Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Efficient Rumor Control via Disseminating Truthful Information by Influential Nodes

1 Library, Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

2 School of Mathematics, Physics and Computing, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, 4350, Australia

3 Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

4 School of Computer Science, Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics, Zhengzhou, 450046, China

* Corresponding Authors: Lingling Li. Email: ; Xuezhuan Zhao. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3583-3598. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066909

Received 20 April 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Rumor Control (RC), aimed at minimizing the spread of rumors in social networks, is of paramount importance, as the spread of rumors can lead to significant economic losses, societal disruptions, and even widespread panic. The RC problem has garnered extensive research attention, however, most existing solutions for rumor control face a trade-off between efficiency and effectiveness, which limits their practical application in real-world scenarios. In this light, this paper studies the Truth-spreading-based Rumor Control (TRC) problem, and introduces the Subgraph-based Greedy algorithm Optimized with CELF (SGOC), which employs subgraph techniques and the CELF strategy, as the basic solution for the TRC problem. To improve the performance of SGOC, we carefully design a shortest path length dictionary SPR and an Immune Nodes Set (INS), leading to the Shortest Path-Based Rumor Control (SPRC) algorithm. To further enhance the SPRC algorithm, we develop a pruning method that accelerates the construction process of INS, proposing the Improved Shortest Path-Based Rumor Control (ISPRC) algorithm, which demonstrates superior efficiency compared to both SPRC and SGOC. Extensive experiments conducted on five real-world datasets, demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed algorithms.Keywords

The explosion of mobile internet and portable devices has propelled social networks like Facebook, Twitter, and WeChat into indispensable platforms for sharing information and exchanging opinions. Yet, this convenience is a double-edged sword: these platforms have also inadvertently become prime breeding grounds for rumors. Characterized by their rapid spread and misleading nature, unverified rumors can inflict substantial economic losses, trigger societal disruptions, and even spark widespread panic. A striking example of this occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, when baseless claims about the efficacy of the Chinese herbal remedy Shuanghuanglian liquid against the virus led to a frantic surge in purchases, causing considerable public alarm and market upheaval. The damaging impact of swiftly spreading rumors on society is undeniable, making effective rumor control an urgent and critical challenge.

As previously established, rumor control (RC) is of paramount importance. In recent years, researchers have developed various solutions, broadly categorized into three main approaches: node blocking, edge blocking, and truth-spreading methods [1]. Node blocking methods aim to stop rumor propagation by identifying and removing highly influential nodes within a social network [2,3]. Similarly, edge blocking methods impede rumor transmission by severing connections between key nodes, specifically by identifying and deleting critical edges to minimize misinformation spread [4,5]. While both node and edge blocking can disrupt rumor flow, they inherently alter the network structure, potentially degrading the user experience and unintentionally hindering the spread of legitimate information. In contrast, truth-spreading methods offer a more nuanced solution. This approach identifies influential nodes that act as “seed nodes” to disseminate factual information. Once users receive this accurate information, they become immune to the rumor, effectively curbing its spread [6,7]. A key advantage of this strategy is that it preserves the social network’s original structure. Crucially, it blocks the spread of false information without impacting the flow of normal, legitimate communication, aligning well with ethical considerations. This makes it a popular and increasingly favored topic in rumor control research. The methods presented in this paper fall squarely within this paradigm.

While numerous solutions have been proposed to tackle rumor control, most approaches grapple with a fundamental trade-off between quality and efficiency. Algorithms offering strong theoretical quality guarantees often demand significant computation time, whereas faster heuristic algorithms may compromise the effectiveness of rumor control. Given this challenge, our paper presents a detailed study of the rumor control problem and introduces novel methods to address it. First, building upon the multi-campaign independent cascade (MCIC) model, we define the truth-spreading-based rumor control (TRC) problem, which aligns with the truth-spreading methods discussed earlier. To solve this problem, we propose the Subgraph-based Greedy algorithm Optimized with CELF (SGOC), which leverages subgraph techniques and the CELF strategy for improved performance. To further enhance the SGOC algorithm, we then introduce the Shortest Path-Based Rumor Control (SPRC) algorithm, which relies on efficient shortest path calculations. Finally, to boost the efficiency of SPRC, we meticulously designed a pruning method, leading to the Improved Shortest Path-Based Rumor Control (ISPRC) algorithm.

The key contributions of this paper are summarized below:

1. We introduce the SGOC algorithm, which utilizes subgraph techniques and the CELF strategy to tackle the TRC problem under the MCIC model, demonstrating superior efficiency compared to conventional greedy algorithms.

2. To further enhance the SGOC algorithm’s performance, we carefully designed the shortest path length dictionary (SPR) and an Immune Nodes Set (INS), leading to the SPRC algorithm, which significantly improves efficiency while maintaining high quality.

3. We developed a novel pruning method to accelerate the INS construction process, resulting in the ISPRC algorithm. This algorithm further boosts efficiency compared to SPRC.

4. We conducted extensive experiments on five real-world datasets, thoroughly demonstrating the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed algorithms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the preliminary background. In Section 3, we introduce SGOC, our foundational solution for the TRC problem. Section 4 describes the proposed SPRC and ISPRC algorithms in detail. Our experiments are presented in Section 5, and finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

Rumor Control (RC), which aims to minimize the spread of rumors and misinformation in social networks, is a variant of Influence Maximization (IM) [8–10]. Current RC approaches can be categorized into three main types: node blocking methods, edge blocking methods, and truth-spreading methods [1].

Node Blocking Methods focus on reducing rumor spread by targeting and removing key nodes within the social network. For example, Matsuta and Uyematsu [11] developed a tree-structured network to locate the source of a rumor within a specific set of nodes while also estimating the distance between the selected node and the rumor source. Xie et al. [12] utilized a dominant tree structure to evaluate the impact of all candidate blocking nodes, achieving efficient rumor control through their AdvanceGreedy (AG) and GreedyReplace (GR) algorithms. Edge blocking methods identify critical edges whose removal can reduce rumor spread. Khalil et al. [5] investigated the removal of edge sets from the network to address the rumor propagation minimization problem, developing a heuristic algorithm that approximates the objective function and accelerates the rumor control process. Truth-spreading methods involve selecting influential nodes that disseminate truthful information to counteract rumor nodes. Once a node is activated by this truthful information, it becomes immune to rumors, effectively limiting their spread. Yang et al. [13] introduced a heuristic method under the competitive diffusion model, allowing for the simultaneous propagation of truth and rumors within the same network, effectively tackling the challenge of minimizing rumor propagation. Zhong et al. [14] studied the interaction with the anti-rumor mechanisms and designed both deterministic and stochastic control strategies with aperiodically intermittent control timing to minimize rumor spread.

The diffusion model is used to simulate the process of information propagation in networks. In recent years, various models have been developed to simulate this propagation, including the Independent Cascade (IC) model [8], the Linear Threshold (LT) model [8], and the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model [15], etc.

Among these, the IC model is the most classic diffusion model. In the IC model, all participants (nodes in the network) are initially divided into two categories: inactive and activated. In each subsequent round, newly activated nodes have one opportunity to activate their neighboring nodes with a probability of

However, the original Independent Cascade (IC) model cannot be directly applied to rumor control. In this context, various rumor propagation models have been developed, such as the rumor propagation model in small-world networks [16], the rumor propagation system proposed in [17], and the multi-campaign Independent Cascade (MCIC) model [18], among others. Among these, the MCIC model is more widely adopted. In the MCIC model, all nodes are classified into three states: rumor nodes, truth nodes, and inactive nodes. Both rumor nodes and truth nodes activate their neighbors in accordance with the same rules as in the IC model. When a node is activated simultaneously by both a rumor node and a truth node, it adopts the state of the truth node. Once a node is activated, its state remains unchanged, and the propagation process concludes when no new nodes can be activated. In this paper, we design rumor control algorithms based on the MCIC model, achieving effective results in controlling the spread of rumors.

Based on the previously discussed MCIC model, this paper investigates the problem of truth-spreading-based rumor control (TRC), which is defined as follows:

Definition 1: TRC problem: Given a social network

In Formula (1), E[∗] represents the expected value and

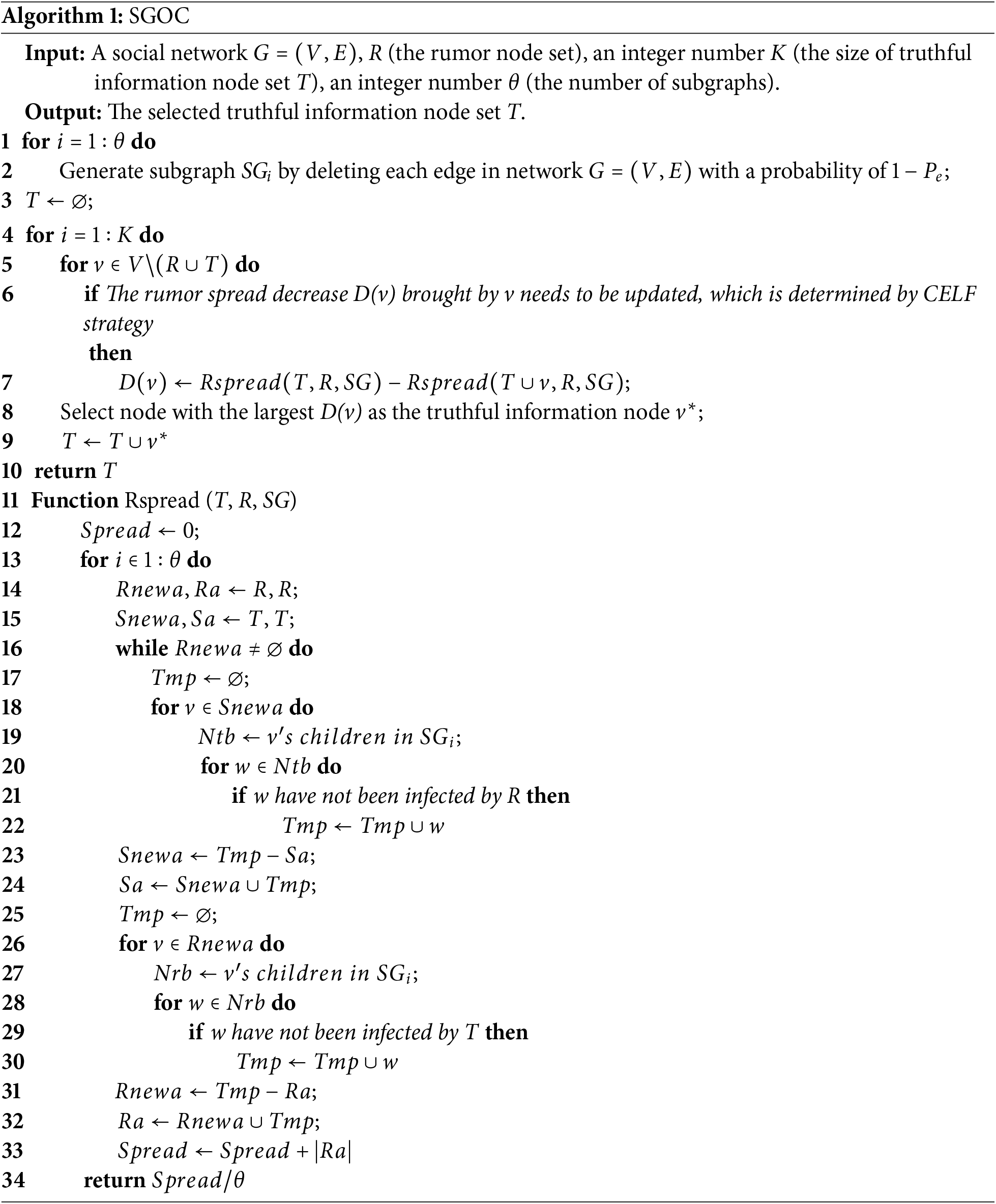

Based on the definition and analysis in Section 2.3, although the conventional greedy algorithm can provide an approximate solution with theoretical guarantees, it relies on Monte Carlo simulations (often more than 100,000 times simulations) to select truthful information nodes, making it excessively time-consuming and impractical for even medium-sized networks. Inspired by the work in [19], we introduce the Subgraph-based Greedy algorithm Optimized with CELF (SGOC) as the basic solution to tackle the TRC problem. SGOC employs a similar strategy to StaticCELF in [19], originally designed for the Influence Maximization (IM) problem. Specially, SGOC improves efficiency by replacing the Monte Carlo simulation with a subgraph technique and leverages the CELF method [20] to select the node that yields the greatest reduction in rumor spread at each iteration, however, unlike StaticCELF, SGOC calculates the spread of rumors R based on the MCIC diffusion model, rather than the IC model.

In SGOC, each edge in the network

In Algorithm 1, we begin by generating

4 The Shortest Path-Based Rumor Control (SPRC) Algorithm

Although the SGOC algorithm described in Section 3 outperforms the conventional greedy algorithm, its computational complexity remains too high for efficient application to real-world networks. To enhance the efficiency of the SGOC algorithm, we propose the Shortest Path-Based Rumor Control (SPRC) algorithm. The SPRC algorithm improves the performance of SGOC by utilizing a carefully designed dictionary data structure, SPR, and an immune nodes set, INS, both of which are derived from shortest path calculations.

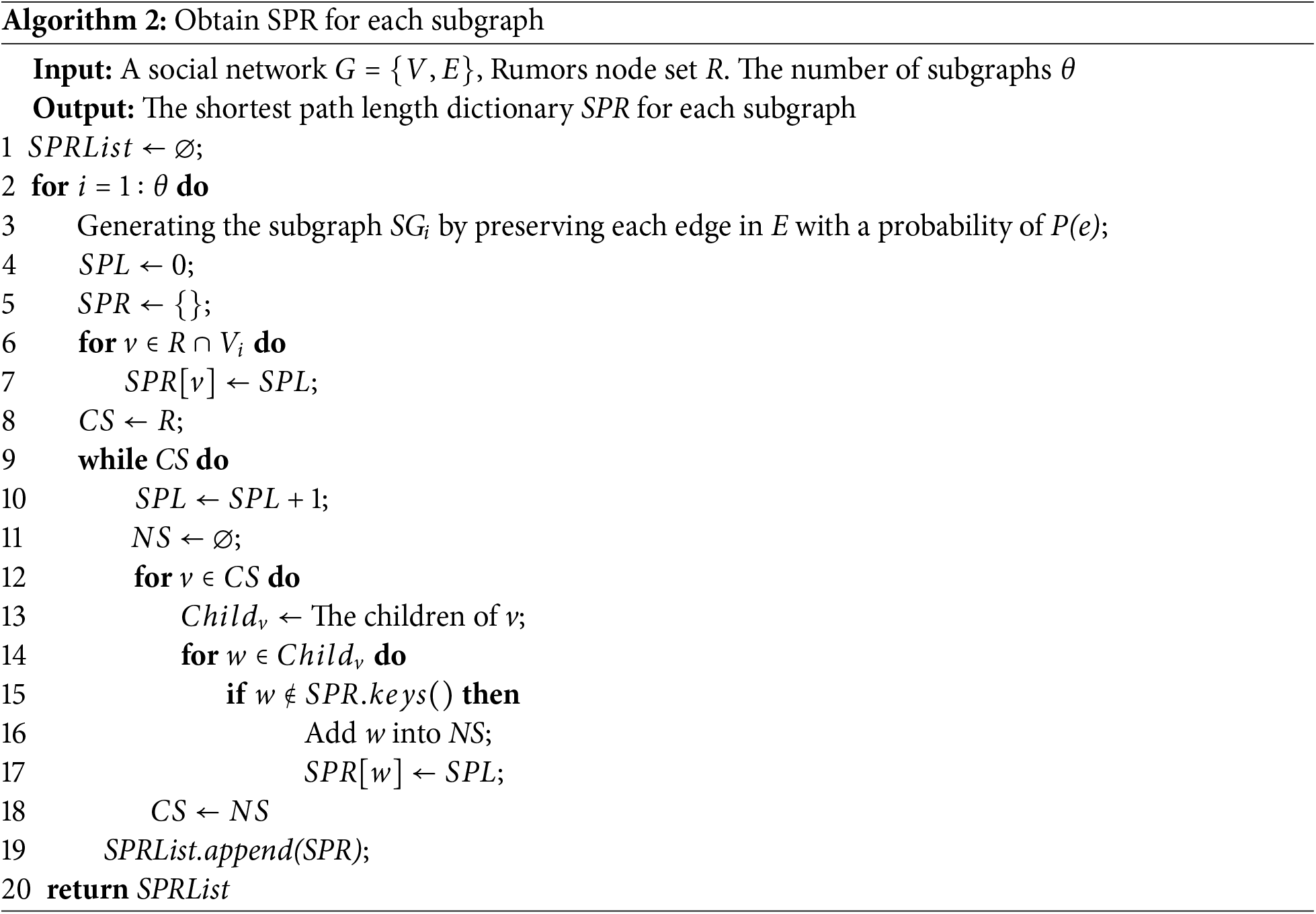

4.1 Shortest Path Length Dictionary SPR

In this subsection, we design a dictionary SPR to record the shortest path lengths between rumor node set R and each of R’s descendant

In Formula 3,

In Algorithm 2, we start by generating

In this subsection, we provide a detailed explanation of the proposed SPRC algorithm. We start by introducing the carefully designed Immune Node Set (INS), followed by an in-depth description of the SPRC algorithm, which is built on INS.

For each node

In Algorithm 3, for each node

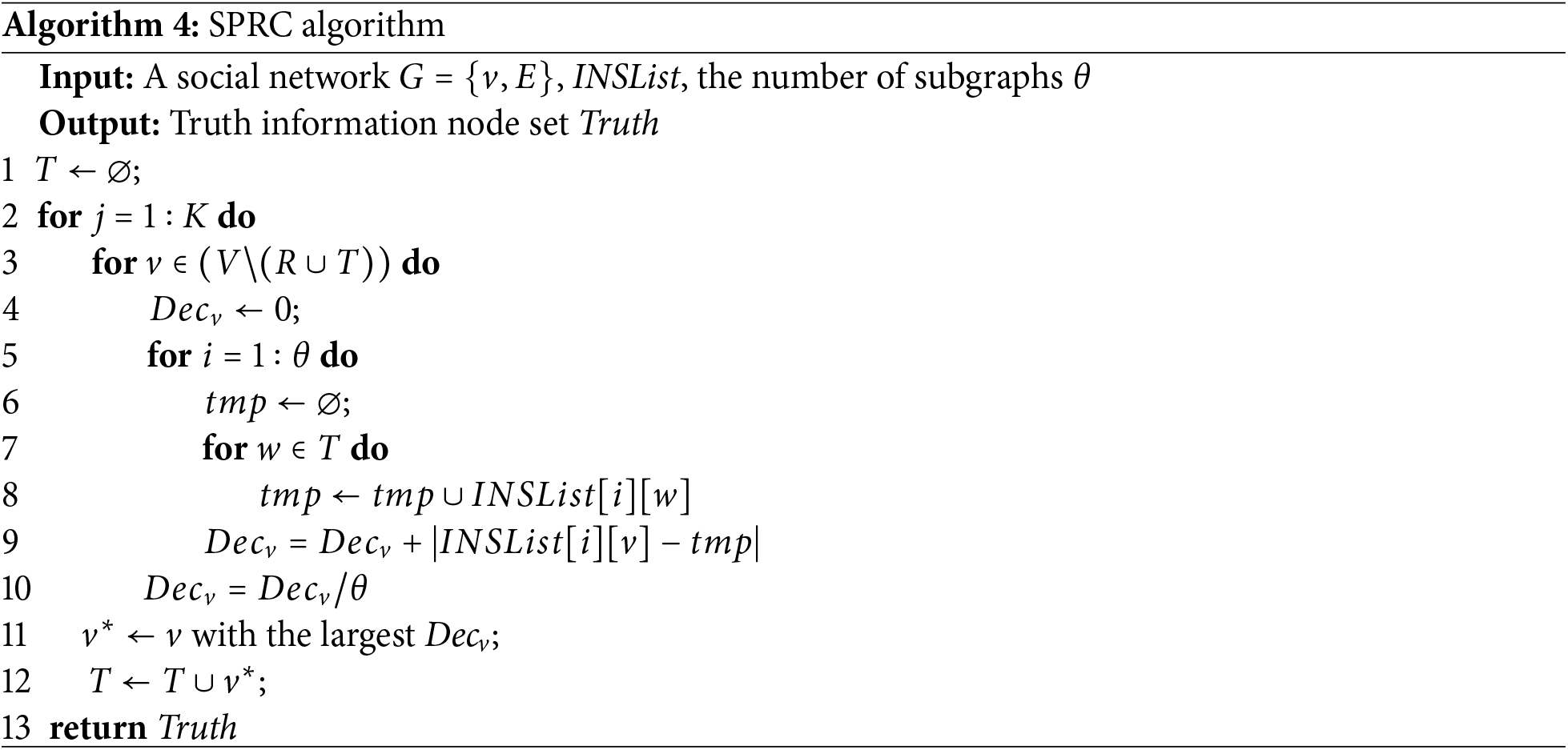

In this subsection, we introduce the proposed SPRC algorithm, which is based on the Immune Nodes Set (INS).

In SPRC, nodes are selected as truthful information seed nodes using a greedy strategy. Specifically, in each round, we choose the node that achieves the largest decrease in rumor spread as a truthful information seed node, continuing until K truthful information seed nodes have been selected.

The reduction in rumor spread caused by a particular node v is calculated based on its INS. Specially, we average the size of v’s INS in each subgraph to estimate the decrease in rumor spread contributed by v. It’s important to note that different nodes may immunize the same target node. Therefore, when calculating the reduction in rumor spread brought by a node v, we should adjust by subtracting the reduction already brought by previously selected seed nodes. The pseudo-code for the SPRC algorithm is provided in Algorithm 4. Additionally, we employ the CELF strategy to accelerate the selection process, which is not displayed in Algorithm 5 due to space limitations.

In Algorithm 4, the truthful information seed node set T is initially empty (Line 1). In each round, we calculate the decrease in rumor spread brought by each node

4.3 Improving SPRC through Pruning Method

Through analysis of the SPRC algorithm, we observed that Algorithm 3, used to obtain INSList, involves a substantial amount of computation and thus is time-consuming. In this section, we introduce a pruning method to reduce the computational burden of Algorithm 3 and present the ISPRC algorithm.

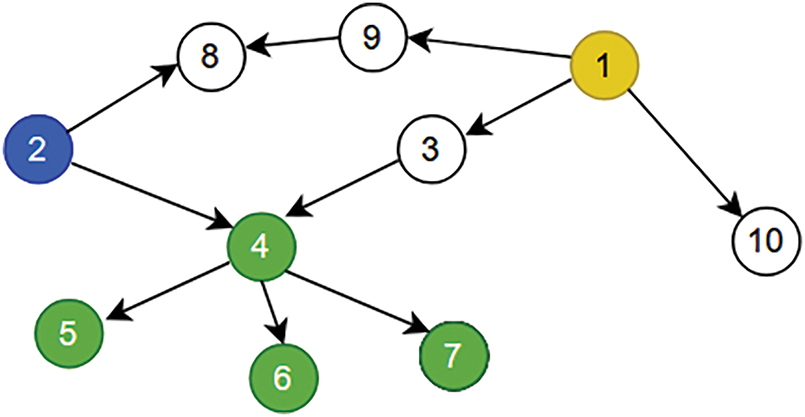

We observe that if node v cannot immunize node w, then v also cannot immunize any of w’s descendants. This is because if the shortest path from v to w is longer than the shortest path from the rumor source set R to w, then the shortest path from v to any descendant of w will likewise be longer than the corresponding path from R. Therefore, when constructing the shortest path length dictionary

Figure 1: An example of the pruning procedure, node 2 in blue represents the rumor node

Based on the observation above, within each subgraph

If this condition holds, w can be pruned from

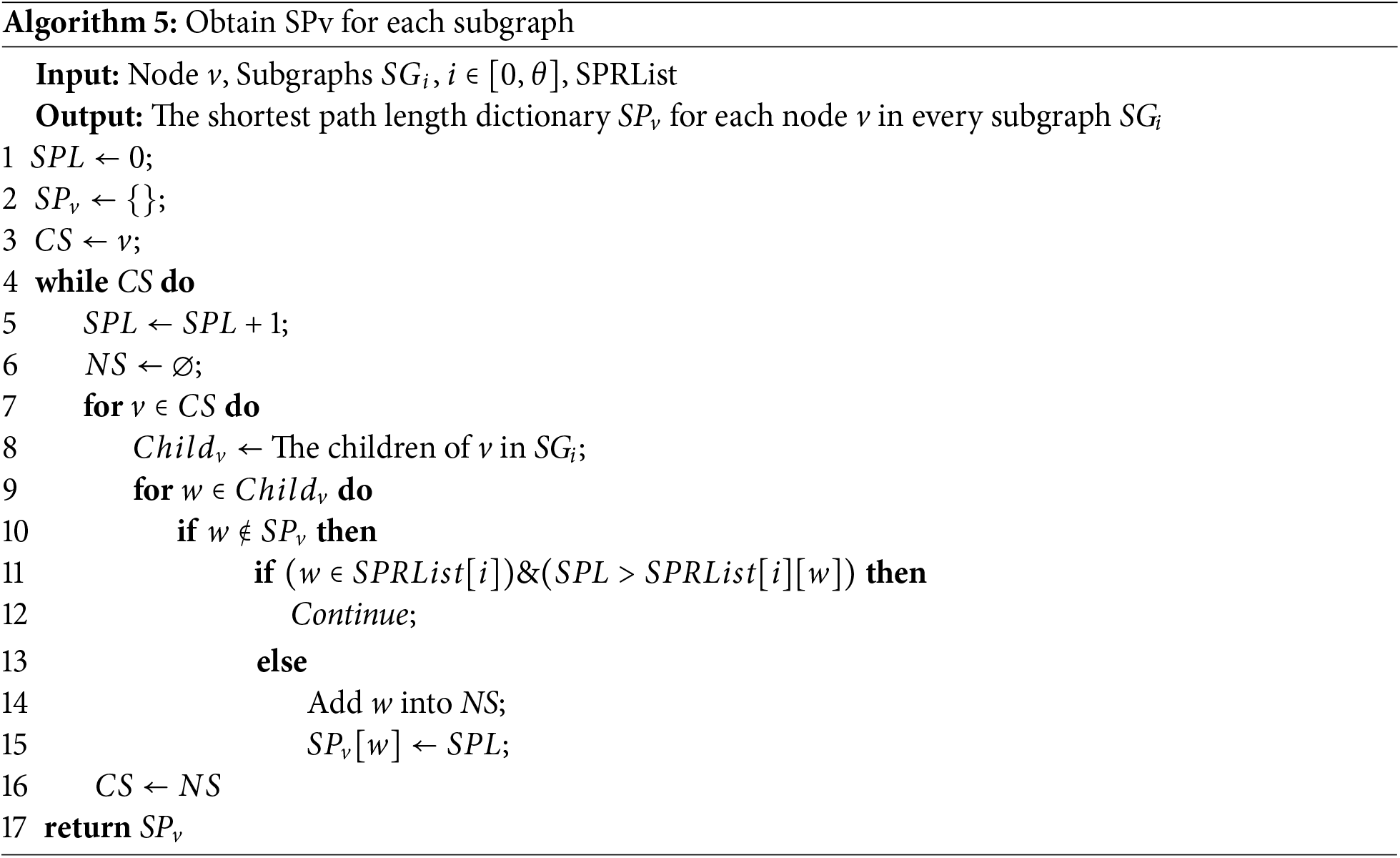

In Algorithm 5, we follow the same process as in Algorithm 2 to construct the shortest path length dictionary

In this section, we conduct experiments using five real-world datasets to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed algorithms.

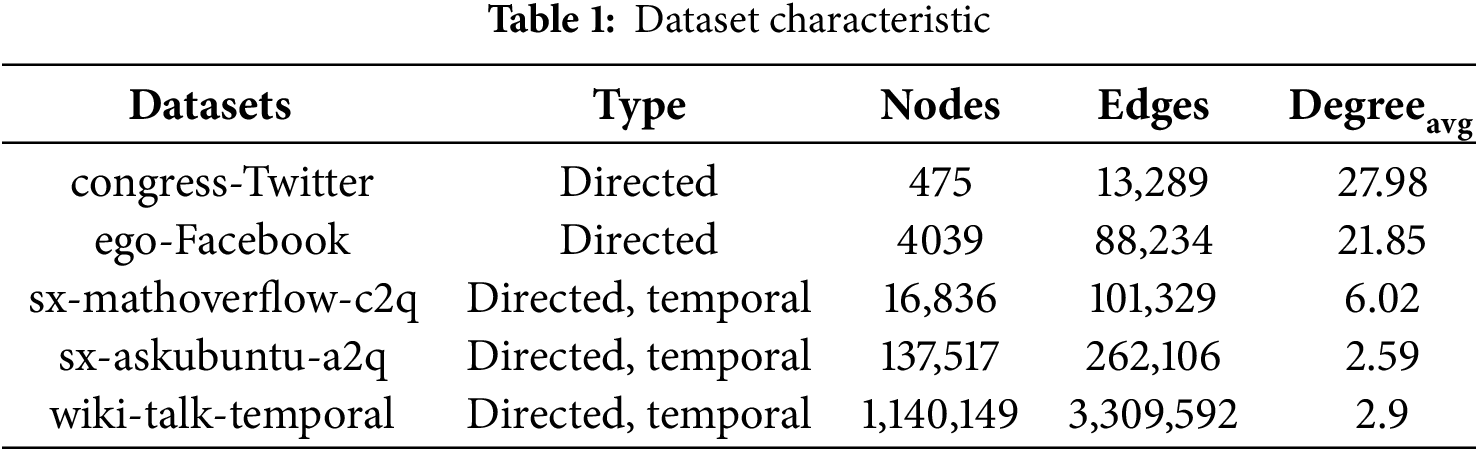

Datasets

For our experiments, we use five real-world datasets: congress-Twitter, ego-Facebook, sx-mathoverflow-c2q, sx-askubuntu-a2q and wiki-talk-temporal. These datasets are available at http://snap.stanford.edu/data/index.html (accessed on 21 July 2025). The congress-Twitter dataset represents the interaction network of the US Congress on Twitter, while the ego-Facebook dataset include connections from

Baselines

Five typical methods are selected as baselines for comparison:

1. Max Degree (MD) method: In this method, the K nodes with the highest out-degree are selected as truthful information node set T.

2. Max Betweenness (MB) method: Here, the K nodes with the largest betweenness centrality are chosen as T.

3. Random (Ran): In this method, K nodes are randomly selected from the network to form T.

4. Max k-core (MC): K nodes with the largest k-core value are selected as T.

5. TIBMM [21]: TIBMM obtains a certain number of Temporal Reverse Reachable Sets using a reverse BFS method. Then, it selects K nodes to form T from these Temporal Reverse Reachable Sets using a Max Cover approach.

Traditional greedy algorithm which is too time-consuming to yield results within an acceptable timeframe was not selected as a baseline due to their high computational cost.

Parameters settings

We conduct our experiments using the MCIC model described in Section 2.2. It is important to note that when both a rumor node and a truthful information node attempt to activate a node simultaneously, the node will be activated by the truthful information node. Additionally, the propagation probability

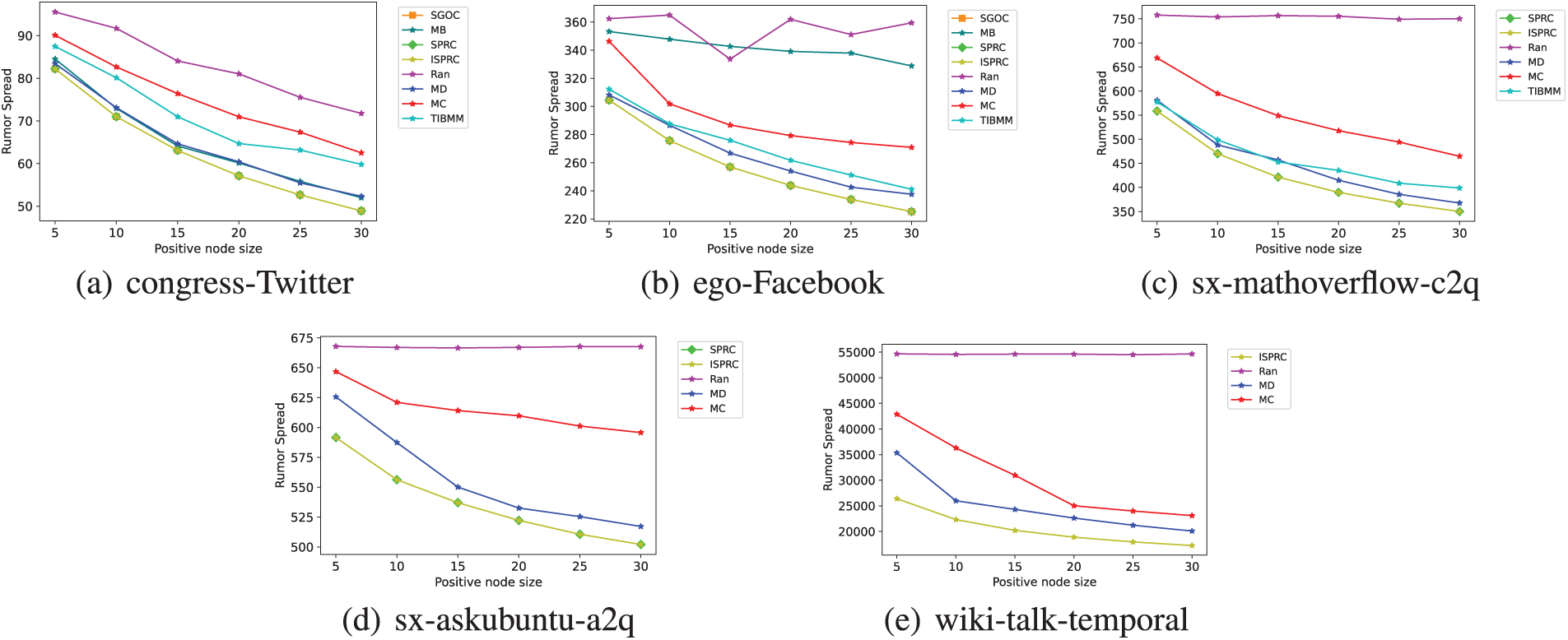

In this subsection, we assess the effectiveness of various algorithms by examining the total spread of rumor set R. Specifically, a smaller total spread indicates more effective rumor control by the corresponding algorithm. Figs. 2–4 illustrate the experimental results for eight algorithms across five datasets, with the sizes of R and T varying within the ranges [10, 20, 30] and [5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30], respectively. Results for some algorithms on sx-mathoverflow-c2q, sx-askubuntu-a2q, and wiki-talk-temporal datasets could not be obtained within a few days, so they are omitted in Figs. 2a–c, 3a–c, 4a–c.

Figure 2: Total rumor spread across different datasets with virous K under constant model when

Figure 3: Total rumor spread across different datasets with virous K under constant model when

Figure 4: Total rumor spread across different datasets with virous K under constant model when

From Figs. 2–4 we observe that the proposed SGOC, SPRC, and ISPRC algorithms consistently achieve the smallest total rumor spread, indicating their superior effectiveness in rumor control. Regarding the MB, MD, MC, and TIBMM algorithms, they show fluctuating performance, but they all underperform compared to SGOC, SPRC, and ISPRC, while the Random algorithm consistently exhibits poor performance across all datasets. This is because the SGOC, SPRC, and ISPRC algorithms proposed in this paper are based on greedy approaches, enabling them to provide approximations to the optimal solutions when solving the TRC problem (whose propagation function is submodular and monotonic), offering theoretical quality assurance in all scenarios.

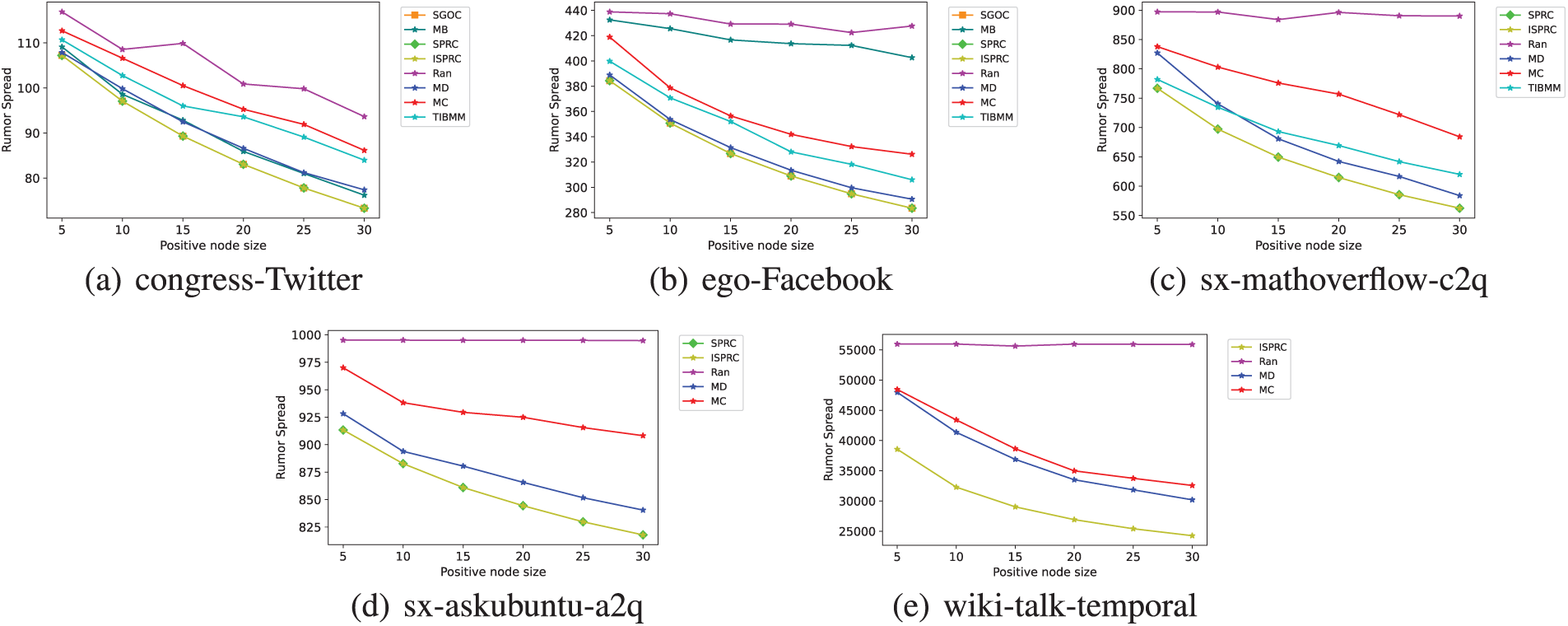

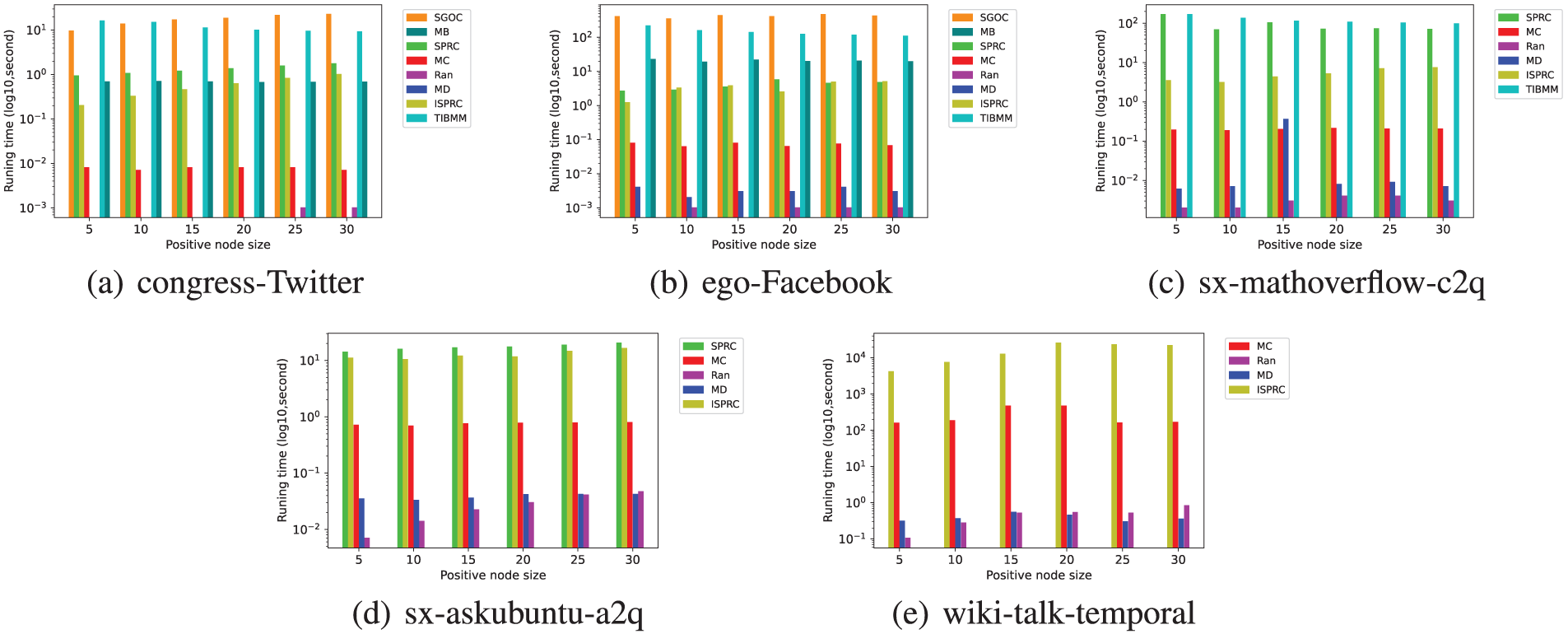

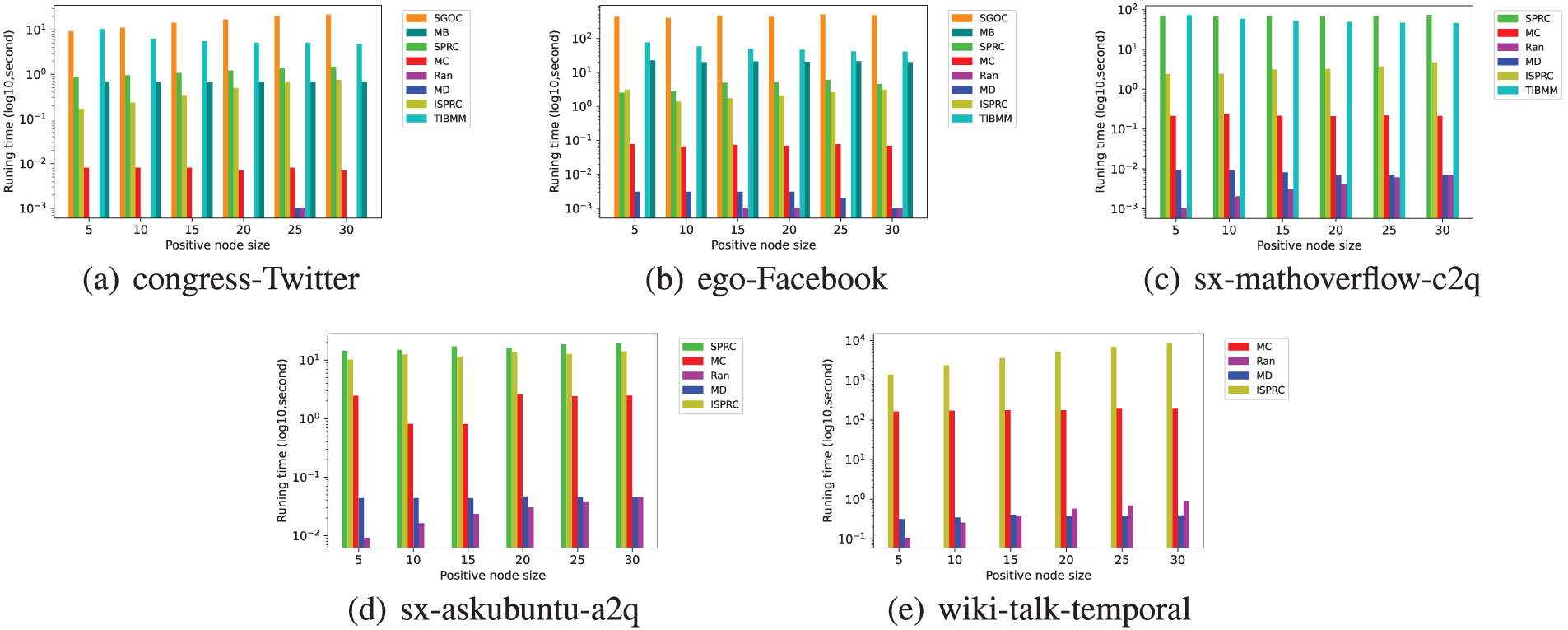

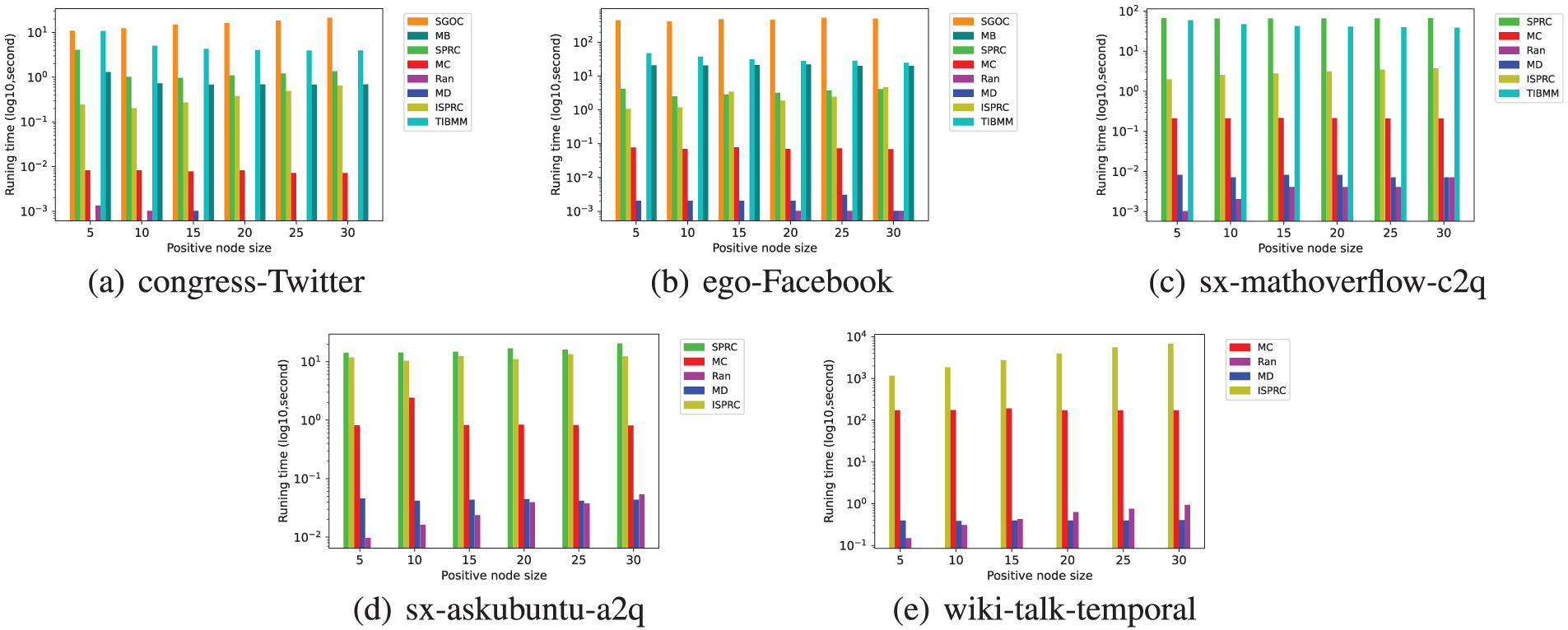

In this subsection, we evaluate the efficiency of various algorithms by comparing their total runtime. Figs. 5–7 show the runtime of different algorithms across five datasets, where |R| ranges between [10, 20, 30] and |T| ranges between [5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30]. Due to excessive runtime, we do not present the experimental results for some algorithms on the sx-mathoverflow-c2q, sx-askubuntu-a2q, and wiki-talk-temporal datasets.

Figure 5: Runtime of eight algorithms across different datasets with varying k under constant model when

Figure 6: Runtime of eight algorithms across different datasets with varying k under constant model when

Figure 7: Runtime of eight algorithms across different datasets with varying k under constant model when

From Figs. 5–7, we observe that the MD, MB, MC, TIBMM, and Ran algorithms exhibit varying execution times, some longer and some shorter. As discussed in Section 4.4, these algorithms do not perform as well as SGOC, SPRC, and ISPRC.

Among the three algorithms (SGOC, SPRC, and ISPRC) that provide theoretical quality guarantees, ISPRC consistently consumes the shortest runtime, followed by SPRC, with SGOC taking the longest time. This can be attributed to the fact that the SPRC algorithm uses an Immune Nodes Set (INS) data structure which accelerates the execution of the algorithm, while the ISPRC algorithm further speeds up the construction process of INS through a pruning method, thereby decreasing computational complexity and improving the running speed.

In this paper, we study the problem of truth-spreading-based rumor control (TRC), which aims to curb the spread of rumors by disseminating truthful information within a social network. Specifically, we first examine the TRC problem under the MCIC model, then propose the SGOC algorithm as a foundational solution for the TRC problem. To enhance the efficiency of SGOC, we introduce the shortest-path-based rumor control algorithm, SPRC, which leverages a shortest path length dictionary (SPR) and an Immune Nodes Set (INS). To further improve the efficiency of the SPRC algorithm, we employ a pruning method to accelerate the construction of INS and propose the ISPRC algorithm. Experiments on five real-world datasets demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed algorithms. In the future, we aim to design diffusion models that more accurately match the rumor propagation process and to develop even more efficient algorithms for rumor control in social networks.

Acknowledgement: We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the relevant projects and express our thanks to all the experts involved in the review process.

Funding Statement: This work was partially supported by Research Programs of Henan Science and Technology Department (252102210022, 232102210054), Henan Province Key Research and Development Project (231111212000), Henan Center for Out-standing Overseas Scientists (GZS2022011), Henan Province Collaborative Innovation Center of Aeronautics and Astronautics Electronic Information Technology, Henan International Joint Laboratory of Aerospace Intelligent Technology and Systems.

Author Contributions: Suqiao Li: Writing—original draft, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization. Taotao Cai: Visualization, Data curation, Software. Lingling Li: Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Xuezhuan Zhao: Software, Resources, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zareie A, Sakellariou R. Minimizing the spread of misinformation in online social networks: a survey. J Netw Comput Appl. 2021;186(5439):103094. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zheng J, Pan L. Least cost rumor community blocking optimization in social networks. In: 2018 Third International Conference on Security of Smart Cities, Industrial Control System and Communications (SSIC); 2018 Oct 18–19; Shanghai, China: IEEE; 2018. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ssic.2018.8556739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wijayanto AW, Murata T. Effective and scalable methods for graph protection strategies against epidemics on dynamic networks. Appl Netw Sci. 2019;4(1):18. doi:10.1007/s41109-019-0122-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dey P, Roy S. Centrality based information blocking and influence minimization in online social network. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS); 2017 Dec 17–20; Bhubaneswar, India: IEEE; 2017. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ANTS.2017.8384117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Khalil E, Dilkina B, Song L. Cuttingedge: influence minimization in networks. In: Proceedings of Workshop on Frontiers of Network Analysis: Methods, Models, and Applications at NIPS; 2013; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

6. Arazkhani N, Meybodi MR, Rezvanian A. Influence blocking maximization in social network using centrality measures. In: 2019 5th Conference on Knowledge Based Engineering and Innovation (KBEI); 2019 Feb 28–Mar 1; Tehran, Iran: IEEE; 2019. p. 492–7. doi:10.1109/KBEI.2019.8734920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fang Q, Chen X, Nong Q, Zhang Z, Cao Y, Feng Y, et al. General rumor blocking: an efficient random algorithm with martingale approach. Theor Comput Sci. 2020;803(6):82–93. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2019.05.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kempe D, Kleinberg J, Tardos É. Maximizing the spread of influence through a social network. In: Proceedings of the Ninth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Washington, DC, USA: ACM; 2003. p. 137–46. doi:10.1145/956750.956769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Borgs C, Brautbar M, Chayes J, Lucier B. Maximizing social influence in nearly optimal time. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. Portland, OR, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 2014. p. 946–57. doi:10.1137/1.9781611973402.70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang K, Cai T, Liu Z, Teng S, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Efficient influential nodes tracking via link prediction in evolving networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(12):20191–202. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3542852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Matsuta T, Uyematsu T. On the distance between the rumor source and its optimal estimate in a regular tree. In: 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT); 2019 Jul 7–12; Paris, France: IEEE; 2019. p. 2334–8. doi:10.1109/isit.2019.8849442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xie J, Zhang F, Wang K, Lin X, Zhang W. Minimizing the influence of misinformation via vertex blocking. In: 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE); 2023 Apr 3–7; Anaheim, CA, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 789–801. doi:10.1109/ICDE55515.2023.00066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang L, Li Z, Giua A. Containment of rumor spread in complex social networks. Inf Sci. 2020;506(5439):113–30. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.07.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhong X, Yang Y, Deng F, Liu G. Rumor propagation control with anti-rumor mechanism and intermittent control strategies. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2023;11(2):2397–409. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2023.3277465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pastor-Satorras R, Castellano C, Van Mieghem P, Vespignani A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev Mod Phys. 2015;87(3):925–79. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.87.925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zanette DH. Dynamics of rumor propagation on small-world networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2002;65(4 Pt 1):041908. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.65.041908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Li B, Zhu L. Turing instability analysis of a reaction–diffusion system for rumor propagation in continuous space and complex networks. Inf Process Manag. 2024;61(3):103621. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Budak C, Agrawal D, El Abbadi A. Limiting the spread of misinformation in social networks. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on World Wide Web. Hyderabad, India: ACM; 2011. p. 665–74. doi:10.1145/1963405.1963499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cheng S, Shen H, Huang J, Zhang G, Cheng X. StaticGreedy: solving the scalability-accuracy dilemma in influence maximization. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management. San Francisco, CA, USA: ACM; 2013. p. 509–18. doi:10.1145/2505515.2505541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Leskovec J, Krause A, Guestrin C, Faloutsos C, VanBriesen J, Glance N. Cost-effective outbreak detection in networks. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. San Jose, CA, USA: ACM; 2007. p. 420–9. doi:10.1145/1281192.1281239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ali Manouchehri M, Helfroush MS, Danyali H. Temporal rumor blocking in online social networks: a sampling-based approach. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2022;52(7):4578–88. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2021.3098630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools