Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Artificial Neural Network Model for Thermal Conductivity Estimation of Metal Oxide Water-Based Nanofluids

1 School of Engineering, Ajeenkya DY Patil University, Pune, 41210, India

2 Department of Material Science & Engineering, Ajou University, Suwon-si, 16499, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Gandhi Academy of Technology and Engineering, Brahmapur, 761008, India

4 Department of Engineering Sciences, Ajeenkya D Y Patil School of Engineering, Pune, 412210, India

5 Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Engineering, OP Jindal University, Punjipathra, Raigarh, 496019, India

* Corresponding Author: Sheetal Kumar Dewangan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Applications of Neural Networks in Materials)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072090

Received 19 August 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The thermal conductivity of nanofluids is an important property that influences the heat transfer capabilities of nanofluids. Researchers rely on experimental investigations to explore nanofluid properties, as it is a necessary step before their practical application. As these investigations are time and resource-consuming undertakings, an effective prediction model can significantly improve the efficiency of research operations. In this work, an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model is developed to predict the thermal conductivity of metal oxide water-based nanofluid. For this, a comprehensive set of 691 data points was collected from the literature. This dataset is split into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) and used to train the ANN model. The developed model is a backpropagation artificial neural network with a 4–12–1 architecture. The performance of the developed model shows high accuracy with R values above 0.90 and rapid convergence. It shows that the developed ANN model accurately predicts the thermal conductivity of nanofluids.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileNanofluids are emerging as effective and efficient alternative fluids in thermal applications. In heat transfer devices like heat exchangers, heat pipes, and microchannels, nanofluids are used as alternative fluids. Nanofluids provide better thermal performance compared to traditional fluids by virtue of their superior thermal conductivity and boiling characteristics [1]. Hence, the nanofluid improves the efficiency of the heat exchange process, making it a popular choice as an alternate fluid. For next-generation thermal management applications, nanofluids show immense potential. Nanofluid materials like carbon-based, metal-based, and metal oxide-based nanofluids are popular. Metal oxide nanofluids show enhanced thermal conductivity and high stability and are also cost-effective [2]. Due to these characteristics, particularly their cost-effectiveness, metal oxide nanofluids are extensively utilized in industrial applications [3,4]. Similarly, the economic feasibility of water has contributed to its widespread use as a base fluid. Aqueous metal oxide nanofluids need further exploration of their behavior, which is essential to enhance their practical applicability further.

Several researchers have explored the thermophysical properties and the mechanisms responsible for their thermal behaviors. Mukherjee et al. [5] investigated the thermal conductivity of MgO-SiO2-water hybrid nanofluid and found that the maximum enhancement was 20.84% compared to water. Mane et al. [6,7] also conducted multiple studies with different dispersants and characterized the thermal conductivity of the hybrid CuO + Fe3O4 nanofluids. Their findings showed that these hybrid nanofluids show considerable improvement compared to water. Soltani et al. [8] investigated the thermal conductivity of tungsten oxide (WO3) and MWCNTs (multiwalled carbon nanotubes) nanofluids. The results showed that nanofluid thermal conductivity enhancement is 19.85% compared to the base fluid. These experimental investigations have significantly contributed to the existing body of knowledge. The current body of knowledge on the thermal conductivity of nanofluids shows that the thermal conductivity of nanofluids significantly varies based on nanoparticle material, size, base fluid, concentration, and temperature. Mane and Hemadri [9] showed that the thermal conductivity is also significantly dependent on the stability. More stable nanofluids, signified by small particle size (less than 100 nm) and polydispersity index (PDI < 0.3), provide better thermal conductivity compared to less stable nanofluids with the same reparation parameters. This interrelational complexity of these and other factors has significantly impacted the understanding of the thermal conductivity of nanofluids. This complexity also made it very hard to predict the thermal conductivity of nanofluid, and hence, investigating the properties of the synthesized nanofluid prior to applications is almost a standard practice in thermal engineering research. However, the characterization study for nanofluid requires a high amount of resources and time. This is not feasible for researchers, especially in investigations where multiple nanofluids are synthesized. Hence, an effective prediction mechanism is required for nanofluid properties.

In engineering, statistical modeling is widely used for prediction, analysis, and optimization in various applications. Statistical techniques provide valuable aid in understanding the data in complex scenarios. Based on the data type and behavior of the system, time series, Regression Design of Experiments, and machine learning-based statistical models are used. Recent computational studies have highlighted the effectiveness of these methods. Mane et al. [10] investigated the thermal performance of pulsating heat pipes. They also developed a statistical model using regression to predict the thermal resistance of the pulsating heat pipe based on filling volume, pipe dimension, heat input, and angle of inclination. They developed a response surface method (RSM) statistical model using an extensive dataset and found that their model has a deviation of 22.52% in actual and predicted values. Prediction modeling is also effectively used in the material science field. Syam et al. [11] investigated convective Darcy–Forchheimer flow in Maxwell nanofluids using innovative iterative methods based on operational matrix techniques. These types of computational studies can complement machine learning methods to provide insights into deeper physical phenomena. Though these modelling techniques like RSM are effectively used by different resrchers, their performance compared ANN is found to be inferior. Saaidia et al. [12] used ANN and RSM for modelling water absorption behavior of biocomposites. This study demonstrated that the values predicted by ANN are closer to the experimental results than those predicted by RSM, highlighting the effectiveness of ANN.

Similar results were observed by Kundu et al. [13] where ANN outperformed RSM in predicting thermo-fluidic characteristics of hybrid nanofluid systems.

Mahmud et al. [14] developed an ANN model to predict thermo-solutal transport rates with MWCNT-CuO-Al2O3-ethylene glycol hybrid nanocoolants. This model predicted heat and mass transfer rates within 1%–2% and 2%–3% error ranges, respectively. However, their work focused specifically on MWCNT-CuO-Al2O3-ethylene glycol and was limited to convective heat transfer. Kamsuwan et al. [15] developed a comprehensive ANN model to predict nanofluid properties for heat exchanger design. This model has prediction errors of 4.1% showing reliable evaluation of nanofluid performance across various nanoparticle types with water as the base fluid. This model focused on heat exchanger applications rather than fundamental properties of nanofluid, limiting its applicability. Dewangan et al. [16] proposed an ANN model to predict the hardness of AlCrFeMnNiWx (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 mol) high entropy alloys. They used a backpropagation ANN model with a 9-9-1 architecture to predict the hardness of alloys. This model has delivered a prediction accuracy of 95.9% with a marginal error of 4.049%. Various researchers have also developed ANN models to predict nanofluid properties. Mohan et al. [17] used ANN modeling for the thermal conductivity of nanoparticle-enhanced phase change material. Their model showed exceptional prediction performance (>99%). Bhat et al. [18] developed ANN model to predict water uptake of nanoclay glass fiber/epoxy composite. They used 3–4–1 ANN architecture trained with the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm and found very good prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.998, MSE = 1.38 × 10−4). This study showed that ANN are relabel prediction tool however also emphasized that expanded dataset are needed for braoder adoption. In the field of nanofluids, many researchers have also used different prediction techniques to predict the viscosity [19], electrical conductivity [20], and transport properties [21] of nanofluids. Though ANNs are predominantly employed for property prediction, their application in nanofluid research extends far beyond simple property estimation and they can also handle complex analytical tasks. Kumar et al. [22] used ANN to solvegoverning equations of Jeffrey hybrid nanofluid flow. They found that ANN efficiently dealt with non-linear coupling between nanoparticle behavior and microorganism movement. Alotaibi et al. [23] used ANN to used to solve the system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) derived from the original Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). ANN showed robust performance in handling the complex nonlinear system governing nanofluid flow. In other applications also, ANN have shown excellent reliability, Luo et al. [24] found error of 0.42% (MAE < 1%) using ANN modelling of real-time SOC estimation in lithium-ion batteries. All these reviewed studies have shown encouraging performance in the prediction of the different parameters in engineering and science applications. However, most of these studies have focused on limited data; hence, due to a lack of diversity, limited or single materials, and most of these models do not account for the complexity of nanofluid, which arises due to the multitude of preparation parameters. Similarly, there is a lack of universal models that are trained on diverse inputs that can be powerful tools for nanofluid thermal conductivity prediction. This shortcoming shows that there is a need for a study to develop a broadly applicable model trained on diverse and strong datasets.

The focus of this investigation is on the development of a reliable and robust ANN model to predict the thermal conductivity of aqueous nanofluids. The study analyzes “intelligence” approaches for modeling nanofluid thermal conductivity, emphasizing the correlation between model accuracy and input variables. It concludes that neural network structure significantly affects output, highlighting the importance of considering all influencing variables for precision. The research employs a “trial-and-error” process to optimize ANN configurations, aiming for improved thermal conductivity predictions. A detailed resource is provided for future research, evaluating input variables, model consistency, and types of nanofluids. Here, a robust data set of 691 data points is collected from the literature and processed to train the ANN model based on nanoparticle thermal conductivity, size, base fluid, concentration, and temperature. The model developed in this study has 4–12–1 architecture, and it is trained using the Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation algorithm. This study provides a reliable tool for thermal conductivity prediction for researchers working in the nanofluids application area. This work can save valuable time for researchers by reducing the heavy dependence on extensive experimental investigations and improving cost and resource efficiency in the research field.

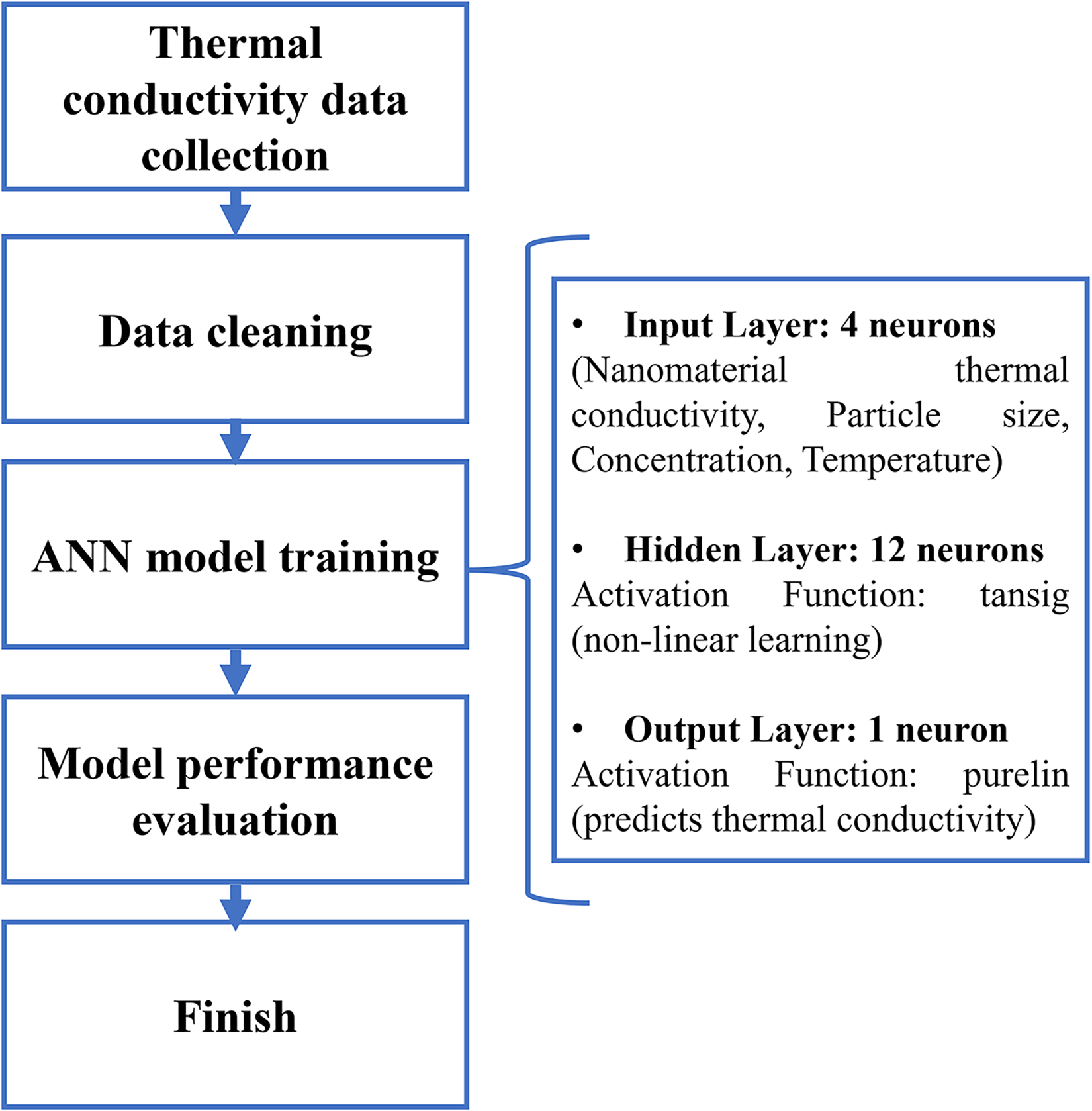

In order to develop an effective, accurate, reliable, and robust model, extensive data is collected. This data is further used for the training of the ANN model, and the prediction performance of this ANN model is evaluated. This process is discussed in detail in the subsequent section of Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the modelling process

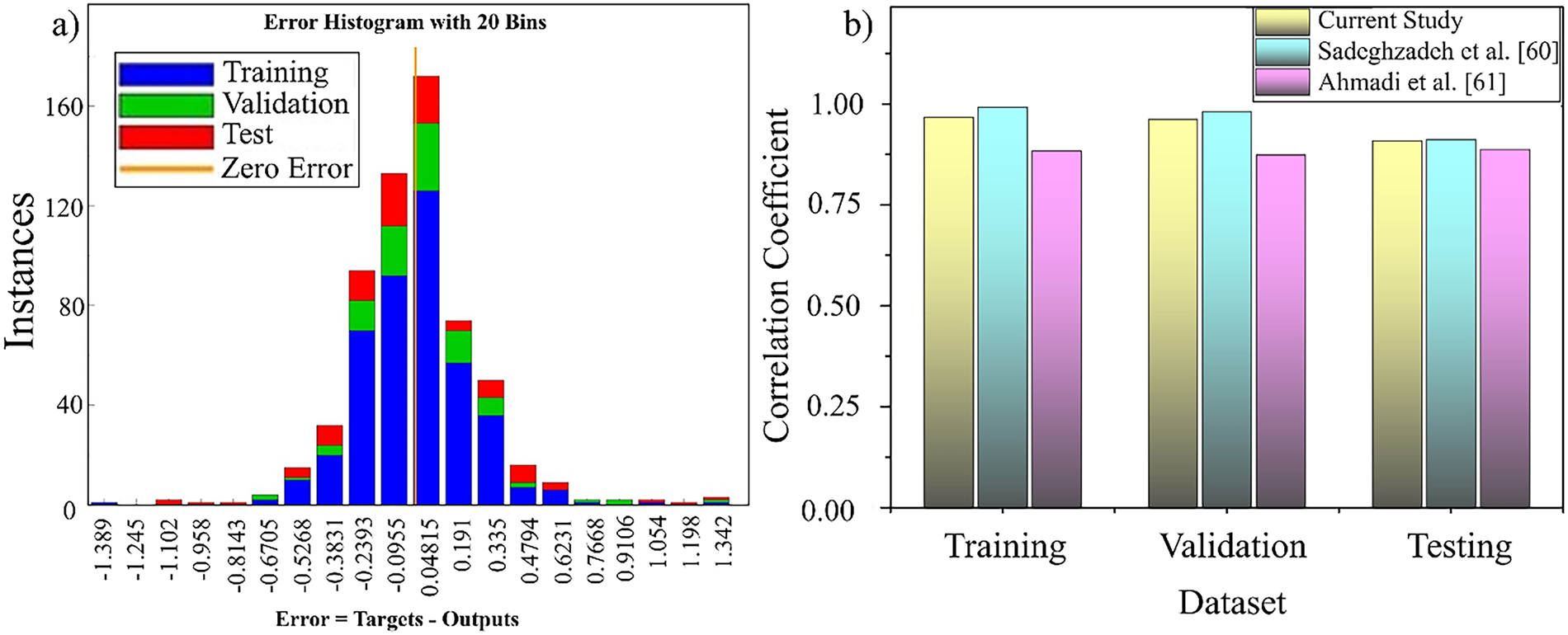

Data collection is an important step in this work. The reliability of the data collection process has a significant impact on the reliability of the developed model. In this work, a large data set is collected from the literature. This study gathers thermal conductivity data from various sources in the literature to ensure data diversity. Additionally, the data collection is restricted only to the studies using metal oxide nanoparticles and water as a base fluid. Restricting the data collection to these factors ensures consistency, reliability, and comparability of the dataset. As discussed earlier, metal oxide nanoparticles are commonly used as they provide good stability, high thermal conductivity, and cost-effectiveness. Hence, aqueous metal oxide nanofluids have wide industrial applicability. Restricting data collection to these specific criteria can lead to more controlled analysis and higher accuracy. Thermal conductivity data of nanofluids is dependent on the preparation parameters like thermal conductivity of the base fluid, nanoparticle materials, concentration, particle size, and temperature. Hence, in this work, data on the thermal conductivity of metal oxide water-based nanofluids are collected from the literature. A total of 691 data points were collected from the sources, as listed in Table 1. This dataset contained thermal conductivity (k) data with key variables such as nanomaterial type, particle size, concentration (wt%), and temperature. The detailed dataset used for training the ANN model is provided in Supplementary Table S1. The nanomaterial type is then converted into nanomaterial thermal conductivity by replacing the material with the bulk thermal conductivity of that material. In the data collection process, no missing parameters are ensured. This dataset is processed with structured data cleaning to ensure its integrity and relevance for analysis. As these data points are collected from various sources across the globe, changes in equipment, instruments, and synthesis processes may lead to anomalies in the data. These anomalies are extreme values that do not match the general pattern of the data and can substantially impact the entire training process. The noise introduced by these outliers can result in the low accuracy and effectiveness of the models. Hence, the removal of these anomalies is necessary to produce a cleaner dataset and ensure the reliable learning of the ANN. The cleaning process of this data set is done using the Isolation Forest method. This algorithm finds the outliers by calculating the degree of isolation for each data point in the entire space of data. The particle size, concentration, temperature, and thermal conductivity are used to compare and identify the anomalies. The contamination parameter was set to 5% so that the algorithm flagged approximately 5% of the dataset as anomalies. These detected anomalies were identified and removed, which reduced the dataset from 691 to 614 observations. This cleaned dataset is then used for further analysis, ensuring the reliability of the learning process.

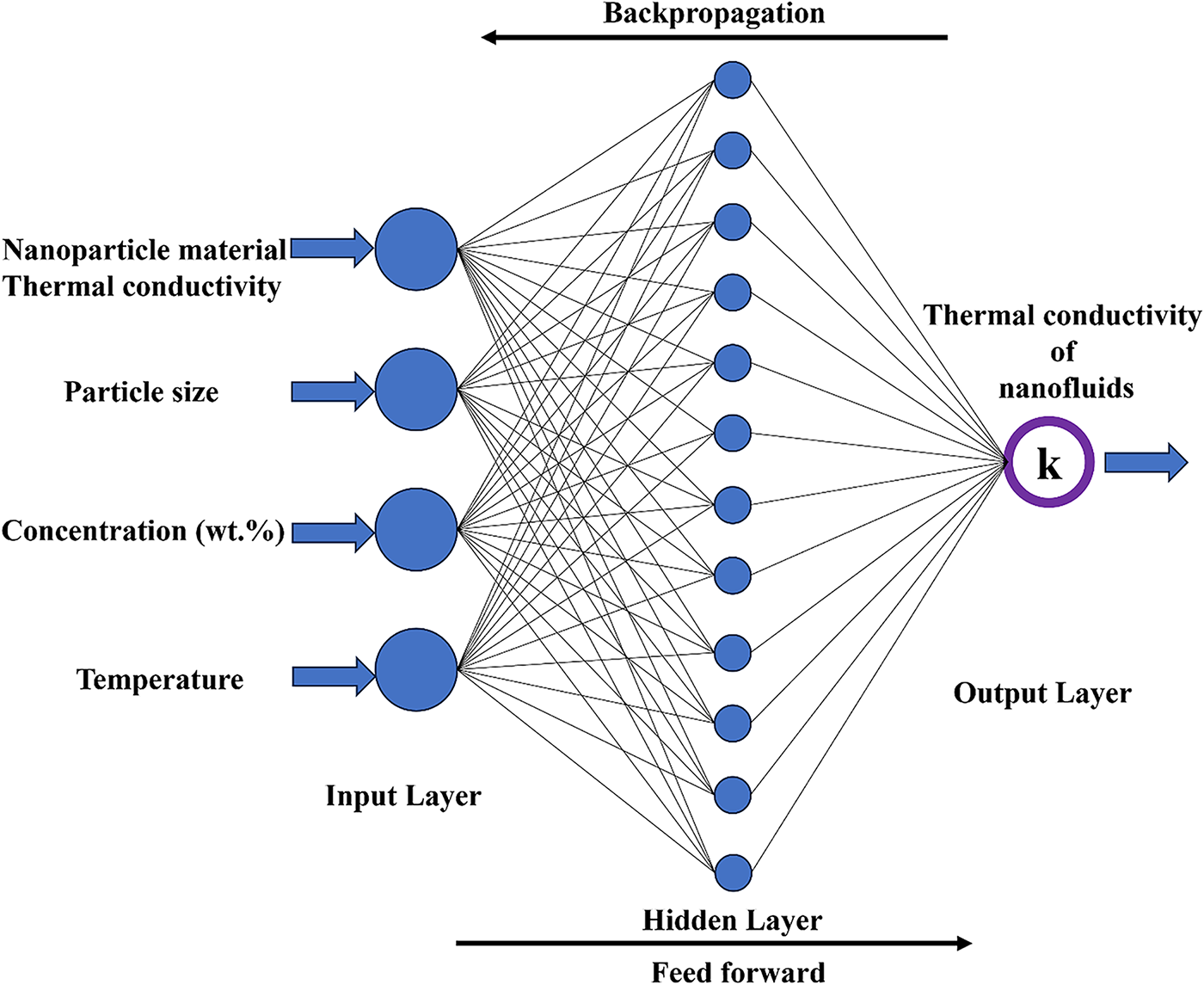

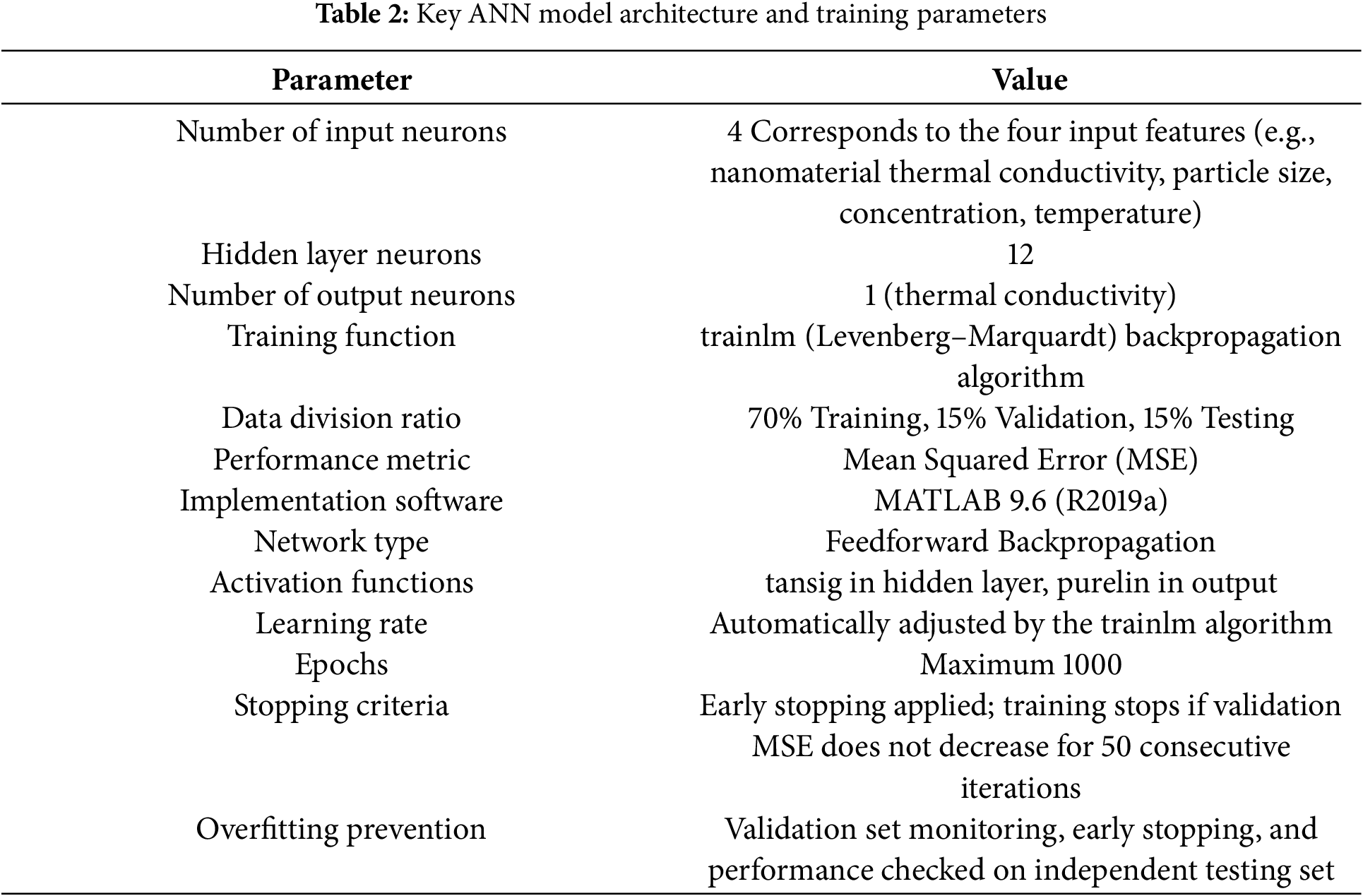

A typical ANN consists of an input layer (representing input parameters), a hidden layer (responsible for processing and extracting patterns from the data), and an output layer (representing the predicted values or target outcomes). The development of the ANN model is based on the data’s characteristics and complexity. The most influential factors affecting the ANN architecture are the input and output parameters. The neurons in the input and output layers are affected by the input and output parameters. However, the complexity of the data mostly affects the hidden layer part of the architecture. As this hidden layer is responsible for the feature extraction and learning process, more complex data need deeper hidden layers. During the modeling process, the dataset is automatically split into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%). The ANN model developed in this work consists of three distinct layers: the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer. Each layer comprises interconnected neurons, and the communication between these neurons occurs via linking weights. Every neuron aggregates multiple signals from the preceding layer and adjusts the corresponding weight values. The final output is determined after multiple training iterations. A backpropagation algorithm, known for its effectiveness in material property predictions, has been employed here to capture the relationship between input and output datasets. In this study, a backpropagation artificial neural network with a 4–12–1 architecture (4 neurons in the input layer, one for each input variable, 12 neurons in the single hidden layer, and one neuron in the output layer) is utilized. The input parameters for the model include the nanomaterial thermal conductivity, particle size (nm), weight concentration (wt%), and temperature, while the output parameter is the thermal conductivity. A standard feedforward neural network (with one hidden layer) trained by the Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation algorithm, designed to model the relationship between four input parameters and one output, i.e., thermal conductivity of nanofluid. MATLAB 9.6 (R2019a) was used to implement and train the model, and the dataset was split into training, validation, and testing subsets. Fig. 2 illustrates the proposed backpropagation ANN model for the present study. Table 2 also shows the key parameters of the ANN.

Figure 2: Architecture of the ANN model

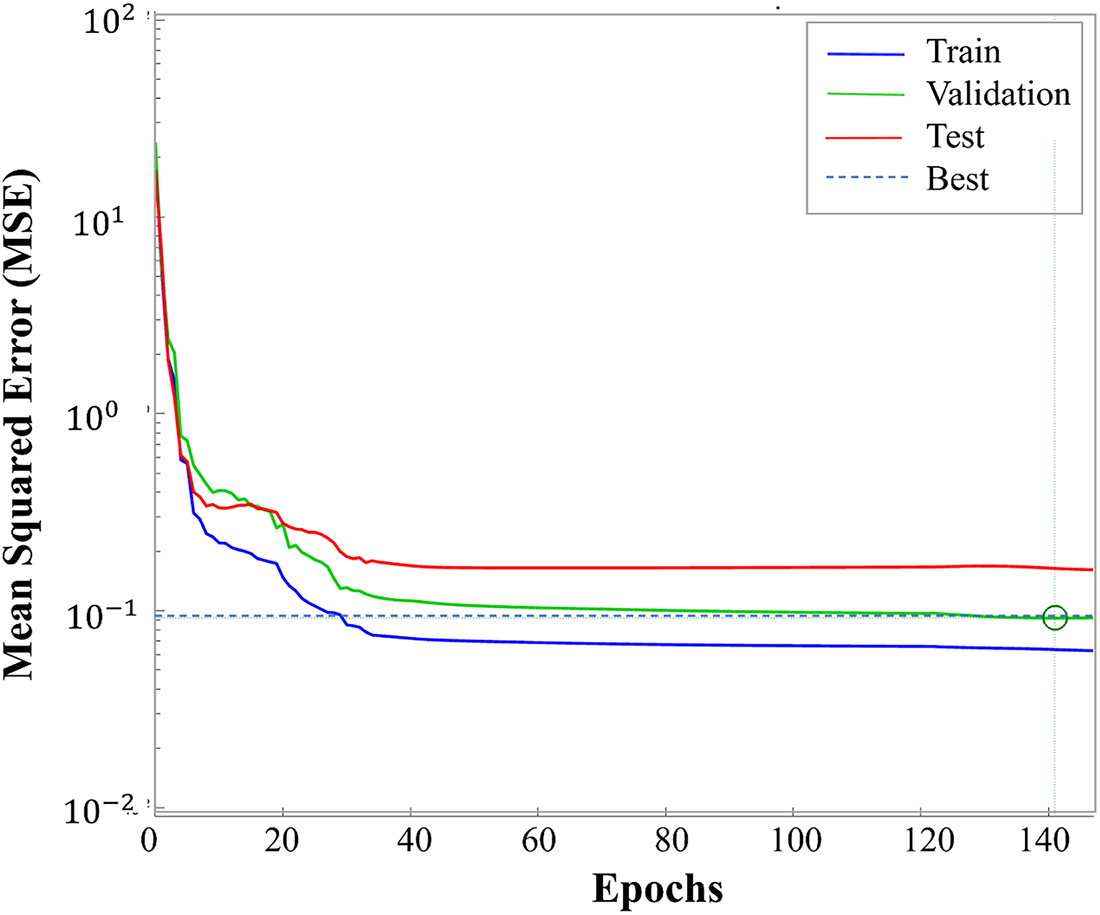

To ensure the selected 4–12–1 architecture accurately captures the relationship between the input parameters and thermal conductivity, several network configurations were systematically tested. The performance of each architecture was evaluated based on the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) on both validation and testing datasets. The hidden layer size of 12 neurons provided the best trade-off between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. To prevent overfitting, early stopping was applied using the validation dataset, and the network’s performance on the independent testing dataset was continuously monitored. The activation functions, training algorithm, and other hyperparameters were optimized iteratively to maximize generalization, ensuring that the ANN model delivers reliable predictions for thermal conductivity across the range of input variables.

The performance evaluation of the ANN model is a crucial step in this study. The performance evaluation of an ANN ensures the reliability of its predictions. In this section, performance matrices of the ANN, i.e., Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R values, are analyzed for the ANN performance. Here MSE is the average squared difference between predicted and actual values. It indicates the error in the prediction of values, and hence, the least MSE value is expected. While R values show predicted and actual values, and 1 value is expected. Similarly, the plot of output and target, i.e., predicted and actual values, also shows comparative matching of values and hence the performance of the ANN. The presence of points closely aligned with the diagonal line indicates optimal model performance. The subsequent discussions provide proof of the reliability and accuracy developed in this study.

Training, testing, and validation of the ANN model

A backpropagation neural network has been applied to the model, which predicts the hardness of the alloys. Initially, all datasets were scaled using the feature scaling function to maintain the stability of the input dataset. The generalized equation of feature scaling is given in Eq. (1) [59].

where xi is the thermal conductivity of the i-th sample.

As discussed earlier, an entirely cleaned dataset of 625 data points is divided into training, validation, and testing to build the model. The ANN architecture is set as 4-12-1 to provide maximum reliability, and it is chosen through the error and trial method. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) quantifies the average squared difference between the network’s predicted outputs and the actual values. A lower MSE indicates a more accurate model. In Fig. 3, an MSE of 0.091786 at 141 epochs represents the lowest validation error achieved, suggesting that the network has optimally learned the underlying relationship at that point. Achieving the best validation performance at 141 epochs with an MSE of 0.091786 not only confirms the model’s effectiveness in capturing the data patterns but also highlights that further training beyond this point might risk overfitting. This balance between training and validation error is critical for ensuring reliable predictions on unseen data.

Figure 3: Convergence of MSE: optimal validation error reached at 141 epochs

Assessment of ANN prediction accuracy

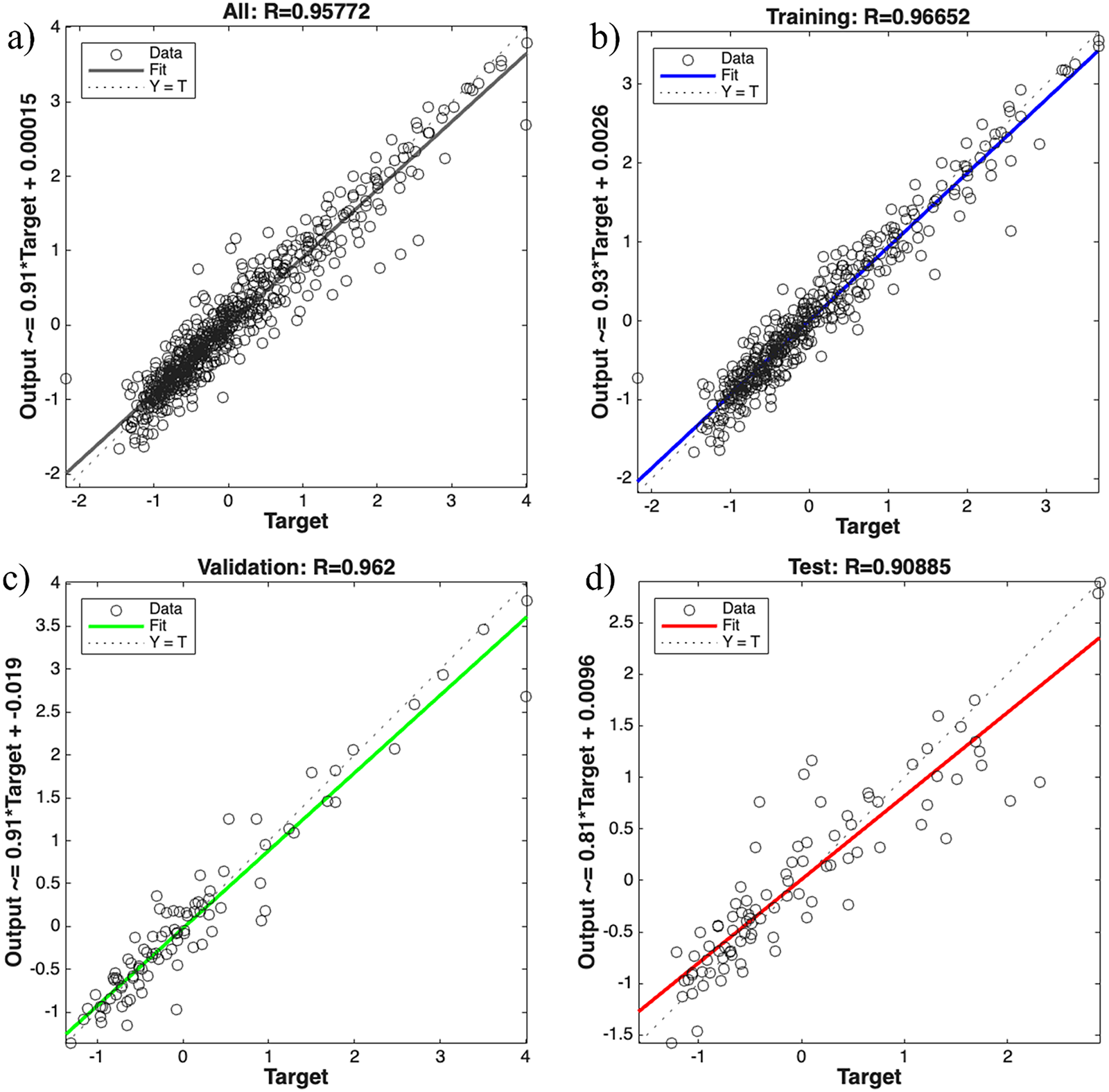

The relationship between the predicted output (thermal conductivity of nanofluid) of the ANN and the target values (actual values from the literature) is discussed in this section. The close alignment of the predicted and target values shows that the ANN model has accurately predicted the thermal conductivity of the nanofluid. Fig. 4 shows that the majority of data points lie close to the line of perfect correlation, which represents a zero-error condition. The points that lie exactly on this line indicate a 100% accurate prediction of the thermal conductivity of nanofluid by the model, with no deviation between the predicted and actual values. Fig. 4a shows that for all data, R is 0.95772, which confirms the reliability of the ANN model. Here, the R-value (correlation coefficient) is the indicator of how well a correlation or model predicts an entity. Fig. 4b shows that for the training set, the R-value is 0.96652; this indicates that the model has learned the underlying patterns exceptionally well. Also, the validation set R-value of 0.962 confirms that the model generalizes effectively and avoids overfitting during the training process, as shown in Fig. 4c. The lowest R-value is covered for the test set in Fig. 4d, i.e., 0.90885, which still demonstrates a strong predictive performance on unseen data, confirming the reliability of ANN. These R values reflect that the ANN model consistently delivers excellent predictive accuracy across all data splits.

Figure 4: Comparison of ANN predicted thermal conductivity vs. actual thermal conductivity values (a) all datasets (b) training datasets (c) validation datasets (d) test datasets

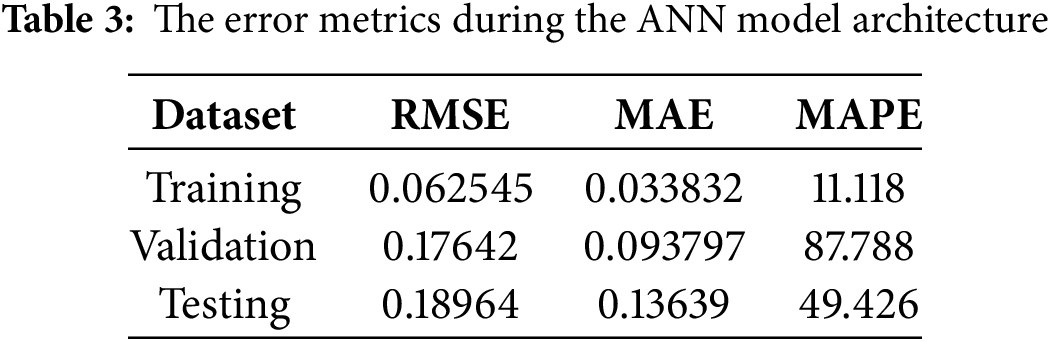

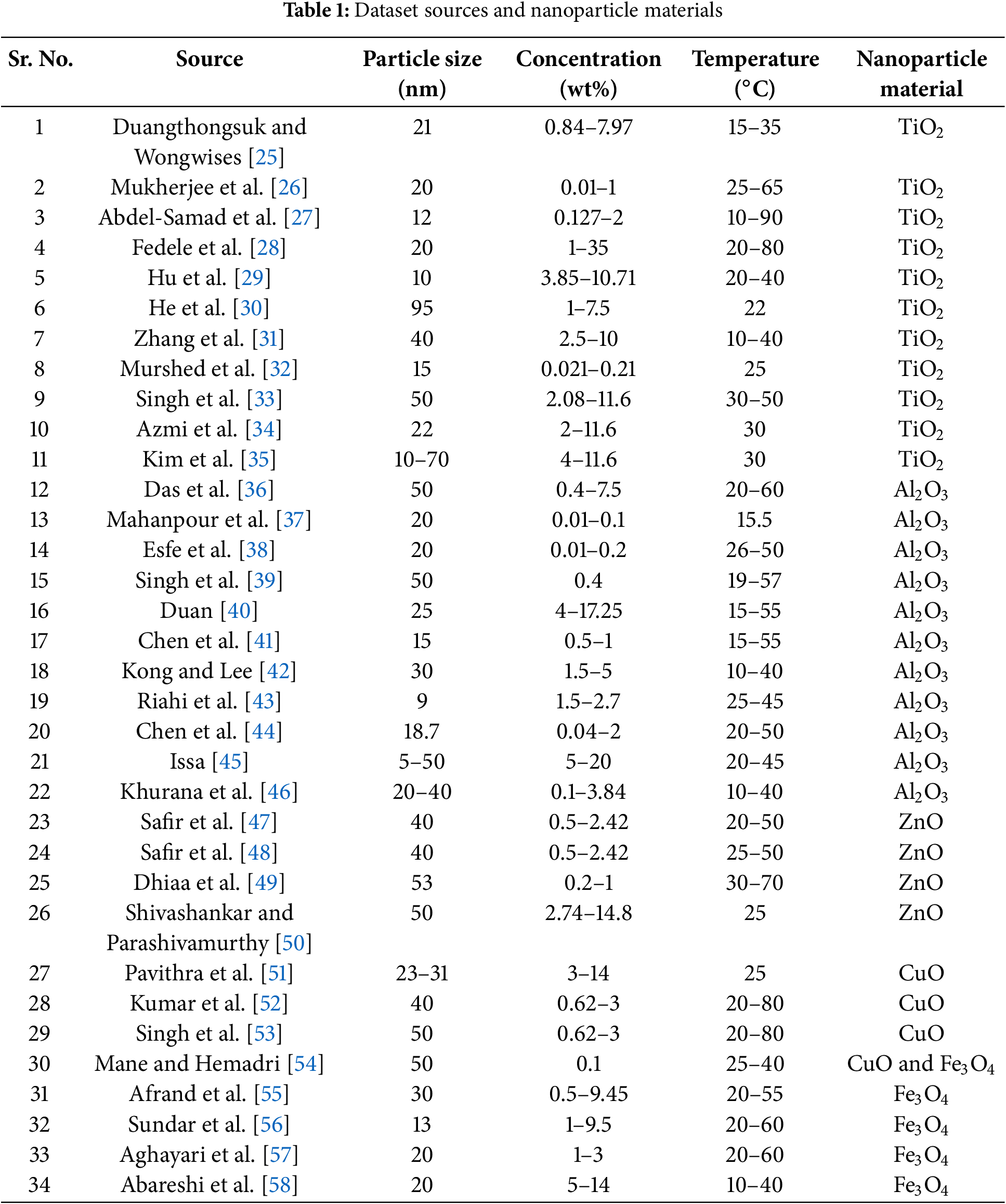

As an overview, Fig. 4 shows strong correlations between predicted and experimental values, with R values of 0.9577 (all data), 0.9665 (training data), 0.962 (validation data), and 0.9089 (test data). The complementary error metrics (RMSE, MAE, MAPE) in Table 3 confirm the model’s reliability. The slightly lower R for the test set reflects natural variability in unseen data, while occasional outliers arise from sparsely sampled regions of the dataset. Overall, the model demonstrates good accuracy and generalization.

To quantify the effectiveness of the developed model, standard regression evaluation metrics were employed, namely R2, MAE, RMSE, and MAPE. Thus, the model performance is evaluated using the following metrics:

(i) Mean Absolute Error (MAE): MAE represents the average of the absolute differences between the actual and predicted values:

It provides a straightforward measure of prediction accuracy. Where y and ŷ are actual data points and predicted data from the model, respectively. n is the total number of points in the dataset.

(ii) Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): RMSE is the square root of the mean of the squared differences between actual and predicted values:

It reflects the magnitude and dispersion of prediction errors.

(iii) Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): MAPE measures the average percentage error between the actual and predicted values:

In this work, ANN is selected because it effectively captures complex nonlinear relationships that empirical correlations and regression models often miss. While approaches such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and decision trees can also be applied, ANN provided higher accuracy (low RMSE/MAE, strong R) and reliable generalization in our case. A detailed benchmarking with other models will be considered in future work. In addition, ANN expresses prediction accuracy as a percentage, making it easy to interpret across different datasets. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of regression model performance, indicating both the accuracy of predictions and the overall goodness of fit, which is presented in Table 3.

Fig. 5 presents the error histogram for the training, validation, and test datasets. Most of the errors are clustered around zero, indicating that the model predictions are unbiased and generally accurate. The narrow distribution further demonstrates that large deviations are rare, with only a small number of outliers observed in the tails. These outliers are likely associated with regions of the dataset where fewer experimental samples were available, making predictions less constrained. Overall, the error distribution confirms the consistency and robustness of the model across all datasets, in agreement with the quantitative metrics (RMSE, MAE, and MAPE) reported in Table 3. Further, the bar chart (Fig. 5b) compares the correlation coefficient (R) of the current study with previous studies [60,61] across three datasets: training, validation, and testing. The correlation coefficient measures how well the predicted outputs from the ANN model align with the actual target values, with values closer to 1 indicating better prediction accuracy.

Figure 5: (a) Histogram analysis between target value and output values and (b) comparison of different study [60,61]

2.4 Generalization Capabilities and Practical Applications

In the current work, the developed ANN model showed a high accuracy (R > 0.90) and rapid convergence for predicting the thermal conductivity of metal oxide water-based nanofluids. However, its generalization to the entire nanofluid spectrum as the training dataset is focused on metal oxide nanofluids only. Additionally, in metal oxide nanofluids, their generalizations and applicability will also be restricted to non-aqueous nanofluids only. The effectiveness of a model may be further restricted for a hybrid nanofluid due to the lack of a training dataset. In this work, the model is trained on specific temperature ranges, nanoparticle concentrations, and particle sizes reported in the literature; hence, the predictive performance of the model may be limited outside the range of these properties within the training data set. Hence, to accommodate the broader generalization and predictive capability of the ANN model, a robust training dataset is required. At present conditions, the proposed ANN model offers engineers and researchers a fast, cost-effective tool for estimating thermal conductivity. This enables preliminary screening and optimization of nanofluid formulations before committing to time-consuming and expensive experimental work. This can be time-saving in the design of thermal management systems in applications such as heat exchangers, cooling systems, and renewable energy technologies.

In this study, an ANN model is developed using an extensive dataset on the thermal conductivity of nanofluids. The dataset includes key parameters such as nanofluid thermal conductivity, nanoparticle material type, concentration, particle size, and temperature. In order to develop a robust prediction tool for nanofluid thermal conductivity, this comprehensive dataset is used to train the ANN. The trained ANN model provided reliable prediction performance and detailed findings of this work are listed below.

• This study developed an ANN model with a 4–12–1 architecture to predict thermal conductivity based on nanomaterial type, particle size, concentration, and temperature.

• The model achieved high correlation coefficients with training, validation, and test R values of 0.96652, 0.962, and 0.90885, respectively, indicating excellent predictive accuracy.

• Rapid convergence was observed, with the MSE stabilizing at 0.18468 in just five epochs and reaching its best validation performance of 0.091786 at epoch 141.

• These results demonstrate that the ANN effectively captures the complex relationships between the input parameters. This ANN model can be effectively applied to understand the complex relationship of input parameters and their role in nanofluid thermal conductivity. The prediction performance of the ANN shows that the model effectively captures the hidden behavior of the data.

• Future scope: The ANN model developed in this study can be improved further by training it on the expanded dataset. Similarly, a few other input parameters that can have influenced the thermal conductivity can also be included in the dataset. This additional parameter can complicate the relationship of input parameters and potentially reduce the prediction accuracy of the model. However, it can be improved using deep learning and optimization algorithms.

These findings show that the ANN model reliably delivers the prediction of thermal conductivity of nanofluids. This also shows that in the thermal engineering field, ANN can be extensively used for statistical modeling, where it can capture the complex behavior of devices, processes, and materials. Using these machine learning techniques, resources, and time efficiency of the researchers can be significantly improved. Additionally, the need for nanofluid characterization can be significantly reduced, which can further boost the research and adaptation of nanofluids in industrial applications. It should be noted that some of the studies included in the training dataset [40,51,52] have been discussed on platforms such as PubPeer, where certain methodological concerns have been noted. While these references were published in reputable journals and form part of the dataset used to train the ANN model, we acknowledge these discussions and have included them here for completeness of the dataset.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their sincere gratitude to ADYPU, Pune, India for providing the necessary resources, technical support, and guidance throughout this research.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1A6A1A10044950).

Author Contributions: Nikhil S. Mane: conceptualization, data analysis, writing—original draft. Sheetal Kumar Dewangan: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, supervision. Sayantan Mukherjee: conceptualization, writing—original draft. Pradnyavati Mane: conceptualization, data analysis, writing—original draft. Deepak Kumar Singh: experimental work, conceptualization, review, editing. Ravindra Singh Saluja: experimental work, conceptualization, review, editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study is provided with this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Table S1: Input parameters and thermal conductivity dataset for ANN training. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.072090/s1.

References

1. Barber J, Brutin J, Tadrist L. A review on boiling heat transfer enhancement with nanofluids. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6(1):280. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-6-280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Suganthi KS, Rajan KS. Metal oxide nanofluids: review of formulation, thermo-physical properties, mechanisms, and heat transfer performance. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;76:226–55. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Syam MM, Syam MI. Investigation of slip flow dynamics involving Al2O3 and Fe3O4 nanoparticles within a horizontal channel embedded with porous media. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;24(3):100934. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li Y, Zhu C, Lyu Z, Yang B, Olofsson T. Thermo-hydrodynamic characteristics of hybrid nanofluids for chip-level liquid cooling in data centers: a review of numerical investigations. Energy Eng. 2025;122(9):3525–53. doi:10.32604/ee.2025.067902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mukherjee S, Chaudhuri P, Mishra PC. Achieving enhanced and sustainable thermo-economic performance with aqueous MgO-SiO2 hybrid nanofluid under controlled mixing ratio: experimental results. J Therm Sci. 2025;34(2):429–47. doi:10.1007/s11630-024-2068-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mane NS, Hemadri V. Experimental investigation of stability, properties and thermo-rheological behaviour of water-based hybrid CuO and Fe3O4 nanofluids. Int J Thermophys. 2022;43(1):7. doi:10.1007/s10765-021-02938-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mane NS, Tripathi S, Hemadri V. Effect of biopolymers on stability and properties of aqueous hybrid metal oxide nanofluids in thermal applications. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2022;643:128777. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.128777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Soltani F, Toghraie D, Karimipour A. Experimental measurements of thermal conductivity of engine oil-based hybrid and mono nanofluids with tungsten oxide (WO3) and MWCNTs inclusions. Powder Technol. 2020;371(2):37–44. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2020.05.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mane NS, Hemadri VA. Study of the effect of preparation parameters on thermal conductivity of metal oxide nanofluids using Taguchi method. J Energy Syst. 2021;5(2):149–64. doi:10.30521/jes.872530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mane NS, Hemadri V, Tripathi S. Investigation of effects of vibrations on nanofluid-filled pulsating heat pipe for efficient electric vehicle battery thermal management. Int J Thermophys. 2025;46(1):6. doi:10.1007/s10765-024-03477-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Syam MM, Morsi F, Abu Eida A, Syam MI. Investigating convective Darcy-Forchheimer flow in maxwell nanofluids through a computational study. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2024;11(3):100863. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2024.100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Saaidia A, Belaadi A, Boumaaza M, Alshahrani H, Bourchak M. Effect of water absorption on the behavior of jute and sisal fiber biocomposites at different lengths: ANN and RSM modeling. J Nat Fibers. 2023;20(1):2140326. doi:10.1080/15440478.2022.2140326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kundu R, Islam S, Aktary R, Khatun S, Islam MS. ANN and RSM-based comparison on a natural convective octagonal cavity containing ternary hybrid nanofluid including external magnetic field. Eng Rep. 2025;7(9):e70348. doi:10.1002/eng2.70348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mahmud T, Saboj JH, Nag P, Saha G, Saha BK. Artificial neural network (ANN) approach in predicting the thermo-solutal transport rate from multiple heated chips within an enclosure filled with hybrid nanocoolant. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;24(1):100923. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kamsuwan C, Wang X, Piumsomboon P, Pratumwal Y, Otarawanna S, Chalermsinsuwan B. Artificial neural network prediction models for nanofluid properties and their applications with heat exchanger design and rating simulation. Int J Therm Sci. 2023;184(12):107995. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dewangan SK, Samal S, Kumar V. Development of an ANN-based generalized model for hardness prediction of SPSed AlCoCrCuFeMnNiW containing high entropy alloys. Mater Today Commun. 2021;27(39):102356. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mohan M, Dewangan SK, Rao KR, Lee K, Ahn B. Experimental investigation and artificial neural network-based prediction of thermal conductivity of metal oxide-enhanced organic phase-change materials. Int J Energy Res. 2024;1(39):9844646. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bhat A, Katagi NN, Gowrishankar MC, Shettar M. Prediction of water uptake percentage of nanoclay-modified glass fiber/epoxy composites using artificial neural network modelling. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;85(2):2715–28. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.069842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alfaleh A, Ben Khedher N, Eldin SM, Alturki M, Elbadawi I, Kumar R. Predicting thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of nanofluid by employment of support vector machines: a review. Energy Rep. 2023;10:1259–67. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2023.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mane NS, Hemadri V, Tripathi S. Exploring the role of biopolymers and surfactants on the electrical conductivity of water-based CuO, Fe3O4, and hybrid nanofluids. J Dispers Sci Technol. 2024;45(5):900–8. doi:10.1080/01932691.2023.2186428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Amoo OM, Ajiboye A, Oyewola MO. Analysis of thermophysical and transport properties of nanofluids using machine learning algorithms. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;21(4):100566. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kumar A, Sharma BK, Almohsen B, Pérez LM, Urbanowicz K. Artificial neural network analysis of Jeffrey hybrid nanofluid with gyrotactic microorganisms for optimizing solar thermal collector efficiency. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4729. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88877-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Alotaibi A, Gul T, Saleh Alotaibi IM, Alghuried A, Alshomrani AS, Alghuson M. Artificial neural network analysis of the flow of nanofluids in a variable porous gap between two inclined cylinders for solar applications. Eng Appl Comput Fluid Mech. 2024;18(1):2343418. doi:10.1080/19942060.2024.2343418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Luo YF, Chen GJ, Liu CL, Chung YT. A neural network-driven method for state of charge estimation using dynamic AC impedance in lithium-ion batteries. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(1):823–44. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Duangthongsuk W, Wongwises S. Measurement of temperature-dependent thermal conductivity and viscosity of TiO2-water nanofluids. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2009;33(4):706–14. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2009.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mukherjee S, Mishra PC, Chaudhuri P. Enhancing thermo-economic performance of TiO2-water nanofluids: an experimental investigation. JOM. 2020;72(11):3958–67. doi:10.1007/s11837-020-04336-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Abdel-Samad SM, Fahmy AA, Massoud AA, Elbedwehy AM. Experimental investigation of TiO2-water nanofluids thermal conductivity synthesized by sol-gel technique. Curr Nanosci. 2017;13(6):586–94. doi:10.2174/1573413713666170619124221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Fedele L, Colla L, Bobbo S. Viscosity and thermal conductivity measurements of water-based nanofluids containing titanium oxide nanoparticles. Int J Refrig. 2012;35(5):1359–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2012.03.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Hu Y, He Y, Wang S, Wang Q, Schlaberg HI. Experimental and numerical investigation on natural convection heat transfer of TiO2-water nanofluids in a square enclosure. J Heat Transf. 2014;136(2):022502. doi:10.1115/1.4025499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. He Y, Jin Y, Chen H, Ding Y, Cang D, Lu H. Heat transfer and flow behaviour of aqueous suspensions of TiO2 nanoparticles (nanofluids) flowing upward through a vertical pipe. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2007;50(11–12):2272–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2006.10.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang X, Gu H, Fujii M. Experimental study on the effective thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of nanofluids. Int J Thermophys. 2006;27(2):569–80. doi:10.1007/s10765-006-0054-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Murshed SM, Leong KC, Yang C. Enhanced thermal conductivity of TiO2-water based nanofluids. Int J Therm Sci. 2005;44(4):367–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2004.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Singh RP, Sharma K, Tiwari AK. An experimental investigation of thermal conductivity of TiO2 nanofluid proposing a new correlation. J Sci Ind Res. 2019;78:620–3. [Google Scholar]

34. Azmi WH, Sharma KV, Sarma PK, Mamat R, Anuar S. Comparison of convective heat transfer coefficient and friction factor of TiO2 nanofluid flow in a tube with twisted tape inserts. Int J Therm Sci. 2014;81(8):84–93. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2014.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kim SH, Choi SR, Kim D. Thermal conductivity of metal oxide nanofluids: particle size dependence and effect of laser irradiation. J Heat Transf. 2007;129(3):298–307. doi:10.1115/1.2427071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Das PK, Islam N, Kumar A, Santra R, Ganguly R. Experimental investigation of thermophysical properties of Al2O3-water nanofluid: role of surfactants. J Mol Liq. 2017;237(2):304–12. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2017.04.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mahanpour K, Sarli S, Saghi M, Asadi B, Aghayari R, Maddah H. Investigation on physical properties of Al2O3/water nanofluid. J Mater Sci Surf Eng. 2015;2(2):114–9. [Google Scholar]

38. Esfe MH, Saedodin S, Mahian O, Wongwises S. Thermal conductivity of Al2O3/water nanofluids. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2014;117(2):675–81. doi:10.1007/s10973-014-3771-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Singh S, Sharma S, Gangacharyulu D. Comparative study of various thermo-physical properties of metallic & oxides nanofluids. Int J Eng Sci Res Technol. 2015;4(7):797–803. [Google Scholar]

40. Duan F. Thermal property measurement of Al2O3-water nanofluids. In: Hashim AA, editor. Smart nanoparticles technology. Rijeka, Croatia: IntechOpen; 2012. p. 335–56. doi:10.5772/33830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen TY, Cho HP, Jwo CS, Jeng LY. Performance analysis of Al2O3/water nanofluid with cationic chitosan dispersant. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2013;2013(1):686409. doi:10.1155/2013/686409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kong M, Lee S. Performance evaluation of Al2O3 nanofluid as an enhanced heat transfer fluid. Adv Mech Eng. 2020;12(8):1687814020952277. [Google Scholar]

43. Riahi A, Khamlich S, Balghouthi M, Khamliche T, Doyle TB, Dimassi W, et al. Study of thermal conductivity of synthesized Al2O3-water nanofluid by pulsed laser ablation in liquid. J Mol Liq. 2020;304(4):112694. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chen Z, Shahsavar A, Al-Rashed AA, Afrand M. The impact of sonication and stirring durations on the thermal conductivity of alumina-liquid paraffin nanofluid: an experimental assessment. Powder Technol. 2020;360(Part C):1134–42. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2019.11.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Issa RJ. Effect of nanoparticles size and concentration on thermal and rheological properties of Al2O3-water nanofluids. In: Proceedings of the World Congress on Momentum Heat and Mass Transfer (MHMT’16); 2016 Apr 4–5; Prague, Czech Republic. 101 p. doi:10.11159/enfht16.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Khurana D, Choudhary R, Subudhi S. Investigation of thermal conductivity and viscosity of Al2O3/water nanofluids using full factorial design and utility concept. Nano. 2016;11(8):1650093. doi:10.1142/s1793292016500934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Safir NH, Razlan ZM, Amin NA, Bin-Abdun NA. Experimental investigation of thermophysical properties of ZnO nanofluid with different concentrations. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Green Design and Manufacture (IConGDM 2019); 2019 April 29–30; Bandung City, Indonesia. p. 020050. [Google Scholar]

48. Safir NH, Razlan ZM, Amin NA, Shahriman AB, Wan WK, Zunaidi I, et al. Fluid flows for heat transfer enhancement by using ZnO/water nanofluids with different concentrations. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;429(1):012076. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/429/1/012076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Dhiaa AH, Salih MA, Al-Yousefi HA. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on the thermo-physical properties and heat transfer of nanofluid flows. Int J Heat Technol. 2020;38(3):715–21. doi:10.18280/ijht.380316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shivashankar M, Parashivamurthy KI. Thermal conductivity augmentation of ZnO nanofluids for coolant applications. Int J Mech Eng Robot Res. 2012;6(1):105–10. [Google Scholar]

51. Pavithra KS, Fasiulla, Yashoda MP, Prasannakumar S. Synthesis, characterisation and thermal conductivity of CuO-water based nanofluids with different dispersants. Part Sci Technol. 2020;38(5):559–67. doi:10.1080/02726351.2019.1574941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kumar S, Sokhal GS, Singh J. Effect of CuO-distilled water based nanofluids on heat transfer characteristics and pressure drop characteristics. Int J Eng Res Appl. 2014;4(9):28–37. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Singh V, Sharma S, Gangacharyulu D. Variation of CuO distilled water based nanofluid properties through circular pipe. Int J Eng Technol Manag Appl Sci. 2015;3:414–20. [Google Scholar]

54. Mane NS, Hemadri V. Effect of surfactants and nanoparticle materials on the stability and properties of CuO-water and Fe3O4-water nanofluids. In: Proceedings of the ASME, 2020 Heat Transfer Summer Conference; 2020 July 13–15; Online. [Google Scholar]

55. Afrand M, Toghraie D, Sina N. Experimental study on thermal conductivity of water-based Fe3O4 nanofluid: development of a new correlation and modeled by artificial neural network. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2016;75:262–9. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2016.04.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sundar LS, Singh MK, Sousa AC. Investigation of thermal conductivity and viscosity of Fe3O4 nanofluid for heat transfer applications. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2013;44(4):7–14. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2013.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Aghayari R, Kerdegari M, Khosravi S, Kia A, Maddah H, Khalaj AH. Synthesis and thermo-physical properties of Fe3O4 nanofluid. J Mater Sci Surf Eng. 2015;2(1):109–13. [Google Scholar]

58. Abareshi M, Goharshadi EK, Zebarjad MS, Fadafan HK, Youssefi A. Fabrication, characterization and measurement of thermal conductivity of Fe3O4 nanofluids. J Magn Magn Mater. 2010;322(24):3895–901. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2010.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Aksoy S, Haralick RM. Feature normalization and likelihood-based similarity measures for image retrieval. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2001;22(5):563–82. doi:10.1016/S0167-8655(00)00112-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Sadeghzadeh M, Maddah H, Ahmadi MH, Khadang A, Ghazvini M, Mosavi A, et al. Prediction of thermo-physical properties of TiO2-Al2O3/water nanoparticles by using artificial neural network. Nanomater. 2020;10(4):697. doi:10.3390/nano10040697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Ahmadi MH, Nazari MA, Ghasempour R, Madah H, Shafii MB, Ahmadi MA. Thermal conductivity ratio prediction of Al2O3/water nanofluid by applying connectionist methods. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2018;541:154–64. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.01.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools