Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Mix Location Privacy Preservation Method Based on Differential Privacy with Clustering

School of Information Science and Engineering, Shenyang Ligong University, Shenyang, 110159, China

* Corresponding Author: Fang Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Differential Privacy: Techniques, Challenges, and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069243

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

With the popularization of smart devices, Location-Based Services (LBS) greatly facilitates users’ life, but at the same time brings the risk of users’ location privacy leakage. Existing location privacy protection methods are deficient, failing to reasonably allocate the privacy budget for non-outlier location points and ignoring the critical location information that may be contained in the outlier points, leading to decreased data availability and privacy exposure problems. To address these problems, this paper proposes a Mix Location Privacy Preservation Method Based on Differential Privacy with Clustering (MLDP). The method first utilizes the DBSCAN clustering algorithm to classify location points into non-outliers and outliers. For non-outliers, the scoring function is designed by combining geographic information and semantic information, and the privacy budget is allocated according to the heat intensity of the hotspot area; for outliers, the scoring function is constructed to allocate the privacy budget based on their correlation with the hotspot area. By comprehensively considering the geographic information, semantic information, and correlation with hotspot areas of the location points, a reasonable privacy budget is assigned to each location point, and finally noise is added through the Laplace mechanism to realize privacy protection. Experimental results on two real trajectory datasets, Geolife and T-Drive, show that the MLDP approach significantly improves data availability while effectively protecting location privacy. Compared with the comparison methods, the maximum available data ratio of MLDP is 1. Moreover, compared with the RandomNoise method, its execution time is 0.056–0.061 s longer, and the logRE is 0.12951–0.62194 lower; compared with KemeansDP, QTK-DP, DPK-F, IDP-SC, and DPK-Means-up methods, it saves 0.114–0.296 s in execution time, and the logRE is 0.01112–0.38283 lower.Keywords

With the rapid development of mobile communication and navigation technologies, a large number of Location-Based Services (LBS) devices [1,2], such as smartphones, smart wearables, and IoT devices, are widely used in people’s lives. These devices have greatly improved people’s lifestyles and provided convenient services through the use of location information. While enjoying the convenience brought by these devices, people also face the risk of location privacy leakage [3,4]. The large amount of location data collected by LBS devices may be misused, and the attackers can utilize these data to obtain the user’s interest, life trajectory, social relationships, and other private information, which poses a threat to the integrity of the user’s property and personal safety. Especially in the context of more and more mobile devices equipped with location features and relying on LBS, how to effectively protect users’ location privacy while safeguarding the quality of service has become an urgent issue.

This paper investigates the issue of location privacy protection, with particular emphasis on the privacy budget allocation for non-outlier points and the privacy protection for outlier points. The main contributions are as follows:

1. For non-outlier points, this paper determines the areaal privacy budget by measuring the thermal intensity of hotspot areas. Subsequently, the scoring function is constructed by combining the geographic and semantic information of the non-outlier points, and the privacy budget is reasonably allocated for each non-outlier point based on the value of the scoring function. This method can take into account the multiple characteristics of the location points to make the privacy budget allocation more reasonable, so as to enhance the degree of privacy protection while improving the availability of data.

2. For outlier points, this paper calculates the Euclidean distance from the center of the hotspot area and constructs a scoring function based on the correlation between the outlier points and the hotspot area. A privacy budget is assigned to the outlier points based on the scoring function value. This method not only effectively protects the outliers that may contain critical information, but also avoids taking up too much computational resources because the scoring function is constructed based on the correlation between the outliers and the hotspot area.

3. In order to evaluate MLDP, we conducted an experimental analysis using two real-world trajectory datasets: Geolife and T-Drive. The experimental results show that MLDP outperforms the existing methods in terms of privacy protection degree and has higher data availability.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the MLDP system model and explains in detail the design and implementation of the MLDP method; Section 3 presents the experimental evaluation to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method; Section 4 summarizes the paper.

In order to cope with these challenges, researchers have proposed a variety of location privacy protection methods, including dummy location method, generalization method and Differential privacy method. The core idea of the dummy location method is to reduce the risk of user location privacy leakage by adding dummy or ambiguous information to the actual location information. Methods have been developed to construct dummy locations based on spatiotemporal correlation, location features, and location rotation [5–8], etc. Hong et al. [9] proposed an method based on dynamic Bayesian game analysis. The method enhances location privacy protection with a small number of dummy locations by strategic dummy location reporting. Tang et al. [10] proposed a differential location privacy (DLP) method that utilizes dummy location generation. DLP provides a flexible and customizable method to store user location data while still retaining the functionality of LBS. While the dummy location method can effectively improve privacy protection, it can also lead to a decrease in positioning accuracy and an increase in computational overhead, especially when the number of dummy locations is small, thus affecting data availability. Shaham et al. [11] proposed an improved dummy location method incorporating transfer entropy indices, which enhances the defenses against the Viterbi attack, and in the case of an attacker possessing a larger amount of multilateral information, significantly improves the the protection effect of user privacy.

The core idea of the generalization method is to generalize the attributes in the trajectory data that uniquely identify the user. This makes it difficult for an attacker to accurately distinguish between real and dummy locations. The best-known technique in this method is K-anonymization. With the increasing demand for privacy protection among users, improved methods based on K-anonymization techniques [12–14] have been widely developed. For example, Kumar et al. [15] proposed an exponential K-anonymity privacy-preserving method. This method provides greater anonymity and reduces the risk of an attacker identifying the true location. Kabir et al. [16] proposed a statistical disclosure control framework based on sequencing for optimizing K-anonymity protection for microdata in cloud computing. By improving the sequencing strategy and microaggregation methods, the framework significantly reduces information loss and outperforms existing techniques in terms of performance. Li et al. [17] proposed a distributed trust-based K-anonymization scheme to improve the reliability and security of location privacy protection by dynamically constructing anonymization areas through trust evaluation among vehicles and securing trusted data using lightweight blockchain technology. Su et al. [18] proposed the use of K-anonymization in the context of realizing multi-party data fusion, and for the situation where redundant attributes of the same set of individuals are stored by multiple parties to store, and design algorithms that satisfy k-anonymity and take into account differential privacy. Zhang et al. [19] proposed a k-anonymity obfuscation strategy based on tensor voting, which effectively protects the trajectory privacy of Location Based Games (LBG) players against tensor voting-based inference attacks. Arshad et al. [20] proposed a k-anonymity dual goal graph partitioning problem and heuristic solutions to integrate k-anonymity into a graph data privacy protection framework, combining authorization and access control to optimize its application. Wang et al. [21] proposed a location privacy protection k-anonymity method based on trusted chains, addressing the issue of sacrificing Quality of Service (QoS) in traditional k-Anonymity Spatial Range Query (K-ASR) methods, ensuring users receive 100% query accuracy while maintaining privacy protection. Kounadi and Leitner [22] proposed a geographic masking method that addresses spatial errors in generalization methods by quantifying errors through perception surveys and spatial statistical analysis.

In contrast, the differential privacy approach provides theoretically stronger privacy protection guarantees by introducing noise. Differential privacy methods [23] were first proposed by Dwork. The core idea of differential privacy is to publish location data by adding random noise so that the true location of any individual has very little impact on the final result. Currently, many improvement methods based on differential privacy have been successively proposed [24–26], to realize the protection of the privacy of trajectory data. For example, Theodorakopoulos et al. Sun et al. [27] proposed the Double Disturbance Localized Differential Privacy (DDLDP) algorithm, which doubly perturbs the location information of users and achieves an optimized enhancement in differential privacy protection. Theodorakopoulos et al. [28] proposed a dynamic privacy method for the location histogram to protect location frequency. The frequency histogram of the location point is perturbed by the user repeatedly providing the location to the location provider. Ma et al. [29] proposed a personalized location privacy protection scheme for infeasible results in existing confusion schemes. The double perturbation composed of connection perturbation and interval perturbation is used to confuse the user’s location. The location privacy budget is fine-tuned to meet the user’s privacy protection needs. Xu et al. [30] proposed a personalized location privacy protection scheme based on differential privacy to solve the problem that existing methods fail to provide differentiated protection. This method calculates the driving route according to the user’s privacy preference, then the distance is perturbed as a privacy demand indicator. This method can provide a higher quality of service. Liu et al. [31] proposed a different strategy, combining a k-d tree structure with differential privacy to protect location privacy. The sensitive locations are generalized by using a k-d tree structure. However, it only perturbs the number of frequent location points of users and does not perturb the location information. However, there are still problems such as insufficient protection of important semantic information in non-sensitive location points and low data availability after protection. Du et al. [32] proposed an improved differential privacy algorithm that combines the Apriori algorithm for data association mining and perturbation, ensuring user privacy protection while maintaining data availability. Zhu et al. [33] proposed a method that combines Local Differential Privacy (LDP) and Conditional Random Fields (CRF) to enable continuous location sharing among mobile users. Yan et al. [34] proposed a privacy protection method based on 3D GPS locations, introducing the 3D Laplace mechanism into the differential privacy framework. Tian and Zhu [35] proposed a differential privacy-based trajectory data storage and publishing method using a radix tree. This method reduces the risk of privacy leakage by incorporating semantic information and Laplace noise, while also improving data availability. Feng et al. [36] proposed the Federated Spatial Range Queries Under Local Differential Privacy (LDP-FSRQ) method based on a hybrid spatial structure and nonuniform perturbation probability. This method effectively improves the utility of spatial range queries through quadtree encoding and multiple local perturbation mechanisms.

Although the above methods have achieved some improvements in data availability and privacy protection, they still have shortcomings in the design of the privacy budget allocation function. Suboptimal privacy budget allocation may lead to reduced data availability, thus weakening the overall effectiveness of these methods. In addition, these methods focus too much on the protection of non-outlier location points and tend to allocate too much privacy budget to them. In contrast, outlier locations are relatively underprotected and tend to be allocated less privacy budget, or even no privacy budget at all in some cases. Although outlier locations are relatively less critical, they may still contain personal information or behavioral patterns. If ignored, an attacker may be able to utilize these location points as entry points to infer a user’s movement patterns, thereby compromising the entire privacy protection system.

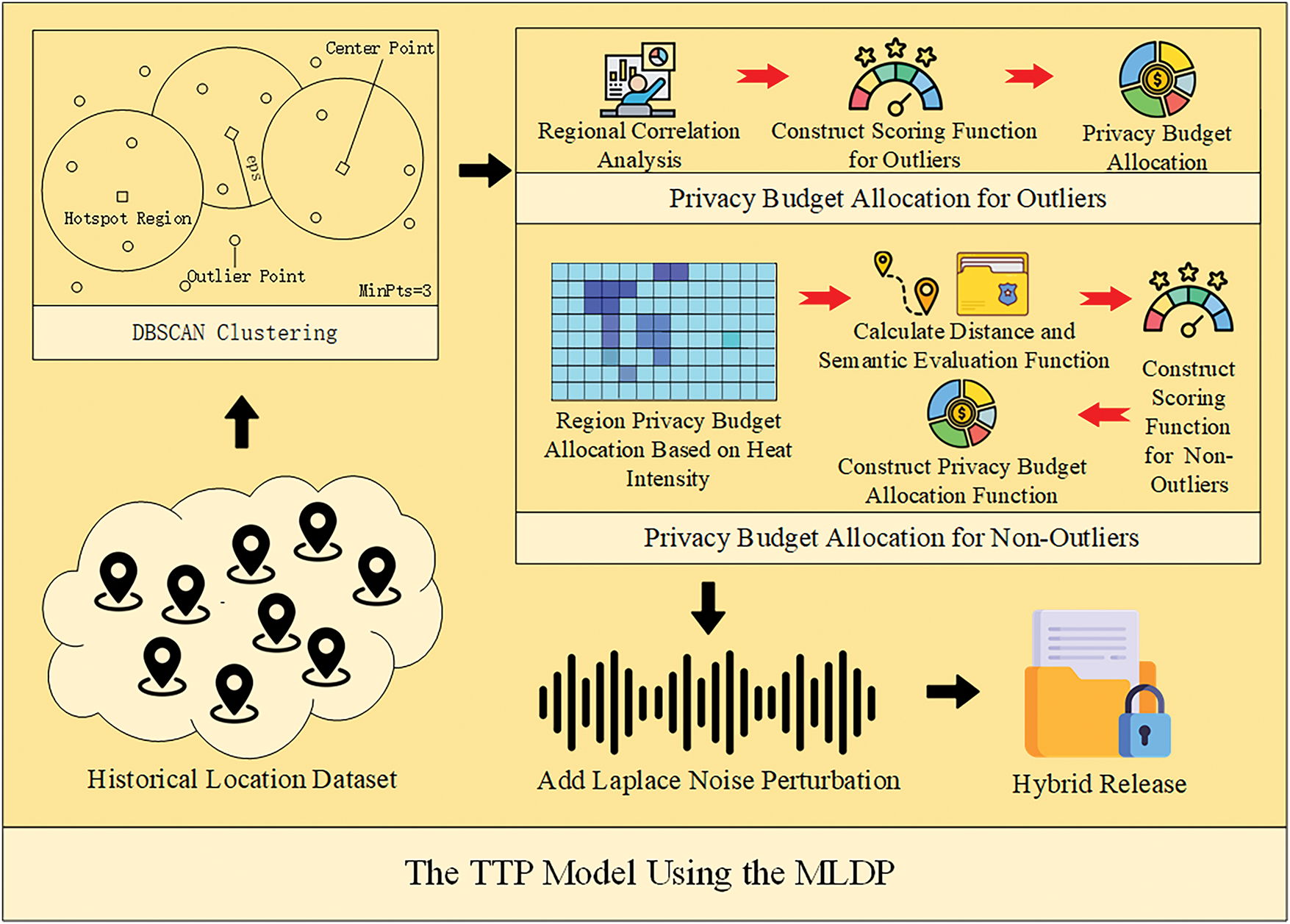

To address the above problems, this paper proposes a hybrid location privacy preserving method (MLDP) based on differential privacy clustering. The method effectively solves the problems of privacy leakage due to important semantic information of outlier points and low availability of published data, thus improving the overall performance of the method. Specifically, the method utilizes DBSCAN clustering to classify location points into non-outliers and outliers, and constructs different privacy budget allocation methods for them. For non-outlier points, a privacy budget is assigned to the hotspot area by the heat intensity metric, and a scoring function is constructed by combining geographic and semantic information to assign a privacy budget to each non-outlier point. For outliers, a scoring function is constructed based on their correlation with the hotspot area, and a privacy budget is assigned to each outlier. At the end of the post, the noise is added to the location data through the Laplace mechanism and then released to achieve privacy protection. This approach not only protects the privacy of the location points, but also ensures the availability of the data.

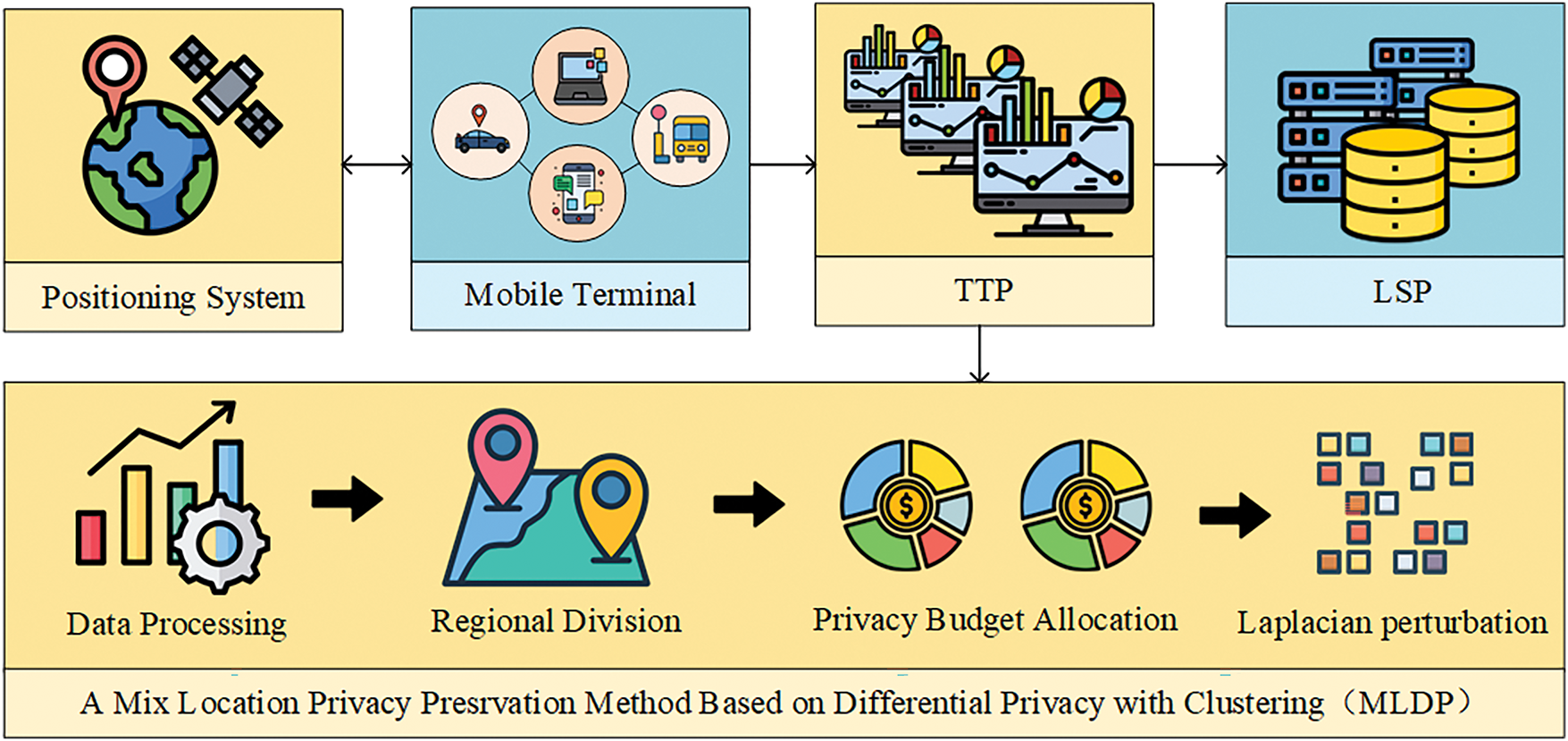

MLDP is based on differential privacy technology and adopts a trusted third-party model as its architecture. The TTP, serving as the core intermediary of the MLDP system, consists of two key modules: the anonymization processing module receives precise location data uploaded by mobile terminals, performs obfuscation processing, and then forwards the processed data to the LBS server; the query result refinement module optimizes and filters the candidate result set returned by the LBS server before delivering the refined final results to the user terminal. To ensure system security, the TTP employs encrypted storage and fine-grained access control mechanisms while incorporating a multi-node consensus mechanism to maintain system trustworthiness, effectively preventing single points of failure and malicious tampering risks. The overall working principle of the MLDP system is shown in Fig. 1, which consists of three main components: the mobile terminal, the trusted third party (TTP), and the location service provider (LSP). Specifically, users obtain historical location data

Figure 1: The system model of MLDP

Figure 2: The principle model of MLDP

First, for a user with N location points, the boundary range of the location point set is determined. To define the boundary scope of the location point set, the maximum longitude, minimum longitude, maximum latitude, and minimum latitude of the area are calculated by Eq. (1), where

Second, the DBSCAN algorithm is used to cluster the points at the location to be protected. The set of outlier points

The privacy budget scheme for outlier points is shown in the following ①; the scheme for non-outlier points is shown in the following ②.

① Privacy budget allocation scheme for non-outliers

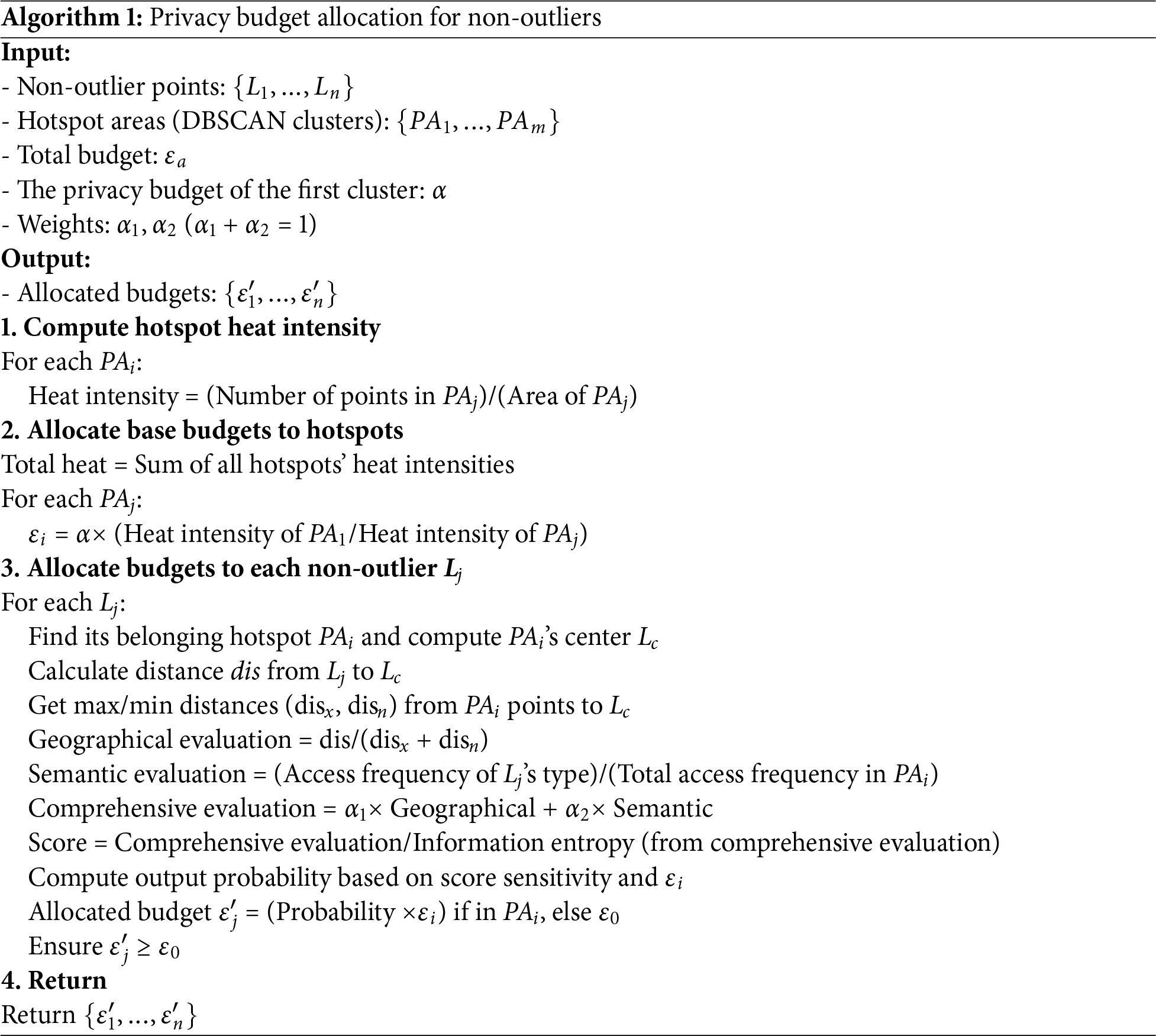

The pseudocode of the Privacy budget allocation scheme for non-outliers is shown in Algorithm 1. The specific implementation is as follows.

To accurately measure users’ privacy protection needs in different areas and distinguish the sensitivity of hotspot areas, the concept of heat intensity is introduced, and privacy budgets are reasonably allocated to each hotspot based on this indicator. Heat intensity can be used to measure users’ privacy protection needs for specific areas, and its essence is the density of clusters. There are differences in user visit frequencies among different clusters, and the heat intensity reflects such differences through the ratio of the number of trajectory points in a cluster to the cluster’s area. The higher the heat intensity, the greater the privacy protection needs of the cluster, and accordingly more noise needs to be added. Therefore, the heat intensity can be used as a reliable alternative indicator of privacy sensitivity. For any

Iterating over all grids, if more than 40% of the area of a grid

Construct scoring function for non-outlier location points. The coordinates of the center position of the hotspot area

The original dataset lacks semantic information, so it is necessary to use the Amap API interface to extract the geographical semantic information of the corresponding location points through reverse geocoding, so as to solve the problem of the original data lacking semantic information. To avoid privacy exposure caused by non-outlier location points containing key semantic information, location semantic attributes are incorporated. Based on this, the distance evaluation function

Information entropy is introduced to calculate the amount of information

Then, the exponential output probability of the non-outlier points is calculated as shown in Eq. (14), where

② Privacy budget allocation scheme for outliers

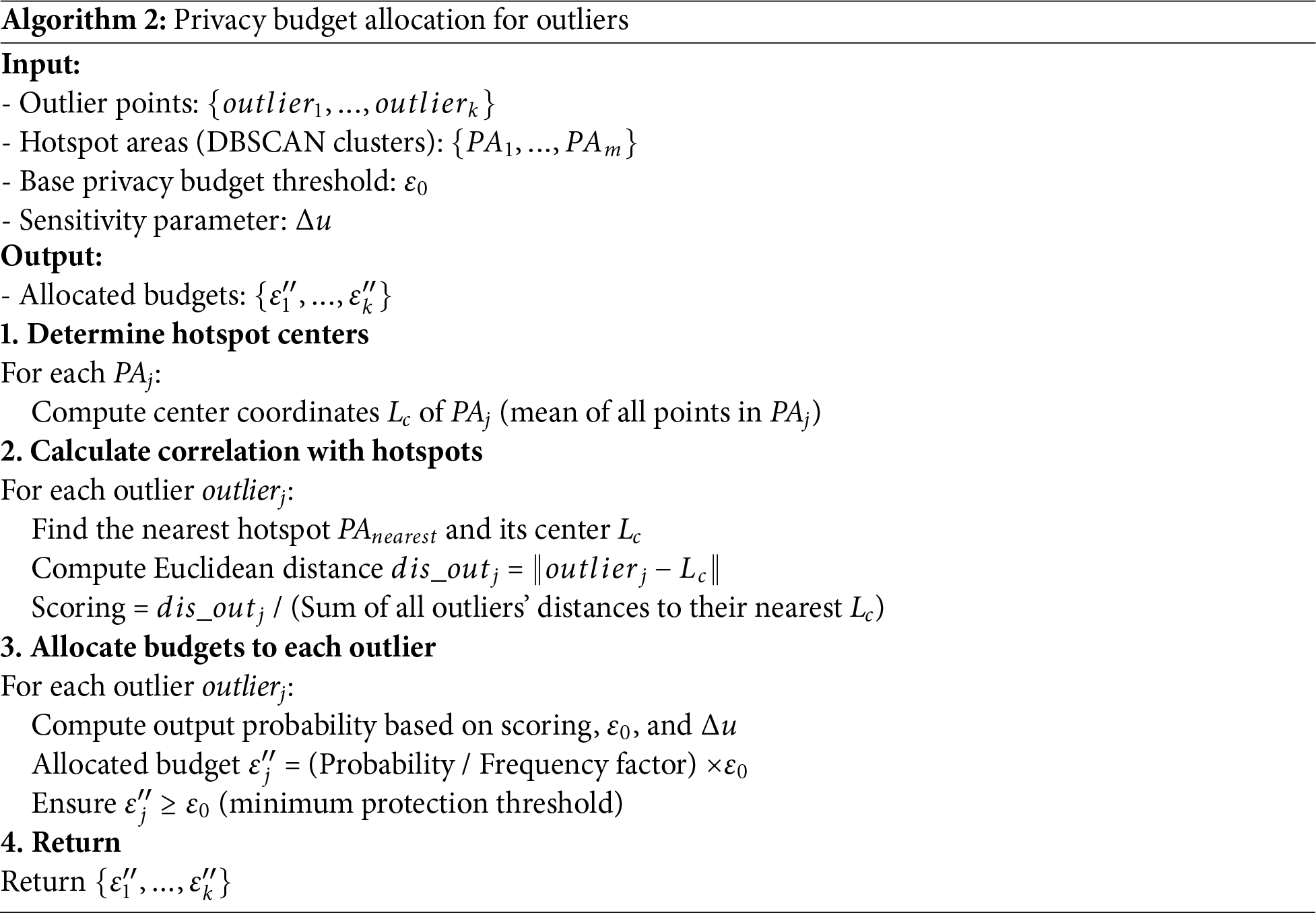

The pseudocode of the Privacy budget allocation scheme for outliers is shown in Algorithm 2. The specific implementation is as follows.

The Euclidean distance

Then calculate the exponential output probability for the outlier points as shown in Eq. (18), where

Finally, the Laplace perturbation process is implemented on the privacy budgets assigned to the outliers and non-outliers, as shown in Eq. (20), where

The above privacy budget allocation process, for non-outlier points, constructs a scoring function by fusing geographical distance and semantic access features, adjusts the scoring weights in combination with information entropy, so that location points with high heat intensity and high semantic value in dense hotspot areas obtain appropriate privacy budgets based on their scores, and adds noise matching the budgets through the Laplace mechanism. For outlier points, a scoring function is constructed with the distance from the hotspot center as the core, ensuring that outlier points in sparse areas receive a basic budget not lower than the threshold

Specifically, for the unpredictability of user movement patterns and frequent changes in dynamic location data, the proposed system ensures strong privacy protection in three aspects: the DBSCAN algorithm adapts to data changes, enabling real-time classification of location points into hotspot members or outliers without recalculating all historical data, reducing computational overhead; heat intensity and scoring functions support dynamic privacy budget allocation for real-time points, achieving real-time adjustment; and the total budget is constrained by the sequential property of differential privacy, safeguarding overall privacy strength amid dynamics.

To ensure the extensiveness and reliability of the experiments, the MLDP experiments were conducted on a computer with a Windows 10 operating system and a hardware configuration of Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6226R CPU (2.90 GHz). The experimental code is written in Python 3.9 and executed in the PyCharm integrated development environment. To test and validate the proposed MLDP, the Geolife dataset and the T-Drive dataset are selected as test data.

To fully evaluate the effectiveness of MLDP, we compare and analyze it with four existing methods. Specifically, the KemeansDP [37] method sorts and divides the surrounding location points based on the density of the location information, implements generalisation with the help of k-means clustering, and subsequently perturbs the location information using the planar Laplace mechanism. The QTK-DP [29] method applies k-means clustering to analyse the user’s historical location dataset in clusters. It classifies the cluster centres of the non-outlying points with the outlying points into four categories and rationally allocates the privacy budget based on the tree height. The DPK-F [38] method combines differential privacy with an improved fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm so that each set of input location data no longer belongs to a specific category but is represented by affiliation, and the noise that satisfies the differential privacy constraints is subsequently added to the cluster centers. The DPK-Means-up [39] method further improves the clustering performance through dynamic updating and k-value optimization, improving the usability and privacy protection of clustering. The IDP-SC [40] method improves the traditional K-means clustering algorithm by introducing a Gaussian kernel function and a noisy adjacency matrix, which enhances the clustering effect when dealing with complex data and outliers. The RandomNoise method directly adds a Laplacian perturbation mechanism to the location data to achieve location privacy protection.

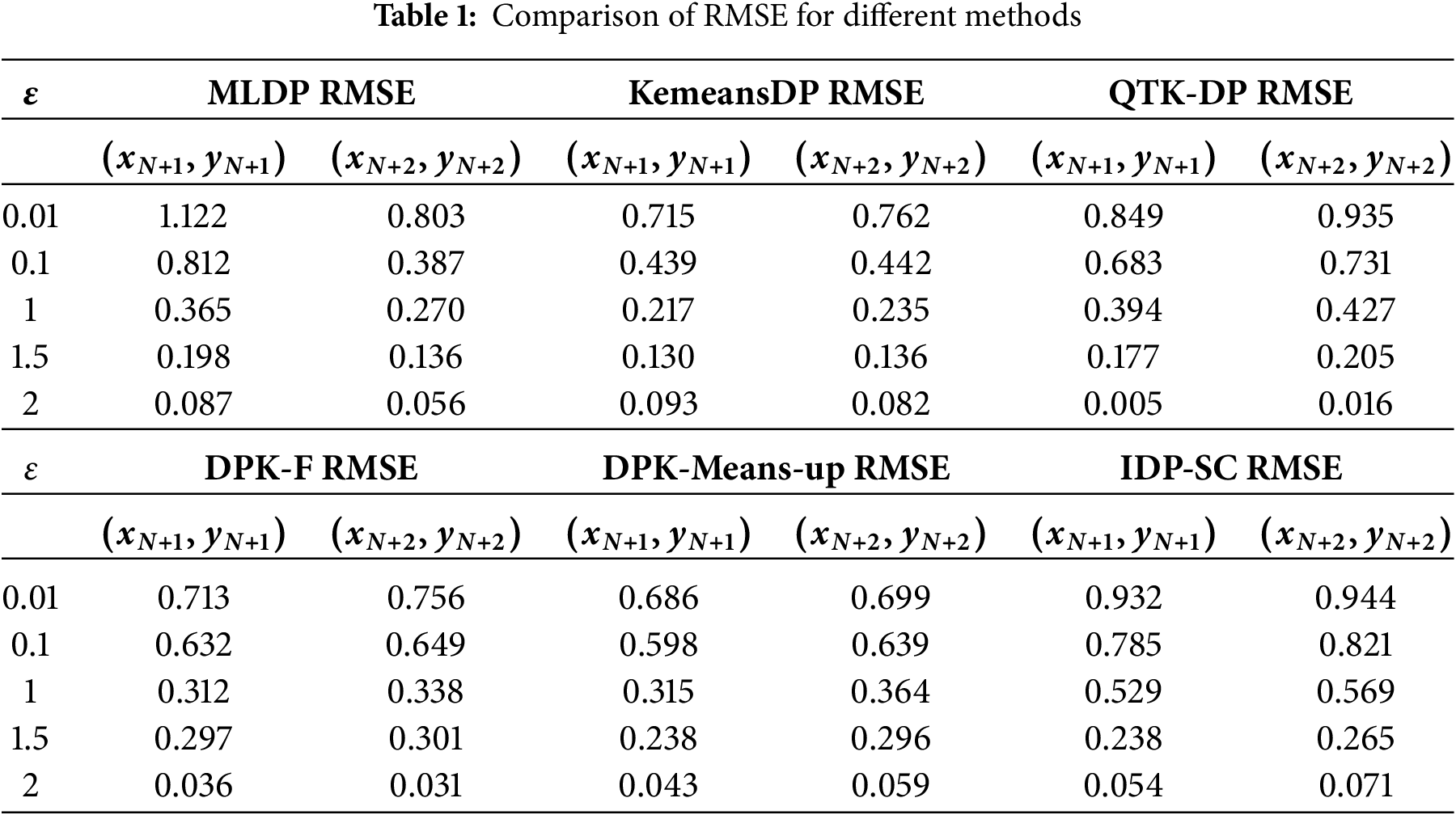

Two key performance indicators, the degree of privacy protection and data availability, are used to assess the effectiveness of the MLDP and comparison methods comprehensively. Among them, the degree of privacy protection is measured using the root mean square error (RMSE) as the primary metric, and the larger the RMSE value, the more interfering information is added and the more significant the privacy protection effect is, as shown in Eq. (21). Data availability is measured by the ratio of available data (rate) and relative error (RE), where the ratio of available data refers to the ratio of the total number of published locations to the total number of locations to be protected after privacy protection, as shown in Eq. (22), the larger the rate value, the closer the number of published locations is to the original number of locations, which indicates that the data availability is higher. The relative error (RE) is shown in Eq. (23), and according to its definition, when the RE value is small, the query result after data release is closer to the real query result, which means the data availability is higher. Where e represents the range of the query, F(e) is the query result after the algorithm protection processing, and R(e) is the query result of the number of unprotected areas.

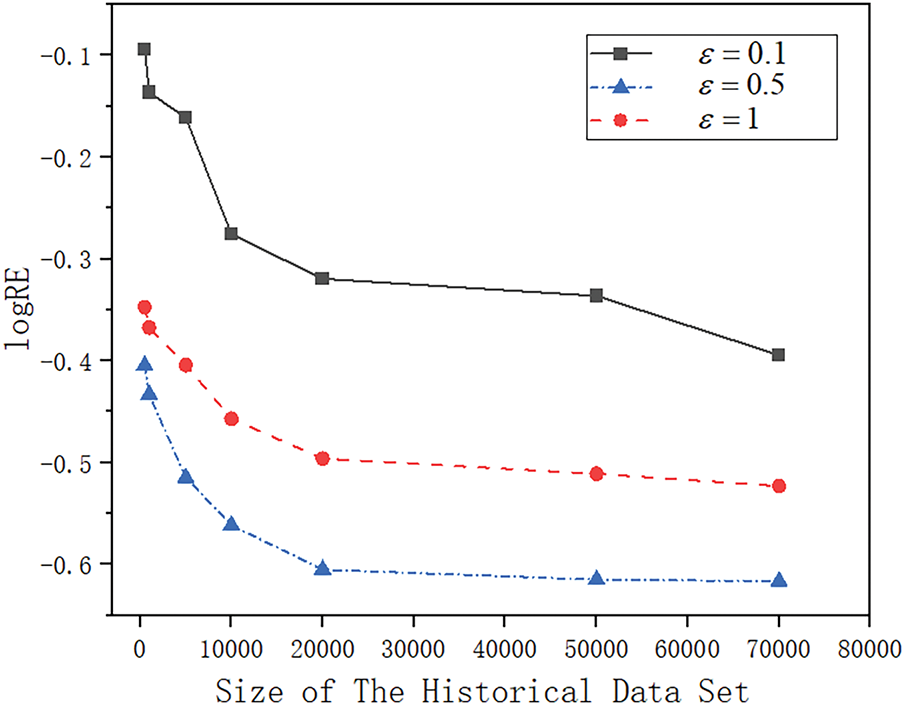

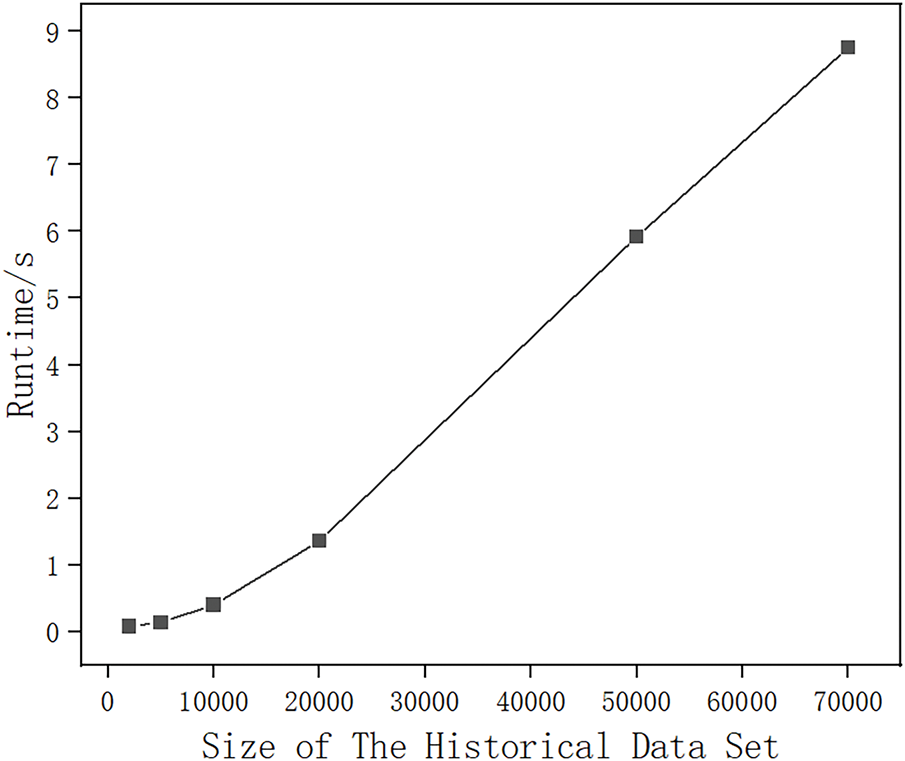

Relevant experiments were conducted to verify the effect of the historical location dataset size on data availability. Different sizes of historical location datasets (500, 1000, 5000, 10,000, 20,000, 50,000, 70,000) with query ranges of 20% of the total range are selected to analyse the relative errors under different conditions, and the experimental results are shown in Fig. 3. It can be observed from the figure that the error value decreases gradually with the increase of the number of location points in the historical data set. This indicates that a larger historical location dataset can enhance the classification accuracy of the location points to be protected, thus improving the usability of the data. In addition, to further explore the influence of the size of historical location dataset on the execution efficiency, the selected historical location datasets with different sizes (1000, 5000, 10,000, 20,000, 50,000, 70,000) are chosen and the algorithm execution time is used as the evaluation index, and the experimental results are shown in Fig. 4. From the figure, it can be seen that the execution time tends to increase as the size of the historical dataset grows. Despite the increase in computational cost, richer historical data helps to improve data availability, indicating that the proposed MLDP method is still practical when facing large-scale historical datasets.

Figure 3: Influence of data set size on relative error logRE

Figure 4: Influence of data set size on method running time

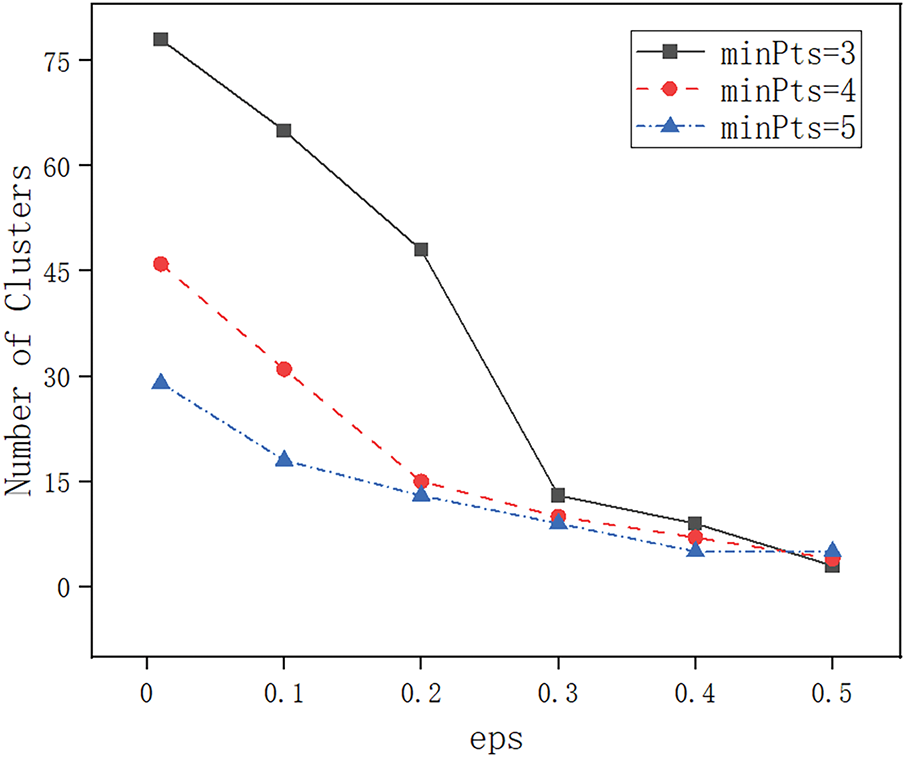

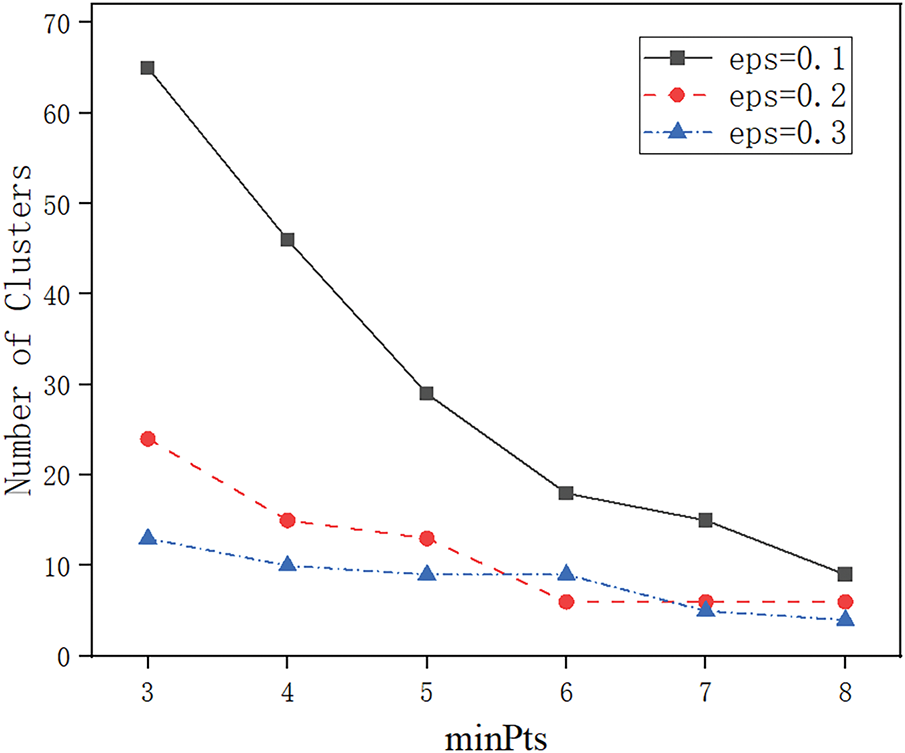

Further, to analyze the influence of DBSCAN clustering parameters on the clustering results, relevant experiments are conducted. DBSCAN characterises the density distribution of location points by setting two parameters, namely, neighbourhood distance and minimum number of samples (MinPts). The experimental results are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that the number of clusters decreases gradually when the neighbourhood distance increases. A larger neighbourhood range allows more points to be grouped into the same cluster, lowering the overall number of clusters. From Fig. 6, it can be seen that increasing the minimum number of samples decreases the number of clusters for a fixed neighbourhood distance because higher clustering criteria require that each cluster contain more points, thus excluding some of the less dense areas.

Figure 5: Influence of neighborhood distance on the number of clusters

Figure 6: Influence of minimum number of samples on the number of clusters

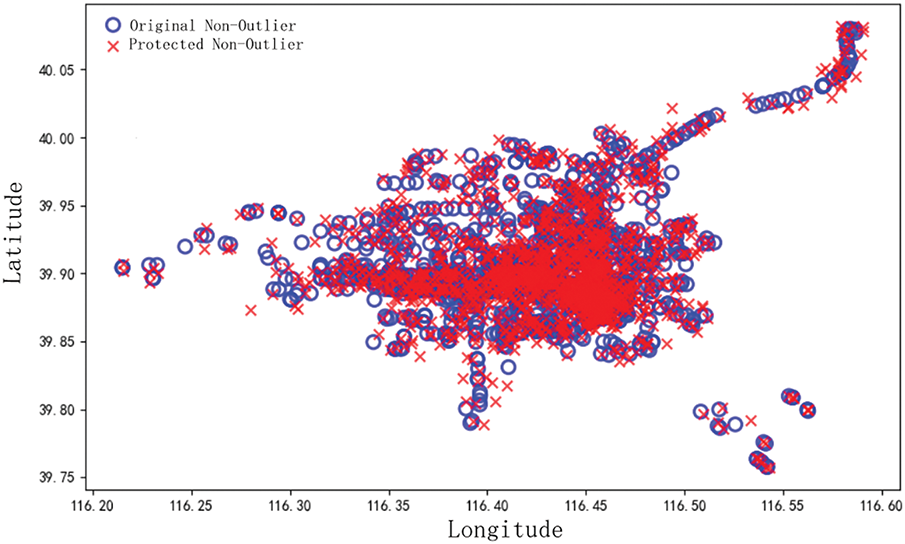

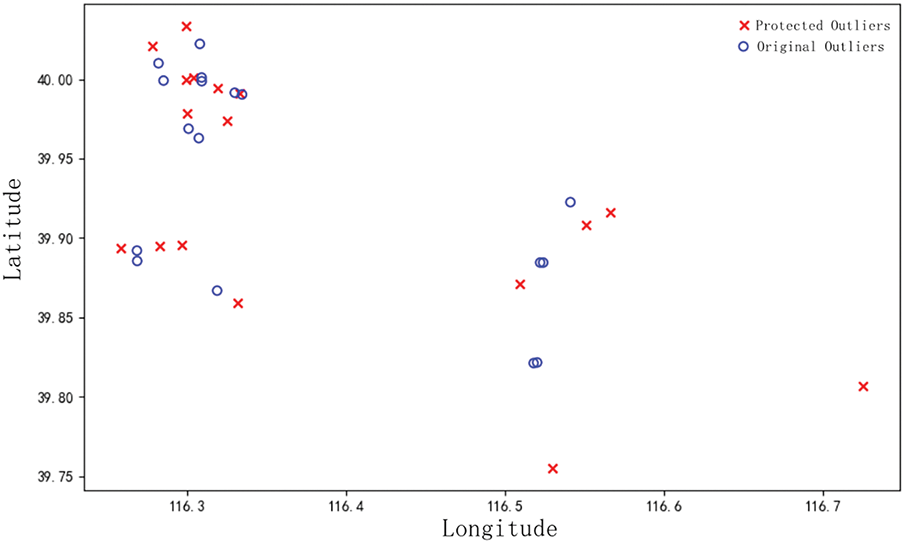

To visually verify the method’s before and after privacy protection effect, the distributions of the to-be-protected location points and the post-protected location points are shown in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. It is observed from the figure that the post-protection non-outlier location points completely retain the positional features presented by the to-be-protected non-outlier location points, which improves the data usability under the guarantee of the overall heat map. The outlier location points correlate with the hotspot area, and different privacy budgets are assigned to the outlier location points according to the distance from the hotspot area, i.e., the size of the correlation, which improves the degree of privacy protection of the outlier location points.

Figure 7: Distribution map of pre-protection location points

Figure 8: Distribution map of post-protection location points

To verify the degree of privacy protection for outlier location points, a correlation test analysis is performed. Two location points to be protected are randomly selected:

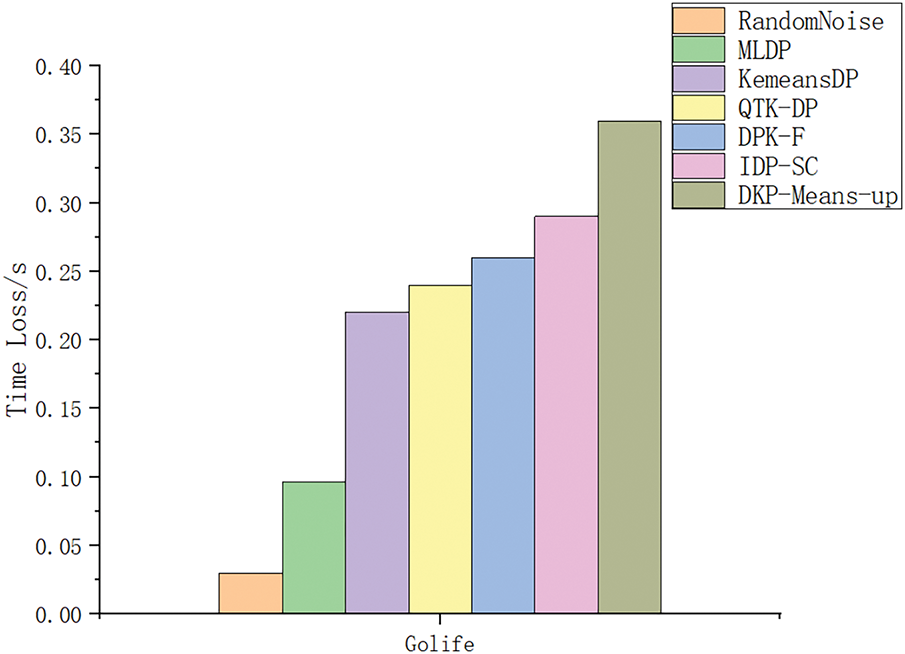

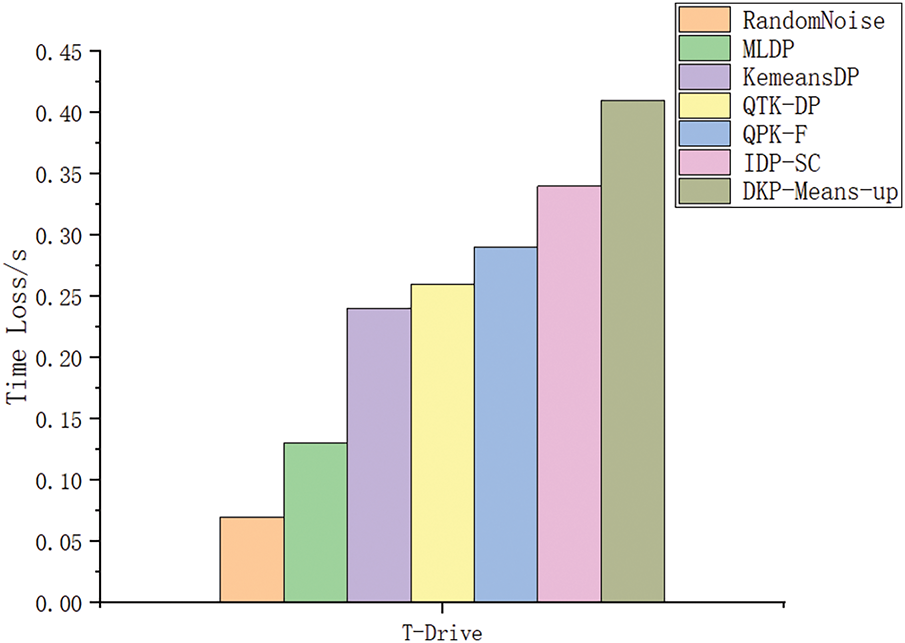

To ensure the accuracy of the statistical results and to examine the time consumption as an indicator of efficiency, the experiments were repeated and executed 50 times on each of the two datasets, and the results of the experiments are shown in Figs. 9 and 10. As can be seen from the figures, the proposed MLDP method takes 0.056–0.061 s longer to execute in the repeated experiments compared to the RandomNoise method, saves 0.114–0.147 s compared to the KemeansDP method, saves 0.137–0.159 s compared to the QTK-DP method, and saves 0.137–0.159 s compared to the DPK-F method, the execution time savings are 0.153–0.186 s; compared to the IDP-SC method, the execution time savings are 0.196–0.213 s; and compared to the DPK-Means-up, the execution time savings are 0.276–0.296 s.

Figure 9: Time loss of different methods on the Geolife dataset

Figure 10: Time loss of different methods on the T-Drive dataset

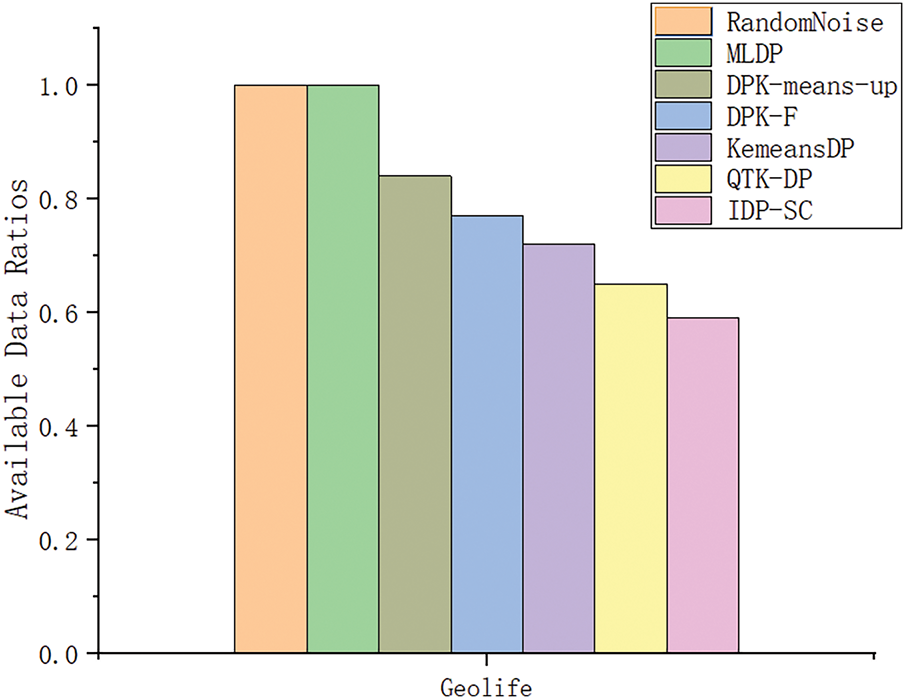

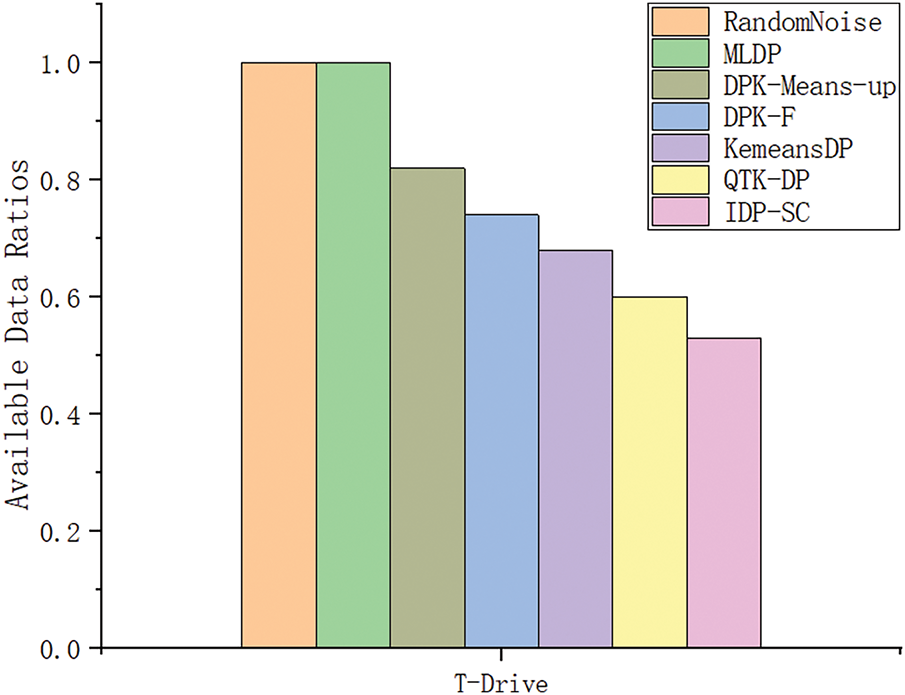

To validate the proposed method, the available data ratio rate assessed the data availability and analysed on two datasets. The available data ratio rate of different methods was analysed, and the experimental results are shown in Figs. 11 and 12. Among these methods, QTK-DP, KemeansDP, DPK-F, DPK-Means-up and IDP-SC have comparatively low usable data ratio rates; This is because the three need to set the initial k-value and only perturb the clustered cluster centres and outliers, while the non-outlier location points within the clusters have not been considered to be assigned a privacy budget. Non-outlier locations have not been released, which reduces the data availability. The RandomNoise method has a usable data ratio of 1. However, RandomNoise is too randomised, and the privacy budget is divided evenly. This randomisation method may lead to too much noise, affecting the validity and accuracy of the data. The MLDP method proposed in this paper considers privacy-preserving treatment for all non-outlier and outlier points, and adding noise after scoring for each location point is reasonable. Therefore, although the MLDP method and the RandomNoise method are the same regarding the ratio of available data, the MLDP method provides higher privacy-preserving efficiency and data availability in practical applications due to the rationality of the privacy-preserving mechanism and noise control.

Figure 11: Available Data Ratios of different methods on the Geolife dataset

Figure 12: Available Data Ratios of different methods on the T-Drive dataset

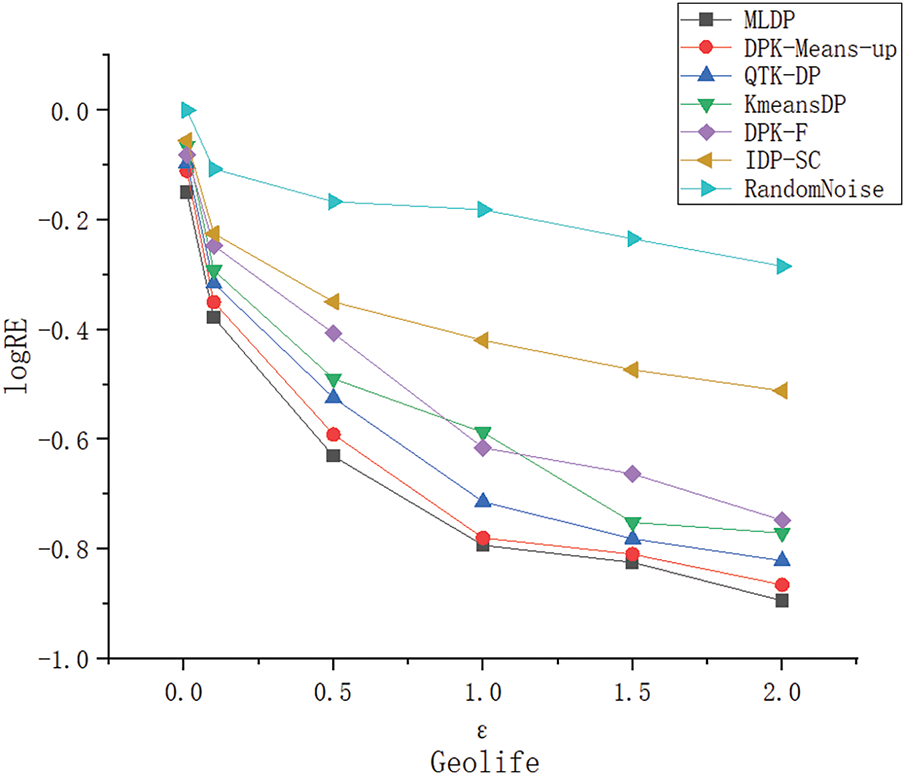

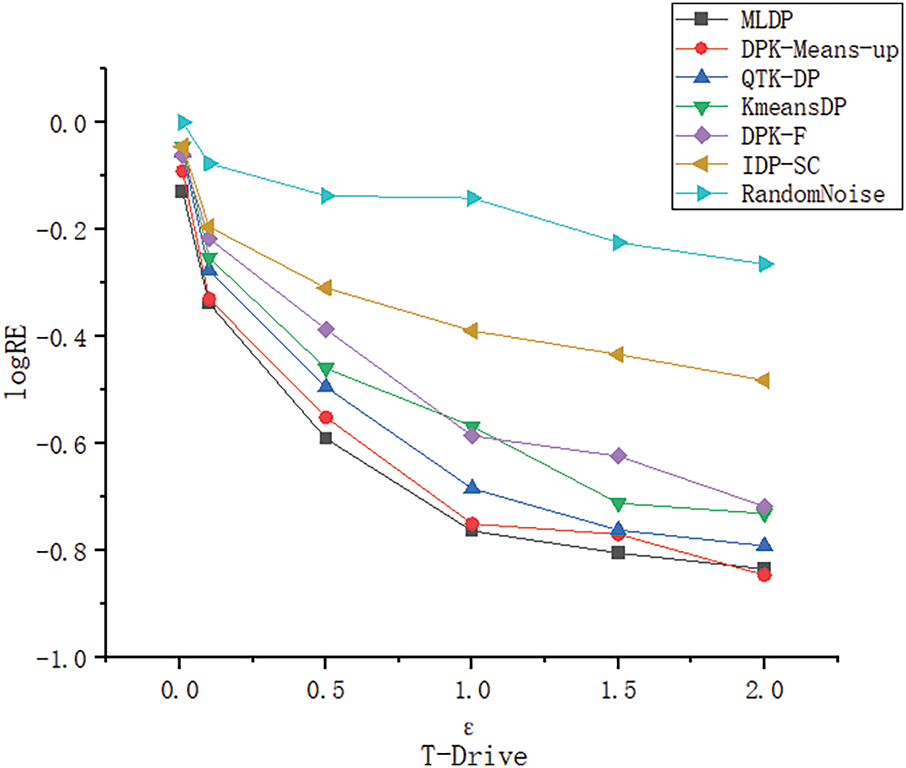

To further validate the data availability of the proposed method, data availability is assessed by relative error

Figure 13: LogRE of different methods on the Geolife dataset

Figure 14: LogRE of different methods on the T-Drive dataset

To solve the problem that existing location privacy protection methods do not allocate a reasonable differential privacy budget to non-outlier location points and do not take into account the fact that there may be relatively important location information in the outlier location points, which leads to low usability of the released data and privacy leakage, MLDP is proposed. It can be seen from the experimental analysis that different degrees of noise can be added according to the correlation magnitude of the outlier points with the hotspot area, which effectively solves the problem of hidden privacy leakage caused by outlier location points. Compared with the comparison methods, MLDP can release the original location points under the premise of privacy protection, and its usable data rate and relative error logRE are both the highest among all methods. In future work, our team will further explore the real-time adjustment mechanism of dynamic privacy budgets, combine users’ real-time behaviors and scenario changes to achieve adaptive allocation of privacy budgets, so as to more accurately balance the intensity of privacy protection and data availability in different dynamic scenarios.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our gratitude to all colleagues and supporters who provided assistance during the writing of this paper. Special thanks are extended to Jiachen Li and Sibo Guo for their contributions to this work. They offered valuable suggestions throughout the writing process, which significantly helped improve the quality of the paper. We sincerely appreciate their selfless dedication and professional expertise, which were crucial factors in the successful completion of this research.

Funding Statement: This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61971291), the Basic Scientific Research Project of the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (LJ212410144013), the Leading Talent of the ‘Xing Liao Ying Cai Plan’ (XLYC2202013), the Shenyang Natural Science Foundation (22-315-6-10), and the Guangxuan Scholar of Shenyang Ligong University (SYLUGXXZ202205).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: paper conception and design: Fang Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Xianghui Meng; draft manuscript preparation: Fang Liu, Xianghui Meng, Jiachen Li, Sibo Guo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this paper did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ren Y, Li X, Miao Y, Deng RH, Weng J, Ma S, et al. DistPreserv: maintaining user distribution for privacy-preserving location-based services. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2023;22(6):3287–302. doi:10.1109/tmc.2022.3141398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li D, Wu J, Le J, Liao X, Xiang T. A novel privacy-preserving location-based services search scheme in outsourced cloud. IEEE Transact Cloud Comput. 2023;11(1):457–69. doi:10.1109/tcc.2021.3098420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xu C, Luo L, Ding Y, Zhao G, Yu S. Personalized location privacy protection for location-based services in vehicular networks. IEEE Wireless Communicat Lett. 2020;9(10):1633–7. doi:10.1109/lwc.2020.2999524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao Y, Chen J. Vector-Indistinguishability: location dependency based privacy protection for successive location data. IEEE Transact Comput. 2024;73(4):970–9. doi:10.1109/tc.2023.3236900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang W, Wang Y, Duan P, Liu T, Tong X, Cai Z. A triple real-time trajectory privacy protection mechanism based on edge computing and blockchain in mobile crowdsourcing. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2023;22(10):5625–42. doi:10.1109/tmc.2022.3187047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li Y, Li X, Luo X, Li Z, Li H, Zhang X. AnotherMe: a location privacy protection system based on online virtual trajectory generation. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2024;21(4):2552–67. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2023.3314200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li B, Liang R, Zhou W, Yin H, Gao H, Cai K. LBS meets blockchain: an efficient method with security preserving trust in SAGIN. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(8):5932–42. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3064357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhao P, Liu W, Zhang G, Li Z, Wang L. Preserving privacy in WiFi localization with plausible dummy locations. IEEE Transact Vehic Technol. 2020;69(10):11909–25. doi:10.1109/tvt.2020.3006363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hong S, Duan L, Huang J. Protecting location privacy by multiquery: a dynamic bayesian game theoretic approach. IEEE Transact Inform Foren Secur. 2022;17:2569–84. doi:10.1109/tifs.2022.3189531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tang J, Zhu H, Lu R, Lin X, Li H, Wang F. DLP: achieve customizable location privacy with deceptive dummy techniques in LBS applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(9):6969–84. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3115849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shaham S, Ding M, Liu B, Dang S, Lin Z, Li J. Privacy preservation in location-based services: a novel metric and attack model. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2021;20(10):3006–19. doi:10.1109/tmc.2020.2993599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang S, Hu B, Liang W, Li KC, Gupta BB. A caching-based dual K-anonymous location privacy-preserving scheme for edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(11):9768–81. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3235707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang X, Ishii H, Du L, Cheng P, Chen J. Privacy-preserving distributed machine learning via local randomization and ADMM perturbation. IEEE Transact Signal Process. 2020;68:4226–41. doi:10.1109/tsp.2020.3009007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ding R, Xu Y, Zhong H, Cui J, Min G. An efficient integrity checking scheme with full identity anonymity for cloud data sharing. IEEE Transact Cloud Comput. 2023;11(3):2922–35. doi:10.1109/tcc.2023.3242140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kumar M, Kavita, Verma S, Kumar A, Ijaz MF, Rawat DB. ANAF-IoMT: a novel architectural framework for IoMT-enabled smart healthcare system by enhancing security based on RECC-VC. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2022;18(12):8936–43. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3181614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kabir ME, Mahmood AN, Wang H, Mustafa AK. Microaggregation sorting framework for K-anonymity statistical disclosure control in cloud computing. IEEE Transact Cloud Comput. 2020;8(2):408–17. doi:10.1109/tcc.2015.2469649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Y, Cao Y, Zhuang Y, Li J, Du G, Chen J. Blockchain-enabled trust management with location privacy preservation in vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Int Things J. 2024;11(14):24659–71. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3350694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Su X, Fan K, Shi W. Privacy-preserving distributed data fusion based on attribute protection. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2019;15(10):5765–77. doi:10.1109/tii.2019.2912175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang X, Wang J, Li Y, Jäntti R, Pan M, Han Z. Catching all pokémon: virtual reward optimization with tensor voting based trajectory privacy. IEEE Transact Vehic Technol. 2019;68(1):883–92. doi:10.1109/tvt.2018.2882733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Arshad MU, Felemban M, Pervaiz Z, Ghafoor A, Aref WG. A privacy mechanism for access controlled graph data. IEEE Transact Depen Sec Comput. 2019;16(5):819–32. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2017.2714660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang H, Huang H, Qin Y, Wang Y, Wu M. Efficient location privacy-preserving k-anonymity method based on the credible chain. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. 2017;6(6):163. doi:10.3390/ijgi6060163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kounadi O, Leitner M. Defining a threshold value for maximum spatial information loss of masked geo-data. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inform. 2015;4(2):572–90. doi:10.3390/ijgi4020572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dwork C, McSherry F, Nissim K, Smith A. Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis. In: Theory of Cryptography Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2006. p. 265–84. [Google Scholar]

24. Qi J, Jia X, Luo M, Feng Q. A privacy-aware K-nearest neighbor query scheme for location-based services. IEEE Inter Things J. 2024;11(6):10831–42. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3328709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li D, Yang Q, An D, Zhang Y. A location-privacy-aware taxi-hailing system: adaptive differential privacy-based dynamic incentive method. IEEE Inter Things J. 2024;11(1):914–30. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3286840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hou Y, Xia X, Li H, Cui J, Mardani A. Fuzzy differential privacy theory and its applications in subgraph counting. IEEE Transact Fuzzy Syst. 2023;31(2):356–69. doi:10.1109/tfuzz.2022.3157385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sun Z, Wang Y, Cai Z, Liu T, Tong X, Jiang N. A two-stage privacy protection mechanism based on blockchain in mobile crowdsourcing. Int J Intell Syst. 2021;36(5):2058–80. doi:10.1002/int.22371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Theodorakopoulos G, Panaousis E, Liang K, Loukas G. On-the-fly privacy for location histograms. IEEE Transact Depend Sec Comput. 2022;19(1):566–78. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2020.2980270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ma B, Wang X, Ni W, Liu RP. Personalized location privacy with road network-indistinguishability. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2022;23(11):20860–72. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3179501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xu C, Ding Y, Chen C, Ding Y, Zhou W, Wen S. Personalized location privacy protection for location-based services in vehicular networks. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2023;24(1):1163–77. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3182019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu Y, Cooke A, Thulasiraman P. Location privacy preservation of vehicle data in internet of vehicles. In: INTERNET 2020: The Twelfth International Conference on Evolving Internet; 2020 Oct 18–22; Porto, Portugal. p. 54–60. [Google Scholar]

32. Du D, Luo E, Yi Y, Peng T, Li X, Zhang S, et al. Differential privacy protection method for trip-oriented shared data. Concurr Comput. 2023;35(19):e7414. doi:10.1002/cpe.7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhu L, Hong H, Xie M, Yu J. DLPM: a dynamic location protection mechanism supporting continuous queries. Concurr Comput. 2023;35(19):e7495. doi:10.1002/cpe.7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yan Y, Yan P, Mahmood A, Xu F, Sheng QZ. Towards achieving geo-indistinguishability for 3D GPS location: a 3D Laplace mechanism approach. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2024;36(14):e8111. doi:10.1002/cpe.8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tian J, Zhu Q. A differential privacy trajectory data storage and publishing scheme based on radix tree. Concurr Comput. 2023;35(22):e7731. doi:10.1002/cpe.7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Feng G, Wang G, Peng T. Toward answering federated spatial range queries under local differential privacy. Int J Intell Syst. 2024;2024(1):2408270. doi:10.1155/2024/2408270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang WY, Tang WB, Chen YJ. Research on location privacy method combining clustering and differential privacy. J Chifeng Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2023;39(11):1–5. [Google Scholar]

38. Lin J, Hu D, Wang K. Differential privacy fuzzy clustering location protection method. Elect Sci Technol. 2022;35(11):1–8. [Google Scholar]

39. Hu C, Yang G, Bai YL. DPK-means-up: clustering algorithm for differential privacy protection. Comput Sci. 2019;46(2):120–6. [Google Scholar]

40. Jin YQ, Zhang YQ, Wang B, Wang X, Li Z. Optimized adaptive spectral clustering alorgrithm based on differential privacy protection. Comput Applicat Softw. 2023;40(9):261–6. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools