Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Advanced AI-Driven Cybersecurity Solutions: Intelligent Threat Detection, Explainability, and Adversarial Resilience

1 Department of Mathematics, Amrita School of Physical Sciences, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, 641112, India

2 School of Computing, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

3 Faculty of Engineering, Uni de Moncton, Moncton, NB E1A3E9, Canada

4 School of Electrical Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa

5 International Institute of Technology and Management (IITG), Av. Grandes Ecoles, Libreville, 1989, Gabon

6 College of Computer Science and Eng., University of Ha’il, Ha’il, 55476, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Kirubavathi Ganapathiyappan. Email: ; Ateeq Ur Rehman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070067

Received 07 July 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

The growing use of Portable Document Format (PDF) files across various sectors such as education, government, and business has inadvertently turned them into a major target for cyberattacks. Cybercriminals take advantage of the inherent flexibility and layered structure of PDFs to inject malicious content, often employing advanced obfuscation techniques to evade detection by traditional signature-based security systems. These conventional methods are no longer adequate, especially against sophisticated threats like zero-day exploits and polymorphic malware. In response to these challenges, this study introduces a machine learning-based detection framework specifically designed to combat such threats. Central to the proposed solution is a stacked ensemble learning model that combines the strengths of four high-performing classifiers: Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), LightGBM (LGBM), and CatBoost (CB). These models operate in parallel as base learners, each capturing different aspects of the data. Their outputs are then refined by a Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC), which serves as a meta-learner to enhance prediction accuracy. To ensure the model remains both efficient and effective, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to reduce feature dimensionality while preserving critical information necessary for malware classification. The model is trained and validated using the CIC-Evasive PDFMalware2022 dataset, which includes a wide range of both malicious and benign PDF samples. The results demonstrate that the framework achieves impressive performance, with 97.10% accuracy and a 97.39% F1-score, surpassing several existing techniques. To enhance trust and interpretability, the system incorporates Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), which provides user-friendly insights into the rationale behind each prediction. This research emphasizes how the integration of ensemble learning, feature reduction, and explainable AI can lead to a practical and scalable solution for detecting complex PDF-based threats. The proposed framework lays the foundation for the next generation of intelligent, resilient cybersecurity systems that can address ever-evolving attack strategies.Keywords

The PDF format has become a widely used medium for document sharing due to its cross-platform compatibility and rich functionalities [1]. However, these same features also make it an attractive target for cybercriminals, who exploit vulnerabilities in PDF readers to inject malicious scripts, bypass security controls, and distribute malware [2,3]. From a cybersecurity perspective, detecting malware in PDF files is a complex issue influenced by the rapidly evolving tactics of attackers, their resilience, and the limitations of outdated detection mechanisms [4,5]. On a technical level, the challenge is further complicated by obfuscation techniques, the execution of embedded JavaScript, and the need to balance static and dynamic analysis approaches. Together, these factors contribute to the ongoing difficulty of identifying evasive malware threats using standard security mechanisms [6].

The emergence of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) has created new opportunities for improving malware detection. While Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based, Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)-based, and Transformer-based models have shown success in cybersecurity applications, they often struggle to effectively capture dependencies among features, especially when it comes to identifying subtle malicious patterns. Our goal is to develop a stacked ensemble learning model that enhances PDF malware detection by combining various classifiers and focusing on feature selection and dependency analysis.

Phuoc et al. [7] introduced uitPDFXAI, a novel method that utilizes explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to identify malicious PDF files using machine learning models such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) and AdaBoost. By employing Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), this approach clarifies how individual features of PDFs influence model predictions, thereby enhancing interpretability. When tested on the CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022 dataset, uitPDFXAI achieved impressive accuracies—99.55% with XGBoost and 98.90% with AdaBoost—highlighting the importance of XAI in malware detection. Similarly, Das et al. [8] proposed an entropy-based feature encoding scheme that optimizes the efficiency and accuracy of machine learning systems for detecting PDF malware. Their method effectively captures the relevance of categorical features while minimizing biases introduced by numerical conversions. Evaluations on various cybersecurity datasets, including CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022, demonstrated that their approach outperformed traditional encoding methods, with ensemble classifiers achieving a peak F1 score of 99.27%.

Togaçar and Ergen [9] took a unique approach by converting textual metadata into two-dimensional barcode images. They utilized metaheuristic-optimized CNNs for detecting malware in PDFs. By integrating architectures such as MobileNetV2, ResNet-18, and ShuffleNet with the Honey Badger Algorithm for feature selection, they achieved an impressive accuracy of 99.73% on the CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022 dataset, showcasing the effectiveness of their hybrid method. In a comprehensive survey, Aryal et al. [10] explored adversarial evasion attacks targeting malware detection systems, particularly those related to PDFs. They identified structural vulnerabilities within PDFs that could be exploited for attacks, including the embedding of malicious payloads and crafted JavaScript, which facilitate detection evasion. The study discussed various adversarial techniques and emphasized the urgent need for robust defenses against these strategies.

Hossain et al. [11] proposed a ML framework focused on feature engineering and interpretability for detecting malware in PDF files. They created a diverse dataset of both benign and malicious PDF samples, utilizing tools such as PDFiD and PDF-PARSER to extract key features. Their findings revealed that the Random Forest (RF) model was particularly effective, achieving an impressive accuracy of 99.24%. This research advanced XAI by generating interpretable decision rules through decision trees. Pandi Chandran and Hema Rajini [12] introduced a novel malware detection approach that combines Mayfly Optimization with a Deep Belief Network (DBN), named MFODBN-MDC. Their method improved classification accuracy through optimized feature selection and hyperparameter adjustment. When evaluated on the CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022 dataset, MFODBN-MDC demonstrated strong performance, achieving a precision of 97.42%, a recall of 97.33%, and an F1-score of 97.33%. This marks a notable contribution to the field of cybersecurity.

Yerima and Bashar [13] developed an explainable ensemble learning method aimed at detecting evasive malicious PDF documents. Their approach combined both structural and anomaly-based features, with a focus on vulnerabilities arising from reverse mimicry injection attacks. By utilizing ensemble classifiers such as Random Committee and AdaBoost, they achieved outstanding detection rates: 100% for embedded JavaScript and EXE content, and 98% for embedded PDF attacks. Additionally, their implementation of SHAP not only enhanced model interpretability but also offered clear insights into the impact of various features, thereby fostering greater trust in AI-driven malware detection.

Singh [14] developed a dynamic feature-based technique for detecting malware in non-executable PDF files using a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN). Their method utilized the PDFMalLyzer tool to extract hidden structural and dynamic features, such as JavaScript sequences, embedded files, and metadata. By integrating feature engineering with principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, the 1D-CNN model was able to effectively differentiate between malicious and benign PDFs, achieving a remarkable accuracy of 99.15% on the CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022 dataset. This work highlights the potential of convolutional neural networks to capture complex, non-linear relationships among features, representing a significant advancement over traditional machine learning methods in the field of PDF malware detection.

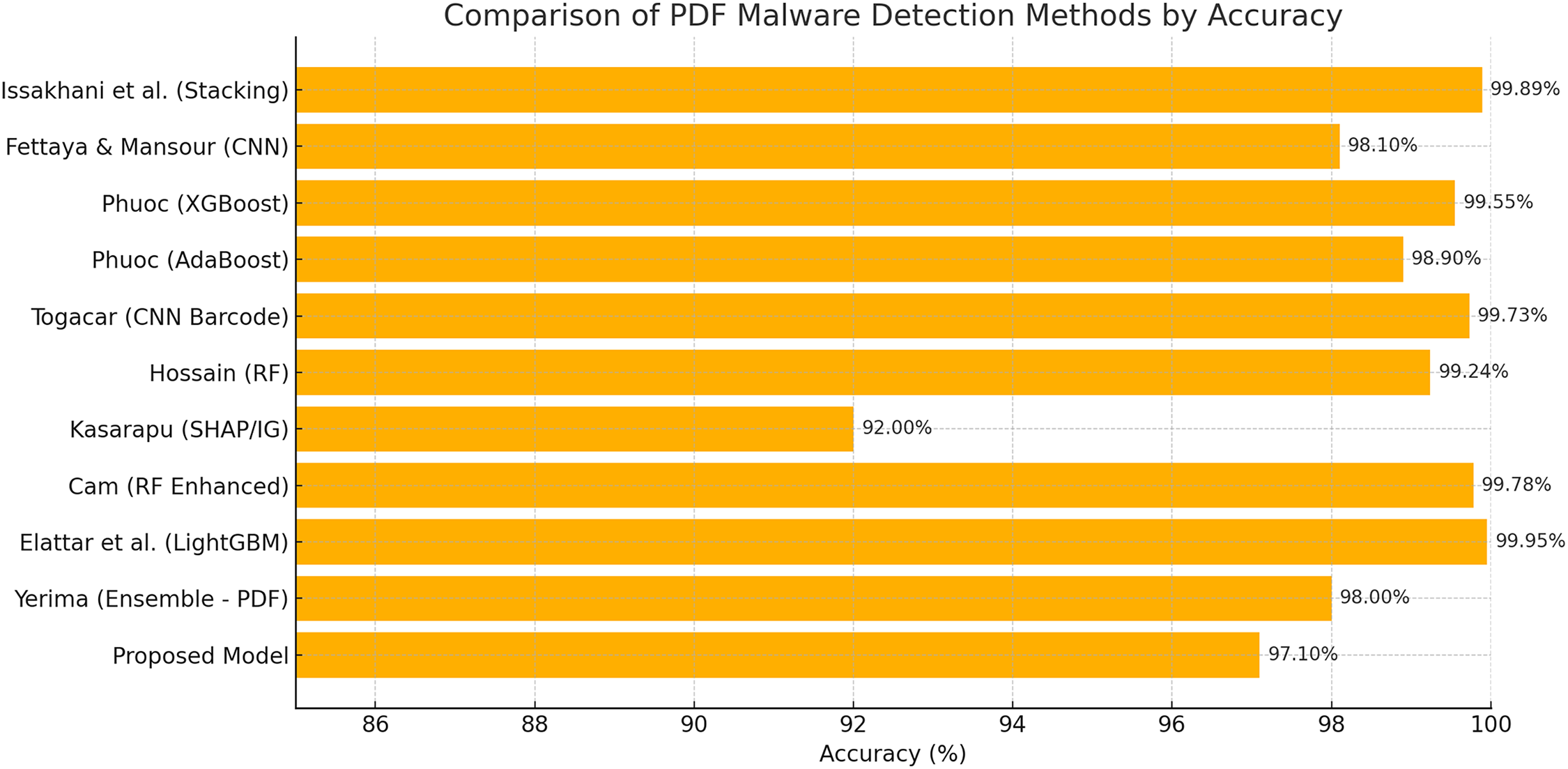

Issakhani et al. [15] introduced a stacking-based machine learning method to improve the detection of evasive malicious PDF files, addressing the limitations of traditional signature-based techniques. Their framework identifies 28 key static and structural features, including JavaScript usage and embedded files. By employing a stacking strategy that combines multiple classifiers—such as RF, Linear Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Multi-Layer Perceptron—with Logistic Regression as the meta-learner, the model achieved remarkable accuracy and F1-scores of 99.89% and 99.86%, respectively, on the Contagio dataset. Additionally, they created a new dataset called “Evasive-PDFMal2022” to evaluate the model’s robustness against evasive attacks, successfully demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting advanced PDF malware. Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of current research, highlighting the methodologies and datasets used in each study.

The significant contributions of this paper are:

• A thorough survey of current PDF malware detection methods, evaluating their merits and demerits in addressing evasive threats.

• Implementing a stacked ensemble learning architecture incorporating Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM (LGBM), and CatBoost (CB) as base learners and a Gradient Boosting meta-learner to improve classification performance.

• Formal testing of the proposed model over the PDFMalware2022 dataset to establish its strength over existing malware detection methods.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews different types of PDF malware, including exploits based on JavaScript and ActionScript, as well as an overview of the PDF file structure. Section 3 outlines the methodology, detailing the dataset used, preprocessing techniques, and dimensionality reduction methods. It also describes the stacked ensemble learning approach and the performance metrics utilized. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and includes an analysis of explainability, comparing the results with state-of-the-art methods. Lastly, Section 5 summarizes the findings and suggests potential directions for future research.

The PDF format is popular for document exchange due to its cross-platform compatibility, lightweight design, and consistent appearance across various devices and operating systems [18]. As a result, PDFs are commonly used in government sectors, business correspondence, legal documents, and numerous other fields. However, these same characteristics have made PDFs attractive targets for online criminals. Their complex structure and numerous features make it relatively easy to embed malicious content that could jeopardize system security [19,20]. Attacks that involve PDFs often exploit vulnerabilities in PDF readers, which can allow hackers to execute arbitrary code, steal sensitive information, or gain unauthorized access to systems. Common attack methods include the use of malicious JavaScript code or exploiting flaws in the PDF parsing process. To bypass standard network defenses, attackers often rely on social engineering techniques to manipulate users into opening these compromised documents. Attackers exploit the flexible nature of PDF files in various ways to achieve their malicious goals. Common attack vectors include:

• JavaScript-Based Exploits: One of the most common methods of exploiting PDFs involves embedding malicious JavaScript code. When the file is opened, this code can trigger exploits that lead to illegal activities such as file downloads, command execution, or data theft. To evade detection by static analysis tools, attackers often obfuscate the JavaScript code using techniques like text encoding, variable renaming, and altering control flows.

• Embedded Files and Obfuscated Content: PDFs allow various types of files, including images, videos, and even executable programs, to be embedded within them. Attackers take advantage of this feature by inserting harmful payloads, such as ransomware or trojans, into seemingly benign documents. They also apply obfuscation techniques to hide the malicious code from common detection tools, such as encrypting content, compressing data streams, or nesting objects.

• Adversarial Manipulation: Adversarial attacks pose a significant threat to malware detectors that rely on machine learning. These attacks involve creating PDF files with subtle modifications—such as adding undetectable objects or altering metadata—that may be invisible to human users but can mislead machine learning classifiers into mistakenly identifying malicious files as safe. This type of manipulation exploits weaknesses in the feature extraction and classification phases of the detection process [21].

• Exploitation of Reader Vulnerabilities: Attackers also target specific vulnerabilities found in PDF readers. For example, they have exploited buffer overflow vulnerabilities in Adobe Reader’s JavaScript engine to execute arbitrary code. By focusing on known weaknesses in PDF readers, attackers can launch exploits simply by convincing users to open the file.

• Social Engineering and Phishing Campaigns: PDF malware is often distributed through phishing emails, where harmful PDFs are disguised as legitimate documents, such as invoices, resumes, or official forms. Users are tricked into opening these attachments, which activate the embedded malicious payloads. These campaigns leverage human psychology to bypass technical defenses by directly targeting the end user.

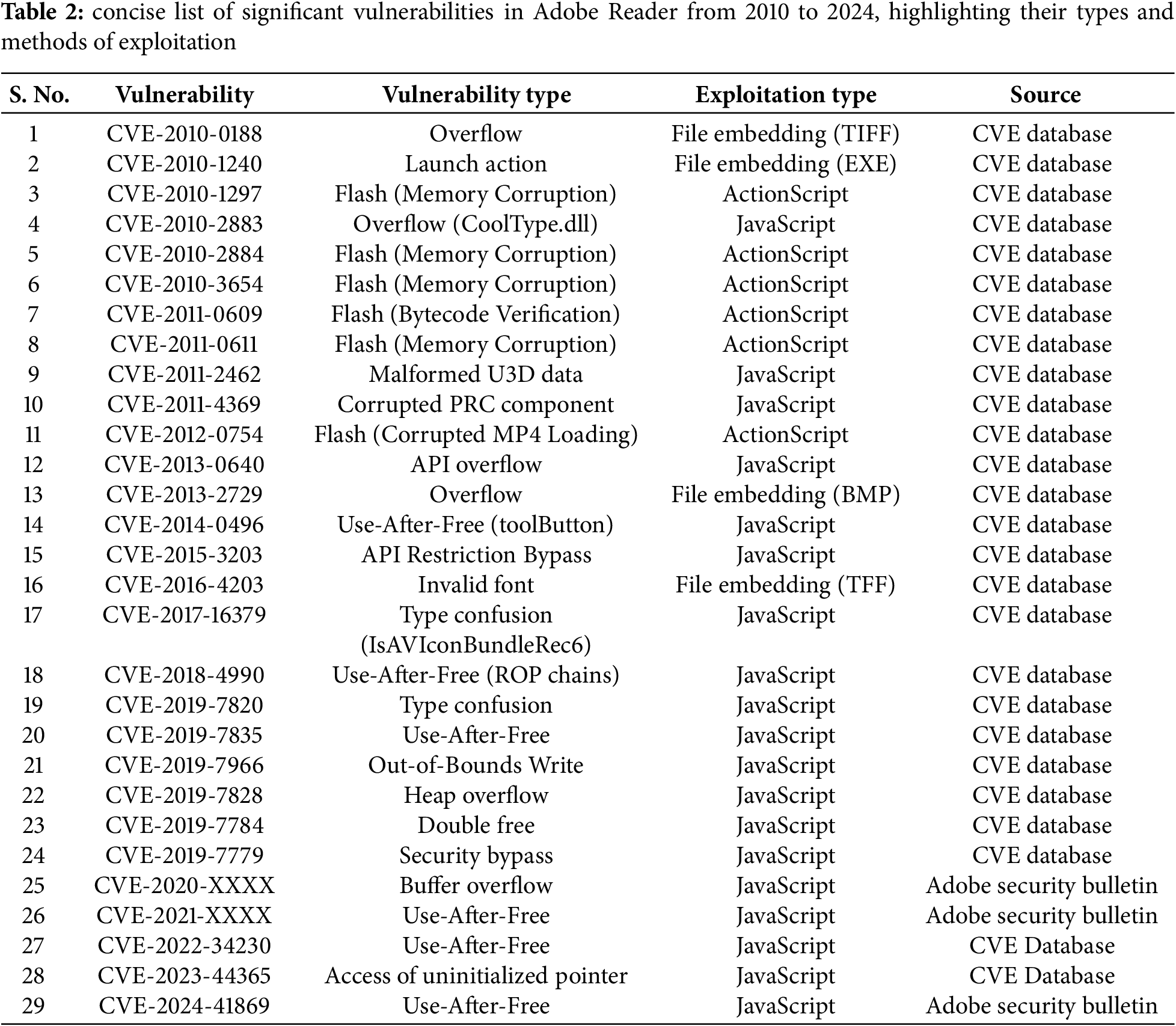

Adobe Reader has long been a favorite target for cybercriminals due to its widespread use and rich feature set. These features often include complex parsing capabilities, which can lead to vulnerabilities. Over the past ten years, numerous security flaws in Adobe Reader have been exploited, resulting in significant security breaches. Table 2 summarizes the major vulnerabilities found in Adobe Reader, detailing their types and common exploitation methods. This information has been gathered from various exploit databases, media reports, security bulletins, and analyses from malware repositories like VirusTotal [21]. These vulnerabilities can be broadly classified into three primary exploitation methods: JavaScript-based, ActionScript-based, and file embedding techniques.

JavaScript-based attacks are the most common type of PDF exploitation, primarily due to the extensive support that Adobe Reader provides for executing scripts within PDF documents. Attackers leverage this scripting feature to run unauthorized code upon opening a PDF, often without any user interaction required [21]. A recent study [22] has identified several types of JavaScript vulnerabilities in PDF files:

• API-Based Overflow: This vulnerability arises from improper handling of arguments in certain Application Programming Interface (API) calls within the PDF parsing library. Attackers exploit these weaknesses to conduct buffer overflow attacks or return-oriented programming (ROP) attacks. Historical examples include CVE-2008-0655 (related to Collab.collectEmailInfo) and CVE-2008–2992 (util.printf), which were among the first to demonstrate such exploits. These attacks typically involve injecting oversized payloads that exceed buffer limits, enabling arbitrary code execution.

• Use-after-Free: This type of vulnerability occurs when a program attempts to access memory that has already been freed, leading to undefined behavior and the potential for code execution. A notable example is CVE-2009-4324, where attackers exploited the media.newPlayer API in Adobe Reader to execute malicious code.

• Malformed Data: Attackers often use compressed, corrupted data to exploit vulnerabilities. During runtime, this malformed data can be decompressed, leading to crashes or uncontrolled code execution. Issues such as faulty object references or malformed streams with incorrect length attributes can cause the PDF reader to misinterpret data.

• Type Confusion: This attack involves manipulating how object types are interpreted by a PDF parser, which can result in improper memory access. By crafting PDFs that circumvent security checks, attackers can exploit the parser’s method of determining object types based on byte sequences to deliver malicious payloads.

Recent research indicates that while traditional static analysis tools can identify basic vulnerabilities in JavaScript, they often miss advanced obfuscation techniques. These techniques include encoding scripts in streams or employing multi-layered encryption. Although machine learning-based detectors have been suggested to address these challenges, they remain susceptible to adversarial attacks that skillfully manipulate PDF structures to deceive the classifiers [23].

2.2 ActionScript-Based Exploits

Even though the use of Flash in PDFs has decreased since Adobe discontinued Flash Player, understanding historical vulnerabilities related to ActionScript is still essential for grasping the evolution of PDF malware. Adobe Reader used to support Flash content embedded in PDFs, which allowed attackers to take advantage of Flash-related vulnerabilities.

In attacks that utilize ActionScript, malicious ShockWave Flash (SWF) files are embedded in the PDF, exploiting Adobe Reader’s integration with Flash Player to run harmful code. These attacks typically combine ActionScript and JavaScript, where ActionScript activates the vulnerability, and JavaScript carries out the exploitation process [24].

Some common vulnerabilities associated with ActionScript include:

• Memory Corruption: This is the most frequently exploited vulnerability in Flash-based attacks. It involves corrupting memory pointers, leading to arbitrary code execution. Vulnerabilities like CVE-2010-2883 took advantage of memory handling issues in the Flash component of Adobe Reader.

• ByteCode Verification Flaws: Certain vulnerabilities in Flash allowed attackers to run unverified bytecode, circumventing standard security measures. For example, CVE-2011-0609 exploited weaknesses in Flash’s bytecode verification process.

• Corrupted File Loading: By embedding malformed multimedia files (such as MP4 or SWF) within PDFs, attackers could exploit vulnerabilities in Adobe Reader’s file parsing libraries. These vulnerabilities often resulted in crashes or enabled code execution when the PDF was opened.

Although the frequency of Flash-based exploits has decreased due to Adobe’s discontinuation of Flash Player, legacy systems and outdated PDF readers remain vulnerable to these types of attacks [11,20].

The structure of a PDF file follows a standardized architecture that is crucial for ensuring document security, interoperability, and integrity—key components of digital document management and cybersecurity, as illustrated in Fig. 1. A PDF file begins with a Header that specifies the file format protocol for readers and indicates its version (e.g., %PDF-1.3). The Body of the document contains its content and metadata, which consists of several objects such as streams and dictionaries. These objects are often compressed using encoding techniques like /FlateDecode. An important feature for scalability and performance is the Cross-Reference Table (xref), which indexes the byte offsets of every object in the file. This allows for efficient random access to the objects without requiring sequential reading. Finally, the Trailer links the xref table to the root object and concludes the file with an end-of-file (EOF) marker, providing proper closure and ensuring compatibility for readers.

Figure 1: PDF file structure

Header: The simplest section of a PDF file is the header, which typically consists of a single line indicating the PDF version (e.g., PDF-1.7). Attackers can modify the header to create corrupted PDFs that exploit vulnerabilities in specific PDF readers, even though they may appear harmless.

Body: The body of a PDF file is its primary section, containing various items that define the document’s content and functionality. This can include text streams, images, annotations, and embedded scripts. Due to its flexibility, the body is an attractive target for attackers. For instance, JavaScript code embedded within these objects could be malicious when the file is opened. To evade detection, attackers may employ obfuscation techniques, such as encoding scripts within compressed streams.

Cross-References (xref): The xref table contains byte offsets for each item in the PDF, acting as a reference guide. This allows PDF readers to quickly locate and analyze specific elements without scanning the entire document. Malicious actors can alter the xref table to conceal harmful elements or deceive parsers. For example, they might create “orphaned” objects—those not included in the xref table—to embed secret payloads that bypass simple static analysis.

Trailer: The trailer marks the conclusion of the PDF file and includes metadata about the document, such as references to the root object and the location of the xref table. It also includes the phrase EOF to indicate the file’s end. Attackers may create multiple EOF markers to mislead parsers and hide malicious content, or they may modify the trailer to redirect the PDF reader toward harmful objects.

To understand how attackers exploit PDF files, it is essential to have a solid grasp of their structure. The four main components of a standard PDF file are the trailer, the cross-reference (xref) table, the body, and the header. Each of these elements influences how PDF readers interpret and display the document. Malicious actors typically target specific parts of this structure to inject harmful payloads or alter the file’s behavior.

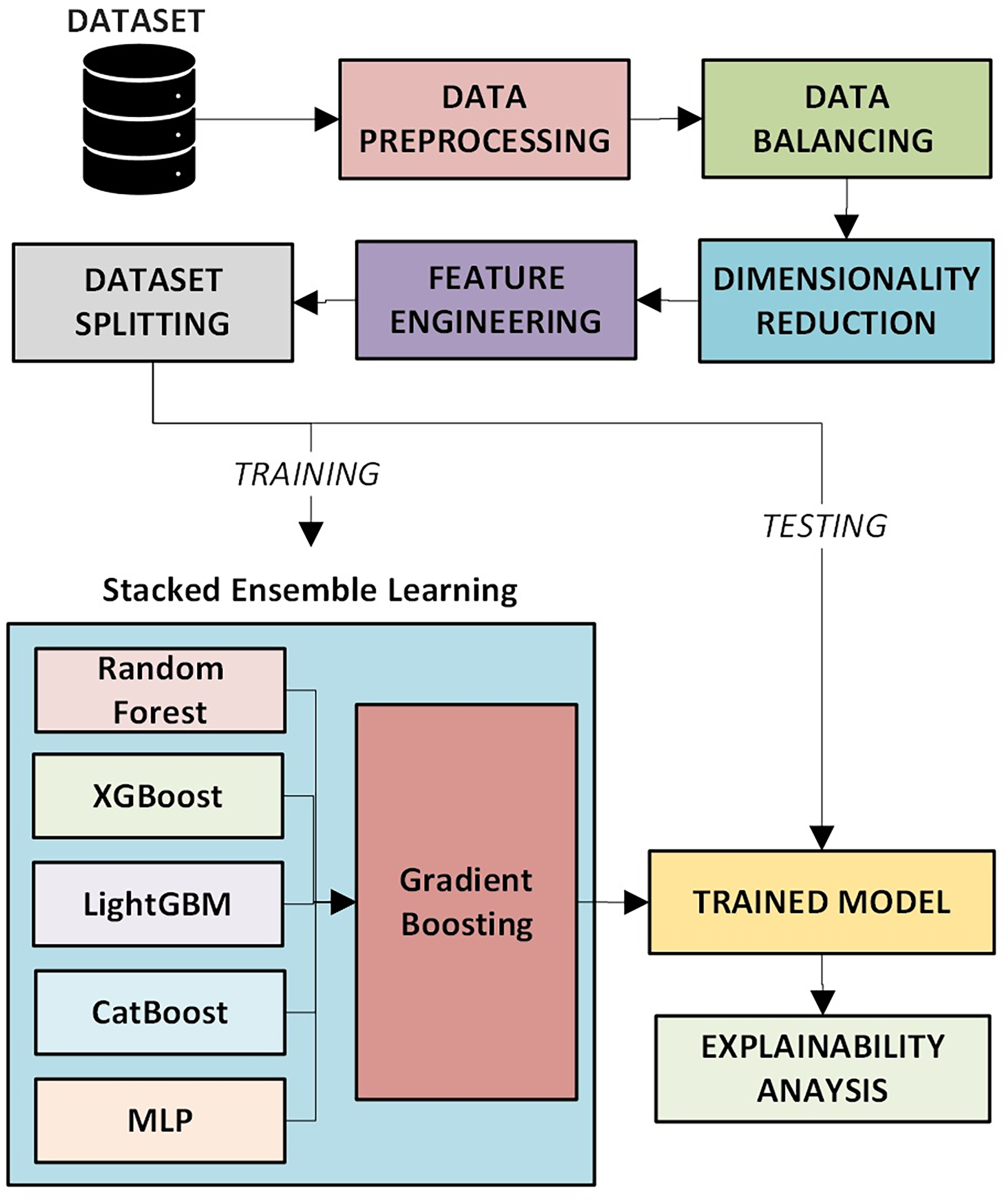

The comprehensive methodology for the proposed PDF malware detection system is depicted in Fig. 2. The workflow consists of several stages, including data pre-processing, feature engineering, model training, and explainability analysis.

Figure 2: Proposed PDF malware detection system

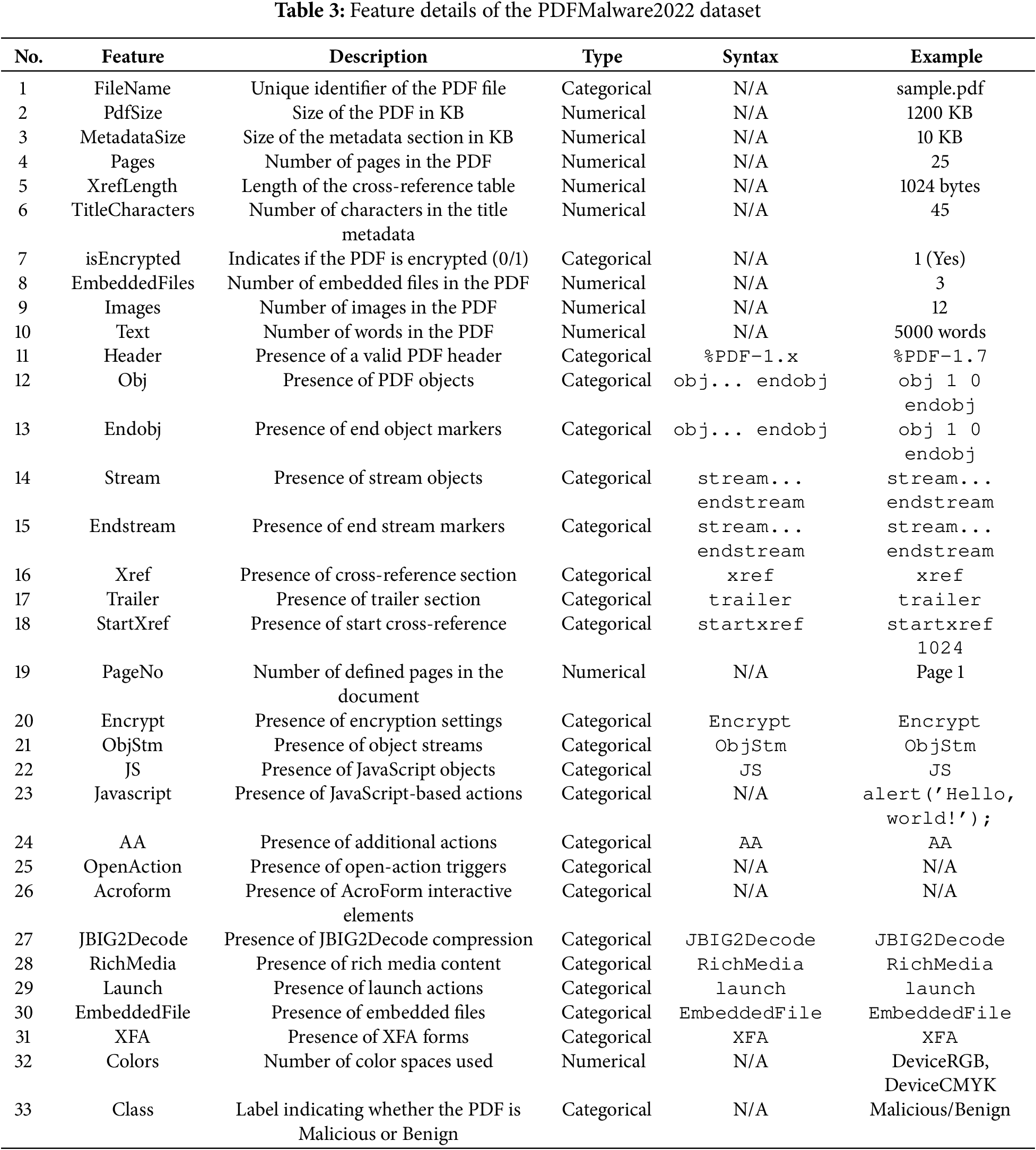

The CIC-Evasive PDFMal2022 dataset, provided by the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security [15], consists of 10,023 PDFs that have been analyzed for structural and content-based features essential for studying malware detection. The dataset includes 33 features that highlight key characteristics, such as file size, metadata attributes, document structure, encryption status, embedded content, and security markers. These features help distinguish between benign and malicious PDFs by identifying potential attack vectors, including JavaScript execution, embedded files, automatic actions, and encryption mechanisms, as illustrated in Table 3. Key structural elements like PdfSize, MetadataSize, Pages, XrefLength, and TitleCharacters define the overall organization and complexity of the document. Security indicators such as isEncrypted, Encrypt, and EmbeddedFiles reveal the methods of encryption and the presence of file attachments, which have been commonly exploited in malicious PDF attacks. Furthermore, content-related features like Images, Text, Stream, and Colours provide insights into embedded objects, while execution-related features, including JS, JavaScript, AA, OpenAction, Launch, and EmbeddedFile, signal potential red flags for exploit mechanisms.

The dataset reveals notable statistical trends, with an average file size of 87.23 KB and a maximum file size of 23,816 KB. Approximately 75% of the documents consist of two pages or fewer, indicating that most malicious PDFs are relatively small. In terms of security-related features, there are significant gaps; for example, the “isEncrypted” attribute is only non-zero in 0.81% of documents, and “EmbeddedFiles” appears in just 2.06% of them. These findings suggest that, although encryption and embedded files can be utilized in certain attacks, they are not commonly employed in this particular sample. Additionally, there is considerable variance in the distribution of features, with many security-related attributes exhibiting a high concentration of zeros. Some features, such as Pages, Colors, and Stream, show moderate correlations, implying that longer documents or those with more content may exhibit patterns associated with potential malware presence.

The dataset contains several missing values, denoted as −1, in various columns related to file properties and security feature attributes. Addressing these missing values is essential for effective model training and analysis. Certain features demonstrate significant correlations; for instance, there is a strong correlation between MetadataSize and TitleCharacters, with a coefficient of 0.865. Additionally, the variable isEncrypted shows a moderate correlation with Encrypt (0.371) and EmbeddedFiles (0.282). This suggests that encrypted PDFs are more likely to contain embedded files, which may indicate targeted document encryption attacks. The PDFMalware2022 dataset serves as a valuable resource for detecting PDF malware using machine learning. Its diverse range of structural, security, and content-based features enables the development of both anomaly detection models and classification methods to identify potentially malicious PDFs. Utilizing this dataset, security researchers and data scientists can create enhanced machine learning models that are capable of identifying threats beyond traditional signature-based methods.

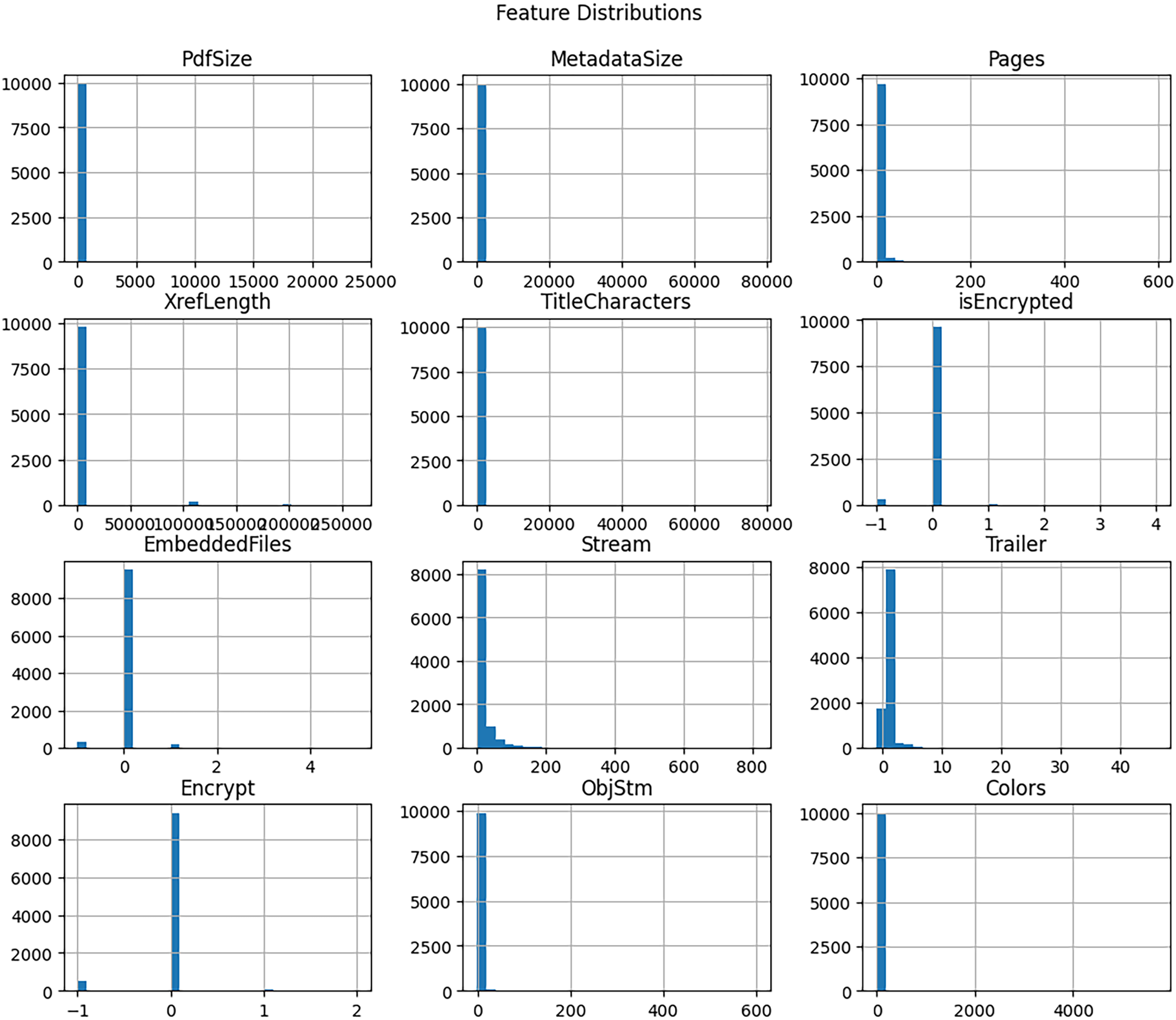

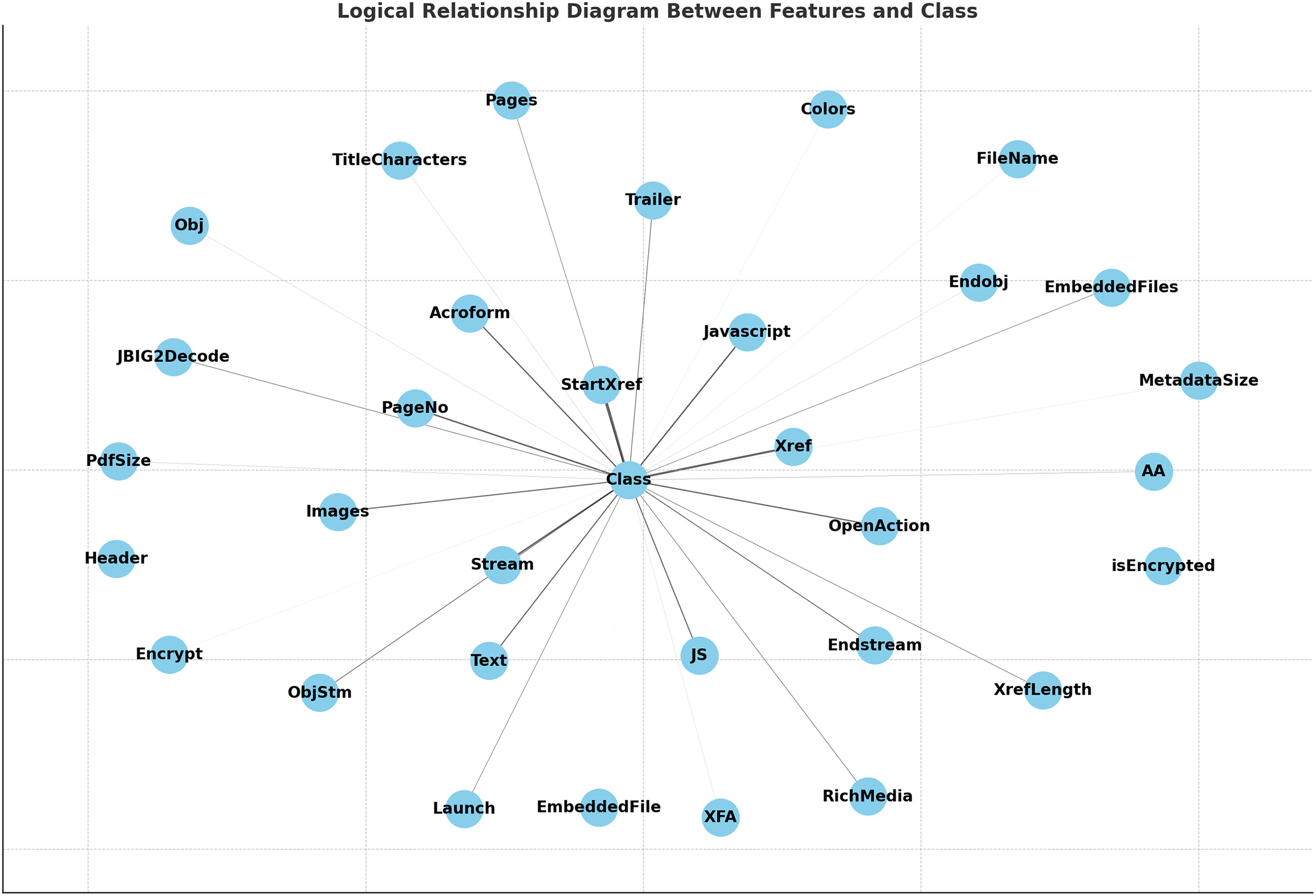

Fig. 3 shows the relationships between different features in the analysis of PDF malware. It reveals that most features have sparse distributions and limited linear correlations, indicating the challenges of identifying malicious PDFs based solely on basic file characteristics. Notably, the clustering of data points near the origin for attributes like PdfSize, MetadataSize, and Pages suggests that benign PDFs usually have smaller file sizes, less metadata, and fewer pages. In contrast, outliers with much larger values may indicate unusual or malicious files, particularly noticeable in the XrefLength and TitleCharacters dimensions. These anomalies indicate potential exploitation strategies, like metadata inflation or cross-reference table manipulation, commonly employed in PDF malware to conceal malicious payloads. The lack of robust linear dependencies underscores the necessity for sophisticated detection techniques, like ML models, to detect fine-grained malicious patterns in sophisticated datasets successfully.

Figure 3: Distribution of features using Pairplot

Fig. 4 offers valuable insights into the structural features of PDF files in the context of malware detection. The distributions indicate that most benign PDFs are small in size, contain minimal metadata, and have a limited number of pages, with values clustered around the origin. However, the XrefLength and TitleCharacters exhibit outlier values, suggesting possible malicious tampering, as attackers often inflate these attributes to disguise harmful payloads. The low frequency of EmbeddedFiles, Encrypt, and the isEncrypted attribute suggests that embedded objects and encryption are uncommon in standard documents; however, their presence may indicate malware in PDFs. Furthermore, the uneven distributions in Stream and ObjStm highlight the complexity of stream objects, which are frequently exploited in malicious PDFs to insert scripts or obfuscate harmful code. This information underscores the importance of employing anomaly detection and machine learning models that can identify subtle yet significant deviations from typical PDF structures, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of malware detection systems.

Figure 4: PDF Feature distribution count

The logical relationship of features, as shown in Fig. 5, illustrates the structural dependencies among key PDF features and their link to the class label (malicious or benign). This diagram shows that features such as StartXref, Xref, Stream, and JavaScript have the strongest ties to the class label, highlighting their crucial role in identifying malicious PDFs. Interestingly, JavaScript and OpenAction are positively associated with malware, pointing to the use of embedded scripts and auto-triggered actions that are often exploited to execute harmful payloads. In contrast, features like StartXref and Xref demonstrate a strong negative correlation, indicating their predictable patterns in benign PDFs and potential manipulation in malicious ones. Features with weaker connections, such as MetadataSize, PdfSize, and Encrypt, suggest less significant but still relevant associations, often used in more sophisticated malware for obfuscation.

Figure 5: Logical relationship between input features and class label

3.2 Data Preprocessing and Balancing

Data preprocessing is a crucial step in ensuring high-quality input for machine learning models, particularly in PDF malware detection. Techniques such as label encoding and dataset balancing are utilized in the preprocessing pipeline to enhance classification performance and prevent bias towards the majority class.

The Label Encoding shown in Algorithm 1 for the PDF Malware Dataset transforms categorical class labels (“benign” and “malicious”) into numerical representations (0 and 1, respectively) to enhance the training of machine learning models. The process commences with the initialization of an empty dictionary (‘label_map’) to retain the label mappings. The algorithm traverses the distinct class labels in the dataset’s label column (L) and designates 0 to benign samples and 1 to malicious samples, thereby establishing a systematic representation for classification tasks. The initial labels in the dataset are subsequently substituted with their respective encoded values, resulting in a new numerical label column (L’). This transformation is essential for allowing machine learning models to efficiently process and understand categorical labels, thus enhancing model performance, computational speed, and compatibility with diverse algorithms, including tree-based models, neural networks, and ensemble methods. The label encoding transformation is represented mathematically as:

where

3.2.2 Data Balancing Using Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE)

The most popular dataset balancing technique for PDF malware is the SMOTE algorithm, which is presented in Algorithm 1.

Mathematically, the synthetic samples generated by SMOTE are as follows:

where

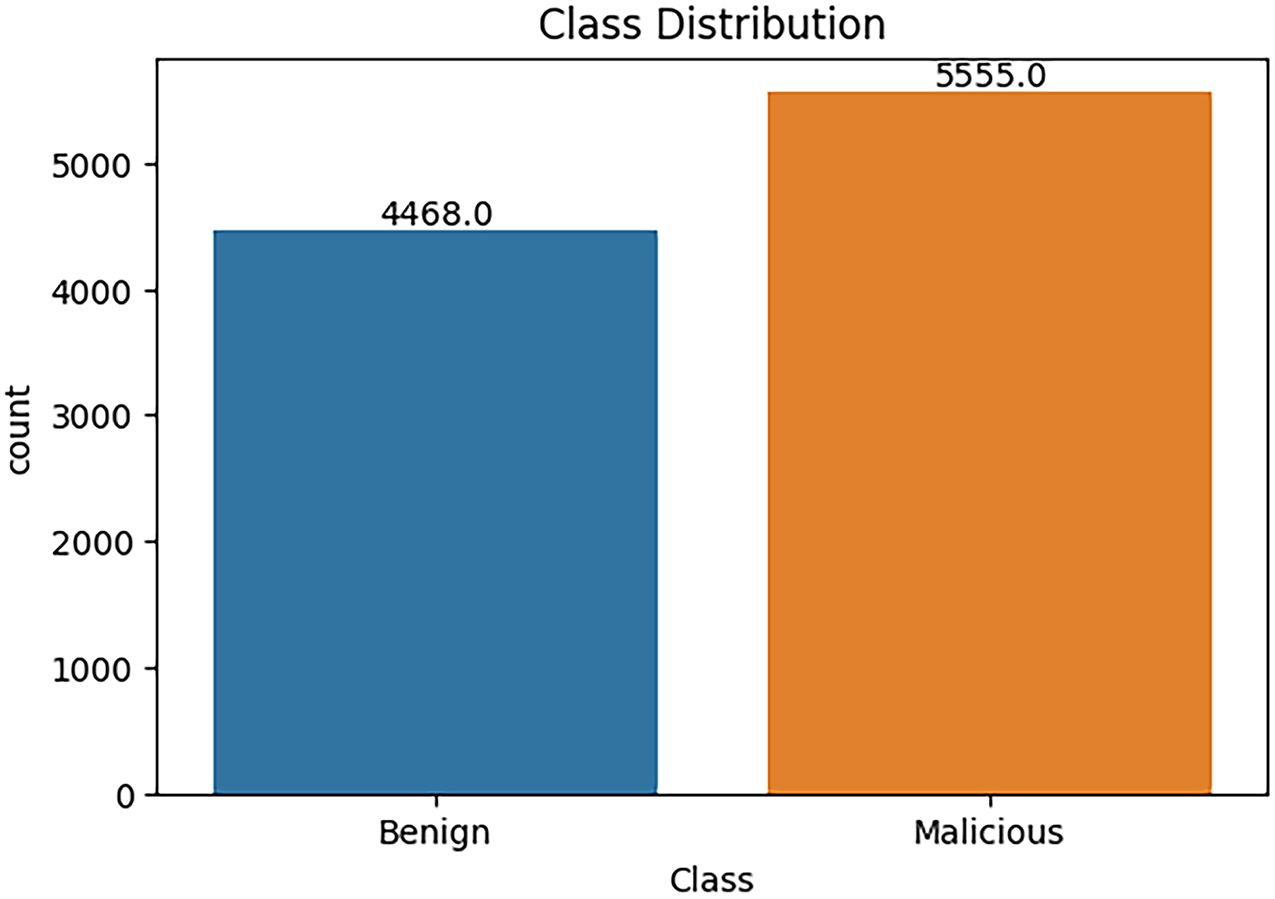

To address class imbalance in the dataset and enhance the model’s ability to identify malicious PDFs, synthetic examples are created for the minority class. The initial step involves locating occurrences of the minority class in the training data. Next, the k-nearest neighbors are identified using relevant PDF attributes such as PdfSize, MetadataSize, and XrefLength. A difference vector is calculated between each minority occurrence and a randomly chosen neighbor. A random scaling factor, denoted as

Figure 6: Class distribution before SMOTE balancing

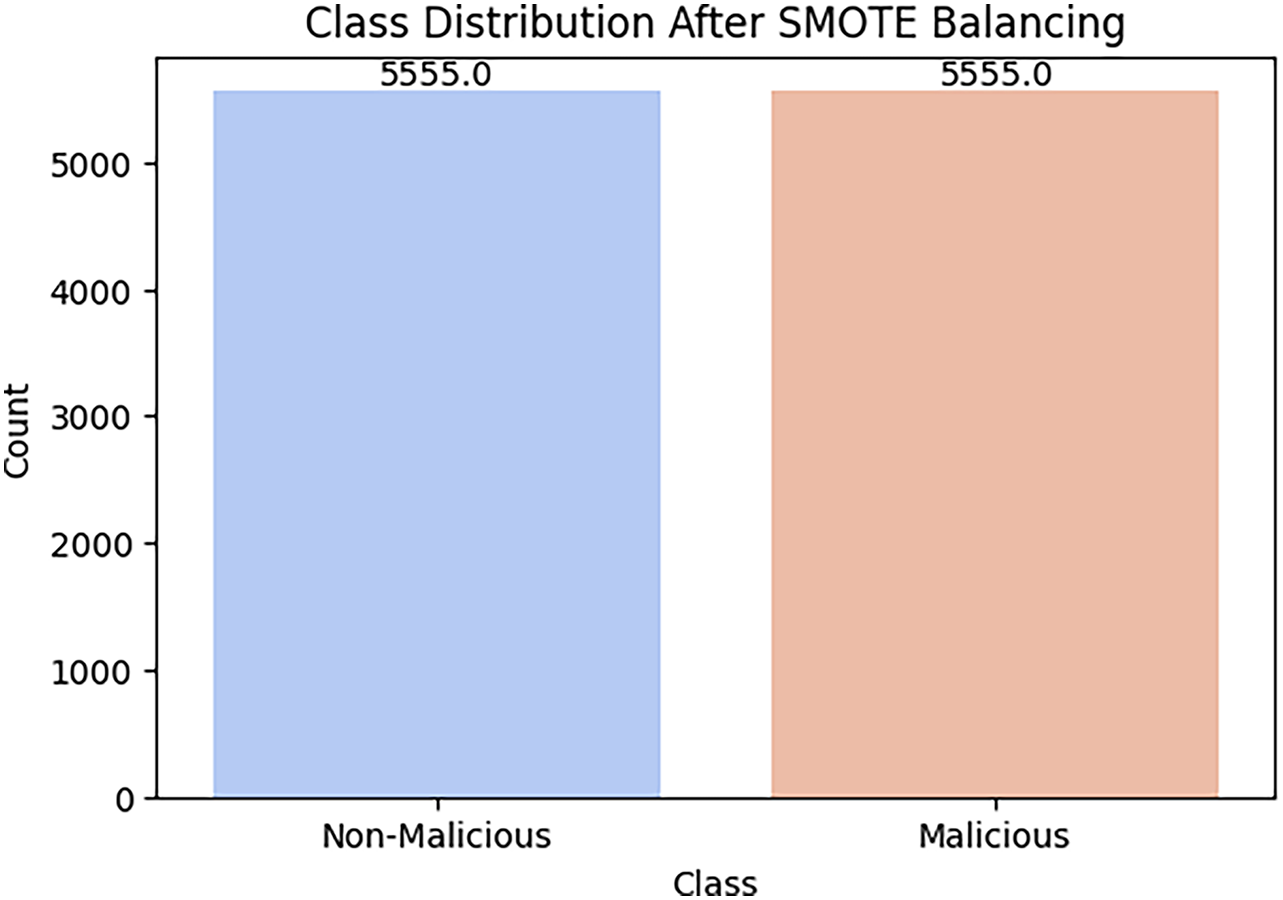

Figure 7: Class distribution After SMOTE balancing

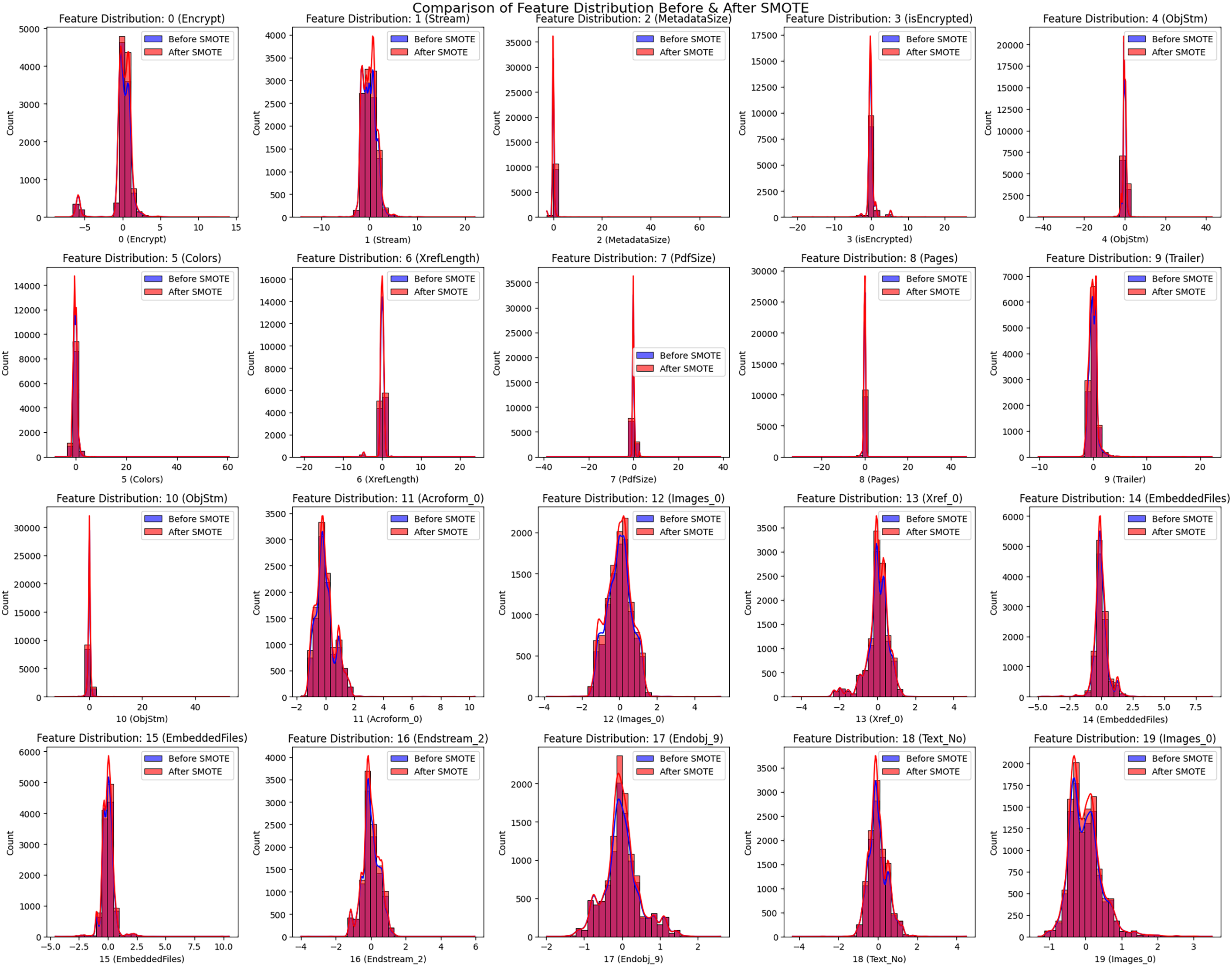

As seen in Fig. 8, the feature distribution comparison before and after employing SMOTE demonstrates how it affects class balance for PDF malware detection. The distributions verify that SMOTE successfully reduces data sparsity in essential features like Encrypt, Stream, and MetadataSize—all of which are commonly associated with malicious PDFs—by increasing the minority class. After applying SMOTE, the distributions show more excellent uniformity, particularly in features like ObjStm, XrefLength, and EmbeddedFiles, which are frequently used for obfuscation in malware. While SMOTE improves the representation of rare but essential patterns, it also preserves the structural integrity of benign PDF characteristics, helping to avoid overfitting. Nonetheless, slight changes in feature densities, particularly in high-variance attributes like Colors and Endstream_2, highlight the need for caution regarding synthetic data artifacts.

Figure 8: Comparison of feature distribution before & after SMOTE

The feature distribution comparison before and after applying SMOTE, as illustrated in Fig. 8, highlights its impact on class balance for PDF malware detection. The distributions confirm that SMOTE effectively reduces data sparsity in key features such as Encrypt, Stream, and MetadataSize, which are often linked to malicious PDFs, by increasing the representation of the minority class. These pre-processing steps significantly enhance the model’s ability to generalize across diverse classes, reduce bias against the majority class, and improve classification performance. By converting categorical labels into numerical values and employing SMOTE, the data becomes well-suited for training robust machine learning models for PDF malware classification. After applying SMOTE, the distributions exhibit greater uniformity, especially in features like ObjStm, XrefLength, and EmbeddedFiles, which are frequently exploited for obfuscation in malware. While SMOTE enhances the representation of rare yet critical patterns, it also maintains the structural integrity of benign PDF characteristics, helping to prevent overfitting. However, minor changes in feature densities, particularly in high-variance attributes like Colors and Endstream_2, indicate the need for caution regarding potential synthetic data artifacts. These pre-processing steps significantly enhance the model’s ability to generalize across diverse classes, reduce bias against the majority class, and improve classification performance. By converting categorical labels into numerical values and employing SMOTE, the data becomes well-suited for training robust machine learning models for PDF malware classification.

3.3 Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Engineering

In improving the detection of PDF malware, selecting the most relevant features is essential for enhancing model performance and interoperability. This section focuses on the impact of dimensionality reduction techniques, particularly PCA, in optimizing the feature set for classification. Additionally, we analyze how class imbalance affects model learning and utilize SMOTE to ensure a balanced representation of both malicious and benign PDFs. We conduct a comparative evaluation of various machine learning models, offering insights into the importance of feature selection in optimizing detection accuracy. By preserving the most informative features for classification, the PCA-based feature selection outlined in Algorithm 1 systematically reduces the dimensionality of the PDF malware dataset. The procedure begins by identifying numerical and categorical features, standardizing the numerical data, and applying one-hot encoding to the categorical elements to ensure compatibility. After calculating the mean vector, covariance matrix, and solving the eigenvalue problem, the preprocessed data is consolidated into a unified matrix using PCA. The top components are selected based on their contribution to cumulative variance, ensuring that the retained components adequately capture the overall variance of the dataset. The explained variance ratio for each principal component is expressed as follows:

where

The comparison of feature distributions before and after applying SMOTE is illustrated in Fig. 8. This comparison highlights how SMOTE affects class balance in PDF malware detection. SMOTE generates synthetic samples using the following formula:

In this equation,

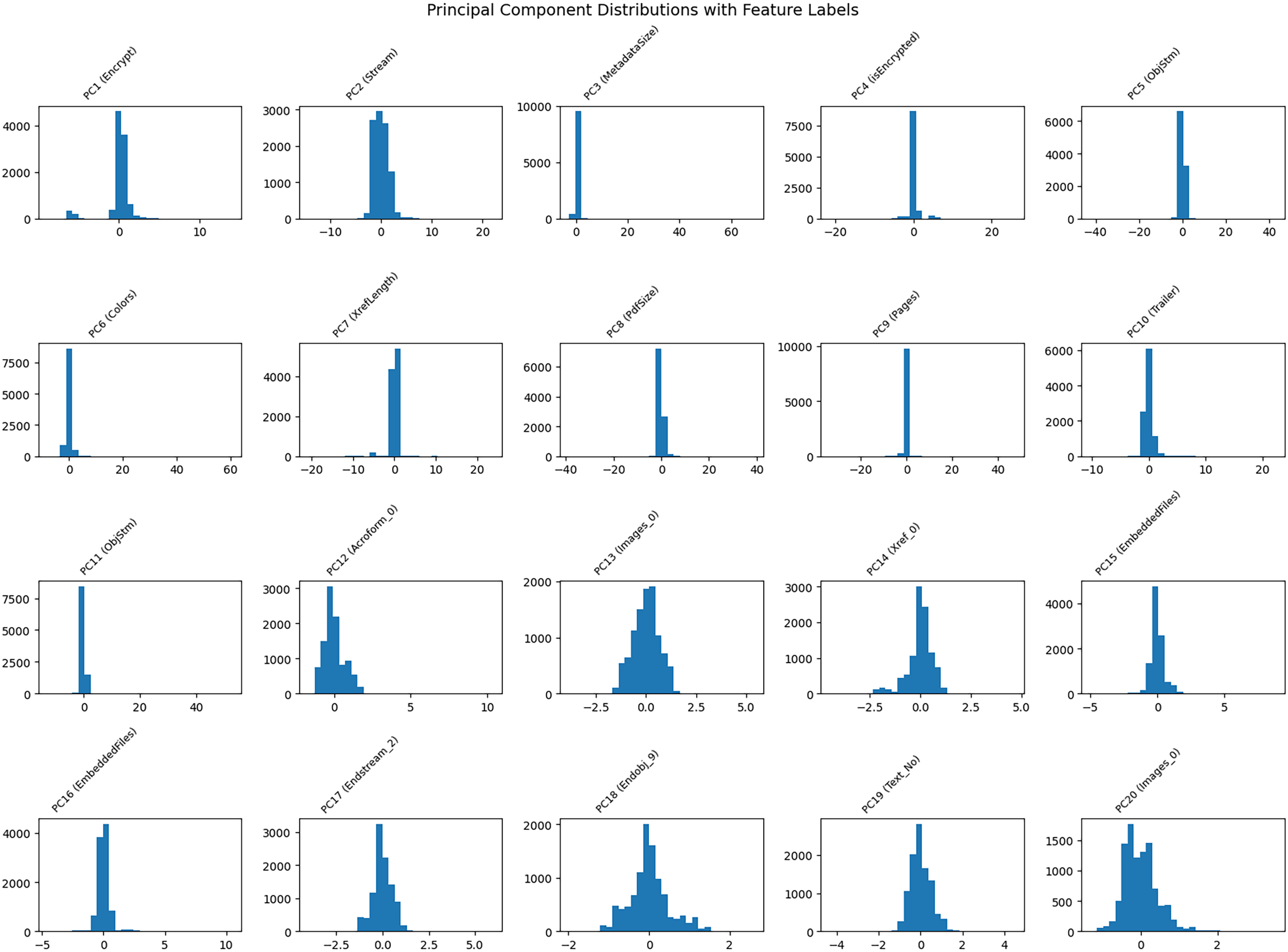

Fig. 9 displays the Principal Component Distributions, which indicate the underlying variance and the influence of features on the classification of PDF malware. While most PDFs exhibit typical structural patterns, anomalies in components like PC3 (MetadataSize), PC5 (ObjStm), and PC7 (XrefLength) may suggest potentially harmful activity, as indicated by the clustering of principal components (PCs) around zero and a few noteworthy outliers. The Mahalanobis distance can quantify anomalies in principal component space:

where

where

Figure 9: Principal component distributions with feature labels

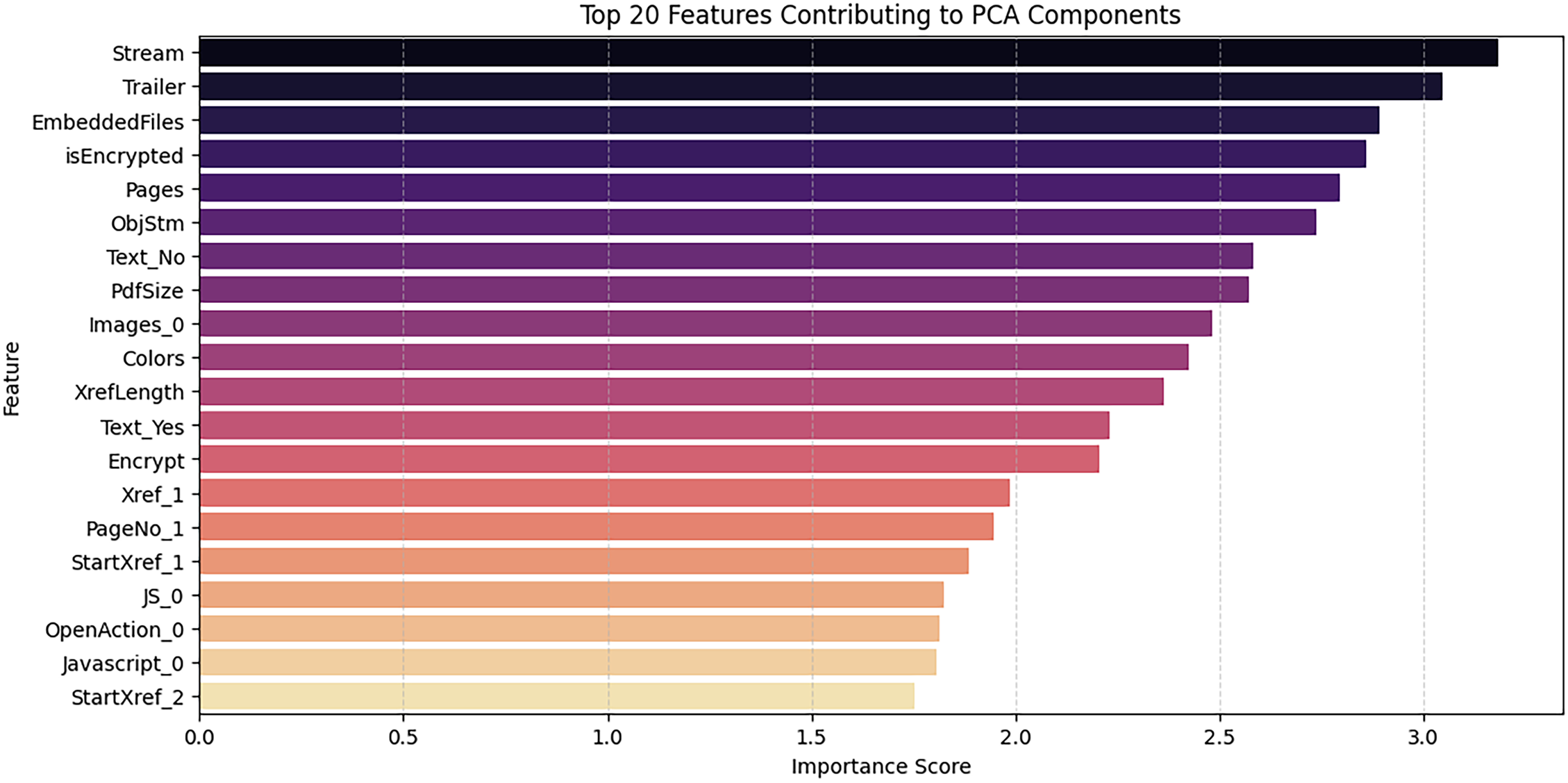

The ranking of feature importance for PCA components highlights key attributes that impact PDF malware detection, as shown in Fig. 10. The analysis identifies Stream, Trailer, and EmbeddedFiles as the primary contributors, indicating their everyday use in malicious PDFs to embed harmful scripts or payloads. The importance of isEncrypted and Pages suggests that encryption and unusual page counts are frequent signs of obfuscation tactics employed by attackers. Additionally, structural features such as ObjStm, PdfSize, and XrefLength also score highly, illustrating how malicious actors manipulate object streams and cross-reference tables to hide harmful content. The presence of Text_No and Text_Yes indicates the significance of textual elements in distinguishing between benign and malicious files. At the same time, attributes like JavaScript_0 and OpenAction_0 directly relate to embedded scripts and automated actions, which are typical vectors for exploits.

Figure 10: Top 20 features contributing to PCA components

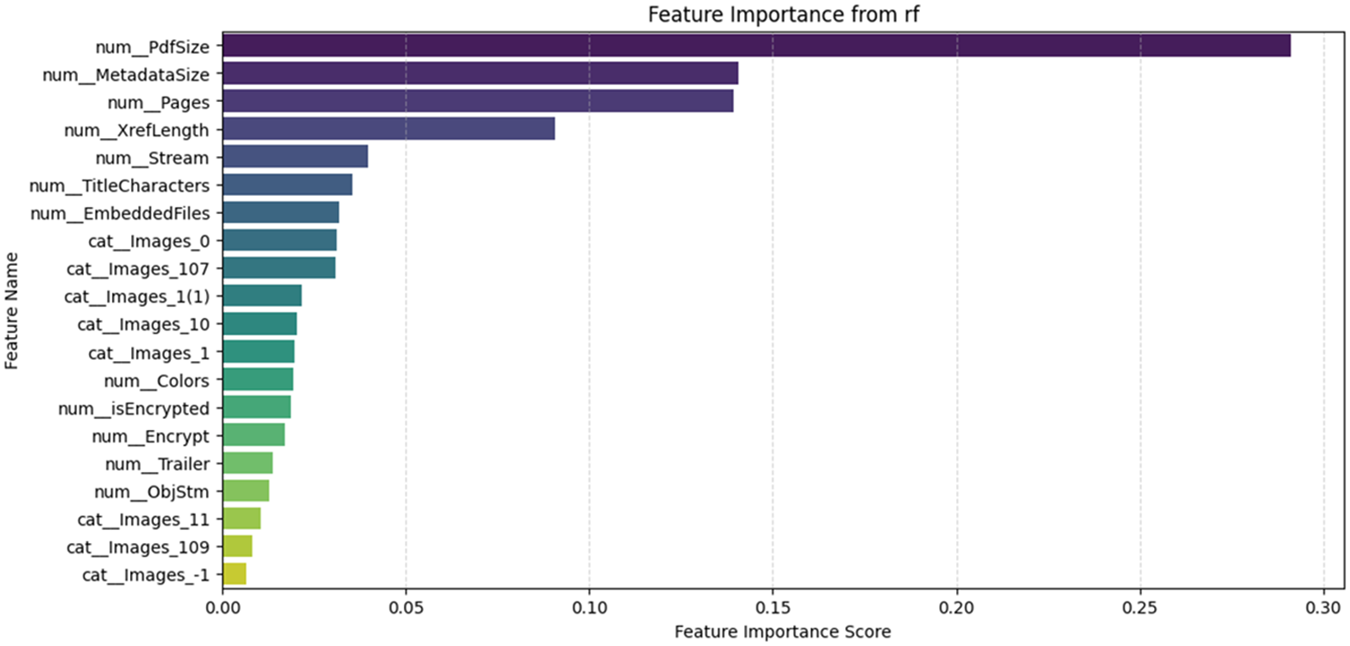

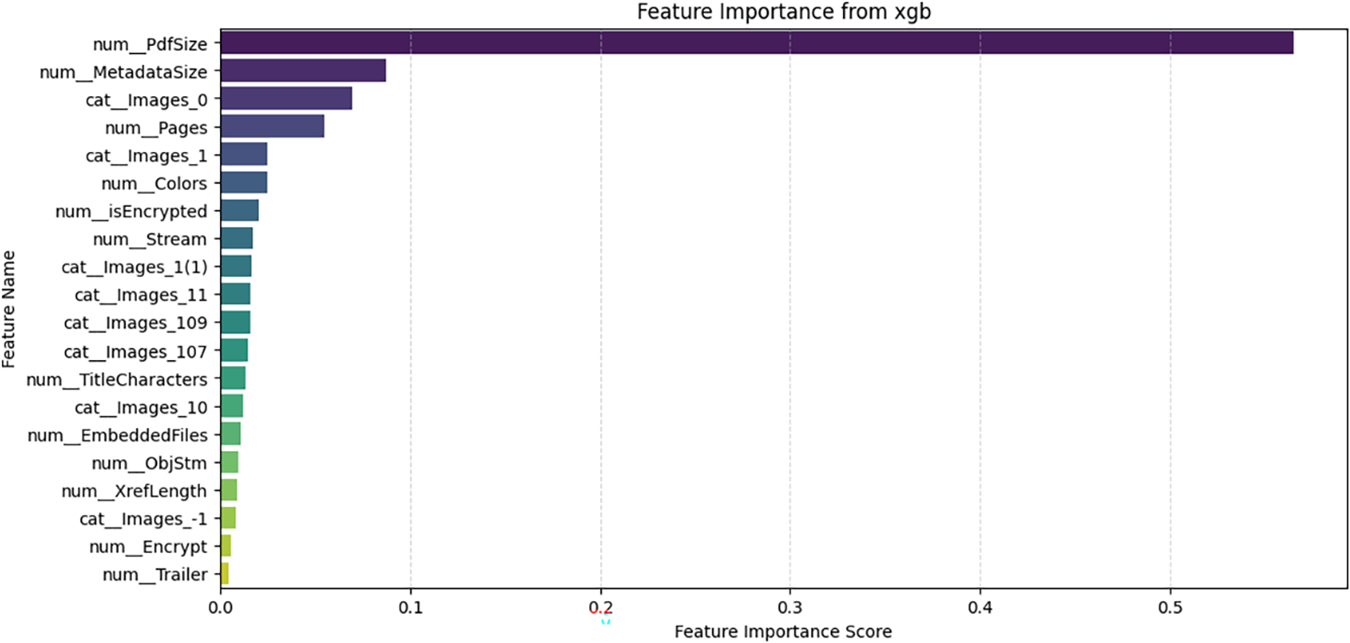

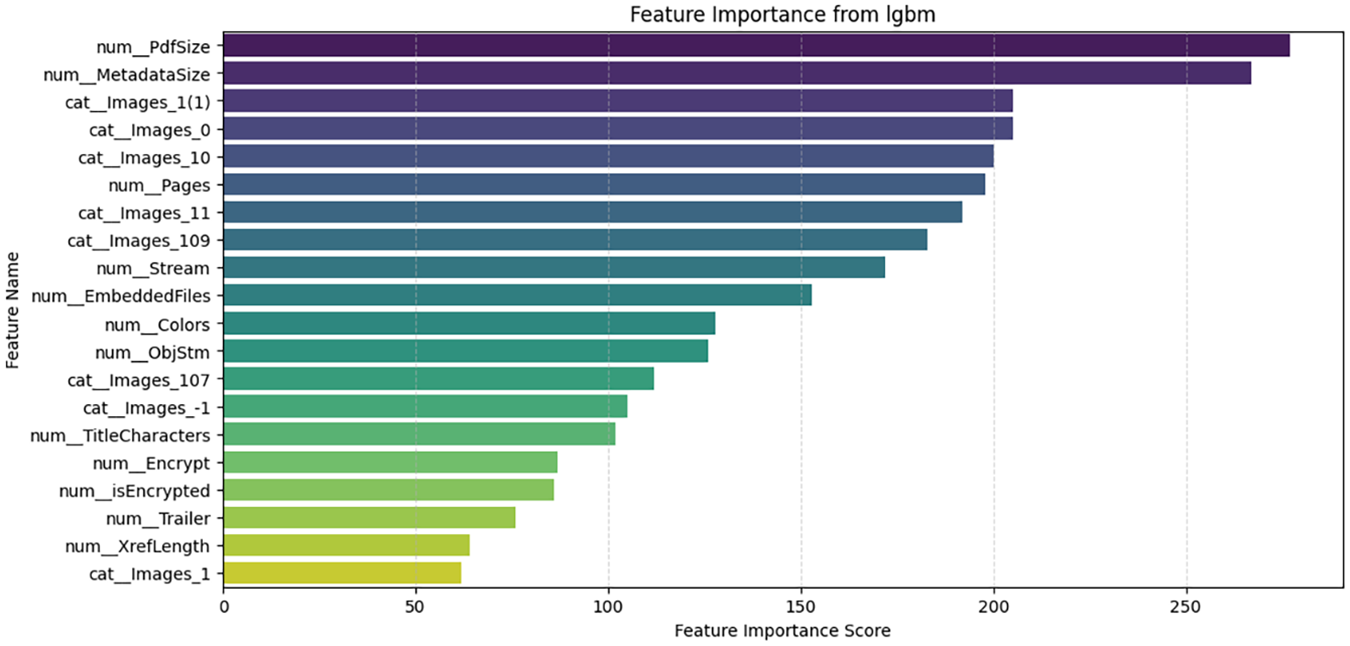

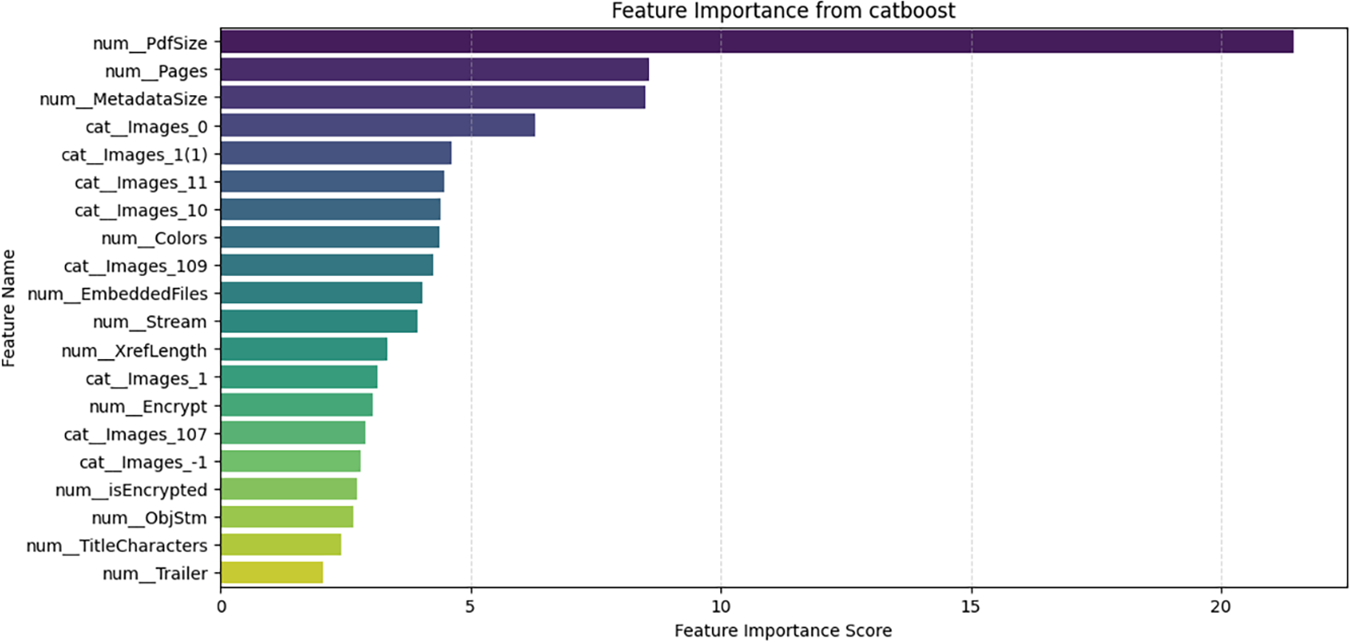

The feature importance analysis presented in Figs. 11–14 highlights that across different models—Random Forest, XGBoost, LGBM, and CatBoost—PdfSize is identified as the most significant factor in detecting PDF malware. This indicates that unusually large or small file sizes often signal malicious intentions, potentially through concealed payloads or obfuscation techniques. In tree-based ensemble methods such as Random Forest, feature importance is calculated using the following formula:

Figure 11: Important features in random forest model

Figure 12: Important features in XGboost model

Figure 13: Important features in LGB model

Figure 14: Important features in Catboost model

In this equation,

The variation in file sizes of PDF documents is a key factor in distinguishing between malicious and harmless files during malware identification. The anomaly score for PDF sizes can be expressed as follows:

In this equation,

3.4 Stacked Ensemble Learning Model

Stacking ensemble learning is an advanced machine learning technique that enhances classification performance by combining multiple base models and a meta-learner. This stacking framework integrates various learning algorithms to capture diverse feature representations, ultimately improving detection accuracy. In the context of PDF malware classification, as illustrated in Algorithm 1, the process begins with an 80-20 split of the data into training and testing sets, ensuring a balanced evaluation. The basic learners include RF, XGB, LightGBM, CB, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). Each of these models is instantiated with distinct learning strategies to maintain diverse feature representations. Specifically, RF utilizes Gini impurity, XGB incorporates regularization to minimize loss, LightGBM optimizes one-sided sampling, CB leverages ordered boosting, and MLP employs ReLU activation. Each base learner is trained independently. The predictions from these models are then fed into a Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC) meta-learner, which combines them to enhance classification accuracy. To ensure the model’s generalizability, the stacking classifier is evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation after optimizing to minimize the overall loss function. The mean accuracy is calculated to assess performance. Finally, to maximize malware detection effectiveness while maintaining computational efficiency, the trained model predicts class labels for new data. This ensemble learning approach offers a reliable and scalable solution for detecting PDF viruses, as it improves detection precision, reduces false positives and negatives, and outperforms single classifiers.

Random Forest is an ensemble learning algorithm that trains multiple decision trees during the training process and outputs the majority vote (classification) from these individual trees. It is particularly effective for handling high-dimensional data and reducing the risk of overfitting by averaging the predictions from multiple trees. In Random Forest, N decision trees are trained, and the final prediction is made through majority voting, represented by the following equation:

In this equation,

3.4.2 Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB)

XGBoost is a boosting framework designed for gradient boosting, optimized for both efficiency and accuracy. It sequentially adds weak learners to correct previous mistakes, thereby minimizing loss functions effectively. In comparison to Random Forest (RF), XGBoost demonstrated superior performance in terms of precision and recall. It handled imbalanced data well and exhibited better generalization capabilities.

LightGBM is a fast and memory-efficient gradient boosting algorithm. It utilizes histogram-based learning to accelerate computation. Unlike traditional methods that perform tree splits depth-wise, LightGBM splits trees leaf-wise, which maximizes loss reduction at each iteration. The formula for loss reduction is as follows:

In this equation, G represents the first-order gradients, and H represents the second-order gradients. LightGBM is efficient in its computations and achieves high accuracy while reducing training time.

CatBoost is specifically designed for processing categorical features. It utilizes ordered boosting to address the issues of overfitting and minimizes target leakage. This approach adapts gradient boosting by incorporating a permutation-based ordering of the data. The model can be represented by the following equation:

where

3.4.5 Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

A Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a type of neural network architecture that can learn complex patterns within data. It consists of multiple hidden layers that use nonlinear activation functions. Each neuron in the network calculates a weighted sum of its inputs, followed by the application of an activation function. The output of a neuron can be represented mathematically as:

In this equation,

3.4.6 Stacking and Performance Improvement

We implemented an ensemble approach by stacking the combined predictions from several models: RF, XGB, LGBM, CB, and MLP. A GBC was used as the meta-learner. This approach helped to minimize the weaknesses of individual models and improve overall generalization. The final prediction is generated by the meta-learner, as shown in the following equation:

where

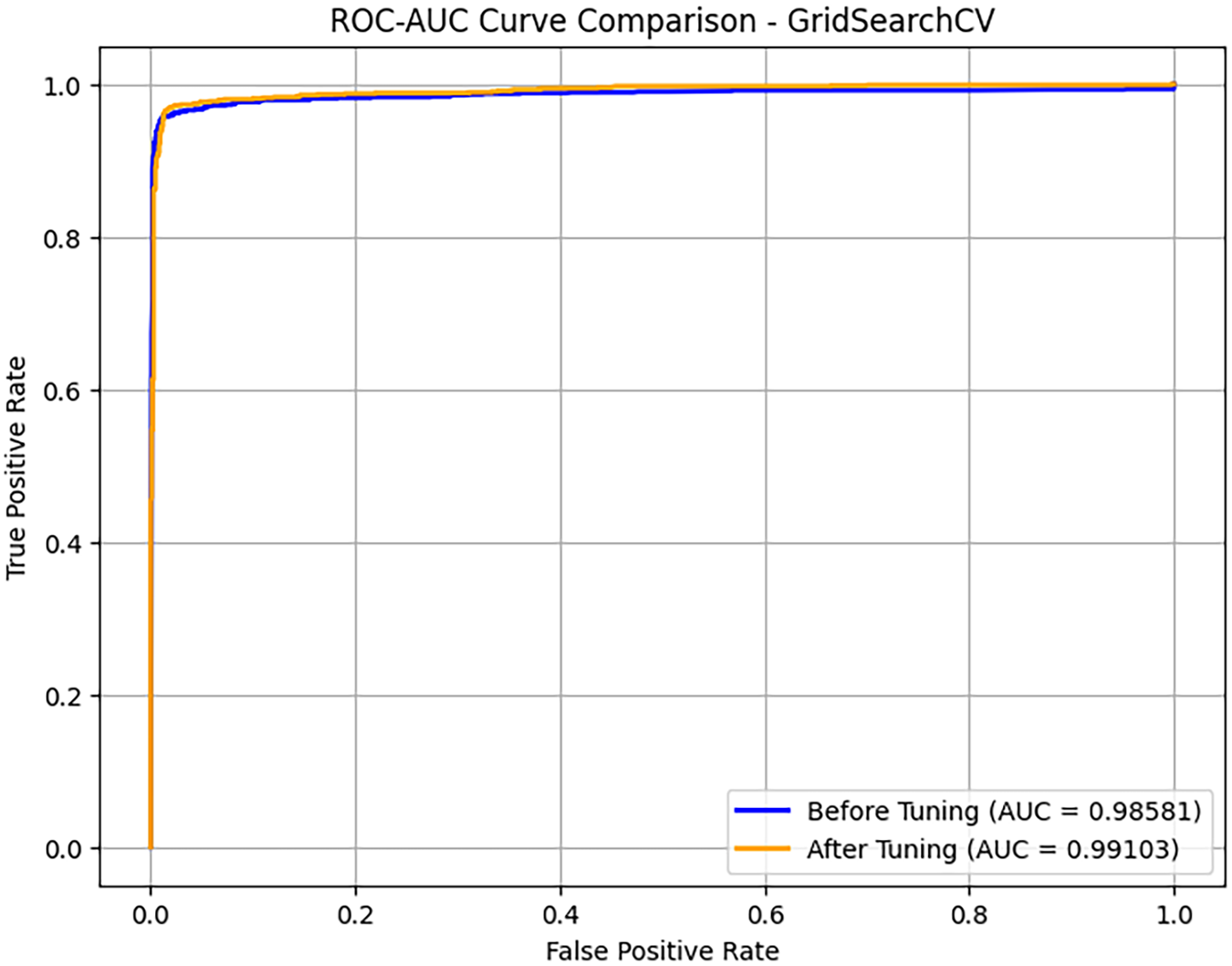

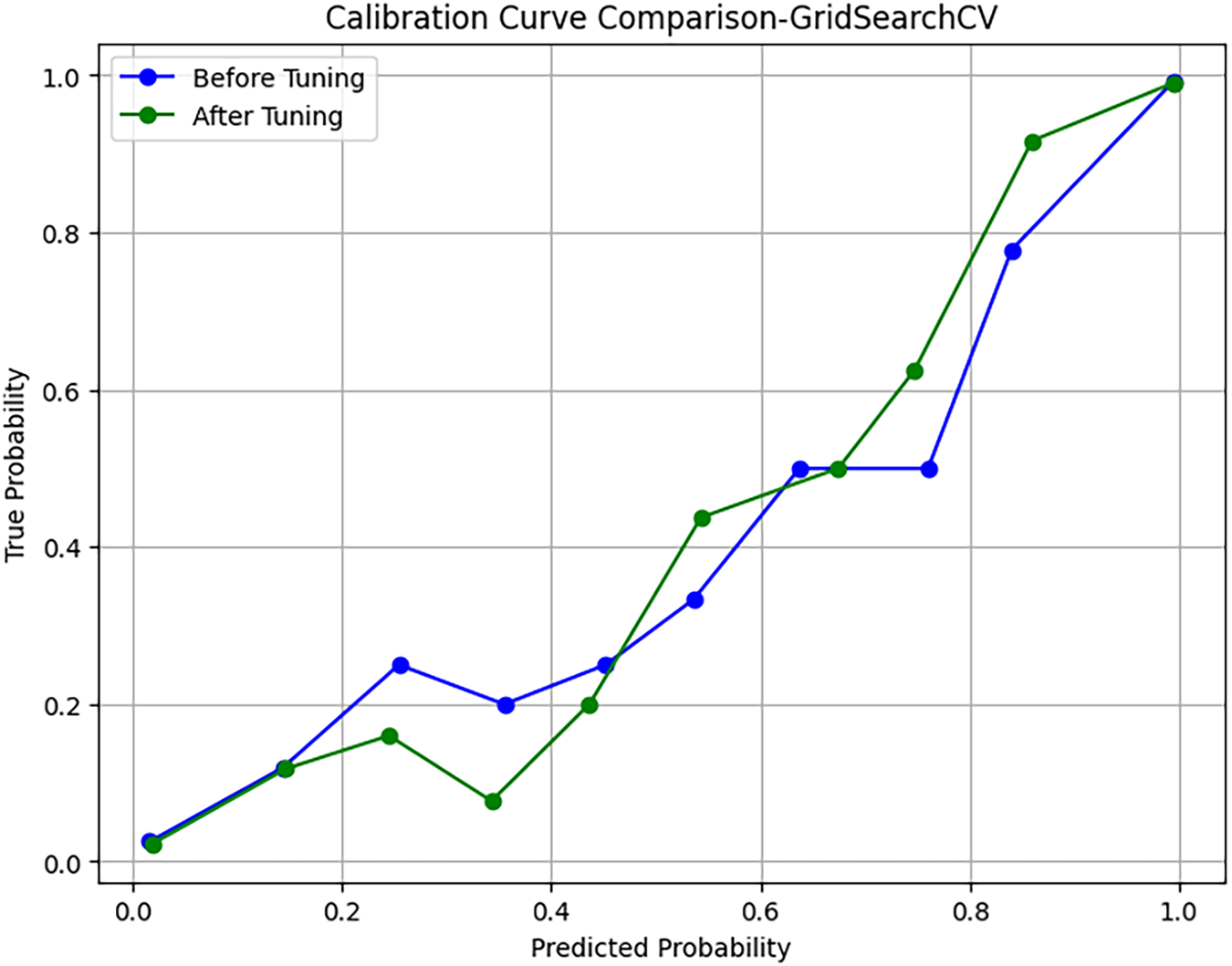

3.5 Experiment and Explainability Analysis

This study uses an experimental setting to provide rigorous, reproducible, and practically applicable results for detecting PDF viruses. The research utilizes the PDFMalware2022 dataset, which includes 33 static attributes related to embedded objects, JavaScript behavior, and metadata. The preprocessing phase involved data cleaning, feature extraction, PCA-based dimensionality reduction, and the application of SMOTE to address class balance. The model was trained on a high-performance computing facility equipped with a 16-core Intel Xeon CPU, 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA A100 GPU. The development utilized Python 3.8 along with libraries such as PyTorch, Scikit-Learn, and boosting libraries including XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost. To optimize the stacked ensemble learning architecture—which incorporates RF, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost as base learners, and GBC as the meta-learner—GridSearchCV and 5-fold cross-validation were employed. Evaluation metrics demonstrated the model’s strong classification capabilities, achieving an accuracy of 97.10%, precision of 97.69%, recall of 97.09%, an F1-score of 97.39%, and AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) and AUC-PR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve) scores indicative of exceptional performance. Confusion matrix analysis aimed at minimizing Type I and Type II errors revealed the model’s effectiveness in accurately identifying 1091 benign PDFs with only 14 false positives and 1108 malicious PDFs with just 9 false negatives. Feature importance analysis identified PdfSize, MetadataSize, XrefLength, and Stream as the most significant features, underscoring common evasion tactics employed in malicious PDFs. After hyperparameter tuning, the ROC-AUC curve comparison showed minimal variance, suggesting that the initial configuration was optimal, with scores ranging from 0.97100 to 0.96797. Additionally, the PR curve yielded a notable AUC-PR score of 0.97092, further demonstrating the model’s robustness against class imbalance.

where

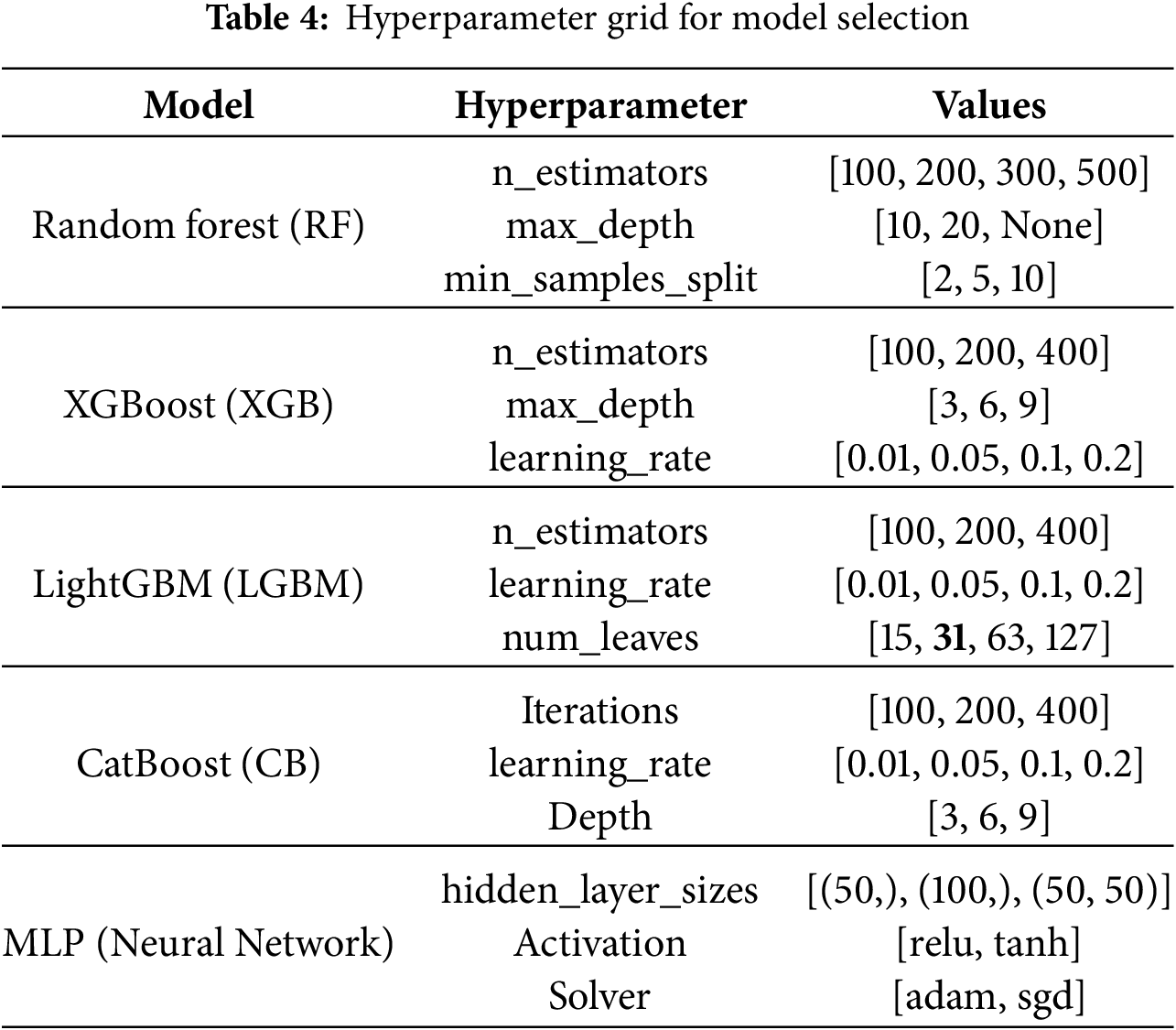

For many ML models used in PDF malware detection, the hyperparameter grid outlined in Table 4 provides an organized method for fine-tuning parameters. Each model’s hyperparameters are adjusted to balance overfitting and generalization, thereby enhancing classification performance. The RF model explores tree depth and the number of estimators to improve decision boundary learning. In contrast, XGB and LightGBM tackle complex decision surfaces by applying gradient boosting with varying learning rates, tree depths, and boosting iterations. CatBoost, which is specifically designed for categorical data, optimizes depth and learning rates to achieve the fastest convergence. Meanwhile, the MLP refines solvers and activation functions to enhance feature abstraction. This structural tuning not only improves the model’s interpretability, accuracy, and robustness against adversarial attacks, but it also strengthens the stacked ensemble learning approach, contributing to effective detection of malicious PDFs. Initially, the evaluation was limited to the CIC-Evasive PDFMal2022 dataset and did not include other widely used datasets, such as Contagio. This restriction hindered the assessment of the model’s adaptability. To address this gap, additional experiments were conducted using the enhanced Contagio dataset [25] within the same experimental framework. This allowed for a more thorough evaluation of the proposed model’s performance across diverse data distributions.

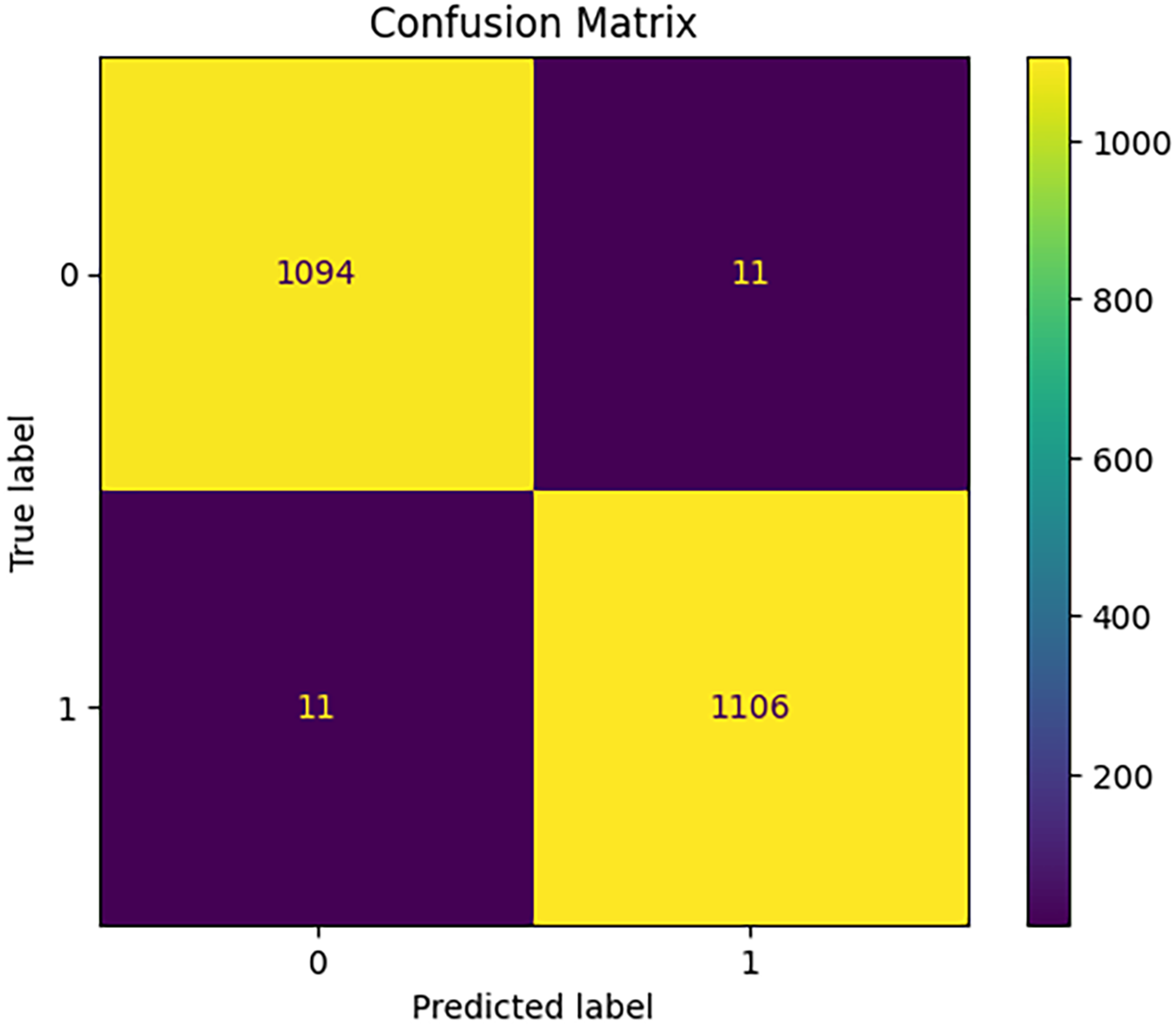

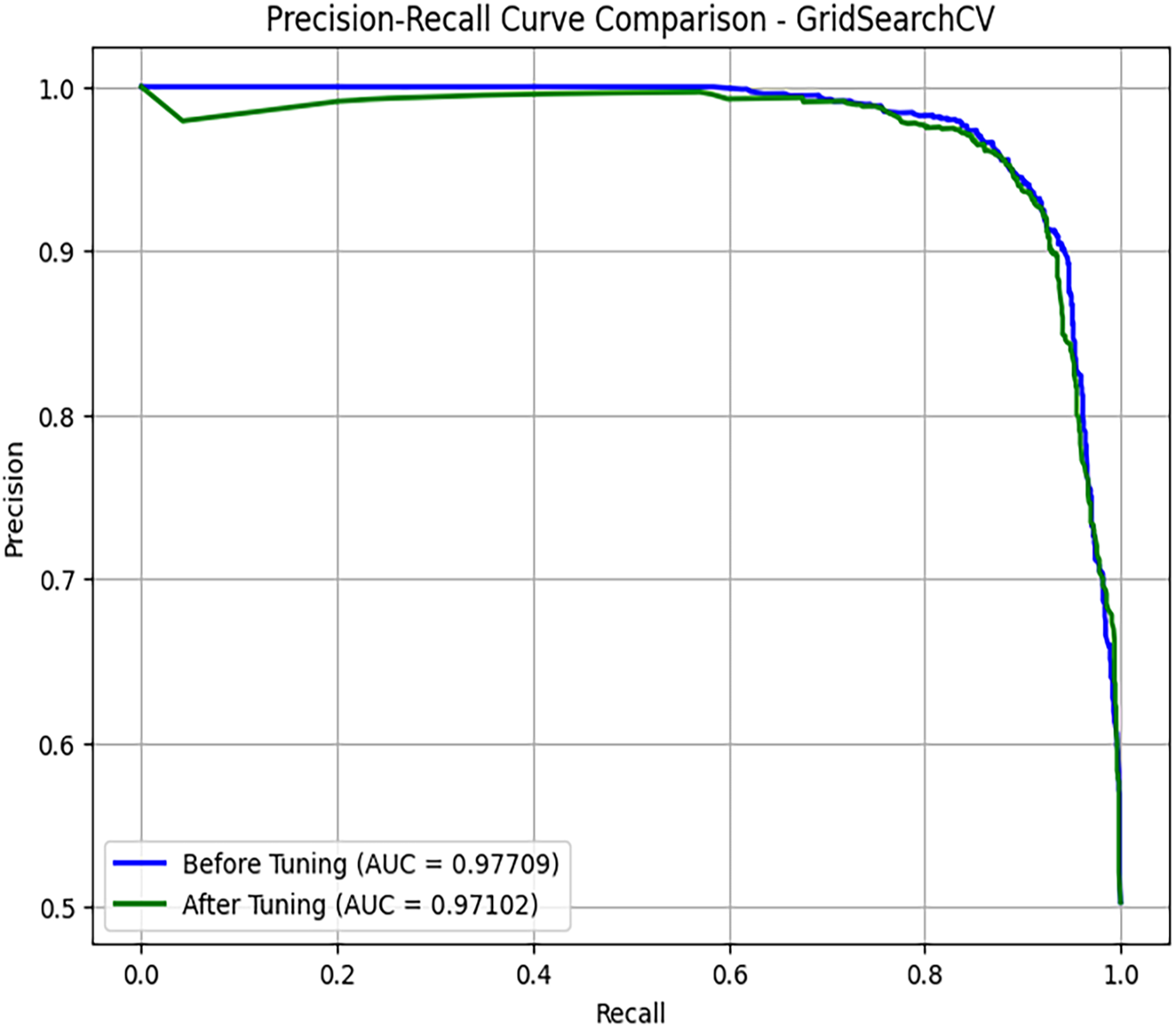

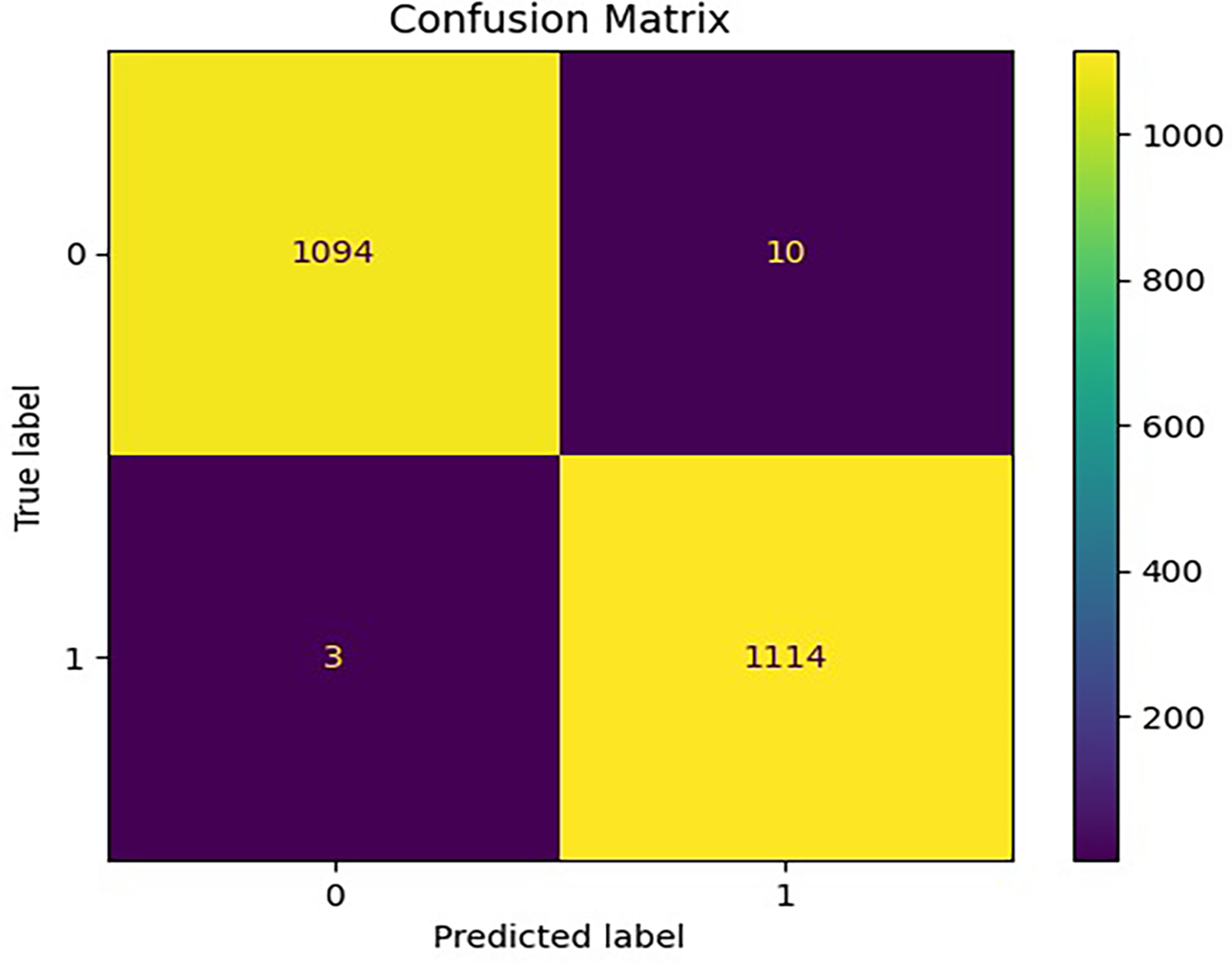

Parameter Selection Justification: A grid search was conducted to identify the optimal hyperparameters for the LightGBM model, specifically with num_leaves values of 15, 31, and 63, and learning_rate values of 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2. The results showed that the combination of num_leaves = 31 and learning_rate = 0.1 consistently achieved the highest validation accuracy and F1-score. This configuration also maintained stable convergence and avoided overfitting. The balance between predictive performance and generalization capability led to the selection of these values as the optimal configuration for LightGBM in our experiments. The confusion matrix for identifying PDF malware through stacked ensemble learning demonstrates strong classification accuracy, highlighting the model’s ability to distinguish between benign and malicious PDFs, as illustrated in Fig. 15. The model correctly identified 1091 benign PDFs with only 14 false positives and classified 1108 malicious PDFs with a maximum of 9 false negatives. These results illustrate the effectiveness of the stacked ensemble method in reducing Type I and Type II errors, leading to accurate virus detection. The low rate of misclassification indicates the model’s reliability, making it a viable solution for real-world cybersecurity challenges in PDF-based threat detection. Maintaining good classification performance, the PR curve indicates that the model performs well in terms of precision at all levels of recall, as shown in Fig. 16. Before hyperparameter tuning, the AUC-PR was 0.97654; it slightly decreased to 0.97092 after adjustment. This suggests that the changes in hyperparameters did not result in significant improvements and may have even slightly reduced the model’s effectiveness in managing class imbalances. The minor variation indicates that the initial configuration was already optimal for detecting PDF viruses.

Figure 15: Confusion Matrix-CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022

Figure 16: Precision-recall curve comparison-GridSearchCV-CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022

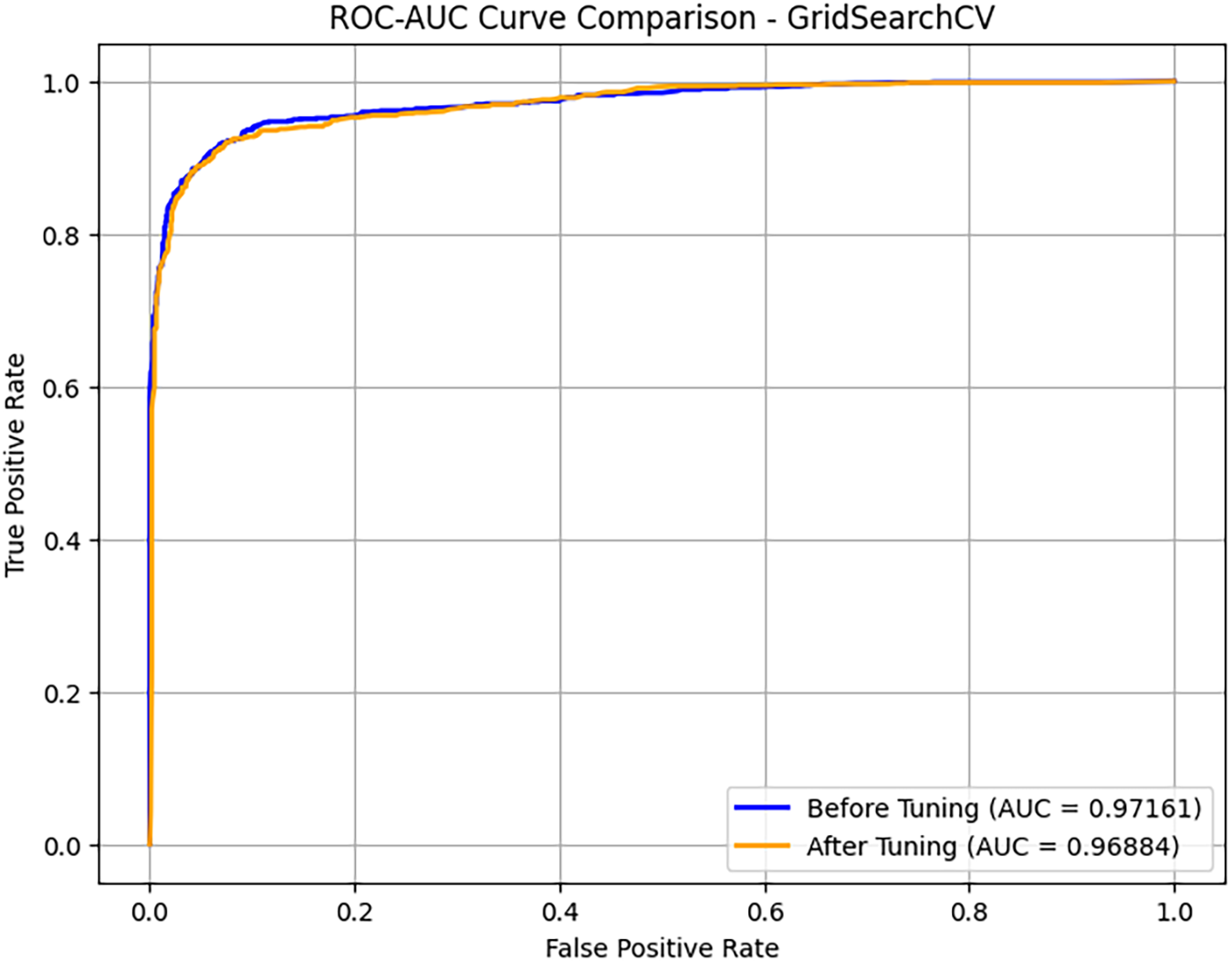

We evaluated the performance of the stacked ensemble learning model for PDF malware detection before and after hyperparameter adjustment using a comparison of the ROC-AUC curves, as shown in Fig. 17. Before tuning, the AUC-ROC was 0.97100; after tuning, it slightly decreased to 0.96797. This suggests that the impact of tuning on the model’s discrimination capability was minimal. Both curves are nearly perfect, demonstrating that the model effectively distinguishes between benign and malicious PDFs. The slight difference in AUC values indicates that the initial hyperparameters were already well-optimized, and additional tuning did not significantly enhance classification performance. We also compared the calibration curves for PDF malware detection probabilities before and after hyperparameter adjustment using GridSearchCV to assess model reliability, as shown in Fig. 18. A well-calibrated model aligns closely with the diagonal line, where projected probabilities match actual outcomes. Before adjustment, the model (represented by the blue line) tended to underestimate probabilities, indicating poor calibration. After tweaking the hyperparameters, the model’s probability estimation improved (represented by the green line), approaching the ideal calibration curve, particularly for lower probability values. Overall, hyperparameter adjustment enhanced the model’s predictive confidence, reduced miscalibration, and made probability scores more interpretable and accurate for decision-making in cybersecurity threat detection.

Figure 17: ROC-AUC curve comparison-GridSearchCV-CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022

Figure 18: Calibration Curve Comparison-GridSearchCV-CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022

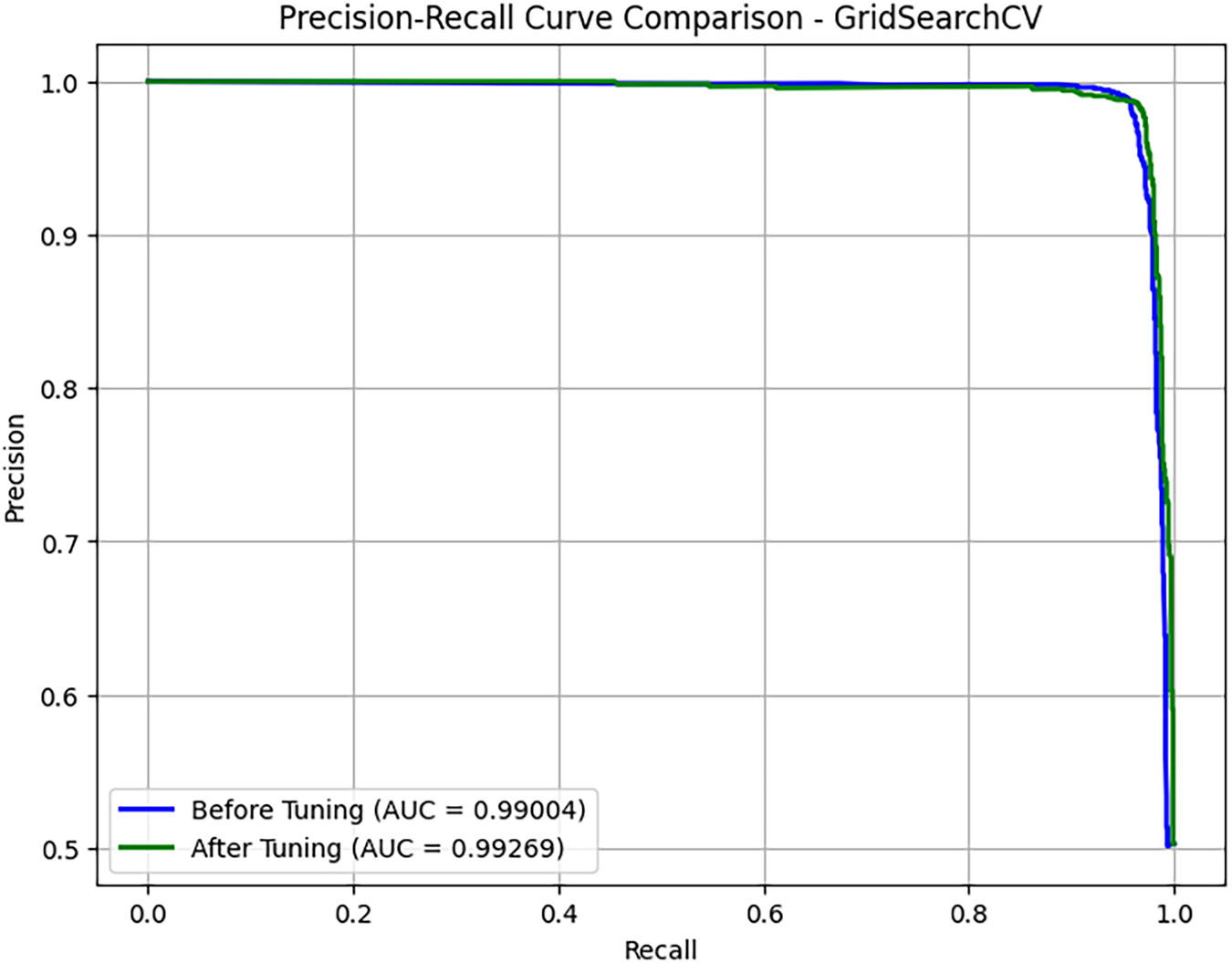

The evaluation on the enhanced Contagio dataset clearly demonstrates the robustness of the proposed stacked ensemble framework. The confusion matrix in Fig. 19 shows near-perfect classification with minimal false positives and negatives, while the precision-recall in Fig. 20 and ROC-AUC in Fig. 21 curves both indicate excellent discriminatory power and stability even after hyperparameter tuning. The calibration curve in Fig. 22 further validates that probability estimates are well-aligned with true outcomes, reflecting improved reliability of the model’s predictions. Collectively, these results confirm that the framework not only achieves high detection accuracy but also maintains strong generalization, reliability, and calibration across diverse performance metrics, thereby underscoring its suitability for real-world PDF malware detection.

Figure 19: Confusion Matrix-enhanced Contagio PDFMalware dataset

Figure 20: Precision-Recall Curve Comparison - GridSearchCV-enhanced Contagio PDFMalware dataset

Figure 21: ROC-AUC curve comparison-GridSearchCV-enhanced Contagio PDFMalware dataset

Figure 22: Calibration curve comparison-GridSearchCV-enhanced Contagio PDFMalware dataset

To enhance statistical robustness, we present the mean alongside standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals for all performance metrics derived from 3-fold cross-validation. The consistently low standard deviations and narrow confidence intervals shown in Table 5 affirm the reliability and stability of the proposed framework.

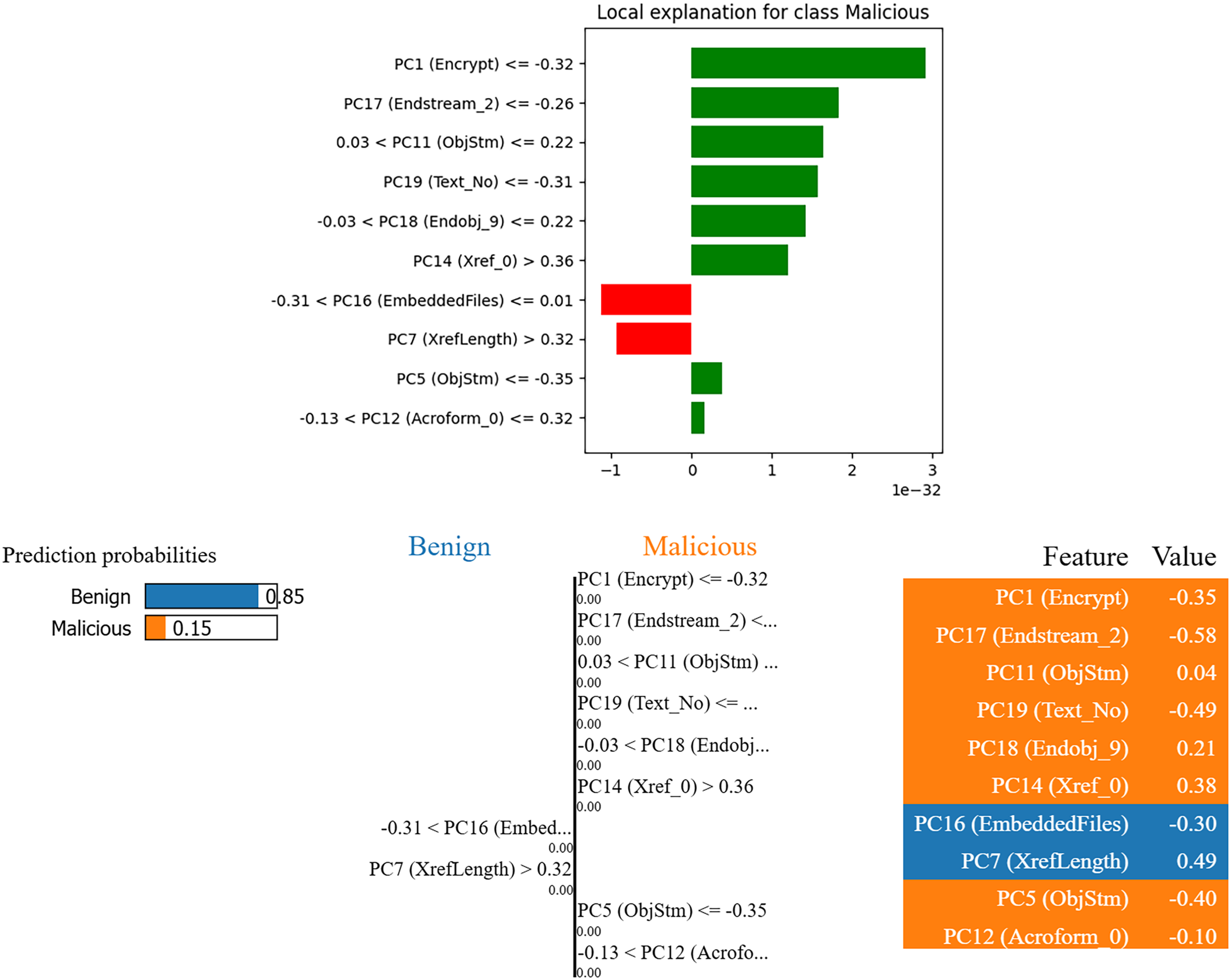

3.5.1 Explainability Analysis with Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME)

The LIME-based explainability analysis reveals the localized decision boundaries of the stacked ensemble model when classifying PDF files as malicious. As illustrated in Fig. 23, certain principal components, such as PC1 (Encrypt), PC17 (Endstream_2), and PC19 (Text_No), demonstrate strong positive contributions to the classification of malicious files. This suggests that encryption patterns, obfuscated streams, and abnormal text objects are critical indicators of malware. On the other hand, features like PC16 (EmbeddedFiles) and PC7 (XrefLength) sometimes behave contrary to expectations, indicating that their mere presence is not enough to establish malicious intent without additional context. The prediction probability distribution further confirms the classifier’s confidence, showing a higher likelihood for benign documents when these risk features fall below suspicious thresholds. Overall, the LIME explanations provide clear evidence of how structural and content-based anomalies in PDFs influence the model’s decisions, thereby enhancing transparency and building trust in the proposed detection framework.

Figure 23: Explainability analysis with LIME- CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022

3.5.2 Implementation of the Proposed Model

The algorithm outlined in 1 presents a comprehensive machine learning pipeline for classifying PDF malware. It incorporates various state-of-the-art techniques to improve detection accuracy and robustness. The process begins with label encoding, where categorical labels are converted into numerical representations to facilitate model processing. To tackle class imbalance, SMOTE is used to generate synthetic samples of minority-class instances. Next, PCA is applied for feature selection and dimensionality reduction while preserving essential information. The classification model employs a stacking ensemble approach, which includes base learners such as RF, XGB, LightGBM, CB, and MLP. This diverse set of models captures a variety of decision-making patterns. The GBC acts as the meta-learner, combining predictions from the base models to enhance classification accuracy. To ensure effective generalization and optimize performance in identifying malicious PDFs, the algorithm is trained and evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation.

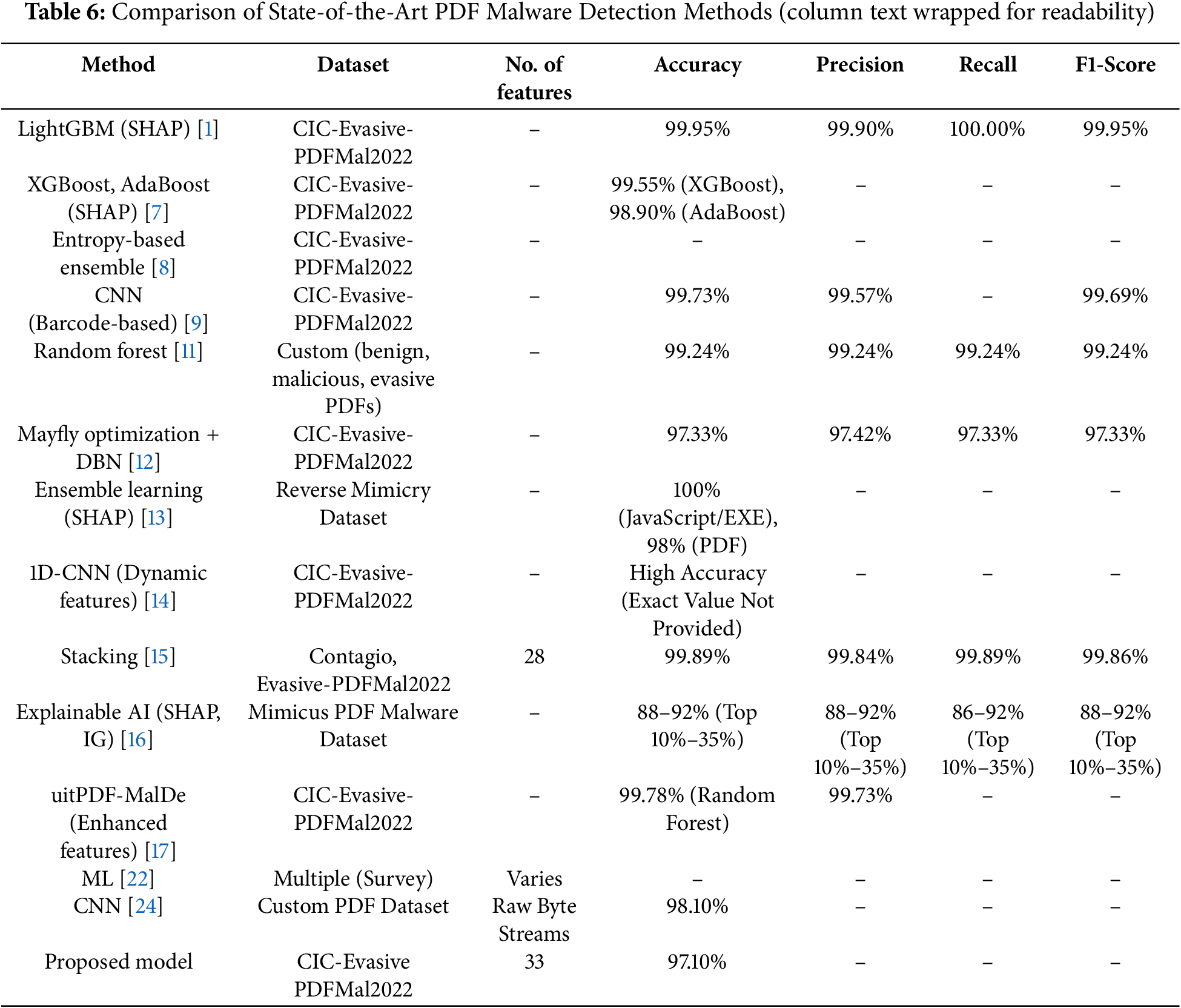

4 Comparison with the State-of-the-Art Methods

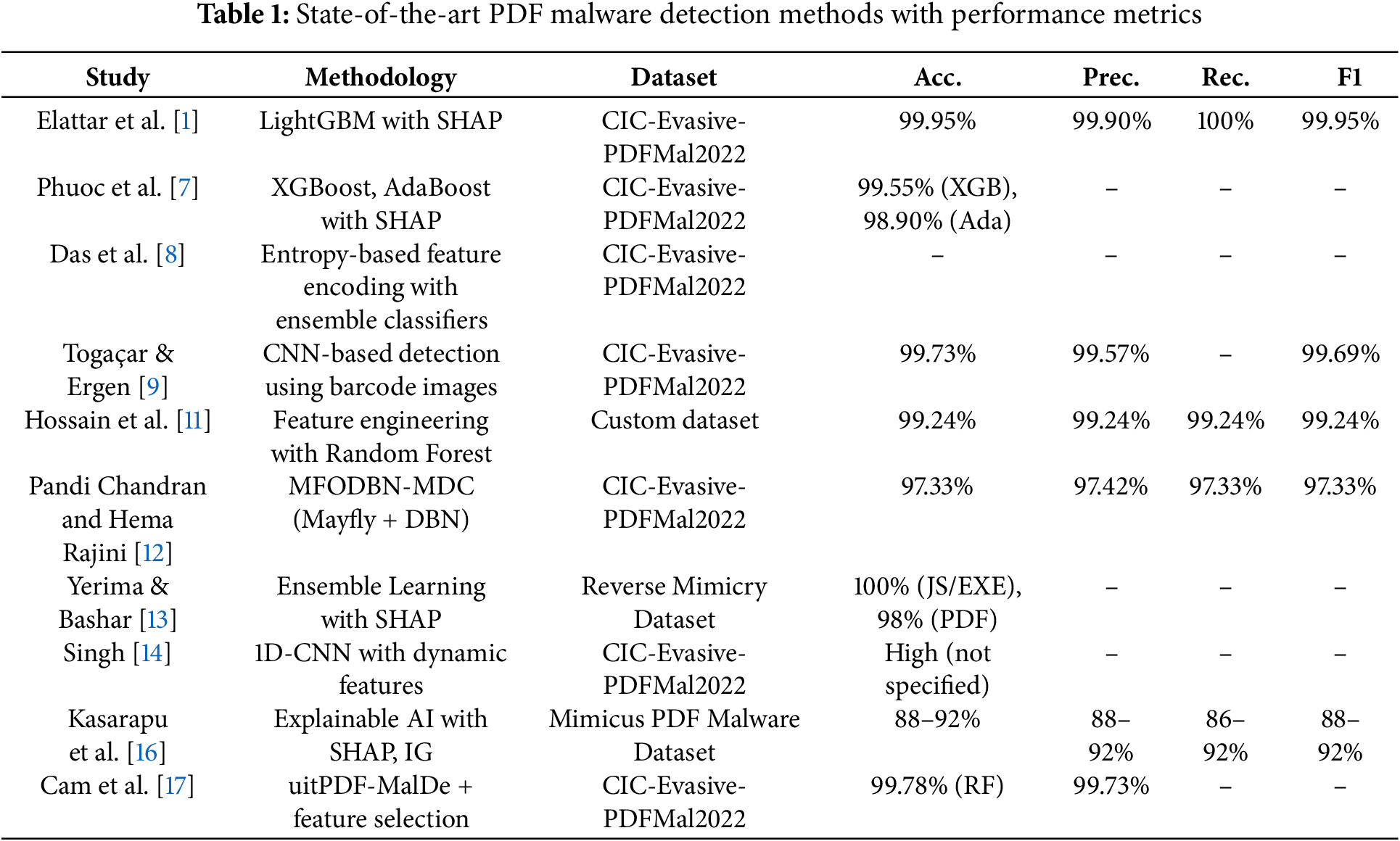

Table 6 and Fig. 24 illustrate the effectiveness of various machine learning approaches in detecting harmful PDFs by comparing modern PDF malware detection systems. Utilizing 28 static characteristics from the Contagio and Evasive-PDFMal2022 datasets, the stacking model developed by Issakhani et al. [15] achieved the highest accuracy of 99.89%, demonstrating excellent generalization capability. By analyzing raw byte streams, Fettaya and Mansour [24] reached an accuracy of 98.10%, which eliminates the need for feature engineering, although it may require more computational resources. Shabtai et al. [22] examined several classifiers using a survey-based machine learning technique but did not provide specific performance metrics. Their proposed stacked ensemble model, which used 33 extracted features, achieved an accuracy of 97.10% on the PDFMalware2022 dataset, while maintaining a high precision of 97.69%, recall of 97.09%, and an F1 score of 97.39%. Although this model strikes a reasonable balance between detection capabilities and real-world applicability—ensuring robust identification of PDF-based malware in cybersecurity systems—it exhibits slightly lower accuracy compared to stacking-based models.

Figure 24: Comparison of State-of-the-Art PDF malware detection methods

This work presents a stacked ensemble learning model designed to detect PDF malware, effectively addressing the shortcomings of traditional machine learning methods. By integrating RF, XGBoost, LGBM, and CB classifiers with a Gradient Boosting meta-learner, our approach enhances classification accuracy and effectively manages feature dependencies. Experiments carried out on the CIC-Evasive PDFMal2022 dataset achieved an accuracy of 97.10%, demonstrating the power of ensemble learning in combating evasive malware attacks. Our research emphasizes the importance of feature selection and dependency analysis in malware detection. Using PCA ensures that only the most informative attributes are retained, maximizing computational efficiency without compromising performance. Furthermore, our model outperforms the leading state-of-the-art systems in advanced malware threat detection. While our proposed model shows great promise, there are several areas for future research and development. Although the stacked ensemble framework has demonstrated strong performance on the enhanced Contagio dataset, we see several exciting research avenues worth exploring. First, we intend to integrate online learning mechanisms that will enable the model to continuously adapt to evolving malware patterns. This will ensure resilience against emerging threats without the need for complete retraining. Second, we plan to extend our experiments to additional datasets, particularly large-scale enterprise PDF logs and real-world security feeds, to further validate the framework’s generalizability across diverse operational contexts. Third, we will explore incorporating adversarial training strategies—such as generating adversarial examples and applying robust optimization—to enhance the system’s resistance to evasion tactics used by sophisticated attackers. These directions aim to strengthen the framework’s robustness and expand its applicability for real-world PDF malware detection and defense.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Kirubavathi Ganapathiyappan conceived the study, designed the experiments, and provided overall supervision. Kiruba Marimuthu Eswaramoorthy contributed to the experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Abi Thangamuthu Shanthamani carried out the primary data collection, preprocessing, and feature engineering. Aksaya Venugopal developed the machine learning models and implemented the optimization algorithms. Asita Pon Bhavya Iyyappan contributed to data visualization, results interpretation, and manuscript editing. Thilaga Manickam assisted with technical validation, performance evaluation, and manuscript revisions. Ateeq Ur Rehman supervised the research, reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, and secured funding for the research. Habib Hamam provided critical insights for the methodology and contributed to the manuscript’s technical content. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data obtained from CIC-Evasive-PDFMal2022, it can be found at https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/pdfmal-2022.html (accessed on 25 September 2025). Enchanced Contagio dataset is obtained from https://github.com/AhmedHaj/PDFInsight/tree/main/Enhanced_PDFMal2022 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Elattar M, Younes A, Gad I, Elkabani I. Explainable AI model for PDFMal detection based on gradient boosting model. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(34):21607–22. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10314-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Abu Al-Haija Q, Odeh A, Qattous H. PDF malware detection based on optimizable decision trees. Electronics. 2022;11(19):3142. doi:10.3390/electronics11193142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, Ke L, Tan Y. A feature-vector generative adversarial network for evading PDF malware classifiers. Inf Sci. 2020;523(9):38–48. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2020.02.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Albahar M, Thanoon M, Alzilai M, Alrehily A, Alfaar M, Algamdi M, et al. Toward robust classifiers for PDF malware detection. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69(2):2181–202. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.018260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Binsawad M. Enhancing PDF malware detection through logistic model trees. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;78(3):3645–63. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.048183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khaleq AHA, Garzón MA. Improving malicious PDF detection with a robust stacking ensemble approach. In: 2023 20th Annual International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST); 2023 Aug 21–23; Copenhagen, Denmark. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

7. Phuoc NCH, Tan VN, Cam NT. UITPDFXAI: malicious PDF files detection with explainable artificial intelligence. In: 2024 14th International Conference on System Engineering and Technology (ICSET); 2024 Oct 2–3; Bandung, Indonesia. p. 186–91. doi:10.1109/ICSET63729.2024.10775017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Das V, Nair BB, Thiruvengadathan R. A novel feature encoding scheme for machine learning based malware detection systems. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):91187–216. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3420080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Toǧaçar M, Ergen B. Processing 2D barcode data with metaheuristic based CNN models and detection of malicious PDF files. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;161:111722. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Aryal K, Gupta M, Abdelsalam M, Kunwar P, Thuraisingham B. A survey on adversarial attacks for malware analysis. IEEE Access. 2025;13(5389):428–59. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3519524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hossain GMS, Deb K, Janicke H, Sarker IH. PDF malware detection: toward machine learning modeling with explainability analysis. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):13833–59. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3357620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pandi Chandran PJM, Hema Rajini N. Optimal deep belief network enabled malware detection and classification model. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2023;35(3):3349–64. doi:10.32604/iasc.2023.029946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yerima SY, Bashar A. Explainable ensemble learning based detection of evasive malicious PDF documents. Electronics. 2023;12(14):3148. doi:10.3390/electronics12143148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Singh NAK. Dynamic feature-based detection of malware in non-executable files using a 1D convolutional neural network. Panam Math J. 2025;35(2s):678–91. doi:10.52783/pmj.v35.i2s.3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Issakhani M, Victor P, Tekeoglu A, Lashkari AH. PDF malware detection based on stacking learning. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP); 2022 Feb 9–11; Online. p. 562–70. doi:10.5220/0010908400003120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kasarapu S, Bhusal D, Rastogi N, Pudukotai Dinakarrao SM. Comprehensive analysis of consistency and robustness of machine learning models in malware detection. In: Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2024 (GLSVLSI ’24); 2024 Jun 12–14; Clearwater, FL, USA. p. 477–82. doi:10.1145/3649476.3658725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cam NT, Hung TQ, Nam PT. UITPDF-MALDE: malicious Portable Document Format files detection using multi machine learning models. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;143(19):110031. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gaber MG, Ahmed M, Janicke H. Malware detection with artificial intelligence: a systematic literature review. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(6):148. doi:10.1145/3638552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ganapathiyappan K, Noorudheen F. A deep learning approach to PDF malware detection enhanced with XAI. In: Cyber warfare, security and space computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2025. p. 337–58. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-73494-6_26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Singh P, Tapaswi S, Gupta S. Malware detection in PDF and Office documents: a survey. Inf Secur J Glob Perspect. 2020;29(3):134–53. doi:10.1080/19393555.2020.1723747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Maiorca D, Biggio B, Giacinto G. Towards adversarial malware detection: lessons learned from PDF-based attacks. ACM Comput Surv. 2019;52(4):78. doi:10.1145/3332184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shabtai A, Moskovitch R, Elovici Y, Glezer C. Detection of malicious code by applying machine learning classifiers on static features: a state-of-the-art survey. Inf Secur Tech Rep. 2009;14(1):16–29. doi:10.1016/j.istr.2009.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jeong YS, Woo J, Kang AR. Malware detection on byte streams of PDF files using convolutional neural networks. Secur Commun Netw. 2019;2019(6):8485365. doi:10.1155/2019/8485365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fettaya R, Mansour Y. Detecting malicious PDF using CNN. arXiv:2007.12729. 2020. [Google Scholar]

25. Contagio Malware Dump Project. Contagio PDF malware dataset–enhanced version; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://contagiodump.blogspot.com/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools