Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GFL-SAR: Graph Federated Collaborative Learning Framework Based on Structural Amplification and Attention Refinement

School of Digital and Intelligence Industry, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, 014010, China

* Corresponding Author: Ruichun Gu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Deep Learning and Neural Networks: Architectures, Applications, and Challenges)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069251

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Graph Federated Learning (GFL) has shown great potential in privacy protection and distributed intelligence through distributed collaborative training of graph-structured data without sharing raw information. However, existing GFL approaches often lack the capability for comprehensive feature extraction and adaptive optimization, particularly in non-independent and identically distributed (NON-IID) scenarios where balancing global structural understanding and local node-level detail remains a challenge. To this end, this paper proposes a novel framework called GFL-SAR (Graph Federated Collaborative Learning Framework Based on Structural Amplification and Attention Refinement), which enhances the representation learning capability of graph data through a dual-branch collaborative design. Specifically, we propose the Structural Insight Amplifier (SIA), which utilizes an improved Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to strengthen structural awareness and improve modeling of topological patterns. In parallel, we propose the Attentive Relational Refiner (ARR), which employs an enhanced Graph Attention Network (GAT) to perform fine-grained modeling of node relationships and neighborhood features, thereby improving the expressiveness of local interactions and preserving critical contextual information. GFL-SAR effectively integrates multi-scale features from every branch via feature fusion and federated optimization, thereby addressing existing GFL limitations in structural modeling and feature representation. Experiments on standard benchmark datasets including Cora, Citeseer, Polblogs, and Cora_ML demonstrate that GFL-SAR achieves superior performance in classification accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness compared to existing methods, confirming its effectiveness and generalizability in GFL tasks.Keywords

With the increasing demand for data privacy protection [1], Federated Learning (FL), as a distributed training paradigm [2], has become an important technical means to solve the problem of data silos. In recent years, the application of FL in financial risk control [3], medical diagnosis [4], and personalized recommendation [5] has become increasingly widespread. At the same time, many real-world data naturally present graph structures, such as user relationships in social networks, paper citations in academic citation networks, and transaction networks in e-commerce platforms. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have become the core tool of Graph Federated Learning (GFL) due to their powerful modeling ability for graph-structured data [6]. However, the complexity and dynamism of graph data pose new challenges [7] for GFL, especially in distributed environments where data heterogeneity, NON-IID characteristics [8], and insufficient representation of important node features significantly affect model performance.

A typical popular application scenario is false information detection on social media [9,10]. In this scenario, the connections between users form a complex social graph, with user behavior data (such as posting, liking, and forwarding) distributed across servers on different platforms or regions. Due to privacy regulations and competition between platforms, data cannot be centrally shared. For example, Twitter and Facebook may each hold some user relationships and behavior data, but cannot directly exchange raw data to train a unified false information detection model. GFL provides a solution to this problem through distributed collaborative training, enabling multiple platforms to jointly learn graph models while protecting privacy. However, the current GFL method still faces many limitations in practical applications.

Firstly, existing methods [11,12] typically adopt a single-perspective neighbor aggregation strategy when aggregating node features, limiting their ability to capture the complex structural features of graph data. In social media graphs, user relationships often exhibit intricate connectivity patterns and varying strengths, posing significant challenges for accurate representation. A single GCN is insufficient to capture global topological patterns, while GAT, despite incorporating attention mechanisms, often struggles to effectively simulate long-term structural dependencies. Then, current approaches often overlook the importance of fine-grained neighborhood feature representation [13]. In tasks such as false information detection, key propagation nodes (e.g., “super spreaders”) play a crucial role. However, many models aggregate neighbor information in a unified manner, which results in important features being diluted by irrelevant or noisy nodes, thereby reducing detection accuracy. Besides, methods such as FedGCN [14] and FedSage+ [15] have not explicitly addressed the need for detailed modeling of key neighborhood features or fine-grained node-level distinctions between clients. FedGCN primarily focuses on structural aggregation without selectively enhancing key relational signals. FedSage+ relies on neighbor sampling and generation mechanisms, which may not preserve high-value node-level semantics. Neither of these methods provide sufficient mechanisms to distinguish important relationships, nor integrate complementary information among decentralized clients. These limitations make it difficult for existing GFL methods to fully utilize the rich structural and relational information embedded in complex social media graphs.

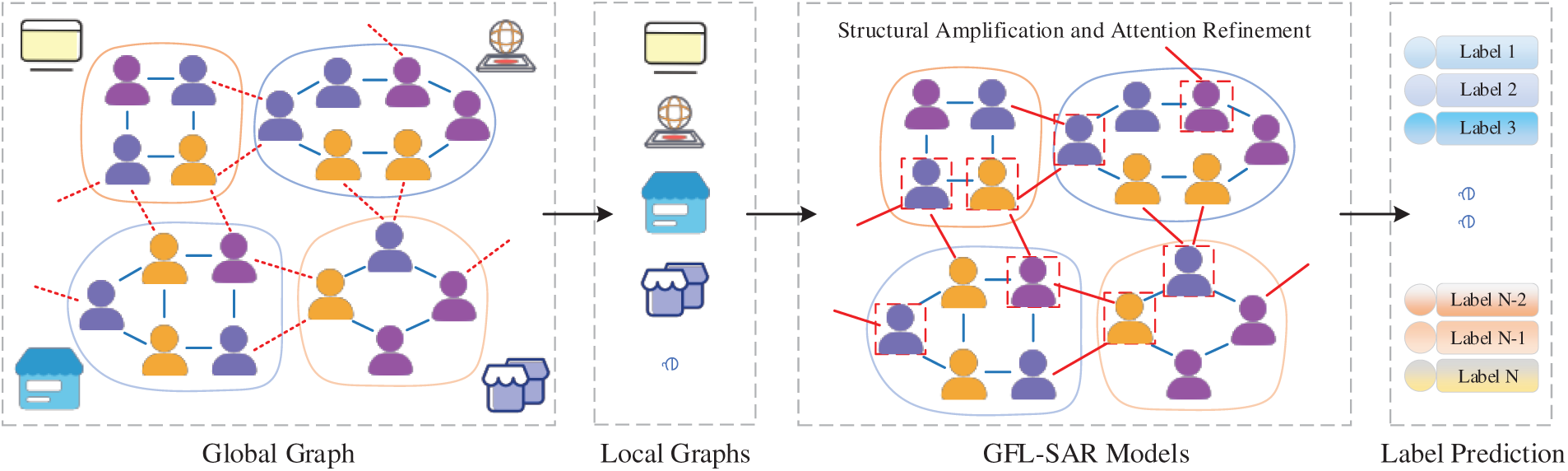

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes an innovative GFL framework GFL-SAR. GFL-SAR integrates the outputs of SIA and ARR through feature fusion and combines them with federated training strategies to achieve efficient collaboration and distributed optimization of multi-scale features in graph data. As illustrated in Fig. 1 (where the red dashed line indicates missing edge information, and the red border highlights the captured key nodes and important neighborhood features after training with GFL-SAR), the proposed framework can effectively identify critical nodes (such as false information spreaders), and improve overall model performance.

Figure 1: GFL-SAR functional principle diagram

Our main contributions are as follows:

• We propose the SIA, which can better capture and model topological patterns. This design strengthens structural representation and is particularly suitable for global structural modeling in real-world scenarios such as social media recommendation.

• We design the ARR, which can dynamically model node relationships and perform fine-grained representation of key neighborhood features. This design effectively mitigates the dilution of crucial node information in tasks such as false information detection, thereby enhancing the model’s local discriminative ability.

• We propose a GFL-SAR framework that enables efficient integration and distributed training of multi-scale structural and relational features through feature collaboration and federated optimization, which provides robust solutions for heterogeneous and NON-IID graph learning scenarios.

• The experimental results on multiple-standard reference network datasets show that GFL-SAR outperforms existing distributed GCN training methods in most cases, exhibiting higher performance and better classification performance.

We introduced the relevant work in Section 2, elaborated on the methods used in Section 3, presented the experiments in Section 4, and presented the conclusions and future work prospects in Section 5.

FL is a distributed machine learning paradigm that allows multiple parties to collaborate in training a global model without sharing raw data, thus balancing privacy and performance. It has been widely used in sensitive privacy fields such as finance, healthcare, and recommendations [16]. As research advances, researchers continue to explore optimization algorithms, communication compression [17], and privacy enhancement, and introduce trust mechanisms, contrastive learning, and graph structure modeling to address complex heterogeneous data. For example, TFL-DT [18] improves system reliability through digital twins, but relies on complex algorithms and is difficult to generalize; The federated graph anomaly detection framework [19] enhances anomaly awareness, but its performance is limited due to frequent communication and it is difficult to directly adapt to heterogeneous graphs; The graph clustering joint learning framework [20] has to some extent alleviated the NON-IID problem, but lacks effective recognition of key features.

In response to these shortcomings, this paper proposes the GFL-SAR framework, which adopts a feature extraction strategy composed of SIA and ARR to enhance the ability of structural modeling and key feature recognition. Compared with existing methods, GFL-SAR significantly improves the understanding and relationship modeling ability of heterogeneous graph data through intuitive architecture design, thereby demonstrating stronger generalization performance in GFL tasks.

The attention mechanism, as a computational paradigm that simulates human perception processes, enables neural networks to flexibly allocate weights between multidimensional features. Since the introduction of Transformer, Multi-Head Attention has been widely applied in natural language processing, computer vision, and GNNs due to its ability to model multi-scale information in parallel [21–24]. The introduction of Channel Attention [25,26] and Spatial Attention [27,28] has further promoted the development of image recognition and object detection [29]. However, existing methods still face challenges in graph structured data. For example, TGC-YOLOv5 [30] relies on global attention to enhance overall modeling, but ignores local neighborhood relationships; CIR-DFENet [31] combines multi-channel CNN and GAM to improve overall feature modeling, but is limited in key feature capture and computational efficiency; Although CFI-LFENet [32] and Lite-FENet [33] emphasize lightweight, they often lack neighborhood information fusion and multi-scale modeling capabilities, resulting in inadequate performance in complex tasks.

To address these issues, this paper designs an ARR module in the GFL-SAR framework and introduces an enhanced graph attention mechanism to achieve precise focusing and selective aggregation of key neighbor nodes. ARR combines channel interaction and weighting strategy, effectively improving the discriminability and stability of feature representation. Compared with existing methods, ARR not only maintains strong expressive power, but also has a more efficient and lightweight structure, thereby enhancing adaptability and generalization performance in heterogeneous graph environments, and supporting a wider range of practical deployments.

GNNs have demonstrated powerful modeling capabilities in tasks such as node classification, graph classification, and link prediction, due to their excellent performance in deep learning for handling graph structured data. In recent years, with the increasing demand for data privacy protection, the application of GNN in FL frameworks has gradually received attention, which has also given rise to emerging research directions in GFL [34,35]. This direction combines the structural perception capability of GNN with the distributed training mechanism of FL. It can achieve joint modeling of graph structure data without exposing the original data, providing a new path for secure integration of multi-source graph data.

Although existing GFL methods have achieved certain results in some tasks, most methods still have the following core bottlenecks: firstly, relying on static graph topology and single-scale feature modeling, it is difficult to adapt to the evolution of dynamic graph structures in time and space dimensions; Secondly, the lack of deep modeling of important structural relationships and key features across clients leads to insufficient generalization ability of the model when dealing with complex tasks. For example, Ref. [36] proposed a federated dynamic graph neural network that initially achieves feature dependency modeling by establishing dynamic relationship links between the same node in different client graphs. However, it lacks deep mining and modeling capabilities for key neighborhood features; Ref. [37] proposed an assessable modular temporal prediction method, which effectively improves learning efficiency, but focuses on the study of timelines and lacks effective processing of multi-scale features and neighborhood key features; Ref. [38] designed a hierarchical method based on graph contrastive learning to counteract relationship masking and improve the detection accuracy of false comments. However, there is a lack of refined modeling of global and local features, as well as a lack of capturing relationships between potential clients. In addition, the latest research [39] adopts the weighted fusion of gated graph convolutional network architecture, which effectively improves the ability of long-distance interaction in data. However, the representation of key neighborhood node features is insufficient, and there is a lack of interaction between global and local features.

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes GFL-SAR, an innovative GFL framework that differs from typical architectures DB-GNN [40] and FedStar [41]. The former mainly relies on client local models for personalized learning. Although it improves personalization capabilities, it lacks the ability to model global graph structures, resulting in limited effectiveness in handling tasks with cross client structural dependencies. The latter adopts a dual branch architecture to enhance graph modeling and federated aggregation, but its structural branches rely on predefined topological features, making it difficult to dynamically capture complex graph structural changes, and ignoring the modeling ability of fine-grained node relationships. In contrast, GFL-SAR integrates SIA and ARR to simultaneously enhance global structural modeling and fine-grained node relationship representation in federated environments. SIA adopts a novel cyclic convolution mechanism with normalized enhancement, effectively capturing complex topological patterns, multi-scale structural features, and potential heterogeneous dependencies between clients, ARR utilizes an enhanced graph attention mechanism to dynamically model key neighborhood features, and introduces a feature preservation mechanism for important client neighborhoods to promote the sharing and transmission of key features between heterogeneous graph structures. This overcomes the limitations of existing GFL methods in processing NON-IID graph data and modeling local structural information, making GFL-SAR particularly effective in complex distributed tasks such as false information detection, abnormal behavior recognition, and error review detection.

In the training scenario of distributed graph learning, it is usually necessary to first partition the entire graph structure reasonably to adapt to the parallel computing requirements of multiple clients. On this basis, this paper will focus on node classification tasks in a single graph partitioning environment based on the GFL-SAR framework, and deeply explore key issues such as feature extraction, neighborhood information modeling, and model aggregation strategies under distributed conditions, to verify the effectiveness and advantages of GFL-SAR in dealing with heterogeneous structures and dynamic dependencies.

We assume graph

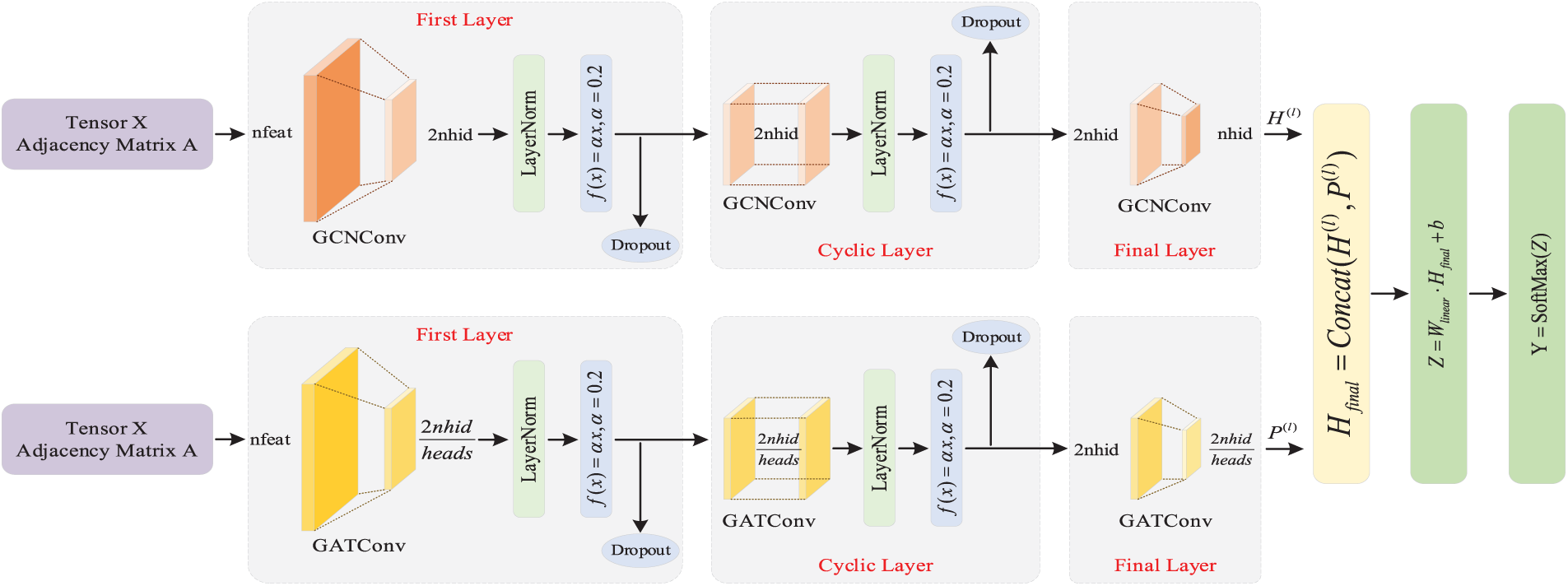

3.1 Structural Insight Amplifier (SIA)

The SIA significantly enhances the representation ability of graph topology by integrating cyclic convolution mechanism and normalization enhancement into GCN structure. This design significantly enhances the model’s ability to capture potential structural dependencies, providing a novel and efficient approach for topological feature modeling. Specifically, the SIA branch achieves precise modeling of each channel through refined channel scaling. This unique channel scaling strategy not only enhances the expression ability of structural features, but also improves the generalization performance of the model in complex graph scenes, laying a solid foundation for robust FL.

Firstly, normalize the adjacency matrix

Definition: Assuming the input feature is

Among them,

For a traditional GCN with an L layer structure, the representation of node i depends on the feature information of its L-hop neighbors, that is, the set of all neighboring nodes starting from node i with a path length not exceeding L (denoted as

In the federated setting, we use c(i) to represent the index of the client containing node i, and

Among them,

However, as the number of layers increases, traditional GCNs suffer from over-smoothing, where node representations become indistinguishable due to uniform aggregation in a single-pass manner per layer. This limits their ability to model complex topological patterns, especially in NON-IID federated settings where cross-client structural dependencies are heterogeneous.

To address these limitations, we introduce the cyclic convolution mechanism in SIA, which extends the single-pass aggregation of traditional GCNs by iteratively refining the convolution within each layer. Cyclic convolution is defined as a recursive aggregation process that applies the normalized adjacency matrix multiple times (C cycles) within a single layer, emphasizing multi-hop structural dependencies while incorporating residual connections and normalization to prevent over-smoothing. Mathematically, the cyclic convolution operation for the l-th layer is defined as:

Among them,

We are currently using the LeakyReLU activation function with α set to 0.2. The ordinary ReLU (

Finally, the final layer adopts a channel compression strategy to converge the feature dimension 2nhid to the target output dimension nhid, to reduce model complexity and improve inference efficiency.

Comparison with Traditional GCN: Unlike the single-pass aggregation in traditional GCN (Eq. (2)), the traditional GCN performs a fixed linear combination of neighbor features once per layer. Cyclic convolution (Eq. (4)) introduces intra-layer iterations to dynamically amplify structural signals by repeatedly applying A. This enables SIA to capture higher-order topological patterns (e.g., motifs or cycles) without the need to add extra layers, thereby reducing the inherent risk of over smoothing in deep traditional GCNs (Eq. (3)). For instance, in a 2-cycle setup (C = 2), the effective receptive field is extended to emphasize 2-hop dependencies within one layer, thereby improving global structural awareness.

Novelty and Advantages: The novelty of cyclic convolution lies in its intra-layer recursive design, which does not exist in previous federated variants like standard GCN or FedGCN [14], which focus on inter-client communication rather than intra-layer refinement. The advantages include: (i) enhanced modeling of long-range dependencies in sparse or heterogeneous graphs, (ii) better preservation of node distinctions in NON-IID scenarios by mitigating uniform aggregation, and (iii) improved convergence speed (as shown in experiments), as the cycles allow for adaptive structural amplification without increasing model depth. This makes SIA particularly suitable for federated graph tasks that require inferring global topology from distributed subgraphs.

3.2 Attentive Relational Refiner (ARR)

The ARR employs an enhanced graph attention network with a cyclic attention mechanism to strengthen key neighborhood feature representation. Cyclic attention is defined as a multi-iteration attention process that dynamically refines attention weights across cycles within each layer, allowing for selective emphasis on important neighbors while adapting to relational heterogeneity.

In the traditional GAT, the neighborhood feature representation

Among them,

Among them,

To overcome this, ARR introduces cyclic attention, which iteratively refines attention coefficients in C cycles, combined with residual updates and normalization to improve stability. Its core goal is to dynamically capture multi-scale correlations between each layer’s neighborhoods and differentially model the interactions between channels. This mechanism significantly enhances the model’s perception of key node relationships and feature dependencies. The cyclic attention operation at layer l is defined as:

Among them,

The final layer converges the feature dimension 2nhid to twice the attention grouping hidden dimension

After the above operations, the embedding of node i in layer l can be expressed as:

Thanks to this design, the ARR branch significantly enhances the model’s ability to represent heterogeneous graph relationships and local-global dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency, laying a solid foundation for subsequent node classification and relationship modeling tasks.

Comparison with Traditional GAT: Traditional GAT (Eqs. (5) and (6)) computes attention in one single iteration and uniformly processes all neighbors in one aggregation step, which may not capture the constantly changing importance of relationships in the iteration. In contrast, cyclic attention (Eq. (7)) performs multiple refinement cycles, allowing attention weights to adapt dynamically—e.g., downweighting noisy nodes in later cycles. Compared to the static mechanism of GAT, this leads to finer grained modeling.

Novelty and Advantages: The novelty stems from the iterative refinement within layers, differing from standard GAT or federated extensions like those in FedGCN [14], which do not incorporate such cycles for attention. These advantages include: (i) reducing feature dilution by gradually focusing on key relationships, (ii) enhancing local discriminative ability in NON-IID graphs where neighbor importance varies across clients, and (iii) superior expressiveness for tasks like false information detection, where identifying “super spreaders” requires adaptive relational modeling. Experimental results have shown that due to this mechanism, convergence speed is faster and accuracy is higher.

3.3 Aggregation and Computation Module

In the GFL-SAR framework, efficient integration of multi-scale features in graph data is achieved through feature fusion and federated collaborative optimization:

Subsequently, the feature representation will be sent to the fully connected layer for further nonlinear mapping and fusion to complete the integration of high-level semantic information. This process not only enhances the discriminative ability of the model, but also lays the representation foundation for the final classification or prediction task. The specific form is as follows:

Among them,

Finally, we perform SoftMax operation on the above output to map the linear output to a normalized probability distribution to support multi classification tasks:

The overall graph federated learning framework is shown in Fig. 2. We will temporarily set the Cyclic layer to 3 in subsequent experiments.

Figure 2: The GFL-SAR overall framework flowchart

Next, we will discuss how each client calculates the loss function on its local data during the training phase:

Among them, θ represents the learnable parameters of the model, and

During each round of global training, the server takes a weighted average of the local model parameters of each client to generate new global model parameters. The total sample size of all client datasets |D| can be described as

After E-round local iteration, the server aggregates the local models of all clients to generate a new global model:

To ensure data privacy during feature aggregation, GFL-SAR employs a secure neighbor feature aggregation mechanism based on homomorphic encryption, following the approach in FedGCN [14] for secure aggregation of neighbor features. Specifically, we leverage the CKKS [42] scheme for handling floating-point model parameters and node features, which may include binary values (e.g., one-hot indicators). To optimize for integer features and avoid separate cryptographic setups (e.g., BGV for integers), we adopt CKKS with a rounding procedure for integers and introduce Boolean Packing, an efficient optimization that packs arrays of boolean values into integers. This reduces the cryptographic communication overhead, with encrypted features requiring only twice the communication cost of raw data, compared to 20× overhead in general encryption schemes.

The core process of this mechanism is as follows: Firstly, all clients collaborate to initialize and share the same pair of public and private keys. Subsequently, each client encrypts its local neighbor feature matrix using a public key and uploads the encrypted feature data to the server. The server directly performs homomorphic encryption on the received encrypted neighbor feature matrix without decryption, thereby achieving secure integration of global features:

Among them,

Our experiment is conducted on a machine equipped with Intel ® Core™ on the computing platform of i7-13700 processor and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 GPU. All GCN structures with NumberLayers adopt a three-layer architecture, with a dataset hidden layer size of 32 and Dropout set to 0.5. For both the Cora and Citeseer datasets, we used SGD optimizer with a learning rate of 0.5 and L2 regularization coefficient of 5e−4. In the federated learning setting, each client performs 3 local steps per round, with training rounds of 100 and 20, respectively. For the Cora_ML and Polblogs datasets, we used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, L2 regularization coefficient of 5e−4, and 50 training rounds. This study used four widely used real-world graph datasets, as detailed in Table 1. The class distribution in Table 1 highlights the balance of node labels across classes, which is important for evaluating model performance in semi-supervised settings. The sparsity metric indicates the connectivity density of each graph. Dataset Polblogs exhibits significantly higher connectivity (sparsity = 0.0224) compared to Cora (0.0015) and Citeseer (0.0009), posing unique challenges for modeling dense neighborhood structures in federated settings.

For semi-supervised node classification, we adopt a standard split strategy where 20% of nodes are randomly selected as labeled nodes for training, 30% for validation, and 50% for testing, following common practice in GNN literature [14,15]. This split simulates realistic label scarcity scenarios, such as social media false information detection. Only a small subset of nodes have known labels, while the majority require prediction based on structural and relational patterns.

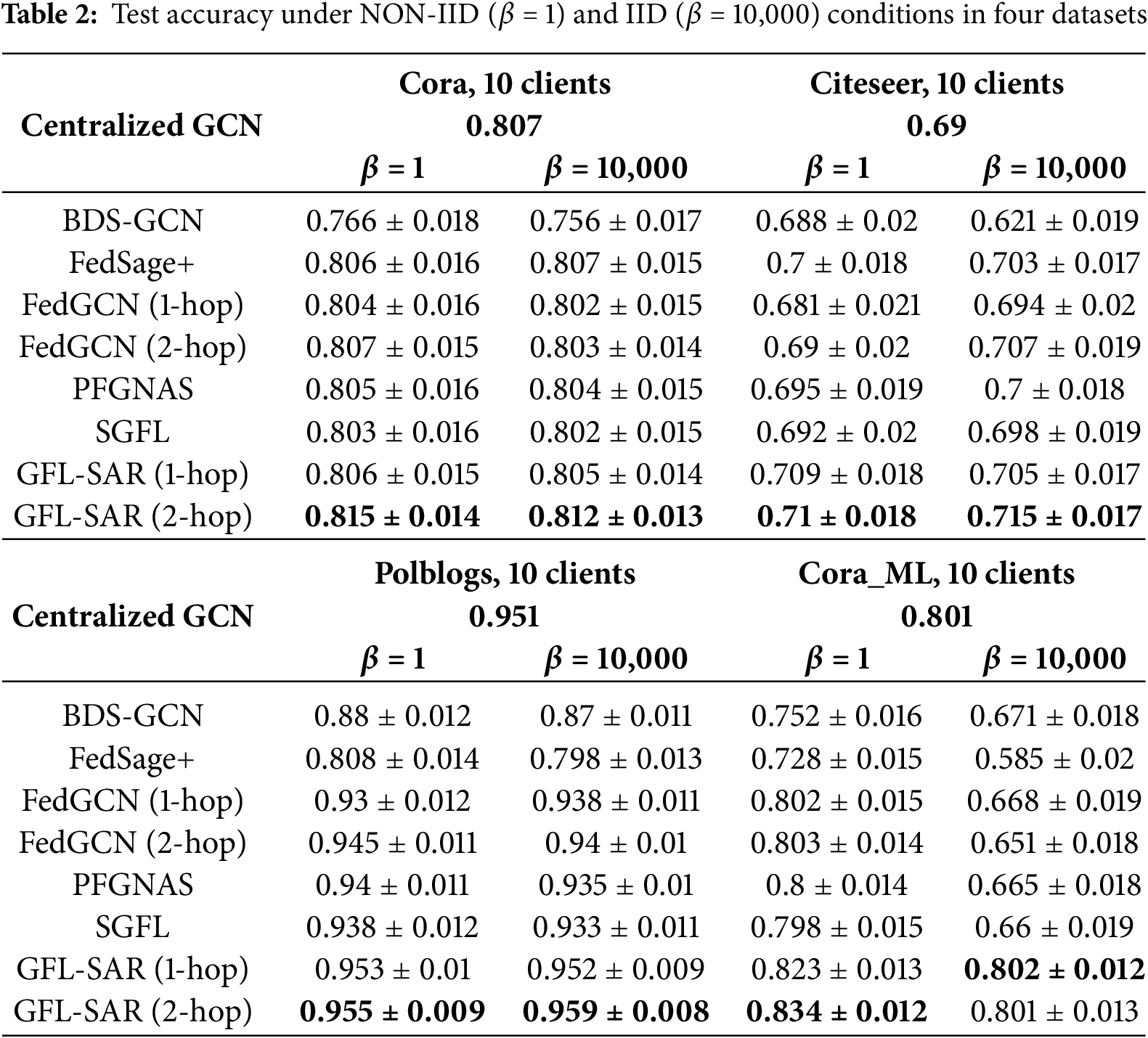

We compare the proposed GFL-SAR method with the following mainstream baseline models: Centralized GCN assumes that a single client can access the entire graph, achieving centralized training as a reference for performance limits; BDS-GCN [43] randomly samples edge information across clients in each round of global training for joint modeling to alleviate information loss caused by graph structure fragmentation; FedSage+ [15] introduces a missing neighbor generator, effectively addressing the issue of missing neighbor information caused by data silos in federated scenarios; FedGCN [14] comprehensively models 1-hop and 2-hop neighbor information in a FL framework, including directly connected nodes and second-order neighbors reachable through an edge; PFGNAS [44] employs task specific prompts to continuously identify and integrate the best GNN architecture. SGFL [45] dynamically constructs FL graphs by utilizing the inherent high-dimensional information between clients.

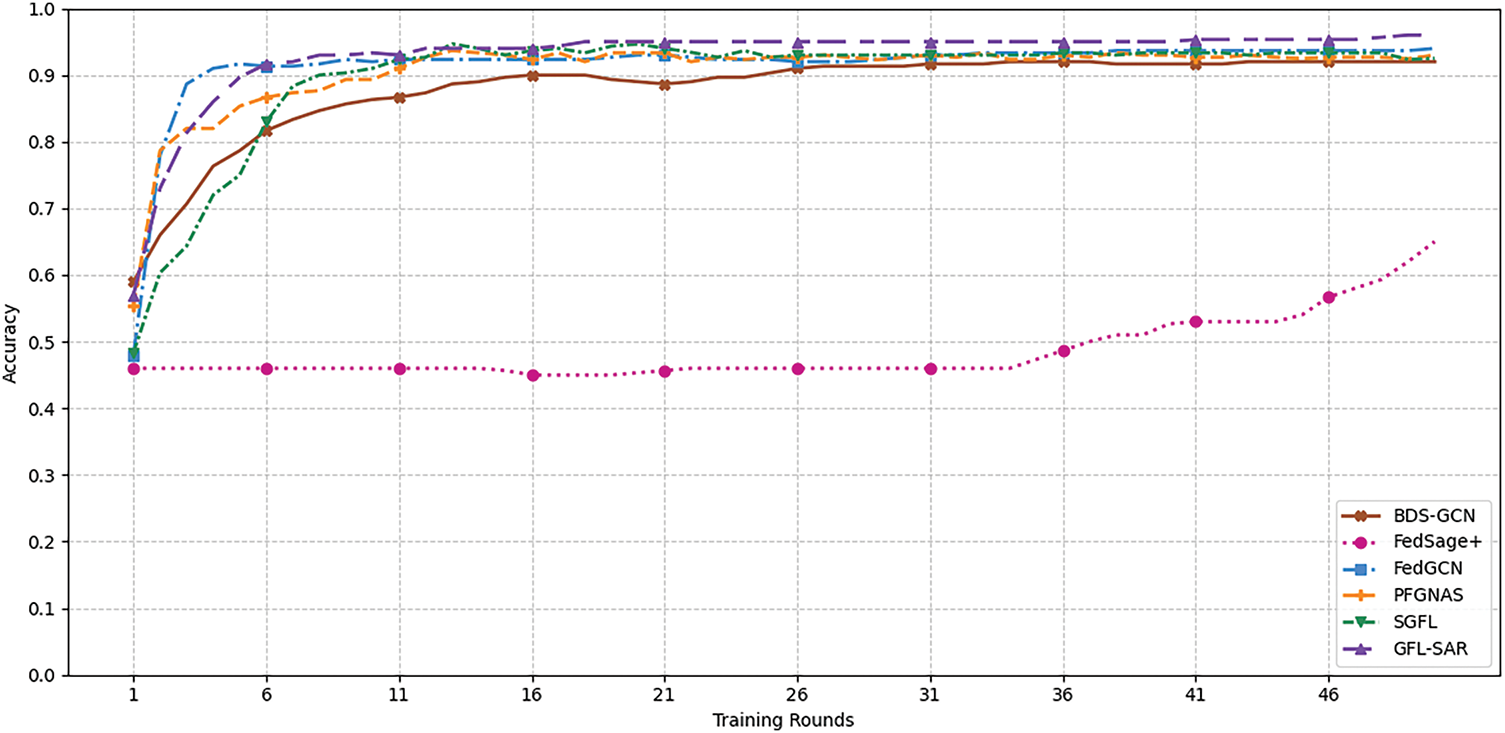

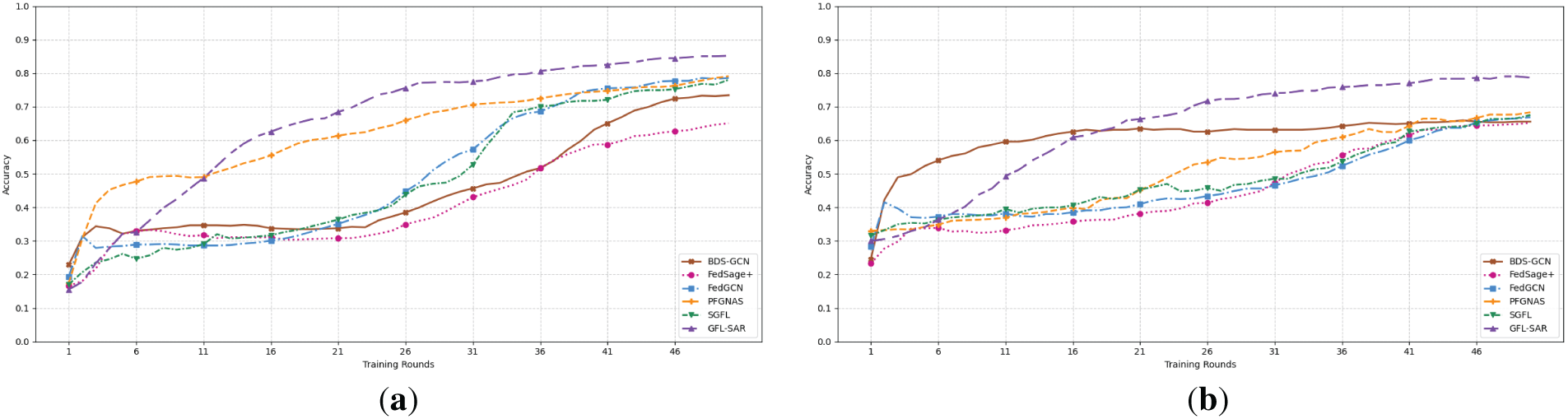

We validated the performance of each method on four datasets under the NON-IID (β = 1) and IID (β = 10,000) Dirichlet data distribution conditions. We set the number of clients to 10 and conducted an average of over 10 independent experimental runs. Table 2 summarizes the final average test accuracy, which shows that GFL-SAR outperforms Centralized GCN, BDS-GCN, FedSage+, and FedGCN in all experimental settings. Moreover, GFL-SAR has achieved higher testing accuracy compared to centralized training and standard GCN, and can still maintain stable performance in NON-IID scenarios. We conducted comparative experiments between GFL-SAR (2-hop) and the second-best baseline (FedGCN (2-hop)) under each setting. The results confirm that the improvement of GFL-SAR is statistically significant in all datasets and conditions, highlighting its robust performance in NON-IID and IID scenarios. This advantage is mainly attributed to GFL-SAR’s ability to effectively handle multi-scale feature fusion problems. Through the collaborative design of SIA and ARR branches, it exhibits stronger neighbor information modeling capabilities when facing heterogeneous graph data, accurately expressing key node features. Especially on the Polblogs dataset, due to its high average degree (i.e., each node has more neighbors), GFL-SAR further validates its effectiveness in capturing closely related user information, as shown in Fig. 3, significantly improving the node classification accuracy and model robustness. In addition, as shown in (a) and (b) of Fig. 4, on the Cora_ML dataset with higher structural complexity and more representative node features and topological relationships, as the number of training rounds gradually increases, GFL-SAR shows a smooth and stable convergence trend under both NON-IID and IID data distribution settings. However, FedGCN and FedSage+ overly rely on neighborhood aggregation, which makes the features of key nodes easily diluted by irrelevant information, while BDS-GCN adopts a static feature aggregation strategy, which lacks flexibility and is difficult to adapt to the multi-scale structural patterns of heterogeneous graphs. PFGNAS and SGFL lack effective strategies for capturing neighborhood features, resulting in a decrease in their ability to model graphs. This phenomenon fully demonstrates the optimization robustness and generalization ability of GFL-SAR in complex heterogeneous graph structures, further verifying its reliability and practicality in distributed heterogeneous environments.

Figure 3: Accuracy comparison of different models in the Polblogs dataset under NON-IID

Figure 4: Accuracy comparison of different models in the Cora_ML dataset under NON-IID (a) and IID (b) conditions

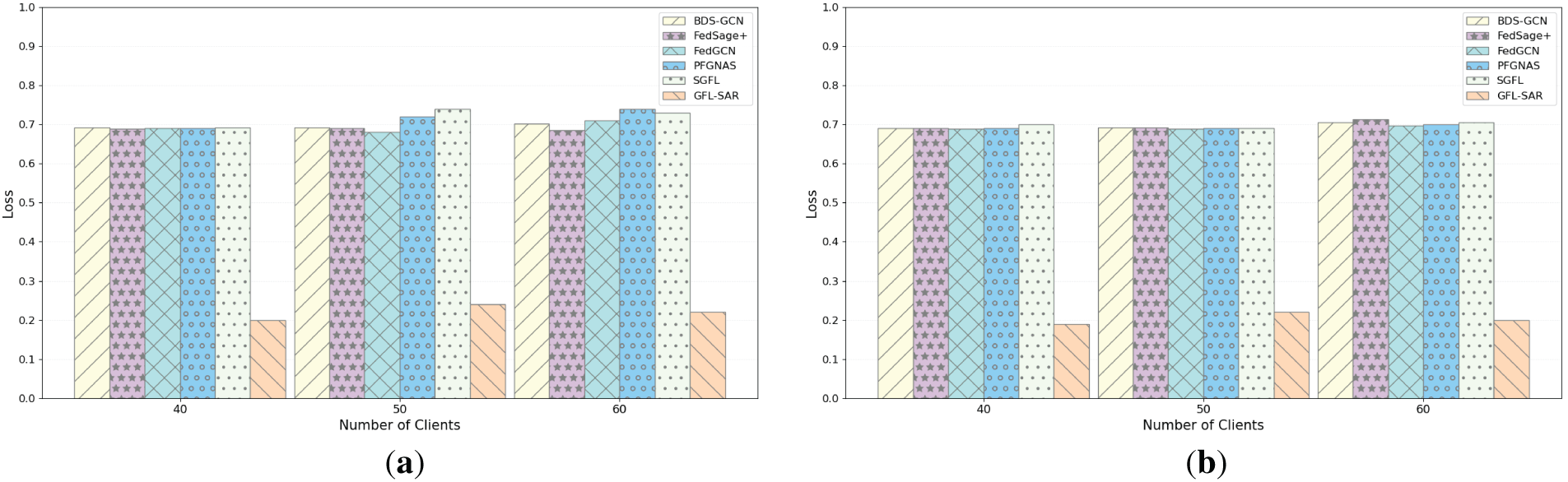

The training results on the Cora and Citeseer datasets show that GFL-SAR outperforms the optimal FedGCN and standard GCN under both NON-IID and IID conditions, with an average loss gap controlled within 0.1 or even lower, fully demonstrating its outstanding performance. This advantage stems from GFL-SAR’s innovative feature collaborative design, which effectively handles multi-scale feature fusion problems and demonstrates strong neighbor information modeling capabilities when facing heterogeneous graph data. It can accurately capture multi-scale features and highlight key node feature expressions. On the Polblogs dataset, as shown in Fig. 5a,b, the average loss of GFL-SAR in NON-IID and IID scenarios is as low as 0.17 and 0.15, respectively, significantly better than other methods, highlighting its strong adaptability to data heterogeneity. In contrast, the average losses of the baseline model under NON-IID and IID conditions are: BDS-GCN (0.69, 0.68), FedSage+ (0.68, 0.67), FedGCN (0.68, 0.67), PFGNAS (0.67, 0.66), SGFL (0.68, 0.66). The loss value is higher, and the stability is insufficient. On the Cora_ML dataset, as shown in Fig. 6a,b, the average loss of GFL-SAR was further reduced to 0.96 (NON-IID) and 0.76 (IID), while the loss values of the baseline model were significantly higher and fluctuated more, as follows: BDS-GCN (1.41, 1.09), FedSage+ (1.45, 1.24), FedGCN (1.42, 0.92), PFGNAS (1.42, 0.98), SGFL (1.43, 1.01). These results indicate that GFL-SAR can achieve higher classification accuracy while maintaining low loss, demonstrating excellent robustness. In contrast, other baseline models fail to effectively handle the integration of multi-scale features, as their designs are often limited to a single-perspective feature extraction strategy. This limitation leads to insufficient adaptability to data heterogeneity, thereby constraining their generalization performance in complex GFL scenarios. Overall, GFL-SAR maintains stable performance in both NON-IID and IID scenarios, and its high adaptability to changes in data distribution is due to its ability to perceive key features. This ability is particularly prominent in scenarios such as social media false information detection, which can efficiently identify key propagation nodes. In addition, GFL-SAR not only enhances the credibility and interpretability of the model by integrating data from multiple clients, but also provides a solid guarantee for the deployment of practical applications, fully verifying its superiority in complex GFL tasks.

Figure 5: Loss comparison of different models in the Polblogs dataset under NON-IID (a) and IID (b) conditions

Figure 6: Loss comparison of different models in the Cora_ML dataset under NON-IID (a) and IID (b) conditions

4.2.3 Varying Numbers of Clients

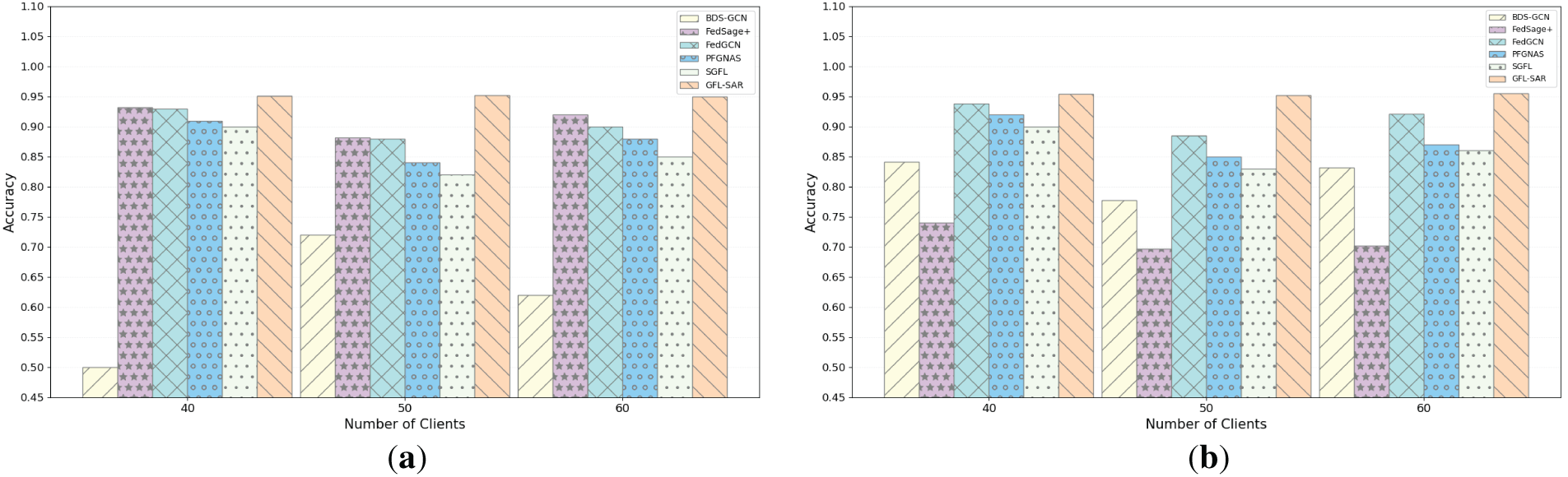

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of GFL-SAR in a large-scale distributed environment, as shown in Fig. 7a,b, we gradually increased the number of clients from 10 to 70 (selecting several representative client numbers) under the NON-IID and IID settings of the Polblogs dataset to examine the performance of different models at various scales. The results indicate that as the number of clients increases, the overall loss of GFL-SAR continues to be lower than that of BDS-GCN, FedSage+, and FedGCN, and exhibits higher stability. This superiority stems from GFL-SAR’s innovative design, which achieves an efficient fusion of multi-scale features and effective relation capture, thereby maintaining robust performance in distributed environments. On the Polblogs dataset, GFL-SAR can accurately capture high-density neighbor relationships (with an average degree of 27.36), ensuring that the expression of key node features is not affected by changes in client size. In contrast, other models are extremely sensitive to changes in the number of clients, with significant fluctuations in losses, especially in NON-IID scenarios, making it difficult to adapt to the needs of large-scale environments and highlighting their limitations in heterogeneous data processing. In addition, as shown in (a) and (b) of Fig. 8, GFL-SAR also performs well in accuracy. As the number of clients increases, its classification accuracy remains stable and higher than other models, further verifying its wide applicability in complex FL scenarios. However, FedGCN mainly emphasizes structural aggregation while neglecting the selective enhancement of salient relational signals, thereby exhibiting limited stability when scaling to a larger number of clients. On the other hand, FedSage+ depends on neighbor sampling and feature generation mechanisms, which may inadequately capture high-value semantic information at the node level, leading to substantial performance degradation under client distribution shifts. The search cost of PFGNAS is high and the space is limited, so its adaptability to changing clients decreases. SGFL has a high preference for gradient consistency and often ignores fine-grained semantics. Overall, GFL-SAR can adapt to changes in the number of clients in both small-scale and large-scale distributed environments, ensuring efficiency and robustness.

Figure 7: Loss comparison of various models under NON-IID (a) and IID (b) in the Polblogs dataset as the number of clients changes

Figure 8: Accuracy comparison of various models under NON-IID (a) and IID (b) in the Polblogs dataset as the number of clients changes

To further evaluate the contribution of each module of the GFL-SAR framework to overall performance, we designed and conducted ablation experiments to systematically analyze the role of its core modules in model optimization. Specifically, we removed the innovative modules of GFL-SAR one by one, tested the performance of each variant, and compared it with the complete framework. The experimental results are shown in Table 3. The complete GFL-SAR framework shows the best performance in all test scenarios, significantly surpassing any single module missing variant. In contrast, the variant that removes any module shows insufficient feature expression or decreased stability in heterogeneous data processing, highlighting the rationality and integrity of the GFL-SAR framework design. These features enable GFL-SAR to demonstrate outstanding application potential in complex GFL scenarios, such as social media false information detection, providing innovative solutions for optimizing distributed graph learning.

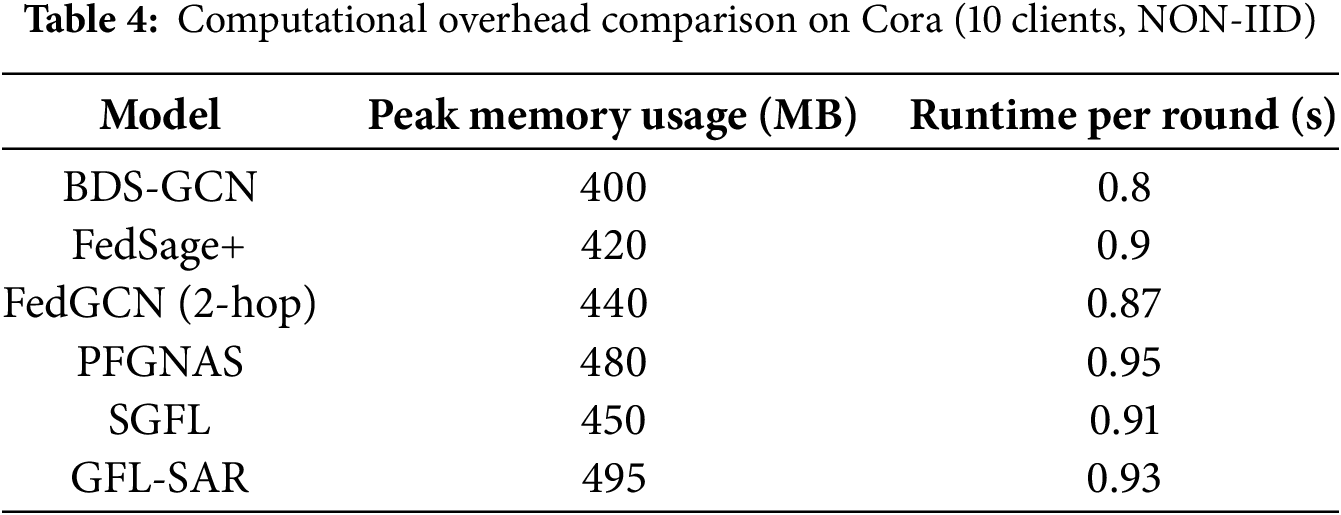

4.2.5 Computational Overhead Analysis

To evaluate the computational efficiency of GFL-SAR, we measured the peak memory usage and average runtime of each training round on the Cora dataset (10 clients, NON-IID setting). Table 4 summarizes the results. Due to the SIA and ARR modules, the GFL-SAR architecture has increased memory usage by approximately 15% compared to FedGCN, but its runtime remains competitive, only increasing by 10% compared to FedGCN. The secure aggregation mechanism has increased moderate overhead (due to encryption/decryption, runtime has increased by 5%). Compared with lightweight methods such as BDS-GCN, GFL-SAR requires more memory but has much higher accuracy, which proves that the trade-off between complex GFL tasks is reasonable.

This paper proposes a novel dynamic feature collaboration framework named GFL-SAR to address key challenges that remain insufficiently explored in existing GFL research. The framework enables efficient fusion and distributed optimization of multi-scale features through an innovative design that incorporates structural amplification of graph topology and attention-based refinement of node relationships. Unlike conventional approaches that often rely on coarse or single-perspective modeling, GFL-SAR introduces a fine-grained and parallel feature modeling mechanism. This architecture represents a significant methodological advancement, as previous research has never explored the refinement of structural and relational information in such depth and synchronization, which reflects the innovation of this paper. The proposed framework offers a fresh perspective for enhancing representation expressiveness and adaptability in GFL, opening new directions for future research. While GFL-SAR demonstrates significant improvements in classification accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness, its structure design introduces a modest increase in computational overhead. In future work, we plan to further optimize computational efficiency through techniques such as model pruning, dynamic client participation, and modular training strategies to ensure scalability in resource-constrained environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62466045), Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation Project (2021LHMS06003) and Inner Mongolia University Basic Research Business Fee Project (114).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu; Methodology: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu; Model implementation: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu; Formal analysis and investigation: Hefei Wang, Jingyu Wang, Xiaolin Zhang, Hui Wei; Resources: Hefei Wang, Jingyu Wang, Xiaolin Zhang, Hui Wei; Writing—original draft preparation: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu, Jingyu Wang, Xiaolin Zhang, Hui Wei; Writing—review and editing: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu, Jingyu Wang, Xiaolin Zhang, Hui Wei; Visualization: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu; Supervision: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu; Project administration: Hefei Wang, Ruichun Gu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen J, Yan H, Liu Z, Zhang M, Xiong H, Yu S. When federated learning meets privacy-preserving computation. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(12):1–36. doi:10.1145/3679013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mahmoud Sajjadi Mohammadabadi S, Zawad S, Yan F, Yang L. Speed up federated learning in heterogeneous environments: a dynamic tiering approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(5):5026–35. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3487473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mao Y, Wang H. Federated learning based on data divergence and differential privacy in financial risk control research. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;75(1):863–78. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.034879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang X, Hu J, Lin H, Liu W, Moon H, Piran MJ. Federated learning-empowered disease diagnosis mechanism in the Internet of medical things: from the privacy-preservation perspective. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2023;19(7):7905–13. doi:10.1109/TII.2022.3210597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Qu Z, Ding J, Jhaveri RH, Djenouri Y, Ning X, Tiwari P. FedSarah: a novel low-latency federated learning algorithm for consumer-centric personalized recommendation systems. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):2675–86. doi:10.1109/TCE.2023.3342100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zou Y, An Q, Shi Y, Bennis M. A graph neural network learning approach to optimize RIS-assisted federated learning. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2023;22(9):6092–106. doi:10.1109/TWC.2023.3239400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu R, Xing P, Deng Z, Li A, Guan C, Yu H. Federated graph neural networks: overview, techniques, and challenges. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(3):4279–95. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3360429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Jamali-Rad H, Abdizadeh M, Singh A. Federated learning with taskonomy for non-IID data. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(11):8719–30. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3152581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Guo Z, Yu K, Jolfaei A, Li G, Ding F, Beheshti A. Mixed graph neural network-based fake news detection for sustainable vehicular social networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(12):15486–98. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3185013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Djenouri Y, Belbachir AN, Michalak T, Srivastava G. A federated convolution transformer for fake news detection. IEEE Trans Big Data. 2024;10(3):214–25. doi:10.1109/TBDATA.2023.3325746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Guo Q, Yang X, Guan W, Ma K, Qian Y. Robust graph mutual-assistance convolutional networks for semi-supervised node classification tasks. Inf Sci. 2025;694(5):121708. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lei R, Wang P, Zhao J, Lan L, Tao J, Deng C, et al. Federated learning over coupled graphs. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2023;34(4):1159–72. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2023.3240527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Baek J, Jeong W, Jin J, Yoon J, Hwang SJ. Personalized subgraph federated learning. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023 Jul 23–29; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1396–415. [Google Scholar]

14. Yao Y, Jin W, Ravi S, Joe-Wong C. FedGCN: convergence-communication tradeoffs in federated training of graph convolutional networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:79748–60. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang K, Yang C, Li X, Sun L, Yiu SM. Subgraph federated learning with missing neighbor generation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:6671–82. [Google Scholar]

16. Al-Huthaifi R, Li T, Huang W, Gu J, Li C. Federated learning in smart cities: privacy and security survey. Inf Sci. 2023;632:833–57. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.03.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Z, Zhao H, Li B, Chi Y. SoteriaFL: a unified framework for private federated learning with communication compression. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:4285–300. [Google Scholar]

18. Guo J, Liu Z, Tian S, Huang F, Li J, Li X, et al. TFL-DT: a trust evaluation scheme for federated learning in digital twin for mobile networks. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2023;41(11):3548–60. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2023.3310094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kong X, Zhang W, Wang H, Hou M, Chen X, Yan X, et al. Federated graph anomaly detection via contrastive self-supervised learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(5):7931–44. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3414326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Xie H, Ma J, Xiong L, Yang C. Federated graph classification over non-IID graphs. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:18839–52. [Google Scholar]

21. Wang Y, Yang G, Li S, Li Y, He L, Liu D. Arrhythmia classification algorithm based on multi-head self-attention mechanism. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;79(21):104206. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen Z, Lin M, Wang Z, Zheng Q, Liu C. Spatio-temporal representation learning enhanced speech emotion recognition with multi-head attention mechanisms. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;281(10):111077. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo B, Qiao Z, Dong H, Wang Z, Huang S, Xu Z, et al. Temporal convolutional approach with residual multi-head attention mechanism for remaining useful life of manufacturing tools. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;128(2):107538. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang Y, Wu H, Xian J, Mei X, Zhang K, Zhang Q, et al. A multihead ProbSparse self-attention mechanism-based high-precision and high-robustness reconstruction model for missing ocean data. IEEE Sens J. 2025;25(8):13374–85. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2025.3543963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang Y, Wang W, Li Y, Jia Y, Xu Y, Ling Y, et al. An attention mechanism module with spatial perception and channel information interaction. Complex Intell Syst. 2024;10(4):5427–44. doi:10.1007/s40747-024-01445-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Si Y, Xu H, Zhu X, Zhang W, Dong Y, Chen Y, et al. SCSA: exploring the synergistic effects between spatial and channel attention. Neurocomputing. 2025;634(6):129866. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.129866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang X, Shang S, Tang X, Feng J, Jiao L. Spectral partitioning residual network with spatial attention mechanism for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:5507714. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3074196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhao S, Zhong RY, Jiang Y, Besklubova S, Tao J, Yin L. Hierarchical spatial attention-based cross-scale detection network for Digital Works Supervision System (DWSS). Comput Ind Eng. 2024;192(3):110220. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2024.110220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yu Y, Zhang Y, Cheng Z, Song Z, Tang C. Multi-scale spatial pyramid attention mechanism for image recognition: an effective approach. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133(10):108261. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhao Y, Ju Z, Sun T, Dong F, Li J, Yang R, et al. TGC-YOLOv5: an enhanced YOLOv5 drone detection model based on transformer, GAM & CA attention mechanism. Drones. 2023;7(7):446. doi:10.3390/drones7070446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao Y, Shao J, Lin X, Sun T, Li J, Lian C, et al. CIR-DFENet: incorporating cross-modal image representation and dual-stream feature enhanced network for activity recognition. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;266(3):125912. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lian C, Zhao Y, Shao J, Sun T, Dong F, Ju Z, et al. CFI-LFENet: infusing cross-domain fusion image and lightweight feature enhanced network for fault diagnosis. Inf Fusion. 2024;104(4):102162. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Q, Sun B, Bhanu B. Lite-FENet: lightweight multi-scale feature enrichment network for few-shot segmentation. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;278(1):110887. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yu W, Chen S, Tong Y, Gu T, Gong C. Modeling inter-intra heterogeneity for graph federated learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(21):22236–44. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i21.34378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xu Z, Li B, Cao W. Enhancing federated learning-based social recommendations with graph attention networks. Neurocomputing. 2025;617(1):129045. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jiang M, Jung T, Karl R, Zhao T. Federated dynamic graph neural networks with secure aggregation for video-based distributed surveillance. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2022;13(4):1–23. doi:10.1145/3501808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wu Z, Zhou J, Zhang J, Liu L, Huang C. A deep prediction framework for multi-source information via heterogeneous GNN. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2024 Aug 25–29; Barcelona, Spain. p. 3460–71. doi:10.1145/3637528.3671966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yao J, Jiang L, Shi C, Yan S. Fake review detection with label-consistent and hierarchical-relation-aware graph contrastive learning. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;302(22):112385. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang Z, Huang L, Tang BH, Wang Q, Ge Z, Jiang L. Non-euclidean spectral-spatial feature mining network with gated GCN-CNN for hyperspectral image classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;272(11):126811. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang X, Xu H, Cai J, Zhou T, Yang X, Xue W. DB-GNN: dual-branch graph neural network with multi-level contrastive learning for jointly identifying within- and cross-frequency coupled brain networks. arXiv:2504.20744. 2025. [Google Scholar]

41. Cao J, Wei R, Cao Q, Zheng Y, Zhu Z, Ji C, et al. FedStar: efficient federated learning on heterogeneous communication networks. IEEE Trans Comput Aided Des Integr Circuits Syst. 2024;43(6):1848–61. doi:10.1109/TCAD.2023.3346274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Cheon JH, Kim A, Kim M, Song Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In: International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 2017 Dec 3–7; Hong Kong, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 409–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-70694-8_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wan C, Li Y, Kim NS, Lin Y. BDS-GCN: efficient full-graph training of graph convolutional nets with partition-parallelism and boundary sampling. In: International Conference on Learning Representations ICLR 2021; 2021 May 4; Vienna, Austria. p. 673–93. [Google Scholar]

44. Fang H, Gao Y, Zhang P, Yao J, Chen H, Wang H. Large language models enhanced personalized graph neural architecture search in federated learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(16):16514–22. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i16.33814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang X, Wang J, Bao W, Peng H, Zhang Y, Zhu X. Structural graph federated learning: exploiting high-dimensional information of statistical heterogeneity. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;304(1):112501. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools