Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hibifolin Modulates the Activation of Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells and Attenuates Contact Dermatitis Induced by 2,4-Dinitro-1-Fluorobenzene

1 Doctoral Program in Medical Biotechnology, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

2 Department of Stomatology, Tungs’ Taichung Metro Harbor Hospital, Taichung, 435, Taiwan

3 Institute of Bioinformatics and Structural Biology and Department of Medical Sciences, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, 300, Taiwan

4 Department of Chest Medicine, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, 500, Taiwan

5 Department of Pharmacy, Tajen University, Pingtung, 907, Taiwan

6 Division of Dermatology, Pingtung Veterans General Hospital, Pingtung, 900, Taiwan

7 Department of Dermatology, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung, 813, Taiwan

8 Department of Hematology and Oncology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, 500, Taiwan

9 Department of Life Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Ruo-Han Tseng. Email: ; Chieh-Chen Huang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Natural and Synthetic Small Molecules in the Regulation of Immune Cell Functions)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1733-1748. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067011

Received 23 April 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Professional antigen-presenting cells known as dendritic cells (DCs) assist as a connection between the innate and adaptive components of the immune response. DCs are attractive targets for immunomodulatory drugs because of their crucial function in triggering immunity. This study set out to examine, for the first time, how hibifolin affected mouse bone-marrow derived (BMDCs) dendritic cells, triggered by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in vitro. Additionally, a mouse model of contact hypersensitivity (CHS) was used to assess its possible therapeutic effects in vivo. Methods: LPS was administered to BMDCs with or without hibifolin. Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class II, cytokine production, and co-stimulatory molecule (CD80, CD86) expression levels were assessed. To evaluate the functional effects on T-cell activation, mixed lymphocyte responses using OVA specific T-cells were conducted. In vivo, immunoregulatory potential of hibifolin was examined using a CHS mouse model sensitized with 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB). Results: Hibifolin significantly reduced the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, as well as the costimulatory molecules CD80, CD86, and MHC II induced by LPS, by about 40–50%. These effects were associated with reduced NF-κB and p38-MAPK pathway activity. JNK and ERK phosphorylation levels did not alter significantly. In vitro, BMDCs treated with hibifolin showed a 40%–45% down-regulated capacity to stimulate T-cell propagation and IFN-γ release. Oral hibifolin treatment in vivo modestly decreased DNFB-induced CHS responses by 30%–40%. Conclusion: Overall, our results offer new insights that by inhibiting NF-κB and p38-MAPK signaling, hibifolin decreases the expression of costimulatory molecules and cytokines, thereby limiting BMDC activation, suppressing T-cell responses, and exerting immunomodulatory effects in the CHS mouse model.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileDendritic cells (DCs), which are primarily antigen-presenting cells, are crucial for inducing T-cell responses and integrating the adaptive and innate immune systems [1,2]. These cells are found in specific locations within the lymphatic system and peripheral non-lymphoid tissues across a spectrum of maturational states [3]. DCs serve as sentinels against tumor and microbial antigens when they are immature and are mostly found in peripheral organs [4,5]. At these sites, DCs are involved in antigen capture and processing, followed by migration to local draining lymph nodes via lymphatic pathways. There, they activate and initiate T-cell responses, resulting in functional, morphological, and phenotypic changes during their process of maturation [6,7]. Reduced phagocytic capability, increased release of proinflammatory cytokines, elevated costimulatory markers, and enhanced levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and chemokines are all signs of mature DCs’ improved immune activation capacities [8]. Instead of successfully activating T cells, immature DCs help T cells develop peripheral tolerance, which includes increasing the production of regulatory-T cells [9,10]. Thus, the properties of DCs make them potential pharmacological targets with broad applications in immunotherapy.

Hibifolin, a flavonol glycoside derived from Abelmoschus manihot (Linn.) Medicus flowers have garnered attention for their diverse biological effect [11–14]. This compound has been shown to offer protective benefits against Alzheimer’s disease [15], exert anticonvulsant and antidepressant effects [16], and also exhibits antibacterial [17] and anti-inflammatory potential [18]. Recent studies have uncovered that hibifolin can mitigate the pathophysiological effects of LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI) [19]. Its efficacy is attributed to its antioxidant capabilities, which not only restore the activity of antioxidative enzymes but also activate the AMPK2/Nrf2 signaling pathway [19]. Despite these findings, the specific interactions of hibifolin within the immune system, particularly its impact concerning DC operations, are still unexplored.

This study presents, for the first time, an integrated in-vitro and in-vivo approach to observe the immunoregulatory impacts of hibifolin on bone marrow-derived dendritic cell (BMDC) function. We employed a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation model of BMDCs and CHS (contact hypersensitivity) triggered by 2,4-dinitro-1-fluorobenzene (DNFB) to comprehensively investigate the potential therapeutic effects of hibifolin on DC functionality and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism. Based on earlier research showing that DCs are essential in allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) triggered by haptens like DNFB, the DNFB-induced CHS model was chosen [20–22], therefore offering a useful in vivo approach to assess hibifolin’s immunomodulatory effects on skin inflammation, possibly involving DCs.

2.1 Experimental Animals and Ethical Values

This study used twenty male mice (6–8 weeks old), comprising ten C57BL/6 mice (National Laboratory Animal Center, Taipei, Taiwan) for bone marrow cells extracted, and five OT-I and five OT-II transgenic mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) for T-cell isolation. Contact hypersensitivity (CHS) was modeled in mice using 2,4-dinitro-1-fluorobenzene (DNFB). Fifteen males C57BL/6 mice (7 weeks old, 18–22 g) were separated into three groups (n = 5) at random for a single experiment: vehicle, control, and hibifolin. The mice were housed in cages with separate ventilation and under specified pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at National Chung Hsing University. The temperature (22 ± 2°C) and relative humidity (55 ± 10%) were maintained within a standard 12:12 h light/dark cycle. Ad libitum access to autoclaved water and regular laboratory mouse food was given to the animals. A randomized controlled design was applied, with group allocation by random number table; investigators measuring ear thickness and histology were blinded to group assignment. Only healthy mice were included, and no animals or data were excluded. All experimental procedures were conducted strictly in accordance with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of National Chung Hsing University (IACUC: 112-074) and the university’s ethical guidelines for the use of laboratory animals.

2.2 Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells (BMDCs) Preparation

To obtain bone-marrow cells, the mice’s femurs were flushed with RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco™, 31800-022, Grand Island, NY, USA) via syringe fitted with a 25-gauge needle. RBCs were subsequently removed using RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend, 420302, San Diego, CA, USA). Bone marrow cells were cultivated in medium (RPMI-1640) added with (10%) heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco™, A52567-01, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin G, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Capricorn Scientific GmbH, AAS-B, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany), 20 ng/mL of recombinant mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and IL-4 (PeproTech, Cat. Nos. 315-03 and 214-14, Cranbury, NJ, USA). Every two days, the cultured media were replaced, and cells were kept at 37°C in an incubator with 5% CO2. Cells that were weakly adherent and nonadherent were gathered on the seventh day of culture. The CD11c+ cells from this population were then magnetically separated using the CD11c MicroBeads UltraPure (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-125-835, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Flow cytometry (Accuri™ C5 flow cytometer; Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) verified that the isolated CD11c+ cells, which represent immature BMDCs, had a purity of more than 80%.

Hibifolin (ChemFaces, CFN70410, Wuhan, China) was diluted to a 1000-fold stock solution using DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide, Alpha Biochemistry, D090405-0500, Taoyuan, Taiwan) as the solvent. The BMDCs (2 × 106 cells/2 mL/well in 6-well) were incubated in medium containing 0.1% DMSO or specific concentrations of hibifolin for 1 h. 100 ng/mL LPS (lipopolysaccharide) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, L2880, Steinheim, Germany) was then used to activate the cells for either 4 or 18 h in order to measure the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23. Following the collection of the culture supernatant, the quantities of these cytokines were measured by ELISA kits (Catalog 430904, 431304, 433604, and 433704, correspondingly) supplied by BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA).

2.4 Cytotoxicity Assay of Hibifolin

The cytotoxicity of hibifolin on BMDCs was assessed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) examination (Sigma-Aldrich, 96992, St. Louis, MO, USA). BMDCs were grown at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/0.1 mL per well in plates with 96 wells at 37°C in an incubator that was humidified with 5% CO2. They were then exposed to different concentrations of hibifolin (6.25 to 50 μM) for 24 h under two experimental conditions: (1) hibifolin by itself, or (2) hibifolin in combination with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/mL). Following the manufacturer’s directions, cell viability was evaluated following incubation.

The phenotypic characteristics of BMDCs cultured for seven days were evaluated via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to assess surface markers. BMDCs were cultured at 2 × 106 cells/mL and treated according to experimental groups, 100 ng/mL LPS was used to excite the experimental groups when either 0.1% DMSO or 25 µM hibifolin was present. The control group received 0.1% DMSO without LPS. Incubated the cells for 30 min at 4°C before being stained with BB515-conjugated anti-mouse CD11c (1:100, Clone N418, Cat. No. 565586) and one of the PE-conjugated antibodies: CD80 (1:100, Clone 16-10A1, Cat. No. 553769), anti-mouse I-A/I-E (MHC class II, 1:100, Clone M5/114.15.2, Cat. No. 557000), or CD86 (1:100, Clone GL1, Cat. No. 553692). BB515 Hamster IgG2, λ1 (Cat. No. 565404), PE Hamster IgG2, κ (Cat. No. 550085), PE Rat IgG2a, κ (Cat. No. 553930), and PE Rat IgG2b, κ (Cat. No. 555848) were used as corresponding isotype controls. The supplier of all antibodies, including isotype standards, was BD Pharmingen™ (San Diego, CA, USA). Every PE-conjugated marker was assessed using a different double-staining setup with CD11c, and all staining was carried out under identical circumstances. The gating strategy for BMDCs is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. BD Accuri C6 Plus software (version 1.0.23.1, Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used to evaluate fluorescence data obtained with an Accuri™ C5 flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

2.6 T-Cell Activation Specific to OVA In Vitro

2 µg/mL OVAP1 (OVA257–264)/OVAP2 (OVA323–339) peptides, provided via Echo Chemical Co., Taiwan, were administered to BMDCs resulting from (OT-I and OT-II) TCR transgenic mice. For one hour, BMDCs (2 × 105 cells/mL) were treated with either 25 µM hibifolin or 0.1% DMSO at 37°C. After that, the cells were stimulated for 18 h using LPS (100 ng/mL), while the control group, given merely 0.1% DMSO. Following the course of treatment, the cells were gathered and given a PBS rinse. OT-I & OT-II animals, used to isolate (OVAP1) specific CD8+ T-cells and (OVAP2) specific CD4+ T-cells using Miltenyi Biotec’s MACS cell separation technology (South San Francisco, CA). To ensure regulated cell interactions, BMDCs and T cells were cocultured at a 1:5 ratio for 96 h. [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured to evaluate T-cell proliferation. After 96 h, ELISA was used to check for the generation of IFN-gamma in the culture supernatants (BioLegend, Catalog 430805, San Diego, CA, USA).

Before being exposed to 100 ng/mL LPS, BMDCs (2 × 106 cells/mL) were pretreated with either 0.1% DMSO or 12.5 μM and 25 μM hibifolin for an hour. Following 18 h of LPS induction, BMDCs were harvested, and whole-cell lysates were then made. The control group consisted of cells that had been exposed to 0.1% DMSO. For protein analysis, the Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ (BCA) Protein Analyses (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Product No. 23227, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure the protein content of each lysate. 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gels were used to run 40 µg of protein lysate, which was then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, 1620177, Hercules, CA, USA). After that, 5% skim milk in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 was used to block these membranes for an hour. The primary antibodies were incubated at 4°C for one night to detect the presence of phospho-p38 (1:1000, Cat. No. 9211S), total p38 (1:1000, Cat. No. 9212S), phospho-p42/44 ERK1/2 (1:1000, Cat. No. 9101S), total p42/44 ERK1/2 (1:500, Cat. No. 4695S), phospho-JNK (1:1000, Cat. No. 4668S), GAPDH (1:20,000, Cat. No. 5174S), or total JNK (1:500) (provided by SC-571; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000, Jackson Immuno-Research, (111-035-003), West Grove, PA, USA) were added to the membranes after the primary antibody had been incubated. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.54p, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), protein bands were analysed using LumiFlash Ultima Chemiluminescent Substrate, HRP System (Visual Protein, LF08-500, Taipei, Taiwan), and the images were visualized with Hansor Luminescence Image System (Taichung, Taiwan).

BMDCs (2 × 106 cells/mL), treated with either (0.1% DMSO) or 12.5 and 25 μM hibifolin for an hour in order to measure NF-κB transcriptional activity. After that, the cells were stimulated for 30 min in 6-well plates using 100 ng/mL LPS. Following stimulation, the BMDCs were gathered, and using the supplied technique, nuclear proteins were extracted using the Cayman Chemical NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction equipment (Item 10009277, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Pierce provided a (BCA) protein analyse kit (Cat. No. 23225, Rock-ford, IL, USA), used to measure protein quantities in the extracts. As directed by the manufacturer, the Active Motif TransAM NF-κB p65 ELISA Kit (Cayman Chemical, Item No. 10007889, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used in each experiment to quantify NF-κB p65 activity using nuclear protein.

2.9 DNFB-Induced CHS and Hibifolin Treatment

DNFB (Thermo Scientific, AAA1187122, Waltham, MA, USA) was dissolved in a mixture of acetone (TEDIA, AS1112-001, Fairfield, OH, USA) and olive oil (Sigma-Aldrich, 01514, Louis, MO, USA) (AOO, 4:1, v/v). For sensitization, 50 μL of 0.5% DNFB was topically applied once daily from day 1 to day 5 to a localized shaved area (approximately 1 cm × 3 cm) on the central abdomen of each mouse. The inner and outer surfaces of each mouse ear, challenged with (20 μL) of 0.2% DNFB on day 6. Supplementary Fig. S2 shows the experimental groups and treatment regimens. To summarize, three groups of mice were created (n = 5) at random: (1) control group, (2) DNFB group, and (3) DNFB plus hibifolin group (50 mg/kg). From day 1 to day 5, hibifolin was given orally by gavage once a day after being dissolved in a vehicle solution made up of 10% Cremophor EL (Merck Millipore, 238470, Darmstadt, Germany) in 0.9% NaCl (Honeywell Fluka, 31434-5KG, Charlotte, NC, USA). Control and DNFB groups received the same volume of vehicle solution following the same schedule. The dosage of hibifolin (50 mg/kg) was selected based on earlier in vivo studies showing therapeutic efficacy in models of infectious pneumonia and LPS-induced acute lung injury without signs of toxicity [19]. Experimental grouping and treatment timeline are summarized in Supplementary Fig. S2.

