colitis mice. Theranostics. 2020;10(26):12204–22. doi:10.7150/thno.47683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Talbott HE, Mascharak S, Griffin M, Wan DC, Longaker MT. Wound healing, fibroblast heterogeneity, and fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29(8):1161–80. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2022.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Henderson NC, Rieder F, Wynn TA. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature. 2020;587(7835):555–66. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2938-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hu G, Huang R, Lu L, Pan Q, Chen X. Vitamin D attenuates TGF-β1-induced lung fibroblast proliferation and migration through repression of RasGRP3. BIOCELL. 2023;47(6):1243–51. doi:10.32604/biocell.2023.027763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ma Z, Bai Z, Li B, Zhang Y, Liu W. Extracts from artemisia annua alleviates myocardial remodeling through TGF-β1/Smad2/3 pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2024;17:e18761429304142. doi:10.2174/0118761429304142240528093541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ren G, Xu G, Li R, Xie H, Cui Z, Wang L, et al. Modulation of bleomycin-induced oxidative stress and pulmonary fibrosis by Ginkgetin in mice via AMPK. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2023;16(2):217–27. doi:10.2174/1874467215666220304094058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Artone S, Ciafarone A, Augello FR, Lombardi F, Cifone MG, Palumbo P, et al. Evaluation of the antifibrotic effects of drugs commonly used in inflammatory intestinal diseases on in vitro intestinal cellular models. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(16):8862. doi:10.3390/ijms25168862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rieder F, Fiocchi C, Rogler G. Mechanisms, management, and treatment of fibrosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):340–50.e6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Yuan S, Wei C, Liu G, Zhang L, Li J, Li L, et al. Sorafenib attenuates liver fibrosis by triggering hepatic stellate cell ferroptosis via HIF-1α/SLC7A11 pathway. Cell Prolif. 2022;55(1):e13158. doi:10.1111/cpr.13158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zheng Z, Xu Y, Krügel U, Schaefer M, Grune T, Nürnberg B, et al. In vivo inhibition of trpc6 by sh045 attenuates renal fibrosis in a New Zealand Obese (NZO) mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(12):6870. doi:10.3390/ijms23126870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lawrance IC, Maxwell L, Doe W. Altered response of intestinal mucosal fibroblasts to profibrogenic cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7(3):226–36. doi:10.1097/00054725-200108000-00008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Bruining DH, Zimmermann EM, Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, Sauer CG, Strong SA, et al. Consensus recommendations for evaluation, interpretation, and utilization of computed tomography and magnetic resonance enterography in patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1172–94. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Fumery M, Yzet C, Chatelain D, Yzet T, Brazier F, LeMouel JP, et al. Colonic strictures in inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, complications, and management. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(10):1766–73. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wang J, Lin S, Brown JM, van Wagoner D, Fiocchi C, Rieder F. Novel mechanisms and clinical trial endpoints in intestinal fibrosis. Immunol Rev. 2021;302(1):211–27. doi:10.1111/imr.12974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. de Jesus SM, Santana RS, Leite SN. Comparative analysis of the use and control of thalidomide in Brazil and different countries: is it possible to say there is safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022;21(1):67–81. doi:10.1080/14740338.2021.1953467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Dsouza NN, Alampady V, Baby K, Maity S, Byregowda BH, Nayak Y. Thalidomide interaction with inflammation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31(3):1167–82. doi:10.1007/s10787-023-01193-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li TH, Huang CC, Yang YY, Lee KC, Hsieh SL, Hsieh YC, et al. Thalidomide improves the intestinal mucosal injury and suppresses mesenteric angiogenesis and vasodilatation by down-regulating inflammasomes-related cascades in cirrhotic rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147212. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Pan J, Dong F, Ma L, Zhao C, Qin F, Wen J, et al. Therapeutic effects of thalidomide on patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2023;8(3):231–40. doi:10.1177/23971983231180077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang H, Yang Y, Wang Y, Wang B, Li R. Renal-protective effect of thalidomide in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats through anti-inflammatory pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:89–98. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S149298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Danese S, Solitano V, Jairath V, Peyrin-Biroulet L. The future of drug development for inflammatory bowel disease: the need to ACT (advanced combination treatment). Gut. 2022;71(12):2380–7. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Chen L, Xu CJ, Wu W, Ding BJ, Liu ZJ. Anti-TNF and immunosuppressive combination therapy is preferential to inducing clinical remission in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2021;22(7):408–18. doi:10.1111/1751-2980.13026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Rodríguez-Lago I, Gisbert JP. The role of immunomodulators and biologics in the medical management of stricturing Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(4):557–66. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Scheibe K, Kersten C, Schmied A, Vieth M, Primbs T, Carlé B, et al. Inhibiting interleukin 36 receptor signaling reduces fibrosis in mice with chronic intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):1082–97.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Sleiman J, El Ouali S, Qazi T, Cohen B, Steele SR, Baker ME, et al. Prevention and treatment of stricturing Crohn’s disease—perspectives and challenges. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(4):401–11. doi:10.1080/17474124.2021.1854732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ke BJ, Abdurahiman S, Biscu F, Zanella G, Dragoni G, Santhosh S, et al. Intercellular interaction between FAP+ fibroblasts and CD150+ inflammatory monocytes mediates fibrostenosis in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Invest. 2024;134(16):e173835. doi:10.1172/JCI173835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Friedrich M, Pohin M, Powrie F. Cytokine networks in the pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2019;50(4):992–1006. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Speca S, Rousseaux C, Dubuquoy C, Rieder F, Vetuschi A, Sferra R, et al. Novel PPARγ modulator GED-0507-34 Levo ameliorates inflammation-driven intestinal fibrosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(2):279–92. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Barbarossa A, Iacopetta D, Sinicropi MS, Franchini C, Carocci A. Recent advances in the development of thalidomide-related compounds as anticancer drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2022;29(1):19–40. doi:10.2174/0929867328666210623143526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Biel C, Faber KN, Bank RA, Olinga P. Matrix metalloproteinases in intestinal fibrosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(3):462–78. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li Y, Cai W, Jin F, Wang X, Liu W, Li T, et al. Thalidomide alleviates pulmonary fibrosis induced by silica in mice by inhibiting ER stress and the TLR4-NF-κB pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5656. doi:10.3390/ijms23105656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Tang Q, Markby GR, MacNair AJ, Tang K, Tkacz M, Parys M, et al. TGF-β-induced PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway controls myofibroblast differentiation and secretory phenotype of valvular interstitial cells through the modulation of cellular senescence in a naturally occurring in vitro canine model of myxomatous mitral valve disease. Cell Prolif. 2023;56(6):e13435. doi:10.1111/cpr.13435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao H, Li C, Li L, Liu J, Gao Y, Mu K, et al. Baicalin alleviates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and fibroblast proliferation in rats via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2020;21(6):2321–34. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Beetz N, Rommel C, Schnick T, Neumann E, Lother A, Monroy-Ordonez EB, et al. Ablation of biglycan attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis after left ventricular pressure overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;101(4):145–55. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.10.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Krull NB, Zimmermann T, Gressner AM. Spatial and temporal patterns of gene expression for the proteoglycans biglycan and decorin and for transforming growth factor-β1 revealed by in situ hybridization during experimentally induced liver fibrosis in the rat. Hepatology. 1993;18(3):581–9. doi:10.1002/hep.1840180317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Gerber EE, Gallo EM, Fontana SC, Davis EC, Wigley FM, Huso DL, et al. Integrin-modulating therapy prevents fibrosis and autoimmunity in mouse models of scleroderma. Nature. 2013;503(7474):126–30. doi:10.1038/nature12614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Liu G, Cooley MA, Jarnicki AG, Borghuis T, Nair PM, Tjin G, et al. Fibulin-1c regulates transforming growth factor-β activation in pulmonary tissue fibrosis. JCI Insight. 2019;5(16):e124529. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.124529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Nakasaki M, Hwang Y, Xie Y, Kataria S, Gund R, Hajam EY, et al. The matrix protein Fibulin-5 is at the interface of tissue stiffness and inflammation in fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):8574. doi:10.1038/ncomms9574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Brina D, Ponzoni A, Troiani M, Calì B, Pasquini E, Attanasio G, et al. The Akt/mTOR and MNK/eIF4E pathways rewire the prostate cancer translatome to secrete HGF, SPP1 and BGN and recruit suppressive myeloid cells. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(8):1102–21. doi:10.1038/s43018-023-00594-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zeng S, Zheng Z, Wei X, Chen L, Lin J, Liu M, et al. Multiomics analysis unravels alteration in molecule and pathways involved in nondiabetic chronic wounds. ACS Omega. 2024;9(18):20425–36. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c01335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Larsen LJ, Møller LB. Crosstalk of hedgehog and mTORC1 pathways. Cells. 2020;9(10):2316. doi:10.3390/cells9102316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zhao X, Yang W, Yu T, Yu Y, Cui X, Zhou Z, et al. Th17 cell-derived amphiregulin promotes colitis-associated intestinal fibrosis through activation of mTOR and MEK in intestinal myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 2023;164(1):89–102. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Mitra A, Luna JI, Marusina AI, Merleev A, Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Fiorentino D, et al. Dual mTOR inhibition is required to prevent TGF-β-Mediated fibrosis: implications for scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(11):2873–6. doi:10.1038/jid.2015.252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Singh S, Murad MH, Fumery M, Sedano R, Jairath V, Panaccione R, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(12):1002–14. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00312-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Rodríguez-Lago I, Hoyo JD, Pérez-Girbés A, Garrido-Marín A, Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, et al. Early treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents improves long-term effectiveness in symptomatic stricturing Crohn’s disease. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(9):1056–66. doi:10.1177/2050640620947579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition: role in physiology and in the pathogenesis of human diseases. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(2):1281–324. doi:10.1152/physrev.00021.2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Jia WX, Yang MY, Han F, Luo YX, Wu MY, Li CY, et al. Effect and mechanism of TL1A expression on epithelial-mesenchymal transition during chronic colitis-related intestinal fibrosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2021;2021(7):5927064. doi:10.1155/2021/5927064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools