Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Smoke Detector for Outdoor Parking Lots Based on Improved YOLOv8

1 State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data, College of Computer Science and Technology, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

2China Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team, Beijing, 100040, China

3 Fengtai Science and Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, 100070, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhenyong Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 729-750. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066748

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 11 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

In rapid urban development, outdoor parking lots have become essential components of urban transportation systems. However, the increasing number of parking lots is accompanied by a rising risk of vehicle fires, posing a serious challenge to public safety. As a result, there is a critical need for fire warning systems tailored to outdoor parking lots. Traditional smoke detection methods, however, struggle with the complex outdoor environment, where smoke characteristics often blend into the background, resulting in low detection efficiency and accuracy. To address these issues, this paper introduces a novel model named Dynamic Contextual Transformer YOLO (DCT-YOLO), an advanced smoke detection method specifically designed for outdoor parking lots. We introduce an innovative Dynamic Channel-Spatial Attention (DCSA) mechanism to improve the model’s focus on smoke features, thus improving detection accuracy. Additionally, we incorporate Contextual Transformer Networks (CoTNet) to better adapt to the irregularity of smoke patterns, further enhancing the accuracy of smoke region detection in complex environments. Moreover, we developed a new dataset that includes a wide range of smoke and fire scenarios, improving the model’s generalization capability. All baseline models were trained and evaluated on the same dataset to ensure a fair and consistent comparison. The experimental results on this dataset demonstrate that the proposed algorithm yields a mAP@0.5 of 85.1% and a mAP@0.5:0.95 of 55.7%, representing improvements of 15.0% and 14.9%, respectively, over the baseline model. These results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed method in accurately detecting smoke in challenging outdoor environments.Keywords

With the acceleration of urbanization, the number of outdoor parking lots has rapidly increased, becoming an essential component of urban transportation systems [1]. However, changes in vehicle materials, construction technologies, and vehicle usage have led to frequent incidents of spontaneous combustion in parked vehicles, significantly raising the risk of vehicle fires and posing serious threats to public safety [2–4]. According to the 2024 China fire accident data, national firefighting teams responded to 908,000 fire incidents, with direct property losses totaling 7.74 billion yuan. Among these, 391,000 were building fires, accounting for 43.1%, and 97,000 were vehicle fires, accounting for 10.7%. Outdoor parking lots exhibit varying environmental conditions depending on geographical locations, further complicating the challenges of smoke detection.

The anticipated rise in electric vehicle (EV) adoption adds layer of complexity, once an EV battery ignites, suppressing the fire becomes exceedingly challenging [5]. Similar to fires in other public spaces, vehicle fires typically occur unexpectedly and may trigger a series of cascading reactions. During the early stages of a fire, smoke often serves as one of the most significant early warning signals, making accurate fire detection crucial at this moment [6]. An efficient smoke detection system can provide timely warnings during the “golden minutes” following the outbreak of a fire, assisting emergency personnel in responding swiftly and minimizing casualties and property loss.

Traditional smoke and fire detection methods rely on physical sensors [7–9]. Although these sensor technologies perform well in enclosed environments and are relatively cost-effective, they face numerous challenges in complex outdoor settings. In outdoor parking lots, environmental factors such as variations in natural light, dust, wind speed, humidity, and other meteorological conditions can lead to high false alarm rates or delayed alerts during critical moments. In contrast, image-based smoke detection methods are less affected by changes in outdoor environments [10]. With advancements in computer vision and image processing, these methods have garnered widespread attention. Unlike traditional physical sensors that depend on a single physical signal, image-based methods utilize visual information captured by cameras to detect smoke or flames. Early image-based smoke detection techniques primarily employed traditional image processing methods to manually extract smoke features, such as optical flow methods [11], wavelet transforms [12,13], frame differencing, and Gaussian mixture model (GMM) segmentation techniques [14,15]. These methods segment images by analyzing motion or pixel changes, relying on handcrafted feature extraction. For instance, Islam et al. introduced a smoke detection technique that utilizes motion analysis and feature classification, achieving an average classification accuracy of 97.34% [16]. The approach involved preprocessing smoke in videos using GMM and subsequently classifying and detecting smoke with a support vector machine (SVM) [17]. However, despite employing effective feature extraction and classification capabilities, the processing speed and computational demands of these methods may limit their applicability in real-time scenarios that require rapid responses. The emergence of deep learning has led to substantial progress in smoke and flame detection technologies. Deep learning-based object detection and recognition methods use neural networks for end-to-end feature learning, as applied in satellite smoke scene detection [18] and image-based smoke recognition [19], providing powerful tools for precise detection in complex scenarios. These models automatically extract multi-layered features, from low-level edges and textures to high-level object shapes and semantic information, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional handcrafted feature methods.

Object detection algorithms are typically classified into two categories: two-stage algorithms and single-stage algorithms. Two-stage algorithms initially generate candidate regions, followed by classification and bounding box regression for the identified objects. Faster R-CNN, a quintessential two-stage model introduced by Ren et al. [20], incorporates a Region Proposal Network (RPN) to generate candidate regions using shared convolutional features. Upon training, the model is capable of adaptively optimizing these regions. Conversely, the You Only Look Once (YOLO) series, first proposed by Redmon et al. [21–23], represents single-stage algorithms. This approach streamlines the task into a single forward propagation process, thereby obviating the need for separate candidate region generation and significantly accelerating detection speed. In summary, two-stage algorithms typically exhibit higher computational complexity and slower processing speeds, while single-stage algorithms can directly predict object locations with comparatively lower complexity, rendering them more suitable for applications demanding high real-time performance. These technologies enable real-time monitoring and dynamic tracking of smoke, greatly improving response times to initial fire outbreaks. To enhance detection accuracy, Chen et al. [24] incorporated an ECA attention module and SIoU loss function along with RepVGG, attaining a detection accuracy of 95.1%. Addressing the uncertainty features of smoke, Wang et al. [25] adopted the YOLOv8 network, which incorporates edge feature enhancement modules, multi-feature extraction modules, and global feature augmentation modules, improving the accuracy of smoke area recognition.

Mamadaliev et al. [26] proposed an improved model named ESFD-YOLOv8n, which significantly enhanced the performance of smoke and fire detection compared to the original YOLOv8n model, reaching a mAP@0.5 of 79.4% with an inference time of 1.0 ms in real-time. Saydirasulovich et al. [27] proposed an improved YOLOv8-based smoke detection model, integrating WIoUv3 loss, BiFormer attention, and GSConv to enhance accuracy and efficiency. It outperforms traditional YOLO models in small object detection and speed but remains sensitive to weather, false alarms, and edge deployment challenges, requiring multimodal fusion and lightweight optimization. Yao et al. [28] developed the FG-YOLO algorithm, enhancing fire and smoke detection by integrating the FSCNet backbone and GScELAN module to improve feature extraction and fusion, achieving higher accuracy and efficiency in detecting small-scale and irregularly shaped flames and smoke. Li et al. [29] proposed a lightweight wildfire smoke detection algorithm for UAVs based on YOLOv7, integrating FasterNet, AFPN, and 3FIoU loss to reduce the model to 27.5 M parameters and 175 FPS with 79.3% mAP@0.5. It enhances small-object detection and robustness but struggles with extreme conditions. Chen et al. [30] introduced IFS-DETR, a Transformer-based detector using LeanNet, AFFNet, and Inner-SIoU, achieving 81.8% mAP@0.5 and up to 137 FPS on Jetson Orin Nano. Despite high performance, both methods rely solely on visible light, suggesting future integration of multi-modal data for improved performance under challenging conditions.

Despite the tremendous potential of deep learning methods in outdoor smoke detection, several challenges remain for effective application in real-world environments. Key issues include enhancing model robustness under varying lighting and weather conditions and optimizing algorithms to reduce computational complexity. Furthermore, most deep learning methods depend on extensive and high-quality datasets, necessitating a reasonable design of network architectures for specific tasks. However, there is currently a lack of public datasets specifically for smoke and fire images in parking lots.

To tackle these challenges, this study proposes an improved outdoor parking lot smoke detection system based on YOLOv8n, providing a novel solution for outdoor smoke detection and contributing to the development of intelligent monitoring systems for public safety. The primary contributions of this study are as follows:

• A dataset of fire scenarios in outdoor parking lots is created. Various methods are employed to collect diverse smoke and fire data, and appropriate images are extracted, cropped, and filtered from parking lot video surveillance frames to constitute a dataset of smoke and fire in real scenes.

• A lightweight YOLOv8n model is employed as the primary detection model, optimized by an innovatively designed Dynamic Channel-Spatial Attention (DCSA) mechanism that dynamically adjusts the weights of channel and spatial features, effectively enhancing the model’s perception of irregular smoke regions in complex scenarios.

• The integration of Contextual Transformer Networks (CoTNet) is innovatively adopted to better capture long-range dependencies in images, allowing the model to more accurately comprehend the spatial characteristics of smoke in complex environments, thereby improving detection accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed description of the Materials and Methods, including the research materials, dataset, and experimental procedures. Section 3 presents the Experimental Results and Analysis, where the experimental results are shown and analyzed to assess the performance of the proposed method. Section 4 describes the System Design, detailing the architecture and implementation of the smoke detection system. Finally, Section 5 offers a Discussion, where the experimental findings are discussed, the strengths and limitations are analyzed, and potential improvements are proposed.

YOLOv8 marks the eighth iteration of the YOLO algorithm sequence, inheriting and enhancing the strengths of its predecessors through a more advanced architectural framework. As a single-stage object detection algorithm, YOLOv8 utilizes a regression-based approach that excels in real-time detection and high-precision classification. Its network architecture comprises several convolutional layers, activation layers, and pooling layers, which facilitate the deep extraction of image features for precise prediction and classification of object locations. In contrast to traditional two-stage algorithms like Mask R-CNN and Faster R-CNN, YOLOv8 implements end-to-end detection, enabling simultaneous object detection and classification through a single network. This design significantly improves inference speed, making YOLOv8 particularly suitable for applications requiring high real-time performance, such as smoke detection in outdoor parking lots. Bakirci applied the YOLOv8n model in intelligent transportation systems, particularly for UAV-based vehicle detection. The model demonstrated outstanding performance, achieving an accuracy of 80.3%, a mAP of 79.7%, and a fast inference time of just 8 ms per frame, making it highly suitable for real-time applications. Furthermore, he validated the real-time capabilities of YOLOv8 in traffic monitoring by employing the lightweight YOLOv8n variant, which reached an inference speed of up to 64 frames per second [31,32]. Compared to earlier models, YOLOv8n achieved a significant breakthrough in processing efficiency while maintaining reasonable accuracy, highlighting its strong potential for real-time detection tasks.

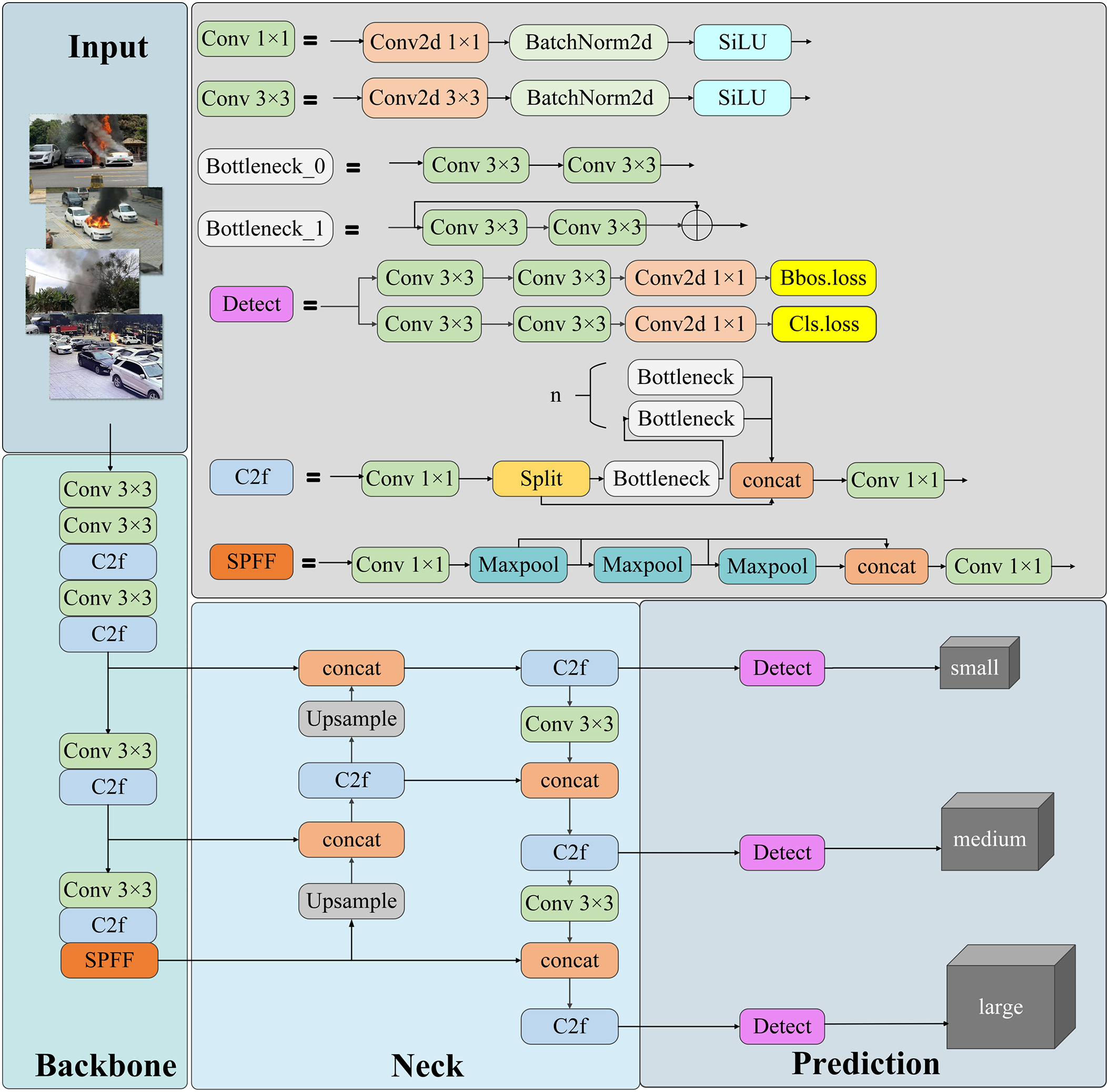

The YOLOv8 framework includes various model variants, such as YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, and YOLOv8x, each tailored for different performance requirements. In real-time scenarios, selecting a lightweight model with high computational efficiency and fast inference is often prioritized. As the smallest variant, YOLOv8n delivers excellent speed and low computational cost, making it suitable for real-time smoke detection in parking lots, though its original accuracy is relatively lower. This study aims to achieve a better balance among computational efficiency, inference speed, and detection accuracy. After evaluating the model structure and practical deployment needs, we selected YOLOv8n as the base model. Compared with larger variants like YOLOv8s and YOLOv8m, YOLOv8n offers greater flexibility to incorporate attention mechanisms and Transformer modules, enhancing accuracy while controlling latency and complexity. Fig. 1 shows the architecture of YOLOv8n, including the input layer, backbone, neck, and prediction head, highlighting its efficient feature extraction and detection capabilities.

Figure 1: Structure of the YOLOv8

Input End: The input layer preprocesses the input images and applies data augmentation techniques, including operations such as scaling, normalization, and random cropping. These processes not only ensure that the images meet the network’s input requirements but also broaden the variety of the training data, thereby improving the model’s generalization abilities.

Backbone: The backbone network extracts deep features from input images through multiple convolutional layers. It captures both spatial structures and semantic information, effectively handling multi-scale features to facilitate robust object detection.

Neck: The neck further processes the multi-scale features extracted by the backbone, enhancing feature fusion and integrating feature maps across different scales. This improves the detection performance, especially for objects of varying sizes.

Prediction Module: The prediction module utilizes the feature maps from the neck to predict the position and category probabilities of each object, enabling accurate object detection.

2.2 Dynamic Channel-Spatial Attention

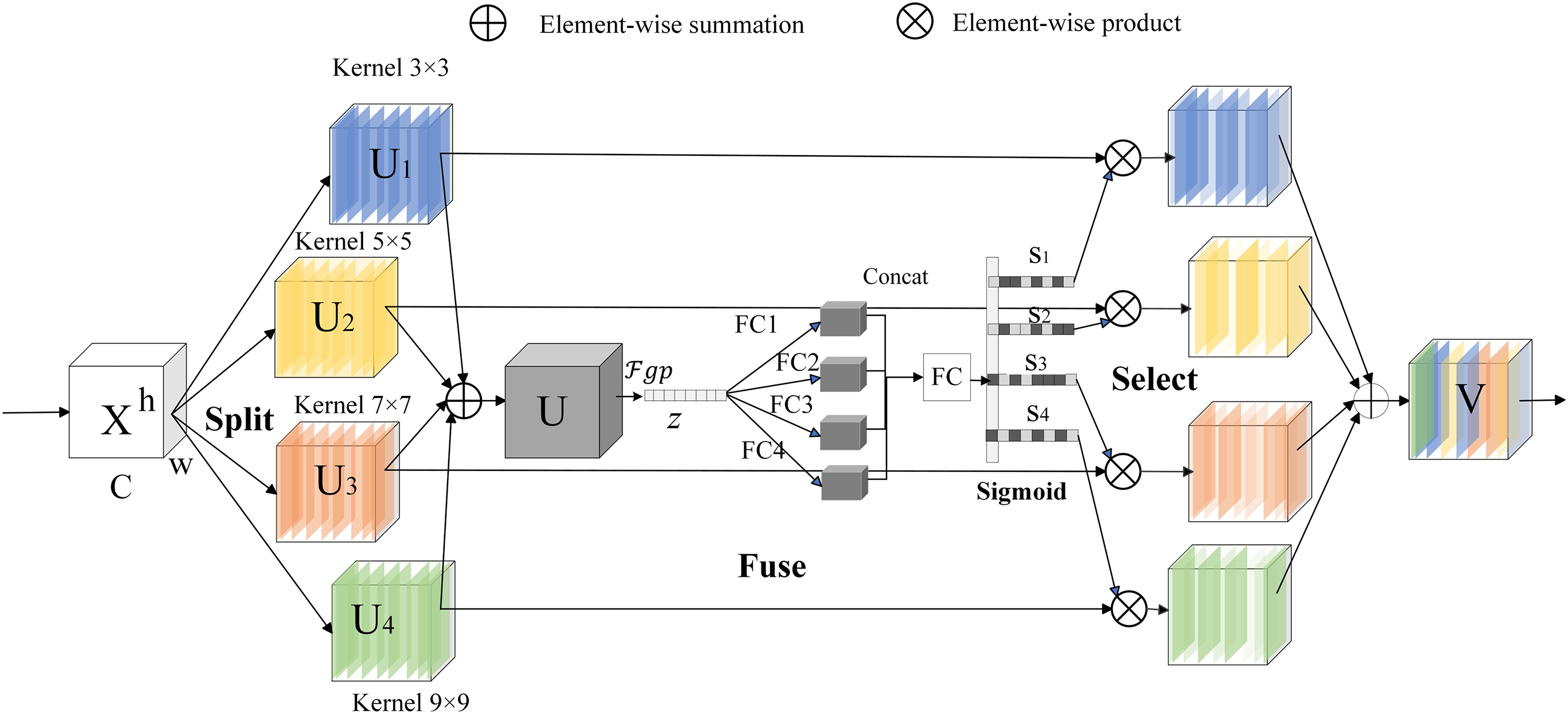

We draw inspiration from the Selective Kernel module proposed by Li et al. [33], which dynamically adjusts the receptive field size based on the features of the input image. We introduce a specialized attention mechanism to better detect smoke regions. To accommodate the irregularities inherent in smoke and fire, we propose the DCSA mechanism, which not only integrates the strengths of existing attention mechanisms but also introduces structural innovations. Compared with SENet [34], which emphasizes channel importance by modeling inter-channel dependencies via global average pooling and fully connected layers. CA [35], which enhances spatial awareness by incorporating coordinate information through directional pooling along horizontal and vertical axes; and SK, which achieves adaptive multi-scale feature representation through dynamic convolutional kernel selection. DCSA is designed to jointly model spatial and channel information in a more coordinated manner. Specifically, DCSA employs four parallel convolutional kernels of varying sizes to extract global spatial features at different receptive fields. Meanwhile, in the channel dimension, it introduces a multi-branch densely connected structure to strengthen nonlinear dependencies across channels. This is followed by a channel recalibration process that adaptively reweights the feature maps, enabling the network to dynamically focus on informative spatial regions and channel-wise features. Such a design significantly improves the model’s representational capacity and robustness in complex smoke detection scenarios. Specifically, we implement three operations—Split, Fuse, and Select. Fig. 2 illustrates the network structure of DCSA.

Figure 2: Dynamic channel-spatial convolution

Split: We assume that for any specified feature map

Fuse: To facilitate neurons in dynamically altering their receptive field (RF) sizes according to diverse stimulus content, we employ gating mechanisms to regulate the flow of multi-scale information from distinct branches, directing it to the neurons in the subsequent layer. To achieve this, the gating mechanism must consolidate the information from the four branches, as shown in Eq. (1). As an initial step, we fuse the outputs from the four branches via element-wise summation, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

where

Using global average pooling (GAP), the spatial characteristics of the input feature map are reduced to a single value for each channel, thereby extracting global information from each channel and reducing the impact of spatial dimensions on the results. After the application of global average pooling, we can obtain the summarized features for each channel. The global features for each channel are presented in Eq. (2) as follows:

where

Next, four fully connected (FC) layers reduce the dimensionality of the input features and apply nonlinear transformations. This approach aims to capture the diverse and complex details within the input features, leading to more enriched feature representations. This is especially important for smoke detection, given the complex and variable nature of the environment, necessitating a model with robust interference resilience. The process is represented, as shown in Eq. (3).

where

Applying the ReLU activation function to the four FC layers generates distinct feature representations. Subsequently, the dimensionality-reduced feature representations are concatenated to form a new feature vector, as shown in Eq. (4). This approach allows us to integrate the diverse information from the various FC layers, thereby enhancing the diversity of the feature representation.

where

Select: This method utilizes a fully connected layer and projects the feature vector back to the original number of channels using a Sigmoid activation function. This process provides the weights for the four branches. This operation is executed using the expression in Eq. (5).

where

Finally, in Eq. (6), the attention weight vectors

where

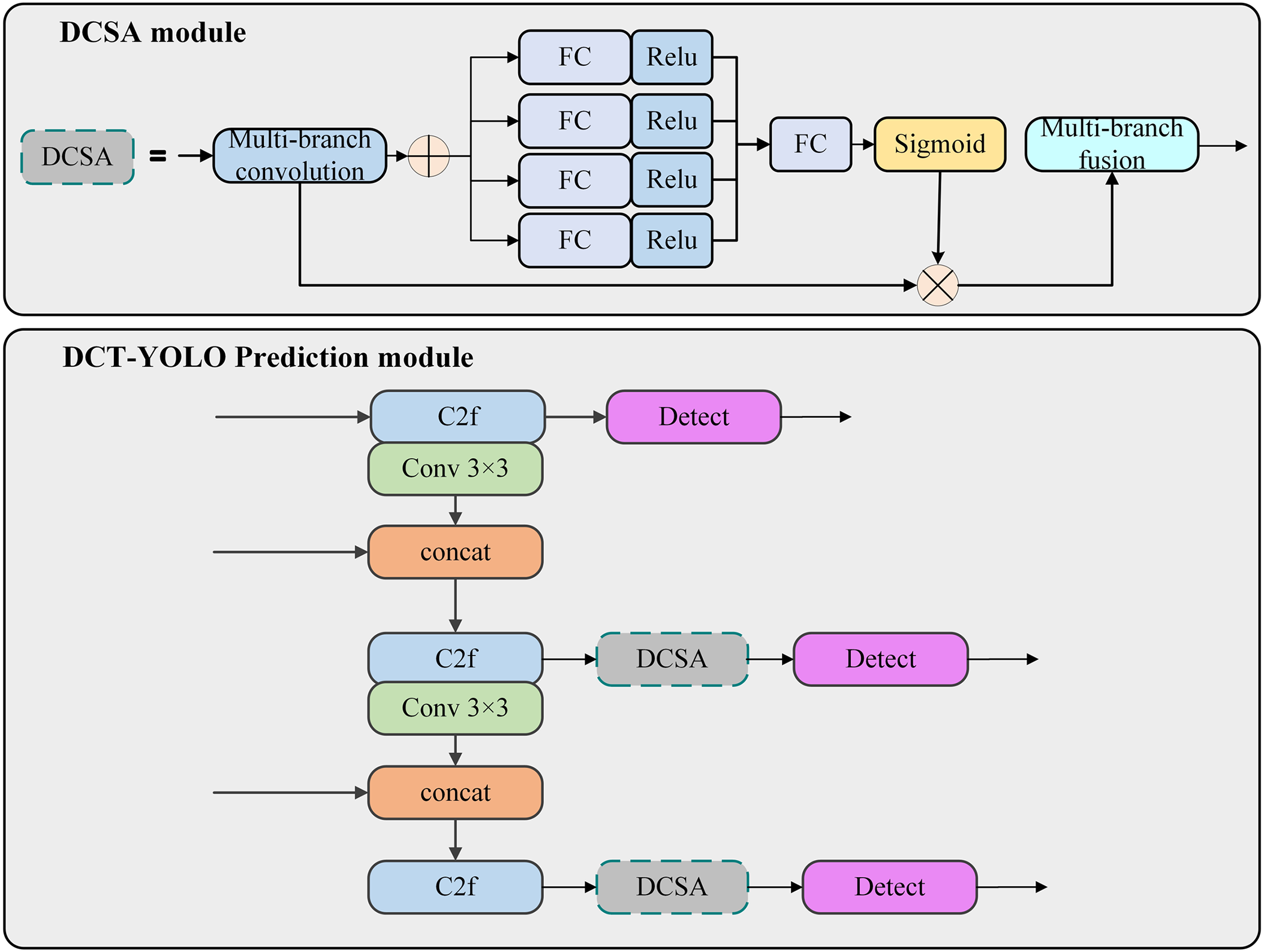

Considering the shooting distance of images in outdoor parking lots, we integrate the Dynamic Channel-Spatial Attention mechanism into the prediction heads for medium and large targets, positioned after the C2f layer in Fig. 3. This configuration aims to enhance the model’s perceptual capability for targets of varying scales through the adaptive adjustment of the receptive field provided by DCSA. For medium and large targets, DCSA effectively captures critical features, particularly in complex backgrounds, thereby improving detection accuracy.

Figure 3: Integration location of DCSA

2.3 Contextual Transformer Networks

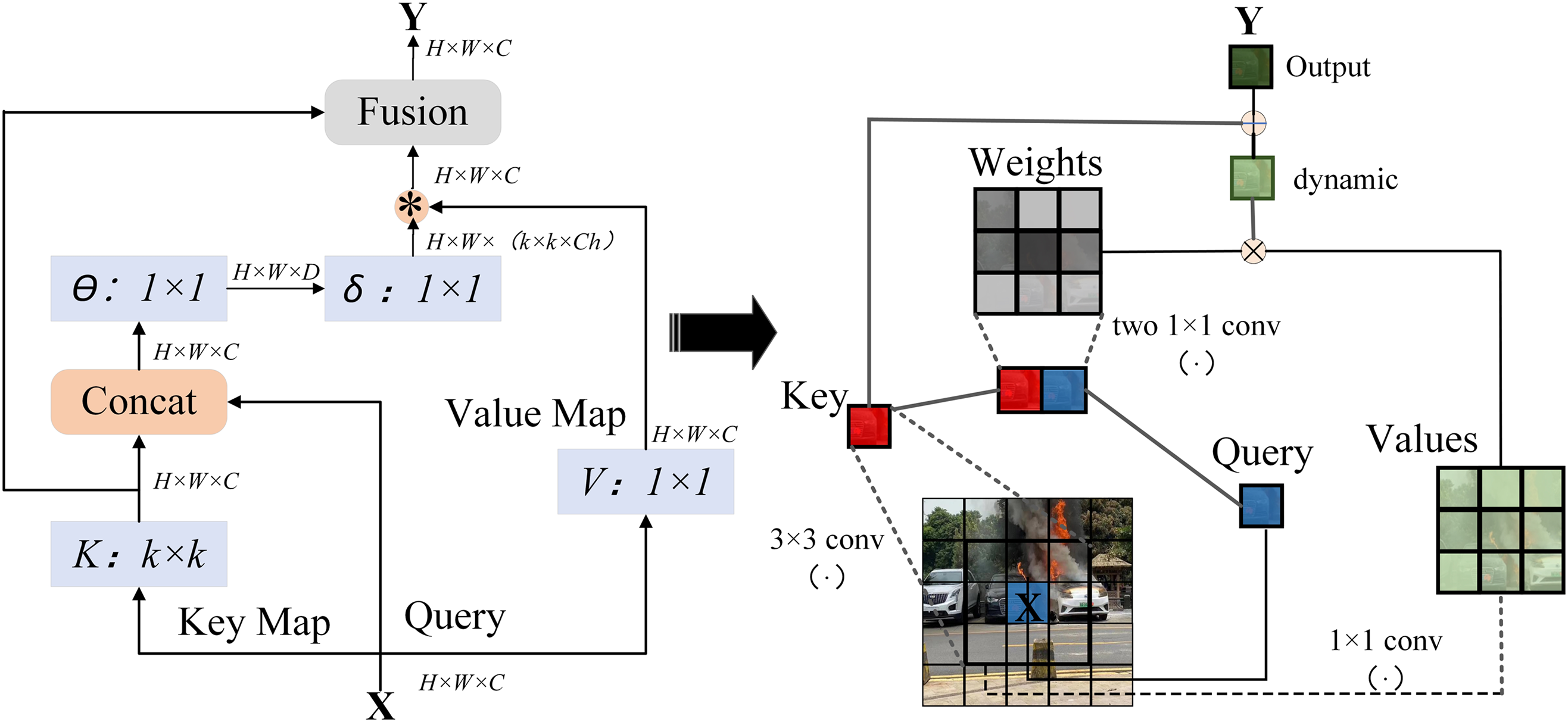

In outdoor parking lot scenarios, the shape and distribution of smoke are often not confined to specific local regions of an image but exhibit a diffuse and random nature. Given the complex environmental factors in such settings, including lighting variations and vehicle occlusions, traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), while adept at capturing local features, exhibit limitations in handling long-range dependencies. Contextual Transformer Networks (CoTNet) [36], with their ability to fuse contextual information, demonstrate superior performance in addressing these challenging scenarios. Considering the requirements of real-time detection, and to enhance contextual feature modeling while maintaining computational efficiency, we adopt CoTNet instead of more complex Transformer-based architectures such as DETR or Swin [37,38]. CoTNet combines the local modeling capability of convolutions with the global context modeling strength of attention mechanisms, enabling the network to better capture smoke and fire targets in complex backgrounds with minimal computational overhead.

In Fig. 4, given an input 2D feature map

where

Figure 4: The left image shows the contextual transformer block and the right image demonstrates operations on smoke images

In this process, the local relevance matrix

where

Finally, the two forms of contextual expression are fused through the attention mechanism to produce the CoT module’s output. CoTNet integrates the local perception capability of convolution with the global modeling strength of Transformers, enabling the adaptive fusion of contextual information across different spatial positions. Specifically, CoTNet introduces a context-aware attention mechanism that models dynamic pixel-level relationships while preserving local feature representations. This is particularly important for smoke detection, as smoke targets typically exhibit blurred edges and semi-transparent diffusion characteristics, making it difficult for conventional methods to accurately localize their boundaries. The context modeling capability of CoTNet effectively incorporates long-range discriminative information, allowing the model to enhance regional awareness and contour representation during the feature extraction stage.

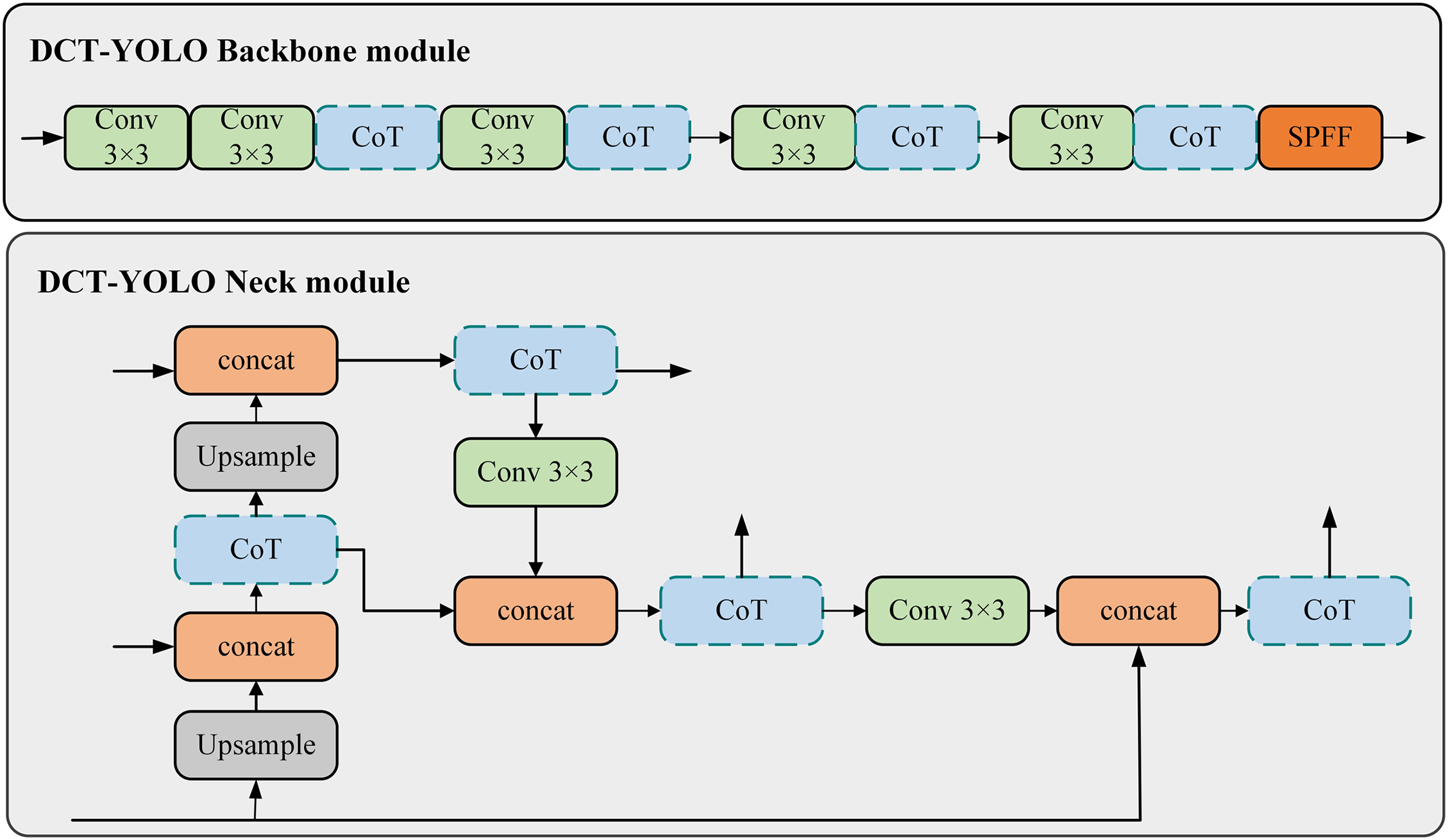

In conclusion, the CoT module demonstrates a clear advantage in capturing smoke dispersion, dynamic changes, and performance across different scenarios by effectively integrating local features with contextual information. In Fig. 5, we replaced the C2f module of YOLOv8n with the CoT module to improve its capability to handle complex environments.

Figure 5: Improved DCT-YOLO backbone and neck modules

To effectively evaluate the model, we will calculate the mean average precision (

where

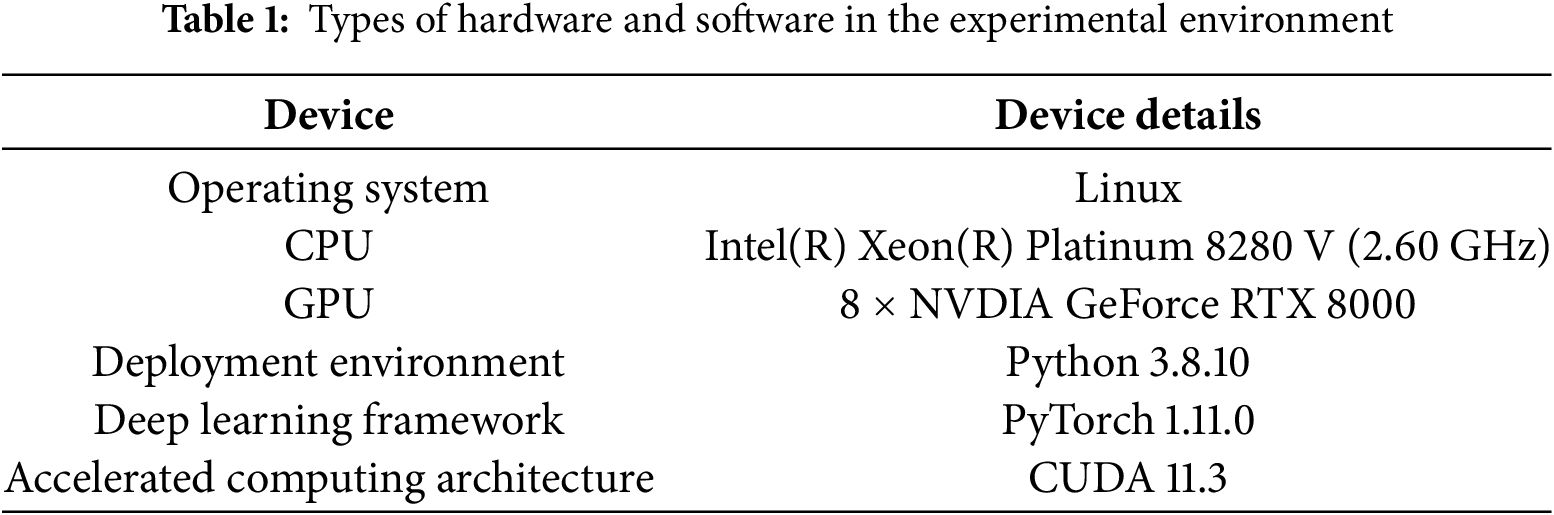

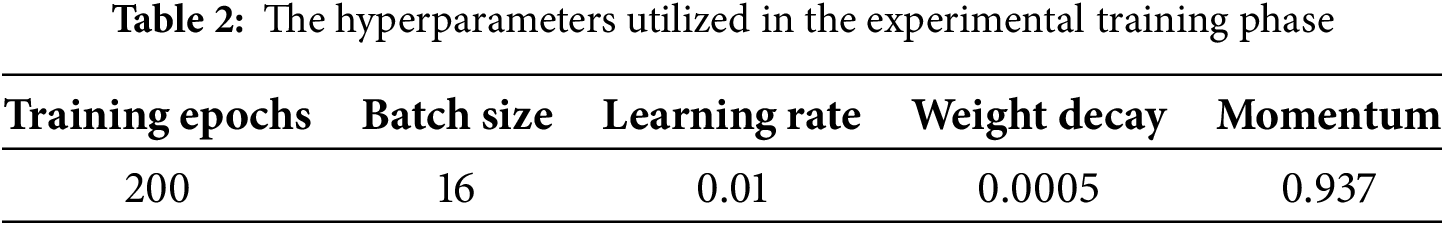

Table 1 presents the hardware configuration and software environment utilized in our experiments, which collectively provide robust computational power to efficiently support deep learning tasks. Additionally, all hyperparameters were meticulously tuned to ensure the reliability and validity of the experimental results. Detailed information on the hyperparameters can be found in Table 2.

3 Experiments Results and Analysis

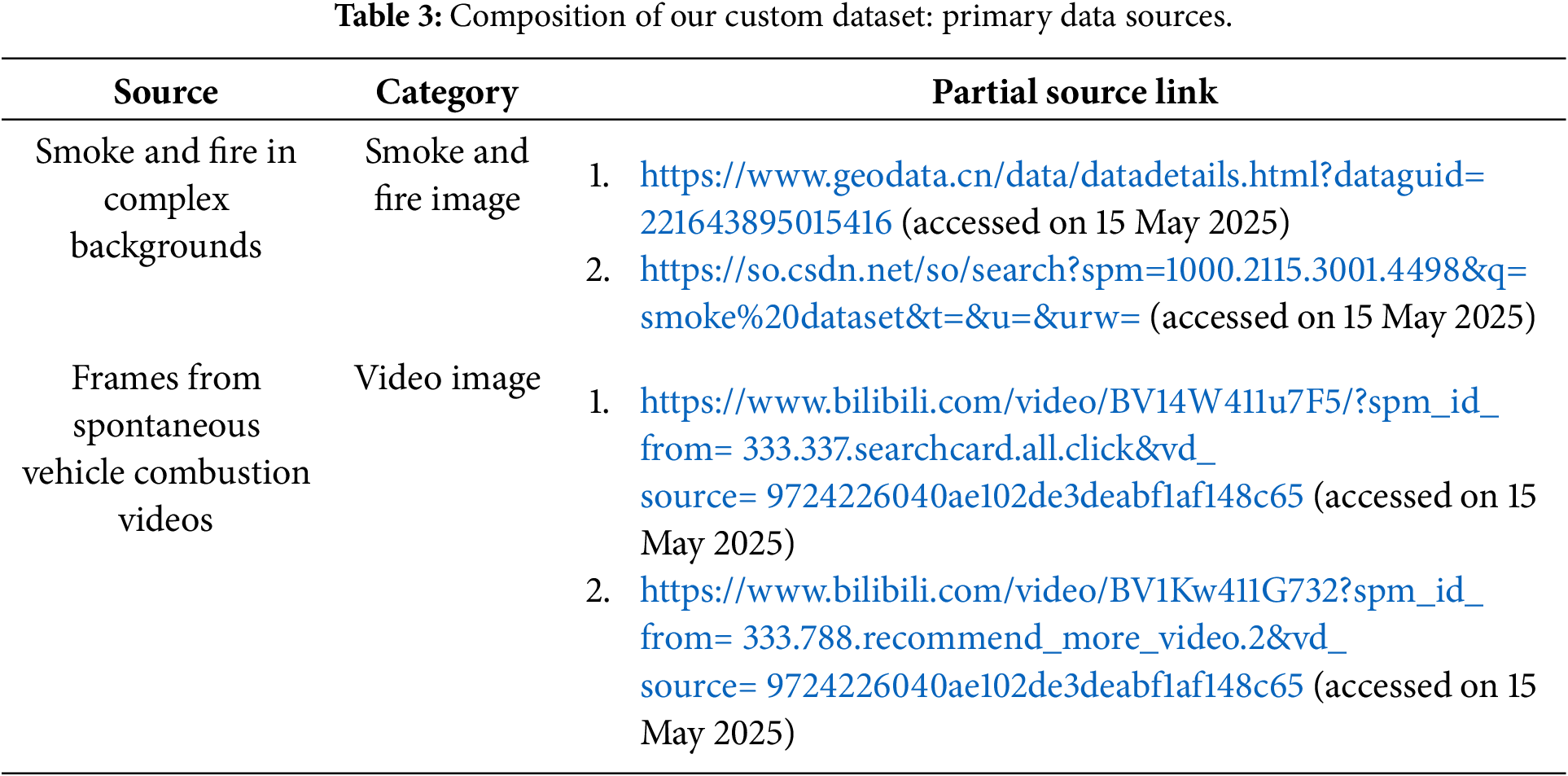

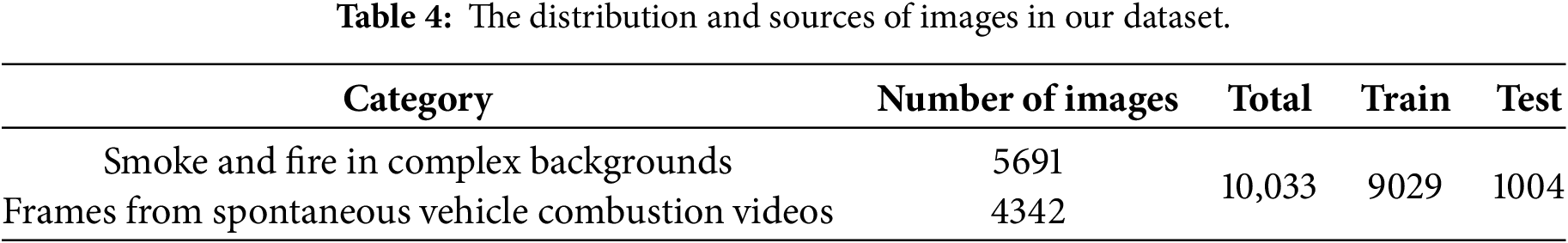

Smoke detection in outdoor parking lots is influenced by both meteorological conditions and the geographic background of the location. To enhance the accuracy of image recognition models and improve their generalization capabilities, it is crucial to develop a diverse and extensive dataset. As shown in Table 3, given the lack of publicly available datasets specifically designed for smoke and fire detection in parking lots, we constructed our dataset by collecting images from multiple online platforms, including Baidu, Douyin, Bilibili, Kuaishou, and Tencent Video. These sources provide diverse visual content covering various lighting conditions, weather scenarios, and viewing angles. To ensure data quality and relevance, we manually selected images that depict smoke or fire events in or around parking lots. After collection, all images underwent standard preprocessing procedures, including normalization to standardize pixel intensity distributions, resizing to a uniform resolution suitable for model input (640 × 640), and denoising to reduce compression artifacts and background noise. These steps help to enhance data consistency and improve model performance during training. A total of 5691 valid images are obtained, including instances of vehicle combustion, forest fires, and building fires. To ensure the model effectively learns the characteristics of outdoor parking lots, we first gather parking lot fire incident videos from online platforms. By extracting frames, selecting relevant instances, normalizing image sizes, and applying appropriate cropping techniques, we enrich the dataset with 4342 valid samples. In total, we compiled 10,033 images from public repositories and online resources. The images are subsequently divided into a training set and a test set at a ratio of 9:1, as illustrated in Table 4.

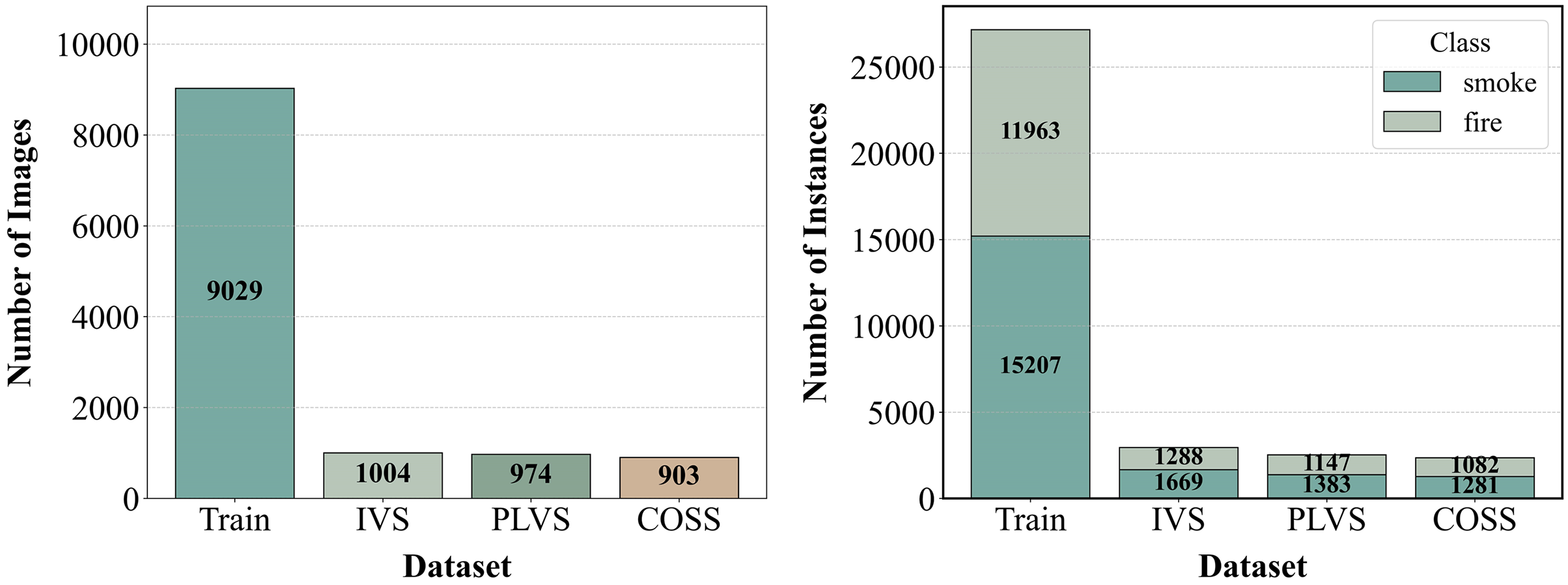

We evaluated the detection accuracy and generalization capability of the trained model in outdoor parking lot scenarios by creating two additional validation sets: the Parking Lot Validation Set (PLVS) and the Complex Outdoor Simulation Set (COSS). The first validation set focuses specifically on parking lot environments, While the second validation set simulates complex outdoor conditions through data augmentation, including brightness shifts (±20%), contrast scaling ([0.8, 1.2]), saturation adjustment ([0.7, 1.3]), and Gaussian noise (σ = 0.05) applied to 30% of images. Detailed information regarding these three datasets is provided in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: The presentation of the dataset utilized in this experiment encompasses the training set, initial validation set (IVS), and the two additional validation sets, PLVS and COSS

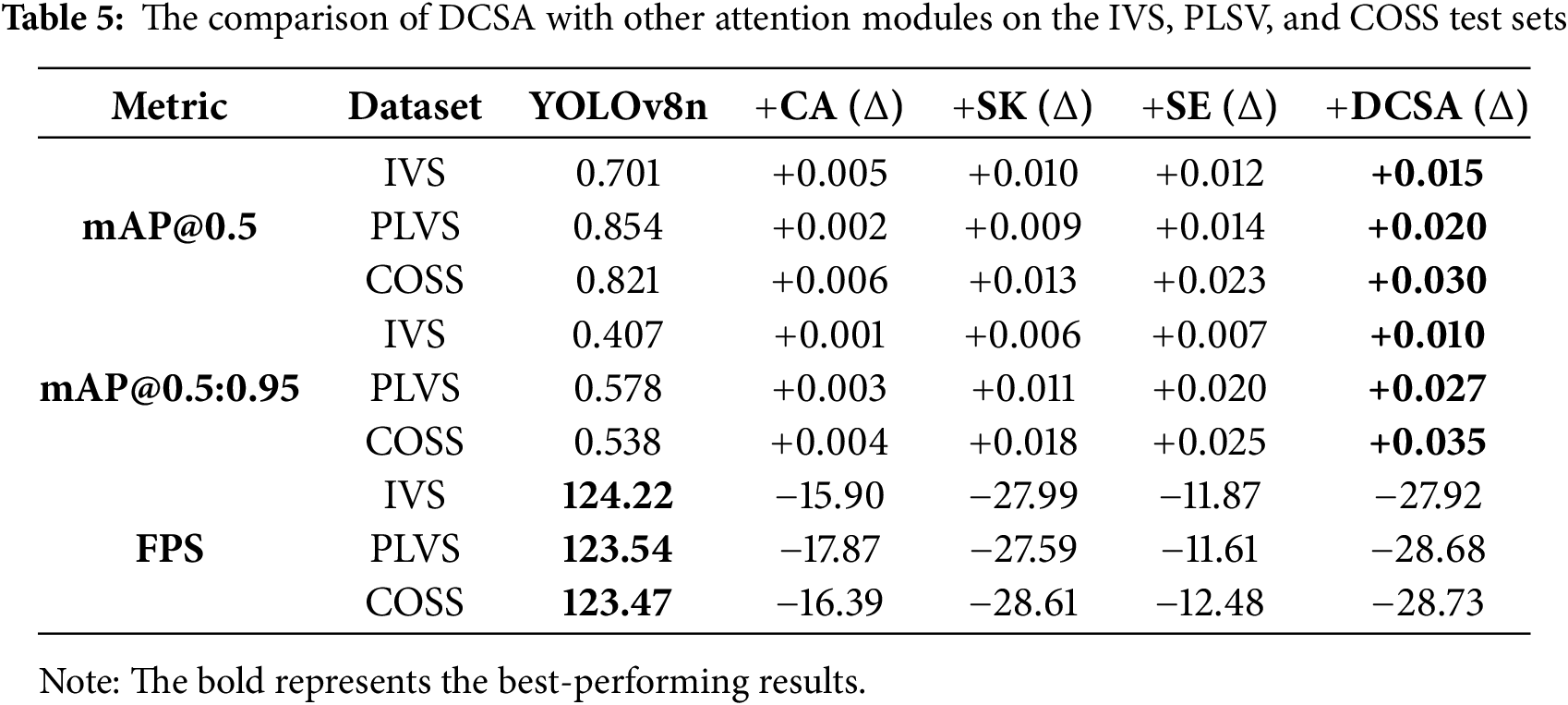

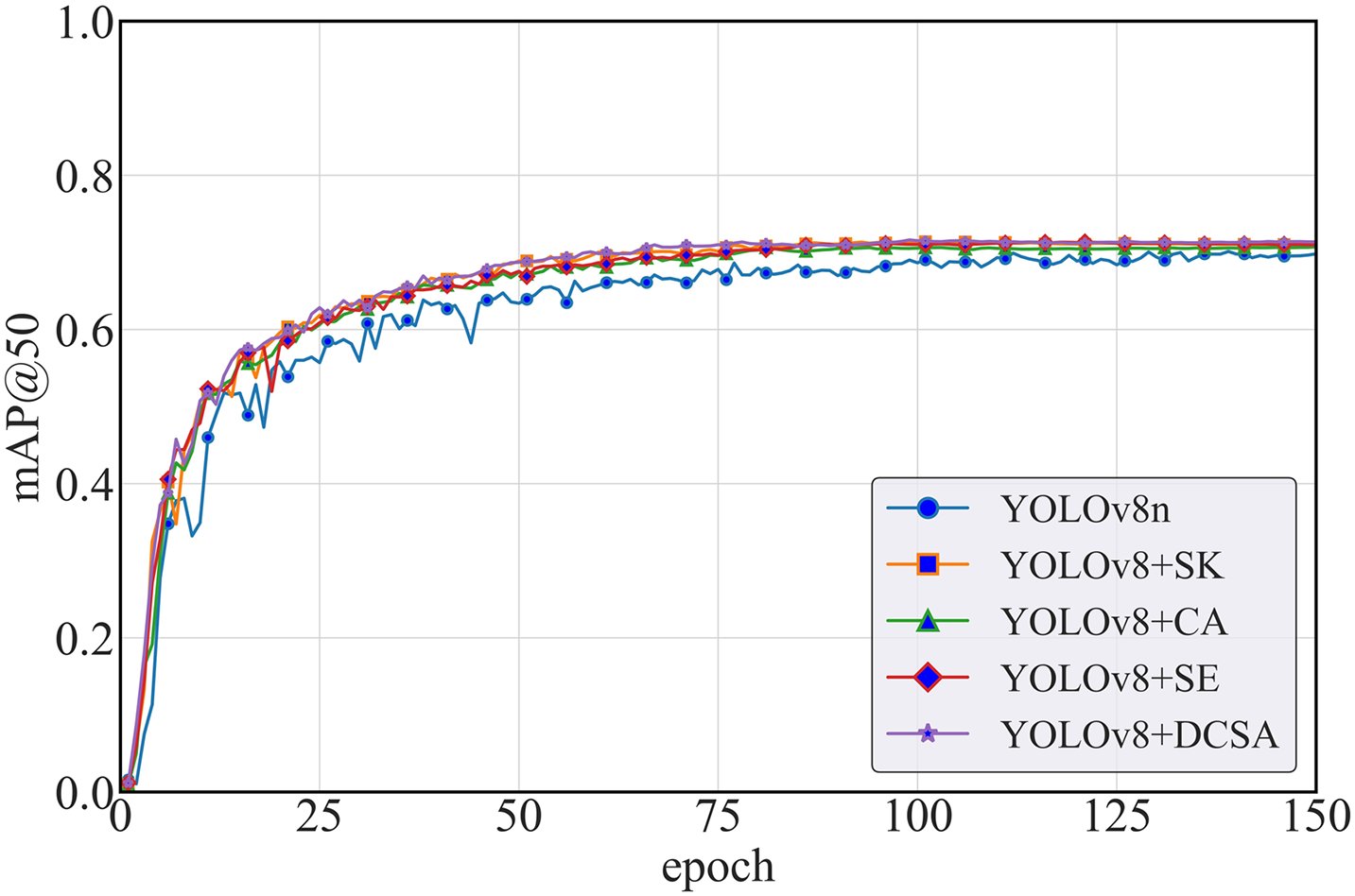

3.2 Validate the Effectiveness of DCSA

In this study, we assess the performance efficiency of the novel DCSA module by conducting comparative experiments. Specifically, we select the commonly used Coordinate Attention (CA) [35] Squeeze-and-Excitation Attention (SE) [34], and elective Kernel (SK) modules [33] as baselines to assess the performance improvements introduced by DCSA in smoke detection tasks. In the experiments, we maintain the same network architecture and training conditions, with the only modification being the replacement of the attention modules. The model performance is assessed using multiple evaluation metrics, as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 7. The DCSA architecture demonstrates accelerated convergence and superior detection accuracy during initial training phases, while maintaining enhanced stability throughout the optimization process, ultimately achieving a competitive mAP@50 score of 0.716.

Figure 7: Comparison results of DCSA with other attention mechanisms on the training set

In Table 5, the experimental results demonstrate that the integration of the DCSA module leads to an improvement of 0.015 in mAP@0.5 and 0.01 in mAP@0.5:0.95 on the Test dataset. On the PLVS dataset, mAP@0.5 increases by 0.02, while mAP@0.5:0.95 improves by approximately 0.027. Similarly, on the COSS dataset, mAP@0.5 exhibits an enhancement of approximately 0.030, and mAP@0.5:0.95 increases by around 0.035. Comparatively, all enhancement modules contribute to improved detection accuracy, yet the DCSA module demonstrates the best performance in terms of both precision and robustness. Although the integration of DCSA results in a reduction in FPS, making its efficiency slightly lower than that of the SE module, real-world testing confirms that its real-time performance fully meets the requirements for smoke detection in outdoor parking lots.

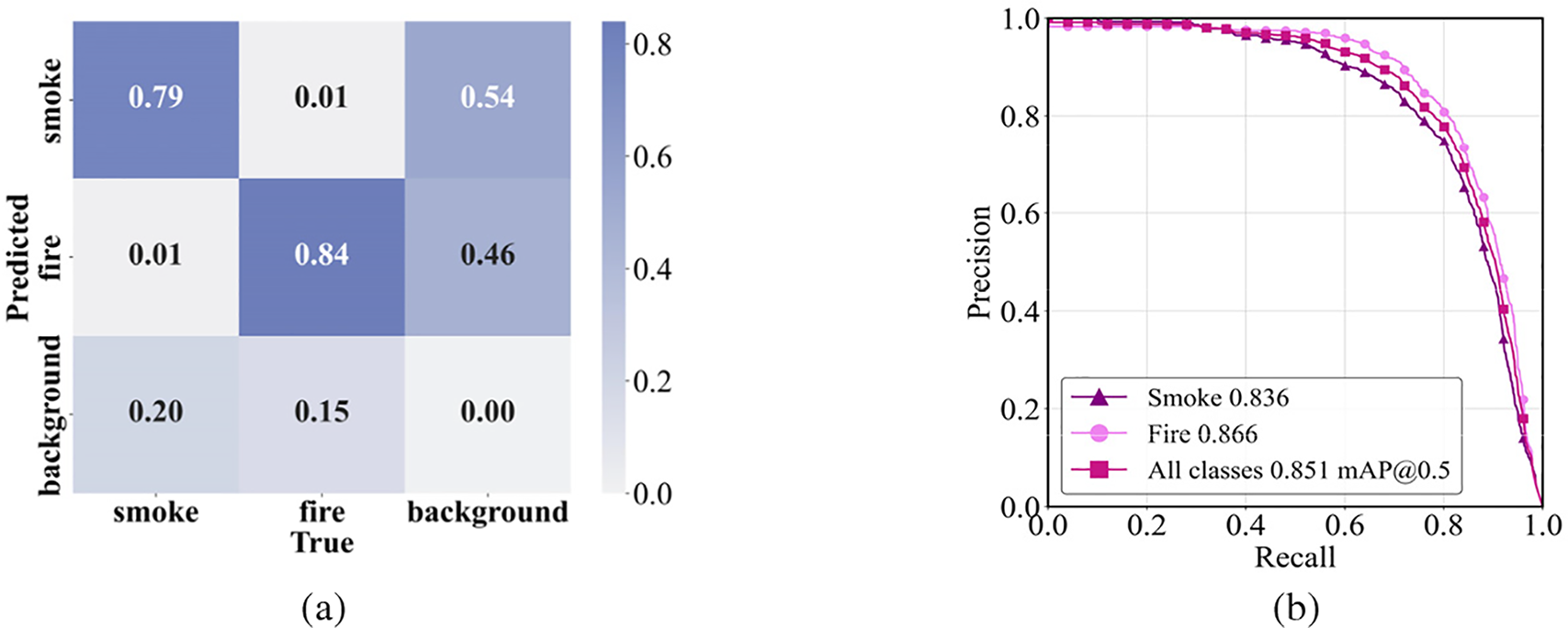

Fig. 8 presents the Precision-Recall (PR) curve and confusion matrix of the improved model trained on our custom dataset. Specifically, the confusion matrix indicates that the correct classification rates for smoke and fire are 79% and 84%, respectively. Furthermore, the Precision-Recall (PR) curve further reveals that these variations across different thresholds reveal key characteristics of our model. High recall and precision at low thresholds indicate strong sensitivity to subtle smoke and fire features, making the model suitable for early detection. As thresholds increase, precision remains stable while recall gradually decreases, reflecting the model’s robustness and ability to suppress false positives without severely affecting accuracy. This consistent behavior highlights the model’s stability, sensitivity, and generalization ability, which are essential in real-world smoke and fire detection tasks. Overall, the mean Average Precision (mAP@0.5) is 0.851, further confirming the outstanding performance of the DCT-YOLO model (our improved model) in the smoke detection task.

Figure 8: Illustration of the trained model's performance: (a) confusion matrix and (b) precision-recall (PR) curve.

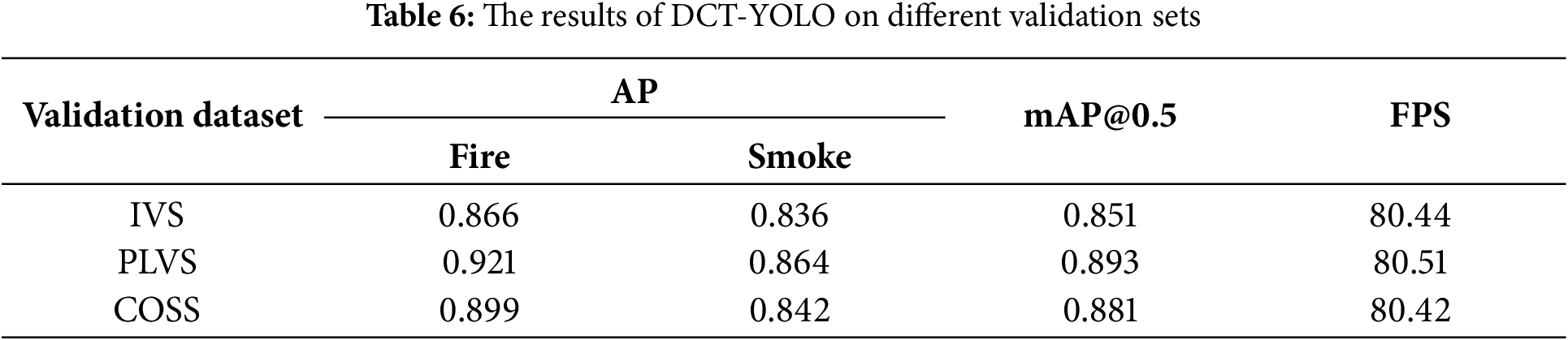

To validate the accuracy and robustness of the model in real-world applications, we introduce two distinct validation datasets: PLSV, which consists entirely of images depicting car fire incidents, and COSS, a dataset simulating complex outdoor environments through image processing techniques. As shown in Table 6, the test results on both datasets demonstrate that the model exhibits high accuracy in the specific application scenario and is minimally affected by complex environments, indicating strong adaptability.

Fig. 9 illustrates the accuracy of detection achieved by the YOLOv8n model compared to the improved DCT-YOLO model. The results show that the enhanced model significantly improves the accuracy of smoke prediction areas, capturing the boundaries and shapes of smoke with greater precision while effectively reducing errors in both overestimation and underestimation. This indicates that the optimized DCT-YOLO model demonstrates a more robust performance in smoke detection tasks, particularly in complex environments, showcasing enhanced detection capabilities and adaptability.

Figure 9: Visualization results of the YOLOv8n model (left) and the improved DCT-YOLO model (right)

3.4 Results and Analysis of Ablation Experiments

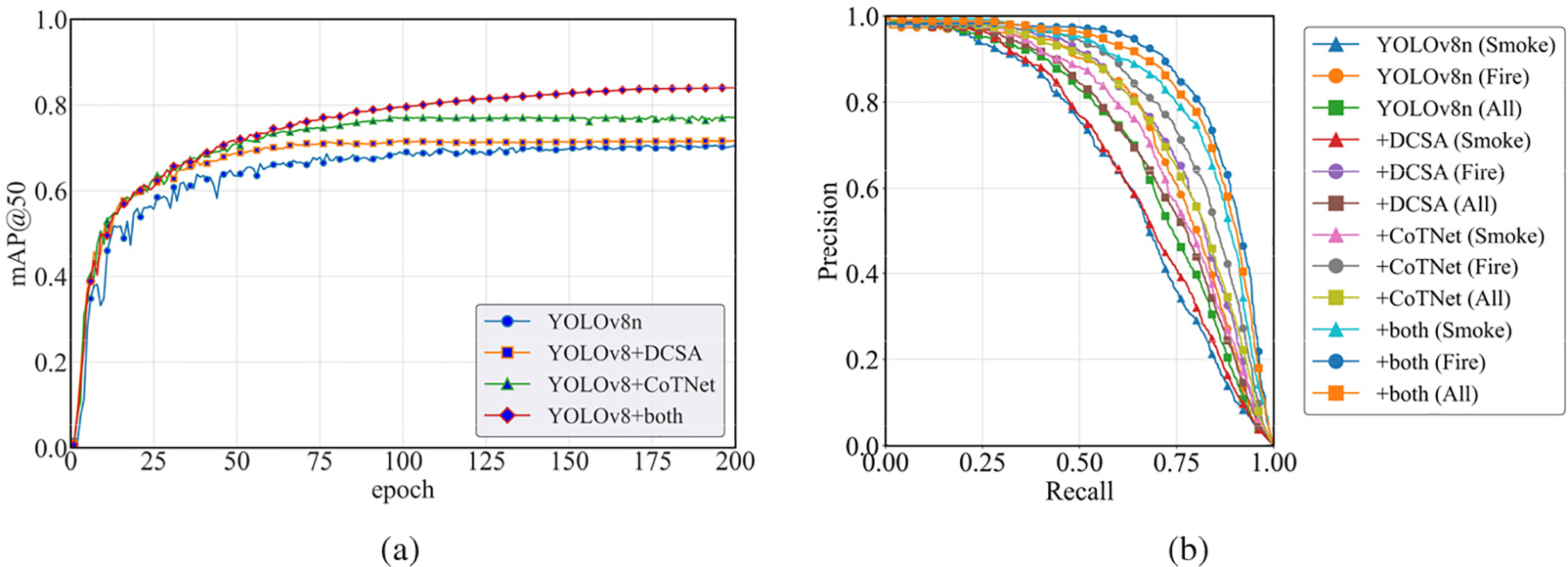

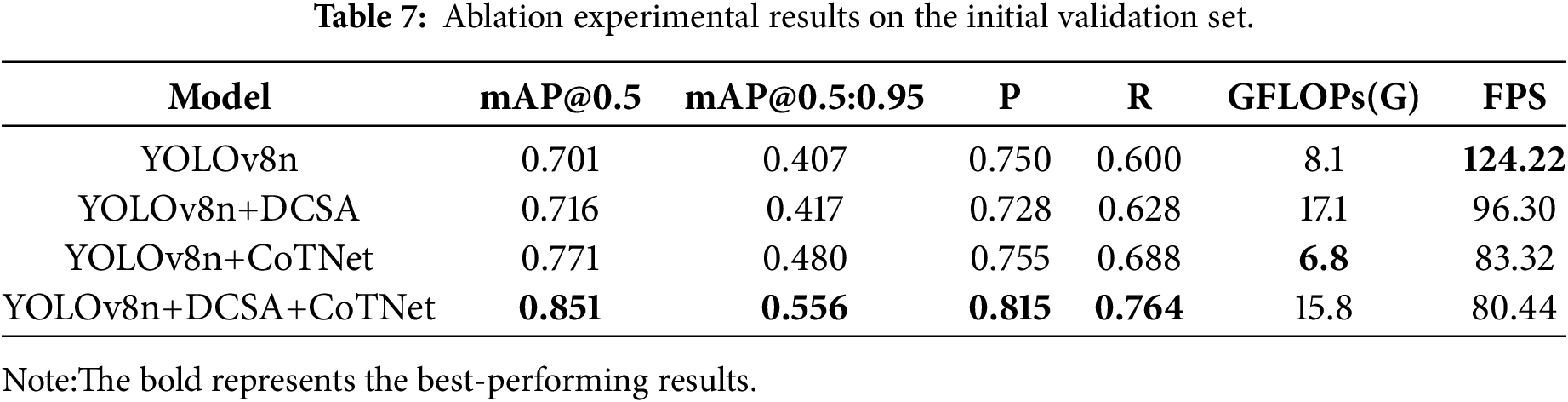

To assess how DCSA and CoTNet contribute to the performance of our proposed model, we carried out ablation studies using the YOLOv8 framework on our custom dataset. Fig. 10 demonstrates the enhancing effect of each improvement on the model’s detection performance, indicating that these improvement strategies have a significant impact on optimizing the model’s overall effectiveness.

Figure 10: Comparative analysis of the effectiveness of improved modules based on ablation experiments. (a) illustrates the trend of mAP (mean Average Precision) across training epochs, while (b) presents the comparative results of the PR (Precision-Recall) curves

In Table 7, the bold entries indicate the results with the highest performance. As shown, the DCT-YOLO model, which integrates both DCSA and CoTNet modules, achieves the highest overall performance. Notably, after incorporating DCSA, the mAP@0.5 increased from 0.701 to 0.716, precision rose from 0.750 to 0.728, and recall improved from 0.600 to 0.628, indicating DCSA’s contribution to enhancing detection stability. With the addition of CoTNet, mAP@0.5 further increased to 0.771, precision reached 0.755, and recall rose to 0.688, suggesting that CoTNet strengthens the model’s robustness and accuracy. When both DCSA and CoTNet were integrated, mAP@0.5 reached 0.851, precision improved to 0.815, and recall increased to 0.764, demonstrating their synergistic effect in significantly boosting both detection accuracy and coverage.

Although the modified model introduces an increase in computational complexity, the performance improvements are substantial, demonstrating the synergistic effect of combining DCSA and CoTNet. Compared to the baseline YOLOv8 model, mAP@0.5 is improved by 15.0%. This highlights that despite the additional computational overhead, the proposed enhancements significantly boost the model’s accuracy, validating the efficacy of our approach.

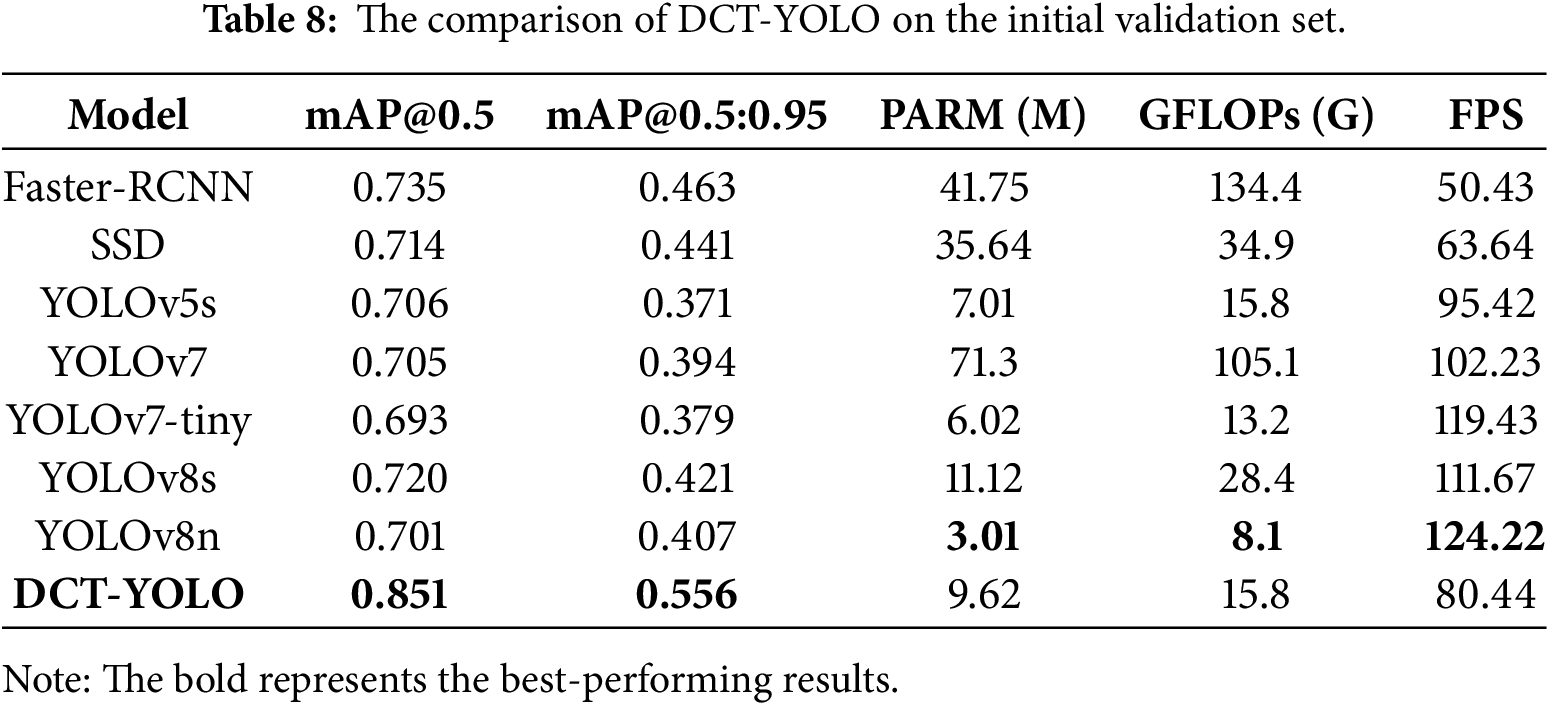

To demonstrate the advantages and effectiveness of the proposed enhanced algorithm, we conducted a comparative evaluation under identical experimental conditions and using the same dataset against various YOLO series algorithms, Faster-RCNN [20], and SSD [41]. YOLOv5s employs the CSPNet architecture, which significantly decreases the transmission of redundant gradient information and enhances the generalization capability of the network. This is particularly beneficial for detecting subtle and edge-blurred targets like smoke, as it helps minimize false positives. YOLOv7 [42], utilizing the ELAN structure, enhances feature reuse, enabling it to better capture multi-scale features of smoke, which is especially useful in scenarios where the smoke exhibits a large dispersion range or complex morphological variations.

As shown in Table 8, DCT-YOLO outperforms other models across various metrics, particularly in the key indicators mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, achieving 0.851 and 0.556, respectively, which are significantly higher than the other models. Compared to YOLOv5s, YOLOv7, YOLOv7-tiny, and YOLOv8s, DCT-YOLO shows improvements of 14.5%, 14.6%, 15.8%, and 13.1% in mAP@0.5, demonstrating a substantial enhancement in detection accuracy. In addition, compared to the baseline model YOLOv8n, although DCT-YOLO introduces an additional 6.61M parameters and increases the complexity by 7.7G, it achieves a 15.0% and 14.9% improvement in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, respectively. More importantly, our model meets the real-time requirements while maintaining high accuracy. This indicates that the additional computational overhead is justified, as the proposed model delivers a remarkable and valuable improvement in accuracy. These results further demonstrate the effectiveness of the modified architecture in smoke detection tasks.

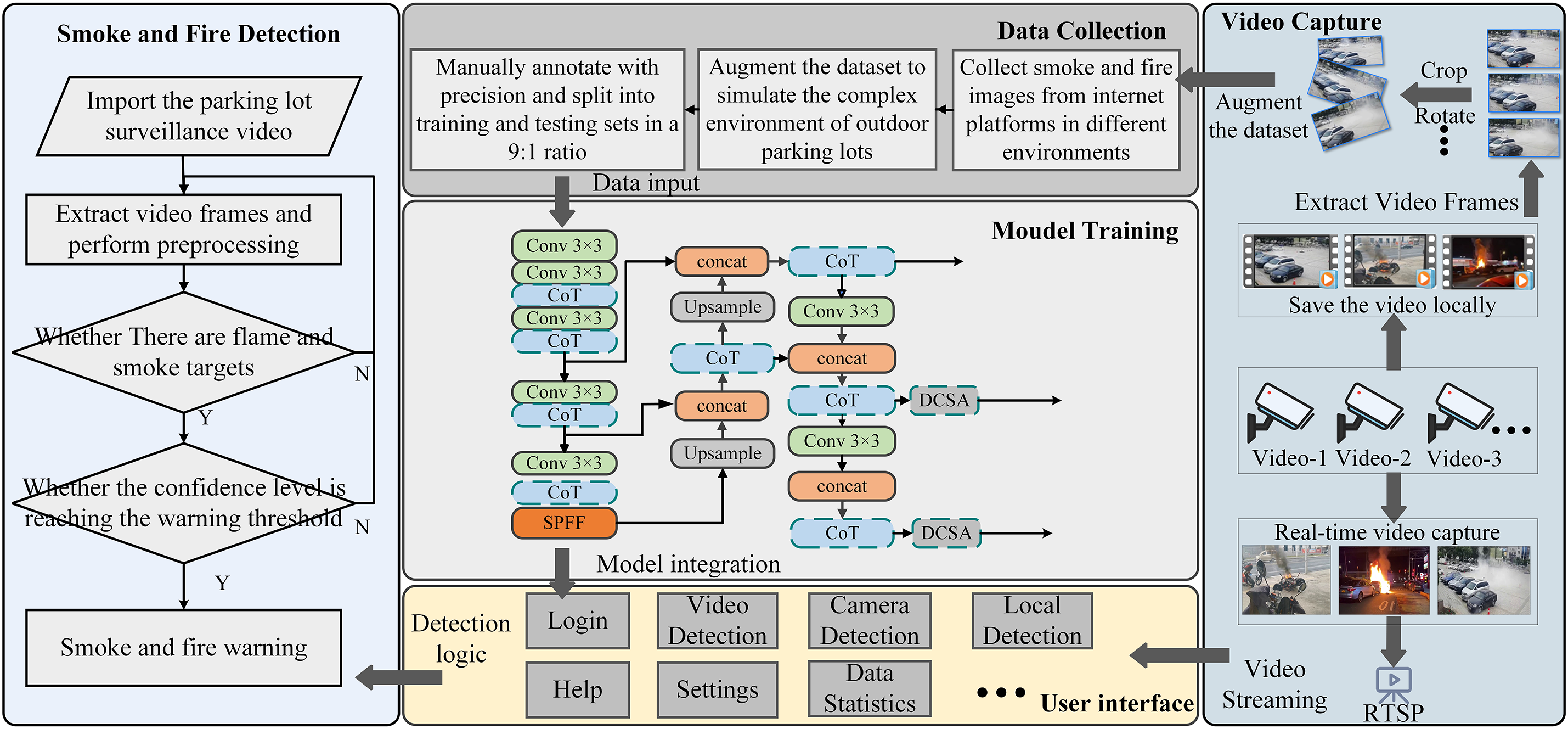

To implement the model in a real-world scenario, we develop an outdoor parking lot smoke detection system based on PyQt5, integrating our innovative, enhanced model. The system architecture is illustrated in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Outdoor parking lot system architecture

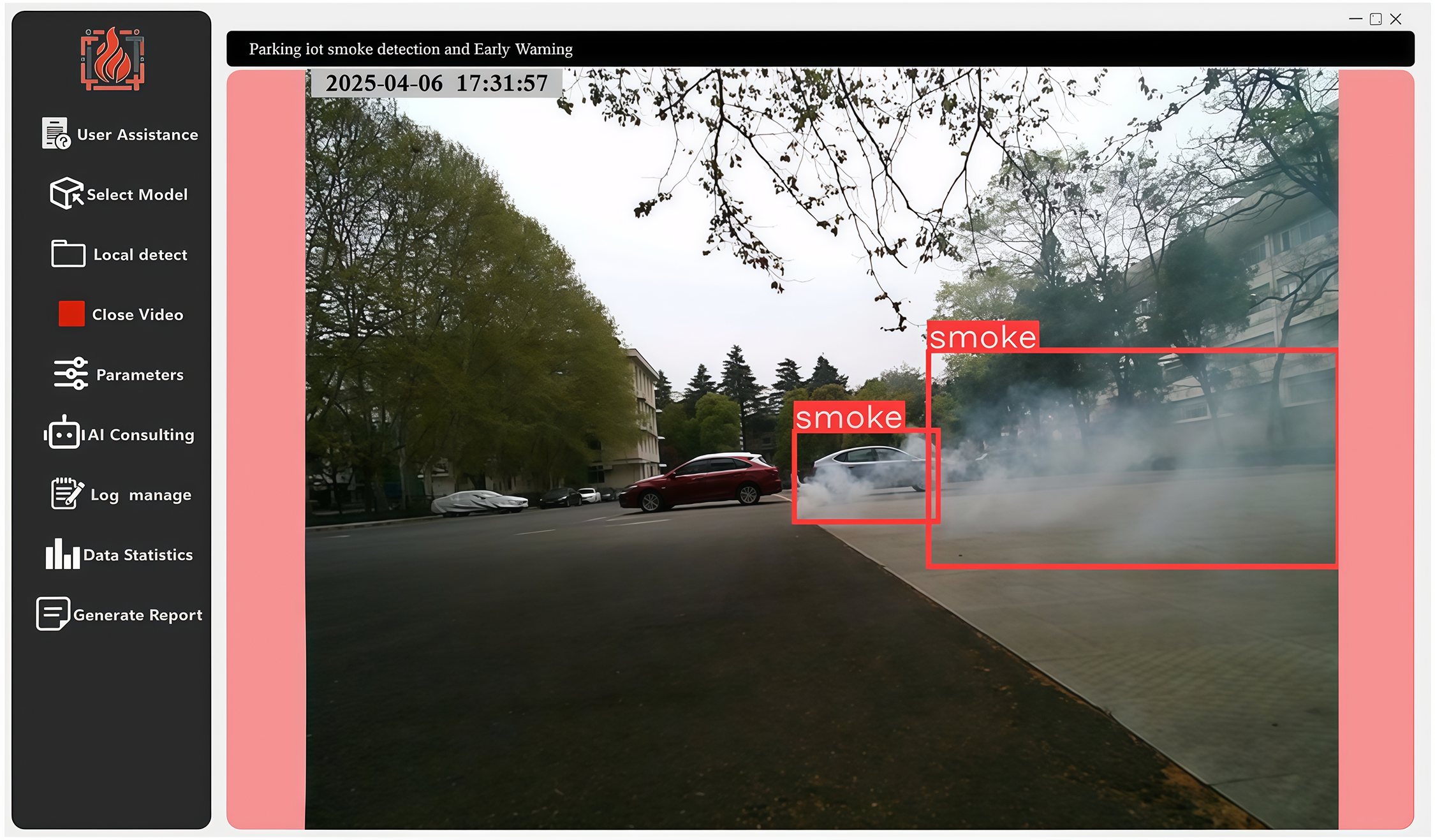

The first step involved data collection and annotation, where smoke and fire targets were manually labeled, and the dataset was then split into training and testing sets. Furthermore, to enhance the diversity of the dataset, we acquired additional smoke and fire images from various online platforms. Subsequently, the collected data was used to train our improved model. After training, the optimized model was integrated into the user interface. The system is capable of extracting image frames from surveillance videos, detecting smoke or fire targets, and assessing their confidence levels. If the confidence exceeds a predefined threshold, an alert is triggered, enabling intelligent monitoring and real-time fire risk warnings for parking lots. More importantly, we stored the detected fire videos locally, providing more realistic training data for further model improvement. Fig. 12 illustrates the visualization interface of the outdoor parking lot smoke detection system based on PyQt5.

Figure 12: The outdoor parking lot smoke detection system, based on PyQt5, triggers a flashing alarm upon detecting smoke or fire

The system supports both local video import and real-time monitoring via camera, enabling prompt detection of smoke or fire events and proactive warning measures. Once smoke or fire is detected, the system highlights the affected area on the screen and triggers an alarm, aiding users in responding quickly. Additionally, the system offers customizable settings, allowing users to switch models and select direct camera connections to adapt to various monitoring scenarios. To facilitate post-event investigation of fire origins and occurrence times, the system offers exportable and viewable detection logs. Users can easily access detailed information on fire incidents, including occurrence time, detected areas, and corresponding image records, providing comprehensive data support for fire investigations. Additionally, to ensure high efficiency and real-time performance in practical applications, we specifically focused on the system’s execution efficiency. By optimizing the model and hardware configuration, our system achieved 35 frames per second (FPS) during testing, which meets the demand for rapid response. This corresponds to an average processing time of approximately 28.6 ms per frame, indicating the system’s ability to perform real-time detection with low latency. This performance allows the system to operate stably and provide effective alerts even in environments with high real-time requirements.

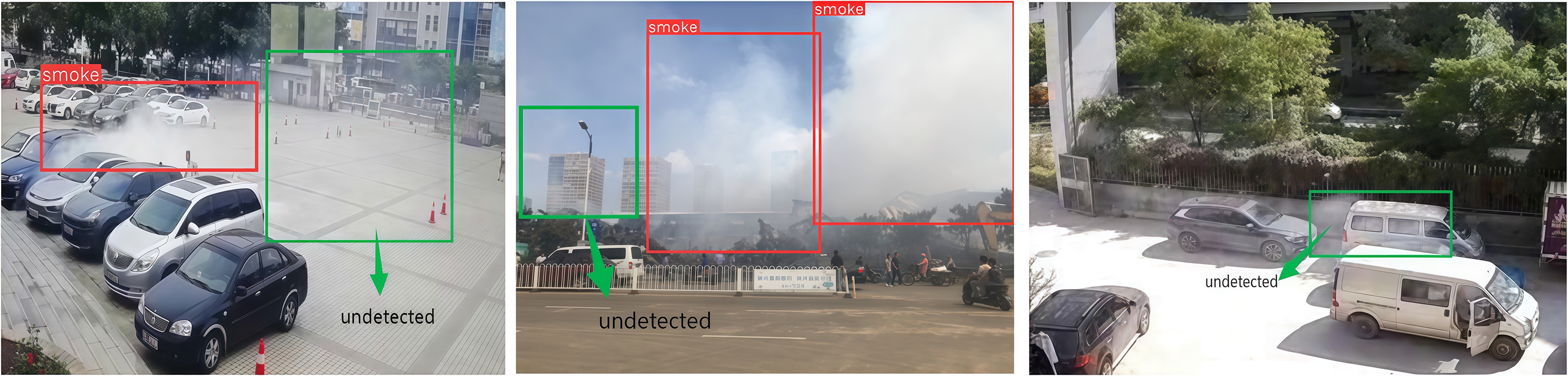

Despite the significant potential demonstrated by the DCT-YOLO model in smoke detection tasks in outdoor parking lots, some areas require further improvement. As illustrated in Fig. 13, our model exhibits high prediction accuracy for clearly visible smoke regions; However, the model exhibits certain limitations in specific scenarios, particularly during the initial diffusion stage of smoke formation. In this phase, the smoke often appears light in color and, when highly similar to the background, it compromises the model’s ability to accurately distinguish smoke regions, resulting in the omission of some smoke targets. This issue indicates that the model’s capability to detect light-colored and thin smoke under varying illumination and background similarity conditions requires further improvement.

Figure 13: The visualization results of missed detections by DCT-YOLO. The improved DCT-YOLO model (right). The green bounding boxes indicate the undetected targets

We examined the limitations of the DCT-YOLO model in smoke detection tasks from multiple perspectives and identified several key contributing factors: First, when processing images with low contrast and saturation, the DCT-YOLO model shows limitations in feature extraction, making it difficult to capture the subtle diffusion characteristics of early-stage smoke that closely resembles the background, leading to missed detections. Second, the training dataset lacks sufficient samples of early smoke diffusion under highly similar background conditions, which constrains the model’s generalization capability in such scenarios. Consequently, our future research will focus on the following pivotal areas:

• Create data augmentation techniques specifically designed for intricate outdoor parking environments to improve detection speed and precision.

• Collect early-stage smoke features to enrich the dataset, thereby improving the model’s generalization capability.

• Design a model architecture that is better suited for detecting irregular smoke patterns to enhance detection performance for atypical smoke formations.

Explore lightweight model design for real-time deployment in resource-constrained environments such as edge devices and embedded systems.

In this study, we innovatively designed a DCSA attention mechanism and combined it with CoTNet to propose an advanced smoke detection algorithm for outdoor parking lots, named DCT-YOLO. This algorithm represents an enhancement derived from the YOLOv8 framework, where the incorporation of the DCSA module substantially improves detection precision, while the CoTNet module facilitates the development of a lightweight and efficient model that better accommodates the complexity and irregularity of smoke. Through experiments conducted on our custom dataset and in contrast with widely used object detection frameworks, DCT-YOLO has demonstrated superior detection accuracy, indicating significant application potential. Nevertheless, there is still room for further enhancement in the accuracy of the model, especially in effectively capturing the subtle features of early-stage smoke. In our future research, we will focus on optimizing the model’s complexity in terms of computation, expanding and enhancing the scale and quality of the dataset to further improve the model’s predictive accuracy and generalization capability. Our goal is to contribute to fire warning systems in outdoor parking lots, safeguarding public life and property.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Major Scientific and Technological Special Project of Guizhou Province ([2024]014).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: research conception and design: Zhenyong Zhang; data collection: Gang He, Zhuoyan Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Gang He, Mufeng Wang, Xingcheng Yang; draft manuscript preparation: Gang He, Zhuoyan Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the sensitive nature of the research data, participants of this study did not consent to public data sharing; therefore, supporting data are not publicly available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Parmar J, Das P, Dave SM. Study on demand and characteristics of parking system in urban areas: a review. J Traffic Transp Eng Engl Ed. 2020;7(1):111–24. doi:10.1016/j.jtte.2019.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Miechówka B, Węgrzyński W. Systematic literature review on passenger car fire experiments for car park safety design. Fire Technol. 2025;61(4):2651–88. doi:10.1007/s10694-025-01701-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kang S, Kwon M, Choi JY, Choi S. Full-scale fire testing to assess the risk of battery electric vehicle fires in underground car parks. Fire Technol. 2025;2025(2):1–31. doi:10.1007/s10694-024-01694-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Boehmer HR, Klassen MS, Olenick SM. Fire hazard analysis of modern vehicles in parking facilities. Fire Technol. 2021;57(5):2097–127. doi:10.1007/s10694-021-01113-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sun P, Bisschop R, Niu H, Huang X. A review of battery fires in electric vehicles. Fire Technol. 2020;56(4):1361–410. doi:10.1007/s10694-019-00944-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kim B, Lee J. A video-based fire detection using deep learning models. Appl Sci. 2019;9(14):2862. doi:10.3390/app9142862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khan F, Xu Z, Sun J, Khan FM, Ahmed A, Zhao Y. Recent advances in sensors for fire detection. Sensors. 2022;22(9):3310. doi:10.3390/s22093310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chen SJ, Hovde DC, Peterson KA, Marshall AW. Fire detection using smoke and gas sensors. Fire Saf J. 2007;42(8):507–15. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2007.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fonollosa J, Solórzano A, Marco S. Chemical sensor systems and associated algorithms for fire detection: a review. Sensors. 2018;18(2):553. doi:10.3390/s18020553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Muhammad K, Khan S, Elhoseny M, Hassan Ahmed S, Wook Baik S. Efficient fire detection for uncertain surveillance environment. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2019;15(5):3113–22. doi:10.1109/tii.2019.2897594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jiang X, Hu C, Fan Z, Zhang P. Research on flame detection method by fusion feature and sparse representation classification. Int J Comput Commun Eng. 2015;5(4):238–45. doi:10.17706/ijcce.2016.5.4.238-245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gubbi J, Marusic S, Palaniswami M. Smoke detection in video using wavelets and support vector machines. Fire Saf J. 2009;44(8):1110–5. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2009.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Medaiyese OO, Ezuma M, Lauf AP, Guvenc I. Wavelet transform analytics for RF-based UAV detection and identification system using machine learning. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2022;82(8–10):101569. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2022.101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kwak JY, Ko BC, Nam JY. Forest smoke detection using CCD camera and spatial-temporal variation of smoke visual patterns. In: Proceedings of the 2011 Eighth International Conference Computer Graphics, Imaging and Visualization; 2011 Aug 17–19; Singapore. doi:10.1109/CGIV.2011.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li C, Yang B, Ding H, Shi H, Jiang X, Sun J. Real-time video-based smoke detection with high accuracy and efficiency. Fire Saf J. 2020;117(7):103184. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2020.103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Islam MR, Amiruzzaman M, Nasim S, Shin J. Smoke object segmentation and the dynamic growth feature model for video-based smoke detection systems. Symmetry. 2020;12(7):1075. doi:10.3390/sym12071075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yang J, Chen F, Zhang W. Visual-based smoke detection using support vector machine. In: 2008 Fourth International Conference on Natural Computation; 2008 Oct 18–20; Jinan, China. doi:10.1109/ICNC.2008.219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ba R, Chen C, Yuan J, Song W, Lo S. SmokeNet: satellite smoke scene detection using convolutional neural network with spatial and channel-wise attention. Remote Sens. 2019;11(14):1702. doi:10.3390/rs11141702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gu K, Xia Z, Qiao J, Lin W. Deep dual-channel neural network for image-based smoke detection. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2020;22(2):311–23. doi:10.1109/TMM.2019.2929009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 June 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Redmon J, Ali F. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2017; 2017 Nov 9; Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

23. Redmon J. Yolov3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

24. Chen X, Xue Y, Hou Q, Fu Y, Zhu Y. RepVGG-YOLOv7: a modified YOLOv7 for fire smoke detection. Fire. 2023;6(10):383. doi:10.3390/fire6100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang Y, Piao Y, Wang H, Zhang H, Li B. An improved forest smoke detection model based on YOLOv8. Forests. 2024;15(3):409. doi:10.3390/f15030409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mamadaliev D, Touko PLM, Kim JH, Kim SC. ESFD-YOLOv8n: early smoke and fire detection method based on an improved YOLOv8n model. Fire. 2024;7(9):303. doi:10.3390/fire7090303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Saydirasulovich SN, Mukhiddinov M, Djuraev O, Abdusalomov A, Cho YI. An improved wildfire smoke detection based on YOLOv8 and UAV images. Sensors. 2023;23(20):8374. doi:10.3390/s23208374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yao J, Lei J, Zhou J, Liu C. FG-YOLO: an improved YOLOv8 algorithm for real-time fire and smoke detection. Signal Image Video Process. 2025;19(5):346. doi:10.1007/s11760-025-03894-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li G, Cheng P, Li Y, Huang Y. Lightweight wildfire smoke monitoring algorithm based on unmanned aerial vehicle vision. Signal Image Video Process. 2024;18(10):7079–91. doi:10.1007/s11760-024-03377-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen J, Han H, Liu M, Su P, Chen X. IFS-DETR: a real-time industrial fire smoke detection algorithm based on an end-to-end structured network. Measurement. 2025;241(3):115660. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bakirci M. Utilizing YOLOv8 for enhanced traffic monitoring in intelligent transportation systems (ITS) applications. Digit Signal Process. 2024;152(2):104594. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2024.104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bakirci M. Enhancing vehicle detection in intelligent transportation systems via autonomous UAV platform and YOLOv8 integration. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164(5):112015. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li X, Wang W, Hu X, Yang J. Selective kernel networks. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hu J, Shen L, Albanie S, Sun G, Enhua W. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. arXiv:1709.01507. 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1709.01507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hou QB, Zhou D, Feng JS. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. arXiv:2103.02907. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2103.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li Y, Yao T, Pan Y, Mei T. Contextual transformer networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(2):1489–500. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3164083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Carion N, Massa F, Synnaeve G, Usunier N, Kirillov A, Zagoruyko S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Everingham M, Van Gool L, Williams CKI, Winn J, Zisserman A. The pascal visual object classes (VOC) challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2010;88(2):303–38. doi:10.1007/s11263-009-0275-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sokolova M, Lapalme G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf Process Manag. 2009;45(4):427–37. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2009.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed SE, Fu CY. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools