Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 Promotes Early Osteogenic Differentiation of H-BMSCs by Activating the JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway

1 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Sinopharm Dongfeng General Hospital, Hubei University of Medicine, Shiyan, 442008, China

2 Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Cell Precision Therapy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Jiujiang University, Jiujiang, 332005, China

* Corresponding Authors: Zhimin Zhang. Email: ; Tao Wang. Email:

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.074782

Received 17 October 2025; Accepted 26 December 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

Objectives: The discovery of novel molecular targets to enhance the osteogenesis of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (H-BMSCs) represents a promising strategy for preventing and treating osteoporosis. Thus, the primary objective of this study is to elucidate the mechanisms by which long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 (lncRNA FOXD2-AS1) regulates early osteogenic differentiation in H-BMSCs, thereby identifying potential therapeutic targets. Methods: Lentivirus-mediated vectors were constructed to either overexpress or silence FOXD2-AS1 in H-BMSCs. The effects of FOXD2-AS1 on osteogenesis were subsequently assessed by analyzing osteogenic marker expression and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining. To clarify the role of the Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3(JAK2/STAT3) pathway in this process, AG490 inhibitor (a JAK2/STAT3 pathway inhibitor) and knockdown of STAT3 were used to investigate the mechanisms of FOXD2-AS1. Results: FOXD2-AS1 overexpression increased ALP activity and osteogenic marker expression, while its knockdown had the opposite effects. From a mechanistic perspective, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression promoted JAK2 and STAT3 phosphorylation, whereas its suppression attenuated their activation. Also, the osteogenic increase induced by FOXD2-AS1 overexpression was reversed by AG490 treatment or STAT3 silencing, indicating that the pathway plays a role in this process. Conclusion: FOXD2-AS1 was identified as a novel genetic switch driving osteogenic commitment via JAK2/STAT3 activation, revealing a new regulatory mechanism and a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe therapeutic potential of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (H-BMSCs) stems from their multipotency, which permits commitment to osteoblastic, adipocytic, and chondrocytic lineages. Osteoblasts generated from H-BMSCs are one of these lineages that are essential for bone production, remodeling, and repair [1]. Extensive evidence indicates that reduced osteogenic differentiation capacity of H-BMSCs disrupts the balance between bone formation and resorption, resulting in abnormal bone metabolism and compromised skeletal homeostasis. This imbalance represents a key pathological factor in the development of osteoporosis. Although anabolic agents such as teriparatide have been introduced to stimulate bone formation, their clinical application is constrained by high cost, potential adverse effects, and limited treatment duration. Therefore, identifying novel molecular targets that enhance H-BMSC osteogenesis represents a promising strategy for the management and prevention of osteoporosis [2,3]. Therefore, promoting osteogenesis in H-BMSCs is an attractive approach for treating osteoporosis.

The transcriptome is rich with long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides that lack open reading frames. These elements have rapidly emerged as essential components in the control of cellular programming and gene regulatory networks [4]. Accumulating evidence establishes long non-coding RNAs as key regulators of diverse biological processes, including cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and metabolic homeostasis. The human gene encoding the long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 (NR_026878) is located on chromosome 1p33 and produces a primary transcript of 2527 nucleotides [5]. Previous studies have reported elevated FOXD2-AS1 expression in multiple malignancies, including esophageal cancer [6], renal cancer [7], oral cancer [8], and ovarian cancer [9], where it enhances the invasive, migratory, and proliferative capacity of cancer cells through various regulatory mechanisms. However, despite its documented functions in cancer biology, the involvement of FOXD2-AS1 in cell differentiation, particularly osteogenic differentiation, remains largely unexplored.

The Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway is a key signaling cascade that mediates cellular responses to growth factors and cytokines. Upon activation, JAKs phosphorylate STAT proteins, promoting their dimerization and subsequent regulation of target gene transcription. As a central signaling hub, the Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK2/STAT3) pathway integrates diverse signals that regulate fundamental processes, including cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and immune function [10,11]. As a result, its dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous pathological conditions. Accumulating evidence now indicates that there exists a regulatory mechanism in which lncRNAs directly influence the JAK/STAT signalling cascade, modulating a wide spectrum of cellular activities [12–14].

Hence, this study hypothesized that FOXD2-AS1 promotes the early osteogenic differentiation of H-BMSCs by activating the JAK2/STAT3 pathway.

2.1 Culture of H-BMSCs and Induction of Osteogenesis

H-BMSCs were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences (cat. no. HUXMA-01001, Guangzhou, China). The phenotypic characteristics of H-BMSCs (cell lots from three donors: 150724I31, 160202I31, and 161125R41) were analyzed to confirm mesenchymal stem cell identity (Figs. S1–S3). Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that ≥95% of cells expressed the mesenchymal markers CD73 (cat. no. 561014, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), CD90 (cat. no. 561969, BD Biosciences), and CD105 (cat. no. 560839, BD Biosciences). In comparison, ≤5% of cells were negative for the hematopoietic and immune markers CD34 (cat. no. 560941, BD Biosciences), CD19 (cat. no. 560994, BD Biosciences), CD11b (cat. no. 561001, BD Biosciences), CD45 (cat. no. 560976, BD Biosciences), and HLA-DR (cat. no. 560944, BD Biosciences), consistent with the established surface marker profile of H-BMSCs. Analyses were performed using a BD FACSAria™ Fusion cell sorter (BD Biosciences). All H-BMSC cultures were routinely screened and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination.

H-BMSCs were cultured in oriCell™ H-BMSC growth medium (cat. no. HUXMA-90011, Cyagen Biosciences, Guangzhou, China) supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), L-glutamine (cat. no. 25030081, Gibco), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no. 10270106, Gibco). Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 and maintained under standard culture conditions at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To ensure cellular consistency, subculturing was performed every 3–4 days using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (cat. no. 25200056, Gibco). Cells at passage 6 were used for all subsequent experiments.

Upon reaching approximately 70% confluency, osteogenic differentiation was initiated by replacing the growth medium with osteogenic induction medium supplemented with ascorbic acid (50 μM; cat. no. A7506, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), dexamethasone (100 nM; cat. no. D4902, Sigma-Aldrich), and β-glycerophosphate (10 mM; cat. no. G9422, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were maintained under induction conditions for the designated differentiation period, with medium changes performed every 3 days.

Lentiviral vectors (Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were employed to either knock down or overexpress FOXD2-AS1 in H-BMSCs. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting FOXD2-AS1 and STAT3 were designed, which are artificial RNA molecules that form a hairpin structure and are processed into mature siRNAs within cells to mediate gene silencing.

FOXD2-AS1 shRNA: 5′-GATCCGCGAAGAGTACGTTGCTATTTCAAGAGAATAGCAACGTACTCTTCGCTTTTTTC-3′; STAT3 shRNA: 5′-AATCGTGGATCTGTTCAGAAACTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAGTTTCTGAACAGATCCACGATC-3′. To control for off-target effects, cells were transduced with a scrambled shRNA construct (5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′). Oligonucleotides were engineered into lentiviral vectors to achieve either knockdown (pGV493-FOXD2-AS1; pGV493-STAT3) or overexpression (pGV280-FOXD2-AS1). Successful transduction was confirmed via the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter present in both vector backbones.

Lentiviral transduction was performed on H-BMSCs seeded at a density of 7.5 × 104 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates. The transduction procedure used a lentiviral stock at 1 × 108 IU/mL, with an MOI of 5, supplemented with 5 μg/mL polybrene, and incubated for 10 h at 37°C. The viral supernatant was then replaced with fresh growth medium, and the cells were cultured for 72 h to recover. Subsequently, stable transfectants were selected by treating the cells with 0.5 μg/mL puromycin for 6 days, with the selection medium being refreshed every 2 days.

H-BMSCs were assigned to the FOXD2-AS1 overexpression group, the FOXD2-AS1 shRNA group, the AG490 group (cells treated with 100 nM of the selective JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor AG490 [15,16]; cat. no. S1143, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), and the STAT3 knockdown group. Corresponding control groups were established for each treatment group. Then, osteogenic culture medium was prepared using specialized media, and subsequent experiments were conducted.

2.4 Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Analysis

Cellular ALP staining was conducted using a commercial detection kit (cat. no. P0321S, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Before staining, cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Following fixation, cells were equilibrated twice for 5 min in ALP buffer containing 50 mM MgCl2·6H2O (pH 9.5), 0.1 M Tris-HCl, and 0.1 M NaCl. Then, 1 mL of ALP substrate solution supplemented with 10 μL NBT and 5 μL BCIP was added to each well, and samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was terminated by rinsing with distilled water, and stained cells were imaged using a light microscope (BX53, Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan).

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was quantitatively measured in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions using a commercial assay kit (cat. no. A059-2, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Ltd., Nanjing, China). To release endogenous ALP, cells were subjected to four freeze–thaw cycles. The resulting lysates were incubated with 100 μL of ALP substrate in 96-well plates at 37°C, after which the addition of stop solution terminated the reaction. ALP activity, calculated from p-nitrophenol concentration, was determined by measuring absorbance at 520 nm with a Bio-Rad microplate reader (Model 680, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.5 Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

The complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from purified total RNA (extracted with TRIzol reagent; cat. no. 15596026, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by reverse transcription using an Oligo (dT) primer system (cat. no. K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocols. The specific operation is as follows: a 20 μL reverse transcription reaction was prepared with 1 μg total RNA, 1 μM Oligo(dT) primer, reaction buffer, 1 mM dNTPs, 100–200 U reverse transcriptase, and RNase inhibitor. The thermal profile consisted of primer annealing (65°C for 5 min) followed by immediate cooling on ice, cDNA synthesis (42°C for 60 min), and final enzyme inactivation (70°C for 5 min). Gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR with the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ kit (cat. no. QPK-212, TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) on an ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). Gene expression levels were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method with β-actin normalization. The sequences of the primers used are as follows:

Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2 (RUNX2):

forward primer:5′-GGACGAGGCAAGAGTTTCACC-3′,

reverse primer:5-GGTTCCCGAGGTCCATCTACT-3′;

Osteocalcin(OCN):

forward primer:5′-TGAGAGCCCTCACACTCCTC-3′,

reverse primer:5′-CGCCTGGGTCTCTTCACTAC-3′;

ALP:

forward primer:5′-CCCCGTGGCAACTCTATCTTT-3′,

reverse primer:5′-GCCTGGTAGTTGTTGTGAGCATAG-3′;

FOXD2-AS1:

forward primer:5′-GCCCAGAACAATTGGGAGGA-3′,

reverse primer:5′-AAGAGAGGGAGAGACGACCC-3′;

STAT3:

forward primer:5′-TGGCCCCTTGGATTGAGAGT-3′,

reverse primer:5′-ATTGGCTTCTCAAGATACCTGCT-3′;

β-actin:

forward primer:5′-GCGAGAAGATGACCCAGATCATGT-3′,

reverse primer:5′-TACCCCTCGTAGATGGGCACA-3′.

Cellular proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer and quantified with a BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. 23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, protein samples were mixed with the BCA working reagent (cat. no. 23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and incubated at 60°C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 562 nm, and protein concentrations were calculated using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard curve (cat. no. 232029, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). For denaturation, equal volumes of protein lysate were mixed with 5× SDS sample buffer and heated for 5 min. Afterwards, 15 μg of total protein per sample was separated on 10% SDS–PAGE gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (cat. no. IPVH00010, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

Membranes were blocked for 2 h in 5% non-fat milk/TBST at 25°C. Subsequently, they probed overnight at 4°C with specific primary antibodies targeting RUNX2 (cat. no. AF5186, Affinity Biosciences, Suzhou, China), OCN (cat. no. DF12303, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), JAK2 (cat. no. AF3024, Affinity Biosciences), phospho-JAK2 (cat. no. AF6022, Affinity Biosciences), STAT3 (cat. no. AF6294, Affinity Biosciences), phospho-STAT3 (cat. no. AF3293, Affinity Biosciences), and β-actin (cat. no. AF7018, Affinity Biosciences) at a 1:1000 dilution. The membranes were subjected to three sequential washes with Tris-Buffered Saline with Tween® 20 (TBST) before a one-hour incubation at ambient temperature with an HRP-linked anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat. no. 7074, Cell Signaling Technology) diluted 1:5000. An enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (BeyoECL Plus, cat. no. P0018; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to identify protein signals. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.53; National Institutes of Health, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), and protein expression levels were normalized to β-actin as a loading control.

For statistical analysis, SPSS v. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Quantitative findings are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from a minimum of three biological replicates. The data were analyzed using a student’s t-test or a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. The results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

3.1 FOXD2-AS1 Expression during Osteogenesis of H-BMSCs

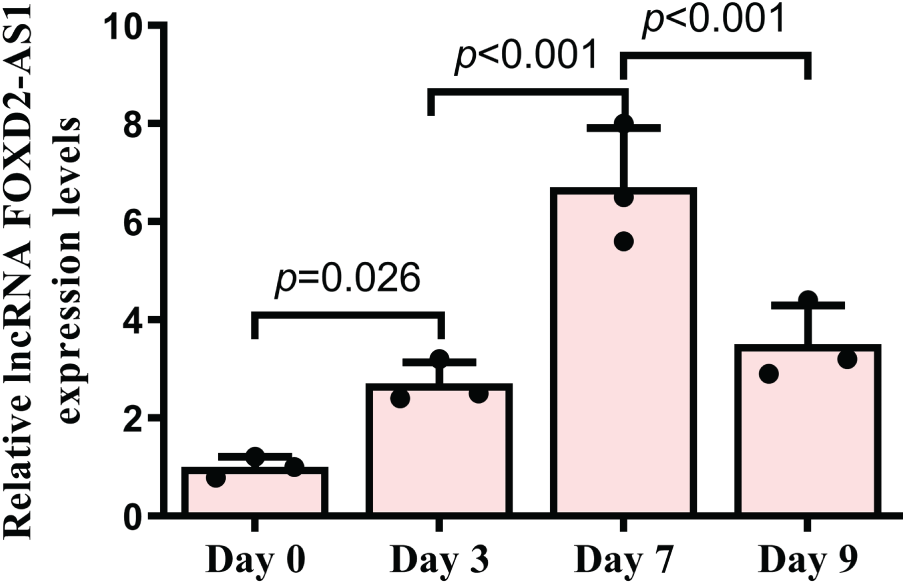

FOXD2-AS1 expression was investigated at days 0, 3, 7, and 9 of differentiation. The results showed a gradual increase in FOXD2-AS1 levels, peaking on day 7 (Fig. 1). These results suggest that FOXD2-AS1 may have a regulatory function in the early stages of osteogenic differentiation in H-BMSCs.

Figure 1: The temporal expression profile of FOXD2-AS1 during H-BMSC osteogenesis was analyzed by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) at serial time points. Results, derived from three independent replicates (n = 3), are expressed as means ± Standard Deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA

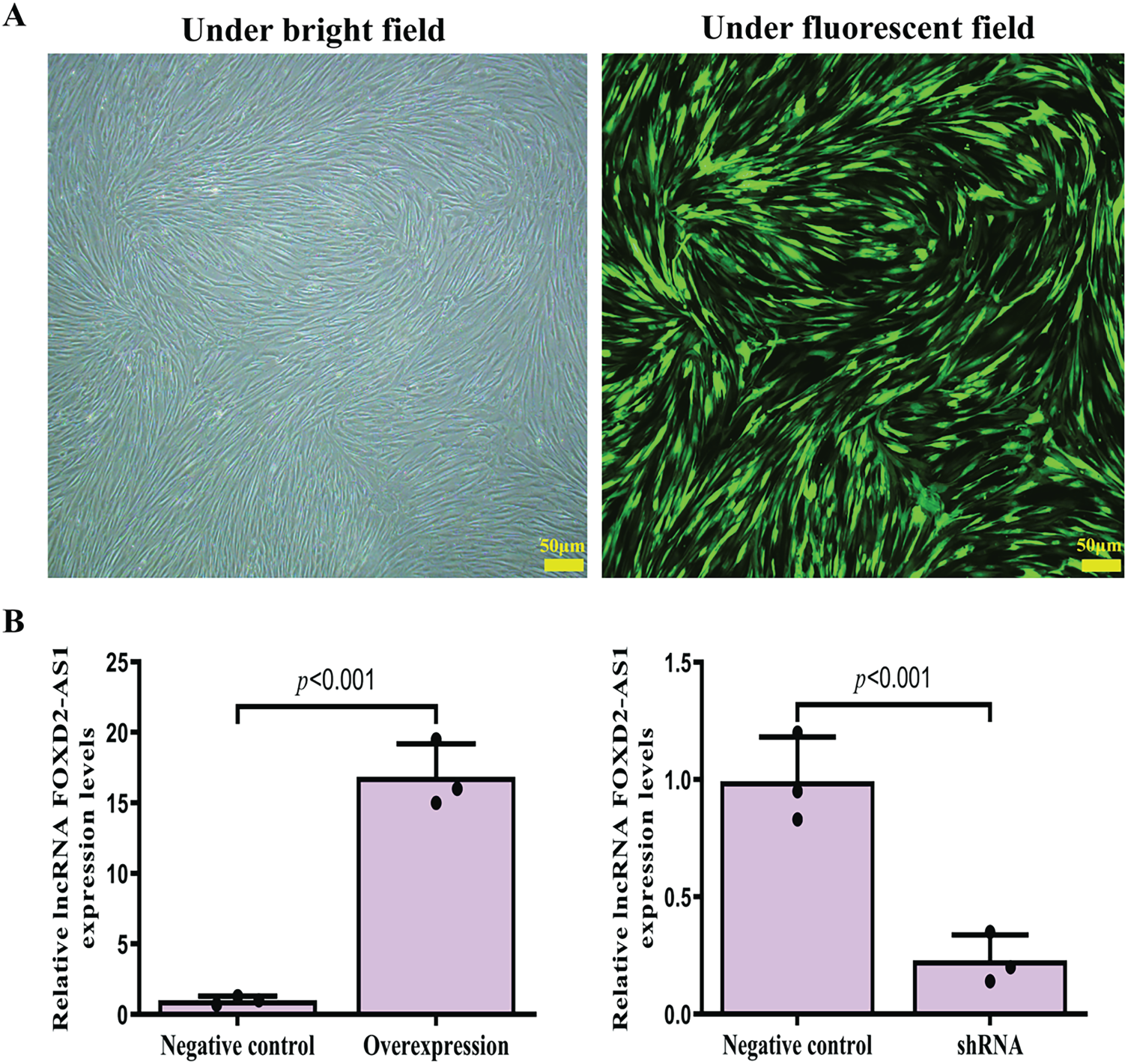

3.2 Efficient Overexpression and Knockdown of FOXD2-AS1 in H-BMSCs

Following lentiviral transduction, H-BMSCs that survived puromycin selection by day 6 showed strong resistance, suggesting a high transduction efficiency. Further, fluorescence microscopy revealed healthy cell morphology and prominent GFP fluorescence (Fig. 2A). RT-qPCR analysis confirmed the efficacy of lentivirus-mediated FOXD2-AS1 overexpression and knockdown (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2: Efficient lentiviral transduction and resultant FOXD2-AS1 expression. (A) Fluorescence and corresponding bright-field micrographs of H-BMSCs captured 6 days after lentiviral infection (10× magnification; scale bar represents 50 μm). (B) RT → qPCR analysis was performed to assess the success of FOXD2-AS1 manipulation, demonstrating significant suppression in the shRNA group and elevation in the overexpression (OE) group compared to controls. Data points are the average of three independent trials ± standard deviation (n = 3; Student’s t-test). Abbreviations: Overexpression, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression; shRNA, FOXD2-AS1 short hairpin RNA

3.3 FOXD2-AS1 Regulates Early Osteogenic Differentiation of H-BMSCs

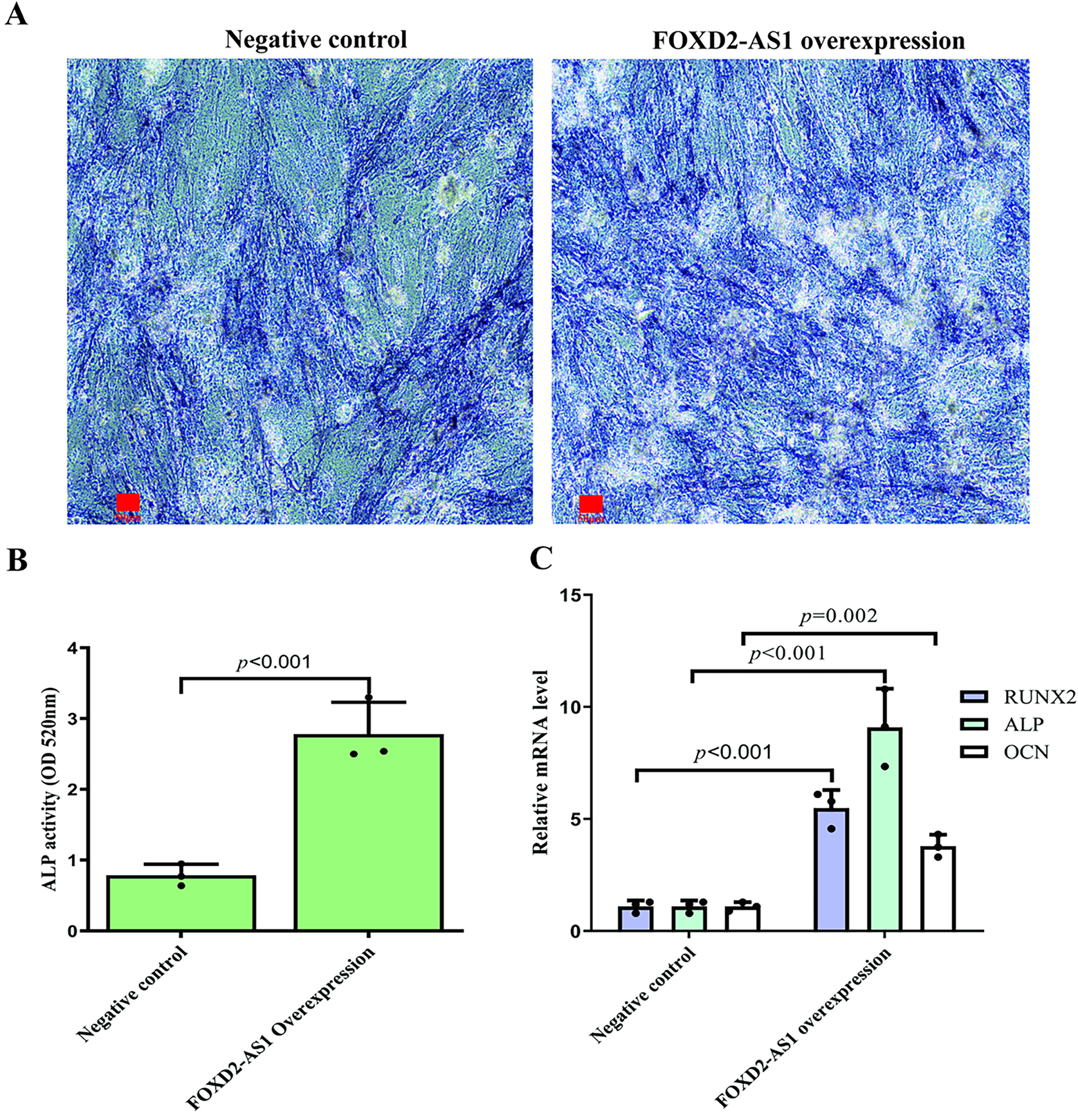

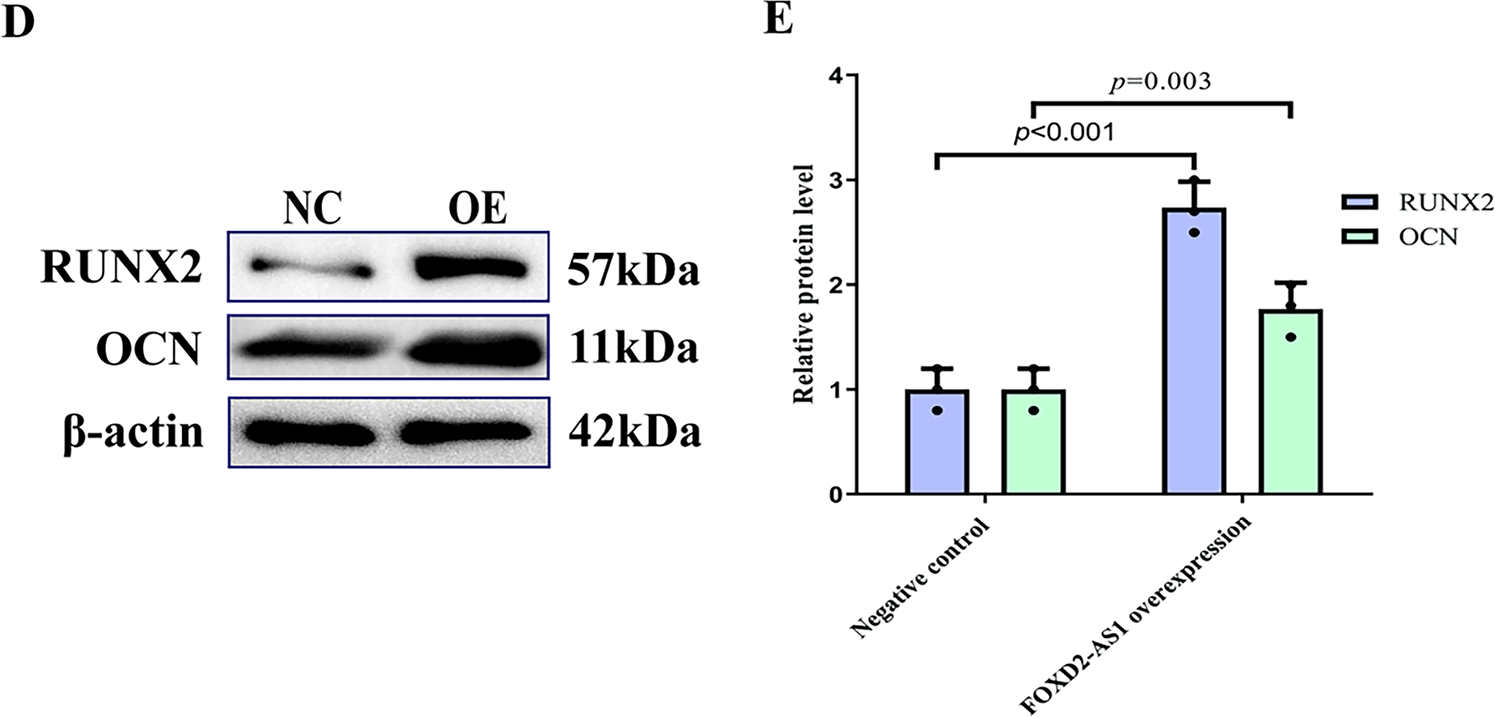

On day 7 of osteogenic induction, the osteogenic capacity of H-BMSCs was evaluated by ALP staining, with ALP-positive cells demonstrating a characteristic blue-violet colour. FOXD2-AS1 overexpression resulted in markedly stronger ALP staining (Fig. 3A). Consistent with this finding, quantitative measurement of intracellular ALP activity demonstrated significantly elevated ALP levels in FOXD2-AS1–overexpressing cells compared with control cells (Fig. 3B). The expression of key osteogenic markers, including OCN, ALP, and RUNX2, was assessed in transduced H-BMSCs. At day 7 of differentiation, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression significantly increased both the mRNA and protein levels of these markers (Fig. 3C–E). Silencing of FOXD2-AS1 led to weaker ALP-positive staining (Fig. 4A) and a corresponding reduction in ALP activity (Fig. 4B). Similarly, FOXD2-AS1 ksnockdown resulted in a pronounced decrease in the transcriptional and protein expression of these osteogenic markers (Fig. 4C–E).

Figure 3: FOXD2-AS1 overexpression enhances the osteogenic potential of H-BMSCs. (A) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, an early osteogenic marker, was visualized by staining at various differentiation stages (bright-field microscopy, 10×; scale bar = 50 μm). (B) ALP enzymatic activity was quantified spectrophotometrically. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. (C) Transcript levels of the osteogenic genes OCN, ALP, and RUNX2 were measured by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. (D,E) Protein expression of OCN and RUNX2 was confirmed by western blot analysis. For all quantitative panels, data are shown as mean ± standard deviation from three biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance vs. the negative control (NC) group was determined by one-way ANOVA. Abbreviations: NC, negative control; OE, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression

Figure 4: Knockdown of FOXD2-AS1 impairs osteogenic differentiation in H-BMSCs. (A) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining at various differentiation time points revealed reduced early osteogenic commitment in knockdown groups (bright-field microscopy, 10×; scale bar = 50 μm). (B) Quantitative analysis of ALP activity showed a significant reduction upon FOXD2-AS1 suppression. The bar plot shows the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. (C) mRNA expression levels of osteogenic markers (OCN, ALP, RUNX2) were downregulated, as measured by RT-qPCR. The bar plot shows the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. (D,E) Western blot analysis confirmed decreased OCN and RUNX2 protein expression. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. Abbreviations: NC, negative control; sh, FOXD2-AS1 shRNA

3.4 FOXD2-AS1/JAK2/STAT3 Regulatory Axis Drives Osteogenesis in H-BMSCs

The activation status of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway under FOXD2-AS1 modulation at day 7 post-osteogenic induction was assessed by western blot analysis. Our results showed that JAK2 and STAT3 phosphorylation levels were significantly increased by FOXD2-AS1 overexpression, while their phosphorylated forms were reduced considerably by FOXD2-AS1 silencing (Fig. 5A–D). To investigate the involvement of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in FOXD2-AS1-induced osteogenesis, cells were treated with the JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor AG490 to block phosphorylation (Fig. 5E,F).

Figure 5: The phosphorylation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway during H-BMSC osteogenesis. (A,B) FOXD2-AS1 overexpression promoted JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation (p-JAK2, normalized to total JAK2; p-STAT3, normalized to total STAT3). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. (C,D) Knockdown of FOXD2-AS1 inhibited p-JAK2/STAT3 levels. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. (E,F) Treatment with the JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor reduced the intracellular p-JAK2/STAT3 levels compared with FOXD2-AS1 overexpression alone. All data are presented as means ± SD (X ± SD, n = 3). Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. The experiment was independently repeated three times. Abbreviations: OE, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression; OE+AG490, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression+inhibitor (AG490); sh, FOXD2-AS1 short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control; T-JAK2, total JAK2; T-STAT3, total STAT3

3.5 The Differentiation-Promoting Effect of FOXD2-AS1 Was Reversed by Signal Pathway Inhibition

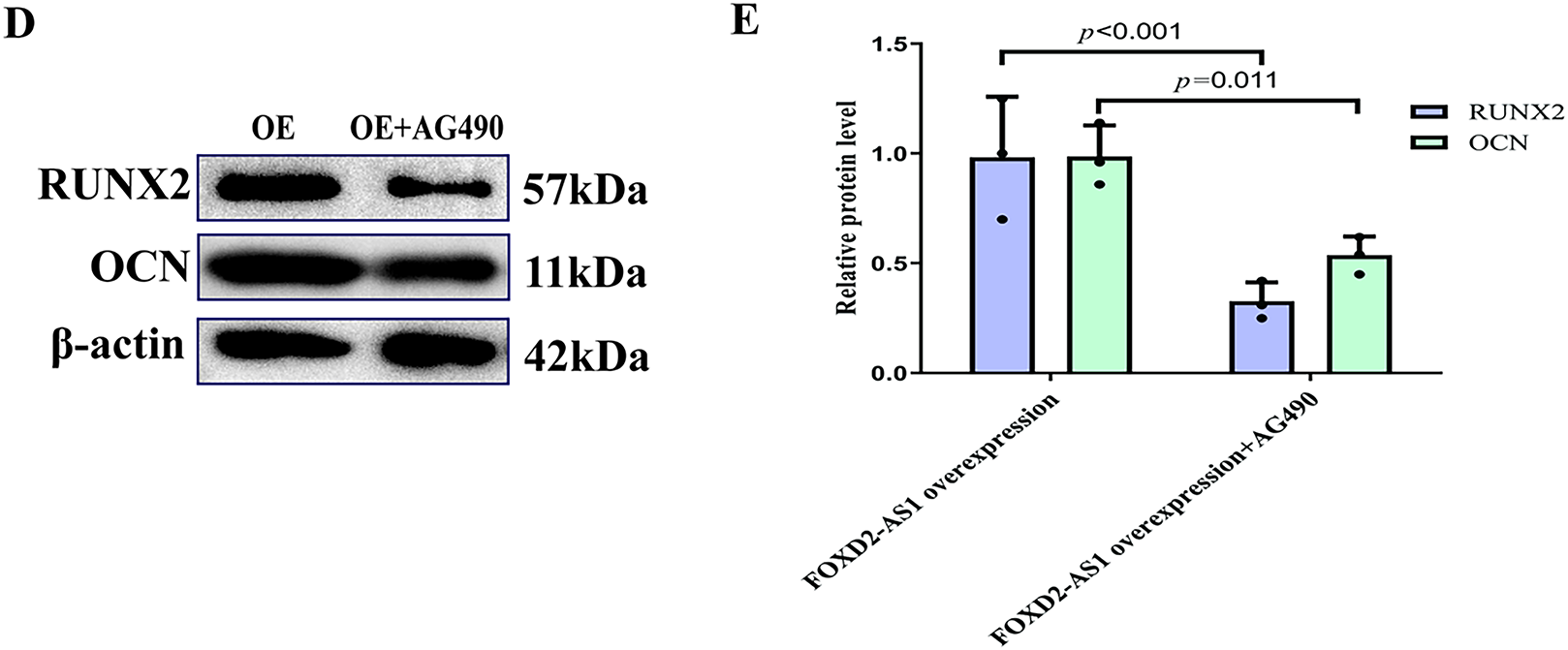

To determine whether the pro-osteogenic effects of FOXD2-AS1 are dependent on AG490-sensitive signaling, we compared H-BMSCs overexpressing FOXD2-AS1 in the presence or absence of AG490. On day 7 of osteogenic induction, ALP staining demonstrated that FOXD2-AS1 overexpression produced more intense staining in the absence of AG490 (Fig. 6A). Similarly, quantitative analysis of intracellular ALP activity revealed significantly higher levels in cells not exposed to AG490 (Fig. 6B). FOXD2-AS1 overexpression significantly increased the mRNA and protein expression of key osteogenic markers, an effect that was substantially diminished following AG490 co-treatment (Fig. 6C–E).

Figure 6: FOXD2-AS1 drives osteogenic differentiation via JAK2/STAT3 Activation. (A) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining demonstrated that inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 signaling partially rescues the pro-osteogenic effect of FOXD2-AS1 overexpression (10×; scale bar = 50 μm). (B) Quantitative ALP activity confirmed a significant reduction upon AG490 treatment in FOXD2-AS1-overexpressing cells. The bar plot shows the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. (C) mRNA levels of osteogenic markers (OCN, ALP, RUNX2) were downregulated following JAK2/STAT3 inhibition. The bar plot shows the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. (D,E) Western blot analysis showed corresponding decreases in OCN and RUNX2 protein expression. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Abbreviations: OE, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression

3.6 STAT3 Silencing Abolished the Osteogenic Enhancement Induced by FOXD2-AS1 Overexpression

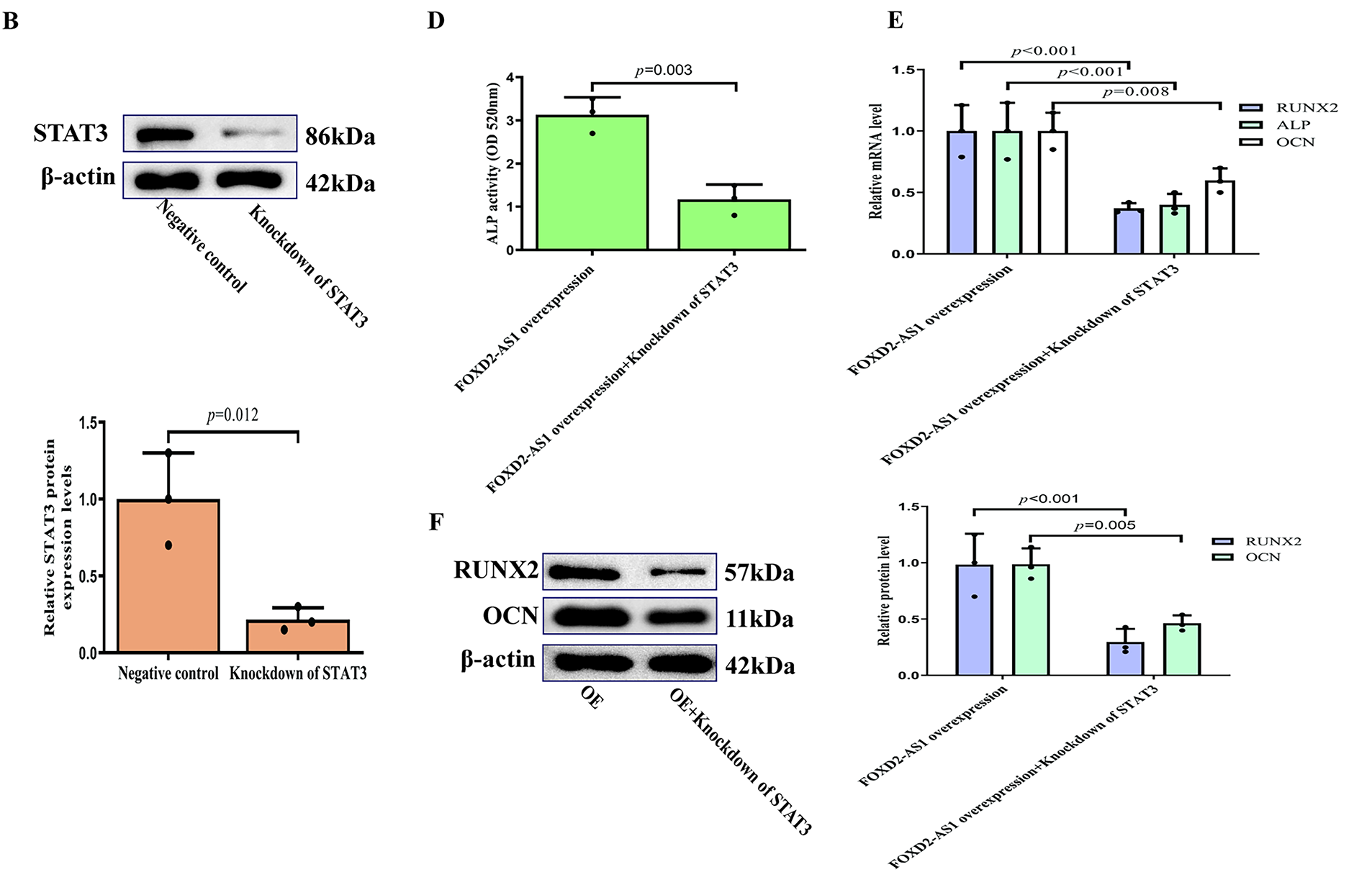

A rescue experiment was conducted by knocking down STAT3 in FOXD2-AS1-overexpressing cells. Following confirmation of efficient STAT3 knockdown (Fig. 7A,B), it was found that silencing STAT3 abolished the increased osteogenic potential conferred by FOXD2-AS1 overexpression on day 7 (Fig. 7C–F). This demonstrates that the pro-osteogenic function of FOXD2-AS1 depends on activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in H-BMSCs.

Figure 7: STAT3 knockdown attenuates the pro-osteogenic effects of FOXD2-AS1 overexpression. (A,B) Efficient STAT3 knockdown at the (A) mRNA and (B) protein levels was confirmed by RT-qPCR and western blot, respectively, following lentiviral transduction. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. (C) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining intensity was visibly reduced in FOXD2-AS1-overexpressing cells upon STAT3 silencing (10×; scale bar = 50 μm). (D) Quantitative analysis of ALP activity confirmed a significant decrease. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. (E,F) The expression of key osteogenic markers (RUNX2, OCN, ALP) was downregulated at the (E) transcriptional and (F) protein levels in STAT3-deficient cells, even in the presence of FOXD2-AS1 overexpression. All quantitative data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Abbreviations: OE, FOXD2-AS1 overexpression

Reduced bone mass and structural degradation are features of osteoporosis, a degenerative skeletal condition that increases bone fragility and fracture risk [17]. Dysfunctional osteogenesis in H-BMSCs is a key etiological factor in osteoporosis, driven by a failure to sustain normal bone formation [18,19]. Therefore, elucidating the precise mechanisms governing osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells provides a crucial foundation for the development of more effective therapeutic strategies for osteoporosis.

FOXD2-AS1 expression was assessed at multiple stages of differentiation (days 0, 3, 7, and 9). The results revealed a dynamic increase in FOXD2-AS1 levels, with peak expression observed on day 7. This stage corresponds to the critical “commitment phase” of BMSC osteogenic differentiation, during which cells become irreversibly directed toward the osteogenic lineage. Subsequent matrix mineralization at later stages largely depends on events that occur during these early differentiation phases [20–23]. These observations prompted us to hypothesize that FOXD2-AS1 acts as a key initiator of the osteogenic differentiation program. Thus, day 7 was chosen as the representative time point for subsequent analyses. FOXD2-AS1 overexpression markedly enhanced osteogenic differentiation, whereas its silencing produced the opposite effect. These results identify FOXD2-AS1 as a positive regulator of early osteoblastogenesis in H-BMSCs, supporting its role in promoting osteogenic commitment and differentiation.

Previous studies have reported elevated FOXD2-AS1 expression in osteoarthritis, where it promotes chondrocyte proliferation and correlates positively with disease severity [24]. However, the role of FOXD2-AS1 in cell differentiation remains poorly understood. To date, only a single study has reported that FOXD2-AS1 overexpression promotes glioma stem cell proliferation while suppressing differentiation by activating the TAF-1–mediated NOTCH signaling pathway [25]. This study broadens this understanding by elucidating the role of FOXD2-AS1 in regulating osteogenic differentiation.

Several lncRNAs critically modulate H-BMSC osteogenesis. lncRNA Ubr5 is a negative regulator that, under weightlessness, suppresses proliferation, promotes apoptosis, and impedes osteogenic differentiation [26]. In comparison, lncRNA SNHG1 inhibits osteogenic differentiation by interacting with HMGB1 [27]. These findings highlight the critical regulatory roles of lncRNAs in H-BMSC osteogenesis. Furthermore, compromised osteogenic potential in H-BMSCs is a well-established pathological mechanism underlying primary osteoporosis [2,3]. Approaches to enhance osteogenic differentiation in H-BMSCs represent a promising therapeutic strategy for osteoporosis. In this context, FOXD2-AS1 was identified as a key regulator of early osteogenesis. Modulation of this pathway may therefore offer a viable approach to alleviating the impaired bone-forming capacity characteristic of osteoporosis.

FOXD2-AS1 has recently gained attention as a pivotal lncRNA, primarily recognized for its role as a molecular sponge that sequesters miRNAs [28]. For example, some studies have reported elevated FOXD2-AS1 expression in multiple malignancies, where it enhances the invasive, migratory, and proliferative capacity of cancer cells through these regulatory mechanisms [8,9]. Beyond miRNA regulation, FOXD2-AS1 also modulates various cellular processes through downstream signaling pathways. For example, it promotes progression of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [29]. At the same time, EGR1-induced upregulation of FOXD2-AS1 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma progression by epigenetically silencing DKK1 and activating the same pathway [30]. Deficiency of FOXD2-AS1 promotes Achilles tendon healing and ameliorates degeneration by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [31]. FOXD2-AS1 acts as a “destroyer” in many cancers, where it promotes tumorigenesis and disease progression. In comparison, within the context of osteogenesis, it assumes a “builder” role by actively facilitating cellular differentiation. These observations highlight the multifaceted regulatory capacity of FOXD2-AS1 and provide the impetus for our investigation into the mechanisms governing its function in osteogenic differentiation.

A key objective of this study was to identify the downstream signaling pathways through which FOXD2-AS1 regulates osteogenesis in H-BMSCs. Several canonical pathways, including BMP/Smad, Hedgehog, Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, and MAPK, are well recognized as central regulators of H-BMSC differentiation [32–35]. Identifying the precise molecular pathway by which FOXD2-AS1 exerts its functional effects remains a crucial objective. The JAK2/STAT3 pathway is increasingly recognized as a central mediator of H-BMSC differentiation into the osteoblastic lineage [36,37]. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is a well-documented conduit for various lncRNAs that regulate critical oncogenic processes, including tumour migration, cell proliferation, and differentiation [38–40]. These findings support a model in which a FOXD2-AS1/JAK2/STAT3 regulatory axis governs early osteogenic fate commitment in mesenchymal stem cells. The central premise is that FOXD2-AS1 promotes osteogenesis by modulating the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. This was substantiated through gain and loss-of-function experiments, together with pharmacological inhibition and genetic knockdown–based rescue assays, which demonstrated that activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is the primary mechanism by which FOXD2-AS1 drives early osteogenic differentiation. Our results further identify the FOXD2-AS1/JAK2/STAT3 axis as a critical interface between non-coding RNA regulation and canonical signaling pathways in the control of bone metabolism. Therefore, this axis is fundamental to understanding defective bone formation in osteoporosis and represents a highly promising therapeutic target. Augmenting its activity provides a direct strategy to enhance bone formation and supports the development of novel bone-anabolic therapies.

Despite this promise, substantial challenges persist, particularly regarding in vivo stability, efficient targeted delivery, and precise regulatory control of lncRNA-based therapeutics. Overcoming these obstacles will be a central objective of future translational research and will ultimately determine their clinical viability. With continued investigation, FOXD2-AS1 may emerge as a meaningful therapeutic target and provide a basis for developing new treatment strategies for osteoporosis.

This study outlines a mechanistic framework in which the lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 facilitates early stages of osteoblastic differentiation in H-BMSCs by modulating the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway. Modulation of FOXD2-AS1, therefore, represents a potentially effective strategy to enhance osteogenesis, although further in vivo studies are required to validate its therapeutic applicability. Targeting lncRNAs to enhance the osteogenic capacity of H-BMSCs is a promising approach for developing novel therapeutic interventions for osteoporosis.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (Grant No. 2023AFB671), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82360177 and 82560182), and the Key Project of Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 20224ACB206011), “Xuncheng Talents” Project in Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province (Grant No. JJXC2023071).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tao Wang, Lihua Wang; data collection: Zhimin Zhang, Lihua Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Lihua Wang, Zhimin Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Lihua Wang, Tao Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: H-BMSCs used in this study were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences Inc. (cat. no. HUXMA-01001, Guangzhou, China). According to the manufacturer’s documentation, these cells were derived from bone marrow obtained from healthy donors who had provided informed consent. The cells were collected in compliance with ethical and regulatory requirements and are intended solely for research use.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.074782/s1.

References

1. Sawada H, Kazama T, Nagaoka Y, Arai Y, Kano K, Uei H, et al. Bone marrow-derived dedifferentiated fat cells exhibit similar phenotype as bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with high osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration ability. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):191. doi:10.1186/s13018-023-03678-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jiang Y, Zhang P, Zhang X, Lv L, Zhou Y. Advances in mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for the treatment of osteoporosis. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(1):e12956. doi:10.1111/cpr.12956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Xia SL, Ma ZY, Wang B, Gao F, Guo SY, Chen XH. Icariin promotes the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with osteoporosis and T2DM by upregulating GLI-1. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):500. doi:10.1186/s13018-023-03998-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tani H. Biomolecules interacting with long noncoding RNAs. Biology. 2025;14(4):442. doi:10.3390/biology14040442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Hu Q, Tai S, Wang J. Oncogenicity of lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 and its molecular mechanisms in human cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(5):843–8. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2019.01.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang Z, Liu XC, Gao ZG, Shi WD, Wang WC. FOXD2-AS1 is modulated by METTL3 with the assistance of YTHDF1 to affect proliferation and apoptosis in esophageal cancer. Acta Pharm. 2025;75(1):69–86. doi:10.2478/acph-2025-0009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Huang Z, Liu B, Li X, Jin C, Hu Q, Zhao Z, et al. FOXD2-AS1 binding to MYC activates EGLN3 to affect the malignant progression of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2024;38(12):e70083. doi:10.1002/jbt.70083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Guo S, Huang B, You Z, Luo Z, Xu D, Zhang J, et al. FOXD2-AS1 promotes malignant cell behavior in oral squamous cell carcinoma via the miR-378 g/CRABP2 axis. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):625. doi:10.1186/s12903-024-04388-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xiang Y, Cheng X, Li H, Xu W, Zhang W. Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 silencing inhibits malignant behaviors of ovarian cancer cells via miR-324-3p/SOX4 signaling axis. Reprod Sci. 2025;32(4):1003–12. doi:10.1007/s43032-024-01719-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mengie Ayele T, Tilahun Muche Z, Behaile Teklemariam A, Bogale Kassie A, Chekol Abebe E. Role of JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in the tumorigenesis, chemotherapy resistance, and treatment of solid tumors: a systemic review. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:1349–64. doi:10.2147/JIR.S353489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Jin L, Cai CL, Lang XL, Li BL. Ghrelin inhibits inflammatory response and apoptosis of myocardial injury in septic rats through JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(22):11740–6. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202011_23825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang J, Li J, Luo Y, Mahony TJ, Gao J, Wang Y, et al. LINC2781 enhances antiviral immunity against coxsackievirus B5 infection by activating the JAK-STAT pathway and blocking G3BP2-mediated STAT1 degradation. mSphere. 2025;10(7):1–19. doi:10.1128/msphere.00062-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li ZY, Yang L, Liu XJ, Wang XZ, Pan YX, Luo JM. The long noncoding RNA MEG3 and its target miR-147 regulate JAK/STAT pathway in advanced chronic myeloid leukemia. EBioMedicine. 2018;34:61–75. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.07.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ahmad Farooqi A, Mukhanbetzhanovna AA, Yilmaz S, Karasholakova L, Yulaevna IM. Mechanistic role of DANCR in the choreography of signaling pathways in different cancers: spotlight on regulation of Wnt/β-catenin and JAK/STAT pathways by oncogenic long non-coding RNA. Non Coding RNA Res. 2021;6(1):29–34. doi:10.1016/j.ncrna.2021.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang TL, Yang YH, Chang H, Hung CR. Angiotensin II signals mechanical stretch-induced cardiac matrix metalloproteinase expression via JAK-STAT pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37(3):785–94. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.06.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Suleman N, Somers S, Smith R, Opie LH, Lecour SC. Dual activation of STAT-3 and Akt is required during the trigger phase of ischaemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79(1):127–33. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvn067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Sung K, Ha J. Platelet count normalization following romosozumab treatment for osteoporosis in patient with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a case report and literature review. J Bone Metab. 2024;31(4):335–9. doi:10.11005/jbm.24.763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. He G, Ke Y, Yuan J, Zhang B, Dai L, Liu J, et al. NSD2-mediated H3K36me2 exacerbates osteoporosis via activation of hoxa2 in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Signal. 2024;121:111294. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2024.111294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhao Q, Feng J, Liu F, Liang Q, Xie M, Dong J, et al. Rhizoma Drynariae-derived nanovesicles reverse osteoporosis by potentiating osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via targeting ERα signaling. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14(5):2210–27. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2024.02.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. van de Peppel J, Strini T, Tilburg J, Westerhoff H, van Wijnen AJ, van Leeuwen JP. Identification of three early phases of cell-fate determination during osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation by transcription factor dynamics. Stem Cell Reps. 2017;8(4):947–60. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.02.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Tye CE, Ghule PN, Gordon JAR, Kabala FS, Page NA, Falcone MM, et al. LncMIR181A1HG is a novel chromatin-bound epigenetic suppressor of early stage osteogenic lineage commitment. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):7770. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11814-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang Q, Dong J, Zhang P, Zhou D, Liu F. Dynamics of transcription factors in three early phases of osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation determining the fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in rats. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:768316. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.768316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ru X, Cai P, Tan M, Zheng L, Lu Z, Zhao J. Temporal transcriptome highlights the involvement of cytokine/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in the osteoinduction of BMSCs. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):289. doi:10.1186/s13018-023-03767-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang Y, Cao L, Wang Q, Huang J, Xu S. LncRNA FOXD2-AS1 induces chondrocyte proliferation through sponging miR-27a-3p in osteoarthritis. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):1241–7. doi:10.1080/21691401.2019.1596940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wang Y, Cheng Y, Yang Q, Kuang L, Liu G. Overexpression of FOXD2-AS1 enhances proliferation and impairs differentiation of glioma stem cells by activating the NOTCH pathway via TAF-1. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26(9):2620–32. doi:10.1111/jcmm.17268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wang D, Gao Y, Tan Y, Li N, Li X, Li J, et al. lncRNA Ubr5 promotes BMSCs apoptosis and inhibits their proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in weightless bone loss. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1543929. doi:10.3389/fcell.2025.1543929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Pan K, Lu Y, Cao D, Peng J, Zhang Y, Li X. Long non-coding RNA SNHG1 suppresses the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by binding with HMGB1. Biochem Genet. 2024;62(4):2869–83. doi:10.1007/s10528-023-10564-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang J, Zhu H, Li L, Gao Y, Yu B, Ma G, et al. New mechanism of LncRNA: in addition to act as a ceRNA. Non Coding RNA Res. 2024;9(4):1050–60. doi:10.1016/j.ncrna.2024.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Rong L, Zhao R, Lu J. Highly expressed long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;484(3):586–91. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lei T, Zhu X, Zhu K, Jia F, Li S. EGR1-induced upregulation of lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via epigenetically silencing DKK1 and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(7):1007–16. doi:10.1080/15384047.2019.1595276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ke X, Zhang W. Pro-inflammatory activity of long noncoding RNA FOXD2-AS1 in Achilles tendinopathy. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):361. doi:10.1186/s13018-023-03681-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang J, Wang M, Chen F, Wei Y, Chen X, Zhou Y, et al. Nano-hydroxyapatite coating promotes porous calcium phosphate ceramic-induced osteogenesis via BMP/smad signaling pathway. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:7987–8000. doi:10.2147/IJN.S216182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Guo J, Chen Z, Xiao Y, Yu G, Li Y. SATB1 promotes osteogenic differentiation of diabetic rat BMSCs through MAPK signalling activation. Oral Dis. 2023;29(8):3610–9. doi:10.1111/odi.14265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Chen Y, Wei Z, Shi H, Wen X, Wang Y, Wei R. BushenHuoxue formula promotes osteogenic differentiation via affecting Hedgehog signaling pathway in bone marrow stem cells to improve osteoporosis symptoms. PLoS One. 2023;18(11):e0289912. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0289912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wang Y, Pan J, Zhang Y, Li X, Zhang Z, Wang P, et al. Wnt and Notch signaling pathways in calcium phosphate-enhanced osteogenic differentiation: a pilot study. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2019;107(1):149–60. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.34105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yu X, Li Z, Wan Q, Cheng X, Zhang J, Pathak JL, et al. Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 signaling suppresses bone marrow stromal cells proliferation and osteogenic differentiation, and impairs bone defect healing. Biol Chem. 2018;399(11):1313–23. doi:10.1515/hsz-2018-0253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chen L, Zhang RY, Xie J, Yang JY, Fang KH, Hong CX, et al. STAT3 activation by catalpol promotes osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling, thus accelerating osteoporotic bone repair. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):108. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02178-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Shi J, Li J, Yang S, Hu X, Chen J, Feng J, et al. LncRNA SNHG3 is activated by E2F1 and promotes proliferation and migration of non-small-cell lung cancer cells through activating TGF-β pathway and IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(3):2891–900. doi:10.1002/jcp.29194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Shin JJ, Suk K, Lee WH. LncRNA BRE-AS1 regulates the JAK2/STAT3-mediated inflammatory activation via the miR-30b-5p/SOC3 axis in THP-1 cells. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25726. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-77265-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Xiong H, Zhang W, Xie M, Chen R, Chen H, Lin Q. Long non-coding RNA JPX promotes endometrial carcinoma progression via Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1340050. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1340050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools