Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Advancements and Challenges of Gamma Delta (γδ) T Cell- and Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapies

ImmuneLink, LLC, Riverside, CA 92508, USA

* Corresponding Author: Kawaljit Kaur. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Role of γδ T Cells and iNKT Cells in Cancer: Unraveling Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.073252

Received 14 September 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

Gamma delta (γδ) T cells and invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are unconventional T cells with limited T cell receptor (TCR) diversity. Both can recognize lipid or non-peptide antigens, often through cluster of differentiation 1d (CD1d), rapidly produce cytokines, express natural killer (NK) cell markers, and are mainly found in mucosal and barrier tissues. Acting as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity, they show great promise for cancer immunotherapy. Developing γδ T and iNKT cells for treatment involves shared features like thymic origin, MHC-independent recognition, rapid cytotoxicity, low graft-vs.-host disease (GvHD) risk, ex vivo expansion, and genetic modification, making them suitable for adoptive cell therapies. While their mechanisms are similar, iNKT cells rely on CD1d-mediated antigen presentation, provided by CD1d-expressing antigen-presenting cells (APCs) or engineered cell lines, to activate their invariant TCR and expand effectively. Chimeric antigen receptors (CAR)-induced functional activations make these cell types viable alternatives to conventional cell-based or CAR-T therapies with additional safety benefits. Early clinical trials have shown encouraging results, and their completion will confirm their potential for future treatments. This review explores the biology and mechanisms of γδ T and iNKT cells, focusing on how APCs, cytokines, feeder cells, and CARs contribute to boosting their cytotoxic function, cytokine production, and expansion, enhancing their promise as cancer immunotherapies. It also explores the advancements and challenges in developing γδ T and iNKT cell-based immunotherapies, with preclinical and early clinical outcomes offering promising insights.Keywords

1 Introduction: Biology of Gamma Delta (γδ) T Cells and Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) Cells

Gamma delta (γδ) T cells are a distinct type of T lymphocyte characterized by specialized γ and δ T-cell receptor (TCR) chains, serving as a bridge γδ [1]. They comprise 1%–10% of human peripheral blood T cells but are more abundant in epithelial and mucosal tissues, such as the skin, gut, lungs, and reproductive tract [2,3]. Discovered in the 1980s, γδ T cells were characterized by 1987 as CD3-associated molecules and a heterodimer consisting of a γ chain and a δ chain [4–6]. They develop in the thymus from common progenitors shared with αβ T cells, emerging early from double-negative thymocytes under the influence of Notch signaling and interleukin-7 (IL-7) [7]. Their lineage commitment is guided by models such as stochastic, instructive, and signal strength-based [7]. Developing in waves, they originate from the fetal liver and thymus, showing distinct tissue dynamics, with Vγ9Vδ2 dominating in the fetal liver and Vδ1 expanding after birth [7]. Their differentiation and function depend on intricate signaling pathways [1,8]. γδ T cells have semi-invariant TCRs with limited diversity compared to αβ TCRs, yet they recognize a wide range of ligands, including non-peptide and stress-related antigens [9,10]. Unlike αβ T cells, they can recognize antigens independently of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) involvement, enabling them to target tumors broadly, respond quickly, and perform diverse roles in cancer defense [7,11]. They quickly produce cytokines like IL-17 and IFN-γ, maintain tissue homeostasis, and exhibit memory-like traits in barrier tissues such as the intestines [12–14]. The main subsets, Vδ1, Vδ2 (primarily Vγ9Vδ2), and Vδ3, vary in location, antigen recognition, and function. Vδ1 T cells reside in tissues like the gut, liver, skin, and spleen, recognizing stress ligands like MICA/B and glycolipids via CD1d [7,15]. They demonstrate strong cytotoxicity, express natural killer (NK) receptors, such as natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D), and resist activation-induced cell death, thereby sustaining anti-tumor activity [16]. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, found in the blood, recognize phosphoantigens (pAgs) such as IPP from disrupted tumor mevalonate pathways and are activated by butyrophilin complexes (butyrophilin subfamily 3 member A1 [BTN3A1] and butyrophilin subfamily 2 member A1 [BTN2A1]) [17,18]. These cells exhibit cytotoxicity, secrete cytokines like IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) through cluster of differentiation-16 (CD16) [19,20]. Vδ3 T cells, less studied, are located in the liver and gut, responding to glycolipids and oxidative stress presented by CD1d [21,22]. In conditions like leukemia and viral infections, Vδ3 cells can also appear in the bloodstream [21].

iNKT cells are a unique type of innate-like T lymphocytes with a semi-invariant T cell receptor (TCR) that recognizes lipid antigens presented by the CD1d molecule [23]. The cytokine environment and availability of ligands regulate iNKT activation, with α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer) serving as a key glycolipid antigen [23,24]. Found in tissues such as the liver, spleen, thymus, and peripheral blood (0.01%–0.1% in humans), iNKT cells bridge innate lipid recognition with adaptive immunity [25–27]. Research highlights their complex development, differentiation, and roles in diseases and therapies. Early microbial exposure plays a role in iNKT development and tissue residency [28–30]. Recent studies highlight skin-homing traits driven by CCR10 expression during thymic development [30,31]. iNKT cells develop in the thymus from CD4+CD8+ double-positive precursors selected on CD1d-expressing cortical thymocytes, with key transcription factors like promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) playing a key role in their effector functions [32–34]. Subsets are defined by transcription factors: T-bet for iNKT1 (IFN-γ producers), GATA binding protein-3 (GATA-3) for iNKT2 (IL-4 producers), and RORγt for iNKT17 (IL-17 producers) [35–37]. Developmental models include the linear maturation model, where iNKT cells progress through stages marked by CD24, CD44, and NK1.1 expression, and the lineage differentiation (branching) model, where iNKT subsets (NKT1, NKT2, NKT17) diverge early from common progenitors based on transcription factor expression rather than surface markers [36,38,39]. iNKT cells rapidly release cytokines like IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-17 upon activation [25]. IL-17 receptor B (IL-17RB)+ CD4+ iNKT cells produce Th2, Th9, and Th17 cytokines in response to IL-25, while IL-17RB+ CD4− iNKT cells (RORγt+) release Th17 cytokines when stimulated by IL-23 [40]. IL-17RB− iNKT cells produce IFN-γ, associated with classical effector roles [40,41]. IL-15 is crucial in maintaining certain iNKT subtypes [42]. These subsets originate in the thymus and migrate to peripheral tissues, where they perform functions including direct cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity is mediated directly via perforin/granzyme and Fas/FasL pathways, as well as indirectly by activating dendritic cells (DCs), NK cells, and T cells [43,44]. Changes in iNKT cell number or function are linked to autoimmune diseases, infections, cancer, and allergic conditions [23,45,46].

Recent research highlights the varied roles of iNKT subsets, shaped by their tissue residency or circulation [25]. Tissue-resident iNKTs maintain local balance and secrete specific cytokines, while circulating iNKTs act as cytotoxic sentinels for antitumor and antiviral defense [25]. These subsets differ in transcriptional profiles, surface markers, cytotoxic molecules, and immune functions, influencing host defense, regulation, and therapies [25]. Tissue-resident iNKTs, found in organs like the liver, thymus, spleen, lungs, intestines, and adipose tissue, are usually CD244−CXCR6+ with T cell–like traits. They secrete cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17, activated by tissue-derived cytokines like IL-7 and IL-15. They support local immunity, homeostasis, and tissue repair, with tissue imprinting adding retention molecules like P2RX7 and CXCR6 [25,47]. Their restricted TCR repertoires reflect local antigen exposure and clonal expansion shaped by the microenvironment [47]. Tissue-resident iNKTs are locally specialized, moderately cytotoxic, and exhibit T cell–like signaling, while circulating iNKTs are mobile, highly cytotoxic, and rapidly respond to infections and tumors [25]. Circulating iNKTs, typically CD244+CXCR6+ with NK cell–like traits, primarily secrete IFN-γ and are activated by IL-15 from medullary thymic epithelium [34]. They are crucial for systemic antitumor and antiviral defense, with functional differences defined by transcription factors, cytokines, and epigenetics [25].

Both γδ T cells and iNKT cells are categorized as unconventional or innate-like T lymphocytes, bridging innate and adaptive immunity with their rapid responses, bypassing classical MHC-restricted peptide antigen presentation [48]. Their TCR diversity is limited compared to conventional αβ T cells; iNKT cells express an invariant αβ TCR, while γδ T cells have heterodimeric γ and δ chains that often detect non-peptide antigens [49]. Both recognize non-peptidic antigens—iNKT cells respond to lipid antigens presented by the CD1d molecule (an MHC-I–like molecule), while some γδ T cell subsets also recognize CD1d-presented lipid antigens or respond to phosphoantigens and stress-induced molecules independently of classical MHC presentation. Unlike conventional αβ T cells, they do not rely on MHC class I or II peptides for activation. Upon activation, both can quickly produce a wide range of cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-17, supporting diverse immune responses (Th1-, Th2-, Th17-like). They influence other immune cells like NK cells, DCs, and conventional T and B lymphocytes, modulating immune responses. These cells exhibit functional plasticity, playing both pro-inflammatory and immunoregulatory roles. Both subsets share NK cell-related surface markers like CD16 and NKG2D, reflecting their intermediate phenotype between T cells and NK cells. They develop primarily in the thymus but are enriched in epithelial and mucosal tissues (e.g., iNKT cells in the liver, γδ T cells in the skin and gut mucosa). Acting as first-line defenders at barrier sites, they recognize stressed, infected, or transformed cells, contributing to tumor immunosurveillance.

This review discusses the role of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), cytokines, feeder cells, and chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) in advancing γδ T cell- and iNKT cell-based immunotherapies. Explored the latest γδ T cell- and iNKT cells-based immunotherapies, the challenges they faced, and highlighted the critical areas to be addressed to push immunotherapies forward.

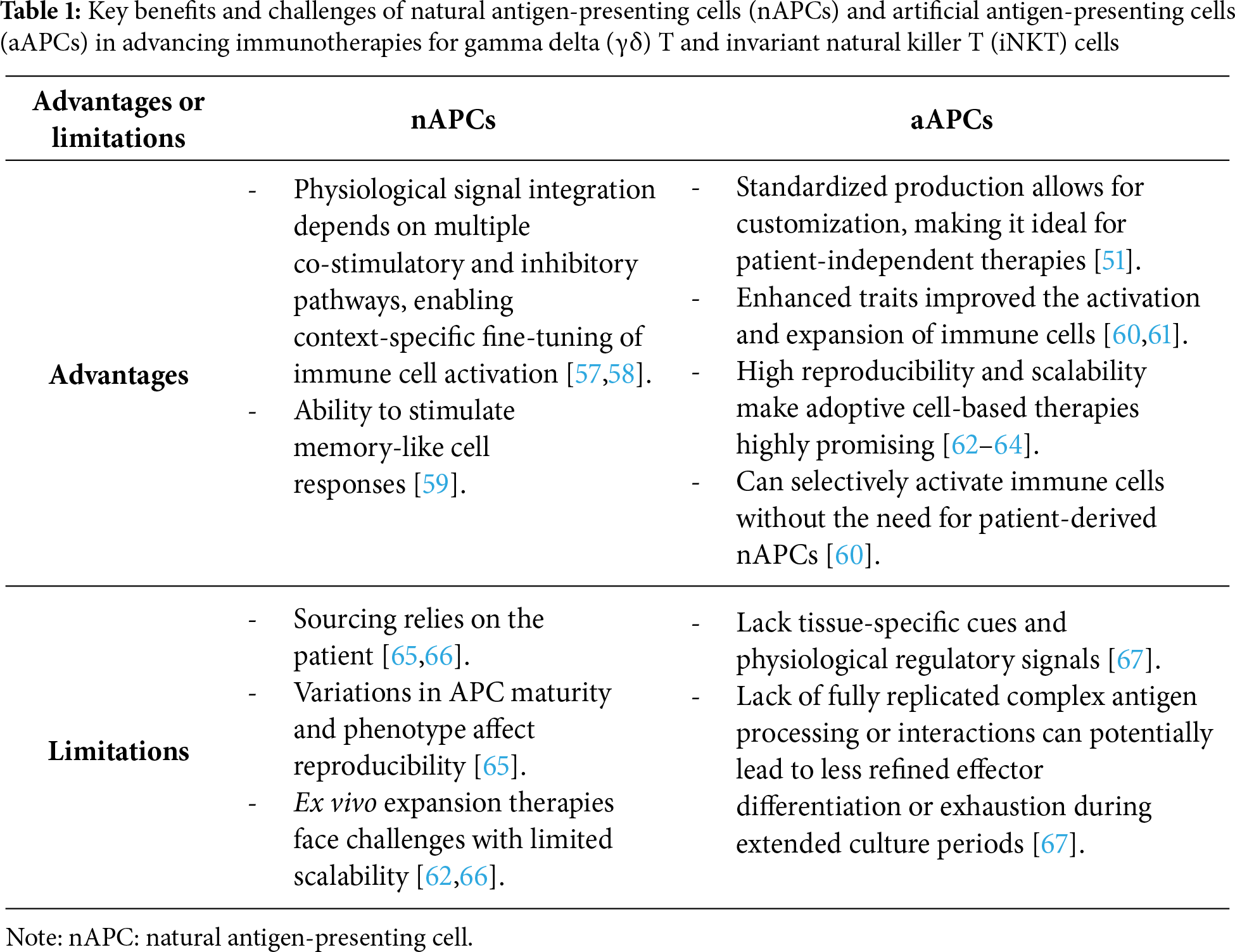

2 Role of APC in Advancing γδ T and iNKT Cell-Based Immunotherapies

APCs play a vital role in initiating adaptive immune responses by presenting processed antigens to γδ T and iNKT cells along with necessary co-stimulatory signals [50]. APCs can be natural or artificial. Natural APCs (nAPCs) are derived from human cells, while artificial APCs (aAPCs) are engineered to replicate their function [50,51]. Both can stimulate γδT and iNKT cells, but they differ in concept, mechanism, and practicality [51]. Examples of nAPCs include dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and B lymphocytes, which specialize in capturing, processing, and presenting antigens through MHC class I, MHC class II, or non-classical MHC molecules like CD1 for lipid antigens. Co-stimulatory signals are delivered via naturally expressed receptors such as CD80/CD86, ICAM-1, LFA-3, CD40, and cytokines like IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, and type I interferons. Found in tissues like the skin, mucosa, and lymphoid organs, nAPCs create dynamic environments for immune interactions. aAPCs use engineered platforms that can be cell-based, such as human leukemia lines, or acellular, like microbeads, nanoparticles, liposomes, or supported lipid bilayers combined with MHC or non-classical ligands and co-stimulatory molecules [51,52]. They can present antigens using phosphoantigens or tumor-associated antigens and achieve MHC-independent presentation with engineered ligands [51]. Controlled co-stimulation allows precise expression of CD80/CD86, ICAM-1, LFA-3, 4-1BBL, and co-stimulatory monoclonal antibodies.

Studies have demonstrated that aAPCs like K562 induce long-term proliferation, enhanced activations, and anti-tumor effects compared to nAPCs, suggesting their use to advance clinical applications and to engineer δ T cell- and iNKT cells [53,54]. Cytokines like IL-2, IL-15, or IL-21 can also be tethered or released to enhance immune cell proliferation ex vivo [51,52]. The interaction between APCs and innate T cell groups like γδ T cells and iNKT cells is key to advancing immunotherapies. By understanding these relationships, we can develop better cancer treatments that utilize the unique traits of these T cells, improving their effectiveness and patient outcomes [55]. With ongoing research, the potential for γδ T and iNKT cells in clinical use looks promising, encouraging deeper exploration of their roles and how they can be modulated within the immune system [55,56]. Key advantages and limitations of nAPCs and aAPCs are listed in Table 1.

3 Role of Cytokines in Advancing γδ T and iNKT Cell-Based Immunotherapies

Tumor recognition without human leukocyte antigen (HLA) dependency makes γδ T and iNKT cells excellent candidates for allogeneic adoptive cell transfer (ACT) [68]. However, their low frequencies in peripheral blood require ex vivo expansion and functional improvements. Cytokines are crucial for enhancing their proliferation, activation, and cytotoxicity, especially in cancer immunotherapy. Advances in cytokine biology and protein engineering have significantly improved these cells’ therapeutic potential. Cytokines like IL-2, IL-15, IL-7, and IL-21 promote their proliferation, survival, and cytotoxic abilities [69]. IL-2 fosters proliferation, boosts cytotoxicity, and encourages an effector memory phenotype [70,71]. IL-15 combined with IL-2 supports long-term memory, while IL-21 improves cytotoxic functions and facilitates expansion with or without feeders [72,73]. IFN-γ aids in anti-tumor activity. In the tumor microenvironment, cytokines help γδ T and iNKT cells avoid exhaustion from continuous antigen exposure [74,75]. However, natural cytokines face challenges like short half-life, pleiotropy, and systemic toxicity, complicating safe clinical use. To overcome these obstacles, various engineering strategies have been developed [76–78]. Engineered cytokines help restore cytotoxicity of these cells in immunosuppressive conditions [79,80].

Mutant or designer cytokines, called “superkines” (e.g., IL-2 superkine, Neo-2/15), specifically target IL-2Rβγ on cytotoxic lymphocytes while avoiding IL-2Rα on Tregs, improving anti-tumor effects and minimizing off-target risks [79,81,82]. These superkines activate effector γδ T and iNKT cells without triggering Tregs, enhancing anti-tumor activity with reduced toxicity. Orthogonal cytokine-receptor pairs enable engineered γδ T and iNKT cells to respond only to modified cytokines, lowering systemic immunotoxicity [81]. Cytokine-polymer conjugates, like PEGylated IL-2 or IL-10 (e.g., Bempegaldesleukin), extend cytokine half-life, enhance tumor targeting, and decrease systemic exposure [83]. Fusion proteins and immunocytokines, created by linking cytokines with Fc domains, albumin, or antibodies, improve serum half-life and allow tumor-specific delivery [77]. Immunocytokines and prodrug cytokines, activated in the tumor microenvironment, provide localized delivery, reduce systemic toxicity, and stimulate γδ T and iNKT cell activation and expansion at tumor sites. Ex vivo protocols use cytokines like IL-2, IL-18, and IL-15 with phosphoantigens or feeder cells to optimize efficiency [77]. Prodrug or masked cytokines selectively activate in the tumor microenvironment, reducing systemic toxicity. Cellular delivery vehicles, such as engineered γδ T and iNKT cells, can locally secrete cytokines, boosting autocrine and paracrine signaling to enhance anti-tumor effects without systemic side effects [84]. Incorporating engineered cytokines into γδ T and iNKT cell therapy aims to increase therapeutic levels, broaden cytotoxicity against various tumors, and lower toxicities linked to high-dose cytokine use. These findings highlight the potential of cytokines in engineered γδ T and iNKT cell platforms as a clinical strategy to improve anti-tumor immunity [77].

iNKT cell activation depends greatly on cytokine signaling, particularly through the JAK/STAT pathway, which regulates their growth, cytotoxicity, and survival [85,86]. Engineered cytokine receptors in iNKT cells activate JAK/STAT signaling independently of external cytokines, ensuring activation only in response to antigens and preventing off-target effects or unwanted differentiation [87]. Controlled cytokine signaling helps maintain memory-like phenotypes and avoids early exhaustion. Enhanced STAT5/STAT1 activation boosts granzyme and perforin levels, increasing iNKT cell cytotoxicity [87,88]. Strategies like generating iNKT cells from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with CAR constructs (e.g., HER2 CAR) can be enhanced by cytokines to improve activation [89]. CAR-iNKT cells release cytokines such as IL-2, IL-15, and IFN-γ upon recognizing antigens, promoting dendritic cell maturation, M1 macrophage polarization, and endogenous CD8+ T cell activation [90,91]. Cytokine release reshapes the tumor or tissue environment to enhance anti-tumor responses while targeted cytokine delivery (e.g., fusion proteins, receptor engineering) minimizes systemic toxicity, avoiding pleiotropic effects and vascular leak syndrome seen with traditional IL-2 therapies [92,93].

By utilizing cytokines and incorporating techniques like protein engineering, antibody-cytokine fusions, PEGylation, and cellular programming, cytokines can effectively boost γδ T and iNKT cell activity while minimizing systemic toxicity [79]. These methods introduce a novel perspective, transforming cytokines from mere soluble mediators into precision tools designed to enhance the effectiveness and durability of γδ T and iNKT cells. CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT combined with cytokines make them highly scalable, setting the stage for a feeder-free approach to generate next-generation γδ T and iNKT cell immunotherapies for clinical applicability.

4 Role of Feeder Cells in Advancing γδ T Cell and iNKT Cells-Based Immunotherapies

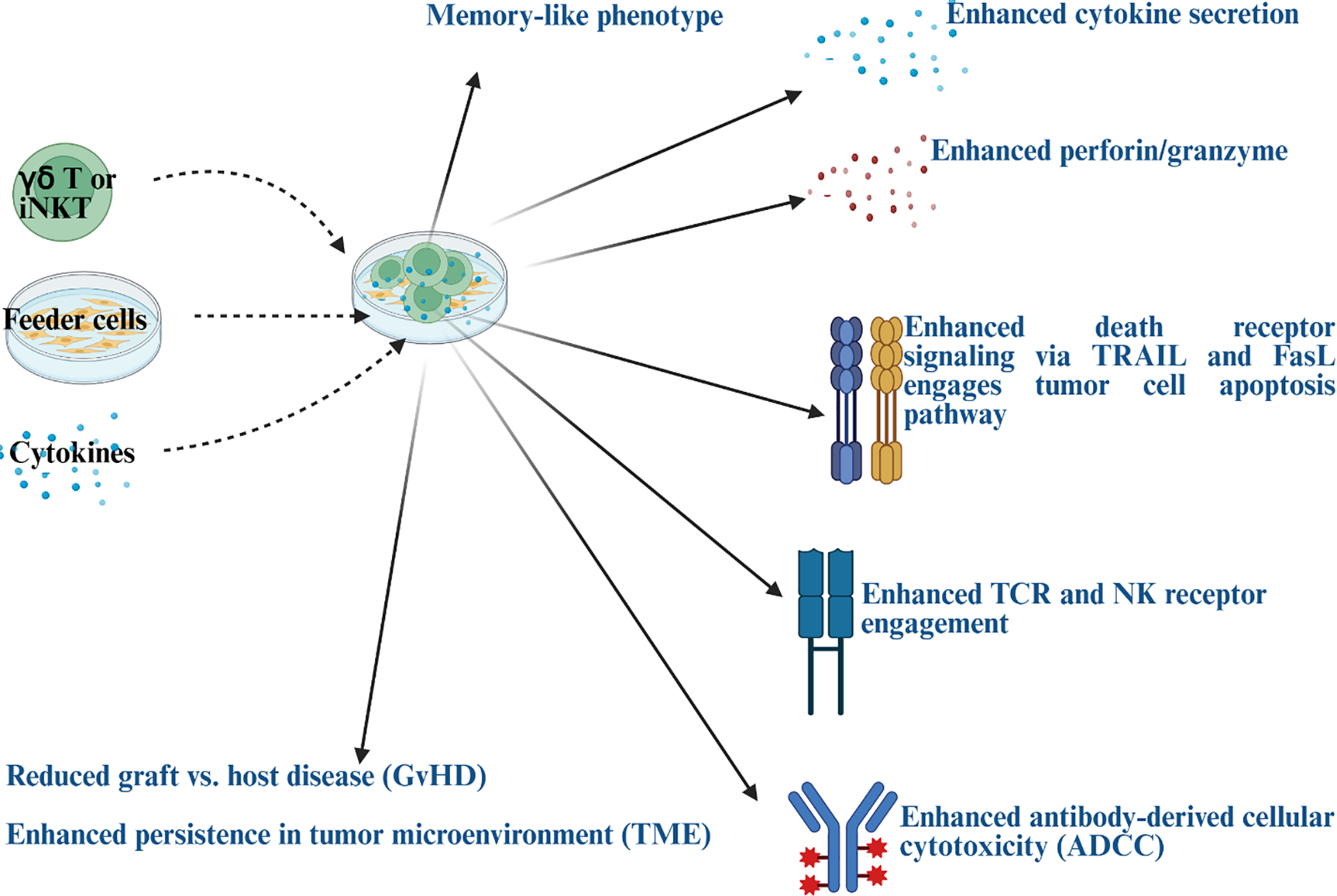

Feeder cells play a crucial role in providing signals and presenting antigens for the development, activation, proliferation, and expansion of γδ T and iNKT cells, especially when starting with limited populations, such as those from peripheral blood [94,95] (Fig. 1). Well-characterized feeder cells for γδ T and iNKT cell expansion are K562 cells (human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line), EBV-transformed lymphoid cell lines (EBV-LCLs), irritated or mitocycin-C-treated PBMCs, and untreated or Zoledronate-treated osteoclasts [96–98]. Most commonly used feeder cells, such as K562 cells, lack MHC class I and II expression, reducing allogeneic immune responses and minimizing GvHD risk [99]. Genetically engineered to express co-stimulatory molecules and membrane-bound cytokines, K562 cells function as aAPCs for γδ T cells. Typical transgenes include CD19, CD64 (FcγRI), CD86, CD137L (4-1BBL), and membrane-bound IL-15 or IL-15/IL-15Rα complexes, providing activation signals and cytokine support for sustained γδ T cell proliferation [96,97]. The expansion process of γδ T cells using K562 feeder cells often starts with activating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using agents like zoledronate (a bisphosphonate) and IL-2 to enrich the γδ T subpopulation, particularly Vγ9Vδ2 cells. The activated PBMCs are then co-cultured with irradiated, modified K562 feeder cells, driving rapid expansion and achieving several thousand-fold increases in γδ T cells within 10–17 days. Large-scale growth is supported in cell culture vessels like G-Rex flasks, designed for enhanced gas exchange and compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards [96]. K562 feeder systems offer significant advantages, including higher expansion rates (~1000–500,000 fold depending on subset and protocol) compared to cytokine-only or bisphosphonate methods [96]. They help maintain the functional properties of γδ T cells, including their cytotoxic potential and memory phenotypes, and enable the expansion of polyclonal γδ T populations (Vδ1, Vδ2, and Vδ3 subsets), broadening therapeutic applications [96]. Studies have shown that osteoclasts treated with zoledronate [100,101] or combined with probiotic bacteria [102] as potent feeder cells to induce cell expansion and functional activation of γδ T cells. Osteoclasts may provide CD1d-mediated antigen presentation, supporting iNKT cell expansion and activation; however, this remains to be investigated.

Figure 1: Illustration to demonstrate anti-cancer activity in gamma delta (γδ) T and invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells after they are co-cultured with feeder cells in the presence of cytokines. Blue color text represents the characteristics of engineered γδ T cells and iNKT generated using feeder cells and cytokines. Note: TRAIL: tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; FasL: fas ligand; TCR: T-cell receptor; NK: natural killer. Created in BioRender. Kaur, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/4mu9q7s (accessed on 29 October 2025)

In addition to above above-listed feeder cells, key feeder cells specifically for iNKT cells include CD1d-expressingAPCs, such as double-positive (CD4+CD8+) thymocytes during thymic development, and dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and B cells in peripheral tissues [23]. In vitro, stromal feeder cells like OP9-DLL1 are used to promote iNKT differentiation from stem cells. CD1d, a non-polymorphic MHC-like molecule, presents glycolipid antigens to the invariant TCR of iNKT cells [103,104]. Other CD1d-expressing lymphoid and myeloid cells or Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-LCLs) also aid iNKT and γδ T cell activation and expansion by presenting antigens [105,106].

Addressing challenges and considerations, removing residual feeder cells after expansion is essential, typically done through irradiation or cell sorting, as feeders are irradiated before culture [107]. Maintaining balanced co-culture ratios, cytokine supplementation (like IL-2, IL-15, IL-21), and appropriate duration is key for achieving optimal expansion without causing γδ T cell exhaustion [94]. The purity of γδ T cell populations is often enhanced using prior isolation methods such as magnetic bead separation and flow cytometric sorting [94]. K562-derived feeder cells enable off-the-shelf expansion of large quantities of γδ T cells suitable for adoptive cell therapy (ACT), avoiding the need for extensive leukapheresis [96]. They support the expansion of γδ T and iNKT cells while preserving their cytotoxicity and memory phenotypes against tumor cells in an MHC-independent way [96]. These feeder-based protocols have been adapted to GMP-compliant workflows critical for clinical manufacturing [96].

5 Role of CAR in Advancing γδ T and iNKT Cell-Based Immunotherapies

CARs have revolutionized cellular immunotherapy, allowing T cells to recognize and destroy specific tumor antigens without needing MHC presentation. While traditional CAR-T therapies primarily target conventional αβ T cells, extending CAR technology to γδ T cells and iNKT cells addresses some of the challenges in current adoptive cell therapies and provides unique therapeutic advantages. Therefore, CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT cells offer an exciting alternative to traditional CAR-T therapy, addressing many of its limitations with unique advantages [11,108,109]. These cells combine CAR-specific targeting with the innate cytotoxic abilities of γδ T or iNKT cells, allowing them to recognize tumor-associated antigens and stress-induced ligands, making them highly effective for allogeneic treatments [11].

Preclinical studies show strong anti-tumor activity, durability, and safety of CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT cells. CAR-γδ T cytotoxicity works through granule exocytosis (perforin/granzyme) and death receptor pathways (FasL/TRAIL), while cytokine secretion (IFN-γ, TNF-α) supports their function without requiring extensive external cytokine support [11]. CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT cells reprogram the tumor microenvironment by targeting immunosuppressive cells like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), while activating dendritic cells, endogenous CD8+ T cells, and promoting M1 macrophage polarization to enhance anti-tumor immunity. With naturally expressed chemokine receptors (e.g., CXCR6, CCR1, CCR6), CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT cells can migrate and stay in peripheral tissues, improving infiltration into solid tumors where CAR-T cells often struggle due to physical barriers like dense stroma and fibrotic extracellular matrix [108]. Their multiple cytotoxic pathways reduce the risk of tumor antigen escape, a common problem in CAR-T therapy, especially in heterogeneous or relapsed leukemias. Being non-alloreactive, they are safe for allogeneic use across HLA barriers without causing GvHD. Early studies show lower risks of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity (ICANS), making them safer than CAR-T cells. Additionally, iPSC-derived CAR-γδ T, CAR-γδ T, and CAR-iNKT cells have shown effectiveness without continuous cytokine exposure, offering a scalable, consistent platform that reduces batch variability and supports off-the-shelf applications [108,110].

CAR-iNKT cells with dual-targeting abilities, such as CD19/CD133, have shown impressive results in eradicating high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in mouse models, achieving durable responses in bone marrow and meninges, unlike conventional CAR-T cells, which only provided temporary clearance [91]. Early human trials for B-cell lymphomas revealed that CAR-iNKT cells had better tissue infiltration and persistence without causing GvHD. In solid tumors, preclinical studies with GD2 (neuroblastoma), CLDN18.2 (pancreatic cancer), and HER2 CAR-iNKT cells demonstrated enhanced anti-tumor activity, tissue penetration, persistence, and TME modulation compared to conventional CAR-Ts, suggesting their potential superiority in this challenging setting [108]. Anti-CD38-CAR-γδ T cells have shown impressive cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma in both in vitro and in vivo studies, demonstrating promise for treating blood cancers [111]. CAR-γδ T cells also show potential against solid tumors, with dual-targeting CAR strategies addressing tumor heterogeneity with early-stage trials of CAR-γδ T have also shown promising results [108,109]. However, clinical data on CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT cells remain limited, and direct comparisons to CAR-T cells in human trials have yet to occur. Obstacles like manufacturing challenges, regulatory hurdles, and reliable large-scale expansion persist, along with the need for more research into solid tumor infiltration and persistence across diverse human cancers [108].

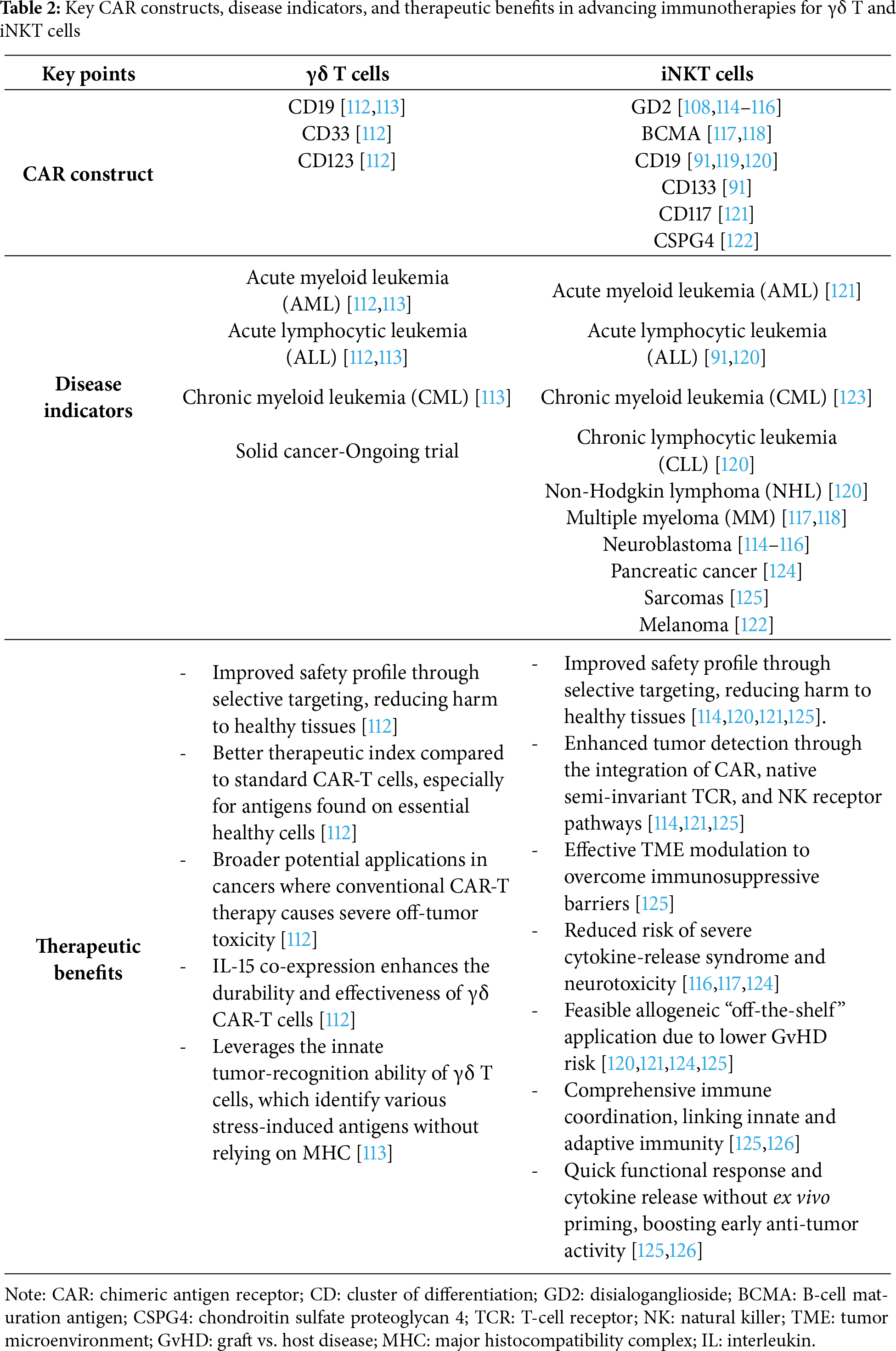

CAR-γδ T and CAR-iNKT cells bring several benefits compared to traditional CAR-T cells, including dual innate and adaptive cytotoxicity, the ability to modulate the tumor microenvironment, lower immunotoxicity, and convenient, ready-to-use availability (Table 2). These features position them as strong candidates to surpass CAR-T therapy, particularly in high-risk blood cancers and solid tumors. Although early results and clinical data are encouraging, comprehensive clinical trials, especially phase II/III studies, are essential to establish clear comparisons, validate their effectiveness, and assess their persistence and long-term safety across a wider range of solid tumor types.

6 Advancements in γδ T Cell- and iNKT Cells-Based Immunotherapies

γδ T cells show great potential in cancer immunotherapy, especially for tumors with low MHC expression or high heterogeneity that pose challenges to traditional treatments [127,128]. Their anti-tumor effects include directly killing tumor cells, activating the immune system through cytokines, and supporting adaptive responses [129,130]. These cells eliminate tumors via granule exocytosis, releasing perforin and granzyme B, activating death receptor pathways like tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and fas ligand (FasL), and performing ADCC by binding CD16 to antibody-coated tumor cells [129,131–133]. They also release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, shaping the tumor microenvironment and stimulating other immune cells [132,134]. Both non-engineered and engineered γδ T cell treatments are under clinical investigation, highlighting their adaptability and promise in cell-based and engager therapies [135]. Non-engineered therapies use ex vivo expanded autologous or allogeneic γδ T cells (primarily Vγ9Vδ2), stimulated by aminobisphosphonates (like zoledronate or pamidronate) and cytokines (like IL-2) to enhance proliferation and activation before infusion [129,135,136].

Clinical trials for hematologic and solid tumors have demonstrated safety, scalable production, and some objective responses, though complete response rates remain low [135,137]. Phase 1 trials using ex vivo expanded donor-derived allogeneic γδ T cells after hematopoietic cell transplantation in high-risk acute myeloid leukemia patients showed promising safety profiles, with no reports of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune neurotoxicity (ICANS), or GVHD [138,139]. Early efficacy signs include sustained complete remission (CR) and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity [140]. In vivo activation of γδ T cells can be achieved using aminobisphosphonates and synthetic phosphoantigens, along with cytokines like IL-2, to stimulate endogenous Vγ9Vδ2 T cells [141,142]. While limited by cell exhaustion and moderate efficacy, this approach remains a valuable adjunct. Bispecific γδ T cell engagers are synthetic molecules that bind γδ TCRs and tumor antigens, specifically redirecting and activating γδ T cells at tumor sites to boost cytotoxicity [143,144]. Examples include bispecifics targeting Her2, CD40, or CD123 to leverage γδ T cell cytotoxicity [145]. The development of banked γδ T cell products for universal use offers an exciting strategy to lower costs and improve accessibility [146].

Advances in genetic engineering, expansion protocols, and clinical trials are driving the development of next-generation treatments, especially for solid tumors and malignancies that resist conventional T cell therapies [147]. Genetic modifications aim to address challenges like limited expansion, persistence, and tumor targeting [147]. CAR-γδT cells, engineered with chimeric antigen receptors targeting tumor antigens, boost specificity and potency [148,149]. These cells merge the innate tumor recognition of γδ TCRs with CAR targeting, offering improved infiltration and reduced GvHD risks [68]. CAR-γδ T cells may outperform αβ CAR-T therapies by reducing toxicity, enhancing tissue penetration, and targeting tumors through multiple receptors [109,150,151]. Preclinical and early clinical studies have demonstrated promising safety and cytotoxicity, including engineered Vδ1 CAR-T cells and γδ T cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [152,153]. TCR gene transfer introduces high-affinity γδ TCRs into T cells to strengthen tumor recognition and anti-tumor responses [154]. CRISPR/Cas9 techniques involve deleting inhibitory receptors to prevent exhaustion or inserting cytokine genes (e.g., IL-15) to enhance proliferation and persistence [155,156].

iNKT cells’ unique innate-adaptive function and rapid cytokine response make them valuable in cancer immunotherapy [157]. They can directly kill CD1d-expressing tumor cells through cytotoxic granules (perforin, granzymes) and Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis [158,159]. While some tumors evade detection by downregulating CD1d, iNKT cells can still target tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), reshaping the TME [160]. When activated (e.g., by α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) loaded dendritic cells), iNKT cells release IFN-γ and other cytokines that help mature dendritic cells via CD40–CD40L interaction, boost priming of tumor-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and activate NK cells to eliminate MHC-negative tumor cells [161,162]. These mechanisms amplify anti-tumor immunity and create lasting immunological memory. Adoptive cell transfer can be achieved by infusing ex vivo expanded autologous or allogeneic iNKT cells [163]. Addressing low iNKT counts in patients through iPSC-derived iNKT cell generation offers scalable cellular solutions [164]. Early-phase trials using α-GalCer-pulsed DCs and expanded iNKT cells have shown safety and some clinical benefits in cancers like non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and head and neck cancer [165–167]. Allogeneic iNKT therapies, such as agenT-797, exhibit durability, tumor infiltration, immune activation, and manageable effects in solid tumors [168]. Challenges include low iNKT cell frequency in humans, tumor metabolic factors (e.g., glycolytic environment, lactic acid) impairing iNKT function, and the need for better manufacturing, expansion, and persistence of therapeutic iNKT cells, as well as overcoming tumor immune evasion through CD1d downregulation [44,158,169]. CAR-engineered iNKT cells maintain their natural immunomodulatory functions while achieving antigen-specific tumor targeting [108]. They offer safety benefits over CAR-T cells, such as a lower risk of graft-vs.-host disease. Clinical trials targeting GD2 (neuroblastoma), CD19 (B-cell malignancies), and other tumor antigens are showing promising early outcomes [108]. Combining iNKT therapies with checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, or vaccines could boost responses, overcome immunosuppressive challenges, and improve therapy persistence [170].

Both γδ T and iNKT cell types exhibit a low risk of GvHD, making them ideal for allogeneic (off-the-shelf) immunotherapies targeting cancer and infectious diseases [171]. They can be expanded and activated ex vivo, with γδ T cells responding to phosphoantigens or aminobisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronate) plus IL-2, and iNKT cells responding to α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) lipid antigens presented by CD1d. Both can be genetically modified with CARs to enhance tumor antigen specificity while preserving natural recognition pathways. Advances in deriving γδ T and iNKT cells from iPSCs now allow scalable and consistent production of cytotoxic lymphocytes with defined phenotypes for clinical applications. With their MHC-unrestricted antigen recognition, strong cytotoxic activity, and immunoregulatory roles combined with low alloreactivity, γδ T and iNKT cells represent complementary, promising platforms for next-generation adoptive cell therapies.

7 Challenges in Advancing Clinical Trials and Persistence of γδ and iNKT Therapies

While significant progress has been made, developing γδ T cell- and iNKT cell-based therapies still encounters challenges, such as limited in vivo expansion, persistence post-transfer, and the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) that reduces their efficacy [127,128,172,173]. The complexity and adaptability of these cell subsets make achieving consistent outcomes difficult, and understanding of their ligands and activation hierarchies, especially for their subsets, remains limited [7]. Current efforts aim to enhance γδ T and iNKT cell persistence and functional activation within TME [172]. Interim clinical data show good tolerance, manageable side effects, and durable immune recovery, supporting further dose-escalation and efficacy studies [138,139]. Engineering strategies can boost therapeutic precision and robustness, while combining these therapies with checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies (to leverage ADCC), chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other immunomodulators may improve their effectiveness [174,175]. Emerging delivery platforms, such as nanoparticle-encapsulated agonists, offer promise for optimizing pharmacodynamics and reducing systemic toxicity [175–177]. Clinical trials are advancing rapidly in both hematologic cancers and solid tumors to refine dosing, persistence, and overall efficacy [138,139].

Clinical trials using γδ and iNKT therapies often fall short compared to preclinical models for several reasons. Common challenges include limited in vivo persistence and expansion, as these cells struggle to maintain sufficient numbers post-infusion, reducing their ability to target tumor cells effectively [172]. The TME adds to the problem with high levels of immunosuppressive cytokines like TGF-β and IL-10, along with inhibitory checkpoint signals that weaken γδ/iNKT cytotoxic functions [172,178]. Suboptimal agonist stimulation is another issue, as clinical protocols using aminobisphosphonates (n-BPs) or phosphoantigens (pAgs) face poor pharmacokinetics, low bioavailability, and limited tumor penetration [172]. Additionally, ligand expression in tumors leads to variability in antigen recognition by γδ or iNKT TCRs, further limiting clinical outcomes. To address these hurdles, current strategies focus on combining these therapies with checkpoint inhibitors, providing cytokine support like IL-2 and IL-15, and using lipid nanocarriers to deliver optimized agonists.

Production or scalability of γδT and iNKT therapies for clinical use is complex and resource-intensive. Autologous products are personalized for each patient, making them time-consuming and difficult to scale, while allogeneic sources face the challenge of immune rejection. The largely manual expansion and activation processes lead to batch variability, complicating consistent potency at scale. Since γδT and iNKT cells are rare in the bloodstream, achieving clinical doses requires billions of functional cells per patient, necessitating large-scale expansion while maintaining stable phenotype and function [172]. Moreover, strict GMP standards for viability, purity, and contamination must be adhered to for each batch. Potential solutions include automated bioreactors, closed-system culture platforms, modular cleanrooms, and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven process controls to reduce variability and enhance production efficiency.

Repeated activation during ex vivo expansion or within the tumor microenvironment causes γδT and iNKT cells to become functionally exhausted, characterized by higher levels of exhaustion markers like PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3, along with reduced cytokine production [172]. This exhaustion leads to weaker effector function, lower proliferation, and limited in vivo persistence, ultimately reducing therapeutic effectiveness [172]. Strategies to address this include enhancing culture media and feeder cells to prevent terminal differentiation, using transient cytokine support (IL-15, IL-21) to improve survival, and employing genetic modifications such as checkpoint gene knockouts or co-expression of memory-related transcription factors.

These issues are interconnected: poor scalability worsens cell exhaustion, leading to therapeutic failures. The field is progressing toward next-generation off-the-shelf allogeneic products that integrate automated, scalable production with engineered exhaustion resistance and better agonist designs for in vivo stimulation.

8 Future Perspective of γδ T Cell and iNKT Cells-Based Immunotherapies

Most current preclinical and early clinical research emphasizes hematological malignancies, while solid tumors remain a significant challenge for immunotherapy. Future efforts aim to enhance γδ T cells and iNKT cells’ infiltration and persistence in solid tumors, addressing tumor microenvironment barriers. Combining γδ T or iNKT cell therapies with treatments like checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and monoclonal antibodies shows promise but requires further study. Adding probiotics to these therapies might also improve outcomes for resistant patients [179]. Chemotherapy or adjuvant therapeutic preconditioning may enhance γδ T or iNKT cell homing and persistence, while experimental approaches like nanoparticle and ligand-targeted delivery and catheter-based methods deserve further investigation. Identifying biomarkers to predict which patients will benefit most from these therapies is vital, as is exploring the tumor’s immunological landscape to discover such markers. Overcoming efficacy and safety challenges in clinical trials is crucial, and ongoing research focuses on manipulating the tumor microenvironment to better support γδ T and iNKT cell activity for more effective treatment options. Therefore, the future of γδ T cell and iNKT cell-based immunotherapies holds great promise, offering innovative approaches to treating various diseases, including cancer.

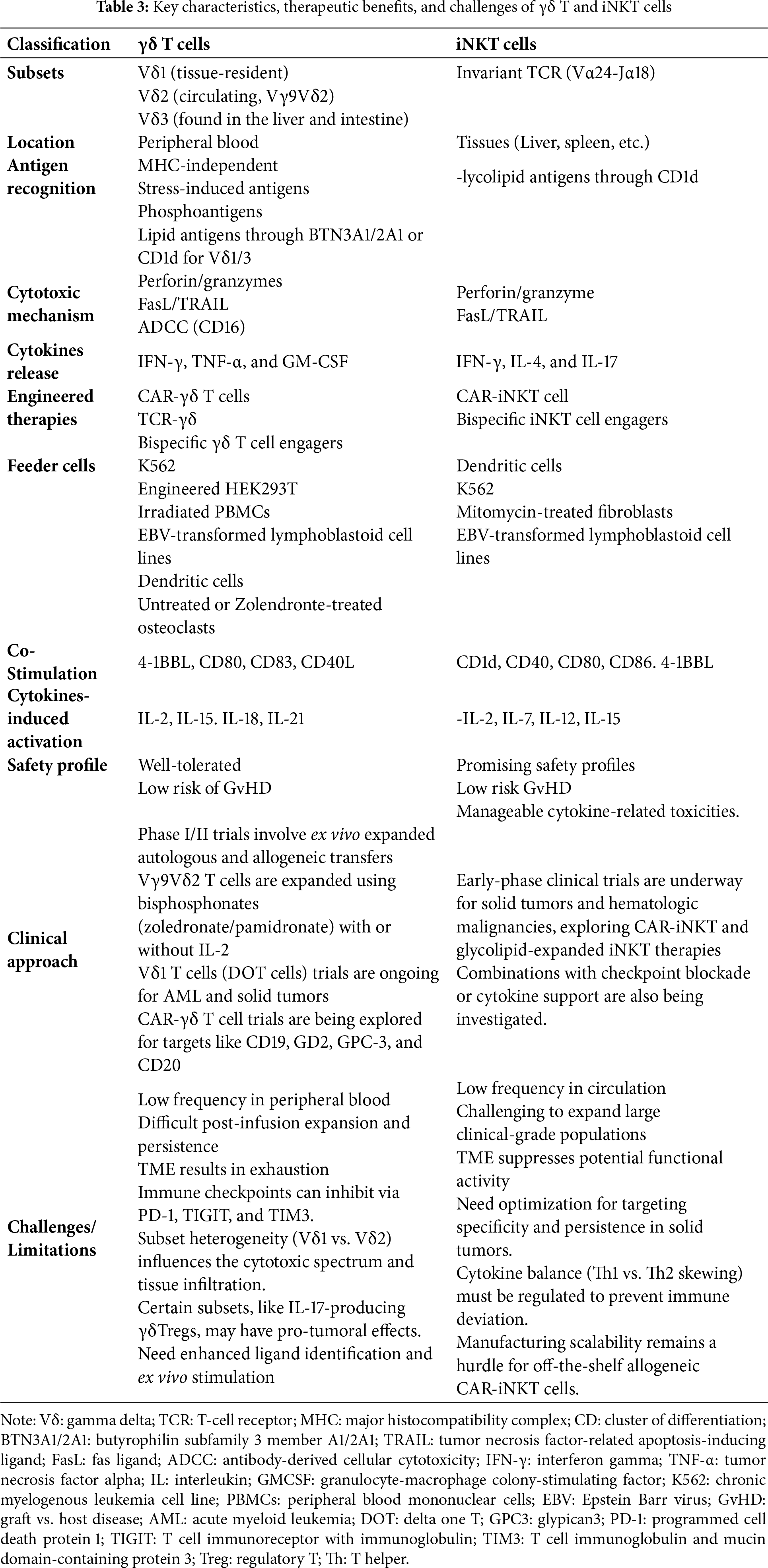

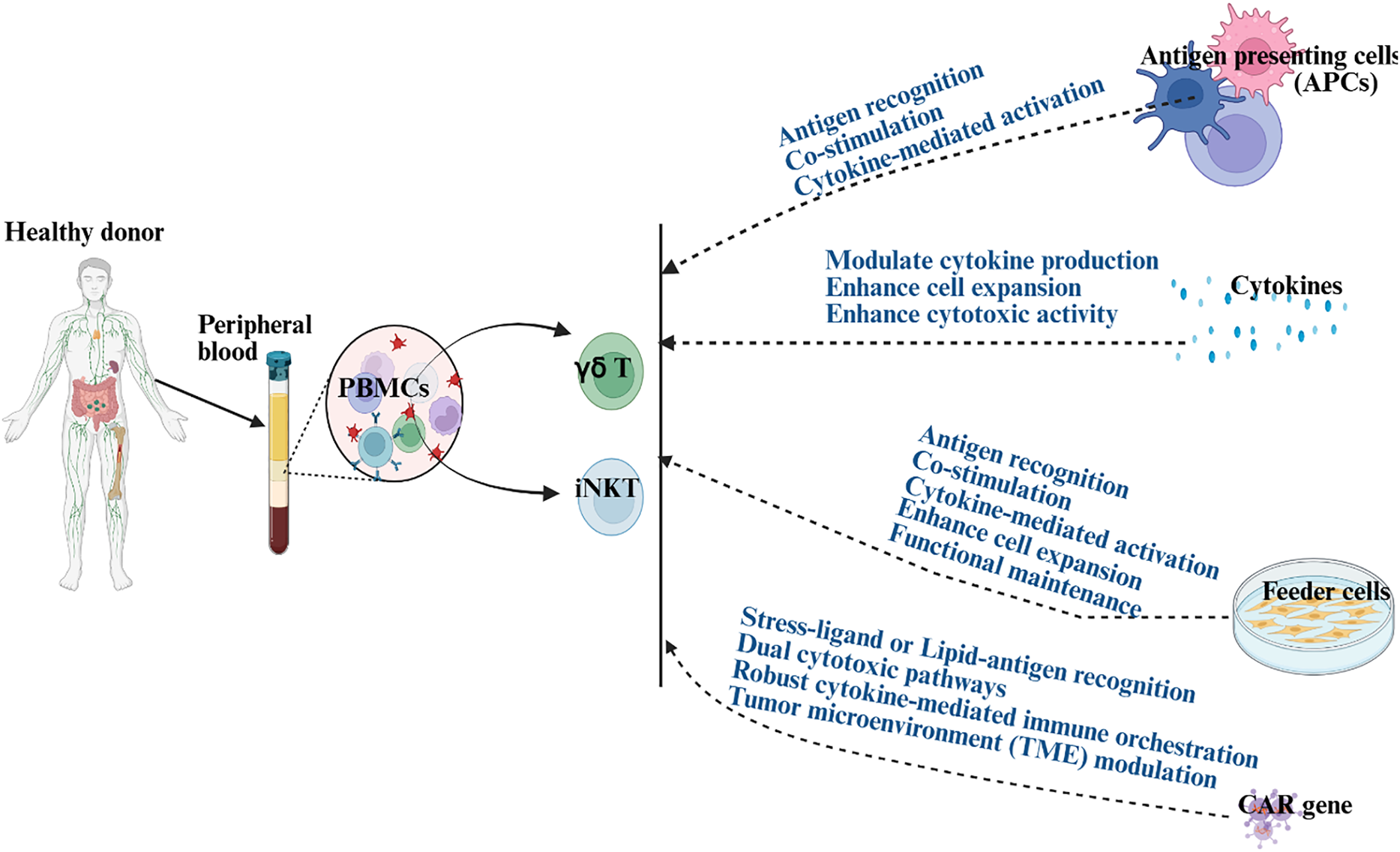

γδ T and iNKT cells play vital roles at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity; key characteristics, therapeutic use, and limitations are listed in Table 3. They respond quickly to stressed, infected, or transformed cells through unconventional antigen recognition that bypasses classical MHC pathways. Advances in molecular markers and single-cell technologies have enhanced our knowledge of their development, diversity, and functions. These discoveries open doors for targeted cancer therapies by focusing on specific γδ T and iNKT subsets or developmental pathways. APCs/feeder cells, cytokines, or CARs can provide continuous activation, proliferation, and anti-cancer support for γδ T and iNKT cells, enabling efficient and scalable expansion for immunotherapy (Fig. 2). Non-engineered methods include in vivo or ex vivo expansion with specific activation signals, while engineered therapies involve CARs, TCR gene transfer, bispecific engagers, and genetic editing to address challenges like persistence and immunosuppression. These strategies aim to develop effective, ready-to-use immunotherapies with wide applications against blood and solid cancers. Current clinical trials utilize their unique MHC-independent ability to recognize tumor-associated and stress ligands, enabling tumor killing, cytokine release, and immune modulation. Although preclinical and early clinical results are encouraging, issues such as TME resistance, cell expansion, and plasticity remain key research areas, and completion of ongoing clinical trials will provide solutions and answers to these.

Figure 2: Illustration demonstrating the role of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), cytokines, feeder cells, and chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) in activating and expanding γδ T and iNKT for immunotherapies. Blue text demonstrates the mechanisms through which APC, cytokines, feeder cells, or CAR induce activation or proliferation in γδ T and iNKT cells. Created in BioRender. Kaur, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hc7ixak (accessed on 29 October 2025). Note: PBMCs: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CAR: chimeric antigen receptor

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that the work reviewed in the article was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The author declares that there is no conflict of interest to report regarding the present review report.

References

1. Biały S, Bogunia-Kubik K. Uncovering the mysteries of human gamma delta T cells: from origins to novel therapeutics. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1543454. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1543454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dar AA, Patil RS, Chiplunkar SV. Insights into the relationship between Toll like receptors and gamma delta T cell responses. Front Immunol. 2014;5:366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. γδ T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(12):733–45. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Brenner MB, McLean J, Dialynas DP, Strominger JL, Smith JA, Owen FL, et al. Identification of a putative second T-cell receptor. Nature. 1986;322(6075):145–9. doi:10.1038/322145a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bank I, DePinho RA, Brenner MB, Cassimeris J, Alt FW, Chess L. A functional T3 molecule associated with a novel heterodimer on the surface of immature human thymocytes. Nature. 1986;322(6075):179–81. doi:10.1038/322179a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Born W, Miles C, White J, O’Brien R, Freed JH, Marrack P, et al. Peptide sequences of T-cell receptor delta and gamma chains are identical to predicted X and gamma proteins. Nature. 1987;330(6148):572–4. doi:10.1038/330572a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hu Y, Hu Q, Li Y, Lu L, Xiang Z, Yin Z, et al. γδ T cells: origin and fate, subsets, diseases and immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):434. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01653-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Boehme L, Roels J, Taghon T. Development of γδ T cells in the thymus—a human perspective. Semin Immunol. 2022;61–64:101662. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2022.101662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Vermijlen D, Gatti D, Kouzeli A, Rus T, Eberl M. γδ T cell responses: how many ligands will it take till we know? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;84:75–86. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Deseke M, Prinz I. Ligand recognition by the γδ TCR and discrimination between homeostasis and stress conditions. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(9):914–24. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-0503-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Lv J, Liu Z, Ren X, Song S, Zhang Y, Wang Y. γδT cells, a key subset of T cell for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1562188. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1562188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Papotto PH, Ribot JC, Silva-Santos B. IL-17+ γδ T cells as kick-starters of inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(6):604–11. doi:10.1038/ni.3726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Chien YH, Zeng X, Prinz I. The natural and the inducible: interleukin (IL)-17-producing γδ T cells. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(4):151–4. doi:10.1016/j.it.2012.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hao J, Wu X, Xia S, Li Z, Wen T, Zhao N, et al. Current progress in γδ T-cell biology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7(6):409–13. doi:10.1038/cmi.2010.50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Adams EJ, Gu S, Luoma AM. Human gamma delta T cells: evolution and ligand recognition. Cell Immunol. 2015;296(1):31–40. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.04.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Nattermann J, Feldmann G, Sievers E, Frank S, Strehl J, et al. Activated gammadelta T cells express the natural cytotoxicity receptor natural killer p 44 and show cytotoxic activity against myeloma cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144(3):528–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03078.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Fulford TS, Soliman C, Castle RG, Rigau M, Ruan Z, Dolezal O, et al. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells recognize butyrophilin 2A1 and 3A1 heteromers. Nat Immunol. 2024;25(8):1355–66. doi:10.1101/2023.08.30.555639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Harly C, Peigné CM, Scotet E. Molecules and mechanisms implicated in the peculiar antigenic activation process of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:657. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Gay L, Mezouar S, Cano C, Frohna P, Madakamutil L, Mège JL, et al. Role of Vγ9vδ2 T lymphocytes in infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:928441. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.928441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sawaisorn P, Gaballa A, Saimuang K, Leepiyasakulchai C, Lertjuthaporn S, Hongeng S, et al. Human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell expansion and their cytotoxic responses against cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1291. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-51794-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Petrasca A, Melo AM, Breen EP, Doherty DG. Human Vδ3(+) γδ T cells induce maturation and IgM secretion by B cells. Immunol Lett. 2018;196:126–34. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2018.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Rice MT, von Borstel A, Chevour P, Awad W, Howson LJ, Littler DR, et al. Recognition of the antigen-presenting molecule MR1 by a Vδ3(+) γδ T cell receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(49):e2110288118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2110288118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Brennan PJ, Brigl M, Brenner MB. Invariant natural killer T cells: an innate activation scheme linked to diverse effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):101–17. doi:10.1038/nri3369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Almishri W, Deans J, Swain MG. Rapid activation and hepatic recruitment of innate-like regulatory B cells after invariant NKT cell stimulation in mice. J Hepatol. 2015;63(4):943–51. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Cui G, Abe S, Kato R, Ikuta K. Insights into the heterogeneity of iNKT cells: tissue-resident and circulating subsets shaped by local microenvironmental cues. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1349184. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1349184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lee You J, Wang H, Starrett Gabriel J, Phuong V, Jameson Stephen C, Hogquist Kristin A. Tissue-specific distribution of iNKT cells impacts their cytokine response. Immunity. 2015;43(3):566–78. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mallevaey T, Selvanantham T. Strategy of lipid recognition by invariant natural killer T cells: ‘one for all and all for one’. Immunology. 2012;136(3):273–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03580.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Gensollen T, Lin X, Zhang T, Pyzik M, See P, Glickman JN, et al. Embryonic macrophages function during early life to determine invariant natural killer T cell levels at barrier surfaces. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(6):699–710. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-00934-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bertrand L, Toubal A, Lehuen A. Macrophages make the bed for early iNKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(6):681–2. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-00938-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, et al. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science. 2012;336(6080):489–93. doi:10.1126/science.1219328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Wang W-B, Lin Y-D, Zhao L, Liao C, Zhang Y, Davila M, et al. Developmentally programmed early-age skin localization of iNKT cells supports local tissue development and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2023;24(2):225–38. doi:10.1038/s41590-022-01399-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hu T, Simmons A, Yuan J, Bender TP, Alberola-Ila J. The transcription factor c-Myb primes CD4+CD8+ immature thymocytes for selection into the iNKT lineage. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):435–41. doi:10.1038/ni.1865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wang K, Zhao W, Jin R, Ge Q. Thymic iNKT cell differentiation at single-cell resolution. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(8):2065–6. doi:10.1038/s41423-021-00697-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Cui G, Shimba A, Jin J, Ogawa T, Muramoto Y, Miyachi H, et al. A circulating subset of iNKT cells mediates antitumor and antiviral immunity. Sci Immunol. 2022;7(76):eabj8760. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.abj8760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Krovi SH, Gapin L. Invariant natural killer T cell subsets-more than just developmental intermediates. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1393. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Baranek T, Lebrigand K, de Amat Herbozo C, Gonzalez L, Bogard G, Dietrich C, et al. High dimensional single-cell analysis reveals iNKT cell developmental trajectories and effector fate decision. Cell Rep. 2020;32(10):108116. doi:10.1101/2020.05.12.070425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Klibi J, Amable L, Benlagha K. A focus on natural killer T-cell subset characterization and developmental stages. Immunol Cell Biol. 2020;98(5):358–68. doi:10.1111/imcb.12322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Liman N, Park J-H. Markers and makers of NKT17 cells. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(6):1090–8. doi:10.1038/s12276-023-01015-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Kwon DI, Lee YJ. Lineage differentiation program of invariant natural killer T cells. Immune Netw. 2017;17(6):365–77. doi:10.4110/in.2017.17.6.365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Watarai H, Sekine-Kondo E, Shigeura T, Motomura Y, Yasuda T, Satoh R, et al. Development and function of invariant natural killer T cells producing T(h)2- and T(h)17-cytokines. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(2):e1001255. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Stock P, Lombardi V, Kohlrautz V, Akbari O. Induction of airway hyperreactivity by IL-25 is dependent on a subset of invariant NKT cells expressing IL-17RB 1. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):5116–22. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0804213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Gordy LE, Bezbradica JS, Flyak AI, Spencer CT, Dunkle A, Sun J, et al. IL-15 regulates homeostasis and terminal maturation of NKT cells. J Immunol. 2011;187(12):6335–45. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Look A, Burns D, Tews I, Roghanian A, Mansour S. Towards a better understanding of human iNKT cell subpopulations for improved clinical outcomes. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1176724. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1176724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Tian C, Wang Y, Su M, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Dou J, et al. Motility and tumor infiltration are key aspects of invariant natural killer T cell anti-tumor function. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1213. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-45208-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Cruz MS, Loureiro JP, Oliveira MJ, Macedo MF. The iNKT cell-macrophage axis in homeostasis and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1640. doi:10.3390/ijms23031640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Yamamura T, Sakuishi K, Illés Z, Miyake S. Understanding the behavior of invariant NKT cells in autoimmune diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;191(1):8–15. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.09.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Li J, Xiao C, Li C, He J. Tissue-resident immune cells: from defining characteristics to roles in diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):12. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-02050-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kurioka A, Klenerman P. Aging unconventionally: γδ T cells, iNKT cells, and MAIT cells in aging. Semin Immunol. 2023;69:101816. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2023.101816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Attaf M, Legut M, Cole DK, Sewell AK. The T cell antigen receptor: the Swiss army knife of the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;181(1):1–18. doi:10.1111/cei.12622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Lee-Chang C, Lesniak MS. Next-generation antigen-presenting cell immune therapeutics for gliomas. J Clin Investig. 2023;133(3):e163449. doi:10.1172/jci163449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Neal LR, Bailey SR, Wyatt MM, Bowers JS, Majchrzak K, Nelson MH, et al. The basics of artificial antigen presenting cells in T cell-based cancer immunotherapies. J Immunol Res Ther. 2017;2(1):68–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

52. Syed Altaf RR, Mohan A, Palani N, Mendonce KC, Monisha P, Rajadesingu S. A review of innovative design strategies: artificial antigen presenting cells in cancer immunotherapy. Int J Pharm. 2025;669(9–10):125053. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.125053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Choi H, Lee Y, Hur G, Lee SE, Cho HI, Sohn HJ, et al. γδ T cells cultured with artificial antigen-presenting cells and IL-2 show long-term proliferation and enhanced effector functions compared with γδ T cells cultured with only IL-2 after stimulation with zoledronic acid. Cytotherapy. 2021;23(10):908–17. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Suhoski MM, Golovina TN, Aqui NA, Tai VC, Varela-Rohena A, Milone MC, et al. Engineering artificial antigen-presenting cells to express a diverse array of co-stimulatory molecules. Mol Ther. 2007;15(5):981–8. doi:10.1038/mt.sj.6300134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Friedl P, Gunzer M. Interaction of T cells with APCs: the serial encounter model. Trends Immunol. 2001;22(4):187–91. doi:10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01869-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Gaudino SJ, Kumar P. Cross-talk between antigen presenting cells and T cells impacts intestinal homeostasis, bacterial infections, and tumorigenesis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:360. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Rossi M, Young JW. Human dendritic cells: potent antigen-presenting cells at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1373–81. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):265–77. doi:10.1038/nrc3258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Almand B, Resser JR, Lindman B, Nadaf S, Clark JI, Kwon ED, et al. Clinical significance of defective dendritic cell differentiation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):1755–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

60. Butler MO, Hirano N. Human cell-based artificial antigen-presenting cells for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2014;257(1):191–209. doi:10.1111/imr.12129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Prakken B, Wauben M, Genini D, Samodal R, Barnett J, Mendivil A, et al. Artificial antigen-presenting cells as a tool to exploit the immune ‘synapse’. Nat Med. 2000;6(12):1406–10. doi:10.1038/82231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Oelke M, Maus MV, Didiano D, June CH, Mackensen A, Schneck JP. Ex vivo induction and expansion of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells by HLA-Ig-coated artificial antigen-presenting cells. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):619–24. doi:10.1038/nm869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Maus MV, Riley JL, Kwok WW, Nepom GT, June CH. HLA tetramer-based artificial antigen-presenting cells for stimulation of CD4+ T cells. Clin Immunol. 2003;106(1):16–22. doi:10.1016/s1521-6616(02)00017-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Kim S, Sohn HJ, Lee HJ, Sohn DH, Hyun SJ, Cho HI, et al. Use of engineered exosomes expressing HLA and costimulatory molecules to generate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells for adoptive cell therapy. J Immunother. 2017;40(3):83–93. doi:10.1097/cji.0000000000000151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ratta M, Fagnoni F, Curti A, Vescovini R, Sansoni P, Oliviero B, et al. Dendritic cells are functionally defective in multiple myeloma: the role of interleukin-6. Blood. 2002;100(1):230–7. doi:10.1182/blood.v100.1.230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Satthaporn S, Robins A, Vassanasiri W, El-Sheemy M, Jibril JA, Clark D, et al. Dendritic cells are dysfunctional in patients with operable breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53(6):510–8. doi:10.1007/s00262-003-0485-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Li J, Zhou W, Wang W. Artificial antigen-presenting cells: the booster for the obtaining of functional adoptive cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81(1):378. doi:10.1007/s00018-024-05412-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Morandi F, Yazdanifar M, Cocco C, Bertaina A, Airoldi I. Engineering the bridge between Innate and adaptive immunity for cancer immunotherapy: focus on γδ T and NK cells. Cells. 2020;9(8):1757. doi:10.3390/cells9081757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Coppola C, Hopkins B, Huhn S, Du Z, Huang Z, Kelly WJ. Investigation of the impact from IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 on the growth and signaling of activated CD4+ T Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):7814. doi:10.3390/ijms21217814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Shouse AN, LaPorte KM, Malek TR. Interleukin-2 signaling in the regulation of T cell biology in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2024;57(3):414–28. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2024.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Paul P, Choong C, Heinemann J, Al-Hallaf R, Agha Z, Ganatra S, et al. The lasting impact of IL-2: approaching 50 years of advancing immune tolerance, cancer immunotherapies, and autoimmune diseases. Immunol Investig. 2025;54(5):589–603. doi:10.1080/08820139.2025.2479609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zhou Y, Husman T, Cen X, Tsao T, Brown J, Bajpai A, et al. Interleukin 15 in cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13):7311. doi:10.3390/ijms23137311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Mathieu C, Beltra J-C, Charpentier T, Bourbonnais S, Di Santo JP, Lamarre A, et al. IL-2 and IL-15 regulate CD8+ memory T-cell differentiation but are dispensable for protective recall responses. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(12):3324–38. doi:10.1002/eji.201546000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Mazet JM, Mahale JN, Tong O, Watson RA, Lechuga-Vieco AV, Pirgova G, et al. IFNγ signaling in cytotoxic T cells restricts anti-tumor responses by inhibiting the maintenance and diversity of intra-tumoral stem-like T cells. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):321. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-35948-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Liu X. The paradoxical role of IFN-γ in cancer: balancing immune activation and immune evasion. Pathol Res Pract. 2025;272:156046. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2025.156046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Vazquez-Lombardi R, Roome B, Christ D. Molecular engineering of therapeutic cytokines. Antibodies. 2013;2(3):426–51. doi:10.3390/antib2030426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Fu Y, Tang R, Zhao X. Engineering cytokines for cancer immunotherapy: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1218082. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1218082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Shi W, Liu N, Lu H. Advancements and challenges in immunocytokines: a new arsenal against cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14(11):4649–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

79. Uricoli B, Birnbaum LA, Do P, Kelvin JM, Jain J, Costanza E, et al. Engineered cytokines for cancer and autoimmune disease immunotherapy. Adv Heal Mater. 2021;10(15):e2002214. doi:10.1002/adhm.202002214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Rokade S, Damani AM, Oft M, Emmerich J. IL-2 based cancer immunotherapies: an evolving paradigm. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1433989. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1433989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Ren J, Chu AE, Jude KM, Picton LK, Kare AJ, Su L, et al. Interleukin-2 superkines by computational design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(12):e2117401119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2117401119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Luo J, Guo M, Huang M, Liu Y, Qian Y, Liu Q, et al. Neoleukin-2/15-armored CAR-NK cells sustain superior therapeutic efficacy in solid tumors via c-Myc/NRF1 activation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):78. doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02158-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Dozier JK, Distefano MD. Site-specific PEGylation of therapeutic proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(10):25831–64. doi:10.3390/ijms161025831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Lucchi R, Bentanachs J, Oller-Salvia B. The masking game: design of activatable antibodies and mimetics for selective therapeutics and cell control. ACS Cent Sci. 2021;7(5):724–38. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c01448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Anderson CK, Reilly SP, Brossay L. The invariant NKT cell response has differential signaling requirements during antigen-dependent and antigen-independent activation. J Immunol. 2021;206(1):132–40. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.2000870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Reilly EC, Wands JR, Brossay L. Cytokine dependent and independent iNKT cell activation. Cytokine. 2010;51(3):227–31. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2010.04.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Lv Y, Qi J, Babon JJ, Cao L, Fan G, Lang J, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: from structural biology to cytokine engineering. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):221. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01934-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Morris R, Kershaw NJ, Babon JJ. The molecular details of cytokine signaling via the JAK/STAT pathway. Protein Sci. 2018;27(12):1984–2009. doi:10.1002/pro.3519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Zhang J, Jia Z, Pan H, Ma W, Liu Y, Tian X, et al. From induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) to universal immune cells: literature review of advances in a new generation of tumor therapies. Transl Cancer Res. 2025;14(4):2495–507. doi:10.21037/tcr-24-1087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Xiao X, Huang S, Chen S, Wang Y, Sun Q, Xu X, et al. Mechanisms of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity of CAR T-cell therapy and associated prevention and management strategies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

91. Niedzielska M, Chalmers A, Popis MC, Altman-Sharoni E, Addis S, Beulen R, et al. CAR-iNKT cells: redefining the frontiers of cellular immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1625426. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1625426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Peng K, Fu Y-X, Liang Y. Engineering cytokines for tumor-targeting and selective T cell activation. Trends Mol Med. 2025;31(4):373–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

93. Yi M, Li T, Niu M, Zhang H, Wu Y, Wu K, et al. Targeting cytokine and chemokine signaling pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):176. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01868-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Verkerk T, Pappot AT, Jorritsma T, King LA, Duurland MC, Spaapen RM, et al. Isolation and expansion of pure and functional γδ T cells. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1336870. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1336870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Llames S, García-Pérez E, Meana Á, Larcher F, del RíoM. Feeder layer cell actions and applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2015;21(4):345–53. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2014.0547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Xiao L, Chen C, Li Z, Zhu S, Tay JC, Zhang X, et al. Large-scale expansion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with engineered K562 feeder cells in G-Rex vessels and their use as chimeric antigen receptor-modified effector cells. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(3):420–35. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.12.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Hernandez Tejada FN, Jawed J, Olivares S, Mahadeo KM, Singh H. Gamma delta T cells for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2022;140(Supplement 1):12696. doi:10.1182/blood-2022-162635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Tanimoto K, Muranski P, Miner S, Fujiwara H, Kajigaya S, Keyvanfar K, et al. Genetically engineered fixed K562 cells: potent off-the-shelf antigen-presenting cells for generating virus-specific T cells. Cytotherapy. 2014;16(1):135–46. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.08.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Day NE, Ugai H, Yokoyama KK, Ichiki AT. K-562 cells lack MHC class II expression due to an alternatively spliced CIITA transcript with a truncated coding region. Leuk Res. 2003;27(11):1027–38. doi:10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00072-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Kaur K, Jewett A. Similarities and differences between osteoclast-mediated functional activation of NK, CD3+ T, and γδ T cells from humans, humanized-BLT mice, and WT mice. Crit Rev Immunol. 2024;44(2):61–75. doi:10.1615/critrevimmunol.2023051091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Park S, Kanayama K, Kaur K, Tseng HC, Banankhah S, Quje DT, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw developed in mice: disease variants regulated by γδ T cells in oral mucosal barrier immunity. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(28):17349–66. doi:10.1074/jbc.m115.652305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Kaur K, Jewett A. Osteoclasts and probiotics mediate significant expansion, functional activation and supercharging in NK, γδ T, and CD3+ T cells: use in cancer immunotherapy. Cells. 2024;13(3):213. doi:10.3390/cells13030213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. de Pooter R, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. T-cell potential and development in vitro: the OP9-DL1 approach. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(2):163–8. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Bonte S, de Munter S, Billiet L, Goetgeluk G, Ingels J, Jansen H, et al. In vitro OP9-DL1 co-culture and subsequent maturation in the presence of IL-21 generates tumor antigen-specific T cells with a favorable less-differentiated phenotype and enhanced functionality. Oncoimmunology. 2021;10(1):1954800. doi:10.1080/2162402x.2021.1954800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Chaudhry MS, Karadimitris A. Role and regulation of CD1d in normal and pathological B cells. J Immunol. 2014;193(10):4761–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Leung CS, Maurer MA, Meixlsperger S, Lippmann A, Cheong C, Zuo J, et al. Robust T-cell stimulation by Epstein-Barr virus–transformed B cells after antigen targeting to DEC-205. Blood. 2013;121(9):1584–94. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-08-450775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Bui KC, Ho VH, Nguyen HH, Dang TC, Ngo TH, Nguyen TML, et al. X-ray-irradiated K562 feeder cells for expansion of functional CAR-T cells. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2023;33(6):101399. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2022.101399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Wang Z, Zhang G. CAR-iNKT cell therapy: mechanisms, advantages, and challenges. Curr Res Transl Med. 2025;73(1):103488. doi:10.1016/j.retram.2024.103488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Xian Y, Wen L. CAR beyond αβ T cells: unleashing NK cells, macrophages, and γδ T lymphocytes against solid tumors. Vaccines. 2025;13(6):654. doi:10.3390/vaccines13060654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Yu J-S, Lin C-H, Tung Y-T, Chang F-P, Chu EP-F, Jian S-L, et al. iPSC-derived CAR-gamma delta T with novel combinatorial KO demonstrated extended longevity and profound anti-tumor efficacy without cytokine support in preclinical studies. Blood. 2024;144(Supplement 1):4790. doi:10.1182/blood-2024-205086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Hattori Y, Kubo T, Nagano S, Miyama T, Taniguchi Y, Iba Y, et al. Anti-CD38-CAR IPS-Derived Cytotoxic T lymphocytes efficiently eliminate myeloma cells treated with daratumumab and isatuximab in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2023;142(Supplement 1):3312. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-173356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Ding L, Li Y, Li J, ter Haak M, Lamb LS. Gamma-delta (γδ) CAR-T cells lacking the CD3z signaling domain enhance targeted killing of tumor cells and preserve healthy tissues. Blood. 2023;142(Supplement 1):6835. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-187287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

113. Rozenbaum M, Meir A, Aharony Y, Itzhaki O, Schachter J, Bank I, et al. Gamma-delta CAR-T cells show car-directed and independent activity against leukemia. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1347. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Heczey A, Xu X, Courtney AN, Tian G, Barragan GA, Guo L, et al. Anti-GD2 CAR-NKT cells in relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: updated phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2023;29(6):1379–88. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02363-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Nazha B, Inal C, Owonikoko TK. Disialoganglioside GD2 expression in solid tumors and role as a target for cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1000. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.01000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Heczey A, Liu D, Tian G, Courtney AN, Wei J, Marinova E, et al. Invariant NKT cells with chimeric antigen receptor provide a novel platform for safe and effective cancer immunotherapy. Blood. 2014;124(18):2824–33. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-11-541235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. O’Neal J, Cooper ML, Ritchey JK, Gladney S, Niswonger J, González LS, et al. Anti-myeloma efficacy of CAR-iNKT is enhanced with a long-acting IL-7, rhIL-7-hyFc. Blood Adv. 2023;7(20):6009–22. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Ponnusamy K, Randzavola L, Ren H, Karaxhuku K, Lye B, Leonardos D, et al. Optimal, off-the-shelf, CAR-iNKT cell platform-based immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2023;142(Supplement 1):3459. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-189905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

119. Zhou X, Wang Y, Dou Z, Delfanti G, Tsahouridis O, Pellegry CM, et al. CAR-redirected natural killer T cells demonstrate superior antitumor activity to CAR-T cells through multimodal CD1d-dependent mechanisms. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(11):1607–21. doi:10.1038/s43018-024-00830-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Ramos CA, Courtney AN, Lulla PD, Hill LC, Kamble RT, Carrum G, et al. Off-the-shelf CD19-specific CAR-NKT cells in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies. Transplant Cell Ther. 2024;30(2 Suppl):S41–2. doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2023.12.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

121. Yan H, Boonchalermvichian C, Gupta B, Wang S, Baker J, Simonetta F, et al. CD117 CAR-iNKT cells as a safe and effective off-the-shelf allogeneic cell therapy for AML. Transplant Cell Ther Off Publ Am Soc Transplant Cell Ther. 2025;31(2):S242–3. doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2025.01.369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

122. Simon B, Wiesinger M, März J, Wistuba-Hamprecht K, Weide B, Schuler-Thurner B, et al. The generation of CAR-transfected natural killer T cells for the immunotherapy of melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2365. doi:10.3390/ijms19082365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Rowan AG, Ponnusamy K, Ren H, Taylor GP, Cook LBM, Karadimitris A. CAR-iNKT cells targeting clonal TCRVβ chains as a precise strategy to treat T cell lymphoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1118681. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1118681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Dai Z, Zhu Z, Li Z, Tian L, Teng KY, Chen H, et al. Off-the-shelf invariant NKT cells expressing anti-PSCA CAR and IL-15 promote pancreatic cancer regression in mice. J Clin Investig. 2025;135(8):e179014. doi:10.1172/jci179014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Ibbett P, Dijk MV, Chantzoura E, Antonopoulos G, Sans GR, Niedzielska M, et al. 374 PRAME-TCR iNKT cell therapy: opportunity for best-in-class off-the-shelf solid tumor therapy targeting PRAME. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2024;12 Suppl 2:A430. doi:10.1136/jitc-2024-sitc2024.0374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

126. Simonetta F, Lohmeyer JK, Hirai T, Maas-Bauer K, Alvarez M, Wenokur AS, et al. Allogeneic CAR invariant natural killer t cells exert potent antitumor effects through host CD8 T-cell cross-priming. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(21):6054–64. doi:10.1101/2021.02.03.428987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

127. Subhi-Issa N, Tovar Manzano D, Pereiro Rodriguez A, Sanchez Ramon S, Perez Segura P, Ocaña A. γδ T cells: game changers in immune cell therapy for cancer. Cancers. 2025;17(7):1063. doi:10.3390/cancers17071063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Park WH, Lee HK. Human γδ T cells in the tumor microenvironment: key insights for advancing cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cells. 2025;48(2):100177. doi:10.1016/j.mocell.2025.100177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Wang CQ, Lim PY, Tan AH. Gamma/delta T cells as cellular vehicles for anti-tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1282758. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1282758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Arias-Badia M, Chang R, Fong L. γδ T cells as critical anti-tumor immune effectors. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(8):1145–57. doi:10.1038/s43018-024-00798-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Cieslak SG, Shahbazi R. Gamma delta T cells and their immunotherapeutic potential in cancer. Biomark Res. 2025;13(1):51. doi:10.1186/s40364-025-00762-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Park JH, Lee HK. Function of γδ T cells in tumor immunology and their application to cancer therapy. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53(3):318–27. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00576-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Luo X, Lv Y, Yang J, Long R, Qiu J, Deng Y, et al. Gamma delta T cells in cancer therapy: from tumor recognition to novel treatments. Front Med. 2024;11:1480191. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1480191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Fiala GJ, Lücke J, Huber S. Pro- and antitumorigenic functions of γδ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54(8):2451070. doi:10.1002/eji.202451070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Barisa M, Nattress C, Fowler D, Anderson J, Fisher J. Chapter 5—γδ T cells for cancer immunotherapy: a 2024 comprehensive systematic review of clinical trials. In: Barisa M, editor. γδT cell cancer immunotherapy. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2025. p. 103–53. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-21766-1.00002-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

136. Li Y, Mo XP, Yao H, Xiong QX. Research progress of γδT cells in tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241284863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

137. Jhita N, Raikar SS. Allogeneic gamma delta T cells as adoptive cellular therapy for hematologic malignancies. Explor Immunol. 2022;2(3):334–50. doi:10.37349/ei.2022.00054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

138. Bejanyan N, Elmariah H, Reid K, Yu B, Kim J, Cox C, et al. Phase I trial of allogeneic donor gamma delta t cell infusion post-hematopoietic cell transplantation, an interim safety report. Blood. 2023;142(Supplement 1):4846. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-187058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

139. Bejanyan N, Elmariah H, Kim J, Cox C, Lowden M, Song X, et al. Phase I trial of ex vivo expanded donor gamma delta T cell immunotherapy to prevent acute myeloid leukemia relapse after allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2024;144(Supplement 1):4826. doi:10.1182/blood-2024-202363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

140. Saura-Esteller J, de Jong M, King LA, Ensing E, Winograd B, de Gruijl TD, et al. Gamma delta T-Cell based cancer immunotherapy: past-present-future. Front Immunol. 2022;13:915837. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.915837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

141. Bold A, Gross H, Holzmann E, Knop S, Hoeres T, Wilhelm M. An optimized cultivation method for future in vivo application of γδ T cells. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1185564. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1185564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]