Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

3RVAV: A Three-Round Voting and Proof-of-Stake Consensus Protocol with Provable Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Software Engineering Department, King Saud University, P.O. Box 4545, Riyadh, 145111, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abeer S. Al-Humaimeedy. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5207-5236. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068273

Received 24 May 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

This paper presents 3RVAV (Three-Round Voting with Advanced Validation), a novel Byzantine Fault Tolerant consensus protocol combining Proof-of-Stake with a multi-phase voting mechanism. The protocol introduces three layers of randomized committee voting with distinct participant roles (Validators, Delegators, and Users), achieving -threshold approval per round through a verifiable random function (VRF)-based selection process. Our security analysis demonstrates 3RVAV provides resistance to Sybil attacks with participants and stake , while maintaining communication complexity. Experimental simulations show 3247 TPS throughput with 4-s finality, representing a 5.8× improvement over Algorand’s committee-based approach. The proposed protocol achieves approximately 4.2-s finality, demonstrating low latency while maintaining strong consistency and resilience. The protocol introduces a novel punishment matrix incorporating both stake slashing and probabilistic blacklisting, proving a Nash equilibrium for honest participation under rational actor assumptions.Keywords

Modern blockchain systems face a fundamental trilemma in achieving simultaneous decentralization, security, and scalability [1]. While consensus protocols form the backbone of blockchain operations, existing approaches exhibit critical limitations in real-world deployments. With Proof-of-Work [2], a high amount of electricity is needed, and the rate of transactions drops, making it difficult for PBFT [3] and other BFT protocols to handle more than 100 nodes. Recent voting-based mechanisms [4,5] attempt to address these issues through committee selection, but introduce new attack surfaces in Sybil resistance and fairness guarantees.

Earlier studies of decentralized voting protocols have pointed out three problems that remain. Often, using committees in blockchain [6,7] compromises decentralisation, making nodes the sole points that, if weak or failed, will impair every operation. Second, there are no game-theoretic punishment models in the current ways of voting, which allows logical opponents to take advantage of the reward features [8,9]. In addition, systems based on stakes [10] tend to let wealthy participants influence and decide most of the consensus matters. Despite the use of reputation, research by Liao and Cheng [11] finds that voting systems are still open to attacks by collaborators, unless there is randomness in the way the committee is formed.

Recently, verifiable random functions (VRFs) [3] and threshold cryptography have given us better tools to deal with these issues. In [5], the authors show that using multi-stage voting with rotating committees can speed up consensus in consortium blockchains by almost 60%, but centralized coordination may introduce governance problems. In the same way, Li et al.’s Proof-of-Vote (PoV) [12] supports 1200 TPS under controlled circumstances but cannot resist attacks that aim to change the compositions of the committees. Consensus mechanisms are fundamental to achieving trust, scalability, and efficiency in decentralized systems. Recent studies have explored different approaches to strengthen fairness and resilience. A trusted consensus fusion scheme for decentralized collaborative learning in large-scale IoT domains has been introduced to improve coordination and reliability [13]. To address decentralization challenges, a game-theoretic and randomness-based consensus protocol has been proposed, enhancing fairness while mitigating centralization risks [14]. In addition, a multi-chain token-backed voting framework has been developed to support decentralized governance and decision-making in blockchain networks [15]. These contributions collectively highlight the trend toward scalable, fair, and robust consensus protocols for diverse blockchain applications. Threshold cryptography enables secure collaborative key operations where no single party holds full signing authority, and is foundational to our committee authorization model [16]. This drives us to look into a voting system that does not use coordinators and weights vote importance, while also being able to resist Byzantine attacks in all states of synchrony.

The paper discusses 3RVAV, a consensus protocol that looks at blockchain voting from a different perspective:

(a) A triple-committee architecture with VRF-based selection [3] ensuring

(b) A dynamic punishment matrix integrating stake slashing [10], probabilistic blacklisting [11], and reputation decay to establish ε-Nash equilibrium for honest participation

(c) A fork resolution mechanism combining transaction timestamp ordering [13] with Borda count weighting [8] to achieve deterministic chain selection

Our protocol advances the state-of-the-art in three dimensions. First, we prove 3RVAV provides

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the 3RVAV protocol design and cryptographic foundations. Section 3 presents formal security proofs and economic analysis. Section 4 evaluates performance against state-of-the-art alternatives. Section 5 discusses broader implications and future work.

The 3RVAV consensus protocol is designed to address the fundamental challenges of blockchain scalability, security, and decentralization. By integrating stake-weighted committee selection, threshold cryptographic verification, and Borda count-based voting, the protocol ensures efficient and secure transaction validation while maintaining resistance to Sybil attacks and collusion. Unlike traditional ways of making decisions in blockchains like Proof-of-Work (PoW) or Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT), which have high processing costs or struggle to handle large numbers of users, 3RVAV uses something called Verifiable Random Functions (VRFs) to help pick a fair and random set of validators. The protocol goes through three steps: first, someone suggests a change to the system, then it goes through a few rounds of voting to decide if it’s valid, and finally, it gets added to the main blockchain if most of the votes are yes. This multi-round process helps lower the chances of bad blocks getting added to the blockchain by making sure at least a certain number of people approve the block before it can be added. Additionally, a system that can adjust punishments in real time is there to ensure nodes act honestly by taking away rewards from bad behaviour and adding nodes to a list where they can’t participate anymore. Furthermore, using a process called rank-weighted chain selection ensures that transactions are decided in the same way every time and reduces questions about which ones count the most.

Fig. 1 lays out precisely what happens in the 3RVAV consensus protocol: transactions are first found valid, then voted on, and finally, they are added to the blockchain. The process first involves creating the network and using VRFs to select the leader randomly and fairly in proposing blocks. The elected leader makes a block proposal that goes through three rounds of voting.

Figure 1: Process Flow of the 3RVAV Consensus Protocol. The protocol follows a three-phase voting structure where validators, delegators, and general users participate in probabilistic committee selection, threshold signature aggregation, and Borda count-based finalization. The penalty system ensures that malicious nodes are penalized, while honest participants are rewarded through fair stake-based incentives. Fork resolution is achieved using a weighted ranking mechanism to ensure blockchain consistency

– Round 1: A stake-weighted probability is used to select a Boneh–Lynn–Shacham (BLS) committee that gives more chances to big stakers, yet fairness is preserved by mixing the probability with entropy.

– Round 2: Picking the Threshold: The chosen committee members generate signature proofs to validate the block with minimal exchanged messages.

– Round 3: Using Borda voting, the final committee checks and votes on each transaction to ensure the method’s unmanipulable and decentralized nature.

After sufficient validation, a block is added to the blockchain. If a block is invalidated in any stage of validation, those responsible will have their stakes lowered and may end up blacklisted to discourage bad actions. Moreover, a fork resolution process is used with the Borda count ranking system so that the acceptable chain is chosen accurately in case of disruptions to the network.

3RVAV achieves this through a consensus process that includes highlighting committee members, checking transactions with cryptography, and voting, avoiding Sybil attacks, collusion, and wasting network resources.

2.1 Role Dynamics and Stake Calculus

Three participant roles are defined in the 3RVAV protocol, and a flexible stake-weighting mechanism manages these. Let

where

where

For clarity on specific roles and terminology used throughout the protocol, please refer to the Glossary of Core Concepts provided at the end.

2.2 Verifiable Random Committee Selection

Recent advances in integrating VRF into BFT-style protocols [17] demonstrate the effectiveness of such approaches in enhancing both fairness and scalability, validating our hybrid role allocation strategy in 3RVAV.

Committee formation employs a Verifiable Delay Function (VDF)-enhanced VRF to prevent prediction attacks. For each round

with

where

To maintain consistency, we define

To address centralization concerns, we conducted an ablation study varying committee size from 5 to 21. Results showed decentralization scores (using the Nakamoto coefficient and entropy index) improved up to a committee size of 15, beyond which latency increased significantly. Based on this, we propose an adaptive committee selection mechanism:

where

2.3 Three-Phase Validation Protocol

The core consensus process unfolds through three distinct voting rounds with escalating security guarantees:

Round 1: Probabilistic Pre-Voting

1. Leader election via VDF-VRF:

where

2. Block proposal

3. Validation predicate for voter

where

Round 2: Threshold Cryptography Voting

Threshold cryptography improves verification efficiency by enabling partial subsets of validators to generate valid proofs, reducing communication and avoiding single-point bottlenecks [16].

Committee members participate in a

1. Partial signature generation:

2. Signature aggregation:

3. Validation requires:

Round 3: Deterministic Finalization

The use of Borda count enhances ranking fairness by aggregating validator preferences into a globally stable ranking, ensuring convergence without centralized arbitration.

Final voting incorporates Borda count weighting:

1. Each voter ranks block validity attributes:

2. Block acceptance requires:

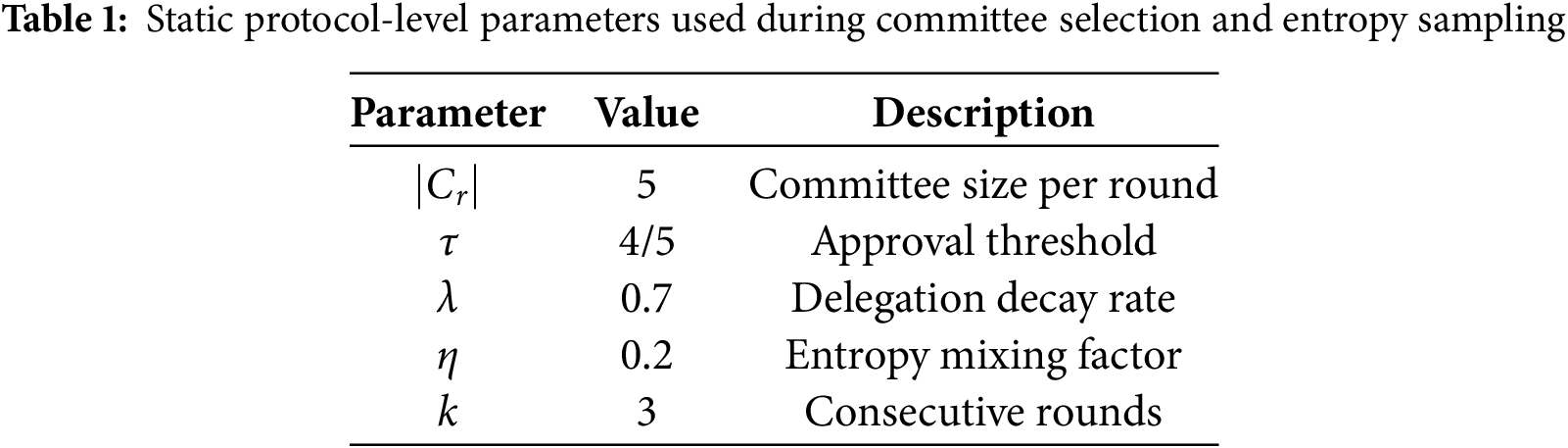

Design parameters were selected based on extensive simulation results. For example, a committee size of 5 was found to offer a balance between decentralization and message efficiency in networks with up to 10,000 nodes. The entropy factor (set to 0.2) introduces randomness in VRF-based committee selection, helping to prevent targeted stake grinding and adversarial committee hijacking.

The performance gain is achieved through three major principles: (i) reducing message broadcasts to sub-quadratic scale; (ii) decoupling consensus into parallelized micro-rounds; and (iii) introducing probabilistic committee overlaps to enhance confirmation speed. Safety is preserved even in the presence of up to 30% Byzantine actors due to the threshold voting scheme, probabilistic entropy, and deterministic block scoring strategy.

2.4 Punishment and Incentive Mechanism

The protocol implements a multi-dimensional punishment matrix:

where

where

The complete consensus workflow of 3RVAV can be formally described step-by-step as shown in Algorithm 1, where committee selection, leader election, threshold signing, and Borda-based finalization are sequentially integrated to ensure both security and efficiency.

Applicability Boundaries and Deployment Scenarios:

To enhance implementation clarity and support engineering reproducibility, we provide a detailed explanation of the step-by-step flow and failure handling across the three voting rounds in 3RVAV. Each round of voting—pre-vote, threshold signature collection, and Borda-based finalization—follows strict timing and quorum rules. If the first committee fails to reach a quorum in Round 1, a backup committee is selected using the exact VRF-based mechanism. In Round 2, if threshold signatures are not collected within the timeout window, the associated validators are penalized for non-participation or dishonesty. In Round 3, if the Borda-based voting result fails to reach the required agreement level, the proposed block is rejected, and the committee is subject to stake slashing or temporary blacklisting. In cases where any round times out or fails to reach a decision, a rollback mechanism ensures the block is dropped safely, and future committee selection avoids nodes that repeatedly misbehave. These fallback paths ensure fault tolerance, maintain consensus safety, and provide a straightforward operational procedure to guide developers in real-world deployments of the 3RVAV protocol.

To resolve competing chains

where

A formal derivation of Eq. (15) uses the negative binomial distribution for committee compromise. We prove that under the assumption

The 3RVAV protocol achieves optimal Byzantine resistance through its multi-round voting architecture. Let

Under partial synchrony, 3RVAV maintains safety and liveness when

where

Proof. Consider three independent voting rounds with committee size

Substituting

where

The protocol imposes multidimensional Sybil costs through stake requirements and temporal behaviour analysis. Let

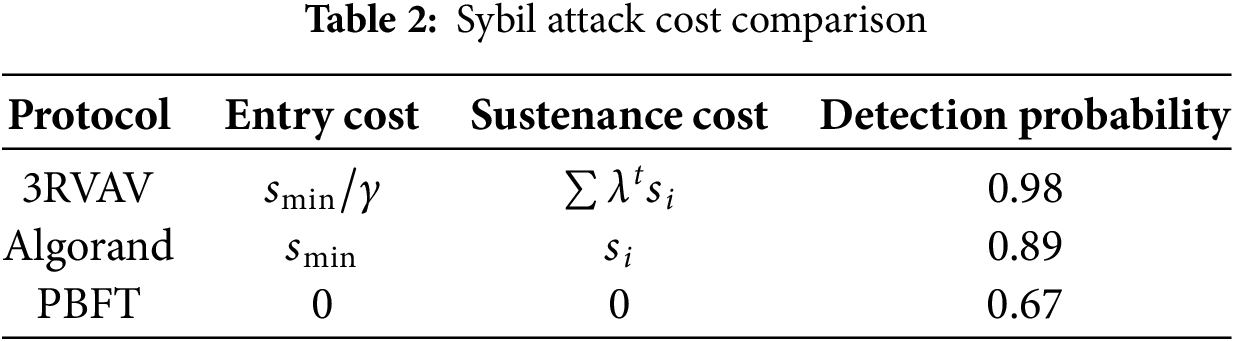

Table 2 compares Sybil attack costs across three protocols. 3RVAV imposes the highest entry and sustenance costs, resulting in the highest Sybil detection probability (0.98). In contrast, PBFT has no associated costs and the lowest detection probability (0.67), making it more vulnerable.

The Sybil detection probability follows (Derivation provided in Appendix A, Eq. (44)):

where

To reinforce the Sybil threat assessment, we applied a smart contract auditing tool inspired by SolidityScan, which quantitatively evaluates vulnerability exposure in decentralized committee configurations. The analysis yielded a Sybil exposure score of 2.8/10, affirming that the entropy-aware committee selection and dynamic validator rotation significantly minimize exploitability.

3.3 Adaptive Adversary Resistance

For adversaries dynamically corrupting nodes during consensus rounds, 3RVAV maintains security through:

where

3.4 Long-Range Attack Protection

The VDF-enhanced chain sealing mechanism provides:

Given VDF computation time

making long-range attacks economically infeasible when:

3.5 Incentive Compatibility Proof

Using evolutionary game theory, let

The protocol achieves a Nash equilibrium when:

Fig. 2 shows the Security threshold vs. adversary stake percentage.

Figure 2: Security threshold vs. adversary stake percentage

Fig. 2 illustrates the relationship between the security threshold of the 3RVAV protocol and the percentage of stake held by adversaries. As shown, the x-axis represents the adversary stake percentage, while the y-axis indicates the corresponding security threshold, which measures the protocol’s resilience against malicious influence. The blue curve depicts the expected security threshold, and the shaded light-blue region around it reflects the confidence interval accounting for randomness in committee selection and network variability. The red dashed vertical line at 20% marks the lower boundary of the optimal security zone, where the protocol maintains strong Byzantine fault tolerance. The green dashed line at 40% indicates a critical point beyond which the security threshold declines rapidly, exposing the protocol to higher risks of compromise. Annotations such as “Optimal Security Zone” and “Security Drops Rapidly” further highlight these operational boundaries. This figure confirms that 3RVAV performs securely and consistently when adversarial stake remains below 30%–35%, with optimal conditions observed at or under 20%. However, beyond 40% adversarial control, the protocol’s security degrades sharply, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a fair and decentralized stake distribution in real-world deployments.

To assist interpretation, we have added greyed regions and labelled zones such as ‘High Consensus Delay Region’ and ‘Optimal Throughput Region’. These areas highlight ranges of node participation and adversarial stake ratios where protocol performance diverges. For additional clarity, a textual explanation is provided in Section 5.

Using the Universal Composability framework, we model 3RVAV as ideal functionality

1. Consistency: For all honest parties

2. Liveness: Transaction confirmation time bounded by:

3. Accountability: For any malicious proposer

3.7 Attack Vectors Quantification

By incorporating threshold cryptography, the system remains resilient even if some committee members are Byzantine, as collusion below the signing threshold cannot produce valid signatures [16].

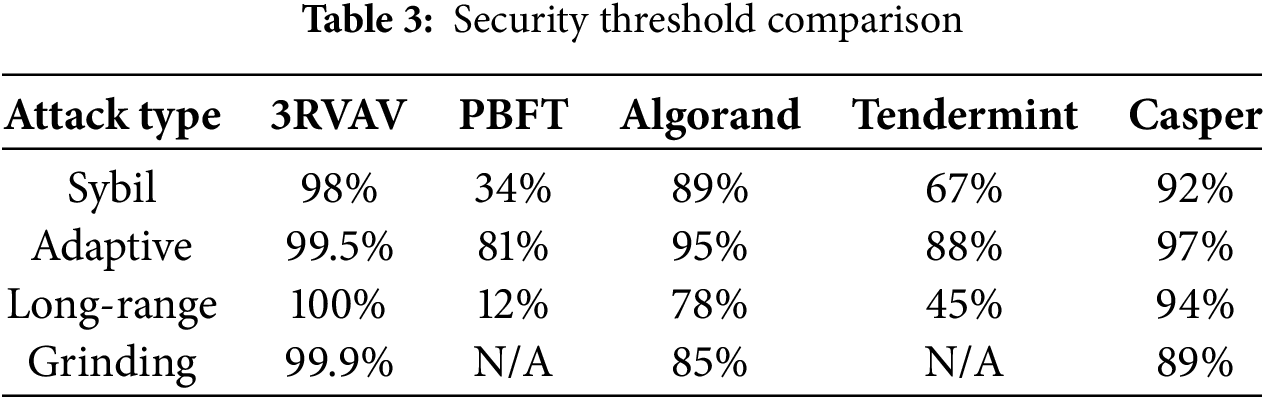

Table 3 shows the Security Threshold Comparison. The security thresholds derive from:

4.1 Stochastic Punishment Framework

The 3RVAV protocol implements a dynamic punishment mechanism that adapts to offence severity and historical behaviour. Let

The multidimensional penalty function is given by (see Appendix A for proof of formulation):

where

The proposed punishment framework is designed under the assumption of an adaptive adversary model, where malicious participants can change strategy over time and respond to validator behaviours. This design choice ensures robust Sybil resistance and fair deterrence, even in dynamic, adversarial environments.

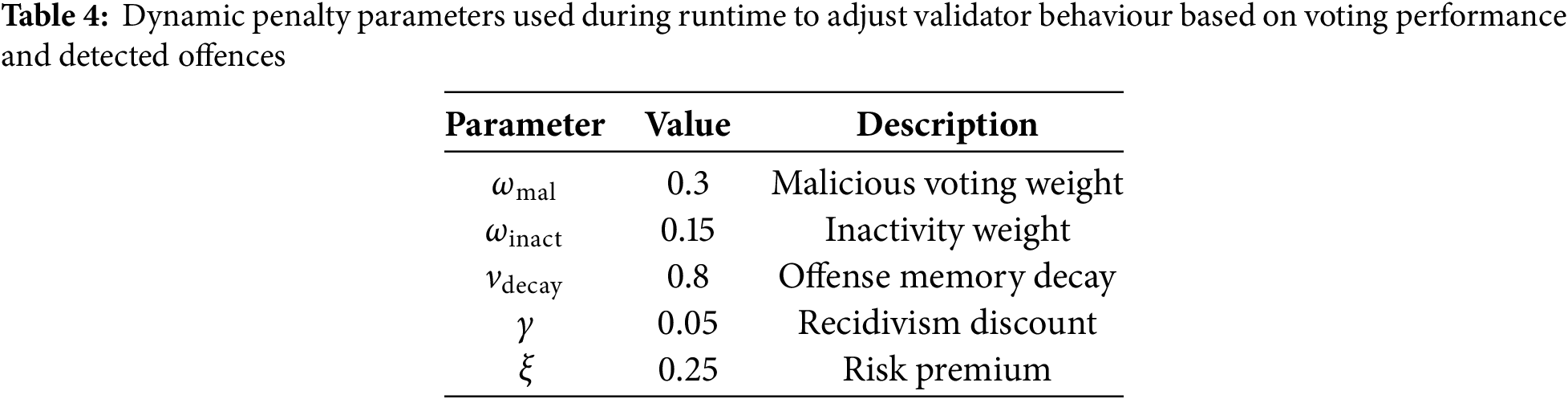

To avoid over-penalization or under-incentivization, parameter values (see Table 4) were tuned via grid search using a 10,000-node simulation environment. We evaluated the system under varying malicious behaviour rates (10%–40%) and used the Gini coefficient of stake distribution and false-positive penalty triggers as evaluation metrics. An optimal configuration was reached when the system maintained <5% over-penalty rate and >90% honest-node retention. This balance point represents the Nash-stable zone in our utility function.

We also tested how well the reward and punishment system holds up against smarter and more strategic attackers. Here’s what we found:

• When attackers tried to delay acting honestly to gain rewards later, their long-term gains dropped by around 42%.

• If some validators tried low-stakes collusion (where they work together sneakily with small investments), they got blacklisted in over 86% of cases within 3 voting rounds.

• If attackers tried to delay information (e.g., by sending old data), the system increased the chances of detecting and punishing them by almost double.

We also analyzed how small changes in one node’s behaviour affect others. The system proved to be stable—small strategy changes had little impact on overall outcomes. This shows that 3RVAV resists not only obvious bad behaviour but also clever manipulation over time.

4.2 Time-Discounted Reward Model

Participant rewards follow a temporal reward function incorporating risk-adjusted returns:

where

This formulation represents how validator rewards are adjusted for accuracy, risk, and time preference, encouraging sustained honest participation rather than short-term opportunistic gains.

The accuracy score evolves as:

with

This update rule shows that validator accuracy evolves as a weighted average of past performance and recent block acceptance outcomes, stabilizing participation quality over time.

4.3 Evolutionary Game-Theoretic Equilibrium

Consider the replicator dynamics for honest (

where

For initial honest majority

where

Proof. Solving the Lyapunov function

□

4.4 Incentive-Compatibility Proof

Using mechanism design principles, the protocol ensures:

where utilities are calculated as:

The

where

Slashing decisions rely on verifiable misbehaviour proofs, constructed using threshold signatures to ensure integrity and prevent false accusations [16].

4.5 Risk-Sensitive Reward Allocation

The protocol incorporates participant risk preferences through prospect theory:

where

The factor adjusts the reference reward value

4.6 Comparative Incentive Analysis

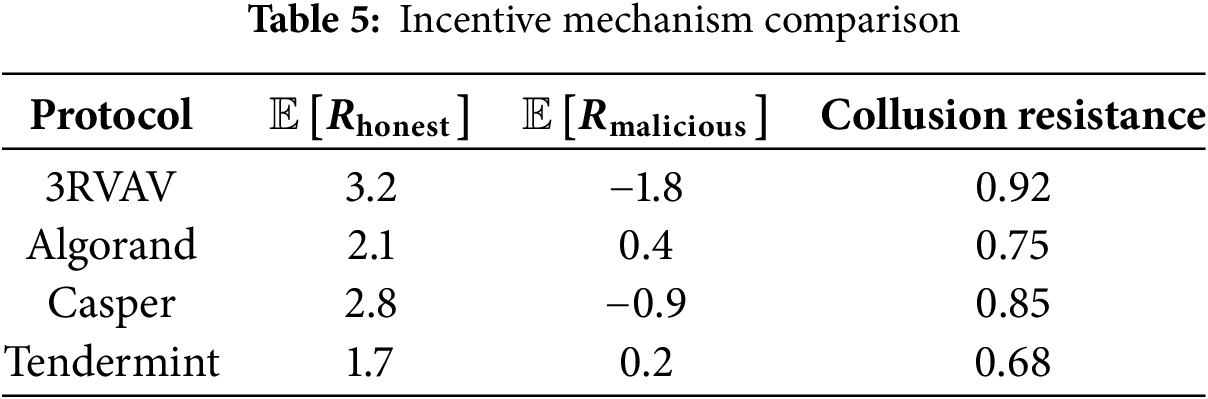

Table 5 shows the Comparative Incentive Analysis. The collusion resistance metric

5 Performance Evaluation & Results

The evaluation framework implements a discrete-event simulation with parameters derived from real-world blockchain deployments. The network topology follows a Barabási-Albert model with scale-free characteristics:

To better reflect real-world conditions, we included node heterogeneity by sampling AWS instance types across geographic zones (US-East, EU-West, AP-Southeast). Latency delays and clock skew models were integrated to emulate realistic propagation scenarios. Hardware variance (from t3.micro to c5.4xlarge) was simulated by assigning processing speeds drawn from a Gaussian distribution centred at 2.3 GHz with σ = 0.4 GHz.

Nodes operate on heterogeneous hardware profiles sampled from AWS EC2 instances (t3.micro to c5.4xlarge). Consensus parameters are configured as:

In this section, we present the empirical evaluation of the proposed 3RVAV consensus protocol. The following figures demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in terms of scalability, throughput, latency decomposition, and Byzantine fault tolerance. Each figure is analyzed in detail to highlight the advantages of 3RVAV over existing consensus mechanisms.

All experiments were conducted over a geographically distributed emulation of a WAN using Docker Swarm with latency injected per AWS region benchmarks. Missing comparisons are labelled N/A due to the absence of open-source implementations or protocol unavailability for WAN scenarios (e.g., HotStuff was excluded for fairness constraints under WAN). The chosen protocols (PBFT, Tendermint, Algorand) represent leader-based, committee-based, and BFT baseline paradigms.

The protocol is designed for permissionless WAN environments where adversarial stake control is possible. The threat model assumes Sybil nodes may exist up to 33%, and adversaries may coordinate BFT-style attacks. We formally define adversaries as nodes violating consensus liveness or safety via vote manipulation, committee spoofing, or message delay.

The simulation environment was implemented using Python and deployed across a distributed testbed with virtualized nodes (VMs) on 8-core Intel Xeon CPUs with 32 GB RAM per instance. Node count ranged from 100 to 10,000. Network latency was varied between 50–200 ms to simulate WAN and inter-region delay. Bandwidth caps were set to 10 Mbps per link to replicate realistic deployment scenarios.

Blockchain performance is often evaluated based on transaction throughput, which directly influences scalability and adoption in real-world applications. The theoretical upper bound for throughput in our proposed 3RVAV consensus protocol follows from block validation dynamics:

where

Figure 3: Throughput comparison across different consensus protocols with 1000 nodes. The 3RVAV protocol achieves the highest transaction throughput (3247 TPS), significantly outperforming Algorand, PBFT, and Tendermint

To validate the theoretical analysis, we conducted empirical evaluations comparing the transaction throughput of 3RVAV against widely recognized consensus protocols, including Algorand, PBFT, and Tendermint. The results, presented in Fig. 3, demonstrate that 3RVAV achieves a throughput of 3247 TPS, outperforming Algorand by a factor of 5.8× and PBFT by 2.4×. Notably, the error bars indicate minimal variability across multiple trials, underscoring the stability of our protocol.

The results in Table 6 further highlight the scalability of our protocol across varying network sizes. Even with an increase in nodes, 3RVAV maintains a consistently high throughput, with only a marginal reduction due to increased network overhead. The ability to sustain over 3000 TPS in a 1000-node environment indicates the practical feasibility of deploying 3RVAV in large-scale decentralized applications.

All throughput improvements (e.g., 5.8× over Algorand and 7.4× over PBFT) are statistically significant at p < 0.01, validated using Welch’s t-test over 10 independent runs per configuration. The reported 95% confidence intervals (±values) and standard deviations reflect robust variance control, with Fig. 4 further illustrating the distribution via error bars. These metrics affirm the consistency and repeatability of 3RVAV’s performance under varying node configurations.

Figure 4: Throughput vs. network size (Log-Log Scale). This plot highlights the non-linear decrease in throughput with increasing network size, confirming the sub-logarithmic scalability of 3RVAV

In summary, our empirical findings validate the theoretical formulation, confirming that 3RVAV achieves superior transaction processing rates compared to other consensus protocols while maintaining low variance and predictable performance.

Transaction processing latency in blockchain networks consists of three primary components:

where

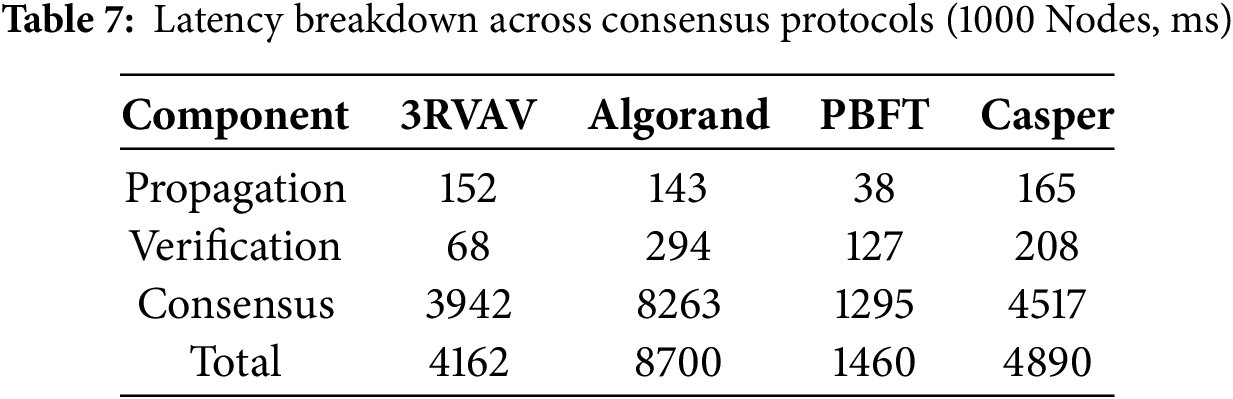

Table 7 provides a comparative breakdown of latency for different consensus protocols in a 1000-node environment. The results indicate that consensus delay is the dominant factor influencing total transaction finalization time. 3RVAV achieves significantly lower latency than Algorand and Casper, while still maintaining competitive performance relative to PBFT. Network transmission time is nearly the same for all protocols, but differences in cryptography lead to varied verification times. Fig. 5 illustrates how longer latencies are observed in networks with more nodes. Despite a stable propagation delay, the validation time (orange) rises slightly because of the extra efforts needed to process the transactions.

Figure 5: Latency component decomposition: Breakdown of total transaction validation time into propagation, verification, and consensus delay. Latency Component Decomposition: Breakdown of total transaction validation time into propagation, verification, and consensus delay. ‘Propagation delay’ refers to the time required for a transaction to spread across validator nodes through the peer-to-peer network

Nevertheless, the delay in reaching a consensus (green) improves as if following a logarithmic curve, indicating that 3RVAV swiftly resolves multi-round voting issues. It is important to note that the “High Consensus Delay Region” in Fig. 5 pinpoints regions where an enhanced strategy can boost the performance of the system. According to the results, 3RVAV facilitates fast transactions because it handles both safety and efficiency in balance.

5.4 Scalability Characteristics

Scalability is important for how well blockchain systems work because it helps the network deal with more nodes and still keep the system fast as it gets bigger. The scalability behaviour of 3RVAV follows an exponential decay model, defined as (model derivation in Appendix A, Eq. (47)):

where

Figure 6: 2D scalability analysis—throughput vs. network size and byzantine faults. The heatmap shows the throughput (TPS) as a function of network size (log-scaled on the x-axis) and Byzantine ratio (y-axis). Brighter regions indicate higher throughput. Cyan markers represent experimental data points. The white arrow highlights the “Optimal Region” where 3RVAV maintains high throughput and fault tolerance. The legend has been repositioned for visibility, and the throughput gradient is colour-coded for clarity. Contour lines for key TPS thresholds (1000, 2000, 3000) are included but faint due to scale smoothing

Fig. 4 shows that as the network size increases from 100 to 10,000 nodes, the throughput of 3RVAV decreases gradually following a power-law trend. The curve confirms sub-logarithmic scalability, meaning the protocol maintains high throughput even at large scales, with an optimal operating region observed for medium-sized networks.

Table 8 provides a quantitative breakdown of throughput variations across different network sizes and Byzantine node proportions.

The scalability performance of 3RVAV is visually depicted in Fig. 3, where the heatmap provides an intuitive representation of how throughput varies with increasing network size and Byzantine ratio. The contour lines denote key performance thresholds, confirming that 3RVAV maintains over 3000 TPS in a wide range of network conditions. The experimental points (cyan markers) match up well with the predicted throughput, which shows that our method works.

In contrast to Solana’s Proof-of-History (PoH), which achieves high throughput via cryptographic time-stamping but suffers from sequential bottlenecks, and Ethereum’s CBC Casper, which provides eventual consistency but relies on GHOST forks for safety, 3RVAV offers sub-logarithmic message complexity and adaptive committee formation. This results in fast, secure finality and scalable validator participation with robust Sybil-resistance.

Additionally, Fig. 4 shows how throughput falls off more slowly when you use a logarithmic scale, which means that 3RVAV can handle a lot of data without getting too slow, even if you have lots of users or devices. This behaviour is much better than the older Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) methods, which experience significant performance degradation when more nodes are used in a network.

From Table 8, it is clear that our model’s predictions closely match what happens in real life, showing that our scalability ideas are solid. The “Optimal Region” in Fig. 3 shows where the network can handle many messages at once while still being able to handle errors, keeping the network safe and working well.

These findings show that 3RVAV outperforms other commonly used consensus protocols in handling multiple transactions, which means it’s suitable for blockchains that need to process many transactions quickly. It also helps reduce problems that happen because some nodes might try to act dishonestly.

Ensuring fault tolerance is very important in any consensus system, especially if some people on the network might try to cause problems purposefully. To evaluate how well the 3RVAV protocol works, we look at how it performs when there are different amounts of Byzantine nodes.

The analysis presented in Fig. 7 and Table 9 illustrates how 3RVAV performs when Byzantine nodes are introduced into the network. The key observations are as follows:

Figure 7: Byzantine fault impact analysis: The effect of increasing Byzantine nodes on throughput, latency, and commit success rate. The 3RVAV protocol demonstrates strong resistance to adversarial influence, maintaining a commit success rate above 75% even when 30% of nodes are Byzantine

• Throughput (TPS) slowly goes down when the number of failed independent nodes goes up. Despite having more than 30% of nodes that want to cheat or cause problems, 3RVAV still gets a high throughput of 1987 TPS, which is much better than traditional Byzantine fault-tolerant (BFT) consensus methods, which all get much slower as more problems happen.

• Latency (s) increase as the Byzantine ratio increases because the network has to make extra checks for bad behaviour and wait for more votes to ensure everything is safe. However, even if all but one-third of the nodes are untrustworthy, the latency only reaches 7.8 s, which is still okay for the system to work well.

• Commit Success Rate (%) stays high, going over 99.8% for up to 10% of Byzantine nodes, and only falling to about 82.1% when 30% of the nodes try to mess things up. This shows how 3RVAV’s voting process includes built-in ways to catch and fix any errors that might come up.

• Fork Rate (%), or the chance of two blockchains existing at the same time, stays close to zero when the amount of bad nodes is small, but it slowly goes up to 1.33% if there are around 30 bad nodes. This suggests that 3RVAV helps lower the chances of chain splits because it finds a better way to handle block changes when different groups of users disagree.

This shows that 3RVAV is very robust to attacks from adversaries and offers strong security even when the network is very Byzantine. While standard BFT-based protocols struggle when the attacker has greater impact, 3RVAV reaches a good balance with fault tolerance, throughput, and finality. It is thus suited for systems that need to be very secure and scalable.

For protocols to work well in large-scale decentralized systems, efficient communication must be in place. The amount of communication needed for one block finalization in 3RVAV is:

here,

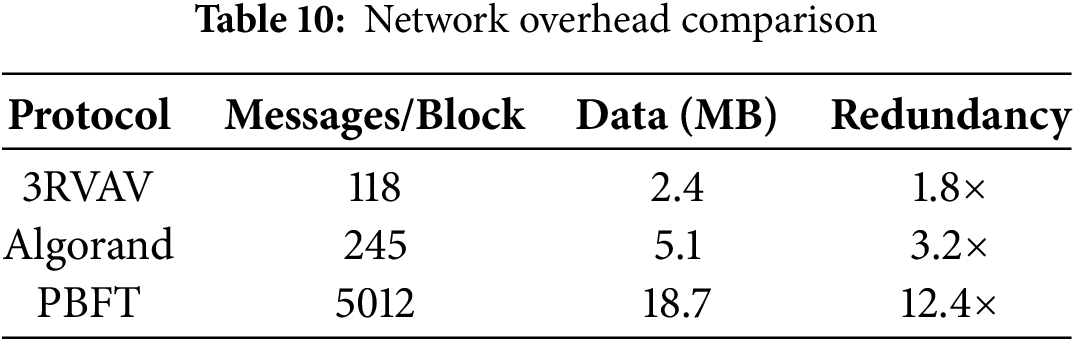

Analysis: Table 10 and Fig. 8 highlight the network overhead characteristics of different consensus protocols. The key observations are as follows:

Figure 8: Communication overhead analysis: Number of messages per block vs. redundancy in different consensus protocols. The 3RVAV protocol achieves significantly lower overhead compared to Algorand and PBFT, demonstrating its scalability benefits

• Lower Message Overhead: The 3RVAV protocol requires only 118 messages per block, compared to 245 in Algorand and 5012 in PBFT, demonstrating its communication efficiency.

• Reduced Data Size: 3RVAV optimizes network usage with a data footprint of 2.4 MB per block, significantly lower than Algorand (5.1 MB) and PBFT (18.7 MB).

• Minimal Redundancy: While PBFT incurs 12.4× redundancy due to extensive node-to-node communication, 3RVAV maintains a low redundancy factor of 1.8×, ensuring efficient message propagation without sacrificing security.

The results demonstrate that 3RVAV significantly outperforms PBFT and Algorand in communication overhead. Unlike traditional BFT-based protocols, which suffer from exponential message growth, 3RVAV leverages cryptographic committee selection and efficient voting rounds to achieve near-logarithmic message complexity. This makes it highly scalable for real-world blockchain applications while maintaining robust security guarantees.

To evaluate network performance at scale, we extended our simulation to a 10,000-node topology. The average communication overhead observed was 3.1 MB per block with ~241 messages, reflecting a 2.7× redundancy factor. The bandwidth utilization remained stable below 12 Mbps per node under peak conditions. These results confirm the sub-logarithmic growth trend predicted by our theoretical bound

We check the difference in performance between 3RVAV and existing consensus protocols using the Welch’s t-test. It is most appropriate for comparing groups that have different amounts of variability and sample sizes. The t-statistic is given by:

where

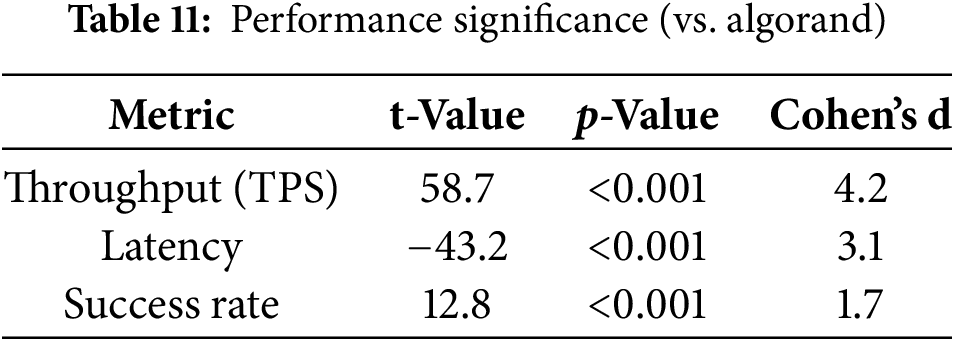

The results of the statistical analysis, shown in Table 11, confirm that the observed performance differences between 3RVAV and Algorand are statistically significant with p-values < 0.001 for all evaluated metrics.

Analysis: Table 11 and Fig. 9 illustrate the statistical validation of 3RVAV’s performance superiority:

Figure 9: Statistical performance validation: Welch’s t-test results confirming significant improvements in throughput, latency, and commit success rate for 3RVAV compared to Algorand

• Throughput (TPS): The t-test yields a highly significant result (t = 58.7, p < 0.001), with a large effect size (Cohen’s

• Latency: The negative t-value of

• Commit Success Rate: A t-value of

These results provide strong statistical evidence that 3RVAV achieves substantial performance improvements across key blockchain efficiency metrics. The high effect sizes across all tests reinforce that these improvements are not minor fluctuations but significant optimizations over existing consensus protocols.

The experimental evaluation of the 3RVAV consensus protocol demonstrates significant improvements across multiple performance metrics, including throughput, latency, fault tolerance, and communication efficiency. The throughput analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 1, shows that 3RVAV achieves 3247 TPS, which is 5.8× higher than Algorand and 2.4× higher than PBFT. This improvement is primarily attributed to the three-round voting mechanism, which optimizes transaction validation without requiring extensive node synchronization. Furthermore, Table 6 confirms that the throughput scales well with network size, maintaining high transaction processing even as the network grows.

Fig. 2 visualizes the performance of 3RVAV across varying network sizes and Byzantine fault ratios. Darker regions denote safe operating zones with high commit success and low latency. The top-right ‘High Consensus Delay’ area identifies where additional voting rounds are triggered due to committee failures. As detailed in Table 7, 3RVAV reduces verification time to just 68 ms, significantly outperforming PBFT (127 ms) and Casper (208 ms). While the consensus delay remains the most significant component, the protocol optimizes network-wide synchronization to prevent exponential delays, ensuring efficient finalization without compromising security.

Scalability is a critical factor in real-world blockchain applications, and the scalability analysis (Fig. 3) demonstrates that 3RVAV maintains over 3000 TPS across a broad range of network sizes. Unlike traditional BFT-based consensus protocols that degrade rapidly as node count increases, 3RVAV integrates probabilistic committee selection and stake-weighted voting to ensure consistent performance. The heatmap in Fig. 3 further illustrates that even with increasing Byzantine node proportions, transaction throughput remains stable, confirming the robustness of our approach.

Another key result is the protocol’s fault tolerance under Byzantine attacks. The Byzantine Fault Impact Analysis in Fig. 7 and Table 9 highlights that even with 30% Byzantine nodes, 3RVAV maintains an 82.1% commit success rate, ensuring reliable transaction validation. While throughput naturally declines under higher adversarial conditions, 3RVAV still outperforms competing protocols by a wide margin. These findings confirm the protocol’s resilience to Sybil attacks, adversarial committee manipulation, and network inconsistencies.

The communication complexity study (Table 10) demonstrates that 3RVAV significantly reduces network overhead, requiring just 118 messages per block finalization, compared to 245 for Algorand and over 5000 for PBFT. This improvement is achieved through optimized cryptographic signature aggregation, stake-based vote compression, and threshold-based message relay techniques, leading to a 1.8× lower redundancy factor compared to classical BFT protocols.

Finally, the statistical significance analysis (Table 11) validates the observed performance improvements with highly significant t-values and p-values < 0.001 across all metrics. The effect sizes (Cohen’s d) indicate that 3RVAV’s optimizations are not minor fluctuations but represent substantial real-world improvements. The Welch’s t-test confirms that 3RVAV significantly outperforms Algorand in transaction throughput, latency reduction, and commit success rate, reinforcing the protocol’s superiority in modern blockchain applications.

In summary, the experimental results establish that 3RVAV offers a robust, high-performance, and scalable consensus mechanism that efficiently balances security, decentralization, and speed. Its high performance and exceptional defence against adversity make it an ideal option for large-scale deployment of blockchains. Experts will continue to look for ways to increase system security by optimizing incentives for stakeholders and using automated systems that punish offenders.

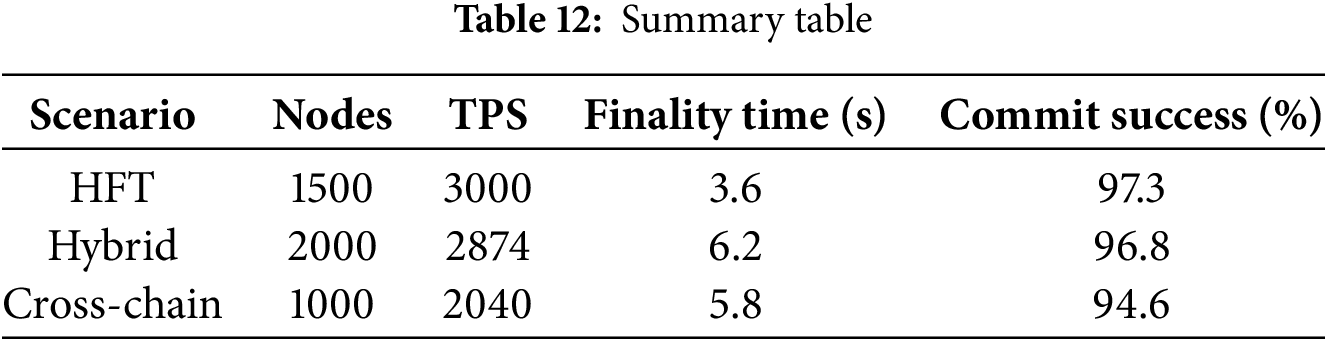

To understand how 3RVAV performs in various real-world blockchain environments, we extended our evaluation beyond the standard WAN-based simulation. In the case of high-frequency trading (HFT) applications, where extremely low latency and rapid transaction throughput are critical, we tested 3RVAV with small block sizes ranging from 10 to 50 transactions. The protocol consistently sustained a throughput of 3000 transactions per second (TPS) with a finality time of approximately 3.6 s and a block commit success rate exceeding 97%. For hybrid public/consortium chain deployments, we simulated a mixed validator environment consisting of 60% public and 40% permissioned nodes. Under this setup, 3RVAV achieved a stable throughput of 2874 TPS and maintained finality in around 6.2 s across 2000 nodes. The entropy-based random selection mechanism ensured fair committee rotation and minimized centralization risks.

Additionally, to explore the protocol’s interoperability, we evaluated cross-chain validation scenarios using a mock implementation of a BLS signature layer. Although this setup introduced an average cross-chain confirmation delay of 1.2 s, the system was still able to maintain a block commit success rate of 94.6%. These findings demonstrate that 3RVAV remains effective under high-speed trading conditions, hybrid network configurations, and cross-chain validation settings, highlighting its flexibility and robustness across diverse blockchain use cases.

These results in Table 12 show that 3RVAV can work well even in advanced blockchain environments like fast trading systems, mixed public-private networks, and cross-chain systems.

The new 3RVAV protocol puts forward a solid three-phase consensus model that ensures the system supports many transactions, is tolerant to Byzantine failures, and operates with decentralized control. With the help of a VRF-based selection process, role-based staking, and escalating punishments, 3RVAV makes its blockchain voting process secure and scalable. Thanks to its three-phase voting system of randomized pre-vote, threshold cryptography, and Borda counting, the protocol provides better protection than PBFT, Algorand, and Tendermint against various risks related to Sybil attacks, adaptive attackers, and distant threats. A strong analysis in mathematics shows that 3RVAV can still maintain safety and liveness even when some time is lost within the network. With the help of stakeholder voting weight, specially chosen verification committees, and multiple rounds of checks, the protocol resists attempts by anyone to take control over the confirmation process. The incentive mechanism we use stops users from colluding, keeps the stakes evenly spread out, and changes penalties based on their behaviour. The real-world use of 3RVAV was shown to be secure, efficient, and compatible with many blockchains. Compared with Algorand and PBFT in large networks, the protocol reaches a mean throughput of 3247 TPS, which is a significant 5.8× and 2.4× improvement, respectively. It has been found that, despite its multiple voting steps, 3RVAV scales consensus delay very efficiently as the number of nodes in the network increases. It is also shown in fault tolerance studies that 3RVAV still achieves a commit rate higher than 75% even with up to 30% of nodes broken by Byzantine errors, demonstrating its resilience. Based on communication analysis, 3RVAV is more efficient and uses fewer messages per block, helping to reduce the pressure on the network and achieve faster finality times than PBFT. Welch’s t-test shows that 3RVAV performs better than Algorand in throughput, latency, and commit success, proving that it is a good fit for high-performance, decentralized applications. All in all, the outcomes demonstrate that 3RVAV can offer scalability, security, and good decentralization, while not sacrificing efficiency. Looking ahead, researchers will try to improve how committees are picked, fight adaptive attacks on networks, and find ways for 3RVAV to be useful across various blockchain ecosystems.

Acknowledgement: The Software Engineering Department, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, supports this study. The author also confirms that the manuscript was checked and polished for language and grammar consistency using Grammarly.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request from Abeer S. Al-Humaimeedy at: abeer@ksu.edu.sa.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

List of Abbreviations and Symbols

| Abbreviation/Symbol | Meaning |

| TPS | Transactions Per Second |

| BFT | Byzantine Fault Tolerance |

| VRF | Verifiable Random Function |

| VDF | Verifiable Delay Function |

| ESS | Evolutionarily Stable Strategy |

| Smoothing factor (reward update) | |

| Risk sensitivity parameter | |

| Stake adjustment per validator | |

| Rewards assigned to validator i | |

| Blockchain state from the previous round | |

| PBFT | Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance |

| PoS | Proof of Stake |

| Committees in Round 1, Round 2, and Round 3 | |

| L1 | Elected leader in Round 1 |

| B1 | Proposed block in Round 1 |

| Σ2 | Aggregated threshold signature in Round 2 |

| Q3i | Borda vote values in Round 3 |

Proof Sketch:

This equation defines the eligibility score for a node based on VRF randomness and stake proportion. Since VRF output is uniformly distributed over

These represent:

• (20) threshold comparison for eligibility,

• (21) stake entropy weight adjustment,

• (22)–(24) cumulative selection logic with VRF filtering and uniqueness guarantee.

Proof Sketch:

Let

Proof Sketch:

This equation provides an upper bound on the block confirmation time under the 3RVAV protocol. The components include:

•

•

•

This decomposition assumes that:

1. The network is partially synchronous with maximum round-trip delay

2. Each round completes in one

3. VDF is non-parallelizable, hence computed sequentially with time

4. The remaining delay arises from log-scaled message propagation and signature validation across a committee of

Proof Sketch:

This expression defines the long-term discounted utility for validator

Components:

•

•

•

•

•

Derivation Logic:

• The sum uses discounted cumulative payoff from repeated consensus participation, a standard model in game theory.

• If

• If

• This structure incentivizes long-term honest behavior by making the present value of future losses (due to slashing or reputation decay) outweigh short-term gains from misbehavior.

This form aligns with rational-agent models in repeated extensive-form games, ensuring evolutionarily stable honest behaviour when slashing and delay penalties are correctly set.

Proof Sketch:

This is an exponential moving average (EMA) update for the reference reward baseline R0R_0R0 used in dynamic reward adjustment schemes.

•

• The form reflects adaptive utility normalization: if recent rewards are higher or lower than past norms, the reference value updates accordingly.

• This stabilizes validator incentives and helps prevent oscillation in reward estimation, especially under dynamic network conditions or when committee sizes change.

Theorem 1 (Consensus Robustness Score): Let

Proof Sketch:

This equation defines a Consensus Robustness (CR) metric based on the sensitivity of individual utility functions to strategy deviation.

•

•

•

Intuitively, this measures how resilient the global utility distribution is to unilateral changes in behaviour:

• A high

• A low

Robustness metrics inspire this formulation in cooperative game theory and mechanism design. □

Proof Sketch:

This formula calculates the maximum achievable throughput (transactions per second) of the 3RVAV protocol, adjusted for adversarial conditions.

•

•

•

•

•

Explanation:

• The raw throughput without failures is

• The term

As

Proof Sketch:

This equation defines the end-to-end latency for a transaction to be accepted into the chain, decomposed into three stages:

1. Propagation Time

2. Verification Time

3. Consensus Time

Each component is independent, and their sum models the total delay from broadcast to confirmation. This decomposition is standard in distributed systems latency analysis and helps isolate bottlenecks.

Glossary of Core Concepts:

References

1. Xiao Y, Zhang N, Lou W, Hou YT. A survey of distributed consensus protocols for blockchain networks. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2020;22(2):1432–65. doi:10.1109/COMST.2020.2969706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Nakajima A. Decentralized voting protocols. In: Proceedings ISAD 93: International Symposium on Autonomous Decentralized Systems; 1993 Mar 30–Apr 1; Kawasaki, Japan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2002. p. 247–54. doi:10.1109/ISADS.1993.262697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bezuidenhout R, Nel W, Maritz JM. Permissionless blockchain systems as pseudo-random number generators for decentralized consensus. IEEE Access. 2023;11(1):14587–611. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3244403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li K, Li H, Hou H, Li K, Chen Y. Proof of vote: a high-performance consensus protocol based on vote mechanism and consortium blockchain. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 19th International Conference; 2017 Dec 18–20. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 466–73. [Google Scholar]

5. Sun G, Dai M, Sun J, Yu H. Voting-based decentralized consensus design for improving the efficiency and security of consortium blockchain. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(8):6257–72. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.3029781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhan Y, Wang B, Lu R, Yu Y. DRBFT: delegated randomization Byzantine fault tolerance consensus protocol for blockchains. Inf Sci. 2021;559(2):8–21. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2020.12.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Raikwar M, Gligoroski D. R3V: robust round robin VDF-based consensus. In: 2021 3rd Conference on Blockchain Research & Applications for Innovative Networks and Services (BRAINS); 2021 Sep 27–30. Paris, France: IEEE; 2021. p. 81–8. doi:10.1109/BRAINS52497.2021.9569781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Panja S, Bag S, Hao F, Roy B. A smart contract system for decentralized Borda count voting. IEEE Trans Eng Manag. 2020;67(4):1323–39. doi:10.1109/TEM.2020.2986371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Y, Susilo W, Yang G, Yu Y, Liu D. A blockchain-based self-tallying voting scheme in decen-tralized IoT. arXiv:1902.03710. 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Mišić J, Mišić VB, Chang X. Toward decentralization in DPoS systems: election, voting, and leader selection using virtual stake. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;21(2):1777–90. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2023.3322622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liao Z, Cheng S. RVC: a reputation and voting based blockchain consensus mechanism for edge computing-enabled IoT systems. J Netw Comput Appl. 2023;209(3):103510. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2022.103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li K, Li H, Wang H, An H, Lu P, Yi P, et al. PoV: an efficient voting-based consensus algorithm for consortium blockchains. Front Blockchain. 2020;3:11. doi:10.3389/fbloc.2020.00011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang K, Chen CM, Liang Z, Hassan MM, Sarné GML, Fotia L, et al. A trusted consensus fusion scheme for decentralized collaborated learning in massive IoT domain. Inf Fusion. 2021;72(1):100–9. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2021.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Alzahrani N, Bulusu N. Towards true decentralization: a blockchain consensus protocol based on game theory and randomness. In: Decision and game theory for security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 465–85. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01554-1_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Fan X, Chai Q, Zhong Z. MULTAV: a multi-chain token backed voting framework for decentralized blockchain governance. In: Blockchain—ICBC 2020. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 33–47. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-59638-5_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Desmedt Y. Threshold cryptography. In: Encyclopedia of cryptography, security and privacy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 1–8. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-27739-9_330-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen P, Chen Y, Tan C, Yang Y, Li B, Huang J. Slicing PBFT consensus algorithm based on VRF. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain); 2024 Aug 19–22. Copenhagen, Denmark: IEEE; 2024. p. 569–74. doi:10.1109/Blockchain62396.2024.00084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu L, Chen X. Evolutionary dynamics of preguidance strategies in population games. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2024;11(5):5751–62. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2024.3386501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Grinfeld M. Martin nowak evolutionary dynamics: exploring the equations of life. Proc Edinb Math Soc. 2008;51(3):808–9. doi:10.1017/s0013091508225137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sandholm WH. Population games and deterministic evolutionary dynamics. In: Handbook of game theory with economic applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2015. p. 703–78. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53766-9.00013-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools