Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

X-MalNet: A CNN-Based Malware Detection Model with Visual and Structural Interpretability

1 Department of Mathematics, Amrita School of Physical Sciences, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, 641112, India

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

3 School of Computing, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

4 Faculty of Engineering, University of Moncton, Moncton, NB E1A 3E9, Canada

5 School of Electrical Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa

6 Research Unit, School International Institute of Technology and Management (IITG), Av. Grandes Ecoles, Libreville, BP 1989, Gabon

7 College of Computer Science and Engineering (Invited Professor), University of Ha’il, Ha’il, 55476, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Ateeq Ur Rehman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069951

Received 04 July 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

The escalating complexity of modern malware continues to undermine the effectiveness of traditional signature-based detection techniques, which are often unable to adapt to rapidly evolving attack patterns. To address these challenges, this study proposes X-MalNet, a lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) framework designed for static malware classification through image-based representations of binary executables. By converting malware binaries into grayscale images, the model extracts distinctive structural and texture-level features that signify malicious intent, thereby eliminating the dependence on manual feature engineering or dynamic behavioral analysis. Built upon a modified AlexNet architecture, X-MalNet employs transfer learning to enhance generalization and reduce computational cost, enabling efficient training and deployment on limited hardware resources. To promote interpretability and transparency, the framework integrates Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and Deep SHapley Additive exPlanations (DeepSHAP), offering spatial and pixel-level visualizations that reveal how specific image regions influence classification outcomes. These explainability components support security analysts in validating the model’s reasoning, strengthening confidence in AI-assisted malware detection. Comprehensive experiments on the Malimg and Malevis benchmark datasets confirm the superior performance of X-MalNet, achieving classification accuracies of 99.15% and 98.72%, respectively. Further robustness evaluations using Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) adversarial attacks demonstrate the model’s resilience against perturbed inputs. In conclusion, X-MalNet emerges as a scalable, interpretable, and robust malware detection framework that effectively balances accuracy, efficiency, and explainability. Its lightweight design and adversarial stability position it as a promising solution for real-world cybersecurity deployments, advancing the development of trustworthy, automated, and transparent malware classification systems.Keywords

The rising complexity and frequency of cyberattacks demand more advanced methods for detecting malware. Traditional techniques, such as signature-based and heuristic approaches, often fail to identify new or disguised variants of malware [1,2]. To address these challenges, machine learning (ML) methods, particularly those that utilize deep learning (DL), have proven to be effective solutions. A prominent technique in this area is the application of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for image-based malware classification. This approach has shown remarkable potential, as CNNs can automatically extract features from malware binaries that are represented as images [3]. AlexNet is a well-established CNN architecture recognized for its efficacy in large-scale image classification tasks, including applications in malware detection research. The complexity of malware classification is exacerbated by the large number of malware families and the need for resilience against adversarial attacks, which prompts researchers to adapt AlexNet specifically for this context. These adaptations typically involve modifications of the network architecture to improve performance when analyzing malware samples in both colored and grayscale images [4]. Integrating AlexNet with complementary classifiers, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), and employing transfer learning techniques can significantly reduce computational overhead while maintaining high levels of classification accuracy, particularly in data-constrained environments [5].

Despite the success of CNNs in malware classification, several challenges still exist. A primary concern is the vulnerability of CNN models to adversarial attacks, where even minor alterations to the input image can deceive the classifier. Additionally, the scalability of these models across different malware families is constrained by the size and complexity of existing datasets, such as the Malimg and Malevis datasets [6,7]. Variations of AlexNet can address these challenges by reducing computational complexity while maintaining high accuracy. Modifications, such as decreasing the number of convolutional layers and increasing the number of fully connected layers, allow the model to better recognize malware-specific features [8]. Additionally, even with a limited amount of training data, employing transfer learning—where pre-trained models are adapted to malware datasets—has significantly enhanced classification performance. The ongoing development of these techniques present a potential path toward creating more effective malware detection systems. The key contributions of the work as given as follows:

• A modified AlexNet architecture tailored for image-based malware detection has been proposed which minimizes the number of convolutional layers while adding more fully connected layers to enhance feature extraction.

• Transfer learning has been employed to fine-tune the pre-trained models for malware detection, even with limited labeled data.

• The proposed model is thoroughly evaluated on the Malimg and Malevis datasets, showing significant improvements in identifying various malware families.

• The modified versions of AlexNet demonstrate strong resistance to adversarial attacks, ensuring reliable detection even with potential input alterations.

• Reducing the number of convolutional layers lowers computational complexity while maintaining roubust detection accuracy.

The field of malware detection has made significant progress due to the application of ML and DL techniques, particularly CNN and transfer learning. However, challenges still exist, including the complexity of real-world Internet of Things (IoT) environments, the limited availability of labeled data, and the necessity for resilience against adversarial attacks. The proposed X-MalNet model aims to address some of these challenges by utilizing image-based malware classification, providing an interpretable and robust solution. Below, we present a synthesis of related studies and clearly position our work within the existing literature.

Recent advances in malware detection have increasingly turned to deep learning to overcome the limitations of manual feature engineering in traditional methods. While recurrent neural network (RNN)-based approaches have been widely applied, but they remain vulnerable to adversarial strategies such as redundant API injections [9]. To address these challenges, researchers have developed CNN-based frameworks that utilize grayscale and RGB malware images for improved robustness. Building on this direction, the authors in [10] introduced a novel image-based malware classification framework that leverages RGB assembly visualization and hybrid deep learning models. Their work presents MalevisAsm, an enriched dataset that integrates MaleVis malware samples with benign files, and proposes a hybrid model combining EfficientNetB0 and DenseNet121 for robust feature extraction. In this approach, portable executable files are transformed into assembly code, opcode transitions are mapped into three-channel images, and a fine-tuned CNN is applied to classify malware families. The framework further integrates uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP), a non-linear dimensionality reduction technique, to improve the identification of previously unseen malware through binary classification by attaining the accuracy of 98.45%, surpassing existing benchmarks on the MaleVis dataset.

The authors in [11] proposed a Deep Neural Network (DNN) for malware detection, focusing on identifying intricate patterns in raw byte sequences. However, their approach overlooked the visual aspects of malware, which can provide valuable insights for classification. Additionally, the study was limited by computational difficulties in training deep networks on large datasets and focused on a narrow range of malware families. In contrast, our model emphasizes the use of image-based representations of malware, which can capture both low- and high-level visual patterns. This approach opens the door to more generalizable detection across diverse malware families.

In [12], Zhao et al. investigated the use of an ensemble of CNN architectures for malware classification. While their approach improved classification accuracy, it was computationally demanding and focused only on grayscale images, missing potentially important features visible in colored images. Furthermore, the study used modest-sized datasets, limiting its generalizability. Our work builds on this by incorporating colored images and exploring more effective ensemble techniques, which can better capture the full range of visual features in malware images.

Yuan et al. explored deep transfer learning for static malware categorization, achieving high accuracy with less training data. However, their study focused exclusively on grayscale images, and the challenges of obtaining labeled data were emphasized. Our work extends their approach by using colored images and addressing the scalability of transfer learning methodologies to classify a wider variety of malware families, making the model more applicable to real-world scenarios [13].

Saxe and Berlin examined CNN architectures for virus detection, emphasizing the ability of CNNs to automatically extract features from raw data without requiring manual feature engineering. While their study showed promising results, it was constrained by the use of a specific CNN architecture and grayscale images, which may not capture the full range of visual information. Our work differs by exploring a broader range of CNN architectures and incorporating colored images to enhance classification accuracy [14].

Vasan et al. proposed a framework for image-based malware classification that used transfer learning to optimize a CNN trained on malware images. While their method achieved excellent accuracy, it did not compare various CNN architectures or loss functions. Our work addresses this gap by exploring a range of architectures, including AlexNet variants, and evaluating their effectiveness in classifying malware images [15].

Li et al. introduced a multi-feature fusion method for Android virus detection using deep learning. Their approach integrated static, dynamic, and hybrid features but did not explore image-based classification. Our work fills this gap by leveraging image-based malware datasets such as Malimg and Malevis, and comparing various CNN architectures and loss functions to improve classification outcomes [16].

While the existing research has made substantial contributions to the field of malware detection, several gaps still exist. Most studies focus either on network traffic data or raw byte sequences, which may overlook valuable visual features present in malware binaries. Additionally, many approaches ignore the importance of adversarial robustness and model explainability, which are crucial for real-world applications. Our work, X-MalNet, addresses these gaps by combining image-based malware classification with adversarial defense and explainability techniques, such as Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). In addition, we introduce a comprehensive evaluation that compares our model with state-of-the-art architectures, such as ResNet and EfficientNet, ensuring a robust and scalable solution for malware detection.

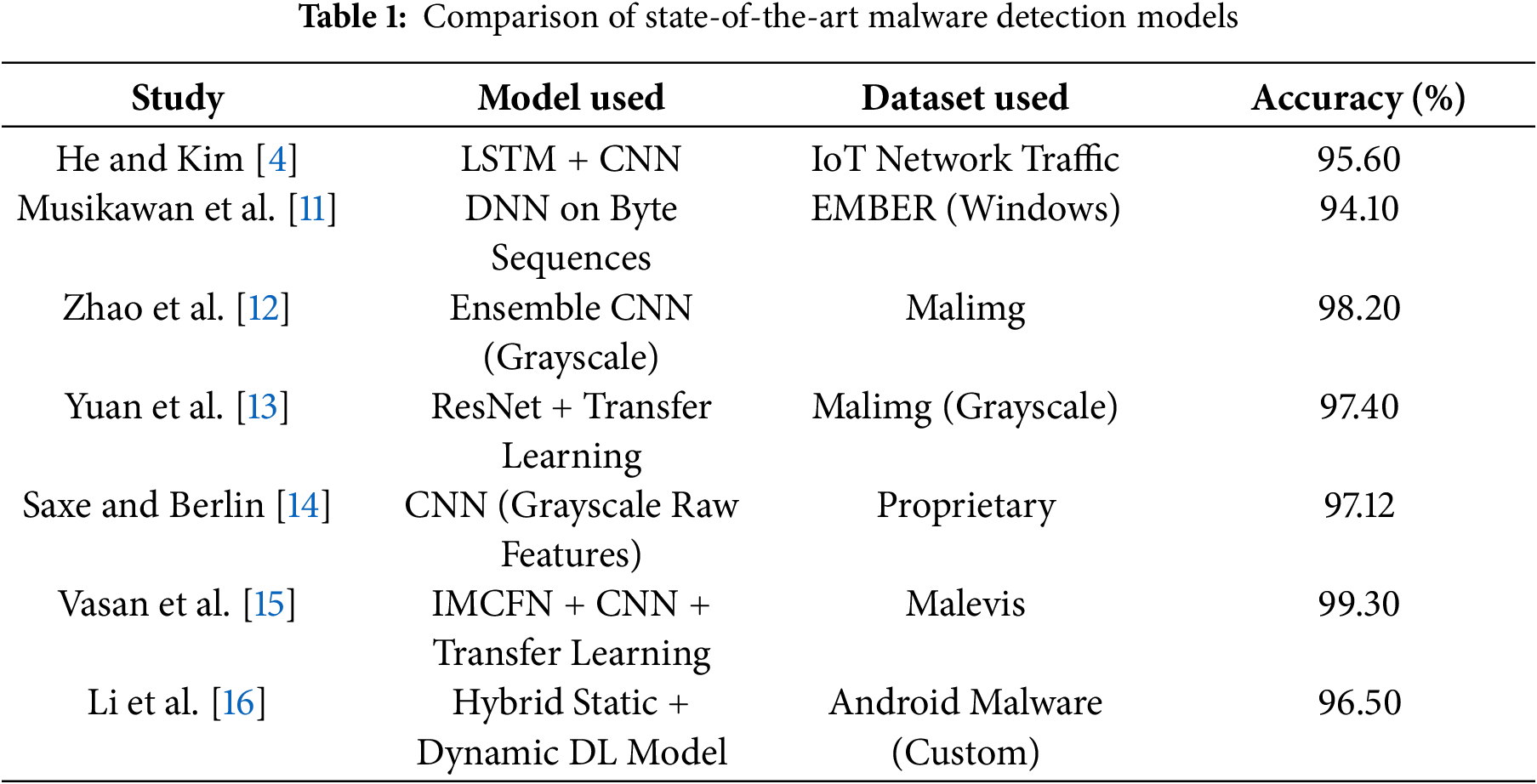

Table 1 summarizes in detail the studies based on the existing research work on the detection approaches and techniques used in the area of malwares. It points out methodologies, detection mechanisms, and key contributions that highlight the overview of progress and challenges faced in the investigation of malware detection.

3.1 Proposed Model Architecture

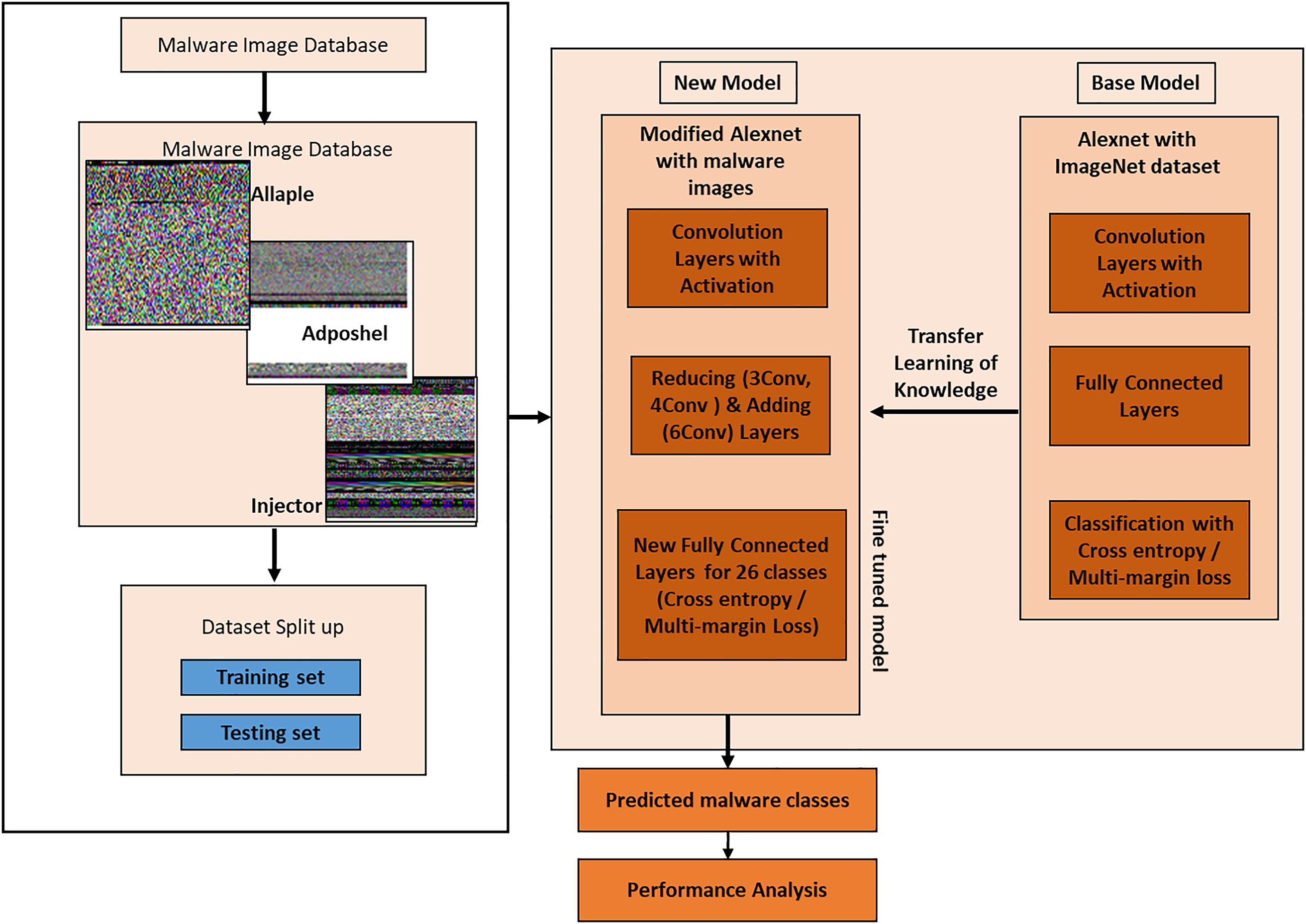

The proposed X-MalNet is a lightweight convolutional neural network designed for static malware classification using visual features derived from binary files as shown in Fig. 1. The model draws inspiration from the AlexNet architecture but is significantly simplified to reduce computational complexity and minimize overfitting, particularly given the texture-specific and low-resolution characteristics of malware images. Specifically, we reduce the number of convolutional layers from five (in the original AlexNet) to three, while retaining ReLU activation functions and max-pooling operations to maintain spatial invariance and feature abstraction. These convolutional layers are followed by two fully connected layers and a softmax output layer. Dropout regularization (

Figure 1: Alexnet framework for image malware detection

3.2 Preprocessing and Data Handling

The Malimg and Malevis datasets differ in image format. While Malimg images are grayscale by default, Malevis images are originally in RGB format. To standardize input across both datasets, all Malevis images were converted to grayscale using the weighted sum method:

This conversion ensures uniform dimensionality and eliminates redundant channel-wise information, making the images compatible with grayscale-based CNN models. All images were resized to

The experimental implementation was carried out in Python 3.8 using PyTorch 1.13. Training was performed on a system equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU (10 GB VRAM) and 32 GB RAM. The model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32, using the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate = 0.0001) and ReLU activation after each convolutional and fully connected layer to introduce non-linearity. Both Multi-Margin Loss and Cross-Entropy Loss functions were evaluated to assess performance sensitivity to different optimization criteria. A learning rate scheduler reduced the learning rate by a factor of 0.1 every 15 epochs, and early stopping with a patience of 10 epochs was applied to prevent overfitting. An 80:20 stratified split was used for training and testing to maintain class balance, and performance was measured using accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score. Grad-CAM [18] and Deep SHapley Additive exPlanations (DeepSHAP) were applied post-training to provide visual explanations of learned patterns, enhancing interpretability.

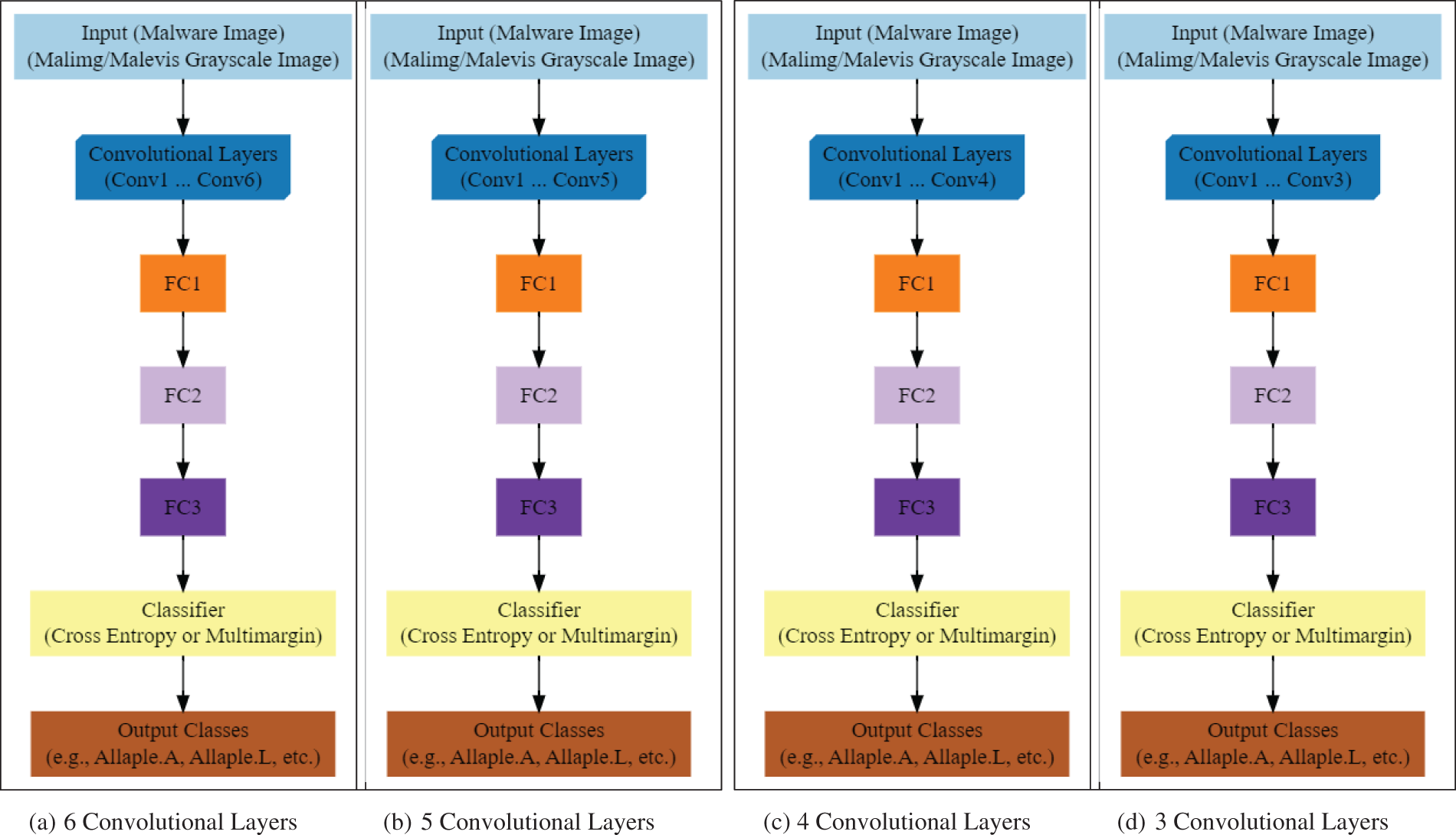

Fig. 2a–d lays down a CNN model for malware image classification based on grayscale images obtained from the Malevis and Malimg datasets, which are binaries of the malware. Layer by layer architecture is used, the main input image of the malware is donated through Conv1 to Conv6 layers which has multiple layers aiming at feature extraction such as edges, texture, structural patterns specific to different malware families. These features are further enhanced in fully connected layers (FC1, FC2, and FC3) to improve the system’s separability of the required features. The classifier then applies a loss function on the results, cross-entropy or multi-margin, etc., to identify specific malware class (as Allaple.A, Allaple.L, etc.). It is similar to the VGG model but uses six convolutional layers; due to these layers, the model is well suited to identifying specific malware groups based on structural patterns in binary representations. Ultimately, by incorporating convolutional layers for feature extraction and fully connected layers for classification, this model can effectively identify various types of malware and improve the identification process. It provides a robust response to malware identification technique aiming at the use of deep learning and picture categorization technique for identification of various viruses.

Figure 2: Structure of the proposed Alexnet variations

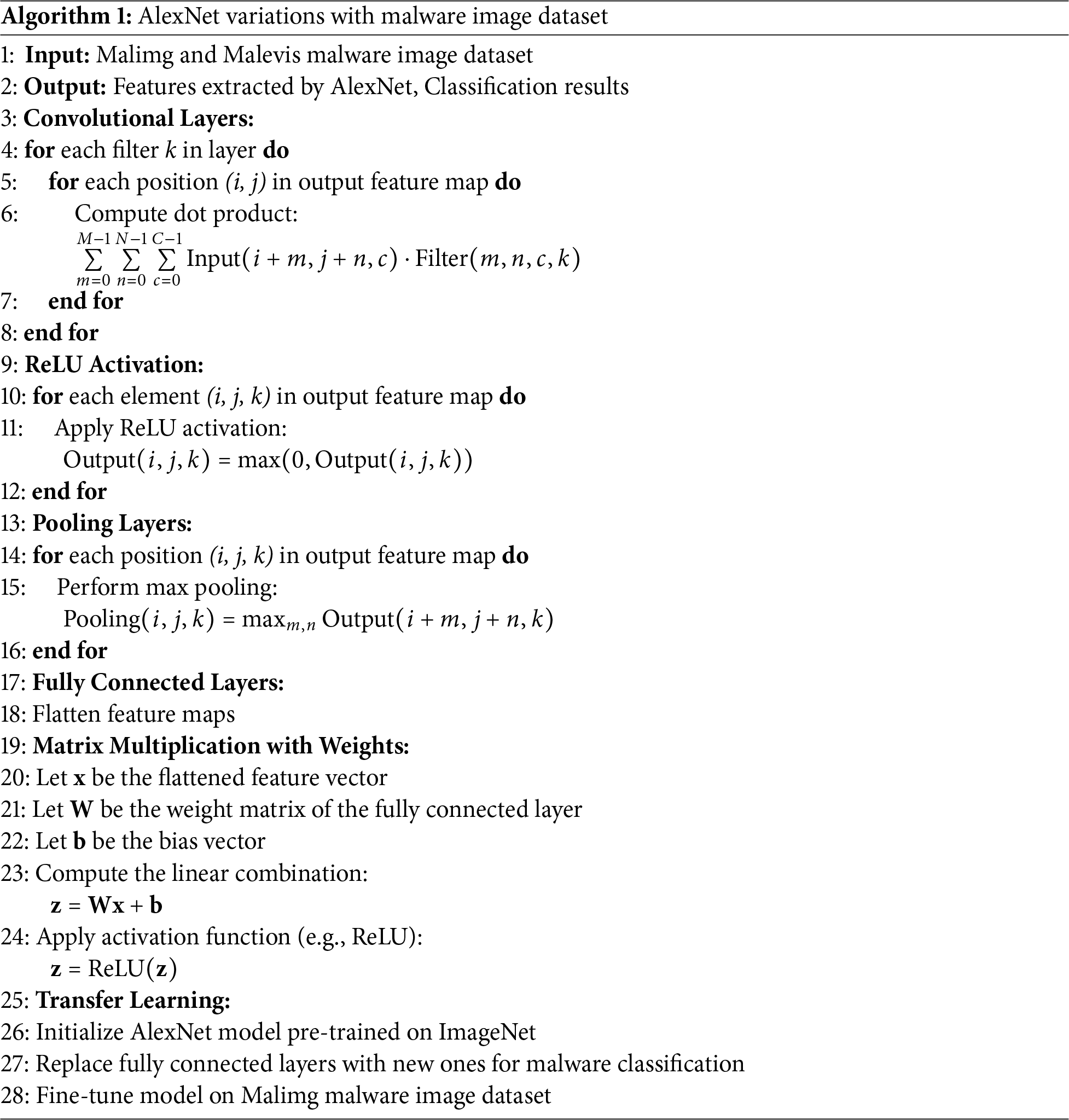

Algorithm 1 details the complete procedural steps of the proposed system. It outlines a modified version of AlexNet that is applied to the Malimg and Malevis malware image datasets. It incorporates convolutional layers, activation functions, pooling layers, fully connected layers, and transfer learning. The process starts with the convolutional layers, where for each filter

This step extracts spatial features from the input image. Following this, the ReLU activation function is applied to each element

This introduces non-linearity and eliminates negative values. Max pooling is then performed at each position

After the convolutional and pooling layers, the feature maps are flattened into a 1D vector,

An activation function, such as ReLU, is applied element-wise to

The proposed framework was evaluated using two benchmark datasets namely, the MalImg dataset and the MaleVis dataset. The MalImg dataset, introduced by [19], consists of 9339 malware images from 25 distinct malware families. It is widely used in malware classification research due to its comprehensive representation of various malware categories. The MaleVis dataset, as described by [20], contains 8750 malware samples, also spanning 25 different families. Like MalImg, the MaleVis dataset is designed to facilitate the visual analysis of malware, enabling researchers to leverage image-based learning approaches for identifying and classifying malware. The dataset is particularly useful in exploring how image-based malware detection models perform across different malware families, further providing a comprehensive platform for testing and refining malware detection techniques. By using both the MalImg and MaleVis datasets, proposed system was subjected to rigorous evaluation, ensuring that the model’s performance is robust across multiple benchmark datasets with varied family distributions. This diverse benchmarking helps in validating the generalization capabilities of the model across distinct image-based malware datasets.

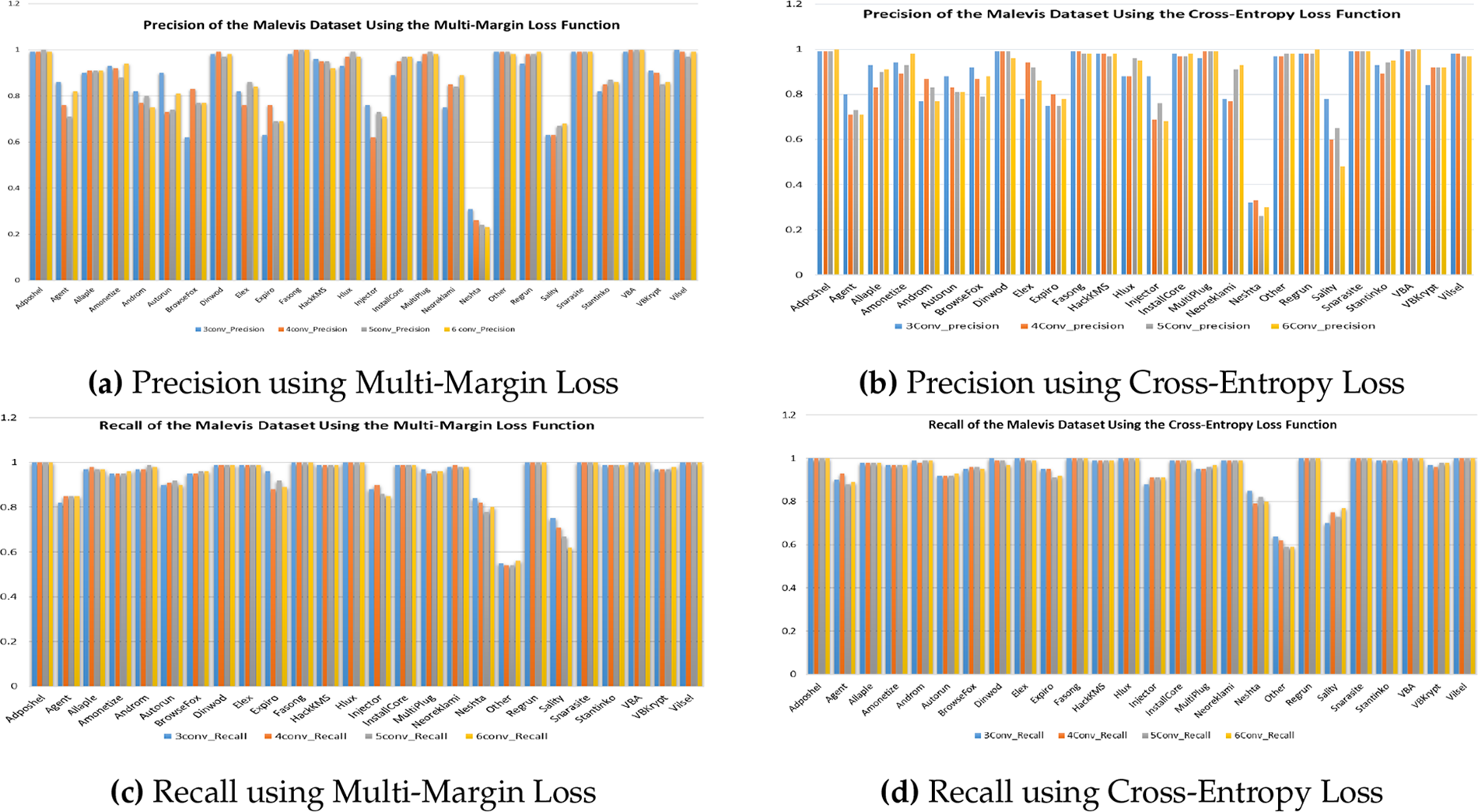

Fig. 3 provides a detailed comparative analysis of class-wise precision and recall across the Malevis dataset, evaluated under two distinct loss functions—Multi-Margin Loss and Cross-Entropy Loss using the 3-layer, 4-layer, and 5-layer variants of the proposed X-MalNet architecture. As shown in Fig. 3a and b, the precision plots reveal that the 5-layer variant consistently outperforms its shallower counterparts, achieving higher accuracy across most malware families. Similarly, the recall analysis presented in Fig. 3c and d underscores the benefit of increased convolutional depth in capturing discriminative structural representations of malware images. Furthermore, the Multi-Margin Loss function is shown in Fig. 3a and c exhibits improved class-wise stability and balanced performance, particularly for visually ambiguous or minority classes such as Allaple.A, VB.AT, and Swizzor.gen!E. In contrast, the 3-layer variant, while competitive in select categories, demonstrates greater variability and reduced recall on several classes as shown in Fig. 3b and d. This performance gap reinforces the efficacy of deeper architectures and highlights the importance of both network depth and appropriate loss function selection in achieving robust generalization across diverse malware families.

Figure 3: Comparison of Precision and Recall of the Malevis malware image dataset under different loss functions

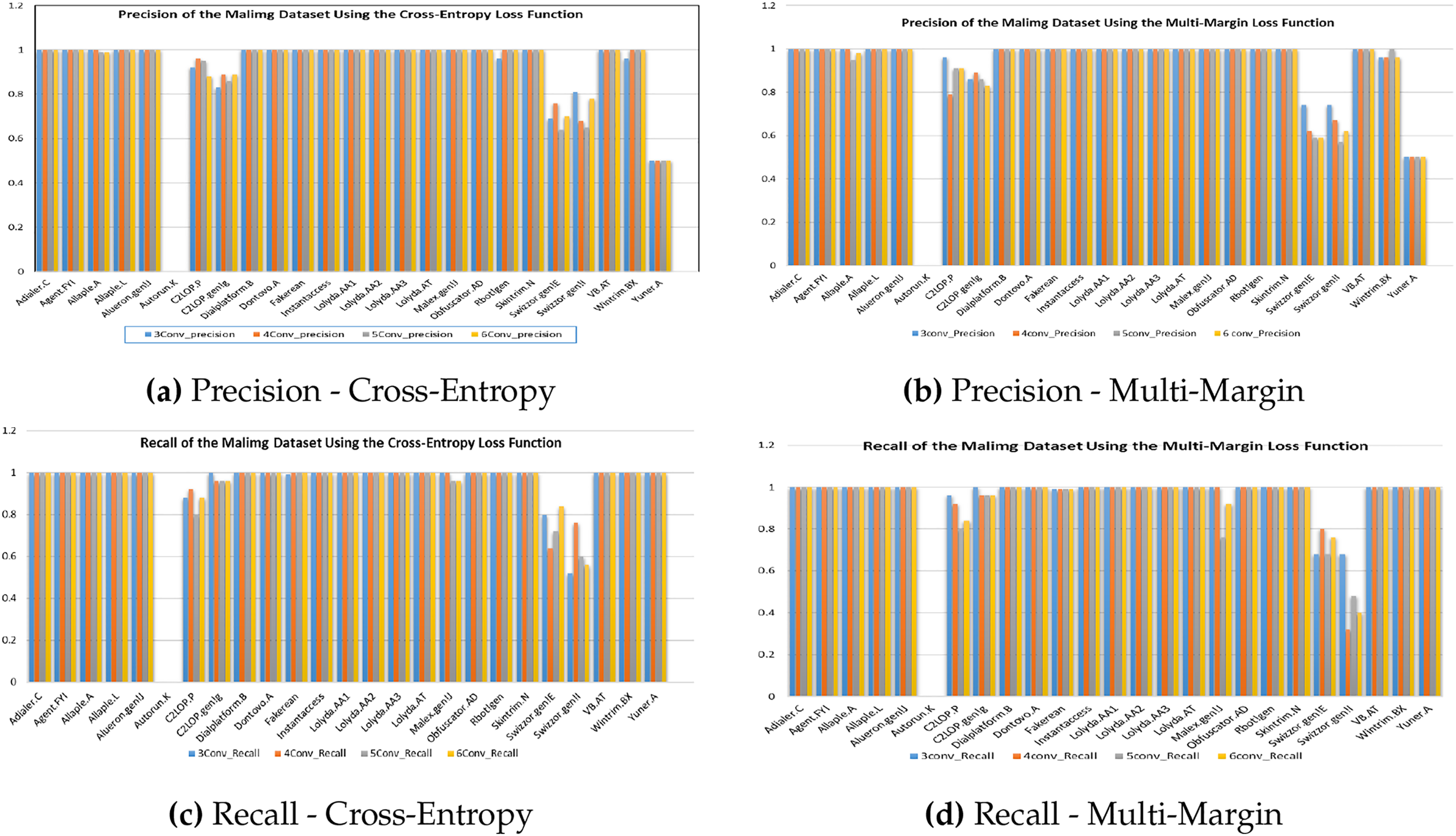

Fig. 4 provides a detailed comparison of class-wise precision and recall for the Malimg dataset under two distinct loss functions—Cross-Entropy and Multi-Margin using the 3-layer, 4-layer, and 5-layer variants of the proposed X-MalNet architecture. The precision analysis shown in Fig. 4a and b reveals that the 5-layer model consistently achieves superior accuracy across most malware families, demonstrating its enhanced ability to capture hierarchical spatial—texture patterns. Similarly, the recall performance illustrated in Fig. 4c and 4d underscores the advantage of deeper convolutional depth in preserving fine-grained structural cues essential for robust malware discrimination. When comparing loss functions, the Multi-Margin Loss is shown in Fig. 4b and d exhibits greater class-wise stability and reduced variance, particularly for ambiguous or under-represented families such as VB.AT, Swizzor.gen!E, and Allaple.A. Conversely, the 3-layer variant shows notable fluctuations and diminished recall as shown in Fig. 4a and c, indicating its limited representational capacity. Overall, these results reinforce the importance of both increased architectural depth and optimal loss-function selection in achieving stable, generalizable, and high-precision malware classification across visually heterogeneous datasets.

Figure 4: Precision and Recall Comparison of the Malimg malware image dataset under Cross-Entropy and Multi-Margin loss functions

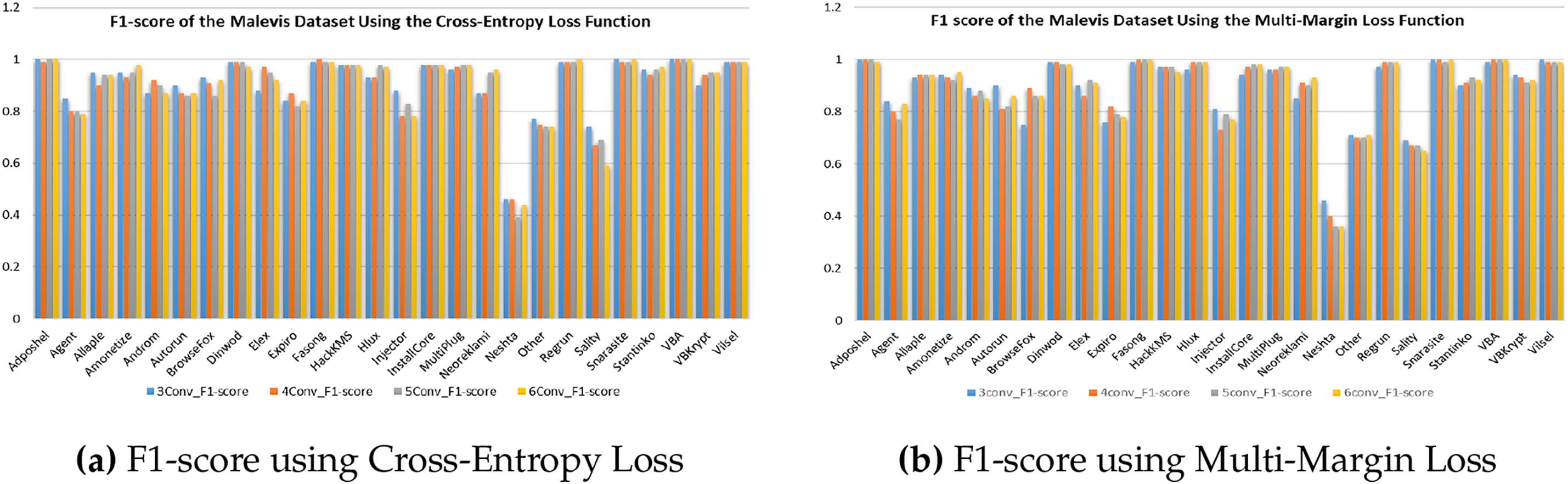

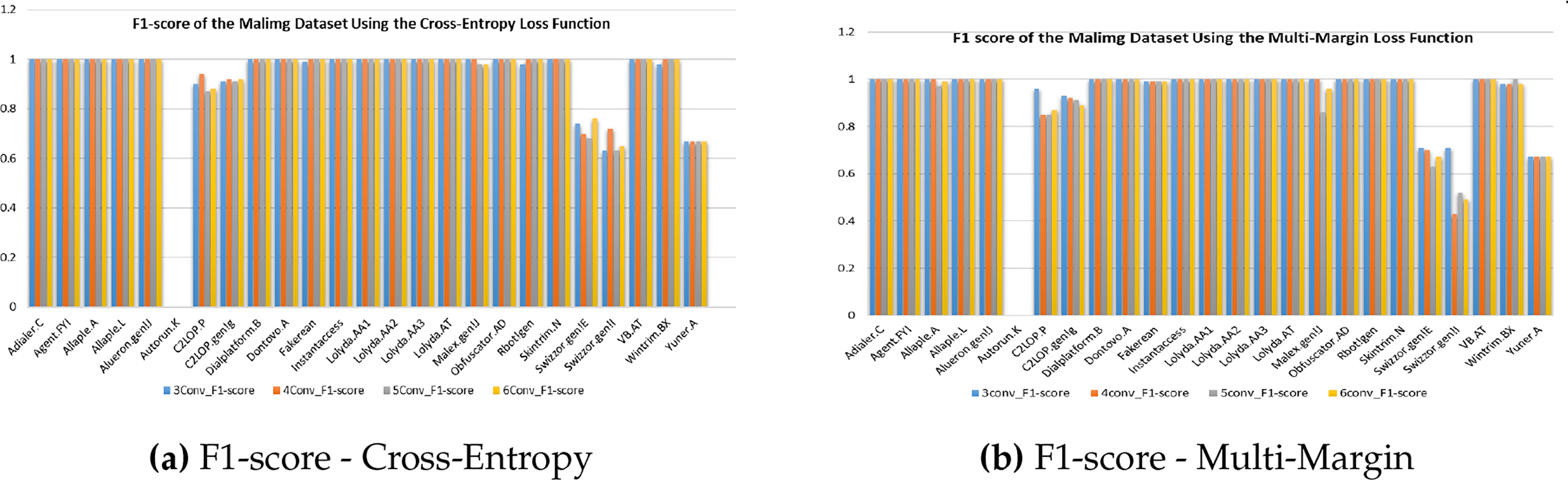

Fig. 5 presents the class-wise F1-score comparison for the Malevis dataset under the Cross-Entropy and Multi-Margin loss functions. As shown in Fig. 5a, the Cross-Entropy–based training yields competitive results for the majority of malware families, though a few visually ambiguous classes exhibit reduced F1-scores due to minor misclassifications. In contrast, Fig. 5b demonstrates that the Multi-Margin Loss enhances inter-class separability, achieving consistently higher F1-scores across nearly all families. Notably, the 5-layer X-MalNet variant trained with Multi-Margin Loss achieves more stable and balanced classification outcomes, reflecting its superior ability to capture subtle visual distinctions between closely related families such as VB.AT, Allaple.A, and Swizzor.gen!E. The marginal improvements observed across these challenging categories further emphasize that loss-function design plays a critical role in optimizing feature discrimination and ensuring uniform class-wise performance across complex malware image datasets. Fig. 6 presents the class-wise F1-score comparison for the Malimg dataset obtained from the 5-layer X-MalNet architecture trained under two different loss functions. As shown in Fig. 6a, the Cross-Entropy Loss yields strong performance across several malware families; however, a few classes with limited training samples or visual overlap display comparatively lower F1-scores. In contrast, Fig. 6b demonstrates that the Multi-Margin Loss provides consistently superior and more balanced results, effectively mitigating class-wise variability and enhancing recognition stability across visually similar families. Specifically, malware types such as Allaple.A, VB.AT, and Swizzor.gen!E achieve near-perfect classification under the Multi-Margin Loss configuration, underscoring the model’s enhanced discriminative learning of structural and texture-level features. Minor confusions are confined to visually analogous or under-represented families, reinforcing that the integration of a deeper architecture with a margin-based loss objective significantly improves generalization and fine-grained separability in malware image classification.

Figure 5: Comparison of F1-scores of Malevis image malware dataset

Figure 6: F1-score Comparison of Malimg malware image dataset

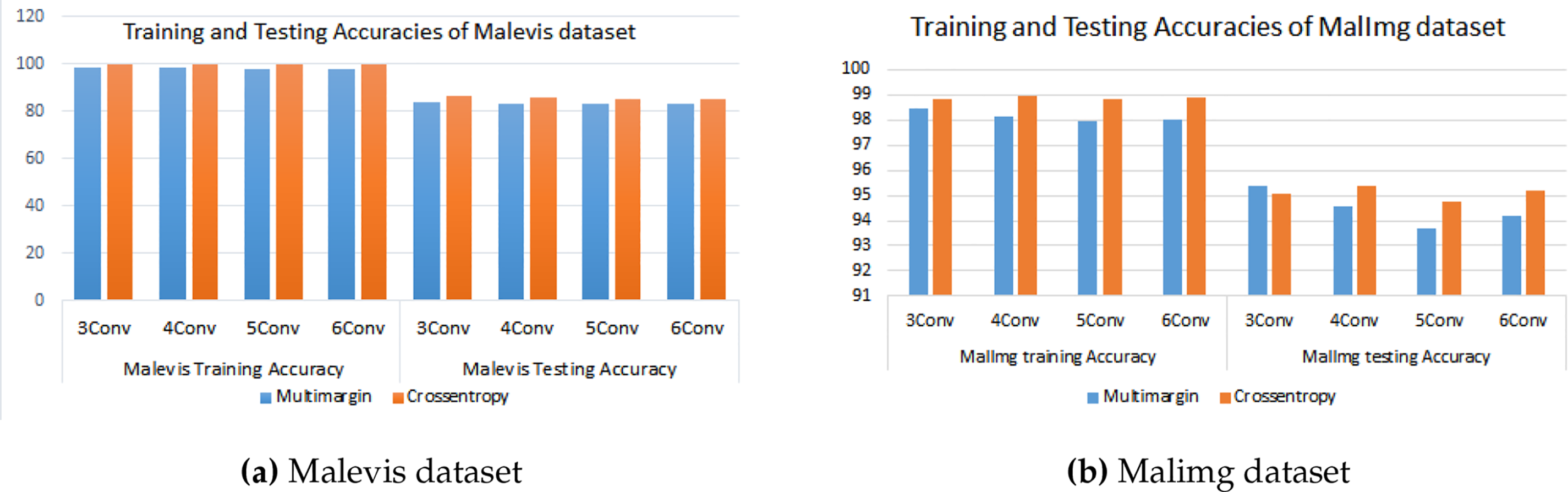

Fig. 7a presents a comparison of Training and Testing Accuracies for a model utilizing the Malevis dataset, focusing on the performance across four convolutional layer configurations (3Conv, 4Conv, 5Conv, and 6Conv) with two distinct loss functions: Multimargin (represented in blue) and Crossentropy (represented in orange). During the training phase, both loss functions achieve nearly 100% accuracy across all convolutional setups, indicating a high level of effective learning from the training dataset. In contrast, the testing accuracy is somewhat lower, which is anticipated, with Crossentropy exhibiting slightly superior generalization capabilities compared to Multimargin, especially in the 3Conv, 4Conv, and 5Conv configurations. Notably, as the number of convolutional layers increases from 3 to 6, the model’s testing accuracies remain stable, suggesting that significant overfitting is not occurring. This observation indicates that Crossentropy may provide a minor advantage in terms of generalization, although both loss functions demonstrate commendable performance overall, underscoring the resilience of the model’s architecture across various configurations and emphasizing the critical role of loss function selection in the performance on unseen data.

Figure 7: Side-by-side comparison of training and testing accuracy trends for Malevis and Malimg datasets

Fig. 7b illustrates the comparison of training and testing accuracy of a model utilizing the Malimg dataset, evaluated across different configurations of convolutional layers (3Conv, 4Conv, 5Conv and 6Conv) with two distinct loss functions: Multimargin and Crossentropy. Regarding training accuracy, both loss functions demonstrate commendable performance, achieving values between 96% and 99%. Notably, Crossentropy exhibits a marginal advantage, especially within the 3Conv and 4Conv architectures. As the number of convolutional layers increases, the training accuracy for both loss functions approaches near-optimal levels, reflecting a robust learning capability. In the testing phase, however, Crossentropy consistently surpasses Multimargin across all convolutional configurations, with a significant disparity observed in the 3Conv and 4Conv models. Although the performance difference diminishes with the addition of convolutional layers, Crossentropy retains a distinct advantage in terms of generalization, rendering it more effective for handling unseen data.

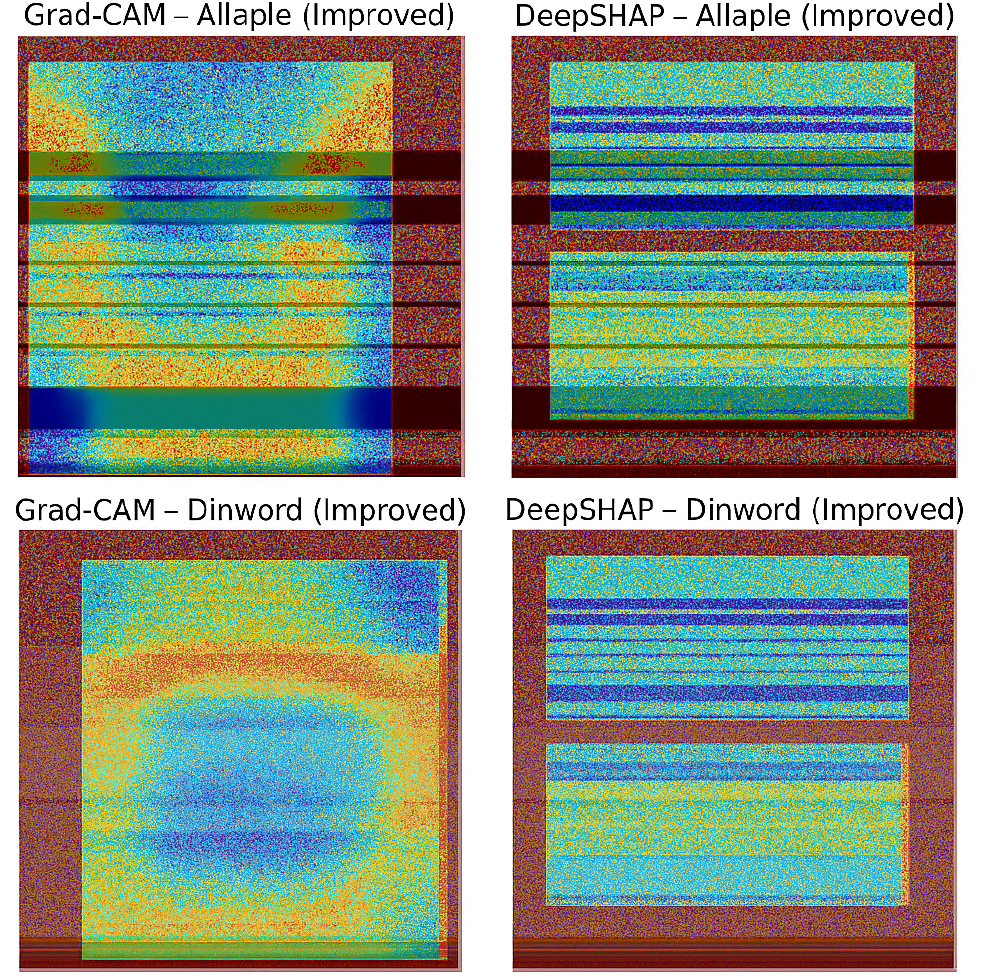

To provide interpretability for the proposed X-MalNet model, we integrated two complementary explainability techniques: Grad-CAM and DeepSHAP. Grad-CAM generates class-discriminative heatmaps by leveraging the gradients of target outputs flowing into the final convolutional layers, enabling visual localization of regions most responsible for a specific classification decision, as shown in Fig. 8. The visual explanations confirm that X-MalNet consistently focuses on malware-relevant structural patterns across both the Malimg and Malevis datasets. Grad-CAM heatmaps highlight spatially discriminative regions such as opcode clusters, entropy-dense segments, and boundary transitions, while DeepSHAP pixel-level attributions corroborate these findings by assigning high relevance scores to the same regions and minimal weight to background pixels. The strong correspondence between coarse-grained (Grad-CAM) and fine-grained (DeepSHAP) analyses indicates that the model’s predictions are driven by semantically meaningful features rather than spurious artifacts. This alignment enhances interpretability, supports analyst validation, and reinforces the model’s suitability for trustworthy malware detection in practical cybersecurity environments.

Figure 8: Explainability analysis using Grad-CAM and DeepSHAP for representative malware samples from the Malimg and Malevis datasets. Grad-CAM highlights spatially salient regions, while DeepSHAP reveals pixel-level contributions influencing classification decisions

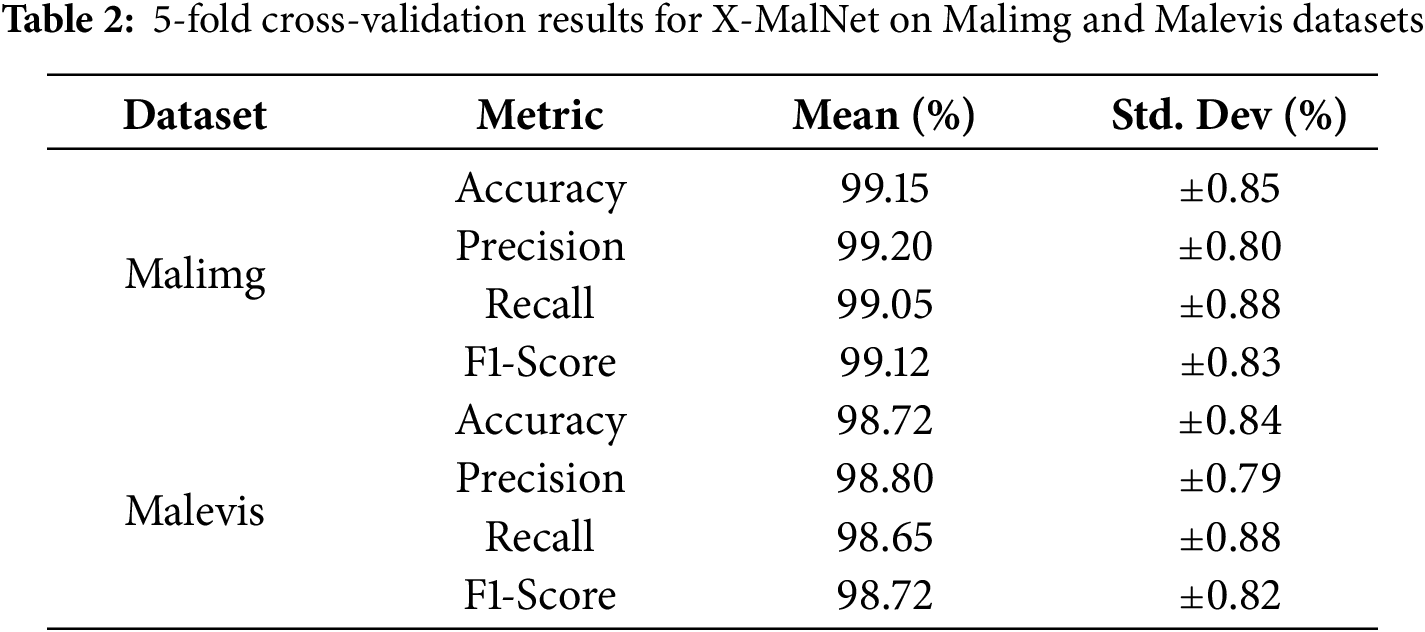

To assess the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed X-MalNet model, we conducted 5-fold stratified cross-validation on both the Malimg and Malevis datasets. Stratification ensured that class distributions were preserved across all folds [21]. In each fold, 80% of the data was used for training and 20% for validation. Performance metrics—accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score—were averaged five times. The results are summarized in Table 2. These values provide a more reliable estimation of model performance and mitigate concerns of overfitting observed in static train-test splits.

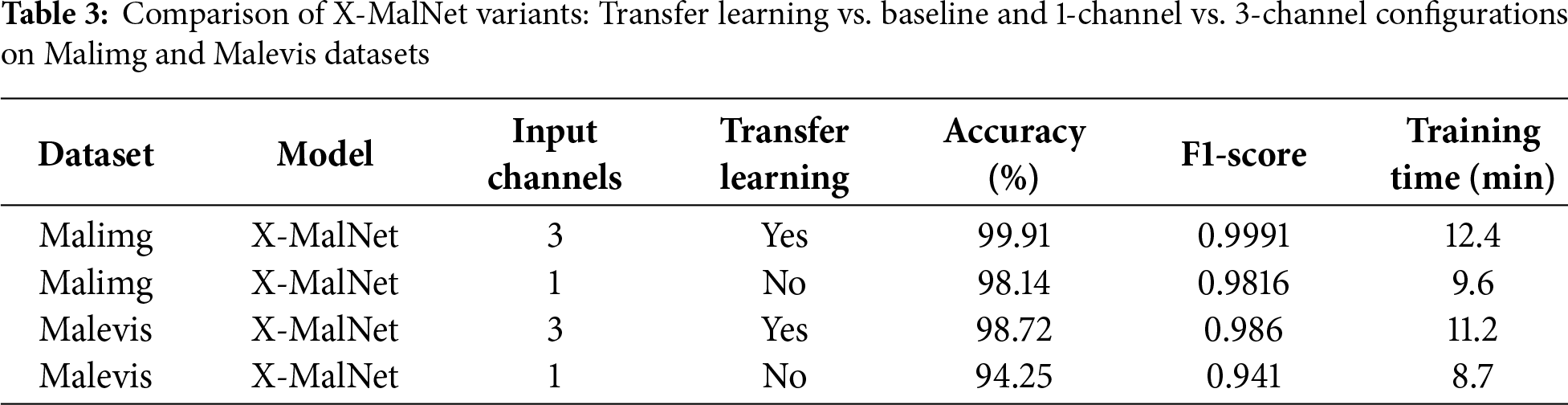

The results indicate that X-MalNet performs consistently across different data partitions. Although the Malimg data set yields high and stable scores, the Malevis data set demonstrates slightly lower performance with higher variance due to its smaller sample size and greater visual variability. Nonetheless, the average performance remains robust, confirming that the proposed model generalizes well even under cross-validation. To assess the impact of the 3-channel replication strategy and transfer learning on classification performance, we compared the proposed X-MalNet in two configurations: (i) a transfer learning-based model using 3-channel replicated grayscale inputs and ImageNet-pretrained AlexNet weights, and (ii) a baseline model trained from scratch on single-channel grayscale inputs. As shown in Table 3, the transfer learning variant achieved markedly higher accuracy and F1-scores on both datasets. For the Malimg dataset, accuracy improved from 98.14% to 99.91% and F1-score from 0.9816 to 0.9991. For the Malevis dataset, accuracy increased from 94.25% to 98.72% and F1-score from 0.9410 to 0.9860. Although transfer learning incurred slightly longer training times (12.4 vs. 9.6 min for Malimg; 11.2 vs. 8.7 min for Malevis) and marginally larger model sizes, the substantial performance gains, enhanced robustness to obfuscated malware patterns, and faster convergence across runs justify this modest computational overhead.

4.3 Experimental Results on Adversarial Conditions

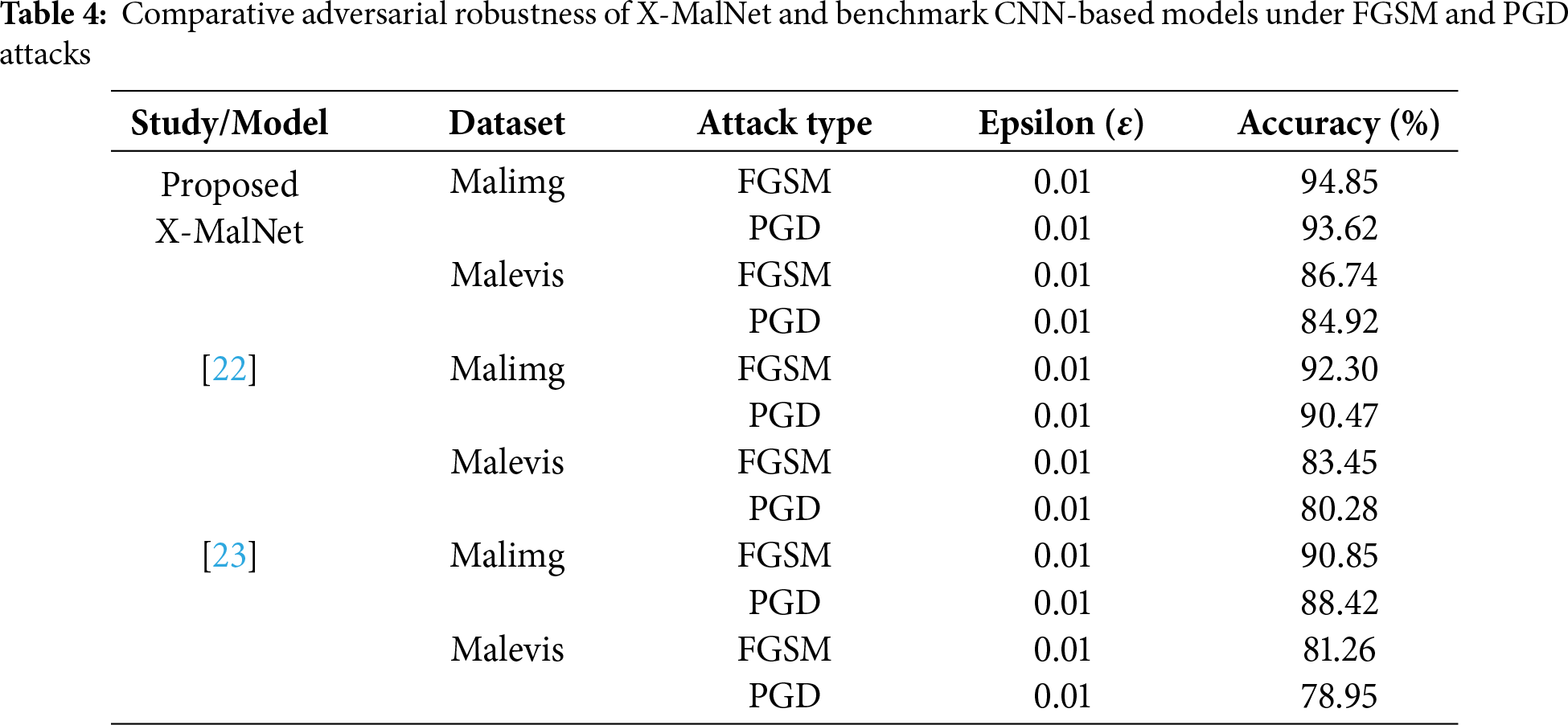

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed X-MalNet model under adversarial conditions, where malware images are perturbed using two widely adopted attack techniques: the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD). FGSM generates adversarial examples by adding small perturbations to the input data in the direction of the gradient of the loss function, making it computationally efficient. PGD extends FGSM by applying iterative perturbations, often achieving more effective attacks through fine-tuning over multiple steps. Both methods are standard in the literature for assessing robustness by testing classification performance on deliberately altered inputs. As shown in Table 4, we benchmark X-MalNet against two widely cited CNN-based malware detection frameworks—Vi et al. [22] and Liu et al. [23]—under identical perturbation settings (

A thorough error analysis reveals that the model struggles with categories such as Neshta and the “Other” category, where precision and recall drop significantly. Neshta, in particular, shows a notable decrease in precision (0.32) and F1-score (0.46), suggesting a high rate of false positives, where benign files are misclassified as malware. This likely arises from overlapping feature representations between malware and benign samples, compounded by limited training data for this specific class. In contrast, the “Other” category exhibits a relatively low recall (0.64) and F1-score (0.77), indicating that the model misses instances of malware, likely due to the diversity of malware within this category, which hinders feature generalization. These errors underscore the importance of addressing both false positives and false negatives, as the former can lead to unnecessary quarantining of non-malicious files, while the latter results in missed malware detections, posing a risk to security in real-time environments. The observed performance limitations are likely due to dataset imbalances, with the “Other” category being particularly challenging due to its large and diverse sample size, which may contribute to an under-representation of certain malware variants. Additionally, feature extraction for specific malware families, such as Neshta, may be inadequate, as the model may fail to capture distinctive visual patterns or textures unique to these variants.

5 Comparison with Cutting-Edge Methods

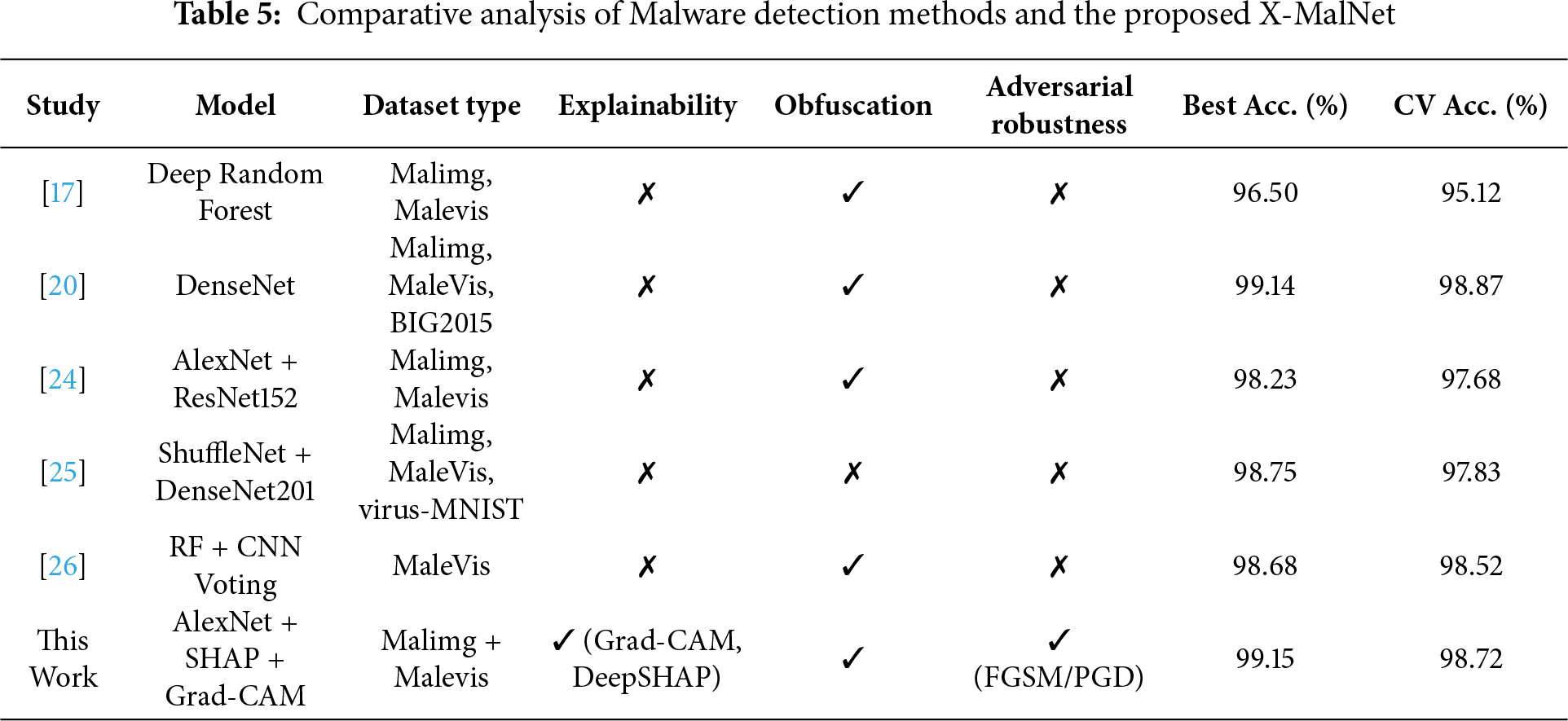

The comparative results in Table 5 highlight the novelty and technical completeness of the proposed X-MalNet framework relative to prior malware detection methods. While earlier approaches achieved competitive classification performance—most notably DenseNet-based models with a best accuracy of 99.14% and cross-validation (CV) accuracy of 98.87%—they lacked essential security-oriented components. Specifically, none incorporated XAI techniques, and none demonstrated resilience to adversarial perturbations. Moreover, only a subset addressed obfuscation robustness, and even then without providing interpretability for decision-making. In contrast, X-MalNet achieves the highest overall accuracy (99.15%) and strong CV performance (98.72%) while uniquely combining spatial (Grad-CAM) and feature attribution (DeepSHAP) explanations. This dual explainability provides transparent, fine-grained insights into model predictions, enhancing analyst trust. Furthermore, X-MalNet demonstrated robustness against obfuscated malware and adversarial attacks (FGSM, PGD), establishing it as not only a high-performing classifier but also a secure and interpretable solution, bridging critical gaps in the existing literature and supporting deployment in operational cybersecurity environments.

This study proposed an explainable, image-based malware detection framework using optimized AlexNet variants, where malware binaries were converted into grayscale images to exploit CNN-based pattern recognition. The architecture, enhanced with fewer convolutional layers, improved fully connected layers, and transfer learning, achieved high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores on the Malimg and Malevis datasets. Grad-CAM and DeepSHAP provided interpretable visual explanations, enhancing transparency and trust in predictions. We acknowledge that the current explainability analysis is qualitative in nature; future work will incorporate quantitative metrics—such as insertion/deletion scores, pointing game accuracy, or localization measures—to objectively assess the fidelity, consistency, and impact of the interpretability methods. Although the model demonstrated resilience against FGSM and PGD attacks, certain malware families, such as Neshta, remained challenging. The robustness evaluation was limited to fixed

Acknowledgement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R140), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R140), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Kirubavathi Ganapathiyappan conceived the study, supervised the research process, and contributed to methodology design. Heba G. Mohamed provided theoretical insights, supervised model development, and refined the manuscript. Abhishek Yadav performed the experimental implementation and data preprocessing. Guru Akshya Chinnaswamy contributed to dataset curation, training, and testing of the deep learning models. Ateeq Ur Rehman contributed to algorithm optimization, statistical validation, and result interpretation. Habib Hamam provided critical revisions, contextualized the findings in cybersecurity applications, and contributed to final manuscript editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed from the from the Kaggle repository at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sohamkumar1703/malevis-dataset/code and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/manmandes/malimg (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kolosnjaji B, Zarras A, Webster G, Eckert C. Deep learning for classification of malware system call sequences. In: AI 2016: Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 29th Australasian Joint Conference; 2016 Dec 5–8; Hobart, TAS, Australia. p. 137–49. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50127-7_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sajid M, Malik KR, Almogren A, Malik TS, Khan AH, Tanveer J, et al. Enhancing intrusion detection: a hybrid machine and deep learning approach. J Cloud Comput. 2024;13(1):123. doi:10.1186/s13677-024-00685-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ahmed U, Jiangbin Z, Almogren A, Khan S, Sadiq MT, Altameem A, et al. Explainable AI-based innovative hybrid ensemble model for intrusion detection. J Cloud Comput. 2024;13(1):150. doi:10.1186/s13677-024-00712-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He K, Kim D-S. Malware detection with malware images using deep learning techniques. In: 2019 18th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy In Computing and Communications/13th IEEE International Conference on Big Data Science and Engineering (TrustCom/BigDataSE); 2019 Aug 5–8; Rotorua, New Zealand: IEEE; 2019. p. 95–102. doi:10.1109/TrustCom/BigDataSE.2019.00022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Marastoni N, Giacobazzi R, Dalla Preda M. Data augmentation and transfer learning to classify malware images in a deep learning context. J Comput Virol Hack Tech. 2021;17:279–97. doi:10.1007/s11416-021-00381-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kalash M, Rochan M, Mohammed N, Bruce NDB, Wang Y, Iqbal F. Malware classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In: 2018 9th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS); 2018 Feb 26–28; Paris, France: IEEE. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/NTMS.2018.8328749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kumar S, Janet B. DTMIC: deep transfer learning for malware image classification. J Inf Secur Appl. 2022;64(12):103063. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ashawa M, Owoh N, Hosseinzadeh S, Osamor J. Enhanced image-based malware classification using transformer-based convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Electronics. 2024;13(20):4081. doi:10.3390/electronics13204081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Majid AM, Alshaibi AJ, Kostyuchenko E, Shelupanov A. A review of artificial intelligence based malware detection using deep learning. Mater Today Proc. 2023;80(1):2678–83. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Eroğlu Demirkan E, Aydos M. Enhancing malware detection via RGB assembly visualization and hybrid deep learning models. Appl Sci. 2025;15(13):7163. doi:10.3390/app15137163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Musikawan P, Kongsorot Y, You I, So-In C. An enhanced deep learning neural network for the detection and identification of Android malware. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(10):8560–77. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3194881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao Z, Zhao D, Yang S, Xu L. Image-based malware classification method with the AlexNet convolutional neural network model. Security Commun Netw. 2023;2023(1):6390023. doi:10.1155/2023/6390023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yuan Z, Lu Y, Xue Y. Deep transfer learning for static malware classification. Comput Secur. 2019;87:101638. [Google Scholar]

14. Saxe J, Berlin K. Deep neural network based malware detection using two dimensional binary program features. In: 2015 10th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE); 2015 Oct 20–22; Fajardo, PR, USA: IEEE. p. 11–20. doi:10.1109/MALWARE.2015.7413680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Vasan D, Debnath N, Seshasayanan A, Anwar S, Sarirete A. IMCFN: image-based malware classification using fine-tuned convolutional neural network architecture. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;171(1):107138. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li S, Li Y, Han W, Du X, Guizani M, Tian Z. Malicious mining code detection based on ensemble learning in cloud computing environment. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2021;113:102391. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2021.102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Roseline SA, Suganya R, Anusha SVKR, Kannan A. Intelligent vision-based malware detection and classification using deep random forest paradigm. IEEE Access. 2020;8:206303–24. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3036491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ahmed IT, Jamil N, Din MM, Hammad BT. Binary and multi-class malware threads classification. Appl Sci. 2022;12(24):12528. doi:10.3390/app122412528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nataraj L, Yegneswaran V, Porras P, Zhang J. A comparative assessment of malware classification using binary texture analysis and dynamic analysis. In: Proceedings of the 4th ACM Workshop on Security and Artificial Intelligence; 2011 Oct 21; Chicago, IL, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM. p. 21–30. doi:10.1145/2046684.2046689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hemalatha J, Sharmila M, Vijayalakshmi K, Saranya R. An efficient densenet-based deep learning model for malware detection. Entropy. 2021;23(3):344. doi:10.3390/e23030344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Vinayakumar R, Alazab M, Soman KP, Poornachandran P, Venkatraman S. Robust intelligent malware detection using deep learning. IEEE Access. 2019;7:46717–38. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2906934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Vi BN, Nguyen HN, Nguyen NT, Tran CT. Adversarial examples against image-based malware classification systems. In: 2019 11th International Conference on Knowledge and Systems Engineering (KSE); 2019 Oct 24–26; Da Nang, Vietnam: IEEE. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/KSE.2019.8919481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu X, Zhang J, Lin Y, Li H. ATMPA: attacking machine learning-based malware visualization detection methods via adversarial examples. In: IWQoS ’19: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Quality of Service; 2019 Jun 24–25; Phoenix, AZ, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM. p. 1–10. doi:10.1145/3326285.3329073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Aslan Ö, Yilmaz AA. A new malware classification framework based on deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access. 2021;9:87936–51. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3089586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wong W, Juwono FH, Apriono C. Vision-based malware detection: a transfer learning approach using optimal ECOC-SVM configuration. IEEE Access. 2021;9:159262–70. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3131713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Atitallah SB, Driss M, Almomani I. A novel detection and multi-classification approach for IoT-malware using random forest voting of fine-tuning convolutional neural networks. Sensors. 2022;22(11):4302. doi:10.3390/s22114302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools