Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Decoupling-Driven Cooperative Pursuit for Multi-UAV Systems: A Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Policy Optimization Approach

1 School of Automation, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

2 National Key Laboratory of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Technology, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, 710072, China

* Corresponding Author: Chengfu Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1339-1363. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067117

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 10 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

This paper proposes a Multi-Agent Attention Proximal Policy Optimization (MA2PPO) algorithm aiming at the problems such as credit assignment, low collaboration efficiency and weak strategy generalization ability existing in the cooperative pursuit tasks of multiple unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Traditional algorithms often fail to effectively identify critical cooperative relationships in such tasks, leading to low capture efficiency and a significant decline in performance when the scale expands. To tackle these issues, based on the proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm, MA2PPO adopts the centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) framework and introduces a dynamic decoupling mechanism, that is, sharing the multi-head attention (MHA) mechanism for critics during centralized training to solve the credit assignment problem. This method enables the pursuers to identify highly correlated interactions with their teammates, effectively eliminate irrelevant and weakly relevant interactions, and decompose large-scale cooperation problems into decoupled sub-problems, thereby enhancing the collaborative efficiency and policy stability among multiple agents. Furthermore, a reward function has been devised to facilitate the pursuers to encircle the escapee by combining a formation reward with a distance reward, which incentivizes UAVs to develop sophisticated cooperative pursuit strategies. Experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in achieving multi-UAV cooperative pursuit and inducing diverse cooperative pursuit behaviors among UAVs. Moreover, experiments on scalability have demonstrated that the algorithm is suitable for large-scale multi-UAV systems.Keywords

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) play a vital role in a variety of fields given their affordability, ease of deployment, high maneuverability, and capability to operate in harsh environments [1]. However, the limited detection range and payload capacity of a single UAV often hinder its ability to complete complex missions alone. Multi-UAV systems, with their flexibility, intelligence, autonomy, and robustness, have garnered significant research attention. Applications of multi-UAV systems include search and rescue (SAR) [2], security patrol systems [3], military reconnaissance [4], wireless communication support [5], medical delivery [6], and civilian agriculture [7].

In the emerging battlefield of the intelligent swarm era, the multi-UAV cooperative pursuit-evasion games represent one of the core applications of UAV cluster systems. Consider the following scenario where multiple UAVs are tasked with intercepting a rogue UAV that has entered restricted airspace. The evading UAV exhibits agile, non-cooperative behavior and dynamically adjusts its trajectory based on the positions of the pursuing UAVs. To achieve successful interception, the pursuers must coordinate their actions in real time under limited communication constraints and capture the intruder before it escapes the designated area. These games involve players with conflicting goals: the pursuer intends to catch the evader while the latter is attempting to avoid being caught as soon as possible [8]. We study a pursuit-evasion game involving cooperative pursuit by UAVs against an escapee. Nonetheless, the high degree of dynamism and uncertainty inherent in adversarial games presents a significant challenge for decision-makers in achieving an optimal solution. Furthermore, the kinematics of UAVs must meet speed and acceleration limits in realistic environments [9], which adds complexity to decision-making control for UAVs in pursuit-evasion games and requires further exploration.

In the field of differential games, several studies have been conducted on pursuit-evasion games. The first of these studies was carried out by Isaacs, who addressed the one-to-one robot pursuit-evasion problem by creating and solving partial differential equations [10]. Pursuit-evasion games are typically modeled using the Hamilton-Jacobi-Isaacs (HJI) equation, which is solved to determine the optimal policy of the tracker [11,12]. In [13], the multi-player pursuit-evasion (MPE) differential game is discussed, and an N-player nonzero-sum game framework is established to study the relationships among players. Nevertheless, these approaches face significant challenges in characterizing cooperation among multiple pursuers or evaders and in the computational complexity associated with solving HJI equations.

Intelligent optimization algorithms that offer novel ideas have also been employed to solve pursuit-evasion problems. Some researchers have proposed a decision-making method for the pursuers using a Voronoi diagram [14] and a fuzzy tree [15]. In [16], inspired by the hunting and foraging behaviors of group predators, the authors suggest a cooperative scheme in which the pursuers regulate the encirclement formed around the evader and continually shrink it until the evader is captured. But these methods are based on environmental models or expert knowledge and do not guarantee the optimality of decision-making.

Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) has proven to be an effective approach for solving multi-UAV pursuit games [17]. These games are represented as a decentralized partially observable Markov decision process (Dec-POMDP) in MARL [18], with training leveraging the widely used centralized training and decentralized execution (CTDE) framework. CTDE facilitates centralized training with access to global information, while agents make decisions based on local observations during execution, resulting in reduced training complexity and more efficient execution [19]. However, the possibility of “lazy agents” arises, where agents’ poor actions are rewarded due to the favorable actions of other agents when they learn independently from global rewards. This is the most common credit assignment problem in MARL [20]. Once agents fall into this trap, they may take profitable actions that result in locally optimal solutions but poor overall performance. Given the objective of training agents to maximize global rewards, addressing this issue is of utmost importance.

The methods for addressing credit assignment in MARL can be classified into two categories: implicit and explicit. An implicit credit assignment is a value-based approach, and some popular algorithms in this category include VDN [21], QMIX [22], and QTRAN [23]. These algorithms are designed to decompose the centralized value function into decentralized value functions in a reasonable manner. On the other hand, explicit assignment algorithms, such as COMA [24], are based on policy gradients and employ a counterfactual baseline to compare the global reward with the reward obtained when the agents’ actions are replaced by default actions. In [25], a meta-gradient algorithm is proposed to achieve credit assignment in fully cooperative environments by calculating the marginal contribution of each agent. Reference [26] improves the pursuit-evasion policies of UAVs by combining imitation learning. To tackle the multi-UAV pursuit-evasion problem, reference [27] proposes a spatiotemporally efficient detection network, while reference [28] introduces a crown-shaped bidirectional cooperative target prediction network tailored for multi-agent collaboration. However, these methods fail to consider the heterogeneity of information provided by different agents and treat all agents equally, leading to inefficient collaboration.

Recent studies have introduced the attention mechanism as a new idea for solving credit assignment problems in MARL. The multi-actor-attention-critic (MAAC) approach [29] shares an attention mechanism among critics of centralized computing, leading to more efficient and scalable learning. Another study [30] introduces a complete graph and a two-stage attention network to study multi-agent games. In addition, the authors of [31] propose a hierarchical graph attention network that models the hierarchical relationship among agents and uses two attention networks to represent the interaction at the individual and group levels. Reference [32] introduces a graph attention-based evaluation framework integrated with factorized normalizing flow algorithms. However, these methods only use the attention mechanism to extract various pieces of information and do not apply the attention further. We apply the attention allowing each agent to temporarily separate from teammates with low attention and work more closely with teammates who have high correlation interaction. Large-scale cooperative activities can be dynamically split into decoupled sub-problems in this fashion, enabling agents to collaborate more effectively.

The design of the reward function is the key to the success of real-time chasing games [33]. Pursuers that only learn inefficient capture strategies may fail to catch the faster escapee in the worst case. Previous work has proposed a decentralized multi-target tracking algorithm based on the maximum reciprocal reward to learn collaborative strategies [34], and constructed a potential-based individual reward function to accelerate policy learning [35]. Reference [36] develops a unique reward mechanism designed to enhance the generation of action sequences in UAVs operations. Nevertheless, they do not contemplate developing a reward function to direct the pursuers to form a formation swarm. To address this issue, we propose a novel reward function that includes a formation reward. This enables the pursuers to acquire intricate pursuit tactics such as interception and encirclement, thus effectively completing the pursuit assignment. Our approach enhances the effectiveness and dependability of multi-UAV cooperation in catching the faster escapee. Our main contributions include:

• We propose a Multi-Agent Attention Proximal Policy Optimization (MA2PPO) algorithm, which builds upon the foundations of proximal policy optimization (PPO) and CTDE. We design a centralized critic network and a decentralized actor network for each UAV to leverage global information during policy training while enabling each UAV to execute its decentralized policy using only its local observation after training. The MA2PPO algorithm enables efficient pursuit strategies for multi-UAV systems in highly dynamic pursuit-escape scenarios.

• We propose a dynamic decoupling to solve the cooperative multi-UAV credit assignment problem. It shares a multi-head attention (MHA) mechanism for critics in centralized training, which makes the pursuers select the relevant information from teammates in real time. Dynamic decoupling identifies highly correlated interactions in the pursuers and eliminates unnecessary and weakly correlated interactions with one another. This approach decomposes the large-scale cooperative problem into smaller, decoupled sub-problems, improving collaboration among agents.

• We design a new reward function that combines a formation reward and a distance reward by selecting the appropriate weights. The distance reward dominates the cooperative reward function when the pursuers are far from the escapee, while the formation reward dominates as the pursuers approach the escapee. The new reward encourages the pursuers to spread out around the escapee and penalizes angular proximity, promoting the learning of complex cooperative pursuit strategies, and improving the capture probability of the multi-UAV system by encouraging the pursuers to quickly obtain the optimal policy.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. We briefly present the basic theoretical knowledge of MARL and MHA in Section 2. Section 3 describes the pursuit-evasion environment, the dynamics equation for UAVs, and Dec-POMDP. In Section 4, the MA2PPO method is developed in detail. Experimental results and discussion are presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 gives conclusions and looks ahead to future work.

2.1 Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

MARL is mathematically modeled by a Dec-POMDP which is a Markov game extending a Markov decision process (MDP) to the multi-agent setting, defined as a tuple

Each agent performs the corresponding action according to its local observation based on the policy

The joint policy of all agents is

where

2.2 Proximal Policy Optimization

PPO [37] is an algorithm that combines the policy gradient and the actor-critic framework. The actor represents a stochastic policy, which generates a probability distribution of actions given a particular state. The critic is a value function estimator that helps train the actor by guiding the policy towards actions that lead to high-value states. One unique feature of PPO is its application of importance sampling, which distinguishes between old and new policies, and allows for the efficient reuse of sampled data, improving the data utilization rate. The PPO optimization function uses a policy pruning mechanism to prevent large changes in the action distribution during updates, and employs the advantage function as the gradient weight. The PPO optimization function can be expressed as follows:

where

When we encounter something in our daily lives, we quickly identify and attend to different parts of our environment [39]. This process can be expressed as

where

The attention mechanism operates in a manner akin to the differentiable key-value memory model [40]. By leveraging the correlation between a given key and query, the attention mechanism enables the model to dynamically focus on relevant information. It maps the pairs of a query

where

MHA uses multiple query vectors

where

3 System Model and Problem Formulation

The pursuit-evasion environment is a continuous, two-dimensional finite area, dimension

To simplify and increase versatility, we consider all UAVs as particles in the environment and assume that they lie at the same altitude. The two-dimensional kinematics model of UAVs [34,41] we considered is as follows:

where

We assume that all UAVs fight with a constant speed, and a similar assumption has been used in [34]. The control variable is

In this subsection, the system model is modeled as the Dec-POMDP. Then, we give the problem formulation of the multi-UAV cooperative pursuit-evasion game.

Each pursuer can be viewed as an agent. The pursuers engage in an interactive process, wherein they gather information on their teammates within the communication range, information on the escapee within the detection range, and information gleaned from their own detection. Based on this information, the pursuers generate observations of their environment and output corresponding actions according to their policy. The environment provides feedback in the form of rewards for the actions taken by the pursuers. The policy is dynamically updated throughout the pursuit process to promote optimal actions and ensure coordinated pursuit by the UAV swarm.

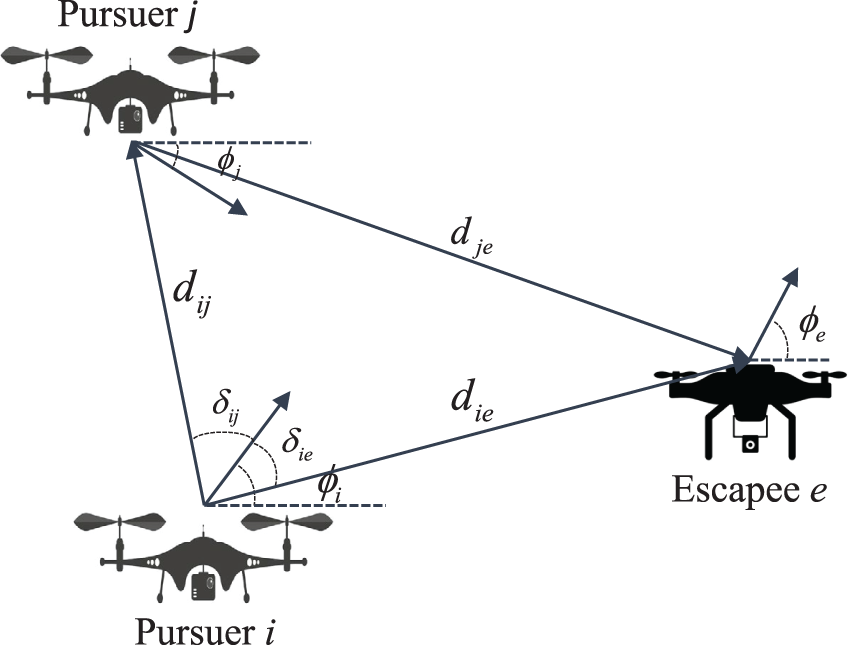

Due to the inherent limitations of their sensing capabilities, each UAV is only able to observe a limited portion of the real environment. As shown in Fig. 1, the observation of UAV

Figure 1: The observation of pursuer

Consequently, the state representation of each pursuer comprises

The action space is the set of all actions that the pursuers can perform. During the multi-UAV confrontation process, each pursuer selects its actions based on its own observations. In a pursuit-evasion scenario where UAVs are flying at a constant speed, the control can be simplified to angular velocity control, ignoring the effect of wind speed on the airspace. As the angular velocity varies, the states of UAVs change accordingly. The range of angular velocity falls within the interval of

It is important to design an effective reward function to guide the learning process of the multi-UAV system. In the pursuit task, the reward function plays a crucial role in controlling the pursuers to chase the escapee while avoiding collisions and staying within the boundaries. We propose two types of rewards: cooperative pursuit reward and punishment reward.

The formation reward received by the pursuers at each step

where

The distance-based reward function for the pursuers is defined as follows:

where

Therefore, the cooperative reward function for the pursuers is defined as:

where

We design a cooperative reward function that encourages pursuers to approach the evader from different directions, forming an encirclement pattern that yields a formation reward. However, if the agents only aim to spread around the evader without moving closer, the pursuit task cannot be completed. To address this, we introduce a dynamically decaying distance reward. When a pursuer is far from the evader, the distance reward dominates the cooperative reward function; as the pursuer approaches the evader, the formation reward becomes more prominent. This new reward formulation encourages pursuers to spread out around the evader while penalizing similar approach angles, thereby promoting the learning of complex cooperative pursuit strategies. It also increases the probability of successful capture in multi-UAV systems by incentivizing agents to quickly acquire optimal policies.

Punishment reward. UAVs need to pursue the evader while avoiding collisions with others and flying out of the mission area to ensure flight safety. Therefore, it is essential to create a justifiable reward function to direct UAVs toward a safe flight. The penalty reward includes the collision penalty and the boundary penalty.

The collision penalty reward is given when two pursuers are closer together than the safe distance

where

There are security risks when UAVs fly outside of the mission area. By flying too close to boundaries, UAVs have a portion of their perception range fall into the non-mission area, which is useless. We define

For the pursuer

The final reward function can be formulated as

The goal is to train the optimal policy for the decentralized execution of each UAV through centralized learning that obtains the states and actions of all UAVs. Each UAV learns to take the optimal flight actions by itself through local observation to complete the pursuit mission. The UAV

where

4 Multi-Agent Attention Proximal Policy Optimization

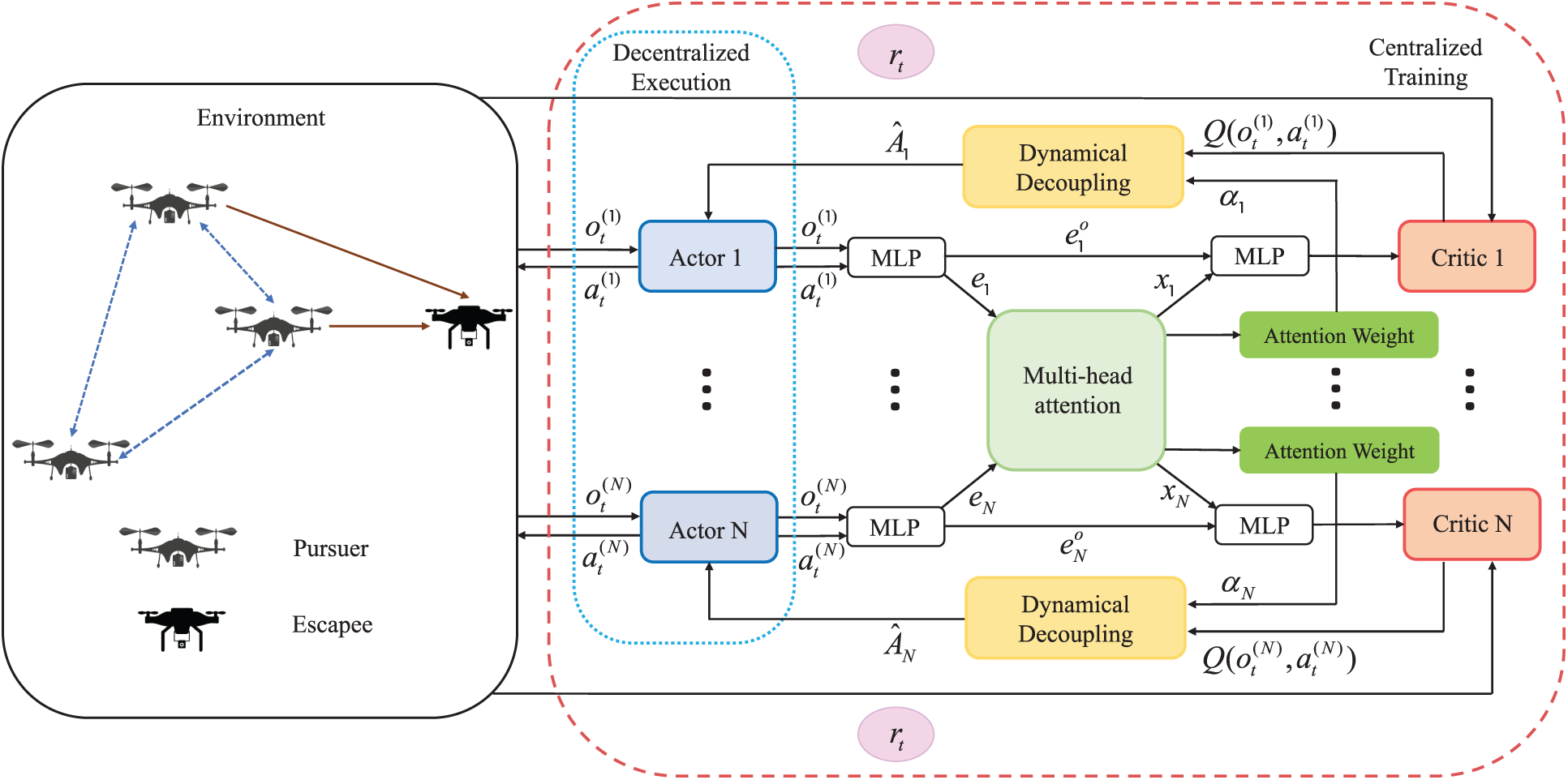

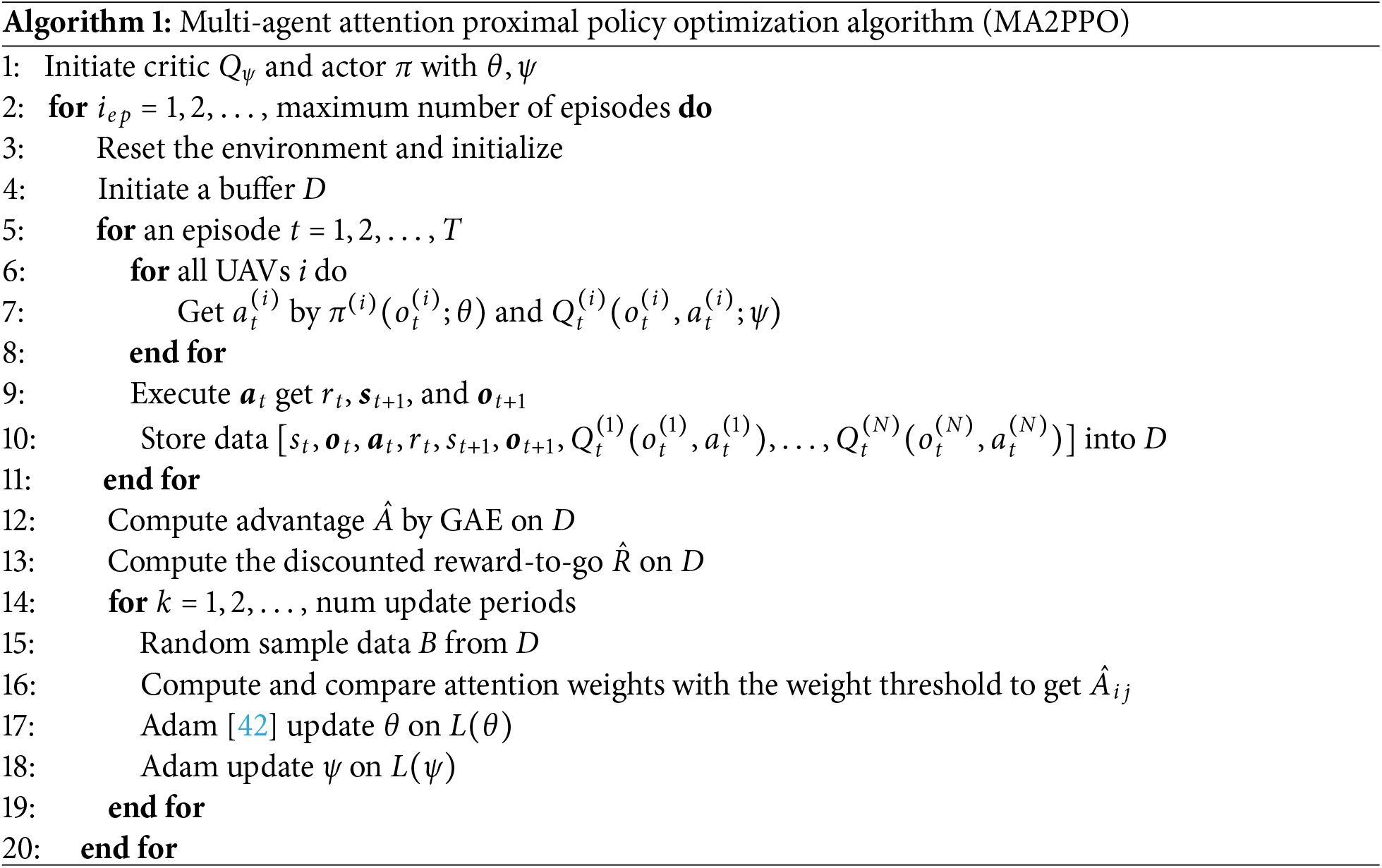

The framework of algorithm MA2PPO is depicted in Fig. 2. Each UAV has a centralized critic network and a decentralized actor network. In the centralized training,

Figure 2: The framework of algorithm MA2PPO

The centralized critics receive joint observations

where

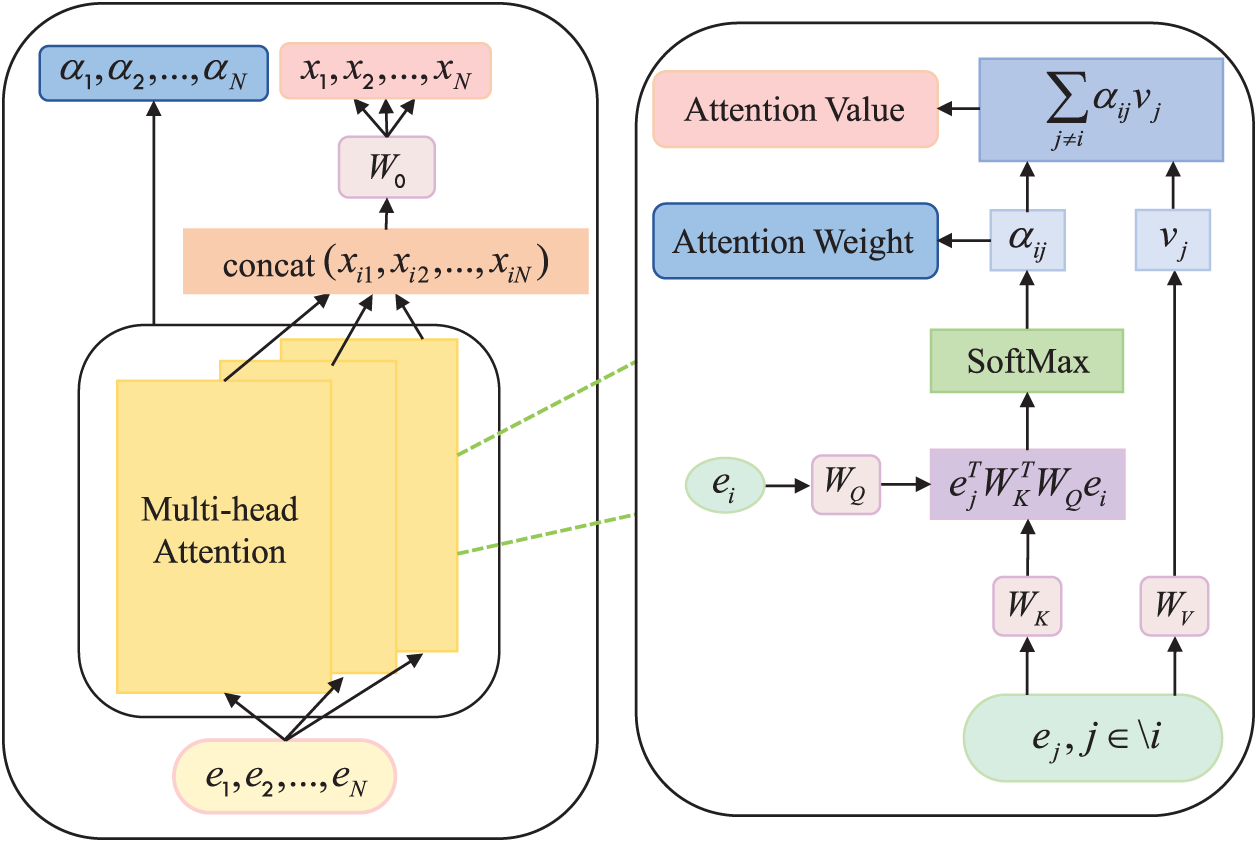

Calculating other UAVs’ levels of attention

where

Figure 3: Calculating other UAVs’ levels of attention

The observation-action embedding

where

where

Taking note of the fact that all UAVs share the weights of the extracted queries, keys, and values for each attention header, which promotes the use of common embedding space. The centralized set of attentional critics is used by UAVs with the same goal. Due to parameter sharing, our method performs well in scenarios where UAVs have different rewards but similar features.

The number of UAVs will change in cooperative pursuit scenarios due to collisions or crashes of UAVs, and some algorithms are unable to handle the emergency. MA2PPO integrates the observations of

UAVs use MHA to pay diverse amounts of attention to other UAVs. In the case that pursuer

The relevant set

The expected future reward of pursuer

Dynamic decoupling addresses the credit assignment problem since it only distributes credit to UAVs that affect the rewards of UAV

UAV

The actor network, represented by

where

We create the MHA-based central critic networks that gather information about the observation and action of all UAVs. MHA gets a fixed-length vector

A centralized group of multi-headed attentional critics is used by UAVs with the same objective. As a result of parameter sharing, the centralized critic networks of all UAVs are updated simultaneously to reduce the joint loss function, which is

where

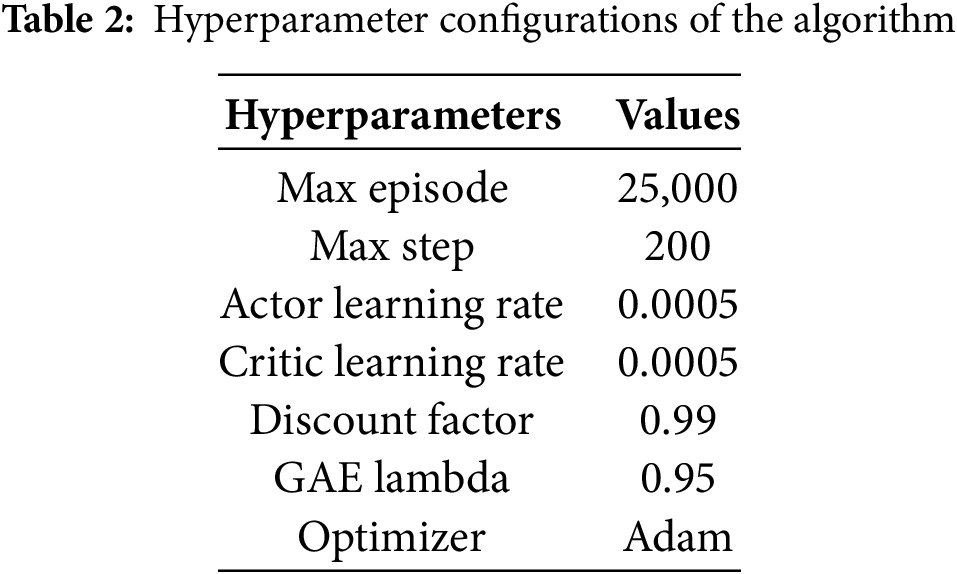

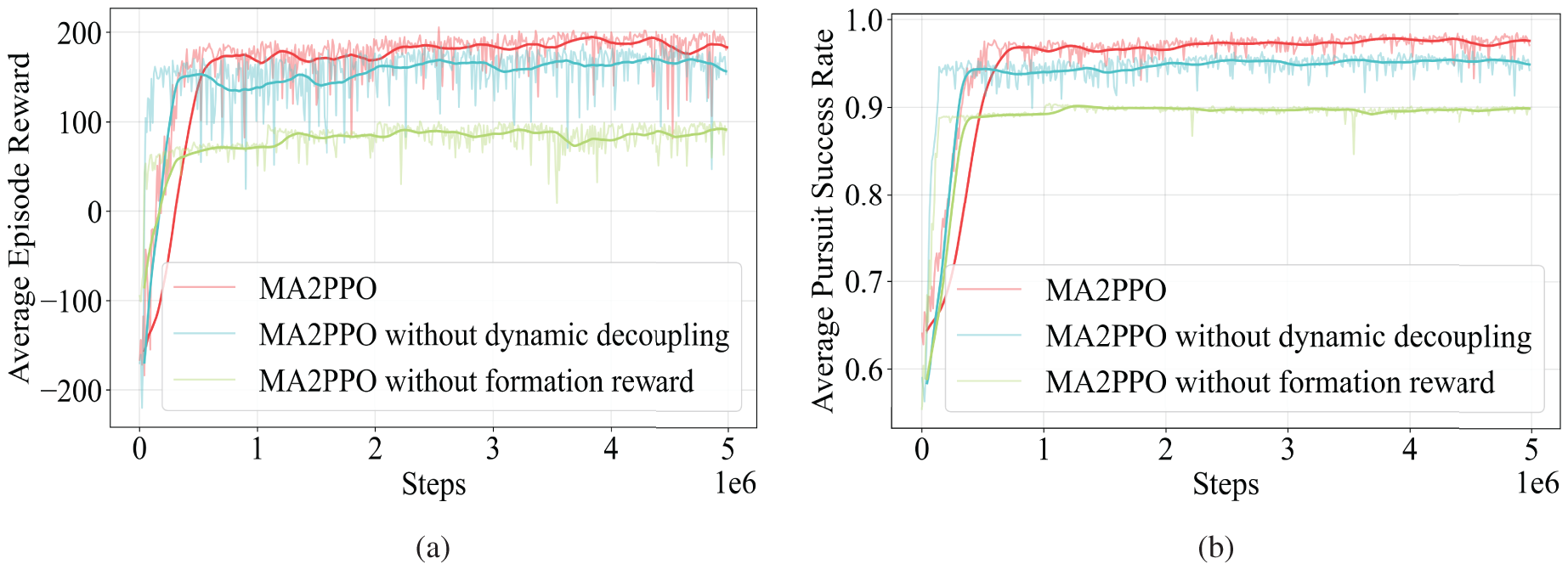

We conduct experiments using the multi-UAV pursuit-evasion model established in Section 3.1. Simulation demonstrates the convergence and effectiveness of the proposed algorithm. In the beginning, the simulation settings, training settings, and evaluation metrics of the proposed algorithm are introduced. Then, we compare the performance of MA2PPO with various baseline methods, including MAPPO, MAAC, and COMA, which are popular MARL algorithms. We also validate the ablation algorithms to confirm the importance and contribution of each component. MA2PPO without dynamical decoupling and MA2PPO without formation reward are the algorithms for the ablation version. Finally, we demonstrate the effectiveness, training efficiency, and scalability of the MA2PPO algorithm by analyzing evaluation criteria and combining results such as multi-UAV pursuit trajectories and attention visualization.

We evaluate the proposed approach and develop a simulation platform that simulates the multi-UAV pursuit-evasion game.

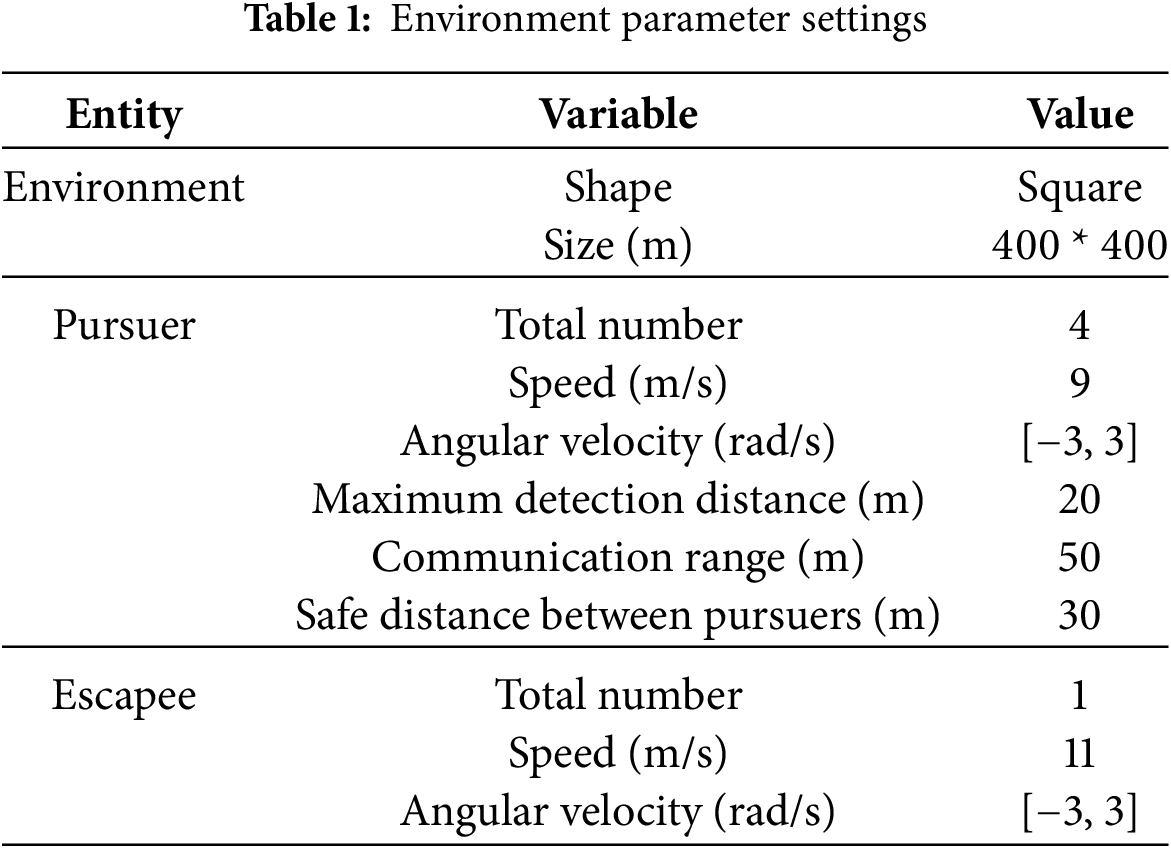

We assume that all UAVs fly at the same altitude and their airspace is limited to an area of 400 m * 400 m. UAVs can begin at any location within the permitted space. The initial locations of all UAVs are provided in relatively stable positions to prevent collisions and facilitate the training process. The aircraft we modeled is a four-rotor UAV. The velocity of a chasing UAV is

The simulation time unit is set to

It is assumed that the maximum communication distance of each UAV is 50 m, the maximum detection distance is 20 m, and the capture range of the pursuer is 15 m. When the distance between the evader and at least one pursuer is less than 15 m, the pursuit task is deemed accomplished due to the air combat simulation platform does not model and simulate the close-range combat missile. The safe distance between UAVs to prevent collisions is 30 m. UAVs modify flight directions to avoid collisions by sharing information with nearby companions.

We train the pursuers using the proposed algorithm, while an escapee can use the DRL model to learn or just follow the rules. The proposed approach is used to control the angular velocity of the pursuers. We adopt the clear and effective rules for a rule-based escapee: within the permissible range of angular velocity, the escapee can choose with greed the maximum angular velocity of a speedier escape. The weights of rewards

All experiments in the training process are performed on a workstation with an Intel i9-10850K CPU and a Nvidia GeForce GTX 3060 GPU. We use PyTorch for network implementation.

The algorithm is trained at 5,000,000 steps with a constant set of 200 steps per episode. The environment and UAVs are reset after the confrontation procedure is finished or when the maximum steps allowed per episode are achieved.

All actor networks in MA2PPO share the same structure, as do all critic networks. A fully connected neural network with two hidden layers makes up the actor networks. We parameterize the actors using the MLP with 128 units per layer. Rectified linear unit (ReLu) functions serve as the activation function in both hidden layers. The network layers of the critics have 256 neurons. As the activation function in the buried layer, we employ Leaky ReLU. There is no activation function in the output layer, which is merely a linear layer. The Adam optimizer is adopted by both the actor network and the critic network, with a learning rate of 0.0005. Other hyperparameters are set to the discount factor

We choose MAAC, COMA, and MAPPO as the benchmark algorithms to compare the performance of the proposed algorithm in dealing with the issue of multi-UAV pursuit game. The implementation details of the benchmark algorithm are shown below.

MAAC: The MAAC algorithm is a traditional MARL algorithm with an attention mechanism built on the soft actor-critic (SAC) and CTDE. The actor networks have a hidden layer unit number of 128, and ReLu is their activation function. Leaky ReLu is an activation function for the output layer of the network. The hidden layer unit number of the critic networks is 256. Its activation function is Leaky ReLu, and the output layer of the network is activated using the ReLu function. The actor and critic networks are optimized using the Adam optimizer, and the learning rate is 0.001. Networks for the target actors and the target critics both employ soft updates. Other hyperparameters include: the buffer size is 1000 K, the batch size is 1024, and the discount factor is 0.9.

COMA: The multi-agent credit assignment problem is the focus of COMA. It utilizes the single, central network to anticipate the Q value of each agent with distinct forwarding. An input layer, two hidden recurrent neural network (RNN) layers and an output layer make up the policy network. There are 64 hidden layer units in the RNN hidden layers, which uses the GRU unit. The critic network has 128 hidden layer units and is a four-layer fully connected linear unit. Both the activation mechanisms of the policy and the critic are ReLu activation functions. The RMS optimizer is used by COMA. The actor network and the critic network have learning rates of 0.0001 and 0.001, respectively. The discount factor is 0.99.

MAPPO: It is a widely used MARL algorithm that has demonstrated strong performance in various applications. Its hyperparameters are similar to those of MA2PPO, and the parameters for various implementation details are set to the same as those from [44].

We employ three evaluation metrics to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Average episode reward (AER): The average episode reward is a significant evaluation criterion in MARL. It measures the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm’s training by tracking its growth and convergence. To demonstrate the optimization process of the model, it is crucial to consider the cumulative reward value of the confrontation and maximize it.

Average pursuit success rate (APSR): The average pursuit success rate is the ratio of the sum of successful steps to all steps in an episode. It is used to evaluate the quality of the pursuit. The algorithm performs better with a higher APSR. We define it as

where

In this section, we present the simulations and analysis of the comparison with baseline algorithms, ablation experiments, scalability tests, and attention visualization of MA2PPO based on the environment settings, hyperparameter settings, and evaluation criteria given in Section 5.1.

5.2.1 Comparison with Baseline Algorithms

We train MA2PPO, MAPPO, MAAC, and COMA in the same environment to evaluate and analyze their performance of learning strategies in the multi-UAV pursuit environment.

Fig. 4 shows that MA2PPO outperforms other algorithms in terms of the AER, the APSR demonstrating its superior and steady performance in the multi-UAV pursuit game. The AER of the four methods is displayed in Fig. 4a. As evidenced by the fact that the AER values of MA2PPO and MAPPO dramatically increase at the beginning of the training period, and both obtain respectably high scores from negative starting values. The AER curve illustrates that both algorithms have learned the pursuit strategy, but MA2PPO has learned it better. For MA2PPO, the AER value can be roughly converged to 50,000 steps. MAPPO takes twice as many convergence steps as MA2PPO, and its AER has a certain gap with MA2PPO. MAAC and COMA both performed poorly overall, and MA2PPO has significantly surpassed them in the AER.

Figure 4: Comparisons of MA2PPO with MAPPO, MAAC, and COMA in terms of the AER and APSR. (a) The AER; (b) The APSR

We can see that the trend of the APSR curve shown in Fig. 4b resembles the AER curve. The pursuers, in the beginning, could not complete the task well. The APSR curve increased notably when the pursuers use the MA2PPO algorithm and begin chasing the escapee effectively as training progresses. At roughly 50,000 steps, the success rate of the pursuers is nearly 98%. MAPPO can also learn successful pursuit strategies, but its average success rate is lower than MA2PPO. There was no significant increase in the APSR values of COMA and MAAC.

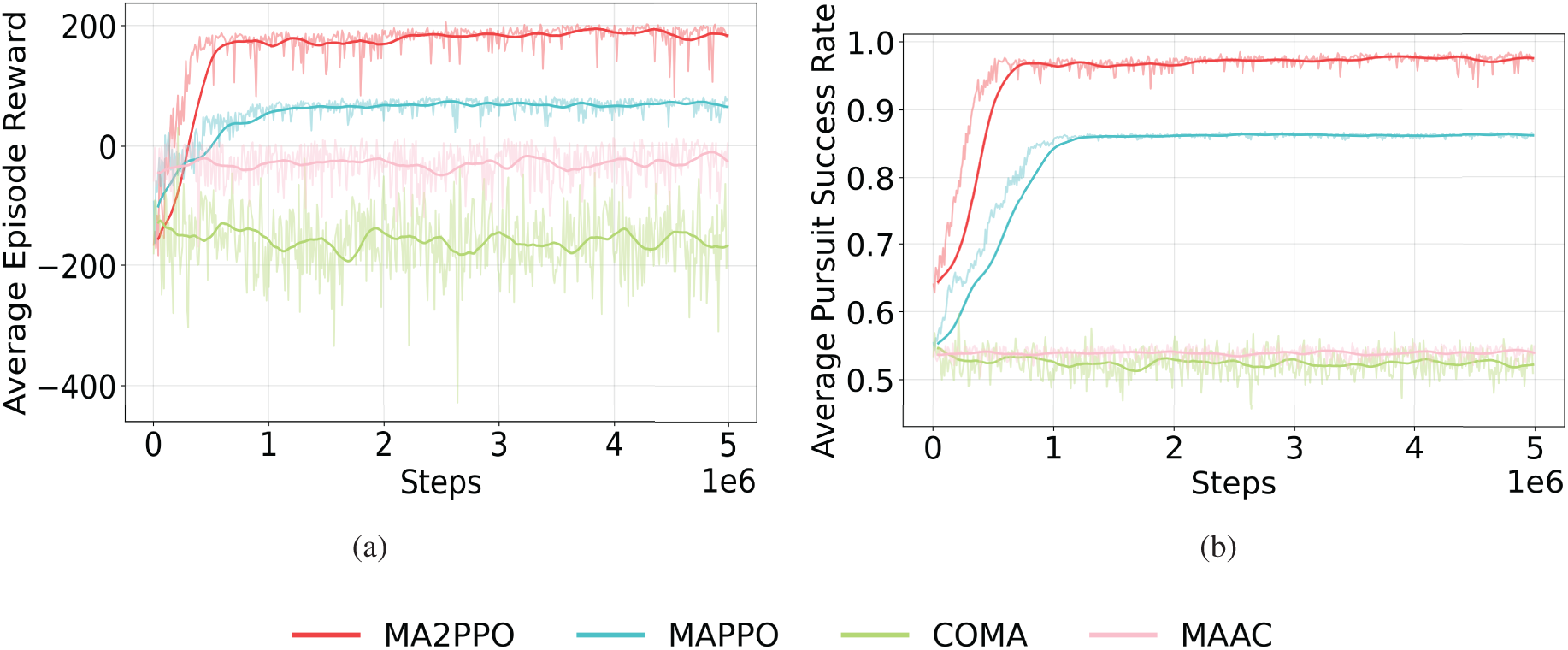

Two ablative versions of MA2PPO, namely MA2PPO without dynamic decoupling and MA2PPO without formation reward, are also contrasted and examined as baselines to show the efficacy of various components. MA2PPO without dynamic decoupling highlights the importance of formation reward. It replaces the simple distance reward with the novel reward function we presented, based on PPO and our suggested framework. The purpose of MA2PPO without formation reward is to confirm how the dynamic decoupling affects the resolution of credit assignment issues. Only the dynamic decoupling portion of the algorithm is kept, and the reward function is just the straightforward distance reward. Fig. 5 displays the MA2PPO and its ablative versions’ training results. The comparisons of two evaluation criteria demonstrate that MA2PPO performs better than the other two algorithms.

Figure 5: Comparisons of the AER and APSR for MA2PPO, MA2PPO without dynamic decoupling, and MA2PPO without formation reward. (a) The AER; (b) The APSR

Ablation Study of Dynamic Decoupling: We employ MHA to decouple the multi-UAV cooperative pursuit problem, as discussed in Section 4.2. Dynamic decoupling is effective at resolving the credit assignment problem and promoting active collaboration between nearby UAVs. By using the attention mechanism, UAVs are incentivized to approach one another when others are helpful for their task. Conversely, collisions between UAVs are penalized in the reward function when they are too close to one another. In situations where they need to avoid each other, UAVs dynamically decouple from one another. These incentives are what propel each UAV forward. Ensuring that UAVs coordinate their motivations to keep an eye on each other while avoiding collisions is critical. Effective tracking of an escapee by UAVs is dependent on ensuring that the incentives of the individual UAVs are aligned. The MA2PPO algorithm, which we propose, facilitates this by enabling UAVs to exhibit a wide range of cooperative behaviors that can be easily adapted to different situations.

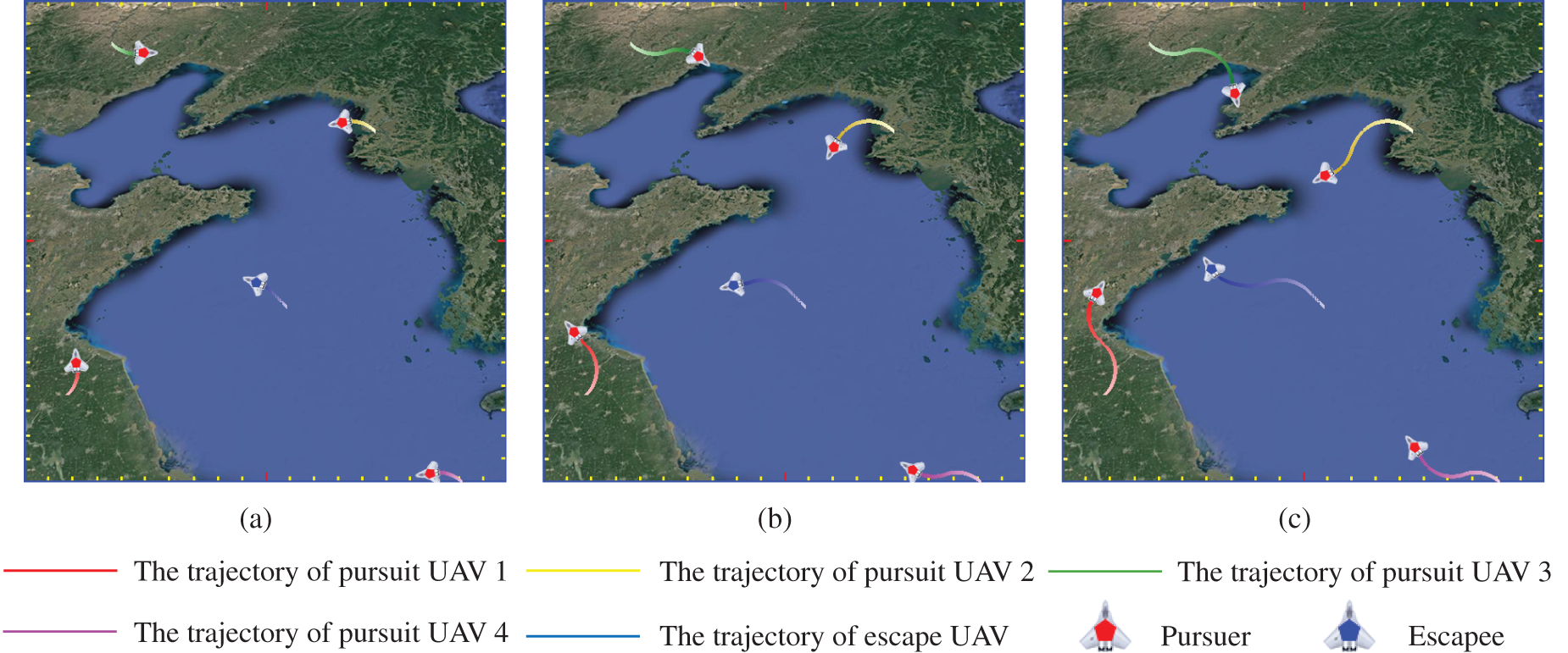

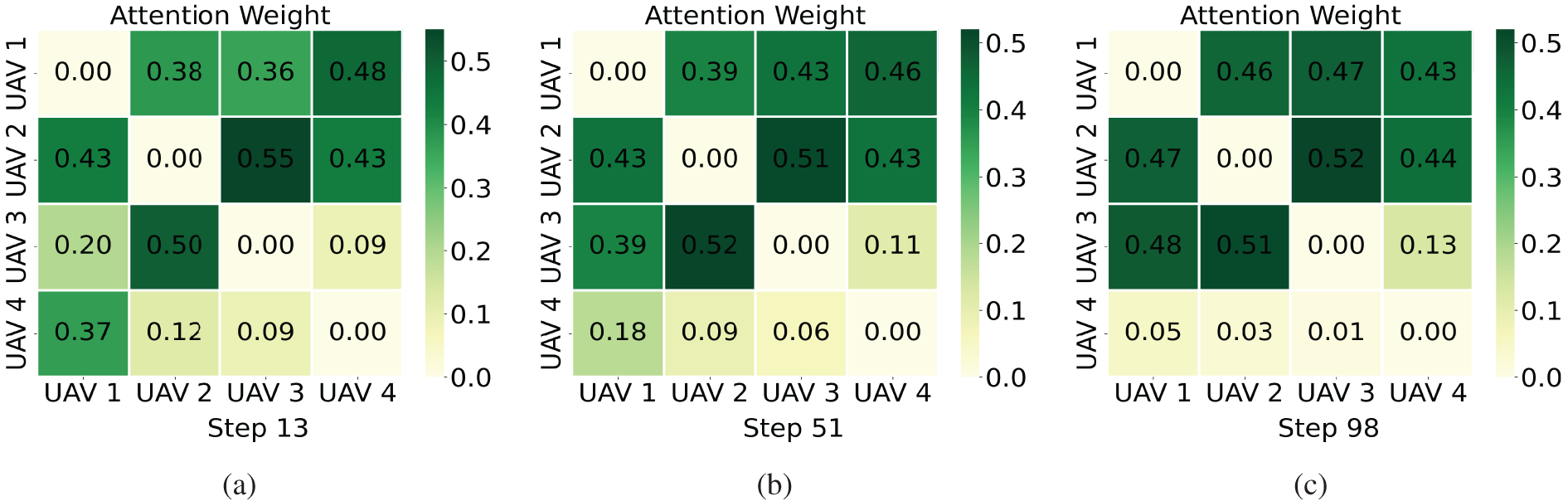

In Figs. 6 and 7, we illustrate the process of dynamic decoupling by visualizing the trajectories of all UAVs and the corresponding attention weights. The trajectories of all UAVs at the 13th step after initialization is shown in Fig. 6a. The escapee flies to the upper left as the pursuers begin their hunt in accordance with the MA2PPO method they have learned. The flight directions of UAVs 1, 2, and 4 make it easier to complete the chase. As seen in Fig. 7a, UAV 1 has a higher attention weight value for UAVs 2 and 4 than UAV 3. UAVs 2 and 3 are more practical than UAV 1 to work with to accomplish the interception of escapees when the distance between them and their respective flight directions is considered. Therefore, UAV 2 pays more attention to UAV 3 than to UAV 1 while UAV 2 is also focused on UAV 1. Similarly, the attention weights of UAVs 3 and 4 in Fig. 7a support our analysis of UAVs 1 and 2.

Figure 6: The trajectories of all UAVs under different steps. (a) The trajectories of all UAVs at the 13th step. (b) The trajectories of all UAVs at the 51st step. (c) The trajectories of all UAVs at the 98th step (The trajectory color of each UAV transitions from light to dark, representing its movement from the start position to the end position, with the lightest color indicating the starting point and the darkest color indicating the end point. The UAV icons mark each UAV’s final position at the corresponding time step)

Figure 7: The attention weights of the pursuers under different steps. (a) The attention weights of the pursuers at the 13th step. (b) The attention weights of the pursuers at the 51st step. (c) The attention weights of the pursuers at the 98th step (The color scale indicates the magnitude of the attention weights: lighter colors represent lower weights, while darker colors represent higher attention weights)

Fig. 6b shows the trajectories of the multi-UAV at the 51st step. UAVs 1, 2, and 4 may be seen flying in the direction of the escapee as the hunt goes on. UAV 3 is currently near the direction of the escapee. Fig. 7b demonstrates that UAVs 1 and 2 both recognize that working with UAV 3 is more favorable to completing the hunt. Hence, the attention weight of UAV 3 is increased by UAV 1 while the attention weight of UAV 4 is decreased. UAV 2 also learned this, which has increased attention to UAVs 1 and 3, reducing attention to UAV 4. UAVs 1, 2, and 3 consequently dynamically disconnect UAV 4 and concentrate more on each other.

The trajectories of pursuers in Fig. 6c serves as a confirmation of the analysis in Fig. 7b. UAVs 1, 2, and 3 fly straight to the escapee, as shown in Fig. 6c, as they prepare to form a round-up state to complete the pursuit of the evader. In Fig. 7c, UAVs 1, 2, and 3 add attention weights to each other, whereas UAV 4 receives nearly no attention. The results demonstrate that the dynamic decoupling enables pursuers to determine in real-time which companions are more beneficial to the pursuit process to pay them more attention and work more closely together. This approach decomposes the large-scale cooperative problem into smaller, decoupled subproblems and eliminates lazy agents, motivating the pursuers to collaborate more effectively with one another.

Ablation Study of Formation Reward: We analyze the outcome of giving each pursuer the formation reward, which is offered to promote a great pursuit manner at each time step. The AER of MA2PPO is higher than MA2PPO without formation reward, as seen in Fig. 5. Additionally, the average pursuit success rate will rise when utilizing the formation reward. The MA2PPO algorithm enables UAVs to engage in effective multi-UAV pursuit cooperation by reshaping their original rewards through the formation reward received from their neighboring UAVs. It also helps to address the drawbacks of the distance reward, hence strengthening system performance and boosting individual UAV rewards. This further emphasizes the value of UAV cluster cooperation.

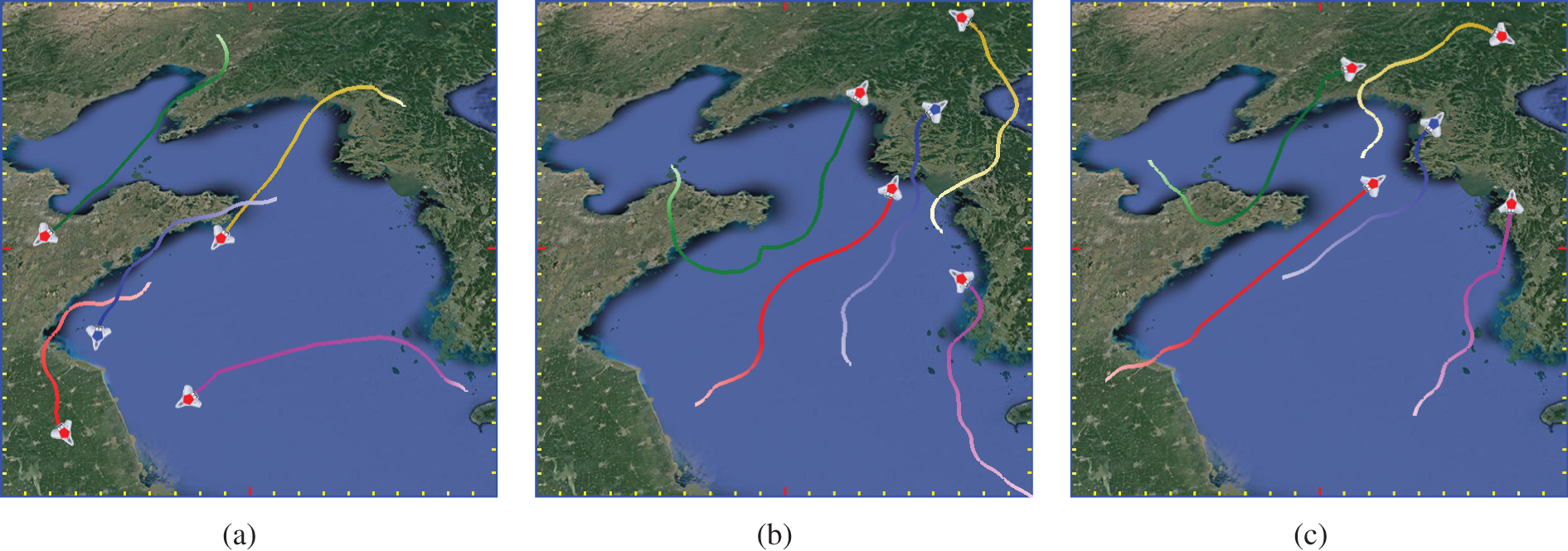

UAVs use the MA2PPO method to work together to track down the escapee and intuitively determine whether they have learned to create a formation by displaying the trajectory visualization of various tracking processes. As seen in Fig. 8a, the pursuers use the cooperative chasing policies in response to the escapee’s unexpected turn and successfully catch up with it. UAV 1 keeps close track of the evader, even if it makes a sudden turn. UAVs 2, 3, and 4 are also flying in the direction of the evader, establishing a hunting state, and effectively intercepting the evader. Fig. 8b and c exhibits the trajectories of pursuers in a variety of additional scenarios. When the escapee flees quickly in one direction in Fig. 8b and 8c, the pursuers are coordinating their activities and pursuing the escapee from various angles. Then, when the besieged state of the escapee is not met, two pursuers closely follow it while others disperse around them. The pursuers then construct an encirclement around the evader to prevent the evader from escaping. While they approach the evader for arrest after the evader is in the encirclement and the encirclement is fulfilled. They coordinate the actions to move from encirclement to capture. Finally, they go straight after the escapee untill it is apprehended. The results demonstrate that the pursuers successfully handle the chase process in various states. The formation reward incentivizes the pursuers to encircle the escapee to meet the siege, then shorten the siege until the escapee is apprehended, enabling closer multi-UAV cooperation.

Figure 8: Visualizing the trajectories of various cooperative pursuit processes (The legend content, the gradient trajectory colors of the UAVs, and the meaning of the UAV icons are all the same as those in Fig. 6)

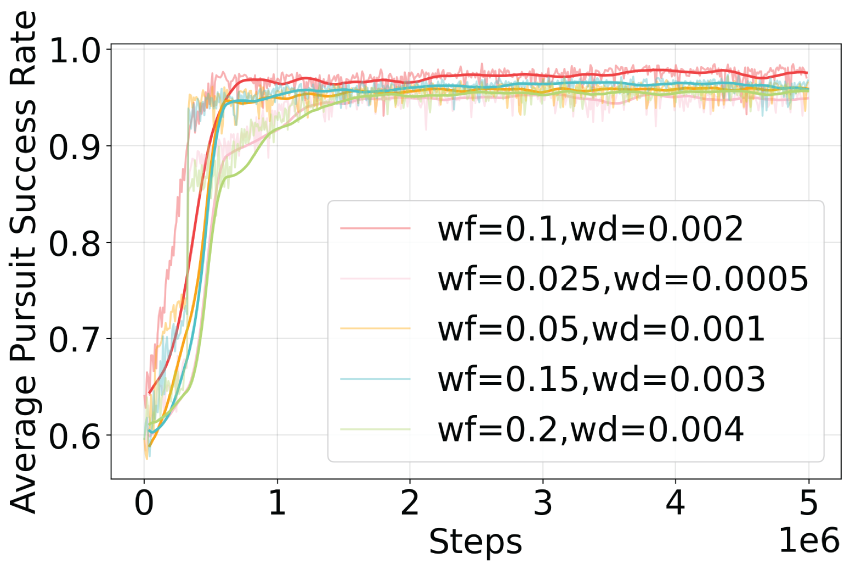

Ablation analysis of reward function weights. To systematically evaluate the impact of the formation reward weight

As shown in Fig. 9, the algorithm achieves the best performance in terms of convergence speed and final success rate when

Figure 9: Calculating other UAVs’ levels of attention

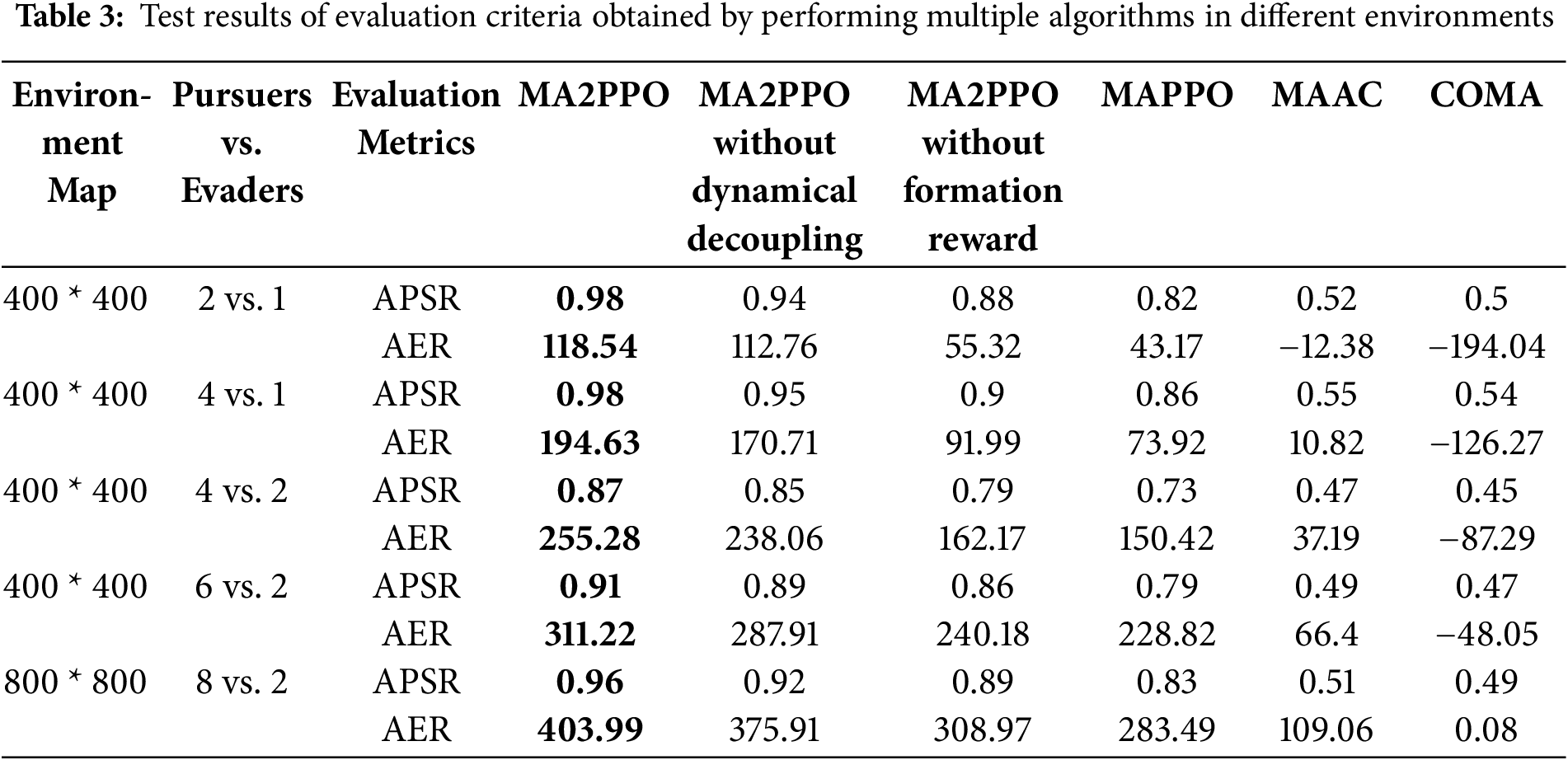

We test the capacity of strategies that are learned by the MA2PPO algorithm to scale in various situations. We trained all six of the algorithms we previously compared in various settings with various numbers of UAVs used for chase and escape. We still evaluated them using the two criteria listed in Section 5.1. Table 3 displays the statistics of the test findings.

From an overall perspective, MA2PPO consistently outperforms the other five baseline methods across all tested scenarios, demonstrating strong stability and generalization capabilities. Notably, in the highly complex 8 vs. 2 task, MA2PPO maintains an APSR of 0.96 and an AER of 403.99, significantly exceeding the performance of the comparative algorithms. These results highlight the superior ability of MA2PPO in multi-target task allocation and strategic coordination under challenging conditions.

The ablation studies on MA2PPO variants without key modules reveal that removing the dynamic decoupling mechanism leads to reduced coordination accuracy, while excluding the formation reward significantly decreases group encirclement efficiency. For instance, in the 6 vs. 2 scenario, the complete MA2PPO achieves an AER of 311.22, which drops to 240.18 when the formation reward is removed, validating the critical role of our proposed modules in enhancing system-level cooperation. In contrast, MAPPO, MAAC, and COMA exhibit a noticeable decline in performance when the number of evaders increases or the task scale expands. Although MAAC also incorporates an attention mechanism, its overall success rate across different scenarios is substantially lower than that of MA2PPO. As the task scale increases, most baseline methods show significant performance fluctuations, whereas MA2PPO maintains relatively stable performance, indicating that MA2PPO-based learning demonstrates superior generalization and scalability across diverse scenarios.

An in-depth analysis is conducted to uncover the reasons behind the advantages of the MA2PPO algorithm. The use of dynamic decoupling may be able to identify those highly correlated connections that are essential and eliminate those weakly correlated interactions. Additionally, the formation reward encourages the pursuers to consider nearby companions that can create a particular form when determining the reward for each UAV. The pursuers can learn better cooperative manners to execute the mission from these nearby companions, which dramatically increases pursuit efficiency.

In summary, the proposed MA2PPO algorithm enhances coordination efficiency and adaptability across different task configurations and can be extended to a variety of cooperative scenarios involving more pursuers and escapees.

5.2.4 Computational Complexity Analysis

We analyze the algorithm from the perspective of computational complexity. There are N homogeneous UAVs, each with a state dimensionality of M, and a continuous action dimensionality of 1. During centralized training, the critic network for each UAV must incorporate the states and actions of the other

Moreover, in the extreme case where each UAV communicates with all other

Our proposed approach, MA2PPO, builds upon the foundations of PPO and CTDE, and improves the efficiency and the capture probability of multi-UAV systems during the pursuit of the escapee. To address the credit assignment problem, we introduce a dynamic decoupling that takes advantage of MHA to enable each pursuer to selectively incorporate information from teammates, and thus dynamically determine which interactions should be decoupled in real-time. It dynamically separates the multi-UAV collaboration problem into decoupled sub-problems, and minimizes the noise introduced, lowering the variance in the strategy gradient estimation. Additionally, we create a novel reward function that combines the formation reward with the distance reward to encourage the pursuers to learn complex cooperative pursuit strategies around the escapee. It empowers UAVs to obtain the optimal policy as soon as possible and improves the capture probability of multi-UAV systems. Experiments demonstrate that MA2PPO effectively enhances cooperation among UAVs and encourages the formation of clusters that exhibit a wide range of cooperative behaviors. Our algorithm can also be applied in collaborative scenarios with more numbers of UAVs.

The primary limitation of the current study lies in the use of a 2D UAV model for experimentation, where all UAVs are assumed to operate at a constant speed. In more realistic settings involving variable-speed scenarios and complex UAV dynamics and perception models in three-dimensional (3D) environments, the proposed MA2PPO algorithm may not be directly applicable to pursuit-evasion games. Compared to the 2D case, UAVs operating in 3D space have more degrees of freedom, such as attitude control and climb rate constraints, and are subject to physical control laws that impose response delays, making the learning task significantly more challenging. To address these issues, we consider adopting a hierarchical architecture that separates high-level decision-making from low-level trajectory tracking. Furthermore, curriculum learning can be employed, starting from pretraining in simplified 2D constant-speed environments and gradually incorporating 3D dynamics to improve policy learning and training stability.

In addition, the current formation reward is based on the relative angular dispersion of any two pursuers with respect to the evader in 2D space, which encourages the UAVs to spread around the evader and form an effective encirclement. However, this 2D angle-based formation reward cannot be directly extended to 3D environments. Designing a robust and differentiable 3D encirclement metric remains a key challenge. A potential solution is to construct a 3D formation reward by modeling the relative spatial distribution between pursuers and the evader using tensor encoding. This would allow for a measurement of spatial coverage in 3D space. Additionally, a vertical separation penalty term could be introduced to discourage UAV stacking, thereby promoting more effective and realistic 3D formations.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely thank the entire editorial team and all reviewers for voluntarily dedicating their time and providing valuable feedback.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research and Development Program of China under Grant JCKY2018607C019, in part by the Key Laboratory Fund of UAV of Northwestern Polytechnical University under Grant 2021JCJQLB07101.

Author Contributions: Lei Lei: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft; Chengfu Wu: Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition; Huaimin Chen: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sun N, Zhao J, Shi Q, Liu C, Liu P. Moving target tracking by unmanned aerial vehicle: a survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(5):7056–68. doi:10.1109/TII.2024.3363084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kashino Z, Nejat G, Benhabib B. Multi-UAV based autonomous wilderness search and rescue using target Iso-probability curves. In: 2019 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS); 2019 Jun 11–14; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 636–43. doi:10.1109/icuas.2019.8798354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wu Y, Wu S, Hu X. Cooperative path planning of UAVs & UGVs for a persistent surveillance task in urban environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;8(6):4906–19. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.3030240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Huang H, Savkin AV. An algorithm of reactive collision free 3-D deployment of networked unmanned aerial vehicles for surveillance and monitoring. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020;16(1):132–40. doi:10.1109/TII.2019.2913683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Huang H, Savkin AV. A method for optimized deployment of unmanned aerial vehicles for maximum coverage and minimum interference in cellular networks. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2018;15(5):2638–47. doi:10.1109/TII.2018.2875041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Fawaz W, Abou-Rjeily C, Assi C. UAV-aided cooperation for FSO communication systems. IEEE Commun Mag. 2018;56(1):70–5. doi:10.1109/mcom.2017.1700320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Schmidt LM, Brosig J, Plinge A, Eskofier BM, Mutschler C. An introduction to multi-agent reinforcement learning and review of its application to autonomous mobility. In: 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); 2022 Oct 8–12; Macau, China. p. 1342–9. doi:10.1109/ITSC55140.2022.9922205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Selvakumar J, Bakolas E. Min-max Q-learning for multi-player pursuit-evasion games. Neurocomputing. 2022;475:1–14. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.12.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shen P, Zhang X, Fang Y, Yuan M. Real-time acceleration-continuous path-constrained trajectory planning with built-In tradeoff between cruise and time-optimal motions. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2020;17(4):1911–24. doi:10.1109/TASE.2020.2980423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fang X, Wang C, Xie L, Chen J. Cooperative pursuit with multi-pursuer and one faster free-moving evader. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;52(3):1405–14. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2019.2958548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Tran HV. Hamilton-Jacobi equations: theory and applications. Providence, RI, USA: American Mathematical Society; 2021. [Google Scholar]

12. Yuan Y, Zhang P, Li X. Synchronous fault-tolerant near-optimal control for discrete-time nonlinear PE game. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32(10):4432–44. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3017762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Xu Y, Yang H, Jiang B, Polycarpou MM. Multiplayer pursuit-evasion differential games with malicious pursuers. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 2022;67(9):4939–46. doi:10.1109/tac.2022.3168430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pan T, Yuan Y. A region-based relay pursuit scheme for a pursuit-evasion game with a single evader and multiple pursuers. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2022;53(3):1958–69. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2022.3210022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wu A, Yang R, Liang X, Zhang J, Qi D, Wang N. Visual range maneuver decision of unmanned combat aerial vehicle based on fuzzy reasoning. Int J Fuzzy Syst. 2022;24(1):519–36. doi:10.1007/s40815-021-01158-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen J, Zha WZ, Peng ZH, Gu D. Multi-player pursuit-evasion games with one superior evader. Automatica. 2016;71:24–32. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2016.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jaderberg M, Czarnecki WM, Dunning I, Marris L, Lever G, Castañeda AG, et al. Human-level performance in 3D multiplayer games with population-based reinforcement learning. Science. 2019;364(6443):859–65. doi:10.1126/science.aau6249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang K, Yang Z, Başar T. Multi-agent reinforcement learning: a selective overview of theories and algorithms. In: Handbook of reinforcement learning and control. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 321–84. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60990-0_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lowe R, Wu Y, Tamar A, Harb J, Abbeel P, Mordatch I. Multi-agent actor-critic for mixed cooperative-competitive environments. In: NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6382–93. [Google Scholar]

20. Hernandez-Leal P, Kartal B, Taylor ME. A survey and critique of multiagent deep reinforcement learning. Auton Agents Multi Agent Syst. 2019;33(6):750–97. doi:10.1007/s10458-019-09421-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sunehag P, Lever G, Gruslys A, Czarnecki WM, Zambaldi V, Jaderberg M, et al. Value-decomposition networks for cooperative multi-agent learning based on team reward. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS); 2018 Jul 10–15; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 2085–7. [Google Scholar]

22. Rashid T, Samvelyan M, Schroeder C, Farquhar G, Foerster J, Whiteson S. Qmix: monotonic value function factorisation for deep multi-agent reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2018 Jul 10–15; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 4295–304. [Google Scholar]

23. Son K, Kim D, Kang WJ, Hostallero D, Yi Y. Qtran: learning to factorize with transformation for cooperative multi-agent reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 5887–96. [Google Scholar]

24. Foerster J, Farquhar G, Afouras T, Nardelli N, Whiteson S. Counterfactual multi-agent policy gradients. In: Proceedings of the 32nd Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence Conference on Artificial General Intelligence (AAAI); 2018 Feb 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 2974–82. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Du Y, Han L, Fang M, Dai T, Liu J, Tao D. Liir: learning individual intrinsic reward in multi-agent reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference Neural Information Process System (NeurIPS); 2019 Dec 8–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 4403–14. [Google Scholar]

26. Fu X, Zhu J, Wei Z, Wang H, Li S. A UAV pursuit-evasion strategy based on DDPG and imitation learning. Int J Aerosp Eng. 2022;2022:1–14. doi:10.1155/2022/3139610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liao G, Wang J, Yang D, Yang J. Multi-UAV escape target search: a multi-agent reinforcement learning method. Sensors. 2024;24(21):6859. doi:10.3390/s24216859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang R, Zong Q, Zhang X, Dou L, Tian B. Game of drones: multi-UAV pursuit-evasion game with online motion planning by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(10):7900–9. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3146976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Iqbal S, Sha F. Actor-attention-critic for multi-agent reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 2961–70. [Google Scholar]

30. Liu Y, Wang W, Hu Y, Hao J, Chen X, Gao Y. Multi-agent game abstraction via graph attention neural network. In: Proceedings of the 34th Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence Conference Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2020 Feb 7–12; New York, NY, USA. p. 7211–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Ryu H, Shin H, Park J. Multi-agent actor-critic with hierarchical graph attention network. In: Proceedings of the 34th Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence Conference Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2020 Feb 7–12; New York, NY, USA. p. 7236–43. [Google Scholar]

32. Peng Z, Wu G, Luo B, Wang L. Multi-UAV cooperative pursuit strategy with limited visual field in urban airspace: a multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2025;12(7):1350–67. doi:10.1109/jas.2024.124965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hu J, Sun Y, Chen H, Huang S, Piao H, Chang Y, et al. Distributional reward estimation for effective multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; Orleans, LA, USA. p. 12619–32. [Google Scholar]

34. Zhou W, Li J, Liu Z, Shen L. Improving multi-target cooperative tracking guidance for UAV swarms using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Chin J Aeronaut. 2022;35(7):100–12. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2021.09.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang T, Qiu T, Liu Z, Pu Z, Yi J, Zhu J, et al. Multi-UAV cooperative short-range combat via attention-based reinforcement learning using individual reward shaping. In: 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2022 Oct 23–27; Kyoto, Japan. p. 13737–44. doi:10.1109/IROS47612.2022.9982096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kutpanova Z, Kadhim M, Zheng X, Zhakiyev N. Multi-UAV path planning for multiple emergency payloads delivery in natural disaster scenarios. J Electron Sci Technol. 2025;23(2):100303. doi:10.1016/j.jnlest.2025.100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017 Apr 24–26; Toulon, France. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

38. Schulman J, Moritz P, Levine S, Jordan MI, Abbeel P. High-dimensional continuous control using generalized advantage estimation. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2016 May 2–4; San Juan, Puerto Rico. p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

39. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference Neural Information Processing System (NeurIPS); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

40. Shi D, Zhao C, Wang Y, Yang H, Wang G, Jiang H, et al. Multi actor hierarchical attention critic with RNN-based feature extraction. Neurocomputing. 2022;471:79–93. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.10.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Xia Z, Du J, Wang J, Jiang C, Ren Y, Li G, et al. Multi-agent reinforcement learning aided intelligent UAV swarm for target tracking. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2021;71(1):931–45. doi:10.1109/TVT.2021.3129504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhang M, Qin H, Lan M, Lin J, Wang S, Liu K, et al. A high fidelity simulator for a auadrotor UAV using ROS and Gazebo. In: Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2015 Nov 9–12; Yokohama, Japan. p. 846–51. [Google Scholar]

44. Yu C, Velu A, Vinitsky E, Gao J, Wang Y, Bayen A, et al. The surprising effectiveness of PPO in cooperative multi-agent games. In: Proceedings of the 36th Conference Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 24611–24. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools