Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FishTracker: An Efficient Multi-Object Tracking Algorithm for Fish Monitoring in a RAS Environment

1 College of Smart Agriculture (College of Artificial Intelligence), Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 210095, China

2 College of Information Technology, Nanjing Police University, Nanjing, 210023, China

3Yuguanjia (Shanghai) Fisheries Co., Ltd., Shanghai, 202178, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhaoyu Zhai. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070414

Received 15 July 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Understanding fish movement trajectories in aquaculture is essential for practical applications, such as disease warning, feeding optimization, and breeding management. These trajectories reveal key information about the fish’s behavior, health, and environmental adaptability. However, when multi-object tracking (MOT) algorithms are applied to the high-density aquaculture environment, occlusion and overlapping among fish may result in missed detections, false detections, and identity switching problems, which limit the tracking accuracy. To address these issues, this paper proposes FishTracker, a MOT algorithm, by utilizing a Tracking-by-Detection framework. First, the neck part of the YOLOv8 model is enhanced by introducing a Multi-Scale Dilated Attention (MSDA) module to improve object localization and classification confidence. Second, an Adaptive Kalman Filter (AKF) is employed in the tracking phase to dynamically adjust motion prediction parameters, thereby overcoming target adhesion and nonlinear motion in complex scenarios. Experimental results show that FishTracker achieves a multi-object tracking accuracy (MOTA) of 93.22% and 87.24% in bright and dark illumination conditions, respectively. Further validation in a real aquaculture scenario reveal that FishTracker achieves a MOTA of 76.70%, which is 5.34% higher than the baseline model. The higher order tracking accuracy (HOTA) reaches 50.5%, which is 3.4% higher than the benchmark. In conclusion, FishTracker can provide reliable technical support for accurate tracking and behavioral analysis of high-density fish populations.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe escalating scale and importance of aquaculture are directly related to the global population growth and the increasing demand for protein-rich food. However, high stocking densities would increase pressure on the aquaculture environment, leading to fish disease, environmental pollution, and low farming efficiency [1]. Fish behavior can reflect their nutritional, reproductive, and physiological health status. For example, when the ammonia nitrogen level is excessively high, largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) would shift from dispersed to concentrated activity, which results in reduced swimming performance [2]. Furthermore, a decline in the dissolved oxygen concentration may force fish to congregate at the substrate of rearing ponds, leading to a marked decrease in the activity level [3]. Therefore, tracking fish movements is of great importance in modern aquaculture. Monitoring fish behavior enables feeding strategy optimization, early disease diagnosis, and environment assessment, consequently mitigating risks and enhancing the economic benefits [4].

Traditional fish monitoring predominantly rely on manual visual inspection and video analysis tools. These methods are often limited due to inefficiency, subjectivity, and inaccuracy. In recent years, advancements in computer vision have provided promising solutions in areas, such as video surveillance [5], autonomous driving [6], and aquaculture [7]. Particularly, multi-object tracking (MOT) algorithms based on deep learning can automatically recognize fish movement trajectories, enabling real-time, high-precision monitoring [8,9]. Early MOT algorithms mainly adopt correlation filtering [10] and particle filtering [11]. These algorithms construct appearance and motion models. However, they are limited to handle deformation and occlusion when targets move rapidly. Tracking-by-Detection (TBD) has emerged as the prevailing framework within the field of MOT. The TBD framework employs a two-stage process. The object position is first obtained by a detector, then, the tracking algorithm is applied to enable continuous and stable object tracking [12]. Representative algorithms, such as Simple Online and Realtime Tracker (SORT) [13], achieve commendable real-time performance by integrating detectors like YOLO [14]. Wu et al. [15] employed the YOLOv5 framework integrated with an enhanced SORT algorithm to build an efficient and reliable multi-species dynamic identification and automatic counting system, which effectively addressed critical challenges in ecological monitoring. The DeepSORT algorithm [16] introduced deep appearance features to enhance identity retention when fish were occluded. Saad et al. [17] proposed a fish tracking framework based on stereo vision that integrated StereoYOLO and DeepSORT to achieve 3D localization and continuous tracking of fish in the complex underwater environment. Recently, tracking algorithms based on Transformers [18] have become popular. Zheng et al. [19] proposed an integrated CNN and Transformer architecture to accurately count fish under high population density and severe occlusion scenarios. Although Transformer architectures have shown to be effective in capturing long-range dependencies between fish in densely populated environments, the high computational load limits their practicality in real-world scenarios. In contrast, TBD provides a lightweight framework that meets real-time monitoring and has lower training data requirements. In addition, TBD, with a modular structure design, enables the de-coupled optimization of detection and tracking algorithms [20].

Despite significant advancements in MOT algorithms, current researches predominantly focus on general target scenarios, such as pedestrians and vehicles. In contrast, fish tracking presents unique and unresolved challenges due to the distinctive nature of both the aquaculture environment and the fish targets. First, while pedestrians typically exhibit stable rigid-body structures and regular motion patterns, fish display considerable morphological diversity across species. Their bodies undergo continuous deformation and bending during swimming, accompanied by highly erratic movement. These characteristics hinder reliable target detection, particularly in high-density scenarios [21]. Second, occlusions in pedestrian tracking usually involve partial overlap between rigid bodies with relatively clear contours. However, in the densely stocked aquaculture environment, fishes are prone to occlusions, such as body intertwining and stacking, leading to blurred target boundaries. This complicates the consistent tracking of individual targets during interaction [22]. Third, pedestrian MOT typically operates under stable background conditions and predictable lighting, whereas aquaculture settings are subject to persistent disturbances, such as water turbidity and underwater light refraction. These factors introduce additional noise and uncertainty. Finally, numerous public datasets (e.g., MOTChallenge) support development and evaluation in pedestrian MOT, however, publicly available datasets for fish MOT are extremely scarce. Moreover, annotation is labor-intensive and error-prone. Most existing studies are confined to controlled laboratory settings, rather than real-world aquaculture production. Therefore, these factors make it considerably more challenging to effectively address the inherent complexity of the global aquaculture environment.

In complex scenes with dense fish populations, the detector must be able to discriminate between targets accurately to avoid false alarms. To meet the requirements of real-time monitoring and accurate fish tracking in the Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) environment, this study proposes a MOT algorithm, namely FishTracker, and the main contributions are summarized as follows.

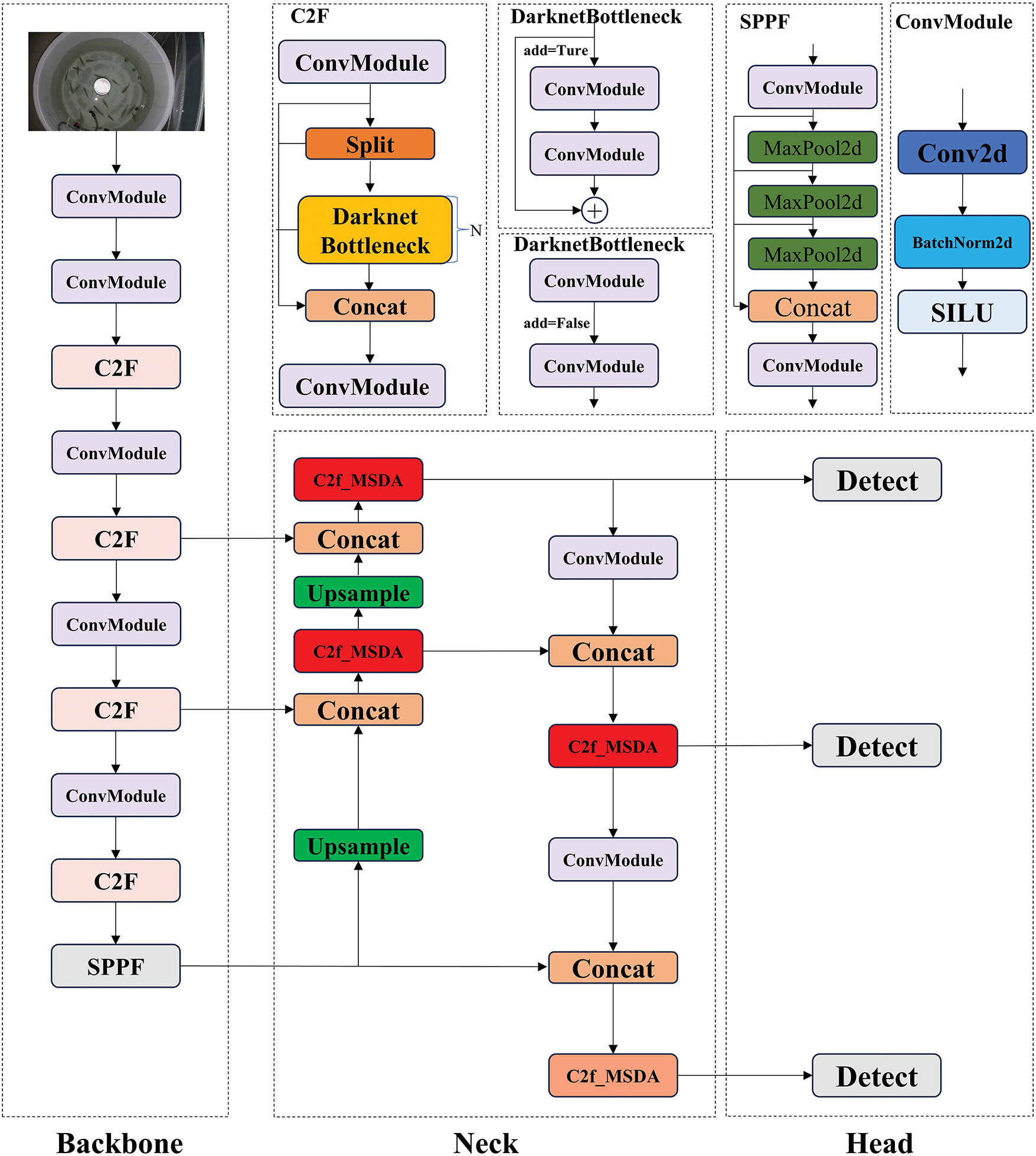

1. For the detection part, we introduce a Multi-Scale Dilation Attention (MSDA) module to the YOLOv8 model. MSDA effectively detects fish targets at different scales through a multi-level feature pyramid network. Experimental results demonstrate that MSDA increases the detection confidence and effectively addresses the tracking challenge arising from low confidence levels in complex underwater environments. Compared to the baseline, the enhanced YOLOv8 model reduces the number of parameters from 3.01M to 2.65M. It achieves an mAP50 of 95%, surpassing the baseline by 1.4%.

2. For the tracking part, we implement an Adaptive Kalman Filtering (AKF) over the ByteTrack baseline. By dynamically adjusting the state transition matrix and the observation noise covariance matrix, AKF effectively resolves the trajectory loss issue during target interaction. Compared to the baseline, the MOTA improves by 7.5% and 3.1% in dark and bright illumination conditions, respectively.

3. In terms of practicality, we conduct the generalization experiments using data from a real RAS production environment. Compared with the baseline, the experimental results show an improvement in MOTA from 71.36% to 76.7%, as well as an improvement in HOTA from 47.1% to 50.5%. FishTracker effectively identifies abnormal fish behavior, indicating its successful deployment in real-world scenarios.

In terms of applying MOT algorithms to the aquaculture domain, a large number of studies have been developed to address the unique challenges posed by underwater and high-density environments.

FishMOT [23] achieved fish tracking by using intersection over union (IoU) matching. However, its performance deteriorated under extreme conditions commonly encountered in industrial aquaculture, such as dense occlusions. Li et al. [24] proposed a MOT by integrating deformable convolution and joint detection-embedding in order to handle scale changes and partial occlusions. While this algorithm performed well on the OptMFT dataset, it lacked validation in the real production environment.

Although broader advances in MOT offer great potentials, they may struggle with aquatic adaptation. AnimalTrack [25], the first wild animal tracking benchmark showed that existing trackers underperformed due to differences in the target’s posture, movement, and appearance. This highlighted the specifics of non-rigid tracking, which was relevant for fish due to their variable swimming patterns. However, this approach focused on land-based scenarios and ignored underwater challenges, such as refraction and turbidity. Wang et al. [26] applied PD-SORT to scenarios involving occlusion, incorporating pseudo-depth information into the extended Kalman filter state vector. PD-SORT performed well on the DanceTrack and MOT17 datasets. However, PD-SORT relied heavily on pseudo-depth estimation, and visual depth cues were severely obscured in the turbid water. CATrack [27] proposed a condition-aware strategy for dense scenarios and performed well on the MOT17 and MOT20 datasets. However, its temporally enhanced appearance features were barely adaptable to the irregular and fast movements of fish.

It was worth noting that most MOT algorithms were validated on public datasets, such as MOT17 and MOT20, which focused on terrestrial scenarios involving distinct, rigid objects. However, these datasets lacked the ecological complexity in the aquaculture environment, such as fish overlapping, water surface reflection, and transient environmental disturbance. This limited their applicability to actual fish tracking.

The application of tracking algorithms in aquaculture aimed to bridge the gap between laboratories and fish farms, but progress remained unsolved. A recent study optimizing ByteTrack [28] for aquaculture addressed issues, such as low-light conditions and feeding-related splashing [29]. However, validating it in semi-controlled ponds failed to replicate the full complexity of the production environment, where high stocking densities and water flow may cause persistent occlusions and motion artefacts. Li et al. [30] introduced the MFT25 dataset and the SU-T framework, which used an unscented Kalman filter to model the nonlinear movements of fish. However, the performance of the SU-T declined in the high-sediment environment.

Existing literature revealed three key limitations. First, specialized fish trackers lacked robustness in the real production environment. Second, general MOT algorithms were not adapted to the complexities of aquatic environments, such as water turbidity and non-linear fish movements. Third, aquaculture applications focused on the laboratory-controlled scenarios, rather than real industrial RAS.

The subjects of this study are California largemouth bass and bighead carp. For the Ethics statement, all procedures in this study are conducted according to the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals (China). The experiment videos are recorded in a laboratory and a commercial production facility.

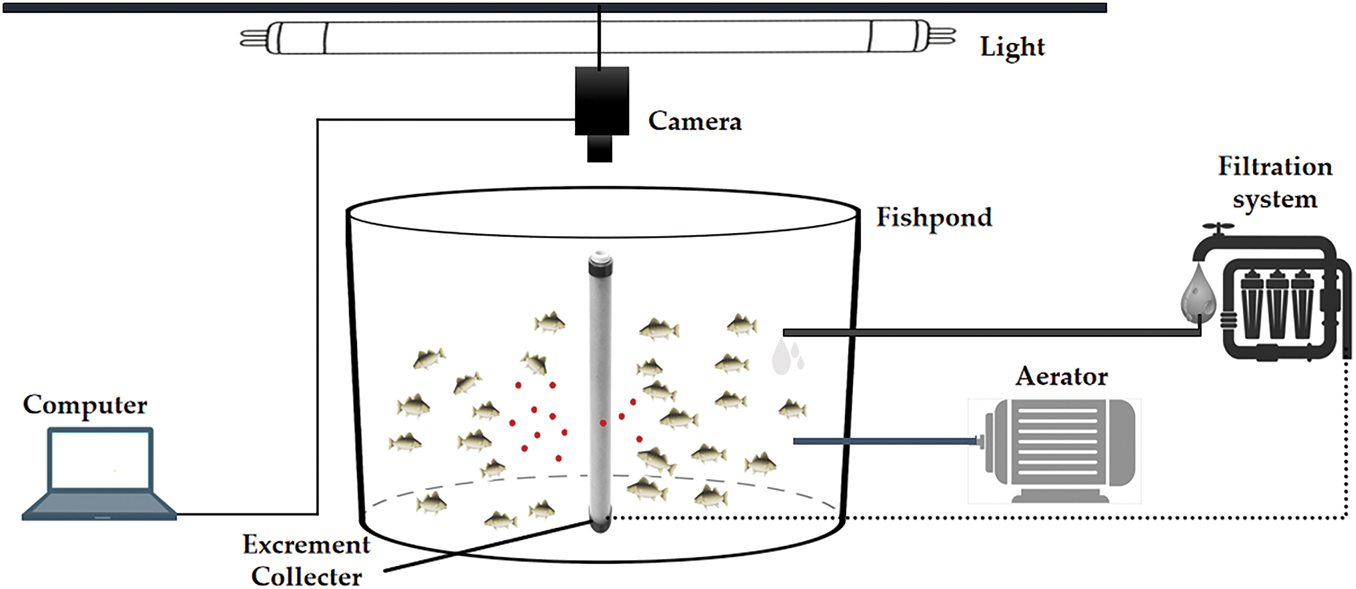

In the laboratory setting, a simple RAS is set up at Nanjing Agricultural University in Nanjing, Jiangsu, China (see Fig. 1). The system comprises a rearing tank, recirculating water treatment equipment, a temperature control system, water quality monitoring equipment, and a video recording system. The tank is made of polyethylene with a size of 1.2 m (top diameter) × 0.73 m (height) × 1.0 m (bottom diameter), and has a water volume of approximately 700 L. The video recording system consists of a computer and a high-definition camera. The camera is positioned above the tank to capture fish activity from a vertical perspective. It has an integrated LED lighting system to provide uniform illumination at night. The experiment uses 25 largemouth bass, with the body length ranging from 8 to 12 cm. The water temperature is maintained at 28°C, the pH level ranges from 6.5 to 8.5, and the level of dissolved oxygen is controlled to remain above 5 mg/L. Prior to data collection, the largemouth bass are acclimated to the environment for one week, and are fed daily at 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. The experiment considers both bright and dark illumination conditions. All videos are recorded in a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels, a frame rate of 25 FPS and a duration of 60 min.

Figure 1: Schema of the experimental setup

In the commercial production facility, videos are obtained from the Lukou base of the Nanjing Institute of Aquaculture Science. Approximately 500 fish with sizes ranging from 25 to 35 cm are fed. An automated temperature control system operates in conjunction with the RAS, maintaining conducive farming conditions through continuous aeration and water purification. A 24-h video monitoring system equipped with high-definition cameras continuously records the fish swimming data.

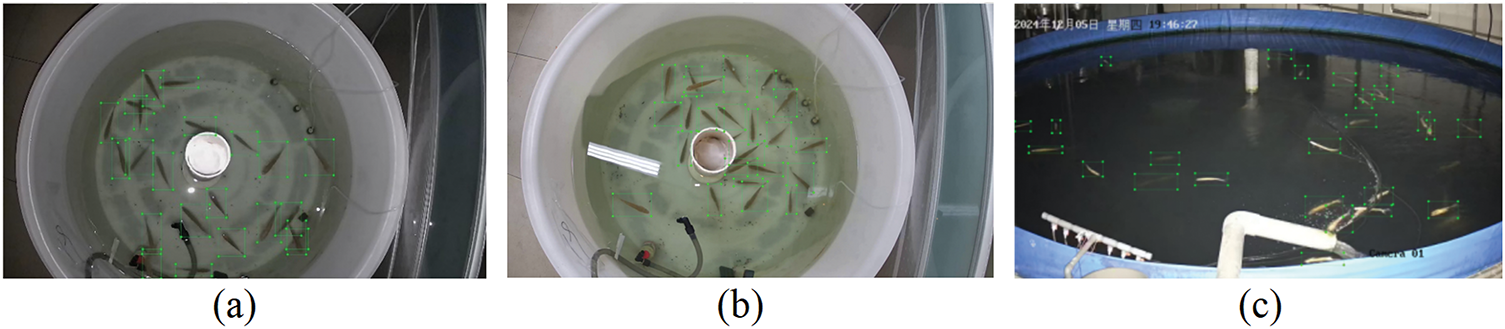

This study establishes two datasets: one for training the fish object detection model, and another for validating the MOT algorithm. To ensure the diversity in the fish object detection dataset, laboratory and commercial production environments with different illumination conditions are considered. We use OpenCV 4.3.0 to convert these videos into images by extracting one frame from every 20 frames and adding them to the dataset. A total of 800 images are annotated using the LabelImg software. After annotation, the dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets by a ratio of 8:1:1. Images from three settings are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Video frame and annotation examples under different scenarios: (a) laboratory (bright); (b) laboratory (dark); (c) production environment. Note: Each individual is labelled by a green anchor

To validate the proposed MOT algorithm and compare its performance in different scenarios, 20 video segments are selected from the laboratory environment videos (under two lighting conditions) and 10 from the commercial production environment. For each video segment, 200 frames are evenly extracted, and the datasets are annotated using the DarkLabel tool.

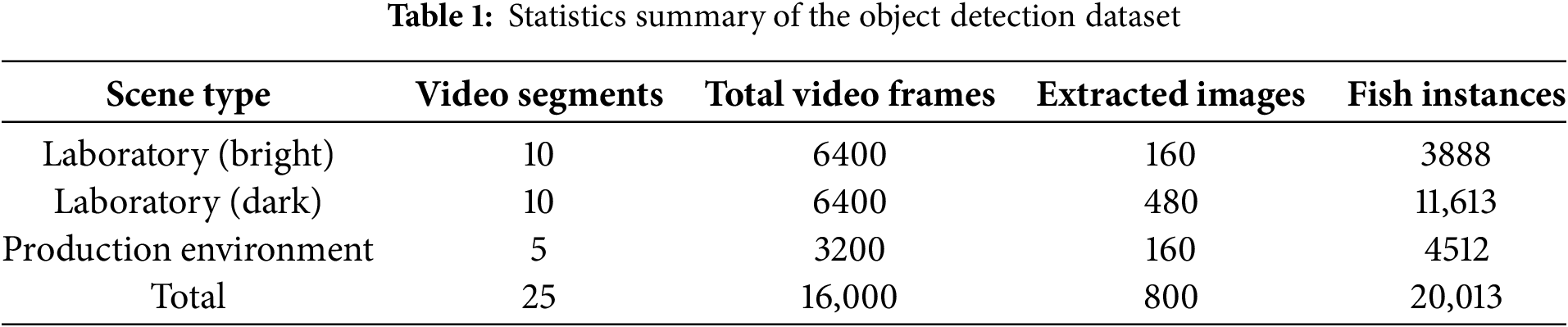

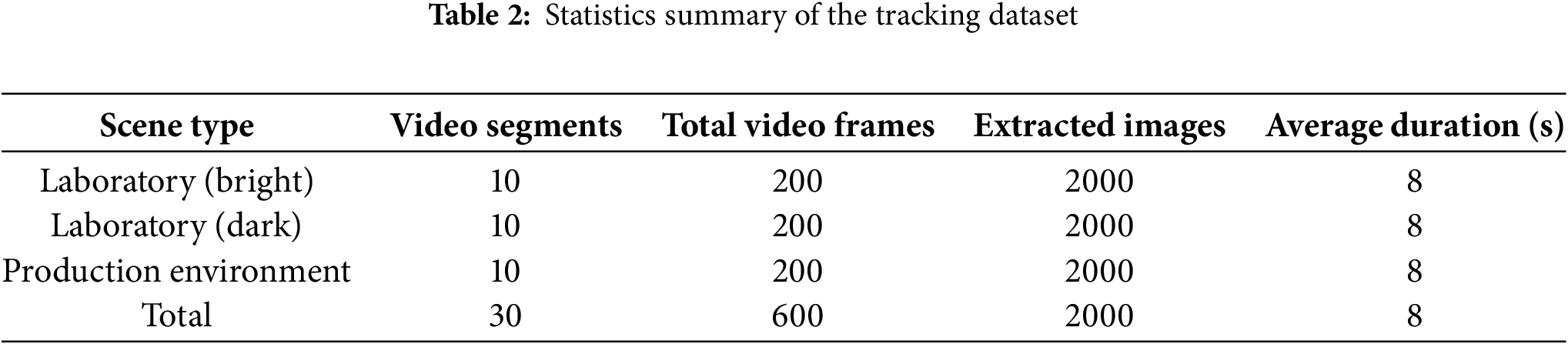

Table 1 lists the scene division, sample quantities, and the proportional allocation of the fish object detection dataset. Table 2 lists the video segments, annotated frame counts, and scene coverage of the MOT algorithm validation dataset.

3.2.1 Introduction of the YOLOv8 Detector

YOLO (You Only Look Once) stands as one of the representative approaches in the object detection task. In this study, we adopt YOLOv8 [31] as the baseline model. YOLOv8 is based on an improved CSPDarknet53 backbone network and a Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast module. It also takes advantage of the Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network structure to enhance the multi-scale feature extraction. YOLOv8 provides a complete task ecosystem for real-time and high-precision object detection, making it particularly suitable for aquacultural applications.

Although YOLOv8 shows excellent performance in object detection, it still faces several challenges in aquacultural applications. Due to complex factors in the fish farming environment, such as variations in light refraction, water turbidity, and dense occlusions, YOLOv8 struggles with low-confidence targets, resulting in missed and false detections that significantly compromise the stability of subsequent tracking algorithms. Therefore, we enhance YOLOv8 by introducing an MSDA module, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Structural diagram of the enhanced YOLOv8 model for fish detection

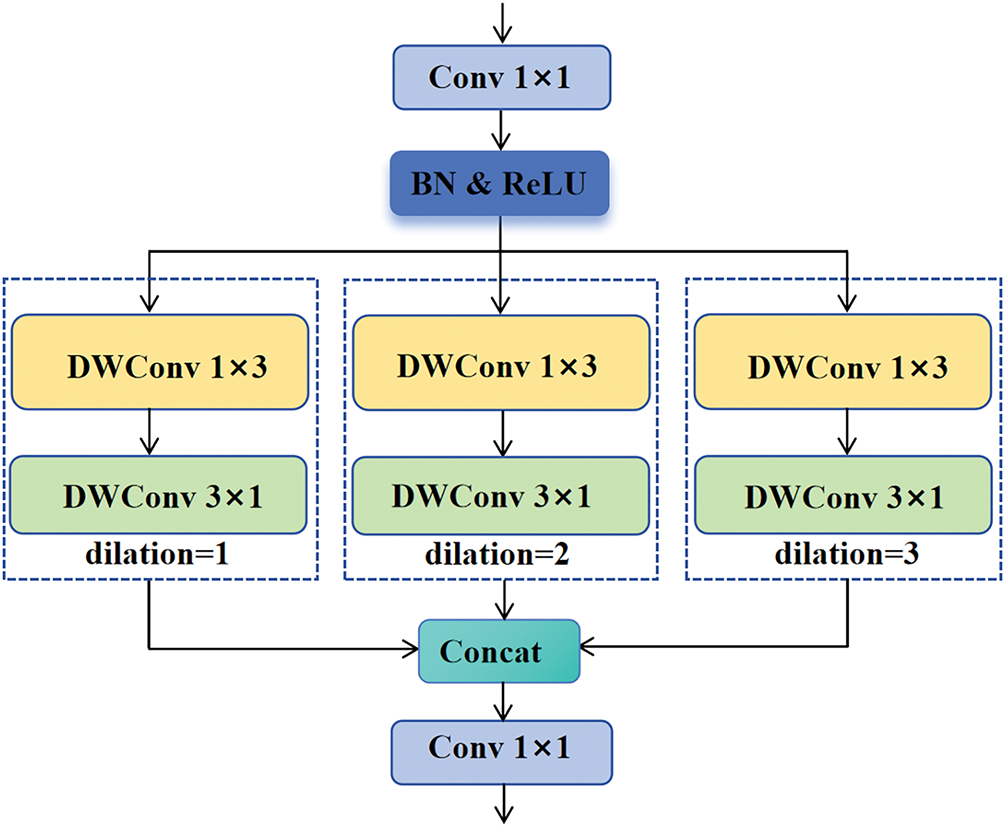

3.2.2 Introduction of the MSDA Module

MSDA introduces the Sliding Window Dilated Attention (SWDA) operation, which selects keys and values within a sliding window centered on the query block under a sparse manner [32]. Self-attention is then employed to these blocks. Formally, the SWDA can be formulated in Eq. (1).

where Q, K, V, and r represent the query, key, value matrices, and the dilation rate, respectively. For the query located at a particular position in the original feature map, SWDA sparsely selects keys and values within a sliding window of size

This module processes the input features at multiple scales via parallel convolutional kernels, capturing both local and global features. Assume the input features are

where

Multi-scale representations capture objects and features across varying scales, allowing comprehensive and accurate information to be captured. The structure of the MSDA module is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Structural diagram of the MSDA module

The MSDA module employs the attention mechanism to enhance the representational capacity of the feature maps. The attention mechanism weights the features along the channel and spatial dimensions. Channel attention enhances the importance of critical feature channels, while spatial attention focuses on prominent target areas. Formulas of the channel and spatial attention are given in Eqs. (4) and (5).

where

By adopting the attention weights, the feature maps at various scales are aggregated and then concatenated, as expressed in Eqs. (6) and (7).

MSDA efficiently fuses cross-scale semantic information by assigning different dilation rates to different attention heads. This design avoids redundant computations in the standard self-attention mechanism and eliminates the need for additional parameters. Consequently, MSDA enhances the feature representation capability for small targets and improves object detection performance in complex scenarios.

3.3 Fish Multi-Object Tracking

3.3.1 Fish Multi-Object Tracking Algorithm

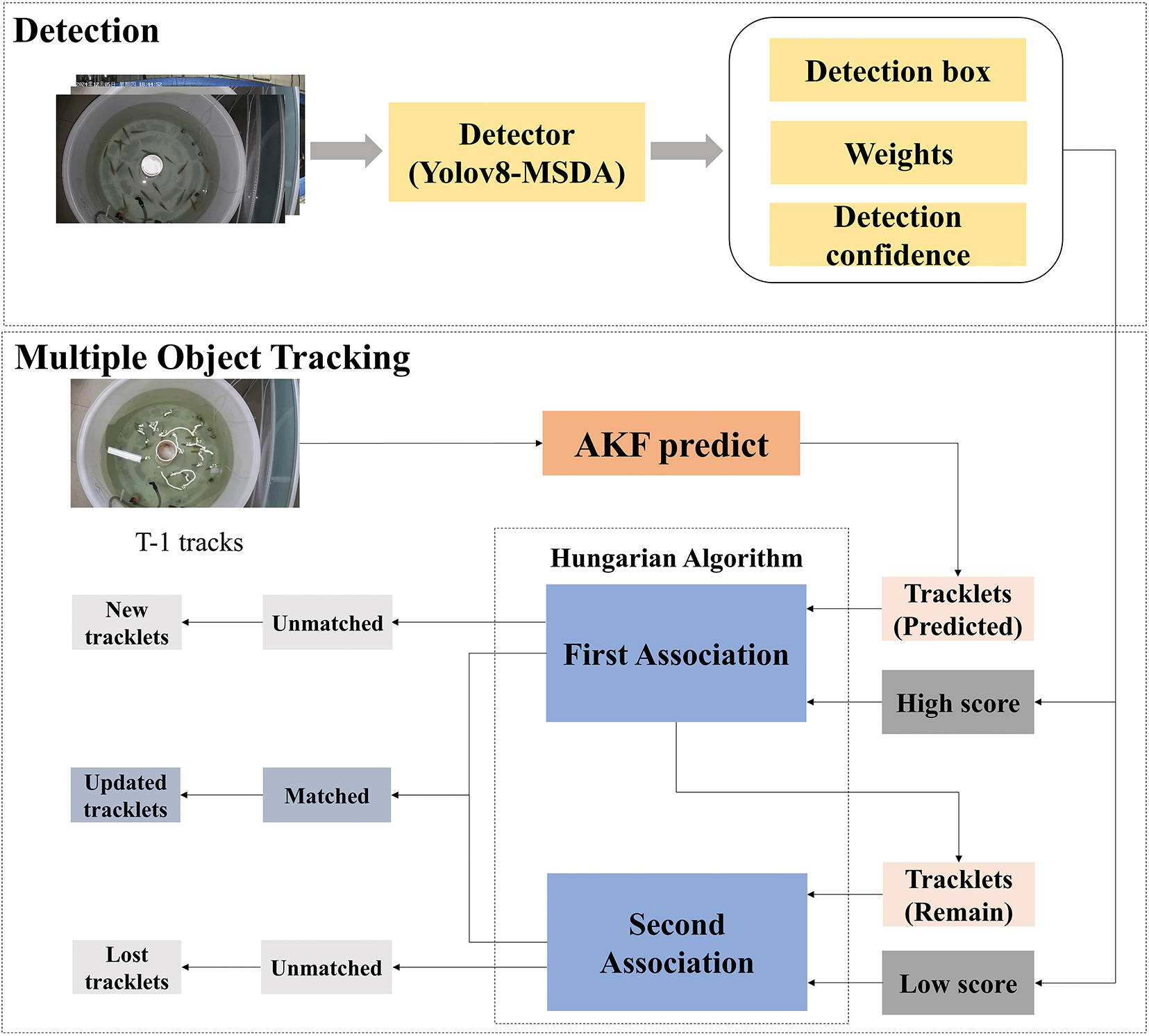

ByteTrack employs a two-stage matching strategy. First, it associates high-confidence detections with existing trajectories, and then it applies a secondary matching to low-confidence detections, effectively reducing tracking failures and identity switches [28]. This mechanism significantly improves tracking robustness in complex scenarios, while maintaining high computational efficiency. Despite its remarkable advances, ByteTrack still faces significant challenges in fish tracking. Frequent occlusions between individuals, high similarity in appearance characteristics, and non-linear movement trajectories can lead to performance degradation of the matching mechanism. The fixed-parameter Kalman filter also struggles with adapting to the dynamic motion patterns of fish swimming, resulting in accumulated motion prediction errors. Furthermore, the highly homogeneous appearance characteristics of the fish exacerbates similarity matching errors, leading to increased identity switching.

To address these challenges, we propose an enhancement over the ByteTrack baseline. This strategy embeds an adaptive Kalman filter (AKF) within ByteTrack to implement a dynamic parameter adjustment mechanism, which substantially increases the robustness of FishTracker when tracking high-density fish populations [33]. The overall multi-object tracking flowchart is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Overall framework of the multi-object tracking algorithm

3.3.2 Improved Tracking Algorithm

In this study, we adopt an AKF that improves state estimation accuracy by dynamically adjusting the process noise covariance matrix

where

After completing the adaptive adjustments of the process noise covariance

In the ByteTrack algorithm, AKF plays a critical role in continuously monitoring changes in target states and dynamically adjusting the process and observation noise covariances. This enables the MOT algorithm to accurately adapt to the time-changing characteristics of the system noise. AKF effectively improves the accuracy of state estimation for fish movement trajectories, whether due to disturbances caused by changes in water currents or the complex motion states generated by rapid fish swimming. This enhances the accuracy and stability of fish tracking.

4.1 Experimental Platform and Parameter Settings

The test platform runs on the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5318Y CPU @ 2.10 GHz processor, 14 GB RAM, and a 100 GB hard drive. An NVIDIA A16 GPU is used. The programming language is Python 3.8, and the deep learning framework is PyTorch 1.8.1. The training image is sized to 640 × 640 pixels. The model hyperparameters are as follows: epoch = 50, batch size = 4, learning rate = 0.01, weight decay = 0.0005, and momentum = 0.937.

4.2.1 Object Detection Performance Evaluation Metrics

Precision (P), Recall (R), mean Average Precision (mAP), and model parameters (params) are used to assess the performance of fish target detection. The formulas are given in Eqs. (15)–(18). In all experiments, the criterion for correct fish detection is based on an IoU threshold of 0.5.

where TP (True Positive) denotes accurately detected positive samples, FP (False Positive) represents incorrectly detected negative samples, and FN (False Negative) signifies undetected positive samples.

4.2.2 Multi-Object Tracking Evaluation Metrics

In this study, we use several metrics to evaluate the performance of the fish MOT algorithms, including Multi-Object Tracking Accuracy (MOTA), identification-related metrics, as well as ID switch and fragmentation. The MOTA metric is used to determine the localization accuracy, defined by Eq. (19).

Identification-related metrics include Identification F1 (IDF1), Identification Precision (IDP), Identification Recall (IDR), and Identity Switch (IDS). The IDF1 score is defined as the harmonic mean of IDP and IDR. Tracking continuity indicators include Identification Switch (IDSW) and Fragmentation (Frags). The IDSW refers to the number of times a single target is assigned different IDs, while Frags measures the number of trajectory interruptions caused by missed detections. The formulas for these metrics are given in Eqs. (20)–(23).

where, IDTP is the number of correctly matched predicted IDs to true IDs. IDFP is the number of incorrectly matched predicted IDs to true IDs. IDR measures the proportion of truly matched IDs, where IDFN is the number of true IDs that are not correctly matched.

We also use Higher Order Tracking Accuracy (HOTA) and Frames Per Second (FPS) as evaluation metrics. HOTA is computed as elaborated in Eq. (24).

where the detection accuracy score is denoted by DetA, and the association accuracy score by AssA. c is a point belonging to TP, and A(c) denotes the association accuracy.

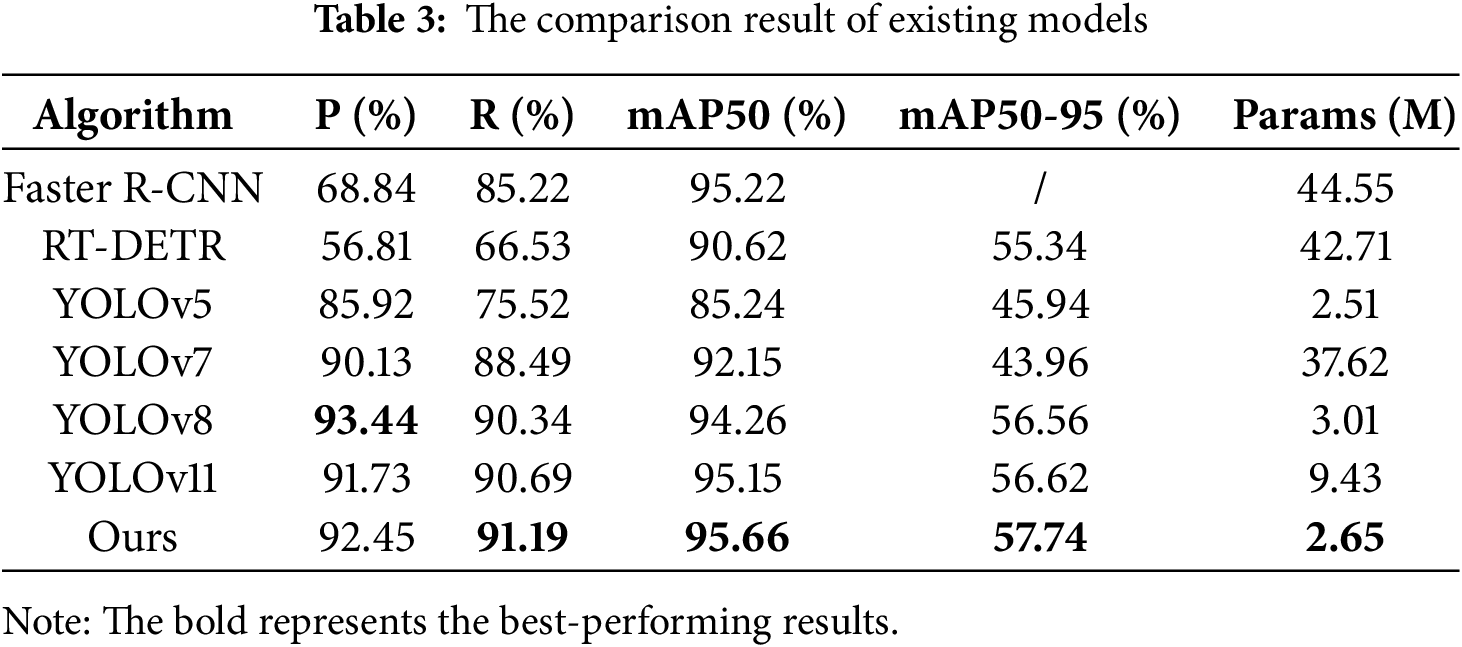

4.3 Analysis and Accuracy Evaluation of Detection Results

To validate the detection performance of the enhanced YOLOv8 model, we select existing object detection models for comparison. The results in Table 3 show that the enhanced YOLOv8 model achieves the optimal performance in Recall, mAP50, and mAP50-95, at 91.19%, 95.66%, and 57.74%, respectively. It surpasses the YOLOv8 baseline model by 0.85%, 1.4%, and 1.18%, respectively.

As shown in Table 3, the low mAP50-95 scores of YOLOv5 and YOLOv7 stem from the structural limitations of their neck parts. The simplified PANet of YOLOv5 and the ELAN-based neck of YOLOv7 hinder effective multi-scale feature fusion, which is crucial for distinguishing between fish and cluttered aquatic backgrounds. Both YOLOv5 and YOLOv7 struggle to cope with the complexities of aquatic environments, such as water turbidity, suspended solids and changes in illumination. Additionally, YOLOv5’s mAP50 is only 85.24%, the lowest among all models, due to its poor performance in detecting low-contrast fish. In contrast, the enhanced YOLOv8 model is better suited to such scenarios. Compared to the YOLOv8 baseline model, our model reduces the number of trainable parameters by 11.96%, yet still achieves better performance.

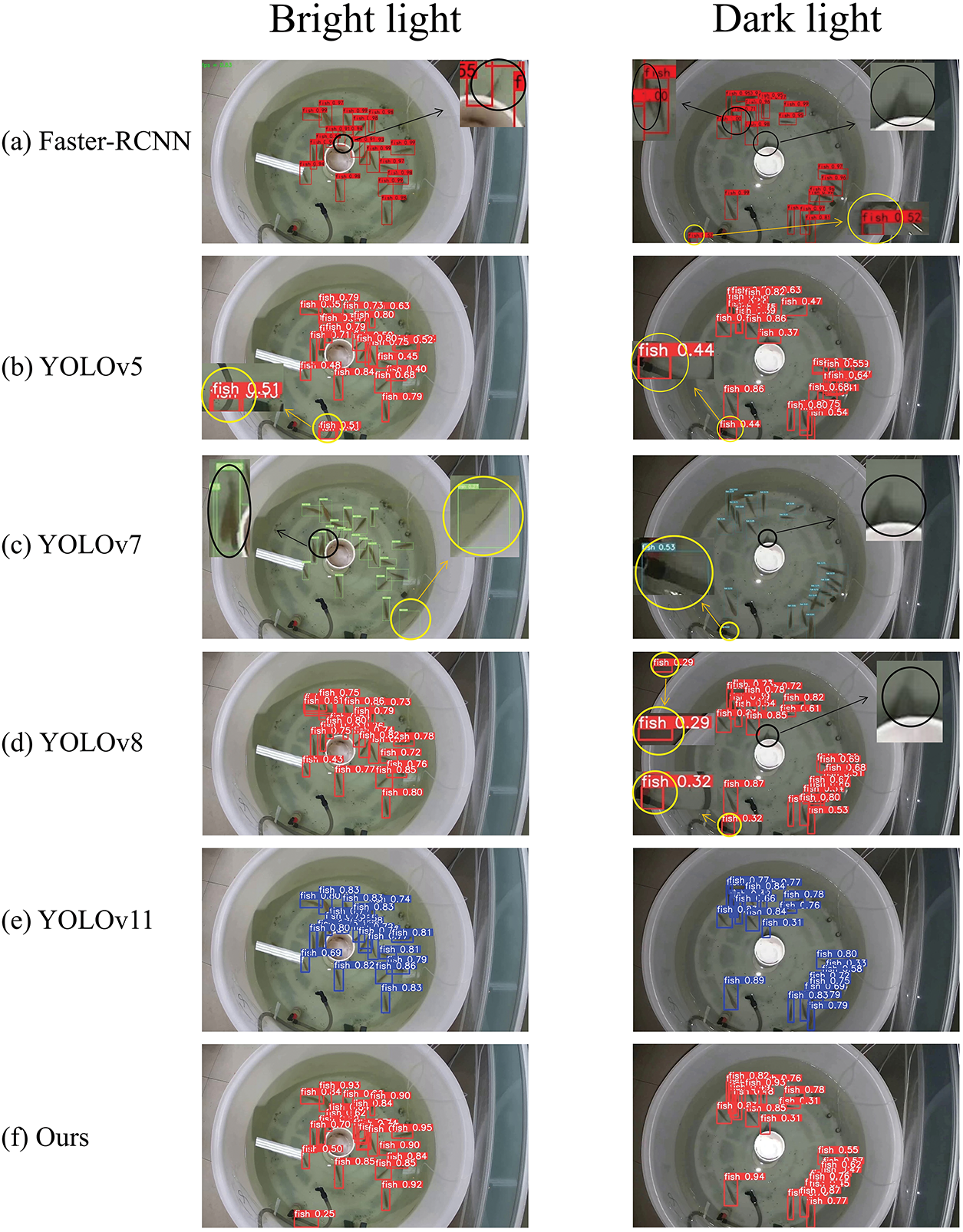

To visualize the performance improvement of the optimized detection framework, we visualize the detection results under different illumination conditions in Fig. 6. We mark false detections with yellow circles and missed detections with black circles. It is observed that our model significantly reduced false detection rates in complex backgrounds, while also improving missed detection rates for small and occluded targets. Under both illumination conditions, the missed detection marked by black circles frames are all detected by the enhanced model, and the overall recognition confidence is far higher than others.

Figure 6: Detection results under bright and dark illumination conditions

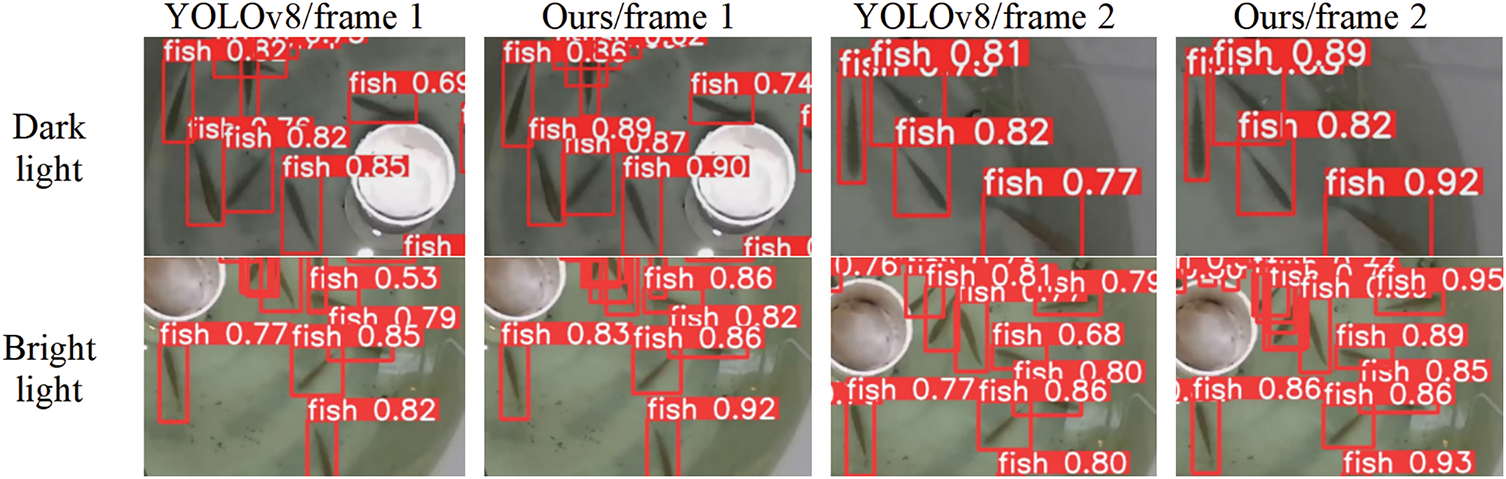

Then, we select two video frames under dark and brightillumination conditions for comparative analysis, as shown in Fig. 7. The results demonstrate that the enhanced YOLOv8 model can achieve higher confidence score for detecting fish objects. In particular, under the dark condition, the average confidence increased by 6.5%. These results demonstrate the significant improvement in feature extraction and noise reduction capabilities of the enhanced YOLOv8 model. This increase in confidence also implies that the enhanced model has greater flexibility in adjusting subsequent decision thresholds, thus meeting more stringent detection requirements in the real-world application.

Figure 7: Confidence score comparison under bright and dark illumination conditions

4.4 Results Analysis of Multi-Object Tracking

4.4.1 Comparison of Existing MOT Algorithms

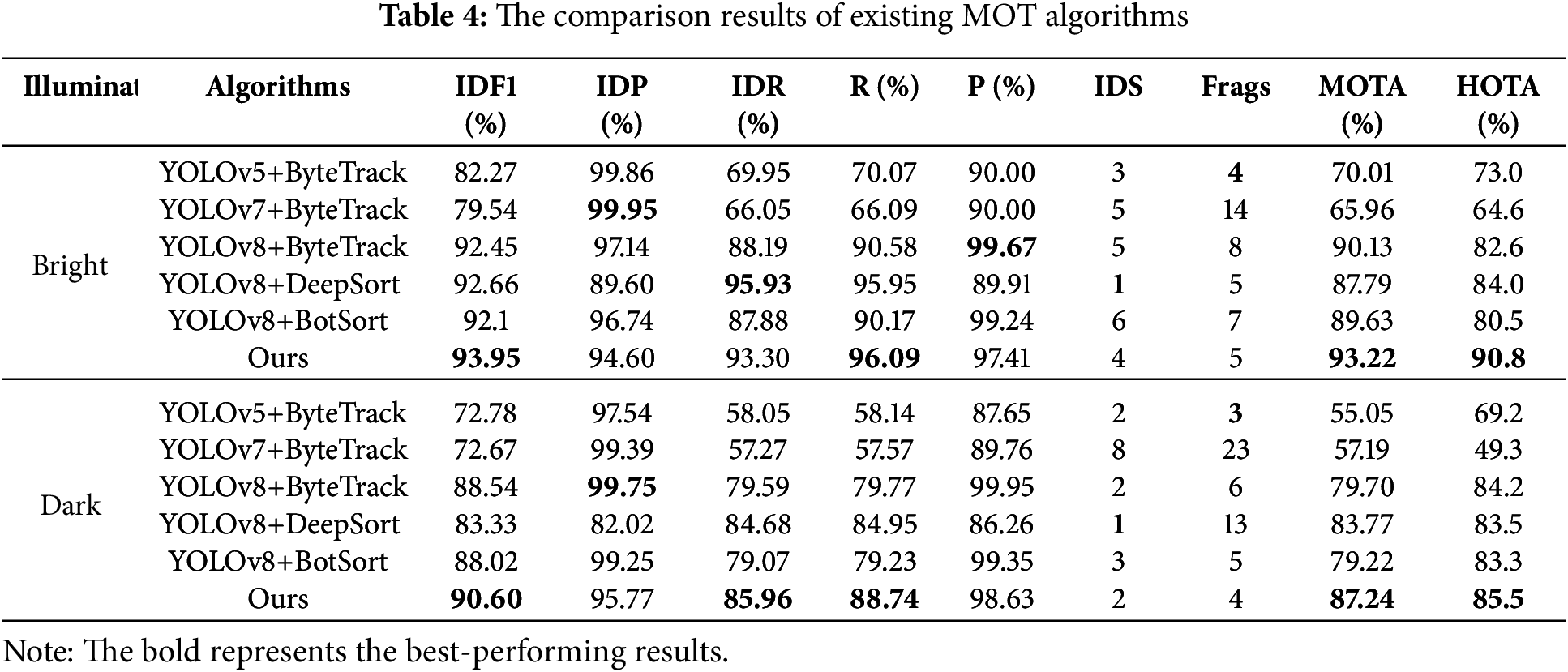

To validate the performance of FishTracker, we perform comparative experiments over existing MOT algorithms. As shown in Table 4, the tracking metrics of all algorithms in the bright illumination generally outperform those in the dark illumination. Under sufficient lighting conditions, targets’ appearance features are clearer, enabling the detector to accurately extract contours and textures. However, in the dark environment, increased image noise and blurred fish features may lead to missed and false detections. This directly degrades the overall performance of tracking algorithms.

FishTracker demonstrates remarkable advantages in the dark condition, achieving a MOTA of 87.24%. This represents significant improvements over other algorithms, with improvements of 32.19% on YOLOv5+ByteTrack and 7.54% on YOLOv8+ByteTrack. Furthermore, FishTracker achieves IDR, R, and P values of 85.96%, 88.74%, and 98.63%, respectively, demonstrating advantages in terms of identity association accuracy, target detection completeness, and detection precision. From the perspective of HOTA, FishTracker also demonstrates exceptional performance. In the bright condition, it achieves a HOTA score of 90.8%, which far exceeds the scores achieved by other algorithms. In the dark condition, FishTracker's HOTA is 85.5%, outperforming YOLOv8+ByteTrack (84.2%).

When we fix the ByteTrack as tracker and compare the performance of YOLOv5, YOLOv7 and YOLOv8 with and without the MSDA module, we find that the tracking metrics increase gradually with each YOLO detector iteration. Notably, the MOTA score rises from 55.05% for YOLOv5 to 79.70% for YOLOv8 in the dark environment. This suggests that optimizing the baseline detection model can significantly enhance the extraction of features. Further comparisons between the enhanced YOLOv8 and the baseline YOLOv8 demonstrate that FishTracker achieves improvements of 1.5%, 5.11%, and 3.09% in the IDF1, IDR, and MOTA, respectively in the bright scenarios. In the dark scenario, these improvements are even more pronounced, with the MOTA score rising from 79.70% to 87.24%. These results validate the effectiveness of the MSDA module, which enhances multi-scale feature extraction and fusion.

When the YOLOv8 detector is fixed as detector, we compare various trackers, such as DeepSort, BotSort, and the AKF enhanced ByteTrack. The combination of YOLOv8 and DeepSort achieves a MOTA of 87.79% in the bright condition. However, FishTracker further boost this value to 93.22%. The MOTA increases from 73.77% to 87.24%, accompanied by a reduction in IDS from 13 to 4, and in trajectory fragments from 6 to 4. The standard Kalman filter is limited to adapt to assumptions of the motion model. In aquacultural scenarios involving the non-linear motion of fish and feature blurring issues, they struggle to accurately predict and associate targets, resulting in tracking failures. A further comparison between YOLOv8+BotSort and FishTracker shows an increase in MOTA from 89.63% to 93.22% in the bright condition and from 79.22% to 87.24% in dark conditions. This is accompanied by a further reduction in IDS and fragments. These results demonstrate that the AKF strategy adaptively addresses interference factors. This significantly reduces trajectory fragmentation and identity switching.

In summary, FishTracker delivers exceptional tracking performance in both bright and dark lighting conditions. This is achieved by enhancing feature extraction at the detection stage via the MSDA module, and by optimizing the association mechanism at the tracking stage via the AKF strategy. Its significant breakthrough in performance validates the robustness of the algorithm in complex lighting environments, providing a more reliable technical solution for real-world dark light tracking scenarios.

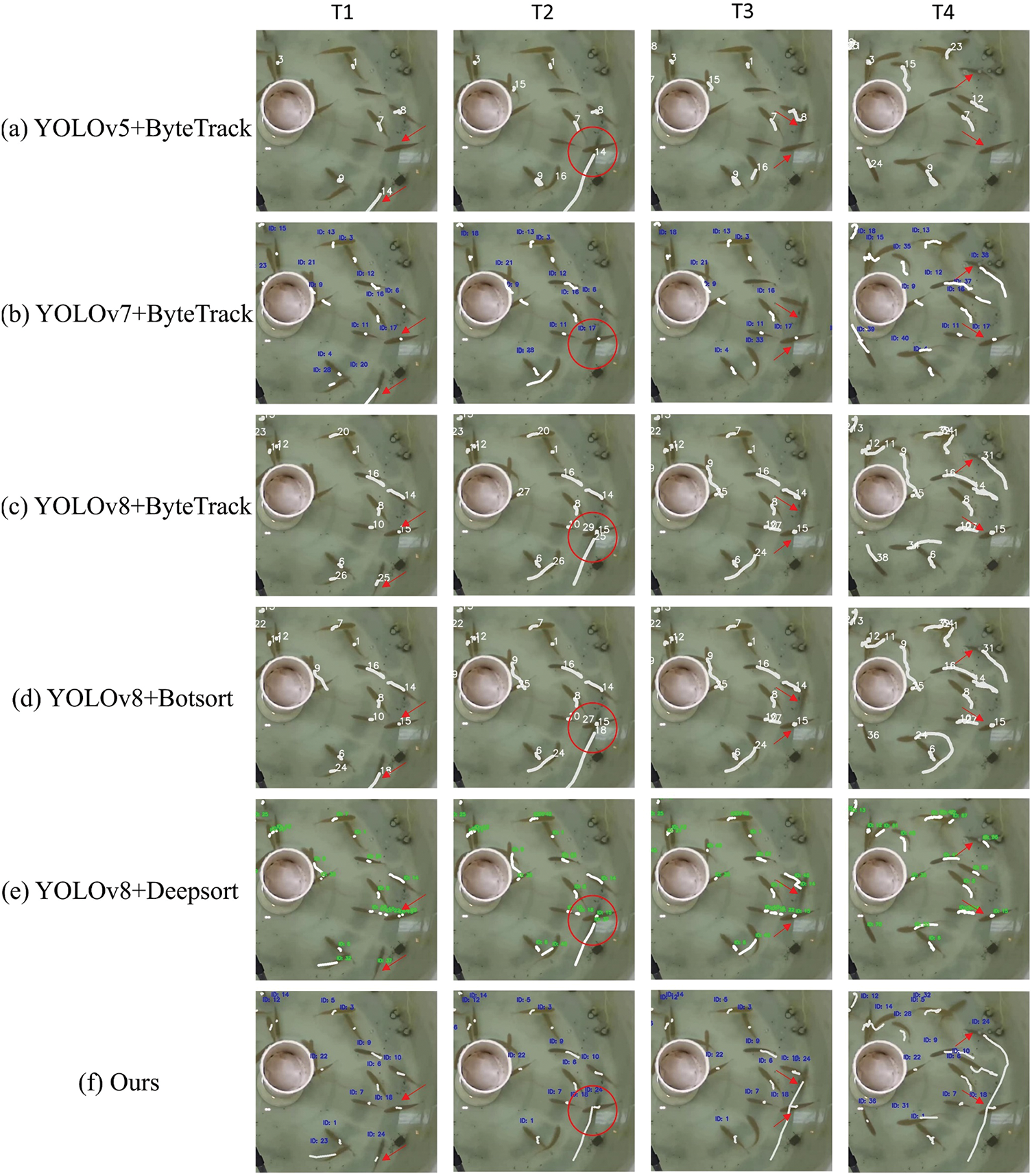

4.4.2 Comparative Results in Complex Interactive Scenes

The videos from the laboratory environment containing complex interactive scenes are selected for comparative experiments. As shown in Fig. 8, a frame-by-frame comparison illustrates the tracking results of different MOT algorithms. For clarity, the red arrows mark the interacting target pairs in each frame, and red circles highlight the interaction locations. The results show that FishTracker shows superior performance in the test scenarios. In particular, during and after the target interactions, the target IDs are consistently maintained, whereas other MOT algorithms experience target losses and ID switches. As can be seen in Fig. 8a,b, one of the two interacting fish is not detected throughout the entire interaction process. In Fig. 8c–f, although both fish are detected, the ID value of one fish changes after the interaction. For example, in Fig. 8c, after interaction, the ID of one fish changes from 25 to 31. In contrast, our model retains the IDs of both fish throughout the interaction.

Figure 8: Trajectory coherence analysis during fish interaction

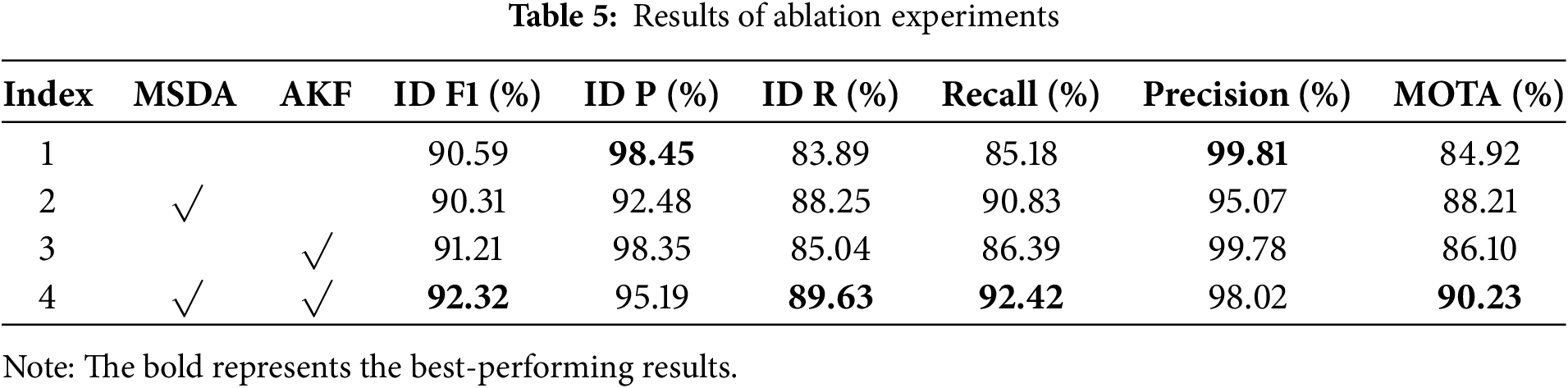

4.4.3 Results of Ablation Experiments

FishTracker is trained under four different configurations: the original YOLOv8+ByteTrack (i.e., baseline), a configuration with only the MSDA embedded, a configuration with only the AKF improved, and a configuration with both the MSDA and the AKF. The results of the experiments are shown in Table 5.

The results in Table 5 indicate that FishTracker significantly outperforms the baseline model for most of the evaluation indicators. FishTracker improves IDF1 and IDR by 1.73% and 5.73%, respectively, while the overall MOTA achieves an improvement of 5.31%. The joint effect of MSDA and AKF originates from their complementary roles. MSDA enhances detection precision by capturing multi-scale features, thereby supplying AKF with reliable observational inputs. Conversely, AKF leverages these high quality detections to dynamically adjust its parameters, which helps mitigate motion prediction errors caused by fish swimming or mutual occlusions. This mutual reinforcement effectively reduces identity switches and tracking failures, ultimately driving the MOTA gain.

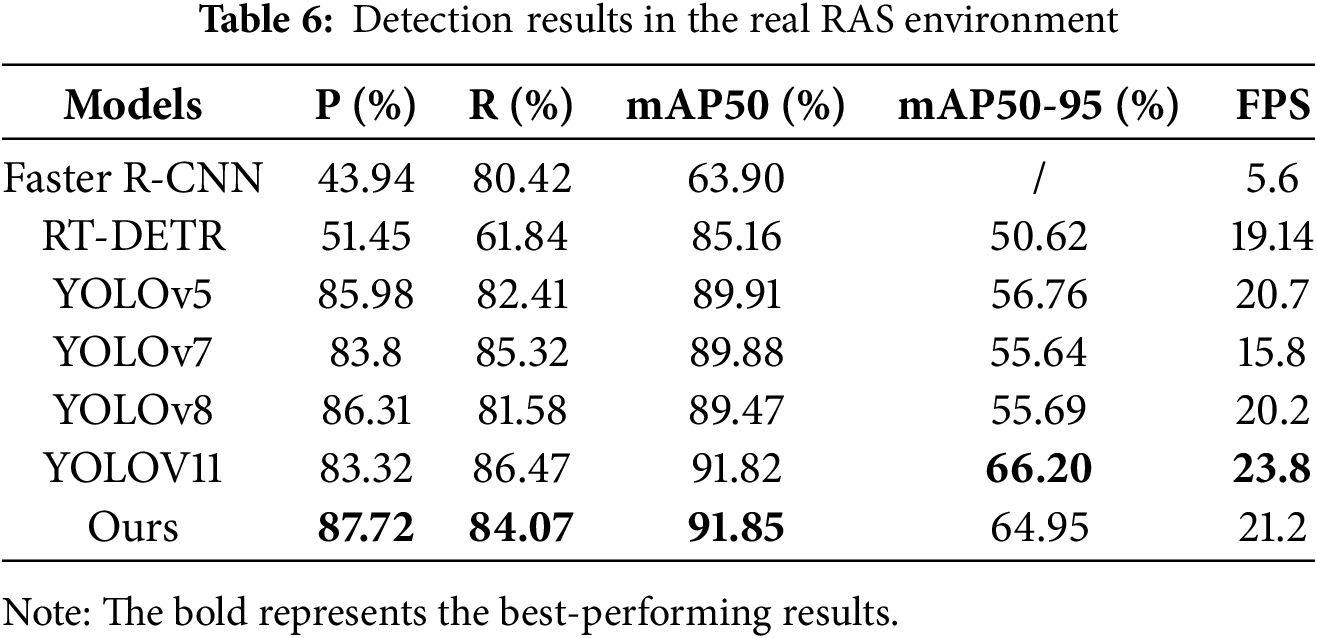

4.4.4 Analysis of Tracking Performance in Real RAS Environments

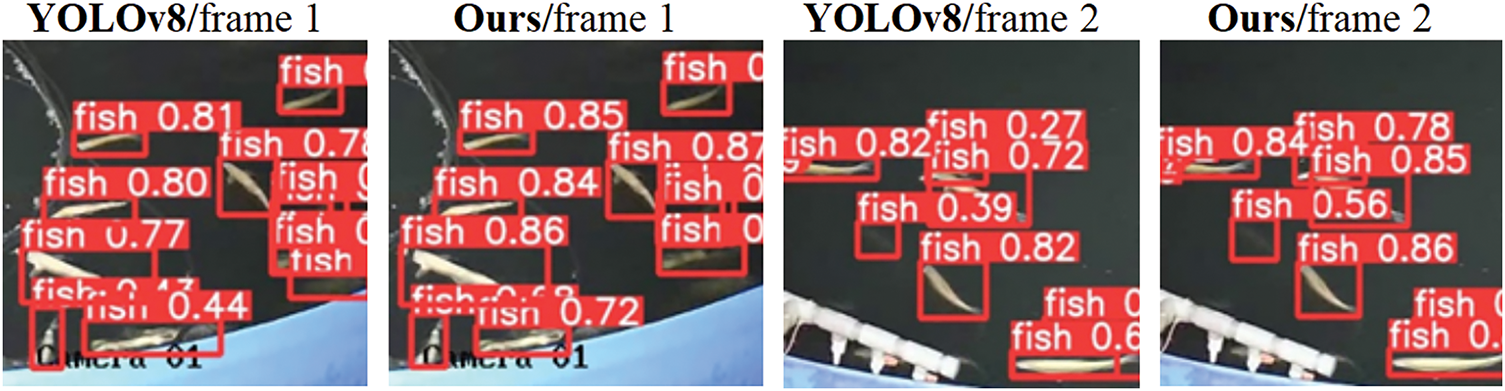

To further assess the effectiveness of FishTracker in the real production scenario, it is tested over the challenging aquacultural scene data. The comparative results of the different detection models are presented in Table 6. FishTracker achieves a detection precision of 87.7%, a recall of 84%, a mAP50 of 91.8%, and a mAP50-95 of 64.9%.

As shown in Fig. 9, the experimental design involves comparing two groups of sequential frames. The left column shows the baseline’s detection results, while the right column presents FishTracker’s detection results. FishTracker achieves higher confidence scores for the detected objects. This performance improvement is particularly evident in scenes with occlusions. On average, confidence increases by 9.6%, and for heavily occluded samples, confidence increases by up to 51%.

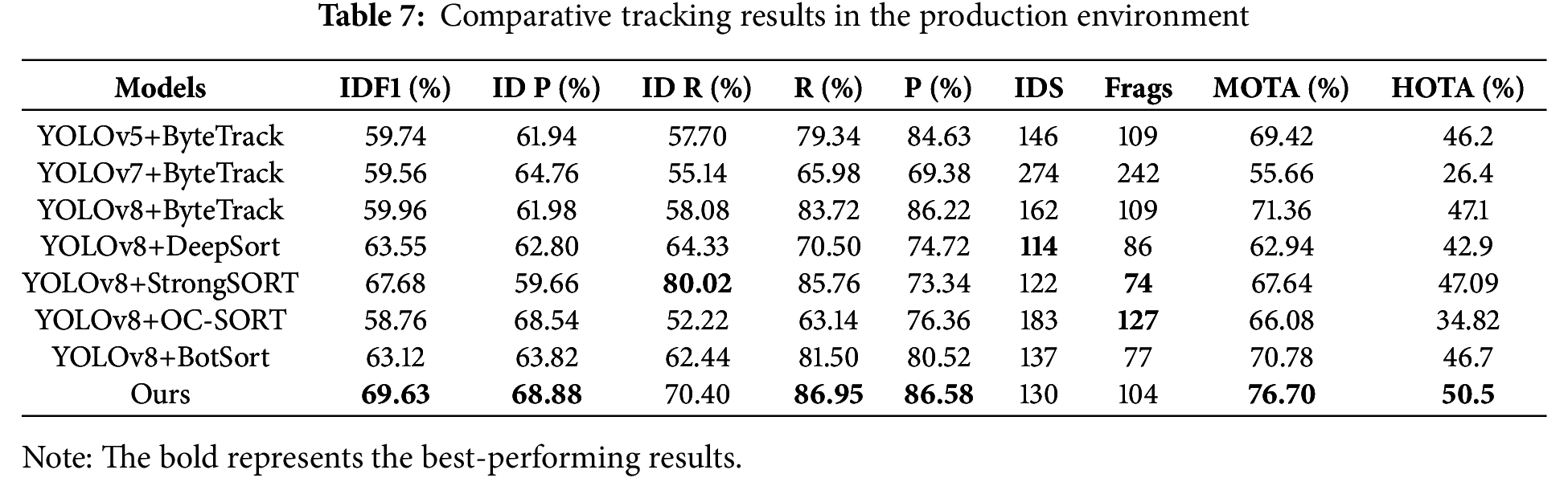

Figure 9: Comparison of confidence scores in the production environment

For quantitative analyses, as demonstrated in Table 7, FishTracker exhibits remarkable performance gain over the validation dataset within the real industrial aquaculture scenarios, achieving a MOTA of 76.70% and an IDF1 of 68.88%. Both of these metrics are greater than existing MOT algorithm. Specifically, the MOTA shows a 5.34% improvement over the baseline, indicating that the detection phase significantly reduced both missed detections and false positives. Additionally, the IDF1 value reflects the accuracy of identity matching, suggesting that FishTracker effectively reduces target ID switching issue. With an HOTA of 50.5%, FishTracker’s ability to integrate precise detection and high-quality tracking is further validated. Compared to algorithms, such as YOLOv8+ByteTrack and YOLOv8+StrongSORT, FishTracker outperforms them in maintaining stable tracking amidst real industrial aquaculture disturbances.

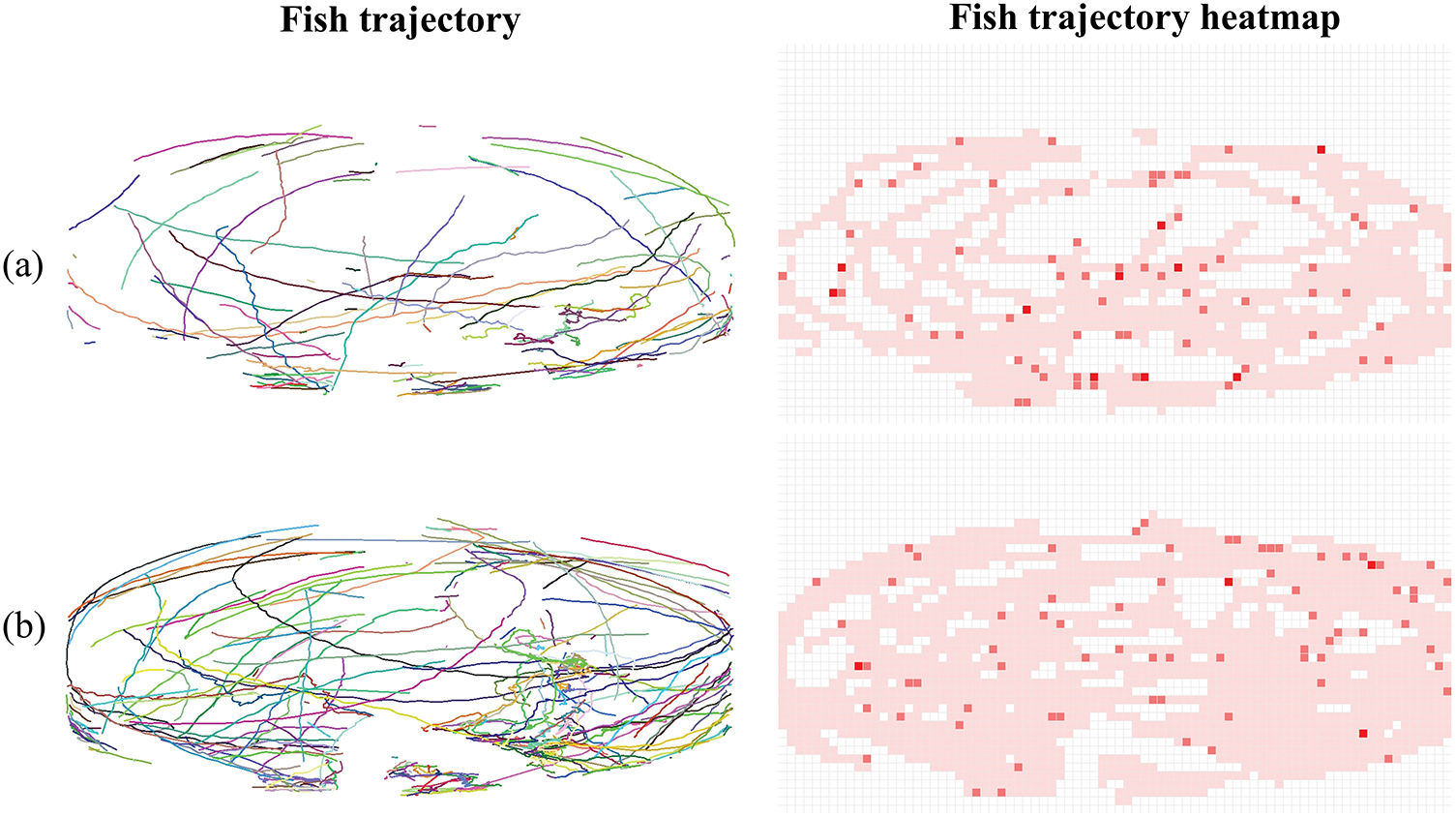

To thoroughly assess the practical application performance of FishTracker, we select two segments of fish monitoring videos from the production environment at night. One segment represents a normal scene, while the other represents an abnormal case. The motion trajectories and trajectory heatmaps in these two videos are shown in Fig. 10. The experimental results clearly show differences in the trajectories between the two scenes. Specifically, in the normal scenario, the spatial span of the fish movement trajectories is larger, and there are fewer targets. In the abnormal scenario, the spatial distribution range of the fish trajectories is further expanded, with a significantly higher number of fish targets than in the normal scene.

Figure 10: Visualization of fish trajectories and their heatmaps in different scenarios: (a) normal; (b) abnormal

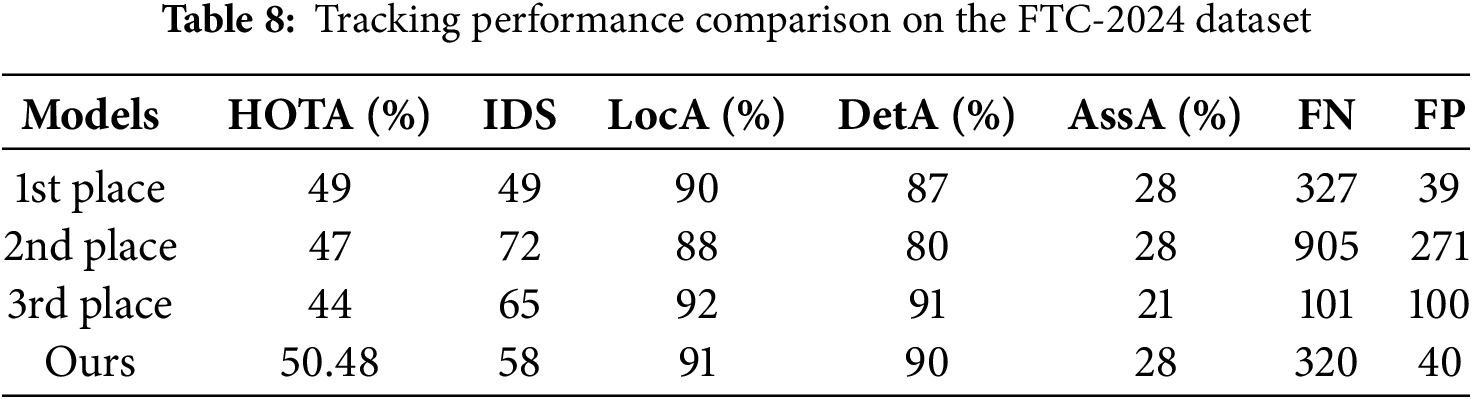

4.4.5 Result in Fish Tracking Challenge 2024

To further validate the generalization capability of our model, we incorporate supplementary experiments using the SweetFish dataset, a newly introduced benchmark from the 2024 Fish Tracking Challenge (FTC-2024, https://ftc-2024.github.io/, accessed on 15 September 2025) [34]. The SweetFish dataset is specifically designed to capture complex collective behaviors of sweetfish, such as group navigation and dynamic aggregation. However, accurate tracking of sweetfish remains a major challenge due to factors including high swimming speeds, frequent target occlusions, and environmental interference. Table 8 presents the tracking performance of FishTracker and the top-3 methods released by the competition on the test dataset. We follow the evaluation indicator specified by this challenge, such as HOTA, IDS, LocA, etc.

FishTracker achieves a HOTA score of 50.78% on the SweetFish dataset, surpassing the first-ranking model in FTC-2024. To visually illustrate the tracking performance, we have included a video demo of our model on the SweetFish dataset (see supplementary material). This video clearly demonstrates the robust and stable tracking performance of our method, even in challenging scenarios involving group movement and partial occlusion.

For the MOT task, the detection model is crucial, with its performance directly impacting subsequent tracking results. Table 4 shows that when ByteTrack is used as tracker, the MOTA of using the YOLOv8 detector exceeds that using the YOLOv5 detector by more than 20%. We have therefore made improvements to the YOLOv8 algorithm by incorporating the MSDA module into the neck part. This module processes feature maps through a multi-scale SWDA mechanism, where varying dilation rates are employed on a per-channel basis. The feature maps are then concatenated and fed into a linear layer, which further optimizes the feature fusion. Extensive experiments have confirmed that in real-time detection scenarios, our method effectively addresses low detection confidence in underwater environments.

When the detector is held constant, the performance of trackers varies significantly. With the enhanced YOLOv8 model as detector, the MOTA of the one using DeepSort can differ by up to 4% compared to ByteTrack. As a result, we have specifically enhanced the ByteTrack algorithm by incorporating a dynamic adjustment of model parameters. This adaptation to variations in system state or environmental noise improves the robustness and accuracy of state estimation.

Current tracking algorithms are predominantly tested within controlled laboratory settings featuring relatively clear water, a low density of fish targets, and few uncertain factors. This limits evaluation regarding the algorithms’ ability to generalize to more complex real-world scenarios. Therefore, this study further collects data from a real factory aquaculture scenario for generalization experiments and assessments of anomalous behavior monitoring. As shown in Fig. 10, we analyze fish trajectories under normal and abnormal conditions at night, with results indicating that FishTracker can efficiently and accurately identify individual fish, thereby providing strong decision support for the intelligent management and anomaly monitoring in aquaculture. In practical aquaculture farming, FishTracker can be integrated with existing video surveillance systems to monitor fish behavior in real-time. Specifically, it can help adjust feeding strategies by analyzing movement patterns, detect hypoxic behavior in fish under a timely manner, and issue early warnings of potential diseases by detecting such hypoxic behavior. Its adaptability to varying light conditions makes it suitable for use in a variety of scenarios, including indoor tanks and outdoor ponds.

However, this work still has certain limitations. In aquacultural environments, suspended solids, feed residues, and reflections from the water surface can significantly degrade image quality, severely affecting the accurate extraction of target features and stable tracking. Current mainstream solutions to this problem include developing adaptive image enhancement algorithms to improve image clarity [35], exploring multispectral imaging technologies to distinguish targets from background clutter [36], and researching feature matching methods based on temporal information to enhance tracking robustness [37]. Although the overall results of FishTracker outperform existing algorithms, the IDSW and Frags remain further enhancement. We believe that this is due to the improved detection capabilities of the enhanced detection model, which result in a higher frequency of target interactions during the tracking process. In the future, we will address these issues by optimizing the data association strategies.

In this paper, we present FishTracker, a MOT algorithm operating within the TBD framework. Specifically, we introduce an MSDA module into YOLOv8 and an AKF into ByteTrack. FishTracker’s performance is validated in both laboratory and real-world production scenarios. FishTracker not only reduces the number of model parameters, but also achieves mAP50s of 95.66% and 91.85% in the aforementioned scenarios respectively. In terms of MOT, the results of FishTracker show an increase in the MOTA of 7.5% and 3.1% under dark light and bright illumination conditions, respectively, while in the aquaculture scenarios, the MOTA improved by 5.34%. Furthermore, FishTracker’s superior integration of detection precision and tracking continuity is reflected in its significant gains in HOTA. This indicates that FishTracker exhibits excellent performance stability and transferability under different lighting conditions and aquaculture scenarios. It effectively addresses the challenges of intelligent monitoring in the production environment and provides strong technical support for the comprehensive digitalization of the aquaculture industry.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 106-YDZX2025022), the Startup Foundation of New Professor at Nanjing Agricultural University (Grant No. 106-804005) and the “Qing Lan Project” of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yuqiang Wu and Huanliang Xu; methodology, Yuqiang Wu and Zhaoyu Zhai; software, Zhao Ji and Guanqi You; validation, Yuqiang Wu and Zhao Ji; investigation, Zhao Ji, Chaoping Lu and Zihan Zhang; data curation, Zhao Ji and Guanqi You; writing—original draft preparation, Yuqiang Wu and Zhao Ji; writing—review and editing, Yuqiang Wu and Zhaoyu Zhai; visualization, Zhao Ji; supervision, Huanliang Xu and Zhaoyu Zhai; project administration, Huanliang Xu and Zhaoyu Zhai. funding acquisition, Zhaoyu Zhai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The Ethics Approval is approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University (NJAULLSC2024032).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.070414/s1.

References

1. Li D, Liu C. Recent advances and future outlook for artificial intelligence in aquaculture. Smart Agric. 2020;2(3):1–20. doi:10.12133/j.smartag.2020.2.3.202004-SA007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xu W, Yu J, Xiao Y, Wang G, Li X, Li D. A new quantitative analysis method for the fish behavior under ammonia nitrogen stress based on pruning strategy. Aquaculture. 2025;600(4):742192. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.742192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mariu A, Chatha AMM, Naz S, Khan MF, Safdar W, Ashraf I. Effect of temperature, pH, salinity and dissolved oxygen on fishes. J Zool Syst. 2023;1(2):1–12. doi:10.56946/jzs.v1i2.198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cui M, Liu X, Liu H, Zhao J, Li D, Wang W. Fish tracking, counting, and behaviour analysis in digital aquaculture: a comprehensive review. arXiv:2406.17800. 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2406.17800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Khan A, Sabeenian RS. Missing object detection and tracking from video surveillance camera footage based on deep learning through convolutional gated recurrent neural networks (CGRNN). J Electr Eng Technol. 2025;4(5):3637–45. doi:10.1007/s42835-025-02244-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li C, Zhu Y, Zheng M. A multi-objective dynamic detection model in autonomous driving based on an improved YOLOv8. Alexandria Eng J. 2025;122(1):453–64. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2025.03.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li D, Du L. Recent advances of deep learning algorithms for aquacultural machine vision systems with emphasis on fish. Artif Intell Rev. 2022;55(5):4077–116. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-10102-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mei Y, Sun B, Li D, Yu H, Qin H, Liu H, et al. Recent advances of target tracking applications in aquaculture with emphasis on fish. Comput Electron Agric. 2022;201(1):107335. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2022.107335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chong C. An overview of machine learning methods for multiple target tracking. In: 2021 IEEE 24th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION); 2021; Washington, DC, USA. p. 1–9. doi:10.23919/FUSION49465.2021.9627045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bai S, Tang X, Zhang J. Research on object tracking algorithm based on KCF. In: 2020 International Conference on Cult-Oriented Science Technology (ICCST). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 255–9. doi:10.1109/ICCST50977.2020.00055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lin Y, Detian H, Weiqin H. Target tracking algorithm based on an adaptive feature and particle filter. Inf. 2018;9(6):140. doi:10.3390/info9060140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sun Z, Chen J, Chao L, Ruan W, Mukherjee M. A survey of multiple pedestrian tracking based on tracking-by-detection framework. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2020;31(5):1819–33. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2020.3009717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bewley A, Ge Z, Ott L, Ramos F, Upcroft B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 3464–8. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2016.7533003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 779–88. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1506.02640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wu B, Liu C, Jiang F, Li J, Yang Z. Dynamic identification and automatic counting of the number of passing fish species based on the improved DeepSORT algorithm. Front Environ Sci. 2023;11:1059217. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1059217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wojke N, Bewley A, Paulus D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 3645–9. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Saad A, Jakobsen S, Bondø M, Mulelid M, Kelasidi E. StereoYolo+ DeepSORT: a framework to track fish from underwater stereo camera in situ. In: Sixteenth International Conference on Machine Vision (ICMV 2023). Singapore: SPIE; 2024. p. 321–9. doi:10.1117/12.3023414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sun P, Cao J, Jiang Y, Zhang R, Xie E, Yuan Z, et al. Transtrack: multiple object tracking with transformer. arXiv:2012.15460. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2012.15460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zheng S, Wang R, Zheng S, Wang L, Jiang H. Adaptive density guided network with CNN and Transformer for underwater fish counting. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(6):102088. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Luo W, Xing J, Milan A, Zhang X, Liu W, Kim T-K. Multiple object tracking: a literature review. Artif Intell. 2021;293(2):103448. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2020.103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang X, Wang X, Gu C. Online multi-object tracking with pedestrian re-identification and occlusion processing. Visual Comput. 2021;37(5):1089–99. doi:10.1007/s00371-020-01854-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Stadler D, Beyerer J. Improving multiple pedestrian tracking by track management and occlusion handling. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 10958–67. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu S, Zheng X, Han L, Liu X, Ren J, Wang F, et al. FishMOT: a simple and effective method for fish tracking based on IoU matching. Appl Eng Agric. 2024;40(5):599–609. doi:10.13031/aea.16092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li W, Li F, Li Z. CMFTNet: multiple fish tracking based on counterpoised JointNet. Comput Electron Agric. 2022;198(3):107018. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2022.107018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang L, Gao J, Xiao Z, Fan H. AnimalTrack: a benchmark for multi-animal tracking in the wild. Int J Comput Vis. 2023;131(2):496–513. doi:10.1007/s11263-022-01711-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang Y, Zhang D, Li R, Zheng Z, Li M. PD-SORT: occlusion-robust multi-object tracking using pseudo-depth cues. IEEE Trans Consumer Electronics. 2025;71(1):165–77. doi:10.1109/TCE.2025.3541839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang Y, Li R, Zhang D, Li M, Cao J, Zheng Z. CATrack: condition-aware multi-object tracking with temporally enhanced appearance features. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;308(23):112760. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Y, Sun P, Jiang Y, Yu D, Weng F, Yuan Z, et al. ByteTrack: multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 1–21. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2110.06864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao H, Cui H, Qu K, Zhu J, Li H, Cui Z, et al. A fish appetite assessment method based on improved ByteTrack and spatiotemporal graph convolutional network. Biosyst Eng. 2024;240(16):46–55. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2024.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li W, Liu Y, Guo Q, Wei Y, Leo HL, Li Z. When trackers date fish: a benchmark and framework for underwater multiple fish tracking. arXiv:2507.06400 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2507.06400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sohan M, Sai Ram T, Rami Reddy CV. A review on YOLOv8 and its advancements. In: International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 529–45. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-7962-2_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jiao J, Tang Y-M, Lin K-Y, Gao Y, Ma AJ, Wang Y, et al. Dilateformer: multi-scale dilated transformer for visual recognition. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25:8906–19. doi:10.1109/TMM.2023.3243616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chen Y, Tu K. Robust self-adaptive Kalman filter with application in target tracking. Meas Control. 2022;55(9–10):935–44. doi:10.1177/00202940221083548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Itoh MM, Hu Q, Niizato T, Kawashima H, Fujii K. Fish tracking challenge 2024: a multi-object tracking competition with sweetfish schooling data. arXiv:2409.00339. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2409.00339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Guo J, Ma J, García-Fernández ÁF, Zhang Y, Liang H. A survey on image enhancement for low-light images. Heliyon. 2023;9(4):e14558. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Tian Q, He C, Xu Y, Wu Z, Wei Z. Hyperspectral target detection: learning faithful background representations via orthogonal subspace-guided variational autoencoder. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(1):1–14. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3393931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Xu S, Chen S, Xu R, Wang C, Lu P, Guo L. Local feature matching using deep learning: a survey. Inf Fusion. 2024;107(10):102344. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools