Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Software Cost Estimation Using Feature Selection and Machine Learning Techniques

1 Department of Software Engineering, FAST-National University of Computer & Emerging Sciences, Karachi, 75030, Pakistan

2 Faculty of Engineering Science and Technology, IQRA University, Karachi, 72500, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science, Bahria Univesity, Karachi, 74800, Pakistan

4 Faculty of Computing, Riphah International University, Islamabad, 44600, Pakistan

5 Faculty of Computing and Informatics, Multimedia University (MMU), Cyberjaya, 63100, Selangor, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Affan Alim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 4603-4624. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057979

Received 02 September 2024; Accepted 23 October 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

Software cost estimation is a crucial aspect of software project management, significantly impacting productivity and planning. This research investigates the impact of various feature selection techniques on software cost estimation accuracy using the CoCoMo NASA dataset, which comprises data from 93 unique software projects with 24 attributes. By applying multiple machine learning algorithms alongside three feature selection methods, this study aims to reduce data redundancy and enhance model accuracy. Our findings reveal that the principal component analysis (PCA)-based feature selection technique achieved the highest performance, underscoring the importance of optimal feature selection in improving software cost estimation accuracy. It is demonstrated that our proposed method outperforms the existing method while achieving the highest precision, accuracy, and recall rates.Keywords

Software development is a complex and multifaceted task that involves various aspects that can affect productivity significantly. Among the stages of software development, estimating and managing software costs presents the most formidable challenge. This is because the right estimates lead to the right development [1]. The fields of budgeting, risk analysis, project planning and control, software enhancement, and investment analysis provide valuable support to project managers when making decisions that are significantly influenced by software cost and estimation [2]. Overestimating can result in resource wastage, while underestimating can result in understaffing, overspending, and late project completion. According to a recent survey, it is estimated that the net worth of the software industry by the end of the year 2023 will reach 659 billion dollars [3]. However, as can be seen from Fig. 1, there are 54% of companies involved in the survey identify that “adapting to changing client requirements” is the biggest challenge among others, which drastically impacts their costing and estimation process [4]. The accuracy of predicting development costs significantly dictates the efficiency of software project management. The machine learning models for software effort estimation were developed under the premise that project development effort is influenced by factors like project size (measured in source lines of code), development environment, personnel, technology, and team experience. These elements, identified as cost drivers, have a pivotal role in defining the development effort. Consequently, endeavours to predict the development efforts have been concentrated on creating functions that encompass these cost drivers [5].

Figure 1: The major challenges encountered in industrial software development [4]

Accurate effort estimation in software development projects holds paramount significance for the successful delivery of the overall solution. Surprisingly, despite its criticality, studies indicate that substantial advancements in enhancing performance estimation techniques have not been widely reported, presenting a major challenge within the software industry [6]. There have been numerous software cost-estimating techniques proposed over the past few decades as shown in Fig. 2. Essentially, these methods are divided into three major groups [7]: (1) Expert judgment: This approach hinges on human judgment, and estimates are formulated following meticulous analysis of past software development projects or datasets. (2) Model-Based: In this category, the estimation is based on a mathematical model. Statistical equations are applied to several software project features to generate the estimation. The well-known ones include the Function Point Analysis Model and CoCoMo. (3)Machine learning (ML) techniques: Include at least one modeling technique, which estimates the cost by taking into account several project features while making no or very few data-related assumptions. It offers an improved approximation ability to resolve challenging issues.

Figure 2: Different methodologies for estimating software costs

Currently, machine learning (ML) techniques are more frequently used compared with the other two aforementioned methods. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Case-Based Reasoning (CBR), classification, and regression trees are some of the methods that have been used in recent years. It is necessary to enhance the output of ML models to attain higher software cost estimation (SCE) accuracy. The machine learning-based implementation is flexible to improve the accuracy using different models with variations of parameters. Essentially, the data undergoes preparation involving wrangling and feature engineering before being fed into machine learning algorithms, which significantly contribute to the development of the model. Feature selection, typically employed to choose informative features, is a widely used technique for enhancing the performance of machine learning models. In this research, we aim to utilize the CoCoMo dataset. This dataset operates under the assumption that software development effort correlates with factors including the number of lines of code, project complexity, team size, and development environment.

CoCoMo is composed of three different models: Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced. The Basic model is suitable for small, simple projects, while the Intermediate and Advanced models are designed for larger, more complex projects. CoCoMo has garnered widespread adoption across both industry and academia, undergoing continual enhancements and updates throughout the years. As a result, it has evolved into one of the most universally embraced models for estimating software costs.

The CoCoMo estimates software efforts by considering code size measured by thousands of lines of code. Eq. (1) is used to calculate the effort basic model of CoCoMo [8].

where size is in thousand lines of codes (KLOC), while a and b are constants that can take on different values by the three modes of organic, semi-detached, and embedded projects.

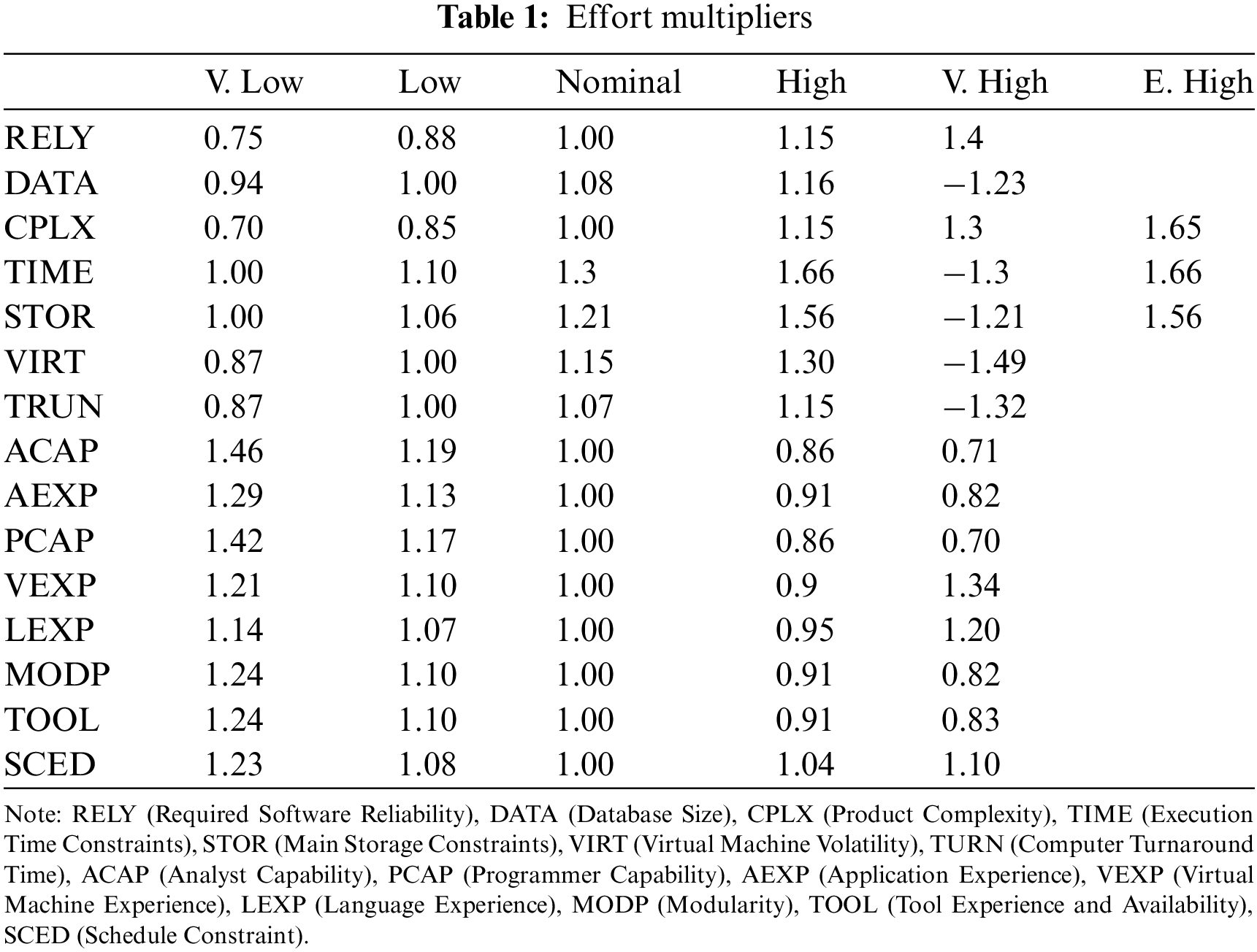

Commonly, the Intermediate Model uses Eq. (1) to determine the effort. Essentially, it takes the project characteristics that are represented by the fifteen drivers as shown in Table 1. These driver values are equivalent to a series of numerical numbers called multipliers. Therefore, the intermediate model uses the Eq. (2) to calculate efforts.

where i = 1 to 15 is the outcome of their multiplication, and EMi stands for the 15 efforts multiplier. It is necessary to specify the size in KLOC. While a and b are constants Values vary across three different project types: organic, semi-detached, and embedded. It is widely recognized that the quality of input features plays a substantial role in shaping the outcome of multi-label learning challenges. Feature selection involves the systematic extraction of a subset from an initial pool of features, guided by specific selection criteria. This process serves to isolate pertinent features within a dataset, effectively filtering out extraneous ones. Beyond this filtration, feature selection plays a crucial role in streamlining data processing by curbing the dimensions under consideration. The elimination of redundant and immaterial features contributes to a more focused and efficient analysis [9]. Machine learning techniques like gradient boosting, random forest, and support vector machines (SVM) are employed for tasks like regression and classification. These techniques come with a set of hyperparameters that need to be configured before the algorithms are executed. Unlike the primary model parameters that are learned during the training process, these secondary tuning parameters require deliberate optimization to attain the best possible performance [10].

The impact of parameter configurations on the precision of trained Machine Learning algorithms’ value estimations is widely recognized. Consequently, the selection of optimal learning parameter values becomes imperative in the pursuit of crafting a precise model. However, the quest for these optimal values is intricate, and the literature has proposed several methodologies to assist in this endeavour. Notably, techniques such as grid search (GS), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and genetic algorithm (GA) have emerged as strategies to navigate this challenging terrain [11].

In the scope of our research, the CoCoMo NASA benchmark dataset has served as the foundation for our investigation. We have meticulously employed four distinct feature selection methodologies, namely Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Sequential Forward Feature Selection, and Mutual Information, to discern optimal feature subsets. This meticulous process is instrumental in enhancing the efficacy of subsequent machine learning models. Moreover, our study delves into a comprehensive comparative analysis of diverse machine learning algorithms. Specifically, we have evaluated the performance of renowned models including Random Forest, Decision Tree, Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Logistic Regression, and Gradient Boosting. Through this rigorous examination, we aim to discern the strengths and weaknesses of each model concerning the CoCoMo dataset, thereby offering valuable insights into their applicability and effectiveness within the context of software cost estimation. Random forest with Mutual information selection achieved the best performance.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: A synopsis of the related work on this topic is given in Section 2. The research methodology is described in Section 3, along with an overview of machine learning techniques, feature selection techniques, and the dataset used in the study. The experiment findings and analysis are presented in Section 4. Conclusion and further work in Section 5.

Many studies have focused on the efficiency of feature selection strategies when using data mining, statistical, and machine learning algorithms for software cost estimation. In machine learning applications, feature extraction and selection represent two fundamental stages. During feature extraction, certain attributes from the given data, which are meant to be informative, are extracted. While engaging in machine learning, not all of the derived features prove to be constructive in the learning process. Consequently, feature selection methods play a crucial role in numerous domains including gene selection, drug design, disease classification, image processing, text mining, handwriting recognition, spoken word recognition, social networks, and several others. Their importance cannot be overstated [10].

Rahmaninia et al. [12] introduced two innovative feature-based Online Stream Feature (OSF) methods designed to attain exceptional classification accuracy while maintaining reasonable processing time. The assumption is that the features emerge incrementally over time, while the number of instances remains fixed. In the first method, a prominent subset of features is selected, aiming for minimal size. Meanwhile, the second method focuses on choosing a set of prominent features with a constant size of k. These methods incorporate the concept of mutual information to assess the relevance and redundancy of features, without relying on any learning model. As a result, the proposed methods fall under the category of filter-based feature selection techniques. For the first time, Huang et al. [7] concluded that a data preprocessing (DP) strategy, such as scaling and feature selection, may considerably affect how well an ML method performs. The efficiency of combining DP approaches is not examined, and they only analyzed a small number of DP strategies. In a recent study, Cabral Jose et al. [13] concluded that the study supports the previous review’s conclusion that machine learning is still the most commonly used method for building software effort estimation (SEE) models. The study also suggests that ensemble techniques outperform individual models in terms of performance, which is consistent with previous research. In a recent study [14], authors proposed that genetic algorithms can help improve the accuracy and efficiency of the estimation process. The genetic algorithm is used to optimize the weights of the input variables used in the estimation process, to improve the accuracy of the estimates. It is suggested in a study [15] that a dual approach to improving software effort estimation. First, they proposed a recursive feature selection approach to determine the most important features. Second, utilizing the best characteristics found by the first suggested technique, an ensemble learning model is created by mixing seven distinct machine learning algorithms. The study’s findings show that both outperform conventional methods for estimating software effort. Overall, the outcomes produced by the suggested procedures are excellent. In research [16], authors utilized 14 algorithms that were evaluated on a variety of performance metrics, including mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), root mean squared error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R2). The results of the study showed that the top-performing algorithms were Random Forest Regression, Gradient Boosting Regression, and Extreme Gradient Boosting Regression. These algorithms outperformed the other algorithms in terms of all performance metrics evaluated in the study. Ucar [17] developed a feature selection method in research titled “Classification Performance-Based Feature Selection Algorithm for Machine Learning: P-Score”. The proposed method tested the effectiveness of features chosen through the P-Score and then assessed the P-Score’s performance by comparing it to 13 other feature selection algorithms from existing literature. Based on their study’s results, the P-Score algorithm is considered a viable technique for machine learning applications. Chandrashekat et al. [18] suggested selecting relevant features from a large set of available features is an important step in machine learning. The choice of a feature selection method depends on the specific problem and the characteristics of the dataset. A comprehensive understanding of the different feature selection methods can aid in selecting the appropriate method for a particular problem.

In the study [7], authors conducted an empirical evaluation of the effectiveness of data preprocessing techniques on ML methods in the context of software cost estimation and concluded that data preprocessing techniques have a significant impact on the final prediction and help in reducing prediction errors. Some researchers [8] employed feature selection strategies in several datasets to increase model performance, decrease data redundancy, and improve model accuracy. They used 13 machine learning algorithms, compared the outcomes using five distinct assessment criteria, and came to the conclusion that feature selection strategies invariably improve prediction model accuracy. A study [11] focused on enhancing software development effort estimation through the application of support vector regression and feature selection techniques. This study delves into the realm of refining software project planning by leveraging advanced regression methods and intelligent feature selection. By incorporating these techniques, the authors aim to contribute to more accurate and efficient estimation models, which have the potential to optimize resource allocation and project management in software development. Kocaguneli et al. [19] described the software effort estimation data by computing the Euclidean distance between instances and features of the data set, then pruning similar features and outliers, and finally evaluating the reduced data by contrasting predictions from a simple learner using the reduced data and a state-of-the-art learner classification and regression tree (CART) using all the Performances were assessed using mean and median values for mean relative error (MRE), mean absolute residual (MAR), prediction error (PRED), mean bias relative error (MBRE), mean inverse bias relative error (MIBRE), and mean magnitude of error rate (MMER) [20]. The results demonstrate that the trimmed data outperforms the whole set of data.

The Analogy-X solution, developed by BaniMustafa [21], is based on Mantel’s correlation randomization test. They made use of the relationship between the distance matrix of the project’s characteristics and the distance matrix of the data set’s known effort values. They used different datasets to showcase the method, which uses Mantel’s correlation to determine whether an analogy is appropriate, a step-by-step process for feature selection, and a statistic for sensitivity analysis to find outlier data points. They conclude that Analogy-X provides a reliable statistical foundation for analogy, does away with heuristic search, and significantly enhances algorithmic performance. Boehm [22] provided a method for data mining historical data in his paper. Machine learning algorithms (Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, and Random Forest) were applied to a CoCoMo NASA preprocessed dataset. The models were tested using five-fold cross-validation, and the results were assessed using Classification, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and area under the curve (AUC) before being compared to CoCoMo. He concluded that data mining is appropriate for evaluating software expenses and that the ML method outperforms CoCoMo.

CoCoMo is a widely used dataset for software cost and line of code estimation, forming the basis for numerous research studies [1,9]. Researchers commonly adopt this standard and popular dataset for their experimental work on cost estimation. Despite its widespread use, three primary gaps remain in cost estimation research: data preprocessing, feature selection, and ensemble methods, as addressed by various studies. Our research specifically focuses on the feature selection gap within the CoCoMo dataset for cost estimation. We applied Wrapper, Filter, and PCA-based feature selection techniques, with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) proposed as an automated method that demonstrated superior performance. The results of our proposed model were compared with previous work, where features were manually selected and followed by an ensemble method for cost estimation [15].

3 Methodology and Associated Tools

In the realm of multi-label learning challenges, the quality of input features holds immense significance. Feature selection, a systematic process involving the extraction of a subset from a larger feature pool, plays a pivotal role in enhancing the effectiveness of machine learning algorithms. This proposed paper explores the intricacies of feature selection and its impact on various machine-learning techniques commonly employed for classification tasks on the CoCoMo dataset (as shown in Fig. 3). By elucidating the importance of configuring hyperparameters and selecting optimal features, this research aims to provide insights into improving the performance of machine learning models in multi-label learning scenarios. The target variable has been transformed from a regression problem into a classification problem with three equally sized classes, using the approach proposed in [21].

Figure 3: The proposed model of SCE using various feature selection and ML techniques

The dataset employed in this study referred to as the CoCoMo NASA 2 dataset [22] serves as a cornerstone of our research. This dataset encompasses a comprehensive collection of data from 93 distinct software projects. Within this dataset, a total of 24 attributes are meticulously recorded, providing detailed insights into various facets of software development. Among these attributes, 15 are designated as standard CoCoMo discrete attributes, each ranging from very low to extra high. These attributes offer valuable information regarding the complexity, scale, and other pertinent factors associated with the software projects under examination.

Additionally, the dataset includes seven supplementary attributes that offer further granularity regarding the nature and characteristics of the projects. These supplementary attributes delve into aspects such as project scope, requirements, and environmental factors, enriching the dataset with additional contextual information.

Furthermore, specific attributes are dedicated to essential metrics within the software development process. For instance, one attribute captures the line of code measure, providing insights into the codebase’s size and complexity. Another attribute is devoted to the goal field, quantifying the actual effort expended in person-months, thereby offering a tangible measure of the resources invested in each project.

The proposed experiment employs a 3-fold cross-validation method for data splitting to enhance generalization and minimize the risk of overfitting.

3.2 Feature Selection Techniques

Feature selection involves the meticulous process of identifying and selecting a subset of pertinent features from a larger pool of available features [23]. The primary objective of feature selection techniques is to reduce the dimensionality of the input space, thereby enhancing the accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of machine learning models. This is achieved by eliminating irrelevant or redundant features that do not significantly contribute to model performance. Researchers commonly employ three broad categories of feature selection techniques: wrapper-based method, filter-based methods, and Embedded approach [24]. Wrapper and filter-based methods are two prominent approaches in feature selection. Wrap-per methods evaluate subsets of features using a predictive model, assessing their performance based on a predefined criterion. These methods involve exhaustive search or heuristic techniques to identify the most informative feature subsets. In contrast, filter-based methods assess feature relevance independently of the learning algorithm. They rely on statistical measures or domain knowledge to rank features and select the most relevant ones for the task at hand. Each method offers distinct advantages and is suited to different scenarios, providing flexibility and effectiveness in feature selection processes. Apart from the earlier discussed methods, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is also a widely used technique in research for dimensionality reduction and data visualization. By transforming high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while retaining the most important information, PCA facilitates analysis and interpretation [25]. It identifies orthogonal axes, known as principal components that capture the maximum variance in the data. This enables researchers to explore patterns, trends, and relationships within complex datasets more efficiently [19]. The selection of an appropriate feature selection technique depends on the characteristics of the dataset and the objectives of the machine learning task at hand. Within the context of our research, we’ve proposed employing all three methods to investigate the optimal combination of dataset attributes.

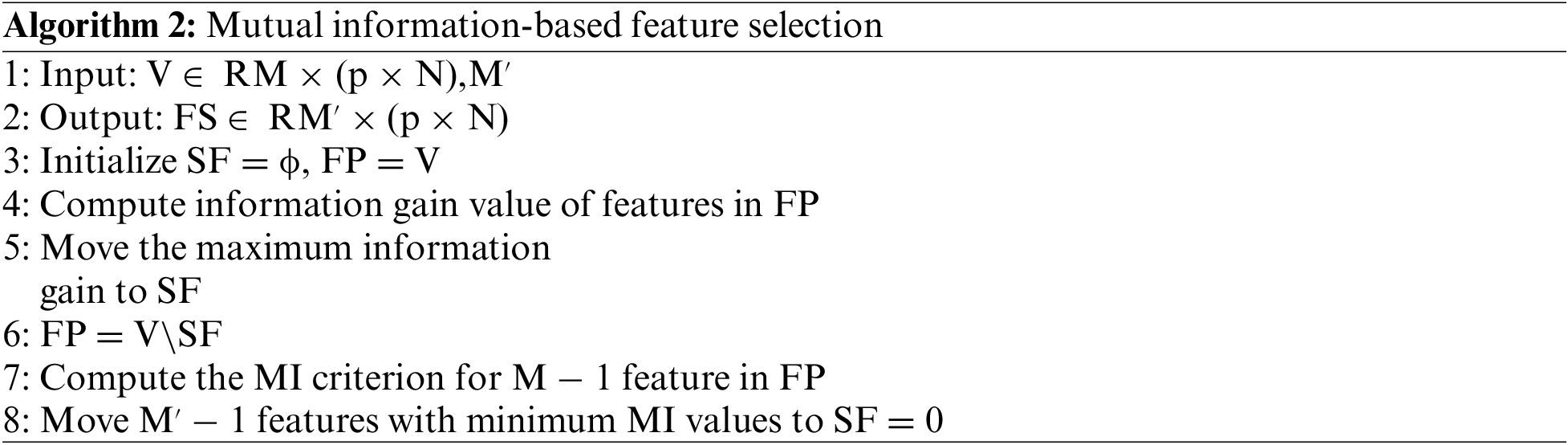

The Sequential Forward Feature Selection (SFFS), operating as part of a wrapper-based approach, and the Mutual Information Feature Selection (MIFS) filter-based method, have been utilized to examine the influence of feature selection on the CoCoMo dataset. The objective is to identify the most effective model for effort estimation. In this connection, 15 features were selected using both methods. The research also involves utilizing the domain transformation technique PCA for feature selection, aiming to choose informative features while reducing dimensionality.

Mutual information (MI) is a statistical method utilized to gauge the degree of information shared between two random variables, as expressed by the provided Eq. (3). Consider two random variables X and Y, denoted by I (X;Y), is defined mathematically as:

where

Mutual information measures the amount of information shared between X and Y. It quantifies the reduction in uncertainty about one variable given the knowledge of another variable. If I(X;Y) = 0, it implies that X and Y are independent. Higher values of mutual information indicate stronger dependencies between the variables. In the context of the feature selection, the mutual information is now computed for each pair of features in the feature pool (FP). At first, the high-information gain feature moves from the FP set to the selected features SF set. Subsequently, the mutual information between each feature of FP and SF is computed, prioritizing those with the lowest mutual information metrics. Subsequent rounds follow a similar pattern, with the mean value being factored in for SF [24]. The algorithm employed in the proposed model for selecting informative features from a pool of features is depicted in Algorithm 1. In this study, a set of 14 distinct features were selected using the aforementioned algorithm.

3.2.2 Sequential Forwarded Feature Selection

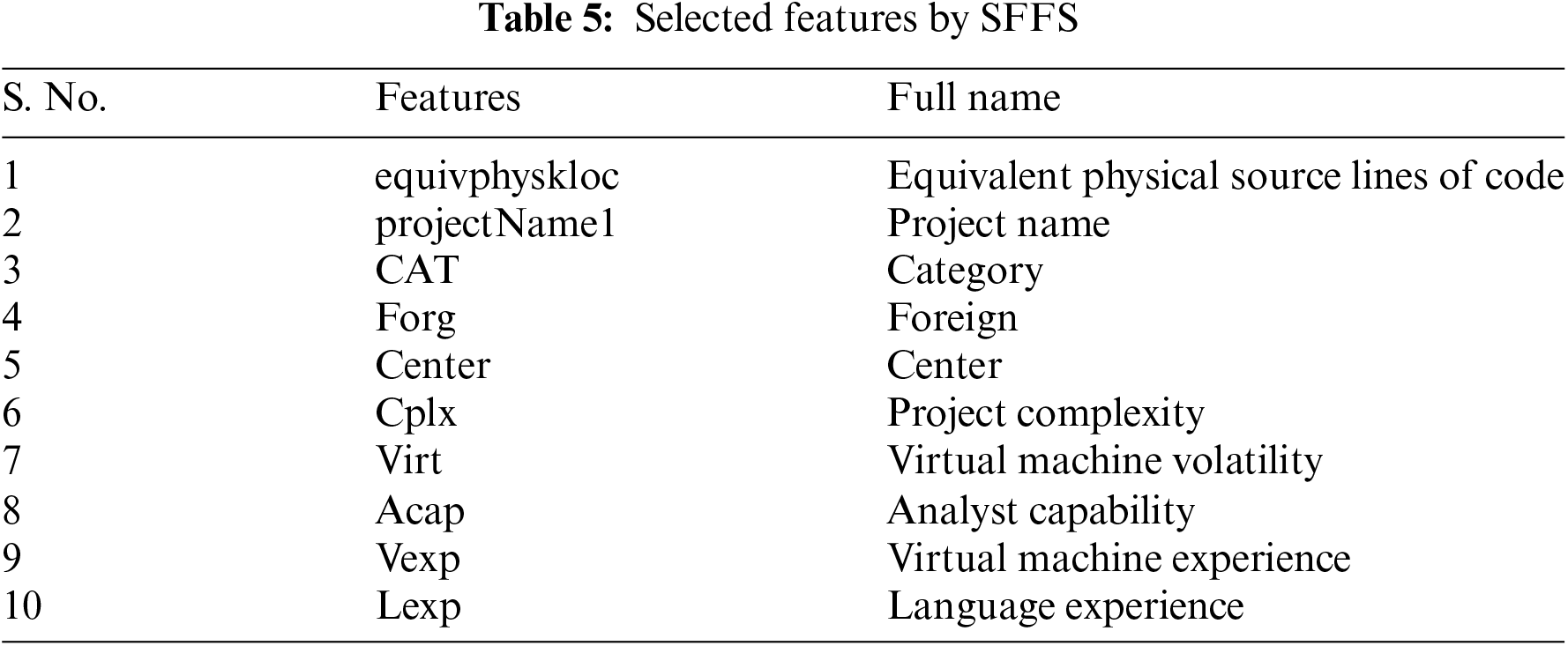

A widely recognized wrapper-based technique known as Sequential Forward Feature Selection is employed to select a subset of features from a larger set of attributes. This method, dependent on the classifier, constructs an informative feature pool through forward selection or backward elimination. Essentially, it iteratively adds or removes features one at a time based on a performance metric. In our research, we have adopted the Forward Feature Selection approach to select a subset of features from the extensive feature set. The algorithm proposed for feature selection is outlined in Algorithm 2. In this research, a group of 10 pertinent features was chosen to utilize the same algorithm.

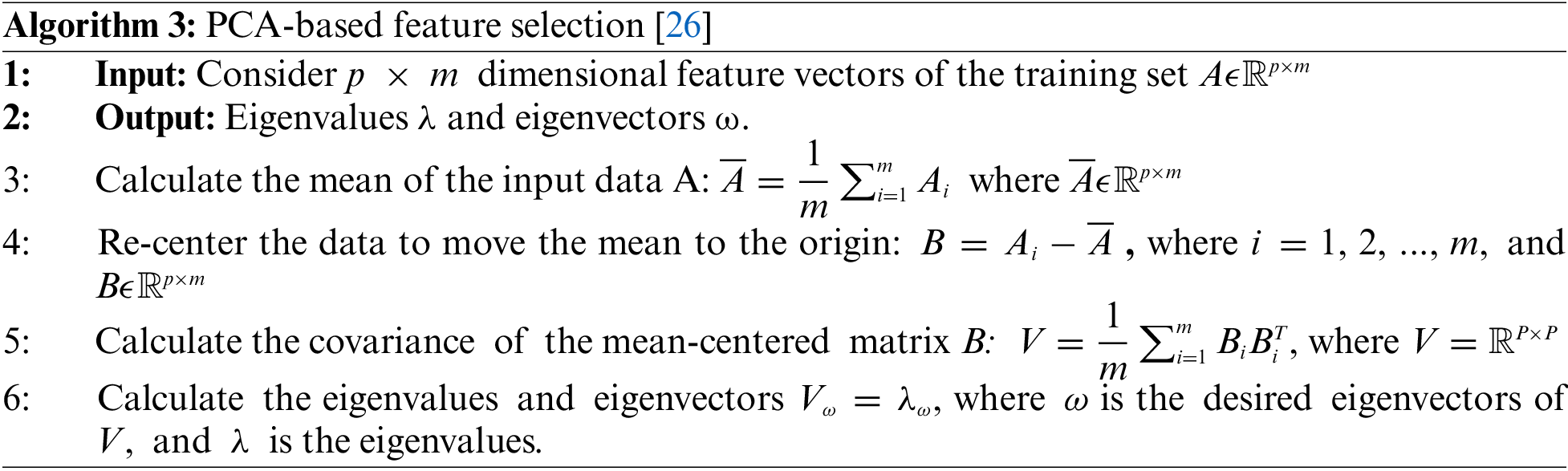

3.2.3 Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis is a popular dimensionality reduction technique used to transform high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional in Eigen-space while preserving most of the variation in the data. PCA achieves this by identifying the directions of maximum variance in the original data and projecting the data onto a new coordinate system defined by these directions, known as principal components. In this study, we’ve proposed employing PCA for reducing dimensionality in addition to the two methods mentioned earlier. The first principal component captures the direction of maximum variance in the data, and each subsequent principal component captures the remaining variance, in decreasing order of importance. In this study, we selected a collection of 13 relevant features using the PCA described in Algorithm 3.

PCA in software cost estimation involves an inherent trade-off between model performance and interpretability. On one hand, PCA can significantly enhance predictive accuracy by reducing the dimensionality of the data and mitigating issues such as multicollinearity, which can lead to more robust models. On the other hand, the transformation of original features into principal components can obscure their direct relationship to real-world factors like team size, project complexity, or development time. This lack of transparency makes it challenging to extract actionable insights or justify cost estimates based on tangible project attributes. As a result, while PCA improves technical performance, it may limit the practical usefulness of the model in decision-making, where interpretability is essential for explaining and understanding the drivers of software costs. This trade-off must be carefully considered when selecting feature reduction methods for software cost estimation, especially in contexts where clarity and explanation are as important as predictive accuracy.

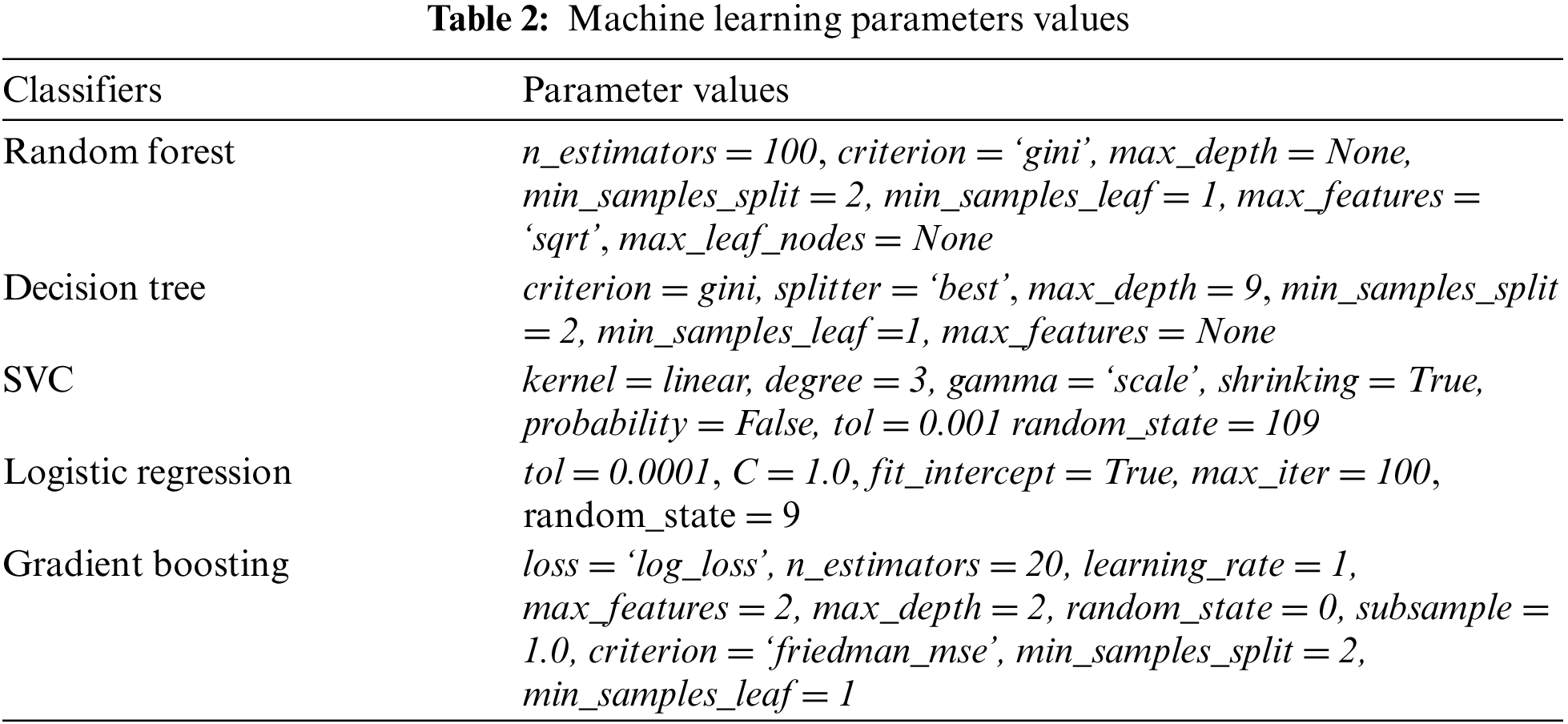

3.2.4 Hyperparameter, Fine Tuning

Hyperparameter optimization, often referred to as fine-tuning, is the process of determining the optimal set of hyperparameters for a machine learning model. These hyperparameters are predetermined parameters that dictate the architecture and learning behavior of the model. The selection of optimized hyperparameters associated with the machine learning algorithm is the same domain problem of feature selection. Usually, the wrapper-based method is used to select the optimized hyperparameters. This endeavor seeks to enhance the performance and effectiveness of the models by fine-tuning the parameters governing feature selection. Through meticulous experimentation and analysis, the aim is to uncover the ideal configuration that maximizes the predictive capabilities of the models in estimating costs accurately. By focusing on hyperparameter optimization specifically tailored to feature selection, this research endeavors to contribute to the advancement of cost estimation techniques in machine learning applications. This research focuses on optimizing hyperparameters related to feature selection, aiming to discover the most pertinent attributes for cost estimation models. Hyperparameters that are used in this study for machine learning algorithms are shown in Table 2.

3.3 Machine Learning Algorithm and Model for Estimating Software Development Effort

Machine learning has made significant contributions to both research and real-world applications, with its adaptations permeating various domains and industries. Researchers leverage machine learning techniques to uncover patterns, trends, and correlations that may otherwise remain hidden, facilitating groundbreaking discoveries and advancements across scientific disciplines.

Before applying various machine learning (ML) algorithms, the target class was segmented into three distinct classes, as suggested in [22]. In a study, a solution for software development effort estimation (SEE) involves integrating the Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) with a Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), forming the GWO-FC approach [27].

With this method, GWO optimizes the FCNN’s parameters, such as weights and biases, to improve estimation accuracy by selecting the most effective parameter values to address SEE challenges. The software cost estimation dataset underwent rigorous evaluation using a diverse array of machine learning algorithms, including logistic regression, decision trees, random forest, support vector machines (SVM), and gradient boosting methods. This multifaceted approach ensures a thorough analysis, leveraging the unique strengths and capabilities of each algorithm to provide a comprehensive assessment of the dataset’s predictive performance. Many machine learning algorithms employed in this context are binary classifiers, which cannot directly manage multi-class datasets. To address this, the one-vs.-all (OvR) technique was employed. In the OvR method, individual binary classifiers are trained for each class. These classifiers categorize instances as belonging to their respective class or not. Subsequently, the class with the highest confidence score across all classifiers is predicted as the final class label.

The reason behind the use of the different machine learning algorithms that belong to different families. Logistic regression is a linear model that models the relationship between an independent variable and the probability of the binary outcome using the logistic function. Support vector machine is a discriminative model that finds the optimal hyperplane to separate the classes in feature space. Random forest is an ensemble model consisting of multiple independent decision trees. Gradient boosting is also an ensemble model that builds an additive model in a forward stage-wise manner. A brief introduction to the machine learning algorithm to refer to [28].

4 Experiment, Results and Discussion

As discussed earlier, it has been identified from the literature that accurate software cost estimation having a lower error rate is crucial, as it directly impacts financial and time predictions, similarly, there is a need to develop and test new models, particularly those that incorporate machine learning techniques, to improve prediction accuracy and efficiency across projects of varying sizes [29]. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed concept, five experiments including two based-line and three proposed were conducted using a state-of-the-art dataset CoCoMo NASA 2 [22]. This dataset includes an extensive compilation of data from 93 unique software projects. It contains 24 meticulously recorded attributes that offer detailed insights into various aspects of software development. Among the various experiments, the proposed model of PCA outperformed compared with the state-of-the-art ensemble method [15], filter and wrapper-based feature selection method, and based-line methods. The high identification accuracy received is

Our analysis revealed that PCA significantly outperformed both SFS and Mutual Information Selection. The key reason for PCA’s success lies in its ability to transform the original features into a set of orthogonal components, which effectively reduces multicollinearity—a common issue in high-dimensional datasets. By retaining the principal components with the highest variance, PCA ensures that the most informative features are selected. On the other hand, SFS, being a greedy algorithm, adds features incrementally without revisiting previous selections, often leading to suboptimal results and computational inefficiencies. Mutual Information, while capable of capturing non-linear relationships, struggled to fully account for feature dependencies in our dataset, resulting in less effective feature subsets. This highlights the robustness of PCA in scenarios involving large, complex datasets.

4.1 Experiment-1: Baseline Experiments

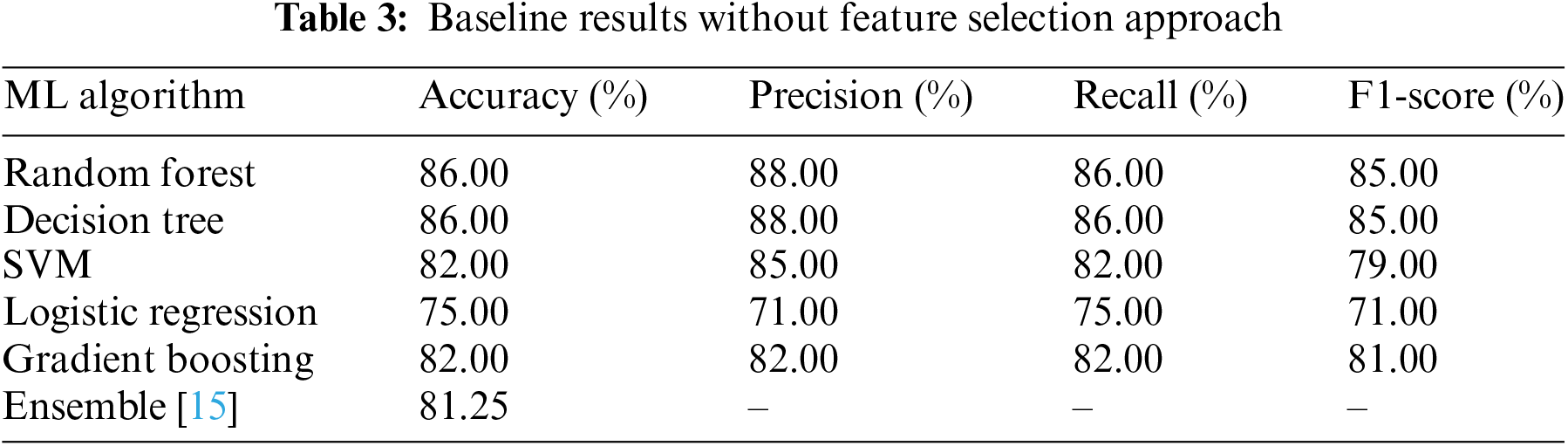

Two experiments were conducted as baseline studies, implementing five different machine learning algorithms belonging to three different families linear, tree-based, and hyperplane-based models. These algorithms were implemented with both standard and fine-tuned parameters. Performance was evaluated using standard metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, allowing for comparisons both within individual methods (local comparisons) and across different methods (global comparisons). Table 3 depicts the detailed results of the baseline standard parameters experiment. Through this approach, a high accuracy of

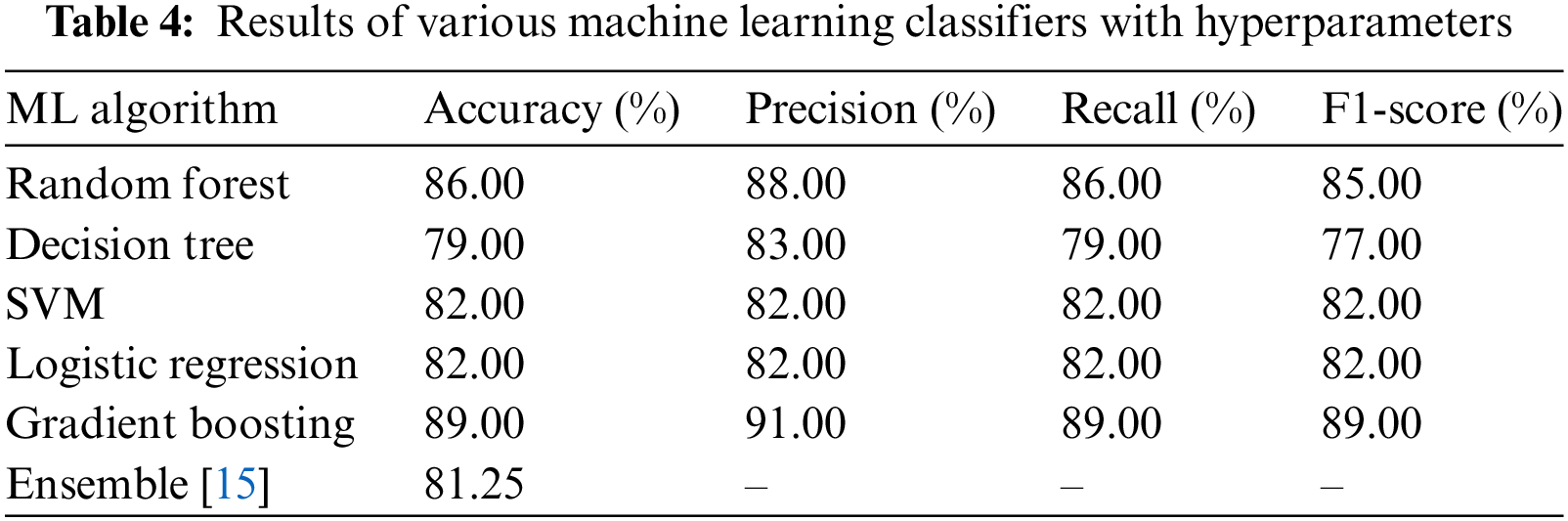

The fine-tuning technique is of utmost importance as it has the potential to significantly improve the performance of the models. By carefully adjusting the hyperparameters, models can be optimized to accurately analyze and interpret the dataset, leading to more precise and reliable predictions. The process of hyper-parameter tuning allows the unlocking of the full potential of the machine learning models, ultimately leading to enhanced performance and better overall results. To elevate the attainment of heightened prediction accuracy, we utilized the randomized search technique as our optimization method, seamlessly integrated with a comprehensive cross-validation procedure. This strategic combination was harnessed to empower the model with the capability to substantially enhance its predictive prowess, yielding more precise and dependable outcomes. By referring to Table 4, it can be visually analyzed the outcomes that have arisen as a consequence of engaging in hyper-parameter tuning for both gradient boosting and logistic regression algorithms. Fine-tuning hyperparameters has significantly enhanced the performance metrics of these algorithms. Gradient boosting achieved an accuracy of

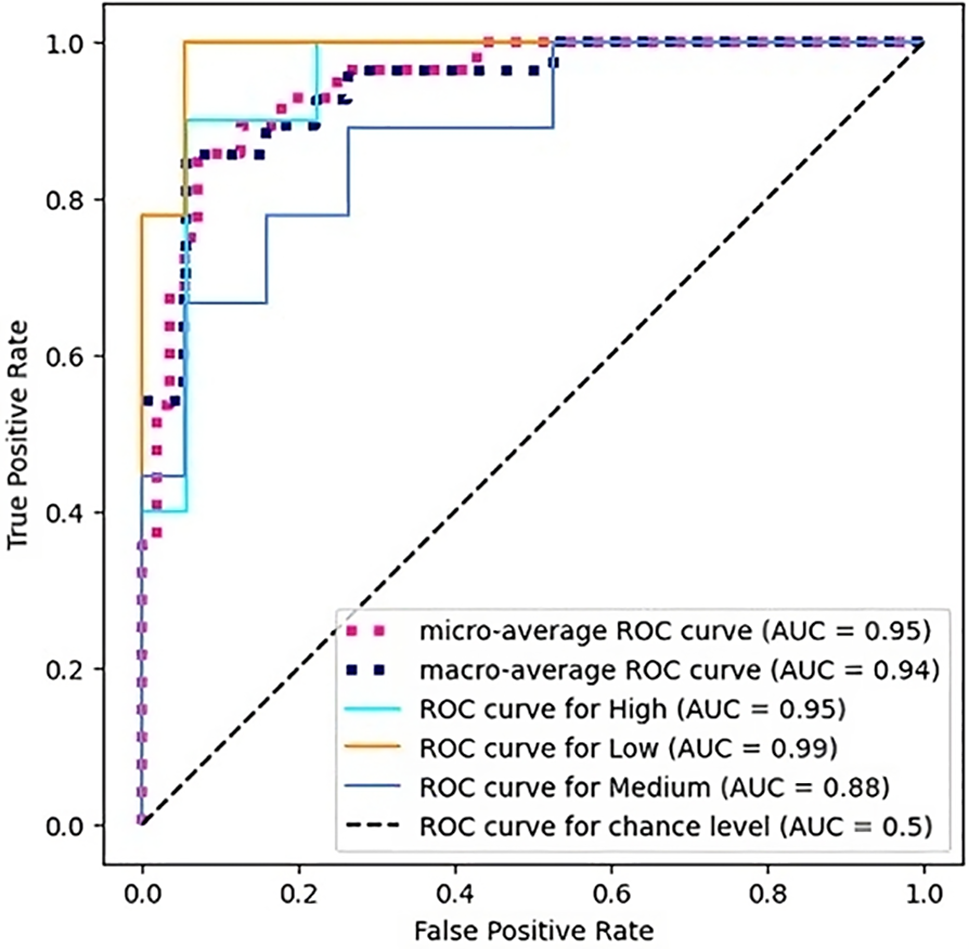

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for hyperparameter tuning in Gradient Boosting is displayed in Fig. 4, highlighting the performance across different classes. The micro-average AUC of 0.95 and macro-average AUC of 0.94 indicate strong overall classification performance. The individual ROC curves for different classes show AUC values of 0.95 for High, 0.99 for Low, and 0.88 for Medium, demonstrating excellent model discrimination, especially for the Low category. These results underscore the effectiveness of hyper-parameter tuning in enhancing model accuracy and class differentiation.

Figure 4: Multiclass ROC curve for gradient boosting with hyperparameters

4.2 Experiment-2: Feature Selection Based Performance

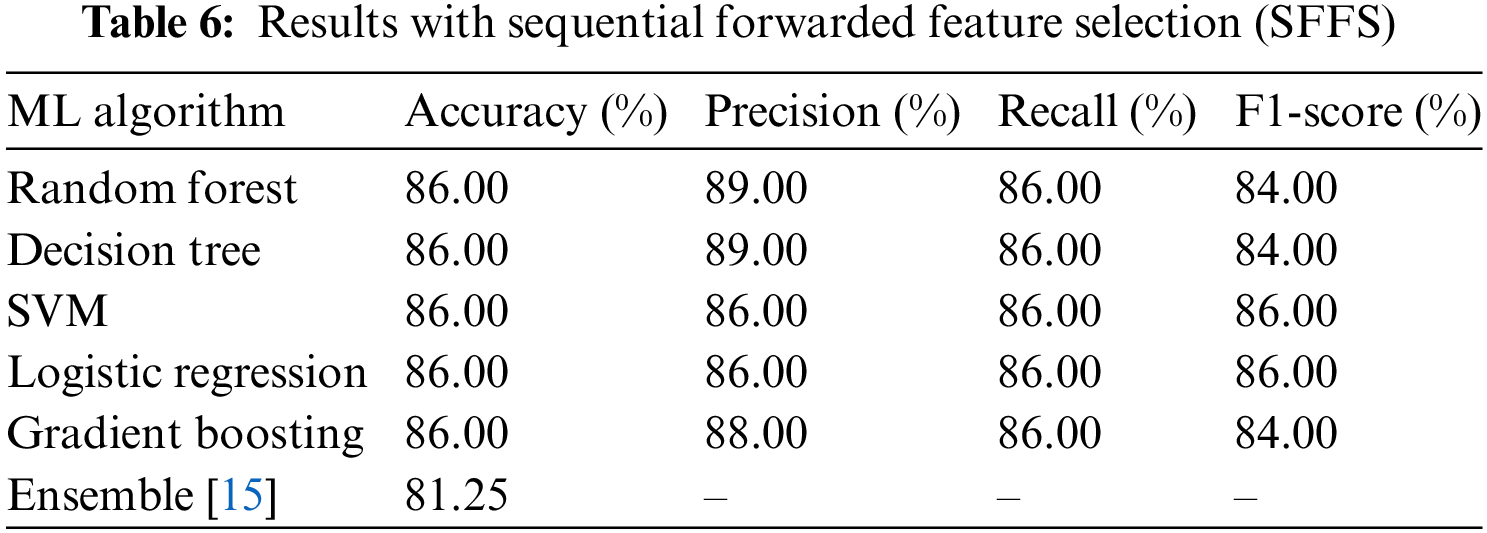

A set of informative features needs to be selected, posing a challenge. In this study, we proposed using two different methods: Sequential Forward Feature Selection (SFFS) and Mutual Information, under wrapper-based and filter-based methods, respectively. Detailed discussions on these methods can be found in Sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2. Currently, feature selection is not focused on saving computational power but rather on improving results by removing unnecessary features.

4.2.1 Sequential Forward Feature Selection (SFFS) and Performance

A dataset of CoCoMo has 24 features, a detail of these features is available at [22]. A cumulative 10 informative features have been selected using the proposed method SFFS, shown in Table 5. A random forest classifier was used to select the feature from a pool of features, a detail of the SFFS working algorithm is presented in Algorithm 1.

Five machine learning algorithms Random Forest, Decision Tree, SVM, Logistic Regression, and Gradient Boosting have been used for predicting the project cost. The performance of each result with comparing the [15], and based-line performance. The accuracy results of all algorithms are the same but it is superior to

Figure 5: Multiclass ROC curve for SFFS with support vector classification

4.2.2 Mutual Information (MI) and Performance

In this experiment, a strategic approach is employed to increase the performance that involved leveraging mutual information to identify the most valuable characteristics from the initial feature set. These selected features were then incorporated as inputs to the machine learning algorithm, to optimize the overall outcome. By meticulously assessing the relationship between features and their relevance to the problem at hand, we were able to curate a more refined set of inputs that would greatly contribute to improved results.

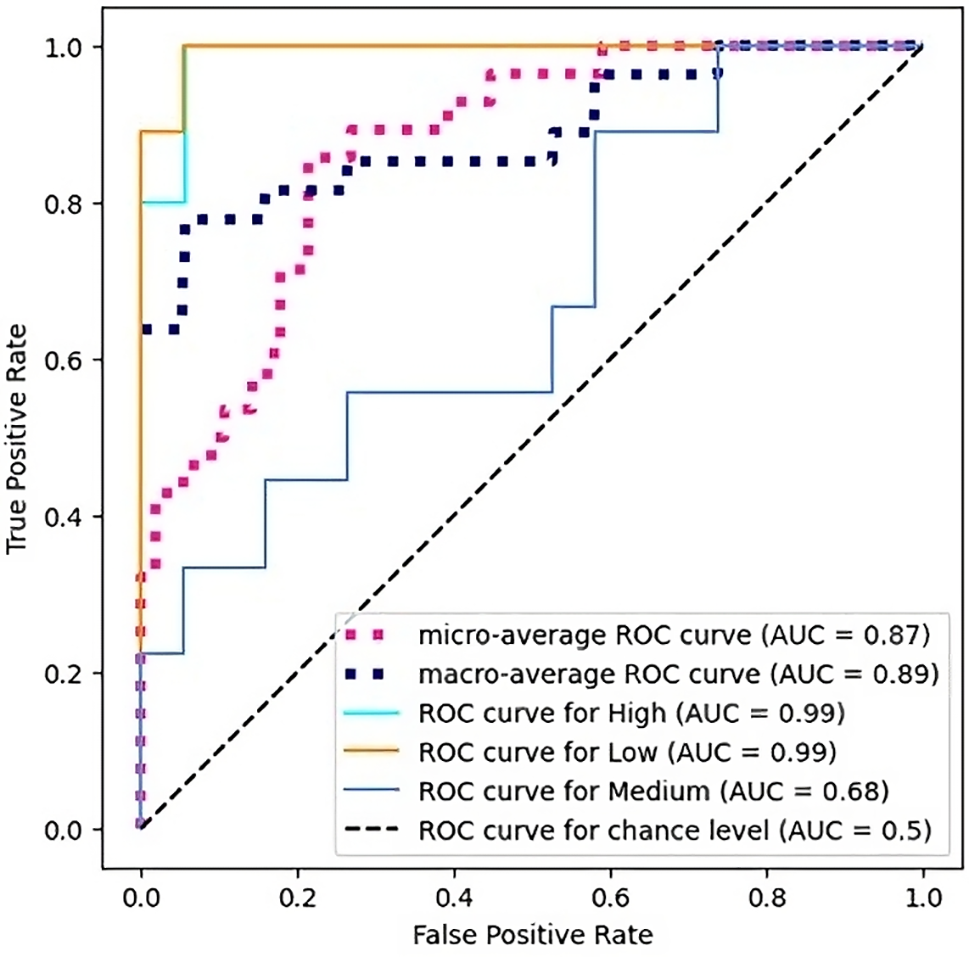

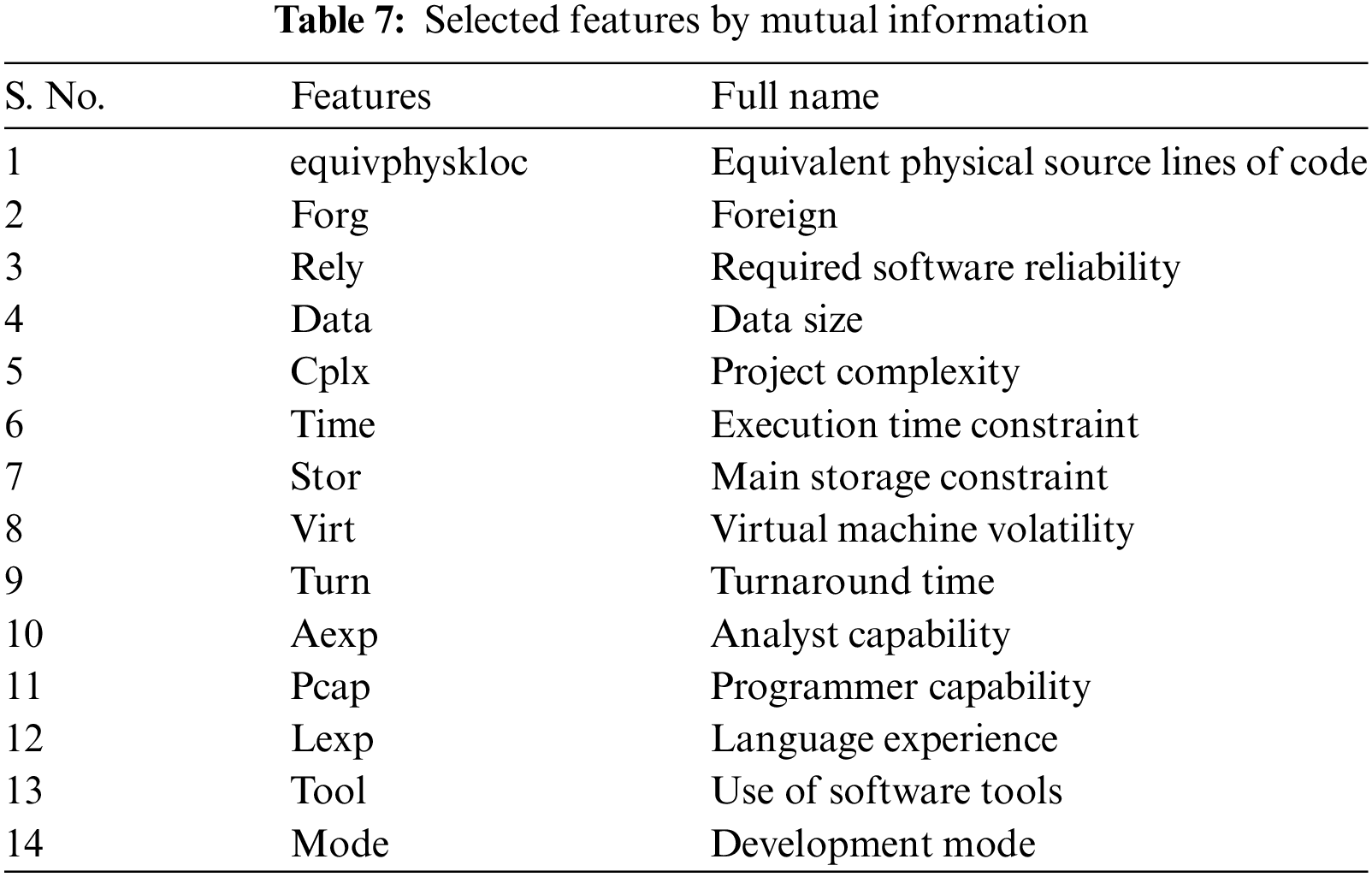

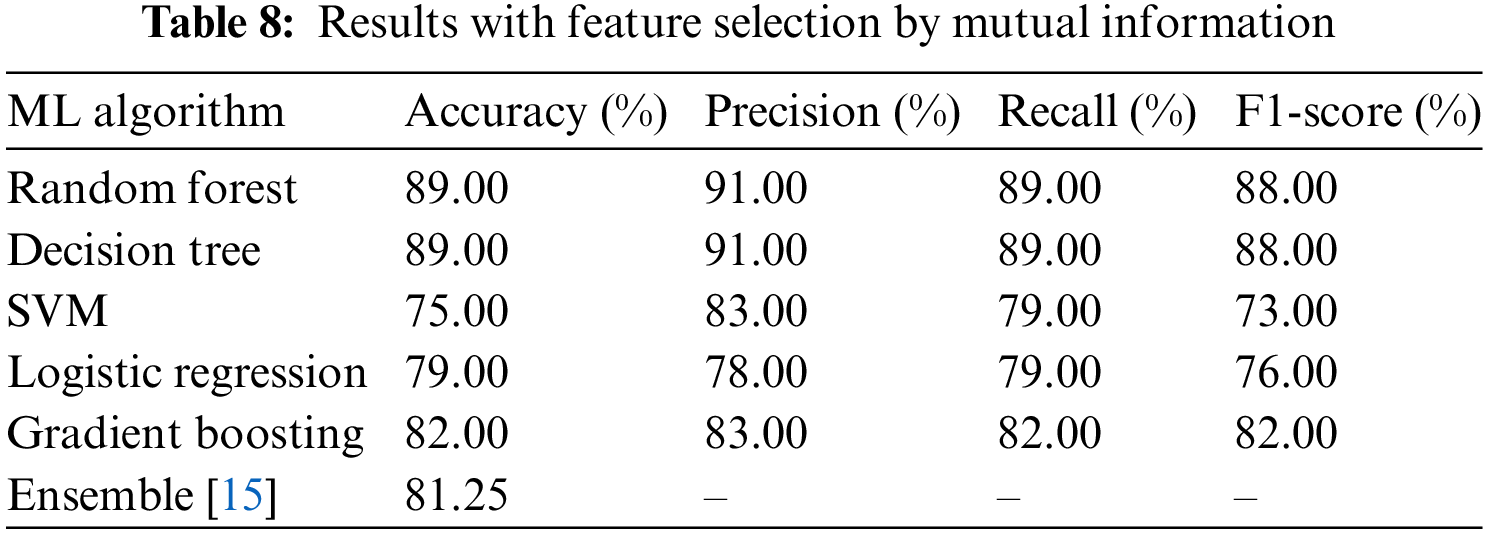

Among the 24 features in the CoCoMo dataset, 14 were selected using the MI approach, proving the outstanding results. The list of the 14 informative selected features is shown in Table 7. The selection process has already been discussed in Algorithm 2. This meticulous feature selection process plays a pivotal role in fine-tuning our model and maximizing its performance, leading to enhanced outcomes and ultimately achieving our objectives. The MI-based performance, as illustrated in Table 8, shows that Random Forest and Decision Tree achieved a precision of

Figure 6: Multiclass ROC curves for feature selection by mutual information with random forest

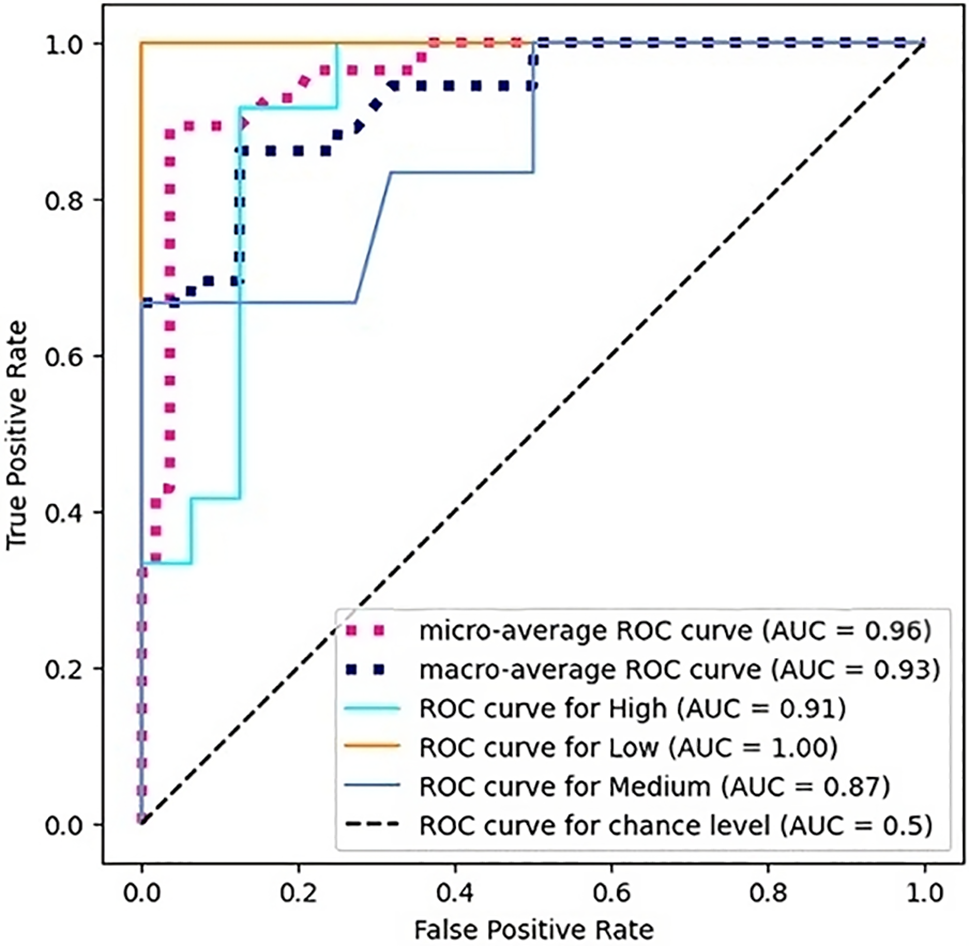

4.3 Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Performance

In Experiment 3, the idea of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was proposed as a technique for obtaining a set of linearly uncorrelated features from the dataset. This method was employed to improve the efficiency of our machine learning systems. We used the extracted features as inputs for our models rather than the original features. This strategy has the potential to increase our model’s overall accuracy while simultaneously reducing the number of features the algorithms need. Our models can produce more informed and precise predictions using PCA to efficiently capture the dataset’s most important patterns and variances. Our workflow’s incorporation of PCA is a potent tool for optimizing our machine.

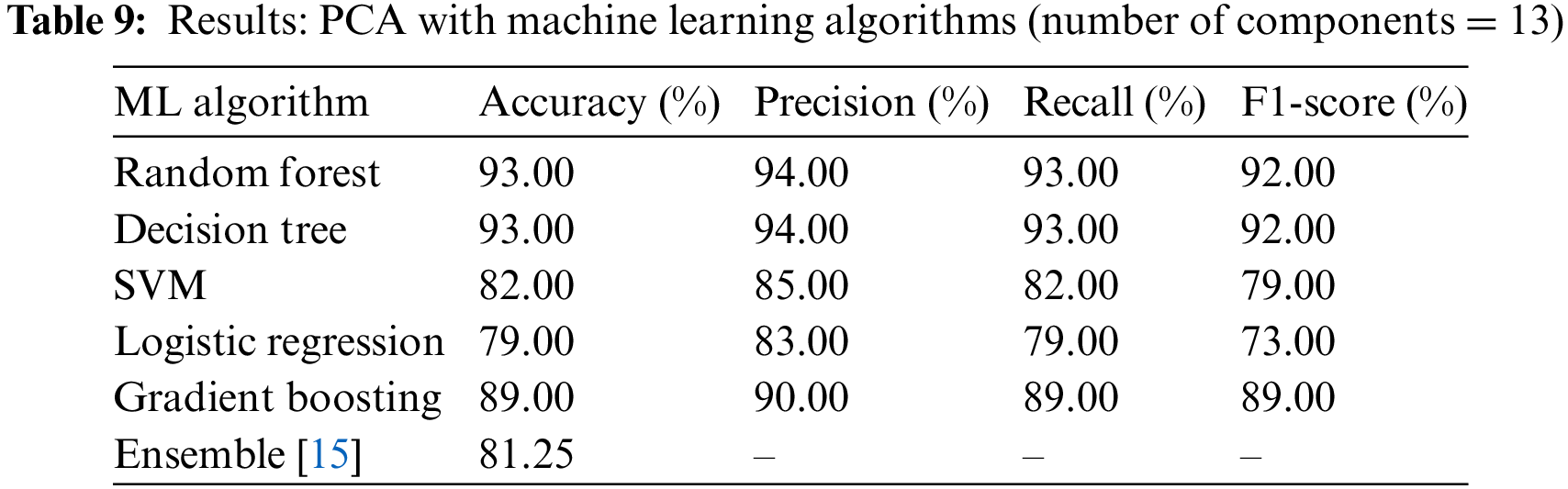

The 13 components were selected using PCA yielded exceptional results. A precision of

Figure 7: Multiclass ROC curves for PCA with random forest

In conclusion, this research has explored the application of machine learning techniques to enhance software cost estimation using the CoCoMo NASA dataset. Through meticulous feature selection processes, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Sequential Forward Feature Selection, and Mutual Information, we identified optimal feature subsets that significantly improved the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning models. Among the evaluated models, Random Forest combined with Principal Component Analysis based selection demonstrated superior performance, achieving the highest, precision, accuracy, and recall rates, while outperforming the previous methods. The findings of our study show that PCA is the most effective feature selection method due to its ability to reduce dimensionality while maintaining significant variance. Its performance in high-dimensional datasets, coupled with its robustness against multicollinearity, makes it a strong candidate for future applications. In contrast, methods like SFS and Mutual Information Selection were less efficient due to computational complexity and difficulty in handling feature dependencies.

Future work could explore the possibilities for integrating additional datasets and refining feature selection techniques to enhance model robustness and adaptability. Additionally, the exploration of other machine learning models and ensemble approaches may offer further improvements in estimation accuracy and efficiency.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our gratitude to all those who contributed to this research. Their support and insights were invaluable in completing this work.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Muhammad Affan Alim, Fizza Mansoor; data collection: Fizza Mansoor, Taha Jilani; analysis and interpretation of results: Fizza Mansoor, Muhammad Affan Alim, Muhammad Mansoor Alam; draft manuscript preparation: Fizza Mansoor, Mazliham Mohd Su’ud. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NASA repository, https://promise.site.uottawa.ca/SERepository/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. N. Sreekanth et al., “Evaluation of estimation in software development using deep learning-modified neural network,” Appl. Nanosci., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 2405–2415, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s13204-021-02204-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. B. Boehm, C. Abts, and S. Chulani, “Software development cost estimation approaches—a survey,” Ann. Softw. Eng., vol. 10, no. 1–4, pp. 177–205, 2000. doi: 10.1023/A:1018991717352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. S. Zoting and A. Shivarkar, “Software market size,” Accessed: Aug. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/software-market [Google Scholar]

4. M. Raymond, Remarkably Useful Stats and Trends on Software Development. “GoodFirms Research,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.goodfirms.co/resources/software-development-research [Google Scholar]

5. P. Singal, A. C. Kumari, and P. Sharma, “Estimation of software development effort: A differential evolution approach,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 167, pp. 2643–2652, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. K. Rak, Ž. Car, and I. Lovrek, “Effort estimation model for software development projects based on use case reuse,” J. Softw.: Evol. Process, vol. 31, no. 2, 2019, Art. no. e2119. [Google Scholar]

7. J. Huang, Y. -F. Li, and M. Xie, “An empirical analysis of data preprocessing for machine learning-based software cost estimation,” Inf. Softw. Tech., vol. 67, pp. 108–127, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2015.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. M. Al Asheeri and M. Hammad, “Improving software cost estimation process using feature selection technique,” in 3rd Smart Cities Sympo. (SCS 2020), IET, 2020, pp. 89–95. [Google Scholar]

9. Z. Sun et al., “Mutual information based multi-label feature selection via constrained convex optimization,” Neurocomputing, vol. 329, no. 9, pp. 447–456, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2018.10.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. P. Probst, A. -L. Boulesteix, and B. Bischl, “Tunability: Importance of hyperparameters of machine learning algorithms,” J. Mach. Learn. Res., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1934–1965, 2019. [Google Scholar]

11. A. Zakrani, M. Hain, and A. Idri, “Improving software development effort estimating using support vector regression and feature selection,” IAES Int. J. Artif.l Intell., vol. 8, no. 4, 2019, Art. no. 399. doi: 10.11591/ijai.v8.i4.pp399-410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. M. Rahmaninia and P. Moradi, “OSFSMI: Online stream feature selection method based on mutual information,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 733–746, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2017.08.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. T. Cabral Jose, A. L. Oliveira, and F. Q. da Silva, “Ensemble effort estimation: An updated and extended systematic literature review,” J. Syst. Softw., vol. 195, 2023, Art. no. 111542. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2022.111542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. S. Hameed, Y. Elsheikh, and M. Azzeh, “An optimized case-based software project effort estimation using genetic algorithm,” Inf. Softw. Tech., vol. 153, 2023, Art. no. 107088. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2022.107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. K. E. Rao and G. A. Rao, “RETRACTED ARTICLE: Ensemble learning with recursive feature elimination integrated software effort estimation: A novel approach,” Evol. Intell., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 151–162, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s12065-020-00360-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. P. Phannachitta and K. Matsumoto, “Model-based software effort estimation-a robust comparison of 14 algorithms widely used in the data science community,” Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 569–589, 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. M. Uçar, “Classification performance-based feature selection algorithm for machine learning: P-score,” IRBM, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 229–239, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.irbm.2020.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. G. Chandrashekar and F. Sahin, “A survey on feature selection methods,” Comput. Elect. Eng., vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 16–28, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2013.11.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. E. Kocaguneli, T. Menzies, A. Bener, and J. W. Keung, “Exploiting the essential assumptions of analogy-based effort estimation,” IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 425–438, 2011. doi: 10.1109/TSE.2011.27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. E. Kocaguneli, T. Menzies, J. Keung, D. Cok, and R. Madachy, “Active learning and effort estimation: Finding the essential content of software effort estimation data,” IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 1040–1053, 2012. doi: 10.1109/TSE.2012.88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. A. BaniMustafa, “Predicting software effort estimation using machine learning techniques,” in 2018 8th Int. Conf. Comput. Sci. Inform. Technol. (CSIT), IEEE, 2018, pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

22. B. W. Boehm, “Software engineering economics,” IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 1, pp. 4–21, 1984. doi: 10.1109/TSE.1984.5010193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. R. Zebari, A. Abdulazeez, D. Zeebaree, D. Zebari, and J. Saeed, “A comprehensive review of dimensionality reduction techniques for feature selection and feature extraction,” J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 56–70, 2020. doi: 10.38094/jastt1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. A. Alim, I. Naseem, R. Togneri, and M. Bennamoun, “The most discriminant subbands for face recognition: A novel information-theoretic framework,” Int. J. Wavelets, Multiresol. Inform. Process., vol. 16, no. 5, 2018, Art. no. 1850040. doi: 10.1142/S0219691318500406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. S. Wold, K. Esbensen, and P. Geladi, “Principal component analysis,” Chemomet. Intell. Lab. Syst., vol. 2, no. 1–3, pp. 37–52, 1987. [Google Scholar]

26. A. Alim, A. Rafay, and I. Naseem, “PoGB-pred: Prediction of antifreeze proteins sequences using amino acid composition with feature selection followed by a sequential-based ensemble approach,” Curr. Bioinform., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 446–456, 2021. doi: 10.2174/1574893615999200707141926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. S. Kassaymeh, M. Alweshah, M. A. Al-Betar, A. I. Hammouri, and M. A. Al-Ma’aitah, “Software effort estimation modeling and fully connected artificial neural network optimization using soft computing techniques,” Cluster Comput., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 737–760, 2024. doi: 10.1007/s10586-023-03979-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. S. B. Kotsiantis, I. D. Zaharakis, and P. E. Pintelas, “Machine learning: A review of classification and combining techniques,” Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 159–190, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s10462-007-9052-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. S. Azzam, O. E. Emam, and M. Draz, “Five decades of software cost estimation models: A survey,” FCI-H Inform. Bull., 2024. doi: 10.21608/fcihib.2024.261210.1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools