Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

IOTA-Based Authentication for IoT Devices in Satellite Networks

Escuela Superior de Ingeniería y Tecnología, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR), Av. de la Paz, 137, Logroño, 26006, La Rioja, Spain

* Corresponding Author: D. Bernal. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-39. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069746

Received 30 June 2025; Accepted 17 October 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

This work evaluates an architecture for decentralized authentication of Internet of Things (IoT) devices in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite networks using IOTA Identity technology. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first proposal to integrate IOTA’s Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based identity framework into satellite IoT environments, enabling lightweight and distributed authentication under intermittent connectivity. The system leverages Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Credentials (VCs) over the Tangle, eliminating the need for mining and sequential blocks. An identity management workflow is implemented that supports the creation, validation, deactivation, and reactivation of IoT devices, and is experimentally validated on the Shimmer Testnet. Three metrics are defined and measured: resolution time, deactivation time, and reactivation time. To improve robustness, an algorithmic optimization is introduced that minimizes communication overhead and reduces latency during deactivation. The experimental results are compared with orbital simulations of satellite revisit times to assess operational feasibility. Unlike blockchain-based approaches, which typically suffer from high confirmation delays and scalability constraints, the proposed DAG architecture provides fast, cost-free operations suitable for resource-constrained IoT devices. The results show that authentication can be efficiently performed within satellite connectivity windows, positioning IOTA Identity as a viable solution for secure and scalable IoT authentication in LEO satellite networks.Keywords

Global connectivity based on the Internet of Things (IoT) is experiencing rapid expansion, driven by the need to transmit data from devices located in remote or hard-to-reach regions. In this context, Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellations have been established as a key infrastructure for extending IoT communications coverage beyond the reach of traditional terrestrial networks [1,2]. Being at a lower altitude than geostationary satellites, LEO satellites reduce latency and increase link availability with devices, making them useful in applications such as fleet management, environmental monitoring, or autonomous vehicles [3,4]. To facilitate these communications, Low-Power Wide-Area Network (LPWAN) technologies are used, enabling the transmission of small volumes of data over long distances and in unlicensed frequency bands [5,6]. Among the LPWAN networks, Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT) stands out, having been included in Release 17 of the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) as part of the 5G standard to enable IoT communications via satellite Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN) [7,8]. This progressive expansion of IoT use cases, from terrestrial deployments to mobile and remote environments, also brings forward new security and authentication requirements. In this context, IoT devices were first deployed in industrial settings, where connectivity was generally stable and authentication relied on centralized mechanisms such as access control lists and conventional network security protocols. With the subsequent expansion of IoT into unattended and mobile environments, including vehicles, ships, and drones, new challenges emerged due to intermittent connectivity and constrained device resources. These scenarios underscore the need for decentralized and resilient authentication schemes that can operate reliably under unstable communication conditions and within the limited computational and energy budgets characteristic of IoT devices [9]. However, the integration of IoT devices into satellite networks poses additional challenges in terms of security and access control [10]. Due to the open nature and wide coverage of satellite communications, these networks may be more vulnerable to interception, cyberattacks, and unauthorized access [11,12]. Furthermore, limited resource capacity and critical infrastructure underscore the importance of robust authentication and protection mechanisms [13] that ensure the availability, confidentiality, and integrity of services [14,15].

Protection strategies in these networks are articulated in various layers. In the top layer, traditional cryptographic techniques such as symmetric and public-key cryptography are employed [16,17]. However, their implementation in IoT devices is limited by computational and energy constraints [18]. In parallel, physical layer security (PLS) techniques have been proposed, which leverage channel properties such as noise or attenuation [19,20]. Additionally, the use of machine learning has been explored to detect anomalous patterns and mitigate attacks, such as DDoS. However, its practical application requires large volumes of data and efficient models for resource-limited environments [21,22]. Device authentication, as an entry point to satellite IoT networks, is therefore a critical security concern [23], which constitutes the first line of defense in satellite network architecture. In recent years, alternative schemes have been proposed, such as the use of zero-knowledge protocols based on modular codes [24] or the integration of blockchain and smart contracts to preserve privacy in cross-constellation collaboration [25,26]. However, centralized solutions and many blockchain architectures present scalability, flexibility, and latency limitations [9,27]. Faced with these limitations, new proposals based on Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) are emerging, such as IOTA’s Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) [28] which allows the creation, storage and verification of Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Credentials (VCs) in an immutable manner, without the need for centralized validation entities [29,30]. This solution offers greater scalability, better privacy controls, and lower operating times than traditional alternatives or blockchain, making it especially suitable for dynamic and distributed environments, such as satellite IoT [31]. Despite the progress made with decentralized authentication mechanisms for IoT, the majority of proposals continue to be grounded in blockchain-based architectures. While these solutions offer transparency and immutability, they typically entail long confirmation times, significant energy consumption, and limited scalability when applied to resource-constrained environments, such as IoT and LEO satellite constellations. These limitations create a research gap for identity management frameworks that can operate efficiently within strict time windows, limited computational resources, and large-scale device populations. In particular, the suitability of DAG-based systems [32], notably IOTA Identity, for satellite-based IoT ecosystems has not yet been systematically analyzed. To address this gap, this work evaluates the performance of IOTA Identity for identity management in LEO satellite constellations, with an emphasis on credential resolution, deactivation, and reactivation. It offers a comparative perspective with blockchain-based authentication schemes, highlighting the potential of DAG-based approaches to overcome latency and scalability limitations [33]. In light of the above, this work aims to evaluate the technical feasibility of IOTA Identity as an authentication system for IoT devices in LEO satellite constellations. To this end, a distributed architecture implemented simulates the authentication process using DIDs. The resolution, deactivation, and reactivation times of digital identities are also empirically analyzed, comparing them with satellite revisit times. This research demonstrates the viability of IOTA Identity as a technology for authenticating IoT devices in LEO satellite environments. For this purpose, the work is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the state-of-the-art in IoT identity management within the satellite environment. Section 3 describes the developed technical architecture and the validation methodology used. Section 4 presents the results obtained from the system and their comparison with orbital operating times. Finally, Sections 5 and 6 present the discussion and conclusions.

The state of the art in authentication and identity management for IoT devices in satellite networks is multifaceted, encompassing traditional centralized approaches, blockchain-based solutions, and emerging DAG technologies. This section first reviews existing authentication methods, highlighting their limitations in resource-constrained and intermittent connectivity environments, which are typical of LEO satellites. It then examines the challenges associated with traditional blockchain architectures, such as high latency and scalability issues. Finally, it examines the benefits of DAG-based systems, such as IOTA, which provide lightweight, feeless operations suitable for decentralized IoT applications, laying the groundwork for the proposed integration in this work.

2.1 IoT, LEO Satellites and Protocols

The IoT has profoundly and transversally transformed all economic and social sectors, driving a new era of efficiency, automation, and data-driven decision-making. In agriculture, the IoT enables real-time monitoring of crops and soils, optimizing resource use and improving yields. In logistics, it facilitates the precise tracking of goods and fleets, increasing traceability and reducing operating costs. In precision agriculture, it optimizes production processes and decision-making, while in critical infrastructure, the IoT enables remote monitoring of parameters and device control. Thanks to the integration of smart sensors and advanced communication networks, the IoT is revolutionizing processes, enhancing productivity, and unlocking new opportunities for innovation in virtually all areas of society [34].

IoT devices connect to the Internet through wireless networks. This research examines the primary network protocols that utilize LPWAN technology. These protocols are designed to connect IoT devices that require low power consumption and long-distance transmission capacity [35]. There are several types of LPWAN networks, each with specific characteristics and applications. Among the most notable technologies is LoRaWAN, which utilizes unlicensed spectrum and is employed in low-cost, long-range applications. Sigfox, an operator network that also operates in unlicensed bands, stands out for its simplicity and low power consumption. In contrast, NB-IoT, which uses licensed spectrum and leverages existing cellular infrastructure, offers higher penetration and reliability. They all differ in terms of spectrum type, speed, and ease of deployment. LoRaWAN and Sigfox stand out for their low cost and rapid implementation, while NB-IoT stands out for its robustness and reliability [36].

The integration of IoT technology with satellites in LEO orbit is revolutionizing global connectivity, enabling the connection and monitoring of critical infrastructure in remote and underserved regions [37]. These satellites stand out for their small size and weight. They are made up of cubic-shaped modules called CubeSats, measuring 10 cm on each side and weighing approximately 1 kg each. Each cubesat can operate individually or in multi-unit configurations. They orbit the Earth at altitudes ranging from 500 to 1500 km. These satellites can mount communication antennas for different protocols, depending on the purpose of the satellite [38], offering low-latency coverage (20–50 ms) and higher transmission speeds than traditional geostationary satellites that orbit at higher altitudes [39]. LEO satellites send a beep signal and activate the standby transmitters of IoT devices within their coverage area, allowing them to send data over the satellite link for as long as the satellite is available in their area, typically 5–10 min. There are two modes of connection between IoT devices and LEO satellites: direct device-to-satellite connection (DtS-IoT) and indirect satellite connection (ItS-IoT), which involves installing an IoT gateway between the two devices [40].

Two physical effects directly affect the links between IoT devices and LEO satellites. On the one hand, the jitter effect is the variability in the arrival time of data packets at the satellite. This variability can be due to orbital dynamics factors or technological limitations and can especially impact time-sensitive applications, such as real-time device authentication and audio and video streaming. On the other hand, the Doppler effect, which causes a shift in the signal frequency due to the relative speed between the satellite and the ground device, necessitates constant synchronization adjustments and increases instability in packet delivery [41].

To increase the revisit frequency and provide more communication windows to each region on the Earth’s surface, groups of satellites are launched into space, creating an orbiting constellation that operates in a coordinated manner, allowing for better coverage and redundancy across the planet’s regions [42].

2.2 Existing Authentication Methods

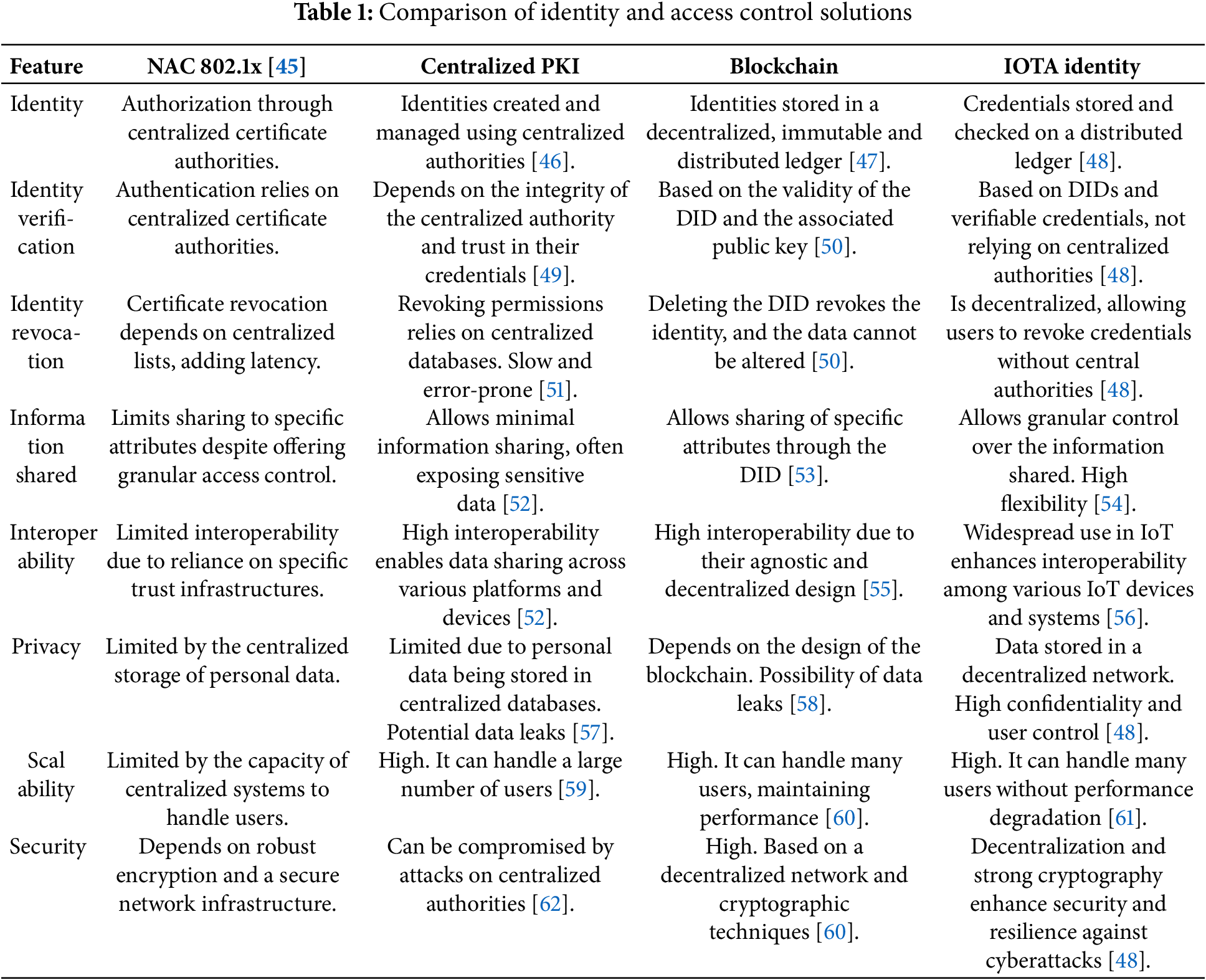

IoT devices typically access the network through access control systems based on Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) and Network Access Control (NAC) protocols, such as 802.1x. These systems follow a centralized model that relies on key components, including certificate authorities (CAs), policy servers, and revocation repositories. In PKI, each device needs an X.509 certificate issued by a trusted root CA. NAC, in turn, uses credentials stored in central directories such as LDAP for authentication. These solutions are widely used in terrestrial environments, but have a limited geographic scope. However, they face challenges in geographically distributed IoT systems that rely on satellite connectivity. A major issue is the lack of synchronization with central servers. This leads to failures when renewing expired certificates, an inability to detect compromises via certificate revocation lists, and connection rejections due to timeouts, which typically occur within 2 to 5 s. Additionally, relying on a central server introduces a single point of failure. It also limits the scalability of the system when managing large numbers of connected devices [43,44]. Table 1 presents a comparison of the main access control and identity verification technologies, summarizing their capabilities in key aspects such as authentication, information management and sharing, interoperability between platforms, privacy protection, security mechanisms, and scalability potential. This comparison offers a comprehensive view of how each approach addresses the requirements of distributed systems, enabling the identification of their advantages and limitations in scenarios where trusted collaboration and data protection are essential.

2.3 Extended Comparison of Identity Management and Authentication Solutions in IoT-Satellite Environments

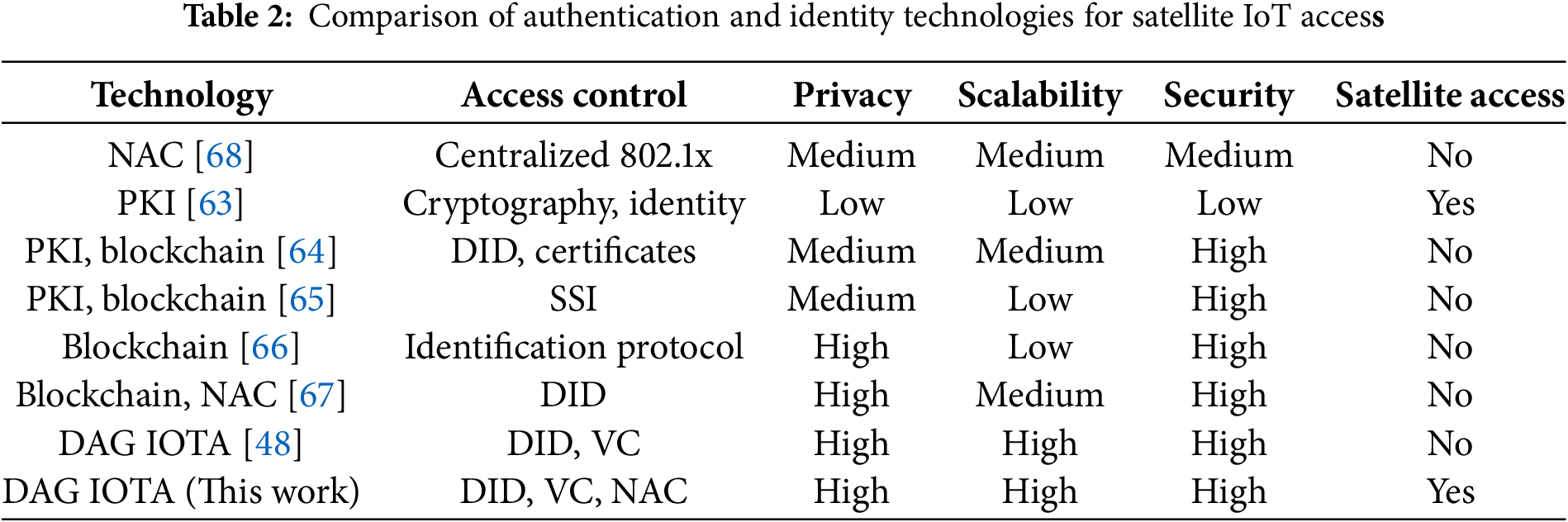

The increasing integration of IoT devices in satellite environments poses significant challenges to identity management and access control, primarily due to the intrinsic resource limitations and intermittent connectivity in LEO satellite networks. Several technologies have been proposed and studied to address these challenges, each with particular strengths and limitations in terms of identity, privacy, scalability, security, and applicability to satellite access. Traditional network NAC-based systems employ a centralized access management model, offering moderate levels of privacy that aim to limit data exposure. They are not designed to support direct access in satellite environments due to the lack of methods adapted to latency and signal intermittency. PKI-based on digital signatures offers identity-centric authentication and access control mechanisms. However, they present privacy vulnerabilities and are prone to bottlenecks that hinder their scalability in massive networks. They also demonstrate a lack of robust techniques for distributed satellite environments [63]. The combination of PKIs with blockchain technologies introduces digital certificates and the management of DIDs, which improve interoperability and decentralization. However, privacy can be compromised by attacks targeting certification authorities, and scalability remains moderate due to the blockchain structure’s dependence and associated costs [64,65]. On the other hand, blockchain-only approaches apply lightweight identification protocols and strong cryptography, facilitating the implementation of Self-Sovereign Identities (SSIs). These schemes offer proprietary control over private information, but demonstrate scalability limitations and a general lack of support for direct satellite access [66,67]. In contrast, DAG-based solutions such as IOTA Identity propose decentralized identity management using DIDs and VCs that incorporate advanced encryption, data sharing minimization, and SSI principles. IOTA’s Tangle-based architecture offers high scalability due to its fee-free design and parallelizable validation, as well as robust security against spoofing attacks, unauthorized access, and other threats. However, these implementations did not initially consider satellite access. In this research, IOTA’s DAG approach is extended by integrating allowlist-based NAC mechanisms tailored to the specific context of satellite IoT networks. This solution provides a highly private, scalable, and secure identity and authentication model that incorporates end-to-end encryption and the immutability of the Tangle, ensuring resistance to impersonation, replay attacks, and unauthorized access. Furthermore, its viability for effective access and authentication in satellite environments with intermittent connectivity and resource constraints is demonstrated in [48] and this work. Table 2 summarizes the features of each type of solution.

The system’s strength stems primarily from the use of DIDs and VCs, both of which are anchored in the immutable, distributed ledger of IOTA. DIDs enable a strong cryptographic link between the digital identity and the unique key pair generated locally by system actors, i.e., IoT devices and satellite operators, thereby effectively eliminating the possibility of impersonation. Verifiable credentials, cryptographically signed using JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) by trusted issuing authorities, ensure the legitimacy and integrity of the attributes associated with each device, facilitating trusted authentication without exposing sensitive information [69]. The verification process incorporates critical mechanisms, such as the inclusion of nonces that prevent replay attacks and expiration fields that limit the validity of credentials, thus strengthening protection against malicious reuse. Cryptographic verification of signatures guarantees non-repudiation and maintains the unalterable integrity of the authentication and proof-providing process. Security guarantees are based on essential premises, including the maintenance of the Tangle’s integrity and immutability, which ensures that identity states and revocation processes cannot be fraudulently altered. Furthermore, the cryptographic strength of the signature schemes employed protects against forgery and collisions. At the same time, the rigorous preservation of private keys under the exclusive control of legitimate actors prevents unauthorized access. The dynamic mechanism for deactivating and reactivating DIDs through IOTA ledger updates offers granular and flexible control over the identity lifecycle, preserving historical traceability. Although this research does not include formal demonstrations under standardized security models or experimental penetration tests, it clearly delineates the operational scenarios and adverse conditions under which the system maintains its robustness and correctness. The importance of future extensions that integrate formal validations and empirical evaluations using simulated attack scenarios to quantify the system’s resilience to conflict situations in real-world environments is recognized.

2.4 Limitations of Traditional Blockchain

To address these limitations, DLT-based approaches have been proposed. These systems are distributed, allowing authentication to be decentralized. They rely on nodes connected via the Internet, each storing a copy of the network structure and all recorded transactions [70]. Some of these solutions are based on DLT-Blockchain. In this research, we analyzed uPort and Ceramic. Both are built on Ethereum and utilize smart contracts to manage digital identities according to W3C standards [71]. They offer interoperability and benefit from a widely adopted network. However, blockchain-based architectures have critical limitations. The immutability of each block, the 15-s delay to confirm blocks, and the high transaction fees paid by users make blockchain unsuitable for IoT authentication. IoT devices require dynamic methods that can quickly allow or deny access to the network, depending on real-time conditions.

An alternative to blockchain is the Tangle. It is a DAG that allows fast and feeless transactions with high scalability. This technology removes the barriers that limit the adoption of distributed systems in IoT. With the Tangle, machines can exchange data and value seamlessly through Machine-to-Machine (M2M) communication. Its architecture avoids centralized validation. Instead, each user or device actively participates in the network consensus. The Tangle is the technological core of IOTA and differs from traditional blockchains in that it does not use blocks; alternatively, it relies on a peer-to-peer network to validate transactions. Rather, each new transaction must confirm two previous transactions, creating a distributed validation structure that eliminates the bottlenecks present in traditional systems. This model offers advantages in terms of scalability, as there is no fixed limit on the number of transactions that can be processed simultaneously. As network activity increases, the Tangle strengthens, improving both validation speed and participant decentralization. The consensus process in IOTA is based on a completely participatory mechanism, where each user contributes to the system’s security and integrity. To ensure the integrity of transactions, the Tangle follows three phases. Before recording a new transaction, a node must verify two previous ones, ensuring the continuity of the validation process. In addition, a small amount of computational work is performed to prevent spam on the network. When a new transaction is issued, others must directly or indirectly select it as a reference for validation. This model eliminates the need for miners, allowing the system to grow without relying on a central authority. Finally, IOTA employs the Random Walk Monte Carlo algorithm, which selects two random transactions to be validated with each new issuance. Over time, a transaction gains trust as other transactions reference it [72]. IOTA incorporates a DLT-based digital identity framework called IOTA Identity. A key element of this framework is the use of DIDs, which are unique identifiers generated and controlled by the user without the need for a central authority. A DID document represents a unique digital identity for a device or entity on the IOTA network, providing a trusted framework for secure interactions and transactions in the decentralized ecosystem. The integration of IOTA Identity with DIDs represents an evolution in how identity is managed in digital environments, fostering greater security, autonomy, and transparency in credential management. Ensuring that credentials are secure, persistent, and verifiable without the need for centralized databases. The DID is a structured JSON file that includes data about cryptographic keys, communication methods, or permission policies. This file is stored in the Tangle and accessed through its alias, a string of 30 to 50 characters that begins with “did:iota:.” IOTA Identity enables the autonomous creation, management, and sharing of credentials, eliminating the need for intermediaries [73]. This approach is based on the concept of Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), where each individual, organization, or device maintains absolute control over their information, deciding what data to share and with whom. This identity system is structured into three fundamental roles: holders, who are the owners of digital identities; issuers, trusted entities that issue verifiable certificates, such as identity documents; and verifiers, third parties that validate the authenticity of data provided by Holders [32]. It also enables agile and flexible credential management, making it useful in networks where devices may require frequent changes to their access permissions, as occurs in dynamic, distributed scenarios where external events condition access. Furthermore, it provides granularity in the control of authentication data, which represents an improvement over conventional models, where certificates typically include fixed and complete subject information [74]. A comparative analysis with other decentralized identity frameworks further clarifies the relevance of IOTA Identity in the context of satellite-based IoT. uPort [75], as one of the earliest implementations of DIDs on Ethereum, inherits the transaction costs, confirmation delays, and scalability limitations of blockchain infrastructures, which are incompatible with the latency and cost constraints of LEO satellite communications. Ceramic [76] introduces greater flexibility for data streams and off-chain document management. However, its reliance on periodic anchoring to linear blockchains still imposes finality delays and additional complexity that hinder real-time or near-real-time authentication [77]. In contrast, IOTA Identity leverages the parallelizable validation of the Tangle to provide cost-free operations with low confirmation times, aligning with the stringent constraints of intermittent connectivity windows and resource-constrained IoT devices in satellite networks. This distinction highlights the suitability of DAG-based identity management for ensuring continuous, lightweight, and efficient authentication in scenarios where blockchain-based solutions face structural limitations.

The novelty of this research lies in the application of DLT technology to secure the process of controlling access to the satellite environment for IoT devices dispersed across the Earth’s surface. Ensuring that only authorized devices can access the system and offering a streamlined process for deactivating or reactivating IoT devices’ permissions to access the satellite system.

2.6 Security Frameworks and Modern Methodologies

Recent advances in IoT-satellite integration have increasingly adopted security paradigms that move beyond traditional perimeter-based defenses. Among these, Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) has emerged as a dominant framework, premised on the principle of “never trust, always verify” [78,79]. In a ZTA context, every entity, whether a device, service, or user, must undergo continuous authentication and authorization based on dynamic policy evaluation, regardless of its network location. This contrasts with earlier models that assumed inherent trust for devices within a predefined network boundary, an assumption that is particularly unsuitable in satellite-IoT ecosystems with intermittent connectivity and heterogeneous device profiles. Related studies have explored the integration of ZTA with distributed ledger technologies to strengthen device identity assurance and reduce reliance on centralized trust anchors [80]. In these approaches, verifiable credentials and decentralized identifiers are used to enforce policy decisions at each transaction or session establishment, leveraging immutable logs for auditability and compliance. Other works combine ZTA principles with secure enclaves and hardware roots of trust, enabling cryptographic attestation of device integrity prior to granting network access [81]. Despite these advances, implementing zero trust in resource-constrained IoT devices that communicate through LEO satellites remains challenging due to the computational cost of continuous verification, the need for efficient policy decision points that can operate under high-latency conditions, and the complexity of revocation in decentralized contexts. Our proposed IOTA-based authentication framework aligns with ZTA principles by enforcing verification at each authentication event, eliminating implicit trust, and enabling ledger-anchored revocation checks. However, unlike conventional ZTA deployments, the reliance on the Tangle as a DAG-based DLT provides scalability advantages. It removes the dependency on centralized policy databases, thereby reducing single points of failure and potential bottlenecks in satellite communication links. On the security front, the system employs a layered defense-in-depth approach tailored for LPWAN satellite communications over LoRaWAN and NB-IoT. Each IoT node is provisioned with a unique cryptographic identity, stored within a secure hardware element to resist tampering. Data payloads are encrypted end-to-end using AES-128 in the case of LoRaWAN [82], while NB-IoT leverages 3GPP-standardized LTE-grade security mechanisms, including mutual authentication and integrity protection [83]. To prevent tampering, message authentication codes (MACs) are appended, and replay attacks are mitigated through sequence counters or timestamping. The satellite and ground/cloud segments of the architecture establish secure tunnels based on TLS or DTLS, ensuring confidentiality and integrity during backhaul transmission. Furthermore, network servers and core platforms enforce fine-grained access control policies to prevent unauthorized queries or command injection, thereby complementing the ZTA principles applied at the device and ledger levels.

In light of the properties of the various authentication technologies analyzed, it is necessary to consider the intrinsic characteristics of satellite connections in LEO, specifically the intermittent communication windows, which last between 2 and 5 min per pass, and the payload limitations inherent in LPWAN protocols. This maximum can range between 51 and 222 bytes, depending on the transmission mode. Adding limitations to the authentication process because the size of the messages sent by DLT technologies during authentication exceeds the frame size limit. This limitation means that the authentication process cannot be initiated directly on the IoT device and must be managed from the ground station, where broadband connectivity enables the generation of DID Documents and VCs outside the satellite infrastructure, thereby minimizing the computational load in orbit and overcoming bandwidth and payload limitations. Although satellite-to-ground downlinks offer greater bandwidth (1–10 Mbps), resource optimization in the space segment prioritizes storing only the necessary keys as a device allowlist for access control. Intensive operations, including identity creation, updating, and revocation, are offloaded to the ground infrastructure, where critical tasks such as these are performed efficiently due to the absence of bandwidth or processing limitations. This strategy overcomes the restrictions imposed by the small frame size of LPWAN protocols.

During the registration or onboarding phase of each IoT device, a DID document compliant with the W3C standard is generated and associated with a unique device identifier, which can be a MAC address, a serial number, or any other data that uniquely identifies it. The DID document is registered in the IOTA Tangle, thus creating an immutable and globally accessible record. When the IoT device needs to authenticate itself to the satellite, it transmits its DID identifier in an optimized frame that takes up minimal space within the payload allowed by LPWAN [35]. The satellite, for its part, maintains a local access control allowlist, storing authorized DID identifiers. This list is updated periodically, leveraging communication windows with the ground station by downloading cryptographic proofs (Merkle Proofs) from the Tangle, which enables verification that the DIDs associated with the IoT devices have not been revoked. In this way, authentication and access control are performed efficiently and securely without overloading satellite communications and ensuring that only authorized devices can interact with the system, even in scenarios of intermittent connectivity and extremely limited resources. Recent literature has not evaluated the applicability of these technologies in emerging satellite environments. Therefore, this research proposes to evaluate the technical feasibility of IOTA Identity as a distributed authentication mechanism for IoT devices in a LEO-based satellite communications architecture. To this end, a distributed infrastructure has been developed that replicates a realistic satellite environment and implements a complete digital identity management workflow using DIDs and VCs stored on the IOTA Tangle network.

3.1 Distributed Architecture for IoT Identity Management

The used physical architecture comprises five main entities: IoT devices, LEO satellites, ground stations, the Tangle network, and an IoT platform that centralizes validation and monitoring operations (Fig. 1). The IoT devices, located in remote areas, capture physical data and transmit messages over LPWAN links to LEO satellites that periodically fly over the coverage area.

Figure 1: Conceptual IoT-satellite architecture

Satellites serve as mobile access nodes, managing device authorization to access their infrastructure before accepting transmissions and temporarily storing the data until a link is established with a ground station. Subsequently, ground stations take over by querying the Tangle to resolve DIDs and verify device legitimacy, then update the device allowlist. The Tangle, functioning as a distributed, immutable database, enables the asynchronous storage and retrieval of these identities, supporting the ground-based validation process. Ground stations transfer the updated list to the satellite as soon as it enters their coverage area.

3.2 Decentralised Authentication Process

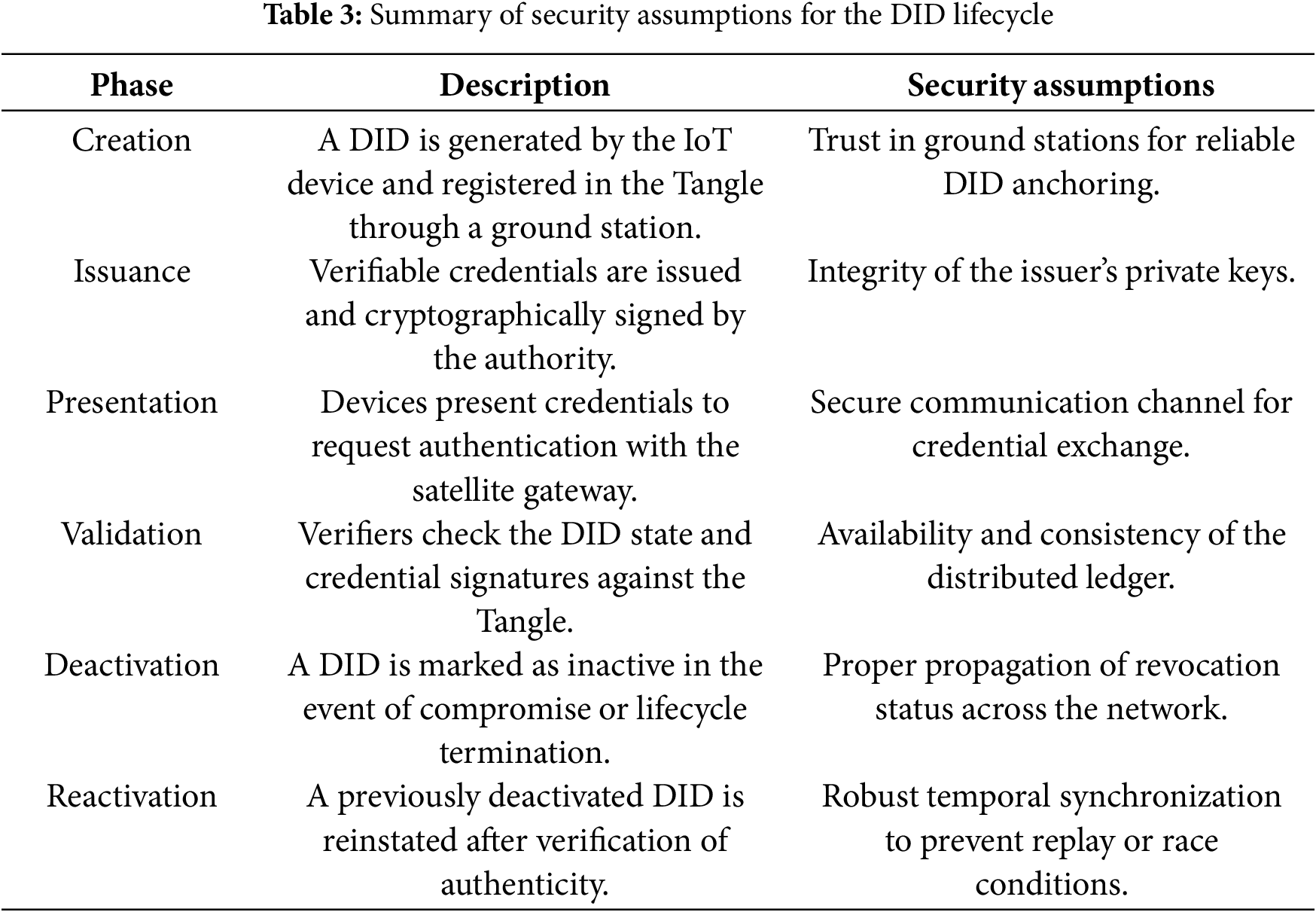

The lifecycle of DIDs in the proposed architecture encompasses the phases of creation, credential issuance, presentation, validation, deactivation, and reactivation. While each of these steps is detailed algorithmically in the manuscript, their integration is now complemented with a concise summary presented in Table 3, which organizes the core functions, actors involved, and security mechanisms supporting each stage of the lifecycle.

The methodological design relies on a set of explicit security assumptions. Ground stations are considered trusted entities, ensuring the correct orchestration of initial communication and propagation of updates. Time synchronization across the network is assumed to be robust enough to preserve consistency in transaction ordering and credential validation. Within these assumptions, the cryptographic mechanisms supporting DID management—namely creation, validation, revocation, and reactivation can be reliably deployed to prevent impersonation or tampering. IOTA Identity provides a framework for developing the decentralized identity management process for IoT devices in a satellite environment. The steps required to manage everything from DID creation to revocation are as follows:

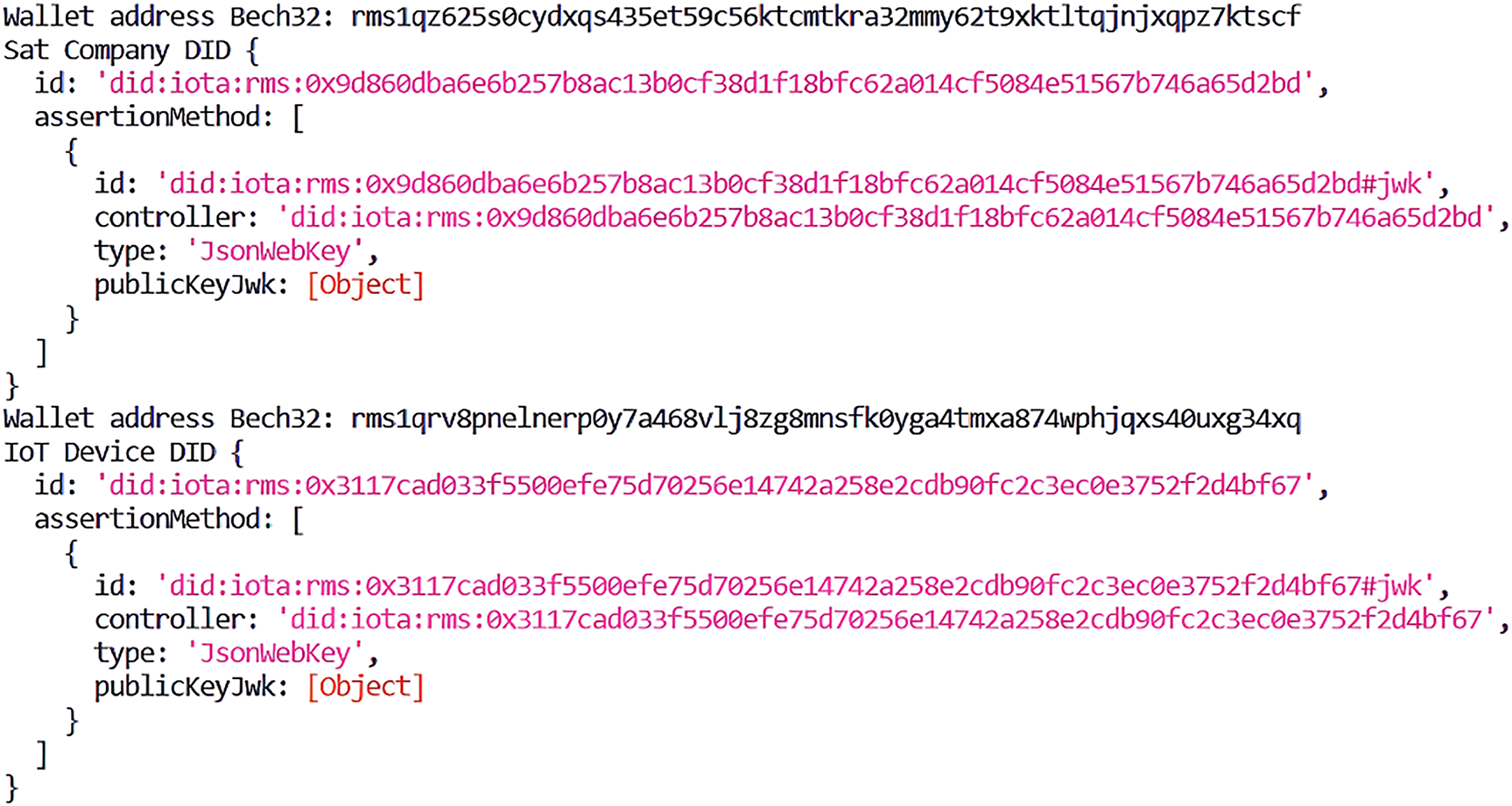

Each IoT device and each satellite operator has a unique DID generated from a cryptographic key pair that complies with W3C specifications. The identifier is registered in the Tangle using a DID document that links an Alias ID to the device’s attributes (e.g., MAC address, serial number). This initial creation is performed outside the satellite channel to avoid interfering with the connectivity window. The generated DID addresses are included in the document as unique and traceable identifiers. Algorithm 1 shows the sequential steps for generating and registering the DIDs of both the IoT device and the satellite operator, establishing the basis for the trust model between the issuer and the holder.

Below is the result of executing the code to create a DID for the IoT device and the satellite operator. (see Fig. 2). The DIDs have been stored in the IOTA Test Tangle (Testnet) with the following addresses:

Figure 2: Result of the creation of DIDs for issuer and holder

DID address of the IoT device:

Satellite operator DID address

Figs. 3 and 4 show the DID information stored in the IOTA Tangle for the issuer and holder.

Figure 3: IoT device DID stored in the tangle

Figure 4: Satellite operator DID stored in tangle

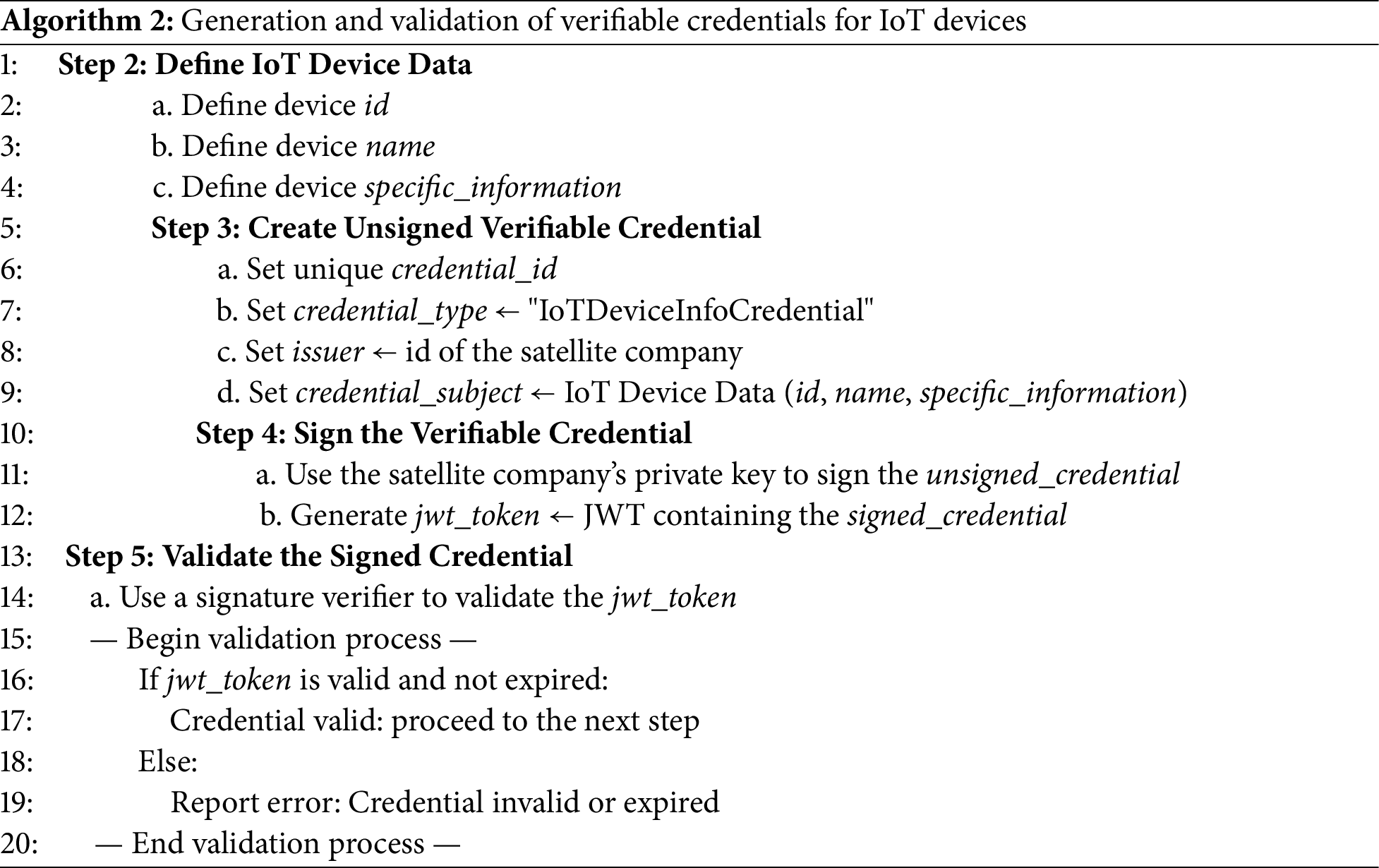

3.2.2 Issuance of the Verifiable Credential

Once the device’s DID is created, the satellite operator, in its role as a trusted issuing authority, generates a VC for the device. This credential contains the device’s identifying attributes, is serialized in JWT format, and is cryptographically signed using the issuer’s private key. This signature ensures the integrity of the credential and authenticates it as issued by a legitimate authority. Algorithm 2 details the process of defining the credential content, generating the JWT, and initially validating it. Verifiable credentials are not stored in the Tangle but rather in secure systems outside the network to preserve their confidentiality and prevent unauthorized access.

As a result of executing Algorithm 2, a verifiable credential is created for the IoT device (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Result of creating verifiable credentials

3.2.3 Generation and Submission of Verifiable Presentation

Each time an IoT device requires authentication, it generates a verifiable presentation (VP) that encapsulates the previously issued VC, along with cryptographic proof of possession of its private key. This presentation includes a nonce (cryptographic challenge) and an expiration field to prevent replay attacks and ensure that the credentials are valid only within a specified time interval. Algorithm 3 describes the procedure for generating the presentation, signing it with the device’s private key, and sending it to the verifier.

As a result of executing Algorithm 3, a verifiable presentation is created that the IoT device can use to prove its identity (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Result of creating verifiable presentation

3.2.4 Verification of the Presentation

The verifier, depending on the use case, could be an accredited verification entity or the satellite operator itself, and executes a complete validation process of the verifiable submission received:

• Validation of the JWT signature of the presentation.

• Verifying the nonce and expiration date.

• Resolving the issuer’s DID in the Tangle to extract the original DID document.

• Validation of the verifiable credential signature and verification of its integrity.

• Confirmation that the credential subject matches the presentation holder.

This process is represented in Algorithm 4 and guarantees the authenticity of the device, the integrity of the authentication channel, and the traceability of the credential issuer. If successful, the device is temporarily registered as authorized to transmit data over the satellite channel.

3.2.5 Dynamic Deactivation and Reactivation of the DID

As shown in Algorithm 5, access revocation is implemented by updating the document associated with the DID’s Alias ID and replacing it with an empty document. This approach enables the identity to be deactivated without deleting the root DID, allowing for subsequent reactivation by restoring the original document. This operation can be performed by the system administrator or the device owner, offering granular control over the identity lifecycle without compromising the system’s traceability or historical integrity.

This complete procedure guarantees the legitimacy of transmissions, the integrity of the channel, and the traceability of the sender. The technical flowchart of the process is shown in Fig. 7. Once authenticated, the device can transmit its data through the satellite channel. If its access needs to be suspended, the document associated with its Alias ID is updated with an empty document. This mechanism effectively revokes the identity without deleting the root DID and facilitates its subsequent reactivation by restoring the original document. This functionality enables the application of dynamic control policies without compromising the historical traceability of the system [84], which is key in contexts where a flexible identity lifecycle is required.

Figure 7: Satellite-connected IoT authentication process based on IOTA Identity

3.3 Experimental Design and Metrics

The experimental setup developed in this work simulates the connection between a ground station and the IOTA Tangle to carry out tasks such as resolving, deactivating, and reactivating DIDs associated with IoT devices. All tests were conducted using a computer connected to a node in the Shimmer Testnet, which serves as the official public testing network for the IOTA protocol. Shimmer is not a simplified or emulated system; rather, it operates under the same core principles, data structures, and consensus logic as the main IOTA Tangle. This architectural parity ensures that the authentication operations evaluated in the testnet reflect the same execution logic as in the production network. Although it operates under test conditions, Shimmer shares the DAG architecture, validation logic, and DID management protocols with the main Tangle. Consequently, while the measurements obtained accurately reflect the essential behavior of the distributed ledger infrastructure, they may not fully capture the performance characteristics observed in a production network. Shimmer maintains a smaller and less geographically distributed set of nodes, often hosted on non-production-grade hardware and subject to variable maintenance cycles. Its validator and coordinator nodes operate under experimental loads, which can cause greater fluctuation in transaction throughput and message propagation times. As a result, absolute latencies in Shimmer, for example, DID resolution, deactivation, or reactivation times, may be slightly higher and exhibit greater variance than those expected in the main network. In a production-grade Tangle deployment, node density is higher, peer connections are more stable, and the infrastructure is optimized for low-latency operation at scale. Consequently, the same authentication workflows would likely benefit from reduced average execution times and improved stability in time-sensitive operations, particularly under high device concurrency or in geographically dispersed IoT deployments. For this reason, the performance results obtained in Shimmer should be interpreted as a conservative baseline: the relative ordering and proportionality of the measured times remain representative. At the same time, actual production deployment would be expected to yield equal or better performance under equivalent operational conditions. To assess the technical feasibility of the proposed system, three main metrics were defined to quantify the performance of the decentralized authentication process: DID resolution time, DID deactivation time, and DID reactivation time. The delay in resolving a DID was calculated from the moment the resolution function is executed, passing the DID alias as input, to the instant when the Tangle returns a response regarding the status (active/inactive) of the DID. For deactivation, the metric corresponds to the time elapsed between the execution of the deactivation function and the receipt of confirmation from the Tangle that the deactivation has been processed. Reactivation time is similarly measured from the execution of the respective function until confirmation that the DID is once again active. The scale of the experiment considered a network of 100 simulated IoT devices, chosen as a representative scenario for satellite constellations with low IoT device density and consistent with the operational capacity anticipated for initial LEO deployments. This configuration provides a realistic and computationally feasible environment for evaluating identity management operations under the constraints imposed by satellite revisit windows. The selection of metrics and the choice of the device from which interactions with the Tangle are made to manage credentials respond directly to the operational requirements and intrinsic limitations of satellite IoT networks, characterized by restricted link availability, limited processing capacity on the satellite, and short communication windows. Furthermore, the relevance of these metrics was reinforced by comparison with satellite revisit times calculated in MATLAB simulations, which determine how frequently a device, whether an IoT node or a ground station, can establish an uplink. This assessment verifies that permission management operations in the Tangle can be completed within the available connectivity window, ensuring the consistency, reliability, and robustness of the proposed identity management system.

3.4 Energy Consumption Measurement Method for DID Operations on IOTA

This work investigates the energy efficiency of IOTA Tangle transactions in the context of DIDs and their associated operations. The analysis focuses on the following message types, as defined by the W3C DID and VC standards:

• DID creation (onboarding of new identities)

• Verification method creation (binding cryptographic material to DIDs)

• Credential revocation (recording the invalidation of issued credentials)

• Credential verification (proving the authenticity of issued credentials)

• Verifiable presentation verification (validating claims shared by an identity holder)

Within the IOTA framework, each of these operations is represented as a message anchored in the Tangle. Following the methodology recommended by the IOTA Foundation, the energy consumed per message is computed as (1)

where

While the present work focuses on latency and operational timing metrics, energy consumption is a critical factor in deploying authentication mechanisms on resource-constrained IoT devices. In this regard, IOTA’s Tangle offers structural advantages over conventional blockchain-based systems [48]. The absence of mining and the use of a lightweight tip-selection algorithm reduce the computational demand during transaction validation, which in turn lowers instantaneous power draw [86]. Although no direct energy measurements were performed in this work, these architectural characteristics suggest that the authentication process described here would require fewer processor cycles and less active time compared to blockchain frameworks employing Proof-of-Work or other computationally intensive consensus mechanisms. This lower processing load is particularly relevant in satellite-IoT scenarios with strict duty cycles and limited energy budgets. As future work, we plan to extend the experimental methodology to include empirical energy profiling on representative low-power IoT hardware, enabling a quantitative comparison between Tangle-based and blockchain-based authentication processes. From a network-level perspective, the number of satellites in a constellation can indirectly influence the energy profile of authentication. Higher satellite densities generally reduce revisit times and improve link availability, potentially lowering the energy cost per authentication by minimizing idle or retry periods. Conversely, more frequent handovers between satellites may introduce additional signaling overhead, increasing instantaneous energy usage during these transitions. Quantifying these trade-offs will require experimental campaigns under varying constellation sizes and link conditions, which we identify as a complementary line of future work to the empirical energy profiling described above.

3.5 Scalability Considerations

The scalability of the proposed authentication framework must be assessed in terms of its ability to accommodate increasing numbers of IoT devices, higher concurrency of authentication requests, and the dynamic topology imposed by LEO satellite constellations. Unlike blockchain-based ledgers that depend on sequential block formation and proof-of-work mechanisms, the Tangle enables parallel transaction validation without a centralized bottleneck. This structural property provides a favourable scaling trajectory, as verification load can be distributed across multiple nodes without degrading consensus finality times. From a functional perspective, the per-device computational load for DID resolution, VC issuance, and verification remains constant with network growth, due to the algorithmic complexity of the employed cryptographic primitives and the absence of mining [48]. Consequently, the principal scalability constraint shifts from computational overhead to communication scheduling within satellite contact windows. In large-scale deployments, simultaneous uplink requests during brief visibility periods can saturate the available link budget, resulting in queuing delays. This effect can be mitigated through distributed ground station coverage, opportunistic scheduling, and prioritization strategies that allocate bandwidth according to authentication urgency. From an architectural perspective, scalability can be enhanced horizontally by increasing the number of verifier nodes connected to the Tangle through geographically dispersed ground stations. This approach reduces contention during peak demand and minimizes latency by allowing authentication requests to be processed at the node with the nearest ledger access. Vertical scalability, improving the processing capabilities of individual verifier nodes, can be achieved by optimizing signature verification routines, employing hardware acceleration for cryptographic operations, and adopting high-throughput networking stacks. Temporal scalability must also be considered in relation to satellite revisit cycles. As the number of satellites in a constellation increases, the effective revisit time decreases, distributing the authentication load over more frequent but shorter contact intervals. While this can reduce average queue depth, it may also introduce additional handover signalling, which requires lightweight session continuity protocols to prevent redundant authentications. Although the present work does not experimentally validate scalability at production-level network sizes, the architectural properties of the Tangle and the proposed distribution of verifier nodes indicate that the system can maintain stable performance in deployments exceeding thousands of active IoT devices [61].

3.6 Analytical Basis for Estimating Latency from Throughput

This analysis follows the fundamental latency-throughput relation [87], expressed as

where

where

Reducing Revocation Latency through Local Mechanisms and Prevalidation

To reduce the latency of effectively turning off devices with intermittent contacts, we integrate two additional local mechanisms, kept consistent with the IOTA Identity source of trust:

• A temporary allowlist stored onboard.

• Pre-validation using short-lived capability tokens.

The standard revocation process updates the device state in the Tangle, recording the revocation in a persistent and immutable manner [88]. However, this operation depends on the required confirmation depth and the propagation times

where

where

to holders that have passed ledger-based verification. Satellites only accept traffic when a valid

where

3.7 Task-Offloading and Response Rate

Task-offloading in the proposed satellite-IoT authentication framework refers to the delegation of computationally intensive operations to avoid overloading resource-constrained devices, such as LEO satellites or IoT devices. Tasks such as DID creation, cryptographic signature verification, revocation list checking, or credential status validation are transferred from resource-constrained LEO satellites or IoT devices to ground stations for processing. In terms of performance, the integration of task offloading has a direct impact on the response rate. At the device level, eliminating the need to execute computationally intensive cryptographic routines reduces active processor cycles and can lower instantaneous power consumption. However, in LEO satellite environments with intermittent connectivity and short contact windows, the net latency benefit depends on whether the local processing time saved outweighs the additional communication delay required to transfer intermediate data to the processing node. This trade-off is exacerbated when considering satellite handovers or high network load, where queuing delays at the gateway or ground station can partially offset the benefits derived from reduced on-device computation. While this work focuses on operational times measured in a direct execution scenario, the experimental results provide relevant boundary conditions for future offloading evaluations. Specifically, the observed DID resolution and wake-up times establish an upper bound on acceptable end-to-end latency when offloading is employed. In contrast, the variability in deactivation times suggests that stringent buffering and retry policies would be required to ensure reliability in offloaded execution. Future work should experimentally quantify these trade-offs by simulating offloading with different link availabilities, constellation sizes, and concurrent authentication loads, allowing for a rigorous evaluation of its impact on both latency and system scalability in the context of the proposed architecture [89].

3.8 Security Model and Cryptographic Assumptions

The authentication protocol

This decomposition separates cryptographic service time, which is under protocol and infrastructure control, from link-induced delay, which is governed by orbital dynamics and scheduling. The analysis shows that the ordering of operations is preserved across conditions; deactivation remains the most sensitive phase because its effect must be recognized across verifiers only after ledger finality, while activation and resolution are primarily bounded by local verification and read-only queries. Privacy considerations arise from metadata in presentations and ledger lookups [91]. The protocol adopts minimal disclosure consistent with verifiable credential practice, avoiding the publication of attribute values on-chain and limiting ledger usage to identifiers and proofs necessary for verification. Residual linkability may occur through correlation of repeated lookups or timing side channels; such risks are mitigated operationally by caching policies at verifiers and, when required by the application, by selective disclosure techniques. A full privacy proof in a formal model is identified as future work and falls beyond the empirical scope of this work. The stated guarantees are contingent on the correctness of cryptographic implementations, the confidentiality of private keys on endpoints, and the ledger’s finality policy. Side-channel resistance, compromise of endpoint keys, and active subversion of verifiers are not modeled here and would require a different class of assurances, typically involving hardware roots of trust and system-level attestation. Likewise, the derivations do not claim bounds on energy or radio-layer leakage, which are orthogonal to the protocol’s cryptographic core. Within these boundaries, and under the standard unforgeability and collision-resistance assumptions, the authenticity, integrity, replay resistance, and post-finality revocation safety of

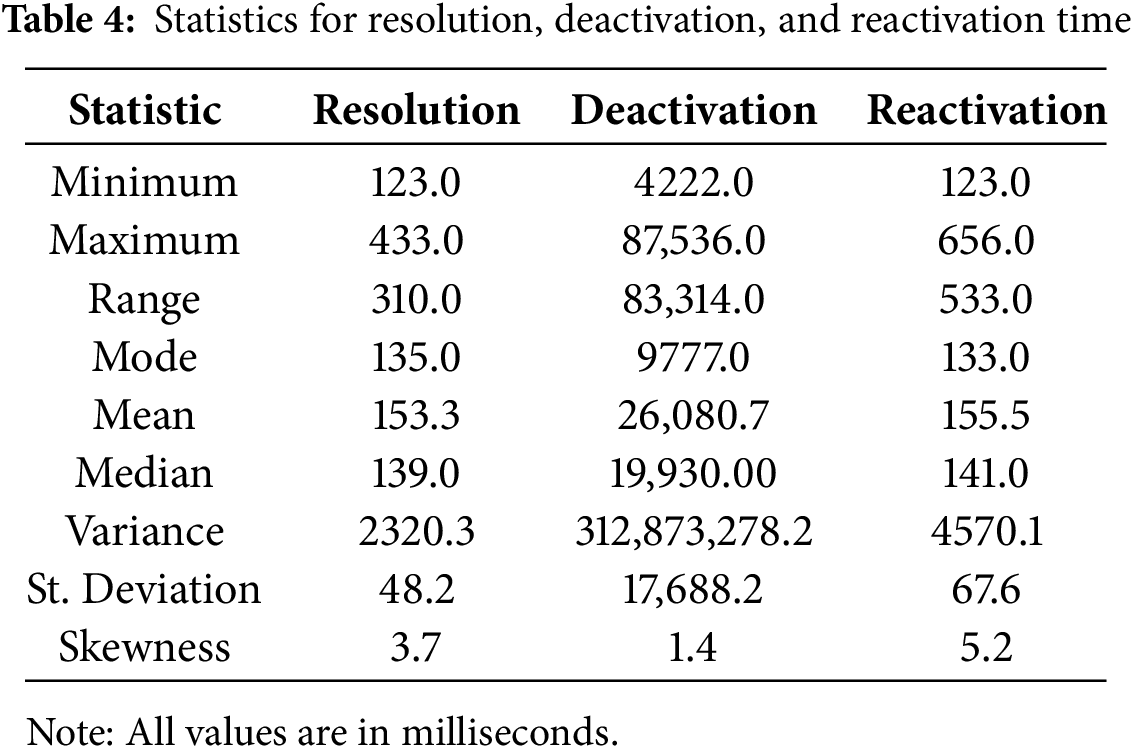

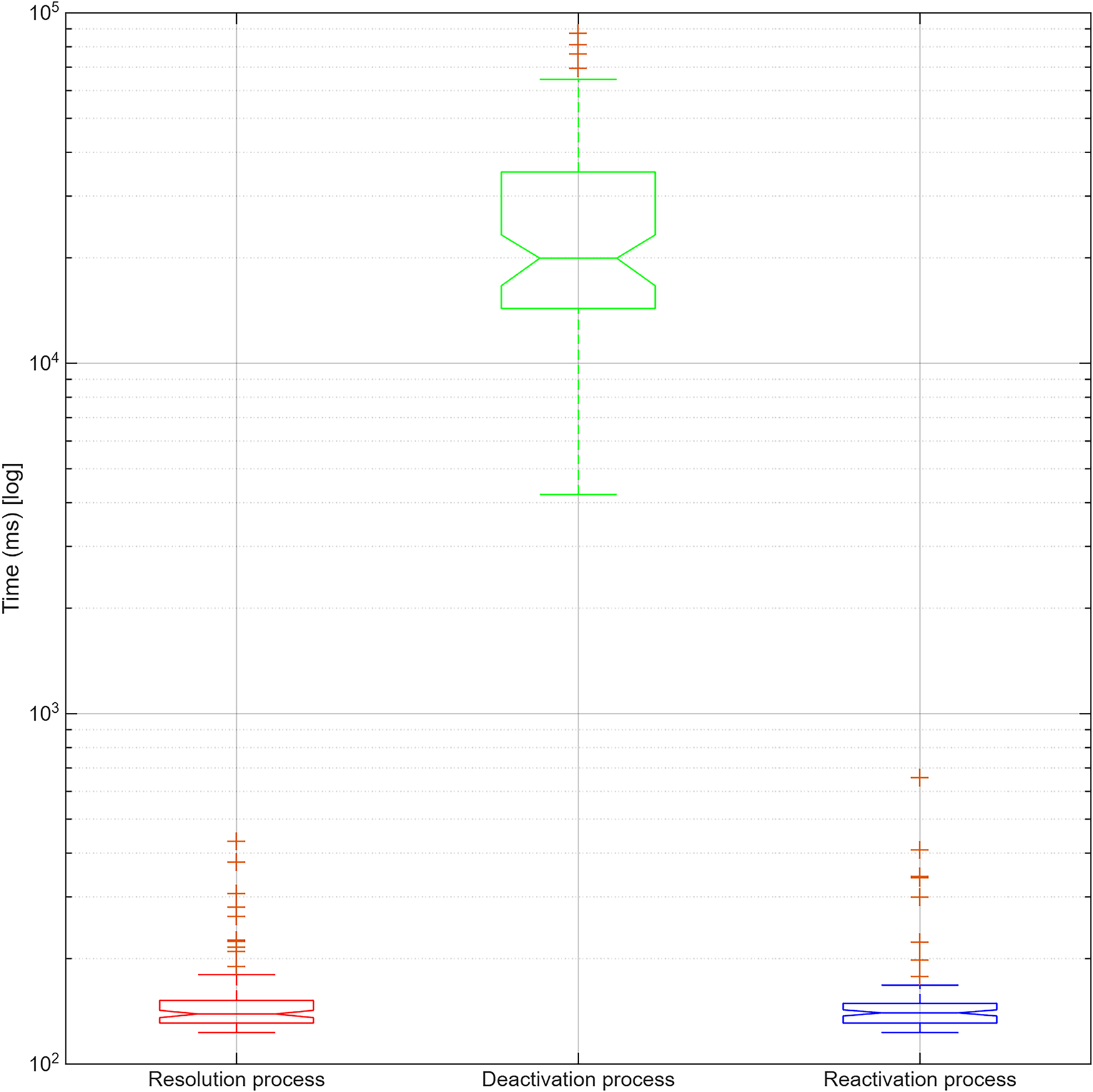

To obtain viable statistical results on the time required to resolve, deactivate, and reactivate DIDs, an experimental infrastructure based on 100 simulated IoT devices was implemented. To this end, 100 DIDs were created. The test consisted of executing 100 DID resolutions, one for each DID created. 100 DID deactivations were also executed for each of the created and resolved DIDs. 100 DID reactivations were also executed for each of the deactivated DIDs. To this end, the official IOTA Identity libraries were used on the Shimmer Testnet. Table 4 lists the main statistics obtained for each of the three metrics evaluated. In addition to the table, the data can also be visualized in Fig. 8, which presents the comparative boxplots for these metrics.

Figure 8: Comparison of time distributions

Regarding resolution time, a mean value of 153.68 ms and a median of 139.00 ms were observed, with a standard deviation of 48.17 ms. The distribution exhibits positive skewness (3.72), indicating the presence of longer outliers, although they are concentrated within a narrow range. This suggests that the operation is highly consistent and suitable for systems requiring predictable latencies.

In the case of deactivation, the system showed greater variability, with a mean time of 26,080.72 ms and a standard deviation of 17,688.22 ms. The median was 20,308.00 ms, and maximum times of up to 87,536.00 ms were recorded. This dispersion is attributed to internal Tangle processes related to resource release and update propagation. However, the skewness analysis (1.36) reveals that most operations were executed faster than average, albeit with a higher dispersion. Reactivating a DID displayed very similar behavior to the resolution process, with an average time of 155.52 ms and a median of 141.00 ms. The standard deviation was 67.61 ms, while the skewness reached 5.22 ms, indicating a strong bias toward low values with a few extreme cases. These results confirm that restoring a previously deactivated identity can be performed quickly, allowing device reauthentication without significant delays.

The statistical characterization of the authentication operations provides further insight into the system’s performance. For credential resolution, the average time was 153.7 s, with a 95% confidence interval of [144.1, 163.3]. The hypothesis test confirmed that the mean is significantly below the 600 s reference threshold (

In parallel, a simulation was developed to estimate LEO satellite revisit times at different latitudes, using a Walker Star-type orbital configuration with an altitude of 400 km and an antenna aperture of

Figure 9: Satellite revisit time as a function of latitude

4.1 Latency and Variance Considerations

The end-to-end latency measured for IOTA-based authentication in this work is 155.5 ms for revocation and 153.3 ms for reactivation events (see Table 4). These stable and bounded values are primarily attributed to optimizations in the decentralized identity resolution process within the Tangle, which validates references on a distributed ledger more efficiently, completing the authentication protocol with less overhead compared to centralized systems. In contrast, deactivation times exhibit greater variability, with occasional values that can exceed the activation latency, largely influenced by network propagation delays, temporary congestion in information selection from the Tangle, and the level of confirmation required for a deactivation to be finalized. These factors are particularly impactful in scenarios where device state changes are infrequent but must be executed quickly for security reasons. Potential optimizations to mitigate these observations include using credential state caching to avoid redundant lookups, dynamically adjusting commit depth based on transaction criticality, and exploring parallel transaction submission to reduce network latency. Future work will evaluate these techniques under realistic LEO satellite link conditions, where intermittent connectivity could amplify both average latency and its variability.

4.2 Energy Consumption Per DID Operation as a Function of Throughput

The experimental environment was configured to emulate a low-power edge node, modeled after a Raspberry Pi 4 or an equivalent platform, serving as an identity node within a decentralized IoT or industrial infrastructure. Measurements were performed under two workload conditions: 100 messages per second, corresponding to a low-intensity identity workload, and 1000 messages per second, representing a high-throughput operational context. A linear interpolation between these measurement points was subsequently employed to estimate energy consumption across intermediate and higher throughput levels. The results indicate that the energy cost per DID-related message decreases notably as the message rate increases. At 100 messages per second, each DID operation (e.g., DID creation or credential verification) requires approximately 0.05 J/message. In contrast, at 1000 messages per second, the energy cost declines to 0.015 J/message, with the model predicting an asymptotic lower bound of approximately 0.011 J/message at higher loads. Fig. 10 summarizes these findings, illustrating that the energy per operation declines with increasing throughput due to the amortization of system overhead. At low message rates, baseline consumption constitutes a significant portion of the total energy demand. However, as throughput increases, the relative impact of this baseline diminishes, thereby enhancing overall system efficiency.

Figure 10: Energy consumption per DID-related message as a function of throughput in the IOTA tangle

4.3 Estimated Latency-Throughput Profile for DID Resolution Messages

The baseline latency parameter was set to

Figure 11: Estimated average latency vs. throughput for did resolution messages in the IOTA tangle

The resulting graph shows that latency remains close to the baseline under light load conditions, indicating that propagation and computation time dominate performance in this regime. As throughput increases, latency gradually grows until it approaches the capacity threshold, where the rise becomes more pronounced. Beyond the assumed capacity, the curve continues to increase linearly, reflecting congestion-driven degradation of performance.

Analysis of the results shows that the distributed authentication system based on IOTA Identity can operate efficiently in intermittent satellite connectivity environments. Resolution and reactivation times consistently remained bellow 160 ms, thus meeting the minimum standard of 400 ms in LEO communications [93], even in the most extreme cases recorded during testing, enabling rapid identity management of IoT devices without generating significant delays in data transmission. This feature is especially relevant in scenarios where devices are subject to constant movement or limited coverage. Recent publications highlight the limitations of low latency in satellite IoT networks, particularly in ensuring continuous device authentication, especially in high-mobility environments and areas with limited satellite coverage [94]. In contrast, the deactivation time showed considerable variability, with maximum values exceeding 80 s. While these results remain manageable for many applications, they reveal the need to improve identity revocation mechanisms in the Tangle to ensure the consistency of information from authorized devices to the satellite infrastructure. The observed dispersion suggests that performance in this operation is influenced by factors related to storage management and update propagation in the distributed network. This behavior has also been observed in previous research on blockchain-based systems, which suggests that revocation operations can be affected by network saturation or peak processing demand [69]. The reactivation time showed very favorable performance, allowing device access to be restored almost immediately once the DID document was resolved. This capability is useful in applications that require frequent activation and deactivation cycles, such as periodic data acquisition systems or low-power devices operating in intermittent mode. The rapid reactivation process minimizes the impact of interruptions in the authentication channel and facilitates more flexible access management [95], highlighting the importance of rapid credential restoration in IoT networks. This emphasizes that it minimizes interruptions in the authentication of devices that require repeated activation and deactivation. From an operational perspective, these times must be analyzed in relation to the connectivity and revisit intervals imposed by satellite orbits. As evidenced in the orbital simulation, revisit times vary depending on latitude and constellation size, being shorter at high latitudes and with a greater number of satellites. In representative configurations with 100 or more satellites, minimum times of up to 36 s were observed, implying that even the slowest system operations (such as deactivation) can be completed within the inter-revisit window. This validates the feasibility of integrating the proposed system into real satellite networks, provided that design policies are considered to avoid critical revocation operations during the shortest link times [92]. The energy consumption of DID operations behavior suggests that IOTA-based identity management becomes increasingly energy-efficient as it scales. In large-scale IoT ecosystems, where thousands of devices regularly generate and verify credentials, the marginal energy cost per transaction approaches negligible levels. Similarly, in industrial infrastructures requiring frequent credential revocations and verifiable presentation checks, the system is capable of sustaining high transaction volumes while maintaining low per-operation energy expenditure. Overall, the results confirm that IOTA Identity constitutes a viable technical alternative to centralized or blockchain-based models for authenticating IoT devices in satellite environments. However, areas for improvement are identified, such as optimizing the deactivation process and evaluating performance under different orbital configurations or device densities. These issues are addressed in the Limitations and Future Research section.

The results highlight the sensitivity of latency in the IOTA Tangle to network load. At low to moderate throughput, the system operates efficiently, with latency remaining close to the propagation baseline. However, as the offered load approaches the network’s capacity, the latency nearly doubles, which could significantly affect the responsiveness of DID resolution operations. This behavior suggests that while the Tangle can handle substantial message volumes without immediate performance loss, sustained operation near or above capacity risks producing delays that could undermine the usability of latency-sensitive applications. Future work could refine this model by distinguishing resolution from other DID message types and by calibrating

5.1 Comparative Analysis between DAG-Based Validation and Block-Based Consensus

Authentication workflows that rely on a ledger incur a ledger-side component whose structure depends on the underlying consistency mechanism [48]. In block-based systems with fixed block interval B and confirmation depth

This bound is structural: even under negligible propagation and abundant processing capacity, the block cadence imposes a floor proportional to

5.2 Scalability beyond 100 Devices: Window-Limited Capacity, Concurrency, and Throughput

Scalability in satellite-IoT deployments is governed jointly by ledger-side service time and the temporal structure of contact windows. Let

When multiple devices attempt authentication concurrently, arrivals during a window can be modeled by an aggregate rate

For constellations exceeding 100 devices or for dense IoT scenarios, the contact schedule modulates concurrency by compressing request arrivals near pass edges. If burstiness concentrates arrivals into a subinterval of width

Local overlays reduce both the mean and variance of the effective deactivation time by removing the dependency on the wait time W until the next contact. When the temporal allowlist is updated on each pass and tokens have short lifetimes,

Resolution and reactivation remain primarily constrained by the ledger at the ground station, so their relative order of deactivation is preserved while the worst-case queue is shortened.

5.3 Limitations and Future Work

This work establishes a feasibility baseline for decentralized authentication in satellite-LEO-IoT environments using IOTA Identity. However, several limitations restrict the scope of the findings. Measurements focus on ledger-side service times and protocol responsiveness under controlled conditions on the Shimmer Testnet, which is functionally aligned with Tangle but operates in a non-productive environment. Although this network is functionally equivalent to the IOTA Tangle, it does not reproduce the conditions of a production deployment in terms of sustained load, long-term resilience, or exposure to adversarial behavior. Consequently, while the obtained results are valid to assess functional feasibility, future validation on a production-grade network is required to confirm robustness under operational stress. The intermittent satellite connection was analytically modeled rather than emulated on the physical link, and experiments focused on single-device sequences without concurrent access pressure. These limits imply that the reported latencies should be interpreted as reference values for the cryptographic and ledger layers, not as end-to-end operational limits on active LEO links.

The deactivation path exhibits greater variance than resolution and reactivation, a behavior consistent with the propagation and confirmation depth in a DAG ledger, as well as the reconciliation time of updates between verifiers. When the effective latency is decomposed as

The random waiting component W associated with the next usable contact window between the satellite and the ground station that will update the list of devices allowed in the system dominates the dispersion in LEO scenarios, while

Overlays present specific disadvantages in terms of security and privacy. Obsolescence is possible if

This work evaluated, for the first time, the feasibility of an authentication framework for IoT devices in LEO satellite constellations based on IOTA Identity. This framework encompasses distributed identity resolution, deactivation, and reactivation tests, as well as simulations of satellite revisit times. The proposed architecture leverages the DAG-based Tangle to manage decentralized identifiers and verifiable credentials, thereby eliminating the computational overhead associated with mining or block-based consensus. This approach reduces latency and processing demands compared to blockchain-based approaches. Experimental results confirm that credential resolution and reactivation times consistently remain within the operating windows defined by the revisit intervals from LEO satellites to the ground station, from where they update the list of authorized devices, enabling reliable authentication and credential restoration under intermittent connectivity conditions. Deactivation times showed greater variability, highlighting the need for targeted algorithmic optimization in scenarios with strict security requirements and rapid revocation demands. Tangle’s structural properties suggest lower power requirements for resource-constrained devices, a factor particularly relevant in IoT satellite deployments with strict duty cycles. In addition to validating operational feasibility, this work lays the groundwork for pilot implementation in simulated and semi-operational satellite environments, paving the way for future large-scale deployments. The findings underscore both the novelty and practical applicability of DAG-based DLT for secure and scalable IoT authentication in hybrid space-to-ground networks, while defining clear guidelines for optimization prior to production-level deployment. Additionally, the measured end-to-end latency for IOTA resolution and wake-up events remains below 400 ms, which is suitable for the context of LEO satellite communications [93].

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Impierce for their support in resolving questions about IOTA Identity.

Funding Statement: This work is part of the ‘Intelligent and Cyber-Secure Platform for Adaptive Optimization in the Simultaneous Operation of Heterogeneous Autonomous Robots (PICRAH4.0)’, with reference MIG-20232082, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. This work is partially supported by the Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR) through the Precompetitive Research Project entitled “Nuevos Horizontes en Internet de las Cosas y NewSpace (NEWIOT)”, reference PP-2024-13, funded under the 2024 Call for Research Projects.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: work conception and design: D. Bernal, O. Ledesma and P. Lamo; data collection: D. Bernal; analysis and interpretation of results: D. Bernal and O. Ledesma; draft manuscript preparation: D. Bernal, O. Ledesma, P. Lamo and J. Bermejo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The source code used for the tests conducted in this work is available at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16940188 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present work.

Glossary

All acronyms that appear in this work are listed below for ease of understanding

| Acronym | Meaning |

| 3GPP | 3rd Generation Partnership Project |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| CA | Certificate Authority |

| CRL | Certificate Revocation List |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology |

| DID | Decentralized Identifier |

| DTLS | Datagram Transport Layer Security |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

| ISL | Inter Satellite Link |

| JWT | JSON Web Tokens |

| LDAP | Lightweight Directory Access Protocol |

| LEO | Low Earth Orbit |

| LPWAN | Low-Power Wide-Area Network |

| M2M | Machine to Machine |

| MAC | Message Authentication Code |

| NAC | Network Access Control |

| NB IoT | Narrowband IoT |

| NTN | Non Terrestrial Networks |

| PKI | Public Key Infrastructure |

| SSI | Self Sovereign Identity |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| VC | Verifiable Credential |

| VP | Verifiable Presentation |

| ZTA | Zero Trust Architecture |

References

1. Qu Z, Zhang G, Cao H, Xie J. LEO satellite constellation for internet of things. IEEE Access. 2017;5:18391–401. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2735988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Khan F, Hervella C, Diez L, Fernández F, Marcano NJH, Jacobsen RH, et al. Realistic assessment of transport protocols performance over LEO-based communications. Comput Netw. 2023;236(7):110008. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lacuna Space. Lacuna space: IoT satellite connectivity. [cited 2025 Mar 1]. Available from: https://lacuna-space.com/. [Google Scholar]

4. Cui J, Yu J, Zhong H, Wei L, Liu L. Chaotic map-based authentication scheme using physical unclonable function for internet of autonomous vehicle. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(3):3167–81. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3227949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ahmed ST, Ahmed AA, Annamalai A, Chouikha M. Efficient rebroadcast location-unaware protocol for LoRaWAN mesh networks in the IoT domain. In: 2024 IEEE 14th Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE); 2024 May 24–25; Penang, Malaysia. p. 104–10. doi:10.1109/ISCAIE61308.2024.10576269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Pablo Becoña J, Grané M, Miguez M, Arnaud A. Sigfox, and NB-IoT: an empirical comparison for IoT LPWAN technologies in the agribusiness. IEEE Embedd Syst Lett. 2024;16(3):283–6. doi:10.1109/LES.2024.3394446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li CF, Hwang JK. Implementation and verification of an SDR-based NB-IoT gNB with two-stage band-edge filter for GEO-relayed NTN scenario. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Microwaves, Communications, Antennas, Biomedical Engineering and Electronic Systems (COMCAS); 2024 Jul 9–11; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/COMCAS58210.2024.10666233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li CF, Hwang JK, Ma C. NB-IoT NTN band-edge attenuation/EVM tradeoff with real-system verification. In: 2023 25th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT); 2023 Feb 19–22; Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea. p. 74–8. doi:10.23919/ICACT56868.2023.10079567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Guo J, Chang L, Song Y, Yao S, Zheng Z, Hao Y, et al. AHA-BV: access and handover authentication protocol with batch verification for satellite-terrestrial integrated networks. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2025;91(9):103870. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2024.103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ragothaman K, Wang Y, Rimal B, Lawrence M. Access control for IoT: a survey of existing research, dynamic policies and future directions. Sensors. 2023;23(4):1805. doi:10.3390/s23041805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ouyang M, Zhang R, Wang B, Liu J, Huang T, Liu L, et al. Network coding-based multipath transmission for LEO satellite networks with domain cluster. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(12):21659–73. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3378177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kumar R, Arnon S. Authentication method for spoofing protection in communication and navigation satellites: utilizing atmospheric signature. Eng IEEE Commun Let. 2024;28(1):128–32. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2023.3334870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Suhaimi NHS, Kamarudin NH, Khalid MNA, Tahir I, Mohamed MAA. State-of-the-art authentication measures in satellite communication networks: a comprehensive analysis. IEEE Access. 2024;12:142241–64. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3467253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Guo W, Xu J, Pei Y, Yin L, Jiang C, Ge N. A distributed collaborative entrance defense framework against DDoS attacks on satellite internet. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(17):15497–510. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3176121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ding X, Ren Y, Xie X, Zou Y, Jia M, Zhang G. Improving user capacity of satellite internet of things via joint user grouping and multi-beam processing. IEEE Trans Commun. 2024;72(7):3957–69. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2024.3370445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]