Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Face Forgery Detection via Multi-Scale Dual-Modality Mutual Enhancement Network

1 School of Information Network Security, People’s Public Security University of China, Beijing, 100038, China

2 Department of Criminal Investigation, Sichuan Police College, Luzhou, 646000, China

* Corresponding Author: Fanliang Bu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Challenges and Innovations in Multimedia Encryption and Information Security)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 905-923. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066307

Received 04 April 2025; Accepted 12 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

As the use of deepfake facial videos proliferate, the associated threats to social security and integrity cannot be overstated. Effective methods for detecting forged facial videos are thus urgently needed. While many deep learning-based facial forgery detection approaches show promise, they often fail to delve deeply into the complex relationships between image features and forgery indicators, limiting their effectiveness to specific forgery techniques. To address this challenge, we propose a dual-branch collaborative deepfake detection network. The network processes video frame images as input, where a specialized noise extraction module initially extracts the noise feature maps. Subsequently, the original facial images and corresponding noise maps are directed into two parallel feature extraction branches to concurrently learn texture and noise forgery clues. An attention mechanism is employed between the two branches to facilitate mutual guidance and enhancement of texture and noise features across four different scales. This dual-modal feature integration enhances sensitivity to forgery artifacts and boosts generalization ability across various forgery techniques. Features from both branches are then effectively combined and processed through a multi-layer perception layer to distinguish between real and forged video. Experimental results on benchmark deepfake detection datasets demonstrate that our approach outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods in terms of detection performance, accuracy, and generalization ability.Keywords

Deepfake refers to the manipulation of videos and images using deep learning technology, with particular attention given to face swapping and facial reenactment. With the rapid advancement of deep learning technology, significant progress has been made in deepfake technology. The realistic deepfake faces and the extremely low technical barriers to their use have led to the widespread dissemination of forged faces on the internet, which are even used illegally, posing serious challenges to social stability and national security. Consequently, the development of effective face forgery detectors to mitigate these potential risks is particularly urgent and vital.

Most deepfake detection methods utilize deep learning-based approaches owing to their capability to automatically learn forged features. This eliminates the need for manual design of feature extractors, which is common in the traditional methods. Similar to other tasks using deep learning technologies, it always involves data preprocessing, feature extraction and learning, and classification for face forgery detection. The feature extraction stage is particularly critical, as it seeks to automatically identify the anomalous structural features introduced by various face forgery techniques, which often indicate signs of forgery. Early studies have mostly used biometric features, such as analyzing the nature of eye blink activity [1], skin color [2], and mouth movements [3] within image sequences, to authenticate the authenticity of videos. As deepfake technologies continue to advance, these anomalous biometric features have become increasingly rare in forged images. Some researchers find that the anomalous structures created by facial forgery are more pronounced in certain specific modalities. Based on a high-frequency component analysis, Durall et al. [4] proposed a simple deepfake classifier. Li et al. [5] introduced a frequency clues mining framework that employs an adaptive frequency feature generation module to improve detection accuracy. However, the model’s generalization ability is limited when faced with unseen datasets. Liu et al. [6] used phase spectrum analysis to detect up-sampling artifacts in face forgery identification. Uddin et al. [7] combined Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) based multi-scale frequency features with vision Transformer representations for deepfake detection, though cross-dataset evaluation was not conducted. Luo et al. [8] introduced a network based on Xception [9], which incorporates high-frequency noise features for effective detection.

Although these methods have achieved remarkable results, their performance often falls short when faced with novel counterfeiting techniques or diverse application scenarios. We observe that existing approaches typically concentrate on features at a single scale while neglecting the correlation and influence of features across different scales. For instance, they may focus solely on color distortion or brightness anomalies at the macro scale, unnatural facial edges at the meso scale, or abnormal pixel blocks and spots at the micro-scale. This narrow focus leads to a limited composition of captured forgery traces and increases susceptibility to overfitting specific types of artifacts associated with a single scale. Intuitively, it is believed that leveraging spatial artifacts across various scales can enhance both detection accuracy and generalization capabilities. Therefore, this paper employs multi-scale feature extraction for learning and enhancement to achieve improved detection of face forgery.

To effectively address the issue of face forgery, we conduct a thorough analysis of the process involved in generating forged faces. As highlighted in reference [10], regardless of the technical approach employed to synthesize a face, the forged facial component must ultimately be integrated into the original video frames. Given that the forged face region and the background originate from different sources, this integration process inevitably introduces new noise patterns. Consequently, we can utilize an analysis of these noise features to detect forgery effectively. However, relying exclusively on noise features for detection presents limitations due to potential vulnerabilities such as image compression effects.

To address these challenges, we innovatively design a dual-branch network architecture that focuses on extracting both texture features and noise features from images. By employing an attention mechanism, these two modalities, which exist at different scales, are skillfully fused. This design aims to comprehensively capture the forgery traces left by different face forgery techniques, spanning multiple scales and modalities, thus enhancing the detection capabilities of the model.

Our main contributions can be summarized as follows:

• A unified network architecture is proposed for face forgery detection, where a dual-branch feature extractor is integrated with a cross-modal fusion module before being fed into a binary classifier. Through this integrated framework, the complementary relationship between texture and noise features is effectively exploited, enabling state-of-the-art detection performance to be achieved while computational efficiency is maintained.

• A dual-branch network is constructed to extract texture features and noise features of facial images in parallel. The texture features and noise features are used together to reveal forgery traces, while the noise features are utilized to suppress the interference of image content. Finally, the two high-level features are effectively fused and sent into a binary classification network to effectively detect deepfake face videos.

• A Dual-modality Feature Fusion module is introduced, which employs the Transformer to fuse the bimodal information, i.e., texture information and noise information, at a specific scale. It effectively captures the long-range dependencies and potential correlations between the modalities. The attention map generated by this attention mechanism guides the learning process concerning texture vs. noise features and significantly improves the network’s capability to detect forged traces. Such a design enables the network to fully exploit the intrinsic connections between multimodal information, thereby improving accuracy in detecting forgeries within videos or images.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a brief review of previous studies in face forgery detection. Section 3 details the framework of the proposed model. Section 4 presents a thorough evaluation of the proposed method through experiments on challenging benchmark datasets. Lastly, Section 5 provides a conclusion with key insights from our research.

Significant efforts have been dedicated to enhancing the performance of face forgery detection. Early approaches primarily relied on established image classification networks, such as Capsule Network, and XceptionNet [9] to extract features for distinguishing between real and fake images. However, a notable distinction from common image classification tasks is that deepfake detection does not primarily rely on the semantic content of images but delves deeply into how forgery operations subtly alter image features, known as forgery traces. As a result, researchers then turn their attention to designing networks to accurately identify these forgery traces. Based on the domain of the image or video features that the detection networks focus on, these algorithms can be broadly categorized into two main classes: spatial domain detection algorithms and frequency domain detection algorithms.

Spatial domain detection algorithms [10–14] identify forged traces by analyzing spatial information such as texture, edges, colors, and other attributes present in the image. Li et al. [10] proposed a Face X-ray model that reveals facial forgery by exploiting blending boundaries present in tampered images. Afchar et al. [11] proposed the MesoNet for facial forgery detection, emphasizing mesoscopic characteristics within images. Wodajo et al. [14] used the Vision Transformer (ViT) [15] which excels at capturing long-range dependencies and global context for deepfake detection. Coccomini et al. [12] improve the detection performance by combining EfficientNet [16] with the Vision Transformer, achieving state-of-the-art performance in terms of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) on the Deepfake Detection Challenge dataset [17]. Zhao et al. [13] designed a multi-attention face forgery detector that amplifies multiple local texture features alongside high-level semantic attributes to distinguish authentic from counterfeit videos. Although these methods exhibit enhanced performance, they fundamentally depend on the specific forgery patterns discerned from the training dataset, resulting in a large decline in effectiveness when confronted with unseen forgery patterns.

Frequency domain detection algorithms convert images from the spatial representation to the frequency representation for analysis. Durall et al. [4] suggested that more anomalies introduced by forgery operations can be observed in high-frequency components, providing a new avenue for improving the robustness and accuracy of face forgery detection. Liu et al. [6] observed that the up-sampling operation commonly used in deepfake generation alters the phase spectrum of the image. They adopt the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) to extract the phase spectrum for detecting deepfakes. However, it might be susceptible to generation techniques that do not incorporate up-sampling. Qian et al. [18] proposed a two-stream collaborative learning framework F3-Net, which uses two distinct yet complementary frequency information to deeply mine the forgery patterns. To improve generalization capabilities, Luo et al. [8] leveraged high-frequency noise for forgery detection based on their observation that image noise tends to suppress color textures while highlighting differences between genuine and tampered regions, regardless of the tampering technique applied. Wang et al. [19] developed a Haar wavelet-based encoder-decoder network trained through self-supervision. Its autoencoder component effectively captures high-frequency features for deepfake detection. In addition to utilizing classical frequency-domain transformation techniques, the development of content-adaptive frequency learning modules can significantly enhance the interaction between frequency features and spatial information within images [20]. This approach facilitates the adaptive processing of manipulated patterns.

2.2 Noise-Based Forgery Detection

The light-sensitive elements built into cameras exhibit unique variations in performance when processing each pixel point. This variation is inherent to each camera and embodies its distinctive light-sensing capability. Based on this characteristic, we can extract the unique differences generated by each camera during the light-sensing process as its characteristic fingerprint, called noiseprint [21]. The noiseprint not only reflects the subtle changes during the camera’s imaging process but also provides it with an identity marker. Cozzolino et al. [22] achieved video tampering detection and localization by extracting the noiseprint from the video and calculating the distance between the noiseprint of the face region and the background region. Rai et al. [23] used the residual noise, defined as the difference between the original and denoised images, for deepfake detection. Kang et al. [24] detected deepfake images by utilizing warping artifacts, residual noise, and blur effects. Luo et al. [8] note that most CNN-based detectors lack dataset generalizability due to their dependence on method-specific color texture. They propose an Xception-based forgery detector that integrates high-frequency noise features, based on their finding that image noise can mitigate color texture interference and reveal traces of forgery. Zhou et al. [25] designed a dual-stream network in which one stream uses CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) to distinguish the authenticity of images, while the other stream classifies based on the distance of steganalysis features within triplets of images. The fusion of these two streams enables image tampering detection. Gu et al. [26] presented a framework for progressive enhancement learning that incorporates both self-enhancement and mutual-enhancement modules. Within the self-enhancement module, spatial noise and channel attention mechanisms are utilized to amplify forgery traces.

Despite these methods achieving notable performance levels, they remain insufficient in exploring the characteristics of the noise domain in images, particularly failing to fully leverage multi-scale noise information and overlooking complex interaction between noise information and RGB texture information within images. In contrast to existing methods, we propose a novel Multi-scale Dual-modality Mutual Enhancement network (MDME-Net), which mutually enhances the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) information alongside the high-frequency noise feature through a two-branch network.

When reviewing the process of generating fake face videos, it is noteworthy that enhancing realism typically involves replacing the facial region within the video while leaving the background unchanged. This processing technique introduces discrepancies in certain features between the authentic background and the fabricated facial region, such as variations in noise distribution characteristics. Based on this observation, we can reformulate the challenge of detecting forged faces into a binary classification task. This involves analyzing these differences in the images to classify each frame as either authentic or forged. Furthermore, the authenticity assessment of the entire video can be achieved by calculating the average of the classification results for all the frames, thus enabling effective detection of face forgery videos.

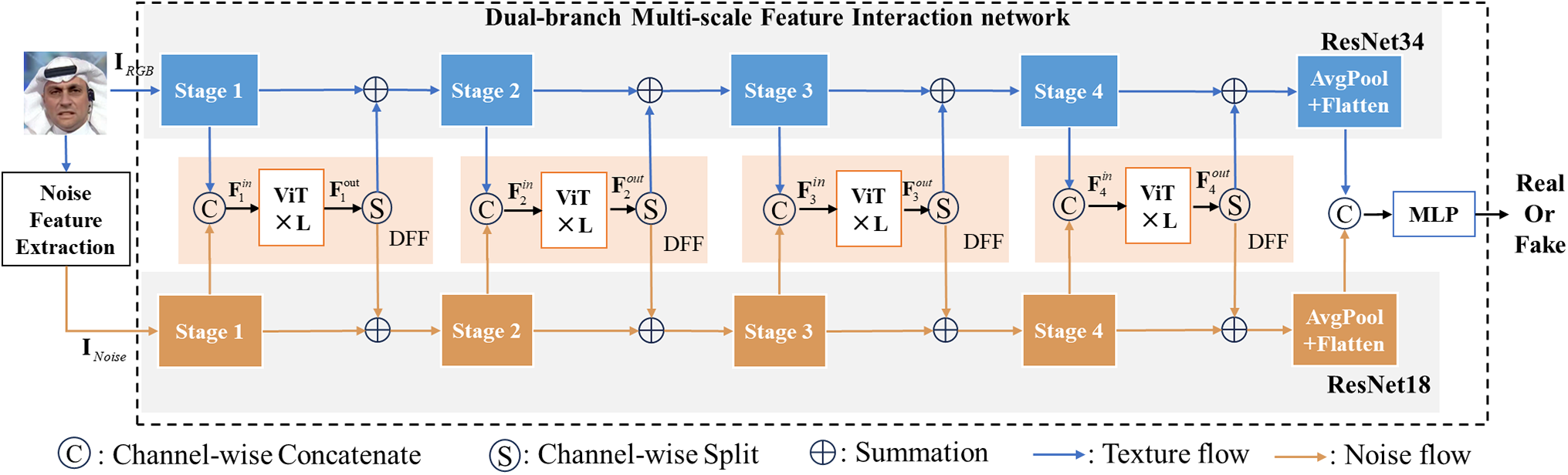

Therefore, our method utilizes noise features extracted from image faces by the widely used high-pass Spatial Rich Model (SRM) filter [27] to discern the authenticity of faces. Since the rich texture details inherent in RGB images can also be used to authenticate images, we innovatively design a dual-branch network that simultaneously processes image texture information and high-frequency noise information. In addition, within the shallow, middle and deep layers of both branches, we integrate Transformer modules using residual connections to enhance the model’s learning capabilities. Notably, these two branches utilize identical Transformer modules, which not only reduces the number of parameters but also facilitates interaction among cross-modal information. This allows the model to more effectively capture long-range dependencies and understand how textures and noise interact in different scales. Ultimately, we effectively fuse the features extracted from both branches and further process them through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) network to generate final Classification Labels (CLS), thereby achieving accurate assessments regarding image authenticity. The overall structure of our proposed method is depicted in Fig. 1, offering a clear visualization of its key components and workflow. We will subsequently delve into each module’s specifics to gain a comprehensive understanding of how the network operates.

Figure 1: The overall structure of the proposed method

3.2 High-Frequency Noise Feature Extraction Module

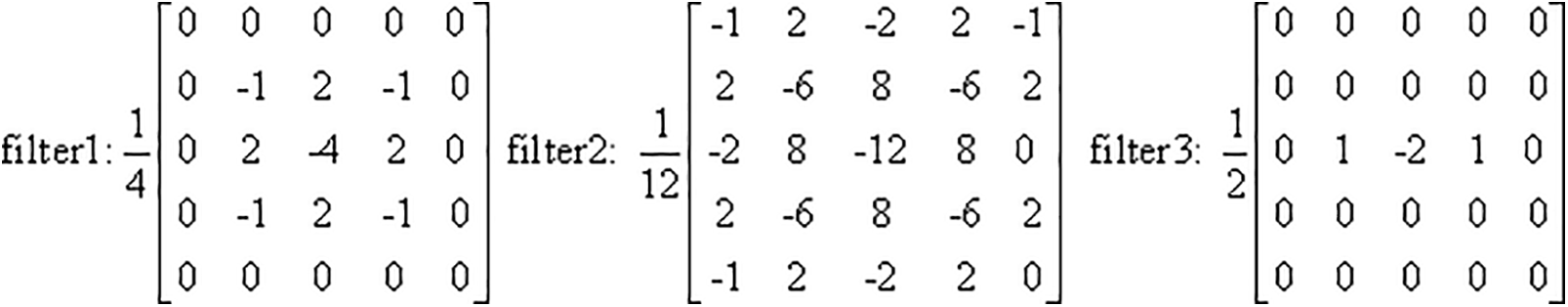

The Spatial Rich Model (SRM) [27], as a key approach in the field of spatial domain-based image steganalysis, excels in the precise extraction of steganographic residual information, enabling effective detection of covert steganographic traces embedded in images. Notably, there are several similarities between steganographic traces and forgery traces: both are extremely subtle and difficult to detect with the naked eye; moreover, their presence subtly alters the correlation between adjacent pixels in an image, having nuanced effects on the original features of the image. Inspired by this commonality, we follow the advanced ideas presented in the literature [28] and apply SRM to the extraction of high-frequency noise features in images, thereby reflecting traces of image forgery. We aim to highlight the noise inconsistencies introduced by counterfeiting operations while reducing potential interference from the image content itself in forgery detection. This allows our method to focus more on capturing the unique and anomalous changes caused by forgery operations, significantly improving the accuracy and reliability of forgery detection.

Specifically, when an RGB image

Figure 2: SRM filter kernels for extracting noise features

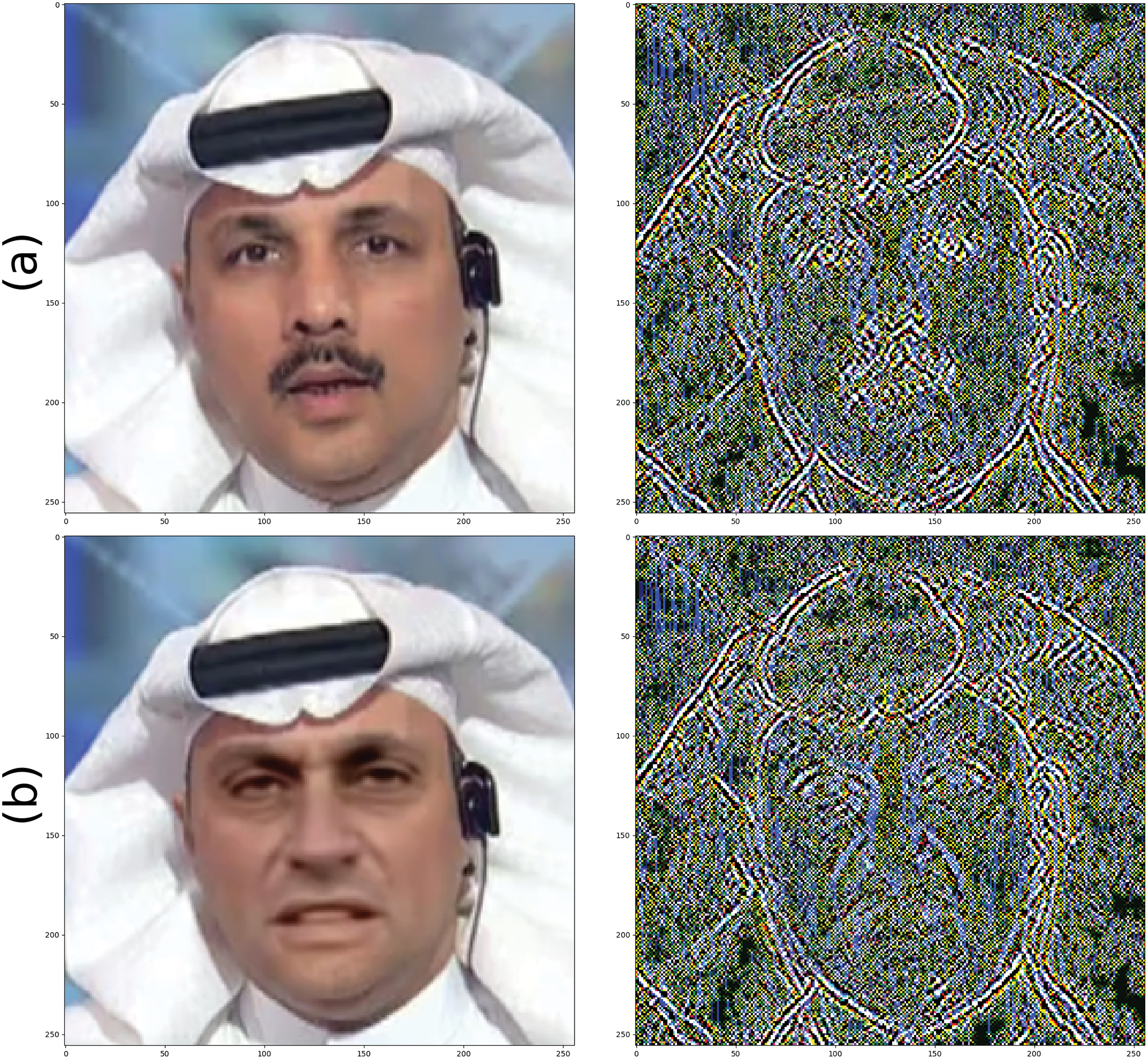

Fig. 3 presents a comparison of noise feature maps for authentic vs. manipulated faces after processing with a high-frequency noise extractor. It can be observed that there exists strong consistency in noise distribution between the facial region and the background area in the authentic face, indicating their similarity concerning noise characteristics. Conversely, there is a significant disparity in noise distribution between the facial region of fake faces and that of their corresponding backgrounds. This inconsistency highlights the impact of the forging process on the image noise characteristics. After applying the SRM filter, forgery traces that were originally difficult to detect in the RGB image become more discernible in the noise feature map.

Figure 3: Noise feature extracted by the High-frequency Noise Extraction Module from (a) authentic face and face manipulated by (b) Deepfakes and (c) FaceSwap

3.3 Vision Transformer Based Dual-Modality Feature Fusion

In both Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Computer Vision (CV), the Transformer [30] has garnered significant attention. Worth mentioning is that ViT models have proven their worth in applications like image classification, image segmentation, and object detection. Its strength lies in its ability to efficiently process images of different scales and resolutions while capturing global information and long-range dependencies between pixels within an image [31]. Feature interactions are essential for revealing the implicit relationships among different modality features [32]. In the context of dual-modality processing using the Transformer networks, Ye et al. [33] effectively captured long-range dependencies between speech and visual features using a specially designed cross-modal self-attention mechanism. The CrossViT [34] uses a dual-branch transformer to process small and large patch tokens separately, followed by integrating these tokens through multiple attention for complementarity.

Inspired by these works, we devise a ViT-based Dual-Modality Feature Fusion (DFF) module. The module first concatenates the texture feature tokens and the noise feature tokens of an image. This fused feature is subsequently fed into the ViT, where the self-attention mechanism is leveraged to produce an attention map. This attention map is then partitioned according to the original sizes of the texture and noise features to ensure that each component receives its corresponding attention weights. These attention weights are subsequently incorporated back into the original texture and noise features via an additive process, fostering a deep interaction and enhancement between the two feature modalities. This innovative attention mechanism effectively captures the potential correlations between texture and noise features. By enhancing the cross-modal information flow and facilitating a deeper level of feature integration, our model can effectively capture anomalies in images, thereby improving accuracy and robustness in forgery detection tasks.

As shown in Fig. 1, the Dual-modality Feature Fusion integrates the intermediate feature maps from both modalities using multiple Transformer modules. Considering one branch as an illustration, given an input face image

where

The Transformer employs linear projections to compute a collection of queries, keys and values (

where

After that, the Transformer employs a non-linear transformation to derive the output features

The output features are divided into two feature maps of size

3.4 Multi-Scale Dual-Modality Mutual Enhancement Network (MDME-Net)

We design a two-branch backbone network, using ResNet34 [35] and ResNet18 [35] respectively as the feature extractors. The dual-modality fusion transformer module described above, which incorporates and fuses the feature information extracted from this backbone network, performs feature fusion at one scale. This fusion process is applied several times for texture features and noise features at various scales, as illustrated in Fig. 2. To mitigate computational costs, we down-sample the feature maps using average pooling prior to inputting them into the transformer. Before performing element-wise summation with the original feature maps, bilinear interpolation is applied to restore the output resolution.

Specifically, the ResNet34 network is selected as the backbone network for the texture branch, while the ResNet18 network is used as the backbone network for the noise branch. Both ResNet34 and ResNet18 consist of a stem layer followed by four stages, as detailed in Table 1. The stem layer comprises a convolutional layer with a 7 × 7 kernel size followed by a max pooling layer with a kernel size of 3 × 3. Conv2_x, Conv3_x, Conv4_x, and Conv5_x correspond respectively to the stages one through four. Each stage is stacked with several residual blocks. The ResNet34 has more residual blocks per stage compared to the ResNet18. As shown in Fig. 2, within each ResNet branch, the output from each stage is sequentially extracted and fed into the dual-modality fusion module. This process facilitates the integration of texture features and noise characteristics at four scales, thereby enhancing the network’s capacity to learn forged traces.

We conduct experiments on three widely recognized public datasets, Deepfake Detection Challenge (DFDC) [17], FaceForensics++ (FF++) [36], and Celeb-DF v2 [37]. The DFDC dataset is a large-scale collection of face-swapping videos released by Facebook. It comprises over 100,000 video clips derived from actor-recorded videos as well as face-swapped videos generated through various Deepfake, GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), and non-learned methods. All data contained in the dataset has been authorized by the image owners themselves. The FF++ dataset serves as a challenging benchmark dataset for face forgery videos, comprising a collection of 1000 original videos. The forgery subsets are produced using four typical forgery methods, i.e., Deepfakes [38], Face2Face [39], FaceSwap [40], and NeuralTextures [41]. For our experiments, we select the high-quality version among the three available quality versions, i.e., raw, high quality, and low quality. The Celeb-DF v2 dataset consists of 590 authentic celebrities’ videos sourced from online platforms alongside 5639 fake videos created by face-swapping techniques.

For data preprocessing, we uniformly select 30 frames from each video during both the training and testing phases. We use MTCNN [42] to extract faces of size 224 × 224. These facial images are then normalized, with a mean value of [0.485,0.456,0.406] and a standard deviation of [0.229,0.224,0.225]. To augment our dataset, we use Albumentations [43]. We set the batch size to 32 and train our model for a maximum of 60 iterations while employing a binary cross-entropy loss function. The optimization is handled by an Adam optimizer, with a learning rate of 0.1e−3 and weight decay configured at 0.1e−6. Our method is implemented in PyTorch and executed on an Nvidia GeForce RTX 3080 GPU.

We evaluate the performance of our model using three key metrics: Accuracy (ACC), which measures the overall correctness of the predictions; the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), offering a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s ability to discriminate between classes at different threshold settings, giving a deeper insight into its discriminative capabilities; and the F1 score. Metrics are calculated at the video level unless specified otherwise.

In addition, we employ three metrics to evaluate the computational complexity and practical application efficiency of the model: the number of model parameters, floating point operations (FLOPs), and average inference time per video.

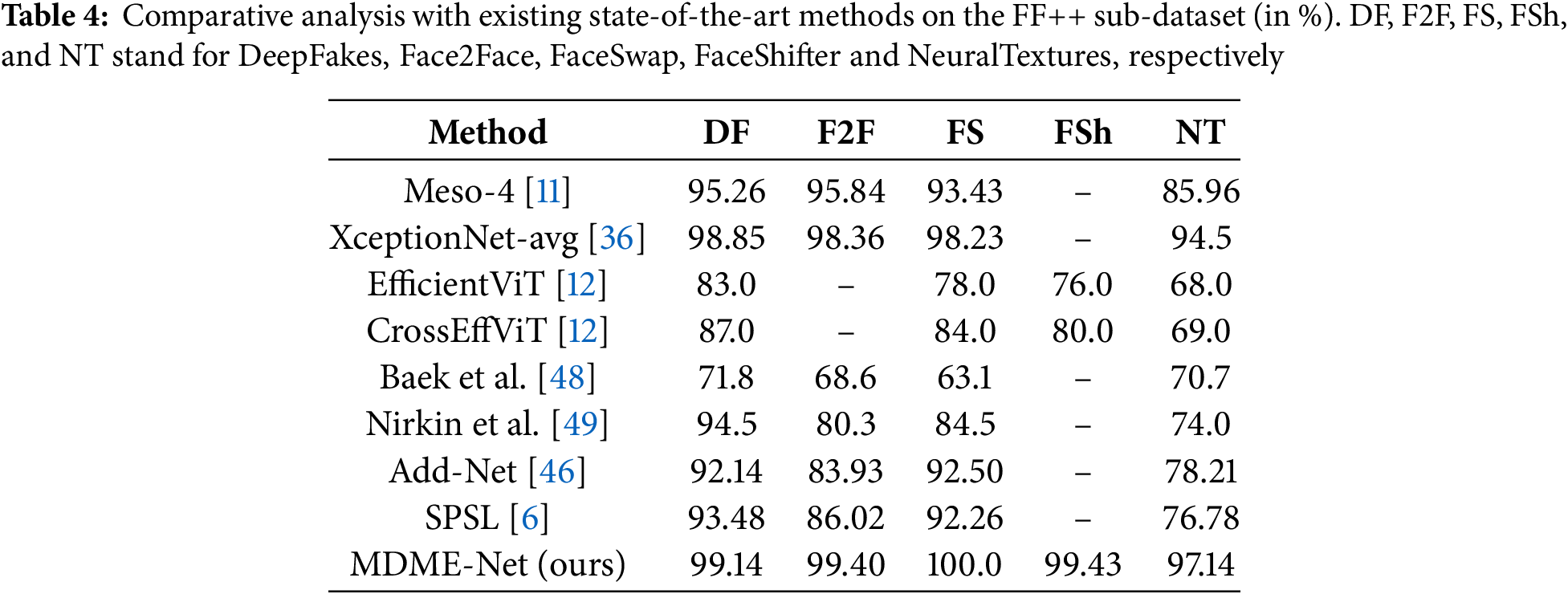

4.2 Within-Dataset Comparison to State-of-the-Art Methods

Firstly, we perform experiments to validate the effectiveness of our model within the DFDC dataset. In this setting, we train our model on the training split of the DFDC dataset and evaluate it on the corresponding test split. As illustrated in Table 2, our model stands out as a clear leader, surpassing existing state-of-the-art methods in terms of both ACC and F1 score metrics. Notably, our model achieves a remarkable 7.16% increase in ACC and a 6.02% enhancement in F1 score over the benchmark CrossEffViT [12] model, demonstrating its superiority in detecting forgery artifacts. The results obtained convincingly demonstrate our model’s capability in identifying intricate forgery patterns, thereby highlighting its potential for practical applications in deepfake detection.

We also compare the in-dataset performance against existing state-of-the-art models utilizing data from the FF++ (HQ) dataset. In this setting, we train our model on the entire FF++ dataset, which includes Deepfakes, Face2Face, FaceSwap, and NeuralTextures manipulation methods. The results are presented in Table 3. Our proposed method surpasses others in this deepfake detection by achieving an impressive ACC of 99.74% along with a top AUC score of 99.31%. The results confirm that our method effectively distinguishes fake videos from real ones within the FF++ dataset even when multiple tampering methods are employed.

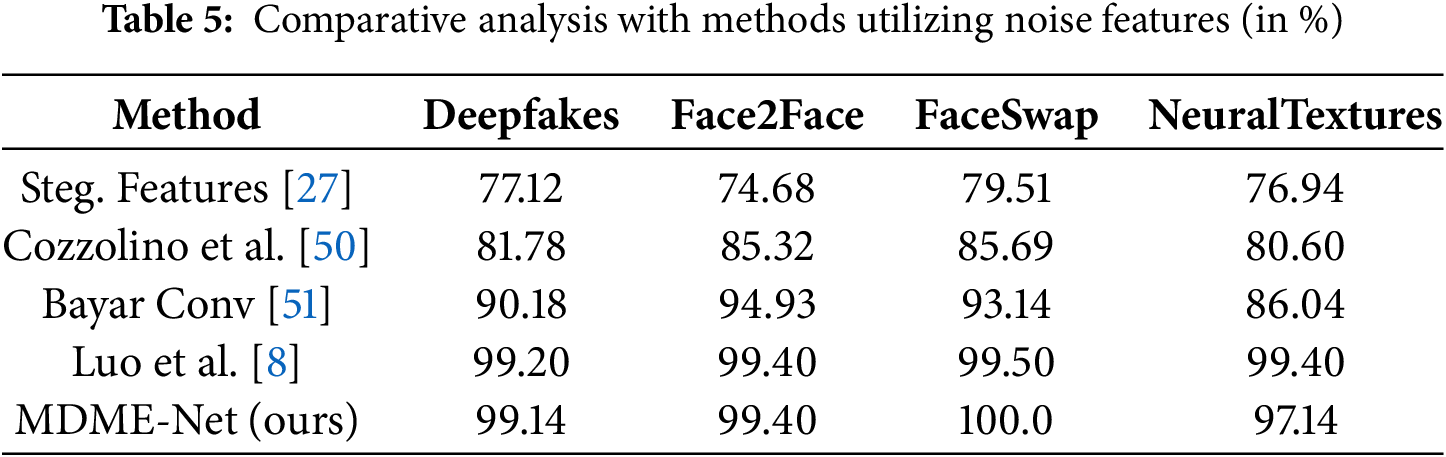

We further assess the model’s capability to learn various forgery techniques individually within the FF++ dataset. Specifically, our model is trained on the training set for each subset of the FF++ dataset and subsequently assessed on the corresponding test set. As illustrated in Table 4, our model beats the best method compared in terms of accuracy. Especially, our model achieves the ACC of 99.14%, 99.40%, 100.0%, and 97.14% for the Deepfakes, Face2Face, FaceSwap, and NeuralTextures manipulation methods respectively, surpassing the benchmark method XceptionNet-avg [36] by margins of 0.29%, 1.04%, 1.77%, and 2.64% ACC correspondingly. These results indicate that our model is proficient at uncovering forgery artifacts for different tampering methods.

Furthermore, we conduct comparisons with methods that utilize noise characteristics for identifying forged images. Specifically, Steg. Features [27] uses SRM to extract steganalysis features for detection. Cozzolino et al. [50] introduce a local descriptor based on noise residuals to improve detection performance. Baryar Conv [51] explores the application of constrained convolution in suppressing high-level image content while emphasizing features such as image noise as a basis for detection. Meanwhile, Luo et al. [8] construct a detector based on the Xception architecture that uses high-frequency noise features filtered by SRM to detect fake faces. The results in Table 5 reflect the accuracies obtained from models trained and tested on the subsets of the FF++ dataset. The findings demonstrate that our model achieves an accuracy level comparable to that of Luo et al.’s method while outperforming other approaches, demonstrating our innovation and effectiveness in utilizing noise features for forgery detection.

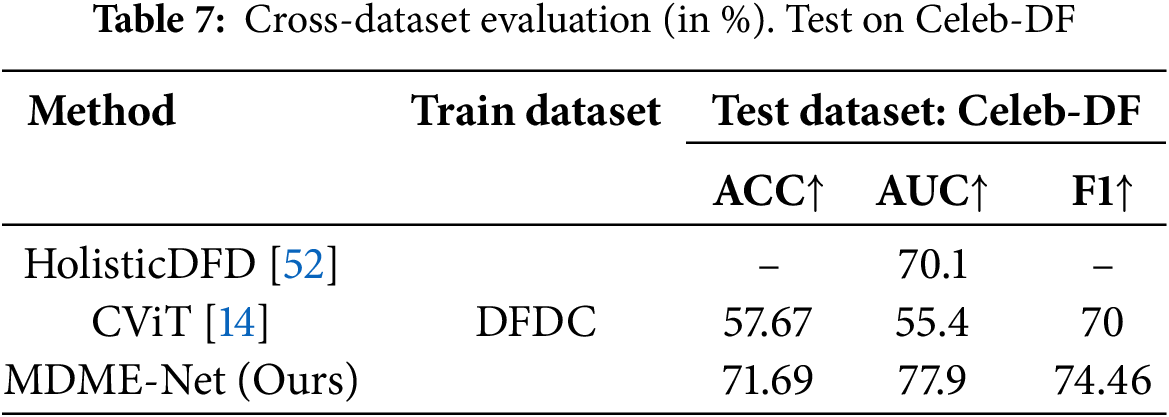

4.3 Cross-Dataset Comparison to State-of-the-Art Methods

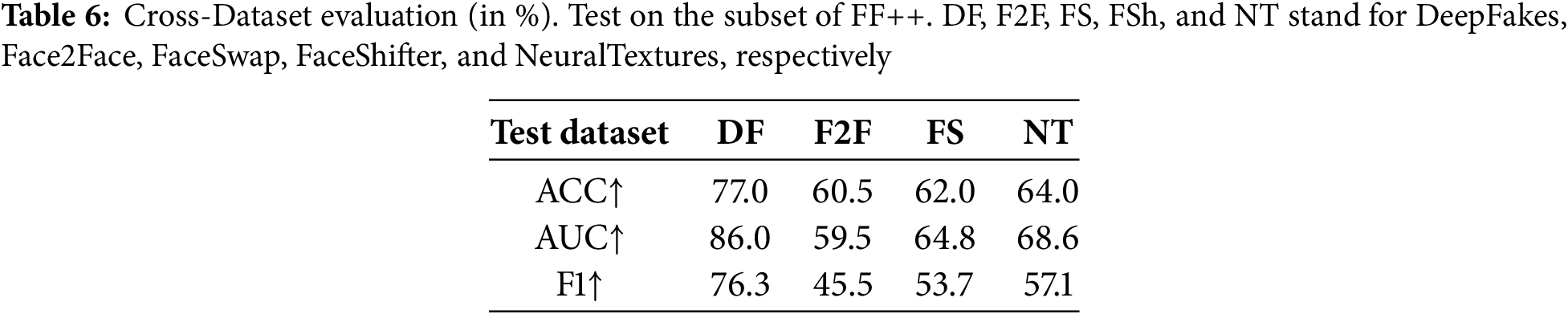

To evaluate our model’s generalization ability, we conduct a cross-dataset evaluation. We train our models on the DFDC dataset followed by cross-dataset testing on FF++ and Celeb-DF v2, respectively. It is challenging since the training sets share little similarity with the testing sets. Results are presented in Tables 6 and 7. Clearly, our model has demonstrated remarkable generalization capabilities when handling unseen data. Specifically, when evaluated on the Deepfakes dataset, our model achieved an AUC of up to 86.0%, providing solid evidence of its robust discriminative power. More encouragingly, the detection results on the Celeb-DF dataset significantly outperformed those of the comparison methods, further reinforcing the advantage of our model in terms of generalization ability. These results undoubtedly confirm the effectiveness of our model design and its great potential for widespread application.

However, for facial reenactment deepfake methods (e.g., Face2Face and NeuralTextures), the model shows some degraded generalization performance. This limitation primarily stems from the fundamental difference between facial reenactment and face swapping: the former achieves expression manipulation through facial muscle movement simulation, leaving more subtle tampering artifacts at the pixel level that are difficult to capture with existing detection features. This phenomenon reveals a core challenge in universal deepfake detection—how to overcome feature dependencies on specific forgery types. As one of our future research directions, we plan to explore the development of a forgery-type-agnostic universal feature extraction framework, with a particular focus on enhancing the model’s adaptability to unknown forgery types through domain generalization approaches.

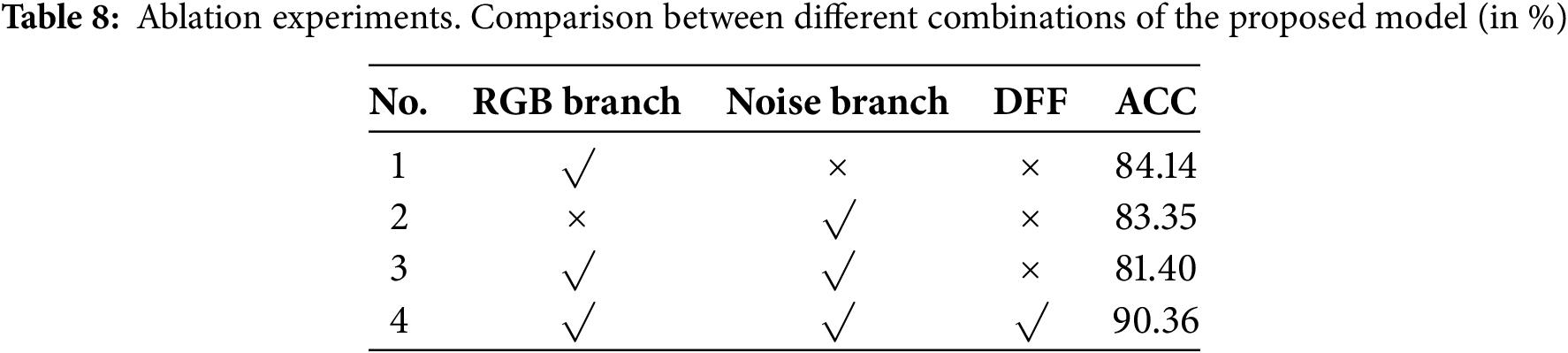

We perform an intra-dataset evaluation using the DFDC dataset to assess our model and its variants to highlight each component’s advantages effectively. The outcomes are summarized in Table 8. Model 1 comprises solely an RGB backbone branch along with a classifier. Model 2 represents the Noise backbone branch with a classifier. Model 3 constitutes a dual-branch network integrating both RGB and Noise branches, without incorporating the DFF module. Model 4 contains all the modules, i.e., the proposed model. Despite Model 3’s attempts to combine texture and noise features, both Model 1 and Model 2 exceed its detection accuracy. However, the performance of Model 3 did not exceed the results obtained using either feature alone. This finding suggests that simply adding two features together may not only fail to improve performance but may also disrupt the network. Nevertheless, the introduction of the DFF module resulted in a remarkable leap in detection performance, with accuracy improvements of 6.22%, 7.01%, and 8.96% over Models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This confirms the effectiveness of the DFF module in fusing texture and noise features, enabling the network to comprehensively capture and identify tampering traces. This outstanding performance is attributed to the attention mechanism embedded in the DFF module, which not only accurately captures the long-range dependencies within the texture and noise modalities, respectively, but also establishes long-range connections between the two modalities. This cross-modal dependency capture facilitates the mutual enhancement of texture and noise features, significantly improving the network’s ability to identify and learn forgery traces.

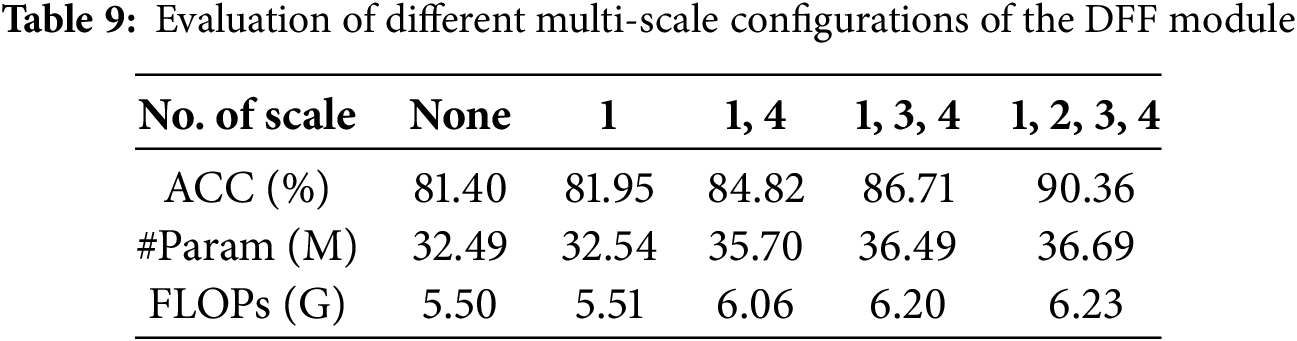

Effects of multi-scale bimodal fusion. To better understand the specific effects of multi-scale bimodal fusion on model performance, we conduct the following experiments aimed at determining both the optimal quantity and configuration of DFF (Dynamic Feature Fusion) modules for our model. Specifically, we utilize four distinct network layers from the dual-branch backbone network—stage 1 to stage 4—which represent a progressive transition from lower-layer to higher-layer. The output generated from each layer serves as the input for its corresponding DFF module, resulting in four DFF modules operating at different scales, denoted as scale1 through scale4. By adopting different scale configurations, we formulate five different models. For example, the “None” indicates that the model does not employ any DFF modules, and “scale1,4” indicates that the model incorporates DFF modules at the outputs of stage 1 and stage 4. We then assess the effectiveness of each model using the DFDC dataset, and the results are presented in Table 9. It is evident that progressively incorporating DFF modules has resulted in a remarkable improvement in model accuracy, from an initial value of 81.40% to an impressive 90.36%. This notable growth demonstrates the efficacy of DFF modules in boosting our model’s detection performance. In particular, by incorporating DFF modules across multiple feature scales, this architecture enables more comprehensive capture and analysis of forgery traces, significantly augmenting detection capabilities. However, it is important to note that as we increase the number of DFF modules, there is also a corresponding rise in both model parameters and Floating Point Operations (FLOPs), indicating a gradual escalation in model complexity and computational cost. Nevertheless, these increases remain within an acceptable range and do not pose insurmountable obstacles to practical applications. Therefore, following an extensive trade-off between model performance and complexity consideration, we have selected a network configuration comprising scale 1 through 4 where DFF modules are introduced sequentially after stages 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. This choice aims to maximize the model’s detection capabilities while retaining its advantages in computational efficiency and practicality.

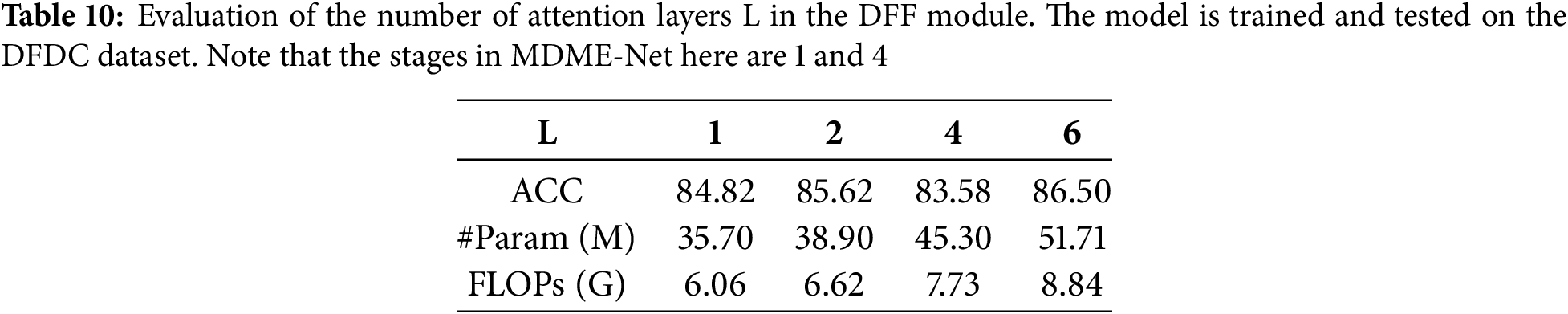

Selection of the Number of Attention Layers in the DFF Module. We provide strong support for the optimal configuration of the DFF module structure by evaluating the impact of varying numbers of attention layers on our model’s detection efficiency. The results for 1-layer, 2-layers, 4-layers, and 6-layers are reported in Table 10. All these models are trained and evaluated on the DFDC dataset exclusively. The experimental results reveal a clear trend of gradual improvement in detection accuracy as the number of attention layers increases from 1 to 6, with a notable jump from 84.82% to 86.50%, representing a significant increase of 1.68%. However, this optimization incurs a significant increase in model complexity, with the number of parameters rising sharply from 35.70 M to 51.71 M, a substantial increase of 45%. At the same time, the number of Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) jumps from 6.06 G to 8.84 G, an increase of 46%. These data indicate that while increasing the number of attention levels can improve the model’s detection performance to some extent, this improvement is accompanied by a significant increase in computational cost and memory requirements. In resource-constrained practical application scenarios, such cost increases cannot be overlooked. Therefore, after carefully balancing model performance against its computational efficiency, we have established that the default number of attention layers in the DFF module should be set to 1. This decision aims to ensure that the model retains good detection capabilities while effectively controlling computational complexity and resource consumption, making it more suited to the needs of practical applications.

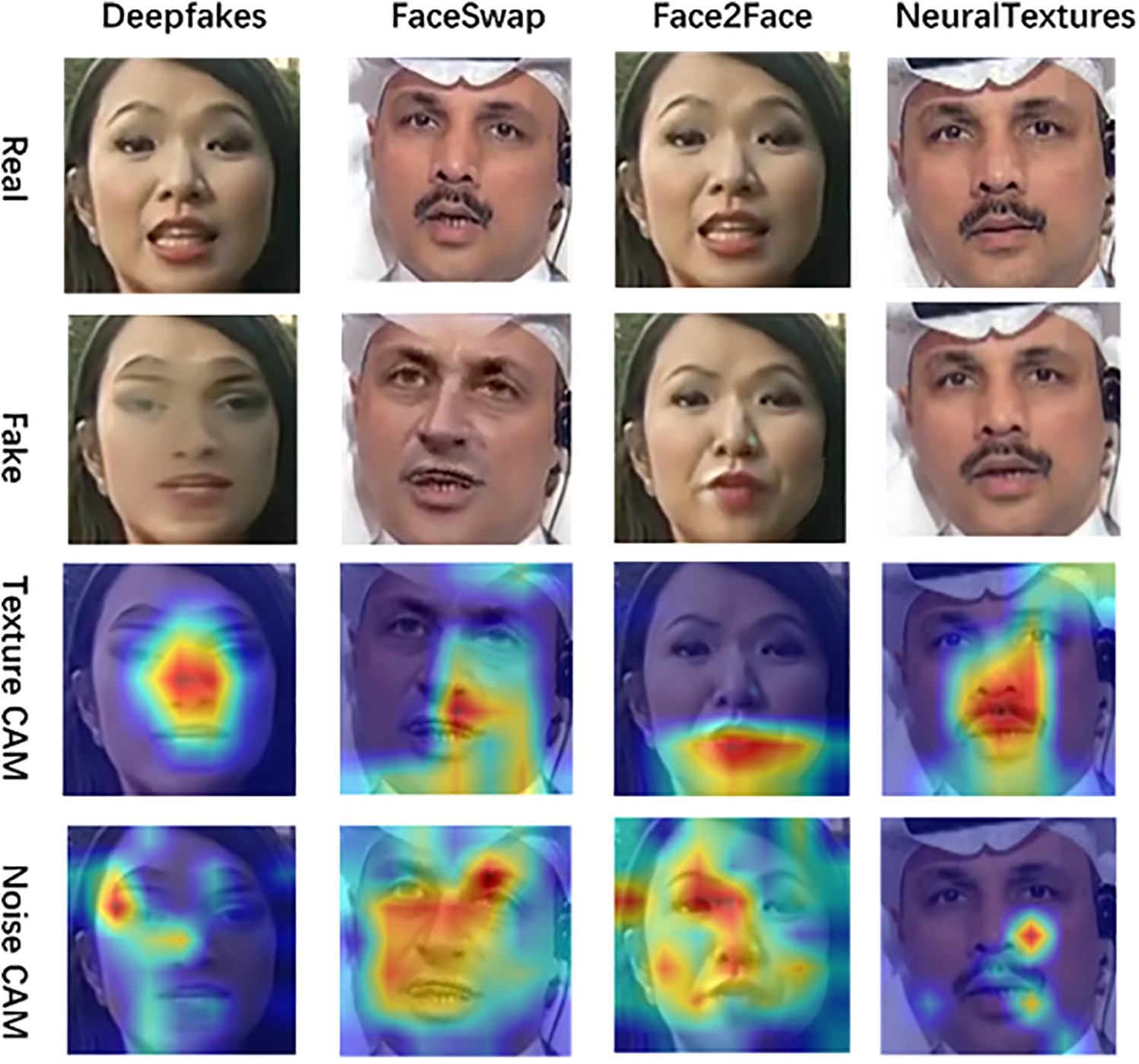

To enhance model interpretability and gain deeper insights into its mechanisms for capturing deepfake artifacts, we employ Grad-CAM to visualize the model’s decision-making process. As shown in Fig. 4, using four subsets from the FF++ dataset, we present four pairs of real and forged face samples alongside Grad-CAM heatmaps from both the texture and noise branches.

Figure 4: Grad-CAM visualizations of forged faces from the texture and noise branches

Experimental results demonstrate the model’s precise localization of manipulated regions across different forgery techniques. For Deepfakes samples generated through face replacement, the Grad-CAM heatmaps prominently highlight facial regions, whereas for Face2Face samples involving mouth-based facial reenactment, the model’s attention focuses primarily on the mouth area. These visualizations qualitatively validate the model’s detection efficacy and result reliability.

Comparative analysis of the texture and noise branch heatmaps reveals their complementary characteristics: the texture branch detects appearance-level anomalies while the noise branch captures steganalysis features. This complementarity aligns with the model’s multimodal design, and their integration enables more comprehensive forgery trace detection, significantly improving overall performance.

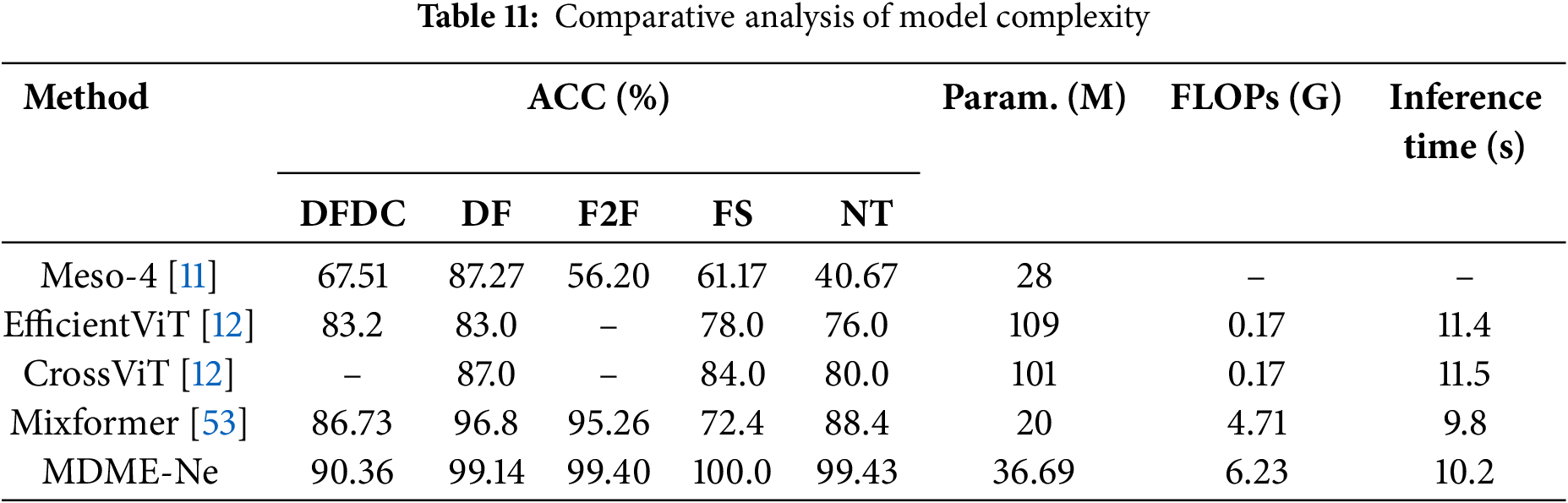

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s practical application efficiency, we conducted systematic complexity analysis experiments. As shown in Table 11, this study selects three core metrics: parameter counts (Param.), floating-point operations (FLOPs), and average inference time per video (Inference Time). Note that the inference times are calculated as the average processing time across all videos in the Celeb-DF test set. The experimental results demonstrate that our model achieves the highest detection accuracy while maintaining a moderate parameter scale. Compared to lightweight models, it shows significant improvements in detection accuracy. When evaluated against high-complexity models, it maintains superior detection accuracy while reducing computational overhead. Collectively, our model strikes an optimal balance between computational resource consumption and detection performance, showcasing its broader potential for application.

This paper presents a dual-branch effective deepfake face detection network. One branch is dedicated to processing RGB images, while the other branch handles noise characteristics extracted by SRM filtering. Each branch independently explores the connections among texture detail, noise pattern, and forgery evidence within the images. The two branches interact through a DFF module, enabling mutual enhancement of texture and noise features, thereby boosting the model’s capability to detect forgery traces. The DFF module operates across multiple layers of the network (including shallow, middle, and deep layers) to achieve multi-scale fusion and enhancement of dual-modal information, comprehensively capturing forgery traces within the images. Comprehensive experiments are conducted on widely utilized deepfake detection datasets. The results show that this dual-branch network not only significantly increases the accuracy of deepfake face detection but also showcases its ability to generalize in complex scenarios, providing robust technical support for combating digital image forgery techniques.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and facilities provided by the People’s Public Security University of China throughout this research endeavor.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Ministry of Public Security Science and Technology Program Project (No. 2023LL35), the Key Laboratory of Smart Policing and National Security Risk Governance, Sichuan Province (No. ZHZZZD2302).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yuanqing Ding; methodology, Yuanqing Ding; software, Yuanqing Ding, Qiming Ma; writing—original draft, Yuanqing Ding; writing—review & editing, Yuanqing Ding, Hanming Zhai; supervision, Fanliang Bu; data curation, Liang Zhang; resources, Lei Shao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li Y, Chang MC, Lyu S. In ictu oculi: exposing AI created fake videos by detecting eye blinking. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS); 2018 Dec 11–13; Hong Kong, China. doi:10.1109/WIFS.2018.8630787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ciftci UA, Demir I, Yin L. FakeCatcher: detection of synthetic portrait videos using biological signals. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell Forthcoming. 2020. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3009287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Agarwal S, Farid H, Fried O, Agrawala M. Detecting deep-fake videos from phoneme-viseme mismatches. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2020 Jun 14–19; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvprw50498.2020.00338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Durall R, Keuper M, Pfreundt FJ, Keuper J. Unmasking DeepFakes with simple features. arXiv:1911.00686. 2019. [Google Scholar]

5. Li J, Xie H, Li J, Wang Z, Zhang Y. Frequency-aware discriminative feature learning supervised by single-center loss for face forgery detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu H, Li X, Zhou W, Chen Y, He Y, Xue H, et al. Spatial-phase shallow learning: rethinking face forgery detection in frequency domain. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.00083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Uddin M, Fu Z, Zhang X. Deepfake face detection via multi-level discrete wavelet transform and vision transformer. Vis Comput. 2025;97(5):1304. doi:10.1007/s00371-024-03791-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Luo Y, Zhang Y, Yan J, Liu W. Generalizing face forgery detection with high-frequency features. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li L, Bao J, Zhang T, Yang H, Chen D, Wen F, et al. Face X-ray for more general face forgery detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Afchar D, Nozick V, Yamagishi J, Echizen I. MesoNet: a compact facial video forgery detection network. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS); 2018 Dec 11–13; Hong Kong, China. doi:10.1109/WIFS.2018.8630761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Coccomini DA, Messina N, Gennaro C, Falchi F. Combining EfficientNet and vision transformers for video deepfake detection. In: Proceedings of the Image Analysis and Processing—ICIAP 2022; 2022 May 23–27; Lecce, Italy. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-06433-3_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao H, Wei T, Zhou W, Zhang W, Chen D, Yu N. Multi-attentional deepfake detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.00222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Deressa DW, Lambert P, Van Wallendael G, Atnafu S, Mareen H. Improved deepfake video detection using convolutional vision transformer. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Gaming, Entertainment, and Media Conference (GEM); 2024 Jun 5–7; Turin, Italy. doi:10.1109/GEM61861.2024.10585593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2020. [Google Scholar]

16. Tan M, Le Q. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. Proc Mach Learn Res. 2019;97:6105–14. [Google Scholar]

17. Dolhansky B, Bitton J, Pflaum B, Lu J, Howes R, Wang M, et al. The DeepFake detection challenge (DFDC) dataset. arXiv:2006.07397. 2020. [Google Scholar]

18. Qian Y, Yin G, Sheng L, Chen Z, Shao J. Thinking in frequency: face forgery detection by mining frequency-aware clues. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58610-2_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Y, Chen C, Zhang N, Hu X. WATCHER: wavelet-guided texture-content hierarchical relation learning for deepfake detection. Int J Comput Vis. 2024;132(10):4746–67. doi:10.1007/s11263-024-02116-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Y, Yu K, Chen C, Hu X, Peng S. Dynamic graph learning with content-guided spatial-frequency relation reasoning for deepfake detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cozzolino D, Verdoliva L. Noiseprint: a CNN-based camera model fingerprint. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2019;15:144–59. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2019.2916364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cozzolino D, Poggi G, Verdoliva L. Extracting camera-based fingerprints for video forensics. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops; 2019 Jun 16–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. El Rai MC, Al Ahmad H, Gouda O, Jamal D, Abu Talib M, Nasir Q. Fighting deepfake by residual noise using convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS); 2020 Nov 25–26; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. doi:10.1109/icspis51252.2020.9340138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kang J, Ji SK, Lee S, Jang D, Hou JU. Detection enhancement for various deepfake types based on residual noise and manipulation traces. IEEE Access. 2022;10:69031–40. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3185121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou P, Han X, Morariu VI, Davis LS. Two-stream neural networks for tampered face detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2017.229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gu Q, Chen S, Yao T, Chen Y, Ding S, Yi R. Exploiting fine-grained face forgery clues via progressive enhancement learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(1):735–43. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i1.19954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fridrich J, Kodovsky J. Rich models for steganalysis of digital images. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2012;7(3):868–82. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2012.2190402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhou P, Han X, Morariu VI, Davis LS. Learning rich features for image manipulation detection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23. Salt Lake City, UT, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Rao Y, Ni J. A deep learning approach to detection of splicing and copy-move forgeries in images. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS); 2016 Dec 4–7; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. doi:10.1109/WIFS.2016.7823911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Vaswani A, Brain G, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

31. Lin X, Sun S, Huang W, Sheng B, Li P, Feng DD. EAPT: efficient attention pyramid transformer for image processing. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;25:50–61. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3120873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xie Z, Zhang W, Sheng B, Li P, Philip Chen CL. BaGFN: broad attentive graph fusion network for high-order feature interactions. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(8):4499–513. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3116209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ye L, Rochan M, Liu Z, Wang Y. Cross-modal self-attention network for referring image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20. Long Beach, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.01075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen CR, Fan Q, Panda R. CrossViT: cross-attention multi-scale vision transformer for image classification. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17. Montreal, QC, Canada. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rossler A, Cozzolino D, Verdoliva L, Riess C, Thies J, Niessner M. FaceForensics++: learning to detect manipulated facial images. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li Y, Yang X, Sun P, Qi H, Lyu S. Celeb-DF: a large-scale challenging dataset for DeepFake forensics. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

38. Deepfakes [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 12]. Available from: https://github.com/deepfakes/faceswap. [Google Scholar]

39. Thies J, Zollhöfer M, Stamminger M, Theobalt C, Nießner M. Face2Face: real-time face capture and reenactment of RGB videos. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Faceswap [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 12]. Available from: https://github.com/MarekKowalski/FaceSwap. [Google Scholar]

41. Thies J, Zollhöfer M, Nießner M. Deferred neural rendering. ACM Trans Graph. 2019;38(4):1–12. doi:10.1145/3306346.3323035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Timesler. Pretrained Pytorch face detection (MTCNN) and recognition (InceptionResnet) models [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 12]. Available from: https://github.com/timesler/facenet-pytorch. [Google Scholar]

43. Buslaev A, Iglovikov VI, Khvedchenya E, Parinov A, Druzhinin M, Kalinin AA. Albumentations: fast and flexible image augmentations. Information. 2020;11(2):125. doi:10.3390/info11020125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Khalifa AH, Zaher NA, Abdallah AS, Fakhr MW. Convolutional neural network based on diverse Gabor filters for deepfake recognition. IEEE Access. 2022;10:22678–86. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3152029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liu J, Xie J, Wang Y, Zha ZJ. Adaptive texture and spectrum clue mining for generalizable face forgery detection. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;19(11):1922–34. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2023.3344293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zi B, Chang M, Chen J, Ma X, Jiang YG. WildDeepfake: a challenging real-world dataset for deepfake detection. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2020 Oct 12–16; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1145/3394171.3413769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Masi I, Killekar A, Mascarenhas RM, Gurudatt SP, AbdAlmageed W. Two-branch recurrent network for isolating deepfakes in videos. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58571-6_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Baek JY, Yoo YS, Bae SH. Generative adversarial ensemble learning for face forensics. IEEE Access. 2020;8:45421–31. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2968612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Nirkin Y, Wolf L, Keller Y, Hassner T. DeepFake detection based on discrepancies between faces and their context. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(10):6111–21. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3093446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Cozzolino D, Poggi G, Verdoliva L. Recasting residual-based local descriptors as convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 5th ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security; 2017 Jun 20–22; New York, NY, USA. doi:10.1145/3082031.3083247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Bayar B, Stamm MC. A deep learning approach to universal image manipulation detection using a new convolutional layer. In: Proceedings of the 4th ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security; 2016 Jun 20–22; Vigo Galicia, Spain. doi:10.1145/2909827.2930786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Anas Raza M, Mahmood Malik K, Ul Haq I. HolisticDFD: infusing spatiotemporal transformer embeddings for deepfake detection. Inf Sci. 2023;645:119352. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ding Y, Bu F, Zhai H, Hou Z, Wang Y. Multi-feature fusion based face forgery detection with local and global characteristics. PLoS One. 2024;19(10):e0311720. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0311720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools