Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Dual-Mode Data-Driven Iterative Learning Control: Applications in Precision Manufacturing and Intelligent Transportation Systems

1 School of Automation, Wuxi University, Wuxi, 214105, China

2 School of Automation, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

3 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University-Wuxi Technology and Innovation Research Institute, Wuxi, 214142, China

4 School of Internet of Things Engineering, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, 214122, China

* Corresponding Author: Xuejian Ge. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Networking Technologies for Intelligent Transportation and Connected Vehicles)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071295

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Iterative Learning Control (ILC) provides an effective framework for optimizing repetitive tasks, making it particularly suitable for high-precision applications in both precision manufacturing and intelligent transportation systems (ITS). This paper presents a systematic review of ILC’s developmental progress, current methodologies, and practical implementations across these two critical domains. The review first analyzes the key technical challenges encountered when integrating ILC into precision manufacturing workflows. Through case studies, it evaluates demonstrated improvements in positioning accuracy, surface finish quality, and production throughput. Furthermore, the study examines ILC’s applications in ITS, with particular focus on vehicular motion control applications including autonomous vehicle trajectory tracking, platoon coordination, and traffic signal timing optimization, where its data-driven characteristics enhance adaptability to dynamic environments. Finally, the paper proposes targeted future research directions that are essential for fully realizing ILC’s potential in advancing these interconnected yet distinct fields.Keywords

Iterative Learning Control (ILC), as an optimization method for repetitive dynamic systems, enhances tracking accuracy through iterative adjustment of control inputs, demonstrating significant potential in both precision manufacturing and intelligent transportation systems (ITS) [1–3]. In manufacturing applications, ILC has been effectively employed to improve positioning accuracy, surface quality, and production throughput [4]. Within transportation domains, its data-driven characteristics enable continuous improvement of autonomous vehicle trajectory tracking [5,6], platoon coordination, and traffic signal timing optimization [7] in dynamic environments.

As an important branch of modern control theory, the theoretical framework of ILC is established upon six fundamental postulates [8].

1. The reference signal

2. The initial state

3. The length of time T of each iteration is fixed.

4. The system dynamics operator G is fixed for each iteration.

5. The input signal update follows the law

6. The system dynamics operator G is invertible.

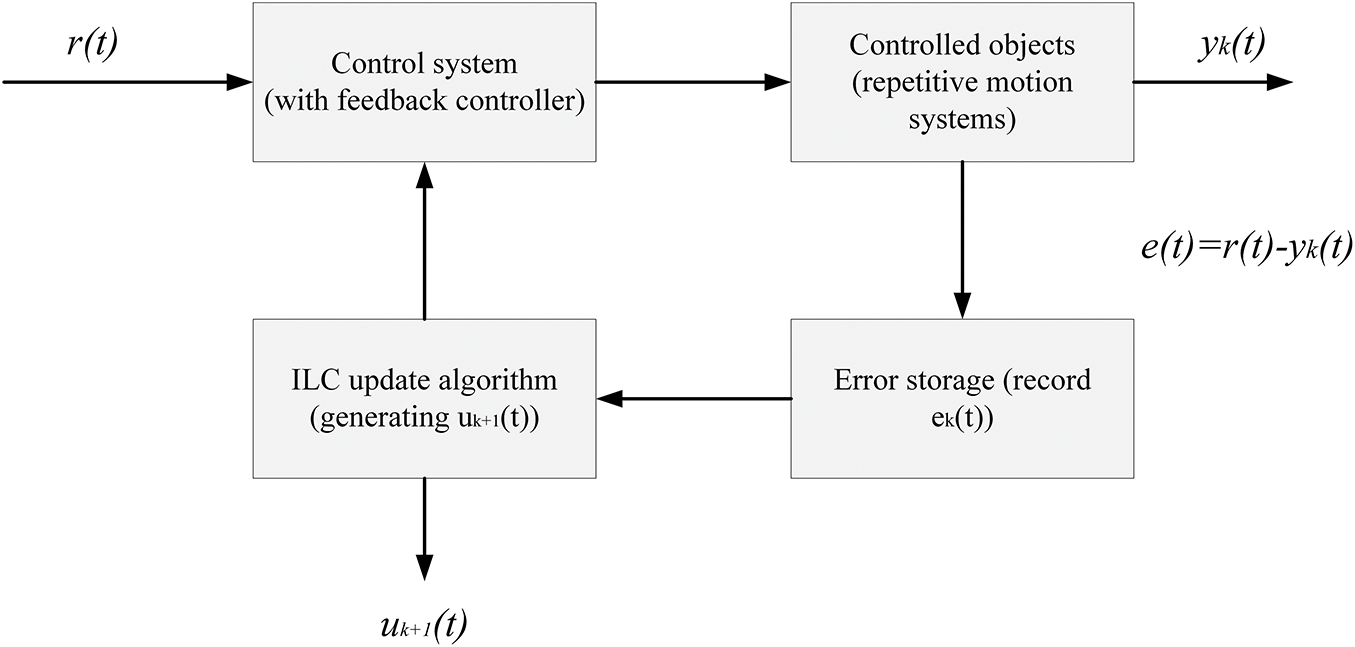

The aforementioned postulates establish the complete theoretical architecture for iterative learning control, with the corresponding framework diagram presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Typical closed-loop structure of ILC

• The error information acquisition link provides the necessary feedback basis for the system.

• The control law updating link is responsible for the dynamic adjustment of the algorithm parameters.

• The input signal correction link completes the optimization of the control command generation.

Through proper algorithm design, this approach theoretically guarantees the convergence of system tracking errors to zero. With demonstrated advantages in both rapid convergence and asymptotic optimization performance [9,10], it exhibits significant application value in control engineering.

In terms of historical development, the initial P-type ILC algorithm features a simple structure but suffers from limited noise robustness and slow convergence rate. The D-type ILC formulation enhances high-frequency noise suppression capability while exhibiting sensitivity to measurement quantization noise due to its derivative operation. The subsequently developed PD-type ILC synergistically combines these approaches, achieving an optimal balance between robustness and convergence performance through gain scheduling. Recently, advanced ILC architectures integrating adaptive control and robust control techniques have demonstrated significant improvements in tracking accuracy, closed-loop stability, and convergence rate [11–13].

The successful application of ILC in industrial robotics provides an effective solution to the accuracy bottleneck problem in repetitive trajectory tracking [14,15]. In precision manufacturing systems, it significantly improves machining accuracy and productivity, thereby promoting the transformation and upgrading of manufacturing industries [16,17]. For motion control platforms, ILC establishes a novel methodology for achieving high-speed and high-precision control objectives [18–20]. The successful applications of ILC not only validate its theoretical foundations but also demonstrate its practical effectiveness for sustainable development. Through continuous technological advancements, ILC has achieved significant breakthroughs in both theoretical system construction and engineering implementations. Current research focuses on three primary directions: the evolution of learning algorithms, improvements in analytical methodologies, and integration with emerging technologies such as precision manufacturing. Furthermore, scholars are making substantial contributions to cutting-edge research areas including frequency-domain analysis, two-dimensional system theory, and energy-based control methods [21–25].

ILC exhibits distinctive advantages in precision manufacturing applications due to its model-independent nature [26,27]. The data-driven characteristic of ILC is particularly well-suited to address the complex challenges inherent in precision manufacturing processes [28]. Precision manufacturing systems involve the coupling of multiple physical fields, including complex phenomena such as thermal-force-fluid coupling, and it is extremely challenging to establish accurate mathematical models [29,30]. ILC effectively addresses modeling challenges by directly optimizing process parameters through iterative refinement of measured part morphology data [31]. In metal additive manufacturing, ILC enables autonomous adjustment of critical parameters including laser power and scanning speed based on layer-by-layer dimensional analysis, eliminating dependence on complex melt pool dynamics models [32].

In the face of repetitive disturbances, ILC demonstrates excellent compensation capabilities [33]. Manufacturing processes exhibit multiple periodic disturbances, including fluctuations in the powder feeding system, thermal accumulation effects, and inter-layer temperature variations [34,35]. Through iteration, ILC automatically identifies these recurring disturbance patterns and compensates for them in subsequent printing cycles. For instance, in polymer 3D printing, ILC adapts to extrusion changes caused by nozzle temperature fluctuations, maintaining consistent layer deposition thickness [36]. Progressive layer deposition enables iterative enhancement of ILC precision, yielding asymptotically diminishing disturbance influence [37,38].

ILC and precision manufacturing technology exhibit inherent synergy, primarily manifested in the strong alignment between their process characteristics and control requirements [39]. The cyclic characteristics inherent in precision manufacturing operations exhibit particular compatibility with the recursive learning paradigm implemented by ILC.

• Firstly, its cyclic machining characteristics provide opportunities for ILC to achieve continuous optimization [40,41].

• Secondly, the repetitive trajectory of equipment actuators represents the ideal control target for ILC.

• Thirdly, multi-physics phenomena in machining processes exhibit complex nonlinear dynamics that can be effectively regulated through ILC-based control systems.

Furthermore, the complex nonlinear dynamic characteristics formed by the heat-force coupling, material removal and other multi-physical fields involved in the machining process can be effectively controlled by the data-driven characteristics of ILC [42–44].

It is noteworthy that the data-driven advantages of ILC extend beyond manufacturing applications, demonstrating significant value in intelligent transportation systems characterized by more complex dynamic behaviors. Building on ILC, researchers have integrated it with fuzzy logic to develop an adaptive data-driven traffic signal control strategy. VISSIM simulation results confirm that this approach significantly outperforms conventional fixed-time and actuated control strategies in terms of both intersection capacity improvement and traffic flow adaptation [45]. Requiring minimal prior knowledge, this method effectively handles stochastic disturbances in transportation systems through synergistic integration with alternating response-based urban control frameworks [46].

In railway control applications, reference [47] proposed a D-type ILC scheme incorporating overspeed protection, subsequently developing a multi-train coordination strategy that achieves precise maintenance of safe headway distances. To address nonlinear parametric uncertainties and multiple unknown state delays in the system, reference [48] designed an adaptive ILC method for high-speed trains that successfully ensures accurate tracking of desired displacement and velocity trajectories. This study innovatively employs spatial state differentiator technology to transform the nonlinear train operation model from the time domain to the spatial domain, thereby constructing a constrained spatial adaptive controller [49]. Furthermore, reference [50] provides a systematic examination of the key technical challenges and future development prospects of deep reinforcement learning in intelligent transportation applications. Beyond specific railway applications, the development of intelligent transportation systems requires integrated solutions across multiple technical dimensions.

To support the development of efficient, secure, and intelligent future transportation systems, a series of studies have proposed targeted solutions from a vehicle-road-cloud cooperative perspective [51]. Reference [52] employs non-orthogonal multiple access and deep reinforcement learning to optimize inter-vehicle communication resource allocation, ensuring information timeliness while reducing energy consumption. Reference [53] introduces an intelligent task offloading mechanism that leverages edge server resources to enhance the energy efficiency and training performance of federated learning. Reference [54] utilizes multi-agent deep reinforcement learning to coordinate digital twin maintenance and real-time task processing in cloud servers, thereby improving resource utilization efficiency. Together, these studies establish a multi-level optimization framework spanning terminal communications, edge computing, and cloud scheduling. While these communication and computing frameworks provide the infrastructure foundation, the core control algorithms operating within this infrastructure require simultaneous advancements in precision and robustness.

The dual-mode framework proposed in this work simultaneously incorporates the capability of iterative learning to asymptotically eliminate repetitive errors and the ability of online adaptation to promptly suppress unexpected disturbances. Precision manufacturing and intelligent transportation systems are adopted as two highly representative application scenarios to validate the effectiveness and superiority of this unified framework across different domains.

This section focuses on the core theory of ILC. It first elaborates on the principle of its core update law, and then analyzes the stability conditions of the update law in time and frequency domains. Based on the special characteristics of ILC, this section strategically relaxes certain constraints, thereby lowering control energy usage without sacrificing system performance.

2.1 Model Free ILC Design Framework

ILC primarily deals with discrete repetitive processes as its core subject. Such systems operate periodically over a finite time duration, with each run referred to as an “iteration”. Their dynamic behavior is characterized by evolution in both the time domain and the iteration domain: the system state evolves along the time axis, while control performance improves with successive iterations. By leveraging this repetitive nature, ILC updates the current control input using information from past iterations, thereby achieving asymptotic convergence of the tracking error over the iteration domain.

As the fundamental ILC algorithm, P-type ILC operates by scaling the tracking error in the

Consider the dynamics of a discrete-time linear system at the

where

The control law of P-type ILC can be expressed in [57] as

where

The P-type ILC law in discrete-time systems takes the following form

where

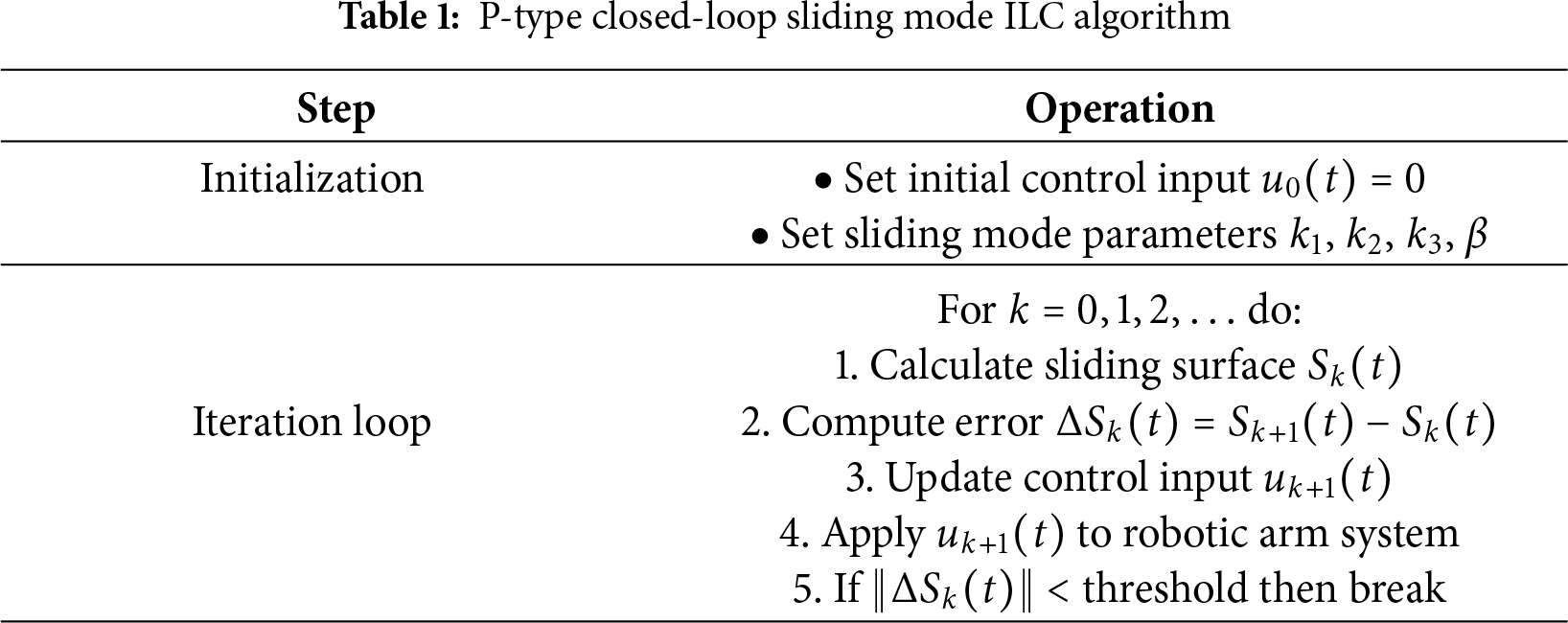

Combining the advantages of P-type ILC and sliding mode control, the work in [59] designed a P-type closed-loop sliding mode iterative learning controller with forgetting factor, as shown in Table 1. This controller first guides the system from an arbitrary starting point to the sliding surface, then ensures rapid convergence to the origin along this surface, effectively eliminating the influence of varying initial conditions across iterations.

The D-type iterative learning algorithm utilizes error derivative components to update control inputs, leveraging the error change rate from previous iterations. Ideal for repetitive motion applications, this technique improves upon basic P-type ILC by adding dynamic error compensation through differentiation, resulting in quicker convergence and better tracking performance [60–62].

The update formula for the control input in [63] as

where

where

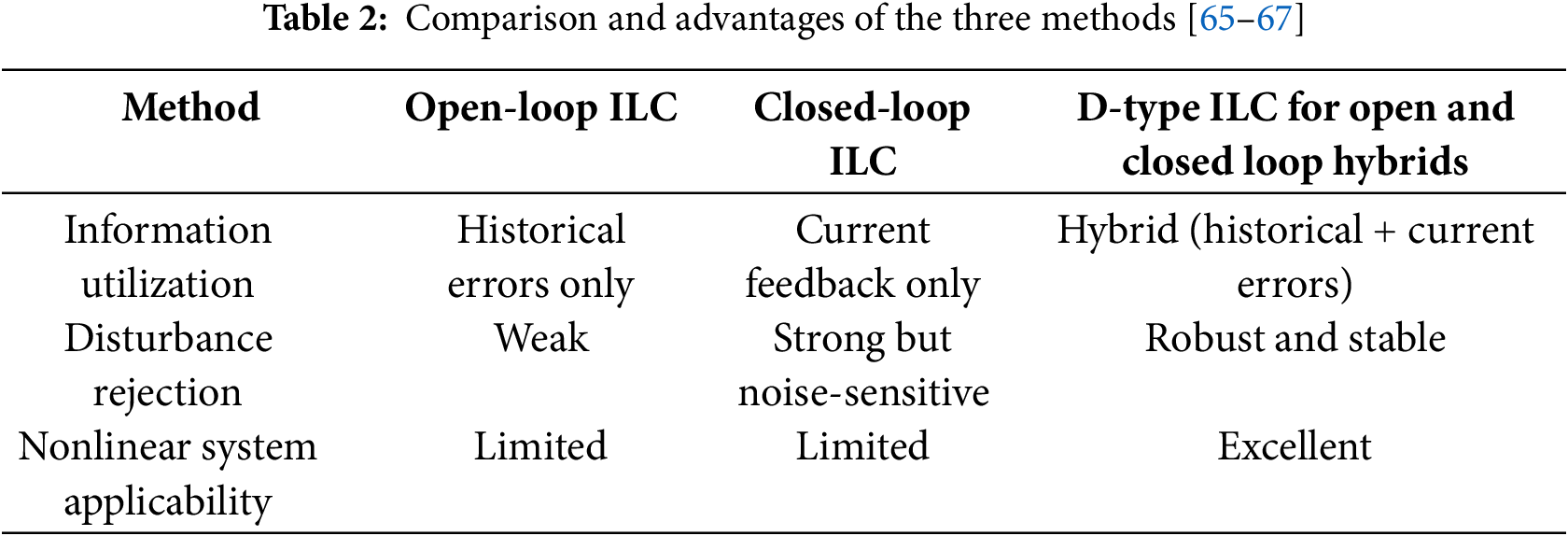

To enhance tracking precision and system robustness, reference [64] develops a combined open/closed-loop D-type iterative learning control scheme for non-canonical nonlinear systems, integrating both historical error data and instantaneous feedback information. For a comparison of the three methods, please refer to Table 2.

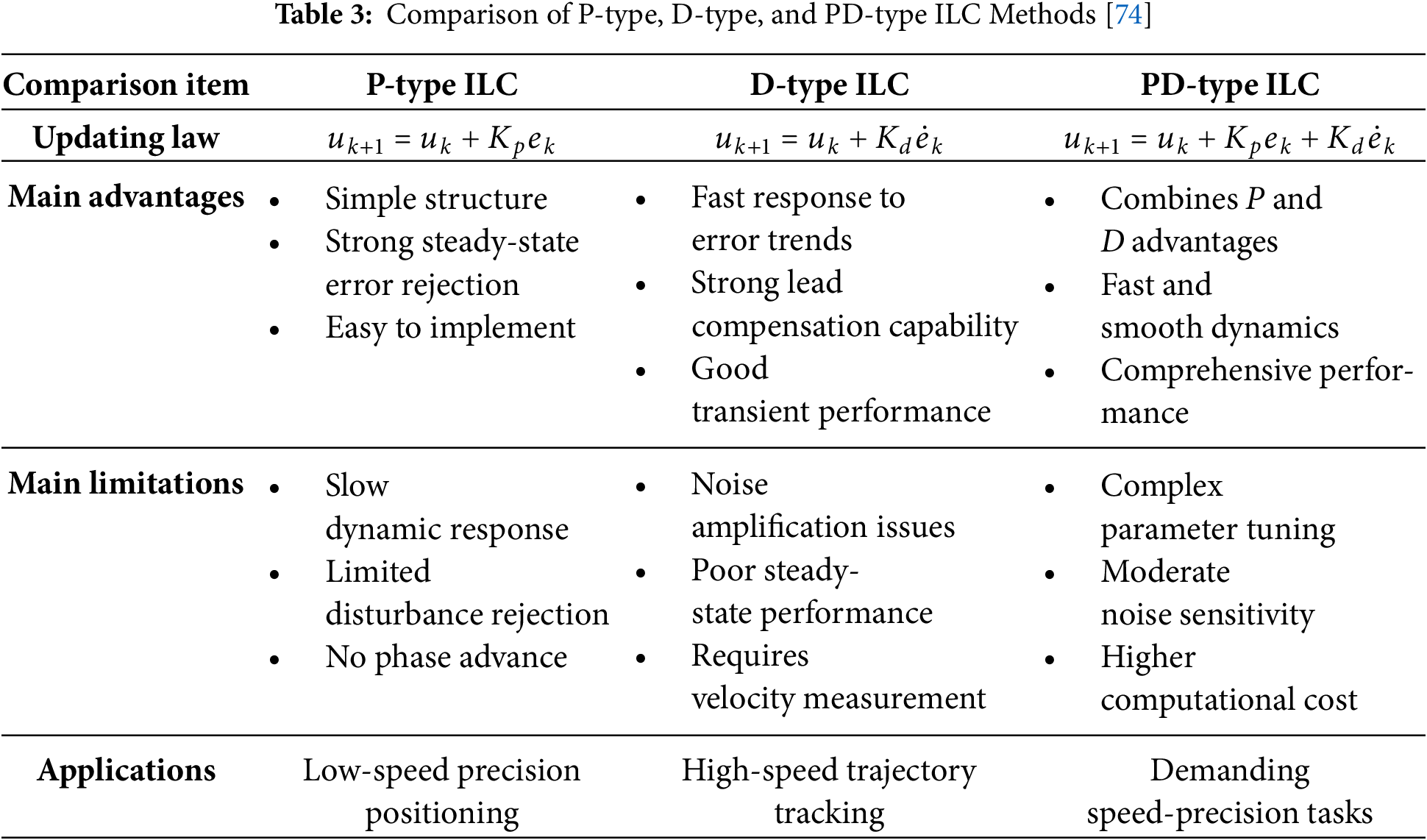

PD-type ILC synergistically combines proportional and derivative feedback mechanisms. Building upon conventional P-type ILC through the incorporation of error differentiation, this approach substantially enhances both transient response characteristics and disturbance rejection performance. The underlying principle operates through dual compensation: the proportional component eliminates steady-state errors to guarantee precision, while the derivative term anticipates error variations to mitigate overshooting and dampen oscillations [68,69]. For a comparison of the three methods, please refer to Table 3.

For the PD-type update law, the iterative update formula for the control inputs is given in [70]

where

Recent advances in PD-type ILC for T-S fuzzy nonlinear systems have addressed key implementation challenges. Reference [71] introduced a finite-frequency domain design to enhance robustness, while reference [72] developed a variable-gain scheme optimizing the convergence-noise trade-off. For non-uniform trial lengths, reference [73] proposed a recursive update mechanism that efficiently constructs complete learning sequences, outperforming conventional zero-padding and search methods in both data utilization and storage efficiency.

Despite benefiting from the proportional term’s accuracy and the derivative term’s predictive correction, PD-type ILC is prone to failure in environments with significant noise or non-repetitive disturbances. The derivative component exacerbates high-frequency noise, leading to control signal chattering that degrades performance and threatens stability. The common solution of adding noise filters introduces its own problems, namely phase lag and the challenge of filter parameter tuning.

2.1.1 Model-Based ILC Design Framework

Model-based ILC can significantly improve the learning efficiency and control accuracy by combining information from system dynamics models [75]. The core idea is to use the model to predict the error evolution dynamics and design a higher-order learning law. In this section, two typical methods, inverse model ILC and optimal control ILC, are introduced in detail, including algorithm design, theoretical analysis, and engineering applications.

The inverse model ILC is implemented as proposed in [76], where a dynamic inverse model of the system is constructed to directly compute control inputs for compensating the tracking error

where

Optimal control ILC transforms an iterative learning problem into a dynamic optimization problem by minimizing a composite objective function containing the error energy and the control energy to solve the optimal input update law [77]. Its generalized form can be formulated as

where Q and R are the weighting matrices for error and control inputs, respectively, and

The performance of inverse-model ILC is critically dependent on model accuracy, as minor mismatches can cause instability, restricting its use in practical scenarios. Conversely, optimal control ILC suffers from the empirical tuning of its weighting matrices and high computational complexity, hindering its real-time implementation.

2.1.2 Data-Driven ILC Design Framework

By integrating ILC with model predictive techniques for repetitive batch processes, the iterative learning model predictive control approach enables progressive enhancement of tracking accuracy while effectively rejecting real-time disturbances [78].

Reference [79] introduced an indirect data-driven ILC strategy for nonlinear repetitive systems, focusing on enhancing PID feedback control performance through reference trajectory adjustment, eliminating dependence on precise system modeling. Subsequently, reference [80] developed an advanced data-driven higher-order optimal ILC algorithm to significantly decrease computational burden.

The higher order learning control law is

where

The mathematical model describing a typical nonlinear batch process [82] is given by

where

A prior-knowledge migration mechanism based on deep neural networks was proposed in [82], and its relationship with the ILMPC controller is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: ILMPC architecture based on a priori knowledge migration mechanism

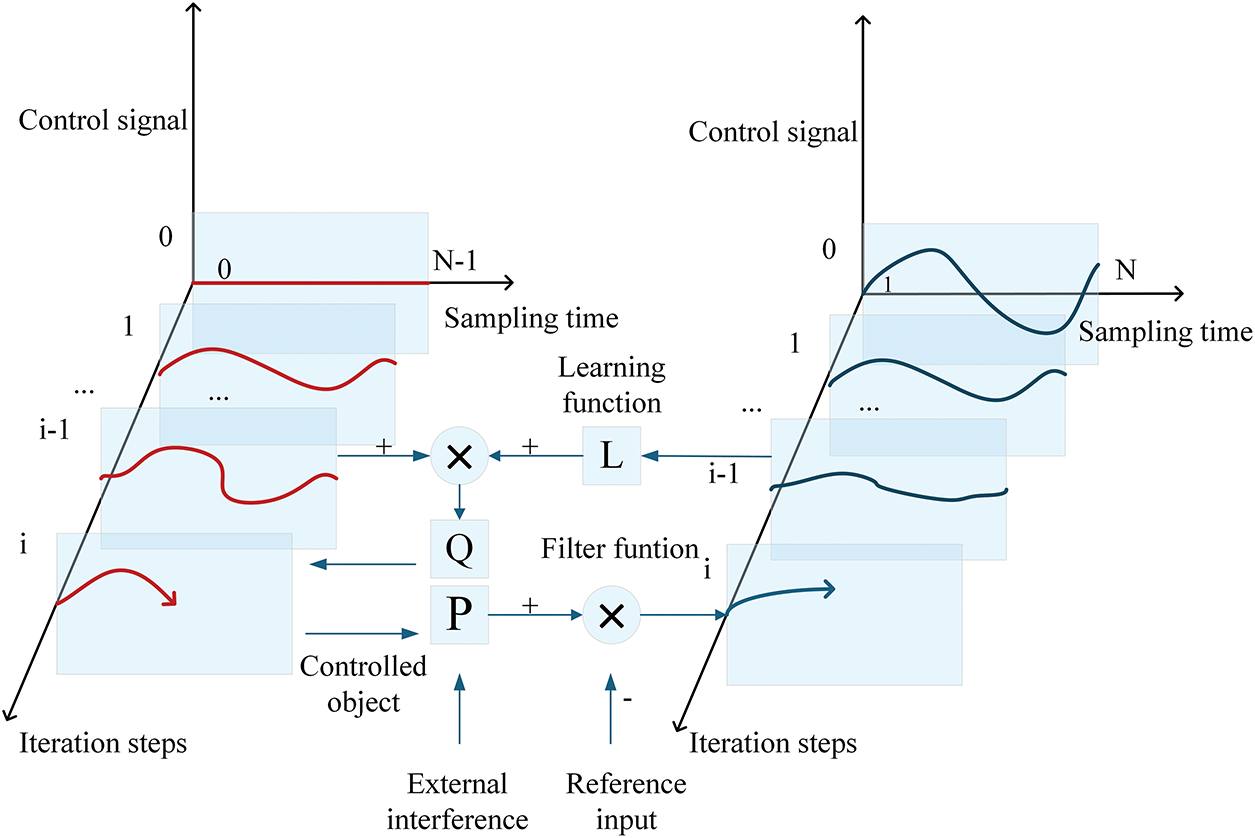

The unified framework of dual-mode data-driven ILC integrates iterative learning control with online adaptation. Its core concept lies in leveraging ILC on the iteration axis to learn and eliminate repetitive disturbances, while online feedback strategies like adaptive control are utilized on the time axis to suppress non-repetitive disturbances and model uncertainties in real time.

This paper presents a general update law for the control signal, formulating the integration of the two modes within a unified mathematical framework.

In this framework,

The inherent gap between the ideal conditions of theoretical assumptions and the pressing demands of practical applications serves as the primary driving force behind the evolution of ILC theory. To successfully deploy ILC in the complex dynamic scenarios discussed in Section 4, such as precision manufacturing and intelligent transportation, it is essential to relax these classical assumptions and develop more robust and adaptive ILC frameworks. The following section will explore a range of advanced ILC strategies designed for this purpose.

3 ILC for Broader Application Scenarios

The theoretical framework of ILC is based on six postulates, which tend to have large limitations in practical applications [83]. To enhance the applicability of ILC, some scholars in recent years have proposed a new idea that ILC is inherently applicable to any control scenario with repetitive characteristics [84,85]. Guided by this idea, researchers have attempted to gain greater flexibility at the algorithm design level by gradually removing single or multiple traditional assumptions [86–88]. However, the sixth postulate, system invertibility, cannot be readily relaxed since it serves as a necessary and sufficient condition for guaranteeing the existence of a unique ideal control input that achieves perfect tracking. Without this assumption, the theoretical basis for asymptotic zero-error convergence would be fundamentally undermined. Therefore, this section focuses only on the first five postulates. Among the six postulates, the sixth is universally applicable across system types, while the first five form the core focus of this section.

In adaptive trajectory tracking for robots, strict time intervals are unnecessary. Thus, reference [89] relaxes time constraints by dynamically optimizing tracking time points (e.g., pick and place times), enabling flexible time allocation. A two-stage optimization framework is then proposed under this relaxed time scheme.

To satisfy the tracking requirements at a finite number of intermediate time points and sub-regions, with the rest of the time free for optimization, the generalized ILC algorithm is designed using a project-by-projection approach in the work of [90]. The iterative update law is

where

•

•

•

•

•

• I: Identity matrix.

To be applicable to spatial path tracking without time constraints, such as laser cutting as well as AM. The work [91] presents an ILC formulation that encodes path tracking requirements via

The study in [92] develops an adaptive ILC scheme with data-driven quantization, requiring only time-specific data sampling while relaxing non-essential trajectory constraints.

Design of quantized adaptive learning control law

where

To reduce point-to-point tracking error, reference [93] proposed an enhanced gradient algorithm with an adaptive gain mechanism for tracking error

where

Meanwhile literature [94] proposes a spatial ILC method based on 2D convolution. The updating law can be expressed in the spatial and frequency domains respectively as

where

The traditional ILC assumes identical initial states for each batch, but in practice, initial states are often unknown and vary due to perturbations, preventing error convergence. Literature [95] addressed this by proposing an initial state learning law that combines with point-to-point iterative learning control (P2PILC) to jointly update control inputs and initial states. The learning law dynamically adjusts the initial state of next batch

where the adjustment is weighted by the control matrix B, learning gain

Gradient-based P2PILC input update law

where

In the work of [96], an interactive adaptive ILC is constructed by simultaneously removing the constraints of iterative parameter changes and initial state from the system, and the parameter estimation update formula

where

where

The work in [97] proposes a finite-time extended state observer that eliminates the conventional requirement for identical initial conditions in iterative learning control systems. The observer dynamics are given by

where

In practice, systems are often subject to uncertainties and disturbances that make strict repeatability difficult to guarantee. Removing this constraint can significantly enhance system adaptability and flexibility, improve the robustness and reliability of the control system, and extend ILC applicability to non-repeatable scenarios.

The article [98] proposes an adaptive ILC method for 2D nonlinear MIMO parameter systems. The method addresses three major non-repeatable uncertainties faced by traditional ILC in practical applications.

• Stochastic initial shifts: The initial state fluctuates randomly around the desired value.

• Non-repetitive references: Reference trajectories may change in each iteration.

• Non-uniform trial lengths: Batch lengths vary randomly in each iteration.

An adaptive control law

where

Literature [99] improves the traditional ILC method by making three main improvements.

• No longer requiring the system dynamics to be repeated in each iteration.

• Removing the restriction that the initial conditions are fixed.

• Allowing the system parameters to vary over time.

To this end, the authors developed a neural network-enhanced adaptive ILC framework, demonstrating improved robustness and practicality. The work in [100] introduces an adaptive Kalman filtering-augmented ILC algorithm, which enables real-time compensation for time-varying dynamics through simultaneous online parameter estimation and covariance matrix adaptation, while maintaining rigorous convergence guarantees.

Literature [101] proposes a D-type iterative modified update law that eliminates the dependence of the system on strict repeatability and ensures convergence and tracking performance of the system under non-repetitive uncertainty

where

In practical systems like aircraft control with variable iteration times, the work in [102] introduced a feedback-assisted PD-type quantized ILC approach for discrete linear systems with random batch lengths and initial conditions. Two quantization schemes were developed

Scheme 1 achieves zero-error convergence, while Scheme 2 achieves bounded convergence.

For discrete-time systems exhibiting nonuniform trial durations, the work in [103] transforms the variable-length problem into a projection problem within a multi-affine subspace using Hilbert space optimization theory, and designs an implementable control algorithm.

The error between desired and actual trajectories is mathematically expressed as

where

In the Hilbert space, the following objective function is minimized

which simultaneously reduces tracking error and input variation, with weight matrices Q and R regulating performance.

The core problem of non-uniform length ILC is solved by the alternating projection method

• The problem is transformed into a multisubspace projection and convergence is rigorously proved.

• Propose a feedback-feedforward structure for causal realization to support input constraints.

The work in [104], on the other hand, transforms the ILC problem into a quadratic programming problem with constraints, as in the following equation, and solves it using the interior point method, which achieves efficient convergence in the presence of input constraints.

where

By removing the constraints of fixed iteration time and a specified update law, the ILC theoretical framework becomes more relevant to engineering needs and adaptable to a wide range of non-repetitive scenarios. To enhance industrial robotic path tracking accuracy, reference [106] developed a dual-phase iterative learning approach comprising sequential model error compensation and motion trajectory optimization. In the model correction phase, difference between actual system and nominal model is quantified by defining a model mismatch quantity

By constructing an objective function containing three regularization constraints as shown in the following equation. Among them, the

The nonlinear optimal control problem in trajectory planning is reformulated as a convex-concave optimization through the introduction of auxiliary variables

The composite cost function comprises two distinct components: the first term

The article [107] achieves control energy minimization and high-precision path tracking by transforming the path tracking problem into a convex optimization problem as shown inthe following equation and incorporating the indirect reference update framework of ILC

where

4 Case Studies: ILC in Precision Manufacturing and ITS

This section presents typical application examples of ILC in the manufacturing field and intelligent transportation, along with an in-depth discussion of the unique advantages and technical details of this method across different processes. Through four representative cases, the analysis demonstrates how ILC can effectively improve both accuracy and efficiency.

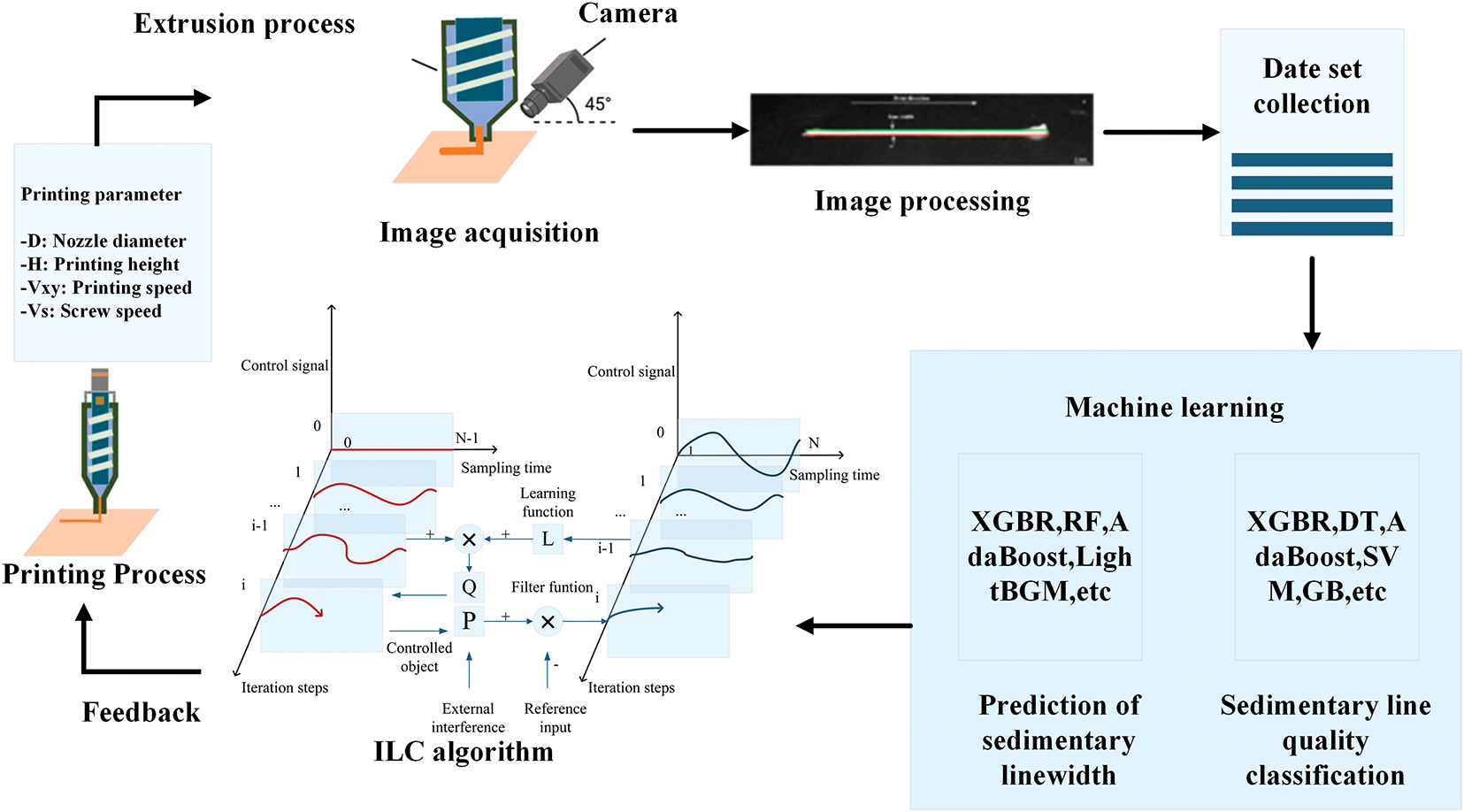

4.1 Extrusion Speed and Trajectory Tracking ILC in FDM Printing

Ceramic paste extrusion faces line inhomogeneity due to viscosity variations and speed mismatches, along with environmental and material fluctuations [108]. Conventional open-loop control relies on trial-and-error parameter tuning, proving inefficient for dynamic disturbances. Current approaches use experimental data to train predictive models [109], but complex paste rheology leads to prediction errors, limiting linewidth control accuracy [110,111]. ILC compensates model errors by identifying perturbations and adjusting extrusion linewidth [112–114]. Its learning capability handles slurry nonlinearities, improving print quality [115], as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: ILC structure diagram

In the extrusion of ceramic materials, there is a clear kinetic relationship between the screw extrusion speed

where

The deposition line width W vs. extrusion speed

Improved algorithms are proposed to improve control performance. Higher-order ILC with forgetting factor

where,

Adaptive gain adjustment rule, adjusted to cumulative error, online adaptation to process perturbations

where

Fig. 4 shows a vision feedback-based extrusion 3D printing process control system, which can be combined with ILC to achieve high-precision closed-loop quality control.

Figure 4: System configuration for closed-cycle quality regulation in 3D printing material deposition processes

The aforementioned study demonstrates the effectiveness of ILC in controlling the ceramic extrusion process—a SISO system—where the screw speed is adjusted to directly compensate for viscosity disturbances, thereby stabilizing the line width. However, the control challenges in additive manufacturing extend far beyond this scenario. When the process involves strong spatiotemporal coupling and interactions among multiple physical fields, such as thermal management in laser powder bed fusion of metals, the complexity of the problem increases significantly. Consequently, the control objective shifts from regulating a single geometric variable to coordinating multiple physical fields, placing greater demands on the control strategy.

4.2 Interlayer Temperature Control in Laser Selective Melting

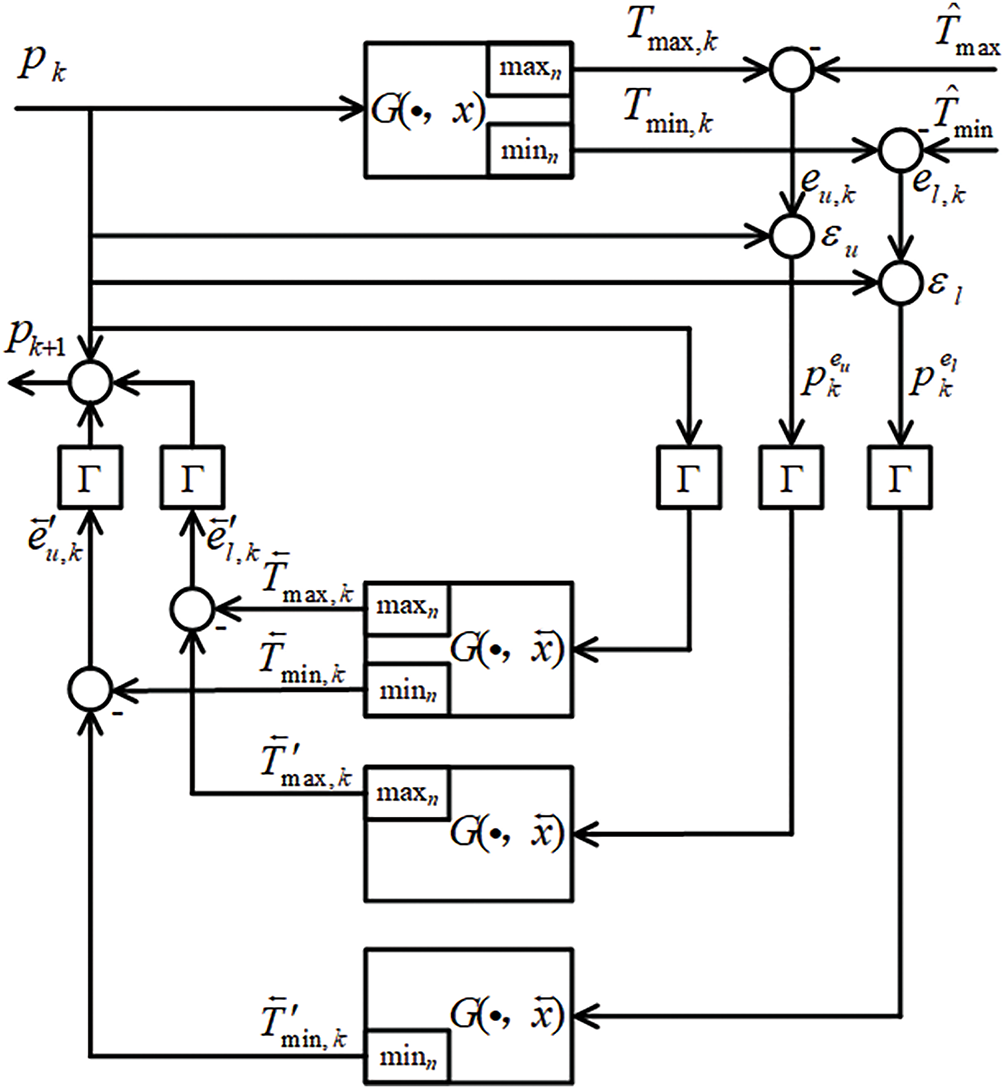

The control of the temperature field in laser selective zone melting (SLM) process faces a key challenge [118]: the need to avoid overheating melt pool while ensuring that material is sufficiently melted [119]. To address this multi-objective control requirement, an innovative model-free ILC scheme has been proposed in the literature [120].

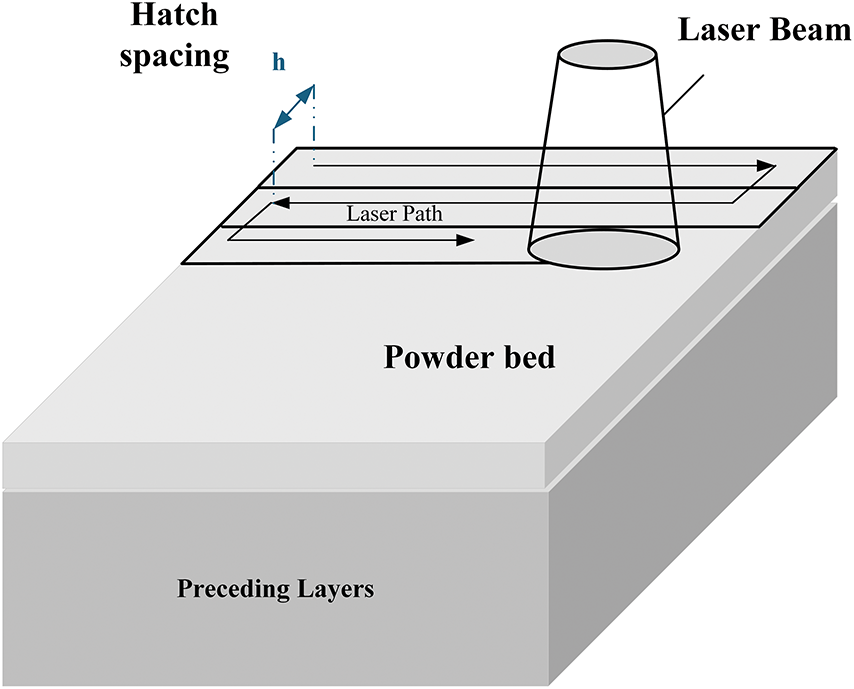

Examining the selective laser melting process depicted in Fig. 5: The laser beam performs raster scanning in the build region with a fixed spot diameter

Figure 5: Illustration of a single-layer SLM process

Setting the laser center

where the temperature

• Lower bound

• Upper bound

For a predefined laser path

where E denotes the cost function that quantifies degree of deviation of temperature extrema from the target interval, and

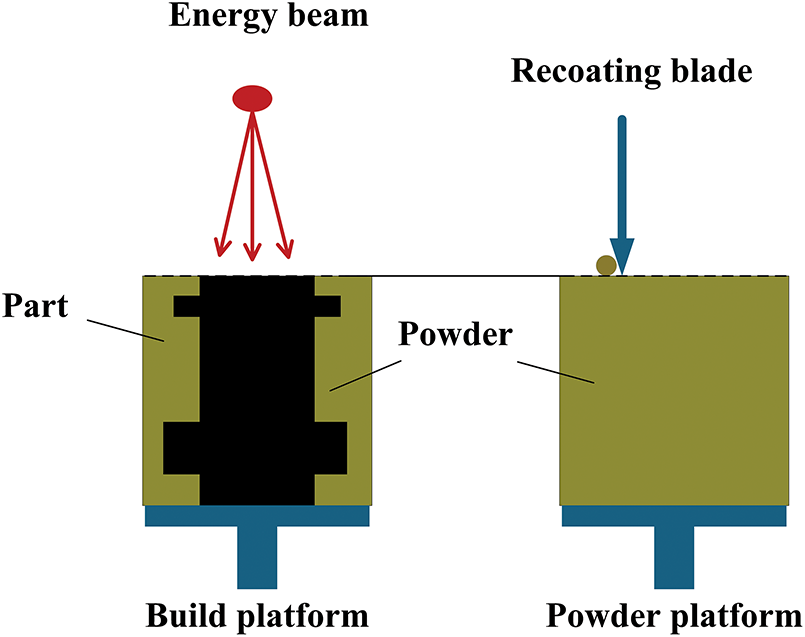

The structure of SLM equipment is shown in Fig. 6, which mainly consists of following components: energy beam, recoating blade, part, powder, build platform, and powder platform [122].

Figure 6: Diagram of SLM machine setup

To solve the difficulty of requiring an exact model for traditional gradient computation, a path inversion gradient estimation method was proposed in the literature [118]. The method first constructs the local linearization matrix of the time-varying system.

where

The computation of the concomitant operator is realized by introducing the time reversal operator T (unit inverse order matrix) and the path backscan response matrix [123], as expressed by

Fig. 7 illustrates the single iteration flow of gradient descent-based model-free ILC algorithm.

Figure 7: Convergence plot of gradient-ILC for SLM thermal control

The case study on interlayer temperature control demonstrates the capability of ILC to handle complex, nonlinear distributed parameter systems that are difficult to model accurately. The control objective in this context extends to stabilizing the entire temperature field. Subsequent research shifts focus from manufacturing processes to motion systems, specifically high-speed train operation control. This domain involves high-order nonlinear complexities, including multi-agent coordination, state constraints, and large-range operation. Such challenges require extending ILC applications from physical field control to the cooperative optimization of multi-body motion systems.

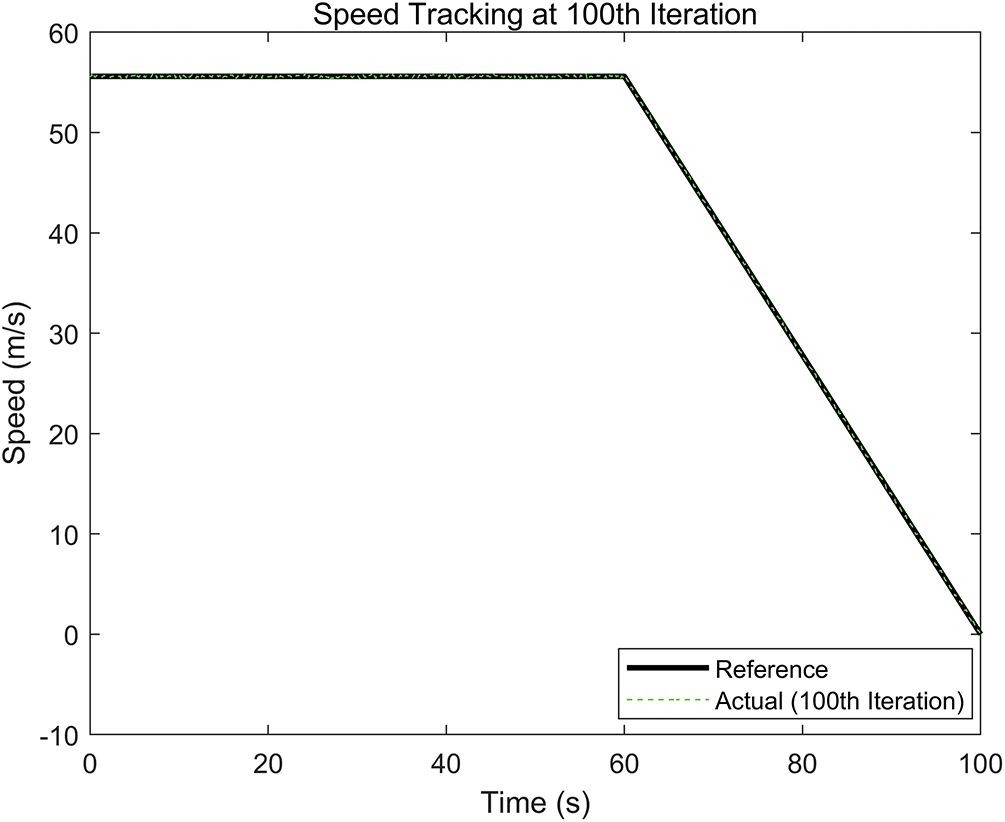

4.3 Trajectory Tracking of High-Speed Train Based on Adaptive ILC

The control system of high-speed trains (HST) [124] must balance safety, energy efficiency, and punctuality. Traditional methods (e.g., PID, model predictive control) rely on precise modeling and struggle to handle time-varying parameters and complex environmental disturbances. In recent years, data-driven and intelligent control methods have significantly improved control performance by leveraging historical data and iterative optimization [125].

Reference [46] designed an adaptive ILC, with its control law formulated as

where

The synchronization of all carriages tracking the reference trajectory is ensured through the consensus error

Figure 8: Tracking effect of the 100th iteration

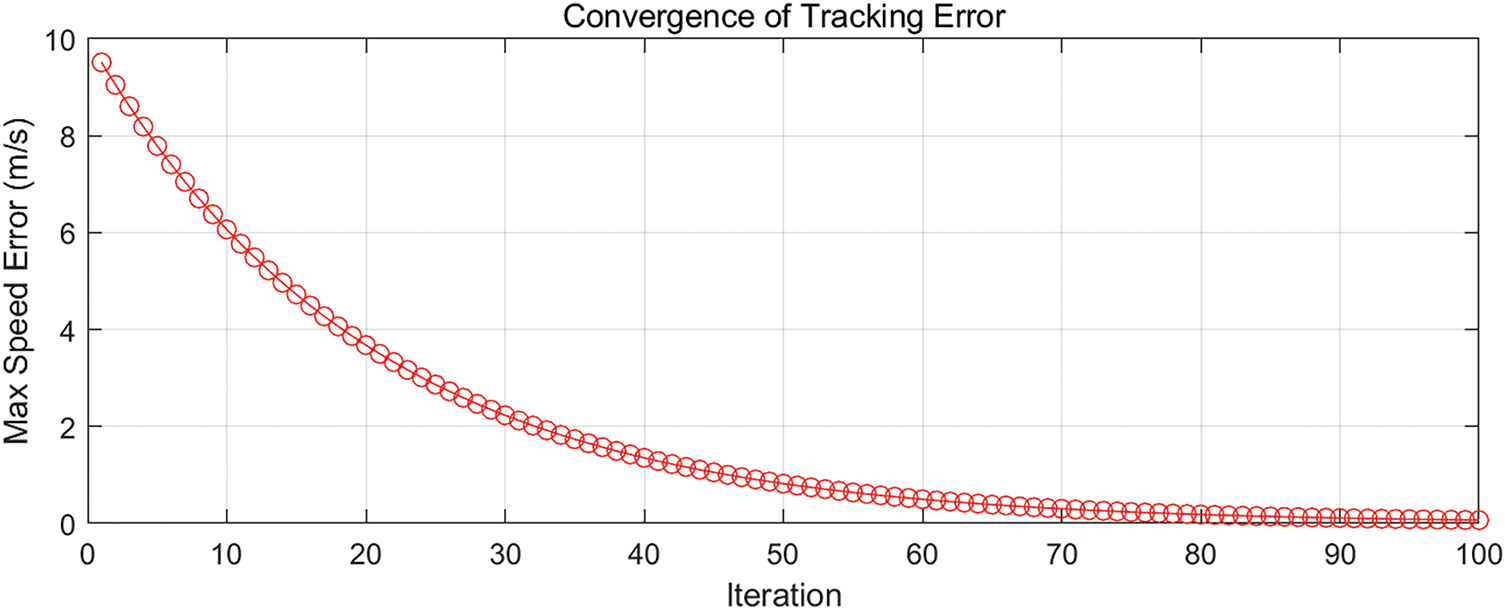

Figure 9: Convergence of maximum tracking error with number of iterations

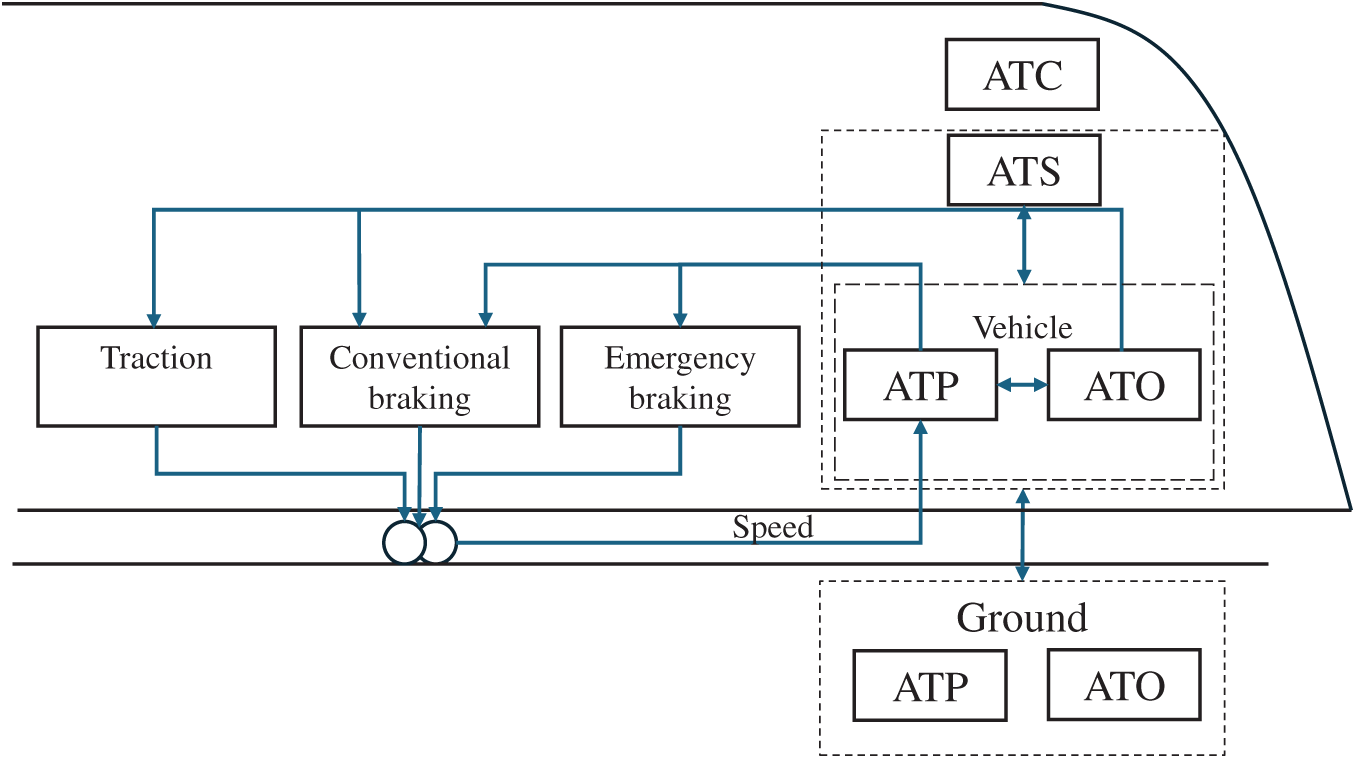

Reference [49] pioneered the solution of state constraints within a spatial iterative learning framework, offering novel insights for nonlinear system control. A constrained spatial adaptive ILC (CSAILC) scheme was designed as illustrated in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Constrained spatial adaptive iterative learning control

Fig. 10 illustrates the CSAILC framework embedded within the hierarchical architecture of a train control system. Its functional modules operate collaboratively as follows: the ATS (Automatic Train Supervision) layer generates operational plans and target commands; the ATO (Automatic Train Operation) module acts as the core actuator, receiving optimized outputs from the ILC algorithm to regulate the traction and conventional braking systems for precise speed tracking; the ATP (Automatic Train Protection) module continuously monitors the system state to ensure all operations remain within the safety envelope, triggering emergency braking immediately upon constraint violation, thereby providing essential safety assurance for the entire learning process. Ground equipment and onboard units exchange data via train-ground communication. The adaptive ILC algorithm developed in this study operates within this framework, dynamically adjusting learning parameters online to achieve high-performance tracking in the iterative domain while strictly adhering to all safety constraints.

The control law is designed to

The parameter update law is designed to

Through the aforementioned design, the convergence performance shown in Fig. 8 can ultimately be achieved.

The HST case demonstrates the effectiveness of ILC in multi-body dynamical systems with state constraints and coordination requirements. Furthermore, the applicability of ILC can be extended to larger-scale urban traffic systems. Highway traffic flow regulation presents challenges such as high stochasticity, interactions among heterogeneous agents (vehicles), and macroscopic periodic characteristics, with system models exhibiting significant uncertainty. This application marks the expansion of ILC from the aforementioned equipment-level control and fleet coordination to the optimized regulation of city-level networked systems.

4.4 ILC for Freeway Traffic Flow Regulation

Traffic congestion in freeway systems remains one of the major challenges in modern urban transportation [126]. Conventional control methods (e.g., ramp metering and variable speed limits) rely heavily on precise traffic modeling, yet real-world traffic systems exhibit strong nonlinearities and uncertainties, resulting in excessive model dependency and limited control efficacy [127].

Reference [128] proposed an ILC-based approach for freeway traffic density control, achieving traffic flow optimization through coordinated ramp metering and speed signaling regulation.

Design of ramp metering control

The speed marker control is designed to

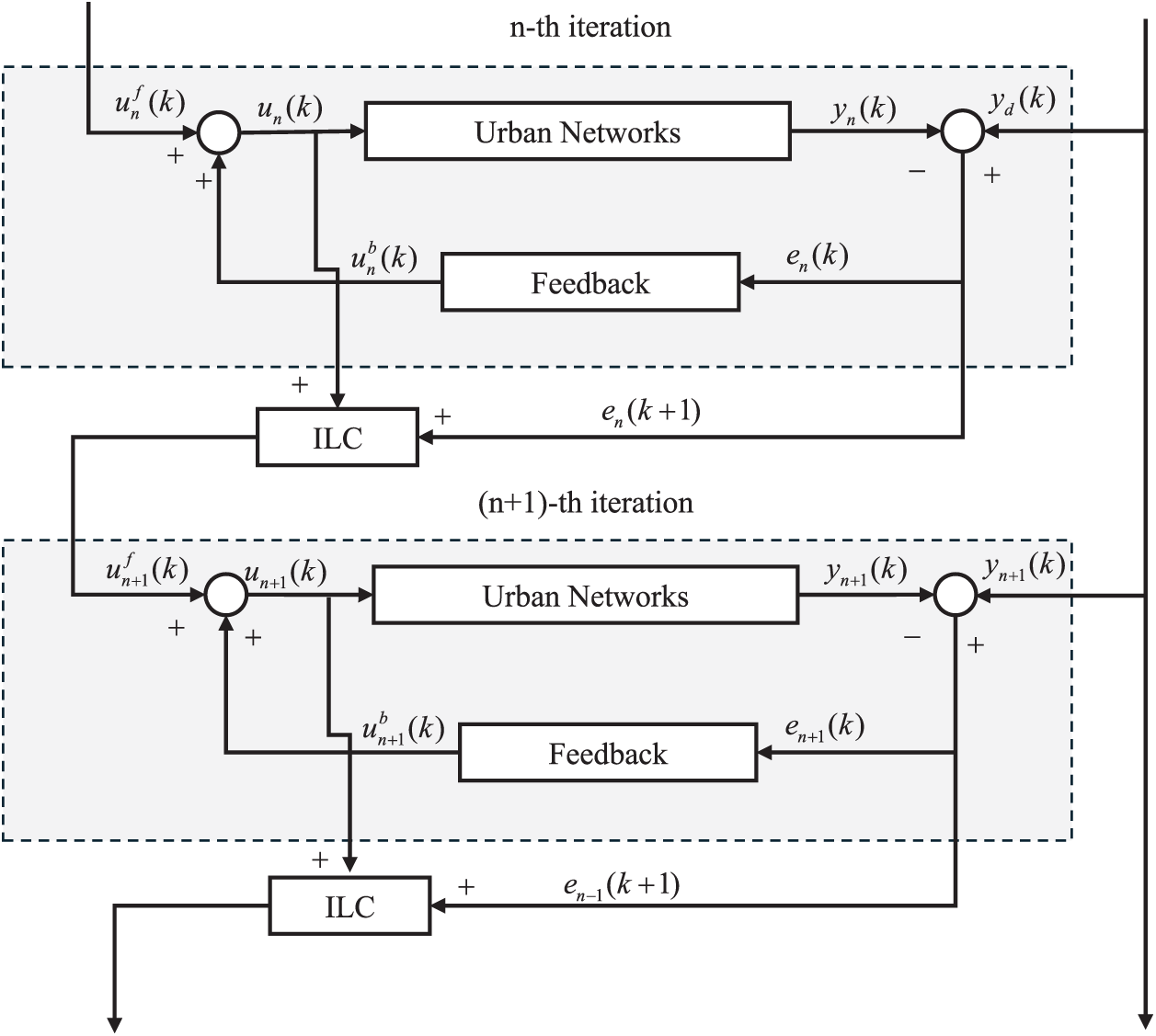

Reference [129] proposed a hybrid strategy (ILC+TUC) that enhances robustness by integrating the iterative learning capability of ILC with the real-time responsiveness of feedback control. The hybrid strategy is formulated as

Fig. 11 illustrates the hybrid strategy, which leverages both offline learning and online adaptation to exploit the periodic characteristics of traffic flow while enhancing system robustness.

Figure 11: Hybrid controller block diagram

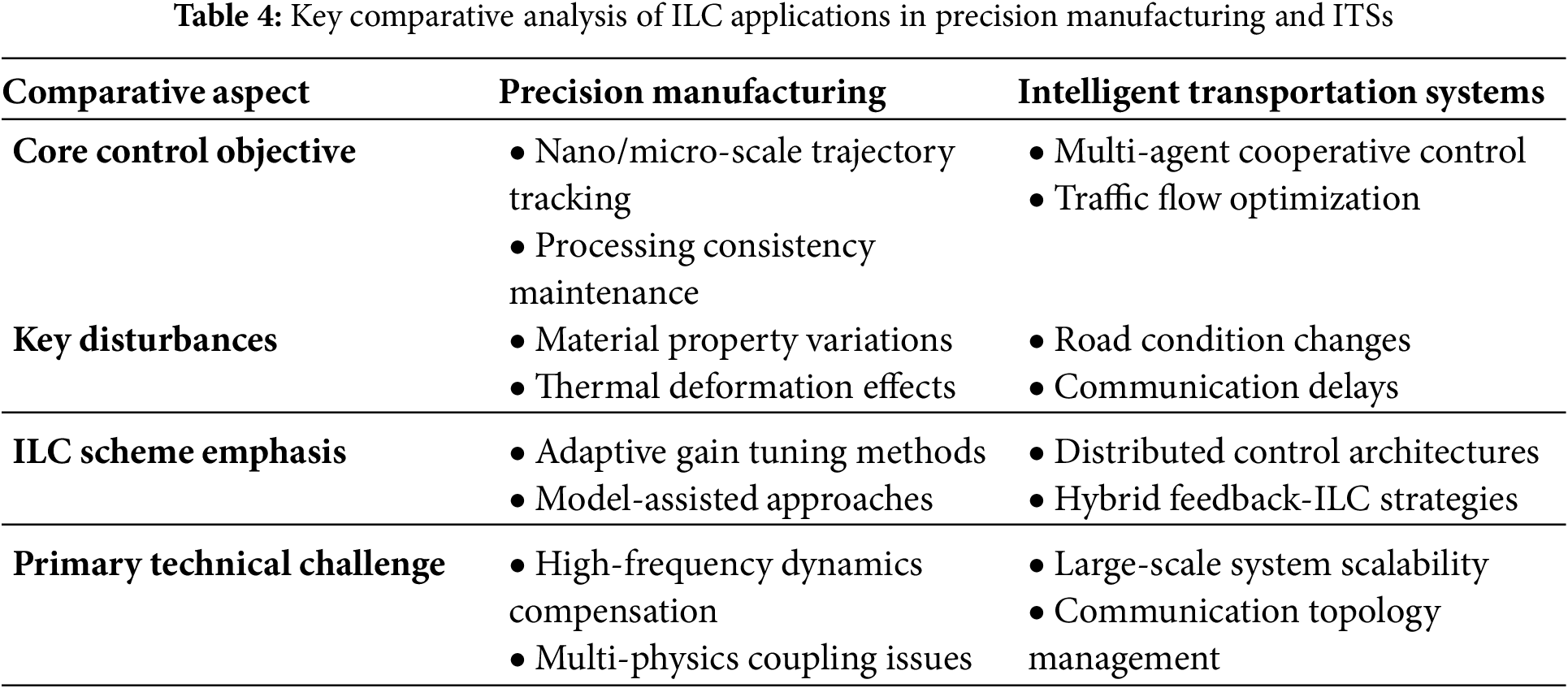

Table 4 provides a systematic comparison of the differentiated applications of ILC in precision manufacturing and ITSs across four dimensions. Precision manufacturing emphasizes micro/nano-scale trajectory tracking and multi-physical field disturbance suppression, often employing model-assisted and adaptive gain methods. In contrast, intelligent transportation systems focus on multi-agent coordination and communication topology optimization, predominantly utilizing distributed and hybrid feedback architectures. This comparison clarifies the distinct technical pathways of ILC across different domains and offers a theoretical basis for cross-disciplinary methodological integration.

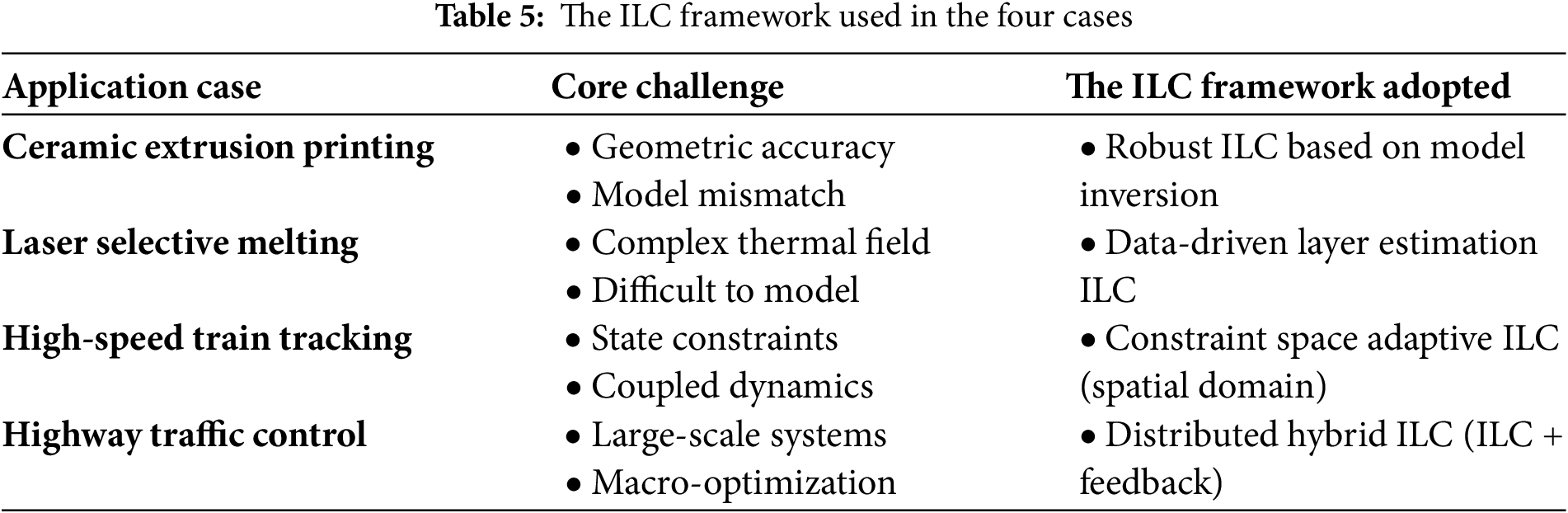

Due to their distinct control objects and performance objectives, each case study adopts a specifically tailored ILC technical approach. The particular ILC framework applied in each case is summarized in Table 5.

The four case studies collectively highlight key commonalities. All processes exhibit distinct cyclic or repetitive characteristics. Each case involves complex dynamics that resist accurate modeling, and each employs historical operational data to compensate for model uncertainties and unknown disturbances. This approach supports high-performance tracking or regulation. Nevertheless, the implementations emphasize distinct aspects. Ceramic extrusion printing focuses on precise closed-loop geometric control. Laser powder bed fusion addresses spatiotemporal temperature optimization and inverse gradient estimation. HST control requires multi-vehicle coordination under state constraints, while highway traffic management emphasizes macroscopic optimization and hybrid integration of control strategies. These distinctions reflect the flexibility of ILC in adapting to diverse applications. They also demonstrate its consistent methodological core in addressing varied control challenges.

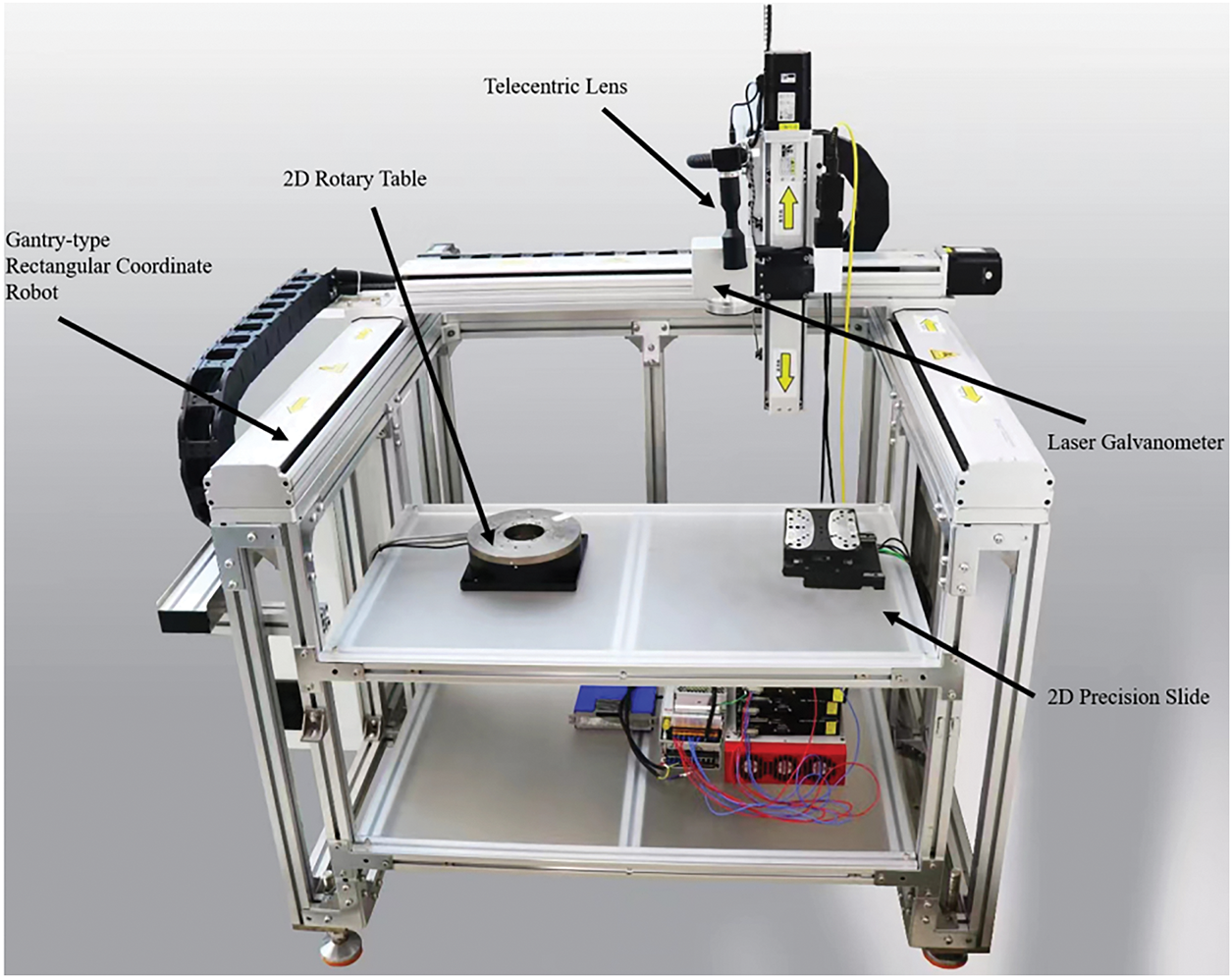

The experimental platform primarily consists of the five components shown in Fig. 12. This experiment involves collaborative operation between two key subsystems: the laser galvanometer system and the 2D precision translation stage. There are usually two mirrors inside the galvanometer, one is the X-axis mirror and the other is the Y-axis mirror. These two mirrors can be rotated at high speed to achieve rapid deflection of the laser beam. By precisely controlling the rotation angle of the mirrors, the pointing of the laser beam can be precisely controlled to realize fine laser processing.

Figure 12: Precision collaborative machining experimental platform

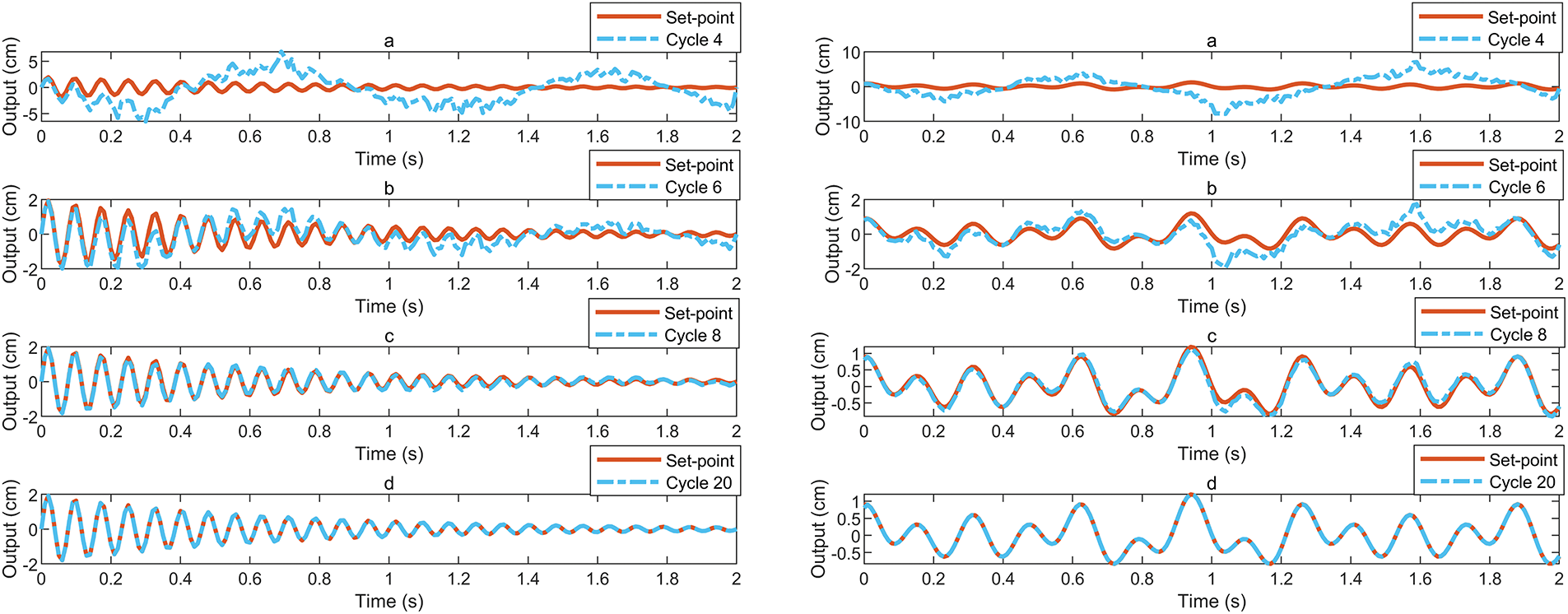

To verify the practical effectiveness of ILC in applications, this study designed and conducted a series of experiments to systematically evaluate system performance regarding tracking capability, fault tolerance, and spatial adaptability. The experiments firstly verified the trajectory tracking ability of ILC. In the test, the system is required to track a predefined complex trajectory, as shown in Fig. 13. The results show that after several iterations of learning, ILC can significantly improve tracking accuracy. The initial tracking deviation is substantial, yet progressive refinement through iterative cycles drives asymptotic convergence toward negligible error levels. This shows that the ILC can effectively optimize the control inputs through the “learning-correction” mechanism to achieve high-precision tracking.

Figure 13: Tracking effect for different number of iterations: (a) 4th tracking; (b) 6th tracking; (c) 8th tracking; (d) 20th tracking

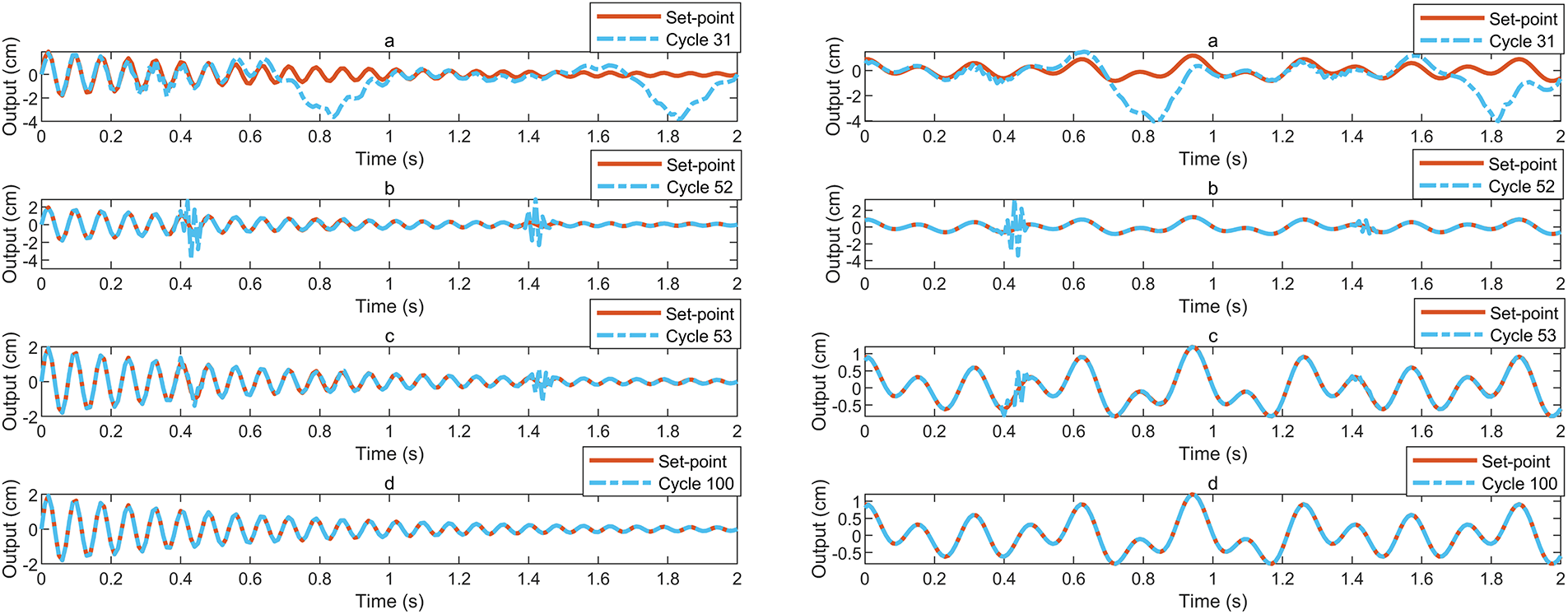

To evaluate ILC stability under perturbation conditions, the experiment simulated common disturbance scenarios in additive manufacturing processes. Test results (Fig. 14) demonstrate that ILC rapidly adapts to perturbations and progressively corrects errors through subsequent iterations. The method exhibits enhanced robustness, particularly in compensating for periodic disturbances.

Figure 14: Tracking effect of different number of iterations after interference: (a) 31st tracking; (b) 52nd tracking; (c) 53rd tracking; (d) 100th tracking

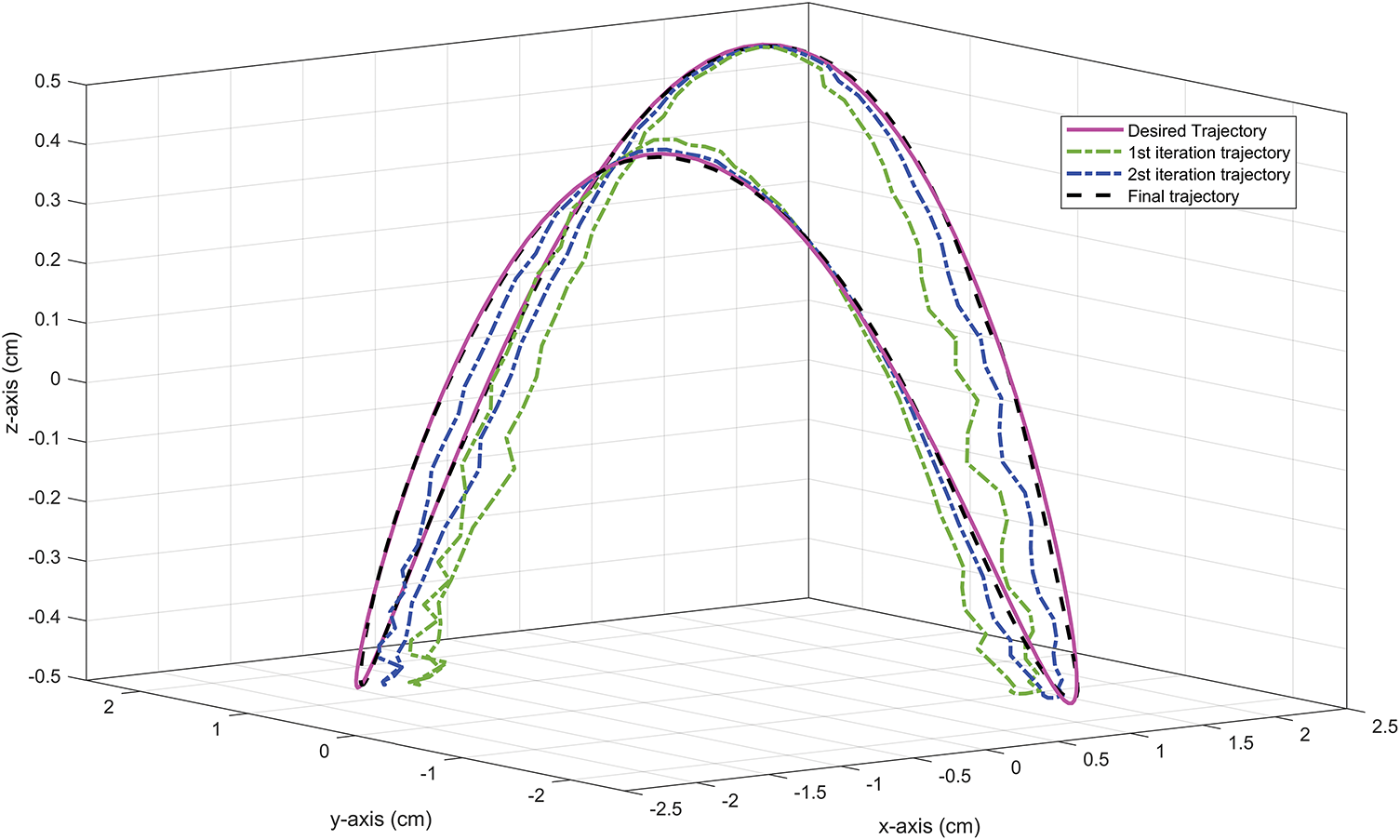

To address spatial path tracking requirements in precision manufacturing, experiments further evaluated ILC performance in three-dimensional space. Complex spatial trajectories (Fig. 15) were designed to verify ILC adaptability in multi-degree-of-freedom systems. Experimental results demonstrate that ILC not only achieves precise spatial path tracking but also effectively responds to geometric variation challenges through dynamic control parameter adjustment.

Figure 15: Performance of ILC in three-dimensional space

This paper systematically reviews the research progress and application achievements of ILC in precision manufacturing and ITS. The results demonstrate that ILC, through its unique iterative optimization mechanism, effectively addresses challenges such as nonlinear dynamics, multi-physics coupling, and periodic disturbances in precision manufacturing, significantly improving the accuracy of extrusion linewidth control in additive manufacturing and interlayer temperature regulation in selective laser melting. In the ITS domain, the integration of ILC with techniques such as fuzzy logic and reinforcement learning enhances the dynamic adaptability of autonomous vehicle trajectory tracking, train cooperative control, and traffic signal optimization. Theoretically, by relaxing traditional assumptions, ILC’s applicability has been extended to non-repetitive scenarios, while advanced variants like PD-type ILC and adaptive ILC further improve system robustness and convergence performance. Experimental validation confirms that ILC exhibits excellent performance in trajectory tracking, disturbance compensation, and spatial path control.

While the effectiveness of ILC is well recognized, it is essential to objectively acknowledge the limitations of current approaches, particularly in complex application scenarios such as multi-axis coordinated systems. Although ILC shows considerable potential in these applications, the existing methods still exhibit several constraints. Firstly, most current ILC designs rely on the assumption of approximately decoupled dynamics across axes, which may lead to degraded performance in strongly coupled and highly nonlinear cooperative motions. Secondly, many algorithms exhibit sensitivity to significant variations in system parameters or environmental disturbances between iterations, indicating that robustness remains an area requiring further improvement. Moreover, current research predominantly focuses on set-point tracking or the replication of predefined trajectories, while capabilities for online real-time trajectory adjustment or responding to unexpected obstacles remain underdeveloped. These limitations highlight clear directions for future in-depth investigation.

Building upon the research foundation and existing limitations identified in this study, future work will advance along four concrete directions. First, multi-axis cooperative control algorithms will be developed. These algorithms will integrate nominal dynamics feedforward with data-driven strategies, focusing on online estimation and compensation of coupling disturbances using iterative-domain disturbance observers. Second, robust adaptive gain scheduling strategies will be designed for time-varying operational conditions. These strategies will dynamically adjust learning gains based on error norms while guaranteeing convergence through Lyapunov-based methods. Third, a hybrid ILC architecture will be constructed to incorporate real-time sensory feedback. This architecture will address frequency-band coordination and stability between the iterative learning loop and the online feedback control loop. Fourth, systematic validation will be conducted on a multi-degree-of-freedom precision motion platform. A multi-objective optimization evaluation framework will be established to quantitatively analyze the Pareto front of various algorithms in terms of convergence speed, precision, and robustness. This effort will facilitate the transition of the methodology toward practical applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Wuxi Young Scientific and Technological Talent Support Initiative, project number: TJXD-2024-203 and the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China, grant number: 24KJB470027.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Lei Wang, Menghan Wei, Ziwei Huangfu and Shunjie Zhu; methodology, Lei Wang, Xuejian Ge and Zhengquan Li; software, Menghan Wei and Shunjie Zhu; validation, Lei Wang, Menghan Wei and Ziwei Huangfu; formal analysis, Lei Wang, Xuejian Ge and Zhengquan Li; investigation, Menghan Wei, Ziwei Huangfu and Shunjie Zhu; resources, Lei Wang, Xuejian Ge and Zhengquan Li; data curation, Menghan Wei, Ziwei Huangfu and Shunjie Zhu; writing—original draft preparation, Lei Wang; writing—review and editing, Lei Wang, Xuejian Ge and Zhengquan Li; visualization, Lei Wang, Menghan Wei; supervision, Xuejian Ge and Zhengquan Li; project administration, Lei Wang and Xuejian Ge; funding acquisition, Lei Wang and Xuejian Ge. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable, as this is a narrative review based on existing literature.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve any human or animal subjects, and therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Huang D, Chen Y, Meng D, Sun P. Adaptive iterative learning control for high-speed train: a multi-agent approach. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2019;51(7):4067–77. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2019.2931289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rotariu I, Steinbuch M, Ellenbroek R. Adaptive iterative learning control for high precision motion systems. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2008;16(5):1075–82. doi:10.1109/tcst.2007.906319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Panomruttanarug B. A comprehensive analysis of iterative learning control for enhanced lateral tracking in autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2025. doi:10.1109/tvt.2025.3594768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Barton KL, Alleyne AG. A cross-coupled iterative learning control design for precision motion control. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2008;16(6):1218–31. doi:10.1109/tcst.2008.919433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gao S, Song Q, Jiang H, Shen D. History makes the future: iterative learning control for high-speed trains. IEEE Intell Transp Syst Magaz. 2023;16(1):6–21. doi:10.1109/mits.2023.3310668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Areerob P, Panomruttanarug B. Iterative learning control for lateral tracking with repeated path in autonomous vehicles for dynamic environments. Intl J Control, Autom Syst. 2023;21(11):3712–23. doi:10.1007/s12555-022-1121-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang S, Wang L, Wang H, Xue B. Consensus control for heterogeneous multivehicle systems: an iterative learning approach. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32(12):5356–68. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2021.3071413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Arimoto S, Kawamura S, Miyazaki F. Bettering operation of robots by learning. J Robotic Syst. 1984;1(2):123–40. doi:10.1002/rob.4620010203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bristow DA, Tharayil M, Alleyne AG. A survey of iterative learning control. IEEE Control Syst Magaz. 2006;26(3):96–114. [Google Scholar]

10. Ahn HS, Chen Y, Moore KL. Iterative learning control: brief survey and categorization. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part C Appl Rev. 2007;37(6):1099–121. doi:10.1109/tsmcc.2007.905759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Boudjedir CE, Boukhetala D. Adaptive robust iterative learning control with application to a Delta robot. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part I J Syst Control Eng. 2021;235(2):207–21. doi:10.1177/0959651820938531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Paszke W, Rogers E, Boski M. Repetitive process based design of PD-type iterative learning control laws. In: 2018 26th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED); 2018 Jun 19–22; Zadar, Croatia: IEEE; 2018. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

13. Ngo TQ, Tran TH. Robust adaptive iterative learning control for de-icing robot manipulator. J Robotics Control (JRC). 2024;5(3):746–55. doi:10.18196/jrc.v4i4.18464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu L, Xiong J, Xie M. Iterative-learning-based tracking control of a two-wheeled mobile robot with model uncertainties and unknown periodic disturbances. J Franklin Inst. 2024;361(11):106962. doi:10.1016/j.jfranklin.2024.106962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li X, Huang D. Adaptive iterative learning control for nonsquare nonlinear systems with various nonrepetitive uncertainties: a unified approach. IEEE Trans Automatic Control. 2023;69(3):1736–43. doi:10.1109/tac.2023.3326707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang L, Dong L, Yang R, Chen Y. Dynamic ILC for linear repetitive processes based on different relative degrees. Mathematics. 2022;10(24):4824. doi:10.3390/math10244824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu L, Zhong W, Lu J, Gao F, Qian F, Cao Z. Learning of iterative learning control for flexible manufacturing of batch processes. ACS Omega. 2022;7(23):19939–47. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c01741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Guan W, Zhou L, Cao Y. Joint motion control for lower limb rehabilitation based on iterative learning control (ILC) algorithm. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6651495. doi:10.1155/2021/6651495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Z, Zhou R, Hu C, Zhu Y. Online iterative learning compensation method based on model prediction for trajectory tracking control systems. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;18(1):415–25. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3085845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dai L, Li X, Zhu Y, Zhang M. Feedforward tuning by fitting iterative learning control signal for precision motion systems. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2020;68(9):8412–21. doi:10.1109/tie.2020.3020032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang Z, Pannier CP, Barton K, Hoelzle DJ. Application of robust monotonically convergent spatial iterative learning control to microscale additive manufacturing. Mechatronics. 2018;56(4):157–65. doi:10.1016/j.mechatronics.2018.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kumar S, Gopi T, Harikeerthana N, Gupta MK, Gaur V, Krolczyk GM, et al. Machine learning techniques in additive manufacturing: a state of the art review on design, processes and production control. J Intell Manuf. 2023;34(1):21–55. doi:10.1007/s10845-022-02029-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhan P, Lou J, Chen T, Li G, Xu C, Wei Y. Dynamic hysteresis compensation and iterative learning control for underwater flexible structures actuated by macro fiber composites. Ocean Eng. 2024;298:117242. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. He S, Chen W, Li D, Xi Y, Xu Y, Zheng P. Iterative learning control with data-driven-based compensation. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2021;52(8):7492–503. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2020.3041705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jin X. Iterative learning control for MIMO nonlinear systems with iteration-varying trial lengths using modified composite energy function analysis. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2020;51(12):6080–90. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2020.2966625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hoelzle DJ, Johnson AJW, Alleyne AG. Bumpless transfer filter for exogenous feedforward signals. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2013;22(4):1581–8. doi:10.1109/tcst.2013.2278534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gu H, Banki T, Soleymani A. Robust frequency control of additive manufacturing based microgrid considering delayed fuel cell dynamics. J New Mat Elect Syst. 2023;26(4):304–11. doi:10.14447/jnmes.v26i4.a09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abdulhameed O, Al-Ahmari A, Ameen W, Mian SH. Additive manufacturing: challenges, trends, and applications. Adv Mech Eng. 2019;11(2):1687814018822880. doi:10.1177/1687814018822880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wong KV, Hernandez A. A review of additive manufacturing. Int Sch Res Notices. 2012;2012(1):208760. [Google Scholar]

30. Gibson I, Rosen D, Stucker B, Khorasani M, Gibson I, Rosen D, et al. Design for additive manufacturing. In: Additive manufacturing technologies. 3rd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 555–607. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56127-7_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Prakash KS, Nancharaih T, Rao VS. Additive manufacturing techniques in manufacturing—an overview. Mater Today Proc. 2018;5(2):3873–82. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Mobarak MH, Islam MA, Hossain N, Al Mahmud MZ, Rayhan MT, Nishi NJ, et al. Recent advances of additive manufacturing in implant fabrication—a review. Appl Surface Sci Adv. 2023;18(59):100462. doi:10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liu C, Ruan X, Liu Y, Chien CJ. Optimization-based iterative learning control scheme for point-to-point tracking of nonlinear systems. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2025;113(3):2487–503. doi:10.1007/s11071-024-10354-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Armstrong M, Mehrabi H, Naveed N. An overview of modern metal additive manufacturing technology. J Manuf Processes. 2022;84:1001–29. doi:10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.10.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chaudhary R, Fabbri P, Leoni E, Mazzanti F, Akbari R, Antonini C. Additive manufacturing by digital light processing: a review. Progress Additive Manuf. 2023;8(2):331–51. doi:10.1007/s40964-022-00336-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sun C, Wang Y, McMurtrey MD, Jerred ND, Liou F, Li J. Additive manufacturing for energy: a review. Appl Energy. 2021;282(10):116041. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu Z, Zhao D, Wang P, Yan M, Yang C, Chen Z, et al. Additive manufacturing of metals: microstructure evolution and multistage control. J Mater Sci Technol. 2022;100:224–36. [Google Scholar]

38. Tao H, Wei J, Hao S, Paszke W, Rogers E. Robust indirect-type iterative learning control design for batch processes with state delay, non-repetitive uncertainties and disturbances. Int J Control. 2025. doi:10.1080/00207179.2025.2479189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ngo TD, Kashani A, Imbalzano G, Nguyen KT, Hui D. Additive manufacturing (3D printinga review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos Part B Eng. 2018;143(2):172–96. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Danh HD, Van CN, Van QV. Tracking iterative learning control of TRMS using feedback linearization model with input disturbance. J Robotics Control (JRC). 2025;6(1):446–55. doi:10.18196/jrc.v6i1.25579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ma L, Liu X, Kong X, Lee KY. Iterative learning model predictive control based on iterative data-driven modeling. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2020;32(8):3377–90. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2020.3016295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lee YH, Rai S, Tsao TC. Data-driven iterative learning control of nonlinear systems by adaptive model matching. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2022;27(6):5626–36. doi:10.1109/tmech.2022.3176984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wu W, Qiu L, Liu X, Guo F, Rodriguez J, Ma J, et al. Data-driven iterative learning predictive control for power converters. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2022;37(12):14028–33. doi:10.1109/tpel.2022.3194518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Xu W, Hou J, Li J, Yuan C, Simeone A. Multi-axis motion control based on time-varying norm optimal cross-coupled iterative learning. IEEE Access. 2020;8:124802–11. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3007422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Hu J. Iterative learning based adaptive traffic signal control. J Transp Syst Eng Inf Technol. 2010;10(6):34–40. doi:10.1016/s1570-6672(09)60070-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ji H, Hou Z, Zhang R. Adaptive iterative learning control for high-speed trains with unknown speed delays and input saturations. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2015;13(1):260–73. doi:10.1109/tase.2014.2371816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sun H, Hou Z, Li D. Coordinated iterative learning control schemes for train trajectory tracking with overspeed protection. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2012;10(2):323–33. doi:10.1109/tase.2012.2216261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Chen Y, Huang D, Xu C, Dong H. Iterative learning tracking control of high-speed trains with nonlinearly parameterized uncertainties and multiple time-varying delays. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(11):20476–88. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3183608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Li Z, Yin C, Ji H, Hou Z. Constrained spatial adaptive iterative learning control for trajectory tracking of high speed train. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;23(8):11720–8. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3106653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Haydari A, Yılmaz Y. Deep reinforcement learning for intelligent transportation systems: a survey. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2020;23(1):11–32. doi:10.1109/tits.2020.3008612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Gao B, Liu J, Zou H, Chen J, He L, Li K. Vehicle-road-cloud collaborative perception framework and key technologies: a review. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(12):19295–318. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3459799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang Z, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Letaief KB. DRL-based optimization for AoI and energy consumption in C-V2X enabled IoV. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2025. doi:10.1109/tgcn.2025.3531902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Gu X, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Letaief KB. DRL-based federated self-supervised learning for task offloading and resource allocation in ISAC-enabled vehicle edge computing. Digit Commun Netw. 2024. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2024.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Xie Y, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Wang J, et al. Resource allocation for twin maintenance and task processing in vehicular edge computing network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(15):32008–21. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3576582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Dai X, Tian S, Peng Y, Luo W. Closed-loop P-type iterative learning control of uncertain linear distributed parameter systems. IEEE/CAA J Automatica Sinica. 2014;1(3):267–73. doi:10.1109/jas.2014.7004684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chi R, Li H, Shen D, Hou Z, Huang B. Enhanced P-type control: indirect adaptive learning from set-point updates. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 2022;68(3):1600–13. doi:10.1109/tac.2022.3154347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Gu P, Tian S. P-type iterative learning control with initial state learning for one-sided Lipschitz nonlinear systems. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2019;17(9):2203–10. doi:10.1007/s12555-018-0891-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Hussain I, Ruan X, Liu C, Liu Y. Linearly monotonic convergence and robustness of P-type gain-optimized iterative learning control for discrete-time singular systems. IEEE Access. 2021;9:58337–50. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3065142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Chunwu Y. P-type closed loop time-varying sliding mode iterative learning control for mechanical arm. Control Eng China. 2023;30:1818–25. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

60. Li G, Hou L, Lu Y. D-type iterative learning control for open container motion system with sloshing constraints. IEEE Access. 2021;9:136666–73. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3117730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Saab SS. Stochastic P-type/D-type iterative learning control algorithms. Int J Control. 2003;76(2):139–48. doi:10.1080/0020717031000077717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Bouakrif F. D-type iterative learning control without resetting condition for robot manipulators. Robotica. 2011;29(7):975–80. doi:10.1017/s0263574711000191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Ouyang P, Pipatpaibul PI. Iterative learning control: a comparison study. In: ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; 2010 Nov 12–18; Vancouver, BC, Canada. New York, NY, USA: ASME; 2010. Vol. 44458, p. 939–45. [Google Scholar]

64. Wang S-K, Zhao J-B, Wang J-Z. Open-closed-loop iterative learning control for hydraulically driven fatigue test machine of insulators. J Vibration Control. 2015;21(12):2291–305. doi:10.1177/1077546313508998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Yu Q, Hou Z, Xu JX. D-type ILC based dynamic modeling and norm optimal ILC for high-speed trains. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2017;26(2):652–63. doi:10.1109/tcst.2017.2692730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Yu M, Li C. Robust adaptive iterative learning control for discrete-time nonlinear systems with time-iteration-varying parameters. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2017;47(7):1737–45. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2017.2677959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Liu X, Ma L, Kong X, Lee KY. Robust model predictive iterative learning control for iteration-varying-reference batch processes. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2019;51(7):4238–50. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2019.2931314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Riaz S, Qi R, Tutsoy O, Iqbal J. A novel adaptive PD-type iterative learning control of the PMSM servo system with the friction uncertainty in low speeds. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0279253. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0279253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Park KH. An average operator-based PD-type iterative learning control for variable initial state error. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 2005;50(6):865–9. doi:10.1109/tac.2005.849249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Yin CW, Riaz S, Zaman H, Ullah N, Blazek V, Prokop L, et al. A novel predefined time PD-type ILC paradigm for nonlinear systems. Mathematics. 2022;11(1):56. doi:10.3390/math11010056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Zou W, Shen Y, Paszke W. Robust PD-type iterative learning control in a finite-frequency range for nonlinear systems based on T-S fuzzy models. Trans Inst Meas Control. 2025;47(4):663–76. doi:10.1177/01423312241246828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Zhang X, Ding H, Li M, Li J. Variable-gain PD-type iterative learning control for a class of nonlinear time-varying systems. Asian J Control. 2024;26(3):1293–308. doi:10.1002/asjc.3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Guan S, Zhuang Z, Tao H, Chen Y, Stojanovic V, Paszke W. Feedback-aided PD-type iterative learning control for time-varying systems with non-uniform trial lengths. Trans Inst Meas Control. 2023;45(11):2015–26. doi:10.1177/01423312221142564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Wang D. On D-type and P-type ILC designs and anticipatory approach. Int J Control. 2000;73(10):890–901. doi:10.1080/002071700405879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Liao-McPherson D, Balta EC, Rupenyan A, Lygeros J. On robustness in optimization-based constrained iterative learning control. IEEE Control Syst Lett. 2022;6:2846–51. doi:10.1109/lcsys.2022.3178877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Lv Y, Ren X, Tian J, Zhao X. Inverse-model-based iterative learning control for unknown MIMO nonlinear system with neural network. Neurocomputing. 2023;519:187–93. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.11.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Yoon D, Ge X, Okwudire CE. Optimal inversion-based iterative learning control for overactuated systems. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2019;28(5):1948–55. doi:10.1109/tcst.2019.2917682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Ahmad N, Hao S, Liu T, Gong Y, Wang QG. Data-driven set-point learning control with ESO and RBFNN for nonlinear batch processes subject to nonrepetitive uncertainties. ISA Trans. 2024;146(3):308–18. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2023.12.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Chi R, Li H, Lin N, Huang B. Data-driven indirect iterative learning control. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2023;54(3):1650–60. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2022.3232136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Chi R, Hou Z, Jin S, Huang B. Computationally efficient data-driven higher order optimal iterative learning control. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29(12):5971–80. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2018.2814628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Chi R, Hou Z, Huang B, Jin S. A unified data-driven design framework of optimality-based generalized iterative learning control. Comput Chem Eng. 2015;77:10–23. [Google Scholar]

82. Yu X, Hou Z, Polycarpou MM, Duan L. Data-driven iterative learning control for nonlinear discrete-time MIMO systems. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2020;32(3):1136–48. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2020.2980588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Freeman CT, Tan Y. Iterative learning control with mixed constraints for point-to-point tracking. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2012;21(3):604–16. doi:10.1109/tcst.2012.2187787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Tao H, Li J, Chen Y, Stojanovic V, Yang H. Robust point-to-point iterative learning control with trial-varying initial conditions. IET Control Theory Appl. 2020;14(19):3344–50. [Google Scholar]

85. Zhuang Z, Tao H, Chen Y, Oomen T, Paszke W, Rogers E. Optimal iterative learning control design for continuous-time systems with nonidentical trial lengths using alternating projections between multiple sets. J Franklin Inst. 2023;360(5):3825–48. doi:10.1016/j.jfranklin.2023.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Zhou C, Tao H, Chen Y, Stojanovic V, Paszke W. Robust point-to-point iterative learning control for constrained systems: a minimum energy approach. Intl J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2022;32(18):10139–61. doi:10.1002/rnc.6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Huang Y, Tao H, Chen Y, Rogers E, Paszke W. Point-to-point iterative learning control with quantised input signal and actuator faults. Intl J Control. 2024;97(6):1361–76. doi:10.1080/00207179.2023.2206496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Gao L, Zhuang Z, Tao H, Chen Y, Stojanovic V. Non-lifted norm optimal iterative learning control for networked dynamical systems: a computationally efficient approach. J Franklin Inst. 2024;361(15):107112. doi:10.1016/j.jfranklin.2024.107112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Chen Y, Chu B, Freeman CT. Point-to-point iterative learning control with optimal tracking time allocation. IEEE Trans Control Systems Technol. 2017;26(5):1685–98. doi:10.1109/cdc.2015.7403177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Chen Y, Chu B, Freeman CT. Generalized iterative learning control using successive projection: algorithm, convergence, and experimental verification. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2019;28(6):2079–91. doi:10.1109/tcst.2019.2928505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Chen Y, Chu B, Freeman CT. Iterative learning control for path-following tasks with performance optimization. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2021;30(1):234–46. doi:10.1109/tcst.2021.3062223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Chi R, Zhang H, Huang B, Hou Z. Quantitative data-driven adaptive iterative learning control: from trajectory tracking to point-to-point tracking. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2020;52(6):4859–73. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2020.3015233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Jiang H, Shen D, Huang S, Yu X. Accelerated learning control for point-to-point tracking systems. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learning Syst. 2022;35(1):1265–77. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3183109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Hoelzle DJ, Barton KL. On spatial iterative learning control via 2-D convolution: stability analysis and computational efficiency. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2015;24(4):1504–12. doi:10.1109/tcst.2015.2501344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Zhao X, Wang Y. Improved point-to-point iterative learning control for batch processes with unknown batch-varying initial state. ISA Trans. 2022;125(2):290–9. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2021.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Geng Y, Ruan X, Zhou Q, Yang X. Robust adaptive iterative learning control for nonrepetitive systems with iteration-varying parameters and initial state. Intl J Mach Learn Cybern. 2021;12(8):2327–37. doi:10.1007/s13042-021-01313-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Li S, Li X. Finite-time extended state observer-based iterative learning control for nonrepeatable nonlinear systems. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2025;113(13):16531–43. doi:10.1007/s11071-025-11016-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Xing J, Chi R, Lin N. Adaptive iterative learning control for 2D nonlinear systems with nonrepetitive uncertainties. Intl J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2021;31(4):1168–80. doi:10.1002/rnc.5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Wang L, Huangfu Z, Li R, Wen X, Sun Y, Chen Y. Iterative learning control with parameter estimation for non-repetitive time-varying systems. J Franklin Inst. 2024;361(3):1455–66. doi:10.1016/j.jfranklin.2024.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Wang L, Zhu S, Wei M, Wang X, Huangfu Z, Chen Y. Iterative learning control with adaptive kalman filtering for trajectory tracking in non-repetitive time-varying systems. Axioms. 2025;14(5):324. doi:10.3390/axioms14050324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Zhang J, Meng D. Iterative rectifying methods for nonrepetitive continuous-time learning control systems. IEEE Trans Cybernetics. 2021;53(1):338–51. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2021.3086091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Wang J, Zhou N, Wang S, Shen D, Bq Li. Feedback-assisted PD-type quantized iterative learning control with randomly iteration varying lengths. Control Decision. 2021;36(10):8. doi:10.1109/ccdc.2016.7531719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Zhuang Z, Tao H, Chen Y, Rogers E, Oomen T, Paszke W. Alternating projection-based iterative learning control for discrete-time systems with non-uniform trial lengths. Int J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2023;33(12):7333–56. doi:10.1002/rnc.6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Zhuang Z, Tao H, Chen Y, Stojanovic V, Paszke W. An optimal iterative learning control approach for linear systems with nonuniform trial lengths under input constraints. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2022;53(6):3461–73. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2022.3225381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Chu B, Freeman CT, Owens DH. A novel design framework for point-to-point ILC using successive projection. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2014;23(3):1156–63. doi:10.1109/tcst.2014.2356931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Steinhauser A, Swevers J. An efficient iterative learning approach to time-optimal path tracking for industrial robots. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2018;14(11):5200–7. doi:10.1109/tii.2018.2851963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Chen Y, Wang Y, Freeman CT. Iterative learning control of minimum energy path following tasks for second-order MIMO systems: an indirect reference update framework. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2025;55(7):3403–16. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2025.3556703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Guilherme P, Ribeiro M, Labrincha J. Behaviour of different industrial ceramic pastes in extrusion process. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2009;108(6):347–51. doi:10.1179/174367609x413874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Ruscitti A, Tapia C, Rendtorff N. A review on additive manufacturing of ceramic materials based on extrusion processes of clay pastes. Cerâmica. 2020;66(380):354–66. doi:10.1590/0366-69132020663802918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Kern F, Gadow R. Extrusion and injection molding of ceramic micro and nanocomposites. Int J Mater Forming. 2009;2(S1):609–12. doi:10.1007/s12289-009-0487-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Li W, Leu MC. Material extrusion based ceramic additive manufacturing. Additive Manuf Processes. 2020;24:97–111. doi:10.31399/asm.hb.v24.a0006562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Ha M, Wang D, Liu D. Discounted iterative adaptive critic designs with novel stability analysis for tracking control. IEEE/CAA J Automatica Sinica. 2022;9(7):1262–72. doi:10.1109/jas.2022.105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

113. Chen T, Chen X, Chen W, Heaton H, Liu J, Wang Z, et al. Learning to optimize: a primer and a benchmark. J Mach Learning Res. 2022;23(189):1–59. [Google Scholar]

114. Yoo HW, Kerschner CJ, Ito S, Schitter G. Iterative learning control for laser scanning based micro 3D printing. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2019;52(15):169–74. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2019.11.669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

115. Zhou J, Li L, Lu L, Cheng Y. Machine learning-based quality optimisation of ceramic extrusion 3D printing deposition lines. Mater Today Commun. 2024;41:110841. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.110841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

116. Wang H, Dong J, Wang Y. High-order feedback iterative learning control algorithm with forgetting factor. Math Probl Eng. 2015;2015(1):826409. doi:10.1155/2015/826409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

117. Glushchenko AI, Petrov VA, Lastochkin KA. Adaptive control system with a variable adjustment law gain based on the recursive least squares method. Autom Remote Control. 2021;82(4):619–33. doi:10.1134/s0005117921040020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

118. Jia H, Sun H, Wang H, Wu Y, Wang H. Scanning strategy in selective laser melting (SLMa review. Intl J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021;113:2413–35. doi:10.1007/s00170-021-06810-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

119. Sefene EM. State-of-the-art of selective laser melting process: a comprehensive review. J Manuf Syst. 2022;63(8):250–74. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2022.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

120. Inyang-Udoh U, Hu R, Mishra S, Wen J, Maniatty A. Model-free multi-objective iterative learning control for selective laser melting. In: American Control Conference (ACC); 2022 Jun 8–10; Atlanta, GA, USA; 2022. p. 2879–85. [Google Scholar]

121. Al-Saadi T, Rossiter JA, Panoutsos G. Initial investigation of online control system for selective laser melting process: multi-layer level. In: UKACC 14th International Conference on Control (CONTROL); 2024 Apr 10–12; Winchester, UK; 2024. p. 268–73. [Google Scholar]

122. Vagenas S, Al-Saadi T, Panoutsos G. Multi-layer process control in selective laser melting: a reinforcement learning approach. J Intell Manuf. 2024;46(3):350. doi:10.1007/s10845-024-02548-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

123. Kouba O, Bernstein DS. What is the adjoint of a linear system? IEEE Control Syst Magaz. 2020;40(3):62–70. doi:10.1109/mcs.2020.2976389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

124. Chen Y, Huang D, Li Y, Feng X. A novel iterative learning approach for tracking control of high-speed trains subject to unknown time-varying delay. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2020;19(1):113–21. doi:10.1109/tase.2020.3041952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

125. Li Z, Hou Z. Adaptive iterative learning control based high speed train operation tracking under iteration-varying parameter and measurement noise. Asian J Control. 2015;17(5):1779–88. doi:10.1002/asjc.1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

126. Yan F, Yan G, Ren M, Tian J, Shi Z. A novel control strategy for balancing traffic flow in urban traffic network based on iterative learning control. Physica A Statistical Mech Appl. 2018;508:519–31. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2018.05.134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

127. Zheng J, Hou Z. Model free adaptive iterative learning control based fault-tolerant control for subway train with speed sensor fault and over-speed protection. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2022;21(1):168–80. doi:10.1109/tase.2022.3225288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

128. Airaldi F, Schutter BD, Dabiri A. Reinforcement learning with model predictive control for highway ramp metering. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2025;26(5):5988–6004. doi:10.1109/tits.2025.3549227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

129. Yan F, Tian F, Shi Z. Iterative learning approach for traffic signal control of urban road networks. IET Control Theory Appl. 2017;11(4):466–75. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools