Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity: STAT3 Interactions with NF-κB Dimer Composition Modulate Mitochondrial Melatonergic Pathway: Tumor, and Viral Infection Treatment Implications#

CRC Scotland & London, Eccleston Square, London, SW1V 1PG, UK

* Corresponding Author: George Anderson. Email:

# This article has been published a preprint:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.073221

Received 13 September 2025; Accepted 14 November 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

As natural killer (NK) cells eliminate cancer cells and virus-infected cells, as well as modulate various other medical conditions, including aging-associated conditions such as neurodegenerative disorders, understanding NK cell regulation is of considerable clinical importance. This article reviews the role of circadian processes (melatonin and the cortisol system), aryl hydrocarbon receptor, and vagal nerve in the modulation of NK cell function, highlighting the importance of the endogenous mitochondrial melatonergic pathway in NK cells. As circadian and exogenous melatonin increase NK cell cytotoxicity, the presence of the endogenous melatonergic pathway may be of some importance not only to NK function and immune checkpoint regulation but also from the efflux of melatonin, which decreases tumor cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis, as well as decreasing immune checkpoint ligands, such as programmed cell ligand 1 (PD-L1). NK cell melatonergic pathway regulation may therefore have significant impacts not only on NK cell cytotoxicity but also on the intercellular interactions within tumors and other pathological microenvironments. As melatonin has anti-viral effects, the regulation of the NK cell melatonergic pathway can have wider impacts on how NK cells regulate viral infections, including in the course of viral-induced susceptibility to neurodegenerative conditions. Recent data indicate that the endogenous melatonergic pathway is regulated by interactions of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) dimer composition. As both STAT3 and NF-κB dimer composition modulate NK cells, their interaction in the modulation of the NK cell melatonergic pathway will be important to determine. This has significant future research and treatment implications, including improving the clinical efficacy of current treatment approaches such as immune checkpoint inhibition and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) NK cell therapy, and may accelerate a means of preventing cancer.Keywords

The capacity of natural killer (NK) cells to kill emerging tumors has long been appreciated [1], although it is still widely recognized that their potential has yet to be fully developed [2]. Tumors have developed mechanisms and responses to inhibit NK cells and CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment, primarily by increasing the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine by the induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and the kynurenine efflux that activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) on NK cells and CD8+ T cells to induce a state of ‘exhaustion’. This state of ‘exhaustion’ is characterized by a failure to upregulate glycolysis and associated upregulation of the expression of immune checkpoints, such as programmed cell death (PD)-1 [3]. The processes driving such a change in NK phenotype still await clarification but involve the suppressed capacity to upregulate energy from glycolysis and, therefore, the enhanced energy availability required for NK cells to have an effective cytotoxic capacity, especially in the prevention of tumor initiation [4].

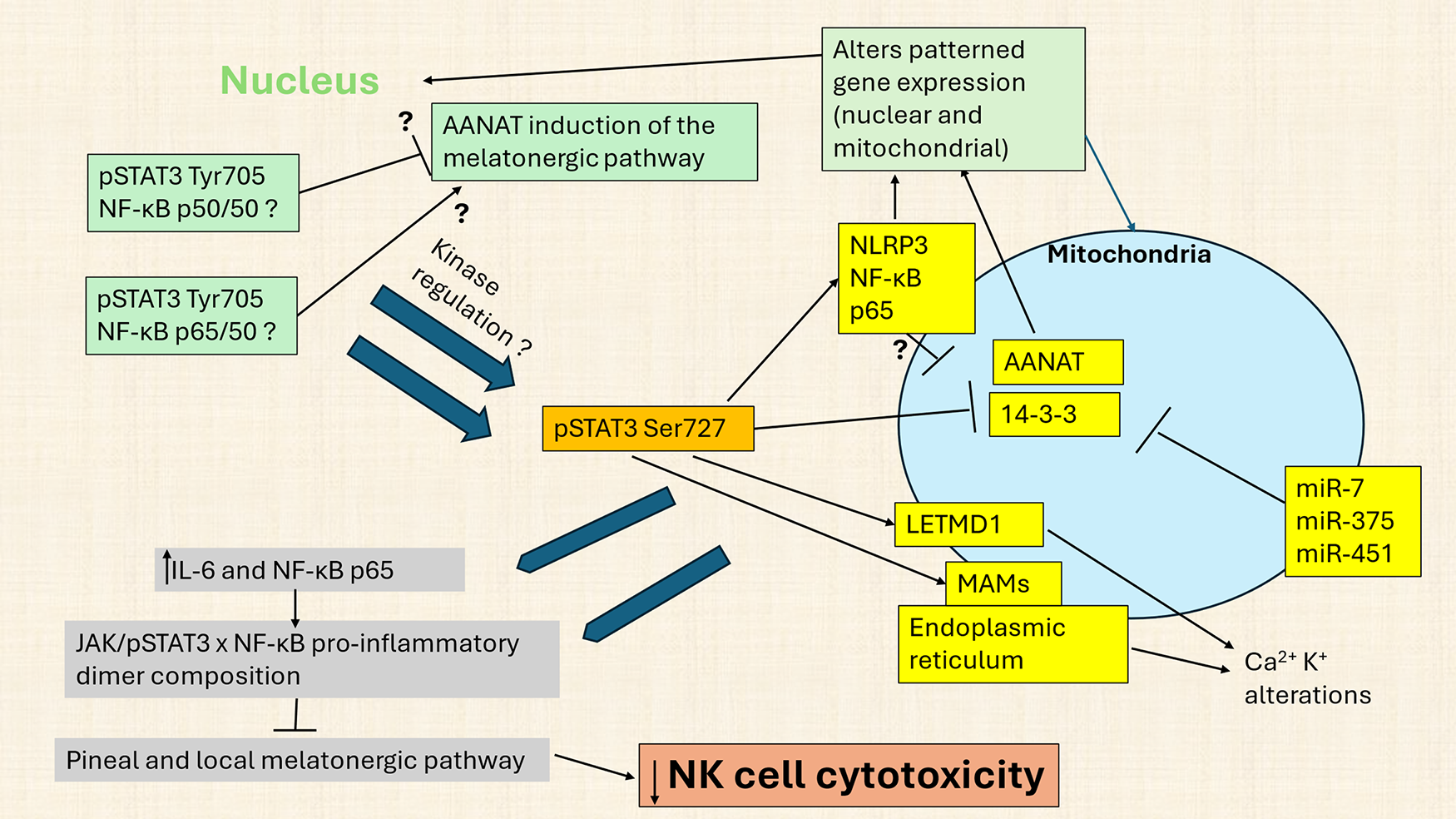

Numerous factors have been linked to alterations in NK cell function, including signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 [5] and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) dimer composition [6]. STAT3 is activated by phosphorylation at Tyrosine 705 (canonical and nuclear translocated) and Serine 727 (non-canonical and mitochondria translocated), with highly distinct consequences [7]. STAT3Tyr705 interacts with NF-κB dimer composition to either suppress or activate the melatonergic pathway, which is dependent upon an NF-κB dimer composition that varies across different cell types [8]. The melatonergic pathway upregulation/downregulation may occur in the nucleus and/or in mitochondria. Nuclear STAT3 interactions with NF-κB may therefore directly regulate the nuclear melatonergic pathway genes or may regulate the kinases that lead to mitochondrial translocation of STAT3Ser727. STAT3Ser727 binds to 14-3-3 and limits 14-3-3 mitochondria availability and therefore the 14-3-3 stabilization of Aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT) in the initiation of the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway [9]. STAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition are therefore a powerful determinant of melatonergic pathway induction or suppression. See Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B (NF-κB) dimer composition interacts with signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) to modulate the melatonergic pathway and NK cell cytotoxicity. Abbreviations: AANAT: aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase; IL: interleukin; JAK: Janus kinase; LETM1: Leucine Zipper EF-hand containing Transmembrane protein 1; LETMD1: LETM1 domain-containing protein 1; MAMs: mitochondria-associated membranes; miR: micro RNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NLRP3: nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich–containing family, pyrin domain–containing-3; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus

Fig. 1 shows how canonical, nuclear translocating pSTAT3Tyr705 interacts with nuclear NF-κB dimer composition to upregulate or downregulate the melatonergic pathway, with NF-κB dimer components cell cell-specific. The melatonergic pathway may be induced in the nucleus, although it is more likely to be present in mitochondria, where over 98% of pinealocyte melatonin is produced [10]. Nuclear (green shade) translocated STAT3Tyr705 interacts with NF-κB dimer components (such as p65/50 and p50/p50) to stimulate or inhibit the melatonergic pathway, with specific effects partly dependent upon cell type [8]. Nuclear STAT3Tyr705 interactions with NF-κB dimer components may also modulate non-canonical, mitochondria translocating pSTAT3Ser727, including alterations in specific kinases that phosphorylate and activate pSTAT3Ser727. Across different cell types, mitochondrial pSTAT3Ser727 regulates many core aspects of mitochondrial function, including: 1) mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), which powerfully determine endoplasmic reticulum-derived Ca2+ influx into mitochondria, a key driver of alterations in mitochondrial function; 2) pSTAT3Ser727 binds and attenuates mitochondrial 14-3-3 availability. 14-3-3 is necessary to stabilize AANAT and, therefore, crucial to the initiation of the melatonergic pathway. Consequently, attenuation of 14-3-3 availability, including by miR-7, miR-375 and miR-451, suppresses the melatonergic pathway; 3) In some cells, mitochondrial pSTAT3Ser727 can form a positive reciprocal feedback loop with LETM1 domain-containing protein 1 (LETMD1), thereby regulating mitochondrial Ca2+ and K+ flux, with most data derived from brown adipocytes; and 4) Mitochondrial translocation of pSTAT3Ser727 enhances the mitochondrial translocation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, NF-κB and p65 with consequences for patterned gene expression in both the nucleus and mitochondria. As LETM1/LETMD1 has a 14-3-3-like matrix motif [11], LETM1/LETMD1 may bind AANAT and/or form a ‘dimer’ complex with 14-3-3, being another possible route for STAT3Ser727 to modulate AANAT stabilization via 14-3-3 availability. These pro-inflammatory processes in a given cell will have consequences for immediately adjacent cells of the local microenvironment, via increased interleukin (IL)-6 and NLRP3 inflammasome-induced IL-1β and IL-18 release, driving inflammatory processes in neighboring cells, including via released IL-6 activating JAK/pSTAT3/NF-κB to stimulate or suppress the melatonergic pathway in cells of the local microenvironment. The specifics of pSTAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition in NK cells over the course of aging and aging-accelerating conditions, such as T2DM, will be important to determine.

STAT3 and NF-κB dimer composition are significant aspects of NK cell cytotoxicity regulation. STAT3 can enhance or suppress NK cell cytotoxicity, with variability proposed to be mediated by host cell-specific factors [5]. As NF-κB dimer composition also regulates NK cell cytotoxicity, with the NF-κB component, c-Rel, increasing perforin and granzyme B expression to enhance NK cell cytotoxicity [6], this would indicate an interaction of STAT3 with NF-κB that may modulate the endogenous melatonergic pathway in NK cells, as shown in several other cell types [8]. In macrophages, the shift from a pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype is driven by NF-κB c-Rel increasing melatonin production and efflux to have autocrine effects that shift macrophages to an M2-like phenotype [12]. Exogenous melatonin has long been appreciated to increase NK cell cytotoxicity [13], partly mediated by JAK3/STAT5 activation that increases T-bet [14]. This would indicate the possible role of STAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition in the modulation of NK cell function by regulating the NK cell endogenous melatonergic pathway.

NK cell cytotoxicity varies over the circadian rhythm [15] and aging [16]. This would indicate a role for aging-linked variations in pineal melatonin and its interaction with the rise in cortisol in the second half of sleep in the modulation of NK cell function [17]. As aging is associated with a dramatic 10-fold decrease in pineal melatonin between adolescence and the 9th decade of life [18], the suppressed availability of pineal melatonin at night will regulate both STAT3 and NF-κB, as well as the numerous kinases that can phosphorylate canonical and non-canonical STAT3 [19,20]. Melatonin generally suppresses STAT3 phosphorylation [19], indicating that the loss of pineal melatonin over aging may be intimately linked to alterations in the regulation of the melatonergic pathway across body cells, including NK cells. The loss of pineal melatonin can also disinhibit the effects of the wider cortisol system [21], including in the regulation of NK cell NF-κB and IL-6-induced JAK/STAT3 [22]. Such data indicate that the changes in night-time dampening and resetting over the course of aging will modulate NK cells to influence their function and cytotoxic capacity.

This article reviews the data about NK cell regulation and cytotoxicity, indicating a significant role for STAT3 and NF-κB dimer composition interaction in the capacity of NK cells to kill tumors and virus-infected cells. It is proposed that aging and aging-accelerating conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), will modulate the night-time circadian priming of NK cells, as well as having direct effects on NK cells that modulate their cytotoxic capacity and therefore the increased emergence of tumors over the course of aging.

The changes in night-time dampening and resetting over aging are reviewed next.

2 Circadian Changes in Night-Time Dampening and Resetting over Aging

The loss of pineal melatonin over aging and aging-associated conditions disinhibits the glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-α, thereby changing how body cells, including immune cells, are dampened and reset at night, with consequences for a host of diverse, aging-linked medical conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases [23] and cancer [24]. This is also relevant to processes proposed to accelerate aging, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [25], where pineal melatonin may be suppressed via an increased gut permeability and the rise in circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that activates toll-like receptor (TLR)4 on pineal microglia to increase tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α to suppress pineal melatonin [26]. As pineal melatonin suppresses gut permeability and associated gut dysbiosis [27], the loss of pineal melatonin over aging will have wider systemic effects, including via the suppression of the gut microbiome short-chain fatty acid, butyrate, which, like melatonin, suppresses cytoplasmic GR-α nuclear translocation [28] and optimizes mitochondrial function systemically [29]. Pineal melatonin suppression may therefore be linked to wider systemic changes that further disinhibit GR-α, leading to alterations in the wider cortisol system, including an enhanced GR-β/GR-α ratio, and GR localization site, which can be cytoplasm, plasma membrane, mitochondrial membrane, and/or mitochondrial matrix. The GR-β and GR-α are present in NK cells as in other circulating leukocytes [30], with the raised pro-inflammatory cytokines evident in cancer and viral infection enhancing the GR-β/GR-α ratio. An increased GR-β/GR-α ratio, significantly more evident in males, suppresses the capacity of cortisol and corticosteroids to dampen inflammatory activity [31], mediated, at least in part, by GR-β attenuating the capacity of GR-α to suppress NF-κB [32]. It requires investigation whether an increase in GR-β/GR-α ratio modulates the specific NF-κB dimer composition and therefore whether the melatonergic pathway is up- or down-regulated.

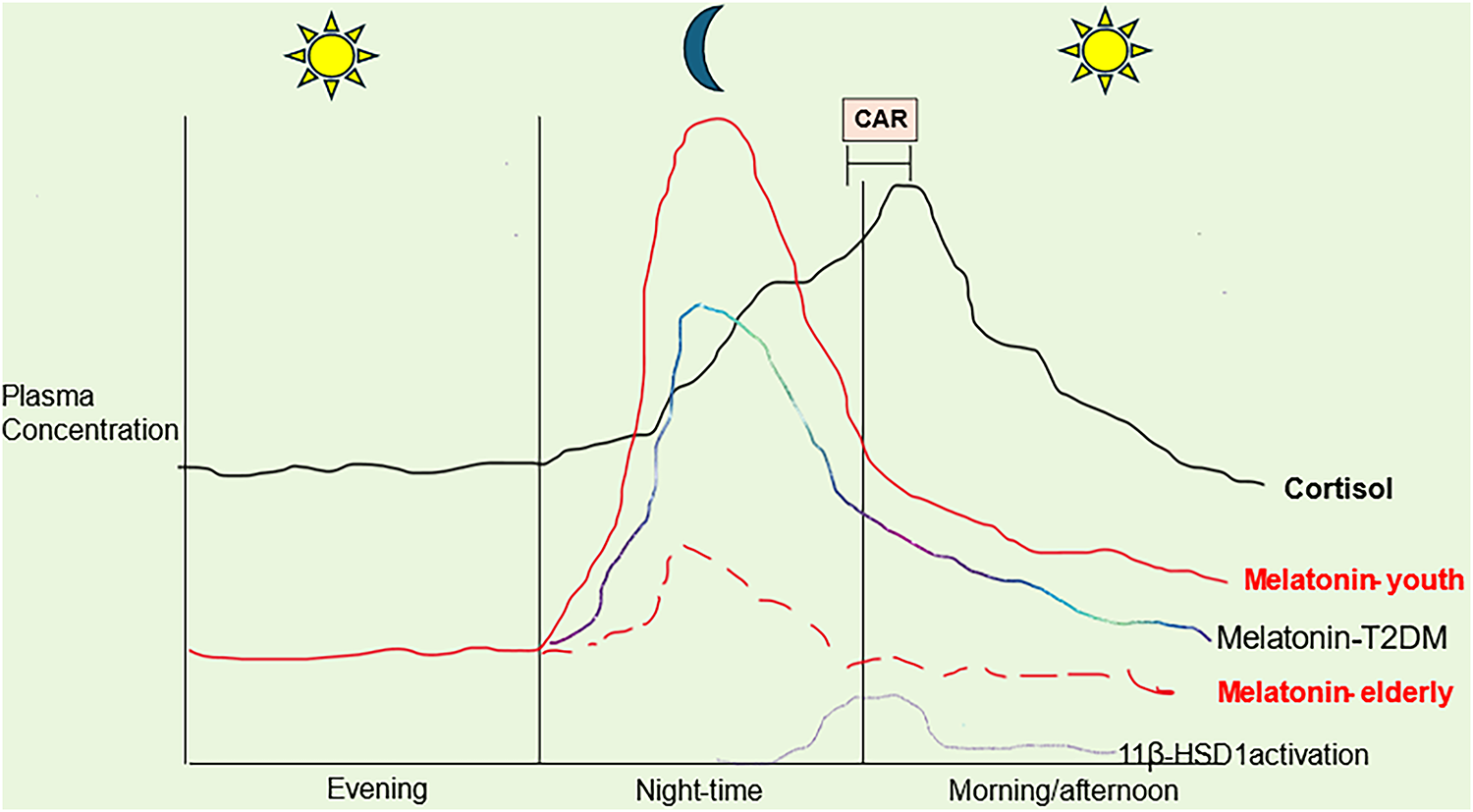

The suppression of pineal melatonin and gut butyrate may therefore have diverse effects as a consequence of changes in GR activation, subtype, and localization site. This may be further confounded by enhanced cortisol and local pro-inflammatory cytokine induction of local cortisol production by 11 beta 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD)1 [33–35], as commonly occurs in many types of cancer, with increased 11β-HSD1 in cells neighboring NK cells suppressing NK cell cytotoxicity [36]. Night-time changes in pineal melatonin and cortisol over the course of aging and aging-accelerating conditions are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Circadian melatonin and cortisol changes over aging and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Abbreviations: 11β-HSD1: 11 beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; CAR: cortisol awakening response; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus

Fig. 2 shows how pineal melatonin can dramatically decrease over aging, whilst T2DM suppresses pineal melatonin to accelerate aging-associated changes. Over aging, nighttime and morning CAR cortisol levels remain similar. Importantly, suppressed melatonin interacts with cortisol effects. This can happen by several means, including melatonin’s suppression of adrenal cortex cortisol production as well as the suppression of the nuclear translocation of the cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-α, via which most of cortisol’s effects have been investigated. The suppression of pineal melatonin over aging and T2DM may therefore act to disinhibit the influence of cortisol on how body cells and systems, including NK cells, are prepared for the coming day. Heightened GR-α activation (as to pro-inflammatory cytokines) increases 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (11β-HSD1) and local cortisol production. Heightened GR-α leads to a negative feedback including GR-β induction, that attenuates GR-α activation as well as having GR-β independent effects on transcription, whilst inhibiting the capacity of GR-α to suppress NF-κB. How aging/T2DM suppressed melatonin modulates the GR localization site (cytoplasm, plasma membrane, mitochondrial membrane, or mitochondrial matrix) is unknown, but is likely to add another layer of complexity to the changes occurring in the course of dampening and resetting at night over aging and aging-accelerating conditions. Other factors decreased over aging and T2DM, including gut microbiome-derived butyrate and Bcl2-associated athanogene (BAG)1, also prevent GR-α nuclear translocation but are not included for clarity [17].

The changes in pineal melatonin and the cortisol system have implications for the regulation of all body cells, including NK cells. Melatonin can upregulate or downregulate canonical and non-canonical STAT3 [37] as well as modulate NF-κB dimer composition [38], indicating that pineal melatonin may regulate the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway by several means that may be dependent on the specific cell and circumstances. In contrast to the stimulatory effects of melatonin on NK cell function and cytotoxicity, cortisol via the GR-α suppresses NK cell cytotoxicity and can epigenetically increase NK levels and efflux of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 [22,39], a major inducer of the JAK/STAT3 pathway. Heightened night-time cortisol/melatonin ratio will therefore suppress NK cell function, which is a significant contributor to the accumulation of senescent cells, given that NK cells are important to the immunosurveillance of senescent cells [40] as well as emerging tumor cells. Consequently, the aging-linked changes in circadian night-time dampening and resetting will have consequences for wider aspects of NK cell function, including potentiating the aging-linked increase in ‘inflammaging’.

3 Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Kynurenine Pathway

Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) on NK cells by tumor-derived kynurenine is a major target for tumor cells and viral infections, as it can induce a state of ‘exhaustion’ in NK cells [41,42], although AhR effects on NK cell cytotoxicity are complex and variable [43]. The tumor achieves NK ‘exhaustion’ by pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and 11β-HSD1-derived cortisol activation of the GR-α to induce tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO). IDO and TDO convert tryptophan to kynurenine, which is released by tumors and virus-infected cells to suppress NK cells via AhR activation [41,42,44]. The AhR is normally expressed in the cytosol and, upon activation, translocates to the nucleus where it regulates a diverse array of genes, including those with a xenobiotic response element. The AhR is also expressed on the mitochondrial membrane, where limited data in other cells indicate its regulation of the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC)1 and, therefore mitochondrial Ca2+ flux [45].

AhR activation also modulates the melatonergic pathway via the upregulation of cytochrome P450 (CYP)1B1 and CYP1A2 that can hydroxylate melatonin and/or O-demethylate melatonin to its precursor, N-acetylmelatonin (NAS), thereby suppressing melatonin levels and availability [46]. The O-demethylation of melatonin to NAS may be especially problematic in cancer, given that NAS is a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mimic via the activation of the BDNF receptor, tyrosine receptor kinase (Trk)B [47]. Should NAS be released by NK cells and CD8+ T cells in the course of AhR activation-induced ‘exhaustion’, NK cells and CD8+ T cells may not only be inhibited from killing cancer cells but may also provide trophic support via NAS activation of TrkB, perhaps especially on cancer stem-like cells, where TrkB activation increases proliferation and survival [48]. Consequently, the role of the AhR in NK cells may be considerably more complex than typically modelled should the melatonergic pathway be present in NK cells, as seems highly likely.

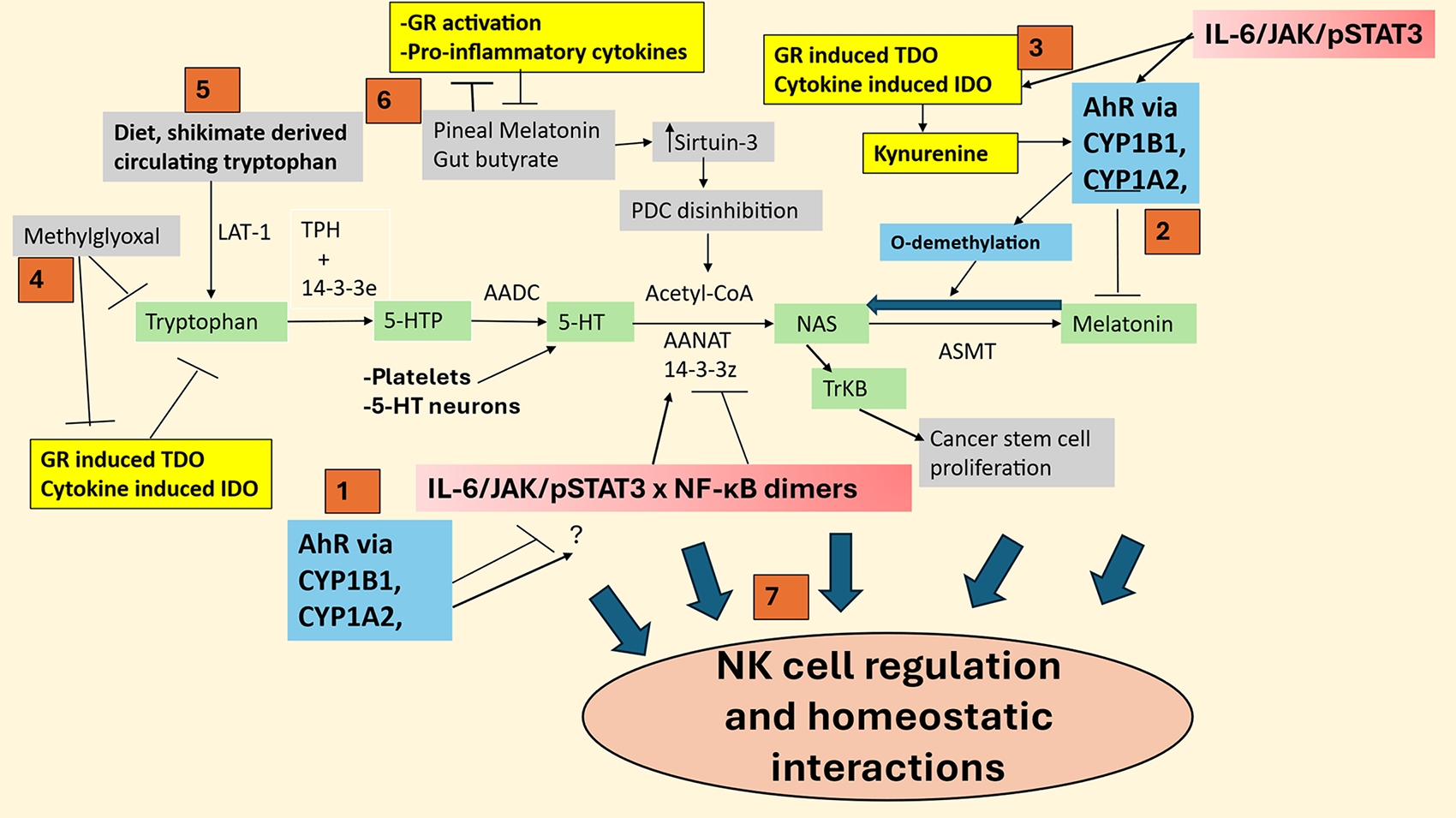

The role of the AhR in NK cell regulation is further complicated by AhR modulation of both STAT3 and NF-κB, as shown across diverse cell types. The AhR is in intimate crosstalk with NF-κB, including the NF-κB components, p65 and RelB [49–51], which increases IL-22 to potentiate tumor cell survival and proliferation [52]. AhR activation can increase NF-κB-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, which is a major inducer of the JAK/STAT3 pathway [53]. The AhR can also directly modulate NF-κB activation, whilst AhR activation can also modulate STAT3, indicating complex interactions [54]. The AhR can therefore have complex effects on STAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition and consequently on the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway. This may be congruous with AhR activation on NK cells suppressing the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway, including via nuclear STAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition and/or STAT3Ser727 mitochondrial translocation, thereby contributing to NK cell ‘exhaustion’. This requires experimental investigation, with incorporation of the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway likely to contribute to a fuller understanding of the invariably ‘complex’ effects of the AhR. How the AhR may interact with other regulators of the melatonergic pathway in the modulation of NK cell function is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Shows how the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (blue) and other natural killer (NK) regulators, such as methylglyoxal and cortisol/GR activation, may act on the tryptophan-melatonin pathway (green shade) to modulate NK cell function and interactions with other microenvironment cells. Abbreviations: 5-HT: serotonin; 5-HTP: 5-hydroxytryptophan; AADC: aromatic-L-amino acid decarboxylase; AANAT: aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase; AhR: aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ASMT: acetylserotonin methyltransferase; CYP: cytochrome P450; GR: glucocorticoid receptor; IDO: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; JAK: Janus kinase; LAT-1: large amino acid transporter 1; NAS: N-acetylserotonin; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NK: natural killer; PDC: pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; ROS: reactive oxygen species; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TDO: tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase; TPH: tryptophan hydroxylase; TrkB:: tyrosine receptor kinase B

Seven points in Fig. 3 (red numbered squares) highlight how factors regulating the tryptophan melatonin pathway modulate NK cells. (1) The AhR modulates both STAT3 and NF-κB dimer composition and, therefore, may be intimately associated with melatonergic pathway regulation, including by STAT3Ser727 suppression of 14-3-3 stabilization of AANAT. (2) AhR/CYP1B 1/CYP1A2 O-demethylates melatonin to NAS and also hydroxylates melatonin, to suppress melatonin availability/effects whilst increasing NAS, which, if released, can activate TrkB to increase tumor stem cell survival and proliferation, indicating that ‘exhausted’ NK cells may paradoxically be a source of trophic support for tumor cells. (3) AhR interactions with NF-κB can increase pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, which activate the JAK/STAT3 pathway to induce STAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition, whilst also increasing IDO and the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine to activate the AhR. (4) Hyperglycemia-derived methylglyoxal, via protein-protein interactions with tryptophan, not only suppresses tryptophan but also tryptophan-derived kynurenine pathway products that can activate the AhR, thereby changing the consequence of AhR activation. (5) Diet (and possibly the gut shikimate pathway) is crucial for tryptophan availability and, therefore, the tryptophan necessary for GR-induced TDO and cytokine-induced IDO to convert tryptophan to kynurenine. (6) Pineal melatonin and gut microbiome-derived butyrate have reciprocated negative interactions with pro-inflammatory cytokines and GR activation, with pineal melatonin and gut butyrate also increasing sirtuin-3, which disinhibits the PDC to increase mitochondrial acetyl-CoA for the conversion of serotonin to NAS in the initiation of the melatonergic pathway. (7) Factors acting to regulate the tryptophan-melatonin pathway are closely associated with alterations in NK function and NK cell interactions with local microenvironment cells and, therefore, in homeostatic intercellular interactions.

4 Vagal Nerve, Melatonergic Pathway, and NK Cells

As highlighted in Fig. 2, attenuated pineal melatonin can have significant impacts on cellular and systemic processes over aging and aging-accelerating conditions such as T2DM. As well as the loss of melatonin’s direct antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and mitochondria-optimizing effects, this has a number of implications for wider dampening processes, including vagal nerve activation, which may be induced by melatonin both directly and via melatonin’s induction of oxytocin [55–57]. The suppression of pineal melatonin and gut microbiome-derived butyrate’s inhibition of the GR-α enhances cortisol activation of the GR-α, which can have complex effects on vagal nerve function, including its suppression [58]. However, this may be confounded by the disinhibited cortisol effects at the GR-α and GR-β as well as the GR localization site (cytoplasm, plasma membrane, mitochondrial membrane, and/or mitochondrial matrix), with diverse effects that are dependent on GR subtype and site. Raised cortisol effects, like heightened levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, induce local production via 11β-HSD1 [33–35]. As such, many of the differential effects of cortisol may occur in the absence of any prolonged rise in cortisol levels per se that are significantly regulated by suppressed pineal melatonin and gut butyrate, culminating in alterations in vagal nerve-induced dampening and resetting, including at night.

The dampening effects of the vagal nerve over the circadian rhythm are driven by acetylcholine (ACh) release that activates ACh receptors, especially the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR). The α7nAChR generally suppresses immune cell activation, partly mediated by the upregulation of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) [59] that are proposed to drive a shift in NF-κB dimer component composition, either directly or via IL-10 [60], leading to an NF-κB dimer that interacts with nuclear pSTAT3 to upregulate the melatonergic pathway [8,9]. Vagal nerve activation increases IL-10 production in macrophages [61], via the induction, release, and autocrine effects of local melatonin [62], with released IL-10 increasing NK cell cytotoxicity [63], possibly via STAT3 interactions with NF-κB, inducing the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway, as in other cell types [8]. Pineal melatonin also increases α7nAChR [64], being another aspect of how suppression of pineal melatonin attenuates systemic dampening by the vagal nerve in the course of inflammation resolution.

The vagal nerve also modulates NK cell function, with vagotomy decreasing NK cell numbers [65]. Data indicate that vagal nerve stimulation decreases transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and macrophage polarization, thereby indirectly, and perhaps more directly, increasing NK cell cytotoxicity [65,66]. Vagal nerve activation also increases CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity [67], indicating wider benefits of vagal stimulation in the tumor microenvironment [66]. A recent meta-analysis shows that suppressed vagal nerve activation is associated with decreased overall survival in cancer patients [68], whilst vagal nerve stimulation is proposed to have benefits in tumor management, including glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) via IL-6 downregulation [69]. The vagal suppression of IL-6 has numerous consequences, including the attenuation of the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway and the interface of STAT3 with NF-κB dimer composition in the modulation of the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway [70]. The vagal nerve is therefore an important contributor to anti-inflammatory processes, including in the course of night-time dampening and resetting, and thereby intimately linked to the regulation of pineal and local melatonin [70]. This links to data showing tumors to emerge from alterations in night-time processes, including the aging-associated decrements in pineal melatonin production [71].

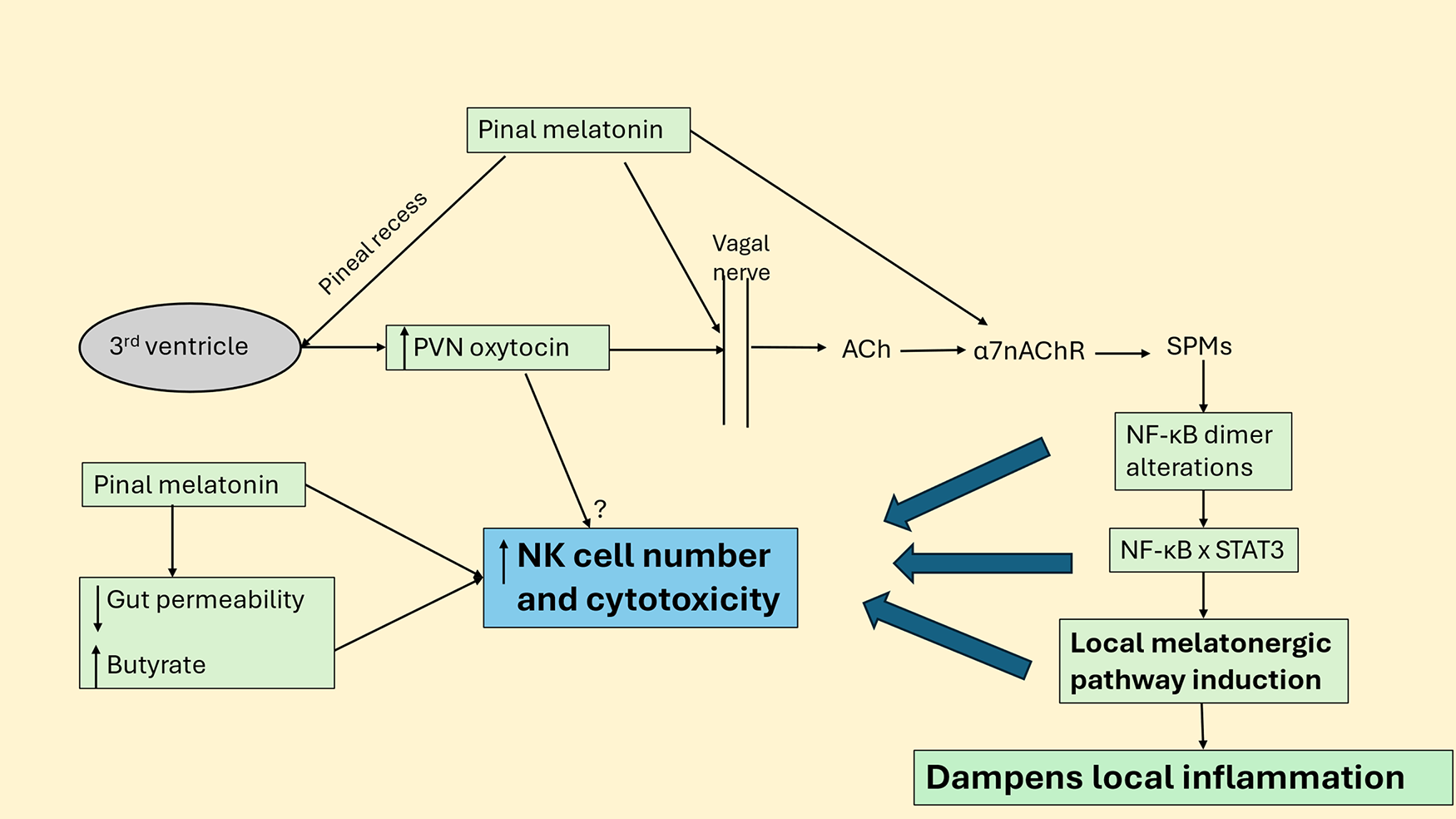

Pineal melatonin, via the pineal recess and third ventricle [72], as well as exogenous melatonin induces oxytocin, which not only activates the vagal nerve [55–57,73] but may also directly modulate NK cells via the robust regulation of C-type lectin-like receptors (CTLRs) in the NK gene complex, which significantly modulates NK cell function, as do CTLRs in other immune cells [74]. How pineal melatonin, including via oxytocin, regulates the vagal nerve to alter inflammatory activity is shown in Fig. 4. Importantly, in contrast to the anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin/oxytocin/vagal nerve stimulation across most immune cells, melatonin/oxytocin/vagal nerve stimulation enhances NK cell numbers and cytotoxicity. As the anti-inflammatory effects of vagal nerve stimulation require the upregulation of local melatonin production at the site of inflammation, mediated by melatonin/oxytocin/vagal ACh/α7nAChR/SPMs/NF-κB dimer composition interactions with sSTAT3, the local regulation of the melatonergic pathway will determine vagal nerve effects [75]. Whether the NK activating effects of melatonin/oxytocin/vagal nerve stimulation are similarly dependent upon the induction of the melatonergic pathway in NK cells will be important to determine.

Figure 4: Pineal melatonin, oxytocin, vagal nerve, local melatonin, and gut dysbiosis/permeability modulate NK cells. Abbreviations: α7nAChR: alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; PVN: Paraventricular Nucleus; SPMs: specialized proresolving mediator; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

Fig. 4 shows how pineal melatonin directly and especially via increasing PVN oxytocin activates the vagal nerve, which releases acetylcholine (ACh) onto several ACh receptors, including the α7nAChR. Activation of α7nAChR generally dampens immune-inflammatory activity, mediated by upregulating specialized proresolving mediators (SPMs) that change the NF-kB dimer composition, allowing NF-kB to interact with nuclear STAT3 to upregulate the melatonergic pathway, which drives inflammation resolution. This would be one mechanism whereby vagal nerve activation increases NK cell number and cytotoxicity, the latter primarily driven by local melatonin, as with pineal melatonin over the circadian rhythm. As pineal melatonin increases the α7nAChR [64], this may be another route whereby suppressed pineal melatonin modulates wider processes of dampening and resetting, including by the vagal nerve and its modulation of NK cells. Pineal and vagal nerve-driven local melatonin [75] also helps maintain the integrity of the gut barrier, leading to decreased gut dysbiosis and circulating lipopolysaccharide, whilst increasing gut microbiome-derived butyrate that enhances NK cell cytotoxicity.

This has a number of future research and treatment implications.

5 Future Research Implications

Is the melatonergic pathway evident in NK cells? If so, is it regulated by the interactions of canonical and non-canonical STAT3 with NF-κB dimer composition to modulate the NK cell tryptophan-melatonin pathway? If the melatonergic pathway is evident in NK cells, do the effects of NAS and melatonin have intracrine and/or intramitochondrial effects, or are NAS and/or melatonin effluxed to have autocrine and paracrine effects, as occurs in macrophages and microglia [62,76].

Are the generally stimulating effects of IL-10 on NK cell cytotoxicity via increased OXPHOS and glycolysis [63] mediated by alterations in canonical and noncanonical STAT3 interactions with the NF-κB dimer composition and therefore the induction of the NK cell mitochondrial melatonergic pathway, as evident in other cell types [8].

Are the NK activating effects of melatonin/oxytocin/vagal nerve stimulation dependent upon the induction of the melatonergic pathway in NK cells, paralleling vagal-induced local melatonin in the dampening of inflammatory processes in preclinical models [75]?

Is the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway evident in the vagal nerve? If so, would this be regulated by STAT3 interaction with NF-κB dimer composition? Does the regulation of the putative vagal melatonergic pathway modulate vagal function and therefore systemic dampening and resetting across body organs and tissues?

Does AhR activation on NK cells suppress the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway, including via nuclear STAT3Tyr705 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition and/or STAT3Ser727 mitochondrial translocation?

Does the tumor-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine induction of IDO and/or cortisol/GR-α induction of TDO increase kynurenine to activate the AhR/CYP1B1/CYP1A2 pathway, leading to an increased NAS/melatonin ratio, with any effluxed NAS from NK cells increasing the survival and proliferation of tumor cells [77]?

Quercetin shows some efficacy in enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity under conditions of NK cell activation in cancer [78]. As quercetin quenches methylglyoxal [79], does quercetin increase tryptophan availability in NK cells? Does quercetin suppress RAGE/STAT3 activation to upregulate the tryptophan-melatonin pathway availability? The naturally occurring 3-O-glucoside of quercetin, isoquercetin, inhibits STAT3 activation [80], indicating that quercetin and isoquercetin, via STAT3 modulation, may regulate the melatonergic pathway, including in NK cells. The impacts of quercetin and isoquercetin on STAT3 (canonical and non-canonical) interactions with NF-κB dimer components in NK cells will be important to determine in future research, with potential implications across a diverse range of aging-associated conditions.

NK cell cytotoxicity decreases over aging and is associated with a wide range of aging-linked conditions, including dementia, tumors, and susceptibility to severe viral infection [40]. Preclinical data show quercetin to increase the proportion and maturation of NK cells over aging, with consequent suppression of an array of diverse aging-linked conditions [81]. Is this particularly relevant in T2DM-driven accelerated aging via quercetin suppression of methylglyoxal to increase the tryptophan-melatonin pathway, including in NK cells? Does increased tryptophan-melatonin pathway availability [82] underpin the classical causal modelling of quercetin benefits in T1DM and T2DM, such as decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokine release, increasing glucose uptake, optimizing pancreatic β-cell function and insulin release, as well as inhibiting α-glucosidase and DPP-IV enzymes, thereby prolonging the half-life of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) [83]. The interface of quercetin with NK cell function may therefore provide a more refined understanding of NK cell function and regulation, and how this interfaces with the regulation of the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway.

Sleep deprivation decreases NK cell number and function, which is proposed to be mediated by decreased melatonin and raised cortisol levels that induce β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-AR) activation in NK cells [84]. Does sleep deprivation impact on NK cell melatonergic pathway regulation, possibly via the interactions of STAT3 and NF-κB dimer composition?

Is Bcl2-associated athanogene (BAG)-1 present in NK cells, and does it decrease over aging in these cells as occurs in many other cells [85]? Would BAG-1 suppress GR-α nuclear translocation and take the GR-α to the mitochondrial matrix, as shown in other cell types [86]? Is there a suppression of BAG-1 levels in NK cells over aging, leading to a compensatory increase in other BAGs, including BAG-6, which blocks NKp30 to suppress NK cell function [87]?

Is LETMD1 present in the mitochondria of NK cells? If so, does it form a positive feedback loop with pSTAT3Ser727 to modulate the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway?

Does an increased GR-β/GR-α ratio in NK cells modulate the specific NF-κB dimer composition as well as NF-κB levels [32], thereby regulating the NK melatonergic pathway?

People on the autistic spectrum (ASD) show suppressed NK cell activity [88,89]. Interestingly, ASD is strongly linked to suppressed melatonergic pathway induction across diverse systemic and CNS cells [90], which has been proposed to be driven by prenatal alterations in placental melatonin production coupled to an increased cortisol influence in prenatal and early post-natal crucial developmental windows [70]. There is some association of ASD with increased cancer risk [91] and death arising from severe SARS-CoV-2 infection during the COVID-19 pandemic [92]. Whether this is driven by suppressed melatonergic pathway availability in NK cells directly and/or via an increased type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presence in ASD [93] and therefore raised levels of methylglyoxal to suppress tryptophan availability for the tryptophan-melatonin pathway [94] and/or decreased melatonin/oxytocin/vagal nerve activation requires further investigation.

The presence and regulation of the melatonergic pathway in NK cells have significant implications for improving current treatment approaches for NK cell-associated conditions, including cancer and viral infections. A large and growing body of data indicates the clinical relevance of adjunctive melatonin in the treatment of cancer [95,96] and viral infections [97,98], which is typically modelled as driven by melatonin’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. However, melatonin can significantly modulate immune checkpoints, including via miR-138 [99] regulation and suppression of programmed cell death (PD)-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated molecule 4 (CTLA-4) [100,101], indicating that targeting the regulation of the NK melatonergic pathway may provide a less toxic way of inhibiting immune checkpoints. Any melatonin released by NK cells would also be expected to suppress PD-L1 in tumor cells, as shown in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [102], as well as having wider consequences in the tumor microenvironment.

There is a growing appreciation of the clinical utility of CAR NK cell therapy [103]. CAR attachment to NK cells enhances their capacity to recognize tumor cells, whilst decreasing potential side effects of CAR T cell therapy and overactive NK cells, such as cytokine release syndrome [103]. Improvements in CAR NK cell therapy are widely expected to make CAR NK cell therapy the major treatment of many cancers and in other NK-linked conditions [104,105]. Clearly, investigation of the presence and regulation of the NK cell melatonergic pathway will have significant impacts on NK cell function and potentially on the intercellular communication within the tumor microenvironment, including by the efflux of melatonin to suppress PD-L1 on cancer cells [102]. Investigation of the presence and regulation of the melatonergic pathway in NK cells may therefore have significant clinical implications. This may be of particular importance in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), where treatment outcomes are currently very poor [106]. Preclinical and in vitro studies indicate that CAR NK cell therapy is likely to have clinical efficacy in GBM treatment, including when combined with other currently available treatments, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors [107]. Investigation of the regulation of the NK cell melatonergic pathway should refine the nature of GBM treatment development, including the role, if any, of the astrocyte melatonergic pathway that was first shown to be present in 2007 [108]. Investigating and incorporating the pSTAT3/NF-κB/melatonergic pathway across GBM microenvironment cells will enhance physiological understanding and should drive the development of much-needed novel treatments.

Notably, NK cell cytotoxicity is powerfully determined by the circadian rhythm, with increased cytotoxicity occurring at night and in the early morning [109]. NK cell prevention of cancer pathogenesis is therefore an aspect of night-time dampening and resetting [110], with an aging-associated decrease in pineal melatonin and relatively disinhibited cortisol effects, attenuating the NK cell cytotoxicity efficacy in tumor elimination.

Quercetin and/or isoquercetin may have enhanced NK cell treatment benefits by upregulating the tryptophan-melatonin pathway, including via altering the interactions of STAT3 and NF-κB with distinct dimer components.

A ketogenic diet can increase NK levels, especially cytotoxic CD56dim, to enhance NK cell response without increasing CD69 expression [111]. In other cells, a ketogenic diet increases the local melatonergic pathway and melatonin receptors [112]. Whether a ketogenic diet, via STAT3 and NF-κB dimer interactions, upregulates the NK melatonergic pathway to enhance cytotoxic CD56dim NK cell effects will be important to determine. A ketogenic diet also increases the cytolytic capacity of CD8+ T cells [113], which is also potentiated by melatonin [114], possibly indicative of a similar importance of the endogenous melatonergic pathway in CD8+ T cells.

Nanoparticle- and exosome-encapsulated melatonin may be preferentially targeted to distinct cells, thereby increasing local concentration effects and coupled to a decrease in melatonin metabolism [95]. The mitochondria-targeting nanoparticle, Mito-Mel, has an effect that is 100-fold enhanced in comparison to free melatonin [115]. The refinement of such treatments will enhance the efficacy of melatonin in the modulation of NK cells and CD8+ T cells, as well as when utilized as an adjuvant to current pharmaceutical treatments. Future research on the regulation of the melatonergic pathway would be expected to further refine melatonin’s clinical utility, as well as identify ways to specifically, and perhaps dynamically, target the melatonergic pathway in NK cells and other cell types.

There is a growing appreciation of the role of NK cells across a range of diverse medical conditions, including subarachnoid hemorrhage [SAH] [116]. The relevance of the IL-6/STAT3/NF-κB pathway in modulating NK cell cytotoxicity in SAH is highlighted by data showing the importance of pSTAT3 inhibition in limiting the IL-6/STAT3 pathway driven inflammation in SAH [117] It will be important for future clinical research to investigate the roles of canonical and non-canonical pSTAT3 and their interactions with NF-κB dimer composition in modulating the NK cell melatonergic pathway and cytotoxicity. As SAH also impairs glymphatic system function in clinical studies [118] and the interrelated meningeal lymphatic system function in preclinical studies [119,120], the role of NK cell driven inflammation in glymphatic/meningeal lymphatic system dysfunction will be important to clarify. As pineal (and possibly local melatonin) enhances glymphatic and meningeal lymphatic system function by upregulating astrocytic end-feet aquaporin (AQP)4 [121], the interface of pineal, local, and NK cell melatonergic pathway in SAH and glymphatic/meningeal lymphatic system interactions will be important to clarify to improve SAH treatment outcomes.

Other neurotraumas are associated with decreased NK cell number and cytotoxicity, such as brain ischemia [122] and chronic spinal cord injury [123] in correlation with trauma severity. Investigation of the interactions of canonical and non-canonical pSTAT3 and NF-κB dimer composition in the modulation of the up- or down-regulation of the NK cell melatonergic pathway should refine treatment for these still poorly managed conditions.

The capacity of NK cells to kill cancer cells and virus-infected cells, as well as modulate many other medical conditions, clearly indicates the importance of investigating the presence and regulation of core processes in NK cells. As indicated above, the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway may be a core, unrecognized aspect of NK cell function, and may integrate many disparate bodies of data on NK cell function, including suppression in T2DM, as well as by methylglyoxal and aging. The capacity of exogenous melatonin to enhance the cytotoxicity of NK cells would indicate that the presence of an endogenous melatonergic pathway may be of some importance to optimized NK cell function. Whether the NK cell melatonergic pathway is regulated by canonical and noncanonical pSTAT3 interactions with NF-κB dimer composition, as found in a wide array of other human cell types, will be important to determine and should provide a mechanism to increase the robustness of NK cell responses, including in solid tumors, where their efficacy is currently limited. As NK cells are particularly important in the early detection and elimination of cancer, the investigation, regulation, and targeting of the NK cell melatonergic pathway should improve the attainment of the ultimate goal of cancer prevention. This article has been published as a preprint [124], which the current article will replace.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hersey P. Natural killer cells—a new cytotoxic mechanism against tumours. Aust N Z J Med. 1979;9(4):464–72. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.1979.tb04183.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Nersesian S, Carter EB, Lee SN, Westhaver LP, Boudreau JE. Killer instincts: natural killer cells as multifactorial cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1269614. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1269614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Anderson G. Tumour Microenvironment: roles of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, O-glcnacylation, acetyl-CoA and melatonergic pathway in regulating dynamic metabolic interactions across cell types-tumour microenvironment and metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):141. doi:10.3390/ijms22010141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cong J, Wang X, Zheng X, Wang D, Fu B, Sun R, et al. Dysfunction of natural killer cells by FBP1-induced inhibition of glycolysis during lung cancer progression. Cell Metab. 2018;28(2):243–55.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Witalisz-Siepracka A, Klein K, Zdársky B, Stoiber D. The multifaceted role of STAT3 in NK-cell tumor surveillance. Front Immunol. 2022;13:947568. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.947568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Vicioso Y, Wong DP, Roy NK, Das N, Zhang K, Ramakrishnan P, et al. NF-κB c-Rel is dispensable for the development but is required for the cytotoxic function of NK cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:652786. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.652786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Millot P, Duquesne L, San C, Porte B, Pujol C, Hosten B, et al. Non-canonical STAT3 pathway induces alterations of mitochondrial dynamic proteins in the hippocampus of an LPS-induced murine neuroinflammation model. Neurochem Int. 2025;186:105979. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2025.105979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Córdoba-Moreno MO, Santos GC, Muxel SM, Dos Santos-Silva D, Quiles CL, Sousa KDS, et al. IL-10-induced STAT3/NF-κB crosstalk modulates pineal and extra-pineal melatonin synthesis. J Pineal Res. 2024;76(1):e12923. doi:10.1111/jpi.12923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Anderson G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: role of altered night-time dampening and resetting processes over aging in modulating STAT3 and mitochondrial function. ResearchGate Forthcoming. 2026. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.14911.01441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Moravcová S, Filipovská E, Spišská V, Svobodová I, Novotntfytf J, Bendová Z. The circadian rhythms of STAT3 in the rat pineal gland and its involvement in arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase regulation. Life. 2021;11(10):1105. doi:10.3390/life11101105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Lupo D, Vollmer C, Deckers M, Mick DU, Tews I, Sinning I, et al. Mdm38 is a 14-3-3-like receptor and associates with the protein synthesis machinery at the inner mitochondrial membrane. Traffic. 2011;12(10):1457–66. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01239.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Muxel SM, Laranjeira-Silva MF, Carvalho-Sousa CE, Floeter-Winter LM, Markus RP. The RelA/cRel nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) dimer, crucial for inflammation resolution, mediates the transcription of the key enzyme in melatonin synthesis in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Pineal Res. 2016;60(4):394–404. doi:10.1111/jpi.12321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Miller SC, Pandi-Perumal SR, Esquifino AI, Cardinali DP, Maestroni GJ. The role of melatonin in immuno-enhancement: potential application in cancer. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006;87(2):81–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Liang C, Song R, Zhang J, Yao J, Guan Z, Zeng X. Melatonin enhances NK cell function in aged mice by increasing T-bet expression via the JAK3-STAT5 signaling pathway. Immun Ageing. 2024;21(1):59. doi:10.1186/s12979-024-00470-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Arjona A, Sarkar DK. Circadian oscillations of clock genes, cytolytic factors, and cytokines in rat NK cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(12):7618–24. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kaur K, Jewett A. Decreased surface receptors, function, and suboptimal osteoclasts-induced cell expansion in natural killer (NK) cells of elderly subjects. Aging. 2025;17(3):798–821. doi:10.18632/aging.206226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Anderson G. Melatonin, BAG-1 and cortisol circadian interactions in tumor pathogenesis and patterned immune responses. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2023;4(5):962–93. doi:10.37349/etat.2023.00176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wurtman RJ. Age-related decreases in melatonin secretion—clinical consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(6):2135–6. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.6.6660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Fang X, Huang W, Sun Q, Zhao Y, Sun R, Liu F, et al. Melatonin attenuates cellular senescence and apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy by regulating STAT3 phosphorylation. Life Sci. 2023;332:122108. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Markus RP, Cecon E, Pires-Lapa MA. Immune-pineal axis: nuclear factor κB (NF-kB) mediates the shift in the melatonin source from pinealocytes to immune competent cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(6):10979–97. doi:10.3390/ijms140610979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Anderson G. Reframing polymyalgia pathoetiology, pathophysiology and treatment: role of aging-linked alterations in night-time dampening and resetting by melatonin and cortisol in modulation of local melatonin production via the STAT3 interface with NF-kB dimer composition, with future research and treatment implications. ResearchGate Forthcoming. 2026. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.15808.03849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Eddy JL, Krukowski K, Janusek L, Mathews HL. Glucocorticoids regulate natural killer cell function epigenetically. Cell Immunol. 2014;290(1):120–30. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.05.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Anderson G. Physiological processes underpinning the ubiquitous benefits and interactions of melatonin, butyrate and green tea in neurodegenerative conditions. Melatonin Res. 2024;7(1):20–46. doi:10.32794/mr11250016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li DD, Zhou T, Gao J, Wu GL, Yang GR. Circadian rhythms and breast cancer: from molecular level to therapeutic advancements. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150(9):419. doi:10.1007/s00432-024-05917-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Z, He X, Sun Y, Li J, Sun J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a metabolic model of accelerated aging—multi-organ mechanisms and intervention approaches. Aging Dis. 2025. doi:10.14336/AD.2025.0233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. da Silveira Cruz-Machado S, Pinato L, Tamura EK, Carvalho-Sousa CE, Markus RP. Glia-pinealocyte network: the paracrine modulation of melatonin synthesis by tumor necrosis factor (TNF). PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40142. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Bonmatí-Carrión MÁ, Rol MA. Melatonin as a mediator of the gut microbiota-host interaction: implications for health and disease. Antioxidants. 2023;13(1):34. doi:10.3390/antiox13010034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Anderson G. Why are aging and stress associated with dementia, cancer, and other diverse medical conditions Role of pineal melatonin interactions with the HPA axis in mitochondrial regulation via BAG-1. Melatonin Res. 2023;6(3):345–71. doi:10.32794/mr112500158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Anderson G, Maes M. Gut dysbiosis dysregulates central and systemic homeostasis via suboptimal Mitochondrial function: assessment, treatment and classification implications. Curr Top Med Chem. 2020;20(7):524–39. doi:10.2174/1568026620666200131094445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lu KD, Radom-Aizik S, Haddad F, Zaldivar F, Kraft M, Cooper DM. Glucocorticoid receptor expression on circulating leukocytes differs between healthy male and female adults. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1(2):108–14. doi:10.1017/cts.2016.20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen X, He H. Expression profiles of glucocorticoid receptor α- and β-isoforms in diverse physiological and pathological conditions. Horm Metab Res. 2025;57(6):359–65. doi:10.1055/a-2619-5035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ramos-Ramírez P, Tliba O. Glucocorticoid receptor β (GRβbeyond its dominant-negative function. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3649. doi:10.3390/ijms22073649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kokkinopoulou I, Moutsatsou P. Mitochondrial glucocorticoid receptors and their actions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):6054. doi:10.3390/ijms22116054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zou C, Li W, Pan Y, Khan ZA, Li J, Wu X, et al. 11β-HSD1 inhibition ameliorates diabetes-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis through modulation of EGFR activity. Oncotarget. 2017;8(56):96263–75. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.22015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Seckl J. 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and the brain: not (yet) lost in translation. J Intern Med. 2024;295(1):20–37. doi:10.1111/joim.13741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kim JE, Kim Y, Bae J, Yoon EL, Kim HS, Lee SR, et al. A novel 11β-HSD1 inhibitor ameliorates liver fibrosis by inhibiting the notch signaling pathway and increasing NK cell population. Arch Pharm Res. 2025;48(2):166–80. doi:10.1007/s12272-025-01534-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Hyun M, Kim H, Kim J, Lee J, Lee HJ, Rathor L, et al. Melatonin protects against cadmium-induced oxidative stress via mitochondrial STAT3 signaling in human prostate stromal cells. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):157. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-04533-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mihanfar A, Yousefi B, Azizzadeh B, Majidinia M. Interactions of melatonin with various signaling pathways: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):420. doi:10.1186/s12935-022-02825-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Misale MS, Witek Janusek L, Tell D, Mathews HL. Chromatin organization as an indicator of glucocorticoid induced natural killer cell dysfunction. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;67:279–89. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.09.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Brauning A, Rae M, Zhu G, Fulton E, Admasu TD, Stolzing A, et al. Aging of the immune system: focus on natural killer cells phenotype and functions. Cells. 2022;11(6):1017. doi:10.3390/cells11061017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Park A, Yang Y, Lee Y, Kim MS, Park YJ, Jung H, et al. Indoleamine-2,3-Dioxygenase in thyroid cancer cells suppresses natural killer cell function by inhibiting NKG2D and NKp46 expression via STAT signaling pathways. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):842. doi:10.3390/jcm8060842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Fang X, Guo L, Xing Z, Shi L, Liang H, Li A, et al. IDO1 can impair NK cells function against non-small cell lung cancer by downregulation of NKG2D Ligand via ADAM10. Pharmacol Res. 2022;177:106132. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sato K, Ohira M, Imaoka Y, Imaoka K, Bekki T, Doskali M, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor maintains antitumor activity of liver resident natural killer cells after partial hepatectomy in C57BL/6J mice. Cancer Med. 2023;12(19):19821–37. doi:10.1002/cam4.6554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Anderson G, Carbone A, Mazzoccoli G. Tryptophan metabolites and aryl hydrocarbon receptor in severe acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pathophysiology. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1597. doi:10.3390/ijms22041597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Hwang HJ, Dornbos P, Steidemann M, Dunivin TK, Rizzo M, LaPres JJ. Mitochondrial-targeted aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the impact of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on cellular respiration and the mitochondrial proteome. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016;304:121–32. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2016.04.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Mokkawes T, Lim ZQ, de Visser SP. Mechanism of melatonin metabolism by CYP1A1: what determines the bifurcation pathways of hydroxylation versus deformylation? J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(46):9591–606. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c07200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Jang SW, Liu X, Pradoldej S, Tosini G, Chang Q, Iuvone PM, et al. N-acetylserotonin activates TrkB receptor in a circadian rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(8):3876–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912531107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yin B, Ma ZY, Zhou ZW, Gao WC, Du ZG, Zhao ZH, et al. The TrkB+ cancer stem cells contribute to post-chemotherapy recurrence of triple-negative breast cancers in an orthotopic mouse model. Oncogene. 2015;34(6):761–70. doi:10.1038/onc.2014.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Øvrevik J, Låg M, Lecureur V, Gilot D, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Refsnes M, et al. AhR and Arnt differentially regulate NF-κB signaling and chemokine responses in human bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12(1):48. doi:10.1186/s12964-014-0048-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Polonio CM, McHale KA, Sherr DH, Rubenstein D, Quintana FJ. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: a rehabilitated target for therapeutic immune modulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2025;24(8):610–30. doi:10.1038/s41573-025-01172-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Vogel CF, Sciullo E, Li W, Wong P, Lazennec G, Matsumura F. RelB, a new partner of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(12):2941–55. doi:10.1210/me.2007-0211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ishihara Y, Kado SY, Bein KJ, He Y, Pouraryan AA, Urban A, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling synergizes with TLR/NF-κB-signaling for induction of IL-22 through canonical and non-canonical AhR pathways. Front Toxicol. 2022;3:787360. doi:10.3389/ftox.2021.787360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. DiNatale BC, Schroeder JC, Francey LJ, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. Mechanistic insights into the events that lead to synergistic induction of interleukin 6 transcription upon activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(32):24388–97. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.118570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Minacori M, Fiorini S, Perugini M, Iannetta A, Meschiari G, Chichiarelli S, et al. AhR and STAT3: a dangerous duo in chemical carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(6):2744. doi:10.3390/ijms26062744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Asker M, Krieger JP, Maric I, Bedel E, Steen J, Börchers S, et al. Vagal oxytocin receptors are necessary for esophageal motility and function. JCI Insight. 2025;10(10):e190108. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.190108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Pellissier S, Dantzer C, Mondillon L, Trocme C, Gauchez AS, Ducros V, et al. Relationship between vagal tone, cortisol, TNF-alpha, epinephrine and negative affects in Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105328. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Everett NA, Turner AJ, Costa PA, Baracz SJ, Cornish JL. The vagus nerve mediates the suppressing effects of peripherally administered oxytocin on methamphetamine self-administration and seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(2):297–304. doi:10.1038/s41386-020-0719-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Landolt K, Maruff P, Horan B, Kingsley M, Kinsella G, O’Halloran PD, et al. Chronic work stress and decreased vagal tone impairs decision making and reaction time in jockeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;84:151–8. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.07.238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Huang Y, Dong S, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Shi J, et al. Electroacupuncture promotes resolution of inflammation by modulating SPMs via vagus nerve activation in LPS-induced ALI. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;147:113941. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Zahoor I, Nematullah M, Ahmed ME, Fatma M, Sajad M, Ayasolla K, et al. Maresin-1 promotes neuroprotection and modulates metabolic and inflammatory responses in disease-associated cell types in preclinical models of multiple sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2025;301(3):108226. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2025.108226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Li S, Qi D, Li JN, Deng XY, Wang DX. Vagus nerve stimulation enhances the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway to reduce lung injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome via STAT3. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):63. doi:10.1038/s41420-021-00431-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Muxel SM, Pires-Lapa MA, Monteiro AW, Cecon E, Tamura EK, Floeter-Winter LM, et al. NF-κB drives the synthesis of melatonin in RAW 264.7 macrophages by inducing the transcription of the arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase (AA-NAT) gene. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Wang Z, Guan D, Huo J, Biswas SK, Huang Y, Yang Y, et al. IL-10 enhances human natural killer cell effector functions via metabolic reprogramming regulated by mTORC1 signaling. Front Immunol. 2021;12:619195. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.619195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Markus RP, Silva CL, Franco DG, Barbosa EM Jr, Ferreira ZS. Is modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by melatonin relevant for therapy with cholinergic drugs? Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126(3):251–62. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ricon-Becker I, Fogel E, Cole SW, Haldar R, Lev-Ari S, Gidron Y. Tone it down: vagal nerve activity is associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-viral factors in breast cancer—an exploratory study. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021;7:100057. doi:10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Reijmen E, Vannucci L, De Couck M, De Grève J, Gidron Y. Therapeutic potential of the vagus nerve in cancer. Immunol Lett. 2018;202:38–43. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2018.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Mihaylova S, Schweighöfer H, Hackstein H, Rosengarten B. Effects of anti-inflammatory vagus nerve stimulation in endotoxemic rats on blood and spleen lymphocyte subsets. Inflamm Res. 2014;63:683–90. doi:10.1007/s00011-014-0741-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Huang WB, Lai HZ, Long J, Ma Q, Fu X, You FM, et al. Vagal nerve activity and cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):579. doi:10.1186/s12885-025-13956-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Brem S. Vagus nerve stimulation: novel concept for the treatment of glioblastoma and solid cancers by cytokine (interleukin-6) reduction, attenuating the SASP, enhancing tumor immunity. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2024;42:100859. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2024.100859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. Controlling inflammation: the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 6):1037–40. doi:10.1042/BST0341037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Anderson G. Daytime orexin and night-time melatonin regulation of mitochondria melatonin: : roles in circadian oscillations systemically and centrally in breast cancer symptomatology. Melatonin Res. 2019. doi:10.32794/mr11250037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Cucielo MS, Tan DX, Rosales-Corral S, Gancitano G, et al. Brain washing and neural health: role of age, sleep, and the cerebrospinal fluid melatonin rhythm. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(4):88. doi:10.1007/s00018-023-04736-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Anderson G. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: roles of STAT3 interactions with NF-kB dimer composition in the modulation of the cardiac mitochondrial melatonergic pathway. Explor Endo Metab Dis Forthcoming. 2026. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.32837.56804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Boender AJ, Johnson ZV, Gruenhagen GW, Horie K, Hegarty BE, Streelman JT, et al. Natural variation in oxytocin receptor signaling causes widespread changes in brain transcription: a link to the natural killer gene complex. bioRxiv:10.26.564214. 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.10.26.564214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Zhang Y, Zou N, Xin C, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Rong P, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation modulates blood glucose in ZDF rats via intestinal melatonin receptors and melatonin secretion. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:1471387. doi:10.3389/fnins.2024.1471387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Markus RP, Fernandes PA, Kinker GS, da Silveira Cruz-Machado S, Marçola M. Immune-pineal axis—acute inflammatory responses coordinate melatonin synthesis by pinealocytes and phagocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(16):3239–50. doi:10.1111/bph.14083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Anderson G, Reiter RJ. Glioblastoma: role of mitochondria N-acetylserotonin/melatonin ratio in mediating effects of miR-451 and aryl hydrocarbon receptor and in coordinating wider biochemical changes. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2019;12:1178646919855942. doi:10.1177/1178646919855942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Oo AM, Mohd Adnan LH, Nor NM, Simbak N, Ahmad NZ, Lwin OM. Immunomodulatory effects of flavonoids: an experimental study on natural-killer-cell-mediated cytotoxicity against lung cancer and cytotoxic granule secretion profile. Proc Singap Healthc. 2020;30(4):279–85. doi:10.1177/2010105820979006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Liu P, Yin Z, Chen M, Huang C, Wu Z, Huang J, et al. Cytotoxicity of adducts formed between quercetin and methylglyoxal in PC-12 cells. Food Chem. 2021;352:129424. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Xuan C, Chen D, Zhang S, Li C, Fang Q, Chen D, et al. Isoquercitrin alleviates diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation and dimerization. Adv Sci. 2025;12(25):e2414587. doi:10.1002/advs.202414587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Su T, Shen H, He M, Yang S, Gong X, Huang C, et al. Quercetin promotes the proportion and maturation of NK cells by binding to MYH9 and improves cognitive functions in aged mice. Immun Ageing. 2024;21(1):29. doi:10.1186/s12979-024-00436-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Anderson G. Type I diabetes pathoetiology and pathophysiology: roles of the gut microbiome, pancreatic cellular interactions, and the ‘bystander’ activation of memory CD8+ T Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3300. doi:10.3390/ijms24043300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Ansari P, Choudhury ST, Seidel V, Rahman AB, Aziz MA, Richi AE, et al. Therapeutic potential of quercetin in the management of type-2 diabetes mellitus. Life. 2022;12(8):1146. doi:10.3390/life12081146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. De Lorenzo BH, de Oliveira Marchioro L, Greco CR, Suchecki D. Sleep-deprivation reduces NK cell number and function mediated by β-adrenergic signalling. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;57:134–43. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Wardhan Y, Vishwas S, Porselvi A, Singh SK, Kakoty V. Exploring the complex interplay between Parkinson’s disease and BAG proteins. Behav Brain Res. 2024;469:115054. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2024.115054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Luo S, Hou Y, Zhang Y, Feng L, Hunter RG, Yuan P, et al. Bag-1 mediates glucocorticoid receptor trafficking to mitochondria after corticosterone stimulation: potential role in regulating affective resilience. J Neurochem. 2021;158(2):358–72. doi:10.1111/jnc.15211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Ponath V, Hoffmann N, Bergmann L, Mäder C, Alashkar Alhamwe B, Preußer C, et al. Secreted ligands of the NK cell receptor NKp30: b7-H6 is in contrast to BAG6 only marginally released via extracellular vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):2189. doi:10.3390/ijms22042189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Ebrahimi Meimand S, Rostam-Abadi Y, Rezaei N. Autism spectrum disorders and natural killer cells: a review on pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17(1):27–35. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2020.1850273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Enstrom AM, Lit L, Onore CE, Gregg JP, Hansen RL, Pessah IN, et al. Altered gene expression and function of peripheral blood natural killer cells in children with autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(1):124–33. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2008.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Pagan C, Goubran-Botros H, Delorme R, Benabou M, Lemière N, Murray K, et al. Disruption of melatonin synthesis is associated with impaired 14-3-3 and miR-451 levels in patients with autism spectrum disorders. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2096. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02152-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Wen Y, Herbert MR. Connecting the dots: overlaps between autism and cancer suggest possible common mechanisms regarding signaling pathways related to metabolic alterations. Med Hypotheses. 2017;103:118–23. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2017.05.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Nijhof D, Sosenko F, Mackay D, Fleming M, Jani BD, Pell JP, et al. A population-based cross-sectional investigation of COVID-19 hospitalizations and mortality among autistic people. J Autism Dev Disord. 2025;11:860. doi:10.1007/s10803-025-06844-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Yu Y, Yang X, Hu G, Tong K, Wu J, Yu R. Risk cycling in diabetes and autism spectrum disorder: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1389947. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1389947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Samsuzzaman Md, Hong SM, Lee JH, Park H, Chang KA, Kim HB, et al. Depression like-behavior and memory loss induced by methylglyoxal is associated with tryptophan depletion and oxidative stress: a new in vivo model of neurodegeneration. Biol Res. 2024;57(1):87. doi:10.1186/s40659-024-00572-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Cao Y, Zhang H, Chen X, Li C, Chen J. Melatonin: a natural guardian in cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1617508. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1617508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Tan DX, Huang G, de Almeida Chuffa LG, Anderson G. Melatonin modulates tumor metabolism and mitigates metastasis. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2023;18(4):321–36. doi:10.1080/17446651.2023.2237103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Anderson G, Reiter RJ. Melatonin: roles in influenza, COVID-19, and other viral infections. Rev Med Virol. 2020;30(3):e2109. doi:10.1002/rmv.2109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Qin J, Wang G, Han D. Benefits of melatonin on mortality in severe-to-critical COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinics. 2025;80:100638. doi:10.1016/j.clinsp.2025.100638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Chen H, Sun H, Yang Y, Wang P, Chen X, Yin J, et al. Engineered melatonin-pretreated plasma exosomes repair traumatic spinal cord injury by regulating miR-138-5p/SOX4 axis mediated microglia polarization. J Orthop Translat. 2024;49:230–45. doi:10.1016/j.jot.2024.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Wei J, Nduom EK, Kong LY, Hashimoto Y, Xu S, Gabrusiewicz K, et al. MiR-138 exerts anti-glioma efficacy by targeting immune checkpoints. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(5):639–48. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Ebrahimi A, Barati T, Mirzaei Z, Fattahi F, Mansoori Derakhshan S, Shekari Khaniani M. An overview on the interaction between non-coding RNAs and CTLA-4 gene in human diseases. Med Oncol. 2024;42(1):13. doi:10.1007/s12032-024-02552-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Guo R, Rao PG, Liao BZ, Luo X, Yang WW, Lei XH, et al. Melatonin suppresses PD-L1 expression and exerts antitumor activity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):8451. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93486-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Jørgensen LV, Christensen EB, Barnkob MB, Barington T. The clinical landscape of CAR NK cells. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025;14(1):46. doi:10.1186/s40164-025-00633-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Kong R, Liu B, Wang H, Lu T, Zhou X. CAR-NK cell therapy: latest updates from the 2024 ASH annual meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2025;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s13045-025-01677-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Lin MH, Hu LJ, Miller JS, Huang XJ, Zhao XY. CAR-NK cell therapy: a potential antiviral platform. Sci Bull. 2025;70(5):765–77. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2025.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Sipos D, Raposa BL, Freihat O, Simon M, Mekis N, Cornacchione P, et al. Glioblastoma: clinical presentation, multidisciplinary management, and long-term outcomes. Cancers. 2025;17(1):146. doi:10.3390/cancers17010146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Strassheimer F, Elleringmann P, Ludmirski G, Roller B, Macas J, Alekseeva T, et al. CAR-NK cell therapy combined with checkpoint inhibition induces an NKT cell response in glioblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2025;132(9):849–60. doi:10.1038/s41416-025-02977-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Liu YJ, Zhuang J, Zhu HY, Shen YX, Tan ZL, Zhou JN. Cultured rat cortical astrocytes synthesize melatonin: absence of a diurnal rhythm. J Pineal Res. 2007;43(3):232–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00466.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Arjona A, Sarkar DK. Evidence supporting a circadian control of natural killer cell function. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20(5):469–76. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Anderson G. Gut microbiome and circadian interactions with platelets across human diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and cancer. Curr Top Med Chem. 2023;23(28):2699–719. doi:10.2174/0115680266253465230920114223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Shaw DM, Keaney L, Maunder E, Dulson DK. Natural killer cell subset count and antigen-stimulated activation in response to exhaustive running following adaptation to a ketogenic diet. Exp Physiol. 2023;108(5):706–14. doi:10.1113/EP090729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Cimen YA, Elibol B, Korkmaz ND, Yuzgulec M, Kinsiz B, Kutlu S, et al. The impact of ketogenic diet consumption on the sporadic Alzheimer’s model through MT1/MT2 regulation. J Neurosci Res. 2025;103(8):e70070. doi:10.1002/jnr.70070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Lussier DM, Woolf EC, Johnson JL, Brooks KS, Blattman JN, Scheck AC. Enhanced immunity in a mouse model of malignant glioma is mediated by a therapeutic ketogenic diet. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:310. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2337-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Anderson G. Tumor microenvironment and metabolism: role of the mitochondrial melatonergic pathway in determining intercellular interactions in a new dynamic homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):311. doi:10.3390/ijms24010311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Chen X, Kadier M, Shi M, Li K, Chen H, Xia Y, et al. Targeting melatonin to mitochondria mitigates castration-resistant prostate cancer by inducing pyroptosis. small. 2025;21(22):e2408996. doi:10.1002/smll.202408996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Pfnür A, Mayer B, Dörfer L, Tumani H, Spitzer D, Huber-Lang M, et al. Regulatory T cell- and natural killer cell-mediated inflammation, cerebral vasospasm, and delayed cerebral ischemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage—a systematic review and meta-analysis approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1276. doi:10.3390/ijms26031276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Lucke-Wold B, Dodd W, Motwani K, Hosaka K, Laurent D, Martinez M, et al. Investigation and modulation of interleukin-6 following subarachnoid hemorrhage: targeting inflammatory activation for cerebral vasospasm. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):228. doi:10.1186/s12974-022-02592-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Eide PK, Undseth RM, Pripp A, Lashkarivand A, Nedregaard B, Sletteberg R, et al. Impact of subarachnoid hemorrhage on human glymphatic function: a time-evolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke. 2025;56(3):678–91. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.124.047739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Wang J, Lv T, Jia F, Li Y, Ma W, Xiao ZP, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage distinctively disrupts the glymphatic and meningeal lymphatic systems in beagles. Theranostics. 2024;14(15):6053–70. doi:10.7150/thno.100982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Zhu B, Liu C, Luo M, Chen J, Tian S, Zhan T, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamic changes of meningeal microenvironment influence meningeal lymphatic function following subarachnoid hemorrhage: from inflammatory response to tissue remodeling. J Neuroinflamm. 2025;22(1):131. doi:10.1186/s12974-025-03460-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Sun H, Cao Q, He X, Du X, Jiang X, Wu T, et al. Melatonin mitigates sleep restriction-induced cognitive and glymphatic dysfunction via Aquaporin-4 polarization. Mol Neurobiol. 2025;62(9):11443–65. doi:10.1007/s12035-025-04992-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Kong Y, Li S, Cheng X, Ren H, Zhang B, Ma H, et al. Brain ischemia significantly alters microRNA expression in human peripheral blood natural killer cells. Front Immunol. 2020;11:759. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Herman P, Stein A, Gibbs K, Korsunsky I, Gregersen P, Bloom O. Persons with chronic spinal cord injury have decreased natural killer cell and increased toll-like receptor/inflammatory gene expression. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(15):1819–29. doi:10.1089/neu.2017.5519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Anderson G. Natural killer cell cytotoxicity: role of STAT3 interactions with NF-kB dimer composition in the modulation of the melatonergic pathway in determining cytotoxicity and the prevention of tumors and viral infection severity. Differential modulation by the circadian rhythm over aging. Preprint. Forthcoming. 2025. doi:10.13140/rg.2.2.20462.88646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.