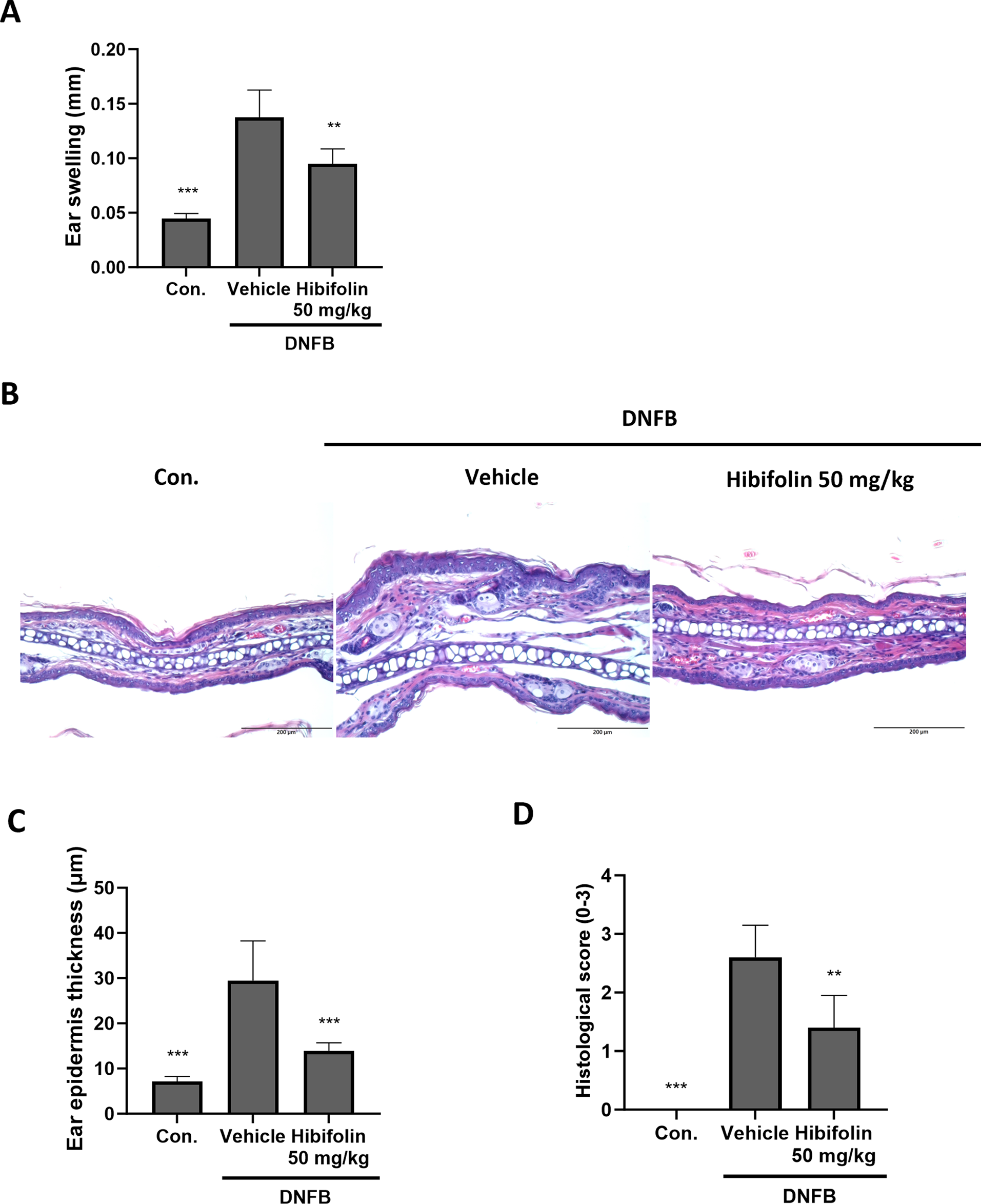

Following CHS induction, mouse ears were removed after euthanasia by CO2, paraffin-embedded, fixed in neutral-buffered formalin (10%), and sliced at a thickness of 4 μm. Sections were photographed via light microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), stained with H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) (Leica Biosystems, 3801522 & 3801600, Richmond, IL, USA). ImageJ software (version 1.54p, Wayne Rasband and collaborators, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), used to measure epidermal thickness. According to the previously established semi-quantitative histological scoring, inflammatory cell infiltration and epidermal thickening were assessed on a measurement of 0–3 (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe) [23]. Three sections per mouse were analyzed by two blinded investigators, with scores summed for final histological severity.

We conducted data analysis via version 10.0 of the soft-ware Graph-Pad Prism suite (GraphPad Soft-ware, Boston, MA, USA). Homogeneity of variances was assessed using the Brown-Forsythe test, and normality of residuals was assessed via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Dunnett’s multiple comparison assessment was used after one-way ANOVA to assess datasets that satisfied both assumptions (Figs. 1–4). Non-normal data were investigated using the Kruskal-Wallis test (Fig. 5) and then Dunn’s post hoc analysis. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) is used to display all data. p-values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

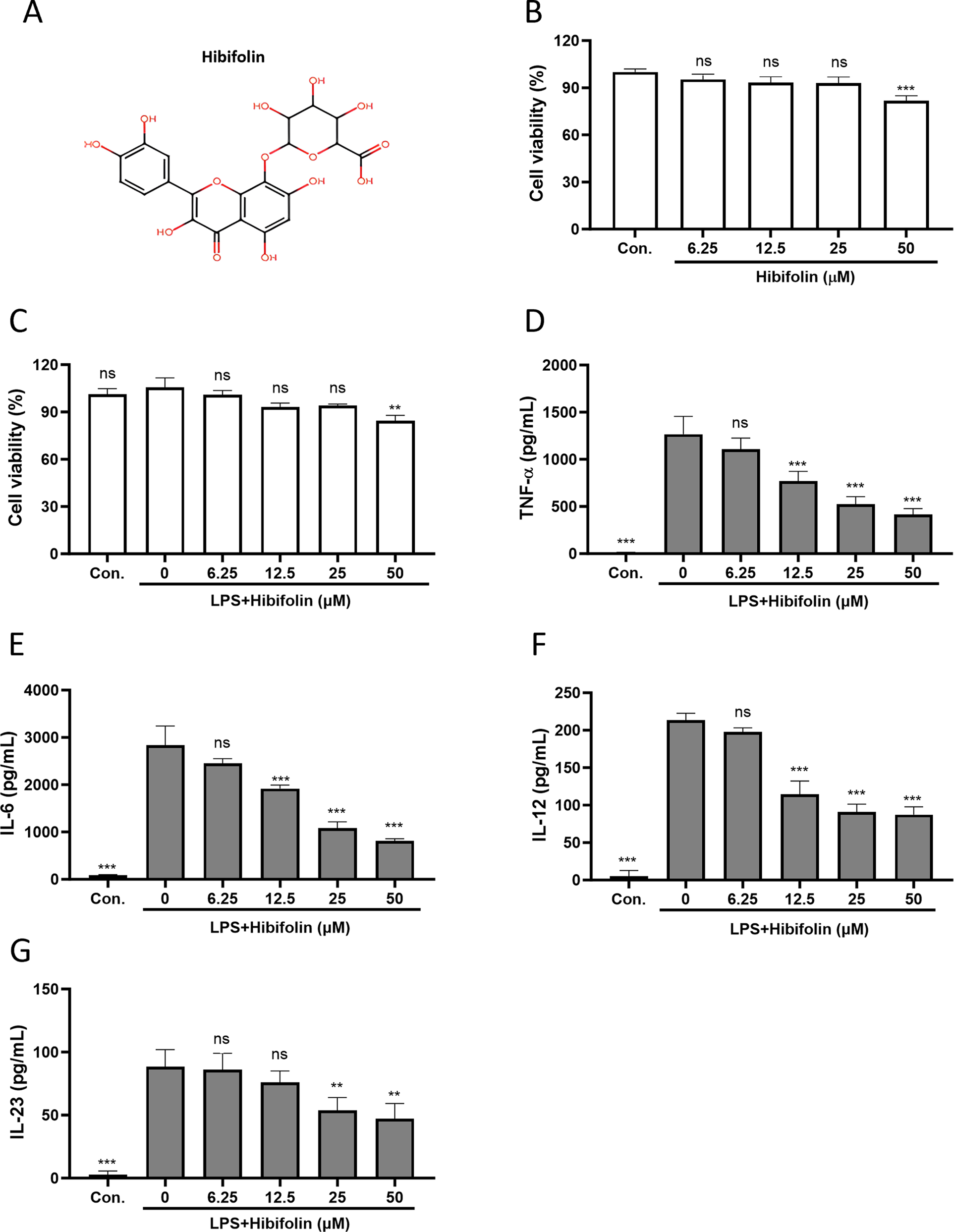

Figure 1: Hibifolin reduces cytokine production in LPS-activated mouse BMDCs. (A) The chemical structure of hibifolin. CCK-8 assays of BMDCs viability (B) after hibifolin treatment alone or (C) LPS in combination with. After 18 h (or 4 h for TNF-α), culture supernatants were obtained in order to use ELISA to quantify the amounts of (D) TNF-α, (E) IL-6, (F) IL-12, and (G) IL-23 cytokines. Every experiment was conducted in triplicate, and mean ± SD (n = 3) is displayed as the outcome. The following is an indication of statistical significance: ** shows p < 0.01, ns shows p > 0.05, and *** shows p < 0.001 associated with 0.1% DMSO (panel B) or 0.1% DMSO-treated BMDCs stimulated with LPS (panels C–G)

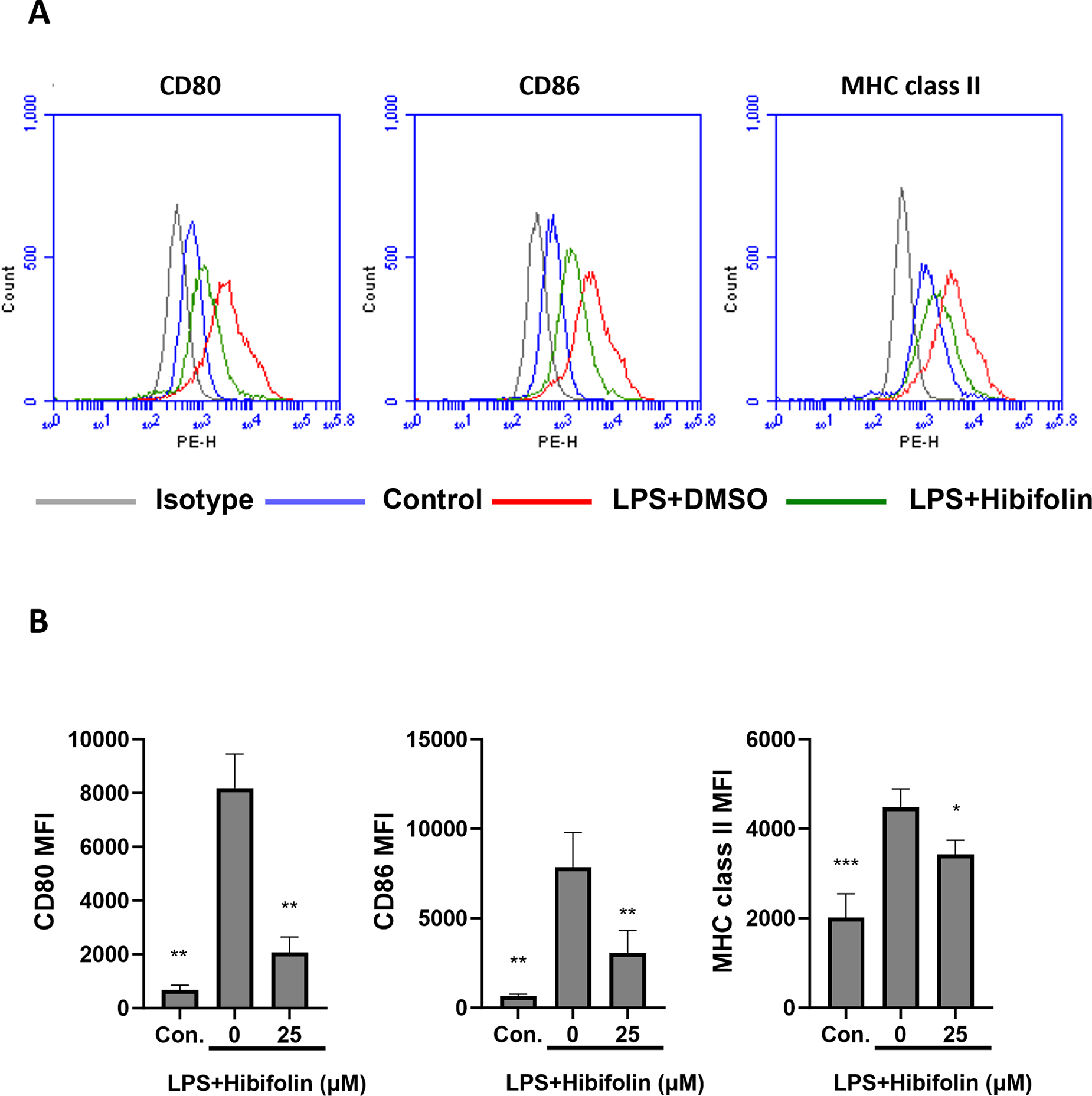

Figure 2: Hibifolin affects the expression of immunoregulatory markers on the surface of BMDCs induced by LPS. As demonstrated in the experiment, the BMDCs were treated with either (100 ng/mL) LPS + (0.1%) DMSO (LPS+DMSO) or (100 ng/mL) LPS + (25 µM) hibifolin (LPS+Hibifolin). Just 0.1% DMSO was administered to the control group (Con.). Following an 18-h culture period, cells were stained using fluorophore-conjugated antibodies that specifically targeted (A) CD80, CD86, and MHC class II. Flow cytometry was then used to evaluate the cells. The data are indicative of at least three biologically separate studies, and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values were measured. (B) A bar graph that shows the three experiments’ average values. The data are revealed as mean ± SD (n = 3), and each experiment was conducted in triplicate. In comparison to the LPS+DMSO group, statistical significance is represented by the subsequent symbols: * shows p < 0.05, ** shows p < 0.01, and *** shows p < 0.001

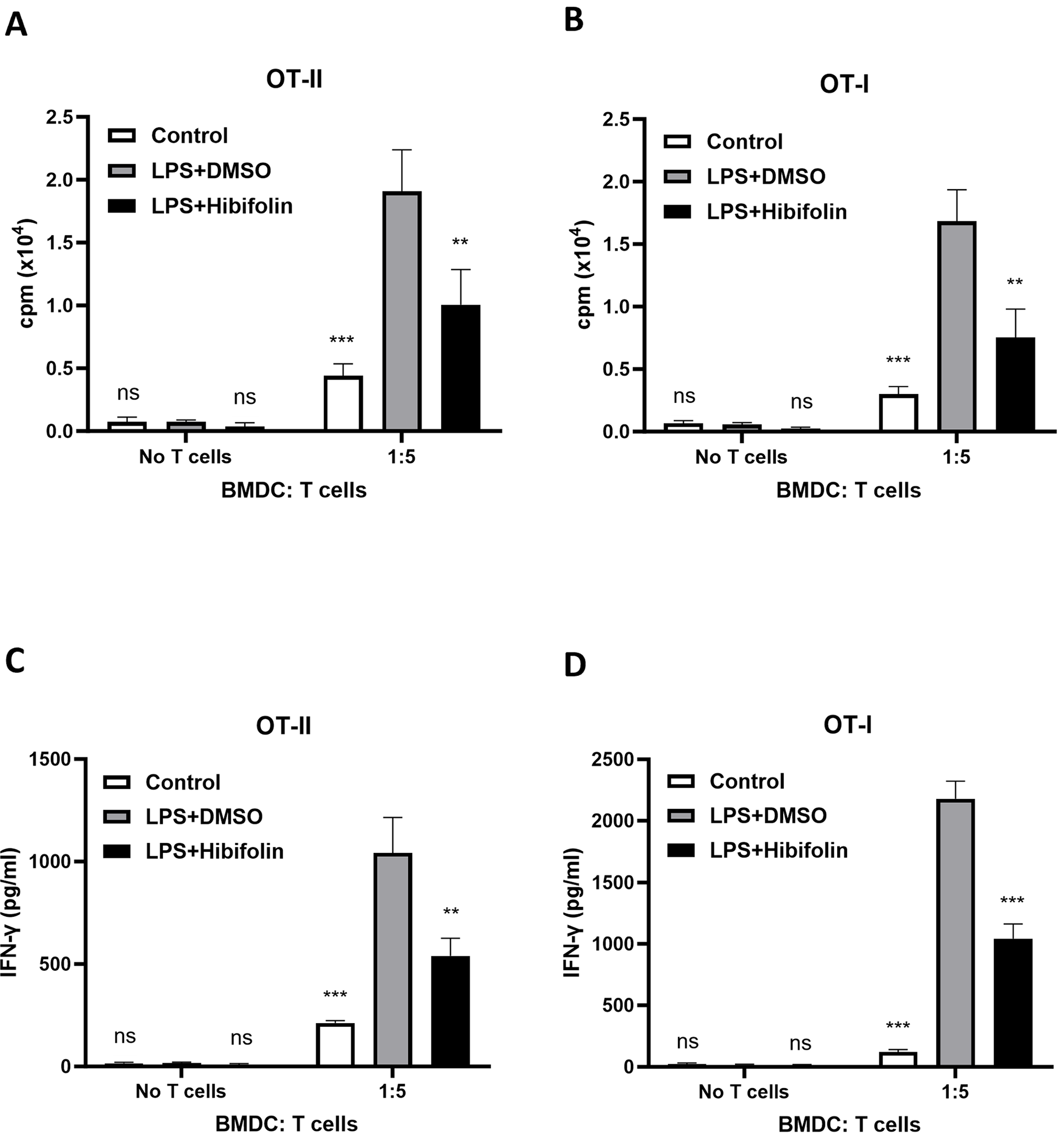

Figure 3: In vitro, hibifolin reduces antigen-specific T-cell activation in BMDCs activated by LPS. BMDCs were pretreated with either 0.1% DMSO or 25 µM hibifolin at (37°C) for 1hr, then treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 18-hrs. Control cells received 0.1% DMSO alone. During the LPS stimulation period, cells were also pulsed with either 2 µg/mL OVA257–264 (OVAP1) or OVA323–339 (OVAP2) peptides. Following treatment, BMDCs were rinsed with PBS and cocultured for 96 h at a 1:5 BMDC-to-T-cell ratio with either (A) OVAP2-specific CD4+ T-cells from OT-II mice or (B) OVAP1-specific CD8+ T-cells from OT-I mice. During the last 18 h of the coculture phase, [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured in order to assess T-cell growth. (C,D) After 96 h, culture Supernatants were gathered, and ELISA was used to quantity the amount of IFN-γ. The data are revealed as mean ± SD (n = 3), and each experiment was conducted in triplicate. Statistical significance was evaluated as follows: ns represents p > 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, and *** represents p < 0.001 when compared to the LPS + DMSO control group

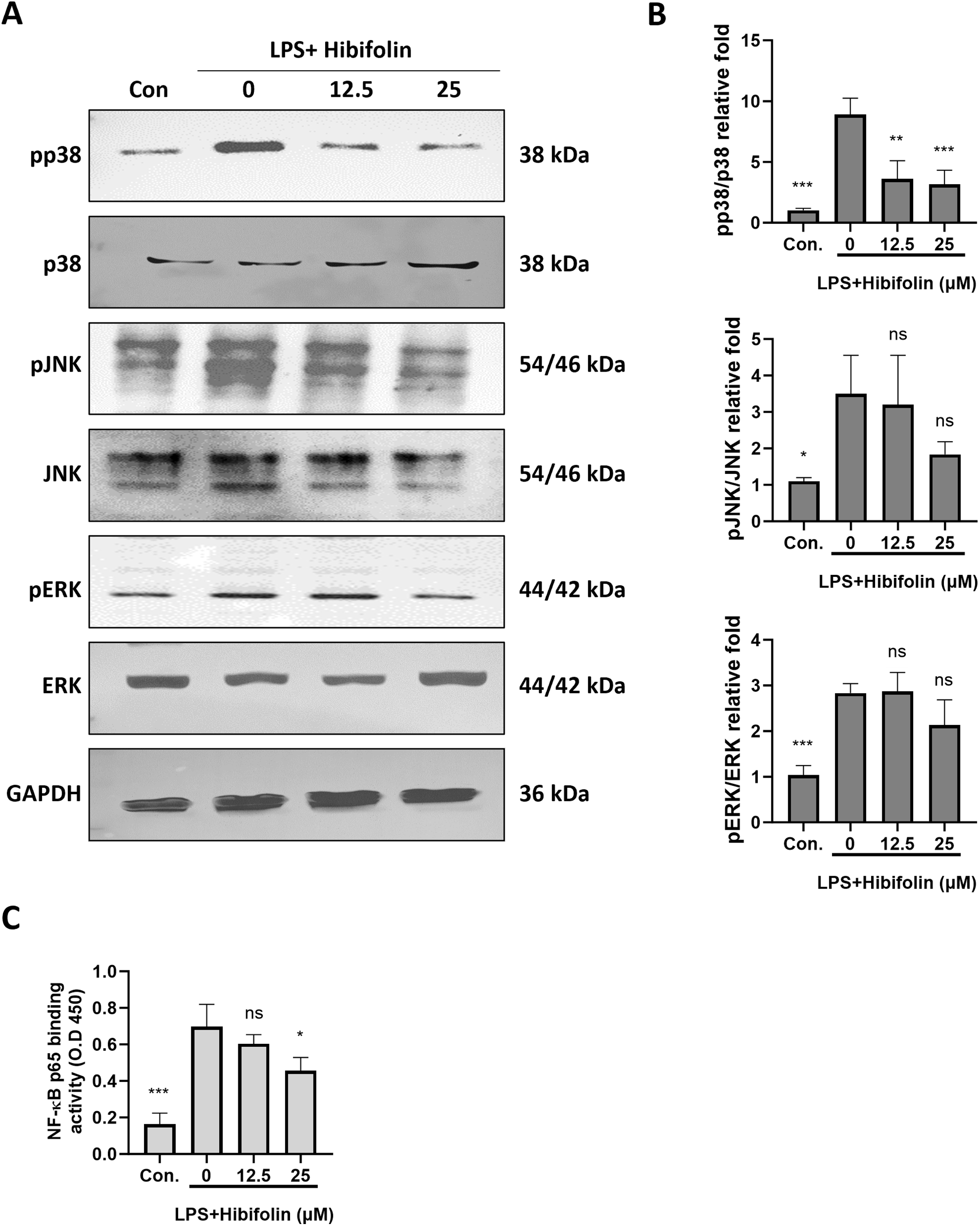

Figure 4: Hibifolin was shown to suppress p38 MAPK signaling pathway activation & activity of NF-κB in BMDCs. BMDC’s, treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) and 0.1% DMSO (LPS+DMSO) or with 100 ng/mL LPS and either 12 µM or 25 µM hibifolin (LPS+Hibifolin), as described in the experiment. The control group received 0.1% DMSO alone (Con.). Cell lysates, including both whole-cell extracts and nuclear extracts, were collected 30 min after LPS administration. (A) Western blot analysis using antibodies specific to both the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated versions of the MAPK proteins (p38, ERK and JNK) was used to determine the phosphorylation state of these proteins. (B) ImageJ was used to measure the protein band intensity and normalize it in relation to GAPDH expression. (C) Using absorbance measurements at 450 nm, NF-κB activation was measured using the procedure mentioned in the section of Materials and methods. Since every experiment was performed in triplicate, results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). When compared to the LPS + DMSO control group, the following is an indication of statistical significance: p > 0.05 is denoted by ns, p < 0.05 by *, p < 0.01 by **, and p < 0.001 by ***

Figure 5: Hibifolin taken orally reduces the mice’s DNFB-induced CHS response (A) Ear thickness was measured 16 h after the DNFB challenge. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained cryosections of ear tissue samples were examined at 200× magnification (scale bar ×200 μm). (C) Quantification of ear epidermal thickness. (D) Histological scores are semi-quantitative. The data, which are mean ± SD of five mice, are taken from two different investigations that yielded comparable results. The following is an indication of statistical significance: When compared to the DNFB + vehicle group, significant differences are indicated by ** for p < 0.01 and *** for p < 0.001

AI-based tools were applied during manuscript preparation. ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA; version GPT-4) was used for grammar editing and rephrasing to reduce textual similarity. All AI-generated content was critically reviewed and revised by the authors to ensure accuracy, originality, and compliance with academic standards. BioRender (BioRender.com) was used to create the graphical abstract.

3.1 Hibifolin Can Reduce the Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines Produced by BMDCs (Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells) Stimulated with Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

The ability of mature dendritic cells (DCs) to generate and release cytokines that control inflammation and T-cell differentiation—two processes essential to adaptive immunity—is one of their main traits. Thus, we used a CCK-8 assay to first assess the possible cytotoxicity of hibifolin. The findings demonstrated that hibifolin (Fig. 1A) had no discernible effect on BMDC viability at concentrations lower than 25 μM (Fig. 1B). Similarly, hibifolin at similar concentrations did not show appreciable cytotoxicity in the existence of LPS (Fig. 1C). We then evaluated how hibifolin affected the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines brought on by LPS. LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine protein expression, such as TNF-α (Fig. 1D), IL-6 (Fig. 1E), IL-12 (Fig. 1F), and IL-23 (Fig. 1G), was considerably and dose-dependently decreased by hibifolin, as illustrated in (Fig. 1D–G).

3.2 Hibifolin Affects the Surface Molecule Expression and Ability of LPS-Stimulated BMDCs

DC activation results in increased production of surface molecules, particularly costimulatory markers involved in antigen presentation and major histocompatibility complex (MHC). In order to engage with naive T-cells and promote their activation, these chemicals are essential [24,25]. We employed flow cytometry to evaluate the impact of hibifolin on the levels of these surface molecules in mouse DCs. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A,B, our findings demonstrate that hibifolin strongly suppresses the effect of co-stimulatory molecules like (CD80 and CD86) and MHC class II that are activated by LPS.

3.3 Influence of Hibifolin on BMDC-Mediated Activation of T-Cell

We investigated, effects of hibifolin on DCs’ capacity to trigger T-cell responses that are specific to the antigen ovalbumin (OVA). Immature DCs from mice were loaded with either OVA323–339 (OVAP2) or OVA257–264 (OVAP1) peptides. Prior to being activated with LPS, these cells were either pretreated with hibifolin or a control solution. Using [3H]-thymidine incorporation assays, we assessed their ability to stimulate the growth of allo-geneic OVA-specific CD4+ OT-II and CD8+ OT-I T-cells. The findings, which are shown in Fig. 3A,B, showed that OT-II and OT-II T-cell growth was strongly increased by LPS-activated BMDCs. Hibifolin pretreatment of BMDCs, however, considerably lessened this effect by reduction of proliferating both OT-II and OT-I cells. This implies that hibifolin hinders LPS-activated BMDCs’ ability to stimulate CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation. Additionally, we evaluated how hibifolin affected T cell production of IFN-γ (interferon-gamma). As seen in Fig. 3C,D, BMDCs treated with hibifolin and subsequently cocultured with OT-II CD4+ & OT-I CD8+ T-cells had a significant decrease in IFN-γ levels in the medium. The reaction of T-cells cocultured with BMDCs treated with DMSO in the existence of LPS, where production of IFN-γ was higher, was in contrast to this observation.

3.4 Hibifolin Reduced, Activation of p38-NF-κB & MAPK Signaling in LPS-Stimulated BMDCs

Prior studies have demonstrated the important functions of NF-κB and MAPKs in DC cytokine generation during LPS stimulation [26,27]. We examined how hibifolin impacts the MAPK & NF-κB pathways in mouse DCs stimulated by LPS in order to look into its suppressive effects. As illustrated in Fig. 5A,B, our findings demonstrated that hibifolin pretreatment reduced p38-MAPK phosphorylation upon LPS induction but had no discernible effect on JNK or ERK phosphorylation. Additionally, using a (TransAM) NF-κB transcription factor test kit to analyze nuclear extracts, the effect of hibifolin on NF-κB was assessed. LPS dramatically raised p65 (nuclear translocation) and NF-κB binding activity within 30 min, as shown in Fig. 5C. However, these increases were greatly diminished in BMDCs that had been pretreated with 25 μM hibifolin. These results imply that hibifolin’s capacity to modify these important signaling pathways may be the reason for its inhibitory influence on DC maturation in response to LPS.

3.5 Hibifolin Reduces Contact Hypersensitivity (CHS) Induced by 2,4-Dinitro-1-Fluorobenzene (DNFB) In Vivo

When skin is exposed to allergens like DNFB, a T-cell-mediated immune response is triggered, resulting in CHS, a common antigen-specific inflammatory response mediated by DC [28]. We then used this model to look at how hibifolin affected the immune responses in vivo. Oral hibifolin administration (50 mg/kg) substantially decreased ear edema when compared to vehicle control (Fig. 4A). H&E staining (Hematoxylin and eosin staining) further exposed reduced epidermal thickness (Fig. 4B,C) and lower histological scores (Fig. 4D). Although its exact cellular targets in vivo are yet unknown, these results imply that hibifolin may function as a molecule with immunomodulatory qualities, perhaps providing therapeutic benefits for allergic contact dermatitis.

The maturation and proinflammatory activity of LPS-stimulated BMDCs (bone marrow-derived dendritic cells) are dramatically inhibited by hibifolin, as demonstrated in this work. In particular, hibifolin decreased the release of important pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-23, IL-12, and IL-6 and downregulated the level of MHC (major histocompatibility complex) class II and classical co-stimulatory molecules such as (CD80, CD86). As demonstrated by a decrease in IFN-γ production, these modifications diminished BMDCs’ ability to stimulate T-cell activation, suggesting a move toward a less inflammatory immunological response. These results emphasize how hibifolin controls the function of dendritic cells (DCs), but it may also have immunomodulatory effects on other cell types. Although DC-driven responses were the main focus of our investigation, it is unclear if hibifolin also directly affects CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. To find out if hibifolin can alter T-cell activation and differentiation without DC participation, more research is required. Furthermore, immunological checkpoint molecules like PD-1 and PD-L1/2 are also essential for DC–T cell interactions, even though we assessed conventional costimulatory pathways [29–31]. Further research is necessary to determine whether hibifolin affects these inhibitory pathways.

Our results show that in LPS-stimulated DCs, hibifolin inhibits DNA-binding activity, NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation, and suppresses p38-MAPK phosphorylation. Given the pivotal roles of both pathways in regulating proinflammatory cytokine production and DC maturation, these outcomes provide mechanistic insight into the anti-inflammatory properties of hibifolin. Interestingly, hibifolin selectively inhibited p38-MAPK with minimal effects on JNK and ERK, suggesting a certain degree of specificity within the MAPK signaling cascade. Nonetheless, we cannot ignore the involvement of other signalling pathways, which warrants further investigation to fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying hibifolin’s immunomodulatory effects.

We used ISO 10993-5 (Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity) to assess if hibifolin is cytotoxic. This standard states that a substance is considered non-cytotoxic if its cell viability surpasses 70% of the untreated control [32,33]. In our study, hibifolin maintained viability above 80% across all tested concentrations, including 50 μM. Although the 50 μM group represented a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.05), viability remained within a non-cytotoxic range. Therefore, the observed inhibition of cytokine expression is unlikely to be due to cytotoxic effects and may reflect a direct immunomodulatory property of hibifolin.

In the current study, we assessed the effects of hibifolin on contact hypersensitivity (CHS) using a systemic administration model and found evidence suggesting its anti-inflammatory potential. However, further investigation into its efficacy via topical application would better simulate clinical scenarios, particularly for sensitized individuals seeking localized relief. Given that hibifolin is a natural compound derived from Abelmoschus manihot flowers [11], its potential use as a dietary supplement or herbal remedy also warrants exploration. Long-term intake studies may help clarify whether such compounds can confer preventive or immunomodulatory benefits. Compared to mechanistic studies alone, these translational approaches may offer more direct insights into the clinical utility of hibifolin as an immunomodulatory agent.

Despite the positive results, it is important to recognize several kinds of design limitations in the animal study used in this investigation. First, only male mice were included to reduce experimental variability, given that immune responses can be influenced by sex hormones and other endocrine factors [34]. However, this single-sex design may limit the generalizability of the results, as female mice could exhibit different immunological responses to hibifolin. Considering a more comprehensive evaluation of hibifolin’s therapeutic potential and potential sex-dependent effects, future research should include both sexes. Second, the current study did not include a standard immunosuppressive agent, such as dexamethasone, as a positive control [35,36]. Including such a comparator would not only validate the model’s responsiveness but also provide a benchmark for assessing the relative efficacy of hibifolin. Incorporating a positive control in future studies will improve the interpretability and translational relevance of the findings. Third, the assessment of in vivo immune responses was limited to ear thickness measurements as a general indicator of inflammation. While effective as an initial readout, this approach lacks resolution regarding specific immunological processes. The absence of detailed analyses—such as cytokine profiling, infiltration of immune cells (such as mast cells and T-cells), and tissue histopathology—limits mechanistic insight. Future work should integrate these immunological parameters to better elucidate the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying hibifolin’s anti-inflammatory activity.

In conclusion, this study indicates that hibifolin exerts potent immunomodulatory effects by selectively inhibiting dendritic cells’ (DCs’) p38-MAPK along with NF-κB signaling pathways, leading to attenuated maturation and reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These in vitro findings are supported by in vivo evidence showing that hibifolin attenuates 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNFB)-induced CHS (contact hypersensitivity) responses in mice. Further investigations are warranted to validate its efficacy in broader inflammatory disease models and to elucidate its full pharmacological profile.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Hira Umbreen for her assistance with the English editing of this manuscript. We also acknowledge the application of AI-based tools for language refinement and the use of BioRender for creating the graphical abstract.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the grant PTVH112-011 from Pingtung Veterans General Hospital.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Ya-Yi Chen, Chieh-Shan Wu, and Chieh-Chen Huang; Methodology: Ya-Yi Chen; Software: Ya-Yi Chen; Validation: Ya-Yi Chen, Ya-Hsuan Chao, and Tzu-Ting chen; Formal analysis: Ya-Yi Chen, and Ya-Hsuan Chao; Investigation: Ya-Yi Chen, Ya-Hsuan Chao, Tzu-Ting Chen, and Wen-Ho Chuo; Resources: Ya-Yi Chen; Data curation: Ya-Yi Chen; Writing—original draft preparation: Ya-Yi Chen, Chieh-Shan Wu, and Chieh-Chen Huang; Writing—review and editing: Chieh-Shan Wu, and Chieh-Chen Huang; Visualization: Ya-Yi Chen; Supervision: Ruo-Han Tseng, and Chieh-Chen Huang; Project administration: Ya-Yi Chen; Funding acquisition: Ya-Yi Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Upon reasonable request, Chieh-Shan Wu and Chieh-Chen Huang, the corresponding authors, will provide the data supporting the study’s findings.

Ethics Approval: The National Chung Hsing University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) examined and approved all animal research and procedures, Taichung, Taiwan (Approval No. 112-074), on 01 October 2024. The investigation was approved strictly in accord with Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at the University. No experiments were performed on client-owned animals, and thus, informed consent was not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.067011/s1.

Abbreviations

| ACD | Allergic contact dermatitis |

| BMDCs | Bone-marrow derived cells |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| CHS | Contact hypersensitivity |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| DNFB | 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| MFI | Mean fluorescence intensity |

| OVA | Ovalbumin |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPF | Specified pathogen-free |

References

1. Clark GJ, Angel N, Kato M, Lopez JA, MacDonald K, Vuckovic S, et al. The role of dendritic cells in the innate immune system. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(3):257–72. doi:10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00302-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yin X, Chen S, Eisenbarth SC. Dendritic cell regulation of T helper cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39(1):759–90. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-025146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu K. Dendritic cells. Encyclop Cell Biol. 2016:741–9. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–52. doi:10.1038/32588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lee HK, Iwasaki A. Innate control of adaptive immunity: dendritic cells and beyond. Semin Immunol. 2007;19(1):48–55. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zanna MY, Yasmin AR, Omar AR, Arshad SS, Mariatulqabtiah AR, Nur-Fazila SH, et al. Review of dendritic cells, their role in clinical immunology, and distribution in various animal species. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8044. doi:10.3390/ijms22158044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Janeway CAJr, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. 5th ed. New York, NY, USA: Garland Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]

8. Cheng H, Chen W, Lin Y, Zhang J, Song X, Zhang D. Signaling pathways involved in the biological functions of dendritic cells and their implications for disease treatment. Mol Biomed. 2023;4(1):15. doi:10.1186/s43556-023-00125-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Fucikova J, Palova-Jelinkova L, Bartunkova J, Spisek R. Induction of tolerance and immunity by dendritic cells: mechanisms and clinical applications. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2393. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cifuentes-Rius A, Desai A, Yuen D, Johnston APR, Voelcker NH. Inducing immune tolerance with dendritic cell-targeting nanomedicines. Nat Nanotechnol. 2021;16(1):37–46. doi:10.1038/s41565-020-00810-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li J, Zhang J, Wang M. Extraction of flavonoids from the flowers of Abelmoschus manihot (L.) medic by modified supercritical CO2 extraction and determination of antioxidant and anti-adipogenic activity. Molecules. 2016;21(7):810. doi:10.3390/molecules21070810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wei C, Wang C, Li R, Bai Y, Wang X, Fang Q, et al. The pharmacological mechanism of Abelmoschus manihot in the treatment of chronic kidney disease. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e22017. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wu C, Tang H, Cui X, Li N, Fei J, Ge H, et al. A single-cell profile reveals the transcriptional regulation responded for Abelmoschus manihot (L.) treatment in diabetic kidney disease. Phytomedicine. 2024;130(11):155642. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao L, Han S, Chai C. Huangkui capsule alleviates doxorubicin-induced proteinuria via protecting against podocyte damage and inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;306:116150. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2023.116150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhu JT, Choi RC, Xie HQ, Zheng KY, Guo AJ, Bi CW, et al. Hibifolin, a flavonol glycoside, prevents beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2009;461(2):172–6. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Guo J, Xue C, Duan JA, Qian D, Tang Y, You Y. Anticonvulsant, antidepressant-like activity of Abelmoschus manihot ethanol extract and its potential active components in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(14):1250–4. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2011.06.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Song W, Wang L, Zhao Y, Lanzi G, Wang X, Zhang C, et al. Hibifolin, a natural sortase a inhibitor, attenuates the pathogenicity of staphylococcus aureus and enhances the antibacterial activity of cefotaxime. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(4):e0095022. doi:10.1128/spectrum.00950-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gil B, Sanz MJ, Terencio MC, Ferrandiz ML, Bustos G, Paya M, et al. Effects of flavonoids on Naja naja and human recombinant synovial phospholipases A2 and inflammatory responses in mice. Life Sci. 1994;54(20):PL333–8. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(94)90021-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ni YL, Shen HT, Ng YY, Chen SP, Lee SS, Tseng CC, et al. Hibifolin protected pro-inflammatory response and oxidative stress in LPS-induced acute lung injury through antioxidative enzymes and the AMPK2/Nrf-2 pathway. Environ Toxicol. 2024;39(7):3799–807. doi:10.1002/tox.24233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Noordegraaf M, Flacher V, Stoitzner P, Clausen BE. Functional redundancy of Langerhans cells and Langerin+ dermal dendritic cells in contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(12):2752–9. doi:10.1038/jid.2010.223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Erkes DA, Selvan SR. Hapten-induced contact hypersensitivity, autoimmune reactions, and tumor regression: plausibility of mediating antitumor immunity. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014(2):175265. doi:10.1155/2014/175265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tanaka M, Kohchi C, Inagawa H, Ikemoto T, Hara-Chikuma M. Effect of topical application of lipopolysaccharide on contact hypersensitivity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;586:100–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.11.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Suzuki T, Nishiyama K, Kawata K, Sugimoto K, Isome M, Suzuki S, et al. Effect of the lactococcus lactis 11/19-B1 strain on atopic dermatitis in a clinical test and mouse model. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):763. doi:10.3390/nu12030763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Thery C, Amigorena S. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20(1):621–67. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Udeshi ND, Xu C, Jiang Z, Gao SM, Yin Q, Luo W, et al. Cell-surface milieu remodeling in human dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2024;213(7):1023–32. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.2400089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu J, Zhang X, Cheng Y, Cao X. Dendritic cell migration in inflammation and immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(11):2461–71. doi:10.1038/s41423-021-00726-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Munera-Rodriguez AM, Leiva-Castro C, Sobrino F, Lopez-Enriquez S, Palomares F. Sulforaphane-mediated immune regulation through inhibition of NF-kB and MAPK signaling pathways in human dendritic cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;177(6):117056. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Miller HL, Andhey PS, Swiecki MK, Rosa BA, Zaitsev K, Villani AC, et al. Altered ratio of dendritic cell subsets in skin-draining lymph nodes promotes Th2-driven contact hypersensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(3e2021364118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2021364118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. The instructive role of dendritic cells on T cell responses: lineages, plasticity and kinetics. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13(3):291–8. doi:10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00218-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kantheti U, Forward TS, Lucas ED, Schafer JB, Tamburini PJ, Burchill MA, et al. PD-L1-CD80 interactions are required for intracellular signaling necessary for dendritic cell migration. Sci Adv. 2025;11(5):eadt3044. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adt3044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Suszczyk D, Skiba W, Zardzewialy W, Pawlowska A, Wlodarczyk K, Polak G, et al. Clinical value of the PD-1/PD-L1/PD-L2 pathway in patients suffering from endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11607. doi:10.3390/ijms231911607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Miller F, Hinze U, Chichkov B, Leibold W, Lenarz T, Paasche G. Validation of eGFP fluorescence intensity for testing in vitro cytotoxicity according to ISO 10993-5. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2017;105(4):715–22. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.33602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Choi YR, Kang MK. Evaluation of cytotoxic and antibacterial effect of methanolic extract of paeonia lactiflora. Medicina. 2022;58(9):1272. doi:10.3390/medicina58091272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Elliott JC, Picker MJ, Nelson CJ, Carrigan KA, Lysle DT. Sex differences in opioid-induced enhancement of contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(5):1053–9. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12569.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li X, Wen R, Chen B, Luo X, Li L, Ai J, et al. Comparative analysis of the effects of cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone on intestinal immunity and microbiota in delayed hypersensitivity mice. PLoS One. 2024;19(10):e0312147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0312147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li T, Chen H, Mei X, Wei N, Cao B. Development and use a novel combined in-vivo and in-vitro assay for anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(3):445–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools