Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GLMCNet: A Global-Local Multiscale Context Network for High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation

1 College of Remote Sensing and Information Engineering, North China Institute of Aerospace Engineering, Langfang, 065000, China

2 Collaborative Innovation Center of Aerospace Remote Sensing Information Processing and Application of Hebei Province, Langfang, 065000, China

3 College of Geography and Oceanography, Minjiang University, Fuzhou, 350108, China

* Corresponding Author: Chuanzhao Tian. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068403

Received 28 May 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

High-resolution remote sensing images (HRSIs) are now an essential data source for gathering surface information due to advancements in remote sensing data capture technologies. However, their significant scale changes and wealth of spatial details pose challenges for semantic segmentation. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) excel at capturing local features, they are limited in modeling long-range dependencies. Conversely, transformers utilize multihead self-attention to integrate global context effectively, but this approach often incurs a high computational cost. This paper proposes a global-local multiscale context network (GLMCNet) to extract both global and local multiscale contextual information from HRSIs. A detail-enhanced filtering module (DEFM) is proposed at the end of the encoder to refine the encoder outputs further, thereby enhancing the key details extracted by the encoder and effectively suppressing redundant information. In addition, a global-local multiscale transformer block (GLMTB) is proposed in the decoding stage to enable the modeling of rich multiscale global and local information. We also design a stair fusion mechanism to transmit deep semantic information from deep to shallow layers progressively. Finally, we propose the semantic awareness enhancement module (SAEM), which further enhances the representation of multiscale semantic features through spatial attention and covariance channel attention. Extensive ablation analyses and comparative experiments were conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed method. Specifically, our method achieved a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 86.89% on the ISPRS Potsdam dataset and 84.34% on the ISPRS Vaihingen dataset, outperforming existing models such as ABCNet and BANet.Keywords

The rapid advancement of remote sensing technology has significantly enhanced the precision and efficiency of acquiring information about the Earth’s surface. HRSIs provide abundant geospatial information and have therefore been widely used in diverse fields such as environmental monitoring [1,2], land use classification [3,4], agricultural production [5,6], and urban planning [7,8]. Semantic segmentation aims to assign a semantic label to every pixel in an image, enabling accurate identification and separation of various features or objects. However, the complex backgrounds, varied spatial scales, and imbalanced class distributions in HRSIs pose significant challenges. One of the key challenges is how to extract and utilize semantic features in such complex scenes effectively.

The complexity and variability of remotely sensed data make traditional segmentation techniques based on artificial features [9–11] less effective. In contrast, deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has been highly successful in image semantic segmentation due to their robust feature extraction capabilities and efficient computational performance. Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) [12] were the first to apply CNNs to pixel-level segmentation, enabling end-to-end training between input images and output maps. However, due to their relatively simple network architecture, FCNs still fall short in capturing high-level semantic information and accurately recovering fine-grained details. In subsequent studies, the encoder-decoder structure has been widely adopted due to its strong performance in semantic segmentation [13–15]. A typical encoder-decoder model, U-Net [16], effectively compensates for the loss of information during upsampling by introducing skip connections. However, if the decoder directly uses low-level features generated by the encoder without additional refinement [17], it may cause feature confusion and compromise the network’s discriminative capability.

Densely distributed features in high-resolution remote sensing images often exhibit noticeable scale differences. In response, multiscale attention mechanisms and related strategies have been widely applied in feature extraction to enhance complex contextual information perception in recent years. Chen et al. [18] proposed DeeplabV3+, which utilizes atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) to capture multiscale contexts by integrating multi-rate atrous convolutions and global average pooling. Li et al. [19] proposed a contextual-aware terrain segmentation network (CTSNet), which enhances terrain segmentation with a triple aggregation strategy combining global semantics, multiscale features, and channel entropy. Ni et al. [20] proposed the category-guided global–local feature interaction network (CGGLNet), which guides global context modeling by estimating the potential class information of pixels. Fu et al. [21] proposed a dual attention network (DANet), which captures global contextual relationships by constructing dual attention mechanisms for both channels and spatial positions. Despite these multiscale attention mechanisms being effective in extracting contextual features across scales, their global context modeling still faces limitations due to homogeneity. Most cannot adaptively adjust feature correlation strength across semantic regions or effectively capture class-sensitive local variations.

In recent years, Transformer models have emerged as a powerful deep learning framework due to their ability to capture long-range feature dependencies, proving highly effective in image processing tasks. Following the widespread adoption of transformers, numerous models have significantly enhanced feature representation and classification performance through integrating transformer strategies. Gu et al. [22] proposed a multipath multiscale attention network (MMA), which adopts a transformer-based encoder and introduces a multiscale global aggregation module to capture global features at multiple scales. Xiao et al. [23] proposed an enhanced multiscale representation network (EMRT), utilizing deformable self-attention to dynamically adjust the receptive field for improved multiscale representation. These studies indicate that the multiscale attention mechanisms are also effective within transformer architectures. Liu et al. [24] introduced the Swin Transformer, leveraging a hierarchical design and shifted windows to efficiently extract global and local features while reducing computational cost. Wu et al. [25] proposed the CNN-transformer fusion network (CTFNet), employing an efficient W/P transformer as a decoder to obtain global context with low computational complexity. While these methods reduce sequence length through hierarchical design and window partitioning, this may compromise the network’s feature extraction capabilities and multiscale information representation.

This paper proposes a novel global-local multiscale context network (GLMCNet) to improve semantic segmentation accuracy for HRSIs. Specifically, ResNet-34 [26] serves as the backbone encoder to extract low-level semantic features from input images. To mitigate the decreased recognition accuracy of small-scale targets and background interference in the local features extracted by ResNet-34, we introduce a detail-enhanced filtering module (DEFM) into the encoder. This module refines and filters the feature maps produced by ResNet-34 to generate more precise inputs for the decoder. In the decoder, we propose a novel transformer structure called the global–local multiscale transformer block (GLMTB) for capturing long-distance dependencies within feature maps. Its window-based pooling multihead self-attention (W-PMSA) facilitates cross-window information exchange with low computational complexity. The MultiAttn module concurrently extracts multiscale, global, and local semantic information using multiscale self-attention branches and a local fine-tuning branch. A CBL layer is applied for initial local feature enhancement. Conventional upsampling typically fuses high and low levels of resolution features through a single pathway. This approach gradually diminishes high-level semantics, impeding effective transfer to low-level features [27,28]. Therefore, an additional path is introduced during the decoder’s upsampling process, enabling the propagation of high-level features multiple times. Finally, before entering the segmentation head, feature maps pass through a semantic awareness enhancement module (SAEM). This module further reinforces the semantic representation of critical regions and channels via spatial and channel attention strategies. This paper makes the following key contributions.

(1) We propose a DEFM module to refine local features and remove redundant information using refinement and filtering branches.

(2) In the encoder, we design the GLMTB to extract global and local multiscale features. Its W-PMSA component enables cross-window information exchange via large kernel pooling and convolution operation. The MultiAttn block enhances multiscale and local feature capture through an improved multiscale self-attention mechanism combined with a local fine-tuning branch, supplemented by a CBL layer for preliminary local feature extraction.

(3) We propose a SAEM module that combines spatial attention with covariance channel attention to enhance semantic information in key spatial regions and the channel dimension, leading to improved discriminative performance in the final results.

(4) We propose a novel architecture, GLMCNet, which integrates CNN and transformer architectures as the encoder and decoder to effectively capture global and local multiscale features from images. Its stair fusion mechanism facilitates the hierarchical integration of features from deep to shallow layers. We perform extensive experiments on the ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen to validate the capabilities of the proposed model.

2.1 CNN-Based Semantic Segmentation for Remote Sensing Images

Remote sensing semantic segmentation aims to classify each pixel in a remote sensing image. Since the advent of deep learning methods, CNN-based semantic segmentation techniques have become widely used in remote sensing applications. For example, FCN [12] first replaced fully connected layers with convolutional layers, achieving pixel-level segmentation and end-to-end modeling for remote sensing tasks. U-Net [16] added skip connections to the FCN framework, effectively fusing low-level and high-level features and achieving notable results in remote sensing. Consequently, encoder-decoder architectures played an important role in remote sensing semantic segmentation [29,30]. Attention mechanisms address convolutional limitations like fixed receptive fields and weak global context modeling. Shu et al. [31] proposed a channel and space compound attention convolutional neural network (CSCA U-Net), which further integrates compound channel and spatial attention into the U-Net to improve segmentation accuracy. Self-attention further supports the global contextual information beyond scaling attention [32]. He et al. [33] proposed a lightweight dual-range context aggregation network (LDCANet), combining local features and global semantic context via convolution and self-attention mechanisms. Similarly, Sun et al. [34] designed SAANet, which reorders features along position and channel dimensions and applies self-attention on subregions to capture the interdependencies between remote contextual information and channels. However, these methods struggle to learn multiscale features amid significant object scale variations in HRSIs.

2.2 Multiscale Context-Based Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images

Multiscale context modeling is a crucial strategy to address the diversity of object scales in HRSIs. It enhances the model’s segmentation capability by combining features from different scales. Li et al. [35] presented an attention aggregation feature pyramid network (A2-FPN). This framework combines feature pyramid networks for spatial and contextual feature extraction with an attention aggregation module (AAM) to strengthen multiscale learning. Li et al. [36] presented a multi-attention network (MANet) that employs the multiscale strategy to merge different scales of semantic information generated by the encoder. The network enhances this process with a self-attention module for hierarchical contextual aggregation. Li et al. [37] proposed a spatially enhanced channel-shuffled network (SECNet). It constructs a spatially enhanced channel-shuffled module by incorporating spatial shift operations, depthwise separable convolutions, and channel shuffle techniques to effectively facilitate multiscale context modeling. Lyu et al. [38] introduced a multiscale successive attention fusion network (MSAFNet) to extract multiscale representations of water bodies via a successive attention fusion module (SAFM), supplemented by a joint attention module (JAM) for global context. Fan et al. [39] proposed a progressive adjacent-layer coordination symmetric cascade network (PACSCNet) that achieves cross-layer and multimodal feature fusion using a symmetric cascade encoder-decoder. Moreover, a pyramid residual integration module progressively integrated four-scale features to suppress noise. Chen et al. [40] proposed a SRCBTFusionNet, extracting local details via a multipath atrous self-attention module (MASM) while fusing multiscale features using a multiscale feature aggregation module (MFAM). Zeng et al. [32] proposed a multiscale global context network (MSGCNet), enhancing encoder multiscale feature interactions through efficient cross-attention and modeling global context with a transformer-based decoder block (TBDB).

2.3 Transformer-Based Semantic Segmentation for Remote Sensing Images

Since Vision Transformer (ViT) [41], transformer-based approaches have gained prominence in remote sensing semantic segmentation [42], demonstrating strong performance through accurate modeling of long-range dependencies. Xie et al. [43] proposed the SegFormer network, utilizing a hierarchical transformer encoder to capture global contextual information throughout the network, yielding excellent results in semantic segmentation. While pure transformers excel at global information extraction, they underperform in capturing local details. Therefore, most approaches currently employ a hybrid architecture to leverage the complementary strengths of CNNs and Transformers. Wang et al. [44] introduced the bilateral awareness network (BANet), which uses ResT to model global dependencies and stacked convolutions for local texture extraction. Cai et al. [45] proposed TransUMobileNet, which employs a CNN-transformer hybrid encoding architecture to leverage transformers for extracting global contextual information from CNN-generated features. Duan et al. [46] proposed LightCGS-Net, combining a lightweight CNN and a Swin Transformer to extract detailed spatial features and global semantic representations from input images. Blaga and Nedevschi [47] proposed a swin-based focal axial attention network (SwinFAN U-Net). It employs the Swin Transformer as the encoder and incorporates guided focal-axial attention in the decoder to extract both global and local semantic representations. Wang et al. [48] further proposed UNetFormer, which adopts ResNet-18 as a backbone and employs an improved transformer attention mechanism to capture global context and local details. He also proposed the BuildFormer network [49] to encode spatial details and global dependencies through a dual-path structure comprising a spatial detail context path and a global context path. Fan et al. [50] proposed the CSTUNet model, which utilizes U-Net as the primary encoder and the Swin Transformer as an auxiliary encoder to enhance the extraction of local and global contexts. However, as targets in remote sensing images often vary significantly in scale, solely leveraging global context may not be sufficient for comprehensively extracting multiscale features.

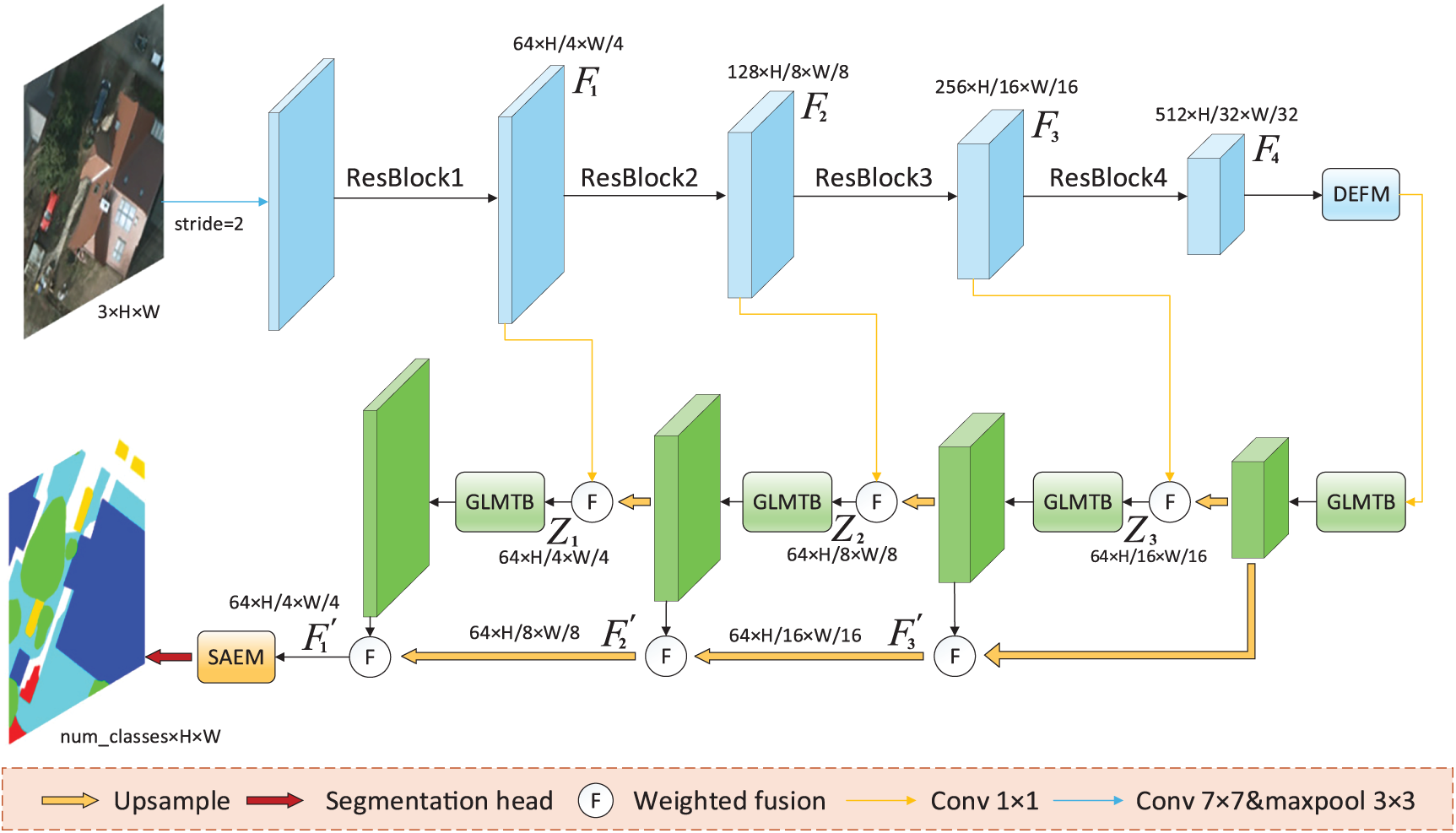

The proposed GLMCNet employs an encoder-decoder framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1, with skip connections enabling efficient information exchange between the encoder and decoder. The encoder integrates a pretrained ResNet-34 backbone and a DEFM module attached to its final stage. Specifically, the input feature

Figure 1: Detailed architecture of GLMCNet. The encoder includes a ResNet-34 backbone and a Detail-Enhanced Filtering Module (DEFM), while the decoder comprises Global-Local Multiscale Transformer Blocks (GLMTB) and a Semantic Awareness Enhancement Module (SAEM) located at the end of the decoder

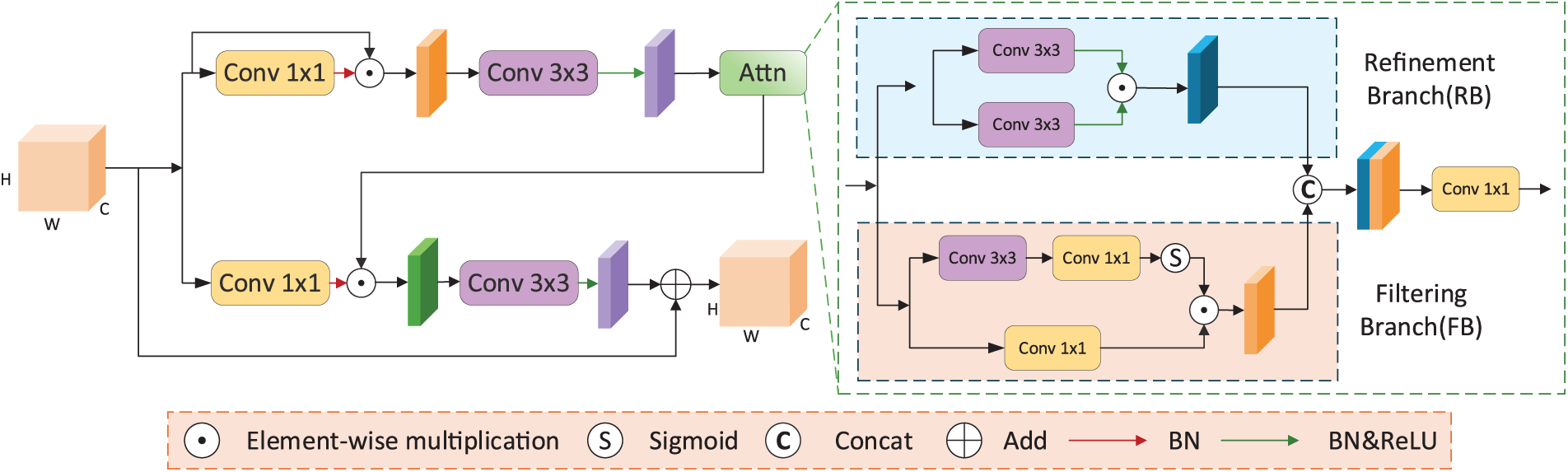

3.2 Detail-Enhanced Filtering Module

In remote sensing semantic segmentation tasks, high-level features primarily encode global semantic information but inadequately represent local fine-grained details. They often contain redundant background noise that degrades segmentation performance. This limitation persists in methods such as CMTFNet and BuildFormer, which typically employ direct cross-layer fusion or global context modeling to leverage high-level features. We propose the DEFM module, which introduces a more proactive and fine-grained strategy. The module adopts a dual-branch design with a refinement branch to obtain detailed representations from high-level features and a filtering branch to suppress irrelevant noise, enhancing the representation of target regions in the encoder. The DEFM structure is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Detailed design of the DEFM

Given the output feature

where BN(·) denotes the batch normalization layer,

where

where

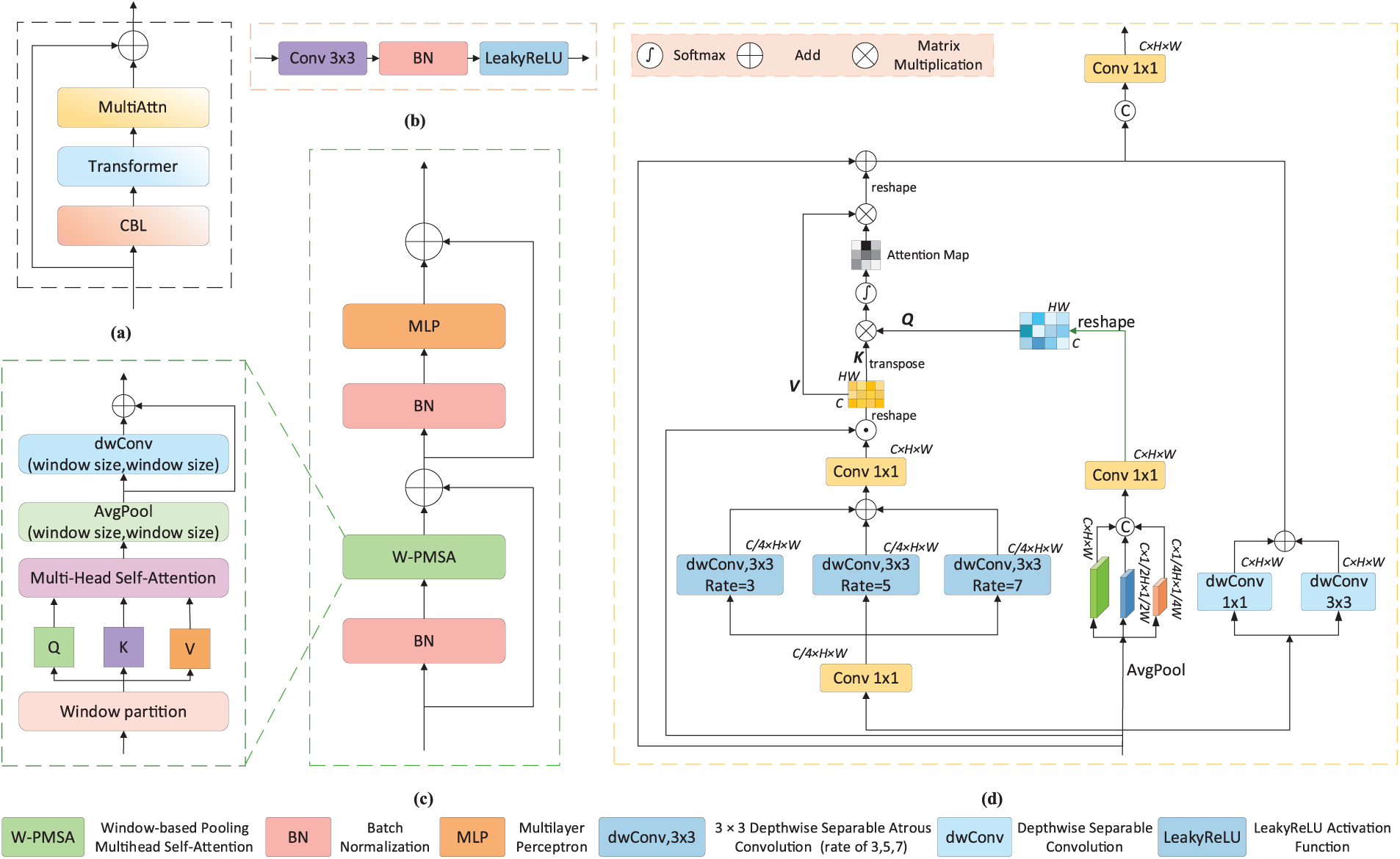

3.3 Global-Local Multiscale Transformer Block

Remote sensing images often exhibit rich multiscale characteristics while facing challenges such as complex background interference and the requirement to capture fine-grained local details. We propose a GLMTB, which combines transformer mechanisms with convolution operations for efficient extraction of multiscale global and local features. The GLMTB module comprises a CBL layer, a transformer block, and a MultiAttn block. Its structure is shown in Fig. 3a.

Figure 3: Detailed design of the GLMTB; (a) Internal structure of the GLMTB; (b) Design details of the CBL layer; (c) Design details of the Transformer block; (d) Design details of the MultiAttn block

The encoder output

where

3.3.2 Window-Based Pooling Multihead Self-Aattention

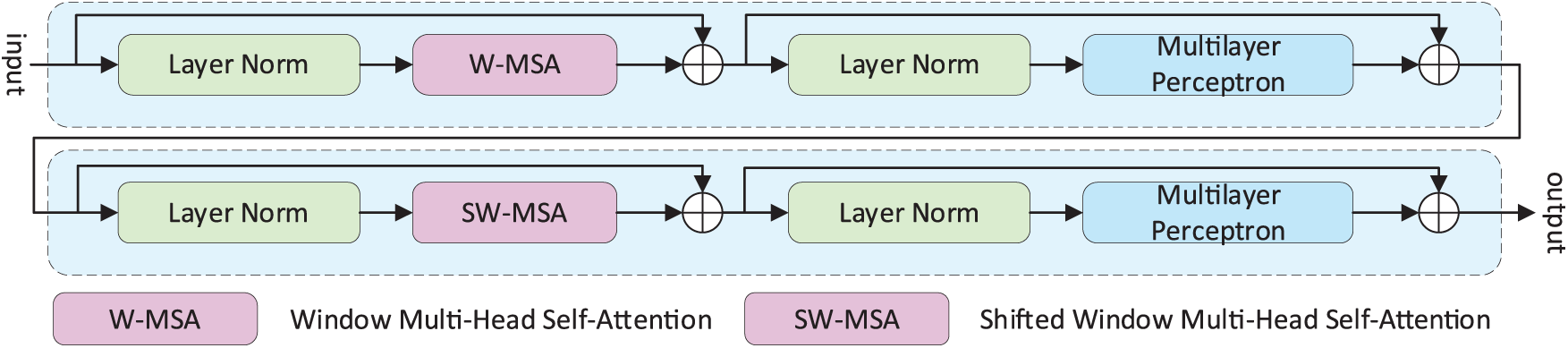

The window-based multihead self-attention in Swin Transformer [24] is widely used for global modeling, as illustrated in Fig. 4. However, its computational overhead increases substantially with network depth due to alternating shifted windows for cross-window interaction [33]. To mitigate this issue, we introduce the W-PMSA module, which enhances cross-window context modeling by integrating large-kernel average pooling and convolution operations, as shown in Fig. 3c. After self-attention, the feature map P undergoes

where

Figure 4: Two consecutive Swin Transformer blocks

Addressing transformer limitations in multiscale fusion, we design a MultiAttn block after the Transformer block in GLMTB, as shown in Fig. 3d. This block employs depthwise separable atrous convolution and standard depthwise separable convolution to capture global and local multiscale features from diverse receptive fields. The feature output W from the transformer block is fed into two parallel branches for further processing. W is initially processed by a 1 × 1 convolution in the multiscale branch, reducing its channel dimension to 1/4 of the original. Then, three parallel depthwise separable convolutions with different dilation rates

where

where

where

Finally, the extracted local features are concatenated with the multiscale features, and a 1 × 1 convolution is utilized to adjust the channel dimensions, leading to the final global-local multiscale feature

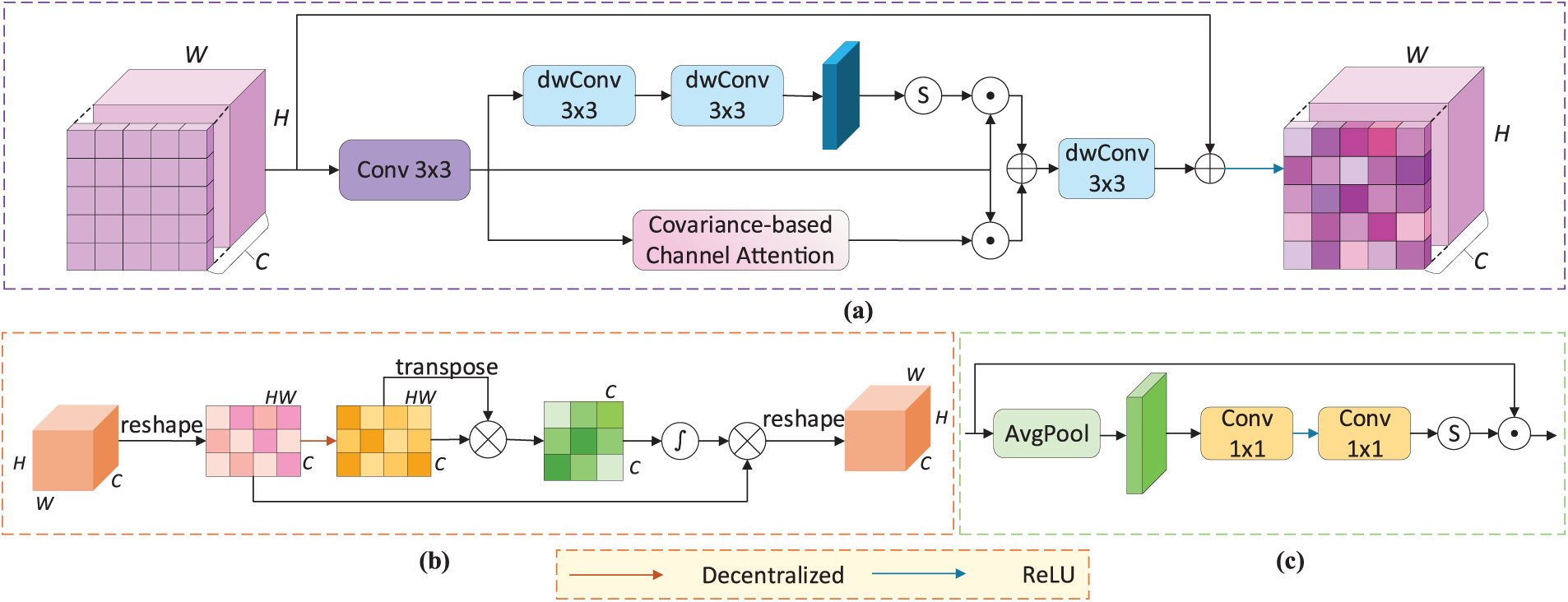

3.4 Semantic Awareness Enhancement Module

In the decoder, each GLMTB block output is weighted and fused with that of the preceding GLMTB block. This stair fusion mechanism enables rich semantic information from deeper layers to be gradually propagated to shallower layers. However, directly fusing features from different hierarchical levels may diminish the expressiveness of multiscale representations [28]. To address this issue, we propose a novel SAEM module that enhances the semantic representation of key spatial regions and channels by integrating spatial and covariance-based attention mechanisms. Prevailing methods [17,51] often employ channel attention mechanisms based on the traditional SENet [52] paradigm, which rely on the mean statistics of individual channels. In contrast, SAEM introduces a covariance-based channel attention strategy that explicitly models higher-order dependencies among channels, thereby capturing co-varying features for improved category discrimination. The SAEM is shown in Fig. 5a.

Figure 5: Detailed design of the SAEM and the structure of the traditional channel attention mechanism; (a) The overall structure of SAEM; (b) Structure of the Covariance-based Channel Attention; (c) Traditional channel attention mechanism

A 3 × 3 convolution is applied to the first-level feature map

In the channel attention branch, as shown in Fig. 5b, feature

where

After summing the results of the spatial and channel attention modules, the result is further fused by a depthwise separable convolution to generate the semantically enhanced feature

The Potsdam dataset comprises 38 high spatial resolution TOP images with a resolution of 6000 × 6000 pixels and a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 5 cm. The dataset includes four multispectral bands (red, green, blue, and near-infrared), as well as the digital surface model (DSM) and normalized DSM (NDSM). It provides labels for six classes: impervious surfaces (imp.surf.), buildings, low vegetation (low.veg.), trees, cars, and background (clutter). In this experiment, only the red, green, and blue bands were used, excluding DSMs and NDSMs data. Similar to previous studies [53], we selected ID: 2_13, 2_14, 3_13, 3_14, 4_13, 4_14, 4_15, 5_13, 5_14, 5_15, 6_13, 6_14, 6_15, and 7_13 (excluding the misannotated image 7_10) for testing, with the remaining 23 images used as the training dataset. All images were partitioned into 512 × 512 pixels.

The Vaihingen dataset comprises 33 high spatial resolution TOP images with an average resolution of 2494 × 2064 pixels with a GSD of 9 cm. The dataset includes three bands (red, green, and near-infrared), and the classification labels are the same as in the Potsdam dataset. Following the works in [50], we used the IDs: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, 22, 24, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, and 38 for testing, and the remaining 16 images served as the training set. All images were partitioned into 512 × 512 pixels.

We conducted all experiments using PyTorch on a system equipped with a 13th Gen Intel Core i5-13600KF CPU, an NVIDIA RTX 4070 Ti SUPER GPU (16 GB), and 64 GB of RAM. The initial learning rate was set to 6e−4, and a cosine annealing strategy was employed to adjust the learning rate. The AdamW optimizer was employed for training. A batch size of 8 was employed, and the maximum number of training epochs was set to 130. In addition, a series of data augmentation strategies were applied during training, including random scaling [0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5], random rotation, and random vertical and horizontal flipping. Test-time augmentation (TTA) was applied during testing to improve performance. All baseline methods employed identical training strategies and hyperparameters for fair comparison.

Our loss function L is constructed by combining the cross-entropy loss

For comprehensive evaluation, the model is assessed using overall accuracy (OA), mean F1 score (mF1), and mean intersection over union (mIoU) as evaluation metrics calculated from the cumulative confusion matrix. Their formulas are presented as follows:

where

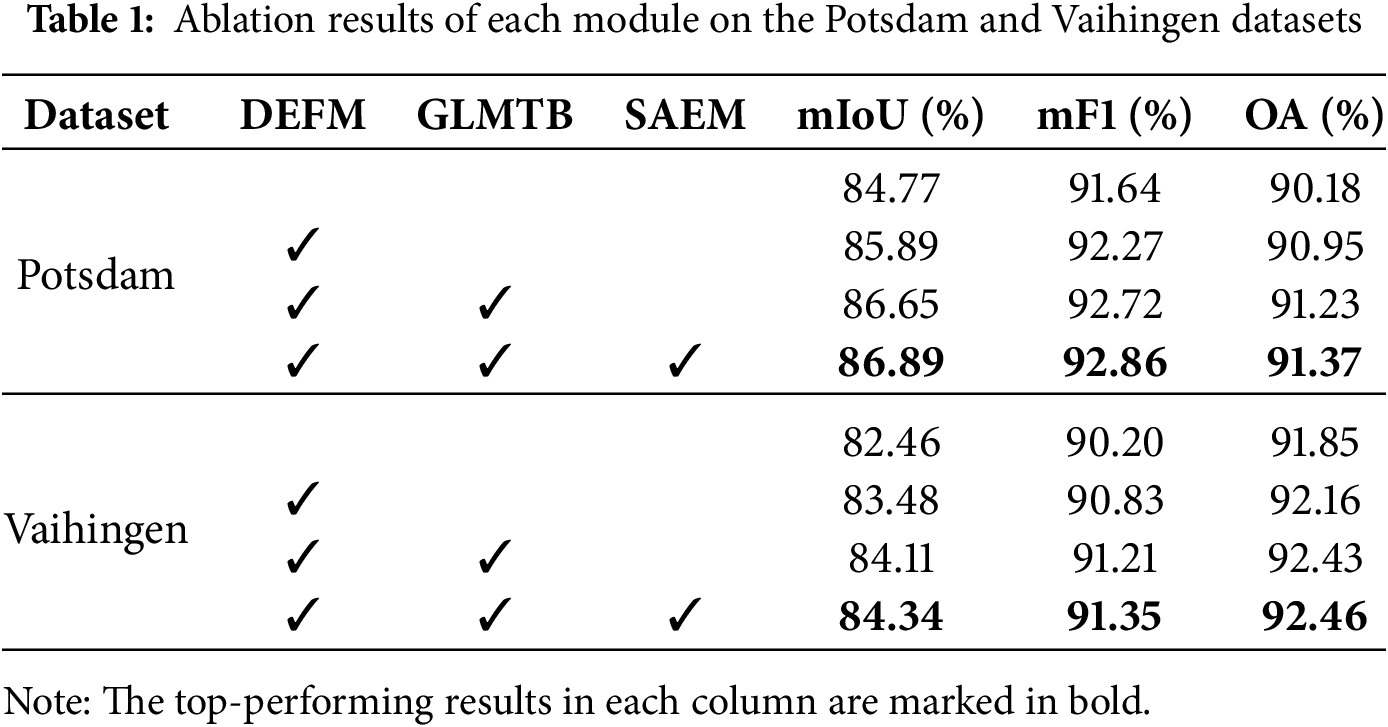

4.5.1 Ablation Study of the Overall Architecture of GLMCNet

We assessed the contribution of each component in GLMCNet through ablation experiments on the Potsdam and Vaihingen datasets, with the results presented in Table 1. The baseline model adopted a U-Net-like structure, with an additional stair fusion mechanism compared to the traditional U-shaped architecture. ResNet-34 was chosen as the backbone despite newer architectures like EfficientNet [54] and ConvNeXt [55]. This choice prioritizes structural stability, reproducibility, and compatibility with our modules, while its validated simplicity provides an optimal encoder foundation.

On the Potsdam dataset, integrating the DEFM module into the baseline model facilitates more refined feature extraction. It effectively filters out redundant information, thereby improving the model’s mIoU by 1.12%, mF1 by 0.63%, and OA by 0.77%. Based on this, the GLMTB module was further added. Four GLMTB blocks enable the learning of richer multiscale information, leading to gains of 0.76% in mIoU, 0.45% in mF1, and 0.28% in OA. The SAEM module further boosts the model’s competence in modeling multiscale semantic features, contributing to additional improvements of 0.24% for mIoU, 0.14% for mF1, and 0.14% for OA. Finally, the model that integrates all modules achieved 86.89% in mIoU, 92.86% in mF1, and 91.37% in overall accuracy.

On the Vaihingen dataset, model performance was likewise enhanced using the proposed modules. Adding the DEFM module to the baseline model resulted in improvements of 1.02% in mIoU, 0.63% in mF1, and 0.31% in OA. Adding the GLMTB module further improved the model performance, with mIoU increasing by 0.63%, mF1 by 0.38%, and OA by 0.27%. The integration of the SAEM module, designed to enhance multiscale semantic information, improved mIoU, mF1, and OA by 0.23%, 0.14%, and 0.03%, respectively. Ultimately, combining all modules raised the baseline performance to 84.34% in mIoU, 91.35% in mF1, and 92.46% in OA. The ablation experiment results on both datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed modules.

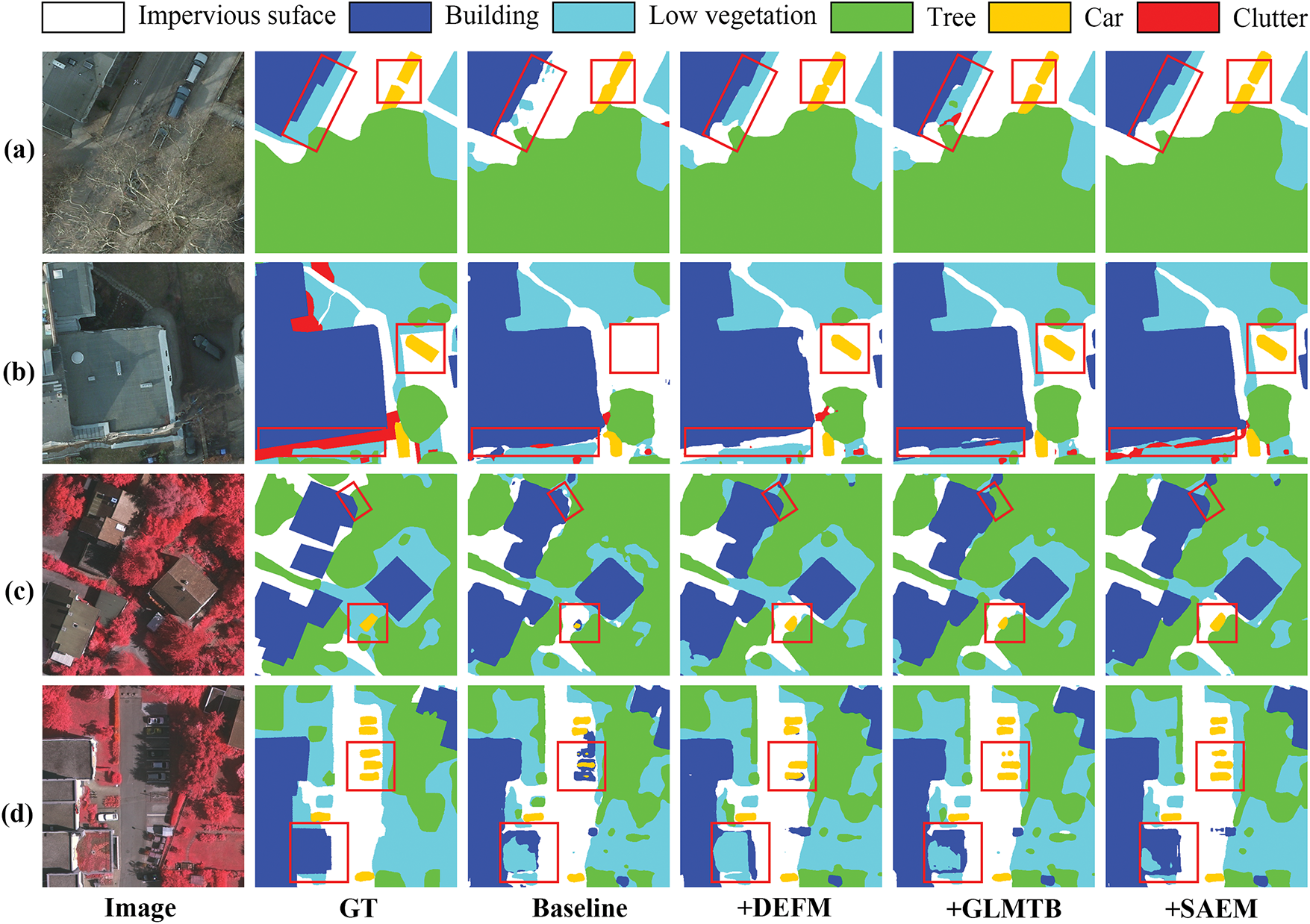

Fig. 6 presents the visualization results of the various modules of our proposed method. Without the DEFM module, the model exhibits significant shortcomings in detail segmentation. For instance, the segmentation boundaries of “cars” and “buildings” are noticeably blurred. Interference from surrounding redundant information may lead to misclassifications, as seen in the baseline results shown in Fig. 6c,d, where cars in shadowed areas are misclassified as buildings. With the addition of GLMTB and SAEM modules, the model more effectively captures global and local multiscale context, enhancing segmentation accuracy in complex scenes and producing smoother object boundaries.

Figure 6: Visualization of ablation experiments for each module of the proposed method; (a,b) are results on the Potsdam dataset; (c,d) are results on the Vaihingen dataset. Baseline denotes a U-Net-like model equipped with a stair fusion mechanism; +DEFM indicates the baseline model with the DEFM module added; +GLMTB represents the model with both DEFM and GLMTB modules; +SAEM denotes the integration of all modules, forming the complete GLMCNet

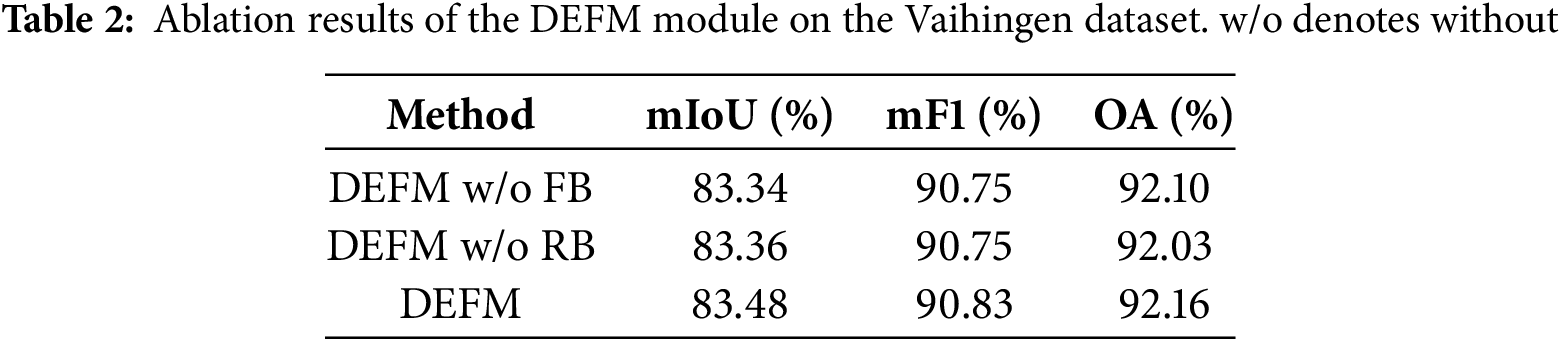

4.5.2 Effectiveness of the DEFM Module

We propose the DEFM module at the encoder’s output stage to extract detailed features while reducing redundancy. Ablation studies evaluated the efficacy of DEFM by excluding either the filtering branch (FB) or refinement branch (RB). Each variant’s performance compared to the complete DEFM module appears in Table 2. The baseline for this partial ablation experiment was a model containing only the DEFM module. Excluding the FB branch reduced the network’s mIoU by 0.14%, while omitting the RB branch reduced mIoU by 0.12%. The results indicate that relying solely on detail enhancement or redundancy filtering during feature extraction in the encoder is insufficient for effectively extracting useful information. The DEFM module enhances the detailed information of valid features by the refinement branch and removes redundant information through the filtering branch, thereby increasing the model’s mIoU, mF1, and OA to 83.48%, 90.83%, and 92.16%, respectively.

4.5.3 Effectiveness of the GLMTB Module

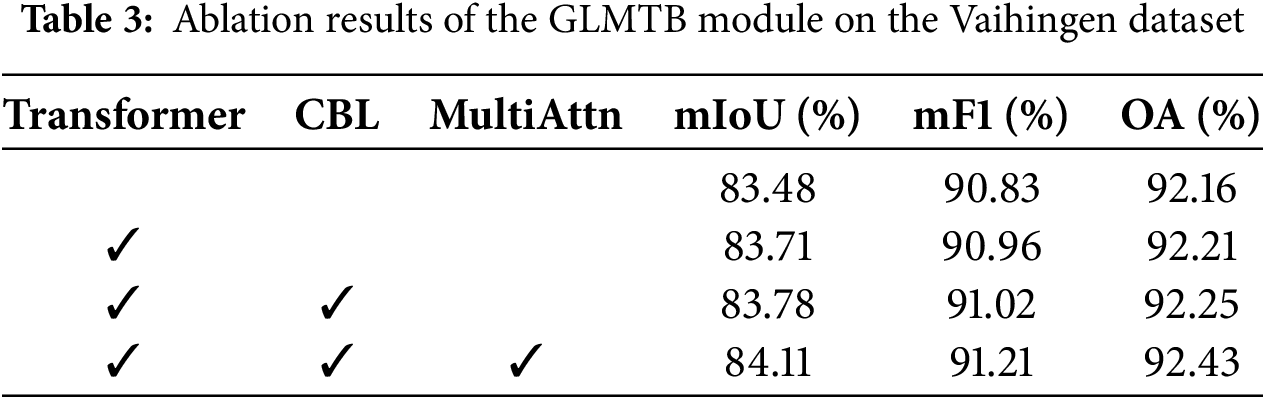

The GLMTB includes a CBL layer, a transformer block, and a MultiAttn block. To assess the impact of each sub-module, we treated the network incorporating the DEFM module as the baseline and performed ablation studies focusing on the internal architecture of GLMTB. The corresponding results are shown in Table 3. After incorporating the transformer block, mIoU improved by 0.23%, thanks to its capability to capture long-distance dependencies and effectively model global context. The CBL layer improved the model’s mIoU by 0.07% by initially enhancing local features. The incorporation of the MultiAttn block significantly improved multiscale feature extraction, leading to mIoU, mF1, and OA values of 84.11%, 91.21%, and 92.43%, respectively.

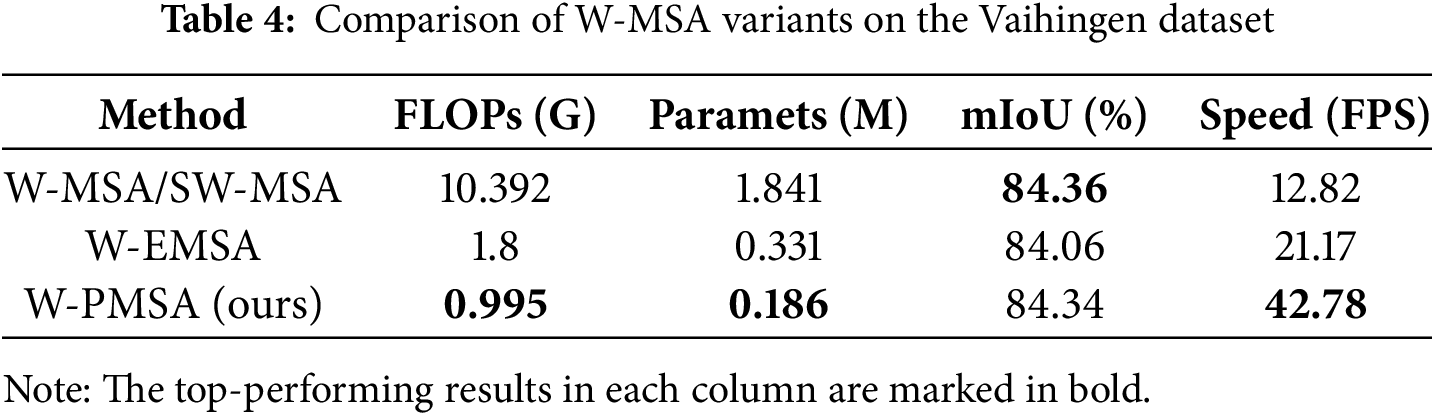

For the W-PMSA evaluation, we substituted it in ablation studies with the Swin Transformer’s window-based multi-head self-attention (W-MSA/SW-MSA) and the MSGCNet’s window-based efficient multi-head self-attention (W-EMSA). The baseline for this partial ablation experiment was the model containing all modules. As shown in Table 4, W-PMSA achieved comparable performance to the original W-MSA/SW-MSA, with only a 0.02% drop in mIoU. However, it significantly reduced computational complexity and parameter count by over 90% and 89%, respectively. Compared to W-EMSA, W-PMSA improved mIoU by 0.28%, while lowering FLOPs and parameters by 44% and 43%, respectively, while also achieving a significant improvement in inference speed. These results demonstrate that W-PMSA achieves a better balance between accuracy and efficiency, further validating its advantage in maintaining high precision with lower computational cost.

4.5.4 Effectiveness of the SAEM Module

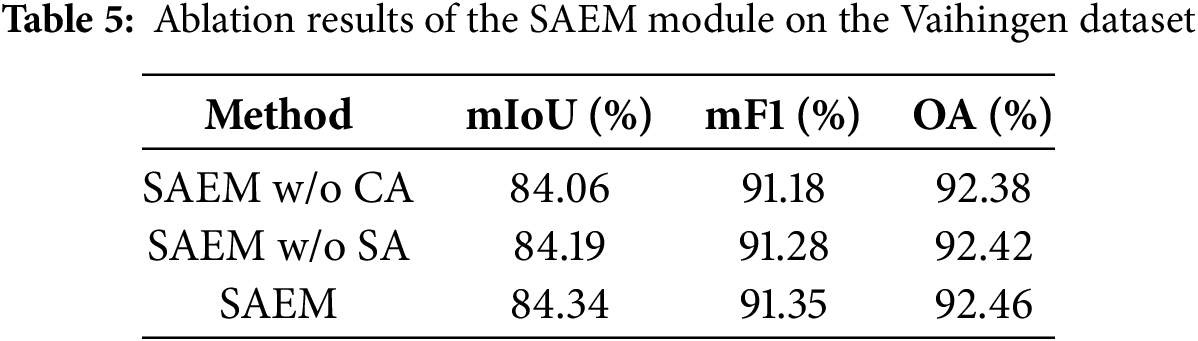

The SAEM module applies spatial and channel attention mechanisms to enhance the multiscale features obtained from the decoder in a semantically meaningful manner. We evaluated SAEM’s components via branch ablation studies. The baseline for this partial ablation experiment was the model containing all modules. Table 5 shows that removing the channel attention branch led to a 0.28% drop in the network’s mIoU, while removing the spatial attention branch led to a 0.15% decrease in mIoU. The complete SAEM module enhances performance by using the spatial attention branch to focus on critical spatial regions and the channel attention branch to strengthen the semantic representation of key channels. As a result, the model’s mIoU, mF1, and OA were improved to 84.34%, 91.35%, and 92.46%, respectively.

4.5.5 Effectiveness of the Stair Fusion Mechanism

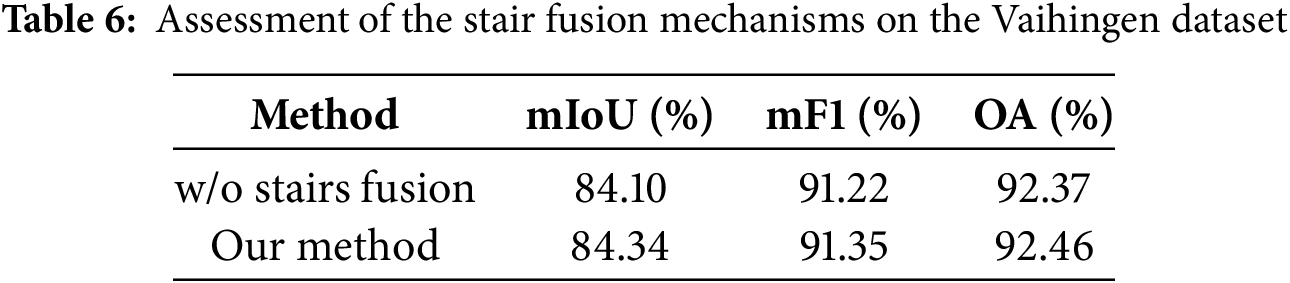

In evaluating the stair fusion mechanism, we compared the standard U-shaped architecture with an improved architecture that introduces the stair fusion mechanism. The baseline for this partial ablation experiment was the model containing all modules. According to the results presented in Table 6, removing the stair connections caused a 0.24% degradation in mIoU and 0.13% in mF1 on the Vaihingen dataset. The stair fusion structure enables the gradual transfer of semantic information from higher to lower layers, which boosts the feature representation capacity. As a result, the model achieved mIoU, mF1, and OA scores of 84.34%, 91.35%, and 92.46%, respectively.

4.6 Comparison with the State-of-the-Art Methods

We compared our GLMCNet method against state-of-the-art approaches on the Potsdam and Vaihingen datasets. These methods include mainstream network architectures, including CNN-based models such as UNet [16] and DeepLabv3+ [18], attention mechanism-based models including A2-FPN [35], ABCNet [30], LANet [56], and MANet [36], and transformer-based models such as BANet [44], BuildFormer [49], UnetFormer [48], and PACSCNet [39].

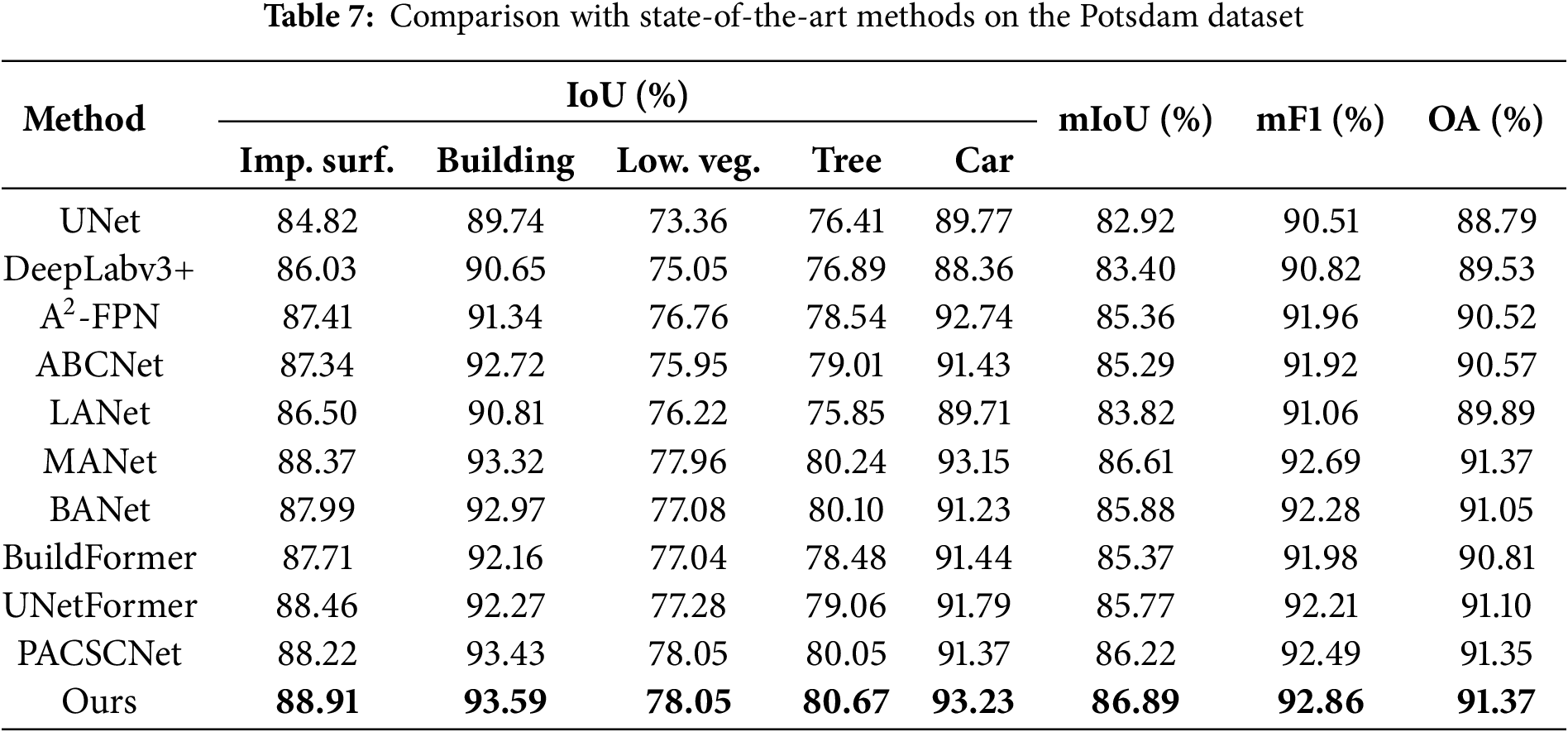

4.6.1 Results on the Potsdam Dataset

The comparative experimental results on the Potsdam dataset are shown in Table 7. The proposed model outperformed other methods with mIoU, mF1, and OA, reaching 86.89%, 92.86%, and 91.37%, respectively. DeepLabv3+ [18] employs an encoder-decoder structure and ASPP to capture multiscale information, which led to a better mIoU. A2-FPN [35] enhances the effectiveness of multiscale feature extraction by introducing an attention mechanism to guide feature aggregation. ABCNet [30] achieves remote sensing image segmentation at a lower cost by integrating a feature aggregation module and an attention enhancement module, leading to a 2.37% mIoU improvement over CNN-based methods. BANet [44] combines the transformer’s dependency modeling with convolutional texture extraction, effectively capturing long-range dependencies, and thus achieved a 0.52% mIoU improvement over A2-FPN. BuildFormer [49] utilizes spatial detail context and global context pathways to capture rich spatial information and long-range dependencies, achieving a mIoU of 85.37%.

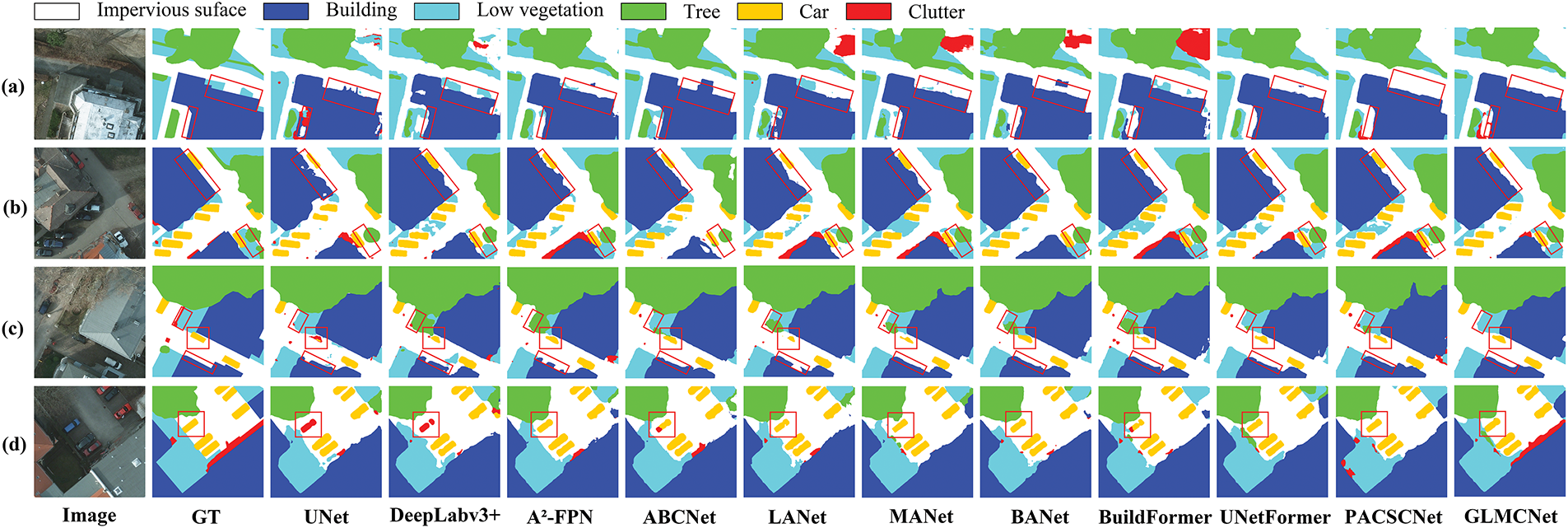

We also visualized the segmentation outcomes, enabling more precise comparison of segmentation performance across different methods. As shown in Fig. 6, GLMCNet outperforms other methods in segmentation quality on the Potsdam dataset. For instance, due to the similar texture and color between some building rooftops and impervious surfaces, methods such as UNet and LANet in Fig. 7a tend to misclassify “impervious surfaces” as “buildings”. In addition, most methods, including UNet and ABCNet in Fig. 7a,b, produce segmentation results with unclear or irregular edges. In contrast, GLMCNet enhances building-edge recognition by refining details and extracting multiscale features, leading to clearer and more accurate boundaries. Because cars are small and typically located in object-intensive and complex areas, most methods often confuse them with the background, leading to misclassification and omission, as shown in Fig. 7c,d. Our model effectively captures the details of “cars” through multiscale feature extraction and global context modeling, while reducing background interference to achieve more accurate car boundary recognition and segmentation. In green vegetation areas, such as Fig. 7b,c, the similar colors of “tree” and “low vegetation”, especially in shadows, cause boundary segmentation confusion for methods like Deeplabv3+, BuildFormer, and PACSCNet. Although our approach improves handling such cases, as seen in Fig. 7c, it still encounters similar class confusion in some shadowed regions, as illustrated in Fig. 7b. This implies that accurately separating visually similar categories remains challenging for our method in complex scenarios. To address this issue, we plan to incorporate boundary-aware loss and class-specific attention mechanisms in future work. This aims to strengthen the model’s discrimination of visually similar categories, particularly between trees and low vegetation in shaded regions.

Figure 7: Visualization of comparative experiments on the ISPRS Potsdam dataset; (a–d) show the segmentation results for four different scenarios. Image denotes the RGB input image, and GT denotes the ground truth label

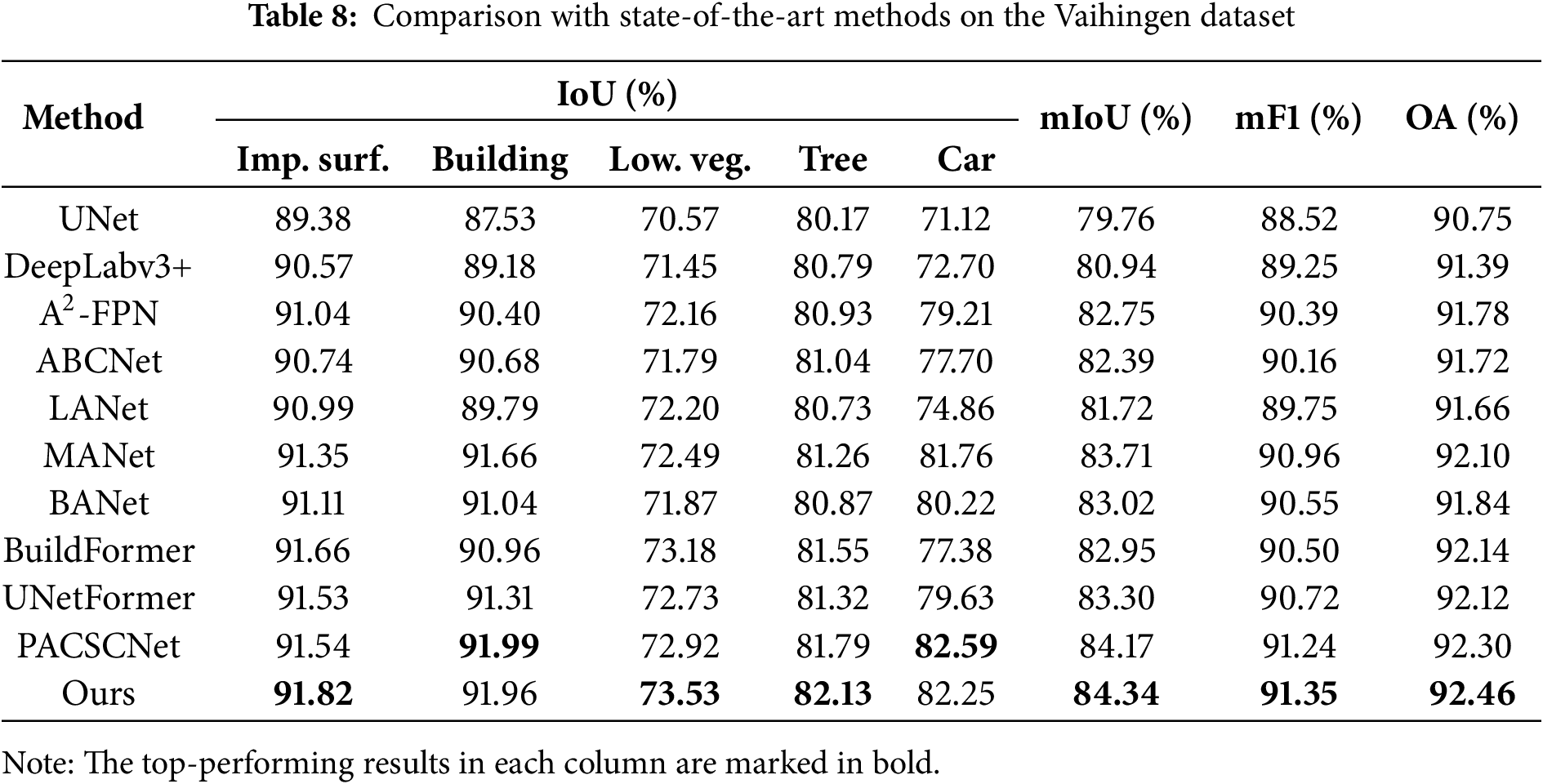

4.6.2 Results on the Vaihingen Dataset

A detailed comparison of experimental results on the Vaihingen dataset is provided in Table 8. Once again, our method achieves the best performance, with mIoU, mF1, and OA reaching 84.34%, 91.35%, and 92.46%, respectively. Owing to its smaller size, the Vaihingen dataset yields slightly lower overall performance compared to the Potsdam dataset. LANet [56] enriches the semantic information of lower-level features by embedding local focus from high-level features. MANet [36] leverages multiple attention modules to model semantic context for better remote sensing segmentation. Compared with traditional CNN-based methods, these attention mechanism-based models improve mIoU by up to 3.95%. UnetFormer [48] employs an efficient global-local attention mechanism in its decoder, achieving a mIoU of 83.30%. PACSCNet [39] performs cross-layer fusion of adjacent features through a dual-encoder structure, reaching a mIoU of 84.17%.

As shown in Fig. 8, our method achieves the best segmentation results compared to other methods on the Vaihingen dataset. CNN-based methods struggle to accurately capture fine-grained objects, such as “low vegetation” and “trees” in complex backgrounds, due to the limited receptive fields of convolutional kernels. For instance, UNet, LANet, and MANet omit the class of “trees” in Fig. 8a,c. These methods also produce rough segmentation boundaries for “buildings”. Attention mechanisms contribute to a more accurate representation of important regions, as evident in the smoother boundary segmentation of “buildings” by MANet in Fig. 8b,c. Transformer-based models address this limitation by integrating global information more effectively, as demonstrated by BANet’s improved “low vegetation” and “tree” segmentation in Fig. 8c,d. However, they show slight deficiencies in local detail recovery, evident in UNetFormer and PACSCNet’s omission and under-segmentation of small objects like “cars”. Our method is optimized in detail enhancement and multiscale global modeling, which can effectively solve the above problems and thus achieve a more accurate segmentation effect with neater edges. In complex regions, classes with similar colors or textures remain prone to misclassification. For instance, in Fig. 8d, “building” and the “impervious surface” share similar visual characteristics, leading to misclassification across all methods. Stronger context modeling or spatial priors will be further explored in future work to improve recognition in such complex scenarios.

Figure 8: Visualization of comparative experiments on the ISPRS Vaihingen; (a–d) show the segmentation results for four different scenarios. Image denotes the false-color composite image, and GT denotes the ground truth label

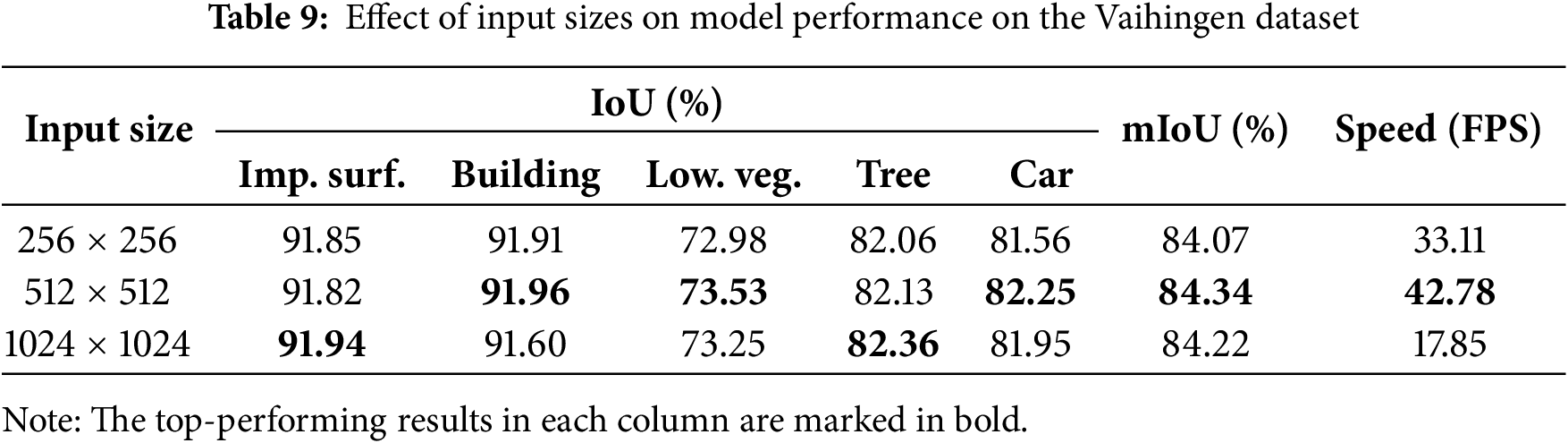

4.7 Stability and Generalization Analysis of the Model

We assessed the model’s stability by testing it on input images with varying sizes. Table 9 shows minimal fluctuations in category IoU values and overall mIoU across different input scales, with variations within approximately 0.5%. This indicates that the model demonstrates a certain degree of robustness to changes in input scale and maintains stable performance. The 512 × 512 input achieves the best trade-off between accuracy and efficiency among the tested sizes.

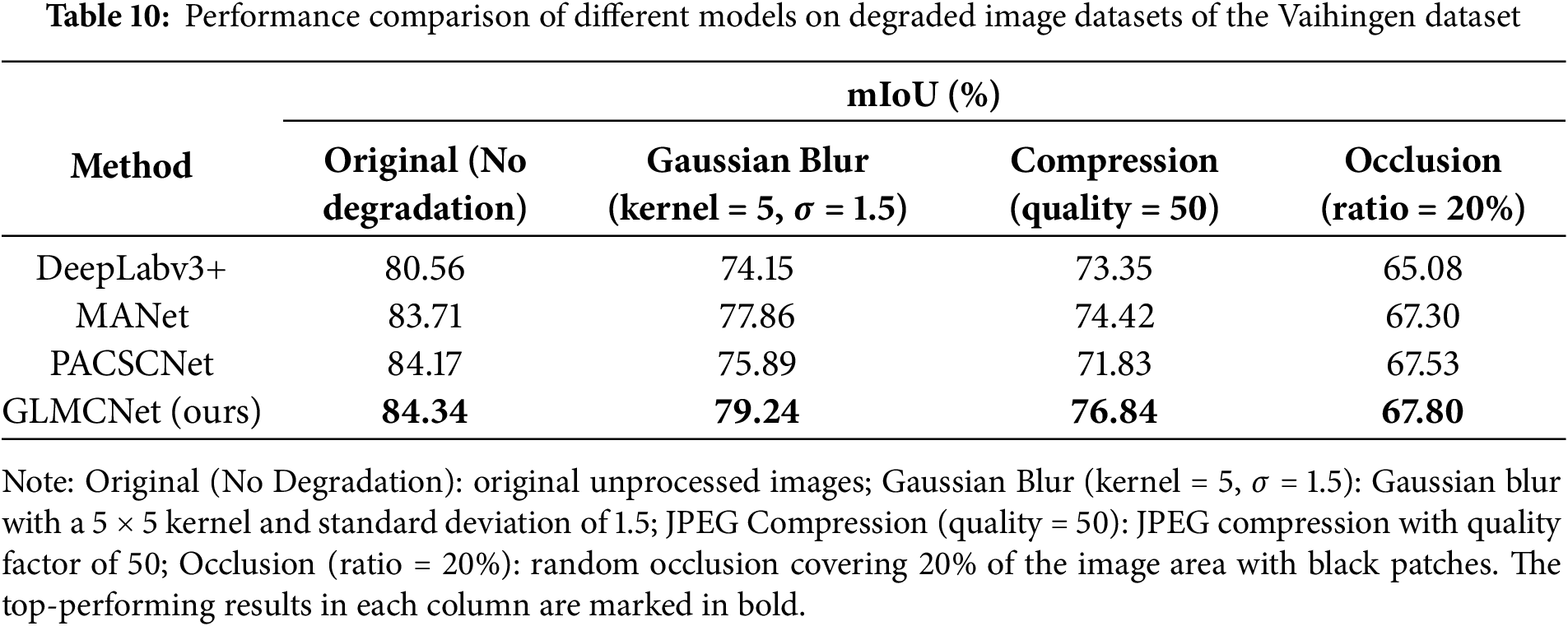

To comprehensively evaluate the generalization ability of our model, we applied three types of image degradation on the Vaihingen dataset, including Gaussian blur, JPEG compression, and random occlusion. These degradations simulate low-quality inputs to test model robustness. We compared our method with one representative method from each category, including the CNN-based DeepLabv3+, the attention-based MANet, and the transformer-based PACSCNet. Table 10 shows that our model achieves the best mIoU under all degradation conditions, demonstrating strong robustness. While all models exhibit performance drops from lost details and contextual information in degraded vs. high-resolution inputs, ours maintains the best overall performance.

4.8 Complexity Analysis of the Models

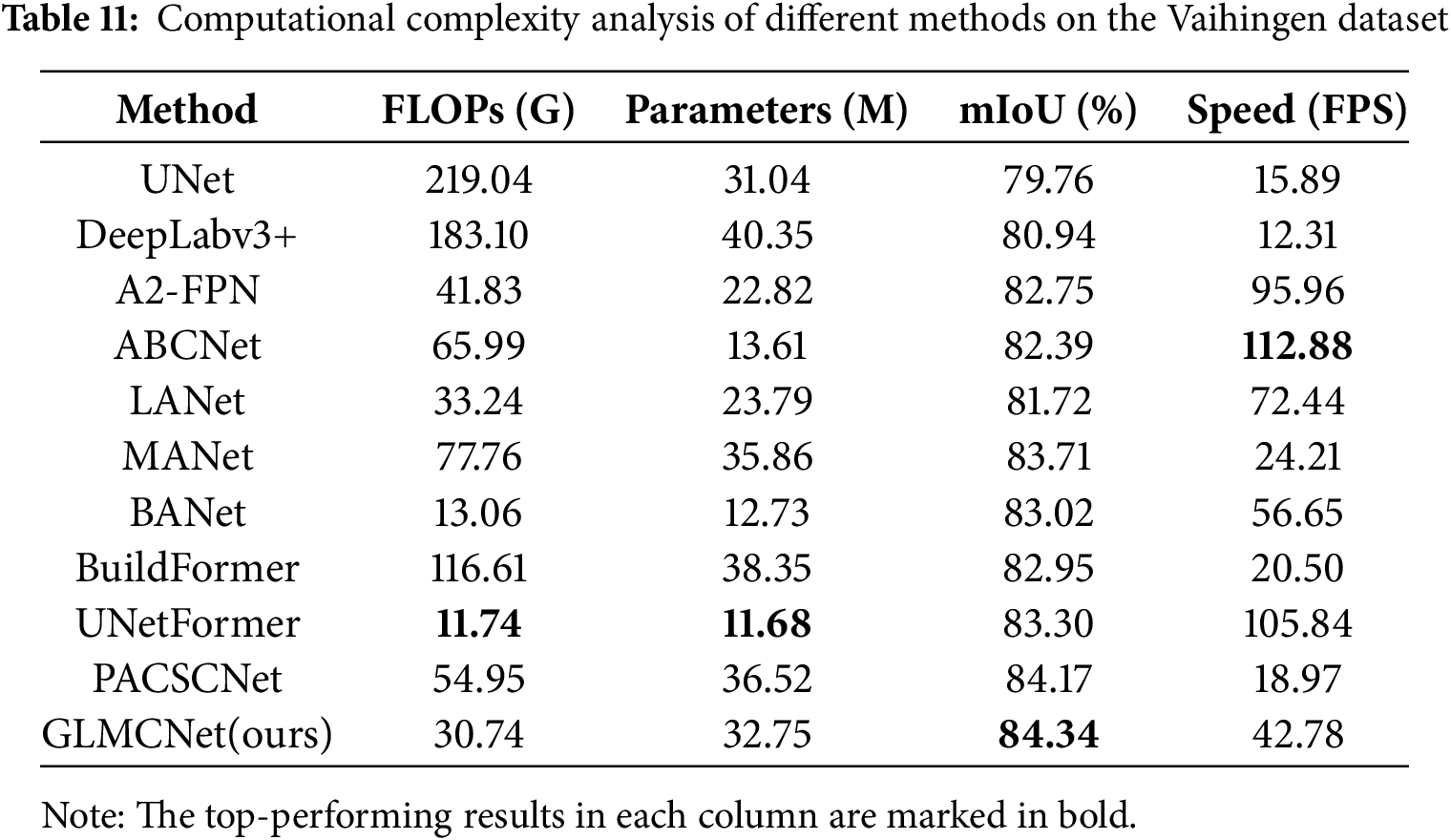

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the models, we measured the computational complexity (FLOPs), number of parameters (Parameters), and inference speed (FPS) for each method under identical experimental conditions. As shown in Table 11, UNetFormer has the lowest FLOPs and parameters, attributed to its lightweight ResNet-18 encoder and a relatively small number of Transformer blocks in the decoder. While this design achieves 105.84 FPS for fast inference, it reduces feature extraction capability, yielding an mIoU 1.04% lower than our model’s on the Vaihingen dataset. Our model uses ResNet-34 as the encoder and incorporates four transformer modules with multiscale feature extraction modules in the decoder, resulting in a slightly higher parameter count than lightweight models. However, the modules are carefully designed to achieve high segmentation accuracy with relatively low computational cost. As shown in Table 11, GLMCNet achieves 42.78 FPS on 512 × 512 image patches of the Vaihingen dataset, meeting near real-time processing requirements while attaining the highest mIoU of 84.34%. For resource-constrained edge devices, the current parameter count still poses some challenges. In future work, we plan to improve deployment efficiency by introducing lightweight backbone networks such as ConvNeXt or applying model compression techniques such as pruning and quantization to enhance adaptability while maintaining accuracy.

In this article, we propose a remote sensing semantic segmentation network, GLMCNet, based on CNN and Transformer. To enhance detail sensitivity, we design a DEFM module at the end of the encoder, which strengthens key detail representation while filtering redundant information. In the decoder, we introduce a GLMTB module to efficiently extract global and local multiscale contextual features, comprising a CBL layer, a Transformer block, and a MultiAttn block. Additionally, we design a stair fusion mechanism in the decoder to progressively merge deep semantic features with shallow ones. At the decoder’s final stage, a SAEM module is introduced to further enhance multiscale semantic representation.

We validated GLMCNet’s effectiveness through comparative and ablation experiments on the public Potsdam and Vaihingen datasets. The results demonstrate that it significantly improves segmentation accuracy for small objects and in complex edge regions, particularly where building and impervious surface boundaries are prone to confusion. This ability to handle complex scenes and fine-grained categories makes GLMCNet applicable to various real-world scenarios, such as innovative city development, disaster assessment, and emergency response. These applications rely heavily on the accurate delineation of object boundaries and subtle changes.

However, segmentation performance declines in shadowed areas due to the high similarity in color and texture between certain land-cover classes. In future work, we will further optimize the network architecture to enhance its adaptability to challenging scenarios, while also exploring a lightweight design approach. The current study primarily focuses on urban remote sensing scenes. We have also tested the model’s generalization ability under degraded image quality, and GLMCNet still achieved excellent segmentation performance. To further improve adaptability to complex scenes and cross-domain tasks, we plan to conduct comprehensive evaluations on more diverse public datasets, such as DeepGlobe and LoveDA. This will allow us to more realistically assess its robustness on data from unseen distributions.

Acknowledgement: During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5) for language polishing and grammar refinement. The authors have carefully reviewed and revised the output and accept full responsibility for all content.

Funding Statement: This research was provided by the Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department under grant No. BJK2024115.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: funding acquisition, Chuanzhao Tian; conceptualization, Yanting Zhang and Qiyue Liu; investigation, Yanting Zhang and Na Yang; methodology, Yanting Zhang and Xuewen Li; software, Feng Zhang; project administration, Hongyue Zhang; validation, Qiyue Liu and Na Yang; writing—original draft preparation, Yanting Zhang and Xuewen Li; writing—review and editing, Chuanzhao Tian and Yanting Zhang; supervision, Chuanzhao Tian. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. For detailed code on the proposed method, please refer to: https://github.com/Qiao03/GLMCNet.git (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| GLMCNet | Global-Local Multiscale Context Network |

| DEFM | Detail-Enhanced Filtering Module |

| GLMTB | Global-Local Multiscale Transformer Block |

| SAEM | Semantic Awareness Enhancement Module |

| W-PMSA | Window-Based Pooling Multihead Self-Aattention |

| W-MSA | Window Multi-Head Self-Attention |

| SW-MSA | Shifted Window Multi-Head Self-Attention |

| n×n Convolution, | |

| n×n Depthwise Separable Convolution, | |

| BN | Batch Normalisation |

| Cat | Concat |

References

1. Gutiérrez-Hernández O, García LV. Robust trend analysis in environmental remote sensing: a case study of cork oak forest decline. Remote Sens. 2024;16:3886. doi:10.3390/rs16203886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tang W, He F, Bashir AK, Shao X, Cheng Y, Yu K. A remote sensing image rotation object detection approach for real-time environmental monitoring. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2023;57:103270. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2023.103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alexander S, Yang B, Hussey O. Examining the land use and land cover impacts of highway capacity expansions in California using remote sensing technology. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board. 2025;2679(2):439–49. doi:10.1177/03611981241262299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mhanna S, Halloran LJS, Zwahlen F, Asaad AH, Brunner P. Using machine learning and remote sensing to track land use/land cover changes due to armed conflict. Sci Total Environ. 2023;898:165600. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ahmed Z, Ambinakudige S. How does shrimp farming impact agricultural production and food security in coastal Bangladesh? Evidence from farmer perception and remote sensing approach. Ocean Coast Manage. 2024;255:107241. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kazemi Garajeh M, Hassangholizadeh K, Bakhshi Lomer AR, Ranjbari A, Ebadi L, Sadeghnejad M. Monitoring the impacts of crop residue cover on agricultural productivity and soil chemical and physical characteristics. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15054. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-42367-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Gangwisch M, Saha S, Matzarakis A. Spatial neighborhood analysis linking urban morphology and green infrastructure to atmospheric conditions in Karlsruhe, Germany. Urban Clim. 2023;51:101624. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jia P, Chen C, Zhang D, Sang Y, Zhang L. Semantic segmentation of deep learning remote sensing images based on band combination principle: application in urban planning and land use. Comput Commun. 2024;217:97–106. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2024.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Geiß C, Aravena Pelizari P, Tunçbilek O, Taubenböck H. Semi-supervised learning with constrained virtual support vector machines for classification of remote sensing image data. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2023;125:103571. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2023.103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Martinez-Sanchez L, See L, Yordanov M, Verhegghen A, Elvekjaer N, Muraro D, et al. Automatic classification of land cover from LUCAS in situ landscape photos using semantic segmentation and a Random Forest model. Environ Model Softw. 2024;172:105931. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2023.105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang Y, Gu L, Li X, Gao F, Jiang T. Coexisting cloud and snow detection based on a hybrid features network applied to remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sensing. 2023;61:1–15. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3299617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shelhamer E, Long J, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(4):640–51. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2572683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li X, Xu F, Tao F, Tong Y, Gao H, Liu F, et al. A cross-Doma in coupling network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2024;21:5005105. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2024.3477609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou L, Chen G, Liu L, Wang R, Knoll A. Real-time semantic segmentation in traffic scene using cross stage partial-based encoder-decoder network. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;126:106901. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hong Q, Zhu Y, Liu W, Ren T, Shi C, Lu Z, et al. A segmentation network for farmland ridge based on encoder-decoder architecture in combined with strip pooling module and ASPP. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1328075. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1328075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention—MICCAI 2015. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 234–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu H, Huang P, Zhang M, Tang W, Yu X. CMTFNet: CNN and multiscale transformer fusion network for remote-sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sensing. 2023;61:1–12. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3314641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen L-C, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

19. Li W, Liao M, Zou W. Contextual-aware terra in segmentation network for navigable areas with triple aggregation. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;287:127906. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ni Y, Liu J, Chi W, Wang X, Li D. CGGLNet: semantic segmentation network for remote sensing images based on category-guided global-local feature interaction. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sensing. 2024;62:1–17. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3379398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Fu J, Liu J, Tian H, Li Y, Bao Y, Fang Z, et al. Dual attention network for scene segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2019 Jun 15–21; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

22. Gu G, Weng L, Xia M, Hu K, Lin H. Multipath multiscale attention network for cloud and cloud shadow segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–15. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3378970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xiao T, Liu Y, Huang Y, Li M, Yang G. Enhancing multiscale representations with transformer for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–16. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3256064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. IEEE; 2021. p. 9992–10002. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.00986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wu H, Huang P, Zhang M, Tang W. CTFNet: CNN-transformer fusion network for remote-sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2023;21:5000305. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2023.3336061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. IEEE; 2016. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu B, Li B, Sreeram V, Li S. MBT-UNet: multi-branch transform combined with UNet for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2024;16(15):2776. doi:10.3390/rs16152776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu J, Hua W, Zhang W, Liu F, Xiao L. Stair fusion network with context-refined attention for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–17. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3359676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wu H, Zhang M, Huang P, Tang W. CMLFormer: CNN and multiscale local-context transformer network for remote sensing images semantic segmentation. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2024;17:7233–41. doi:10.1109/jstars.2024.3375313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li R, Zheng S, Zhang C, Duan C, Wang L, Atkinson PM. ABCNet: attentive bilateral contextual network for efficient semantic segmentation of fine-resolution remotely sensed imagery. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2021;181:84–98. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2021.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shu X, Wang J, Zhang A, Shi J, Wu XJ. CSCA U-Net: a channel and space compound attention CNN for medical image segmentation. Artif Intell Med. 2024;150:102800. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2024.102800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zeng Q, Zhou J, Tao J, Chen L, Niu X, Zhang Y. Multiscale global context network for semantic segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–13. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3393489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. He G, Dong Z, Feng P, Muhtar D, Zhang X. Dual-range context aggregation for efficient semantic segmentation in remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2023;20:1–5. doi:10.1109/lgrs.2023.3233979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sun L, Zou H, Wei J, Cao X, He S, Li M, et al. Semantic segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing images based on sparse self-attention and feature alignment. Remote Sens. 2023;15(6):1598. doi:10.3390/rs15061598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li R, Wang L, Zhang C, Duan C, Zheng S. A2-FPN for semantic segmentation of fine-resolution remotely sensed images. Int J Remote Sens. 2022;43(3):1131–55. doi:10.1080/01431161.2022.2030071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li R, Zheng S, Zhang C, Duan C, Su J, Wang L, et al. Multiattention network for semantic segmentation of fine-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2021;60:1–13. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2021.3093977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li B, Li W, Wang B, Liu Z, Huang J, Wang J, et al. SECNet: spatially enhanced channel-shuffled network with interactive contextual aggregation for medical image segmentation. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;290:128409. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.128409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Lyu X, Jiang W, Li X, Fang Y, Xu Z, Wang X. MSAFNet: multiscale successive attention fusion network for water body extraction of remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023;15:3121. doi:10.3390/rs15123121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fan X, Zhou W, Qian X, Yan W. Progressive adjacent-layer coordination symmetric cascade network for semantic segmentation of multimodal remote sensing images. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238:121999. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen J, Yi J, Chen A, Lin H. SRCBTFusion-net: an efficient Fusi on architecture via stacked residual convolution blocks and transformer for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–16. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2023.3336689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929 2020. [Google Scholar]

42. Xiong YG, Xiao XM, Yao MB, LiuHQ, YangH, FuYG. MarsFormer: martian rock semantic segmentation with transformer. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–12. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3302649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Xie E, Wang W, Yu Z, Anandkumar A, Alvarez JM, Luo P. SegFormer: simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2021;34:12077–90. [Google Scholar]

44. Wang L, Li R, Wang D, Duan C, Wang T, Meng X. Transformer meets convolution: a bilateral awareness network for semantic segmentation of very fine resolution urban scene images. Remote Sens. 2021;13:3065. doi:10.3390/rs13163065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Cai S, Jiang Y, Xiao Y, Zeng J, Zhou G. TransUMobileNet: integrating multi-channel attention fusion with hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture for medical image segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;107:107850. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2025.107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Duan Y, Yang D, Qu X, Zhang L, Qu J, Chao L, et al. LightCGS-Net: a novel lightweight road extraction method for remote sensing images combining global semantics and spatial details. J Netw Comput Appl. 2025;242:104247. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2025.104247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Blaga BCZ, Nedevschi S. Semantic segmentation of remote sensing images with transformer-based U-Net and guided focal-axial attention. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Observations Remote Sens. 2024;17:18303–18. doi:10.1109/jstars.2024.3470316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang L, Li R, Zhang C, Fang S, Duan C, Meng X, et al. UNetFormer: a UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2022;190:196–214. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2022.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wang L, Fang S, Meng X, Li R. Building extraction with vision transformer. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–11. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2022.3186634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Fan L, Zhou Y, Liu H, Li Y, Cao D. Combining swin transformer with UNet for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:1–11. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3329152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Tong Q, Zhu Z, Zhang M, Cao K, Xing H. CrossFormer embedding DeepLabv3+ for remote sensing images semantic segmentation. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;79(1):1353–75. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.049187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. [Google Scholar]

53. He X, Zhou Y, Zhao J, Zhang D, Yao R, Xue Y. Swin transformer embedding UNet for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–15. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2022.3144165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Tan M, Le Q. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

55. Liu Z, Mao H, Wu CY, Feichtenhofer C, Darrell T, Xie S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In: Proceedings of 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 19–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

56. Ding L, Tang H, Bruzzone L. LANet: local attention embedding to improve the semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2020;59:426–35. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2020.2994150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools