Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

How Do LncRNAs Talk to miRNAs? Decoding Their Dialogue in Atherosclerosis

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, 530000, China

2 Department of Genomic Function and Diversity, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Science, Tokyo, 162-8601, Japan

3 Department of Cardiology, Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, 530000, China

4 Department of Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Xiamen, 361000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Rongzong Ye. Email: ; Chaoqian Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Cell Signaling Pathways in Health and Disease)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 5 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072780

Received 03 September 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

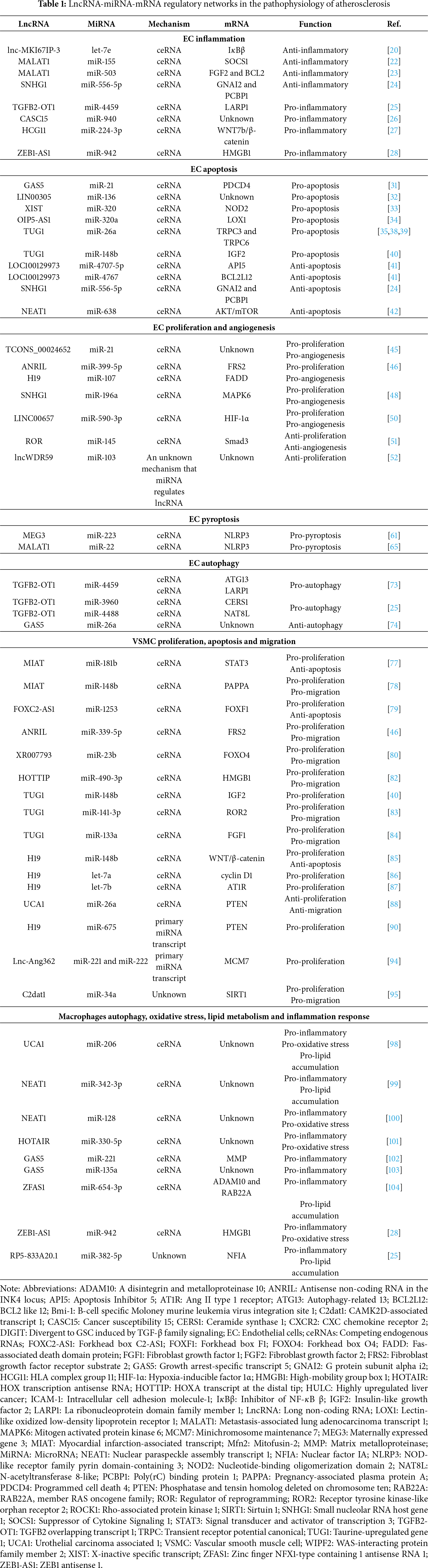

Atherosclerosis, characterized by the formation of fibrofatty lesions in the arterial wall, remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. Emerging evidence highlights the critical regulatory roles of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) in atherogenesis. LncRNAs can function as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) by sponging miRNAs, thereby modulating the expression of downstream target mRNAs. This review summarizes current knowledge on lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks and their functional roles in the three major cell types involved in atherosclerotic plaque development: endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and macrophages. In ECs, these networks are implicated in inflammation, apoptosis, proliferation, angiogenesis, pyroptosis, and autophagy. In VSMCs, they regulate proliferation, apoptosis, and migration. In macrophages, they influence lipid metabolism, inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and autophagy. Although the ceRNA mechanism is predominant, some lncRNAs also act as primary transcripts for miRNAs. Additionally, exosome-mediated non-coding RNA delivery mediates intercellular crosstalk, further expanding the complexity of RNA-based regulation in atherosclerosis. Despite significant progress, challenges remain due to the complexity and context-specificity of these networks. Further research is essential to elucidate these mechanisms and explore their potential as therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis.Keywords

Atherosclerosis is defined as the formation of fibrofatty lesions in the artery wall, causing high morbidity and mortality worldwide. Atherogenesis is a slowly progressive process characterized by multifocal structural alterations in the walls of large- and medium-sized arteries and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and macrophages are the major cells in atherosclerotic plaques [1–3].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous small (20–22 nucleotides long) non-coding RNAs that can regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences on 3′-untranslated regions of their target mRNAs, thereby inhibiting mRNA translation or promoting mRNA degradation [4,5]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are extensively classified as transcripts > 200 nucleotides with limited coding potential [6]. A classical regulation of lncRNAs is acting as a miRNA ‘sponge’. All RNA transcripts that contain miRNA-binding sites can communicate with and co-regulate each other by competing specifically for shared miRNAs. Thus, lncRNAs can serve as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or miRNA sponges to downregulate miRNA expression and activities. The regulation mechanisms of lncRNAs are very complicated, and current research shows that lncRNAs play an important role as miRNA sponges. Although this theory has received some criticism, it is still the mainstream of current research. This research field is expected to yield great insight into the overall mechanics of lncRNAs’ function [7,8]. Additionally, some lncRNAs can encode miRNAs as miRNA primary transcripts [9,10].

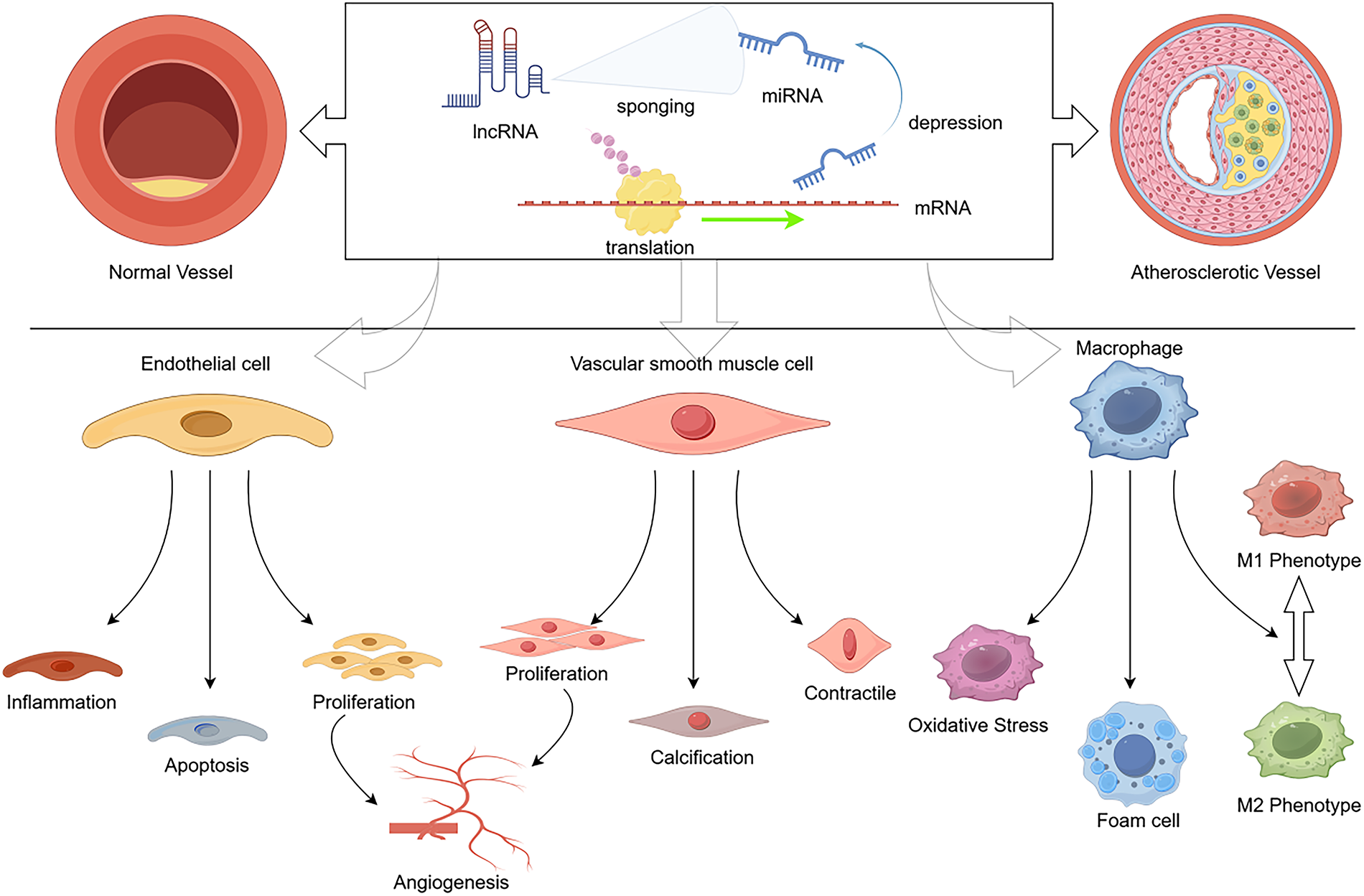

Emerging evidence has indicated that lncRNAs and miRNAs modulate many pathophysiological processes of atherosclerosis. For instance, LncRNA HYMAI can promote EC autophagy while inhibiting their apoptosis, thereby alleviating disease progression in As mice [11]. Adipose tissue-derived exosomes deliver miR-132/212, thereby promoting EC apoptosis as well as the proliferation and migration of VSMCs within atherosclerotic plaques in vivo, and exacerbating atherosclerosis progression [12]. Notably, interactions between lncRNAs and miRNAs, as exemplified by lncRNA sponging miRNA, have gained widespread attention. Some lncRNAs specifically interact with miRNAs and then influence the target mRNAs. In recent years, novel regulatory roles of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks have been revealed in various pathophysiological processes [13–15]. Notably, intercellular communication is a key link in the development of atherosclerosis, and exosomes (phospholipid bilayer nanoparticles with a diameter of 30–150 nm) have been identified as critical mediators in this process. They can selectively encapsulate and deliver miRNAs, lncRNAs, and mRNA, shuttling between vascular ECs, VSMCs, and macrophages to form a regulatory layer complementary to the intracellular RNA network. This review summarizes the current research (Fig. 1) on the regulatory role of the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network in ECs, VSMCs, and macrophages, discusses the function of exosome-mediated non-coding RNA delivery in atherosclerosis, and explores its potential translational value in disease-specific biomarker screening and the development of targeted therapy strategies.

Figure 1: The lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA axis regulates atherosclerosis progression. This figure intuitively reveals the regulatory logic of the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory axis in atherosclerosis progression, clearly presenting the functional changes of endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and macrophages during AS progression, as well as the impact of this regulatory network on the occurrence and development of atherosclerosis. (Created with figdraw.com. ID: ORIOP4e165)

2 LncRNA-miRNA-mRNA Networks in the Regulation of Endothelial Cell Functions

2.1 Endothelial Cell Inflammation

Atherosclerosis is likely to start with dysfunction of ECs, which express adhesion molecules, attracting various mononuclear leukocytes, leading to inflammatory reactions [16,17]. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) is an important mediator involved in endothelial inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque formation and progression [18,19]. Lin et al. found that the lncRNA MKI67IP-3, the microRNA let-7e, and inhibitor of NF-κB β (IκBβ) are abnormally expressed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and atherosclerotic plaques [20]. Let-7e plays pro-inflammatory roles through targeting IκBβ. Moreover, MKI67IP-3 can inhibit inflammatory responses in HUVECs by acting as a ceRNA against let-7e [20]. These studies suggest that modulation of the MKI67IP-3-let-7e-IκBβ axis may alleviate EC inflammation and provide a potential therapeutic strategy for atherosclerosis. Another lncRNA, termed metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) was previously confirmed to regulate endothelial function [21]. Recently, Li et al. demonstrated that MALAT1 exerts anti-inflammatory roles in endothelial injury [22]. The underlying mechanism is that MALAT1 contains a target site for miR-155, which can directly inhibit miR-155 expression and activity. Then, miR-155 inhibition significantly alleviated inflammation and apoptosis of ECs by increasing the level of Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 1 (SOCS1) [22]. Another study by Cremer et al. showed that MALAT1 inhibited the activity of miR-503 by sponging it, thereby reducing the excessive adhesion between bone marrow cells and inflammation-activated endothelial cells, and thus protected endothelial cells against inflammation-related injury [23]. These data indicate that MALAT1 can ameliorate inflammatory responses in ECs by modulating multiple miRNAs with distinct mechanisms. In addition, lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 (SNHG1) was found to attenuate cell injury and inflammatory response in HUVECs by sponging miR-556-5p and upregulating G protein subunit alpha i2 (GNAI2) and poly(rC) binding protein 1 (PCBP1) [24]. Above lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks exert anti-inflammatory function in ECs.

On the contrary, lncRNA TGFB2 overlapping transcript 1 (TGFB2-OT1) plays a pro-inflammatory role in vascular ECs [25]. TGFB2-OT1 sponges miR-4459 to increase the La ribonucleoprotein domain family member 1 (LARP1) level, which ultimately promotes the production of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β [25]. Similarly, by sponging miR-940 and thereby regulating the expression of inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1), lncRNA cancer Susceptibility 15 (lncRNA CASC15) could promote ox-LDL-induced inflammatory response in vascular endothelial cells and subsequent atherosclerotic events [26]. In Zhou and Song’s study, long noncoding RNA HLA complex group 11 (lncRNA HCG11) exerts its regulatory function by acting as a molecular sponge for miR-224-3p: this interaction blocks miR-224-3p from binding to its target gene JAK1, thus abrogating miR-224-3p-mediated JAK1 inhibition. Subsequent activation of endothelial cell inflammation and pyroptosis, driven by the HCG11/miR-224-3p/JAK1 axis, ultimately accelerates the pathological progression of atherosclerosis [27]. Furthermore, Hua et al. found that lncRNA ZEB1 antisense 1 (ZEB1-AS1) contributes to injury of human carotid artery ECs, via a novel miR-942-high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) axis [28]. Blocking these inflammatory targets may contribute to the treatment of atherosclerosis.

2.2 Endothelial Cell Apoptosis

Apoptosis in ECs is closely associated with the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [17,29]. LncRNA growth arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) was found to be increased in plaques collected from patients and animal models. Exosomes derived from GAS5-overexpressing THP-1 macrophages promoted the apoptosis of ECs, while exosomes shed by GAS5 knockdown THP-1 macrophages showed the opposite effects. These results suggested some potential functions of lncRNA GAS5 in atherogenesis by regulating the apoptosis of ECs [30]. Furthermore, there is an article reporting that in ECs, lncRNA GAS5 binds to miR-21 as a ceRNA to upregulate programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), which is a target of miR-21 and an important factor in EC apoptosis [31]. Another study revealed a pro-apoptotic role of lncRNA LINC00305 in HUVECs by sponging miR-136, but the downstream targets remain unknown [32]. Moreover, it was reported that knockdown of lncRNA X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) suppresses EC apoptosis and alleviates EC injury. Mechanistically, XIST sponges miR-320 and reduces its targeting concentration, resulting in the derepression of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) [33]. Similarly, a recent study revealed that depletion of lncRNA OIP5-AS1 inhibits apoptosis by sponging miR-320a targeting Lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX1) [34].

Additionally, Chen et al. demonstrated that tanshinol (3,4-dihydroxyphenyl lactic acid) could attenuate EC apoptosis in atherosclerotic ApoE−/− mice [35]. Specifically, the mRNA level of the lncRNA taurine-upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) was decreased, and the expression of miR-26a was increased by tanshinol in ECs. Further experimental results showed that TUG1 could directly sponge miR-26a. Therefore, low TUG1 expression and high levels of miR-26a are associated with the endothelial protective effect of tanshinol [35]. Transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) has been reported to be involved in the development of atherosclerosis by promoting EC apoptosis [36,37]. Importantly, miR-26a prevents EC apoptosis during atherosclerosis by directly targeting TRPC3 and TRPC6 for repression [38,39]. Taken together, these data highlight a possible TUG1-miR-26a-TRPC3/6 pathway in the regulation of EC apoptosis, which may be a novel therapeutic target for further research. Moreover, a recent study showed the therapeutic effect of TUG1 inhibition on atherosclerotic development by attenuating HUVEC apoptosis, possibly by sponging miR-148b targeting the insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) [40].

In contrast, a novel lncRNA termed LOC100129973 had a negative effect on HUVEC apoptosis. LOC100129973 upregulated the expression of Apoptosis Inhibitor 5 (API5) and BCL2 like 12 (BCL2L12) by respectively sponging miR-4707-5p and miR-4767, ultimately relieving HUVEC apoptosis and improving endothelial function, which helps maintain vascular integrity and delay plaque formation [41]. Moreover, the newly identified ceRNA axis of SNHG1-miR-556-5p-GNAI2&PCBP1 also showed the anti-apoptotic effects in HUVECs [24]. Another lncRNA, nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1), altered the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway by sponging miR-638 to suppress their apoptosis [42].

Thus, these studies suggested that lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks play a critical role in the regulation of EC apoptosis. Further studies are expected to elucidate the specific mechanisms of these pathways in atherosclerotic EC apoptosis.

2.3 Endothelial Cell Proliferation and Angiogenesis

EC proliferation and angiogenesis significantly influence plaque growth and instability in atherosclerotic lesions [43,44]. Increasing studies have shown the involvement of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks in EC proliferation and angiogenesis.

Several lncRNAs have been shown to promote EC proliferation and angiogenesis through the ceRNA mechanism. The lncRNA TCONS_00024652 was found to be overexpressed in TNF-α-stimulated HUVECs, and its dysregulated expression enhanced EC proliferation and angiogenesis. The underlying mechanisms may be that TCONS_00024652 endogenously competes with miR-21. However, the downstream target involved in the interaction of TCONS_00024652 with miR-21 remains unclear [45]. In a recent trial, lncRNA antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus (ANRIL) promoted HUVEC proliferation and migration by sponging miR-399-5p targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2 (FRS2) [46]. Huang et al. reported that the expression level of lncRNA H19 in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) is closely associated with cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis capacity. These biological effects are mediated through the pyroptosis pathway, which is regulated by the H19/miR-107/FADD axis. Transplantation of H19-overexpressing EPCs in a mouse model of limb ischemia significantly promotes angiogenesis and blood flow recovery in the ischemic region, while activating angiogenesis-related pathways. Mechanistically, H19 overexpression upregulates the expression level of the target gene Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD) through competitive binding with miR-107, thereby enhancing the proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis capacity of EPCs and inhibiting their pyroptosis, which facilitates vascular repair under ischemic conditions [47]. Similarly, Zhang et al. reported that the lncRNA SNHG1-miR-196a-mitogen activated protein kinase 6 (MAPK6) axis has the function of promoting EC proliferation and angiogenesis [48]. Additionally, the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is involved in angiogenesis [49]. LncRNA LINC00657 acts as a miR-590-3p sponge to attenuate the suppression of miR-590-3p on HIF-1α, and to enhance angiogenesis [50].

However, research on the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA pathway with anti-angiogenic effects remains relatively limited. Liang et al. found that lncRNA regulator of reprogramming (ROR) suppresses the proliferation, migration, and in vitro angiogenesis of human umbilical cord blood-derived EPCs. ROR may exert an anti-atherosclerotic effect by sponging microRNA-145 (miR-145). Further results of their study demonstrated that ROR, through sponging miR-145, can upregulate the expression of Smad3 (Sma- and Mad-related protein 3), a key signaling molecule involved in endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) and angiogenic function. Thus, lnc ROR can sponge miR-145, thereby upregulating the expression of Smad3 [51].

Interestingly, an article about miRNA regulating lncRNA was reported [52]. This article reported that miR-103 inhibited the proliferation of ECs by regulating lncRNA WD Repeated Domain 59 (lncWDR59). Although the underlying mechanism is not clear yet, it suggests a new direction for researchers.

2.4 Endothelial Cell Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is recognized as a new type of inflammatory programmed cell death. Different from apoptosis, pyroptosis responds to pathogen-associated molecular patterns and leads to the release of cytokines. Pyroptosis is initiated by the binding of intracellular pathogens to NOD-like receptors, resulting in the formation of inflammasomes, in which pro-caspase-1 becomes activated caspase-1. Activated caspase-1 can cleave the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, inducing their maturation [53–55]. Emerging literature suggests that EC pyroptosis has some significant impacts on atherosclerotic progression [56,57].

NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) is crucial to EC pyroptosis, and the NLRP3 inflammasome is considered a link between lipid metabolism and inflammation in atherosclerosis [58–60]. Zhang et al. used high-fat diet-treated ApoE−/− mice to demonstrate that intragastric administration of melatonin significantly alleviates atherosclerosis and suppresses the expression of pyroptosis-related genes, including the NLRP3 gene. These researchers hypothesized that melatonin prevented EC pyroptosis via lncRNA MEG3, which can enhance pyroptosis by sponging miR-223 [61]. Moreover, several studies have reported that miR-223 could negatively regulate NLRP3 [62–64]. Hence, the MEG3-miR-223-NLRP3 pathway likely accounts for the anti-atherosclerosis effects of melatonin [61]. In another study, knockdown of lncRNA MALAT significantly suppressed high glucose-induced pyroptosis in ECs [65]. NLRP3 expression was also significantly suppressed after MALAT1 knockdown, and miR-22 overexpression reversed the effect of MALAT1 on pyroptosis. These results highlight the involvement of MALAT1 sponging miR-22, which targets NLRP3, thereby exacerbating endothelial inflammation and pyroptosis to accelerate atherosclerosis [65]. However, this study has some limitations. First, this study only focused on EA.hy926 ECs and was not comprehensive enough to draw sufficient experimental conclusions. Second, the relationship between lncRNA MALAT1 and other potentially related genes needs further study.

2.5 Endothelial Cell Autophagy

EC injury and autophagic dysfunction occupy an important position in the atherosclerotic process. The autophagic response to ox-LDL in vascular tissue is most likely a mechanism of cell survival that protects them from dying. However, excessive autophagy in ECs may cause autophagic cell death and contribute to atherosclerosis [66,67]. Therefore, how to prevent excessive autophagy in ECs is also a direction for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a central regulator of autophagy, is involved in cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis [68–70]. The urgent challenge is to discover novel mTOR downstream components [71,72]. Ge et al. identified 3-benzyl-5-((2-nitrophenoxy) methyl)–dihydrofuran-2(3h)-one (3BDO) as a new activator of mTOR, and 3BDO can inhibit autophagy in HUVECs. Their data showed that 3BDO significantly downregulated the level of lncRNA TGFB2-OT1. By sponging miR-4459, TGFB2-OT1 upregulates autophagy-related 13 (ATG13), suggesting TGFB2-OT1 as a novel promoter of autophagy [73]. Moreover, in their further study, TGFB2-OT1 sponges miR-4459 to upregulate LARP1, to elevate the levels of ATG3 and ATG7. Additionally, TGFB2-OT1 sponges miR-3960 and miR-4488, then respectively upregulates ceramide synthase 1 (CERS1) and N-acetyltransferase 8-like (NAT8L), which can both participate in autophagy by affecting mitochondrial function [25]. Collectively, TGFB2-OT1 can promote autophagy via CERS1, NAT8L, ATG3, ATG7 and ATG13 [25,73]. A recent study showed that lncRNA GAS5 expression is increased and miR-26a is decreased in the plasma samples of atherosclerosis patients and ECs [74], which is in accordance with the previous studies [30,38,39]. In ECs, GAS5 knockdown restored impaired autophagic flux, whereas the inhibition of miR-26a reversed this effect. The authors found that the underlying molecular mechanism is GAS5 sponging miR-26a [74]. These studies suggest that TGFB2-OT1 and GAS5 may be novel therapeutic targets for further research on EC autophagy.

3 LncRNA-miRNA-mRNA Networks in the Regulation of VSMC Functions

VSMC Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Migration

Aberrant proliferation, apoptosis, and migration of VSMCs have been demonstrated to play crucial roles in atherosclerotic lesion development [75,76]. At present, most studies exploring the lncRNA-related regulation of VSMC functions only focus on the ceRNA mechanism.

Researchers found that lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) acts as an induction factor of atherosclerosis. MIAT facilitates VSMC proliferation, accelerates cell cycle progression, and inhibits apoptosis by sponging miR-181b and upregulating its target, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [77]. Also, as a ceRNA, MIAT promotes the proliferation and migration of VSMCs via the MIAT-miR-148b-pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPPA) axis [78]. There is an article reporting that lncRNA forkhead box protein C2-AS1 (FOXC2-AS1) might endogenously compete with miR-1253, whose repression increases the forkhead box F1 (FOXF1) expression, thereby enhancing VSMC proliferation [79]. The previously discussed lncRNAANRIL-miR-399-5p-FRS2 axis also has these impacts [46]. In another trial, lncRNA XR007793 serves as a ceRNA of miR-23b to upregulate forkhead box O4 (FOXO4) [80], a promoter of smooth muscle dedifferentiation genes and an activator of VSMC migration [81]. Recently, a study revealed that depletion of lncRNA HOXA transcript at the distal tip (HOTTIP) represses proliferation and migration in VSMCs by sponging miR-490-3p targeting HMGB1 [82]. In addition, Tang et al. showed that lncRNA TUG1 sponges miR-141-3p to upregulate receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2 (ROR2), ultimately facilitating VSMC proliferation and migration [83]. Moreover, it was reported that the TUG1-miR-148b-IGF2 axis and TUG1-miR-133a-fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) axis also show pro-proliferation effects on VSMCs [40,84]. In another study, lncRNA H19 endogenously competes with miR-148b and then enhances the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, ultimately aggravating the VSMC proliferation [85]. Furthermore, by sponging microRNA let-7a and let-7b, H19 can play similar roles by respectively upregulating cyclin D1 and Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) [86,87]. Conversely, lncRNA UCA1 was reported to attenuate VSMC proliferation and migration against atherosclerosis by sponging miR-26a and relieving its inhibition of PTEN [88].

Interestingly, in addition to lncRNAs with the ability to downregulate the levels of miRNAs by acting as miRNA sponges, some lncRNAs can upregulate the levels of miRNAs by acting as miRNA primary transcripts. LncRNA H19 has been found to serve as the primary transcript for miR-675 [89]. H19 downregulates phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) by encoding miR-675 and subsequently accelerates VSMC proliferation [90]. A growing body of evidence has indicated a negative correlation between PTEN and VSMC proliferation [91–93]. Similar effects were detected for lncRNA Ang362, which is regulated by angiotensin II [94]. Ang362 upregulates miR-221/222 by functioning as their primary transcripts, and these two miRNAs are both implicated in VSMC proliferation. Ang II treatment increased the levels of Ang362 and miR-221/222. Knockdown of lncRNA Ang362 downregulated the expression of miR-221/222 and minichromosome maintenance 7 (MCM7) and reduced VSMC proliferation. These results suggest that Ang362 aggravates Ang II-induced vascular dysfunction by upregulating miR-221/222, but the specific involvement of MCM7 remains unknown [94].

A novel lncRNA termed CAMK2D-associated transcript 1 (C2dat1) was highly expressed in coronary artery disease tissues and the proliferating VSMCs. C2dat1 promotes VSMC growth and migration by decreasing miR-34a expression, as well as increasing Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) expression [95], which has been demonstrated to be an important factor in senescence and proliferation of VSMCs [96]. However, the mechanism by which C2dat1 decreases miR-34a expression remains unknown [95].

Collectively, lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks in VSMCs appear to be complicated. A better understanding of the VSMC-related lncRNA-miRNA axes mentioned above may provide novel tools for protection against atherosclerosis.

4 LncRNA-miRNA-mRNA Networks in the Regulation of Macrophage Functions

Macrophages can engulf modified lipoproteins and transform themselves into foam cells, leading to the formation of the necrotic core in atheromatous plaques [97]. A recent trial revealed that ox-LDL significantly increases lncRNA UCA1 expression in THP-1 macrophages, and UCA1 knockdown significantly inhibited CD36 expression, a vital biomarker in atherosclerosis. In addition, foam cell formation and the triglyceride and total cholesterol levels induced by ox-LDL were all suppressed by UCA1 knockdown. The authors hypothesized that UCA1 endogenously competes with miR-206 to exacerbate atherosclerotic events in THP-1 macrophages [98]. Another lncRNA, nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1), showed similar effects on macrophages by sponging miR-342-3p [99] and miR-128 [100]. The lncRNA HOX transcription antisense RNA (HOTAIR) sponging miR-330-5p axis was also demonstrated to aggravate atherosclerosis events in macrophages [101]. Moreover, it was reported that lncRNA GAS5 acts as a ceRNA of miR-221 to trigger the inflammatory response and MMP expression in THP-1 macrophages [102]. Zhang et al. reported that GAS5 knockdown suppresses inflammation and oxidative stress in macrophages by sponging miR-135a [103]. LncRNA zinc finger NFX1-type containing 1 antisense RNA 1 (ZFAS1) was identified as a functional sponge of miR-654-3p. By sponging miR-654-3p, ZFAS1 elevated ADAM10 and RAB22A expression to reduce the cholesterol efflux rate and enhance inflammatory responses in THP-1 macrophages [104]. Furthermore, the previously discussed lncRNA ZEB1-AS1 also facilitates the oxidative stress and inflammatory events of THP-1 cells via the miR-642-HMGB1 axis [28]. Thus, based on emerging evidence, there is a good reason to propose that the lncRNA sponging miRNA axis may play an important role in atherosclerosis development in macrophages.

In addition, Hu et al. reported that nuclear factor IA (NFIA) overexpression in ApoE−/− mice enhances reverse cholesterol transport and decreases circulating inflammatory cytokines, thereby promoting the regression of atherosclerosis. Moreover, these researchers demonstrated that lncRNA RP5-833A20.1 suppresses NFIA expression by promoting miR-382-5p expression rather than inhibiting it [25]. Functionally, intervention targeting this pathway has been proven to improve plasma lipoprotein profiles, enhance reverse cholesterol transport, reduce systemic inflammatory cytokines, and ultimately promote the regression of atherosclerosis.

5 The Role of Exosome-Mediated Non-Coding RNA Delivery in Intercellular Communication during AS

Exosomes are nanoparticles (30–150 nm in diameter) actively secreted by cells and encapsulated by a phospholipid bilayer, capable of delivering various bioactive molecules—including proteins, DNA, RNA, and lipids—to recipient cells [105]. In the pathogenesis of AS, exosomes act as key mediators of intercellular communication, establishing a complex crosstalk network among the core cells involved in AS [106–108]. In-depth investigation of exosome-mediated ceRNA regulatory networks not only deepens the understanding of AS pathogenesis but also opens up novel avenues for the diagnosis and treatment of AS.

5.1 Exosome-Mediated Intercellular Transfer of Non-Coding RNAs: A Complex Regulatory Network

Exosomes can selectively package and deliver various non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), such as miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circular RNAs (circRNAs) [109]. They transmit signals among AS-related ECs, VSMCs, and macrophages, establishing a sophisticated and multidirectional regulatory system characterized by distinct bidirectionality [110].

Upon exposure to pathological stimuli, the ncRNA composition of exosomes secreted by cells undergoes remodeling, thereby rendering these exosomes “amplifiers” that promote AS progression [111]. For instance, exosomes secreted by TNF-α-stimulated endothelial cells (exo-T) can be internalized by macrophages, inducing their polarization toward the pro-atherogenic M1 phenotype while exacerbating lipid deposition and apoptosis in macrophages, ultimately facilitating AS development. MiRNA-Seq analysis has identified 104 significantly differentially expressed miRNAs in exo-T, including 33 upregulated and 71 downregulated ones. Further mechanistic studies have demonstrated that these exosomes can reshape the transduction of key signaling pathways such as MAPK in macrophages through their specific miRNA profiles [112]. VSMCs also secrete exosomes involved in AS pathoregulation: under melatonin stimulation, VSMC-derived exosomes deliver miR-204/miR-211 to adjacent VSMCs, synergistically inhibiting vascular calcification and senescence in a paracrine manner by targeting BMP2 [113]. Curcumin, on the other hand, prompts VSMCs to secrete exosomes enriched in miR-92b-3p, which significantly influences vascular calcification via the exosome-miR-92b-3p/KLF4 axis [114]. Furthermore, macrophages stimulated by ox-LDL deliver miR-320b to VSMCs through exosomes. Once inside recipient cells, miR-320b directly targets and inhibits the expression of PPARGC1A, thereby activating the downstream MEK/ERK signaling pathway. This enhances VSMC viability and invasiveness, triggering their phenotypic switch from the contractile to the synthetic type—a series of changes that constitute the core pathological process underlying AS plaque progression and instability, directly driving disease deterioration [115].

In contrast, under physiological or protective signal stimulation, exosomes can deliver anti-atherogenic ncRNAs, exerting a “brake function” in disease suppression. Exosomes secreted by M2 macrophages are enriched in miR-7683-3p, which can be delivered to VSMC-derived foam cells. By directly targeting the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of HOXA1 mRNA, miR-7683-3p relieves the inhibitory effect of HOXA1 on the PPARγ-LXRα-ABCG1 signaling pathway, thereby significantly activating cholesterol efflux. This mechanism effectively reduces lipid accumulation in VSMCs in vitro; in ApoE−/− mouse models, it exhibits therapeutic effects such as reducing atherosclerotic plaque area, decreasing the necrotic core, increasing fibrous cap thickness, and enhancing plaque stability. Clinical data further show that the level of miR-7683-3p in the peripheral blood of AS patients is significantly lower, suggesting its potential as a diagnostic biomarker for AS [116]. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) also possess distinct anti-AS therapeutic potential. Studies have confirmed that Msc-Exos can deliver their enriched lncRNA FENDRR to ox-LDL-injured human vascular endothelial cells, significantly reducing AS plaque volume and lipid infiltration in mice. The core mechanism involves MSCs delivering FENDRR via exosomes, which regulates the miR-28/TEAD1 axis through a ceRNA mechanism, thereby protecting endothelial function and delaying AS progression [117].

5.2 Clinical Translation: From Biomarkers to Cutting-Edge Therapeutic Strategies

The core regulatory role of exosomes in intercellular communication during AS endows them with dual core values in clinical translation—serving not only as highly specific biomarkers for disease diagnosis but also as natural carriers for targeted therapy. The inherent advantages of natural exosomes, such as favorable biocompatibility, inherent targeting ability, and low immunogenicity, have provided novel breakthroughs for the clinical diagnosis and targeted treatment of AS [44,118]. In studies exploring exosome-derived ncRNAs as biomarkers, their high stability, strong specificity, and good accessibility have made them a core research direction: the membrane structure of exosomes protects internal ncRNAs from degradation by plasma nucleases, conferring greater in vivo stability compared to free ncRNAs. Moreover, they can be easily obtained through liquid biopsies such as serum, plasma, and saliva, making them suitable for long-term dynamic monitoring and therapeutic effect evaluation of AS [119,120].

In specific research, Hu et al. found that the level of lncRNA LIPCAR in blood samples from AS patients was significantly higher than that in healthy individuals, and LIPCAR levels were also elevated in exosomes secreted by THP-1 stimulated with ox-LDL. These exosomes can affect the proliferation of VSMCs by regulating the levels of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in VSMCs, thereby participating in AS progression [121]. Based on this, lncRNA LIPCAR is considered a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for AS. Additionally, clinical studies have confirmed that lncRNA AC100865.1 is abnormally expressed in patients with cardiovascular diseases and is closely related to macrophage adhesion and ox-LDL uptake, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular-related diseases and providing new prospects for AS treatment [122].

In the field of therapeutic translation, exosome-mediated ncRNA delivery systems have demonstrated significant clinical translation potential in AS treatment due to the inherent advantages of natural carriers [123]. Preclinical studies have shown that adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs) can stabilize atherosclerotic plaques, reduce inflammation, and promote myocardial repair through mechanisms such as regulating macrophage polarization, protecting endothelial function, and promoting angiogenesis. AD-MSCs genetically modified (overexpressing SIRT1, IGF-1, PD-L1) or pretreated with bioactive compounds exhibit superior therapeutic effects compared to unmodified cells. These modifications enhance cell survival, immune efficacy, and repair capacity, highlighting the application potential of personalized therapies. However, the clinical translation of AD-MSC therapy faces multiple obstacles. Although recent clinical trials have confirmed its safety, therapeutic efficacy remains inconsistent. Donor variability, especially in patients with complications such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, can reduce the therapeutic effect of AD-MSCs. Exosomes derived from AD-MSCs offer a promising cell-free alternative that retains therapeutic benefits while reducing associated risks, opening up new avenues for clinical translation [124].

Meanwhile, engineered exosome technology can further improve therapeutic efficiency. For example, constructing “exosome mimetics (EMs)” via bioorthogonal functionalization technology or modifying targeting ligands (e.g., hydroxyapatite-binding groups) on the exosome surface can significantly enhance tissue specificity. This property enables precise delivery of protective ncRNAs to target organs and cells, reducing off-target effects [125]. Modifying exosomal membrane proteins—such as overexpressing specific membrane proteins in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos)—can enhance affinity for specific cells and further reduce off-target risks [126]. Regulating the miRNA composition of MSC-Exos through miRNA inhibitors or mimics allows for pathway-specific functions, avoiding non-specific effects. Studies have shown that specific miRNA combinations can precisely regulate immune responses or tissue regeneration [127]. Additionally, small exosomes encapsulated with off-on fluorescent complexes can real-time monitor the binding efficiency between miRNAs and target mRNAs, providing support for optimizing therapeutic doses and visualizing off-target effects [128].

In conclusion, this review consolidates compelling evidence that intricate lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA regulatory networks are fundamentally involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis by modulating the core functions of endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and macrophages (Table 1). These networks exert critical control over a wide spectrum of cellular processes, including inflammation, apoptosis, proliferation, migration, lipid metabolism, and autophagy, primarily through the ceRNA mechanism. Furthermore, the discovery of exosome-mediated intercellular delivery of non-coding RNAs adds a sophisticated layer of intercellular communication, amplifying and propagating pathogenic or protective signals among the key cellular players in the atherosclerotic plaque. The elucidation of these complex RNA dialogues not only significantly deepens our mechanistic understanding of atherogenesis but also firmly establishes specific lncRNAs, miRNAs, and their axes as promising candidates for novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, heralding a new era in RNA-based cardiovascular medicine.

Looking ahead, several promising yet challenging avenues warrant further exploration. A primary future direction involves moving beyond correlative studies to definitively establish the causal roles of these specific ceRNA networks in atherosclerosis in vivo, utilizing sophisticated genetic models such as cell-specific and inducible knockout or overexpression systems. The context-specificity and sheer complexity of these networks demand the application of advanced multi-omics approaches and computational biology to map the entire “RNA interactome” within the atherosclerotic microenvironment. From a translational perspective, the potential of engineered exosomes as natural, targeted delivery vehicles for therapeutic ncRNAs (e.g., miRNA mimics or lncRNA inhibitors) represents a frontier with immense clinical potential. Overcoming challenges related to specific targeting, loading efficiency, and scalable production will be crucial. Ultimately, integrating these mechanistic insights into the development of targeted RNA therapeutics and leveraging stable exosomal ncRNAs as sensitive biomarkers for early diagnosis, risk stratification, and monitoring therapeutic responses could revolutionize the clinical management of atherosclerosis, paving the way for more precise and effective interventions.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82360024).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yating Wei; data collection: Hongkang Yao, Xian Shi, Hong Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Rongzong Ye, Chaoqian Li; draft manuscript preparation: Yating Wei, Rongzong Ye. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ECs | Endothelial cells |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| ceRNAs | Competing endogenous RNAs |

| ox-LDL | Oxidized low density lipoprotein |

| HUVECs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| MALAT1 | Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 |

| SOCS1 | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 1 |

| SNHG1 | Small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 |

| NEAT1 | Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 |

| GAS5 | Growth arrest-specific transcript 5 |

| XIST | X-inactive specific transcript |

| TUG1 | Taurine-upregulated gene 1 |

| IGF2 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 |

| ANRIL | Antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| MEG3 | Maternally expressed gene 3 |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| MIAT | Myocardial infarction-associated transcript |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten |

| HOTAIR | HOX transcription antisense RNA |

| ZFAS1 | Zinc finger NFX1-type containing 1 antisense RNA 1 |

| NFIA | Nuclear factor IA |

| EPCs | Endothelial progenitor cells |

| ncRNAs | Non-coding RNAs |

| exo | Exosome |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

References

1. Wu W, Sui W, Chen S, Guo Z, Jing X, Wang X, et al. Sweetener aspartame aggravates atherosclerosis through insulin-triggered inflammation. Cell Metab. 2025;37(5):1075–88.e1077. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2025.01.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Tan Y, Huang Z, Jin Y, Wang J, Fan H, Liu Y, et al. Lipid droplets sequester palmitic acid to disrupt endothelial ciliation and exacerbate atherosclerosis in male mice. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):8273. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-52621-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Benedicto I, Hamczyk MR, Dorado B, Andrés V. Vascular cell types in progeria: victims or villains? Trends Mol Med. 2025;140:2603. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2025.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kosek DM, Petzold K, Andersson ER. Mapping effective microRNA pairing beyond the seed using abasic modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(8):gkaf364. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaf364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Dao K, Jungers CF, Djuranovic S, Mustoe AM. U-rich elements drive pervasive cryptic splicing in 3′ UTR massively parallel reporter assays. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):6844. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-62000-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Behl T, Kyada A, Roopashree R, Nathiya D, Arya R, Kumar MR, et al. Epigenetic biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: diagnostic and prognostic relevance. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;102:102556. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2024.102556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yi Q, Feng J, Lan W, Shi H, Sun W, Sun W. CircRNA and lncRNA-encoded peptide in diseases, an update review. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):214. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02131-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Farberov S, Ziv O, Lau JY, Ben-Tov Perry R, Lubelsky Y, Miska E, et al. Structural features within the NORAD long noncoding RNA underlie efficient repression of Pumilio activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2025;32(2):287–99. doi:10.1038/s41594-024-01393-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Di Leva F, Arnoldi M, Santarelli S, Massonot M, Lemée MV, Bon C, et al. SINEUP RNA rescues molecular phenotypes associated with CHD8 suppression in autism spectrum disorder model systems. Mol Ther. 2025;33(3):1180–96. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.12.043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kim H, Lee YY, Kim VN. The biogenesis and regulation of animal microRNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2025;26(4):276–96. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00805-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ouyang S, Zhou ZX, Liu HT, Zhou K, Ren Z, Liu H, et al. LncRNA HYMAI promotes endothelial cell autophagy via miR-19a-3p/ATG14 to attenuate the progression of coronary atherosclerotic disease. Curr Med Chem. 2025. doi:10.2174/0109298673428431250917095939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Guo B, Zhuang TT, Li CC, Li F, Shan SK, Zheng MH, et al. MiRNA-132/212 encapsulated by adipose tissue-derived exosomes worsen atherosclerosis progression. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):331. doi:10.1186/s12933-024-02404-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Desideri F, Grazzi A, Lisi M, Setti A, Santini T, Colantoni A, et al. CyCoNP lncRNA establishes cis and trans RNA-RNA interactions to supervise neuron physiology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(16):9936–52. doi:10.1093/nar/gkae590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Chen Y, Ye Z, He RQ, Chen G, Zhang DX. Landscape of non-coding RNAs in cancer treatment-induced cardiovascular toxicity: from mechanistic insights to clinical implications. Semin Cancer Biol. 2025;115(8):16–39. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2025.07.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen X, Chen Z, Watts R, Luo H. Non-coding RNAs in plant stress responses: molecular insights and agricultural applications. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025;23(8):3195–233. doi:10.1111/pbi.70134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Xue Z, Han M, Sun T, Wu Y, Xing W, Mu F, et al. PIM1 instigates endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition to aggravate atherosclerosis. Theranostics. 2025;15(2):745–65. doi:10.7150/thno.102597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhong C, Deng K, Lang X, Shan D, Xie Y, Pan W, et al. Therapeutic potential of natural flavonoids in atherosclerosis through endothelium-protective mechanisms: an update. Pharmacol Ther. 2025;271(2):108864. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2025.108864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang Y, Xing W, Li Z, Zhao D, Xiu B, Xi Y, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor alleviates endothelial inflammation in atherosclerosis through regulation of integrin β1-NLRP3 inflammasome. FEBS J. 2025;292(1):191–205. doi:10.1111/febs.17308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hu G, Zhou H, Yuan Z, Wang J. Vascular cellular senescence in human atherosclerosis: the critical modulating roles of CDKN2A and CDK4/6 signaling pathways. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;237:116916. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2025.116916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Lin Z, Ge J, Wang Z, Ren J, Wang X, Xiong H, et al. Let-7e modulates the inflammatory response in vascular endothelial cells through ceRNA crosstalk. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):42498. doi:10.1038/srep42498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Khojali WMA, Khalifa NE, Alshammari F, Afsar S, Aboshouk NAM, Khalifa AAS, et al. Pyroptosis-related non-coding RNAs emerging players in atherosclerosis pathology. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;255:155219. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2024.155219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Li S, Sun Y, Zhong L, Xiao Z, Yang M, Chen M, et al. The suppression of ox-LDL-induced inflammatory cytokine release and apoptosis of HCAECs by long non-coding RNA-MALAT1 via regulating microRNA-155/SOCS1 pathway. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;28(11):1175–87. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2018.06.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Cremer S, Michalik KM, Fischer A, Pfisterer L, Jaé N, Winter C, et al. Hematopoietic deficiency of the long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes atherosclerosis and plaque inflammation. Circulation. 2019;139(10):1320–34. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.117.029015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lu Y, Xi J, Zhang Y, Chen W, Zhang F, Li C, et al. SNHG1 inhibits ox-LDL-induced inflammatory response and apoptosis of HUVECs via up-regulating GNAI2 and PCBP1. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:703. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hu YW, Zhao JY, Li SF, Huang JL, Qiu YR, Ma X, et al. RP5-833A20.1/miR-382-5p/NFIA-dependent signal transduction pathway contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis and inflammatory reaction. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(1):87–101. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.114.304296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li T, Yang Z, Zhang K, Song W, Liu B, Xiao S, et al. CASC15 participated in the damage of vascular endothelial cells in atherosclerosis through interaction with miR-940. BMC Med Genomics. 2025;18(1):153. doi:10.1186/s12920-025-02211-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou H, Song WH. LncRNA HCG11 accelerates atherosclerosis via regulating the miR-224-3p/JAK1 axis. Biochem Genet. 2023;61(1):372–89. doi:10.1007/s10528-022-10261-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Hua Z, Ma K, Liu S, Yue Y, Cao H, Li Z. LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 facilitates ox-LDL-induced damage of HCtAEC cells and the oxidative stress and inflammatory events of THP-1 cells via miR-942/HMGB1 signaling. Life Sci. 2020;247:117334. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Deng Y, Liu L, Li Y, Ma H, Li C, Yan K, et al. pH-sensitive nano-drug delivery systems dual-target endothelial cells and macrophages for enhanced treatment of atherosclerosis. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2025;15(8):2924–40. doi:10.1007/s13346-025-01791-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen L, Yang W, Guo Y, Chen W, Zheng P, Zeng J, et al. Exosomal lncRNA GAS5 regulates the apoptosis of macrophages and vascular endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shen Z, She Q. Association between the deletion allele of ins/del polymorphism (Rs145204276) in the promoter region of GAS5 with the risk of atherosclerosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;49(4):1431–43. doi:10.1159/000493447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang BY, Jin Z, Zhao Z. Long intergenic noncoding RNA 00305 sponges miR-136 to regulate the hypoxia induced apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94(5):238–43. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Xu X, Ma C, Liu C, Duan Z, Zhang L. Knockdown of long noncoding RNA XIST alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-mediated endothelial cells injury through modulation of miR-320/NOD2 axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(2):586–92. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang C, Yang H, Li Y, Huo P, Ma P. LNCRNA OIP5-AS1 regulates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-mediated endothelial cell injury via miR-320a/LOX1 axis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;467(1–2):15–25. doi:10.1007/s11010-020-03688-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen C, Cheng G, Yang X, Li C, Shi R, Zhao N. Tanshinol suppresses endothelial cells apoptosis in mice with atherosclerosis via lncRNA TUG1 up-regulating the expression of miR-26a. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(7):2981–91. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Vazquez G. TRPC channels as prospective targets in atherosclerosis: terra incognita. Front Biosci. 2012;4(1):157–66. doi:10.2741/258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Vazquez G, Solanki S, Dube P, Smedlund K, Ampem P. On the roles of the transient receptor potential canonical 3 (TRPC3) channel in endothelium and macrophages: implications in atherosclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;898(4):185–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26974-0_9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Feng M, Xu D, Wang L. miR-26a inhibits atherosclerosis progression by targeting TRPC3. Cell Biosci. 2018;8(1):4. doi:10.1186/s13578-018-0203-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang Y, Qin W, Zhang L, Wu X, Du N, Hu Y, et al. MicroRNA-26a prevents endothelial cell apoptosis by directly targeting TRPC6 in the setting of atherosclerosis. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):9401. doi:10.1038/srep09401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wu X, Zheng X, Cheng J, Zhang K, Ma C. LncRNA TUG1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis by regulating miR-148b/IGF2 axis in ox-LDL-stimulated VSMC and HUVEC. Life Sci. 2020;243:117287. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Lu W, Huang SY, Su L, Zhao BX, Miao JY. Long noncoding RNA LOC100129973 suppresses apoptosis by targeting miR-4707-5p and miR-4767 in vascular endothelial cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):21620. doi:10.1038/srep21620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang X, Guan MX, Jiang QH, Li S, Zhang HY, Wu ZG, et al. NEAT1 knockdown suppresses endothelial cell proliferation and induces apoptosis by regulating miR-638/AKT/mTOR signaling in atherosclerosis. Oncol Rep. 2020;44(1):115–25. doi:10.3892/or.2020.7605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Han M, Liu Z, Liu L, Kang Z, Huang X, Smart N, et al. Spatio-temporal proliferative heterogeneity of intra-organ endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2025;137:7. doi:10.1161/circresaha.125.326748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Raju S, Turner ME, Cao C, Abdul-Samad M, Punwasi N, Blaser MC, et al. Multiomic landscape of extracellular vesicles in human carotid atherosclerotic plaque reveals endothelial communication networks. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2025;45(7):1277–305. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.124.322324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Halimulati M, Duman B, Nijiati J, Aizezi A. Long noncoding RNA TCONS_00024652 regulates vascular endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis via microRNA-21. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(4):3309–16. doi:10.3892/etm.2018.6594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Huang T, Zhao HY, Zhang XB, Gao XL, Peng WP, Zhou Y, et al. LncRNA ANRIL regulates cell proliferation and migration via sponging miR-339-5p and regulating FRS2 expression in atherosclerosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(4):1956–69. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202002_20373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Huang L, Ye Y, Sun Y, Zhou Z, Deng T, Liu Y, et al. LncRNA H19/miR-107 regulates endothelial progenitor cell pyroptosis and promotes flow recovery of lower extremity ischemia through targeting FADD. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024;1870(7):167323. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang L, Zhang Q, Lv L, Zhu J, Chen T, Wu Y. LncRNA SNHG1 regulates vascular endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis via miR-196a. J Mol Histol. 2020;51(2):117–24. doi:10.1007/s10735-020-09862-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Lee JW, Bae SH, Jeong JW, Kim SH, Kim KW. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)alpha: its protein stability and biological functions. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36(1):1–12. doi:10.1038/emm.2004.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Bao MH, Li GY, Huang XS, Tang L, Dong LP, Li JM. Long noncoding RNA LINC00657 acting as a miR-590-3p sponge to facilitate low concentration oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced angiogenesis. Mol Pharmacol. 2018;93(4):368–75. doi:10.1124/mol.117.110650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liang J, Chu H, Ran Y, Lin R, Cai Y, Guan X, et al. Linc-ROR modulates the endothelial-mesenchymal transition of endothelial progenitor cells through the miR-145/Smad3 signaling pathway. Physiol Res. 2024;73(4):565–76. doi:10.33549/physiolres.935303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Natarelli L, Geissler C, Csaba G, Wei Y, Zhu M, di Francesco A, et al. miR-103 promotes endothelial maladaptation by targeting lncWDR59. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2645. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05065-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Liu Z, Wang C, Lin C. Pyroptosis as a double-edged sword: the pathogenic and therapeutic roles in inflammatory diseases and cancers. Life Sci. 2023;318(5):121498. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Yuan J, Ofengeim D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(5):379–95. doi:10.1038/s41580-023-00689-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wu J, Wang H, Gao P, Ouyang S. Pyroptosis: induction and inhibition strategies for immunotherapy of diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14(10):4195–227. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2024.06.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Chen X, Yang Z, Liao M, Zhao Q, Lu Y, Li Q, et al. Ginkgo flavone aglycone ameliorates atherosclerosis via inhibiting endothelial pyroptosis by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Phytother Res. 2024;38(11):5458–73. doi:10.1002/ptr.8321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Sheng W, Wu Z, Wei J, Wang J, Zhang S, Ding Z, et al. Astrocyte-derived CXCL10 exacerbates endothelial cells pyroptosis and blood-brain barrier disruption via CXCR3/cGAS/AIM2 pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage. Cell Death Discov. 2025;11(1):373. doi:10.1038/s41420-025-02658-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wang Y, Fang D, Yang Q, You J, Wang L, Wu J, et al. Interactions between PCSK9 and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in atherosclerosis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1126823. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1126823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zhong S, Shen H, Dai X, Liao L, Huang C. BAM15 inhibits endothelial pyroptosis via the NLRP3/ASC/caspase-1 pathway to alleviate atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2025;406:119226. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2025.119226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Fan X, Li Q, Wang Y, Zhang DM, Zhou J, Chen Q, et al. Non-canonical NF-κB contributes to endothelial pyroptosis and atherogenesis dependent on IRF-1. Transl Res J Lab Clin Med. 2023;255:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2022.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhang Y, Liu X, Bai X, Lin Y, Li Z, Fu J, et al. Melatonin prevents endothelial cell pyroptosis via regulation of long noncoding RNA MEG3/miR-223/NLRP3 axis. J Pineal Res. 2018;64(2):12449. doi:10.1111/jpi.12449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Bauernfeind F, Rieger A, Schildberg FA, Knolle PA, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hornung V. NLRP3 inflammasome activity is negatively controlled by miR-223. J Immunol. 2012;189(8):4175–81. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Lee S, Choi E, Cha MJ, Hwang KC. Looking for pyroptosis-modulating miRNAs as a therapeutic target for improving myocardium survival. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:254871. doi:10.1155/2015/254871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Qin D, Wang X, Li Y, Yang L, Wang R, Peng J, et al. MicroRNA-223-5p and -3p cooperatively suppress necroptosis in ischemic/reperfused hearts. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(38):20247–59. doi:10.1074/jbc.M116.732735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Song Y, Yang L, Guo R, Lu N, Shi Y, Wang X. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes high glucose-induced human endothelial cells pyroptosis by affecting NLRP3 expression through competitively binding miR-22. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509(2):359–66. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Pan Y, Li Y, Zhou X, Luo J, Ding Q, Pan R, et al. Extracellular matrix-mimicking hydrogel with angiogenic and immunomodulatory properties accelerates healing of diabetic wounds by promoting autophagy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2025;17(3):4608–25. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c18945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Chang X, Zhou H, Hu J, Ge T, He K, Chen Y, et al. Targeting mitochondria by lipid-selenium conjugate drug results in malate/fumarate exhaustion and induces mitophagy-mediated necroptosis suppression. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(14):5793–811. doi:10.7150/ijbs.102424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Niu Z, An R, Shi H, Jin Q, Song J, Chang Y, et al. Columbianadin ameliorates myocardial injury by inhibiting autophagy through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in AMI mice and hypoxic H9c2 Cells. Phytother Res. 2025;39(1):521–35. doi:10.1002/ptr.8387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Liu L, An Z, Zhang H, Wan X, Zhao X, Yang X, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles alleviate diabetes-exacerbated atherosclerosis via AMPK/mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy-related macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24(1):48. doi:10.1186/s12933-025-02603-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Wang A, Yue K, Zhong W, Zhang G, Zhang X, Wang L. Targeted delivery of rapamycin and inhibition of platelet adhesion with multifunctional peptide nanoparticles for atherosclerosis treatment. J Control Release. 2024;376:753–65. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.10.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Zhang X, Evans TD, Chen S, Sergin I, Stitham J, Jeong SJ, et al. Loss of Macrophage mTORC2 drives atherosclerosis via FoxO1 and IL-1β signaling. Circ Res. 2023;133(3):200–19. doi:10.1161/circresaha.122.321542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Poznyak AV, Sukhorukov VN, Zhuravlev A, Orekhov NA, Kalmykov V, Orekhov AN. Modulating mTOR signaling as a promising therapeutic strategy for atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1153. doi:10.3390/ijms23031153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Ge D, Han L, Huang S, Peng N, Wang P, Jiang Z, et al. Identification of a novel MTOR activator and discovery of a competing endogenous RNA regulating autophagy in vascular endothelial cells. Autophagy. 2014;10(6):957–71. doi:10.4161/auto.28363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Liang W, Fan T, Liu L, Zhang L. Knockdown of growth-arrest specific transcript 5 restores oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced impaired autophagy flux via upregulating miR-26a in human endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;843:154–61. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Yang Y, Zhang Q, Liu S, Yuan H, Wu X, Zou Y, et al. Suv39h1 regulates phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells and contributes to vascular injury by repressing HIC1 transcription. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2025;45(6):965–78. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.124.322048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Huang QH, Tang XY, Huang QY, Zhi SB, Zheng XQ, Gan CY, et al. IFITM1 promotes proliferation, migration and macrophage-like transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells via c-Src/MAPK/GATA2/E2F2 pathway in atherosclerosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;239:117014. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2025.117014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Zhong X, Ma X, Zhang L, Li Y, Li Y, He R. MIAT promotes proliferation and hinders apoptosis by modulating miR-181b/STAT3 axis in ox-LDL-induced atherosclerosis cell models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;97:1078–85. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.11.052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhou Y, Ma W, Bian H, Chen Y, Li T, Shang D, et al. Long non-coding RNA MIAT/miR-148b/PAPPA axis modifies cell proliferation and migration in ox-LDL-induced human aorta vascular smooth muscle cells. Life Sci. 2020;256:117852. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Wang YQ, Xu ZM, Wang XL, Zheng JK, Du Q, Yang JX, et al. LncRNA FOXC2-AS1 regulated proliferation and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cell through targeting miR-1253/FOXF1 axis in atherosclerosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(6):3302–14. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202003_20698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Wu YX, Zhang SH, Cui J, Liu FT. Long noncoding RNA XR007793 regulates proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cell via suppressing miR-23b. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5895–903. doi:10.12659/msm.908902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Liu ZP, Wang Z, Yanagisawa H, Olson EN. Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells through interaction of Foxo4 and myocardin. Dev Cell. 2005;9(2):261–70. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Guo X, Liu Y, Zheng X, Han Y, Cheng J. HOTTIP knockdown inhibits cell proliferation and migration via regulating miR-490-3p/HMGB1 axis and PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in ox-LDL-induced VSMCs. Life Sci. 2020;248:117445. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Tang Y, Hu J, Zhong Z, Liu Y, Wang Y. Long noncoding RNA TUG1 promotes the function in ox-LDL-treated HA-VSMCs via miR-141-3p/ROR2 axis. Cardiovasc Ther. 2020;2020:6758934. doi:10.1155/2020/6758934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Zhang L, Cheng H, Yue Y, Li S, Zhang D, He R. TUG1 knockdown ameliorates atherosclerosis via up-regulating the expression of miR-133a target gene FGF1. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2018;33:6–15. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2017.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Zhang L, Cheng H, Yue Y, Li S, Zhang D, He R. H19 knockdown suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis by regulating miR-148b/WNT/β-catenin in ox-LDL-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biomed Sci. 2018;25(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12929-018-0418-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Sun W, Lv J, Duan L, Lin R, Li Y, Li S, et al. Long noncoding RNA H19 promotes vascular remodeling by sponging let-7a to upregulate the expression of cyclin D1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;508(4):1038–42. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Su H, Xu X, Yan C, Shi Y, Hu Y, Dong L, et al. LncRNA H19 promotes the proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells through AT(1)R via sponging let-7b in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):254. doi:10.1186/s12931-018-0956-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Tian S, Yuan Y, Li Z, Gao M, Lu Y, Gao H. LncRNA UCA1 sponges miR-26a to regulate the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Gene. 2018;673:159–66. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Cai X, Cullen BR. The imprinted H19 noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. RNA. 2007;13(3):313–6. doi:10.1261/rna.351707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Lv J, Wang L, Zhang J, Lin R, Wang L, Sun W, et al. Long noncoding RNA H19-derived miR-675 aggravates restenosis by targeting PTEN. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497(4):1154–61. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Horita H, Wysoczynski CL, Walker LA, Moulton KS, Li M, Ostriker A, et al. Nuclear PTEN functions as an essential regulator of SRF-dependent transcription to control smooth muscle differentiation. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):10830. doi:10.1038/ncomms10830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Mitra AK, Jia G, Gangahar DM, Agrawal DK. Temporal PTEN inactivation causes proliferation of saphenous vein smooth muscle cells of human CABG conduits. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(1):177–87. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00311.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Moon SK, Kim HM, Kim CH. PTEN induces G1 cell cycle arrest and inhibits MMP-9 expression via the regulation of NF-kappaB and AP-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;421(2):267–76. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2003.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Leung A, Trac C, Jin W, Lanting L, Akbany A, Saetrom P, et al. Novel long noncoding RNAs are regulated by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2013;113(3):266–78. doi:10.1161/circresaha.112.300849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Wang H, Jin Z, Pei T, Song W, Gong Y, Chen D, et al. Long noncoding RNAs C2dat1 enhances vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration by targeting MiR-34a-5p. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(3):3001–8. doi:10.1002/jcb.27070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Gorenne I, Kumar S, Gray K, Figg N, Yu H, Mercer J, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell sirtuin 1 protects against DNA damage and inhibits atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2013;127(3):386–96. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.112.124404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Wells AT, Bossardi Ramos R, Shen MM, Binrouf RH, Swinegar AE, Lennartz MR. Identification of myeloid protein kinase C epsilon as a novel atheroprotective gene. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2025;45(9):e392–411. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.125.323005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Hu X, Ma R, Fu W, Zhang C, Du X. LncRNA UCA1 sponges miR-206 to exacerbate oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by ox-LDL in human macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(8):14154–60. doi:10.1002/jcp.28109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Wang L, Xia JW, Ke ZP, Zhang BH. Blockade of NEAT1 represses inflammation response and lipid uptake via modulating miR-342-3p in human macrophages THP-1 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(4):5319–26. doi:10.1002/jcp.27340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Chen DD, Hui LL, Zhang XC, Chang Q. NEAT1 contributes to ox-LDL-induced inflammation and oxidative stress in macrophages through inhibiting miR-128. J Cell Biochem. 2018;120(2):2493–501. doi:10.1002/jcb.27541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Liu J, Huang GQ, Ke ZP. Silence of long intergenic noncoding RNA HOTAIR ameliorates oxidative stress and inflammation response in ox-LDL-treated human macrophages by upregulating miR-330-5p. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(4):5134–42. doi:10.1002/jcp.27317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Ye J, Wang C, Wang D, Yuan H. LncRBA GSA5, up-regulated by ox-LDL, aggravates inflammatory response and MMP expression in THP-1 macrophages by acting like a sponge for miR-221. Exp Cell Res. 2018;369(2):348–55. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.05.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Zhang Y, Lu X, Yang M, Shangguan J, Yin Y. GAS5 knockdown suppresses inflammation and oxidative stress induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein in macrophages by sponging miR-135a. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476(2):949–57. doi:10.1007/s11010-020-03962-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Tang X, Yin R, Shi H, Wang X, Shen D, Wang X, et al. LncRNA ZFAS1 confers inflammatory responses and reduces cholesterol efflux in atherosclerosis through regulating miR-654-3p-ADAM10/RAB22A axis. Int J Cardiol. 2020;315:72–80. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Ohayon L, Zhang X, Dutta P. The role of extracellular vesicles in regulating local and systemic inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Res. 2021;170(7):105692. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Takahashi Y, Takakura Y. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: extracellular vesicles as therapeutic targets and agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;242:108352. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Zhang Y, Zhang W, Wu Z, Chen Y. Diversity of extracellular vesicle sources in atherosclerosis: role and therapeutic application. Angiogenesis. 2025;28(3):34. doi:10.1007/s10456-025-09983-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Li J, Wen T, Li X, Cheng R, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Harnessing extracellular vesicles to tame inflammation: a new strategy for atherosclerosis therapy. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1625958. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1625958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Alidadi M, Hjazi A, Ahmad I, Mahmoudi R, Sarrafha M, Reza Hosseini-Fard S, et al. Exosomal non-coding RNAs: emerging therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;212:115572. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Zhang Z, Zou Y, Song C, Cao K, Cai K, Chen S, et al. Advances in the study of exosomes in cardiovascular diseases. J Adv Res. 2024;66:133–53. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2023.12.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Wehbe Z, Wehbe M, Al Khatib A, Dakroub AH, Pintus G, Kobeissy F, et al. Emerging understandings of the role of exosomes in atherosclerosis. J Cell Physiol. 2025;240(1):e31454. doi:10.1002/jcp.31454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Lin W, Huang F, Yuan Y, Li Q, Lin Z, Zhu W, et al. Endothelial exosomes work as a functional mediator to activate macrophages. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1169471. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1169471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Xu F, Zhong JY, Lin X, Shan SK, Guo B, Zheng MH, et al. Melatonin alleviates vascular calcification and ageing through exosomal miR-204/miR-211 cluster in a paracrine manner. J Pineal Res. 2020;68(3):e12631. doi:10.1111/jpi.12631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Chen C, Li Y, Lu H, Liu K, Jiang W, Zhang Z, et al. Curcumin attenuates vascular calcification via the exosomal miR-92b-3p/KLF4 axis. Exp Biol Med. 2022;247(16):1420–32. doi:10.1177/15353702221095456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Ren L, Chen S, Liu W. OxLDL-stimulated macrophages transmit exosomal microRNA-320b to aggravate viability, invasion, and phenotype switching via regulating PPARGC1A-mediated MEK/ERK pathway in proatherogenic vascular smooth muscle cells. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2024;262(1):13–22. doi:10.1620/tjem.2023.J082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Wang S, Lv Y, Wang X, Zhang Z, Li J, Pan TI, et al. MiR-7683-3p from M2-exosomes attenuated atherosclerosis by activating the PPARγ-LXRα-ABCG1 pathway mediated cholesterol efflux of vascular smooth muscle cell derived foam cells. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23(1):618. doi:10.1186/s12951-025-03690-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Zhang N, Luo Y, Zhang H, Zhang F, Gao X, Shao J. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice via FENDRR. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2022;22(6):528–44. doi:10.1007/s12012-022-09736-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Brandes F, Meidert AS, Kirchner B, Yu M, Gebhardt S, Steinlein OK, et al. Identification of microRNA biomarkers simultaneously expressed in circulating extracellular vesicles and atherosclerotic plaques. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1307832. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2024.1307832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Xiao D, Chen G, Ming Z, Jin D, Zhang Y, Zhang GJ. Spherical nucleic acids-based nanomachines enable in situ tracing of exosomal lncRNA at the single-vesicle level. Biosens Bioelectron. 2025;289:117852. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2025.117852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Wang M, Chen Y, Xu B, Zhu X, Mou J, Xie J, et al. Recent advances in the roles of extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular diseases: pathophysiological mechanisms, biomarkers, and cell-free therapeutic strategy. Mol Med. 2025;31(1):169. doi:10.1186/s10020-025-01200-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Hu N, Zeng X, Tang F, Xiong S. Exosomal long non-coding RNA LIPCAR derived from oxLDL-treated THP-1 cells regulates the proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;575:65–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.08.053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Ren Y, Liang J, Chen B, Liu X, Chen J, Liu X, et al. LncRNA AC100865.1 regulates macrophage adhesion and ox-LDL intake through miR-7/GDF5 pathway. Cell Signal. 2025;131:111748. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2025.111748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Wen Z, Zhang W, Wu W. The latest applications of exosome-mediated drug delivery in anticancer therapies. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2025;249(1):114500. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2025.114500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Dabravolski SA, Popov MA, Utkina AS, Babayeva GA, Maksaeva AO, Sukhorukov VN, et al. Preclinical and mechanistic perspectives on adipose-derived stem cells for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease treatment. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;480(8):4647–70. doi:10.1007/s11010-025-05285-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Lee CS, Fan J, Hwang HS, Kim S, Chen C, Kang M, et al. Bone-targeting exosome mimetics engineered by bioorthogonal surface functionalization for bone tissue engineering. Nano Lett. 2023;23(4):1202–10. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c04159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Vogt S, Bobbili MR, Stadlmayr G, Stadlbauer K, Kjems J, Rüker F, et al. An engineered CD81-based combinatorial library for selecting recombinant binders to cell surface proteins: laminin binding CD81 enhances cellular uptake of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10(11):e12139. doi:10.1002/jev2.12139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Fei Z, Zheng J, Zheng X, Ren H, Liu G. Engineering extracellular vesicles for diagnosis and therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2024;45(10):931–40. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2024.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Fu P, Guo Y, Luo Y, Mak M, Zhang J, Xu W, et al. Visualization of microRNA therapy in cancers delivered by small extracellular vesicles. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):457. doi:10.1186/s12951-023-02187-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools