Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhanced Cutaneous Melanoma Segmentation in Dermoscopic Images Using a Dual U-Net Framework with Multi-Path Convolution Block Attention Module and SE-Res-Conv

1 College of Mechanical Engineering, Quzhou University, Quzhou, 324000, China

2 Department of Rehabilitation, Quzhou Third Hospital, Quzhou, 324000, China

3 Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Macau, Macau, 999078, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaoliang Jiang. Email: ; Jianzhen Cheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multi-Modal Deep Learning for Advanced Medical Diagnostics)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(3), 4805-4824. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065864

Received 23 March 2025; Accepted 29 May 2025; Issue published 30 July 2025

Abstract

With the continuous development of artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques, there have been effective methods supporting the work of dermatologist in the field of skin cancer detection. However, object significant challenges have been presented in accurately segmenting melanomas in dermoscopic images due to the objects that could interfere human observations, such as bubbles and scales. To address these challenges, we propose a dual U-Net network framework for skin melanoma segmentation. In our proposed architecture, we introduce several innovative components that aim to enhance the performance and capabilities of the traditional U-Net. First, we establish a novel framework that links two simplified U-Nets, enabling more comprehensive information exchange and feature integration throughout the network. Second, after cascading the second U-Net, we introduce a skip connection between the decoder and encoder networks, and incorporate a modified receptive field block (MRFB), which is designed to capture multi-scale spatial information. Third, to further enhance the feature representation capabilities, we add a multi-path convolution block attention module (MCBAM) to the first two layers of the first U-Net encoding, and integrate a new squeeze-and-excitation (SE) mechanism with residual connections in the second U-Net. To illustrate the performance of our proposed model, we conducted comprehensive experiments on widely recognized skin datasets. On the ISIC-2017 dataset, the IoU value of our proposed model increased from 0.6406 to 0.6819 and the Dice coefficient increased from 0.7625 to 0.8023. On the ISIC-2018 dataset, the IoU value of proposed model also improved from 0.7138 to 0.7709, while the Dice coefficient increased from 0.8285 to 0.8665. Furthermore, the generalization experiments conducted on the jaw cyst dataset from Quzhou People’s Hospital further verified the outstanding segmentation performance of the proposed model. These findings collectively affirm the potential of our approach as a valuable tool in supporting clinical decision-making in the field of skin cancer detection, as well as advancing research in medical image analysis.Keywords

As a vital tissue of the human body, the skin is in constant contact with people’s surrounding environment, serving as a protective barrier against external irritation and damage. Due to continuous metabolism, skin cells are constantly renewed and replaced. However, unhealthy lifestyle and habits, as well as possible unexpected radiation exposure, could cause cellular malignancies. According to credible studies, the incidence rate of skin cancer is projected to substantially increase over the coming decades [1]. In 2020, approximately 325,000 new cases of skin cancer were reported worldwide, a number expected to rise to 510,000 by 2040. Furthermore, the number of skin cancer-related deaths is anticipated to surge from 57,000 in 2020 to 96,000 in 2040. Among all types of skin cancer, melanoma stands out as the most aggressive and lethal type, with an alarmingly high fatality rate. Therefore, early detection of melanoma is crucial, as it could significantly improve patient prognosis. If melanoma is identified and treated in its early stages, the survival rate can reach as high as 95%. Conversely, delayed diagnosis allows cancer cells to metastasize, spreading to internal organs or lymph nodes, potentially leading to secondary malignancies such as lung cancer. Therefore, the early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma is essential for effective treatment and can significantly improve patient outcomes. By identifying and treating melanoma at an early stage, healthcare providers can enhance treatment success rates and reduce overall mortality rate associated with this deadly disease.

In skin cancer screening, dermoscopy is one of the effective methods. It is a non-invasive and non-contact imaging technique, able to capture highly detailed images of diseased tissue while minimizing interference from a patient’s skin condition. This advanced imaging method enhances diagnostic precision by providing a clearer and more detailed view of potential skin lesions. However, dermoscopy still relies heavily on manual interpretation by dermatologists, lead to several inherent limitations. For example, manual diagnosis is not only time-consuming and labor-intensive, but also prone to subjectivity. Variability in physicians’ expertise and experience can result in diagnostic inconsistencies, increasing the possibility of human error.

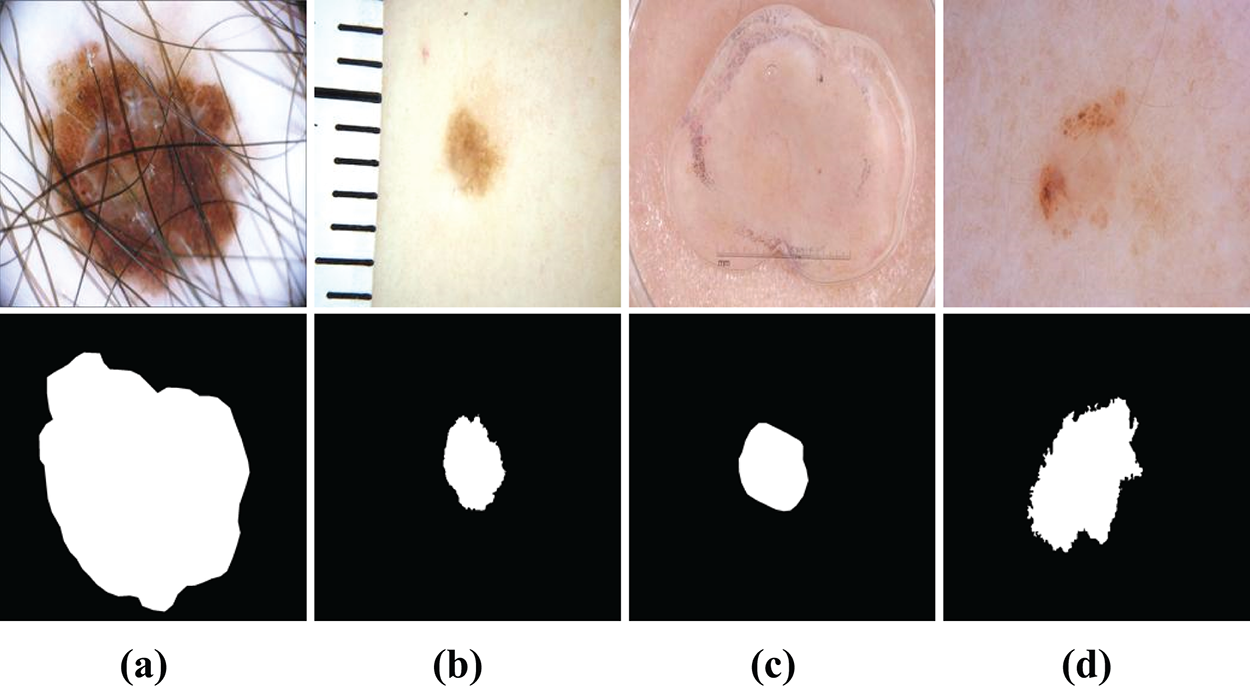

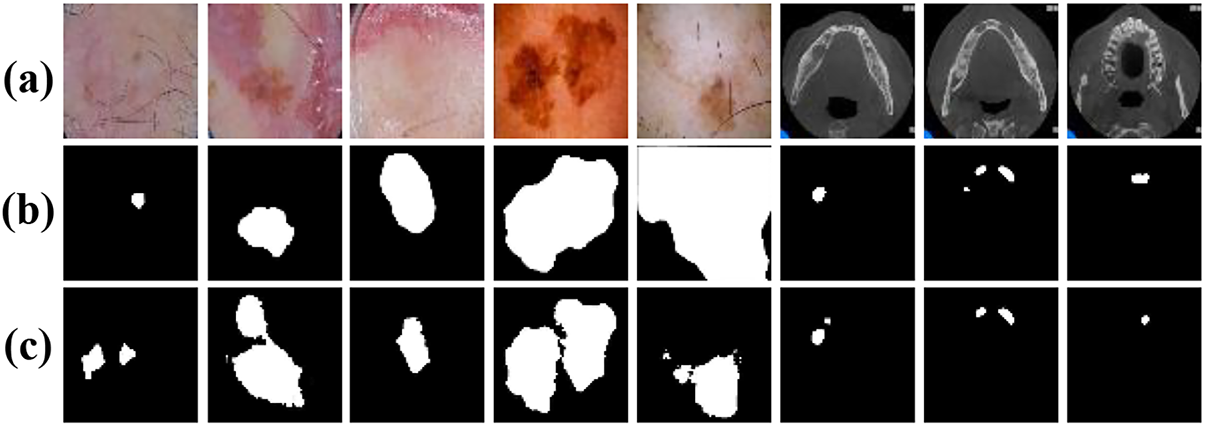

The emergence of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) technology provides possible solutions to minimizing overlooked symptoms and misdiagnoses caused by human oversight. CAD provides more objective and accurate pathological information, which could significantly improve diagnostic reliability. However, lesion segmentation in dermoscopic images remains a challenging and complex task, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Specifically, lesions in dermoscopic images exhibit diverse shapes and scales, which are often undergoing irregular and unpredictable changes. This variability complicates the development of a generalized segmentation approach. Additionally, objects such as hair, bubbles, and scales further interfere with the segmentation process, potentially obscuring critical lesion features and leading to inaccurate diagnoses. Furthermore, variations in image acquisition lighting can result in low contrast in the lesion area, making boundary identification difficult. Inconsistent illumination may obscure the true extent and characteristics of the lesion, complicating accurate segmentation and diagnosis.

Figure 1: Examples of challenging in dermoscopic images, including: (a) hair; (b) scale; (c) bubble; (d) low contrast. The first row: original images, the second row: mask images

To address these challenges, early CAD systems—primarily including clustering, region growing, and GrabCut—were developed to preprocess dermoscopic images [2–4]. However, these approaches have several limitations, particularly in segmentation tasks. One notable drawback is that, when the interfering objects are removed, partials of the lesion could also be lost during preprocessing. Additionally, traditional image segmentation techniques often require extensive prior knowledge and are not well-suited for batch processing of large datasets. Nowadays, the design of dermoscopic image segmentation algorithms has made significant advancements, with most approaches being based on end-to-end foundational architectures [5,6]. Since the creation of U-Net [7,8], researchers have developed various adaptations and enhancements to overcome specific challenges in melanoma segmentation. For instance, to overcome the limited feature extraction capability of the standard U-Net approach, Yu et al. [9] proposed an enhanced method for skin lesion segmentation, known as EIU-Net. First, the inverted residual block and efficient pyramid extraction block are utilized as the encoder to strengthen feature extraction. Additionally, a novel multi-layer fusion block is integrated between the encoder-decoder pairs to facilitate comprehensive information exchange and improve segmentation quality. Furthermore, a reconstructed decoder fusion architecture is employed to capture multi-scale features, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the final results. Xu et al. [10] developed a PHCU-Net network architecture, which is composed of global and local features along with a double-path hierarchical attention mechanism. The design enables the decoder to capture image feature information without redundancy. Sharen et al. [11] implemented the feature pyramid network within the U-Net framework to capture nuanced information and contextual features crucial for guiding skin lesion segmentation effectively. Baccouche et al. [12] introduced a dual U-Net architecture named Connected-UNets, which enhances breast cancer analysis by incorporating attention mechanisms and residual connections. In addition, various networks are being developed, mainly including dialated convolution [13,14], residual connection [15,16], transformer module [17,18] and attention mechanism [19,20].

Inspired by the unique characteristics of melanoma and the U-Net architecture, we propose a dual U-Net network segmentation framework. Our contributions focus on three key areas: (a) We design a framework that integrates two simplified U-Nets, enabling seamless information exchange and functional integration across the network; (b) As part of the cascading process in the second U-Net, we introduce a jump connection between the decoder and encoder networks, further enhancing it with the MRFB. This module improves the ability to capture multi-scale contextual information, leading to a more robust representation of features across different spatial resolutions; (c) To further refine the encoding process, we augment the first U-Net with a MCBAM applied to its initial two encoding layers. This module selectively emphasizes informative features while suppressing irrelevant ones. Complementing this, we integrate a novel SE-Res-Conv module equipped with residual connections into the second U-Net, which dynamically recalibrates channel-wise feature responses to strengthen inter-channel relationships.

We provide a detailed overview of our architecture and outline the design principles of its individual modules, including MCBAM, SE-Res-Conv module, and MRFB. We will also introduce the loss function employed in this study.

The traditional U-Net architecture is effective for many image segmentation tasks but has certain limitations when applied to skin lesion segmentation. In dermoscopic images, skin lesions can vary significantly in size, shape, and texture. A single U-Net may struggle to integrate contextual information from different regions, particularly when dealing with complex or irregularly shaped lesions. Additionally, dermoscopic images often contain objects such as hair, bubbles, and scales, which can obscure lesion features or be misinterpreted as part of the lesion, thereby affecting segmentation accuracy.

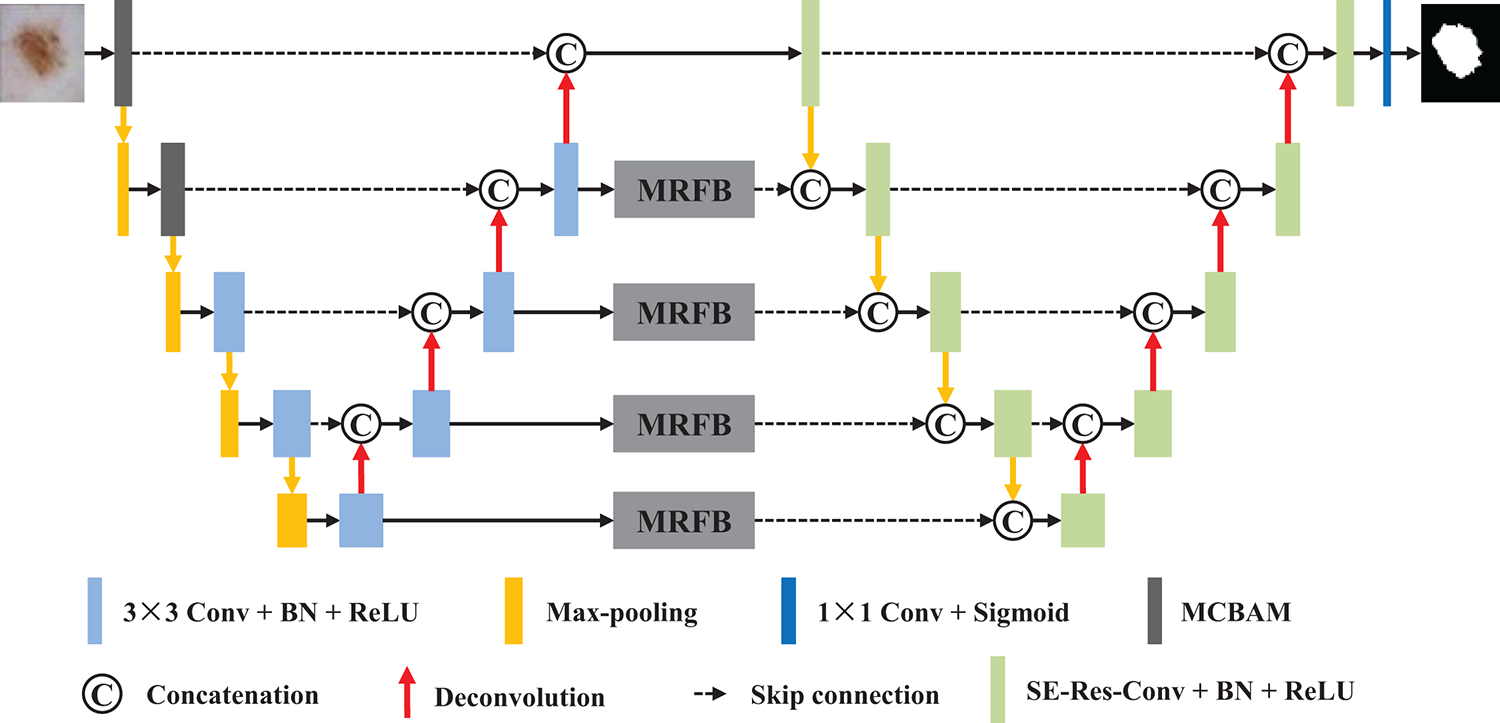

Inspired by the encoding-decoding architecture, we propose a novel framework that seamlessly integrates two U-Nets through jump connections. As illustrated in Fig. 2, our approach consists of two conventional encoder-decoder structures, with an essential MRFB block strategically positioned between the decoder of the first U-Net and the encoder of the second U-Net.

Figure 2: Network architecture of the proposed method

In the initial two encoder blocks of the first U-Net, we integrate the multi-path convolution block attention module, which is specifically employed to improve feature discrimination. For the remaining encoder-decoder layers, a sequence of two convolutional layers is employed, where each convolutional layer utilized 3 × 3 convolutional operations to introduce non-linearity and enhance feature representation. Before passing features to the next encoder block, a max-pooling operation is applied to down-sample the feature maps. The decoder blocks utilize 2 × 2 transposed convolutions, which connect to the output of the corresponding encoder and feed the results into two additional convolutional layers.

The second U-Net maintains the same structural design as the first, except that SE-Res-Conv modules replace traditional convolutional blocks. Another key innovation in our model is that the decoder output of the first U-Net is connected to the encoder of the second U-Net after passing through the MRFB. Finally, the features are processed through a 1 × 1 convolution layer, and the predicted segmentation mask is generated via a sigmoid activation layer.

Overall, our dual U-Net configuration consists of two interconnected U-Nets. Compared to a single U-Net, this architecture enables a more comprehensive exchange of information between the networks, enhancing their ability to capture both local details and global contextual information in the image data.

2.2 Multi-Path Convolution Block Attention Module

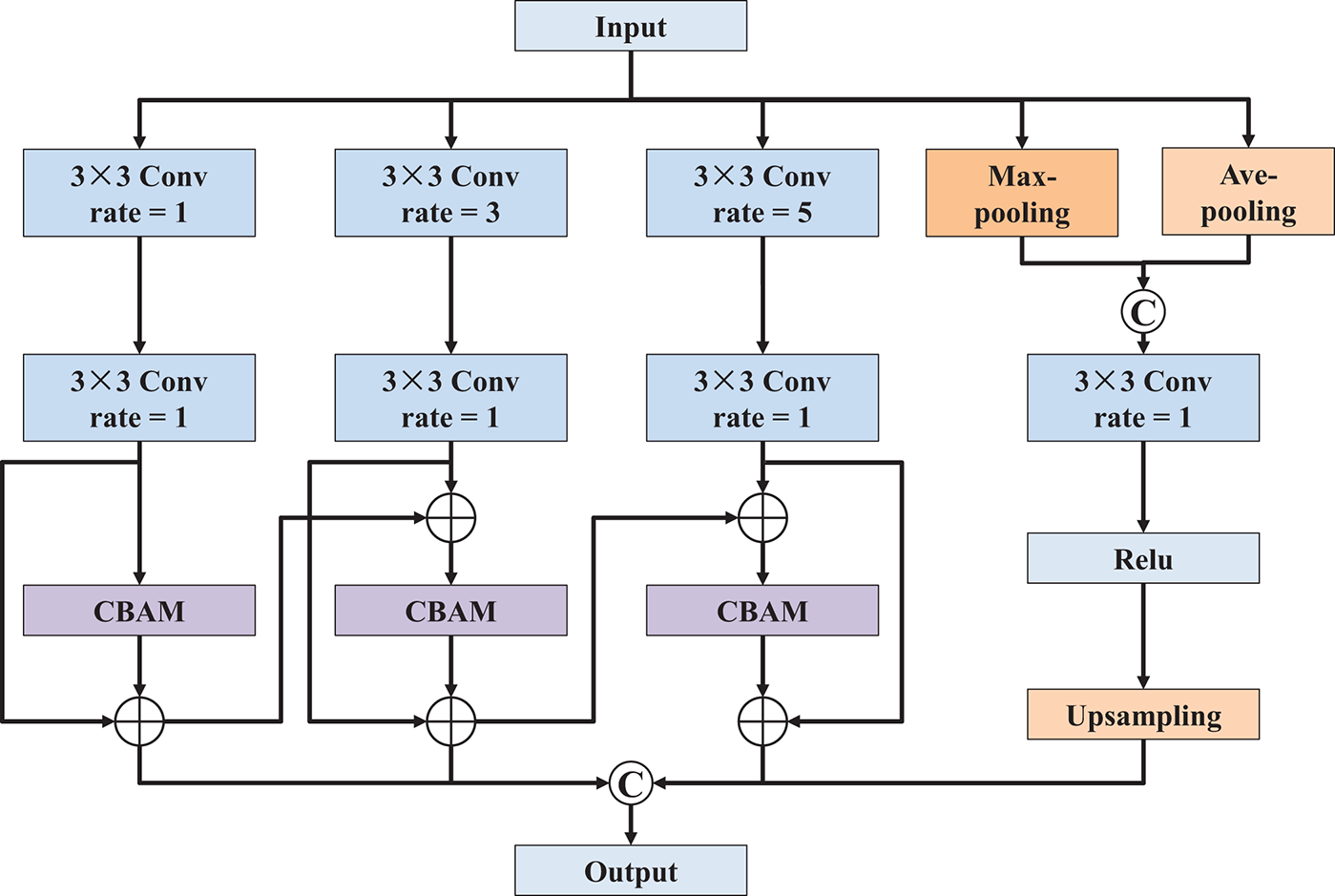

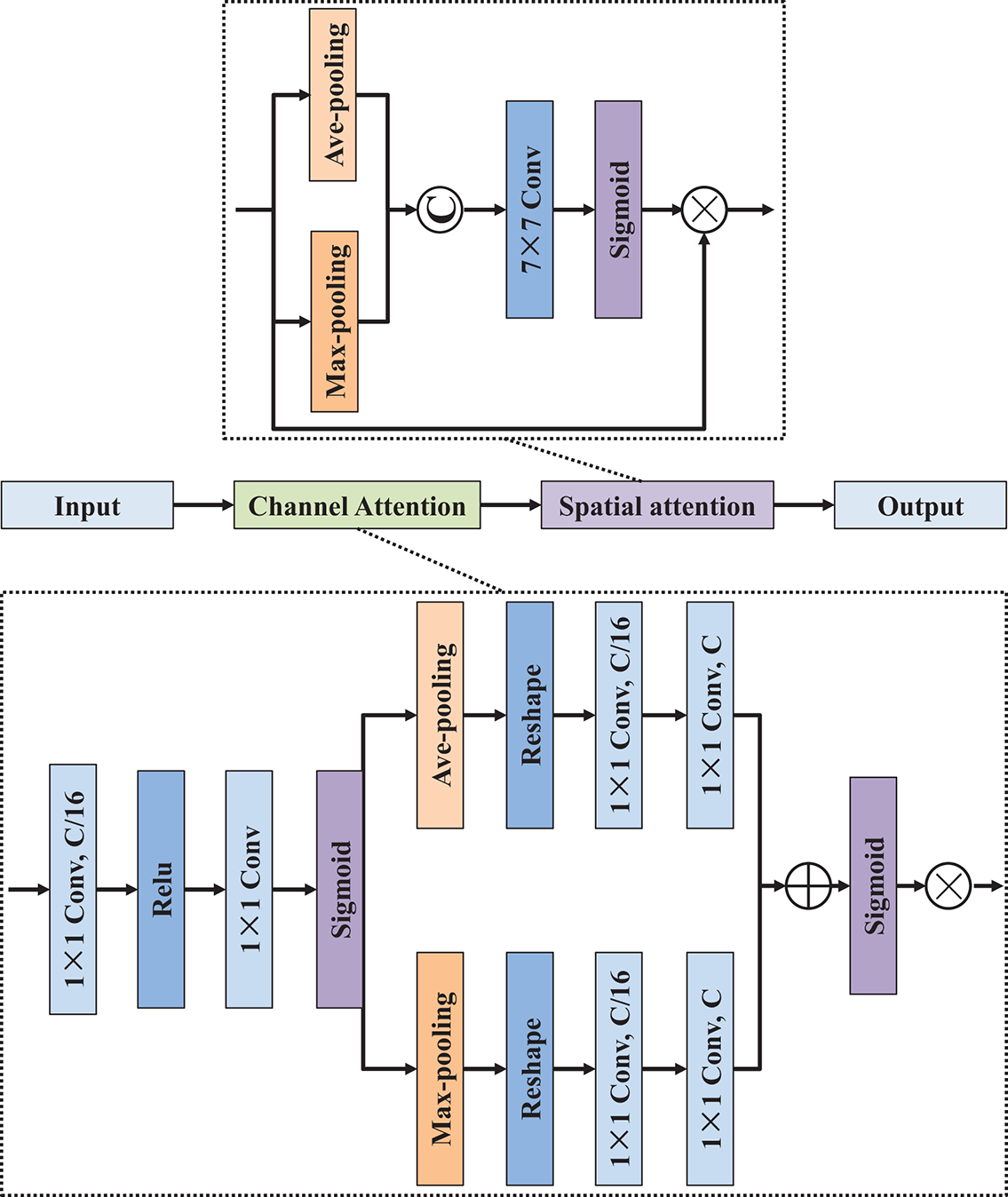

To effectively extract features across multiple spatial scales and enhance semantic representation, the multi-path convolution block attention module was designed, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This module integrates parallel convolutional branches with varied dilation rates and attention mechanisms to refine the input feature map comprehensively. Specifically, the structure consists of four parallel processing paths. The first three paths each begin with a dilated 3 × 3 convolutional layer, using dilation rates of 1, 3, and 5, respectively. These varying dilation rates enable the network to capture features at different field sizes. Each dilated convolution is followed by a standard 3 × 3 convolution to stabilize the receptive field expansion and normalize the feature distribution. To further enhance discriminative power, a CBAM [21] is incorporated after each pair of convolutions in these three branches. As shown in Fig. 4, the CBAM adaptively recalibrates the feature maps by sequentially applying channel and spatial attention mechanisms, allowing the model to focus on informative regions while suppressing irrelevant or noisy features. The fourth path performs a complementary operation, where both max-pooling and average-pooling are applied to the input feature map. The outputs of these pooling layers are concatenated and passed through a 3 × 3 convolution to unify the representation. Then, a ReLU activation function is applied to introduce non-linearity, followed by an up-sampling operation to match the spatial dimensions of the other branches. Finally, the outputs of all four paths are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a unified, multi-scale, and attention-refined feature map. This fused output effectively integrates local and global context, enhances semantic richness, and serves as an optimized representation for downstream segmentation tasks.

Figure 3: Network architecture of multi-path convolution block attention module

Figure 4: Network architecture of convolution block attention module

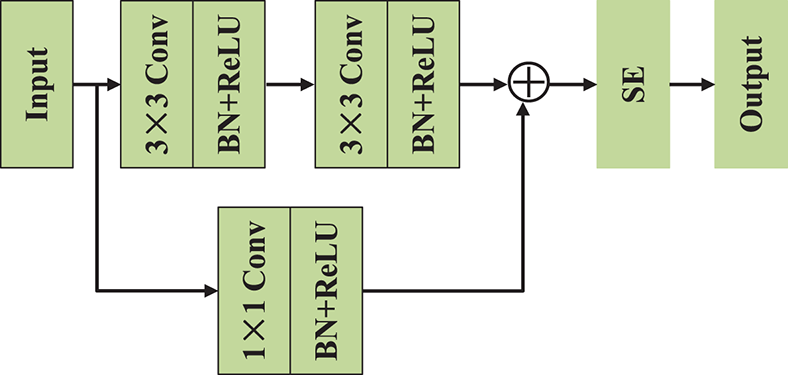

Deep neural networks represent a significant leap in improving machine learning model performance, but they also possess substantial challenges, primarily the issues of gradient vanishing or exploding. To address these challenges effectively, we employ the residual learning framework and propose the SE-Res-Conv module, as shown in Fig. 5. This module consists of two consecutive 3 × 3 convolutional layers arranged in series, along with batch normalization (BN) and ReLU activations. We also incorporate identity mapping to create a direct connection between the input and output of feature information. Inspired by the work of [22,23], we integrate the SE layer as a content-aware mechanism into the residual network. During operation, the SE layer recalibrates channel weights, enables the network to cultivate robust feature representations. This enhances the network’s sensitivity to relevant features while suppressing the influence of irrelevant ones. The Res-Conv operation can be formulated as follows:

where

Figure 5: Network architecture of SE-Res-Conv module

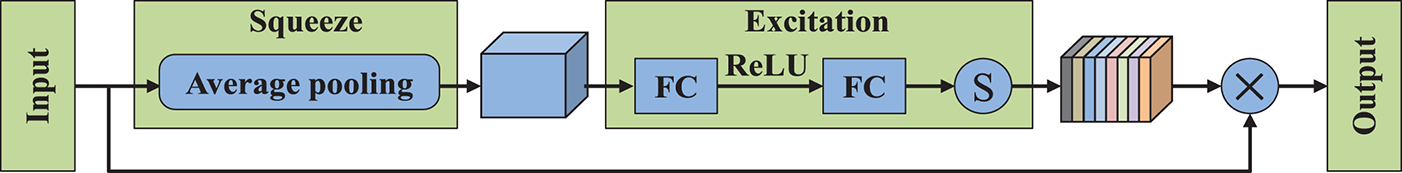

As shown in Fig. 6, the SE mechanism unfolds in two distinct stages: initially, the feature map is compressed by applying global average pooling to generate concise feature vectors of size

where

Figure 6: Network architecture of SE module

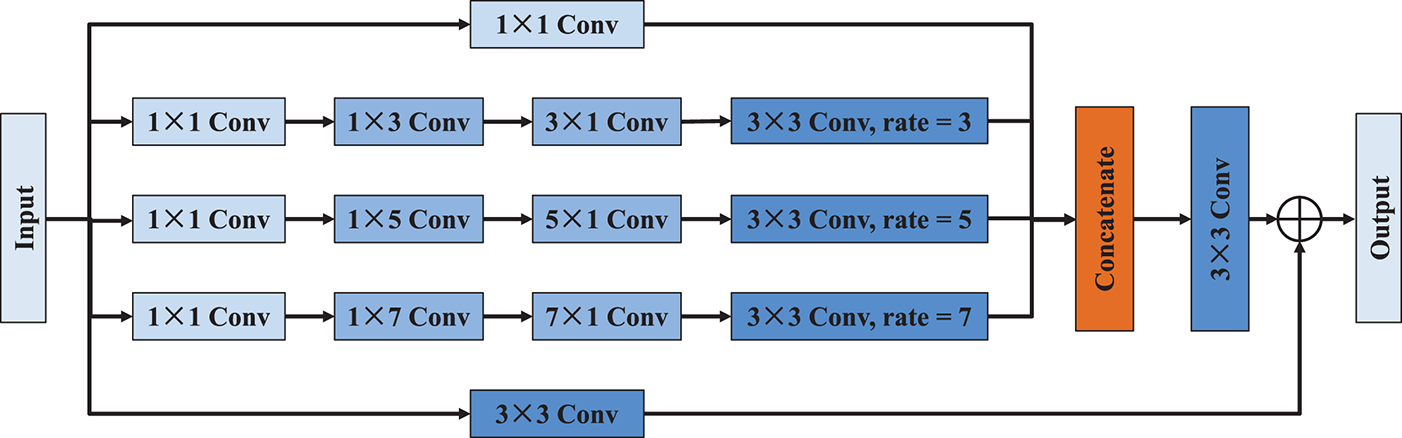

2.4 Modified Receptive Field Block

To enhance the model’s ability to capture contextual information at multiple spatial scales, the modified receptive field block is constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Inspired by the principles of multi-branch convolutional design and atrous spatial pyramid pooling [24,25], MRFB introduces a flexible and efficient architecture for extracting multi-scale features while preserving spatial resolution and minimizing computational overhead. The MRFB begins by applying several parallel convolutional operations to the input feature map. Each branch starts with a 1 × 1 convolution that serves to reduce dimensionality and facilitate channel-wise transformation. These branches are followed by asymmetric convolutional kernels (including 1 × 3 followed by 3 × 1, 1 × 5 followed by 5 × 1, and 1 × 7 followed by 7 × 1) to capture features with elongated receptive fields along different orientations. This asymmetric design helps extract both local details and extended contextual patterns without increasing the kernel size significantly. Then, each of these convolutional paths is extended by a 3 × 3 convolution, with dilation rates of respectively 3, 5, and 7. Once all branches have processed the input, their outputs are concatenated along the channel dimension, combining feature representations from different receptive fields and orientations. Subsequently, this fused representation is then passed through a 3 × 3 convolution layer to refine and unify the aggregated features. Additionally, another independent 3 × 3 convolution path ensures that the shallow features are preserved for later fusion. In summary, MRFB effectively balances local and global context modeling through multi-scale atrous convolutions, asymmetric kernels, making it a powerful module for improving the semantic segmentation performance of the overall network.

Figure 7: Network architecture of MRFB

In image segmentation, Dice loss [26–28] is a widely recognized and extensively used metric for evaluating segmentation performance. It is especially effective for imbalanced datasets, where the background often dominates the foreground. Given the image characteristics of melanoma, we have chosen Dice loss as the loss function:

where

We choose the indices IoU (Intersection over Union) [29,30] and Dice [29,31] to quantify the performance of the segmentation models. Both metrics are known for their effectiveness in measuring the overlap between the predicted segmentation result and the ground truth. Their respective equations are as follows:

where

3 Experimental Results and Discussion

All experiments were conducted on a Dell computer workbench equipped with an i7-10700 CPU and an NVIDIA Quadro RTX 6000 GPU with 24 GB of GPU memory. The deep learning framework used was TensorFlow version 2.4.0. In the experiment, the Adam optimizer was employed with an initial learning rate of 10−4, which was automatically adjusted during model training. The batch size during training was 16, and training was conducted for 200 epochs to accommodate hardware limitations and achieve the optimal training effectiveness.

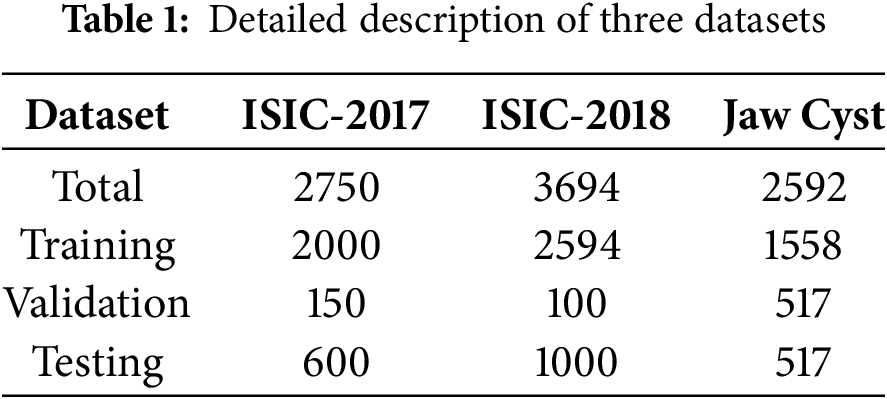

Two of the experimental datasets are publicly available in 2017 [32] and 2018 [33] from the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). These datasets can be accessed on their official website. The datasets include the original images along with the corresponding mask images that show the skin lesion segmentation labels annotated by professional dermatologists, aim to facilitate the automatic identification of clinically common skin diseases such as melanoma. The ISIC-2017 dataset comprises a total of 2750 images, partitioned into 2000 training images, 150 validation images, and 600 test images. The ISIC-2018 dataset consists of 3694 skin lesion images, with 2594 designated for training, 100 for validation, and 1000 for testing. Furthermore, we also incorporated the clinical-related dataset of jaw cyst cases from Quzhou People’s Hospital. This dataset includes cone-beam computed tomography scans, resulting in a total of 2592 cross-sectional images. To ensure reliable evaluation and prevent overfitting, the dataset was randomly shuffled and divided into three different subsets: 60% for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for testing. Detail information about the data partitioning and the specifics of each dataset are presented in Table 1.

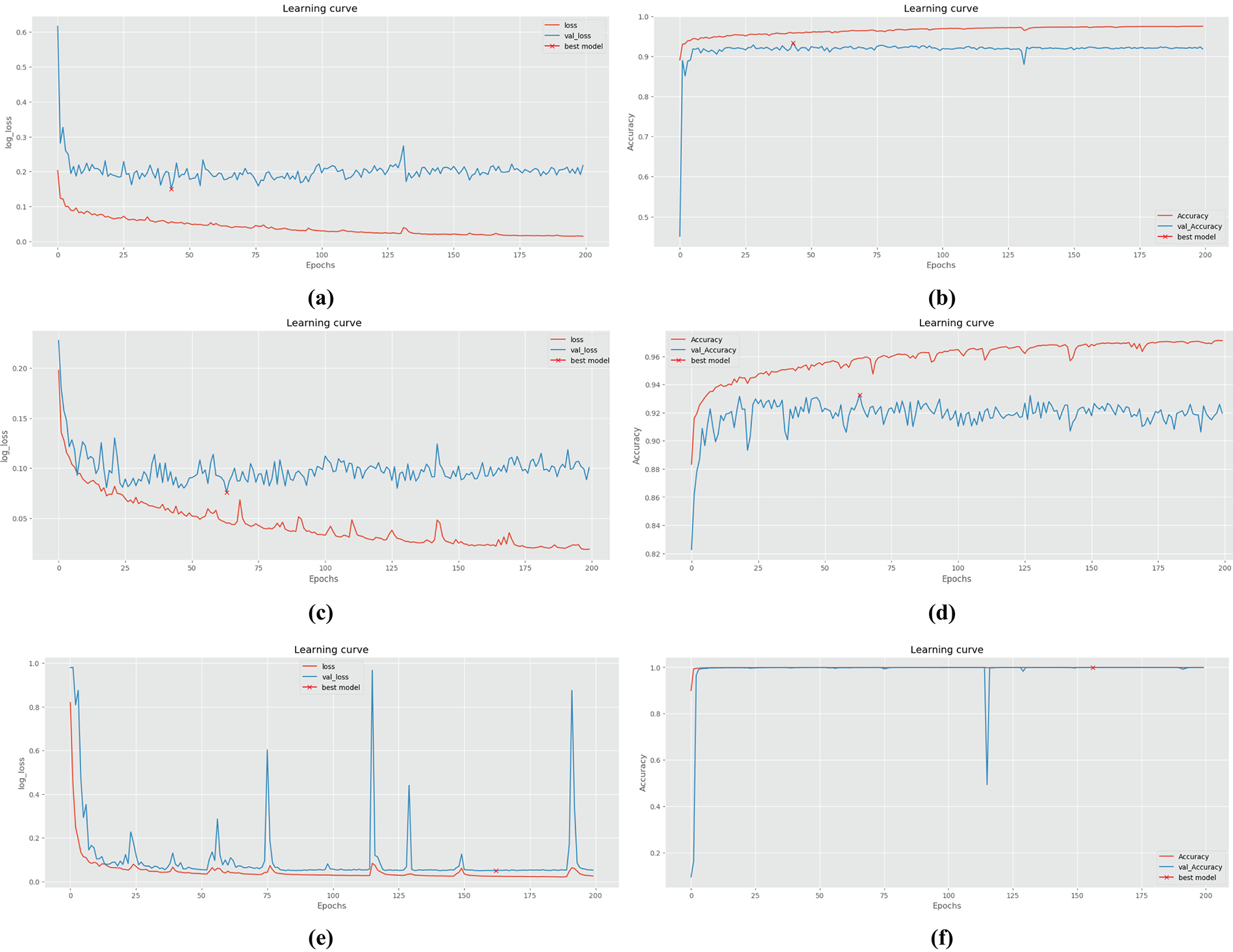

Recognizing the computational constraints and the need for consistency in data pre-processing, during the experiment, image size for all data samples is set to 256 × 256 pixels. Fig. 8 illustrates the changes in loss value and accuracy during the training and verification processes on the ISIC-2017, ISIC-2018 and jaw cyst datasets. Across all three datasets, the proposed model exhibits a clear pattern of effective learning, as reflected by the steadily decreasing trends in both training and validation loss curves. Concurrently, accuracy metrics consistently improved and eventually stabilized at high levels, suggesting that the model is well generalized during training. Nevertheless, in the case of skin lesion datasets such as ISIC-2017 and ISIC-2018, noticeable discrepancies between training and validation performance can be observed. These differences are likely attributed to class imbalance, diverse lesion appearances, and inherent noise within the skin image data, which collectively hinder optimal generalization. In contrast, for the jaw cyst dataset, the learning process appears significantly more stable and reliable, with the training and validation curves closely aligned throughout, indicating strong consistency and minimal overfitting during the training process. These results provide researchers with a comprehensive understanding of the model’s performance trajectory and convergence behavior.

Figure 8: The changes of quantitative metrics during the training and verification process of different datasets: (a) Loss on ISIC-2017; (b) Accuracy on ISIC-2017; (c) Loss on ISIC-2018; (d) Accuracy on ISIC-2018; (e) Loss on jaw cyst; (f) Accuracy on jaw cyst

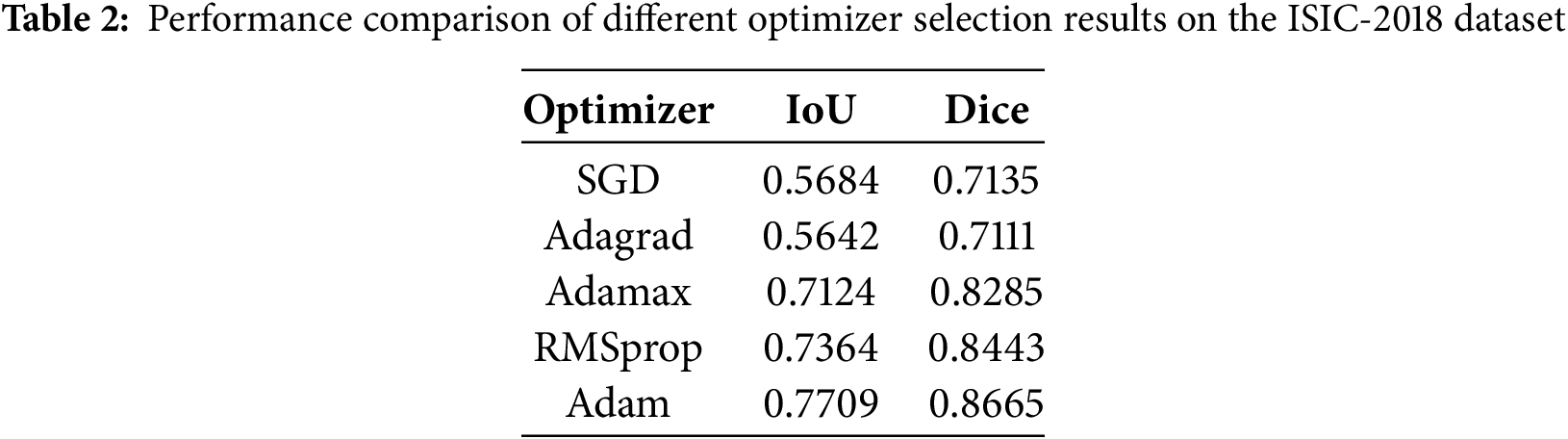

The choice of optimizer can significantly impact the performance of the segmentation algorithm, hence it is crucial to select an appropriate optimizer to achieve optimal segmentation accuracy. Table 2 lists five different optimizers: SGD, Adagrad, Adamax, RMSprop, and Adam, along with their corresponding IoU and Dice coefficient scores on the ISIC-2018 dataset. It is evident from the table that the Adam optimizer yields the highest scores for both IoU and Dice coefficients, indicating superior segmentation performance compared to using other optimizers. Adamax and RMSprop also perform well, while SGD and Adagrad show comparatively lower performance in this context. Based on these findings, Adam has been selected as the optimizer for the models presented in this paper. By standardizing the optimizer choice to Adam across all models, we ensure a fair and consistent comparison while leveraging the optimizer’s capability to maximize segmentation performance.

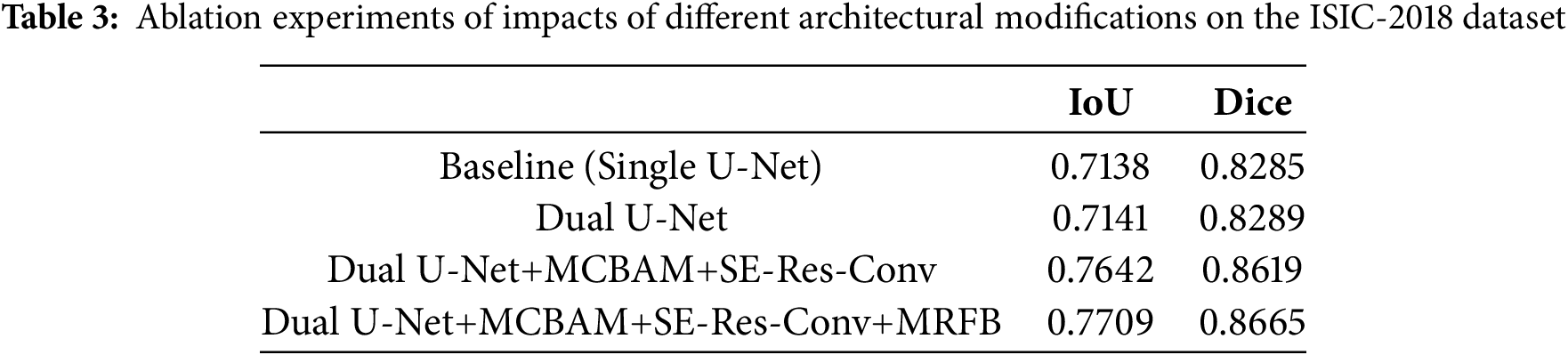

Table 3 showcases the results of ablation experiments on the ISIC-2018 dataset to assess the impact of different architectural modifications on the model structure towards their respective segmentation performances, as measured by IoU and Dice coefficient. Baseline (Single U-Net) refers to the performance of the segmentation algorithm based on a single U-Net architecture, serving as the reference point for comparison. Dual U-Net involves using a dual U-Net architecture, which comprises two interconnected U-Net structures. Dual U-Net+MCBAM+SE-Res-Conv represents the dual U-Net architecture augmented with MCBAM and SE-Res-Conv blocks. Dual U-Net+MCBAM+SE-Res-Conv+MRFB is a further enhanced version integrating MRFB into the structure, which enables the capability of capturing multi-scale contextual information efficiently.

The results demonstrate a progressive improvement in segmentation performance with each architectural modification. Specifically, the addition of MCBAM and SE-Res-Conv blocks leads to a notable enhancement in both IoU and Dice scores compared to the baseline and dual U-Net configurations. Furthermore, the inclusion of MRFB further boosts segmentation accuracy, resulting in the highest IoU and Dice scores observed in the experiments. Overall, the ablation experiments validate the effectiveness of each architectural module in contributing to the overall segmentation accuracy.

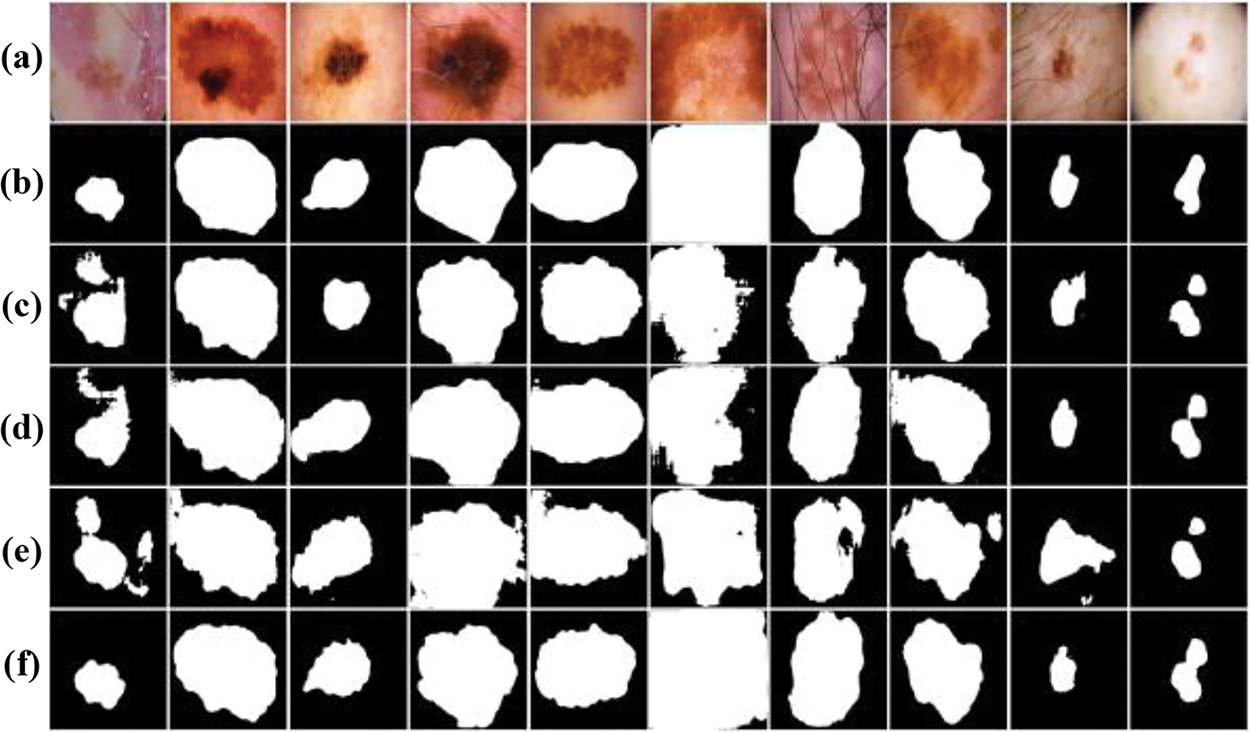

In order to provide a clearer understanding of the segmentation outcomes resulting from the ablation experiments on the ISIC-2018 dataset, a thorough visual comparative analysis was conducted isn this chapter, exemplified in Fig. 9. The segmentation results of the baseline U-Net network are relatively poor, and the location of lesions can only be roughly outlined. With the incorporation of the Dual U-Net architecture, there is a noticeable improvement in the segmentation results compared to the baseline. However, the segmentation still lacks precision. Upon the integration of the MCBAM and SE-Res-Conv blocks into the dual U-Net framework, a notable refinement in segmentation outcomes becomes palpable. Significantly, the segmentation results closely approximate to the gold standard, indicating a substantial augmentation in network performance benefitted from the MCBAM and SE-Res-Conv mechanisms. In addition, with the integration of the MRFB, the segmentation quality is further improved, where the model not only accurately locates the spatial position information of the lesion, but also has a strong ability to recover the boundary and local details.

Figure 9: Visual comparison of ablation experiments on the ISIC-2018 dataset: (a) Original images; (b) Label images; (c) Baseline (Single U-Net); (d) Dual U-Net; (e) Dual U-Net+MCBAM+SE-Res-Conv; (f) Dual U-Net+MCBAM+SE-Res-Conv+MRFB

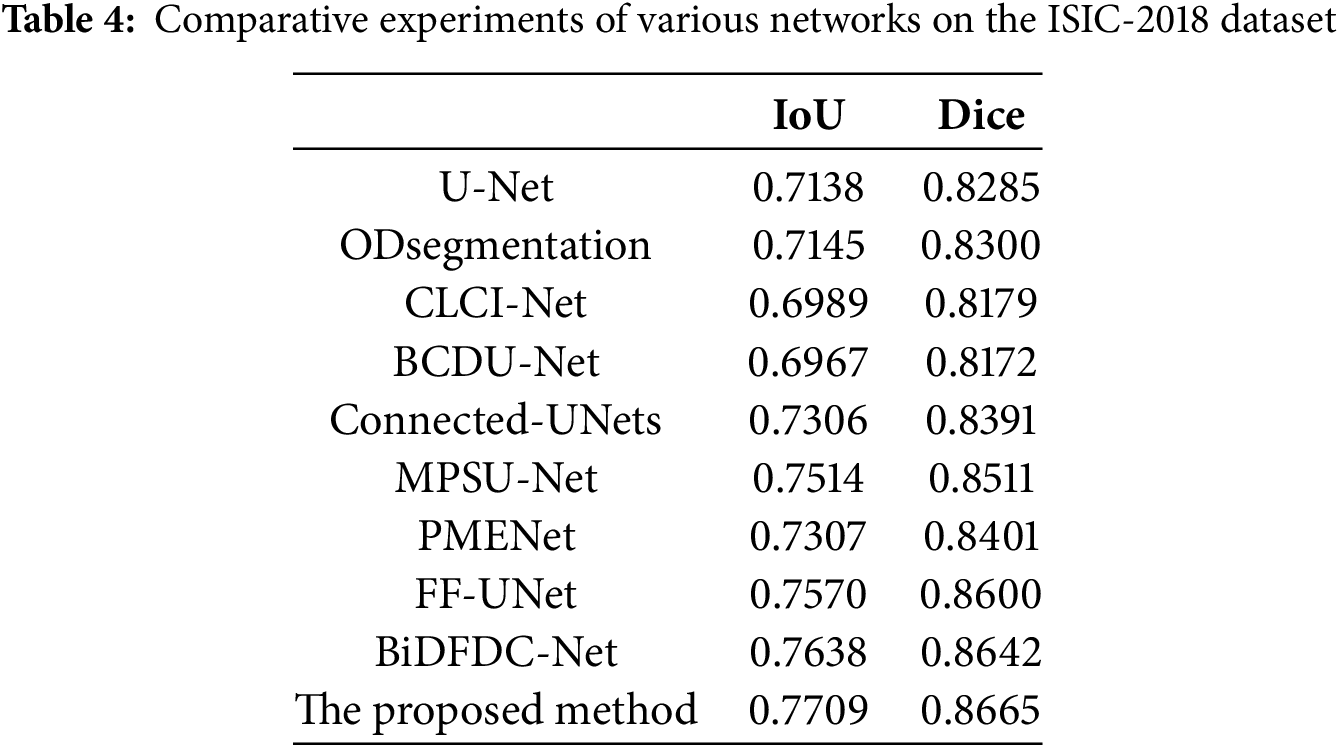

To further demonstrate the efficacy of our proposed model, we conducted comprehensive comparative experiments on the ISIC-2018 dataset with classic models such as U-Net [7], ODsegmentation [34], CLCI-Net [35], BCDU-Net [36], Connected-UNets [12], MPSU-Net [37], PMENet [38], FF-UNet [39] and BiDFDC-Net [40]. After basic pre-processing of the ISIC-2018 dataset, the above models were trained respectively. Each network structure was trained for 200 epochs, and the results were summarized in Table 4. Among the comparison methods, BCDU-Net and CLCI-Net exhibited relatively lower performance, with IoU values of 0.6967 and 0.6989, Dice scores of 0.8172 and 0.8179. Observing the results, U-Net is a widely used architecture for semantic segmentation tasks, achieving an IoU of 0.7138 and a Dice coefficient of 0.8285. The performance of the other six models differs mildly comparing to U-Net, while our algorithm shows remarkable enhancements over other models, augmented IoU and Dice by 5.71 and 3.80 percent, respectively. Notably, our method emerged as the top performer across all comparison experiments. These results underscore the capability of our algorithm not only on effectively delineate areas of pronounced contrast but also on accurately predicting the rough contours of lesions in skin melanoma image segmentation. Moreover, even in scenarios with diminished contrast levels, our model consistently ensures that the focal area remains encompassed within the segmentation boundary, highlighting its robustness and adaptability in diverse conditions.

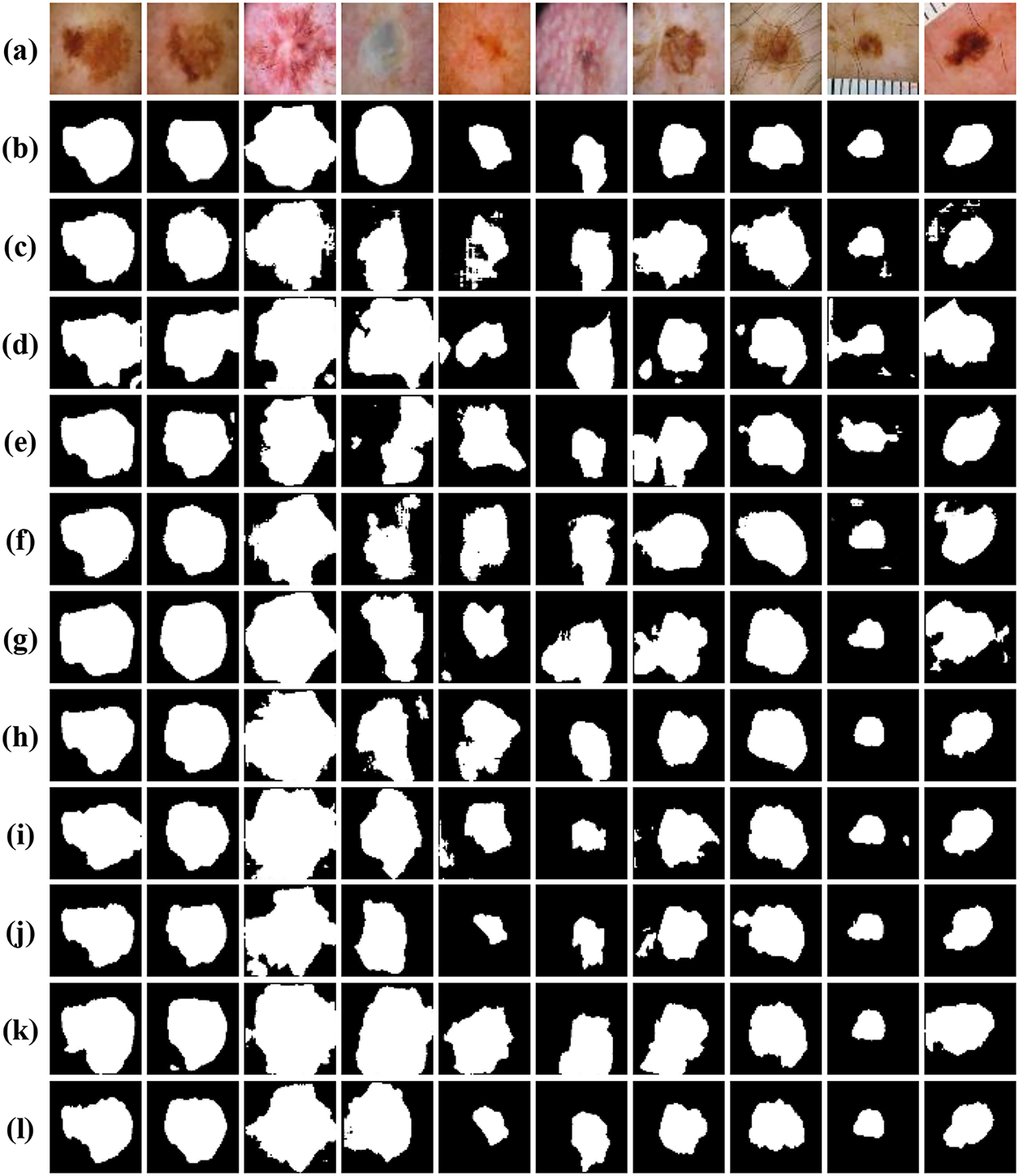

To comprehensively assess the performance of various encoder-decoder models, we provide visual insights as shown in Fig. 10, showing segmentation outcomes for 10 images from the testing subset of ISIC-2018 dataset. Notably, our method consistently demonstrates superior segmentation accuracy, particularly in scenarios marked by intricate brightness distributions and indistinct boundaries, which present the most formidable challenges. Unlike U-Net, ODsegmentation, CLCI-Net, BCDU-Net, Connected-UNets, MPSU-Net, PMENet, FF-UNet and BiDFDC-Net segmentation networks, which predominantly rely on convolutional techniques, our approach utilizes modules such as the squeeze-and-excitation module, residual connections, MCBAM and MRFB that effectively address limitations associated with extracting global information, especially in instances where the target area is relatively diminutive, or the contrast within the lesion area is notably subdued comparing to normal skin regions. By leveraging these advancements, our method excels in capturing finer segmentation details, as evidenced by the visual results presented herein. This not only demonstrates the robustness of our approach but also highlights its capability to overcome the inherent complexities of dermatological image segmentation tasks.

Figure 10: Visual comparison of different networks on the ISIC-2018 dataset: (a) Original images; (b) Label images; (c) U-Net; (d) ODsegmentation; (e) CLCI-Net; (f) BCDU-Net; (g) Connected-UNets; (h) MPSU-Net; (i) PMENet; (j) FF-UNet; (k) BiDFDC-Net; (l) The proposed method

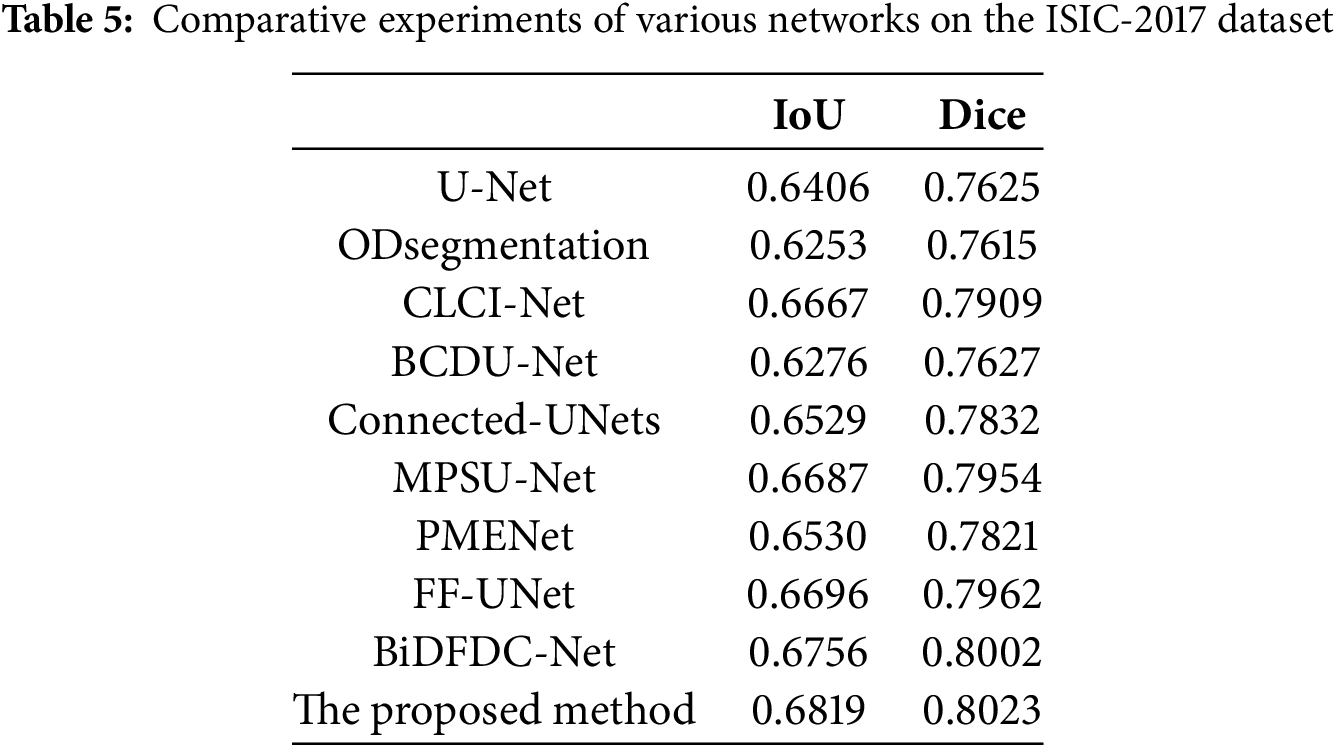

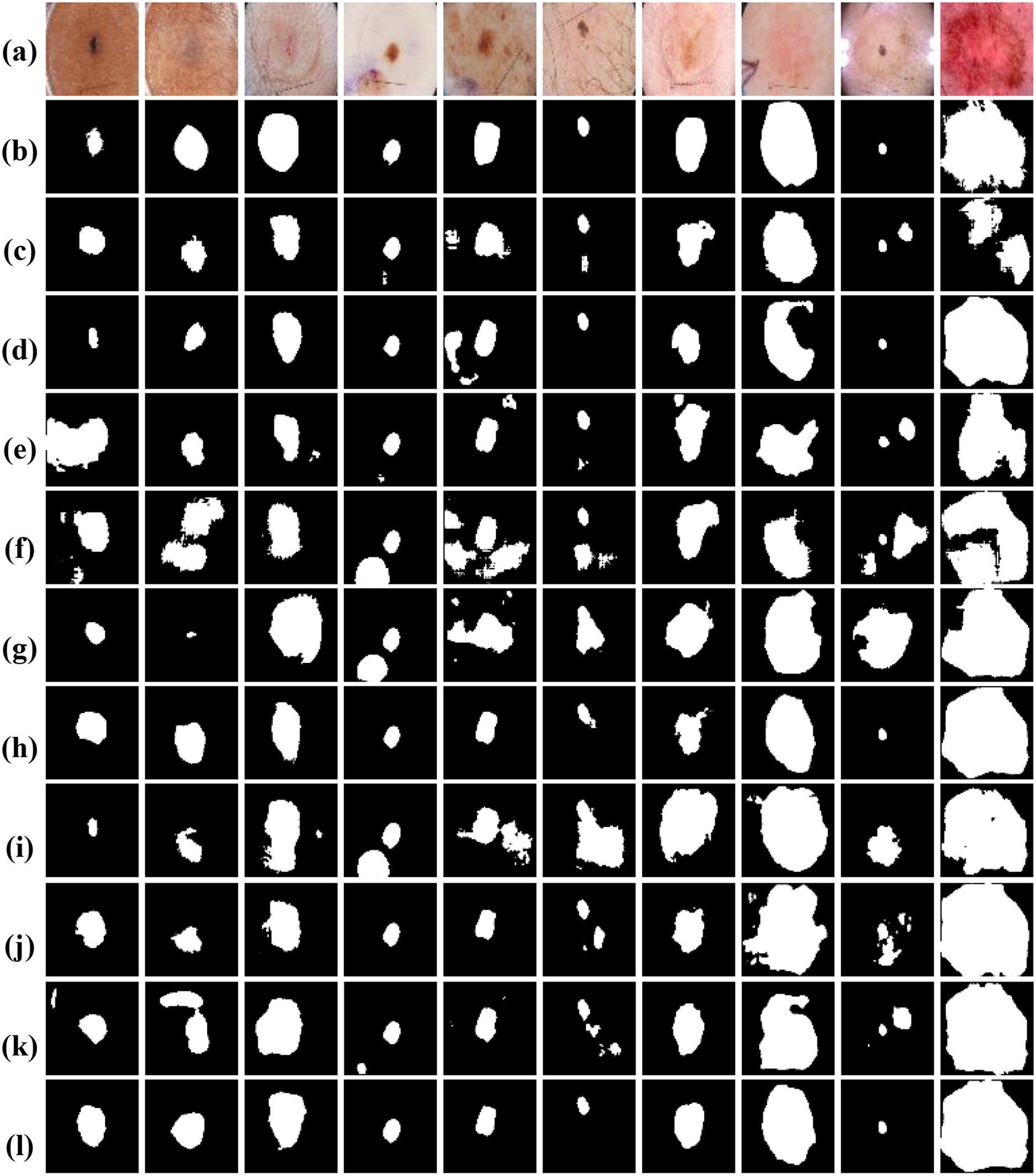

To demonstrate the generalization and robustness of our proposed model, we extended our experiments to the ISIC-2017 dataset. This dataset was chosen due to its challenging nature of containing many images that are difficult to segment accurately. Table 5 provides a detailed quantitative comparison of the segmentation performance of our proposed model against other established methods. The comparison reveals that, while the metric scores of other models on this dataset are generally unsatisfactory due to the complexity of the images, our proposed model consistently achieves satisfactory evaluation indicators. The robustness of our network is further accentuated in Fig. 11, which visually presents the segmentation results. The figure showcases specific portions where our network performs exceptionally well, demonstrating its ability to handle challenging segmentation tasks effectively. Overall, the combination of quantitative metrics and visual results underscores the superiority of our proposed network in achieving robustness and generalized performance. This shows that our innovative approach, combining the dual mechanism, squeeze-and-excitation module, MCBAM and MRFB, effectively improves the accuracy and adaptability of the model in diversed and challenging scenarios.

Figure 11: Visual comparison of different networks on the ISIC-2017 dataset: (a) Original images; (b) Label images; (c) U-Net; (d) ODsegmentation; (e) CLCI-Net; (f) BCDU-Net; (g) Connected-UNets; (h) MPSU-Net; (i) PMENet; (j) FF-UNet; (k) BiDFDC-Net; (l) The proposed method

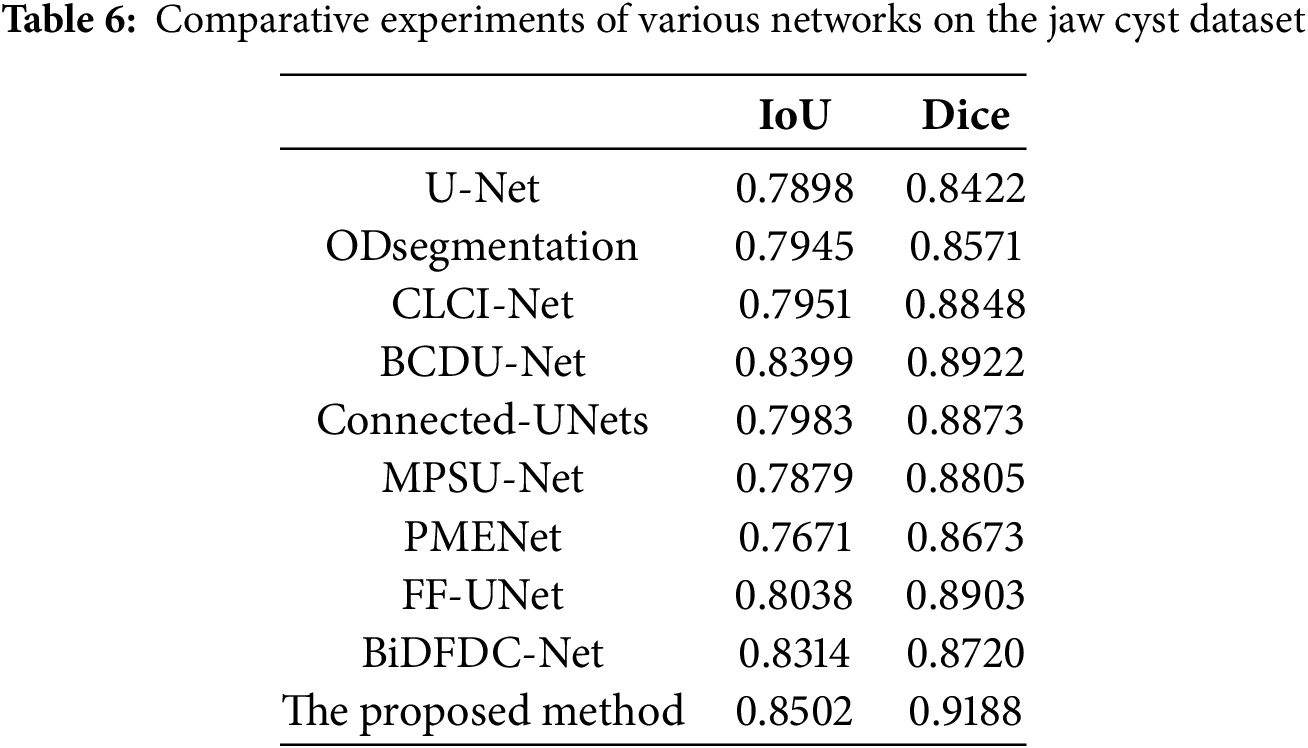

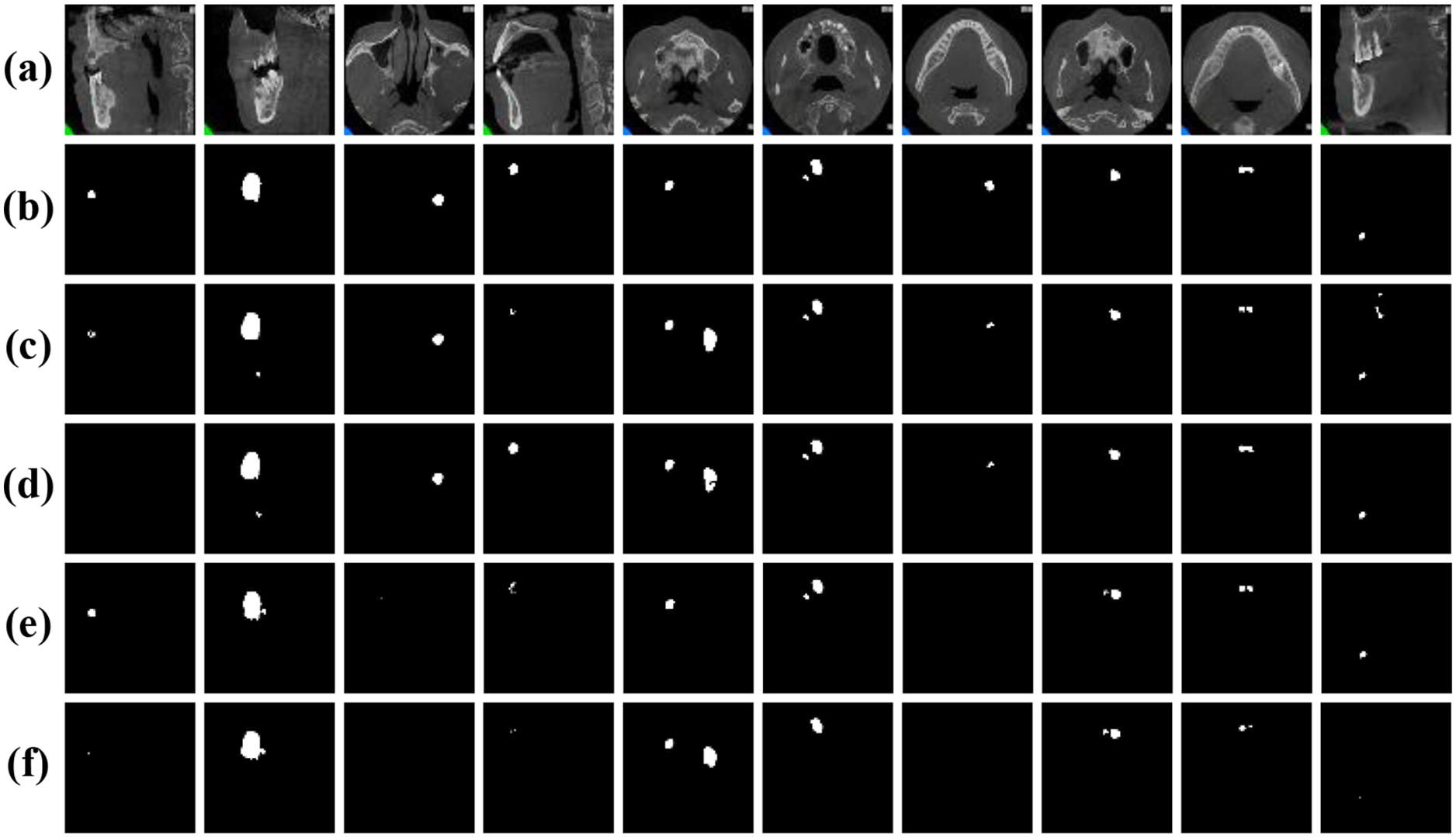

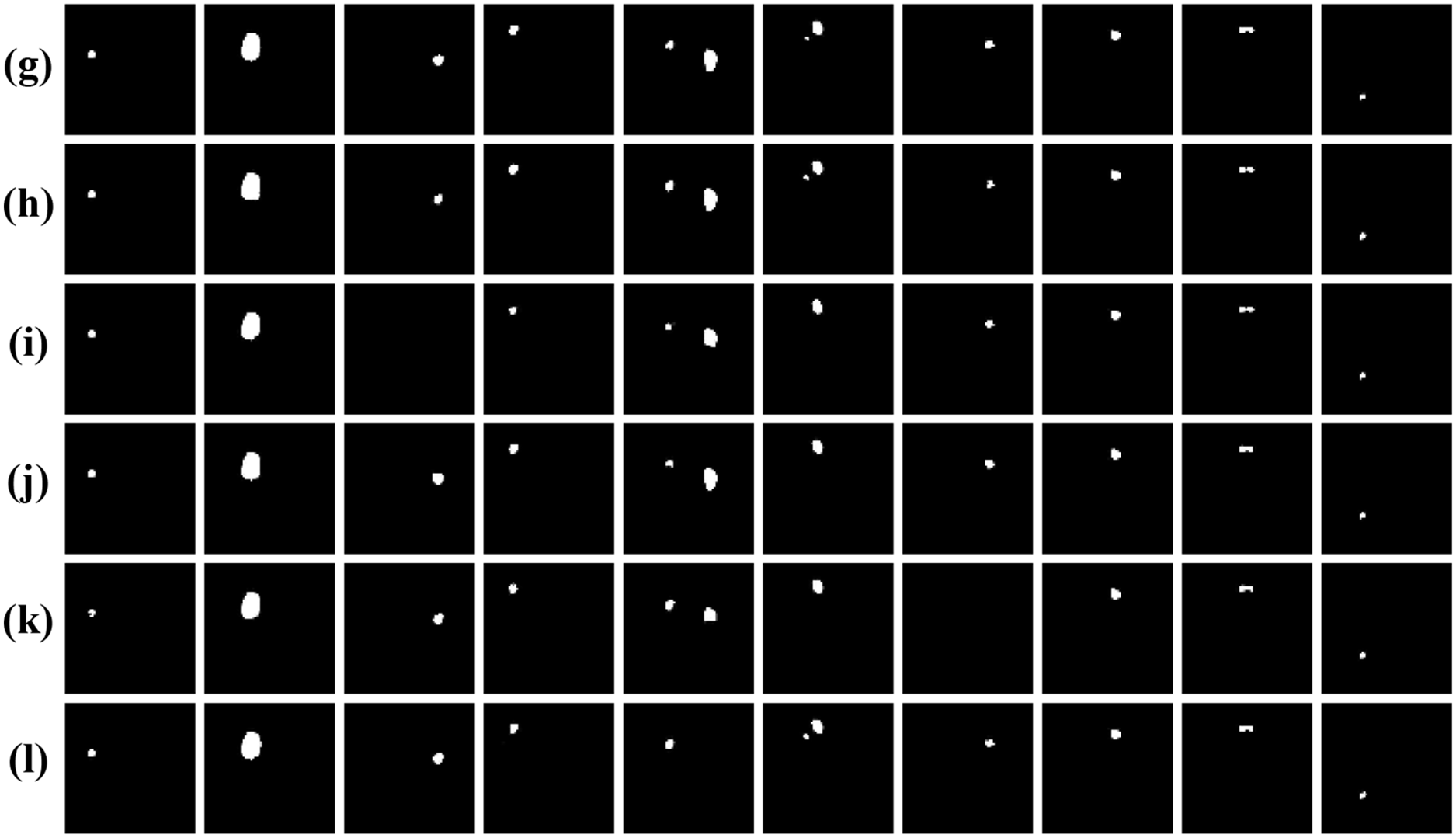

To further assess the generalization and robustness of our proposed method, we conducted comprehensive experiments on the jaw cyst dataset. This dataset poses unique challenges, such as small lesion sizes, low contrast boundaries, and anatomical variations across patients. Table 6 presents a detailed quantitative comparison of our proposed model with several classic segmentation networks, while Fig. 12 presents visual comparison of the results. From the metrics in Table 6, it is evident that our proposed method significantly outperforms all competing models, achieving the highest IoU of 0.8502 and Dice coefficient of 0.9188. These scores clearly demonstrate the method’s superior segmentation accuracy and how closely its outcomes match the ground truth masks, even in challenging images. As observed in the original cone-beam computed tomography slices and corresponding ground truth masks, the cyst regions are often small, low contrast, and embedded in complex jaw structures. Notably, our proposed method exhibits the highest fidelity in segmenting cyst regions, accurately capturing both the shape and size of the lesions with minimal false positive rates. In summary, both the quantitative results in Table 6 and the visual comparisons in Fig. 12 strongly affirm the effectiveness of our proposed method.

Figure 12: Visual comparison of different networks on the jaw cyst dataset: (a) Original images; (b) Label images; (c) U-Net; (d) ODsegmentation; (e) CLCI-Net; (f) BCDU-Net; (g) Connected-UNets; (h) MPSU-Net; (i) PMENet; (j) FF-UNet; (k) BiDFDC-Net; (l) The proposed method

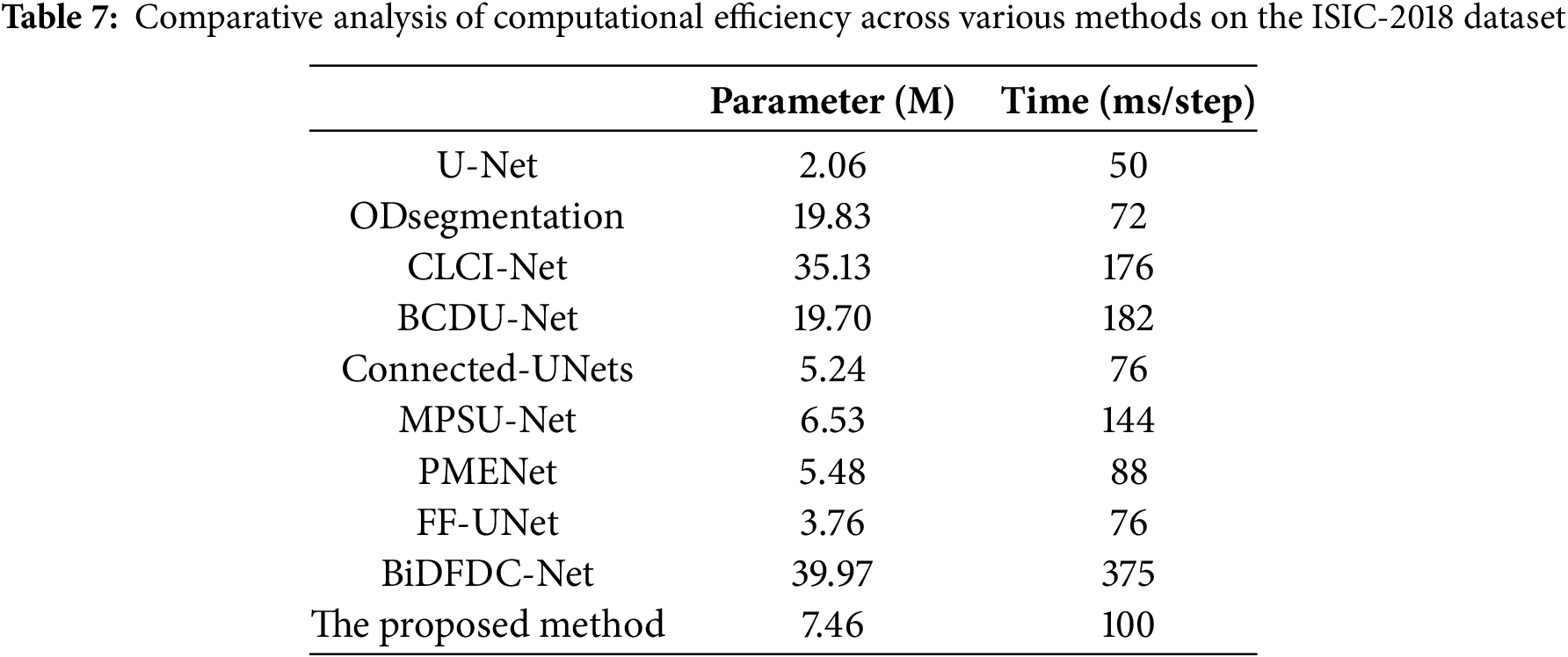

To further evaluate the practicability of each network, we conducted a comparative analysis of computational efficiency and model complexity between all comparison models and our proposed model usingthe ISIC-2018 dataset. Table 7 summarizes the number of parameters (in millions) and the average inference time per step (in milliseconds) for each model. Among the comparison models, U-Net possesses the lowest parameter count at 2.06 M and takes the fastest runtime of 50 ms/step. However, its segmentation performance is comparatively limited. ODsegmentation and BCDU-Net exhibits a balance between accuracy and complexity, with parameter sizes of approximately 19 M and inference times around 70–180 ms/step. CLCI-Net and BiDFDC-Net, though achieving competitive accuracy, incur significant computational overhead, with BiDFDC-Net reaching 39.97 M parameters and the highest inference time of 375 ms/step. In contrast, our proposed method maintains a relatively lightweight structure with 7.46 M parameters and an inference time of 100 ms/step. It demonstrates a favorable balance between computational cost and segmentation accuracy, indicating its suitability for real-world clinical applications where both precision and efficiency are essential.

3.6 Incorrectly Segmented Samples

Fig. 13 presents several representative cases where the proposed segmentation model did not produce accurate results across the three datasets. For the skin lesion datasets, in several instances (first and second columns), the model over-segmented, incorrectly including surrounding areas. This often occurs when color and texture variations mislead the network into expanding the lesion boundaries. In other samples, the proposed method under-segments lesions, capturing only partial areas of the ground truth region. This may be due to low contrast between lesion boundaries and surrounding healthy skin, as well as the presence of interfering objects (such as hair) or reflective lighting. While the model performs relatively well on jaw cyst images, minor discrepancies still appear. For example, in the last three columns, the predicted region is smaller than the annotated label, suggesting under-segmentation of small or low-contrast cysts. Overall, these segmentation failures highlight the challenges caused by low contrast, visual noise, anatomical variability, and ambiguous lesion boundaries.

Figure 13: Incorrectly segmented samples: (a) Original images; (b) Label images; (c) The proposed method

Based on in-depth research and experiments, we propose a framework for cutaneous melanoma segmentation in dermoscopic images. Through careful architectural design, we introduced several novel components aim to enhance the performance and versatility of the traditional U-Net structure. Our main contribution is the integration of two simplified U-Nets within a unified framework, facilitating seamless information exchange and feature fusion across the network. Additionally, the jump connection between the encoder and decoder network, coupled with the MRFB, enables the network to efficiently capture multi-scale contextual information, further improving segmentation accuracy. To enhance feature representation capabilities, we introduce the MCBAM and SE-Res-Conv module, which combines extrusion and excitation mechanisms with residual connections.

We conducted extensive experiments on our proposed model comparing to other existing segmentation models using the ISIC-2017 and ISIC-2018 datasets, which accentuate the effectiveness of our moodel, showing significant improvements in segmentation performance. In the ISIC-2017 dataset, we achieved an IoU value of 0.6819 and a Dice coefficient of 0.8023. For the ISIC-2018 dataset, the IoU value was 0.7709, and the Dice coefficient was 0.8665. Furthermore, on the jaw cyst dataset, the IoU was 0.8502 and Dice coefficient was 0.9188. In conclusion, our dual U-Net network framework represents a significant advancement in skin melanoma segmentation, providing increased accuracy and performance. This study not only offers valuable diagnostic support for dermatologists, but also possesses great potential for the broader clinical application of dermatology. As part of our future research efforts, we aim to evaluate the model’s performance directly in clinical environments, where factors such as variability in image quality and patient diversity present additional complexities. Furthermore, we intend to prioritize the development of lightweight, resource-efficient versions of the model that maintain high segmentation accuracy while reducing computational overhead.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Zhejiang Basic Public Welfare Research Project, grant number LZY24E060001. This work was also supported by Guangzhou Development Zone Science and Technology (2021GH10, 2020GH10, 2023GH02), the University of Macau (MYRG2022-00271-FST), and the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) of Macau (0032/2022/A).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Kun Lan, Xiaoliang Jiang; data collection: Feiyang Gao; analysis and interpretation of results: Kun Lan, Jianzhen Cheng; draft manuscript preparation: Kun Lan, Simon Fong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in ISIC Challenge Datasets at https://challenge.isic-archive.com/data/ (accessed on 01 May 2025).

Ethics Approval: The International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) datasets 2017 and 2018 are publicly available from their official website. The clinical-related dataset jaw cyst comes from the de-privatized data provided by the Department of Stomatology of Quzhou People’s Hospital. The two medical institutions concerned, together with those two universities, where the authors of this paper are based, have jointly undertaken the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) of Macau Project (A Cross Deep Learning System for Fast Automated Gastric Cancer Diagnosis from Real-Time Endoscopic Videos; Grant No. 0032/2022/A), and provides de-privatized data for medical AI technology research. This paper belongs to the research results of the above collaborative project and can use the de-privatized data involved in the project for research. This study does not involve any human or animal clinical trials.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Suleman M, Ullah F, Aldehim G, Shah D, Abrar M, Irshad A, et al. Smart MobiNet: a deep learning approach for accurate skin cancer diagnosis. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;77(3):3533–49. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.042365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Guo Y, Ashour AS, Smarandache F. A novel skin lesion detection approach using neutrosophic clustering and adaptive region growing in dermoscopy images. Symmetry. 2018;10(4):119. doi:10.3390/sym10040119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Tan TY, Zhang L, Lim CP, Fielding B, Yu Y, Anderson E. Evolving ensemble models for image segmentation using enhanced particle swarm optimization. IEEE Access. 2019;7:34004–19. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2903015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jaisakthi SM, Mirunalini P, Aravindan C. Automated skin lesion segmentation of dermoscopic images using GrabCut and k-means algorithms. IET Comput Vis. 2018;12(8):1088–95. doi:10.1049/iet-cvi.2018.5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li X, Peng B, Hu J, Ma C, Yang D, Xie Z. USL-Net: uncertainty self-learning network for unsupervised skin lesion segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;89:105769. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li Z, Zhang N, Gong H, Qiu R, Zhang W. SG-MIAN: self-guided multiple information aggregation network for image-level weakly supervised skin lesion segmentation. Comput Biol Med. 2024;170:107988. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.107988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference; 2015 Oct 5–9; Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

8. Lan K, Cheng J, Jiang J, Jiang X, Zhang Q. Modified UNet++ with atrous spatial pyramid pooling for blood cell image segmentation. Math Biosci Eng. 2023;20(1):1420–33. doi:10.3934/mbe.2023064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yu Z, Yu L, Zheng W, Wang S. EIU-Net: enhanced feature extraction and improved skip connections in U-Net for skin lesion segmentation. Comput Biol Med. 2023;162:107081. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Xu J, Wang X, Wang W, Huang W. PHCU-Net: a parallel hierarchical cascade U-Net for skin lesion segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;86:105262. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sharen H, Jawahar M, Anbarasi LJ, Ravi V, Alghamdi NS, Suliman W. FDUM-Net: an enhanced FPN and U-Net architecture for skin lesion segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;91:106037. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Baccouche A, Garcia-Zapirain B, Castillo Olea C, Elmaghraby AS. Connected-UNets: a deep learning architecture for breast mass segmentation. npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):151. doi:10.1038/s41523-021-00358-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kumar MD, Sivanarayana G, Indira D, Raj MP. Skin cancer segmentation with the aid of multi-class dilated D-net (MD2N) framework. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(23):35995–6018. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-14605-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Saadati D, Manzari ON, Mirzakuchaki S. Dilated-UNet: a fast and accurate medical image segmentation approach using a dilated transformer and U-Net architecture. arXiv:2304.11450. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2304.11450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hosny KM, Kassem MA. Refined residual deep convolutional network for skin lesion classification. J Digit Imaging. 2022;35(2):258–80. doi:10.1007/s10278-021-00552-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Alenezi F, Armghan A, Polat K. Wavelet transform based deep residual neural network and ReLU based extreme learning machine for skin lesion classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213:119064. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nakai K, Chen YW, Han XH. Enhanced deep bottleneck transformer model for skin lesion classification. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2022;78:103997. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2022.103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Dong Z, Li J, Hua Z. Transformer-based multi-attention hybrid networks for skin lesion segmentation. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;244:123016. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.123016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Y, Feng Y, Zhang L, Zhou JT, Liu Y, Goh RSM, et al. Adversarial multimodal fusion with attention mechanism for skin lesion classification using clinical and dermoscopic images. Med Image Anal. 2022;81:102535. doi:10.1016/j.media.2022.102535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wu H, Pan J, Li Z, Wen Z, Qin J. Automated skin lesion segmentation via an adaptive dual attention module. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;40(1):357–70. doi:10.1109/TMI.2020.3027341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Xiao G, Zhu B, Zhang Y, GaoH. FCSNet: a quantitative explanation method for surface scratch defects during belt grinding based on deep learning. Comput Ind. 2023;144:103793. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2022.103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. Tomar NK, Jha D, Riegler MA, Johansen HD, Johansen D, Rittscher J, et al. Fanet: a feedback attention network for improved biomedical image segmentation. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;34(11):9375–88. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3159394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wu Y, Chang J, Ma N, Yang Y, Ji Z, Huang Y. DBPFNet: a dual-band polarization image fusion network based on the attention mechanism and atrous spatial pyramid pooling. Opt Lett. 2023;48(19):5125–28. doi:10.1364/OL.500862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Tian X, Liu X, Zhang T, Zhang W, Zhang L, Shi X, et al. Effective electrical impedance tomography based on enhanced encoder-decoder using atrous spatial pyramid pooling module. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(7):3282–91. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2023.3265385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Tang H, Chen Y, Wang T, Zhou Y, Zhao L, Gao Q, et al. HTC-Net: a hybrid CNN-transformer framework for medical image segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;88:105605. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu R, Liang P, Huang X, Shi L, Gu Y, Zhu H, et al. MHorUNet: high-order spatial interaction UNet for skin lesion segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;88:105517. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abdel-Nabi H, Ali MZ, Awajan A. A multi-scale 3-stacked-layer coned U-net framework for tumor segmentation in whole slide images. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;86:105273. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Muhammad Z-U-D, Huang Z, Gu N, Muhammad U. DCANet: deep context attention network for automatic polyp segmentation. Vis Comput. 2023;39(11):5513–25. doi:10.1007/s00371-022-02677-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Huang C, Wan M. Automated segmentation of brain tumor based on improved U-Net with residual units. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(9):12543–66. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-12335-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Selvaraj A, Nithiyaraj E. CEDRNN: a convolutional encoder-decoder residual neural network for liver tumour segmentation. Neural Process Lett. 2023;55(2):1605–24. doi:10.1007/s11063-022-10953-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Codella NC, Gutman D, Celebi ME, Helba B, Marchetti MA, Dusza SW, et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: a challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBIhosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018); 2018 Apr 4–7; Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

33. Codella N, Rotemberg V, Tschandl P, Celebi ME, Dusza S, Gutman D, et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection 2018: a challenge hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). arXiv:1902.03368. 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1902.03368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang L, Gu J, Chen Y, Liang Y, Zhang W, Pu J, et al. Automated segmentation of the optic disc from fundus images using an asymmetric deep learning network. Pattern Recognit. 2021;112:107810. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2020.107810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yang H, Huang W, Qi K, Li C, Liu X, Wang M, et al. CLCI-Net: cross-level fusion and context inference networks for lesion segmentation of chronic stroke. In: Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2019: 22nd International Conference; 2019 Oct 13–17; Shenzhen, China. [Google Scholar]

36. Azad R, Asadi-Aghbolaghi M, Fathy M, Escalera S. Bi-directional ConvLSTM U-Net with densley connected convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2019 Oct 27–28; Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

37. Wang B, Li J, Dai C, Zhang W, Zhou M. MPSU-Net: quantitative interpretation algorithm for road cracks based on multiscale feature fusion and superimposed U-Net. Digit Signal Process. 2024;153:104598. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2024.104598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang B, Dai C, Li J, Jiang X, Zhang J, Jia G. PMENet: a parallel UNet based on the fusion of multiple attention mechanisms for road crack segmentation. Signal Image Video Process. 2024;18(S1):757–69. doi:10.1007/s11760-024-03190-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Iqbal A, Sharif M, Khan MA, Nisar W, Alhaisoni M. FF-UNet: a U-shaped deep convolutional neural network for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Cogn Comput. 2022;14(4):1287–302. doi:10.1007/s12559-022-10038-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jiang J, Sun Z, Zhang Q, Lan K, Jiang X, Wu J. BiDFDC-Net: a dense connection network based on bi-directional feedback for skin image segmentation. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1173108. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1173108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools