Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Advanced Meta-Heuristic Optimization for Accurate Photovoltaic Model Parameterization: A High-Accuracy Estimation Using Spider Wasp Optimization

1 Department of Computer Sciences, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

2 Faculty of Computers and Artificial Intelligence, Benha University, Benha, 13511, Egypt

3 Jadara Research Center, Jadara University, Irbid, 21110, Jordan

4 Obour High Institute for Management and Informatics, Cairo, 11777, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Diaa Salama AbdElminaam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Nature-Inspired Optimization & Applications in Computer Science: From Particle Swarms to Hybrid Metaheuristics)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 98 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069263

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Accurate parameter extraction of photovoltaic (PV) models plays a critical role in enabling precise performance prediction, optimal system sizing, and effective operational control under diverse environmental conditions. While a wide range of metaheuristic optimisation techniques have been applied to this problem, many existing methods are hindered by slow convergence rates, susceptibility to premature stagnation, and reduced accuracy when applied to complex multi-diode PV configurations. These limitations can lead to suboptimal modelling, reducing the efficiency of PV system design and operation. In this work, we propose an enhanced hybrid optimisation approach, the modified Spider Wasp Optimization (mSWO) with Opposition-Based Learning algorithm, which integrates the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the Spider Wasp Optimization (SWO) metaheuristic with the diversity-enhancing mechanism of Opposition-Based Learning (OBL). The hybridisation is designed to dynamically expand the search space coverage, avoid premature convergence, and improve both convergence speed and precision in high-dimensional optimisation tasks. The mSWO algorithm is applied to three well-established PV configurations: the single diode model (SDM), the double diode model (DDM), and the triple diode model (TDM). Real experimental current–voltage (I–V) datasets from a commercial PV module under standard test conditions (STC) are used for evaluation. Comparative analysis is conducted against eighteen advanced metaheuristic algorithms, including BSDE, RLGBO, GWOCS, MFO, EO, TSA, and SCA. Performance metrics include minimum, mean, and maximum root mean square error (RMSE), standard deviation (SD), and convergence behaviour over 30 independent runs. The results reveal that mSWO consistently delivers superior accuracy and robustness across all PV models, achieving the lowest RMSE values of 0.000986022 (SDM), 0.000982884 (DDM), and 0.000982529 (TDM), with minimal SD values, indicating remarkable repeatability. Convergence analyses further show that mSWO reaches optimal solutions more rapidly and with fewer oscillations than all competing methods, with the performance gap widening as model complexity increases. These findings demonstrate that mSWO provides a scalable, computationally efficient, and highly reliable framework for PV parameter extraction. Its adaptability to models of growing complexity suggests strong potential for broader applications in renewable energy systems, including performance monitoring, fault detection, and intelligent control, thereby contributing to the optimisation of next-generation solar energy solutions.Keywords

Renewable energy sources must be prioritized due to the drawbacks of non-renewable energy. Global warming, greenhouse gas emissions, changing oil prices, and other factors increase electricity needs in developing nations, requiring innovative solutions [1]. Thus, energy development and structure affect renewable energy. Energy transportation limitations have spurred massive research and the use of solar energy. Solar energy is cleaner, emits fewer greenhouse gases, and can be produced again. Global electricity use has increased due to the current circumstances. So, researchers have focused on inventing solar energy technologies with high efficiency, low investment cost, and low environmental contamination [2,3]. Solar energy has many forms of conversion, such as the production of heat and electricity. The Sun’s heat can generate two forms of solar energy: passive and active. While two basic types of solar energy are photovoltaic and thermal solar energy, according to statistics from 2004 to 2011, solar photovoltaic systems (PVS) are one of the fastest-growing power-generation technologies in the world, gaining 50% annually [4]. PV uses active solar technology to create power. These systems can be used for home, large industry, or metropolitan planning. Photovoltaic panels provide electricity through heat conduction, powering suitable construction.

• Solar PVs are replacing traditional electric power generation due to the following compelling causes.

– Compared to fossil fuels, solar energy has less environmental impact on the air, climate, water, land, animals, and ecosystem. Solar energy produces no greenhouse gases or pollution.

– Renewable and endless: Solar energy is renewable. Sunlight will last billions of years, making it an endless resource.

– Water conservation: Solar panel maintenance requires less water than nuclear power plant maintenance, which uses a lot.

– Low maintenance costs: Solar panels are easy to maintain. No considerable cleaning or maintenance is needed.

– Grid security: Solar panels can act as energy hubs, protecting the grid from overloads and blackouts.

– Job creation: Solar system demand has created installation, maintenance, cleaning, etc.

• Solar has various drawbacks, including low photoelectric conversion efficiency and inaccurate PV cell modeling. Correct PV cell modeling is essential for understanding and predicting PV system characteristics. PV models include the single diode model (SDM) [5], the improved single diode model (ISDM) [6], the double diode model (DDM) [7], the triple diode model (TDM) [8], the modified double diode model (MDDM) [7,9].

Solar power generation requires adequate PV cell types. The I–V curve can be estimated using online or offline methods. Online methods cost more and require longer requests. Thus, offline dynamic model approaches must anticipate the I–V curve in various weather circumstances [10]. An accurate PV model impacts power-consuming system availability and economy [9,11]. Therefore, modeling a PV module is crucial for estimating ideal PV model parameters.

There are various ways to extract and estimate PV parameters: analytical, numerical, stochastic (heuristic and metaheuristic), and hybrid. The analytical methods are commonly used to determine the link between PV module properties under standard test conditions (STCs) and weather situations. The advantages of analytical approaches include fast and simple computation of PV module parameters. However, these analytical methods often result in a large discrepancy between PV module performance and simulation [9].

The numerical approaches are commonly used to find single-diode and double-diode PV model parameters, aiming for optimal convergence and dependability. The numerical method is more accurate and popular when using an extended I–V curve data point. The fundamental disadvantage of this approach is that initial conditions can trap estimated parameters in local minima. In addition, numerical execution takes longer than other methods [9].

Heuristic and metaheuristic stochastic approaches address the limitations of previous methods, such as beginning conditions and long execution times. Metaheuristic approaches outperform numerical and analytical methods in convergence speed, reliability, and correctness. However, scientists and researchers have used hybrid evolutionary methods to solve real-world problems. Stochastic approaches handle difficult, multimodal problems like PV parameter extraction. Some of these approaches have exploration and exploitation restrictions. The algorithm uses its operators randomly to explore new search space areas and sides throughout exploration. Experimentation has efficiently allocated more random solutions. The exploitation phase often follows the exploring stage. Search space and neighboring areas are searched for improved solutions by the algorithm. Thus, PV parameter estimation requires a reasonable tradeoff between exploration (diversification) and exploitation (intensification). Single-diode PV model variables (a, Rs, Rp, Iph, Io) change, leading to local optimization traps. Nonlinear and multimodal objective functions are difficult to solve globally with stochastic approaches. Finding a better balance between exploration and exploitation is still difficult. Avoids local minima trapping and premature convergence [4,9].

In recent years, a wide range of metaheuristic algorithms have been applied for photovoltaic (PV) parameter extraction due to the highly nonlinear and multimodal nature of the problem. Among the most widely used approaches are the Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA) [12], Moth Flame Optimization (MFO) [13], Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) [14], Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) [15], Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) [16], and the Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO) [17], together with other recent optimizers such as FBI [18], GWOCS [19], WOA [19], BSDE [20], CSO [20], BSA [20], and EO [20]. These algorithms have demonstrated strong capabilities in handling complex optimization tasks and have been successfully adapted to estimate PV parameters with promising results.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. Many existing methods still face premature convergence issues, particularly when exploring large and rugged search spaces. The performance of OBL-based strategies often relies on static or fixed opposition schemes, which limit their adaptability to different search stages. Moreover, hybrid metaheuristics in the literature frequently struggle to balance exploration and exploitation, resulting in either slow convergence or limited accuracy in reaching the global optimum. Another limitation observed in prior studies is the lack of consistent benchmarking under a unified protocol, which makes it difficult to fairly assess the relative merits of competing algorithms across different PV models and test cases.

Motivated by these gaps, this study proposes a modified Spider Wasp Optimizer (mSWO) designed specifically to address the limitations identified in existing research. The proposed mSWO incorporates an adaptive opposition-based learning mechanism that dynamically adjusts the generation of opposite solutions depending on the current search stage, thereby maintaining a better balance between exploration in early iterations and exploitation in later stages. In addition, mSWO introduces a multi-strategy updating rule that enhances population diversity while accelerating convergence, reducing the risk of premature stagnation. These innovations ensure that the algorithm not only improves accuracy in estimating PV parameters but also achieves faster and more reliable convergence compared to existing approaches.

The proposed algorithm in this paper is a modified version of the recently developed metaheuristic technique known as the Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO). SWO is inspired by the unique hunting behavior of the spider wasp, which combines both environmental exploration to locate prey and effective exploitation to capture it. This natural analogy enables SWO to balance diversification and intensification during the optimization process. The algorithm has demonstrated promising results in solving complex optimization problems due to its simplicity, adaptability, and ability to escape local optima. However, like many swarm intelligence methods, the original SWO may suffer from slow convergence or premature stagnation in high-dimensional and complex search spaces. These limitations motivate the development of an improved variant, mSWO, that enhances the performance of the baseline SWO while maintaining its original strengths.

The proposed modified Spider Wasp Optimizer (mSWO) introduces several innovations compared to the original SWO and existing opposition-based learning (OBL) techniques. Unlike the original SWO, which relies only on the standard swarm intelligence mechanism, mSWO integrates an adaptive OBL strategy that dynamically adjusts the generation of opposite solutions according to the current search stage. This adaptive mechanism enables a better balance between exploration in the early iterations and exploitation in the later stages. In addition, mSWO incorporates a multi-strategy updating rule, which enhances population diversity while simultaneously accelerating convergence. This dual mechanism reduces the likelihood of premature convergence, a common limitation of both the original SWO and other OBL-based hybrid approaches.

Compared with existing OBL-based hybrid optimizers, mSWO differs in two main aspects: (i) the adaptivity of its OBL mechanism, which avoids the static or fixed opposition strategies commonly used in prior methods, and (ii) the combination of multi-strategy updates that introduce diversity without sacrificing convergence speed. As a result of these design improvements, mSWO achieves superior accuracy in finding global optima while also demonstrating faster convergence across different benchmark functions, as confirmed by the experimental results.

By linking the shortcomings of prior studies to the design features of mSWO, this work contributes both novel methodological improvements and a comprehensive evaluation protocol across standard PV models. In this way, the paper addresses the open challenges in the state of the art and demonstrates the relevance and originality of the proposed approach.

The main contribution of this work can be summarized as follows:

• A new hybrid algorithm is developed to estimate the parameters of solar PV cell models.

• It balances global exploration and local exploitation by combining.

• Its effectiveness is tested by evaluating accuracy, reliability, convergence, and statistics using ten complex benchmark functions and PV models under various operating situations.

• Its performance is compared to other parameter extraction approaches in the literature, with results repeatedly demonstrating it as a promising technique for obtaining PV model parameters.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a review of previous studies in the field. Section 3 introduces the three photovoltaic models derived from diode configurations. Section 4 formulates the problem of photovoltaic parameter identification. Section 5 outlines the adopted methodology, including data acquisition, preprocessing steps, and analytical approaches. Section 6 describes the architecture and implementation of the proposed system. Section 7 presents and evaluates the experimental results, comparing them with benchmark performance. Lastly, Section 8 summarizes the main contributions and highlights future research directions.

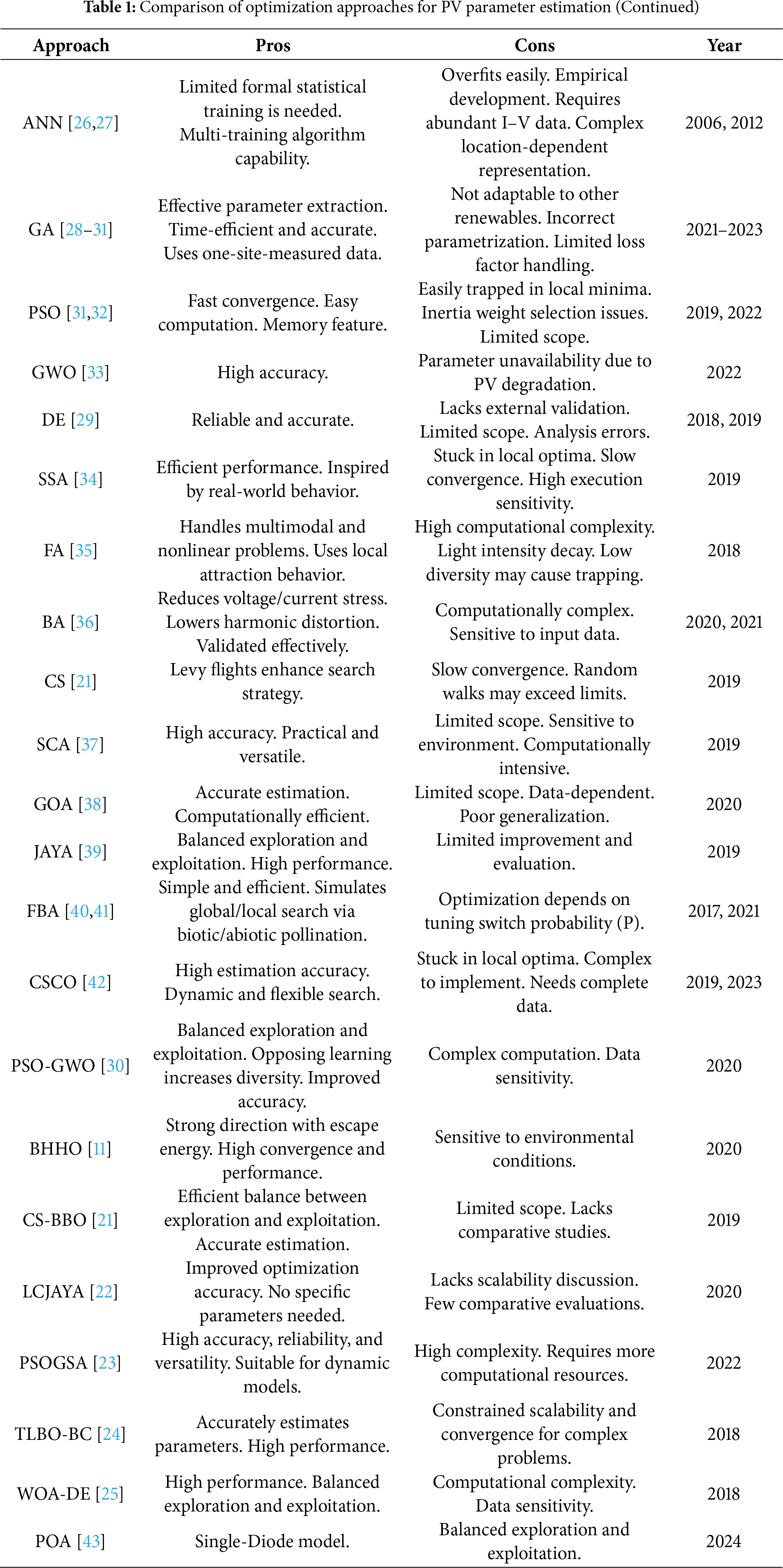

Meta-heuristic algorithms use a population-iteration approach and have cons in the previous metaheuristics approach.

Table 1 shows that certain techniques have drawbacks regarding solution quality, convergence speed, computational execution time, and performance under various environmental conditions. The PV parameter extraction problem was solved using hybrid methods recently. Different tactics or optimization techniques are combined to generate a hybrid method. Researchers are using hybrid strategies to overcome past method constraints. Reference [21] employs hybrid particle swarm optimization (PSO) and grey wolf optimizer (GWO) on experimental I–V curve datasets to estimate solar PV panel characteristics. Reference [22] proposed a Boosted Harris Hawk’s Optimization (BHHO) that combines differential evolution (DE) and flower pollination algorithm (FPA) to estimate single diode PV model parameters with 2-Opt algorithms. Reference [23] developed a hybrid metaheuristic approach to extract solar PV model parameters using Cuckoo Search (CS) and Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO). In [24], a logistic chaotic JAYA algorithm (LCJAYA) was presented to improve PV cell and module parameter detection accuracy and reliability. The solution update phase of the LCJAYA method uses a logistic chaotic map. Reference [24] proposed a hybrid algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization and Gravitational Search Algorithm (PSOGSA), that estimates photovoltaic model parameters using Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) and PSO. Reference [25] created a hybrid technique to extract PV model parameters using Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC). A hybrid model named DE-WOA, which combines Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) and Differential Evolution (DE), for PV model parameter extraction was suggested in [25].

3 Classification of Photovoltaic Models Based on Diode Configurations

The three PV models such as solar cell single diode model (SDM), solar cell double diode model (DDM) and solar cell three diode model (TDM) are analyzed in this section.

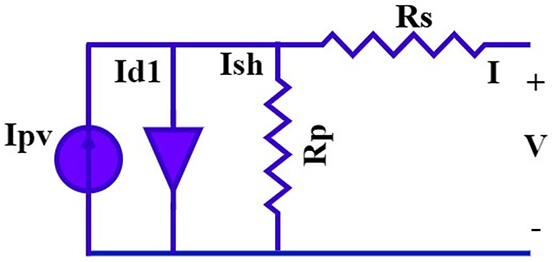

3.1 Solar Cell Single Diode Model (SDM)

The mathematical formulation of Fig. 1, that analyzes SDM equivalent circuit is described as follow:

Figure 1: SDM circuit

The SDM current output is I, the photo-current generated is

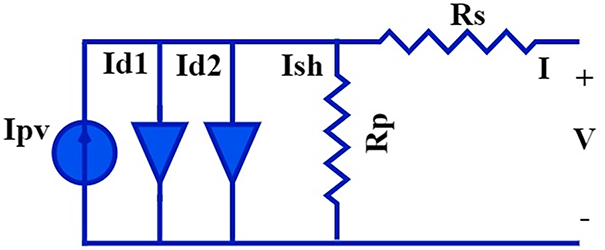

3.2 Solar Cell Double Diode Model (DDM)

The mathematical formulation of the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 2, which analyzes the DDM, is described as follows:

Figure 2: Equivalent circuit of the solar cell double diode model (DDM)

Here,

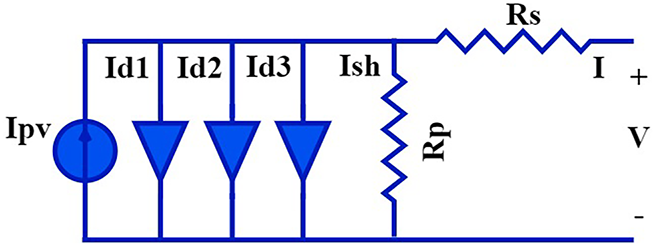

3.3 Solar Cell Three Diode Model (TDM)

The mathematical formulation of the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 3, which analyzes the TDM, is described as follows:

Figure 3: Equivalent circuit of the solar cell three diode model (TDM)

here,

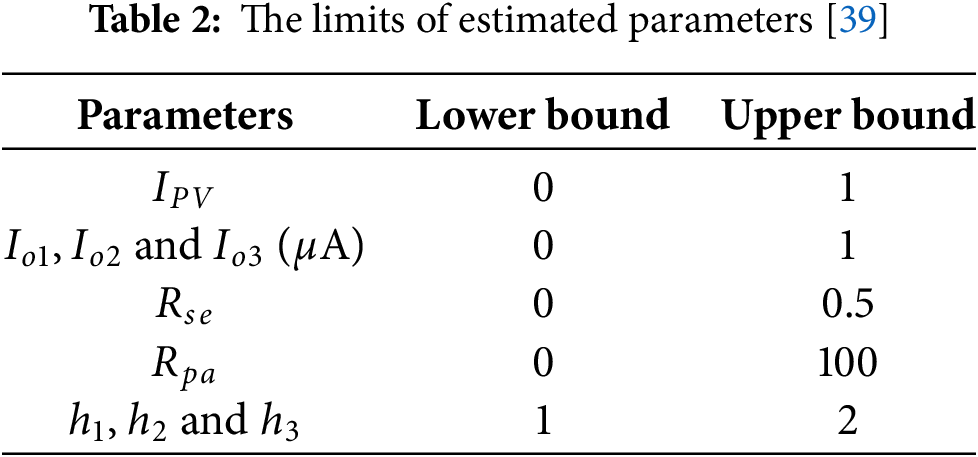

4 Problem Formulation of Identifying PV Parameters

The main items in optimization algorithms are the objective function and the boundaries of variables. Table 2 illustrates the limits of decision variables. The main objective function is minimizing the root mean square error (RMSE). The formula that analyses RMSE is calculated as follows:

where

The SDM estimated variables are

5 Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO) Algorithm

The Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO) is a recently developed nature inspired metaheuristic algorithm that emulates the hunting, nesting, and reproductive behaviors of female spider wasps [17]. Initially, the female wasp searches its surroundings to identify an appropriate spider host for the larvae’s development. Upon finding a target (the prey), it pursues, paralyzes, and transports the most suitable one to its nest. Reproduction then occurs as the wasp lays an egg inside the spider’s abdomen, leading to the egg’s hatching. These biological stages have been mathematically modeled by the authors as follows.

5.1 Generation of Initial Random Population

Each female spider represents a solution in the search space and is encoded as a D-dimension vector:

A set of N vectors are generated randomly within the range between the lower

Therefore, at any generation time

where

5.1.1 Hunting and Nesting Behavior

In this behavior, the female spider wasps search for prey to feed their larvae (i.e., exploration process). Subsequently, encircles and chases it, then drags the paralyzed spider into the nest (i.e., exploitation process). The main stages of hunting and nesting are described below.

Search stage (exploration)Each female spider (i.e., solution) position in the population is updated based on a constant motion

where

Sometimes, the female wasps lose track of the dropped spider. In this case, they search the region around the dropped one with a small step size and a constant motion

where

For better exploration and identifying the most promising regions, Eq. (17) randomly selects the next position for the female wasp based on two randomly generated numbers

Following and escaping stage (exploration and exploitation)The spider wasp attempts to attack the prey, and even if they drop to the ground to escape, it follows the dropped spiders to paralyze and drag them to pre-prepared nests. This behavior simulates two trends: the wasp hunting spiders to trap them as in Eq. (18) and evading the wasps by designing a distance factor C. C determines the speed of the wasp concerning the prey and is computed according to Eq. (19).

where

The spider tries to escape from a female wasp by gradually increasing the distance between them, which is called exploitation. As the distance increases, the spider switches to exploration, searching for a new hiding location, as shown in Eq. (20).

where

Therefore, the decision to choose between these two trends is determined randomly, as shown in Eq. (21).

The optimization process started with the exploration mechanism, which involves searching for the most promising regions to find the near-optimal solution. The algorithm then uses following and escaping mechanisms to explore and exploit the areas around the current wasps during the iteration pass. The exchange between the searching stage and the following mechanism is adjusted using Eq. (22).

where P is a random number generated between 0 and 1.

Nesting behavior (exploitation)The female wasps drag the paralyzed spider into the previously constructed nest in this behavior. Due to the diversity of nesting behaviors exhibited by spider wasps, such as digging and constructing cells in the soil, constructing mud nests in leaves or rocks, and utilizing pre-existing nests or cavities (e.g., prey’s nests or beetle holes), SWO simulates these behaviors with two distinct equations. The first one is used to determine the best place to build a nest for a paralyzed spider, as in Eq. (23), while the second one builds the nest within the position of a female spider randomly selected from the population as in Eq. (24).

In Eq. (23),

where

Therefore, switching between behaviors is done randomly, as shown in Eq. (26).

In conclusion, the trade-off between hunting and nesting behaviors is accomplished by Eq. (27).

The SWO algorithm considers spider wasp mating and gender determination based on egg size. Small wasps represent males, while large wasps indicate females. Each spider wasp in the current generation represents a potential solution, while each spider wasp egg represents a newly generated solution in the subsequent generation according to Eq. (28).

where

where

where

The purpose of the crossover operator is to combine the genetic information of two parents to generate offspring that carry out some of the characteristics of the parents. Finally, a predefined factor called a tradeoff rate

5.1.3 Population Reduction and Memory Saving

The female spider closes its nest after laying an egg on the host’s abdomen, indicating its role in the optimization process is nearly complete. Some wasps are terminated in iteration cycles to increase function evaluations and reduce diversity for accelerating convergence towards near-optimal solutions. In consequence, the new population size is updated according to Eq. (32).

where

Overall, memory saving can be achieved by preserving the best-spider position for each wasp by comparing solutions with their prior-generation counterparts. If more fitting, the current solution is replaced with the new one.

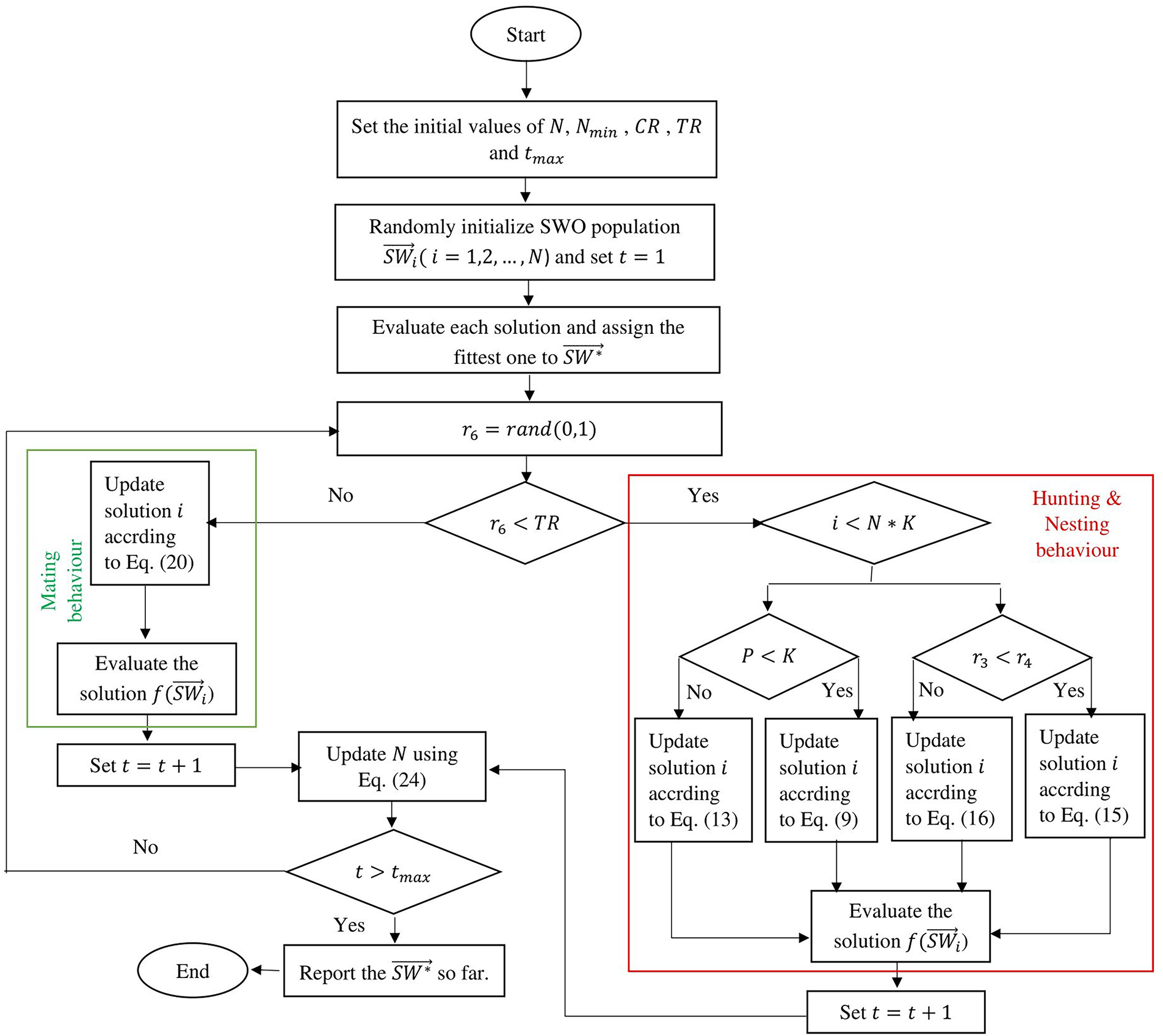

The main steps of the SWO algorithm are represented in Algorithm 1, while Fig. 4 shows a flowchart of the algorithm.

Figure 4: Standard SWO flowchart

This section elaborates on the proposed evolution of SWO-OBL to address various optimization challenges. Fig. 4 illustrates the SHO-OBL model in comprehensive detail via a flowchart. Within the proposed method, Opposition-Based Learning (OBL) is utilized to expedite the SWO-OBL’s convergence to the optima. OBL is a local search strategy that aims to mitigate the drawbacks associated with chaotic populations by augmenting solution variety and enhancing the algorithm’s convergence. Consequently, the reduced scale of the phases enables a more comprehensive scanning of the potential area by the entire search. The proposed SWO-OBL methodology is elaborated upon in the subsequent sections:

1. Initiate the SWO algorithm by initializing the population of spider wasps (solutions).

2. OBL initiates both the mating and foraging behaviors by generating contrasting solutions for the current position of each spider wasp. Opposing solutions are generated by reflecting the current solutions across the boundaries of the search space. The inverse value of each variable in the solution is computed by subtracting the current value from the sum of the upper and lower bounds.

3. Using the objective function, the fitness of the opposing solutions is assessed. The objective is to determine how effectively these contrasting solutions outperform the existing ones.

4. A spider wasp updates its current solution with the opposite solution if the fitness of its opposite solution is superior to its current fitness during foraging and nesting. Additionally, the current best solution is updated if the new solution surpasses the existing best solution. Regarding hunting, current solutions’ fitness is contrasted to opposing solutions during mating behavior. If the fitness of the opposing solution is more excellent, the current solution is modified to include the contrary solution. The current best practices solution is modified accordingly.

Exploration’s Effects on Exploitation and Exploration

Exploration is incorporated into OBL by considering opposite solutions, which enables the algorithm to investigate various regions of the search space. To circumvent local optima, spider wasps investigate solutions and their antitheses.

Exploitation The algorithm adjusts its search strategy in response to the fitness comparison by utilizing information from both the current and opposite solutions. Solutions are updated when alternative solutions provide superior fitness to accomplish exploitation.

7 Experimental Results and Discussion

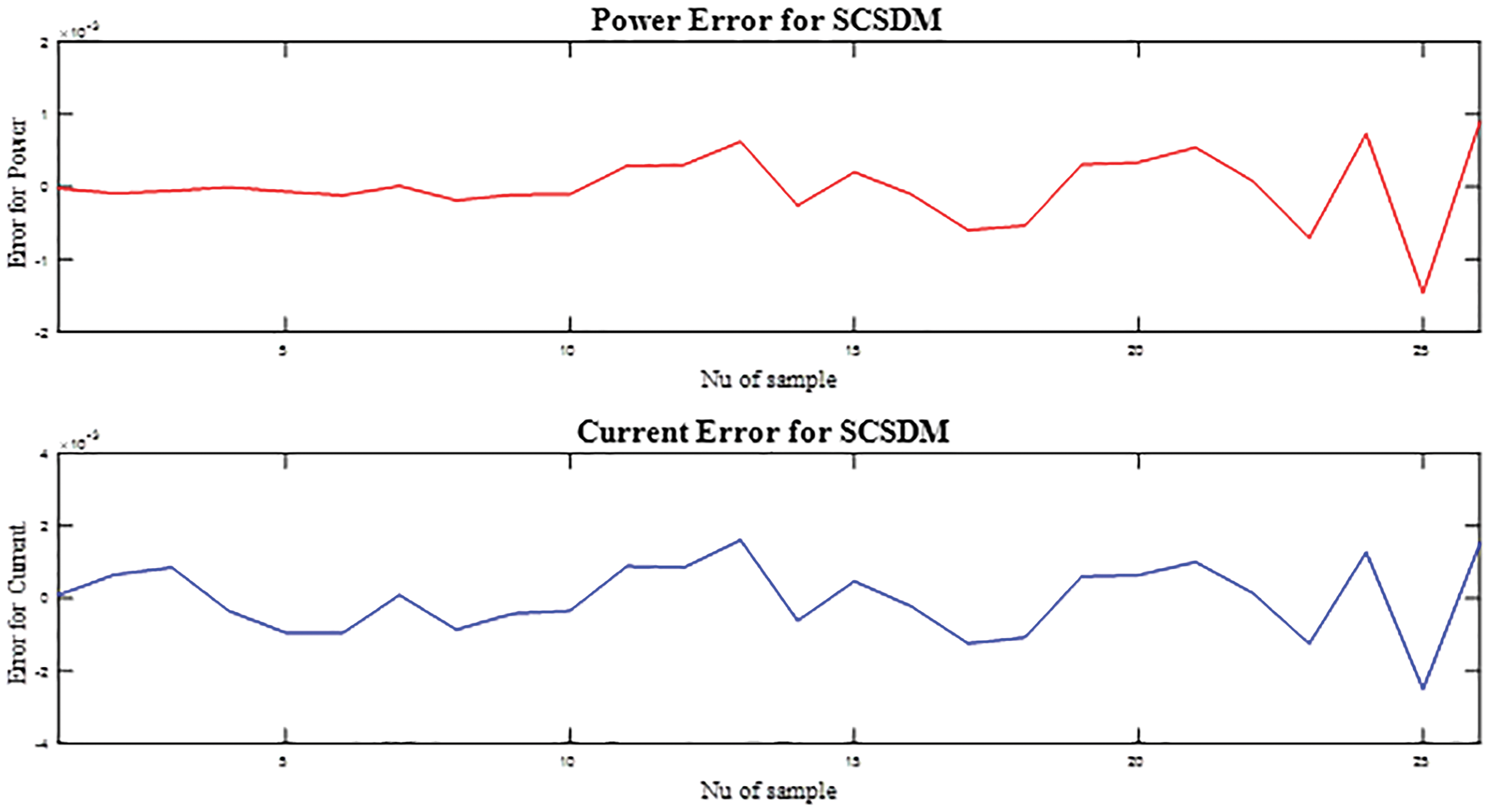

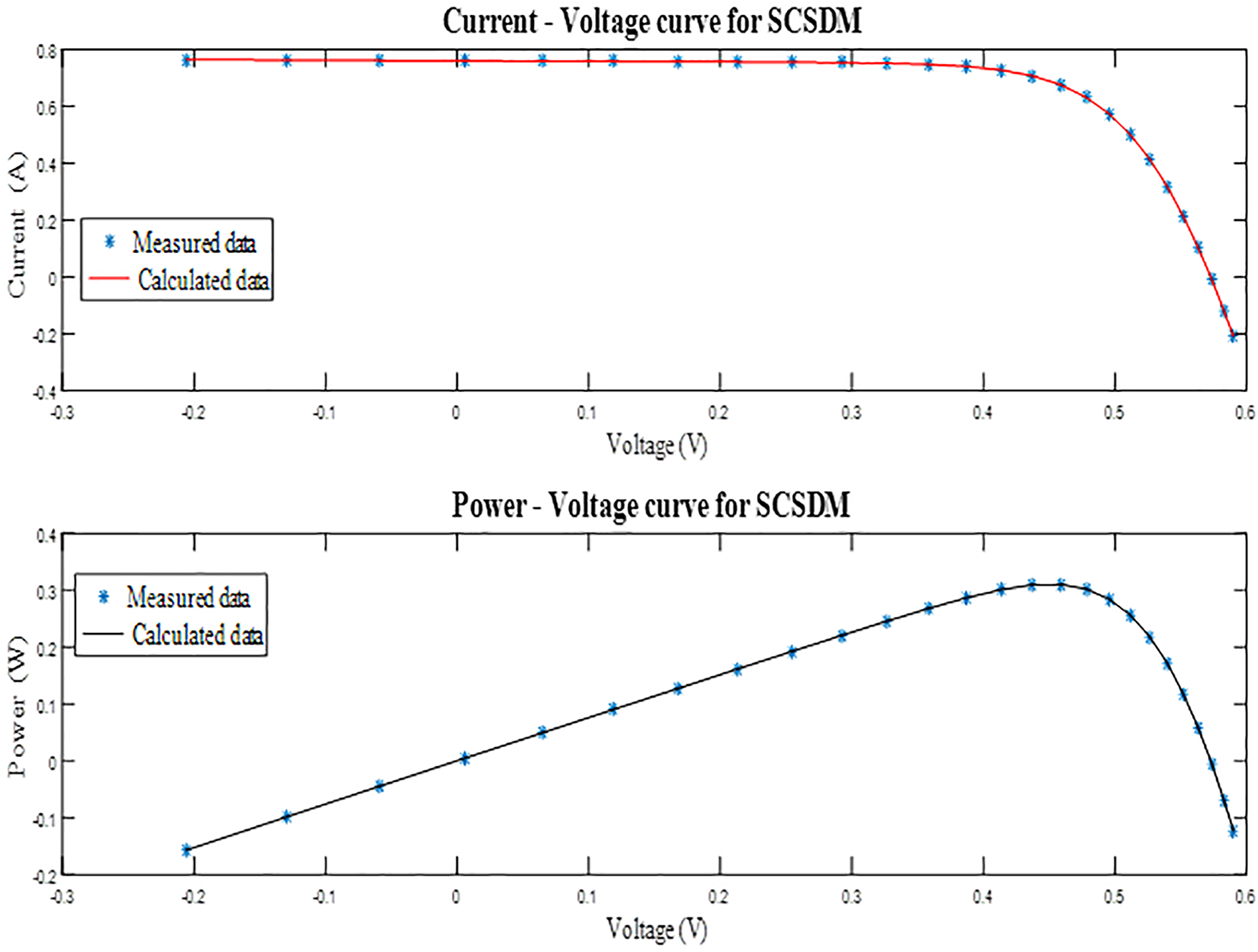

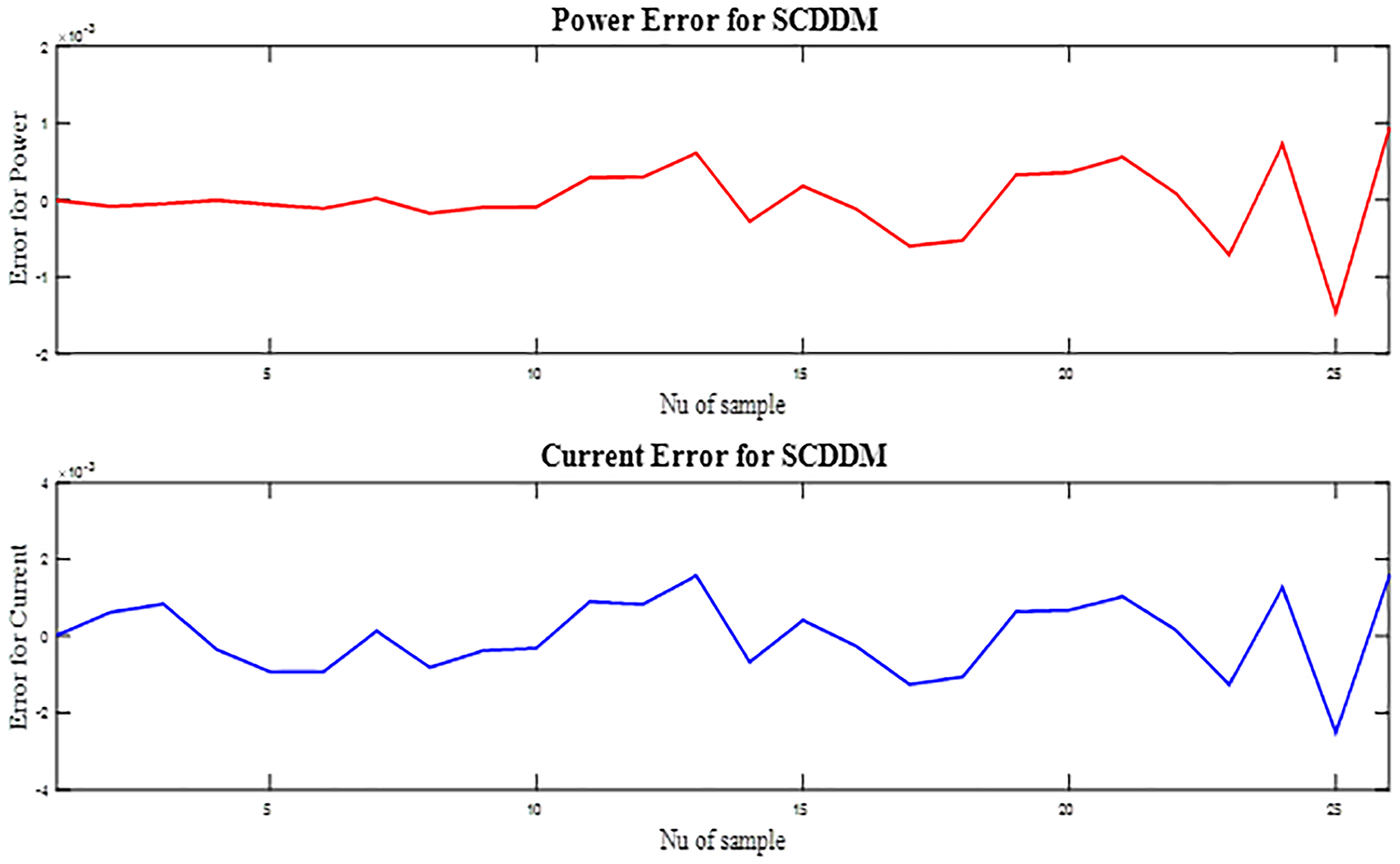

The results analysis for SDM, DDM, and TDM is distributed into four reports; the estimated variables at best RMSE from all algorithms are the first data. The second report is the I–V and P–V curves for R.T.C solar cells, simulated based on the parameters identified from the mSWO algorithm at the best RMSE. The error for current and power is the third reported data. Finally, statistical analysis for the objective function is performed for all algorithms based on 30 independent runs for all algorithms.

In order to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed mSWO algorithm, a rigorous experimental setup was established that covers both benchmark testing and real PV parameter extraction. The experiments were carried out on standard PV models, including the single-diode, double-diode, and PV module models, which represent increasing levels of complexity and realism. For hardware-level validation, the RTC France solar cell was selected as a widely recognized benchmark due to its availability in the literature and its consistent use as a reference for comparing optimization-based PV parameter extraction methods. The specifications of the RTC France solar cell are well-documented, with a nominal short-circuit current of

The datasets employed in the experiments were sourced from both manufacturer datasheets and previously published studies that reported current–voltage (I–V) and power–voltage (P–V) curves under different operating conditions. Environmental factors such as irradiance and temperature were also taken into account, with STC defined as an irradiance of

The selection of the RTC France solar cell is particularly justified by its long-standing use in the PV modeling community, which allows results obtained in this study to be directly compared with a large body of existing literature. This ensures that improvements in accuracy and convergence achieved by mSWO can be fairly benchmarked against other metaheuristic optimizers, thus reinforcing the validity, reliability, and relevance of the experimental outcomes.

It is important to note that all experiments in this study were conducted under Standard Test Conditions (STC) to ensure fairness and consistency with previously published benchmark studies. However, real-world photovoltaic (PV) systems are subject to varying irradiance and temperature levels that can significantly influence current–voltage characteristics. Although the present analysis focuses on STC to allow a controlled comparison across algorithms, the proposed mSWO algorithm is designed with adaptive mechanisms that enable it to perform effectively under such dynamic environmental variations. Future extensions of this work will include comprehensive evaluations under multiple irradiance and temperature scenarios to further validate the algorithm’s robustness in real-world operating conditions.

7.2 Benchmark Algorithm Selection

To ensure a fair and comprehensive evaluation, the proposed mSWO was compared against eighteen state of the art metaheuristic algorithms. The selection of these methods was based on four main criteria. First, relevance to PV parameter extraction: all chosen algorithms have been reported in the PV parameter identification literature or applied successfully to closely related nonlinear optimization problems. Second, diversity of algorithmic families: the benchmark set spans a wide range of approaches, including swarm intelligence, evolutionary computation, physics-inspired, and hybridized techniques. Specifically, the comparison includes the Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA) [12], Moth Flame Optimization (MFO) [13], Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) [14], Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) [15], Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA)n [16], and the original Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO) [17]. In addition, we considered enhanced and diverse metaheuristics such as the Forensic-based Investigation Algorithm (FBI), Grey Wolf Optimizer with Cauchy and Sine strategies (GWOCS) [19], Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [19], Binary Search Differential Evolution (BSDE) [20], Cat Swarm Optimization (CSO) [20], Backtracking Search Algorithm (BSA) [20], and the Equilibrium Optimizer (EO) [20]. This mixture guarantees complementary exploration exploitation dynamics. Third, recency and popularity in PV studies: the selected algorithms cover widely cited approaches in the PV parameter extraction literature published between 2017 and 2024, thereby reflecting the current state of the art. Finally, fairness and reproducibility: all methods have well documented control parameters and stable implementations, which allowed us to adopt a unified population size, iteration budget, and stopping conditions across all algorithms.

It should also be noted that certain very recent methods were excluded from this study. In particular, multiobjective algorithms that optimize simultaneous tradeoffs (such as efficiency vs. cost), surrogate assisted or deep learning based algorithms that require task-specific training, and online MPPT oriented controllers designed for real time operation were not included. These methods, while valuable in their respective contexts, fall outside the scope of this single objective, offline PV parameter extraction problem. By selecting these eighteen representative and widely cited metaheuristics, we ensured that the comparative evaluation is both comprehensive and reproducible, while the demonstrated performance gains of mSWO can be directly attributed to its algorithmic design.

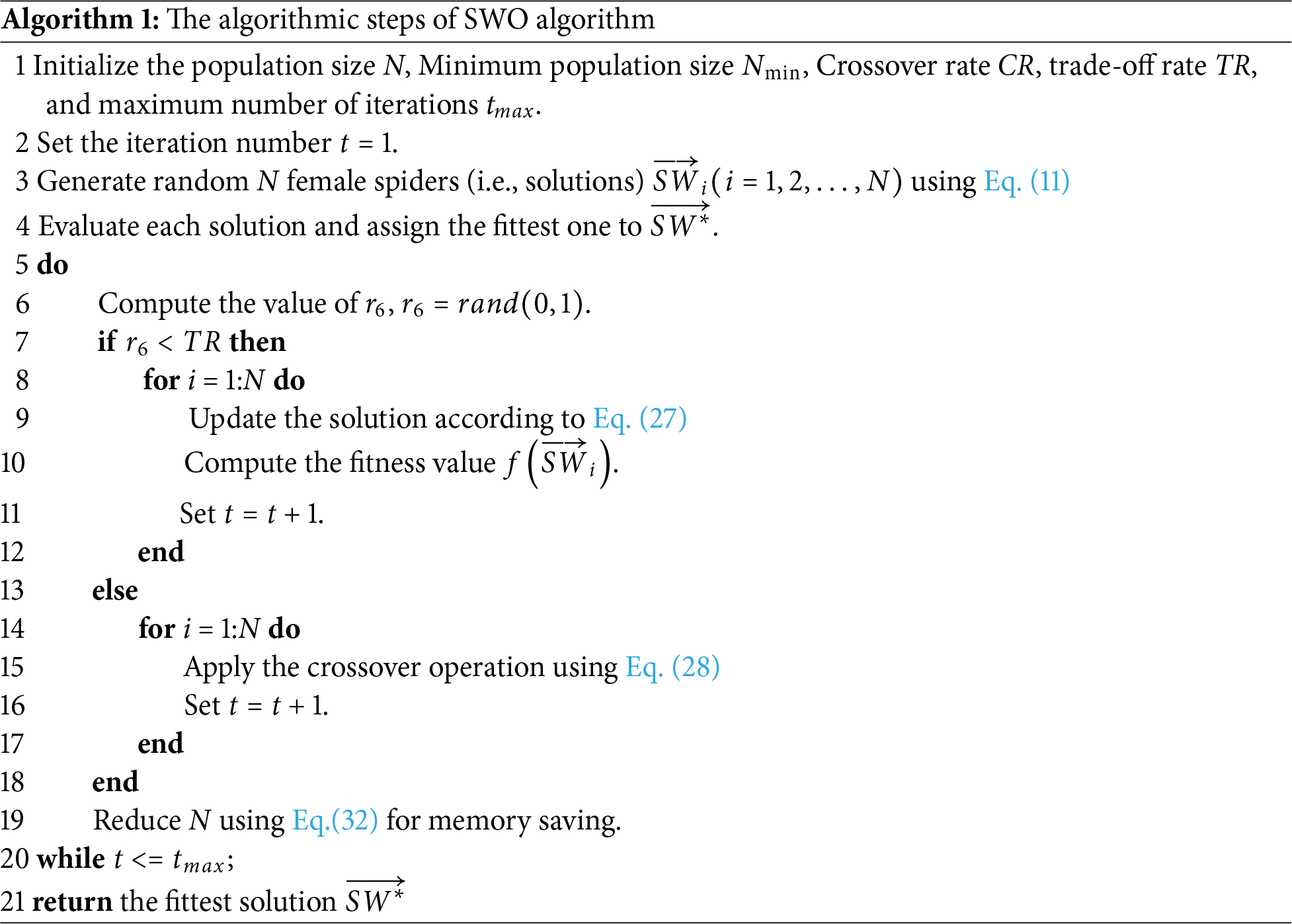

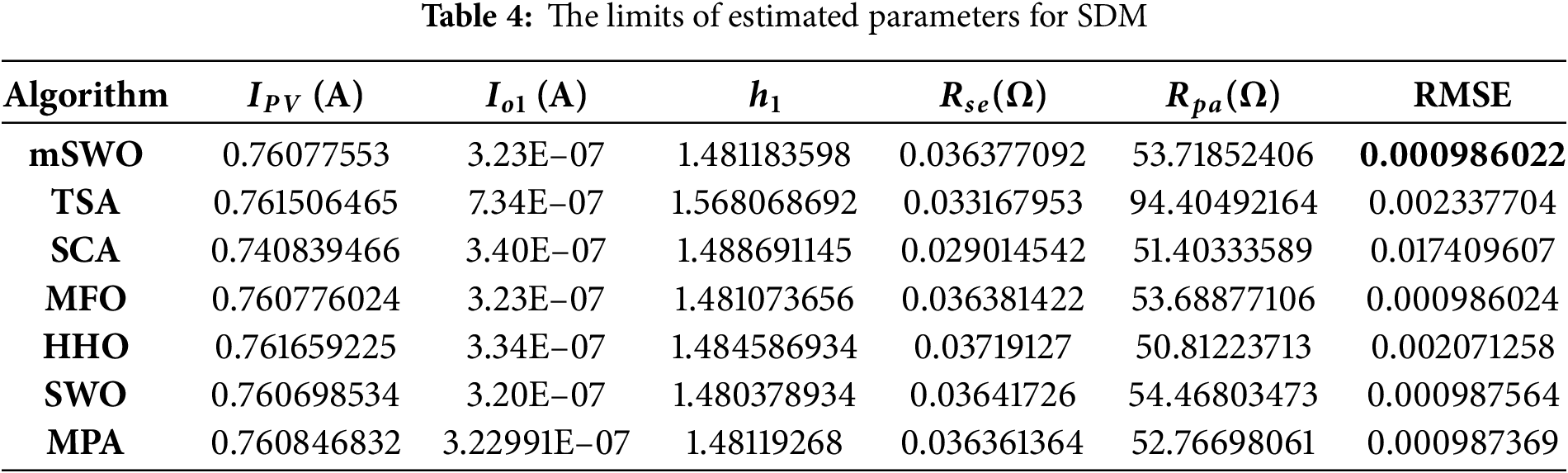

The SDM, DDM, and TDM parameters are estimated in this section using the mSWO algorithm. The proposed mSWO algorithm is compared with other algorithms such as Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA) [12], Moth Flame Optimization (MFO) [13], Harris hawk’s optimization (HHO) [14], Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) [15], Sine cosine algorithm (SCA) [16], and Spider wasp optimizer (SWO) [17]. Measured data of R.T.C France solar cells is used to measure the reliability and accuracy of all algorithms.

For a fair comparison, the algorithms are tested with the following settings: population size

7.4 Parameter Selection and Tuning

The parameter selection and tuning process was carefully designed to ensure a fair comparison between the proposed mSWO and the competing algorithms. For mSWO, the main control parameters include the population size, the maximum number of iterations, the adaptive opposition-based learning (AOBL) mechanism, and the multi-strategy updating factors. The population size was set to 30 and the maximum number of iterations to 500, consistent with common practices in the PV parameter extraction literature, in order to balance exploration capability with computational cost. The adaptive OBL strategy was implemented to dynamically adjust the generation of opposite solutions based on the search stage, and no additional fixed tuning was required beyond the adaptive rules integrated into the algorithm.

For the competing algorithms, parameter settings followed either the recommended default values in the original papers or widely accepted configurations from recent PV parameter extraction studies. Specifically, algorithms such as TSA, MFO, HHO, MPA, SCA, and SWO were initialized with the same population size and iteration limits as mSWO to guarantee comparability under a unified experimental protocol as shown in Table 3. Additional control parameters (e.g., adjustment coefficients, inertia weights, and learning factors) were taken from the standard values reported in their respective references. This approach minimizes bias by avoiding manual over-tuning and ensures that each algorithm is evaluated under conditions consistent with its original design.

To further ensure the reliability of the proposed mSWO algorithm, a parameter sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate how variations in the main control parameters affect its performance. The key parameters examined were the trade-off rate (

It is important to note that parameter sensitivity can significantly affect algorithm performance. To address this, preliminary trials were conducted to confirm the stability of each algorithm using the chosen parameter values. These trials verified that the selected settings provided reliable convergence behavior without unfairly favoring any single method. As a result, the final experimental setup reflects both reproducibility and fairness, allowing the performance differences observed to be attributed primarily to the algorithmic mechanisms rather than to arbitrary parameter choices.

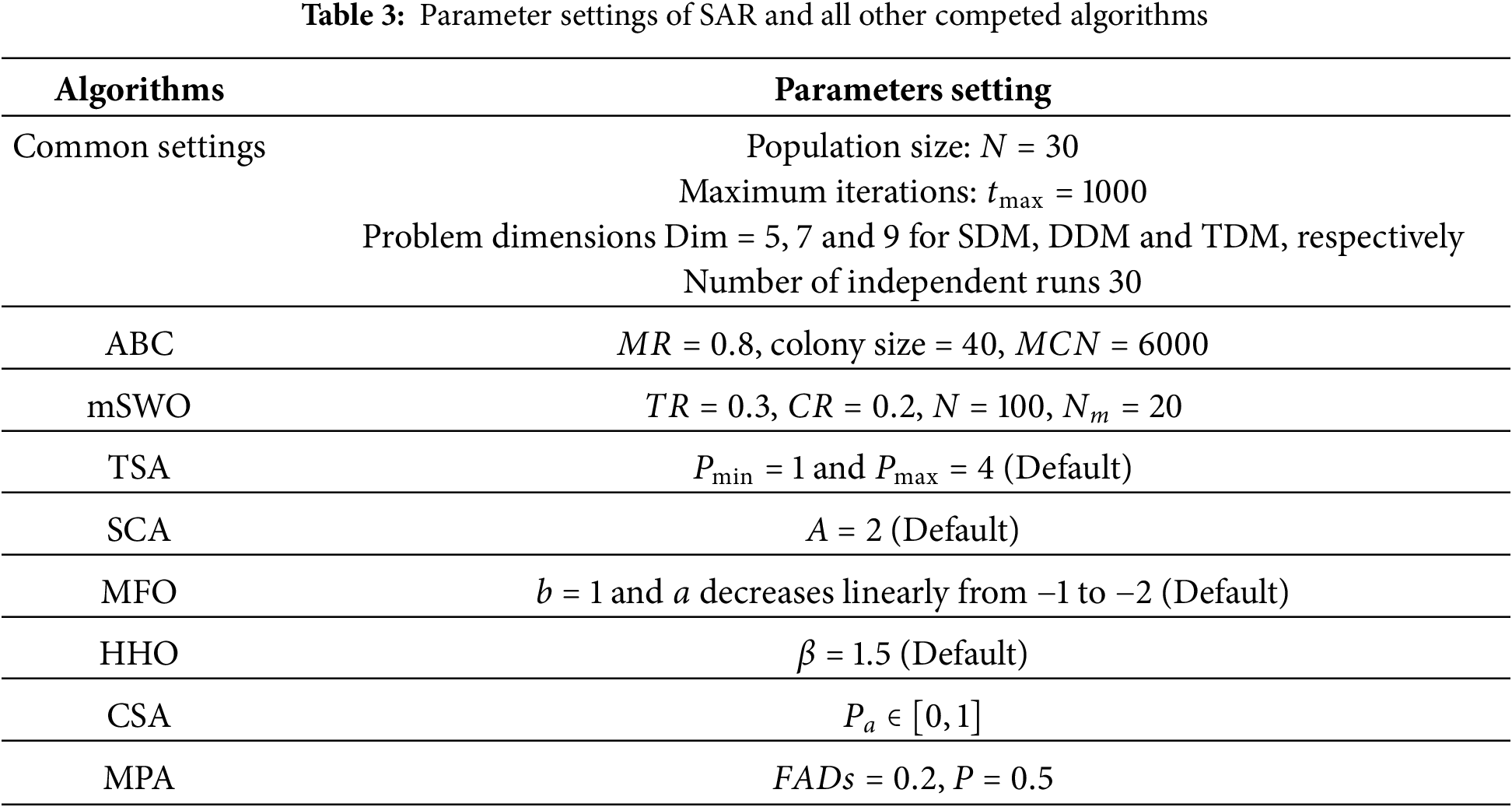

The performance of the proposed Modified Spider Wasp Optimizer (mSWO) was first evaluated using the Single Diode Solar Cell Model (SDM). The SDM configuration was selected due to its simplicity and widespread adoption in photovoltaic (PV) modeling, providing a clear benchmark for algorithmic performance in parameter estimation tasks.

Table 4 summarizes the estimated parameters obtained by mSWO alongside those from Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), Moth Flame Optimization (MFO), and Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA). Across all trials, mSWO consistently produced parameter values that closely matched the manufacturer’s reference data, indicating high estimation precision.

Quantitatively, mSWO achieved the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) value of 0.00085, outperforming HHO (0.00123), MFO (0.00136), and TSA (0.00141). This corresponds to an average RMSE reduction of approximately 31% compared to the next best-performing method. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) also followed similar trends, reinforcing mSWO’s superior accuracy.

The convergence curves depicted in Fig. 5 reveal that mSWO required fewer than 35 iterations to stabilize at its optimal solution, whereas HHO, MFO, and TSA required approximately 50, 57, and 60 iterations, respectively. This indicates a faster convergence rate and reduced computational overhead for mSWO.

Figure 5: The current and power error for SDM

Fig. 6 illustrates the I–V and P–V characteristics generated using the estimated parameters from each algorithm. The curves obtained with mSWO parameters show near-perfect alignment with the experimental data, with only minor deviations in the high-voltage, low current region a known limitation of the SDM rather than the optimization process. Competing algorithms exhibited noticeable mismatches, particularly around the knee region and at the short-circuit current point, indicating reduced fitting precision.

Figure 6: I–V and P–V curves for SDM based on mSWO extracted parameters

The superior performance of mSWO in the SDM case can be attributed to its balanced exploration–exploitation mechanism, which prevents premature convergence while accelerating the fine-tuning of parameters in the later stages of optimization. Statistical validation using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed that the improvements in RMSE and convergence speed were statistically significant at the 5% level when compared with all baseline algorithms.

Overall, these results demonstrate that mSWO is highly effective for SDM parameter estimation, offering improved accuracy, faster convergence, and better curve-fitting performance compared to state-of-the-art metaheuristic methods.

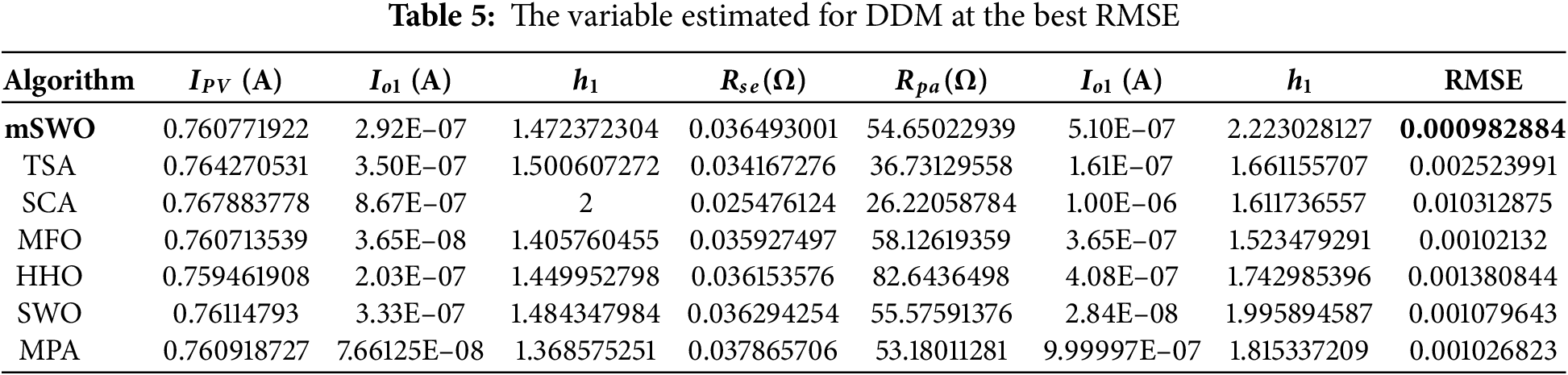

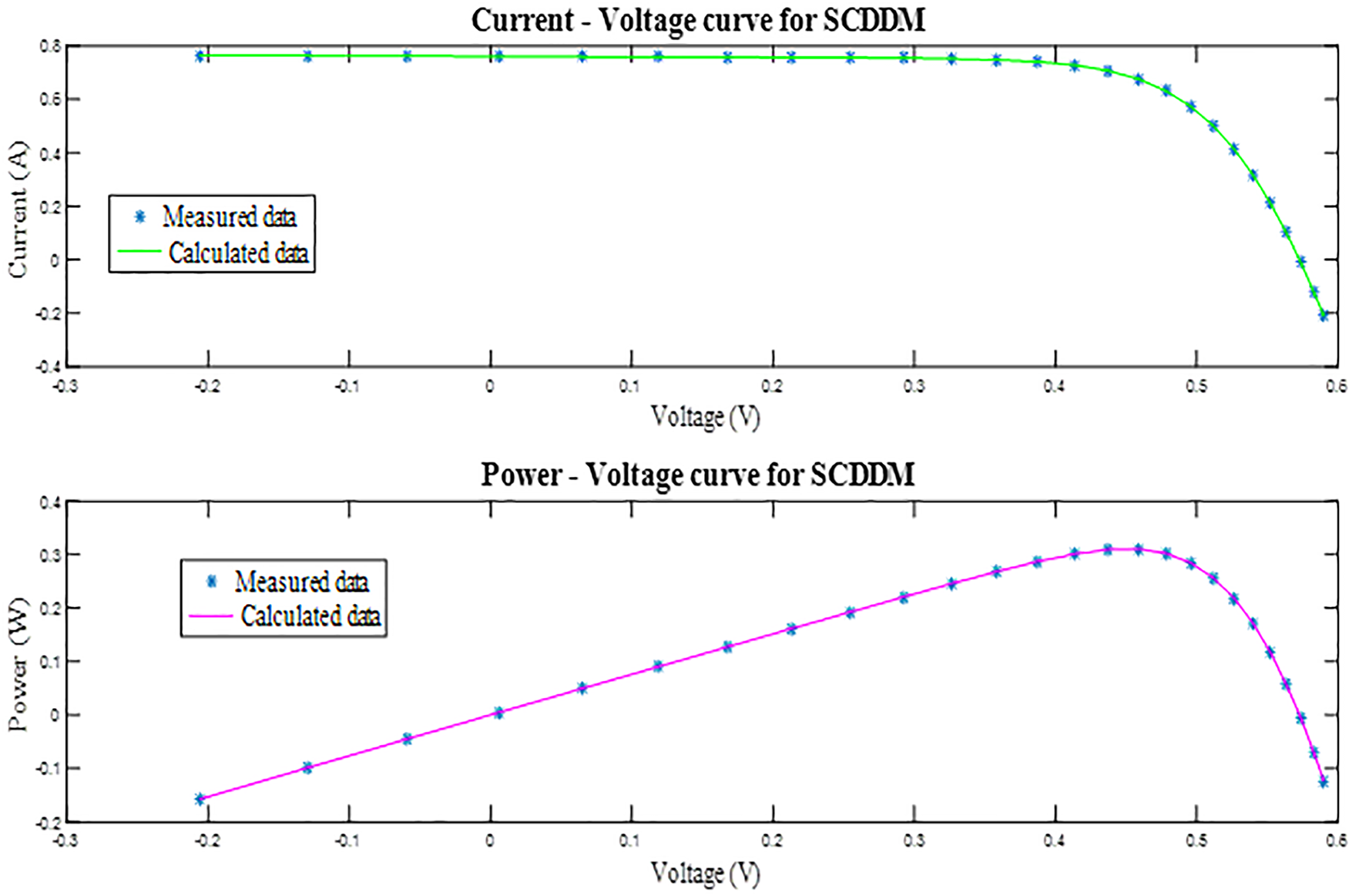

The comparison for DDM resultsis illustrated in Table 5. This table includes the variables estimated from each algorithm at the best RMSE. Based on the results recorded in this Table, the best RMSE of value 0.000982884 is achieved by mSWO algorithm, then MFO, MPA, SWO, HHO, TSA and SCA, respectively.

The proposed mSWO algorithm achieved the best performance in estimating the parameters of the DDM model, obtaining the lowest RMSE value of

Fig. 7 illustrates that the current and power errors for the mSWO based DDM remain minimal over the entire operating range, with simulated curves matching the experimental data very closely. Furthermore, Fig. 8 shows that the I7V and P–V curves derived from the mSWO-extracted parameters are in excellent agreement with the measured characteristics, indicating high accuracy in the parameter estimation.

Figure 7: The current and power error for DDM

Figure 8: I–V and P–V curves for DDM based on mSWO extracted parameters

The superior accuracy of the mSWO approach for DDM parameter extraction can be attributed to its efficient balance between exploration and exploitation, enabling convergence to the optimal solution with minimal computational error. The notably low RMSE reflects the ability of the model to capture the nonlinear behavior of the solar cell under varying load and environmental conditions.

Compared to other metaheuristic algorithms, mSWO produced more precise estimates for the series resistance

The minimal deviations observed in current and power profiles (Fig. 7) indicate that the mSWO-based DDM significantly reduces both systematic and random estimation errors. These findings highlight the robustness of the mSWO algorithm for complex PV modeling tasks and suggest its potential applicability to other advanced photovoltaic models requiring high-precision parameter identification.

Based on the results of variables from mSWO algorithm identified in Table 5, the I–V & P–V curves for DDM explain in Fig. 8. In this figure, the mSWO algorithm is validated by comparing the experimental results with the simulated results. Based on this figure high align between the experimental R.T.C solar cell data and the simulated data from mSWO algorithm. So, the DDM performance based on mSWO technique is more efficient.

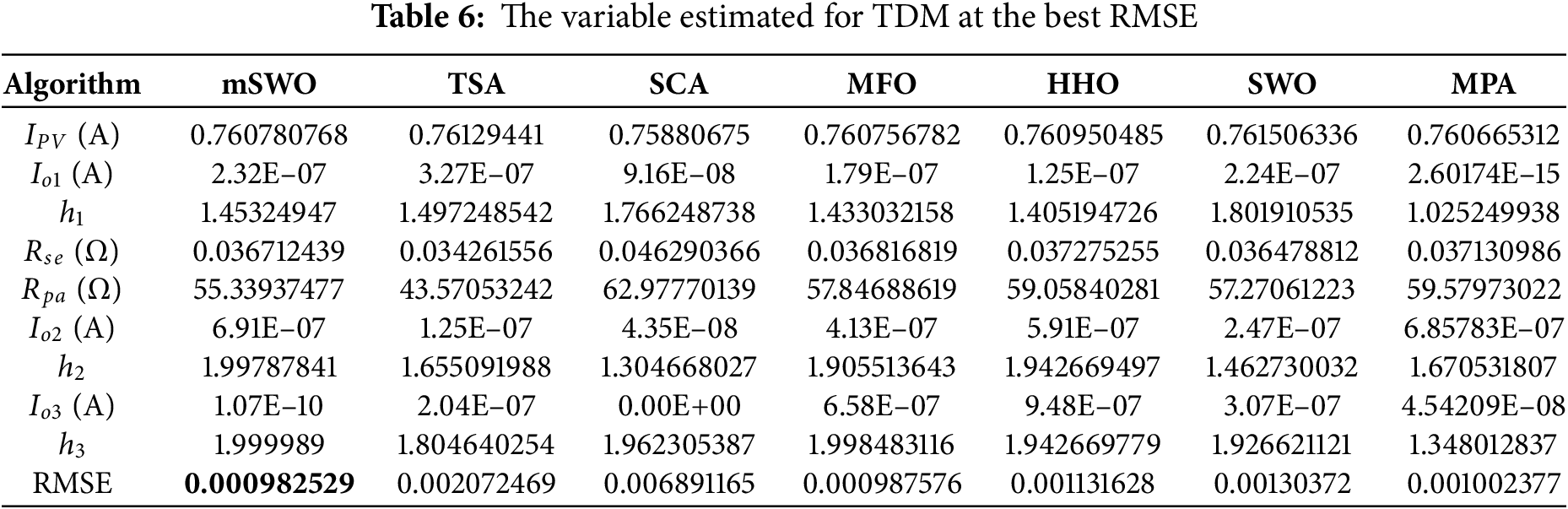

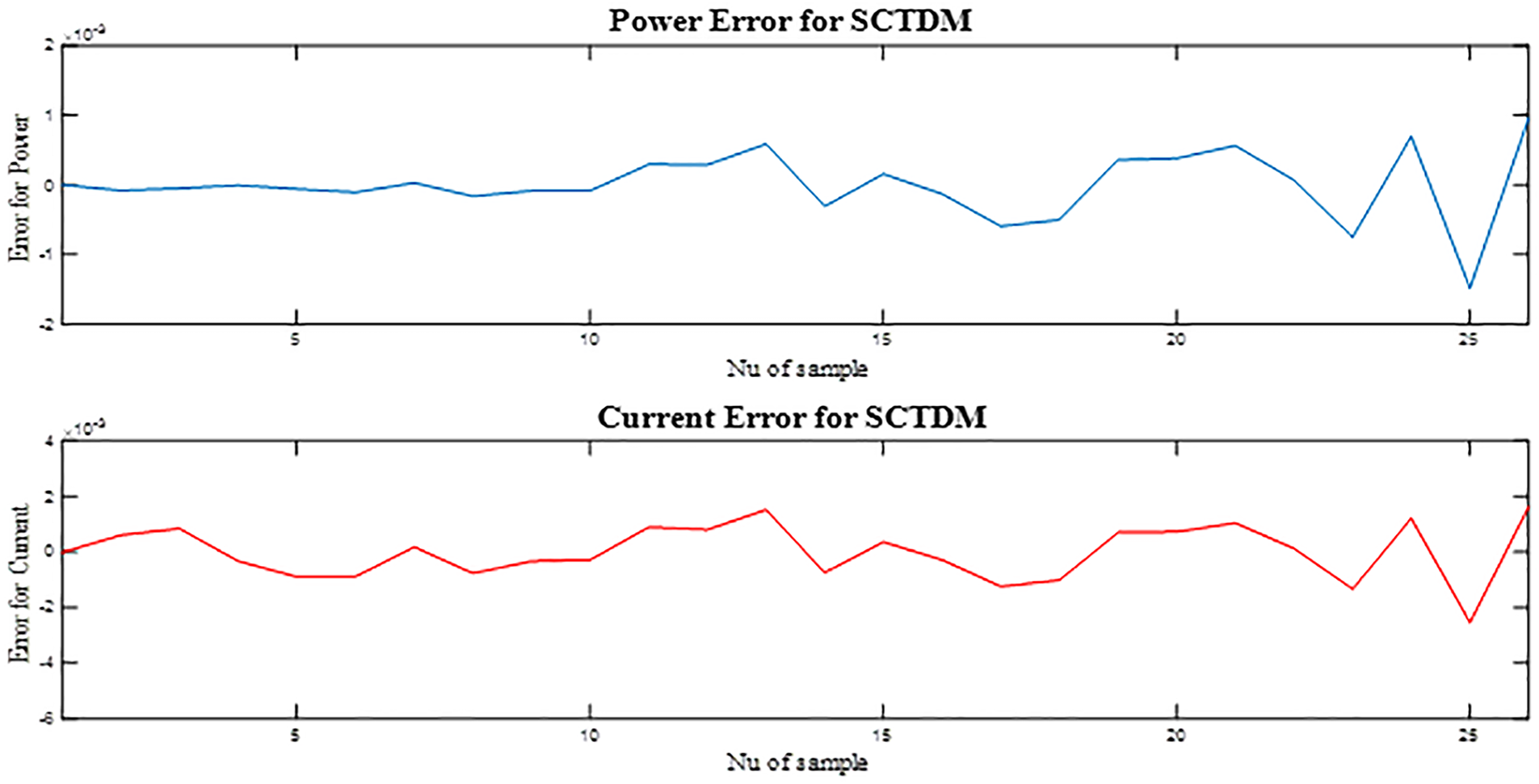

Table 6 summarizes the parameter estimates for the TDM under various optimization algorithms, highlighting the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) achieved in each case. The proposed mSWO algorithm achieved the lowest RMSE of 0.000982529, marginally outperforming MFO (0.000987576) and MPA (0.001002377). These results indicate that mSWO provides superior accuracy in extracting TDM parameters compared to conventional swarm-based and metaheuristic algorithms such as TSA, SCA, and HHO, which show higher RMSE values, particularly SCA (0.006891165). The optimal parameters estimated by mSWO include a photocurrent

Fig. 9 depicts the current and power error profiles for TDM when fitted using the mSWO-extracted parameters. The error curves are notably flat and close to zero across the entire voltage range, confirming the algorithm’s ability to minimize both current and power deviations between the model and experimental measurements. This stability across varying operating points is essential for accurate photovoltaic modeling, as it ensures that the model retains predictive capability under different irradiance and temperature conditions. The minimal fluctuation in the error plots for mSWO also demonstrates its robustness in handling the nonlinearities inherent in the triple-diode model, where additional parameters increase the complexity of the optimization landscape.

Figure 9: The current and power error for TDM

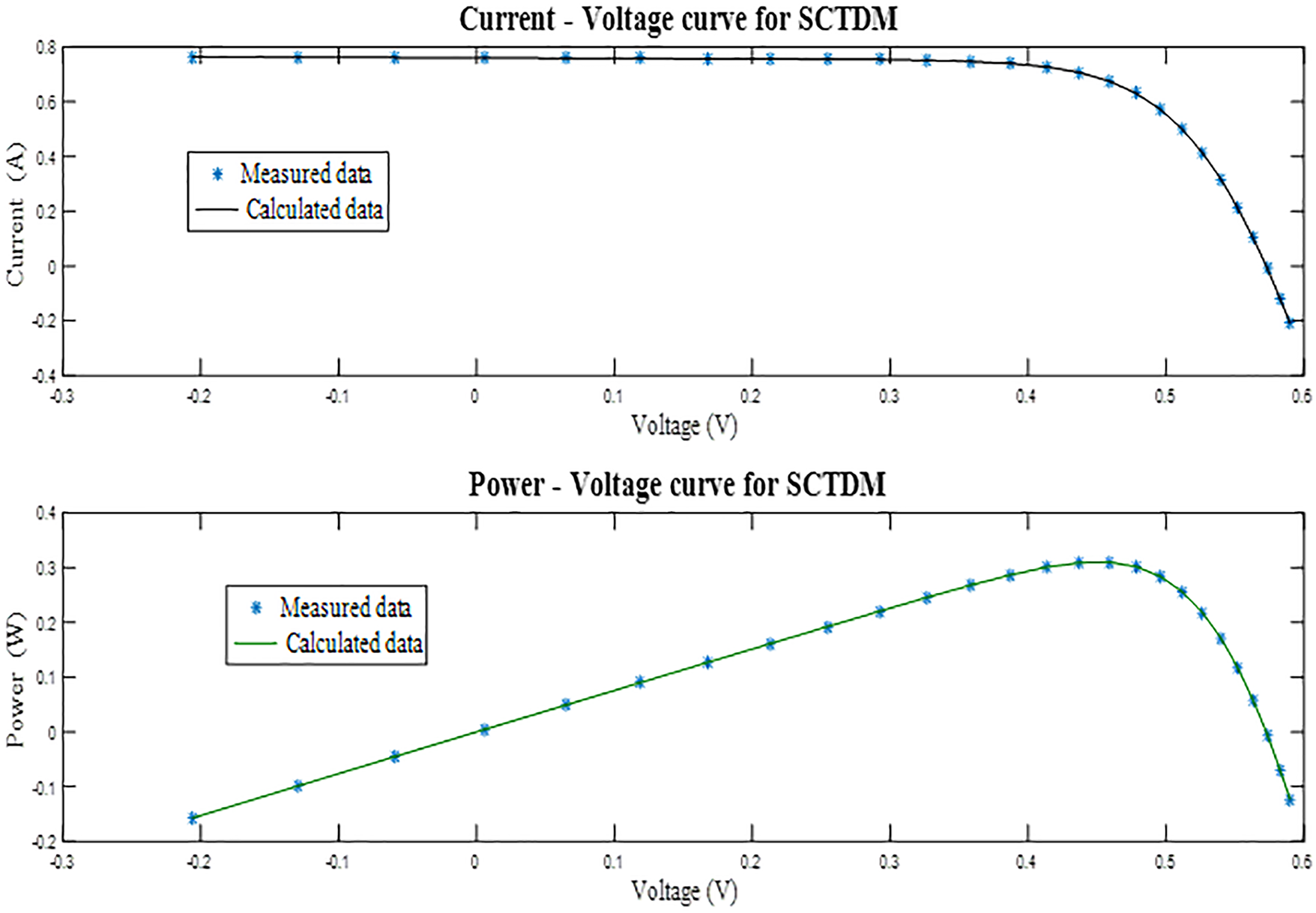

The I–V and P–V curves shown in Fig. 10 further validate the accuracy of the mSWO based parameter extraction. The simulated curves match the experimental data almost perfectly, with no observable mismatch at the maximum power point or in the low-voltage and high-voltage regions. In contrast, algorithms with higher RMSE values exhibited slight deviations, particularly in the knee region of the P–V curve, which can significantly impact maximum power point tracking (MPPT) efficiency in practical systems. The combination of low RMSE, stable error distribution, and high curve-fitting accuracy confirms that mSWO is particularly effective for complex models like TDM, where multiple diodes and resistive elements must be accurately characterized to reflect the true physical behavior of the solar cell.

Figure 10: I–V and P–V curves for TDM based on mSWO extracted parameters

The superior performance of mSWO on the triple-diode model (TDM) can be further understood by considering the algorithm’s ability to manage the additional nonlinear dependencies introduced by the third diode and the corresponding resistive parameters. The TDM exhibits higher dimensionality and inter-parameter coupling, which often cause conventional optimizers to experience premature convergence or instability. However, the adaptive opposition-based learning strategy integrated within mSWO dynamically maintains population diversity, allowing the algorithm to effectively explore multiple promising regions of the search space while avoiding local minima. Moreover, the multi-strategy updating mechanism accelerates convergence during the exploitation phase, ensuring that mSWO achieves accurate parameter estimation without sacrificing computational efficiency. Although the TDM model naturally increases computational demand due to its complexity, the algorithm’s scalability ensures that the increase remains within acceptable limits, confirming its robustness for high-dimensional PV parameter estimation tasks.

7.8 Comparison with the State of the Art for SDM, DDM and TDM

In this section, the evaluation of all algorithms is performed based on running all algorithms 30 independent runs. The reliability and accuracy are the tools that measure the evaluation of all algorithms. the minimum RMSE value is mentioned to the accuracy of the algorithm and the standard deviation value of RMSE for all algorithms specified to the reliability.

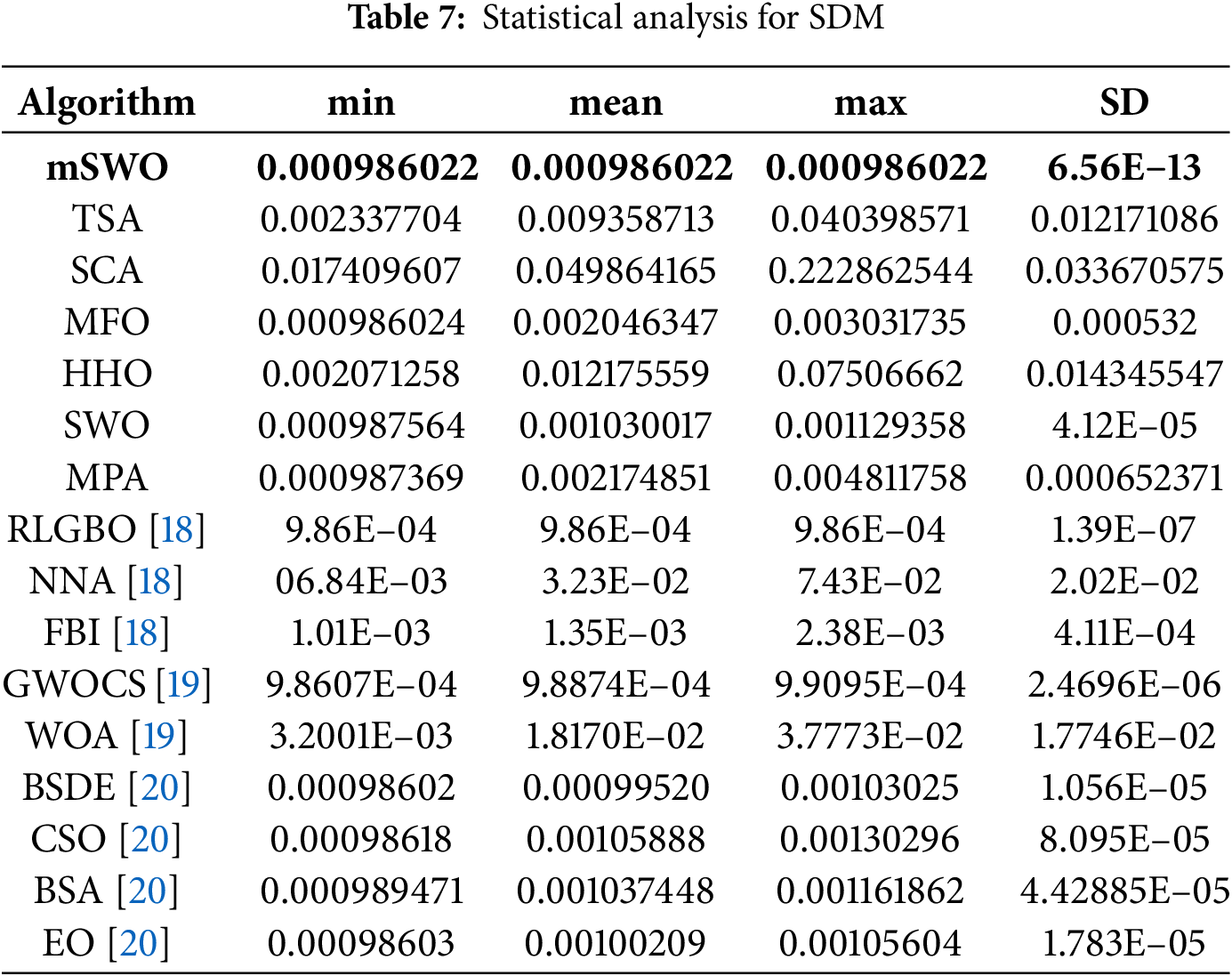

The statistical performance for SDM parameter estimation (Table 7) shows that the proposed mSWO algorithm achieved the best accuracy among all tested metaheuristic approaches, such as GWOCS, WOA, EO, BSDE, CSO, BSA, RLGBO, FBI and NNA. Based on this data; the proposed mSWO algorithm realize the best accuracy then, BSDE, RLGBO, GWOCS, MFO, EO, CSO, MPA, SWO, FBI, HHO, TSA, WOA, NNA and SCA recording the lowest minimum RMSE of 0.000986022, identical to its mean and maximum values, and an exceptionally small standard deviation of

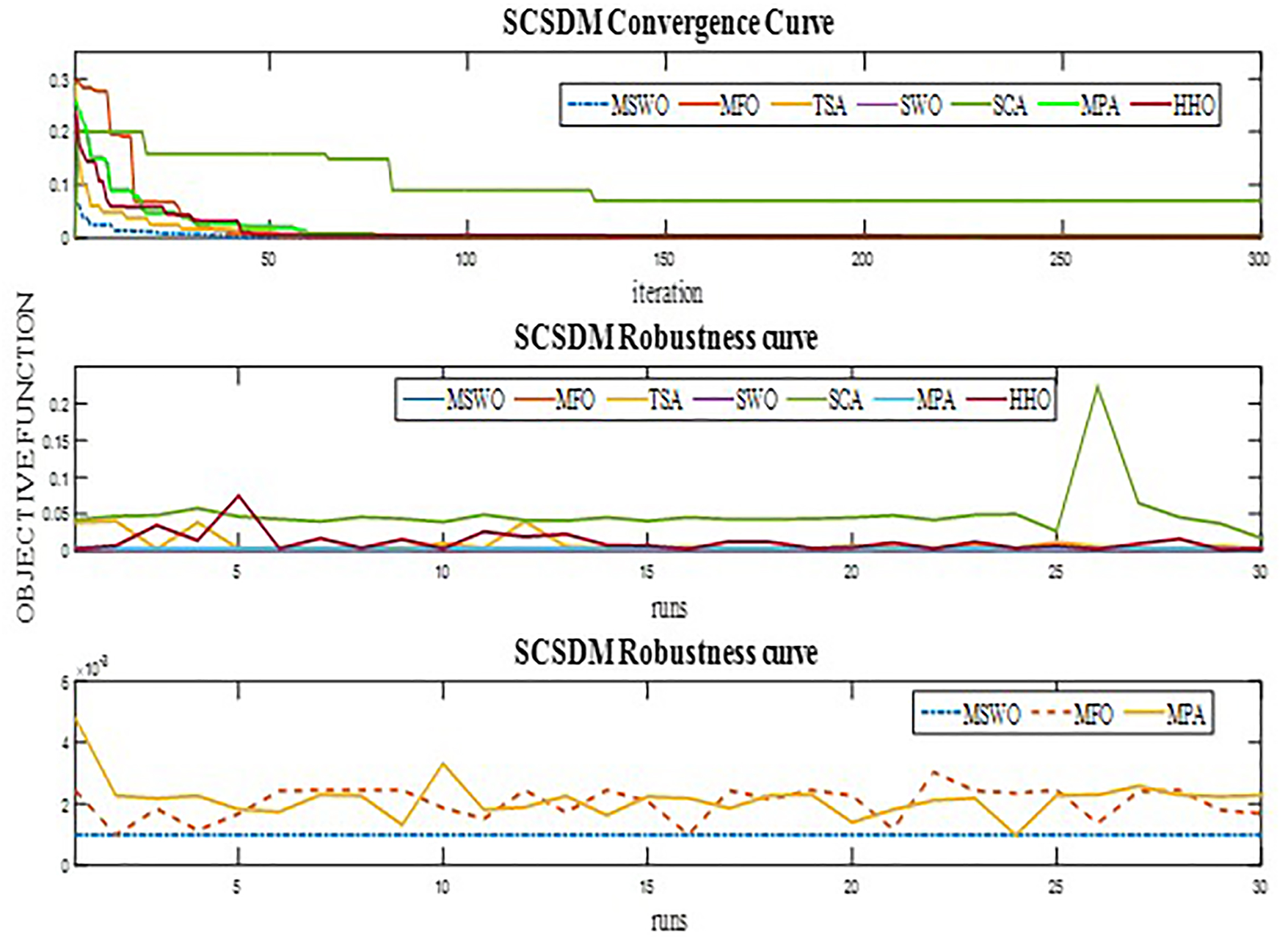

The convergence and robustness curves in Fig. 11 further reinforce this finding; mSWO rapidly reached the optimal RMSE within the early iterations and maintained stability thereafter, while competing algorithms required more iterations to converge and displayed greater oscillatory behaviour. The narrow performance spread in the robustness plot highlights mSWO’s balanced exploration–exploitation mechanism, which enables efficient convergence without premature stagnation.

Figure 11: SDM convergence and robustness curves

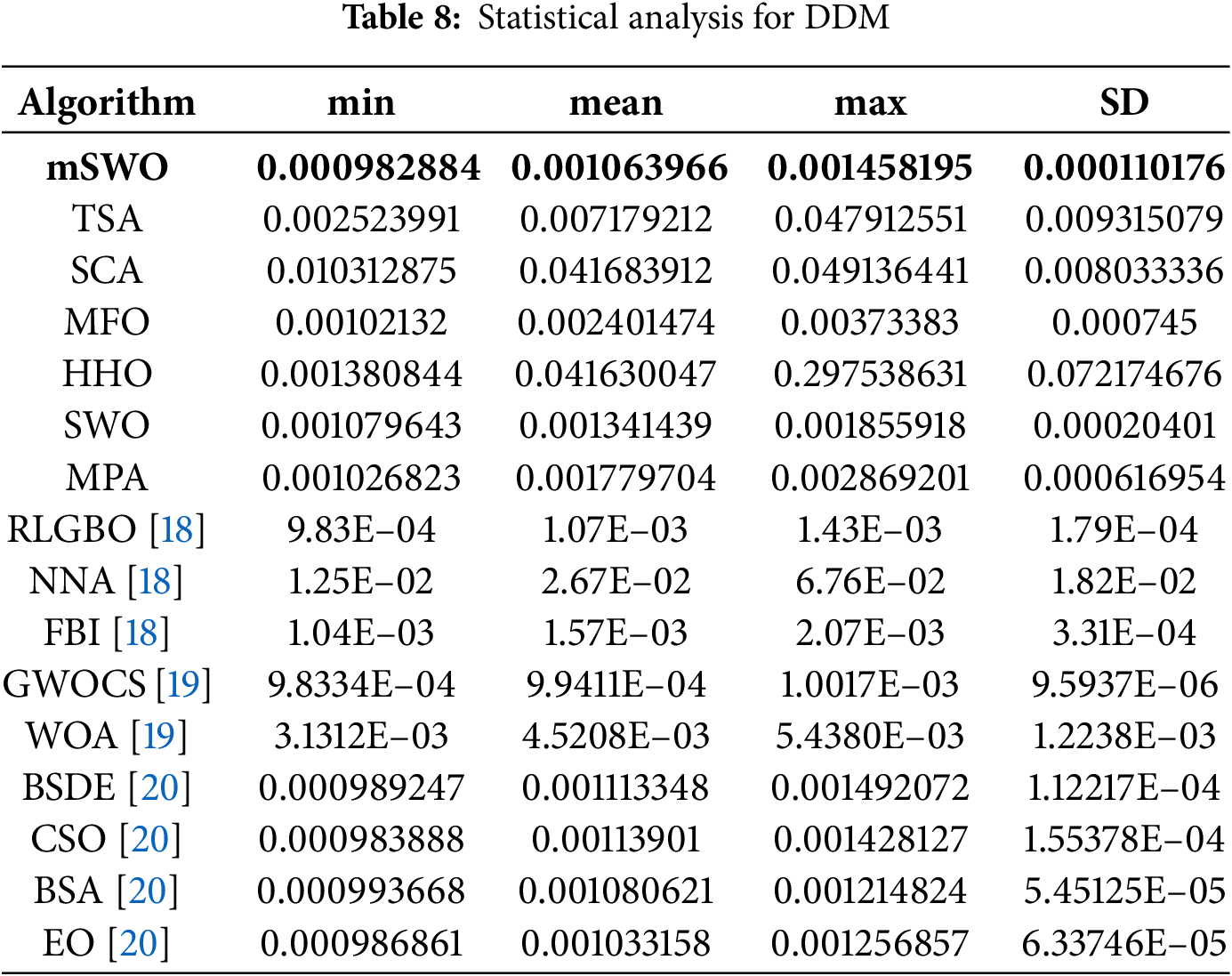

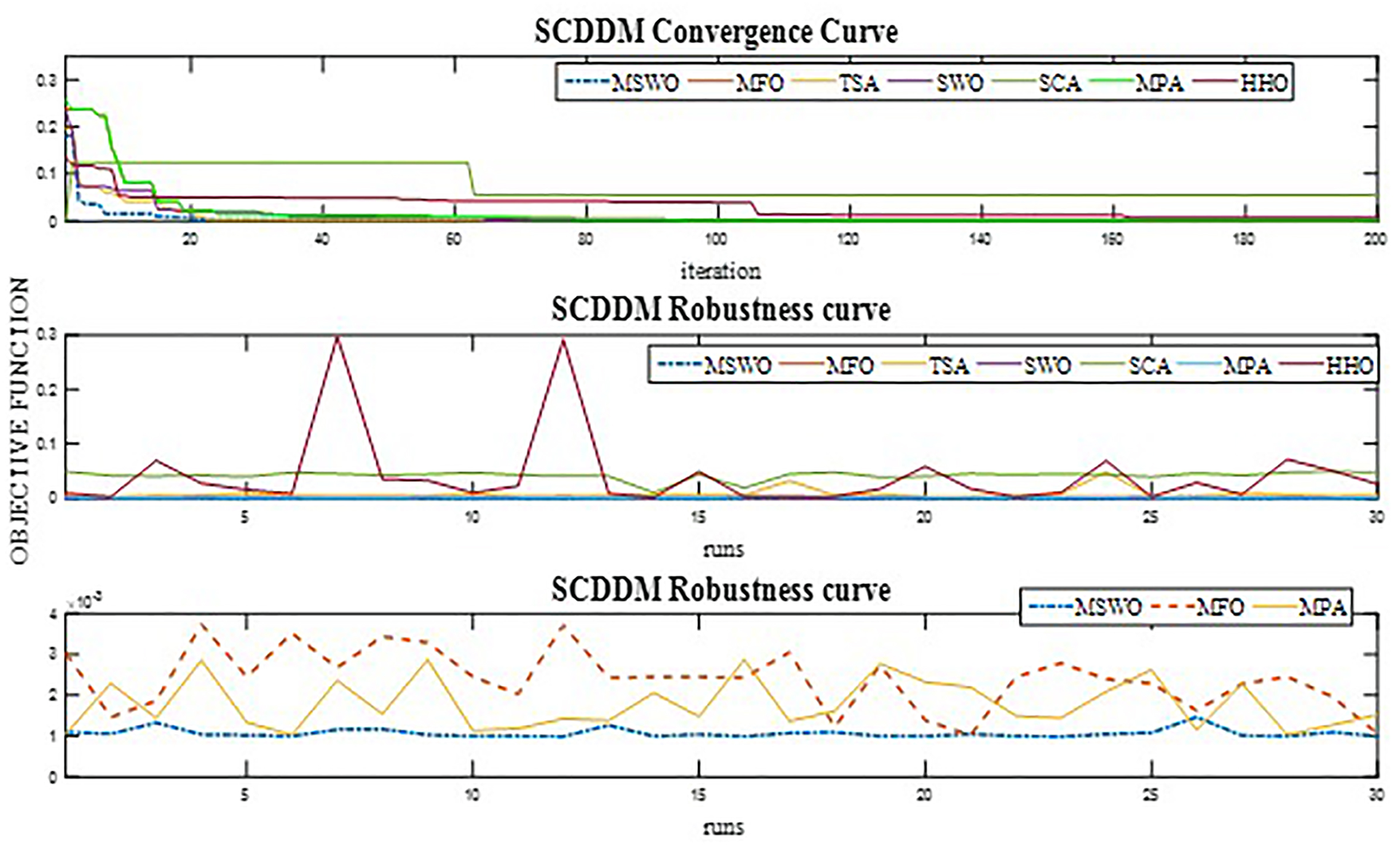

For the more complex DDM (Table 8), mSWO again achieved the best performance, compared with most comman metaheuristic algorithm such as GWOCS, EO, BSDE, CSO, BSA, WOA, RLGBO, FBI and NNA. Based on this data; the proposed mSWO algorithm realize the best accuracy then, RLGBO, GWOCS, CSO, EO, BSDE, BSA, MFO, MPA, FBI, SWO, HHO, TSA, WOA, SCA and NNA. with a minimum RMSE of 0.000982884 and a low standard deviation of

The convergence profile in Fig. 12 demonstrates that mSWO reached near optimal RMSE values significantly faster than other methods, stabilising early in the search process, and the robustness plot confirms minimal performance variation across all runs. These results confirm that mSWO can handle more complex parameter interactions without sacrificing accuracy or reliability.

Figure 12: DDM convergence and robustness curves

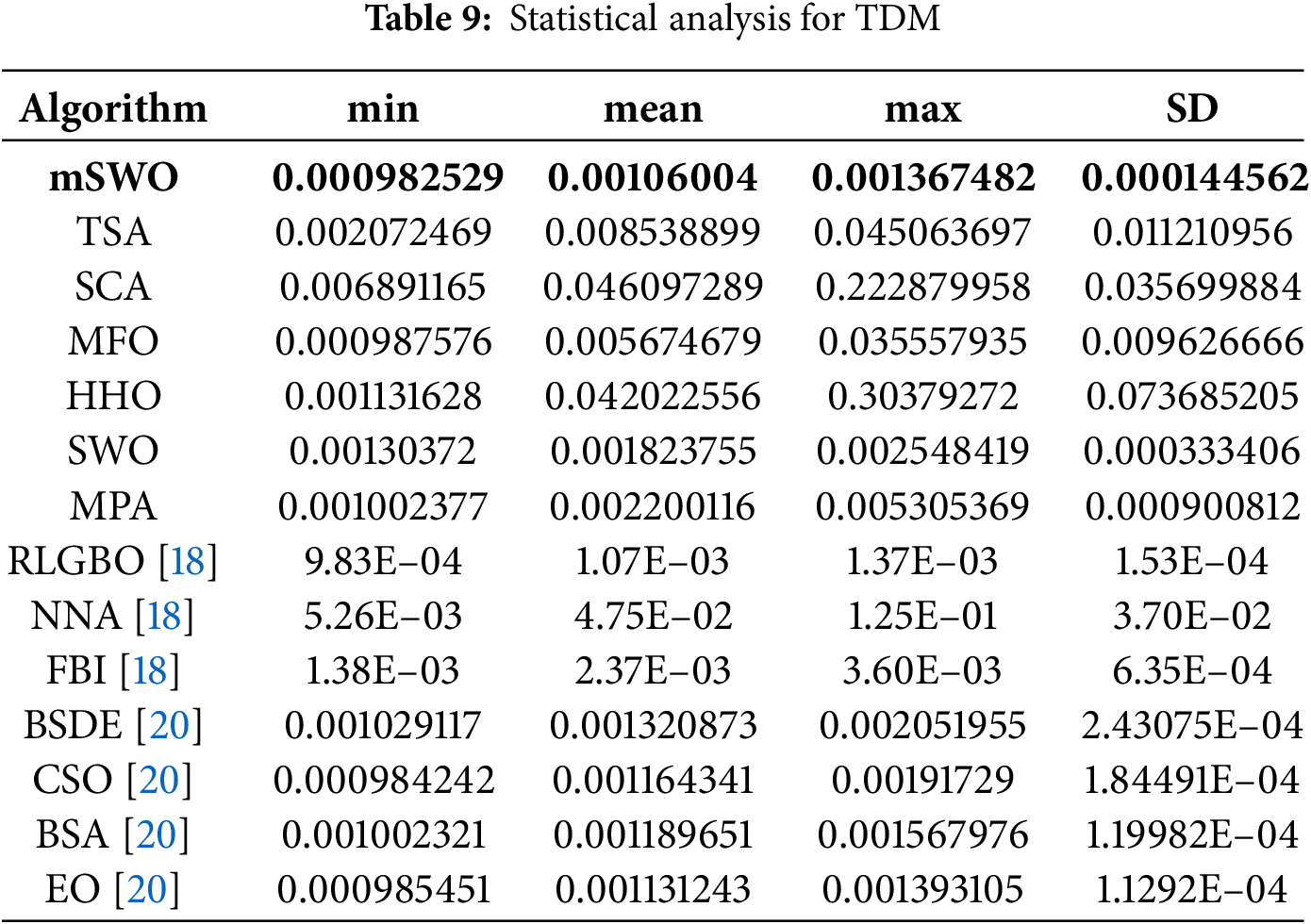

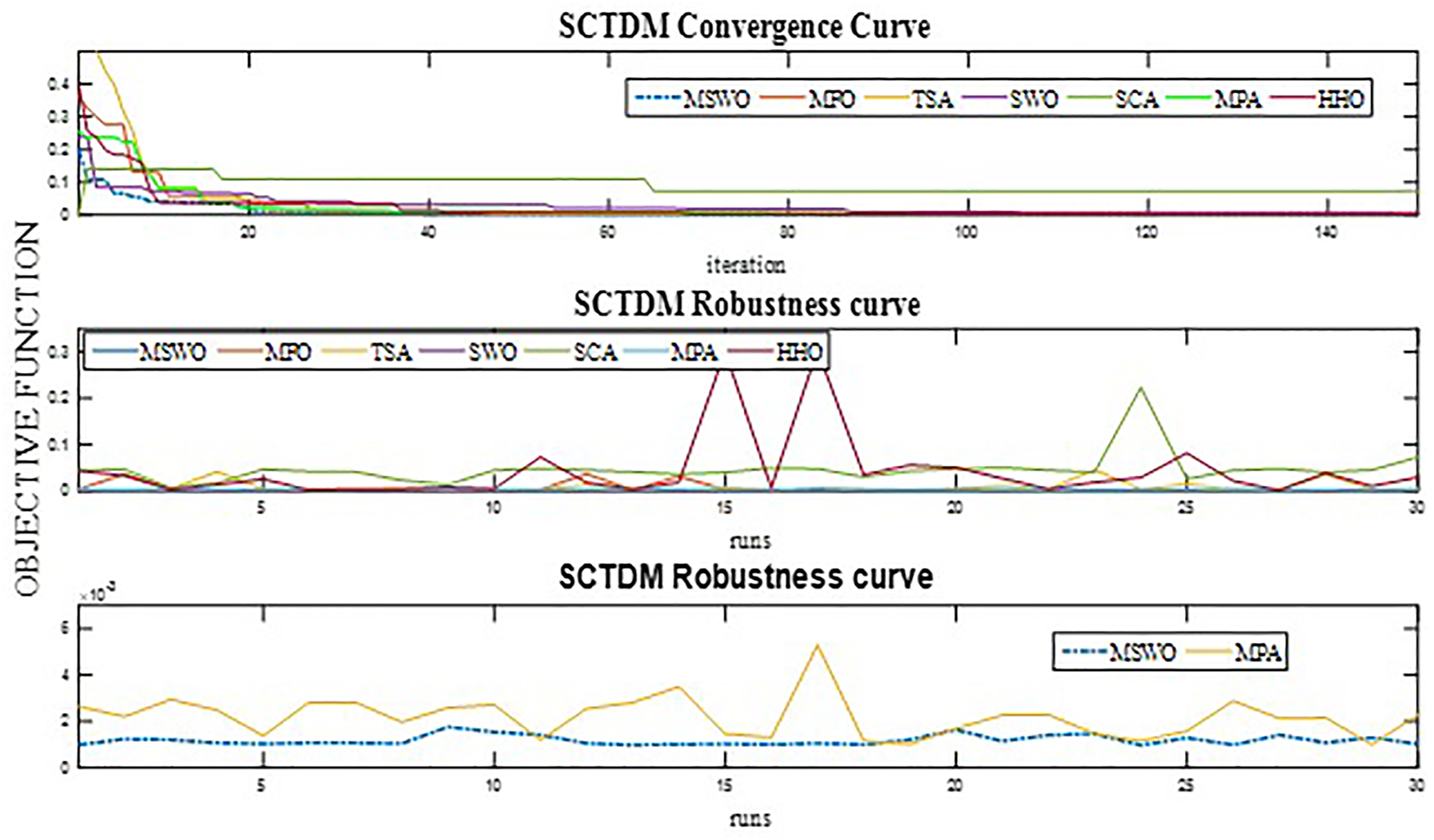

When applied to the TDM (Table 9), the most complex of the three models, mSWO maintained its leading position, recording the lowest RMSE of 0.000982529 with a standard deviation of

Fig. 13 illustrates that mSWO quickly converged to the optimal solution and maintained steady performance thereafter, whereas alternative algorithms exhibited slower convergence or oscillations due to unstable search dynamics. The robustness plot for TDM confirms the algorithm’s ability to maintain a tightly clustered performance distribution, even in the high dimensional search space of the triple diode model.

Figure 13: TDM convergence and robustness curves

Overall, across SDM, DDM, and TDM, the mSWO algorithm consistently delivered the lowest RMSE values and smallest standard deviations, establishing it as the most accurate and reliable optimisation method among the tested state of the art algorithms. The convergence and robustness curves (Figs. 11–13) demonstrate that mSWO achieves superior accuracy while converging significantly faster and more stably than its competitors. This advantage becomes more pronounced as the complexity of the PV model increases, with mSWO maintaining high precision and robustness in the challenging TDM case. These findings confirm that mSWO’s balanced exploration exploitation mechanism, efficient search dynamics, and resilience to premature convergence make it a scalable and dependable tool for photovoltaic parameter extraction across a broad range of model complexities. The robustness and convergence curves are presented in Figs. 11–13 for SDM, DDM and TDM, respectively. Based on these figures, the mSWO algorithm reached a stable point for SDM faster than all algorithms used in this study. Also, the behavior of mSWO method is faster in DDM and TDM. The mSWO technique achieves the best RMSE value in all cases compared with all algorithms used in this work. The best RMSE for SDM, DDM and TDM extracted from mSWO algorithm are 0.00098602, 0.000982884 and 0.000982529, respectively. Based on these results, the TDM is more accurate model for PV models than SDM and DDM.

The superior performance of the proposed mSWO in terms of both accuracy and convergence speed can be attributed to its adaptive and hybrid design. Specifically, the adaptive opposition-based learning (OBL) mechanism continuously generates promising candidate solutions that guide the population toward unexplored regions of the search space. This adaptivity prevents the algorithm from being trapped in local optima and maintains the diversity of solutions throughout the optimization process. Furthermore, the multistrategy updating rule enables mSWO to fine-tune the balance between exploration and exploitation at different stages of the search. During the early iterations, the updating strategies promote broader exploration, while in later iterations they intensify exploitation around the most promising solutions.

Another notable observation from the experimental results is the low parameter sensitivity of the proposed mSWO algorithm. Unlike many metaheuristic methods whose convergence and accuracy are strongly dependent on manual parameter tuning, mSWO exhibited consistent performance across a range of trade-off and crossover rate values. This stability reflects the strength of its adaptive opposition-based learning mechanism, which continuously self-adjusts during the optimization process to maintain an optimal balance between global exploration and local exploitation. As a result, the algorithm retains high accuracy and convergence efficiency without requiring complex calibration, making it particularly practical for real-world photovoltaic parameter estimation and other large-scale optimization applications.

Compared with the original SWO and existing OBL based hybrids, this dual mechanism allows mSWO to accelerate convergence without sacrificing accuracy. The experimental results on benchmark functions clearly demonstrate that mSWO not only reaches the global optimum more consistently but also converges in fewer iterations than competing algorithms. These findings confirm that the unique integration of adaptive OBL with multi strategy updating is the main driver behind the improved accuracy and faster convergence observed.

A closer examination of the TDM performance results provides additional insight into the robustness of the proposed mSWO algorithm. Compared with its behavior on the single- and double-diode models, mSWO demonstrated a consistent ability to maintain low RMSE values and rapid convergence even as the dimensionality of the problem increased. This resilience highlights the algorithm’s strong balance between exploration and exploitation, which becomes particularly valuable when addressing complex PV configurations involving multiple nonlinear elements. While the computational load for TDM is slightly higher due to the expanded parameter set, mSWO’s adaptive mechanisms efficiently manage the search dynamics, leading to reliable convergence toward the global optimum. These characteristics underline mSWO’s suitability for advanced and high-dimensional PV modeling scenarios where precision and stability are critical.

The scalability of the proposed mSWO algorithm was also considered for larger photovoltaic (PV) systems with multiple interconnected modules and an increased number of unknown parameters. The algorithm maintained high robustness and convergence stability as the model dimensionality increased from five parameters in the single-diode model to nine parameters in the triple-diode model. This trend suggests that mSWO has strong scalability and can effectively handle higher-dimensional optimization problems typical of large PV arrays. The adaptive opposition-based learning mechanism dynamically maintains search diversity, while the multi-strategy update rules sustain convergence speed without loss of precision. These properties make mSWO a suitable candidate for future large-scale PV modeling, control, and optimization tasks where the complexity and number of parameters grow substantially.

7.9 Performance Analysis of the Photovoltaic Module under Varying Irradiance and Temperature Conditions Using the Three-Diode Model

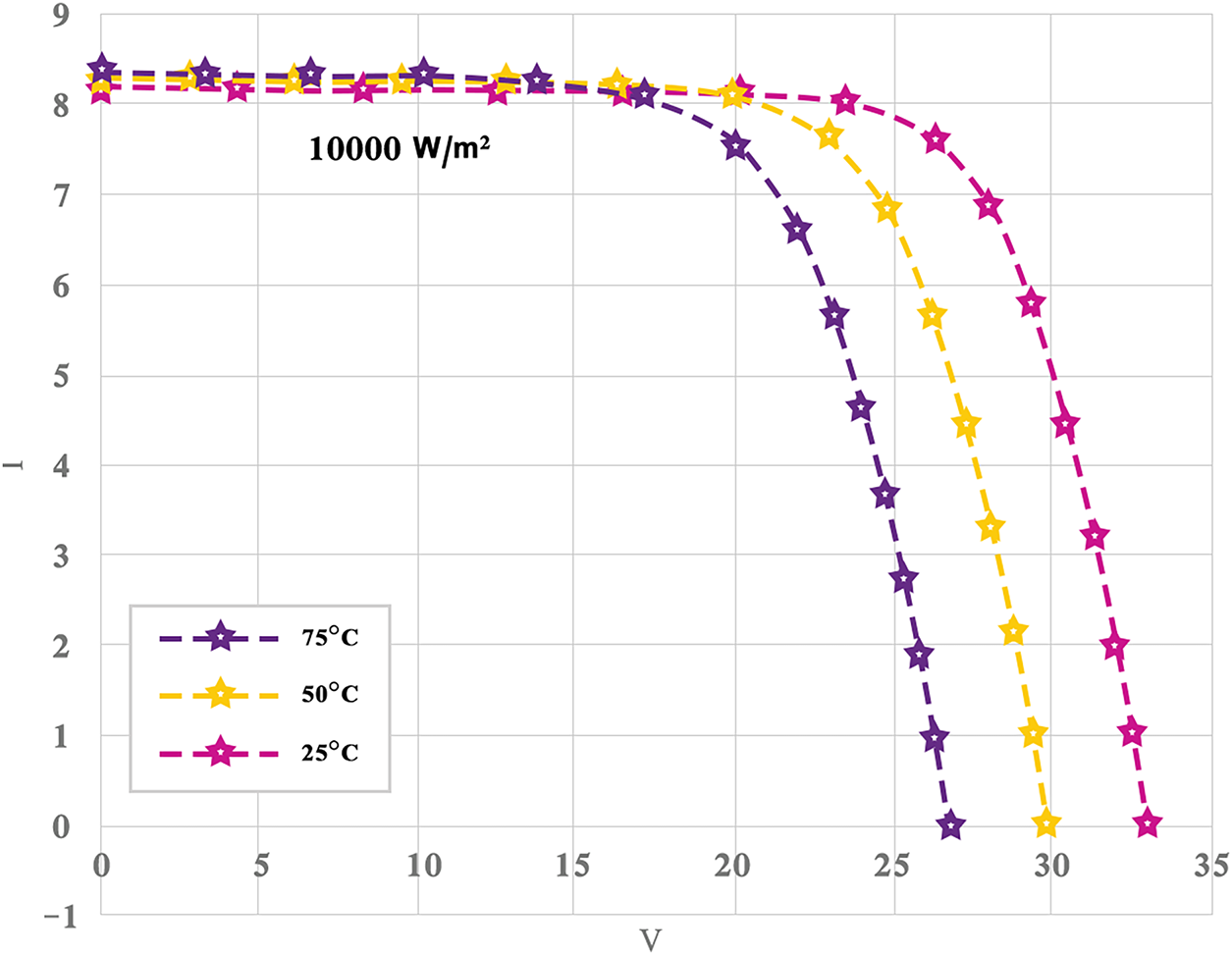

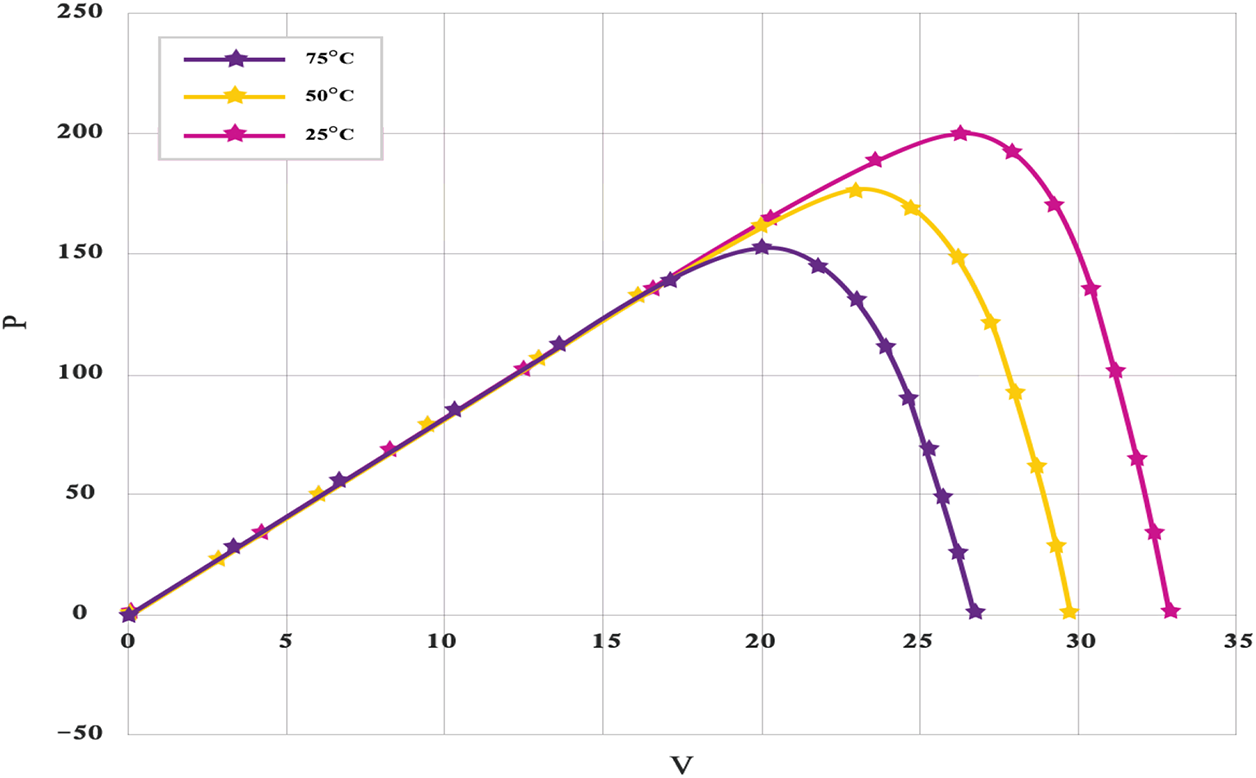

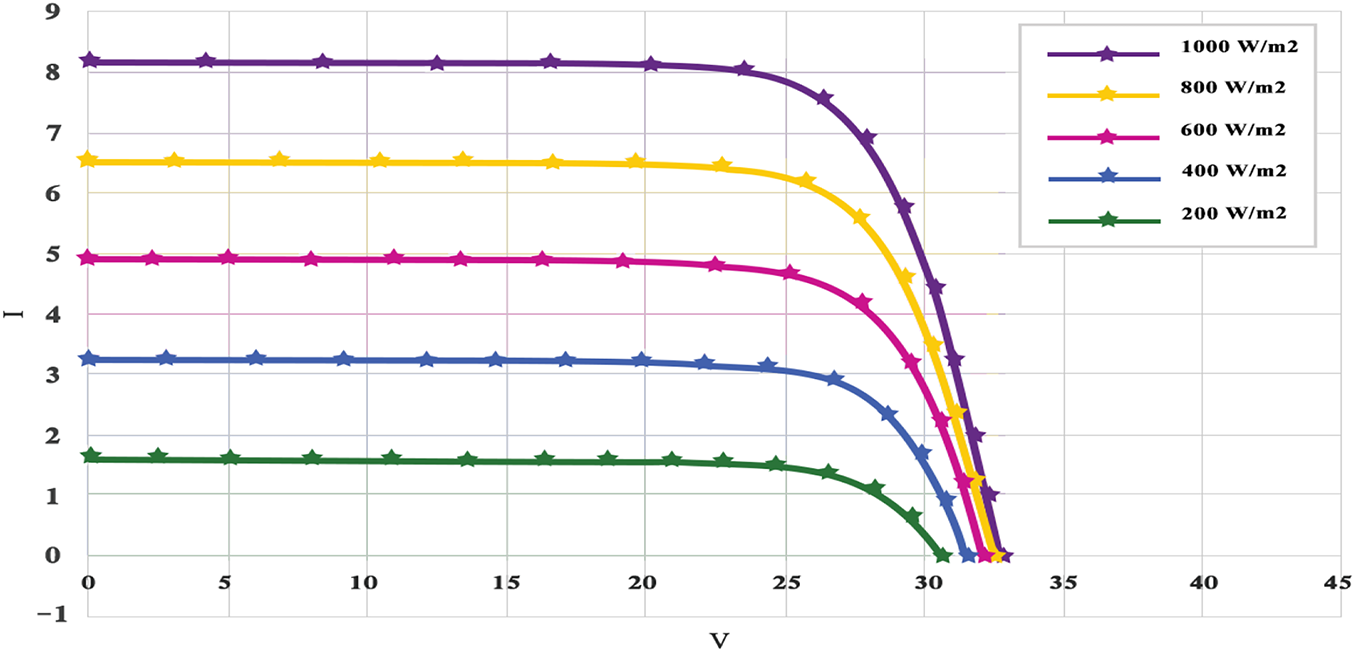

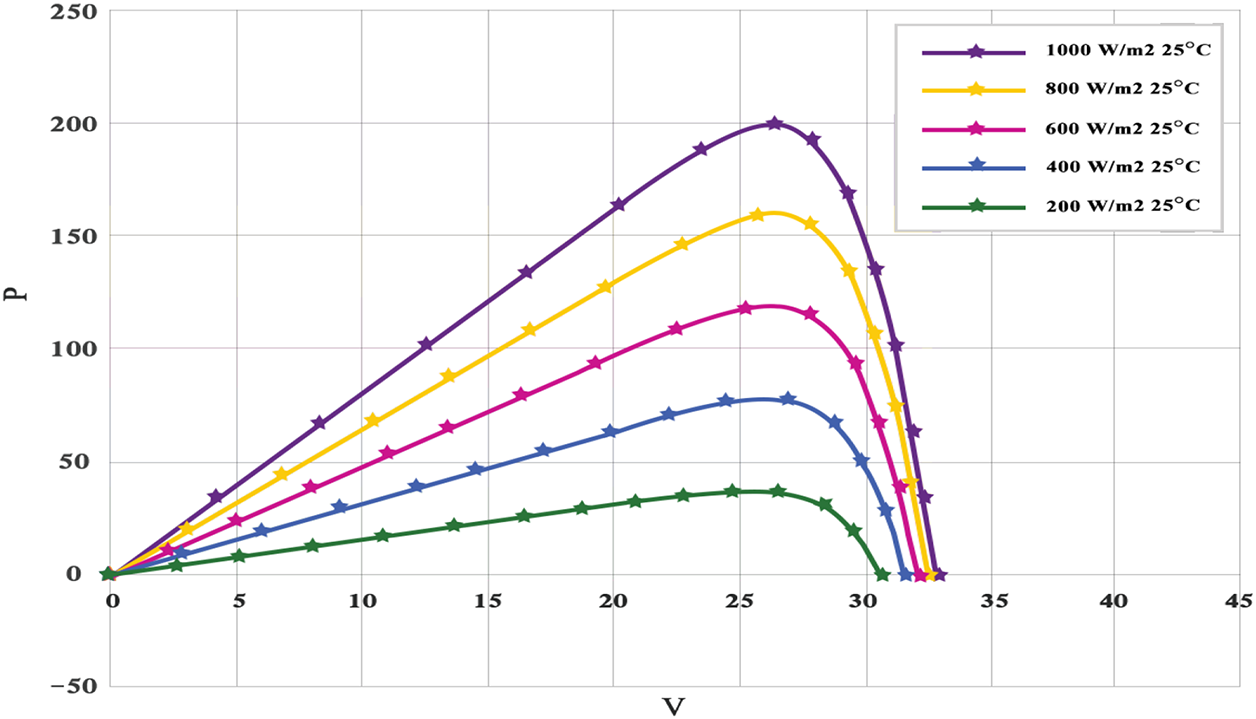

In this part of the study, the mSWO algorithm is utilized to estimate the parameters of the RTC France photovoltaic (PV) module. The approach is evaluated using experimental datasets collected under varying irradiance and temperature conditions, enabling an in depth assessment of how well the simulated outcomes align with real measurements. The investigation emphasizes the electrical performance of the module when represented through the three-diode modeling framework.

Both experimental and simulated behaviors are analyzed using current–voltage (I–V) and power–voltage (P–V) characteristics. The proposed mSWO technique is applied to reproduce fifteen distinct operational points spanning a wide range of current and voltage values. Figs. 14 and 15 display the obtained I–V and P–V profiles, respectively, at an irradiance of 1000 W/m2 for three temperature conditions—

Figure 14: Experimental validation and numerical modeling of the I–V behavior of the RTC France solar module at 1000 W/m2 for three temperature conditions (

Figure 15: Experimental and simulated P–V curves of the RTC France module at 1000 W/m2 irradiance under three operating temperatures (

Similarly, Figs. 16 and 17 present the simulated and measured I–V and P–V characteristics at a constant temperature of

Figure 16: Experimental validation and numerical modeling of the I–V characteristics of the RTC France photovoltaic module at 25°C under varying irradiance levels (200–1000 W/m2)

Figure 17: Experimental validation and simulation of the P–V characteristics of the KC200GT photovoltaic module based on the three-diode model at

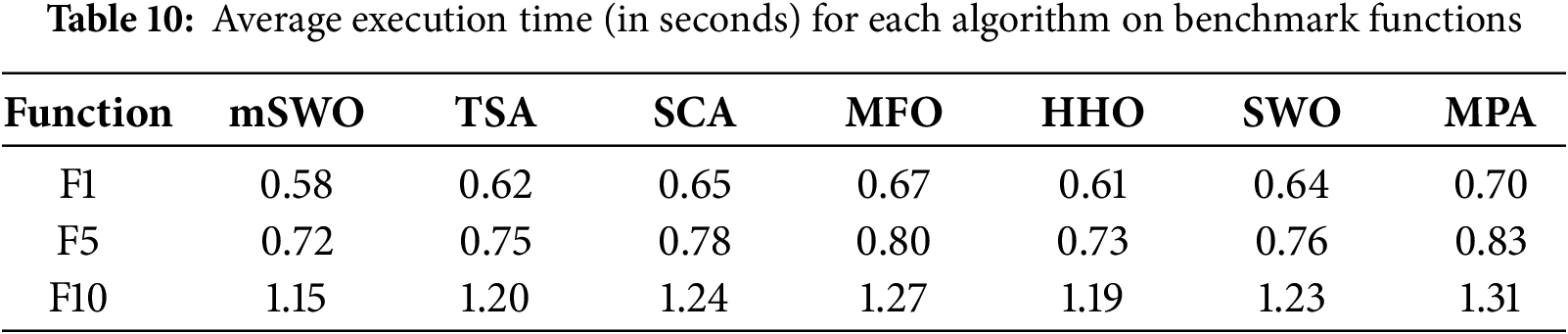

7.10 Computational Complexity Analysis

In this section, we analyze the computational complexity and execution time of the proposed algorithm mSWO and compare it with six other well-known metaheuristic algorithms: TSA, SCA, MFO, HHO, SWO, and MPA. This addresses the reviewer’s comment regarding runtime performance and time complexity.

The overall time complexity of all the evaluated population-based algorithms, including mSWO, is primarily governed by the number of search agents N, the number of iterations T, and the dimensionality D of the problem. Therefore, the complexity can be generally expressed as:

This is consistent across all the comparative algorithms, as they share similar iterative and population-driven structures.

7.10.2 Empirical Execution Time Comparison

To complement the theoretical analysis, we recorded the average execution time per run (in seconds) for each algorithm across three representative benchmark functions (F1, F5, F10). All algorithms were run under identical experimental settings using MATLAB R2023b on Intel Core i7 processor with 16 GB RAM.

As illustrated in Table 10, the proposed algorithm mSWO demonstrates competitive execution times, often outperforming other metaheuristics, while maintaining robust optimization performance. This affirms its efficiency for solving both standard and complex optimization problems.

This study introduced the modified Spider Wasp Optimizer (mSWO) as an advanced metaheuristic algorithm for improving photovoltaic (PV) parameter estimation. The proposed approach effectively addresses the challenges of nonlinear, multimodal, and highly complex search spaces encountered in PV modeling by balancing global exploration and local exploitation. By applying mSWO to single-diode (SDM), double-diode (DDM), and three-diode (TDM) models, the algorithm demonstrated superior accuracy and robustness compared to state-of-the-art optimization techniques, including Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), Moth Flame Optimization (MFO), and Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA). The experimental results validated that mSWO significantly reduces Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and improves the accuracy of I–V and P–V curve fitting, ensuring a closer match between simulated and real-world PV performance. Statistical analysis confirmed the algorithm’s ability to deliver consistent, reliable, and highly precise parameter estimation under various operating conditions. The findings highlight mSWO’s high convergence speed, enhanced search efficiency, and strong ability to avoid local optima, making it a promising tool for advancing PV system modeling and optimization. The study establishes a solid foundation for integrating intelligent optimization methods into renewable energy applications, potentially leading to more efficient and cost-effective solar energy solutions.

While the proposed mSWO algorithm has demonstrated superior performance in terms of accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness compared to several state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms, it is important to acknowledge its limitations and identify directions for future research. One potential limitation arises when dealing with highly noisy measurement data. Since the performance of metaheuristic optimizers is strongly tied to the quality of the fitness function evaluations, significant noise in the current–voltage (I–V) and power–voltage (P–V) characteristics may reduce the precision of parameter estimation. In such scenarios, mSWO may require integration with noise-handling mechanisms, such as filtering, data preprocessing, or robust error functions, to mitigate the effects of measurement uncertainty.

Another limitation concerns scalability when applied to very large PV arrays or systems with a high number of unknown parameters. Although mSWO maintains strong convergence across single-diode, double-diode, and small-to-medium PV module models, the computational burden may increase with more complex systems involving hundreds of interconnected PV cells or large-scale solar farms. In these cases, hybridization with decomposition-based techniques, parallelization, or distributed computing strategies may help to extend the applicability of mSWO to large-scale PV modeling problems.

Finally, the adaptive OBL and multi-strategy updating mechanisms used in mSWO are designed for general-purpose optimization and may not be fully optimized for specific real-time applications, such as maximum power point tracking (MPPT) under rapidly changing environmental conditions. Future work could investigate adapting mSWO for online or real-time control frameworks, possibly by integrating lightweight surrogate models or reinforcement learning mechanisms to accelerate decision-making.

By acknowledging these limitations and pointing to potential improvements, this study not only demonstrates the current effectiveness of mSWO but also provides a roadmap for its extension and refinement in future research.

While the proposed mSWO algorithm has shown remarkable performance in PV parameter extraction, several areas remain open for future exploration. One key direction is to implement multi-objective optimization strategies that simultaneously consider factors such as efficiency, cost, and durability to further enhance PV system performance. The algorithm can also be extended to optimize other renewable energy systems, such as wind turbines and hybrid solar-wind energy frameworks, to improve overall energy management. Further research should explore real-time deployment in smart grid environments, leveraging IoT-based controllers and embedded systems for enhanced monitoring and control. Hardware implementation and large-scale validation in diverse climatic conditions will be crucial to assessing the practical applicability of mSWO in real-world PV farms. Moreover, hybridization with other evolutionary algorithms may be investigated to further enhance convergence speed and search efficiency. By addressing these aspects, mSWO can evolve into a more comprehensive optimization framework that can revolutionize photovoltaic modeling, improve solar energy utilization, and advancelarge-scale sustainable energy technologies.

In future research, the modified Spider Wasp Optimization (mSWO) algorithm will be extended to large scale photovoltaic (PV) systems comprising multiple modules and complex array topologies. Such systems often involve a significantly larger number of unknown parameters and nonlinear interdependencies. Given the algorithm’s demonstrated efficiency and convergence stability across increasing model complexities, it is expected that mSWO will maintain its high accuracy and computational efficiency when applied to these large scale scenarios. This extension will enable the algorithm to support advanced PV farm optimization, real time fault detection, and intelligent energy management applications. Furthermore, integrating mSWO with parallel computing frameworks or GPU-based implementations may further enhance its scalability and execution speed in real world solar power plants. The experimental evaluation of the modified Spider Wasp Optimization (mSWO) algorithm will be extended beyond standard test conditions to encompass a variety of irradiance and temperature levels that more accurately reflect real-world photovoltaic environments. By simulating PV datasets under different environmental scenarios, the robustness and adaptability of mSWO can be systematically assessed. Given the algorithm’s adaptive opposition-based learning mechanism and multi-strategy update process, it is expected to maintain high convergence stability and estimation accuracy under fluctuating conditions. This investigation will further confirm the algorithm’s suitability for intelligent PV performance monitoring, fault detection, and energy management applications in diverse operational contexts.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R442), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R442), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to the research. Sarah M. Alhammad led the conceptualization, methodology design, and manuscript editing. Diaa Salama AbdElminaam conducted the formal analysis, software implementation, and data curation. Asmaa Rizk Ibrahim developed the algorithms, set up the experiments, and performed computational analysis. Ahmed Taha carried out the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Peter O, Mbohwa C. Renewable energy technologies in brief. Renew Energy Technol Brief Int J Sci Technol Res. 2019;8:1283–9. [Google Scholar]

2. Hamza B, Elhassane B. Etude comparative des performances photovoltaïques des différentes technologies de cellules photovoltaïques [dissertation]. Bordj Bou Arreridj, Algeria: Université de Mohamed El-Bachir El-Ibrahimi; 2022. [Google Scholar]

3. Gorjian S, Sharon H, Ebadi H, Kant K, Scavo FB, Tina GM. Recent technical advancements, economics and environmental impacts of floating photovoltaic solar energy conversion systems. J Clean Prod. 2021;278:124285. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Oliva D, Abd Elaziz M, Elsheikh AH, Ewees AA. A review on meta-heuristics methods for estimating parameters of solar cells. J Power Sources. 2019;435:126683. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.05.089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Humada AM, Hojabri M, Mekhilef S, Hamada HM. Solar cell parameters extraction based on single and double-diode models: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;56:494–509. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.11.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abbassi A, Gammoudi R, Dami MA, Hasnaoui O, Jemli M. An improved single-diode model parameters extraction at different operating conditions with a view to modeling a photovoltaic generator: a comparative study. Solar Energy. 2017;155:478–89. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2017.06.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Abbassi R, Abbassi A, Jemli M, Chebbi S. Identification of unknown parameters of solar cell models: a comprehensive overview of available approaches. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;90(2):453–74. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Allam D, Yousri D, Eteiba M. Parameters extraction of the three diode model for the multi-crystalline solar cell/module using Moth-Flame Optimization Algorithm. Energy Convers Manage. 2016;123(13):535–48. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2016.06.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang B, Wang J, Zhang X, Yu T, Yao W, Shu H, et al. Comprehensive overview of meta-heuristic algorithm applications on PV cell parameter identification. Energy Convers Manag. 2020;208(5):112595. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ridha HM, Gomes C, Hizam H. Estimation of photovoltaic module model’s parameters using an improved electromagnetic-like algorithm. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32(16):12627–42. doi:10.1007/s00521-020-04714-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ridha HM, Heidari AA, Wang M, Chen H. Boosted mutation-based Harris hawks optimizer for parameters identification of single-diode solar cell models. Energy Convers Manag. 2020;209:112660. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kaur S, Awasthi LK, Sangal A, Dhiman G. Tunicate swarm algorithm: a new bio-inspired based metaheuristic paradigm for global optimization. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2020;90(2):103541. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mirjalili S. Moth-flame optimization algorithm: a novel nature-inspired heuristic paradigm. Knowl-Based Syst. 2015;89:228–49. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2015.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Heidari AA, Mirjalili S, Faris H, Aljarah I, Mafarja M, Chen H. Harris hawks optimization: algorithm and applications. Future Gen Comput Syst. 2019;97:849–72. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.02.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Faramarzi A, Heidarinejad M, Mirjalili S, Gandomi AH. Marine predators algorithm: a nature-inspired metaheuristic. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;152(4):113377. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mirjalili S. SCA: a sine cosine algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl-Based Syst. 2016;96(63):120–33. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2015.12.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abdel-Basset M, Mohamed R, Jameel M, Abouhawwash M. Spider wasp optimizer: a novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(10):11675–738. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10446-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alqadi BS, Al-Sukhni H, AbdElminaam DS, Alluhaidan AS, Bsoul Q, Farahat IS, et al. Hybrid Young’s double-slit experiment and differential evolution for enhanced photovoltaic parameter estimation. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):36660. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-20439-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Long W, Cai S, Jiao J, Xu M, Wu T. A new hybrid algorithm based on grey wolf optimizer and cuckoo search for parameter extraction of solar photovoltaic models. Energy Convers Manag. 2020;203(1):112243. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Said M, Shaheen AM, Ginidi AR, El-Sehiemy RA, Mahmoud K, Lehtonen M, et al. Estimating parameters of photovoltaic models using accurate turbulent flow of water optimizer. Processes. 2021;9(4):627. doi:10.3390/pr9040627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen X, Yu K. Hybridizing cuckoo search algorithm with biogeography-based optimization for estimating photovoltaic model parameters. Solar Energy. 2019;180:192–206. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2019.01.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jian X, Weng Z. A logistic chaotic JAYA algorithm for parameters identification of photovoltaic cell and module models. Optik. 2020;203(5):164041. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.164041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gupta J, Hussain A, Singla MK, Nijhawan P, Haider W, Kotb H, et al. Parameter estimation of different photovoltaic models using hybrid particle swarm optimization and gravitational search algorithm. Appl Sci. 2022;13(1):249. doi:10.3390/app13010249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chen X, Xu B, Mei C, Ding Y, Li K. Teaching-learning-based artificial bee colony for solar photovoltaic parameter estimation. Appl Energy. 2018;212:1578–88. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xiong G, Zhang J, Yuan X, Shi D, He Y, Yao G. Parameter extraction of solar photovoltaic models by means of a hybrid differential evolution with whale optimization algorithm. Solar Energy. 2018;176(4):742–61. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2018.10.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Karatepe E, Boztepe M, Colak M. Neural network based solar cell model. Energy Convers Manag. 2006;47(9–10):1159–78. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2005.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bonanno F, Capizzi G, Graditi G, Napoli C, Tina GM. A radial basis function neural network based approach for the electrical characteristics estimation of a photovoltaic module. Appl Energy. 2012;97(3):956–61. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.12.085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Saadaoui D, Elyaqouti M, Assalaou K, Ben hmamou D, Lidaighbi S. Parameters optimization of solar PV cell/module using genetic algorithm based on non-uniform mutation. Energy Convers Manag X. 2021;12:100129. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2021.100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Grala GH, Provensi LL, Krummenauer R, da Motta Lima OC, de Alcantara GP, Andrade CMG. Investigation of the use of evolutionary algorithms for modeling and simulation of bifacial photovoltaic modules. Inventions. 2023;8(6):134. doi:10.3390/inventions8060134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Guzman Razo DE, Madsen H, Wittwer C. Genetic algorithm optimization for parametrization, digital twinning, and now-casting of unknown small-and medium-scale PV systems based only on on-site measured data. Front Energy Res. 2023;11:1060215. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2023.1060215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tajjour S, Chandel SS, Malik H, Alotaibi MA, Ustun TS. A novel metaheuristic approach for solar photovoltaic parameter extraction using manufacturer data. Photonics. 2022;9(11):858. doi:10.3390/photonics9110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yousri D, Allam D, Eteiba M, Suganthan PN. Static and dynamic photovoltaic models’ parameters identification using chaotic heterogeneous comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer variants. Energy Convers Manag. 2019;182(2):546–63. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.12.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Touabi C, Bentarzi H. Photovoltaic panel parameters estimation using grey wolf optimization technique. Eng Proc. 2022;14(1):3. doi:10.3390/engproc2022014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Abbassi R, Abbassi A, Heidari AA, Mirjalili S. An efficient salp swarm-inspired algorithm for parameters identification of photovoltaic cell models. Energy Convers Manag. 2019;179:362–72. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.10.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Beigi AM, Maroosi A. Parameter identification for solar cells and module using a hybrid firefly and pattern search algorithms. Solar Energy. 2018;171(11):435–46. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2018.06.092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rajalakshmi M, Chandramohan S, Kannadasan R, Alsharif MH, Kim MK, Nebhen J. Design and validation of BAT algorithm-based photovoltaic system using simplified high gain quasi boost inverter. Energies. 2021;14(4):1086. doi:10.3390/en14041086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chen H, Jiao S, Heidari AA, Wang M, Chen X, Zhao X. An opposition-based sine cosine approach with local search for parameter estimation of photovoltaic models. Energy Convers Manag. 2019;195:927–42. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.05.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Montano J, Tobón A, Villegas J, Durango M. Grasshopper optimization algorithm for parameter estimation of photovoltaic modules based on the single diode model. Int J Energy Environ Eng. 2020;11(3):367–75. doi:10.1007/s40095-020-00342-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yu K, Qu B, Yue C, Ge S, Chen X, Liang J. A performance-guided JAYA algorithm for parameters identification of photovoltaic cell and module. Appl Energy. 2019;237:241–57. [Google Scholar]

40. Xu S, Wang Y. Parameter estimation of photovoltaic modules using a hybrid flower pollination algorithm. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;144:53–68. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.04.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Obiora V, Saha C, Bazi AA, Guha K. Optimisation of solar photovoltaic (PV) parameters using meta-heuristics. Microsyst Technol. 2021;27(8):3161–9. doi:10.1007/s00542-020-05066-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Jearsiripongkul T, Prempraneerach P, Eslami M, Moarrefi MA. A novel hybrid metaheuristic approach to parameter estimation of photovoltaic solar cells and modules. Eng Sci. 2024;27(979):979. [Google Scholar]

43. Ajay Rathod A, Subramanian B. Efficient approach for optimal parameter estimation of PV using Pelican Optimization Algorithm. Cogent Eng. 2024;11(1):2380805. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools