Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Melatonin and Related Compounds as Enzymatic Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Theoretical Study

1 Departamento de Química, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Av. Ferrocarril San Rafael Atlixco 186, Col. Leyes de Reforma 1 A Sección, Alcaldía Iztapalapa, México City, 09310, México

2 Department of Cellular and Structural Biology, UT Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

* Corresponding Author: Annia Galano. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071635

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Objectives: Oxidative stress (OS) plays a pivotal role in chronic and neurodegenerative diseases, which has sparked interest in molecules that modulate redox-regulating enzymes. Melatonin and its metabolites exhibit antioxidant properties; however, their molecular mechanisms of enzymatic and transcriptional modulation remain unclear. This study aimed to investigate, through an exploratory in silico approach, the interactions of melatonin and related compounds with OS-related enzymes to generate hypotheses about their role in cellular redox control. Methods: A rational selection of antioxidant, pro-oxidant, and transcriptional targets was performed. Ligands were optimized at the DFT level (M05-2X/6-311+G(d,p)) and docked to OS related enzymes. Docking results were analyzed using polygenic antioxidant indices (PAOX) and a similarity interaction index (SSI). Molecular dynamics simulations of selected complexes provided additional insight into potential ligand–protein interaction mechanisms. Results: In silico analyses revealed that N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK), N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK), and 3-hydroxymelatonin (3OH-M) could partially inhibit pro-oxidant enzymes such as neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX), thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX5). The N-(2-(2-acetyl-6,7-dihydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)acetamide (IIcD) and N-(2-(6-hydroxy-7-mercapto-5-methoxy-1H-indol)ethyl)acetamide (dM38) derivatives could potentially stabilize superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and catalase (CAT) enzymes, respectively. Finally, AFMK and dM38 showed consistent interactions with transcriptional regulators, particularly peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). Conclusion: These studies about melatonin-related compounds support a multifactorial profile of redox modulation and provide mechanistic hypotheses for future experimental validation. Among these approaches, the interaction-similarity index is introduced as a novel tool to facilitate the identification of promising redox-active candidates.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileOxidative stress (OS) is a pathophysiological condition characterized by a disruption of intracellular redox homeostasis that arises when the rate at which oxidants are produced surpasses the detoxification and repair capacity of the endogenous antioxidant system. Under such conditions, critical biomolecules undergo structural modifications leading to lipid peroxidation in membranes [1,2], protein carbonylation [3,4], and oxidative DNA damage in both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes [5,6]. These alterations may trigger cellular signaling pathways associated with inflammation, autophagy, senescence, and apoptosis, thereby compromising cell viability and tissue integrity [7–10]. Persistent redox imbalance has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic and degenerative diseases, including cancer, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disorders [11–14], and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [15,16].

In humans, melatonin originates from two main sources. The pineal gland produces less than 5% of the body’s total, releasing it circadianly into the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid to synchronize the biological clock. In contrast, most melatonin is generated in extrapineal tissues, predominantly in mitochondria, where it acts locally as an antioxidant and metabolic regulator. This synthesis does not follow a circadian rhythm and can be activated under OS conditions [17]. This indolamine exhibits antioxidant properties through direct and indirect mechanisms. Directly, it acts as a scavenger of radical species [18–20]. Indirectly, it modulates the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes, inhibits pro-oxidant enzymes, and regulates transcription factors involved in redox homeostasis [21–23]. This versatility positions melatonin as a multifunctional regulator that preserves cellular integrity under OS conditions. In addition, its principal metabolites also significantly contribute to the overall antioxidant capacity of the melatonin family [24–26]. N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK) and N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK) are reactive toward various radical species [26]. AMK can also interact with enzymatic targets involved in redox signaling pathways, such as cyclooxygenase 2 and nitric oxide synthases [27,28]. N-acetylserotonin (NAS), an intermediate in the melatonin biosynthesis, not only retains specific antioxidant properties but also activates cellular signaling pathways with neuroprotective effects [29,30]. Hydroxylated melatonin metabolites, such as 6-hydroxymelatonin (6OH-M) and 4-hydroxymelatonin (4OH-M), are highly efficient as free radical scavengers [31–33].

In addition, various structural derivatives of melatonin have been designed, synthesized, and evaluated in terms of their chemical stability, bioavailability, and biological activity, particularly their antioxidant potential [34–37]. In this context, compounds IIcD and dM38—in their anionic forms, and IIcD also in its neutral form—have notable radical scavenging activity. They also exhibit pharmacological affinity toward key therapeutic targets in neurodegeneration, including acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), which are implicated in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, respectively [38–40]. Furthermore, dM38 can repair critical biomolecules, such as DNA, lipids, and proteins, after being oxidatively damaged, as well as reduce free radical production by inhibiting Fenton-type reactions [41].

Another way to mitigate OS–induced damage is to modulate the enzymes implicated in redox regulation, which can be broadly categorized into three main groups: antioxidant enzymes, pro-oxidant enzymes, and redox-sensitive transcription factors. Antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase, constitute the first line of cellular defense against excessive accumulation of free radicals. Their primary function is to catalyze the conversion of reactive species into less harmful products, such as water and molecular oxygen. The activation of these enzymes through small-molecule modulators is expected to enhance the endogenous antioxidant capacity, thereby contributing to cellular protection under OS conditions [42]. In contrast, pro-oxidant enzymes—including NADPH oxidases, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, and certain mitochondrial enzymes—actively contribute to radical species generation. Their overactivity is frequently associated with pathological states in which OS plays a central role. Thus, selective inhibition of such enzymes would reduce the production of oxidants and help restore intracellular redox balance [43]. Transcription factors such as nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2(Nrf2), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), and activator protein 1(AP1) are essential players in controlling how cells activate genes to deal with OS. Nrf2, for example, promotes the expression of antioxidant enzymes by binding to antioxidant response elements within DNA [44]. Conversely, NF-κB and AP1 are known to activate pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant signaling pathways. Accordingly, modulating these transcription factors may shift the cellular transcriptomic profile toward a more protective and less damaging phenotype [45].

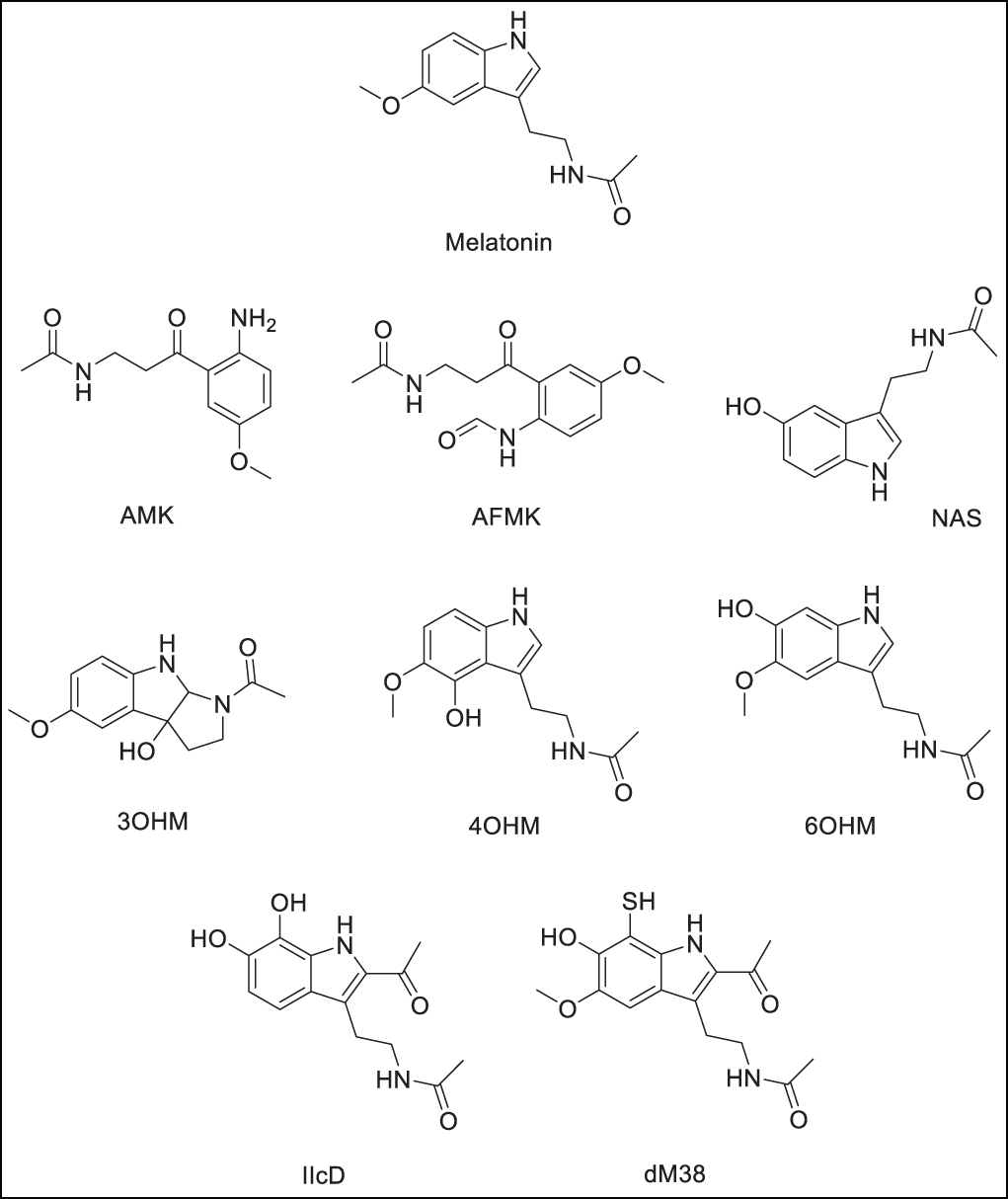

The primary goal of this study is to evaluate the modulatory potential of melatonin and related compounds (Scheme 1) on key enzymatic and transcriptional components of the redox regulatory network. Specifically, their capacity to influence the activity of both antioxidant and pro-oxidant enzymes, as well as redox-sensitive transcription factors. By targeting these molecular regulators, this research seeks to uncover novel mechanistic pathways through which melatonin-related compounds may mitigate OS and preserve cellular homeostasis. Molecular docking is used for that purpose. This valuable tool allows for the identification of potential molecular targets and provides mechanistic insights into ligand-receptor interactions. The presented results are expected to contribute to the understanding of the role of melatonin and related compounds in redox biology, as well as to the rational development of multifunctional therapeutic agents for OS-associated pathologies.

Scheme 1: Melatonin and related compounds. Metabolites: N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK), N-acetyl-N-formyl-5-methoxykynurenamine (AFMK), N-acetylserotonine (NAS), 3-hydroxymelatonin (3OH-M), 4-hydroxymelatonin (4OH-M), and 6-hydroxymelatonin (6OH-M). Derivatives: N-(2-(2-acetyl-6,7-dihydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)acetamide (IIcD), and N-(2-(6-hydroxy-7-mercapto-5-methoxy-1H-indol)ethyl)acetamide (dM38). The Scheme was created using Perkin Elmer, ChemDraw 21.0.0 software

2.1 Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations and Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Charges Estimation

Molecular structure calculations were performed using DFT for geometric optimization, vibrational analysis, and determination of partial atomic charges via NBO analysis. These calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 Rev. E.01 (Gaussian Inc., Wallingford, CT, USA) [46]. The molecular geometries of the target compounds were optimized under unconstrained conditions using the hybrid meta-GGA functional M05 [47], specifically designed to improve the treatment of noncovalent interactions and dispersion effects in complex organic systems. The 6-311+G(d,p) basis set was used, which incorporates diffuse and polarization functions on all atoms to ensure accurate electronic descriptions. The SMD protocol [48] was used to mimic the environment, with water as a solvent. The nature of the optimized stationary points was verified through harmonic vibrational frequency analyses performed at the same level of theory (M05/6-311+G(d,p)). The absence of imaginary frequencies confirmed that the structures correspond to true minima on the potential energy surface. Partial atomic charges were determined via Natural Bond Orbitals (NBO) analysis [49], as implemented in the Gaussian software suite (Gaussian Inc.). NBO charges, derived from quantum chemical calculations, offer a more accurate and chemically intuitive representation of the electron density distribution within a molecule. In the context of molecular docking, the use of NBO-derived charges enhances the reliability of the ligand electrostatic potential, leading to a more refined depiction of non-covalent interactions with the target protein, including hydrogen bonding and electrostatic contacts. This approach is particularly advantageous over empirically derived charge models when dealing with systems containing extended conjugation and has proven its worth in previous reports [50–52].

Starting point structures for ligands, substrates, and reference compounds were obtained from the PubChem database [53]. Molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina v1.2.3 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA), a widely adopted open-source docking engine known for its efficient optimization algorithm and empirical scoring function [54]. Ligand structures were pre-optimized at the DFT level and subsequently converted to the pdbqt format with Open Babel v3.1.1 (Open Babel development team, http://openbabel.org/ (accessed on 01 August 2025)) [55], ensuring the export of NBO charges. Proteins under study were classified into three groups:

Group 1. Pro-oxidant enzymes:

a. NADPH oxidase 5 (NOX5)

b. Proline rich region peptide (p22-47phox)

c. Xanthine Oxidase (XO)

d. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2)

e. Lipooxygenase 5 (5-LOX)

f. neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase (nNOS)

g. Myeloperoxidase (MPO)

h. Thioredoxin Reductase (TrxR)

Group 2. Antioxidant enzymes:

a. Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase (SOD1)

b. Catalase (CAT)

c. Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX4)

d. Glutathione Reductase (GR)

e. Peroxiredoxin V (PrxV)

Group 3. Transcription Factors

a. Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1 (KEAP1)

b. Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ)

c. Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Alpha (PPARα)

d. Inhibitor of nuclear factor Kappa-B Kinase subunit Beta (IKKβ)

The protein structures were selected based on biological relevance and crystallographic resolution ≤2.0 Å and retrieved from the RCS Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/ (accessed on 01 August 2025)) [56]. Docking parameters and protein ID can be found in Supplementary Materials, SM (Table S1). The selection of reference ligands (RL) was based on a trimodal functional philosophy to ensure mechanistic relevance and for their established biological function, corresponding to each target group. Inhibition of pro-oxidant systems, activation or preservation of antioxidant enzyme activity, and transcriptional modulation of nuclear factors. This approach ensures that the RL comparison is biologically meaningful and aligned with the expected therapeutic role of melatonin-derived compounds.

Repair of missing residues and energy minimization were performed with DeepView/Swiss PDB Viewer 4.1.0 (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland) software [57] using the GROMOS 98 force field [58]. Receptor preparation was performed using AutoDockTools v1.5.7 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) [59], including removal of co-crystallized ligands and water molecules, addition of polar hydrogens, and Kollman charge assignment. Blind docking simulations were performed on antioxidant proteins, while for pro-oxidant enzymes and transcription factors, grids centered on the allosteric or cellular activating sites of each protein were defined. The dimensions and coordinates of these search spaces were carefully selected to encompass the entire binding pocket, avoiding solvent-exposed regions. These spaces are detailed in the SM (Table S1) to ensure reproducibility. The exhaustiveness parameter in AutoDock Vina was set to 128 to allow for adequate conformational sampling, and the 100 most stable conformations within 3 kcal/mol of energy difference were selected. For each ligand, the best-ranked positions based on the predicted docking score (ΔGB, in kcal/mol) were chosen for further analysis. For IIcD derivative, the reported score was weighted since the molar fraction of the anionic (IIcD_a) and neutral (IIcD_n) are both relevant at physiological pH. The weighted docking score for this compound was estimated as:

where

To analyze the predicted affinities of molecular docking and identify candidates with the highest antioxidant potential, we developed a polygenic antioxidant activity (PAOX) index. For the inhibition of pro-oxidant enzymes, two index where used

where

In the absence of empirical data on compounds that enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes, the polygenic antioxidant activity index associated with antioxidant protein activation (

where

Similar to pro-oxidant protein inhibition, the polygenic antioxidant index for transcription factor modulation (

Post-docking visualization and interaction analysis were performed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021(v21.1.0.20298. Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, París, France) [60]. This tool enabled comprehensive inspection of key molecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking, π-cation interactions, and salt bridges. 2D interaction diagrams and 3D conformational alignments were generated to facilitate structural interpretation of the binding modes. Except for blind experiments, method validation was performed using redocking experiments, in which co-crystallized native ligands were redocked to their respective protein-binding sites using the same protocol. Root means square deviation (RMSD) values between predicted and experimental poses were calculated. RMSD values ≤ 3.0 Å were considered indicative of methodological reliability, in line with established criteria in structure-based drug design [61].

For the compounds with the best polygenic score, a Similarity Interaction Score (SSI) values were computed using interaction fingerprints derived from Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021 and compared across all ligands bound to each protein. The robustness of the index was assessed by verifying that compounds with a threshold value (

2.3 Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the GROMACS 2024.4 software package [62]. Protein topologies were parameterized with the CHARMM36m force field [63], while ligand parameters for UNL were generated with CGenFF via the CHARMM-GUI platform [64]. The protein–ligand complex was embedded in a rectangular box with a 1.0 nm buffer distance to the edges, solvated with explicit TIP3P water molecules [65], and neutralized with counterions. Na+ and Cl− ions were included to reach an ionic strength of 0.15 M, similar to physiological conditions. The system was subjected to energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm until 5000-step convergence [66], followed by equilibration under NVT and NPT ensembles [67]. The temperature was maintained at 300 K using the V-rescale thermostat [68], and the pressure was adjusted to 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat [69]. Both equilibration steps were prolonged to 1 ns each, ensuring system stability prior to production. The production step ran for 100 ns under the NPT ensemble with a 2 fs integration step. Long-range electrostatics were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method [70], applying a 1.2 nm cutoff for Coulomb and van der Waals interactions. The Verlet cutoff scheme was employed with a neighbor list update frequency of every 20 steps. Bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the LINCS algorithm [71]. System coordinates were saved every 100 ps, and energies were recorded every 1 ps for later analysis. Trajectory analyses included calculations of the root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of the protein structure to assess structural stability and flexibility. The RMSD of the ligand relative to the binding site was also determined. Protein-ligand interactions were characterized by calculating hydrogen bonds (cutoff distance of 0.35 nm). System equilibrium and interaction stability were verified by monitoring the potential energy profile throughout the production cycle (Fig. S1). In addition, radial distribution function analyses for short-range contact persistence were generated during simulations (Fig. S2).

2.4 Computer-Assisted Retrosynthetic Analysis

The retrosynthetic design of the target compound was performed using ChemPlanner (https://rxn.app.accelerate.science/rxn (accessed on 01 August 2025)), a module of CAS SciFinder®, which integrates a curated reaction database and machine learning-based prediction tools [72]. This platform combines expert-coded transformation rules with data-driven algorithms to generate feasible synthetic routes based on over 100 million documented reactions [73–75]. The input structure was analyzed using SMILES notation, and ChemPlanner proposed retrosynthetic steps based on synthetic accessibility, precedent reliability, and atom economy. Reaction pathways were evaluated for the number of steps (≤10 steps), reactant availability, maximum price (1000 USD/100 g), and predicted yields, with an emphasis on functional group compatibility and green chemistry principles. The selected routes prioritized robust C-C bond formation, minimized protecting group manipulation, and provided referenced experimental conditions for each transformation. Method validation and pathway traceability were ensured by integrating the retrosynthetic logic system and bibliographic precedents [74].

Through in in silico simulations, such as molecular docking, it is possible to predict the binding affinity and interaction modes of melatonin-derived compounds with key proteins involved in cellular redox balance. This approach enables the assessment of their potential to stabilize or activate antioxidant enzymes, inhibit pro-oxidant enzymes, and modulate transcription factors associated with OS responses. These analyses provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the biological antioxidant activity of the compounds, as well as guidance for optimizing the design of derivatives with enhanced therapeutic potential.

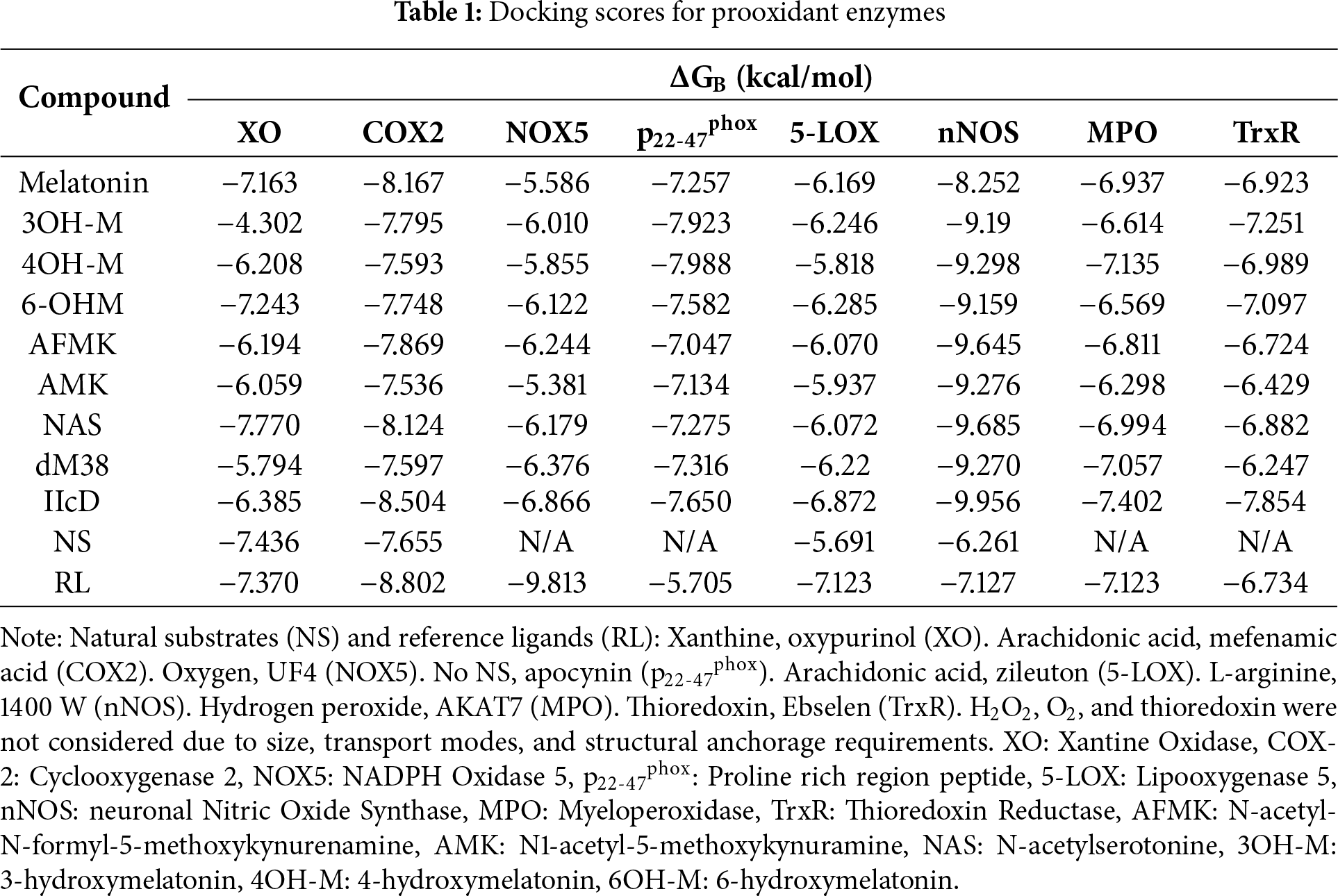

3.1 Interaction of Melatonin and Related Compounds with Prooxidant Enzymes

Pro-oxidant proteins have been widely studied because their inhibition can reduce OS, protect key biomolecules, and prevent or treat various diseases. The capacity of melatonin and some of its derivatives to interfere with the function of these pro-oxidant enzymes remains an open mechanistic question. To provide clues about possible inhibition mechanisms, the molecular docking of the compounds under study was studied and compared with that of some known inhibitors and the natural substrates of these enzymes. The stability of the docked protein-ligand complexes was estimated with the docking scores. At this point, it is worth noting that the more negative the binding energy, the more stable the complex is. Table 1 presents the results obtained for melatonin-related compounds, NS, and RL detailed in Table S1.

In addition to the stability of the complexes, molecular docking can provide insights about the possible modes of inhibition, such as the ligand binding site (active or allosteric) and the ligand’s conformation, as well as the type of interactions that stabilize the adduct. Table S2 in the SM presents the amino acid residues involved in interactions with melatonin and its related compounds, as well as the types of noncovalent interactions responsible for stabilizing protein-ligand complexes. Only selected data from the relevant candidates are included, indicating a high probability of enzyme inhibition. Almost all complexes were located within, or near to, the active site, except for p22-47phox, which inherently lacks a defined catalytic site, and TrxR, for which docking simulations predicted different ligand binding sites.

To identify the most likely targets for pro-oxidant inhibition, the

Figure 1: The

A quick analysis of the

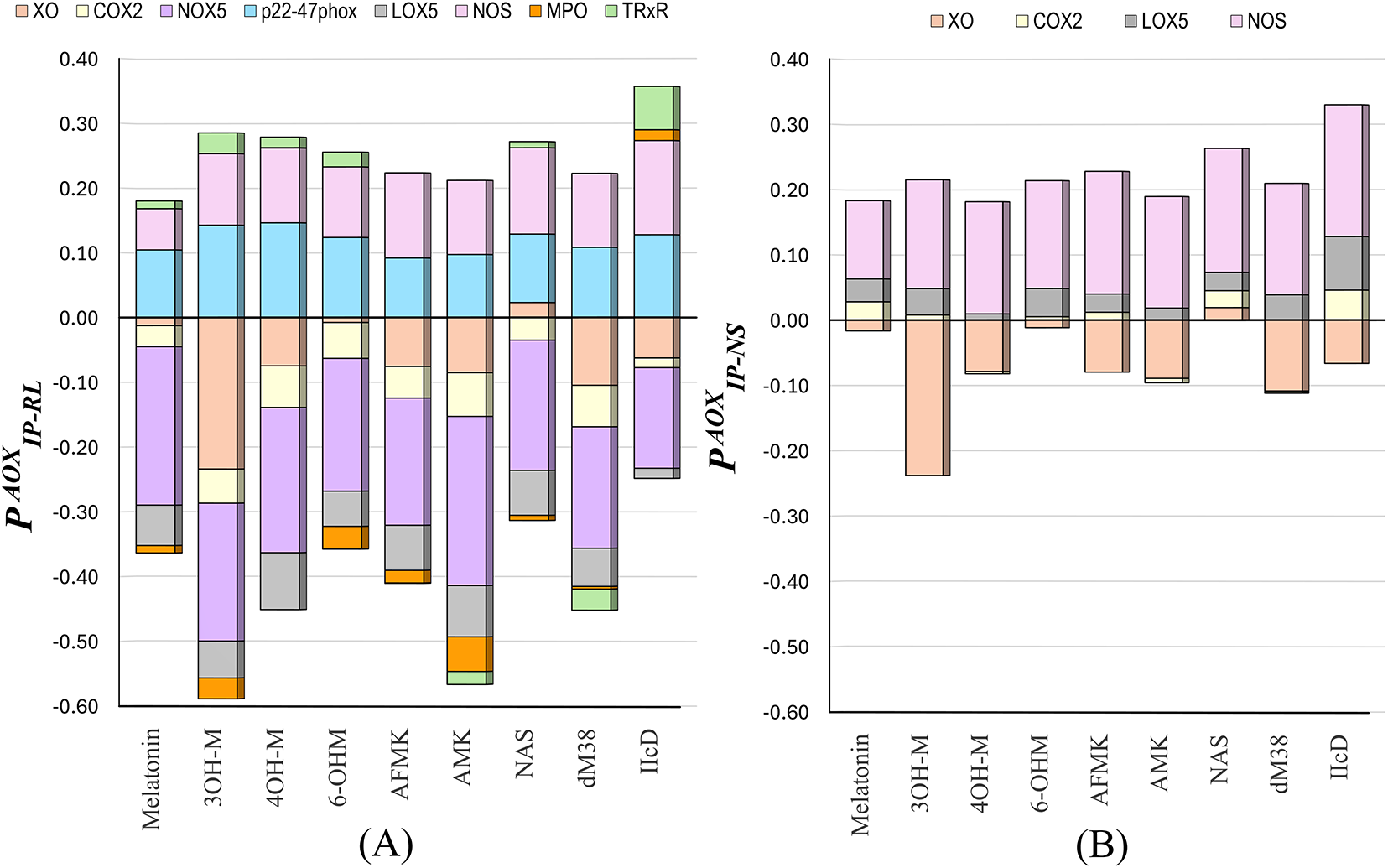

In addition to docking-derived binding affinities, it is essential to assess whether a candidate’s binding mode reproduces the functional interaction pattern of a known ligand or substrate. To this end, we developed the Similarity Interaction Index (SSI), a dimensionless index designed to quantify the mechanistic consistency between a candidate compound and a reference ligand bound to the same site. The SSI is defined as follows:

where NMR is the number of residues interacting with both the compound and the reference ligand, NMI is the number of exact matches in the interaction type (H-bond, π-forces, etc.) with those residues, and NRR is the total number of residues involved in the interaction between the enzyme and the reference ligand. The SSI is normalized to 1.0 for an identical interaction pattern and 0 for no overlap. This normalization anchors the reference ligand as an upper bound (SSI = 1.0), allowing for meaningful relative comparisons between novel compounds. In practice, candidates with values equal to the threshold (

Based on the affinity, interaction profiles, and similarity, the most promising candidates for each target are proposed to be: (i) AFMK, AMK, NAS, dM38, and IIcD for nNOS inhibition; (ii) melatonin, 3OH-M, and AFMK for p22-47phox; (iii) NAS and AMK for 5-LOX; and (iv) 3OH-M for TrxR. According to the docking results, none of the studied melatonin-like compounds is expected to have a significant role in modulating the other investigated receptors.

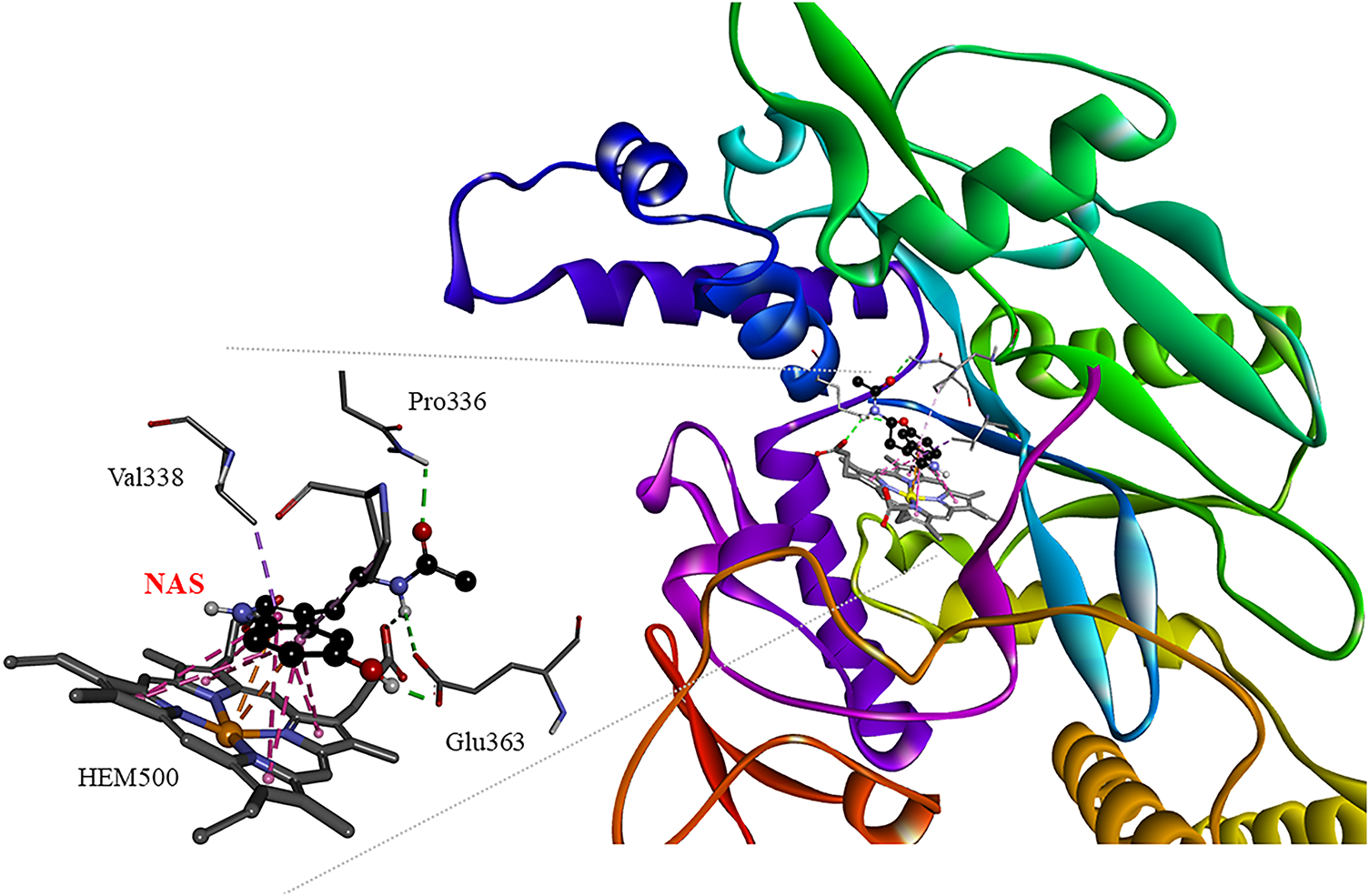

Analyzing in more detail the interactions that stabilize the [NAS:nNOS] complex (Fig. 2), it is possible to observe that this metabolite forms many connections with nNOS, which explains its high affinity, even more potent than classical inhibitors such as 7-nitroindazol and 1400w [76,77]. NAS interacts with key catalytic residues such as Glu363, Gln249, Pro336, Val338, and the heme group through hydrogen and coordination bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and stacking interactions.

Figure 2: 3D interaction network in the [NAS:nNOS] complex. Non-covalent interactions are depicted in doted lines: H-bonds (green), π forces (pink and orange). Pro: Proline, Val: Valine, Glu363: Glutamate, HEM500: Hemo group, NAS: N-acetylserotonin. The figure was made with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

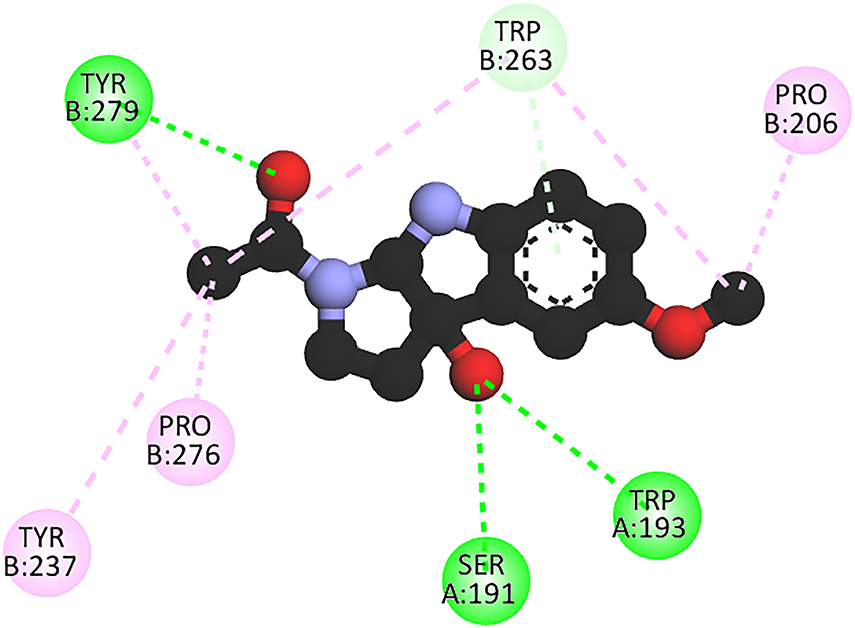

The 2D map of the interactions in the p22-47phox complex with 3OH-M (Fig. 3) shows that the ligand preferentially localizes at the interface between p22 (chain A) and p47 (chain B) peptides, establishing distinct intermolecular interactions with residues from both chains. 3OH-M establishes two conventional hydrogen bonds, one with Tyr279 (chain B) and another with Trp193 (chain A). Stabilization is complemented by multiple hydrophobic interactions, pi-alkyl forces with Trp263, as well as alkyl interactions with Pro276, Tyr237, and Pro206, all from chain B. This conformation, while establishing bonds with both chains, shows a significant dependence on the hydrophobic residues of chain B.

Figure 3: 2D interaction profiles in [3OH-M:p22-47phox] complex. Stabilizing interactions are represented in dotted lines: H-bonds (green), π-alkyl and alkyl (pink), and no conventional H-bond (light green). Tyr: Tyrosine, pro, Proline, Trp: Tryptophan, Ser: Serine. A: protein chain A, B: protein chain B. Figure was made with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

In the case of TrxR, both 3OH-M and IIcD exhibit favorable binding affinities. However, their interactions occur at distinct sites, as illustrated in SM (Fig. S3). 3OH-M binds proximal to the catalytic selenocysteine, in a position similar to that observed for Ebselen, a well-characterized TrxR inhibitor [78]. In contrast, IIcD interacts close to redox centers, approximately 5 Å from the FAD cofactor, which is reflected by its low SSI. On the other hand, the best-docked conformations of Zileuton and AMK with 5-LOX indicate that both compounds are located near the enzyme’s active site (SM: Fig. S4). Zileuton directly coordinates to the catalytic Fe2+ ion, which is consistent with its known mechanism of redox inhibition [79].

3.2 Binding Melatonin-Related Compounds to Antioxidant Enzymes

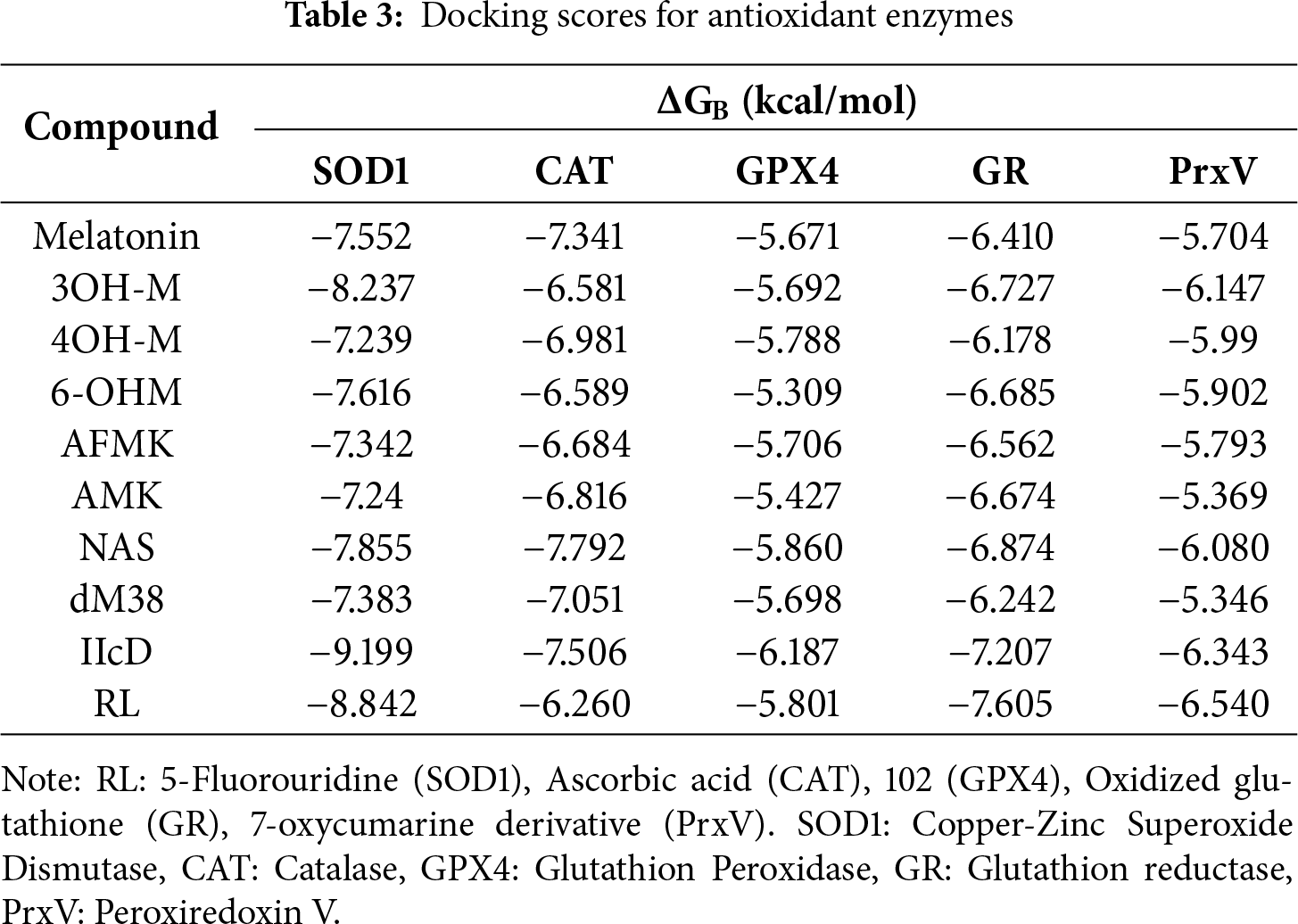

The study of direct activators of antioxidant enzymes is in its early stages, with few well-characterized examples [80–84]. A notable advance is the identification of allosteric activators of GPx4 [85], while recent analyses highlight interactions of known antioxidants with key antioxidant enzymes. Activators could increase catalytic activity, reduce OS, and protect mitochondrial function, with potential therapeutic applications in neurodegeneration, ischemia, degradation, and aging [86–88]. In contrast, although melatonin and its metabolites indirectly stimulate the expression and activity of enzymes such as SOD1, CAT, and GPX [17,89], their potential as direct activators has been explored little. Table 3 shows the scores obtained in this work for the studied compounds, along with the corresponding values for other compounds considered as agonists or RL of these enzymes, which are included for comparison purposes.

The simulations were performed blindly, i.e., the entire enzyme surface was explored. As a result, the most stable conformations were not clustered in a single region. While this type of simulation alone cannot elucidate the activation mechanism, it can help identify potentially relevant binding sites and offer initial clues about the activation process. For example, it can suggest functional regions if ligands tend to cluster near catalytic residues, dimer interfaces, or other key structural areas, and allows the generation of mechanistic hypotheses based on recurring interaction patterns between different ligands and specific regions. The stabilizing interactions of the best candidates, including potential activators and the RL, are presented in the SM (Table S3).

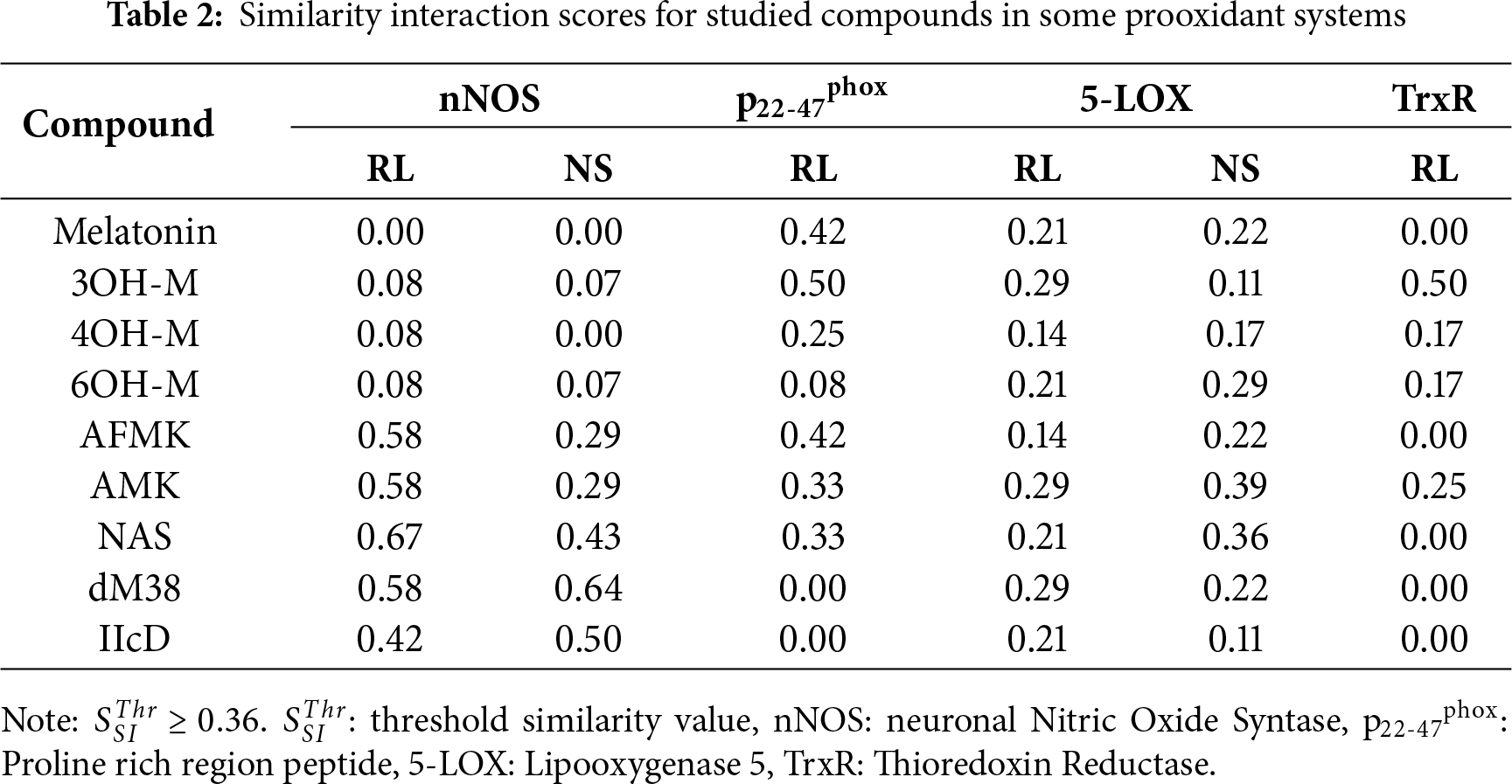

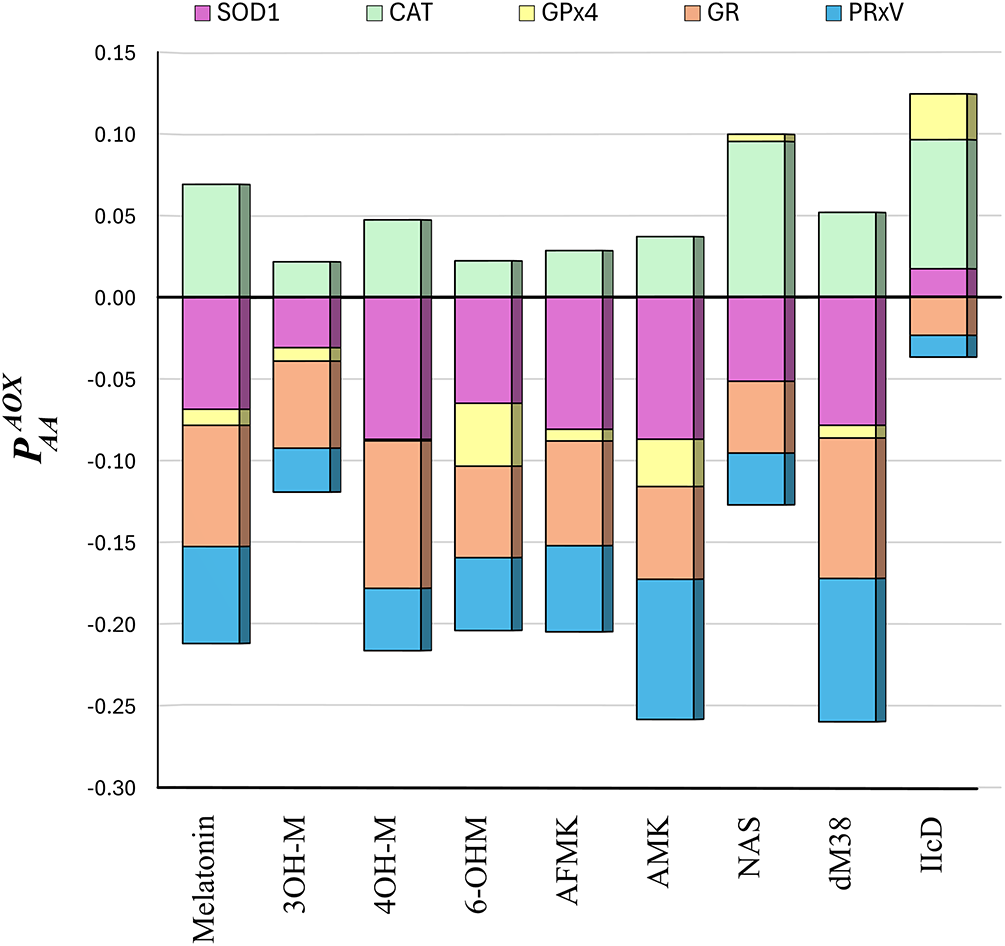

The index of activation of antioxidant enzymes (

Figure 4: The

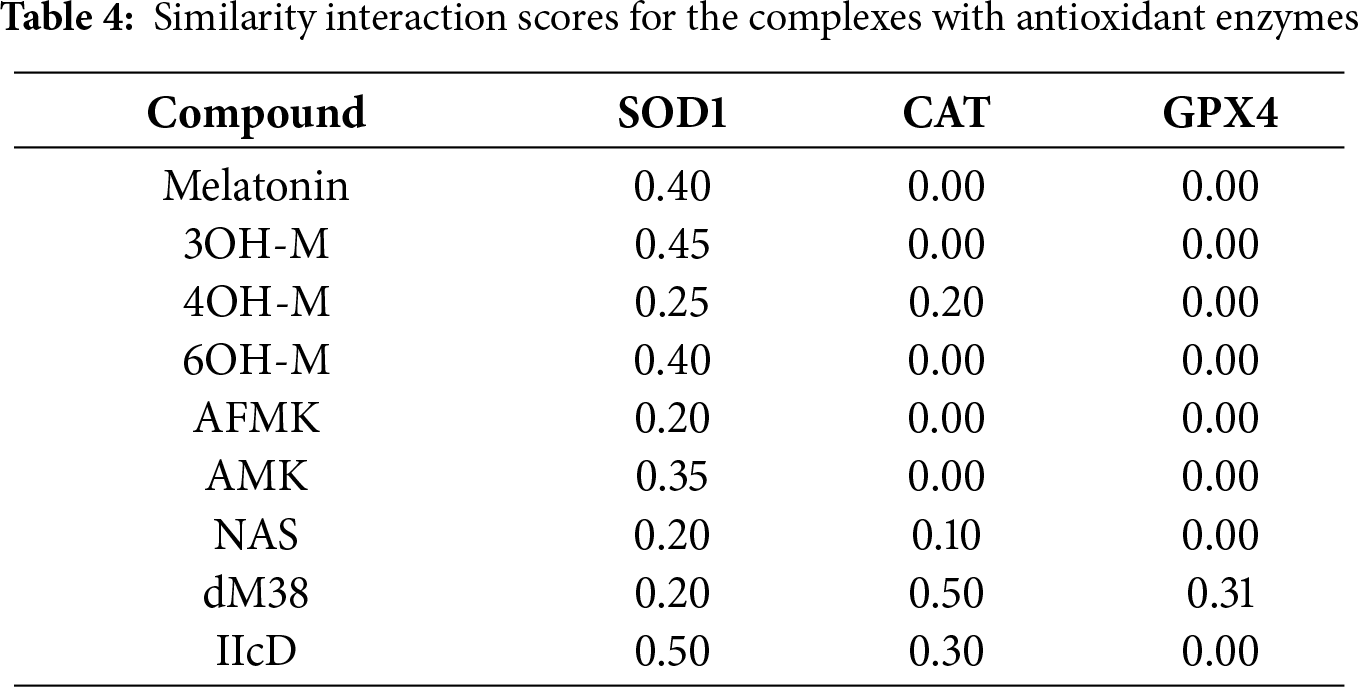

Based on their relative affinities, CAT was identified as the most promising enzyme target for direct activation by melatonin-like compounds. However, NAS was also found to bind to GPx4 with significant strength, and IIcd to interact with GPx4 and SOD1 through relatively strong binding. To identify if their interactions are similar to those of reference activators, the SSI scores were calculated (Table 4).

According to the SSI scores, the interactions of most compounds with SOD1 show low to moderate structural similarity with respect to the reference compounds. The highest SSI value corresponds to IIcD (0.50), which is also the candidate that binds the strongest to this enzyme. In the complexes involving CAT and GPX4, the similarity indices are generally low or negligible, except for dM38. This melatonin derivative was the only compound with significant SSI values for both enzymes (0.50 and 0.31, respectively). When the similarity indices and estimated affinities are integrated into the analysis, IIcD emerges as the most promising candidate for activating SOD1, while dM38 is the best agonist for CAT. For GPX4, on the other hand, the interaction pattern of dM38 exhibits a moderate conformational similarity compared to that of the reference ligand, while its moderate binding energy suggests that it might activate the enzyme efficiently.

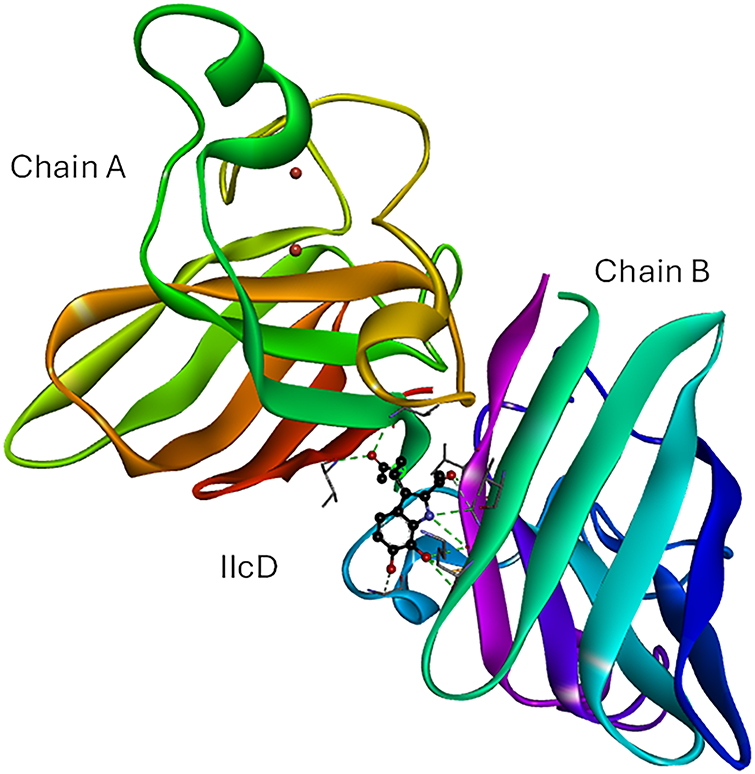

The interactions in the [IIcD: SOD1] and [dM38:CAT] complexes are further analyzed to extract more details about the possible activation mechanisms. Molecular docking analysis of the [IIcD: SOD1] complex indicates that IIcD binds with good affinity to the dimer interface (Fig. 5). Stabilization of the complex occurs through multiple hydrogen bonds and other non-covalent interactions with residues from both SOD1 chains (Val7, Val146, Cys144, Gly54, Gly145).

Figure 5: Best docked pose for IIcD in its complex with SOD1. IIcD is placed in the interface of the homodimer. Intermolecular H-bonds are represented in green dotted lines). IIcD: N-(2-(2-acetyl-6,7-dihydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)acetamide. The figure was made with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

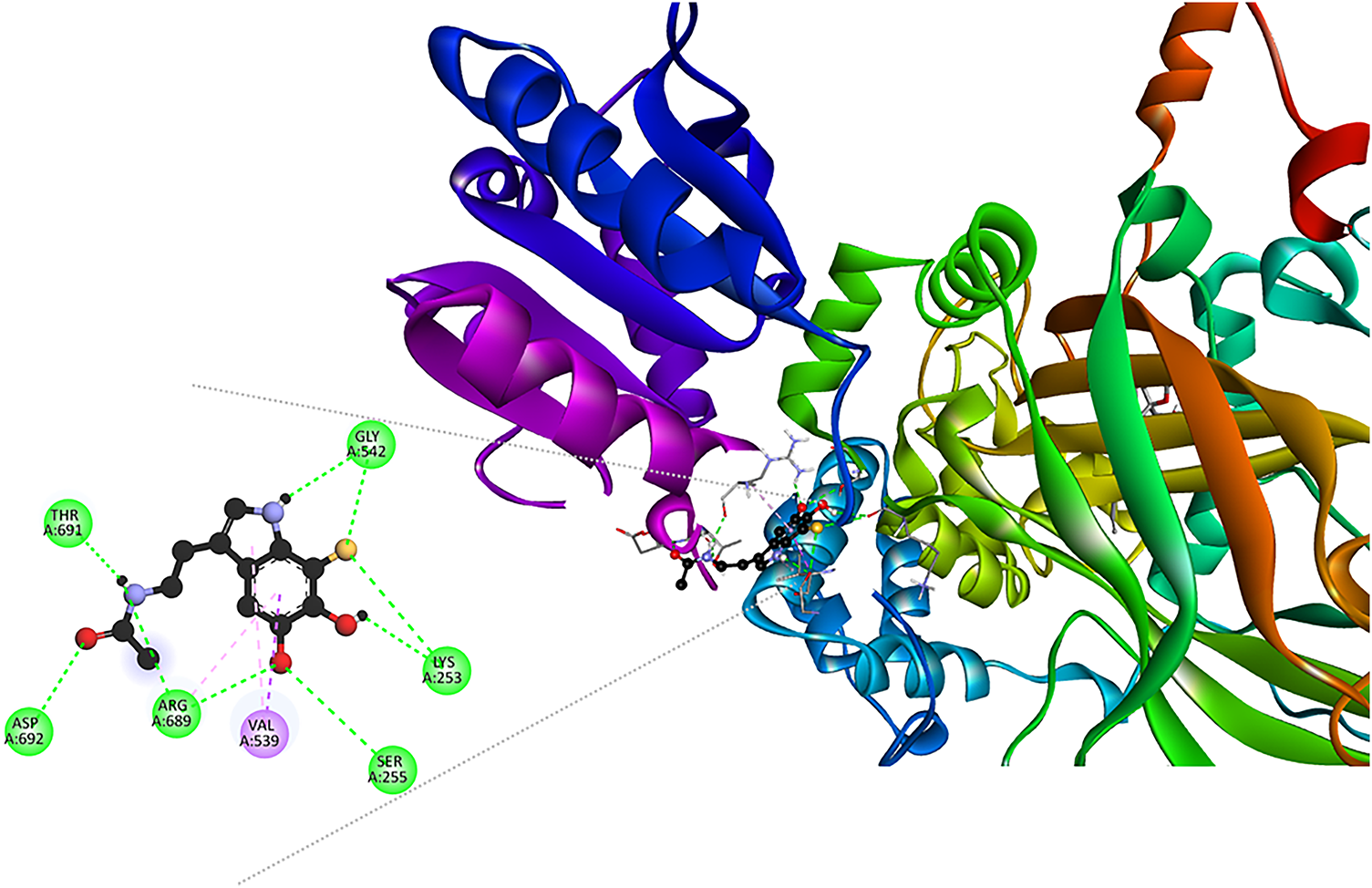

The interaction profile reveals that dM38 binds to CAT in an allosteric site through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with various residues (Fig. 6). This form of interaction suggests a possible stabilizing effect without interfering with the active site. The location and type of interactions, particularly those near the substrate-accessing channel [90], point to a possible modulatory effect on the dynamics of this enzyme. The conformation of dM38 is similar to that observed for ascorbic acid, which has been reported to be an allosteric agonist of CAT [86].

Figure 6: Interaction network in the [dM38:CAT] complex. Intermolecular bonds are depicted in doted lines: H-bonds (green), π-forces (pink and purple). Asp: aspartate, Gly: glycine, Lys: lysine, Arg: arginine, Ser: serine, Thr: threonine, Val: valine. The figure was made with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

3.3 Transcriptional Control of Redox and Inflammatory Homeostasis

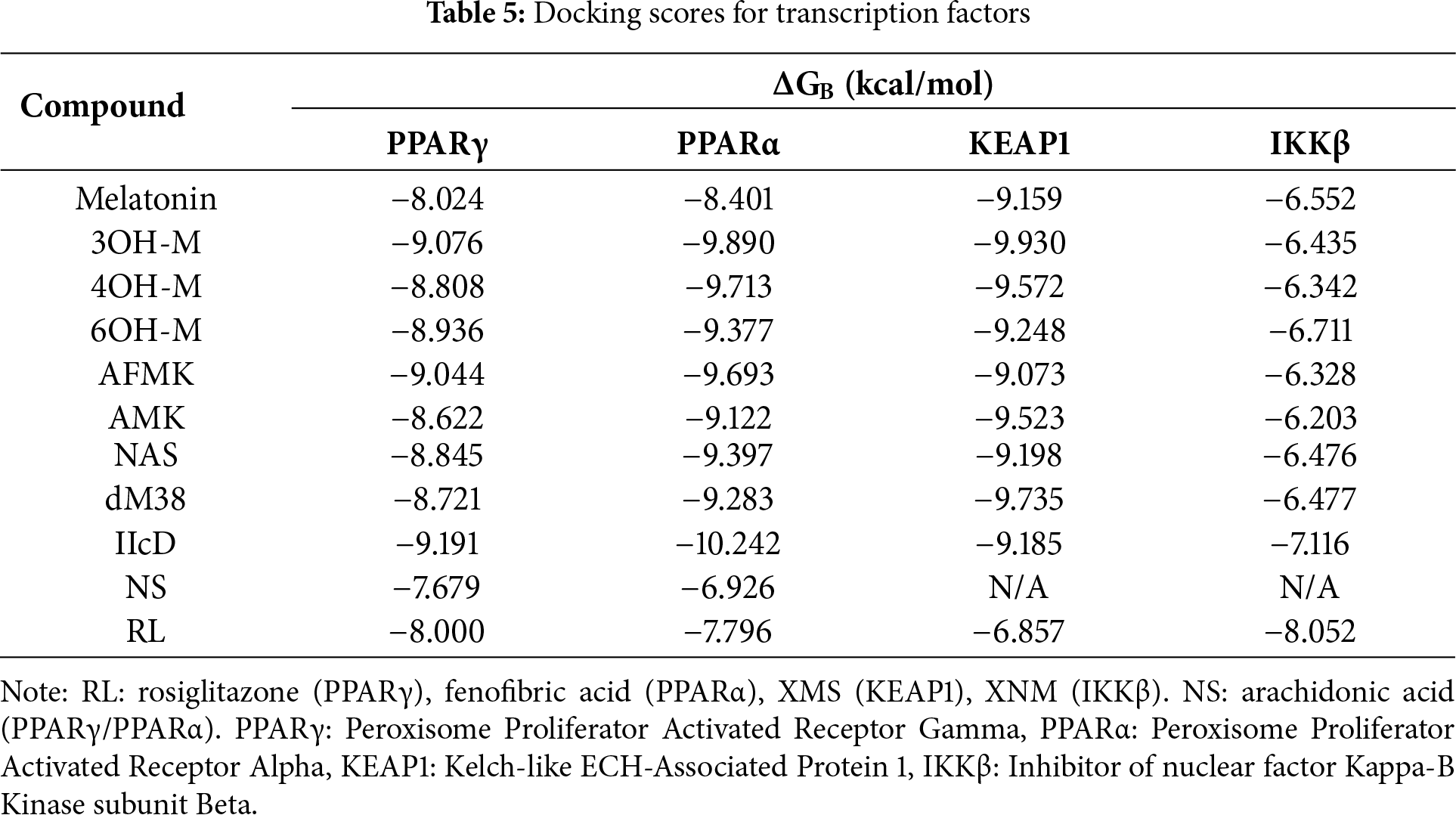

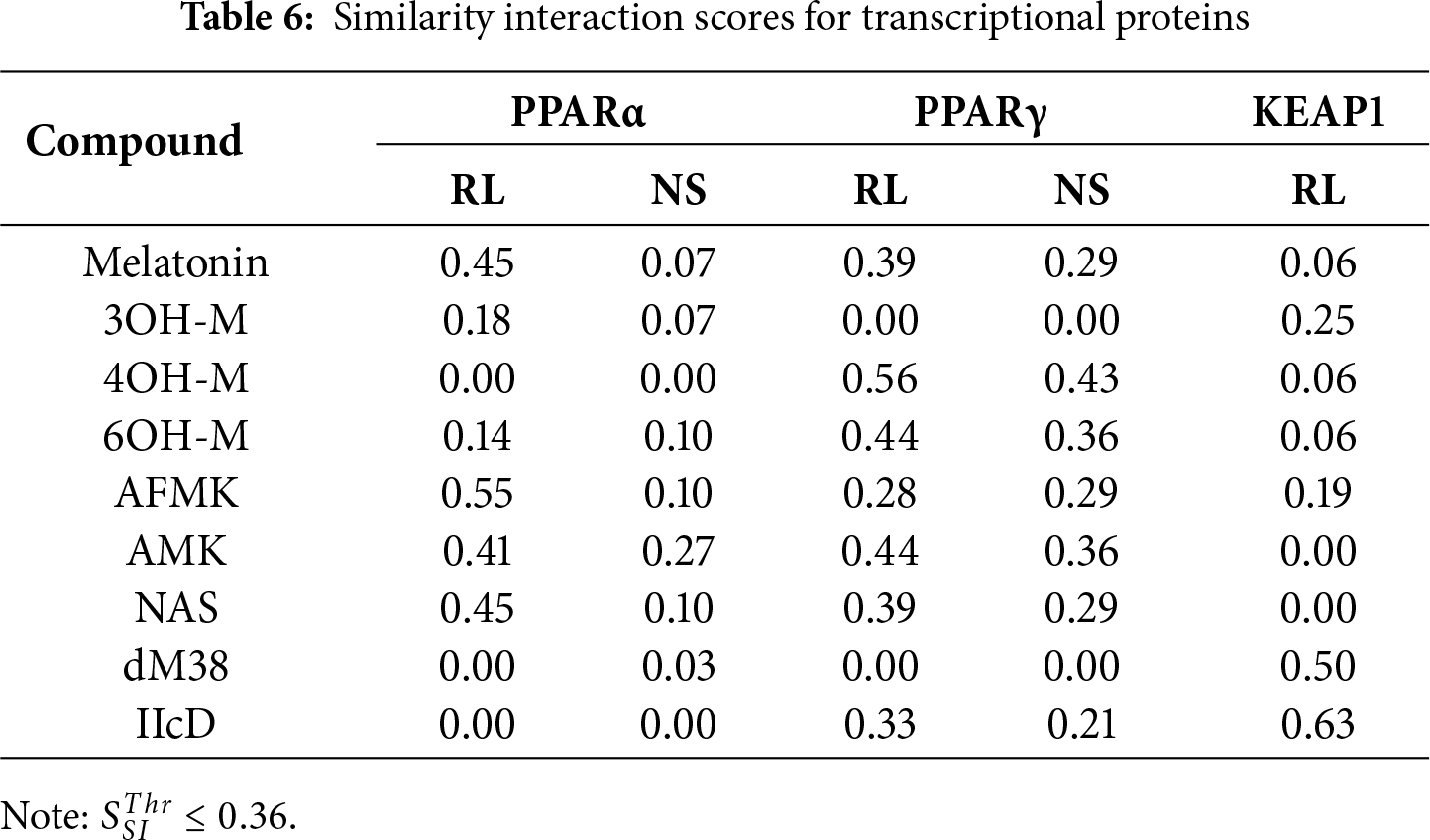

Regarding the study of the modulation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, PPARα/PPARγ activators and Nrf2–KEAP1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1) pathway modulators represent the most studied systems with the strongest experimental evidence for opposing OS through genomic regulation [91–93]. NF-κB, on the other hand, is primarily addressed through indirect inhibition, by some recognized inhibitors of IKKβ (inhibitors of κB kinase); its study as a direct target is still incipient. In vitro studies have shown that melatonin and its derivatives can modulate these key oxidative stress pathways [94,95]. They are capable of activating Nrf2, inhibiting NF-κB, and acting as weak PPARγ agonists [94–97], supporting their role as indirect regulators of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses. However, the modulation mechanisms remain unclear. Table 5 summarizes the docking indices obtained for interactions between melatonin-related compounds and transcription factors. For comparison, values corresponding to NS, when available, and to RL are also included.

The general trend is that melatonin-related compounds have a higher affinity than reference ligands to proteins PPARα, PPARγ, and KEAP1.

Studying the interaction pattern for the compounds studied and comparing them with those of reference ligands on these key proteins constitutes a rational strategy for inferring possible mechanisms of redox modulation at the transcriptional level. The identification and characterization of relevant intermolecular interactions and their similarities with respect to those involving known modulating compounds may suggest comparable functional effects, either as an agonist, antagonist, or modulator. Key interactions of melatonin-related compounds with their most likely targets, namely PPARα, PPARγ, and KEAP1, are shown in the SM (Table S4).

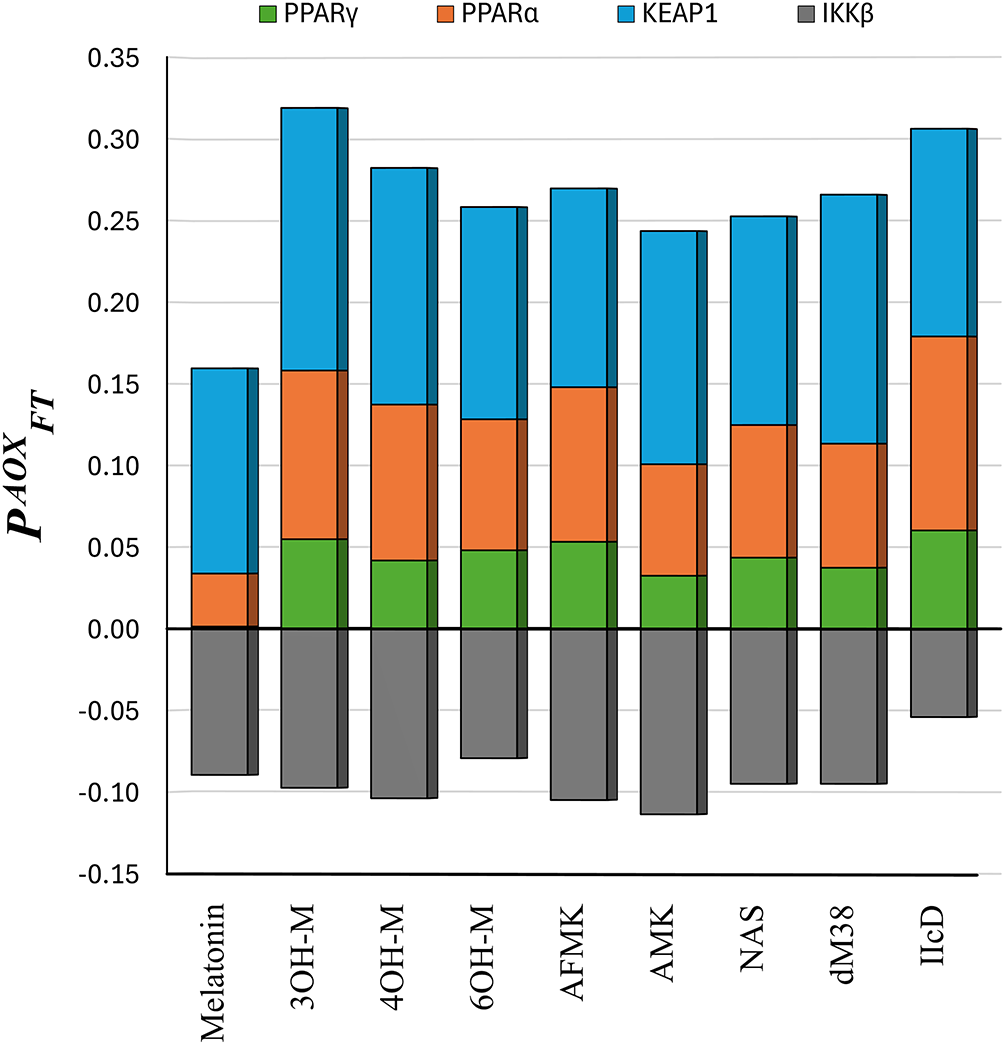

Analogously to the

Figure 7: The

According to the

Melatonin, AFMK, AMK, and NAS show the greatest similarity with RL (fenofibric acid, FFA) for PPARα. This suggests that these molecules could act as agonists or modulators of PPARα, as FFA does [99]. Regarding PPARγ, the highest interaction similarity scores were obtained for 4OH-M, 6OH-M, AMK, NAS, and melatonin. However, the latter was discarded as a likely modulator due to its low affinity to this enzyme. 4OH-M, 6OH-M, AMK, and NAS may function as PPARγ agonists similarly to rosiglitazone (the RL used in the SSI calculations), which is a drug used to activate PPARγ [100]. IIcD and dM38 show significant similarities with XMS (the reference ligand) in their interactions with KEAP1. Since XMS interferes with the Nrf2 by binding to KEAP1 and promoting its activation [98], a similar action might be expected from IIcD and dM38. The other compounds have low SSI values for their interactions with KEAP1.

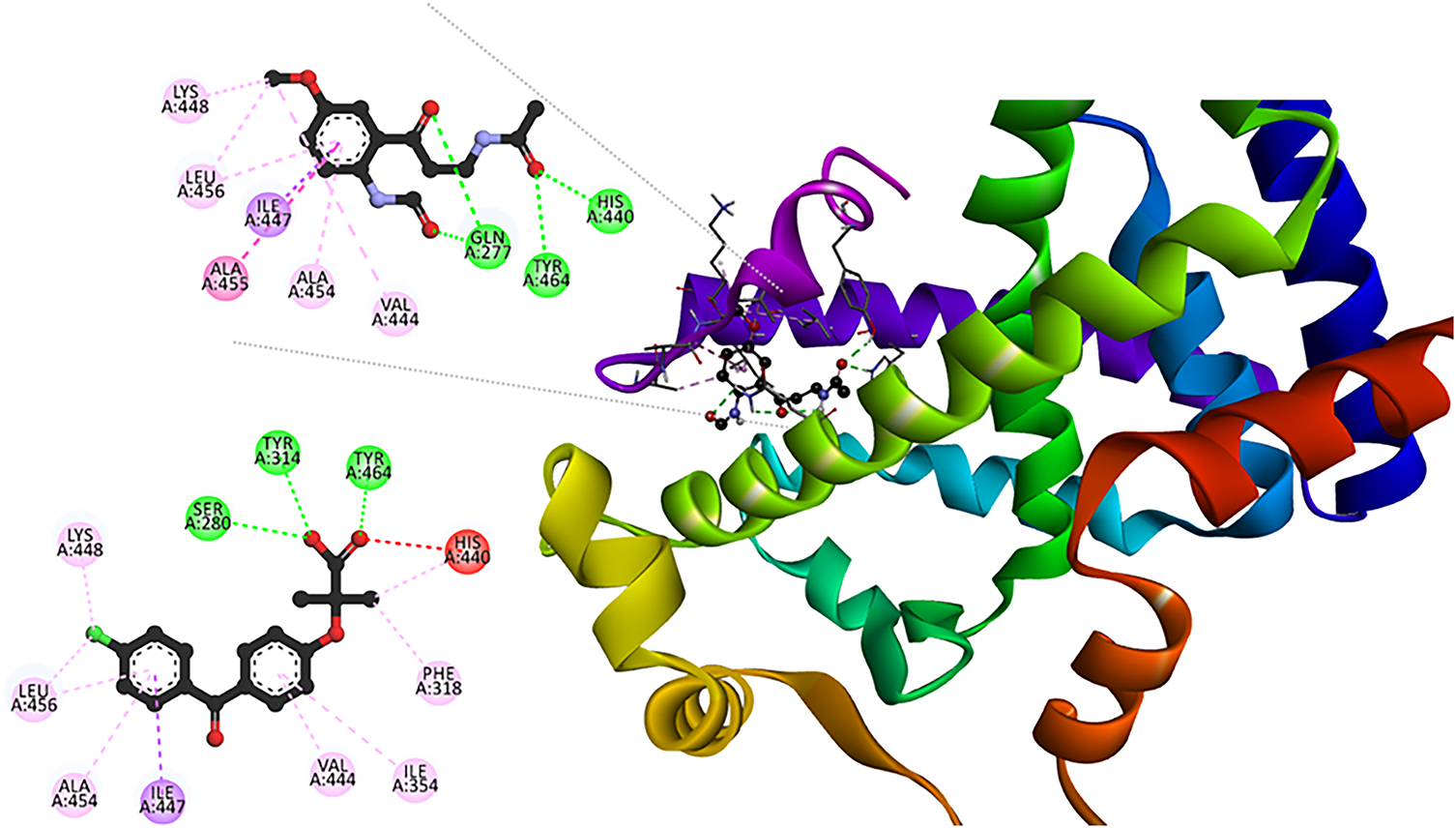

The interaction mode of the best candidates, regarding transcriptional factors modulation, was analyzed. The interaction network of the [AFMK: PPARα] complex (Fig. 8) reveals hydrogen bond formation with Gln277, His440, and Tyr464, the latter being a key residue for ligand-binding domain (LBD) activation [101]. Multiple hydrophobic and stacking interactions, which stabilize the ligand in the hydrophobic cavity, were also found. They involve residues such as Ala454, Ile447, and Val444. Both AMFK and FFA interact with key amino acids. However, the elongated conformation and additional interactions of AFMK with other important residues, such as Gln277, maximize hydrophobic contact through a more diversified and stable binding profile. These structural features, combined with the estimated high affinity, support the hypothesis that AMFK may act as a PPARα agonist, modulating both lipid metabolism and the antioxidant response. This suggests its potential as a multifunctional modulator with applications in metabolic and inflammatory diseases.

Figure 8: Interaction profile in the [AMFK: PPARα]. For comparison purposes, the 2D map for [FFA: PPARα] (PDB Id: 6LX4) is presented. Intermolecular bonds are depicted in doted lines: H-bonds (green), π-forces (pink and purple), and unfavorable contacts (red). Lys: lysine, Leu, leucine, Ala: alanine, Ile: isoleucine, Gln: glutamine, Tyr: tyrosine, His: histidine, Ser: serine, Phe: phenylalanine. The figure was made with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

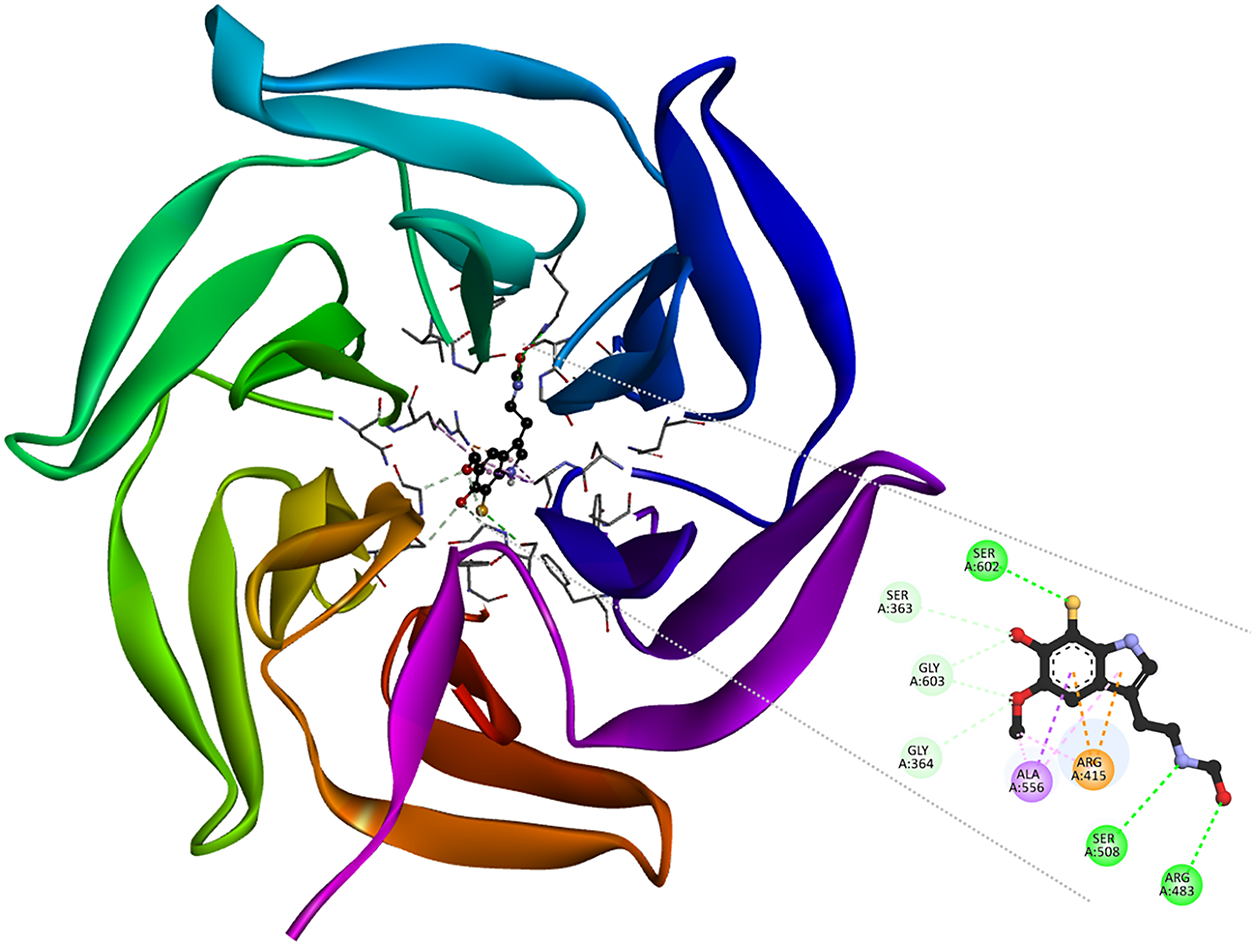

The [dM38:KEAP1] complex formation (Fig. 9) involves hydrogen bonds with Arg415 and Arg483, which are residues critical for Nrf2 electrostatic recognition [102]. The same kind of interaction was also found with Ser508 and Ser602, as well as non-classical interactions with Ser363, Gly364, and Gly603; and a π-sigma interaction between the indole moiety of dM38 and Ala556. This network of contacts allows dM38 to efficiently occupy the polar and hydrophobic pockets of the Kelch domain, mimicking elements of the ETGE peptide, which is crucial for Nrf2 binding [103–105]. These findings suggest that dM38 may act as a noncovalent competitive inhibitor of KEAP1, interfering with the KEAP1-Nrf2 system and promoting activation of antioxidant pathways. Given its free radical scavenging potential [40,41], dM38 may offer a dual antioxidant action, combining Nrf2 modulation with its ability to neutralize radical species. Based on these results, dM38 is proposed as a promising candidate for the development of redox-modulating therapies for OS-related diseases, inflammation, and degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ELA, and Huntington’s diseases.

Figure 9: 3D and 2D interaction map in the [dM38:KEAP1] complex. Intermolecular bonds are depicted in doted lines: H-bonds (green), non-conventional H-bonds (light green), π-forces (yellow, pink, and purple). Ser: serine, Gly: glycine, Ala: alanine, Arg: arginine. The figure was made with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

The interaction network of 4OH-M with PPARγ (SM: Fig. S5) shows partial similarities with the reference agonist, rosiglitazone, especially in the hydrophobic interactions with residues such as Cys285, Met364, and Leu330. These residues have been identified to contribute to ligand-binding in the LBD domain [97]. However, the lack of some connections, such as with Tyr473 and His323, suggests that 4OH-M may act only as a moderate modulator of PPARγ, which agrees with previous reports describing melatonin metabolites as weak agonists of this receptor [97]. This type of conformation may confer a softer profile, possibly helpful in fine-tuning antioxidant pathways without inducing extensive PPARγ activation.

3.4 Validation of Docking Poses by Molecular Dynamics

To complement the docking-derived static interaction models, molecular dynamics simulations were performed to assess the temporal stability, conformational adaptability, and persistence of key interactions within representative protein-ligand complexes. These analyses provide validation of the proposed binding hypotheses and shed light on the structural determinants underlying redox modulation.

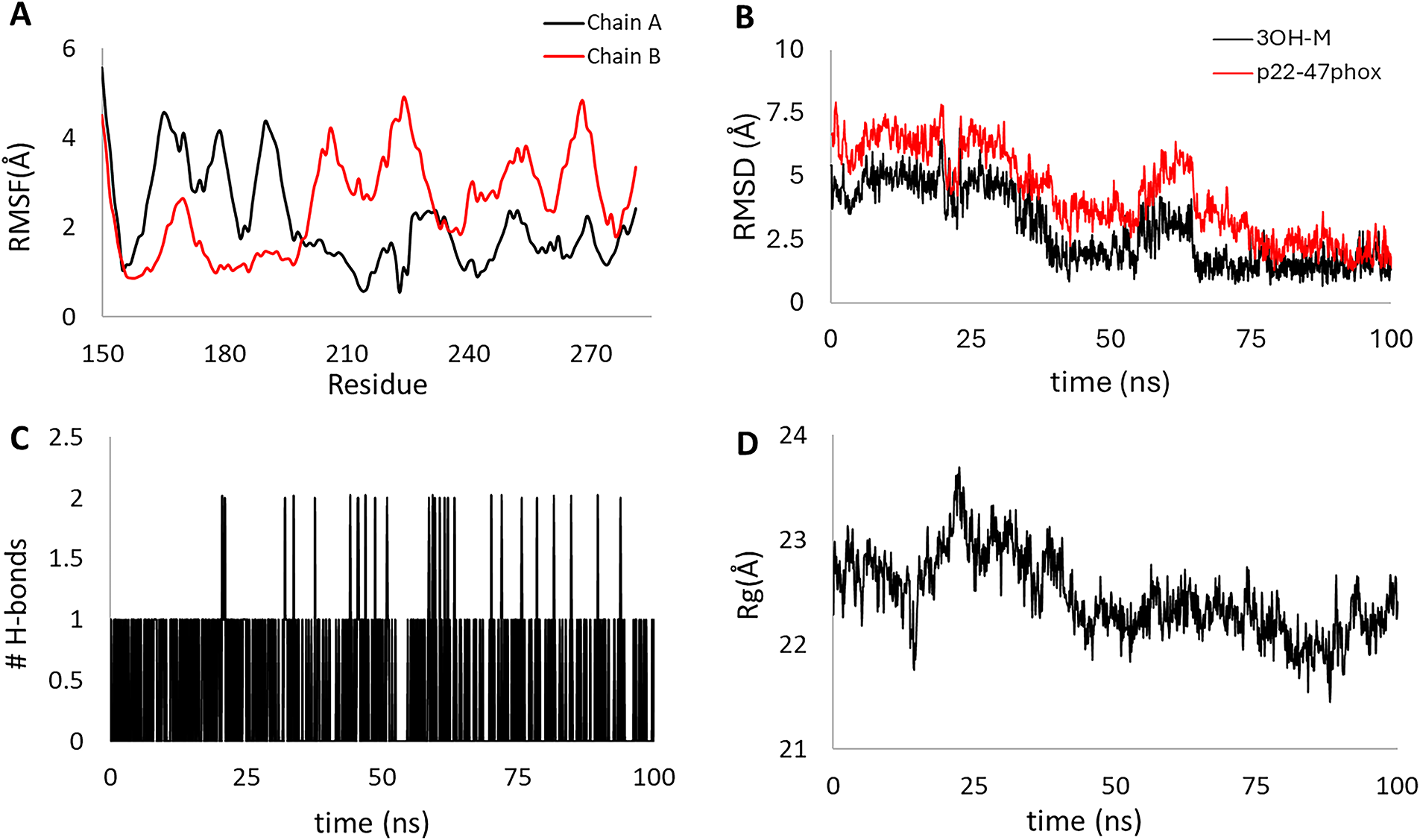

Dynamic analysis (Fig. 10A–D) revealed that the [3OHM-p22-47phox] complex undergoes a steep conformational transition (0–60 ns) to reach a new equilibrium state (60–100 ns) relative to the initial position. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of p22-47phox (Fig. 10B, red line) showed a sustained decrease from 8.0 to 2.0 Å (60 ns), and 3OH-M experienced an abrupt drop from 6.0 to 1.5 Å, indicating a coordinated dynamic re-equilibration toward a new stable conformation. The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF, Fig. 10A) confirms the high intrinsic flexibility of both peptide chains, with peaks up to 5.0 Å in regions of the proline-rich region, consistent with its structurally disordered nature [106]. The radius of gyration (Rg, Fig. 10D) of the complex exhibits a decrease during the first 60 ns, which is consistent with the drop in RMSD, which could be due to a structural compaction of the complex during the re-stabilization process. The interaction between the ligand and the peptide is characterized by a low (usually 1–2) and fluctuating number of H-bonds (Fig. 10C). This conformational contraction of the protein can be clearly observed in SM Video 1 (Available to download in: https://github.com/luckhdz/MD_mela_OS/blob/main/Video1.mpg (accessed on 01 August 2025)).

Figure 10: Stability parameters for the 100 ns molecular dynamics of the [3OHM-p22-47phox] complex. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of chains A and B (A), root mean square deviation (RMSD) for p22-47phox (red line) and 3OH-M (black line) (B), the number of hydrogen bonds formed within the complex (C), and the radius of gyration (Rg) for the complex (D)

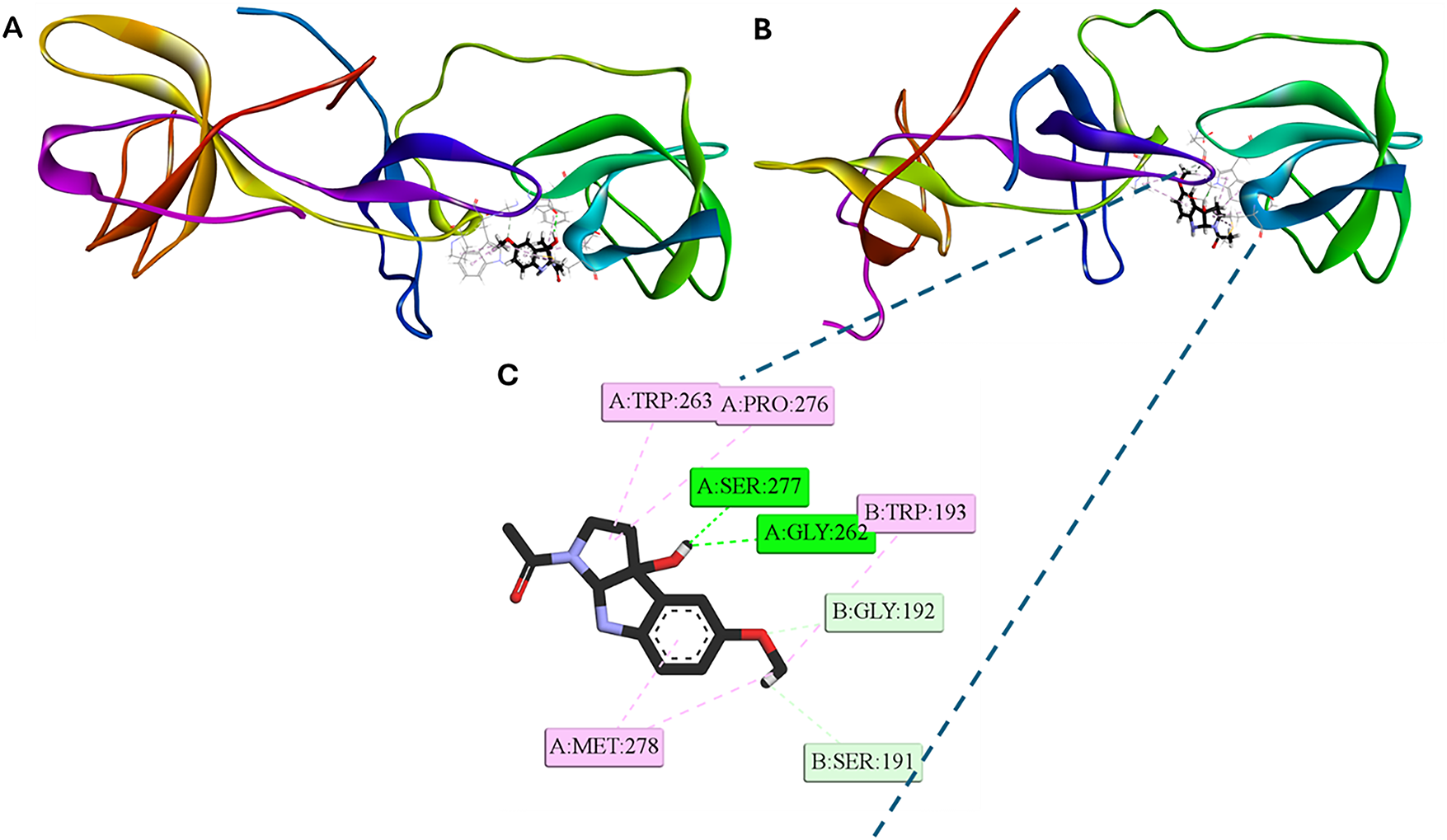

Comparative analysis of the equilibrium conformations at the beginning (docking pose, Fig. 11A) and at the end of the molecular dynamic simulation (Fig. 11B) reveals that the reorientation of the 3OH-M ligand at the dimeric interface of the p22-47phox peptide is associated with a structural contraction of the protein. The 2D interaction map (Fig. 11C) shows two hydrogen bonds with the A chain: one between the hydroxyl group of the indole ring and the Ser277 residue, and another between Gly262 and the oxygen of the hydroxyl group of the ligand. Furthermore, the methoxy group of 3OH-M establishes C–H···O contacts with Ser191 and Gly192 of chain B. These polar interactions are complemented by hydrophobic contacts with Trp263, Pro276, and Met278 of chain A and Trp193 of chain B. This conformation is characterized by a more balanced interaction network than the initial docking pose (Fig. 3), utilizing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts with residues from both chains (A and B) but maximizing hydrophobic contacts with residues from chain A.

Figure 11: Representative [3OH-M:p22-47phox] 3D and 2D interaction profiles. (A) 3D conformation at the beginning of the dynamic (doking pose). (B) 3D and (C) 2D conformations at the end of the dynamic simulation (100 ns). Intermolecular bonds are depicted in doted lines: H-bonds (green), non-conventional H-bonds (light green), π-forces (pink). Ser: serine, Gly: glycine, Met: methionine, Trp: tryptophan, Pro: proline. The figure was created with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

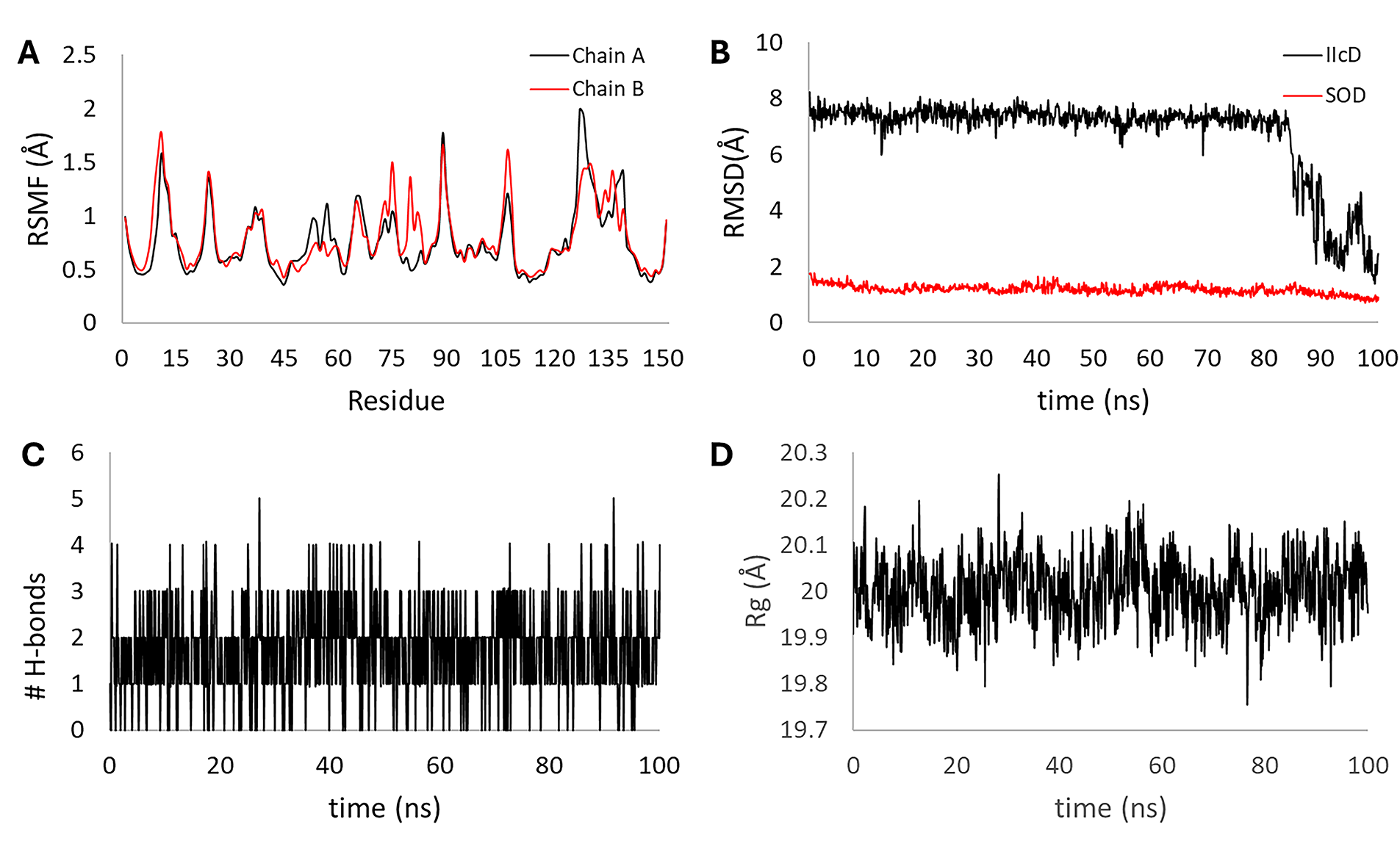

The 100 ns molecular dynamics of the [IIcD: SOD1] complex revealed a globally stable protein structure and late conformational rearrangement of the ligand. The RMSF (Fig. 12A) of the main chain remained below 1.5 Å for most residues in both monomers, confirming the structural rigidity of the dimeric enzyme. The RMSD of the SOD1 (Fig. 12B, red line) main chain fluctuated around 1.5–2.0 Å throughout the simulation, indicating equilibrium stability, whereas the RMSD of IIcD (Fig. 12B, black line) was high (7 Å) for the first 85 ns, followed by a sharp decrease to 2 Å, consistent with a relocation to a more stable binding pocket. The number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Fig. 12C) ranged between 1 and 3 along most of the trajectory, increasing slightly in the final segment. The Rg (Fig. 12D) ≈ 20 Å remained constant, supporting the overall compactness of the enzyme during ligand migration.

Figure 12: Stability parameters for the 100 ns molecular dynamics of the [IIcD:SOD1] complex. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of chains A and B (A), root mean square deviation (RMSD) for SOD1 (red line) and IIcD (black line) (B), the number of hydrogen bonds formed within the complex (C), and the radius of gyration (Rg) for the complex (D)

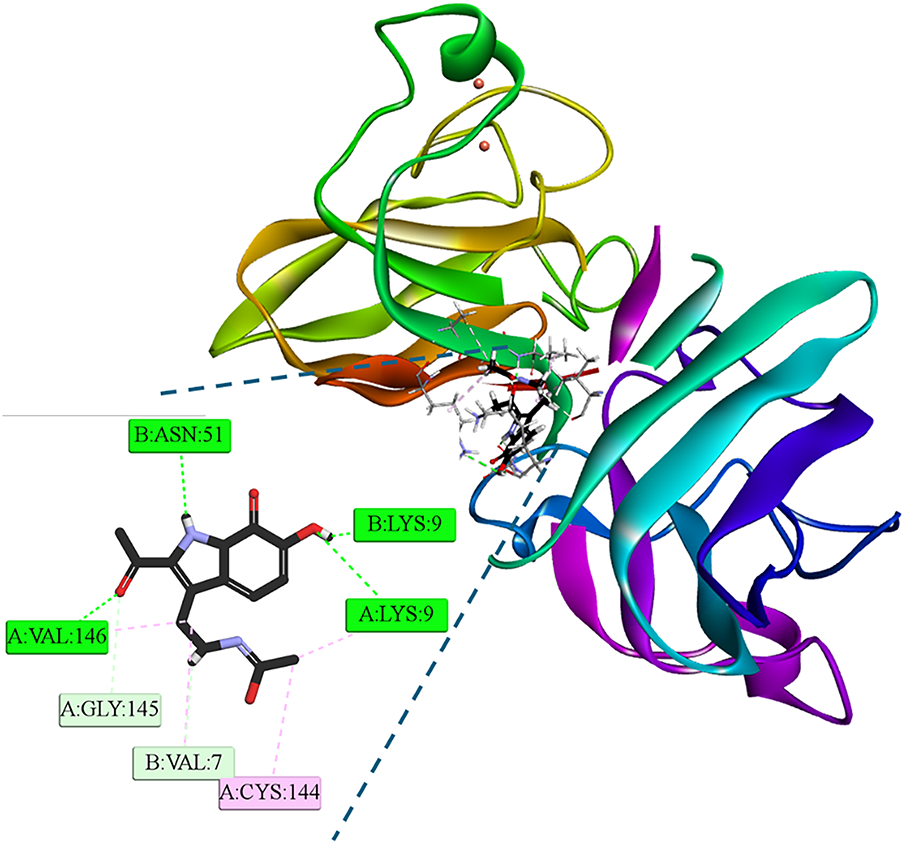

At the end of the 100 ns simulation, the IIcD ligand remained anchored at the dimeric interface of the Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) enzyme (Fig. 13). A cooperative network of interactions at the dimeric interface explains the stability observed in the RMSD of the final part of the trajectory. IIcD acts as a molecular bridge that stabilizes the SOD1 dimer, firmly anchored to both subunits. On the A chain, hydrogen bonds are formed with Lys9 and Val146, and hydrophobic and unconventional interactions are formed with Cys144 and Gly145, respectively. Binding to the B chain involves hydrogen bonds with Lys9 and Asn5, and an unconventional C-H···O interaction with Val7. The complete trajectory can be visualized in SM Video 2. (Available to download in: https://github.com/luckhdz/MD_mela_OS/blob/main/Video2.mpg (accessed on 01 August 2025)).

Figure 13: 3D and 2D interaction profiles at the end of the dynamic simulation (100 ns) of [IIcD: SOD1] complex. Intermolecular bonds are depicted in doted lines: H-bonds (green), non-conventional H-bonds (light green), π-forces (pink). Asn: asparagine, Gly: glycine, cysteine, Lys: Lysine, Val: valine. The letter Figure was created with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

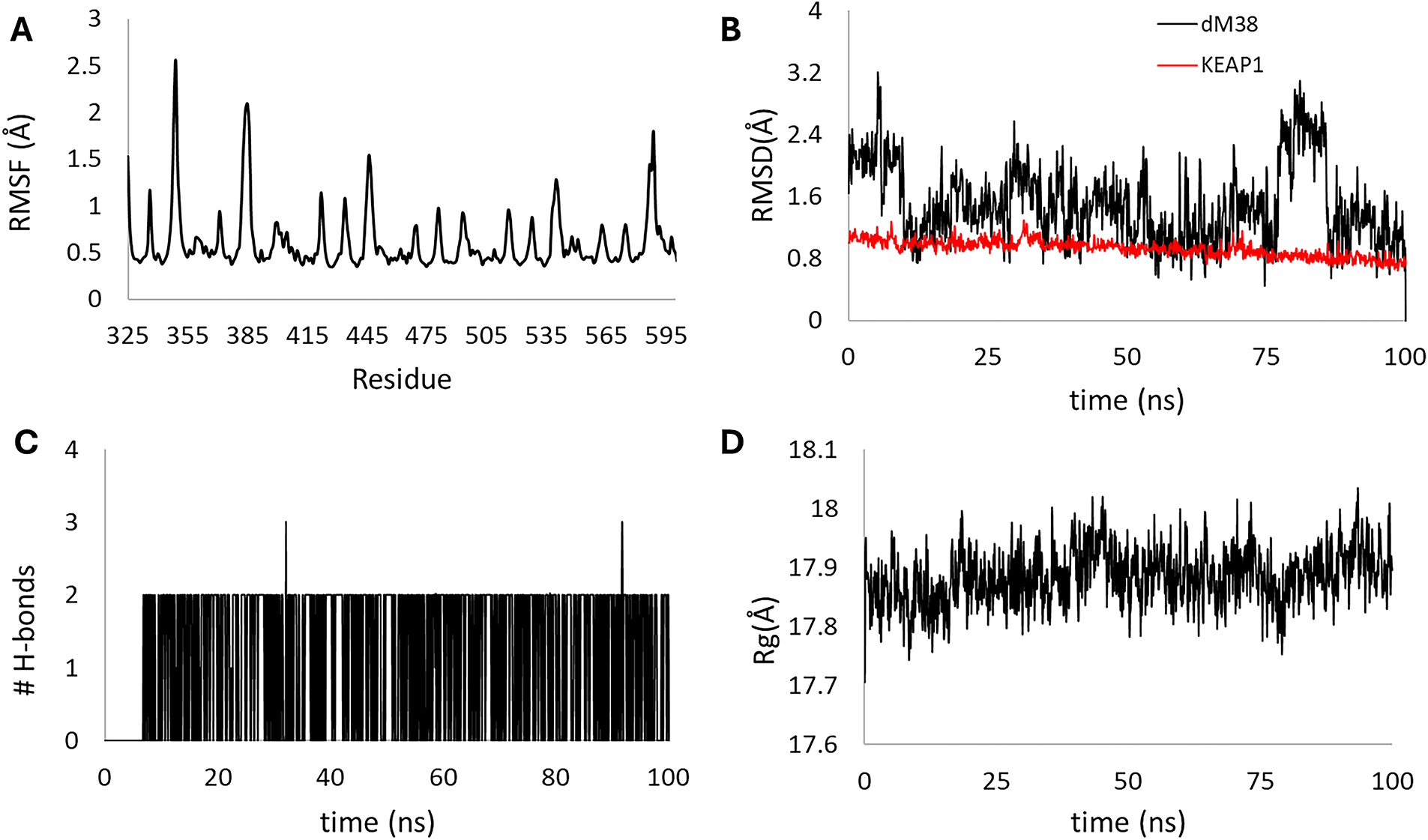

Dynamic analysis of the [dM38:KEAP1] complex over 100 ns demonstrated high structural stability and rapid convergence to equilibrium. The RMSF (Fig. 14A) confirmed the structural rigidity of the protein, with localized fluctuations not exceeding 2.5 Å. The RMSD (Fig. 14B, red line) of the KEAP1 protein rapidly settled to a low, constant plateau (≈0.8 Å), which, together with the consistency of the Rg ≈ 17.8 Å (Fig. 14D), confirms the preservation of the overall compactness of the enzyme. Although the dM38 ligand (Fig. 14B, black line) exhibited greater fluctuation at equilibrium (≈1.5 Å to 2.5 Å), no sharp transitions or dissociation were observed. Finally, the persistence of a continuous network of polar hydrogen bonds (Fig. 14C) along the entire trajectory is consistent with RMSD stability and suggests robust polar anchoring of dM38 in the binding site.

Figure 14: Stability parameters for the 100 ns molecular dynamics of the [dM38:KEAP1] complex. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of chains A and B (A), root mean square deviation (RMSD) for KEAP1 (red line) and dM38 (black line) (B), the number of hydrogen bonds formed within the complex (C), and the radius of gyration (Rg) for the complex (D)

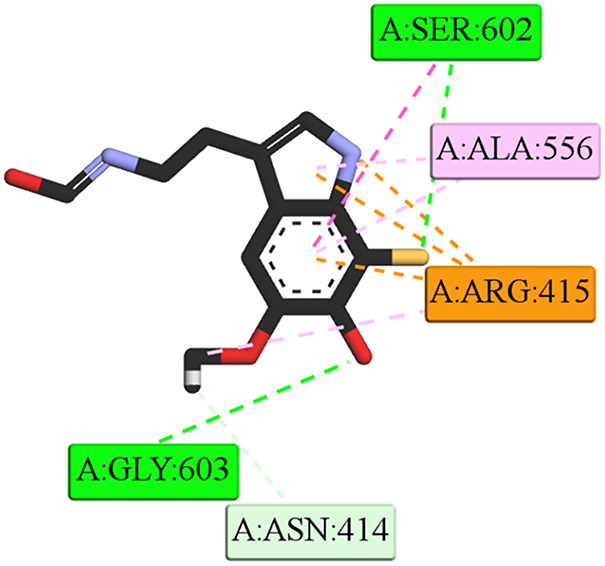

The steady-state interaction profile (Fig. 15) reveals that the dM38 ligand binds to the Kelch domain of KEAP1 via a network of contacts involving both polar and hydrophobic interactions. Key polar contacts include conventional hydrogen bonds with Ser602 and Gly603, and unconventional ones with Asn414. The most significant docking is observed through diverse electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions with the Arg415 residue, involving the dM38 heteroatoms and the amino acid guanidinium group. These polar interactions are complemented by π-alkyl contacts with Ala556 and other cavity residues. Complete trajectory can be visualized in SM Video 3. (Available to download in: https://github.com/luckhdz/MD_mela_OS/blob/main/Video3.mpg (accessed on 01 August 2025)).

Figure 15: 2D interaction profiles at the end of the dynamic simulation (100 ns) of [dM38:KEAP1] complex. Intermolecular bonds are depicted in doted lines: electrostatic/π-cation (orange), H-bonds (green), non-conventional H-bonds (light green), π-forces (purple and pink). Asn: asparagine, Gly: glycine, cysteine, Lys: Lysine, Val: valine. The letter Figure was created with BOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer

3.5 Retrosynthetic Path to Obtain Melatonin Derivatives

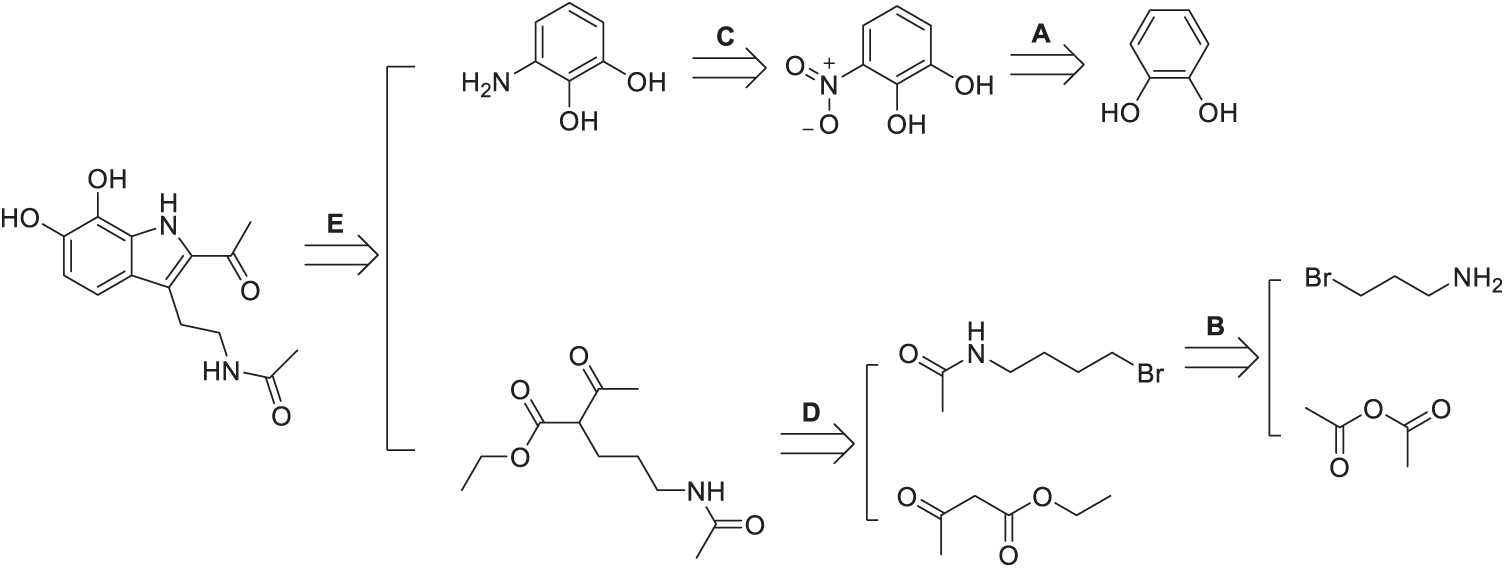

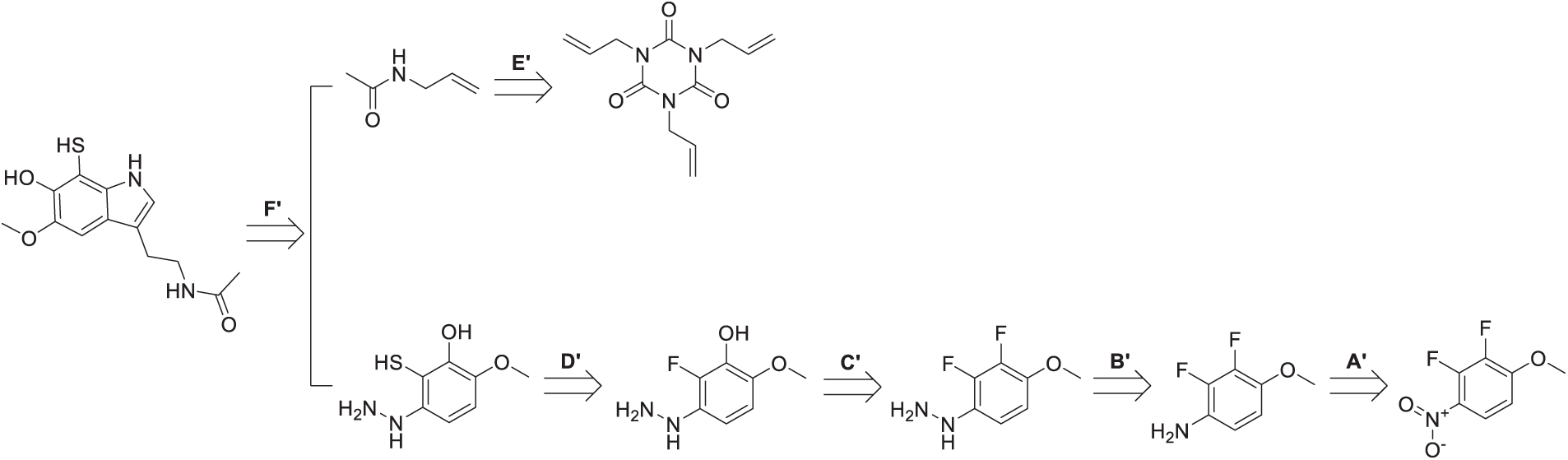

Since the IIcD and dM38 derivatives exhibited promising interaction profiles with enzymes involved in OS processes and considering that their potential as multifactorial drug candidates has already been demonstrated [42–45], retrosynthetic pathway predictions were explored to assess their synthetic feasibility. The retrosynthetic pathways of compounds IIcD and dM38 are depicted in Schemes 2 and 3, respectively. The detailed reaction conditions for each step are summarized in the SM (Tables S5 and S6).

Scheme 2: Retrosynthetic path of IIcD. The Scheme was created using Perkin Elmer, ChemDraw 21.0.0

Scheme 3: Retrosynthetic path of dM38. The Scheme was created using Perkin Elmer, ChemDraw 21.0.0

The retrosynthetic analysis of the IIcD reveals a convergent strategy based on amide bond formation from a catechol core functionalized with an amino group. The first stage (A) involves the nitration of catechol to yield a nitro derivative, followed by its reduction (C) to an aromatic amine. In parallel, two acylating fragments are constructed: one through aminolysis (D) of an ester or anhydride with a branched aliphatic amine, and the other via nucleophilic alkylation (B) of a primary amide with 1,4-dibromobutane to introduce a functionalized aliphatic chain. Finally, in step (E), these fragments are coupled to the aminocatechol via amide bond formation, completing the melatonin-derived structure of the final product. Key transformations include electrophilic aromatic substitution, reduction, aminolysis, and nucleophilic substitution.

The retrosynthetic analysis of dM38 derivative reveals two converging synthetic pathways. The first one (lower route in Scheme 3) originates from a fluorinated aromatic nitro compound (A′), which is reduced to form the corresponding aniline derivative (B′). Subsequent nucleophilic substitution introduces a hydrazine moiety (C′), followed by an aromatic nucleophilic substitution to replace a fluorine atom with a hydroxyl group. A thiol group is then introduced to yield the multi-functionalized intermediate (D′). This fragment is further modified via condensation with a carbonyl compound to form a hydrazone linkage. The second pathway (upper route) involves the derivatization of a maleic acid analogue (E′) through acid activation, enabling nucleophilic acyl substitution with the previously obtained hydrazine derivative. The final assembly of dM38 is accomplished by coupling these two key fragments, employing a sequence of well-defined transformations, including reduction, nucleophilic substitution, condensation, and acylation.

4.1 Rationalization of Target Selection and Proposed Mechanisms of Interaction

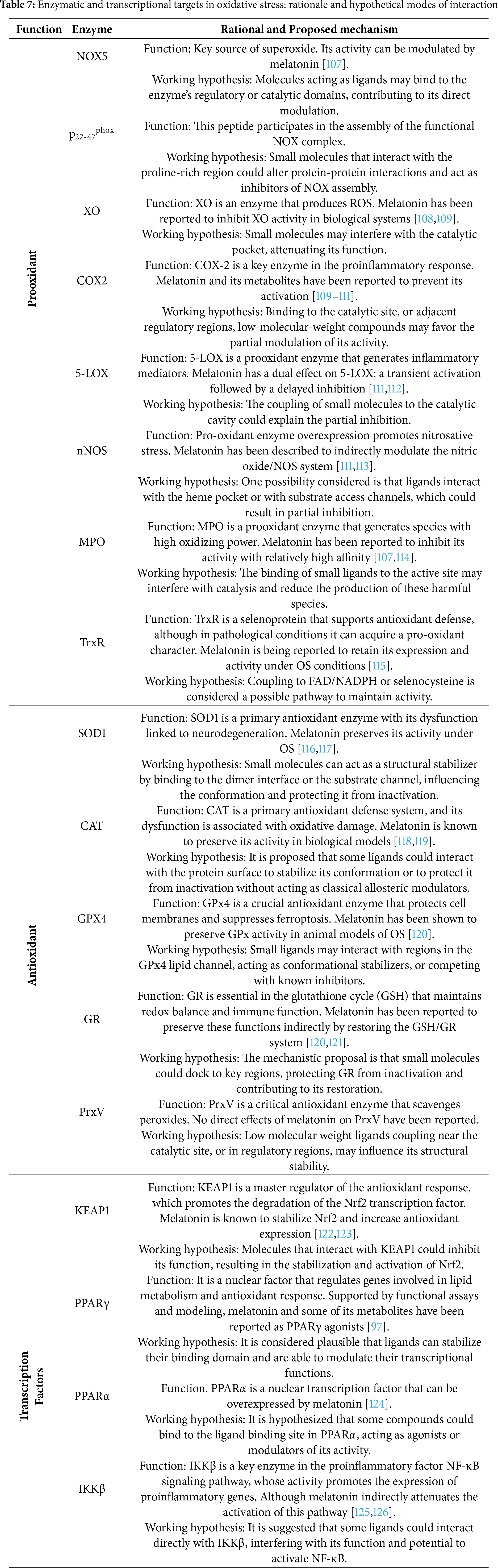

The enzymes and transcription factors included in this study were selected based on their central role in redox regulation and the available evidence linking melatonin to their activity. Table 7 summarizes their relevance to oxidative stress, the experimental evidence associated with melatonin, and the hypothesized mechanisms by which small molecules could modulate their activity.

Overall, the analyzed targets constitute pharmacologically relevant components of the oxidative stress regulatory network [42,87]. Through their interactions with pro-oxidant enzymes, antioxidant systems, and transcriptional regulators such as PPARα, PPARγ, and KEAP1, melatonin-related compounds could exert integral redox control. These findings highlight potential multifunctional pharmacological targets for the design of redox-modulating agents.

4.2 Downregulation of Pro-Oxidant Enzymes

The calculated data suggest that the aromatic core of NAS could be the source of the affinity towards nNOS, participating in multiple interactions with the heme group. Three-dimensional modeling indicates a deep insertion into the active site, compatible with a possible competitive inhibition mechanism that would limit substrate access and disrupt the electron transfer necessary for the generation of nitric oxide, thus producing partial inhibition under nitrosative conditions. This type of selective and non-disruptive modulation is consistent with previous reports describing melatonin and its metabolites as regulators of the NO/NOS system [105].

The interaction pattern of 3OH-M with p22-47phox is consistent with the experimentally described ability of melatonin to attenuate NOX activity and superoxide generation [127]. Data suggest that 3OH-M might act at the p22-47phox interface, disrupting the cytosolic-membrane coupling required for NOX activation [128]. This mode of action is similar to the proposed regulatory mechanism for NOX5, in which small molecules might inhibit NOX assembly.

The proximity of 3OH-M and IIcD to the catalytic and redox centers of TrxR suggests a possible modulation of electron transfer efficiency rather than direct inhibition, consistent with a mechanism based on weak redox coupling to flavin or selenocysteine domains. These results agree with experimental observations where melatonin has been shown to preserve TrxR expression and activity under oxidative stress [115], indicating that the binding of such ligands may contribute to the functional stabilization of TrxR and the maintenance of cellular redox balance under oxidative stress.

The interaction pattern of AMK with 5-LOX suggests a non-competitive mode of inhibition, consistent with its proximity, although not directly coordinating, to the iron catalytic center. This orientation could interfere with substrate access or electron communication, rather than metal catalysis, resulting in partial inhibition of the enzyme. Experimentally, melatonin has been reported to exert a dual effect on 5-LOX activity, with an initial transient activation followed by delayed inhibition [111,112]. Computational results are consistent with this late inhibitory phase, suggesting that metabolites such as AMK could contribute to the down-modulation of 5-LOX activity.

Overall, the observed interaction patterns suggest that melatonin-derived molecules may modulate pro-oxidant signaling in a coordinated and adaptive manner, rather than through complete enzymatic blockade. This precise regulation aligns with melatonin’s physiological role in maintaining redox balance and limiting the excessive formation of reactive species. From a therapeutic perspective, this behavior supports the concept of redox-sensitive multitarget modulation as a biologically compatible strategy for cellular protection under conditions of oxidative and inflammatory stress.

4.3 Upregulation of Antioxidant Enzymes

Computational analyses suggest that melatonin-derived compounds may enhance the structural resilience of antioxidant enzymes through conformational stabilization rather than direct catalytic activation. Among the molecules studied, IIcD displayed a stable and coherent interaction network with GPX4, SOD1, and CAT, consistent with structural reinforcement under oxidative stress conditions. In the case of SOD1, interactions localized at the dimer interface indicate potential stabilizing effects that could prevent subunit dissociation and reduce the propensity for aggregation associated with oxidative damage and neurodegeneration [129,130]. These findings are in agreement with IIcD acting as a SOD1 stabilizer, similarly to the RL, 5-fluorouridine [131]. However, both present opposite pharmacological profiles, while 5-fluorouridine promotes oxidative stress [132], IIcD exhibits a radical scavenging tendency [39].

NAS also showed a consistent stabilizing pattern with CAT and GPX4, in regions associated with redox regulation, suggesting a role in preserving enzymatic integrity during oxidative challenge. The interaction similarity between dM38 and ascorbic acid reinforces the hypothesis of a positive allosteric modulation of CAT, where ligand binding could favor conformations that facilitate hydrogen peroxide detoxification [133].

Taking together, these results point to a nonclassical mechanism of antioxidant upregulation based on protein stabilization and dynamic protection, rather than enzyme activation. From a biological perspective, this behavior supports the concept of redox resilience: a finely tuned modulation of the enzyme structure that could bolster endogenous antioxidant defenses under conditions such as inflammation, ischemia, or neurodegenerative stress [134,135].

4.4 Modulation of Transcription Factors

The predicted binding profiles of melatonin derivatives suggest that these compounds may interact with oxidation-reduction-sensitive transcriptional regulators through structurally coherent and stabilizing interactions, acting as partial or moderate modulators rather than classical agonists.

In the case of PPARα, the interaction pattern involving AFMK and AMK, with extended hydrophobic contacts and interaction with Gln277, could represent a partial modulatory mode, capable of stabilizing the receptor conformations that allow transcriptional control without inducing full activation. This mechanism would be consistent with an adaptive modulation of lipid metabolic and antioxidant pathways, in line with previous evidence that melatonin derivatives can influence nuclear receptor signaling [99].

Regarding PPARγ, 4OH-M displayed a more compact and less extensive binding topology, consistent with a moderate modulatory profile. This milder mode of interaction may favor subtle conformational adjustments of PPARγ that fine-tune antioxidant and metabolic gene expression, justifying the mild context-dependent regulatory effects attributed to melatonin [100].

In the case of KEAP1, the interaction profile of dM38 aligns with the structural features of the Nrf2 recognition interface, particularly in the region adjacent to the ETGE. This configuration is consistent with a noncompetitive inhibition mechanism, in which dM38 partially overlaps or stabilizes elements of the binding cleft without directly displacing Nrf2. This arrangement may attenuate the association dynamics between KEAP1 and Nrf2, promoting transient Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation. Combined with its intrinsic radical-scavenging properties [40,41], dM38 could exert a dual protective effect: it strengthens antioxidant transcriptional responses and mitigates oxidative damage.

Considered altogether, these findings support a plausible mechanism by which melatonin-related compounds could indirectly modulate transcriptional redox control, acting as structural stabilizers and partial modulators of PPARα and KEAP1. This interpretation suggests their potential role as adaptive regulators of the antioxidant defense network, offering promising therapeutic prospects in metabolic, inflammatory, and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, and Huntington’s disease.

Overall, molecular modeling and docking analyses support the idea that melatonin-related compounds exhibit a versatile redox modulation profile. They can attenuate pro-oxidant enzymatic activity, contribute to the structural stabilization of antioxidant systems, and interact with transcriptional regulators through interactions consistent with partial or adaptive modulation. These effects describe a coherent framework in which melatonin and its derivatives reinforce cellular redox resilience by stabilizing enzymatic and transcriptional components of the antioxidant defense network.

4.5 Dynamic Behavior of Selected Complexes

Given the exploratory nature of this study, molecular dynamics analyses were limited to a subset of representative complexes selected from the docking results, one for each functional category (pro-oxidant, antioxidant, and transcriptional). The objective was not exhaustive sampling, but rather to verify the structural stability and dynamic plausibility of the proposed interaction models. These simulations provide complementary evidence supporting the viability of the hypothesized binding modes under near-physiological conditions.

The dynamics of the [3OH-M:p22–47phox] complex revealed that the ligand remained associated at the interchain interface and a contraction of the peptide during the simulation. The redistribution of interactions between the A and B chains indicates a spontaneous structural adjustment consistent with dynamic stabilization after approximately 60 ns. The final configuration shows a balanced interaction network reoriented toward the A chain. This rearrangement, although different from molecular docking, is also consistent with a mechanism by which melatonin-derived molecules, such as 3OHM, could transiently interfere with the p22–47phox coupling required for NOX complex assembly. This supports a non-disruptive modulation and is consistent with previous reports of indirect attenuation of NOX activity by melatonin [106].

The dynamic profile of the [SOD1:IIcD] complex indicated ligand stabilization at the protein dimeric interface without altering its folding. The observed intersubunit crosslinking, dominated by short-range hydrophobic and polar interactions, supports a fine-tuning effect on local flexibility near the entrance to the active site. This induced-fit adaptation towards the end of the simulation reflects a gradual optimization of the binding geometry, rather than a disruptive conformational change. Such stabilization at the interfacial cavity, known to be crucial for preserving the structural and catalytic competence of SOD1 [136,137], could contribute to the antioxidant synergy between melatonin-derived compounds and enzymatic defense systems, consistent with the hypothesis of structural reinforcement, rather than direct catalytic modulation.

The interaction of dM38 with KEAP1, observed by molecular dynamics, aligns with the regulatory framework of the Nrf2-KEAP1 axis. KEAP1 acts as a key cytosolic repressor of Nrf2, targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation under homeostatic conditions, while melatonin has been shown to promote Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation, enhancing antioxidant gene expression [122]. In the [dM38:KEAP1] complex, the ligand remained stably lodged near Arg415 within the ETGE recognition cleft, forming persistent contacts along the trajectory. This configuration suggests a non-covalent modulatory interaction capable of attenuating KEAP1-Nrf2 coupling rather than inducing complete inhibition. By partially occupying this interface, dM38 promote Nfr2 stabilization, a mechanism consistent with experimental observations of melatonin-induced activation of the Nrf2 pathway [123]. This dual mode of action, structural modulation of KEAP1 together with intrinsic radical scavenging properties, could synergistically strengthen antioxidant defenses under oxidative stress.

Molecular dynamics simulations did not accurately reproduce the docking positions. In two of the three representative complexes, the trajectories revealed stable protein-ligand associations and reorientations toward more energetically coherent configurations. These findings reinforce the dynamic plausibility of the docking-derived hypotheses, demonstrating that ligand binding modulates key structural regions without altering protein stability. Therefore, molecular dynamics simulations serve as a complementary approach to assess interaction persistence, conformational adaptation, and the feasibility of the proposed redox modulation mechanisms.

The proposed retrosynthetic designs for dM38 and IIcD follow convergent and efficient strategies that seek to minimize synthesis time and enable modular construction from readily available, low-cost, precursors. For IIcD, the transformation proposals are based on consolidated reactions, improving their feasibility and scalability. Their modular structure also allows for variation in reaction conditions, potentially reducing environmental and economic costs while maintaining operational robustness. In the case of dM38, the manipulation of reactive functionalities, such as hydrazine and thiol groups, requires rigorous safety measures and controlled atmospheres. Future optimization under catalytic or greener conditions could improve the environmental profile of this route, although the balance between sustainability and operational cost should be carefully evaluated.

The incorporation of retrosynthetic analysis provides a crucial bridge between theoretical design and experimental implementation, offering a preliminary assessment of synthetic accessibility prior to biological validation. These analyses highlight the chemical feasibility of translating the modeled ligands into tangible molecules and encourage future synthetic exploration. Ultimately, the development of dM38- and IIcD-like scaffolds could contribute to multifunctional strategies for managing oxidative stress-related pathologies, including neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

This study is based on computational models, and their interpretations should be considered accordingly, i.e., within the limits of theoretical prediction. Docking-based approaches provide structural hypotheses for molecular recognition, but they cannot fully capture the conformational flexibility and domain coupling present in multidomain or highly dynamic enzymes such as nNOS or 5-LOX. Consequently, the binding patterns described under this approach are mechanistic proposals rather than definitive evidence of inhibition or activation.

Experimental validation using kinetic, biophysical, and cellular assays remains essential to confirm the biological relevance of these hypotheses. These efforts will be the next step in establishing the functional implications of melatonin-derived compounds and their potential as redox modulators in oxidative stress-related diseases.

This study provides a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding how melatonin and its derivatives may influence redox homeostasis through complementary molecular mechanisms. Integrative docking analyses suggest that these compounds could interact with key enzymes and transcriptional regulators involved in oxidative stress, showing two main mechanistic trends: (i) partial inhibition or interference with pro-oxidant enzymes such as nNOS, 5-LOX, TrxR, and the NOX assembly-associated peptide p22-47phox, and (ii) structural stabilization of antioxidant enzymes, exemplified by the behavior of IIcD with SOD1 and dM38 with CAT.

At the transcriptional level, AFMK and dM38 appear to interact with regulatory proteins such as PPARα and KEAP1, consistent with modulation of antioxidant gene expression rather than direct activation or inhibition. These complementary interactions describe a multifaceted redox modulation strategy, in which melatonin-related compounds could bolster antioxidant defense and limit pro-oxidant signaling.

Furthermore, the proposed Interaction Similarity Index (ISI) represents a novel methodological contribution, offering a quantitative criterion for comparing interaction patterns between structurally diverse ligands. Its application facilitates the prioritization of compounds with convergent binding behaviors, supporting the rational selection of candidates for further computational and experimental validation.

While the findings remain predictive, they are consistent with experimental evidence describing melatonin’s ability to preserve enzymatic function and regulate redox-sensitive transcription factors. The proposed interaction patterns, supported by the ISI framework, constitute testable hypotheses for future studies aimed at developing melatonin-derived multifunctional agents for the treatment of oxidative stress-related diseases, including neurodegenerative, inflammatory, and metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgement: The Authors acknowledge the support from Estancias Posdoctorales por México (2022). The authors also thank the SECIHTI project (No. CBF2023-2024-1141) for financial support, as well as LANCAD and the Miztli and Yoltla clusters for providing supercomputing resources.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the SECIHTI project Ciencia Básica y de Frontera (No. CBF2023-2024-1141) https://secihti.mx/ (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Author Contributions: Luis Felipe Hernández-Ayala: data curation, simulations, curate, editing, writing and analyses. Annia Galano: conceptualization, editing, writing, analysis, and supervision. Russel J. Reiter: editing, writing, analysis, and supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Table S1: Protein crystal structures Id’s and docking simulation details. Table S2: Selected interaction of melatonin-related compounds with prooxidant enzymes. Table S3: Selected interaction of melatonin-related compounds with antioxidant proenzymes. Table S4: Selected interaction of melatonin-related compounds with transcriptional proteins. Table S5: Synthetic conditions for the IIcD retrosynthetic path. Table S6: Synthetic conditions for the dM38 retrosynthetic path. Fig. S1: Potential energy vs. time for the KEAP1, SOD1, and p22-47phox systems. Fig. S2: Radial distribution function (RDF) profiles for the ligand-residue in H-bond interactions in the SOD1, KEAP1, and p22-47phox complexes. Fig. S3: Best docked pose for 3OH-M, ebselen, and IIcD in complex with TrxR. Fig. S4: Best docked pose for Zileuton and AMK in complex with 5-LOX. Fig. S5: 2D interaction map for rosiglitazone and for all melatonin-like compounds with PPAR-γ. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.071635/s1.

References

1. Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(1):44–84. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sies H, Jones DP. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(7):363–83. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (OUP); 2007. [Google Scholar]

4. Pham-Huy LA, He H, Pham-Huyc C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci. 2008;4(2):89–96. doi:10.59566/ijbs.2008.4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417(1):1–13. doi:10.1042/bj20081386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003;17(10):1195–214. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0752rev. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(11):1603–16. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Filomeni G, De Zio D, Cecconi F. Oxidative stress and autophagy: the clash between damage and metabolic needs. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(3):377–88. doi:10.1038/cdd.2014.150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Colavitti R, Finkel T. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of cellular senescence. IUBMB Life. 2005;57(4–5):277–81. doi:10.1080/15216540500091890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Mol Cell Res. 2016;1863(12):2977–92. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Leyane TS, Jere SW, Houreld NN. Oxidative stress in ageing and chronic degenerative pathologies: molecular mechanisms involved in counteracting oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13):7273. doi:10.3390/ijms23137273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dos Santos JM, Zhong Q, Benite-Ribeiro SA, Heck TG. New insights into the role of oxidative stress in the development of diabetes mellitus and its complications. J Diabetes Res. 2023;2023:9824864. doi:10.1155/2023/9824864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Reddy VP. Oxidative stress in health and disease. Biomedicines. 2023;11(11):2925. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11112925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Martemucci G, Fracchiolla G, Muraglia M, Tardugno R, Dibenedetto RS, D’Alessandro AG. Metabolic syndrome: a narrative review from the oxidative stress to the management of related diseases. Antioxidants. 2023;12(12):2091. doi:10.3390/antiox12122091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wen P, Sun Z, Gou F, Wang J, Fan Q, Zhao D, et al. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment: key drivers in neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res Rev. 2025;104:102667. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2025.102667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lin J, Jiang L, Tu J, Wang X, Li W. Editorial: oxidative stress in degenerative bone and joint diseases: novel molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1213380. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2023.1213380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Tan DX, de Almieda Chuffa LG, da Silva DGH, Slominski AT, et al. Dual sources of melatonin and evidence for different primary functions. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1414463. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1414463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Tesoriere L, D’Arpa D, Conti S, Giaccone V, Pintaudi AM, Livrea MA. Melatonin protects human red blood cells from oxidative hemolysis: new insights into the radical-scavenging activity. J Pineal Res. 1999;27(2):95–105. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079x.1999.tb00602.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Galano A, Reiter RJ. Melatonin and its metabolites vs oxidative stress: from individual actions to collective protection. J Pineal Res. 2018;65(1):e12514. doi:10.1111/jpi.12514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Süzen S, Atayik MC, Sirinzade H, Entezari B, Gurer-Orhan H, Cakatay U. Melatonin and redox homeostasis. Melatonin Res. 2022;5(3):304–24. doi:10.32794/mr112500134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Estaras M, Gonzalez-Portillo MR, Martinez R, Garcia A, Estevez M, Fernandez-Bermejo M, et al. Melatonin modulates the antioxidant defenses and the expression of proinflammatory mediators in pancreatic stellate cells subjected to hypoxia. Antioxidants. 2021;10(4):577. doi:10.3390/antiox10040577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Rosales-Corral S, Galano A, Zhou XJ, Xu B. Mitochondria: central organelles for melatonin’s antioxidant and anti-aging actions. Molecules. 2018;23(2):509. doi:10.3390/molecules23020509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Florido J, Rodriguez-Santana C, Martinez-Ruiz L, López-Rodríguez A, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Rusanova I, et al. Understanding the mechanism of action of melatonin, which induces ROS production in cancer cells. Antioxidants. 2022;11(8):1621. doi:10.3390/antiox11081621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Maharaj DS, Anoopkumar-Dukie S, Glass BD, Antunes EM, Lack B, Walker RB, et al. The identification of the UV degradants of melatonin and their ability to scavenge free radicals. J Pineal Res. 2002;32(4):257–61. doi:10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.01866.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kamfar WW, Khraiwesh HM, Ibrahim MO, Qadhi AH, Azhar WF, Ghafouri KJ, et al. Comprehensive review of melatonin as a promising nutritional and nutraceutical supplement. Heliyon. 2024;10(2):e24266. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Galano A, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin’s metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J Pineal Res. 2013;54(3):245–57. doi:10.1111/jpi.12010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Tan DX, Hardeland R, Leon J, Rodriguez C, et al. Anti-inflammatory actions of melatonin and its metabolites, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK) and N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMKin macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;165(1–2):139–49. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.05.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. León J, Escames G, Rodríguez MI, López LC, Tapias V, Entrena A, et al. Inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase activity by N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine, a brain metabolite of melatonin. J Neurochem. 2006;98(6):2023–33. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04029.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Álvarez-Diduk R, Galano A, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. N-acetylserotonin and 6-hydroxymelatonin against oxidative stress: implications for the overall protection exerted by melatonin. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119(27):8535–43. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b04920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Wölfler A, Abuja PM, Schauenstein K, Liebmann PM. N-acetylserotonin is a better extra- and intracellular antioxidant than melatonin. FEBS Lett. 1999;449(2–3):206–10. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00435-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Pérez-González A, Galano A, Alvarez-Idaboy JR, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Radical-trapping and preventive antioxidant effects of 2-hydroxymelatonin and 4-hydroxymelatonin: contributions to the melatonin protection against oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2017;1861(9):2206–17. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.06.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, Flores LJ, Reiter RJ. One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res. 2007;42(1):28–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(3):313–6. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Galano A, Guzmán-López EG, Reiter RJ. Potentiating the benefits of melatonin through chemical functionalization: possible impact on multifactorial neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11584. doi:10.3390/ijms222111584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gurer-Orhan H, Karaaslan C, Ozcan S, Firuzi O, Tavakkoli M, Saso L, et al. Novel indole-based melatonin analogues: evaluation of antioxidant activity and protective effect against amyloid β-induced damage. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24(8):1658–64. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2016.02.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Guo Y, Yu H, Wang C, Chen Y, Wang Y. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of melatonin derivatives as potential neuroprotective agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;192:112193. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Shirinzadeh H, Neuhaus E, Ince Erguc E, Tascioglu Aliyev A, Gurer-Orhan H, Suzen S. New indole-7-aldehyde derivatives as melatonin analogues; synthesis and screening their antioxidant and anticancer potential. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:104219. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Millán-Pacheco C, Serratos IN, del Rosario Sánchez González S, Galano A. Newly designed melatonin analogues with potential neuroprotective effects. Theor Chem Acc. 2022;141(9):49. doi:10.1007/s00214-022-02907-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tyagi E, Agrawal R, Nath C, Shukla R. Effect of melatonin on neuroinflammation and acetylcholinesterase activity induced by LPS in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;640(1–3):206–10. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]